Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 08/99/04. The contractual start date was in February 2010. The final report began editorial review in January 2015 and was accepted for publication in October 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Sabita Uthaya is currently in the process of applying for a patent for the trial parenteral nutrition formulations. Jane Warwick has had personal fees paid for consultancy work by Novo Nordisk (Bagsværd, Denmark).

Corrections

-

This article was corrected in June 2017. See Uthaya S, Liu X, Babalis D, Dore C, Warwick J, Bell J, et al. Corrigendum: Nutritional Evaluation and Optimisation in Neonates (NEON) trial of amino acid regimen and intravenous lipid composition in preterm parenteral nutrition: a randomised double-blind controlled trialEfficacy Mech Eval2016;3(2):8182. https://doi.org/10.3310/eme03020-c201706

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Uthaya et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Preterm infants

Extremely preterm infants, born before 31 weeks of gestation, account for 1–1.5% of deliveries in the UK. Of around 70,000 infants born preterm in the UK each year, about 8000 are born before 31 weeks of gestation. The UK has one of the highest rates of preterm birth in Europe, as well as one of the highest rates of neonatal mortality. These infants spend a prolonged period in hospital and are subject to long periods of poor nutrition. By the time preterm infants reach term age, the overwhelming majority exhibit ‘growth failure’ when compared with healthy term-born infants. 1 Long-term follow-up studies show that there appears to be catch-up growth in infancy and through adolescence. 2 Although this may be reassuring, catch-up growth is associated with adverse metabolic health and renal impairment. 3,4 However, growth failure is associated with neurodevelopmental impairment and cerebral palsy. 5,6

Rationale for trial

Nutrition is a major factor influencing growth and possibly long-term metabolic health. Protein deficiency and a high-fat, high-carbohydrate diet characterises preterm nutrition during this period regardless of whether it is provided intravenously or enterally. A low-protein diet and low protein-to-energy ratio in preterm infants results in a decrease in lean body mass (LBM) and increased deposition of adipose tissue (AT). 7 Thus, weight gain per se may not be as important as weight gain composition. In preterm infants, a low-protein, high-carbohydrate diet has also been shown to be associated with insulin resistance in adolescence. 8 Preterm infants, at present, do not receive routine metabolic follow-up assessments and so the exact burden of subsequent metabolic ill health cannot be quantified. 9

There is good evidence that there are critical periods in development where nutrition has long-term effects on later health. It has been shown that by the end of the first week of life, cumulative energy and protein deficits in infants born before 30 weeks of gestation are 400 kcal/kg and 14 g/kg, respectively. 10,11 Preterm formulae and fortified maternal milk meet the recommended daily intake (RDI) of macronutrients, but deficits accumulated in the period after birth combined with factors that increase requirements result in a progressive deficit that is not made up or increases the magnitude of later catch-up growth.

Preterm infants have increased prepubertal insulin resistance compared with term-born infants. 12 Compared with term-born infants, as adults they have higher blood pressure13,14 and are more likely to have glucose intolerance,15 insulin resistance and dyslipidaemia. 16 Insulin resistance in prepubertal children born extremely preterm has been associated with neonatal nutrition. Preterm infants were found to be insulin resistant compared with term-born infants. The diet of preterm infants was characterised as being low in protein in the first month and high in fat subsequently. Those who gained most weight in infancy were most insulin resistant and found to have a high carbohydrate intake in the first month of life. 8

Another group has demonstrated that a period of nutritional deprivation (though not specifically of any one macronutrient) in the early postnatal period may have beneficial effects on insulin resistance in preterm infants in adolescence. 17 We have previously shown aberrant AT partitioning, increased intrahepatocellular lipid (IHCL) content and increased insulin resistance in preterm infants at term age equivalent compared with healthy term infants. 18,19 Our data suggest that, even as early as at term equivalent age, preterm infants demonstrate the manifestations of cardiovascular risk factors.

Improving the quality and quantity of nutrition in this period has the potential to improve not just short-term outcomes but also the long-term neurodevelopmental and metabolic health of this vulnerable group of infants. Preterm infants constitute a group that continues to utilise NHS resources throughout life because of the long-term sequelae of prematurity. On average, health and societal costs for preterm children at 6 years of age exceed that of a child born at term by approximately threefold. 20

Nutritional requirements of preterm babies

Traditionally, RDIs have been based on the composition of fetal and newborn weight gain. Source data are derived from the studies of Fomon and Nelson21 and Ziegler et al. 22 on fetal cadavers of different gestational ages. Based on the weight-gain composition at different periods of gestation and hence the accretion rate of lean mass and fat mass, the dietary intake of energy necessary for preterm newborns to achieve an intrauterine growth rate has been estimated as:

where excreted energy comprises faeces and urine, stored energy is energy stored as protein and fat (based on fetal accretion rate) and expended energy = resting metabolic rate + energy of activity + thermoregulation (based on studies in growing preterm infants).

Using the above data, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition have published RDIs for preterm infants. 23–25 These RDIs have been used to inform this study. Putet et al. 7 have pointed out that knowledge of growth rate is insufficient to derive the optimum nutritional intake of preterm infants. The authors suggests that knowledge of weight gain composition (lean and fat mass) is essential to estimate the ideal ratio of protein to energy in order to avoid the deposition of excess energy as fat. Our previous work lends strength to this concept as we have shown that preterm infants receiving current conventional intakes have a carbohydrate and fat-rich diet, with a deficiency of protein and that they have a higher proportion of AT than term-born infants. 11

In a non-randomised study, Roggero et al. 26, used whole-body plethysmography to measure weight gain and LBM accural at 1 month post-term age in preterm infants fed either a high-protein diet (> 3 g/kg/day) (n = 26) or a low-protein diet (< 3 g/kg/day) (n = 22). Weight gain was significantly lower in the high-protein group than in the low-protein group {mean [standard deviation (SD)]: 946.7 g [375.2 g] vs. 1238 g [407 g]; p < 0.05}, but LBM accrual was asignificantly higher (approximately 4% higher as a percentage of body weight).

Recent reviews have concluded that current nutritional practices contribute to long-term impairment and recommend early introduction of the RDI of macronutrients. 27,28 However, the evidence for this is based on tolerability and growth outcomes, and not on body composition.

Parenteral nutrition

Early nutritional intake in extremely preterm infants is wholly or in part delivered intravenously as parenteral nutrition (PN) because of immaturity of the gastrointestinal system. The median duration of PN after birth in infants born before 31 weeks of gestation is 12 days. Often PN is recommenced later in an infant’s neonatal course if the clinical condition precludes enteral feeding. Each day of PN costs the NHS £80–100 per infant. A typical tertiary neonatal unit spends up to £150,000 per year on PN. There are currently various PN preparations in routine use that vary in both composition and usage, but none has previously been tested in this country in the setting of a large randomised controlled trial (RCT). Some solutions are commercially prepared, whereas others are made up in local hospital pharmacies.

This has been the focus of a scoping exercise that was commissioned by the Department of Health because of serious concern of clinical risk to patients. 29 The survey carried out as part of the exercise confirmed that current practice among neonatologists with respect to PN varies widely and is based on limited evidence. There was also considerable variation in the preparation of PN and guidelines for use. One hundred and sixteen hospitals reported providing PN to neonates and completed the survey relating to neonates. The principal investigator was a member of the clinical group that developed and analysed the survey and prepared the report. The report, which was published in November 2011, called for urgent measures to standardise practice in both the technical and clinical aspects of use of PN in neonates and children, and for the development of evidence-based guidelines for the use of PN. 29 A further report from the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD), to which the principal investigator contributed, came to similar conclusions. 30

Current widespread practice is to institute PN several hours to days after birth and to introduce macronutrients in PN at a dose below that of the RDI and increase the quantity slowly over a period of 3–4 days, sometimes longer, often not achieving the RDI. This practice is non-evidence based and results in cumulative deficits in protein and energy over the first 2 weeks of life. This practice is more prevalent with respect to amino acids than carbohydrates and fat. Long-term use of PN results in liver impairment and even failure. This is a particular problem in neonatal units caring for infants with bowel problems that preclude or limit enteral feeding. There are now newer preparations of fat (SMOFlipid®; Fresenius Kabi AG, Richmond Hill, ON, Canada) that have been found to be liver protective and are currently used in infants on long-term PN. 31 There is a need for studies to investigate the efficacy of these newer lipid solutions in reducing liver impairment.

Previous studies of parenteral nutrition

Recent reviews have concluded that current nutritional practices contribute to growth failure and recommend early introduction of the RDI of macronutrients in PN. 27,28 However, the quality of the evidence on which this is based is grade B (RCT with minor limitations, overwhelming consistent evidence from observational studies) and only based on outcomes such as tolerability and growth, despite recognition that the ideal postnatal growth rate of a preterm infant is unknown. No data exist on the effect on body composition.

We have shown that the body composition of preterm infants is different from that of healthy term-born infants. Preterm infants had a significantly reduced LBM and pattern of AT distribution associated with metabolic complications. 19 Tan et al. 32,33 studied the effect of hyperalimentation on head growth. No differences between the two groups were found, but non-randomised analyses showed protein and energy deficits to be correlated with poor head growth. Eighty per cent of babies in the intervention group had significant protein/energy deficits at the end of the first 4 weeks. A major drawback of this study was that participants in this study were recruited up to 7 days after birth, by which time significant deficits are known to have developed. The study was also underpowered to detect a significant effect on the primary outcome.

A systematic review of the effect of early administration of PN on growth outcomes in preterm infants included eight RCTs and 13 observational studies. 34 The review was limited by the disparate growth outcome measures. Early PN reduced the time to regain birthweight by (a mean) 2.2 days [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1 to 3.2 days] in RCTs and 3.2 days (95% CI 2.0 to 4.4 days) in observational studies. The maximum percentage weight loss with early PN was lower by (a mean) 3.1% (95% CI 1.7% to 4.5%) for RCTs and by 3.5% (95% CI 2.6% to 4.3%) for observational studies. Early PN also improved weight at discharge or 36 weeks postmenstrual age by (a mean) 14.9 g (95% CI 5.3 to 24.5 g) in observational studies, but no benefit was shown for length or head circumference. 34

A trial comparing two different amounts of amino acids (2.4 g/kg/day vs. 3.6 g/kg/day, with a lipid intake of 2–3 g/kg/day; and an additional third arm of 2.4 g/kg/day of amino acids, with a delayed introduction of lipids) from birth demonstrated an improved nitrogen balance on day 2 in the arms with early initiation of lipids. There was no improvement in nitrogen balance with greater amounts of amino acids. 35

A systematic review of the early introduction of lipids (defined as introduction within the first 2 days after birth) and the use of new lipid emulsions included 14 RCTs. 36 Early initiation of lipids had no impact on any of the outcome measures, including death, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotising enterocolitis, patent ductus arteriosus, sepsis, intraventricular haemorrhage, significant jaundice and hypertriglyceridaemia. The meta-analysis of the effects of lipid emulsions that are not purely soya bean based showed no difference in outcomes of death, duration of respiratory support or rate of weight gain. There was a lower rate of sepsis with the lipid emulsions that were not purely soya bean based, but the difference was not statistically significant. However, the authors concluded that large-scale RCTs are needed to determine the efficacy of newer lipids. 36

We recently published a systematic review of preterm PN summarising the evidence to date. 37 The review concludes that the evidence base for current recommendations is based on historical evidence and there are no long-term studies of the impact of PN on health and neurodevelopment.

Risks and benefits of parenteral nutrition

Parenteral nutrition is an independent risk factor for sepsis in neonates, associated with a 40-fold greater risk, which makes its judicious use a priority. The risks associated with any form of PN are metabolic disturbances (hyperglycaemia, hyperlipidaemia, electrolyte imbalances), infection38 and catheter-related complications. However, these risks are unavoidable as PN is the only option for feeding extremely preterm infants until they are established on enteral nutrition.

Parenteral nutrition is also associated with cholestasis and liver impairment. 39 Instituting PN containing the RDI of amino acids on the day of birth, as in the intervention arm, may result in a higher incidence of metabolic acidosis and high concentrations of urea nitrogen in the blood. Until now, only one study has investigated the efficacy of the early introduction of amino acids (3.5 g/kg/day) combined with a lipid emulsion (3 g/kg/day), in high concentrations, within the first 2 hours of life. Early lipid introduction resulted in an increased positive nitrogen balance without an increased incidence of metabolic or respiratory complications. 40 However, there was a small, but statistically significant, increase in serum bilirubin, without clinical implications. Other studies in preterm infants using this approach have not found an increased incidence of this problem. 40–42

The lipid solution currently used, Intralipid 20% (Fresenius Kabi AG, Richmond Hill, ON, Canada), is a first-generation lipid emulsion based on soya bean oil, which is very rich in n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. However, an excess intake of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in PN is associated with an unbalanced fatty acid pattern in cell membranes, with possible modified function, and with increased lipid peroxidation. 43 Second-generation emulsions are represented by medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) and long-chain triglyceride (LCT) mixtures, and emulsions containing olive oils. MCT–LCT mixtures are cleared from the bloodstream more quickly and generate more immediate energy. Emulsions containing olive oils provide a more physiological mixture of fatty acids with less lipid peroxidation. An example of a third-generation emulsion is SMOFlipid (a mixture of soya bean oil, MCTs, olive oil and fish oils, supplemented with vitamin E). This emulsion is designed to increase the amount of n-3 fatty acids, thereby reducing the ratio of n-6 to n-3 fatty acids (in accordance with current recommended levels). 43 SMOFlipid 20% is well tolerated in infants without changing lipid peroxidation parameters,31,44 and beneficial effects on liver function and serum triglyceride concentrations have been described. 31

Need for the Nutritional Evaluation and Optimisation in Neonates trial

In spite of evidence demonstrating that introducing the RDI of macronutrients early appears to be safe and results in improved protein retention and better growth in the short term, clinical practice has remained variable because of the absence of evidence from RCTs with clinically meaningful outcomes. If early introduction of the RDI of macronutrients was shown, in the setting of a RCT, to improve not just growth measured by anthropometry, but a better measure of growth (i.e. increase in LBM and better brain growth, with the long-term benefits that in turn result from these) it has the potential to impact the vast majority of neonatal unit graduates. There is an urgent need for therapy with PN to be evidence based.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

The two main research objectives were to study the effects of two parenteral nutrition interventions (amino acid quantity and lipid composition) in extremely preterm infants.

Amino acid intervention

To evaluate whether or not immediate rather than incremental introduction of the RDI of amino acids (Imm-RDI) in extremely preterm infants results in:

-

higher non-adipose (lean) body mass at term (primary objective)

-

increased brain volume at term (secondary objective)

-

reduced insulin resistance at term (secondary objective)

-

lower ratio of internal to subcutaneous AT at term (secondary objective)

-

the standard deviation (SD) score for weight undergoing a smaller drop between birth and term equivalent (secondary objective).

Lipid intervention

To evaluate whether or not 20% SMOFlipid (with a lower ratio of n-6 to n-3 fatty acids) compared with 20% Intralipid in extremely preterm infants results in:

-

reduced IHCL content at a term age equivalent (primary objective)

-

a reduced incidence of hypertriglyceridaemia and hyperbilirubinaemia (secondary objective).

Chapter 3 Methods

Trial design

This was a multicentre, randomised, 2 × 2 factorial and double-blind controlled trial in four London and south-east England centres in the UK. Eligible preterm infants were randomised within 24 hours of birth to receive (1) either incremental amino acids (Inc-AA) in PN or the Imm-RDI from day 1; and (2) either 20% Intralipid or 20% SMOFlipid.

There were four randomised groups:

-

Inc-AA and 20% Intralipid (Inc-AA/Intralipid)

-

Inc-AA and 20% SMOFlipid (Inc-AA/SMOFlipid)

-

Imm-RDI and 20% Intralipid (Imm-RDI/Intralipid)

-

Imm-RDI and 20% SMOFlipid (Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid).

Participants

Preterm infants (born before 31 weeks of gestation) requiring nutritional support in the form of PN.

Inclusion criteria

-

Preterm infants born before 31 weeks of gestation (defined as ≤ 30 weeks and 6 days).

-

Written informed consent from parents.

Exclusion criteria

-

Major congenital or life-threatening abnormalities.

-

Inability to randomise in time to allow administration of trial PN within 24 hours of birth.

Interventions

There were two main interventions, namely the amount of amino acids in PN and the type of lipid formulation. All other components of PN were consistent across the four treatment groups. The intervention was commenced within 24 hours after birth. Nutritional intake, both parenteral and enteral, was guided by prespecified protocols that were provided in an investigator’s manual.

The interventions ceased once the infant was established, for at least 24 hours, on enteral feeds of 150 ml/kg/day. If the infant was subsequently nil by mouth after this point, PN was prescribed in accordance with local practice as determined by the supervising clinician.

A summary of the interventions is provided in Table 1.

| Intervention component | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 onwards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inc-AA/Intralipid | |||

| Volume (excluding lipid volume) (ml/kg/day) | 90 | 90 | 120 |

| Protein (g/kg/day) | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.4 |

| Amino acid equivalent (g/kg/day) | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.7 |

| Carbohydrate (glucose) (g/kg/day) | 8.6 | 8.6 | 8.6 |

| 20% Intralipid (g/kg/day) | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Inc-AA/SMOFlipid | |||

| Volume (excluding lipid volume) (ml/kg/day) | 90 | 90 | 120 |

| Protein (g/kg/day) | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.4 |

| Amino acid equivalent (g/kg/day) | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.7 |

| Carbohydrate (glucose) (g/kg/day) | 8.6 | 8.6 | 8.6 |

| 20% SMOFlipid (g/kg/day) | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Imm-RDI/Intralipid | |||

| Volume (excluding lipid volume) (ml/kg/day) | 90 | 90 | 120 |

| Protein (g/kg/day) | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Amino acid equivalent (g/kg/day) | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.6 |

| Carbohydrate (glucose) (g/kg/day) | 8.6 | 8.6 | 8.6 |

| 20% Intralipid (g/kg/day) | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid | |||

| Volume (excluding lipid volume) (ml/kg/day) | 90 | 90 | 120 |

| Protein (g/kg/day) | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Amino acid equivalent (g/kg/day) | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.6 |

| Carbohydrate (glucose) (g/kg/day) | 8.6 | 8.6 | 8.6 |

| 20% SMOFlipid (g/kg/day) | 2 | 3 | 3 |

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

The efficacy of the early introduction of the RDI of amino acids was assessed by whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure lean mass, and by the quantity and distribution of AT. This assessment was done at term age equivalent. The infants were scanned between 37 and 44 weeks postmenstrual age.

Measurement of lean body mass

Lean body mass was calculated by subtracting AT mass from the weight of the infant on the day of the scan.

Measurement of intrahepatocellular lipid content

The efficacy of SMOFlipid was assessed by liver magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to measure IHCL content. This was done at term age equivalent, between 37 and 44 weeks postmenstrual age.

Secondary outcomes

-

Quantity and distribution of AT.

-

Total and regional brain volumes.

-

Metabolic index of insulin sensitivity [qualitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI)].

-

Serum lipids and bilirubin.

-

Incidence of death.

-

Anthropometry.

Data collection

Electronic case record form

Data management was through the InForm 4.6 (SP0c, build 1088; Oracle Corporation, Redwood, CA, USA) integrated trial management system, a web-based data entry system that builds an Oracle Database 10g (Enterprise Edition release 10.2.0.4.0 – 64bit; Oracle Corporation, Redwood, CA, USA) for each individual clinical trial. Trial data were captured on a bespoke web-based electronic case record form (eCRF) with built-in validation rules to identify data entry errors in real time and a full audit trail of data entry and changes. All persons entering data were trained prior to start-up and given personal login details, with access to forms restricted according to site and role. The eCRF was designed in accordance with the requirements of the trial protocol and access to the eCRF was password protected and included a controlled level of access.

Timescale of trial evaluations

Daily evaluations

The first daily evaluation started at the time of birth and was completed when the first bag of trial PN was changed and on the first day of postnatal life. Subsequent evaluations occurred 24 hours from this time point (± 2 hours), every day from birth and until 37 weeks postmenstrual age or discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (where days were calculated from the date PN was initiated).

Weekly evaluations

The first weekly evaluation occurred 7 ± 2 days from randomisation and each 7 days (± 2 days) thereafter until 37 weeks corrected age or discharge from the NICU.

Monthly evaluation

The first monthly evaluation occurred 30 days (± 5 days) from randomisation and each 30 days (± 5 days) thereafter until 37 weeks corrected age or discharge from the NICU.

For infants who received long-term PN, which is for at least 28 continuous days, serum trace elements were measured.

The 37-week evaluation

This evaluation took place when the infant reached 37 weeks postmenstrual age (± 1 week) or when the infant was discharged from the NICU, whichever occurred sooner.

The end-of-study evaluation

The end-of-study evaluation took place as soon as possible after the infant was discharged from the NICU at 37–44 weeks postmenstrual age. In the case of one hospital (Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Trust) with onsite access to a magnetic resonance (MR) scanner, infants aged between 37 and 44 weeks postmenstrual age who were otherwise well but not ready for discharge, were scanned prior to discharge.

Schedule of investigations

A summary of tests and investigations performed is provided in Table 2.

| Evaluation | Baseline | Daily | Weekly | Monthly | 37 weeks corrected age | End of study (37–44 weeks and discharge from the NICU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informed consent | ✓ | |||||

| Eligibility | ✓ | |||||

| Randomisation | ✓ | |||||

| Weight | a | a,b | a | ✓ | ||

| Length | a | a | ✓ | |||

| Head circumference | a | a | ✓ | |||

| Blood pressure | a | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Nutritional intake | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Safety | ||||||

| Blood glucose (highest and lowest in previous 24 hours) | a,b | |||||

| Worst base deficit on blood gas (in previous 24 hours) | a,b | |||||

| Serum bilirubin, LFTs, serum urea, creatinine and electrolytes | a,b | a | ||||

| Serum lipid and cholesterol | a,b | |||||

| Trace elements (zinc, copper, manganese, aluminium and selenium) | a,b | |||||

| AE tracking | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Efficacy | ||||||

| QUICKI | ✓ | |||||

| Whole-body and brain MRI, MRS | ✓ | |||||

| Blood spot | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Urine sample and stool sample | ✓ | |||||

Clinical investigations

Anthropometry

Weight, length and head circumference measurements are routinely used to monitor infant growth. Weight was recorded on a daily basis until discharge and at the end of study visit while the infant received PN, and weekly when the infant did not receive PN. Length and head circumference were recorded on a weekly basis until discharge and at the end of study visit.

Blood pressure measurements

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured in the right upper limb using a non-invasive blood pressure monitor and a cuff that covered at least two-thirds of the right upper limb and encompassed the entire arm in the resting state.

Magnetic resonance imaging

The MRI measurements were carried out during normal sleep without the need for sedation. All the MRI measurements (body composition, hepatic MRS and brain MRI) took a total of 45–60 minutes. The infants were monitored with pulse oximetry and a trained neonatal doctor was present throughout the scan. Parents were invited to be present in the console room.

Magnetic resonance imaging body composition

Acquisition of images

Scans were undertaken after discharge from hospital at the Robert Steiner MR Unit, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust at a dedicated research scanning facility on a 1.5-T Phillips Achieva scanner (Philips, Best, the Netherlands). Babies born at the lead site (Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Hospital) who were still inpatients between 37 and 44 weeks postmenstrual age and unlikely to be discharged home in time to be scanned in the research scanner were scanned while inpatients at Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Hospital scanner on a 1.5-T Siemens Avanto scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany).

For images that were acquired on the Phillips 1.5-T system, a T1-weighted rapid-spin-echo sequence (repetition time of 500 milliseconds, echo time of 17 milliseconds, echo train length of 3) using a Q body coil was used. The slice thickness was 5 mm and the interslice difference was 5 mm. Voxel size was 0.31 × 0.31 × 0.31 cm. Acquisition time was approximately 12 minutes. For images acquired on the Siemens scanner a T1 turbo-spin-echo sequence was used (with a repetition time of 514 milliseconds and an echo time of 11 milliseconds).

Analysis of images

Analysis of all MR images was undertaken independently of the investigators, blind to subject identity and treatment, by Vardis Group (London, UK; www.vardisgroup.com). Images were analysed by a single observer, using a commercially available software program (SliceOMatic, Version 4.2; Tomovision, Montreal, QC, Canada). A filter was used to distinguish between different grey-level regions on each slice. This was then verified and, where necessary, edited using the interactive slice editor program. AT area (cm2) for each slice was calculated as the sum of the voxels multiplied by the voxel area. AT volume (cm3) for each slice was calculated by multiplying the tissue area by the sum of the slice thickness and the interslice distance. The coefficient of variation for these measurements was < 3%. 45 AT volume in litres was converted to AT mass in kg, assuming a value for the density of AT of 0.90 kg/l. 46,47

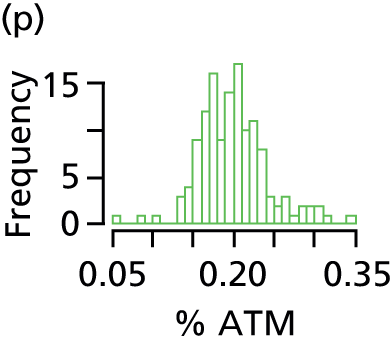

Adipose tissue mass was used to determine percentage AT as:

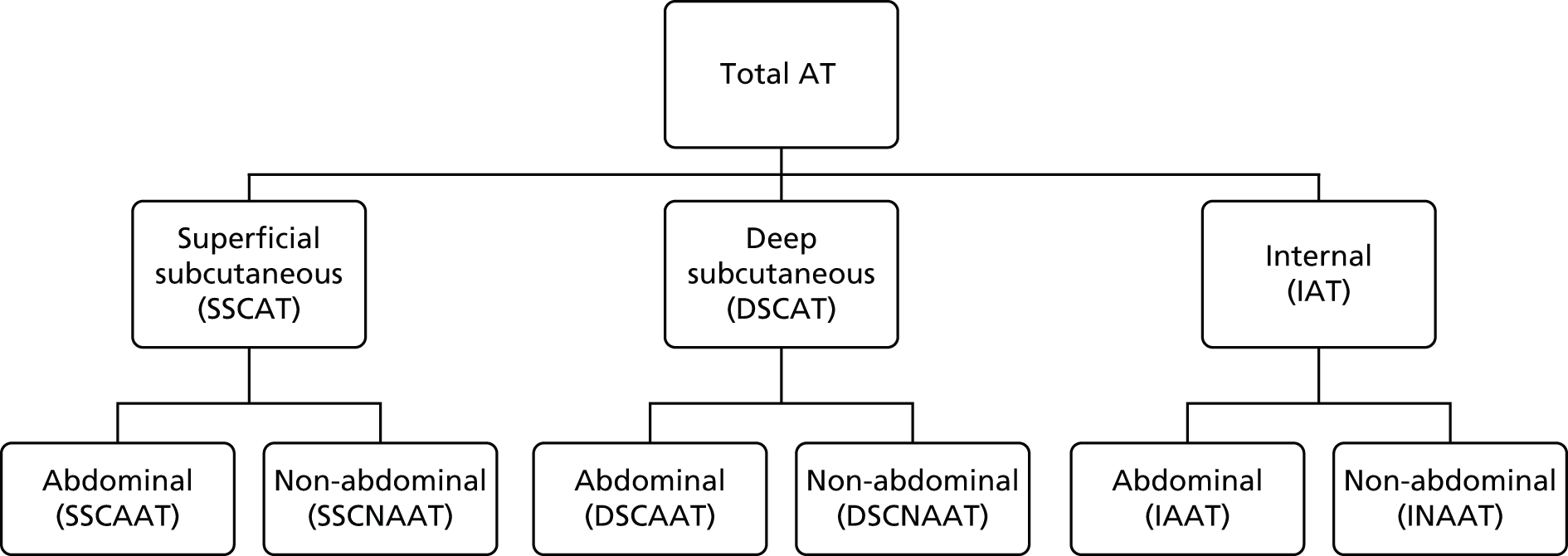

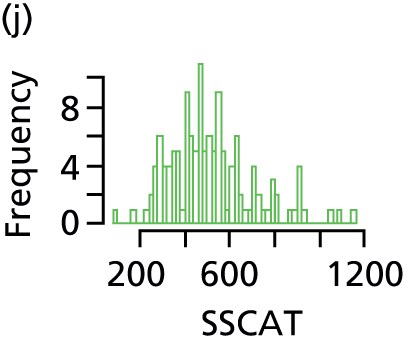

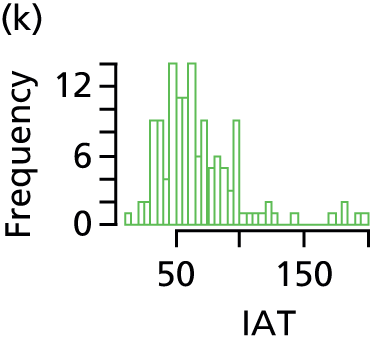

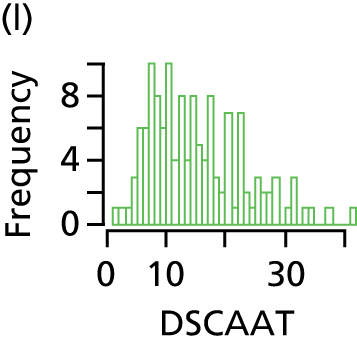

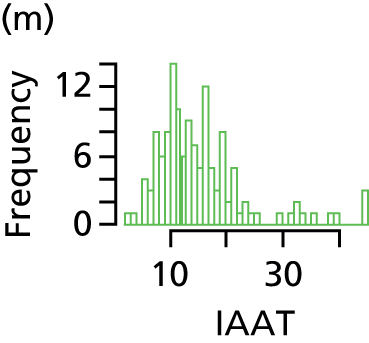

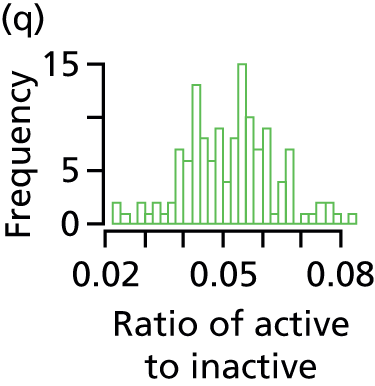

Total AT volume was calculated as the sum of six individually quantified AT compartments – superficial subcutaneous abdominal AT, superficial subcutaneous non-abdominal AT, deep subcutaneous abdominal AT, deep subcutaneous non-abdominal AT, internal abdominal AT and internal non-abdominal AT – as previously described45 (Figure 1). Total subcutaneous AT was calculated as the sum of abdominal superficial subcutaneous, abdominal deep subcutaneous, non-abdominal superficial subcutaneous and non-abdominal deep subcutaneous AT. Total internal AT was calculated as the sum of internal abdominal and internal non-abdominal AT.

FIGURE 1.

Classification of AT depots. DSCAAT, deep subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue; DSCAT, deep subcutaneous adipose tissue; DSCNAAT, deep subcutaneous non-abdominal adipose tissue; IAAT, internal non-abdominal adipose tissue; IAT, internal adipose tissue; INAAT, internal non-abdominal adipose; SSCAAT, superficial subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue; SSCAT, superficial subcutaneous adipose tissue; SSCNAAT, superficial subcutaneous non-abdominal adipose tissue. Adapted with permission from Modi N et al. , Pediatric Research 2009;65:584–7. 45

Hepatic magnetic resonance spectroscopy

Acquisition of spectra

Hydrogen-1 (1H) MR spectra were acquired at 1.5 T from the right lobe of the liver using a point-resolved spectroscopy sequence (repetition time 1500 milliseconds/repetition time 135 milliseconds) without water saturation and with 128 signal averages. Transverse images of the liver were used to ensure accurate positioning of the (20 × 20 × 20 mm) voxel in the liver, avoiding blood vessels, the gall bladder and fatty tissue. For spectra acquired on the 1.5-T Siemens Avanto scanner a voxel size of 15 × 15 × 15 mm was used.

Analysis of spectra

Spectra were analysed in the time domain using the advanced method for accurate robust and efficient spectral fittings algorithm included in the Java-based MR user interface software package (version 1.3; MRUI consortium; www.jmrui.eu/) by a single investigator (LT) who was blind to the treatment category. 48–50 Peak areas for all resonances were obtained and lipid resonances were quantified with reference to water resonance, after correcting for T1 and T2. Hepatic water, known to be relatively constant, was used as an internal standard and the results are presented as the percentage ratio of fat CH2 to water.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging

Acquisition of images

Brain imaging was performed on infants using a dedicated eight-channel paediatric coil. Three-dimensional T1-weighted fast-gradient echo images were acquired in a sagittal plane with using the following parameters: field of view (FOV) 220 × 158 mm; 192 slices; slice thickness 1 mm; an acquired voxel size 0.82 × 0.97 mm; matrix 256; echo time 4.6 milliseconds; repetition time 17 milliseconds; flip angle 13°; and acquisition time 6 minutes.

Whenever possible, and with time permitting, the following brain scans were also undertaken:

-

T2-weighted turbo-spin-echo sequence acquired in an axial plane with FOV 220 × 220 mm; 94 slices; slice thickness 2 mm; acquired voxel size 1.15 × 1.42 mm; slice gap 1 mm; matrix 256; echo time 160 milliseconds; repetition time 15,077 milliseconds; flip angle 90°; and acquisition time 2 minutes.

-

A three-dimensional time-of-flight MR angiography sequence to assess the anterior cerebral artery, middle cerebral artery and posterior cerebral artery. The imaging parameters used were FOV 175 × 144 mm; 75 slices; one stack; slice thickness 0.8 mm; slice gap 0 mm, voxel size 0.61 × 0.61 mm; echo time 12 milliseconds; repetition time 23 milliseconds; flip angle 16°; matrix 512; and acquisition time 5 minutes.

-

Fifteen direction diffusion tensor imaging for assessment of white matter integrity also formed part of the protocol, with the following imaging parameters: FOV 224 × 224 mm; 49 slices; slices thickness 2.5 mm; slice gap 0 mm; acquired voxel size 2 × 2 mm; matrix 128; echo time 49 milliseconds; repetition time 49,709 milliseconds; maximum b factor 750; number of b factors 2; and acquisition time 6 minutes.

Analysis of images

A specialist in neonatal neurology reported all brain MRI images for clinical purposes. A note was made of any congenital or acquired lesions. The type and severity of these was recorded for all cases. Scans with parenchymal brain lesions were excluded from subsequent quantitative analysis.

A quantitative whole-brain segmentation program was used to segment the brain and its constituent structures using the T2-weighted image data. 51 These volumetric data could be obtained only from images that were of adequate quality with good signal-to-noise ratio and absence of motion artefact.

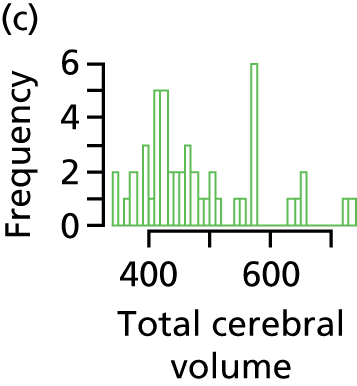

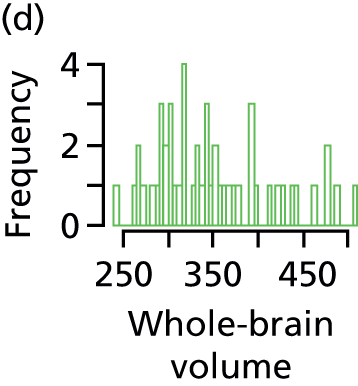

The following outcomes were measured:

-

total cerebral volume: sum of the volumes of basal ganglia, thalami (deep grey matter), cerebrospinal fluid, grey matter, white matter and lateral ventricles

-

whole-brain volume: sum of the volumes of basal ganglia, thalami (deep grey matter), grey matter and white matter

-

posterior fossa volume: sum of the volumes of cerebellum and brainstem.

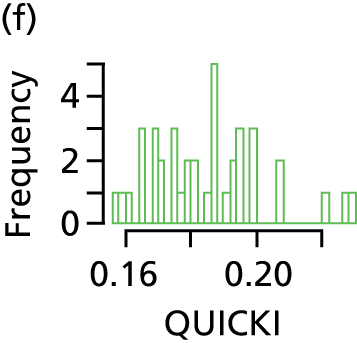

Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index

The QUICKI is a marker of insulin resistance calculated from pre-feed serum insulin and blood glucose. Homeostatic model assessment is the gold standard for measuring insulin resistance, but is invasive and cannot be justified ethically in this patient group. Furthermore, the QUICKI has been validated against homeostatic model assessment52 and has been used in neonates before. 53 Measurement of the QUICKI was carried out at term age and samples taken at the time of routine (pre-feed) blood tests.

Pharmacovigilance definitions and procedures

Serious adverse events

An adverse event (AE) was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a patient administered an investigational medicinal product (IMP), in accordance with clinical trial regulations. An AE was considered serious and reportable via the eCRF if any of the following criteria occurred:

-

it resulted in death

-

it was life-threatening

-

it resulted in prolongation of existing inpatient hospitalisation

-

it resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity.

Expectedness and causality of serious adverse events

The trial protocol specified that a range of serious adverse events (SAEs) would be expected, either as a consequence of preterm birth or if they were listed in any of the summaries of product characteristics, and this expectedness was recorded on the eCRF for each SAE report.

Causal relationship to the IMP was defined according to Table 3.

| Relationship | Description |

|---|---|

| Unrelated | There is no evidence of any causal relationship |

| Unlikely | There is little evidence to suggest there is a causal relationship (e.g. the event did not occur within a reasonable time after administration of the trial medication). There is another reasonable explanation for the event (e.g. the patient’s clinical condition, other concomitant treatment) |

| Possiblea | There is some evidence to suggest a causal relationship (e.g. because the event occurs within a reasonable time after administration of the trial medication). However, the influence of other factors may have contributed to the event (e.g. the patient’s clinical condition, other concomitant treatments) |

| Probablea | There is evidence to suggest a causal relationship and the influence of other factors is unlikely |

| Definitelya | There is clear evidence to suggest a causal relationship and other possible contributing factors can be ruled out |

| Not assessable | There is insufficient or incomplete evidence to make a clinical judgement of the causal relationship |

Reporting of adverse events

The trial eCRF included dedicated forms for reporting SAEs. Investigators were advised to report SAEs via the eCRF within 24 hours of becoming aware of the event and to include an assessment of expectedness and causality in the SAE report. The clinical trials unit and chief investigator reviewed each SAE report within 2 working days.

Adverse events

The only non-serious AEs that were reportable were values of triglycerides, bilirubin and other safety parameters above or below prespecified levels, and these are summarised in Table 4. These were labelled as ‘specific adverse events’ (SpAEs) reportable via the eCRF. The eCRF incorporated in-built checks to flag any occurrence of a SpAE during the data entry process to the local teams. Guidance for the management of these events was provided to the participating centres in a trial-specific investigator’s manual. SpAEs related to safety parameters were collected daily during the period of trial PN administration.

| Assessment (blood test) | Level requiring SpAE report | Level requiring reporting to the DMEC |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | < 2.6 mmol/l or > 15 mmol/l | Not reported to the DMEC |

| Worst base deficit in previous 24 hours | > 15 mmol/l | > 15 mmol/l |

| Total serum bilirubin | > 150 µmol/l | > 150 µmol/l, only after 3 weeks on PNa |

| Conjugated bilirubin | > 40 µmol/l | > 40 µmol/l |

| Cholesterol | > 6 mmol/l | > 10 mmol/l |

| Triglycerides | > 2.5 mmol/l | > 5 mmol/l |

| Sodium | < 131 mmol/l or > 150 mmol/l | Not reported to the DMEC |

| Potassium | < 3.2 mmol/l or > 9 mmol/l | Not reported to the DMEC |

| Phosphate | < 1.5 mmol/l or > 3 mmol/l | Not reported to the DMEC |

| Calcium | < 1 mmol/l or > 3 mmol/l | Not reported to the DMEC |

| Urea | < 1.5 mmol/l or > 7 mmol/l | > 10 mmol/l |

| Creatinine | > 170 µmol/l | Not reported to the DMEC |

| Alanine transaminase | > 60 IU/l | Not reported to the DMEC |

| Zinc | < 8 µmol/l | Not reported to the DMEC |

| Copper | < 2 µmol/l | Not reported to the DMEC |

| Manganese | > 30 nmol/l | Not reported to the DMEC |

| Aluminium | > 0.4 µmol/l | Not reported to the DMEC |

| Selenium | < 20 µg/l | Not reported to the DMEC |

As the levels selected for SpAEs were consistent with normal ranges used in standard neonatal clinical care and, in accordance with the new Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) guidance on risk-adapted approach to managing clinical trials, the Nutritional Evaluation and Optimisation in Neonates (NEON) trial was equivalent to standard care, additional reporting and review of SpAEs were not required. The trial Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) reviewed a selection of SpAEs throughout the duration of the trial.

The thresholds for SpAEs as well as those requiring reporting to the DMEC are summarised in Table 4.

Annual safety reports

Annual safety reports were provided to the Research Ethics Committee and MHRA, in accordance with clinical trial regulations, on the anniversary of the clinical trial authorisation each year. A total of three annual safety reports were submitted over the course of the trial.

Statistical considerations

Sample size

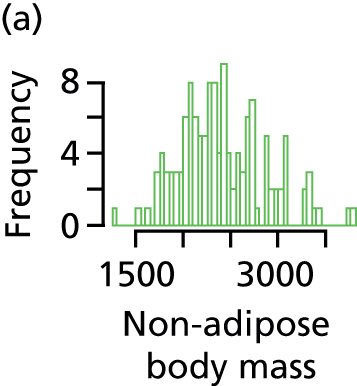

The mean directly measured LBM of preterm infants when studied in 2003 was 2.1 kg (SD 0.4 kg). 17 The mean in healthy term-born infants was 2.6 kg (SD 0.21 kg; mean difference 450 g, 95% CI 300 to 610 g). A sample size of 64 infants in each group was therefore chosen, as this would allow detection of a 200 g difference between the groups with 80% power and at 5% significance. This was considered a clinically important increase in lean mass.

Since the publication of our paper on IHCL,18 measurements were available for a total of 15 infants with gestational ages ranging from 24 weeks to 32.6 weeks. IHCL had a mean lipid-to-water ratio of 1.75 (SD 1.85, range 0.14–7.72); the distribution is clearly positively skewed. A loge-transformation was therefore used to achieve approximate normality. On the natural logarithmic scale the mean IHCL lipid-to-water ratio was 0.121 (SD 1.052, range –1.97 to 2.04). A sample size of 64 infants in each group would therefore have 80% power to detect a difference in means of 0.526 on the logarithmic scale as significant at the 5% significance level (with a t-test). Transforming back to the original scale of measurement, this is equivalent to a 40% decrease in IHCL content in the intervention group.

Assuming a 10% mortality prior to term and a 10% dropout rate, the aim was to recruit 80 infants to each group or until 64 infants in each group had undergone MRI and MRS, a total of 128 scans.

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed using an interactive voice recognition system (IVRS) telephone randomisation system. Sealed Envelope Ltd (London, UK) provided the IVRS and randomisation list.

Randomisation was performed using minimisation, with a 25% chance of simple random allocation (based on the procedure outlined in Pocock54). Randomisation was stratified by gestational age at birth (23–26 or 27–31 completed weeks of gestation), birthweight (< 500 g, 500–1000 g, > 1000 g) and centre. Multiple births were randomised individually.

Blinding

Unblinded trial PN was delivered to the pharmacy department at each participating centre. Trained pharmacy staff were responsible for blinding the trial PN prior to dispensing the supply for administration to each infant.

Secure copies of the randomisation list were held by each pharmacy team in case of the need for emergency unblinding. There was no requirement for unblinding at any point over the course of the study.

Statistical methods

The analysis of this 2 × 2 factorial randomised trial was performed ‘at the margins’ of the 2 × 2 table, assuming that the two factors are operating independently. In addition, summary measures were presented for each cell of the 2 × 2 table and an interaction ratio/difference was calculated. 55 A ‘modified’ intention-to-treat method was used to analyse the results as it was accepted that a proportion of infants would not be able to attend for MRI. With the exception of infants in whom MRI assessment was not completed, all infants were analysed according to their allocation.

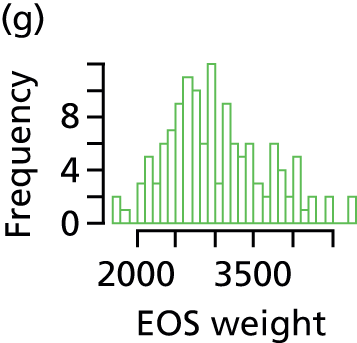

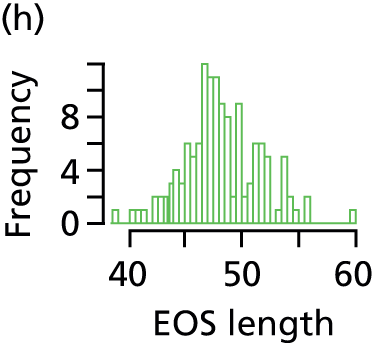

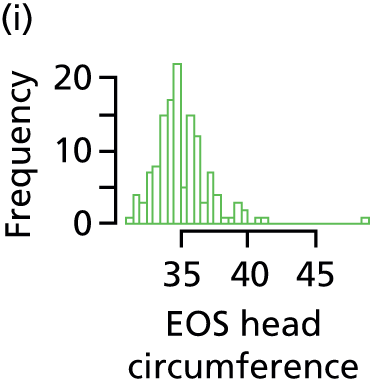

The primary outcome measures for this trial were non-adipose (lean) body mass and IHCL content; the secondary outcomes were growth (weight, length and head circumference), brain growth and development (assessed by MRI) and measure of insulin sensitivity (by the QUICKI). Growth parameters are the only outcomes that were measured sequentially; all other outcomes, including the two primary outcomes, were measured on a single occasion at term age equivalent.

For outcomes measured on a single occasion, a regression model containing the stratifying variables (gestational age, birthweight and centre), nutritional interventions (amino acid and lipid), sex and age at time of measurement were used to estimate the effects of each intervention.

For the amino acid intervention primary outcome, a multiple regression was used with non-adipose body mass (g) as the dependent variable and amino acids (incremental vs. RDI), lipids (20% SMOFlipid vs. Intralipid), gestational age, birthweight, centre, sex and age at MRI as the independent variables to assess the effect of amino acids on non-adipose body mass. An interaction term was also included to assess whether or not the effect of amino acids regimen on non-adipose body mass is influenced by choice of lipids.

Similarly, for the lipid intervention primary outcome, a multiple regression was used with IHCLs at natural logarithmic scale as the dependent variable and amino acid (incremental vs. RDI), lipids (20% SMOFlipid vs. Intralipid), gestational age, birthweight, centre, sex and age at MRI as the independent variables to assess the effect of lipids on IHCL content. Again, an interaction term was included to assess whether or not the effect of lipids on IHCL content is affected by amino acid quantity.

A planned secondary analysis was used to investigate the role of illness severity and nutritional intake as potential modifiers of the effects of each intervention by adding these variables to the regression models.

The secondary analysis investigated the role of illness severity, maternal breast milk and post-PN intake, including PN period and post-PN period, as potential modifiers of the effects of each intervention by adding these variables to the regression model. All analyses were performed using Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

All analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis, but as the primary outcomes can be ascertained in only those infants attending the end of study evaluation, up to 20% of primary outcomes are expected to be missing. We have assumed that these outcomes are missing at random.

Missing data

Owing to the nature of this study, it was expected that a number of infants would not undergo the end-of-study MRI (primarily because of death, ill-health or withdrawal of the subject). This was taken into account when calculating the sample size. The statistical analysis plan prespecified that we would analyse only those infants who could be scanned. The reasons for non-attendance were recorded in the withdrawal form. We aimed to comment on the implications that the missing data patterns had on the results from the analysis.

No missing data imputation was carried out except for infant weight over study period. Infant weight was recorded every day during the trial study period and weekly once infants were off the trial. As the daily infant weight was used in the descriptive analysis only, we did not carry out multiple imputations. Instead, we used simple imputation by using the nearest measured weight, either before or after the day of missing weight, to impute the missing data.

Statistical analysis plan

A statistical analysis plan was prepared by the trial investigators and trial statistician and reviewed and agreed by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and DMEC prior to the end of the recruitment period.

Trial organisation

Trial management

The UK Clinical Research Collaboration-registered Imperial Clinical Trials Unit (ICTU) was responsible for trial management, quality assurance, trial statistics, and development and maintenance of the trial database. The Clinical Trials and Evaluation Unit at the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust carried out trial and data management, which was one of the ICTU groups at the time of the trial.

The ICTU core staff and the InForm team are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London.

Trial sponsor

The sponsor of the trial was Imperial College London. The sponsor’s role is clearly set out in the European Clinical Trials Directive (http://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/clinical-trials/directive/index_en.htm) and NHS Research Governance documents (www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/139565/dh_4122427.pdf). Imperial College London signed a clinical trial agreement with each of the participating centres prior to the start of the trial.

Ethical considerations

The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki on research involving human subjects. The study protocol, parent information sheet (PIS) and consent form were submitted to the Research Ethics Committee prior to the start of the study and a favourable opinion was obtained on 8 December 2009.

Consent

Where possible, parents were approached prior to their infant’s birth to give them the PIS and discuss the trial. Full written informed consent was taken after birth using the ethically approved PIS and consent form.

Research governance

The trial was carried out in accordance with the NHS Research Governance Framework, and local NHS permission was granted by the research and development departments at each participating site prior to recruitment commencing.

Regulatory requirements

As a randomised trial of an IMP, the NEON trial was conducted in accordance with the European Clinical Trials Directive and the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004. 56 The trial received clinical trials authorisation from the MHRA on 8 January 2010 and was registered in the European Community with the European Clinical Trials Database (EudraCT) number 2009-016731-34.

Trial registration

The trial was registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) clinical trial database with reference ISRCTN29665319.

National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network portfolio

The NEON trial was adopted on the NIHR Clinical Research Network and Medicines for Children Research Network portfolios. Accrual data were uploaded onto the NIHR Clinical Research Network database on a monthly basis.

Summary of protocol amendments

The ethics committee and MHRA made the following amendments to the trial protocol following approval of the first version of the document:

-

Protocol version 2:

-

Clarifications implemented following review by TSC:

-

clarification that randomisation would be performed by minimisation with 25% chance of random allocation

-

randomisation to be stratified by birthweight in addition to existing factors (centre and gestational age at birth)

-

addition of a monthly evaluation to assess trace elements for infants on PN for > 28 days.

-

-

Administrative corrections.

-

Addition of a metabonomic substudy (funded separately and not reported in this article).

-

-

Protocol version 3:

-

Additional blood samples on days 1 and 5 of life to assess inflammatory markers and lipid profile. The intention was to conduct a substudy to collect these samples at the lead site but it was never implemented.

-

Clarification of randomisation time window. The protocol previously stated that infants must be randomised within 12 hours of birth. The purpose of this time window was to allow adequate time for preparation and dispensing of trial PN. The time window was revised for this version of the protocol so that infants needed to be randomised in enough time to allow administration of PN within 24 hours.

-

Administrative corrections.

-

-

Protocol version 4:

-

The protocol was amended to include a follow-up visit for neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years corrected age using the Bayley Scale of Infant Development, the Hammersmith Optimality Score as well as parental questionnaires (Social-Emotional scale of the Bayley Scales and the Quantitative Checklist for Autism in Toddlers). A funding application for this additional visit was not successful, so the additional visit was not implemented.

-

Trial committees

Trial steering committee

A TSC was established to oversee the conduct of the study. The TSC met three times over the course of the trial: on 26 February 2010, 14 December 2011 and 22 November 2012. Copies of the minutes from each meeting were sent to the funder, the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) programme of the NIHR. The TSC approved the trial protocol prior to the start of the study and received regular recruitment reports throughout the duration of the trial.

The TSC membership is listed below.

-

Independent members:

-

Professor Richard Cooke (chairperson).

-

Mrs Lorraine Dob (parent representative).

-

Dr Paul Clarke.

-

Professor Robert Hume.

-

-

Investigators:

-

Dr Sabita Uthaya (chief investigator).

-

Professor Neena Modi.

-

Caroline Doré.

-

Professor Ian Wong.

-

Professor Jimmy Bell.

-

Professor Deborah Ashby.

-

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

An independent DMEC was established to review SAE reports and the results of interim analyses. The DMEC meetings took place on 2 August 2010, 13 October 2011 and 27 September 2012.

The first DMEC meeting, to agree the charter outlining operational details and responsibilities, took place early in the trial, on 2 August 2010. The second meeting to review interim data for the first 32 infants was on 13 October 2011 and the final interim analysis for 64 infants took place on 27 September 2012. The DMEC provided feedback reports for each meeting to the chairperson of the TSC and this was reviewed, as applicable, at subsequent TSC meetings.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee membership:

-

Professor Peter Brocklehurst (chairperson).

-

Professor Tim Cole (independent statistician).

-

Professor Tony Nunn.

-

Dr Helen Mactier.

Data management

Predefined data ranges were included in the eCRF, which raised automated queries if data outside of the expected range were entered. In addition to the automated queries, the trial data were reviewed on a regular basis by the data manager to look for discrepancies and errors. Furthermore, the trial statistician also performed a series of checks on snapshots of data to look for inconsistencies. The checks performed by the data manager and statistician were documented in a prespecified data management plan, which was updated over the course of the study as required.

Risk assessment and monitoring plan

A risk assessment was performed by the ICTU quality assurance manager prior to the start of the trial. The result of the risk assessment indicated that the study was low risk and that 20% of trial data, 100% consent forms and 100% SAEs should be source verified. A monitoring plan was prepared in accordance with the risk assessment to specify the frequency of monitoring visits and number of source data verification required.

Monitoring visits

A site initiation visit was performed at all participating centres. Interim monitoring visits were carried out approximately annually, depending on the recruitment rate, and closeout visits were carried out at all centres following the final follow-up visit for the last patient recruited. The monitoring visits were conducted by the trial manager.

Investigational medicinal product manufacturer

The IMP for the NEON trial was manufactured by Bath-ASU (Wiltshire, UK), a MHRA-licensed manufacturing unit, with expertise in producing aseptic products.

Patient and public involvement

The TSC membership included a parent representative who was invited to attend all TSC meetings and included in all relevant correspondence. The long-term follow-up of the infants involved in the trial was something parents of babies who took part in the study were keen to see.

Parents were consulted during preparation of the PIS and the charity Bliss was also approached during the design phase of the study. Parent representatives contributed by suggesting changes to the PIS, including reducing the length and complexity of information.

Chapter 4 Results

Participant flow

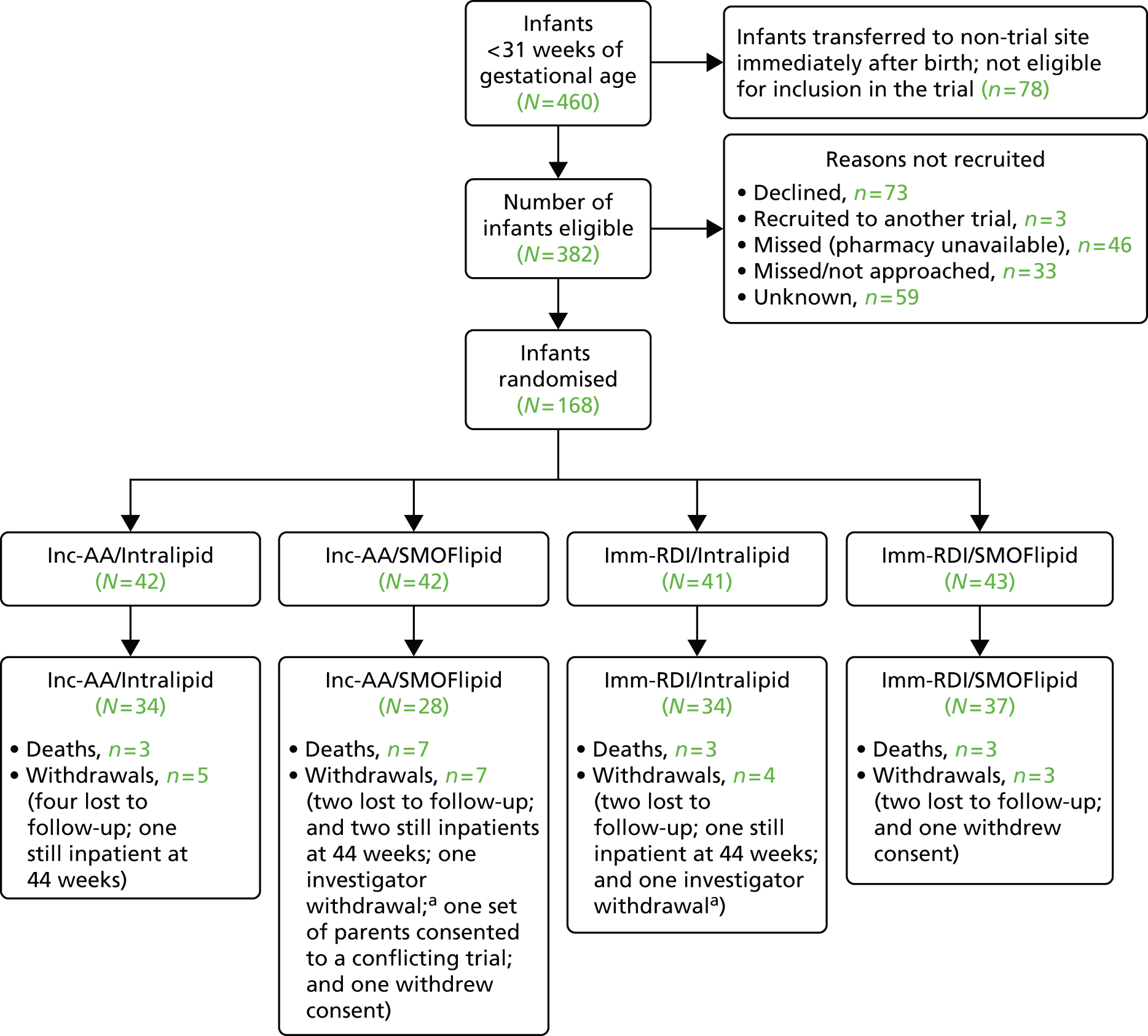

The flow of patients is summarised in Figure 2, including the number of patients screened, randomised and completing the trial.

FIGURE 2.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram. a, Investigator withdrawal: in both cases, this occurred when the infant was transferred to a non-trial site very soon after randomisation and was therefore unable to receive the trial intervention.

Screening

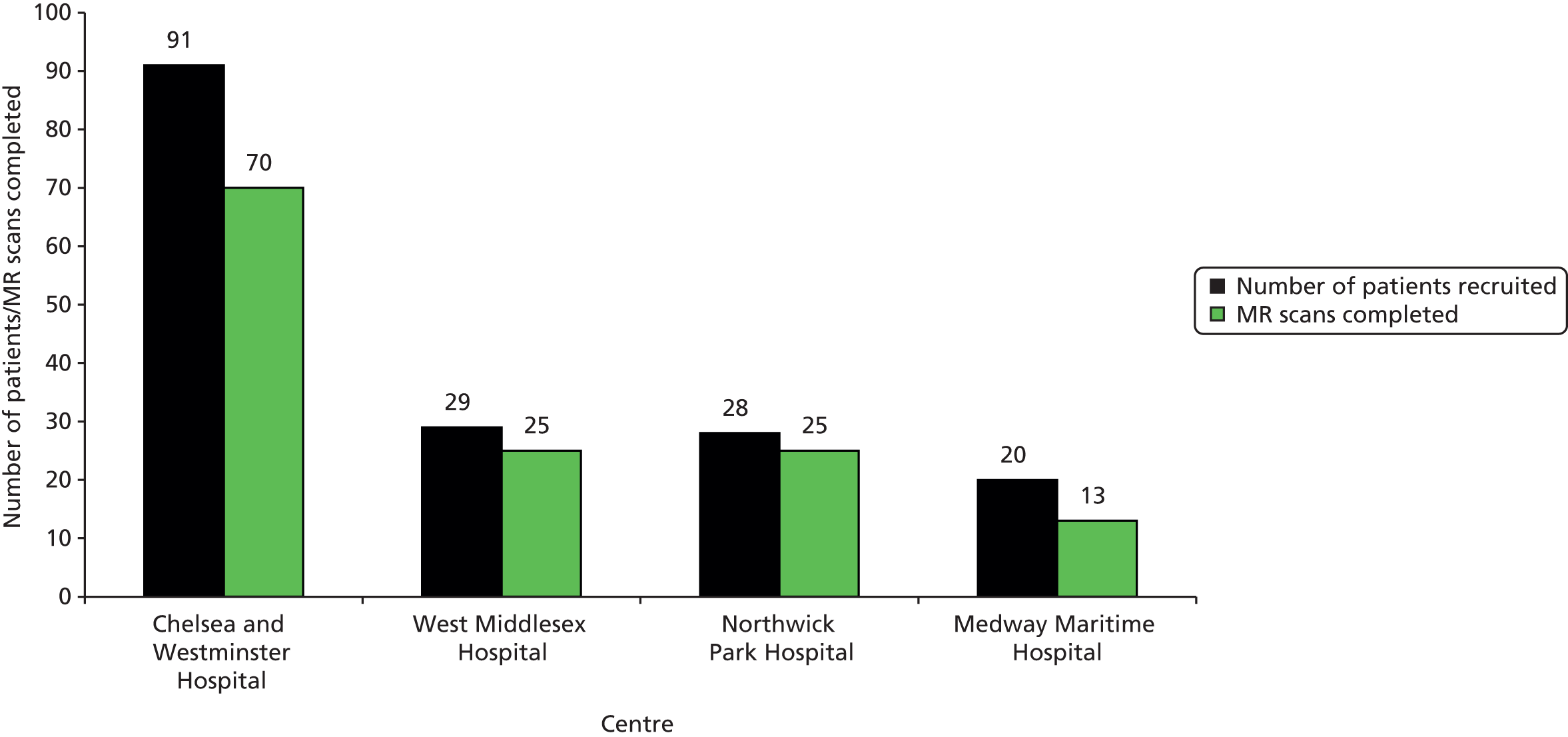

Four hundred and sixty infants below 31 weeks of gestational age were admitted to the participating hospitals over the duration of the trial. Of the 382 infants meeting the eligibility criteria, 168 were randomised to the trial. Figure 3 summarises the percentage of eligible patients recruited to the trial and reasons for non-recruitment.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of screening data for all trial sites.

Recruitment and retention

Recruitment lasted for 3 years; the first infant was recruited on 6 July 2010 and the last on 31 July 2013. The actual recruitment period was longer than the original target of 2.5 years because of delays starting the trial at all sites. The delays in starting the trial were associated with the following:

-

Identifying a suitable manufacturer for the trial with an IMP licence to produce PN and the capacity to support the trial.

-

Agreement from each centre to support excess treatment costs because of the cost difference between standard hospital PN and trial PN supply, including signing a procurement contract for each participating pharmacy.

-

Obtaining NHS permission at each site was lengthy, the procurement process was a factor for this.

-

Inability to recruit during weekends and holidays. Pharmacy departments at three out of four sites could not support recruitment at weekends or during Christmas and Easter, which reduced the recruitment rate.

Recruitment rate

The target recruitment rate for the study was six patients per month, based on all four centres recruiting. The average monthly recruitment rate once all centres were activated (January 2012) was consistent with the target, that is, six patients per month.

Figures 4–6 summarise cumulative recruitment and retention over the course of the study, and recruitment and retention per centre.

FIGURE 4.

Cumulative recruitment vs. target recruitment for the duration of the trial.

FIGURE 5.

Cumulative retention (number of MR scans) vs. target retention for the duration of the trial.

FIGURE 6.

Total recruitment and retention per centre.

Baseline data

The baseline characteristics of the infants recruited to the study and those who completed the MR assessment of primary outcome measures are shown in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. Of the 437 infants born before 31 weeks of gestation, 168 infants were randomised. A total of 133 infants were available for assessment of the primary outcome measures. Baseline characteristics of sex, gestational age at birth, anthropometry, maternal demographics, mode of delivery, antenatal steroid use and time to commencing PN were similar across the four groups.

| Characteristic | Inc-AA/Intralipid (N = 42) | Inc-AA/SMOFlipid (N = 42) | Imm-RDI/Intralipid (N = 41) | Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid (N = 43) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 28 (66.7) | 26 (61.9) | 21 (51.2) | 22 (51.2) |

| Gestational age (weeks), mean (SD) | 27.8 (1.9) | 27.5 (2.4) | 28.1 (2.1) | 27.8 (2.1) |

| Multiple births, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 6 (14.3) | 6 (14.3) | 9 (22.0) | 15 (34.9) |

| Birthweight (kg), mean (SD) | 1.03 (0.29) | 1.05 (0.34) | 1.04 (0.28) | 1.06 (0.29) |

| Birth length (cm), mean (SD) | 35.1 (3.5); n = 31 | 34.6 (4.2); n = 32 | 35.1 (3.9); n = 26 | 35.2 (5.2); n = 32 |

| Head circumference (cm), mean (SD) | 25.3 (2.0); n = 41 | 25.0 (3.0); n = 40 | 25.3 (1.9); n = 37 | 25.6 (2.9); n = 39 |

| Birthweight (z-score), mean (SD) | –0.2 (1.0); n = 42 | 0.1 (1.0); n = 41 | –0.2 (1.0); n = 41 | 0 (0.9); n = 43 |

| Birth length (z-score), mean (SD) | –1.0 (1.0); n = 30 | –0.9 (1.2); n = 24 | –1.1 (1.0); n = 25 | –0.8 (1.5); n = 29 |

| Head circumference (z-score), mean (SD) | –0.5 (0.9); n = 41 | –0.3 (1.0); n = 39 | –0.7 (0.9); n = 37 | –0.2 (1.6); n = 41 |

| Mother’s age (years), mean (SD) | 32.9 (5.3); n = 42 | 31.3 (7.7); n = 42 | 32.9 (6.3); n = 40 | 32.5 (6.6); n = 43 |

| Mother’s weight (kg),b mean (SD) | 66.4 (13.3); n = 34 | 65.9 (11.4); n = 25 | 64.9 (13.0); n = 30 | 68.5 (15.2); n = 33 |

| Mother’s height (cm),b mean (SD) | 161.9 (7.8); n = 33 | 164.9 (7.7); n = 27 | 161.3 (9.2); n = 27 | 164.5 (8.6); n = 32 |

| Father’s weight (kg),b mean (SD) | 80.8 (10.7); n = 27 | 82.3 (13.2); n = 22 | 85.3 (16.1); n = 24 | 86.3 (14.9); n = 31 |

| Father’s height (cm),b mean (SD) | 178.4 (6.5); n = 28 | 179.6 (6.8); n = 22 | 175.7 (10.0); n = 22 | 182.0 (9.7); n = 30 |

| Mother’s ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 16 (38.1) | 19 (45.2) | 21 (51.2) | 21 (48.8) |

| Asian | 14 (33.3) | 7 (16.7) | 12 (29.3) | 12 (27.9) |

| Black | 6 (14.3) | 13 (31.0) | 6 (14.6) | 6 (14.0) |

| Mixed | 2 (4.8) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.7) |

| Other | 3 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.7) |

| Missing | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mode of delivery, n (%) | ||||

| Vaginal | 8 (19.1) | 18 (42.9) | 16 (39.0) | 17 (39.5) |

| Elective caesarean | 7 (16.7) | 3 (7.1) | 4 (9.8) | 2 (4.7) |

| Emergency caesarean | 27 (64.3) | 21 (50.0) | 21 (51.2) | 24 (55.8) |

| Antenatal steroids, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 30 (71.4) | 34 (81.0) | 32 (78.1) | 35 (81.4) |

| No | 7 (16.7) | 6 (14.3) | 7 (17.1) | 4 (9.3) |

| Unknown | 5 (11.9) | 2 (4.8) | 2 (4.9) | 4 (9.3) |

| Time from birth to starting PN, (hours),c median (IQR) | 18.4 (12.3–22.7); n = 42 | 19.5 (13.6–22.8); n = 41 | 20.4 (12.6–23.6); n = 40 | 17.7 (13.0–22.4); n = 43 |

| Characteristic | Inc-AA/Intralipid (N = 34) | Inc-AA/SMOFlipid (N = 28) | Imm-RDI/Intralipid (N = 34) | Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid (N = 37) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 20 (58.8) | 18 (64.3) | 17 (50.0) | 19 (51.4) |

| Gestational age (weeks), mean (SD) | 28.0 (1.8) | 28.0 (2.1) | 28.4 (2.1) | 27.7 (2.0) |

| Multiple births, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 4 (11.8) | 3 (10.7) | 8 (23.5) | 13 (35.1) |

| Birthweight (kg), mean (SD) | 1.06 (0.29) | 1.10 (0.32) | 1.09 (0.28) | 1.06 (0.29) |

| Birth length (cm), mean (SD) | 35.5 (3.5); n = 28 | 35.1 (4.0); n = 24 | 35.6 (3.5); n = 24 | 34.9 (4.9); n = 27 |

| Head circumference (cm), mean (SD) | 25.3 (2.0); n = 34 | 25.6 (2.6); n = 26 | 25.5 (1.9); n = 32 | 25.7 (2.9); n = 34 |

| Birthweight (z-score), mean (SD) | –0.1 (0.9) | 0 (1.0) | –0.2 (1.0) | 0.1 (0.9) |

| Birth length (z-score), mean (SD) | –0.9 (1.1); n = 28 | –1.0 (1.3); n = 21 | –1.0 (1.0); n = 23 | –1.1 (1.4); n = 25 |

| Head circumference (z-score), mean (SD) | –0.5 (0.9); n = 34 | –0.4 (1.0); n = 26 | –0.7 (0.9); n = 32 | –0.2 (1.7); n = 34 |

| Mother’s age (years), mean (SD) | 32.6 (5.4); n = 34 | 30.3 (7.8); n = 26 | 32.2 (6.4); n = 33 | 32.7 (6.7); n = 34 |

| Mother’s weight (kg),b mean (SD) | 67.6 (14.5); n = 27 | 63.8 (11.5); n = 17 | 64.7 (13.3); n = 26 | 68.5 (16.1); n = 29 |

| Mother’s height (cm),b mean (SD) | 162.4 (7.2); n = 26 | 165.1 (7.3); n = 19 | 162.1 (9.1); n = 23 | 164.8 (9.1); n = 28 |

| Father’s weight (kg),b mean (SD) | 82.3 (11.5); n = 21 | 81.5 (14.0); n = 15 | 84.1 (15.9); n = 22 | 87.8 (14.7); n = 28 |

| Father’s height (cm),b mean (SD) | 177.8 (6.1); n = 22 | 179.3 (7.4); n = 15 | 175.6 (10.2); n = 20 | 182.8 (9.6); n = 27 |

| Mother’s ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 13 (38.2) | 11 (39.3) | 17 (50.0) | 19 (51.4) |

| Asian | 10 (29.4) | 6 (21.4) | 11 (32.4) | 9 (24.3) |

| Black | 5 (14.7) | 10 (35.7) | 5 (14.7) | 6 (16.2) |

| Mixed | 2 (5.9) | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.4) |

| Other | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.7) |

| Missing | 1 (2.94) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mode of delivery, n (%) | ||||

| Vaginal | 6 (17.6) | 9 (32.1) | 13 (38.2) | 15 (40.5) |

| Elective caesarean | 5 (14.7) | 2 (7.1) | 4 (11.8) | 1 (2.7) |

| Emergency caesarean | 23 (67.7) | 17 (60.7) | 17 (50.0) | 21 (56.8) |

| Antenatal steroids, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 24 (70.6) | 21 (75.0) | 26 (76.5) | 30 (81.1) |

| No | 5 (14.7) | 5 (17.9) | 6 (17.7) | 4 (10.8) |

| Unknown | 5 (14.7) | 2 (7.1) | 2 (5.9) | 3 (8.1) |

| Time from birth to starting PN, (hours),c median (IQR) | 16.9 (10.5–22.3); n = 34 | 19.4 (12.1–22.3); n = 28 | 20.0 (12.4–23.5); n = 34 | 17.7 (13.2–22.4); n = 37 |

The time to achieve a milk intake of 150 ml/kg/day for 24 hours for all infants randomised was similar across the four groups [Inc-AA/Intralipid, median 12 days, interquartile range (IQR) 9–17.5 days; Inc-AA/SMOFlipid, median 11.5 days, IQR 9–16 days; Imm-RDI/Intralipid, median 11 days, IQR 10–14 days; Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid, median 13 days, IQR 9.5 –18 days]. The length of hospital stay for all infants randomised was similar across the four groups (Inc-AA/Intralipid, median 69.5 days, IQR 52–95 days; Inc-AA/SMOFlipid, median 61 days, IQR 5–88 days; Imm-RDI/Intralipid, median 63 days, IQR 45–95 days; Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid, median 66.5 days, IQR 44–98 days) (Tables 7 and 8).

| Characteristic | Inc-AA/Intralipid (N = 42) | Inc-AA/SMOFlipid (N = 42) | Imm-RDI/Intralipid (N = 41) | Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid (N = 43) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Route of PN administration, median (IQR) | ||||

| Peripheral (days) | 0 (0–2); n = 42 | 1 (0–5); n = 41 | 0.5 (0–2.5); n = 40 | 1 (0–3); n = 43 |

| Central (days) | 11.5 (8–20); n = 42 | 13 (8–20); n = 41 | 11 (9–15.5); n = 40 | 12 (9–18); n = 43 |

| Days from delivery to achieve milk intake of 150 ml/kg/day for 24 hours | 12 (9–17.5); n = 32 | 11.5 (9–16); n = 28 | 11 (10–14); n = 30 | 13 (9.5–18); n = 36 |

| Reason for stopping PN,a frequency (%) | ||||

| Investigator’s decision | 5 (11.9) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (7.3) | 9 (20.9) |

| Investigator’s decision and investigator manual | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Investigator’s manual | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.9) | 2 (4.7) |

| Operational | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.9) | 3 (6.7) |

| Withdrawal | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| SAE | 0 (0) | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Positive blood culture,b frequency (%) | 15 | 13 | 9 | 14 |

| Fungus | 2 (13.3) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) |

| Gram-negative bacilli | 5 (33.3) | 4 (30.8) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (7.1) |

| Gram-positive bacilli | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gram-positive cocci CoNS | 2 (13.3) | 3 (23.1) | 4 (44.4) | 7 (50.0) |

| Gram-positive cocci excluding CoNS | 3 (20.0) | 4 (30.8) | 1 (11.1) | 5 (35.7) |

| Gram-positive cocci not specified | 2 (13.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Positive blood cultures (while on PN)b | 8 | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| Length of stay in hospital (days), median (IQR) | 69.5 (52–95); n = 38 | 61 (45–88); n = 33 | 63 (45–95); n = 38 | 66.5 (44–98); n = 38 |

| Characteristic | Inc-AA/Intralipid (N = 34) | Inc-AA/SMOFlipid (N = 28) | Imm-RDI/Intralipid (N = 34) | Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid (N = 37) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Route of PN administration, median (IQR) | ||||

| Peripheral (days) | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–5.5) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) |

| Central (days) | 11 (8–17) | 13.5 (8.5–19.5) | 10.5 (9–15) | 12 (9–18) |

| Days from delivery to achieve milk intake of 150 ml/kg/day for 24 hours, median (IQR) | 11 (9–16); n = 28 | 11.5 (9–16); n = 22 | 11 (10–13.5); n = 28 | 13 (10–18); n = 33 |

| Reason for stopping PN,a frequency (%) | ||||

| Investigator’s decision | 3 (8.8) | 2 (7.1) | 3 (8.8) | 6 (16.2) |

| Investigator’s manual | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.7) |

| Operational | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.9) | 3 (8.1) |

| Positive blood culture,b frequency (%) | 9 | 4 | 5 | 12 |

| Fungus | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) |

| Gram-negative bacilli | 3 (33.3) | 3 (75.0) | 3 (60.0) | 0 (0) |

| Gram-positive bacilli | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gram-positive cocci CoNS | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) | 6 (50.0) |

| Gram-positive cocci excluding CoNS | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (41.7) |

| Gram-positive cocci not specified | 1 (11.1) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) |

| Positive blood cultures (while on PN)b | 5 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Length of stay in hospital (days), median (IQR) | 69.5 (55–96); n = 34 | 59 (44–85); n = 28 | 60.5 (44–88); n = 34 | 67 (47–98.5); n = 36 |

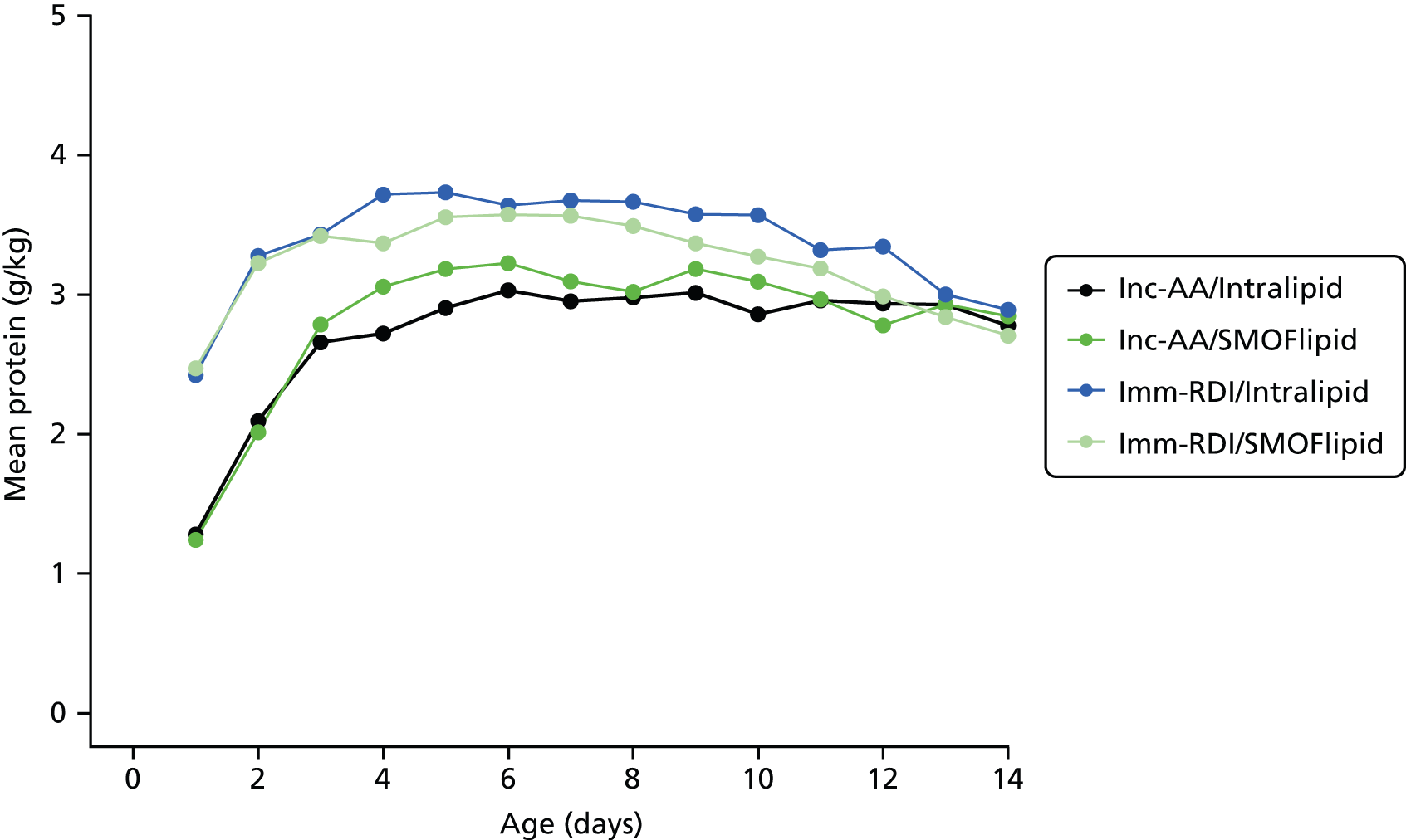

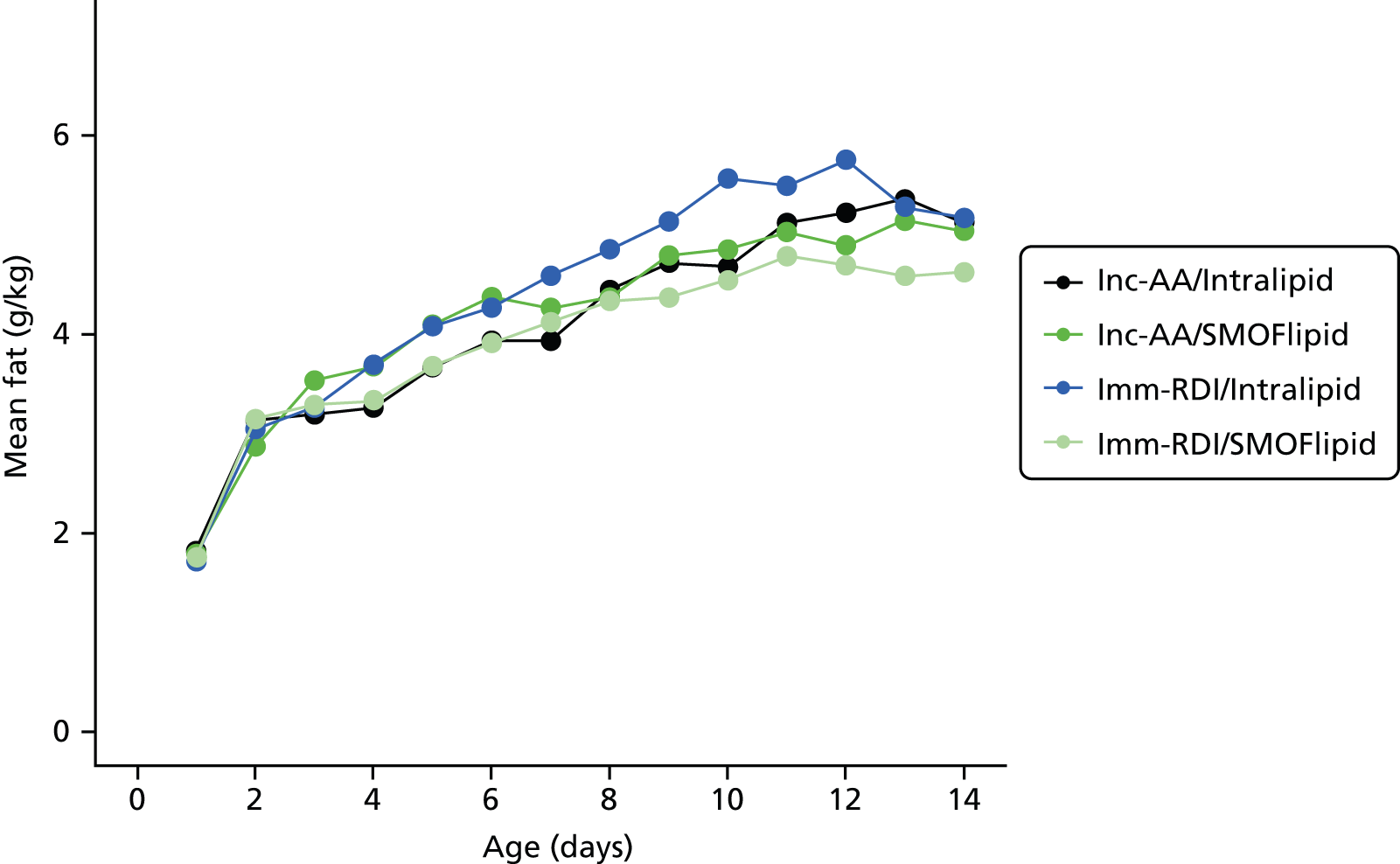

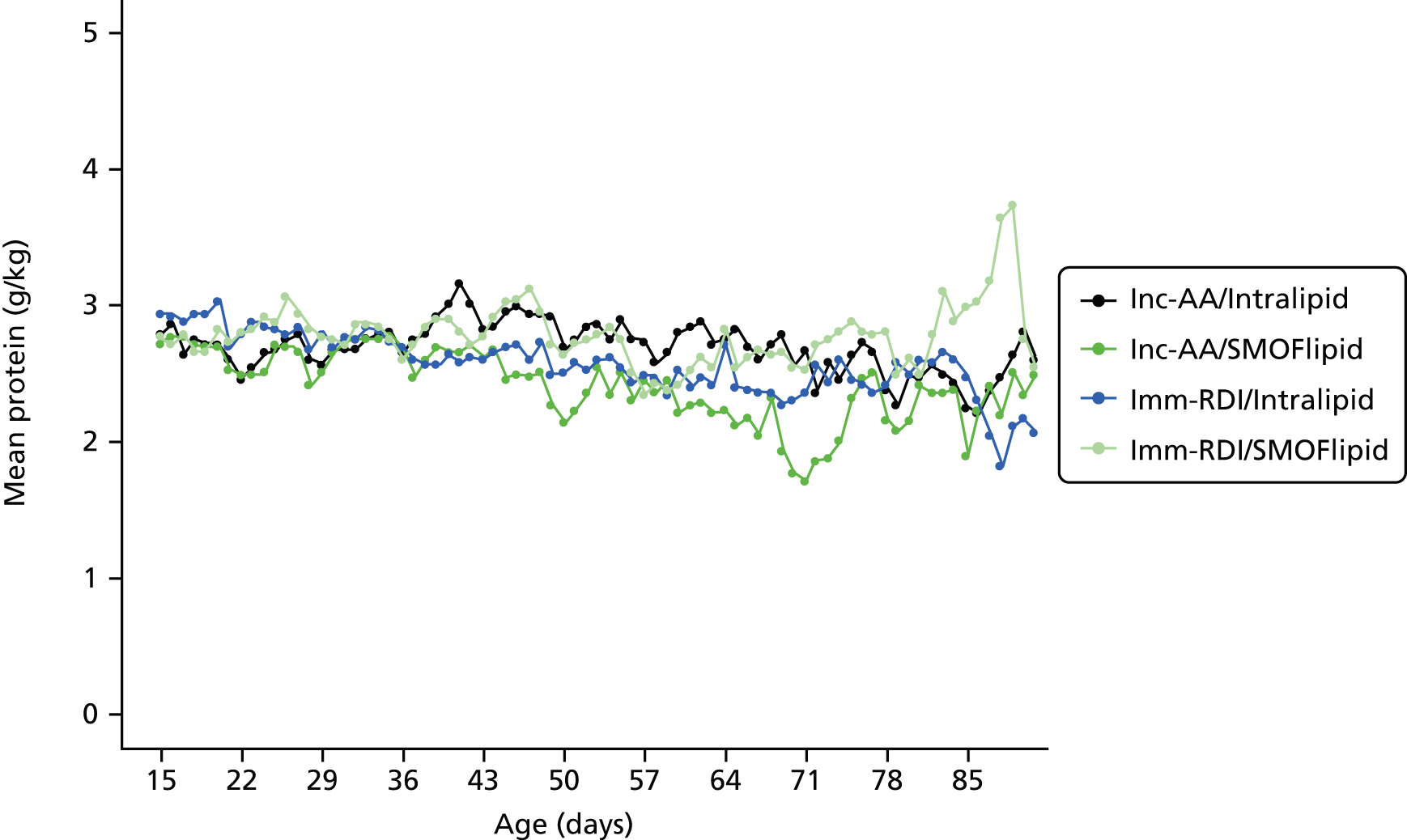

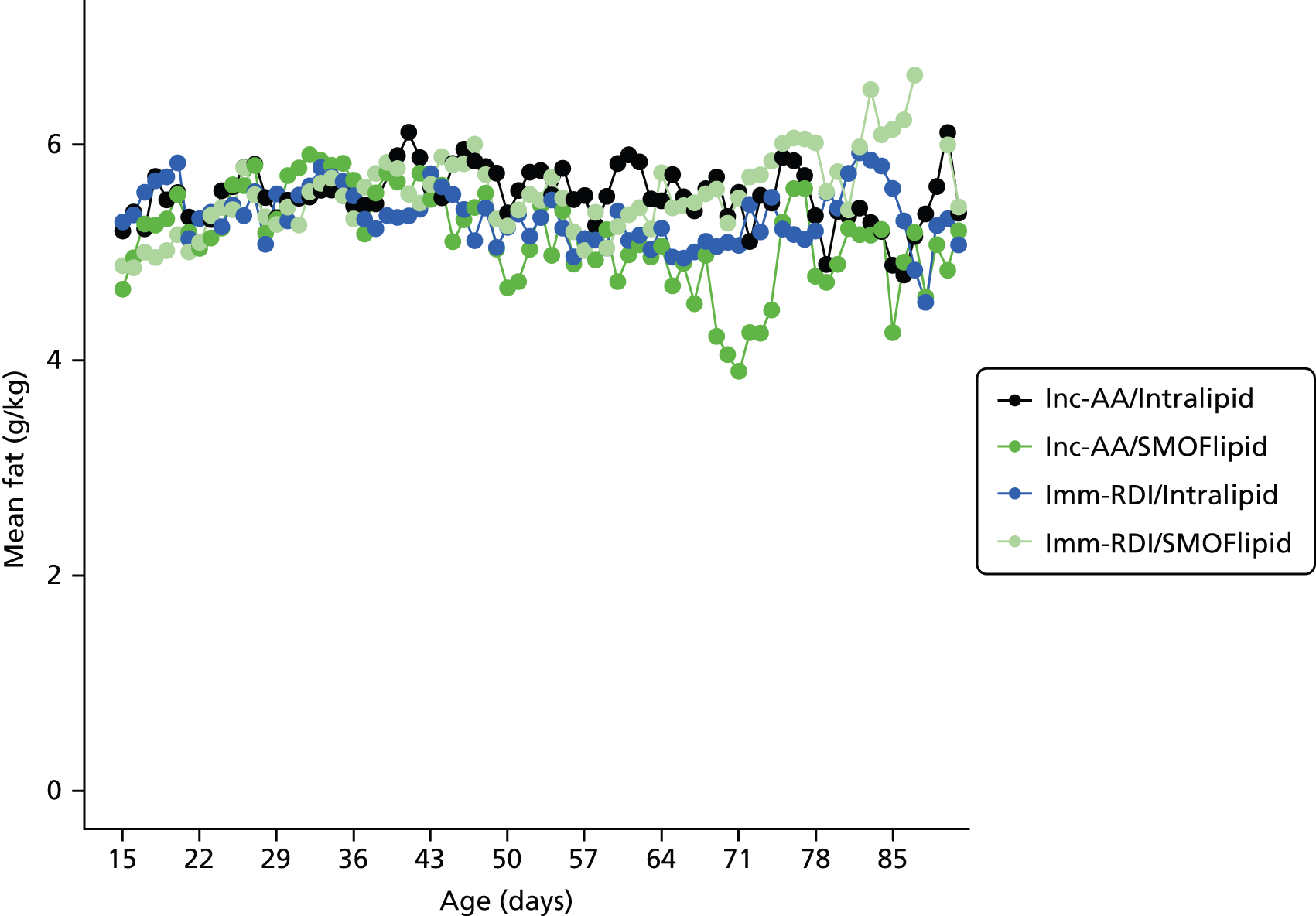

Nutritional intake from trial PN during the first week was similar across the four groups, except for the intake of protein. On day 4, for all infants randomised, when infants randomised to Inc-AA intake achieved the maximum intake, the protein intake was 2.5 g/kg and 2.6 g/kg in the Inc-AA/Intralipid and Inc-AA/SMOFlipid groups, respectively, compared with 3.3 g/kg and 3.1 g/kg in the Imm-RDI/Intralipid and Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid groups, respectively for all infants randomised (Table 9). Table 10 shows data for babies who completed the MR scan. The median cumulative protein intake from trial PN during the first 2 weeks after birth for all randomised infants in the incremental arm was 22.4 g (IQR 16.0–28.4 g) and 20.9 g (IQR 15.3–28.4 g) in the Inc-AA/Intralipid and Inc-AA/SMOFlipid groups, respectively, compared with 25.9 g (IQR 22.6–32.5 g) and 29.5 g (IQR 23.2–37.2 g) in the Imm-RDI/Intralipid and Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid groups, respectively. The median cumulative protein intake from all sources between birth and 34 weeks postmenstrual age for all babies randomised was 138.2 g (IQR 109.9–170.7 g) and 119.0 g (IQR 91.1–161.0 g) in the Inc-AA/Intralipid and Inc-AA/SMOFlipid groups, respectively, compared with 124.8 g (IQR 103.1–175.3 g) and 148.3 g (IQR 122.1–170.7 g) in the Imm-RDI/Intralipid and Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid groups, respectively. Tables 11–13 show data of nutritional intake for all babies randomised. Tables 14 and 15 show data of nutritional intake for babies who completed the MR scan.

| Trial PN intake by day | Inc-AA/Intralipid (N = 42) | Inc-AA/SMOFlipid (N = 42) | Imm-RDI/Intralipid (N = 41) | Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid (N = 43) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1,a mean (SD) | n = 39 | n = 34 | n = 37 | n = 41 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 71.1 (36.2) | 69.5 (34.3) | 69.2 (36.7) | 68.1 (35.6) |

| Lipid volume (ml/kg) | 8.8 (5.2) | 8.6 (4.6) | 8.5 (5.3) | 7.9 (4.5) |

| Protein (g/kg) | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.6) | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.3) |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg) | 6.8 (3.5) | 6.7 (3.3) | 6.6 (3.5) | 6.4 (3.4) |

| Fat (g/kg) | 1.8 (1.0) | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.6 (0.9) |

| Day 2, mean (SD) | n = 39 | n = 38 | n = 39 | n = 42 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 96.5 (20.8) | 89.9 (31.1) | 94.9 (16.8) | 94.5 (20.9) |

| Lipid volume (ml/kg) | 14.8 (9.9) | 12.8 (5.2) | 13.7 (2.6) | 14.1 (4.0) |

| Protein (g/kg) | 2.1 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.7) |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg) | 8.6 (1.8) | 8.1 (2.8) | 8.4 (1.4) | 8.2 (1.8) |

| Fat (g/kg) | 3.0 (2.0) | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.7 (0.5) | 2.8 (0.8) |

| Day 3, mean (SD) | n = 39 | n = 37 | n = 38 | n = 42 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 114.4 (22.4) | 112.8 (29.1) | 112.6 (25.1) | 114.0 (23.2) |

| Lipid volume (ml/kg) | 14.3 (3.2) | 14.7 (3.8) | 13.4 (3.8) | 13.4 (4.8) |

| Protein (g/kg) | 2.5 (0.5) | 2.5 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg) | 8.5 (1.8) | 8.3 (2.1) | 8.4 (1.8) | 8.3 (1.8) |

| Fat (g/kg) | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.9) |

| Day 4, mean (SD) | n = 40 | n = 37 | n = 38 | n = 40 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 111.4 (26.0) | 117.0 (21.5) | 123.4 (14.7) | 115.9 (20.2) |

| Lipid volume (ml/kg) | 14.2 (5.3) | 14.6 (4.2) | 15.3 (4.4) | 14.0 (4.1) |

| Protein (g/kg) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.6 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.4) | 3.1 (0.5) |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg) | 8.1 (2.1) | 8.4 (1.6) | 8.9 (1.1) | 8.4 (1.4) |

| Fat (g/kg) | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.7) |

| Day 5, mean (SD) | n = 42 | n = 38 | n = 38 | n = 41 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 106.5 (29.9) | 111.3 (23.7) | 114.0 (25.1) | 112.4 (22.1) |

| Lipid volume (ml/kg) | 14.4 (4.7) | 14.9 (4.3) | 14.8 (4.1) | 13.7 (4.7) |

| Protein (g/kg) | 2.4 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.7) | 3.0 (0.6) |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg) | 7.7 (2.2) | 8.1 (1.6) | 8.2 (1.8) | 8.1 (1.6) |

| Fat (g/kg) | 2.5 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.8) |

| Day 6, mean (SD) | n = 42 | n = 38 | n = 38 | n = 41 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 100.9 (34.0) | 103.0 (31.6) | 103.0 (31.3) | 107.5 (27.8) |

| Lipid volume (ml/kg) | 13.1 (5.4) | 13.8 (4.9) | 13.2 (6.0) | 12.8 (5.7) |

| Protein (g/kg) | 2.3 (0.8) | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.9 (0.7) |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg) | 7.3 (2.5) | 7.4 (2.3) | 7.4 (2.3) | 7.7 (2.0) |

| Fat (g/kg) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.0) |

| Day 7, mean (SD) | n = 41 | n = 36 | n = 36 | n = 38 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 93.4 (35.7) | 92.4 (31.3) | 101.3 (28.2) | 100.9 (25.6) |

| Lipid volume (ml/kg) | 11.1 (6.1) | 11.1 (6.0) | 13.1 (7.5) | 11.6 (5.6) |

| Protein (g/kg) | 2.1 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.7) | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.7) |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg) | 6.8 (2.6) | 6.7 (2.3) | 7.3 (2.0) | 7.3 (1.8) |

| Fat (g/kg) | 2.0 (1.1) | 1.9 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.0) |

| Trial PN intake by day | Inc-AA/Intralipid (N = 34) | Inc-AA/SMOFlipid (N = 28) | Imm-RDI/Intralipid (N = 34) | Imm-RDI/SMOFlipid (N = 37) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1,a mean (SD) | n = 32 | n = 25 | n = 31 | n = 36 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 69.5 (36.2) | 70.1 (34.4) | 70.9 (37.6) | 67.8 (36.0) |

| Lipid volume (ml/kg) | 8.4 (5.0) | 8.7 (4.5) | 8.9 (5.5) | 8.1 (4.7) |

| Protein (g/kg) | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.6) | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.3) |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg) | 6.7 (3.5) | 6.7 (3.3) | 6.8 (3.6) | 6.4 (3.4) |

| Fat (g/kg) | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.6 (0.9) |

| Day 2, mean (SD) | n = 33 | n = 27 | n = 34 | n = 36 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 92.9 (18.5) | 89.5 (22.6) | 97.3 (15.3) | 97.1 (20.2) |

| Lipid volume (ml/kg) | 14.7 (10.7) | 13.2 (4.4) | 13.8 (2.6) | 14.6 (3.8) |

| Protein (g/kg) | 2.0 (0.4) | 1.9 (0.5) | 3.2 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.6) |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg) | 8.3 (1.7) | 8.0 (1.9) | 8.5 (1.3) | 8.4 (1.7) |

| Fat (g/kg) | 2.9 (2.1) | 2.7 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.5) | 2.9 (0.7) |

| Day 3, mean (SD) | n = 32 | n = 28 | n = 34 | n = 36 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 116.8 (21.5) | 112.2 (32.7) | 111.8 (26.3) | 117.5 (19.2) |

| Lipid volume (ml/kg) | 14.6 (3.4) | 14.4 (4.3) | 13.3 (4.0) | 13.9 (4.6) |

| Protein (g/kg) | 2.6 (0.5) | 2.5 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.6) |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg) | 8.6 (1.8) | 8.3 (2.4) | 8.4 (1.9) | 8.6 (1.6) |

| Fat (g/kg) | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.9) |

| Day 4, mean (SD) | n = 33 | n = 28 | n = 34 | n = 35 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 112.4 (26.8) | 117.4 (24.4) | 123.2 (14.9) | 118.5 (14.6) |

| Lipid volume (ml/kg) | 13.9 (5.6) | 14.8 (4.7) | 15.6 (3.7) | 14.4 (3.5) |

| Protein (g/kg) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.6 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.4) | 3.2 (0.3) |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg) | 8.2 (2.1) | 8.5 (1.8) | 8.9 (1.1) | 8.6 (0.9) |

| Fat (g/kg) | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.6) |

| Day 5, mean (SD) | n = 34 | n = 28 | n = 34 | n = 36 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 107.6 (32.1) | 111.0 (25.2) | 113.3 (26.2) | 112.3 (23.1) |

| Lipid volume (ml/kg) | 14.3 (5.1) | 15.2 (4.1) | 14.7 (4.3) | 13.5 (5.0) |

| Protein (g/kg) | 2.4 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.6) | 3.0 (0.7) | 3.0 (0.6) |

| Carbohydrate (g/kg) | 7.7 (2.3) | 8.0 (1.8) | 8.2 (1.9) | 8.1 (1.7) |

| Fat (g/kg) | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.9) |

| Day 6, mean (SD) | n = 34 | n = 28 | n = 34 | n = 35 |

| Aqueous volume (ml/kg) | 101.4 (36.8) | 104.6 (33.7) | 101.5 (32.5) | 111.0 (24.1) |