Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 13/119/18. The contractual start date was in February 2016. The final report began editorial review in December 2020 and was accepted for publication in March 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Green et al. This work was produced by Green et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Green et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this report are reproduced or adapted with permission from Green et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Scientific background

Intervention evaluation research in autism spectrum disorder (hereafter ‘autism’) has recently accelerated, with studies across a range of interventions considered in recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance,2 Cochrane Library reviews3 and other reviews. 4–6 The pattern of findings across a number of early childhood interventions is for reproducible moderate-to-good effects on targeted ‘proximal’ or intermediate outcomes, such as improvement in social interaction and communication in the local treatment context. 7–9 However, for an intervention to demonstrate a tangible impact on a child’s life and overall development, the challenge is to show effects beyond the immediate intervention context, for instance that changes are also seen in non-direct treatment contexts, such as in interactions with other people inside or outside the classroom or in the family home setting, or an impact identified on other developmental function or symptom outcomes over time and in a variety of settings. In this regard, there is much less evidence,4,6 despite the fact that without such changes the claim that autism interventions are truly effective is harder to substantiate.

Reinforcing the transmission of targeted ‘proximal’ intervention effects into functional change seen in the wider context pervading the child’s life is, thus, a key current challenge for autism treatment research,6,10 and raises the question why does this appear to be so difficult in autism? The capacity to generalise acquired skills flexibly across different situations, people and environmental contexts – a central feature of skill acquisition in neurotypical development – has often been suggested to be a core difficulty for individuals with autism. In this context, one can consider two different forms or concepts of generalisation, which will be referenced throughout this report. First, the concept of generalisation of specific behaviours (for instance the observation of a specific newly acquired skill or behaviour in one setting that then occurs in another) has been commonly investigated in behavioural learning theory and could be termed ‘homotypic’ generalisation. Second, the concept of a ‘developmental cascade’ from precursor skills through to developmentally related but different subsequent skills (e.g. specific vowel sounds in infant development through to evolved language) is the subject of much study in general developmental science, and might be characterised as ‘heterotypic’ (‘homotypic’ and ‘heterotypic’ being terms originating in the longitudinal epidemiology literature). Although a recent systematic review concludes that the empirical evidence for difficulty in generalisation in the first sense is inconsistent,11 many single-subject design studies using behavioural learning methods have described difficulties that autistic children have in transferring newly taught skills to different settings, people or materials/activities, and it has been an assumption in developmental science, as well as from clinical experience, that there is additional difficulty in generalisation in both senses for autistic children. However, these are assumptions that have not been fully evaluated.

Possible explanations, particularly for the second, heterotypic, form of generalisation, include the autistic child’s well-documented lack of internal symbolic representation, which is likely to interfere with the consolidation and thus transfer of procedural aspects of skill across contexts into different forms of behaviour, independent of the specific context in which the skill was acquired. Another related barrier may be weaknesses in autistic cognitive central coherence, associated with an over-reliance on concrete behavioural prompts or reinforcers, which can lead to fragmented learning dissociated from the social pragmatic context as a whole rather than a more diverse integration of learning with connected understanding in context. There may be further factors related to a general lack of behavioural flexibility in applying new skills across different environments. Plausible approaches to helping overcome some of these generalisation difficulties in autism include embedding the intervention into the social environment through parent mediated and education staff-mediated learning, which may optimise the interpersonal cues and continuity of learning across contexts. 12 This method supports opportunities for incidental or naturalistic learning, by weaving functional social and communication learning into the child’s daily experiences, where skills are acquired. Working with children in naturalistic environments is now often highlighted as best practice for early intervention. 13

Early social communication intervention, delivered through parents, therapists or teachers, is the only early autism intervention with a ‘consider’ recommendation by NICE. 2 The Preschool Autism Communication Trial (PACT)7 tested a clinic-delivered, parent-mediated social communication intervention against regular care in what was, to the best of our knowledge, one of the largest randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in the field. 14 The therapy showed a substantial impact on the targeted immediate outcome of parental communicative synchrony with the child [effect size (ES) 1.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85 to 1.59)] and also on the child’s communication initiations with the parent (ES 0.41, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.74). The original publication7 demonstrated that PACT was associated with non-significant effects on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2) social communication domain when considered alone, but subsequent analysis of outcome on the full autism symptom phenotype [measured across both social communication and repetitive behaviour and sensory symptom domains in the ADOS-2 Calibrated Severity Score (CSS)] found a significant intervention effect at the end point, with a log-proportional odds ratio of 0.64. 14 Subsequent follow-up of the PACT7 cohort 6 years after treatment end, when participant mean age was 10.5 years, with blinded assessment of the original randomly allocated groups (80% follow-up completeness on the primary outcome) found evidence suggesting further sustained effect on reduced autism symptom severity on the ADOS-2 (log-odds ES 0.70, 95% CI –0.05 to 1.47), and a significant overall treatment effect when calculated over the treatment and follow-up time period (log-odds ES 0.55, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.91). Non-blind, parent-rated autism symptoms on the Social Communication Questionnaire (lifetime version) (SCQ) (ES 0.40, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.77) and repetitive and sensory behaviours on the Repetitive Behaviour Questionnaire (RBQ) (ES 0.87, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.35) also showed comparable improvement at follow-up. 14

To our knowledge, the PACT intervention was the first study in the field to show that a preschool autism intervention could have downstream developmental effects to reduce child autism symptom severity for a substantial period after treatment end. This PACT treatment7 was 93% clinic delivered and the key outcomes were measured in a research context; there was little measurement of effects within educational or home environments. Consequently, in the Paediatric Autism Communication Trial – Generalised (PACT-G), we aimed to extend the work of the original PACT,7 with the aim of (1) reinforcing the extension of treatment effects within the different naturalistic environments of the child’s early life, in home and educational settings, and (2) responding to moves towards home-based therapy delivery. The intervention was taken into the child’s daily naturalistic home and nursery/school setting, incorporating parent- and education staff-mediated interventions, and embedding individualised strategies within these naturalistic learning contexts.

A further development was the extension of the intervention into the primary school years, up to the age of 11 years. Autism intervention studies to date have been largely limited to preschool (< 5 years) interventions; however, early communication development continues into the school years,15 and social communication skills in the early school-age period are strong predictors for later development. 16 The persisting and significant impairments in social interaction and communication among children with autism argue for a developmentally sustained intervention into middle childhood, utilising the child’s naturalistic learning environments. However, because of the focus of the intervention on early social communication skill development, the cohort of autistic children of school age (> 5 years) receiving the treatment was restricted to those who had no more than a 4 years’ language-equivalent level.

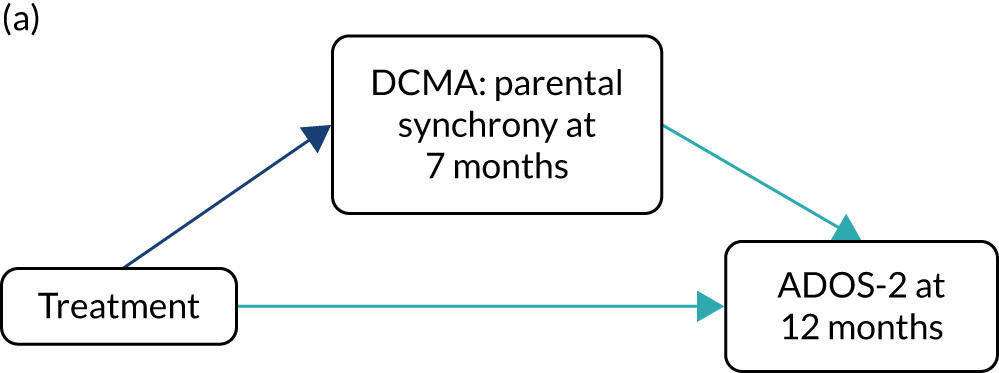

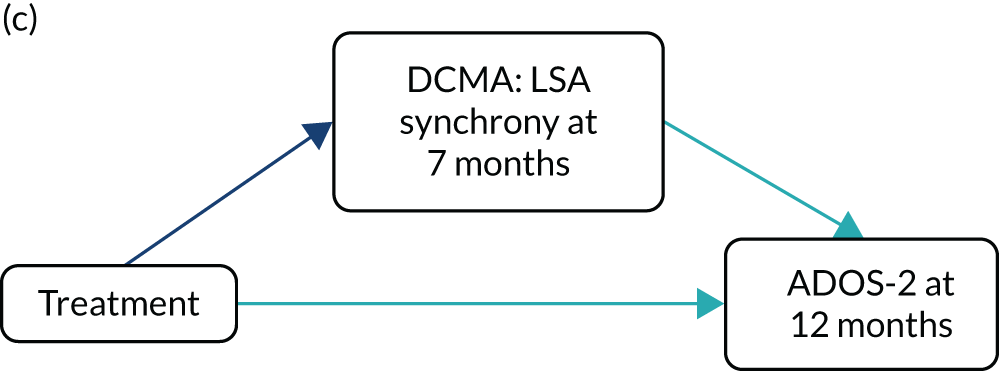

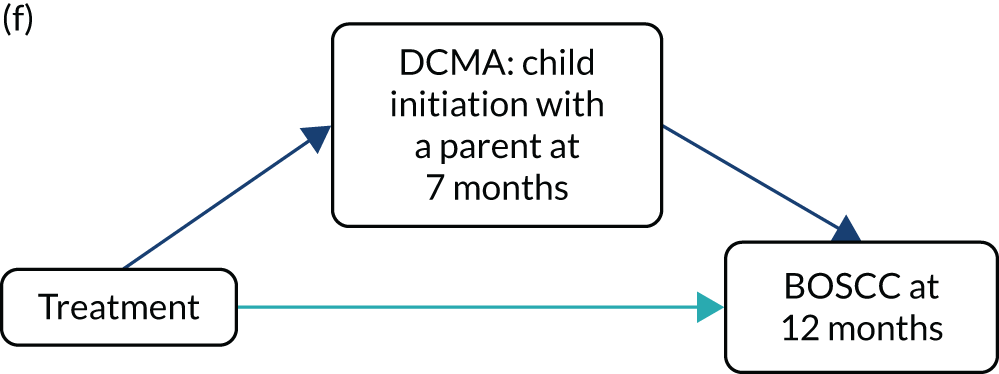

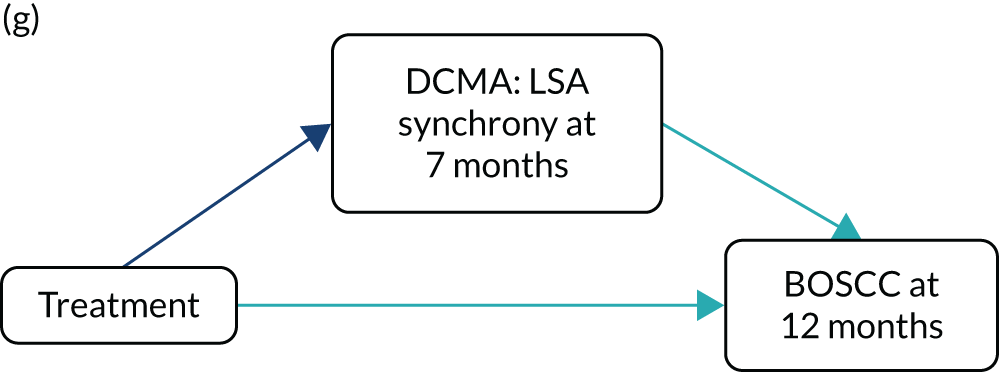

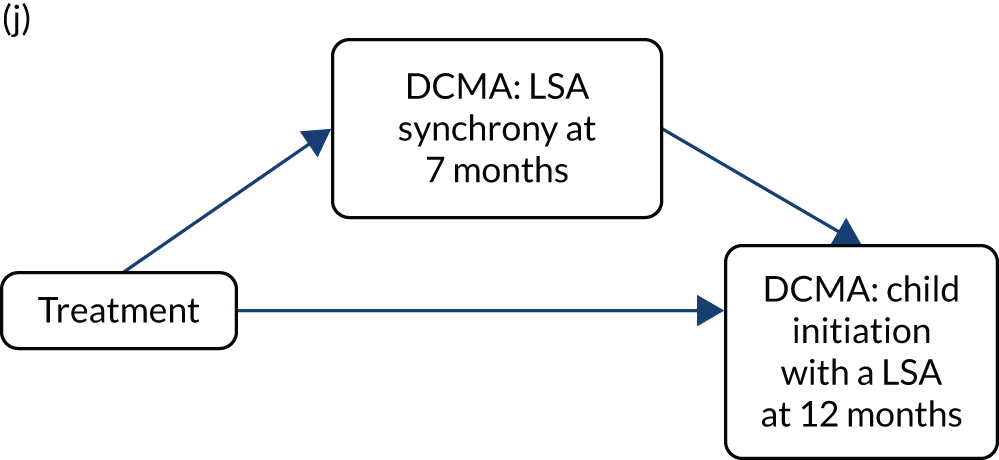

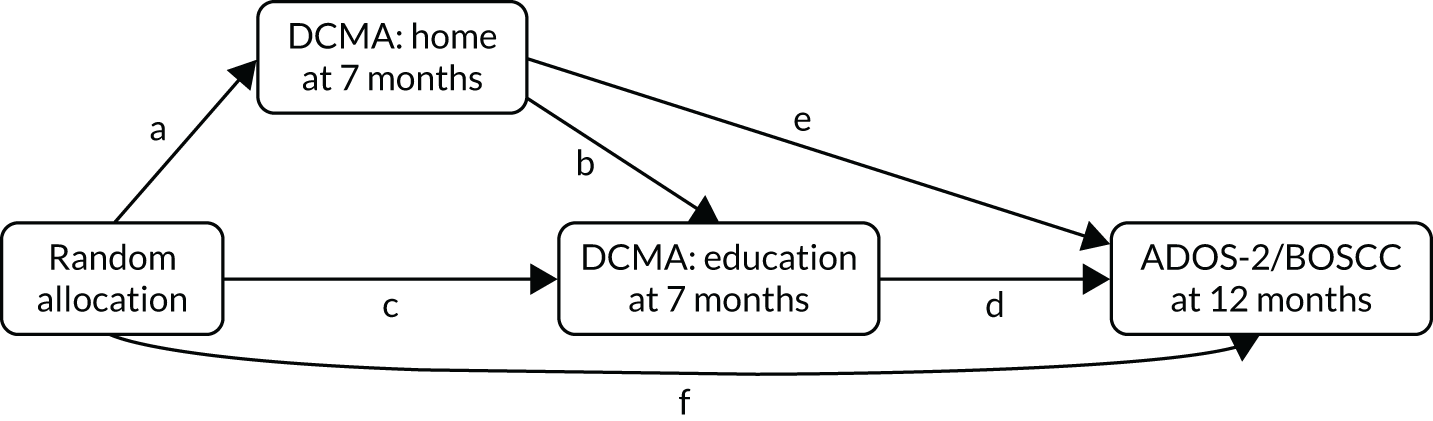

In addition, a mechanism study within PACT-G built on the understanding gained from the mediation analysis in the original PACT. 17 This previous analysis had tested for mediation of primary treatment effects on child autism symptoms (ADOS-G) through the proximal intervention target of improvement in parental synchronous response to child communication, and an increase in child communication initiations with the parent within dyadic communication (both of which were researcher assessed by video-coding blind to intervention group). In this analysis, increases in child initiations with a parent were shown to be strongly (mediated 80%) by the change in parental synchronous response produced by the treatment. These changes in child initiation with a parent then, in turn, were shown to strongly mediate (97%) the change in child autism symptoms. This mediation analysis had supported the theoretical logic model of the PACT7 intervention by showing a causal-effect chain from parent response to child, to child communication with a parent, and from child communication with a parent to a generalised social communication change in child symptoms. A similar mediation effect had been shown previously in the smaller PACT. 18 In the PACT-G mechanism design, we aimed to test whether or not a similar chain of mediation effect would be maintained when measured in the home and educational settings, and whether or not such changes in two parallel naturalistic settings simultaneously might be further additive in mediating an enhanced effect on symptom outcomes in the research context. In addition, the assessment of mediators and outcomes in different simultaneous naturalistic contexts might provide an innovative opportunity to study key mechanisms of child developmental learning across contexts and whether or not different contextual learning might generalise in an additive way to related downstream symptom outcomes.

Background literature on autism intervention

A significant evidence base from RCTs of early interventions for young children with autism has accumulated over the past 15 years. 4,6,19 Many of these interventions aim to ameliorate the impact of core social communication impairments on early social interactions, particularly with parents, who often find their child’s behaviour perplexing and challenging. The tested interventions have varied in design, duration and intensity, and include developmental and behavioural approaches20 that are mediated through parents and delivered directly by therapists, and there is significant study-to-study variation in the effects found. However, robust evidence now exists that some aspects of social communication can be improved for many young children with autism. 4

The most consistent findings are improvements in dyadic interaction between children and their parents or another adult. 7,9,21–25 Although many studies report improvements in language and communication on unblinded parent-report measures,7,14,25–27 findings on observational or standardised measures of communication and language ability are more variable. Thus, some studies report improvements7,14,23,26–28 whereas others do not. 7,21,24 Only a few studies have demonstrated treatment reductions in autism symptom severity,14,27 whereas most have not. 25,26,28 A recent review4 contains a thorough review of this literature in the context of study design and reporting quality.

Despite this promising evidence base, there is wide recognition that the early autism intervention research field faces challenges. 29–31 Even trials demonstrating group-level improvements report modest ESs,4 reflecting, in part, that a significant proportion of participants in many studies do not benefit. There are sparse examples of designs that would better inform ‘personalised medicine’ approaches (i.e. ‘who benefits from which treatments?’), including comparative or equivalence trials, and rigorous examination of which children benefit from these interventions (moderating effects) and how (mediating effects). Only two long-term follow-ups have been conducted to assess maintenance of effects,14,21 and there has generally been a lack of independent replication of substantial findings. In addition, reporting standards have been variable and there has been inadequate measurement of and attention to the critical importance of testing if and how interventions have an impact on everyday functional abilities that extend beyond the proximal intervention context. 11

In an earlier study, we found that a therapist-directed, parent-mediated intervention that uses video-guided feedback to and coaching for parents, following a transactional developmental model,32 resulted in improvements in parental synchrony and child initiations when interacting with each other. We also found moderate ES reductions in overall autism symptom severity on a blinded observational measure at treatment end point (log-proportional odds ES 0.64, 95% CI 0.07 to 1.20), which was sustained at the 6-year follow-up (log-proportional odds ES 0.70, 95% CI –0.05 to 1.47), with an overall log-proportional odds ES of 0.55 (95% CI 0.14 to 0.91; p = 0.004), as was the improvement in child initiations. 14

A qualitative interview study with parents who had received PACT therapy within the previous PACT7 confirmed the largely positive evaluation of the core effects of the therapy on communication, interaction and child progress, as well as emphasising valued improvements in the parents’ sense of the relationship with their child and enhanced parental and family well-being. However, the study revealed practical difficulties for some families in attending therapy sessions within a clinic environment,33 including the inconvenience (travel, child care), unfamiliarity with and lack of preparedness for autism in therapy venues, and challenges with occupying the child during video-feedback sessions and discussion. Delivery of the intervention within the home and educational settings and the use of video telecommunication software aimed to address some of these practical challenges, while also, importantly, in theory, providing a method of enhancing the adoption and generalisation of therapeutic strategies within the child’s family and everyday naturalistic environments. The use of teleconferencing technology was also thought to have the potential to remove practical barriers, as video material of adult–child interactions could be made in either the home or educational setting prior to the session, and then shared and discussed between the therapist and parent/member of education staff through teleconferencing at a later time without the child present. The advantages and disadvantages of these adjustments found in practice are discussed further below.

Interventions for autism in the educational setting

There are a number of programmes delivered within UK educational contexts to support children with autism. 34 The focus of many of these is on enhancing cognition and learning and reducing challenging behaviours. The majority of interventions fall into two broad categories: comprehensive treatment models (CTMs) and focused interventions. CTMs tend to be developmentally focused, multicomponent educational programmes, aiming to improve functioning across cognition, emotional and social development. They are often embedded within the classroom setting itself and delivered by members of staff. 35 A common UK example of a CTM is the Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication-Handicapped Children (TEACCH) programme, which incorporates the use of classroom-based visual schedules and prompts. 36 In the USA, Social Communication, Emotional Regulation, and Transactional Support (SCERTS)37 and the Learning Experiences and Alternative Program for Preschoolers and their Parents38 have also been used; these are also occasionally available in UK specialist autism schools. Although these approaches may be based on different conceptual models,39 they share similar general goals of embedding group, class-based support for children with autism within the educational setting.

Focused interventions tend to target specific skills;40 for example, the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) is used to support picture exchange as an alternative form of making a child’s needs known. 41 Alternative and augmentative language systems (e.g. Makaton)42 and the use of technology, such as voice output communication aids, are also sometimes available in the UK. A teacher-delivered interactive communication intervention for specific language impairments [the Social Communication Intervention Project (SCIP)]43 is also applicable to high-functioning autistic children in middle childhood. Peer-mediated interventions promote naturalistic peer socialisation and support in the school environment44,45 and have face validity. 46 In contrast to CTMs, the model by which many of these interventions are delivered is through consultation with schools by specialist health professionals (e.g. psychologists, speech and language therapists or trained teachers), but with the aim of collaborating with ‘non-specialists’ in their implementation [e.g. peers and learning support assistants (LSAs)]. 47 Funded LSAs are often allocated for differentiated support and learning in the classroom for individual children. There is a relative lack of high-quality implementation trials of such interventions in educational settings. 34,48

Education provision for children with autism in the UK

In the UK, 71% of children with a diagnosis of autism attend a mainstream educational setting. 49 Despite the benefits of inclusion in mainstream schools (notably the, potentially, wider participation in the educational experience, peer role models, acceptance and opportunities to develop academic, social and emotional skills50) access to specialist professional support and guidance is often very limited. Depending on the level of special educational needs (SEN), pupils receive non-specialist LSA support, but this is highly variable between schools. 51,52 LSA roles are wide-ranging and include supporting children with complex health, medical, behavioural and learning needs. 53 LSAs in special schools are more likely to work in a team with the teacher and support the whole class of children than they are to work one to one with an individual child.

Chapter 2 Study aims

PACT-G had two aims. The first aim was to test whether or not the multicomponent PACT-G social communication intervention protocol, extended from the original PACT7 intervention and implemented in both home and educational settings simultaneously, would show treatment effects on (1) autism symptom outcomes, as measured in an independent research setting (primary outcome), and (2) dyadic social communication, functional adaptation and autism symptoms in the separate home and educational settings (secondary outcomes). These objectives were tested using blinded measures, maximising the ability to detect meaningful change (see Chapter 5, Measures), and were evaluated by analysis at the 12-month trial end point.

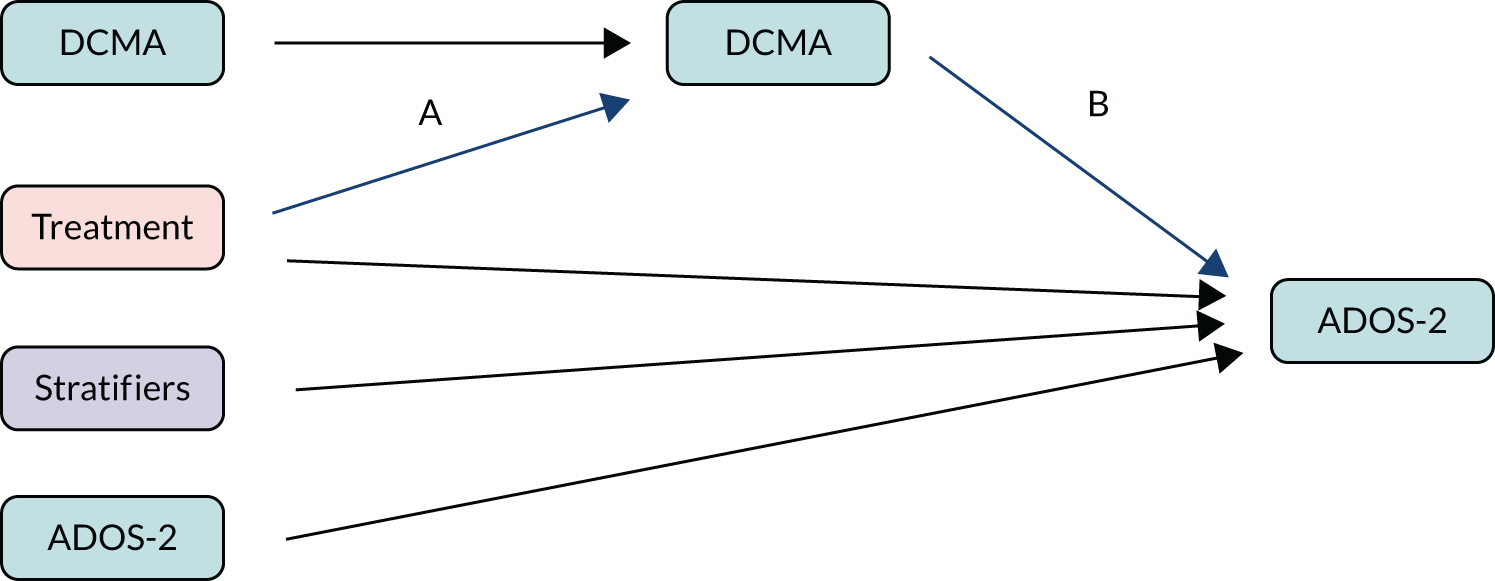

The second aim was a mechanism analysis using the experimental trial to investigate aspects of the developmental and cross-context generalisation of specific acquired competencies in autism. We built on the mediation analysis from our previous PACT7 (see Pickles et al. 14) to test the mediation of the generalised treatment effect in the home and educational settings. We tested how effects in naturalistic contexts might combine to enhance transmission of treatment effect to research-assessed symptoms in a standardised test setting. In doing this, we used prespecified measures of mediation that were identified in our previous PACT. 7

Chapter 3 Organisation

Trial organogram

The organisation of the three-site trial is shown in Figure 1, with the trial principal investigators named and their roles given. The full trial team is named and acknowledged in Acknowledgements. The study progress Gantt chart is shown in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Trial organogram.

| PACT-G timeline task | Month | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | |

| 2016 | ||||||||||||

| Start of grant | ||||||||||||

| Recruit research associates | ||||||||||||

| Research associates in post (36 months) | ||||||||||||

| Recruit SALTs | ||||||||||||

| SALTs in post (33 months) | ||||||||||||

| Recruit research assistants | ||||||||||||

| Research assistants in post (26 months) | ||||||||||||

| Pilot study | ||||||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||||||

| Research associates in post (36 months) | ||||||||||||

| SALTs in post (33 months) | ||||||||||||

| Research assistants in post (26 months) | ||||||||||||

| Main trial | ||||||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||||||

| Research associates in post (36 months) | ||||||||||||

| SALTs in post (33 months) | ||||||||||||

| Research assistants in post (26 months) | ||||||||||||

| Main trial | ||||||||||||

| Video scoring, data checking and entry | ||||||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||||||

| Research associates in post (36 months) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||||||

| SALTs in post (33 months) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||||||

| Research assistants in post (26 months) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||||||

| Main trial | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||||||

| Video scoring, data checking and entry | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||||||

| Analysis | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||||||

Chapter 4 Pilot feasibility study

PACT-G formally started on 1 February 2016. As per the deliverability project plan from January 2016 (see Appendix 3), the management team was contracted to demonstrate by month 12 that the following success criteria had been met in relation to two stop–go decision points to allow progression to the main trial:

-

Stop–go 1: at the end of the pilot phase of the trial, a minimum of 27 educational settings have been engaged with the educational setting buy-in protocol, with a written Memorandum of Agreement (MoA) from at least 11.

-

Stop–go 2: by the end of the 6-month pilot phase (month 12 of the study), the team will have identified, assessed for eligibility and consented a sufficient number of patients to proceed to treatment in 24 patients (eight in each site).

Stop–go 1: educational engagement

Contact with educational settings

The process for contacting educational settings varied between the sites (Manchester, Newcastle upon Tyne, London), depending on the size and type of provision. Sites mainly approached specialist schools and schools with significant specialist provision with which they were familiar. For most of the younger children recruited to the pilot phase, who had been referred through clinical services, we contacted their nursery or preschool at the point of the family’s consent to seek their engagement in the project.

Table 2 shows each educational setting that was contacted, as well as those where further discussions took place and the outcome of the engagement. A small number of educational settings that were contacted did not want further information. For those educational settings that wanted to learn more about the study, we sent the study information sheet and produced a standard presentation that was given at most educational setting visits. We also collected standardised information from the educational settings, including information about their provision of specialist education, the educational setting size and key staff involved in this service.

| Site | Number initially contacted | Number engaged | Number that signed the MoA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manchester | 17 | 14 | 10 |

| Newcastle upon Tyne | 10 | 10 | 6 |

| London | 7 | 7 | 2 |

| Total | 34 | 31 | 18 |

Numbers of educational settings contacted, engaged and agreeing to participate

Table 2 shows the number of educational settings at each site that were contacted, the number that received further information and engaged with the study team, and the number that signed the MoA. The results clearly demonstrate our achievement in meeting the success criteria for stop–go 1; we engaged 31 educational settings against a target of 27, and had signed MoAs from 18 educational settings against a target of 11.

Stop–go 2: pilot phase recruitment

Identified families

In total, we contacted 34 families during the pilot phase of the study. We consented and then assessed the children against the prespecified eligibility criteria on three assessments:

-

observed autism symptom severity on the ADOS-2

-

reported autism symptom severity in the parental autism diagnostic interview (preschool-aged children) or parent-rated SCQ (school-aged children)

-

necessary developmental level (i.e. 12 months) on the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (preschool-aged children) or British Ability Scales (school-aged children).

Three families dropped out after consent: one family worried about the impact of participating in an autism study and the potential stigma in the community, one family dropped out because of family pressures and one family could not be contacted to arrange eligibility assessments following initial consent.

Number of families approached, consented and assessed as eligible

Table 3 sets out the number of families contacted at each site, those that consented and the number of participants assessed as eligible and ready to proceed to treatment. A full anonymised recruitment log showing dates of birth and dates of consent is available from the authors.

| Site | Number approached | Number consented | Number assessed as eligible |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manchester | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| Newcastle upon Tyne | 12 | 9 | 8 |

| London | 13 | 10 | 8 |

| Total | 34 | 27 | 24 |

The results indicate our success against the criteria in stop–go 2; we assessed eight patients as eligible in each site.

In November 2016, the team reviewed progress in the pilot feasibility study, with the results being signed off on 3 November in a meeting with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), that supported trial progression.

Chapter 5 The PACT-G randomised controlled trial

Design

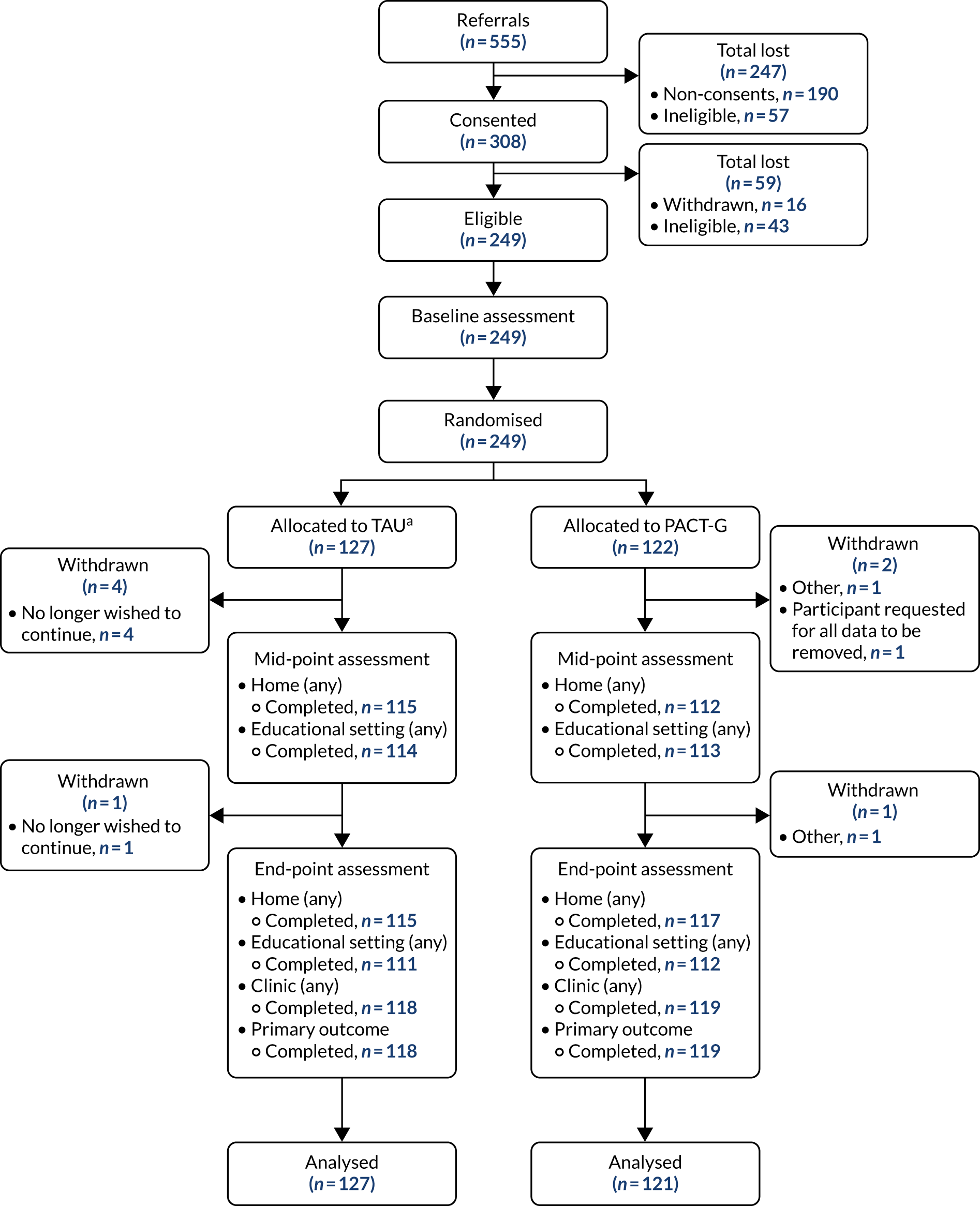

The trial was a three-site, two-group, RCT of the experimental treatment plus treatment as usual (TAU) compared with TAU alone. Children aged 2–10 years with autism were recruited to the trial in the local areas following referral by clinical specialists and education professionals. Consented families were then randomised to three sites around the UK to receive either the PACT-G social communication intervention in addition to TAU (referred to as the PACT-G group) or TAU alone (referred to as the TAU group). Assessments were administered on entry (baseline) to the trial, at the 7-month mid-point and at the 12-month end point. An embedded mechanism study aimed to test specific mediation hypotheses in the trial and to, potentially, use the experimental intervention design with repeated measures to contribute to a general understanding of the generalisation of acquired skills in autism development across both time and setting, and also in terms of downstream predicted developmental cascades to symptom and adaptive outcomes for the child.

Settings

The settings for the trial were family homes, mainstream nurseries and preschools, specialist nurseries, mainstream schools with specialist autism units and specialist SEN/autism school settings, all of which were in Greater Manchester, London or Newcastle upon Tyne.

Study population

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Participants aged 2–10 years.

-

Diagnosis of autism given by referral services.

-

Meeting criteria for autism on the ADOS-2.

-

Scoring ≥ 15 (school aged) or ≥ 12 (preschool aged) on the SCQ – the accepted clinical cut-off points for children at these ages.

-

Children aged ≥ 5 years between P3 and P8 for the English curriculum. (In England, at the time of the study, P scales described targets for children aged 5–16 years with special educational needs. P3 communication skills indicate that a child is beginning to use ‘intentional communication’. P8 was taken to represent an expressive language age-equivalent of approximately 4 years in a typically developing child.)

-

Parents with sufficient English to potentially participate in the intervention and who speak English to their child at least some of the time.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

having a sibling with autism already in the trial

-

participation in the PACT-G pilot phase

-

children aged ≤ 12 months with a non-verbal age-equivalent level

-

epilepsy not controlled by medication

-

children with an identified genetic disorder that would impact on their ability to participate or affect the validity of data

-

severe hearing or visual impairment in parent or child

-

current severe learning disability in the parent or current severe parental psychiatric disorder

-

current safeguarding concerns or other family situation that would affect child/family participation in the trial

-

no agreement to participate from child’s educational setting.

Sample size

The PACT7 showed an ES of 1.22 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.59) on parental synchrony [Dyadic Communication Measure for Autism (DCMA)], which mediated 70% of the ES of 0.41 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.74) on child communication, which in turn mediated 72% of the ES of 0.24 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.11) on symptom outcome (ADOS-2). The intervention strategies in PACT-G were specifically targeted to enhance generalisation of the child communication to increase primary outcome effects in home, educational and research settings. Therefore, we expected the ES for the symptom outcome to be substantially above 0.24 and clinically meaningful.

For PACT-G, power was calculated using the sampsi command in Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), for an analysis using analysis of covariance with α = 05, with pre- and post-measures correlated 0.67 (from PACT7). With 110 patients followed up in each group (70/70 preschool-aged and 40/40 school-aged children), 80% power was retained for an ES of 0.28 and 90% power for an ES of 0.33. Allowing for 10% attrition (compared with 4% in PACT7), we proposed to recruit 244 families (rounding up to 82 per site: 52 with preschool-aged children and 30 with school-aged children).

Interventions

The PACT-G intervention is an adaptation and extension of the original, largely clinic-delivered, PACT7 intervention into home and educational settings (93% of original PACT7 sessions were delivered in a clinic setting, whereas all of the PACT-G sessions were delivered in a home setting, in an educational setting or by teleconferencing). PACT7 is a ‘caregiver-mediated’ intervention; in this context, the carers are the parents and education professionals who are the primary recipients of the individualised intervention sessions. PACT-G utilises videos of caregiver–child interaction to provide feedback and guide caregivers to adapt their communication with the child. Therapists support caregivers to adopt evidence-based strategies in their communication so as to enhance child communication development,7,54 and to practise these strategies initially during the 30-minute home practice sessions and eventually throughout the day. Recent research indicates that optimal interaction with a sensitive and responsive communication partner can be effective in increasing communication and social interaction skills in children with autism. 4 In the original PACT,7 this caregiver-mediated approach was found to be effective in increasing the quality of parental communicative responses to the child, which in turn led to increased child-initiated communications with the parent and generalised effects on reduced child autism symptom severity. 7

The PACT-G intervention retains these effective elements, but encourages generalisation of the child’s newly acquired skills into other settings. For instance, the design of PACT-G includes more integration of PACT7 techniques into daily routines and play, and the addition of an adult from the child’s educational setting supports skill development in school. 55,56 The intervention is intended to begin with the caregiver at home and then extend into the child’s educational setting. However, sometimes the contingencies of school term times meant that sessions were coincident in timing. Furthermore, the PACT-G intervention incorporated more recent advances in research17 since the publication of the original PACT. 7 These included focusing on specific strategies to enhance the child’s response to shared attention with objects and play as precursors to the early stages of language development. 57,58 These modifications allow more differentiation of the starting point of the intervention to ensure that it is appropriate for the individual child’s initial level of object play and social engagement.

In common with the original PACT7 therapy, PACT-G therapy takes a staged approach that is based on theoretically informed precursor skills for typical communication development, as well as on addressing atypical communication and language development in autism. 15,59,60 Caregivers are initially encouraged to adopt strategies for establishing essential foundation skills for the child’s communication and language development, including shared attention57 and initiating social communication skills,37 before moving on to strategies that support and enhance the child’s receptive and expressive language development8,58 and reciprocal conversation. 43

In contrast to many manualised intervention programmes, PACT7 and PACT-G do not provide a curriculum or prescribed topic guide for sessions. The manual instead outlines six stages, each with a ‘toolbox’ of strategies that could be used to facilitate development. Therapists are trained to minutely analyse videos of caregiver–child interactions to assess the areas for further development and the potential strengths. 61 Based on these observations, therapists then establish which of the manualised therapy targets are most appropriate for that dyad at that stage of development, and agree these as targets for intervention with the caregiver. Therefore, targets and strategies are individualised for each child, depending on their interactive style. Progress is evaluated and subsequent targets for each dyad are based on that pair’s progress, allowing for a highly individualised intervention approach that accommodates each individual, but can remain within a well-defined framework. This is described further below.

The PACT-G method of video feedback facilitates a collaborative partnership, empowering caregivers. 22,33 A new caregiver–child interaction video is recorded at each session, and the therapist guides the caregiver in observing and analysing the most successful moments of dyadic interaction on video, thereby helping the caregiver to see how their use of strategies promotes and enhances the development of the child’s communication. Insights from this discussion are then used to set individual step-by-step caregiver goals (i.e. strategies they will adopt) within the stages of the manual that are appropriate to the identified individual needs of the child. Between sessions, caregivers are encouraged to practise using these strategies with the child, initially in protected time and later at opportune moments throughout the day. The PACT-G intervention is designed for preschool- and primary school-aged children, from those with little communication or no language to children who use spoken sentences. Progression through the stages of PACT-G is individually differentiated so it is related to both the caregiver and the child’s readiness to progress. Many dyads may remain at the early stages focusing on shared attention, caregiver-adapted responding and child communication initiation; others may progress to later PACT-G stages of language expansion and reciprocal conversation.

The PACT-G intervention manual provides clearly defined stage aims, child outcomes, therapy targets and a range of caregiver strategies. Each of the six stages includes a list of objective measures to determine a dyad’s readiness to progress to the next stage.

Stage 1

‘Establishing shared attention’ helps the caregiver to establish and maintain extended periods of mutual shared attention with the child. 8,57 All dyads complete at least one session at stage 1. For dyads already showing extended periods of mutual shared attention, the focus of the single stage 1 session ensures caregiver understanding of the concept of shared attention and highlights successful strategies that are applied. For dyads at the very earliest stages of development, with fleeting or no shared attention, further sessions at stage 1 are needed and include play with or without toys and caregiver modelling. In stage 1, the caregiver learns to sensitively observe the child’s focus, as well as non-verbal and verbal signals, and thereby to identify opportunities for shared attention.

Stage 2

‘Synchronicity and sensitivity’ emphasises caregiver sensitivity in responding, with a focus on the child’s perspective and experiences. 54 Caregivers are encouraged to closely observe the child to identify opportunities to respond, thereby reducing asynchronous communication (mistimed responses that place a demand on the child) and increasing adult synchronous communication. Caregiver observations from video help them identify and reduce demands, instructions and directive responses, and replace them with synchronous responses to the child’s communicative behaviours and social initiations, commenting on or acknowledging intentions.

Stage 3

‘Focusing on language input’ helps the caregiver to model language that accurately matches the child’s interests and communication competencies. 8,13,58 Caregiver language and non-verbal gestures are carefully monitored and modified to be contingent on the child’s focus and comprehension. The caregiver is assisted to respond to the child’s non-verbal communication and to model complementary verbal responses that express the child’s inferred communication intent.

Stage 4

‘Establishing routines and anticipation’ is a consolidation phase that aims to develop child verbal understanding, anticipation and participation using repetitive rhymes, predictable routine phrases and familiar interactive play. 54

Stage 5

‘Increasing communication functions’ is carried out by eliciting communication acts through the sensitive use of communication ‘teasers’ to provide opportunities for child initiation. For example, the caregiver may make use of pauses and gaps within familiar, predictable play situations that the child fills with social and verbal responses. Communicative teasers entice the child to initiate intentional communication. 17,37 These are gradually extended to pose deliberate problems and/or to introduce ‘sabotage' in situations where the caregiver makes obvious mistakes (e.g. offering an empty cup or unopened snack, or a puzzle/game with pieces missing). A range of pragmatic communication acts can be elicited in this way, including requesting, negating, directing and commenting.

Intervention delivery

Parent sessions

Parents were offered 12 intervention sessions at home over 6 months. This was a reduction from the original PACT,7 in which 18 sessions were offered over 12 months. In the previous trial, the best proximal effect of intervention on parent–child dyadic interaction was achieved by 12 sessions (6–8 months), and this proximal dyadic effect strongly mediated the reduction in 13-month end-point autism symptom severity. Pragmatically, we needed to adopt this reduced session number for each setting in this trial so as to make the treatment in the parallel home and educational settings feasible within a fixed time frame.

Prior to starting the PACT-G programme, a home visit was conducted to introduce the intervention to the parents, understand the family context and set expectations. The PACT-G approach to parent sessions differed from that of the original PACT7 in setting, number of sessions and nature of delivery. The therapy sessions were delivered in the home and, instead of the solely in-person sessions in PACT,7 the therapy sessions alternated between home-based in-person sessions and video conferencing or telephone-delivered consultations, with the delivery style being flexible in accordance with the needs of the family. This approach aimed to promote generalisation of new skills development in the home setting. Other clinical and research experience has indicated that video conferencing session formats were popular with parents. 62

Each parent session began with a discussion and review of the progress made since the last session. The parent and child were then filmed while playing for 10 minutes. Immediately after this, the therapist and parent watched the video, or, during video conferencing sessions, the therapist and parent watched a 1- to 2-minute parent-filmed video of a home-based practice session. The therapist facilitated parents to identify child communications and to adopt PACT-G strategies in their interactions with the child. Parents were assisted to set goals for themselves based on the interaction strategies discussed. The parent and therapist discussed the opportunities to practise these strategies each day at home for half an hour, as in the original PACT. 7

Educational setting sessions

In most cases, therapy in the educational setting began after the parent had commenced therapy at home. The start times and duration of educational setting-based therapy were aimed to fit in two education terms, where possible. In the educational setting, PACT-G sessions were delivered by a LSA or equivalent, nominated by the senior management team. LSAs and other education staff received an initial training session to introduce them to PACT-G therapy. The education-based intervention then consisted of therapist–LSA sessions that mirrored the therapist–parent sessions in the home. Videos recordings of the LSA and the child were used to coach the LSA in the use of PACT-G strategies in a similar procedure to the parent. The LSA was then asked to implement these with the child daily – inside or outside class. There was a maximum of 12 therapist–LSA sessions over 6 months, alternating educational setting visits and video conference or telephone consultations. PACT-G strategies were expected to be integrated in a complementary way with other communication strategies that may already have been in use in the educational setting. This combination of therapist–parent and therapist–LSA sessions resulted in a maximal offer of 24 sessions for PACT-G across home and educational settings.

Collaboration between parent and education staff

The separate therapeutic work with parents and LSAs described above was designed to be supplemented with a schedule of joint parent–LSA meetings [i.e. home–school conversations (HSC)] to support communication and complementary use of strategies across the home and education settings. These meetings used the manualised and validated technique of HSC. 63,64 Meetings were structured around ‘explore’, ‘focus’, ‘plan’ and ‘review’ stages, which allowed the LSA and parent to share experiences to promote generalisation of techniques across settings. HSCs have been shown to be highly effective in motivating parents and education staff. 63,64 HSC sessions were designed to take place in the educational setting and were planned to occur as regularly as possible during the intervention period, in association with therapist’s visits to the educational setting. This allowed for up to six HSC sessions, with the minimum acceptable number set at three per child. Table 4 summarises the intervention procedure over time.

| Session type | Month | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (baseline) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 (end point) | |

| Researcher assessment |

ADOS-2 BOSCC |

ADOS-2 BOSCC |

|||||||||||

| Parent assessment |

BOSCC DCMA |

BOSCC DCMA |

BOSCC DCMA |

||||||||||

| Intervention with parent |

Initial home visit 12 intervention sessions (home-based sessions and telephone/video conference support sessions) HSC sessions in educational setting |

HSC sessions continue for the period of the educational setting-based intervention. The number will vary depending on term times, but with a minimum number of three sessions | |||||||||||

| School assessment |

BOSCC DCMA |

BOSCC DCMA |

BOSCC DCMA |

||||||||||

| Intervention in educational setting |

Initial LSA in educational setting training visita Up to 12 intervention sessions (educational setting alternating with video conference/telephone support) incorporating HSC meetings with parents |

HSC sessions continue until final assessment | |||||||||||

Training and fidelity of treatment

Training in the PACT-G therapy was conducted centrally by the lead speech and language therapists, who undertook overall co-ordination of the therapy in the trial and organised quarterly across-site therapist meetings. Therapists were regularly supervised by the clinical lead in each site. All therapy sessions were videotaped, and randomly selected tapes of one home and one education in-person session per therapist were independently rated using the PACT-G fidelity rating scale (see Appendix 4) at regular intervals across the trial period. Therapists and research staff were trained in practices that minimise non-compliance and dropout. Arrangements were also made at each site to ensure that PACT-G therapists had no contact with TAU only (control intervention) families. Therapy compliance and receipt of other interventions outside the protocol were monitored.

Treatment as usual

The control intervention was TAU only. We had detailed information on TAU in the preschool population from the group’s previous work on the original PACT and in older children from the PACT 7–11 follow-up study. 65 Data on the services received by all families recruited to PACT-G were collected by the research team.

Avoidance of contamination

There were separate clinical and research leads at each site and separate training and supervision structures. Researchers were housed separately from the staff involved in the delivery of the PACT-G intervention. Mid- and end-point research interviews and assessments were conducted so as to avoid inadvertent divulging of information that could reveal treatment status. The assessment suite and materials used were different in type and location to those used for the therapy intervention in home or educational settings to avoid any familiarity effect for children in the treatment group.

Measures

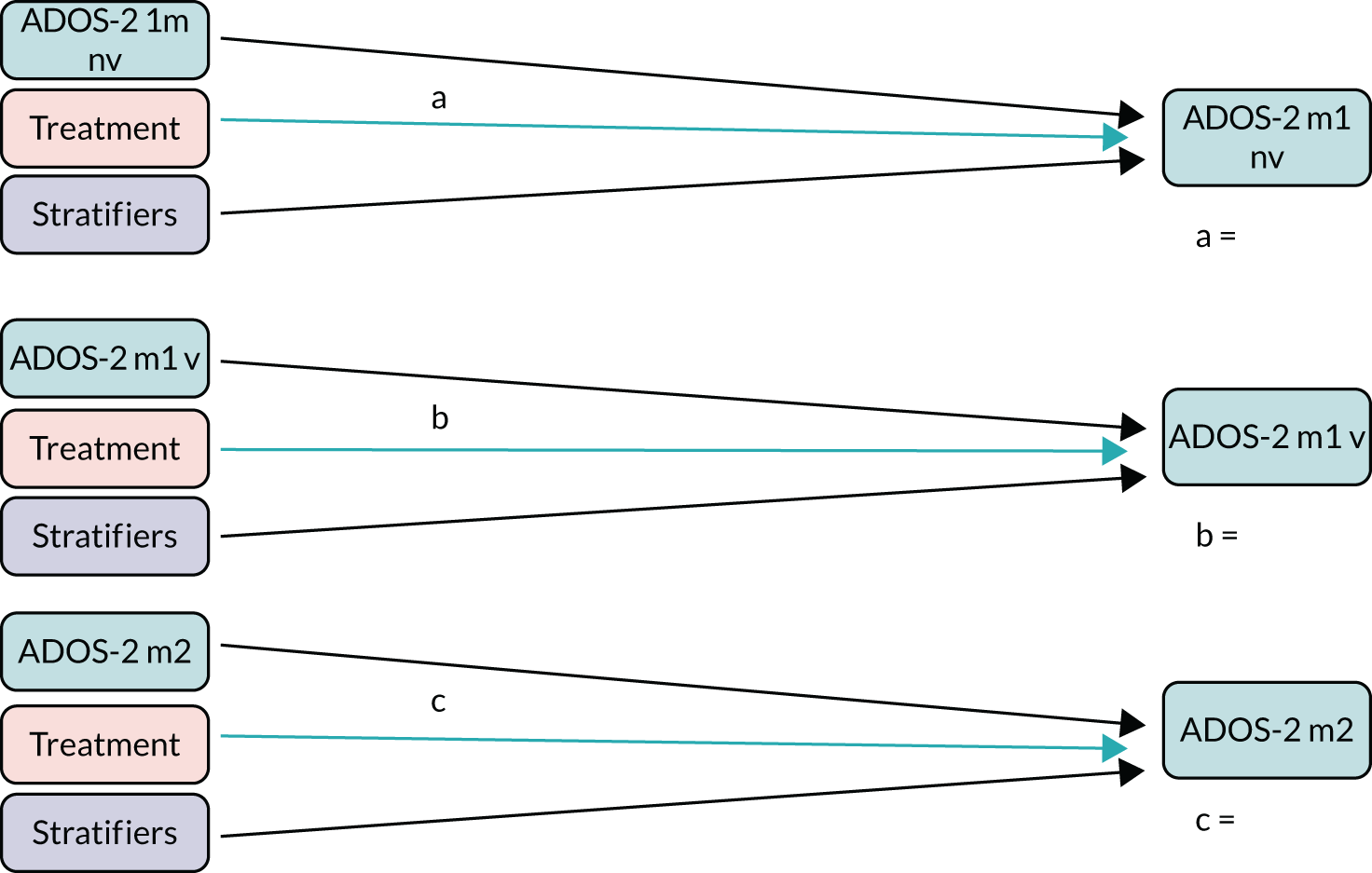

Primary outcome: ADOS-2

The ADOS-266,67 is a standard autism diagnostic symptom measure with good external validity for long-term outcomes in autism development. The assessment was undertaken during researcher–child interaction using a standardised set of social presses and was video-recorded for later coding to preserve blindness in follow-up assessments. The scoring metrics of ADOS-2 have been modified in line with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition,68 with social communication and repetitive behaviour symptom domains combined into a unitary total symptom score [social affect (SA) and restricted and repetitive behaviour (RRB) overall total raw score]. ADOS-2 modules are available for different stages of child development and were assigned at baseline accordingly. The same module was used at the end point as the baseline for each child. Recent studies14,69 have demonstrated the ability of the ADOS-2 to measure treatment effects; for instance, in the PACT follow-up study,14 effects were sustained for 6 years after treatment end.

Other measures

Diagnostic inclusion

The Mullen Scales of Early Learning70 or British Ability Scales71 were used depending on the child’s age and ability level. These are standard measures of early development that enable a developmental level of non-verbal abilities to be ascertained for inclusion criteria and allow characterisation of the cohort in relation to other autism treatment trials.

The SCQ72 is a brief (40-item) parent-report screening measure that identifies characteristics associated with autism. Items cover three subdomains: reciprocal social interaction; communication; and restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour. The ‘lifetime’ version refers to the entire developmental history of the child.

Secondary outcomes

The Brief Observation of Social Communication Change (BOSCC) with a researcher73–75 involved the researcher coding the autism symptoms from videotaped child–adult interactions. It addresses the same autism symptom constructs as the ADOS-2, but is designed to detect clinically meaningful symptom change in treatment studies. Codings combine symptom frequency, severity and atypicality on a 16-item, 0–5 scale (overall range 0–80). The BOSCC is designed to be a standard treatment outcome measure for the autism field and is currently used in large, funded trials in the USA and the European Union. The BOSCC has high-to-excellent inter-rater and test–retest reliability and has convergent validity with measures of communication and language skills. It demonstrated increased sensitivity to change over time compared with the ADOS-2 CSS in an observational study. 75 Three moderate-sized RCTs applying the standard naturalistic BOSCC as an outcome measure reported small and non-significant ESs. 76–78 When applying the standard BOSCC coding scheme to a non-standard, structured parent–child interaction, one study27 found a large, significant intervention effect.

For module 1 BOSCC (non-verbal or minimally verbal children), the recommended protocol consists of 4 minutes of free play followed by 2 minutes of bubble play, which is then repeated with a new set of toys. From this, 4 minutes of free play and 1 minute of bubble play were coded for each of the two segments. For module 2 BOSCC (phrase speech), as there was no recommended administration procedure developed at the start of PACT-G, a play and conversation administration was agreed with the developers in which the children had 4 minutes of free play followed by 2 minutes of conversation, which was then repeated with a new set of toys, before 2 minutes of bubble play.

The BOSCC with a parent and LSA73–75 was a measure of the intervention effect in the naturalistic settings in which the intervention took place. It involved the coding of video-recordings of child–parent play sessions in the home setting (at baseline, 7-month mid-point and 12-month end point) and child–LSA play sessions in the educational setting (baseline, 7-month interim and 12-month end point). BOSCC ratings were made from the same video-capture as for the DCMA (see below) and, to allow this, its administration deviated slightly from the recommended BOSCC protocol. For module 1 BOSCC, each child had 8 minutes of free play with the adult with the same box of toys, followed by 2 minutes of bubble play. From this, 4 minutes of free play and 1 minute of bubble play were coded for each BOSCC segment. For module 2 BOSCC, parent and teacher BOSCCs had 8 minutes of free play with the same set of toys, 4 minutes of conversation, and then 2 minutes of bubble play, based on a prototype ‘verbal’ BOSCC administration using module 1 toys. It became apparent during the trial that the conversation element was too challenging for the majority of module 2 children and it was decided, in discussion with the BOSCC developers, to code the module 2 items from 4 minutes of free play and 1 minute of bubble play in each segment.

The DCMA with parent and with LSA14 was coded from the same videos as for the BOSCC. This measure includes independent codes of adult communication (synchronous response) and child communication (child initiations). The DCMA synchronous response variable is defined as the proportion of the adult’s total communication acts that are synchronous with the child, where a synchronous communication act is a comment or acknowledgement that follows the child’s focus of play, actions, thoughts or intentions. Requests, directions, commands, questions and negations are not considered synchronous, even if related to the child’s focus of attention. The DCMA child initiations variable is defined as the proportion of the child’s total communication acts that are initiations, where initiations are verbal or non-verbal communication acts that serve to start an episode of interaction. This measure had proved sensitive in the original PACT mediation analysis and is used in PACT-G to test treatment effect and mediation in home and educational settings.

The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS) (parent and teacher versions)79 includes domains of communication, daily living skills and socialisation; it has been used widely and measures child functional ability in the home and educational settings.

The MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories (MCDIs) (word and gestures, sentences and grammar),80 the Receptive and Expressive One-word Picture Vocabulary Test (EOWPVT)81 and the Preschool Language Scale-5 (PLS-5)82 are standardised assessments used to measure children’s overall language level to supplement the measures of autism-specific communication included in the BOSCC and ADOS-2.

The Very Early Processing Skills (VEPS)59,60 assesses children’s sociocognitive skills (social responsiveness, joint attention and symbolic comprehension).

The RBQ83 is a 26-item parent questionnaire for assessing repetitive behaviours in children with autism.

The Developmental Behaviour Checklist (DBC) – Parent (2nd edition)84 is a 96-item instrument used for the assessment of behavioural and emotional problems in young people aged 4–18 years with developmental and intellectual disabilities. It includes two subscales, the Disruptive/Anti-social Subscale and the Anxiety Subscales (36 items), and is completed by a parent or carer.

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) – parent and teacher versions85 – is a 25-item brief measure of psychological well-being in 2- to 17-year-olds and is completed by parents and teachers.

The Child Health Utility 9D (CHU9D)86 is a paediatric measure of health-related quality of life. It consists of nine items, rated on five levels (ranging from no problems to severe problems). It is designed to be completed by children aged 7–17 years. Proxy completion by parents on behalf of their child is also possible for younger or children with developmental disabilities.

The Warwick–Edinburgh Mental-Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS)87 is a self-rated parental well-being questionnaire recommended by the UK Department of Health and Social Care as the preferred measure of mental well-being to incorporate in studies of this kind.

The Tool tO measure Parenting Self-Efficacy (TOPSE)88 is a 48-item, self-reported measure of parenting competence. It is a measure of possible change in parents’ confidence in their ability to make a difference to their child’s development. It was completed at baseline and end-point assessments.

The Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule (CASUS) and the School Service Use Schedule65 were developed to record therapies and service use accessed throughout the study. Forms were adapted to young populations with autism in PACT7 and PACT 7–11. 6

The Working Alliance Inventory-Short Revised (WAI-SR)89 is a measure of engagement with therapy for parents and LSAs in group only. For parents and LSAs, there is a simple rewording of the client and therapist versions of the Working Alliance Inventory, which has been validated and is now frequently used. It was completed at the 2- and 5-month stages of the intervention.

Demographic, clinical and family language information comprised relevant demographic and clinical information and details of home language(s) spoken with the child. The intervention schedule is summarised in Table 5.

| Time point | Measure |

|---|---|

| Eligibility | ADOS-2 |

| SCQ | |

| Mullen Scales of Early Learning (preschool-aged children) | |

| British Ability Scales (school-aged children) | |

| Baseline | BOSCC – researcher |

| BOSCC/DCMA – parent | |

| BOSCC/DCMA – LSA | |

| VABS – parent interview | |

| VABS – teacher survey | |

| VEPS | |

| EOWPVT | |

| RBQ | |

| WEMWBS | |

| MCDIs (word and gestures; sentences and grammar) | |

| SDQ – parent | |

| SDQ – teacher | |

| TOPSE | |

| CHU9D | |

| Key information and demographics | |

| Clinical information and service use | |

| School Service Use Schedule | |

| Family language interview | |

| Mid-point home/parent | BOSCC/DCMA – parent |

| Status form | |

| Mid-point LSA/school | BOSCC/DCMA – LSA |

| End point | ADOS-2 |

| RBQ | |

| BOSCC – researcher | |

| BOSCC/DCMA – parent | |

| BOSCC/DCMA – LSA | |

| PLS-5 | |

| EOWPVT | |

| VABS – parent interview | |

| VABS – teacher survey | |

| WEMWBS | |

| MCDIs (word and gestures) | |

| DBC – parent (disruptive/antisocial and anxiety subscales) | |

| SDQ – parent | |

| SDQ – teacher | |

| TOPSE | |

| Changes to key information and demographics | |

| School Service Use Schedule | |

| CASUS | |

| CHU9D |

Procedures

Data collection

Research staff confirmed eligibility and obtained consent. Baseline assessments were undertaken prior to treatment assignment.

Randomisation

Randomisation took place using a web-based service hosted at the King’s Clinical Trial Unit. 90 This system was accessed only by trained trial staff who had previously been allocated a username and password. Requests for passwords were sent through the trial manager to the King’s Clinical Trial Unit. Randomisation was at the level of the individual participant, 1 : 1, stratified for site, age group (2–4 years and 5–11 years) and gender imbalance using random block sizes. Once randomised, the system automatically generated and sent an unblinded e-mail confirmation to the therapy lead (for records, blinded copy was sent to the local researcher who made the request and to the Manchester trial manager).

Blinding/concealment

Researchers who administered assessments were blind to participants’ group allocation and every effort was made to maintain blindness throughout the trial: research staff were located separately from therapists, parents were reminded at every meeting with the researchers not to divulge allocation information, staff in the educational settings were given photographs to distinguish therapists from research staff, and, where possible, different school staff signed in therapists and researchers.

To preserve blinding in follow-up visits, the primary outcome and putative mechanisms at the end points were cross-coded from videos by researchers at the other sites who had been trained to high levels of reliability and blinded to intervention allocation. A randomly selected proportion of assessments were double rated for reliability. All other researcher assessments were also blinded; however, parent and teacher questionnaires and interview measures were unblinded. Participant families could not be blinded to allocation. All therapy sessions were video-recorded. Variability due to therapist effects was minimised by frequent clinical supervision and checks of continuing therapist fidelity against the treatment manual; randomly selected sessions for each therapist were formally coded for fidelity over the course of the study by independent clinicians using the model successfully used in the PACT.

Engagement with referrers, schools and families

Extensive information-sharing and engagement activities with clinical teams and local mainstream and specialist educational settings were undertaken to promote clinical referrals and engagement with both home and educational aspects of the intervention. Regular trial newsletters to participating families, schools and nurseries and clinical teams, along with voucher payments to educational settings (schools and nurseries), acted to maintain involvement and adherence. Families received an individualised feedback report on the assessments conducted with their child, copied to school and clinical teams with parental consent, if desired. Parents received a small voucher payment at the end of their participation to thank them for their time and efforts. A local referring clinician for each participant was informed of the study progress and findings, with procedures for clinical support and aftercare beyond the study, should this be necessary.

Memorandum of Agreement with participating educational settings

There has been a recent emphasis on the need for collaborative research partnerships between educational settings and evidence-focused partners. 91,92 To address this call,46 more research teams are utilising MoAs or similar to formalise partnerships with the educational settings that participate in their large-scale trials. 93 Although traditionally used in school–school partnerships to share best practice, there is a clear benefit to developing mutually beneficial links between educational settings and evidence-focused partners. There is a great need for collaboration in these contexts and stakeholders to understand how effective interventions for children with autism can be developed. 54,55,94

A MoA was developed for PACT-G to develop working relationships with participating educational settings. The MoA and accompanying information sheet contained information about the PACT-G intervention, explaining the requirements of the randomised control design of the trial and the need for an appropriate member of staff to be available to attend intervention sessions and participate in research assessments, and providing information on how the educational setting would benefit for taking part.

The decision on who to nominate as the intervention partner was made by the educational setting; however, we theorised that the LSA would best fit this role because of the likelihood that they would spend the most contact time with children out of all education staff and because they had more time in the school day than teachers.

The MoA itself required a signature from a senior member of management and a member of the governing body, when applicable, which meant that ‘buy-in’ was formalised for the educational setting. Evidence shows that the drive for improvement and demonstration of good practice from senior leadership has a downstream positive effect on school culture. 95 Moreover, Goodrich and Cornwell96 suggest that the influence of organisational culture, routines and training plays a substantial role in the quality of care and outcomes.

Data management

All data in the trial were anonymised. Site files were held at each site and a trial master file was held centrally by the trial manager at the University of Manchester. This contained the key linking the anonymised trial name to personal details. The main trial data were entered into the web-based data entry service of King’s Clinical Trials Unit, which has a full audit trail. Appropriate quality control was carried out during the trial and before the database lock, and recorded in a standard operating procedure (SOP). This included data entry checking of:

-

all measures of the first two cases entered by each individual carrying out data entry

-

10% source data verification on data entry for all measures

-

all the primary and secondary outcome data entries, including ADOS-2 and researcher BOSCC data.

Primary analysis of the data was undertaken by the trial statisticians, with senior statisticians masked to treatment allocation. Analyses involving therapy data were not masked and were undertaken in part by the chief investigator’s administrative team. Full data sets were also shared with each site in the collaboration.

Adverse events

Adverse events (AEs) were enquired about systematically by researchers at each meeting with the family. AEs were also collected in parallel by trial therapists, as and when a situation became known to them, and documented separately in a therapy log. As well as recording AEs in a predefined standard format, we included AEs relating to child health, well-being and behaviour; significant issues in the educational setting; and family events such as separation or significant parental ill health. AEs were monitored using a bespoke semistructured interview and documented by the research team post intervention and as they arose during intervention sessions, regardless of the relationship to the study intervention or research procedures. Hospitalisation and bereavement in a family member residing in the home were considered severe AEs. We reported on all serious AEs (any AE which results in death, is life-threatening, requires hospitalisation or prolongs hospitalisation, causes persistent or significant disability, or results in birth defects) and all suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (serious AEs that are believed to have a causal relationship with the PACT-G treatment). We also recorded events particularly relevant to this trial, such as significant changes in family or school situation. The clinical principal investigators (JG, TC, JP, ALC, HMc, VS, CA, VG) reviewed and agreed all AEs at the end of the study. An unblinded list of AEs by group was prepared by the statistical team and reviewed by the study Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee.

Adherence to allocated treatment, session validity and manual fidelity

Any departures from intended treatment assignment were described. The total numbers of sessions with parents, LSAs and in HSCs were reported, as well as the number of sessions that met the criterion for satisfactory quality. The service use form was used to identify any TAU families who had made use of the PACT treatment outside the trial. Therapists were regularly supervised by the clinical lead at each site.

Intervention manual fidelity

All therapy sessions were video-recorded at regular intervals across the trial period; one in-person session in the home setting and one in the educational setting were randomly selected per therapist for rating (CT, JG and PH), independent of therapy delivery and supervision, using the PACT fidelity rating scale (see Appendix 4). The scale has 16 items, rated 0 or 1, and was used to assess adherence to the PACT-G protocol. The proportion of tapes above the 80% fidelity threshold was reported.

Remote sessions and HSCs were not formally rated because of anticipated difficulties in recording these adequately, but they were informally monitored by the therapy supervisors during therapy supervision. The independent fidelity raters did, however, review a selection of remotely delivered sessions in the home and educational settings, chosen to reflect the range of remote sessions delivered, to assess the acceptability of remote intervention in the different settings.

Session validity from therapist logs

A key component of the PACT-G therapy is the use of video-mediated feedback. However, as the PACT-G therapy was being delivered in both home and educational settings, and often in challenging circumstances, a set of criteria was developed against which therapists could judge the ‘acceptability’ of each session. Detailed therapist logs were maintained through the course of the trial. Information from these was used to collate (1) the number of sessions delivered in each category, (2) the acceptability of these sessions against quality criteria and (3) qualitative notes on treatment setting, barriers to delivery, feasibility and acceptability. A number of ‘exclusion deviations’ were prespecified which, if present, resulted in the session being rated as falling below an acceptability threshold. Criteria for a number of ‘acceptable deviations’ were also prespecified. These were deviations from the content of an ‘ideal’ session that, despite the deviation, the therapist rated as a good enough therapy session to be valid.

The home–school conversation sessions

Home–school conversation sessions were not video-recorded or rated for acceptability or fidelity purposes. However, the number of sessions and session length were recorded. HSCs lasting < 30 minutes were deemed unacceptable as a valid session.

Chapter 6 Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement input into original intervention development

Ongoing sequential development of the PACT intervention has been carried out in close collaboration with families and service users. At an early stage, the team co-developed with service users the first user-nominated measure of treatment outcome in autism,97 which helped focus on key parent-nominated priorities. Parent reports on the experience of receiving PACT therapy in the initial stages were evaluated through independently conducted interviews and the results were fed back into the design of the next iteration of the therapy within PACT-G. 33 This feedback, including around clinic visits and home-based practice, informed the design of the home-based aspects in PACT-G.

Patient and public involvement review following the pilot phase

This planned review included input into research design and adaptation of the intervention prior to finalisation of the trial protocol.

Aim

We aimed to involve parents and education staff as service users in the design and piloting of novel aspects of the intervention, including generalisation of the parent training sessions into the home and educational settings and joint working with educational settings.

Methods

At the end of the pilot phase, we carried out a feedback exercise with pilot families and education staff. We interviewed seven parents, five members of nursery/school management and two LSAs to obtain feedback on the participant information sheet (PIS) provided about the study, trial documentation, baseline assessment burden and intervention process. We asked about their experiences of taking part in the intervention and how intervention sessions could be delivered in a way that minimised any additional burden to families or educational settings. Additional feedback from therapists and research staff was also incorporated. This feedback was summarised and fed back to the PACT-G trial team.

Results and subsequent actions

Generally speaking, interviewees spoke positively about their experience of the study. They reported that the research burden was acceptable. A summary of the main points from their feedback is given below. This feedback was shared with the PACT-G trial team and led to multiple changes in our procedures that are also detailed below.

Participant information sheet

The PIS could be easily understood by most; however, one parent commented that she found the PIS to be too long and complicated:

-

We obtained an ethics committee amendment agreement for a short and easy-read version of the PIS. This was offered to parents alongside the full PIS.

Running the research in educational settings

The combination of written and verbal information sources provided to educational settings was appropriate in quantity and accessibility. The research team were advised to make sure that LSAs had all the practical information that they required for intervention delivery, as they did not always attend the initial orientation session. Education staff suggested that the time commitment involved in the study needed to be presented much more clearly from the outset and that it was important for appointments to be booked as far in advance as possible. This was fed back to all trial staff working with educational settings. Education staff also commented that they needed clearer guidance on aspects of research design, such as the inclusion criteria, avoiding group contamination and researcher unblinding:

-

Members of education management teams were encouraged to attend the orientation session, as this provided them with the practical details of the study. A copy of the information sheet was also available for reference and to share with other staff members. We adjusted procedures to ensure that education staff fully understood the time commitment to the study from the earliest stages.

-

Steps were taken to ensure that parents and staff in educational settings understood the different roles of researchers/therapists. A handout was produced for education staff, summarising research design issues and how educational settings can help with these. Posters with photographs of research/therapy personnel were made available so that all staff in educational settings knew who was who to prevent unblinding.

Burden of baseline assessments on parents

The burden of baseline assessments was acceptable to parents. Some thought that the child assessment session was tiring and one parent felt awkward in the play assessment:

-

Research staff recognised that child assessment sessions mean a long day for the child and did what they could to reduce burden (offer breaks, etc.). They also reassured parents that the researchers recognised that some aspects of the play assessments might not seem as natural as usual.

Organising research assessments/therapy sessions

No parents reported problems with organising appointments, but flexibility of therapists in accommodating them was appreciated by a number of parents. Staff in educational settings found this more challenging because of practical and logistical reasons:

-

Therapists booked therapy sessions and research assessments well in advance/at regular times to allow educational settings to organise rooms/staff cover.

Video-conferencing/telephone sessions

Problems were described by parents and LSAs/education management (and by therapists) in terms of making videos (if no other adult was present or if the child did not like being video-recorded), and sending videos [problems with system, parent has limited internet capacity, handing over universal serial buses (USBs) instead of using video-sharing software/education information technology (IT) set-up/difficulty if only one device for looking at video and Skyping (Skype™; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) simultaneously]:

-

Written information on using technology (Skype/video-sharing) was produced for parents/LSAs.

Home–school conversations

All parents reported HSCs to be easy or fairly easy to arrange and found these to be helpful or very helpful – they liked hearing how their child was getting on in an educational setting and sharing their experiences. Both LSAs who were interviewed had a HSC and found these easy to organise. One LSA found these HSCs to be very informal and was unclear on the objective of the session:

-

LSAs were given an initial explanation about the purpose and format of HSCs and how they are different from the more usual type of education planning meetings they might have been involved in.

Critical reflections on this process

This feedback was very informative and ensured that parents and particularly education staff were fully informed about the commitment required for the research and key aspects of trial design. It also meant that members of the trial therapy team understood how best to support allocated education staff to access and benefit from the therapy sessions.

Patient and public involvement input to the Trial Steering Committee and Local Steering Groups