Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 12/10/19. The contractual start date was in April 2014. The final report began editorial review in April 2019 and was accepted for publication in March 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Melanie Calvert reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, the NIHR Surgical Reconstruction and Microbiology Research Centre at the University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Birmingham. Melanie also reports grants from Innovate UK (Swindon, UK) and Macmillan Cancer Support (London, UK) and personal fees from Glaukos Corp. (San Clemente, CA, USA), Daiichi Sankyo Company Ltd (Tokyo, Japan), Merck Sharp & Dohme (Kenilworth, NJ, USA), the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (Washington, DC, USA) and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company (Tokyo, Japan) outside the submitted work. James P Fisher reports grants from the NIHR during the conduct of this study. He also reports grants from Bristol Myers Squibb (New York, NY, USA) and Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA) outside the submitted work. Paulus Kirchhof is a board member of the European Society for Cardiology (ESC) and has received travel support from the ESC, including support for meetings pertinent to this work, during the conduct of the study. He has received research support from the European Union, the British Heart Foundation (London, UK), Leducq Foundation (Paris, France), the Medical Research Council (MRC; London, UK), the German Centre for Heart Research (Berlin, Germany) and from several drug and device companies active in atrial fibrillation outside the submitted work. Furthermore, he has received honoraria from several such companies outside the submitted work. Paulus is listed as inventor on two patents held by the University of Birmingham (Atrial Fibrillation Therapy, WO 2015140571; Markers for Atrial Fibrillation, WO 2016012783). Gregory YH Lip reports speaker and/or consultancy fees from Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany), Janssen: Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson (Beerse, Belgium), Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer Inc., Medtronic plc (Dublin, Ireland), C.H. Boehringer Sohn AG & Co. KG (Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany), Novartis International AG (Basel, Switzerland), Verseon Corporation (Fremont, CA, USA) and Daiichi Sankyo Company Ltd. No fees are directly received personally by him. Jonathan J Deeks reports grants from the MRC–NIHR Efficacy Mechanism and Evaluation programme during the conduct of this study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Shantsila et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Patients with heart failure (HF) and atrial fibrillation (AF) have a poor prognosis. Major advances have been achieved in the management of patients with HF and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) but there is lack of established treatments for patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). HF is common in patients with AF with preserved cardiac contractility. In the Framingham Heart Study, 37% of participants with new AF had HF, and the presence of AF was strongly related to incident HFpEF (hazard ratio 2.34). 1 Despite the preservation of LVEF, patients with HFpEF have poor quality of life and high morbidity and mortality. 2 Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, such as spironolactone, improve cardiac function and exercise tolerance (and mortality) in patients with HF with a reduced LVEF. However, improvements in morbidity and mortality with conventional treatments used in patients with reduced LVEF have not translated to patients with HFpEF. 3

Atrial fibrillation represents a separate, clinically and numerically significant, phenotype of HFpEF. 4 The arrhythmia is present in about 40% of people with HFpEF, being associated with higher N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) levels and increased risk of death and hospitalisations related to HF. 5–8

The mechanisms leading to symptoms, morbidity and mortality in patients with HFpEF and AF are probably related to the disturbed diastolic function that results from lack of atrial stiffness and myocardial fibrosis and stiffening. 9,10 In HFpEF, the diastolic filling is compromised as a result of aggravation in active and passive relaxation (increased cardiac stiffness). 11 This ventricular filling abnormality, in turn, reduces cardiac output and leads to symptoms of HF. 12 This theory is supported by both interventional experiments and large population-based studies carried out using a non-invasive approach to measure diastolic stiffness. 13–15 A stiff ventricle may possess only a limited ability to use the Frank–Starling mechanism to increase stroke volume during exercise with increasing heart rates. 16

Aldosterone is implicated in cardiac collagen deposition and left ventricular fibrosis. 17 Mechanisms of aldosterone-related cardiac fibrosis include myocardial inflammation, oxidative stress and direct stimulation of cardiac fibroblasts to produce collagen. 18,19 Cardiac expression of mineralocorticoid receptors is increased in AF, thus augmenting the genomic effects of aldosterone. 20

The effectiveness of spironolactone in HFpEF predominantly related to hypertension has been tested in two clinical trials [i.e. ALDO-DHF (ALDOsterone receptor blockade in Diastolic Heart Failure)21 and TOPCAT (Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist)22]. Although 92% of ALDO-DHF trial patients had hypertension only, 5% of the study population (n = 22) had AF at presentation. 21 The TOPCAT study22 involved a higher proportion of patients with AF (mainly paroxysmal AF) but the trial included patients with both preserved LVEF (i.e. ≥ 55%) and mild systolic dysfunction (i.e. LVEF ≥ 45%). 22 Note that the above studies focused on people who had clearly progressed to the stage of symptomatic HF, rather than the more numerous overall population with permanent AF at risk of developing HF or already exhibiting features of heart failure. Thus, the current evidence on the clinical effectiveness of spironolactone in patients with AF with preserved LVEF on morbidity and quality of life is sparse.

Study objectives

The IMproved exercise tolerance in heart failure with PReserved Ejection fraction by Spironolactone on myocardial fibrosiS in Atrial Fibrillation (IMPRESS-AF) trial aimed to evaluate the effect of mineralocorticoid receptor inhibition with spironolactone on exercise tolerance [assessed as peak oxygen consumption (VO2) using cardiopulmonary exercise testing] in participants with permanent AF with preserved LVEF compared with placebo (primary outcome), and its effect on quality of life, diastolic function, all-cause hospital admissions and spontaneous return to sinus rhythm (secondary outcomes).

Chapter 2 Methods

The IMPRESS-AF trial is a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled single-centre trial conducted in Birmingham, UK. The trial aimed to randomise 250 participants with permanent AF and preserved left ventricular function 1 : 1 to either spironolactone or placebo. The trial protocol was developed following the Standard Protocol Items for Randomized Trials (SPIRIT) statement and the latest patient-reported outcome (PRO)-specific guidance from the International Society for Quality of Life Research’s best practice for PROs in clinical trials taskforce. 23–25

Eligibility

The main inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in Table 1. Eligible patients were male or female and aged ≥ 50 years. Permanent AF was defined by the European Society of Cardiology’s criteria. 26,27 All participants had LVEF ≥ 55% at recruitment, as established by echocardiography during screening. 28 The participants had to be able to perform cardiopulmonary exercise testing using a cycling ergometer and to complete quality-of-life questionnaires in their native language. An interpreter and translated materials were provided if English was not the participant’s first language. Average values from 10 consecutive cardiac cycles were calculated to establish the LVEF and the ratio of mitral peak velocity of early filling (E) to early diastolic mitral annular velocity (E′) (E/E′ ratio). In patients with hypertension, antihypertensive treatment was established before recruitment. Furthermore, patients with systolic blood pressure > 160 mmHg were excluded.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Permanent AF | LVEF < 55% (as determined via echocardiography) |

| Age ≥ 50 years | Severe systemic illness (with a life expectancy < 2 years) |

| Ability to understand and complete questionnaires (with or without the use of an interpreter/translated materials) | Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (i.e. requiring home oxygen or chronic oral steroid therapy) |

| Severe mitral/aortal valve stenosis/regurgitation | |

| Significant renal dysfunction (i.e. serum creatinine levels ≥ 220 µmol/l), anuria, active renal insufficiency, rapidly progressing or severe impairment of renal function, confirmed or were diabetic and suspected renal insufficiency/diabetic nephropathy | |

| Increase in potassium level to > 5 mmol/l | |

| Recent coronary artery bypass graft surgery (i.e. within 3 months) | |

| Use of an aldosterone antagonist within 14 days before randomisation | |

| Use of a potassium-sparing diuretic within 14 days before randomisation | |

| Systolic blood pressure > 160 mmHg | |

| Addison’s disease | |

| Hypersensitivity to spironolactone or any of the ingredients in the product | |

| Any characteristic that may interfere with adherence to the trial protocol |

To improve generalisability, the trial did not include a requirement for evidence of diastolic dysfunction, as the trial patients would have impaired diastolic function due to AF. The principal exclusion criteria were designed to exclude patients with contraindications to spironolactone or with significant comorbidities, or that would prevent the prospective participants from completion of the study without relation to the study objectives. All participants received the current optimised treatment following established clinical guidelines on management of AF, HF and hypertension. 12

Trial setting and identification of participants

The trial was co-ordinated by the Primary Care Clinical Research and Trials Unit (PC-CRTU), which was later merged into the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit (BCTU), both at the University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK. The PC-CRTU co-ordinated the participant searches through the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network West Midlands (www.nihr.ac.uk/nihr-in-your-area/west-midlands/; accessed 18 April 2020).

All patients were seen, investigated and managed in the Research Clinic in the Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences (RC-ICS), City Hospital, Birmingham, UK.

Trial participants were recruited from primary care AF registers in general/family practices and outpatient AF clinics in Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals Trust, Birmingham, UK. At the screening visit to the RC-ICS, participants were consented into the study and screened for eligibility. During the baseline visit, eligible patients underwent cardiopulmonary exercise testing using a cycling ergometer (to measure peak VO2) and a 6-minute walk test (6MWT), and completed quality-of-life questionnaires [specifically the validated Minnesota Living with Heart Failure (MLWHF)29–31 and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L),32,33 questionnaires].

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation was performed after baseline assessments were completed using a secure, web-based randomisation system to ensure concealment of allocation. Participants were randomised 1 : 1, stratified by their baseline peak VO2 (two stratification groups: participants with VO2 ≤ 16 ml/minute/kg and participants with VO2 > 16 ml/minute/kg) using a block size of four. The randomisation list was produced by an independent statistician from the trials unit. The system allocated a unique investigational medicinal product number to each participant. Trial participants, the trial team in contact with the patient, care providers, outcome assessors and data analysts all remained blinded to the treatment.

Blinding was achieved by overencapsulating the spironolactone and manufacturing a matching placebo. Spironolactone and placebo were packaged into identical containers that were labelled with the corresponding unique investigational medicinal product number (Catalent Pharma Solutions, Bathgate, UK). The allocation list was known only to the BCTU database programmer and Catalent Pharma Solutions. For the purposes of emergency unblinding, a sealed copy of the randomisation list was kept at the Pharmacy Department at City Hospital, Birmingham, UK (it was independent of the trial, and operated 24 hours a day). The protocol indicated that patients would be withdrawn from the trial treatment if the code was broken, as they would become unblinded to their trial drug.

Treatment and dosing schedule

Participants randomised to spironolactone received 25 mg once daily. This dose has been shown to improve outcomes in systolic HF, improve diastolic function in HFpEF and to reduce collagen turnover, a marker for fibrotic signalling, in the Randomised Aldactone Evaluation Study (RALES) population. 34 The same dose of spironolactone significantly improved diastolic function within 1 year in participants with HFpEF from the ALDO-DHF trial. 21

Potassium levels were monitored in all patients. In the case of an increase in potassium level to 5.1–5.5 mmol/l or in the presence of other non-life-threatening side effects (such as gynaecomastia) the trial drug was down-titrated to 25 mg every second day. In such cases, the investigators were advised to re-up-titrate the trial medication if the reason for down-titration had resolved.

Drug toxicity was defined as an increase in potassium level to > 5.5 mmol/l. In the case of toxicity or suspected toxicity, the trial medication was stopped for the duration of the trial, but the patients were requested to attend the remaining follow-up visits and their outcomes were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. Blood pressure was controlled throughout the duration of the study, with particular attention to blood pressure levels after beginning the study drug and after any changes in antihypertensive agents or their doses.

Follow-up schedule

The participants underwent routine safety follow-up assessments at months 1 and 3 and then 3-monthly thereafter (Table 2). The study primary and secondary outcomes were collected at month 24. In addition, the quality-of-life questionnaires were completed after 12 months of study treatment.

| Trial procedure | Time point | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Baseline | Follow-up | |||||||||

| Month 1 | Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 9 | Month 12 | Month 15 | Month 18 | Month 21 | Month 24 | |||

| Additional visits were arranged to reassess potassium levels if the patient’s blood results showed a potassium level > 5.0 mmol/l | |||||||||||

| Eligibility check | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Informed consent | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Relevant medical history taken | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Concomitant medication | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Standard clinical examination, including BP check | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Clinical biochemistry | |||||||||||

| Full blood count | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Renal function and potassium and sodium levels | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| HbA1c levels (for diabetics) | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Lipid levels | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Electrocardiography | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Echocardiography | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| BNP test | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Randomisation | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Dispensing of study drug | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Cardiopulmonary exercise testing | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| 6MWT | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Quality-of-life questionnaires | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

Study end points

Primary efficacy end point

The primary efficacy end point was exercise tolerance at 2 years. This was assessed by the difference between trial groups in peak VO2 on cardiopulmonary exercise testing at 24 months, adjusted for the baseline values.

Secondary efficacy end points

The secondary efficacy end points were quality of life and diastolic function, and also all-cause hospital admissions and spontaneous return to sinus rhythm. These were assessed by:

-

exercise tolerance, as measured by the 6MWT (a simple test of exercise performance), at 2 years

-

quality of life (as measured using the MLWHF and EQ-5D-5L32,33 questionnaires) over the 2-year duration of the study

-

left ventricular diastolic function (as measured using the E/E′ ratio35–41 on echocardiography) at 2 years

-

rates of all-cause hospitalisations during 2 years’ follow-up31,32

-

spontaneous return to sinus rhythm on electrocardiography (ECG) after 2 years of treatment.

All analyses of secondary outcomes (other than hospitalisation rates) were adjusted for the baseline value of each variable. In addition, all major adverse clinical events were recorded, such as death from all causes, death from cardiac causes, hospitalisation for cardiac causes, and the occurrence of stroke or systemic thromboembolism.

Adverse events and safety outcomes were collected at all study visits. Prespecified safety outcomes were occurrence of breast pain, breast swelling, allergic reaction, raised serum creatinine levels (> 220 µmol/l), low estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFRs) (< 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2) and hyperkalaemia (≥ 5.1 and ≥ 6.0 mmol/l). Changes between baseline and 24 months were estimated and compared for levels of serum creatinine, eGFRs, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure in each trial arm to estimate the magnitude of the impact of the active drug. Spontaneously reported adverse events and serious adverse events were recorded throughout the trial.

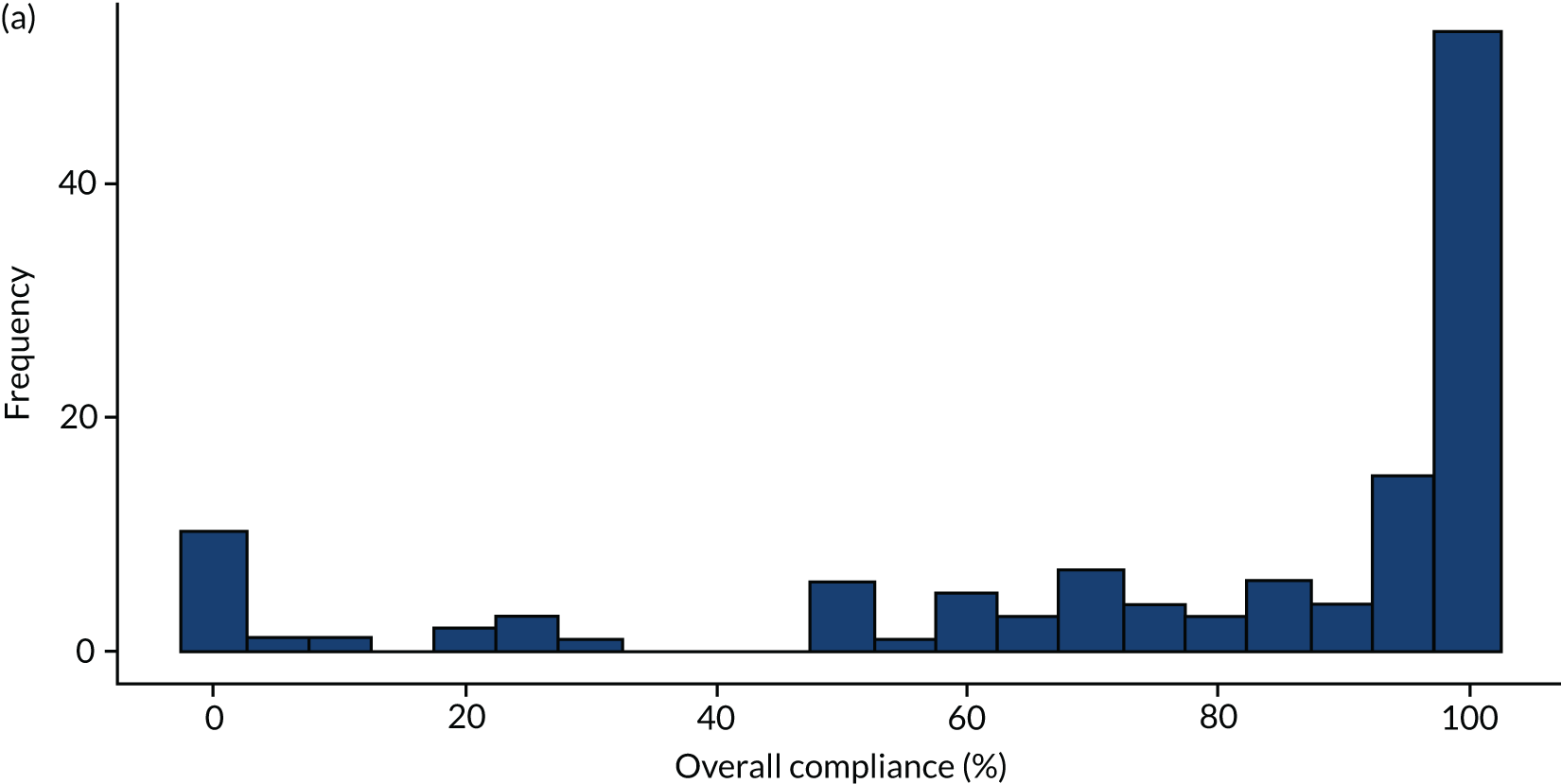

Measurement of compliance

Patients’ compliance with treatment was determined by computing the percentage of allocated capsules taken across the full 24 months (or up to the date of death). Adequate compliance was defined as ≥ 80% allocated capsules taken. Compliance was computed based on prescribing records and returned pill counts. Caution is required when interpreting the compliance data, as partway through the trial it was discovered that errors had been made in the packaging of the drug containers, such that several containers did not contain the correct number of tablets. The recorded returned pill counts did not always appear to match with the expected data range. Compliance is likely to have been underestimated when calculating tablets remaining on withdrawal of patients during the study period.

Statistical analysis

Definition of the intention-to-treat population and imputation rules for the primary outcome

The primary analysis followed intention-to-treat principles, including participants regardless of their compliance with the medication. Participants with missing data for the final assessment were excluded, except for those participants who died before the 24-month follow-up assessment. For these participants, their peak VO2 scores at 24 months were imputed as zero values regardless of cause. Although the value of zero was not actually measured, it allowed inclusion of the patient in the study and it should be a suitable reflection of the health state of the patient. The imputation rules were defined prior to any data analysis and reported in the statistical analysis plan.

Sensitivity analyses for different analysis of populations and imputation methods

The following sensitivity analyses were undertaken:

-

Per-protocol analysis – participants with ≥ 80% allocated capsules taken with a final follow-up assessment for peak VO2 (with zero imputed if they died, as in the intention-to-treat analysis). Participants for whom compliance data could not be obtained were excluded from the per-protocol analysis.

-

Complete-case analysis – participants who completed the 24-month follow-up assessment.

-

Multiple imputation – outcomes for participants missing the 24-month follow-up assessment who had not died were imputed using a multivariate imputation approach, which filled in missing values in multiple variables iteratively by using chained equations that assumed an arbitrary missing data pattern. The predictive mean matching (PMM)42 method was implemented, which produces imputed values that better match the observed values than linear regression models, especially when peak VO2 scores are not normally distributed. Missing data for participants in the spironolactone group and the placebo group were imputed separately, which would allow unbiased estimates for any interaction effects between the treatment and any covariate in the analysis model. Baseline peak VO2, age, body mass index (BMI), systolic/diastolic blood pressure, 6MWT, B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level, E/E′ ratio, EQ-5D-5L scores, MLWHF scores and sex were included in the imputation model and used to generate 20 simulated data sets. Analyses were then performed on each set, with the results combined using Rubin’s rules43 to obtain a single set of results.

The analyses had been repeated by including additional adjustments for age, sex and BMI at baseline.

Definition of the intention-to-treat population and imputation rules for the secondary outcomes

Analyses of secondary outcomes were performed on the intention-to-treat basis as for the primary outcome. For the 6MWT, the analysis substituted a zero value for those participants who had died before the 24-month follow-up assessment regardless of cause. For the EQ-5D-5L and MLWHF questionnaires at 12 and 24 months, scores indicating the worst level of quality of life observed across the whole data set were substituted for those who had died before the 12- and 24-month follow-up assessment, respectively, regardless of cause; a higher score reflects a poorer quality of life for the MLWHF questionnaire and better quality of life for the EQ-5D-5L. For the MLWHF questionnaire, if up to four of the 21 responses were missing, mean substitution was used to impute the missing responses and compute the overall score; otherwise, the score was coded as missing. Analyses for the remaining secondary outcomes were undertaken on complete cases only.

Analysis methods

The primary outcome analysis was undertaken using multiple linear regression, including the baseline continuous peak VO2 score and treatment group as covariates. Multiple linear regression was also used for the following continuous outcomes, adjusting for the corresponding baseline value of each outcome in addition to the baseline continuous peak VO2 score (accounting for the stratifying variable used in the randomisation):

-

exercise tolerance measured by 6MWT at 2 years

-

quality of life as measured by the MLWHF and EQ-5D-5L questionnaires at 1 and 2 years

-

left ventricular diastolic function as measured by the E/E′ ratio at 2 years

-

BNP level at 2 years.

In all cases, the treatment effect estimate was a difference in mean values (i.e. spironolactone minus placebo), with the uncertainty in the estimate expressed using a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Multiple logistic regression was carried out, analysing the spontaneous return to sinus rhythm (on the ECG) at 2 years, adjusting only for baseline continuous peak VO2 score. An additional analysis was undertaken, adjusting for the log-transformed BNP level at baseline, as this is known to be predictive of this outcome. The treatment effect estimate was an odds ratio (odds on spironolactone compared with placebo), with the uncertainty expressed using a 95% CI.

A Cox regression model was used to analyse the time-to-hospitalisation event data (for any cause) over 2 years, adjusted for baseline continuous peak VO2 score. Data on participants who had not been hospitalised over the 2-year period were censored at the date of their last attendance for clinical events; those who died who were lost to follow-up were censored on their last visit date if they had not been hospitalised. A Kaplan–Meier plot of time to the first hospitalisation for any cause was presented. The treatment effect estimate was a hazard ratio (hazard on spironolactone compared with placebo), with the uncertainty expressed using a 95% CI.

Subgroup analyses for primary outcome

The following predefined subgroups at baseline were compared with the primary outcome, peak VO2, by inclusion of an interaction term (treatment by subgroup) in the linear regression model in addition to their main effects and baseline continuous peak VO2 score:

-

peak VO2 categories – ≤ 16 vs. > 16 ml/minute/kg

-

sex – male versus female

-

age groups (years) – split at median

-

BMI groups – < 25 kg/m2 (normal or underweight), 25–30 kg/m2 (overweight) and ≥ 30 kg/m2 (obese)

-

systolic blood pressure groups (mmHg) – split at median

-

diastolic blood pressure groups (mmHg) – split at median.

Analysis of adverse events and known safety issues

Any cases of major adverse clinical events were recorded, such as:

-

death from all causes

-

death from cardiac causes

-

hospitalisation for cardiac causes

-

stroke

-

systemic thromboembolism.

Major adverse clinical events were compared between the two treatment groups using Fisher’s exact test.

Absolute changes in creatinine, eGFR, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure from baseline to 24 months were computed within each trial arm, and compared as a difference in mean change between trial arms (with statistical significance assessed using a t-test).

The known safety issues with the intervention drug were assessed at each visit and reported by trial arm. Formal comparisons had not been undertaken. The known safety issues were as follows:

-

eGFR < 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2

-

hyperkalaemia (≥ 5.1 mmol/l)

-

hyperkalaemia (≥ 6.0 mmol/l)

-

creatinine level > 220 µmol/l

-

breast pain

-

breast swelling

-

allergic reaction to the trial medication.

In addition, the spontaneously reported adverse events were classified by the principal and chief investigator, and tabulated by treatment group.

Stata® version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all analyses.

Deviations from the protocol

The statistical analysis plan was refined prior to data analysis and compared with methods stated in the protocol. The key differences are:

-

The outcomes are defined as ‘differences in final values’ rather than ‘improvement in final values’. This is mainly a semantic change, as the prespecified model always included adjustment for baseline variables rather than the outcome being a change score. It also was considered a preferable wording as it is a non-directional hypothesis.

-

The final model did not include GP practice as a random effect as the numbers recruited from each practice were very small.

-

Adjustment for baseline blood pressure values was not included as these values were not considered prognostic of outcome.

-

Repeated measures models were not used for the small number of quality-of-life outcomes that were assessed at both time points; the study authors preferred to use separate estimates at 6 and 12 months as this allowed for estimation of treatment effects at both time points.

-

Subgroup (interaction) effects were considered only for the primary outcome. The variables investigated were determined by the Trial Management Group prior to any data analysis.

-

The New York Heart Association (NYHA) class analysis was not undertaken because of difficulties in obtaining the required data.

Sample size

The sample size required to show a clinically important difference in the primary outcome of peak VO2 was determined. Published values of peak VO2 in subjects with HF give a mean baseline value of 16 ml/minute/kg [standard deviation (SD) 5 ml/minute/kg]44 and data for HFpEF suggest that a difference of 2 ml/minute/kg would be clinically relevant. These data were used for the design of the recent ALDO-DHF study of spironolactone in patients with HFpEF, 95% of whom were free from AF. 21,45 Unfortunately, the study by Cicoira et al. ,44 used for power calculation does not give a SD in peak VO2; however, a similar trial, Edelmann et al. 46 provides that statistic (i.e. 5 ml/minute/kg) and also reports a similar magnitude of the effect. A sample size of 100 participants in each trial arm would give the power of at least 80% to detect differences in primary and secondary end points of a magnitude consistent with published results from similar studies using a 5% two-sided statistical significance level. The sample size was increased to 125 participants per arm for provision for a 20% dropout rate. Statistical power would be higher should this rate be too pessimistic, and with the benefits of adjusting for baseline values.

Key changes to the protocol

1 May 2015

Inclusion in the trial is no longer conditional on the patient having normal BNP levels (i.e. < 100 pg/ml). The amendment was based on failure to identify suitable participants when this inclusion criterion was applied.

5 January 2017

The threshold of potassium for withdrawal, as a result of hyperkalaemia, increased from > 5.5 mmol/l to > 6.0 mmol/l. The amendment was based on current practice for use of spironolactone.

Study funding and management

The IMPRESS-AF trial was funded by the NIHR, UK. The University of Birmingham is the sponsor of this trial. The day-to-day management of the trial was co-ordinated by the PC-CRTU/BCTU at the University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, and registered by the NIHR as a trials unit. A Trial Steering Committee was responsible for overseeing the progress of the trial. An independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee was responsible for the regular monitoring of trial data and adverse events. The study design was helped by a patient representative, who reviewed the study proposal and provided their comments (which were included in the proposal). Another patient representative was a member of the Trial Steering Committee, but no comments or criticisms were received from them.

Study ethics

The study was approved by the National Research and Ethics Committee (REC) West Midlands – Coventry and Warwickshire (REC reference number 14/WM/1211). All participants provided signed informed consent.

Trial registration

The study was registered with the European Union Clinical Trials Register (EudraCT number 2014-003702-33) and with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02673463), and has been adopted by the NIHR Clinical Research Network.

Chapter 3 Results

A total of 250 patients were randomised to spironolactone or placebo (125 patients per group) between October 2014 and June 2016 (in accordance with the projected recruitment completion date, 30 June 2016). Two-year follow-up was completed in June 2018. Patients were elderly (mean age 72.3 years, SD 7.4 years), with a mean BMI of 30.5 kg/m2 (SD 5.4 kg/m2) and predominantly male (76.4%) and of white ethnicity (94.4%). The trial arms appear to be well balanced on all important variables (Table 3). Results are presented in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) and CONSORT PRO guidelines. 47 The final study visit was attended by 101 (81%) patients randomised to the spironolactone group and 106 (85%) patients randomised to placebo (Figure 1).

| Characteristic | Trial arm | Overall (N = 250) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spironolactone (N = 125) | Placebo (N = 125) | ||

| Stratification variables | |||

| Peak VO2 (ml/minute/kg)a | |||

| ≤ 16 ml, n (%) | 77 (61.6) | 78 (62.4) | 155 (62.0) |

| > 16 ml, n (%) | 48 (38.4) | 47 (37.6) | 95 (38.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 14.5 (4.6) | 14.6 (5.1) | 14.5 (4.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 13.9 (10.8–18.3) | 14.4 (10.8–17.5) | 14.1 (10.8–17.8) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Demographic and other baseline variables | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 72.4 (7.1) | 72.3 (7.9) | 72.3 (7.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 72.8 (68.3–77.2) | 72.4 (67.4–77.6) | 72.6 (67.6–77.6) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 30.4 (5.2) | 30.5 (5.6) | 30.5 (5.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 29.1 (26.4–33.2) | 30.1 (26.1–33.9) | 29.7 (26.3–33.3) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (0.8) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 28 (22.4) | 31 (24.8) | 59 (23.6) |

| Male | 97 (77.6) | 94 (75.2) | 191 (76.4) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Current medication, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 123 (98.4) | 124 (99.2) | 247 (98.8) |

| No | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Current smoker | 6 (4.8) | 8 (6.4) | 14 (5.6) |

| Ex-smoker | 66 (52.8) | 68 (54.4) | 134 (53.6) |

| Non-smoker | 53 (42.4) | 49 (39.2) | 102 (40.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Alcohol use (units per week) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.2 (9.9) | 8.8 (10.8) | 8.0 (10.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (0.0–12.0) | 6.0 (0.0–14.0) | 4.0 (0.0–13.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 6MWT (metres) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 256.7 (83.4) | 270.4 (89.5) | 263.6 (86.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 266.0 (196.0–316.0) | 271.0 (200.0–330.0) | 266.0 (200.0–322.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Resting heart rate (b.p.m.) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 87.3 (19.4) | 86.7 (18.7) | 87.0 (19.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 85.0 (74.0–99.0) | 83.0 (74.0–97.0) | 84.0 (74.0–97.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Peak heart rate during CPET (b.p.m.) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 128.4 (26.1) | 129.9 (25.4) | 129.1 (25.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 129.0 (109.0–150.0) | 126.0 (112.0–148.0) | 127.0 (110.0–149.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 118 (94.4) | 118 (94.4) | 236 (94.4) |

| Mixed | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Black | 3 (2.4) | 3 (2.4) | 6 (2.4) |

| Asian | 3 (2.4) | 2 (1.6) | 5 (2.0) |

| Other ethnic group | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (0.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| BNP concentration (pg/ml) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 163.5 (125.4) | 183.3 (168.5) | 173.4 (148.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 122.0 (73.0–230.0) | 136.0 (81.7–241.0) | 127.0 (77.9–236.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 129.2 (15.5) | 130.1 (15.0) | 129.6 (15.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 130.0 (117.0–140.0) | 129.0 (118.0–142.0) | 129.0 (117.0–140.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 75.7 (10.9) | 75.6 (13.9) | 75.7 (12.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 75.0 (67.0–83.0) | 74.0 (68.0–82.0) | 74.0 (68.0–82.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 99.5 (12.5) | 100.3 (14.4) | 99.9 (13.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 99.0 (91.4–106.7) | 101.0 (91.0–106.7) | 99.1 (91.4–106.7) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (0.8) |

| Hip circumference (cm) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 107.4 (10.0) | 108.0 (13.2) | 107.7 (11.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 106.7 (101.0–112.0) | 106.7 (100.0–114.3) | 106.7 (100.0–114.3) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (0.8) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 60.4 (5.4) | 60.5 (5.7) | 60.5 (5.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 58.0 (56.6–62.0) | 58.0 (56.3–63.0) | 58.0 (56.4–63.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mitral valve measurement: E/E′ ratio | |||

| Mean (SD) | 10.7 (4.4) | 10.6 (4.2) | 10.7 (4.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 9.8 (8.0–12.0) | 9.7 (7.5–13.0) | 9.8 (7.8–12.6) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| EQ-5D-5L score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.81 (0.19) | 0.83 (0.16) | 0.82 (0.18) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.84 (0.74–0.94) | 0.88 (0.74–0.94) | 0.87 (0.74–0.94) |

| Missing, n (%) | 4 (3.2) | 5 (4.0) | 9 (3.6) |

| MLWHF scoreb | |||

| Mean (SD) | 22.9 (20.4) | 21.9 (22.9) | 22.4 (21.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 17.0 (6.3–35.8) | 14.0 (5.8–30.0) | 14.0 (6.0–33.8) |

| Missing, n (%) | 8 (6.4) | 4 (3.2) | 12 (4.8) |

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram. a, Figures include participants who discontinued the investigational medicinal product, but provided data.

Primary outcome

The data on the primary outcome, peak VO2, at the end of the trial were analysed for the available 106 patients in the placebo group and 103 patients in the spironolactone group (Table 4 and Appendix 1). In both trial arms, three patients were not able to perform a cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) because of frailty. In the primary intention-to-treat analysis (imputing the peak VO2 score at 24 months for the three placebo and five spironolactone group patients who died with a zero value during the treatment period), peak VO2 changed from a mean of 14.5 ml/minute/kg (SD 4.6 ml/minute/kg) to a mean of 14.03 ml/minute/kg (SD 5.4 ml/minute/kg) in the spironolactone group (n = 103) and from a mean of 14.6 ml/minute/kg (SD 5.1 ml/minute/kg) to a mean of 14.5 ml/minute/kg (SD 5.1 ml/minute/kg) in the placebo group (n = 106). The treatment effect showed no difference between the trial groups(differences in means –0.28 ml/minute/kg, 95% CI –1.27 to 0.71 ml/minute/kg; p = 0.58). The estimates and CIs for primary outcome measures were all smaller than the minimal clinically important difference of 2 units used in the sample size calculation, which provides a basis for claiming that the study has proven no difference rather than just failing to show a difference. The findings were consistent across the sensitivity analyses performed (see Table 4).

| Analysis | Trial arm | Treatment effect (95% CI)c | p-valuec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spironolactone | Placebo | |||||

| Mean (SD)b | n | Mean (SD)b | n | |||

| Primary analysisd (adjusted for stratification variable) | 14.03 (5.38) | 103 | 14.45 (5.14) | 106 | –0.28 (–1.27 to 0.71) | 0.58 |

| Sensitivity analysis (adjusted for stratification variable) | ||||||

| Per-protocol analysise | 14.84 (4.32) | 57 | 14.88 (4.90) | 77 | 0.21 (–0.78 to 1.21) | 0.67 |

| Complete-case analysis | 14.75 (4.45) | 98 | 14.87 (4.57) | 103 | –0.09 (–0.86 to 0.68) | 0.81 |

| Multiple imputation methodf | 13.39 (6.04g) | 125 | 14.02 (5.48g) | 125 | –0.53 (–1.57 to 0.51) | 0.32 |

| Sensitivity analysis (additionally adjusted for age, sex and BMI) | ||||||

| Primary analysis with the additional adjustment | 14.03 (5.38) | 103 | 14.47 (5.16) | 105 | –0.32 (–1.32 to 0.68) | 0.53 |

| Per-protocol analysise | 14.84 (4.32) | 57 | 14.91 (4.92) | 76 | 0.17 (–0.81 to 1.14) | 0.73 |

| Complete-case analysis | 14.75 (4.45) | 98 | 14.89 (4.59) | 102 | –0.14 (–0.89 to 0.61) | 0.71 |

| Multiple imputation methodf | 13.39 (6.04g) | 125 | 14.02 (5.48g) | 125 | –0.53 (–1.57 to 0.51) | 0.31 |

The subgroup analyses (Table 5) showed no significant interaction of the treatment with baseline peak VO2 values (≤ 16 ml/minute/kg vs. > 16 ml/minute/kg; p = 0.535), BMI (< 25 vs. 25–30 vs. ≥ 30 kg/m2; p = 0.131), sex (p = 0.906) and median blood pressure (p = 0.358 for systolic blood pressure and p = 0.926 for diastolic blood pressure). There was a significant interaction between the treatment and age, evaluated by splitting the study population by median age (72.6 years): higher peak VO2 values were observed in older patients in the spironolactone group (p = 0.025 for the interaction).

| Analyses | Trial arm | Treatment effect (95% CI)b | Estimate of difference (95% CI)b,c | p-value for interactionb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spironolactone | Placebo | ||||||

| Mean (SD)a | n | Mean (SD)a | n | ||||

| Peak VO2 (ml/minute/kg) | |||||||

| ≤ 16 | 11.15 (4.39) | 60 | 11.87 (3.73) | 63 | –0.56 (–1.85 to 0.73) | 0.64 (–1.38 to 2.66) | 0.54 |

| > 16 | 18.05 (3.86) | 43 | 18.23 (4.58) | 43 | 0.07 (–1.47 to 1.62) | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| ≤ mediand | 14.38 (6.25) | 54 | 16.61 (4.78) | 53 | –1.40 (–2.76 to –0.05) | 2.24 (0.28 to 4.20) | 0.025 |

| > median | 13.65 (4.26) | 49 | 12.29 (4.58) | 53 | 0.83 (–0.55 to 2.22) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||

| < 25 | 14.71 (3.92) | 14 | 15.18 (4.85) | 14 | 0.30 (–2.40 to 2.99) | – | 0.13 |

| 25–30 | 14.91 (6.47) | 43 | 16.37 (4.98) | 36 | –1.59 (–3.21 to 0.02) | –1.89 (–5.05 to 1.27) | |

| ≥ 30 | 13.01 (4.49) | 46 | 13.04 (5.00) | 55 | 0.58 (–0.85 to 2.00) | 0.28 (–2.79 to 3.35) | |

| Sex (n) | |||||||

| Female | 10.95 (3.73) | 20 | 12.07 (2.87) | 26 | –0.41 (–2.54 to 1.72) | 0.14 (–2.28 to 2.57) | 0.91 |

| Male | 14.77 (5.47) | 83 | 15.22 (5.48) | 80 | –0.27 (–1.39 to 0.86) | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | |||||||

| ≤ mediand | 13.46 (6.22) | 52 | 14.78 (5.23) | 54 | –0.71 (–2.10 to 0.68) | 0.93 (–1.06 to 2.93) | 0.36 |

| > median | 14.62 (4.36) | 51 | 13.99 (5.05) | 51 | 0.23 (–1.19 to 1.64) | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | |||||||

| ≤ mediand | 13.45 (5.63) | 54 | 13.67 (5.17) | 58 | –0.24 (–1.58 to 1.11) | –0.09 (–2.08 to 1.90) | 0.93 |

| > median | 14.68 (5.08) | 49 | 15.29 (5.01) | 47 | –0.33 (–1.78 to 1.12) | ||

The magnitude of the differences was small, with the point estimates for the treatment effect in each subgroup being smaller than the pre-stated clinically important treatment effect.

Secondary outcomes

For the secondary efficacy end points, the 6MWT distance increased from a mean of 257 m (SD 83 m) to a mean of 313 m (SD 108 m) in the spironolactone group and from a mean of 270 m (SD 90 m) to a mean of 330 m (SD 112 m) in the placebo group (treatment effect –8.47 m, 95% CI –31.87 to 14.93 m; p = 0.48) (Table 6). A measure of left ventricular diastolic function, the E/E′ ratio, changed from a mean of 10.7 (SD 4.4) to a mean of 9.0 (SD 3.1) in the spironolactone group and from a mean of 10.6 (SD 4.2) to a mean of 9.7 (SD 3.57) in the placebo group (treatment effect –0.68, 95% CI –1.52 to 0.17; p = 0.12). Similarly, there was no significant treatment effect differences in BNP concentration, which changed from a mean of 164 pg/ml (SD 125 pg/ml) to a mean of 179 pg/ml (SD 171 pg/ml) in the spironolactone group and from a mean of 183 pg/ml (SD 169 pg/ml) to a mean of 186 pg/ml (SD 110 pg/ml) in the placebo group (treatment effect 4.95 pg/ml, 95% CI –28.26 to 38.16 pg/ml; p = 0.77). The study treatment was also not associated with significant treatment effect for quality-of-life scores (a p-value of 0.77 for the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire and a p-value of 0.84 for the MLWHF questionnaire) (see Table 6). The findings remained consistent after additional adjustment of age, sex and BMI for all outcomes.

| Analyses | End point | Trial arm | Treatment effect (95% CI)b | p-valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spironolactone | Placebo | ||||||

| Mean (SD)a | n | Mean (SD)a | n | ||||

| Primary analysis (adjusted for stratification variable) | |||||||

| 6MWT (metres) | 24 monthsc | 312.90 (108.12) | 105 | 330.43 (112.16) | 107 | –8.47 (–31.87 to 14.93) | 0.48 |

| LV diastolic function as measured by the E/E′ ratio | 24 months | 9.00 (3.05) | 101 | 9.72 (3.57) | 106 | –0.68 (–1.52 to 0.17) | 0.12 |

| BNP concentration (pg/ml) | 24 months | 179.43 (170.55) | 101 | 185.61 (109.65) | 105 | 4.95 (–28.26 to 38.16) | 0.77 |

| EQ-5D-5L | 12 monthsd | 0.83 (0.21) | 106 | 0.84 (0.18) | 111 | –0.009 (–0.049 to 0.032) | 0.67 |

| 24 monthsd | 0.82 (0.24) | 98 | 0.84 (0.20) | 104 | –0.007 (–0.051 to 0.038) | 0.77 | |

| MLWHFe | 12 monthsf | 18.44 (20.89) | 101 | 16.90 (17.76) | 110 | 1.24 (–2.48 to 4.96) | 0.51 |

| 24 monthsf | 17.39 (22.72) | 96 | 15.34 (20.35) | 104 | 0.49 (–4.32 to 5.29) | 0.84 | |

| Secondary analysis (additionally adjusted for age, sex and BMI) | |||||||

| 6MWT (metres) | 24 monthsc | 312.90 (108.12) | 105 | 331.13 (112.46) | 106 | –8.30 (–31.89 to 15.28) | 0.49 |

| LV diastolic function as measured by the E/E′ ratio | 24 months | 9.00 (3.05) | 101 | 9.69 (3.57) | 105 | –0.64 (–1.48 to 0.20) | 0.13 |

| BNP concentration (pg/ml) | 24 months | 179.43 (170.55) | 101 | 187.13 (109.06) | 104 | 4.37 (–28.53 to 37.28) | 0.79 |

| EQ-5D-5L | 12 monthsd | 0.83 (0.21) | 106 | 0.85 (0.18) | 109 | –0.006 (–0.047 to 0.034) | 0.75 |

| 24 monthsd | 0.82 (0.24) | 98 | 0.84 (0.20) | 103 | –0.004 (–0.049 to 0.041) | 0.88 | |

| MLWHFe | 12 monthsf | 18.44 (20.89) | 101 | 16.29 (17.32) | 108 | 1.35 (–2.40 to 5.10) | 0.48 |

| 24 monthsf | 17.39 (22.72) | 96 | 15.29 (20.44) | 103 | 0.27 (–4.60 to 5.14) | 0.91 | |

Spontaneous return to sinus rhythm as demonstrated by ECG performed after 2 years of treatment was uncommon in both study groups [four participants (3.8%) in the placebo group and eight participants (7.9%) in the spironolactone group; p = 0.21] (Table 7). Further adjustment for log-transformed BNP level at baseline made little difference.

| Analyses | Trial arm | Odds ratio (95% CI)a | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spironolactone | Placebo | |||

| Primary analysis (adjusted for stratification variable) | ||||

| Total (n) | 101 | 106 | 2.19 (0.64 to 7.52) | 0.21 |

| Yes,b n (%) | 8 (7.9) | 4 (3.8) | ||

| No, n (%) | 93 (92.1) | 102 (96.2) | ||

| Secondary analysis (additionally adjusted for the log-transformed BNP level at baseline) | ||||

| Total (n) | 101 | 105 | 2.15 (0.63 to 7.38) | 0.23 |

| Yes,b n (%) | 8 (7.9) | 4 (3.8) | ||

| No, n (%) | 93 (92.1) | 101 (96.2) | ||

| Secondary analysis (additionally adjusted for age, sex and BMI) | ||||

| Total (n) | 101 | 105 | 2.14 (0.62 to 7.35) | 0.23 |

| Yes,b n (%) | 8 (7.9) | 4 (3.8) | ||

| No, n (%) | 93 (92.1) | 101 (96.2) | ||

| Secondary analysis (additionally adjusted for the log-transformed BNP level at baseline, age, sex and BMI) | ||||

| Total (n) | 101 | 104 | 2.09 (0.61 to 7.20) | 0.24 |

| Yes,b n (%) | 8 (7.9) | 4 (3.9) | ||

| No, n (%) | 93 (92.1) | 100 (96.2) | ||

Other outcomes

At least one hospitalisation for any reason was observed in 15.3% of patients in the spironolactone group and 22.8% in the placebo group (p = 0.15; p = 0.12 after adjustment for age, sex and BMI) (Table 8 and Figure 2). Three patients were admitted more than once (Table 9). There was no significant difference in overall mortality, death from cardiac causes, hospitalisations due to cardiac causes, and rates of stroke and systemic thromboembolism between the trial arms (Table 10).

| Analyses | Trial arm | Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | p-valuea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spironolactone | Placebo | |||||||

| n | Participants with at least one event, n (%) | Incidence rate (number per 10,000 person-days) | n | Participants with at least one event, n (%) | Incidence rate (number per 10,000 person-days) | |||

| Primary analysis (adjusted for stratification variable) | ||||||||

| Hospitalisation for all causes | 118 | 18b (15.3) | 2.46 | 123 | 28 (22.8) | 3.78 | 0.65 (0.36 to 1.17) | 0.15 |

| Secondary analysis (additionally adjusted for age, sex and BMI) | ||||||||

| Hospitalisation for all causes | 118 | 18b (15.3) | 2.46 | 121 | 27c (22.3) | 3.69 | 0.62 (0.34 to 1.14) | 0.12 |

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot of time to first hospitalisation.

| Number of hospitalisations | Trial arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Spironolactone (n = 125) | Placebo (n = 125) | |

| None | 106 (84.8) | 97 (77.6) |

| One | 17 (13.6) | 22 (17.6) |

| Two | 1 (0.8) | 5 (4.0) |

| Three | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Four | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) |

| AEs/SAEs | Trial arm | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spironolactone (n = 125) | Placebo (n = 125) | ||

| All SAEs | |||

| Total number of patients experiencing at least one SAE, n (%) | 23 (18.4) | 32 (25.6) | |

| Total number of SAEs | 27 | 42 | |

| Prespecified major adverse clinical events (SAEs), n (%) | (n = 121c) | (n = 123c) | |

| Death from all causes | 5 (4.1) | 3 (2.4) | 0.50 |

| Death from cardiac causes | 5d (4.1) | 1 (0.8) | 0.12 |

| Hospitalisation for cardiac causes | 2 (1.7) | 6e (4.9) | 0.28 |

| Stroke | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 0.50 |

| Systemic thromboembolism | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| Prespecified safety outcomes (AEs) , n (%) | |||

| Number of patients experiencing at least one episode | |||

| Breast pain | 17 (13.6) | 5 (4.0) | |

| Breast swelling | 11 (8.8) | 4 (3.2) | |

| Allergic reaction | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hyperkalaemia (≥ 5.1 mmol/l) | 46 (36.8) | 17 (13.6) | |

| Hyperkalaemia (≥ 6.0 mmol/l) | 3 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Serum creatinine level > 220 µmol/l | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| eGFR < 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2 | 8 (6.4) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Total number of episodes | |||

| Breast pain | 40 | 9 | |

| Breast swelling | 26 | 10 | |

| Allergic reaction | 2 | 0 | |

| Hyperkalaemia (≥ 5.1 mmol/l) | 72 | 30 | |

| Hyperkalaemia (≥ 6.0 mmol/l) | 3 | 0 | |

| Serum creatinine level > 220 µmol/l | 1 | 0 | |

| eGFR < 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2 | 8 | 2 | |

Compliance with the allocated treatment with at least 80% of capsules taken was recorded in 58 (46.4%) participants in the spironolactone group and 80 (64.0%) in the placebo group. Among patients randomised to the spironolactone group systolic blood pressure fell by –7.2 mmHg (95% CI –12.3 to –2.2 mmHg) after 2 years of treatment, whereas there was almost no change in blood pressure in the placebo group (Table 11 and Appendix 2). There was no significant treatment effect for diastolic blood pressure. Spironolactone increased serum creatinine levels by 6.9 µmol/l (95% CI 3.4 to 10.5 µmol/l) and lowered eGFR by 6 ml/minute/1.73 m2 (95% CI –9.3 to –2.8 ml/minute/1.73 m2) after 2 years’ treatment. Deviations from the study protocol are reported in Appendix 3.

| Changes in clinical characteristics | Trial arm | Mean difference (95% CI)a | p-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spironolactone | Placebo | |||||

| Mean (SD) | n (%) | Mean (SD) | n (%) | |||

| Exploratory outcomes (changes in clinical characteristics) | ||||||

| Serum creatinine (µmol/l) | ||||||

| Baseline | 90.20 (23.45) | 125 (100) | 90.20 (20.22) | 125 (100) | ||

| 24 months | 98.95 (23.30) | 101 (80.8) | 91.64 (21.47) | 106 (84.8) | ||

| Change from baseline to 24 months | 8.88 (13.75) | 101 (80.8) | 1.96 (12.14) | 106 (84.8) | 6.92 (3.37 to 10.47) | 0.0002 |

| eGFR (ml/minute/1.73 m2) | ||||||

| Baseline | 70.25 (16.40) | 125 (100) | 68.55 (16.64) | 125 (100) | ||

| 24 months | 63.59 (15.13) | 101 (80.8) | 68.61 (13.98) | 106 (84.8) | ||

| Change from baseline to 24 months | –6.82 (11.34) | 101 (80.8) | –0.80 (12.32) | 106 (84.8) | –6.02 (–9.27 to –2.77) | 0.0003 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||||

| Baseline | 129.16 (15.54) | 125 (100) | 130.06 (15.02) | 124 (99.2) | ||

| 24 months | 122.98 (18.21) | 101 (80.8) | 129.94 (16.07) | 106 (84.8) | ||

| Change from baseline to 24 months | –6.66 (19.75) | 101 (80.8) | 0.55 (17.01) | 105 (84.0) | –7.22 (–12.27 to –2.16) | 0.005 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||||

| Baseline | 75.72 (10.91) | 125 (100) | 75.59 (13.94) | 124 (99.2) | ||

| 24 months | 71.82 (11.06) | 101 (80.8) | 74.09 (11.54) | 106 (84.8) | ||

| Change from baseline to 24 months | –3.90 (12.21) | 101 (80.8) | –1.32 (14.39) | 105 (84.0) | –2.58 (–6.325 to 1.09) | 0.17 |

Chapter 4 Discussion

The principal finding was that treatment with spironolactone does not improve either physical capacity or quality of life in this cohort of stable patients with permanent AF without systolic dysfunction. Given that there was no trend towards improvement in exercise tolerance or quality of life, it is unlikely that a larger study size would change the outcome if the same populations were studied.

It needs to be considered that the study aimed to be generalisable to the wider population of patients with AF. The inclusion criteria did not mandate evidence of HF and participants had a mean ejection fraction of 60%. In addition, the participants were not mandated to have echocardiographic evidence of diastolic dysfunction, as patients with AF have intrinsic diastolic dysfunction. As a result, the mean E/E′ ratio in the study patients was < 10, thus pointing towards the milder spectrum of diastolic dysfunction defined by echocardiographic parameters. Given the above considerations, it is possible that aldosterone receptor inhibition may still have potential in selected patients with advanced HFpEF or in unstable patients.

Atrial fibrillation has a prominent role in prognostication in HF. In the Candesartan in Heart failure–Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) programme, AF was associated with increased risk of death or hospitalisation for worsening HFpEF (hazard ratio 1.72). 6 Clinical trials of aldosterone antagonists [e.g. RALES, Eplerenone Post–Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study (EPHESUS), Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure (EMPHASIS-HF)] uniformly show clinical benefit in systolic HF. 48–50 However, there is no established treatment for patients with AF with HFpEF. Currently there is no established treatment to improve HF-related outcomes in AF, and the IMPRESS-AF study has not improved the assessed outcomes in AF patients without systolic impairment.

Although there were numerically more cases of spontaneous return to sinus rhythm in the spironolactone group, such patients were few in both trial arms; the difference was not significant statistically and could therefore be a chance finding. Patients in the spironolactone group had one-third fewer hospitalisations for any reason, but the study was not powered to accurately assess this outcome. However, even if the difference was significant in a bigger study, use of spironolactone would be difficult to justify in view of its detrimental effects on renal function. Hospitalisations for cardiac cause were few in both trial groups, although the number of such cases was smaller in the spironolactone group.

Our findings generally agree with the results of the ALDO-DHF21 and TOPCAT22 trials, which did not demonstrate obvious clinical benefits of aldosterone antagonism in patients with HFpEF, mainly secondary to hypertension. In the IMPRESS-AF trial, positive effects were not found on any of the secondary outcomes despite a clear reduction in systolic blood pressure. This contrasts with clearly positive effects of the treatment in patients with systolic HF.

The study planning was based on expectations that spironolactone would improve exercise tolerance by inhibition and possible reversal of excessive cardiac fibrosis. According to a substudy of RALES, the improved survival in participants treated with spironolactone was linked to the ability of spironolactone to reduce serum markers of ongoing fibrosis (i.e. type I and III collagen synthesis). 34 In addition, aldosterone leads to cardiac invasion by proinflammatory mononuclear cells. 51 Aldosterone antagonists (i.e. spironolactone or eplerenone) ameliorate left ventricular fibrosis in animal models and reduce levels of serum markers of collagen turnover in humans with HFpEF (n = 44). 52,53 However, the antifibrotic effects of spironolactone seen in systolic HF did not translate into similar benefits in the IMPRESS-AF trial population.

Overall, spironolactone was well tolerated in according to its known profile of side effects and there were comparable rates of withdrawal from the study in the treatment and control trial groups. As expected, spironolactone reduced blood pressure, thus demonstrating adequate overall compliance with the drug as confirmed by the expected effect. However, there is a safety signal as there was a highly significant reduction of 6 ml/kg/1.73 m2 in eGFR over 2 years of treatment. These data indicate potential harm from treating patients with AF with spironolactone and this needs to be considered and monitored if starting spironolactone in this population.

Limitations

The IMPRESS-AF trial did not mandate evidence of congestive HF and, given the need for exercise testing, it is possible that more fit patients were more likely to respond to the invitation. Although a large proportion of the study patients were recruited from primary care, improving generalisability of the results, patients unfamiliar with cycling were less likely to respond, which might have contributed to the higher proportion of male responders.

The study outcomes were assessed by tests of physical capacity, but these tests could be inherently affected by various musculoskeletal problems despite every effort to perform the tests until the limits of the cardiac reserve are reached. Although recognised questionnaires were used to assess quality of life, the tests were not specifically validated in patients with HFpEF.

Overall, 16% of participants did not complete the primary outcome tests and a proportion of patients did not adhere to the trial treatment, for example because of poor tolerance of the study drug. However, the study was powered to allow an estimated loss to follow-up of 20% of participants, and, therefore, the validity of the findings is likely to be maintained.

Recommendations for research

The trial did not have power to reliably define effects of spironolactone in patients with the most severe forms of HFpEF. However, given the significant detrimental effects of the drug in this trial population, further testing of spironolactone in patients with more advanced disease would be difficult to justify.

Chapter 5 Conclusions

Treatment of patients with AF and preserved ejection fraction with the aldosterone antagonist spironolactone does not improve exercise tolerance. The treatment also failed to improve quality of life and diastolic function in the tested population. Furthermore, spironolactone led to significant worsening of renal function, which may need to be considered if it is used in this patient population. The differences observed in the primary and key secondary outcomes reached neither statistical nor clinical significance and, since it was a well-powered trial, further RCTs of spironolactone in this patient population are not warranted.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the members of the Trial Steering Committee [Professor Diana Adrienne Gorog (chairperson), Dr Andrew Appelboam and Dr Sajjad Sarwar]; the members of the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (Dr Derick Todd, Dr Paul Ewings and Mr Norman Paul Briffa); the members of the Trial Management Team in City Hospital, Birmingham, UK; and the team of staff from the BCTU, who managed the trial.

Contributions of authors

Eduard Shantsila (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2429-6980) was involved in study design and data collection, wrote the first draft of the report and was involved in the editing of the manuscript.

Farhan Shahid (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7635-5703) and was involved in data collection and editing of the manuscript.

Yongzhong Sun and Jonathan J Deeks (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8850-1971) performed statistical analysis and edited the manuscript.

Ronnie Haynes (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1935-1420) was involved in data collection and editing of the manuscript.

Melanie Calvert (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1856-837X), James P Fisher (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7851-9222), Paulus Kirchhof, Paramjit S Gill (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8756-6813) and Gregory YH Lip (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7566-1626) were involved in study design and edited the manuscript.

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to anonymised data may be granted following review.

Patient data

This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. Using patient data is vital to improve health and care for everyone. There is huge potential to make better use of information from people’s patient records, to understand more about disease, develop new treatments, monitor safety, and plan NHS services. Patient data should be kept safe and secure, to protect everyone’s privacy, and it’s important that there are safeguards to make sure that it is stored and used responsibly. Everyone should be able to find out about how patient data are used. #datasaveslives You can find out more about the background to this citation here: https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/data-citation.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research. The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, the MRC, NETSCC, the EME programme or the Department of Health and Social Care. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the EME programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- Santhanakrishnan R, Wang N, Larson MG, Magnani JW, McManus DD, Lubitz SA, et al. Atrial fibrillation begets heart failure and vice versa: temporal associations and differences in preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. Circulation 2016;133:484-92. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018614.

- Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, et al. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:768-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.064.

- Paulus WJ, van Ballegoij JJ. Treatment of heart failure with normal ejection fraction: an inconvenient truth!. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:526-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.067.

- Senni M, Paulus WJ, Gavazzi A, Fraser AG, Díez J, Solomon SD, et al. New strategies for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the importance of targeted therapies for heart failure phenotypes. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2797-815. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehu204.

- Linssen GC, Rienstra M, Jaarsma T, Voors AA, van Gelder IC, Hillege HL, et al. Clinical and prognostic effects of atrial fibrillation in heart failure patients with reduced and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:1111-20. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfr066.

- Olsson LG, Swedberg K, Ducharme A, Granger CB, Michelson EL, McMurray JJ, et al. Atrial fibrillation and risk of clinical events in chronic heart failure with and without left ventricular systolic dysfunction: results from the Candesartan in Heart failure–Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:1997-2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.060.

- McKelvie RS, Komajda M, McMurray J, Zile M, Ptaszynska A, Donovan M, et al. Baseline plasma NT-proBNP and clinical characteristics: results from the irbesartan in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction trial. J Card Fail 2010;16:128-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.09.007.

- Fung JW, Sanderson JE, Yip GW, Zhang Q, Yu CM. Impact of atrial fibrillation in heart failure with normal ejection fraction: a clinical and echocardiographic study. J Card Fail 2007;13:649-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.04.014.

- Dzeshka MS, Lip GY, Snezhitskiy V, Shantsila E. Cardiac fibrosis in patients with atrial fibrillation: mechanisms and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:943-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1313.

- Normand C, Kaye DM, Povsic TJ, Dickstein K. Beyond pharmacological treatment: an insight into therapies that target specific aspects of heart failure pathophysiology. Lancet 2019;393:1045-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32216-5.

- Zile MR, Baicu CF, Gaasch WH. Diastolic heart failure – abnormalities in active relaxation and passive stiffness of the left ventricle. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1953-9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa032566.

- McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1787-847. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104.

- Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Borlaug BA, Rodeheffer RJ, Kass DA. Age- and gender-related ventricular-vascular stiffening: a community-based study. Circulation 2005;112:2254-62. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.541078.

- Lam CS, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Bursi F, Borlaug BA, Ommen SR, et al. Cardiac structure and ventricular-vascular function in persons with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Circulation 2007;115:1982-90. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659763.

- Westermann D, Kasner M, Steendijk P, Spillmann F, Riad A, Weitmann K, et al. Role of left ventricular stiffness in heart failure with normal ejection fraction. Circulation 2008;117:2051-60. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.716886.

- Kitzman DW, Higginbotham MB, Cobb FR, Sheikh KH, Sullivan MJ. Exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure and preserved left ventricular systolic function: failure of the Frank–Starling mechanism. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;17:1065-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/0735-1097(91)90832-T.

- Weber KT. Aldosterone in congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1689-97. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra000050.

- Burniston JG, Saini A, Tan LB, Goldspink DF. Aldosterone induces myocyte apoptosis in the heart and skeletal muscles of rats in vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2005;39:395-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.04.001.

- Brilla CG, Zhou G, Matsubara L, Weber KT. Collagen metabolism in cultured adult rat cardiac fibroblasts: response to angiotensin II and aldosterone. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1994;26:809-20. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmcc.1994.1098.

- Tsai CT, Chiang FT, Tseng CD, Hwang JJ, Kuo KT, Wu CK, et al. Increased expression of mineralocorticoid receptor in human atrial fibrillation and a cellular model of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:758-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.045.

- Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt AG, Kraigher-Krainer E, Colantonio C, Kamke W, et al. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Aldo-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2013;309:781-91. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.905.

- Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Claggett B, et al. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1383-92. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1313731.

- Kyte D, Duffy H, Fletcher B, Gheorghe A, Mercieca-Bebber R, King M, et al. Systematic evaluation of the patient-reported outcome (PRO) content of clinical trial protocols. PLOS ONE 2014;9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110229.

- Calvert M, Kyte D, Duffy H, Gheorghe A, Mercieca-Bebber R, Ives J, et al. Patient-reported outcome (PRO) assessment in clinical trials: a systematic review of guidance for trial protocol writers. PLOS ONE 2014;9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110216.

- Calvert M, Kyte D, von Hildebrand M, King M, Moher D. Putting patients at the heart of health-care research. Lancet 2015;385:1073-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60599-2.

- Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SH, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2719-47. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253.

- Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2010;31:2369-429. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278.

- Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification. Eur J Echocardiogr 2006;7:79-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euje.2005.12.014.

- Rector TS, Carson PE, Anand IS, McMurray JJ, Zile MR, McKelvie RS, et al. Assessment of long-term effects of irbesartan on heart failure with preserved ejection fraction as measured by the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire in the Irbesartan in heart failure with preserved systolic function (I-PRESERVE) trial. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:217-25. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.964221.

- Rector TS, Kubo SH, Cohn JN. Validity of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire as a measure of therapeutic response to enalapril or placebo. Am J Cardiol 1993;71:1106-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(93)90582-W.

- Rector TS, Cohn JN. Assessment of patient outcome with the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire: reliability and validity during a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pimobendan. Am Heart J 1992;124:1017-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-8703(92)90986-6.

- Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996;37:53-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6.

- Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 2001;33:337-43. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890109002087.

- Zannad F, Alla F, Dousset B, Perez A, Pitt B. Limitation of excessive extracellular matrix turnover may contribute to survival benefit of spironolactone therapy in patients with congestive heart failure: insights from the randomized aldactone evaluation study (RALES). Rales Investigators. Circulation 2000;102:2700-6. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.102.22.2700.

- Sohn DW, Song JM, Zo JH, Chai IH, Kim HS, Chun HG, et al. Mitral annulus velocity in the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function in atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1999;12:927-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0894-7317(99)70145-8.

- Kusunose K, Yamada H, Nishio S, Tomita N, Niki T, Yamaguchi K, et al. Clinical utility of single-beat E/E′ obtained by simultaneous recording of flow and tissue Doppler velocities in atrial fibrillation with preserved systolic function. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:1147-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.05.013.

- Aljaroudi W, Alraies MC, Halley C, Rodriguez L, Grimm RA, Thomas JD, et al. Impact of progression of diastolic dysfunction on mortality in patients with normal ejection fraction. Circulation 2012;125:782-8. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066423.

- Nagueh SF, Kopelen HA, Quiñones MA. Assessment of left ventricular filling pressures by Doppler in the presence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 1996;94:2138-45. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.94.9.2138.

- Temporelli PL, Scapellato F, Corrà U, Eleuteri E, Imparato A, Giannuzzi P. Estimation of pulmonary wedge pressure by transmitral Doppler in patients with chronic heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 1999;83:724-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00978-3.

- Chirillo F, Brunazzi MC, Barbiero M, Giavarina D, Pasqualini M, Franceschini-Grisolia E, et al. Estimating mean pulmonary wedge pressure in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation from transthoracic Doppler indexes of mitral and pulmonary venous flow velocity. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30:19-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00130-7.

- Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2016;29:277-314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2016.01.011.

- Little RJA. Missing-data adjustments in large surveys. J Business Economic Statistics 1988;6:287-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.1988.10509663.

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1987.

- Cicoira M, Zanolla L, Rossi A, Golia G, Franceschini L, Brighetti G, et al. Long-term, dose-dependent effects of spironolactone on left ventricular function and exercise tolerance in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:304-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01965-4.

- Shafiq A, Brawner CA, Aldred HA, Lewis B, Williams CT, Tita C, et al. Prognostic value of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. The Henry Ford HospITal CardioPulmonary EXercise Testing (FIT-CPX) project. Am Heart J 2016;174:167-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2015.12.020.

- Edelmann F, Gelbrich G, Düngen HD, Fröhling S, Wachter R, Stahrenberg R, et al. Exercise training improves exercise capacity and diastolic function in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: results of the Ex-DHF (Exercise training in Diastolic Heart Failure) pilot study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1780-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.054.

- Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG, Revicki DA, Moher D, Brundage MD. CONSORT PRO Group . Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA 2013;309:814-22. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.879.

- Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. N Engl J Med 1999;341:709-17. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199909023411001.

- Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, Neaton J, Martinez F, Roniker B, et al. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1309-21. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa030207.

- Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, van Veldhuisen DJ, Swedberg K, Shi H, et al. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 2011;364:11-2. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1009492.

- Weber KT. The proinflammatory heart failure phenotype: a case of integrative physiology. Am J Med Sci 2005;330:219-26. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-200511000-00004.

- Endemann DH, Touyz RM, Iglarz M, Savoia C, Schiffrin EL. Eplerenone prevents salt-induced vascular remodeling and cardiac fibrosis in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 2004;43:1252-7. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000128031.31572.a3.

- Deswal A, Richardson P, Bozkurt B, Mann DL. Results of the Randomized Aldosterone Antagonism in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction trial (RAAM-PEF). J Card Fail 2011;17:634-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.04.007.

Appendix 1 Characteristics of those patients included in the primary analysis compared with those randomised

| Baseline characteristics | Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All randomised | Only those who contributed to the primary outcome | |||||

| Trial arm | Overall (N = 250) | Trial arm | Overall (N = 209) | |||

| Spironolactone (N = 125) | Placebo (N = 125) | Spironolactone (N = 103) | Placebo (N = 106) | |||

| Minimisation variables | ||||||

| Peak VO2 (ml/minute/kg)a | ||||||

| ≤ 16 ml, n (%) | 77 (61.6) | 78 (62.4) | 155 (62.0) | 60 (58.3) | 63 (59.4) | 123 (58.9) |

| > 16 ml, n (%) | 48 (38.4) | 47 (37.6) | 95 (38.0) | 43 (41.7) | 43 (40.6) | 86 (41.1) |

| Mean (SD) | 14.5 (4.6) | 14.6 (5.1) | 14.5 (4.8) | 14.9 (4.6) | 15.1 (5) | 15 (4.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 13.9 (10.8–18.3) | 14.4 (10.8–17.5) | 14.1 (10.8–17.8) | 14.5 (11.3–18.8) | 14.6 (11.1–17.9) | 14.5 (11.3–18.3) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Demographic and other baseline variables | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||