Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 09/20/16. The contractual start date was in October 2010. The final report began editorial review in May 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Lam et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Existing research

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the commonest conditions seen by gastroenterologists, experienced by 1 in 10 of the population at some time in their lives and accounting for up to 40% of new referrals to gastroenterology outpatients departments. The condition is characteristically heterogeneous but all patients have abdominal discomfort and disturbed bowel habit. 1 The other feature found in at least half of patients with IBS is a history of anxiety or depression, and the presence of multiple unexplained physical symptoms, otherwise known as ‘physical symptom disorder’ or ‘somatisation’, is present in two-thirds of patients. Patients often believe that stress aggravates their symptoms but the effect does not appear to be immediate, as there is a poor correlation between stress and symptoms on a day-to-day basis. 2 The effect appears to be more long term and patients with chronic stressors rarely recover until these are relieved. 3 In animals, chronic stress causes diarrhoea, an effect that appears to be mediated through the release of corticotropin-releasing factor within the brain, where it activates descending autonomic pathways, delaying gastric emptying and accelerating colonic transit. Corticotropin-releasing factor is also found locally in the mucosa, where its release may activate mast cells. In addition to these effects of acute stress, chronic stress in experimental animals, generated by repetitive water avoidance or lifelong stress following maternal deprivation in the neonatal period, increases the number of mast cells within the mucosa. This leads to increased gut permeability and increased translocation of bacteria with associated low-grade immune activation within the mucosa. 4

More recently, evidence has been accumulating that similar activation of mast cells can occur in stressed humans. Acute stress induced by immersion of the hand into ice-cold water has been shown to stimulate jejunal water secretion and the release of mast cell products, including tryptase and histamine, in healthy volunteers (HVs). 5 In patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D), mast cell numbers have been shown to be increased in jejunal biopsies, along with intraepithelial CD3+ T lymphocytes (CD3). 6 This study also showed higher tryptase concentration in aspirated jejunal fluid, suggesting that the mast cells were activated,6 and more recent studies show that the ensuing increase in gut permeability is confined to females, suggesting an important gender difference in susceptibility to stress-induced gut changes, which accords with the known female predominance of IBS. We have recently confirmed increased numbers of mast cells and intraepithelial lymphocytes in duodenal biopsies from patients with IBS-D in Nottingham, who also show increased tryptase release into the supernatants of incubated duodenal biopsies. 7

Importance of mast cells in generating irritable bowel syndrome symptoms

There are numerous reports now of increased mast cell numbers in patients with IBS, in the terminal ileum,8,9 caecum10 and rectum. 11–13 Mast cells contain many mediators, including histamine, serotonin (5-HT) and tryptase. 14 Recent interest has focused on the tryptase content because it has been shown to activate protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) receptors, which are found on afferent nerves, and their activation increases sensitivity of the bowel to distension. Supernatants from IBS mucosal biopsies have been shown to activate afferent nerves in an isolated mouse jejunal segment,15 and, more recently, in human colonic submucosal nerves. 14 We propose that anxiety and chronic stressors act in humans to increase the number of activated mast cells throughout the gut in patients with IBS, thereby inducing the characteristic visceral hypersensitivity and abdominal pain. We hypothesised that mesalazine slow-release granule formulation (2 g; PENTASA®, Ferring Pharmaceuticals Ltd) treatment, through its anti-inflammatory effects, would reduce the number of mast cells and thereby reduce abdominal pain, stool looseness and stool frequency.

Previous studies of mast cell stabilisers and anti-inflammatory agents in irritable bowel syndrome

Although there were some poorly designed trials two decades ago, claiming to show that sodium cromoglycate was effective for IBS,16–18 these studies remain unconfirmed and the treatment is not widely used. There have been other smaller studies targeting mast cells with antihistamines, such as ketotifen;19 although this reduced visceral hypersensitivity, it had no effect on mast cell numbers or release of mast cell mediators. Our own trial of prednisolone in postinfective IBS (PI-IBS) was of limited duration – just 3 weeks – and, although this showed a halving of CD3, patient symptoms were already subsiding and we were not able to show any difference from the control subjects. In that study, the fall in mast cell numbers on prednisolone was twice that on placebo but this difference was not statistically significant. We felt that 3 weeks was too short a time period to make an impact on mucosal histology. A strategy that reduced mast cell numbers over the long term might well be more effective than specific inhibitors of mast cell activation, or indeed any specific mast cell products, as these are numerous [histamine, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), prostaglandin, substance P, mast cell tryptase and nerve growth factor (NGF)], all with quite variable modes of action.

Previous studies of mesalazine treatment for irritable bowel syndrome

The first anecdotal open-label trial of 12 patients with resistant IBS-D who responded to mesalazine20 showed a benefit that took about 2–3 months to become apparent. There have since been two further reports of open-label treatment21,22 and two small randomised controlled trials. 23,24 All but the Corinaldesi et al. 23 trial used patients with IBS-D. The Bafutto et al. trial22 used mesalazine 800 mg three times a day for 30 days in 61 patients with IBS-D – 18 of whom had PI-IBS and showed benefit with a reduction in stool frequency, stool consistency and abdominal pain – but was uncontrolled, with no placebo arm. The Andrews et al. study21 involved just six patients but this showed that mesalazine decreased biopsy proteolytic activity. Both of the randomised controlled trials23,24 are rather too small for their significance to be sure, with n = 20 and n = 17, respectively. One study23 showed a significant reduction of mast cell numbers and an overall reduction in inflammatory cells.

Risk and benefits

Mesalazine has been widely used for > 45 years and there are extensive data on its side effects. In general, the drug is well tolerated. Nephrotoxicity is seen at a rate of about 1 per 100,000 prescriptions;25 commoner, but less serious, side effects include diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, together with headaches, pancreatitis and blood disorders, which are all rare. Balancing this, patients with IBS suffer a marked decrease in quality of life, similar to that of other chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart failure. They also spend significant amounts of time off work and when they are at work they work less efficiently. A simple safe and effective treatment would be of undoubted benefit to what is a substantial subgroup of the population, given that IBS-D affects around 3% of the general population.

Rationale for the current study

Studies in Nottingham over the last decade have identified the importance of inflammation in various subgroups of IBS. We have focused on the group of patients with IBS who develop symptoms following acute bacterial gastroenteritis, the so-called postinfectious IBS. In this group, we have been able to show that the acute inflammatory insult associated with acute Campylobacter jejuni enteritis is followed by a more prolonged indolent phase with increased chronic inflammatory cells long after the infecting organism has left the body. In this subgroup of IBS we have demonstrated activated circulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells with increased cytokine production and an associated increase in inflammatory gene expression. 26 We have also demonstrated the importance of anxiety and depression,27 which, along with adverse life events, increase the risk of PI-IBS. 28 The changes observed in PI-IBS are similar to those in IBS-D, the predominant bowel disturbance being diarrhoea with a similar prognosis. 29 This work has been supported by others who have shown inflammatory changes in patients with IBS-D who do not have a background of previous infection. 30,31 Such studies have also shown increased inflammatory cells and increased expression of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β). 32 Increased gut permeability has also been shown in IBS-D,33 making a trial of an anti-inflammatory treatment a logical choice. Safety is of pre-eminent importance with IBS drugs, as can be seen by the recent withdrawal of tegaserod34 (Zelnorm®, Novartis) and the previous withdrawal of alosetron (Lotronex®, Prometheus). 35 Both drugs, which were therapeutically effective, had to be withdrawn as a result of rare side effects (incidence < 1 per 700 patients treated). This leaves such patients bereft of effective treatments, a gap that mesalazine might well fill. Our hypothesis was that mesalazine, by virtue of its anti-inflammatory actions, would alter the inflammatory mediators leading, over a number of weeks, to a reduction in the number of mast cells and a reduction in the release of inflammatory mediators, and hence to a reduction in symptoms. Previous studies have shown that 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) inhibits the release of inflammatory mediators, including histamine and prostaglandin D2. 36 It also inhibits activation of the transcription factor ‘nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer’ of activated B cells, which is a major link in the inflammatory cascade. 37 More recently, it has been recognised that 5-ASA exerts an anti-inflammatory effect that is mediated via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ receptors). 38 Whether directly or indirectly, 5-ASA has also been reported to inhibit inducible nitric oxide synthetase production and also prostaglandin production via its cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory effects. 39 Mesalazine, therefore, both by virtue of inhibiting other inflammatory pathways and by directly inhibiting mast cell pathways, may reduce mucosal immune activation. We plan to investigate the effect of long-term mesalazine on mast cell numbers, the chronic inflammatory cells and the mucosal production of inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) as well as mast cell-specific tryptase. We also examined its effect on stool calprotectin, a marker of colonic inflammation, which is widely used to exclude inflammatory bowel disease and is also recognised to be modestly elevated in around 25% of most IBS series.

Chapter 2 Trial/study purpose and objectives

Purpose

The purpose of the trial was to define the clinical benefit and possible mediators of the benefit of mesalazine in IBS-D.

We therefore evaluated symptoms (primarily bowel frequency) and objective biomarkers reflecting mast cell activation and small bowel tone.

Primary objective

Effect of mesalazine on stool frequency in weeks 11 and 12.

Secondary objectives

Effect of mesalazine on the following:

-

overall IBS symptoms

-

mast cell numbers, mucosal lymphocytes and faecal tryptases

-

small bowel tone by measurement of fasting small bowel water content through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Our overall aim was to assess the ability of the biomarkers listed above to predict treatment response.

Chapter 3 Trial/study design

Trial/study configuration

This was a multicentre, two-arm, parallel-group, double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial comparing mesalazine with placebo in patients with IBS-D. The design of the study was modified after consultation with a selection of interested patients from the Nottingham Digestive Diseases Biomedical Research Unit patient advisory group, who provided a lay member for the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Randomisation and blinding

This was a double-blind, parallel-group study. The participant, supervising doctor and study nurse were not aware of the treatment allocation.

The randomisation was based on a computer-generated pseudo-random code using random permuted blocks of randomly varying size, created by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) in accordance with their standard operating procedure (SOP), and held on a secure server. The randomisation was stratified by the recruiting centre. The supervising doctor or study nurse obtained a randomisation reference number for each participant by means of a remote, internet-based randomisation system that was developed and maintained by the Nottingham CTU.

The sequence and decode of treatment allocations were concealed until all interventions were assigned, recruitment, data collection and all other trial-related assessments were complete, and data files were locked.

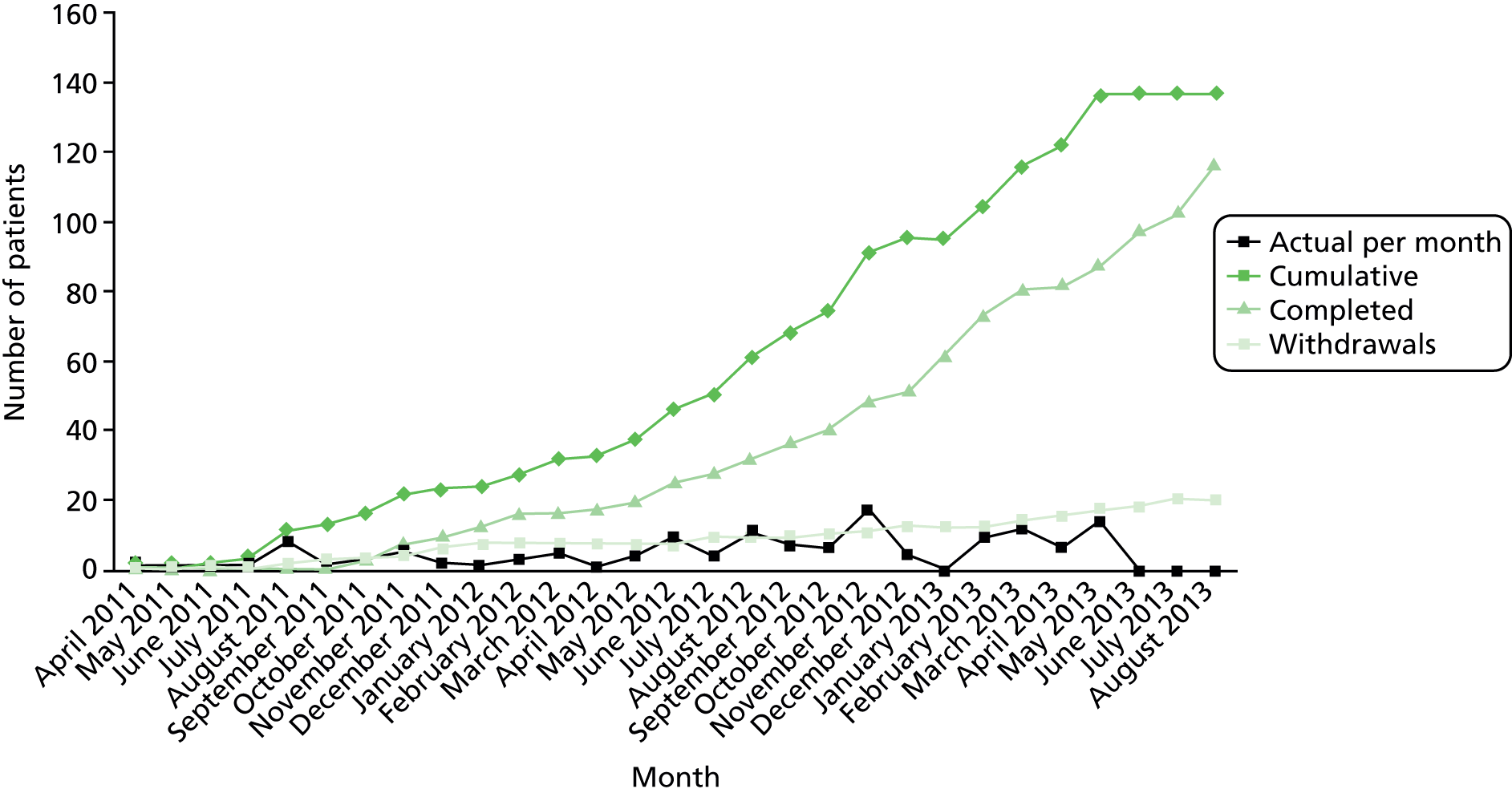

Participants

Recruitment

Participants were recruited between April 2011 and May 2013, with the last patient completed in August 2013. Recruitment was from IBS clinics at the investigators’ hospital, or from lists of patients who had previously taken part in research studies and had indicated that they would like to be contacted about future relevant research projects. In addition, we had, in conjunction with the local Primary Care Research Network (PCRN), approached general practitioners to ask them to search their databases for eligible participants and send out letters of invitation along with participant information sheets (PISs). Either way, the initial approach was from a member of the patient’s usual care team or from appropriately authorised research nurses. We also advertised in the local newspaper. Initial recruitment into this trial was slow, using the Rome III criteria1 based on daily diary recordings, whereas previous studies had used reported symptoms based on recall. We felt that the eligibility criteria for IBS-D were too demanding. We therefore modified the eligible criteria for IBS-D following registration with ‘ClinicalTrials.gov’ to reflect the fact that, as others have found, the bowel habit of patients with IBS-D is less abnormal than patients’ reported symptoms suggest. 40

The patients were required to meet the modified Rome III criteria for IBS-D,1 defined as a stool frequency of ≥ 3 per day for > 2 days per week and ≥ 25% of stools to be of types 5–7 [i.e. unlike standard Rome III criteria,1 which state Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) 6 and 7, to include stool form 5 as well] and < 25% of types 1 and 2 according to the BSFS. 41 To exclude other causes of diarrhoea, we required normal colonoscopy and colonic biopsies, normal full blood count, serum calcium and albumin, C-reactive protein and negative serological test for coeliac disease. Lactose intolerance was tested by asking patients to consume 568 ml of milk per day and performing a lactose breath hydrogen test if they developed diarrhoeal symptoms within 3 hours. If the stools were watery and frequent then the patient underwent a 7-day retention of selenium-75-labelled homocholic acid taurine test or a trial of cholestyramine to exclude bile acid malabsorption. If any of these tests were positive then the patient was excluded from the study. All patients gave written consent. Another inclusion criterion was age 18–75 years. Exclusion criteria were prior history of major abdominal surgery; liver or kidney impairment; or chronic ingestion of any anti-inflammatory drugs or medications that could affect the gut motility. All childbearing female patients tested negative on the pregnancy test during the randomisation day and had to agree to adequate contraception during the trial. Patients who were on long-term selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) were included if they were on a stable dose for 3 months and undertook to maintain the dose unaltered throughout the trial. During the screening period of 2 weeks, patients were allowed a maximum of only two doses of 4 mg loperamide (Immodium®, Janssen) per week and discontinued any IBS medication. Once randomised, patients were allowed to take loperamide to control their symptoms, as we hypothesised that mesalazine would take at least 6 weeks to exert its effect on the gut. During the last 2 weeks of the trial when the primary end points were being assessed, patients were not allowed loperamide or any antibiotics. Ethical approval was sought for any adverts or posters displayed in the relevant clinical areas. Patients were seen in the research centres in participating hospitals and enrolled by research nurses or doctors.

Patient visits and contacts are shown in Table 1.

| Procedure | Visit 1: screening (T = –2) | Visit 2: randomisation (T = 0, from first dose) | Telephone contact (T = 1) | Telephone contacta (T = 3) | Visit 3 (T = 6) | Telephone contacta (T = 9) | Visit 4: final visit (T = 12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Check eligibility | • | • | Check on diary completion, AE check, concurrent medication and treatment tolerance with particular reference to the step increase in IMP dose | Check on diary completion, AE check, concurrent medication and treatment tolerance | Check on diary completion, AE check, concurrent medication and treatment tolerance | |||

| Informed consent | • | |||||||

| Demographics and bowel symptoms | • | |||||||

| Physical examination and history | • | |||||||

| Daily symptom and stool diaryb | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Sigmoidoscopy with biopsy to exclude microscopic colitisc | • | |||||||

| Pregnancy test | • | |||||||

| Randomisation | • | |||||||

| Questionnairesd | • | • | ||||||

| Blood and stool sample | • | • | • | |||||

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy and biopsiese | • (Nottingham only) | • (Nottingham only) | ||||||

| MRI scanse | • (Nottingham only) | • (Nottingham only) | ||||||

| IMP | Dispense | • | • | |||||

| Return | • | • | ||||||

| Adverse reaction recording | • | • | ||||||

Inclusion criteria

-

Male or female patients, aged 18–75 years, able to give informed consent.

-

Patients should all have had a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy within the last 12 months to exclude microscopic or any inflammatory colitis (if not, but they have had a negative colonoscopy within 5 years and symptoms are unchanged, then a sigmoidoscopy and mucosal biopsy of the left colon would be sufficient to exclude microscopic or any inflammatory colitis).

-

Patients with IBS-D, meeting Rome III criteria1 prior to screening phase.

-

Patients with ≥ 25% soft stools (score > 4, i.e. 5–7) and < 25% hard stools (score 1 or 2) during the screening phase, as scored by the daily symptom and stool diary.*

-

Patients with a stool frequency of ≥ 3 per day for ≥ 2 days per week during the screening phase.*

-

Satisfactory completion of the daily stool and symptom diary during the screening phase at the discretion of the investigator.

-

Women of childbearing potential willing and able to use at least one highly effective contraceptive method throughout the study. In the context of this study, an effective method is defined as those that result in low failure rate (i.e. < 1% per year) when used consistently and correctly, such as implants, injectables, combined oral contraceptives, sexual abstinence or vasectomised partner.

*If inclusion criterion 4 and/or 5 is/are not met but the results are considered atypical (as observed from medical history and patient recall) then the patient can be rescreened on one occasion only. There must be sufficient data completed during the screening phase to allow adequate classification.

Definition of diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome meeting the Rome III criteria

This was defined as abdominal pain or discomfort at least 2–3 days per month in the last 3 months (criterion fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to screening) associated with two or more of the following:

-

improvement with defecation

-

onset associated with a change of stool frequency

-

onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.

Exclusion criteria

-

Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

-

Prior abdominal surgery that may cause bowel symptoms that are similar to IBS (note appendectomy and cholecystectomy will not be exclusions).

-

Patients unable to stop antimuscarinic drugs, antispasmodic drugs, high-dose TCAs (i.e. > 50 mg/day), opiates/antidiarrhoeal drugs,* non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (occasional over-the-counter use and topical formulations are allowed), long-term antibiotic drugs, other anti-inflammatory drugs or 5-ASA-containing drugs.

-

Patients on SSRIs and low-dose TCAs (i.e. ≤ 50 mg/day) for at least 3 months, previously unwilling to remain on a stable dose for the duration of the trial.

-

Patients with other gastrointestinal diseases, including colitis and Crohn’s disease.

-

Patients with the following conditions: renal impairment, severe hepatic impairment or salicylate hypersensitivity.

-

Patients currently participating in another trial or who have been involved in a trial within the previous 3 months.

-

Patients who in the opinion of the investigator are considered unsuitable owing to an inability to comply with instructions.

-

Patients with serious concomitant diseases, for example cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, etc.

(A full list of excluded or dose-controlled medications can be found in Appendix 1.)

*Loperamide is allowed as rescue medication throughout the trial; however, if > 2 doses per week are taken during the screening phase then they are not eligible, although they can be rescreened on one occasion only.

Expected duration of participant participation

Study participants participated in the study for 14 weeks.

Removal of participants from therapy or assessments

The following subject withdrawal criteria applied:

-

Non-compliance – if < 75% of the investigational medicinal product (IMP) doses are taken between visits, at the investigator’s discretion. (Dose as advised by the study doctor, taking into account that not all participants will be advised to take the full study dose owing to intolerance.)

-

If the participant has remained on the initial lower dose of 2 g once a day for 3 weeks and the medication is still not tolerated, at the investigator’s discretion.

-

Adverse reaction (serious and non-serious) with clear contraindications.

-

Participant withdraws consent.

-

Safety reasons, for example pregnancy.*

-

Lost to follow-up.

-

Participant develops an excluded/contraindicated condition.

-

Investigator discretion (e.g. protocol violations).

-

Unblinding, at the discretion of the principal investigator in conjunction with the chief investigator.

*In the event of a pregnancy occurring in a trial participant or the partner of a trial participant, monitoring will occur during the pregnancy and after delivery to ascertain any trial-related adverse events (AEs) in the mother or the offspring. When pregnancy occurs in the partner of a trial participant, consent will be obtained for this observation from both the partner and her medical practitioner.

Participants withdrawn from the study were replaced. The participants were told that withdrawal would not affect their future care. Participants were also made aware (via the information sheet and consent form) that, should they withdraw, the data collected up to their withdrawal could not be erased and may still be used in the final analysis.

Chapter 4 Main outcome measures

Clinical outcomes

Primary outcome

-

Daily mean stool frequency during weeks 11–12 of the treatment period.

Secondary outcomes (all assessed during weeks 11–12 of the treatment period)

-

Average daily severity of abdominal pain on a 0–10 scale.

-

Days with urgency during weeks 11–12 post randomisation.

-

Mean stool consistency using BSFS.

-

Global satisfaction with control of IBS symptoms, as assessed from the answer to the question ‘Have you had satisfactory relief of your IBS symptoms this week? Yes/no’.

Ancillary secondary end points

-

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D).

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention health-related quality of life Healthy Days Core Module (CDC HRQOL4).

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

-

Patient Health Questionnaire 15 (PHQ-15).

Safety end points

-

AEs related to the trial treatment.

-

Withdrawal from the trial treatment as a result of AEs.

Mechanistic outcomes

Primary outcome

-

Mast cell numbers (mean percentage area stained) at week 12.

Secondary outcomes

-

Mast cell tryptase release during 6-hour biopsy incubation.

-

IL-1β, TNF-α, histamine and 5-HT secretion during same incubation.

-

Small bowel tone assessed by volume of fasting small bowel water.

-

Faecal tryptases and calprotectin.

-

Difference in primary outcome measure between those with different TNFSF15 polymorphism will be assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Chapter 5 Sample size

Our previous study on patients with IBS-D gives a mean stool frequency of 3.1 [standard deviation (SD) 2.0]. Tuteja et al. 24 reported mesalazine decreasing stool frequency by 1.4 bowel movements per day. Our study had 80% power to detect such an effect at the 1% two-sided alpha level. We aimed to randomise at least 125 patients to allow for 20% dropout rate but, owing to recruitment ongoing at multiple sites and patient requests, we actually recruited 136.

Much smaller numbers are needed to assess the effect of mesalazine on mast cell numbers and tryptase release. Corinaldesi et al. 23 reported a 36% decrease in mast cell numbers from a mean of 9.2% over lamina propria area, that is 2.96% over lamina propria area (SD 2.5% over lamina propria area), which, assuming average change on placebo is 0, requires just 16 patients to show a significant difference with a power of 90% at the 5% alpha level.

Chapter 6 Data analysis

Analysis and presentation of data was in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidance. The primary data set included stool diary filled for at least 10 days out of 14. Balance between the trial arms at baseline was examined using appropriate descriptive statistics. For continuous variables, data were summarised in terms of the mean, SD, median, lower and upper quartiles, minimum, maximum and number of observations. Categorical variables were summarised in terms of frequency counts and percentages.

The general approach for between-group comparisons was intention to treat (ITT). Appropriate regression modelling was used to evaluate the primary and secondary outcomes, and safety data, with due emphasis placed on clinical importance of 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for between-group estimates.

No formal adjustment for multiple significance testing was applied. We also performed a sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation of missing data for the primary outcome.

Full details were given in a separate Statistical Analysis Plan approved before data lock.

The safety monitoring functions of the trial was undertaken by the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC).

Assessment of efficacy

We used descriptive statistics to compare the randomised groups at baseline. The primary outcome was assessed using ITT without imputation. We used a generalised linear mixed model to compare the mesalazine group and placebo group for the primary outcome, with adjustment for the baseline value of the outcome, and study centre as a random effect. Additionally, we adjusted for any variables showing imbalance at baseline in secondary models. We compared the characteristics of participants who did and did not adhere with the study medication before estimating the treatment effect if the medication was actually taken using Complier Average Causal Effect (CACE) analysis. We investigated the effect of missing primary outcome data using multiple imputation. The secondary outcomes were assessed using similar models as for primary outcome, or logistic or Poisson regression, as appropriate, dependent on outcome type.

We undertook subgroup analyses by including appropriate interaction terms in the linear mixed model for primary outcome according to baseline daily mean stool frequency, baseline mean abdominal pain score and baseline mean HADS anxiety score.

Secondary outcomes were treated similarly, after transformation if appropriate, whereas binary and count outcomes were handled by multiple logistic or Poisson regression, as appropriate. Given the large number of potential comparisons, p-values for mechanistic variables will not be presented. All analyses were performed using Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) adopting the ITT principle without imputation for missing data (with a sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation for the primary outcome).

We planned to conduct a number of prespecified subgroup analyses.

For each of the three outcomes listed below, we investigated whether or not there were any differences in between-group effects according to the following baseline variables: anxiety, stool frequency, abdominal pain and mast cell activation:*

-

stool frequency during weeks 11–12

-

number of days with any stool consistency scoring 6 or 7 during weeks 11–12

-

mean score of worst pain for each day, averaged over weeks 11 and 12.

*Mast cell activation will be defined as elevation of any of the inflammatory mediator components, such as mast cell tryptase, IL-1β, TNF-α, histamine and 5-HT in biopsy supernatant.

These subgroup analyses were conducted by including appropriate interaction terms in the regression models and, as the study has not been powered to detect any such subgroup effects, were considered as exploratory and would require confirmation in future research.

The primary mechanism hypothesis to be investigated was that treatment with mesalazine reduces inflammation, which, in turn, reduces clinical symptoms. The aim of this type of analysis is to estimate how much of any observed treatment effect can be attributed to a variable that is thought to be an intermediate on the causal pathway, or mediator.

After summarising inflammatory markers at baseline and 11–12 weeks’ follow-up by trial arm using appropriate descriptive statistics, we will examine change in these markers (stool calprotectin, mast cell tryptase, mast cell percentage area stained) and change in stool frequency using a scatter plot.

Definition of populations analysed

Safety set All randomised participants who receive at least one dose of the study drug. All AEs in this set are reported.

ITT set All randomised participants for whom at least one post-baseline assessment of the primary end point is available.

Stool samples and sigmoid colon biopsies

These were collected at week 0 and the end of trial (EOT) from patients recruited in Nottingham. Stools collected were analysed for calprotectin. A commercially available calprotectin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Buhlmann, Schönenbuch, Switzerland) was used for extraction and quantification of stool calprotectin. Samples were analysed for faecal tryptase based on a method published recently by our group. 42 Faecal protease activity is expressed in trypsin units per mg of protein.

Sigmoid biopsies were collected for immunohistochemistry for mast cell tryptase, CD3, CD68 (a marker of macrophage) and 5-HT, and tissues were processed and stained in the histopathology laboratory in Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, UK. A further set of biopsies was maintained in culture and supernatants collected were assayed for (1) mast cell tryptase, chymase, carboxypeptidase A3 (CPA3) and histamine, and (2) IL-1β and TNF-α levels. The biopsy tissues were incubated immediately in Hanks’ medium for 30 minutes before storing at –80 °C until assays for (1) mast cell mediators were performed by the Immunopharmacology Group at the University of Southampton; and (2) IL-1β and TNF-α levels were performed by RI, Research Fellow in Centre of Biomolecular Science, University of Nottingham. Levels of IL-1β and TNF-α was analysed by using a commercial kit V-PLEX immunoassay (Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, MD, USA).

Histological methods (see Appendix 2)

Mast cell numbers were assessed as the mean of area percentage stained per region of interest (m2).

Faecal tryptase

Stool samples were collected at baseline (randomisation day) and at the EOT (end of week 12).

Chapter 7 Results

Of 221 patients initially screened, 185 were eligible and 136 were enrolled and randomised into the study (Figure 1). Follow-up was completed in August 2013. The most frequent reason for exclusion was disinclination to participate. The commonest reason for not meeting inclusion criteria was that the patients’ diaries during the 2 weeks’ run-in period indicated that they did not have loose stools ≥ 25% of the time or stool frequency of ≥ 3 per day for ≥ 2 days per week.

FIGURE 1.

Patient flow chart (CONSORT diagram).

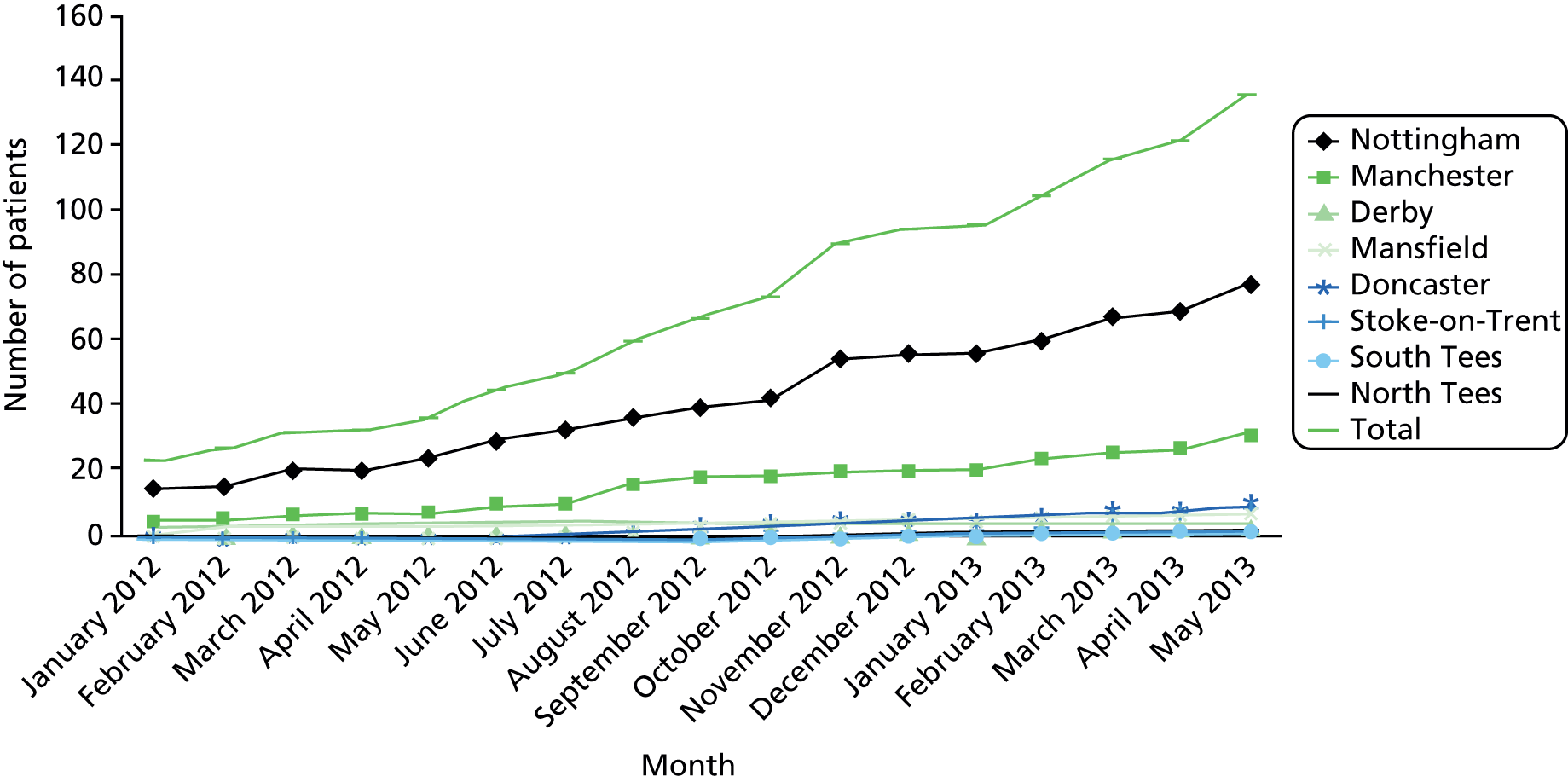

Demographics

A total of eight sites participated in this study. Table 2 and Appendix 2 (see Table 16) show a summary of recruitment by site and by treatment arm.

| Site | Placebo, n | Mesalazine, n |

|---|---|---|

| Nottingham | 38 | 40 |

| Manchester | 16 | 15 |

| Derby | 2 | 2 |

| Mansfield | 4 | 3 |

| Doncaster | 5 | 5 |

| Stoke-on-Trent | 1 | 1 |

| South Tees | 1 | 1 |

| North Tees | 1 | 1 |

Characteristics of enrolled patients in both groups were similar at baseline (Table 3).

| Characteristic | Mesalazine (n = 68) | Placebo (n = 68) | Total (n = 136) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrolment (years), mean (SD) | 42.6 (15.2) | 47.1 (13.5) | 44.8 (14.4) |

| Gender, (male), n (%) | 26 (38.2) | 28 (41.2) | 54 (39.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 66 (97.1) | 66 (97.1) | 132 (97.1) |

| Black | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) |

| Asian | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Mixed | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) |

| Daily mean stool frequency, mean (SD) | 3.6 (1.6) | 3.6 (1.8) | 3.6 (1.7) |

| Daily mean abdominal pain score, mean (SD) | 4.1 (2.2) | 3.6 (2.0) | 3.6 (1.7) |

| Number of days with urgency, median (IQR) | 13 (10–14) | 12 (9–14) | 12.5 (9–14) |

| Stool consistency, mean (SD) | 5.4 (0.7) | 5.6 (1.0) | 5.5 (4.4) |

| HADS score, mean (SD) | 9.1 (4.5) | 8.6 (4.3) | 8.8 (4.4) |

| PHQ-15 score, mean (SD) | 12.6 (5.2) | 13.1 (5.6) | 12.8 (5.4) |

Primary and secondary outcome data were collected for 115 (85%) and 116 (85%) participants, respectively, at 11–12 weeks of follow-up.

Clinical primary outcome

The primary ITT comparison showed no evidence of any clinically significant difference between mesalazine and placebo for the primary outcome (Table 4). Additional adjustments for variables (age, abdominal pain score, number of days with urgency and PHQ-15 score) displaying imbalance at baseline did not materially change the results (Table 5a) and nor did multiple imputation analysis or CACE analysis (Table 5b–c).

| Group/comparison | Daily mean stool frequency at 11–12 weeks, mean (SD) | Between-group difference at 11–12 weeks (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 2.7 (1.9) (n = 58) | – | – |

| Mesalazine | 2.8 (1.2) (n = 57) | – | – |

| Mesalazine vs. placebo | – | 0.10 (–0.33 to 0.53) | 0.658 |

| Comparison | Adjusteda difference in mean frequency | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesalazine vs. placebo | 0.13 | 0.562 | –0.31 to 0.57 |

| Comparison | Adjusteda difference in mean frequency | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesalazine vs. placebo | 0.06 | 0.172 | –0.18 to 0.99 |

| Comparison | Adjusteda difference in mean frequency | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesalazine vs. placebo | 0.16 | 0.669 | –0.58 to 0.91 |

Subgroup analyses (Table 6a) of the primary outcome by baseline daily mean stool frequency suggest that mesalazine may be more effective among patients with greater baseline stool frequency and is associated with larger treatment effect, but this could be a chance finding and would require confirmation in further studies. There was no evidence that treatment effect differed according to baseline pain or HADS (Table 6b and c). Our sensitivity analysis, using multiple imputation of missing data for the primary outcome, showed no effect on primary outcome (see Table 6b).

| Baseline frequency | Placebo (n = 58) | Mesalazine (n = 57) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily mean stool frequency at 11–12 weeks by baseline frequency, mean (SD) | |||

| ≤ 2.4 | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.4) | |

| > 2.4 and ≤ 3.4 | 2.2 (1.1) | 2.2 (0.5) | |

| > 3.4 and ≤ 4.6 | 2.7 (0.9) | 3.1 (1.3) | |

| > 4.6 | 4.7 (2.9) | 4.1 (1.1) | |

| Estimatesa for interaction in primary analysis model with 95% CI and p-value | |||

| Primary outcome by baseline stool frequency | –0.26 (–0.51 to –0.01); p = 0.043 | ||

| Baseline pain score | Placebo (n = 58) | Mesalazine (n = 57) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily mean stool frequency at 11–12 weeks by baseline abdominal pain score, mean (SD) | |||

| ≤ 2.2 | 2.9 (2.8) | 2.7 (0.9) | |

| > 2.2 and ≤ 4.1 | 2.6 (1.4) | 2.4 (0.7) | |

| > 4.1 and ≤ 5.3 | 2.4 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.6) | |

| > 5.3 | 3.2 (1.7) | 2.9 (1.3) | |

| Estimatesa for interaction in primary analysis model with 95% CI and p-value | |||

| Primary outcome by baseline pain score | –0.03 (–0.10 to 0.04); p = 0.361 | ||

| Baseline HADS score | Placebo (n = 58) | Mesalazine (n = 57) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily mean stool frequency at 11–12 weeks by baseline HADS score, mean (SD) | |||

| ≤ 5.0 | 3.1 (3.2) | 3.0 (1.4) | |

| > 5.0 and ≤ 9.0 | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.2) | |

| > 9.0 and ≤ 11.5 | 3.0 (1.5) | 2.9 (1.3) | |

| > 11.5 | 2.0 (0.9) | 2.6 (1.3) | |

| Estimatesa for interaction in primary analysis model with 95% CI and p-value | |||

| Primary outcome by baseline HADS score | –0.01 (–0.04 to 0.03); p = 0.792 | ||

Clinical secondary outcomes

No differences were apparent for any of the secondary outcomes, with the exception of number of days with urgency (Table 7), which were increased by about 20% on mesalazine treatment compared with placebo.

| Treatment outcome with mesalazine or placebo | Baseline | 11–12 weeks | Between-group comparison at 11–12 weeks (95% CI)a | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily mean abdominal pain score, mean (SD) | ||||

| Placebo | 3.6 (2.0) | 2.2 (2.1) (n = 59) | – | – |

| Mesalazine | 4.1 (2.2) | 2.8 (2.1) (n = 57) | – | – |

| Mesalazine vs. placebo | – | – | 0.07 (–0.54 to 0.68)b | 0.828 |

| Number of days with urgency, median (IQR) | ||||

| Placebo | 12 (9–14) | 8 (1–13) (n = 59) | – | – |

| Mesalazine | 13 (10–14) | 11 (5–14) (n = 57) | – | – |

| Mesalazine vs. placebo | – | – | 1.22 (1.07 to 1.39)c | 0.003 |

| Weekly mean stool consistency, mean (SD) | ||||

| Placebo | 5.6 (1.0) | 4.7 (1.1) (n = 59) | – | – |

| Mesalazine | 5.4 (0.7) | 4.7 (1.0) (n = 57) | – | – |

| Mesalazine vs. placebo | – | – | 0.13 (–0.21 to 0.48)b | 0.452 |

| Number of days with consistency score 6 or 7, median (IQR) | ||||

| Placebo | 11 (8–13) | 6 (2–9) (n = 59) | – | – |

| Mesalazine | 11 (8–13) | 7 (2–11) (n = 57) | – | – |

| Mesalazine vs. placebo | – | – | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.27)c | 0.210 |

| Mean HADS score | ||||

| Placebo | 8.6 (4.3) | 6.9 (3.6) (n = 59) | – | – |

| Mesalazine | 9.0 (4.5) | 7.5 (5.0) (n = 57) | – | – |

| Mesalazine vs. placebo | – | – | 0.67 (–0.38 to 1.72)b | 0.210 |

| Mean PHQ-15 score, mean (SD) | ||||

| Placebo | 13.1 (5.6) | 9.4 (5.0) (n = 59) | – | – |

| Mesalazine | 12.6 (5.2) | 10.0 (5.2) (n = 57) | – | – |

| Mesalazine vs. placebo | – | – | 0.63 (–0.93 to 2.20)b | 0.428 |

| Number of people with satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Placebo | 0 | 24 (40.7) (n = 59) | – | – |

| Mesalazine | 0 | 25 (43.9) (n = 57) | – | – |

| Mesalazine vs. placebo | – | – | 1.13 (0.51 to 2.47)d | 0.762 |

| EQ-5D: five division components that have no problems, n (%) | Baseline | After treatment | ||

| Placebo | Mesalazine | Placebo | Mesalazine | |

| Mobility | 46 (67.6) | 53 (77.9) | 47 (79.3) | 44 (77.2) |

| Self-care | 66 (97.1) | 63 (92.6) | 57 (96.6) | 52 (91.2) |

| Usual activity | 39 (57.4) | 44 (64.7) | 44 (74.6) | 45 (78.9) |

| Pain/discomfort | 7 (10.3) | 8 (11.8) | 15 (25.4) | 15 (26.3) |

| Anxiety/depression | 39 (57.4) | 39 (57.4) | 37 (62.7) | 35 (61.4) |

| EQ VAS score, mean (SD) | Baseline | After treatment | Between-group comparison (95% CI) | p-value |

| Placebo | 64.3 (20.2) | 69.7 (18.3) (n = 59) | – | – |

| Mesalazine | 64.2 (20.6) | 72.6 (19.2) (n = 57) | – | – |

| Mesalazine vs. placebo | – | – | 2.39 (–3.24 to 8.02)b | 0.406 |

Compliance

Compliance was defined a priori as taking ≥ 75% of the medication throughout the 12 weeks. Each patient was given two boxes of medication during the 12-week study, each box containing 100 sachets. The amount of medication taken was calculated by 200 minus the number of medication sachets returned at EOT. Compliance with medication (Table 8) and baseline characteristics of compliers (defined as taking ≥ 75% of the medication throughout the 12 weeks) were similar in both groups. Analysis of the primary outcome using the CACE approach showed no difference between the two treatment arms (mean difference 0.2, 95% CI –0.6 to 0.9).

Adverse events

The most frequently occurring side effect was exacerbation of IBS symptoms, which could be worsening abdominal pain or diarrhoea. Two patients (3%) from the mesalazine group and three (5%) from the placebo group complained of this and were withdrawn from the study. Other less frequent side effects are listed in Appendix 2 (see Table 15). One patient was pregnant in the middle of the trial period, although she had a negative result in a pregnancy test at the start of the trial. She was withdrawn from study with no adverse consequence to her or her newborn. 43 One patient from the mesalazine group was found to have breast cancer and she was withdrawn from the study, as her IBS symptoms and stool diary would have been very difficult to interpret. All participants who developed these AEs were withdrawn from the study and their symptoms settled on follow-up – see Appendix 2, Table 15.

Mechanistic primary outcome

Mast cells

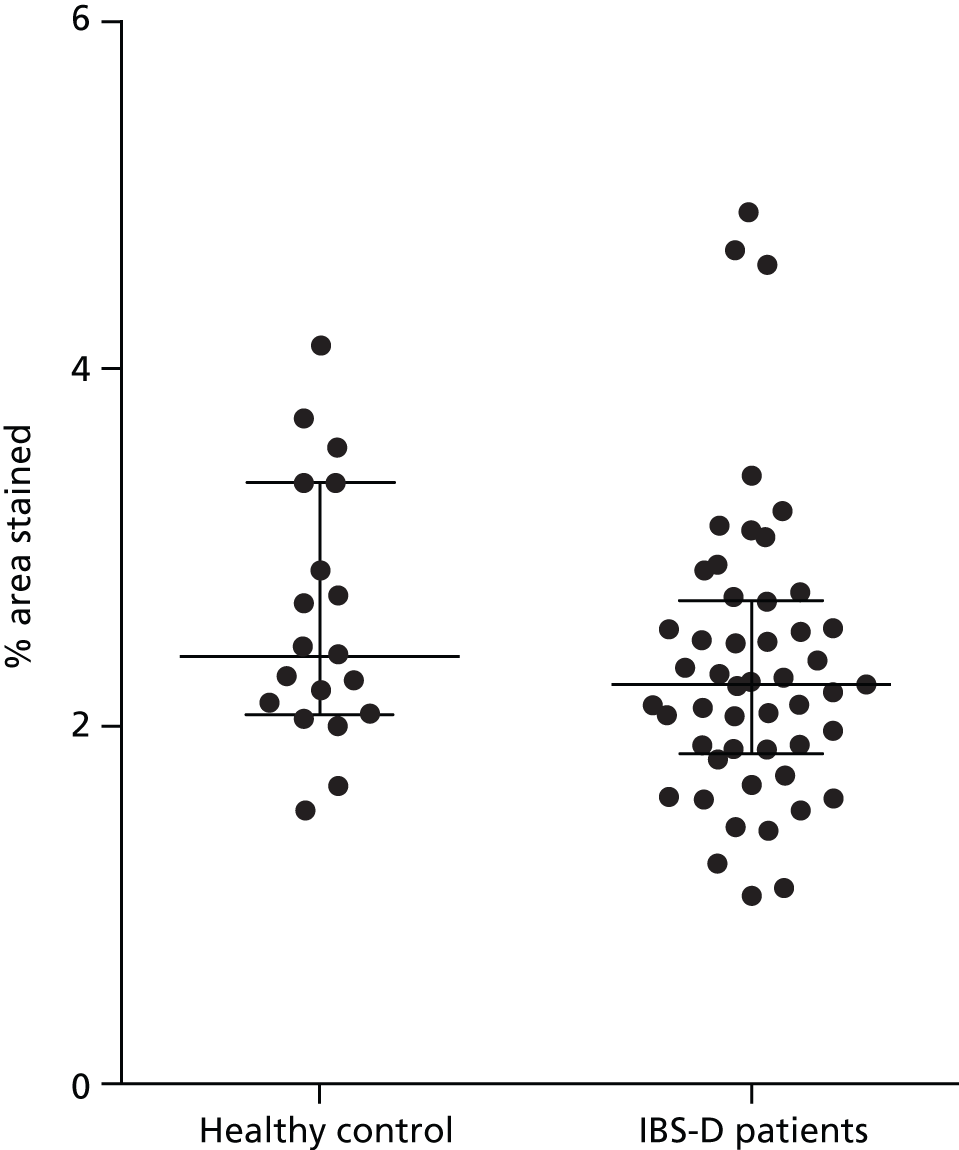

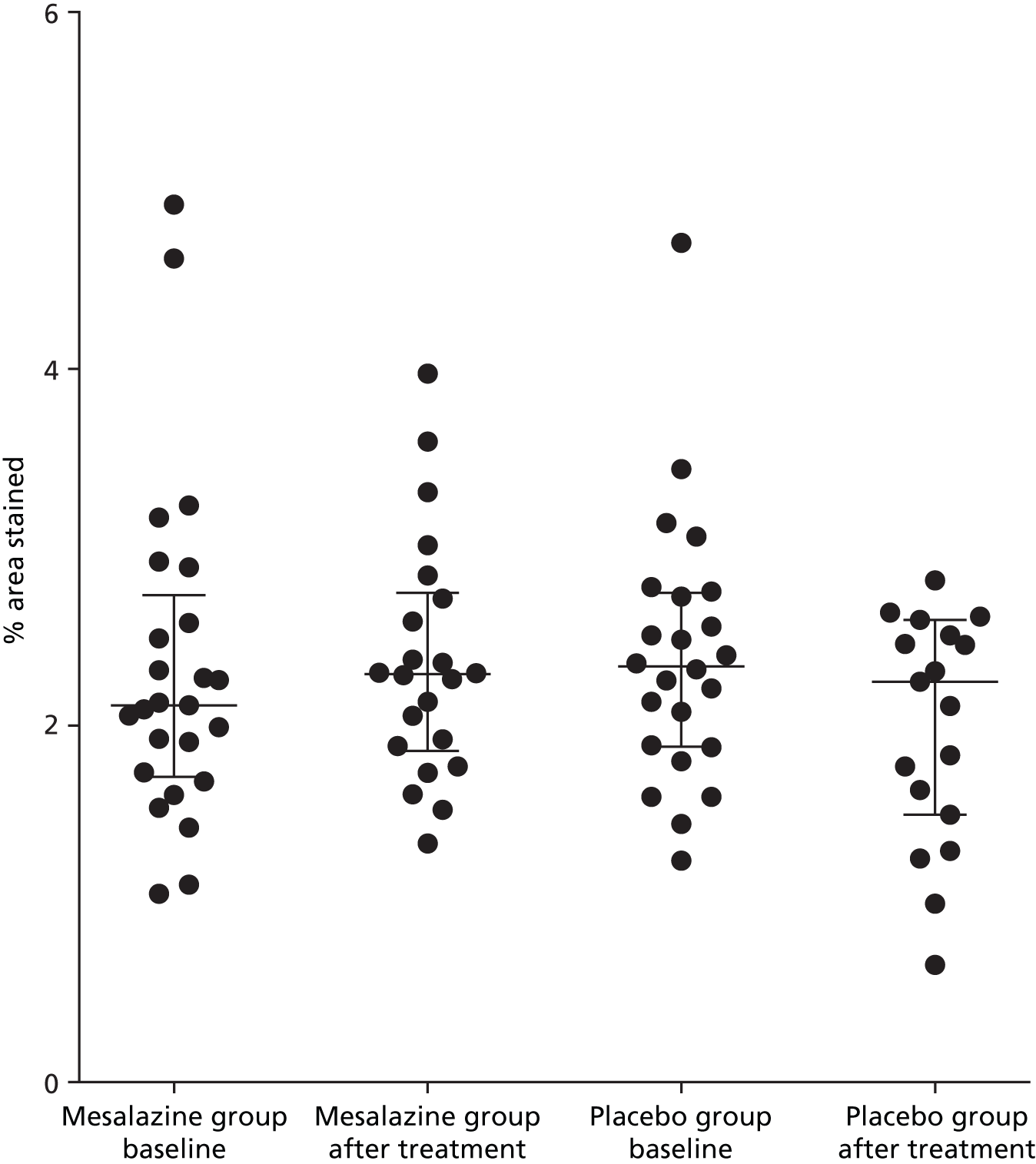

The mast cell percentage area stained was not elevated in patients with IBS-D compared with our normal range that was established previously in our laboratory. The baseline mast cell percentage area stained for patients with IBS-D was median 2.25% [interquartile range (IQR) 1.86–2.73%], compared with median 2.42% (IQR 2.09–3.39%) in the healthy control subjects (Figure 2). There was no reduction in mast cell percentage area stained following treatment with mesalazine (Figure 3 and Table 9).

FIGURE 2.

Mast cell count assessed from percentage area stained comparing healthy control subjects and patients with IBS-D (median, IQR).

FIGURE 3.

Effect of mesalazine vs. placebo on mast cell percentage area stained in patients with IBS-D (median, IQR).

| Mesalazine | Placebo | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | After treatment | Baseline | After treatment |

| 2.11 (1.06–2.11) | 2.29 (1.86–2.75) | 2.33 (1.88–2.74) | 2.25 (1.5–2.59) |

Mechanistic secondary outcome

Mast cell tryptase and other mediator release during biopsy incubation

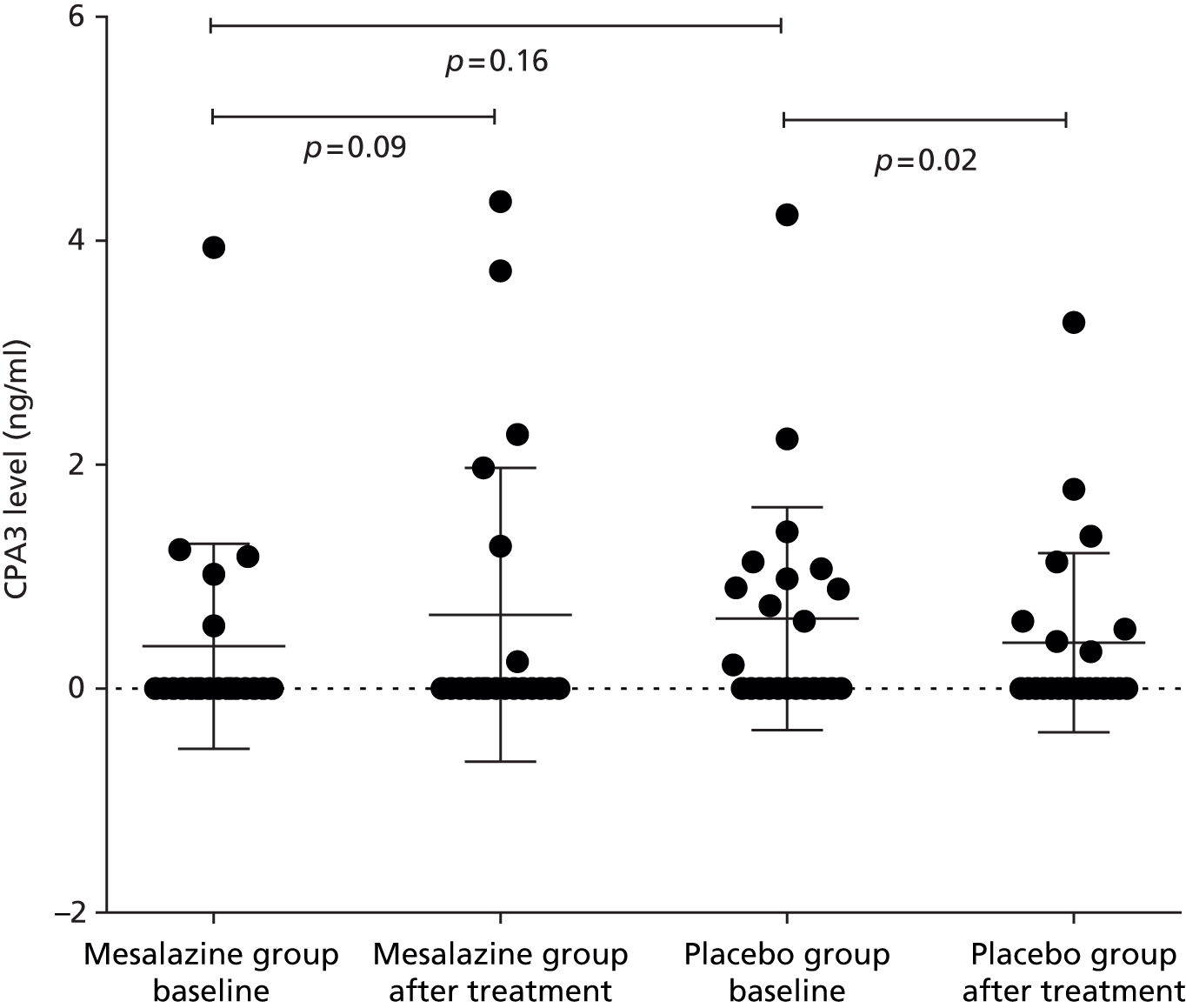

Baseline supernatant levels were compared between patients with IBS-D and our normal range in healthy volunteers. There was no significant increase in the baseline mediator levels except CPA3 (Figure 4 and Table 10).

FIGURE 4.

Baseline CPA3 levels in patients with IBS-D. Shaded area indicates normal range in HVs (median, IQR).

| Mediator | HVs, n = 21 | IBS-D patients, n = 45 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptase | 6.7 (3.8–11.4) | 4.3 (1.8–8.9) | 0.07 |

| Chymase | 0 | 0 (0–0.9) | 0.14 |

| CPA3 | 0.34 (0.28–0.52) | 0 (0–0.9) | 0.0496 |

| Histamine | 1.6 (0.7–3.8) | 0.7 (0–1.3) | < 0.01 |

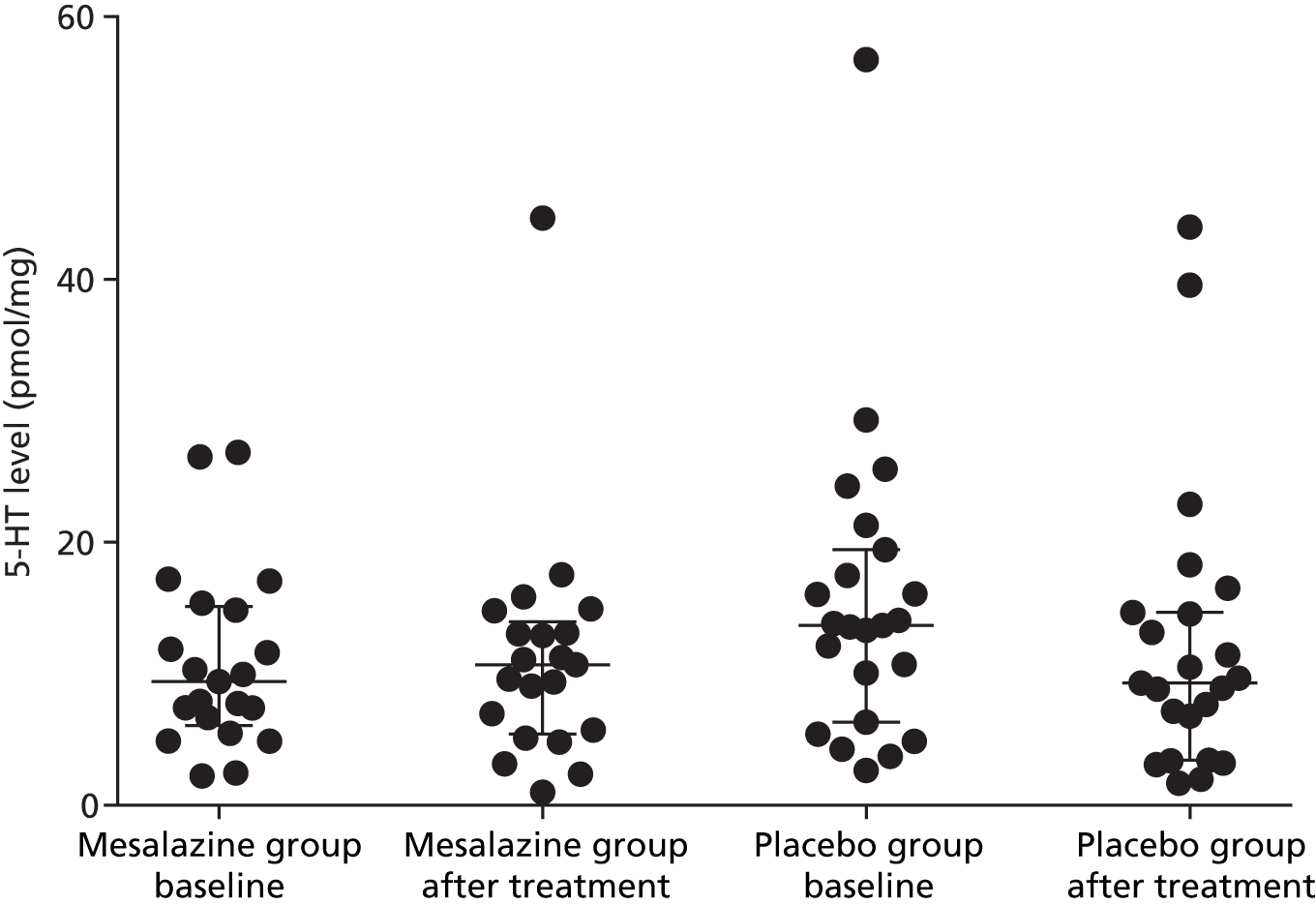

Following treatment with either mesalazine or placebo in the patients with IBS-D, there was no change in the supernatant levels of the mediators (Table 11 and Figures 5–9).

| Supernatant mediators | Mesalazine baseline (n = 21) | Placebo baseline (n = 23) | Mesalazine after treatment | Placebo after treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptase | 4.3 (1.5–8.6) | 4.6 (2.5–9.1) | 4.9 (1.8–8.2) | 5.8 (2.1–10.3) |

| Chymase | 0 (0–0.3) | 0 (0–0.8) | 0 (0–1.7) | 0 (0–0.4) |

| CPA3 | 0 (0–0.3) | 0 (0–1.0) | 0 (0–0.8) | 0 (0–0.5) |

| Histamine | 0.9 (0.3–1.4) | 0.7 (0–1.4) | 0.8 (0–1.2) | 0.7 (0.2–1.0) |

| 5-HT | 9.4 (6.1–15.1) | 6.3 (2.7–13.7) | 10.7 (5.4–14.0) | 9.3 (3.4–14.7) |

FIGURE 5.

Tryptase levels before and after treatment with mesalazine or placebo (median, IQR).

FIGURE 6.

Chymase levels before and after treatment with mesalazine or placebo (median, IQR).

FIGURE 7.

Carboxypeptidase A3 levels before and after treatment with mesalazine or placebo (median, IQR).

FIGURE 8.

Histamine levels before and after treatment with mesalazine or placebo (median, IQR).

FIGURE 9.

Serotonin levels before and after treatment with mesalazine or placebo (median, IQR).

Interleukin-1 beta, tumour necrosis factor alpha

Levels of IL-1β and TNF-α in supernatant were below the level of detection.

Small bowel tone assessed by volume of fasting small bowel water

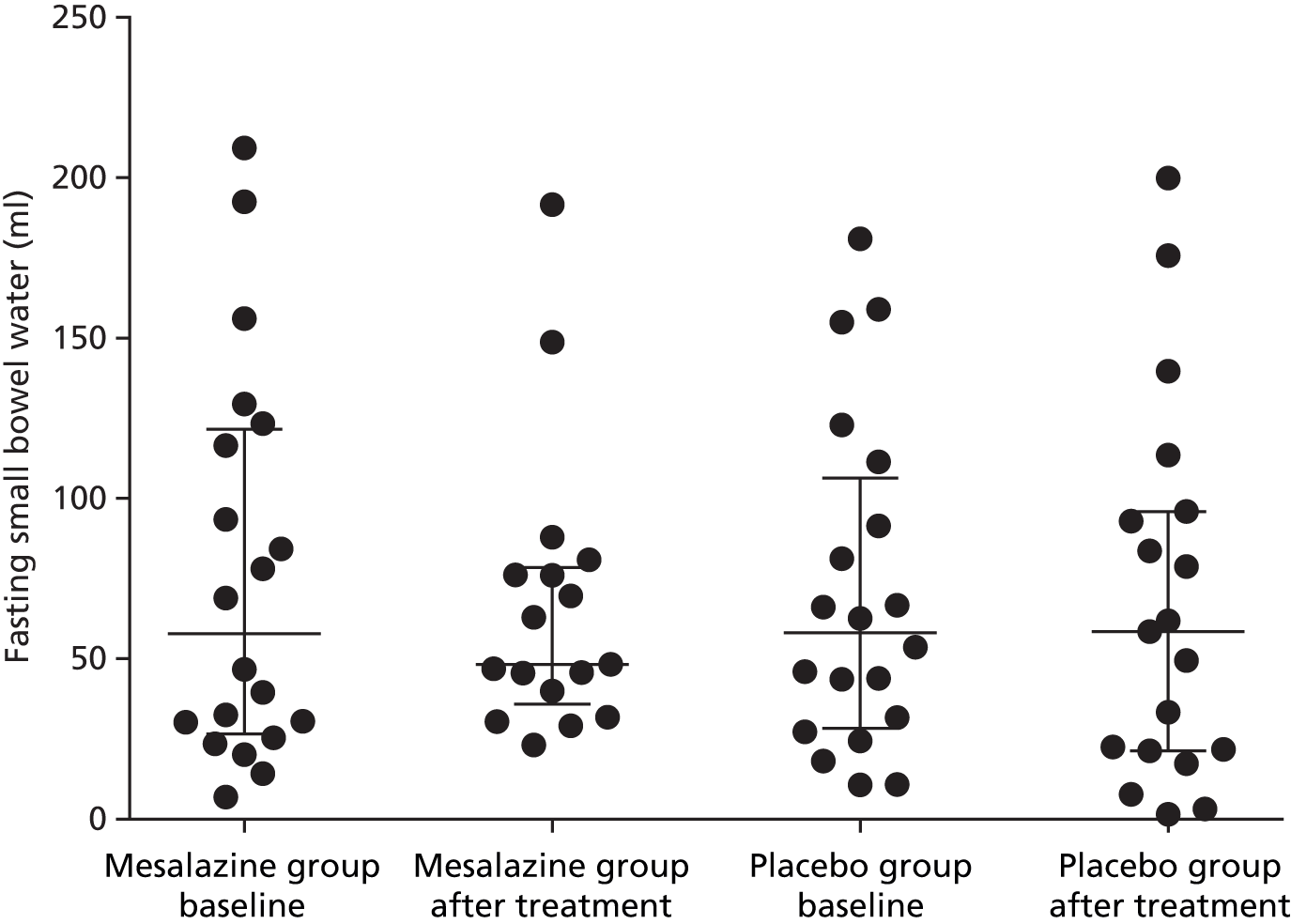

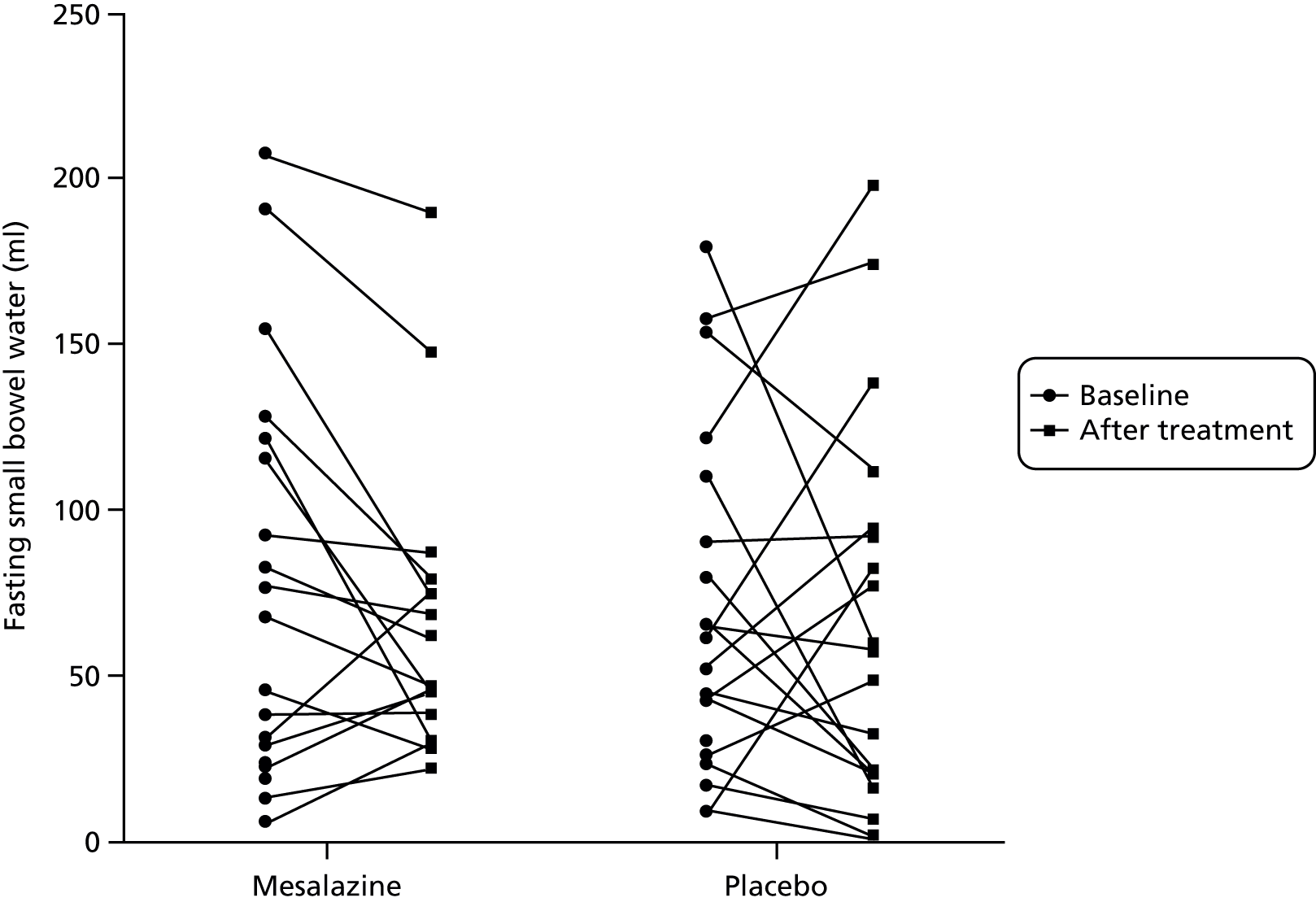

Fasting small bowel water showed wide variability, ranging from 5 to 220 ml. This did not alter significantly after treatment with either mesalazine or placebo (Table 12, Figures 10 and 11).

| Fasting small bowel water content (ml), median (IQR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesalazine baseline (n = 17) | Placebo baseline (n = 20) | Mesalazine after treatment | Placebo after treatment |

| 58 (27–122) | 58 (28–106) | 48 (36–79) | 58 (21–96) |

FIGURE 10.

Fasting small bowel water before and after treatment with mesalazine or placebo (median, IQR).

FIGURE 11.

Changes in fasting small bowel water before and after treatment with either mesalazine or placebo.

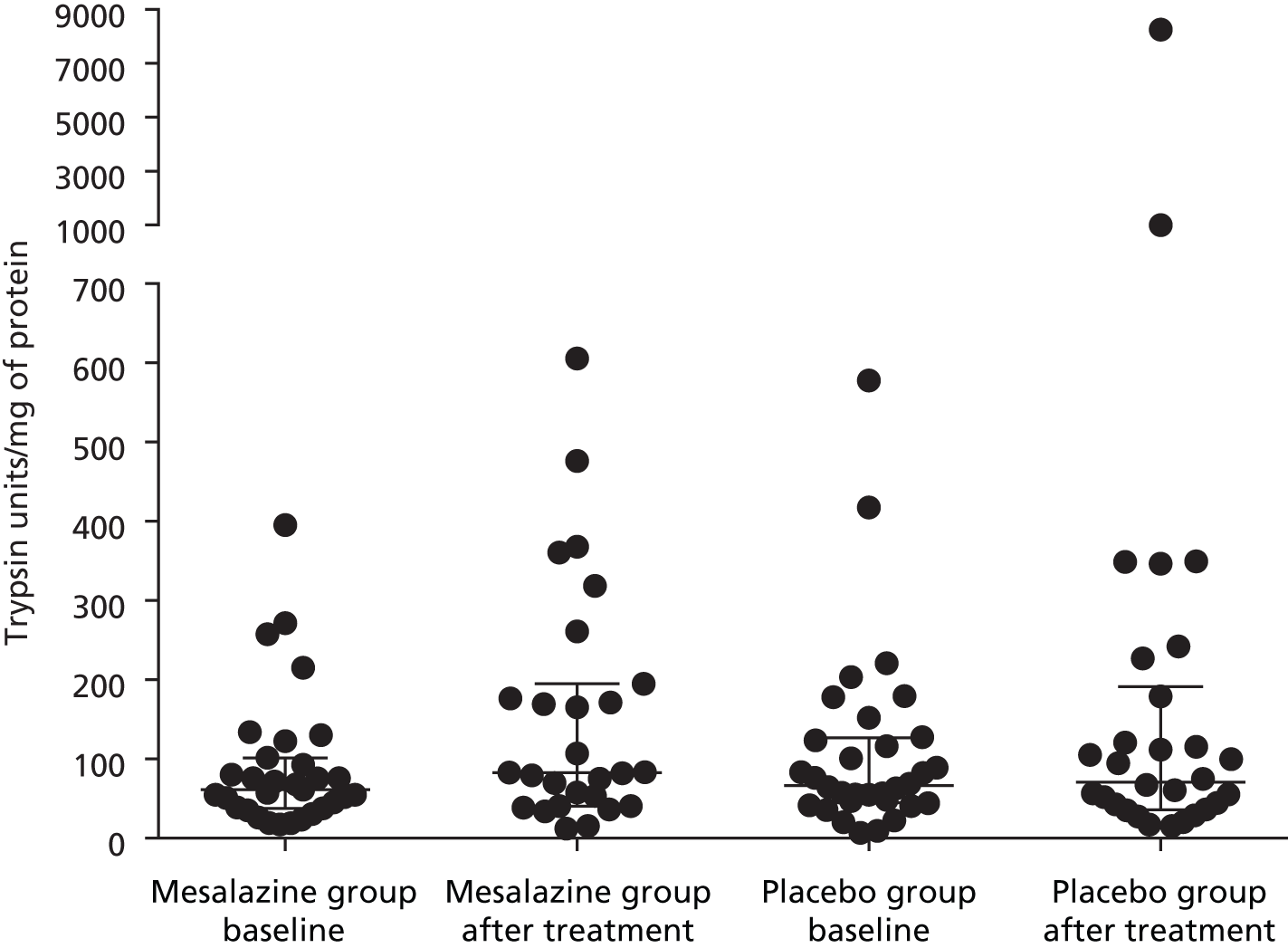

Faecal tryptases

Totals of 27 and 30 pairs of stool samples were collected in the mesalazine and placebo groups, respectively. The baseline faecal tryptase level was in the range of between 6.8 and 577.8 trypsin units/mg of protein, which was highly variable. There was a significant increase in faecal tryptase after treatment with mesalazine (Table 13 and Figure 12). There was no correlation between baseline faecal tryptase level and baseline supernatant tryptase level: Spearman’s r = 0.13, p = 0.41. There was no significant correlation between baseline faecal tryptase level and anxiety, depression or bowel symptoms.

| Baseline, median (IQR) | After treatment, median (IQR) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesalazine (n = 30) | Placebo (n = 27) | Mesalazine | Placebo |

| 61.2 (37.6–101.4) | 66.5 (44.8–126.5) | 82.7 (40.5–194.8) | 70.9 (36.0–191) |

FIGURE 12.

Change in faecal tryptase following treatment with mesalazine compared with placebo (median, IQR).

Difference in primary outcome measure between those with different TNFSF15 polymorphism

Genotyping has yet to be done but, given the predicted small numbers with the risk allele and the lack of evidence of immune activation, a significant gene effect is unlikely to be detected.

Post hoc analysis

Mast cell percentage area stained

There was no correlation between mast cell percentage area stained with clinical features, such as abdominal pain severity, urgency, bloating, daily mean stool frequency or stool consistency.

We found no significant correlation of mast cell percentage area stained with objective measures of tryptase, chymase, CPA3 and histamine in biopsy supernatants.

Other immune cells, for example CD3+ T lymphocyte, CD68- and serotonin-containing enterochromaffin cells

There was no effect on either treatment with mesalazine or placebo on CD68-staining macrophages or on 5-HT-containing enterochromaffin cells. There was a paradoxical increase in CD3 count following treatment with mesalazine for reasons which are unclear (Figure 13).

FIGURE 13.

CD3+ T lymphocyte count before and after treatment with mesalazine or placebo (median, IQR).

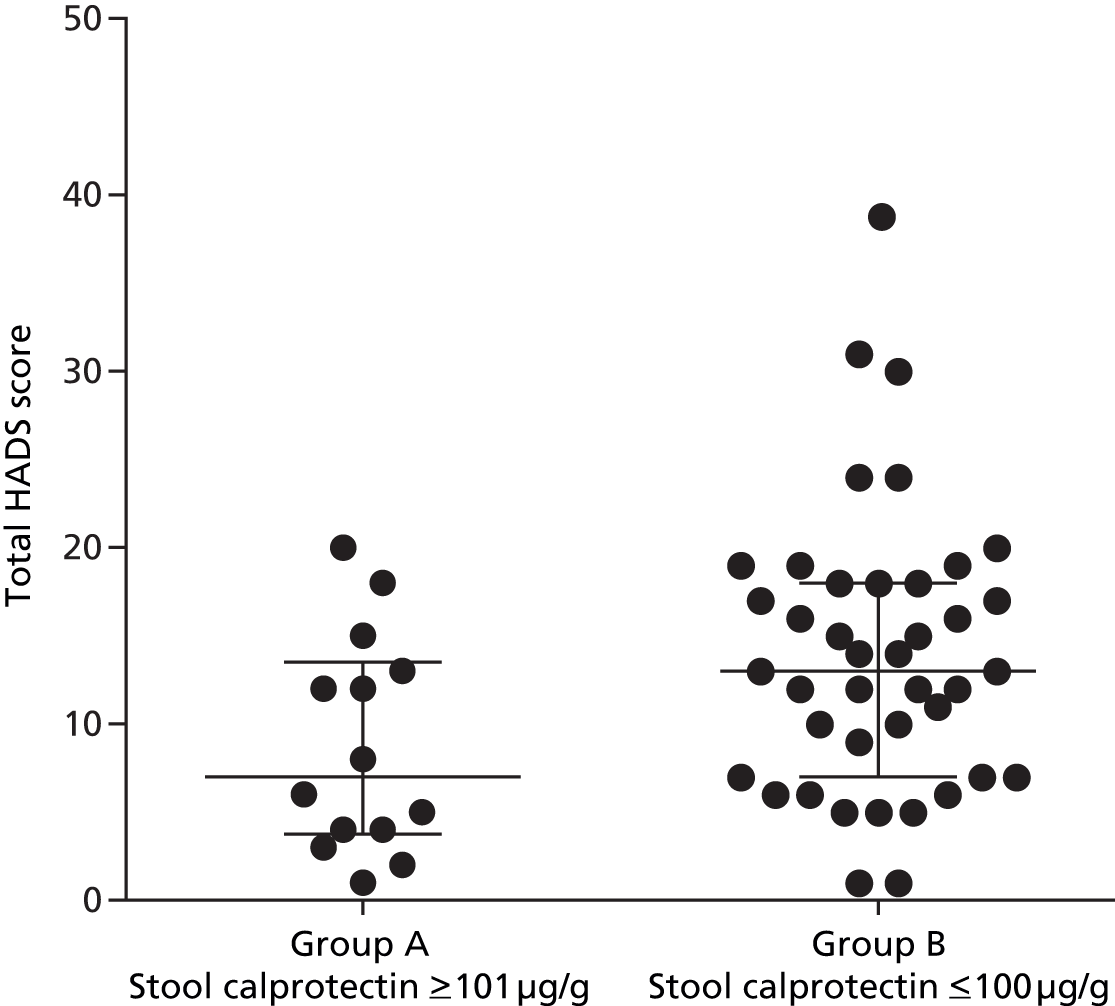

Stool calprotectin

Samples were obtained from 53 patients (30 placebo group, 23 mesalazine group). Baseline stool calprotectin levels varied widely, ranging from undetectable to as high as 420 µg/g. There was a negative correlation between calprotectin levels and baseline total HADS score but this did not reach significance (r = 0.25, p = 0.07) (Figure 14).

FIGURE 14.

Correlation between baseline calprotectin levels (µg/g) and baseline total HADS score.

When patients were divided into two groups based on stool calprotectin levels of ≤ 100 µg/g (group B) and ≥ 101 µg/g (group A), the group with higher calprotectin levels (≥ 101 µg/g, group A) at baseline showed a significantly lower total HADS score than the normal calprotectin level group (group B) (Figure 15). Otherwise, comparing these two groups, there were no differences with their baseline clinical characteristics such as abdominal pain severity, average daily stool frequency and stool consistency.

FIGURE 15.

Baseline stool calprotectin levels when divided into two groups (median, IQR).

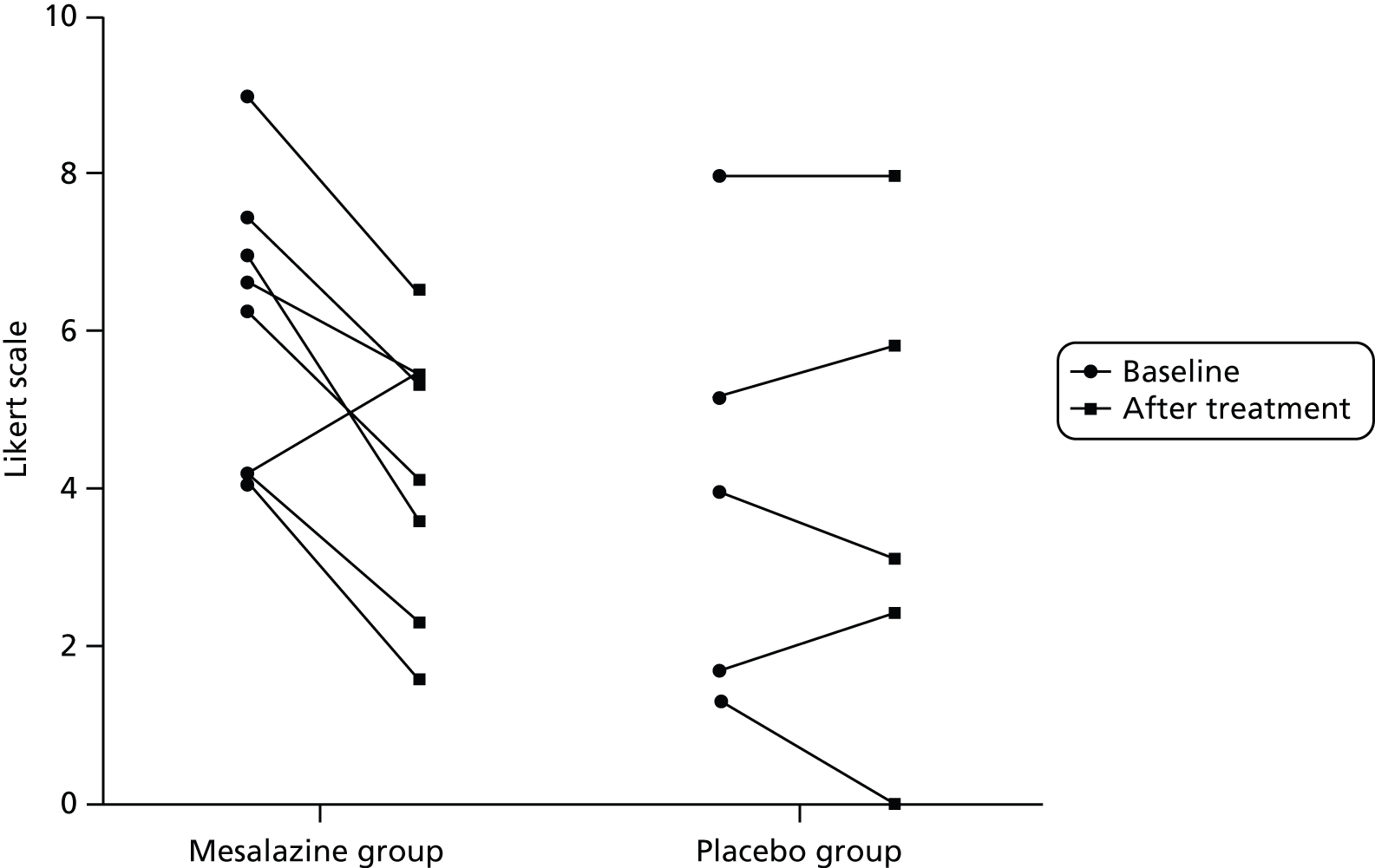

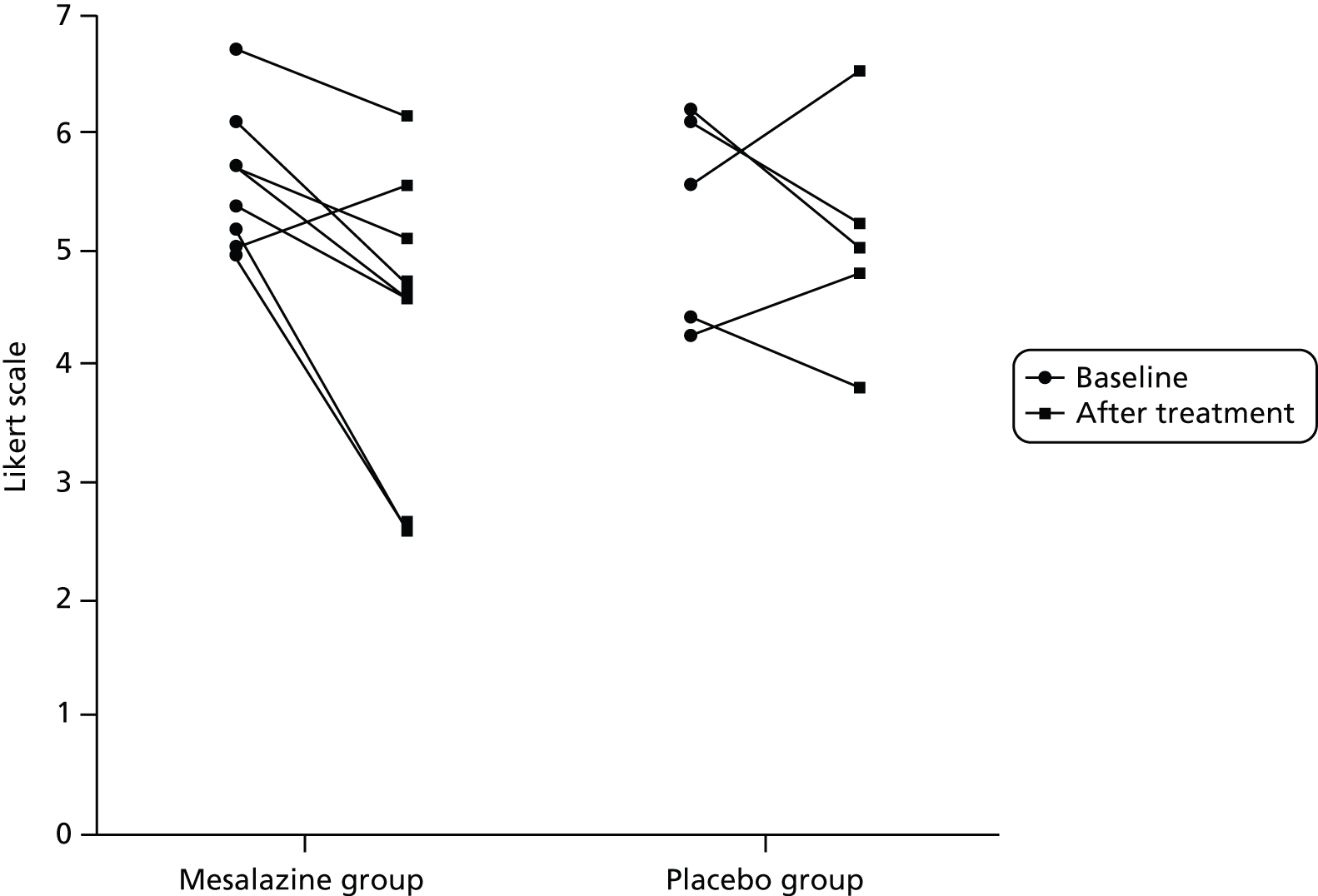

Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome

Thirteen participants met the previously published criteria for PI-IBS. 11 They had to meet Rome III criteria1 for IBS following an episode of infectious gastroenteritis characterised by ≥ 2 of the following symptoms: fever, vomiting, diarrhoea and positive stool culture. 11 Eight participants were randomised into the mesalazine group and five were allocated to the placebo group. There was significant improvement in clinical symptoms – such as abdominal pain, urgency and stool consistency – following treatment with mesalazine but not with placebo (Figures 16–18).

FIGURE 16.

Abdominal pain severity before and after treatment with mesalazine or placebo.

FIGURE 17.

Urgency symptoms before and after treatment with mesalazine or placebo.

FIGURE 18.

Stool consistency before and after treatment with mesalazine or placebo.

Chapter 8 Discussion

Over the past decade, there have been several promising studies using 5-ASA for treatment of both IBS-D23,44 and PI-IBS45,46 but sample sizes were small and their significance was uncertain. These studies were motivated by recent findings of ‘immune activation’ in the gut mucosa of patients with IBS, dominated by mast cells and T lymphocytes rather than the polymorphonuclear leucocytes that are characteristic of colitis. These studies were supported by several studies suggesting impaired mucosal barrier in IBS,47 which, by allowing access of luminal bacterial products to the mucosal immunocytes, might cause this activation. 48 These data suggested that mesalazine, being an anti-inflammatory agent, might benefit this condition. Our study is one of the largest trials so far looking at the treatment of patients with IBS-D with mesalazine following best practice to ensure that both investigators and patients were blinded to the study and that data analysis was carried out by independent statisticians. We analysed the effect of mesalazine only after 12-week treatment, as we felt that mesalazine was a disease-modifying treatment rather than a symptomatic treatment, and early reports suggested that benefit was most obvious after 2–3 months. 20 Our study showed that mesalazine did not improve bowel frequency after 12 weeks’ treatment when compared with placebo in unselected patients. As with other studies of IBS, we found a strong placebo effect on bowel symptoms and also on the total HADS and somatic scores, suggesting that patients felt better, in general, after taking part in the trial.

Despite lack of benefit in unselected patients, we had preplanned subanalysis of the primary outcome of stool frequency in patients who were divided according to severity. This suggested that a group of patients who had the greatest bowel frequency did show a small benefit from mesalazine (mean difference –0.26, p = 0.04). Our clinical findings seem consistent with another recent report. 49 There was no significant improvement, however, in other IBS symptoms, such as abdominal pain, bloating and stool consistency. There is strong evidence from our study that mesalazine treatment increases the number of days with urgency by about 20%. There have been previous case studies reporting treatment with mesalazine worsening diarrhoea in colitis. 50,51 This may represent an allergic response to the drug, as we did find an increase in T lymphocytes.

Raised mast cells numbers in the gut mucosa have been implicated in all subtypes of IBS,52 but mainly in IBS-D. Mast cells contain many mediators, including histamine, 5-HT and proteases such as tryptase. 14 Recently, there has been focus of interest on tryptase content, as it has been shown to activate PAR-2, which is found on afferent nerves and can lead to increased sensitivity of bowel distension. 53 In our study, the mast cell percentage area stained in patients with IBS-D was not elevated, compared with that in our previously studied healthy subjects. Despite our large numbers we were able neither to confirm the gender difference in mast cell count of patients with IBS-D, as previously described by others,54 nor find any gender effect on other immune cells such as CD3-, CD68- and 5-HT-containing enterochromaffin cells.

Similarly, the supernatant levels of tryptase in patients with IBS-D were not significantly elevated, compared with healthy control subjects. Median (IQR) tryptase levels for IBS-D compared with healthy control subjects were 4.3 (1.8–8.9) ng/ml and 6.7 (3.8–11.4) ng/ml; p = 0.07. We were not, therefore, able to confirm either increased mast cell numbers or increased mast cell tryptase release from biopsies, as some,14,15 but not all,19 investigators have found. Our study provides no support for the previous suggestion that mesalazine can reduce mast cell numbers. 23

Surprisingly, supernatant histamine levels in our study were lower in patients with IBS-D than in healthy control subjects [mean 0.7 (SD 0.6) and mean 1.1 (SD 0.8) ng/ml, respectively; p = 0.02]. Supernatant levels of tryptase and histamine were not altered following treatment with mesalazine. Disappointingly, we found no apparent association correlation between mast cell percentage area stained and supernatant levels of release of the mast cell mediators examined, whether those released by all mast cells (tryptase, histamine) or those restricted to a subpopulation (chymase, CPA3). This suggests that the overall degree of mediator release from colonic mast cells is independent of mast cell numbers, suggesting that factors other than mere numbers determine mediator release.

Stool collected in Nottingham was used to obtain calprotectin level at baseline and EOT. Although a small proportion of patients had raised calprotectin levels (≥ 100 µg/g), we had excluded organic diseases – such as inflammatory bowel disease – in gastroenterology clinics using standard tests prior to the patients entering the study. Others have also reported that up to one-quarter of patients with IBS have marginally elevated calprotectin levels, although the origin of this is unclear. 55,56 Interestingly, the subgroup of patients (group A) who had raised calprotectin levels (≥ 101 µg/g) have significantly less psychological distress than the group with stool calprotectin level of ≤ 100 µg/g (group B). We speculate that subgroup A symptoms are secondary to local gut inflammation, whereas subgroup B symptoms are driven primarily by distress, which causes gut symptoms secondarily. Unfortunately, numbers were too small to answer the question of whether or not subgroup A responded better to mesalazine. Stool calprotectin could, therefore, be used as a screening tool to allow more detailed studies of the mucosa in IBS-D in the future.

One uncontrolled study45 has suggested that mesalazine might be effective in treating patients with PI-IBS, but the only randomised controlled trial of mesalazine in this condition was negative, although possibly underpowered. 46 In our post hoc analysis, a small subgroup fulfilling criteria for PI-IBS appeared to benefit from mesalazine, but our study was also underpowered. Confirming this would require a larger and more adequately powered study.

Although mesalazine has been available to use for many decades with a good safety profile, our adequately powered study has shown that it does not help the majority of patients with IBS-D. The fact that certain subgroups might benefit emphasises that there is still a need for better phenotyping of this heterogeneous group of patients when evaluating new treatments.

Limitations

Despite strict entry criteria, our population was still heterogeneous. In retrospect, it would have been better if we had stratified by postinfectious onset. We did consider this but felt that this would make it very difficult to recruit to the trial. We could overcome this in future studies by having a great many more recruitment sites and around five times as many participants, given that PI-IBS accounts for only around 20% of all cases of IBS-D, but this would require more resources than those that we had available to us. It is worth noting that there is an appreciable loss to follow-up (15.5%) but this is not out of line with other similar studies. Dropouts are mostly likely due to failure of treatment and so are unlikely to account for our negative result.

Research recommendations

-

Our data suggest that it is unlikely that future trials of mesalazine in unselected IBS would be fruitful.

-

If there is a subgroup that may benefit it is likely to be those with postinfective IBS, particularly those postinfective patients with more severe diarrhoea.

-

The link between mast cells and clinical symptoms is weak and, again, future work on the role of mast cells needs to better characterise the patients, as the majority of unselected patients with IBS do not have elevated mast cell numbers. It may be that, as others have reported, it is the number of activated mast cells that are important53 and better markers of activation would be useful rather than the current gold standard of electron microscopy, which is expensive and time-consuming.

-

Finally, the release of mediators from biopsies does not link well to symptoms or mast cell numbers. The dominant factor for release is likely to be crushing and tissue injury by the biopsy process, which is not well standardised and may overwhelm other factors that would be of more interest. We need a better way of assessing in vivo activity of the mucosal cells.

Chapter 9 Conclusions

This randomised placebo-controlled trial in 115 unselected patients with IBS-D showed that mesalazine 4 g per day was no better than placebo in relieving the symptoms of abdominal pain or disturbed bowel habit. However, contrary to the previous report in just 10 patients, mesalazine did not reduce mast cell percentage area stained. Further post hoc analysis showed that raised calprotectin level was associated with less psychological distress, implying a more gut-centred abnormality. A small subgroup of patients with PI-IBS appeared to benefit but a larger adequately powered study is required to confirm this finding.

Further phenotyping of the heterogeneous group of patients with IBS-D is needed to allow better evaluation of new treatments.

Acknowledgements

Contributions of authors

Ching Lam (clinical research fellow/trial manager): managed, overall, the running of the whole trial, managed the clinical trial site in Nottingham, the analysis of data and the writing of reports/abstracts.

Wei Tan (statistician): data analysis for the clinical primary outcome data.

Matthew Leighton (research manager): trial manager for initial set-up of the study.

Margaret Hastings (research nurse): study supervision and recruitment of participants into study.

Melanie Lingaya (technician): analysis and technical support.

Yirga Falcone (technician): analysis and technical support.

Xiaoying Zhou (technician): analysis and technical support.

Luting Xu (research fellow): analysis and technical support.

Peter Whorwell (principal investigator): study concept and design.

Andrew F Walls (reader in immunopharmacology): analysis and technical support.

Abed Zaitoun (consultant histopathologist): analysis and technical support.

Alan Montgomery (senior statistician): statistical analysis and interpretation of data.

Robin C Spiller (chief investigator and senior author): obtained funding, study concept and design, interpretation of data, study supervision, recruitment.

We would like to thank:

-

The Clinical Research Network (CLRN) in assisting with the set-up of study in other centres and providing research nurses to assist in this study.

-

The PCRN who assisted with identifying potential patients with IBS in primary care.

-

Ferring Pharmaceuticals for sponsoring mesalazine and the placebo medication.

-

The CTU, University of Nottingham, for its information technology/electronic database support.

-

Nurses and technicians from the NIHR Nottingham Digestive Diseases Biomedical Research Unit, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, for assisting and supporting this study.

-

Dr Andrew F Walls, Xiaoying Zhou and Laurie Lau from the Immunopharmacology Group, University of Southampton, who helped in processing the biopsy supernatants for tryptase, histamine, CPA3 and chymase.

-

Dr Abed Zaitoun and the histopathology/immunohistochemistry laboratory in the Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, who helped with preparation of biopsy samples for histology/immunochemistry stains.

-

All participating principal investigators and CLRN nurses who have assisted in the recruitment and running of this study in other sites:

-

Dr Jessica Williams, Gastroenterology, Royal Derby Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Dr Stephen Foley, Gastroenterology, King’s Mill Hospital

-

Dr Anurag Agrawal, Gastroenterology, Doncaster Royal Infirmary

-

Dr Sandip Sen, Gastroenterology, United Hospitals North Staffordshire

-

Dr Matthew Rutter, Gastroenterology, University Hospital of North Tees

-

Dr Arvind Ramadas, Gastroenterology, James Cook University Hospital

-

Professor Peter Whorwell, Neurogastroenterology Unit, University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust.

-

Publication

Leighton MP, Lam C, Mehta S, Spiller RC. Efficacy and mode of action of mesalazine in the treatment of diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2013;14:10.

Notes

This study was accepted as an oral presentation in the Digestive Disease Week 2014 in Chicago, IL, USA. See Appendix 3 for abstract.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research. The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, NETSCC, the EME programme or the Department of Health. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the EME programme or the Department of Health.

References

- Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480-91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061.

- Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Robinson JC, Heller BR, Schuster MM. Effects of stressful life events on bowel symptoms: subjects with irritable bowel syndrome compared with subjects without bowel dysfunction. Gut 1992;33:825-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.33.6.825.

- Bennett EJ, Tennant CC, Piesse C, Badcock CA, Kellow JE. Level of chronic life stress predicts clinical outcome in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 1998;43:256-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.43.2.256.

- Söderholm JD, Yates DA, Gareau MG, Yang PC, MacQueen G, Perdue MH, et al. Neonatal maternal separation predisposes adult rats to colonic barrier dysfunction in response to mild stress. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2002;283:G1257-63.

- Santos J, Saperas E, Nogueiras C, Mourelle M, Antolín M, Cadahia A, et al. Release of mast cell mediators into the jejunum by cold pain stress in humans. Gastroenterology 1998;114:640-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70577-3.

- Guilarte M, Santos J, de Torres I, Alonso C, Vicario M, Ramos L, et al. Diarrhoea-predominant IBS patients show mast cell activation and hyperplasia in the jejunum. Gut 2007;56:203-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.2006.100594.

- Foley S, Garsed K, Singh G, Duroudier NP, Swan C, Hall IP, et al. Impaired uptake of serotonin by platelets from patients with irritable bowel syndrome correlates with duodenal immune activation. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1434-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.052.

- Weston AP, Biddle WL, Bhatia PS, Miner PB. Terminal ileal mucosal mast cells in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 1993;38:1590-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01303164.

- Wang LH, Fang XC, Pan GZ. Bacillary dysentery as a causative factor of irritable bowel syndrome and its pathogenesis. Gut 2004;53:1096-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.2003.021154.

- O’Sullivan M, Clayton N, Breslin NP, Harman I, Bountra C, McLaren A, et al. Increased mast cells in the irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2000;12:449-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2982.2000.00221.x.

- Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Spiller RC. Distinctive clinical, psychological, and histological features of postinfective irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1578-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07542.x.

- Park CH, Joo YE, Choi SK, Rew JS, Kim SJ, Lee MC. Activated mast cells infiltrate in close proximity to enteric nerves in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. J Korean Med Sci 2003;18:204-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2003.18.2.204.

- Campbell E, Richards M, Foley S, Hastings M, Whorwell P, Mahida Y. Markers of inflammation in IBS: increased permeability and cytokine production in diarrhoea-predominant subgroups. Gastroenterology 2006;130.

- Buhner S, Li Q, Vignali S, Barbara G, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, et al. Activation of human enteric neurons by supernatants of colonic biopsy specimens from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2009;137:1425-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.005.

- Barbara G, Wang B, Stanghellini V, De Giorgio R, Cremon C, Di Nardo G, et al. Mast cell-dependent excitation of visceral-nociceptive sensory neurons in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2007;132:26-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.039.

- Stefanini GF, Prati E, Albini MC, Piccinini G, Capelli S, Castelli E, et al. Oral disodium cromoglycate treatment on irritable bowel syndrome: an open study on 101 subjects with diarrheic type. Am J Gastroenterol 1992;87:55-7.

- Lunardi C, Bambara LM, Biasi D, Cortina P, Peroli P, Nicolis F, et al. Double-blind cross-over trial of oral sodium cromoglycate in patients with irritable bowel syndrome due to food intolerance. Clin Exp Allergy 1991;21:569-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.1991.tb00848.x.

- Leri O, Tubili S, De Rosa FG, Addessi MA, Scopelliti G, Lucenti W, et al. Management of diarrhoeic type of irritable bowel syndrome with exclusion diet and disodium cromoglycate. Inflammopharmacology 1997;5:153-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10787-997-0024-7.

- Klooker TK, Braak B, Koopman KE, Welting O, Wouters MM, van der Heide S, et al. The mast cell stabiliser ketotifen decreases visceral hypersensitivity and improves intestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2010;59:1213-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.213108.

- Aron J. Response to mesalamine and balsalazide in patients with irritable bowel syndrome refractory to alosetron and tegaserod. Gastroenterology 2005;128:A329-30.

- Andrews CN, Petcu R, Griffiths T, Vergnolle N, Surette MG, Rioux KP, et al. Mesalamine alters colonic mucosal proteolytic activity and fecal bacterial profiles in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D). Gastroenterology 2008;134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(08)62558-5.

- Bafutto M, Almeida JR, Almeida RC, Almeida TC, Leite NV, Filho JR, et al. Treatment of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and non infective irritable bowel syndrome with mesalazine. Gastroenterology 2008;134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(08)63136-4.

- Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V, Cremon C, Gargano L, Cogliandro RF, De Giorgio R, et al. Effect of mesalazine on mucosal immune biomarkers in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled proof-of-concept study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:245-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04041.x.

- Tuteja A, Hale D, Fang JC, Al-Suqi M, Stoddard G. Double-blind placebo controlled study of mesalamine in post-infective irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103.

- Ransford RA, Langman MJ. Sulphasalazine and mesalazine: serious adverse reactions re-evaluated on the basis of suspected adverse reaction reports to the Committee on Safety of Medicines. Gut 2002;51:536-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.51.4.536.

- Spiller RC, Garsed K, Cox J, Kelly FM, Zaitoun AM, Dukes GE, et al. Elevated chemokine mRNA in rectal mucosa following gastrointestinal infection and in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2009;136:A105-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(09)60475-3.

- Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Neal KR, Spiller RC. Relative importance of enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia, anxiety, and depression in postinfectious IBS. Gastroenterology 2003;125:1651-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.028.

- Gwee KA, Leong YL, Graham C, McKendrick MW, Collins SM, Walters SJ, et al. The role of psychological and biological factors in postinfective gut dysfunction. Gut 1999;44:400-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.44.3.400.

- Neal KR, Barker L, Spiller RC. Prognosis in post-infective irritable bowel syndrome: a six year follow up study. Gut 2002;51:410-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.51.3.410.

- Chadwick VS, Chen W, Shu D, Paulus B, Bethwaite P, Tie A, et al. Activation of the mucosal immune system in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1778-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/gast.2002.33579.

- Liebregts T, Adam B, Bredack C, Röth A, Heinzel S, Lester S, et al. Immune activation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2007;132:913-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.046.

- Gwee KA, Collins SM, Read NW, Rajnakova A, Deng Y, Graham JC, et al. Increased rectal mucosal expression of interleukin 1β in recently acquired post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2003;52:523-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.52.4.523.

- Dunlop SP, Hebden J, Campbell E, Naesdal J, Olbe L, Perkins AC, et al. Abnormal intestinal permeability in subgroups of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1288-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00672.x.

- Pasricha PJ. Desperately seeking serotonin . . . A commentary on the withdrawal of tegaserod and the state of drug development for functional and motility disorders. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2287-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.057.

- Andresen V, Hollerbach S. Reassessing the benefits and risks of alosetron: what is its place in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome?. Drug Saf 2004;27:283-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200427050-00001.

- Fox CC, Moore WC, Lichtenstein LM. Modulation of mediator release from human intestinal mast cells by sulfasalazine and 5-aminosalicylic acid. Dig Dis Sci 1991;36:179-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01300753.

- Bantel H, Berg C, Vieth M, Stolte M, Kruis W, Schulze-Osthoff K, et al. Mesalazine inhibits activation of transcription factor NF-kappaB in inflamed mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:3452-7.

- Rousseaux C, Lefebvre B, Dubuquoy L, Lefebvre P, Romano O, Auwerx J, et al. Intestinal antiinflammatory effect of 5-aminosalicylic acid is dependent on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. J Exp Med 2005;201:1205-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1084/jem.20041948.

- Stolfi C, Fina D, Caruso R, Caprioli F, Sarra M, Fantini MC, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-dependent and -independent inhibition of proliferation of colon cancer cells by 5-aminosalicylic acid. Biochem Pharmacol 2008;75:668-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2007.09.020.

- Palsson OS, Baggish JS, Turner MJ, Whitehead WE. IBS patients show frequent fluctuations between loose/watery and hard/lumpy stools: implications for treatment. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:286-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2011.358.

- Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32:920-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/00365529709011203.

- Tooth D, Garsed K, Singh G, Marciani L, Lam C, Fordham I, et al. Characterisation of faecal protease activity in irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea: origin and effect of gut transit. Gut 2014;63:753-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304042.

- Ban L, Tata LJ, Fiaschi L, Card T. Limited risks of major congenital anomalies in children of mothers with IBD and effects of medications. Gastroenterology 2014;146:76-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.061.

- Andrews CN, Griffiths TA, Kaufman J, Vergnolle N, Surette MG, Rioux KP, et al. Mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) alters faecal bacterial profiles, but not mucosal proteolytic activity in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:374-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04732.x.

- Bafutto M, Almeida JR, Leite NV, Oliveira EC, Gabriel-Neto S, Rezende-Filho J, et al. Treatment of postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome and noninfective irritable bowel syndrome with mesalazine. Arq Gastroenterol 2011;48:36-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0004-28032011000100008.

- Tuteja AK, Fang JC, Al-Suqi M, Stoddard GJ, Hale DC. Double-blind placebo-controlled study of mesalamine in post-infective irritable bowel syndrome: a pilot study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2012;47:1159-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/00365521.2012.694903.

- Camilleri M, Madsen K, Spiller R, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Verne GN. Intestinal barrier function in health and gastrointestinal disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;24:503-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01921.x.

- Martinez C, Lobo B, Pigrau M, Ramos L, González-Castro AM, Alonso C, et al. Diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: an organic disorder with structural abnormalities in the jejunal epithelial barrier. Gut 2013;62:1160-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302093.

- Barbara G, Cremon C, Bellacosa L, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, Corinaldesi R. Randomized placebo controlled mulicenter trial of mesalazine in patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). Gastroenterology 2014;146.

- Shimodate Y, Takanashi K, Waga E, Fujita T, Katsuki S, Nomura M, et al. Exacerbation of bloody diarrhoea as a side effect of mesalamine treatment of active ulcerative colitis. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2011;5:159-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000326931.