Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 08/43/52. The contractual start date was in September 2009. The final report began editorial review in April 2013 and was accepted for publication in January 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Wardlaw et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Stroke remains a major public health burden. In the UK, about 150,000 people have a stroke each year. About 30% die within 6 months and another 30% survive dependent on others for everyday activities, making stroke the commonest cause of dependency in adults and the third commonest cause of death in the world. Eighty per cent of strokes are ischaemic and most ischaemic strokes are due to a blocked (thrombosed) artery. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA, alteplase) reopens blocked arteries and was first licensed for use in the USA following publication of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) trial,1 but only for highly selected patients within 3 hours of acute ischaemic stroke in the USA. Cumulative evidence from other trials since then, summarised in the Cochrane Review of all data from randomised trials of rt-PA2 and individual patient data meta-analyses,3,4 plus data from an observational patient registry,5 have been published since, showing a reduction in poor functional outcome in spite of increased risk of symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage (SICH). However, confidence intervals (CIs) for some outcomes remained wide with unexplained heterogeneity for primary outcomes, the licensing and guideline treatment criteria remained highly restrictive and usage of rt-PA was limited. 6,7

Against this background, the International Stroke Trial 3 (IST-3) started in May 2000, aiming to provide robust evidence on the use of rt-PA in a wider range of patients, including those aged over 80 years, at later time windows and with comorbidities such as prior stroke or diabetes. Practical questions also remained concerning how to reduce the major hazard (intracranial haemorrhage) and how to identify determinants of the latest time after stroke when thrombolysis might still be effective. Focusing treatment on patients with still-viable tissue or persistent arterial occlusion might help to reduce the risk of intracranial haemorrhage and death with thrombolysis, particularly at later time windows. 4,8 However, there were uncertainties about how to identify still-viable at-risk tissue and arterial occlusion, as well as about whether or not patients with these features were most likely to benefit from rt-PA treatment.

Brain imaging is essential prior to rt-PA to exclude intracranial haemorrhage (an absolute contraindication to rt-PA) and lesions that can mimic acute stroke (e.g. brain tumours). Patient assessment for rt-PA in most trials to date was based on a plain computed tomography (CT) brain scan. CT is very practical for use in patients with acute stroke and, in many ischaemic stroke patients, especially those with moderate to severe stroke symptoms, may show early ischaemic changes. 9–14 However, early ischaemic tissue changes that occur during the first few hours after stroke onset and that are thought to indicate irreversible injury, though frequent,9 are subtle;15 lack of confidence among clinicians in recognising these early signs is thought to be one factor that might contribute to the underuse of rt-PA, as many patients who might benefit from thrombolysis remain untreated. Magnetic resonance (MR) brain imaging with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) shows acute ischaemia very clearly, but is not widely available as an emergency investigation for stroke16,17 and is not well tolerated by hyperacute stroke patients. 18,19

Identifying the full extent of brain tissue where blood flow is reduced but tissue is still viable outside the non-viable ‘core’ of the infarct could help select patients for treatment with rt-PA – referred to as the ‘ischaemic penumbra’, ‘tissue at risk’ or ‘mismatch’. Imaging the perfusion defect with an intravenous (i.v.) injection of MR contrast agent had been available for MR imaging (MRI) for about 10 years, and became available for CT about 6 years prior to the start of the IST-3 substudy. 20,21 However, a consensus on how the perfusion data should be processed,22–24 or which thresholds distinguish tissue at risk,25 was still to be established. Thus, it had long been considered that advanced imaging methods with CT perfusion (CTP) or MR DWI and perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI) could help focus use of rt-PA on patients with large amounts of tissue at risk and avoid exposing those with little at-risk tissue to the risk of rt-PA. Although some stroke experts strongly advocate using this imaging approach,26 and some observational studies provided encouraging results,27 several randomised trials that used MR DWI/PWI mismatch had been inconclusive,28–30 or conflicting. 31 Indirect comparisons between randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which used plain CT and MR DWI/MR perfusion showed no clear improvement in functional outcome or in SICH risk according to MR DWI/MR perfusion (MRP) tissue status. 32,33 The few studies which included patients without MR DWI/PWI mismatch found that about half of those without mismatch also had infarct growth and, therefore, presumably might have benefited from treatment. 34,35 Similarly, some observational data suggest that CTP did not differentiate core from salvageable tissue. 36 There are no randomised rt-PA studies based on CT with CTP [although some patients were included in the Desmoteplase in Acute Stroke (DIAS) 2 trial with CT/CTP, these data are not available separately].

The other information that might guide the use of thrombolysis, derivable from CT or MRI, is the presence and location of an occluded artery as this determines the likely extent of the tissue affected by the stroke. 37 An occluded artery may be suspected by the presence of a hyperattenuated artery on plain CT or an absent flow void or a hypointense artery on T2/fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) or T2* MR, respectively. Disappearance of the hyperattenuated artery/absent flow void (i.e. presumed recanalisation) is associated with improved clinical outcome with or without rt-PA38,39 and its persistence is associated with poor clinical outcome. 40 Arterial occlusion may be identified with CT angiography (CTA) or MR angiography (MRA) with an i.v. injection of contrast agent. The angiographic images are generally faster to acquire than perfusion imaging, and require some image reconstruction and careful interrogation but there is, in general, less scope for variation in acquisition, processing or interpretation, and the acquisition and image processing are faster than for perfusion imaging. However, there have been far fewer publications on angiographic imaging and the relationship to likely rt-PA response and clinical outcomes than on perfusion imaging. As with perfusion imaging, several factors need to be addressed before CTA or MRA can be used reliably to inform clinical practice.

It is clear that improved outcome after ischaemic stroke is associated with arterial recanalisation in observational studies whether spontaneous or rt-PA induced,41 but there is disagreement about how information from angiography should be used. Some consider that rt-PA may be effective only when a visible thrombus is present. Others consider that the absence of a visible occlusion may simply reflect lack of sensitivity of imaging to small peripheral thrombi or to occlusion at the origin of a proximal major branch point making that branch ‘invisible’ angiographically, that in any case the major arteries may be patent when the tissue arterioles/capillaries are not, and that patients without a visible arterial occlusion should not be denied thrombolytic treatment in the absence of further information from RCTs. The marginal benefit or hazard of rt-PA in the presence or absence of a visible arterial occlusion was unknown as there were no completed randomised trials of rt-PA where randomisation was on the basis of presence or absence of arterial occlusion. Previous, recently completed trials [e.g. Systemic versus Intra-arterial thrombolysis for Ischaemic Stroke (SYNTHESIS) Expansion42 and International Management of Stroke (IMS) 11143,44] and (still) ongoing trials have included only patients with angiography-confirmed arterial occlusion (e.g. DIAS 3 and 445). Angiographic interpretation is based on visual assessment. Multiple visual rating scores have been described, but all appear to conflate several items in one score and there was little information on observer reliability or which score was best when deciding whether or not to use rt-PA treatment. The very limited data on observer reliability of angiography scoring indicated poor agreement: the intraobserver agreement between nine neuroradiologists reading intra-arterial angiograms using the Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (TICI) score was poor (к< 0.2) with little evidence of improvement with training, possibly because of the conflation of three concepts inherent in the score. 37,46 A detailed discussion of the scores and problems with their use was provided in the IST-3 perfusion and angiography imaging protocol paper. 47

Other factors derivable from angiographic imaging may help guide rt-PA therapy. Some thrombi may dissolve more easily with rt-PA. Thrombus composition influences its appearance on imaging. However, the reliability of the imaging appearance–composition relationship is unknown. Despite this, there is emerging (although conflicting) literature on thrombus attenuation, probable composition and likelihood of rt-PA responsiveness48–52 which required further testing prior to clinical use. Other angiographic features that may influence both tissue viability and rt-PA response are the burden of occlusive thrombus53 and the adequacy of collateral pathways. 54 Several scores exist to code the collateral circulation55,56 but these, in general, had undergone little independent validation.

The IST-3 Perfusion and Angiography Study was embedded in the IST-3 main trial and aimed to determine whether or not there is a differential benefit of rt-PA in patients with, compared with patients without, perfusion lesions or arterial occlusion. If, as suggested in recent studies, very high proportions of patients with large artery territory cortical ischaemic symptoms have MR DWI/MRP mismatch within 6 hours of stroke,30 and if rt-PA is effective in those with mismatch, then simply determining the clinical stroke syndrome and time lapsed since stroke may be almost as effective as complex imaging in guiding patient selection (as well as being quicker and less expensive). If, on the other hand, the benefits of rt-PA are confined to those either with imaging evidence of tissue at risk or with arterial occlusion, regardless of time lapsed since onset, and who cannot be identified by other means, then it will require substantial investment in imaging services to deliver effective thrombolysis. If the presence of perfusion-visible at-risk tissue has no impact on responsiveness to rt-PA treatment, then clinicians will have greater confidence to treat patients on the basis of plain CT (or MR DWI) and thorough clinical assessment alone, which would immediately improve access to rt-PA.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

The original research objectives of the IST-3 perfusion and angiography substudy were to determine:

-

whether acute ischaemic stroke patients with versus without imaging evidence of tissue at risk (perfusion lesion or mismatch), on either CT with CTP or MR DWI/PWI, have (a) less infarct growth and (b) better functional outcome if treated with rt-PA versus control?

-

which perfusion parameter [cerebral blood flow (CBF), cerebral blood volume (CBV) or mean transit time (MTT)], processing method (qualitative, quantitative) and threshold best predicts (a) infarct growth and (b) poor functional outcome at 6 months?

-

if patients with angiographic evidence of an occluded artery on either CT or MR angiography have (a) less infarct growth and (b) better clinical functional outcome if treated with rt-PA versus control?

Secondary questions included:

-

what is the threshold of reduced cerebral perfusion that can be tolerated, and for what period of time after stroke onset, which determines whether tissue ultimately survives or infarcts?

-

are there imaging features on plain CT or MR DWI that differentiate viable from non-viable tissue?

-

determining the interobserver reliability of perfusion and angiography scoring methods

-

determining the influence on the plain-scan rating of knowing what the perfusion or angiography imaging shows.

We also aimed to:

-

establish a core of interested physicians and radiologists in IST-3 to guide the proposed advanced imaging substudy, inform and participate in the analysis and prepare manuscripts for publication and presentation; and

-

contribute data to the Stroke Imaging Repository (STIR), an international, multicentre project which aims to standardise stroke perfusion imaging.

Chapter 3 Methods

We provide minimum details of the IST-3 main trial, followed by the specific methods in the perfusion and angiography substudy. The full IST-3 trial protocol, details of the patients’ baseline demographic variables, the statistical analysis plan and primary results57–60 and the protocol for the Perfusion and Angiography Substudy47 have all been published. The protocol was approved by the Multicentre Research Ethics Committees (MREC/99/0/78) and by local ethical committees. The trial was registered as ISRCTN25765518.

Main trial

The IST-3 was an international, prospective, randomised, open, blinded, end-point (PROBE) controlled trial of i.v. rt-PA within 6 hours of onset of acute ischaemic stroke (see www.ist3.com). 60 Plain CT brain scanning was the primary imaging modality for the main trial.

Participants

Patients with suspected acute ischaemic stroke who reached hospital, could be assessed and treated within 6 hours of stroke onset. Patients in whom rt-PA was ‘promising but unproven’ could be randomised in the trial after informed consent was obtained.

Inclusion criteria

(a) Symptoms and signs of clinically definite acute stroke, (b) time of stroke onset definitely < 6 hours previously, (c) CT or MR brain scanning has excluded intracranial haemorrhage and (d) treatment can be started within 6 hours of stroke. Patients with symptoms of large and medium-sized cortical, lacunar and posterior circulation stroke were all included, with no upper age limit. Patients with early visible infarct signs were also included (though not if established infarct signs were present, as these suggest a stroke onset of more than > 6 hours previously).

Exclusion criteria

Age < 18 years, imaging signs that the stroke might be older than 6 hours, and usual contraindications to rt-PA. 60

Interventions

Intravenous rt-PA (total dose 0.9 mg/kg to a maximum of 90 mg, 10% as bolus and the rest infused over 1 hour) compared with ‘open control’ (avoid rt-PA and receive stroke care in exactly the same clinical environment as those allocated ‘immediate rt-PA’).

Baseline assessment

All patients were assessed for stroke severity [National Institutes of Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score], stroke subtype [total anterior circulation infarct (TACI); partial anterior circulation infarct (PACI); lacunar infarct (LACI); or posterior circulation infarct (POCI), clinical syndrome], presence of atrial fibrillation (AF), systolic and diastolic blood pressure and blood glucose.

Objectives

To determine if rt-PA, given to a wider range of patients up to 6 hours after stroke, would improve functional outcome by 6 months net of any hazard.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was alive and independent [Oxford Handicap Score (OHS) 0–2,61 which is very similar to modified Rankin 0–262] at 6 months after stroke. Symptomatic and fatal intracranial haemorrhage, death and recurrent stroke within 7 days and death at 6 months were also assessed.

Brain scanning

All patients had a CT or MR brain scan before randomisation and a follow-up scan at 24–48 hours. A repeat brain scan was required if the patient deteriorated neurologically or intracranial haemorrhage was suspected for any reason. All scans were sent to the trial centre in Edinburgh for blinded central rating of any signs of visible early ischaemia (presence and extent of hypoattenuation, swelling, hyperattenuated artery), haemorrhage, and background brain changes (leukoaraiosis, atrophy, prior stroke lesions, non-stroke lesions) with validated rating tools. 15,63–67 Images were assessed blindly, and assessed via a secure web-based image viewing system by an international panel of expert radiologists.

Sample size

The IST-3 main trial was powered to detect a 4.7% absolute improvement with rt-PA compared with no rt-PA in the number alive and independent at 6 months with power 80% at p = 0.05 with 3100 patients. 57 This effect size was based on the Cochrane Thrombolysis Review in 2000,2 but remained unaltered following the update in 2008. 32

Randomisation

Randomisation was via a secure central telephone or web-based computer system, which recorded all of the baseline data and generated the treatment allocation. A minimisation algorithm was used to achieve optimum balance for key prognostic factors. 57,59

Follow-up

Follow-up of 6-month outcomes was by central office staff blinded to treatment allocation, by postal questionnaire or telephone for non-responders (by an experienced, blinded assessor).

Statistical methods59

The statistical analysis plan was published59 prior to unblinding to the data. To avoid complicating the estimation of the effect of treatment overall and in subgroups,57 the primary analysis was logistic regression for linear effects adjusted for the following covariates: age; NIHSS score; time from onset of stroke symptoms to randomisation; and presence (vs. absence) of ischaemic change on the pre-randomisation brain scan according to the expert read. Unadjusted analyses were also performed. 60 The statistical analysis plan writing committee, while still blinded, adopted the ordinal method, as it is statistically more efficient (effectively reducing the sample size required in stroke trials68). The OHS as a dependent variable had five levels: levels four, five and six were combined into a single level and levels zero, one, two and three were retained as distinct. In this model, the treatment odds ratios between one level and the next are assumed constant, so a single parameter summarises the shift in outcome distribution between treatment and control groups. Analyses were carried out with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Any changes to protocol

Two changes occurred. The first was the change from placebo-controlled to open-label treatment after the first 297 patients due to withdrawal of support for the trial by Boehringer Ingelheim (Bracknell, UK). The second was the revised sample size estimation and introduction of the ordinal analysis described above as a secondary outcome analysis.

The Third International Stroke Trial Perfusion and Angiography Substudy

In centres where perfusion and/or angiography imaging with CT or MR were performed routinely for acute stroke, data from these imaging modalities were collected centrally according to established IST-3 methods. In those centres, patients were randomised into IST-3 according to plain CT or MR criteria so that decisions were not influenced by knowledge of perfusion or angiography information.

Participants, interventions, clinical outcomes, randomisation and blinding were the same as for the main trial and detailed above except that, as per routine clinical practice, patients with definite renal impairment [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2] or on metformin were excluded from the perfusion/angiography study. Reduced eGFR is common on admission to hospital in patients with acute ischaemic stroke and usually normalises with rehydration;69 therefore, patients with an eGFR of 30–59 ml/minute/1.73 m2 could be included if there was no documented history of renal impairment and the low eGFR was considered likely to reflect dehydration, at the discretion of the recruiting physician. Low-risk MR contrast agents were to be used. Oxygen was continued in MR or CT where necessary.

Objectives

The basic questions to be addressed are ‘should “perfusion-structural imaging mismatch” or “arterial occlusion” influence whether or not patients receive rt-PA?’ Here, the key question was whether or not rt-PA is more effective in patients with imaging evidence of tissue at risk than in those without apparent tissue at risk. Tissue at risk was defined as:

-

the difference between the extent of core damaged tissue on MR DWI or plain CT and the extent of the MR or CT perfusion lesion (further details of perfusion lesion measurements and comparisons below); or

-

evidence of arterial occlusion on CT or MR angiography.

Imaging acquisition

Where possible, patients were to be examined on the same scanner at baseline and at follow-up, although combinations, for example CT pre randomisation and MR at 24-hour follow-up, were allowed as local clinical practice dictated. Basic minimum acquisition standards were required (see Appendix 1). We provided basic minimum acquisition standards to encourage best practice in perfusion or angiography imaging while allowing for the considerable variation that exists in available scanning technology. Thus, it would have been counterproductive to provide overly narrow acquisition criteria that only a proportion of centres might have been able to meet, as that would have further limited the sample size and generalisability of the data. Full details of the minimum acquisition criteria as sent to participating centres are given in Appendix 1. In addition, before a centre could participate in the Perfusion and Angiography Study, a test perfusion and/or angiogram image data set had to be sent to the IST-3 trial co-ordinating centre to ensure that the imaging met minimum standards and that the data could be processed centrally.

The trial image data were received at the IST-3 trial co-ordinating centre, linked with their demographic data and trial records, anonymised and transferred into the image-processing pipeline. Plain CT and MR images were read according to the IST-3 established structured image analysis protocol by a panel of experts via a web-based image reading system, the Systematic Image Review System (SIRS: see www.neuroimage.co.uk/) as detailed above.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measures were the same clinical measures as for the IST-3 main trial above: functional outcome (OHS 0–2), symptomatic and fatal intracranial haemorrhage, early and late death and massive infarct swelling.

The secondary outcomes were absolute infarct growth, defined qualitatively as a change in the extent of hypoattenuated tissue on CT or of hyperintense tissue on MR FLAIR between baseline and 24–48-hour follow-up, of one point or more on either the IST-3 scale score,64,70 in any arterial territory, or the Alberta Stroke Program Early CT score (ASPECTS)63 if in the middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory; defined quantitatively as the difference in measured lesion volume on plain CT or MR DWI between randomisation and follow-up scans.

Blinding

All image data were collected centrally in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format, matched with the patient record, anonymised and identified only by the study identification number. All image data analyses were performed centrally, blind to treatment allocation, baseline demographic information and follow-up.

Perfusion analysis

We produced perfusion parameter maps for each patient for visual rating and measurement of lesion volume without any threshold applied (Figure 1; Table 1): quantitative (q) perfusion with deconvolution CBF quantitative (CBFq), CBV quantitative (CBVq), MTT quantitative (MTTq), time to maximum flow quantitative (time to peak of the residue function) (Tmaxq) and relative (r) perfusion, that is to say without deconvolution relative CBF (rCBF); relative arrival time fitted; relative time to peak; relative peak time fitted; relative maximum concentration peak; relative full width at half maximum. Full details of the perfusion processing are given in Appendix 2. We also produced a set of parameter maps with thresholds applied (see Table 1). These parameters and thresholds were based on literature values that had been proposed for identifying still-viable but at-risk tissue and core tissue, of which there were many, but none had been validated independently. 71 This was because the IST-3 perfusion substudy was not large enough to generate new thresholds in one half of the data set and validate these in the other half. Therefore, we focused on validating ones which had been reported previously.

| MR perfusion | CT perfusion | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual score | Volume | Visual score | Volume |

| Raw data | Raw data | ||

| rCBF | rCBF | ||

| rCBV | rCBV | ||

| rMTT (first moment) | rMTT (1.45) | ||

| TTP (various thresholds) | TTP (1.4 wrt normal side) | ||

| Tmax plus 6 seconds | Tmax plus 6 seconds | ||

| ATF | ATF | ||

| CBFq | CBFq (including 12.7 ml/100 g/minute) | ||

| CBVq | CBVq (including < 2.2 ml/100 g) | ||

| MTTq | MTTq | ||

FIGURE 1.

Example of CT perfusion parameter maps. (a) CT with plain structural image at randomisation and post randomisation, with infarct outlined, perfusion maps and various thresholds below; (b) MR with acute DW1 and T2, follow-up T2, perfusion maps and various thresholds below. ROI, region of interest.

Maps of the following perfusion thresholds were produced for volumetric and visual measurement (details in Table 1):

-

Representing non-salvageable tissue:

-

Representing at-risk tissue:

These perfusion parameters reflected commonly applied thresholds and image types while keeping the total number of comparisons manageable and reducing the potential for false-positive results. Our systematic review had not identified a specific parameter or threshold that seemed optimum;71 different research groups had not identified an agreed perfusion parameter/threshold since the systematic review. We therefore tested several perfusion parameters/thresholds which covered the most easily available and most promising derived from the most recent research. Many of these thresholds have been defined for one modality only (mostly CTP) but could equally be applied to MR data and, therefore, were tested.

Perfusion lesion extent was quantified visually by one expert neuroradiologist, blind to all other data. We used the ASPECTS,63 subtracting one point from a total of 10 for each MCA ASPECTS region that is in part or wholly affected by the perfusion lesion, even where perfusion image does not cover the whole ASPECTS region. We also recorded if there was (a) no visible perfusion lesion, (b) a visible perfusion lesion that was < 80%, (c) about the same size as or (d) ≥ 20% larger than the structural ischaemic lesion by visually-estimated volume on plain CT or MR DWI/FLAIR. 27,30 ‘Mismatch’ was defined as a perfusion lesion > 20% larger than the structural lesion. We validated these methods in a separate three-centre study (Translational Medicine Research Collaboration Multicentre Acute Stroke Imaging Study47). Visual coding forms are available in Appendix 3. Perfusion lesion volume was measured by manual outlining the lesion by a trained observer blind to all other data on two of the unthresholded parameter maps from above (MTTq and rCBF perfusion lesions) to represent at-risk tissue and non-salvageable tissue respectively. The perfusion lesion volume was also measured on thresholded parameter maps listed in Table 1 using automated thresholding.

Angiography analysis

The randomisation CT angiography images were scored by a blinded neuroradiologist who also measured thrombus density on a workstation in Hounsfield Units (HU). The hyperattenuated artery sign (HAS) was scored on the available imaging, that is to say thin section if available or routine 5 mm section if not, depending on what imaging had been received. Separately, a panel of 11 experts also read all of the CT and MR angiograms using the web-based SIRS (SIRS2), which we modified so as to be able to see the plan scan and angiographic image on the same screen and record both the plain-scan findings and angiographic appearance (SIRS2, sirs2/neuroimage.co.uk/sirs2; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Screen capture of web interface used to visually assess angiographic images.

We assessed the location, extent of vessel affected and degree of obstruction to the lumen of any arterial occlusion, the presence of collateral pathways, the clot burden53 and the attenuation properties of the occluding thrombus. Location and extent of thrombus was coded in the internal carotid artery (ICA), MCA mainstem or sylvian branch, anterior cerebral artery (ACA), posterior cerebral artery (PCA), basilar artery, vertebral artery or combinations thereof. 15,38,40 We debated, at length, the best score to use. Several scores are available to classify the degree of major arterial obstruction (Table 2). These mostly conflate three different concepts – peripheral microvascular tissue perfusion, primary arterial patency, and recanalisation – in a single score, thereby mixing three separate and probably semi-independent entities. 87 This, no doubt, contributes to the poor observer reliability. We previously used the Mori82 and Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI)83 scores purely to classify arterial patency at the primary point of obstruction on CTA and MRA and, separately, used CTP or MRP to classify tissue-level perfusion and reperfusion which worked well. Other scores (summarised in Table 2) mixed primary occlusion, perfusion and recanalisation. 37,56,84,85 Therefore, in IST-3 we used a score that combines the best elements of the TICI (including 2a and 2b) and arterial occlusive lesion (AOL) scores that only scored angiographic patency at the main point of occlusion and filling of immediate distal vessels, but not tissue perfusion or recanalisation. This score, used in DIAS 3 and 4 and IMS-3,43–45 is described in the protocol paper. 47

| TIMI score83 | Mori score82,86 |

|---|---|

| 0: No flow/patency | 0: No flow/patency |

| 1: Minimal flow/patency | 1: Minimal flow/patency |

| 2: Partial flow/patency | 2: Flow/patency of less than half of the territory of the occluded artery |

| 3: Flow/patency of more than half of the territory of the occluded artery | |

| 3: Complete flow/patency37 | 4: Complete flow/patency82,86 |

| AOL score37 | TIMI score, adapted for the intracranial circulation in ischaemic stroke37 |

| Grade 0: No recanalisation of the primary occlusive lesion | Grade 0: No perfusion |

| Grade 1: Incomplete or partial recanalisation of the primary occlusive lesion with no distal flow | Grade 1: Perfusion past the initial occlusion, but no distal branch filling |

| Grade 2: Incomplete or partial recanalisation of the primary occlusive lesion with any distal flow | Grade 2: Perfusion with incomplete or slow distal branch filling |

| Grade 3: Complete recanalisation of the primary occlusion with any distal flow | Grade 3: Full perfusion with filling of all distal branches, including M3, 4 |

| TICI score, adapted the TIMI score with further granularity for partial patency 56 | |

| Grade 0: No perfusion. No antegrade flow beyond the point of occlusion | |

| Grade 1: Penetration with minimal perfusion. The contrast material passes beyond the area of obstruction but fails to opacify the entire cerebral bed distal to the obstruction for the duration of the angiographic run | |

| Grade 2: Partial perfusion. The contrast material passes beyond the obstruction and opacifies the arterial bed distal to the obstruction. However, the rate of entry of contrast into the vessel distal to the obstruction and/or its rate of clearance from the distal bed are perceptibly slower than its entry into and/or clearance from comparable areas not perfused by the previously occluded vessel, e.g. the opposite cerebral artery or the arterial bed proximal to the obstruction | |

| Grade 2a: Only partial filling (less than two-thirds) of the entire vascular territory is visualised | |

| Grade 2b: Complete filling of all of the expected vascular territory is visualised, but the filling is slower than normal | |

| Grade 3: Complete perfusion. Antegrade flow into the bed distal to the obstruction occurs as promptly as into the obstruction and clearance of contrast material from the involved bed is as rapid as from an uninvolved other bed of the same vessel or the opposite cerebral artery | |

| Two further variations of the TICI score | |

| TICI grade of perfusion confuses arterial patency/recanalisation and perfusion including grades 0 to 3 and subscores 2a to 2c84 | TICI reperfusion (I): essentially the same as TIMI score applied in IMS 1 with grade 2 further divided into 2a, partial filling (less than half) of, and 2b, partial filling (half or more) of, for post hoc analysis85 |

| Score to be used in IST-3: TICI–AOL hybrid (see Figure 1) | |

| 0: No patency – artery completely blocked at main obstruction point | |

| 1: Minimal patency – some contrast penetrates main obstruction point but no/minimal opacification of artery or branches distally | |

2: Patency of less than half of the lumen at the point of obstruction and

|

|

| 3: Patency of more than half of the lumen at the point of obstruction and filling of most of the major branches of the affected artery | |

| 4: Complete patency – normal | |

Recanalisation was indicated by a change of one point or more on the scale between randomisation and follow-up scans.

We also coded thrombus burden using the clot burden score,53 where one or two points are subtracted from a normal score of 10 for each segment of the main intracranial arteries or their branches that is abnormal on angiography; thus, a score of zero indicates that all major intracranial arteries on one side of the head are thrombosed. We also scored visible HASs on CT and abnormal arteries on CTA whether the abnormality was in a proximal (internal carotid or basilar artery), middle (ACA, MCA or PCA) or distal (sylvian branches of MCA) artery. The resulting proximal-middle-distal (PMD) score value ranges from 1 to 6, where 1 = only distal vessel, 2 = only middle vessel, 3 = middle and distal vessels, 4 = proximal vessel, 5 = proximal and middle vessels and 6 = proximal, middle and distal vessels.

We scored the adequacy of the collateral pathways54 in patients with ICA/MCA main stem occlusion only using the Score for Collateral Status,55 a three-point scale of good, moderate or poor based on the number of opacified arteries visible in the peripheral parts of the affected tissue. Examples are provided for comparison.

The resulting coding forms are available in Appendix 3 and can be seen at www.bric.ed.ac.uk/research/imageanalysis.html#ais.

A neuroradiologist also measured the mean density of any HAS in HU (i.e. standard units used to assess tissue X-ray beam attenuation) using a region of interest cursor placed on the affected artery and also of the unaffected arteries (i.e. basilar, left or right middle cerebral arteries) on a personal computer workstation running Digital Jacket software (an in-house image server application allowing manipulation of DICOM data sets; DesAcc, Bellevue, WA, USA). Ovoid ‘regions of interest’ were applied to the HAS or normal artery and three measurements were taken from each artery at similar locations for each patient; natural anatomical and scan parameter variability meant that measurement location could not always be identically reproduced, though this was attempted as near as possible.

Observer reliability

We tested the interobserver reliability of angiographic image analysis by inviting the expert panel to read the same 10 angiograms using the SIRS2 blind to all other data including their initial analysis. We tested observer reliability of the perfusion imaging by inviting as many raters as possible to rate 20 perfusion images using the modified SIRS2 system that was able to handle colour images and to view two image modalities from the same acquisition time point (e.g. a perfusion and a structural CT image) side by side (SIRS2: sirs2/neuroimage.co.uk/sirs2). These analyses are ongoing at the time of writing.

Sample size

The IST-3 perfusion analysis aimed to examine primarily whether or not rt-PA improves functional outcome more in those with, than without, tissue at risk and secondarily reduced infarct growth. Based on systematic reviews of all available data34 and recent studies,27,30 we estimated that 60% will have mismatch overall;27 70% with mismatch will have infarct growth compared with 30% without mismatch; and rt-PA will reduce infarct growth by 20% in those with, but not those without, mismatch. 34 At 80% power and α = 0.05, a sample of 100 patients would detect a 27% difference in infarct growth, with rt-PA compared without rt-PA, in the presence of mismatch compared with the absence of mismatch; 160 patients would detect a 20% difference in infarct growth; and 400 patients would detect a 15% difference in infarct growth. We acknowledged that, with, at most, 300 patients in the perfusion study, the perfusion study would be underpowered to detect a ‘mismatch × treatment effect’ interaction on the primary clinical outcome. We therefore selected infarct growth as an outcome for the perfusion analysis (as in EPITHET)30 to increase statistical power.

The centres that were using perfusion imaging were among the most active in IST-3. Therefore, we estimated that in 3 years, in up to 15 active centres recruiting between four and eight patients per year each, a total of between 100 and 300 patients with baseline perfusion and or angiography data would be recruited. We estimated that approximately two patients would have CTA/CTP for every one with MRA/MRP. However, that may change as more centres are now acquiring CT perfusion equipment, and so the proportion may end up being nearer to four patients having CTA/CTP for every one with MRA/MRP.

Statistical methods

We first compared imaging variables with each other, then with clinical features and clinical outcomes, and then tested for interactions between imaging variables and rt-PA effects. Thus, we assessed:

-

variation in the size of perfusion lesions and proportion with mismatch for each perfusion parameter tested

-

associations between clinical and structural imaging variables at baseline, perfusion lesion extent and presence/absence of angiography lesions

-

associations between baseline perfusion or angiography imaging variables and subsequent infarct growth, swelling and haemorrhagic transformation on follow-up scanning

-

associations between baseline perfusion and angiography lesions and 6-month functional outcome

-

test for an interaction between treatment with rt-PA and perfusion lesion extent, presence or absence of mismatch, angiographic arterial occlusion and SICH and 6-month functional outcome.

All analyses were unadjusted and adjusted for key baseline variables using an established prognostic model determined in the IST-3 main trial analysis. 59 We also performed ordinal analysis as this increases the statistical power. 68,88

Secondly, we also compared quantitative perfusion lesion volume with qualitative visual perfusion lesion assessment as coded by the ASPECTS; different perfusion processing algorithms [in this case, the in-house software and MiStar (Apollo Medical Imaging Technology Pty. Ltd, Melbourne, VIC, Australia)]; and test if relative (i.e. to the contralateral hemisphere) parameters are more consistent than quantitative parameters between different software, by comparing (a) the measured volumes of different perfusion parameter lesions, that is mm3, and (b) also by taking account of geometric concordance.

Statistical analyses for the CTA data presented here were performed with Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) software (v. 20, IBM, New York, NY, USA). Chi-squared testing was used for comparisons between dichotomous data. Simple t-tests were employed to compare normally distributed continuous and dichotomous data, while Mann–Whitney U-testing was employed where continuous or ordinal data were skewed (ASPECT and clot burden scores, HAS length). Similarly, both Pearson and Spearman’s rank-order correlations were applied as appropriate. Significance was taken as p < 0.05.

Any changes to protocol

There were two minor changes to process rather than to fundamental study design.

-

We originally planned to analyse infarct growth as the primary outcome and functional status, with death and SICH as secondary outcomes. However, in view of the clinical importance of functional outcome, and because infarct growth is less clinically relevant to patients, we reordered the primary outcome to be clinical and the secondary outcome to be infarct growth. Additionally, infarct growth can be assessed only in patients with visible infarction – those without a visible infarct do not contribute to this analysis, leading to distorted and potentially misleading results. Hence we focused on the influence of baseline perfusion imaging on clinical outcomes.

-

At the time of original submission, perfusion imaging was thought to be the more important advanced imaging modality to test in stroke and, hence, the focus of planned analysis was on perfusion imaging, which draws heavily on centralised computational analysis. However, in the 4 years since the original submission, angiographic imaging has come into prominence in stroke, and indeed we received far more angiography images than originally expected, almost three times as many as we received of perfusion images. The original planned analysis had been set up for perfusion imaging; angiographic imaging analysis is largely visual and so required a completely different approach. In the event, in order to cope with the number of angiography data efficiently, we had to redesign a visual web-based image viewing and data recording tool (SIRS2) to handle plain scan and angiographic images and then identify several expert neuroradiologists to assist with reading the angiograms. This took extra time, and hence the completion of the angiographic imaging analysis has been delayed. We were, however, fortunate to attract a senior neuroradiology trainee to the project who has been assisting by reading the CT angiograms and measuring thrombus density on a workstation. The results of this latter analysis are included in the report. However, to avoid biasing the analyses, the observers are all still blinded to treatment allocation and the final unblinded analysis has not yet been performed. The unblinded analysis will be presented to the investigators before being presented in public or submitted for publication, as with the perfusion imaging results, and as is proper in clinical trials.

The costs of the programming to redesign the SIRS2 web-based scan-viewing system, the time of the additional neuroradiology expert readers and the neuroradiology trainee’s time to undertake the work on the angiography is all outside the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) funding provided for the original project. There were no other changes.

Patient and public involvement

The IST-3 trial was designed with input from focus group discussions with stroke patients and their carers in the late 1990s. 89 A lay representative was on the IST-3 steering committee and also contributed to the discussions on design of the perfusion and angiography substudy. The lay representative also contributed to the writing of the main trial primary results paper60 and accompanying systematic review. 8 Her input will be sought on all publications arising from the perfusion and angiography substudy.

Chapter 4 Results

Participant flow and recruitment

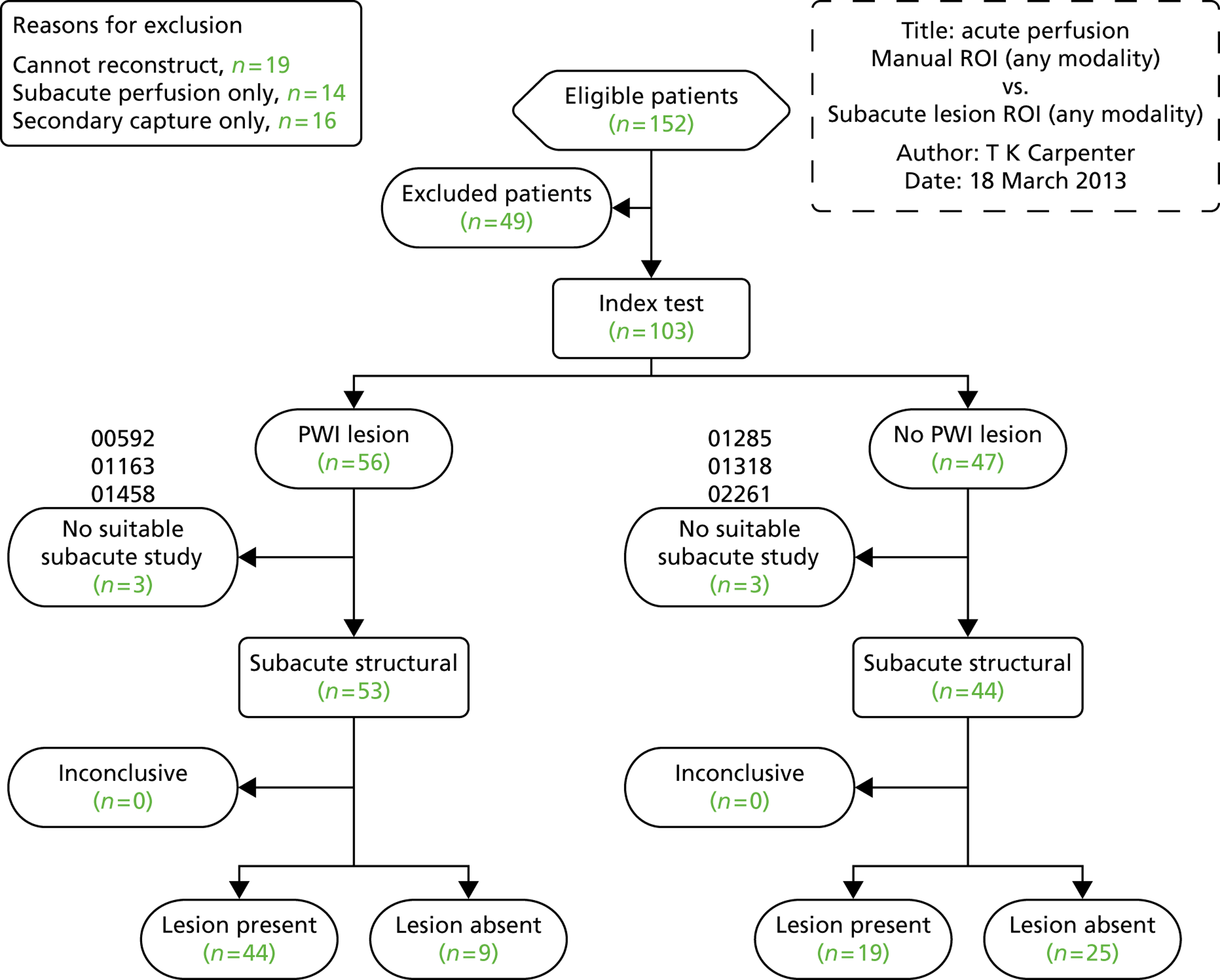

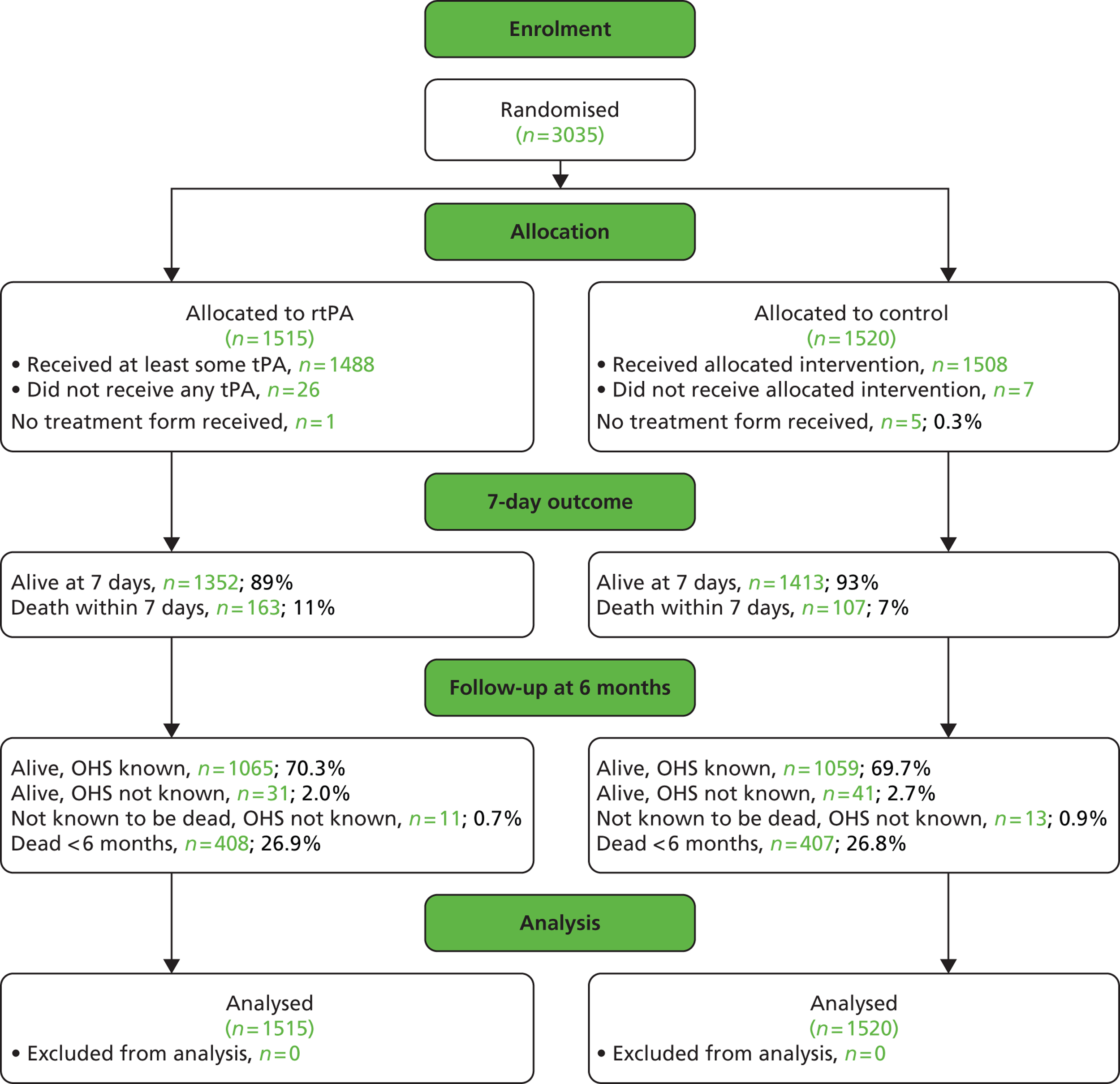

When randomisation ceased in IST-3 in July 2011, 3035 patients had been randomised to rt-PA or control in 156 centres in 12 countries in the main trial [Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram; see Appendix 4]. 60 The total patient recruitment in the Perfusion and Angiography Study was 472 patients from 47 centres in eight countries performing CT perfusion and/or angiography and 36 centres in 11 countries performing MR perfusion and/or angiography (the flow diagram for perfusion and angiography patients is shown in Figure 3). The cumulative recruitment with perfusion and/or angiography is shown in Figure 4. The 472 total included 49 patients with only perfusion imaging, 321 patients with only angiography imaging and 102 patients with both perfusion and angiography imaging. At randomisation, 123 patients had perfusion and 265 patients had angiography imaging. At follow-up, 10 patients had perfusion and 116 patients had angiography imaging. A further 18 patients and 42 patients had perfusion and angiography imaging, respectively, at both randomisation and follow-up. Therefore, allowing for some patients having both randomisation and follow-up imaging, the total number of patients with perfusion imaging is 141 at randomisation and 28 at follow-up and with angiographic imaging is 307 at randomisation and 158 at follow-up. The cumulative recruitment according to whether MR or CT was used is shown in Figure 5. Participating centres are listed in Appendix 5.

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram of recruitment into the perfusion and angiography substudy, the image analysis and final numbers of sufficient quality for statistical analysis. R, randomisation; P, post randomisation.

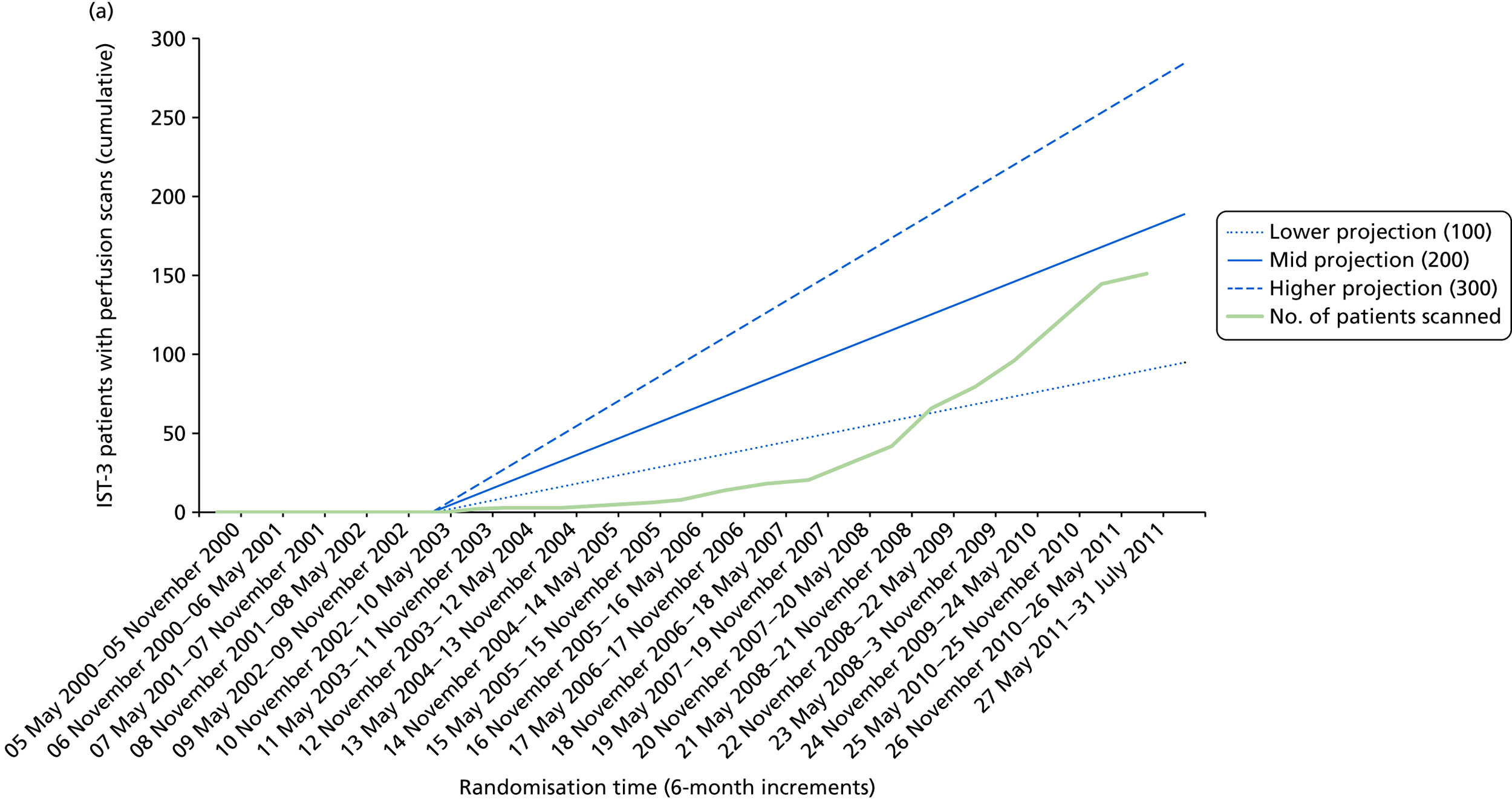

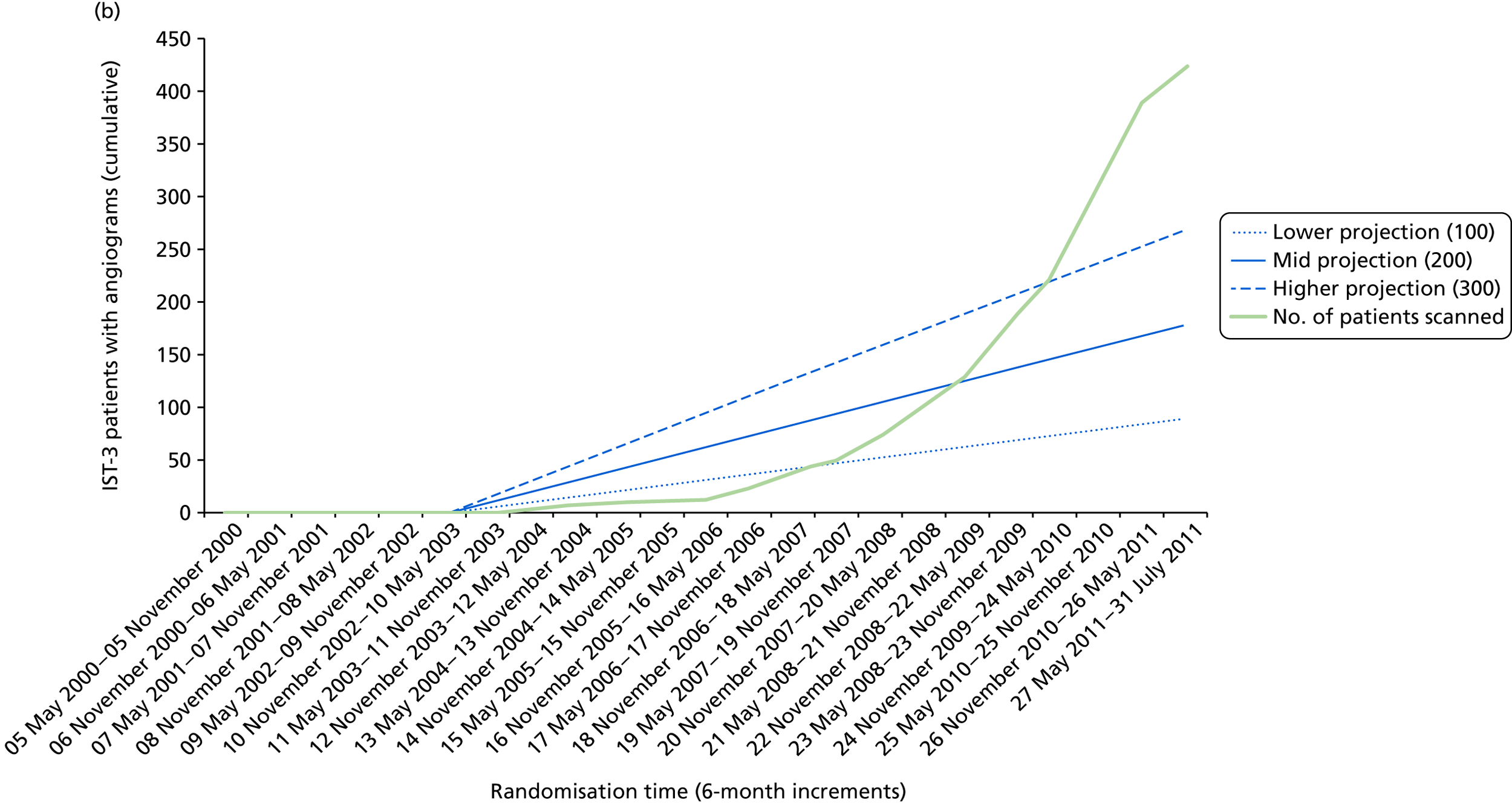

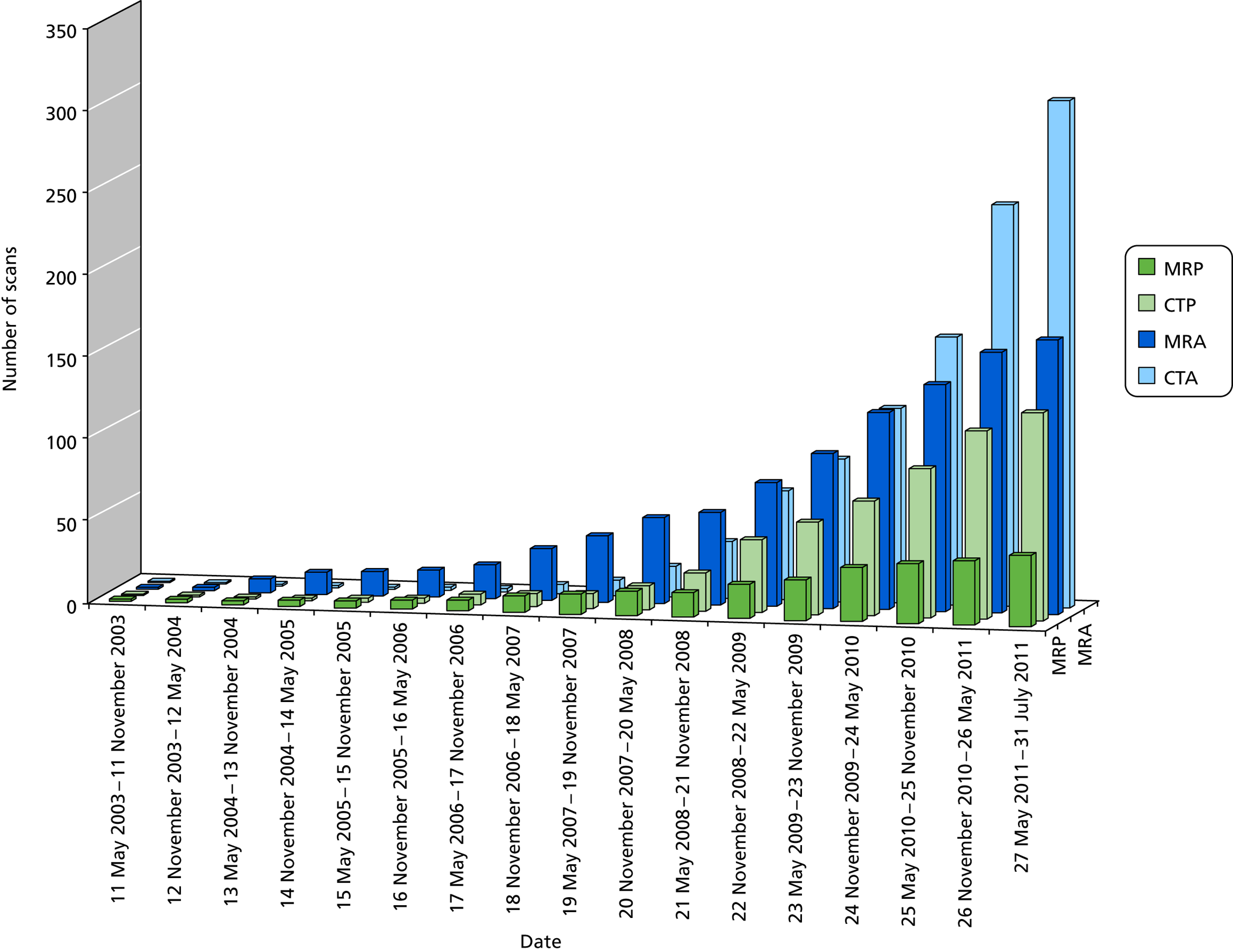

FIGURE 4.

Patient accrual in the (a) IST-3 perfusion study; and (b) IST-3 angiograph study against anticipated targets. Blue lines indicate projected target recruitments; green line indicates actual recruitment.

FIGURE 5.

Cumulative recruitment by CT and MR, perfusion and angiography usage.

Most imaging at randomisation was with CT and at follow-up was with MR, a consistent pattern throughout the trial. At randomisation, more patients had CT (n = 125/141, 89% perfusion; n = 277/307, 88% angiography) with little MR (n = 16/141, 11% perfusion; n = 30/307, 10% angiography). The expected against actual recruitment is shown in Figure 4. We anticipated recruiting between four and eight patients per year per centre in up to 15 active centres (i.e. between 180 and 360 in total), most of which we expected to be with perfusion imaging. In fact, there were more centres that recruited to the substudy than expected, and angiography proved to be more accessible for acute stroke than perfusion imaging; therefore, we exceeded our overall target, with 472 patients.

Few patients met the prevailing rt-PA licence criteria at the time of recruitment. Only 3 of 121 patients randomised with perfusion imaging met the conditional rt-PA licence criteria as granted in 2003. Considering the period after publication of the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) III in 2008,6 only eight of 121 patients (8.4%) met rt-PA licence criteria. Only three patients (1%) randomised with angiography imaging met the 2003 conditional licence criteria and only 12 patients (5%) met the criteria after publication of ECASS III in 2008.

Baseline clinical and plan scan data

The baseline demographic data of the patients recruited with perfusion or angiography imaging compared with patients recruited without perfusion or angiography imaging are given in Table 3.

| Baseline characteristic | No perfusion scan, n (%) | Perfusion scan, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| All | 2894 | 141 |

| Baseline variables collected before treatment allocation | ||

| Region | ||

| North-west Europe (UK, Austria, Belgium, Switzerland) | 1506 (52) | 83 (59) |

| Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden) | 485 (17) | 16 (11) |

| Australasia | 154 (5) | 25 (18) |

| Southern Europe (Italy, Portugal) | 394 (14) | 14 (10) |

| Eastern Europe (Poland) | 345 (12) | 2 (1) |

| Americas (Canada, Mexico) | 11 (0) | – |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–50 | 118 (4) | 9 (6) |

| 51–60 | 195 (7) | 7 (5) |

| 61–70 | 350 (12) | 15 (11) |

| 71–80 | 693 (24) | 31 (22) |

| 81–90 | 1338 (46) | 69 (49) |

| > 90 | 201 (7) | 9 (6) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1497 (52) | 73 (52) |

| NIHSS | ||

| 0–5 | 587 (20) | 25 (18) |

| 6–10 | 810 (28) | 42 (30) |

| 11–15 | 581 (20) | 20 (14) |

| 16–20 | 507 (18) | 36 (26) |

| > 20 | 410 (14) | 17 (12) |

| Delay in randomisation | ||

| 0–3 hours | 806 (28) | 43 (31) |

| 3–4.5 hours | 1131 (39) | 46 (33) |

| 4.5–6 hours | 956 (33) | 51 (36) |

| > 6 hours | 2 (0) | – |

| AF | ||

| Number with AF | 865 (30) | 49 (35) |

| Systolic BP | ||

| ≤ 143 mmHg | 937 (32) | 42 (30) |

| 144–164 mmHg | 977 (34) | 39 (28) |

| ≥ 165 mmHg | 981 (34) | 59 (42) |

| Diastolic BP | ||

| ≤ 74 mmHg | 862 (30) | 45 (32) |

| 75–89 mmHg | 1074 (37) | 55 (39) |

| ≥ 90 mmHg | 940 (33) | 40 (29) |

| Blood glucose | ||

| ≤ 5 mmol/l | 515 (20) | 24 (18) |

| 6–7 mmol/l | 1239 (47) | 63 (46) |

| ≥ 8 mmol/l | 862 (33) | 49 (36) |

| Treatment with antiplatelet drugs in previous 48 hours | 1493 (52) | 69 (49) |

| Clinician’s assessment of pre-randomisation scan | ||

| No evidence of recent ischaemic change | 1739 (60) | 53 (38) |

| Possible evidence of recent ischaemic change | 675 (23) | 26 (19) |

| Definite evidence of recent ischaemic change | 481 (17) | 61 (44) |

| Predicted probability of poor outcome at 6 months | ||

| < 40% | 697 (24) | 32 (23) |

| 40–50% | 312 (11) | 17 (12) |

| 50–75% | 693 (24) | 25 (18) |

| ≥ 75% | 1193 (41) | 66 (47) |

| Stroke syndrome | ||

| TACI | 1249 (43) | 56 (40) |

| PACI | 1094 (38) | 53 (38) |

| LACI | 320 (11) | 12 (9) |

| POCI | 228 (8) | 18 (13) |

| Other | 4 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Baseline variables collected from blinded reading of pre-randomisation scan | ||

| Expert reader’s assessment of acute ischaemic change on initial scan | ||

| Scan completely normal | 255 (9) | 14 (10) |

| Scan not normal but no sign of acute ischaemic change | 1444 (50) | 77 (55) |

| Signs of acute ischaemic change | 1174 (41) | 49 (35) |

| Lesion territory | ||

| Indeterminate | 1704 (59) | 92 (66) |

| MCA or ACA or borderzone | 1098 (38) | 45 (32) |

| Posterior | 56 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Lacunar | 15 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Lesion size | ||

| 0 | 1704 (59) | 92 (66) |

| 1 | 199 (7) | 8 (6) |

| 2 | 470 (16) | 30 (21) |

| 3 | 254 (9) | 7 (5) |

| 4 | 246 (9) | 3 (2) |

| Depth of tissue damage | ||

| None | 1720 (60) | 91 (65) |

| Mild | 957 (33) | 37 (26) |

| Severe | 196 (7) | 12 (9) |

| Degree of swelling | ||

| None | 2207 (77) | 113 (81) |

| Mild sulcal | 525 (18) | 22 (16) |

| Mild ventricular | 139 (5) | 5 (4) |

| Moderate | 1 (0) | – |

| Severe | 1 (0) | – |

| Location of hyperdense arteries | ||

| None | 2164 (75) | 114 (81) |

| Anterior | 678 (24) | 24 (17) |

| Posterior | 31 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Evidence of atrophy | 2211 (77) | 112 (80) |

| Evidence of periventricular lucencies | 1476 (51) | 67 (48) |

| Evidence of old lesions | 1275 (44) | 58 (41) |

| Evidence of non-stroke lesions | 142 (5) | 8 (6) |

| Baseline variables collected from 7-day form | ||

| Pre-trial history of stroke | 670 (23) | 29 (21) |

| Pre-trial treatment with antiplatelet drugs | ||

| Pre-trial treatment with aspirin | 1253 (48) | 53 (39) |

| Pre-trial treatment with dipyridamole | 122 (5) | 3 (2) |

| Pre-trial treatment with clopidogrel | 131 (5) | 15 (11) |

| Pre-trial treatment with anticoagulants | ||

| Warfarin or other oral anticoagulant | 112 (4) | 6 (4) |

| Heparin (low dose) | 20 (1) | – |

| None of the above | 2470 (95) | 131 (96) |

| Pre-trial treatment for hypertension | 1856 (64) | 98 (71) |

| Pre-trial treatment for diabetes | 369 (13) | 19 (14) |

| Phase of trial in which patient recruited | ||

| Blinded | 272 (9) | 4 (3) |

| Open | 2623 (91) | 136 (97) |

| Patients recruited in centre with pre-trial experience of thrombolysis | 1071 (37) | 72 (51) |

| Baseline characteristic | No angiography scan, n (%) | Angiography scan, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| All | 2728 | 307 |

| Baseline variables collected before treatment allocation | ||

| Region | ||

| North-west Europe (UK, Austria, Belgium, Switzerland) | 1434 (53) | 155 (51) |

| Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden) | 441 (16) | 60 (20) |

| Australasia | 148 (5) | 31 (10) |

| Southern Europe (Italy, Portugal) | 380 (14) | 28 (9) |

| Eastern Europe (Poland) | 315 (12) | 32 (10) |

| Americas (Canada, Mexico) | 11 (0) | – |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–50 | 113 (4) | 14 (5) |

| 51–60 | 183 (7) | 19 (6) |

| 61–70 | 324 (12) | 41 (13) |

| 71–80 | 641 (23) | 83 (27) |

| 81–90 | 1279 (47) | 128 (42) |

| > 90 | 189 (7) | 21 (7) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1398 (51) | 172 (56) |

| NIHSS | ||

| 0–5 | 523 (19) | 89 (29) |

| 6–10 | 769 (28) | 83 (27) |

| 11–15 | 551 (20) | 50 (16) |

| 16–20 | 496 (18) | 47 (15) |

| > 20 | 390 (14) | 37 (12) |

| Delay in randomisation | ||

| 0–3 hours | 760 (28) | 89 (29) |

| 3–4.5 hours | 1092 (40) | 85 (28) |

| 4.5–6 hours | 875 (32) | 132 (43) |

| > 6 hours | 2 (0) | – |

| AF | ||

| Number with AF | 836 (31) | 78 (25) |

| Systolic BP | ||

| ≤ 143 mmHg | 890 (33) | 89 (29) |

| 144–164 mmHg | 916 (34) | 100 (33) |

| ≥ 165 mmHg | 923 (34) | 117 (38) |

| Diastolic BP | ||

| ≤ 74 mmHg | 803 (30) | 104 (34) |

| 75–89 mmHg | 1022 (38) | 107 (35) |

| ≥ 90 mmHg | 885 (33) | 95 (31) |

| Blood glucose | ||

| ≤ 5 mmol/l | 477 (19) | 62 (21) |

| 6–7 mmol/l | 1167 (48) | 135 (45) |

| ≥ 8 mmol/l | 807 (33) | 104 (35) |

| Treatment with antiplatelet drugs in previous 48 hours | 1403 (52) | 159 (52) |

| Clinician’s assessment of pre-randomisation scan | ||

| No evidence of recent ischaemic change | 1627 (60) | 165 (54) |

| Possible evidence of recent ischaemic change | 641 (23) | 60 (20) |

| Definite evidence of recent ischaemic change | 461 (17) | 81 (26) |

| Predicted probability of poor outcome at 6 months | ||

| < 40% | 632 (23) | 97 (32) |

| 40–50% | 290 (11) | 39 (13) |

| 50–75% | 660 (24) | 58 (19) |

| ≥ 75% | 1147 (42) | 112 (37) |

| Stroke syndrome | ||

| TACI | 1207 (44) | 98 (32) |

| PACI | 1010 (37) | 137 (45) |

| LACI | 307 (11) | 25 (8) |

| POCI | 201 (7) | 45 (15) |

| Other | 4 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Baseline variables collected from pre-randomisation scan | ||

| Expert reader’s assessment of acute ischaemic change on initial scan | ||

| Scan completely normal | 247 (9) | 22 (7) |

| Scan not normal but no sign of acute ischaemic change | 1346 (50) | 175 (58) |

| Signs of acute ischaemic change | 1117 (41) | 106 (35) |

| Lesion territory | ||

| Indeterminate | 1598 (59) | 198 (65) |

| MCA or ACA or borderzone | 1047 (39) | 96 (32) |

| Posterior | 50 (2) | 8 (3) |

| Lacunar | 15 (1) | 1 (0) |

| Lesion size | ||

| 0 | 1598 (59) | 198 (65) |

| 1 | 185 (7) | 22 (7) |

| 2 | 450 (17) | 50 (17) |

| 3 | 246 (9) | 15 (5) |

| 4 | 231 (9) | 18 (6) |

| Depth of tissue damage | ||

| None | 1613 (60) | 198 (65) |

| Mild | 912 (34) | 82 (27) |

| Severe | 185 (7) | 23 (8) |

| Degree of swelling | ||

| None | 2073 (76) | 247 (82) |

| Mild sulcal | 504 (19) | 43 (14) |

| Mild ventricular | 131 (5) | 13 (4) |

| Moderate | 1 (0) | – |

| Severe | 1 (0) | – |

| Location of hyperdense arteries | ||

| None | 2023 (75) | 255 (84) |

| Anterior | 658 (24) | 44 (15) |

| Posterior | 29 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Evidence of atrophy | 2082 (77) | 241 (80) |

| Evidence of periventricular lucencies | 1380 (51) | 163 (54) |

| Evidence of old lesions | 1198 (44) | 135 (45) |

| Evidence of non-stroke lesions | 132 (5) | 18 (6) |

| Baseline variables collected from 7-day form | ||

| Pre-trial history of stroke | 633 (23) | 66 (22) |

| Pre-trial treatment with antiplatelet drugs | ||

| Pre-trial treatment with aspirin | 1161 (48) | 145 (48) |

| Pre-trial treatment with dipyridamole | 113 (5) | 12 (4) |

| Pre-trial treatment with clopidogrel | 120 (5) | 26 (9) |

| Pre-trial treatment with anticoagulants | ||

| Warfarin or other oral anticoagulant | 107 (4) | 11 (4) |

| Heparin (low dose) | 17 (1) | 3 (1) |

| None of the above | 2315 (95) | 286 (95) |

| Pre-trial treatment for hypertension | 1731 (64) | 223 (73) |

| Pre-trial treatment for diabetes | 343 (13) | 45 (15) |

| Phase of trial in which patient recruited | ||

| Blinded | 270 (10) | 6 (2) |

| Open | 2459 (90) | 300 (98) |

| Patients recruited in centre with pre-trial experience of thrombolysis | 1014 (37) | 129 (42) |

The median age of the 141 patients randomised in IST-3 with perfusion imaging was 81.0 years, the NIHSS was 11.0, the median time to randomisation was 3.9 hours and 48% were male. These data were identical for the 2986 patients randomised in IST-3 without perfusion imaging.

Of the patients with angiography imaging, we will focus on those with CTA at randomisation as there were many more with CTA than with MRA. The median age of the 271 patients with CTA at randomisation was 81 years [interquartile range (IQR) 71–85 years], the youngest patient was 18 years and the oldest was 102 years; 41.5% were male. The stroke syndrome was TACI in 34%, PACI in 39%, LACI in 10% and POCI in 17%. The median time to pre-randomisation CT (taken from the CT scan) was 2.8 hours (IQR 1.8–4.2 hours), minimum 0.5 hours and maximum 5.4 hours. AF was noted in 61 out of 234 (26.1%) patients at admission.

We were concerned that patients randomised in IST-3 with perfusion or angiography imaging would be different to those randomised with a plain CT or MR scan. However, the only difference in patients with perfusion imaging (but not those with angiography) was that the randomising clinician thought that more patients had a possible or definite visible ischaemic lesion on structural imaging (63% vs. 40%, respectively; p < 0.0001) than patients without perfusion imaging. However, the blinded central expert panel image readings (which were performed without knowledge of the perfusion imaging) showed no difference in the proportion of patients with visible infarction at randomisation (41% vs. 35% had visible infarction on structural scanning with vs. without perfusion imaging; p = not significant). Among the patients randomised with angiography, there was no difference in the proportion with visible infarction according to either the randomising clinician (46% vs. 40%) or the expert panel. Otherwise, there was no difference in age, NIHSS, proportion with AF, predicted outcome, or in any other variables. The blinded expert scan readers did not have access to the perfusion and angiography imaging. This illustrates the importance of separating the perfusion/angiography images from the structural image interpretation when trying to determine the true additional contribution of the perfusion and angiography.

Perfusion imaging

Numbers analysed

We received perfusion imaging on 151 patients in total (see Figure 3). Of these, 10 had perfusion imaging performed post randomisation only. In 21 it was not possible to process the image data, mainly due to incomplete image acquisition, leaving 123 with perfusion imaging at randomisation and that were rated visually. Of these, in 16 patients we did not receive ‘raw’ perfusion data, only the ‘already processed’ screen capture images created on the scanner where the images were obtained, on which it was not possible to measure lesion volume, although it was possible to perform visual scoring. Hence there were more visual readings than volume measures. Additionally, the ‘already processed’ images tended to have fewer perfusion parameters and, therefore, the full list of perfusion parameters was incomplete for some patients. The majority were CT perfusion imaging. Details of the data available for volume measures are given in Figure 3.

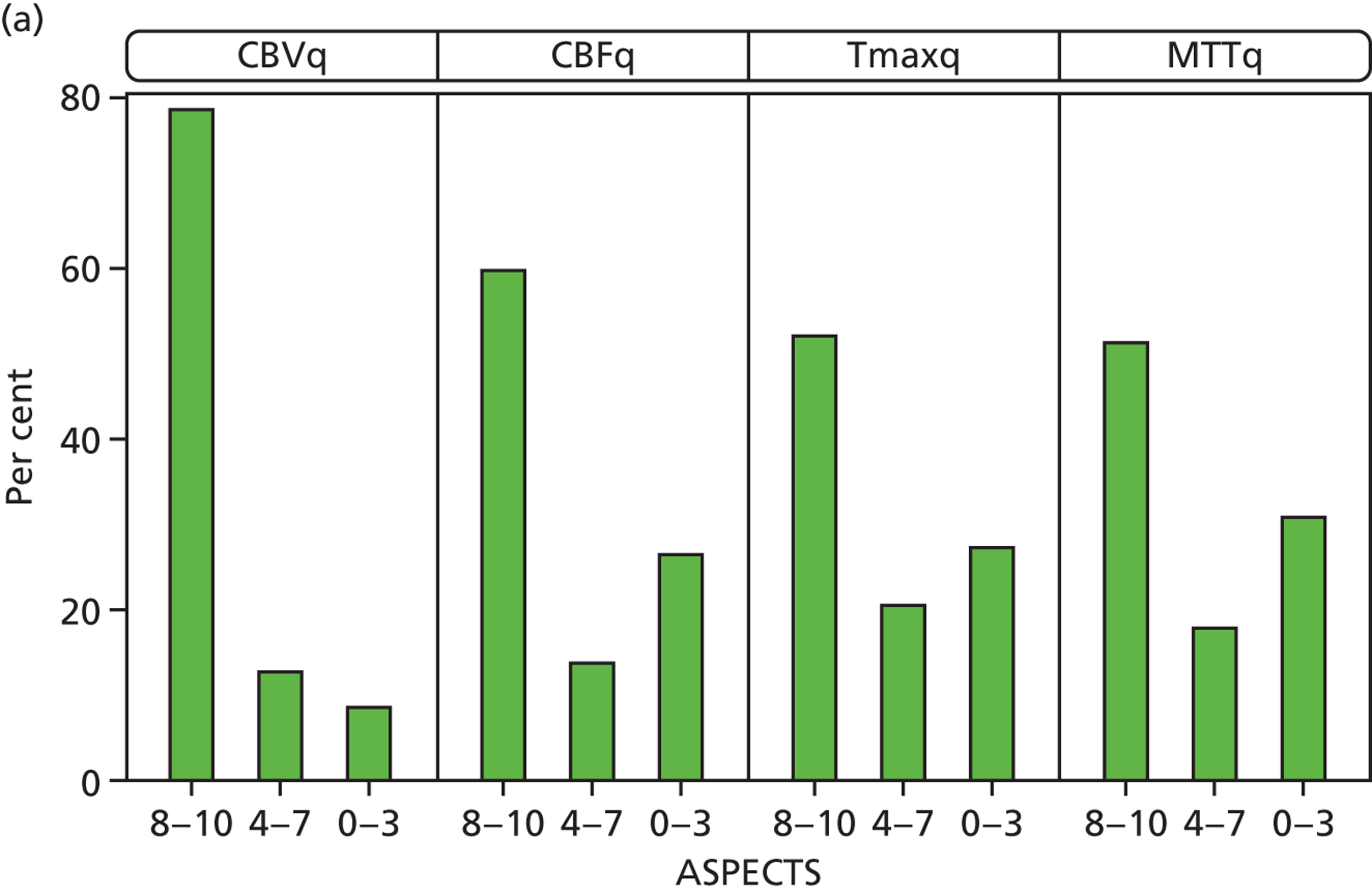

Perfusion parameters variation in perfusion lesion size

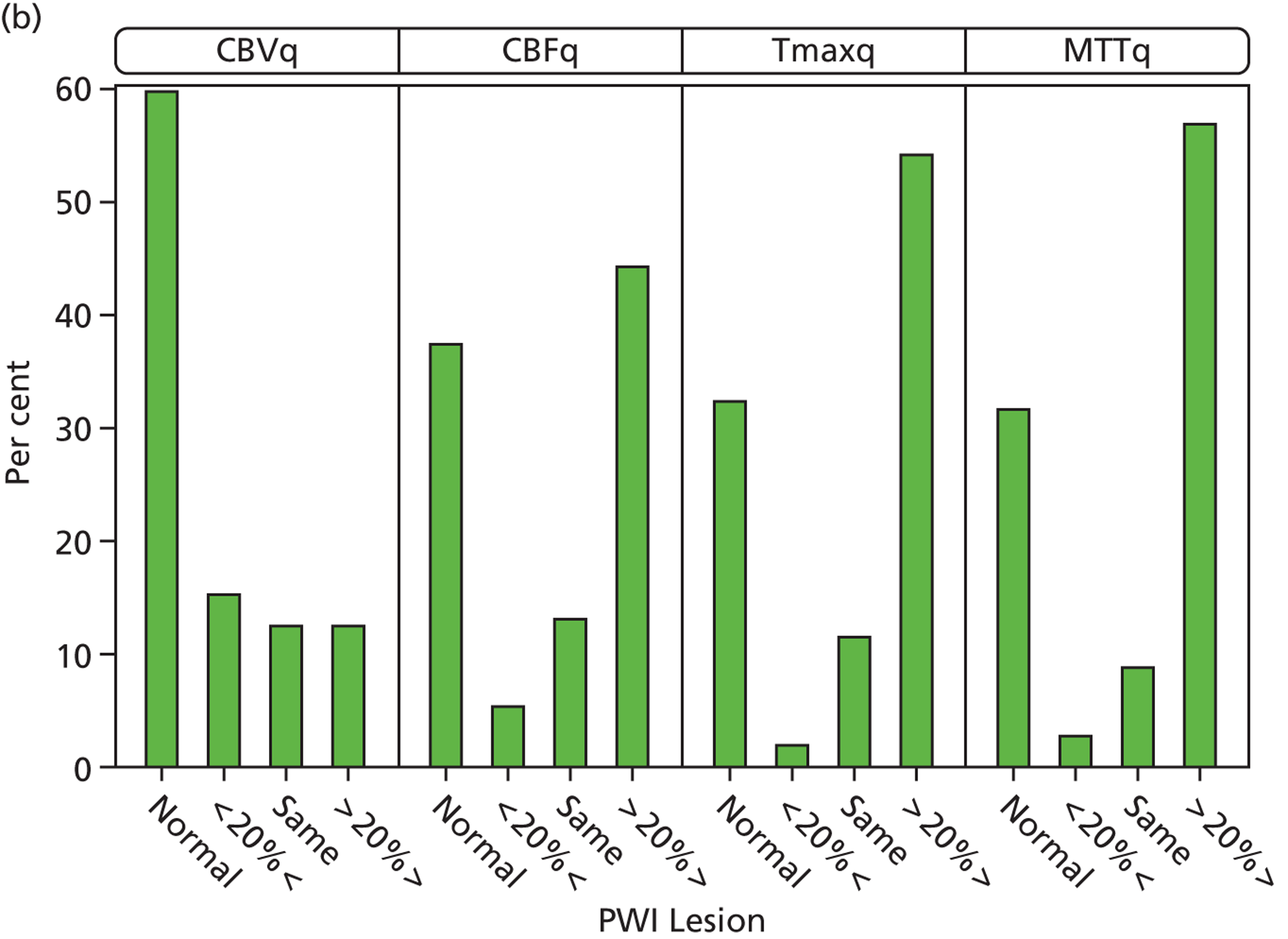

We compared CBVq, CBFq, Tmaxq and MTTq lesions at randomisation using ASPECTS and relative to the plain-scan acute ischaemic lesion. Lesion size was smallest for CBVq; CBVq was significantly smaller than CBFq (p < 0.000), which was the same as Tmaxq, which was significantly smaller than MTTq (p < 0.002) (Figure 6). We found similar lesion size variation when the perfusion lesion was expressed in terms of ‘mismatch’ with respect to the plain-scan lesion size. On Tmaxq, 53 out of 116 (46%) patients had mismatch (perfusion lesion 20% larger by visual estimation than the plain-scan lesion).

FIGURE 6.

Perfusion lesion size (a) on ASPECTSs scores by different parameters: 8–10 is no or small lesion, 0–3 is large lesion; (b) relative to the structural imaging lesion by different perfusion parameters.

Perfusion parameters and plain scan findings

The acute ischaemic lesion on the plain scan was not significantly different in size to the CBVq perfusion lesion, but was significantly smaller than the CBFq, Tmaxq and MTTq lesion sizes (all p < 0.0000, t-tests). For example, the CBFq lesion had, on average, an ASPECTS that was 2.1 [standard deviation (SD) 3.4] points larger than the plain scan (p < 0.000); the MTTq lesion ASPECTS was 2.7 (SD 3.6) points larger than the plain-scan lesion (p < 0.000).

Perfusion parameters and baseline clinical features

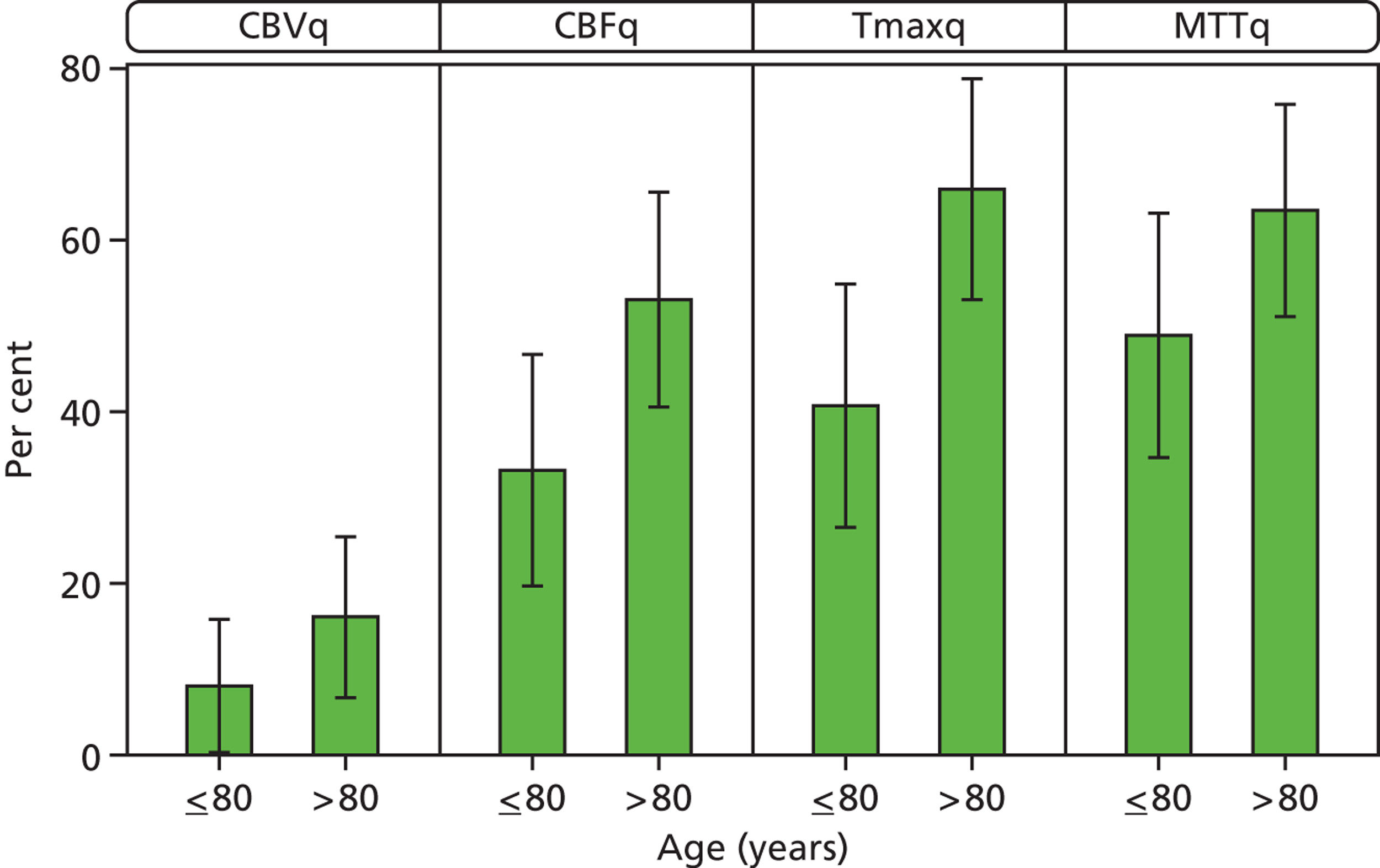

Older patients had larger perfusion lesions on all perfusion parameter maps, and more often had perfusion–plain scan lesion mismatch (Figure 7). For example, in patients aged > 80 years, 67% had mismatch on Tmaxq compared with 41% of patients aged ≤ 80 years (p < 0.04). ASPECTS were lower (i.e. larger lesion) for CBFq and Tmaxq in patients aged >80 years compared with ≤ 80 years (p < 0.05).

FIGURE 7.

Perfusion lesion and plain scan mismatch extent by age ≤ 80 years vs. > 80 years. Error bars represent 95% CIs. Older patients had larger perfusion lesions with more perfusion–plain scan mismatch: CBFq, Tmaxq; p = 0.04. They also had lower ASPECTS: CBFq, Tmaxq; p < 0.05.

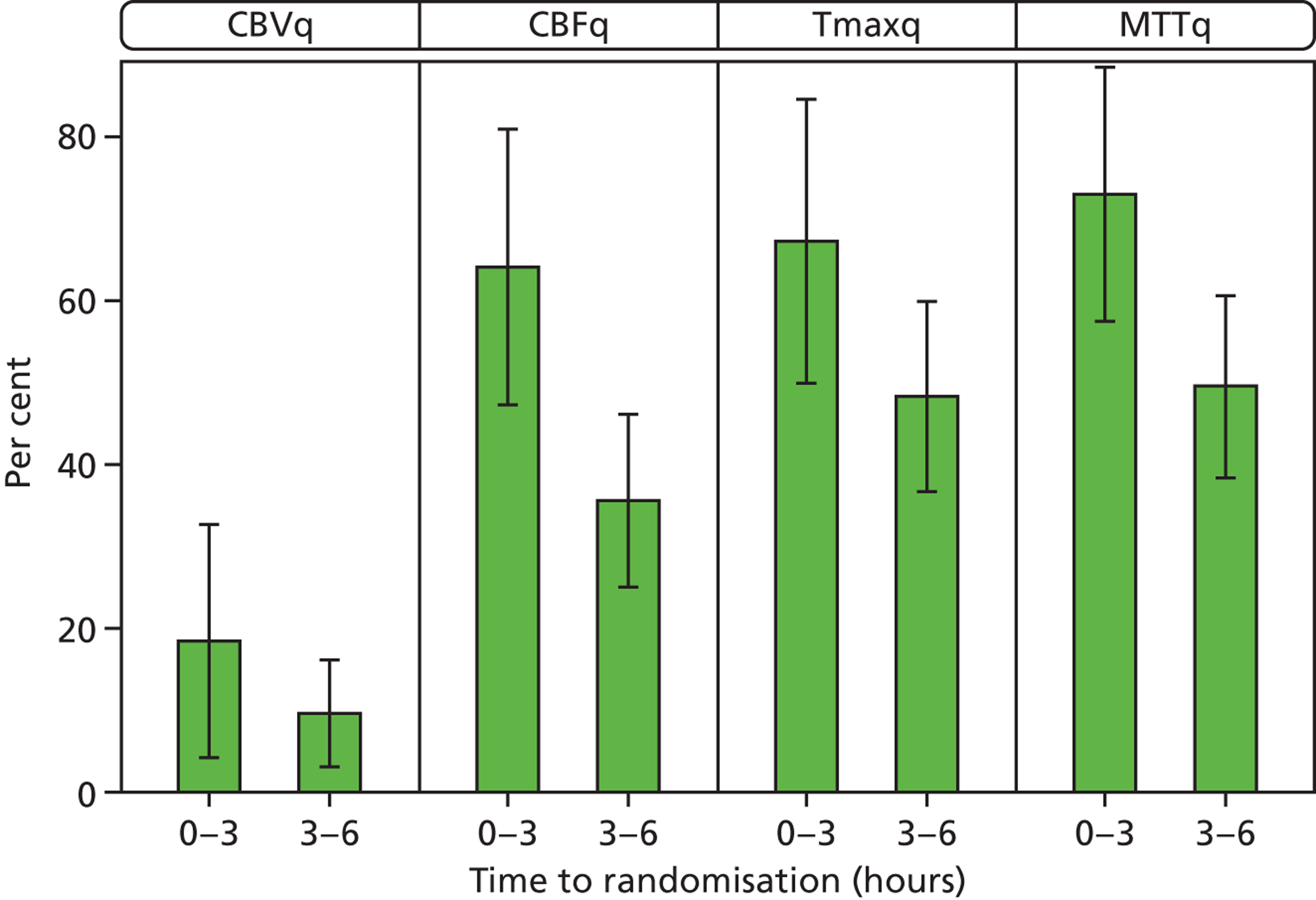

Patients scanned within 3 hours of stroke had larger perfusion lesions (lower ASPECTS) and more often had perfusion–plain-scan lesion mismatch than did patients scanned between 3 and 6 hours after stroke, which was significant for CBFq (ASPECTS < 3 hours, 5.4; 4.5–6 hours, 7.7; p < 0.05) (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Perfusion lesion: mismatch and ASPECTS by time to randomisation 0–3 hours vs. 3–6 hours. Error bars represent 95% CIs. Larger perfusion imaging lesions at 0–3 hours than at 4.5–6 hours: more mismatch; lower ASPECTSs e.g. for CBFq < 3 hours, 5.4; 4.5–6 hours, 7.7; p < 0.05.

There was a strong correlation between increasing stroke severity as measured by NIHSS score and larger perfusion lesions on all perfusion parameters, according to both the ASPECTS and perfusion–plain scan mismatch (Table 4). The Spearman rank-order correlation coefficients ranged from 0.54 to 0.58 (all p < 0.000) for ASPECTS and 0.38 to 0.48 (all p < 0.000) for mismatch.

| Perfusion parameter | NIHSS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 5 | 6 to 14 | 15 to 24 | ≥ 25 | |

| CBFq | ||||

| n | 23 | 45 | 39 | 6 |

| Mean ASPECTS | 9.4 | 7.9 | 4.3 | 3.2 |

| CBVq | ||||

| n | 23 | 45 | 39 | 6 |

| Mean ASPECTS | 10.0 | 9.2 | 7.4 | 4.3 |

| MTTq | ||||

| n | 23 | 45 | 39 | 6 |

| Mean ASPECTS | 8.6 | 7.3 | 3.7 | 2.5 |

| Tmaxq | ||||

| n | 23 | 45 | 39 | 6 |

| Mean ASPECTS | 9.0 | 8.0 | 4.1 | 2.8 |

| Perfusion parameter | NIHSS score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 5, n (%) | 6 to 14, n (%) | 15 to 24, n (%) | ≥ 25, n (%) | |

| PWI_CBFq | ||||

| Missing | 10 (43.5) | 15 (33.3) | 8 (20.5) | 1 (16.7) |

| Normal | 7 (30.4) | 6 (13.3) | 2 (5.1) | |

| < 20% < (CT or DWI) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (4.4) | 2 (5.1) | |

| Same as (CT or DWI) | 1 (4.3) | 6 (13.3) | 4 (10.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| > 20% > (CT or DWI) | 4 (17.4) | 16 (35.6) | 23 (59.0) | 4 (66.7) |

| PWI_CBVq | ||||

| Missing | 10 (43.5) | 16 (35.6) | 8 (20.5) | 1 (16.7) |

| Normal | 11 (47.8) | 16 (35.6) | 9 (23.1) | |

| < 20% < (CT or DWI) | 1 (4.3) | 5 (11.1) | 10 (25.6) | |

| Same as (CT or DWI) | 2 (4.4) | 9 (23.1) | 2 (33.3) | |

| > 20% > (CT or DWI) | 1 (4.3) | 6 (13.3) | 3 (7.7) | 3 (50.0) |

| PWI_MTTq | ||||

| Missing | 10 (43.5) | 15 (33.3) | 8 (20.5) | 1 (16.7) |

| Normal | 4 (17.4) | 6 (13.3) | 1 (2.6) | |

| < 20% < (CT or DWI) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (2.2) | ||

| Same as (CT or DWI) | 4 (8.9) | 3 (7.7) | 1 (16.7) | |

| > 20% > (CT or DWI) | 8 (34.8) | 19 (42.2) | 27 (69.2) | 4 (66.7) |

| PWI_Tmaxq | ||||

| Missing | 10 (43.5) | 15 (33.3) | 9 (23.1) | 1 (16.7) |

| Normal | 4 (17.4) | 8 (17.8) | ||

| < 20% < (CT or DWI) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Same as (CT or DWI) | 6 (13.3) | 5 (12.8) | 1 (16.7) | |

| > 20% > (CT or DWI) | 9 (39.1) | 15 (33.3) | 24 (61.5) | 4 (66.7) |

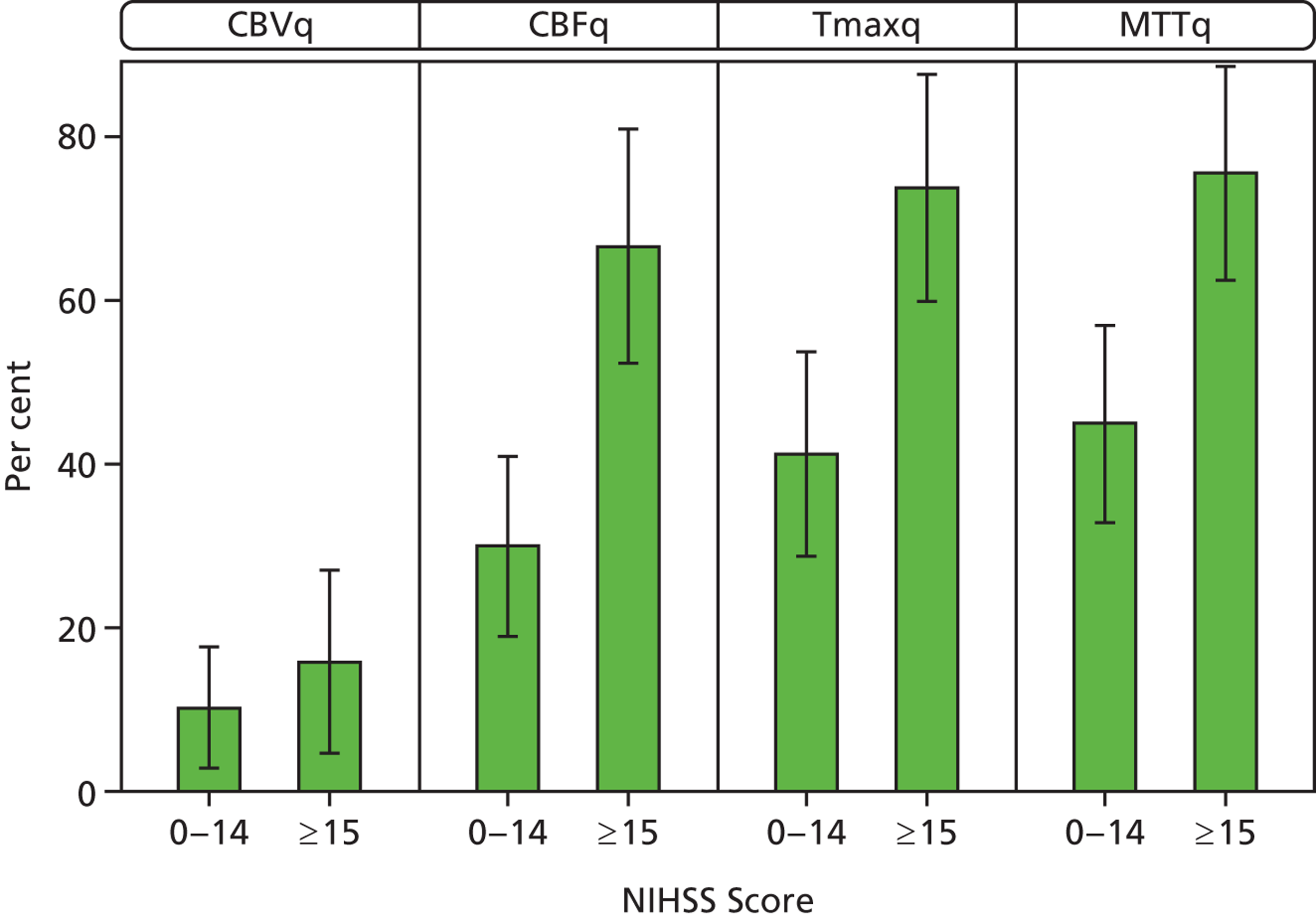

Patients with higher NIHSS scores were also more likely to have mismatch (Figure 9); 72% of patients with NIHSS ≥ 15 had mismatch on Tmaxq or MTTq compared with about 45% of those with NIHSS < 15.

FIGURE 9.

Proportion of patients with perfusion–plain scan mismatch by NIHSS score. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Perfusion parameters and symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage, death and functional outcome

Larger perfusion lesions were associated with worse functional outcomes (Table 5). Patients with perfusion lesion–plain-scan mismatch on CBFq, Tmaxq or MTTq were less likely to be alive and independent at 6 months, all significant at the p < 0.05 level on unadjusted analyses; after adjusting for baseline prognosis, only CBFq and MTTq mismatch was significantly associated with worse outcome. Similarly, larger perfusion lesion ASPECTSs were associated significantly with poor functional outcome, for CBVq, CBFq, Tmaxq and MTTq on unadjusted analyses (all p < 0.001); on adjusted analyses, all parameters except MTTq retained their significance. The odds of being alive and independent decreased by about 20% for every point worsening of the ASPECTS, significant for CBVq and Tmaxq.

| Perfusion parameter | n | Dead ≤ 7 days (%) | Symptomatic ICH in 7 days (%) | Dead by 6 months (%) | OHS 0–2 at 6 months (%) | OHS 0–1 at 6 months (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWI_CBFq | ||||||

| Normal | 35 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 5.7 | 65.7 | 31.4 |

| < 20% < (CT or DWI) | 5 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 20.0 |

| Same as (CT or DWI) | 12 | 16.7 | 8.3 | 33.3 | 50.0 | 25.0 |

| > 20% > (CT or DWI) | 49 | 8.2 | 6.1 | 28.6 | 22.4 | 10.2 |

| PWI_CBVq | ||||||

| Normal | 58 | 3.4 | 5.2 | 12.1 | 55.2 | 27.6 |

| < 20% < (CT or DWI) | 16 | 12.5 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 18.8 | 0.0 |

| Same as (CT or DWI) | 13 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 30.8 | 23.1 | 7.7 |

| > 20% > (CT or DWI) | 13 | 15.4 | 0.0 | 23.1 | 23.1 | 15.4 |

| PWI_MTTq | ||||||

| Normal | 30 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 66.7 | 23.3 |

| < 20% < (CT or DWI) | 2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| Same as (CT or DWI) | 8 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 |

| > 20% > (CT or DWI) | 61 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 26.2 | 27.9 | 16.4 |

| PWI_Tmaxq | ||||||

| Normal | 31 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 67.7 | 25.8 |

| < 20% < (CT or DWI) | 2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Same as (CT or DWI) | 12 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 50.0 | 33.3 | 16.7 |

| > 20% > (CT or DWI) | 55 | 9.1 | 5.5 | 25.5 | 29.1 | 18.2 |

| Perfusion parameter | n | Dead ≤ 7 days (%) | Sympt ICH in 7 days (%) | Dead by 6 months (%) | OHS 0–2 at 6 months (%) | OHS 0–1 at 6 months (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASPECTS for CBFq | ||||||

| 0–3 | 31 | 12.9 | 6.5 | 35.5 | 16.1 | 6.5 |

| 4–7 | 16 | 12.5 | 6.3 | 25.0 | 43.8 | 25.0 |

| 8–10 | 66 | 6.1 | 3.0 | 18.2 | 53.0 | 27.3 |

| ASPECTS for CBVq | ||||||

| 0–3 | 10 | 30.0 | 10.0 | 60.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 4–7 | 15 | 13.3 | 6.7 | 26.7 | 20.0 | 6.7 |

| 8–10 | 88 | 5.7 | 3.4 | 19.3 | 50.0 | 26.1 |

| ASPECTS for MTTq | ||||||

| 0–3 | 36 | 11.1 | 5.6 | 38.9 | 16.7 | 8.3 |

| 4–7 | 21 | 14.3 | 4.8 | 19.0 | 52.4 | 28.6 |

| 8–10 | 56 | 5.4 | 3.6 | 16.1 | 53.6 | 26.8 |

| ASPECTS for Tmaxq | ||||||

| 0–3 | 32 | 12.5 | 6.3 | 34.4 | 15.6 | 9.4 |

| 4–7 | 24 | 12.5 | 4.2 | 33.3 | 37.5 | 25.0 |

| 8–10 | 57 | 5.3 | 3.5 | 14.0 | 57.9 | 26.3 |

More patients with larger perfusion lesion ASPECTSs on all parameters except CBFq were dead at 6 months (p < 0.05 unadjusted), although not on adjusted analyses. There were more patients with SICH and who died within the first 7 days after stroke with larger perfusion lesions on all parameters but these differences were not statistically significant. Similar associations were seen for perfusion lesion size expressed as the perfusion–plain-scan mismatch.

Treatment interaction

We examined for any evidence that the effect of rt-PA was different in the presence of a perfusion lesion mismatch or with increasing perfusion lesion size by testing for an interaction between the perfusion lesion size and rt-PA on the proportion of patients with SICH within 7 days, who had died, or who were alive and independent at 6 months on ordinal analysis (Table 6). We found no evidence that rt-PA effects differed in patients with or without mismatch, or who had large or small perfusion lesions by ASPECTSs on any perfusion parameter. This was true for OHS 0–1, 0–2, SICH, death within 7 days or death within 6 months.

| Perfusion parameter | OHS 0–2 rate | OHS 0–2 risk (%) | Odds | rt-PA effect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | rtPA | Control | rtPA | Control | rtPA | Control | Risk ratio | Odds ratio | p-value for interactiona | |

| CBFq | No mismatch (normal/less/same) | 14/27 | 22/37 | 51.9 | 59.5 | 1.077 | 1.467 | 0.872 | 0.734 | 0.701 |

| CBFq | Mismatch (> 20%) | 5/23 | 6/28 | 21.7 | 21.4 | 0.278 | 0.273 | 1.014 | 1.019 | * |

| CBVq | No mismatch (normal/less/same) | 16/43 | 26/55 | 37.2 | 47.3 | 0.593 | 0.897 | 0.787 | 0.661 | 0.246 |

| CBVq | Mismatch (> 20%) | 2/6 | 1/8 | 33.3 | 12.5 | 0.500 | 0.143 | 2.667 | 3.500 | * |

| MTTq | No mismatch (normal/less/same) | 10/21 | 18/28 | 47.6 | 64.3 | 0.909 | 1.800 | 0.741 | 0.505 | 0.225 |

| MTTq | Mismatch (> 20%) | 9/29 | 9/36 | 31.0 | 25.0 | 0.450 | 0.333 | 1.241 | 1.350 | * |

| Tmaxq | No mismatch (normal/less/same) | 9/19 | 17/29 | 47.4 | 58.6 | 0.900 | 1.417 | 0.808 | 0.635 | 0.519 |

| Tmaxq | Mismatch (> 20%) | 8/26 | 9/31 | 30.8 | 29.0 | 0.444 | 0.409 | 1.060 | 1.086 | * |

Ancillary analyses

Lesion volumes were measurable in 56 out of 103 patients with perfusion data that could be processed centrally. Additionally, infarct size was measured on the post-randomisation follow-up scan in 63 patients with a visible lesion. Figure 10 shows the breakdown of patients by lesion presence for analysis. These data are still being analysed.

FIGURE 10.

Perfusion imaging flow chart showing numbers for computational analysis, lesion presence or absence. ROI, region of interest.

Angiography imaging

Analysis by the blinded expert panel is complete but still under analysis at the time of submission of this report. There are 11 raters who have read all 423 scans. The total number of angiograms received is documented in Figure 3.

Of the 307 randomisation CT or MR angiograms received, 277 were CT and 30 were MR; seven of the CT and one MR angiogram were not readable due to incomplete, inadequate (missed correct area of brain) or corrupted data; therefore, analysis is based on 271 CT and 29 MR angiograms at randomisation. Analysis of the 271 patients with CT angiography at randomisation by the neuroradiologist, including measurement of thrombus density scores and interaction with rt-PA, is provided here.

Hyperdense artery sign and clinical findings

Among these 271 patients with CTA at randomisation, a recent acute ischaemic lesion was visible in 74 (27%, Table 7), most in the MCA territory (67 out of 74, 91%, Table 8). The median ASPECTS on these initial scans was 10 (IQR 9–10).

| Ischaemia visible | Initial scan, n (%) | Follow-up scan, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Whole group (n = 271) | 74 (27) | 192 (71) |

| HAS (n = 69) | 45 (65) | 62 (90) |

| χ2 | 67; p < 0.001 | 31; p < 0.001 |

| Abnormal CTA (n = 113) | 58 (5) | 103 (91) |

| χ2 | 56; p < 0.001 | 49.0; p < 0.001 |

| Hyperdense artery, n (%) | Abnormal CTA, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ICA | 4 (5.8) | 5 (4.4) |

| ICA and MCA main stem | 15 (13.3) | |

| ICA, MCA main stem, sylvian branch | 7 (6.2) | |

| ACA | 1 (0.9) | |

| MCA main stem | 42 (60.9) | 29 (25.7) |

| MCA main stem and sylvian branch | 2 (2.9) | 26 (23.0) |

| Sylvian branch | 19 (27.5) | 19 (16.8) |

| Vertebral | 5 (4.4) | |

| Basilar | 2 (2.9) | 4 (1.8) |

| PCA | 2 (1.8) | |

| Totals | 69 | 113 |

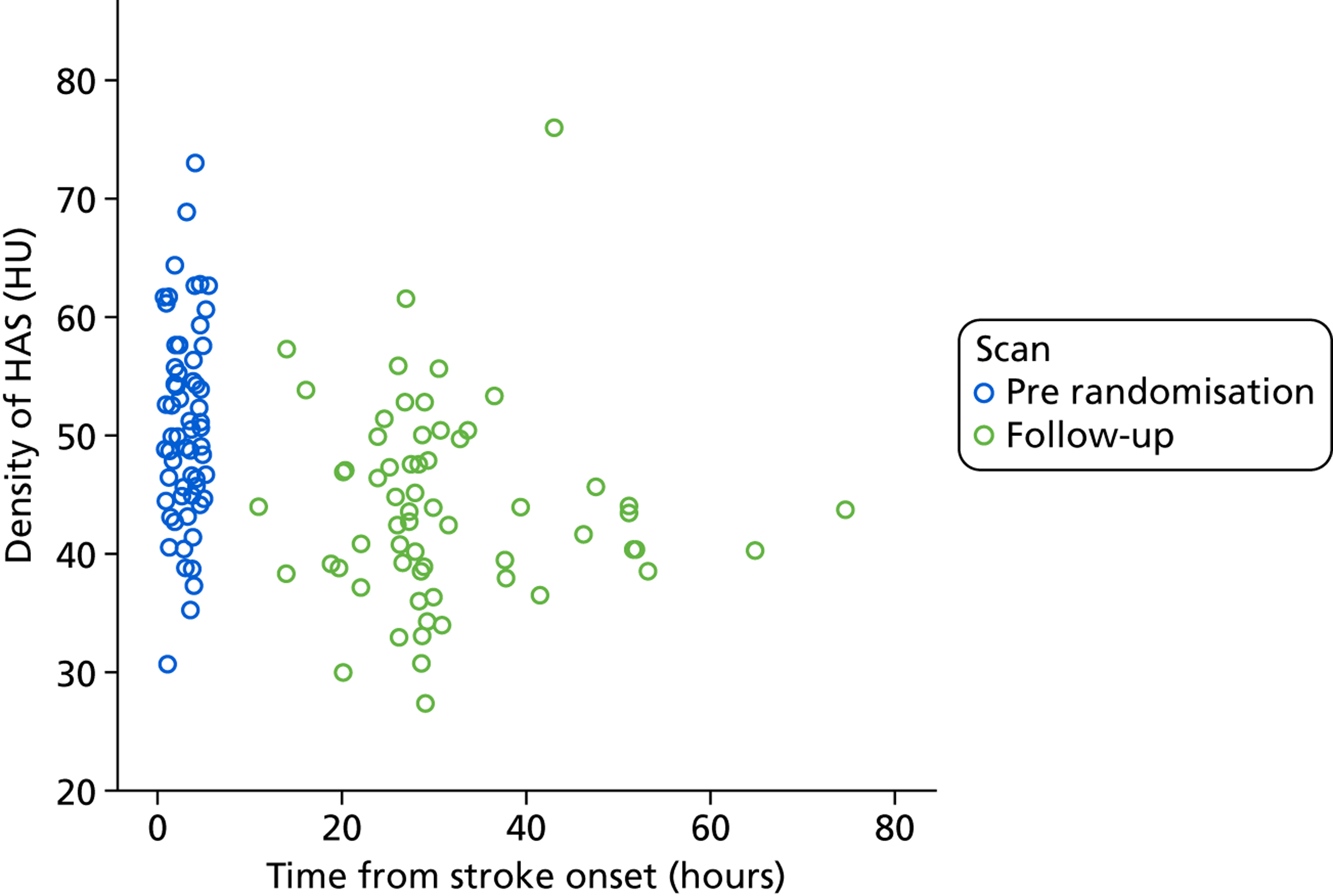

On plain CT, 69 out of 271 patients (25.5%) had a HAS indicating arterial thrombus. Hyperdensity involved a MCA main stem in 44 cases (64%) and had a mean length of 17.5 mm (SD 8.9 mm). The next most frequent site was the MCA sylvian branch (27%). The mean density within these hyperdense vessels was 51.0 HU (SD 8 HU). This compares with mean densities of non-hyperdense arteries of 40.1 HU (SD 5.6 HU), 40.3 HU (SD 7.0 HU) and 39.2 HU (SD 7.1 HU) for the basilar, left and right MCAs, respectively (these differences are significant, with p < 0.001 in all cases). The density ratio of normal to abnormal vessel was 1.4 in those with a HAS in one artery compared with 1.0 in those without any HAS (p < 0.001).

Patients with a HAS were more likely to have acute ischaemia on the plain CT scan (χ2 = 67; p < 0.001); acute ischaemia was found at the higher-than-background rate of 65.2%.

Patients with a HAS were significantly more likely to be female (χ2 = 4.9; p = 0.028) and have a higher NIHSS score at presentation (mean difference 7.2 points; p < 0.001) than those without a HAS. In addition, patients with a HAS were more likely to have a TACI or PACI syndrome (χ2 = 33.3; p < 0.001) with nearly two-thirds of all TACI being associated with a HAS. There was no difference in age, presence of AF, hypertension, previous stroke or time to CT between those with or without a HAS. Neither HAS length, PMD score (or a combination of the two) nor HAS density were related to NIHSS, time to CT, or the presence of AF.

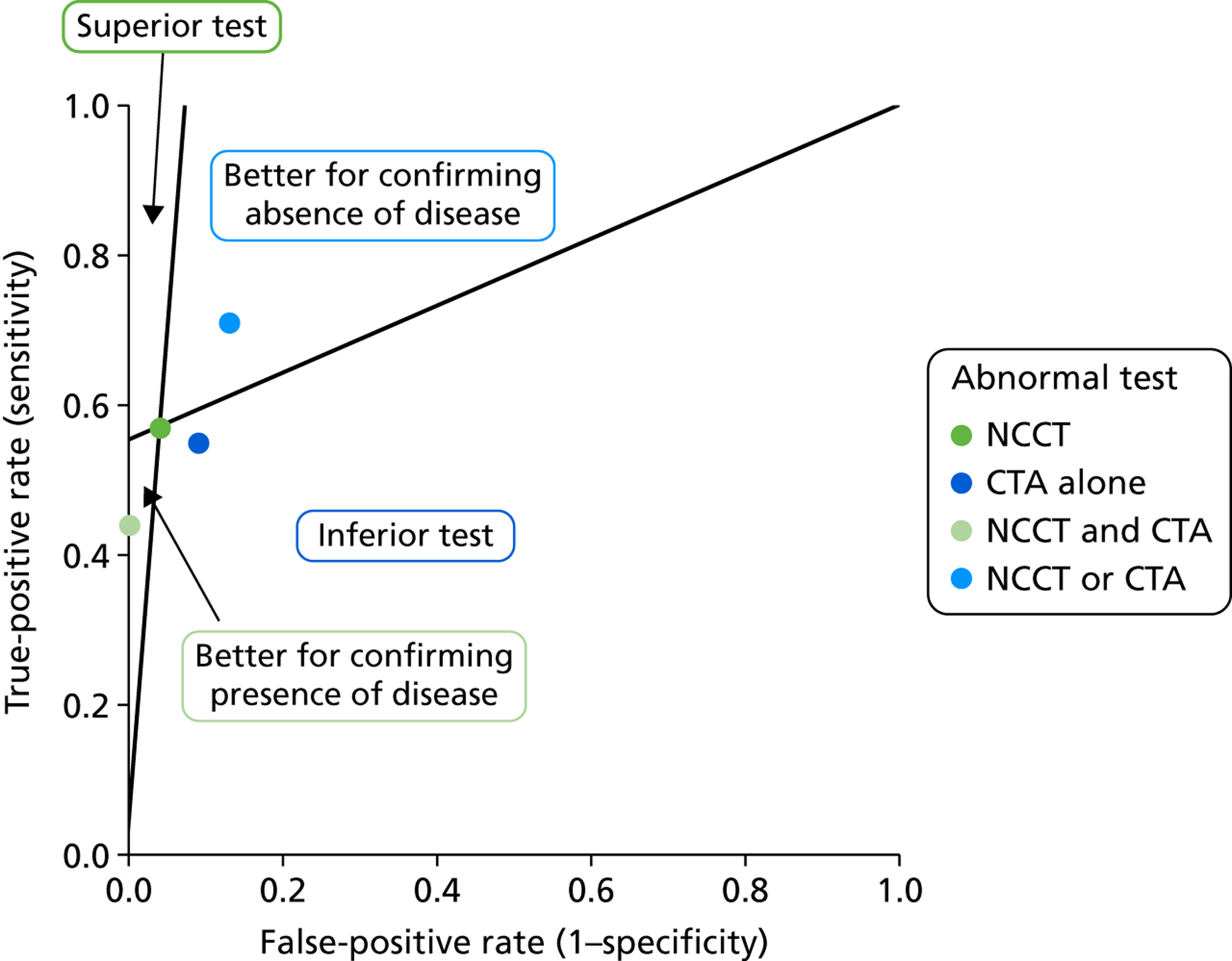

Computed tomography angiography abnormalities, plain computed tomography and clinical findings

There were 113 out of 253 patients (41.7%) with an abnormality on CTA at randomisation (see Table 8). The MCA main stem was most frequently affected (53%), followed by a MCA main stem plus sylvian branch (30%) or a sylvian branch alone (17%). Among patients with an abnormal artery, the TIMI scores were equally spread across degrees of obstruction from complete to sight. Collateral status was defined as ‘good’ (32.5%), ‘moderate’ (37.3%) or ‘poor’ (30.1%). A ‘poor’ collateral supply was associated with lower initial ASPECT scores (p = 0.014) and an increased likelihood of acute ischaemia on the initial scan (χ2 = 4.8; p = 0.028). Similar trends were demonstrated for ischaemic change on follow-up scans but these changes were not significant.