Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 08/43/03. The contractual start date was in November 2009. The final report began editorial review in January 2015 and was accepted for publication in June 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jonathan Grigg received personal fees for Advisory Board membership for new asthma treatments in children from GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis Pharmaceuticals while the study was being done. David Price has received fees paid to Research in Real Life Ltd (RIRL) for Board membership from Aerocrine, Almirall, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Meda, Mundipharma International Ltd, Napp, Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Teva; for consultancy fees from Almirall, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Meda, Mundipharma International Ltd, Napp, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Nycomed, Pfizer and Teva; for grants (received or pending) from Aerocrine, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Meda, Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd, Mundipharma International Ltd, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Nycomed, Orion, Pfizer, Takeda, Teva and Zentiva; for lecture and speaking engagements from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline, Kyorin, Meda, Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd, Mundipharma International Ltd, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, SkyePharma, Takeda and Teva; for manuscript preparation from Mundipharma International Ltd and Teva; for travel, accommodation and meeting expenses from Aerocrine, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mundipharma International Ltd, Napp, Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Teva; for patient enrolment or completion of research from Almirall, Chiesi, Teva and Zentiva; for contract research from Aerocrine, AKL Research and Development Ltd, Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Meda, Mundipharma International Ltd, Napp, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Orion, Takeda and Zentiva; has an AKL Research and Development Ltd patent pending; and has shares in AKL Research and Development Ltd, which produces phytopharmaceuticals and owns 80% of RIRL and its subsidiary social enterprise, Optimum Patient Care.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Nwokoro et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Preschool wheeze

One-quarter of preschool children between 1 and 5 years of age will develop at least one attack of wheeze. 1 The majority of affected children have several attacks of wheeze triggered by viral colds, with minimal or no symptoms between attacks. 2 A minority of preschool children will also wheeze between colds. Preschool wheeze is a major clinical problem, with significant costs to primary and secondary care. 3,4 There are at least two clinical patterns of preschool wheeze: (1) episodic virus-triggered wheeze, which affects the majority of wheezing children; and (2) multitrigger wheeze, which affects the minority of children.

Montelukast in preschool wheeze

A promising therapy for both clinical phenotypes of wheeze is montelukast (Singulair ®, Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd), currently the only cysteinyl leukotriene (cLT) receptor antagonist licensed for use in young children. This beneficial effect of inhibition of cLTs, a class of potent bronchoconstrictors, in preschool wheeze was suggested by a study of urinary cLTs, where levels of urinary leukotriene E4 (LTE4) were elevated during acute attacks of preschool wheeze and then, on convalescence, fell into the normal range. 5 A study relevant to ‘multitrigger’ preschool wheeze is a randomised controlled trial of 689 young children in whom regular oral montelukast given over a 12-month period reduced the rate of exacerbations by 30%. 6 In the case of episodic (viral) preschool wheeze, Bisgaard et al. 7 reported that regular daily use of oral montelukast over 12 months reduced the rate of preschool wheezing episodes by 32% compared with placebo. We recruited a heterogeneous group of children aged between 2 and 14 years with intermittent asthma into a 12-month placebo-controlled randomised controlled trial of oral montelukast (the Pre-Empt study). 8 Trial medication was started at the onset of a viral upper respiratory tract infection and continued for a minimum of 7 days, or until symptoms had resolved for 48 hours. 8 The montelukast-treated group had 162 unscheduled health-care resource utilisations for wheeze, compared with 288 in the placebo group, and symptoms were significantly reduced by 14% in the montelukast-treated group. 8 As intermittent therapy may be effective in preschool wheeze, the aim of the Wheeze And Intermittent Treatment (WAIT) trial was to assess whether or not parent-initiated montelukast therapy is efficacious in this condition.

Genetics of montelukast response and study rationale

The beneficial effect of montelukast, albeit consistent, is clinically relatively modest. 8 The overall modest benefit of montelukast is thought to be due to marked heterogeneity of response: that is, some children respond very well while others do not respond at all. One explanation for this marked heterogeneity in response is variation in the genes coding for components of the leukotriene (LT) pathway. 9 The first step in LT production is the creation of leukotriene A4 (LTA4) by arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase (ALOX5; other names for ALOX5 are 5-lipoxygenase and LTA4 synthase) and ALOX5-activating protein (encoded by the ALOX5AP gene). The regulatory domain of ALOX5 controls leukotriene synthesis by catalysing the conversion of arachidonic acid to 5(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid and further dehydration to LTA4. The ALOX5 promoter polymorphism results in a variation in the number of specificity protein 1 (SP1) transcription factor-binding motifs – which alters transcription factor binding and influences ALOX5 gene expression. 10 The five SP1 repeats in the ALOX5 gene promoter are classified as the wild type, with other numbers of repeats reflecting the mutant genotype. Lima et al. 11 found that adults carrying a variant number of repeats on one allele (x/x or 5/x, where x ≠ 5) have a 73% reduction in the risk of having an asthma attack on montelukast compared with homozygotes for the five-repeat (5/5; wild-type) allele. Therefore, we hypothesised that, overall, parent-initiated montelukast therapy in preschool wheeze would be clinically moderately effective, but that there would be a highly responsive subgroup of children defined by ALOX5 polymorphism status (i.e. carrying a variant number of repeats on at least one allele). In this trial we therefore included a stratification step for ALOX5 promoter polymorphism status, to ensure that an equal number of children with the variant and wild-type number of SP1 repeats in the ALOX5 promoter receive placebo and active medication.

Study objectives

Primary objectives

-

To assess the efficacy of parent-initiated intermittent montelukast for the reduction of unscheduled medical attendances for preschool wheeze.

-

To explore the role of the ALOX5 promoter genotype in montelukast efficacy.

Secondary objectives

-

To assess the impact on intermittent montelukast on respiratory morbidity.

-

To assess the impact of montelukast on health service usage.

-

To assess the impact of intermittent montelukast on concomitant medication use.

-

To assess the impact of intermittent montelukast on adverse events (AEs).

-

To gather exploratory data on related LT pathway genes.

-

To gather exploratory data on urinary LT/eicosanoid output.

-

To assess the impact of intermittent montelukast on economic outcomes.

-

To assess qualitative outcomes related to parent-initiated intermittent therapy for preschool wheeze and participation in a genetically stratified interventional trial.

Chapter 2 Methods

Overall study design

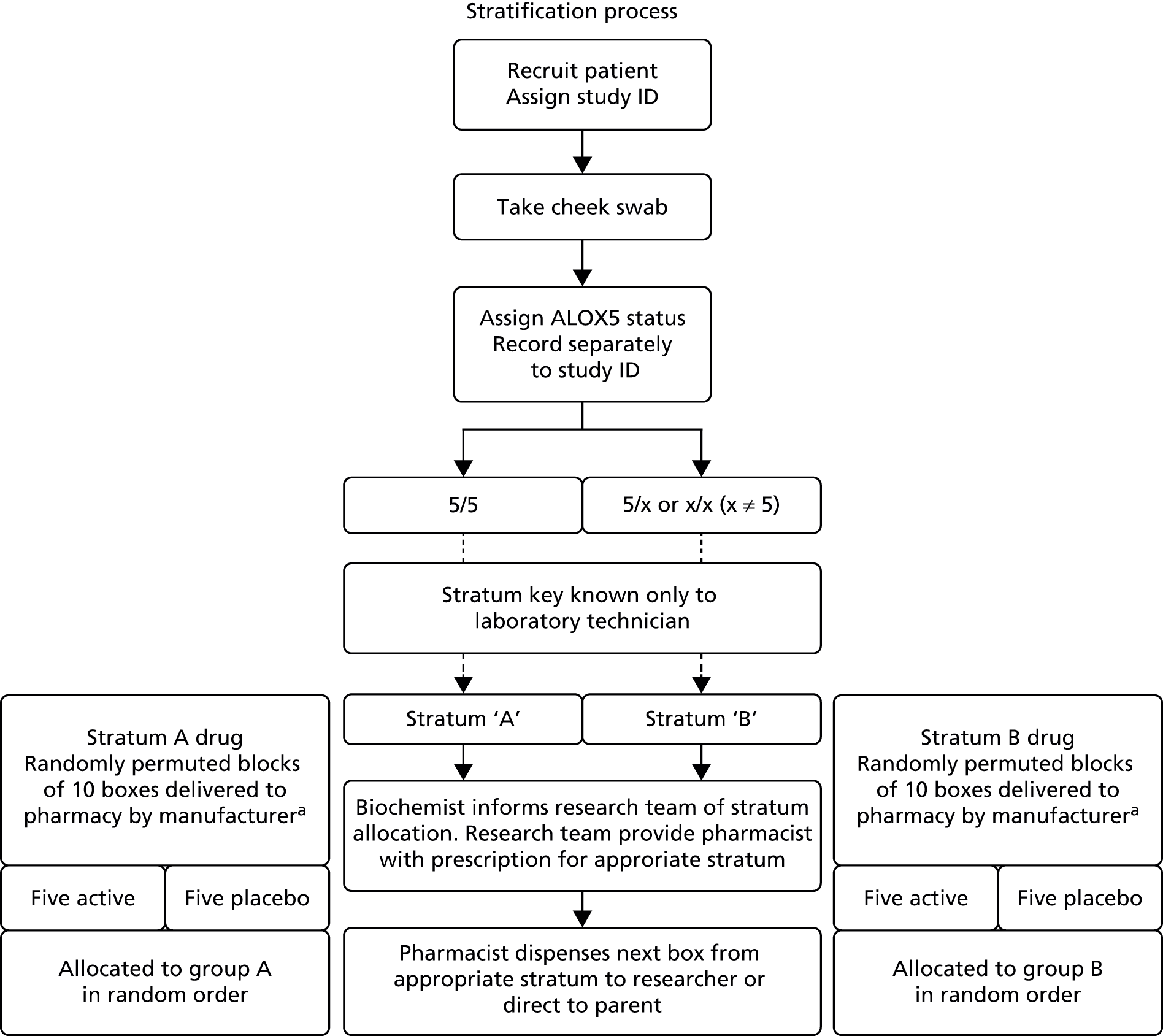

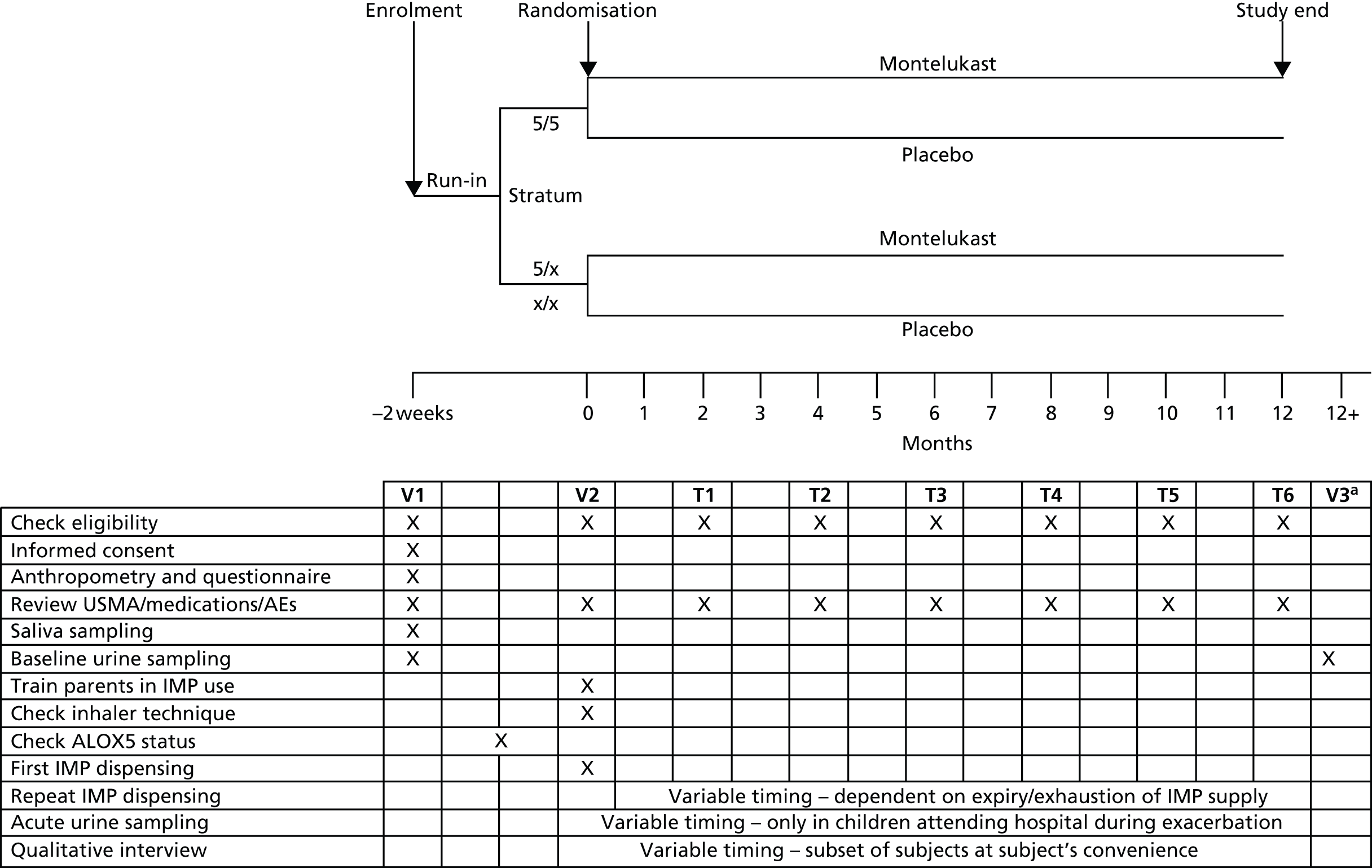

This was a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of intermittent montelukast therapy. The study population comprised preschool children (aged 10 months to 5 years, inclusive) who had experienced two previous episodes of wheeze. Target accrual was 1300 patients. Eligibility criteria were as stated in Participants. An overview is provided in Figure 1. Patients were recruited in primary and secondary care, and were stratified according to ALOX5 promoter genotype. Patients were then randomised within their stratum to receive either intermittent montelukast or placebo for 10 days from the start of a viral cold or wheezing episode, with the need for unscheduled medical attention monitored over a 12-month follow-up period.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic chart of trial protocol. a, Subset of participants. ID, identification number.

Participants

Eligibility criteria

Patients were eligible for the study if they fulfilled the following criteria:

-

aged ≥ 10 months and ≤ 5 years on the day of the first dose of the investigational medicinal product (IMP)

-

two or more attacks of parent-reported wheeze

-

at least one attack with wheeze validated by a clinician (nursing or medical)

-

the most recent attack within the last 3 months

-

contactable by telephone and able to attend one face-to-face review

-

parent or guardian able to give written informed consent for their child to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

The following characteristics rendered patients ineligible for the study:

-

any other chronic respiratory condition diagnosed by a clinician, including structural airway abnormality (e.g. floppy larynx) and cystic fibrosis

-

any chronic condition that increases vulnerability to respiratory tract infection, such as severe developmental delay with feeding difficulty or sickle cell disease

-

history of neonatal chronic lung disease

-

current continuous oral montelukast therapy

-

in a trial using an IMP in the previous 3 months prior to recruitment.

Selection of study population

As indicated previously, wheezing is common in otherwise healthy preschool children; however, safe effective treatment options are limited. We therefore sought to conduct a pragmatic trial with the widest possible useful application. Thus, participants were not limited in terms of wheeze severity or concomitant medications, notwithstanding the prohibition of regular montelukast. We did not include children aged less than 10 months and greater than 5 years in order to exclude children with classical bronchiolitic or asthmatic phenotypes, for which treatment strategies differ.

Recruitment and patient journey

Recruitment setting

Participants were identified in primary and secondary care centres. Recruitment was planned to encompass only three secondary care centres (the Royal London Hospital, University Hospital Leicester and the Royal Aberdeen Children’s Hospital), but increased to 41 secondary care centres in England and Scotland (see Acknowledgements) in response to observed recruitment rates.

Invitation of potential study participants to attend screening visit

A member of the child’s usual general practitioner (GP) care team or the hospital paediatric team (as appropriate) identified potentially eligible children based on age and history of wheeze from reviewing surgery and emergency department records. The parent/guardian was then approached in person or via a posted invitation letter and/or information sheet, to ask if they would like to be contacted about the study by a member of the research team. Individuals who agreed to be contacted about the study were then contacted by a research nurse or research assistant, who briefly described the study to them, and asked them if they would like to read a patient information sheet (PIS; see Appendix 1) if not already given. The research nurse or research assistant then provided a PIS to parents who expressed an interest in the study; those who subsequently confirmed their interest in participation were offered a screening appointment at a study site. A second invitation letter was posted to individuals who did not respond to the first invitation letter.

Screening visit 2 weeks prior to first investigational medicinal product dispensing

At the screening visit, an investigator, or a suitably trained person delegated by the investigator (a research nurse or a research assistant who had attended a UK good clinical practice training course), gave an adequate explanation of the aims, methods, anticipated benefits and potential hazards of the study. The eligibility of children to participate in the study was assessed in accordance with the criteria documented in Participants. The investigator then obtained written informed consent (see Appendix 2) from the parent or guardian prior to participation in this study. A period of at least 24 hours, or an overnight stay in hospital (for patients recruited during an acute admission), was required for consideration by the parent or guardian before they gave consent to enter the study. During the consent process it was made clear that parents or guardians were completely free to refuse to enter the study or to withdraw at any time during the study, for any reason. The parents of all eligible children were asked to complete baseline assessments of their child’s wheeze status including recording of baseline demographic and clinical data and details of concomitant medications (see Appendix 3). They also underwent measurement of weight and height, provided a salivary sample for genotyping (see Salivary sample) and gave a urine sample for LT analysis (see Urine sample and Appendix 4). A follow-up appointment was arranged for the issue of the IMP.

Stratification (–1 week)

Saliva samples were posted to the Blizard Institute, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK, where deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted and children assigned either to the ALOX5 promoter polymorphism 5/5 stratum or to the [5/x + x/x] stratum, depending on the number of copies of the ALOX5 promoter polymorphism they had on each allele. Extracted DNA was stored in a freezer at –70 °C for later batch analysis of > 150 polymorphisms in 10 genes encoding components of the LT biosynthetic pathway and the LT receptors. The study pharmacist then randomised subjects within their strata, and the corresponding box of active or placebo medication was dispensed for issue at the time of first IMP dispensing (T0) visit (see Figures 1 and 2).

FIGURE 2.

Stratification and randomisation schematic. a, Randomisation key provided by manufacturer, held in sealed envelope by pharmacist and Data Monitoring Committee. T, telephone call; USMA, unscheduled medical attendance; V, visit.

Method of assigning patients to treatment groups: randomisation

Nova Laboratories Ltd (Novalabs, Leicester, UK) prepared the IMP for this trial. Preparation was intended to comprise 6-monthly batches tailored to recruitment rate, with an expectation that 1300 boxes of 50 sachets containing active montelukast and 1300 containing placebo would be produced at a minimum. However, a national shortage of montelukast necessitated a production of boxes containing between 20 and 50 sachets, so as to maintain supply and not compromise recruitment and subject retention. The change in box size received approval from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) prior to implementation. Boxes were allocated randomisation numbers in blocks of 10 using a computer-generated random sequence. Novalabs was responsible for generation of the random number sequence and labelling of boxes. Boxes bearing randomisation numbers were initially delivered to the pharmacy at participating sites. Subsequently, the expansion of site numbers prompted a move to central randomisation and distribution of IMP (from the sponsor pharmacy to participating sites). Novalabs produced additional boxes of IMP for those children whose IMP supply was lost, reached expiry or was exhausted such that they required additional boxes during the 1-year follow-up period. Clinicians remained blinded to allocation throughout.

Randomisation was stratified according to the ALOX5 promoter polymorphism status yielding two genotype groups:

-

Group 1: children with the 5/5 ALOX5 promoter polymorphism genotype.

-

Group 2: children with the [5/x + x/x] ALOX5 promoter polymorphism genotype, where x ≠ 5 SP1 repeats. (Groups were referred to as stratum A or B.)

Children in each of these two genotype groups (strata) were assigned consecutive randomisation numbers from randomised permuted blocks of 10 representing the randomisation numbers on the IMP boxes. Within each block, equal numbers of children were randomly allocated to placebo and active treatment. When all numbers from the first block had been assigned, a new block of randomisation numbers was allocated to that stratum until a total of 1300 children in the two strata combined had been assigned a randomisation number (see Figure 2).

Blinding

Novalabs produced a corresponding randomisation code denoting whether a given IMP box contained active medication or placebo. This was kept sealed and held only by the clinical trials pharmacist and a member of the Independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC); in this way all other clinical investigators and participants remained blinded to treatment allocation.

T0 visit (0 months)

The research nurse or research assistant met with parents, confirmed eligibility and issued parents a box containing IMP sachets. Parents were taught how to use the IMP. They were also provided with one study diary card (see Appendix 3) and one Freepost return envelope (addressed to the sponsor organisation) per 10 sachets. Parents were asked to return completed diary cards and empty sachets at completion of a course of IMP. Each diary card recorded clinical and IMP usage data for the 10 days of the IMP course.

Telephone calls at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 months

At approximately 2-month intervals following the T0 visit, a research nurse or research assistant telephoned the subject’s carer to check if the parent had initiated the IMP, the numbers of days the IMP had been used, the use of health-care resources, any concomitant medications, any procedures, number of days lost from childcare and parent days lost from work. Any AEs experienced were also recorded.

Qualitative interview visit (variable timing)

Qualitative interviews were conducted in a subgroup of families recruited at the sponsor site. The aim of these was to establish attitudes towards genetic testing to guide personalised therapy, acceptability of parent-initiated therapy for preschool wheeze, the expected advantages and disadvantages of using the IMP, and their views on the consent process and PIS. Interviews included either or both parents and, where possible, were conducted at the parental home. Interviewing, transcribing and analysis of interviews was performed by a researcher skilled in qualitative research, in the presence of a translator where necessary.

Withdrawal of patients from therapy or assessment

Patients were free to withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason. Patients were advised that if they requested to withdraw from the study, at any time during the trial, then this would have no negative consequences. Investigators could also withdraw patients from the trial if they deemed it appropriate for safety or ethical reasons or if it was considered to be detrimental to the well-being of the patient. Where possible, patients who withdrew or were withdrawn underwent a final telephone or face-to-face evaluation. Those participants who withdrew and provided permission to use their data were included in the analysis up to the point of withdrawal. Full documentation was made of any withdrawals that occurred during the study in the case report form (CRF). The investigator documented the date and time of the withdrawal and results of any assessments made at this time. If the patient withdrew because of an AE or a serious adverse event (SAE), then details were forwarded to the Research Ethics Committee, as required, and to the sponsor, who forwarded details to the regulatory authorities as appropriate.

Interventions

Details of the IMP are as shown in Table 1.

| Detail | Active drug | Placebo |

|---|---|---|

| Trade name | Singulair granules | Mannitol EP (PEARLITOL® 200 SD) |

| Composition | 4 mg of montelukast sodium (which is equivalent to 4 mg of montelukast) granules with mannitol excipient | Mannitol granules |

| ATC code | R03DC03 | Not applicable; drug master file lodged with the EP commission |

| Pharmaceutical form | Granules | Granules |

| Dosage regimen | One sachet to be given once a day at the start of a cold or wheezy episode, and continued for 10 days | One sachet to be given once a day at the start of a cold or wheezy episode, and continued for 10 days |

| Route of administration | Oral | Oral |

| Manufacturer | Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd (purchased on the open market) | Roquette Pharma |

Administration of the investigational medicinal product

Subsequent to stratification, children were randomised within their stratum to receive either montelukast or identical placebo. All study treatment was dispensed from the study pharmacy either directly to the patient carer or to the study investigator or designated member of staff for distribution to the carer. The IMP was administered unsupervised by the patients’ carers in their usual place of residence. The IMP was presented as white granules administered either directly into the child’s mouth, or mixed with a spoonful of cold or room-temperature soft food (e.g. apple sauce, ice cream, carrots and rice). The IMP was used according to the primary manufacturer’s instructions. Specifically, parents were advised not to open the sachet containing the granules until ready to use. After opening the sachet, the full dose of granules was administered within 15 minutes. If mixed with food, the granules would not be stored for future use. The granules were not intended to be dissolved in liquid for administration; however, liquids could be taken subsequent to administration. The granules could be administered without regard to the timing of food ingestion. The dose was one 4 mg sachet per day, started when the child had evidence of a viral cold or had a wheeze, and stopped after 10 days. Children were permitted to commence a second course of IMP should the wheeze not resolve within 10 days. If a child vomited after the administration of the IMP, no additional dose was given and parents recorded this on the diary chart.

Selection of doses in the study

Montelukast is an established medication in this patient population with an accepted dosing of 4 mg daily. The granule formulation was selected to achieve the broadest tolerability across the preschool age group. The IMP was administered at the first sign of a cold and continued for 10 days to give the best chance of covering the entire duration of any virus-induced LTE4 overproduction. There was no variation of dosing strategy or posology between patients.

Prior and concomitant therapy

Subjects were eligible for the study as long as they were not taking regular montelukast. No limitations were placed on concomitant medications; however, medications were recorded on the CRFs at study entry and during follow-up.

Other measurements

Safety measurements

Montelukast is an established drug with a good safety profile. Safety assessments were limited to standard AE reporting, with patterns monitored by the DSMC.

Other measurements

Subjects underwent the following assessments during the study (see Figure 1 for timings).

Weight

Weight in light clothing was measured with weighing scales and recorded in kilograms.

Height

Height without shoes was measured using a stadiometer.

Salivary sample

A sample of DNA was collected from saliva using the Oragene™ infant sponge system (DNA Genotek Inc., Kanata, ON, Canada). The sponge tips were cut into an Oragene DNA kit (DNA Genotek Inc., Kanata, ON, Canada) to preserve the DNA and prevent bacterial growth. This method yields high-quality DNA and eliminates the need for traditional cheek-scraping methods.

The ALOX5 polymorphism status was determined within 1 week of sampling in the sponsor’s laboratory. DNA was extracted in accordance with a standard operating procedure and the manufacturer’s instructions (DNA Genotek Inc., Kanata, ON, Canada). Products of the polymerase chain reaction were analysed by capillary electrophoresis on a 3130xl Genetic Analyser [Applied Biosystems (a brand of Thermo Fisher Scientific), MA, USA]. Polymerase chain reaction amplicons were obtained, varying in size depending on the copy number of the repeat sequence, and were visualised using GeneMapper v4 software [Applied Biosystems (a brand of Thermo Fisher Scientific), MA, USA]. Genotypes were called from duplicate amplifications, with respect to standards run on each plate that are verified by direct DNA sequence analysis. In addition, 150 polymorphisms in 10 genes encoding components of the LT biosynthetic pathway and the LT receptors were assessed: ALOX5, ALOX5AP, LTC4S (leukotriene C4 synthase), CYSLTR1 (cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1), CYSLTR2 (cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2), PLA2G4A (phospholipase A2 Group 4A), LTA4H (leukotriene H4 hydrolase), LTB4R1 (leukotriene B4 receptor 1), LTB4R2 (leukotriene B4 receptor 2) and MRP (ribonucleic acid component of mitochondrial ribonucleic acid processing endoribonuclease). These included all single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located in promoter regions, exons, intron–exon boundaries and the SNPs within the ALOX5AP haplotypes (referred to as HapA and HapB). Additional tag SNPs were selected using the LDselect algorithm (version 1; University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA) on the basis of linkage disequilibrium patterns across the genes using data from both our own previous studies in cardiovascular disease and asthma, as well as resequencing data available from the Seattle SNPs and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences SNPs databases. SNP genotyping was carried out using the KBioscience™ competitive allele-specific polymerase chain reaction (KASPar) method (KBioscience Ltd, Hoddesdon, UK).

Urine sample

A urine sample was to be collected from children in spontaneously voided urine using an age-appropriate method into a sterile receptacle. A first urine sample was obtained when patients were well and a second, where possible, during an acute wheezing illness. In a subset of children whose parents agreed, repeat ‘well’ urine samples were obtained on study exit to assess repeatability. Urinary leukotriene level was assessed using a high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry technique (see Appendix 4). Values were indexed to urinary creatinine.

Appropriateness of measurements

The primary outcome measure was one that is of importance to patient/carers, clinicians and policy-makers and was deemed more robust to local variations in treatment practices than other measures. It has previously been used in similar studies in this population and is measurable without undue patient inconvenience.

Urine LTE4 level reflects leukotriene metabolism and has been correlated with asthma severity and bronchoconstriction. 12 A significant correlation with montelukast efficacy would provide both a non-invasive and inexpensive marker to guide treatment.

The anthropomorphic and urine measurements are of minimal inconvenience, while the Oragene saliva kit (DNA Genotek Inc., ON, Canada) yields high concentrations of DNA and is well tolerated by patients.

Data quality assurance

Data from source material and CRFs were entered into a secure electronic database managed by a clinical trials unit data manager. Prior to analysis, 10% of records were randomly checked against source data by the co-ordinating principal investigator (PI), with good concordance. All available data can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Primary outcome

The number of times a child attends for an unscheduled medical opinion with respiratory problems over a 12-month period was recorded on diary cards and in bimonthly telephone calls, and was confirmed from clinical records.

Secondary outcomes

The following outcomes were assessed as indicated via diary card, telephone call and health records.

Respiratory morbidity

-

Number of admissions to hospital over the 12-month trial period.

-

Duration of admissions to hospital over the 12-month trial period.

-

Time to first attack of wheeze.

-

Number of unscheduled GP consultations for wheeze.

-

Duration of episodes as recorded in the diary card.

-

Severity of episodes as recorded in the diary card.

-

Parents’ overall impression of efficacy of the IMP.

Health service use

-

Unscheduled GP consultation with exacerbation of wheeze, expressed as time from randomisation to first attendance and annual attendance rate.

-

Accident and emergency attendance with wheeze exacerbation, expressed as time from randomisation to first attendance and annual attendance rate.

-

Unscheduled hospital admission with wheeze exacerbation, expressed as time from randomisation to first admission and annual rate of admissions.

-

Total duration of hospital admissions for exacerbation of wheeze.

Adverse events

-

SAEs.

-

Withdrawal from the trial.

-

Mortality due to exacerbation of asthma.

-

Mortality due to respiratory infection.

-

All-cause mortality.

Medication use

-

Use of oral corticosteroids, expressed as number of courses taken per year and proportion of children receiving at least one course of oral corticosteroids during the trial.

-

Use of inhaled relief medication (salbutamol), expressed as mean use per wheeze episode as recorded in the diary card by a parent/guardian.

Inflammatory outcomes

Association between baseline urinary cLT level and:

-

arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase status

-

other polymorphisms of leukotriene genes

-

previous history of virus-triggered episodic and multitrigger wheeze

-

responsiveness to montelukast

-

acute history of wheeze

-

urinary cotinine.

Genetic parameters

-

Differential responsiveness to montelukast for the primary outcome in the stratum with ALOX5 promoter polymorphism (5/5), compared with the stratum with the ALOX5 [5/x + x/x] genotype.

-

Differential responsiveness to montelukast for the primary outcome resulting from other polymorphisms in genes influencing LT synthesis, metabolism and activity.

Qualitative outcomes (parental)

-

Attitudes towards genetic testing in order to personalise therapy.

-

Acceptability of parent-initiated therapy for preschool wheeze.

-

Experience of using the trial medication.

-

Difficulties/advantages of the parent-initiated approach.

-

Views on the PIS.

Study definitions

Need for unscheduled medical attention

This was defined as an episode requiring an unscheduled attendance at either a general practice or an accident and emergency department, or a combination of both, where wheeze is diagnosed by a clinician.

Time from randomisation to first attack of severe wheeze

This was defined as the number of days from the date of administration of first dose of the IMP to the first date on which a wheeze exacerbation meets the criteria for severity stated in Need for unscheduled medical attention.

Number of days with parent-reported wheeze

This was defined as the number of days with wheeze over the 12-month trial period obtained by telephone contact with the researcher and recorded in the diary card.

Use of inhaled relief medication

This was expressed as the total number of occasions inhaled relief medication was used over the 12-month trial period. The mean number per wheeze episode was obtained from the number of actuations calculated from records in the diary card.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis plan

The statistical analysis plan is available in Appendix 5. The analysis was based on intention-to-treat (ITT) principles.

Determination of sample size

This trial was powered to detect a clinically significant difference in the number of attacks of wheeze between the intervention and control arms. The trial also had power to detect large differential responsiveness (in terms of the primary outcome) to montelukast in the stratum with the ALOX5 promoter polymorphism 5/5 compared with the stratum with the ALOX5 [5/x + x/x] genotype.

Prior to the start of the trial, data on the mean (0.76) and standard deviation (SD) (1.22) number of attacks of wheeze came from the UK GP Research Database on courses of oral steroids (a proxy for number of episodes). These data followed an overdispersed Poisson distribution. To take account of this, a Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation in WinBUGS™ (version 1.4.3; MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK) was used to estimate the sample sizes required to detect a 33% drop in attack rate requiring medical attention, with a power of 90%, a significance level of 5% and a 6% loss to follow-up. In total, 1050 children were required. A 33% drop in attack rates equates to an attack rate of 0.51 for the treatment group. The clinical significance of these changes is that approximately four children will need to be treated to prevent one clinically severe attack. A sample size of 1200 also gave just over 80% power at the 5% significance level to detect an interaction between treatment and genotype if the effect was a 60% reduction in the [5/x + x/x] genotype and a 20% reduction in the 5/5 stratum. In addition, assuming a 6% dropout, 1300 children needed to be recruited.

Analysis of primary end points

Initial analyses were performed according to ITT for all participants with outcome data. Per-protocol efficacy analyses were also performed, excluding data collected after discontinuation of the IMP for those participants who discontinued using the IMP. We used Poisson regression with a random effect representing individuals to account for overdispersion. Fixed effects represent the stratification factor (ALOX5 promoter) and treatment centre. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) (relative risk) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. The analysis was to be conducted in Stata V12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). To test for a differential effect by stratum an interaction between stratum and treatment was fitted to this model as described in Genetic analysis.

Analysis of secondary end points

A Poisson regression analysis with a random effect for individuals to allow for overdispersion was applied to determine the influence of treatment allocation on number of days with parent-reported wheeze, number of hospital attendances and number of admissions to hospital. An IRR for each factor is presented with 95% CIs.

Time to first attack of wheeze was analysed using a log-rank test with adjustment for clustering and (where hazards are proportional) Cox’s proportional hazards models adjusting for clustering. In the Cox model, stratum and centre were included as covariates.

Other continuous variables were analysed with analysis of covariance. Dichotomous variables were analysed with logistic regression analysis. AEs are analysed with descriptive statistics.

Genetic analysis

To assess the difference in responsiveness to montelukast in the two ALOX5 strata, an interaction term was fitted for each treatment arm to test for the interaction between montelukast and stratum in our main model. The associations between genotype and clinical phenotype, urinary LT level and clinical outcome were reported. To test the polymorphisms in each gene in combination, a composite likelihood approach was used, which combines the regression coefficients for all polymorphisms at each locus. Analysis of clinical effectiveness (utility) of stratification of ALOX5 status utilised in vitro diagnostic multivariate index assays. The benefits of a multivariate index assay were estimated based on the data in both clinical and economic terms (e.g. days off school, days off work for parents, costs of attendance at GP and hospital, and costs of treatment).

Changes in the conduct of the study or planned analyses

No scientifically significant protocol changes occurred during the study. All amendments were approved by the ethics committee unless the sponsor deemed them to be minor amendments. A list of changes is included in Appendix 6. No changes in planned analysis occurred after the database was locked.

Discussion of study design

The study design reflects previous work in this area. Short of meta-analysis, an adequately powered, double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT is the gold standard for assessing therapeutic efficacy. The unique aspect of this study was the attempt not only to assess whether or not intermittent montelukast was effective in preschool wheeze, but to prospectively investigate whether or not genetic mutations affecting the metabolism of the cLTs (the endogenous ligand for its target receptor) influenced its efficacy. Previous studies have retrospectively suggested a role for ALOX5 polymorphisms in LT production, wheeze severity13 and montelukast efficacy. 11,14 However, this is the first study to prospectively test this association. Prospective genetic stratification was necessary to address this pharmacogenetic question.

Study duration

The study was intended to recruit for 24 months. Slower than predicted early recruitment necessitated an increase in recruitment period to 26 months and an expansion of recruitment sites. This extension was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, the regulatory authority and also by the funding body. Thus, recruitment spanned from October 2010 to December 2012 and follow-up was completed in December 2013, with data cleaning, verification and database locking completed by January 2014.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment and retention

A total of 1358 subjects were recruited, with 97% in both arms taking part in at least one bimonthly telephone call and thus eligible for inclusion in the primary analysis as per Figure 3 and Table 2.

FIGURE 3.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram.

| Patient disposition | Montelukast | Placebo | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled (N) | 669 | 677 | 1358 |

| Permitted use of data, n (%) | Unknown | Unknown | 1346 |

| Received at least one telephone call, n (%) | 652 (97) | 656 (97) | 1308 (96) |

| Completed 12 months’ follow-up, n (%) | 579 (87) | 575 (85) | 1154 (85) |

| Withdrawn, n (%) | 90 (13) | 102 (15) | 192 (14) |

| Lost to follow-up, n (%) | 51 (8) | 36 (5) | 87 (6) |

| AE, n (%) | 4 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) | 7 (0.5) |

| Death, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other, n (%) | 37 (6) | 60 (9) | 97 (7) |

Protocol deviations

There were 31 reported protocol deviations throughout the study. Very few necessitated withdrawal from the trial, no deviations from protocol exposed a participant to risk of harm, or appeared systematic or particular to an individual site, or had the potential to compromise study validity. Most protocol deviations were addressed by a gentle reminder of the study requirements to the parent or carer. Table 3 gives details of the study protocol deviations.

| Deviation | Recruiting site | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BR | BD | BI | CA | CO | DE | WH | CH | PO | NO | RO | HG | ST | |

| Entry criteria (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Withdrawal criteria (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Concomitant treatment/medication (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Incorrect dosing regimen (n) | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Expired medication (n) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Incorrect administration (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Lost samples (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data sets analysed

All analyses were performed on the ITT population (or available case population where outcome data were not available for analysis) unless otherwise stated. These populations are indicated in Table 4.

| Montelukast group | Placebo group | |

|---|---|---|

| ITT population, n (%) | 669 (100) | 677 (100) |

| Timing of last contact | ||

| Withdrew before T0 (no data), n (%) | 16 (2) | 16 (2) |

| T0 or earlier (no telephone call data), n (%)a | 17 (3) | 21 (3) |

| T2 (month 2), n (%) | 21 (3) | 20 (3) |

| T4 (month 4), n (%) | 15 (2) | 12 (2) |

| T6 (month 6), n (%) | 12 (2) | 19 (3) |

| T8 (month 8), n (%) | 13 (2) | 15 (2) |

| T10 (month 10), n (%) | 12 (2) | 15 (2) |

| T12 (month 12), n (%) | 579 (87) | 575 (85) |

| Per-protocol population, n (%) | 579 (87) | 575 (87) |

Demographic and other baseline characteristics

Subjects appeared well matched between genotype strata and treatment groups (Table 5).

| Characteristic | Montelukast group (N = 669) | Placebo group (N = 677) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5/5 | 5/x + x/x | Total | 5/5 | 5/x + x/x | Total | |

| n (%) | 416 (62) | 253 (38) | 669 (100) | 426 (63) | 251 (37) | 677 (100) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 90.0 (10.3) | 89.8 (10.5) | 89.9 (10.4) | 89.9 (10.5) | 91.8 (11.7) | 90.6 (11.0) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 14.0 (3.0) | 13.9 (3.7) | 14.0 (3.3) | 14.0 (3.3) | 14.6 (3.8) | 14.2 (3.5) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.8 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.1) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 262 (63) | 164 (65) | 426 (64) | 276 (65) | 161 (64) | 437 (65) |

| Ethnic origin | ||||||

| White, n (%) | 335 (81) | 179 (71) | 514 (77) | 338 (79) | 174 (69) | 512 (76) |

| Black, n (%) | 5 (1) | 14 (6) | 19 (3) | 4 (1) | 14 (6) | 18 (3) |

| Asian, n (%) | 55 (13) | 37 (15) | 92 (14) | 58 (14) | 46 (18) | 104 (15) |

| Other, n (%) | 21 (5) | 23 (9) | 44 (7) | 26 (6) | 17 (7) | 43 (6) |

| Preterm birth (< 37 weeks), n (%) | 58 (14) | 40 (16) | 98 (14) | 56 (13) | 42 (17) | 98 (15) |

| Birthweight (< 2500 g), n (%) | 51 (12) | 28 (11) | 79 (12) | 42 (10) | 28 (11) | 70 (10) |

| Food allergy, n (%) | 64 (15) | 44 (18) | 108 (16) | 64 (15) | 47 (19) | 111 (17) |

| Drug allergy, n (%) | 26 (6) | 12 (5) | 38 (6) | 23 (6) | 19 (8) | 42 (6) |

| Itchy rash (> 6 months, ever),a n (%) | 98 (23) | 64 (25) | 162 (24) | 104 (25) | 60 (24) | 164 (25) |

| Eczema (ever),b n (%) | 207 (49) | 121 (48) | 328 (48) | 215 (52) | 134 (53) | 349 (52) |

| History of asthma in mother, n (%) | 156 (37) | 95 (38) | 251 (37) | 141 (34) | 89 (35) | 230 (34) |

| History of asthma in father, n (%) | 126 (30) | 73 (29) | 199 (29) | 126 (30) | 81 (32) | 207 (31) |

| Age at first wheeze (months), mean (SD) | 12.4 (9.8) | 13.5 (10.5) | 12.8 (10.1) | 12.4 (10.4) | 13.6 (11.5) | 12.9 (10.8) |

| Children with episodic viral wheeze, n (%) | 296 (71) | 181 (72) | 477 (71) | 295 (69) | 191 (76) | 486 (72) |

| Children with multitrigger wheeze, n (%) | 120 (29) | 72 (28) | 192 (29) | 131 (31) | 60 (24) | 191 (28) |

| Interval between onset of URTI and wheezing (hours),c mean (SD) | 31.6 (27.4) | 28.8 (25.2) | 30.5 (26.6) | 27.3 (23.4) | 28.2 (26.0) | 27.7 (24.4) |

| Children with more than one hospital admission for wheeze in the past year, n (%) | 363 (87) | 216 (85) | 579 (87) | 351 (82) | 203 (81) | 554 (82) |

| Courses of oral corticosteroids in past year, mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.9) | 1.8 (1.8) | 1.9 (1.8) | 1.9 (1.9) | 1.8 (2.0) | 1.9 (2.0) |

| USMA in previous year, mean (SD) | 5.5 (4.3) | 5.4 (4.1) | 5.4 (4.2) | 5.7 (5.3) | 5.6 (4.6) | 5.6 (5.1) |

| Continuous inhaled corticosteroids, n (%) | 118 (28) | 66 (26) | 184 (28) | 144 (34) | 69 (27) | 213 (31) |

Assessment of treatment compliance

To assess compliance, patient carers were asked to return empty/unused/expired sachets to the sponsor in self-addressed prepaid envelopes; however, returns were too low to provide any meaningful data.

Efficacy results and tabulations of patient data

Primary outcome

There was no difference between the montelukast and placebo group for the primary outcome (Table 6).

| Outcome measure | Montelukast group | Placebo group | Adjusted IRR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis population, n (%) | 652 (50) | 656 (50%) | ||

| Unscheduled medical attendance for wheeze episodes, mean (SD) | 2.0 (2.6) | 2.3 (2.7) | 0.88 (0.77 to 1.01) | 0.06 |

Secondary outcomes

A possible effect was seen within the 5/5 genotype stratum (Figure 4), with a suggestion of increased responsiveness in this group.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of unscheduled medical attendances by genotype stratum. USMA, unscheduled medical attendance.

Statistical/analytical issues

The study was limited in that, although adequately powered to address the efficacy of intermittent montelukast in preschool wheeze, it had the power to detect only a rather substantial interaction between genotype and efficacy. Thus, the suggestion (p = 0.01) of improved efficacy in the 5/5 stratum is not mathematically robust when exposed to a test for interaction (p = 0.08; Table 7). The interquartile range for the time to first unscheduled medical attendance (USMA) was not calculable, as more than 25% of children never required an USMA.

| Outcome measure | Montelukast group | Placebo group | Adjusted IRR (95% CI) | p-value | p-value (interaction) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USMA in the 5/5 stratum, mean (SD) | 2.0 (2.7) | 2.4 (3.0) | 0.80 (0.68 to 0.95) | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| USMA in the [5/x + x/x] stratum, mean (SD) | 2.0 (2.5) | 2.0 (2.3) | 1.03 (0.83 to 1.29) | 0.79 |

There was no apparent influence of wheeze phenotype, use of inhaled steroids at baseline or alternative genotype stratum on USMA (Table 8).

| Outcome measure | Montelukast group, mean (SD) | Placebo group, mean (SD) | Adjusted IRR (95% CI) | p-value | p-value (interaction) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USMA in the 5/5 + 5/x stratum | 2.0 (2.6) | 2.3 (2.8) | 0.88 (0.76 to 1.00) | 0.06 | 0.93 |

| USMA in the x/x stratum | 1.7 (1.8) | 1.9 (2.0) | 0.85 (0.44 to 1.66) | 0.64 | |

| Inhaled corticosteroid use at baseline | 2.0 (3.0) | 2.0 (2.3) | 1.01 (0.82 to 1.24) | 0.92 | 0.09 |

| No inhaled corticosteroid use at baseline | 2.0 (2.2) | 2.5 (3.0) | 0.80 (0.67 to 0.96) | 0.01 | |

| Multitrigger wheezea | 2.1 (3.0) | 2.0 (2.5) | 1.01 (0.79 to 1.31) | 0.90 | 0.19 |

| Episodic viral wheezeb | 2.0 (2.4) | 2.3 (2.9) | 0.83 (0.71 to 0.97) | 0.03 |

There was an increased time to first USMA requiring hospital admission for wheeze in the montelukast group (but not for other types of USMA) and a decreased use of rescue oral corticosteroids (Table 9).

| Outcome measure | Montelukast group | Placebo group | Adjusted IRR, OR or HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children with one or more USMAs, n (%) | 426 (65) | 456 (70) | OR 0.83 (0.66 to 1.04) | 0.10 |

| Time (days) to first USMA, median (interquartile range)a | 147 (50–365) | 130 (38–)b | HR 0.89 (0.78 to 1.02) | 0.09 |

| Need for rescue oral steroids (courses per child), mean (SD)c | 0.26 (0.7) | 0.33 (0.9) | IRR 0.75 (0.58 to 0.98) | 0.03 |

| Wheeze episodes, mean (SD)c | 2.7 (2.9) | 2.6 (3.0) | IRR 1.02 (0.91 to 1.16) | 0.68 |

| Duration (days) of wheeze episodes, mean (SD) | 5.2 (4.0) | 5.4 (3.9) | IRR 0.97 (0.89 to 1.06) | 0.53 |

| Duration (days per child) of hospital admission, mean (SD)d | 1.8 (1.3) | 1.7 (1.1) | IRR 1.05 (0.94 to 1.18) | 0.40 |

| Symptomatic days per wheeze episode, mean (SD) | 4.9 (3.5) | 4.8 (3.8) | IRR 0.96 (0.88 to 1.05) | 0.36 |

Chapter 4 Safety evaluation

Adverse events

Table 10 shows AEs reported during the duration of the trial. Section A shows a breakdown by intensity, followed by category (B) for all AEs. Subsequent sections (C–G) reflect the likelihood, as assessed by the (blinded) local PI, that the AE was attributable to the trial drug. Of the 940 AEs reported in the study, 657 (70%) were classified as definitely not related to study drug, 179 (19%) as probably not related, 93 (10%) as possibly related, 11 (1%) as probably related and no AE was definitely related. We recorded one SAE, which was a skin reaction in a child allocated to placebo. The distribution of AEs was similar between treatment groups. There were no recorded deaths.

| Event numbers | Montelukast group (N = 669) | Placebo group (N = 677) | Total (N = 1346) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Total number of events | 397 (100) | 543 (100) | 940 (100) |

| Total number of participants | 197 (29) | 235 (35) | 432 (32) |

| (A) Intensity | 397 | 543 | 940 |

| Mild | 314 (79) | 426 (78) | 740 (79) |

| Moderate | 77 (19) | 108 (20) | 185 (20) |

| Severe | 6 (2) | 9 (2) | 15 (2) |

| (B) Category | 397 | 543 | 940 |

| Minor injury | 27 (7) | 22 (4) | 49 (5) |

| Gastrointestinal | 86 (22) | 122 (22) | 208 (22) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 73 (18) | 103 (19) | 176 (19) |

| Central nervous system | 25 (6) | 46 (8) | 71 (8) |

| Minor infection | 87 (22) | 107 (20) | 194 (21) |

| Allergy | 16 (4) | 20 (4) | 36 (4) |

| Cutaneous | 32 (8) | 54 (10) | 86 (9) |

| Respiratory | 34 (9) | 54 (10) | 88 (9) |

| Haematological | 5 (1) | 7 (1) | 12 (1) |

| Genitourinary | 10 (3) | 6 (1) | 16 (2) |

| Major injury | 2 (1) | 1 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) |

| Musculoskeletal | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

| (C) Total number of events: definitely not related | 281 | 376 | 657 |

| Minor injury | 27 (10) | 22 (6) | 49 (7) |

| Gastrointestinal | 40 (14) | 62 (16) | 102 (16) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 63 (22) | 88 (23) | 151 (23) |

| Central nervous system | 8 (3) | 10 (3) | 18 (3) |

| Minor infection | 76 (27) | 91 (24) | 167 (25) |

| Allergy | 13 (5) | 16 (4) | 29 (4) |

| Cutaneous | 18 (6) | 32 (9) | 50 (8) |

| Respiratory | 25 (9) | 47 (13) | 72 (11) |

| Haematological | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Genitourinary | 7 (2) | 4 (1) | 11 (2) |

| Major injury | 2 (1) | 1 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) |

| Musculoskeletal | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

| (D) Total number of events: probably not related | 80 | 99 | 179 |

| Minor injury | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal | 26 (33) | 33 (33) | 59 (33) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 10 (13) | 15 (15) | 25 (14) |

| Central nervous system | 5 (6) | 8 (8) | 13 (7) |

| Minor infection | 11 (14) | 16 (16) | 27 (15) |

| Allergy | 3 (4) | 4 (4) | 7 (4) |

| Cutaneous | 10 (13) | 13 (13) | 23 (13) |

| Respiratory | 9 (11) | 7 (7) | 16 (9) |

| Haematological | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 4 (2) |

| Genitourinary | 3 (4) | 2 (2) | 5 (3) |

| Major injury | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Musculoskeletal | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| (E) Total number of events: possibly related | 33 | 60 | 93 |

| Minor injury | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal | 19 (58) | 23 (38) | 42 (45) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Central nervous system | 10 (30) | 25 (42) | 35 (38) |

| Minor infection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Allergy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cutaneous | 4 (12) | 8 (13) | 12 (13) |

| Respiratory | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Haematological | 0 (0) | 4 (7) | 4 (4) |

| Genitourinary | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Major injury | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Musculoskeletal | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| (F) Total number of events: probably related | 3 | 8 | 11 |

| Minor injury | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal | 1 (33) | 4 (50) | 5 (45) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Central nervous system | 2 (67) | 3 (38) | 5 (45) |

| Minor infection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Allergy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cutaneous | 0 (0) | 1 (13) | 1 (9) |

| Respiratory | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Haematological | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Genitourinary | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Major injury | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Musculoskeletal | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| (G) Total number of events: definitely related | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Safety conclusions

This study supports the position that montelukast is safe in this age group. No excess of AEs was observed in the treatment group, nor were any novel AEs identified over and above those known prior to study commencement.

Chapter 5 Clinical laboratory evaluation

Urinary eicosanoids

Urinary eicosanoids were evaluated at baseline and, in a subset of recruits, during exacerbation of wheeze. The numbers providing paired (baseline and exacerbation of wheeze) urine samples were insufficient to justify detailed analysis; however, samples are stored for further analysis and data remain available for future use. Baseline urine was analysed by genotype stratum (Figure 5). There was a statistically significant increase in baseline level of LT activation in subjects with no wild-type (5 repeat) ALOX5 promoter allele. This is contrary to the direction predicted from the non-significant genotype–efficacy interaction suggested in Table 7. The numbers in the x/x group are very small; thus, this observation must be treated with caution.

FIGURE 5.

Urinary LTE4 levels by ALOX5 promoter genotype.

Genetics

Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase genotype was compared with self-reported ethnicity (Table 11). There was marked genotypic variation between ethnicities, with black subjects having a lower frequency of 5/5 alleles than whites or Asians, and also having the highest frequency of x/x alleles. A clinical correlation has not been established.

| Genotype | White, n (%) | Black, n (%) | Asian, n (%) | Bangladeshi, n (%) | Mixed, n (%) | Other, n (%) | All, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3/3 | 0 (0.00) | 4 (10.81) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (0.29) |

| 3/4 | 1 (0.10) | 2 (5.41) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.75) | 2 (2.78) | 1 (2.70) | 7 (0.51) |

| 3/5 | 4 (0.39) | 6 (16.22) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 10 (13.89) | 4 (10.81) | 24 (1.76) |

| 3/6 | 0 (0.00) | 2 (5.41) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.15) |

| 3/7 | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.39) | 1 (2.70) | 2 (0.15) |

| 4/4 | 18 (1.75) | 0 (0.00) | 8 (13.34) | 5 (3.73) | 2 (2.78) | 1 (2.70) | 34 (2.49) |

| 4/5 | 285 (27.78) | 10 (27.03) | 18 (30) | 33 (24.63) | 11 (15.28) | 7 (18.92) | 364 (26.65) |

| 4/6 | 6 (0.58) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.67) | 2 (1.49) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.70) | 10 (0.73) |

| 5/5 | 677 (65.98) | 9 (24.32) | 27 (45) | 83 (61.94) | 43 (59.72) | 19 (51.35) | 858 (62.81) |

| 5/6 | 30 (2.92) | 4 (10.81) | 5 (8.33) | 10 (7.46) | 3 (4.17) | 2 (5.41) | 54 (3.95) |

| 6/6 | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.67) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.07) |

| 2/4 | 1 (0.10) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.07) |

| 5/8 | 1 (0.10) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.07) |

| 5/7 | 2 (0.19) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.15) |

| 2/5 | 1 (0.10) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.07) |

| 3/8 | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.70) | 1 (0.07) |

| Total | 1026 (100) | 37 (100) | 60 (100) | 134 (100) | 72 (100) | 37 (100) | 1366a (100) |

| 5/5 | 677 (65.98) | 9 (24.32) | 27 (45.00) | 83 (61.94) | 43 (59.72) | 19 (51.35) | 858 (62.81) |

| 5/X | 323 (31.48) | 20 (54.05) | 23 (38.33) | 43 (32.09) | 24 (33.33) | 13 (35.14) | 446 (32.65) |

| X/X | 26 (0.19) | 8 (21.62) | 10 (16.67) | 8 (5.97) | 5 (6.94) | 5 (13.51) | 62 (4.54) |

| Total | 1026 (100) | 37 (100) | 60 (100) | 134 (100) | 72 (100) | 37 (100) | 1366a (100) |

Exploratory SNP analysis is under way and will form the basis of a future manuscript. Consent exists for future related genetic analyses to be performed by this team and others.

Concomitant medication use

Subjects were permitted to use any concomitant medications excluding LT receptor antagonists. A record was kept of concomitant medication usage. There was no difference in reported salbutamol usage between treatment groups. A statistically significant reduction in oral corticosteroid usage was observed (p = 0.03; see Table 9).

Qualitative study outcomes

The parents of 42 subjects agreed to a qualitative interview; a sizeable proportion of these were of Bangladeshi origin. Interview design is detailed elsewhere,15 but where necessary a Bangladeshi translator was available. From this study, Bangladeshi families appear particularly motivated to participate in clinical trials, despite their understanding of study concepts being limited by educational attainment or language. The decision to participate was driven primarily by rapport with the researcher, with quality of study literature being of less importance. Where a study population has a Bangladeshi (or perhaps south Asian) bias, particular emphasis should be placed on face-to-face verbal explanation of trial concepts and procedures. Further detail regarding qualitative study outcomes is beyond the scope of this report and the article is available via Open Access Online. 15

Health economic outcomes

The health economic analysis was dependent upon a demonstrable treatment effect. In the absence of a treatment effect of montelukast, further analysis was deemed unwarranted.

Chapter 6 Discussion and overall conclusions

This study is, overall, negative with regard to the primary outcome, indicating no benefit from intermittent montelukast treatment in preschool children with wheeze. This supports the recent findings of Valovirta et al. ,16 who compared intermittent and regular montelukast with placebo and found no benefit. There was an increased time to first USMA requiring hospital admission for wheeze in the montelukast group (but not for other types of USMA) and an increased use of rescue oral corticosteroids; however, the study was not powered to demonstrate these effects and the patchiness of the effect makes its validity questionable. There was no apparent influence of wheeze phenotype, use of inhaled steroids at baseline or alternative genotype stratum on USMA, although wheeze phenotype was based on parental reporting and mean daily dose of inhaled steroids was not assessed. The IRR seen in the montelukast group compared with placebo was 0.88 (p = 0.06) in favour of montelukast, not meeting statistical significance. A larger trial might have power to identify a difference of this magnitude, but the clinical benefit may not justify the exercise; this should be considered in the design of future studies.

A possible effect was seen within the 5/5 genotype stratum, with a suggestion of increased responsiveness in this group (contrary to Lima’s et al. finding,11 but consistent with Telleria et al. 14), but the test for genotype–efficacy interaction was not confirmatory. Furthermore, the small effect seen in urinary LTE4 levels at baseline was not supportive. Future work will prospectively study montelukast efficacy in the 5/5 genotype stratum and explore the role of putative response modifiers like environmental tobacco smoke exposure17 and air pollution.

The search for an effective therapy for preschool wheezing illness is hampered by the lack of a clearly defined phenotype with robust biomarkers. This study adopted a pragmatic approach, recruiting a heterogeneous population encompassing numerous likely aetiologies, in the hope that inhibition of LT activity might address a mechanistic pathway common to these probably distinct but overlapping clinical entities. There is evidence to implicate cLTs in a proportion of preschool wheezing disease5,12 and a greater success in assessing LTE4 levels during wheeze exacerbation (as opposed to at baseline) might have shed light on the value of this hypothesis and thus the viability of montelukast as a therapeutic target. The lack of a clear genotype–urinary LTE4 level correlation may reflect a lower than anticipated importance of ALOX5 promoter polymorphism genotype or perhaps that the differences become more evident during exacerbation compared with during convalescence. The LT pathway is complex, and it is possible that several mutations (perhaps in combination, perhaps with an epigenetic influence17) play a more important role in determining LT activity and montelukast response in this population than ALOX5. Future work will investigate the role of other genes on LTE4 output and montelukast response, and consideration should be given to stratification of montelukast response trials by LTE4 levels measured during wheeze exacerbation (or perhaps following a standardised challenge).

Acknowledgements

The National Institutes of Health Research Efficacy and Mechanisms Evaluation programme funded and supported the research. Support was also provided by the Medicines for Children Research Network, the Primary Care Research Network and the Pragmatic Clinical Trials Unit at Queen Mary University of London. We are grateful for the support of the following (Table 12).

| Title | Name | Affiliation |

|---|---|---|

| Chief investigator | Professor Jonathan Grigg | Queen Mary University of London |

| Co-ordinating PI | Dr Chinedu Nwokoro | Queen Mary University of London |

| PI | Professor Chris Griffiths | Queen Mary University of London |

| Dr Steve Turner | Royal Aberdeen Children’s Hospital | |

| Dr Hitesh Pandya | University Hospitals Leicester | |

| See Acknowledgements for other PIs | ||

| Statistics team | Dr Sandra Eldridge | Queen Mary University of London |

| Miss Clare Rutterford | Queen Mary University of London | |

| Independent Trial Steering Committee | Professor Warren Lenney | University Hospitals, North Staffordshire |

| Professor David Price | University of Aberdeen | |

| Dr Jay Panickar | Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital | |

| Dr Hussain Mulla | University Hospitals Leicester | |

| Dr Edward Simmonds | Walsgrave General Hospital | |

| Professor Robert Walton | Queen Mary University of London | |

| Professor John Holloway | University of Southampton | |

| DSMC | Professor Andy Bush (chairperson) | Royal Brompton Hospital |

| Paul Lambert (statistician) | University of Leicester | |

| Ian Jarrold | British Lung Foundation | |

| Sponsor | Mr Gerry Leonard | Queen Mary University of London |

| Project managers | Ms Suzi Miranbeg | Queen Mary University of London |

| Miss Cassie Brady | Queen Mary University of London | |

| Research nurses | Mrs Teresa McNally | University Hospitals Leicester |

| Ms Belinda Howell | Queen Mary University of London | |

| Ms Donna Nelson | Royal Aberdeen Childrens’ Hospital | |

| Laboratory investigator | Dr Tom Vulliamy (Lead) | Queen Mary University of London |

| Mr Iain Dickson | Queen Mary University of London | |

| Ms Lee Koh | Queen Mary University of London | |

| Professor Marek Sanak | Jagellionian University, Krakow | |

| Data management | Miss Hafiza Khatun | Queen Mary University of London |

| Miss Sandy Smith | Queen Mary University of London | |

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee: Professor Andy Bush (chairperson), Professor Paul Lambert (statistician) and Ian Jarrold (Head of Research, British Lung Foundation).

Independent members of the Trial Steering Committee: Professor Warren Lenney (chairperson) and Dr Edward Simmonds.

Trial Support Group: Ms Catherine Brady, Ms Amy Hoon (data monitoring), Ms Donna Nelson, Ms Bea Howell, Ms Theresa McNally (multicentre co-ordination), Ms Hafiza Khatun (data audit), Ms Suzi Miranbeg (trial co-ordination), Mr Gordon Forbes (statistics), Ms Mandy Wan and Ms Nanna Christiansen (pharmacy).

Local investigators in secondary care centres: Dr Christopher Upton (Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Trust), Dr Maria O’Callaghan (Barts Health NHS Trust, Whipps Cross Hospital), Dr S Murthy Saladi (Countess of Chester NHS Foundation Trust), Dr Catherine Tuffrey (Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust), Dr Sheng-Ang Ho (East Cheshire NHS Trust), Dr Robert Ross Russell (Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust), Dr Anil Tuladhar (North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Trust), Dr Edwin Osakwe (Oxford Radcliffe Hospitals NHS Trust), Dr Paul McNamara (Alder Hey Children’s NHS Trust), Dr James Y Paton (NHS Lothian University Hospitals, Royal Hospital for Sick Children), Dr Mansoor Ahmed (Burton Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust), Dr John Alexander (University Hospital of North Staffordshire NHS Trust), Dr Deepthi Jyothish (Birmingham Children’s Hospital NHS Trust), Dr John Scanlon (Worcestershire Acute NHS Trust), Dr Edward Simmonds (University Hospitals of Coventry NHS Trust), Dr James Crossley (Chesterfield Royal NHS Foundation Trust), Dr Shakeel Rahman (Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust), Professor Harish Vyas (Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust), Dr Will Carroll (Royal Derby Hospitals NHS Trust), Dr Diarmuid P Kerrin (Barnsley NHS Foundation Trust), Dr Hazel Evans (Southampton University Hospitals NHS Trust), Dr Anna Mathew (Western Sussex NHS Hospitals Trust), Dr Anne Prendiville (Royal Cornwall Hospital Trust), Professor Mark Everard (Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust), Dr Lakshmi Chilukuri (St Helens and Knowsley Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust), Dr Sharryn Gardner (Southport and Ormskirk NHS Trust), Dr Gary Ruiz (King’s College Hospital Foundation NHS Trust), Dr Simon Langton Hewer (University Hospitals Bristol NHS Trust), Dr Peter DeHalpert (Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust), Dr Paul Seddon (Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust), Dr Tim Adams (NHS Ayrshire and Arran), Dr David Cremonesini (Hinchingbrooke Health Care NHS Trust), Dr Jonathan Garside (Calderdale and Huddersfield NHS Trust), Dr Anil Shenoy (Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust), Dr Matthew Babirecki (Airedale NHS Foundation Trust), Dr Anne Ingram (Luton and Dunstable Hospital NHS Trust), Dr John Furness (County Durham and Darlington NHS Trust), Dr David Lacy (Wirral University Teaching Hospital NHS Trust) and Dr Mike Linney (Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Trust).

Primary care recruitment: Springfield GP-led Health Centre, Lower Clapton Practice, The Lawson Practice, Neaman Practice, Elm Practice, Sandringham Practice, Queensbridge Group Practice, Latimer Health Centre, Statham Grove Surgery. In Tower Hamlets Primary Care Trust: Strouts Place Medical Centre, Jubilee Street Practice, Wapping Health Centre, East One Health, Barkantine Health Centre, Blithehale Health Centre, Albion Health Centre, Chrisp Street Practice, Bromley-By-Bow Health Centre, XX Place Surgery, St Andrews Health Centre and Mission Practice.

Finally, we thank our participants and their caregivers.

Contributions of authors

Chinedu Nwokoro supervised the study, and wrote with Jonathan Grigg the first and final drafts of the report.

Hitesh Pandya, Stephen Turner, Christopher J Griffiths and David Price contributed to study planning and to the final manuscript.

Sandra Eldridge contributed to study planning and supervised the statistical analysis.

Tom Vulliamy contributed to study planning, supervised genotype analysis and contributed to the final manuscript.

Marek Sanak performed the urinary LT analysis and contributed to the final manuscript.

John W Holloway contributed to study planning, advised on genotype analysis and contributed to the final manuscript.

Rossa Brugha supervised the study, did the combined analysis and contributed to the final manuscript.

Lee Koh performed genotyping and was responsible for the audit of genotype data.

Iain Dickson contributed to study planning, genotype analysis and the final manuscript.

Clare Rutterford supported the data monitoring committee, wrote the final statistical analysis plan and did the statistical analysis.

Jonathan Grigg was the chief investigator, planned and provided overall supervision of the study, wrote with Chinedu Nwokoro the first and final drafts of the report and vouches for these data.

Publications

MacNeill V, Nwokoro C, Griffiths C, Grigg J, Seale C. Recruiting ethnic minority participants to a clinical trial: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002750. 15

Nwokoro C, Pandya H, Turner S, Eldridge S, Griffiths CJ, Vulliamy T, et al. Intermittent montelukast in children aged 10 months to 5 years with wheeze (WAIT trial): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:796–803. 18

Conference abstracts

Brady C. Delivering WAIT Across Multiple Settings. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Annual Meeting, Birmingham, UK, 28–30 April 2015.

Grigg J. The WAIT Study of Parent-determined Oral Montelukast Therapy for Pre-school Wheeze – Introduction to the Study, Key Findings, and Plans for Further Research. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Annual Meeting, Birmingham, UK, 28–30 April 2015.

Nwokoro C. The Wheeze and Intermittent Treatment (WAIT) Trial: Results and What Next? John Price Respiratory Conference, London, UK, 24–25 March 2015.

Nwokoro C. WAIT – Working Together to Deliver a Large Paediatric Trial. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Annual Meeting, Glasgow, UK, 5–8 June 2013.

Nwokoro C. Recruiting Ethnic Minority Participants to a Clinical trial: Qualitative Study. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Annual Meeting, Glasgow, UK, 5–8 June 2013.

Nwokoro C. Lipid Mediators in Preschool Wheezing Disorders. Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry. Paediatric Research Seminar. London, UK 14 February 2013.

Nwokoro C. Urinary Eicosanoids and Preschool Wheeze Phenotype. European Respiratory Society Annual Congress, Vienna, Austria, 1–5 September 2012.

Data sharing statement

All available data can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research. The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, the MRC, NETSCC, the EME programme or the Department of Health. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the EME programme or the Department of Health.

References

- Kuehni CE, Davis A, Brooke AM, Silverman M. Are all wheezing disorders in very young (preschool) children increasing in prevalence?. Lancet 2001;357:1821-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04958-8.

- Grigg J, Silverman M. Wheezing disorders in young children: one disease or several phenotypes? Respiratory diseases in infants and children. ERS Monogr 2006;37:153-69.

- Davies G, Paton JY, Beaton SJ, Young D, Lenney W. Children admitted with acute wheeze/asthma during November 1998–2005: a national UK audit. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:952-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/adc.2007.133868.

- Stevens CA, Wesseldine LJ, Couriel JM, Dyer AJ, Osman LM, Silverman M. Parental education and guided self-management of asthma and wheezing in the pre-school child: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2002;57:39-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thorax.57.1.39.

- Oommen A, Grigg J. Urinary leukotriene E4 in preschool children with acute clinical viral wheeze. Eur Respir J 2003;2:149-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.02.00021202.

- Knorr B, Franchi LM, Bisgaard H, Vermeulen JH, LeSouef P, Santanello N, et al. Montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, for the treatment of persistent asthma in children aged 2 to 5 years. Pediatrics 2001;108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.3.e48.

- Bisgaard H, Zielen S, Garcia-Garcia ML, Johnston SL, Gilles L, Menten J, et al. Montelukast reduces asthma exacerbations in 2- to 5-year-old children with intermittent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:315-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200407-894OC.

- Robertson CF, Price D, Henry R, Mellis C, Glasgow N, Fitzgerald D, et al. Short-course montelukast for intermittent asthma in children: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:323-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200510-1546OC.

- Lima JJ. Treatment heterogeneity in asthma: genetics of response to leukotriene modifiers. Mol Diagn Ther 2007;11:97-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03256228.

- In KH, Asano K, Beier D, Grobholz J, Finn PW, Silverman EK, et al. Naturally occurring mutations in the human 5-lipoxygenase gene promoter that modify transcription factor binding and reporter gene transcription. J Clin Invest 1997;99:1130-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1172/JCI119241.

- Lima JJ, Zhang S, Grant A, Shao L, Tantisira KG, Allayee H, et al. Influence of leukotriene pathway polymorphisms on response to montelukast in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:379-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200509-1412OC.

- Marmarinos A, Saxoni-Papageorgiou P, Cassimos D, Manousakis E, Tsentidis C, Doxara A, et al. Urinary Leukotriene E4 levels in atopic and non-atopic preschool children with recurrent episodic (viral) wheezing: a potential marker?. J Asthma 2015;52:554-9.

- Mougey E, Lang JE, Allayee H, Teague WG, Dozor AJ, Wise RA, et al. ALOX5 polymorphism associates with increased leukotriene production and reduced lung function and asthma control in children with poorly controlled asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2013;43:512-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cea.12076.

- Telleria JJ, Blanco-Quiros A, Varillas D, Armentia A, Fernandez-Carvajal I, Jesus Alonso M, et al. ALOX5 promoter genotype and response to montelukast in moderate persistent asthma. Respir Med 2008;102:857-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.01.011.

- MacNeill V, Nwokoro C, Griffiths C, Grigg J, Seale C. Recruiting ethnic minority participants to a clinical trial: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2013;3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002750.

- Valovirta E, Boza ML, Robertson CF, Verbruggen N, Smugar SS, Nelsen LM, et al. Intermittent or daily montelukast versus placebo for episodic asthma in children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2011;106:518-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2011.01.017.

- Rabinovitch N, Reisdorph N, Silveira L, Gelfand EW. Urinary leukotriene E(4) levels identify children with tobacco smoke exposure at risk for asthma exacerbation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:323-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.035.

- Nwokoro C, Pandya H, Turner S, Eldridge S, Griffiths CJ, Vulliamy T, et al. Intermittent montelukast in children aged 10 months to 5 years with wheeze (WAIT trial): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:796-803. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70186-9.

- Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994;81:515-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/biomet/81.3.515.

Appendix 1 Patient information sheet

Appendix 2 Informed consent form

Appendix 3 Case report forms

All CRF copyright is owned by the WAIT trial team and the forms may be reproduced with appropriate accreditation and citation of their origin.

Two weeks prior to first investigational medicinal product dispensing assessment and randomisation case report form

T0 trial entry case report form

T0 researcher aide-memoire

2 months to 12 months prior to time of first investigational medicinal product dispensing telephone call case report form

2 months to 12 months prior to time of first investigational medicinal product dispensing medical attendance verification case report form

Diary card case report form

Non-serious adverse event case report form

Serious adverse event case report form

Withdrawal case report form

Appendix 4 Laboratory procedures

Laboratory quality assurance standard operating procedure (London)

Urinary Eicosanoid – high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry standard operating procedure (Krakow)

Marek Sanak and Anna Gielicz 2 August 2009

Standard operating procedure: urinary eicosanoids measurements

Platform

-

High-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry.

-

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.

Sample requirements:

-

Frozen urine, two aliquots of 1 ml (Eppendorf tubes).

Sample preparation