Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as award number 09/800/05. The contractual start date was in August 2008. The draft manuscript began editorial review in May 2023 and was accepted for publication in September 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Phillips et al. This work was produced by Phillips et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Phillips et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Paget’s disease of bone (PDB) is a condition associated with abnormalities in the renewal and repair of bone, which has been reported to affect up to 1% of British people over the age of 55 years. The disease is characterised by increased and disorganised bone formation secondary to a focal increase in osteoclastic bone resorption at one or more sites throughout the skeleton. While many patients are asymptomatic, others develop complications such as bone deformity, deafness, pathological fracture and secondary osteoarthritis. 1 Quality of life is adversely affected by these complications resulting in a loss of mobility and independence. 2,3

Genetic factors are important in PDB, and the disease can be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait in some families. 4–6 Genetic studies have identified 14 genes and/or genomic loci that predispose to PDB and related conditions,7 but the most important of these is SQSTM1, which encodes p62, a scaffold protein in the NFκB signalling pathway. 8–10 Between 20% and 50% of patients with a family history of PDB carry SQSTM1 mutations and the mutations also occur in between 5% and 20% of patients without a known family history of the disease. 11–17 Individuals with mutations of the SQSTM1 gene have an earlier age at diagnosis and more clinically severe PDB than those without the mutations. 18 Penetrance has been estimated to be about 80% by the seventh decade. 11,12,14,15,17,19–22 The mutations are highly specific for PDB, and are extremely rare in age and sex-matched controls. 14,15,17,19,23

Bisphosphonates are regarded as the treatment of choice for PDB. They are highly effective at suppressing biochemical markers of bone turnover and can help in the treatment of bone pain. Various bisphosphonates have been licensed for the treatment of PDB, but the most potent bisphosphonate is zoledronic acid (ZA),24,25 which can result in a sustained reduction in biochemical markers of bone turnover in more than 95% of subjects with PDB for up to 6.5 years following a single injection. 25,26 The symptomatic benefits of bisphosphonates in people with advanced PDB who already have disease complications such as deformity, deafness and fractures is blunted as these drugs cannot reverse skeletal damage that has already occurred. 27,28

Objectives

The primary objective of the zoledronic acid in the prevention of Paget’s disease (ZIPP) trial was to determine if targeted intervention with ZA can prevent the development of new focal bone lesions with the characteristics of PDB in subjects who are genetically predisposed to develop the disease, because they carry pathogenic mutations in SQSTM1.

The secondary objectives of the trial were to evaluate whether ZA treatment can:

-

alter the progression of existing bone lesions in carriers of SQSTM1 mutations

-

decrease or prevent Paget’s disease-related skeletal complications in carriers of SQSTM1 mutations

-

reduce or prevent elevated bone turnover carriers of SQSTM1 mutations

-

improve quality of life, bone pain, anxiety and depression in carriers of SQSTM1 mutations

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from Cronin et al. 29 and from Philips et al. Randomised trial of genetic testing and targeted intervention to prevent the development and progression of Paget’s disease of bone. Ann Rheum Dis 2024;83:529-536. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard-2023-224990 under licence CC BY 4.0.

This study was a multicentre double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial of intravenous ZA or placebo in SQSTM1 mutation carriers.

The study involved an initial phase of genetic screening to identify eligible participants. Patients with PDB attending outpatient clinics (n = 1428) underwent genetic testing for SQSTM1 mutations using Sanger sequencing of exons 7 and 8 of SQSTM1 and the intron–exon boundaries using DNA extracted from a venous blood sample according to standard techniques. If the result was positive, 1307 first-degree relatives of these individuals (primarily children) were offered genetic testing for the study. Individuals who consented to undergo testing (n = 750) and were found to be positive for SQSTM1 mutations (n = 350) were invited to participate in the interventional phase of the ZiPP study. Two sites in Auckland and Oswestry did not require the participant’s parents to be tested since potential participants had already undergone genetic testing for SQSTM1 as the result of a previous study.

Individuals found to have SQSTM1 mutations were counselled and randomised to receive either ZA 5 mg or an identical placebo by intravenous infusion. Participants who tested negative for SQSTM1 mutations were invited to take part in the observational study, which will be described elsewhere. Participants completed a baseline visit, at which point they had safety blood tests, blood and urine tests for biochemical markers of bone metabolism, and had imaging by radionuclide bone scan to look for any evidence of PDB. They were contacted by telephone 1 week after the baseline visit to determine if any adverse effects had occurred following the infusion. Following this, annual visits were carried out when information was collected on medical history, medication, quality of life, pain, anxiety and depression by questionnaires. Blood samples were taken for biochemical markers of bone turnover at each annual visit, and questionnaires were administered to assess quality of life, pain, anxiety and depression. At the end-of-study visit, a radionuclide bone scan and the other assessments performed at the baseline visit were repeated. A summary of the procedures performed at screening and during the study is shown in Table 1.

| Screening visit | Baseline visit | +1 week | Annual review | End of study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical history | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Current medication | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Physical examination | ✓ | ||||

| Height, weight, blood pressure | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Routine biochemistrya | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Routine haematologyb | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Blood for specialised biomarkersc | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Urine for specialised biomarkersd | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| SQSTM1 genotyping | ✓ | ||||

| 25(OH) vitamin D | ✓ | ||||

| Pregnancy teste | ✓ | ||||

| Radionuclide bone scan | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Radiographs or other imagingf | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Infusion | ✓ | ||||

| Telephone review | ✓ | ||||

| Food frequency | ✓ | ||||

| SF-36, HADS and BPIg | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| PDRSEh | ✓ | ✓ |

Radionuclide bone scan

Bone lesions were assessed by Technetium-99 radionuclide bone scan, which is recognised to be the most sensitive imaging technique for identifying bone lesions in PDB. 30,31 Participants thought to have PDB-like bone lesions on scan had further imaging performed by X-ray, CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan if the local investigator considered it clinically indicated. Anonymised bone scans and X-ray images were uploaded to the study database for review. All scans were reviewed by an imaging expert blinded to treatment allocation and were independently reviewed by a second imaging expert, also blinded to treatment allocation, to evaluate the concordance between the observers. The images selected included all of those considered by the primary imaging expert to represent PDB-like lesions. If the experts disagreed on a specific image, it was agreed that a third imaging expert (also blinded to treatment allocation) would be asked to adjudicate but this was not required.

Routine biochemistry

Measurements of serum creatinine, urea and electrolytes, serum total alkaline phosphatase (ALP), serum calcium, albumin and liver function tests – which consisted of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) and bilirubin, along with a full blood count (FBC) – were performed using standard techniques at the local laboratories in participating centres. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated from serum creatinine, gender and weight by the Cockcroft–Gault equation. 32

Specialised biochemical markers

Specialised biochemical markers of bone turnover that were measured were urine N-telopeptide collagen cross links (NTX) corrected for urinary creatinine, C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX), bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BAP) and the N-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen (PINP). These measurements were made on fasting samples collected between 09:00 and 12:00 hours, as previous studies have shown that markers of bone resorption have a circadian rhythm and are influenced by food intake. 33 The urine samples were second-voided ‘spot’ samples collected after an overnight fast. Markers of bone resorption were urinary NTX and serum CTX-I. These have been found to be elevated in patients with PDB in case–control studies and to correlate with the extent of bone lesions as determined by scintigraphy in PDB30,34 The markers of bone formation were PINP and BAP since both have been shown to be superior to total ALP at detecting PDB in case–control studies. 30

Health-related quality of life

At all annual visits, the participants' health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed by the completion of the Short Form (36) Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaire. The SF-36 is a widely used, validated questionnaire35 previously used to assess quality of life in patients with established PDB. 27,36

Brief Pain Inventory

The presence and location of pain were assessed by completion of the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI). 37 The BPI was originally developed to evaluate the location and severity of pain in patients with malignant disease, but has since been validated in people with chronic, non-malignant pain. 38 In addition to completing BPI, participants were also asked if they had experienced any pain and bone pain, and to provide information on the site of the pain using a manikin.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression questionnaire

Anxiety and depression were assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). 39 This questionnaire was chosen since it was quick and simple to administer, and it has been extensively validated in many countries and settings. 40

Paget’s disease-related skeletal events

Participants were evaluated clinically at the end of study for the presence of Paget’s disease-related skeletal events (PDRSE). These included pathological fractures, bone deformity, deafness due to skull involvement and joint replacement surgery or other surgical procedures that are carried out because of PDB. Administration of an antiresorptive drug during the study because of signs or symptoms that are thought to be due to PDB was considered as a PDRSE.

Changes to trial design

In the original protocol, participants in the active treatment arm were to have a second infusion of the study investigational medicinal product (IMP) at 30 months to further suppress bone turnover. However, soon after the ZiPP study had commenced a study by Reid et al. 26 showed that a single infusion of ZA could suppress bone turnover in established PDB for at least 6.5 years. This indicated that there was no need to administer a second infusion 30 months after the baseline infusion. The protocol was amended to reflect this change.

The exclusion criteria were updated to be consistent with the ZA summary of product characteristics (SmPC). This involved removing the abnormalities of liver function as exclusion criteria since ZA are not contraindicated in patients with liver disease and can be used without adjustment in patients with abnormal liver function. The exclusion criterion of hypocalcaemia was amended – it was originally an exclusion criterion with a cut-off value of < 2.2 mmol/l. However, due to the different laboratories involved in the study having different reference ranges for serum calcium, it was not viewed as a reliable cut-off value. Therefore, the cut-off value of < 2.2 mmol/l was removed but hypocalcaemia, as defined by the local laboratory reference range, was retained as an exclusion criterion because hypocalcaemia is a contraindication to the use of ZA. The trial was extended by 22 months to 31 May 2022. The trial extension provided additional time for sites to complete interventional final study visits, as the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted sites from completing end-of-study visits in a timely manner.

Participants

Probands were eligible for genetic testing if they had been diagnosed with PDB and had any relatives who were aged 30 years or older and who had not been diagnosed with PDB. If the proband tested positive for SQSTM1, their relatives were offered genetic testing provided they were aged 30 years or older and had not already been diagnosed with PDB. Relatives of probands who tested positive for SQSTM1 mutations were invited to take part in the trial.

Study setting

This was a multicentre trial that was conducted at 27 secondary care referral centres for bone disease in 7 countries. All the visits were conducted within a secondary healthcare setting. Table 2 summarises the sites that enrolled participants into the ZiPP trial.

| Country | City |

|---|---|

| UK | Edinburgh |

| London – Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital | |

| Manchester | |

| Oswestry | |

| Liverpool | |

| Bristol | |

| London – King’s College Hospital | |

| Portsmouth | |

| Nottingham | |

| Ireland | Dublin |

| Spain | Barcelona – Hospital Clinic |

| Barcelona – Hospital del Mar | |

| Salamanca | |

| Italy | Turin |

| Siena | |

| Florence | |

| Belgium | Brussels |

| Australia | Perth |

| Geelong | |

| Bone and Joint Institute, Royal Newcastle Centre | |

| Rural Clinical School, Toowoomba | |

| Sydney | |

| Brisbane | |

| New Zealand | Auckland |

| Christchurch |

Interventions

The IMP or placebo was given by a single intravenous infusion and comprised of either ZA (Aclasta®) (5 mg in 100 ml ready-to-infuse solution) or an identical looking placebo (0.9% saline). Both were given at a constant infusion rate over not < 15 minutes.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measures

The studies primary outcome measure was defined as the total number of participants who developed new bone lesions on radionuclide bone scans with the characteristics of PDB between the baseline visit and the final end-of-study visit. Imaging experts blinded to treatment allocation assessed the lesions. The definition of a new bone lesion was one that had evidence of involvement of a new bone or part of an existing bone at the end-of-study visit that was not thought to be involved at the baseline visit.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures were:

-

Number of new bone lesions on radionuclide bone scan. A new bone lesion was defined as evidence of involvement of a new bone or part of an existing bone at the end-of-study visit that was not thought to be involved at the baseline visit.

-

Change in activity of existing bone lesions at end of study that were present at the baseline assessed by semiquantitative analysis of radionuclide bone scans.

-

The development of PDRSE in carriers of SQSTM1 mutations, defined as any one of the following:

-

Development of new bone lesions (as defined previously thought to be due to PDB on imaging).

-

Development of complications thought to be due to the development or progression of PDB, including pathological fractures, bone deformity, deafness, joint-replacement surgery or other orthopaedic procedures.

-

Administration of treatment for PDB with an antiresorptive drug because of the development of signs or symptoms thought to be due to PDB, such as pain localised to an affected site or neurological symptoms.

-

-

The development of increased bone turnover, as assessed by measurement of biochemical markers of bone resorption [urinary N-telopeptide collagen crosslinks as a ratio to urinary creatinine (uNTX/Cr) and CTX] and bone formation (BAP, PINP). These markers were measured using samples provided at baseline, annual visits and the end-of-study visit.

-

Quality of life, pain, anxiety and depression assessed by the validated SF-36,35 BPI38 and HADS questionnaires. 40 These questionnaires were completed at baseline, annual visits and the end-of-study visit.

-

Presence and severity of localised bone pain as assessed by the BPI pain manikin at baseline, annual visits and the end-of-study visit.

Changes to outcomes

During the study, two secondary outcome measures were introduced. One was to conduct a semi-quantitative analysis of bone lesions found on imaging and the second was to add PDRSE as a composite end point as described in subsection 3 of the secondary outcome measures.

Sample size

The sample size was chosen assuming that 15% of patients in the placebo group and 1.5% of patients in the active (ZA) treatment group would develop new PDB-like bone lesions during follow-up. This estimate of progression of lesions in the placebo group was based on previous cross-sectional studies. 21 The effect size of the intervention was based on the observation that ZA has been reported to normalise biochemical markers of bone turnover for up to 6.5 years in 95% of patients with established PDB. 26 With this assumption, 85 subjects in each group would provide 89% power to detect a treatment effect of this magnitude at an alpha of 0.05. Since it is possible that more than one affected subject per family could be enrolled, the sample size was inflated to account for relatedness of individuals. This was done by calculating the mean squared ALP values in patients within families who carried the same mutation (271.3) and the mean squared ALP values between families (619.7), and combining this with the estimated average number of two subjects per family who may be enrolled in the study. This resulted in a design effect factor of 1.39, inflating the required sample size to 118 per group. In addition to this, the sample size was further inflated to account for a 10% rate of participants lost to follow-up resulting in a total sample size of 130 subjects per group or 260 subjects in total. The actual number of subjects randomised to the interventional study by the time recruitment had closed in April 2015 was 222 and to the observational study was 135. The decision to stop recruitment was based on funding and justified by recalculating the design factor based on the actual number of subjects per family that had been enrolled into the study (1.5 on average). The design factor was recalculated to be 1.26.

Interim analyses and stopping guidelines

Not applicable.

Randomisation: sequence generation

Randomisation was performed at the individual level with a treatment allocation in a 1 : 1 ratio. The randomisation algorithm was developed by data programmers from the Edinburgh Clinical Trials Unit and was used to generate the randomisation sequence and allocation concealment. The programme was located on the web-based study database following the collection of baseline details for each participant. The baseline information allowed the system to populate the required minimisation input variables, thereby determining which arm the participant was to be randomised to. Once the participant was enrolled and randomised, treatment code was generated. All treatment codes were supplied by the drug manufacturer and were built in blocks of four. This treatment code was then presented to the local hospital pharmacy and the treatment dispensed.

Randomisation: type

Patients were randomised to either ZA or matched placebo infusion, with a treatment allocation ratio of 1 : 1. The randomisation was minimised according to the type of mutation (missense vs. truncating or frameshift), by gender (male/female); on the basis of whether or not bone lesions suggestive of PDB are present on the baseline bone scan, whether ALP levels are elevated at baseline (yes/no) and by age (years) in increments as follows: 30–40, 41–50, 51–60, 61–70, 71+. A random element was incorporated in which there was a 1 in 10 chance of the determined treatment being reversed.

Randomisation: allocation concealment mechanism

Allocation concealment was assured by the fact that the ZA and placebo were prepacked in identical containers and provided by the manufacturer each with its own unique treatment code. Following randomisation, each participant was assigned a treatment number and received the treatment in the corresponding prepacked bottle from the pharmacy at study centres.

Randomisation: implementation

The programme used to generate the randomisation sequence and allocation concealment was generated by data programmers from the Edinburgh Clinical Trials Unit. The programme for randomisation was loaded onto the web-based interface linked to the study database, where the researcher would enter the participant’s information required for the randomisation process. Randomisation occurred after the baseline details for a participant had been collected. Therefore, there was adequate information about the participant to allow the system to populate the required minimisation input variables, including which arm the participant was to be randomised to. Once the participant was enrolled, randomisation occurred, which was blinded to both the research team and the subject. The researcher was given a treatment code, which was provided by the drug manufacturer and was built in blocks of four. This treatment code was then presented to the pharmacy and treatment was dispensed.

Blinding

The participants and investigators were blinded to treatment allocation. The ZA and placebo infusions were identical. Breaking the blind would only be performed where knowledge of the treatment is necessary for further management of the patient and was only performed by contacting the local hospital pharmacy, which had the restricted code break details.

Similarity of interventions

The interventions were 100 ml bottles containing clear liquid with an identical appearance. Both were given by intravenous infusion at a constant infusion rate over not < 15 minutes.

Statistical methods

The principal analysis was based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle incorporating all randomised participants, regardless of treatment received. It was originally anticipated that a binary logistic regression analysis would be fitted to compare the number of patients developing new bone lesions between treatment groups. The proposed model included terms for treatment group (ZA vs. placebo) adjusted for the minimisation variables used in the randomisation (type of mutation, gender, presence of bone lesions suggestive of PDB, elevated ALP levels, age – all fitted as fixed effects if appropriate).

Due to small numbers of outcome events that resulted in model non-convergence, it was not possible to adjust for the minimisation variables. Instead, an unadjusted Fisher’s exact test was used, modelling the odds of developing new lesions, presenting a median unbiased estimate. A median unbiased estimate and a one-sided p-value are presented for the primary outcome of new lesions.

Similarly, the planned sensitivity analyses relating to missing data were not conducted due to the smaller-than-expected number of lesions occurring in both treatment arms.

Repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to analyse specialised markers of bone turnover and quality-of-life questionnaires. This technique makes use of all available data and has the capacity to handle unbalanced data under the assumption of missing at random.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome measures were as follows.

The number of new bone lesions

Like the primary outcome, summaries by treatment group and overall were presented, detailing:

-

the number of lesions at baseline

-

the number of lesions at the end of the study

-

the number of new lesions at the end of the study.

Statistical analyses were by Poisson regression analysis, with the plan to adjust for the minimisation variables and, if required, including an overdispersion parameter to account for wide variability in the data. An offset term would also be included in the model to account for differing lengths of patient follow-up.

The number of outcome events was so small that a maximum-likelihood Poisson regression, either with or without covariate adjustment, was not possible. Therefore, an exact Poisson regression (a small sample alternative) was performed. The effect of randomised treatment was measured by the unadjusted rate ratio [and 95% confidence interval (CI)] for ZA versus placebo.

Change in activity of existing bone lesions that were present at baseline

Change in bone lesion activity was analysed using binary logistic regression where change was categorised as disappeared/decreased/showed no change/increased. For those with no lesion at baseline, developing new bone lesions was seen as a poor outcome. For those with lesions at baseline: lesion increase, the development of additional lesions, or no change in existing lesions was seen as a poor outcome. If data had allowed, the analysis would have been stratified by the baseline status of lesion(s)/no lesion. However, there were insufficient lesions for this stratification to be implemented.

Specialised markers of bone turnover

Results of each biomarker sample were modelled using a repeated measures ANCOVA adjusting for the relevant baseline measure and the minimisation variables. The estimated treatment effect and 95% CI were presented for each outcome. An exception was NTX/creatinine since this was only measured once at the beginning and the end of study.

Quality-of-life questionnaires

The following quality-of-life measures were formally analysed:

-

BPI

-

the SF-36 physical component score (PCS), mental component score (MCS)

-

HADS interference score, severity score, anxiety score, depression score, total score.

A repeated measures ANCOVA adjusting for the relevant baseline quality-of-life measure and the minimisation variables was undertaken. The estimated treatment effect and 95% CI were presented for each outcome.

Bone pain scores (BPI Manikin)

Patients experiencing bone pain were asked to score their pain by location and severity via the BPI manikin with scores ranging from 1 (very mild pain) to 10 (most severe pain).

Pain scores were categorised as mild (1–4), moderate (5–6) and severe (7–10), and were summarised by treatment group and visit (baseline, annual review and end of study), assessing the number of patients experiencing pain, and also the number of incidences of pain.

Additionally, a listing of those patients with lesions at baseline and/or the end of the study who also noted bone pain at the site of the lesion was presented. This was with a view to establishing whether there is a link between location of lesions and severity of pain at that location.

Safety

Adverse events (AEs) were summarised by treatment received, and by seriousness, outcome, causality, expectedness and severity. AEs were also summarised by bodily system category [musculoskeletal (MSK), respiratory, cardiovascular etc.]. (No formal testing, safety population.)

Serious adverse events (SAEs) were summarised and listed in line with AE. (No formal testing, safety population.)

Routine biochemistry results were summarised by treatment and visit (baseline, annual review and end-of-study visit). (No formal testing, ITT population.)

For ALP, a formal analysis of the results was undertaken, using a repeated measures ANCOVA approach. The model adjusted for baseline ALP and the minimisation variables. The estimated treatment effect and 95% CI were presented. (ITT population.)

Details were provided of any patients who became pregnant or who have a partner who became pregnant during the study. (No formal testing, safety population.)

Additional analyses

Not applicable.

Chapter 3 Results

Participant flow (consort) diagram

Losses and exclusions

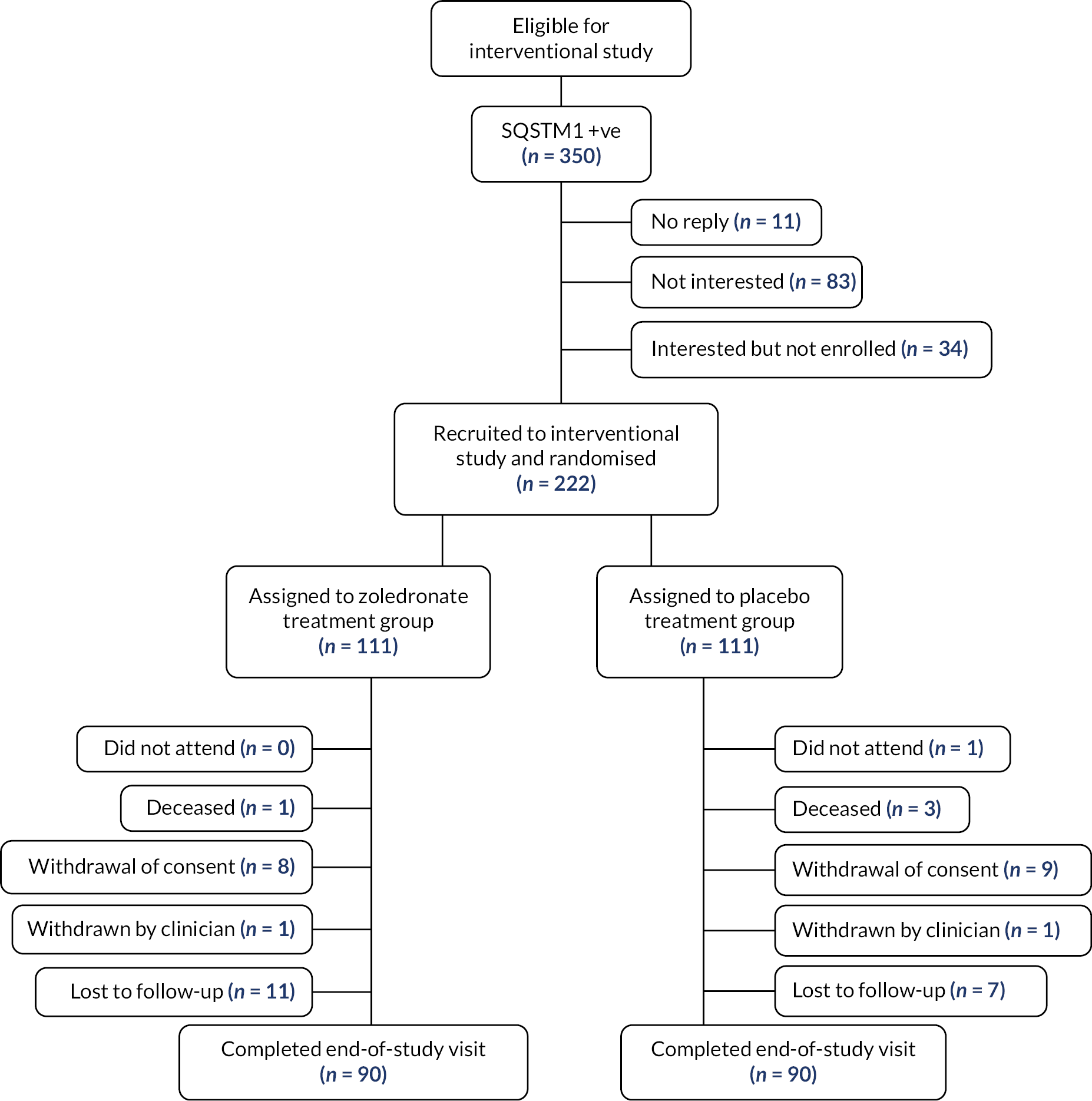

The number of participants who were lost from the study was 42: 21 in the zoledronate arm and 21 in the placebo arm. A summary of the reason for withdrawals and deaths can be found in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Disposition of participants.

Recruitment

The first patient was randomised to the study on 5 March 2010, and the final patient was randomised on 16 April 2015. In total, 222 participants were randomised with 50% (N = 111) being allocated to each treatment group (placebo and zoledronate 5 mg). The recruitment of participants occurred at 25 sites across 7 countries, the distribution of recruitment at each site is shown in Table 3.

| Location | Zoledronate 5 mg (N = 111) | Placebo (N = 111) |

|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh | 16 (14.4%) | 22 (19.8%) |

| London – Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital | 16 (14.4%) | 21 (18.9%) |

| Manchester | 12 (10.8%) | 15 (13.5%) |

| Oswestry | 3 (2.7%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Liverpool | 6 (5.4%) | 6 (5.4%) |

| Bristol | 4 (3.6%) | 6 (5.4%) |

| London – King’s College Hospital | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Portsmouth | 1 (0.9%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Nottingham | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Dublin | 6 (5.4%) | 4 (3.6%) |

| Barcelona – Hospital Clinic | 5 (4.5%) | 4 (3.6%) |

| Barcelona – Hospital del Mar | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Salamanca | 4 (3.6%) | 4 (3.6%) |

| Turin | 9 (8.1%) | 5 (4.5%) |

| Siena | 2 (1.8%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Florence | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Brussels | 1 (0.9%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Perth | 6 (5.4%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Geelong | 4 (3.6%) | 4 (3.6%) |

| Royal Newcastle Centre | 4 (3.6%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| St Vincent’s Hospital, Toowoomba | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Sydney | 4 (3.6%) | 5 (4.5%) |

| Brisbane | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Auckland | 1 (0.9%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Christchurch | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

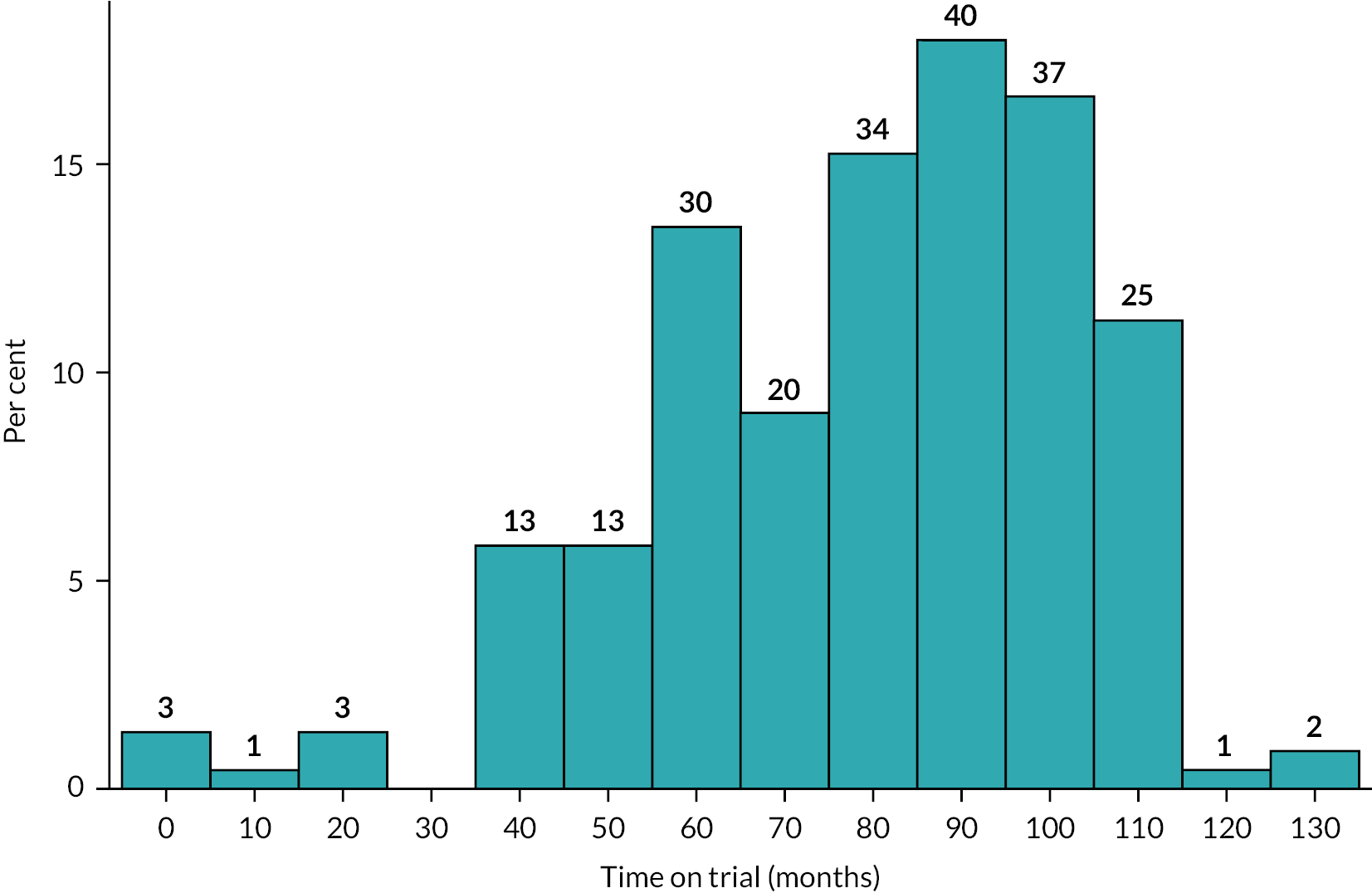

Recruitment to trial ran from 5 March 2010 to 15th April 2015, when the last participant completed their first visit. Due to the length of time the trial ran for, participants were followed up for a varying length of time, with the mean months of follow-up for the ZA arm being 78.4 [standard deviation (SD) 24.5] and the placebo arm 79.0 (SD 24.3). The mean duration overall in both groups combined was 78.7 (SD 24.0) months. A graphical summary of the duration of follow-up in the trial is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Duration of participation in the ZiPP study.

Baseline data

Out of the 222 participants randomised, 101 were male (45.5%), with a mean age of 50.2 years (SD 9.1). Full characteristics of participants in both the ZA and the placebo arm are shown in Table 4.

| Zoledronate (N = 111) | Placebo (N = 111) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Male | 50 (45.0%) | 51 (45.9%) |

| Female | 61 (55.0%) | 60 (54.1%) |

| Age (years) | 49.8 (8.8) | 50.5 (9.3) |

| Relatedness | ||

| Family clusters | 60 | 73 |

| Number of family members | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.9 (1.2) |

| Median (range) of family members | 1.0 [1–5] | 1 [1–7] |

| Lifestyle | ||

| Current smoker | 13 (11.7%) | 20 (18.0%) |

| Previous smoker | 45 (40.5%) | 55 (49.5%) |

| Regular drinker | 70 (63.1%) | 71 (64.0%) |

| Physical examination | ||

| Weight (kg) | 79.5 (17.7) | 82.0 (19.6) |

| Height (cm) | 168 (9.0) | 169 (9.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.9 (5.3) | 28.5 (6.3) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 129 (17.0) | 130 (15.0) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 79.6 (13.4) | 78.4 (10.5) |

| Pulse rate (bpm) | 70.3 (10.3) | 69.7 (11.2) |

| General appearance | ||

| Normal | 109 (98.2%) | 109 (98.2%) |

| Skin | ||

| Normal | 99 (89.2%) | 104 (93.7%) |

| Head/neck/ear, nose and throat/eyes | ||

| Normal | 106 (95.5%) | 108 (97.3%) |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Normal | 103 (92.8%) | 105 (94.6%) |

| MSK | ||

| Normal | 101 (91.0%) | 101 (91.0%) |

| Central nervous system | ||

| Normal | 109 (98.2%) | 108 (97.3%) |

| Numbers are N (%), or mean (SD), unless stated | ||

The results of routine biochemistry and haematology at baseline are shown in Table 5. Mean values were similar in both treatment groups except for GGT, which was slightly higher in the placebo treatment arm (37.9, SD 50.6) compared with the ZA arm (27.7, SD 17.3).

| Zoledronate (N = 111) | Placebo (N = 111) | |

|---|---|---|

| Raised ALP, N (%) | 4 (3.6%) | 4 (3.6%) |

| ALP (U/l) | 78.2 (41.7) | 80.1 (53.1) |

| ALP (adjusted)a | 0.44 (0.32) | 0.47 (0.37) |

| Calcium (adjusted) (mmol/l)b | 2.40 (0.11) | 2.41 (0.12) |

| Albumin (g/l) | 44.3 (3.6) | 44.0 (3.6) |

| AST (U/l) | 24.0 (8.4) | 25.1 (11.7) |

| ALT (U/l) | 28.4 (17.1) | 27.7 (19.5) |

| GGT (U/l) | 27.7 (17.3) | 37.9 (50.6) |

| Bilirubin (µmol/l) | 10.2 (5.7) | 10.4 (5.9) |

| Serum 25(OH) D (nmol/l) | 66.7 (46.1) | 64.9 (34.1) |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/l) | 72 (13) | 74 (13) |

| Urea (mmol/l) | 5.2 (1.3) | 5.2 (1.5) |

| eGFR | 86.1 (21.1) | 83.3 (17.4) |

| Routine haematology | ||

| White blood cell count (109/l) | 6.36 (1.55) | 6.21 (1.69) |

| Haemoglobin (g/l) | 141 (13) | 142 (13) |

| Platelets (109/l) | 243 (57) | 240 (63) |

| Numbers are mean (SD), unless otherwise stated | ||

The percentages of participants in each treatment arm that were either above the upper limit of the reference range for each biochemistry measure is shown in Table 6. An exception is serum 25(OH) vitamin D3 where information is provided on the number of individuals deficient, sufficient or normal.

| Zoledronate 5 mg (N = 111) | Placebo (N = 111) | |

|---|---|---|

| Serum 25(OH)D3 (nmol/l) | ||

| Deficient (< 25) | 10 (9.0%) | 10 (9.0%) |

| Insufficient (25–50) | 39 (35.1%) | 30 (27.0%) |

| Normal (> 50) | 61 (55.0%) | 71 (64.0%) |

| uNTX/Cr (upper limit = 65) | ||

| Above limit | 30 (27.0%) | 39 (35.1%) |

| Below limit | 73 (65.8%) | 61 (55.0%) |

| CTX (ng/ml) (upper limit = 0.704 male/1.018 female) | ||

| Above limit | 2 (1.8%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Below limit | 101 (91.0%) | 100 (90.1%) |

| BAP (U/I) (upper limit = 42) – baseline visit | ||

| Above limit | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Below limit | 102 (91.9%) | 99 (89.2%) |

| PINP (ng/ml) (upper limit = 76) – baseline visit | ||

| Above limit | 19 (17.1%) | 17 (15.3%) |

| Below limit | 84 (75.7%) | 84 (75.7%) |

| Numbers are N (%), unless otherwise stated. The numbers do not add up to 100% due to missing values in some individuals | ||

Details of mutations in SQSTM1 are shown in Table 7. The majority of participants (n = 202, 91%) had a missense mutation and the remaining 20 had a truncation mutation. The most common missense mutation was 1175C > T resulting in a Pro392Leu amino acid change (P392L).

| Zoledronate (N = 111) | Placebo (N = 111) | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of mutation | ||

| Missense | 101 (91.0%) | 101 (91.0%) |

| Truncating | 10 (9.0%) | 10 (9.0%) |

| Protein coding change | ||

| c.1165 + 1G>Aa | 5 (4.5%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| p.Phe406Val | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| p.Gly411Ser | 7 (6.3%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| p.Gly425Arg | 13 (11.7%) | 11 (9.9%) |

| p.Gln371Ter | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| p.Glu396Ter | 1 (0.9%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| p.Ile424Ser | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| p.Lys378Ter | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| p.Met404Val | 13 (11.7%) | 12 (10.8%) |

| p.Pro392Leu | 64 (57.7%) | 77 (69.4%) |

| p.Thr350fs | 2 (1.8%) | 1 (0.9%) |

Previous self-reported fracture history was assessed at baseline as summarised in Table 8. In total, 103 (46.4%) out of the 222 participants had fractures at baseline, the most common of which were fractures of wrist (n = 31, 14.0%) and other bones (n = 31, 14.0%) not categorised in the list. The study did not collect information on the circumstances that led to these fractures occurring.

| Zoledronate (N = 111) | Placebo (N = 111) | |

|---|---|---|

| Fractures | 48 (43.2%) | 55 (49.5%) |

| Tibia | 6 (5.4%) | 6 (5.4%) |

| Femur | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Humerus | 1 (0.9%) | 5 (4.5%) |

| Wrist | 12 (10.8%) | 19 (17.1%) |

| Clavicle | 3 (2.7%) | 5 (4.5%) |

| Ribs | 5 (4.5%) | 5 (4.5%) |

| Hand | 6 (5.4%) | 8 (7.2%) |

| Foot | 11 (9.9%) | 8 (7.2%) |

| Skull | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Lumbar spine | 2 (1.8%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Facial bones | 3 (2.7%) | 6 (5.4%) |

| Any other bone | 15 (13.5%) | 16 (14.4%) |

Numbers analysed

Of the 222 patients enrolled, 180 patients completed the final study visit. In the ZA arm, 90 (81.1%) completed; there were 21 (18.9%) withdrawals: 8 (7.2%) who withdrew consent; 1 (0.9%) who was withdrawn by the clinician; 1 (0.9%) who was deceased; and 11 (9.9%) who were lost to follow-up. In the placebo arm, 90 (81.1%) attended the final visit, with 21 (18.9%) withdrawals: 9 (8.1%) withdrawing consent, 1 (0.9%) withdrawn by clinician, 3 (2.7%) deceased, 7 (6.3%) lost to follow-up; and 1 (0.9%) who failed to attend the final visit. Participant 9038801 within the placebo treatment arm attended the final study visit but declined to have an end-of-study bone scan.

Outcomes and estimation

Primary outcome

At baseline, 9 (8.1%) patients in the ZA group were found to have bone lesions typical of PDB, compared with 12 (10.8%) in the placebo group. By the end of the study, only 1 (0.9%) patient had evidence of a bone lesion in the ZA group, compared with 11 (9.9%) in the placebo group.

A summary of participants with bone lesions detected by bone scan at baseline and end of study is provided in Table 9.

| Patients with lesions | Zoledronate (N = 111) | Placebo (N = 111) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||

| Yes | 9 (8.1%) | 12 (10.8%) |

| No | 102 (91.9%) | 99 (89.2%) |

| End of study | ||

| Yes | 1 (0.9%) | 11 (9.9%) |

| No | 89 (80.2%) | 78 (70.3%) |

| No assessment | 21 (18.9%) | 22 (19.8%) |

In the ZA group, none of the participants developed a new bone lesion during the study, while two patients developed new lesions in the placebo group [odds ratio (OR) 0.406, 95% CI 0.000 to 3.425; p = 0.246]. The OR of < 1 indicates a treatment effect in favour of zoledronate. One patient with lesions at baseline in the placebo group required rescue therapy with ZA and declined to have a repeat bone scan at the end-of-study assessment.

Secondary outcomes

Two new PDB lesions developed in patients allocated to placebo compared with no new lesions in the ZA group. There was a highly significant difference between the groups in the appearances of existing lesions as assessed by a semi quantitative analysis of bone scans by imaging experts blinded to treatment allocation. In the ZA group, 13/15 lesions had disappeared (86.7%), 2/15 had decreased (13.3%) and none remained stable or had progressed. In the placebo group, 1/25 had disappeared (3.4%), 12 were thought to have decreased in intensity (41.4%), 8 were thought to be unchanged (27.6%) and 4 had increased in intensity and/or extent (13.8%). None of the participants allocated to ZA had a poor outcome (defined as the development of new lesions, lesions remaining unchanged, or having progressed) compared with eight in the placebo group (OR 0.08, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.42; p = 0.003). A summary of the changes in bone lesions that occurred during the trial is presented in Table 10.

| Zoledronate (N = 111) | Placebo (N = 111) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of lesions at baseline | 15 | 29 |

| Number of lesions at end of study | 2 | 26 |

| Change in activity of existing lesions | ||

| Disappeared | 13 (86.7%) | 1 (3.4%) |

| Decreased | 2 (13.3%) | 12 (41.4%) |

| No change | 0 (0%) | 8 (27.6%) |

| Increased | 0 (0%) | 4 (13.8%) |

| No end-of-study assessment | 0 (0%) | 4 (13.8%) |

A summary of change in bone lesions at the individual patient level is summarised in Table 11.

| Zoledronate (N = 111) | Placebo (N = 111) | |

|---|---|---|

| No lesion at baseline or end of study | 81 (73.0%) | 77 (69.4%) |

| No lesion at baseline; new lesions at end of studya | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Lesion(s) at baseline; fewer lesions at end of study or existing lesions decreased | 9 (8.1%) | 4 (3.6%) |

| Lesions(s) at baseline; lesions unchanged at end of study | 0 (0%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Lesion(s) at baseline; existing lesions increased in activity at end of study | 0 (0%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| No end-of-study assessment | 21 (18.9%) | 22 (19.8%) |

The location and outcome of the bone lesions are summarised for the ZA treatment arm and placebo arm in Tables 12 and 13, respectively. Note that it was not possible to evaluate patient-level changes in lesion activity in one participant allocated to placebo who received rescue therapy with ZA since they declined to have an end-of-study bone scan. This individual had four lesions at baseline, affecting the left pubic ramus, cervical vertebrae four and five, the ischium and the sacrum. Various skeletal sites were affected with a distribution consistent with PDB and several participants had more than one lesion. As mentioned previously, the most striking finding was the fact that, out of 15 lesions present at baseline in the ZA treatment arm, 13 had disappeared (86.6%), 2 (13.3%) had diminished in activity and no new lesions developed.

| Skeletal site | Lesions at baseline | Lesion disappeared | Lesion reduced | Lesion stable | Lesion increased | Lesions at end of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (R) Calcaneus | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| (L) Femur | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| (R) Femur | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (L) Ilium | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (R) Ilium | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (L) Ischium | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (R) Ischium | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L/spine (L1) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L/spine (L4) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 15 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Skeletal site | Lesions at baseline | Lesion disappeared | Lesion reduced | Lesion stable | Lesion increased | Lesions at end of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (R) Ilium | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| C/spine (C2) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| (R) Femur | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| (R) Humerus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| (L) Humerus | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| (L) Ilium | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| (L) Ischium | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| (R) Ischium | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| L/spine (L4) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| L/spine (L5) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| (L) Radius | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sacrum | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| T/spine (T12) | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| T/spine (T2) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| T/spine (T7) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| T/spine (T9) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Skull (right) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 25 | 1 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 26 |

Paget’s disease-related skeletal events

The PDRSE reported by the local principal investigator are shown in Table 14. This identified 3 PDRSEs in the ZA treatment arm compared to 13 in the placebo treatment arm.

| Zoledronate 5 mg (N = 111) | Placebo (N = 111) | |

|---|---|---|

| Spinal cord compression | 1 (0.9%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Deafness | 1 (0.9%) | 7 (6.3%) |

| Nerve root compression | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Cranial nerve compression | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Bone pain at affected site | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Total | 3 (2.7%) | 13 (11.7%) |

| Numbers are N (%), unless otherwise stated. | ||

On review of these responses at individual participant level it was noted that most participants did not have PDB lesions on scan at either the beginning or end of study, suggesting that there had been a misunderstanding of the definition of PDRSE at a site level. Because of this, two independent adjudicators were appointed to review the PDRSEs. Following the adjudication, it was concluded that only one participant in the placebo treatment arm had experienced a PDRSE. The PDRSE was nerve root compression presenting with local pain and visualised by imaging at the C3–C5 region in the cervical spine. This participant was given ZA treatment for PDB as rescue therapy.

Specialised biomarkers of bone turnover

Changes in specialised markers of bone turnover are summarised in the graphs in the following sections. Numerical values giving information on means, SDs and numbers of observations at each time point according to treatment group are also provided in Appendix 1.

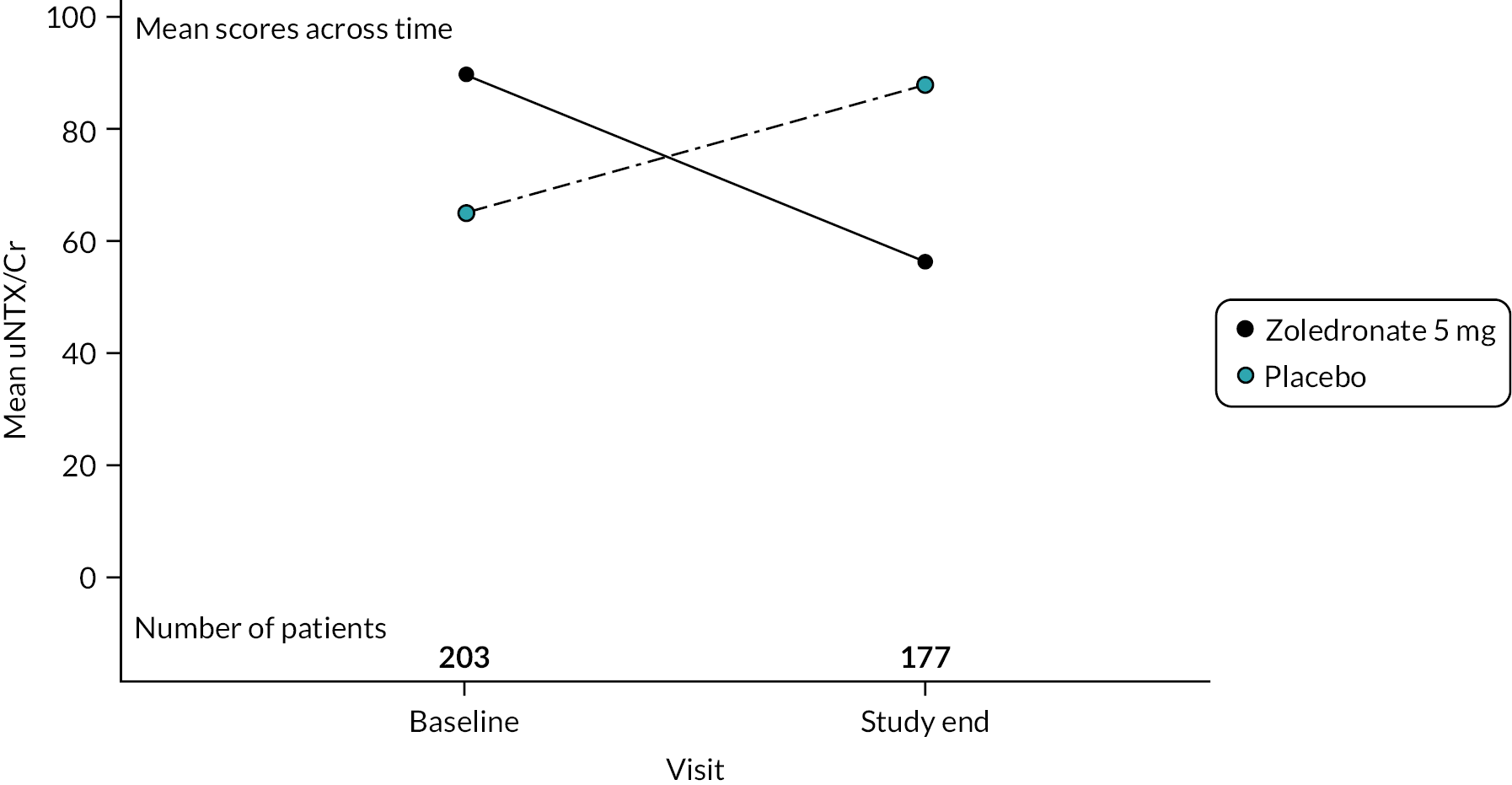

Urinary N-telopeptide as a ratio of creatinine – uNTX/Cr

This analyte is a biochemical marker of bone resorption. Measurements were made at baseline and end of study only. Mean values at baseline and end of study are shown in Figure 3, expressed as a ratio to urine creatinine – uNTX/Cr. At baseline, the uNTX/Cr was higher in the ZA treatment arm (89.7 SD 315.6) group compared to the placebo group. (64.7 SD 56.2). When uNTX/Cr was measured at the end of the study, values had decreased in the ZA group to 56.6 (SD 65.3) but increased in the placebo group, 88.0 (SD 174.8). No formal statistical analysis was conducted for this parameter since results were available only at baseline and study end in contrast to the other three specialised markers of bone marker for which results were available annually up to study end.

FIGURE 3.

Changes in uNTX during the study. Values are means in units of a ratio of uNTX to creatinine – uNTX/Cr.

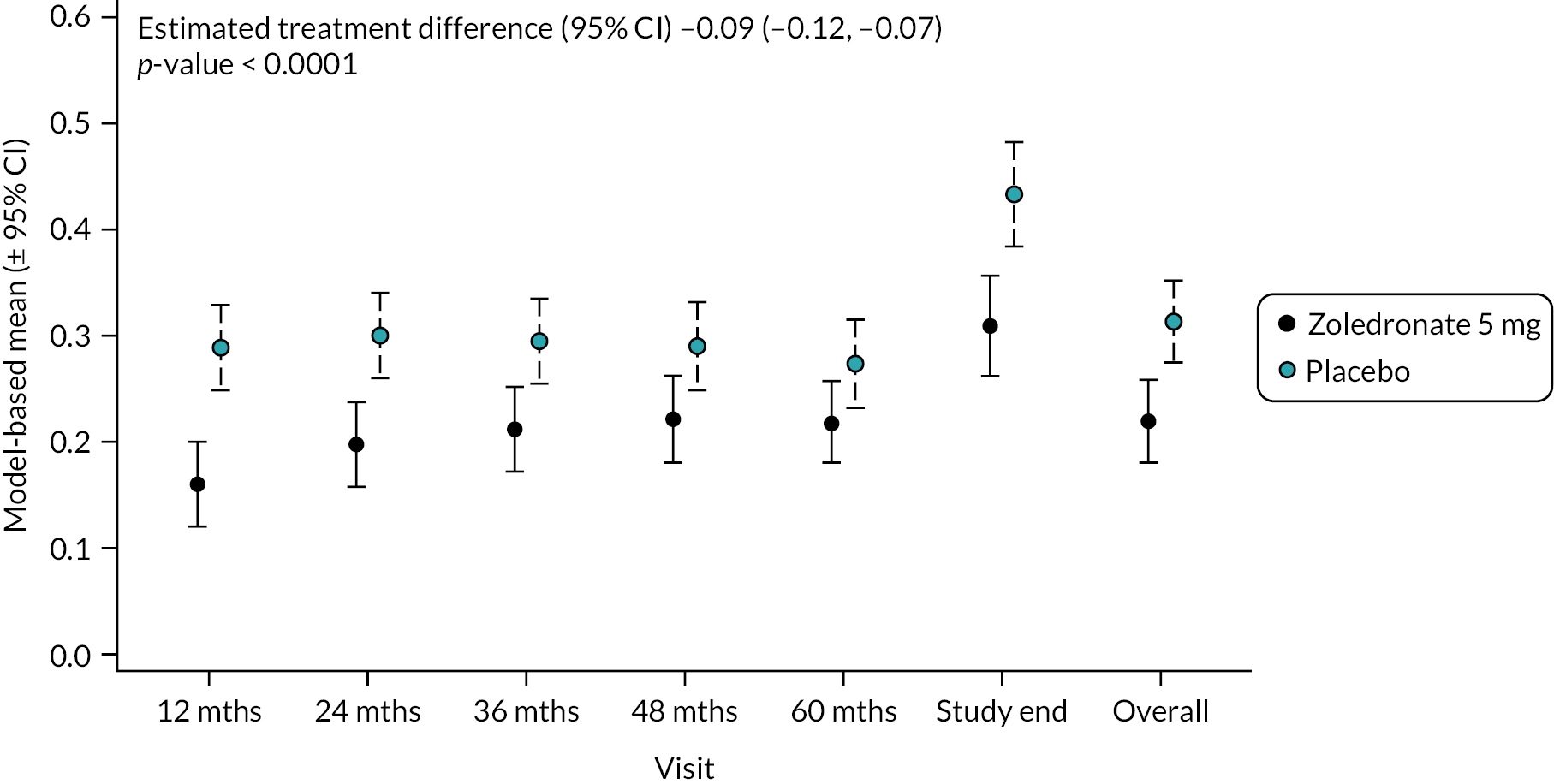

Circulating C-terminal telopeptide fragments of collagen

Circulating C-terminal fragments of collagen (CTX) act as a biochemical marker of bone resorption. Changes in CTX are shown in Figure 4. Mean baseline levels were similar in the two groups: ZA 0.33 ng/ml (SD 0.17) versus placebo 0.35 ng/ml (SD 0.17). By the end of study, CTX was slightly higher than at baseline in the placebo treatment group (0.41 ng/ml SD 0.20) but had fallen in the ZA group to 0.28 ng/ml (SD 0.14). Overall, there was a significant reduction in CTX in the ZA group as shown in Figure 4 (−0.09, 95% CI −0.12 to −0.07; p-value < 0.0001). The unadjusted mean and SD values for each treatment group and numbers of observations at each timepoint are shown in Appendix 1, Table 17.

FIGURE 4.

Model-based changes in CTX during the study. Values are in ng/ml. Bars are 95% CI. The total number of observations at each of the time points was: baseline – 204, 12 months – 197; 24 months – 188; 36 months – 189; 48 months – 149; 60 months – 112; study end – 178.

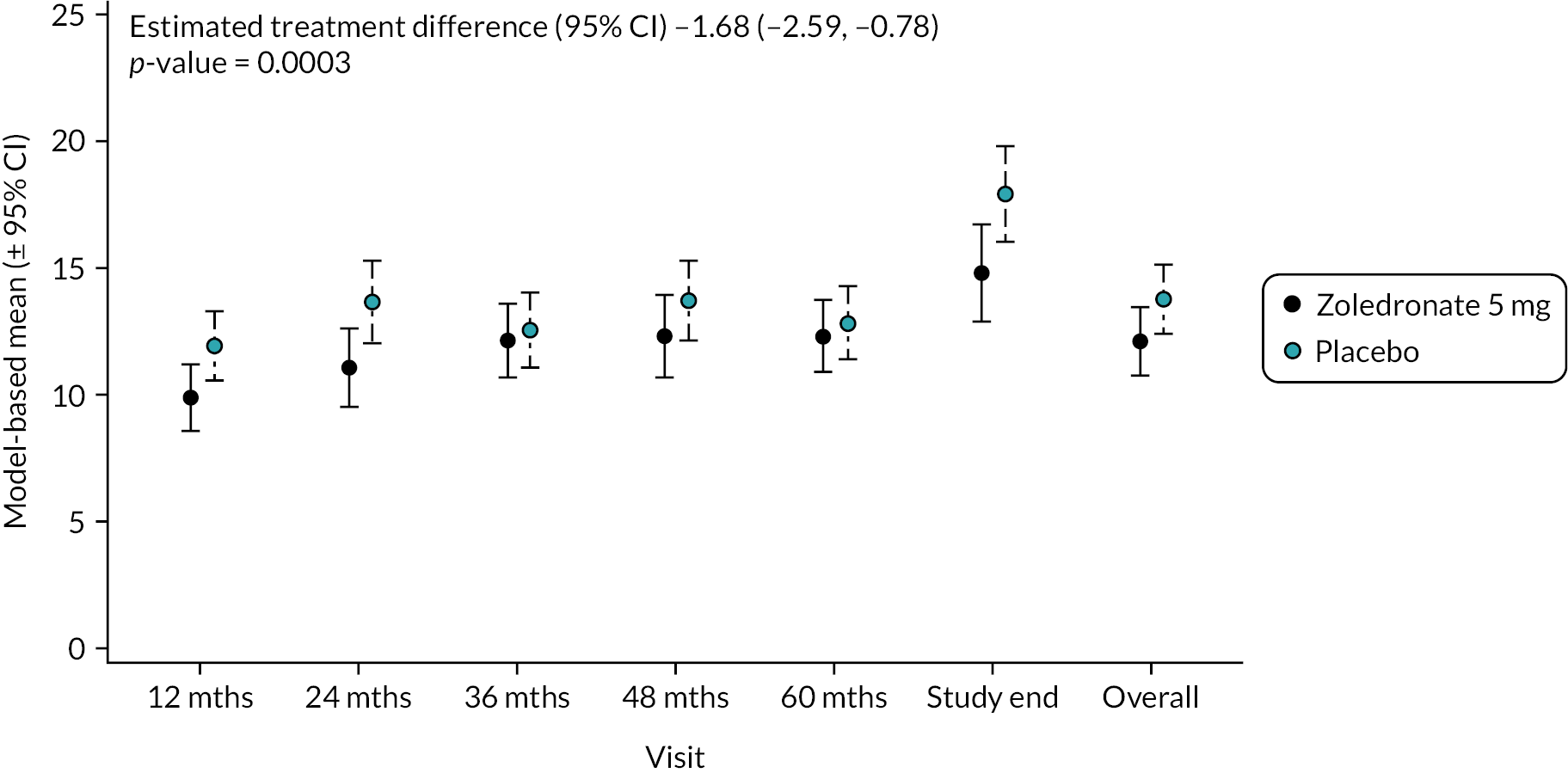

Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase

Circulating concentrations of BAP act as markers of osteoblast activity. Values are shown in Figure 5. At baseline, mean values were similar in the two groups (ZA 11.0 U/I SD 7.5 vs. placebo 10.5 U/I SD 8.0). At the end of study, concentrations of BAP had increased in participants treated with ZA (14.1 U/I SD 5.9) and the placebo group (17.2 U/I SD 10.2). Overall, there was a significant reduction in BAP in the ZA group compared with placebo (−1.68, 95% CI −2.59 to −0.78; p-value = 0.0003). The unadjusted mean and SD values for each treatment group and numbers of observations at each timepoint are shown in Appendix 1, Table 18.

FIGURE 5.

Model-based mean changes in BAP during the study. Values are in U/l. Bars are 95% CI. The total number of observations at each of the time points was: baseline – 204, 12 months – 197; 24 months – 188; 36 months – 189; 48 months – 149; 60 months – 112; study end – 178.

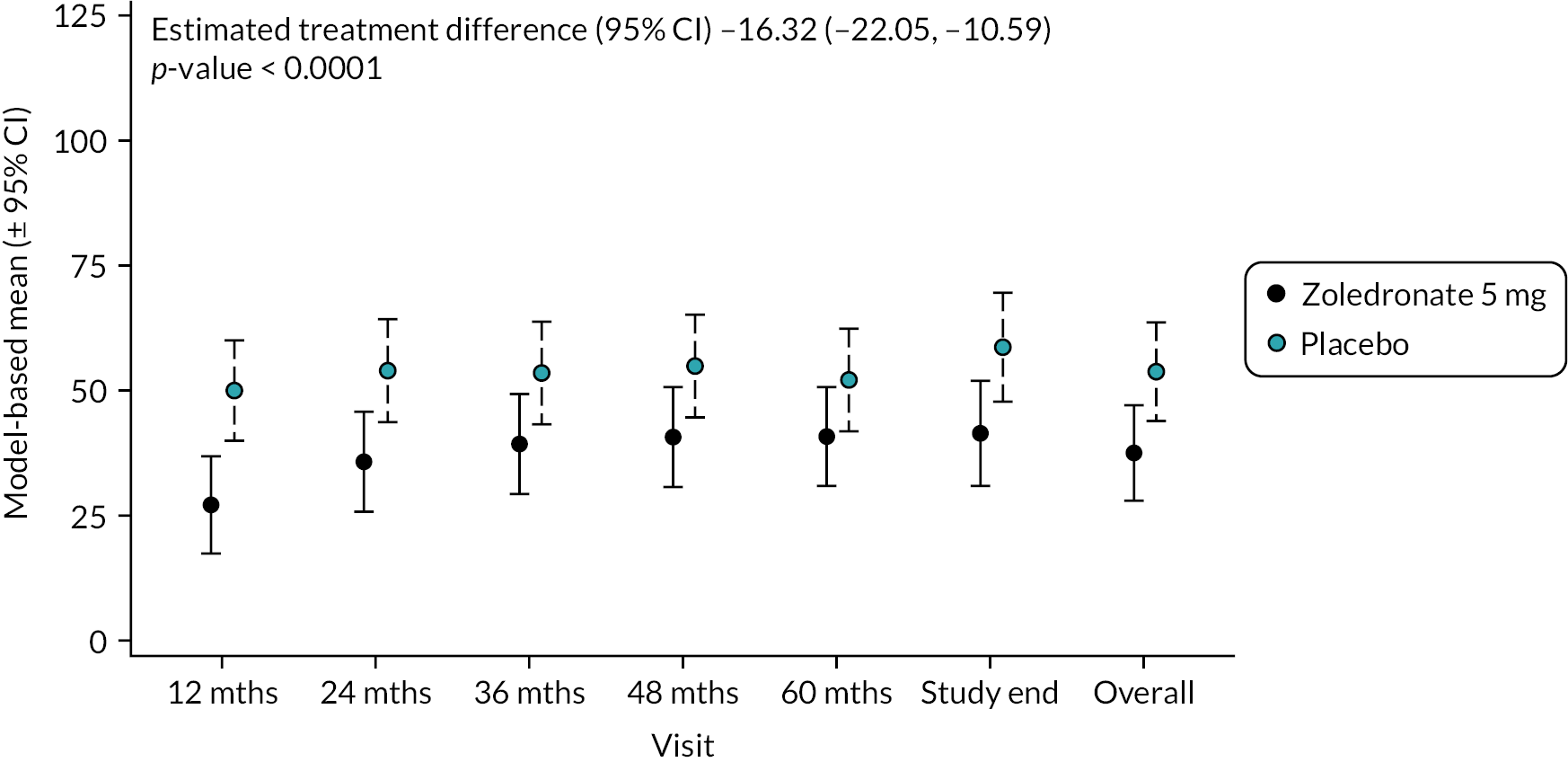

Procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide

Circulating concentrations of the procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide act as a marker of bone formation. Values are shown in Figure 6. Mean (SD) baseline PINP levels were similar in the two groups (ZA 55.0 ng/ml SD 27.0 vs. placebo 59.5 ng/ml SD 40.8). At the end of study, PINP had fallen in the ZA group (44.0 ng/ml SD 17.4) but increased in the placebo group (63.9 ng/ml SD 67.0). Overall, there was a significant reduction in PINP in the ZA group compared with placebo [−16.32 (−22.05 to −10.59); p-value < 0.0001]. The unadjusted mean and SD values for each treatment group and numbers of observations at each timepoint are shown in Appendix 1, Table 19.

FIGURE 6.

Model-based changes in N-terminal PINP during the study. Values are in ng/ml. Bars are 95% CI. The total number of observations at each of the time points was: baseline – 204, 12 months – 197; 24 months – 188; 36 months – 189; 48 months – 149; 60 months – 112; study end – 178.

Pain, quality of life, anxiety and depression

Changes in pain, HRQoL and anxiety and depression are summarised in the graphs in the following sections. Numerical values giving information on means, SDs and numbers of observations at each time point according to treatment group are also provided in Appendix 1.

Brief Pain Inventory

Pain was assessed using the BPI questionnaire. Two components of pain, interference to life and severity were assessed.

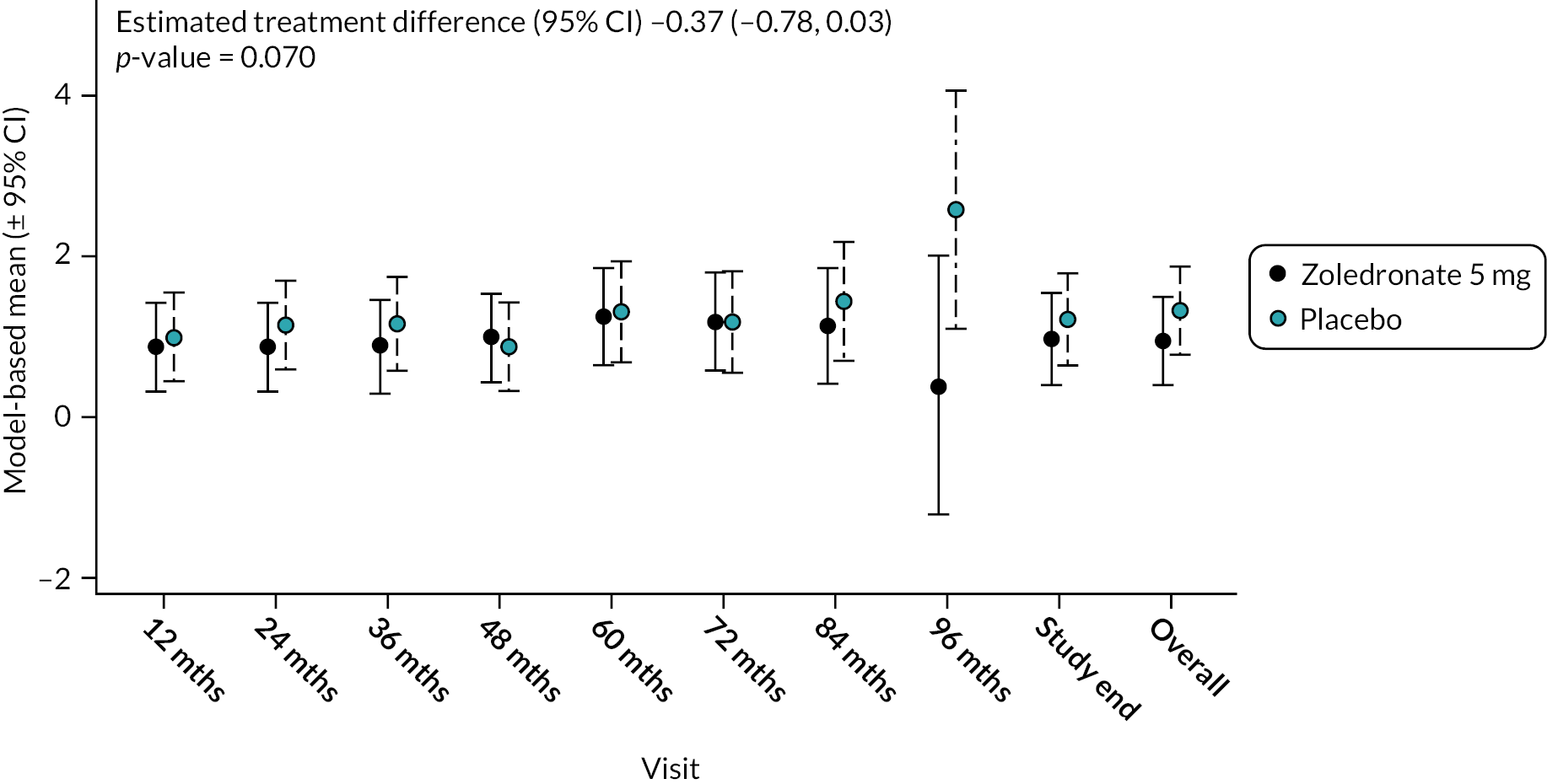

Pain interference score

At baseline, the mean interference score was numerically higher in the ZA group (1.00 SD 1.71) compared to the placebo group (0.82 SD 1.49). During the study interference scores increased with a trend for a lesser increase in the ZA group (Figure 7). Overall, there was no significant difference between the groups (−0.37, 95% CI −0.78 to 0.03; p-value = 0.070). The unadjusted mean and SD values for each treatment group and numbers of observations at each timepoint are shown in Appendix 2, Table 20.

FIGURE 7.

Model-based estimates of pain interference score during the study. Scores range between 0 and 10. Higher scores indicate greater pain. Bars are 95% CI. The total number of observations at each of the time points was: baseline – 222, 12 months – 205; 24 months – 198; 36 months – 189; 48 months – 147; 60 months – 113; 72 months – 79; 84 months – 36; 96 months – 11; study end – 177.

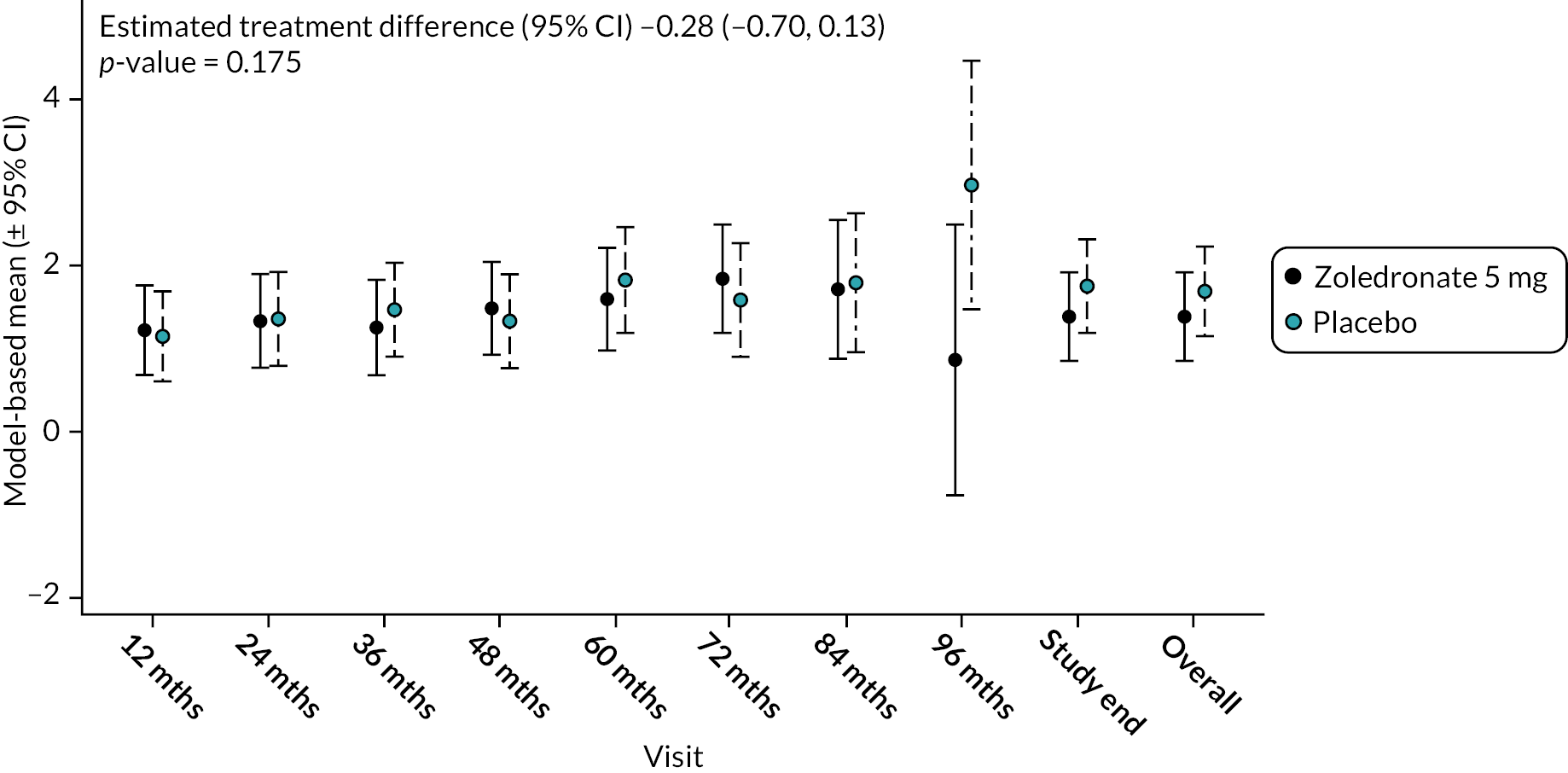

Pain severity score

At baseline, the mean BPI severity scores were similar in the two groups: ZA 1.34 SD 1.68 versus 1.24 SD 1.53. During the study, scores in both groups increased but there was no significant difference between the groups (−0.28, 95% CI −0.70 to 0.13; p-value = 0.175) (Figure 8). The unadjusted mean and SD values for each treatment group and numbers of observations at each timepoint are shown in Appendix 2, Table 21.

FIGURE 8.

Model-based changes in BPI severity score during the study. Scores range between 0 and 10. Higher scores indicate greater pain. Bars are 95% CI. The total number of observations at each of the time points was: baseline – 221, 12 months – 204; 24 months – 199; 36 months – 188; 48 months – 148; 60 months – 112; 72 months – 78; 84 months – 36; 96 months – 11; study end – 176.

SF-36 quality-of-life questionnaire

The quality of physical and mental components of a participant’s life were assessed by the SF-36 questionnaire.

Physical component summary

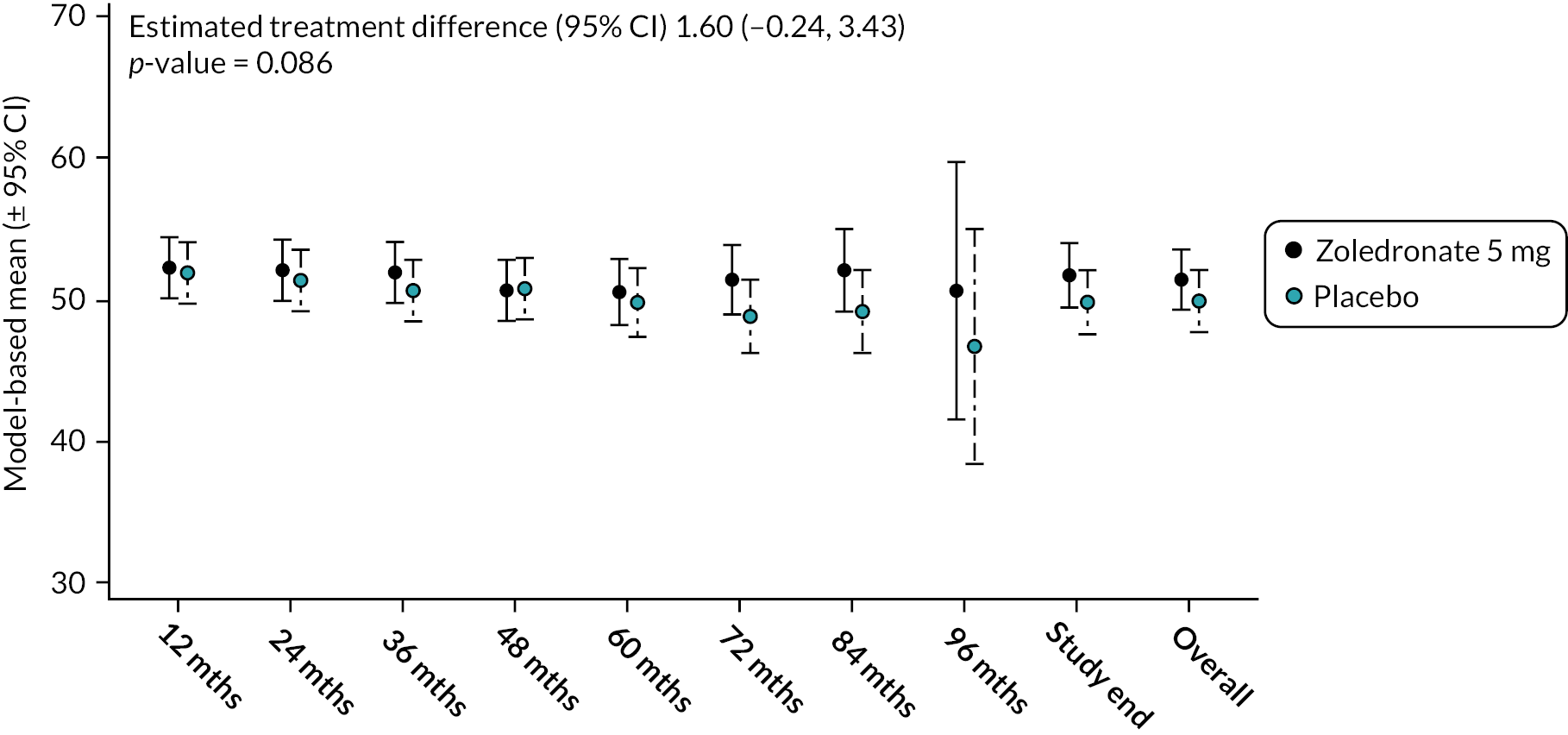

At baseline, the mean physical component summary scores (PCSS) were similar in the ZA arm 51.4 (SD 8.1) and placebo arm 51.9 (SD 8.6) (see Figure 9). By the end of the study, values had fallen slightly in both arms but there was no significant difference between the groups (mean difference, 95% CI) 1.60 (−0.24 to 3.43; p-value = 0.086). The unadjusted mean and SD values for each treatment group and numbers of observations at each timepoint are shown in Appendix 2, Table 22.

FIGURE 9.

Model-based changes in SF-36 physical component summary during the study. A score < 50 indicates health status below average and vice versa. Bars are 95% CI. The total number of observations at each of the time points was: baseline – 222, 12 months – 207; 24 months – 201; 36 months – 187; 48 months – 150; 60 months – 115; 72 months – 81; 84 months – 36; 96 months – 11; study end – 178.

Mental component summary

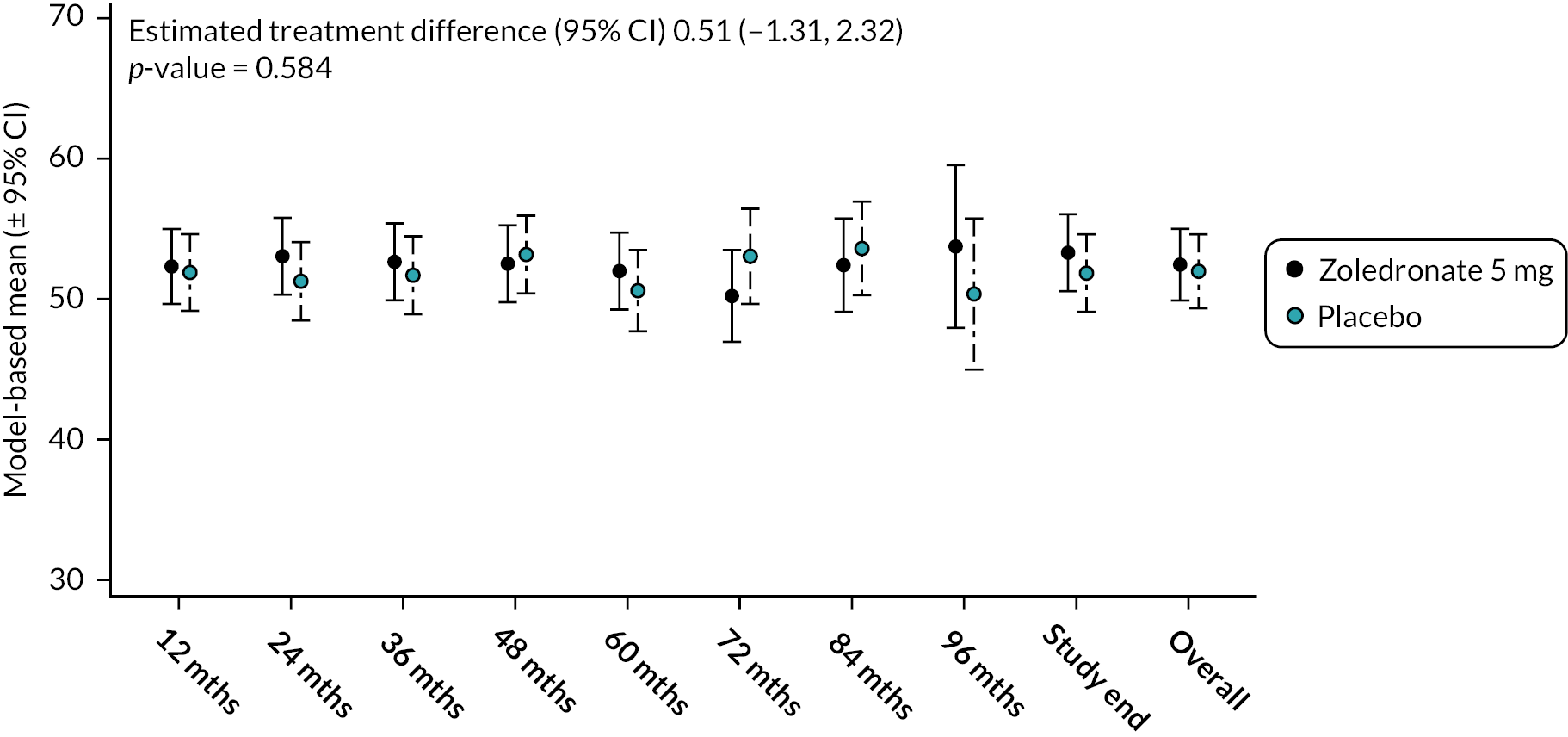

Values for the SF-36 – mental component summary score (MCSS) were identical at baseline with a mean value of 52.5 (SD 8.5) in both groups (Figure 10). During the study, scores tended to increase in the ZA arm but had decreased slightly in the placebo arm. Overall, there was no difference between the groups (mean difference 0.51, 95% CI −1.31 to 2.32; p-value = 0.584). The unadjusted mean and SD values for each treatment group and numbers of observations at each timepoint are shown in Appendix 2, Table 23.

FIGURE 10.

Model-based changes in SF-36 mental component summary during the study. A score < 50 indicates health status below average and vice versa. Bars are 95% CI. The total number of observations at each of the time points was: baseline – 222, 12 months – 207; 24 months – 201; 36 months – 187; 48 months – 150; 60 months – 115; 72 months – 81; 84 months – 36; 96 months – 11; study end – 178.

Anxiety and depression

Anxiety and depression were assessed by the HADS.

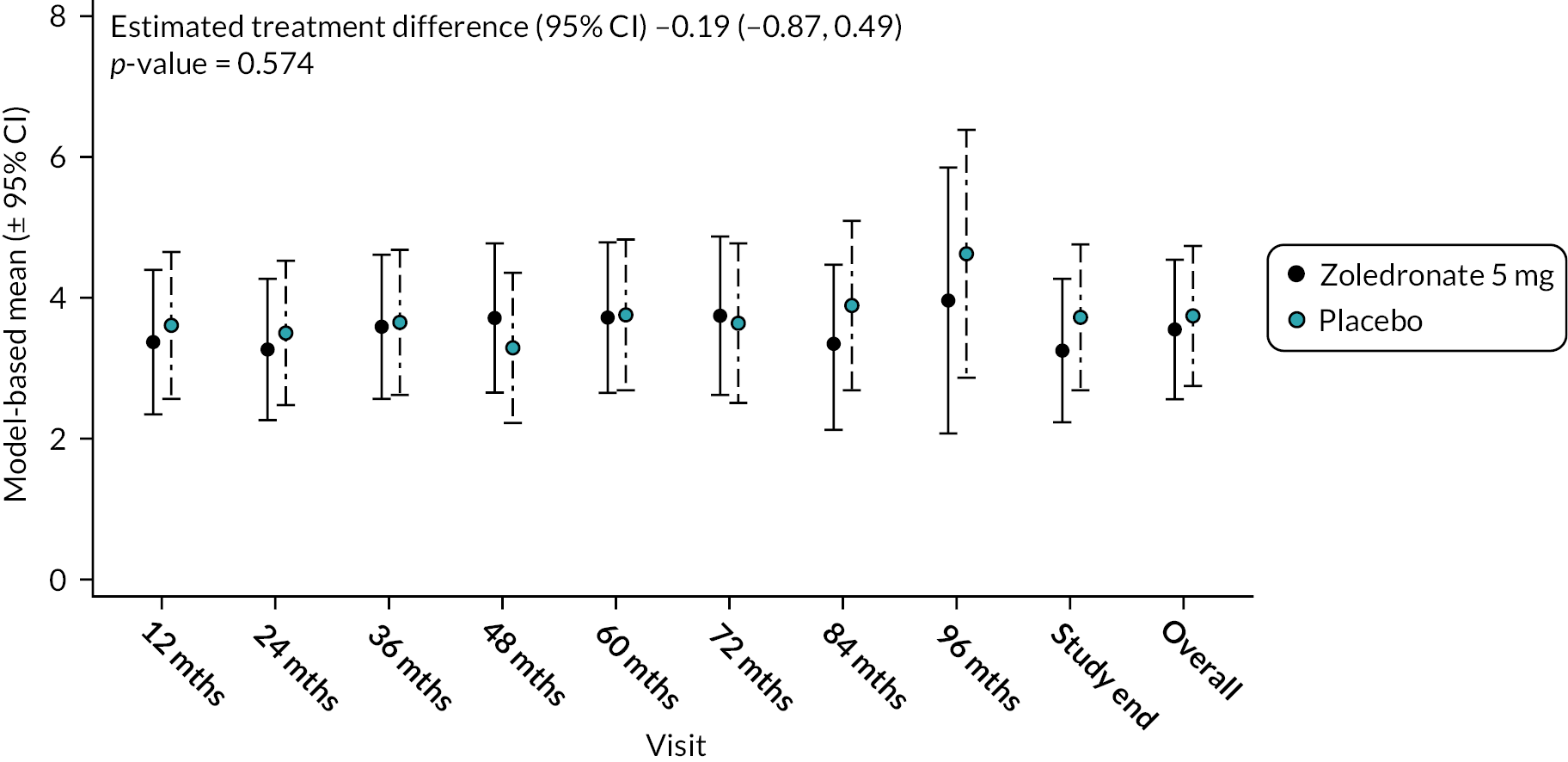

Anxiety

At baseline, there was no significant difference between the groups in levels of anxiety and no difference between groups during the study (Figure 11). The unadjusted mean and SD values for each treatment group and numbers of observations at each timepoint are shown in Appendix 2, Table 24.

FIGURE 11.

Model-based changes in anxiety scores during the study. Scores range between 0 and 10. Higher scores indicate greater levels of anxiety. Bars are 95% CI. The total number of observations at each of the time points was: baseline – 222, 12 months – 207; 24 months – 200; 36 months – 189; 48 months – 150; 60 months – 115; 72 months – 81; 84 months – 36; 96 months – 11; study end – 178.

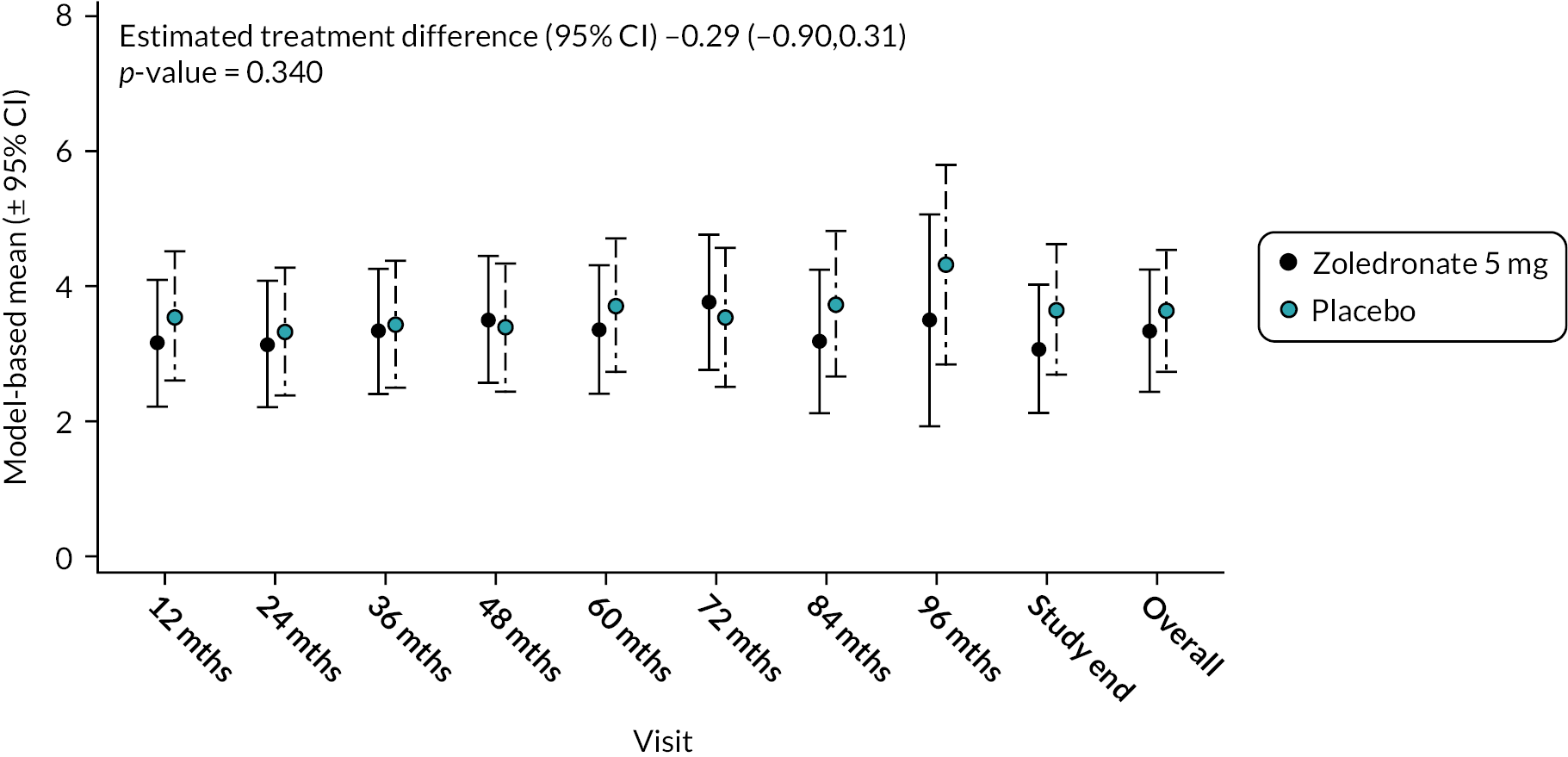

Depression

At baseline, mean depression scores were marginally lower in the ZA group compared to the placebo group [3.3 (SD 3.0) vs. 3.5 (SD 2.8)]. As the trial progressed, the ZA treatment group depression score tended to decrease but increased in the placebo group. However, there was no significant difference between the two treatments: mean difference (95% CI) −0.29 (−0.90 to 0.31); p-value = 0.340 (Figure 12). The unadjusted mean and SD values for each treatment group and numbers of observations at each timepoint are shown in Appendix 2, Table 25.

FIGURE 12.

Model-based changes in depression scores during the study. Scores range between 0 and 10. Higher scores indicate greater levels of depression. Bars are 95% CI. The total number of observations at each of the time points was: baseline – 222, 12 months – 207; 24 months – 200; 36 months – 189; 48 months – 150; 60 months – 115; 72 months – 81; 84 months – 36; 96 months – 11; study end – 178.

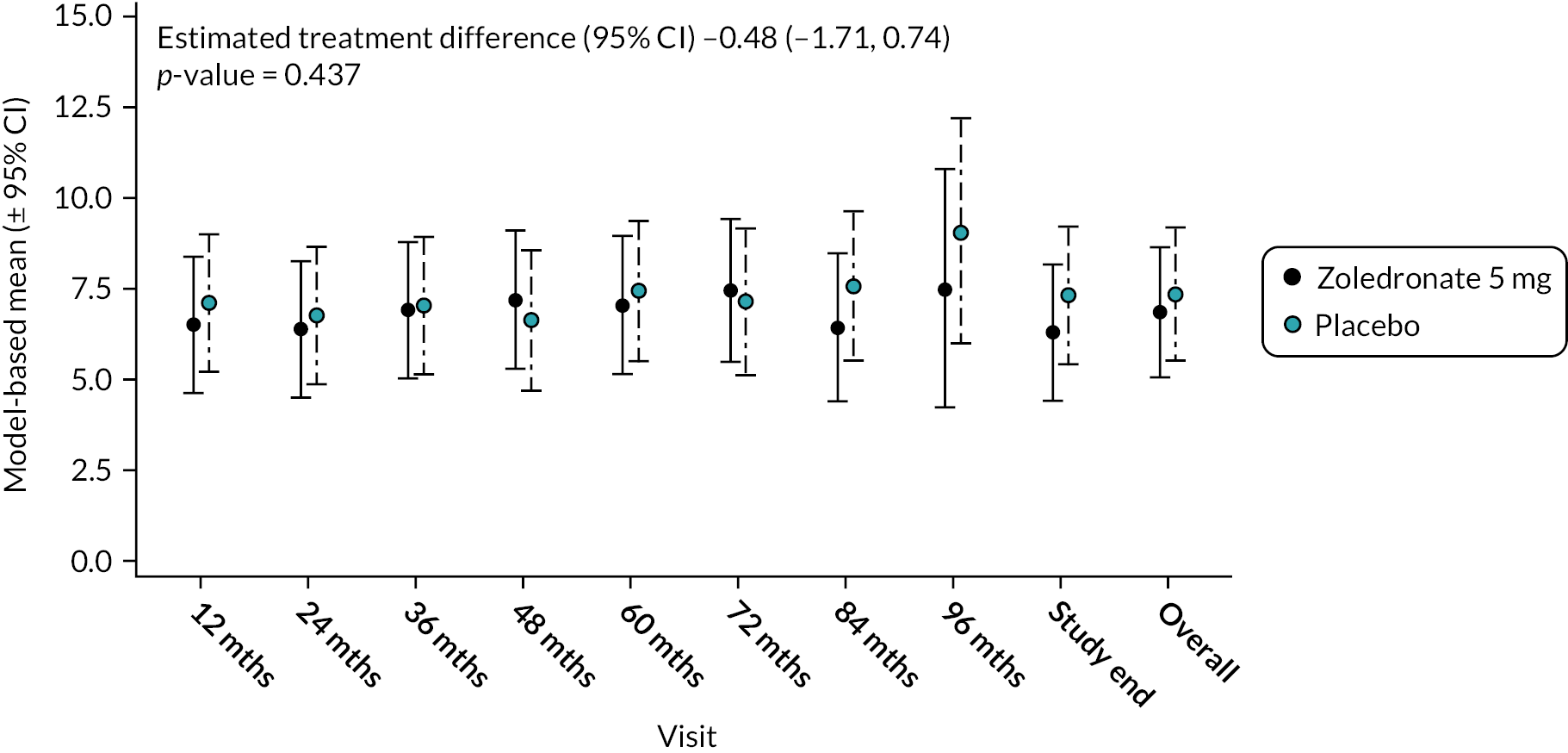

Total score – anxiety and depression

There was no significant difference between the two treatments in terms of combined scores for anxiety and depression at baseline or during the study as shown in Figure 13. Mean difference −0.48 (95% CI −1.71 to 0.74); p-value = 0.437. The unadjusted mean and SD values for each treatment group and numbers of observations at each timepoint are shown in Appendix 2, Table 26.

FIGURE 13.

Model-based changes in combined anxiety and depression score during the study. Scores range between 0 and 10. Higher scores indicate greater levels of anxiety and depression. Bars are 95% CI. The total number of observations at each of the time points was: baseline – 222, 12 months – 207; 24 months – 200; 36 months – 189; 48 months – 150; 60 months – 115; 72 months – 81; 84 months – 36; 96 months – 11; study end – 178.

Binary outcomes

Not applicable.

Ancillary analyses

Not applicable.

Harms

Adverse events

The proportion of patients experiencing any adverse event (AE) was similar between the ZA and placebo groups: 85 (76.6%) of 111 and 87 (78.4%) of 111, respectively. The total number and type of individual AE according to the MedDRA system organ class (SOC) classification was also similar in both groups (Table 15).

| MedDRA System Organ Class (SOC) | ZA (N = 111) | Placebo (N = 111) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total AEs | 583 | 644 | 1227 |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.5%) | 3 (0.2%) |

| Cardiac disorders | 3 (0.5%) | 4 (0.6%) | 7 (0.6%) |

| Congenital, familial and genetic disorders | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | 6 (1.0%) | 9 (1.4%) | 15 (1.2%) |

| Endocrine disorders | 4 (0.7%) | 3 (0.5%) | 7 (0.6%) |

| Eye disorders | 5 (0.9%) | 6 (0.9%) | 11 (0.9%) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 30 (5.1%) | 47 (7.3%) | 77 (6.3%) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 10 (1.7%) | 21 (3.3%) | 31 (2.5%) |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (0.9%) | 6 (0.5%) |

| Immune system disorders | 2 (0.3%) | 1 (0.2%) | 3 (0.2%) |

| Infections and infestations | 149 (25.6%) | 116 (18.0%) | 265 (21.6%) |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 38 (6.5%) | 51 (7.9%) | 89 (7.3%) |

| Investigations | 45 (7.7%) | 57 (8.9%) | 102 (8.3%) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 8 (1.4%) | 11 (1.7%) | 19 (1.5%) |

| MSK and connective tissue disorders | 97 (16.6%) | 110 (17.1%) | 207 (16.9%) |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified (including cysts and polyps) | 12 (2.1%) | 7 (1.1%) | 19 (1.5%) |

| Nervous system disorders | 36 (6.2%) | 31 (4.8%) | 67 (5.5%) |

| Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.3%) | 2 (0.2%) |

| Product issues | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 10 (1.7%) | 17 (2.6%) | 27 (2.2%) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 4 (0.7%) | 10 (1.6%) | 14 (1.1%) |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 14 (2.4%) | 16 (2.5%) | 30 (2.4%) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 10 (1.7%) | 18 (2.8%) | 28 (2.3%) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 9 (1.5%) | 17 (2.6%) | 26 (2.1%) |

| Social circumstances | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.3%) | 2 (0.2%) |

| Surgical and medical procedures | 86 (14.8%) | 68 (10.6%) | 154 (12.6%) |

| Vascular disorders | 5 (0.9%) | 10 (1.6%) | 15 (1.2%) |

The study also analysed AEs that occurred within the first week after the infusion and there was no difference in the number of events between treatment groups (data not shown). There were 8 out of 583 (1.4%) AEs in the ZA-treated group that were judged to be related to the drug, while in the placebo-treated group there were 2 (0.3%) events reported as directly drug-related.

Serious Adverse Eventes

The number of serious adverse events (SAE) in the treatment groups is shown in Table 16. The proportion of individuals experiencing SAEs was lower in the ZA group compared with the placebo group: 18/111 (16.2%) versus 25/111 (22.5%) respectively. No SAEs reported were suspected to be drug-related.

| MedDRA System Organ Class (SOC) | Zoledronate 5 mg (N = 111) | Placebo (N = 111) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | N = 23 | N = 45 |

| Cardiac disorders | 3 (13.0%) | 3 (6.7%) |

| Congenital, familial and genetic disorders | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 1 (4.4%) | 4 (8.9%) |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Infections and infestations | 4 (17.4%) | 5 (11.1%) |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 1 (4.4%) | 4 (8.9%) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| MSK and connective tissue disorders | 1 (4.4%) | 4 (8.9%) |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified (including cysts and polyps) | 2 (8.8%) | 3 (6.7%) |

| Nervous system disorders | 6 (26%) | 4 (8.9%) |

| Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.4%) |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 1 (4.4%) | 3 (6.7%) |

| Surgical and medical procedures | 4 (17.4%) | 9 (20.0%) |

| Vascular disorders | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.2%) |

Statistical analysis was not conducted to compare the number or type of AEs by study group.

Serious adverse events

See Table 16.

Chapter 4 Discussion

Limitations

There were several limitations to the study. The first was that the study did not anticipate that 9.5% of participants would have already shown bone scan evidence of Paget’s disease at the baseline visit. Since the primary end point was the number of participants with new lesions with the characteristics of PDB this reduced the power to detect an effect of treatment. A second limitation was the fact that the proportion of participants developing new lesions was very small; only two participants in the placebo group developed new lesions compared with the 15% expected over a 5-year follow-up when the study was being designed. It should be noted that this assumption was based on historical cross-sectional data and the known increase in occurrence of PDB with increasing age. Up until this study was performed, there has been no prospective study that has looked at the rate of development of PDB with age, with or without treatment. Because of the small number of events, it was not feasible to conduct a logistic regression analysis to look at the influence of baseline characteristics on the development of new lesions or any potential effects of familial clustering. The study also focused on bone scan evidence of PDB lesions as the primary end point, rather than complications of the disease, such as bone pain, pathological fractures or deformity. Although such complications are of clinical importance, it is thought that they occur as the result of uncontrolled active PDB over many decades. It would be very unlikely for an experimental medicine study such as this to detect an effect of ZA treatment on these clinical outcomes over a relatively short period of 5 to 8 years follow-up. Despite this, the study was able to show a significant inhibitory effect of ZA on evolution of existing lesions. The study also observed a numerical decrease in new lesions, albeit not significantly. Since the complications of PDB are thought to arise as the result of uncontrolled increases in disorganised bone remodelling, it is conceivable that the reversal of bone lesions with ZA demonstrated here may translate into more tangible clinical benefits in the long term.

Generalisability

The findings reported here are generalisable to individuals with a family history of Paget’s disease who are willing to undergo genetic testing for SQSTM1 mutations. The study had remarkably good retention of participants when one considers the extended duration of follow-up and the fact that, for many centres, follow-up and closeout of the trial occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Interpretation

Although the primary end point was not met in the study due to the small number of participants with new bone lesions, the study clearly showed that ZA was highly effective at favourably modifying the appearances of existing bone lesions as assessed by bone scan. In the placebo group, only 1/25 lesion disappeared (3.4%), 12/25 were thought to have improved (48.0%); 8/25 were thought to have remained static (32.0%); and 4/25 to have progressed (12.0%). In comparison, 13/15 (86.7%) existing lesions disappeared in the ZA group, 2 (13.3%) improved and none remained static or progressed.

Another important point to emerge from the study was that the intervention with ZA was well tolerated, with an overall balance of AEs and SAEs that was almost identical between the study groups. This also held true when the study looked at the number of AEs which were reported at the telephone review at one week post infusion. The study’s conclusion is that it is feasible to offer people with a family history of PDB genetic testing for SQSTM1 mutations followed by the offer of a radionuclide bone scan in those who test positive, in the knowledge that this is likely to pick up early disease in about 10% of individuals. It would then be possible to offer these individuals ongoing surveillance or prophylactic treatment with ZA to reduce the risk of the disease progressing with the aim of favourably modify evolution of the disease. It is clinically relevant to consider that the effects of a single infusion of ZA were still apparent in terms of biochemical markers and evidence of lesions on bone scan at a mean of 78.7 months follow-up. Because of this, delivery of this intervention would be eminently feasible in routine clinical practice.

Our study indicates that further research to evaluate the potential clinical and health economic benefits of prophylactic ZA would be indicated in this patient group. While only one patient in the placebo group developed a complication related to PDB, further follow-up of these subjects is in progress in the form of an extension study (ZIPP-long term extension) and it will be interesting to see whether further individuals start to develop symptoms of PDB or complications.

The results of the ZIPP study provide an impetus to consider introducing a programme of genetic testing for SQSTM1 mutations coupled with bone scan examination in people who have a family history of PDB with the offer of intervention with ZA in those who are found to have bone scan signs of the disease, although it is less clear at the present time whether people who do not have bone scan evidence of PDB would benefit from prophylactic ZA.

Additional information

CRediT contribution statement

Jonathan Philips (https://orcid.org/0009-0006-9027-2668): Project administration, Resources, Visualisation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing. Deepak Subedi (https://orcid.org/0009-0004-7832-7019): Data curation, Writing – review and editing. Steff C Lewis (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1210-2314): Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review and editing. Catriona Keerie (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5459-6178): Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review and editing. Stuart H Ralston (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2804-7586): Conceptualisation, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the study was provided by the Medical Research Council (MRC) (UK) and Arthritis Research Council (ARC) (UK). The IMP, ZA (Aclasta®) 5 mg, and its subsequent labelling and packaging wassupplied by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Limited.

The protocol can be requested from the chief investigator at stuart.ralston@ed.ac.uk or it can be located at https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN11616770

Participating sites

| Liverpool Principal investigator Lakshminarayan Ranganath Department of Clinical Biochemistry and Metabolic Medicine The University of Liverpool Liverpool L69 3GA United Kingdom Tel: 0151 706 4197 E-mail: lrang@liv.ac.uk |

Manchester Principal investigator Peter Selby Department of Medicine Manchester Royal Infirmary Manchester M13 9WL United Kingdom Tel: 0161 276 8917 E-mail: peter.selby@mft.nhs.uk |

|

London Guy’s & St Thomas’ Hospital Principal investigator Geeta Hampson Department of Rheumatology St Thomas’ Hospital London SE1 7EH United Kingdom Tel: 0207 188 1284 E-mail: geeta.hampson@kcl.ac.uk |

Oswestry Principal investigator Shu Ho The Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic and District Hospital Oswestry SY10 7AG United Kingdom Tel: 0169 140 4354 E-mail: shu.ho@nhs.net |

|

London King’s College Hospital Principal investigator Rama Chandra Clinical Biochemistry King’s College Hospital London SE5 9RS United Kingdom Tel: 0203 299 3275 E-mail: rama.chandra@nhs.net |

Portsmouth Principal investigator Steven Young Min Department of Rheumatology Queen Alexandra Hospital Portsmouth PO6 3LY United Kingdom Tel: 0239 228 6199 E-mail: steven.youngmin@porthosp.nhs.uk |

|

Bristol Principal investigator Jon Tobias Musculoskeletal Research Unit University of Bristol BS10 5NB United Kingdom Tel: 0239 228 6199 E-mail: jon.tobias@bristol.ac.uk |

Norwich Principal investigator William Fraser Norwich Medical School Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences University of East Anglia Norwich NR4 7TJ United Kingdom Tel: 0115 969 1169 E-mail: w.fraser@uea.ac.uk |

|

Wrexham Principal investigator Mark Garton Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board/Bwrdd Iechyd Prifysgol Betsi Wrexham Technology Park Wrexham LL13 7YP United Kingdom Tel: 0300 085 8034 E-mail: mark.garton@wales.nhs.uk |

Dublin Principal investigators Malachi McKenna Rachel Crowley Endocrinology Department St. Vincent’s University Hospital Dublin 4 Republic of Ireland Tel: +353 1 22 14407 E-mail: malachimckenna@gmail.com; rcrowley@svhg.ie |

|

Norwich Principal Investigator Dr Jonathan Tang Norwich Medical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, NR4 7TJ, United Kingdom Tel: 01159 691 169 E-mail: Jonathan.Tang@uea.ac.uk |

Siena Principal investigators Luigi Gennari Rannuccio Nuti Department of Medicine Surgery and Neurosciences University of Sienna Sienna 53100 Italy Tel: +39 577 585 362 E-mail: gennari@unisi.it; nutir@unisi.it |

|

Hospital Clinic, Barcelona Principal investigator Nuria Guanabens Department of Rheumatology Hospital Clinic CIBERehd Barcelona 8036 Spain Tel: +34 93 227 5400 E-mail: nguanabens@ub.edu |

Hospital Del Mar, Barcelona Principal investigator Josep Blanch Bone Metabolism Unit Rheumatology Division University Hospital del Mar Barcelona 8003 Spain Tel: +34 93 367 4126 E-mail: jblanch@parcdesalutmar.cat |

|

Salamanca Principal investigators Ana Isabel Turrión Nieves Javier del Pino Montes Institute for Biomedical Research University Hospital of Salamanca Salamanca 37007 Spain Tel: +34 923 504 376 E-mail: anaturrion@usal.es; jpino@usal.es |

Florence Principal investigator Maria Brandi Department of Internal Medicine University Hospital of Careggi Florence 50139 Italy Tel: +39 554 296 586 E-mail: m.brandi@dmi.unifi.it |

|

Turin Principal investigators Giancarlo Isaia Marco Di Stefano Geriatrics and Metabolic Bone Diseases AOU San Giovanni Battista di Torino Corso Torino10126 Italy Tel: +39 011 663 7140 E-mail: giancarlo.isaia@unito.it; mdistefano@cittadellasalute.to.it |

Brussels Principal investigators Anne Durnez Jean-Pierre Devogelaer Service de Rhumatologie Clinique Universitaires Saint-Luc BrusselsB-1200 Belgium Tel: +32 477 677 606 E-mail: anne.durnez@uclouvain.be; jean-pierre.devogelaer@uclouvain.be |

|

Sydney Concord Principal investigator Markus Seibel Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism Concord Repatriation General Hospital Sydney New South Wales 2139 Australia Tel: +61 297 676 109 E-mail: markus.seibel@sydney.edu.au |

Geelong Principal investigator Mark Kotowicz Department of Endocrinology and Diabetes The University of Melbourne Geelong 3220 Australia Tel: +61 352 267 764 E-mail: markk@barwonhealth.org.au |

|

Perth Principal investigator John Walsh Department of Endocrinology and Diabetes Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital Perth 6009 Australia Tel: +61 893 462 466 E-mail: John.Walsh@health.wa.gov.au |

Brisbane Principal investigator Emma Duncan Endocrinology Department Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Brisbane 4029 Australia Tel: +61 736 368 111 E-mail: emma.duncan@qut.edu.au |

|

Toowoomba Principal investigator Geoffrey Charles Nicholson Rural Clinical School, The University of Queensland, Queensland 4350 Australia Tel: +61 746 339 702 E-mail: geoff.nicholson49@gmail.com |

Auckland Principal investigator Anne Horne Bone & Joint Research Group Department of Medicine University of Auckland Auckland New Zealand Tel: +64 99 239 787 E-mail: a.horne@auckland.ac.nz |

|

Newcastle Principal investigator Gabor Major Rheumatology Bone and Joint Institute Royal Newcastle Centre New Lambton Heights 2305 Australia Tel: +61 249 223 500 E-mail: gabor.major@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au |

Christchurch Principal investigator Nigel Gilchrist The CGM Research Trust Christchurch 8022 New Zealand Tel: +64 33 377 820 E-mail: nigel.gilchrist@cgm.org.nz |

Equality, diversity and inclusion

No restrictions were placed on recruitment to the study based on ethnic background or sex. Recruitment was restricted to individuals > 30 years because Paget’s disease increases in incidence with age. It was therefore considered that recruitment of those under the age of 30 years would not be informative. The proportion of females recruited to the study was higher than males (54.5% vs. 45.4%) but this was based on participant choice. All participant information leaflets and documents were available in a selection of languages (English, Italian and Spanish) depending on where the recruitment was carried out. Each of the sites involved used their own staff members, which were representative of suitably qualified individuals from that specific geographic region. The study team was diverse in terms of background and experience, and included clinical support workers, trial managers, research nurses, data managers, statisticians and clinicians with experience of managing Paget’s disease. The research uncovered a gap in knowledge about how best to identify individuals with a family history of Paget’s disease for further evaluation. The results showed that it may be appropriate to offer people with a family history of Paget’s genetic testing for SQSTM1 mutations coupled with a radionuclide bone scan to detect early disease and the offer of therapeutic intervention with ZA.

Patient data statement

This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS and secondary healthcare institutions around the world. Using patient data is vital to improve health and care for everyone. Patient data should be kept safe and secure to protect everyone’s privacy, and it is important that there are safeguards to make sure that they are stored and used responsibly. Everyone should be able to find out about how patient data are used. You can find out more about the background to this citation here: https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/data-citation

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to anonymised data may be granted following review.

Ethics statement

The study was reviewed by a Research Ethics Committee (REC). The decision made by the REC is based on the UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research, which sets out principles of good practice in the management and conduct of health and social care research in the UK. These principles protect and promote the interests of patients, service users, and the public in health and social care research, by describing ethical conduct and proportionate, assurance-based management of health and social care research, to support and facilitate high-quality research in the UK that has the confidence of patients, service users and the public.

The study was approved by the Fife and Forth Valley REC on 22 December 2008 (08/S0501/84).

Information Governance statement

The University of Edinburgh is committed to handling all personal information in line with the UK Data Protection Act (2018) and the General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) 2016/679.

Under the Data Protection legislation, University of Edinburgh and NHS Lothian is the Data Controller, and you can find out more about how we handle personal data, including how to exercise your individual rights and the contact details for our Data Protection Officer here.

Disclosure of interests

Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/FTKC2007.

The institution received financial support from the following bodies: Efficacy and Mechanisms Evaluation Programme (NIHR), Versus Arthritis (formerly Arthritis Research UK) European Commission, Wellcome Trust and Medical Research Council (MRC). The Paget’s Association provided non-financial support. Novartis provided the IMP. Stuart H Ralston is the Chair of the Paget’s Association. Deepak Subedi received funding from GE Healthcare to deliver lectures.

Steff C Lewis was a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Efficient Study Designs Committee (2015–6) and HTA General Committee (2016–21). Jonathan Phillips declared no conflicts. Catriona Keerie declared no conflicts.

Publications

Cronin O, Forsyth L, Goodman K, Lewis SC, Keerie C, Walker A, et al. Zoledronate in the prevention of Paget’s (ZiPP): protocol for a randomised trial of genetic testing and targeted zoledronic acid therapy to prevent SQSTM1-mediated Paget’s disease of bone. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030689. https://doi/org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030689