Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 11/133/07. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The final report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in December 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Beardsall et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this report have been reproduced with permission from Thompson et al. 1 and Beardsall et al. 2–4 in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Increasing numbers of infants are being born preterm. These infants require intensive care and have a high risk of early mortality and short-term morbidity. 5 Among surviving infants, the incidence of long-term health problems, including learning difficulties, is high, with significant long-term costs to the NHS and society. 6 Treatable neonatal causes of long-term health problems have been difficult to establish. National priorities for research include investigation of the management of infants who are born too early or too small, and evaluation of the reasons for variations in outcome of ‘high-risk’ neonates. Early postnatal glucose control may be an important and modifiable risk factor for clinical outcomes. In utero, glucose levels are normally maintained between 4 and 6 mmol/l,7 but infants born preterm are at risk of both hyperglycaemia (20–86%, depending on how it is defined) and hypoglycaemia (17%; blood glucose level < 2.6 mmol/l). 8

Existing research

Hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia in the preterm infant

Hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia have both been associated with increased mortality and morbidity for preterm infants. 9,10 Hyperglycaemia can lead to acute problems of persistent osmotic diuresis and metabolic acidosis, which can be difficult to control, and has been associated with increased risk of intraventricular haemorrhage. 11 Hyperglycaemia has also been associated with increased long-term morbidity, including increased risk of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). 9,12,13 Pivotal single-centre studies in adult intensive care have demonstrated that tight glycaemic control can reduce both mortality and morbidity. 14 However, these results have been difficult to replicate because of the risk of hypoglycaemia. 15 A trial in paediatric intensive care, targeted to reduce hyperglycaemia, demonstrated a reduction in length of intensive care admission and mortality, but a significant increase in hypoglycaemia. 16 This is of particular concern as attempts to reduce the prevalence of hyperglycaemia may increase the risk of hypoglycaemia in preterm infants because of their variable sensitivity to insulin. In addition, the developing brain appears to be particularly vulnerable to both hyperglycaemic17 and hypoglycaemic insults. A Cochrane review9 has highlighted the need for further studies into the impact of interventions to improve glucose control in these infants.

Current glucose monitoring in neonatal intensive care

Although glucose monitoring is implemented in all very preterm infants, it is currently limited to intermittent blood sampling, with long periods when glucose levels are unknown. The reason for the intermittent nature of glucose monitoring is that current methodologies for measurement of glucose levels are dependent on blood sampling either from a central arterial line or by heel prick. The very small circulating volumes of blood in preterm infants mean that it is also important to minimise the number of blood samples and volume of blood sampled in this way. Furthermore, current practice in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) aims to reduce the frequency of handling of infants, as this has been shown to improve outcomes. 18 By contrast, other physiological parameters, such as oxygen saturation, blood pressure and heart rate, are all monitored continuously to prevent wide fluctuations. It is increasingly thought that fluctuations in glucose levels may also have a significant impact on long-term outcomes. 19

If clinical interventions to optimise glucose control are to be safe and effective in the intensive care setting, robust methods of monitoring glucose levels in real time need to be in place. Furthermore, to fully understand the clinical significance of hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia, it is imperative that robust data are available regarding their true prevalence throughout the period of intensive care. Current follow-up studies are dependent on infrequent measurements of blood glucose, typically taken for clinical reasons and with the inherent associated bias. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) therefore has the potential to both safely guide acute clinical management to optimise control and provide robust data on which to assess the long-term impact.

Continuous glucose monitoring

A range of technological methods have been tested for their abilities to support CGM. Currently, the only CGM method used in clinical practice for the management of patients with diabetes involves measurement of interstitial glucose levels, which are calibrated against blood glucose measurements. CGM devices comprise a disposable subcutaneous oxidase-based platinum electrode that catalyses interstitial glucose, generating an electrical signal that is transmitted to a monitor for recording or display. Three companies have devices on the market for CGM: Dexcom Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA), Abbott Laboratories UK (Berkshire, UK) and Medtronic plc (Watford, UK). However, because of the size of extremely preterm infants and issues of insertion and attachment to these small infants, only the Medtronic plc devices are currently suitable for use in the extremely preterm infant.

Although this is a rapidly changing field, early CGM devices were used to collect data in real time, but these data could be downloaded only retrospectively to be reviewed and used to guide future clinical treatment. This is useful (1) in the setting of research, (2) to provide advice on long-term behavioural or medical interventions and (3) in the case of patients with stable diabetes, to review patterns of glucose control over time. These devices have also been used in preterm infants without side effects and identified significant periods of both hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia that were undetected clinically. 20–22 However, they are not suitable for providing data that is useful for acute clinical management. Newer CGM devices allow the data to be viewed in real time, providing information on glucose trends, with the potential to identify episodes of hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia, thus allowing the possibility of earlier intervention and prevention.

Development of continuous glucose monitors

The development of CGM devices provides the opportunity for data on glucose levels to be recorded every 5 minutes and viewed continuously. A number of different devices are available for clinical use and they are increasingly found to help reduce glycated haemoglobin and glycaemic variability in patients with type 1 diabetes without increasing the risk of hypoglycaemia. These devices allow patients to monitor their glucose levels by displaying absolute glucose concentrations as well as trends. Some systems depend on intravenous access, some use microdialysis and others measure interstitial glucose levels. Their use has been trialled in adults in intensive care and in patients requiring cardiac surgery. 23 Although these studies have been limited, they have shown that the devices are accurate and safe in cardiac surgical patients and can reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia in adults in intensive care. 24 Some have raised concerns about the lack of absolute sensitivity of individual readings at glucose thresholds, emphasising the potential importance of CGM as an early-warning system for both hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia. 25

These studies have highlighted the need for methodologies that can provide real-time data and allow adjustment of clinical management in the setting of a rapidly changing clinical picture of intensive care. 26,27 These benefits have been seen in the adult intensive care setting, where blood glucose levels are routinely measured much more frequently than in NICUs. Therefore, the potential for benefits in the NICU setting, where the frequency of blood glucose measurements is much lower, is likely to be more clinically significant. Key recent developments in these devices include extended sensor life, such that sensors can now remain in situ for 6 days (previously 72 hours), and changes to the sensor construction and the calibration algorithms, which have led to improved overall accuracy. 28 This is particularly important in terms of sensitivities to detect threshold levels of hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia.

Previous use of continuous glucose monitors in neonates

There is limited use of CGM in NICUs. We have used blinded CGM devices as part of an international multicentre trial in preterm infants and assessed the accuracy of these devices compared with current clinical practice. 29,30 These studies suggested that the value of CGM could be in providing early warning of fluctuations in glucose levels to guide the need for blood glucose assessment. In addition, by providing a continuous readout, episodes of hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia could be anticipated and therefore avoided. We have previously collected ‘blinded’ CGM data as part of the Neonatal Insulin Therapy [Nirture (Neonatal Insulin Replacement Therapy in Europe Study)] trial using a CGM (Medtronic plc)21 and in a small feasibility study using the iPro™2 (Medtronic plc). In the small feasibility study of 10 infants with a birthweight ≤ 1200 g monitored from birth for up to 7 days, infants had a median gestational age at birth of 28.4 weeks and a median birthweight of 840 g. The median time in the target glucose range of 2.6–10 mmol/l was 58% and the median time in the target glucose range of 4–8 mmol/l was 40%.

The REACT project

The purpose of the REACT project was to evaluate the role of CGMs in the detection and management of hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia in NICUs. The project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programme, with additional support of CGM equipment provided by Medtronic plc and sponsorship from the University of Cambridge Addenbrookes Hospital NHS Trust (Cambridge, UK). There were three stages:

-

to undertake a single-centre feasibility study to inform the design of a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT)

-

to evaluate the clinical role of CGMs, in terms of efficacy, safety, utility and cost-effectiveness, through a multicentre RCT

-

to pilot the potential use of a closed-loop system for glucose control using CGMs.

Chapter 2 Feasibility study

Aim

The aim of the study was to carry out preliminary evaluation of feasibility of real-time CGM to inform the design of a larger RCT in the preterm population.

Objectives

The objectives of the feasibility study were to determine provisional data regarding:

-

recruitment potential for a RCT

-

accuracy and safety of the devices for use in the preterm population

-

user acceptability, including the impact on clinical care and frequency of blood glucose testing

-

prevalence of the anticipated primary outcome measure (i.e. time in glucose target range of 2.6–10 mmol/l).

Methods

Study design

This was a single-centre study, with infants recruited from the NICU at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Ethics and trust research and development approval were obtained prior to the start of study recruitment, and informed parental consent was obtained prior to any study procedures. Inclusion criteria were infants with a birthweight ≤ 1200 g and aged ≤ 48 hours for whom informed parental consent had been received. Infants were excluded if they had a major congenital malformation or an underlying metabolic disorder, or if the mothers had a pregnancy complicated with diabetes. The intervention lasted for up to 7 days. Data regarding glucose levels, clinical condition and nutritional intake, as well as insulin use, were collected prospectively.

Continuous glucose monitoring and management

Real-time CGM was performed using the Paradigm® Veo™ system (Medtronic plc) (Figure 1). Enlite™ sensors (Medtronic plc) were linked to the Paradigm® Veo™. The sensor glucose data could be viewed in real time and were used in conjunction with the guideline to support clinical management. The guideline provided simple guidance, was not a rigid guideline and had not undergone formal in silico testing. The nurses recorded the sensory glucose value, alongside standard hourly clinical observation, using it to guide the need for blood glucose testing. The guideline prompted review and intervention based on both absolute glucose levels and change. The CGM devices were calibrated at least twice daily using a blood glucose measured on the point-of-care (POC) StatStrip® meter (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA, USA). The StatStrip meter was chosen because it has been validated for accuracy in the newborn and intensive care settings.

FIGURE 1.

Continuous glucose monitoring system. (a) Enlite sensor; (b) Paradigm Veo and MiniLink® REAL-Time Transmitter (Medtronic plc) attached to a sensor; and (c) preterm infant with device in situ. Reproduced with permission from Thomson et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Blood glucose monitoring

Blood glucose levels were measured using a combination of arterial, venous and capillary samples, and were tested on the blood gas analyser (cobas b 221; Roche Diagnostics, Welwyn Garden City, UK) and the Nova StatStrip.

Analyses

Accuracy of the continuous glucose monitor

Prespecified comparative analyses were based on any glucose levels that were recorded within 5 minutes of each other. The median relative difference was calculated as the percentage difference between the two measures. Absolute differences were determined at each time point in terms of compliance with International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 2003 and 2013 standards. 31,32 Bland–Altman analysis was used for assessment of error between glucose measurements and error grid plots were used to explore potential clinical impact.

Safety of the continuous glucose monitor

Safety outcomes were defined as prevalence of hypoglycaemia (percentage of time with sensor glucose level < 2.6 mmol/l) and any single blood glucose reading of < 2.6 mmol/l, and/or more than six sensor glucose readings of < 2.6 mmol/l (i.e. > 30 minutes).

Utility

The clinical care team were invited to complete a comments sheet daily for immediate feedback, as well as an anonymised questionnaire for summative review. The questionnaires explored initial expectations and experiences of using the CGM. These questionnaires were developed in collaboration with nurses on the unit to ensure that questions were easy to understand and relevant to the individuals concerned.

Efficacy outcome

Predefined efficacy outcomes included time in target range (i.e. percentage of time with a sensor glucose level 2.6–10 mmol/l or 4–8 mmol/l), prevalence of hyperglycaemia (i.e. percentage of time with a sensor glucose level > 10 mmol/l) and prevalence of severe hyperglycaemia (i.e. percentage of time with a sensor glucose level > 15 mmol/l).

Results are expressed as mean [standard deviation (SD)], median [interquartile range (IQR)] or frequencies (percentages), as appropriate.

Results

Recruitment

Twenty-one infants were successfully recruited to the feasibility study. One infant was withdrawn because of failure of sensor insertion. The baseline demographic details of the remaining 20 infants with CGM data are shown in Table 1. The recruitment rate fluctuated widely from month to month and was delayed by two factors: (1) availability of eligible infants to approach and (2) availability of appropriately trained staff to undertake the study procedures. During the recruitment period, the NICU underwent a period of reduced admissions associated with the introduction of a new electronic medical records system, resulting in fewer infants being admitted and available for recruitment. In addition, sensor insertion was initially limited to key study staff to facilitate a core of experience within the team. However, the unpredictability of preterm deliveries, combined with the need for many mothers to be transferred from other hospitals, resulted in a very small window for recruitment and meant that staff with the key skills for sensor insertion were not always available.

| Baseline demographic data | Feasibility study (N = 20) |

|---|---|

| Gestational age at birth (weeks), mean (SD) | 26.14 (1.9) |

| Birthweight (g), mean (SD) | 809 (156) |

| Sex (male-to-female) | 10 : 10 |

| Antenatal variable, n (%) | |

| Antenatal steroids | 19 (95) |

| Maternal smoking | 5 (25) |

| Chorioamnionitis | 1 (5) |

| PROM | 6 (30) |

| Hypertension | 1 (5) |

Accuracy of continuous glucose monitors

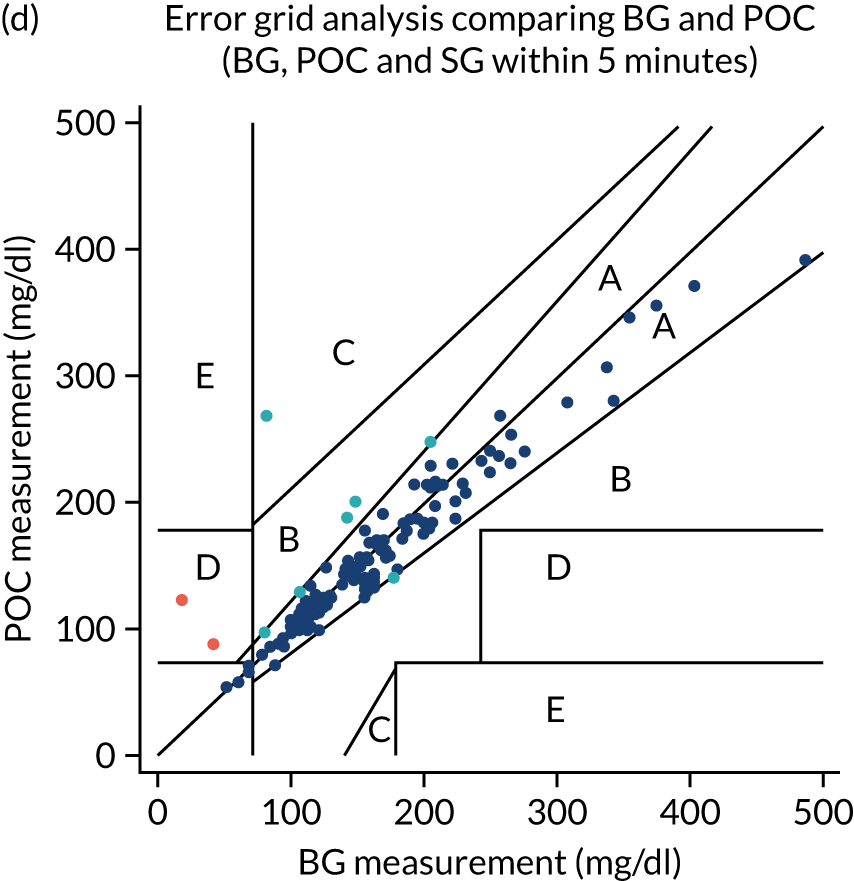

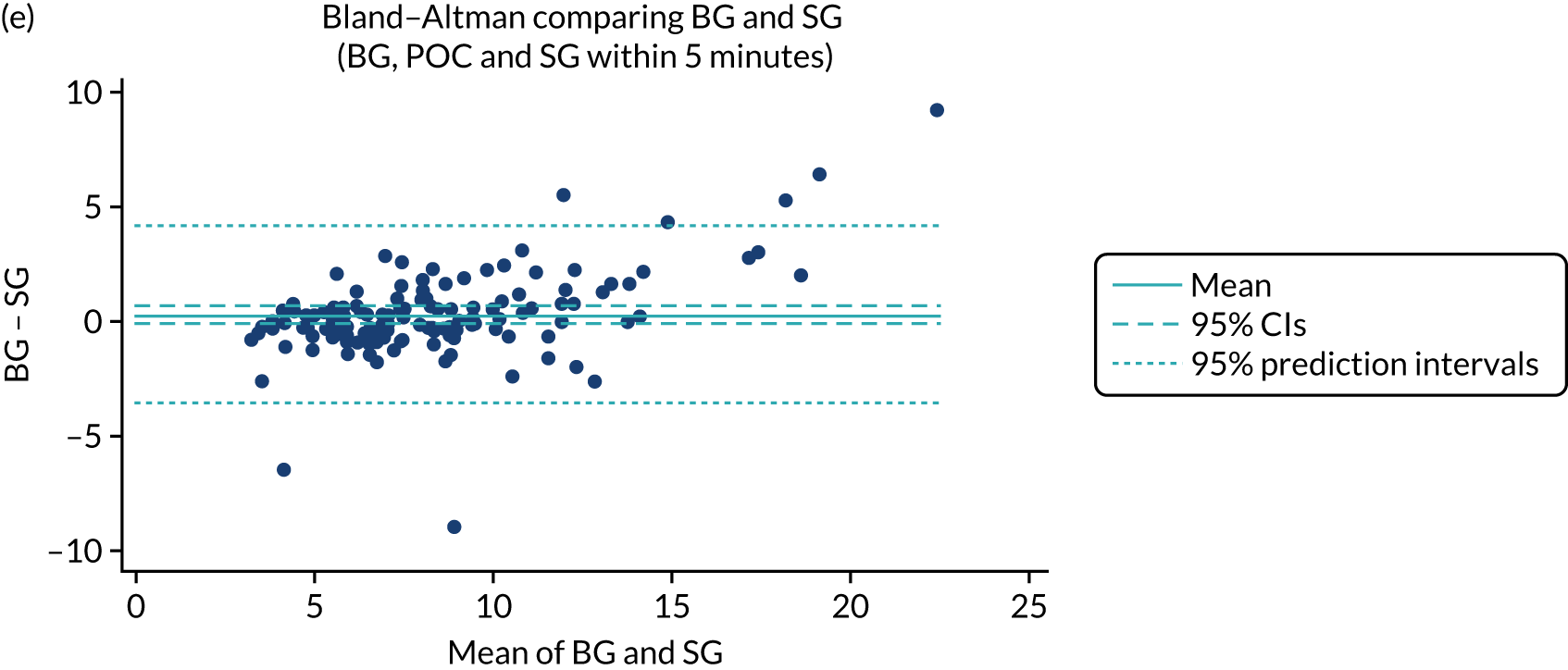

Comparative data providing more than two glucose measurements (blood glucose or sensor glucose) taken within 5 minutes of each other were available at 247 time points. Bland–Altman analyses provided a mean bias between POC and CGM of –0.27 [95% confidence interval (CI) –0.35 to –0.19] (Figure 2). Error grid analyses (comparing sensor glucose with either blood glucose methodology) demonstrated that 98% of values lay within area A or B (see Figure 2). Performance in relation to the ISO 200331 and ISO 201332 standards is provided in Table 2.

FIGURE 2.

Feasibility study: Bland–Altman and error grid plots. 33 (a) Bland–Altman comparison of CGM sensor glucose with StatStrip meter; (b) error grid plot comparing CGM sensor glucose with StatStrip meter or blood gas (cobas b 221) glucose values; (c) Bland–Altman comparison of POC StatStrip meter with blood gas (cobas b 221) glucose values; (d) error grid plot comparing POC StatStrip meter with blood gas (cobas b 221) glucose values; (e) Bland–Altman comparison of CGM sensor glucose with blood gas (cobas b 221) glucose values; and (f) error grid plot comparing CGM sensor glucose with blood gas (cobas b 221) glucose values. BG, blood glucose; SG, sensor glucose. Orange dots represent outliers whose results were reviewed and were deemed to be secondary to pre-analytical error in blood glucose sampling. The reference lines show the estimate of the mean difference, 95% CIs around the mean estimate and the predictive interval, the region in which a new observation would be expected, with 95% confidence, to be observed. Reproduced with permission from Thomson et al. 1 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

| Standard | Criterion | Blood glucose (%) | POC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MARD | Per cent difference between sensor glucose and reference (sensor glucose – reference)/reference × 100 | 11 | 10 |

| ISO 200331 | Per cent of sensor glucose values within ± 20% of the blood glucose value | 84 | 90 |

| ISO 201332 | Per cent of sensor glucose values within ± 0.83 mmol/l of blood glucose value | 73 | 78 |

Safety

There were no serious adverse device effects (SADEs). One infant died prior to discharge from hospital, but after the intervention period. Death was due to prematurity and felt to be unrelated to the study intervention. One infant was withdrawn from the study early as the mother became acutely unwell and, in the light of the mother’s mental health, it was felt appropriate to withdraw the infant from the study. One infant was withdrawn because of failure of sensor insertion. This was the second infant recruited to the study. The Enlite sensor failed to insert on two attempts and remained within the needle guard. There were no concerns about infection or trauma at the site of sensor insertion and the CGM device did not interfere with clinical care.

There were three infants who had clinically documented episodes of hypoglycaemia, defined as any blood glucose measurement < 2.6 mmol/l. In each of these infants, the falling sensor glucose level had prompted action to be taken to check the blood glucose level. There were no concerns about the infants during these episodes and without the falling sensor glucose level the blood glucose level would not have been checked. After confirming a blood glucose level < 2.6 mmol/l, these infants were treated with intravenous dextrose. In two cases, the falling sensor glucose level also revealed failure of central access. In two of these episodes, sensor glucose values were also < 2.6 mmol/l (recorded on the CGM devices as episodes lasting 40 and 25 minutes, respectively). In the other case, the lowest sensor glucose value was 2.7 mmol/l. There was one further episode when the sensor glucose fell to < 2.6 mmol/l for 70 minutes, but this was not documented clinically because of a protocol deviation, as blood glucose was not measured at this time. There were no concerns about any of the infants during any of these episodes and the infants were not receiving any insulin.

Utility

The overall assessment of the CGM devices by research and clinical staff was that they were easy to use in terms of insertion and calibration. There were occasions when there was loss of connectivity between the sensor and the monitor (e.g. if an infant was moved out of an incubator for kangaroo care or someone stood between the infant and the monitor). On such occasions, it was evident that the transmitter range was limited if transmission was blocked by objects between the sensor and the monitor. This could be resolved by moving the monitor closer to the infant. Staff found the use of both predictive and threshold alarms challenging, considering them an unnecessary addition to recording sensor glucose levels hourly. As a result of frequent requests to silence these alarms, they were subsequently turned off in the early stages of the study to ensure continued staff engagement.

With a need for twice-daily calibrations, the median number of blood samples taken for glucose measurement per 24-hour period did not appear to be excessive or significantly different from the number of samples taken in other infants of similar gestational and postnatal age on the unit. The median of the mean number of samples per day per infant was 4.1 (range 3.3–4.3).

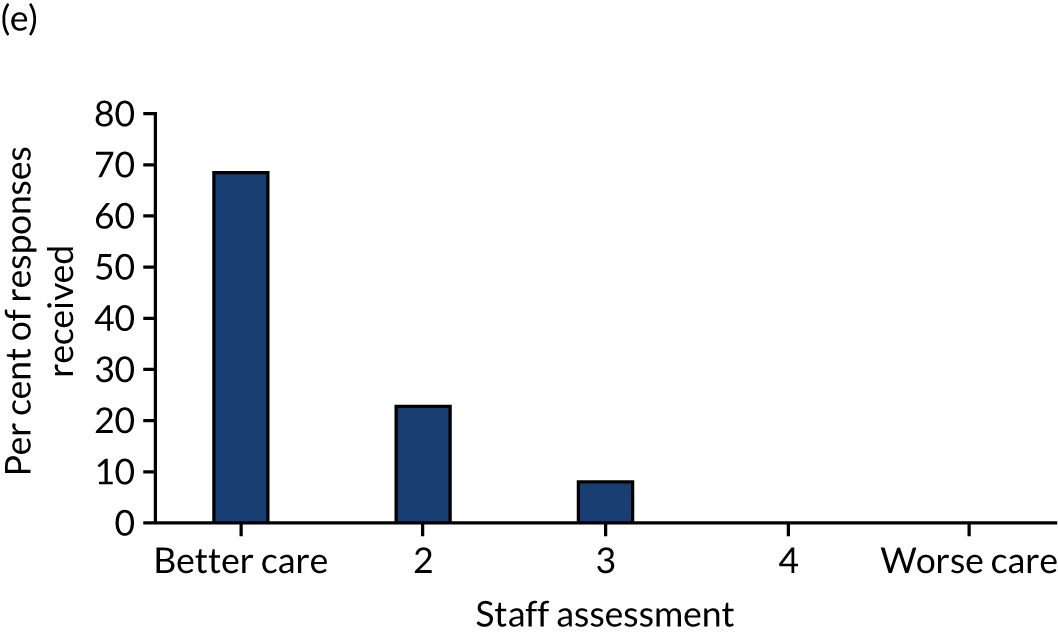

Staff expectations varied greatly, with some nurses excited about the potential to limit the need for frequent blood glucose sampling and avoiding ‘hurting the baby’; however, others had concerns about increased workload, sensor insertion, risk of ‘tissue damage’ or difficulties in positioning an infant following sensor insertion. Comments varied from ‘exciting’ to ‘how much extra time will it take up?’. After caring for an infant using CGM, there was an over-riding view that the intervention improved the quality of care (Figure 3). Comments included ‘found the monitor to be useful when the infant was on insulin’, ‘the chart . . . is really useful’, ‘I think this is the best treatment’ and ‘it is not extra workload’. Nursing staff reported positively about the impact on care in terms of feeling more empowered to manage the infant’s glucose control. They did not report any significant negative effects for the infant or the clinical/nursing team caring for the infant.

FIGURE 3.

Feasibility study: staff assessment of the use of continuous glucose monitoring. 1 (a) Do you think the baby is distressed?; (b) How did you find the monitor to read and calibrate?; (c) Do you think the device has interfered with the nursing care?; (d) Did having the baby on the monitor significantly affect your workload?; and (e) Did you think that being able to monitor glucose continuously had an impact on clinical care? Data are presented as a per cent of the responses received. Reproduced with permission from Thomson et al. 1 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Efficacy

A total of 2626 hours of CGM data were collected from 20 infants, with a median for individual infants of 144 (range 7–166) hours. There was wide variability in glucose control in this population. Data demonstrating the percentage of time within different target thresholds are provided in Table 3. The median percentage of time in the target range of 2.6–10 mmol/l was 78% (IQR 59–94%), with values > 10 mmol/l recorded 22% of the time.

| Outcome | Value (n = 20) |

|---|---|

| Percentage of time sensor glucose in range | |

| 2.6–10.0 mmol/la | 78 (59–94) |

| 4.0–8.0 mmol/l | 46 (35–66) |

| > 10.0 mmol/l | 22 (6–41) |

| < 2.6 mmol/l | 0 (0–0) |

| Mean sensor glucose (mmol/l) | 8.3 (7.4–9.4) |

| SD of sensor glucose (mmol/l) | 2.39 (1.77–3.67) |

| Hypoglycaemia (sensor data) | |

| Number of infants with more than one episode of hypoglycaemia | 2 |

| Number of episodes of hypoglycaemia | 2 |

| Total length of episodes (minutes) | 40–70 |

| Blood glucose (< 2.6 mmol/l) | |

| Number of episodes of hypoglycaemia | 3b |

Discussion

This study was the first to explore the potential role of ‘real-time’ CGM to support targeting of glucose control, with guidance on insulin and glucose delivery in preterm infants. The feasibility study highlighted the challenges of recruiting to a complex interventional study when recruitment has to occur at unpredictable times and within a very short time frame. The devices were found to be sufficiently accurate to guide clinical management and the sensors were well tolerated, despite the infants’ low birthweight, limited subcutaneous tissue and potential risk of infection. Furthermore, the staff felt that the intervention led to improved care.

Recruitment within the feasibility study was noted to be onerous to the research team. This was related to the unpredictability of infants being delivered, combined with the tight time frame. The feasibility study also showed that the burden of recruitment, combined with a complex intervention, was likely to present considerable challenges to the delivery of a multicentre trial. In most units, key staff are usually trained to undertake consent for trials, but interventions such as a change in feeding practice or even investigational medicinal product delivery can be undertaken by core clinical staff. As a device study, identifying the key skill sets needed to undertake the study and the optimal number of staff needed to support recruitment was seen as critical. There was a need for staff with the key skills for sensor insertion and who were able to guide the clinical team regarding the protocol to be available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for optimal recruitment. This informed the development of training packages for unit staff, including a video guide to sensor insertion and packages of example cases for the use of the guideline for glucose control and further informed the plans for the subsequent RCT.

The data showed the CGM devices to be of comparable accuracy to the POC devices that are currently used in clinical practice. The median absolute relative difference was similar to that reported in other paediatric and intensive care studies. 34,35 There were episodes when only one of sensor glucose or blood glucose level reached the threshold for hypoglycaemia, but the trend in falling sensor glucose level had prompted the measurement of blood glucose. The blood glucose level would not have been checked if the sensor had not triggered a clinical concern and the episode of hypoglycaemia would have been clinically undetected. Differences may, in part, be related to the physiological differences between blood and interstitial glucose levels, particularly with rapidly changing blood glucose levels. 36

There was no increase in risk of hypoglycaemia with a more proactive approach to management of hyperglycaemia, that is when using the guideline alongside the real-time monitoring. This is in contrast to previous attempts to target glucose control with insulin in adult or neonatal intensive care, which have resulted in significant increases in the prevalence of hypoglycaemia. 15 In this study, use of CGM devices provided an opportunity to track changes in glucose control in real time. This was important in providing guidance to clinical staff about glucose management in a population, that is infants in the NICU, in whom drug infusions (both types of drugs and dosing), as well as insulin sensitivity and secretion, change both frequently and rapidly, leading to a risk of hypoglycaemia. This was highlighted by the fact that two infants experienced hypoglycaemic episodes (related to loss of central access) that first became apparent because of the falling sensor glucose value.

The aim was not for CGM to replace blood glucose sampling, but to augment it, and the number of blood glucose samples taken in these infants was comparable to the number of samples taken from other infants of a similar gestational and postnatal age within the unit. This is in keeping with the advice given to the clinical nurses during the study, which was to check blood glucose values before modifying any aspect of the management of glucose control. For example, changes in insulin dosing were undertaken only in response to a persistent rising glucose level on the CGM device and supported by a confirmatory blood glucose measurement. During the study, however, nursing staff became more confident in the accuracy of the sensor glucose values and, with the guideline, they began to change dosing based on sensor glucose values alone. They began to use blood glucose values in a more proactive way to confirm observed trends in the CGM. Increasing confidence in the accuracy of CGM devices and the desire to limit handling of preterm infants may lead to reduced blood glucose sampling in the future.

One infant (the second infant recruited) was withdrawn from the study because of failure on two occasions to successfully place a sensor. For this infant, on both occasions, the sensor remained within the needle guard and did not insert into the thigh. This event had been previously reported in paediatric and adult patients, but had not been experienced by the research team with previous Softsense sensors (Medtronic plc). On reviewing the potential causes, the advice on insertion technique was modified to focus on ensuring that the needle and sensor remained at 90° to the hub until after the introducer needle was removed. There were no further occurrences during the feasibility study. The sensor appeared to be safe, with no reports of infection or debridement of skin at the sensor site in this preterm population.

The lack of benefit from predictive trend alarms was disappointing, but it may be that with more experience the alarms could be used. However, the system was reported by the nursing staff to be beneficial to clinical care. The clinical team reported feeling that the combination of the CGM device and guideline was useful in caring for the infant.

We chose a strategy that aimed to optimise nutritional intake, using the intervention to inform decisions on insulin and glucose therapy in the event of hyperglycaemia or hypoglycaemia. Other strategies can also be used to target glucose control in preterm infants, each with different risks and benefits. One such alternative strategy, that of reducing parenteral intake, risks compromised nutritional delivery, as found in a recent study in preterm infants using CGM and a computer algorithm to modify glucose intake in response to hyperglycaemia. 37 Our study is unique in combining the use of a CGM with a guideline for the use of insulin and glucose therapy. This design is easy to adopt in clinical practice as it does not involve the need for frequent changes to parenteral nutrition, which may affect nutritional and electrolyte delivery, as well as staff workload and cost. Moreover, we have shown in this feasibility study that this strategy does not increase the risk of hypoglycaemia.

The efficacy outcome of percentage of time with glucose level in the target range (i.e. 2.6–10 mmol/l) was reviewed by the trial statistician to inform power calculations for the planned multicentre RCT of real-time CGM compared with standard care. The data were used to confirm sample size considerations based on a final analysis comparing the percentage of time in the target range (2.6–10 mmol/l), that is a continuous variable, in terms of the mean values between the treatment arms. Based on these data, the SD of this end point was conservatively estimated at 22%; hence, a sample size of 200 infants would provide 90% power to detect a difference of 10% at the 5% significance level. Consensus was reached among expert opinion at the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring Ethics Committee (DMEC) meetings that a 10% difference would be clinically meaningful. The comparison between the mean values in Table 3 provides support to an effect size of 10%, or more being plausible.

Summary

The feasibility study confirmed reasonable accuracy and utility of the combination of CGM plus the guideline for blood glucose testing and subsequent intervention within a clinical trial. It further informed the need to innovate to maximise recruitment potential and staff engagement, while providing data to substantiate the power calculations for the primary outcomes within such a trial.

Chapter 3 REACT trial design

Introduction

Data from the feasibility study helped to design this RCT. Those involved in recruitment pointed out that the short time period from birth to study entry was a challenge and, therefore, an online training video was developed to enable training of a larger number of staff in recruiting sites to support recruitment and delivery of the intervention. There were no safety flags in terms of the CGM device itself. In the context of using CGM as an adjunct to current methods of blood glucose monitoring, CGM was confirmed to be sufficiently accurate to safely support glucose management. Provisional data on the combination of the CGM and guideline to guide targeting of glucose control did not give rise to any safety concerns in terms of risks of hypoglycaemia. Data on the prevalence of the anticipated primary outcome measure of time in glucose target range (i.e. 2.6–10 mmol/l) confirmed an estimated SD of 22%, which was in keeping with the planned sample size of 200 infants. Furthermore, the staff questionnaire demonstrated that the clinical team caring for infants felt that CGM has the potential to improve clinical care.

Aim

To evaluate the clinical role of CGM in the preterm infant, in terms of efficacy, safety, utility and cost-effectiveness, through a multicentre RCT.

Hypothesis

We hypothesised that the use of real-time CGM could increase the amount of time that an infant’s glucose levels (measured using CGM) are within the target range of 2.6–10 mmol/l (i.e. the widely accepted clinical target for glucose control) compared with standard clinical practice (with blinded CGM data collection).

Trial objectives

The primary efficacy outcome was percentage of time for which glucose levels were within the glucose target range of 2.6–10 mmol/l over 6 days, following recruitment within 24 hours of birth.

Secondary outcomes related to:

-

efficacy (i.e. mean sensor glucose level, percentage of time sensor glucose levels are in the target range of 4–8 mmol/l, sensor glucose level variability, percentage of time sensor glucose levels are > 15 mmol/l)

-

safety, as measured by both device effects and incidence of hypoglycaemia

-

utility assessed by staff and parent questionnaires

-

cost-effectiveness

-

exploratory analyses.

Methods

Study design

This study was an international open-label parallel-group RCT, with infants recruited between July 2016 and January 2019 from 13 NICUs in the UK, Spain and the Netherlands. The protocol has been published. 2

Eligibility criteria

Infants were eligible if they were within 24 hours of birth, weighed ≤ 1200 g and were born at ≤ 36+6 weeks gestation, and if written parental consent had been obtained. Exclusion criteria included any lethal congenital malformations and any congenital metabolic disorder known at trial entry. Infants were also ineligible if, in the opinion of the treating clinical consultant, they had no realistic prospect of survival.

Recruitment procedure

All infants were recruited within 24 hours of birth at one of the NICUs that had been approved for study participation as a level 3 unit with capacity and capability to recruit. Owing to the short time frame from birth to recruitment, potentially eligible infants were identified in a number of ways: (1) liaison with the obstetric team to highlight mothers at risk of preterm delivery, (2) liaison with the neonatal transport team to identify infants who had been born in local units and being transferred to a study centre and (3) liaison with the NICU clinical team of study centres. Screening of eligible infants was undertaken in collaboration with the clinical team and families were approached for consent only if they were considered eligible. Screening logs were reviewed regularly by the co-ordinating centre to identify any issues around recruitment. The investigator or a suitably qualified person designated by the principal investigator was able to receive written informed consent from the infant’s parent/legally acceptable representative before any trial-specific activity was performed.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation to the standard-care and CGM arms of the study in a 1 : 1 ratio was undertaken centrally using a web randomisation system, Trans European Network ALEA software (TENALEA; ALEA Clinical, Abcoude, The Netherlands). This used block randomisation, with blocks of random size (i.e. 4, 6, 8) stratifying by recruiting centre and gestation (< 26 or ≥ 26 weeks’ gestation). The management of glucose control and use of CGM from recruitment at aged ≤ 24 hours until day 7 were predetermined in the protocol for each study arm. 2 Clinical outcome data were collected until 36 weeks’ corrected gestational age. No other aspects of concomitant care were prohibited during the trial.

Intervention

All infants were fitted with a sensor (i.e. the Enlite glucose sensor) that was linked to a MiniMed™ 640G System (Medtronic plc). Sensors were inserted subcutaneously (into the thigh) by hand and not using the standard insertion device, thereby ensuring that the sensor was inserted into the subcutaneous tissue. The sensors are soft and flexible, approximately 8.75 mm in length, and are mounted inside a hollow needle to allow for subcutaneous insertion. Once the sensor was inserted, the introducer needle was withdrawn and the sensor attached to a small Guardian™ 2 Link transmitter [Medtronic plc; Conformité Européenne (CE) Mark 2013; certificate number 8858] for data transfer to the MiniMed 640G System for data viewing. The sensors were secured with a clear occlusive dressing so that the insertion site could be inspected daily. A blood sample was required every 12 hours for calibration. For consistency across sites, all units were provided with Nova StatStrip meters for calibration of the CGM.

Intervention: real-time continuous glucose monitoring with guideline

The CGM data were available to view by the clinical team during the first week of life. Clinical staff were advised to read and record the sensor glucose data hourly as part of standard clinical care. They were provided with a specifically designed guideline to guide the management of glucose control and the use of insulin. The guideline was developed during the REACT feasibility study. 1

Control: standard care with blinded continuous glucose monitor data collection

Blinding of the study intervention between study groups was not feasible. To ensure that CGM data were not available to the clinical team caring for infants in the standard-care arm, the monitors were secured in an opaque bag with a tamper-proof seal. The bags were opened for calibration every 12 hours and a time log was kept of when the tamper tag was broken/resealed to document compliance.

Infants’ glucose control was monitored and managed in accordance with standard clinical practice based on intermittently sampled blood glucose levels. Nutritional requirement and insulin delivery were prescribed in accordance with standard clinical guidelines within each unit. The CGM device collected glucose data continuously, but the clinical team were masked to the data, as described above.

Medical devices: MiniMed 640G System

The MiniMed 640G System is indicated for glucose monitoring for the management of diabetes (Figure 4). The system being used comprised the Enlite sensor linked using the Guardian™ 2 Link transmitter to the MiniMed 640G. The Enlite sensor (CE certificate number 21024) has been described previously and comprises a disposable subcutaneous oxidase-based platinum electrode that catalyses interstitial glucose, generating an electrical current every 10 seconds that is transmitted to a monitor. The data were recorded as an averaged value every 5 minutes, giving a total of 288 readings per day. Glucose values outside the range of 2.2–24 mmol/l (40–430 mg/dl) are reported as < 2.2 mmol/l (40 mg/dl) or > 24 mmol/l (430 mg/dl).

FIGURE 4.

The MiniMed 640G System (courtesy of Medtronic plc). (a) The Enlite glucose sensor; (b) the Enlite glucose sensor with the Guardian 2 Link transmitter attached; and (c) the MiniMed 640G.

Data management and schedule of assessments

Data collection was undertaken from birth to 36 weeks’ corrected gestational age, and comprised the collection of clinical data recorded on a paper case report form (CRF) and electronic transfer of CGM data. Key time points for clinical data collection were recruitment, daily for the first week, day 14 followed by end of study at 36 weeks’ corrected gestational age and, if appropriate, at the point of withdrawal from the study. Parent and staff questionnaires were completed in the CGM group at study days 3 and 7. CGM data were transferred electronically after download from the CGM device on study day 7 or the day of sensor removal. Safety data were collected and reported in accordance with regulatory guidance. If an infant was discharged from their recruiting NICU, the research team used local and national databases, local contacts and links with parents to ensure that complete follow-up data were obtained. All CRF data were sent to the co-ordinating centre in Cambridge to be entered onto a macro-database. All CGM files were sent to the co-ordinating centre in Cambridge for validation on format and consistency before processing and analysis. All data were collected, transferred (using a study identifier), cleaned and stored to comply with good clinical practice and data protection legislation.

Efficacy

Efficacy was assessed by comparing the data collected from the CGM in the CGM and standard-care arms of the study.

Safety

Safety was assessed in three areas: (1) incidence of hypoglycaemia, measured as part of clinical care (blood glucose levels) and after review of sensor glucose data; (2) device safety through adverse device effect (ADE) reporting; and (3) acute mortality and morbidity outcomes as part of the CRF.

Utility

Nursing staff and parents caring for the infants in the CGM arm of the study were asked to complete a study-specific questionnaire.

Health economic evaluation

Data were collected on the health service resources used in the treatment of infants during the period between randomisation and 36 weeks’ gestational age, and based on the British Association of Perinatal Medicine standard criteria for level of care,38 as well as neonatal complications. Current UK unit costs were applied to each resource item and a per diem cost for each level of neonatal care was based on Department of Health and Social Care reference costs calculated on a full absorption costing basis. 39

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was defined as the percentage of time that the sensor glucose level was in the target range of 2.6–10 mmol/l. This was selected as the internationally most widely accepted clinical target range for glucose control in this population.

Secondary outcomes

Efficacy

-

Percentage of time sensor glucose level is in the target range of 4–8 mmol/l.

-

Mean sensor glucose level during the first 6 days.

-

Sensor glucose level variability within infants (as assessed by within-infant SD).

-

Percentage of time that glucose levels are in hyperglycaemic range (i.e. a sensor glucose level > 15 mmol/l).

Safety

-

Incidence of moderate hypoglycaemia, defined as any episode of blood glucose > 2.2 mmol/l and < 2.6 mmol/l.

-

Incidence of severe hypoglycaemia, defined as any episode of blood glucose ≤ 2.2 mmol/l.

-

Incidence of continuous hypoglycaemia, defined as a continuous episode of sensor glucose level < 2.6 mmol/l for > 1 hour.

Utility

-

The questionnaire comprised key questions that were scored using a Likert scale.

Health economic outcomes

Cost-effectiveness was expressed in terms of incremental cost per additional case of adequate glucose control between 2.6 and 10 mmol/l.

Exploratory outcomes

Exploratory outcomes included mortality before 36 weeks’ corrected gestational age, maximum severity of ROP, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) (i.e. the need for supplemental oxygen or respiratory support at 36 weeks’ corrected gestational age), microbiologically confirmed or clinically suspected late-onset invasive infection, necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) requiring medical or surgical treatment, maximum grade of intracranial haemorrhage (Papile and Burstein grading), growth (weight, length and head circumference at the end of week 1 and at 36 weeks’ corrected gestational age), nutritional intake during the first week of life (carbohydrate, protein and lipid), and use of insulin during the first and second week of life.

Sample size

The sample size was based on data from the REACT feasibility study and historical control data, which conservatively assumed that the SD of the primary end point (i.e. time in sensor glucose target range of 2.6–10 mmol/l over a 6-day period) would be 22%. A sample size of 200 participants would enable a treatment effect of a 10% increase in the mean value of the primary end point to be detected with 90% power using a two-sided 5% significance test in the primary analysis. Based on a consensus of expert opinion, a difference of 10% was believed to be of clinical relevance. It was expected that a small number of infants would be withdrawn from the study because of transfer to local units, withdrawal of parental consent or death.

At an interim analysis, a revised blinded estimate of the SD for the primary end point suggested that the original sample size would provide 92.5% power. After review of recruitment rates and undertaking a revised power calculation using the revised blinded estimate of the SD for the primary end point, a decision was made by the independent DMEC, TSC and sponsor to stop recruitment when 182 infants had been recruited. At this time, it was considered that concluding the study with 182 infants rather than the planned 200 would reduce the conservative estimate of power from 92.5% to 90%, which was felt to be an acceptable compromise to be able to report trial results within the desired timelines.

Statistical analyses

Efficacy analyses

Analyses were predetermined to be undertaken based on ‘full analysis’ (primary outcome) and ‘per-protocol’ populations to compare the CGM group with the standard-care group and were prespecified in the statistical analysis plan. Linear regression was used to estimate the absolute difference in the percentage of time that the sensor glucose level was in the target range of 2.6–10 mmol/l, adjusting for baseline variables (i.e. centre and gestation). Estimates of treatment effect, with 95% CIs and p-values, were calculated. Secondary end points that were continuous variables were analysed in a similar fashion and binary/ordinal variables were analysed using logistic/ordinal logistic regression.

To control the study-wide significance level to 5%, a Benjamini–Hochberg multiple testing procedure was applied to three end points of equal importance (i.e. the percentage of time that the sensor glucose level was in the target range of 2.6–10 mmol/l, the percentage of time that the sensor glucose level was in the target range of 4–8 mmol/l and mean sensor glucose level), followed by a gatekeeping sequence applied in the following order: sensor glucose variability, as assessed by within-infant SD; and percentage of time that glucose levels were in the hyperglycaemic range (i.e. sensor glucose level > 15 mmol/l). Nominal p-values and CIs are presented, unless otherwise stated.

Predefined subgroup analyses were undertaken by estimating, using the regression framework in an exploratory, non-confirmatory manner, treatment interaction effects with the following baseline variables: centre, sex, corrected gestational age, birthweight standard deviation score (SDS), use of antenatal steroids, maternal chorioamnionitis, maternal diabetes and first sensor glucose level.

Utility analyses

Acceptability of the intervention was assessed by a specifically designed staff questionnaire, which was completed anonymously by staff caring for an infant in the CGM arm on days 3 and 7, and by a similar parent questionnaire (completed on day 7). Compliance in the CGM group was assessed as a percentage of time that sensor glucose readings were recorded on the CRF and when the insulin rate of infusion was recorded if the sensor glucose > 8 mmol/l. In the standard-care group, non-compliance was defined as 12 or more CGM readings available during the time between the tamper tag being broken and resealed on at least one occasion.

Cost-effectiveness analyses

An incremental cost-effectiveness analysis was performed, details of which are presented in Chapter 5.

Study management

The study was co-ordinated and monitored by the Cambridge Clinical Trials Unit (Cambridge, UK) in accordance with international guidelines. The study was adopted onto the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network portfolio of studies.

Regulatory requirements

Ethics and regulatory approvals were obtained and the protocol is in the public domain (ISRCTN12793535),2 with a list of protocol amendments provided in Appendix 1. A DMEC and TSC were appointed and reviewed the data in accordance with their formal charters (see Appendices 2 and 3). Research teams at each site were required to have up-to-date good clinical practice training and have undertaken training in study procedures, including the use of the CGMs and Nova Biomedical POC devices. Paper and online resources, as well as a call line, were available to support the research teams.

Clinical trial authorisation was granted by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) (reference CI/2016/0011). Written approvals were received from individual hospital sites prior to recruitment. Approvals were also obtained from the Medical Ethics Review Committee (Vrije Universiteit University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and Heath Care Inspectorate (Heerlen, the Netherlands) (reference 2017-1 398434/VlO 14949), the Research Ethics Committee, Sant Joan de Déu Research Foundation (Barcelona, Spain), and the Ministry of Health Social Services and Equality (reference 591/16/EC) (Madrid, Spain). The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki40 and in conformity with the European Union medical devices regulations and any relevant amendments. 41

Monitoring

Data returns were continually monitored by the central team for the completeness and timeliness of all data returned. Compliance with intervention strategy in each study arm was also reviewed to ensure that there was no ‘crossover’ between study arms. A monitoring plan was in place, determining frequency and scope of site monitoring based on continuing risk review. Face-to-face monitoring visits were initially undertaken within the first 6 months; the interval between visits was then adjusted following assessment of recruitment rate and the number of data queries and serious adverse event (SAE) reports. The study sites were provided with direct access to all trial-related source data and reports for the purpose of monitoring and auditing by the central study team, sponsor and regulatory authorities, as required.

Data and safety monitoring

The DMEC chairperson was responsible for safeguarding the interests of the trial participants and making recommendations to the TSC. The REACT DMEC roles and responsibilities and operating procedures are defined in the REACT DMEC Charter (see Appendices 2 and 3). The DMEC was composed of three independent multidisciplinary experts who were not involved in the conduct of the trial in any way. They met prior to the initiation of enrolment and determined a plan to review the protocol, compliance, safety and adverse events (AEs), and outcome data after a prespecified number of infants had been recruited. The TSC was composed of six independent members, whose roles and responsibilities were defined by a charter. The TSC provided advice, through its chairperson, to the chief investigator and reported to the trial sponsor and trial funder.

Safety was assessed continuously during each infant’s stay in NICU. The frequency of AEs and SAEs that would normally require reporting within a clinical trial, as defined by the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use,42 was anticipated to be high in the population being studied, despite the low risk of the study intervention. Following discussions with the MHRA and in accordance with regulatory guidance that allows for exceptions in such circumstances, a modified reporting plan was agreed.

Any ADE was recorded and reported to the co-ordinating centre. All device deficiencies that might have led to a SADE if suitable action had not been taken, the intervention had not been made or if circumstances had been less fortunate were reported to the sponsor, as for SAEs and SADEs. AEs were recorded in the notes and captured as exploratory outcomes as part of the CRF. SAEs are known to be common in this population and, therefore, the MHRA requested the following expectations for safety reporting.

During the intervention period of the study (study days 1–7)

The following expected SAEs were required to be recorded in the CRF (safety log) and reported, using the CRF, to the sponsor within 24 hours of awareness of the event: (1) death, (2) culture-positive infection, (3) severe hypoglycaemia (glucose level < 2.6 mmol/l), (4) seizures and (5) any other related SAE.

Post intervention period (study day 8 until end of study)

It was agreed with the MHRA that important medical outcomes, including those normally considered as a SAE for a clinical trial, would be captured in the CRF at the 36 weeks’ corrected gestational age assessment (i.e. SAEs were viewed to be anticipated events for this study population and, therefore, they were not required to be recorded or reported separately as a SAE, if judged by the clinical team to be unrelated to the study).

Patient and public involvement

Members of the local parent support group were consulted to help inform trial design. Parents were asked to provide feedback on study involvement as part of the protocol, through both formal review of the protocol/patient information sheet and informal discussions at parent groups within the local NICU. The TSC included a lay person. We sent newsletters to parents to update them on study progress, and an end-of-study update for families.

Dissemination

The findings of the trial have been presented at national meetings, published in international journals and communicated back to the families involved.

Chapter 4 REACT trial results

Recruitment

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram is presented in Figure 5. A total of 1350 families were screened based on an anticipated birthweight ≤ 1200 g, with 918 families not approached because of the short recruiting window of 24 hours. Of the remaining 360 families who were approached, 182 consented, resulting in a consent rate of 51%. Two infants were excluded prior to randomisation, as they were > 24 hours of age. One infant who was found to be ineligible was excluded post randomisation. There were 11 withdrawals from the trial and eight deaths (control, n = 6; intervention, n = 2).

FIGURE 5.

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram. Reproduced with permission from Beardsall et al. 4 in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Demographic details

Demographic details of all recruited infants are provided in Table 4. These data show no apparent differences between study arms at baseline in terms of premorbidity and the results are in keeping with what would be anticipated for this preterm population.

| Variable | Statistic | Standard-care arm | CGM arm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (weeks) | n | 95 | 84 |

| Mean (SD) | 27.4 (1.9) | 27.7 (2.1) | |

| Sex, % (n/N) | Male | 47 (45/95) | 54 (45/84) |

| Ethnicity, % (n/N) | Asian | 12 (11/95) | 8 (7/84) |

| Black | 8 (8/95) | 8 (7/84) | |

| Mixed | 5 (5/95) | 7 (6/84) | |

| Other | 5 (5/95) | 4 (3/84) | |

| White | 69 (66/95) | 73 (61/84) | |

| Number of infants delivered, % (n/N) | Singleton | 74 (70/95) | 77 (65/84) |

| Multiple | 26 (25/95) | 23 (19/84) | |

| CRIB II score | n | 91 | 80 |

| Mean (SD) | 10 (2.9) | 10 (2.9) | |

| Median | 10 | 10 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 4, 19 | 4, 19 | |

| Birthweight (g) | n | 95 | 84 |

| Mean (SD) | 880 (180) | 910 (160) | |

| Median | 920 | 930 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 470, 1170 | 390, 1190 | |

| Birthweight SDS | n | 95 | 84 |

| Mean (SD) | –0.8 (0.92) | –0.82 (0.98) | |

| Median | –0.66 | –0.76 | |

| Minimum, maximum | –2.6, 1.32 | –2.97, 1.2 | |

| Use of antenatal steroids > 24 hours prior to delivery, % (n/N) | Yes | 73 (69/95) | 82 (69/84) |

| Use of antibiotics in 24 hours prior to delivery, % (n/N) | Yes | 34 (32/94) | 30 (25/84) |

| Maternal diabetes, % (n/N) | Yes | 8 (8/95) | 6 (5/84) |

| Maternal chorioamnionitis, % (n/N) | Yes | 22 (21/95) | 23 (19/84) |

| Delivery mode, % (n/N) | Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 33 (31/95) | 35 (29/84) |

| Caesarean section pre onset of labour | 42 (40/95) | 49 (41/84) | |

| Caesarean section post onset of labour | 23 (22/95) | 1 (13/84) | |

| Assisted vaginal delivery | 2 (2/95) | 1 (1/84) |

Compliance with intervention and control procedures

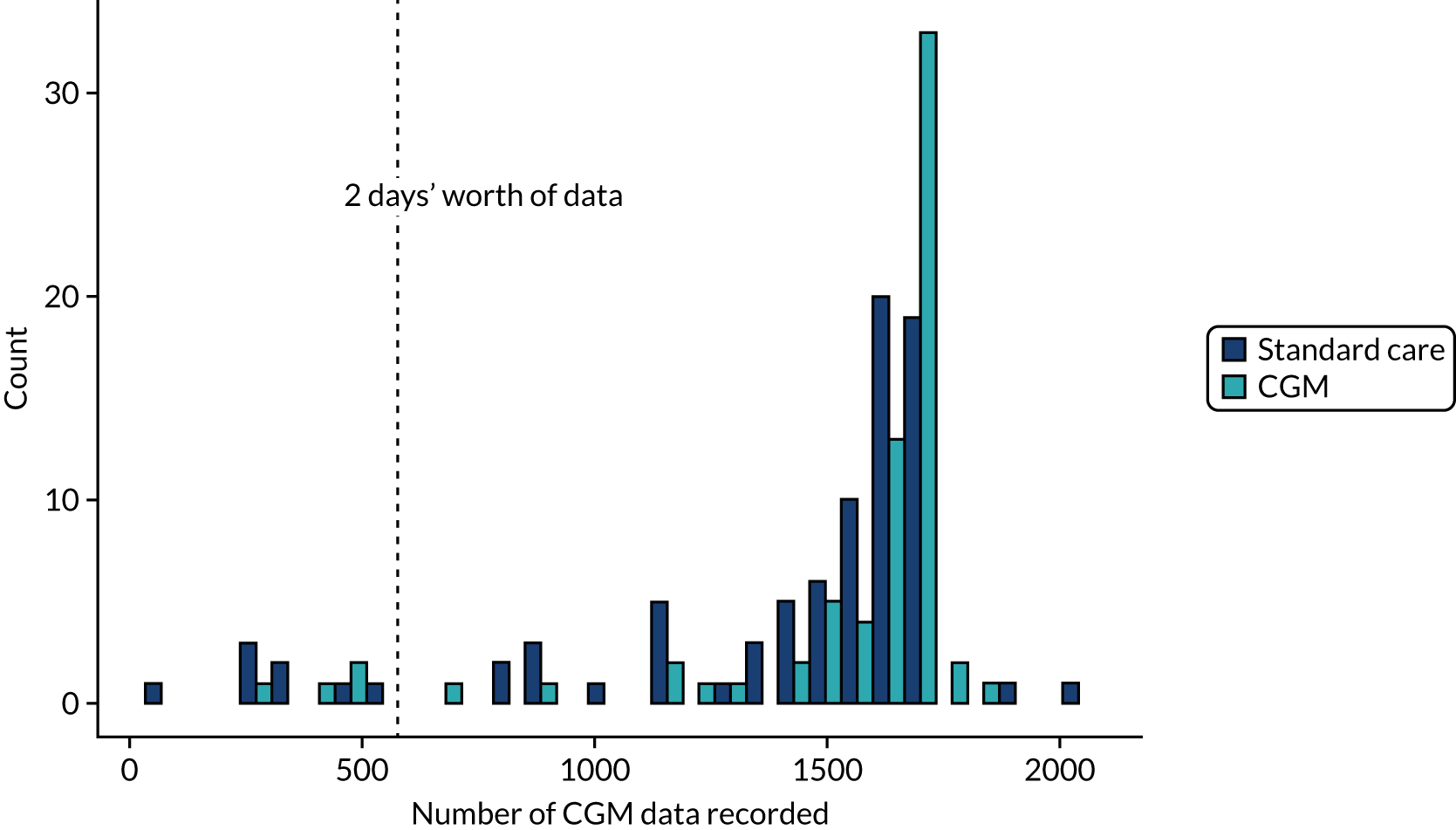

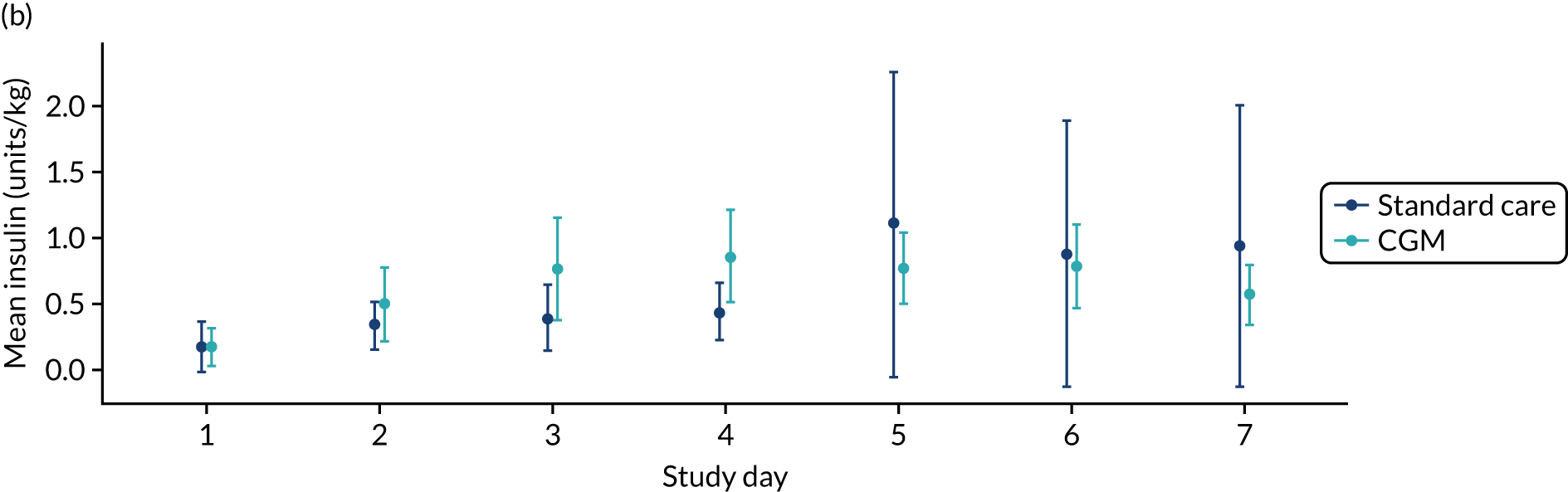

The number of CGM data points in the CGM and standard-care arms was a comparable mean of 1538 (SD 341) and 1412 (SD 424), respectively (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Randomised controlled trial: CGM data recorded by treatment group.

In the CGM group, the median number of times sensor glucose was recorded per hour on the CRF was 0.98 (range 0.56–1.45) based on hours’ worth of data (number of CGM readings/12) and 0.90 (range 0.29–1.28) based on total sensor duration (hours). The mean percentage of time that the insulin rate of infusion was recorded when the sensor glucose was > 8 mmol/l was 54% (SD 38%). Assessment of compliance with blinding in the control study arm was recorded using a log of time between the tamper tag being opened and resealed. Failure to comply with blinding [prespecified as 12 or more CGM readings available (equivalent to 60 minutes of time) between the tag being opened and resealed] occurred in 15% (14/95) of infants. The median length of time the tags were open for was 0.167 (range 0–23.9) hours, with a mean of 0.377 (SD 1.34) hours. These figures are represented graphically in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7.

Randomised controlled trial: clinically recorded glucose profiles and use of insulin in the CGM intervention study arm. SG, sensor glucose.

Primary outcome measure

The primary results for the full analysis population demonstrated that the time during which sensor glucose was in the target range of 2.6–10 mmol/l was 9% higher in the CGM arm than in the standard-care arm (95% CI 3% to 14%; p = 0.002) (Table 5). Full model-fitting results exploring the effect of centre and gestation ≥ 26 weeks (Table 6), and a range of sensitivity analyses (see Appendix 4, Tables 24 and 25), all gave similar treatment effects, suggesting that the results are robust. In per-protocol analyses, CGM, compared with standard control, resulted in a 10 percentage-point increase in the time that sensor glucose was in the target range of 2.6–10 mmol/l (95% CI 4% to 17%; p = 0.002). Model-fitting results for per-protocol analyses are provided in Appendix 4, Table 25.

| Variable | Statistic | Standard-care arm | CGM arm | Linear regression model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted mean differencea (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| Percentage of time sensor glucose is in target range of 2.6–10 mmol/l | n | 85 | 70 | 8.9 (3.4 to 14.4) | 0.002 |

| Mean (SD) | 84 (22) | 94 (11) | |||

| Median | 97 | 99 | |||

| Minimum, maximum | 14, 100 | 51, 100 | |||

| Mean sensor glucose level (mmol/l) | n | 85 | 70 | –0.46 (–1 to 0.09) | 0.99 |

| Mean (SD) | 7 (2.1) | 6.5 (1.2) | |||

| Median | 6.5 | 6.4 | |||

| Minimum, maximum | 3.1, 12.2 | 3, 9.9 | |||

| Percentage of time sensor glucose is in target range of 4–8 mmol/l | n | 85 | 70 | 11.5 (3.7 to 19.2) | 0.004 |

| Mean (SD) | 62 (29) | 74 (20) | |||

| Median | 65 | 78 | |||

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 100 | 16, 100 | |||

| Sensor glucose variability (mmol/l) | n | 85 | 70 | –0.01 (–0.15 to 0.13) | 0.9 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.6 (4.3) | 2.7 (3) | |||

| Median | 2.1 | 1.9 | |||

| Minimum, maximum | 0.07, 22 | 0.6, 23.1 | |||

| Percentage of time in hyperglycaemic range (i.e. > 15 mmol/l) | n | 85 | 70 | –0.92 (–2.03 to 0.19) | 0.1 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.3 (4.2) | 0.3 (2.1) | |||

| Median | 0 | 0 | |||

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 24 | 0, 16 | |||

| Outcome | Covariate | Estimate (SE) | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of time sensor glucose is in the target range 2.6–10 mmol/l | Intercept | 80.6 (3.7) | 73.4 to 87.9 | < 0.001 |

| CGM vs. standard care | 8.9 (2.8) | 3.4 to 14.4 | 0.002 | |

| N36 (reference N01) | –7.9 (12.3) | –32.2 to 16.5 | 0.5 | |

| N42 | 7.6 (5.9) | –4.1 to 19.3 | 0.2 | |

| N43 | 0.2 (4.2) | –8.2 to 8.6 | 0.96 | |

| N68 | 0.2 (4.2) | –8.1 to 8.5 | 0.97 | |

| N73 | 0.3 (5.5) | –10.6 to 11.2 | 0.95 | |

| N74 | 10 (12) | –14 to 34 | 0.4 | |

| N85 | 8.2 (6.9) | –5.4 to 21.8 | 0.2 | |

| N86 | –16 (8.9) | –33.7 to 1.6 | 0.08 | |

| N87 | –12.2 (12.4) | –36.6 to 12.2 | 0.3 | |

| N88 | –29 (8) | –44.8 to –13.2 | < 0.001 | |

| ND3 | 6.9 (6.9) | –6.7 to 20.5 | 0.3 | |

| SP3 | 9.6 (8.9) | –8 to 27.2 | 0.3 | |

| Gestation ≥ 26 weeks | 4.9 (3.6) | –2.1 to 12 | 0.2 | |

| RSD = 17.02 |

Significant subgroup effects included sex (compared with standard care, CGM resulted in a 15 percentage-point increase in the time that sensor glucose level was in the target range in male infants and a 2 percentage-point increase in female infants; see Appendix 4, Table 26).

Secondary outcomes

Efficacy

Secondary outcome analyses showed that time in the target range of 4–8 mmol/ was 12 percentage-points higher in the CGM arm than in the standard-care arm. The mean sensor glucose level, sensor glucose variability and percentage of time sensor glucose level was > 15 mmol/l were all lower in the CGM arm than in the standard-care arm, but none of these differences reached statistical significance. Results are provided with multiple testing procedure data (see Appendix 4, Table 27).

Safety

Continuous glucose monitor data showed that more infants in the standard-care arm (15%) than in the CGM arm (6%) were exposed to at least one episode of sensor glucose < 2.6 mmol/l for > 1 hour. Safety outcome data are provided in Table 7. AEs and ADEs are reported in Tables 8 and 9, respectively. The tables show that episodes of blood glucose levels ≤ 2.2 mmol/l and 2.2–2.6 mmol/l occurred in 7% and 12%, respectively, of the standard-care group, and in 13% and 15%, respectively, of the CGM group. Collection of the blood glucose data was biased by the result of a low sensor glucose level in the CGM arm, prompting blood glucose to be checked, and is reflected in the higher percentage of infants in the standard-care arm who were exposed to at least one episode of hypoglycaemia lasting > 1 hour. Owing to the small numbers and interinfant variability, none of these differences was statistically significant.

| Variable | Statistic | Standard-care arm | CGM arm | Logistic regression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| Blood glucose level range 2.2–2.6 mmol/l | 12% (11/93) | 15% (11/75) | 1.2 (0.48 to 3.2) | 0.7 | |

| Blood glucose level ≤ 2.2 mmol/l | 7% (6/93) | 13% (10/75) | 2.2 (0.7 to 7.1) | 0.2 | |

| Continuous episode of sensor glucose < 2.6 mmol/l for > 1 hour | 15% (13/85) | 6% (4/70) | 0.361 (0.0919 to 1.2) | 0.1 | |

| Length of time sensor glucose level is < 2.6 mmol/l (hours) | n | 85 | 70 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.0 (3.2) | 0.5 (1.7) | |||

| Median | 0 | 0 | |||

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 22 | 0, 11.2 | |||

| Percentage of time that the sensor glucose level is < 2.6 mmol/l | n | 85 | 70 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.1 (3.2) | 1 (5.3) | |||

| Median | 0 | 0 | |||

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 17 | 0, 41 | |||

| Variable | Statistic | Standard-care arm, % (n/N) | CGM arm, % (n/N) | Total, % (n/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE description | Culture-positive infection | 0 (0/95) | 1 (1/84) | 1 (1/179) |

| Moderate hypoglycaemia (sensor): sensor glucose 2.2–2.6 mmol/l for > 1 hour | 0 (0/95) | 6 (5/84) | 3 (5/179) | |

| Moderate hypoglycaemia: blood glucose level range 2.2–2.6 mmol/l | 9 (9/95) | 6 (5/84) | 8 (14/179) | |

| Persistent pulmonary hypertension | 1 (1/95) | 0 (0/84) | 1 (1/179) | |

| Pulmonary haemorrhage | 1 (1/95) | 0 (0/84) | 1 (1/179) | |

| Seizures | 1 (1/95) | 0 (0/84) | 1 (1/179) | |

| Severe hypoglycaemia: blood glucose level ≤ 2.2 mmol/l | 5 (5/95) | 10 (8/84) | 7 (13/179) | |

| Severe prematurity | 2 (2/95) | 0 (0/84) | 1 (2/179) | |

| Transient: sensor glucose level < 2.6 mmol/l for < 1 hour | 0 (0/95) | 2 (2/84) | 1 (2/179) |

| Variable | Statistic | Standard-care arm, % (n/N) | CGM arm, % (n/N) | Total, % (n/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADE description | Bruising at sensor site | 3 (3/95) | 4 (3/84) | 3 (6/179) |

| Clinically significant discrepancy between sensor glucose and blood glucose levels | 0 (0/95) | 8 (7/84) | 4 (7/179) | |

| Excoriated skin at sensor site | 1 (1/95) | 0 (0/84) | 1 (1/179) | |

| Failure to re-establish connectivity during intervention | 4 (4/95) | 2 (2/84) | 3 (6/179) | |

| Failure to transmit data to the MiniMed 640G because of loss of connectivity | 7 (7/95) | 6 (5/84) | 7 (12/179) | |

| Pressure mark on skin | 2 (2/95) | 0 (0/84) | 1 (2/179) | |

| Sensor displaced | 1 (1/95) | 2 (2/84) | 2 (3/179) | |

| Sensor insertion failure | 22 (21/95) | 13 (11/84) | 18 (32/179) | |

| Transient: sensor glucose level < 2.6 mmol/l for < 1 hour | 0 (0/95) | 2 (2/84) | 1 (2/179) | |

| Unable to calibrate | 23 (22/95) | 20 (17/84) | 22 (39/179) | |

| User error | 1 (1/95) | 0 (0/84) | 1 (1/179) |

The mean percentage of time for which sensor glucose level was < 2.6 mmol/l was 1% (SD 3.2%) in the standard-care group and 1% (SD 5.3%) in the CGM group. The percentage of time that sensor glucose level was < 2.6 mmol/l depended on the number of CGM data available, which explains why it is similar in both groups, despite the total length of time that sensor glucose level was < 2.6 mmol/l being greater in the standard-care arm. Further details of SAEs and SADEs are provided in Tables 8 and 9, and details of withdrawals from the intervention or study, and deaths are shown in Appendix 4, Tables 28–30.

Utility

Table 10 shows summary statistics for the number of sensors used, the individual sensor duration and the number of CGM data collected (hours). We received CGM data from 155 infants, with loss of data due to reported failure of sensor insertion, calibration failure and lack of data at download. Insertion of the first sensor failed in 18% of infants and, therefore, the average number of sensors needed per infant was 1.2. Details of withdrawals are provided in Appendix 4, Tables 28 and 29. The success of sensor insertion varied markedly between centres. Difficulties in calibrating the sensor with the blood glucose level were reported in 22% of infants and episodes where data could not be linked between the transmitter and monitor occurred in 7% of infants. ADEs reported included bruising at the sensor site in 3% of infants, and significant discrepancy between sensor glucose and blood glucose in seven (4%) infants in the CGM study arm. In three infants, the sensor became displaced from under the skin (fell out).

| Variable | Statistic | Standard-care arm | CGM arm | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor duration (hours) | n | 92 | 81 | 173 |

| Mean (SD) | 128 (47) | 127 (48) | 127 (48) | |

| Median | 145 | 145 | 145 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 4, 192 | 2, 191 | 2, 192 | |

| Number of CGM data (hours) | n | 85 | 70 | 155 |

| Mean (SD) | 118 (35) | 128 (28) | 122 (33) | |

| Median | 133 | 140 | 136 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 6, 170 | 24, 155 | 6, 170 | |

| Number of sensors used | n | 95 | 84 | 179 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.25 (0.48) | 1.13 (0.43) | 1.20 (0.46) | |

| Median | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 3 | 0, 2 | 0, 3 |

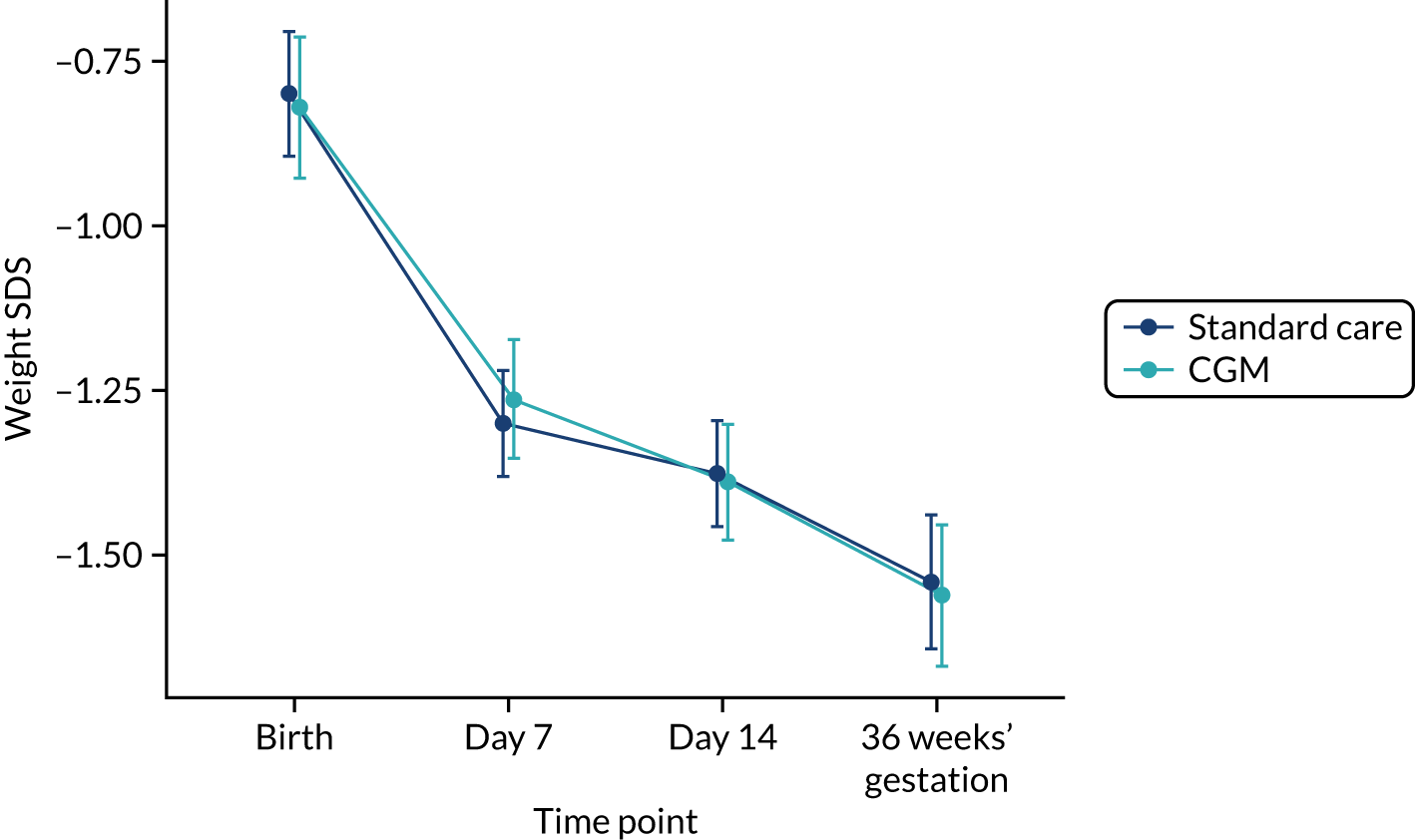

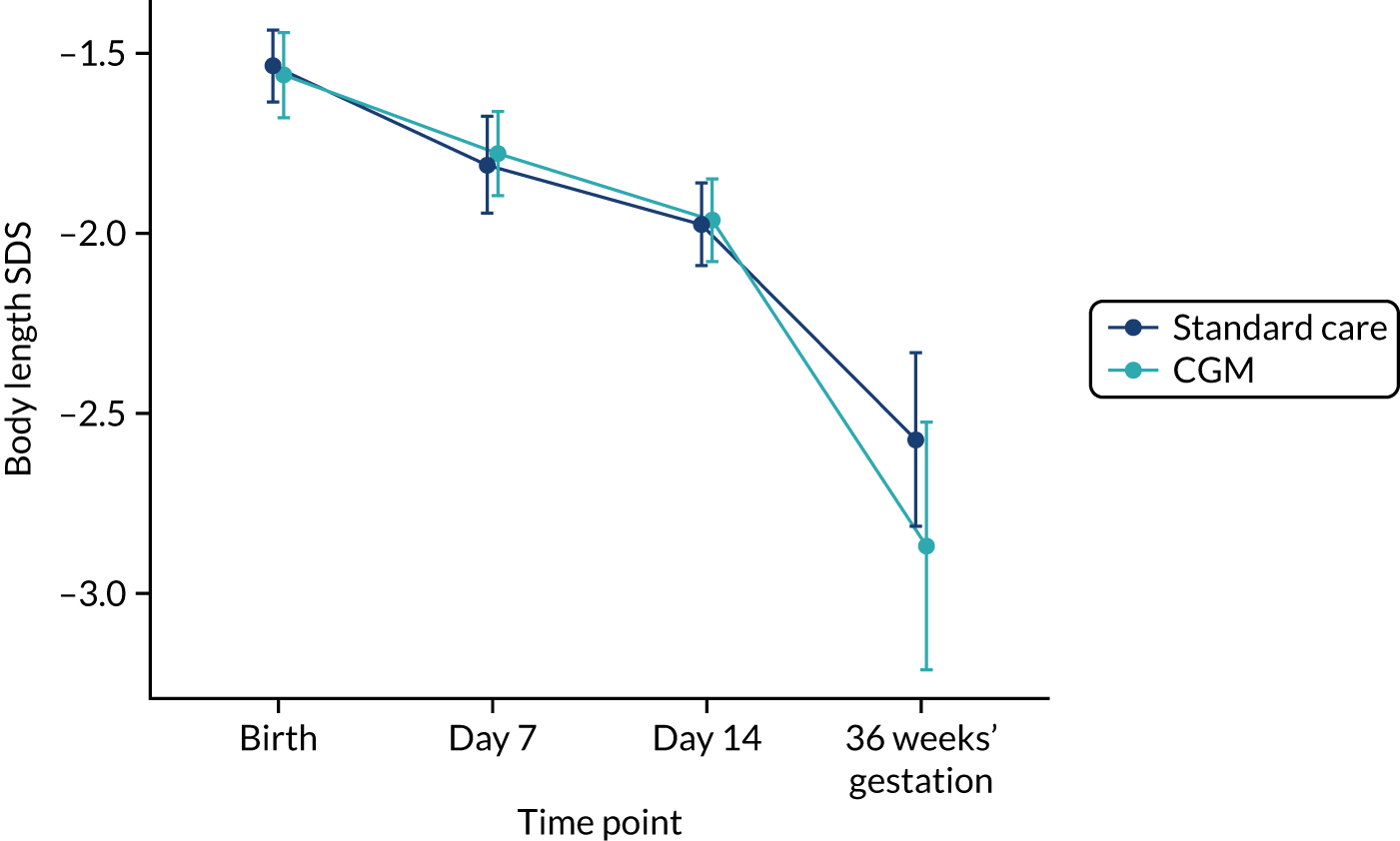

The staff and parent questionnaire results are presented in Figures 8 and 9, respectively. Most staff found the devices easy to calibrate (86%) and did not think that the CGM device interfered with the infant’s nursing care (87%) or caused any distress (94%). Seventy per cent of staff felt that the use of CGM improved clinical care. The majority of parents reported that the CGM did not interfere with the infant’s nursing care (96%) or cause any distress (89%), and 80% felt that the use of CGM improved clinical care.

FIGURE 8.

Randomised controlled trial: staff questionnaires of utility. Stacked bar chart showing proportion of response for each Likert question. Reproduced with permission from Beardsall et al. 4 in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

FIGURE 9.

Randomised controlled trial: parent questionnaire of acceptability. Stacked bar chart showing proportion of response for each Likert question. Reproduced with permission from Beardsall et al. 4 in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Concomitant medications

Details of complementary medical treatment received during the intervention period in both study arms are provided in Table 11. These data are in keeping with what would be considered standard clinical care for this population and there were no apparent differences between study arms.

| Variable | Statistic | Standard-care arm | CGM arm | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inotropes given (days) | n | 94 | 80 | 174 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.8 (1.6) | 0.7 (1.5) | 0.7 (1.5) | |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 7 | 0, 7 | 0, 7 | |

| Antibiotics given (days) | n | 94 | 80 | 174 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.3 (2.3) | 4.5 (2.4) | 4.4 (2.4) | |

| Median | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 7 | 0, 7 | 0, 7 | |

| Caffeine given (days) | n | 94 | 80 | 174 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.4 (1.6) | 6.6 (1.4) | 6.5 (1.5) | |

| Median | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 1, 7 | 1, 7 | 1, 7 | |

| Morphine given (days) | n | 94 | 80 | 174 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.7 (2.5) | 1.8 (2.6) | 1.7 (2.5) | |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 7 | 0, 7 | 0, 7 | |

| Corticosteroids given (days) | n | 94 | 80 | 174 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.12 (0.53) | 0.09 (0.51) | 0.1 (0.52) | |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 4 | 0, 4 | 0, 4 | |

| Insulin given (days) | n | 94 | 80 | 174 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.6 (2.4) | 2.6 (2.5) | 2.1 (2.5) | |

| Median | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 7 | 0, 7 | 0, 7 | |

| Insulin units, days 1–7 (per kg per day) | n | 94 | 80 | 174 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.6 (2.1) | 0.6 (0.94) | 0.6 (1.7) | |

| Median | 0 | 0.19 | 0 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 19.8 | 0, 5.39 | 0, 19.8 | |

| Insulin units, days 8–14 (per kg per day) | n | 88 | 75 | 163 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.15 (0.34) | 0.16 (0.43) | 0.16 (0.38) | |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 1.72 | 0, 2.83 | 0, 2.83 | |

| Glucose (g/kg/day) | n | 95 | 84 | 179 |

| Mean (SD) | 9.1 (2.6) | 9.5 (3.1) | 9.3 (2.9) | |

| Median | 9.3 | 10.1 | 9.9 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 14.9 | 0, 17.2 | 0, 17.2 | |

| Glucose (ml/kg/day) | n | 95 | 84 | 179 |

| Mean (SD) | 84 (24) | 85 (28) | 84 (26) | |

| Median | 86 | 92 | 88 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 143 | 0, 185 | 0, 185 | |

| Lipids (g/kg/day) | n | 92 | 80 | 172 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.95 (0.78) | 1.89 (0.77) | 1.92 (0.78) | |

| Median | 2.1 | 1.95 | 2 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.04, 3.9 | 0.04, 4.7 | 0.04, 4.7 | |

| Lipids (ml/kg/day) | n | 92 | 80 | 172 |

| Mean (SD) | 9.9 (3.7) | 9.7 (3.7) | 9.8 (3.7) | |

| Median | 10.6 | 9.9 | 10.4 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 1.8, 19.5 | 1.9, 23.7 | 1.8, 23.7 | |

| Amino acids (g/kg/day) | n | 94 | 81 | 175 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.2 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.2) | 2.2 (1.3) | |

| Median | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 7.2 | 0, 6.1 | 0, 7.2 | |

| Oral nutrition (ml/kg/day) | n | 94 | 81 | 175 |

| Mean (SD) | 18 (23) | 20 (21) | 19 (22) | |

| Median | 11 | 14 | 12 | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 108 | 0, 94 | 0, 108 |

Exploratory outcome measures

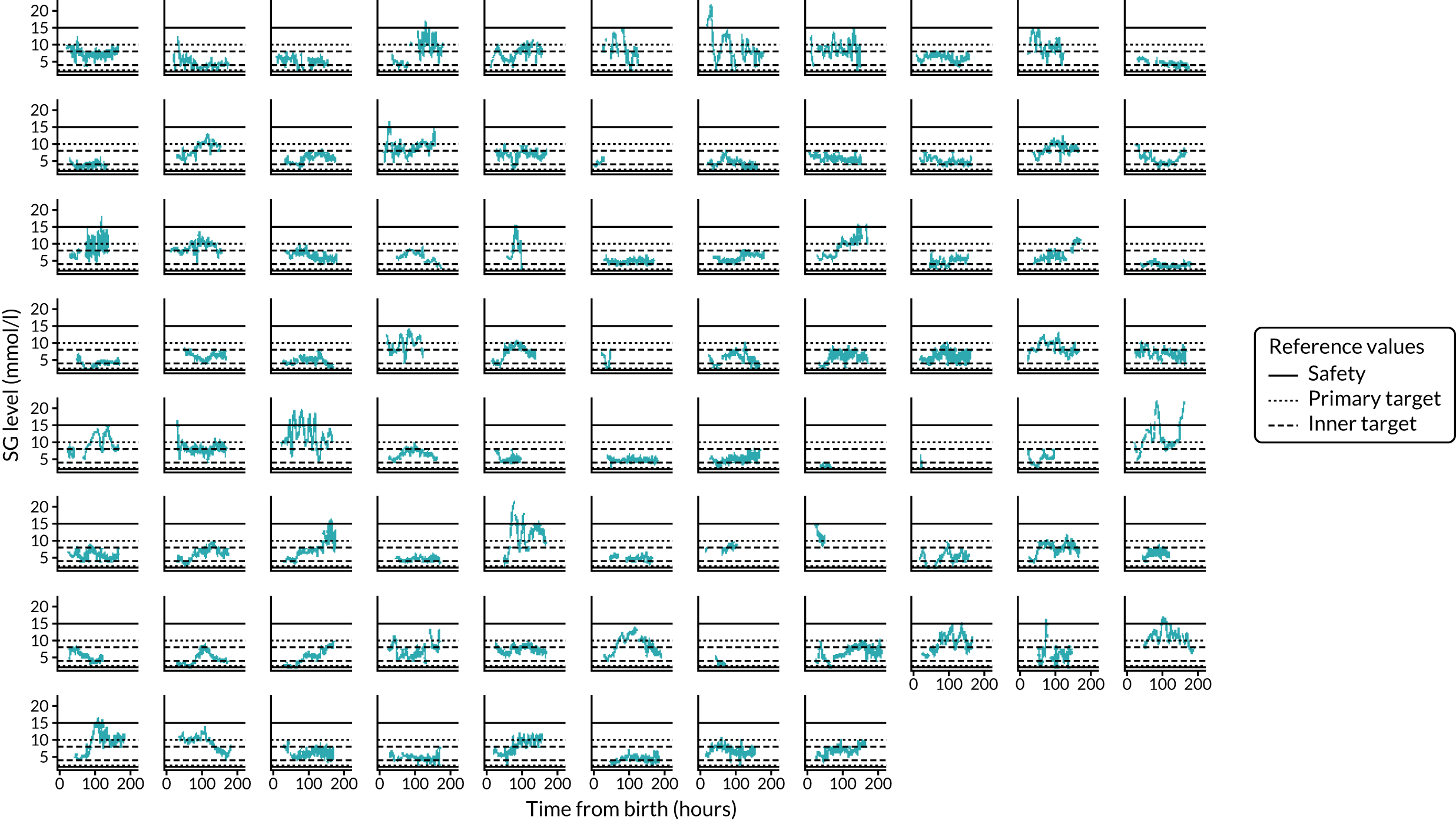

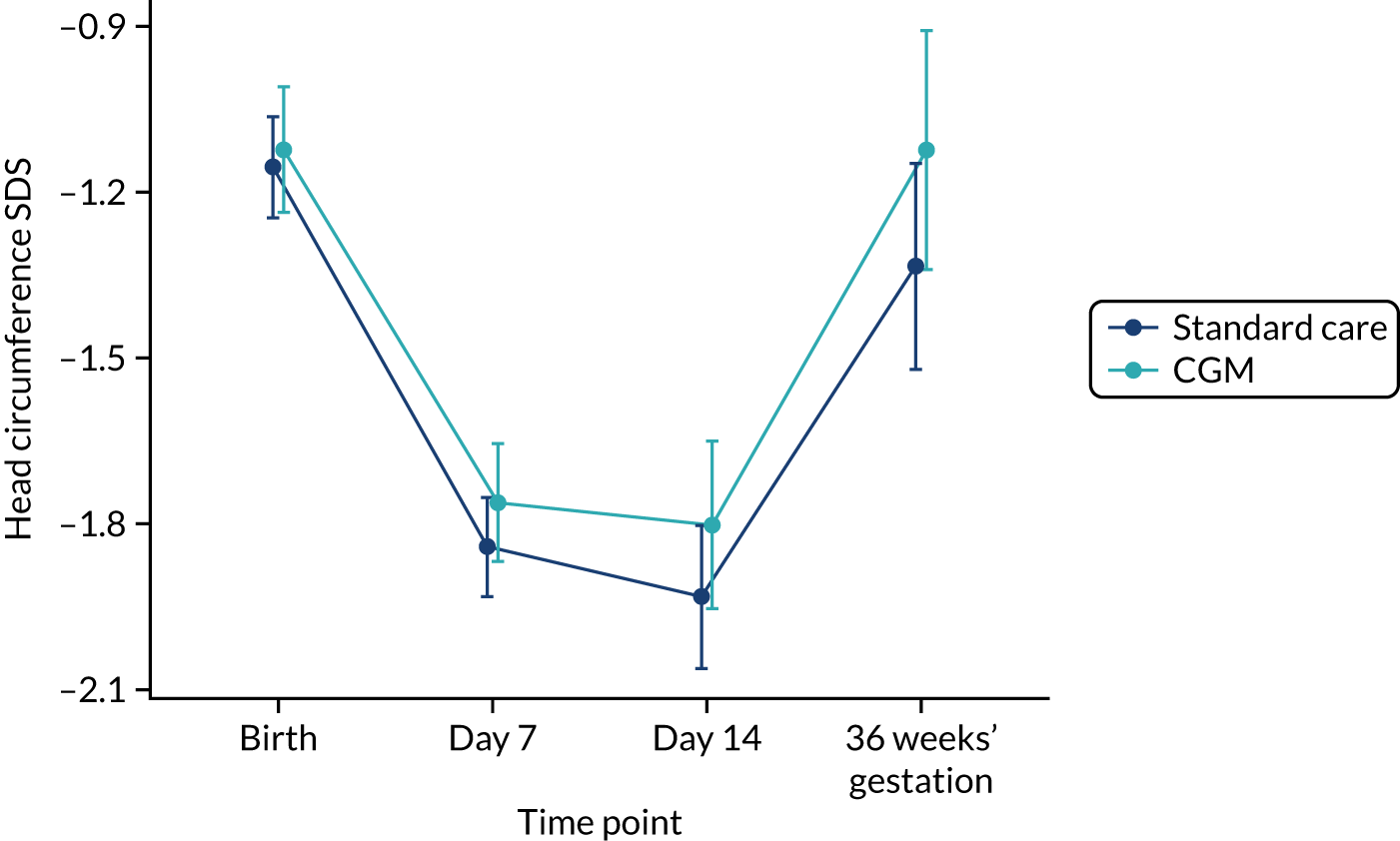

Further data on glucose profiles in the CGM and standard-care arms are provided in Figures 10 and 11, respectively.

FIGURE 10.

Randomised controlled trial: profile plots of CGM data – CGM arm. SG, sensor glucose.

FIGURE 11.

Randomised controlled trial: profile plots of CGM data – standard-care arm. SG, sensor glucose.