Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as award number 12/205/46. The contractual start date was in January 2015. The draft manuscript began editorial review in May 2022 and was accepted for publication in August 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Moots et al. This work was produced by Moots et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Moots et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Behçet syndrome (BS; also called Behçet’s disease or, simply, Behçet’s) is a systemic inflammatory vasculitis of unknown aetiology, characterised by recurrent episodes of acute inflammation in a variety of organs, typically including mucus ulceration in the mouth and genitally, but also manifestations in other organs from the skin to the eyes, where it can cause blindness. 1,2 These clinical features, the absence of specific autoantibodies and its spontaneously relapsing and remitting nature have led to its characterisation as a polygenic autoinflammatory disorder. It is considered to be a very rare disease in the UK. The early estimates of prevalence in the UK ranged from 0.27 to 0.64 per 100,000, but a recent unvalidated population-based estimate utilising a large primary care database suggested a higher range of between 12 and 14/100,000, with the rider that this may be an overestimate as a proportion of such cases will not have been validated by an expert multidisciplinary team (MDT). Behçet’s disease is up to 10-fold more prevalent in the Middle East and Far East along the ‘silk route’ to Japan and increases towards Southern Europe.

There is considerable variation in its clinical presentation between and within individuals, and there appear to be differences in disease manifestations and response to therapy in patients in the UK compared to those in southern European or Far East countries. While little is known about the underlying pathophysiological processes, recent years have witnessed the successful application of biologic therapies, with good outcomes in patients who had not previously responded to standard therapy with steroids and/or immunosuppressants such as azathioprine. 3–5 Much of the evidence base for biologic therapy has arisen from case series or other uncontrolled trials performed in countries outside the UK – where the phenotype appears to differ. For example, more severe ocular disease is reported in patients in Turkey and Japan compared to the UK and Western populations, where mucocutaneous and gastrointestinal (GI) manifestations are more prevalent. Accordingly, most trials have reported effects on ocular disease. Very few data are available to inform useful systematic reviews, and most guidelines therefore stem from expert-based consensus. 6

The establishment of three National Centres of Excellence for Behçet’s disease in England7 led to the creation of a national cohort of patients with agreed pathways for assessment and treatment by MDTs, comprising the specialist and support staff needed to cover the wide spectrum of organ involvement and the ability to fund biologic therapy when indicated. At the time of the trial, it was generally considered that only two biologics, infliximab and alpha interferon (Roferon), had sufficient evidence to support their use as first-line biologics in refractory disease. Other biologics, such as alemtuzumab, with a less favourable adverse event (AE) profile, were reserved for patients who were refractory to or intolerant of infliximab and alpha interferon.

Infliximab is a mouse/human chimeric monoclonal antibody originally developed for use in rheumatoid arthritis that works by neutralising tumour necrosis factor (TNF) alpha. Its long-term safety record is well established in rheumatoid arthritis,8 and its utility in Behçet’s disease reported, typically in uncontrolled studies and in countries outside the UK. 3 In 2011, Arida et al. conducted an extensive PubMed/MEDLINE search on the published experience of 375 patients treated with a TNF-inhibitor for Behçet’s disease9 and with a variety of organ systems involved. Of these, the vast majority (325) were treated with infliximab, and all had been inadequately controlled with, or were intolerant to, other immunosuppressive regimens such as glucocorticoids, azathioprine and ciclosporin. Sustained organ-specific clinical responses were evident in 90%, 89%, 100% and 91% of patients with resistant mucocutaneous, ocular, GI and central nervous system involvement, respectively. None of those trials were randomised or placebo controlled.

At the time of the trial, Roferon was used in several inflammatory and rheumatic disorders, including Behçet’s disease, and was well summarised by Kotter et al. in 2010. 10 Much of the reported experience of alpha interferon in Behçet’s disease originated from uncontrolled studies in patients with ocular disease. Kotter et al. reported in 2003 an open, non-randomised, uncontrolled prospective study using Roferon in 50 patients with inflammatory eye disease due to Behçet’s disease. 11 An overall ocular response rate of 92% was reported. A rapid response: with the posterior uveitis score of the affected eye falling by 46% per week and full remission achieved by week 24. A retrospective single-centre uncontrolled series reported by Bodaghi et al. 12 of ocular Behçet’s disease also reported a high response rate of 82.6%, with other groups reporting similar findings. Reports of controlled trials of alpha interferon and its efficacy in extraocular disease are limited. Alpsoy et al. 13 published a randomised placebo-controlled study of 50 patients with mucocutaneous Behçet’s disease randomised to alpha interferon or placebo, reporting that alpha interferon was effective in the management of mucocutaneous lesions, with a trend towards improvement of joint symptoms. The formulation of and dosing regimens for alpha interferon have varied between these studies, most utilising the preparation Roferon, with short half-life and more frequent administration. The subsequent development of pegylated alpha interferon (Viraferon Peg)14 allowed dosing once a week. However, a UK prospective trial evaluating Viraferon Peg in Behçet’s disease reported only modest benefit, with responses far less than that for Roferon. 15

Assessment of disease activity: As a multisystem disease with lack of laboratory biomarkers to determine activity and limited disease-specific outcome measures, devising and undertaking a clinical trial of active medicinal products in Behçet’s disease is challenging, and international standards for this have not yet been adopted. Mumcu et al. 16 summarised the various methods used to measure overall clinical activity. The International Scientific Committee on Behçet’s disease produced the ‘Behçet’s Disease Current Activity Form’ (BDCAF), with investigators from five countries participating. 17 Thirty dichotomous questions were reduced to a Behçet’s disease activity index (BDAI) lying between 0 and 12 but then transformed to a 0–20 scale for international comparisons. In Iran, the Iranian Behçet’s Disease Dynamic Measure is used. 18 The Behçet’s Syndrome Activity Scale was developed as a patient-reported outcome measure, which correlates with the BDCAF. 19 A Behçet’s Disease-specific quality-of-life measure (BD-QoL) was derived by the Psychometric Group in the Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, Leeds University; it consists of 30 easily answered dichotomised questions. 20 Other disease activity measurements have been proposed for specific organ symptoms. We chose to use a slightly modified form of the BDAI as the primary outcome for the proposed clinical trial, as this is a verified measure of the overall severity of the disease and is routinely used in the three UK Centres of Excellence.

As in other complex chronic diseases, there is a need in BS to not only better understand the phenotype of patients in clinical trials but also to explore the potential to identify biomarkers that may help target therapies and minimise AEs. No such biomarkers are currently available. We, therefore, built into the study the exploratory analysis of two potential genetic and metabolomic biomarkers that focused on potential responses to alpha interferon and infliximab, respectively. Three genome-wide association studies in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection implicated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the vicinity of the interferon lambda 3 (IFNL3) [interleukin 28B (IL28B)] gene on chromosome 19q13.13 with response to alpha interferon therapy. 21–23 Patients with the CC genotype at rs12979860 had higher response rates to alpha interferon. 24 A recent parallel sequencing study25 was able to show that rs4803221 and rs7248668 predicted failure to respond better than rs12979860. IFNL3 encodes a lambda type of infliximab, while the SNP at rs12979860 affects interferon-stimulated gene production as part of the innate immune response, but the actual mechanism is unclear. 26 Despite this, treatment algorithms incorporating IFNL3 genotyping are now used in many clinics for the treatment of hepatitis C. 27 A recent study28 showed that rs12979860 is in linkage disequilibrium with a frameshift variant, ss469415590[ΔG], which also creates a new gene, interferon lambda 4 (IFNL4), reduced expression of which may be associated with reduced responsiveness of cells to alpha interferon 8. Whether the same SNPs affect response to alpha interferon in other diseases is unclear, but given the role of the innate immune system in the pathogenesis of BS,29 it was biologically plausible that a similar effect to that seen in hepatitis C with alpha interferon may be operating in BS. We intended to test this hypothesis in this trial.

To our knowledge, no convincing genetic predictors had been identified through genome-wide association studies as determinants of response to infliximab. We therefore chose initially to pursue a metabolomic route to explore this. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-based metabolomics allows the examination of the changes in hundreds or thousands of low-molecular-weight metabolites in an intact tissue or biofluid and offers several distinct advantages in a clinical setting since it can be carried out on standard preparations of blood cells, serum, plasma or urine. Pattern recognition techniques are applied to the NMR spectra of samples taken from individuals. Metabolomic analysis was able to distinguish between patients with rheumatoid arthritis who responded to anti-TNF therapy compared to those who did not, with a sensitivity of 88.7% and a specificity of 85.9%. 30 We have previously shown that metabolomic analysis of vitreous humour could separate with high sensitivity and specificity samples from patients with two inflammatory conditions, lens-induced uveitis and idiopathic chronic uveitis with urea and oxaloacetate levels associated with the different conditions. 31 There is therefore a sound rationale for exploring similar methodology in the current study of patients with BS.

Assessing biomarkers as part of this trial also promised the potential to not only help in identifying determinants of response but also provide insights into the potential mechanisms of action of these biologics in BS patients.

Rationale

Behçet syndrome is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in the UK and abroad. In the UK, it can take up to 12 years to diagnose, leads to blindness and stroke, often does not respond to simple immunosuppressive therapy and, as we have previously reported, has a major impact on quality of life (QoL). 32 Although the biologic drugs infliximab and alpha interferon have been reported to be effective in refractory BS, they are expensive [at the time of starting the trial, the cost of infliximab was < £20,000/year and alpha interferon (Roferon) was £4000/year] and have not been subjected to rigorously undertaken randomised controlled trials (RCTs) compared directly against each other for efficacy and safety. Evidence for their efficacy arose from uncontrolled studies in other countries, where the disease phenotype may exhibit subtle differences from that in the UK. 6 Funding for biologic drugs for BS in England is held by the three National Centres of Excellence, allocated from highly specialised NHS commissioning. 33 Anecdotal experiences from the three centres of excellence also indicated that response rates to the individual biologics used in this study might differ when used within a UK population compared to results reported from other international cohorts. While these biologic drugs were generally considered effective for patients with BS in the UK, the national centres anecdotally observed efficacy rates to differ from those reported in other countries, with variable and unpredictable responses, and therefore there was a poor evidence base on which to inform clinical decisions. The identification of novel biomarker(s) predicting response to biologic therapy was deemed necessary to allow a more precision-based approach to treatment. A polymorphism in the IFNL3 (IL28B) was predictive of reduction in viral load in response to alpha interferon in hepatitis B or C infections. 21,34,35 As similar alpha interferon-mediated pathways of innate immunity are involved in BS, the potential effect of IFNL3 SNP on response to therapy with alpha interferon may well be relevant in BS. Similarly, metabolic analyses of urine samples from patients afforded the potential to provide biomarkers for treatment response to infliximab and/or alpha interferon.

Objectives

The aim of the study was to create the evidence base to underpin clinically effective prescribing of the biological drugs infliximab and alpha interferon for BS.

The objectives of the study were to:

-

Undertake a RCT to compare infliximab versus alpha interferon in patients with BS who were unresponsive to standard oral therapy.

-

Examine whether IFNL3 and IFNL4 SNPs can predict responses to alpha interferon and/or infliximab in BS.

-

Examine the potential for urine metabolomics to act as biomarkers for drug responses to infliximab and/or alpha interferon in BS.

Chapter 2 Research methods

Trial design

Bio Behçet’s was a randomised, two-arm, parallel design comparing the efficacies of infliximab versus alpha interferon. The population was patients with refractory disease eligible for the first biologic drug. Patients were recruited from the National Behçet’s Centres and supporting clinics in England and randomised to the two arms of the trial with stratification by centre. A total of 80 patients were to be randomised on a 1 : 1 ratio for arms. Recruitment was scheduled to take approximately 36 months. Assessments were made at baseline, 12, 24 and 36 weeks. The end of study was when the final patient completed their 6-month follow-up assessment.

Study setting and study population

Study setting

The study was carried out in the three Behçet’s Centres of Excellence in England, with additional recruiting clinics. The additional recruiting centres were chosen on the basis of:

-

having at least one lead clinician with a specific interest in, and responsibility for, supervising and managing patients with BS

-

showing significant enthusiasm to participate in the study

-

ensuring that sufficient time, staff and adequate facilities were available for the trial

-

providing information to all supporting staff members involved with the trial or with other elements of the patient’s management

-

acknowledging and agreeing to conform to the administrative and ethical requirements and responsibilities of the study, including signing up to good clinical practice (GCP) and other regulatory documentation.

Each recruiting centre then met the following inclusion criteria:

-

positive Site-specific Assessment by local NHS research and development offices

-

local Health Research Authority approval

-

signed Research Site Agreement

-

receipt of evidence of completion of (1) and (2) by Liverpool Clinical Trials Consortium (LCTC)

-

completion and return of ‘Signature and Delegation Log’ to LCTC

-

curriculum vitae (CV), including a record of International Conference for Harmonisation (ICH) of GCP training – principal investigator (PI)

-

curriculum vitae, including a record of ICH GCP training – other personnel on the delegation log

-

Clinical Study Protocol Receipt Form:

-

Investigator Brochure’s Receipt Form

-

-

local laboratory accreditation/Quality Check

-

local laboratory reference ranges

-

patient information sheet, consent form and general practitioner letter on trust-headed paper

-

local pharmacy practice form.

Centres that did not meet the above criteria were excluded from the trial.

Study population

The population studied was drawn from patients attending the three Behçet’s Centres of Excellence in England, with additional recruiting sites working in collaboration. There were an estimated 800 patients with BS in England. The Behçet’s Centres, established by UK National Specialist Commissioning in 2012, are funded to provide a comprehensive service for diagnosis and management of BS, including full funding for biologic drugs in patients with refractory disease who are intolerant of or inadequate responders to therapy with corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants. Each centre runs at least weekly multidisciplinary clinics for patients with Behçet’s disease, attended by consultants in oral medicine, ophthalmology, neurology, dermatology, genito urinary medicine medicine or gynaecology and rheumatology and supported by a specialist nurse, clinical psychologist and support worker.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria:

-

Diagnosed to have BS by International Study Group (ISG) criteria or International Criteria for Behçet's Disease.

-

Had refractory disease as defined by the UK Centres of Excellence criteria (failure to respond to steroid and/or immunosuppressive therapy with significant or major organ-threatening disease) and therefore qualify for biologic therapy with either infliximab or alpha interferon. Patients who had failed to respond to, or been intolerant of, azathioprine at a dose of > 2 mg/kg (or comparable drug) and/or prednisolone at a dose of > 40 mg/day typically for more than 3 months, or with evidence of either organ-threatening disease or unacceptable AEs from immunosuppressive medication.

-

Able to give informed consent.

-

Have not previously received a biologic agent.

-

Aged over 18 years.

Exclusion criteria:

-

Contraindication to either infliximab or alpha interferon (e.g. active infection, severe liver disease, neutropenia, previous malignancy).

-

Unlikely to comply (e.g. cannot attend for assessments because of excessive travel requirements).

-

A strong preference for one of the two potential therapies.

-

Severe heart failure that would contraindicate the use of infliximab.

-

Diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.

-

Evidence of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV):

-

Women of childbearing potential (WOCBP) who were unwilling or unable to use an acceptable method to avoid pregnancy for the study duration plus 6 months.

-

Women who were pregnant or breastfeeding.

-

Sexually active, fertile men, not using effective birth control if their partners are WOCBP.

-

-

Active tuberculosis.

Trial interventions

Arm A infliximab intravenous infusion (Remicade®)

Remicade (and not biosimilar infliximab) was used in this study and was supplied from local stock. No additional labelling by site pharmacy was required.

The cost of the investigational medicinal product (IMP) was covered by existing funding arrangements with the National Behçet’s Centres.

Patients continued with concomitant immunosuppressants such as methotrexate or azathioprine unless otherwise clinically indicated.

Patients in Arm A received Remicade at a standard dose of 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2 and 6 as loading, then every 8 weeks for the remaining length of the trial (unless there was primary ocular, neurological or vascular disease when infusions were repeated at 6 weekly intervals after loading).

Remicade was administered according to the standard preparation and infusion procedures of each investigational centre.

Arm B alpha interferon (Roferon-A®) prefilled syringes

Roferon was used in this study and was supplied from local stock and handled according to the instructions within the corresponding summary of product characteristics. No additional labelling by site pharmacy was required.

The cost of the IMP was covered by existing funding arrangements with the National Behçet’s Centres.

A decreasing dose of Roferon-A was given to patients randomised to Arm B. All doses were given subcutaneously. See Table 1.

| Dose | Frequency | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| 3 million units | Daily | 3 days |

| 6 million unitsa | Daily | 2–4 weeks |

| 4.5 million units | Daily | 2–4 weeks |

| 3 million units | Daily | 2–4 weeks |

| 3 million units | 3 times a week | 2–4 weeks |

| 3 million units | Twice weekly | To trial end |

Immunosuppressants were discontinued in Arm B by rapid tapering after commencement of therapy. In the absence of an AE, tapering down of Roferon occurred at 4-weekly intervals. The development of an AE [such as leucopenia, persistent fever, raised liver function tests (alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase ˃ 3 times the upper limit of normal), persistent unacceptable fatigue, flu-like symptoms or severe depression] prompted a reduction in dose and/or frequency according to the above schedule.

Roferon-A prefilled syringes were dispensed from hospital stocks using the usual prescribing and dispensing practices.

Schedule of trial procedures

The schedule of trial procedures are listed in Table 2.

| Time (weeks) | Screening | 0 | 12 weeks | 24 weeks | 36 weeksa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomisation/baselineb | End of trial | End of trial | |||

| Informed written consent | x | ||||

| Assessment of eligibility criteria | x | ||||

| Review of medical history | x | ||||

| Review of concomitant medications | x | x | x | x | x |

| Pregnancy test | x | x | x | x | x |

| Randomisation | x | ||||

| Compliance with study intervention | x | x | x | ||

| Height | x | ||||

| Weight | x | x | x | x | x |

| Heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure | x | x | x | x | x |

| EQ-5D-5L Health Questionnaire | x | x | x | x | |

| BD-QoL questionnaire | x | x | x | x | |

| BDAI | x | x | x | x | |

| Collection of 9 ml blood for translational research | x | ||||

| Collection of (3 × 1 ml) urine for translational research | x | x | x | x | |

| Laboratory assessments (FBC) | x | x | x | x | x |

| Laboratory assessments – biochemical profile (liver, bone and renal) | x | x | x | x | x |

| Laboratory assessments (ESR) | x | X | X | X | |

| Laboratory assessments (CRP) | x | X | X | X | |

| Laboratory assessments (hepatitis B and C serology) | xc | ||||

| HIV screening | xc | ||||

| TB screening | x | ||||

| Assessment of AEs | x | x | x | x | |

| Routine clinical assessment [eyes, ulcers (mouth/genital), musculoskeletal, skin and systemic problems] as clinically indicatedb | x | x | x | x | x |

| Steroid use | x | x | x | x | x |

| Visual acuity (using LogMAR chart)b | x | x | x | x | x |

| Intraocular inflammation (SUN grading)b | x | x | x | x | x |

| Burden of skin rashb | x | x | x | x | x |

| Musculoskeletal Likert pain scoreb | x | x | x | x | x |

| Genital Ulcer Severity Scoreb | x | x | x | x | x |

| Oral Ulcer Severity Scoreb | x | x | x | x | x |

| PHQ-9 Questionnaire | x | x | x | x | x |

Data capture

Trial data were captured using electronic Case Report Forms (eCRFs) and transcribed to a MACRO database. This database was designed and maintained by the LCTC, which was also responsible for the randomisation. The eCRF was the primary data collection instrument for the study.

All eCRFs were entered directly into a MACRO database and accessed via a secure web page by research site staff and the clinical trial co-ordinator at LCTC. The client application was secured with a unique username/password combination allocated to each delegated member of the research team. When data were entered into an eCRF, it was electronically stamped with the date, time and the person who entered it. If data were changed on an eCRF, it was electronically stamped with the change and would be accompanied with the date, time, person and a reason for making the change or correction. The previous value was recorded in an audit trail for each data item.

Each eCRF contained specific validation checks on the data being entered. If any values were outside what was expected, or data missing, this was flagged up and raised as a discrepancy on the main database system. Regular reports were generated to identify discrepancies in the data and allow for follow-up. Comprehensive guidelines for eCRF data entry were provided to all staff who have been delegated the responsibility for data collection. Where the site was unable to upload data using the eCRF, a backup paper CRF was available to use and accessed from the LCTC portal. In such cases, the site research staff would enter the data onto the trial MACRO database following the assessment.

Electronic and paper screening logs were kept in clinics to record the number of patients declining participation and, when volunteered, the reason given. All data were kept in a secure, locked location on NHS premises. All routine eCRFs were to be completed within 14 days of the study visit occurring.

Paper versions of the CRFs were available for download from the LCTC website, www.LCTC.org.uk and used as an aid to research staff. Quality control (QC) processes, including onsite source data verification for primary and secondary end points, were put in place in line with the eCRF platform.

Biological samples

Blood samples/genotyping

A 9 ml blood sample was collected at baseline and then transported using Royal Mail Safeboxes to the Wolfson Centre for Personalised Medicine, University of Liverpool. Following this, DNA was extracted using an automated Chemagic platform (Perkin Elmer), and four SNPs were genotyped including rs12979860, rs4803221, rs7248668 and rs368334815 using ‘off the shelf’ validated allelic discrimination assays (Applied Biosystems). This was carried out by a trained technician with Real-Time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) utilising a QuantStudio six Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Strict QC measures were followed to ensure systematic validation of the genotype results.

The genotypic analysis was an exploratory analysis to determine whether any of the SNPs show an effect of efficacy of alpha interferon based on primary and secondary outcomes.

Urine metabolite

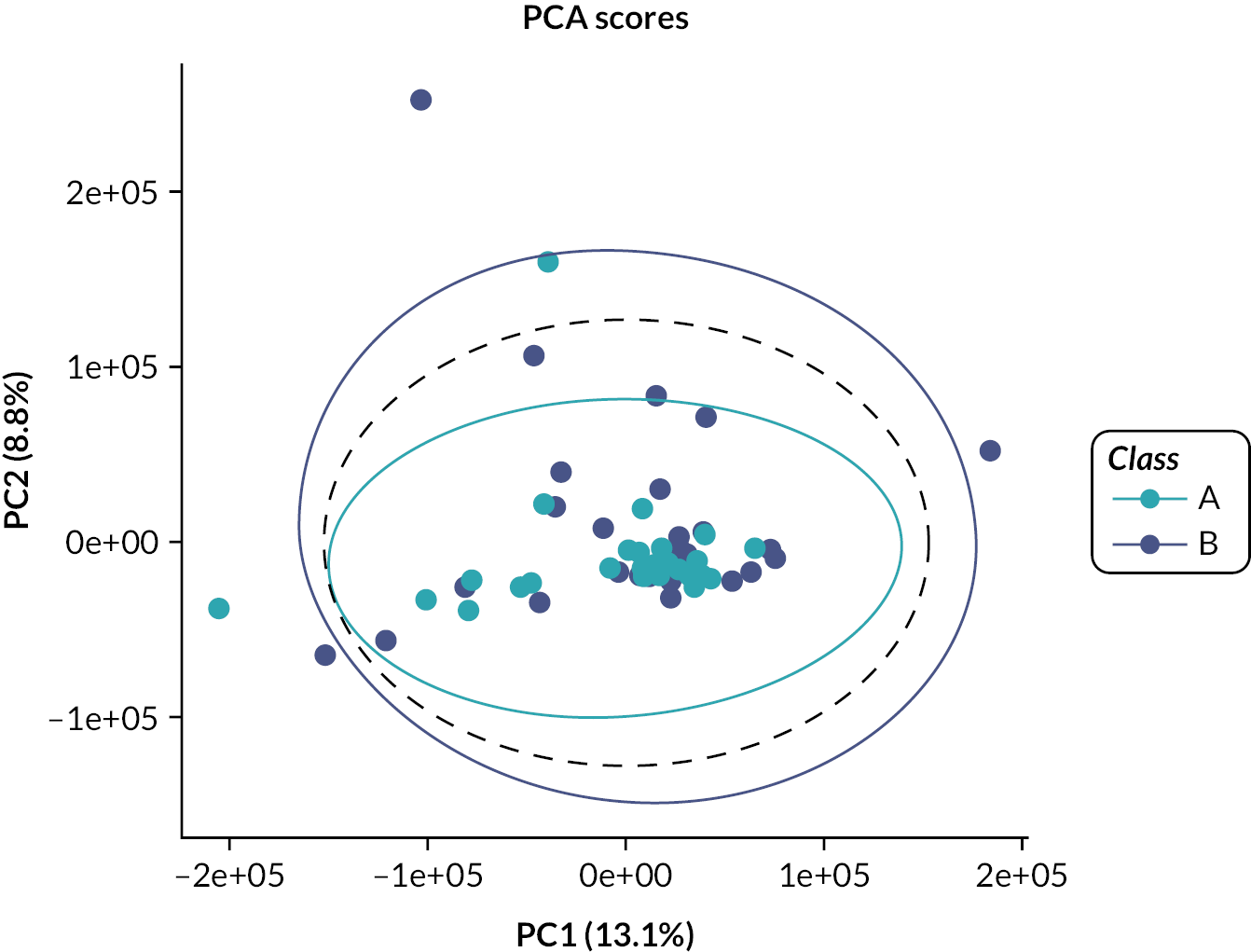

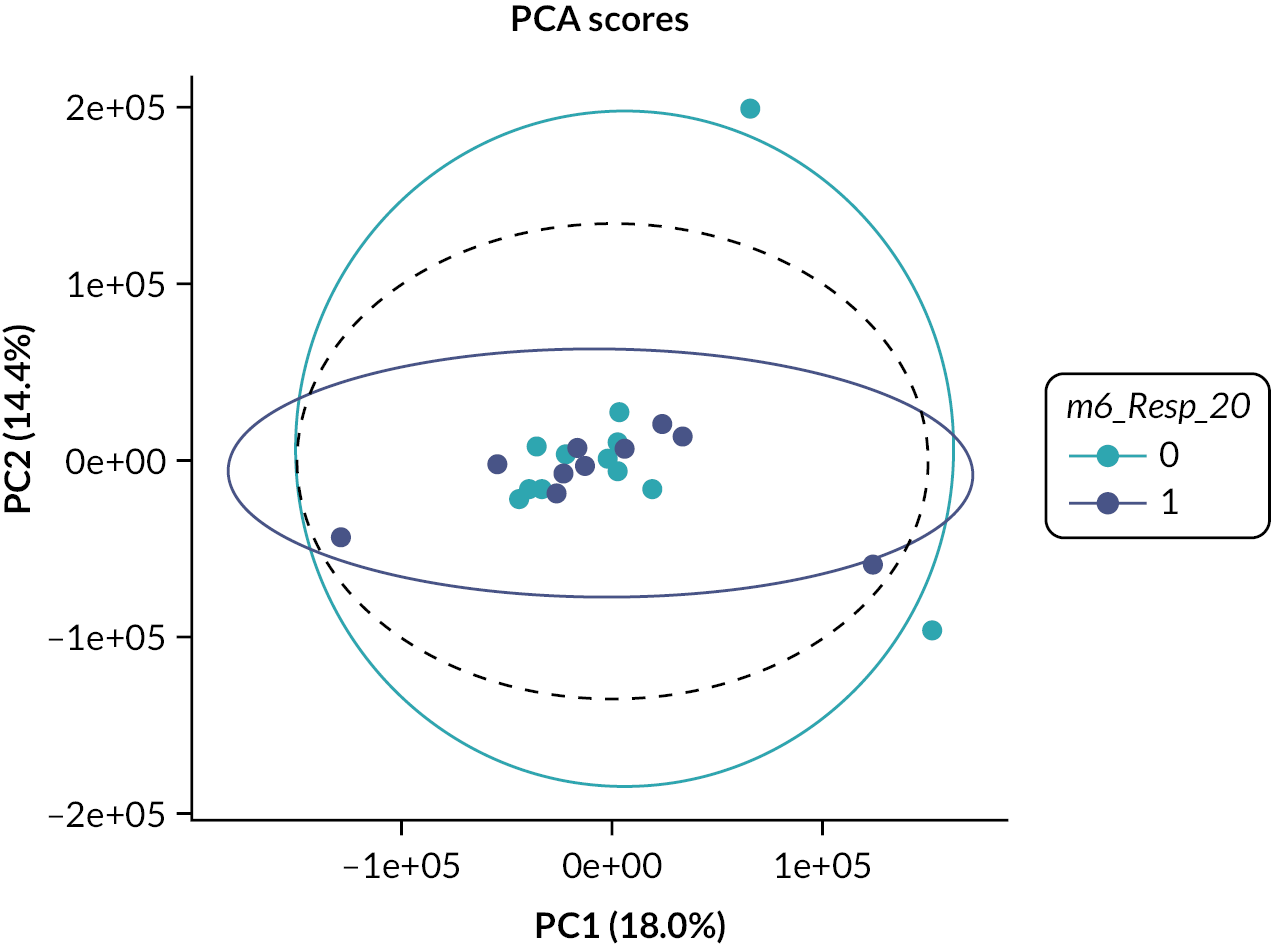

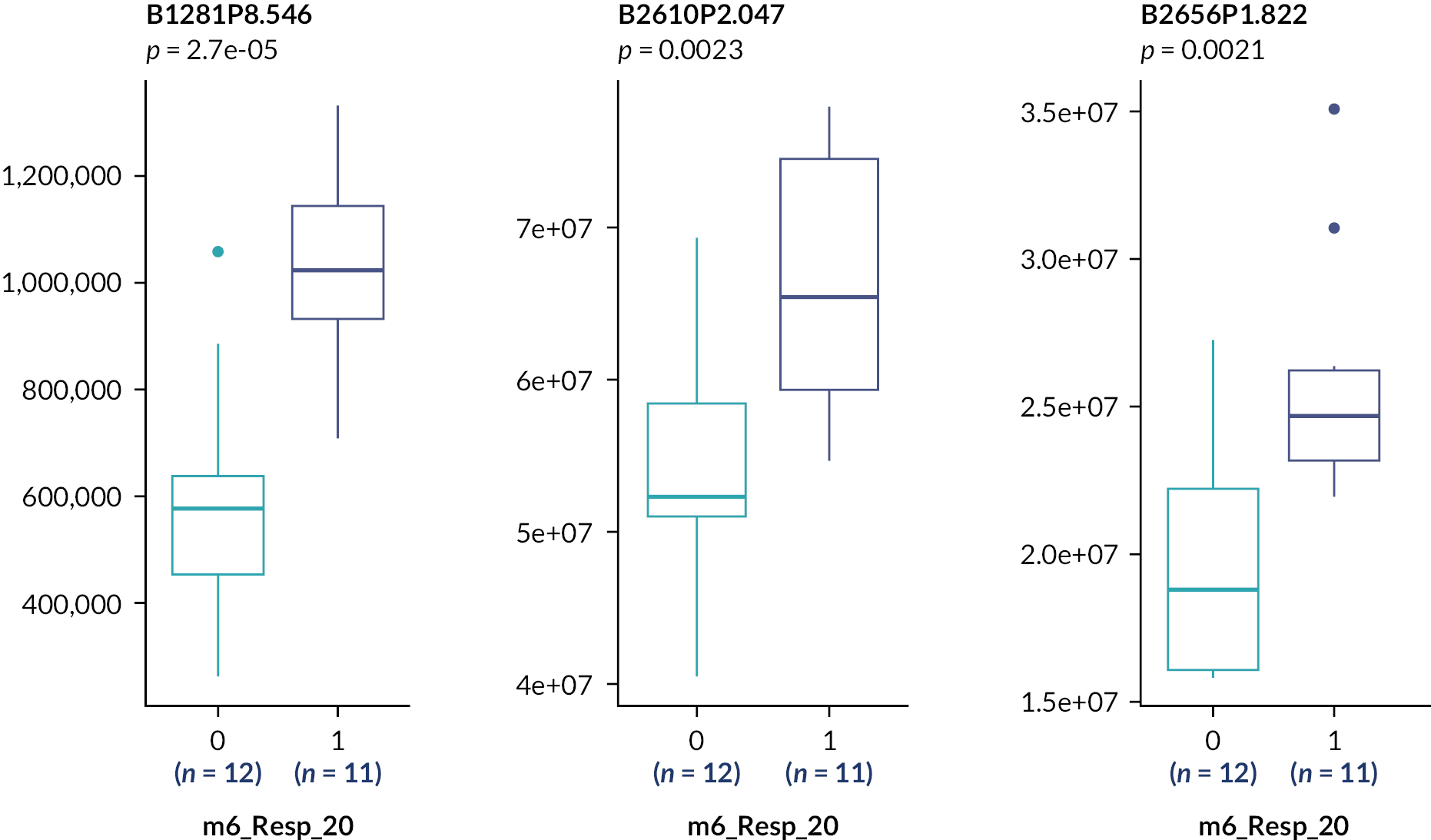

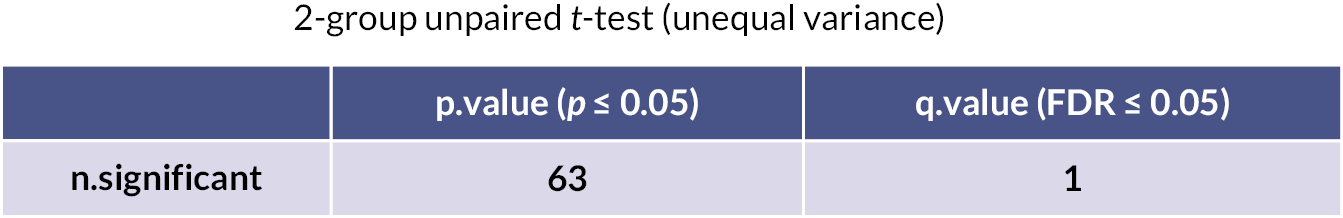

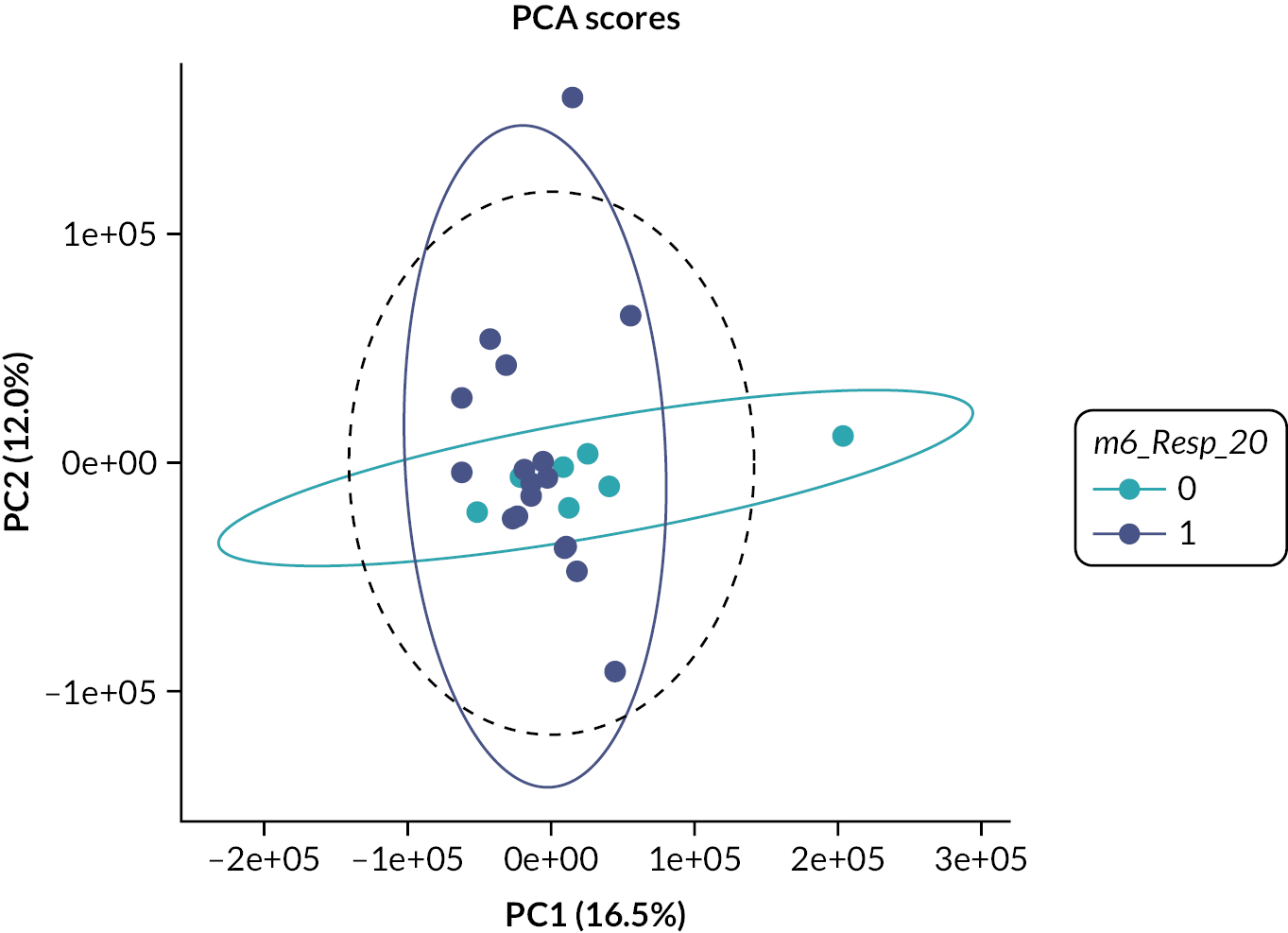

Urine samples from the patients were analysed by NMR spectroscopy and principal component analysis. Urine samples (3 × 1 ml) were collected at baseline, week 12, week 24 and week 36, snap frozen and stored at –80 °C and then transported to the Centre for Translational Medicine, The University of Birmingham. After thawing, urine samples were centrifuged at 13,000 g, prepared using a standard protocol and loaded into a standard 5-mm NMR tube for spectroscopy. For sample preparation, 450 µl of urine was mixed with 150 µl of 400 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.0. 1D-NOESY presaturation 1H NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker 600 MHz IvDR NMR system equipped with a z-axis gradient 5 mm TXI probe. Sixteen steady-state scans and a total of 128 transients were acquired per spectrum. All samples were shimmed to achieve a TMSP linewidth below 1 Hz prior to data acquisition. The spectral width was set to 20 ppm, the interscan relaxation delay was set to 10 seconds and a total of 32,768 complex data points were acquired. All spectra were processed using the MetaboLabPy software, including manual phase correction and data pre-processing. Data pre-processing included excluding regions > 9.8497 ppm, between 6.4522 and 5.6194 ppm and < 0.3168 ppm; segmental alignment of 71 spectral regions; noise filtering; bucketing of 32 data points (0.005 ppm); spectral normalisation using probabilistic quotient normalisation; variance stabilisation using Pareto scaling and finally export into an Excel spreadsheet for statistical data analysis.

Lists of metabolites providing the greatest discrimination between groups were identified using multivariate analyses and metabolites identified using an NMR database (Human Metabolome Database version 2.5) and Chenomx NMR suite. Strict QC measures were adhered to, ensuring proper validation of genotype results.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

Modified Behçet’s disease activity index (mBDAI) after 3 months of treatment (week 12 visit), with 20% change in means being defined as the zone of equivalence of treatment.

Secondary outcomes

Modified Behçet’s disease activity index after 6 months of treatment (week 24 visit).

-

Original BDAI after 3 and 6 months of treatment (week 12 and week 26 visits).

-

Significant improvement in organ systems after 3 and 6 months (week 12 and week 24 visits) assessed by:

-

Ocular: reduction in vitreous haze using the SUN consensus group grading scale and best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) change (using the LogMAR chart at 4 m) from baseline. A reduction of 2 or more in vitreous haze and a difference of 15 letters or more in BCVA are considered to be clinically significant.

-

Oral ulcer activity: change in ulcer severity score. An improvement of 20% is considered to be clinically meaningful.

-

Change in number of genital ulcers: a reduction of 20% is considered to be clinically significant.

-

Musculoskeletal: Likert pain score assessed by arthritis pain (10 cm) Likert scale on Rheumatology and Flare Data Collection Form (an improvement of 20% is considered to be clinically meaningful).

-

-

Adverse events in each group.

-

Reduction in dose of prednisolone (or equivalent glucocorticoid) at 3 months (week 12 visit): a clinically meaningful reduction is considered to be 50% of baseline or dose of < 15 mg/day prednisolone.

-

Reduction in dose of prednisolone (or equivalent glucocorticoid) at 6 months (week 24 visit): a clinically meaningful reduction is considered to be 50% of baseline or dose of < 7.5 mg/day prednisolone.

-

Quality-of-life scores at 3 and 6 months (week 12 and week 24 visits) compared to baseline. The QoL instruments used will be EuroQol-5 Dimensions and BD-QoL: a reduction of 20% would be of clinical importance.

-

Physician’s Global Assessment of disease activity [a 7-point Likert scale completed as part of (but assessed independently of) the BDAI] at 3 and 6 months (week 12 and week 24 visits) (a change of 2 points is considered to be clinically meaningful).

Chapter 3 Statistical methods

Sample size

The primary outcome was a modified version of the BDAI after 3 months of therapy, which will range from 0 to 30 for a patient.

If a traditional frequentist equivalence design were to be used, then based on equivalence being defined as the difference in means being < 20% (i.e. 20% of mean BDAI of 10 = 2), then for significance level, 0.20 and power 90%, a sample size of 176 (88 per arm) is required. (Here we have assumed standard deviation of 4 for BDAI at 3 months, a difference in means of 0.5, in accordance with the opinions of the international experts recruited for the Bayesian design. Also, baseline measurements have not been taken into account which would be expected to reduce the sample size to some extent.) As the recruitment of this number of patients is not feasible, the Bayesian design is adopted.

Bayesian design: Analysis of the data obtained from the small survey of experts both from the UK and regions of high prevalence of BS internationally, described in Chapter 4 (Research Design), gives a prior distribution of the difference in mean values of BDAI as N (0.52, 1.062) and < 24% difference in means to define equivalence. The mode for the latter was 20%, and this value is used in the sample size calculation as it fits better with FDA guidelines.

If the difference in means, D, of BDAI at 3 months is considered without the use of baseline BDAI, then (assuming the above) prior for D and a normal distribution, N (10, 42) for the distribution of the 3-month BDAI scores. For a sample size of 45 per arm, the Bayesian power based on an equi-tailed 80% credible interval for testing for equivalence is 0.71.

To be more accurate, a simulation exercise was carried out using R and WinBUGS to establish the sample size for the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model. For one arm, random baseline and 3-month BDAI scores were generated from a bivariate normal distribution with mean vector (12, 10), variances 4.0 for both and correlation r. For the other arm, random baseline and 3-month BDAI scores were generated from a bivariate normal distribution with mean vector (12, 10+ m), variances 4.0 for both and correlation r. For each simulation, r was randomly chosen from a uniform distribution (0.05, 0.5) and m from a N (0.52, 1.062) distribution. For a sample size of 45 per arm, testing for equivalence using an 80% equi-tailed credible interval calculated from the posterior distribution, Bayesian power of 91% was obtained. When a 90% credible interval was used, the Bayesian power dropped to 73%.

Using this design with the 80% credible interval, a sample size of 45 patients per arm was deemed suitable, which, allowing for 10% dropout, requires 100 patients to be recruited.

Following recommendations to reduce the overall length of the study, the study was amended to recruit a total of 80 patients. Including a 10% dropout rate, estimates of study power are based on 72 evaluable patients (36 on each arm). Here, when an 80% equi-tailed credibility interval is used, a power of 88% is obtained; when a 90% credible interval is used, the power drops to 71%.

Randomisation

Stratified block randomisation, based on randomly permuted blocks with random block sizes of 2 and 4, was employed. The randomisation code list was generated by the LCTC trial statistician with the software package Stata® using the ‘ralloc’ statement. The trial was open-labelled. The stratification factor included in the design is Centre. Data from the eCRFs will be entered onto a MACRO4 database with extensive data validation checks alerting all missing data to be queried. Missing data were monitored, and strategies were developed to minimise its occurrence. Central statistical data monitoring will summarise missing or inconsistent data periodically.

Analysis

Primary outcome

Alpha interferon. A Bayesian ANCOVA model will be used:

y = β0 + β1 × x + α × tr + ε,

where y = BDAI at 3 months, x = baseline BDAI, tr = 0 if a patient is in the infliximab group and tr = 1 if a patient is in the alpha interferon group. β0, β1 and α are the parameters to be estimated, and ε is the error term with variance σ2 (to be estimated). The parameter of particular interest is α, as it measures the difference between the two treatment groups. Prior distributions will be placed on β0, β1, α and σ2 WinBUGS will be used to fit the model.

Prior information

Vague priors for β0 and β1 were set as following a normal distribution with mean zero and a larger variance [i.e. ~ N (0.0, 100,000)]. The prior distribution for σ was set as a uniform distribution with limits of 0 and 3, respectively [i.e. ~ U (0, 3)].

The prior distribution for alpha is based on data obtained from a small group of international BS experts using the question:

On the assumption that the average BDAI score for patients treated with infliximab is 10, share out 100 points on the following scale on how better or worse alpha interferon is compared to infliximab at relieving/controlling BS symptoms.

| Alpha interferon better | Alpha interferon worse |

|---|---|

| Scale: 21% + 16–20% 11–15% 6–10% 0–5%| | 0–5% 6–10% 11–15% 16–20% 21%+ |

| For example 0 0 10 20 3 20 10 10 0 0 |

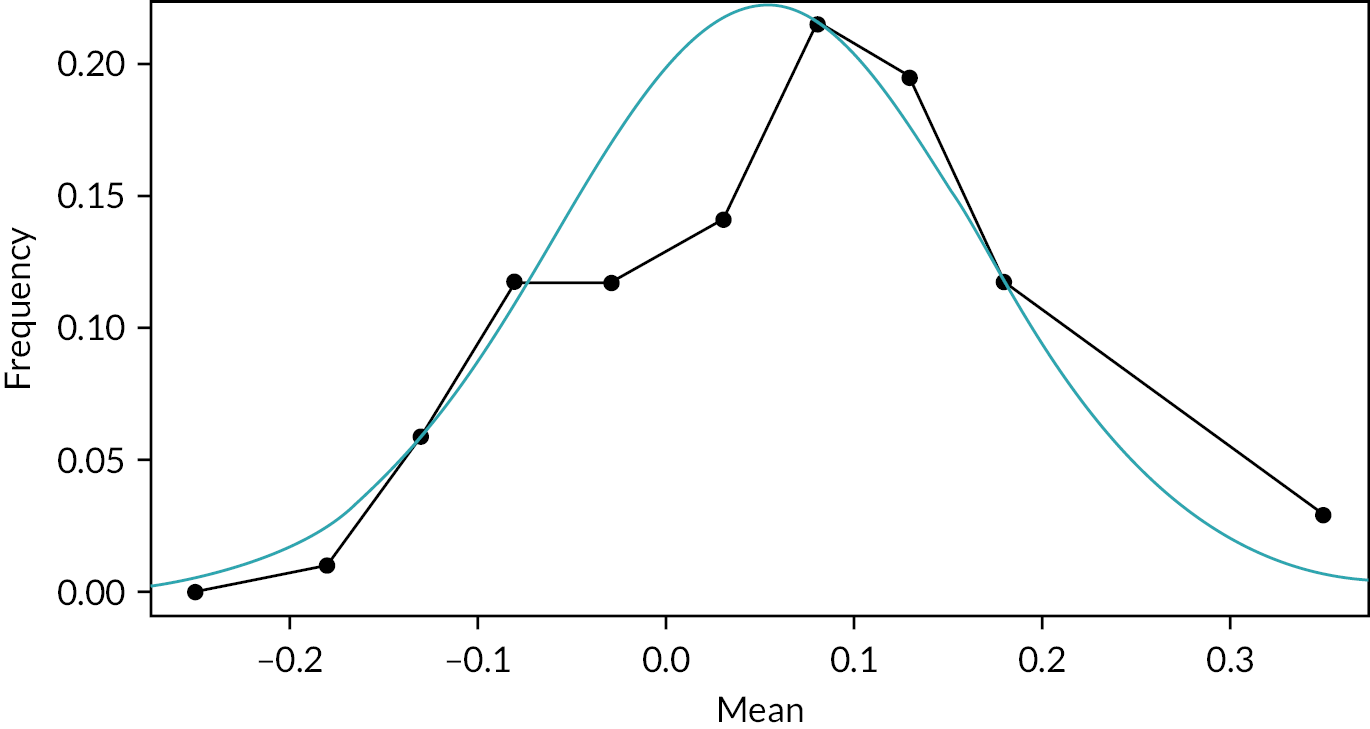

The experts’ answers revealed a mean of 0.053 and a variance equal to 0.0126. The results are also shown in Table 3 and Figure 1.

| Difference | Expert 1 | Expert 2 | Expert 3 | Expert 4 | Expert 5 | Expert 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| –18 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| –13 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| –8 | 10 | 0 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 5 |

| –3 | 15 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 10 |

| 3 | 30 | 5 | 20 | 5 | 10 | 20 |

| 8 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 25 | 10 | 30 |

| 13 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 25 | 10 | 20 |

| 18 | 5 | 30 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| 25 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 5 |

FIGURE 1.

Prior distribution.

A second question assessed where a point of equivalence between the two drugs was reached. The question posed was:

Suppose you are generally prescribing just one of the two drugs (infliximab or alpha interferon) at the moment. If you were told that the efficacies of infliximab and alpha interferon are exactly the same, then presumably you would not change to prescribing the other drug. However, if you were told that the other drug is 40% more efficacious than the one you are currently prescribing, then you would presumably change. Somewhere between 0% and 40% you would probably change from prescribing the current drug to the other. What % would this be? (Ignore any other factors such as cost of drug. Percentages are based on a mean of 10 for the BDAI.)

The responses to the second question informed the boundaries as to where infliximab and alpha interferon can be considered to be equivalent and also where one is superior to the other.

Let the equivalence boundary be given by γ. Then the equi-tailed, 80% Bayesian credible region (αL, αU) obtained from the posterior distribution for α will be used to describe the difference in efficacy for the two treatments, guided by the following:

-

if (αL, αU) lies between (–γ, γ), then equivalent. if αU < –γ, then infliximab is superior

-

if αU < –γ and αU < γ, then infliximab could be equivalent or superior. if αU < –and αU > γ, then equipoise

-

if αU > –γ and αU > γ, then alpha interferon could be equivalent or superior. if αL > γ, then alpha interferon is superior.

Secondary outcomes

As this trial is for a very rare disease, clinical decisions and recommendations were based on the analyses of both primary and all secondary outcomes, weighing up the evidence in the true spirit of statistics but keeping in mind the problems of multiple testing and overinterpretation.

The intention-to-treat (ITT) principle will be used for the primary analysis. Secondary sensitivity analyses will be carried out on (1) all patients including the data for both arms for patients who switched treatment (the ANCOVA model can cope with this); (2) those patients who responded to treatment, whether it was their original treatment or the one to which they may have switched; and (3) all patients who remained on their original treatment and complied with the protocol. Data on the number of patients who switch treatments and their reasons for doing so will be recorded and analysed. Another sensitivity analysis will be carried out to investigate the effect of the prior distributions in the Bayesian analysis, especially on the parameter of prime interest (the difference in means between treatments), where results using a vague prior will be compared to those using the prior based on expert opinion.

The Independent Safety and Data Monitoring Committee (ISDMC) reviewed safety and the data after 12 patients had their 3-month follow-up visit and again when 45 patients had their 3-month follow-up visit. In addition, the ISDMC met before the trial commenced and at least yearly during the trial. No specific stopping rules were to be applied, but the ISDMC was able to recommend continuation or stopping of the trial based on safety data and efficacy data based on the primary and secondary outcomes. The recommendation to stop the trial would only have been made if the reasons for stopping would convince clinical experts in BS.

A single statistical analysis plan was produced during the trial. This document detailed how the final analysis and interim analysis shall be carried out, as well as including all relevant information for inspection by the IDSMC. This document was approved by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the IDSMC prior to any analysis being carried out.

Separate protocols and statistical analysis plans were produced for the second two objectives of the study (genotyping and metabolomics), which are discussed briefly below.

Genotyping for IFNL3 and IFNL4 SNPs: DNA was extracted from all blood samples after recruitment and transported to the Wolfson Centre for Personalised Medicine using Royal Mail Safe Boxes. Genotyping for four SNPs was undertaken (rs12979860, rs4803221 and rs7248668 and ss469415590[∆G]) using Real-Time PCR utilising a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Genotyping was performed by a trained technician. Test-specific standard operating procedures were written prior to the start of genotyping, and strict QC measures were adhered to ensure proper validation of genotype results. This was an exploratory analysis to determine whether any of the SNPs showed an effect with respect to the efficacy of alpha interferon based on the primary and secondary outcomes. If a strong effect was found for a SNP based on one of the primary and secondary outcomes, or as a ‘trend’ over several of the outcomes, the SNP with the highest predictive value was to be tested in approximately 200 other patients (based on power calculations) where DNA is available from our collaborators or in future studies.

Metabolomic analysis: (3 × 1 ml) urine samples were taken from patients at each trial visit, snap frozen and stored at –800 °C before transporting the Birmingham in batches. After thawing, urine samples were centrifuged at 13,000 g and prepared using a standard protocol and loaded into a standard 5-mm NMR tube for spectroscopy. One-dimensional (1-D) 1H spectra were acquired at 300 °K using a standard spin-echo pulse sequence with water suppression using excitation sculpting on a Bruker DRX 500 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a cryoprobe. Glutamine levels were measured in the urine samples using high-performance ion exchange chromatography. Xanthurenic acid levels were measured using a fluorometric method.

Lists of metabolites providing the greatest discrimination between groups will be identified using multivariate analyses, and metabolites will be identified using a NMR database (Human Metabolome Database version 2.5) and Chenomx NMR suite.

Rationale for mechanistic studies

The mechanistic studies were designed to (1) lead to important developments in the elucidation of the as-yet-unknown pathophysiological processes underlying BS; (2) clarify the role of two inflammatory pathways involved in a variety of manifestations of the disease and responses (or not) to two distinct biologic drugs that target different inflammatory processes; and (3) identify the potential usefulness of two promising novel biomarkers to facilitate cost-effective targeting of therapy, derived from the greater mechanistic understanding of disease processes that (1) and (2) will provide. Assuming the frequency of the CC genotype is 55%, then the power is approximately 75% for detecting a difference in response of 20% (CC genotype 95% vs. non-CC genotype 75%, giving an overall response rate of approximately 85%) using a one-sided test and significance level 0.2. This high significance level is inevitable for a sample size of 45. However, if the overall response rate is 80%, then a difference in response rate of 35% (CC genotype 95% vs. non-CC genotype 60%) could be detected with 75% power with a two-sided test and significance level 0.05. To further strengthen the power of the analyses, patient responses will also be classified on an ordinal scale of ‘no response’, ‘poor response’ and ‘good response’ according to BDAI score. Results from techniques such as ordinal logistic regression might then be more conclusive. It should be noted that analysis of the mechanistic study is limited to observable differences within treatment groups as opposed to measuring the effect of differences between groups. This is primarily due to the study sample size, but it does limit the utility of any conclusions that may be drawn.

Chapter 4 Results

Trial recruitment and disposition

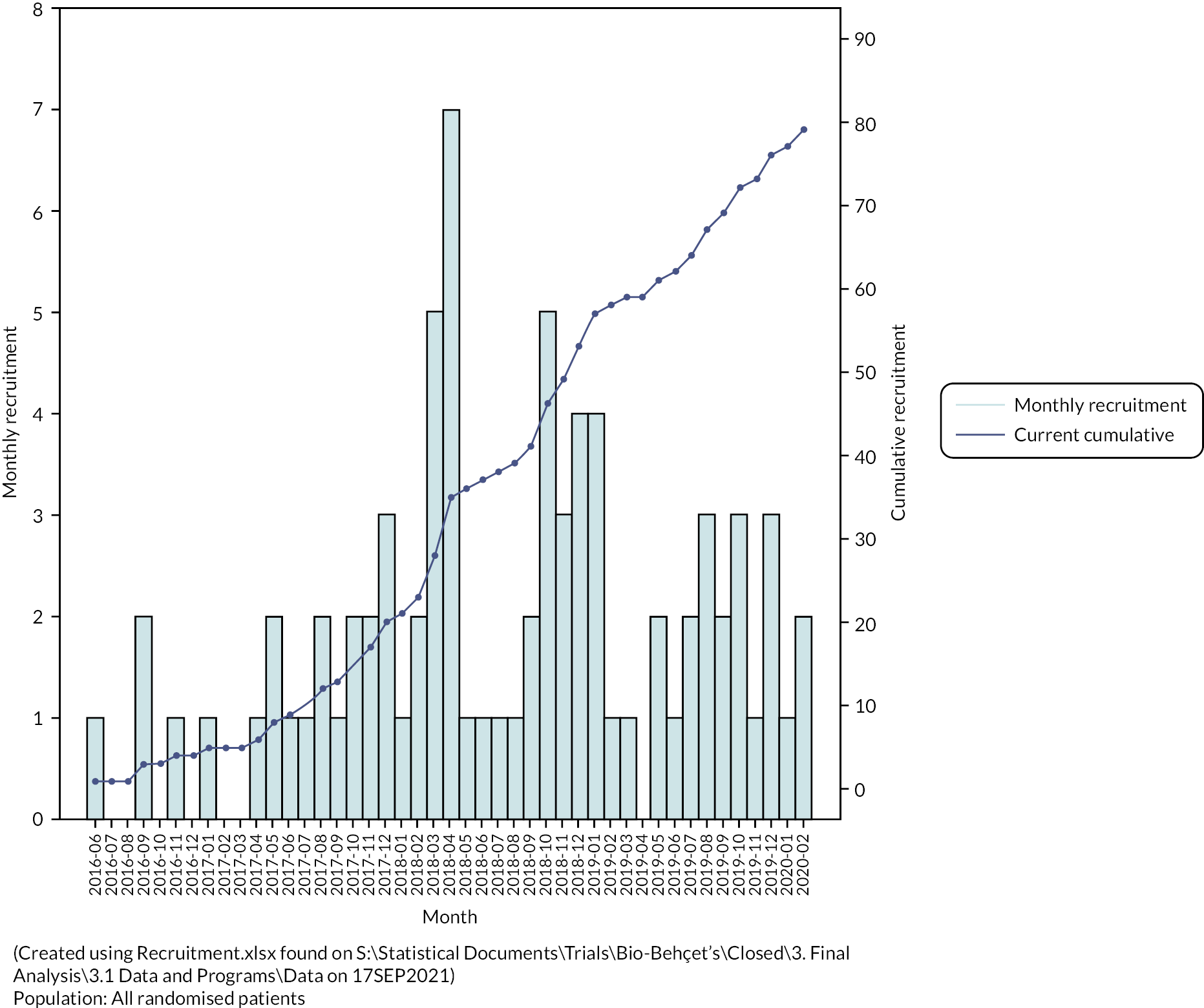

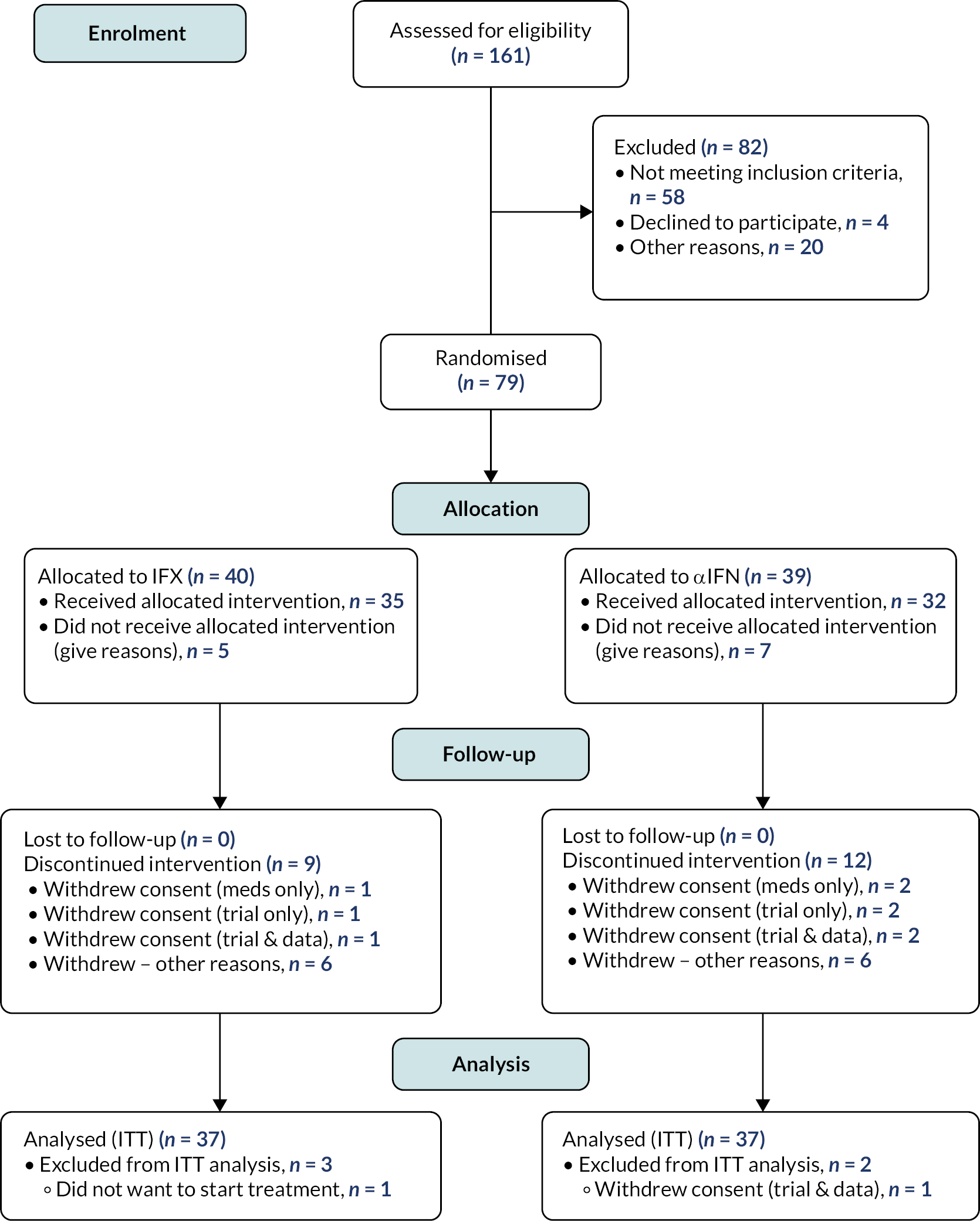

Patients were recruited between June 2016 and February 2020. Recruitment by centre is summarised in Table 23 (see Appendix 1) and occurred at a linear rate that was slower than anticipated (Figure 2), resulting in the premature termination of the trial and fewer participants than originally planned. One hundred and sixty-one patients were screened, and seventy-nine patients randomised. The subsequent disposition of the randomised patients is summarised in Figure 3.

FIGURE 2.

Trial recruitment over time.

FIGURE 3.

Patient disposition. αIFN, alpha interferon; IFX, infliximab.

For the reasons outlined, the ITT analysis was restricted to 37 subjects allocated to infliximab and 37 to Roferon.

Assessment of data quality

Withdrawals from the study protocol within each treatment arm are summarised, together with their reasons and losses to follow-up, in Table 4.

| Reason | Infliximab (N = 37) | Roferon (N = 37) | Total (N = 74) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total discontinued protocol treatment, n (%) | |||

| Clinician decision (not AE) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 3 (4) |

| Inadequate response | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Other | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 5 (7) |

| Unacceptable AE | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 3 (4) |

| Reason missing | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Days from randomisation to withdrawal from protocol treatment | |||

| Median (IQR) | 169.0 (144.0–205.0) | 164.5 (58.0–186.5) | 169.0 (85.0–191.0) |

| Range | 30.0–455.0 | 28.0–269.0 | 28.0–455.0 |

| Total withdrawn from trial, n (%) | |||

| Lost to follow-up | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) |

| Other | 3 (8.1) | 6 (16.2) | 9 (12.2) |

| Reason missing | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) |

| Days from randomisation to withdrawal from trial | |||

| Median (IQR) | 8.0 (0.0–91.0) | 68.5 (39.5–126.0) | 51.0 (8.0–105.0) |

| Range | 0.0–169.0 | 20.0–153.0 | 0.0–169.0 |

A summary of study protocol deviations is provided in Appendix 1 of Table 24: Summary of study protocol deviations. Patients with a major protocol deviation were removed from analyses performed on the per-protocol data set.

Description of baseline subject characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the study population are summarised in Table 4 for the 74 trial participants. Mean age [interquartile range (IQR)] was 39.1(31.6–47.2) and did not differ significantly between the two treatment arms. There were 50 (68%) female and 24 male (32%) participants with similar proportions in each treatment arm by sex. Ethnic profile and baseline disease characteristics did not differ between treatment arms. Steroid use was also similar in each treatment arm (IFX 49%, alpha interferon 51%). These are detailed in Table 5.

| Characteristic | Infliximab (N = 37) | Roferon (N = 37) | Total (N = 74) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | |||

| Median (IQR) | 38.9 (31.8–48.7) | 39.3 (31.6–46.5) | 39.1 (31.6–47.2) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 24 (65) | 26 (70) | 50 (68) |

| Male | 13 (35) | 11 (30) | 24 (32) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White – British | 34 (92) | 30 (81) | 64 (86) |

| Caribbean | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Black – other | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) |

| White – European | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (3) |

| White – other | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 2 (3) |

| White and black Caribbean | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Pakistani | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Current smoker | 8 (22) | 6 (16) | 14 (19) |

| Ex-smoker | 17 (46) | 9 (24) | 26 (35) |

| Never smoked | 12 (32) | 21 (57) | 33 (45) |

| Alcohol status, n (%) | |||

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) |

| None | 14 (38) | 11 (30) | 25 (34) |

| Sporadic | 18 (49) | 18 (49) | 36 (49) |

| Regular | 5 (14) | 7 (19) | 12 (16) |

| Steroid use, n (%) | |||

| Missing | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| No | 18 (49) | 18 (49) | 36 (49) |

| Yes | 18 (49) | 19 (51) | 37 (50) |

| Ocular, n (%) | |||

| Missing | 11 (30) | 8 (22) | 19 (26) |

| Primary | 10 (27) | 7 (19) | 17 (23) |

| Other | 16 (43) | 22 (59) | 38 (51) |

| Oral, n (%) | |||

| Missing | 12 (32) | 7 (19) | 19 (26) |

| Primary | 12 (32) | 15 (41) | 27 (36) |

| Other | 13 (35) | 15 (41) | 28 (38) |

| Genital, n (%) | |||

| Missing | 12 (32) | 7 (19) | 19 (26) |

| Primary | 11 (30) | 14 (38) | 25 (34) |

| Other | 14 (38) | 16 (43) | 30 (41) |

| Musculoskeletal, n (%) | |||

| Missing | 16 (43) | 13 (35) | 29 (39) |

| Primary | 10 (27) | 10 (27) | 20 (27) |

| Other | 11 (30) | 14 (38) | 25 (34) |

| Previous septic arthritis in the last 12 months, n (%) | |||

| No | 37 (100) | 37 (100) | 74 (100) |

| Previous septic arthritis in prosthetic joints ever, n (%) | |||

| No | 37 (100) | 37 (100) | 74 (100) |

| Malignancy, n (%) | |||

| No | 36 (97) | 37 (100) | 73 (99) |

| Yes | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Urine catheter, n (%) | |||

| No | 37 (100) | 37 (100) | 74 (100) |

| Heart failure, n (%) | |||

| No | 37 (100) | 37 (100) | 74 (100) |

| Skin rash, n (%) | |||

| No | 23 (62) | 23 (62) | 46 (62) |

| Yes | 14 (38) | 14 (38) | 28 (38) |

Exposure to treatment and compliance

Summary information is provided in Appendix 1: describing patients’ exposure to treatment with infliximab (mean dose per patient and the percentage of patients continuing to receive treatment over time) and interferon (dose changes over time and mean number of missed doses recorded at weeks 12, 24 and 36 reviews).

Analysis of primary outcome measures

The primary outcome for the trial was defined as the change in mBDAI between baseline and 3 months (with 6 months as a secondary outcome). The statistical analysis examined the difference in mean mBDAI scores between the two treatment arms at 3 and 6 months, with clinically significant response defined as a difference in 20% or more between the two treatment arms (assessed using Bayesian ANCOVA for change in mean from baseline adjusted for baseline score). Analysis based on planned ITT therefore included 37 patients allocated to infliximab and 37 to Roferon.

Table 6 presents the results from the Bayesian linear regression model to estimate the impact of treatment group on mBDAI. The linear model includes as an adjusting covariate the baseline mBDAI, and so there are three parameters presented:

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | 80% credibility interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| β 0 | 0.13 | 0.35 | (–0.31 to 0.59) |

| β 1 | 0.54 | 0.19 | (0.29 to 0.78) |

| α (Roferon vs. infliximab) | 0.13 | 0.25 | (–0.19 to 0.46) |

-

β0: model intercept

-

β1: covariate associated with baseline mBDAI

-

α (alpha interferon vs. infliximab): impact of treatment group.

Results are presented in terms of model estimates [standard error (SE)] and the 80% credibility interval, which is consistent with the study design.

The results show that 3-month BDAI is reliant on the baseline BDAI, which is demonstrated by an 80% credibility interval which does not include zero for the β1 parameter. The impact of treatment is not statistically significant based on the 80% credibility interval [Est (SE) = 0.13 (0.25), 80% CI = (–0.19 to 0.46)]. So the two treatment arms did not differ significantly with respect to change in BDAI at 3 or 6 months. These results show that, after adjustment for baseline BDAI, patients who were treated with alpha interferon had a BDAI score of 0.13 points higher than those on infliximab. The study set a margin of equivalence of 20% change between the two treatment arms. Here, for example, a patient with a baseline BDAI score of 8 points could expect a follow-up BDAI score of approximately 4.45 on infliximab and 4.58 on alpha interferon, representing an approximate 3% change between the two treatment groups.

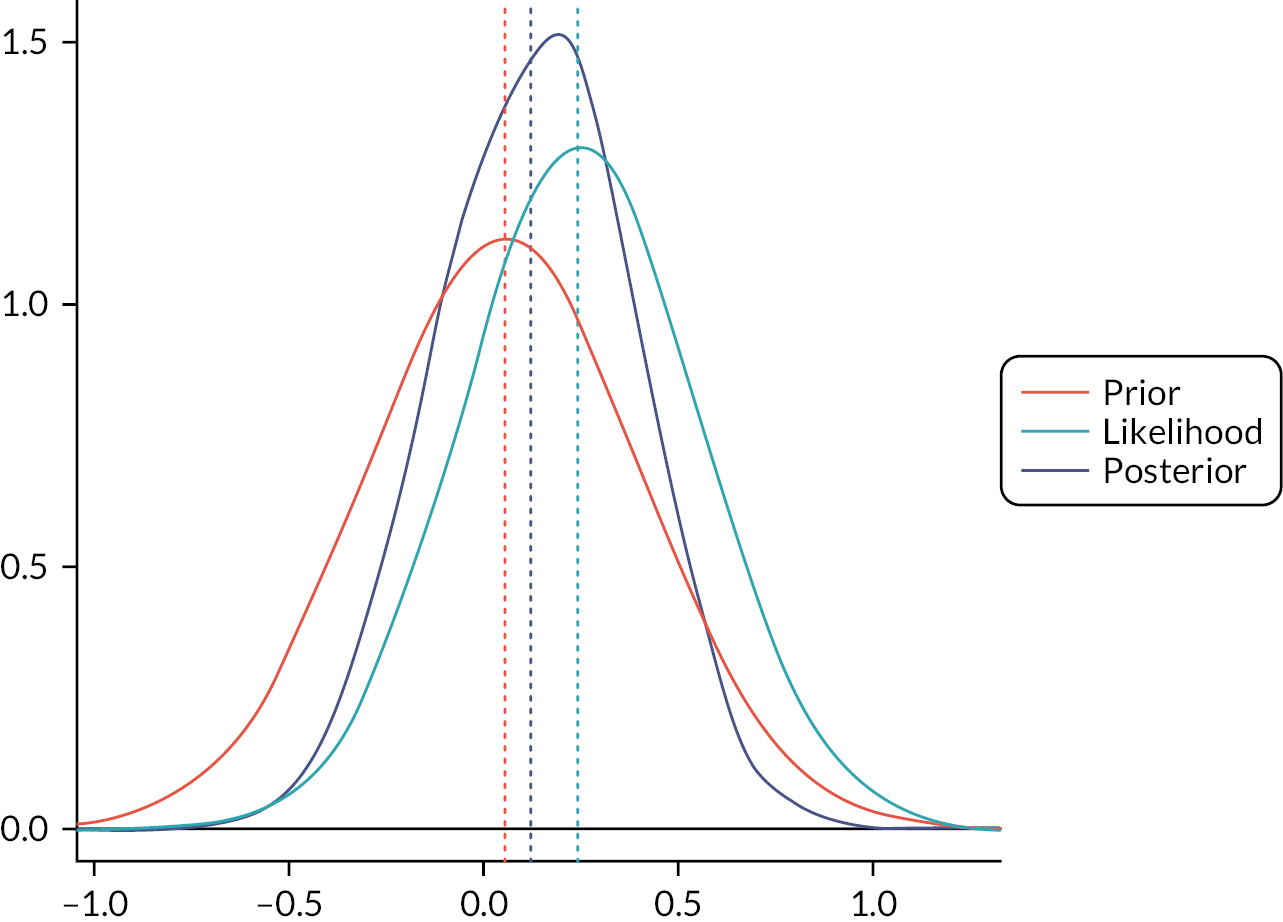

Figure 4 demonstrates this graphically, as the probability density for the prior does not differ significantly from the posterior.

FIGURE 4.

Density of prior distribution, likelihood and posterior distribution for mBDAI.

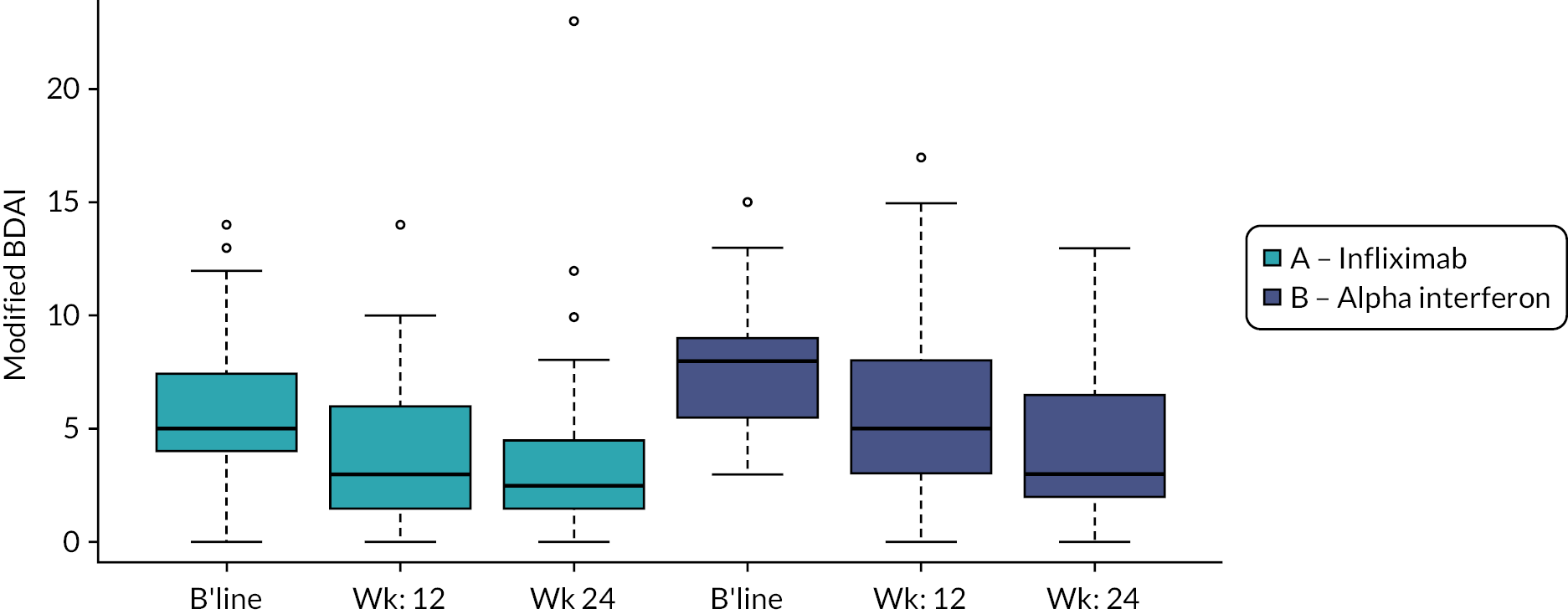

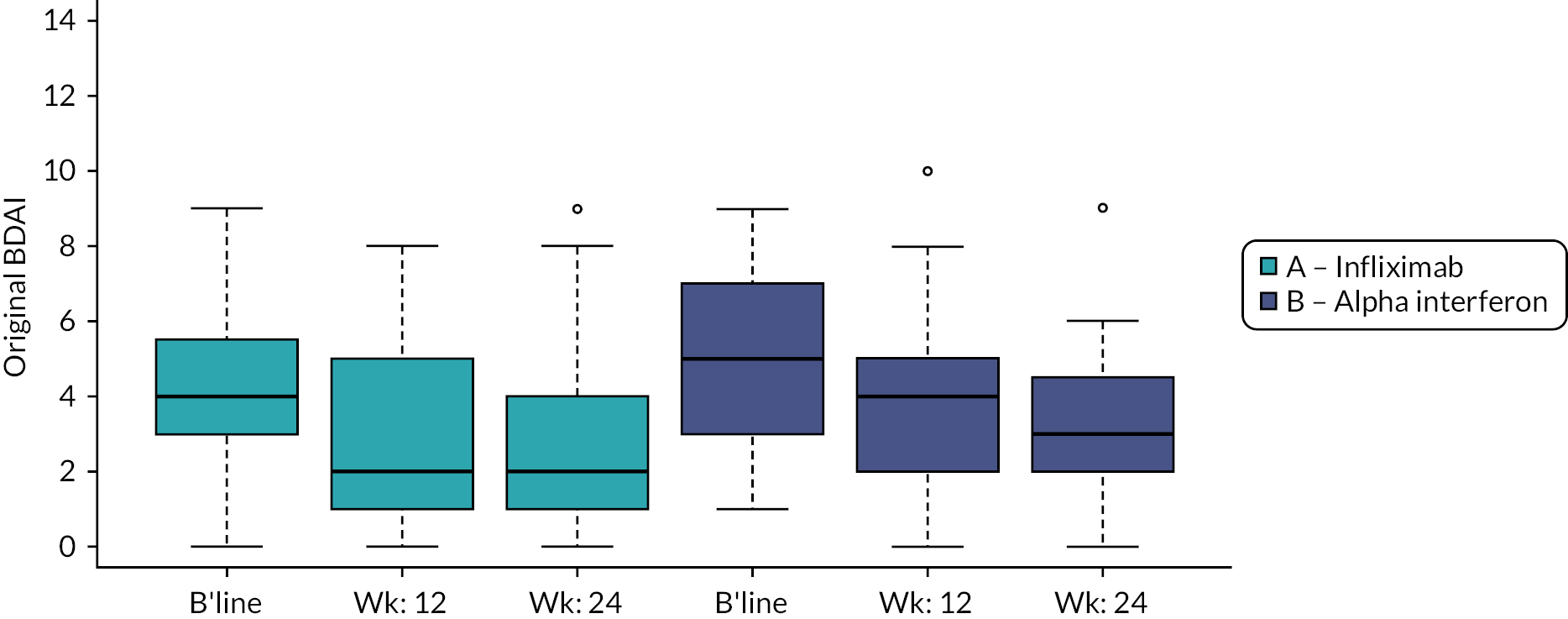

However, Figure 5 also shows that both treatments appear to be associated with significant improvements in BDAI at 3 and 6 months. Defining response categories as 20%, 50% and 70% improvement with respect to baseline revealed that for infliximab, 17, 13 and 8 patients met the 20%, 50% and 70% response definitions. For Roferon, figures were 22, 12 and 7, respectively.

FIGURE 5.

Boxplot of mBDAI at baseline, 3 and 6 months across treatment groups.

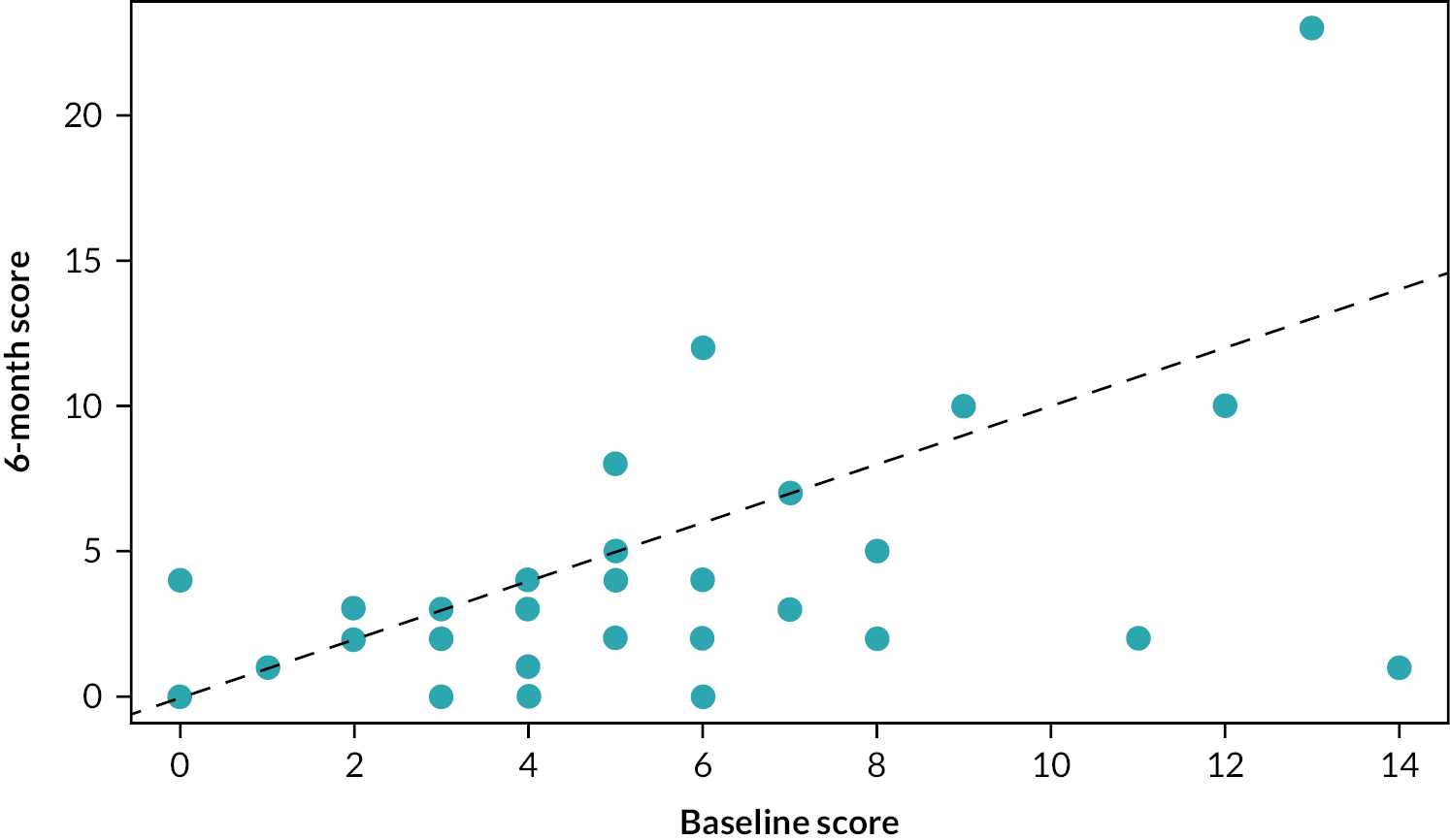

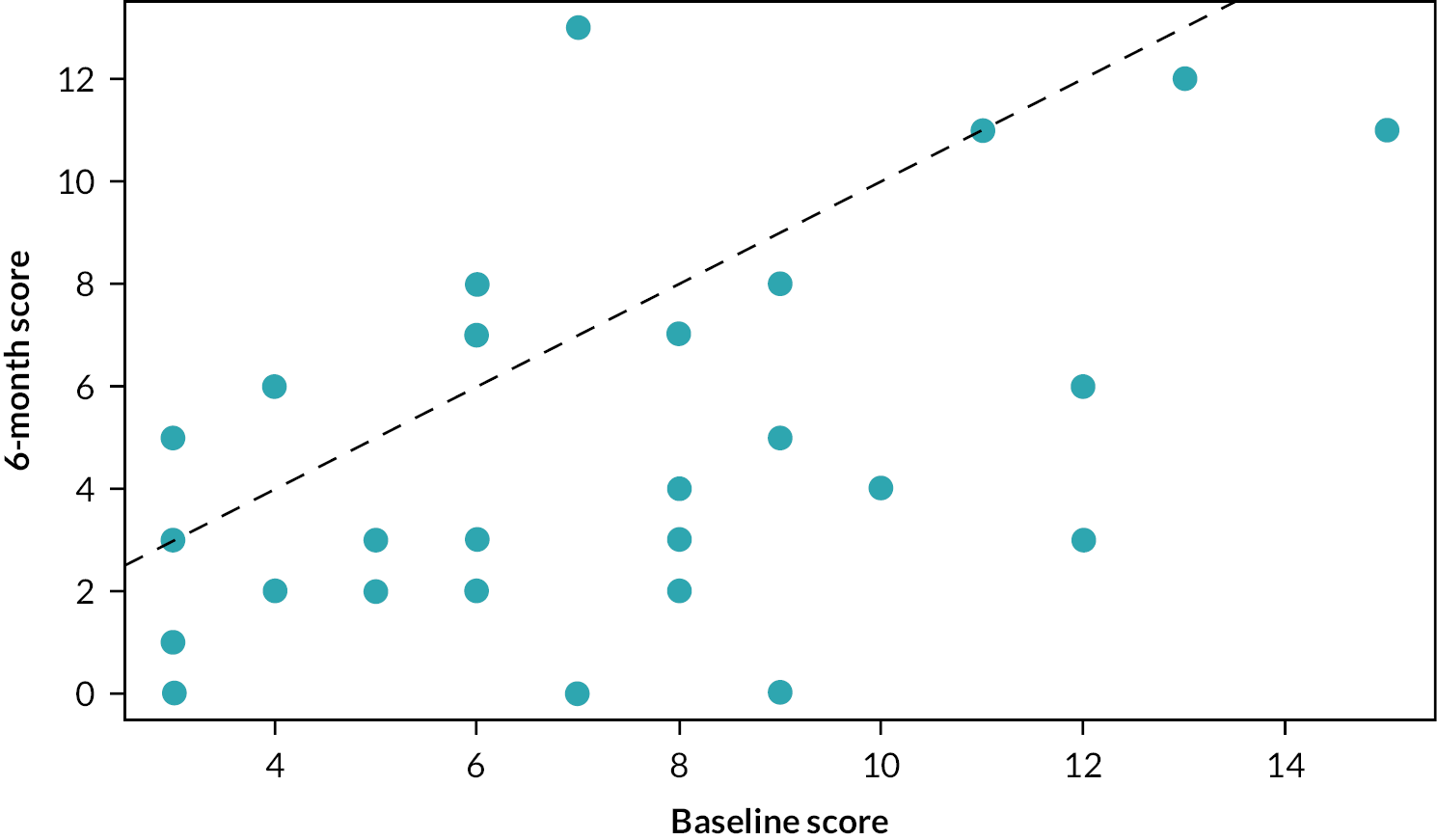

The improvement in mBDAI within both treatment arms is illustrated further in Figures 6 and 7 which show the BDAI score measured at baseline and 6 months for infliximab and Roferon.

FIGURE 6.

Change in BDAI score – infliximab.

FIGURE 7.

Change in BDAI score – Roferon.

If there were no impact of treatment, we would expect each point to lie close to the diagonal red dashed line. However, most points lie above the line, showing a higher BDAI at baseline than at 6 months. This illustrates the reduction in BDAI associated with both treatments. The median (IQR) change for infliximab is –1.5 (–4 to 0) BDAI, and regressing the 6-month BDAI data against the baseline BDAI reveals a significant difference and estimated that on average, the 6-month BDAI score is 70% [0.7 (0.109); p < 0.001] that of the baseline score (i.e. a 30% reduction). The median (IQR) change for Roferon is –3 (–5.25 to –1) BDAI and regressing the 6-month BDAI data against the baseline BDAI also indicates a significant difference and estimates that, on average, the 6-month BDAI score is 61% [0.61 (0.069); p < 0.001] that of the baseline score (i.e. a 39% reduction).

Results of the sensitivity analyses demonstrate that the protocol variations and switches did not influence the conclusion that the two treatments did not differ overall in relation to response and provide confidence that the estimate of the difference between the two treatments is reliable.

A significantly higher proportion of patients randomised to alpha interferon swapped away from their randomised treatment compared to those randomised to infliximab treatment (Roferon 11 of 37, infliximab 3 of 37; Table 7, p = 0.0104) (Table 6).

| Infliximab (N = 37) | αIFN (N = 37) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| n | 19 | 25 | |

| Median (IQR) | 26.0 (22.0–42.0) | 25.0 (16.0–34.0) | |

| 6 months | |||

| n | 19 | 25 | |

| Median (IQR) | 14.0 (7.0–27.0) | 14.0 (5.0–23.0) | |

| Difference between baseline and 6 months | |||

| Absolute difference – median (IQR) | –8.0 (–26.0 to 12.0) | –11.0 (–20.0 to 0.0) | |

| Percentage difference – median (IQR) | –53.8 (–69.0 to –10.0) | –53.8 (–66.7 to –24.0) | |

| Proportion with at least 20% reduction | 11 (58%) | 16 (64%) | 0.7600 |

Reasons for switching are summarised in Table 8. It should be noted that for four of the patients switching away from alpha interferon, the reason for the switch was not recorded.

| Reason | Infliximab (N = 37) | Roferon (N = 37) |

|---|---|---|

| Reason switched treatments, n (%) | ||

| Clinician decision (not AE) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Inadequate response | 1 (3) | 3 (9) |

| Unacceptable AE | 0 (0) | 4 (12) |

| Missing reason | 0 (0) | 4 (12) |

Analyses of secondary outcome measures

Improvements in organ systems after 3 and 6 months compared to baseline were evaluated as secondary outcome measures.

Original Behçet’s disease activity index

The box plot results for the original BDAI at baseline and after 3 and 6 months by treatment group are presented in Figure 5 and Table 27 (see Appendix 1) and, as expected, did not differ from those presented for the mBDAI. There were no statistically significant differences demonstrated between groups for the Bayesian linear model comparing the original BDAI at baseline and 3 months and between baseline and 6 months. Statistics for within-group changes over time are not presented, but they show that both treatments appear to be associated with significant improvements in BDAI at 3 and 6 months.

Ophthalmological assessments included assessment for intraocular inflammation (vitreous haze) and visual function (BCVA; numbers of letters read) at baseline, 3 months and 6 months. For vitreous haze at baseline, 11 patients (infliximab) and 16 patients (Roferon) were evaluated. For BCVA, 18 patients underwent baseline assessments. Not all patients had follow-up assessments. As ocular examination was symptom-directed, the number of patients with these measurements was small. Tables 28–31 (see Appendix 1) summarise the results for vitreous haze and BCVA, respectively, comparing measurements at baseline with results at 3 and 6 months for each eye. For each of the outcome measures, there were no notable differences between treatment groups.

Oral ulcer activity score

Most patients experienced a reduction in their oral ulcer activity score between baseline and 3 months (Table 9) and between baseline and 6 months (Table 7), with a median reduction (for both treatment arms) of 50% at 3 months and 53.8% at 6 months.

| Infliximab (N = 37) | Roferon (N = 37) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| n | 19 | 25 | |

| Median (IQR) | 26.0 (22.0–42.0) | 25.0 (16.0–34.0) | |

| 3 months | |||

| n | 19 | 25 | |

| Median (IQR) | 8.0 (0.0–22.0) | 18.0 (8.0–20.0) | |

| Difference between baseline and 3 months | |||

| Absolute difference – median (IQR) | –13.0 (–25.0 to 0.0) | –7.0 (–21.0 to 0.0) | |

| Percentage difference – median (IQR) | –50.0 (–100 to –8.3) | –50.0 (–68.0 to –20.0) | |

| Proportion with at least 20% reduction | 11 (58%) | 16 (64%) | 0.7600 |

Using caution, due to small sample sizes, a slightly higher proportion of patients randomised to alpha interferon experienced a clinically significant (at least 20%) reduction compared to patients randomised to infliximab (64% and 58%, respectively) at both 3 and 6 months; however, this small difference was not statistically significant at the 5% level (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.7600).

Genital ulcer activity

A similar pattern emerged for genital ulceration. Most patients experienced a reduction in their genital ulcer activity between baseline and 3 months (Table 10) and between baseline and 6 months (Table 11), with a median percentage reduction (for both treatment arms) of 100% at 3 months and 100% at 6 months.

| Infliximab (N = 37) | Roferon (N = 37) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| N | 11 | 10 | |

| Median (IQR) | 17.0 (0.0–32.0) | 22.5 (0.0–34.0) | |

| 3 months | |||

| N | 11 | 10 | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–14.0) | |

| Difference between baseline and 3 months | |||

| Absolute difference – median (IQR) | –17.0 (–24.0 to 0.0) | –11.0 (–29.0 to 0.0) | |

| Percentage difference – median (IQR) | –100.0 (–100 to –75.0) | –100.0 (–100 to –32.4) | |

| Proportion with at least 20% reduction | 7 (64%) | 7 (70%) | 1.0000 |

| Infliximab (N = 37) | Roferon (N = 37) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| N | 11 | 10 | |

| Median (IQR) | 17.0 (0.0–32.0) | 22.5 (0.0–34.0) | |

| 6 months | |||

| n | 11 | 10 | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–16.0) | |

| Difference between baseline and 6 months | |||

| Absolute difference – median (IQR) | –17.0 (–32.0 to 0.0) | –13.5 (–29.0 to 0.0) | |

| Percentage difference – median (IQR) | –100.0 (–100 to –100) | –100.0 (–100 to –18.9) | |

| Proportion with at least 20% reduction | 7 (64%) | 5 (50%) | 0.7600 |

Noting the small sample sizes, there was no statistically significant difference (at the 5% level) in the proportion of patients in each treatment arm who experienced a clinically significant (at least 20%) reduction in their genital ulcer activity at 3 months (Fisher’s exact test p = 1.0000) and 6 months (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.7600).

Likert pain score

Though sample sizes were small, there was no statistically significant difference (at 5% level) in the proportion of patients in each treatment arm who experienced a clinically significant (at least 20%) improvement in their Likert pain score at 3 months (Fisher’s exact test p = 1.0000) and 6 months (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.1142). Summary data (see Appendix Tables 32 and 33) indicate modest early improvements for both infliximab and Roferon which were lost by 6 months for the infliximab group.

Prednisolone usage

Prednisolone use was reported as a binary (yes/no) variable longitudinally throughout the study. Table 12 details the number (percentage) of patients receiving prednisolone (or another steroid). The two groups were well matched a baseline with similar proportions receiving steroids [20/39 (51.3%)] and there appeared a modest steroid-sparing effect observed in each group. For infliximab at baseline, 15 patients were using steroids, reducing to 12 at 24-week follow-up. This results in 20% of patients on steroids ceasing their use. The overall rate decreased from 15/29 (52%) to 12/29 (41%). For Roferon at baseline, 16 patients were using steroids which reduced to 9 at 24-week follow-up. This results in 44% of patients on steroids ceasing their use. Two patients on Roferon began taking steroids; therefore, the overall rate decreased from 16/32 (50%) to 11/32 (34%).

| Timepoint | Infliximab (n = 39) (%) | Roferon (n = 29) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 20/39 (51.3) | 20/39 (51.3) |

| Week 12 review | 16/34 (47.1) | 18/33 (54.5) |

| Week 24 review | 12/29 (41.4) | 11/32 (34.4) |

| Week 36 review | 1/2 (50) | 5/9 (55.6) |

The results of a logistic regression model are presented in Table 13 to explore the impacts of time points and treatment on the use of steroids. Treatment and time are included as an interaction to detect either a consistent overall difference due to treatment or a difference between treatments that appears over the course of the study. No significant differences are observed, showing that there is no evidence of any difference in prednisolone (or other steroid) dose reduction between the treatment groups. Further analysis using actual steroid doses will be explored.

| Model term | Est (SE) | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.05 (0.32) | 1.05 (0.562 to 1.972) | 0.873 |

| Treatment (αIFN vs. infliximab) | 0 (0.453) | 1 (0.411 to 2.43) | 1 |

| Baseline | –0.17 (0.47) | 0.84 (0.336 to 2.121) | 0.719 |

| Week 12 | –0.4 (0.495) | 0.67 (0.254 to 1.768) | 0.419 |

| Week 24 | –0.05 (1.45) | 0.95 (0.055 to 16.294) | 0.972 |

| Baseline: treatment (Roferon vs. infliximab) | 0.3 (0.667) | 1.35 (0.365 to 4.995) | 0.653 |

| Week 12: treatment (Roferon vs. infliximab) | –0.3 (0.697) | 0.74 (0.189 to 2.91) | 0.669 |

| Week 24: treatment (Roferon vs. infliximab) | 0.22 (1.629) | 1.25 (0.051 to 30.477) | 0.891 |

Clinician’s overall perception (Physician’s Global Assessment disease activity)

The physician’s overall perception of disease activity (a 7-point Likert scale) was completed as part of (but assessed independently of) the BDAI at baseline, 3 and 6 months. A change of 2 points in the score was considered a clinically meaningful change. The clinician’s overall perception of disease activity indicated a reduction in disease activity for most patients between baseline and 3 months and between baseline and 6 months, with a median reduction of –2.0 (infliximab) and –1.0 (Roferon) at 3 months and –3.0 (infliximab) and –2.0 (Roferon) at 6 months. There was a statistically significant difference (at the 5% level) between treatment arms in the change in clinician’s overall perception of disease activity at 3 months from baseline (Wilcoxon test p = 0.0421) and at 6 months from baseline (Wilcoxon test p = 0.0420) in favour of infliximab providing a greater reduction in the clinician’s overall perception of disease activity.

At 3 months, physician’s overall perception of disease activity was higher for the alpha interferon arm compared to the IFX arm at the 5% level (p = 0.002) and remained significantly higher at 6 months at the 5% level (p = 0.001).

These results are summarised in Tables 14 and 15.

| Infliximab (N = 37) | Roferon (N = 37) | p-valuea | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| n | 31 | 29 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.8 (1.28) | 4.9 (1.22) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | ||

| 3 months | ||||

| n | 31 | 29 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.5 (1.29) | 3.8 (1.57) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) | ||

| Difference between baseline and 3 months | ||||

| Mean (SD) | –2.3 (1.81) | –1.1 (1.99) | 0.0187 | |

| Median (IQR) | –2.0 (–4.0 to –1.0) | –1.0 (–3.0 to 0.0) | 0.0421 | |

| Infliximab (N = 37) | Roferon (N = 37) | p-valuea | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| N | 26 | 29 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.9 (1.26) | 4.9 (1.14) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | ||

| 6 months | ||||

| N | 26 | 29 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.46) | 3.2 (1.28) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | ||

| Difference between baseline and 6 months | ||||

| Mean (SD) | –2.6 (1.86) | –1.7 (1.51) | 0.0550 | |

| Median (IQR) | –3.0 (–4.0 to –2.0) | –2.0 (–3.0 to –1.0) | 0.0420 | |

Quality-of-life measures

Quality-of-life measures included the number of patients with reported problems (levels 2, 3, 4, 5) in the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) domains of Mobility, Self-Care, Usual Activities, Pain/Discomfort and Anxiety/Depression at baseline, 3 and 6 months for infliximab and Roferon. There were no differences between groups for these important subdimensions of the EQ-5D-5L score evaluating the number of patients who reported problems.

There were also no significant differences between the two treatment groups for EQ-visual analogue score assessment comparing the difference between baseline versus 3 months and baseline versus 6 months comparing infliximab with alpha interferon (3 months Wilcoxon test, p = 0.8318; 6 months Wilcoxon test, p = 0.8600).

For BD-QoL, only minor differences emerged in favour of infliximab compared to Roferon when comparing differences in scores for QoL at 3 months versus baseline between the two treatment groups (Wilcoxon test, p = 0.0274), but this was no longer present at 6 months (Wilcoxon test, p = 0.3029).

Quality-of-life measures results are summarised in Tables 35–39 (see Appendix 1).

Analysis of safety and tolerability

Table 40 evaluates the difference in AE severity across the two treatment arms for all reported AEs. In total, 46 patients reported 270 events. A proportion test shows that there were a greater number of AEs observed on alpha interferon (p < 0.001). A Fisher’s test to evaluate any differences in the distribution of AEs across treatment arms was not significant (p = 0.224). The overview of AEs by severity can be found in Table 16.

| Patient group | Mild (%) | Moderate (%) | Severe (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A – Infliximab | 51 (50) | 47 (47) | 3 (3) | 101 |

| B – Roferon | 80 (47) | 88 (52) | 1 (1) | 169 |

| Total | 131 (49) | 135 (50) | 4 (1) | 270 |

In total, eight serious adverse events (SAEs) from five patients were reported across the study. One patient on the infliximab arm reported four SAEs [hypertension (×2), bacterial urinary tract infection and blood pressure inadequately controlled]. In total, three patients (six events) were reported on the infliximab arm and two patients (two events) were reported on the alpha interferon arm. There were no suspected drug interactions and no suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARS) reported in the study.

Summaries of all study-related SAEs together with an aggregated summary of AEs are listed in Table 40 (see Appendix 1).

Genetics analysis

Four SNPs within the IFNL4 gene locus were selected owing to a priori knowledge of effects on gene/protein function or clinical association.

Genotyping was undertaken, and a summary of genotype counts and minor allele frequencies can be found in Table 17. Hardy–Weinberg p-values were within the tolerable threshold (> 0.0001), indicating that genotype distributions are not significantly different to those that might be expected, and therefore there were no quality control issues associated with the genotyping assays.

| rs number | Chr (position) (GRCh38.p13) | Locus position | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs12979860 | chr19:39248147 | g.5710 | Intronic variant |

| rs368234815 | chr19:39248514-39248515 | n.343del | Non-coding transcript variant |

| rs4803221 | chr19:39248489 | n.368G > C | Non-coding transcript variant |

| rs7248668 | chr19: 39253181 | g.676C > T | Promoter variant |

Genotypes were obtained for a total of 62 individuals (30 in Arm A and 32 in Arm B) for all SNPs except for rs7248668 where a genotype for one individual (Arm B) could not be obtained despite repeated attempts.

The data suggest that there is high linkage disequilibrium between rs12979860 and rs368234815, and rs4803221 and rs7248668, summarised in Table 18.

| A1 | A2 | A1/A1 | A1/A2 | A2/A2 | MAF | HW p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs12979860 | C | T | Arm A (n = 30) | 17 | 11 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.90 |

| Arm B (n = 32) | 17 | 11 | 4 | 0.30 | 0.32 | |||

| Total (n = 62) | 34 | 22 | 6 | 0.27 | 0.39 | |||

| rs368234815 | TT | G | Arm A (n = 30) | 17 | 11 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.90 |

| Arm B (n = 32) | 16 | 12 | 4 | 0.31 | 0.47 | |||

| Total (n = 62) | 33 | 23 | 6 | 0.28 | 0.51 | |||

| rs4803221 | C | G | Arm A (n = 30) | 21 | 8 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.83 |

| Arm B (n = 32) | 22 | 8 | 2 | 0.19 | 0.31 | |||

| Total (n = 62) | 43 | 16 | 3 | 0.18 | 0.36 | |||

| rs7248668 | G | A | Arm A (n = 30) | 21 | 8 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.83 |

| Arm B (n = 31) | 22 | 7 | 2 | 0.18 | 0.21 | |||

| Total (n = 61) | 43 | 15 | 3 | 0.17 | 0.28 |

Genotype association with a binary response outcome based on either 20%, 50% or 70% response was undertaken using a Pearson’s chi-squared test for all SNPs in all individuals plus stratifying for Arm A or Arm B only (Table 19).

| Arm A (n = 30) | Arm B (n = 32) | Overall (n = 62) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs12979860 | C/C | C/T | T/T | Total | MAF | p -value | C/C | C/T | T/T | Total | MAF | p -value | C/C | C/T | T/T | Total | MAF | p -value | |

| 20% | Non-responder | 7 | 4 | 2 | 13 | 0.31 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 10 | 0.35 | 11 | 9 | 3 | 23 | 0.33 | |||

| Responder | 10 | 7 | 0 | 17 | 0.21 | 0.239 | 13 | 6 | 3 | 22 | 0.27 | 0.454 | 23 | 13 | 3 | 39 | 0.24 | 0.640 | |

| 50% | Non-responder | 8 | 7 | 2 | 17 | 0.32 | 12 | 7 | 1 | 20 | 0.23 | 20 | 14 | 3 | 37 | 0.27 | |||

| Responder | 9 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 0.15 | 0.303 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 0.42 | 0.237 | 14 | 8 | 3 | 25 | 0.28 | 0.824 | |

| 70% | Non-responder | 13 | 7 | 2 | 22 | 0.25 | 14 | 9 | 2 | 25 | 0.26 | 27 | 16 | 4 | 47 | 0.26 | |||

| Responder | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.511 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 0.43 | 0.347 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 15 | 0.33 | 0.731 | |

| rs368234815 | TT/TT | TT/G | G/G | Total | MAF | p -value | TT/TT | TT/G | G/G | Total | MAF | p -value | TT/TT | TT/G | G/G | Total | MAF | p -value | |

| 20% | Non-responder | 7 | 4 | 2 | 13 | 0.31 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 10 | 0.35 | 11 | 9 | 3 | 23 | 0.33 | |||

| Responder | 10 | 7 | 0 | 17 | 0.21 | 0.239 | 12 | 7 | 3 | 22 | 0.30 | 0.616 | 22 | 14 | 3 | 39 | 0.26 | 0.716 | |

| 50% | Non-responder | 8 | 7 | 2 | 17 | 0.32 | 11 | 8 | 1 | 20 | 0.25 | 19 | 15 | 3 | 37 | 0.28 | |||

| Responder | 9 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 0.15 | 0.303 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 0.42 | 0.252 | 14 | 8 | 3 | 25 | 0.28 | 0.745 | |

| 70% | Non-responder | 13 | 7 | 2 | 22 | 0.25 | 13 | 10 | 2 | 25 | 0.28 | 26 | 17 | 4 | 47 | 0.27 | |||

| Responder | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.511 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 0.43 | 0.344 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 15 | 0.33 | 0.787 | |

| rs4803221 | C/C | C/G | G/G | Total | MAF | p -value | C/C | C/G | G/G | Total | MAF | p -value | C/C | C/G | G/G | Total | MAF | p -value | |

| 20% | Non-responder | 9 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 0.19 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 10 | 0.20 | 15 | 7 | 1 | 23 | 0.20 | |||

| Responder | 12 | 5 | 0 | 17 | 0.15 | 0.492 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 22 | 0.18 | 0.304 | 28 | 9 | 2 | 39 | 0.17 | 0.814 | |

| 50% | Non-responder | 11 | 5 | 1 | 17 | 0.21 | 14 | 6 | 0 | 20 | 0.15 | 25 | 11 | 1 | 37 | 0.18 | |||

| Responder | 10 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 0.12 | 0.597 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 0.25 | 0.144 | 18 | 5 | 2 | 25 | 0.18 | 0.483 | |

| 70% | Non-responder | 16 | 5 | 1 | 22 | 0.16 | 18 | 7 | 0 | 25 | 0.14 | 34 | 12 | 1 | 47 | 0.15 | |||

| Responder | 5 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 0.19 | 0.628 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 0.36 | 0.021 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 0.27 | 0.201 | |

| rs7248668 | G/G | G/A | A/A | Total | MAF | p -value | G/G | G/A | A/A | Total | MAF | p -value | G/G | G/A | A/A | Total | MAF | p -value | |

| 20% | Non-responder | 9 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 0.19 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 0.17 | 15 | 6 | 1 | 22 | 0.18 | |||

| Responder | 12 | 5 | 0 | 17 | 0.15 | 0.492 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 22 | 0.18 | 0.472 | 28 | 9 | 2 | 39 | 0.17 | 0.934 | |

| 50% | Non-responder | 11 | 5 | 1 | 17 | 0.21 | 14 | 5 | 0 | 19 | 0.13 | 25 | 10 | 1 | 36 | 0.17 | |||

| Responder | 10 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 0.12 | 0.597 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 0.25 | 0.172 | 43 | 15 | 3 | 61 | 0.17 | 0.550 | |

| 70% | Non-responder | 16 | 5 | 1 | 22 | 0.16 | 18 | 6 | 0 | 24 | 0.13 | 34 | 11 | 1 | 46 | 0.14 | |||

| Responder | 5 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 0.19 | 0.628 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 0.36 | 0.025 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 0.27 | 0.201 | |

These analyses suggest the only statistically significant associations are for the rs4803221 and rs7248668 SNPs in Arm B and only when applying the 70% response binary phenotype (p = 0.021 and 0.025, respectively). However, after correction for multiple testing [false discovery rate (FDR)], these associations are no longer significant (p > 0.05).

Subsequent analysis determined genetic association with four continuous variable outcome measures: BDAI at baseline, 3 months, 6 months and a baseline-adjusted BDAI area under the curve (AUC). This used an ANOVA with Bonferroni correction (Table 20).

| Arm A (mean ± SD) | Arm B (mean ± SD) | Overall (mean ± SD) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs368234815 | TT/TT | TT/G | G/G | ANOVA p-value | TT/TT | TT/G | G/G | ANOVA p-value | TT/TT | TT/G | G/G | ANOVA p-value |

| rs4803221 | C/C | C/G | G/G | ANOVA p-value | C/C | C/G | G/G | ANOVA p-value | C/C | C/G | G/G | ANOVA p-value |

| rs7248668 | G/G | G/A | A/A | ANOVA p-value | G/G | G/A | A/A | ANOVA p-value | G/G | G/A | A/A | ANOVA p-value |

| rs12979860 | C/C | C/T | T/T | ANOVA p -value | C/C | C/T | T/T | ANOVA p -value | C/C | C/T | T/T | ANOVA p -value |

| BDAI (baseline) | 6.15 ± 2.94 | 6.67 ± 3.48 | 7.00 | 0.877 | 6.89 ± 2.85 | 8.07 ± 3.08 | 8.80 ± 4.71 | 0.390 | 6.51 ± 2.88 | 7.34 ± 3.31 | 8.50 ± 4.28 | 0.278 |

| BDAI (3 months) | 4.50 ± 3.12 | 4.58 ± 3.96 | 7.00 ± 1.41 | 0.625 | 6.47 ± 4.00 | 6.58 ± 4.93 | 3.67 ± 2.52 | 0.555 | 5.52 ± 3.68 | 5.58 ± 4.49 | 5.00 ± 2.65 | 0.956 |

| BDAI (6 months) | 4.67 ± 5.92 | 2.81 ± 1.72 | 5.50 ± 2.12 | 0.547 | 3.94 ± 2.86 | 5.45 ± 3.78 | 4.25 ± 5.97 | 0.559 | 4.13 ± 4.64 | 4.13 ± 3.17 | 4.67 ± 4.76 | 0.961 |

| Baseline-adjusted BDAI AUC | –1.21 ± 1.81 | –2.00 ± 2.50 | 2.25 ± 3.89 | 0.055 | –1.31 ± 2.82 | –1.27 ± 2.94 | –2.25 ± 3.68 | 0.866 | –1.26 ± 2.32 | –1.64 ± 2.69 | –0.45 ± 4.08 | 0.639 |

| BDAI (baseline) | 6.15 ± 2.94 | 6.67 ± 3.48 | 7.00 | 0.877 | 6.83 ± 2.92 | 8.07 ± 2.96 | 8.80 ± 4.71 | 0.367 | 6.47 ± 2.91 | 7.37 ± 3.25 | 8.50 ± 4.28 | 0.254 |

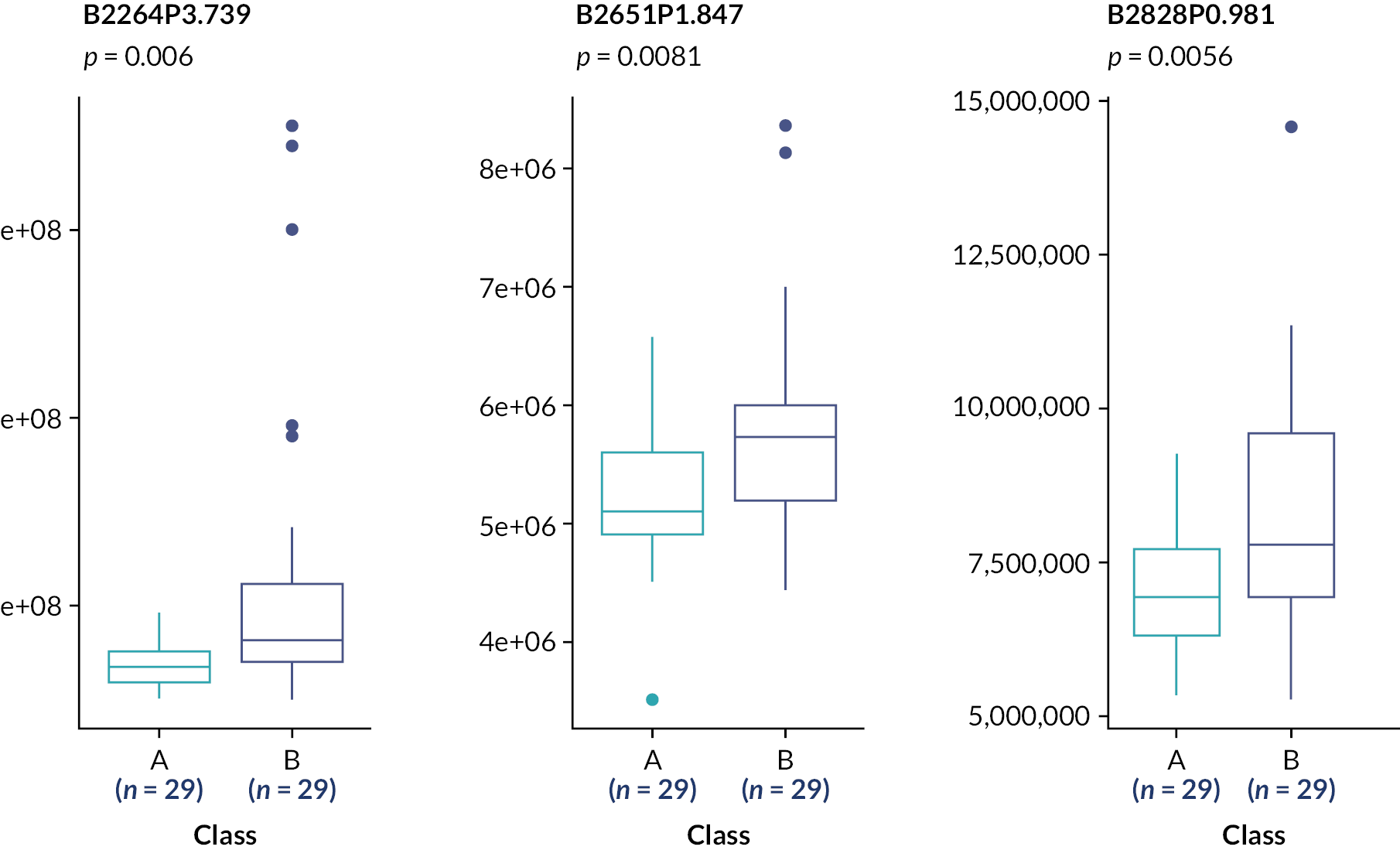

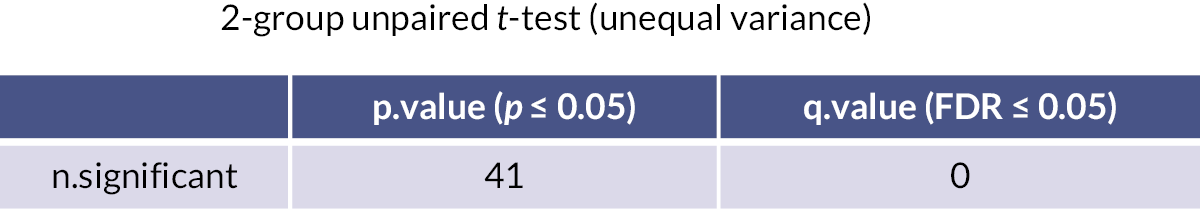

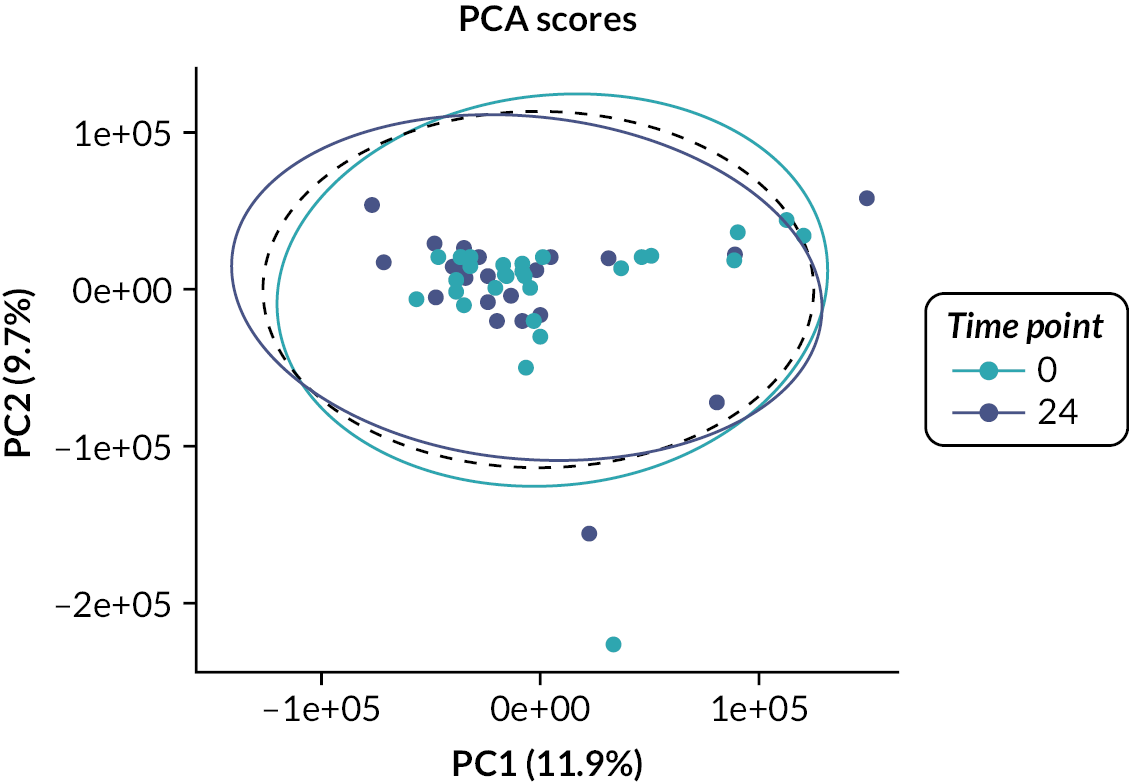

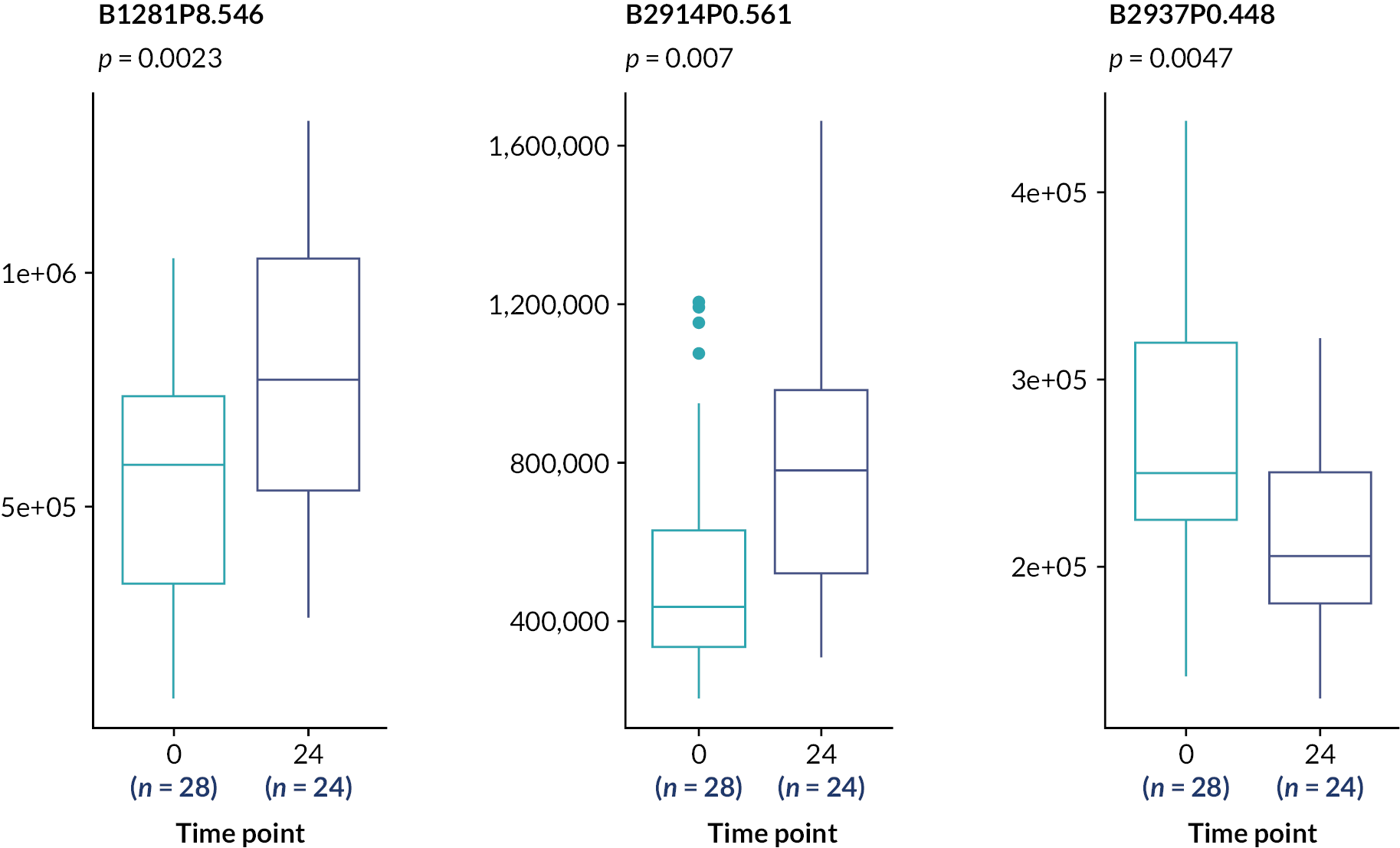

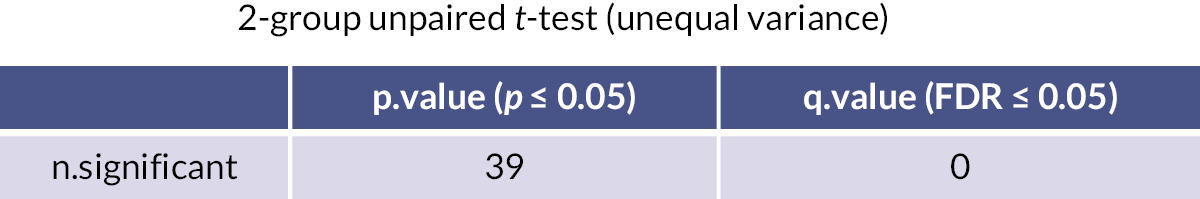

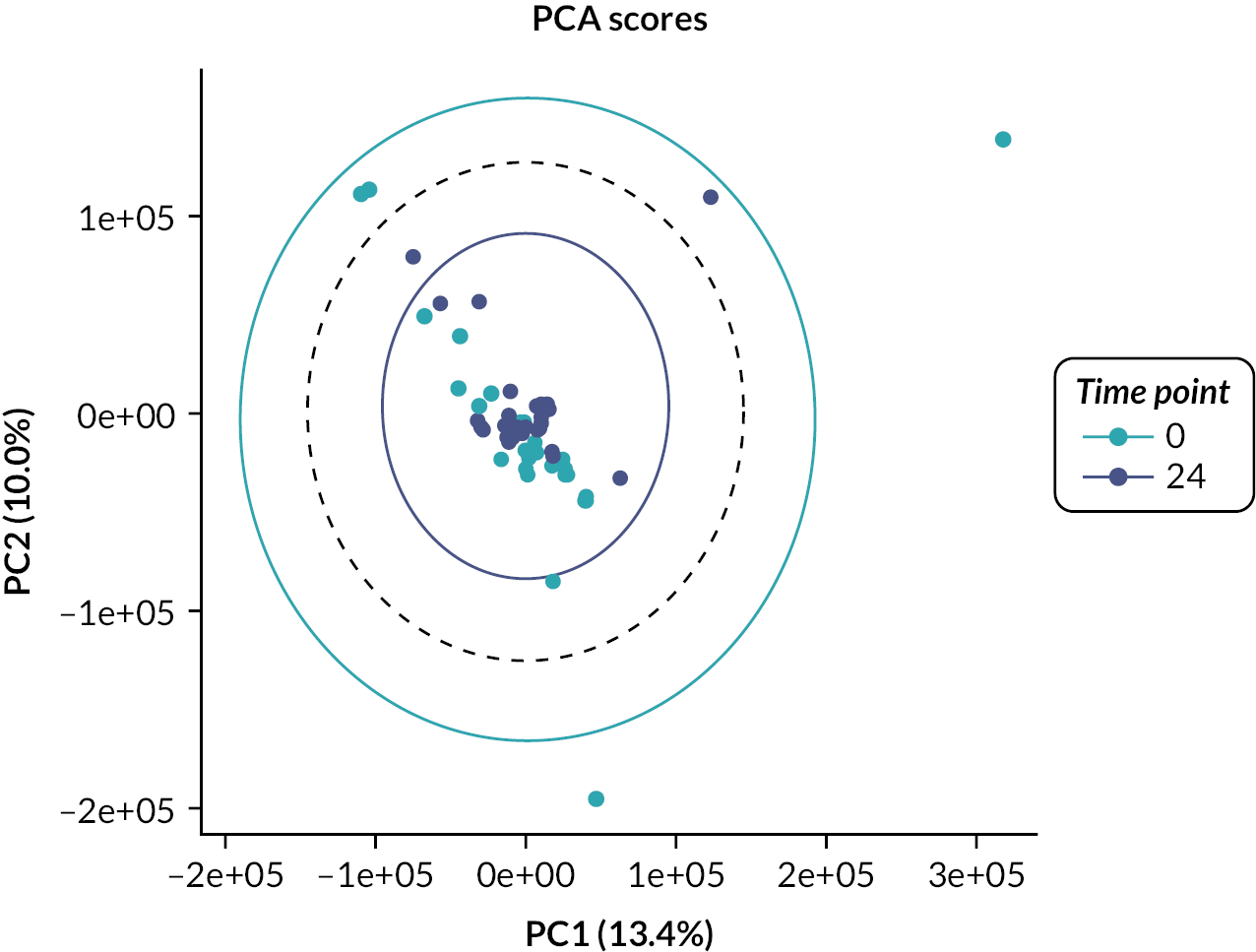

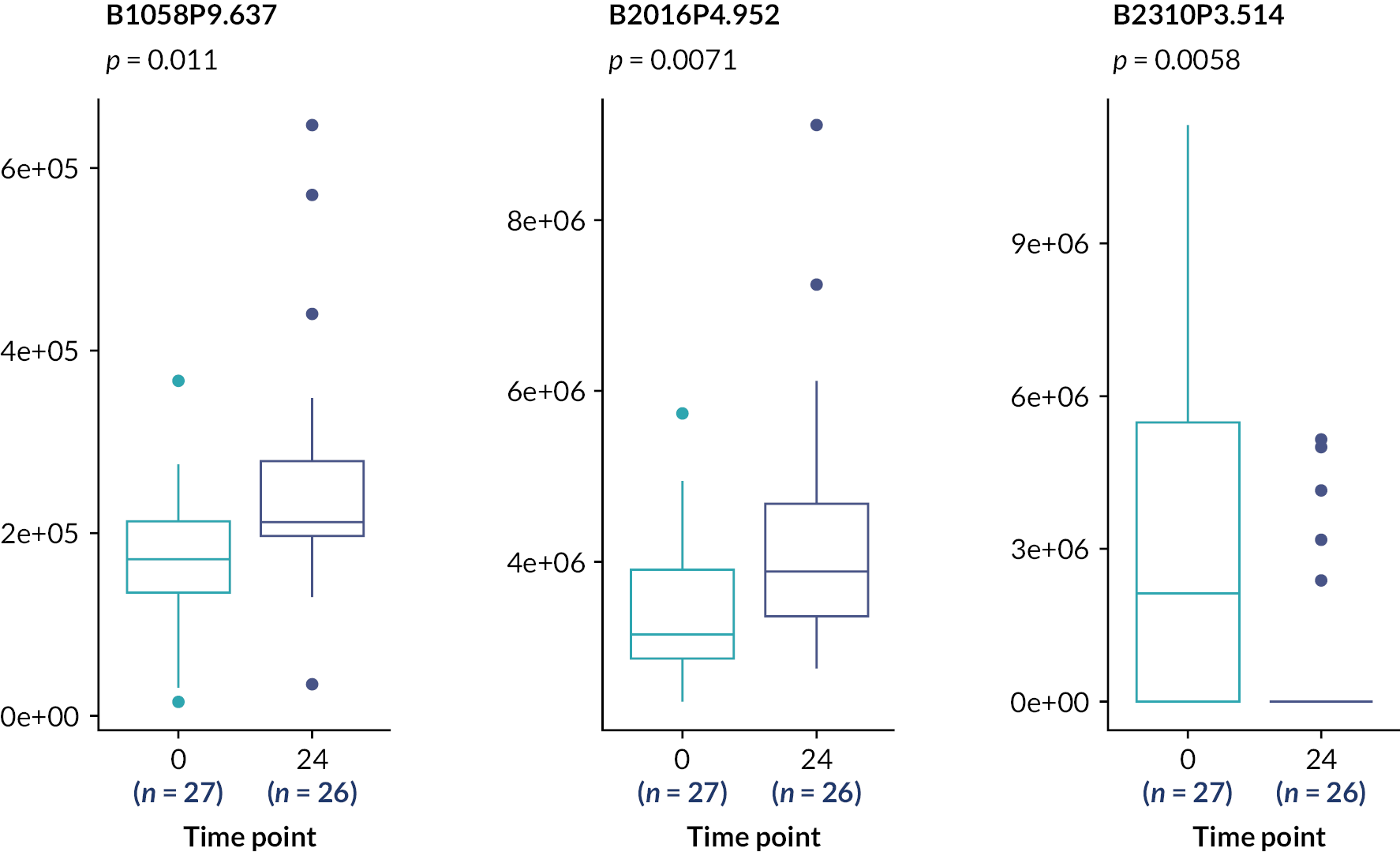

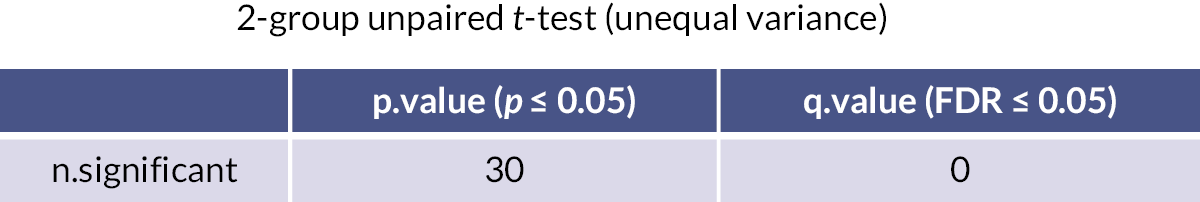

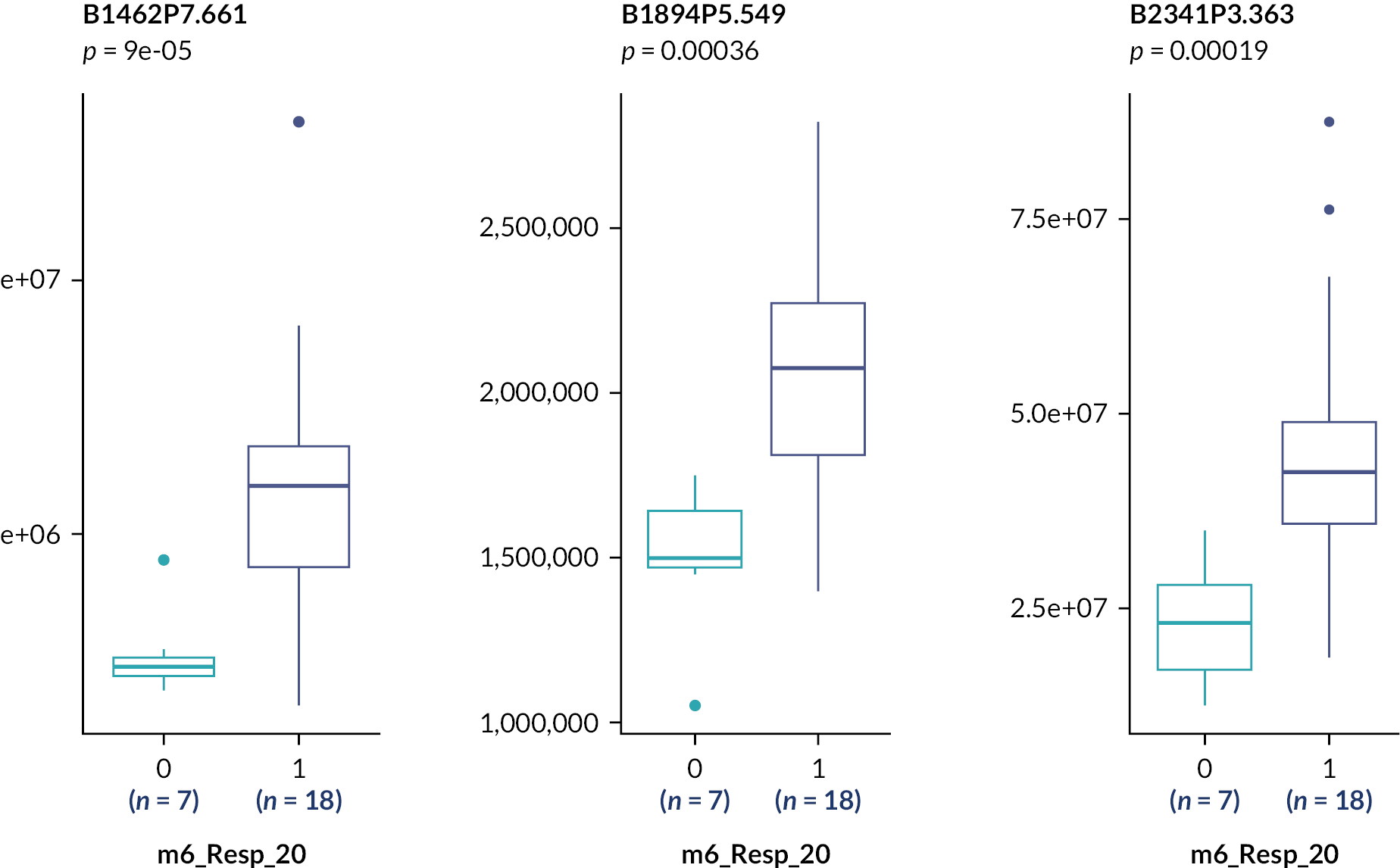

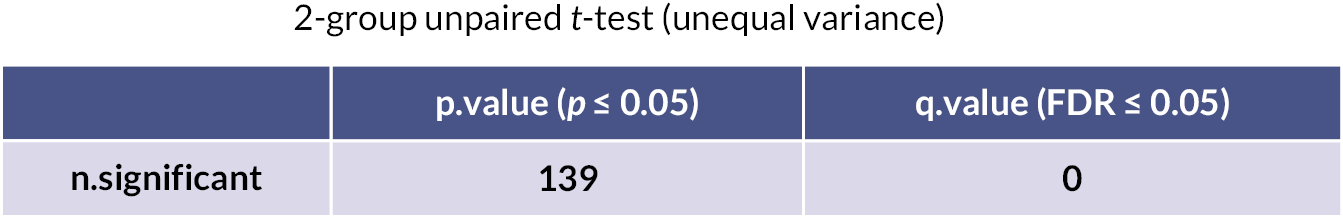

| BDAI (3 months) | 4.50 ± 3.12 | 4.58 ± 3.96 | 7.00 ± 1.41 | 0.625 | 5.93 ± 3.45 | 7.23 ± 5.26 | 3.667 ± 2.52 | 0.401 | 5.22 ± 3.32 | 5.96 ± 4.78 | 5.00 ± 2.65 | 0.748 |