Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 13/121/07. The contractual start date was in February 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2019 and was accepted for publication in December 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Miras et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

At least 11 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that bariatric surgery, and, in particular, the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), is substantially more effective than intensive medical care for the treatment of the hyperglycaemia of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). 1,2 The effects of surgery are so profound that approximately 50% of patients achieve ‘diabetes mellitus remission’, (i.e. euglycaemia) in the absence of glucose-lowering medications. 3

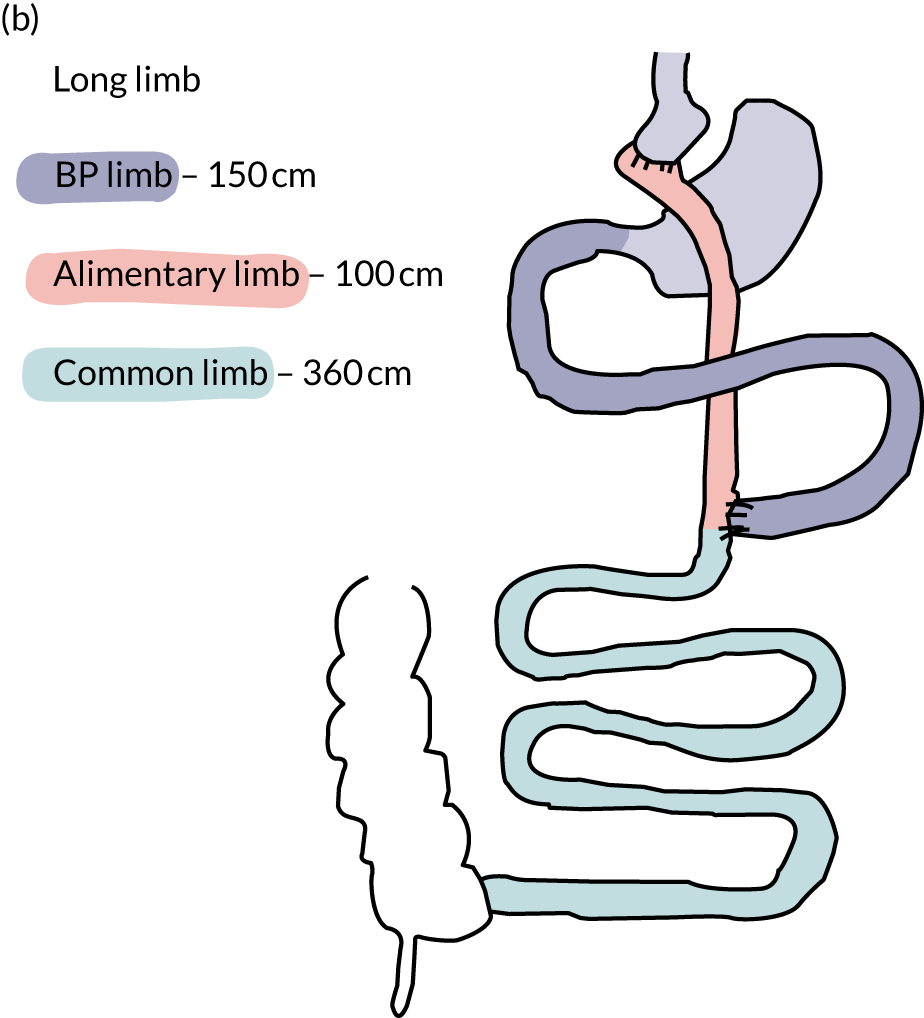

The anatomical rearrangements of RYGB result in three intestinal segments or ‘limbs’: the ‘alimentary limb’, through which food enters the small intestine; the ‘biliopancreatic limb’, which includes the bypassed segments of duodenum and proximal jejunum, through which the biliopancreatic secretions flow; and the ‘common limb’, in which food and biliopancreatic secretions mix (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic drawing of the standard limb and the long limb RYGB. a, Standard limb; b, long limb. BP limb, biliopancreatic limb. Reprinted with permission from The American Diabetes Association. Copyright 2020 by the American Diabetes Association. 4

The profound improvements in glucose control after RYGB have led to the recognition of the intestine as an organ with a major impact on glucose regulation. Thus, surgeons have experimented with different intestinal limb lengths to enhance the clinical effect of RYGB. However, the optimal length of each of these limbs remains controversial, with substantial variation in practice. The reason underlying this inconsistent clinical practice is that the physiological role of each of the limbs in glucose regulation has until recently been unclear. Indeed, it is challenging to determine the precise physiological impact of each of these intestinal segments because changes in the length of one will invariably result in the change in the length of the others. The matter is complicated further by the variability in the total length of the human small intestine. 5

Although many of the benefits of RYGB on glucose control can be attributed to weight loss, both early and longer-term substantial improvements in glycaemia also take place independently. This has led to the concept of ‘metabolic surgery’. 6,7 Human and rodent studies suggest that the bypass of the proximal intestine might be the component of RYGB underlying, at least in part, its weight loss-independent effects on glucose regulation. 8 Beta cell function and early postprandial release of insulin are enhanced after RYGB. 9 The prevailing view is that the dominant mechanism underlying this observation is the early and enhanced secretion of the incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP–1). 10 It is thought that the rapid delivery of nutrients to the enteroendocrine cells (EECs) of the distal small intestine triggers the exaggerated release of GLP-1 within the gut and the circulation. 11 At the same time, the simultaneous postprandial release of other hormones from the EECs, such as peptide YY (PYY) and oxyntomodulin, leads to synergistic effects on increased satiety and, perhaps, increased energy expenditure. 12,13

Hypothesis

The aim was to address the gap in knowledge with regard to the optimal lengths of the RYGB limbs through the understanding of the physiology of glucose regulation after surgery. Therefore, a reductionist approach was applied to examine the effects of a longer biliopancreatic limb on glucose control in this double-blind, mechanistic RCT. It was hypothesised that a long biliopancreatic limb RYGB would enable an even faster delivery of undigested nutrients to the distal small intestine, resulting in an even greater release of GLP-1 and insulin, than a ‘standard’ biliopancreatic limb RYGB.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

This was a prospective, randomised, double-blind RCT. Fifty-three patients with T2DM and obesity due to undergo RYGB surgery were recruited from the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust by the clinical and the research team and randomised at a ratio of 1 : 1 to either a 150-cm (long limb) or a 50-cm (standard limb) RYGB while keeping the alimentary limb constant at 100 cm (see Figure 1). Both the patient and the clinical/research teams (except the operating surgeon) were blinded to treatment disposition. Participants were randomised to either long limb or standard limb RYGB surgery in a 1 : 1 ratio using an online randomisation program (www.randomisation.com; accessed 1 July 2015) by Dr Victoria Salem, who was not otherwise involved in the trial. No stratification variables were used.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Key inclusion criteria were aged 18–70 years, a diagnosis of T2DM treated with at least one glucose-lowering medication, a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2 and eligible for metabolic surgery based on the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Clinical Guideline Number 189. 14 Key exclusion criteria were any surgical, medical or psychological contraindications to metabolic surgery, pregnancy and currently breastfeeding.

Ethics approval

The trial was approved by the West London Research Ethics Committee (reference number 15/LO/0813) and registered in the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial registry (as ISRCTN 15283219). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to participation in the trial.

Intervention and follow-up

Patients were assessed by the multidisciplinary clinical team as part of routine NHS care preoperatively and at 2 weeks, and 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery, unless clinical need dictated more frequent consultations. Operations were performed laparoscopically by four surgeons, who followed a standard operating protocol agreed before the trial commenced (see Appendix 1). The procedures were filmed to enable independent assessment of the consistency of the surgical technique among the operating surgeons. The total length of the small intestine was measured from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocaecal valve. This was performed using set distance markers on laparoscopic graspers, running the bowel segment by segment along the antimesenteric border. The management of glucose-lowering medications was performed by a single consultant diabetologist (ADM), who was blind to treatment allocation. Glucose-lowering medications were discontinued during the course of the 12-month follow-up depending on glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) concentrations and capillary glucose measurements, and when clinically safe. Glycaemic remission was defined based on a variation of the American Diabetes Association’s criteria15 as an HbA1c concentration < 48 mmol/mol and fasting glucose level of < 5.6 mmol/l in the absence of glucose-lowering medication for a minimum of 12 months. Micronutrient supplementation was based on the British Obesity & Metabolic Surgery Society’s guidance. 16

Mechanistic visits

Mechanistic assessments took place at three time points: preoperatively, at 2 weeks after surgery to examine the effects of the interventions before substantial weight loss has taken place and when 20% of weight loss was achieved in order to remove weight loss as a confounding variable. Five days prior to the mechanistic visits, all glucose-lowering medications were discontinued and intermediate-acting insulin used as ‘rescue’ treatment if necessary. Patients were asked to refrain from consuming alcohol and strenuous physical activity for 48 hours before the visit. The patients were admitted to the Imperial College London or King’s College London National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) clinical research facilities in the evening and consumed a standardised meal. The next morning the patients underwent a two-stage hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp with the stable isotope [6,6-2H2]glucose using a validated protocol. 17 Stage 1 consisted of an insulin infusion at 0.5 mU/kg/minute (low dose) for 120 minutes to measure hepatic insulin sensitivity based on endogenous glucose production; and stage 2 consisted of an insulin infusion at 1.5 mU/kg/minute (high dose) for 120 minutes to measure peripheral insulin sensitivity based on glucose uptake. On the morning of the third, and final, day of their visit the patients underwent a mixed-meal tolerance test. Blood samples were obtained before and at 180 minutes following a liquid meal [Ensure® Compact (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA), 300 kcal in 125 ml].

Trial outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of this trial was postprandial peak of active GLP-1 concentration at 2 weeks after intervention.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes of this trial were:

-

fasting and postprandial glucose and insulin concentrations in the mixed-meal tolerance test and insulin sensitivity in the hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp at 2 weeks after the surgery and at the 20% total body weight loss time point

-

glycaemic control

-

weight loss at 12 months after surgery

-

safety of participants

-

intra- and perioperative outcomes.

The complete LONG LIMB trial protocol can be accessed an the NIHR project web page [www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/eme/1312107 (accessed 1 February 2019)].

Sample analysis

Plasma and serum samples were stored at –80 °C until further analysis. Glucose was measured on the ARCHITECT ci8200 (Abbott Laboratories) platform using a hexokinase method. Insulin was measured using the ARCHITECT i2000SR (Abbott Laboratories) immunoassay. GLP-1, PYY and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) were measured using the MAGPIX® (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX, USA) assay. Glucose isotopic enrichment was measured by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry on a HP 5971 A mass selective detector (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Rates of glucose appearance (Ra) and disappearance (Rd) from plasma were calculated using non-steady-state equations proposed by Steele et al. 18 and modified for stable isotopes.

Sample size calculations

The majority of published studies have shown that peak active GLP-1 concentrations are approximately twofold greater after standard limb RYGB,19,20 compared with preoperatively. It was estimated that peak active GLP-1 levels after long limb RYGB will be tripled at 2 weeks after surgery. The trial was powered to detect a minimum clinically significant difference between the groups in mean peak active GLP-1 of 10.0 pmol/l, assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 10.8 pmol/l in each group. With a sample size of 20 completers in each arm, the statistical power was 80% to detect this difference at an alpha of 0.05. Based on the centre’s experience, a predicted 20% dropout rate was predicted; therefore, the recruitment target was 25 patients in each arm.

Statistical analyses

A detailed statistical analysis plan is available in Appendix 2. In summary, continuous variables were summarised using the number of (non-missing) data points, mean and SD if found to follow a normal distribution. Continuous variables not found to be normally distributed were summarised by the number of data points, median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were summarised by the frequency and percentage (based on the non-missing sample size) of values in each category. All the analyses presented in this report were based on the full analysis population, which consisted of patients in the groups to which they were randomised, regardless of deviation from the protocol or whether or not they received the allocated surgery. Patients with completely missing data at the outcome time point were excluded from this data set for the particular outcome for which they had missing data.

The analysis of the primary outcome was performed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). In the analysis, the peak of active GLP-1 concentration at the early mechanistic postoperative visit at 2 weeks was considered as the outcome measure, whereas the baseline peak of active GLP-1 was included as a covariate. The baseline-adjusted differences in outcome values between groups were reported, along with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Secondary outcomes were measured on a continuous scale, with a baseline measurement, and were analysed using a similar approach to that outlined for the primary efficacy outcome. The data from each postoperative time point will be analysed in a separate analysis. For continuous secondary outcomes with no baseline measurement, the two groups were compared using the unpaired t-test. Alternatively, the Mann–Whitney U-test was used if the assumptions of the t-test were not met. Binary and nominal outcomes were compared between the two study groups using either the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test if the number of responses in some categories was low. Ordinal outcomes were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U-test to allow for the natural ordering of the response categories. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of < 0.05. Association between outcomes were performed using Pearson’s correlation. Alternatively, Spearman’s rank-order correlation was used if the Pearson’s correlation assumptions (e.g. non-linear relationship, both variables non-normally distributed) were not met. The data analyses were performed using the statistical software packages Stata® (version 15.1; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism (version 6; GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA).

Public and patient involvement

The research and clinical teams engaged closely and formed an active partnership with the following key contacts during the application process: Ms Georgina Hayman, lead of the British Obesity Surgery Patient Association (BOSPA) west-London branch; and Dr Shamil Chandaria, Patron of the National Obesity Forum, an independent charity supporting patients and health-care professionals.

Ms Danielle Neal, the communications and public and patient involvement (PPI) officer, NIHR North West London, approached the Diabetes Research Network PPI group and asked members the following questions:

-

What are your initial feelings about the research?

-

Do you think the research question is important?

-

What issues do you feel will prevent people from taking part in the study?

-

Do you feel that the treatment and assessment plan will be acceptable to the participants?

This feedback direct from the patient contact influenced the direction of both the clinical trial and the mechanistic studies in this proposal.

All three PPI representatives contributed to the development of the grant application, starting from its design, and to undertaking the research and the choice of research topics, and will help with dissemination of the study findings through their organisations.

During the course of the project Ms Hayman conducted patient support groups every 2 months. These support groups served to support patients following their operations and acted as an avenue for the patient voice to be heard. The Trial Steering Committee and researchers conducting the day-to-day running of the trial obtained feedback from patients and optimised the conduct of the trial to make it more acceptable. Numerous minor and major modifications were made to the way the clinical and mechanistic assessments and follow-up were performed as a result this feedback. This helped the trial immensely with recruitment and retention. Only one patient dropped out of the trial. Patients were so excited about contributing to this important study that many refused to accept the allocated reimbursement at the end of the trial.

Patients did not take part in the data analyses. However, the above patient support groups will be approached to help disseminate the findings of the trial to the local patient and health-care communities. How this will take place practically is currently being decided on. The contribution of patients has been acknowledged in both the report and the draft manuscripts for publication.

Chapter 3 Results

Trial participants

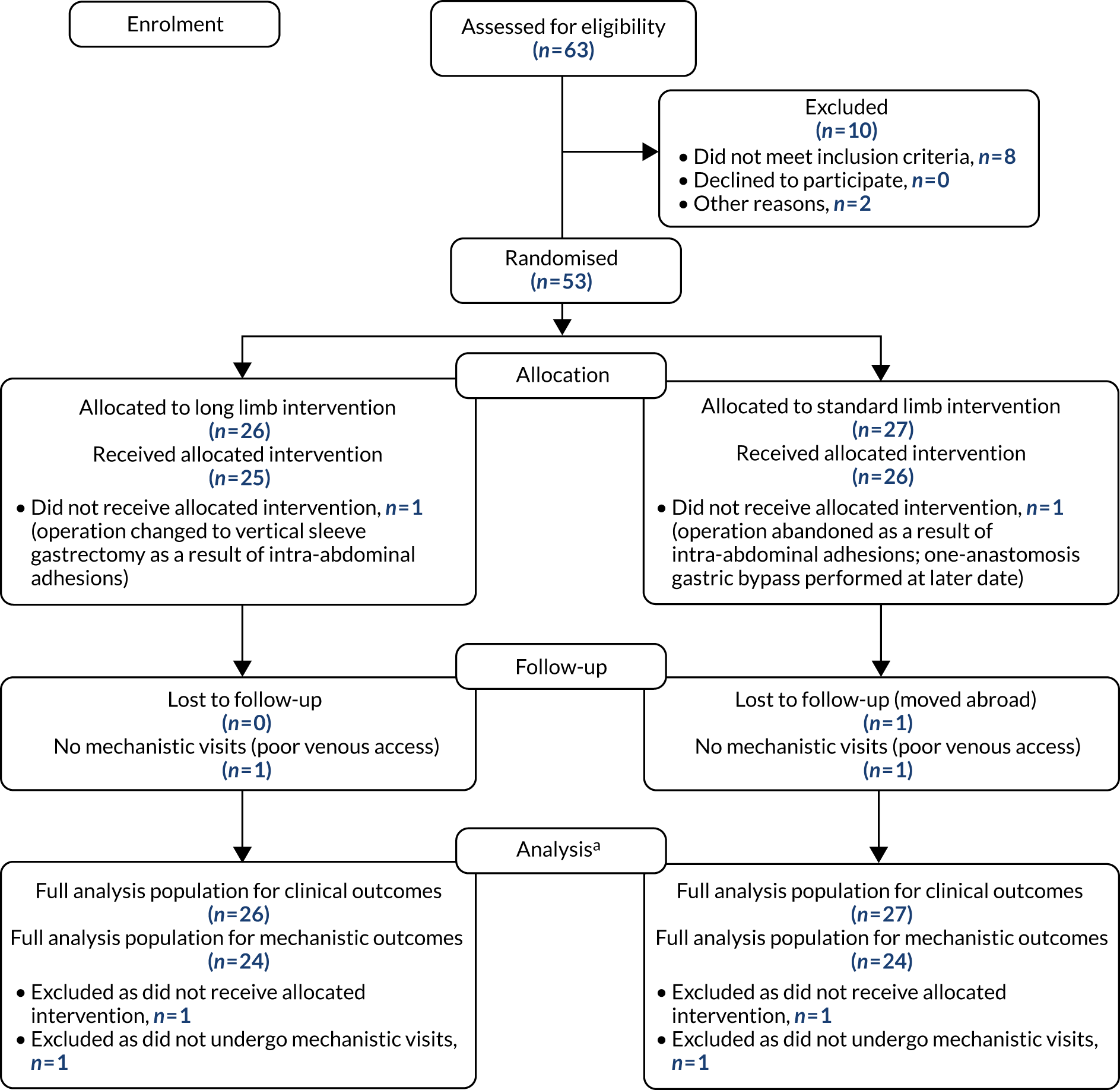

Fifty-three participants were recruited into the study between August 2015 and November 2017. Twenty-seven participants were randomised to standard limb and 26 to long limb RYGB (Figure 2). For anatomical reasons, one patient in the standard limb group underwent a vertical sleeve gastrectomy and one patient in the long limb group underwent a one-anastomosis gastric bypass. The final visit of the last patient took place in December 2018. After dropouts resulting from failure to undergo mechanistic visits and loss to follow-up, 24 participants completed the 12-month mechanistic visit in the long limb group and 24 in the standard limb group.

FIGURE 2.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram. a, For more details on the full analysis population see the statistical analysis plan (in Appendix 2).

Clinical parameters at baseline

Clinical parameters were well balanced between trial groups at baseline (Table 1). The majority of the patients were middle-aged, white, European and female. The mean (SD) BMI was 42 kg/m2 (6 kg/m2) in the standard limb group and 43 kg/m2 (8 kg/m2) in the long limb group. Patients in the standard limb group had a mean HbA1c level of 73 mmol/mol (SD 17 mmol/mol), a median duration of T2DM of 8 years (IQR 6–10 years) and were taking a median number of three (IQR 2–3) glucose-lowering medications (Table 2). Patients in the long limb group had a mean HbA1c level of 76 mmol/mol (SD 16 mmol/mol), a median duration of T2DM of 8 years (SD 6–9 years) and were taking a median of 3 (IQR 2–3) glucose-lowering medications.

| Outcome | Trial group | n | Time point, mean (SD) | Treatment effect (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 months | |||||

| HbA1c (mmol/mol)a | Standard limb | 26 | 71 (15) | 43 (10) | 0 | 0.20 |

| Long limb | 26 | 76 (16) | 41 (5) | –3 (–8 to 2) | ||

| % weight lossb | Standard limb | 26 | – | 30 (8) | 0 | 0.52 |

| Long limb | 26 | – | 29 (8) | –1 (–6 to 3) | ||

| Weight (kg)a | Standard limb | 26 | 117 (18) | 82 (13) | 0 | 0.36 |

| Long limb | 26 | 121 (28) | 87 (24) | 2 (–3 to 8) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2)a | Standard limb | 26 | 41.8 (5.7) | 29.2 (4.9) | 0 | 0.43 |

| Long limb | 26 | 43.4 (7.8) | 31.1 (7.0) | 0.8 (–1.1 to 2.6) | ||

| Circumference (cm)a | ||||||

| Waist | Standard limb | 24 | 129 (12) | 97 (12) | 0 | 0.39 |

| Long limb | 23 | 128 (14) | 99 (16) | 3 (–4 to 9) | ||

| Hip | Standard limb | 24 | 129 (9) | 105 (7) | 0 | 0.16 |

| Long limb | 23 | 134 (17) | 111 (15) | 4 (–1 to 9) | ||

| Neck | Standard limb | 24 | 43.6 (3.7) | 37.1 (4.1) | 0 | 0.87 |

| Long limb | 23 | 43.8 (5.8) | 37.2 (4.8) | –0.1 (–1.7 to 1.4) | ||

| Total body fat (%)a | Standard limb | 21 | 43.1 (6.5) | 26.6 (8.4) | 0 | 0.32 |

| Long limb | 24 | 44.4 (6.4) | 29.8 (9.4) | 1.9 (–1.9 to 5.7) | ||

| Fat-free mass (%)a | Standard limb | 21 | 63 (13) | 55 (9) | 0 | 0.30 |

| Long limb | 24 | 66 (15) | 56 (12) | –1 (–3 to 1) | ||

| Basal metabolic rate (kcal/24 hours)a | Standard limb | 20 | 2026 (401) | 1680 (292) | 0 | 0.72 |

| Long limb | 20 | 2194 (548) | 1832 (418) | 12 (–57 to 82) | ||

| Blood pressure (mmHg)a | ||||||

| Systolic | Standard limb | 26 | 134 (13) | 123 (12) | 0 | 0.43 |

| Long limb | 26 | 135 (14) | 126 (16) | 3 (–5 to 11) | ||

| Diastolic | Standard limb | 26 | 77 (10) | 71 (9) | 0 | 0.03 |

| Long limb | 26 | 78 (10) | 76 (9) | 5 (0 to 10) | ||

| King’s scorea | Standard limb | 25 | 11.1 (3.2) | 5.3 (2.2) | 0 | 0.08 |

| Long limb | 25 | 11.6 (4.0) | 4.7 (2.2) | –0.8 (–1.7 to 0.1) | ||

| HOMA IRa | Standard limb | 25 | 8.1 (5.0) | 1.4 (0.8) | 0 | 0.64 |

| Long limb | 25 | 7.6 (4.4) | 1.3 (0.7) | –0.1 (–0.5 to 0.3) | ||

| Cholesterol concentration (mmol/l)a | ||||||

| Total | Standard limb | 26 | 4.5 (0.9) | 4.0 (0.8) | 0 | 0.88 |

| Long limb | 26 | 4.7 (1.2) | 4.2 (0.9) | 0.0 (–0.4 to 0.5) | ||

| LDL | Standard limb | 26 | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.2 (0.7) | 0 | 0.39 |

| Long limb | 24 | 5.6 (0.9) | 2.5 (0.7) | 0.1 (–0.2 to 0.5) | ||

| HDL | Standard limb | 26 | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.3) | 0 | 0.06 |

| Long limb | 26 | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.2) | –0.1 (–0.2 to 0.0) | ||

| Glucose concentration (mmol/l)a | Standard limb | 25 | 11.2 (3.1) | 5.6 (1.4) | 0 | 0.43 |

| Long limb | 26 | 10.3 (2.7) | 5.4 (0.9) | –0.3 (–0.9 to 0.4) | ||

| Haemoglobin concentration (g/l)a | Standard limb | 26 | 134 (13) | 133 (9) | 0 | 0.27 |

| Long limb | 26 | 131 (16) | 135 (12) | 3 (–2 to 8) | ||

| Iron concentration (µmol/l)a | Standard limb | 23 | 13.4 (4.8) | 17.1 (5.5) | 0 | 0.79 |

| Long limb | 26 | 13.1 (5.1) | 16.5 (6.5) | –0.4 (–3.5 to 2.7) | ||

| Transferrin saturation (%)a | Standard limb | 24 | 19 (8) | 24 (9) | 0 | 0.96 |

| Long limb | 26 | 19 (8) | 24 (10) | 0 (–5 to 5) | ||

| Folate concentration (µg/l)a | Standard limb | 24 | 10.5 (5.6) | 11.1 (4.8) | 0 | 0.56 |

| Long limb | 24 | 9.5 (4.8) | 10.0 (4.5) | –0.7 (–3.2 to 1.7) | ||

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D concentration (nmol/l)a | Standard limb | 25 | 69 (30) | 83 (34) | 0 | 0.18 |

| Long limb | 26 | 61 (27) | 126 (16) | –11 (–28 to 6) | ||

| Pulse (beats/minute)a | Standard limb | 26 | 86 (15) | 66 (8) | 0 | 0.26 |

| Long limb | 26 | 88 (11) | 70 (12) | 3 (–2 to 9) | ||

| Oxygen saturation (%)a | Standard limb | 25 | 99.3 (1.4) | 99.4 (1.1) | 0 | 0.13 |

| Long limb | 23 | 97.7 (1.6) | 98.8 (1.4) | –0.6 (–1.4 to 0.2) | ||

| Outcome | Trial group | n | Time point, median (IQR) | Ratio of difference (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Baseline | 12 months | |||||

| Bowel frequency (per day)c | Standard limb | 26 | – | 1 (1–2) | 1 | 0.48 |

| Long limb | 26 | – | 1 (1–1) | 1.07 (0.80 to 1.43) | ||

| Outcome | Trial group | n | Time point, median (IQR) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Baseline | 12 months | |||||

| Vitamin B12 concentration (ng/l)a,d | Standard limb | 25 | 354 (252–479) | 405 (323–608) | 1 | 0.89 |

| Long limb | 25 | 362 (274–467) | 399 (307–620) | 0.98 (0.75 to 1.29) | ||

| Triglycerides concentration (mmol/l)a,d | Standard limb | 26 | 2.1 (1.2–3.4) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1 | 0.45 |

| Long limb | 26 | 2.0 (1.3–3.0) | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) | 1.08 (0.88 to 1.33) | ||

| Characteristic | Time point | p-value (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 months postoperatively | ||||

| Long limb (n = 26) | Standard limb (n = 27) | Long limb (n = 26) | Standard limb (n = 26) | ||

| Duration of T2DM (years), median (IQR) | 8 (6–9) | 8 (6–10) | |||

| Number of glucose-lowering medications, median (IQR) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.71 |

| T2DM remission | 77% (20) | 62% (16) | 0.23 (0.62 to 6.96) | ||

Primary outcome

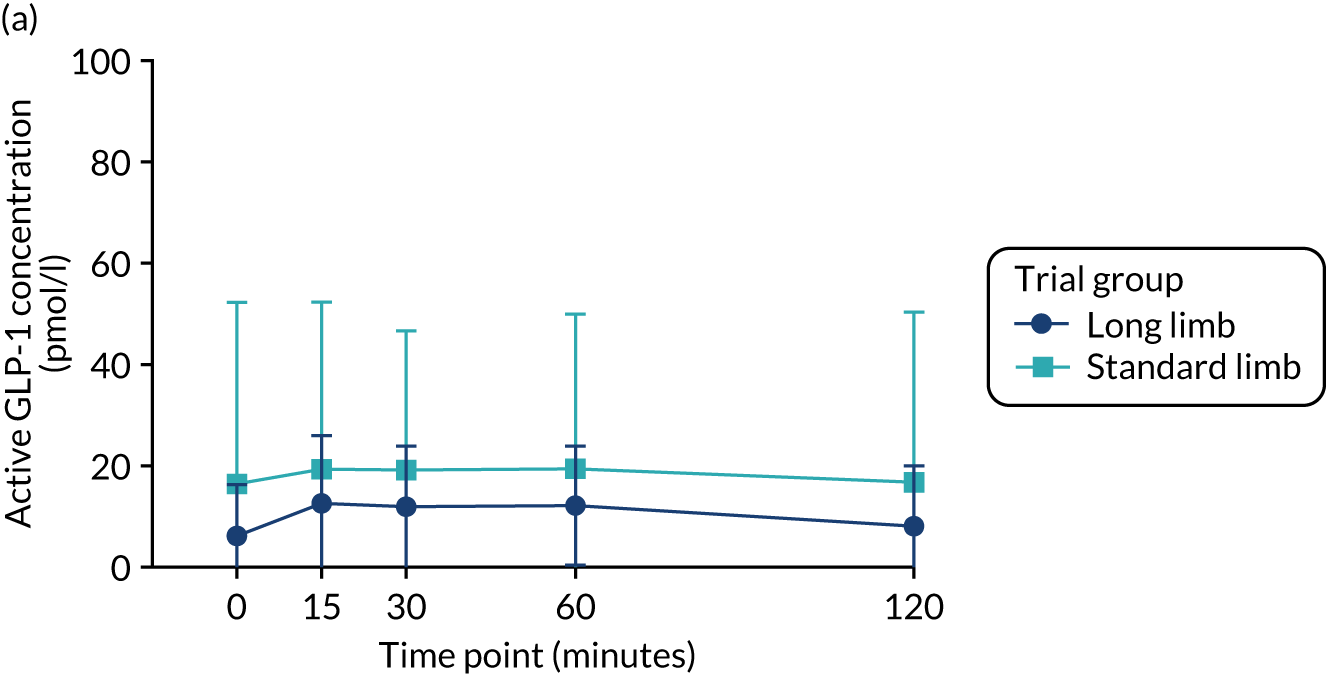

There were significant increases compared with baseline in the postprandial peak of active GLP-1 concentration in both trial groups at the 2-week time point, but there were no significant differences between the standard and long limb trial groups (Table 3 and Figure 3). There were significant increases at the point of 20% weight loss compared with baseline in the postprandial peak active GLP-1 concentration and the area under the curve (AUC) in both trial groups; however, there were no significant differences between the trial groups.

| Outcome | Trial group | n | Time point, mean (SD) | Treatment effect (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperatively | 2 weeks postoperatively | |||||

| GLP-1 active peak (pmol/l) | Standard limb | 24 | 24 (33) | 78 (41) | 0 | 0.34 |

| Long limb | 24 | 16 (13) | 62 (30) | –8 (–25 to 9) | ||

| GLP-1 active AUC (pmol/l/minute) | Standard limb | 19 | 2574 (4082) | 5338 (3968) | 0 | 0.68 |

| Long limb | 21 | 1384 (1404) | 4528 (1764) | 215 (–831 to 1261) | ||

| GLP-1 total peak (pmol/l) | Standard limb | 24 | 13 (6) | 105 (49) | 0 | 0.48 |

| Long limb | 24 | 14 (10) | 96 (33) | –9 (–34 to 16) | ||

| GLP-1 total AUC (pmol/l/minute) | Standard limb | 24 | 1017 (394) | 6190 (2566) | 0 | 0.68 |

| Long limb | 24 | 1044 (543) | 6487 (1987) | 278 (–1057 to 1613) | ||

| Insulin peak (mU/l) | Standard limb | 24 | 29 (14) | 37 (16) | 0 | 0.93 |

| Long limb | 23 | 28 (16) | 36 (21) | 0 (–9 to 8) | ||

| Insulin AUC (mU/l/minute) | Standard limb | 24 | 5281 (2464) | 6259 (3088) | 0 | 0.89 |

| Long limb | 23 | 5128 (2833) | 6037 (3481) | –102 (–1623 to 1418) | ||

| Outcome | Trial group | n | Time point, median (IQR) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Preoperatively | 2 weeks postoperatively | |||||

| PYY peak (pmol/l) | Standard limb | 16 | 56 (31–75) | 125 (106–151) | 1 | 0.26 |

| Long limb | 12 | 33 (27–69) | 115 (90–154) | 0.86 (0.65 to 1.13) | ||

| PYY AUC (pmol/l/minute) | Standard limb | 10 | 6012 (5310–10,072) | 12,583 (11,336–14,536) | 1 | 0.55 |

| Long limb | 4 | 7348 (6563–9986) | 13,054 (11,073–15,911) | 0.92 (0.69 to 1.24) | ||

| GIP peak (pmol/l) | Standard limb | 24 | 75 (39–110) | 120 (40–205) | 1 | 0.69 |

| Long limb | 23 | 101 (31–171) | 110 (76–160) | 1.11 (0.66 to 1.86) | ||

| GIP AUC (pmol/l/minute) | Standard limb | 18 | 5276 (1219–9671) | 4329 (1537–11,941) | 1 | 0.22 |

| Long limb | 15 | 11,641 (1965–14,666) | 9184 (4782–9829) | 1.56 (0.75 to 3.25) | ||

| Glucose peak (mmol/l) | Standard limb | 24 | 15.3 (13.2–17.2) | 10.3 (8.7–12.6) | 1 | 0.76 |

| Long limb | 24 | 14.4 (11.4–17.5) | 10.5 (8.9–11.1) | 1.02 (0.88 to 1.20) | ||

| Glucose AUC (mmol/l/minute) | Standard limb | 24 | 2828 (2450–3172) | 1828 (1553–2189) | 1 | 0.66 |

| Long limb | 24 | 2647 (2103–3221) | 1862 (1632–2006) | 1.04 (0.88 to 1.22) | ||

FIGURE 3.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 response during the mixed-meal tolerance test. (a) Plasma-active GLP-1 concentration preoperatively; (b) plasma-active GLP-1 concentration at 2 weeks postoperatively; and (c) plasma-active GLP-1 concentration at 20% weight loss time point. Data were plotted as means (SDs). n = 24 in each trial group. Reprinted with permission from The American Diabetes Association. Copyright 2020 by the American Diabetes Association. 4

Secondary outcomes

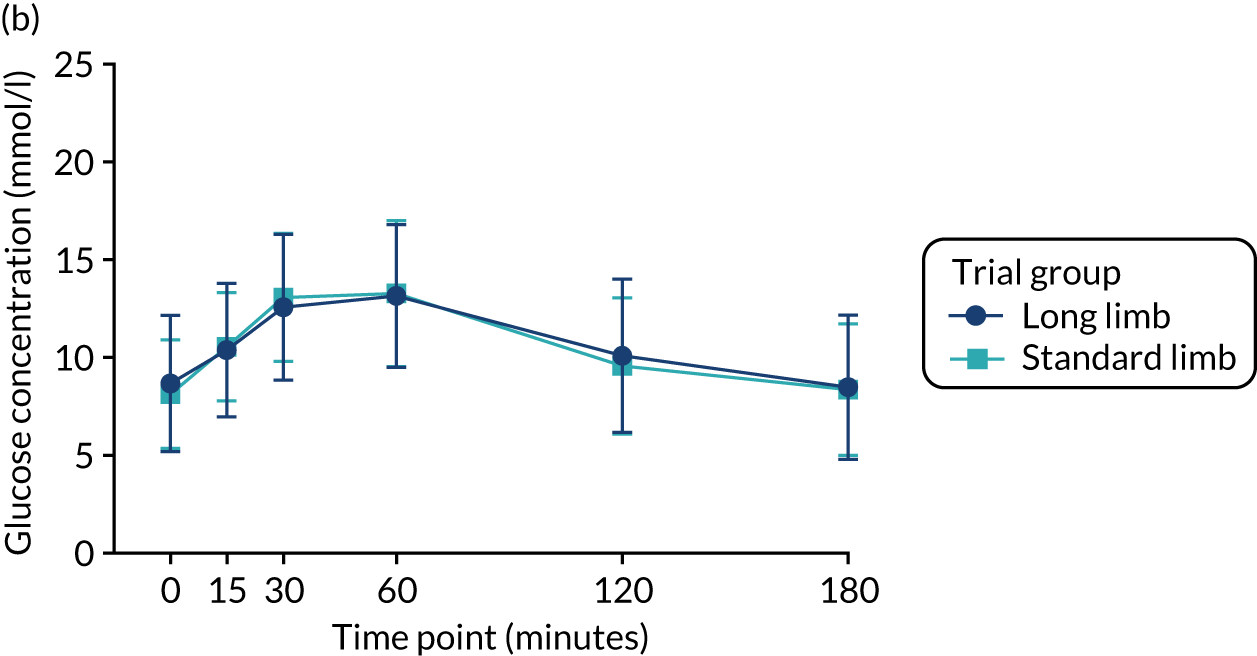

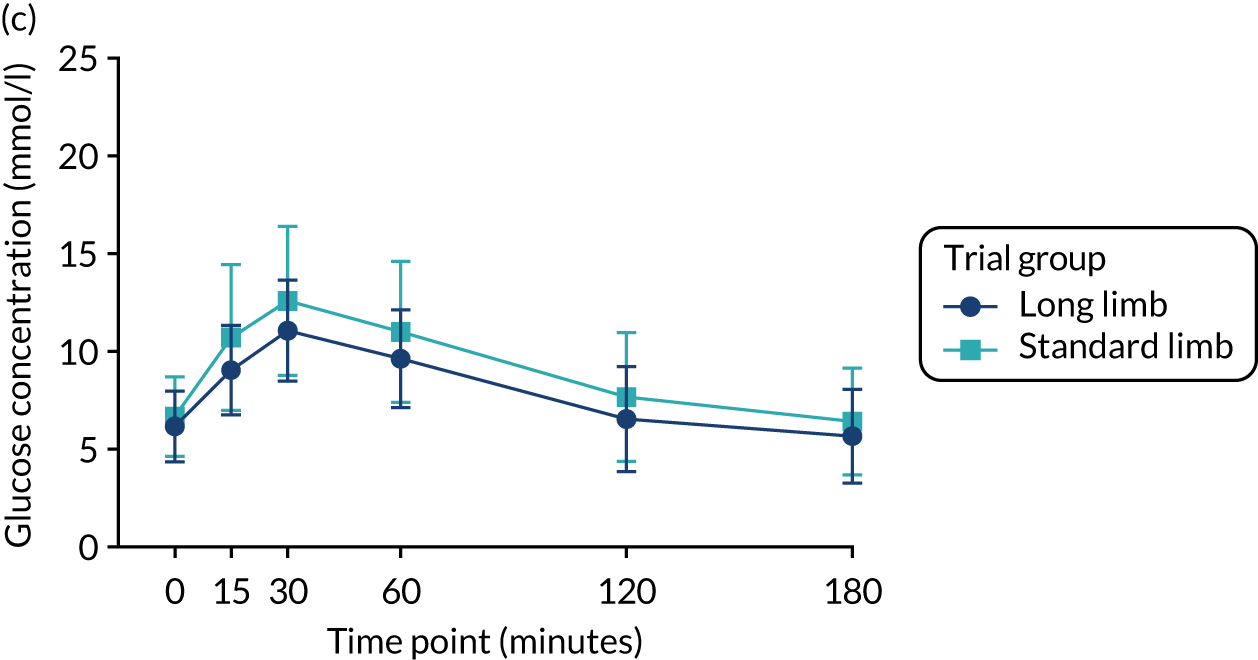

Glucose tolerance

At the 2-week time point and at the point of matched 20% weight loss, fasting and postprandial glucose concentrations (as assessed via AUCs) during the mixed-meal tolerance test were significantly reduced compared with baseline in both trial groups. However, there were no significant differences between the standard and long limb trial groups (Tables 3 and 4 and Figure 4).

| Outcome | Trial group | n | Time point, mean (SD) | Treatment effect (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperatively | 20% weight loss | |||||

| GLP-1 active peak (pmol/l) | Standard limb | 24 | 24 (33) | 70 (32) | 0 | 0.43 |

| Long limb | 23 | 16 (14) | 70 (19) | 5 (–8 to 18) | ||

| GLP-1 active AUC (pmol/l/minute) | Standard limb | 18 | 2496 (4219) | 5312 (3711) | 0 | 0.18 |

| Long limb | 18 | 1292 (1497) | 3812 (1327) | –529 (–1315 to 256) | ||

| GLP-1 total peak (pmol/l) | Standard limb | 24 | 13 (6) | 117 (57) | 0 | 0.68 |

| Long limb | 24 | 14 (10) | 112 (38) | –6 (–35 to 23) | ||

| GLP-1 total AUC (pmol/l/minute) | Standard limb | 24 | 1017 (394) | 6281 (2586) | 0 | 0.69 |

| Long limb | 24 | 1044 (543) | 6039 (2555) | –285 (–1726 to 1155) | ||

| Insulin peak (mU/l) | Standard limb | 24 | 29 (14) | 42 (20) | 0 | 0.37 |

| Long limb | 23 | 28 (16) | 38 (18) | –3 (–10 to 4) | ||

| Insulin AUC (mU/l/minute) | Standard limb | 24 | 5281 (2464) | 6433 (3058) | 0 | 0.34 |

| Long limb | 23 | 5128 (2833) | 5716 (2879) | –594 (–1828 to 641) | ||

| Outcome | Trial group | n | Time point, median (IQR) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Preoperatively | 20% weight loss | |||||

| PYY peak (pmol/l) | Standard limb | 16 | 56 (31–75) | 104 (85–158) | 1 | 0.29 |

| Long limb | 12 | 33 (27–69) | 101 (74–120) | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.13) | ||

| PYY AUC (pmol/l/minute) | Standard limb | 8 | 8163 (5419–10,539) | 14,472 (10,444–16,385) | 1 | 0.78 |

| Long limb | 3 | 5966 (2576–7536) | 11,189 (5514–12,851) | 0.96 (0.68 to 1.35) | ||

| GIP peak (pmol/l) | Standard limb | 24 | 75 (39–110) | 129 (61–259) | 1 | 0.20 |

| Long limb | 23 | 101 (31–171) | 88 (38–181) | 0.56 (0.23 to 1.37) | ||

| GIP AUC (pmol/l/minute) | Standard limb | 15 | 5139 (1489–8472) | 9185 (4006–15,486) | 1 | 0.69 |

| Long limb | 16 | 11,203 (2614–13,665) | 6041 (4174–11,893) | 0.87 (0.44 to 1.74) | ||

| Glucose peak (mmol/l) | Standard limb | 24 | 15.3 (13.2–17.2) | 9.3 (7.7–11.0) | 1 | 0.32 |

| Long limb | 24 | 14.4 (11.4–17.5) | 8.0 (6.9–9.3) | 0.93 (0.81 to 1.07) | ||

| Glucose peak (mmol/l) | Standard limb | 24 | 2828 (2450–3172) | 1564 (1276–1896) | 1 | 0.38 |

| Long limb | 24 | 2647 (2103–3221) | 1301 (1170–1580) | 0.94 (0.80 to 1.09) | ||

FIGURE 4.

Plasma glucose excursion during the mixed-meal tolerance test. (a) Plasma glucose concentrations preoperatively; (b) plasma glucose concentrations 2 weeks postoperatively; and (c) plasma glucose concentrations at the 20% weight loss time point. Data were plotted as means (SDs). n = 24 in each trial group. Reprinted with permission from The American Diabetes Association. Copyright 2020 by the American Diabetes Association. 4

Insulin secretion

At the 2-week time point and at the point of matched 20% weight loss, peak postprandial insulin concentrations during the mixed-meal tolerance test were significantly increased compared with baseline in both trial groups. However, there were no significant differences between the standard and long limb trial groups (see Tables 3 and 4; Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Serum insulin excursion during the mixed-meal tolerance test. (a) Serum insulin concentrations preoperatively; (b) serum insulin concentrations 2 weeks postoperatively; and (c) serum insulin concentrations at the 20% weight loss time point. Data were plotted as means (SDs). n = 24 in each trial group. Reprinted with permission from The American Diabetes Association. Copyright 2020 by the American Diabetes Association. 4

Secretion of other gut hormones

There were no significant differences in the peak concentration or AUC of postprandial PYY or GIP secretion between the standard and long limb trial groups (see Tables 3 and 4).

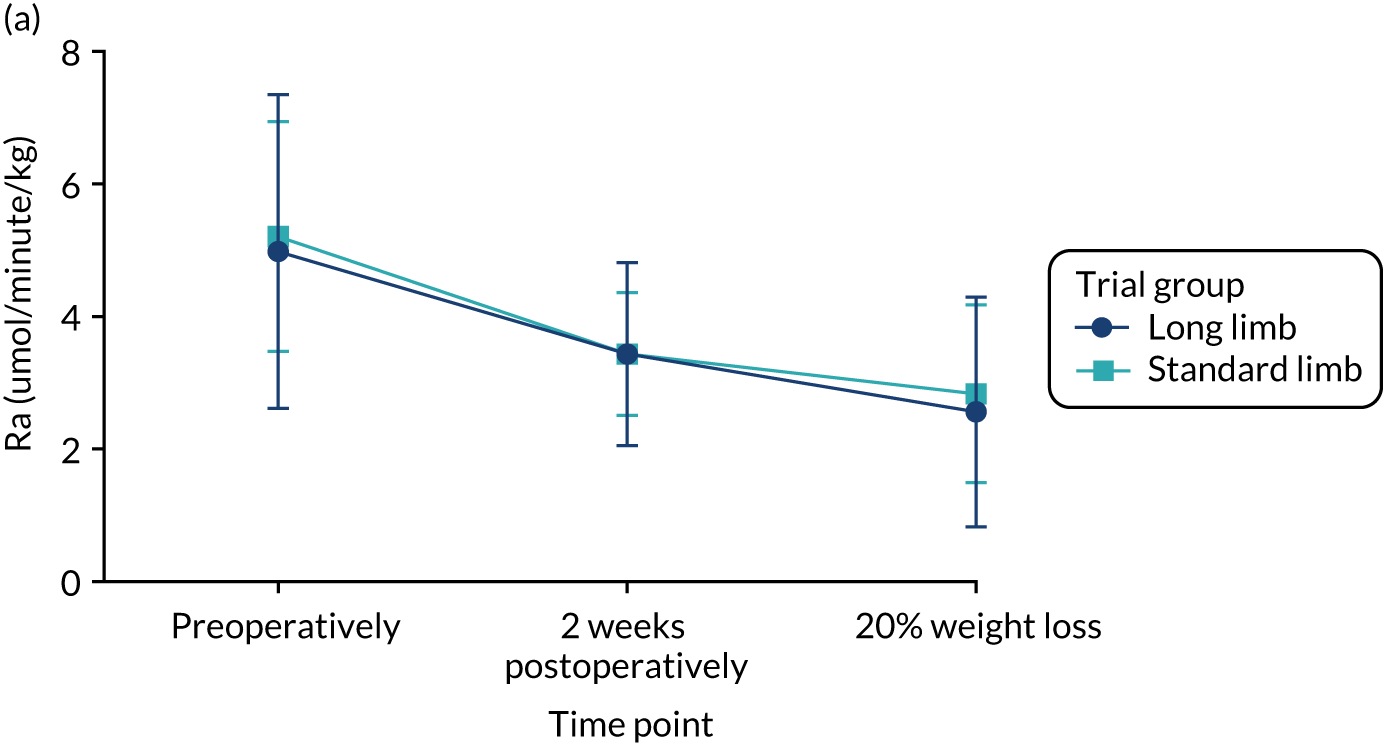

Insulin sensitivity

At the 2-week time point and at the point of matched 20% weight loss, the rate of glucose appearance during the low-dose phase of the hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp (i.e. Ra), which is a measure of hepatic insulin sensitivity, had decreased significantly compared with baseline in both trial groups. This decrease of Ra denotes an improvement in insulin sensitivity. However, there were no significant differences between the standard and long limb trial groups (Tables 5 and 6 and Figure 6).

At the 2-week time point and at the point of matched 20% weight loss, the rate of glucose disappearance during the high-dose phase of the hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp (i.e. Rd), which is a measure of peripheral insulin sensitivity, had increased significantly compared with baseline in both trial groups. This increase in Rd denotes an improvement in insulin sensitivity. However, there were no significant differences between the standard and long limb trial groups (Tables 5 and 6 and Figure 6).

| Outcome | Trial group | n | Time point, mean (SD) | Treatment effect (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperatively | 2 weeks postoperatively | |||||

| Ra | ||||||

| Basal | Standard limb | 23 | 11.1 (2.0) | 9.6 (1.0) | 0 | 0.23 |

| Long limb | 23 | 10.9 (1.5) | 10.0 (1.5) | 0.4 (–0.3 to 1.1) | ||

| Low | Standard limb | 23 | 5.1 (1.7) | 3.4 (0.9) | 0 | 0.94 |

| Long limb | 23 | 5.0 (2.4) | 3.4 (1.4) | 0.0 (–0.6 to 0.7) | ||

| High | Standard limb | 23 | 1.9 (2.4) | 0.6 (1.7) | 0 | 0.86 |

| Long limb | 23 | 1.1 (2.0) | 0.7 (1.7) | 0.1 (–0.9 to 1.1) | ||

| Rd | ||||||

| Basal | Standard limb | 23 | 11.2 (2.0) | 9.7 (1.0) | 0 | 0.23 |

| Long limb | 23 | 10.9 (1.5) | 10.1 (1.5) | 0.4 (–0.3 to 1.2) | ||

| Low | Standard limb | 23 | 9.8 (1.6) | 11.8 (2.9) | 0 | 0.18 |

| Long limb | 23 | 10.6 (3.6) | 13.6 (4.2) | 1.3 (–0.6 to 3.2) | ||

| High | Standard limb | 23 | 18.7 (7.6) | 29.0 (9.1) | 0 | 0.98 |

| Long limb | 23 | 19.1 (9.4) | 29.2 (9.9) | 0.1 (–5.2 to 5.3) | ||

| MCR | ||||||

| Basal | Standard limb | 23 | 1.9 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.2) | 0 | 0.05 |

| Long limb | 23 | 1.9 (0.3) | 1.9 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.3) | ||

| Low | Standard limb | 23 | 1.7 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.6) | 0 | 0.23 |

| Long limb | 23 | 1.9 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.8) | 0.2 (–0.1 to 0.6) | ||

| High | Standard limb | 23 | 3.2 (1.3) | 5.3 (1.8) | 0 | 0.89 |

| Long limb | 22 | 3.6 (2.2) | 5.6 (2.0) | 0.1 (–1.0 to 1.1) | ||

| Outcome | Trial group | n | Time point, mean (SD) | Treatment effect (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperatively | 20% weight loss | |||||

| Ra | ||||||

| Basal | Standard limb | 24 | 11.1 (2.0) | 10.6 (1.4) | 0 | 0.28 |

| Long limb | 23 | 10.9 (1.5) | 11.0 (2.2) | 0.6 (–0.4 to 1.5) | ||

| Low | Standard limb | 24 | 5.2 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.3) | 0 | 0.62 |

| Long limb | 23 | 5.0 (2.4) | 2.6 (1.7) | –0.2 (–1.0 to 0.6) | ||

| High | Standard limb | 24 | 2.0 (2.4) | 0.0 (1.8) | 0 | 0.09 |

| Long limb | 23 | 1.2 (2.0) | –1.0 (1.3) | –0.8 (–1.8 to 0.1) | ||

| Rd | ||||||

| Basal | Standard limb | 24 | 11.2 (2.0) | 10.7 (1.4) | 0 | 0.28 |

| Long limb | 23 | 10.9 (1.5) | 11.1 (2.2) | 0.5 (–0.4 to 1.5) | ||

| Low | Standard limb | 24 | 9.8 (1.6) | 15.2 (2.9) | 0 | 0.36 |

| Long limb | 23 | 10.6 (3.6) | 16.5 (4.1) | 0.9 (–1.1 to 2.9) | ||

| High | Standard limb | 24 | 18.5 (7.6) | 36.1 (8.5) | 0 | 0.47 |

| Long limb | 23 | 19.1 (9.4) | 38.1 (9.2) | 1.8 (–3.2 to 6.9) | ||

| MCR | ||||||

| Basal | Standard limb | 24 | 1.9 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.2) | 0 | 0.17 |

| Long limb | 23 | 1.9 (0.3) | 2.2 (0.5) | 0.1 (–0.1 to 0.3) | ||

| Low | Standard limb | 24 | 1.7 (0.3) | 2.7 (0.4) | 0 | 0.10 |

| Long limb | 23 | 1.9 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.8) | 0.3 (–0.1 to 0.7) | ||

| High | Standard limb | 24 | 3.2 (1.2) | 6.7 (1.7) | 0 | 0.57 |

| Long limb | 23 | 3.6 (2.1) | 7.1 (1.7) | 0.3 (–0.7 to 1.2) | ||

FIGURE 6.

(a) Rate of glucose appearance (Ra) at low-dose insulin infusion; and (b) rate of glucose disappearance (Rd) at high-dose insulin infusion. Data are plotted as means (SDs). n = 23 in each trial group. Reprinted with permission from The American Diabetes Association. Copyright 2020 by the American Diabetes Association. 4

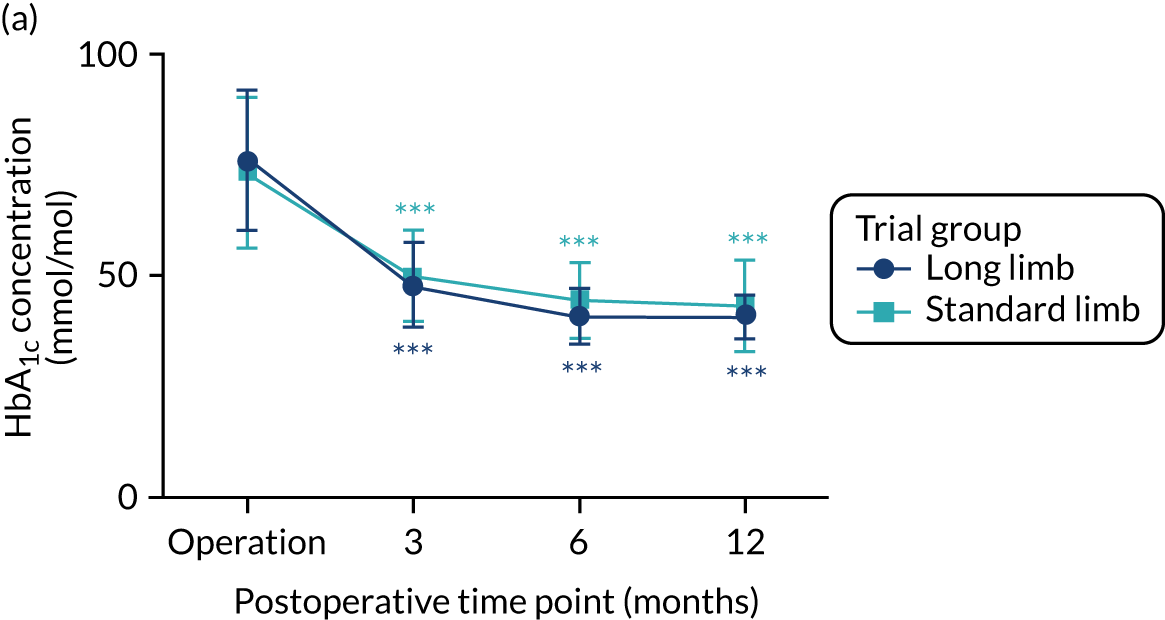

Glycaemic control and weight loss

There were no significant differences in the levels of HbA1c between the standard limb and long limb trial groups at any time point postoperatively. At 3 months postoperatively, the level of HbA1c in the standard limb group was 50 mmol/mol (SD 10 mmol/mol), compared with 48 mmol/mol (SD 10 mmol/mol) in the long limb group (p = 0.40). At 6 months postoperatively, the level of HbA1c in the standard limb trial group was 44 mmol/mol (SD 8 mmol/mol), compared with 41 mmol/mol (SD 6 mmol/mol) in the long limb trial group (p = 0.07). At 12 months postoperatively, the level of HbA1c in the standard limb trial group was 43 mmol/mol (SD 10 mmol/mol), compared with 41 mmol/mol (SD 5 mmol/mol) in the long limb trial group (p = 0.20) (see Table 2 and Figure 7). There were no significant differences in the percentage of patients achieving glycaemic remission at 12 months between the trial groups (standard limb 62% vs. long limb 77%; p = 0.23).

FIGURE 7.

Level of (a) glycated haemoglobin and (b) total body weight loss within the first postoperative year. Data are expressed as means (SDs). n = 26 in each trial group. Asterisks in aqua and navy compare the values with baseline within each group. ***p < 0.001.

The usage of glucose-lowering medications decreased in both trial groups (see Appendix 3). At baseline, 100% of patients were on pharmacotherapy. At 3 months postoperatively, 38% of standard limb and 24% of long limb trial group participants required medications. At 6 months the corresponding figures were 28% and 24%. Only one participant from the long limb trial group was on glucose-lowering pharmacotherapy at 12 months, with none in the standard limb group.

At 2 weeks postoperatively, patients in both trial groups lost similar percentages of body weight [standard limb 6.2% (SD 2.3%) vs. long limb 6.1% (SD 1.6%); p = 0.97]. As per protocol, both trial groups were studied again at the point of matched 20% weight loss; this occurred, on average, 4.5 months after surgery. At this time point, mean percentage weight loss was 21.5% (SD 2.8%) in the standard limb group and 20.6% (SD 2.7%) in the long limb trial group. There were no differences in total body weight loss percentage between the trial groups at any time point postoperatively. At 3 months postoperatively, mean weight loss was 19% (SD 4%) in both trial groups (p = 0.99). At 6 months postoperatively, mean weight loss was 26% (SD 6%) in the standard limb group and 24% (SD 4%) in the long limb trial group (p = 0.11). At 12 months postoperatively, the corresponding figures were 30% (SD 8%) and 29% (SD 8%) (p = 0.52) (see Figure 7).

Surgical outcomes

The median total small intestinal length was 615 cm (range 320–740 cm; n = 26) in the standard limb group and 610 cm (range 520–910 cm; n = 25) in the long limb group. The median common channel length was 465 cm (range 170–590 cm) in the standard limb group and 360 cm (range 250–660 cm) in the long limb trial group. The median biliopancreatic limb-to-total small intestinal length ratio was 8% (range 7–16%) in the standard limb group and 25% (range 16–29%) in the long limb trial group (Table 7). There were no significant differences in the operative time or length of hospital stay [mean, 2 days (SD 0.7 days)] between the two surgical procedures. The safety profile of the procedures was similar, with no signal for excess malabsorption of macronutrients or micronutrients in the long limb trial group (Table 8).

| Measurement | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| Long limb (n = 25) | Standard limb (n = 26) | |

| Common channel length (cm) | 360 (IQR 305–435); range 250–660 | 465 (IQR 320–528); range 170–590 |

| Total small intestinal length (cm) | 610 (IQR 555–685); range 520–910 | 615 (IQR 470–678); range 320–740 |

| Biliopancreatic limb-to-total small intestinal length ratio (%) | 25 (IQR 22–27); range 16–29 | 8 (IQR 7–11); range 7–16 |

| Common channel-to-total small intestinal length ratio (%) | 59 (IQR 55–64); range 48–73 | 76 (IQR 68–78); range 53–80 |

| Operating time (minutes) | 164 (SD 51); range 59–241 | 146 (SD 42); range 79–250 |

| Adverse event | Trial group, number of adverse events | |

|---|---|---|

| Long limb (n = 26) | Standard limb (n = 27) | |

| Cardiovascular | 0 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Anastomotic stricture | 1 | 0 |

| Anastomotic ulcer | 0 | 1 |

| Perioperative bleeding | 2 | 0 |

| Gallstones | 1 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 0 |

| Laparotomy for purulent peritonitis | 1 | 0 |

| Gastritis | 1 | 0 |

| Diarrhoea | 1 | 2 |

| Constipation | 0 | 1 |

| Infections | ||

| Wound infection | 4 | 2 |

| Pneumonia | 4 | 2 |

| Viral tonsillitis | 1 | 0 |

| Soft tissue and musculoskeletal | ||

| Incisional hernia | 1 | 0 |

| Limb fracture | 0 | 1 |

| Nutritional and metabolic | ||

| Intravenous treatment for dehydration | 0 | 1 |

| Acute kidney injury | 0 | 2 |

| Anaemia | 2 | 2 |

| Vasovagal | 1 | 2 |

| Hypoglycaemic episode | 2 | 4 |

| Adverse events leading to hospitalisation | 5 (in three participants) | 4 (in four participants) |

| Clavien–Dindo classification of complications (grades) | ||

| I | 6 | 11 |

| II | 14 | 9 |

| IIIa | 1 | 0 |

| IIIb | 1 | 0 |

| IV | 1 | 0 |

| V | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 23 | 20 |

Correlation between intestinal limb length ratios and key clinical and mechanistic outcomes

No significant correlations were found between the ratio of the biliopancreatic or common limb length to the total small bowel length and total body weight loss, reduction in level of HbA1c and T2DM remission at 1 year. Similarly, no significant correlations were found between the limb length ratios and postprandial active GLP-1, glucose and insulin excursions in the mixed-meal tolerance tests, or in Ra and Rd in the hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamps, at any time point.

Remission of other comorbidities

The prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidaemia and sleep apnoea at 12 months was reduced at 12 months in both trial groups; however, none of these remission rates was statistically significantly different between the standard and long limb surgery trial groups (Table 9).

| Outcome | Trial group | N | Time point, n (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 months | |||||

| Hypertensiona | Standard limb | 26 | 19 (73) | 15 (58) | 1 | 0.58 |

| Long limb | 26 | 18 (69) | 13 (50) | 0.73 (0.25 to 2.19) | ||

| Dyslipidaemiaa | Standard limb | 26 | 18 (69) | 17 (65) | 1 | 1.00 |

| Long limb | 26 | 20 (77) | 17 (65) | 1.00 (0.32 to 3.13) | ||

| Sleep apnoeab | Standard limb | 26 | 12 (46) | 3 (12) | – | 0.24 |

| Long limb | 26 | 7 (27) | 0 (0) | – | ||

Secondary outcomes not included in the report

Results on gut microbiota have not been reported in this trial, as the analysis is still ongoing. Samples for metabolomics, bile acids and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 19 and 21 assays were not processed, as no differences between the study arms were expected based on the available mechanistic and clinical outcomes. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure AUCs and heart rate AUC from the mixed-meal tolerance tests were not analysed as single point measurements from the clinical visits would suffice.

Chapter 4 Discussion

This trial has shown that patients with diabetes mellitus and obesity benefit significantly from both standard and long limb RYGB. The trial did not demonstrate that a RYGB with a biliopancreatic limb of 150 cm is superior to a RYGB with a biliopancreatic limb of 50 cm with regard to fasting and postprandial glycaemia, GLP-1 secretion, insulin secretion or insulin sensitivity. In line with these mechanistic measurements, there were no differences between the two trial groups in terms of HbA1c level or weight reduction at 12 months. There was no difference in the safety profile of the two procedures.

Previous studies have compared RYGB designs with varying biliopancreatic and alimentary limbs, making it challenging to determine which segment was responsible for superior clinical benefits, if any. 21–25 To our knowledge, this is the first double-blind RCT to conduct such a systematic head-to-head comparison of these two RYGB designs and an in-depth metabolic phenotyping of its participants. In this trial, a reductionist approach was used and the alimentary limb length was kept constant in an attempt to isolate the contribution of the length of the biliopancreatic limb to glucose control. Owing to the inherent nature of RYGB anatomy, and as per trial design, the length of the common channel was also different between the trial groups. Considering the variability in the length of the human small intestine, we were relieved to observe that this difference was serendipitously 100 cm, thus reducing even further the number of variables that could have confounded the results. The study was powered to detect significant differences in mechanistic, but not clinical, outcomes. It was postulated that the lack of even a trend for a difference in fasting and postprandial glucose concentrations between the study groups makes it unlikely that trials with even bigger sample sizes will find clinically significant differences in HbA1c levels and weight, at least within the first postoperative year.

The findings of the study are in line with several other clinical studies in which a longer biliopancreatic limb showed no additional benefit in terms of reduction in level of HbA1c, T2DM remission or weight loss. Any differences in the weight loss were either only short-lived or not clinically significant. 21–25 In the only other study in the literature that kept the alimentary limb length fixed,26 patients in the long biliopancreatic limb RYGB achieved higher rates of T2DM remission 2 years postoperatively. However, this study was retrospective in nature and patients were not randomised. 26

In the only other retrospective case–control mechanistic study of long limb RYGB,27 it was found that postprandial GLP-1 concentrations were higher in patients who underwent a long limb RYGB 4 years previously; however, this finding was not replicated in this trial. In the report by Patrício et al. ,27 the higher concentrations of GLP-1 did not translate to enhanced postprandial insulin secretion or lower concentrations of glucose, which is not consistent with the well-established insulinotropic actions of GLP-1. One explanation for the discrepant results between the two studies could be that in this trial GLP-1 and other mechanistic responses were measured at 2 weeks and at the point of matched 20% weight loss, which occurs approximately 4 months after surgery. This may not have been enough time for the full physiological impact of intestinal adaptation that takes place after RYGB to come into play. In addition, the cohort of patients studied in the report of Patrício et al. 27 did not have T2DM and the length of the biliopancreatic limb used was 200 cm. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that the use of a longer biliopancreatic limb and/or a longer follow-up period might reveal differences in GLP-1 concentrations between the two trial designs that could drive superior reductions in glycaemia and/or weight. In addition, although it may be argued that our failure to find any difference in GLP-1 secretion might be due to a type II error, our gut hormone secretion data (which revealed no significant difference between the interventions) and our data on glucose and insulin dynamics (which also revealed no significant difference between the interventions) suggest that our mechanistic conclusions are robust.

The absence of either an earlier or a higher peak in postprandial GLP-1 concentrations after the long biliopancreatic limb RYGB also challenges the hypothesis that the delivery of nutrients to more distal segments of the small intestine, where the density of EECs is higher, triggers the enhanced secretion of incretin and anorexigenic hormones such as GLP-1 and PYY. 28 The study did not observe any differences between the two RYGB designs either within 2 weeks after the operation or after 4 months, at which time at least part of the intestinal adaptation after the RYGB has taken place. One plausible explanation of this unexpected finding is that there is no linear relationship between GLP-1 secretion and the length of intestine exposed to ingested nutrients, as previously suggested, but a ‘ceiling’ effect such that the delivery of nutrients beyond a certain critical point in the jejunum does not result in further enhancement of the GLP-1 response. A second, alternative, hypothesis is that the regulation of GLP-1 secretion does not take place exclusively through the interaction of nutrients with the distal small intestine. A third possibility is that the difference in biliopancreatic limb length tested in the study (i.e. 50 vs. 150 cm) was not long enough to trigger the enhanced secretion of GLP-1, PYY, etc.; as mentioned in the discussion above, a longer biliopancreatic limb length of 200 cm might be more effective. The similarities in postprandial GLP-1 responses after sleeve gastrectomy and RYGB in both humans and animal models raise the possibility that the secretion of this incretin may, at least in part, be regulated by gastric neural and/or hormonal mechanisms. 29 It should be noted that our findings do not question the substantial impact of enhanced GLP-1 secretion after a RYGB on insulin secretion or appetite regulation, but only challenge commonly held beliefs regarding the regulation of its secretion.

The study did not observe any differences between the groups in terms of insulin sensitivity at 2 weeks or 4 months after surgery. Studies in humans and animal models of procedures, including the duodenal–jejunal bypass operation and the duodenal-jejunal bypass liner, in which food bypasses the proximal intestine, have demonstrated caloric restriction- and weight loss-independent reductions in fasting glucose and markers of insulin sensitivity. 8,30,31 Additional support for this concept comes from elegant studies on patients undergoing the biliopancreatic diversion procedure in which the biliopancreatic limb is at least 200 cm long. These studies demonstrated profound improvements in hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity within weeks after the intervention. 32 The mechanisms underlying these observations are thought to involve altered glucose-sensing in the distal and mid-jejunum33,34 and/or the reduction in the secretion of insulin ‘desensitising’ factors from the duodenum and the proximal jejunum. 35 Based on these studies it was expected that a RYGB with a 150-cm biliopancreatic limb would be superior to a standard RYGB in terms of insulin sensitivity, but without the potentially severe macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies associated with the biliopancreatic diversion. Similar to the GLP-1 story, it is postulated that beyond the bypass of a critical length of the duodenum and jejunum, no additional effects on insulin sensitivity take place. The surprising impact of the duodenal mucosal resurfacing intervention, in which only 12 cm of the duodenum is thermally ablated, on glucose regulation and markers of insulin sensitivity36 provides further support that the key segment of the bypassed intestine, or ‘sweet spot’, responsible for insulin sensitisation might be confined to the duodenum. 37

The study’s findings are strengthened by key aspects of the trial design. These include (1) the double-blinded, randomised approach, (2) the measurement of the entire length of the small intestine during surgery, (3) the robust way of ensuring that the surgical approach used was consistent between surgeons and in line with a pre-agreed standard operating procedure, (4) the use of the gold standard method of measuring insulin sensitivity through hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamps with stable isotopes, (5) the conduct of the mechanistic studies after washout of diabetes mellitus medications and (6) the longitudinal metabolic phenotyping of participants both early and at matched weight loss after the two interventions. What the study authors also wanted to demonstrate when designing this trial was that the clinical and scientific communities are now able to rationally optimise the efficacy of metabolic surgery operations through the available knowledge on their mechanisms of action. This represents a paradigm shift in a field in which, until recently, surgical experimentation took place in the absence of mechanistic information to guide it. The study demonstrated that, in certain circumstances, double-blind RCTs are ethical and feasible in the field of surgery and, hopefully, set a precedent for future studies.

The trial has narrowed down the number of intestinal segments that can be manipulated in an attempt to improve the impact of metabolic surgery on glycaemic control. Future physiological and clinical studies could investigate the role of the common channel and explore novel mechanisms through which the intestine regulates glycaemia. Recent findings from humans and animal models have demonstrated that the common channel is the intestinal segment where the majority of ingested glucose uptake takes place after surgery. 38 This process is dependent on the interaction of glucose and the sodium content of bile with the sodium-dependent glucose co-transporter 1. Thus, a RYGB with a common channel short enough to selectively reduce the absorption of glucose, but not other nutrients, could prove to be superior to the standard RYGB design for patients with T2DM. Building on from this trial, such experimentation could involve the use of limb length ratios, rather than absolute lengths, in an attempt to personalise surgery to the patient’s total small intestinal length.

The main limitations of this trial, including the relatively short follow-up and elongation of the biliopancreatic limb to a fixed length of 150 cm, have already been mentioned. For the purposes of standardisation, the study defined the ‘standard RYGB’ as one with a biliopancreatic limb of 50 cm and an alimentary limb of 100 cm based on the popularity of this design in current surgical practice. However, it is appreciated that there is substantial variation in practice around the world and that not all surgeons will agree with this definition.

Recommendations

It is hoped that the trial design and findings lay the foundation for a new generation of experimental medicine studies that aim to optimise the clinical efficacy of metabolic surgery, and indeed non-surgical interventions, through interrogation of the elusive physiology of the intestine and the impact of its various segments on metabolic regulation.

Based on the findings of this trial, an application for a follow-up extension to 5 years has been submitted and successfully secured. It will include a mixed-meal tolerance test 2 years after surgery, followed by yearly clinical follow-ups. This will enable the measurement of any differences in the long-term impact of the long limb compared with the standard limb RYGB.

Should further trials on the biliopancreatic limb length be planned, this study recommends consideration of a longer biliopancreatic limb length and using limb lengths in proportion to the total small bowel length instead of the absolute values. Furthermore, investigating intestinal remodelling and its impact on the postoperative outcomes could be considered by taking intestinal biopsies intraoperatively and then endoscopically at least 12 months after the surgery.

However, it is possible that no further improvement in glucose homeostasis can be achieved with manipulation of the biliopancreatic limb length and, therefore, the research should be directed towards investigating the common limb.

Chapter 5 Conclusions

In conclusion, this trial has demonstrated that people with diabetes mellitus and obesity do benefit metabolically from a RYGB; however, the study did not demonstrate a physiological rationale for the elongation of the biliopancreatic limb of the RYGB to 150 cm to achieve superior metabolic outcomes for patients with T2DM and obesity. Confirmation of the findings in larger clinical trials with longer follow-up is necessary.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programme. Infrastructure support was provided by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre, the NIHR Imperial Clinical Research Facility and NIHR King’s Clinical Research Facility. The report does not make recommendations about policy or practice. We would like to thank the patients who took part in the trial and all the staff at the Imperial Weight Centre.

Acknowledgement of other investigators not in list of authors

Dr Julian Marchesi and Professor Elaine Holmes are co-investigators. They are currently collaborating on further analysis, which includes the gut microbiota data.

Dr Paul Bassett is the trial statistician and is independent of the study.

Dr Victoria Salemis is an independent researcher from Imperial College London and is responsible for the randomisation of trial patients.

Contributions of authors

Alexander Dimitri Miras (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3830-3173) (Co-investigator; Senior Clinical Lecturer in Endocrinology, Imperial College London) contributed to the study concept, design and conduct, data analysis and manuscript writing.

Anna Kamocka (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6242-0639) (Clinical Research Fellow and Specialty Registrar in Bariatric Surgery, Imperial College London) contributed to the conduct of the study, data collection and analysis, and manuscript writing.

Tricia Tan (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5873-3432) (Co-investigator; Professor of Metabolic Medicine and Endocrinology, Imperial College London) contributed to the study concept and design, and data analysis and manuscript writing.

Belén Pérez-Pevida (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8632-488X) (Clinical Research Fellow, Imperial College London) contributed to the conduct of the study, data collection and analysis, and manuscript editing.

Harvinder Chahal (Co-investigator; Consultant Endocrinologist, Imperial College London) contributed to the study design and manuscript editing.

Krishna Moorthy (Co-investigator; Senior Clinical Lecturer in Upper Gastrointestinal and Bariatric Surgery, Imperial College London) contributed to the study design, was an operating surgeon and was involved with manuscript editing.

Sanjay Purkayastha (Co-investigator; Senior Clinical Lecturer in Bariatric Surgery, Imperial College London) contributed to the study design, was an operating surgeon and was involved with manuscript editing.

Ameet Patel (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8637-0963) (Co-investigator; Professor of Surgery, King’s College London) was an operating surgeon and contributed to manuscript editing.

Anne Margot Umpleby (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6147-7919) (Co-investigator; Professor of Diabetes and Metabolic Medicine, University of Surrey) contributed to the study design, data analysis and manuscript editing.

Gary Frost (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0529-6325) (Co-investigator, Imperial College London) contributed to the study concept and design.

Stephen Robert Bloom (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1542-2348) (Principal Investigator; Professor of Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism, Imperial College London) contributed to the study concept and design and manuscript editing.

Ahmed Rashid Ahmed (Co-investigator; Senior Clinical Lecturer in Bariatric Surgery, Imperial College London) contributed to the study concept and design, was an operating surgeon and was involved in manuscript writing.

Francesco Rubino (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8581-2515) (Co-investigator; Professor of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, King’s College London) contributed to the study concept and design, was an operating surgeon and was involved in manuscript writing.

Publication

Miras AD, Kamocka A, Pérez-Pevida B, Purkayastha S, Moorthy K, Patel A, et al. The effect of standard versus longer intestinal bypass on GLP-1 regulation and glucose metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: The Long-Limb Study. Diabetes Care 2020;43:dc20076.

Data-sharing statement

Data are archived at the National Institute for Health Research Imperial Clinical Research Facility. All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to anonymised data may be granted following review.

Patient data

This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. Using patient data is vital to improve health and care for everyone. There is huge potential to make better use of information from people’s patient records, to understand more about disease, develop new treatments, monitor safety, and plan NHS services. Patient data should be kept safe and secure, to protect everyone’s privacy, and it’s important that there are safeguards to make sure that it is stored and used responsibly. Everyone should be able to find out about how patient data are used. #datasaveslives You can find out more about the background to this citation here: https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/data-citation.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research. The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, the MRC, NETSCC, the EME programme or the Department of Health and Social Care. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the EME programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Nanni G, et al. Bariatric-metabolic surgery versus conventional medical treatment in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: 5 year follow-up of an open-label, single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:964-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00075-6.

- Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Aminian A, Brethauer SA, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes – 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 2017;376:641-51. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1600869.

- Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, Schauer PR, Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care 2016;39:861-77. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-0236.

- Miras AD, Kamocka A, Pérez-Pevida B, Purkayastha S, Moorthy K, Patel A, et al. The effect of standard versus longer intestinal bypass on GLP-1 regulation and glucose metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: The Long-Limb Study. Diabetes Care 2020;43. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-0762.

- Tacchino RM. Bowel length: measurement, predictors, and impact on bariatric and metabolic surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015;11:328-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2014.09.016.

- Gastaldelli A, Iaconelli A, Gaggini M, Magnone MC, Veneziani A, Rubino F, et al. Short-term effects of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Diabetes Care 2016;39:1925-31. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc15-2823.

- Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Leccesi L, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1577-85. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1200111.

- Rubino F, Forgione A, Cummings DE, Vix M, Gnuli D, Mingrone G, et al. The mechanism of diabetes control after gastrointestinal bypass surgery reveals a role of the proximal small intestine in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Ann Surg 2006;244:741-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000224726.61448.1b.

- Camastra S, Muscelli E, Gastaldelli A, Holst JJ, Astiarraga B, Baldi S, et al. Long-term effects of bariatric surgery on meal disposal and β-cell function in diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Diabetes 2013;62:3709-17. https://doi.org/10.2337/db13-0321.

- Salehi M, Prigeon RL, D’Alessio DA. Gastric bypass surgery enhances glucagon-like peptide 1-stimulated postprandial insulin secretion in humans. Diabetes 2011;60:2308-14. https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-0203.

- Gribble FM. The gut endocrine system as a coordinator of postprandial nutrient homoeostasis. Proc Nutr Soc 2012;71:456-62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665112000705.

- Tan T, Behary P, Tharakan G, Minnion J, Al-Najim W, Albrechtsen NJW, et al. The effect of a subcutaneous infusion of GLP-1, OXM, and PYY on energy intake and expenditure in obese volunteers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:2364-72. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2017-00469.

- le Roux CW, Batterham RL, Aylwin SJ, Patterson M, Borg CM, Wynne KJ, et al. Attenuated peptide YY release in obese subjects is associated with reduced satiety. Endocrinology 2006;147:3-8. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2005-0972.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . Obesity: Identification, Assessment and Management 2014. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg189/resources/obesity-identification-assessment-and-management-pdf-35109821097925 (accessed 1 February 2019).

- Buse JB, Caprio S, Cefalu WT, Ceriello A, Del Prato S, Inzucchi SE, et al. How do we define cure of diabetes?. Diabetes Care 2009;32:2133-5. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-9036.

- British Obesity & Metabolic Surgery Society (BOMSS) . BOMSS Guidelines on Peri-Operative and Postoperative Biochemical Monitoring and Micronutrient Replacement for Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery 2014. www.bomss.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/BOMSS-guidelines-Final-version1Oct14.pdf.

- Shojaee-Moradie F, Baynes KC, Pentecost C, Bell JD, Thomas EL, Jackson NC, et al. Exercise training reduces fatty acid availability and improves the insulin sensitivity of glucose metabolism. Diabetologia 2007;50:404-13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-006-0498-7.

- Steele R, Bishop JS, Dunn A, Altszuler N, Rathbeb I, Debodo RC. Inhibition by insulin of hepatic glucose production in the normal dog. Am J Physiol 1965;208:301-6. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplegacy.1965.208.2.301.

- Bradley D, Magkos F, Klein S. Effects of bariatric surgery on glucose homeostasis and type 2 diabetes. Gastroenterology 2012;143:897-912. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2012.07.114.

- Laferrère B, Heshka S, Wang K, Khan Y, McGinty J, Teixeira J, et al. Incretin levels and effect are markedly enhanced 1 month after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1709-16. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc06-1549.

- Brolin RE, Kenler HA, Gorman JH, Cody RP. Long-limb gastric bypass in the superobese. A prospective randomized study. Ann Surg 1992;215:387-95. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199204000-00014.

- Homan J, Boerboom A, Aarts E, Dogan K, van Laarhoven C, Janssen I, et al. A longer biliopancreatic limb in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass improves weight loss in the first years after surgery: results of a randomized controlled trial. Obes Surg 2018;28:3744-55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3421-7.

- Inabnet WB, Quinn T, Gagner M, Urban M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in patients with BMI < 50: a prospective randomized trial comparing short and long limb lengths. Obes Surg 2005;15:51-7. https://doi.org/10.1381/0960892052993468.

- Nergaard BJ, Leifsson BG, Hedenbro J, Gislason H. Gastric bypass with long alimentary limb or long pancreato-biliary limb – long-term results on weight loss, resolution of co-morbidities and metabolic parameters. Obes Surg 2014;24:1595-602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1245-7.

- Pinheiro JS, Schiavon CA, Pereira PB, Correa JL, Noujaim P, Cohen R. Long-long limb Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is more efficacious in treatment of type 2 diabetes and lipid disorders in super-obese patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2008;4:521-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2007.12.016.

- Kaska L, Kobiela J, Proczko M, Stefaniak T, Sledziński Z. Does the length of the biliary limb influence medium-term laboratory remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in morbidly obese patients?. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2014;9:31-9. https://doi.org/10.5114/wiitm.2014.40383.

- Patrício BG, Morais T, Guimarães M, Veedfald S, Hartmann B, Hilsted L, et al. Gut hormone release after gastric bypass depends on the length of the biliopancreatic limb. Int J Obes 2018;43:1009-18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0117-y.

- Larraufie P, Roberts GP, McGavigan AK, Kay RG, Li J, Leiter A, et al. Important role of the GLP-1 Axis for glucose homeostasis after bariatric surgery. Cell Rep 2019;26:1399-408.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.047.

- Patel RT, Shukla AP, Ahn SM, Moreira M, Rubino F. Surgical control of obesity and diabetes: the role of intestinal vs. gastric mechanisms in the regulation of body weight and glucose homeostasis. Obesity 2014;22:159-69. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20441.

- Klein S, Fabbrini E, Patterson BW, Polonsky KS, Schiavon CA, Correa JL, et al. Moderate effect of duodenal-jejunal bypass surgery on glucose homeostasis in patients with type 2 diabetes. Obesity 2012;20:1266-72. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.377.

- Cohen R, le Roux CW, Papamargaritis D, Salles JE, Petry T, Correa JL, et al. Role of proximal gut exclusion from food on glucose homeostasis in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2013;30:1482-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12268.

- Guidone C, Manco M, Valera-Mora E, Iaconelli A, Gniuli D, Mari A, et al. Mechanisms of recovery from type 2 diabetes after malabsorptive bariatric surgery. Diabetes 2006;55:2025-31. https://doi.org/10.2337/db06-0068.

- Salinari S, Carr RD, Guidone C, Bertuzzi A, Cercone S, Riccioni ME, et al. Nutrient infusion bypassing duodenum-jejunum improves insulin sensitivity in glucose-tolerant and diabetic obese subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2013;305:E59-66. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00559.2012.

- Breen DM, Rasmussen BA, Kokorovic A, Wang R, Cheung GW, Lam TK. Jejunal nutrient sensing is required for duodenal-jejunal bypass surgery to rapidly lower glucose concentrations in uncontrolled diabetes. Nat Med 2012;18:950-5. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2745.

- Salinari S, Debard C, Bertuzzi A, Durand C, Zimmet P, Vidal H, et al. Jejunal proteins secreted by db/db mice or insulin-resistant humans impair the insulin signaling and determine insulin resistance. PLOS ONE 2013;8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056258.

- Rajagopalan H, Cherrington AD, Thompson CC, Kaplan LM, Rubino F, Mingrone G, et al. Endoscopic duodenal mucosal resurfacing for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: 6-month interim analysis from the first-in-human proof-of-concept study. Diabetes Care 2016;39:2254-61. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-0383.

- Rubino F, Amiel SA. Is the gut the ‘sweet spot’ for the treatment of diabetes?. Diabetes 2014;63:2225-8. https://doi.org/10.2337/db14-0402.

- Baud G, Daoudi M, Hubert T, Raverdy V, Pigeyre M, Hervieux E, et al. Bile diversion in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass modulates sodium-dependent glucose intestinal uptake. Cell Metab 2016;23:547-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.01.018.

Appendix 1 The LONG LIMB trial surgical standard operating procedure

Detailed standard operating procedure for the standard and long limb Roux-en-Y gastric bypass operations.

| Standard limb RYGB | |

|---|---|

| 1. | The procedure is performed by a consultant surgeon using Covidien (Dublin, Ireland) instruments |

| 2. | The patient is placed on the operating table. General anaesthesia is administered |

| 3. | The patient’s abdomen is prepped and draped in sterile fashion |

| 4. | The abdominal cavity is entered and the pneumoperitoneum is established to a pressure of 15 mmHg of carbon dioxide. The procedure is filmed |

| 5. | Laparoscopic bladeless 12-mm trocars are passed obliquely through the abdominal wall, including the left upper quadrant, left flank and umbilical midline |

| 6. | The omentum and the transverse colon are then reflected cephalad to expose the ligament of Treitz |

| 7. | From this position, the small intestine (jejunum) is measured with 5-cm marks (Steri-Strip™; 3M, Saint Paul, MN, USA) placed on graspers |

| 8. | The small bowel is divided 50 cm from the ligament of Treitz with an endostapler. This proximal segment of intestine defines the biliopancreatic limb |

| 9. | The distal segment of intestine is then further measured to 100 cm and this is the length of the Roux/alimentary limb |

| 10. | A side-to-side enteroenterostomy is performed by stapling the biliopancreatic limb to the 100-cm mark on the alimentary limb, making parallel antimesenteric enterotomies and firing the endostapler into the lumen of each. The enterotomy is closed |

| 11. | All mesenteric defects will be closed |

| 12. | A completely isolated proximal gastric pouch 30–40 ml in volume is created using endostaplers. The actual length of the pouch may vary depending on the anatomical conditions seen at the time of surgery, but, in general terms, the horizontal transection of the pouch will be at the level of the second gastric vein, lesser curve side, below the fat pad |

| 13. | The previously measured alimentary/Roux limb is taken up to the gastric pouch (antecolic) with the 100-cm alimentary limb on the patient’s right and a 50-cm biliopancreatic limb on the patient’s left. The antecolic antegastric approach will be used unless during the surgery there is a clinical need to use the retrocolic approach |

| 14. | The alimentary limb is anastomosed with a circular or linear stapler to the gastric pouch and a leak test is performed with the Roux loop occluded |

| 15. | The pneumoperitoneum is allowed to escape |

| 16. | The trocars are withdrawn under laparoscopic vision, ensuring that there is no bleeding from the port site |

| 17. | The wound is irrigated with normal saline, infiltrated with 0.25% Marcaine® (Cook-Waite Laboratories, Inc., New York, NY, USA) and closed with staples |

| Long limb RYGB | |

| 1. | The procedure is performed by a consultant surgeon using Covidien instruments |

| 2. | The patient is placed on the operating table. General anaesthesia is administered |

| 3. | The patient’s abdomen is prepped and draped in sterile fashion |

| 4. | The abdominal cavity is entered and pneumoperitoneum is established to a pressure of 15 mmHg of carbon dioxide. The procedure is filmed |

| 5. | Laparoscopic bladeless 12-mm trocars are passed obliquely through the abdominal wall, including the left upper quadrant, left flank and umbilical midline |

| 6. | The omentum and the transverse colon are then reflected cephalad to expose the ligament of Treitz |

| 7. | From this position, the small intestine (jejunum) is measured with 5-cm marks (Steri-Strip) placed on graspers |

| 8. | The small bowel is divided 150 cm from the ligament of Treitz with an endostapler. This proximal segment of intestine defines the biliopancreatic limb |

| 9. | The distal segment of intestine is then further measured to 100 cm and this is the length of the Roux/alimentary limb |

| 10. | A side-to-side enteroenterostomy is performed by stapling the biliopancreatic limb to the 100-cm mark on the alimentary limb making parallel antimesenteric enterotomies and firing the endostapler into the lumen of each. The enterotomy is closed |

| 11. | All mesenteric defects will be closed |

| 12. | A completely isolated proximal gastric pouch 30–40 ml in volume is created using endostaplers. The actual length of the pouch may vary depending on the anatomical conditions seen at the time of surgery, but, in general terms, the horizontal transection of the pouch will be at the level of the second gastric vein, lesser curve side, below the fat pad |

| 13. | The previously measured alimentary/Roux limb is taken up to the gastric pouch (antecolic) with the 100-cm alimentary limb on the patient’s right and a 150-cm biliopancreatic limb on the patient’s left. The antecolic antegastric approach will be used unless during the surgery there is a clinical need to use the retrocolic approach |

| 14. | The alimentary limb is anastomosed with a circular or linear stapler to the gastric pouch and a leak test is performed with the Roux loop occluded |

| 15. | The pneumoperitoneum is allowed to escape |

| 16. | The trocars are withdrawn under laparoscopic vision, ensuring there is no bleeding from the port site |

| 17. | The wound is irrigated with normal saline, infiltrated with 0.25% Marcaine and closed with staples |

Appendix 2 The LONG LIMB trial statistical analysis plan

Appendix 3 The LONG LIMB trial supplementary data

| Characteristic | Time point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1 year postoperatively | |||

| Long limb RYGB (n = 26) | Standard limb RYGB (n = 27) | Long limb RYGB (n = 26) | Standard limb RYGB (n = 27) | |

| Number of glucose-lowering medications at baseline (classes) | ||||

| 1 | 11% (3) | 4% (1) | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 27% (7) | 44% (12) | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 35% (9) | 26% (7) | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 27% (7) | 19% (5) | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0% (0) | 7% (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Classes of medications | ||||

| Biguanides | 92% (24) | 93% (25) | 1 | 0 |

| SGLT-2 inhibitors | 54% (14) | 56% (15) | 1 | 0 |

| Sulfonylurea | 50% (13) | 48% (13) | 0 | 0 |

| GLP-1 agonists | 35% (9) | 15% (4) | 1 | 0 |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | 31% (8) | 52% (14) | 0 | 0 |