Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 09/800/04. The contractual start date was in October 2007. The final report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in March 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jack Satsangi reports personal fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd, AbbVie Inc. and Dr Falk Pharma UK Ltd, and research funding from the European Commission. Nicholas A Kennedy reports grants from The Wellcome Trust; personal fees from Merck & Co., Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd, Dr Falk Pharma UK Ltd, Allergan, plc, and Pharmacosmos A/S; non-financial support from Norgine BV, AbbVie Inc., Shire, plc, and Janssen Global Services, LLC; and other support from Merck & Co., Inc., AbbVie Inc. and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd outside the submitted work. Ian Arnott reports personal fees from Vifor Pharma Management Ltd, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd and Dr Falk Pharma UK Ltd. Steff Lewis reports membership of the Health Technology Assessment Efficient Study Designs Board and University of Edinburgh grant funding.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Satsangi et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory illness that can involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract, but most commonly involves the terminal ileum. The prevalence in northern England has been estimated to be 144 per population of 100,000. 1 The incidence among young people in Scotland is the highest in the UK, and continues to rise. 2 Although the mortality associated with CD is low, there is significant morbidity, with serious effects on growth, development, education and employment potential.

Crohn’s disease treatment

Treatment algorithms for the medical management of active CD have evolved very rapidly in recent years, and the relative importance of thiopurines in induction of remission, and in maintenance, has been re-evaluated since this study was first designed. Although steroids, biological therapies and combination therapies (biologics used together with thiopurine agents) have an evidence basis for induction of remission, a recent Cochrane review suggested that there was no place for monotherapy with thiopurine in induction of remission. 3

However, for patients entering medically induced remission, immunosuppression with azathioprine or mercaptopurine (MP) is an effective maintenance strategy (odds ratio 3.17, number needed to treat 3.3 favouring 2 mg/kg azathioprine over placebo), offering an acceptable balance of efficacy, tolerability and cost. 4 The relative merits of monotherapy with thiopurines alone, anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) agents or combination regimes of thiopurines and biological agents remain contentious in this setting of maintenance therapy.

Despite current medical therapy, up to 50% of patients have aggressive disease and require surgery within 5 years of diagnosis. 5 Unfortunately, disease relapse rates are high within 2 years of surgery for both endoscopic (72–98%) and clinical recurrence (37–70%). 6 Re-operation rates cumulate at 5% of patients per year. 7

Evidence for postoperative use of thiopurines

The development of strategies to prevent or delay postoperative recurrence of CD is therefore of major clinical importance; however, there is a paucity of evidence to support any particular drug strategy. 8,9 The thiopurines, azathioprine and MP have an established role in inducing remission in CD and in the maintenance of medically induced remission. These agents have historically been suggested in treatment algorithms for patients at ‘high risk’ of postoperative relapse, but the evidence basis for their use in this context, and indeed the evidence that clinical parameters may predict patients at ‘high risk’ of relapse, is weak. 7 A meta-analysis conducted by Jones et al. 10 found that the efficacy data for thiopurines in the postoperative setting were inconclusive and, aside from smoking, there were no consistent predictors of postoperative relapse. A 2014 Cochrane review also concluded that, although there was evidence to suggest that thiopurines may reduce endoscopic and clinical recurrence, the quality of evidence was degraded by small numbers and flawed study designs. 3 The value of thiopurine metabolites in this situation is unknown. 11 More recently, the role of biological therapies in postoperative prophylaxis has received considerable attention. Following smaller randomised studies of infliximab in postoperative disease, the recent Post-Operative Crohn’s Endoscopic Recurrence (POCER) study demonstrated that targeted escalation of immune-modulatory therapy (thiopurines followed by adalimumab) in patients with early endoscopic evidence of recurrence may delay subsequent endoscopic, although not clinical, recurrence. 11–13

Current practice

Currently no medical therapy is licensed to prevent postoperative recurrence in CD. As well as thiopurine agents and anti-TNF-α agents, 5-aminosalicylates, corticosteroids and metronidazole have all been suggested, but the evidence in favour of these drugs is weak and none is widely used in the UK. 6 Postoperative maintenance therapy with azathioprine or MP is more widely used and is included in a number of clinical algorithms, but trial data from controlled trials available thus far have failed to demonstrate whether or not this is an effective therapy. Existing studies have been underpowered, poorly designed or used an inappropriate drug dose. 6,14–19

For these reasons, we consider that evidence-based strategies to prevent postoperative recurrence are both an unmet clinical need and a research priority.

Controversies in use of thiopurines in postoperative use

As we discussed in our recent review (see Jones et al. 10), there are many unresolved controversies associated with the use of thiopurines in the prevention of postoperative recurrence in CD, and this remains contentious. The definition of recurrence itself, specifically the distinction between endoscopic, clinical and surgical recurrence, the identification of high-risk individuals, the influence of pre-operative therapies on responsiveness, and the relative merits of thiopurines compared with anti-TNF-α therapies are key issues; however, no real evidence-based consensus has emerged. 10 The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) 2010 guidelines recommend their use postoperatively in ‘high-risk’ patients (defined as smokers and those with previous intestinal surgery, penetrating disease, perianal disease or extensive small bowel section). 20 The British Society of Gastroenterology’s guidelines are more cautious in emphasising the weak evidence base for risk factors in predicting disease recurrence (with the exception of smoking) and for the use of thiopurines in this setting. 8

The use of thiopurines by women, or the male partners of women, trying to conceive or in pregnancy

With respect to safety, use in patients of childbearing age has been a key issue. When the trial commenced, the published guidelines of both ECCO and the British Society of Gastroenterology supported the use of thiopurines in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in women of childbearing potential and during pregnancy on the grounds that the risk to the unborn child from disease activity appeared greater than continued therapy. As part of the initial trial assessment by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, supporting documentation was reviewed and the inclusion of women of childbearing potential was approved without inclusion criteria of agreement to the use of contraceptives. No comment was made for inclusion of males who could potentially father a child while receiving MP. However, the sponsor, Trial Management Group (TMG) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) examined this position in more detail in 2010.

The TMG and TSC considered the evidence and decided not to exclude female patients who either were planning to become pregnant or became pregnant, or male patients whose partners were planning to become pregnant. The existing patient information sheets, however, were revised to detail the potential risks to male patients. All enrolled male patients were also reconsented to the new information sheets and consent forms. Pregnancy data were also included in the TSC and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) standard reports.

Since 2010, several large studies have been published examining thiopurine use for IBD during pregnancy, which provided further support for the initial guidelines. The Cancers Et Surrisque Associé aux Maladies inflammatoires intestinales En France (CESAME) study group examined 215 pregnancies in 204 women and concluded that thiopurine use during pregnancy was not associated with increased risks, including an increased risk of congenital abnormalities. 21 This has been supported by the findings of two further studies published in 2013 and 2014: Casanova et al. 22 included a cohort of 187 pregnancies in participants using thiopurines in IBD and found no evidence of an increased risk of complications, whereas Ban et al. 23 included a cohort of 115 pregnancies in participants using thiopurines for CD and found no evidence of an increased risk of major birth defects.

Potential health-care impact

The present study has an important potential impact on health care in terms of defining, with accuracy, the clinical effectiveness of thiopurine therapy in the prevention of postoperative relapse. The data from the study overall suggest that routine postoperative use of MP in all patients undergoing surgery is not justified as a preventative measure. The subgroup analyses have helped identify smokers as the subgroup of individuals at highest risk of relapse, and helped to demonstrate that this subgroup is most likely to benefit from thiopurine therapy, thereby helping to target immunomodulatory therapy towards patients most likely to benefit. The important secondary objectives allowed comparison of clinical and endoscopic recurrence rates, and analysis of clinical as well as biomarker predictors of disease recurrence. Importantly, we have assessed age, the need for previous surgery, previous thiopurine use and smoking as potential determinants of outcome.

Rationale for research

At present, there is no widely accepted algorithm or management plan in preventing postoperative relapse of CD. Non-evidence-based algorithms have been widely used and the present study will allow clear evidence to be defined in the largest study carried out in the use of thiopurine therapy.

The secondary objectives allowed comparison of clinical and endoscopic recurrence rates, and the effects of thiopurine therapy on each of these aspects. The study design has also allowed examination of drug safety, tolerability and adherence to therapy. The biomarkers in the study allow the relative predictive value of faecal calprotectin levels in assessing recurrence to be defined, as well as the relationship between thiopurine use and calprotectin levels. Quality of life was also measured in the present study. The primary objective of this study was to assess if MP can prevent or delay postoperative recurrence in CD.

Study aims

The primary objective of the Trial Of Prevention of Post operative Crohn’s disease (TOPPIC) was to assess if MP can prevent or delay postoperative recurrence of CD.

Secondary objectives included if MP can prevent or delay endoscopic evidence of recurrence and, finally, whether or not endoscopic recurrence can predict clinical recurrence, whether or not faecal calprotectin levels can be used as a non-invasive marker of disease recurrence that may remove the need for colonoscopy in some patients, whether or not drug metabolite levels relate to clinical efficacy of MP, and whether or not we can predict postoperative recurrence using clinical, genetic or serological data.

Development of TOPPIC

Development of TOPPIC was initiated in 2006 by a team of collaborators based in Scotland, with ethics and clinical trial authorisation sought in 2007. The trial was extended throughout the UK in 2010 to include collaborators from across England and Wales.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

This was a multicentre, parallel-group, double-blind, randomised controlled study conducted in the UK (29 sites). Participants were allocated 1 : 1 to active treatment with MP or a matching placebo.

Following slower than projected recruitment in the first 24 months, the protocol was modified to reduce the number of colonoscopies performed as part of the trial and to allow the inclusion of patients with a previous history of malignancy, providing that they had been in remission for 5 years.

Participants

Participants were adults aged ≥ 16 years in Scotland (≥ 18 years in England and Wales) with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of CD (according to the Lennard-Jones criteria) undergoing ileocolonic or small bowel resection. 24 Patients were approached ≤ 3 months after surgery during the perioperative period and, following consent for screening, underwent a screening assessment consisting of a blood sample to check thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) activity and a postoperative stool sample to exclude enteric infection.

One week prior to randomisation, eligible participants underwent standard safety blood tests (including checks of liver function, haemoglobin levels, and white blood cell, neutrophil and platelet counts) in addition to a urinary pregnancy test.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in the following sections.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged ≥ 16 years in Scotland and ≥ 18 years in England and Wales.

-

Established diagnosis of CD confirmed at recent resection.

-

Ileocolonic or small bowel resection ≤ 3 months before screening.

-

Had ≤ 100 cm of fixed small bowel resected in total; a previous ileocolonic resection was accepted.

-

Able to start oral nutrition in the first 2 postoperative weeks.

-

Normal or heterozygous TPMT (activity present or reduced, consistent with carrier status).

-

Able to provide written informed consent prior to screening and comply with the requirements of the study protocol.

-

Not taking antibiotics at least 2 weeks prior to randomisation.

Exclusion criteria

-

Pregnancy at baseline or breastfeeding.

-

Known hypersensitivity or intolerance to MP.

-

Pancreatitis associated with azathioprine.

-

Receiving experimental treatment for CD ≤ 4 weeks prior to study entry.

-

Known to require further surgery at study entry (i.e. for the removal of an abscess developing from the primary surgery).

-

Strictureplasty procedure alone (strictureplasty and resection procedure together will not be considered an exclusion criterion).

-

Presence of a stoma.

Identifying participants

The study aimed to recruit and randomise from participating sites. Potentially eligible patients were identified by clinicians and research/specialist nurses at sites following ileocolonic or small bowel resection.

Settings and locations where the data were collected

The study took place in the following tertiary referral hospitals in the UK: Western General Hospital, Edinburgh; Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen; Ninewells Hospital, Dundee; Glasgow Royal Infirmary and Stobhill Hospital, Glasgow; Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, Exeter; University Hospital Coventry, Coventry; Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Liverpool; Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester; Bristol Royal Infirmary, Bristol; University College Hospital, Royal Free Hospital and Royal London Hospital, London; John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford; Salford Royal Hospital, Salford; Singleton Hospital, Swansea; Torbay Hospital, Torquay; Southampton General Hospital, Southampton; County Durham and Darlington Memorial Hospitals, Durham and Darlington; Royal Stoke University Hospital, Stoke-on-Trent; Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham; St Mark’s Hospital, Harrow; Rotherham General Hospital, Rotherham; Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham; and Raigmore Hospital, Inverness. Randomisation was open from May 2008 until June 2012 (a total of 49 months).

Interventions

The intervention was a random allocation to MP in 50-mg tablets or placebo in identical 50-mg tablets and matched packaging supplied to sites by the manufacturer.

Outcomes

The primary study outcome was clinical recurrence of CD defined by a Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score of ≥ 150 points together with a 100-point rise in the CDAI score from baseline, with the need for anti-inflammatory rescue therapy or primary surgical intervention. 25

The secondary study outcomes were as follows:

-

clinical recurrence defined by a CDAI score of ≥ 150 points together with a 100-point rise in the CDAI score from baseline, or anti-inflammatory rescue therapy or primary surgical intervention

-

the need for a second operation to remove recurrent CD from the anastomotic site

-

endoscopic recurrence using the Rutgeerts and Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity (CDEIS) scoring systems26,27

-

faecal calprotectin levels

-

thioguanine (TGN) levels

-

changes in self-rated quality-of-life scores.

Measurements

Following patient consent for screening, the trial screening process consisted of analysis of TPMT activity and a postoperative stool sample to exclude enteric infection. One week prior to randomisation, eligible participants underwent blood tests (including liver function tests, haemoglobin concentration tests, and white blood cell, neutrophil and platelet counts) and a urinary pregnancy test. Patients returned to designated clinics run by clinical teams for a baseline assessment including the CDAI, patient-reported outcome measures including the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ), a physical examination and a blood sample for assay of drug metabolite level. 28 Additional blood samples for genetic and serological analysis were also taken, and results are reported separately.

Patients were randomised at baseline to receive either MP or placebo. MP was given at a dose of 1–1.5 mg/kg of body weight, rounded to the nearest 25 mg as a single daily dose in the morning. Patients with low TPMT activity were prescribed MP at half the normal dose. Treatment was on a maintenance basis for 3 years, with the dose adjusted up or down for weight changes during the study.

Follow-up data were collected at 10 time points, at weeks 6, 13, 31, 49, 67, 85, 103, 121, 139 and 157 post randomisation. At each visit, the following data were collected: CDAI score, physical characteristics (as measured by examination), concomitant medications taken and patient-reported outcomes including the IBDQ. At weeks 0, 13, 49, 103 and 157 post randomisation, patients were also asked to provide additional stool and blood samples for the central assessment of faecal calprotectin and TGN metabolite levels, with endoscopic assessment at weeks 49 and 157 post randomisation.

Sample processing

Stool samples were collected at participating centres and frozen on site at –80 °C. Samples were then shipped on dry ice in two batches during 2014 and 2015 to a central biochemistry laboratory at NHS Lothian Western General Hospital in Edinburgh. Faecal calprotectin levels were all assessed using the CALPRO® calprotectin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (alkaline phosphatase) (NovaTec Immundiagnostica GmbH, Dietzenbach, Germany) and processed by technicians blinded to the treatment allocation. Blood samples for TGN testing were sent ambient to Viapath (formerly GSTS Pathology; London, UK) for analysis in the Purine Research Laboratory. An independent analyst blinded to the treatment allocation then assessed each level.

Therapeutic monitoring

All patients underwent regular safety blood monitoring every week for the initial 6 weeks and thereafter at 6-weekly intervals as long as the patient remained on the study drug. Blood samples were processed at participating site laboratories. An independent central clinician who was blinded to the treatment allocation reviewed results. Prespecified dose reduction or cessation then occurred in the event of abnormal monitoring parameters. In the event of patient intolerance (profound nausea or persistent influenza-like symptoms), protocol-driven dose reduction was also undertaken. If abnormal parameters improved after a temporary stop, treatment was started again at a lower level. The central clinicians, blinded to the treatment allocation, made all of these decisions.

To protect blinding, a programme of sham dose reductions was planned for patients on placebo. On the advice of the DMC these were not undertaken, although the investigators were not informed of this decision, hence protecting the study blinding.

Dose changes

All randomised patients allocated to the treatment group were given 1–1.5 mg/kg body weight, rounded to the nearest 25 mg, to be taken as single daily dose in the morning. Treatment was on a maintenance basis for 3 years or until the study drug was discontinued. Patients heterozygous for TPMT mutations were prescribed MP at half the normal dose. The dose was adjusted up or down for weight changes according to Table 1.

| Body weight (kg) | Initial dose MP (mg) | Amount per body weight (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| < 33 | 50 alternate days | 1–1.5 |

| 33–49.9 | 50 daily | 1–1.5 |

| 50–74.9 | 50/100 alternate days | 1–1.5 |

| 75–99.9 | 100 daily | 1–1.33 |

| 100–150 | 150 daily | 1–1.5 |

| > 150 | 200 daily | > 1 |

The blinded treatment of either MP or placebo could also be reduced or temporarily stopped following patient intolerance (profound nausea or persistent influenza-like symptoms) or abnormal blood safety results. In these cases, the dose was reduced in accordance with Table 2 and not increased again during the course of the trial. If symptoms or blood safety test result abnormalities persisted and were, in the view of the investigator, of sufficient severity, the drug could be stopped. One of the blinded clinicians assessing safety blood test results could also stop the drug.

| Initial dose of MP (mg) | Reduced dose of MP (mg) | Per cent reduction |

|---|---|---|

| 50 alternate days | Stop | 100 |

| 50 daily | 50 alternate days | 50 |

| 50/100 alternate days | 50 daily | 33 |

| 100 daily | 50 daily | 50 |

| 150 daily | 50/100 alternate days | 50 |

| 200 daily | 100 daily | 50 |

Sample size

It was estimated that a study population of 182 evaluable patients would provide the trial with 80% power to detect a reduction in the frequency of recurrence from 50% in the placebo group to 30% in the treatment arm by 3 years at the 5% level of significance. Preliminary data from surgical and pathology databases at the five Scottish recruiting sites indicated that this was an achievable target. In 2006–7, approximately 130 ileocolonic resections were performed annually at the five Scottish recruiting sites initially proposed. We estimated that 60% of the potential patients could be recruited, giving a sample population of 234 patients and allowing for a 15% dropout rate. This would leave an evaluable population of 200 patients over 3 years.

These figures were based on an intention-to-treat analysis, with the number needed to treat in order to prevent one recurrence predicted to be five. It is notable that the treatment effect of 20% was lower than in previously conducted studies (40% reduction in mild CD lesions and 75% reduction in more severe lesions in Hanauer et al. ;18 25% in Ardizzone et al. 19). We also judged a treatment effect of 20% to be appropriate because, given the side-effect profile of MP, it was arguable that a treatment effect of significantly < 20% would be of limited clinical significance.

The sample size chosen had 80% power to detect a reduction in the frequency of recurrence from 50% in the placebo group to 30% in the treatment arm by 3 years at the 5% level of significance.

Interim analyses and stopping guidelines

An independent DMC reviewed trial data throughout the course of the trial, and there were no formal stopping rules. The study recruitment period was extended and additional sites in England and Wales were opened up to address concerns regarding the recruitment rate. Aside from this, the trial recruited according to plan.

Randomisation

Sequence generation

Randomisation was by a central, internet-based, secure password-protected randomisation database. Patient identifiers and some clinical details were entered to confirm eligibility (inclusion and exclusion criteria) and to prevent re-recruitment. The random allocation sequence was generated by the programmers at a UK Clinical Research Collaboration-registered trials unit [Edinburgh Clinical Trials Unit (ECTU)].

Type of randomisation

Randomisation was stratified according to smoking status at baseline (yes/no) and by recruiting site (31 blocks in total).

Implementation

Patients were individually enrolled by clinicians and research/specialist nurses at participating centres (predominantly nursing staff) to one of the two parallel treatment groups. Randomisation had to be within ≤ 3 months of surgery.

Once the randomisation procedure had been completed, a prescription was generated and provided to the participant by a research nurse. The prescription contained details of the number of tablets and bottle codes. The participant was asked to take the prescription to the site pharmacy to receive their allocated blinded treatment. All subsequent prescriptions were generated and processed in the same way.

Blinding

Trial medication and packaging were identical in appearance. All study staff involved in the day-to-day management of the trial, hospital staff and patients were blind to the study intervention. It was not possible to tell which treatment a patient had been allocated from the study numbers, medication packets or prescriptions. To further reduce the opportunity for accidental unblinding, the routine safety blood test results were sent to a blinded central reader for assessment by an independent monitor at each participating site who was not involved in the day-to-day management of the trial or the patient. The clinicians assessing blood results and the study management team based in Edinburgh were blind to the assigned intervention. Blinding was broken only for patients in whom an urgent clinical need was identified in terms of their clinical management, typically following a CD relapse.

Trial data management

Trial data were manually entered into a web-based data collection system by researchers at participating sites. In this system, active server pages supported web-based electronic case report forms and queried a Microsoft SQL Server 2000 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Data were automatically encrypted (using Secure Sockets Layer protocol V329) when entered into the forms, transferred via the internet, decrypted and stored in a secure maintained network at the University of Edinburgh. The level of encryption was dependent on the client’s web browser and operating system, but University of Edinburgh servers could offer up to 256-bit encryption. In the same network, data were then queried using statistical software (SAS; version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for the purposes of data analysis. All changes to electronic data by site staff were traceable by date and user. A copy of the trial electronic case report form is given in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Statistical methods

An analysis was undertaken using SAS. The full statistical analysis plan is given in Report Supplementary Material 2.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome variable was postoperative recurrence of CD and its timing if it recurred. Analysis was intention to treat and was based on the application of a Cox proportional hazards model. The primary analysis included terms for treatment, the variables on which the randomisation was stratified (smoking status and recruitment site) and adjusted for baseline values of previous treatment with MP and previous treatment with azathioprine. Adjusted and unadjusted Cox proportional hazard ratios (HRs) are presented as the comparison of MP versus placebo (reference), with a HR of < 1 indicating a treatment effect in favour of MP. The adjusted analysis was considered to be the primary analysis of the primary outcome.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome variable of clinical recurrence of CD (defined by a CDAI score of ≥ 150 points together with a 100-point rise in the CDAI score from baseline) or the need for anti-inflammatory rescue therapy or primary surgical intervention was analysed in the same manner as the primary outcome. For this secondary outcome, as for the primary outcome, the adjusted analysis was considered the primary analysis.

Endoscopic recurrence using both the Rutgeerts and CDEIS scoring systems was summarised by time and treatment group. Colonoscopy results at week 157 post randomisation (study visit 12) were compared between the treatment groups using a chi-squared test to compare the incidence of positive colonoscopies in the MP group and the placebo group. Both adjusted and unadjusted analyses were performed, with the adjusted analysis incorporating the same covariates as for the primary outcome, with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) presented. CDEIS scores at week 157 post randomisation were compared between treatment groups using a t-test. Adjusted and unadjusted analyses were performed, with treatment effects and 95% CIs presented. Faecal calprotectin results were summarised by time and treatment group, both as a continuous measure and categorically.

The use of faecal calprotectin levels as a non-invasive marker of disease recurrence was examined in two ways: first, it was considered as a time-dependent covariate in Cox proportional hazards model and, second, levels were compared descriptively between those with negative and positive colonoscopies (defined as negative if the Rutgeerts score was < i2 and positive if the Rutgeerts score was ≥ i2) at weeks 49 and 157 post randomisation. Similarly, TGN levels of the MP drug metabolite were also considered as a time-dependent covariate in the Cox proportional hazards model.

The quality-of-life variables were analysed using repeated measures analysis of covariance to evaluate treatment and treatment by time interactions. Quality of life, as measured by the IBDQ, was summarised at each visit based on observed scores and change from baseline scores for each of the four IBDQ subscales (bowel symptoms, emotional health, systemic systems and social function). Averages and totals across all subscales were summarised similarly. In addition, the overall average and overall total scores were analysed using a change from baseline repeated measures analysis of covariance to evaluate the effect of treatment over time. Quality of life, as measured by the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), was summarised by treatment group across study visits.

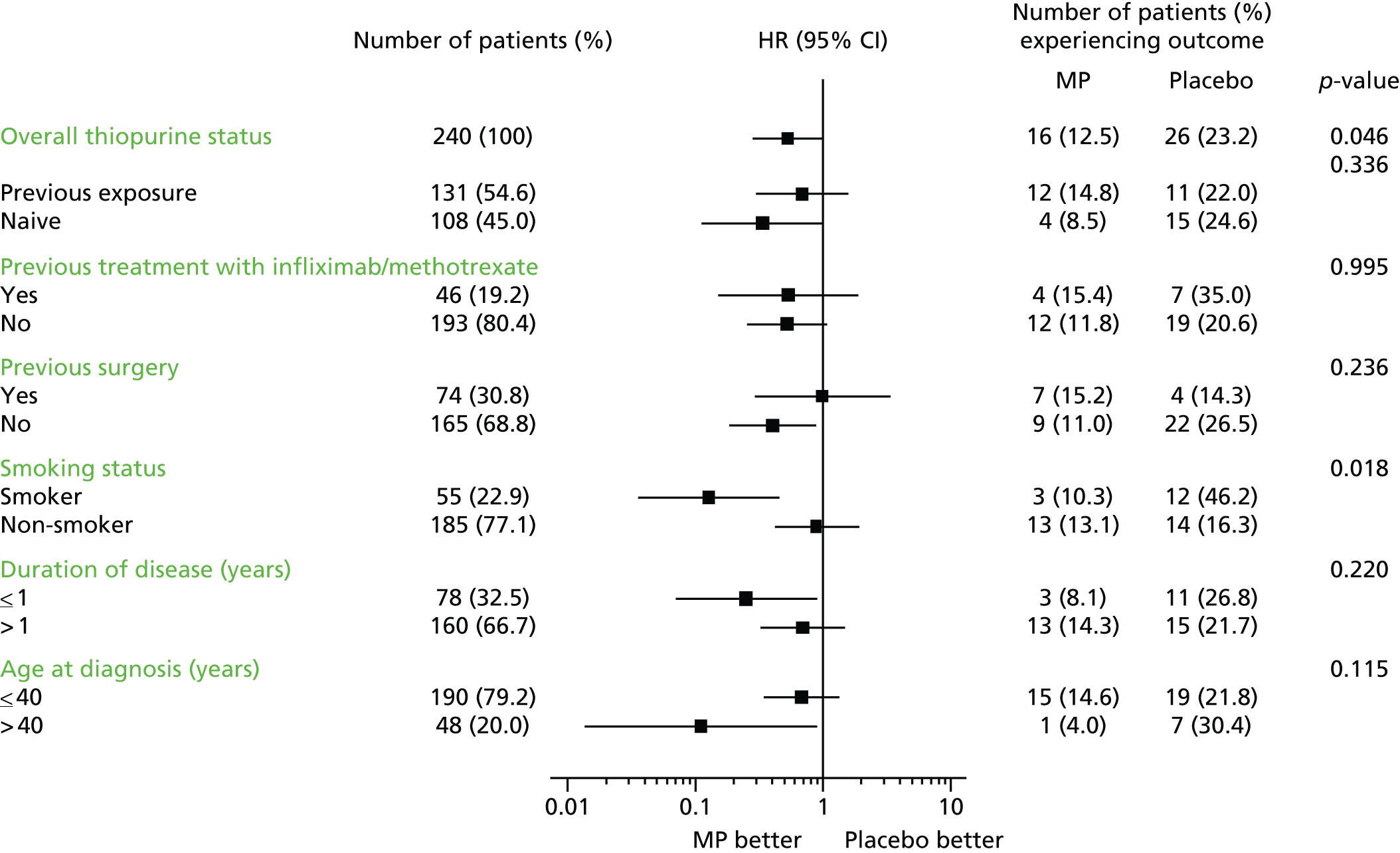

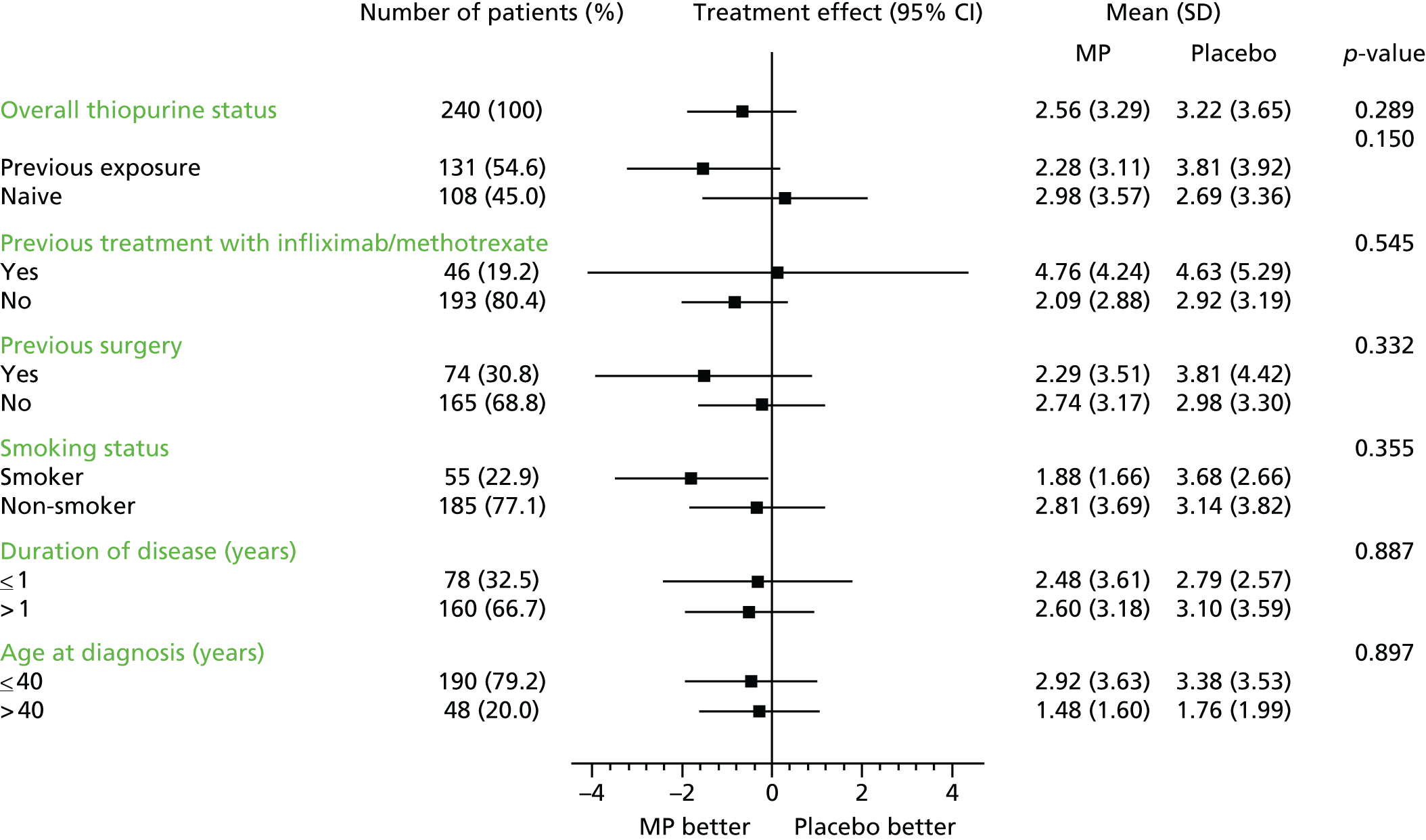

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes were carried out to assess for a treatment effect in terms of thiopurine naivety, previous treatment with infliximab or methotrexate, previous surgery, smoking status, duration of disease and age at diagnosis. The interaction between subgroup and treatment was included in the Cox regression model to determine if the treatment effect differed by subgroup. The same subgroups analysed for the primary and secondary outcomes were also analysed with respect to colonoscopy results and CDEIS scores.

Publication policy

To safeguard the integrity of the trial, the primary results of the trial were published by the group as a whole in collaboration with local investigators, and local investigators were acknowledged. 30 The success of the trial was dependent on the collaboration of many people and, particularly, the local investigators. The results were, therefore, presented to the trial local investigators first.

Organisation

A TSC and a DMC were established. No formal charter was put in place, but both committees met formally every 6 months throughout the trial in accordance with Medical Research Council (MRC)/Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) programme requirements following circulation of a standardised report. Day-to-day management of the trial was overseen by a TMG comprising the chief investigator, the principal investigator at the lead site in Edinburgh, the lead research nurse and the trial manager. Support from the Chief Scientist Officer enabled a dedicated specialist nurse to support the trial at the initial five Scottish sites. The local Comprehensive Local Research Networks supported research nursing time and employed or re-allocated a research nurse to support all aspects of the trial at sites across England and Wales.

Confidentiality

Patients were identified by their trial number to ensure confidentiality. Stringent precautions were taken to ensure confidentiality of names and addresses at ECTU and the sites. The chief investigator and local investigators ensured conservation of records in areas to which access is restricted.

Audit

A risk-based monitoring strategy was implemented for all participating sites with onsite monitoring conducted by either the sponsor’s monitoring team or a member of the TMG at a selected number of sites depending on the issues identified at each site. Site visits were conducted during the course of the trial at University College Hospital, London, on 5 December 2012, Torbay Hospital, Torquay, on 6 November 2013, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, on 12 March 2014, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen, on 11 September 2015, Bristol Royal Infirmary, Bristol, on 30 September 2015 and St Marks Hospital, Harrow, on 7 October 2015. A central audit of trial management was conducted on 12 December 2012 at the central co-ordinating site at ECTU. In addition, an investigation was conducted by the sponsor following the lodging of a formal complaint to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency in July 2013 regarding the wording on an information newsletter sent to a site regarding withdrawal procedures. Recommendations were made following the investigation, but no evidence was found of improper conduct regarding withdrawal procedures.

Termination of the study

Before termination of recruitment, ECTU contacted all sites by telephone or e-mail in order to inform sites of the final date for recruitment. Once the recruitment period had expired, the internet-based randomisation database was disabled to prevent further recruitment. All recruited patients received trial medication for a maximum of 3 years (36 months) post randomisation. The final patient’s final visit took place in April 2015 and the database was locked in June 2015. A declaration of the end of trial form was sent to the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee following the formal trial end date of 30 September 2015. The following documents were archived in each site file to be kept for at least 20 years in accordance with MRC policy: original consent forms, data forms, trial-related documents and correspondence. The trial master files at ECTU will be archived for at least 20 years.

Funding

The costs for the study itself were covered by a grant from the MRC. See the MRC/EME programme website for further project information. 31 Additional support was provided by the Chief Scientist Officer.

Indemnity

If there was negligent harm during the clinical trial, then the NHS body owes a duty of care to the person harmed and NHS indemnity covered NHS staff, medical academic staff with honorary contracts and those conducting the trial. NHS indemnity did not offer no-fault compensation. The co-sponsors were responsible for ensuring that proper provision was made for insurance or indemnity to cover their liability and the liability of the chief investigator and staff.

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval for the study was given by Scotland A Research Ethics Committee in August 2007 (reference number 07/MRE00/74). Local NHS management approval and appropriate site-specific assessments were obtained at each participating NHS trust. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register under the reference number ISRCTN89489788 along with the European Clinical Trials Database under the reference number 2006-005800-15, and the UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio Database under the reference number 5813. A summary of the changes made to the original protocol is given in Report Supplementary Material 3 and an overview of all participant information and consent forms is given in Report Supplementary Material 4.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

Patients were recruited from the following dates: June 2008 to April 2012 (46 months). The addition of 24 sites in England and Wales was in response to slower than anticipated recruitment over the initial 24 months. Initial study recruitment projection figures were based on surgical data collected from the five original Scottish hospitals in the 5 years prior to the grant application. These data indicated that 60% of patients would proceed from surgery into the trial. In practice, the proportion of patients recruited into the trial following surgery at the initial five sites was 30% as a result of higher than expected contraindications to the trial entry and patients’ greater than anticipated reluctance to receive placebo. An extension to the study recruitment period was granted in 2010, along with approval for the trial to be extended to additional centres across England and Wales. The trial completed recruitment on target according to the revised schedule on 23 April 2012, with the final patient’s final visit completed on schedule in April 2015.

Participant flow

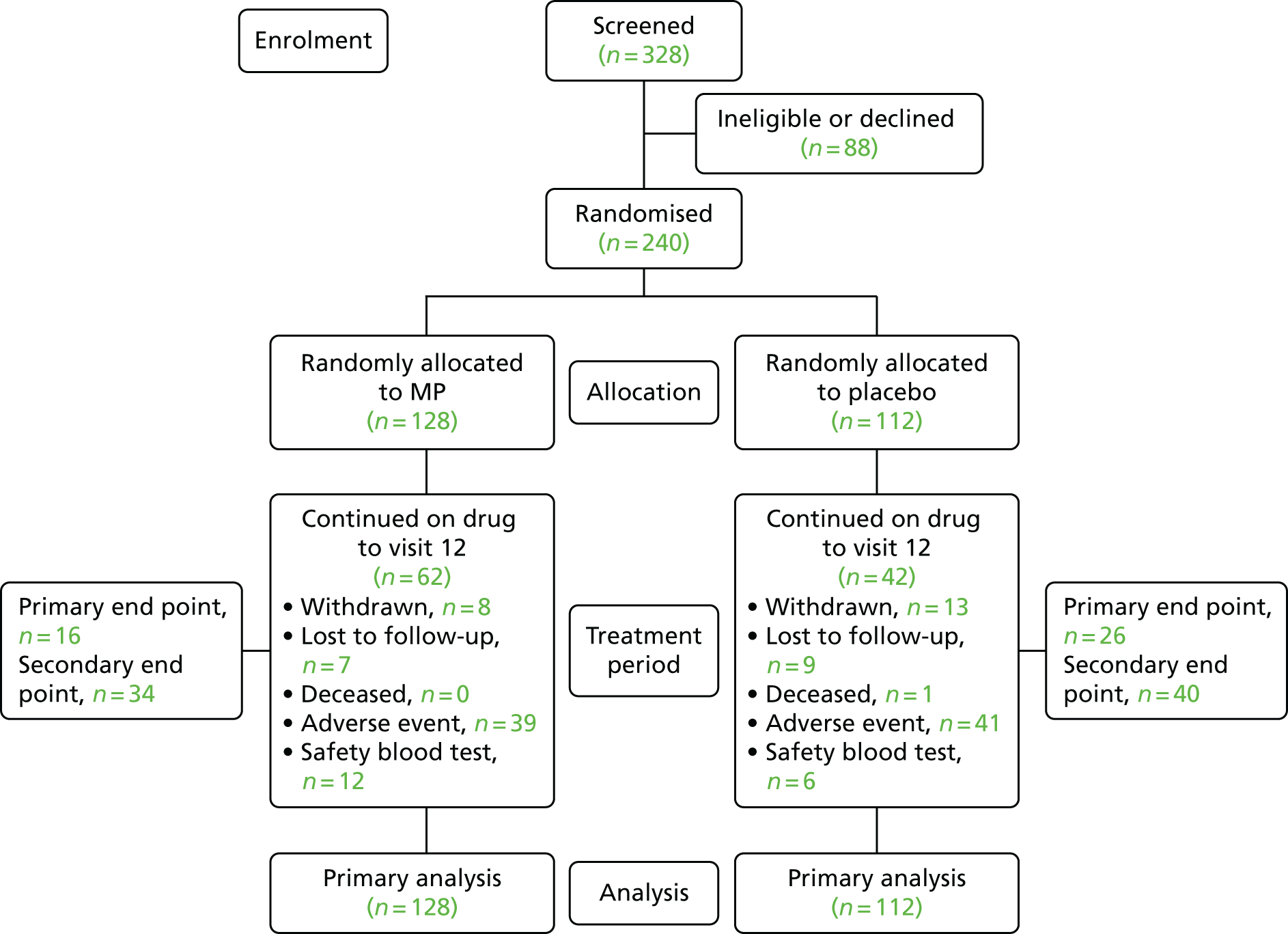

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram for recruitment is provided in Figure 1. In total, 328 patients were screened and 240 were randomised, thereby meeting and slightly exceeding the recruitment target of 234. Seventy-eight per cent of eligible patients were randomised to the study following screening, with 22% of patients declining to take part.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT diagram for TOPPIC.

All 240 randomised patients were analysed. A total of 128 (53%) participants were randomised to receive MP and 112 (47%) to placebo. All randomised patients received at least one dose of study drug. A protocol violation was recorded involving a participant who was prescribed a study drug from the wrong treatment arm 6 weeks post randomisation; the error was reported and the correct study drug issued.

Summary of ineligible and non-recruited patients

Table 3 summarises the number of ineligible and non-recruited patients at the participating centres. Five centres did not randomise any patients during the recruitment period and were closed early.

| Centre number | Centre name | Pre-screening ineligibles | Number of candidates | Number randomised | Number of ineligibles | Number of non-recruits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | Edinburgh | 150 | 91 | 78a | 1 | 14 |

| 12 | Aberdeen | 62 | 23 | 17 | 1 | 4 |

| 13 | Dundee | 49 | 29 | 21 | 2 | 6 |

| 14 | Glasgow Stobhill | 15 | 25 | 19 | 3 | 3 |

| 15 | Glasgow Royal Infirmary | 29 | 15 | 8 | 1 | 6 |

| 16 | Exeter | 25 | 28 | 11 | 0 | 17 |

| 17 | Coventry | 15 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | Liverpool | 25 | 14 | 8 | 2 | 3 |

| 19 | Manchester | 20 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 20 | Bristol | 3 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| 21 | UCLH | 59 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| 24 | Oxford | 32 | 12 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| 25 | Salford | 31 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 26 | Swansea | 11 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 27 | Royal Free | 14 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 28 | Barts | 24 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 29 | Torbay | 11 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 | Norfolk & Norwich | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 31 | Stockton | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 32 | Southampton | 18 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 33 | Plymouth | 20 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 34 | Durham | 34 | 8 | 6b | 1 | 2 |

| 35 | Hull | 22 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 36 | Leeds | 36 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| 38 | Wolverhampton | 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 39 | North Staffordshire | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 40 | Nottingham | 15 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 42 | St Marks | 14 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 43 | Rotherham | 20 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 44 | Birmingham Queen Elizabeth | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 45 | Inverness | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 46 | Darlington | 14 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 47 | Bradford | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 48 | Birmingham City | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Characteristics used for stratification of randomisation

Randomised patients were stratified according to centre and smoking status (31 blocks in total). Table 4 shows the numbers of patients randomised per recruiting centre, with the Edinburgh site recruiting the highest proportion of patients (32.5%). Smoking status (defined as those patients smoking more than one cigarette per day) is shown in Table 5.

| Centre name | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Edinburgh | 38 (29.7) | 40 (35.7) | 78 (32.5) |

| Aberdeen | 9 (7.0) | 8 (7.1) | 17 (7.1) |

| Dundee | 11 (8.6) | 10 (8.9) | 21 (8.8) |

| Glasgow Stobhill | 10 (7.8) | 9 (8.0) | 19 (7.9) |

| Glasgow Royal Infirmary | 5 (3.9) | 3 (2.7) | 8 (3.3) |

| Exeter | 6 (4.7) | 5 (4.5) | 11 (4.6) |

| Coventry | 3 (2.3) | 3 (2.7) | 6 (2.5) |

| Liverpool | 6 (4.7) | 2 (1.8) | 8 (3.3) |

| Manchester | 2 (1.6) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) |

| Bristol | 2 (1.6) | 3 (2.7) | 5 (2.1) |

| UCLH | 3 (2.3) | 2 (1.8) | 5 (2.1) |

| Oxford | 5 (3.9) | 4 (3.6) | 9 (3.8) |

| Salford | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) |

| Swansea | 3 (2.3) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (1.7) |

| Royal Free | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) |

| Barts | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Torbay | 4 (3.1) | 2 (1.8) | 6 (2.5) |

| Southampton | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) |

| Plymouth | 2 (1.6) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) |

| Durham | 3 (2.3) | 3 (2.7) | 6 (2.5) |

| Hull | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.8) | 3 (1.3) |

| Leeds | 4 (3.1) | 4 (3.6) | 8 (3.3) |

| North Staffordshire | 1 (0.8) | 4 (3.6) | 8 (3.3) |

| Nottingham | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) |

| St Marks | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) |

| Rotherham | 2 (1.6) | 2 (1.8) | 4 (1.7) |

| Birmingham Queen Elizabeth | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Inverness | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Darlington | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) |

| Smoking status | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Smoker | 29 (22.7) | 26 (23.2) | 55 (22.9) |

| Non-smoker | 99 (77.3) | 86 (76.8) | 185 (77.1) |

Characteristics at pre-assessment

Characteristics of randomised patients at pre-assessment are shown in Table 6. The group randomised to MP had slightly more patients who had previously been treated with MP, azathioprine and immunosuppressant agents, although all other demographics and characteristics were similar.

| Patient characteristic | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 79 (61.7) | 67 (59.8) | 146 (60.8) |

| Male | 49 (38.3) | 45 (40.2) | 94 (39.2) |

| Previous treatment with MP | |||

| Yes | 14 (10.9) | 5 (4.5) | 19 (7.9) |

| No | 114 (89.1) | 106 (94.6) | 220 (91.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| Previous treatment with azathioprine | |||

| Yes | 80 (62.5) | 47 (42.0) | 127 (52.9) |

| No | 48 (37.5) | 64 (57.1) | 112 (46.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| Previous treatment with infliximab | |||

| Yes | 21 (16.4) | 15 (13.4) | 36 (15.0) |

| No | 104 (81.3) | 96 (85.7) | 200 (83.3) |

| Missing | 3 (2.3) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (1.7) |

| Previous treatment with methotrexate | |||

| Yes | 8 (6.3) | 7 (6.3) | 15 (6.3) |

| No | 120 (93.8) | 104 (92.9) | 224 (93.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| Previous treatment with other corticosteroids | |||

| Yes | 97 (75.8) | 79 (70.5) | 176 (73.3) |

| No | 31 (24.2) | 32 (28.6) | 63 (26.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| Any previous immunosuppressants | |||

| Yes | 112 (87.5) | 86 (76.8) | 198 (82.5) |

| No | 16 (12.5) | 25 (22.3) | 41 (17.1) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| CD location | |||

| Ileal | 54 (42.2) | 39 (34.8) | 93 (38.8) |

| Colonic | 4 (3.1) | 2 (1.8) | 6 (2.5) |

| Ileocolonic | 70 (54.7) | 70 (62.5) | 140 (58.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| CD type | |||

| Non-stricturing non-penetrating | 50 (39.1) | 45 (40.2) | 95 (39.6) |

| Stricturing | 63 (49.2) | 46 (41.1) | 109 (45.4) |

| Penetrating | 15 (11.7) | 19 (17.0) | 34 (14.2) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Previous surgery | |||

| Yes | 46 (35.9) | 28 (25.0) | 74 (30.8) |

| No | 82 (64.1) | 83 (74.1) | 165 (68.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| TPMT | |||

| Normal | 116 (90.6) | 96 (85.7) | 212 (88.3) |

| Heterozygous | 12 (9.4) | 16 (14.3) | 28 (11.7) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||

| ≤ 40 | 103 (80.5) | 87 (77.7) | 190 (79.2) |

| > 40 | 25 (19.5) | 23 (20.5) | 48 (20.0) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Duration of CD (years) | |||

| ≤ 1 | 37 (28.9) | 41 (36.6) | 78 (32.5) |

| > 1 | 91 (71.1) | 69 (61.6) | 160 (66.7) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean | 39.2 | 38.2 | 38.7 |

| Median | 38.0 | 36.0 | 38.0 |

| SD | 12.8 | 13.4 | 13.1 |

| Q1, Q3 | 28, 50 | 28, 48 | 28, 48 |

| Min., max. | 17, 67 | 17, 75 | 17, 75 |

| n (missing) | 128 (0) | 112 (0) | 240 (0) |

| Duration of CD (years) | |||

| Mean | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.6 |

| Median | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 |

| SD | 9.7 | 9.5 | 9.6 |

| Q1, Q3 | 0,11 | 0, 11 | 0,11 |

| Min., max. | 0, 39 | 0, 47 | 0,47 |

| n (missing) | 128 (0) | 110 (2) | 238 (2) |

Patient characteristics at randomisation

Table 7 shows the baseline characteristics of participants at randomisation (week 0). The two treatment groups were similar across the variables assessed, which included weight, faecal calprotectin levels, and CDAI or IBDQ scores.

| Patient characteristic | Treatment | Overall (N = 240) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Weight (kg) | |||

| Mean | 70.7 | 70.7 | 70.7 |

| Median | 69.9 | 68.8 | 69.4 |

| SD | 14.4 | 13.7 | 14.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 58.5, 80.1 | 62.0, 76.8 | 60.0, 78.1 |

| Min., max. | 44.3, 111.9 | 43.6, 123.8 | 43.6, 123.8 |

| n (missing) | 128 (0) | 112 (0) | 240 (0) |

| Height (cm) | |||

| Mean | 168 | 169 | 169 |

| Median | 168 | 168 | 168 |

| SD | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Q1, Q3 | 161, 175 | 162, 177 | 161, 176 |

| Min., max. | 149, 193 | 150, 193 | 149, 193 |

| n (missing) | 128 (0) | 112 (0) | 240 (0) |

| Faecal calprotectin (µg/g of faeces) | |||

| Mean | 124.4 | 160.1 | 141.2 |

| Median | 80.0 | 77.5 | 80.0 |

| SD | 170.9 | 213.9 | 192.7 |

| Q1, Q3 | 30, 125 | 40, 165 | 40, 140 |

| Min., max. | 0, 920 | 0, 1040 | 0, 1040 |

| n (missing) | 108 (20) | 96 (16) | 204 (36) |

| Neutrophil count (109/l) | |||

| Mean | 4.45 | 4.22 | 4.34 |

| Median | 4.20 | 3.88 | 4.10 |

| SD | 1.76 | 1.63 | 1.70 |

| Q1, Q3 | 3.4, 5.2 | 3.0, 5.0 | 3.2, 5.1 |

| Min., max. | 1.5, 13.8 | 1.7, 8.9 | 1.5, 13.8 |

| n (missing) | 127 (1) | 111 (1) | 238 (2) |

| CDAI score | |||

| Mean | 130 | 121 | 125 |

| Median | 111 | 112 | 112 |

| SD | 86 | 72 | 80 |

| Q1, Q3 | 63, 179 | 63, 161 | 63, 169 |

| Min., max. | 2, 459 | 5, 368 | 2, 459 |

| n (missing) | 128 (0) | 112 (0) | 240 (0) |

| IBDQ: overall average | |||

| Mean | 5.19 | 5.31 | 5.24 |

| Median | 5.38 | 5.56 | 5.47 |

| SD | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.97 |

| Q1, Q3 | 4.4, 5.9 | 4.9, 6.0 | 4.7, 6.0 |

| Min., max. | 1.9, 7.0 | 2.7, 6.7 | 1.9, 7.0 |

| n (missing) | 128 (0) | 111 (1) | 239 (1) |

| IBDQ: overall total | |||

| Mean | 166 | 170 | 168 |

| Median | 172 | 178 | 175 |

| SD | 32 | 30 | 31 |

| Q1, Q3 | 142, 188 | 156, 191 | 150, 191 |

| Min., max. | 61, 223 | 85, 215 | 61, 223 |

| n (missing) | 128 (0) | 111 (1) | 239 (1) |

| SF-36: physical component score | |||

| Mean | 44.2 | 42.6 | 43.5 |

| Median | 45.0 | 43.2 | 44.5 |

| SD | 9.4 | 10.5 | 9.9 |

| Q1, Q3 | 37, 52 | 36, 51 | 36, 52 |

| Min., max. | 22, 60 | 6, 60 | 6, 60 |

| n (missing) | 124 (4) | 110 (2) | 234 (6) |

| SF-36: mental component score | |||

| Mean | 45.3 | 46.4 | 45.8 |

| Median | 47.0 | 49.7 | 47.7 |

| SD | 11.9 | 12.5 | 12.3 |

| Q1, Q3 | 38, 55 | 39, 56 | 38, 56 |

| Min., max. | 13, 66 | 15, 69 | 13, 69 |

| n (missing) | 124 (4) | 110 (2) | 234 (6) |

| EQ-5D: mobility, n (%) | |||

| I have no problems in walking about | 107 (83.6) | 87 (77.7) | 194 (80.8) |

| I have some problems in walking about | 21 (16.4) | 24 (21.4) | 45 (18.8) |

| I am confined to bed | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| EQ-5D: self-care, n (%) | |||

| I have no problems with self-care | 125 (97.7) | 104 (92.9) | 229 (95.4) |

| I have some problems washing or dressing myself | 3 (2.3) | 7 (6.3) | 10 (4.2) |

| I am unable to wash or dress myself | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| EQ-5D: usual activities, n (%) | |||

| I have no problems | 75 (58.6) | 61 (54.4) | 136 (56.7) |

| I have some problems | 47 (36.7) | 41 (36.6) | 88 (36.7) |

| I am unable to perform my usual activities | 6 (4.7) | 9 (8.0) | 15 (6.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| EQ-5D: pain/discomfort, n (%) | |||

| I have no pain or discomfort | 64 (50.0) | 56 (50.0) | 120 (50.0) |

| I have moderate pain or discomfort | 61 (47.7) | 54 (48.2) | 115 (47.9) |

| I have extreme pain or discomfort | 3 (2.3) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (1.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| EQ-5D: anxiety/depression, n (%) | |||

| I am not anxious or depressed | 93 (72.7) | 74 (66.1) | 167 (69.6) |

| I am moderately anxious or depressed | 33 (25.8) | 34 (30.4) | 67 (27.9) |

| I am extremely anxious or depressed | 2 (1.6) | 3 (2.7) | 5 (2.1) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

Adherence to trial protocol

Adherence to trial medication

A summary of the duration of trial medication is shown in Table 8, with Figure 2 showing a Kaplan–Meier plot of the duration of medication in years. The reasons for non-completion of the full treatment period are detailed in Table 9. One hundred and thirty-six patients (56.7%) did not complete 3 years of trial medication, with 80 (58.8%) patients not completing as the result of adverse events, 21 (15.4%) because of early withdrawal, 18 (13.2%) because of abnormal safety blood results, 16 (11.8%) being lost to follow-up and one (0.7%) patient dying.

| Duration of trial medication (years) | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 62 (48.4) | 42 (37.5) | 104 (43.3) |

| < 3 | 66 (51.6) | 70 (62.5) | 136 (56.7) |

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot showing duration of trial medication in years.

| Reason | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Adverse event | 39 (59.1) | 41 (58.6) | 80 (58.8) |

| Blood test result | 12 (18.2) | 6 (8.6) | 18 (13.2) |

| Early withdrawal | 8 (12.1) | 13 (18.6) | 21 (15.4) |

| Deceased | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) |

| Lost to follow-up | 7 (10.6) | 9 (12.9) | 16 (11.8) |

Dosage was adjusted throughout the trial in accordance with the protocol (see Tables 1 and 2). Table 10 provides a summary of doses at first and final visits. Table 11 summarises doses at final visit compared with dose first allocated. Only a small proportion of patients continued on the same dosage (n = 63, 26.3%) or at an increased dosage (n = 13, 5.4%); in the majority either the dose was decreased (n = 68, 28.3%) or the trial medication was stopped altogether (n = 96, 40.0%). The dosage was decreased in a higher proportion of patients in the MP group (39.1%) than in the placebo group (16.1%), whereas a higher proportion in the placebo group than in the MP group remained on the same dosage (37.5% compared with 16.4%, respectively) or stopped trial medication (42.9% compared with 37.5, respectively). The dose was increased in a small number of patients, but the proportion was marginally higher in the MP group than in the placebo group (7.0% compared with 3.6%).

| Dosage | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Dose (mg) allocated at first visit | |||

| 50 alternate days | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| 50 daily | 17 (13.3) | 17 (15.2) | 34 (14.2) |

| 50/100 alternate days | 73 (57.0) | 62 (55.4) | 135 (56.3) |

| 100 daily | 34 (26.6) | 27 (24.1) | 61 (25.4) |

| 150 daily | 4 (3.1) | 5 (4.5) | 9 (3.8) |

| Dose allocated at final visit | |||

| Stop | 48 (37.5) | 48 (42.9) | 96 (40.0) |

| 50 alternate days | 17 (13.3) | 5 (4.5) | 22 (9.2) |

| 50 daily | 33 (25.8) | 20 (17.9) | 53 (22.1) |

| 50/100 alternate days | 17 (13.3) | 25 (22.3) | 42 (17.5) |

| 100 daily | 13 (10.2) | 13 (11.6) | 26 (10.8) |

| 150 daily | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| Final dose change | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Dose decreased | 50 (39.1) | 18 (16.1) | 68 (28.3) |

| Dose stayed the same | 21 (16.4) | 42 (37.5) | 63 (26.3) |

| Dose increased | 9 (7.0) | 4 (3.6) | 13 (5.4) |

| Trial medication stopped | 48 (37.5) | 48 (42.9) | 96 (40.0) |

Adherence to the trial visits and withdrawal

Table 12 shows the number of patients who reached the end of the study (week 157 post randomisation; n = 161, 67.1%). Seventy-nine patients did not reach the final study visit, with 52 withdrawn early at their own choice or by their clinician and a further 26 being lost to follow-up or non-attenders; there was one death.

| Parameter | Category | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | |||

| Week 12 (week 157, n = 161) | Patient attended | 89 (69.5) | 72 (64.3) | 161 (67.1) |

| Patient did not attend | 7 (5.5) | 2 (1.8) | 9 (3.8) | |

| Early withdrawal | 24 (18.8) | 26 (23.2) | 50 (20.8) | |

| Withdrawn by clinician | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 7 (5.5) | 10 (8.9) | 17 (7.1) | |

| Deceased | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | |

The length of patient follow-up, in months, is shown in Table 13. The mean follow-up period was 28.6 months overall (maximum follow-up was 48 months), with a slightly longer follow-up in the MP group than in the placebo group (29.3 months vs. 27.8 months).

| Months | Treatment | Overall (N = 240) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Mean | 29.3 | 27.8 | 28.6 |

| Median | 36.0 | 36.0 | 36.0 |

| SD | 12.2 | 12.2 | 12.2 |

| Q1, Q3 | 28, 36 | 20, 36 | 23, 36 |

| Min., max. | 0, 48 | 0, 38 | 0, 48 |

| n (missing) | 128 (0) | 112 (0) | 240 (0) |

Adherence to study blinding

Treatment blinding was broken for 12 patients, and the reasons are listed in Table 14.

| Patient ID | Centre | Date | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomisation | Unblinding | |||

| Treatment group | ||||

| MP | ||||

| 11003 | Edinburgh | 13 June 2008 | 27 January 2009 | Primary end point reached |

| 11030 | Edinburgh | 3 November 2009 | 27 February 2014 | Adverse event post trial |

| 11064 | Edinburgh | 21 February 2011 | 5 April 2012 | Other |

| Placebo | ||||

| 11053 | Edinburgh | 18 August 2010 | 29 February 2012 | Other |

| 11078 | Edinburgh | 5 September 2011 | 31 May 2012 | Other |

| 11082 | Edinburgh | 13 September 2011 | 2 September 2013 | Other |

| 12002 | Aberdeen | 30 October 2008 | 3 February 2009 | SUSAR |

| 12014 | Aberdeen | 31 March 2010 | 17 May 2010 | SUSAR |

| 14010 | Glasgow Stobhill | 6 October 2009 | 26 October 2009 | SUSAR |

| 16004 | Exeter | 17 June 2010 | 25 November 2010 | SUSAR |

| 18007 | Liverpool | 3 May 2011 | 9 July 2013 | SUSAR |

| 44003 | Birmingham Queen Elizabeth | 16 January 2012 | 17 March 2015 | Adverse event post trial |

Adherence to trial procedures

A total of nine protocol violations were recorded during the course of the study: five relating to study sample storage and four relating to study dosage and affecting specific sites and specific patients. A total of 216 deviations were recorded. The deviation categories are provided in Table 15.

| Protocol deviation | Overall (n) |

|---|---|

| Study visit missed or out of window | 49 |

| Safety bloods missed or out of window | 89 |

| Colonoscopy missed or out of window | 22 |

| Questionnaire missed or out of window | 3 |

| Calprotectin sample missed or out of window | 25 |

| Medication miscounted or taken incorrectly | 11 |

| TGN sample missed or out of window | 3 |

| Other | 14 |

Concomitant medication

Concomitant medications are shown in Table 16.

| Parameter | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Concomitant medications taken? | |||

| Yes | 119 (93.0) | 111 (99.1) | 230 (95.8) |

| No | 9 (7.0) | 1 (0.9) | 10 (4.2) |

| Total number of concomitant medications | 1051 | 965 | 2016 |

| Number of prohibited and non-prohibited medications | |||

| Prohibited | 93 (8.8) | 126 (13.1) | 219 (10.9) |

| Non-prohibited | 958 (91.2) | 839 (86.9) | 1797 (89.1) |

| Number of occasions concomitant medications taken | |||

| 1 | 7 (5.9) | 7 (6.3) | 14 (6.1) |

| 2 | 10 (8.4) | 12 (10.8) | 22 (9.6) |

| 3 | 9 (7.6) | 7 (6.3) | 16 (7.0) |

| 4 | 9 (7.6) | 5 (4.5) | 14 (6.1) |

| 5 | 12 (10.1) | 12 (10.8) | 24 (10.4) |

| 6–10 | 31 (26.1) | 33 (29.7) | 64 (27.8) |

| 11–15 | 22 (18.5) | 21 (18.9) | 43 (18.7) |

| > 15 | 19 (16.0) | 14 (12.6) | 33 (14.3) |

| Requiring rescue therapy for CD? | |||

| Yes | 30 (25.2) | 37 (33.3) | 67 (29.1) |

| No | 89 (74.8) | 74 (66.7) | 163 (70.9) |

| Number of occasions rescue therapy taken for CD | |||

| 1 | 10 (33.3) | 10 (27.0) | 20 (29.9) |

| 2 | 3 (10.0) | 11 (29.7) | 14 (20.9) |

| 3 | 8 (26.7) | 6 (16.2) | 14 (20.9) |

| 4 | 4 (13.3) | 4 (10.8) | 8 (11.9) |

| 5 | 1 (3.3) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (4.5) |

| > 5 | 4 (13.3) | 4 (10.8) | 8 (11.9) |

Outcomes and estimation

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was postoperative clinical recurrence of CD, defined as a CDAI score of > 150 points with an increase from baseline of 100 points, together with the need for anti-inflammatory rescue therapy or primary surgical intervention.

As shown in Tables 17 and 18, the primary outcome was reached by 42 patients (17.5%); 16 out of 128 (12.5%) on MP versus 26 out of 112 (23.2%) on placebo (HR 0.535, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.06; adjusted p = 0.073; HR 0.527, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.99; unadjusted p = 0.046). Of the 42 who reached the primary end point, 37 participants (88%) met the CDAI score trigger and had rescue therapy initiated, whereas five (12%) met the CDAI score trigger and had both rescue therapy and primary surgical intervention.

| Primary outcome | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Primary outcome met? | |||

| Yes | 16 (12.5) | 26 (23.2) | 42 (17.5) |

| No | 112 (87.5) | 86 (76.8) | 198 (82.5) |

| Analysis type | HR | 95% CI level | p > χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Adjusted | 0.535 | 0.27 | 1.06 | 0.073 |

| Unadjusted | 0.527 | 0.28 | 0.99 | 0.046 |

The HR of < 1 for both the adjusted and unadjusted analyses indicates a treatment effect in favour of MP. The associated confidence limits for the adjusted and unadjusted results demonstrate borderline statistical significance at the 5% level.

For the 42 patients who reached primary outcome, Table 19 shows the follow-up and recurrence for the 26 (10.8%) participants reaching the primary outcome and completing the full 36-month follow-up, and for the 16 (6.7%) participants reaching the primary outcome with < 36 months of follow-up in the trial.

| Follow-up and recurrence | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Follow-up of ≥ 3 years and primary outcome | 11 (8.6) | 15 (13.4) | 26 (10.8) |

| Follow-up of < 3 years and primary outcome | 5 (3.9) | 11 (9.8) | 16 (6.7) |

| Other | 112 (87.5) | 86 (76.8) | 198 (82.5) |

Secondary outcome: clinical recurrence

The secondary outcome of clinical recurrence was postoperative clinical recurrence of CD, defined as a CDAI score of > 150 points with an increase from baseline of 100 points, or the need for anti-inflammatory rescue therapy or primary surgical intervention.

The secondary outcome events and statistical analysis are summarised in Tables 20 and 21 respectively. The secondary outcome was reached by 74 (30.8%) patients: 34 out of 128 (26.6%) on MP versus 40 out of 112 (35.7%) on placebo (HR 0.737, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.23; adjusted p = 0.243; HR 0.746, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.18; unadjusted p = 0.211). Similar to the primary outcome, the HRs are in favour of MP, but the associated CIs indicate a lack of statistical significance.

| Secondary outcome | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Secondary outcome met? | |||

| Yes | 34 (26.6) | 40 (35.7) | 74 (30.8) |

| No | 94 (73.4) | 72 (64.3) | 166 (69.2) |

| Analysis type | HR | 95% CI limit | p > χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Adjusted | 0.737 | 0.44 | 1.23 | 0.243 |

| Unadjusted | 0.746 | 0.47 | 1.18 | 0.211 |

Crohn’s Disease Activity Index score

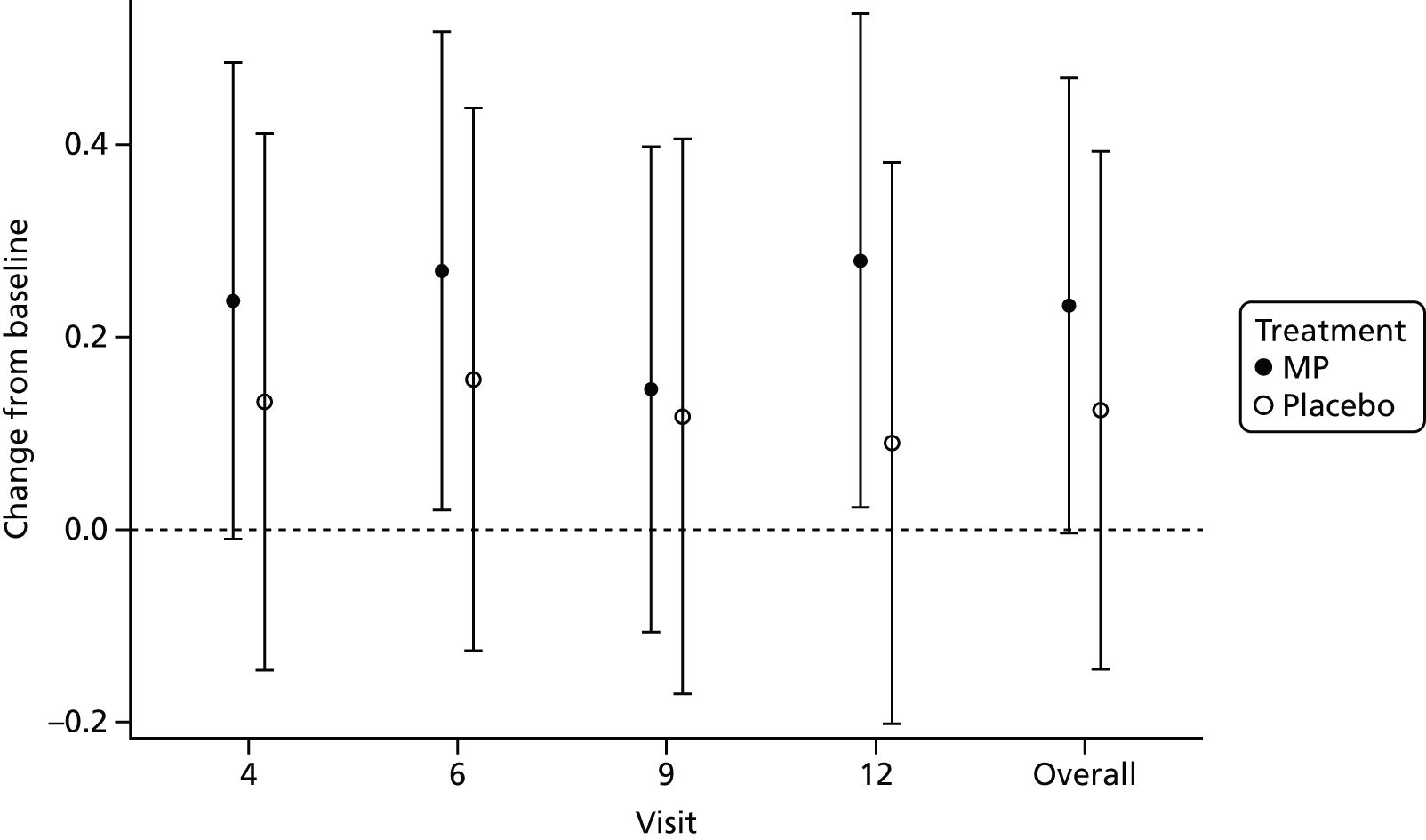

The mean score change from baseline in the CDAI for patients is shown in Figure 3 from randomisation at visit 2 (week 0) to the final study visit at visit 12 (104 weeks post randomisation).

FIGURE 3.

Mean change from baseline in CDAI scores per study visit.

Secondary outcome: surgical intervention

Tables 22 and 23 present a summary of the patients who have had surgical intervention and the associated time (in days) to the intervention.

| Days | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Had surgical intervention? | |||

| Yes | 3 (2.3) | 4 (3.6) | 7 (2.9) |

| No | 125 (97.7) | 108 (96.4) | 233 (97.1) |

| Number of occasions that surgery was undertaken | |||

| 1 | 2 (66.7) | 4 (100) | 6 (85.7) |

| 2 | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) |

| Time to surgical intervention (days) | Treatment | Overall (N = 240) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Mean | 460.7 | 582.8 | 530.4 |

| Median | 629.0 | 581.0 | 629.0 |

| SD | 357.6 | 511.7 | 421.7 |

| Q1, Q3 | 50, 703 | 149, 1017 | 60, 924 |

| Min., max. | 50, 703 | 60, 1109 | 50, 1109 |

| n (missing) | 3 (0) | 4 (0) | 7 (0) |

A small number of patients (7, 2.9%) had a secondary surgical intervention during the course of the trial, with similar numbers across the MP and placebo groups. The mean time to surgical intervention was 530.4 days, with a mean time being shorter in the MP group than in the placebo group (460.7 days vs. 582.8 days).

Secondary outcome: endoscopic recurrence

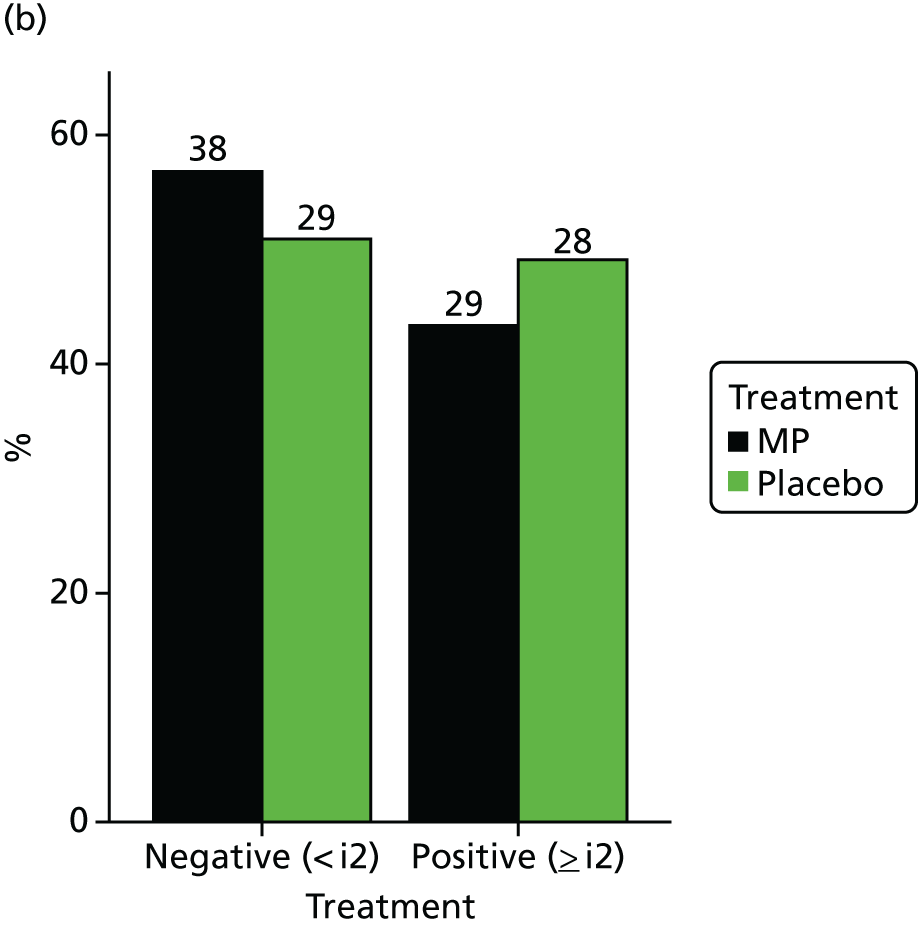

Tables 24 and 25 present a summary of endoscopic recurrence, as defined by Rutgeerts score, at visits 6 (week 49) and 12 (week 157), categorised by overall score and as either negative or positive. Figure 4 presents the number of negative and positive scores as bar charts.

| Time point | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Visit 6 (week 49, n = 208) | |||

| i0: no lesions | 33 (29.7) | 14 (14.4) | 47 (22.6) |

| i1: ≤ 5 aphthous ulcers | 24 (21.6) | 28 (28.9) | 52 (25.0) |

| i2: > 5 aphthous ulcers | 18 (16.2) | 19 (19.6) | 37 (17.8) |

| i3: diffuse aphthous ileitis | 11 (9.9) | 13 (13.4) | 24 (11.5) |

| i4: diffuse ileal inflammation | 5 (4.5) | 3 (3.1) | 8 (3.8) |

| Other | 4 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.9) |

| Missing | 16 (14.4) | 20 (20.6) | 36 (17.3) |

| Visit 12 (week 157, n = 161) | |||

| i0: no lesions | 20 (22.5) | 9 (12.5) | 29 (18.0) |

| i1: ≤ 5 aphthous ulcers | 18 (20.2) | 20 (27.8) | 38 (23.6) |

| i2: > 5 aphthous ulcers | 18 (20.2) | 11 (15.3) | 29 (18.0) |

| i3: diffuse aphthous ileitis | 4 (4.5) | 5 (6.9) | 9 (5.6) |

| i4: diffuse ileal inflammation | 7 (7.9) | 12 (16.7) | 19 (11.8) |

| Other | 2 (2.2) | 2 (2.8) | 4 (2.5) |

| Missing | 20 (22.5) | 13 (18.1) | 33 (20.5) |

| Time point | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Visit 6 (week 49, n = 208) | |||

| Negative (< i2) | 57 (51.4) | 42 (43.3) | 99 (47.6) |

| Positive (≥ i2) | 34 (30.6) | 35 (36.1) | 69 (33.2) |

| Other | 4 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.9) |

| Missing | 16 (14.4) | 20 (20.6) | 36 (17.3) |

| Visit 12 (week 157, n = 161) | |||

| Negative (< i2) | 38 (42.7) | 29 (40.3) | 67 (41.6) |

| Positive (≥ i2) | 29 (32.6) | 28 (38.9) | 57 (35.4) |

| Other | 2 (2.2) | 2 (2.8) | 4 (2.5) |

| Missing | 20 (22.5) | 13 (18.1) | 33 (20.5) |

FIGURE 4.

Colonoscopy by study visit (visit 6 was week 49 post randomisation and visit 12 was week 157 post randomisation). (a) Visit 6 and (b) visit 12.

Colonoscopy results (defined as negative or positive using the Rutgeerts score) are also summarised and the results of the statistical analysis of visit 12 colonoscopy results are presented in Table 26.

| Analysis type | Visit 12 odds ratio | 95% CI limit | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Adjusted | 0.66 | 0.26 | 1.67 | 0.382 |

| Unadjusted | 0.79 | 0.39 | 1.61 | 0.516 |

Comparing the incidence of positive colonoscopies at visit 12 for the MP group with the placebo group gave an adjusted odds ratio of 0.66 (95% CI 0.26 to 1.67; p = 0.382) and an unadjusted odds ratio of 0.79 (95% CI 0.39 to 1.61; p = 0.516), indicating no significant difference between treatment arms.

Endoscopic recurrence was also assessed using CDEIS score. Figure 5 shows CDEIS scores in a box plot, with a higher CDEIS score indicating greater severity of disease. The results of the statistical analysis are shown in Table 27, with an adjusted treatment effect of –0.612 (95% CI –1.92 to 0.69; p = 0.354), where an effect < 0 indicates a treatment effect in favour of MP. Higher CDEIS scores were recorded for the placebo group than for those patients allocated to MP at visits 6 and 12, although the difference was not statistically significant.

FIGURE 5.

Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of severity score by study visit (visit 6 was 49 weeks post randomisation and visit 12 was 157 weeks post randomisation). (a) Visit 6 and (b) visit 12. Mean CDEIS scores are indicated by a diamond in the box plot. The minimum is indicated by the bottom of the lower whisker, the maximum is indicated by the top of the upper whisker. The lower quartile is indicated by the horizontal line at the bottom of the box and the upper quartile is indicated by the horizontal line at the top of the box. Outliers are shown as small circles, identified as being 1.5 times outside the interquartile range. A higher CDEIS score indicates greater severity of the disease.

| Analysis type | Visit 12 treatment effect | 95% CI limit | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Adjusted | –0.612 | –1.92 | 0.69 | 0.354 |

| Unadjusted | –0.661 | –1.89 | 0.57 | 0.289 |

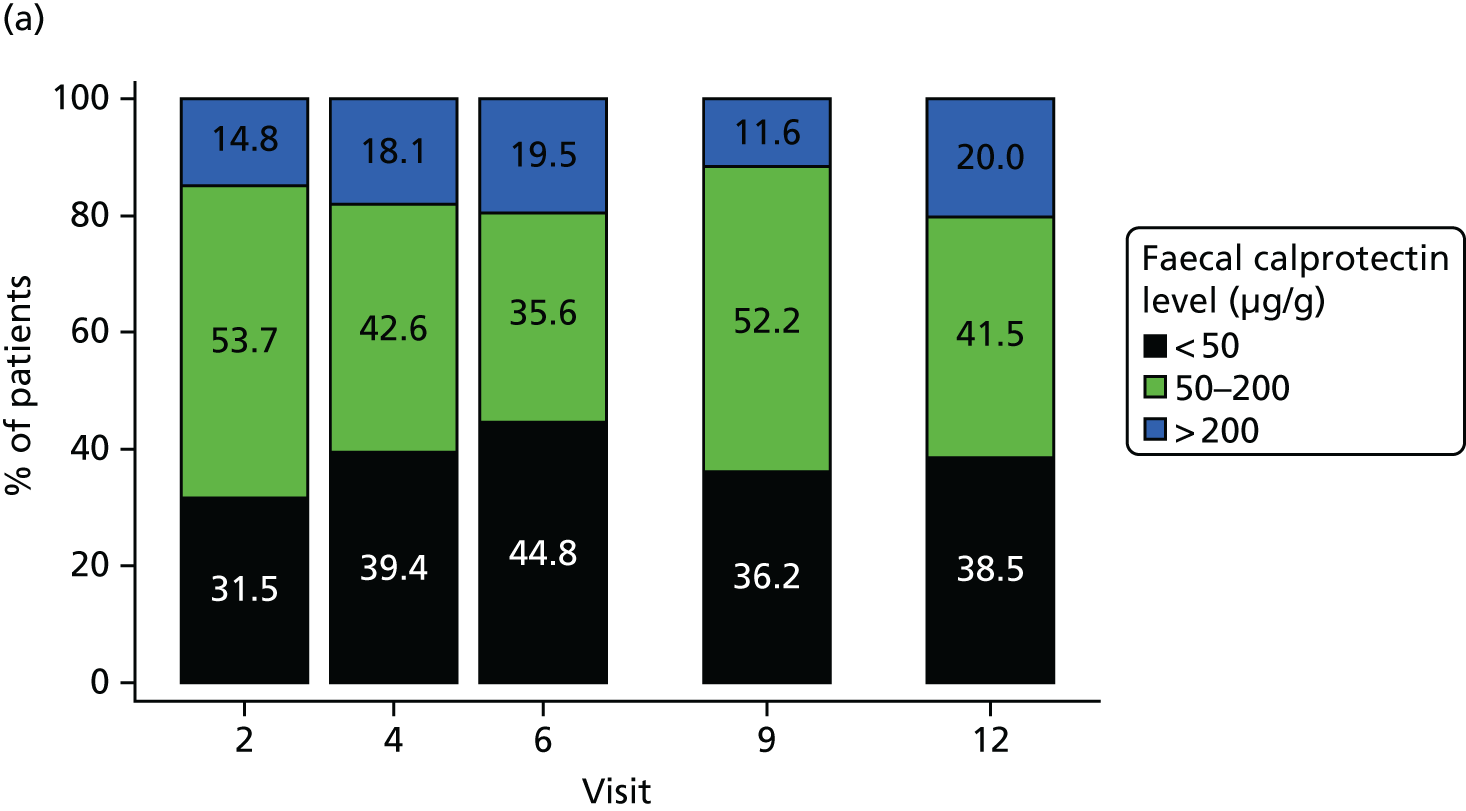

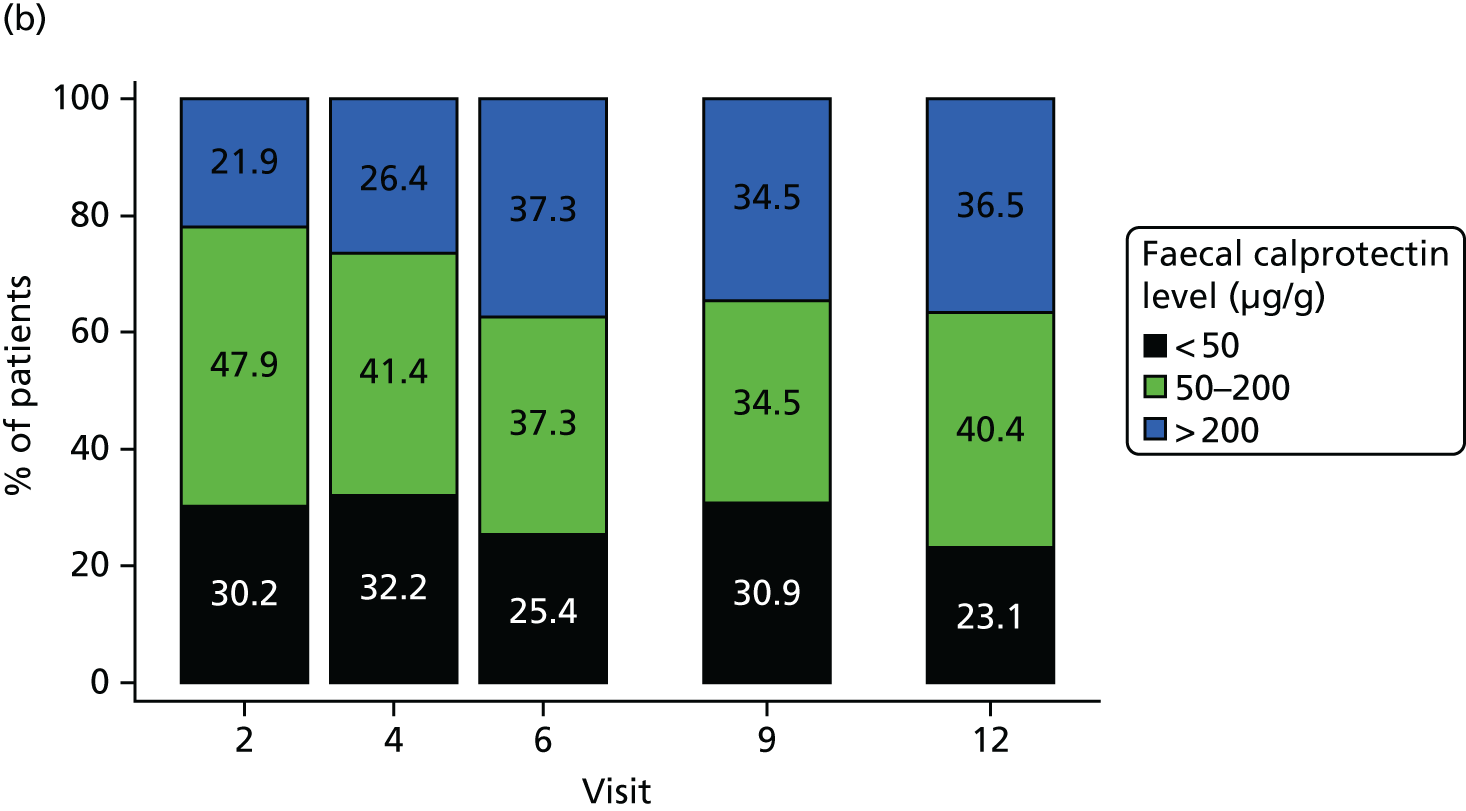

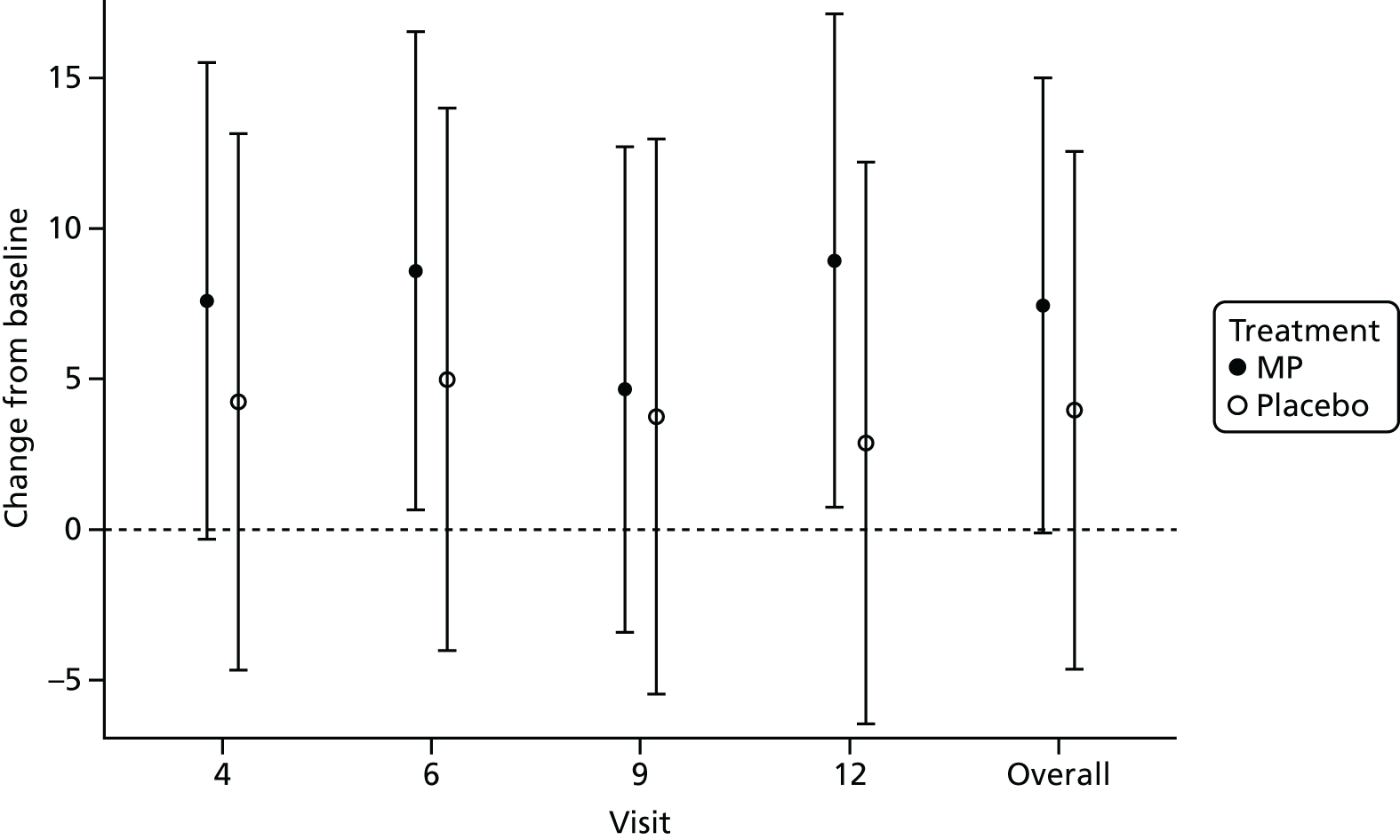

Secondary outcome: faecal calprotectin levels

Faecal calprotectin results were summarised by time and treatment group both as a continuous measure and categorically. The continuous change from baseline to each time point was also summarised and is presented in Figure 6, indicating an increase from baseline across all visits in the placebo group, in contrast to a decrease from baseline across all visits in the MP group. Figure 7 shows a categorical summary of faecal calprotectin levels, indicating the proportions in both MP and placebo groups.

FIGURE 6.

Mean change from baseline in faecal calprotectin level. Faecal calprotectin results of < 20µg/g faeces have been included in the summary with a value of 0.

FIGURE 7.

Categorical summary of faecal calprotectin levels (µg/g) in faeces. (a) MP group and (b) placebo group. Percentages are determined on non-missing data only.

Faecal calprotectin levels were also assessed as a non-invasive marker of clinical recurrence of CD by incorporating it as a time-varying covariate in the Cox proportional hazards model. Tables 28 and 29 summarise faecal calprotectin levels by colonoscopy result at visits 6 and 12. The results of the statistical analysis are presented in Table 30 and indicate that faecal calprotectin levels are a significant predictor of the primary outcome. For each 100 µg/g increase in faecal calprotectin, the probability of reaching the primary outcome increased by 17.7%. These results should, however, be treated with caution as only 31 out of 42 events have been included in this analysis as a result of missing data.

| Colonoscopy result | Treatment | Overall (N = 240) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Negative (< i2) (n = 99, 47.6%) | |||

| Mean | 98 | 181 | 133 |

| Median | 45 | 110 | 60 |

| SD | 148 | 243 | 197 |

| Q1, Q3 | 20, 90 | 30, 180 | 20, 130 |

| Min., max. | 20, 810 | 20, 1080 | 20, 1080 |

| n (missing) | 44 (13) | 33 (9) | 77 (22) |

| Positive (≥ i2) (n = 57, 35.4%) | |||

| Mean | 240 | 353 | 291 |

| Median | 170 | 220 | 170 |

| SD | 305 | 308 | 308 |

| Q1, Q3 | 50, 260 | 120, 590 | 90, 350 |

| Min., max. | 20, 1200 | 20, 1130 | 20, 1200 |

| n (missing) | 27 (7) | 22 (13) | 49 (20) |

| Colonoscopy result | Treatment | Overall (N = 240) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Negative (< i2) (n = 99, 47.6%) | |||

| Mean | 141 | 133 | 137 |

| Median | 45 | 70 | 60 |

| SD | 174 | 170 | 170 |

| Q1, Q3 | 20, 260 | 20,200 | 20, 200 |

| Min., max. | 20, 660 | 20,750 | 20, 750 |

| n (missing) | 24 (14) | 23 (6) | 47 (20) |

| Positive (≥ i2) (n = 57, 35.4%) | |||

| Mean | 146 | 262 | 200 |

| Median | 110 | 200 | 140 |

| SD | 143 | 203 | 181 |

| Q1, Q3 | 50, 180 | 130, 270 | 80, 240 |

| Min., max. | 20, 530 | 30, 750 | 20, 750 |

| n (missing) | 22 (7) | 19 (9) | 41 (16) |

| Model | HR | 95% CI limit | p > χ2 | Number of primary events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| 100-unit change in calprotectin | 1.177 | 1.082 | 1.282 | 0.0002 | 31 |

Secondary outcome: thioguanine nucleotide concentration levels

Thioguanine levels were summarised by time and treatment group both as a continuous measure and categorically following independent blind review. Figure 8 shows the mean change from baseline in TGN levels, with a slight and unexplained rise in TGN levels in the placebo arm. Figure 9 presents a categorical summary of TGN levels in the MP group at each of the five time points measured throughout the trial.

FIGURE 8.

Mean change from baseline in TGN levels. RBC, red blood cell.

FIGURE 9.

Categorical summary of TGN levels (pmol/8 × 108 red blood cells). Percentages are determined on non-missing data only. RBC, red blood cell.

In a similar manner to faecal calprotectin levels, TGN was assessed as a non-invasive marker of clinical recurrence of CD by incorporating results from MP patients only as a time-varying covariate in the Cox proportional hazards model. As shown in Table 31, the corresponding time-varying covariate analysis of TGN concentrations (data available for 14 of the 16 patients receiving MP only) indicated that, for every 100-pmol/8 × 108 red blood cell increase in TGN, the hazard of reaching the primary out come decreased by 20% (HR 0.800, 95% CI 0.565 to 1.132; p = 0.207).

| Model | HR | 95% CI limit | p > χ2 | Number of primary events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| 100-pmol/8 × 108 red blood cells change in TGN | 0.800 | 0.565 | 1.132 | 0.207 | 14 |

Secondary outcome: changes in self-rated quality-of-life scores

Patient-reported outcome measures (as measured by IBDQ) were summarised at each visit based on observed scores and change from baseline scores for each of the four IBDQ subscales (bowel symptoms, emotional health, systemic systems and social function). Averages and totals across all subscales were summarised similarly.

In addition, the overall average IBDQ score and overall total IBDQ score were statistically analysed using a repeated measures analysis of covariance, modelling change from baseline, fitting terms for treatment, visit and the interaction between treatment and time.

For both the overall average and overall total, there were no significant differences between treatment and placebo groups across all study visits and the study overall. However, both treatment groups showed an improvement in quality of life across all study visits in comparison with baseline, with the MP group demonstrating the greater change across all visits. Figures 10 and 11 depict the results of the statistical analysis for the overall average IBDQ and overall total IBDQ, respectively.

FIGURE 10.

Change from baseline final model treatment effects and 95% CIs for overall average IBDQ.

FIGURE 11.

Change from baseline final model treatment effects and 95% CIs for overall total IBDQ.

Safety outcomes

Adverse events

Of 1747 reported adverse events, 355 (20.3%) were infections, although only seven (0.4%) necessitated hospitalisation, with higher rates in the group allocated to placebo. The majority of adverse events were classed as either mild or moderate in severity [868 (91.6%) in the MP group and 728 (91.1%) in the placebo group]. Adverse events caused discontinuation of treatment in 80 patients overall (33%): 39 of the 128 (30%) patients in the MP group versus 41 of the 112 (36.6%) patients in the placebo group. Adverse events in the trial cohort overall are shown in Table 32, with serious adverse events in Table 33. There were two cases of pancreatitis (0.1%, one in the MP group and one in the placebo group) and four malignancies (0.2%, three in the MP group and one in the placebo group): basal cell carcinoma, breast cancer and two cases of lentigo maligna. One participant died of coronary heart disease in the placebo group.

| Parameter | Treatment, n (%) | Overall (N = 240), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP (N = 128) | Placebo (N = 112) | ||

| Had adverse event | |||

| Yes | 121 (94.5) | 105 (93.8) | 226 (94.2) |

| No | 7 (5.5) | 7 (6.3) | 14 (5.8) |

| Severity of worst event | |||

| Mild | 14 (11.6) | 8 (7.6) | 22 (9.7) |

| Moderate | 65 (53.7) | 59 (56.2) | 124 (54.9) |

| Severe | 41 (33.9) | 38 (36.2) | 79 (35.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Total number of adverse events | 948 | 799 | 1747 |

| All adverse events split by category | |||

| Uncoded | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) |

| GI symptoms: nausea/vomiting | 78 (8.2) | 41 (5.1) | 119 (6.8) |

| GI symptoms: abdominal pain | 132 (13.9) | 141 (17.6) | 273 (15.6) |

| GI symptoms: constipation/diarrhoea | 54 (5.7) | 56 (7.0) | 110 (6.3) |

| GI symptoms: other | 53 (5.6) | 40 (5.0) | 93 (5.3) |

| Worsening CD | 41 (4.3) | 37 (4.6) | 78 (4.5) |