Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 08/52/01. The contractual start date was in March 2010. The final report began editorial review in March 2018 and was accepted for publication in March 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Alessio Pigazzi is a consultant and proctor for Intuitive Surgical Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and receives personal fees from Covidien plc (Medtronic plc; Dublin, Ireland) and Ethicon, Inc. (Somerville, NJ, USA) outside the submitted work. David Jayne is a proctor for Intuitive Surgical Inc. and was formerly a member of the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) Strategy Group and the EME Prioritisation Group, and was previously involved in an EME Intraoperative Imaging Review. Claire Hulme was formerly a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board. Julia Brown is a member of the HTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board, HTA Funding Board Policy Group, HTA Mental, Psychological and Occupational Health Methods Group, HTA Post-Board Funding Teleconference Group and NIHR Standing Advisory Committee.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Jayne et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Total mesorectal excision (TME) is the standard of care in rectal cancer surgery, involving complete removal of the tumour along with the draining lymphatics within an intact mesorectal envelope. 1 The feasibility and safety of laparoscopic surgery has been established for colon cancer. 2–4 The case for rectal cancer is less clear, and, of the reported multicentre trials at the time of study design in 2010, only the MRC CLASICC trial included an evaluation of laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery compared with open rectal cancer surgery. 5 Although both laparoscopic and open rectal cancer resection were associated with similar lymph node yields, concern was expressed at the higher rate of circumferential resection margin (CRM) involvement in the laparoscopic group (12.4%) than in the open group (6.3%) for patients undergoing anterior resection (AR). This, however, did not translate into a difference in local recurrence at either 3-year2 or 5-year follow-up. 6 The difference in CRM involvement was felt to reflect the increased technical difficulties associated with the laparoscopic technique in the rectal cancer subgroup. This was supported by the higher conversion rate in the laparoscopic rectal subgroup (34%) than the laparoscopic colon subgroup (25%). 5 Analysis of CLASICC data revealed higher morbidity and mortality rates associated with laparoscopic cases converted to open operation. Some of this increased morbidity may be related to more advanced cancers requiring conversion, but a proportion of it will inevitably have resulted from the increased operative time, increased technical difficulty and the need for a laparotomy wound in converted cases.

Since completion of the CLASICC trial, there have been several other large studies comparing laparoscopic with open surgery for rectal cancer. A large European randomised controlled trial, COLOR II, recruited 1103 participants to a non-inferiority study involving 30 centres in eight countries. 7 Laparoscopic surgery was reported to be advantageous in terms of short-term outcomes (quicker return of bowel function, reduced hospital stay), with similar morbidity and pathological outcomes to open surgery. The 3-year results from the same study were reported in 2015 and showed similar rates of locoregional recurrence and disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in both the laparoscopic and the open groups. 8 These findings were echoed by the results of the COREAN trial, which again reported better short-term outcomes following laparoscopic rectal cancer resection and similar pathological outcomes compared with open surgery. 9

In contrast, there have been two large randomised trials, ALaCaRT10 and ACOSOG,11 that have cast doubt on the benefits of laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery compared with open rectal cancer surgery. Both were non-inferiority studies and both used a novel composite primary outcome combining rates of negative circumferential and distal cancer margins with completeness of mesorectal excision as a measure of oncological clearance. Both studies failed to demonstrate the non-inferiority of the laparoscopic compared with the open surgery approach, concluding that the evidence was not sufficient to support the routine use of the laparoscopic technique.

Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery was introduced into clinical practice in the early 1990s with the promise to eliminate many of the technical difficulties inherent in laparoscopic surgery. The technical advantages associated with robotic-assisted surgery include intuitive manipulation of the laparoscopic instruments with 7 degrees of freedom of movement, a three-dimensional field of view, a stable camera platform with zoom magnification, dexterity enhancement and an ergonomic operating environment.

The feasibility of robotics for TME rectal cancer resection was established by Pigazzi et al. in a series of six low rectal cancers. 12 A subsequent follow-up study of 39 rectal cancers treated prospectively by robotic-assisted resection reported a zero rate of conversion with a mortality of 0% and morbidity of 12.8%. 13 The only randomised trial at the time of design of the ROLARR study compared 18 patients assigned to robotic-assisted resection with 18 patients assigned to standard laparoscopic resection. 14 No difference was observed in the operative times, the conversion rates (two laparoscopic, zero robotic), or the quality of mesorectal resection. The only difference was the length of hospital stay, which was significantly shorter following robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery (robotic assisted: 6.9 ± 1.3 days; standard laparoscopic: 8.7 ± 1.3 days; p < 0.001) and attributed by the authors to a reduction in surgical trauma. Since the commencement of the ROLARR trial, there have been numerous reports from single centres, analyses of national databases,15 and several systematic reviews and meta-analyses,16–18 but no large randomised comparison with laparoscopic or open rectal cancer surgery. Results from the meta-analyses tell a broadly similar story, with no clear advantage for robotic over laparoscopic surgery in terms of short-term outcomes, with the exception of lower conversion rates and a suggestion of improved postoperative bladder and sexual function. 19 The disadvantage of robotic surgery, compared with laparoscopic surgery, appears to be the longer operating times and perhaps an increase in operative blood loss. Importantly, the hospital costs associated with the use of the robot are higher, which has fuelled the ongoing debate about whether or not robotic-assisted rectal cancer surgery can be justified in the absence of clear patient benefits and considering its higher hospital costs. 15,20,21

The ROLARR trial was designed with the above concerns in mind and with the primary objective to evaluate the short-term safety and efficacy of robotic-assisted surgery compared with laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer resection. The primary end point chosen was conversion to open surgery, on the basis that if the robot offered a technical advantage over laparoscopic surgery it should be reflected in a reduced conversion rate. Secondary end points were chosen to reflect the oncological nature of the investigation and the compelling need for rigorous patient-reported outcomes and cost-effectiveness evaluation.

Chapter 2 Methods

Objectives

The purpose of the trial was to perform a rigorous evaluation of robotic-assisted rectal cancer surgery by means of a randomised controlled trial. The chosen comparator was standard laparoscopic rectal cancer resection, which is essentially the same procedure but without the use of the robotic device. The two operative interventions were evaluated for short- and longer-term outcomes. The key short-term outcomes included assessment of technical ease of the operation, as determined by the clinical indicator of low conversion rate to open operation, and clear pathological resection margins as an indicator of surgical accuracy and improved oncological outcome. In addition, quality-of-life (QoL) assessment and analysis of cost-effectiveness were performed to aid evidence-based knowledge to inform the NHS and other service providers and decision-makers. The short-term outcomes were analysed after the last randomised patient had had 6 months of follow-up, to provide a timely assessment of the new technology, and were made available to the public, clinicians and health-care providers to inform health-care decision-making. Longer-term outcomes concentrated on oncological aspects of the disease and its surgical treatment with analysis of DFS, OS and local recurrence rates at 3 years’ follow-up.

Trial design

The ROLARR trial was an international, multicentre, prospective, unblinded, parallel-group randomised controlled trial22 comparing robotic-assisted with laparoscopic surgery for the curative treatment of rectal cancer (defined as an adenocarcinoma whose distal extent was situated at or within 15 cm of the anal margin) by low anterior resection (LAR), high anterior resection (HAR) or abdominoperineal resection (APR). The trial design required that each participating surgeon had performed a minimum of 30 minimally invasive (laparoscopic or robotic) rectal cancer resections (at least 10 laparoscopic and at least 10 robotic). The trial received national ethics approval in the UK and either ethics committee or institutional review board (IRB) approval as was required at the location of each of the international centres; all participants gave written informed consent. The trial conduct was overseen by an independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). The trial was registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) register (ISRCTN80500123).

Participants

The inclusion criteria were:

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Able to provide written informed consent.

-

Diagnosis of rectal cancer (defined as an adenocarcinoma for which distal extent is situated at or within 15 cm of the anal margin, as assessed by endoscopic examination or radiological contrast study) amenable to curative surgery by LAR, HAR or APR, for example, staged T1–3, N0–2, M0 by imaging as per local practice. Although not mandated, computed tomography (CT) imaging with either additional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or transrectal ultrasound is recommended to assess distant and local disease.

-

Rectal cancer suitable for resection by either standard laparoscopic procedure or robotic-assisted laparoscopic procedure.

-

Fit for robotic-assisted or standard laparoscopic rectal resection.

-

An American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status of ≤ 3.

-

Capable of completing required questionnaires at time of consent (provided questionnaires were available in a language spoken fluently by the participant).

The exclusion criteria were:

-

benign lesions of the rectum

-

benign or malignant diseases of the anal canal

-

locally advanced cancers not amenable to curative surgery

-

locally advanced cancers requiring en bloc multivisceral resection

-

synchronous colorectal tumours requiring multisegment surgical resection (a benign lesion within the resection field in addition to the main cancer would not exclude a patient)

-

coexistent inflammatory bowel disease

-

clinical or radiological evidence of metastatic spread

-

concurrent or previous diagnosis of invasive cancer within 5 years that could confuse diagnosis (non-melanomatous skin cancer or superficial bladder cancer treated with curative intent were acceptable; other cases were individually discussed with the chief investigator)

-

history of psychiatric or addictive disorder or other medical condition that in the opinion of the investigator would preclude the patient from meeting the trial requirements

-

pregnancy

-

participation in another rectal cancer clinical trial relating to surgical technique.

Preoperative investigation and preparation was as per institutional protocol. Laparoscopic mesorectal resection was performed in accordance with each surgeon’s usual practice. Robotic surgery involved either a totally robotic approach or a hybrid approach; the only absolute requirement was that the robot had to be used for mesorectal resection. For the purposes of the trial, a totally robotic operation was defined as a resection of the entire surgical specimen with the use of robotic assistance. A hybrid operation was defined as use of laparoscopic techniques to mobilise the proximal colon, with robotic assistance employed to perform the rectal mesorectal dissection. It was permissible to perform a partial mesorectal excision with a suitable distal margin, rather than a TME.

The specifics of each operation were at the discretion of the operating surgeon (e.g. port-site placement, mobilisation of the splenic flexure, inferior mesenteric artery/vein division, high vs. low vascular division, etc.), as was the decision to convert to an open operation. Detailed guidance was provided to ensure consistent histopathological analysis and reporting of the rectal dissection specimens in accordance with internationally agreed criteria. 23 Digital photographs of the anterior and posterior of the specimen and sequential cross-sectional views of the surgical specimen, as well as close-ups of the front and back of the levator/anal sphincter (if appropriate), were collected (prior to dissection) to allow blinded assessment of the quality of the plane of surgery. To enable a central pathology review, the tissue slides (or high-quality digital slide images) were submitted.

Postoperative care was as per institutional protocol; however, the protocol required that patients underwent a clinical assessment at 30 days and at 6 months post operation. Any further visits were in accordance with local standard clinical practice. Follow-up data were collected on an annual basis until the last participant reached 3 years post randomisation.

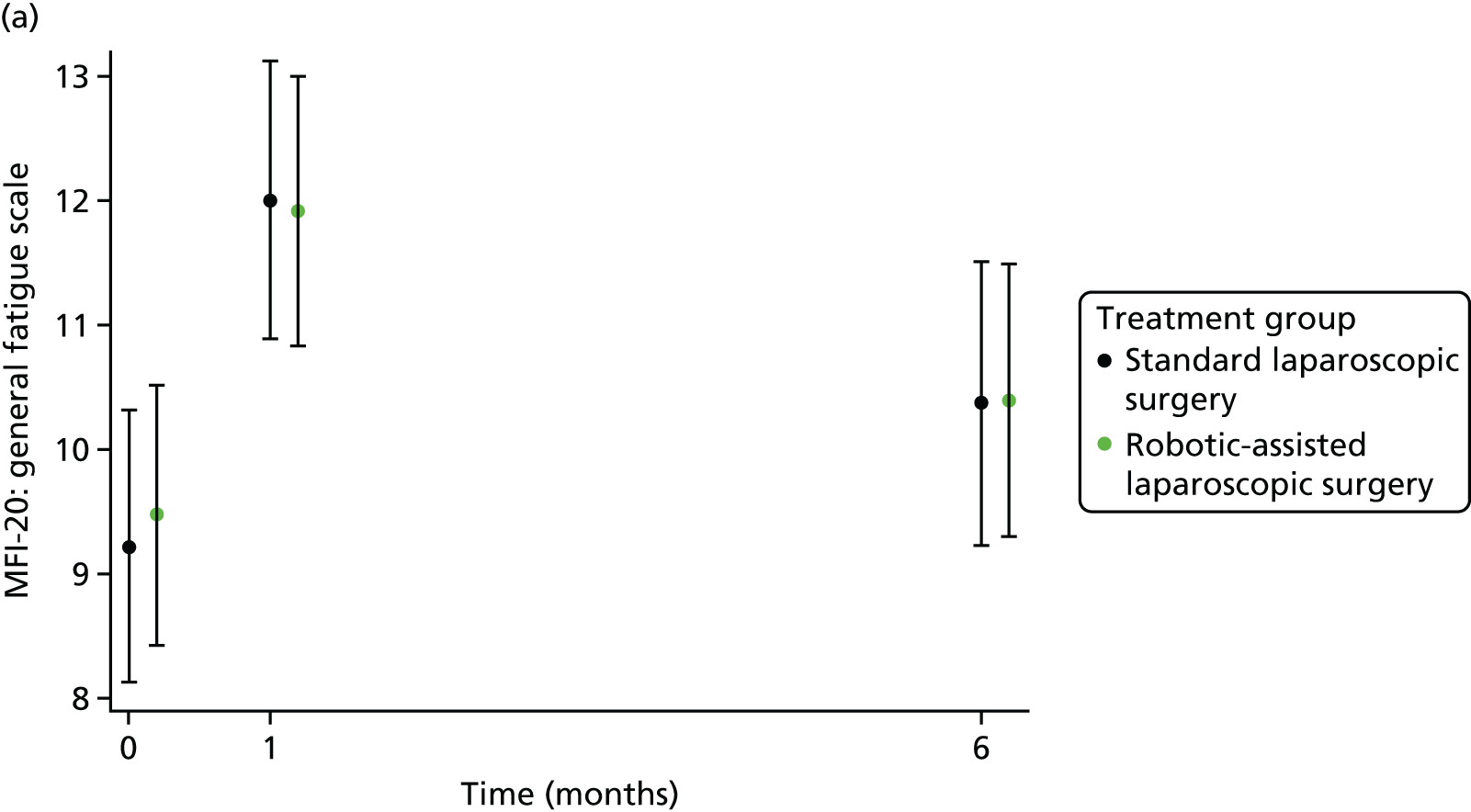

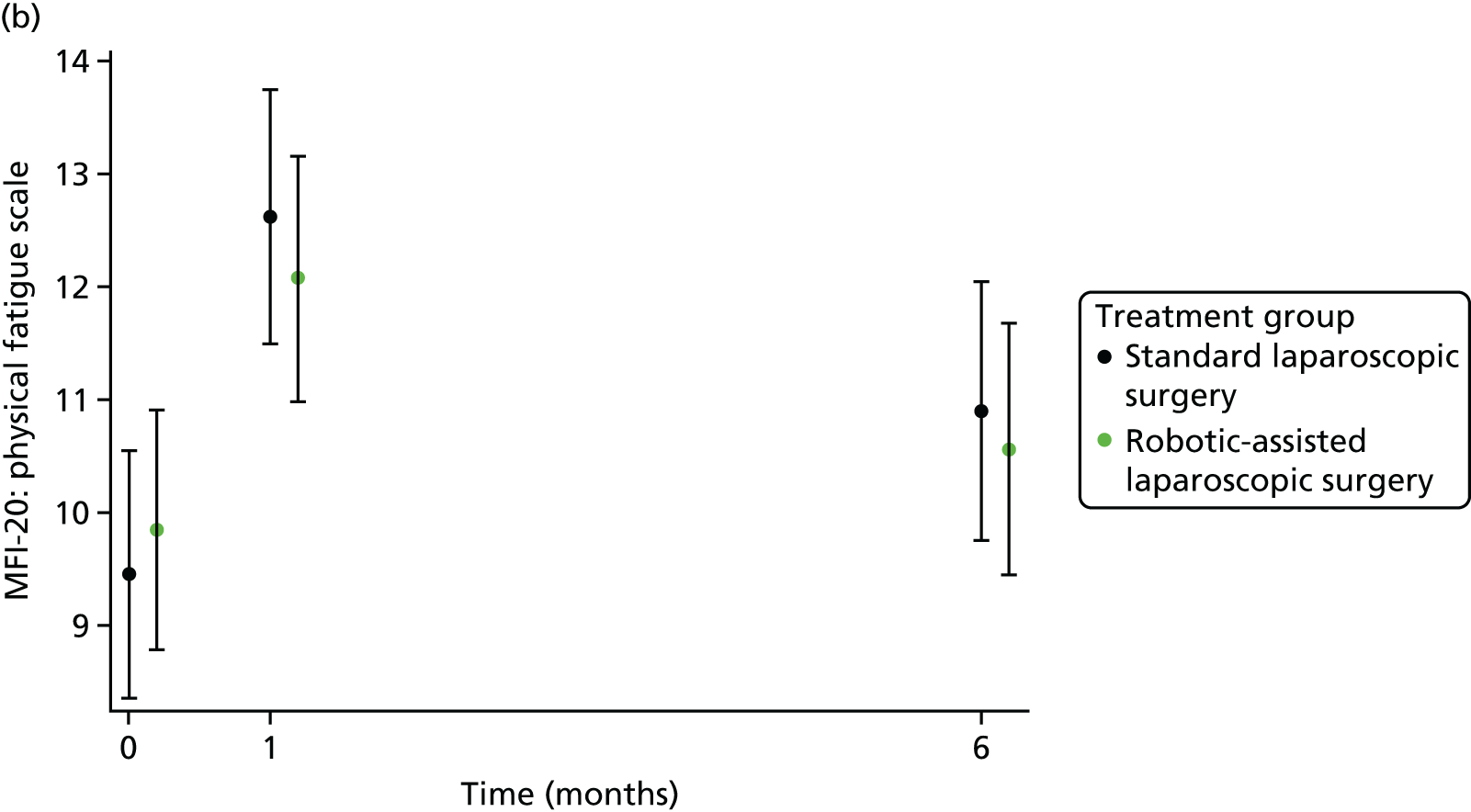

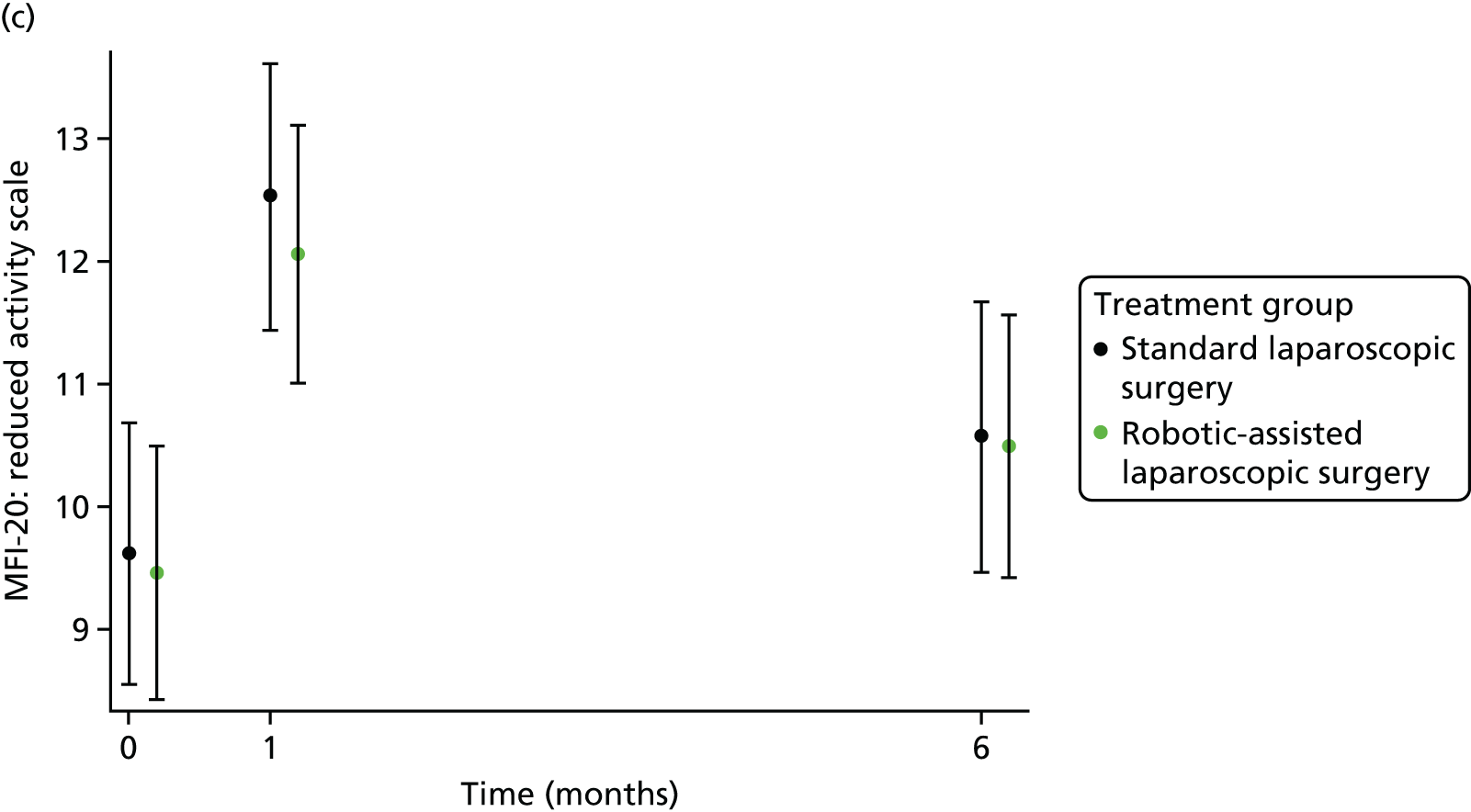

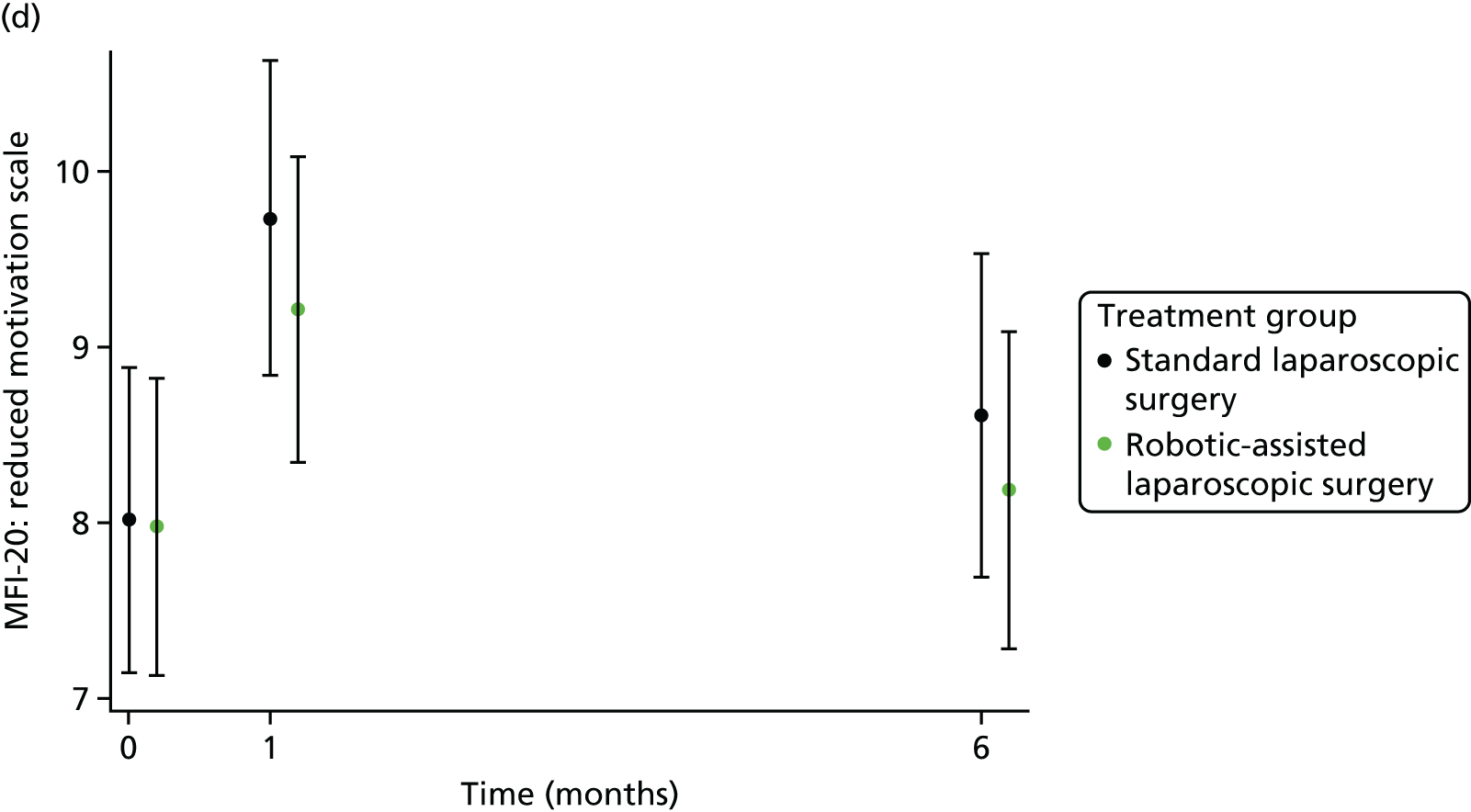

Participants completed questionnaires prior to randomisation (baseline), and at 30 days and 6 months postoperatively. General QoL [Short Form questionnaire-36 items version 2 (SF-36v2)] and fatigue [Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory-20 (MFI-20)] data were collected at baseline and at the 30-day and 6-month postoperative visits. In addition, bladder and sexual function questionnaires [International Prostatic Symptom Score (I-PSS) and International Index of Erectile Function/Female Sexual Function Index (IIEF/FSFI)] were completed by patients at baseline and at 6 months post operation. Participants in the UK and USA also completed the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) at baseline and at 30 days and at 6 months post operation, and a resource utilisation questionnaire at 30 days and at 6 months post operation for the health economic component of the trial.

The SF-36v2,24 a well-validated, multipurpose standard health-related QoL evaluation questionnaire, was used to assess generic QoL. It generates an eight-scale profile of functional health and well-being scores, as well as summary measures of physical and mental health. This information related to the previous 4-week time period.

The MFI-20 was used to assess fatigue;25 it is a 20-item self-report validated instrument designed to measure current fatigue. It creates a global score as well as individual scale scores that cover the following dimensions: general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced activity, reduced motivation and mental fatigue.

The I-PSS26 was used to assess bladder function. This questionnaire includes seven questions relating to lower urinary tract function, which form an overall symptom score that can be used to classify bladder dysfunction as mild, moderate or severe. To assess sexual function, the IIEF27 and FSFI28 were used. Both are brief male-/female-specific questionnaires developed to assess various domains of sexual function. The IIEF, FSFI and I-PSS questionnaires obtained information relating to the patient’s functioning over the previous 4 weeks.

For the health economic analysis, the EQ-5D questionnaire was used to assess self-reported utility. This is a standardised non-disease-specific instrument that describes and values health-related QoL and provides a single index value for a number of different health states. In addition, the resource utilisation questionnaire collected information on community-based medical resource usage [e.g. general practitioners (GPs), nurses, physiotherapists/occupational therapists, outpatients and medications]. Please refer to Appendix 12 for a summary of protocol changes.

End points

Primary end point

Rate of intraoperative conversion to open surgery

Conversion to open surgery was defined as the use of a laparotomy wound for any part of the mesorectal dissection. The use of a small abdominal wound to facilitate a low, stapled anastomosis and/or specimen extraction was permissible and not considered as a conversion to open surgery. The decision to convert to an open operation was at the discretion of the operating surgeon. Details relating to the planned and actual operation were collected on the baseline and operative case report forms (CRFs).

Key secondary end points

Pathological circumferential resection margin positivity

Pathological circumferential resection margin positivity (CRM+) was defined as a distance of ≤ 1 mm of the cancer from the CRM as recorded on the local histopathology review.

Three-year local recurrence

Local recurrence was defined as evidence of locoregional disease within the surgical field. Time to local recurrence was calculated from the date of randomisation to the date of local recurrence, defined as the date of the relevant assessment (i.e. clinical, radiological and pathological) that first detected the local recurrence.

Further secondary end points

Intraoperative complications

Defined as adverse events occurring during surgery related to the surgical or related procedures (e.g. anaesthetic).

Thirty-day postoperative complications

Defined as an adverse event occurring during the first 30 days postoperatively and related to surgery or related procedures (e.g. anaesthetic).

Six-month postoperative complications (after 30 days)

Defined as an adverse event occurring during the first 6 months (after 30 days) postoperatively and related to surgery or related procedures (e.g. anaesthetic).

Thirty-day postoperative mortality

Defined as death from any cause within 30 days postoperatively.

Patient self-reported bladder function

Assessed by the patient self-reported I-PSS.

Patient self-reported sexual function

Assessed in males by the patient self-reported IIEF questionnaire and in females by the patient self-reported FSFI questionnaire.

Patient self-reported generic health

Assessed by the patient self-reported SF-36v2 questionnaire.

Patient self-reported fatigue

Assessed by the patient self-reported MFI-20 questionnaire.

Quality of the plane of surgery

Defined by the grading criteria using the local histological review. For an AR there was only one criterion: the quality of the mesorectum. For APR, the quality of the plane of surgery was assessed by the grade for the mesorectum and a second grade for the anorectal dissection below the levators. The quality of resection of the mesorectum was assessed as muscularis propria plane (worst), intramesorectal plane (intermediate) and mesorectal plane (best). The quality of surgery of the anorectum below the levators was assessed as intrasphincteric/submucosal plane (worst), sphincteric plane (intermediate) and levator plane (best).

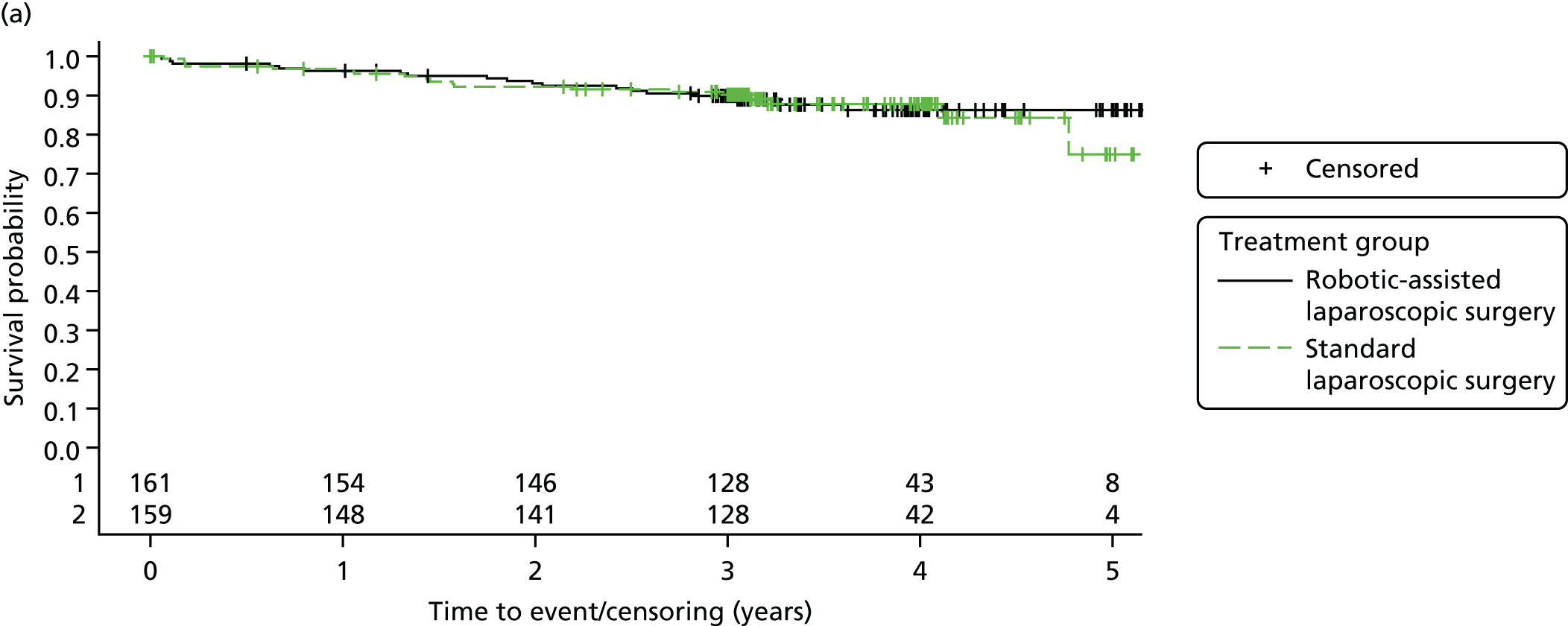

Three-year disease-free survival

Disease-free survival time was defined as the time from date of randomisation to date of death from any cause, recurrent disease (locoregional or distant recurrence) or occurrence of a second primary cancer.

Three-year overall survival

Overall survival time was calculated from the date of randomisation to the date of death from any cause.

-

Health economics evaluation (see Health economic evaluation).

Pathology central review

Local pathology data were used to carry out the analyses. A central blinded review of the local pathology data for all assessable patients was carried out. The agreement of local pathology and central pathology with respect to factors feeding into the analyses (e.g. T-staging) was assessed via summaries.

Sample size

Original sample size calculation and justification

The sample size calculation was based on ensuring that sufficient numbers of patients were recruited to address the primary end point of conversion to open rectal resection. A relative reduction of at least 50% (in absolute terms, 25% to 12.5% in the robotic-assisted laparoscopic group) was strongly believed to be achievable and also represented an extremely clinically important difference, not only in terms of outcomes for health-care providers but also in terms of patient-related outcomes, as it had been shown that patients who convert during surgery have worse outcomes. Therefore, using a conversion rate of 25% for standard laparoscopic surgery and a 50% relative reduction to be clinically relevant, with 80% power and a 5% (two-sided) significance level, 336 patients were required using a two-group continuity corrected chi-squared test of equal proportions (nQuery Advisor 6.01, Statistical Solutions, Saugus, MA, USA). Therefore, it was planned to recruit 400 patients (200 per group) to allow for early withdrawals, cross-over, protocol violations (e.g. benign tumours) and missing follow-up data.

Updated sample size

Recruitment to the original target sample size of 400 patients was completed 5 months earlier than planned and was under budget. Note that the original sample size of 400 patients aimed to achieve 80% power. Although this is conventionally considered to be sufficient, it is also commonly argued that 90% power is preferable. Given this, coupled with the fact that there was the opportunity to continue recruitment as a result of reaching the target of 400 patients early and under budget, we proposed to continue to recruit to the ROLARR trial until the date that was originally set to end recruitment. The aim of recruitment during this period was to recruit as many additional patients as possible to maximise power, up to a maximum of 520 patients (which, under the original sample size assumptions, would provide 90% power to detect a difference of at least 12.5% in conversion rates between the groups). This plan was endorsed by the EME programme, the DMEC and the TSC. This decision to continue recruitment was made before seeing any data or interim analyses. Consequently, a total of 471 patients had been randomised by the time the trial closed to recruitment. Under the original sample size assumptions, this provides around 86% power to detect a difference of at least 12.5% in conversion rates between the groups.

Randomisation

Randomisation took place as soon as possible after consent was obtained and after patients had completed their baseline patient-reported questionnaires (I-PSS, IIEF/FSFI, SF-36v2, MFI-20, EQ-5D). Randomisation took place as close to the date of surgery as possible. Surgeons were strongly encouraged to consent and randomise patients within 14 days of the planned surgery date whenever possible.

Following confirmation of written informed consent and eligibility, patients were randomised into the trial by authorised members of staff at the trial sites. Randomisation was performed centrally using the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) automated 24-hour telephone randomisation system. Authorisation codes and personal identification numbers (PINs), provided by the CTRU, were required to access the randomisation system.

Patients were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis to receive either robotic-assisted or standard laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery and were allocated a unique trial number. A computer-generated minimisation programme that incorporated a random element was used, with the following minimisation factors:

-

treating surgeon

-

patient sex (male or female)

-

neo-adjuvant therapy (yes or no)

-

nature of intended procedure (HAR, LAR or APR)

-

body mass index (BMI) [calculated automatically from height (cm) and weight (kg) provided at randomisation and classified according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria29]:

-

underweight/normal

-

overweight

-

obese class I

-

obese class II

-

obese class III.

-

Participating research sites were required to complete a log of all patients screened for eligibility who were not randomised either because they were ineligible or because they declined participation. Anonymised information was collected including:

-

age

-

sex

-

date screened

-

reason not eligible for trial participation

-

eligible but declined and reason for this

-

other reason for non-randomisation.

Blinding

As the two surgical procedures create incisions that can allow the patient to be blinded to the operative procedure performed, it arguably would have been scientifically preferable to blind patients to their surgical procedure, particularly in respect of patient-reported outcomes. However, it was anticipated that in practice maintaining the blind would have been extremely problematic (e.g. in countries such as the USA where private health-care insurance companies require disclosure of surgery details). Furthermore, it was anticipated that patients would also be seen by many health-care professionals throughout their time in the trial, increasing the risk that the blind may be broken. As a consequence, the trial design did not involve blinding patients to the operative procedure.

It should be noted that the trial end points are mainly objective measures and a central blinded assessment of these measures was included when possible (e.g. blinded central assessment of the quality of the plane of surgery).

Statistical methods

Unless otherwise stated, all analyses were prespecified and conducted on the intention-to-treat population (i.e. all randomised patients were categorised into treatment groups based on their randomisation, regardless of what treatment they subsequently received). All hypothesis tests were two-sided and conducted at the 5% level of significance. Estimates and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values are presented for fixed effects. For the (random) surgeon effect, the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC), estimated via the analysis-of-variance method, and bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% CIs are reported.

For most end points there was only a small number of missing data, such that a complete-case analysis was appropriate. For end points with non-negligible numbers of missing data, exploratory analyses were performed to consider the potential impact of the missing data. All models were fitted using SAS® version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

All analyses, unless otherwise stated, adjusted for the minimisation factors only (see Randomisation). For each end point, sensitivity analyses to include adjustment for treating centre and country were considered; Subgroup analyses gives further details of this.

Primary end point: conversion to open surgery

The primary analysis was a complete-case analysis. Multilevel logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) between treatment groups for conversion to open surgery, adjusting for all minimisation factors. All minimisation factors were included as fixed effects except intended operating surgeon, which was included as a random effect. A random intercept model was fitted first, then a model with both a random intercept and a random slope (i.e. random treatment effect) was fitted (hereafter referred to as the ‘random slope’ model). The need for the random slope term was assessed via consideration of a likelihood ratio test and the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The models were fitted using SAS version 9.4 glimmix procedure.

A number of prespecified sensitivity analyses were also performed.

Additional covariates

Fixity of tumour, whether or not the tumour was an obstructing tumour, T-stage or N-stage, whether or not the patient had abdominal surgery prior to their ROLARR operation and the level of scarring, whether or not adhesions were identified and whether or not there was a tumour perforation (non-iatrogenic) or abscess were all considered for inclusion in the model via examination of their effect on the model fit.

Actual operating surgeon

The primary analysis adjusted for the minimisation factors (i.e. the values of those factors that were used in the minimisation, regardless of whether or not those values were correct). In some cases, patients may have been allocated treatment under incorrect minimisation factors. In particular, their intended operating surgeon (used for minimisation) may not have been their actual operating surgeon. A sensitivity analysis was performed that incorporated actual operating surgeon rather than intended operating surgeon as a random effect in the model.

Learning effects

For each surgeon, the number of robotic-assisted and laparoscopic rectal operations relevant to the ROLARR trial performed by that surgeon was collected at regular intervals throughout the trial. From this, the number of ROLARR-relevant robotic-assisted and laparoscopic operations previously performed by the operating surgeon before each patient’s operation was derived, assuming that the timings of all counted previous operations were uniformly distributed across the interval in which they occurred. These patient-level covariates (‘number of previous robotic operations’ and ‘number of previous laparoscopic operations’) were included in the multilevel model used in the primary analysis to explore potential associations between increased numbers of operations and patient outcomes. Interactions between the numbers of operations performed and the treatment effect were also considered.

Actual operation (post hoc)

The primary analysis adjusted for the minimisation factors (i.e. the values of those factors that were used in the minimisation, regardless of whether or not those values were correct). In some cases, patients may have been allocated treatment under incorrect minimisation factors. In particular, their intended procedure (used for minimisation) may not have been the actual procedure that they received. A sensitivity analysis was performed that incorporated actual procedure rather than intended procedure as a fixed effect in the model.

Key secondary end points

Circumferential resection margin positivity

The analysis of CRM+ was a complete-case analysis. Multilevel logistic regression was used to estimate the ORs between treatment groups for CRM+, adjusting for all minimisation factors. All minimisation factors were included as fixed effects except intended operating surgeon, which was included as a random effect. A random intercept model was fitted first, then a random slope model was fitted and the need for the random slope term was assessed via consideration of a likelihood ratio test and the AIC. The models were fitted using SAS version 9.4 glimmix procedure.

A number of prespecified sensitivity analyses were also performed.

Additional covariates

Fixity of tumour, T-stage and N-stage (post neo-adjuvant therapy) and whether or not there was a tumour perforation (non-iatrogenic)/abscess were all considered for inclusion in the model via examination of their effect on the model fit.

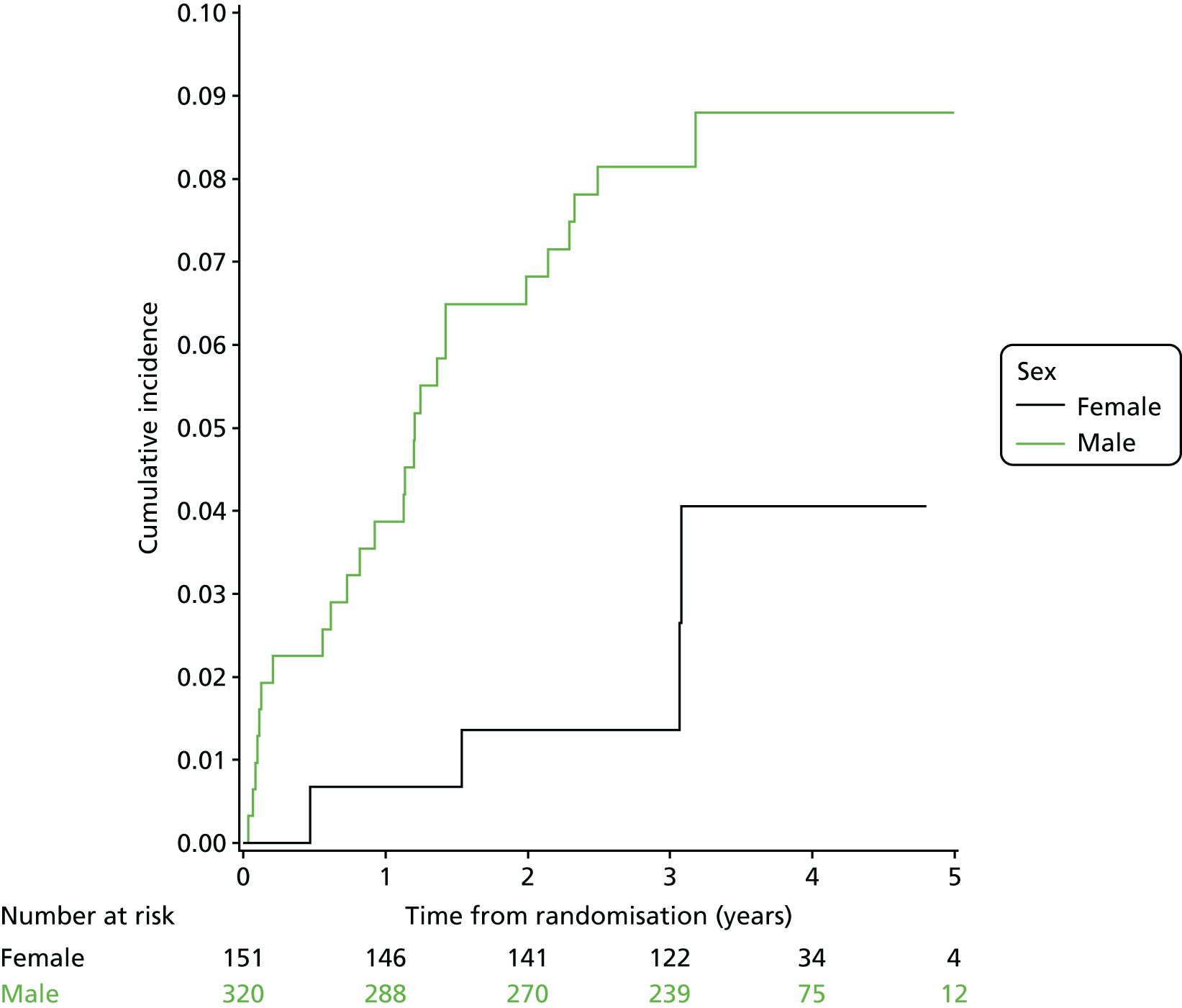

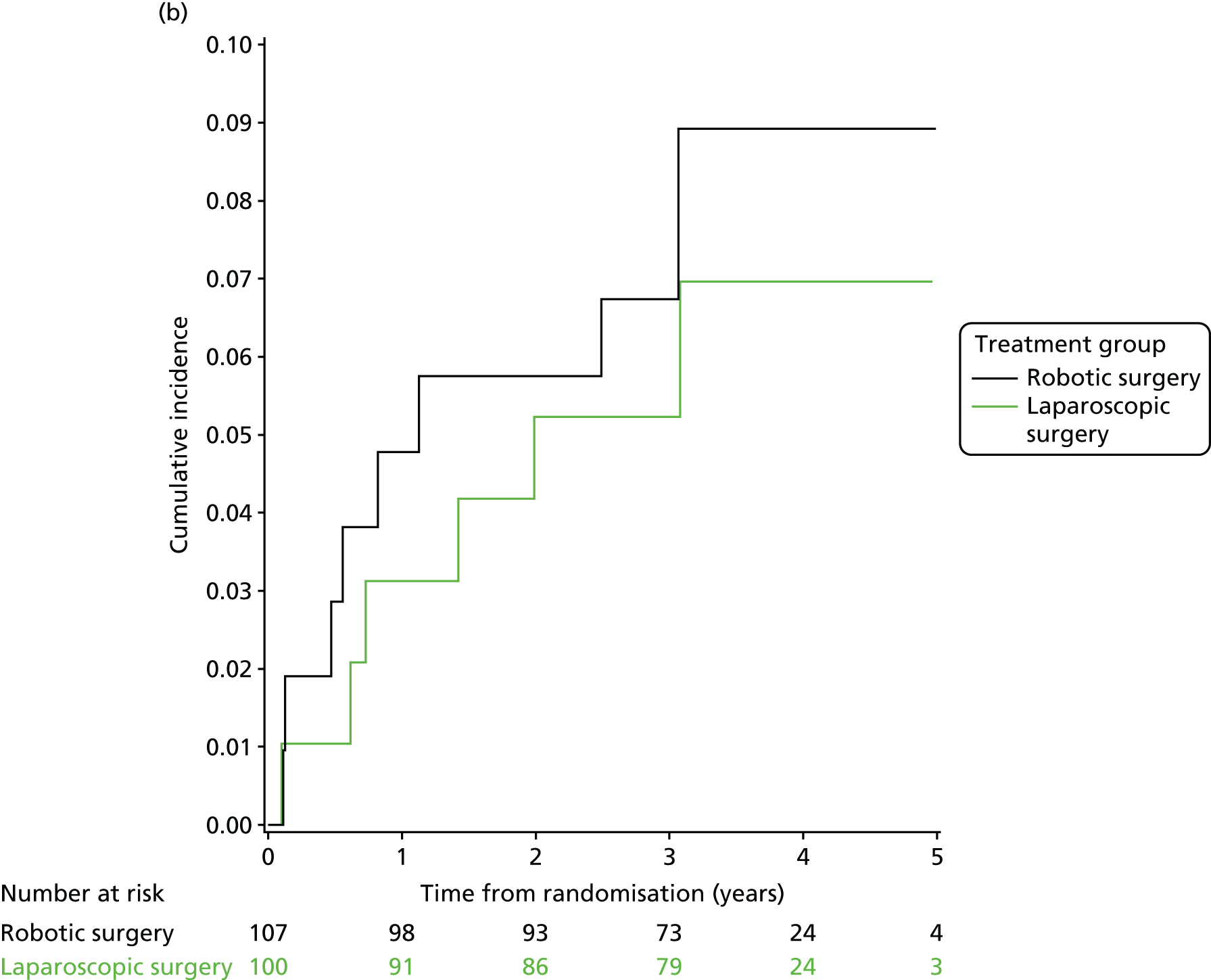

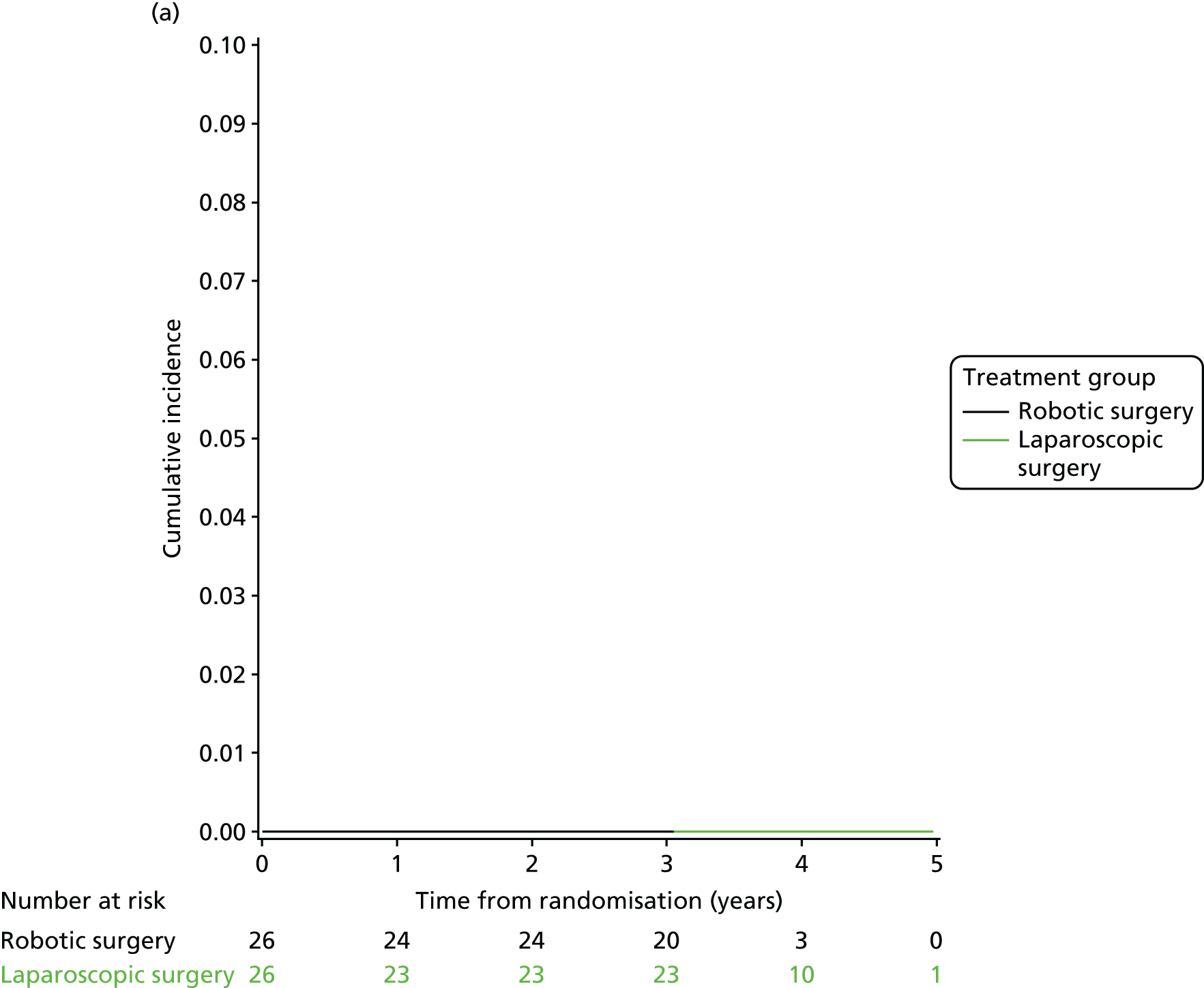

Three-year local recurrence

All patient follow-up, including follow-up beyond 3 years post randomisation, was incorporated into the analysis of local recurrence. Time to local recurrence was defined as the time from randomisation to the date of the relevant assessment (i.e. clinical, radiological and pathological) that first detected the local recurrence.

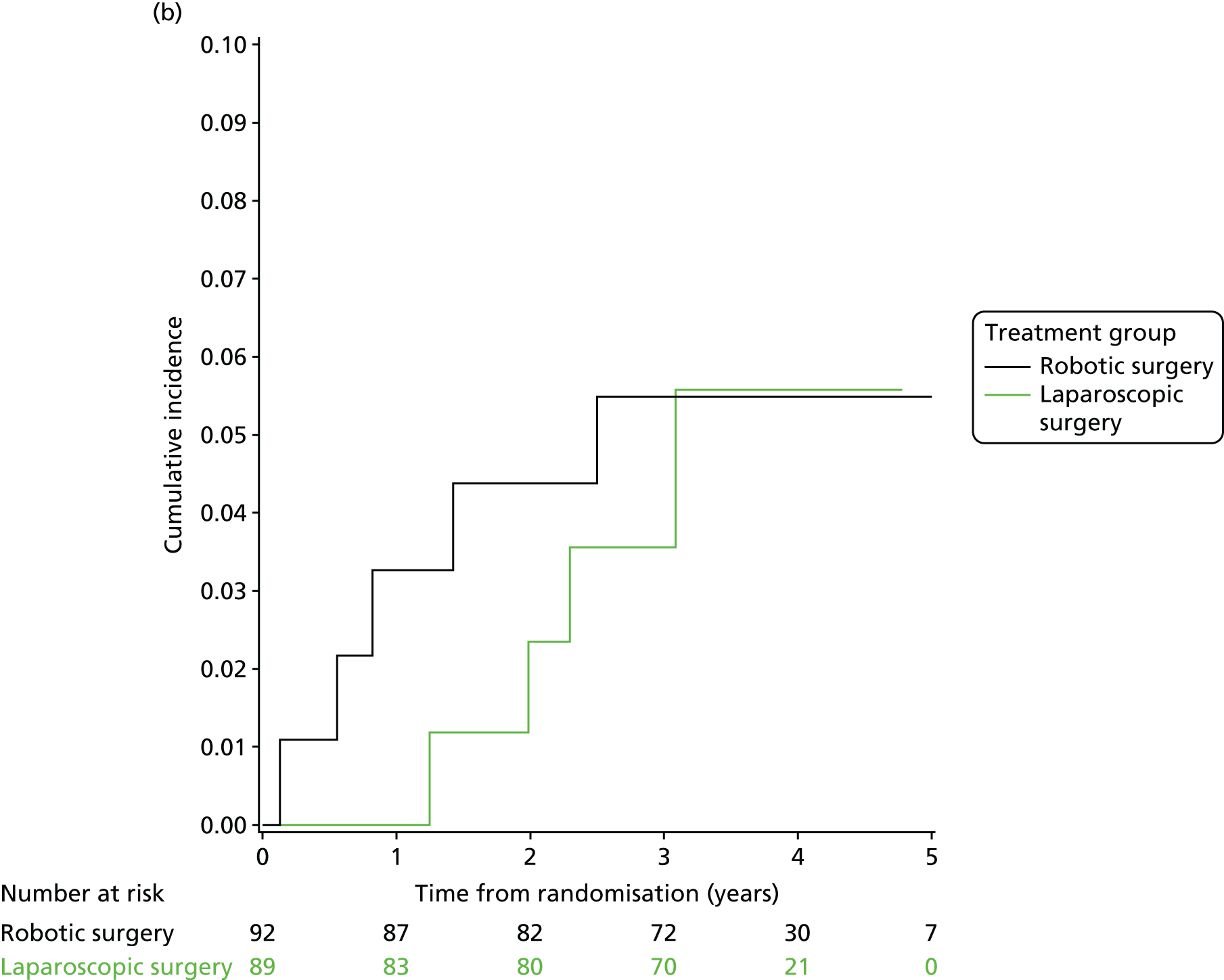

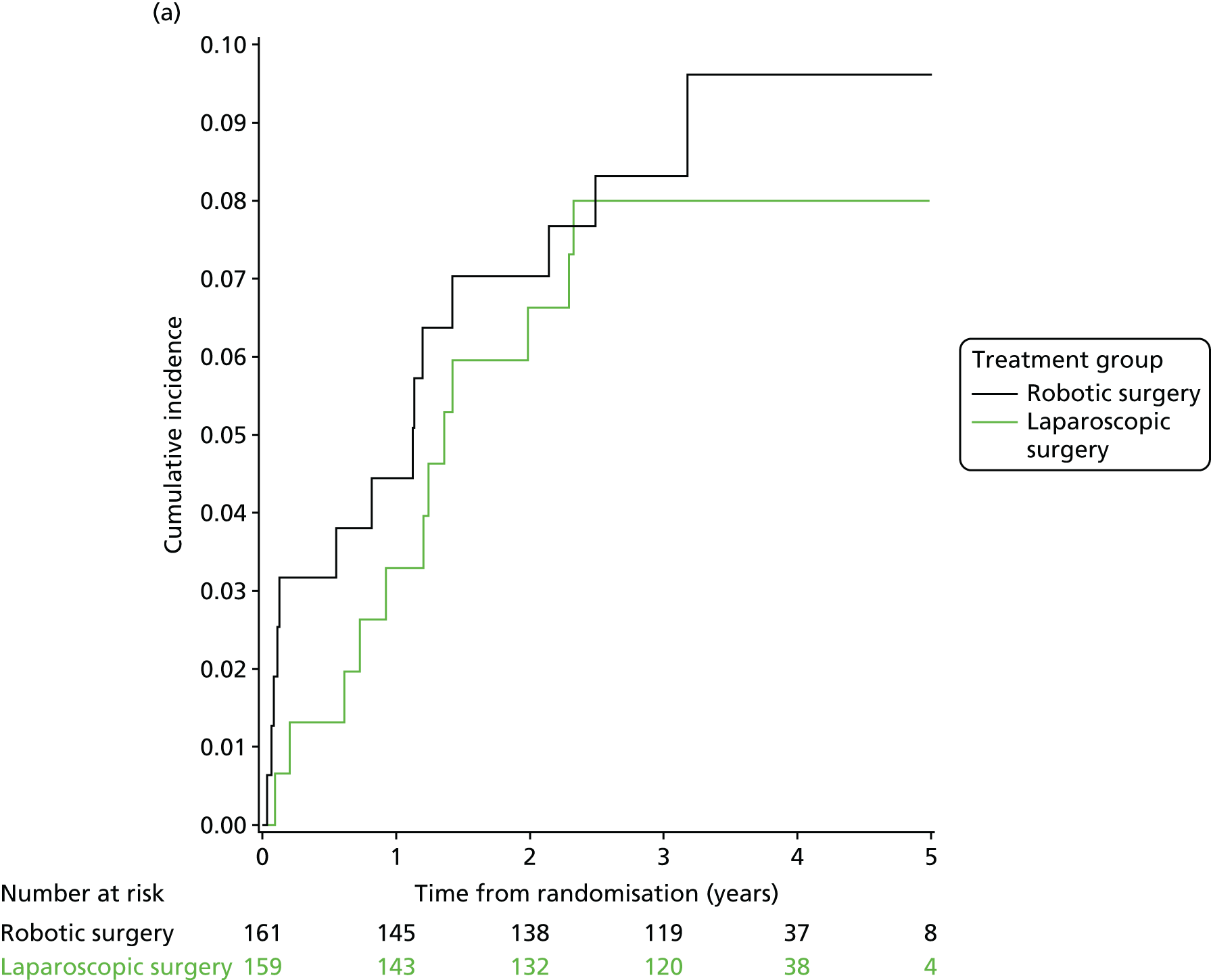

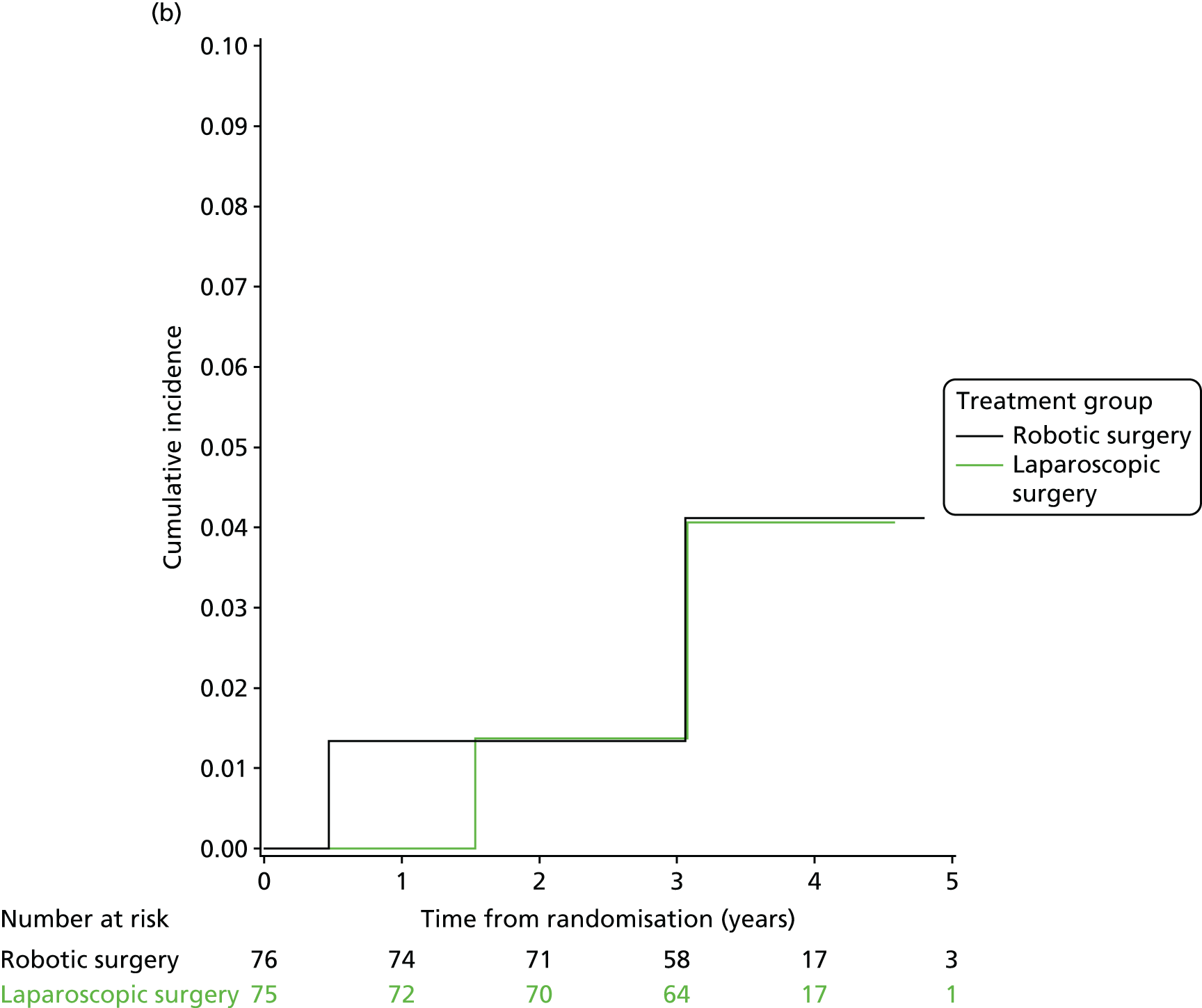

Differences in time to local recurrence between the treatment groups were estimated using a shared frailty model (Cox proportional hazards regression with mixed effects), including intended operating surgeon as a random effect. The models were fitted using SAS version 9.4 phreg procedure. The 3-year local recurrence rate was estimated using cumulative incidence functions for time to local recurrence, treating death as a competing risk.

Patients who were alive and without any local recurrence at the time of analysis were censored at the time they were last known to be alive and local recurrence free. If patients were lost to follow-up, they were also censored at the time they were last known to be alive and local recurrence free. Patients who died without any local recurrence were censored at date of death in analyses estimating treatment effects, but were classed as having a competing risk event in the analysis estimating incidence of local recurrence (as calculated using cumulative incidence functions) to avoid overestimation of cumulative incidence. 30 In certain non-standard circumstances (prespecified in the statistical analysis plan), patients were censored at time 0. Patients with non-standard circumstances who were censored at time 0 are summarised, and reasons are given in the results (see Chapter 3, Disease-free survival).

Further secondary end points

The analyses of further binary secondary end points – intraoperative complications, postoperative complications within 30 days, after 30 days and within 6 months, and quality of the plane of surgery (i.e. mesorectal plane Yes/No) – were complete-case analyses. Multilevel logistic regression was used to estimate the ORs between treatment groups for each end point, adjusting for all minimisation factors. All minimisation factors were included as fixed effects except intended operating surgeon, which was included as a random effect via a random intercept term. The models were fitted using SAS version 9.4 glimmix procedure.

For further continuous secondary end points [bladder function (I-PSS), sexual function in males (IIEF) and in females (FSFI), generic health-related QoL (SF-36v2) and fatigue (MFI-20)], multilevel generalised linear models were used to estimate the mean difference between treatment groups, adjusting for all minimisation factors and the baseline score. All minimisation factors were included as fixed effects except intended operating surgeon, which was included as a random effect via a random intercept term. The I-PSS, IIEF and FSFI were modelled using a two-level model: patients nested within surgeon. The SF-36v2 questionnaire and MFI-20 were modelled using a three-level model: repeated assessments within patient within surgeon. The models were fitted using the SAS version 9.4 glimmix procedure.

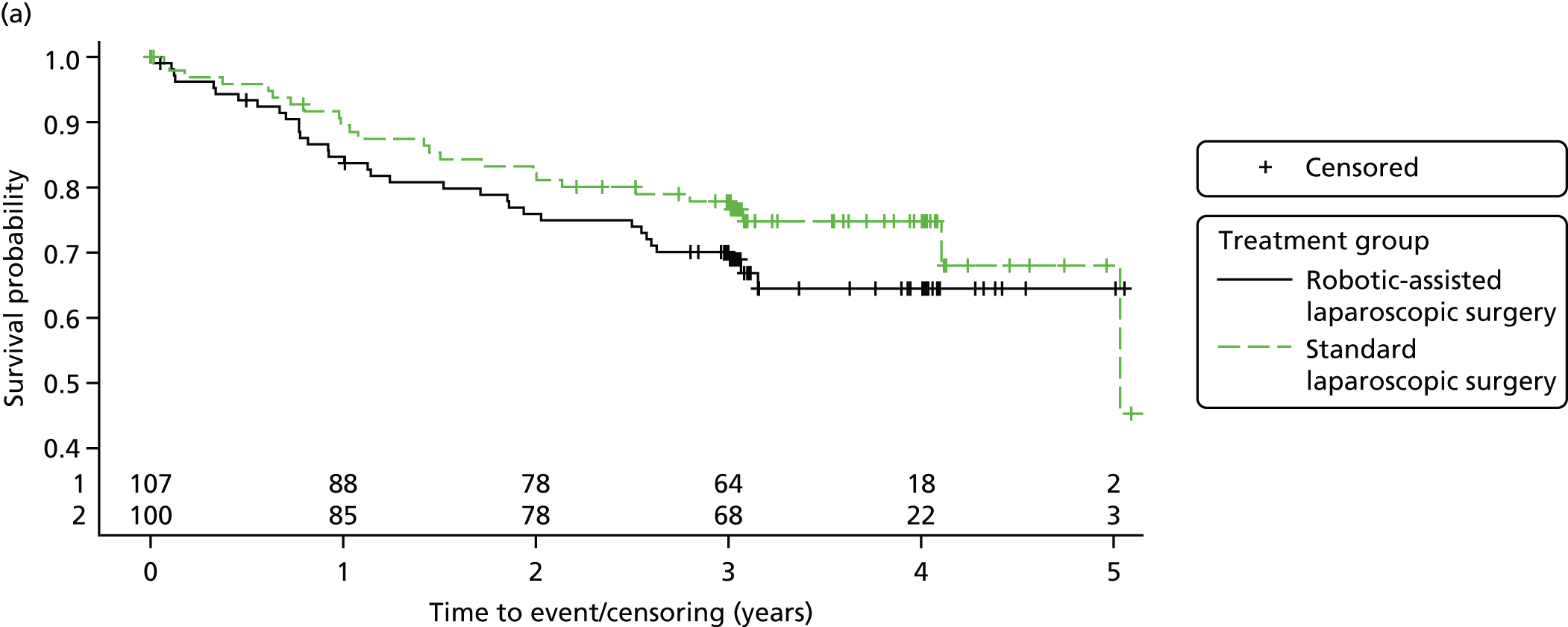

All patient follow-up, including follow-up beyond 3 years post randomisation, was incorporated into the analysis of DFS and OS. For DFS and OS, shared frailty models were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) between treatment groups, adjusting for all minimisation factors. All minimisation factors were included as fixed effects except intended operating surgeon, which was included as a random effect via a random intercept term. In certain non-standard circumstances (prespecified in the statistical analysis plan), patients were censored at time 0. Patients with non-standard circumstances who were censored at time 0 are summarised and reasons are given in the results (see Chapter 3, Disease-free survival). The models were fitted using SAS version 9.4 phreg procedure.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses relating to the primary end point across sex, BMI class and procedure received, as well as relating to CRM+ across sex, BMI class and T-stage, were performed. Subgroup analyses relating to each of local recurrence, DFS and OS across type of operation, T-stage and neo-adjuvant therapy were also performed. All subgroup analyses tested heterogeneity of the treatment effect across the subgroups and also estimated the treatment effect within each subgroup, via the addition of an appropriate interaction term to the primary analysis model.

Model diagnostics

Multilevel logistic regression models

Model fit was assessed by examining the raw residuals on the probability scale outputted from SAS version 9.4 glimmix procedure, for example the residual for patient i:

in which:

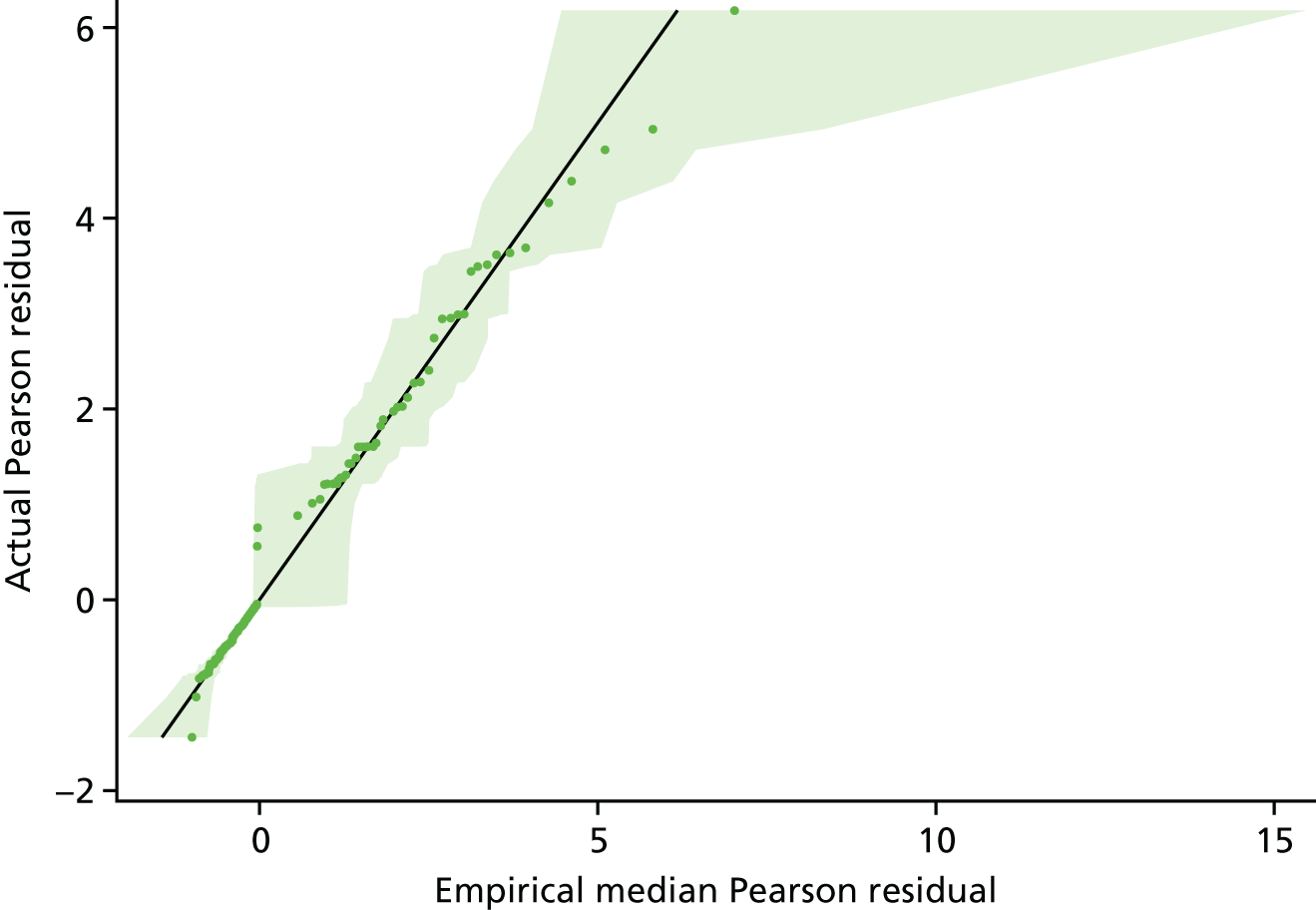

and p^i is the predicted probability of the event (e.g. conversion to open surgery) for patient i [including empirical Bayes’ estimate (EBE) of the random effect]. Index plots (plots of the raw residuals vs. patient identification) were used to identify potential outliers. Empirical probability plots were also used to assess model fit and identify potential outliers. These plots plotted the observed, ordered Pearson residuals (outputted from SAS version 9.4 glimmix procedure) against expected, ordered Pearson residuals under the model assumptions – analogous to a normal Q–Q plot for normal-errors regression. The expected sampling distributions of Pearson residuals were determined empirically via simulations. Specifically, for each simulation each patient’s outcome was randomly drawn from a Bernoulli (p) distribution with:

for patient i.

The model was refitted to this simulated data set and the Pearson residuals recorded.

This was repeated 100 times to yield an empirical sampling distribution of Pearson residuals for each patient. In the empirical probability plot, the actual observed Pearson residuals for each patient were plotted against the median, 2.5th percentile and 97.5th percentile of the empirical sampling distribution. Observations were considered to be potential outliers if they lay outside the 2.5th percentile to 97.5th percentile range [analogous to considering Pearson residuals lying outside the interval (–2,2) to be potential outliers in a normal-errors regression].

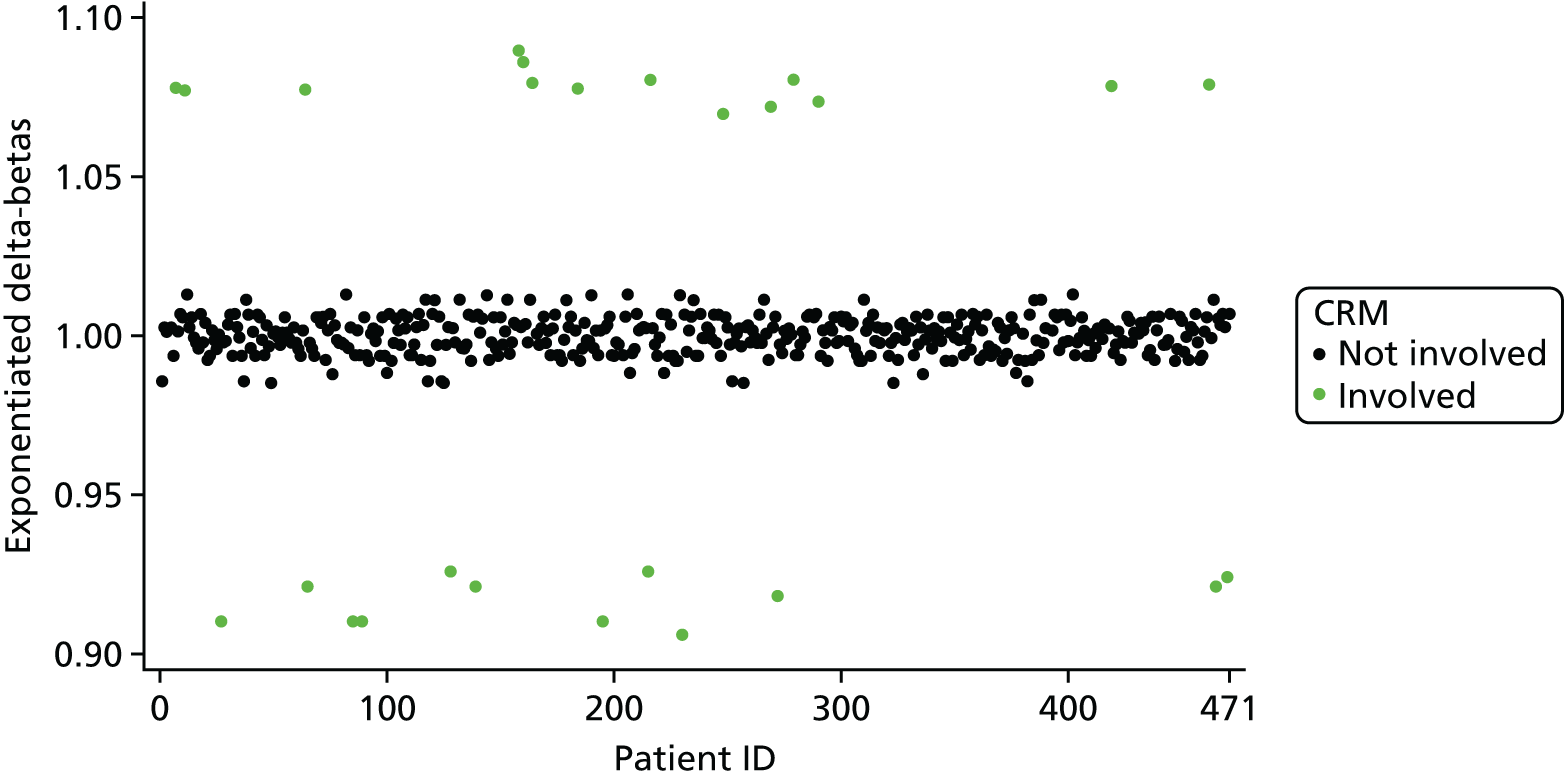

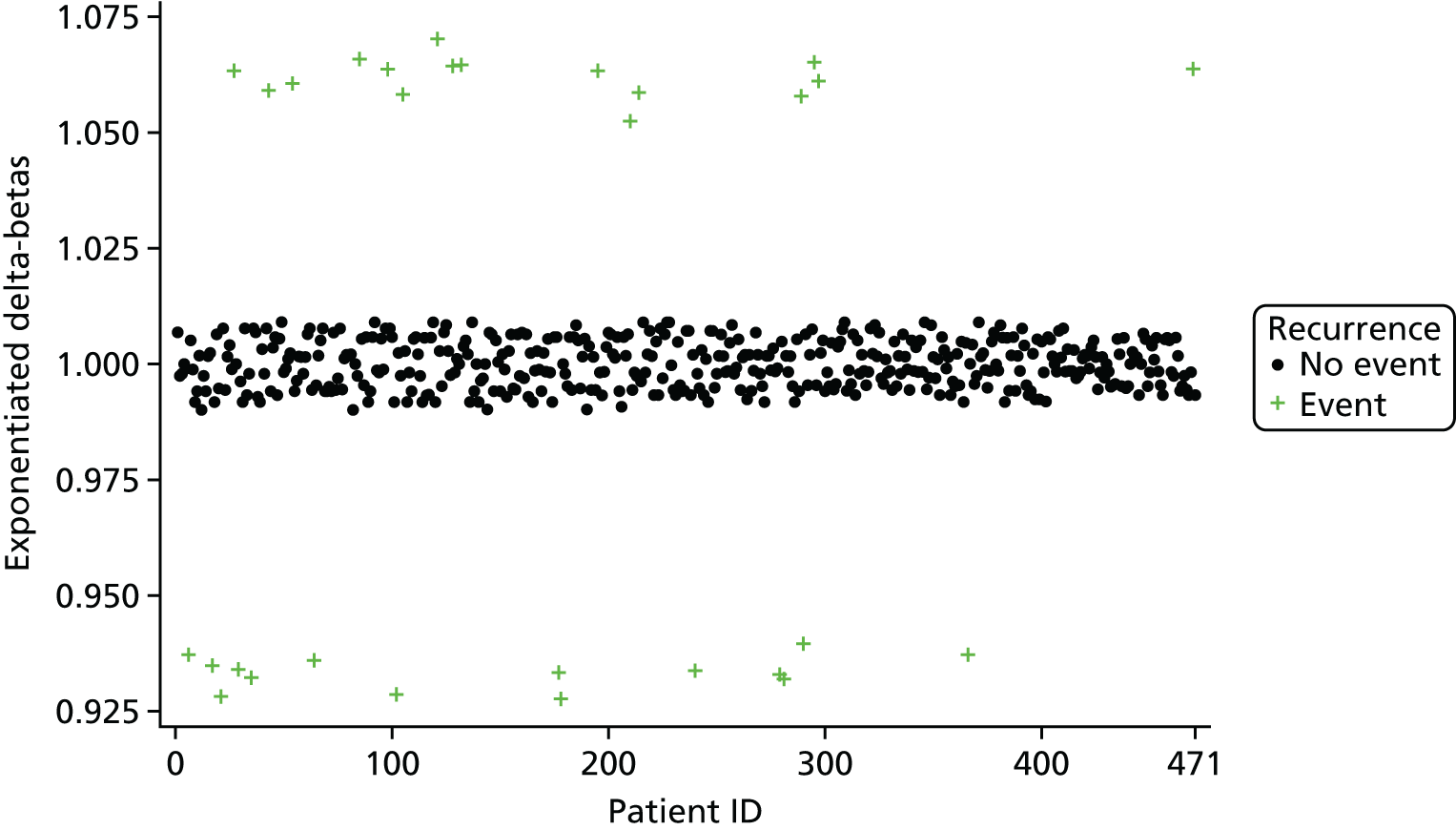

Overly influential observations on the treatment effect regression coefficient were identified via the calculation of exponentiated delta-betas. The exponentiated delta-beta was calculated for each patient; for example, for patient i, the exponentiated delta-beta for the treatment effect regression coefficient was:

in which β1 is the regression coefficient for the treatment effect in the full model and β1(i) is the treatment effect regression coefficient in the model where patient i has been omitted. Note that this is the ratio of the estimated ORs from the two models; for example, an exponentiated delta-beta for the treatment effect for patient i of 1.05 would imply that the inclusion of patient i increases the treatment effect OR estimate by 5% compared with the omission of patient i. The exponentiated delta-betas were plotted against patient identifier (ID) in order to visually identify highly influential observations.

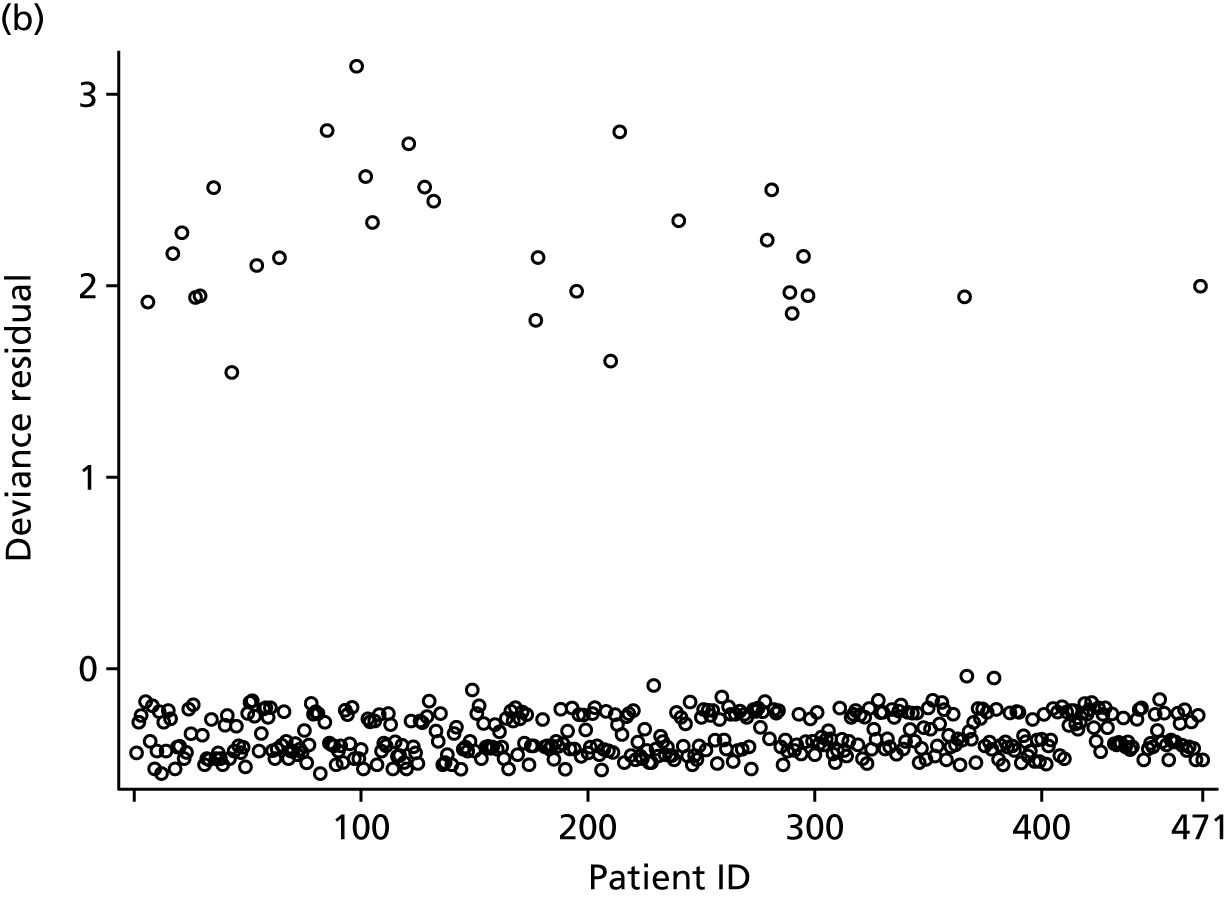

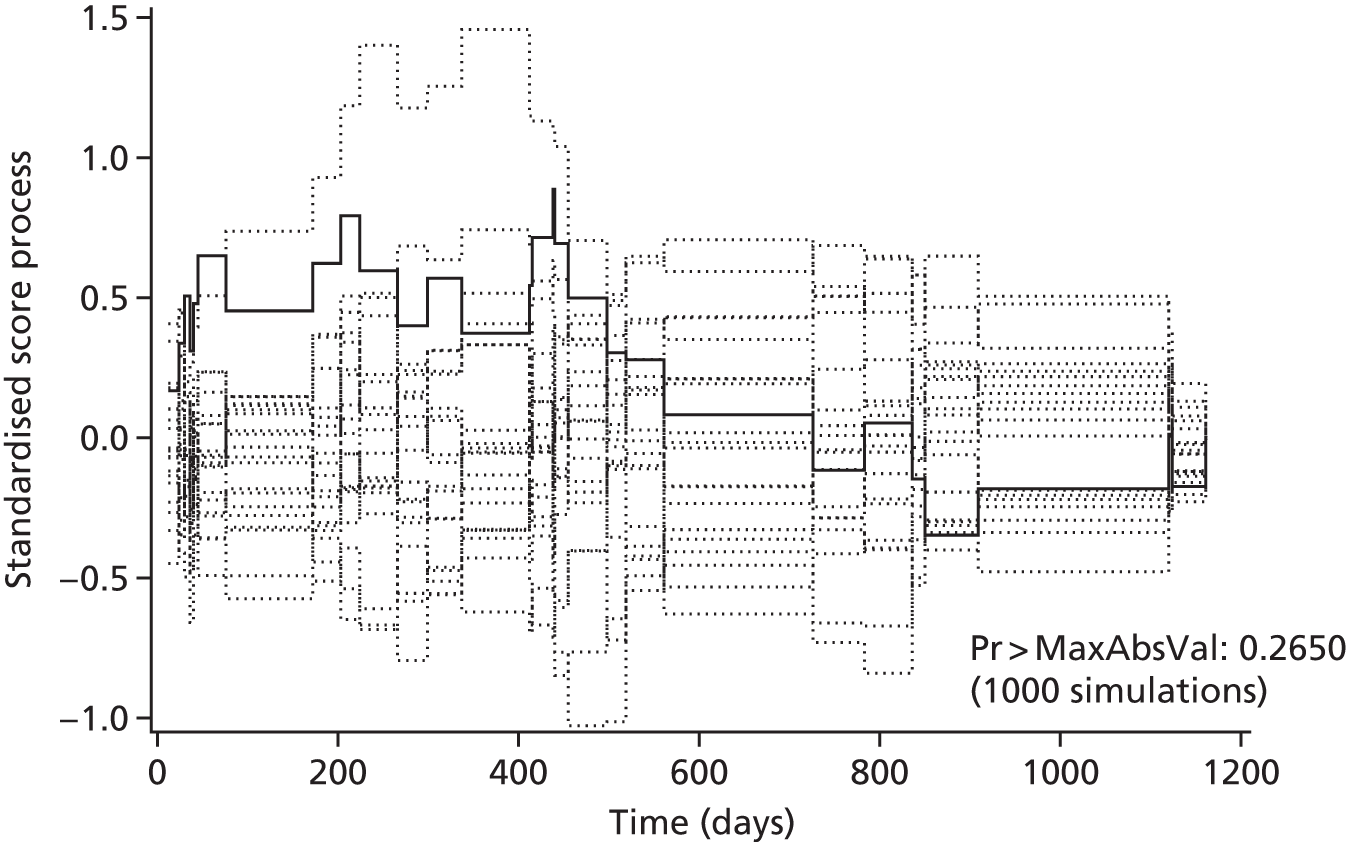

Shared frailty models

Models were refitted as Cox proportional hazards models with robust standard errors, without the random effect for operating surgeon. This gave the same point estimates as the shared frailty model, and broadly similar standard errors. Deviance residuals were used to identify any potential outliers. The proportional hazards (PH) assumption for the treatment effect was assessed via a plot of the standardised Schoenfeld residuals over time, as well as a plot of the observed standardised score process versus simulated standardised score processes under PH. The PH assumption was also tested via the Supremum test. Exponentiated delta-betas (as described in Multilevel logistic regression models) were used to identify overly influential observations.

Health economic evaluation

An economic evaluation was performed using a UK NHS perspective to aid the development of an evidence base to support NHS service providers and budget holders in their decision-making processes. Costs associated with robotic surgery excluded acquisition and maintenance costs. The evaluation estimated the expected incremental cost-effectiveness of robotic resection compared with laparoscopic resection at 6 months. It was planned that this would be extrapolated using a decision-analytic model to estimate lifetime cost-effectiveness.

The ROLARR trial collected information on the nature of all initial resection operations using trial CRFs. This included information on the type of operation and resources used within this operation, including instrumentation and times for operation theatres and staff. CRF data also captured information on postoperative and distal complications on all trial patients.

However, many types of resource utilisation were not collected for all patients in the ROLARR trial. In particular, given the challenges of conducting research within global trials, data on resource utilisation after the initial operation were collected only on patients from the UK and the USA. As the adjuvant chemotherapy is likely to both vary widely and be expensive, there is a danger that any small differences at this stage will be both unrelated to the surgery received and, given the cost of chemotherapy, outweigh any cost differences that are related to the intended type of surgery. For this reason, the cost data do not attempt to consider the chemotherapies received or antinausea drugs attached to these chemotherapies.

For patients in the UK and USA, information was collected alongside the trial-related questionnaires at approximately 30 days and at 6 months. It was expected that data collection might be poor and as a result it would be necessary to impute data for a substantial number of these patients.

Data were collected on both primary care and secondary care, including contact with GPs and primary care physicians (including the location of any contacts), nurse contacts (including at primary care, district/at home nursing, and stoma nursing) and outpatient visits.

The analysis considered costs in GBP with 2015 as the base year, from an NHS-payer perspective. Given the focus of this perspective, when clinical practice appeared to differ in the USA, particularly around pain medication, the approach taken was the one that appeared to apply in the UK. This perspective also means that unit costs are those costs that apply within the NHS.

Costing individual resource utilisation

Surgery

Surgical costs were computed by first identifying an overall global average for resection surgeries, for which a weighted sum of non-elective complex large intestine operative costs was used. Individualised surgical costs allowed for both excess bed-days (at £326.11 per day) and differences in the time and staffing within the theatre. For the laparoscopic group, costs were calculated based on data provided on the operative team and time, and it was assumed that on average this group would cost the same as the baseline surgical cost. Therefore, those patients receiving a laparoscopic operation might have had a cheaper or more extensive operation than ‘average’ but would be similar overall. Given that robotic surgeries were expected to require longer use of the operating theatre (e.g. including greater setup time), incorporating staffing/time costs modifies the resection surgery costs to reflect this. The instrumentation costs were included separately for those items that, in the opinion of the chief investigator, would not necessarily be considered an automatic inclusion within the operating theatre. (So, for instance, although data were collected on suction, this is not costed.)

As staff costs appear below (Table 1), and instrument costs are assessed, it is not appropriate to include these. Excluding these costs, the use of theatres costs £339 per hour.

| Surgical costs | Unit | Cost (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline resection surgery: operative cost | Per operation | 8307.78 | a NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 201531 |

| Baseline resection surgery: operative cost – excess bed-days | Per excess bed-dayb | 326.11 | a NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 201531 |

| Other surgeries for complications | Per operation | 8307.78 | c NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 201531 |

| Surgeon | Per hour | 138.00 | Personal Social Services Research Unit32 |

| Anaesthetist | Per hour | 60.74 | Personal Social Services Research Unit32 |

| First surgical assistant (band 7) | Per hour | 60.00 | Personal Social Services Research Unit32 (including qualifications) |

| Subsequent surgical assistants (band 5) | Per hour | 43.00 | Personal Social Services Research Unit32 (including qualifications) |

| Operating theatre (no staff or specialist instruments) | Per hour | 339.00 | dDerived from Information Services Division, NHS National Services Scotland33 |

Instrumentation costs were identified in discussion with the chief investigator who provided data on which of the instruments to specifically include (and which were more or less trivial given operating theatre costs) and unit costs for each instrument (Table 2).

| Robotic | Unit | Cost (£) |

|---|---|---|

| Aspirator | Each | 150 |

| Bipolar forceps | Each | 150 |

| Vessel sealer | Each | 500 |

| Graspers | Each | 150 |

| Haemolock | Initial | 150 |

| Per clip | 30 | |

| Hook | Each | 150 |

| Needle driver | Each | 150 |

| Scissors | Each | 150 |

| Stapler | Per firing | 150 |

| Laparoscopic and open | ||

| Disposable Babcock | Each | 150 |

| Graspers | Each | 100 |

| Stapler (including open staplers) | Initial | 300 |

| Per reload | 80 | |

| Scissors | Each | 100 |

| Vascular clips | Each | 80 |

| Wound protector | Each | 50 |

| Wound retractor | Each | 50 |

| Vessel sealers (e.g. Ligasure) | Each | 500 |

An overall in-theatre cost was calculated for each surgery (where data were complete on the fields above) and calculated, including the theatre, staff and instrumental costs. The mean of these costs among the group who received laparoscopic surgery (as opposed to allocated) was identified, and this was subtracted from all individual cost figures to indicate how costs would be likely to differ from a typical operation. As such, the average laparoscopic difference is zero, although the robotic difference could be positive (if more expensive) or negative (if less expensive). The difference in the cost figure was then added back onto the reference cost to give an estimated cost for each individual surgery.

It should be noted that the analysis presented here does not include the cost of the surgical robot (when applicable), in order to provide an optimistic case figure for the cost-effectiveness of robotic surgery.

Other inpatient visits

The main inpatient costs assessed after the initial surgery were for stoma reversal operations and for other related colorectal surgeries identified from the CRFs. When other major related surgery was indicated, this was coded as an average of complex large intestine surgeries at £7621.24. 31

Following approaches used elsewhere, stoma reversals are coded as elective intermediate procedures (FZ50Z, intermediate large intestine procedures, aged ≥ 19 years) at £1691.06 per case. 31

The unit costs of all other inpatient visits are taken from NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 201531 and are shown in Table 3.

| Procedure | Code | Unit costsa (£) |

|---|---|---|

| Non-reversal stoma operations | FZ50Z. Elective inpatient | 1691.06 |

| Transient ischaemic attack | AA29F. Transient ischaemic attack with a CC score of 0–4 (Non-elective) | 1252.81 |

| Deep-vein thrombosis | YQ51E. Deep-vein thrombosis with a CC score of 0–2 | 1361.97 |

| Pulmonary embolism | DZ09 K. Pulmonary embolus with interventions, with a CC score of 0–8 | 3509.12 |

| Renal failure | Acute kidney injury without interventions, with a CC score of 0–3 | 1785.63 |

| LA07 K. Acute kidney injury with interventions, with a CC score of 0–5 | 3784.72 | |

| Abdominal infections, anastomotic leak | FZ36L Gastrointestinal infections with single intervention, with a CC score of 0–1 | 3610.31 |

| Inpatient urinary tract infections | LA04S. Kidney or urinary tract infections, without interventions, with a CC score of 0–1 | 1502.55 |

| Haemorrhage | FZ38P. Gastrointestinal bleed without interventions, with a CC score of 0–4 | 1370.09 |

| Cardiac events | EB12C. Unspecified chest pain with a CC score of 0–4 | 1088.68 |

| Protracted ileus | FZ13C. Minor therapeutic or diagnostic, general abdominal procedures, ≥ 19 years. Non-elective | 3471.40 |

| Urinary retention | LA09Q. General renal disorders without interventions, with a CC score of 0–2 | 1399.13 |

| Gastrointestinal obstruction | FZ27G. Intermediate therapeutic general abdominal procedures, ≥ 19 years and over, with a CC score of 0 | 3335.27 |

| High stoma output (not coded as serious though) | FZ50Z Intermediate large intestine procedures, ≥ 19 years | 1836.19 |

| Respiratory inpatient (non-infection) | DZ19 N. Other respiratory disorders without interventions, with a CC score of 0–4 | 1163.67 |

| Not specified | Average of all elective inpatients, all sources | 3573.02 |

Primary care

When possible, unit costs for GPs were taken from the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) 201532 using qualification costs and direct care staff costs, with similar figures (without direct care staff costs) used for nurse-based visits. For primary care, GP costs assumed a mean duration of surgery visits of 11.7 minutes (£44) and of 11.4 minutes for home visits (plus 10 minutes of travel) (£81), and a cost of £27 for telephone consultations. Nurse costs were assessed based on location, assuming 15.5 minutes of contact for each visit, with an additional 10 minutes of travel for visits away from surgeries (surgery £14.47, other £21.25).

Outpatient and other health professional visits

Outpatient visits costed using unit costs (consultant-led outpatient attendances) from NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 15,31 after grouping most visits into colorectal surgery, gastroenterology, medical oncology, medical ophthalmology, trauma and orthopaedics, nephrology, urology and others. Accident and emergency visits were costed using the overall average of all emergency medical attendances with the NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 2015. 31

Contacts for many of the remaining health professionals were taken from the PSSRU costs, including occupational therapy (PSSRU 201532) and counselling (PSSRU 201434), and chiropody/podiatry (PSSRU 201035), with costs inflated to 2015 figures using either the HCHS (Health and Community Health Service) price index for health or mid-point changes in Agenda for Change pay bands. 36

Stoma costs

The costs of ongoing stoma were calculated from Jones,37 who reported on figures from the Cwm Taf Health Board (NHS Wales) (Table 4). This assumes a monthly cost of £84 per 30 colostomy bags and £94 per 30 ileostomy bags. These 2011/12 figures were inflated to 2014/15 figures using the HCHS price index. 32 It should be noted that this is likely to underestimate the true costs of stoma, as this does not include items such as wipes, although there do not appear to be clear, published figures available that include such items.

| Stoma costs | Unit | Unit cost | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colostomy costs @ two bags per day (2011/12) | Per 30 days | £84.00 | Cwm Taf Health Board (Jones, 201537) |

| Ileostomy costs @ one bag per day (2011/12) | Per 30 days | £94.00 | Cwm Taf Health Board (Jones, 201537) |

| Inflation between 2011/12 and 2014/15 using HCHS (293.1 vs. 282.5) | 3.75% | ||

| Stoma reversals | Per operation | £1691.06 | a NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 201531 |

| Colostomy costs @ two bags per day (2011/12) | Per 30 days | £84.00 | Cwm Taf Health Board (Jones, 201537) |

| Ileostomy costs @ one bag per day (2011/12) | Per 30 days | £94.00 | Cwm Taf Health Board (Jones, 201537) |

| Inflation between 2011/12 and 2014/15 using HCHS (293.1 vs. 282.5) | 3.75% | ||

| Stoma reversals | Per operation | £1691.06 | a NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 201531 |

Medication costs

Medication costs were found by coding responses from UK/US patients on a line-by-line basis initially and then across all responses for specified pharmaceuticals (Table 5). When possible, individual statements about frequency and duration of treatment were used to inform assumptions about utilisation. In cases where no statements were made to identify utilisation, the British National Formulary38 was used to identify an indicative strength/dosage. Unit costs are taken from eMIT (the drugs and pharmaceutical electronic market information tool),39 when possible, or the NHS Indicative Drug Tariff40 figures, when not.

| Symptom | Drug | Unit | Cost (£) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac/statins | Simvastatin | Per 28 units | 0.16 |

| Cardiac/statins | Atorvastatin | Per 28 units | 0.49 |

| Cardiac/statins | Rosuvastatin | Per 28 units | 18.03 |

| Cardiac/statins | Doxazosin | Per 28 units | 0.19 |

| Cardiac/statins | Candesartan | Per 28 units | 0.55 |

| Cardiac/statins | Losartan | Per 28 units | 0.30 |

| Cardiac/statins | Olmesartan (Benicar®) | Per 28 units | 10.95 |

| Cardiac/statins | Lisinopril | Per 28 units | 0.29 |

| Cardiac/statins | Perindopril | Per 30 units | 0.61 |

| Cardiac/statins | Ramipril | Per 28 units | 0.27 |

| Cardiac/statins | Bisprolol | Per 28 units | 0.25 |

| Cardiac/statins | Metaprolol (plus unspecified beta blocker) | Per 28 units | 0.55 |

| Cardiac/statins | Carvedilol | Per 28 units | 0.59 |

| Cardiac/statins | Propranolol | Per 56 units | 1.67 |

| Cardiac/statins | Atenolol | Per 28 units | 0.18 |

| Cardiac/statins | Amlodipine | Per 28 units | 0.16 |

| Cardiac/statins | Feoldipine | Per 28 units | 0.55 |

| Cardiac/statins | Lercanidipine | Per 28 units | 1.42 |

| Cardiac/statins | Nifedipine | Per 56 units | 21.00 |

| Cardiac/statins | Cartia | Per 56 units | 41.87 |

| Cardiac/statins | Furosemide | Per 28 units | 0.13 |

| Cardiac/statins | Indapamide | Per 28 units | 1.02 |

| Cardiac/statins | Esomeprazole | Daily | 2.22 |

| Cardiac/statins | Lansoprazole | Per 28 units | 0.98 |

| Cardiac/statins | Glytrin | Daily | 1.13 |

| Cardiac/statins | Amiodarone | Once | 13.17 |

| Pain | Tramadola | Per 14 units | 1.67 |

| Pain | Paracetamolb | Per 16 units | 0.13 |

| Pain | Ibuprofen | Per 16 units | 0.17 |

| Pain | Codeine phosphatec | Per 28 units | 0.37 |

| Pain | Gabapentin | Per 100 units | 1.30 |

| Pain | Cocodamol | Per 30 units | 0.65 |

| Pain | Codrydramol | Per 30 units | 0.47 |

| Pain | Oramorph | Single use | 1.89 |

| Pain | Oxycodone | Per 56 units | 6.06 |

| Pain | Indomethacin | Single pack | 0.55 |

| Pain | Meloxicam | Single pack | 0.43 |

| Pain | Solaraze | Single pack | 0.67 |

| Pain | Naproxen | Per 28 units | 0.70 |

| Anticoagulants | Aspirin | Per 28 units | 0.14 |

| Anticoagulants | Clopidogrel | Per 30 units | 4.58 |

| Anticoagulants | Heparin | Per 10 units | 16.62 |

| Anticoagulants | Delteparin | Per 10 units | 51.22 |

| Anticoagulants | Warfarin | Per 28 units | 0.25 |

| Anticoagulants | Tinzaparin | Per 10 vials | 105.66 |

| Anticoagulants | Enoxaparin | Per 10 units | 20.86 |

| Anticoagulants | Rivaroxaban | Per 28 units | 50.40 |

| Antibiotics and immunological | Amoxicillin (plus unspecified antibiotics) | Per 21 units | 0.45 |

| Antibiotics and immunological | Trimethoprim | Per 14 units | 0.89 |

| Antibiotics and immunological | Nitrofurantoin | Per 28 units | 3.57 |

| Antibiotics and immunological | Cephalexin | Per 28 tablets | 0.73 |

| Antibiotics and immunological | Lexofloxacin | Per 5 tablets | 0.92 |

| Antibiotics and immunological | Bactrim | Per 28 units | 3.03 |

| Antibiotics and immunological | Oxytetracycline | Per 28 units | 0.43 |

| Antibiotics and immunological | Vancomycin | Per 28 units | 32.90 |

| Antibiotics and immunological | Ciprofloxacin | Per 20 units | 0.42 |

| Antibiotics and immunological | Metronidazole | Per 21 tablets | 0.39 |

| Antibiotics and immunological | Fluconazole | Per unit | 0.22 |

| Stool thickeners | Loperamide | Per 30 units | 1.61 |

| Stool thickeners | Atropine diphenoxylate | Per 100 units | 10.74 |

| Stool softeners/laxatives | Domperidone | Per 100 units | 0.91 |

| Stool softeners/laxatives | Lactulose (laxative if not clearly stated) | Per bottle | 1.21 |

| Stool softeners/laxatives | Docusate | Per 30 units | 2.09 |

| Stool softeners/laxatives | Metamucil | Per 10 units | 4.22 |

| Stool softeners/laxatives | Movicol/Laxido | Per 30 units | 2.99 |

| Stool softeners/laxatives | Clorphenamine | Per 28 units | 0.84 |

| Stool softeners/laxatives | Fluticasone | Per bottle | 4.17 |

| Other stomach/digestive | Mebeverine | Per unit | 4.68 |

| Other stomach/digestive | Ranitidine | Per 12 units | 0.30 |

| Other stomach/digestive | Omeprazole | Per 28 units | 0.44 |

| Urinary | Bendoflumethiazide | Per 28 units | 0.11 |

| Urinary | Tamsulosin | Per 30 units | 0.73 |

| Urinary | Solifenacin succinate | Per 30 units | 27.62 |

| Antidepressants/anti-anxiety | Alprazolam | Per 60 units | 3.18 |

| Antidepressants/anti-anxiety | Citalopram | Per 28 units | 0.18 |

| Antidepressants/anti-anxiety | Diazepam | Per 28 units | 0.23 |

| Antidepressants/anti-anxiety | Lorazepam | Per 28 units | 1.19 |

| Antidepressants/anti-anxiety | Sertraline | Per 28 units | 0.48 |

| Antidepressants/anti-anxiety | Duloxetine | Per 28 units | 22.40 |

| Antidepressants/anti-anxiety | Amitripyline | Per 28 units | 0.14 |

| Sexual dysfunction | Tadalafil | Per 28 units | 54.99 |

| Sexual dysfunction | Sildenafil | Per 28 units | 0.92 |

| Sleeping pills | Zopiclone | Per 28 units | 0.41 |

Medications for unrelated events (e.g. shingles, thyroid conditions, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, glaucoma) were ignored. Information on dietary supplementation (e.g. vitamins) was provided infrequently but was not included.

For some pain medications, differences in clinical practice mean that medications have been recoded. For example, although hydrocodone is widely used in the USA, it does not appear within the (UK) British National Formulary;38 codeine phosphate is used in preference to hydrocodone. Codeine phosphate is also used when several other medications (i.e. Norco®, codeine sulphate) are indicated.

Given the cost of chemotherapies and the relatively sparse information collected on these (and the danger that the costs involved mask all useful information), these have been ignored in the range of medications being considered. Furthermore, most of the stoma-related costs are removed, as the stoma unit costs specified in Table 4 include a range of costs that may overlap. Chemotherapies as adjunct therapies and anti-emetic/anti-nausea drugs (including anti-psychotics) are also ignored, since the cost of these drugs risks swamping any useful information provided.

Quality of life

The outcome measure for the economic evaluation was the quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured using the EQ-5D and valued using the standard UK tariff. 41 The EQ-5D data were obtained using English-language version questionnaires completed by patients recruited from UK and North American trial sites. The data were collected alongside resource data at baseline and at 30 days and at 6 months postoperatively. Multiple imputation methods were used to estimate HRQoL for those patients not completing this questionnaire. In this way, the analysis includes HRQoL for all patients in the trial, regardless of language.

Quality-of-life estimates were constructed using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), responses, valued using the standard UK tariff. Responses were in most cases valued as an area under the curve. The exception to this was when the data indicated that a stoma reversal operation occurred between 30 days and 6 months postoperatively; in this case, the 30-day figure was assumed to apply between 30 days and the reversal operation, and the 6-month figure was assumed to apply from the reversal date through to the end of follow-up.

As a sensitivity analysis (which has been run but is additional to those analyses displayed here), values were also inferred from the SF-36v2 data obtained from all patients in the ROLARR trial. Health-related quality-of-life figures were obtained as Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) utilities by applying the algorithm developed by Brazier et al. 42

Imputing costs and quality of life

Given that not all UK and US patients answered the medical resource utilisation questionnaire, imputation was necessary within the trial. Values were multiply imputed by category of variable and timing, using 100 imputations for each incomplete observation. By using a large number of multiple imputations, we aimed to more accurately reflect uncertainty.

The first set of variables imputed as chained equations related to the original inpatient admission, being the duration of surgery, the number of assistants and length of stay. These figures were imputed based on the procedure reviewed, whether or not this was a low anterior operation, whether or not there was evidence of locoregional spread, whether or not there had been any CT staging and using age/sex as demographics. Once these figures for the incomplete variables were imputed (and so non-missing), then they were used to inform subsequent variables. These figures also allowed the calculation of a (complete) series of figures for operative costs.

Figures were then imputed to find both the number of other surgeries required and the number of days a stoma would be in place and the type of stoma.

Quality-of-life observations were imputed next, with the EQ-5D-3L and SF-6D data as chained equations using age/sex and information about baseline health conditions. For time periods after baseline, the previous observation for both the EQ-5D and the SF-6D were also used as predictors. With data now complete on these observations, and for the number of stoma days, QALYs could then be calculated.

Other costs were imputed based on the EQ-5D-3L utilities and observed complications, as represented by dummy variables representing common (n > 10) complications graded on the Clavien–Dindo classification to ≥ 3. As these equations were lengthy, each equation was examined and terms removed where p > 0.200. For all health professional and outpatient visits, the equations estimated the number of events. In order to turn these into costs, these utilisation figures were multiplied by the average cost of events observed within the data. There were no clear significant predictors of medication costs within the data. Medication costs were imputed by predicting first whether or not any medication costs existed for that patient, within the relevant period (i.e. post discharge within the first 30 days, between 30 days and 6 months), and then as random variables reflecting those patients with data in that period.

Analysis

Data for all cost items were combined together to form an estimate of total costs, alongside the estimated total number of QALYs within the first 6 months. Because this covers only a 6-month time period, the maximum number of QALYs that could be observed is 0.500 QALYs (or, more properly, 0.499, given that 182 days are used).

With these figures, total costs and costs within different cost categories are presented in terms of both tables and probabilistic sensitivity analyses. As missing data are multiply imputed, it is efficient to conduct the probabilistic sensitivity analysis by bootstrapping (sampling with replacement) among the relevant data set, selecting from the imputed data set until the number of patients in the initial sample has been reached. For example, if a laparoscopic group had 75 patients within a particular scenario, the multiply-imputed data set would have 75 × 100 = 7500 observations, and the procedure would choose one of these 7500 observations, 75 times, in order to obtain a resampled estimate. The results in terms of total costs and total QALYs for each group are then compared and assessed to identify the most cost-effective option. Repeating this resampling procedure 10,000 times provides an estimate of the distribution of incremental costs and incremental benefits between the two options under consideration. This also allows the calculation of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, which display the probability of each of the options under consideration being cost-effective at different values of the cost-effectiveness threshold. By convention, the values of £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY are focused on,43 although the evidence is that the true cost-effectiveness threshold may be lower than these figures. 44

The primary analysis used imputed data for UK and US patients (n = 190). Secondary analyses were undertaken using the following:

-

complete data for all patients (n = 97)

-

imputed data for UK and US patients intended to receive low anterior surgery (n = 135)

-

imputed data for all observations (n = 471).

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

Between 7 January 2011 and 30 September 2014, 1276 patients were assessed for eligibility by 40 surgeons from 26 sites across 10 countries (i.e. UK, Italy, Denmark, USA, Finland, South Korea, Germany, France, Australia and Singapore). In total, 471 (36.9%) of these patients were randomised: 234 to laparoscopic and 237 to robotic surgery (Figure 1). Four patients withdrew from data collection before their operation and one patient did not undergo surgery because of a complete clinical response to neo-adjuvant therapy. The remaining 466 patients underwent an operation, with 456 (97.9%) undergoing the allocated treatment.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram. ITT, intention to treat.

Baseline data

All minimisation factors except treating surgeon are summarised by treatment group across all randomised patients in Table 6. The minimisation factor intended operating surgeon is summarised by treatment group for all randomised patients in Table 7. Summaries of selected additional baseline fields are given in Table 8.

| Minimisation factor | Treatment group, n (%) | Total, n (%) (N = 471) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard laparoscopic surgery (N = 234) | Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery (N = 237) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 159 (67.9) | 161 (67.9) | 320 (67.9) |

| Female | 75 (32.1) | 76 (32.1) | 151 (32.1) |

| BMI classification | |||

| Underweight/normal | 87 (37.2) | 93 (39.2) | 180 (38.2) |

| Overweight | 92 (39.3) | 90 (38.0) | 182 (38.6) |

| Obese class I | 38 (16.2) | 41 (17.3) | 79 (16.8) |

| Obese class II | 10 (4.3) | 9 (3.8) | 19 (4.0) |

| Obese class III | 7 (3.0) | 4 (1.7) | 11 (2.3) |

| Neo-adjuvant therapy | |||

| Yes | 103 (44.0) | 109 (46.0) | 212 (45.0) |

| No | 131 (56.0) | 128 (54.0) | 259 (55.0) |

| Intended procedure | |||

| HAR | 34 (14.5) | 35 (14.8) | 69 (14.6) |

| LAR | 158 (67.5) | 159 (67.1) | 317 (67.3) |

| APR | 42 (17.9) | 43 (18.1) | 85 (18.0) |

| Surgeon ID | Treatment group, n (%) | Total, n (%) (N = 471) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard laparoscopic surgery (N = 234) | Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery (N = 237) | ||

| 1 | 20 (47.6) | 22 (52.4) | 42 (8.9) |

| 2 | 20 (57.1) | 15 (42.9) | 35 (7.4) |

| 3 | 17 (51.5) | 16 (48.5) | 33 (7.0) |

| 4 | 17 (51.5) | 16 (48.5) | 33 (7.0) |

| 5 | 11 (40.7) | 16 (59.3) | 27 (5.7) |

| 6 | 12 (46.2) | 14 (53.8) | 26 (5.5) |

| 7 | 13 (52.0) | 12 (48.0) | 25 (5.3) |

| 8 | 11 (52.4) | 10 (47.6) | 21 (4.5) |

| 9 | 9 (50.0) | 9 (50.0) | 18 (3.8) |

| 10 | 10 (55.6) | 8 (44.4) | 18 (3.8) |

| 11 | 9 (50.0) | 9 (50.0) | 18 (3.8) |

| 12 | 9 (50.0) | 9 (50.0) | 18 (3.8) |

| 13 | 7 (43.8) | 9 (56.3) | 16 (3.4) |

| 14 | 6 (46.2) | 7 (53.8) | 13 (2.8) |

| 15 | 6 (46.2) | 7 (53.8) | 13 (2.8) |

| 16 | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | 11 (2.3) |

| 17 | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) | 10 (2.1) |

| 18 | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | 10 (2.1) |

| 19 | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | 9 (1.9) |

| 20 | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | 9 (1.9) |

| 21 | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 7 (1.5) |

| 22 | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (1.3) |

| 23 | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | 5 (1.1) |

| 24 | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 5 (1.1) |

| 25 | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 5 (1.1) |

| 26 | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 4 (0.8) |

| 27 | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 4 (0.8) |

| 28 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100.0) | 3 (0.6) |

| 29 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (0.6) |

| 30 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (0.6) |

| 31 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (0.6) |

| 32 | 3 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) |

| 33 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (0.6) |

| 34 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| 35 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| 36 | 2 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| 37 | 2 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| 38 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| 39 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| 40 | 1 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Treatment group, n (%) | Total, n (%) (N = 471) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopic surgery (N = 234) | Robotic surgery (N = 237) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 65.5 (11.93) | 64.4 (10.98) | 64.9 (11.01) |

| ASA classification | |||

| I: A normal healthy patient | 52 (22.2) | 39 (16.5) | 91 (19.3) |

| II: A patient with mild systemic disease | 124 (53.0) | 150 (63.3) | 274 (58.2) |

| III: A patient with severe systemic disease | 52 (22.2) | 46 (19.4) | 98 (20.8) |

| IV: A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 5 (2.1) | 2 (0.8) | 7 (1.5) |

| Prior abdominal surgery | |||

| Yes | 67 (28.6) | 62 (26.2) | 129 (27.4) |

| No | 162 (69.2) | 174 (73.4) | 336 (71.3) |

| Missing | 5 (2.2) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (1.3) |

Operative and pathology summaries

Crude summaries of operative and local pathology data fields are given in Table 9. The primary end point, conversion to open surgery, is summarised here but is considered in more detail in Primary end point: conversion to open surgery. The key secondary end point, CRM+, is also summarised here but is considered in more detail in Key secondary end point: circumferential resection margin positivity (CRM+).

| Operative | Treatment group, n (%) | Total, n (%) (N = 466) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopic surgery (N = 230) | Robotic surgery (N = 236) | ||

| Operation performed | |||

| HAR | 19 (8.3) | 28 (11.9) | 47 (10.1) |

| LAR | 165 (71.7) | 152 (64.4) | 317 (68.0) |

| APR | 45 (19.6) | 52 (22.0) | 97 (20.8) |

| Othera | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.7) | 5 (1.1) |

| Operative time (minutes) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 261 (83.24) | 298.5 (88.71) | 280.0 (87.98) |

| Missing | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Stoma formation | |||

| Temporary | 157 (68.3) | 142 (60.2) | 299 (64.2) |

| Permanent | 49 (21.3) | 53 (22.5) | 102 (21.9) |

| No | 24 (10.4) | 41 (17.4) | 65 (13.9) |

| Length of stay (days) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8.2 (6.03) | 8.0 (5.85) | 8.1 (5.94) |

| Missing | 13 | 14 | 27 |

| Intraoperative conversion to open surgery | |||

| Yes | 28 (12.2) | 19 (8.1) | 47 (10.1) |

| No | 202 (87.8) | 217 (91.9) | 419 (89.9) |

| Pathologyb | |||

| T-stage | |||

| 0 | 24 (10.4) | 22 (9.3) | 46 (9.9) |

| 1 | 20 (8.7) | 24 (10.2) | 44 (9.4) |

| 2 | 61 (26.5) | 64 (27.1) | 125 (26.8) |

| 3 | 114 (49.6) | 117 (49.6) | 231 (49.6) |

| 4 | 8 (3.5) | 5 (2.1) | 13 (2.8) |

| Tx or missing | 3 (1.3) | 4 (1.7) | 7 (1.5) |

| N-stage | |||

| 0 | 150 (65.2) | 146 (61.9) | 296 (63.5) |

| 1 | 58 (25.2) | 63 (26.7) | 121 (26.0) |

| 2 | 21 (9.1) | 25 (10.6) | 46 (9.9) |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (0.6) |

| Lymph node yield | |||

| Mean (SD) | 24.1 (12.91) | 23.2 (11.97) | 23.6 (12.43) |

| Missing | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| Plane of surgery | |||

| Mesorectal area (all specimens) | |||

| Mesorectal plane | 173 (75.2) | 178 (75.4) | 351 (75.3) |

| Intramesorectal plane | 38 (16.5) | 33 (14.0) | 71 (15.2) |

| Muscularis propria plane | 12 (5.2) | 22 (9.3) | 34 (7.3) |

| Missing | 7 (3.1) | 3 (1.3) | 10 (2.1) |

| Sphincter area (APRs only) | (n = 45) | (n = 52) | (n = 97) |

| Levator plane | 18 (40.0) | 18 (34.6) | 36 (37.1) |

| Sphincteric plane | 19 (42.2) | 22 (42.3) | 41 (42.3) |

| Intrasphincteric/submucosal plane | 5 (11.0) | 9 (17.3) | 14 (14.4) |

| Missing | 3 (6.7) | 3 (5.8) | 6 (6.2) |

| CRM involvement | (n = 224) | (n = 235) | (n = 459) |

| Yes | 14 (6.3) | 12 (5.1) | 26 (5.7) |

| No | 210 (93.7) | 223 (94.9) | 433 (94.3) |

Table 10 presents the different pathways of intraoperative conversions between robotic, laparoscopic and open surgery. For example, the pathway ‘Laparoscopic → Robotic’ indicates that the patient’s operation began as a standard laparoscopic operation, but was converted to a robotic operation intraoperatively. A pathway with only one type of operation indicates no conversions, for example ‘Laparoscopic’ indicates that the patient’s operation began as a standard laparoscopic operation and was completed without conversion to robotic or open surgery.

| Intraoperative conversion pathway | Treatment group, n (%) | Total, n (%) (N = 471) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard laparoscopic surgery, (N = 234) | Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery (N = 237) | ||

| Laparoscopic | 194 (82.9) | 3 (1.3) | 197 (41.8) |

| Laparoscopic → Open | 28 (12.0) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (5.9) |

| Laparoscopic → Robotic | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Robotic | 7 (3.0) | 209 (88.2) | 216 (45.9) |

| Robotic → Open | 0 (0.0) | 14 (5.9) | 14 (3.0) |

| Robotic → Laparoscopic | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.1) | 5 (1.1) |

| Robotic → Laparoscopic → Open | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.1) | 5 (1.1) |

| Did not receive surgery | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.8) |

Primary end point: conversion to open surgery

The rate of conversion to open surgery was 47 out of 466 (10.1%) patients overall: 28 out of 230 (12.2%) in the laparoscopic group and 19 out of 236 (8.1%) in the robotic group (unadjusted difference in proportions 4.12%, 95% CI –1.35% to 9.59%). There was no statistically significant difference between robotic surgery and conventional laparoscopic surgery with respect to odds of conversion (adjusted OR 0.614, 95% CI 0.311 to 1.211; p = 0.16).

The random intercept model was preferred to the random slope model, because the random slope model did not offer sufficient improvement in model fit, which is clear from both the non-significant likelihood ratio test result and the increase in AIC (see Appendix 1, Table 51).

Table 11 presents adjusted estimates of ORs and 95% CIs from the random intercept model, as well as crude summaries and unadjusted risk difference estimates and 95% CIs for conversion to open surgery by treatment group and also by each of the minimisation factors. The model shows significantly increased odds of conversion in obese patients versus underweight/normal patients (adjusted OR 4.691, 95% CI 2.080 to 10.581; p < 0.01) and in males versus females (adjusted OR 2.444, 95% CI 1.047 to 5.708; p = 0.04). Patients whose intended procedure was a LAR had a significantly higher rate of conversion than patients whose intended procedure was APR (adjusted OR 5.435, 95% CI 1.595 to 18.519; p = 0.007). Operating surgeon had a mild to moderate effect on odds of conversion, as reflected by the ICC estimate of 0.056 (95% CI 0.007 to 0.056).

| Effect: comparator group (vs. reference group) | Group [number of conversions/number of patients (%)] | Risk difference (unadjusted 95% CI) | OR (adjusted) | 95% CI for OR (adjusted) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Comparator | |||||

| Treatment: robotic surgery (vs. laparoscopic) | 28/230 (12.2) | 19/236 (8.1) | 4.1 (–1.4 to 9.6) | 0.614 | 0.311 to 1.211 | 0.16 |

| Sex: male (vs. female) | 8/149 (5.4) | 39/317 (12.3) | –6.9 (–12.1 to –1.8) | 2.444 | 1.047 to 5.708 | 0.04 |

| BMI class: overweight (vs. underweight/normal) | 13/179 (7.3) | 9/180 (5.0) | 2.3 (–2.7 to 7.2) | 0.538 | 0.210 to 1.374 | 0.19 |

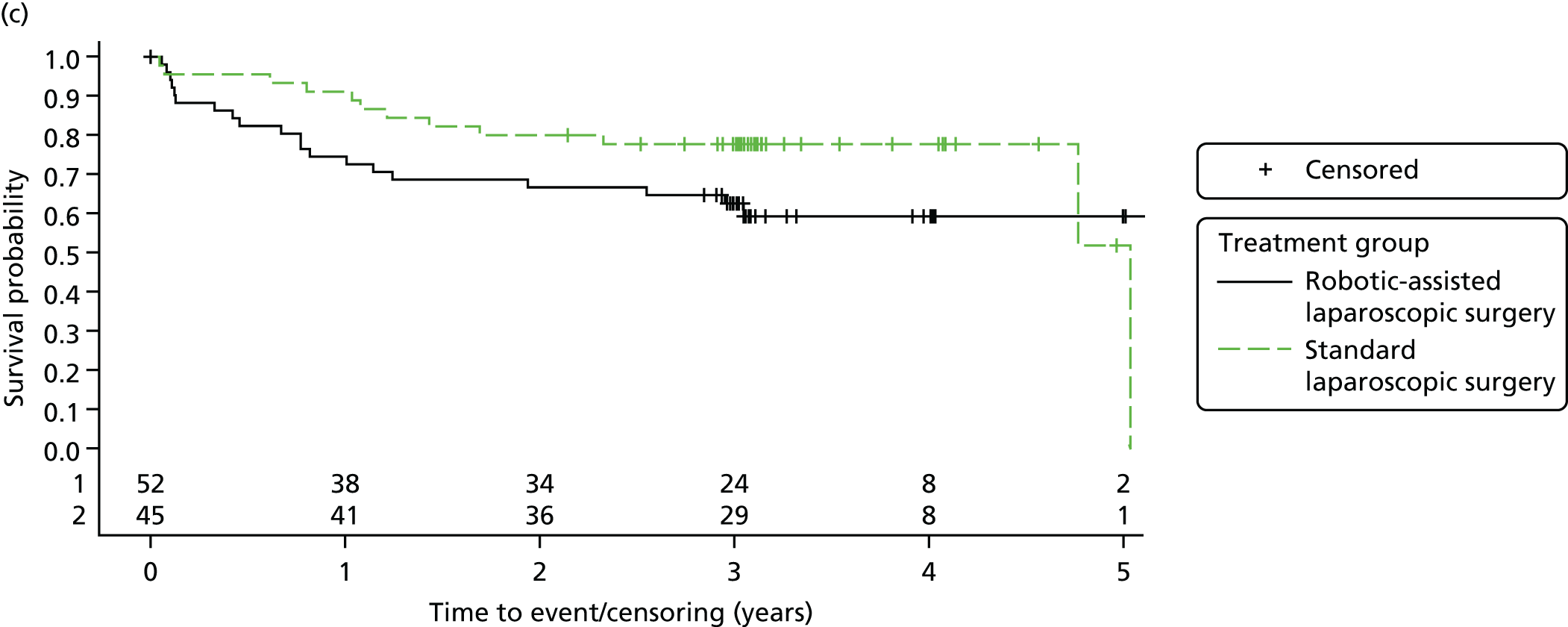

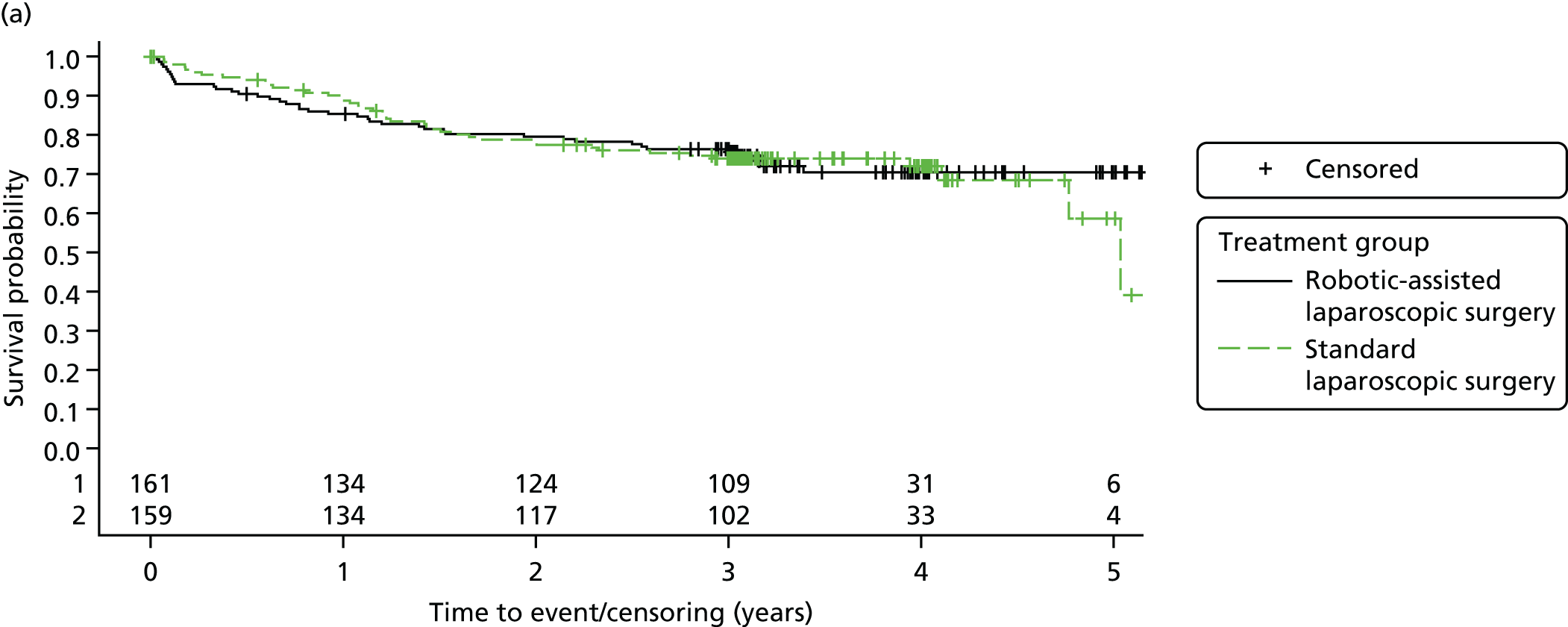

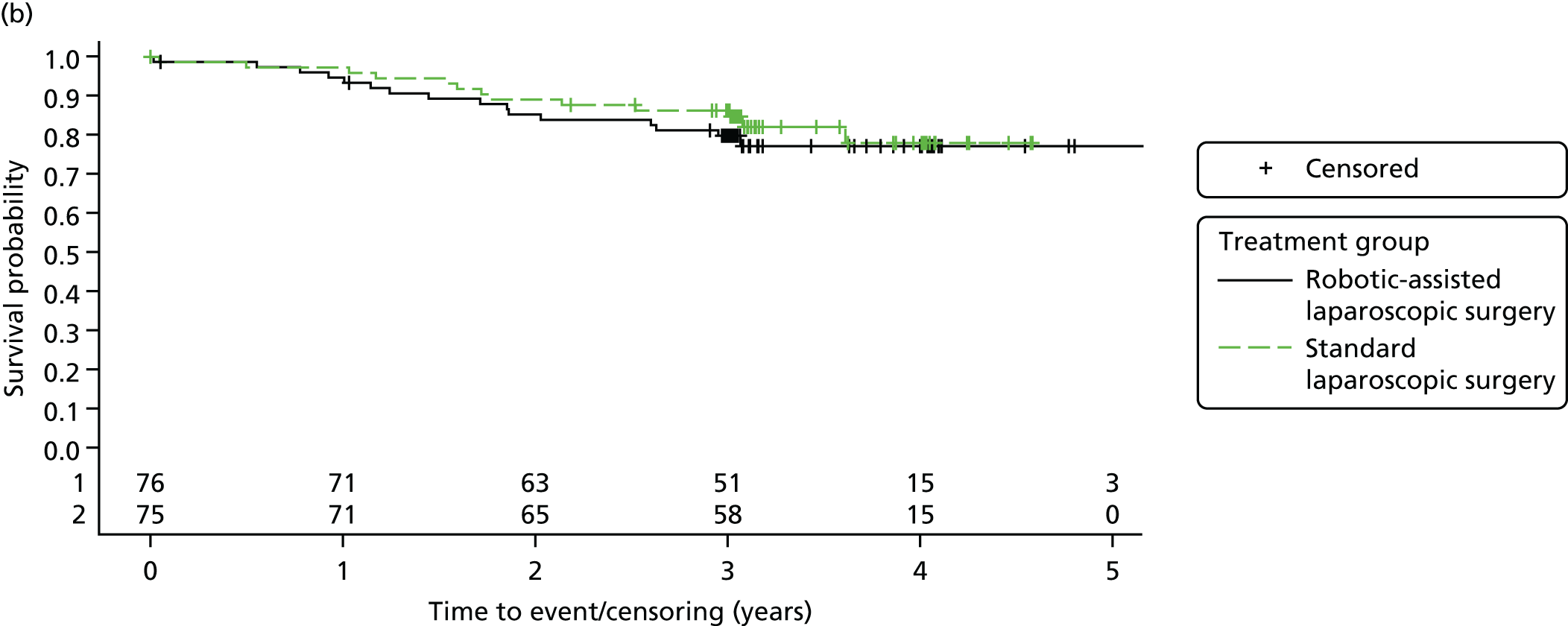

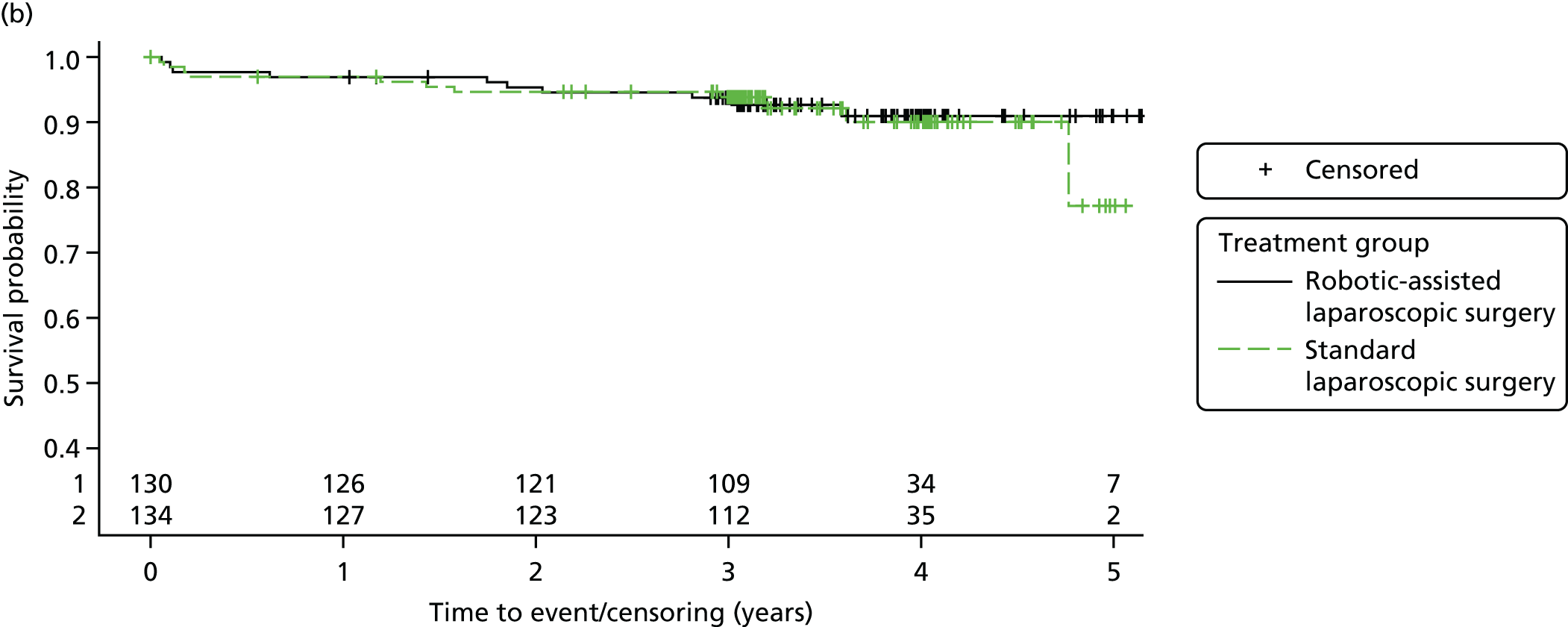

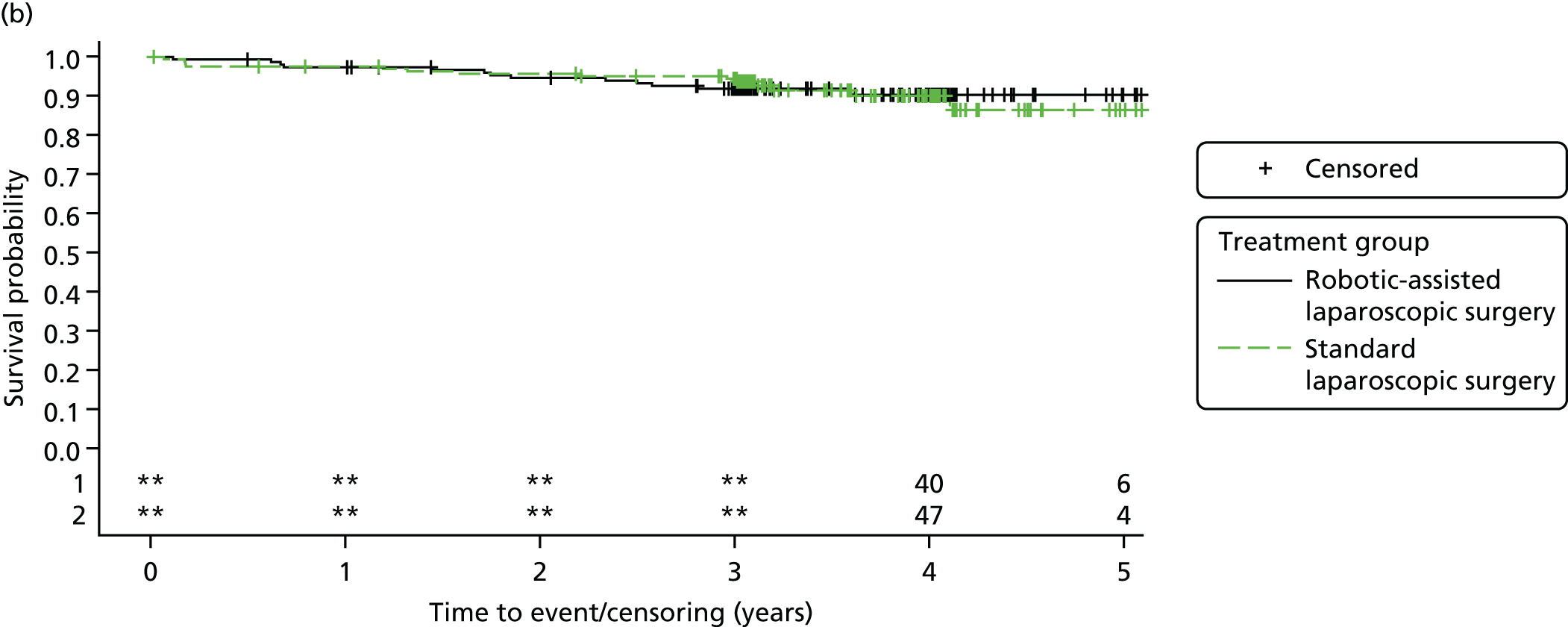

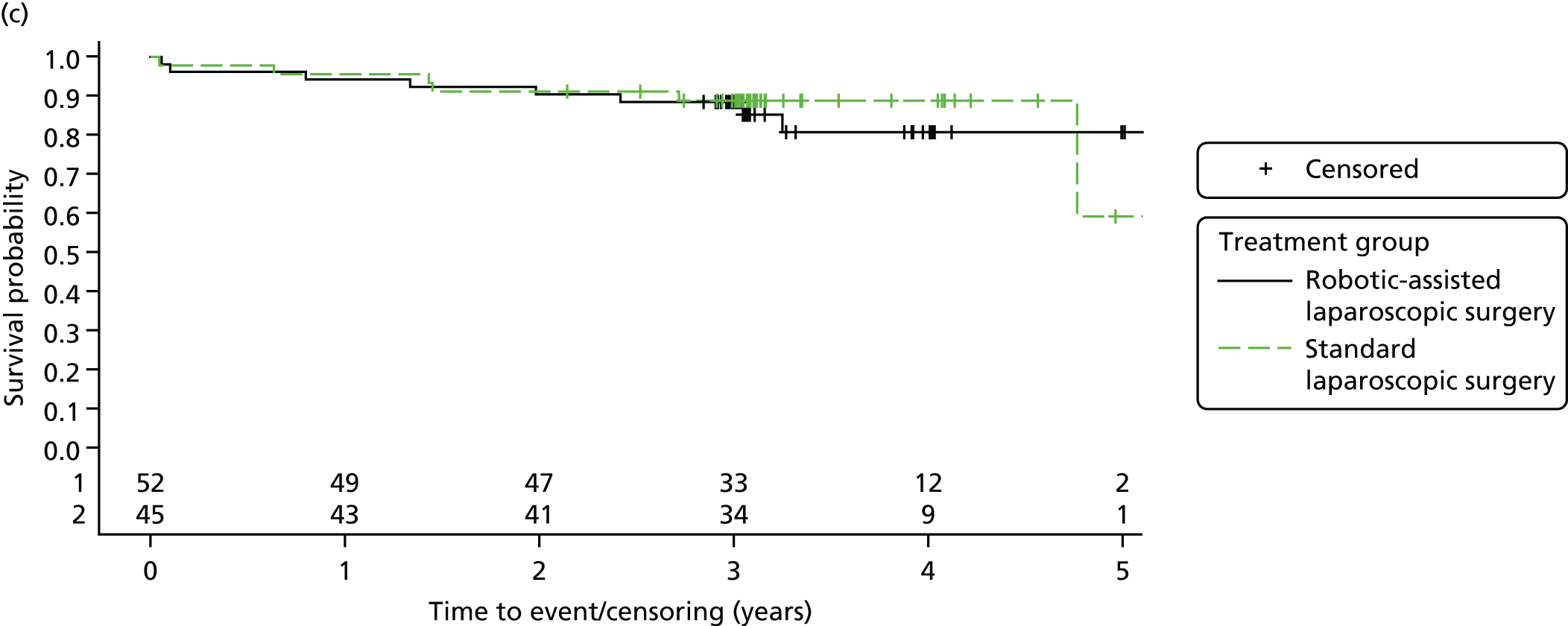

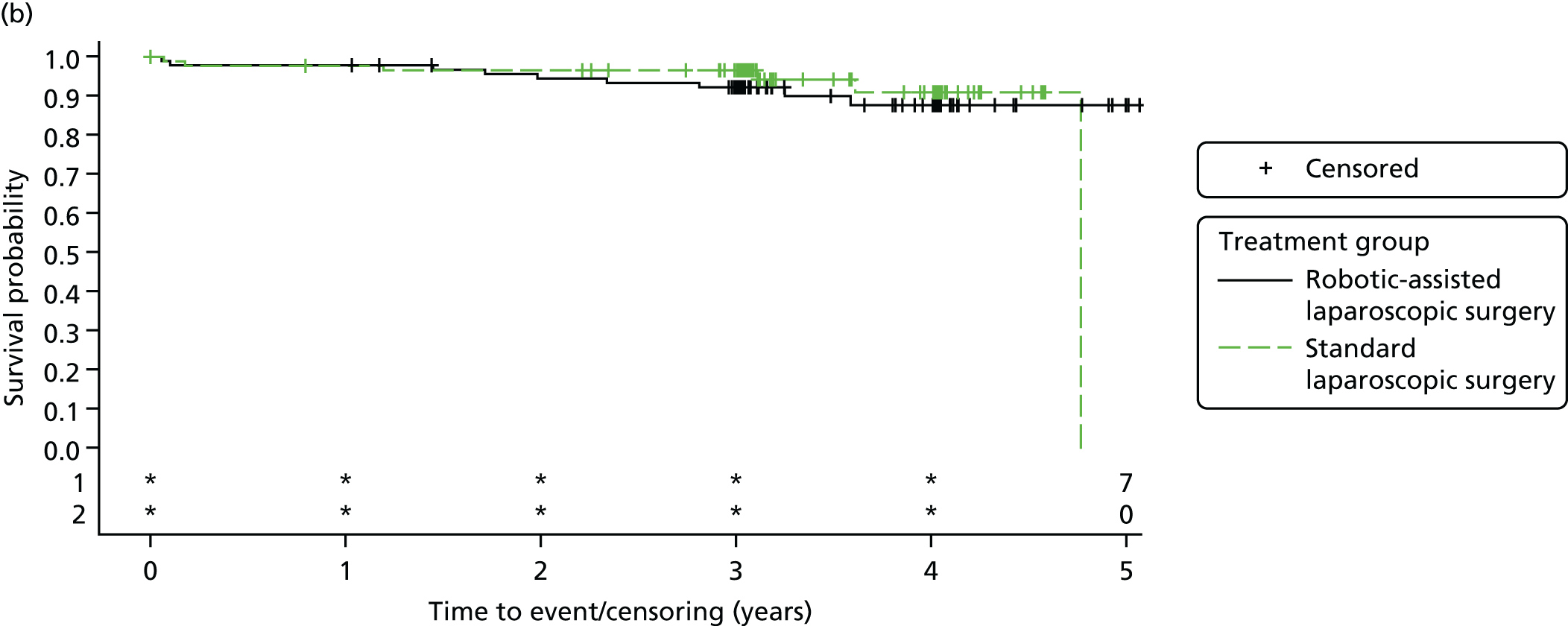

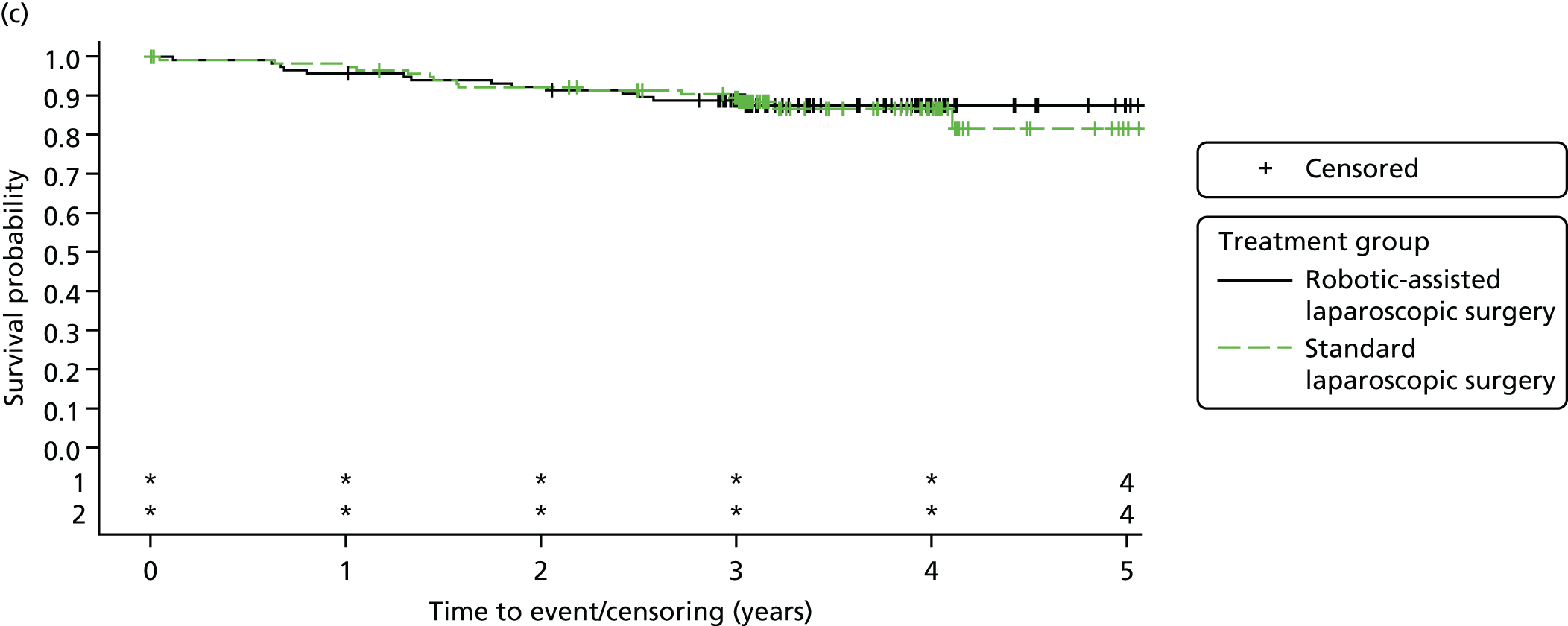

| BMI class: obese (vs. underweight/normal) | 13/179 (7.3) | 25/107 (23.4) | –16.1 (–25.0 to –7.2) | 4.691 | 2.080 to 10.581 | 0.0002 |