Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 11/100/50. The contractual start date was in April 2013. The final report began editorial review in October 2021 and was accepted for publication in May 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Brown et al. This work was produced by Brown et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Brown et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Approximately 16,000 people die from colorectal cancer (CRC) in the UK every year, making it the second most common cause of cancer death in the UK and accounting for 10% of all cancer deaths in the country. 1 Given that the concept of one treatment for all patients with a particular type of cancer has become outdated, the major challenge for oncologists is the identification of effective treatments for patients with CRC, given the limited benefits demonstrated of bevacizumab and cetuximab and the failure of multiple other agents in recent trials. 2 To this end, the use of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeted therapy has highlighted the importance of BRAF, PIK3CA, KRAS and NRAS mutations for predicting a lack of response to EGFR-targeted therapy. 3 However, there is also a need for a new approach to the design of clinical trials, allowing for the evaluation of multiple treatments in patients stratified based on biomarkers that are considered to be predictive of a treatment response.

The FOCUS4 trial was designed to enable the rapid identification of patients whose tumours could be characterised based on the presence of specific mutations or validated biomarkers that characterise biological subgroups. This trial was designed to characterise the tumours and stratify eligible patients into comparison subtrials, which, by being a component of a large national study, allow efficient adaptation of the biomarker eligibility criteria within the trial and enable the rapid accrual of patients, even those with the rare subtypes, such as those with the BRAF mutation, who account for only 8% of the population of patients with metastatic CRC.

The design of the FOCUS4 trial was considered to be efficient in that it exploited the concept of a population-enriched design, with the aim of evaluating multiple treatments and multiple biomarkers and, thereby, including most patients with a given type of cancer in the trial, irrespective of their biomarker categorisation. Each treatment was evaluated first in the cohort of patients for whom the biomarker was hypothesised to be predictive of response. If appropriate, the hypothesis of the predictive ability of the biomarker was subsequently tested by evaluating the agent in the biomarker-negative patients. It was not assumed that a treatment would work only in biomarker-positive patients, although it was assumed that a treatment that did not demonstrate efficacy in the selected or enriched cohort did not require further evaluation in a biomarker-negative patient population. This more efficient sequential testing approach had been favourably compared with other existing trial designs. 4

The random assignment of each comparison with placebo within the biomarker-defined groups in the FOCUS4 trial design removed the potential bias of the prognostic effects of certain biomarker-defined groups. In addition, the FOCUS4 trial was adaptive in that random assignment to treatments that did not seem to be sufficiently active could be discontinued; new biomarkers and treatments could be introduced when warranted; and biomarkers could be refined as new information from within or outside the trial emerged.

The approach used in the FOCUS4 trial was driven by advances in the molecular understanding of CRC and the development of new targeted therapies, which demand the evaluation of these therapies in subsets of the CRC patient population that are mostly likely to derive benefit from the treatment. This need is evidenced by the failure of many classic trials to show benefit for new treatments in CRC,2 demonstrating the clear need for a new paradigm in the drive for progress.

Use of molecular classification in FOCUS4

In the FOCUS4 trial, patients were allocated to the comparison subtrials, which were initially defined by four specific molecular cohorts, with another cohort for patients whose cancer could not be classified into a specific molecular cohort. Cohorts could change as data became available during the trial.

The initial five molecular cohorts in the FOCUS4 trial, which were allocated to comparison subtrials referred to as FOCUS4-A, -B, -C, -D and -N, were as follows:

-

BRAF mutation (FOCUS4-A). BRAF mutations are more frequent in the presence of microsatellite instability (MSI) and arise more commonly in right-sided colon carcinomas and have a reasonably consistent gene expression signature. 5 In the Medical Research Council (MRC) COntinuous or INtermittent (COIN) trial,6 8% of patients had BRAF mutations. Patients with this molecular classification and with normal platelets in the intermittent arm of the COIN trial had a median overall survival (OS) of 14.8 months and a median progression-free survival (PFS) in the interval off therapy of 3.1 months.

-

PIK3CA mutation or profound loss of phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) expression (FOCUS4-B). These mutations lead to activation of the protein kinase B (AKT) signalling network, and approximately half of the patients also have KRAS mutations. In addition, approximately 10% of patients have a loss of PTEN expression by various mechanisms, including mutation, methylation silencing of the promoter and microRNA inhibition. The TCGA report7 has identified increased signalling through the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor owing to amplification of IGF2 as an important additional driver within this pathway. PIK3CA mutations have been identified as one of the most common mutations in cancer and were identified in 13% of patients in the COIN trial. 6 Patients with PIK3CA or PIK3R1 mutations or profound loss of PTEN expression account for approximately 20–30% of the CRC population and have activated AKT signalling. Patients with this molecular classification and with normal platelets in the intermittent arm of the COIN trial had a median OS of 16.9 months and a median PFS in the interval off therapy of 2.7 months. These figures were similar whether or not a KRAS/NRAS mutation was also present.

-

KRAS or NRAS mutation (FOCUS4-C). Expression profile analysis shows a variation in gene expression patterns in tumours with KRAS mutation, with signalling down the canonical RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway dominating in about one-quarter, signalling through the PIK3-AKT-mTOR pathway in others and diverse signalling in other tumours. 8 In the COIN trial,6 44% of patients exhibited either KRAS or NRAS mutations, rising to 52% of those who also exhibited PIK3CA mutation. Patients with this molecular classification and with normal platelets in the intermittent arm of the COIN trial6 had a median OS of 18.4 months and a median PFS in the interval off therapy of 3.0 months.

-

Wild type for all the above mutations (EGFR dependent) (FOCUS4-D). Patients with these tumours are wild type for BRAF, PIK3CA, KRAS and NRAS and do not have loss of PTEN, and include the subset of patients who respond best to EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies. In addition, mutations or amplification in human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) 2 occur in around 5% and overexpression of HER3 in around 50% of these patients. In the COIN trial,6 42% of patients were free from all four above mutations. Patients with this molecular classification and with normal platelets in the intermittent arm of the COIN trial6 had a median OS of 19.1 months and a median PFS in the interval off treatment of 3.3 months. In the COIN-B trial,9 the equivalent figures were 20.0 months and 4.4 months, respectively, albeit with small patient numbers, indicating that prognosis is potentially good among such patients.

-

Non-stratified group (unclassified) (FOCUS4-N). Approximately 2% of patients with CRC have tumours that cannot be classified successfully; these patients were included in the non-stratified group. In addition, this cohort included those patients eligible for comparisons that were suspended between novel therapy evaluations or patients who chose not to participate in their specific molecular comparison for reasons such as distance to an experimental therapy centre. Once a patient entered a particular comparison subtrial, they could not enter another FOCUS4 comparison at another time.

The identification of novel biomarkers and their link to the selection of patients for specific therapy is a fast-moving field. Therefore, an essential feature of FOCUS4 was the capacity to introduce novel biomarkers once they had been sufficiently validated to identify newly characterised tumour subgroups for evaluation of therapies hypothesised to be effective in the identified patient subpopulations. Therefore, the FOCUS4 trial incorporated some accepted biomarkers (e.g. KRAS mutation), some biomarkers reaching consensus (e.g. BRAF mutation) and other biomarkers for which further development and refinement was required (e.g. PTEN, mRNA for epiregulin) but could be accomplished within the trial itself.

FOCUS4 was structured to provide an overarching recruitment and biomarker identification strategy, which was linked to a series of randomised comparison subtrials between novel and control treatments for the identified subpopulations. During the trial, some of these interventions could have been shown to lack sufficient activity and would be accordingly withdrawn and replaced by new agents or by new biomarker-defined groups.

Within the individual comparison subtrials for each molecular cohort, the novel therapy comparisons were double blind and placebo controlled where possible. However, patients in FOCUS4-N were allocated to either capecitabine or active monitoring; this was, therefore, an open-label, unblinded subtrial.

Aims and objectives

The primary objectives of the FOCUS4 trial were to answer the following research questions:

-

Clinical benefit . In the interval following standard first-line chemotherapy, do the proposed interventions improve PFS and eventually OS compared with a control group in the biomarker-defined cohorts?

-

Improvement in trial design and conduct. To understand better the challenges and efficiencies of conducting a large, molecularly stratified platform trial in metastatic CRC in the UK health-care system.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

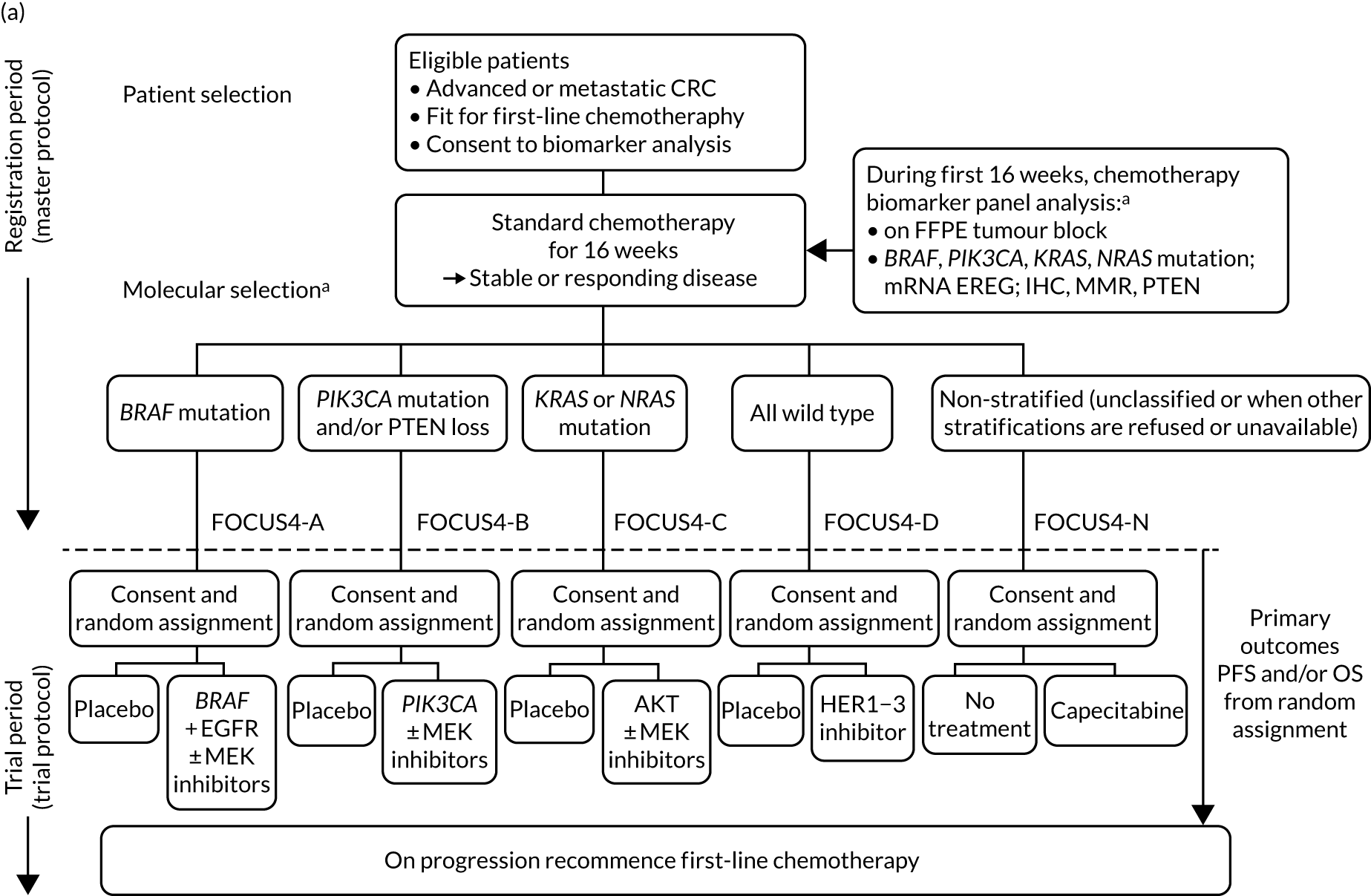

FOCUS4 used some of the methods of the multiarm, multistage (MAMS) randomised trial design. 10–12 After registration and biomarker assessment during a planned 16 weeks of standard first-line chemotherapy, patients were stratified into one of four biologically defined cohorts (A to D), as detailed in Figure 1. Figure 1a presents the original trial schema when the trial was activated in 2014, but the adaptive nature of the design allowed it to change over time, and many iterations occurred before the final schema, which is presented in Figure 1b. If stable or responding disease was confirmed at the end of 16 weeks, patients were then enrolled into the corresponding randomised trial of the novel targeted agent(s) or, for travel, logistic or technical reasons, to the one conventional chemotherapy maintenance trial (i.e. FOCUS4-N).

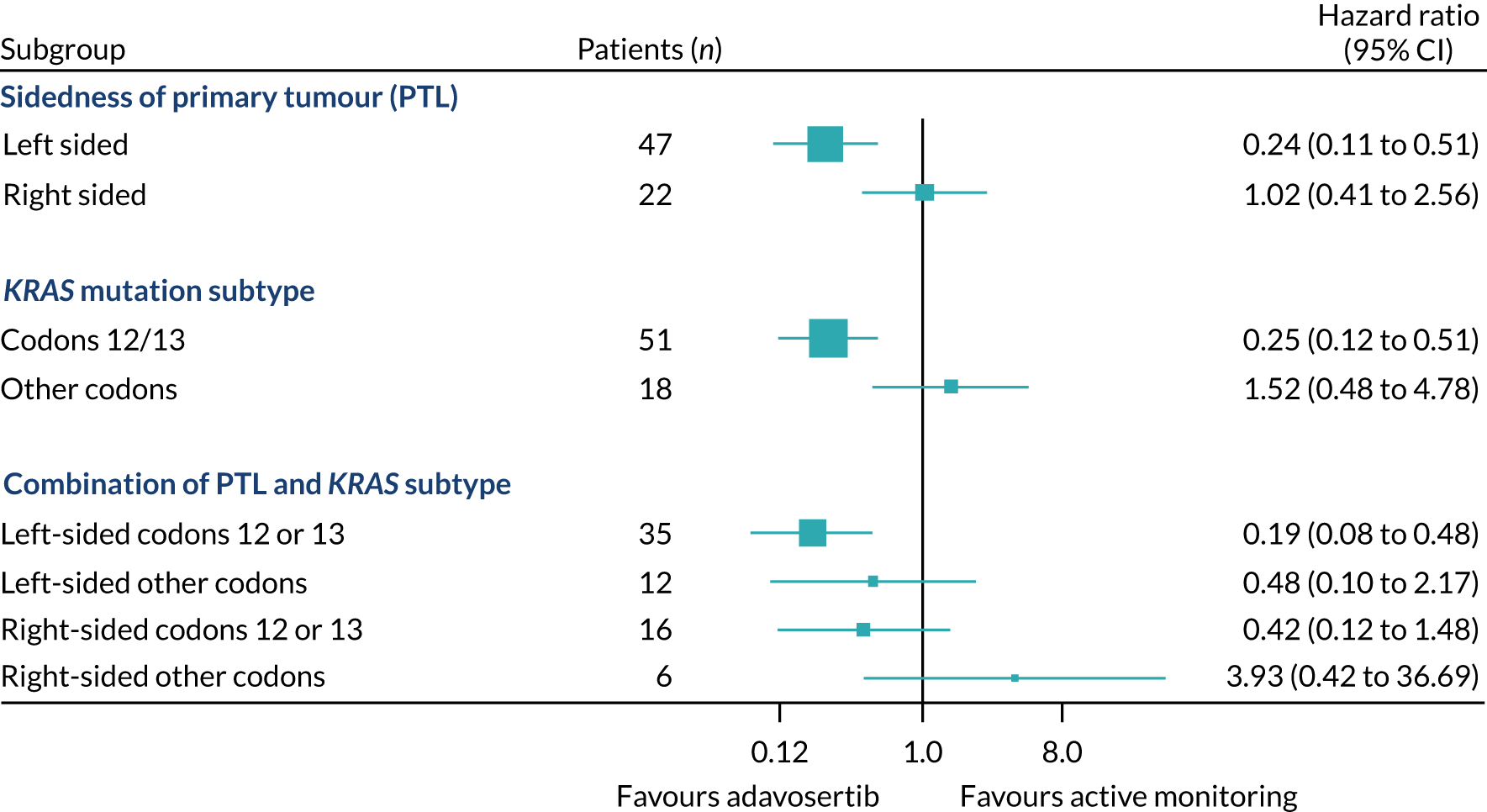

FIGURE 1.

FOCUS4 trial programme schema: registration, randomisation and treatment. (a) Original schema; and (b) final schema. a, The molecular cohorts are arranged in a hierarchy from left to right. For example, a patient with both a BRAF and a PIK3CA mutation are classified into the BRAF mutation cohort. AM, active monitoring; EREG, epiregulin; FFPE, formalin fixed, paraffin embedded; HER, human epidermal growth factor receptor; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homologue.

Key principles of the FOCUS4 trial design

The design of the FOCUS4 trial was based on seven key principles, as discussed below. These principles are also described by Kaplan et al. 13

Key principle 1

Key principle 1 was to evaluate multiple treatments and biomarkers in the same protocol, including as many patients as possible with a given disease, with separate clinical questions for as many marker-defined subgroups as are supported by current evidence.

Incorporating multiple treatments across multiple population-enriched biomarker-defined trials fits into conventional clinical practice patterns, in which patients with one type of cancer are managed in a common manner with similar protocols. In CRC, this single treatment approach for all has evolved into two clinical pathways: first, for patients with KRAS wild-type tumours (for whom EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies may be planned) and, second, for those with KRAS-mutated tumours. As further individualisation of treatment approaches occurs, managing separately co-ordinated clinical research efforts, which often involve different collaborators and different research teams, becomes progressively more unwieldy and inefficient. The approach used in FOCUS4 filters all eligible patients into one overarching clinical trial programme; this design offers clear efficiency gains in both cost and time compared with running multiple individual trials to evaluate different treatments under separate protocols. This design also increases the likelihood that the investment leads to discovery of effective treatments and halts further development of ineffective treatments in this disease setting. Further efficiency is inherent in biomarker analysis being set up to include all diagnostic tests for the differing subgroups. So far as is scientifically feasible, an inclusive trial allows the maximum number of patients to participate and maximises the potential to recruit rare subtypes. It allows for maximum flexibility in refinement of the biomarker cohort definitions in response to developing clinical data from both within and outside the trial, and provides administrative and organisational efficiencies.

Key principle 2

For key principle 2, in the initial stages, assess each treatment in the presumptive biomarker-enriched subset (thus exploiting the putative link between biomarkers and novel treatments with corresponding mechanisms of action), but without assuming that this association would be confirmed in later stages.

In oncology, even when novel agents are found to be active, the expected biomarker selection may not apply. 14 A key strength of the FOCUS4 protocol is that it neither assumes that any encouraging outcome results are limited to the biomarker selection nor expends numbers of biomarker-negative patients until there is a positive signal from the initial staged analyses (stages 1 to 2). Therefore, entry into the earlier phases of the evaluation of a novel treatment was restricted to those patients who were thought to be most likely to respond. Once the significance level associated with the activity of the experimental treatment fell to less than a given value, there was the option to open a similar efficacy evaluation among those patients who did not show the positivity of the biomarker in their tumour (i.e. off-target effect), using the same type of lack-of-activity assessments, to refute or confirm activity in this complementary population of patients. This approach builds on the putative link between the biomarker and drug efficacy but does not presume that this is a certainity.

Key principle 3

Key principle 3 was to use randomised evidence with a control group for each biomarker/treatment cohort evaluation (eliminating confounding resulting from prognostic biomarker effects).

Constructing the protocol as a set of parallel randomised comparisons ensured that the measured or unmeasured prognostic effects of different biomarkers did not confound the assessment of treatment efficacy, meaning that any benefits were ascribed to the new treatment and not the potential prognostic effect of the marker.

Key principle 4

Key principle 4 was to ensure rapid evaluation of each new treatment, which involves (1) incorporating the flexibility of Phase II and III components into each trial and (2) targeting a reasonably large treatment effect, with discontinuation of random assignment to treatments that are unpromising or overwhelmingly effective as early and reliably as possible.

For the individual trials within the protocol, a larger effect size could be targeted than might be chosen in a more traditional trial. This could be undertaken for two reasons. First, enrichment of the population meant that a somewhat larger effect could be expected, even if enrichment excluded only a proportion of those who did not benefit. Second, there are currently a large number of potential treatments available for evaluation and, therefore, it was reasonable to seek a larger treatment effect than if only a limited number of new treatments were available for testing.

A key aspect of the FOCUS4 protocol was the flexibility to have both Phase II and Phase III components for each randomised comparison, with the potential to move seamlessly from Phase II to Phase III. The aim of the Phase III component was to determine if, in the interval after standard first-line chemotherapy, the proposed novel agents improved PFS and potentially (in some of the larger cohorts) OS, compared with placebo, within the biomarker-defined populations. Use of PFS and OS could be particularly important when agents with different mechanisms of action are being tested. This is in preference to other earlier outcomes of treatment response (e.g. disease response by response evaluation criteria in solid tumours), which may not reliably translate into longer-term outcomes of importance to the patient. For each agent-versus-placebo comparison, FOCUS4 employed a maximum of four stages:

-

stage 1 – safety and screening for sufficient activity (relevant primary end point: PFS)

-

stage 2 – screening for sufficient activity (relevant primary end point: PFS)

-

stage 3 – efficacy (relevant primary end point: PFS)

-

stage 4 – efficacy [relevant primary end point: OS (for those cohorts with sufficient patients)].

Stages 1 and 2 together can be considered analogous to a traditional Phase II trial, whereas continuing into stages 3 and 4 can be considered functionally to complete a traditional Phase III trial. Such designs can be adapted for different end points at different stages and use different decision criteria for moving from one stage to another.

For all therapies that passed activity screening in stage 2, a number of paths were possible. If no major changes were to be made to the research arm (e.g. in biomarker selection criteria or agent dosing), a seamless move to stage 3 was possible, with outcome data on all patients entered during stages 1 and 2 being used in stages 3 and 4. Alternatively, if a major change to a research arm was made, the trial could still continue to the Phase III component (stages 3 and 4), but with outcome data from only newly entered patients from that time forward contributing to the final (Phase III) analysis. However, there was considerable efficiency even in this situation. This so-called new Phase III trial did not require a new protocol and could be initiated by amendment and activated rapidly at all of the sites already participating in the single FOCUS4 protocol. A final possibility was that, for reasons external to the trial itself, the sponsor or funder could decide not to support continuation to the Phase III stages. This could also happen in the face of a positive outcome in the activity screening stages (e.g. if testing of the agent in other settings was planned). Note that such an outcome would still be appropriately viewed as useful if it served to stimulate or facilitate additional trials. In such a situation, other novel agent(s) could then be tested in the relevant cohort of FOCUS4.

For each of the trials within FOCUS4, the overall power was maintained at 80%, allowing for multiple interim data looks, with a maximum 5% two-sided overall significance level (type I error rate). To maintain 80% power overall (for each trial), the power of each trial for the primary analysis varied from 85% to 95%, depending on the number and timing of the interim analyses.

Each biomarker-defined trial was considered separately in terms of the effect size (hazard ratio) to be detected to suit issues relevant to specific biomarker cohorts or agents. An important distinction between stage 2 (lack of sufficient activity) and stage 3 (efficacy) was the difference in type I error, which was set higher for the stage 2 interim PFS analysis (one-sided 10%) than for the stage 3 main PFS efficacy analysis (one-sided 2.5%).

Data for each of the trials were reviewed by the Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) at each interim analysis. The committee could advise early closure of a trial in the event of overwhelming evidence of efficacy, using a significance level of p = 0.001 as a guideline on the Phase III efficacy outcome measure. This was considered at approximately the halfway point in terms of accrued number of events for each biomarker-defined trial.

Key principle 5

Key principle 5 was to allow the possibility of refining any biomarkers throughout the course of the trial, from either internal data or, more typically, data emerging outside the trial.

Biomarker definitions are constantly evolving. Although, for example, KRAS mutation was a multiply confirmed predictive marker for use of anti-EGFR antibody therapy, it subsequently became clear that not all KRAS mutations had identical effects, with some perhaps not even carrying the same negative predictive value (e.g. KRAS G13D). 3 Evolving data now suggest that expression of EGFR ligands, such as epiregulin and amphiregulin, may also modulate response to this class of agents. 15 Other alterations elsewhere in the RASRAF–MEK–ERK and interacting pathways [e.g. phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)–AKT–mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)] are almost certainly also of considerable importance. An example of biomarker refinement would be the introduction of a new platform for mutation assessment. Developments in molecular diagnostics are occurring at such a pace that older technologies are continually being outperformed by newer technologies in cost and sample requirements. Such refinements could be introduced into a continuing programme, such as FOCUS4, but with close attention to quality assurance and a pre-planned parallel evaluation using both platforms for a period of time to ensure comparability of assessment. If there proved a need to revise one or another biomarker assay during the first two (signal-seeking) analysis stages, patients assigned on the basis of the earlier assay would probably have had to be excluded from the definitive third- and fourth-stage analyses and their possible use towards registration. The third-stage sample size might need to be increased, but the overall time delay introduced in the stage 3 analysis would be minimal (months), because the trial would already be activated and recruiting from a large number of sites.

Key principle 6

Key principle 6 was to allow the possibility of introducing a new biomarker and treatment pairing into the overall trial programme when evidence warranted.

The flexibility inherent in the FOCUS4 design created opportunities to further adapt the trial to accommodate additional findings, typically from other research outside the trial. For instance, it is well known that there is a cohort of patients with MMR deficiency within CRC. In earlier disease, these patients amount to 15% of the total, but they have an improved prognosis, and series among metastatic patients reveal only approximately 4% prevalence of MMR deficiency. At the time that FOCUS4 was designed, there was no convincing case for testing a specific class of agent in this cohort. However, during this period, the rapid emergence of immune checkpoint inhibitors transformed cancer therapy and it is in the MMR-deficient subgroup of CRC that these agents have made a major impact. In principle, if such evidence emerged during the course of the study, the protocol could be amended to open up a new biomarker/treatment cohort by identifying the MMR-deficient cohort and testing the appropriate novel agent(s) compared with placebo in this group. The introduction of such a new biomarker-defined cohort during the trial would remove such patients from the other cohorts, but the introduction of a new cohort would not compromise the study design, requiring only sample size adjustments.

Key principle 7

Key principle 7 was to investigate new treatments in the earliest and most likely responsive settings that are clinically feasible. With many agents being developed and recognition that drug development is a lengthy and expensive process, it is critical to seek strong positive signals as early as possible in testing. When new agents are tested against all-comers and late in the natural history of the disease, it is usually difficult to determine whether or not observed modest improvements are likely to hold up with further testing, especially in earlier stages of disease.

In the FOCUS4 protocol, a four-stage selection process of patients for each trial was used, which improves the chance of identifying clinical benefit from novel agents. First, patients with aggressive disease, as manifested in a raised baseline platelet count, were excluded; this exclusion was later removed following full analysis of the effect of raised baseline platelet count (thrombocytosis) in other trials. Second, only those patients with stable or responding disease during 16 weeks of first-line systemic therapy were included. This, therefore, specifically selected responding patients, in comparison with most study designs, which select patients resistant to evaluate novel agents. Third, by testing the novel agents first in the molecular cohort in which theoretically they should have the greatest benefit, the likelihood of success was maximised. Finally, new agents are used on their own or in novel–novel combinations, after standard treatment, thereby avoiding unpredictable negative pharmacological or toxicity interactions with conventional chemotherapy, which has been seen repeatedly in CRC chemotherapy. Consequently, randomisation occurs in a treatment window of opportunity or treatment break, which is a clinically reasonable and safe strategy on the basis of randomised data from the COIN trial. 16 Although this strategy is somewhat unusual in CRC, there are many settings in the management of other tumours in which periods of observation of patients off treatment are standard and could be used for such window-of-opportunity trials. In FOCUS4, the setting has the advantage of allowing relatively new agents to be tested in patients before the onset of chemotherapy resistance and yet well before comprehensive data would become available with regard to combined administration along with chemotherapy.

Patient consent, registration and biomarker panel testing

Patients were approached to take part in FOCUS4 using a two-stage consent process. Initially, patient consent was obtained for registration and permission for biomarker testing of their tumour tissue; consent was also obtained when eligibility for particular comparisons had been established on the basis of the test results. Patient information sheets were provided for each stage of consent and signed consent forms were required prior to registration or randomisation.

Patients were registered via an online registration platform managed at the MRC Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) at University College London (UCL). Male or female patients aged ≥ 18 years with World Health Organization (WHO) status of 0, 1 or 2 were eligible for registration providing that they had histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the small bowel or colon or rectum, with an accessible diagnostic formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumour block taken prior to the commencement of standard first-line treatment. They were required to have inoperable metastatic or locoregional disease (synchronous or metachronous) that could be RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours) reported (v1.1) with unidimensionally measurable disease identified by computed tomography (CT) no more than 6 weeks before registration.

The movement of samples was tracked by the MRC CTU from the local site pathology department to one of two mutually quality-assured laboratories in Cardiff (Department of Cellular Pathology and All Wales Molecular Genomics Laboratory, Institute of Molecular Genetics, both located at University Hospital of Wales) or one in Leeds (Division of Pathology and Data Analytics, Leeds Institute of Medical Research at St James’s, University of Leeds). Laboratory testing initially comprised pyrosequencing of the mutation hotspots, then, from August 2017, the use of whole-gene next-generation sequencing (NGS), plus immunohistochemistry (IHC) for MMR proteins and PTEN. The technical components of the biomarkers and inter-laboratory quality assurance have been described previously. 17

Initially, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted from FFPE tissue and analysed using pyrosequencing to obtain the tumour mutation profile across known mutation hotspots in KRAS, NRAS, PIK3CA and BRAF. Further sections were stained on a DAKO Autostainer Link 48™ (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) to determine the protein expression of four mismatch repair (MMR) markers (MLH1, MSH2, MHS6 and PMS2) and PTEN. From August 2017, when FOCUS4-C was opened, the sequencing methodology was changed to NGS to allow coverage of the full sequence of KRAS, NRAS, PIK3CA and BRAF, and the addition of TP53. The GeneRead Clinically Relevant Mutation panel (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) was used, adhering to the manufacturer’s instructions. Results were uploaded to the centralised trial database from each laboratory. Where FFPE tumour blocks contained insufficient tumour tissue, an alternative tumour block was requested. If an alternative was unavailable, the patient was still eligible for entry into FOCUS4-N.

Participating sites

A total of 104 hospitals were activated in FOCUS4 across all four devolved UK nations. All sites were able to register patients into FOCUS4; however, given that the drugs being tested in the randomised comparisons varied widely, and included novel unlicensed drugs and generic therapies, sites were assessed for relevant capacity and expertise for participation in each of the comparisons. Sites were classified into three levels:

-

Level 1 sites (n = 51). Hospitals with clinical trial experience but without the required expertise for testing unlicensed therapies. Level 1 sites could register patients and recruit into FOCUS4-B (testing aspirin) and FOCUS4-N (testing capecitabine).

-

Level 2 sites (n = 29). Hospitals with experience of testing both licensed and unlicensed drugs but without extensive early phase experience. Level 2 sites could register patients and randomise into FOCUS4-B, FOCUS4-D, FOCUS4-N and eventually into FOCUS4-C when safety and tolerability of the wee-1 inhibitor had been assessed by the IDMC.

-

Level 3 sites (n = 23). Hospitals with early phase experience and extensive clinical trials experience of licensed and unlicensed drugs. Level 3 sites could register and randomise into all comparisons.

Statistical design and methods

FOCUS4 was designed to allow comparisons to be added into the platform as new agents became available or drop agents if prespecified interim analyses indicated a lack of sufficient drug activity. Decisions on the stopping of particular comparisons were based on MAMS statistical methodology such that the IDMC were provided with prespecified stopping guidelines for each comparison and asked to review the data in confidence at interim analyses and make recommendations on whether to continue or stop the comparison; the statistical analysis plan (SAP) is presented at www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/11/100/50. These recommendations were considered by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Trial Management Group (TMG) without sight of any data before a stop/go decision was made for that comparison.

Molecular assays

Details of the molecular assays used for molecular characterisation of the tumour samples are presented in the following sections. Parts of this section are reproduced by Richman et al. 17 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

In addition, a copy of the Biomarker Laboratory Manual is provided in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Sample processing

A series of 5-mm-thick sections were taken from each block, the first of which was used for haematoxylin and eosin staining, to identify the area of greatest tumour density, and the rest made available for DNA extraction and whole-section IHC. From the residual blocks, tissue microarrays (TMAs) were created, comprising four 0.6-mm tumour tissue cores and one core, if available, of ‘tumour-associated’ normal tissue. To reduce tissue use, the TMAs were prepared only once, in Cardiff, and then shipped to Leeds, where sections were cut and used for IHC.

DNA macrodissection and extraction

The spare sections from the resection blocks were marked out for the richest areas of neoplastic cell content, using the corresponding haematoxylin- and eosin-stained section as a guide, and were macrodissected. DNA was extracted in Leeds using the QIAGEN QIAamp DNA Extraction Kit and in Cardiff using the QIAGEN EZ1 following the manufacturer’s standard protocol.

Mutation detection

The analysis of mutation hotspots was carried out by pyrosequencing within KRAS codons 12, 13, 61 and 146 (exons 2, 3 and 4); BRAF codon 600 (exon 15); NRAS codons 12, 13 and 61 (exons 2 and 3); and PIK3CA codons 542, 545, 546 and 1047 (exons 9 and 20). Pyrosequencing was carried out in each laboratory using a PyroMark Q96 (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). A negative water control and a positive control for each assay were included in every sample run. Raw data files were used to generate pyrograms for interpretation by qualified personnel.

Next-generation sequencing

Next-generation sequencing was used for the detection of mutations in the KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and TP53 genes. All samples were analysed for mutations at specified codons/exons within the following genes: BRAF codons 599, 600 and 601 (exon 15); KRAS codons 12 and 13 (exon 2), 61 (exon 3), 117 and 146 (exon 4); NRAS codons 12 and 13 (exon 2), 61 (exon 3), 117 and 146 (exon 4); PIK3CA codons 542, 545, 546 (exon 10*), 1047 and 1049 (exon 21*); and TP53. *Note: PIK3CA numbering corrected from previous standard operating procedures versions in line with ref sequence NM_006218.2 (previously referred to as exons 9 and 20).

Any changes in these specific codons were reported, as long as they were not considered to be polymorphisms. Full details of the NGS methods can be found in the Laboratory Manual.

Mismatch repair status determination

All four immunohistochemical analyses were carried out on a DAKO Autostainer Link 48 (Ely, UK) using DAKO pre-programmed protocols, which were available with the Autostainer. Antigen retrieval was performed in the accompanying PT-Link chamber with high-pH DAKO target retrieval solution, in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were rinsed with DAKO wash buffer prior to loading into the Autostainer. DAKO ready-to-use antibodies were used for MLH1 (IR079), MSH2 (IR085) and MSH6 (IR086). DAKO PMS2 (M3674) was used at a dilution of 1 : 40. Sections from the two validation TMAs were stained with each antibody, then corresponding whole sections were also stained in cases where the cores appeared negative or equivocal or for cases where all cores had been lost from the TMA section. Tumours were deemed positive if any proportion of the tumour nuclei was positively stained, or negative where all discernible tumour nuclei were negative in the local presence of positively staining stromal and infiltrating lymphocytic cells. Any samples appearing wholly negative with respect to both tumour and stromal components were deemed to be of indeterminate status.

Phosphatase and tensin homologue protein expression

Immunohistochemical staining was carried out using the DAKO Autostainer Link 48. Antigen retrieval was carried out in the accompanying PT-Link chamber with high-pH DAKO target retrieval solution, in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were rinsed with DAKO wash buffer prior to loading into the Autostainer. DAKO PTEN antibody (M3627) was used at a predetermined dilution of 1 : 100. Both validation TMAs were stained, along with all corresponding whole sections. The presence and intensity grade of cytoplasmic staining in the tumour component was noted (0 = negative; 1 = weak cytoplasmic staining, less intense than the surrounding stroma; 2 = moderate cytoplasmic staining, where staining is equal in intensity to the adjacent stromal staining; and 3 = strong cytoplasmic staining, where staining is stronger in intensity to the adjacent stromal staining). For the purposes of randomised stratification of patients, any positive result was reported as ‘no loss’ of PTEN, whereas the negative result was reported as ‘absence’ of PTEN. Three FFPE cell lines (LNCaP, PTEN negative; ZR-75–1, a weak expresser of PTEN; and MCF7, which overexpresses PTEN) were used to create a mini control TMA, which was stained along with each section. A suspension was generated from each cell line, which was subsequently spun down, fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, added to 12% Noble agar at a 1 : 1 ratio, processed and paraffin embedded. Three cores were taken from each and embedded into a new paraffin block to create the mini ‘control TMA’. A section of this was cut onto the same slide as each of the 97 validation samples.

Data validation

Each laboratory sent the results of all analyses directly to the MRC CTU for independent cross-referencing. Any discrepant results were discussed between the biomarker teams from both laboratories until a final unanimous result was agreed on.

A copy of the master protocol and of the protocols for the comparison subtrials can be found on the FOCUS4 trial website (www.focus4trial.org/; accessed 28 October 2022).

Chapter 3 Results from the registration period

Details of the methods used for the registration period can be found in Chapter 2.

Activation and recruitment

FOCUS4 was approved by the UK National Ethics Committee Oxford – Panel C (reference 13/SC/0111) and by the relevant regulatory body, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) (CTA 20363/0400/001 and EudraCT 2012-005111-12), in May 2013. FOCUS4 opened to recruitment in January 2014, with two subtrials activated (FOCUS4-D and FOCUS4-N). Over the following 6 years, 103 UK sites were opened and subsequent substantial amendments approved the inclusion of two further subtrials (FOCUS4-B and FOCUS4-C). The trial centres, investigators and co-investigators are listed in Report Supplementary Material 2. Considerable challenges were encountered in engaging pharmaceutical companies to test therapies in the platform, with 20 drug combinations explored for inclusion. Of the five subtrials that had been planned to open at the design stage (FOCUS4-A, -B, -C, -D and -N), only four were activated (FOCUS4-B, -C, -D and -N) and only three reported results (FOCUS4-C, -D and -N), with FOCUS4-B stopping early on grounds of futility (see Figure 1).

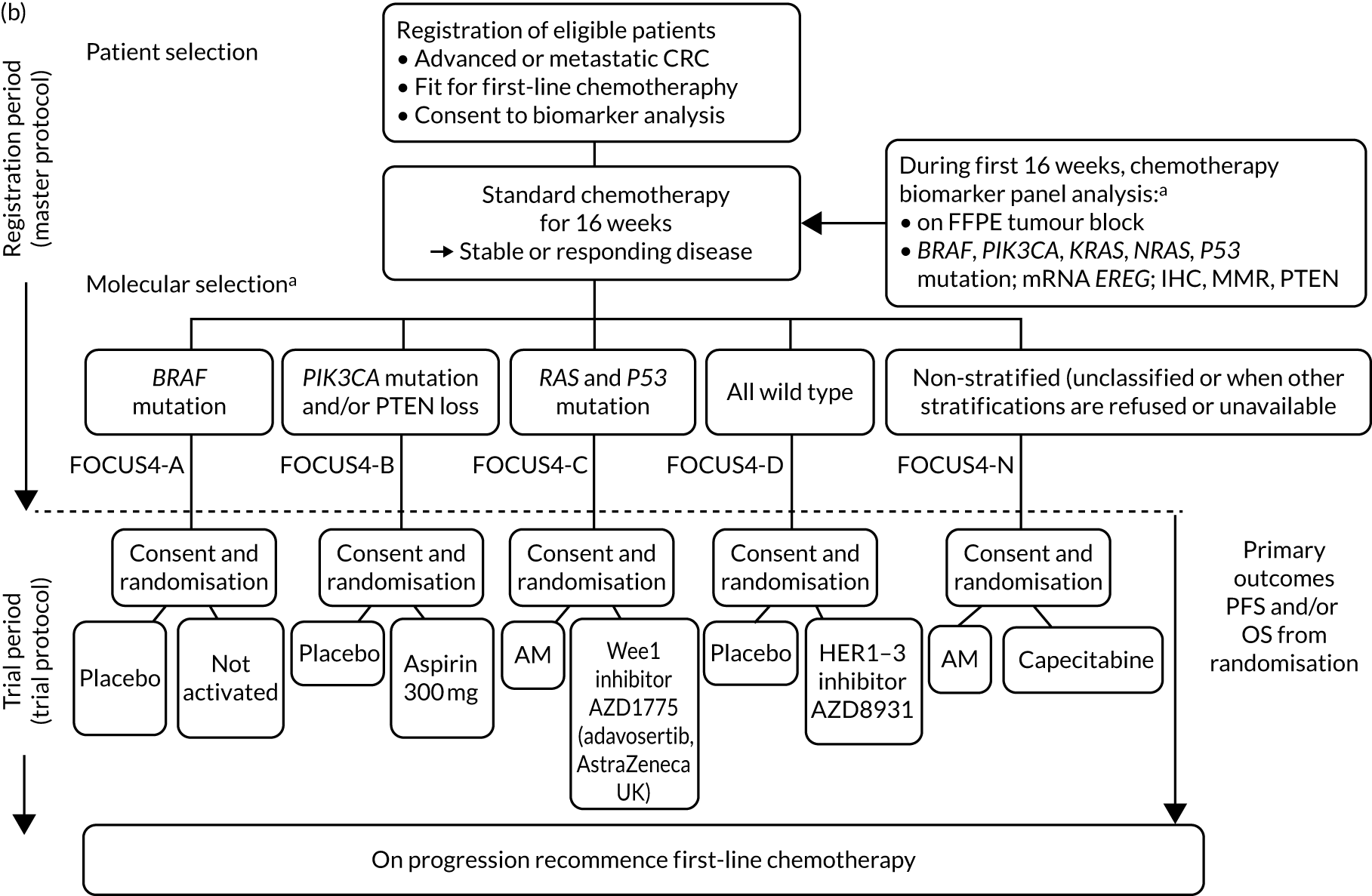

Results from registration

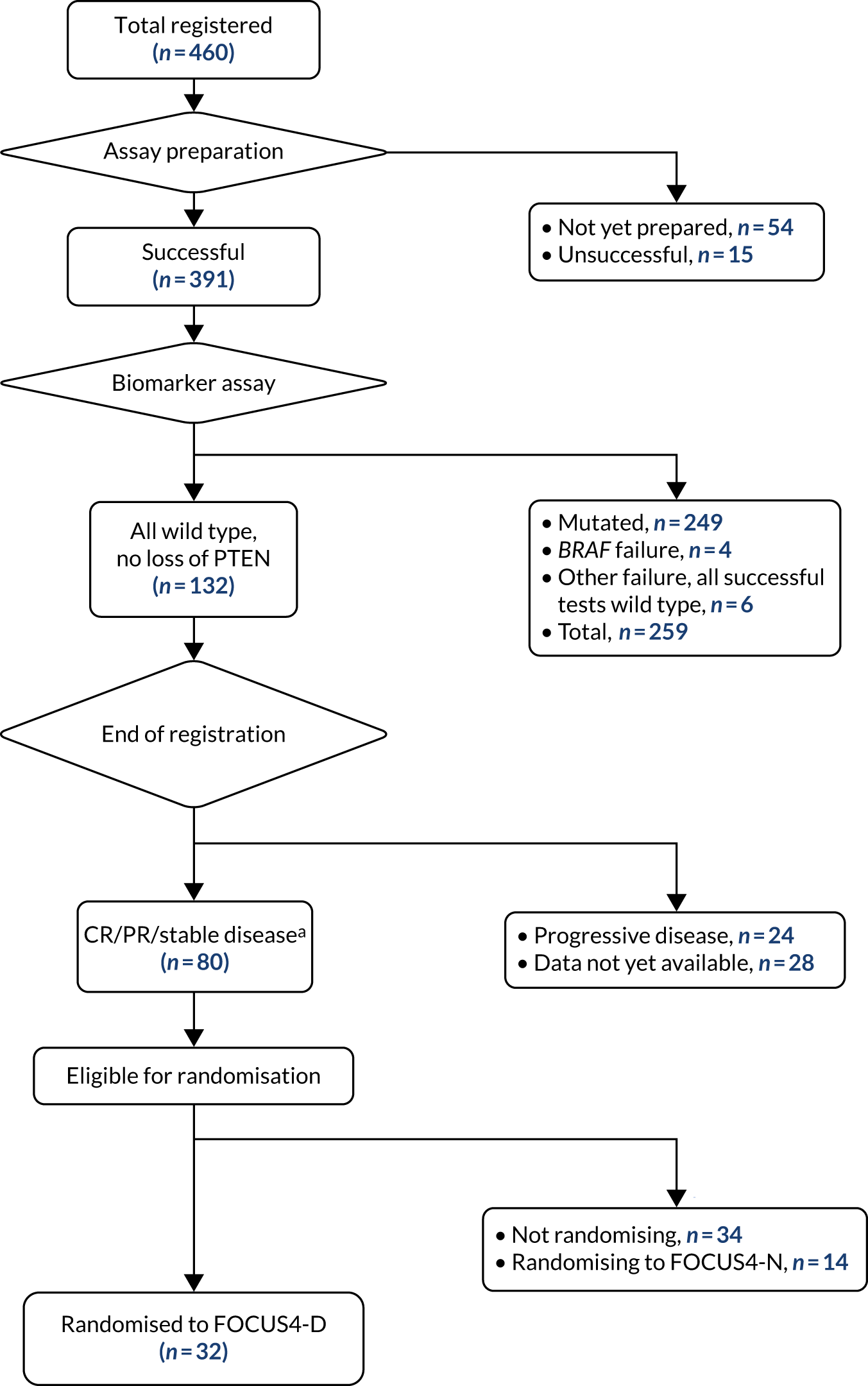

Between January 2014 and October 2020, 1434 patients were registered from 88 UK hospitals, and 316 were randomised into a comparison subtrial (25%). A flow chart of patients during the registration period is presented according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) criteria in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram of patients during registration period of FOCUS4.

Biomarker analysis was undertaken on 1382 samples and the median time from registration to the availability of the biomarker results was 6 weeks [interquartile range (IQR) 4.3–8.3 weeks]. Molecular stratification was successful in 1291 out of 1382 (93%) samples received and was processed with mutations identified in the following genes: BRAF (10%), PIK3CA (14%), KRAS (53%), NRAS (6%), TP53 (69%), RAS + TP53 (32%), BRAF-PIK3CA-RAS wild type (26%) and deficient MMR (3%), as presented in Table 1.

| Biomarker | Total with successful test result (n)a | Total with mutations, PTEN loss or MSI (n) | Observed (%) | Expected (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF mutation | 1260 | 125 | 10 | 8 |

| PIK3CA mutation | 1245 | 179 | 14 | 13 |

| KRAS mutation | 1264 | 666 | 53 | 42 |

| NRAS mutation | 1264 | 72 | 6 | 4 |

| PTEN loss | 1260 | 91 | 7 | 10 |

| Wild type (i.e. none of the above, c.f. FOCUS4-D) | 1243 | 328 | 26 | 42 |

| TP53 | 805 | 556 | 69 | NR |

| TP53 + RAS mutation (cf. FOCUS4-C) | 805 | 332 | 41 | 23 |

| Presence of deficient MMR | 1255 | 33 | 3 | 4 |

Three molecularly targeted subtrials were activated:

-

FOCUS4-D –

-

February 2014 to March 2016

-

evaluated ErbB kinase inhibitor sapitinib (AZD8931, AstraZeneca UK, Cambridge, UK) in the BRAF-PIK3CA-RAS wild-type subgroup.

-

-

FOCUS4-B –

-

February 2016 to July 2018

-

evaluated aspirin in the PIK3CA-mutant subgroup.

-

-

FOCUS4-C –

-

June 2017 to October 2020

-

evaluated adavosertib (AstraZeneca Ltd, Cambridge, UK) in the RAS + TP53 double-mutant subgroup.

-

-

FOCUS4-A for the BRAF-mutant subgroup was not activated, despite a full protocol being prepared, because the data emerging from studies of the planned triplet combination (dabrafenib, panitumumab and trametinib) were determined not to warrant further investigation by the company involved.

In addition, FOCUS4-N was active throughout and evaluated capecitabine monotherapy compared with a treatment break.

Of the 1315 patients completing 16 weeks of first-line therapy, 908 (68%) had disease stabilisation or response and were potentially eligible for randomisation. Of these, 361 were randomly allocated to one of the comparison subtrials: FOCUS4-B (n = 6), FOCUS4-C (n = 69), FOCUS4-D (n = 32) and FOCUS4-N (n = 254).

The choice of first-line therapies used during the registration period is summarised in Table 2.

| Chemotherapy regimen (ordered by frequency) | All registered patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| FOLFIRI | 422 (29) |

| CAPOX | 301 (22) |

| FOLFIRI + CET/PAN | 218 (15) |

| FOLFOX | 215 (15) |

| CAP alone | 47 (3) |

| FOLFOX + CET/PAN | 46 (3) |

| FOLFOXIRI | 28 (2) |

| CAPIRI | 20 (1) |

| FOLFOX + BEV | 16 (1) |

| CAPOX + CET/PAN | 15 (1) |

| FOLFIRI + BEV | 10 (1) |

| Other | 46 (3) |

| Data not available | 50 (4) |

Treatment with EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies was administered according to NHS access or Cancer Drug Fund restrictions.

Details on biomarker prevalence and rates of disease progression during the registration period are presented in Table 3 (see also Table 1).

| Molecular cohort | Randomisation status | Disease assessment, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR/PR/stable disease | PD | Missinga | Total | ||

| BRAF mutant | Not randomised | 43 (48) | 40 (45) | 6 | 89 |

| FOCUS4-N | 30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | |

| Subtotal | 73 (61) | 40 (34) | 6 | 119 | |

| PIK3CA mutantb | Not randomised | 60 (60) | 38 (38) | 2 | 100 |

| FOCUS4-B | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| FOCUS4-N | 26 | 0 | 0 | 26 | |

| Subtotal | 92 (70) | 38 (29) | 2 | 132 | |

| RAS mutantc | Not randomised | 142 (59) | 82 (34) | 18 | 242 |

| FOCUS4-N | 103 | 0 | 0 | 103 | |

| Subtotal | 245 (71) | 82 (24) | 18 | 345 | |

| RAS + TP53 mutantd | Not randomised | 85 (47) | 87 (48) | 10 | 182 |

| FOCUS4-C | 69 | 0 | 0 | 69 | |

| FOCUS4-N | 13 | 0 | 0 | 13 | |

| Subtotal | 167 (63) | 87 (33) | 10 | 264 | |

| All wild type | Not randomised | 159 (65) | 74 (30) | 12 | 245 |

| FOCUS4-D | 32 | 0 | 0 | 32 | |

| FOCUS4-N | 57 | 0 | 0 | 57 | |

| Subtotal | 248 (74) | 74 (22) | 12 | 334 | |

| Non-stratified | Not randomised | 58 (60) | 35 (36) | 3 | 96 |

| FOCUS4-N | 25 | 0 | 0 | 25 | |

| Subtotal | 83 (69) | 35 (29) | 3 | 121 | |

| Overall | Not randomised | 547 (57) | 356 (37) | 51 | 954 |

| FOCUS4-B | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| FOCUS4-C | 69 | 0 | 0 | 69 | |

| FOCUS4-D | 32 | 0 | 0 | 32 | |

| FOCUS4-N | 254 | 0 | 0 | 254 | |

| Total | 908 (69) | 356 (27) | 51 | 1315 | |

Failed endeavours

The continuous pursuit of new agents for testing in the FOCUS4 platform accounted for a lot of the investigator’s time. During the course of the trial, a total of 20 therapeutic interventions were explored and presented to the joint National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME)/Cancer Reserch UK funding subboard for peer-review approval, but only four culminated in an activated comparison (Table 4). Reasons for non-activation were predominantly failure of drugs at early clinical testing in this advanced metastatic disease setting; however, protocol development and contract negotiations had often progressed a long way and considerable resource had been used up for ultimately futile collaborations. Other endeavours failed bceause of strategic shifts

| Cohort | Biomarker | Biomarker incidence | Intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | BRAF V600E mutation | 10% | BRAF inhibitor and MEK inhibitor | Science evolved |

| A2 | BRAF V600E mutation | 10% | Dabrafenib (tafinlar, Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd, London, UK), trametinib (mekinist, Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd) and panitumumab (vectibix, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA) | GlaxoSmithKline plc (Brentford, UK) sold oncology portfolio to Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). Novartis found activity insufficient to support trial |

| B1 | PIK3CA mutant or PTEN loss on IHC | 22% | Dual PI3K inhibitor/mTOR inhibitor | Insufficient evidence of benefit with evolving data to obtain pharmaceutical engagement |

| B2 | PIK3CA mutation | 12% | Aspirin | FOCUS4-B trial |

| C1 | KRAS/NRAS mutation | 45% | MEK inhibitor and PI3K inhibitor | Found to be too toxic in early studies |

| C2 | RAS mutation + HLA A-2 | 20% | IMA 190 peptide vaccine (Immatics, Tuebingen, Germany) | Company did not commit |

| C3A | H3K36me3 loss | < 2% | Wee1 inhibitor, AZD1775 (adavosertib, AstraZeneca UK) | Biomarker validation showed very low incidence of loss in CRC |

| C3B | RAS + TP53 double mutation | 30% | Wee1 inhibitor, AZD1775 | FOCUS4-C trial |

| C3C | ATM loss | 6% | ATM inhibitor, AZD6738 | Company did not support concept |

| D1 | KRAS, NRAS and BRAF wild type | 40% | pan-HER inhibitor, AZD7941 | FOCUS4-D trial |

| D2 | KRAS, NRAS and BRAF wild type | 40% | MM151 | Company sold asset prior to contract |

| D3 | Triple wild type, HER2 negative | 25% | Cetuximab and CDK4/6 inhibitor | Data from SCCHN19 |

| D4 | Triple wild type, HER2 overexpressed | 2% | Trastuzumab (Herceptin, F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) and CDK4/6 inhibitor | Biomarker incidence too low |

| E1 | MMR deficient and POLE mutant | 4% | Avelumab (Bavencio, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany and Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA) | Company did not support concept |

| E2 | MMR deficient or TGFb activated | 30% | Bintrafusp alpha | EME programme did not extend grant |

| F | Wnt ligand dependant, axin 2 overexpressed | 9% | RXC004 porcupine inhibitor | EME programme did not extend grant |

| G | ALK/ROS rearrangements | 2% | Crizotinib (Zalkori, Pfizer Inc.) | Biomarker incidence too low |

| N1 | Non-stratified group | N/A | Capecitabine | FOCUS4-N trial reported and met primary end point |

| N2 | Non-stratified group | N/A | Add TAS-102 randomisation | Global company did not support concept |

| N3 | Non-stratified group | N/A | Metronomic cyclophosphamide | EME programme did not extend grant |

within companies, including the selling of assets suddenly and unexpectedly. Markers with incidence below 5% were also generally deemed too infrequent to pursue, although we have seen the very successful evaluation and licensing of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the MSI-high subgroup, which occurs in only 4% of metatastic CRCs.

Discussion and conclusions

Parts of this section have been reproduced with permission from Brown et al. 20 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Adaptive trials not only provide significant advantages in the evaluation of multiple novel therapies in a disease setting, but also provide major challenges in their design, funding and delivery. FOCUS4 was jointly funded by the MRC/NIHR EME programme and Cancer Research UK (CRUK), with a combined budget (£3.6M) that was large in 2012 but small compared with current major molecularly stratified platform studies. Joint funding added a delay to trial initiation and review of amendments (performed via a sub-board representing both funders). For these trials to fulfil their aim of flexibility and nimbleness, it is important to learn and implement the lessons of undertaking complex trials in the era of the pandemic, particularly in terms of protocol and amendment approval, as recently espoused in the UK. 21

The key features of the FOCUS4 design have all proved to be robust in the application. The use of PFS in the maintenance setting as the primary end point has been shown to be an effective indicator of agents with activity, which may not have been revealed through a more conventional assessment of response in end-stage patients. This is of particular relevance for trials in the maintenance therapy setting. It was not possible to progress a therapy as planned through to evaluate whether or not the activity was specific to the molecular subgroup initially identified. Nor did it prove possible to move from Phase II to Phase III testing. These limitations were due to timing and funding availability rather than design failure.

The setting of the interval after 16 weeks of induction chemotherapy for patients with metastatic disease is a novel one. The registration of olapraib (Lynparza, Astrazeneca) in this setting of olaparib in platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer has made this a more recognisable route to registration. It builds on a pattern of practice of allowing patients a complete break from therapy following several months of induction chemotherapy, which is evidence based. Although this method is not unique to the UK, it is perhaps more widely utilised in the UK than in many other countries. This may change as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, as patients now choose to spend more time away from hospitals and many have preferred a move to remote monitoring.

Adding the complexity of molecular stratification to allocate patients into the optimal biomarker-defined subgroup adds an extra layer of challenges, including the developmental status of the biomarker, the predictive power of the biomarker and selectivity for the therapy being evaluated (which is usually underdeveloped for any novel agent). Timely and reproducible delivery of the biomarker-testing panel, understanding the prognostic impact of the biomarker selection and the need to accommodate biomarker-negative patients remains critical to success. During FOCUS4, the simple mutation-based stratification process for many of the biomarkers that we tested has become part of standard care. In the future, despite the now more widespread routine availability of NGS-based tumour profiling, trial-based stratification testing will continue to need to provide transcriptomic and other more sophisticated analyses. It may be that the revolution in digital pathology and artificial intelligence will enable some biological stratification to be achieved directly from routine images, as shown recently with consensus molecular subgroup subtyping. 22

Rates of allocation into biomarker-selected groups are often very low in precision medicine studies, as exemplified by the Lung-Matrix Trial23 and the Lung-Map Trial. 24 In the largest study of this kind, National Cancer Institute (NCI)-Match,25 5954 patients were enrolled with refractory malignancies, of whom 17.8% were assigned to a targeted therapy. Among these, 848 patients with CRC were registered, 13.7% of whom were assigned and 10% enrolled into a specific therapy trial. 26 In FOCUS4, rather than assigning patients in non-randomised cohorts to therapies with hypothesised efficacy, 361 out of 1434 (25%) registered patients were randomised into a specified subtrial, and 107 (7.5%) of the registered patients were randomised into molecularly stratified subtrials. This attrition related to three main factors: (1) inadequacy of sample submission or analysis (10%), (2) death or progressive disease during induction therapy (27%) or (3) lack of availability of a suitable molecular subtrial or lack of patient consent when the patient was eligible for randomisation (60% of those potentially eligible). However, as shown in the evaluation of adavosertib in FOCUS4-C,27 randomisation against a control arm was critical to demonstrating efficacy, which would probably have been overlooked in a non-randomised design.

It is notable from the RECOVERY trial28 that negative results are more likely but are just as important as positive results in tackling diseases of high unmet clinical need. To date, the RECOVERY trial28 has identified four positive results [dexamethasone, tocilizumab, baricitinib (Olumiant®, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IND, USA) and the combination of Casirivimab and imdevimab (Ronapreve, Roche, Basel, Switzerland)] and seven negative results since its set-up in March 2020. NCI-Match has 39 cohorts: 12 have published final results to date,29 of which six have shown positive results. In FOCUS4, two positive results (capecitabine and adavosertib) were reported, one clear negative result and one feasibility failure.

Although non-commercial organisations may be best placed to set up and run such studies enabling collaboration with different pharmaceutical companies for different agents, engagement with the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries is critical to success. A large amount of investigator time was spent negotiating with companies to test their agents in the platform, but only 4 out of 20 drug combinations explored came to fruition. To obtain approval from companies to include their agents, a very robust approach to the development of preclinical data packages to support the selection of particular drug/biomarker combinations is essential. This requires a well-funded, preclinical testing collaboration, ideally with disease subtype-specific models using genetically engineered mouse models, patient-derived xenograft and patient-derived organoids linked to detailed disease stratification information. From this basis, strong applications can be made to pharma to include agents in such precision medicine studies with a higher likelihood of success than was observed in FOCUS4. Only in the last 2 years has this been available through separate funding streams (the MRC stratified medicine consortium S:CORT30 and the ACRCelerate collaboration31 jointly funded by CRUK, the Italian Association for Cancer Research and the Spanish Association Against Cancer) and the fruit of this is yet to be seen to feed into an updated precision medicine study in CRC.

The enterprise of precision medicine adaptive platform trials is a massive exercise in team science. It is a tribute to the large body of investigators, research nurses and data managers at sites, laboratory scientists and trial unit staff, with the support from the institutions, funders and pharmaceutical companies, and, central to all of this, our patients, who have enabled us to complete this FOCUS4 trial.

Chapter 4 Results from FOCUS4-B

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Brown et al. 20 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Scientific rationale for FOCUS4-B

PIK3CA is one of the most commonly altered genes in CRC, with mutations found in 12–20% of cases depending on whether the sequencing is limited to hotspot exons or covers the entire gene (i.e. broader genetic testing of the entire gene identifies a higher number of mutations than testing limited to the most common sites of mutation). 32 PIK3CA encodes the catalytic p110α subunit of PI3K, a key node in the PI3K–AKT pathway, which regulates cellular proliferation, apoptosis and metabolism. 33 Approximately two-thirds of PIK3CA mutations cluster to codons 542 and 545 in the exon 9 helical domain or to codon 1047 in the exon 20 kinase domain. Although they act through different mechanisms, both helical and kinase domain substitutions cause constitutive activation of the PI3K–AKT pathway and are strongly oncogenic in preclinical models. 34 PIK3CA mutations in CRC are often associated with KRAS-activating mutations35 (and also with NRAS- and BRAF-activating mutations) and are reported to correlate with other clinicopathological features, such as right-sided cancers and tumoural MMR deficiency. 36,37 Importantly, in contrast to other molecular aberrations, such as MMR deficiency, the frequency of PIK3CA mutation in metastatic CRC is broadly similar (12.7%) to that observed in early-stage disease,18 consistent with data indicating that neither exon 9 nor exon 20 mutations are prognostic in isolation in early CRC. 38 Similarly, PIK3CA mutation does not appear to be prognostic in metastatic disease. 18 Although it has been suggested that CRCs with mutation of both PIK3CA exon 9 and PIK3CA exon 20 display poor outcome,35 the low frequency (approximately 0.6%) of such double mutants means that validation is required. Emerging data suggest that, similar to KRAS, BRAF and NRAS mutations, PIK3CA mutation may predict resistance to cetuximab in metastatic CRC; however, the current evidence is conflicting (perhaps because of the high frequency of concurrent activating mutations in KRAS and NRAS) and there are insufficient analyses to inform practice. 39,40

Unsurprisingly, given the high frequency of PIK3CA mutation in CRC and other solid tumours, much attention has focused on the development of PI3K inhibitors. Although the high degree of conservation of PI3K with other kinases has made the design of specific agents challenging, compounds with nanomolar affinity have recently entered clinical practice. 41 Disappointingly, emerging data from current early phase clinical trials42 indicate that these drugs lack significant activity against CRC (either alone or in combination with MEK inhibitors) and, therefore, are poor candidates for further development in this particular disease. Our initial efforts to obtain these agents were, therefore, unfruitful. Therefore, at present, no specific therapeutic strategies exist for the subgroup of patients with PIK3CA-mutant CRC.

Aspirin as an anti-cancer agent in colorectal cancer

Over the past two decades, multiple retrospective and prospective studies have unequivocally demonstrated that regular use of aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) protects against the development of colorectal adenoma and CRC. 43–46 More recently, aspirin has also been shown to reduce the incidence of metastatic disease following CRC resection. 47,48 In both cases, the antineoplastic activity of aspirin is not only seen with high, multiple-daily dosing (300–600 mg four times per day) required for its systemic anti-inflammatory effect owing to inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase 2 (COX-2), but also seen with low, once-daily dosing (70–100 mg once daily) at which the action of aspirin is thought to be limited to an antiplatelet effect from irreversible inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase 1. 48,49 Platelets promote tumour growth and metastasis through multiple mechanisms, including protection of circulating tumour cells from immune destruction by microthrombi formation, facilitation of tumour cell extravasation at distant sites and secretion of tumourigenic growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor. 50 Thrombocytosis predicts poor outcome in patients with metastatic CRC,51 and platelet depletion inhibits tumour growth in animal models. 52–54 These data, together with the recent demonstration that tumour self-seeding by circulating tumour cells is an important promoter of cancer growth in mice,55 suggest that aspirin may demonstrate anti-tumour activity in the context of advanced disease. Such an evaluation would complement the investigation of aspirin as adjuvant therapy in CRC, which is to be determined by large randomised trials that are currently recruiting (ASCOLT56) or in set-up (Add-Aspirin57).

PIK3CA mutation as an aspirin biomarker

Two large, retrospective studies35,58 have suggested that mutations in exons 9 and 20 of PIK3CA strongly predict benefit of aspirin in CRC. The first, reported by Liao et al. ,35 retrospectively analysed 964 patients with a mixture of disease stages (stages 1–4). The subgroup of patients with stage 4 CRC in this study was small (64 patients, 7% of the total of 964 patients). The study demonstrated that, among patients with PIK3CA-mutant tumours, reduction in CRC-specific mortality was significantly greater in those who were regular users of aspirin after diagnosis than in non-users of aspirin [multivariate adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 0.18, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.06 to 0.61; p = 0.0001]. By contrast, patients with tumours lacking PIK3CA mutations did not appear to benefit from aspirin use (HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.32; p = 0.76). Statistical analysis demonstrated a significant interaction between PIK3CA mutation and aspirin use (p = 0.02).

These data were supported by analysis of the VICTOR study: a large, randomised controlled trial (RCT) that compared the cyclo-oxygenase-2-specific inhibitor rofecoxib with placebo following completion of adjuvant therapy for stage 2/3 CRC. 58 It should be noted that there were no patients with stage 4 CRC in this study. Although the study protocol did not permit concomitant NSAID or high-dose aspirin use, low-dose (≤ 100 mg daily) aspirin was allowed and was recorded both at randomisation and during follow-up. As in the study by Liao et al. ,35 the benefit of aspirin appeared to be restricted to patients with PIK3CA-mutant cancers, with no recurrences in the subgroup of regular aspirin users whose tumours harboured PIK3CA exon 9 or 20 mutations (multivariate adjusted HR 0.11, 95% CI 0.001 to 0.832; p = 0.027; p-interaction = 0.024), compared with similar outcome of aspirin users and non-users in those lacking tumour PIK3CA mutation (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.42; p = 0.71).

Although these data are provocative, it is important to note that other retrospective analyses have not confirmed improved outcome with aspirin use in PIK3CA-mutant CRC and have indeed suggested other biomarkers that may predict benefit from aspirin (Table 5). 60 Furthermore, these studies were all limited by their retrospective nature, variable aspirin dose used, differing end points (e.g. relapse-free survival, CRC-specific mortality, OS) and small numbers of patients with advanced CRC. Therefore, prospective evaluation in a randomised, controlled trial is essential to determine the efficacy of aspirin as an anti-cancer therapy in PIK3CA-mutant stage 4 CRC.

| Study | Stage | End point | PIK3CA wild type | PIK3CA mutant | Reference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No aspirin (n) | Aspirin (n) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | No aspirin (n) | Aspirin (n) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| Liao X et al.35 | I–IV | CRC-specific survival | 466 | 337 | 0.93 (0.68 to 1.28) | 0.76 | 95 | 66 | 0.18 (0.05 to 0.6) | < 0.001 | 34 |

| OS | 0.94 (0.75 to 1.17) | 0.96 | 0.54 (0.31 to 0.94) | 0.01 | |||||||

| Domingo E et al.58 | II, III | RFS | 681 | 111 | 0.92 (0.6 to 1.42) | 0.71 | 90 | 14 | 0.11 (0.001 to 0.81) | 0.027 | 57 |

| OS | 1.05 (0.62 to 1.77) | 0.85 | 0.29 (0.04 to 2.33) | 0.245 | |||||||

| Murphy C et al.59 | II, III | RFS | 235 | 66 | 0.77 (0.34 to 1.73) | 0.53 | 40 | 16 | 0.45 (0.06 to 3.70) | 0.48 | 63 |

| OS | NR | NR | 2.50 (1.46 to 4.28) | 0.0008 | 1.76 (0.51 to 6.04) | 0.37 | |||||

| Reimers MS et al.60 | I–IV | OS | 384 | 147 | 0.55 (0.40 to 0.75) | 0.001 | 73 | 27 | 0.73 (0.33 to 1.63) | 0.4 | 58 |

Potential toxicities of aspirin

Although concerns regarding the potential toxicities of aspirin, particularly that of gastrointestinal haemorrhage, have limited the use of aspirin as a chemopreventative agent,61 the absolute increase in risk of significant toxicities from low-dose therapy for patients without established risk factors for such toxicity is modest. A meta-analysis62 of RCTs that investigated the benefits of low-dose aspirin (75–500 mg daily) for primary cardiovascular prevention, including over 95,000 partipants, demonstrated that aspirin increased the incidence of serious extracranial bleeding (usually defined as requiring transfusion or resulting in death) from 0.07% per year to 0.1% per year (HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.30 to 1.82). Furthermore, although participants in the recent CAPP2 study63 were perhaps younger than the anticipated population in FOCUS4-B, in the CAPP2 study aspirin at 600 mg daily for 25 months was not associated with an excess of adverse events compared with placebo.

To minimise potential harm to trial participants, several measures proven to reduce the risk of serious adverse events from aspirin were recommended,64 including exclusion of patients with a high risk of complications (e.g. previous peptic/duodenal ulcer or gastrointestinal bleed); careful management and treatment of symptoms, such as dyspepsia; blood pressure monitoring; and avoidance of concomitant NSAID use. Testing and eradication of Helicobacter pylori was also recommended and proton pump inhibitors were used where appropriate.

Aspirin dosing

Although evidence indicates that aspirin at doses of 75–100 mg daily exerts an antineoplastic effect, at present the mechanism of action of aspirin is unclear and potentially multifactorial. Taking into account the possibility that some or all of these mechanisms could be dose dependent, and the data suggesting that the impact on CRC mortality is greater for patients taking the highest aspirin doses (> 6× 325 mg tablets per week vs. 2–5 × 325 mg per week),65 while recognising that gastrointestinal toxicity is likely to increase with doses higher than 325 mg daily, the recommended aspirin dose for patients in FOCUS4-B is 300 mg daily. This dose permits the evaluation of both the antiplatelet effect of aspirin and possible additional mechanisms underlying its antineoplastic effect.

FOCUS4-B research objectives

FOCUS4-B aims to determine whether or not regular, intermediate-dose aspirin improves PFS when used as maintenance therapy following initial disease stabilisation or response from first-line treatment in patients with PIK3CA exon 9/exon 20 mutant CRC.

Translational studies, including analysis of tumour blocks for other putative aspirin biomarkers and analysis of cell-free DNA, were planned. The purpose of the former was to increase our understanding of determinants of response to antiplatelet therapy in malignant disease, whereas the latter could generate insights into the dynamics of tumour clones under therapy if efficacy was demonstrated.

Study methods

Trial approvals, patient eligibility and recruitment

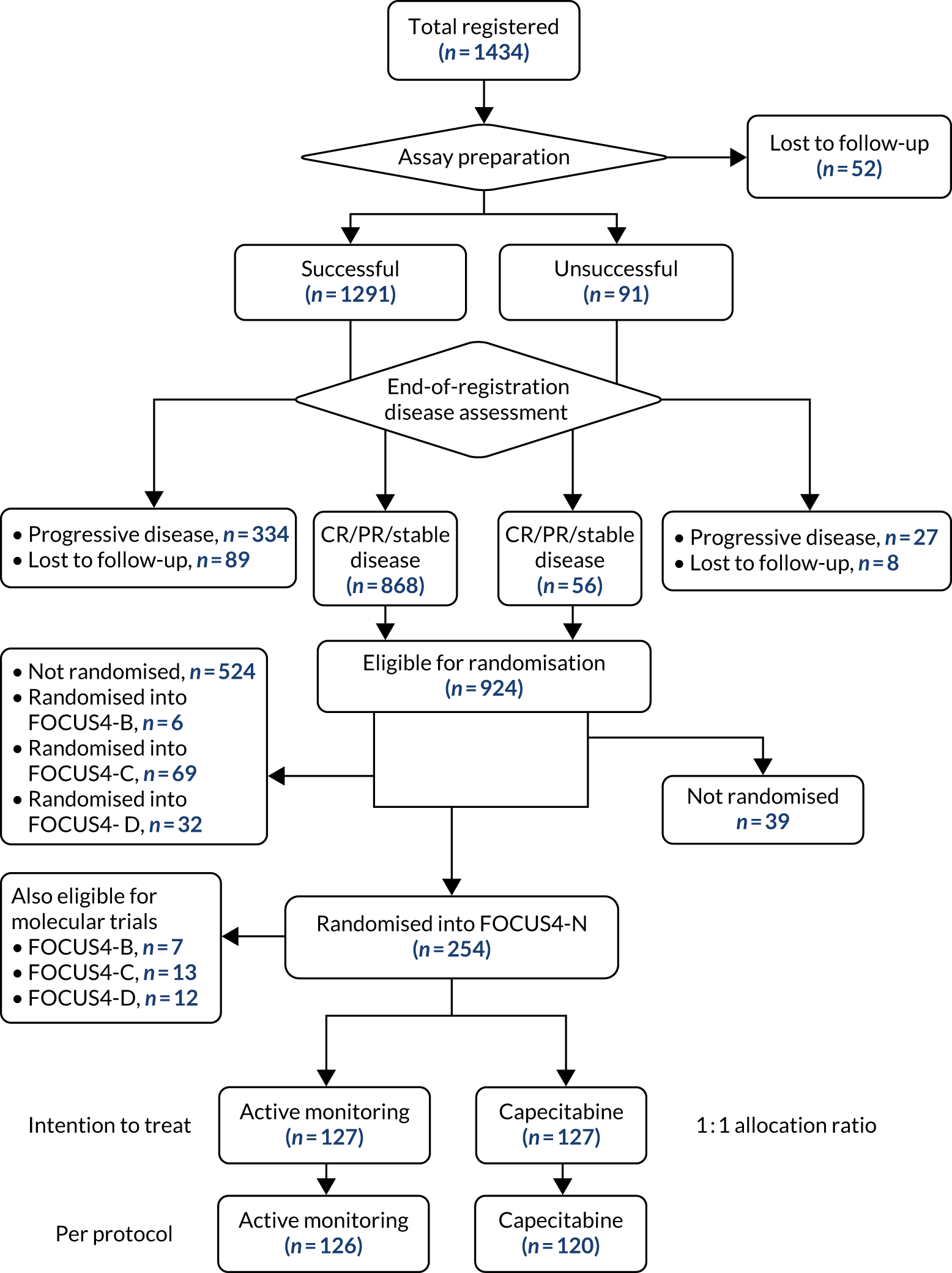

The trial and subsequent amendments were approved by the UK National Ethics Committee Oxford, panel C, and by the MHRA. Patients with newly diagnosed metastatic CRC were registered into the FOCUS4 trial programme from 88 UK hospitals (Figure 3). Patients were randomised into the FOCUS4-B trial in all participating hospitals, starting in February 2016. Patients aged ≥ 18 years with newly diagnosed locally advanced or metastatic CRC were assessed for eligibility for FOCUS4-B if their tumour was confirmed to have a PIK3CA exon 9 or exon 20 mutation (using a NGS platform), and if they had remained stable or were responding after 16 weeks of first-line treatment. Patients were required to undergo baseline CT within 4 weeks prior to randomisation; a minimum 3-week washout period after the last dose of chemotherapy or biological therapy and before the first dose of aspirin or matched placebo; adequate renal (creatinine clearance of > 50 ml/minute) and liver function; and a WHO performance status of 0–2.

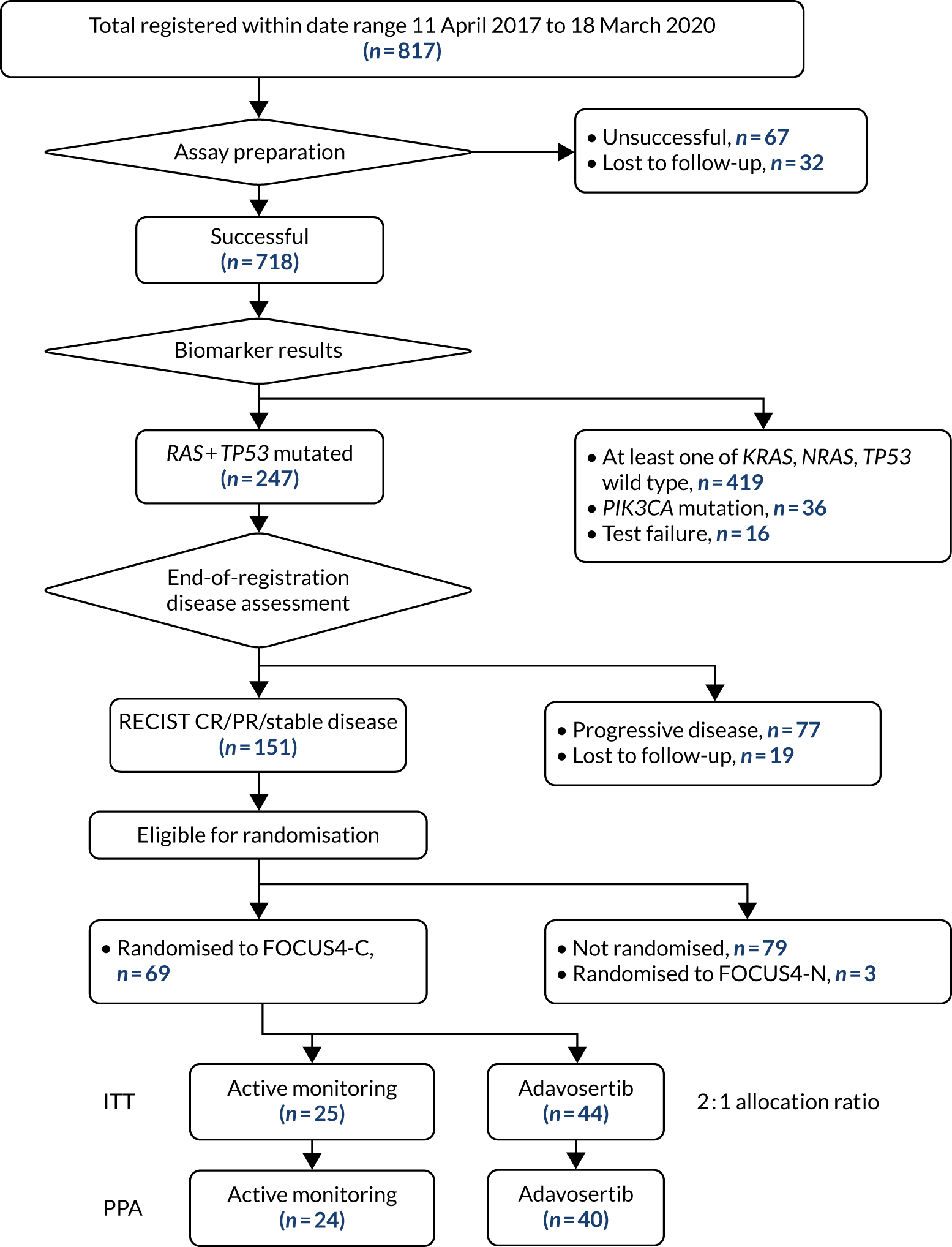

FIGURE 3.

FOCUS4-B schema.

The aspirin 300-mg tablets and matched placebo were supplied by Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany). The packaging, labelling and distribution of aspirin were undertaken by Alcura UK Ltd (Northampton, UK).

Patients randomised to receive aspirin or placebo continued to take the drug until disease progression, death or intolerable toxicity. The patients received 300 mg of aspirin or matched placebo once daily. Patients underwent clinical evaluation after the first 4 weeks from day 1 of randomised trial treatment by a research nurse or doctor to determine if there were any toxicity or tolerability issues. Patients were assessed by CT every 8 weeks from randomisation, together with full reporting of safety outcomes. PFS was the primary outcome measure for FOCUS4-B and, therefore, clinicians were required to use a consistent approach to treatment duration. Trial treatment was planned to be continued until progressive disease was identified on radiological grounds (RECIST v1.1), the development of cumulative toxicity or the patient chose to stop treatment. Patients were considered to be off trial treatment (but still in the trial) if there was a continuous break in their trial treatment of more than 28 days. If this occurred, trial medication was permanently discontinued and this was appropriately documented.

However, patients who discontinued the trial drug for reasons other than objective disease progression were to be followed up with tumour assessments every 8 weeks until objective disease progression as assessed by RECIST v1.1, even if they had started subsequent anti-cancer therapies. Toxicity assessments were to be carried out until the patient stopped trial treatment. On disease progression, patients were to restart their first-line treatment or move onto a standard second-line therapy at the discretion of the treating clinician. After progression, a progress electronic case report form was to be completed at 3 months and then every 6 months until patient death or the end of the trial.

Statistical methods

Treatment allocation

Once patients had been consented and deemed eligible for FOCUS4-B, they were randomly assigned to one of the following treatment arms (in a 2 : 1 ratio for aspirin vs. placebo):

-

arm B1 – placebo once daily

-

arm B2 – aspirin 300 mg once daily.

Both patients and treating clinicians were blinded to patient allocation to 300 mg aspirin once daily or placebo.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome for FOCUS4-B was PFS, defined as the time from randomisation to either disease progression (according to RECIST criteria) or death from any cause. OS was a secondary outcome, defined as the time from randomisation to death from any cause. Other secondary outcomes included safety, toxicity and tumour response.

Sample size calculation

For FOCUS4-B, a randomisation ratio of 2 : 1 was used in favour of the active arm. A summary of the operating characteristics for FOCUS4-B, with predicted timelines for the staged interim analyses, is presented in Table 6. It was anticipated that all data were to be released at the end of stage 3 to allow an open decision on whether or not to proceed to an assessment of OS.

| Characteristic | Stage 1: safety | Stage 2: LSA | Stage 3: efficacy for PFS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | PFS | PFS | PFS |

| One-sided alpha | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.025 |

| Power (overall power maintained at 80%) | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.82 |

| Target HR | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| Critical HR | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.75 |

| Time required (months) | 24.5 | 15.9 | 17.3 |

| Cumulative time (months) | 24.5 | 40.4 | 57.6 |

| Cumulative events required in control arm (total) | 24 (65) | 45 (126) | 68 (195) |

| Total expected cumulative randomisations | 98 | 162 | 231 |

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed in accordance with a predefined SAP that was agreed before database lock and were undertaken using Stata statistical software, version 16.1 (Stata Corporation, TX, USA). Given that this was a Phase II efficacy signal-seeking study, the primary analysis was prespecified as the per-protocol analysis, which was defined by patients who had completed at least one cycle of trial treatment. Analyses were also performed according to intention to treat. Patients were censored according to the following criteria:

-

For survival status, patients were censored on the date that they were last known to be alive because they collected a prescription from their hospital pharmacy or attended a follow-up visit or a CT appointment.

-

For PFS, patients were censored without progression on the date of the last CT scan, showing no progression.

-

For patients who died before any follow-up visit or CT appointment, the date of death was used as the date of the event and assumed death without progression providing the death occurred within 3 months of randomisation or any previous CT scan confirming no progression.

Kaplan–Meier curves were used to present survival data and Cox regression modelling to estimate HRs between randomised groups. Unadjusted HRs were estimated, as well as HRs adjusted for the stratification factors that were used to minimise patients into allocated groups (primary analysis). A further analysis also adjusted for resection status, timing of metastatic disease, alkaline phosphatase, white blood cell count, age of tumour sample and use of aspirin at baseline. Deviation from non-proportional hazards was assessed using regression of scaled Schoenfeld residuals against the log of time.

Study results

Recruitment and patient characteristics

By December 2017, a total of 47 PIK3CA-mutated patients had been identified. Of these patients, six entered FOCUS4-B, four entered FOCUS4-N, 12 progressed, nine refused owing to patient or clinician decision, two were not randomised owing to toxicity concerns, five were ineligible for various reasons, two died during their first-line therapy and seven were still in the registration phase. Between June 2016 and September 2017, six patients were randomised into FOCUS4-B using a 2 : 1 ratio: four pateints to aspirin and two patients to placebo. An overview of the baseline and demographic characteristics for the six patients randomised into FOCUS4-B is presented in Table 7.

| Characteristic | Placebo (N = 2) | Aspirin (N = 4) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 67.0 (7.1) | 49.6 (13.5) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 1 (50) | 2 (50) |

| Female | 1 (50) | 2 (50) |

| Current WHO performance status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 2 (100) | 2 (50) |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 2 (50) |

| Site of primary of tumour, n (%) | ||

| Right colon | 1 (50) | 1 (25) |

| Left colon | 0 (0) | 2 (50) |

| Rectum | 1 (50) | 1 (25) |

| Current state of primary tumour, n (%) | ||

| Resected primary | 2 (100) | 3 (75) |

| Unresected primary | 0 (0) | 1 (25) |

| Timing of metastases, n (%) | ||

| Metachronous | 1 (50) | 2 (50) |

| Synchronous | 1 (50) | 2 (50) |

| Number of metastatic sites, n (%) | ||

| One | 1 (50) | 2 (50) |

| Two or more | 1 (50) | 2 (50) |

| Disease assessment at end of first-line treatment, n (%) | ||

| Partial response | 0 (0) | 3 (75) |

| Stable disease | 2 (100) | 1 (25) |

| First-line treatment regimen, n (%) | ||

| FOLFIRI | 2 (100) | 1 (25) |

| FOLFIRI + CET | 0 (0) | 1 (25) |

| CAPOX | 0 (0) | 2 (50) |

| RAS mutation status, n (%) | ||

| Mutation | 2 (100) | 2 (50) |

| Wild type | 0 (0) | 2 (50) |

| Total | 2 (100) | 4 (100) |

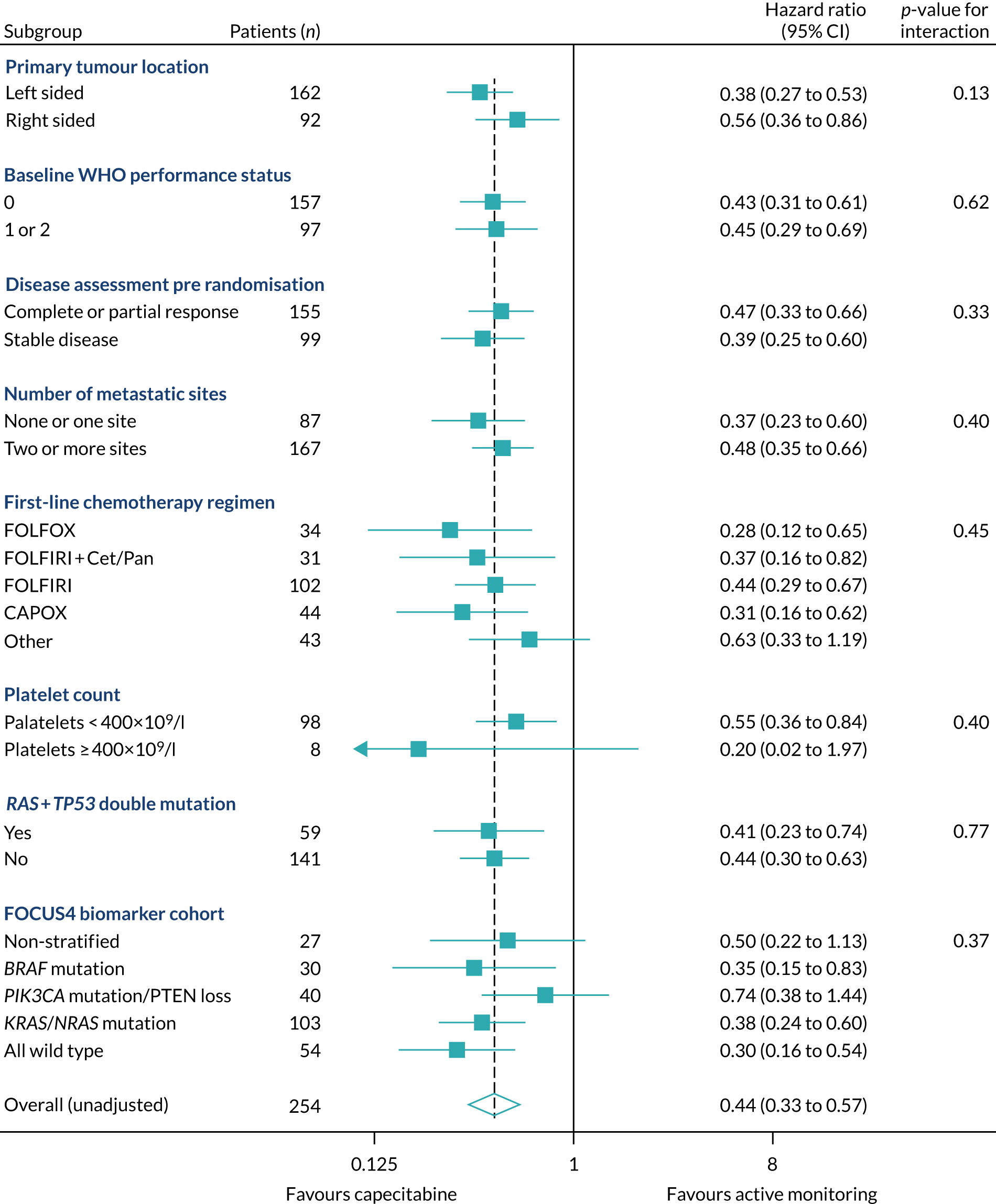

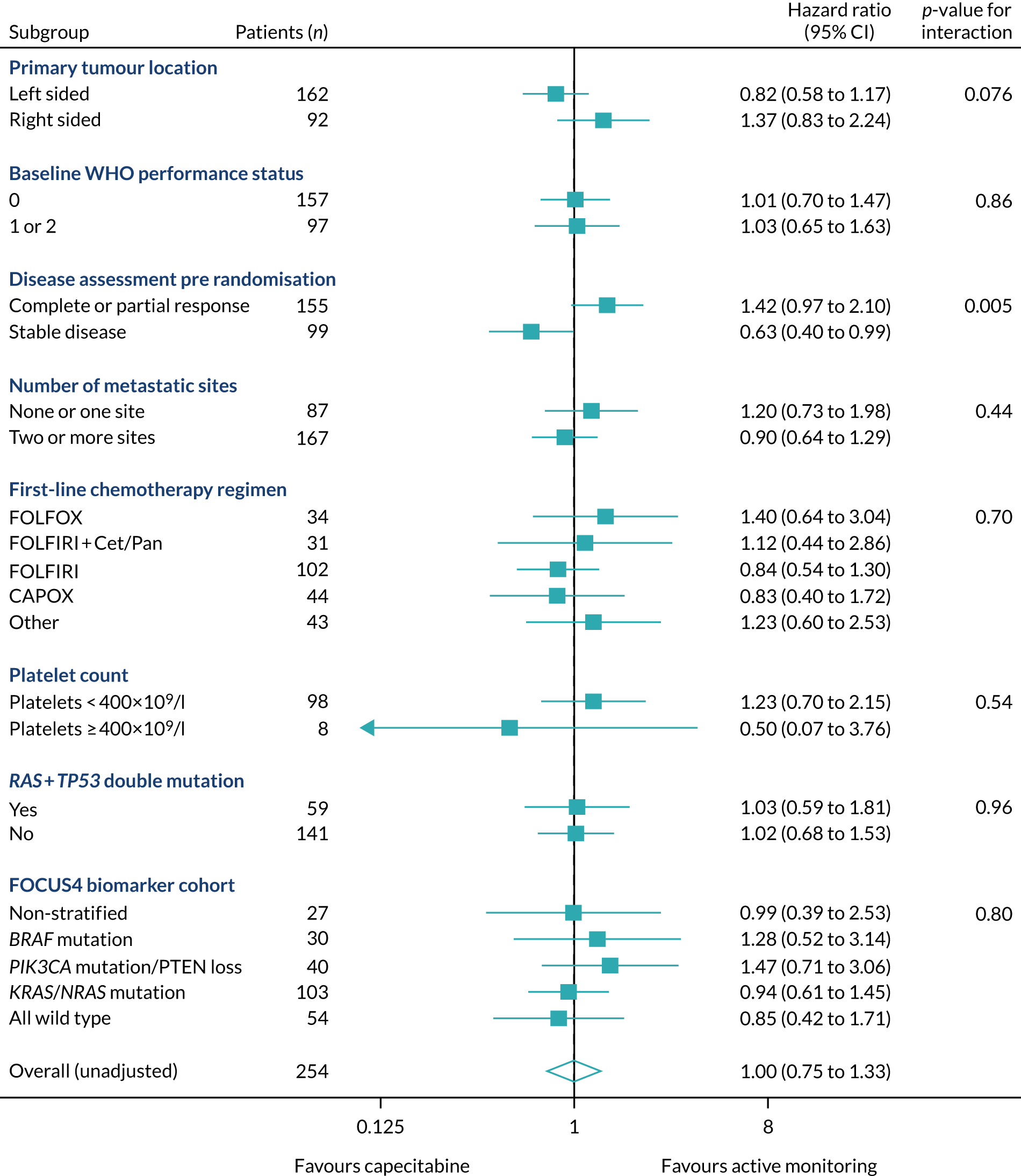

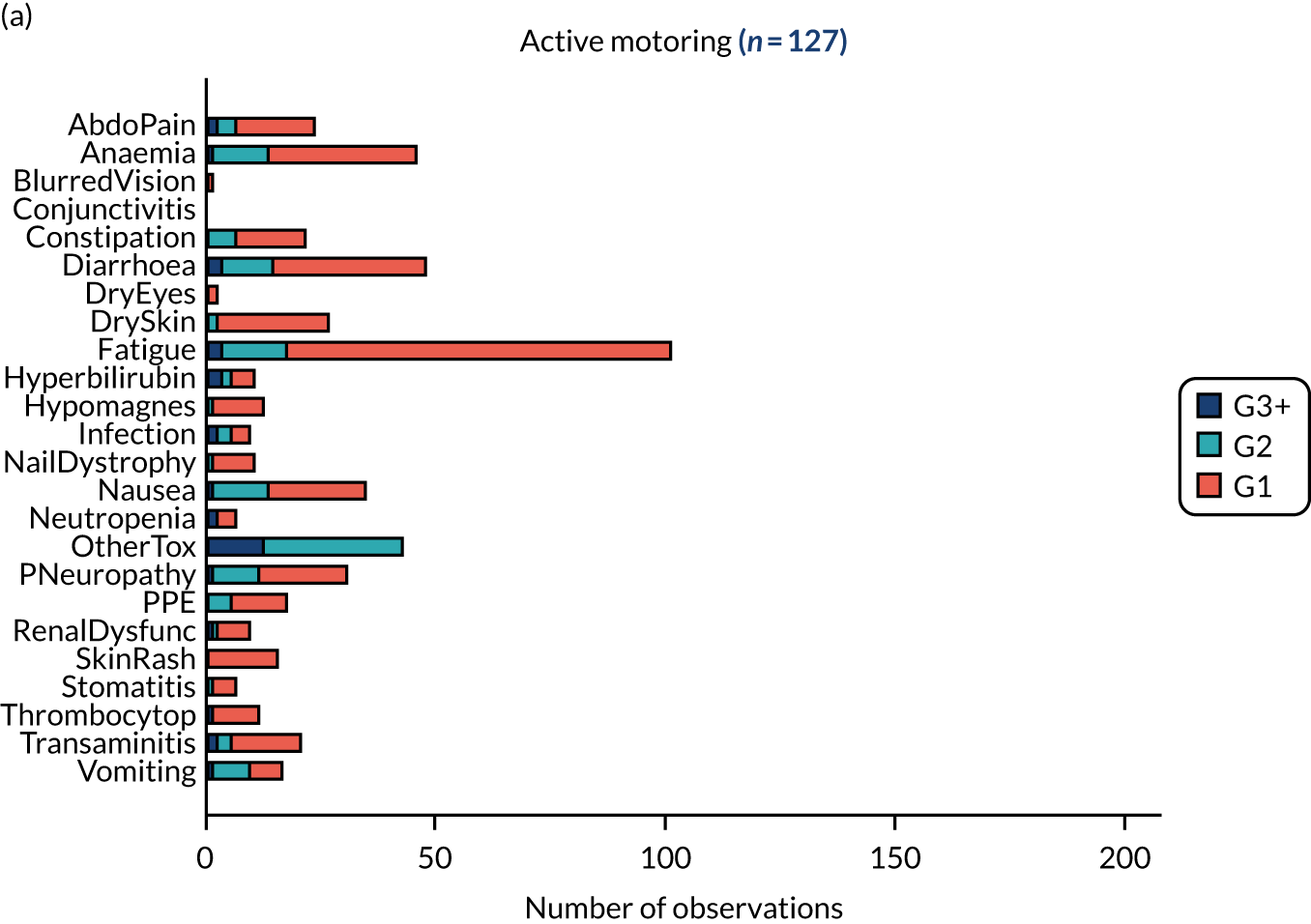

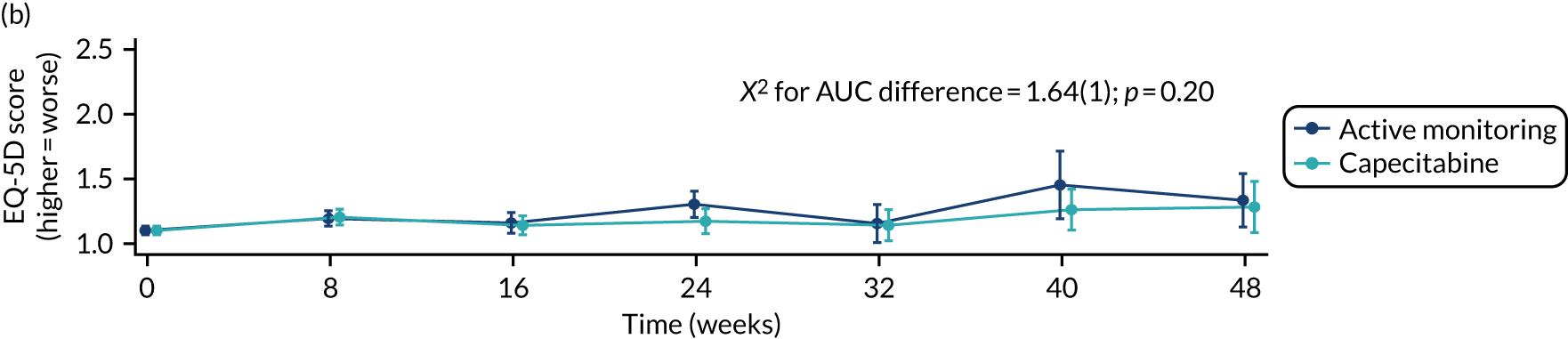

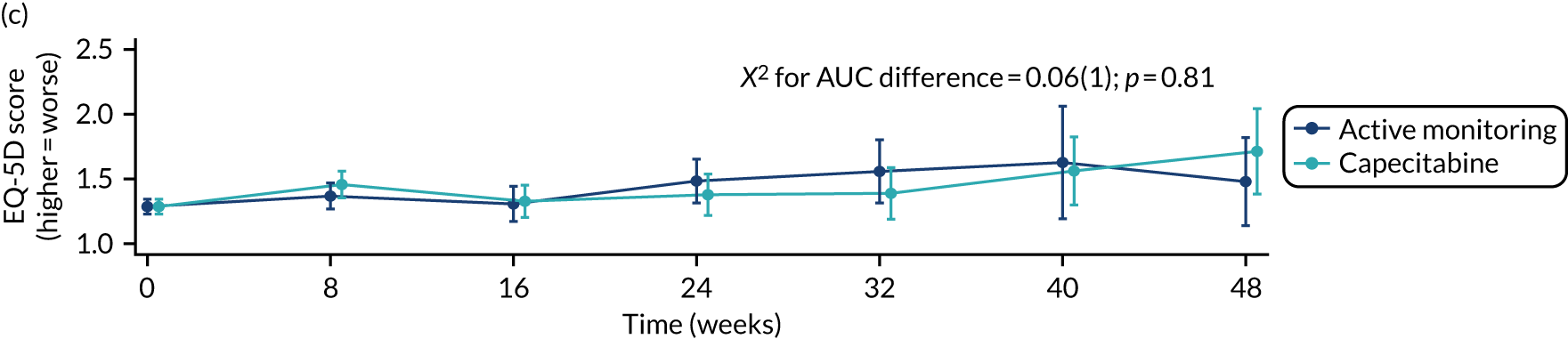

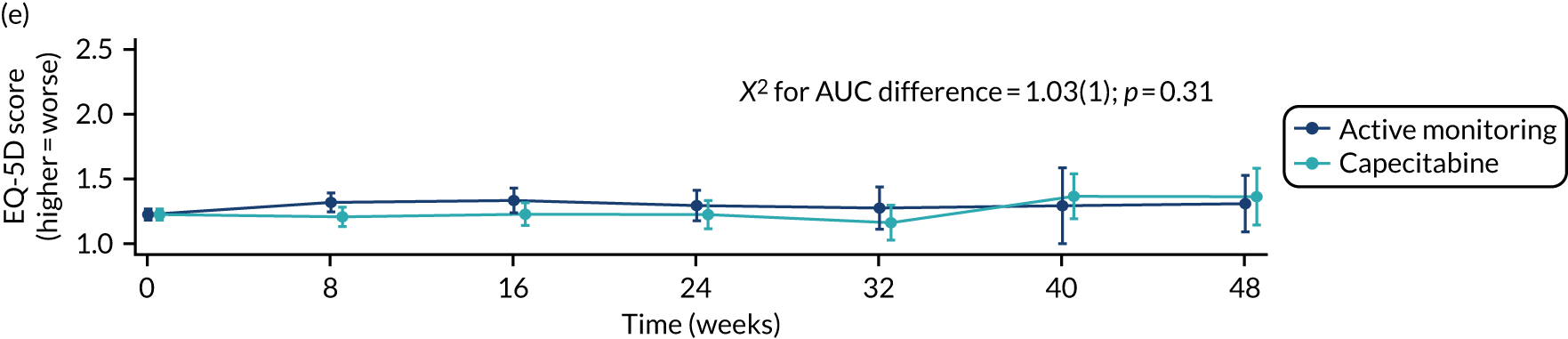

Outcome data