Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as award number 14/144/08. The contractual start date was in April 2017. The draft manuscript began editorial review in December 2023 and was accepted for publication in May 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Vollebregt et al. This work was produced by Vollebregt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Vollebregt et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The SUBsensory Sacral Neuromodulation for InContinence (SUBSoNIC) protocol has been published in part in the Trials journal. 1

Background and rationale

Faecal incontinence (FI), defined as the recurrent involuntary loss of faecal material leading to a social or hygienic problem2 is a common3–5 and debilitating condition with profound effects on quality-of-life6 and high societal costs. 7

Initial treatments. including pharmacological and behavioural therapies (e.g. biofeedback), have variable outcomes and are poorly evidenced. 8 Traditional surgical approaches focusing on anal sphincter reconstruction or augmentation are invasive, irreversible, and risk significant morbidity. 9 A stoma is the final option.

Chronic low-amplitude stimulation of the mixed sacral spinal nerves using an implanted electrode and generator – sacral neuromodulation (SNM) is a less invasive alternative, now considered the first-line surgical treatment option for adults with FI in whom non-operative therapies have failed to alleviate symptoms. 7 Current evidence for SNM is based on extensive observational data2,10 and a paucity of randomised trials that are heterogeneous in design and outcomes. 11 Despite having widespread regulatory approval, SNM remains an expensive intervention with need for greater confidence in efficacy. This is especially relevant as SNM is challenged by cheaper forms of neuromodulation including percutaneous12 and implantable tibial nerve stimulation. 13 A further concern regarding SNM therapy is the lack of proof of mechanism. 2,14

Evidence base for SNM: efficacy

Numerous observational studies (systematically10 and narratively2 reviewed) show that SNM leads to a substantial health gain for adults with FI who have low levels of operative morbidity compared to alternative surgical strategies. Reduced FI episodes correlate with objective QoL improvements15 and SNM has been shown to be cost effective with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of £25,070 per quality-adjusted life-year lying within the threshold recommended by NICE as an effective use of NHS resources. 2,15 However, reviews also highlight the generally poor methodological quality of included data that derive almost universally from single centre retrospective or prospective clinical case series with unblinded observers and failure to report outcomes on an intention to treat basis. The latter point is especially important since significant attrition bias undermines nearly all studies even including the higher quality pivotal trial for Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval (a prospective multi-centre US case series of 120 patients16,17). More recent publications from Europe, that have reported large patient series using the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, have shown less encouraging results (circa 45% long-term success). 18–20

Data supporting experimental efficacy for SNM are lacking. A 2015 Cochrane review11 included only six studies comprising four crossover designs and two parallel group randomised controlled trials (RCTs). One crossover included only two patients;21 a further study published only in abstract form reported mainly mechanistic outcomes in only seven patients. 22 The remaining two crossover studies included the widely cited study by Leroi et al. ,23 which enrolled 34 patients pre-selected on the basis of a successful prior SNM implantation. Only 27 participated in the crossover and only 24 completed the study (10 excluded patients included four explanations due to adverse events (AEs) and others due to lack of efficacy or protocol violations). Although the majority (18/24) of analysed patients preferred ‘ON’ versus ‘OFF’ at the end of study, the study failed to show a clinically meaningful reduction of symptoms between ON and OFF periods for example difference in median FI episodes per week of only one episode. This was suggested to result in part from a short washout period (1 week) and a carry-over effect. A further crossover study24 employed an identical trial design but with smaller numbers of patients, randomising only 16 of 31 preselected implanted patients and thence only for two 3-week crossover periods. In contrast to the earlier study, significant decreases in FI episodes and summative symptom scores were observed in the ON versus OFF periods despite having no washout.

The Cochrane review included two randomised comparison trials. Tjandra et al. 25 compared SNM to optimal medical therapy showing superiority for SNM [mean difference: −5.20, 95% confidence interval (CI) −9.15 to −1.25 at 3 months; −6.30, 95% CI −10.34 to −2.26 at 12 months]. An NIHR-funded observer-blinded RCT of SNM versus a less invasive form of neuromodulation: percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS)10 demonstrated within a group effect size that was greater for SNM than PTNS. While pilot in design and with small numbers (n = 40 total), this effect was still modest compared to most observational case series. Since the Cochrane review, a further comparison trial randomised 99 patients to either SNM or magnetic sphincter augmentation using the FENIXTM (Torax Medical, Minneapolis, MN, USA) device. Overall, only 10 of 80 patients, with analysable data, met the predefined success criterion with no significant difference between the groups. 26

Evidence base for SNM: mechanism

While it is now generally accepted that the pathophysiology of FI goes far beyond physical damage to the barrier (mainly the sphincters),27 the exact effect of SNM on neuromuscular continence functions of the anorectum (e.g. on local reflexes or on cortical pathways) is broadly unknown.

SNM was developed for FI with the view that it would augment defective sphincteric function. 28 It is now well appreciated that patients with FI resulting from pathophysiology other than primary sphincter dysfunction also benefit from treatment. 29 The importance of sensory dysfunction on both urinary and bowel control is being increasingly appreciated and there is strong evolving evidence in humans30 and experimental animals31 that the mechanism of action of SNM for FI results primarily from modulation of afferent nerve activity either as it contributes to local reflexes or, via the somatosensory pathway, to conscious perception.

Chapter 2 Objectives

The primary objectives of the study were:

-

to determine clinical efficacy of sub-sensory chronic low voltage electrical sacral nerve stimulation: SNM using a commercially-available implantable device: Medtronic InterStimTM (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) in adults with FI in whom conservative treatment has failed

-

to identify whether clinical responses to sub-sensory SNM were biologically related to changes in the central pathway between the brain and anorectum.

Chapter 3 Methods

Clinical trial methods

This report has been written using the framework provided by the CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised crossover trials. 32

Trial design

The overall design encompassed a randomised double-blind crossover trial (to address experimental efficacy) and a follow-up cohort study. A mechanistic sub-study was included.

Randomised double-blind crossover design

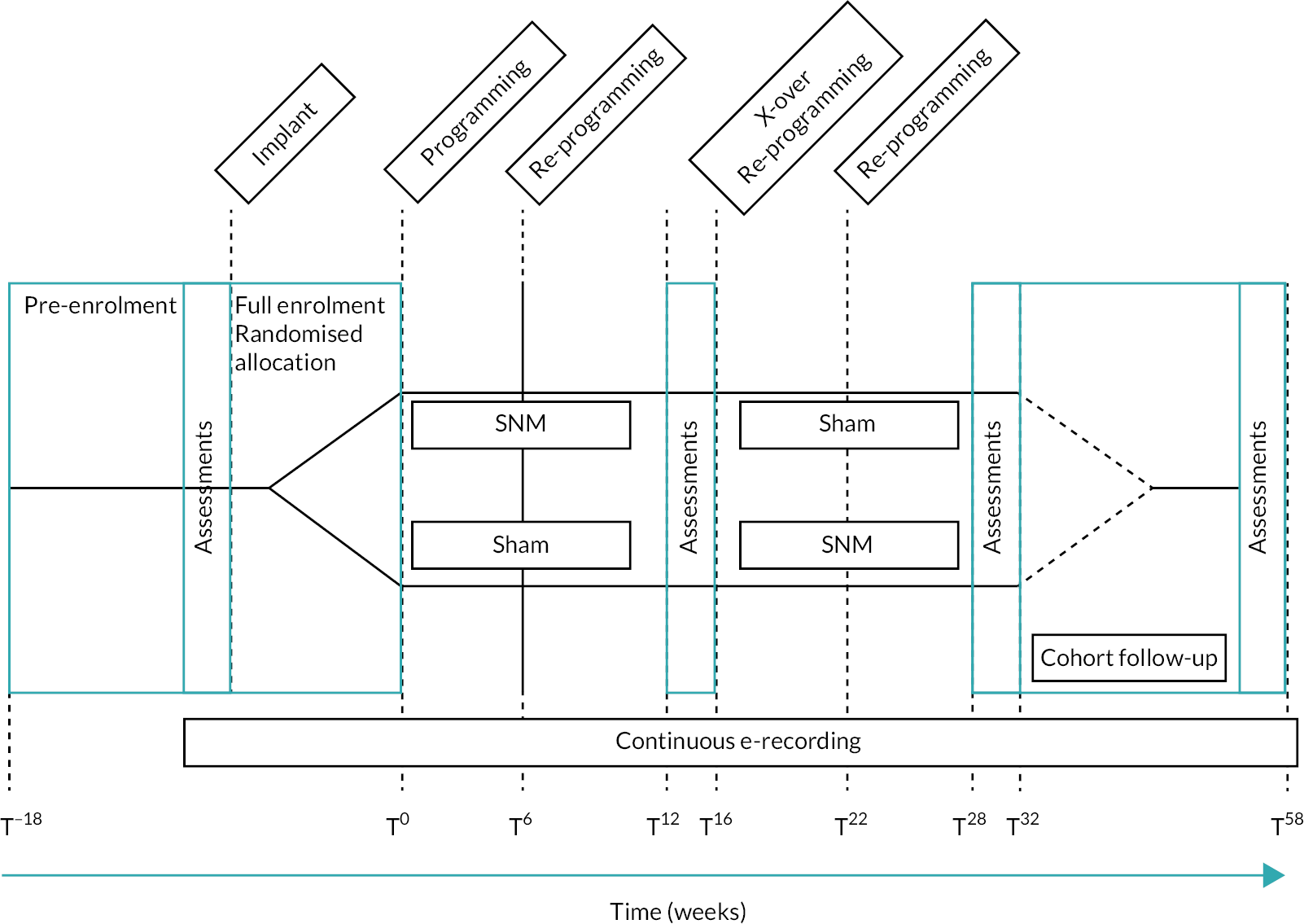

Eligible participants were randomly allocated to two study arms after SNM implantation (see Figure 1). Both arms had two intervention periods of 16 weeks duration (T0–T16 and T16–T32). Efficacy outcomes were derived from assessments in the final 4 weeks of each cross-over period (T12–T16 and T28–T32) thus allowing for almost 3 months intervention before outcome assessments. In accord with usual clinical practice, a reprogramming (or sham reprogramming) session was conducted by the routine clinical care team at 6 weeks in both periods of both arms (T6 and T22). Time-points had an interval tolerance of ±1 week.

FIGURE 1.

Timeline.

Cohort study: 12-month outcomes

After completing the crossover section of the study, participants were followed up for a further 26 weeks. During this time, they had ‘open label’ stimulation, being able to choose between sub- or supra-sensory stimulation settings as would have been normal for routine clinical practice. Further efficacy outcomes were recorded at T54–T58. While it is accepted that these did not represent true 1-year outcomes (16 weeks had been sham treatment during the crossover), these were included to provide an indication of the short-term effectiveness of SNM within the rigor of a CTU-monitored prospective study.

Mechanistic studies

Mechanistic studies were performed in the final 2 weeks of the 4-week assessment periods in a subgroup of consecutively consenting patients from both arms until saturation (anticipated sample size: n = 20).

Justification of a crossover design

The rationale for a crossover design considered the statistical efficiency of assessing both interventions (active SNM vs. sham stimulation) in the same participant. Its justification was based on the condition in question (FI) being considered chronic and stable over the total period of study (32 weeks). This is especially true for the subpopulation of FI included in the study that is patients with chronic symptoms which have already failed to respond to lifestyle and first line medical interventions (those suitable for SNM7). Concerns regarding carryover effects from SNM were mitigated by a 2 × 16-week design (enabling 12 weeks of washout).

Changes to protocol after trial commencement

Several actions were approved by the trial steering committee to mitigate barriers to recruitment during the early phase of the study (see Appendix 7). None affected fundamental design assumptions:

-

Increase in age limit to 80 years. The initial age range (18–75 years) was set to reduce population heterogeneity. This led to exclusion of healthy patients who would otherwise have met inclusion criteria.

-

Removal of Longo score33 from the exclusion criteria. The Longo score was initially included to exclude patients with symptoms of obstructed defecation. However, it was noted that some of the questions were ambiguous and could easily be answered in the affirmative for incontinence symptoms. Also, the use of loperamide for incontinence symptoms could result in higher scores on the Longo score. Both could result in patients being incorrectly considered ineligible for the study.

-

Minimum severity criterion for FI episode frequency. Originally, eight faecal incontinence episodes in 4 weeks were required to meet eligibility. This was changed to reflect the importance of urgency as well as urge FI in many patients with no effect on the original sample size calculation (which was based on real life data in which a proportion of patients have few FI episodes). Urgency episodes were already being collected as a secondary outcome.

Participants and eligibility criteria

Adults aged 18–80 years with chronic FI symptoms were consecutively assessed for broad eligibility from the SNM waiting lists of participating centres. These patients had been determined clinically suitable for SNM based on routine clinical evaluation and subsequent multidisciplinary team discussion [as mandated by NHS England specialist commissioning guidance (www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/nice-interventional-procedures-guidance)]. Eligibility for full enrolment and randomisation followed assessment of pre-surgery 4-week bowel diaries for a minimum FI severity criterion.

Inclusion criteria

-

Adults aged 18–80 years.

-

Meeting Rome III and ICI definitions of FI (recurrent involuntary loss of faecal material that is a social or hygienic problem and not a consequence of an acute diarrhoeal illness). 2,34

-

Failure of non-surgical treatments to the NICE standard: diet, bowel habit and toilet access addressed; medication for example loperamide, advice on incontinence products, pelvic floor muscle training, biofeedback and rectal irrigation should be offered if appropriate. 7

-

Minimum severity criteria of eight FI or faecal urgency episodes (including a minimum of four FI episodes) in a 4-week screening period.

-

Ability to understand written and spoken English or relevant language in European centres (due to questionnaire validity).

-

Ability and willingness to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

A standard list of exclusions (disease variants; surgical fitness, specific contraindications to implantation) were used. 10 Note that these are routine clinical exclusions to the use of SNM rather than participation in the research:

-

Known communication between the anal and vaginal tracts.

-

Prior diagnosis of congenital anorectal malformations.

-

Previous rectal surgery (rectopexy/resection) performed < 12 months ago (24 months for cancer).

-

Present evidence of full thickness rectal prolapse or a high-grade intussusception.

-

Prior diagnosis of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases.

-

Symptoms of chronic constipation with over-flow incontinence.

-

Structural abnormality of the pelvic floor leading to clear evidence of obstructed defaecation based on examination and/or imaging.

-

Presence of active perianal sepsis (including pilonidal sinus).

-

Defunctioning loop or end stoma in situ.

-

Diagnosed with neurological diseases, such as diabetic neuropathy, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease.

-

Current or future need for MR imaging based on clinical history.

-

Complete or partial spinal cord injury.

-

Bleeding disorders for example haemophiliac, warfarin therapy.

-

Pregnancy or intention to become pregnant during the study period.

-

Not fit for surgeon preferred method of anaesthesia.

Settings and locations

Participating centres were selected based on experience of performing SNM and case workload using written feasibility assessments. Centres in England, Scotland, Ireland and Germany were identified, on this basis. Not all originally selected sites opened to recruitment.

The following sites recruited patients for the study: Barts Health NHS Trust, University Hospital Southampton, University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust, Cambridge University Hospital, University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust, Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust, Ashford and St Peters Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, St Vincent’s University Hospital (Dublin), University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, and University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust.

The following sites were opened for recruitment but did not recruit any patients: NHS Lothian, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, St Mark’s Hospital, Sheffield Teaching hospital, and University College London Hospital.

Clinical trial interventions

Chronic low voltage stimulation of the third sacral mixed nerve was achieved by surgical implantation of a commercially available Conformité Européenne (CE)-marked active implantable (class III) medical device (Medtronic InterStim) used in accord with manufacturer’s instructions and local practice.

Brief description of SNM surgery

Patients meeting the mandated response using the test phase (monopolar temporary wire or quadripolar tined lead based on local preferred practice) underwent implantation of the permanent InterStim system under general or local anaesthesia (with sedation) by trained expert colorectal surgeons following recommended procedural steps35 in brief: fluoroscopic-aided percutaneous insertion of 3889, 978A1 or 978B1 lead using curved stylet and accepting position only when 3 of 4 electrodes provide low voltage (< 3 V) contraction of the anal sphincter and pelvic floor ± big toe. The implantable pulse generator (IPG; 3058; Medtronic or InterStim Micro rechargeable model 97810) were placed as pre-marked in the ipsilateral buttock.

The device was activated as per local policy, either on the same day of surgery or after a surgical stabilisation period of up to 2 weeks. General programming parameters followed a written algorithm based on best clinical practice and manufacturer’s guidelines. Prior to programming, an impedance check was performed and recorded to ensure integrity of the electrical system.

Active intervention (sub-sensory stimulation)

The clinical team set the electrode configuration to achieve sensory threshold defined as the stimulation amplitude where the patient felt the first sensation of stimulation in the anus or perineum at 14 Hz frequency, pulse width 210 μs. The amplitude was increased in 0.1 V increments from zero until the sensory threshold was reached for each electrode and optimal electrode configuration defined. Sub-sensory chronic stimulation was then initiated on the patient controller device at a level just below the habituated sensory threshold (for blinding). This process was repeated at the 6-week time point.

Sham intervention (stimulation off)

Sensory thresholds were recorded identically; however, the level was then adjusted to 0 V. An identical procedure (to active) was repeated at the 6-week time point.

Commercially available devices evolved during the course of the trail and were adopted in some centres. The new TH90P03 handset could not be blinded to allocation if the voltage was set to 0 V as participants only had the ability to turn the device on. Participants were unable to turn the stimulator off as the handset deemed 0 V as off. The sham setting for participants with this programmer was 0.05 V as this setting is considered well below the therapeutic dose.

Schedule of clinical visits

Participants underwent a total of 10 visits from pre-eligibility to final follow-up visit with T0 defined as the start of the randomised periods. These included implantation at visit three, and main assessments (for primary and other outcomes) at visit six (16 weeks) and visit nine (32 weeks); open label cohort visit nine to 10 (58 weeks). A full schedule of visits (including mechanistic studies) is shown in Table 1.

| Visits | 0 | 1 | 2a | 2b | 3a | 3b | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIMEPOINT (weeks ± 1 week) | Screen | Baseline | Test Stim. | Mech. | SNM Impl. | T 0 | T + 6 | T + 12 to +16 | T + 16 | T + 22 | T +28 to +32 | T +32 | T +54 to +58 |

| Screening and enrolment | |||||||||||||

| Eligibility screen/confirmation | x | x | |||||||||||

| Informed consent | x | ||||||||||||

| e-diary training | x | ||||||||||||

| Check MDT decision (UK patients) | x | ||||||||||||

| Full eligibility and randomisation | x | ||||||||||||

| Interventions (un-blinded) | |||||||||||||

| SNM test phase | x | ||||||||||||

| SNM implantation | x | ||||||||||||

| Post-operative check | x | ||||||||||||

| SNM device programming/re-programming | x | x | x | x | x | X | |||||||

| Crossover | x | x | |||||||||||

| Assessments (blinded) | |||||||||||||

| Demographics/medical and surgical history, physical exam, pregnancy test | x | ||||||||||||

| e-event recordings (continuous) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | X | |

| Paper bowel diary and viscerosensory bowel diary | x | x | x | X | |||||||||

| Questionnaires (St Mark’s, Deferment Time, OAB-Q-SF, SF-ICIQ-B, FI-QOL, EQ-5D-5L, satisfaction VAS scorea) | x | x | x | X | |||||||||

| AEs | x | x | x | x | x | x | X | ||||||

| Mechanistic studies (blinded)b | |||||||||||||

| Information and consent | xb | ||||||||||||

| MRI | xb | ||||||||||||

| MEG studies | xb | xb | xb | ||||||||||

| Anorectal studies | xb | xb |

Visit 0: screening (face-to-face in clinic or phone)

Patients were assessed for eligibility against the inclusion and exclusion criteria checklist. The indication for SNM implantation required approval by the pelvic floor multidisciplinary team (MDT) prior to visit one. Patients who were initially found to be ineligible but who became eligible prior to any surgery were rescreened. Eligible patients were given the study invitation letter and participant information sheet (PIS). Patients were given adequate time to review the PIS prior to consent. All patients screened were added to the screening log and were given a study ID.

Visit 1: baseline (face-to-face)

Eligibility against the inclusion/exclusion criteria was re-reviewed, the study and the PIS were discussed and those patients in agreement completed written informed consent. A maximum of 18 weeks before permanent implantation was allowed for this visit. Once a patient was consented, the following assessments were completed:

-

demographics, standardised medical/surgical history including history of incontinence symptoms, gynaecological history and pregnancy test (females of childbearing potential)

-

clinical exam of perineum, anus and rectum (if not documented within the previous 6 months)

-

baseline outcome assessments: St Mark’s continence score, deferment time, OAB-q SF, International Consultation on Incontinence Bowel (SF-ICIQ-B) questionnaire, FI QoL score and EQ-5D-5L/visual analogue scale (VAS).

At this visit patients were given the 4-week paper bowel diary (which also recorded loperamide usage) and taught how to use the electronic diary, which started from this visit. A paper viscerosensory bowel diary was also provided with instructions for completion over 5 days.

Visit 2a: test stimulation (face-to-face)

Test stimulation was performed according to routine clinical practice and not considered a study intervention. Data (see below) were only collected at this visit if a tined lead was implanted.

Visit 2b: MEG study enrolment (face-to-face)

Before permanent device implantation, participants who met the locally agreed criterion for progress based on the test stimulation phase, or those who had a tined lead inserted with a high probability of going through to permanent stimulation, were selected for and consented to the magnetoencephalography (MEG) studies depending on geographical location and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) eligibility.

Visit 3a: permanent SNM implantation (face-to-face)

Following test stimulation, participants were admitted as a day case for permanent device implantation. Eligibility for full enrolment was re-confirmed (including assessment baseline diary data). Participants were randomised prior to knife to skin to either one of the two trial arms:

-

Arm 1: SNM/sham

-

Arm 2: sham/SNM

Intraoperative data were collected including: (1) lead position (radiological side, foramen level, number of electrodes in foramina); (2) motor thresholds for each of the four electrodes on the quadripolar lead; (3) physiological motor (± sensory) response for chosen foramen for lead implantation; and (4) other intraoperative data including length of operation, type of anaesthesia (including use of any muscle relaxant agent), blood loss, any other complications. If the tined lead was inserted at the start of the test stimulation phase, these data were collected during this test stimulation visit (visit 2a).

Visit 3b: initial programming (T0) (face-to-face)

Post-operative baseline checks were performed including impedance measurements of the four electrodes to ensure integrity of the electrical system. Participants had their SNM programmed as per routine care. This was undertaken in the immediate post-operative recovery period or up to 2 weeks post-surgery. All further follow-up visits were counted from the initial programming day and not from the day of surgery.

To reduce selection bias, no consenting patient with an implant in situ was excluded from participation that is regardless of the surgeon’s views on success or otherwise of implantation. At each follow-up visit, impedance measurements were repeated to ensure maintained integrity of the electrical system. If a closed or open circuit was detected (suggesting possible neurostimulator or lead malfunction) then this was documented. If a better (stronger perception at lower amplitude) sensory response was achieved using an alternative electrode configuration, the device was re-programmed and so the patient could continue in the study. In the absence of a satisfactory sensory response with an abnormal impedance measurement the patient was still followed up as per ITT and any changes to treatment were recorded in the deviation log.

At each visit, any change in electrode configuration, sensory threshold and location of maximum bodily sensation were recorded. Any AEs were systematically questioned and recorded at this visit and all subsequent face-to-face visits.

Programming was performed either using the Model 8840 N’VisionTM (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) clinical programmer (InterStim II) or the Model A51200 Micro Clinician app for the InterStim Micro rechargeable neurostimulator or A510 Clinician app for Models 3023 and 3058 InterStim neurostimulators with the HH90 Handset and TM90 Communicator. Tamper-proof tape was applied to the areas of the screen that could unblind the patient, but leaving areas of the screen where they could access the apps to turn on/off and recharge if applicable. Following initial programming:

-

Arm 1: the subsensory amplitude was recorded along with the electrode configuration used

-

Arm 2: the subsensory amplitude was recorded along with the electrode configuration used before returning the amplitude to 0.05/0.00 V (depending on which programmer the patient has).

Visit 4: 6-week reprogramming visit (T + 6) (face-to-face)

This visit was only completed if this was part of routine care. The tamper-proof tape was left on the patient’s programmer, programming was done via the clinician’s programmer if the older device was used. If the Smart programmer was used the clinician removed the tape to be able to perform the programming via the clinician app and reapplied new tape once finished:

-

Arm 1: the patient was assessed for sub-optimal efficacy or unwanted effects of stimulation. In the presence of sub-optimal efficacy or adverse effects the electrode configuration was changed as per reprogramming algorithm. The sensory threshold was once again recorded, and the device was returned to the sub-sensory setting.

-

Arm 2: the sensory threshold was recorded; the electrode configuration could be changed if the site of stimulation appeared to be suboptimal (aim for anal stimulation) before the device was returned to 0.05 or 0.00 V.

Visit 5: diary assessment (T + 12 to +16)

All participants completed the 4-week paper bowel diary and 5-day viscerosensory diary. Participants undergoing mechanistic studies had their first follow-up MEG study.

Visit 6: crossover visit (T + 16) (face-to-face)

At crossover, the device was turned off for 20 minutes followed by re-evaluation of the sensory threshold and best electrode configuration in the manner outlined above. The intervention was then reversed for each arm. Paper diaries and follow-up assessment questionnaires (St Mark’s continence score, deferment time, OAB-q SF, International Consultation on Incontinence Bowel (SF-ICIQ-B) questionnaire, FI QoL score and EQ-5D-5L/VAS) were completed. Participants also recorded their satisfaction on a Likert scale.

Visit 7: 6-week reprogramming visit (T + 22) (face-to-face)

All participants had a further follow-up 6 weeks after crossover at T22 if this was part of routine care. This visit was identical to visit 4 (see above).

Visit 8: diary assessment (T + 28 to +32)

All participants completed the 4-week paper bowel diary and 5-day viscerosensory diary. Patients undergoing mechanistic studies had their first follow-up MEG study.

Visit 9: end of crossover (T + 32) (face-to-face)

A further full set of outcomes was collected including the 4-week paper bowel and 5-day viscerosensory diaries (as per visit 6). After collection of these final crossover study data, participants entered the follow-up phase with patient chosen stimulation (sub- or supra-sensory) as would be normal for routine clinical practice. A member of the clinical team reprogrammed the device accordingly. As blinding was no longer necessary, participants had the option of changing their patient programmer for the new Samsung patient programmer. Further programming and advice were provided as per routine care during the period 32–58 weeks. All visits or contact with the clinical team during this time was recorded.

Visit 10: final assessment (T + 54 to + 58)

Participants completed a further full set of outcome questionnaire assessments and diaries, including the 4-week bowel diary (T54–58). During the final visit both the e-diary and paper diaries were collected. Participants underwent final re-programming and were then discharged from the study into normal clinical care.

Outcomes

Primary clinical outcome

The primary clinical outcome was reduction in FI events per week (recorded on paper bowel diaries over a 4-week period) in SNM versus sham periods of crossover (16 and 32 weeks).

While the limitations of bowel diaries are well-established,36 they remain the gold-standard in FI trials. 10,23,37,38 Although 2-week bowel diaries were the norm in these studies, we elected to use a 4-week recording period following international guidance. 39

The measure of treatment effect was the reduction in FI events per week whilst undergoing SNM as compared with undergoing sham stimulation.

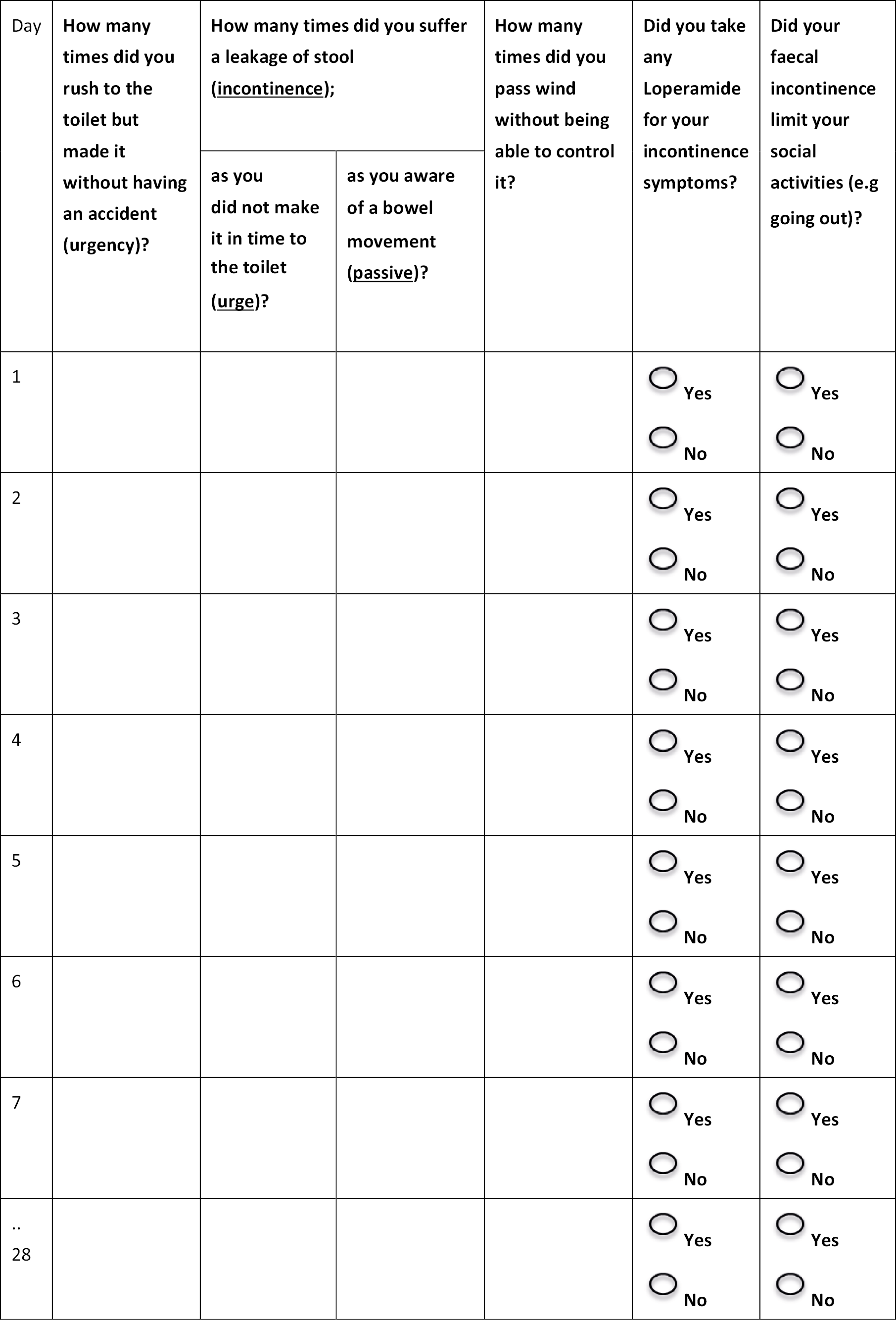

The paper diary (see Appendix 1) was completed prior to implantation, then at the end of each cross-over period, and again at the end of the cohort follow-up. The degree of faecal loss was not quantified. While this is an acknowledged (and regularly debated) limitation of all existing outcome instruments, we believed that simplicity would be sacrificed if participants were required to judge the semantic differences between ‘staining’, ‘leakage’ and ‘frank incontinence’. Patients were asked (in notes at top of bowel diary) to fill a zero on days where no events occurred.

Secondary clinical and mechanistic outcomes

Other bowel diary measures, e-event recording and a panel of summative questionnaires were recorded at 16, 32 and 58 weeks.

-

E-event recorder including episodes of faecal material, leakage of flatus, urgency without incontinence, social and physical activity.

-

Other bowel diary measures: urgency, urge and passive faecal incontinence episodes, use of loperamide and social functioning.

-

Summative questionnaire assessments: St Mark’s continence score;40 OAB-q SF score, FI QoL score;41 International Consultation on Incontinence Bowel (SF-ICIQ-B) questionnaire. 42

-

Viscerosensory bowel diary recording quality, site and intensity of defacatory urge. 43

-

Generic QOL: EQ-5D-5L. 44

-

Likert scale of patient’s global impression of treatment success (scale 0–10) and patient perception of treatment or sham allocation (blinding success).

-

Electrode settings (inc. motor, first and habituated sensory thresholds), programming (and if applicable re-programming data).

-

Adverse event reporting.

E-event recording

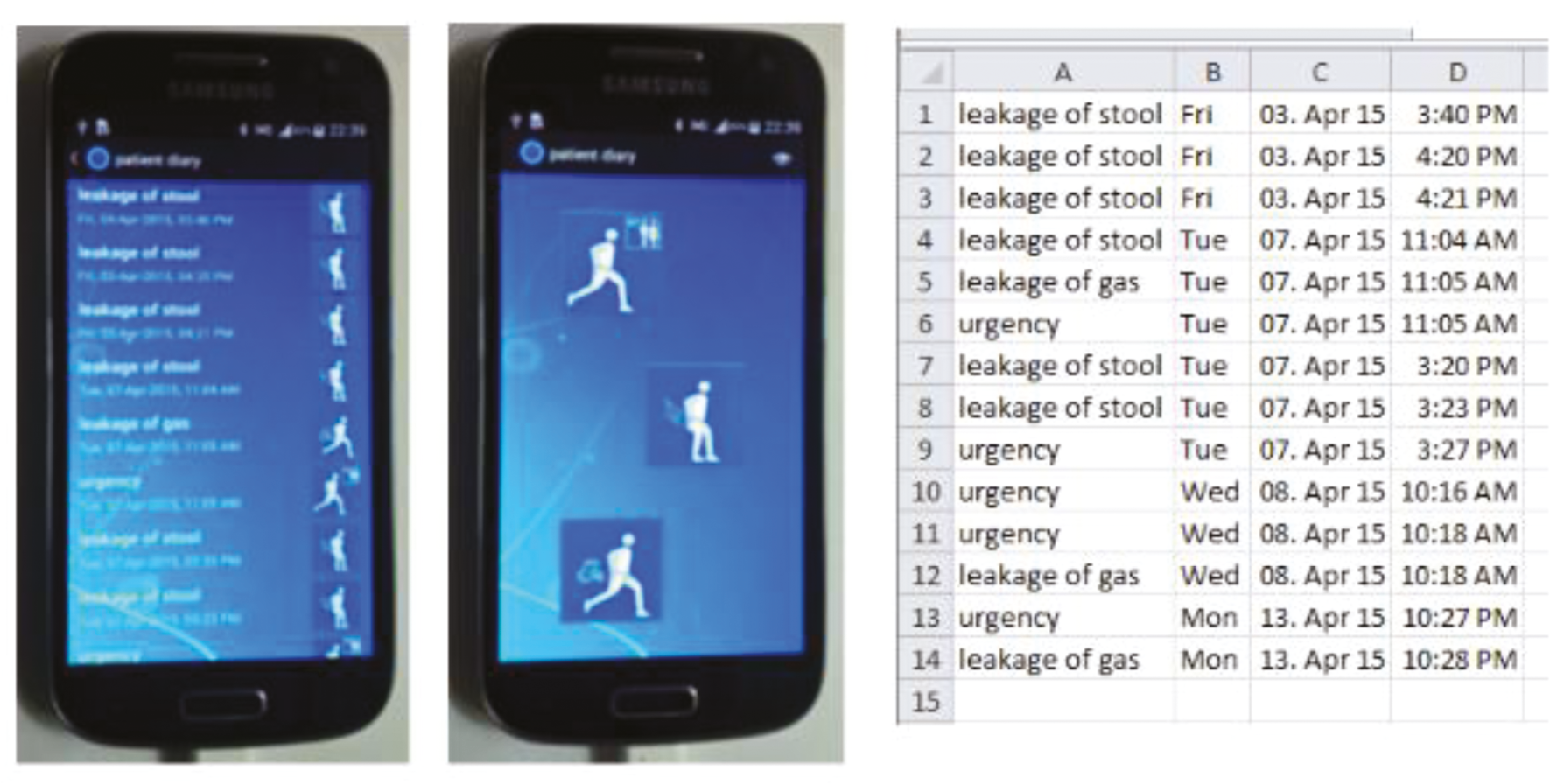

A simple touch screen electronic device (Figure 2) developed with Medtronic allowed participants to record real-time-indexed episodes of leakage of faecal material, leakage of flatus and urgency without incontinence. In addition to comparing fidelity of events recorded by the current gold-standard (paper), the Samsung device provided opportunities to analyse novel similarly time-indexed measures for example social and physical activity using embedded android hardware device (GPS, accelerometer). GPS data were recorded but not analysed due to problems of data processing/acquisition.

FIGURE 2.

Example photograph of touchscreen icons on e-recording device.

The same device was used as a touchscreen application for digitalisation of established and new (SF-ICIQ-B) summative scoring questionnaires. The touch screen was used from the baseline visit throughout the crossover and cohort follow-up studies.

The information collected in the touch screen electronic device was logged in real calendar time and stored as time-linked data. It was downloaded by hardwire (USB) connection. The app was not simply an e-version of a paper bowel diary. Rather we developed a new app that greatly simplified use whilst also improving the accuracy of data over paper bowel diaries which are acknowledged to have major insufficiencies due to patient compliance,36 retrospective completion,45 and interpretative bias (if unblinded assessors).

Sample size

The sample size was based on the primary outcome that is faecal incontinence episodes per unit time as recorded using the 4-week paper bowel diary at the end of each 16-week cross-over period. The study was powered to detect a ratio of 0.7. This is not to be confused with the reduction in the actual number of events post-intervention for a given patient, where a 50% reduction has frequently been employed, albeit subjectively, to define ‘success’ for that patient. 10,38 Rather, we used number of events as a quantitative outcome, achieving greater power than a dichotomous outcome of successful/unsuccessful, and we powered to detect a 30% reduction, on average, in this outcome on ITT principles.

We assumed that for an inactive device in a typical participant, the number of events in 4 weeks would have an over-dispersed Poisson distribution with mean 28 and 95% range 7–112. We also assumed there would be variation between individuals, such that the mean number of events in 4 weeks might vary from 14 in some individuals to 56 in others (95% range). A consequence of these assumptions is that the correlation between log (number of events) for the same individual in two different months will be 0.2, and the standard deviation of log (number of events) in each month will be 0.775. (These values are consistent with results from two previous NIHR trials in similar populations10,12 and with our clinical experience.) Thus, it was calculated that to detect a 30% reduction in FI event rate [i.e. a difference of log(0.7) in log(number of events)] with 90% power at the 5% significance level with a cross-over design required a minimum of 80 participants.

Allowing for 10% loss to follow-up a total of 90 participants needed to be randomised (45 to each arm). This sample was also sufficient to detect changes in mechanistic outcomes (90% power) based on pilot data. MEG studies were mainly exploratory and sample size was based on feasibility.

Randomisation

Participants were not eligible for randomisation until the baseline (pre-surgery) bowel diary had been assessed for minimum FI severity, and they had completed the temporary evaluation phase having met the locally implemented minimum clinical response (usually defined as a 50% reduction in FI episodes on a 2-week diary) required to proceed to permanent implantation; as per NICE guidance. The conduct of the temporary evaluation was performed in accord with local clinical practice.

Randomised allocation (1 : 1) to arm 1 (SNM/sham) or arm 2 (sham/SNM) was performed at the time of surgery using an online randomisation system managed by the Pragmatic Clinical Trials Unit at QMUL, with a randomisation list generated by an independent statistician to ensure allocation concealment. Randomisation was stratified by sex and centre with block sizes of four. The inclusion of sex as a stratification factor was justified by the potential differences in pathophysiology in the small number of male patients with significant FI. 46

Participants were, if possible, randomised prior to knife to skin so they entered the study independent of the outcome of the surgical procedure. Randomisation could also be delayed up until the initial programming giving a window of 2 weeks, or alternatively emergency randomisation was performed by an unblinded member of the coordinating team. To reduce selection bias, no consenting patient with an implant in situ was excluded from participation that is regardless of success or otherwise of implantation.

Blinding

Members of the research team, statisticians, surgeons who performed the surgical procedure and participants were blinded to intervention status (SNM or sham). Participants were informed of the allocation ratio of 1 : 1 and that blinding prevented them from knowing in which arm they were participating (and therefore their order of intervention sequence). Participants were issued with an InterStim iCon Patient Programmer Model 3037 with tamper-proof tape cut so as to obscure the stimulator setting but not obscure the on-off icon (which is in the top left-hand corner of the screen). This enabled the patient to switch off the stimulator in an emergency for example for sudden unwanted stimulation effects but not vary the amplitude whilst the stimulation was active. For participants with the InterStim II stimulator (around 80% of implants) and Icon programmer, the ability to turn off and back on to original settings meant that driving was possible (manufacturer’s guidance recommends that the stimulator should be turned off for driving). In those with an InterStim Micro system, driving was not recommended as once the device was turned off, the stimulation voltage returned to zero and needed to be increased manually, unblinding the patient. The adequacy of blinding was assessed as an outcome by patient reporting of perceived allocation in each period of each arm.

The following members of the research team were not blinded:

-

Dedicated members of the Trial Management Group.

-

One dedicated clinician per site involved in programming and re-programming of the stimulation settings.

-

The Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC).

Statistical methods

All analyses were performed by staff of the Pragmatic Clinical Trials Unit (PCTU) using Stata V17.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). No interim analyses were planned.

Baseline data

Baseline characteristics and questionnaires were summarised by sequence (those randomised to SNM/sham vs. those randomised to sham/SNM) using descriptive statistics. Baseline (pre-surgery) assessments of the outcome measures were used to screen patients for eligibility and to provide a baseline for the longer-term cohort analysis. They are not adjusted for in the analysis of the crossover trial as they would only provide a baseline for the first treatment period and not the second.

Primary analysis: randomised crossover

All outcomes were summarised according to treatment arm and period, as recommended in the CONSORT extension for crossover trials. 32

The planned analysis pre-specified in the SAP for the primary outcome was as follows: to compare sham and active therapy in both arms of the cross-over trial, at T12–T16 and T28–T32, using mixed Poisson regression analysis to adjust for a fixed effect of period and a random effect of individual. Including a random effect for participant accounts for correlation between observations in different periods within the same participant and provides unbiased estimates even if some participants only provide data at one of the two periods, under the missing at random assumption implied by the model. To allow observed numbers of events before and after activation in the same individual to have an over-dispersed Poisson distribution, a random effect of time within individual was included. To allow for varying completeness of the 28-day diaries between subjects, an offset for the (log) completed days would be included in the model. All non-missing data were included in the analysis (i.e. not only those with data in both periods of the crossover), adjusting for the stratification variables (random effect of centre and fixed effect of sex). This approach is unbiased if missingness is related to observed outcome data or stratification factors from the same participant (a ‘missing at random’ assumption).

Analyses of secondary outcomes used the same mixed models as described for the primary outcome: Poisson regression for outcomes that are counts, and linear regression for other quantitative outcomes.

However, when running the analyses it was found that the Poisson regression models for the count outcomes failed to converge, even after following the strategy pre-specified in the SAP (replace random effect for centre with fixed effect, not allow for overdispersion, remove stratification covariates). Therefore, an alternative simpler analysis was used whereby the comparison of FI rate between sham and active therapy was done using paired t-tests, and treatment effects summarised by mean differences in number of episodes per week (with 95% CIs). For these analyses, only participants with outcome data in both periods of the crossover could be included. The paired t-test analyses assume no period effect, as the within-participant difference in outcomes is calculated regardless of the order of sham versus active therapy received. For consistency and ease of interpretation, secondary outcomes such as questionnaire measures were also analysed using paired t-tests. Stratification variables (centre and sex) were not considered when using paired t-tests.

To assess the effect of incomplete paper diary completion on the analysis of the primary outcome, a sensitivity analysis was done using a best-case scenario imputing a zero for days when some (but not all) of the count outcomes were left blank.

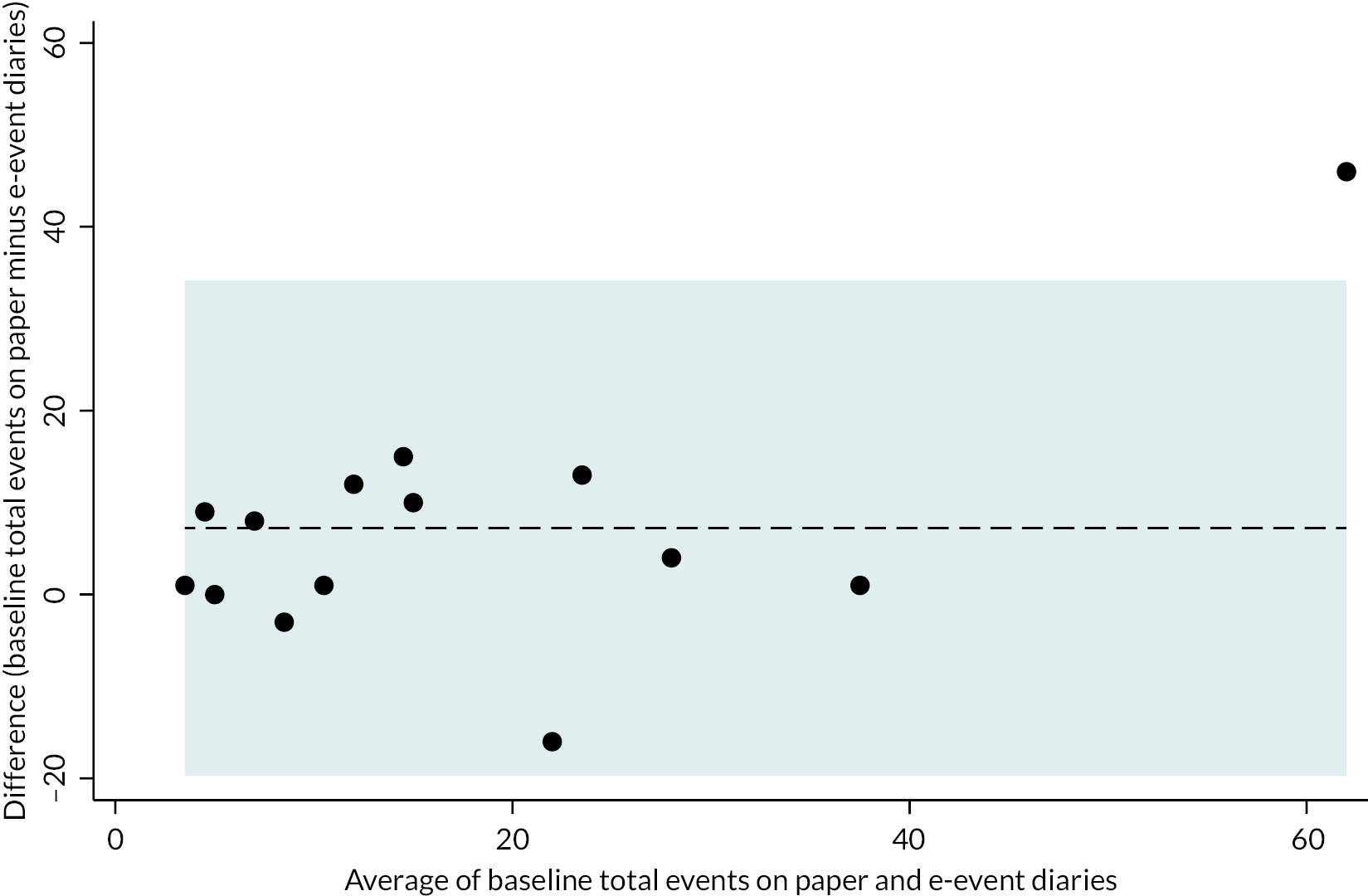

E-event time-linked recordings of the number of faecal leakage and urgency episodes were intended to be analysed using the same Poisson regression mixed-effects model as the primary outcome, but without inclusion of an offset as the e-recordings are continuous. However, as the regression models also failed to converge for e-recordings, paired t-tests were adopted instead. Unlike paper bowel diary outcomes, due to the continuous nature of e-recordings zero episodes were assumed for days when no event was reported. Outcomes reported on the paper bowel diaries were compared with the e-recording equivalent to assess agreement between the two modes of outcome measurement and summarised in Bland–Altman plots.

Original plans to derive measures of social and physical activity from the geospatial data were discarded as the data were shown to be unreliable, with highly improbable measurements recorded.

Programming data were summarised descriptively for each time-point. Analyses followed the modified ITT principle, including all participants according to randomised allocation and with available outcome data. There was no imputation of missing data other than the for the sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome described above.

Cohort study analysis

Data for participants with outcome measurements at baseline and at the end of the study (58 weeks) were summarised descriptively at each time-point, with no formal statistical analysis.

Statistical considerations due to COVID-19

The assumption for the primary analysis was that for participants paused in one of the cross-over periods, the eventual outcome in that period is unaffected by the extra time spent in the allocated treatment condition. We hypothesised that after the scheduled 6-week interval between reprogramming and assessment, a participant’s outcomes would stabilise. Too few participants were randomised for sensitivity analysis to be performed to investigate this.

Mechanistic study methods

Mechanistic study: participant selection

A subgroup of participants underwent central nervous system mechanistic studies at the Institute of Health and Neurodevelopment (IHN) at Aston University. These patients were identified and offered participation based on the following: (1) geographical location (Midlands residents); (2) if they were known to be proceeding to implantation (and therefore participation in the main efficacy trial); and (3) if a standard NHS safety checklist indicated suitability for MRI. Separate (secondary) written, informed consent was obtained locally.

Mechanistic study: interventions

MEG scanner

Magnetoencephalography is non-invasive technique that provides a direct measure of postsynaptic cortical neural activity in real time with a millisecond temporal resolution. The measurement is achieved by placing an array of Superconducting Quantum Interference Devices (SQUIDs) mounted in a helmet structure close to the scalp. These devices, when supercooled in liquid helium, act as transducers, converting minute magnetic fields that pass into the device into electrical current. The magnetic fields generated by large numbers of synchronously active neurons in the cortical surface can then be displayed and recorded in real time.

The MEG system used in the study was an Elekta TRIUX system comprising 306 SQUID devices mounted in a helmet providing coverage of the entire scalp, mounted within a helium dewar structure. This structure keeps the SQUID at a constant temperature of minus 269 °C. The system in turn is housed in a magnetically shielded room to reduce electromagnetic environmental interference. By placing small electrical coils on the surface of the participants head, the system also allows for continuous monitoring of the head position relative to the SQUID detectors.

Transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation

Two disposable self-adhesive electrode pads were placed transcutaneously over the posterior tibial nerve just posterior to the right medial malleolus with the end of the leads connected to a stimulator. Stimulation levels (SLs) were slowly increased from zero in increments of 0.1 mA at a rate of 2 Hz until sensory level was reached when sensation was reported in their foot. This level was then reduced by 0.05 mA at a rate of 2Hz until the sensation disappeared, before increasing the intensity again by increments of 0.01 mA until a sensation was detected again. This level was determined as the sensory threshold (ST). The SL was calculated at 2.5 X ST and the SL was increased slowly in increments of 0.1 mA at a rate of 2 Hz. The patient experienced a ‘strong but not painful’ sensation. This level was reduced to a more tolerable level if the initial calculated SL was not tolerated by the patient. The maximum SL permitted was as high as three times the ST if the calculated SL was not able to produce a strong enough sensation. Stimulation was delivered at an average of 400 stimulations at an Interstimulus Interval (ISI) of 700–800 ms at a rate of 2 Hz.

Anal electrical stimulation

A custom-designed anal plug electrode designed by the medical physics team based at Salford Royal Hospital (Manchester) was inserted into the anal canal with lubrication (using electro-conductive jelly) by the researcher and the patient positioned themselves as before with their head positioned within the MEG helmet. SLs were slowly increased from zero in increments of 0.1 mA at a rate of 2 Hz until sensory level was reached when sensation was reported in their anal canal. This level was then reduced by 0.05 mA at a rate of 2 Hz until the sensation disappeared, before increasing the intensity again by increments of 0.01 mA until a sensation was detected again. This level was determined as the sensory threshold (ST). The SL was calculated at 1.5 X ST and the SL was increased slowly in increments of 0.1 mA at a rate of 2 Hz. The patient experienced a ‘strong but not painful’ sensation. This level was reduced to a more tolerable level if the initial calculated SL was not tolerated by the patient. The maximum SL permitted was as high as two times the ST if the calculated SL was not able to produce a strong enough sensation. Stimulation was delivered at an average of 200 stimulations at an ISI of 1900–2100 ms at a rate of 0.5 Hz.

Fist clenching and anal squeezing paradigm

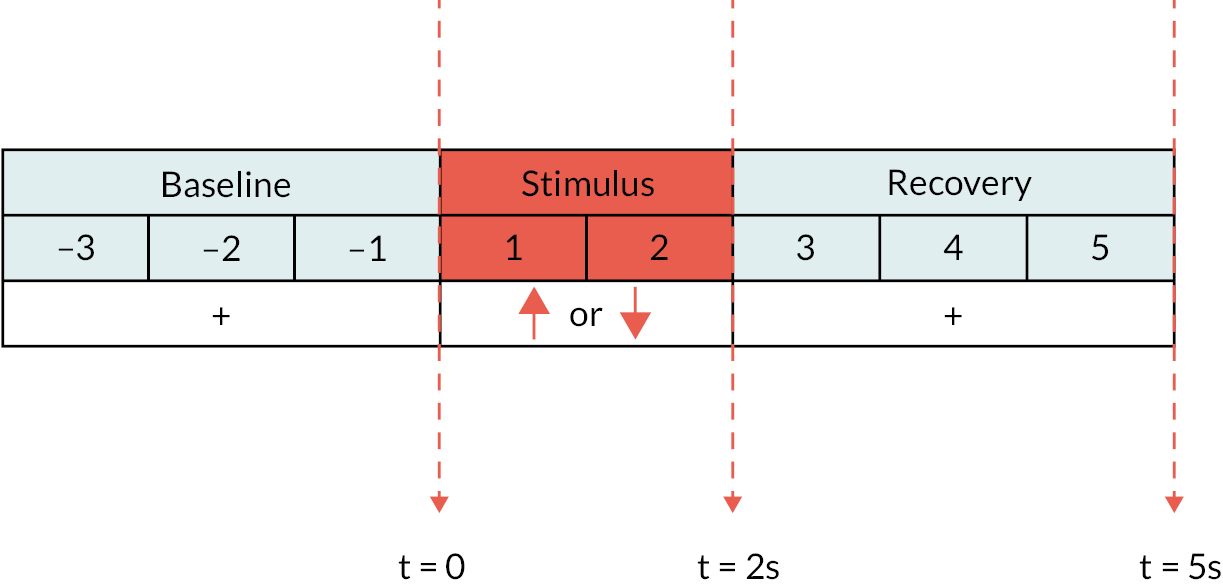

Verbal instructions were given to the patient to squeeze onto the anal probe if a ‘down’ arrow was shown on the screen and to make a fist with their right hand if an ‘up’ arrow was shown on the screen. The patient was asked to perform each task for as long as the arrow appeared on the screen. Each trial lasted for 8 seconds, which comprised a baseline (pre-stimulus) phase (fixation cross for 3 seconds), followed by a stimulus phase (red arrow pointing up or down for 2 seconds) before the recovery phase (fixation cross for 3 seconds) (Figure 3). The ratio of anal squeeze: fist activity was 2 : 1. Electromyography (EMG) activity of the anal probe was concurrently recorded to confirm that anal squeezing activity was adequately performed in a timely manner when a ‘down’ arrow was shown on the screen.

FIGURE 3.

MEG protocol for induced activity: fist clench/anal squeezing paradigm: baseline (pre-stimulus) phase with fixation cross = 3 seconds, stimulus phase with ‘up’ (fist) or ‘down’ (anal squeeze) arrow = 2 seconds, recovery phase with fixation cross = 3 seconds.

Mechanistic study: visit schedule

Patients who expressed an interest were invited to three visits to the Aston University IHN. At the first visit, they were shown the clinical facilities and had the opportunity to enter the MRI scanner to exclude claustrophobia. A baseline MEG was acquired followed by a 3T MRI head scan (N.B. the order of this is important since the MR scanner can induce tiny levels of magnetism in materials such as make-up and hair dye that can affect MEG recordings). At the second and third visits (SNM or sham in random sequence), the patient had further MEG acquisitions only.

Baseline visit

To study the somatosensory pathway, MEG acquisitions were first obtained during three ramped anal electrical stimulations [AEs; each providing an average of 200 stimuli at an ISI of 1900–2100 ms at a rate of 0.5 Hz; total duration 400 seconds]. An identical control paradigm was applied to the right posterior tibial nerve using surface electrodes.

To study the cortico-anal pathway, MEG (and synchronous anal EMG) was acquired during a protocol of volitional actions. A monitor screen provided a series of simple visual stimuli to cue voluntary squeeze of the anal sphincter or to make a fist with their right hand (control pathway) (in random sequence at a ratio of 50 : 25).

Upon completion of the MEG acquisition, the patient was returned to the changing room where the anal plug electrode was removed and the patient was left to privately wash and dress.

Visits 2 and 3

At visits 2 and 3, MEG acquisitions were obtained with the patient’s SNM implanted pulse generated either active or inactive (sham) according to allocation period. An identical paradigm incorporating the evoked somatosensory and induced motor recordings was undertaken at each visit.

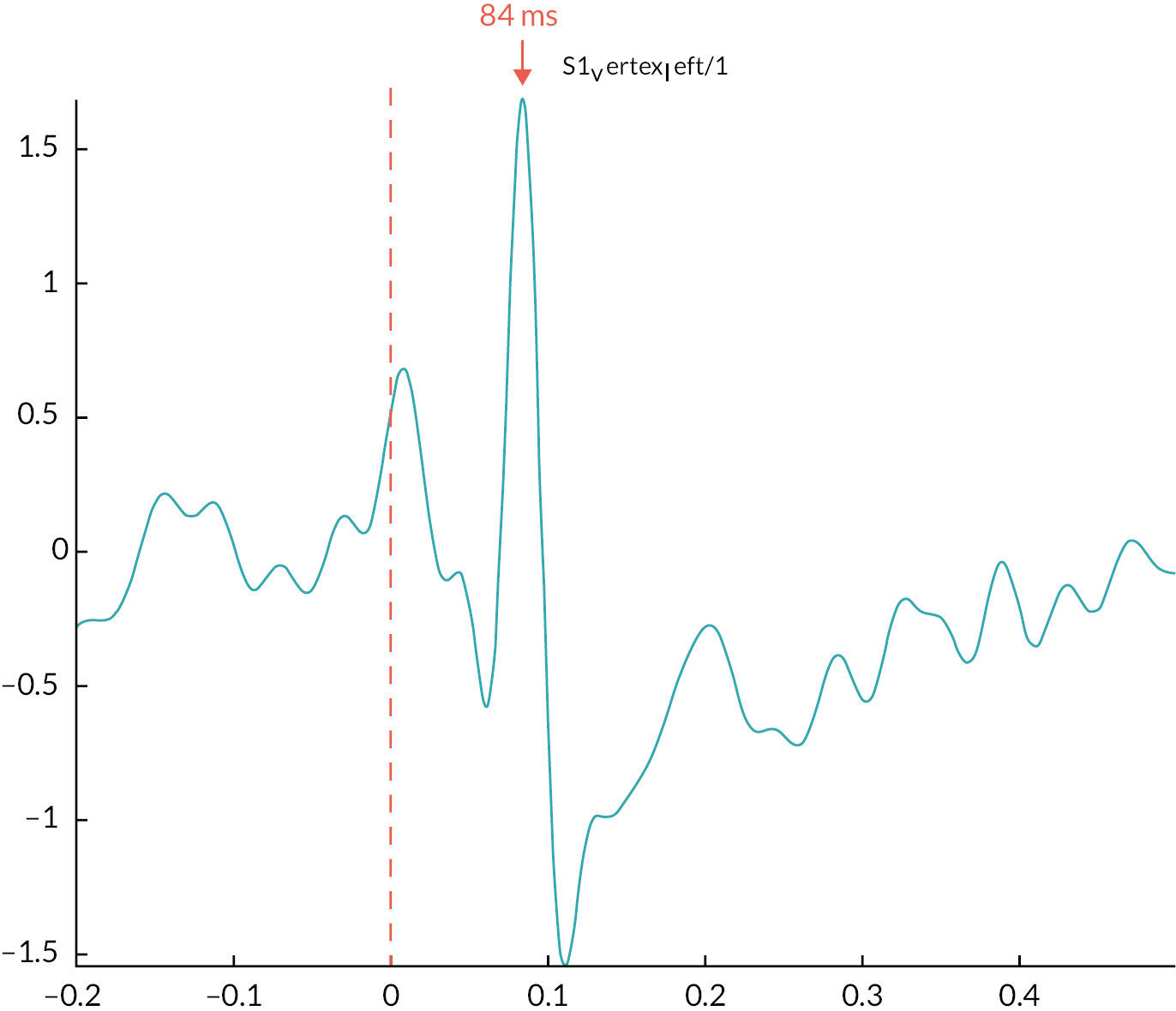

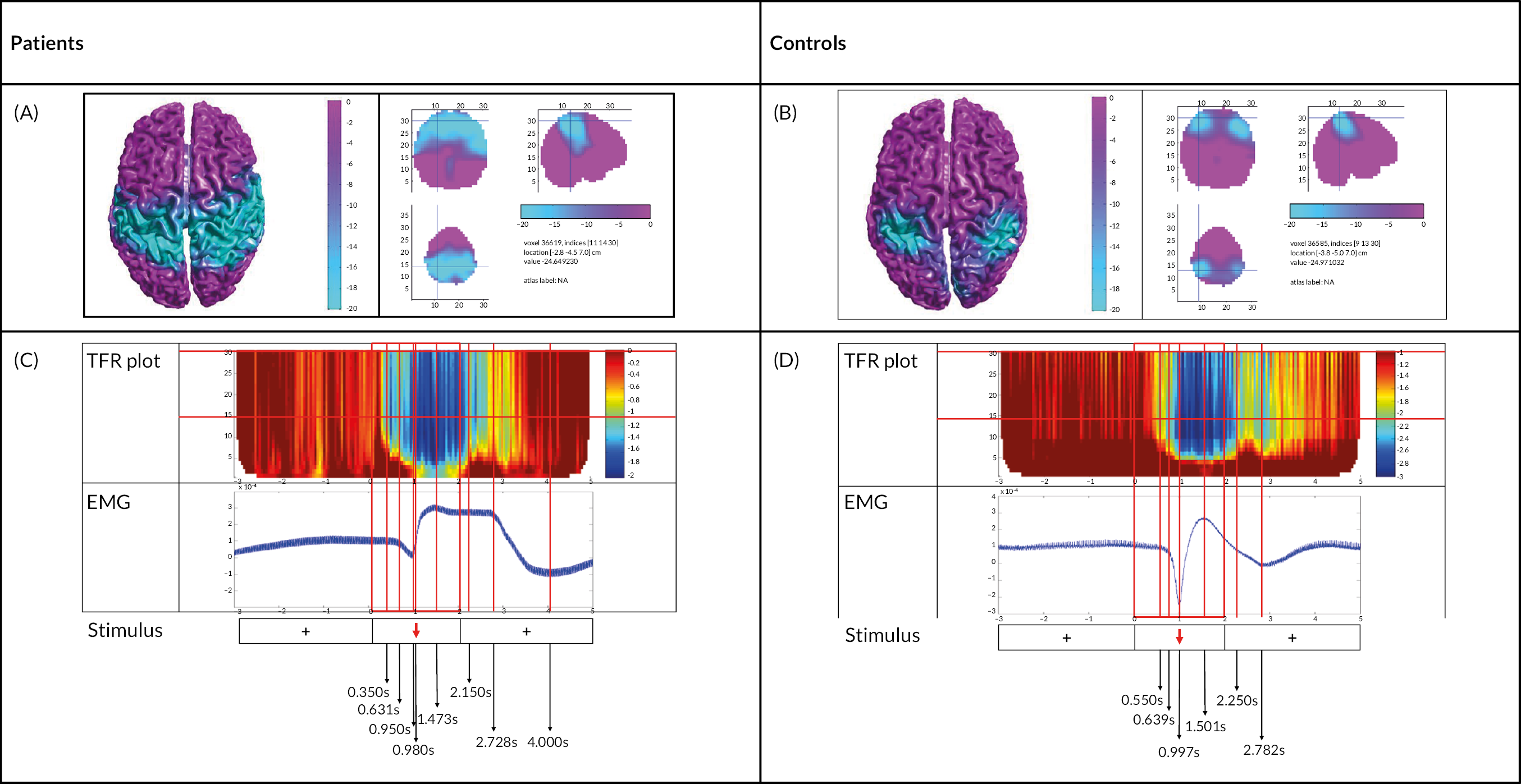

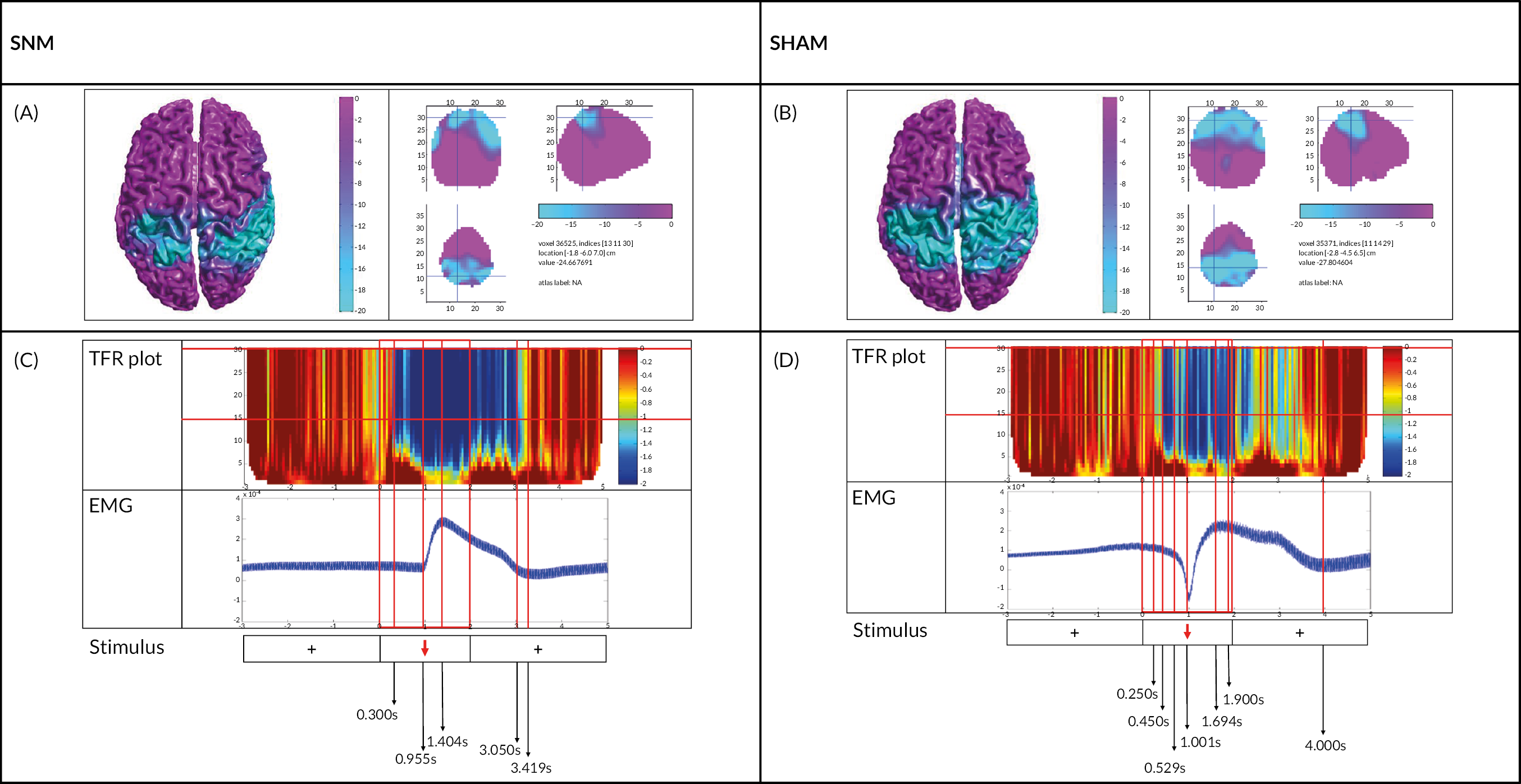

Mechanistic study: outcomes

Whole cortical data were obtained using standard methods on an Elekta Neuromag® (Elekta: Stockholm, Sweden) Triux 306 channel system utilising noise cancellation methods to eliminate implant and stimulator artefacts. A beam-former analysis methodology was employed to evaluate both evoked and induced changes in brain activity associated with SNM and anal stimulation. Brain sources were constructed using individual co-registered T1-weighted MRI brain volumes. The outcome of this process was a measure of the changes in brain oscillatory power and/or frequency changes computed from brain structures where maximum changes associated with anal stimulation were observed. These changes were depicted in statistical brain volumetric images.

Mechanistic study: data analysis

MEG data were analysed by the IHN using existing bespoke computer analysis packages [Graph (ElektaTM Elekta: Stockholm, Sweden); MatlabTM (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) and FieldTripTM (Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour, Radboud University: Nijmegen, the Netherlands) and SPM8TM (Functional Imaging Laboratory, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology: London, UK)]. A beam-former analysis methodology47 was employed to evaluate both evoked and induced changes in brain activity associated with SNM and anal stimulation.

Group analysis of these data allowed determination of any functional cortical changes associated with chronic SNM. This was achieved by the spatial normalisation of individual MRI volumes into a grid based on the Montreal Neurologic Institute standard template.

Statistical analysis employed a non-parametric cluster-based permutation test. 48 Firstly, an uncorrected dependent-samples t-test was performed on pre- and post-stimulus brain activity across the entire brain volume. All voxels exceeding a 5% significance threshold was grouped into clusters. A null distribution was obtained by randomising the condition label (pre- or post-stimulus data) 1000 times and calculating the largest cluster-level t-value for each permutation. This methodology has been shown to adequately control for issues of multiple comparisons. 49

Trial committees

The project fell under the auspices of the Chief Investigator and the PCTU. The project was overseen by a Trial Steering Committee (TSC). The role of the TSC was to provide overall supervision of the study on behalf of the sponsor and funder to ensure the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and relevant regulations.

A Trial Management Group (TMG) met monthly initially during study set up and then less frequently, every 2 months. The TMG was responsible for day-to-day project delivery across participating centres, and reported to the TSC.

A Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) met at least 4 weeks prior to the TSC to enable recommendations to be fed forward. The DMEC reviewed unblinded comparative data, and made recommendations to the TSC on whether there were any ethical or safety reasons why the trial should not continue. The DMEC membership fell in accordance with NIHR/MRC as well as PCTU guidelines.

Chapter 4 Results

Clinical trial results

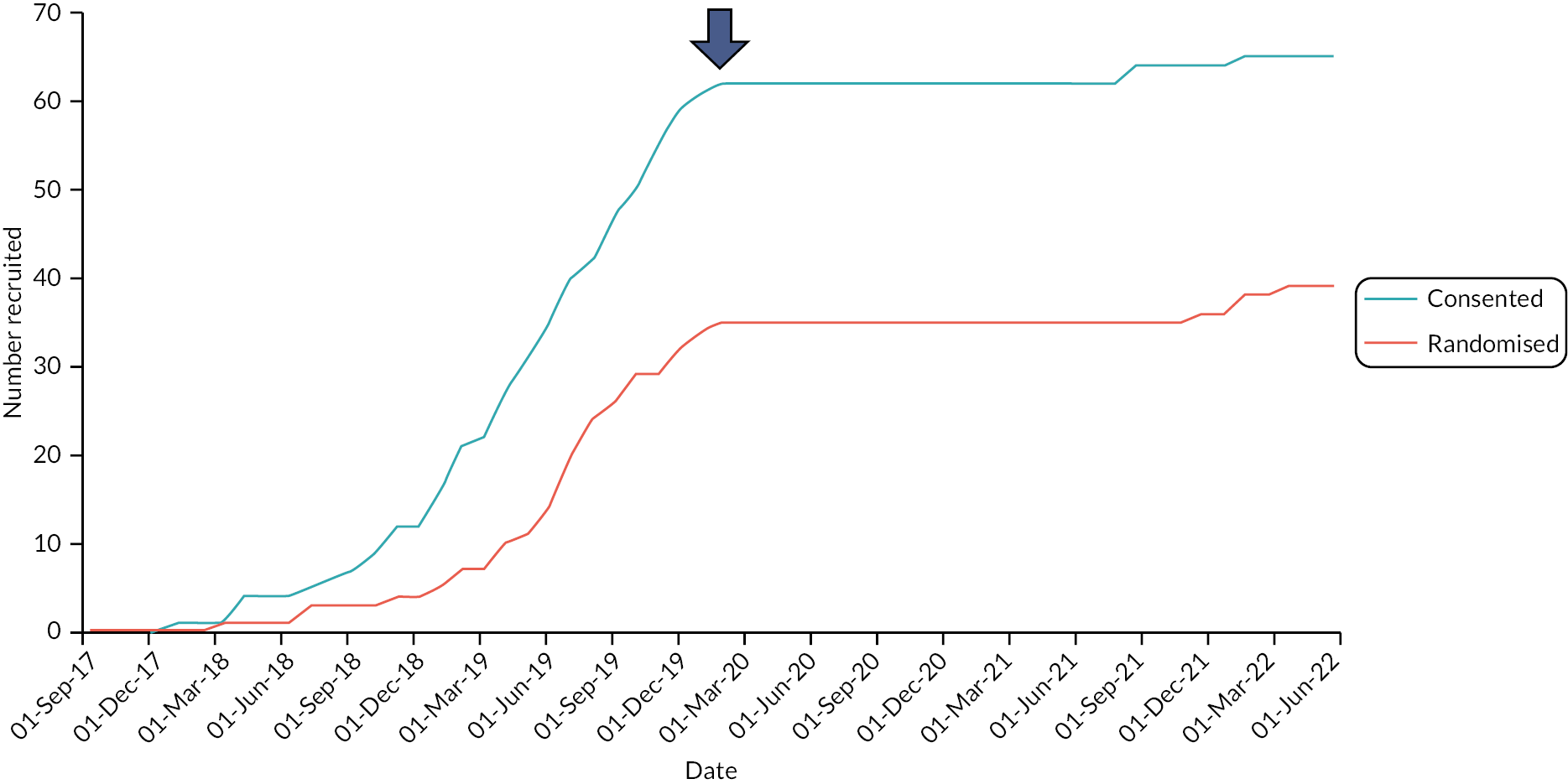

Participant recruitment and flow

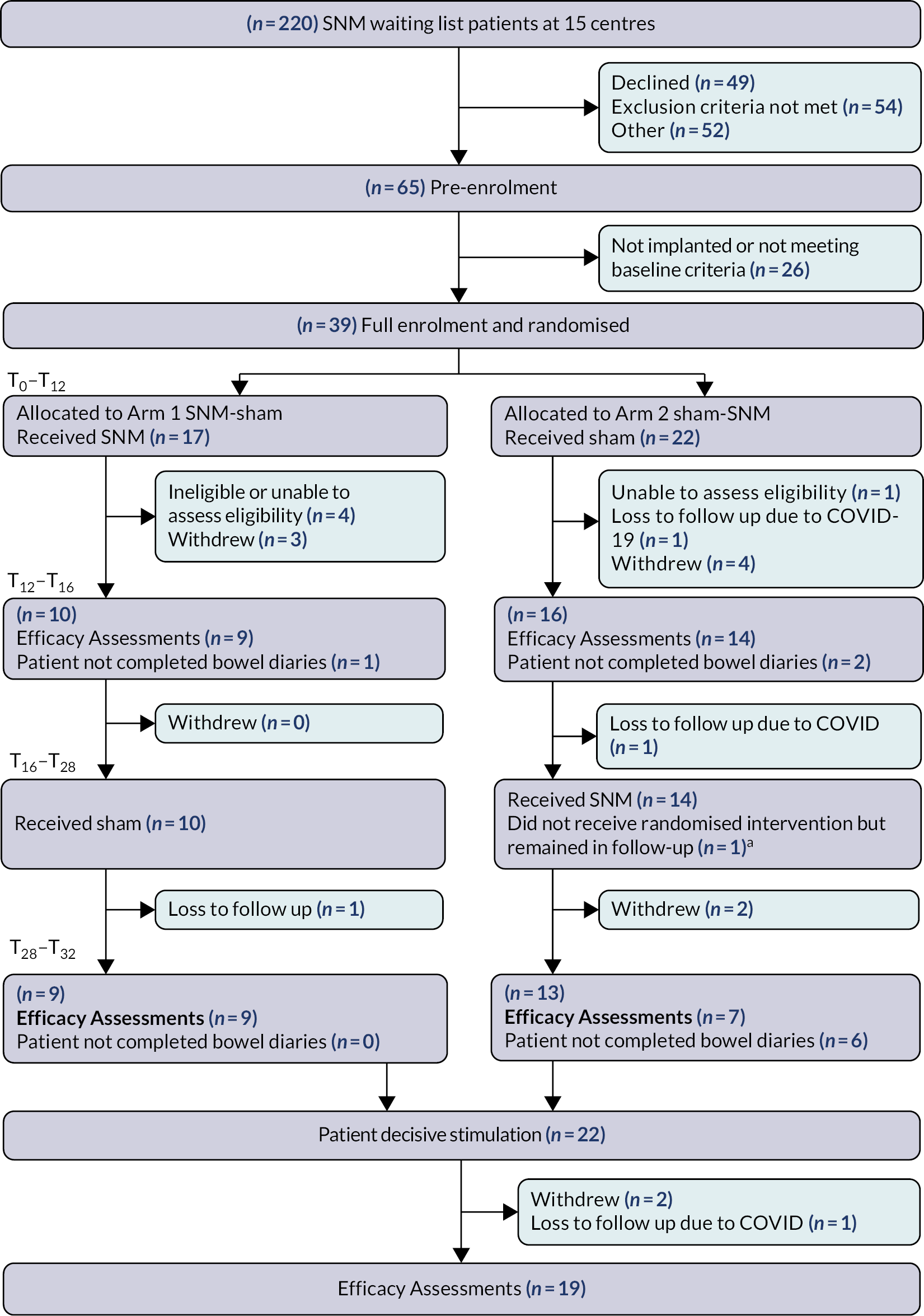

A flow diagram is included as Figure 4. The first patient was recruited on 2 February 2018; the trial was terminated on 24 July 2022 on advice of the DMEC. This decision was reached on the basis of futility given the ongoing significant barriers to recruitment posed by COVID-19 (see barriers to recruitment).

FIGURE 4.

Flow diagram. a, Patient no longer wanted to be randomised and blinded to treatment, but remained in follow-up for cohort analysis.

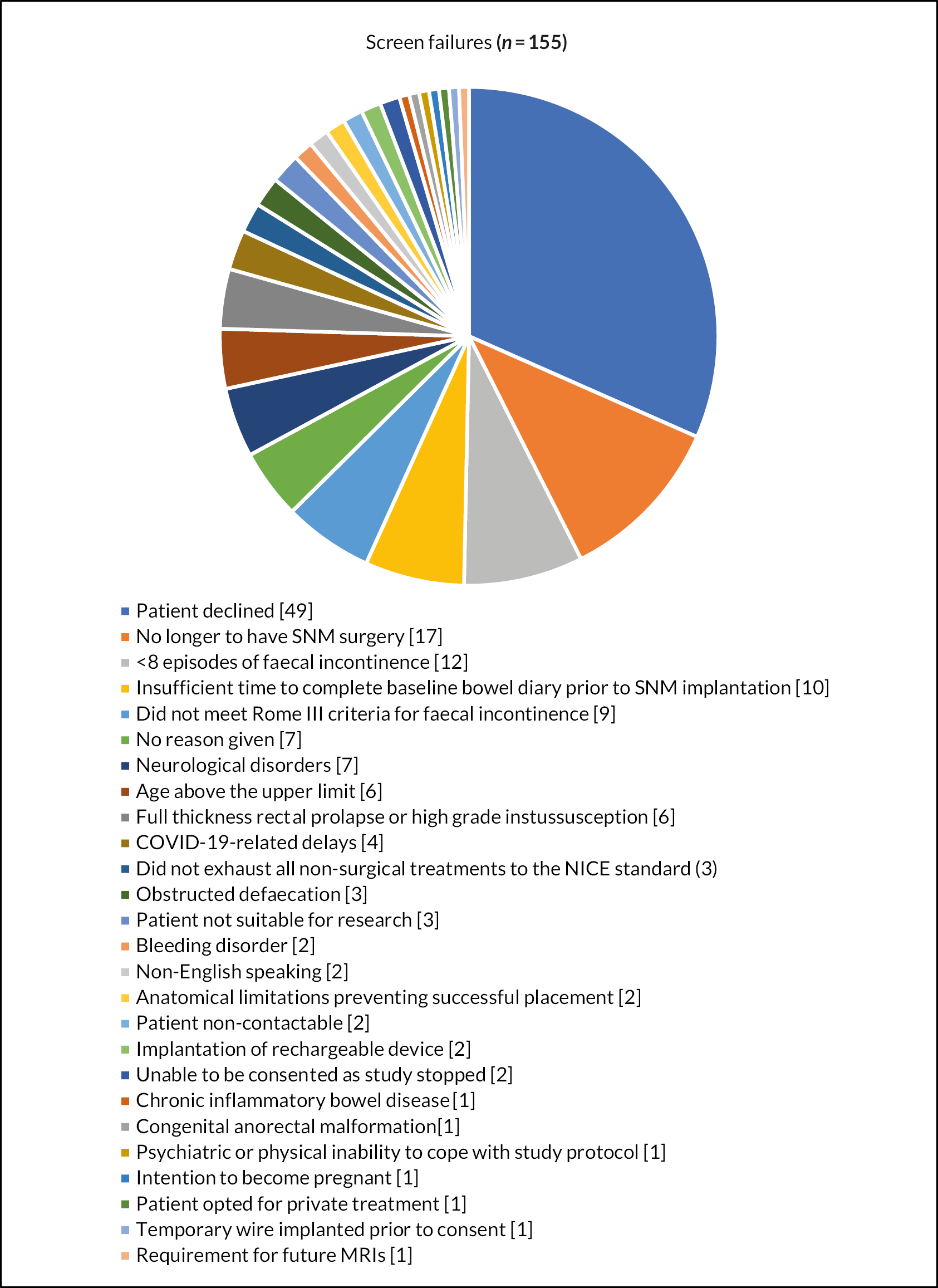

In total, 220 patients were screened for eligibility at nine sites from the UK and one site from Ireland between February 2018 and July 2022 (see Appendix 2). A total of 49 patients declined study participation and 106 were ineligible due to study specific exclusion criteria (Figure 5). A total of 65 patients were pre-enrolled and consented to the study, of whom 26 did not meet the baseline minimum frequency criteria of faecal incontinence episodes or did not receive an implantation. The remaining 39 patients were randomised (arm 1: N = 17; arm 2: N = 22); however, only 16 completed the primary outcome during both cross-over periods (arm 1: N = 9; arm 2: N = 7). The remaining 23 patients withdrew from the study (N = 12), some were excluded on the basis of problems of eligibility (N = 5) (see Appendix 2) or did not complete the primary outcome data (N = 6: still included in the cohort follow-up period).

FIGURE 5.

Number of patients who declined study participation and reasons for ineligibility.

A total of 22 patients started the cohort follow-up period, although 3 of these patients did not complete the final follow-up visit, leaving 19 patients for the open label efficacy assessment.

Barriers to recruitment

The trial was affected by several barriers to recruitment, with the COVID-19 pandemic being the main reason for termination before the required sample size was achieved.

By the beginning of 2020 the number of patients screened and randomised had improved after the changes were made to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, bringing the study close to the trajectory needed to complete recruitment by August 2020. The imminent opening of two large volume sites (St Mark’s Hospital, London and Erlangen, Germany) would have added to the certainty that the study would have finished on time. The outbreak of COVID-19 quickly brought all study activities to a halt. The impact of COVID-19 on the study included:

-

All face-to-face patient visits stopped. All study visits apart from initial screening required face-to-face contact, therefore almost all study activities stopped.

-

Most of the clinical and research staff were redeployed to COVID-19 facing clinical roles.

-

All non-urgent surgical procedures, including all SNM procedures, were cancelled.

-

Multiple staff changes (due to redeployment) amongst the research teams resulted in loss of commitment to the study.

Once the first COVID-19 wave had subsided, sites remained unable to recruit further patients as UK incontinence surgery (including SNM) was graded in the lowest urgency of surgery category (priority 4) by the Joint Surgical Colleges guidance (www.rcseng.ac.uk/coronavirus/surgical-prioritisation-guidance/). Face-to-face visits restarted over the summer of 2020 at some sites (but certainly not all) allowing follow-up visits to gradually restart.

In June 2021, the decision to restart recruitment was made on the balance of some key sites having restarted SNM surgery with the large backlog of patients available. Unfortunately, the Omicron strain of COVID-19 caused further disruptions over the winter period (2021–2). SNM surgery remained low priority, behind the backlog of cancer related and other surgical procedures, resulting in many sites not having restarted in early 2022. Once recruitment restarted, patients appeared more reluctant to take part in the research as their SNM implantation would be delayed.

Mitigations

The researchers undertook the following actions to mitigate the COVID-19 barriers as detailed in Appendix 7:

-

The study moved away from the 2-step (including a ‘test phase’) procedure to a 1-step (straight to permanent implantation) procedure. Several (North European) sites were already using this strategy.

-

The researchers worked closely with Medtronic representatives and organised refresher trainings in order to engage research staff at the participating sites.

-

The researchers opened additional sites to recruitment (St Mark’s Hospital and Sheffield Teaching Hospital).

-

The study allowed the sites to miss out the 6-week reprogramming visits if this was not part of their routine clinical follow-up, to decrease the workload (data on the primary endpoint was not collected during these visits).

Despite re-opening the study and undertaking the above-mentioned actions only three further patients were randomised and most patients that had been awaiting surgery prior to the pandemic had become lost to follow-up. These datasets were provided to the DMEC leading it to advise cessation of recruitment on 24 July 2022.

Introduction of Medtronic (InterStim Micro system) and a smart programmer

In 2019 Medtronic launched the rechargeable battery (InterStim Micro system) and the Smart programmer (TH90P03 handset). Due to the touch screen of the Smart programmer (in contrast to the original Icon programmer) the researchers were not able to maintain blinding of study participants with tamper-prove tape. The decision was made that participants in the study would remain using the original Icon programmer as few sites offered the rechargeable system. The new system was offered to patients at most study sites when recruitment restarted in 2021. Substantial changes to the protocol were required to allow participants with the new system to be recruited for the study. The new TH90P03 handset could not be blinded to allocation as setting the device to 0 V was deemed by the handset to be OFF. Therefore, for the sham setting for participants with this programmer 0.05 V was used. In addition, participants had to commit to not driving during the study period if they were implanted with a rechargeable device and this may have affected recruitment. A substantial amendment as detailed in Appendix 7, covering these changes was submitted in November 2021 and approved in December 2021, but some possible recruits were still lost as a consequence of device changes.

Participant retention and data completeness

The effects of COVID-19 were not limited to recruitment, but also played a major role in participant retention and data collection.

-

Delays in patient follow-up led to an increase in patient withdrawals as they faced an unknown delay in the cross-over period as well as extra visits to hospital that increased the risk of becoming infected with COVID-19. The two participants randomised in Ireland became lost to follow-up due to the much stricter and longer lockdown rules imposed there. A further two withdrew in the UK.

-

Data quality: across all sites research staff were redeployed to clinical care or COVID-19 research. Even after routine outpatient care resumed, research teams were not able to fully support data collection and checking. This affected the data collection in two ways. First, at one site, data collection became much less thorough as the research team were less able to support the clinical team who themselves were under pressure with the backlog of work. This meant that bowel diaries were poorly checked for patient completion. Secondly, data entry also became severely delayed. Centralised data entry was in place with sites emailing completed case report forms via NHS.net. This meant that any issues with protocol deviations such as missing baseline diaries were not detected in a timely manner so changes could not be made to further prevent any issues. COVID-19 also delayed rollout of the trial database thus further reducing the ability to detect and act on data completeness concerns.

Protocol violations

Two patients were found to have their devices switched off when they should have been receiving SNM. The first patient had turned off the device for driving but did not turn it back on again. This was discovered at visit 6, but the amount of time the patient had not been receiving treatment was unable to be determined. The second patient was found to have a defective programmer at visit 9 and not receiving treatment. This occurred during the period when visits were delayed due to COVID-19.

Statisticians were informed both times but not unblinded. The first patient was analysed as per ITT. The second patient had not completed the bowel diaries. As the visits were disordered due to COVID-19 and the site had made the decision to withdraw her from the study at visit 9. As these patients had not completed the bowel diaries they were not included in the final analysis of the primary outcome.

Baseline data

Clinical characteristics

Clinical characteristics at baseline by randomised treatment sequence allocation are detailed in Table 2 for the 39 patients who were randomised with no major differences between arms. As predicted, about 90% of the participants were female with mean age about 57 years. Significant comorbidities and previous surgical procedures were reported in the majority of participants.

| Randomised allocation | ||

|---|---|---|

| SNM/sham | Sham/SNM | |

| N = 17a | N = 22a | |

| Age (years) | N = 17 | N = 22 |

| Mean (SD) | 55.9 (14.1) | 58.2 (11.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 58.0 (44.0–66.0) | 63.5 (47.0–66.0) |

| Sex (%) | N = 17 | N = 22 |

| Male | 1 (6) | 2 (9) |

| Female | 16 (84) | 20 (91) |

| Ethnicity (%) | N = 17 | N = 22 |

| White | 17 (100) | 19 (86) |

| Black | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Mixed | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | N = 17 | N = 18 |

| Mean (SD) | 29.5 (6.84) | 28.6 (5.87) |

| Median (IQR) | 28.3 (26.0–30.2) | 27.4 (23.9–32.8) |

| Significant medical history (%) | N = 17 | N = 22 |

| No | 4 (24) | 6 (27) |

| Yes | 13 (76) | 16 (73) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 |

| (If yes) Medical history b (%) | N = 13 | N = 16 |

| Cardiovascular | 2/13 (15) | 6/16 (38) |

| Respiratory | 2/13 (15) | 2/16 (13) |

| Gastrointestinal | 4/13 (31) | 7/16 (44) |

| Metabolic | 2/13 (15) | 2/15 (13) |

| Haematological | 2/13 (15) | 0/15 (0) |

| Warfarin/heparin therapy | 0/13 (0) | 0/15 (0) |

| Hepatic | 0/13 (0) | 0/15 (0) |

| Renal | 0/13 (0) | 0/15 (0) |

| Genitourinary | 1/13 (8) | 4/15 (27) |

| Neurological/CNS | 1/13 (8) | 3/15 (20) |

| Psychiatric | 2/13 (15) | 5/15 (33) |

| Dermatological | 1/13 (8) | 1/15 (6) |

| Musculoskeletal | 2/13 (15) | 6/15 (40) |

| Any other | 5/13 (39) | 1/14 (7) |

| Significant surgical history (%) | N = 17 | N = 22 |

| No | 2 (12) | 3 (14) |

| Yes | 15 (94) | 19 (86) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 |

| (If yes) Surgical history b (%) | N = 15 | N = 19 |

| Abdominal | 7/15 (47) | 8/18 (44) |

| Urogynaecological | 8/15 (53) | 13/19 (68) |

| Proctological and perineal | 5/15 (33) | 8/19 (42) |

| Neuromodulation | 5/15 (33) | 2/18 (11) |

| Other | 5/14 (36) | 6/18 (33) |

| Duration of faecal incontinence symptoms (years) | N = 17 | N = 22 |

| Mean (SD) | 9.5 (4.8) | 6.5 (4.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 10.0 (6.0–13.0) | 5.5 (4.0–8.4) |

| Preceding events (%) | N = 17 | N = 21 |

| No | 6 (35) | 9 (43) |

| Yes | 11 (65) | 12 (57) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

| Faecal incontinence symptoms b (%) | ||

| Urgency | 12/13 (92) | 15/16 (94) |

| Passive incontinence | 12/17 (71) | 19/22 (86) |

| Urge incontinence | 15/17 (88) | 21/22 (96) |

| Flatus incontinence | 13/17 (76) | 20/22 (91) |

| Prolapse symptoms b (%) | ||

| Sensation of rectal prolapse | 3/17 (18) | 3/22 (14) |

| Sensation of vaginal prolapse (female only) | 3/16 (19) | 2/20 (10) |

| Sensation of vaginal bulging (female only) | 2/16 (13) | 1/20 (5) |

| Anti-diarrhoeal medications b (%) | ||

| Loperamide | 14/17 (82) | 16/22 (73) |

| Other | 4/17 (24) | 5/21 (24) |

| Urinary symptoms history b (%) | ||

| Increased frequency | 5/17 (29) | 14/21 (67) |

| Urgency | 5/17 (29) | 14/22 (64) |

| Stress incontinence | 7/17 (41) | 10/22 (45) |

| Urge incontinence | 6/17 (35) | 12/22 (55) |

| Previous faecal incontinence treatments b (%) | ||

| Pelvic floor exercises | 16/17 (94) | 19/22 (86) |

| Conservative management | 17/17 (100) | 22/22 (100) |

| Biofeedback | 9/17 (53) | 16/22 (73) |

| Anal irrigation | 4/17 (24) | 7/22 (32) |

| PTNS | 8/17 (47) | 9/22 (41) |

| Sphincter repair | 3/17 (18) | 2/22 (9) |

Almost all participants reported symptoms of urgency, combined with varying combinations of passive and urge faecal incontinence. All participants reported previous conservative management for their FI symptoms (as per NICE guidance7). Clinical examination findings, gynaecological and obstetric history at baseline are reported in Appendix 3. All but one female patient had obstetric history (median two vaginal deliveries in both arms).

Symptoms at baseline

Numbers of FI events at baseline for all 39 randomised patients were concordant with design assumptions (based on approx. seven events in a 1-week period; Table 3). FI episodes per week did not significantly vary between patients who participated (mean 6.4; SD 6.2) or were excluded from the crossover (mean 7.6; SD 8.2; p = 0.81). Data for all other variables were similar between arms apart from mean number of urgency episodes per week (without incontinence) which were higher in the sham/SNM arm (although this was less evident based on the median). E-event recordings were only successfully used by a minority (14/39) of participants and high data variability was evident.

| Outcome | Randomised allocation | |

|---|---|---|

| SNM/sham | Sham/SNM | |

| N = 13 | N = 20 | |

| Primary outcome | ||

| Number of FI episodes per week (urge + passive) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 6.6 (6.6) | 7.1 (7.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 5.0 (2.3–8.4) | 3.1 (1.3–9.2) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Other paper bowel diary measures | ||

| Number of urgency episodes per week | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.1 (3.4) | 9.6 (9.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 5.5 (2.8–6.8) | 7.0 (4.1–11.3) |

| Number of urge episodes per week | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.3 (2.0) | 3.1 (3.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–2.8) | 1.9 (0.9–3.3) |

| Number of passive FI episodes per week | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.3 (6.5) | 4.1 (5.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 2.9 (0.0–5.6) | 1.8 (0.0–7.1) |

| Number of episodes of leakage of flatus per week | ||

| Mean (SD) | 9.5 (10.0) | 39.3 (41.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 8.3 (0.5–16.5) | 22.9 (8.1–66.6) |

| % of days patient used loperamide (%) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 49.8 (38.6) | 35.4 (41.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 56.5 (22.2–75.0) | 9.1 (0.0–71.4) |

| % of days faecal incontinence limited a patient’s social activities (%) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 32.9 (41.2) | 61.2 (39.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 12.5 (0.0–56.5) | 76.4 (18.5–96.4) |

| E-event time-linked recordings | N = 8 | N = 6 |

| Number of episodes of faecal material per week | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.2 (3.7) | 2.8 (2.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 2.5 (1.6–7.9) | 1.9 (0.8–4.3) |

| Number of episodes of leakage of flatus per week | ||

| Mean (SD) | 11.5 (12.5) | 9.0 (11.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 9.9 (0.1–18.8) | 4.8 (2.3–11.5) |

| Number of episodes of urgency without incontinence per week | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.8 (2.4) | 12.3 (13.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 5.9 (3.9–8.0) | 6.5 (4.3–20.8) |

Summative symptom scores and QOL measures at baseline are shown in Table 4. Median St Mark’s incontinence score (max score 2440) was approx. 19 in both arms, indicating severe symptoms. Quality of life measured with different instruments was almost identical in the two arms, except for overactive bladder symptoms (OAB-q SF), which were more severe in the sham/SNM arm compared to the SNM/sham arm (mean score 42 vs. 24).

| Questionnaire outcome | Randomised allocation | |

|---|---|---|

| SNM/sham | Sham/SNM | |

| N = 17a | N = 22a | |

| St Mark’s incontinence score b | N = 17 | N = 22 |

| Original St Mark’s score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 18.2 (2.6) | 19.1 (1.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 19.0 (16.0–20.0) | 19.0 (18.0–20.0) |

| Modified St Mark’s score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 17.8 (2.9) | 18.5 (2.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 19.0 (16.0–20.0) | 19.0 (17.0–20.0) |

| St Mark’s deferment time (how long patients can defer going to the toilet) (%) | ||

| < 1 minute | 10 (59) | 10 (45) |

| 1–5 minutes | 7 (41) | 10 (45) |

| 6–15 minutes | 0 (0) | 2 (9) |

| > 15 minutes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Assessment of OverActive Bladder symptoms short form (OAB-q SF) | N = 17 | N = 22 |

| OAB-q SF score c | ||

| Mean (SD) | 24.3 (23.0) | 42.4 (27.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 13.3 (13.3–26.7) | 38.3 (23.3–60.0) |

| Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FI QOL)d | ||

| Lifestyle mean score | N = 17 | N = 21 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.8 (1.6–2.1) | 1.8 (1.6–2.5) |

| Coping behaviour mean score | N = 13 | N = 19 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.3 (1.0–1.4) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) |

| Depression/self-perception mean score | N = 13 | N = 17 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.1 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.6–2.5) | 1.9 (1.8–2.2) |

| Embarrassment mean score | N = 17 | N = 21 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.8 (1.0) | 1.5 (0.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.3 (1.0–2.0) | 1.3 (1.3–1.7) |

| Short form International Consultation on Incontinence Bowel Questionnaire (SF-ICIQ-B) | N = 17 | N = 22 |

| SF-ICIQ-B mean scoree | ||

| Mean (SD) | 9.3 (0.9) | 9.2 (1.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 9.9 (8.5–10.0) | 9.6 (8.8–10.0) |

| EuroQol Health Outcome Measure (EQ-5D-5L) | N = 17 | N = 21 |

| Summary index value f | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.71 (0.21) | 0.79 (0.16) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.78 (0.64–0.85) | 0.83 (0.75–0.90) |

| EQ-VAS score g | ||

| Mean (SD) | 66.7 (19.3) | 70.2 (14.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 70.0 (50.0–80.0) | 70.0 (60.0–80.0) |

Results of the 5-day viscerosensory bowel diary at baseline are detailed in Appendix 3. Approximately 10 toilet attempts were reported per patient in each period of each arm during the 5-day periods of recording. Most toilet attempts were successful and preceded by a sensation of urge. The urge sensation was described using a variety of terms, most often as a sensation of ‘pressure’ or ‘fullness’, with a median intensity score of 8 (6–9) on a VAS scale in both arms.

Implantation details and intraoperative data

Implantation details, including intraoperative sensory and motor responses are detailed in Appendix 4. Test stimulation was performed using a tined lead in 68.6% of the participants. The lead was positioned in the S3 foramina in most participants (91.4%). General anaesthesia was used in 70.6% of the procedures and median operating time was 36 minutes [interquartile range (IQR) 30–55 minutes]. The implantation was considered successful in all cases, and a median post-operative stay was 3 hours (2–4 hours).

Motor responses were used in most participants to guide correct lead placement. There were some variations in fidelity of siting based on individual electrode responses. Bellows contraction was observed in the majority of implantations (93.5%), followed by big toe flexion (80.0%) and anal sphincter contraction (62.5%). An ideal intraoperative motor response (all 4 electrodes < 1 V, bellows contraction, and big toe flexion) was only recorded in 18% of participants. Sensory responses were only used in a small number of participants (n = 3). A total of 50% lead placements achieved motor or sensory responses for 3 electrodes < 1 V. Initial programming data are shown in Appendix 5.

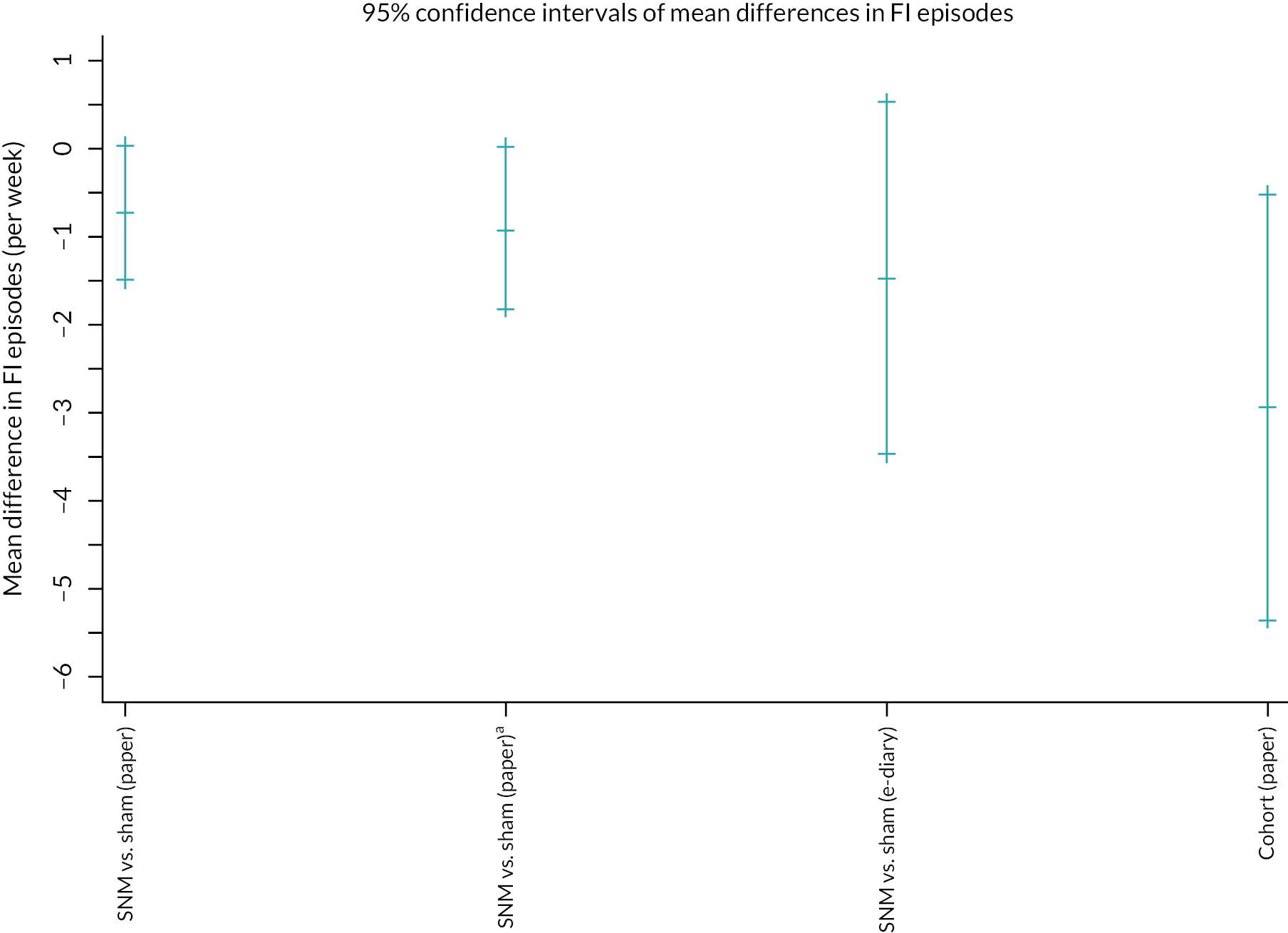

Primary outcome

Due to the under-recruitment it is important to interpret the findings as exploratory. The effect of SNM versus sham on total FI events per week is shown in Table 5 for the 16 participants with complete data. A table including these data and the effect by allocated arm are supplied in Appendix 6. Compared to sham, SNM led to a non-significant mean difference of < 1 episode per week (−0.7, 95% CI −1.5 to 0.0; p = 0.06; see Table 5). The number of days the paper bowel diaries were completed for the primary outcome throughout the entire study by all randomised participants is shown in Table 6. A sensitivity analysis (Table 7) using a best-case scenario in which missing counts were imputed as zero when at least one item had been completed for that day led to a slightly greater effect size (paired t-test: −0.9, −1.8 to 0.0; p = 0.04). The treatment effect was greater but less precise in the small number of participants (N = 7) who used e-event recordings as an alternative method of measurement of the primary outcome (paired t-test: −1.5, −3.5 to + 0.5; p = 0.12).

| Outcome | N = 16 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNM Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

Sham Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

Mean differencea (95% CI) | p-valueb | |

| Primary | ||||

| Number of FI episodes per week (urge + passive) | 2.3 (2.8) 1.4 (0.5–2.8) |

3.0 (3.7) 1.4 (0.8–4.3) |

−0.7 (−1.5 to 0.0) | 0.06 |

| Secondary | ||||

| Number of urgency episodes per week | 3.2 (2.5) 3.1 (1.1–4.5) |

2.7 (2.6) 1.6 (0.8–3.8) |

0.5 (−0.4 to 1.4) | 0.23 |

| Number of urge incontinence episodes per week | 0.6 (0.8) 0.3 (0.0–0.9) |

0.9 (1.4) 0.5 (0.1–1.0) |

−0.3 (−0.8 to 0.2) | 0.27 |

| Number of passive faecal incontinence episodes per week | 1.7 (2.8) 0.8 (0.0–1.4) |

2.1 (3.8) 0.4 (0.0–1.6) |

−0.5 (−1.3 to 0.4) | 0.28 |

| Number of episodes of leakage of flatus per week | 15.0 (22.4) 4.8 (1.6–19.1) |

24.7 (38.2) 5.9 (1.4–31.9) |

−9.6 (−20.9 to 1.6) | 0.09 |

| % of days patient used loperamide for their incontinence symptoms (%) | 30.0 (37.3) 9.1 (1.8–64.3) |

32.7 (43.2) 7.3 (0.0–83.9) |

−2.7 (−8.6 to 3.2) | 0.34 |

| % of days faecal incontinence limited a patient’s social activities (%) | 15.6 (25.9) 0.0 (0.0–20.1) |

18.7 (33.6) 3.7 (0.0–15.4) |

−3.1 (−19.4 to 13.3) | 0.69 |

| E-event recordings | N = 7 | |||

| Number of episodes of leakage of faecal material per week | 0.8 (1.0) 0.5 (0.0–1.3) |

2.2 (2.0) 2.3 (0.0–2.8) |

−1.5 (−3.5 to 0.5) | 0.12 |

| Number of episodes of leakage of flatus per week | 8.8 (6.5) 9.0 (2.0–15.8) |

10.3 (11.7) 6.5 (3.5–11.8) |

−1.5 (−12.0 to 8.9) | 0.73 |

| Number of episodes of urgency without incontinence per week | 1.8 (1.7) 1.0 (0.8–4.0) |