Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as award number 14/23/09. The contractual start date was in February 2016. The draft manuscript began editorial review in August 2022 and was accepted for publication in November 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Boughton et al. This work was produced by Boughton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Boughton et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Management of newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents is challenging for patients, families, carers and healthcare professionals. Glucose is the dominant metabolic substrate for brain function1 and the glycaemic instability inherent in type 1 diabetes is known to affect brain structure and function in those with poorly controlled disease. 2 Severe hypoglycaemia, particularly nocturnal episodes, is more common in children3 and has a negative impact on the developing brain. 2,4 Fear of hypoglycaemia is common,5 impacts quality of life and psychological well-being of young people and their families6 and often leads to suboptimal glucose control. 6 Glycaemic control usually deteriorates during adolescence. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) revealed both higher glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels and a 50% increase in the rate of severe hypoglycaemia in intensively treated adolescents compared to adults. 7 Teenagers with type 1 diabetes face the burden of diabetes management in addition to major physiological and psychological changes accompanying puberty. Only 22% of children and adolescents aged 19 years and younger in the UK reach the international target glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) of < 53 mmol/mol (< 7.0%). 8

Preservation of C-peptide: evidence and approach

Type 1 diabetes is characterised by autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta-cells. 9 Loss of beta-cells is gradual10 and at the clinical diagnosis of diabetes most people with type 1 diabetes have residual pancreatic beta-cells which can continue to secrete insulin for several additional years. Amelioration of hyperglycaemia after diagnosis allows partial recovery of beta-cell insulin secretory function, leading to a ‘honeymoon period’ with relatively low exogenous insulin requirements. 9 In the DCCT, 35% of participants with diabetes duration of 1–5 years had persistent islet cell function (meal-stimulated C-peptide levels of 0.2–0.5 pmol/ml). 7

Persistence of residual functioning beta-cells, measured by C-peptide secretion, is associated with improved glycaemic control, reduced risk of hypoglycaemia and lower incidence of microvascular complications. 11,12 In the DCCT, those who had ≥ 0.20 pmol/ml C-peptide initially or sustained over a year had markedly fewer complications – a 79% decrease in the relative risk of retinopathy. 12 Importantly, these benefits were seen in the face of less hypoglycaemia events. Individuals in the intensive treated group with ≥ 0.20 pmol/ml C-peptide had about the same frequency of severe hypoglycaemia as those in the standard care group; a 30% reduction as compared to those in intensive therapy without this level of C-peptide. A linear relationship between frequency of retinopathy progression and C-peptide as low as 0.03 pmol/ml has been reported. 11 Islet transplant studies have also shown that even small amounts of residual beta-cell function are clinically important. Vantyghem et al. showed that, while significant beta-cell function was required to improve mean glucose, lower glucose excursions, and result in insulin independence, participants who maintained minimal beta-cell function experienced almost no severe hypoglycaemic events. 13 Interventions which can preserve endogenous insulin secretion prior to and following clinical diagnosis of type 1 diabetes are therefore clinically important. 14,15

Assignment to the intensively managed group in the DCCT reduced the risk for loss of C-peptide by 57% over the mean 6.5 years of study. This suggests that metabolic control soon after the onset of type 1 diabetes may have a significant effect on preservation of residual islet cell function. However, intensification of insulin therapy inevitably hits the barrier of hypoglycaemia. 16

Previous studies have investigated whether an early period of islet cell rest achieved by intensive glycaemic control following diagnosis of type 1 diabetes can prevent the decline in endogenous insulin secretion with conflicting results. An early exploratory study in adolescents reported improved stimulated C-peptide levels (0.51 pmol/ml) at 12 months following a period of intensive insulin treatment in hospital for 2 weeks after diagnosis. 17 However, a more recent study applying a short period of hybrid closed-loop (CL) within 7 days of diagnosis, followed by sensor-augmented pump therapy, did not alter C-peptide secretion at 12 months compared with standard care, but there was no difference in glucose control between the two treatment groups over the 12-month study period. 18

It has yet to be determined whether sustained intensive glycaemic control following diagnosis can ameliorate the decline in endogenous insulin secretion in youth with type 1 diabetes.

Closed-loop technology

The emergence of new technologies including continuous glucose monitoring (CGM),19 sensor-augmented pump therapy (SAP)20 and threshold pump suspend21,22 provides new opportunities to improve outcomes for people with type 1 diabetes. The most promising approach is CL insulin therapy23 which combines real-time CGM with insulin pump therapy to achieve glucose responsive subcutaneous (s.c. ) insulin delivery. The vital component of such a system, also known as an artificial pancreas (AP), is a computer-based algorithm. The role of the control algorithm is to translate, in real time, the information it receives from the CGM and to compute the amount of insulin to be delivered by the pump. The other components include a real-time continuous glucose monitor and an infusion pump to titrate and deliver insulin.

Cambridge closed-loop research

Previous research conducted at the University of Cambridge focused on developing a CL system for overnight glucose initially and then day-and-night control in people with type 1 diabetes. Studies employed model predictive control (MPC) – this algorithm estimates user-specific parameters from CGM measurements taken every 1–15 minutes and makes predictions of glucose excursions, which are then used to direct insulin infusion between meals and overnight while a standard bolus calculator is used to deliver prandial insulin. 24 The MPC algorithm has been studied extensively using in silico testing, utilising a simulator developed by members of the study team. 25 The simulations suggested a reduced risk of nocturnal hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia with the use of the MPC algorithm. 26

Previous studies of CL in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes in the clinical research facility showed that overnight CL therapy increased the time spent in target glucose range by 37% and reduced the risk of overnight hypoglycaemia eightfold, as compared to conventional insulin pump therapy in a randomised, crossover design. 27

Following demonstration of safety and efficacy of CL insulin delivery in the research facility, in a multicentre, crossover, randomised, controlled study, we compared 12-week use of an overnight CL insulin delivery system with SAP in children and adolescents aged 6–18 years. 28 The proportion of time with the night-time glucose level in the target range (3.9–8.0 mmol/L) was higher during the CL phase than during the control phase [by 24.7 percentage points; 95% confidence interval (CI) 20.6 to 28.7; p < 0.001], and the mean night-time glucose level was lower (difference, −1.6 mmol/l; 95% CI−2.2 to − 1.1; p < 0.001).

We completed a randomised, crossover design study in adolescents aged 10–18 years who underwent two 7-day home periods of sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy or CL insulin delivery without supervision or remote monitoring. 29 The proportion of time when the sensor glucose level was in the target range (3.9–10.0 mmol/l) was increased during CL insulin delivery compared with sensor-augmented pump therapy (72% vs. 53%, p < 0.001), the mean glucose concentration was lower (8.7 vs. 10.1 mmol/l, p = 0.028), and the time spent above the target level was reduced (p = 0.005) without changing the total daily insulin amount (p = 0.55). The time spent in the hypoglycaemic range was low and comparable between interventions.

The CL approach has been successfully evaluated in children and adolescents in controlled laboratory studies27,30,31 and in home settings. 28,29,32–37 The results demonstrate improved glucose control and reduced risk of hypoglycaemia events. Hybrid CL systems have also been shown to accommodate variability in exogenous insulin requirements. 38,39 Psychosocial assessments support acceptability and positive impact of this novel therapeutic approach among children/adolescents and carers,40 although the potential benefit in preserving cognitive function is, as yet, unknown. The CL approach promises to transform management of type 1 diabetes and may provide a tangible option to improve residual beta-cell function.

Rationale for the study

The purpose of the study is to test the impact of continued intensive metabolic control using CL insulin delivery after diagnosis on preservation of C-peptide residual secretion. The study enrols children aged 10 and older, as they are characterised by higher residual C-peptide secretion at diagnosis compared to younger children. The present study will also test the feasibility and acceptance of this therapy so that it could be considered as a standard treatment modality in the future.

External funding has been secured to continue with the treatment allocated by randomisation for 48 months to allow ongoing assessment of the impact of continued intensive metabolic control using CL insulin delivery on residual C-peptide and will test acceptability of this therapy over a longer duration.

Hypothesis

We hypothesised that a sustained period of intensive glucose control with hybrid CL for 12 months following diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents can preserve C-peptide secretion compared to standard insulin therapy.

Chapter 2 Objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective is to evaluate the effect of continued intensive metabolic control using CL insulin delivery after diagnosis on preservation of C-peptide residual secretion by comparing the area under the stimulated C-peptide curve (AUC) of a mixed-meal glucose tolerance test conducted at the 12-month visit in participants receiving CL insulin delivery with those receiving standard therapy – that is, multiple daily injections applying basal bolus regimen.

The objective of the internal pilot phase is to carry out preliminary evaluation of recruitment, randomisation, treatment and follow-up assessments at the five participating sites.

Secondary objectives

Glucose control

The objective is to examine the efficacy of day-and-night CL compared with standard basal bolus regimen as far as glucose control is concerned. We will compare between-group differences in HbA1c, and parameters based on subcutaneous CGM, such as the percentage of time spent within, below and above the target range from 3.9 to 10.0 mmol/l.

Safety

The objective is to evaluate the safety of day-and-night automated CL glucose control in terms of episodes of severe hypoglycaemia and other adverse events (AEs).

Utility

The objective is to determine the frequency and duration of use of the automated CL system.

Human factors

The objective is to assess emotional and behavioural characteristics of participating subjects and family members and their response to the CL system and clinical trial in order to aid interpretation of trial results and inform recommendations for future use of CL systems.

Interviews were conducted with healthcare professionals to explore their views and experiences of delivering the trial and supporting participants using the CL system.

Chapter 3 Trial design

The study adopted an open-label, multicentre, randomised, parallel design comparing hybrid CL insulin delivery and standard insulin therapy (control) over 12 months. The study protocol has been previously reported. 41

Internal pilot phase

The purpose of the internal pilot study was to estimate the rate of recruitment, and to pilot randomisation, treatment and follow-up assessments at the initial participating sites. During the pilot phase, we aimed to recruit at least 10 subjects – that is, 2 per site. All participants recruited during the pilot phase proceeded to the full study.

Full study

Following the internal pilot phase and consecutive re-evaluation of recruitment procedures and follow-up assessments, recruitment for the study resumed at full rate, and all randomised subjects were followed up until study completion. External funding was secured to allow participants to continue with the treatment allocated at randomisation for a further 12 months. Study processes are therefore referred to over the 24-month study period, but this report focuses on the 12-month results which includes the primary end point. The study flow chart is outlined in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow chart.

Extension phase

At 24 months, all participants were invited to participate in an optional extension phase to continue with their current treatment (automated CL glucose control or standard insulin therapy) for a further 24 months. Permission has also been sought from participants and their carers for ongoing submission of routine clinical data to the research team for a further 9 years to enable long-term outcomes to be reported.

Approval was received from Cambridge East Research Ethics Committees (16/EE/0286) and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Safety aspects were overseen by an independent data safety monitoring board. The study is registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02871089).

Study participants

Participants were recruited from seven paediatric diabetes clinics in the UK (Cambridge, Edinburgh, Leeds, Liverpool, Nottingham, Oxford, Southampton). Eligible participants were identified by clinical teams at each centre. Participants aged 16 years and parents/guardians of participants < 16 years gave written informed consent. Written assent was obtained from participants < 16 years.

Following the initial 24 months of the study, all participants opting to continue with the extension phase of the study were re-consented.

Inclusion criteria

-

Diagnosis of type 1 diabetes within previous 21 days. Day 1 will be defined as the day insulin was first administered. Type 1 diabetes will be defined according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria using standard diagnostic practice. WHO definition: ‘The aetiological type named type 1 encompasses the majority of cases with are primarily due to beta-cell destruction, and are prone to ketoacidosis. Type 1 includes those cases attributable to an autoimmune process, as well as those with beta-cell destruction for which neither an aetiology nor a pathogenesis is known (idiopathic). It does not include those forms of beta-cell destruction or failure to which specific causes can be assigned (e.g. cystic fibrosis, mitochondrial defects, etc.).’

-

The subject is at least 10 years and not older than 16.9 years.

-

The subject/carer is willing to perform regular capillary blood glucose monitoring, with at least four blood glucose measurements taken every day.

-

The subject is literate in English.

-

The subject is willing to wear glucose sensor.

-

The subject is willing to wear CL system at home.

-

The subject is willing to follow study-specific instructions.

-

The subject is willing to upload pump and CGM data at regular intervals.

Exclusion criteria

-

Physical or psychological condition likely to interfere with the normal conduct of the study and interpretation of the study results as judged by the investigator.

-

Current treatment with drugs known to interfere with glucose metabolism – for example, systemic corticosteroids, non-selective beta-blockers and MAO inhibitors, etc.

-

Known or suspected allergy to insulin.

-

Regular use of acetaminophen.

-

Lack of reliable telephone facility for contact.

-

Pregnancy, planned pregnancy or breastfeeding.

-

Living alone.

-

Severe visual impairment.

-

Severe hearing impairment.

-

Medically documented allergy towards the adhesive (glue) of plasters or unable to tolerate tape adhesive in the area of sensor placement.

-

Serious skin diseases (e.g. psoriasis vulgaris, bacterial skin diseases) located at places of the body, which potentially are to be used for localisation of the glucose sensor.

-

Illicit drugs abuse.

-

Prescription drugs abuse.

-

Alcohol abuse.

-

Sickle cell disease, haemoglobinopathy, receiving red blood cell transfusion or erythropoietin within 3 months prior to time of screening.

-

Eating disorder such as anorexia or bulimia.

-

Milk protein allergy.

Randomisation

Eligible participants were randomised after baseline mixed-meal tolerance test (MMTT) using block randomisation (block sizes of two and four were used with equal probability) and central randomisation software to CL therapy or standard insulin therapy. Randomisation was stratified by site and age (10–13 years and 14–16 years); the randomisation ratio was 1 : 1 within each stratum.

Closed-loop system

The Cambridge MPC algorithm (version 0.3.71) was run in two hardware configurations, the initial FlorenceM configuration followed by the CamAPS FX (CamDiab, Cambridge, UK) configuration to improve usability and therapy adherence (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Hybrid CL configurations used in the CL group. Panel A shows FlorenceM configuration and panel B shows CamAPS FX configuration.

FlorenceM

The FlorenceM configuration comprised a locked smartphone (Samsung Galaxy S4, South Korea) running an app with the Cambridge control algorithm (version 0.3.71), a Medtronic prototype phone enclosure with an embedded modified Carelink USB to allow the smartphone to wirelessly communicate with a modified Medtronic MiniMedTM 640G insulin pump (Medtronic, Northridge, CA, USA). This pump had low glucose suspend enabled and received glucose sensor data from the Medtronic MiniMedTM GuardianTM 3 sensor, which requires finger-stick calibrations.

CamAPS FX

The CamAPS FX configuration superseded FlorenceM in July 2019. The CamAPS FX system comprised an unlocked smartphone (Samsung Galaxy S8, South Korea) hosting the CamAPS FX app running the Cambridge control algorithm (version 0.3.71), which communicated wirelessly with both the Dana Diabecare RS insulin pump (Sooil, Seoul, South Korea) and Dexcom G6 transmitter (Dexcom, San Diego, CA, USA).

In both configurations, algorithm-driven insulin delivery was adjusted automatically every 8–12 minutes, with the app-based control algorithm communicating the insulin infusion rate to the insulin pump wirelessly. The control algorithm was initialised using total daily insulin dose and body weight, and incorporated adaptive learning with regard to total daily insulin requirements, diurnal variations, meal patterns, and duration of insulin action.

In both configurations, when auto mode was not operational, the insulin pump reverted to pre-programmed basal rates. The treat-to-target adaptive control algorithm had a nominal glucose target level of 5.8 mmol/l, which was adjustable in the CamAPS FX configuration between 4.0 mmol/l and 11.1 mmol/l across different times of day. The CamAPS FX app contained a bolus calculator to initiate bolus delivery from the phone, a user-selectable ‘Ease-off’ mode to reduce insulin delivery around activity/exercise, and a ‘Boost’ mode to intensify insulin delivery when insulin needs were elevated. The CamAPS FX app streamed data to Diasend data ecosystem (Glooko/Diasend, Sweden).

Procedures

Screening and baseline evaluation

The screening assessment included written informed consent/assent, checking inclusion and exclusion criteria, medical (diabetes) history, body weight and height measurement, calculation of body mass index (BMI), blood pressure measurement, record of current insulin therapy and urine pregnancy test (females of child-bearing potential). If not done at diagnosis, a blood sample was taken for assessment of full blood count, thyroid function (TSH, fT4), anti-transglutaminase antibodies and IgA (measured locally).

Education for both arms

At entry to the study, all participants completed a structured educational programme delivered to the participants and their families in accordance with the standards of the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD). 42 All participants were trained on the use of multiple daily injection therapy (MDI) regimen. Participants and their families were educated in:

-

type 1 diabetes

-

the use and administration of insulin

-

hyperglycaemia and correction doses

-

hypoglycaemia symptoms and treatment

-

exercise

-

sick-day rules

-

carbohydrate counting and dietetic education

-

the benefits of maintaining optimal glycaemic control for long-term health

-

blood glucose monitoring.

Baseline visit

Within 21 days of diagnosis, participants attended for the baseline MMTT. Blood samples were taken for HbA1c, lipid profile and immunological parameters. Computerised cognitive tests and validated questionnaires to assess quality of life and diabetes management were completed. A masked CGM device was applied to assess baseline glycaemic control.

Mixed-meal tolerance tests

Mixed-meal tolerance tests were conducted at baseline, 6, 12 and 24 months post diagnosis following an overnight fast. Participants were given a liquid meal (Boost, Nestlé, Switzerland) according to bodyweight [6 ml/kg (maximum 360 ml), 17 g carbohydrate, 4 g protein, 3 g fat per 100 ml] and venous blood samples for measurement of C-peptide and glucose were collected at –10, 0, 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes.

Questionnaires

At baseline, 12 and 24 months participants and caregivers completed the following questionnaires:

-

Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) Diabetes;

-

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ);38

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). 43

At baseline, 12 and 24 months participants and caregivers in the CL arm completed the INsulin Dosing Systems: Perceptions, Ideas, Reflections and Expectations (INSPIRE) questionnaire. At baseline, 12 and 24 months participants completed the problem areas in diabetes (PAID)-Teen questionnaire.

Intervention period

Study visit schedules and flow chart are shown in Table 1, Table 2 and Figure 1. Following randomisation, participants randomised to the CL group were trained to use the study insulin pump and glucose sensor prior to starting CL insulin delivery within 6 weeks of diagnosis. Participants continued with CL therapy for 24 months with no remote monitoring or study-related restrictions. Participants randomised to standard insulin therapy received additional training to complement the core training and to match contact time with the CL group. Participants continued with standard insulin therapy for 24 months but could switch to insulin pump therapy and/or use flash/CGM or approved CL systems if clinically indicated, applying National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) criteria. 43 The recommended glycaemic target for both groups was HbA1c < 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) as per the NICE guidelines. 43

| Visit/contact | Description | Start relative to previous/next visit/activity | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run-in period | Visit 1 | Recruitment and screening visit: Consent/assent; inclusion, exclusion; screening blood sample | Within 21 days of diagnosis | 2 hours |

| Visit 2 | Baseline visit: HbA1c, MMTT, blinded CGM, questionnaires, computerised cognitive testing, bloods for immunological analyses | 7–21 days after diagnosis | 3–4 hours | |

| Randomisation | ||||

| Insulin pump and CGM training | Visit 3 | Insulin pump training, initiation study pump | Within 1 week of Visit 2 | 3–4 hours |

| Visit 4 | CGM training, initiation of CGM | Within 0–7 days of Visit 3 (Visit 4 may coincide with Visit 3; Training visits can be repeated) | 2 hours | |

| Closed-loop insulin delivery (24 months) | Visit 5a | CL initiation at clinic/home | Within 6 weeks of diagnosis | 3–4 hours |

| Contact | Review use of study devices, study update | 1 week after Visit 5 (± 3 days) | < 0.5 hour | |

| Visit 6a | HbA1c, data download, blinded CGM | After 3 months of diagnosis (± 1 week) | < 1 hour | |

| Visit 7 | MMTT, HbA1c, bloods for immunological analyses, data download, blinded CGM, sleep quality assessment | After 6 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | 3–4 hours | |

| Visit 8a | HbA1c, data download, blinded CGM | After 9 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | < 1 hour | |

| Visit 9 | MMTT, HbA1c, bloods for immunological analyses, data download, blinded CGM, questionnaires, computerised cognitive testing, interviews, sleep quality assessment | After 12 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | 3–4 hours | |

| Visit 10a | HbA1c, data download, blinded CGM | After 15 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | < 1 hour | |

| Visit 11a | HbA1c, data download, blinded CGM | After 18 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | < 1 hour | |

| Visit 12a | HbA1c, data download, blinded CGM | After 21 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | < 1 hour | |

| Visit 13a | Blinded CGM, sleep quality assessment | Between Visit 12 and Visit 14 (Visit 13 may coincide with Visit 14) | < 0.5 hour | |

| Visit 14 | End of CL treatment: MMTT, HbA1c, data download, bloods for immunological analyses, questionnaires, computerised cognitive testing, focus groups |

After 24 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | 4–5 hours |

| Visit/contact | Description | Start relative to previous/next visit/activity | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run-in period | Visit 1 | Recruitment and screening visit: Consent/assent; inclusion, exclusion; screening blood sample | Within 21 days of diagnosis | 2 hours |

| Visit 2 | Baseline visit: HbA1c, MMTT, blinded CGM, questionnaires, computerised cognitive testing, bloods for immunological analyses | 7–21 days after diagnosis | 3–4 hours | |

| Randomisation | ||||

| Additional training | Visit 3 | Training on carbohydrate counting | Within 1 week of Visit 2 | 2 hours |

| Visit 4 | Training on insulin dose adjustment | Within 0–7 days of Visit 3 (Visit 4 may coincide with Visit 3; Training visits can be repeated) | 2 hours | |

| Standard insulin therapy (24 months) | Visit 5a | Control arm start visit | Within 6 weeks of diagnosis | < 1 hour |

| Contact | Study update | 1 week after Visit 5 (± 3 days) | < 0.5 hour | |

| Visit 6b | HbA1c, blinded CGM | After 3 months of diagnosis (± 1 week) | < 1 hour | |

| Visit 7 | MMTT, HbA1c, bloods for immunological analyses, blinded CGM, sleep quality assessment | After 6 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | 3–4 hours | |

| Visit 8b | HbA1c, blinded CGM | After 9 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | < 1 hour | |

| Visit 9 | MMTT, HbA1c, bloods for immunological analyses, blinded CGM, questionnaires, computerised cognitive testing, sleep quality assessment |

After 12 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | 3–4 hours | |

| Visit 10b | HbA1c, blinded CGM | After 15 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | < 1 hour | |

| Visit 11b | HbA1c, blinded CGM | After 18 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | < 1 hour | |

| Visit 12b | HbA1c, blinded CGM | After 21 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | < 1 hour | |

| Visit 13b | Blinded CGM, sleep quality assessment | Between Visit 12 and Visit 14, (may coincide with visit 14) | < 1 hour | |

| Visit 14 | End of control treatment: MMTT, HbA1c, bloods for immunological analyses, questionnaires, computerised cognitive testing | After 24 months of diagnosis (± 2 weeks) | 4–5 hours |

Study contacts

Participants were followed up at 3-monthly intervals. At each follow-up visit, HbA1c was measured and participants wore a masked glucose sensor (LibrePro; Abbott Diabetes Care, Alameda, CA, USA) for 14 days. MMTTs were conducted at 6, 12 and 24 months post diagnosis following an overnight fast.

Participants/parents and/or the local diabetes clinical team were free to adjust insulin therapy, but no active treatment optimisation was undertaken by the research team. Participants were able to contact a 24-hour telephone helpline to the local research team.

Assays

C-peptide and glucose were measured centrally (Swansea University, Swansea, UK); C-peptide was measured using a sensitive, luminescence immunoassay (IV2-004, Invitron, UK) and glucose using a glucose oxidase method (YSI 2300 stat plus, YSI Life Sciences, USA). HbA1c was measured centrally (Swansea University) using an International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC)-aligned method and following National Glycohemoglobin Standardisation Program (NGSP) standards; Tosoh GX (Tosoh Bioscience, UK). Lipid profile was measured locally.

Study end points

The primary end point was the between-group difference in mean stimulated C-peptide AUC of the 12-month MMTT. Key secondary end points included time in target glucose range 3.9–10.0 mmol/l, HbA1c, and time < 3.9 mmol/l at 12 months tested sequentially to control the type I error. Sensor glucose end points were based on data from a masked glucose sensor worn for 14 days.

Additional secondary end points included mean stimulated C-peptide at 6 and 24 months, plasma glucose and fasting C-peptide divided by fasting glucose at 6, 12 and 24 months during MMTT, HbA1c at 6 and 24 months, percentage of participants in each group with HbA1c < 7.5% (58 mmol/mol) at 12 and 24 months. Secondary end points based on masked sensor glucose data collected every 3 months included time in range, mean glucose, standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation of glucose, time spent in hyperglycaemia, time with glucose < 3.5 mmol/l, < 3.0 mmol/l and < 2.8 mmol/l and AUC of glucose < 3.9 mmol/l and < 3.5 mmol/l. Insulin metrics (total, basal and bolus insulin dose), BMI SD score, blood pressure and lipid profile were compared between groups at 12 and 24 months.

Safety evaluation comprised the frequency of severe hypoglycaemia and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), and other AEs and SAEs.

Power calculation

The primary analysis compares the difference between groups in the 2-hour AUC-mean using the ln(mean C-peptide + 1). The residual SD of the ln(x + 1) transformed C-peptide AUC analysis of covariance is referred to by TrialNet44 as the root mean squared error (RMSE). The back-transform, exp(y) – 1, of the mean of the transformed values is referred to by TrialNet as the geometric-like mean. In the DirecNet/TrialNet new-onset studies,44 the point estimate for RMSE was 0.18 (transformed scale) and was used in the power calculations. As in the TrialNet sample size calculations, a 50% improvement was assumed in the geometric-like mean C-peptide AUC. The sample size depends on the geometric-like mean value in the control group. The original TrialNet sample size calculations assumed a value of 0.37 pmol/ml for the control group based on the lower 90% confidence limit from previous data. 44 The present power calculation applied the same value. A 50% increase in the intervention group of the geometric-like mean C-peptide AUC gives 0.37*1.50 = 0.555 pmol/ml. After ln(x + 1) transformation, the mean values in the control and treatment groups are 0.315 and 0.441 (transformed scale), respectively, the treatment effect is 0.441–0.315 = 0.126. The treatment effect of 0.126 with a SD of 0.18 requires 44 subjects per group at 90% power for a two-sided test at the 0.05 level. Allowing for 10% loss to follow-up means we aimed to recruit a total of 96 randomised participants (48 per group).

Statistical analysis

Primary analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis with each participant analysed according to the treatment assigned by randomisation. All randomised participants were included in the intention-to-treat population and all enrolled participants were included in the safety cohort. Comparison of safety outcomes between the two treatment groups only included those events occurring on or after randomisation. All randomised participants with at least one CGM reading were included in the CGM analyses following a modified intention-to-treat approach. Treatment interventions were compared using a longitudinal mixed effects linear model adjusting for baseline value, gender, presence/absence of DKA at diagnosis and age as fixed effects, and clinical site as a random effect. A 95% CI was reported for the difference between the interventions based on the model. The log (C-peptide AUC + 1) values at 12 months post randomisation were compared for the primary analysis. For highly skewed residuals for secondary outcomes winsorisation was used. Mixed effects regression models addressed missing data by using maximum likelihood estimation incorporating data from all randomised participants, which assumes data were missing at random.

A per-protocol analysis restricted to participants in the CL group who used the system at least 60% of the time and those in the control group who did not start insulin pump therapy was conducted.

The primary and key end points comparing between-group differences at 12 months post diagnosis were tested sequentially to maintain a type 1 error rate of 5%. If C-peptide AUC was significant at α = 0.04, then key end points were tested at α = 0.05. Otherwise, they were tested at α = 0.01. If all three key end points were significant at α = 0.01, then this alpha was recycled to the primary outcome and C-peptide AUC was tested at α = 0.05. Secondary end points were adjusted for multiple comparisons to control the false discovery rate using the two-stage adaptive Benjamini–Hochberg method. 45 Analyses were conducted with SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Health economics analysis was not included in the NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation contract and is therefore not included in this report.

Participant withdrawal criteria

The following pre-randomisation withdrawal criterion will apply:

-

Subject/Family is unable to demonstrate safe application of MDI during run-in period as judged by the investigator.

The following pre- and post-randomisation withdrawal criteria will apply:

-

Subject is unable to demonstrate safe use of MDI or study insulin pump and/or CGM during post-randomisation training period as judged by the investigator.

-

Subject fails to demonstrate compliance with MDI therapy or study insulin pump and/or CGM during post-randomisation training period.

-

Subjects may terminate participation in the study at any time without necessarily giving a reason and without any personal disadvantage.

-

Significant protocol violation or non-compliance.

-

Recurrent severe hypoglycaemia events not related to the use of the CL system.

-

Recurrent severe hyperglycaemia event/DKA unrelated to infusion site failure and related to the use of the CL system.

-

Decision by the investigator or the Sponsor that termination is in the subject’s best medical interest.

-

Allergic reaction to insulin.

-

Allergic reaction to adhesive surface of infusion set or glucose sensor.

-

If patient cannot be contacted in 12 weeks subject will be considered lost to follow-up.

Protocol and statistical analysis plan amendments can be found in Appendices 2 and 3.

Chapter 4 Results

Recruitment

Pilot study for recruitment

Recruitment for CLOuD commenced in February 2017. An internal pilot study randomising 10 participants tested the feasibility of recruitment to the study protocol. The first 10 participants were recruited within the first 4 months after recruitment commenced. Over 30% of subjects who were eligible and invited to participate in the study were successfully recruited and therefore the internal pilot study continued to the full study.

Full study recruitment

Table 3 shows the recruitment success rate overall and by individual site. We applied no exclusions at enrolment such as technology propensity or healthcare professional considerations about suitability, minimising selection bias. The study population is therefore representative of the general population of youth newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, improving generalisability of the findings.

| Site | Number of newly diagnosed T1D patients aged 10–16.9 years | Number of patients approached (given PIS) | Number of patients eligible for CLOuD | Number of participants recruited to CLOuD | Recruitment success rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37 | 35 | 33 | 19 | 57.6 |

| 2 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 6 | 42.9 |

| 3 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 12 | 52.2 |

| 4 | 25 | 21 | 20 | 17 | 85.0 |

| 5 | 29 | 26 | 26 | 21 | 80.8 |

| 6 | 32 | 30 | 27 | 14 | 51.9 |

| 7 | 21 | 21 | 19 | 12 | 63.2 |

| Total | 182 | 171 | 162 | 101 | 62.4 |

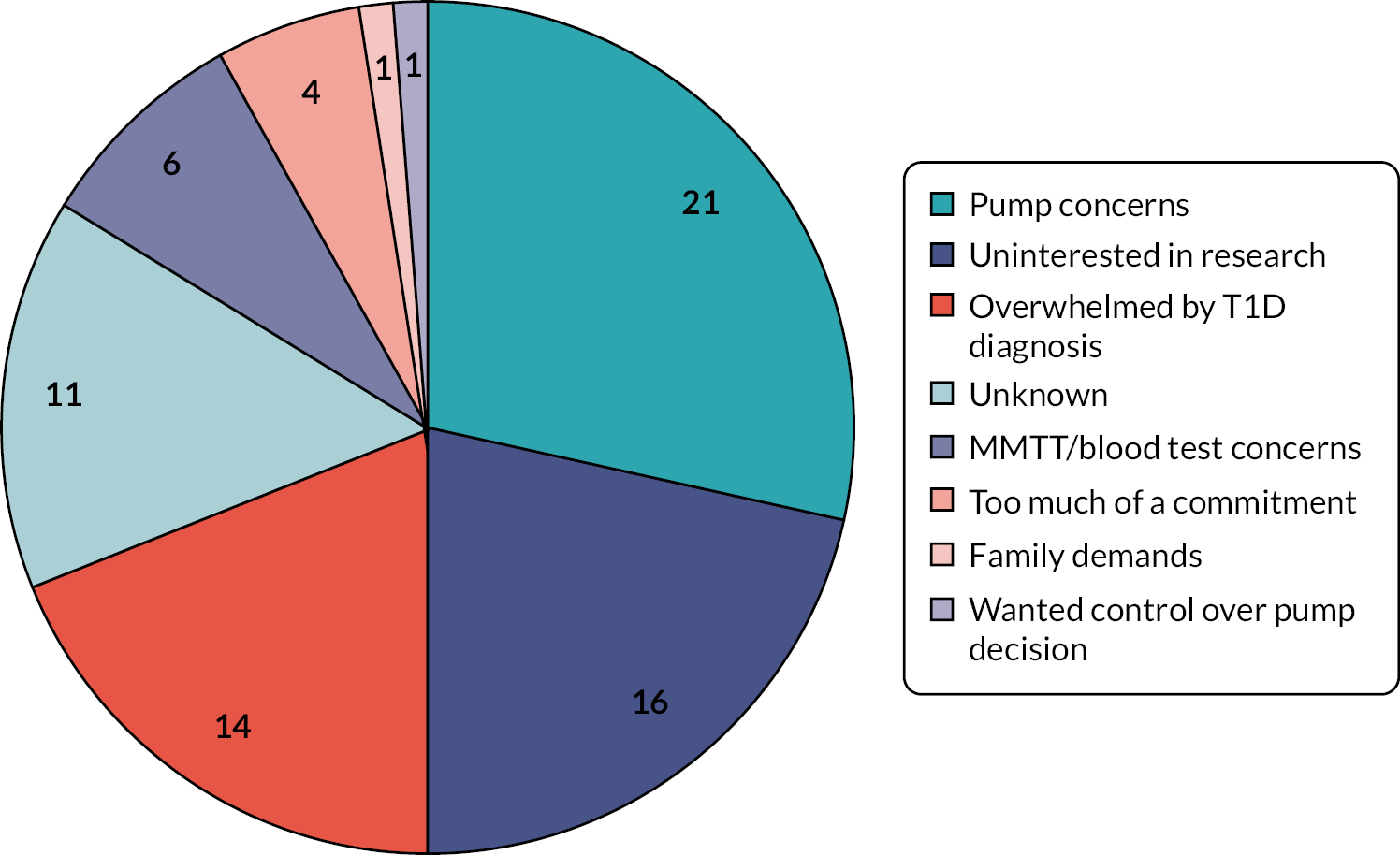

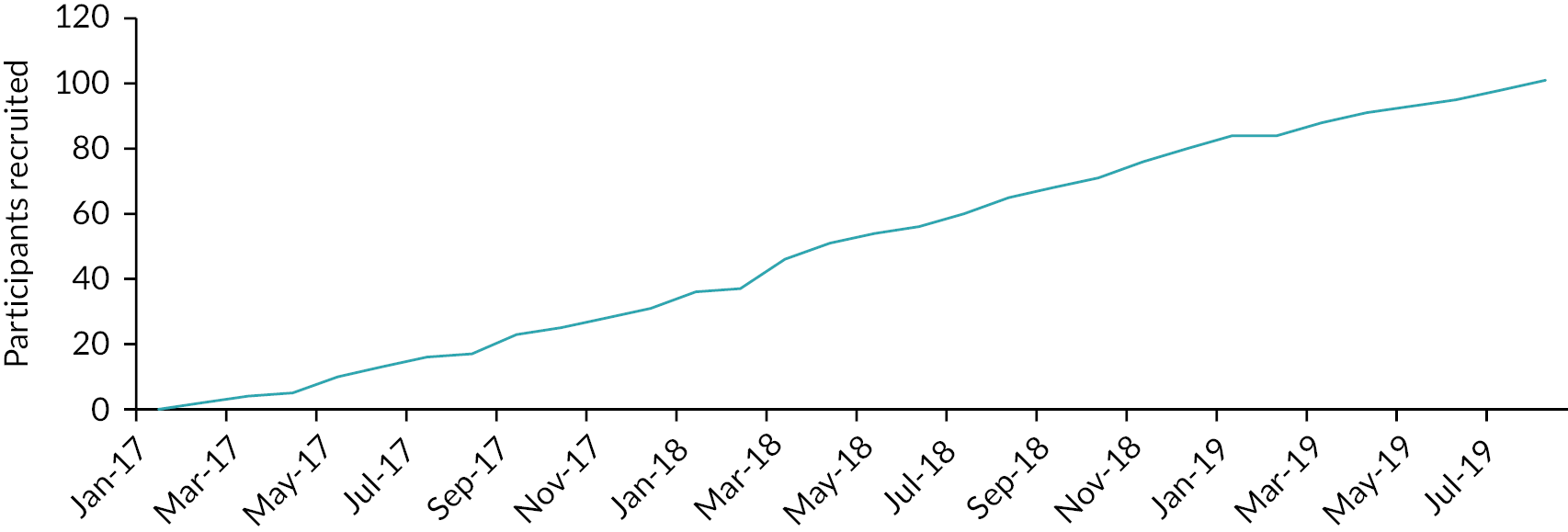

The reasons potential participants declined to take part in CLOuD were recorded and are shown in Figure 3. The most common reason for declining to take part in the study was concerns using an insulin pump (21%) or being uninterested in research (16%). Recruitment completed in July 2019. The cumulative rate of recruitment is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 3.

Reasons given for declining to participate in the CLOuD study (%).

FIGURE 4.

Rate of recruitment.

Between 6 February 2017 and 18 July 2019, 101 participants were enrolled. Four participants withdrew prior to randomisation; 97 participants were randomised [mean ± SD age 12 ± 2 years, 44% (n = 43) female, baseline HbA1c 93 ± 18 mmol/mol (10.6 ± 1.7%) and 29% (n = 28) presented in DKA at diagnosis], 51 to the CL group and 46 to control group (Table 4). Mean ± SD time to randomisation from diagnosis was 9.5 ± 6.2 days (Figure 5).

| Overall (N = 97) | Closed-loop (N = 51) | Control (N = 46) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12 ± 2 | 12 ± 2 | 12 ± 2 |

| Distribution, n (%) | |||

| 10–13 years | 79 (81) | 41 (80) | 38 (83) |

| 14–< 17 years | 18 (19) | 10 (20) | 8 (17) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 43 (44) | 25 (49) | 18 (39) |

| Male | 54 (56) | 26 (51) | 28 (61) |

| BMI percentile | 52 ± 31 | 53 ± 29 | 51 ± 34 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 79 (81) | 44 (86) | 35 (76) |

| Black | 3 (3) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) |

| Asian | 6 (6) | 2 (4) | 4 (9) |

| More than one race | 5 (5) | 4 (8) | 1 (2) |

| Unknown/not reported | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (9) |

| Baseline glycated haemoglobin (mmol/mol) | 93 ± 18 | 94 ± 20 | 91 ± 17 |

| Baseline glycated haemoglobin (%) | 10.6 ± 1.7 | 10.7 ± 1.8 | 10.5 ± 1.6 |

| Presence of DKA at diagnosis, n (%) | 28 (29) | 17 (33) | 11 (24) |

FIGURE 5.

Participant flow CONSORT diagram.

Retention

There were 10 post-randomisation withdrawals by 12 months, 4 in the CL group and 6 in the control group. Two participants, one in each treatment group, were withdrawn by the clinic due to safety concerns and the other eight participant withdrawals were voluntary (Table 5).

| Treatment | Last visit | Reason for withdrawal |

|---|---|---|

| Closed-loop | Randomisation | Participant decided they did not want to use the study pump. |

| Closed-loop | Randomisation | Participant struggled with numerous device issues and did not wish to continue to be involved in the research. |

| Control | Randomisation | Participant did not wish to be cannulated during MMTTs and also wanted to be randomised to CL treatment. |

| Control | Randomisation | Participant was unhappy that they were not randomised to CL. |

| Closed-loop | 3 months | Parent asked that participant be dropped from the study. |

| Control | 3 months | Participant was unhappy they were not randomised to CL. |

| Control | 3 months | Clinicians felt the participant was more likely to have type 2 diabetes. Participant was withdrawn by the site. |

| Closed-loop | 6 months | Decision by ethics board following intentional over bolusing and concerns regarding impact of study on mental health. |

| Control | 9 months | Participant indicated they did not want to continue with study-related activities. |

| Control | 9 months | Participant withdrew as they had a funny turn when getting bloods taken at their previous visit. |

Primary and key end points

Primary and key end points for all randomised participants at 12 months are shown in Table 6. There was no difference in C-peptide AUC between treatment groups at 12 months {primary end point: geometric mean CL 0.35 pmol/ml [interquartile range (IQR) 0.16–0.49] compared with control 0.46 pmol/ml (IQR 0.22–0.69); mean adjusted difference –0.06 pmol/ml (95% CI –0.14 to 0.03)}.

| Baseline | 12 months | Mean adjusted difference (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-loop | Control | Closed-loop | Control | Closed-loop minus control at 12 months | |

| Primary end point (at 12 months) | |||||

| C-peptide AUC (pmol/ml)b | (N = 49) | (N = 45) | (N = 46) | (N = 37) | |

| 0.56 (0.41, 0.74) |

0.64 (0.43, 0.81) |

0.35 (0.16, 0.49) |

0.46 (0.22, 0.69) |

–0.06 (–0.14 to 0.03) |

|

| Key end points (at 12 months) | |||||

| Time spent at glucose level (%)c | (N = 50) | (N = 43) | (N = 44) | (N = 33) | |

| 3.9–10.0 mmol/l | 74 ± 14 | 72 ± 13 | 64 ± 14 | 54 ± 23 | 10 (2 to 17) |

| (N = 51) | (N = 46) | (N = 46) | (N = 39) | ||

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 94 ± 20 | 91 ± 17 | 52 ± 8 | 56 ± 12 | –4 (–8 to 0) |

| HbA1c (%) | 10.7 ± 1.8 | 10.5 ± 1.6 | 6.9 ± 0.7 | 7.3 ± 1.1 | –0.4 (–0.7 to 0.0) |

| Time < 3.9 mmol/l (%)c,d | (N = 50) | (N = 43) | (N = 44) | (N = 33) | |

| 9.1 ± 6.3 | 10.7 ± 7.1 | 6.2 ± 3.8 | 5.4 ± 4.7 | 0.9 (–1.0 to 2.8) | |

| Secondary end points | |||||

| Sensor glucose end points c | (N = 50) | (N = 43) | (N = 44) | (N = 33) | |

| Mean glucose (mmol/l) | 7.2 ± 1.6 | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 8.5 ± 1.6 | 9.8 ± 3.3 | –1.5 (–2.6 to –0.5) |

| Standard deviation (mmol/l) | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 1.4 | –0.2 (–0.6 to 0.2) |

| CV of glucose (%) | 38 ± 7 | 39 ± 7 | 42 ± 7 | 39 ± 8 | 4 (1 to 8) |

| Time spent at glucose level (%)d | |||||

| < 3.5 mmol/l | 5.2 ± 4.8 | 6.6 ± 5.2 | 3.6 ± 2.6 | 3.3 ± 3.1 | 0.3 (–1.0 to 1.6) |

| < 3.0 mmol/l | 2.0 ± 2.5 | 2.8 ± 2.8 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 1.6 | –0.2 (–0.8 to 0.5) |

| < 2.8 mmol/l | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 1.9 ± 2.2 | 0.9 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 1.4 | –0.3 (–0.8 to 0.2) |

| > 10.0 mmol/l | 15 ± 9 | 14 ± 10 | 29 ± 14 | 40 ± 25 | –11 (–19 to –3) |

| > 16.7 mmol/l | 1.0 ± 1.6 | 1.0 ± 1.5 | 4.2 ± 3.8 | 10.0 ± 12.4 | –5.9 (–9.7 to –2.1) |

| Area above curve 3.9 mmol/l | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.0 (–0.2 to 0.3) |

| Area above curve 3.5 mmol/l | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.4 | 0.0 (–0.2 to 0.1) |

| HbA1c < 7.5%, n (%) | (N = 51) | (N = 46) | (N = 46) | (N = 39) | |

| 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 36 (78) | 22 (56) | 21 (–1 to 42) | |

| Insulin end points (U/kg/day) | (N = 47) | (N = 44) | (N = 46) | (N = 39) | |

| Total daily insulin | 0.87 ± 0.33 | 0.82 ± 0.38 | 0.96 ± 0.45 | 0.84 ± 0.39 | 0.10 (–0.11 to 0.30) |

| Total daily basal insulin | 0.33 ± 0.12 | 0.36 ± 0.21 | 0.52 ± 0.31 | 0.37 ± 0.26 | 0.14 (–0.01 to 0.29) |

| Total daily bolus insulin | 0.54 ± 0.24 | 0.46 ± 0.28 | 0.44 ± 0.22 | 0.46 ± 0.23 | –0.06 (–0.17 to 0.05) |

| Fasting C-peptide divided by fasting glucose (pmol/ml per mmol/l)e | (N = 49) | (N = 45) | (N = 44) | (N = 36) | |

| 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | –0.01 (–0.02 to 0.00) | |

| Plasma glucose AUC (mmol/l)e | 12.6 ± 2.6 | 12.3 ± 2.1 | 14.2 ± 2.3 | 14.4 ± 3.0 | –0.4 (–1.9 to 1.0) |

| BMI percentile (%) | (N = 51) | (N = 46) | (N = 43) | (N = 37) | |

| 53 ± 29 | 51 ± 34 | 70 ± 26 | 68 ± 29 | 0.0 (–0.1 to 0.1) | |

| Blood pressure (mmHg)d | (N = 51) | (N = 46) | (N = 44) | (N = 37) | |

| Systolic | 110 ± 9 | 108 ± 8 | 113 ± 8 | 111 ± 9 | 2 (–2 to 6) |

| Diastolic | 65 ± 6 | 66 ± 8 | 65 ± 7 | 64 ± 8 | 1 (–2 to 4) |

| Lipid profile (mmol/l) d | (N = 46) | (N = 44) | (N = 42) | (N = 38) | |

| Total cholesterol | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | –0.1 (–0.3 to 0.1) |

| Triglycerides | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | –0.1 (–0.2 to 0.1) |

| HDL cholesterol | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | –0.1 (–0.2 to 0.1) |

| LDL cholesterol | (N = 46) | (N = 44) | (N = 41) | (N = 36) | |

| 2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 0.0 (–0.2 to 0.2) | |

The proportion of time in target range 3.9–10.0 mmol/l based on masked LibrePro sensor glucose data at 12 months was 10 percentage points (95% CI 2 to 17) higher in the CL group (mean ± SD 64 ± 14%) compared to control group (mean ± SD 54 ± 23%) (Table 6). As this end point did not reach the threshold of 0.01 in the analysis, other key secondary end points were not tested for statistical significance. HbA1c was lower in the CL group by 4 mmol/mol (0.4%) [95% CI 0 to 8 mmol/mol (0.0% to 0.7%)] at 12 months. The mean difference in time spent < 3.9 mmol/l between groups was 0.9 percentage points (95% CI –1.0 to 2.8).

Secondary end points

Secondary end points for all randomised participants at 12 months are shown in Table 6.

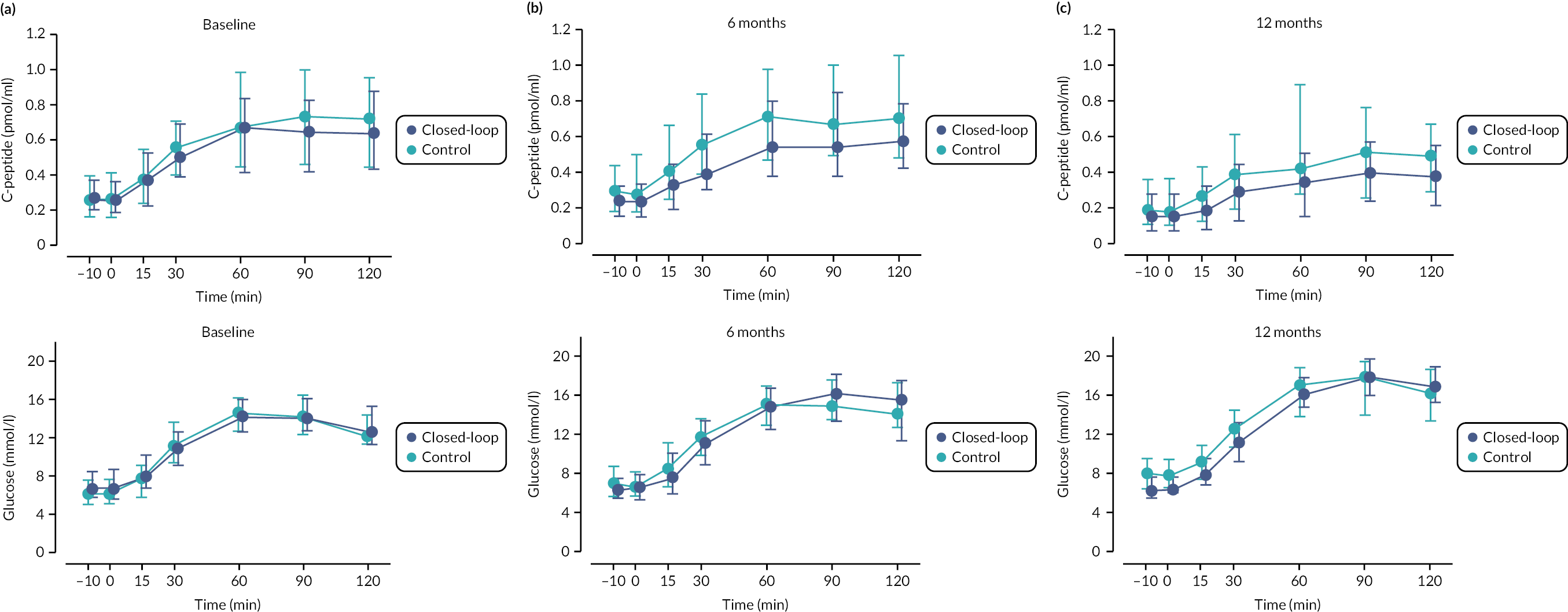

C-peptide end points

C-peptide AUC declined following diagnosis in both treatment groups (see Table 6, Figures 6 and 7). Plasma glucose AUC was similar between groups at 12 months. There was no difference in fasting C-peptide divided by fasting glucose between treatment groups at 12 months. The proportion of participants with negative C-peptide stimulation in response to mixed-meal test (defined as non-fasted C-peptide < 0.2 pmol/ml), increased in both groups from baseline to 12 months but was similar between treatment groups and is provided in Table 7.

FIGURE 6.

The area under the curve for plasma C-peptide in response to a mixed-meal tolerance test at baseline, 6 and 12 months post diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. Panel A; geometric mean [IQR] and the glycated haemoglobin from baseline to 12 months. Panel B; median [IQR]. C-peptide AUC at baseline (n = 49 CL, n = 45 control), 6 months (n = 45 CL, n = 38 control), 12 months (n = 46 CL, n = 37 control). HbA1c at baseline (n = 51 CL, n = 46 control), 3 months (n = 48 CL, n = 44 control), 6 months (n = 46 CL, n = 42 control), 9 months (n = 46 CL, n = 38 control), 12 months (n = 46 CL, n = 39 control).

FIGURE 7.

Stimulated C-peptide at MMTT at baseline (panel A), 6 (panel B) and 12 (panel C) months. Circles indicate the median, and the bars represent the 25th and 75th percentiles. Baseline (n = 49 CL, n = 45 control), 6 months (n = 45 CL, n = 38 control), 12 months (n = 46 CL, n = 37 control).

| Closed-loop | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | (n = 51) | (n = 46) |

| 1 (2) | 1 (2) | |

| 6 months | (n = 45) | (n = 41) |

| 4 (9) | 3 (7) | |

| 12 months | (n = 46) | (n = 38) |

| 10 (22) | 5 (13) |

Glycaemic end points

End points by treatment group at 6 months is shown in Table 8. C-peptide AUC was lower in the CL group compared to the control group (0.51 vs. 0.70 pmol/ml). Time in target glucose range was higher (70 vs. 65%) and mean glucose lower (8.0 vs. 8.9 mmol/l) in the CL group compared to control group at 6 months but HbA1c was similar. Time in hypoglycaemia (< 3.9 mmol/l) was higher (6.1 vs. 4.2%) in the CL group compared to control group at 6 months.

| Closed-loop | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| C-peptide AUC (pmol/ml)a,b | (N = 45) | (N = 38) |

| 0.51 (0.36–0.71) | 0.70 (0.44–0.89) | |

| Time spent at glucose level 3.9–10.0 mmol/l (%) | (N = 44) | (N = 37) |

| 70 ± 15 | 65 ± 22 | |

| (N = 46) | (N = 42) | |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 6.7 ± 0.9 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 49 ± 9 | 50 ± 9 |

| Time spent at glucose level < 3.9 mmol/l (%)c | (N = 44) | (N = 37) |

| 6.1 ± 5.7 | 4.2 ± 3.9 | |

| CGM end pointsd | (N = 44) | (N = 37) |

| Mean glucose (mmol/l) | 8.0 ± 1.9 | 8.9 ± 2.7 |

| Standard deviation (mmol/l) | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 1.3 |

| CV of glucose (%) | 38 ± 6 | 36 ± 7 |

| Time spent at glucose level (%) | ||

| < 3.5 mmol/lc | 3.4 ± 3.4 | 2.3 ± 2.4 |

| < 3.0 mmol/lc | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 0.8 ± 0.9 |

| < 2.8 mmol/lc | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.5 ± 0.6 |

| > 10.0 mmol/lc | 23 ± 16 | 30 ± 21 |

| > 16.7 mmol/lc | 2.5 ± 3.6 | 4.8 ± 6.4 |

| Area above curve 3.9 mmol/l (mmol/l) | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.4 |

| Area above curve 3.5 mmol/l (mmol/l) | 0.3 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.2 |

| HbA1c < 7.5%, n (%) | (N = 46) | (N = 42) |

| 38 (83) | 33 (79) | |

| Insulin end points (U/kg/day) | (N = 45) | (N = 40) |

| Total daily insulin | 0.73 ± 0.33 | 0.69 ± 0.41 |

| Total daily basal insulin | 0.33 ± 0.16 | 0.29 ± 0.20 |

| Total daily bolus insulin | 0.40 ± 0.23 | 0.40 ± 0.24 |

| Fasting C-peptide divided by fasting glucose (pmol/ml per mmol/l)b | (N = 44) | (N = 41) |

| 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | |

| Plasma glucose AUC (mmol/l)b | 13.0 ± 2.7 | 13.3 ± 2.9 |

| (N = 42) | (N = 40) | |

| BMI percentile (%) | 66 ± 26 | 60 ± 33 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | (N = 46) | (N = 41) |

| Systolicc | 111 ± 7 | 109 ± 10 |

| Diastolicc | 64 ± 8 | 66 ± 8 |

Day and night glucose control is shown in Table 9. Daytime glucose control deteriorated in both groups from baseline to 12 months. Daytime glucose control measured by time in target glucose range and mean glucose was better in the CL group than the control group at 12 months. Night-time glucose control deteriorated in the control group from baseline to 12 months (72% at baseline and 57% at 12 months) but was maintained in the CL group (75% at baseline and 71% at 12 months).

| Daytime (8:00–23:59) | Night-time (00:00–07:59) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 months | Baseline | 12 months | |||||

| Closed-loop | Control | Closed-loop | Control | Closed-loop | Control | Closed-loop | Control | |

| (N = 50) | (N = 43) | (N = 44) | (N = 33) | (N = 50) | (N = 43) | (N = 44) | (N = 33) | |

| Time in range 3.9–10.0 mmol/l (%) | 73 ± 14 | 72 ± 13 | 60 ± 15 | 52 ± 23 | 75 ± 16 | 72 ± 17 | 71 ± 15 | 57 ± 26 |

| Mean glucose (mmol/l) | 7.3 ± 1.7 | 7.2 ± 1.7 | 8.9 ± 1.7 | 10.1 ± 3.4 | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 6.5 ± 1.9 | 7.5 ± 1.6 | 9.1 ± 3.1 |

| Glucose SD (mmol/l) | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 1.2 |

| Time < 3.0 mmol/l (%)a | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 1.9 ± 1.9 | 0.9 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 2.6 ± 4.1 | 4.0 ± 4.8 | 2.2 ± 2.4 | 1.7 ± 2.5 |

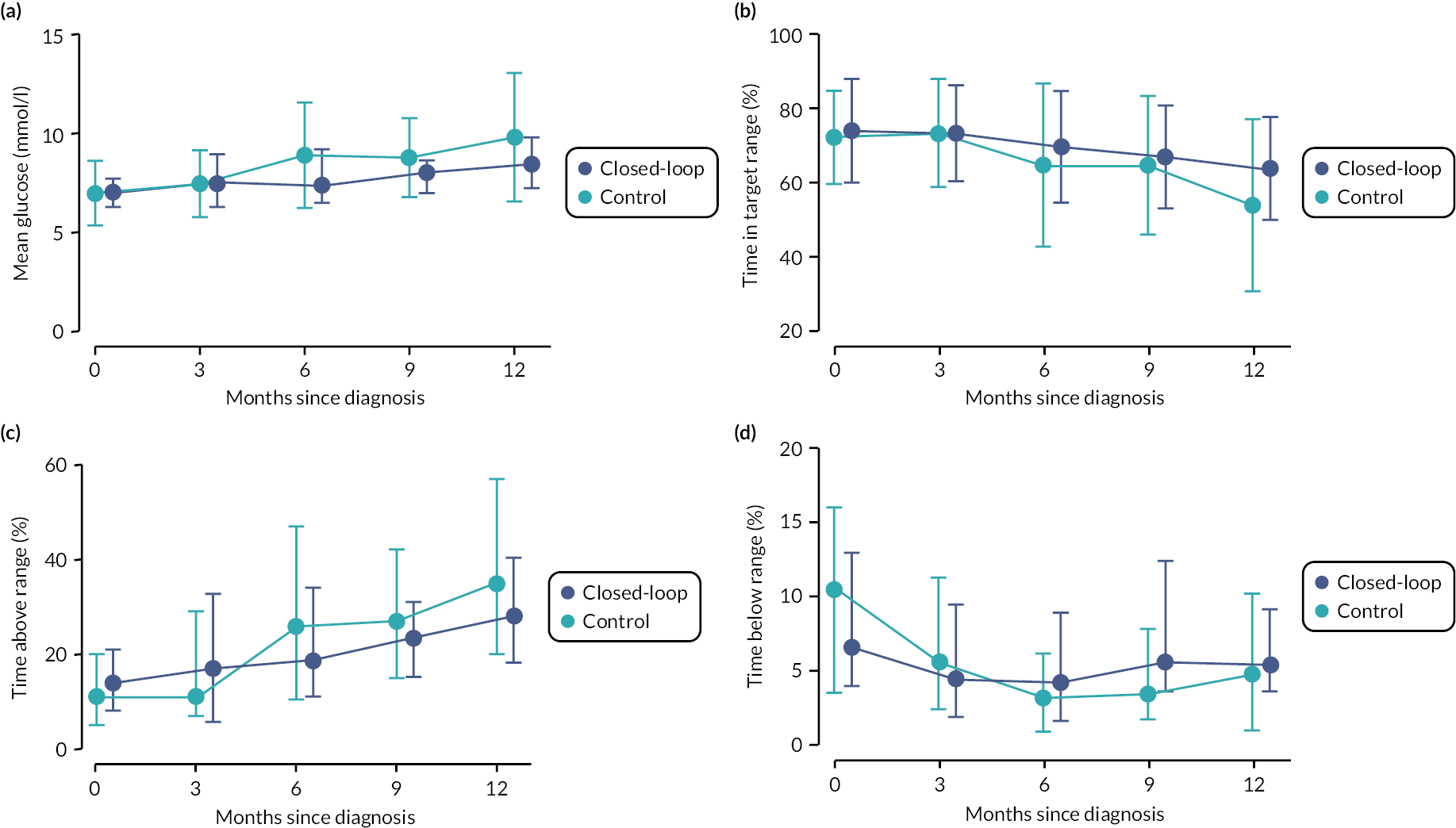

Longitudinal sensor glucose end points are shown in Table 10 and Figure 8. Although glucose control as measured by sensor glucose metrics time in range, time above range and mean glucose deteriorated in both groups from baseline to 12 months, this was more pronounced in the control group. There was a trend towards a reduction in the proportion of time spent in hypoglycaemia in both groups over time.

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-loop (N = 50), control (N = 43) | Closed-loop (N = 46), control (N = 41) | Closed-loop (N = 44), control (N = 37) | Closed-loop (N = 42), control (N = 35) | Closed-loop (N = 44), control (N = 33) | |

| Time in range 3.9–10.0 mmol/l (%) | |||||

| Closed-loop | 74 ± 14 | 73 ± 13 | 70 ± 15 | 67 ± 14 | 64 ± 14 |

| Control | 72 ± 13 | 73 ± 15 | 65 ± 22 | 65 ± 19 | 54 ± 23 |

| Mean glucose (mmol/l) | |||||

| Closed-loop | 7.2 ± 1.6 | 7.6 ± 1.6 | 8.0 ± 1.9 | 8.0 ± 1.6 | 8.5 ± 1.6 |

| Control | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 7.4 ± 1.7 | 8.9 ± 2.7 | 8.8 ± 2.0 | 9.8 ± 3.3 |

| Glucose SD (mmol/l) | |||||

| Closed-loop | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 2.8 ± 0.9 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 0.9 |

| Control | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 1.4 |

| Glucose CV (%) | |||||

| Closed-loop | 38 ± 7 | 37 ± 7 | 38 ± 6 | 41 ± 8 | 42 ± 7 |

| Control | 39 ± 7 | 37 ± 6 | 36 ± 7 | 38 ± 7 | 39 ± 8 |

| Time < 3.9 mmol/l (%)a | |||||

| Closed-loop | 9.1 ± 6.3 | 6.3 ± 5.3 | 6.1 ± 5.7 | 7.5 ± 5.2 | 6.2 ± 3.8 |

| Control | 10.7 ± 7.1 | 7.0 ± 5.4 | 4.2 ± 3.9 | 4.4 ± 3.2 | 5.4 ± 4.7 |

| Time < 3.5 mmol/l (%)a | |||||

| Closed-loop | 5.2 ± 4.8 | 3.7 ± 3.8 | 3.4 ± 3.4 | 4.6 ± 4.0 | 3.6 ± 2.6 |

| Control | 6.6 ± 5.2 | 3.8 ± 3.7 | 2.3 ± 2.4 | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 3.3 ± 3.1 |

| Time < 3.0 mmol/l (%)a | |||||

| Closed-loop | 2.0 ± 2.5 | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 2.2 ± 2.6 | 1.4 ± 1.2 |

| Control | 2.8 ± 2.8 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 0.8 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 1.3 | 1.5 ± 1.6 |

| Time < 2.8 mmol/l (%)a | |||||

| Closed-loop | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 1.1 ± 1.4 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 2.1 | 0.9 ± 0.9 |

| Control | 1.9 ± 2.2 | 0.8 ± 1.1 | 0.5 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 1.4 |

| Area over curve < 3.9 mmol/l (mmol/l)a | |||||

| Closed-loop | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 0.7 ± 0.8 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 0.7 ± 0.5 |

| Control | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.6 |

| Area over curve < 3.5 mmol/l (mmol/l)a | |||||

| Closed-loop | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.3 |

| Control | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.4 |

| Time > 10.0 mmol/l (%)a | |||||

| Closed-loop | 15 ± 9 | 19 ± 14 | 23 ± 16 | 24 ± 11 | 29 ± 14 |

| Control | 14 ± 10 | 18 ± 13 | 30 ± 21 | 30 ± 16 | 40 ± 25 |

| Time > 16.7 mmol/l (%)a | |||||

| Closed-loop | 1.0 ± 1.6 | 1.9 ± 2.7 | 2.5 ± 3.6 | 2.5 ± 2.7 | 4.2 ± 3.8 |

| Control | 1.0 ± 1.5 | 1.4 ± 2.4 | 4.8 ± 6.4 | 3.1 ± 3.1 | 10.0 ± 12.4 |

FIGURE 8.

Longitudinal glycaemic control from baseline to 12 months based on masked sensor glucose data collected by Freestyle LibrePro for up to 14 days. Panel A shows mean glucose levels. Panel B shows time in target glucose range 3.9–10.0 mmol/l. Panel C shows time with glucose above 10.0 mmol/l. Panel D shows time with glucose below 3.9 mmol/l. Full circles indicate the median, and the bars represent the 25th and 75th percentiles. Baseline (n = 50 CL, n = 43 control), 3 months (n = 46 CL, n = 41 control), 6 months (n = 44 CL, n = 37 control), 9 months (n = 42 CL, n = 35 control), 12 months (n = 44 CL, n = 33 control).

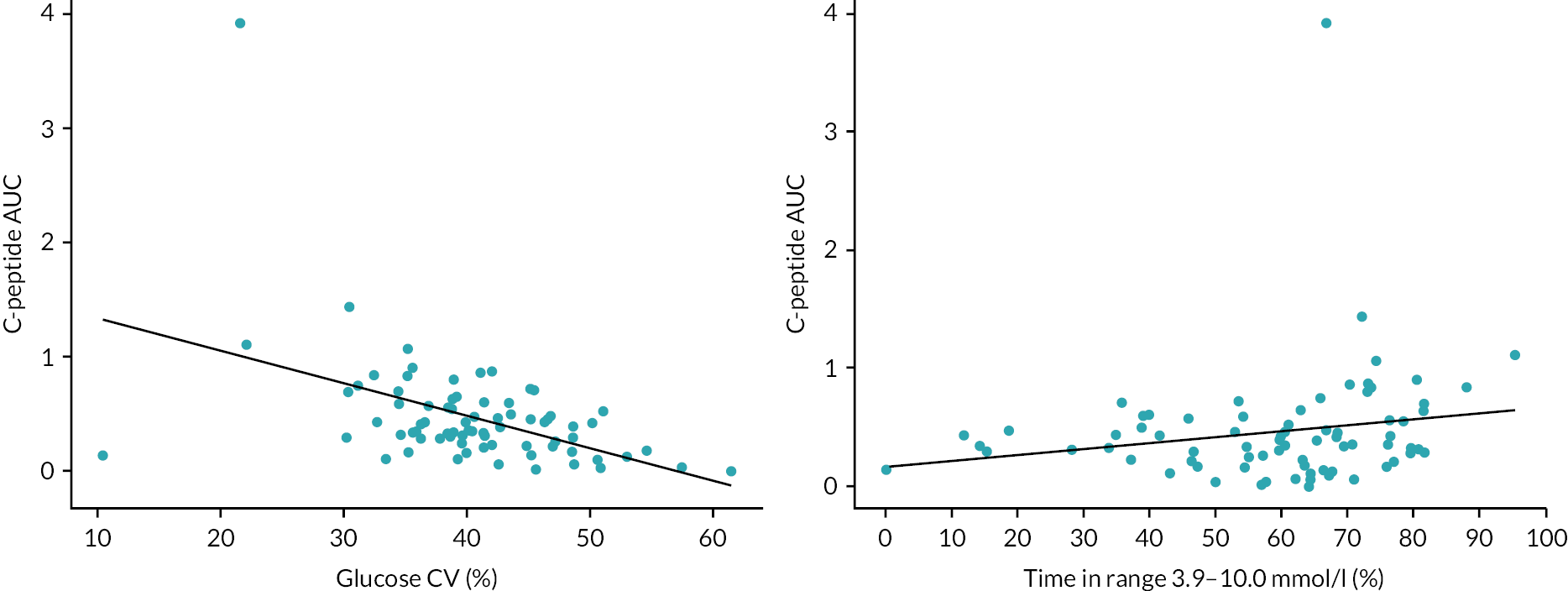

C-peptide AUC by HbA1c, coefficient of variation of glucose, and time in target range 3.9–10.0 mmol/l are shown in Table 11 and Figure 9. Higher C-peptide AUC was associated with lower glucose variability as measured by coefficient of variation of glucose, and higher time in target glucose range (see Figure 9). There was no clear relationship between C-peptide AUC quartiles and HbA1c quartiles (see Table 11).

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) quartiles | C-peptide AUC (pmol/ml) quartiles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 0.16 | 0.16–< 0.32 | 0.32–< 0.49 | ≥ 0.49 | |

| < 46 | 1 (9) | 5 (42) | 2 (17) | 4 (36) |

| 46–< 50.5 | 6 (55) | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 3 (27) |

| 50.5–< 57 | 3 (27) | 2 (17) | 4 (33) | 2 (18) |

| ≥ 57 | 1 (9) | 4 (33) | 5 (42) | 2 (18) |

FIGURE 9.

Relationship between glucose CV, time in range and C-peptide AUC at 12 months (CL and control participants combined). The black line represents the least squares linear regression line. Baseline (n = 48 CL, n = 42 control), 12 months (n = 44 CL, n = 32 control).

Insulin end points

Total, basal and bolus insulin dose were similar between treatment groups at 12 months (see Table 6). The ratio of basal to bolus insulin was higher in the CL group compared to control group at 12 months (1.2 vs. 0.8).

Clinical end points

Blood pressure, lipid profile and BMI percentile were similar between treatment groups at 12 months (see Table 6). Total and LDL cholesterol decreased and BMI increased in both groups from baseline to 12 months. There were no clinically relevant between-group differences in blood pressure, BMI percentile or components of lipid profile at 12 months.

Per-protocol analysis

The primary end point was similar in a per-protocol analysis using data from randomised participants in the CL group with at least 60% CL use and those in the control group who did not start insulin pump therapy (Table 12). The improved glycaemic control in the CL group compared to the control group was slightly more pronounced in the per-protocol analysis of key secondary end points.

| Baseline | 12 months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-loop | Control | Closed-loop | Control | |

| Primary end point | ||||

| C-peptide AUC (pmol/ml)a | (N = 31) | (N = 37) | (N = 32) | (N = 32) |

| 0.54 (0.34, 0.70) | 0.65 (0.43, 0.81) | 0.33 (0.13, 0.43) | 0.47 (0.22, 0.70) | |

| Key end points | ||||

| Time in range 3.9–10.0 mmol/l (%)b | (N = 33) | (N = 37) | (N = 32) | (N = 29) |

| 76 ± 10 | 74 ± 11 | 68 ± 10 | 53 ± 24 | |

| (N = 33) | (N = 38) | (N = 32) | (N = 34) | |

| HbA1c (%) | 10.5 ± 1.6 | 10.5 ± 1.6 | 6.8 ± 0.7 | 7.3 ± 1.1 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 92 ± 17 | 91 ± 18 | 50 ± 7 | 57 ± 12 |

| Time with glucose < 3.9 mmol/l (%)b | (N = 33) | (N = 37) | (N = 32) | (N = 29) |

| 8.0 ± 5.9 | 11.2 ± 6.9 | 6.8 ± 4.0 | 5.3 ± 4.7 | |

Adverse events

Safety-related events are summarised in Table 13. Three severe hypoglycaemia events occurred in two participants randomised to the CL group and one severe hypoglycaemia event occurred in one participant randomised to control group. There was one DKA in the CL group and none in control group. Details of the events are in Table 14. Two non-treatment related SAEs occurred in the CL group and four in control group. A total of 71 other AEs (34 in the CL group, 37 in control group) were reported (Table 15).

| Closed-loop (N = 51) | Control (N = 46) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe hypoglycaemic events, n | 3 | 1 | |

| Number of events per subject, mean ± SD | 0.06 ± 0.31 | 0.02 ± 0.15 | 0.39 |

| Incidence rate per 100 person-years | 3 | 1 | 0.41 |

| Number of subjects with ≥ 1 event, n (%) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | > 0.99 |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis events, n | 1 | 0 | |

| Number of events per subject, mean ± SD | 0.02 ± 0.14 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.97 |

| Incidence rate per 100 person-years | 1 | 0.0 | 0.97 |

| Number of subjects with ≥ 1 event, n (%) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.50 |

| Serious adverse events, n | 2 | 4 | |

| Number of events per subject, mean ± SD | 0.04 ± 0.20 | 0.09 ± 0.28 | 0.53 |

| Other AEs, n | 34 | 37 | |

| Number of events per subject, mean ± SD | 0.67 ± 1.18 | 0.80 ± 1.31 | 0.43 |

| Event | Treatment group | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Severe hypoglycaemia | Closed-loop | Participant administered meal-time bolus but did not finish the meal. Participant felt dizzy, collapsed and had seizures. |

| Severe hypoglycaemia | Closed-loop | Participant had a large carbohydrate meal and then walked up hill to school. Despite oral hypoglycaemia treatment the participant collapsed, had a hypoglycaemic seizure and required paramedic treatment. |

| Severe hypoglycaemia | Control | Participant administered pre-breakfast bolus but breakfast was delayed. The participant felt dizzy and shaky and required the parent to give dextrose tablets. |

| Severe hypoglycaemia | Closed-loop | Participant had hypoglycaemic seizure after participating in rugby and gymnastics without adjustment of meal-time bolus and inadequate treatment of hypoglycaemia when sensor alerted. |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | Closed-loop | Participant developed abdominal pain and vomiting while fasting during Ramadan. Admitted to hospital in DKA with severe dehydration, contributed to by fasting and gastroenteritis. |

| Closed-loop (N = 51) | Control (N = 46) | |

|---|---|---|

| Skin or soft tissue | 7 | 12 |

| Upper respiratory tract symptoms | 7 | 9 |

| Headache or visual symptoms | 9 | 4 |

| Abdominal symptoms | 4 | 6 |

| Injury | 4 | 2 |

| Hypoglycaemia | 2 | 1 |

| Other | 1 | 3 |

Technology usage

In the CL group, CL use was 66% (IQR 44–80) over the 12-month period over the two CL platforms (Table 16). At 12 months, 10% of participants in the control group (n = 4) were using insulin pump therapy and 57% (n = 21) were using a flash or real-time continuous glucose sensor (Table 17).

| Baseline to 12 months (N = 50) | |

|---|---|

| Time using the CL system, n (%)a | |

| 0–< 20% | 3 (6) |

| 20–< 40% | 6 (12) |

| 40–< 60% | 8 (16) |

| 60–< 80% | 21 (42) |

| ≥ 80% | 12 (24) |

| Median (IQR) use (%) | 66 (44, 80) |

| 6 months | 12 months | |

|---|---|---|

| (N = 42) | (N = 39) | |

| Use of an insulin pump, n (%) | 4 (10) | 4 (10) |

| (N = 32) | (N = 37) | |

| Use of a glucose sensor, n (%)a | 17 (53) | 21 (57) |

Chapter 5 Discussion

The present study shows that CL glucose control over a period of up to 12 months does not slow the decline in C-peptide secretion in children and adolescents with new-onset type 1 diabetes.

Stimulated C-peptide declined in both treatment groups by 12 months. The proportion of participants with negative C-peptide stimulation in response to mixed-meal test also increased over time and was similar between treatment groups. The stimulated C-peptide at 12 months in the present study (0.35 pmol/ml in the CL group and 0.46 pmol/ml in the control group) are in keeping with those reported by Buckingham et al. where there was also no difference between a 3-day period of early intensive CL glucose control, initiated within the first 7 days following diagnosis and usual care (0.43 pmol/ml in the intensive group and 0.52 pmol/ml in the control group). 18 However, as glycaemic control in the Buckingham et al. study was similar between groups following the initial intensive period, the study was not able to determine the impact of a sustained period of optimised glucose control on C-peptide secretion. 18

Total daily exogenous insulin requirements, a surrogate marker of residual insulin secretion, were similar between groups at all time points after diagnosis. However, this comparison may be hampered by any between-group differences in glycaemic control.

Mean time in range was 10 percentage points higher and mean HbA1c was 0.4% (4 mmol/mol) lower in the CL group compared with the control group at 12 months, but these end points did not reach the pre-specified significance thresholds and it is possible that a greater improvement in glucose control with attainment of normoglycaemia could prevent the decline in C-peptide secretion. 46 Further work is needed to definitively rule out a role of glycaemic burden in the decline of C-peptide secretion. Additionally, the greater mean time below range and mean glycaemic coefficient of variation observed in the CL group may have reduced beta-cell viability. 47

It is likely that there are factors other than glycaemic control, such as autoimmune response that determine the rate of C-peptide decline following diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, and CL glucose control for 12 months following diagnosis is unable to preserve endogenous insulin secretion. It is possible that other factors act in concert with dysglycaemia on C-peptide secretion. Future research may utilise CL therapy to optimise glucose control as an adjunctive tool to evaluate the impact of immunotherapies on preserving residual C-peptide.

The present study demonstrates that hybrid CL therapy is effective in new-onset type 1 diabetes in youth and can safely accommodate the variability in exogenous insulin requirements which occur with beta-cell recovery post diagnosis. Glycaemic control was sustained over 1 year in the CL group, whereas glycaemic control started to deteriorate in the control group 6 to 9 months after diagnosis (see Figure 6). At 12 months post diagnosis, only 56% of youth in the control group (78% in the CL group) were able to achieve a HbA1c of < 58 mmol/mol (< 7.5%) which is above the current national and international glycaemic targets43,48 despite high uptake of diabetes technology in the control group. Analysis of data from the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications study suggests reduced risk of renal and cardiovascular complications with earlier implementation of intensive therapy compared to later implementation, despite similar overall glycaemic control. 49 This highlights the need for improved therapies to allow youth to achieve recommended glycaemic targets from onset of type 1 diabetes irrespective of the lack of effect on residual C-peptide secretion.

Strengths of this study include the multicentre, randomised parallel design and the 1-year study duration. We applied no exclusions at enrolment such as technology propensity or healthcare professional considerations about suitability, minimising selection bias. The study population is representative of the general population of youth newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. There were no limitations to diabetes therapies used in the control group supporting generalisability of the findings. The study had limitations. There was no central measurement of auto-antibodies at diagnosis. There was imbalance in the rate of DKA at diagnosis which is associated with a more rapid decline in C-peptide secretion. 50 The rate was higher in the CL group (33%) than in the control group (24%) but this was adjusted for in the analyses. Retention of participants was lower in the control group reflecting a lower level of motivation compared to the CL group, but this was within the anticipated withdrawal rate for the analysis of the primary end point. We did not undertake separate analysis of glycaemic control by CL system as participants switched systems at different time points which would limit any comparisons given the different time after diagnosis that this occurred. We recorded a higher number of unscheduled contacts in the CL group. Recording of these contacts was inconsistent longitudinally within and between clinical sites preventing coherent interpretation.

In conclusion, a sustained period of hybrid CL glucose control following diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents does not appear to prevent the decline in residual C-peptide secretion.

Chapter 6 Human factors assessments

We broadly refer to human factors as the emotional and behavioural characteristics of the participants in the study. The human factors assessment battery is grounded in two principles: (1) it is critical to use evidence-based methods that are reliable, valid, and have parallel forms for youth and their caregivers and (2) both quantitative (i.e. surveys) and qualitative (i.e. interviews) data need to be gathered to provide the richest, most comprehensive characterisation of the sample and their response to the CL system and clinical trial.

Questionnaires

Surveys and tests used in this trial are listed in Table 18. Participants/guardians completed the questionnaires at time points as indicated in the table. Additionally, feedback questionnaires on CL specific experience were distributed to participants/guardians randomised to the CL intervention arm.

| Measure | Respondent | Construct measured/relevant points | Time point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) Diabetes51 | All youth and all parents | All youth ages 10–18 completed age-appropriate PedsQL Diabetes module. Parents also completed a proxy version. | Baseline, 12 months |

| Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)52 | All youth and all parents | Self-report inventory behavioural screening questionnaire for children and adolescents. The same items are included in questionnaires for completion by the parents. | Baseline, 12 months |

| Hypoglycaemia Fear Survey (HFS)53–55 | All youth and all parents | Validated questionnaires (HFS child version, HFS parent version) to measure several dimensions of fear of hypoglycaemia. They consist of a ‘Behaviour subscale’ that measures behaviours involved in avoidance and over-treatment of hypoglycaemia and a ‘Worry subscale’ that measures anxiety and fear surrounding hypoglycaemia. | 12 months |

| INSPIRE | Youth and parents in CL arm | Measures the psychological side of automated insulin delivery. Child (6–12), adolescent versions (13–18) and parent versions. | 12 months |

| PAID-Teen | All youth | Measures related to the daily hassles of managing type 1 diabetes, and the degree of diabetes distress that arises from diabetes management. | 12 months |

Questionnaire results

Responses to the HFS (Table 19), PedsQL (Table 20), PAID (Table 21) and SDQs (Table 22) were similar in both children and parents between treatment groups at 12 months. Scores for the INSPIRE questionnaire were high in children, teenagers and parents suggesting positive expectancies regarding automated insulin delivery in this population (Table 23).

| 12 months | p-valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-loop (N = 43) | Control (N = 37) | ||

| Child Questionnaire Total Score (range 0–92) mean (SD) | 28 (15) | 27 (12) | 0.95 |

| Behaviour Subscale Total Score (range 0–40) mean (SD) | 15 (7) | 16 (7) | 0.87 |

| Worry Subscale (range 0–52) Total Score mean (SD) | 13 (10) | 11 (7) | 0.64 |

| Parent Questionnaire Total Score (range 0–92) mean (SD) | 40 (14) | 41 (15) | 0.99 |

| Behaviour Subscale Total Score (range 0–40) mean (SD) | 18 (7) | 18 (7) | 0.99 |

| Worry Subscale Total Score (range 0–52) mean (SD) | 22 (9) | 22 (10) | 0.99 |

| Baseline | 12 months | p-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-loop (N = 51) | Control (N = 46) | Closed-loop (N = 44) | Control (N = 38) | ||

| Child Questionnaire Total Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 72 (13) | 68 (13) | 74 (13) | 71 (12) | 0.99 |

| Diabetes Subscale Total Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 62 (13) | 57 (15) | 65 (13) | 62 (13) | 0.99 |

| Treatment I Subscale Total Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 78 (13) | 77 (12) | 82 (14) | 77 (15) | 0.35 |

| Treatment II Subscale Total Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 85 (13) | 84 (12) | 89 (11) | 85 (12) | 0.45 |

| Worry Subscale Total Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 77 (19) | 69 (20) | 74 (22) | 71 (22) | 0.99 |

| Communication Subscale Total Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 82 (15) | 82 (16) | 79 (19) | 83 (17) | 0.64 |

| Parent Questionnaire Total Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 64 (15) | 65 (12) | 70 (12) | 65 (14) | 0.35 |

| Diabetes Subscale Total Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 58 (16) | 58 (15) | 64 (13) | 61 (16) | 0.95 |

| Treatment I Subscale Total Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 66 (16) | 69 (15) | 70 (12) | 63 (15) | 0.11 |

| Treatment II Subscale Total Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 75 (15) | 77 (14) | 84 (13) | 80 (15) | 0.37 |

| Worry Subscale Total Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 62 (19) | 58 (18) | 73 (17) | 65 (20) | 0.37 |

| Communication Subscale Total Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 72 (22) | 76 (21) | 68 (23) | 66 (24) | 0.73 |

| 12 months | p-valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CL (N = 26) | MDI (N = 20) | ||

| PAID-Teen Questionnaire Total Score (range 0–130) mean (SD) | 25 (19) | 23 (17) | 0.99 |

| Baseline | 12 months | p-valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-loop (N = 51)a | Control (N = 46)a | Closed-loop (N = 46)a | Control (N = 38)a | ||

| Child Questionnaire Results mean (SD) | |||||

| Emotional Symptoms Subscale Total Score (range 0–10) | 2.4 (1.9) | 2.8 (2.0) | 2.4 (2.3) | 2.8 (2.1) | 0.69 |

| Conduct Problems Subscale Total Score (range 0–10) | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.6) | 1.8 (1.3) | 0.87 |

| Hyperactivity/Inattention Subscale Total Score (range 0–10) | 3.5 (2.6) | 4.1 (2.2) | 3.8 (2.5) | 4.2 (2.6) | 0.99 |

| Peer Relationship Problems Subscale Total Score (range 0–10) | 1.3 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.6) | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.9 (1.8) | 0.99 |

| Total Difficulties Score (range 0–40) | 8.8 (5.7) | 10.8 (5.4) | 9.5 (6.3) | 11.1 (6.1) | 0.99 |

| Prosocial Behaviour Subscale Total Score (range 0–10) | 8.2 (1.4) | 8.1 (1.4) | 7.9 (1.8) | 7.9 (1.5) | 0.99 |

| Internalising Problems Subscale Total Score (range 0–20) | 4.0 (3.4) | 4.9 (3.3) | 4.1 (3.6) | 4.9 (3.4) | 0.95 |

| Externalising Problems Subscale Total Score (range 0–20) | 4.8 (3.4) | 5.9 (3.3) | 5.4 (3.8) | 6.2 (3.8) | 0.99 |

| Impact Supplement Total Score (range 0–10) | 0.9 (1.1) | 1.0 (1.0) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.37 |

| Parent Questionnaire Results mean (SD) | |||||

| Emotional Symptoms Subscale Total Score (range 0–10) | 3.0 (2.3) | 3.0 (2.3) | 2.3 (2.2) | 2.7 (2.3) | 0.64 |

| Conduct Problems Subscale Total Score (range 0–10) | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.5) | 0.99 |

| Hyperactivity/Inattention Subscale Total Score (range 0–10) | 3.5 (2.5) | 3.2 (2.7) | 2.7 (2.0) | 3.5 (2.6) | 0.35 |

| Peer Relationship Problems Subscale Total Score (range 0–10) | 1.7 (1.8) | 1.6 (1.8) | 1.8 (2.0) | 1.9 (1.9) | 0.95 |

| Total Difficulties Score (range 0–40) | 9.9 (6.2) | 9.6 (6.2) | 8.4 (5.5) | 10.2 (6.4) | 0.37 |

| Prosocial Behaviour Subscale Total Score (range 0–10) | 8.8 (1.4) | 8.3 (1.4) | 8.3 (1.7) | 8.2 (1.4) | 0.68 |

| Internalising Problems Subscale Total Score (range 0–20) | 4.9 (3.9) | 4.7 (3.8) | 4.2 (3.6) | 4.8 (3.5) | 0.60 |

| Externalising Problems Subscale Total Score (range 0–20) | 5.0 (3.3) | 4.8 (3.5) | 4.3 (3.0) | 5.4 (3.7) | 0.45 |

| Impact Supplement Total Score (range 0–10) | 1.6 (1.5) | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.0 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.5) | 0.81 |

| 12 months | |

|---|---|

| Child Questionnaire Mean Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 81 (12) |

| Teen Questionnaire Mean Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 83 (16) |

| Parent Questionnaire Mean Score (range 0–100) mean (SD) | 90 (11) |

Closed Loop from Onset in Type 1 Diabetes: qualitative substudy

Introduction

This report details work undertaken by Edinburgh University on two qualitative substudies conducted as part of the NIHR-funded Closed Loop from Onset in Type 1 Diabetes (CLOuD) trial and an interim analysis of data to provide feedback to the trial team while the qualitative work was ongoing.

In the original trial protocol, the Edinburgh team had proposed to carry out one study to compare the experiences of youths in the intervention (CL) arm, and their parents’ views, with those of youths and their parents taking part in the control [multiple daily injections (MDIs)] arm. Early consultation with the trial team highlighted the pressing importance of seeking staff perspectives on the implications for roll-out of CL technology in routine clinical care. In addition, a review of an extensive body of literature, which has explored this age group and their parents’ experiences of using MDI, indicated that no further primary research involving these groups was required. Following the consultation and literature review, a whole-team decision was taken to revise the aims and scope of the original substudy to no longer interview those in the MDI arm in order to focus on exploring the views and experiences of participants using closed loops and their parents’ views, and to compare these with youth MDI users’ and their parents’ accounts in the existing literature. In so doing, this enabled us to free up capacity to develop and undertake a second substudy to look at the experiences and views of staff members delivering the CLOuD trial and supporting participants in the CL arm.

In light of these changes and having sought requisite ethics approvals, the two qualitative substudies included: (1) a substudy which explored youth participants’ and their parents’ experiences of using the FlorenceM CL in everyday life; (2) a substudy which explored the views and experiences of health professionals who delivered the trial and provided support to study participants in the CL arm. The remainder of this document reports the aims, methods, key findings and recommendations which resulted from these two substudies. We also report interim feedback about CL users’ and parents’ experiences of recruitment and views about the training they received, which was given to the trial team while data collection was ongoing.

Study 1: participants’ and their parents’ experiences of using the FlorenceM CL system

Aims

Original aims: In the original protocol, it was proposed that the qualitative study would explore parents’ and youths’ views about using the FlorenceM CL system and how these compare to accounts of those using MDI to:

-