Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 11/116/03. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The final report began editorial review in April 2022 and was accepted for publication in February 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final manuscript document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Maher et al. This work was produced by Maher et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Maher et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from the published protocol paper by Peter Saunders et al.,1 an Open Access article which is distributed in accordance with Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which allows anyone unrestricted use, to distribute, adapt work or build upon the material for any purpose, including commercially, under the condition that appropriate credit is given to the original author(s). See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below encompasses minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is characterised by inflammation and/or fibrosis that results in thickening and distortion of the alveolar wall with consequent impairment of gas exchange. Affected individuals typically present with progressive breathlessness which frequently causes respiratory failure and death. There are many described causes of ILD, however, one of the commonest is that resulting from lung involvement by systemic autoimmune disease. This group of conditions, the connective tissue diseases (CTDs), are an important cause of disability and death in the working-age population. Over the last 20 years improvements in therapy for the CTDs has seen the prognosis for individuals with these conditions dramatically improve. Despite these improvements in care there has been little change in therapy for ILD occurring as a consequence of CTD. For this reason, for those individuals with CTD, respiratory disease has grown in importance. For many CTD sufferers ILD is now the major cause of disability and exercise limitation while in systemic sclerosis it is now the principal cause of mortality. 2 In scleroderma approximately 60% of sufferers develop ILD,3 in mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) the proportion is similar4 while in idiopathic inflammatory myositis (IIM) the figure is estimated to be as high as 75% depending on auto-antibody subtype. 5

The pathogenesis of CTD-ILD is complex and poorly understood. It is however, generally accepted that underlying immune system dysfunction and immune-mediated pulmonary inflammation are critical to CTD-ILD development and progression. Abnormalities of cellular and humoral immune function have been described in ILD associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc),6–8 idiopathic inflammatory myopathy9 and several other CTDs. 9 The mechanism by which these processes lead to fibrosis remains poorly understood as do the factors that determine which individuals with CTD develop ILD. Nonetheless evidence from treatment trials suggests that modulation of inflammation with immunosuppressant therapies, particularly cyclophosphamide (CP), results in some regression of ILD and prevents the development of further fibrosis.

Different CTDs manifest varying forms of ILD. Individuals with scleroderma and MCTD most commonly develop the histological lesion of non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). Those with IIM typically have combined organising pneumonia and NSIP (referred to in the literature as fibrosing organising pneumonia). By contrast to these conditions, individuals with rheumatoid disease frequently have fibrosis with the histological pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) and tend to be resistant to therapy with high-dose immunosuppression. For this reason, the current study excluded individuals with rheumatoid-associated ILD.

Evidence for existing connective tissue disease-interstitial lung disease therapies

The field of rheumatology has seen rapid developments over the 20 years with the introduction of a range of monoclonal antibody therapies that have revolutionised the standard of care for this patient group. Despite this, at the time of the planning of this research there had been few, if any, improvements in the management of CTD-associated ILD. The trial evidence existing at the time (and even now) was limited to individuals with scleroderma-associated ILD with treatment approaches being extrapolated to cover individuals with other forms of CTD-ILD.

The long-standing standard of care for severe, progressive CTD-ILD in the UK has been immunosuppression with intravenous CP administered monthly for 6 months, followed by maintenance oral immunosuppression. 10,11 The rationale for this strategy is based on two clinical trials performed in scleroderma-associated ILD. The first of these, Scleroderma Lung Study (SLS),12 was a multicentre study conducted at 13 centres in the USA. The trial recruited 158 subjects with scleroderma ILD who had evidence of a restrictive defect on spirometry, exertional dyspnoea and an inflammatory cell infiltrate on bronchoalveolar lavage. Subjects were administered oral CP at a dose of ≥2 mg/kg of body weight per day or matching placebo for 52 weeks. The primary end point was the baseline adjusted FVC at week 52 expressed as a % of predicted. The mean absolute difference between groups at 52 weeks was 2.53% (0.28–4.79%) favouring CP. A greater number of subjects (20 vs. 13) were discontinued in the CP arm. There were a greater number of adverse events (AEs) in the treatment arm compared to placebo and these included haematuria, neutropenia and lymphopenia. A smaller, 45-patient, UK-based multicentre trial6 assessed the efficacy of 6, once-monthly intravenous infusions of CP combined with low-dose prednisolone and followed by oral azathioprine compared with placebo over 52 weeks in subjects with scleroderma-associated ILD. The study demonstrated a 4.19% difference in 52-week FVC between groups favouring active treatment although this did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.08). Two subjects withdrew from the active group because of side effects but there were no reported cases of haematuria or cytopenia.

The use of CP is limited by a number of toxicity-related issues. Common side effects with treatment include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, abdominal discomfort, diarrhoea and hair loss. These are especially common with oral dosing of CP. High doses of CP are associated with haemorrhagic cystitis. The drug also causes cumulative toxicity to the epithelial lining of the bladder leading to an appreciable risk of bladder cancer in individuals receiving a lifetime dose of >20 g (a 6-month treatment course of CP is usually between 6 and 8 g). CP use is also associated with irreversible gonad failure in both males and female. For these reasons, CP treatment is usually limited to individuals with severe or life-threatening ILD and even in those for whom treatment is deemed successful, longer term or repeated cycles of therapy are avoided.

Since initiation of RECITAL there have been further treatment developments for individuals with scleroderma-associated ILD. The SLS2 study,13 another US-based multicentre trial, compared mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) at a dose of 1500 mg twice daily for 24 months to oral CP (target dose 2 mg/kg/day) for 12 months followed by placebo for 12 months in 142 subjects with scleroderma ILD. The primary end point of change in FVC over 24 months was not different between groups. The baseline adjusted %predicted FVC improved by 2.19% in the mycophenolate group and by 2.88% in the CP group. Mycophenolate was better tolerated with 20 discontinuations over 24 months compared with 32 in the CP arm. Leucopoenia and thrombocytopaenia occurred more commonly in the CP group. Tocilizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-6 has recently been approved in the USA and Europe as a treatment for systemic sclerosis-associated ILD. This was on the basis of two trials, both of which were primarily designed to test tocilizumab as a treatment for the skin thickening seen as part of scleroderma. In the first of these trials (the phase 2 faSScinate study),14 subjects with rapidly deteriorating diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis and evidence of active inflammation (defined as the presence of arthritis or an elevated C-reactive protein) were randomised to receive weekly subcutaneous tocilizumab or matched placebo. There was a trend towards improvement in skin thickening in the active treatment group and an exploratory analysis suggested a benefit on change in FVC with tocilizumab; although it should be noted that not all patients in the trial had ILD. A subsequent phase 3 study (focuSSed)15 again recruited individuals with rapidly progressive diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis and evidence of inflammation. The primary end point was also change in skin thickening measured using the modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) at 48 weeks. Change in FVC was a key secondary end point. The study failed to meet its primary end point. However, subjects in the tocilizumab arm had stabilisation of FVC over 48 weeks while subjects on placebo lost FVC. Presence of ILD was not an inclusion criterion for the study; however, of the 210 subjects who were randomised, 136 (65%) had evidence of ILD on computer tomography (CT) scan performed at enrolment. Post hoc analysis of this subgroup with ILD showed a change of FVC of −0.1% in the treatment arm compared with −6.3% in the placebo group.

Nintedanib, a multityrosine kinase inhibitor, was approved as a therapy for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in 2014. IPF is the most rapidly progressive of the fibrotic ILDs encountered in routine clinical practice. In paired phase three trials nintedanib was shown to reduce the rate of decline in FVC over 52 weeks by approximately 50%. 16 Consequently, nintedanib was assessed as a potential therapy for scleroderma-associated ILD in the multicentre SENSCIS trial. 17 In this study 576 patients with >10% fibrosis on CT scan in the context of a diagnosis of scleroderma-associated ILD were randomised 1 : 1 to receive nintedanib or matched placebo. Subjects were permitted to be on stable background therapy with either MMF or methotrexate. The primary end point was 52-week change in FVC. Over the course of the study the placebo group lost 93 ml in FVC (less than half the rate of decline seen in IPF) while the treatment group lost 52.4 ml, a difference of 41 ml (2.9 to 79 ml) between groups (p = 0.04). In general, nintedanib was well tolerated with gastrointestinal upset, especially diarrhoea, being the commonest side effect. A pre-planned subgroup analysis suggested that the greatest therapeutic benefit was seen in subjects treated with both nintedanib and MMF in combination. 18 A further study with nintedanib was conducted in patients with progressive fibrotic ILD of any cause (INBUILD trial). 19 Of the 663 subjects in the trial, 170 (26%) had an autoimmune ILD (including scleroderma, MCTD and myositis-associated ILD). Overall, the trial showed a benefit of treatment with nintedanib compared to placebo on the primary end point of 52-week change in FVC. This effect was consistent across subgroups including the autoimmune ILD group. On the strength of SENSCIS and INBUILD nintedanib has been approved as a treatment for scleroderma ILD and for chronic fibrosing ILD with a progressive phenotype.

Current treatment practice

While scleroderma ILD has been a major focus for clinical trials, no randomised controlled trials have been performed for ILD in the context of MCTD or IIM. In both disease groups current best practice is derived by extrapolation from scleroderma trials supported by evidence from retrospective cohort analyses. For both disease groups the most commonly used therapies include corticosteroids, MMF and CP. When it comes to treating scleroderma-associated ILD, there are now two approved therapies in nintedanib and tocilizumab. However, in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, neither of these drugs has received approval from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and as such neither is routinely used as a treatment for scleroderma ILD (however, nintedanib received approval from NICE in November 2021 for the treatment of progressive pulmonary fibrosis of any cause and is therefore available for a subset of patients). No guidelines currently exist for the treatment of CTD-ILD. However, a recent European-based Delphi exercise provided recommendations for the use of MMF, CP and nintedanib as treatments for progressive or extensive scleroderma-associated ILD. 20

Rituximab

Scleroderma-associated ILD remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality despite the widespread use of CP and MMF. 21 The same is true for MCTD and the idiopathic inflammatory myositidies where the lack of evidence-based therapies further complicates treatment choice. Rituximab (RT), a chimeric (human/mouse) monoclonal antibody with a high affinity for the CD20 surface antigen expressed on pre-B and B-lymphocytes, results in rapid depletion of B cells from the peripheral circulation for 6–9 months. 22,23 Evidence for the efficacy of B cell depletion exists in a number of immune-mediated conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis,24–26 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis,27,28 immune thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP),29 membranous nephropathy and pemphigus. In these conditions RT tends to be better tolerated than previously used immunosuppressant regimens and, in many cases, was associated with reductions in corticosteroid usage.

Several case series suggest RT may also be effective in ILD occurring in the context of immunological over-activity, with favourable responses reported in antisynthetase (ASS) associated ILD30 and SSc-ILD. 31,32 Our own experience has demonstrated RT to be an effective, potentially life-saving therapeutic intervention in the treatment of very severe, progressive CTD-ILD unresponsive to conventional immunosuppression. 33 In a retrospective analysis34 of 50 subjects with ILD due to a variety of aetiologies all of whom had failed multiple prior therapies we demonstrated that RT therapy was associated with an average improvement in FVC and stabilisation of DLco in the subsequent 6–12 months following treatment. In an open-label prospective study31 of 14 individuals with scleroderma ILD, 8 were randomised to receive two cycles (each cycle being 4, weekly doses of RT at a dose of 375 mg/m2) while the remaining 6 subjects received standard care. At 1 year FVC improved from 68.1 ± 19.7% predicted to 75.6 ± 19.7% predicted in the RT group compared with a drop from 86.0 ± 19.5% predicted to 81.7 ± 20.7% predicted in the standard of care group. Although these data suggest a benefit of RT it should be noted that in addition to being a small open-label study there were clear differences in baseline disease severity between the RT and the standard of care arms. Another recently published open-label trial35 compared RT (two times 1000 mg) to intravenous CP (500 mg/m2) in 60 subjects with scleroderma ILD with the primary outcome being change in FVC at 24 weeks. RT was associated with an improvement in FVC (from 61.3 ± 11.3 to 67.5 ± 13.6% predicted) while the CP arm saw a loss of FVC over 6 months (from 59.3 ± 13.0 to 58.1 ± 11.2% predicted). RT, but not CP, was associated with an improvement in skin score. There were fewer side effects in the RT arm. The major limitations of the study were the open-label design and the exclusion of subjects aged over 60.

Potential risks of rituximab

Rituximab was first approved for clinical use in 1997 for the treatment of relapsed or refractory CD20 positive B-cell low grade or follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. 36 Since then, it has been widely used as a treatment for a broad range of conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with angiitis, idiopathic thrombocytopaenia purpura, pemphigus vulgaris and myasthenia gravis. The safety profile of RT is therefore well-established. Common side effects include rash, itchiness, hypotension and dyspnoea at, or close to, the time of infusion and are usually associated with hypersensitivity to the drug (this is more likely in those who have had occupational or domestic exposure to mice). RT is also associated with an increased risk of infection. Severe but very rare side effects include reactivation of hepatitis B, progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) and toxic epidermal necrolysis syndrome. The risk of hepatitis B can be mitigated by pre-treatment testing. The potential adverse effects of RT are comparable, or even less frequent, than those associated with other commonly used treatments for CTD-ILD, especially CP.

Rationale for current study

Despite current best treatment, individuals with extensive ILD due to scleroderma have a median survival of less than 5 years and a similar poor prognosis is observed in individuals with inflammatory myositis and MCTD. 33 This high level of morbidity and mortality associated with CTD-ILD and the absence of clinical trial data in MCTD and the idiopathic inflammatory myositidies speaks to the need for more effective and better-tolerated therapies for this group of diseases. Available data suggest that RT is effective in improving lung function in people with CTD-associated ILD and multiple studies show that it tends to be better tolerated than CP. The current study is the first to assess a broad-based, pragmatic population of patients with CTD-associated ILD. This is important for establishing best care for a group of patients who are normally disenfranchised from clinical trials because of the rarity of their condition.

Drug costs are higher for RT than for CP and this often represents a barrier for use of the drug in the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK. Assuming that RT is associated with fewer AEs and better efficacy then it is to be anticipated that increased drug costs will be offset by reduced healthcare costs overall. To assess whether this is the case the trial includes a Full Economic Costing (FEC) so that the true costs of both RT and CP can be analysed.

The aim of the study was to compare the safety and efficacy of RT against that of CP as first-line therapy in patients with severe, progressive CTD-associated ILD. The study therefore tested the hypothesis that RT is superior to intravenous CP, in terms of both safety and efficacy, as a treatment for extensive and progressive CTD-ILD.

Rationale for primary outcome

The primary outcome for this study was rate of change in FVC over 24 weeks. FVC provides a measure of lung volume. With worsening pulmonary fibrosis FVC tends to diminish. In trials of patients with a range of fibrotic ILDs (including IPF, scleroderma ILD and progressive fibrotic ILD of any cause) change in FVC has been accepted by the Federal Drugs Administration (FDA) in the USA and the European Medicines Agency as a surrogate for survival. 37 As such, FVC has been the regulatory end point of choice for the approval of medications targeting ILD. Additionally, in scleroderma ILD both baseline FVC and change in FVC over time have been linked to longer-term prognosis and survival. 33,38 Twenty-four weeks was chosen for the primary end point as this was felt to be the time-point at which the effect of RT and CP alone could best be measured. Beyond 24 weeks subjects were permitted to receive other immunosuppressants according to the recommendation of their treating clinician (and as tends to happen in routine clinical practice). FVC change at 48 weeks was captured as a secondary end point with the prior recognition that this might also be influenced by treatments received beyond 24 weeks.

Rationale for biomarkers

There are currently no available biomarkers for assessing response to therapy or risk of disease progression in CTD-ILD. By closely studying patients in each treatment arm and undertaking exploratory biomarker analysis it was hoped that we might identify potential disease and therapy-specific biomarkers for future development and use in clinical practice. Serial samples of whole blood [for ribonucleic acid (RNA) and DNA analysis], serum and plasma were collected to explore changes in the levels of a range of candidate biomarkers. The choice of biomarkers was driven by insights derived from other fibrotic and inflammatory ILDs and included measures of extra cellular matrix turnover (collagen neoepitopes, matrix metalloprotease-7),39 epithelial damage [cancer antigen 125 (CA125), cytokeratin 19 fragment, Krebs von den lungen-6]40 and inflammatory cell activation (IL-6, monocyte chemotractant protein-1, Chitinase-3-like protein-1, CC motif chemokine ligand 18). 40 The aim of this part of the study was to identify a candidate biomarker panel for use in future studies and for development as a clinical tool for guiding therapeutic decision making.

Aims and objectives

The primary aim of the study was to compare the safety and efficacy of RT against that of CP as first-line therapy in patients with severe, progressive CTD-ILD. Secondary aims of the study were to compare the full economic cost of both RT and CP and to assess a range of circulating protein and cellular biomarkers for their ability to predict response to therapy and to provide early insights into treatment outcomes.

Primary objective

-

To demonstrate that intravenous RT has superior efficacy compared to current best treatment (intravenous CP) for CTD-ILD as measured by change in FVC at 24 weeks.

Secondary objectives

-

To compare the safety profile of RT to intravenous CP in individuals with CTD-ILD.

-

To assess the health economic benefits of RT compared to current standard of care for CTD-ILD – including measurements of healthcare utilisation, quality of life (QoL) and carer burden.

-

To evaluate a range of exploratory biomarkers for disease severity, prognosis and treatment response in CTD-ILD.

Chapter 2 Research methods/design

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from the published protocol paper by Peter Saunders et al.,1 an Open Access article which is distributed in accordance with CC BY 4.0 license, which allows anyone unrestricted use, to distribute, adapt work or build upon the material for any purpose, including commercially, under the condition that appropriate credit is given to the original author(s). See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below encompasses minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The study was a Phase 2b, UK multicentre, prospective, randomised, double-blind, double-dummy trial of intravenous RT compared with intravenous CP in patients with severe, progressive CTD-ILD. Patients were randomised to one of two groups; both groups received placebo to match the opposite regimen. The aim was to recruit 116 subjects (aiming for 52 patients reaching end-of-study in each arm and anticipating a 10% drop out).

As a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, in April 2020, the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), endorsed by Sponsor, Trial Management Group (TMG) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) recommended ending the study after the 101st subject completed treatment. There was consensus agreement that recruiting further patients (to achieve the pre-specified plan of 104 subjects completing treatment) would have only a limited impact on the power of the study to show an advantage of RT over CP. Given that the COVID-19 pandemic had major implications for the benefit : risk ratio of starting new immunosuppressant therapy and that it was unclear how long the pandemic would last, early closure of the RECITAL study was strongly recommended. Patients were followed up for 48 weeks. The end of trial, defined as when the last patient randomised had completed their last visit at 48 weeks, was reached in January 2021. The schedule for study visits including the assessments and procedures performed is presented in Table 1. The scheduled study visits occurred at the specified week postrandomisation ±7 days unless otherwise specified. Figure 1 is the flow diagram of the study design schedule.

| Time | Screening visit(s) | Randomise | Treatment visits | Follow-up visit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | Visit day 0 | Visit week 2 |

Visit week 4 | Visit week 8 |

Visit week 12 |

Visit week 16 |

Visit week 20 |

Visit week 24 | Visit week 48 | ||

| Consent | X | ||||||||||

| Study drug | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| AE checking | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Physical exam | X | ||||||||||

| Vital signs (pulse, BP) |

X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Routine bloods tests | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Spirometry | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Blood sample for lymphocyte subsets/Ig level | X | X | X | ||||||||

| CK (in myositis patients) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Ig levels | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| ECG | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Lung function tests | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| 6 MWT* | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Urinalysis | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Pregnancy test | X | ||||||||||

| QoL questionnaires | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Health economic diary | X | X | |||||||||

| mRSS (scleroderma) | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Hepatitis B and C serology | X | ||||||||||

| Blood sample biomarker(s) | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Blood sample genetics | X | ||||||||||

| Concomitant medication | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram.

The study was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice (GCP). The study protocol received ethical approval from National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee London – Westminster on 15 July 2013 (Reference No.: 13/LO/0968). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) clinical trial authorisation was received on 18 October 2013.

The process for obtaining participant informed consent was in accordance with Research Ethics Committee (REC) guidance, GCP and all other applicable regulatory requirements. All study subjects provided written informed consent, this included consent to inform the participant’s general practitioner (GP) or, when appropriate, the local consultant of involvement in the study. A separate consent was obtained to provide blood for RNA, DNA and biomarker analysis. The study was registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry on 01 April 2015 under reference number 16474148 and ClinicalTrial.gov on 22 May 2013 under reference number NCT01862926. The first participant was randomised on 2 January 2015 and the last participant was randomised on 24 February 2020.

Methods

Study setting

RECITAL study was conducted at 11 UK sites, all of which were accredited by NHS England as specialist ILD or Rheumatology centres. The investigators were qualified by education, training and experience to assume responsibility for the proper conduct of the trial and provided evidence of such qualifications through up-to-date curriculum vitae and GCP training certificates. The local principal investigator (PI), who could be either a respiratory physician or rheumatologist, was responsible for the proper conduct of the study, for the safety and welfare of study participants and being thoroughly familiar with the appropriate use of the investigational products. They were responsible for ensuring that all persons supporting the trial were appropriately qualified and trained, adequately informed about the protocol, the investigational product(s), and their trial-related duties and functions. Both the Sponsor and local trust legal representatives signed the site agreements. GCP training was required for all staff responsible for trial activities. The frequency of repeat training was dictated by the requirements of their employing institution, or two yearly where the institution had no policy. The PI or delegate was required to document and explain any deviation from the approved protocol and to communicate this to the Sponsor.

Study population

Participant inclusion criteria

-

A diagnosis of CTD, based on internationally accepted criteria, in one of the following categories:41–44

-

systemic sclerosis

-

idiopathic interstitial myopathy (including polymyositis/dermatomyositis)

-

MCTD.

-

-

Severe and/or progressive ILD associated with the underlying CTD.

-

Chest high-resolution computer tomography performed within 12 months of randomisation.

-

Intention of the caring physician to treat the ILD with intravenous CP (with treatment indications including; deteriorating symptoms attributable to ILD, deteriorating lung function tests, worsening gas exchange or extent of ILD at first presentation) and where there is a reasonable expectation that immunosuppressive treatment will stabilise or improve CTD-ILD. In individuals with scleroderma it is anticipated that patients will fulfil the criteria for extensive disease defined by Goh et al. 33

-

Written informed consent.

Participant exclusion criteria

-

Age <18 or >80 years.

-

Previous treatment with RT and/or intravenous CP.

-

Known hypersensitivity to RT or CP or their components.

-

Significant (in the opinion of the investigator) other organ comorbidity including cardiac, hepatic or renal impairment.

-

Coexistent obstructive pulmonary disease (e.g. asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema) with pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 70%.

-

Patients at significant risk for infectious complications following immunosuppression including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive or other immunodeficiency syndromes such as hypogammaglobulinaemia.

-

Suspected or proven untreated tuberculosis.

-

Viral hepatitis.

-

Infection requiring antibiotic treatment in the preceding 4 weeks.

-

Unexplained neurological symptoms [which may be suggestive of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML)]. Neurological symptoms arising as a consequence of the underlying CTD do not necessitate exclusion.

-

Other investigational therapy (participation in research trial) received within 8 weeks of randomisation.

-

Immunosuppressive or CTD disease-modifying therapy (other than corticosteroids) received within 2 weeks of the first intravenous treatment.

-

Pregnant or breastfeeding women, or women of child-bearing potential, not using a reliable contraceptive method for up to 12 months following investigational medicinal product (IMP).

-

Unexplained haematuria or previous bladder carcinoma.

-

CT scan > 12 months from randomisation.

-

Unable to provide informed written consent.

Recruitment

The study was conducted in rheumatology or ILD units at 11 UK centres. The diagnosis of CTD and associated ILD was confirmed by the local study PI or coinvestigator, where delegated by the local PI in accordance with the study delegation of responsibilities log. Potential patients were assessed for eligibility and approached for written informed consent. All potential patients were given an ethically approved patient information sheet (PIS) and an appointment was made for them with the research nurse or another member of the research team delegated the responsibility to discuss enrolment into the study. The patients were allowed to specify the time they wished to spend deliberating, usually up to 24 hours. Periods shorter or longer than 24 hours were permitted when the patient requested it. The informed consent form (ICF) was signed and dated by the participant before entering the study. The participants received a copy of the signed and dated consent form and the original was retained with the study data. A second copy was filed in the participant’s medical notes.

Patients undertook a screening assessment to ensure they met all the eligibility criteria. Screening and enrolment logs were kept of all patients with CTD-ILD considered for the study.

Intervention

As summarised in Table 2, patients were randomised on a 1 : 1 double-blind basis to receive either:

-

RT 1000 mg given for two doses at day 0 and day 14. Placebo was administered monthly from week 4 to week 20.

-

CP given at a dose of 600 mg/m2 body surface area (BSA) rounded to the nearest 100 mg every 4 weeks from day 0 through to week 20. Placebo was given at day 14.

| RT group | CP group | |

|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | IV active RT 1000 mg | IV 600 mg mg/m2 BSA |

| Day 14 | IV active RT 1000 mg | Placebo |

| Week 4 | Placebo | IV 600 mg mg/m2 BSA |

| Week 8 | Placebo | IV 600 mg mg/m2 BSA |

| Week 12 | Placebo | IV 600 mg mg/m2 BSA |

| Week 16 | Placebo | IV 600 mg mg/m2 BSA |

| Week 20 | Placebo | IV 600 mg mg/m2 BSA |

Cyclophosphamide and RT usually have different infusion regimens. For the first dose, RT is infused at slowly ascending rates to minimise the risk of significant hypersensitivity/anaphylactic reactions. To maintain study blind, the day 0 dose (which could be either RT or CP) was infused according to the ascending rate regimen used for RT.

To ensure an equal representation of CTD subtypes in each treatment arm, randomisation was stratified based upon underlying CTD diagnosis (according to the three diagnostic categories listed in the inclusion criteria).

Non-IMP permitted concomitant medication (NIMPs) administered to both groups at day 0, prior to administration of study IMP were mesna (as a prophylactic treatment against CP-induced haemorrhagic cystitis), hydrocortisone, chlorphenamine and paracetamol (all as prophylaxis against RT-induced allergic reactions); at day 14 hydrocortisone, chlorphenamine and paracetamol; and at visits from week 4 to 20 mesna. Post treatment, subjects were provided a 2-day supply of ondansetron for use if experiencing nausea.

Drug preparation and supply

Bath ASU was responsible for manufacture of the IMPs and matched-placebo to standards compliant with good medical practice (GMP) requirements.

The IMPs used in this study were infusions of either CP, RT or matching placebo. All products were compounded using licensed starting materials as per the relevant summary of product characteristics (SmPC). All active drugs were prepared by the addition of drug solution to a 250 ml NaCl 0.9% Freeflex® infusion bag following the withdrawal of a comparable volume of solution to ensure the final bag volume remained at 250 ml. The matching placebo was a suitability labelled 250 ml NaCl 0.9% Freeflex bag.

Starting materials: RT (Roche EU/1/98/067/001 EU/1/98/067/002).

Cyclophosphamide (Baxter PL 001 16/0388).

Sodium chloride infusion (Fresenius Kabi PL 08828/0084).

Following manufacturing, the fully reconstituted study IMP was transported, in a temperature-monitored environment (by Movianto UK limited) to study sites. Each infusion bag arrived together with the qualified person (QP) batch release certificate. A copy of the QP release was filed in the site pharmacy file along with the shipping paperwork. Temperature monitoring during transit occurred via a temperature monitoring device within the shipment. Any identified temperature excursions during transit to site was reported by pharmacy to the Trial Manager, using the Temperature Excursion Report Form. Site pharmacies documented receipt of IMP using the IMP accountability Log.

Randomisation allocation was performed using an Interactive Web-based Randomisation System (InForm). Randomised patients were given a study specific 24 hours emergency contact immediately following randomisation. The card included: study title, details of the IMPs, patient trial number, chief investigator (CI)/PI’s contact details along with out-of-hours contact details in case of emergency.

A patient was withdrawn if their treatment code was unblinded by the investigator or treating physician. The primary reason for discontinuation (the event or condition which led to the unblinding) was recorded in the electronic case report form.

Dispensing procedure

It was the responsibility of the site pharmacy to dispense IMP in accordance with the study protocol and against a prescription provided by the medical team. The study-specific prescription and accountability logs were used by all sites.

Initial infusion

Site pharmacies documented the dispensing details on the prescription form. Details were also recorded on a subject-specific IMP accountability log (one log used per patient). Entries on the accountability log were signed by the dispenser and checked by a second member of staff. The IMP accountability log was updated with the date of dispensing.

Ongoing infusions

A new prescription was completed for each dose required for each subject recruited. Site pharmacies checked the details on the prescription against the corresponding subject-specific IMP accountability log to ensure the correct patient number and visit number. Site pharmacies completed the next entry on the accountability log for each ongoing prescription received. The IMP accountability log was updated with the date of dispensing.

Blinding

The study was double-blind. Medication was identified by a unique trial identifier (randomisation code). Patients and investigators remained blinded until after database lock and only the DMC had access to unblinded information.

The investigator was encouraged to maintain the blind as far as possible. Investigators were able to unblind individual patient’s treatment via the eCRF in the case of an emergency, when knowledge of the study treatment was essential for the appropriate clinical management or welfare of the patient. The PI was asked to provide a reason for unblinding and was required to enter their password as confirmation. The PI was then shown which treatment arm the patient was allocated to. The investigator referred to the unblinding instructions stored securely in the investigator site file (ISF). An email notification stating that a patient was unblinded was sent out to local investigator, pharmacy and the Trial Manager.

A decision to unblind was made in three cases prior to week 24 where information of the treatment allocation was deemed essential (to allow the treatment of disease progression for two patients and because of a SAE in one case). There were five other instances where patients were unblinded; this occurred after they had received all doses of IMP, either during the follow-up period or following study completion and was performed to enable appropriate choice of therapy for ongoing disease worsening. All details of the eight instances of unblinding were recorded in the eCRF, the ISF/trial master file (TMF) (or pharmacy file when manual unblinding was used).

Backup manual unblinding

When the investigator needed to unblind the treatment for the patient in case of electronic failure of the database (InForm), a manual backup system was also provided. A randomisation list was provided to the Sponsor pharmacy department. During normal hours the investigator was able to contact the Sponsor pharmacy department via switchboard on 020 7352 8121. Outside of normal hours, the Sponsor pharmacy on-call pharmacist could be contacted via the same number.

Storage and administration

The investigational products were stored securely in a temperature-controlled unit between 2 and 8°C within a pharmacy department. Temperature logs were kept and made available for monitoring and audit purposes. Specific instructions for storage and administration were provided in a study-specific IMP handling manual which was provided in the ISF and pharmacy file.

Accountability procedures for the investigational medicinal product(s)

The site hospital pharmacy department was responsible for maintaining and updating the study pharmacy IMP Accountability Log, filed in the hospital pharmacy file. A study prescription form documented the dispensing of IMP to the research nurse or doctor; this was retained in the pharmacy file. The research nurse or doctor was responsible for completing an IMP Administration Record Form at the point of administration; the completed form was filed in the ISF.

Any IMP dispensed to the research nurse or doctor that was not administered, for example due to cancellation, was returned to pharmacy for destruction. All unused IMP, including unused returns, were destroyed by the site pharmacy in accordance with local pharmacy practice, once agreed by the local PI and Sponsor. Destruction of unused IMP was documented on the IMP Destruction Form and filed in the hospital pharmacy file.

All used or partially used IMP was discarded in accordance with local cytotoxic waste disposal procedures; no used IMP was returned to pharmacy. A record of discarded used IMP was made on the IMP Administration Form and filed in the ISF.

Prohibited concomitant medication

-

Pre-existing immunosuppression (including azathioprine, MMF, methotrexate, and ciclosporin) was stopped, following signed informed consent and during the screening period, at least 14 days prior to the first intravenous treatment. Hydroxychloroquine was on the list of prohibited medications until the last amendment of the study protocol. Following identification of a number of protocol deviations, due to administration of hydroxychloroquine, the CI confirmed that inclusion of hydroxychloroquine on the proscribed list was an oversight by the protocol design team. The topic was discussed by the DMC who agreed that hydroxychloroquine posed no risks to patients enrolled in the study and receiving IMP. Consequently, hydroxychloroquine was removed from the list of withheld concomitant medications with study amendment 13, approved in April 2018.

-

Between weeks 0 and 24, patients were not permitted to receive additional immunosuppression (including oral agents, intravenous immunoglobulins or other monoclonal antibody therapies) other than corticosteroids.

Missing data

Every effort was made to minimise missing baseline and outcome data during the trial. Reasons for non-entry were collected using the InForm database comment facilities.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

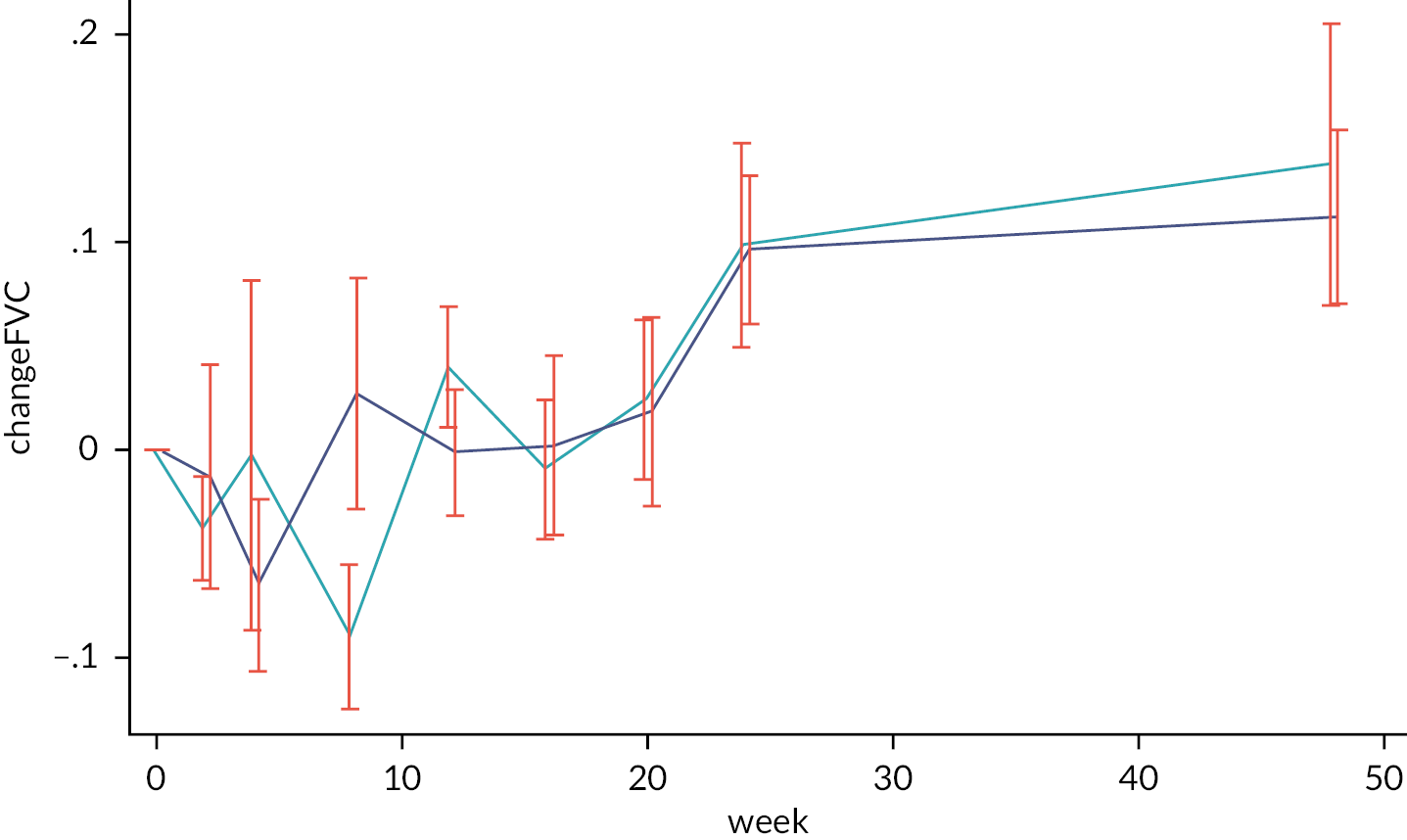

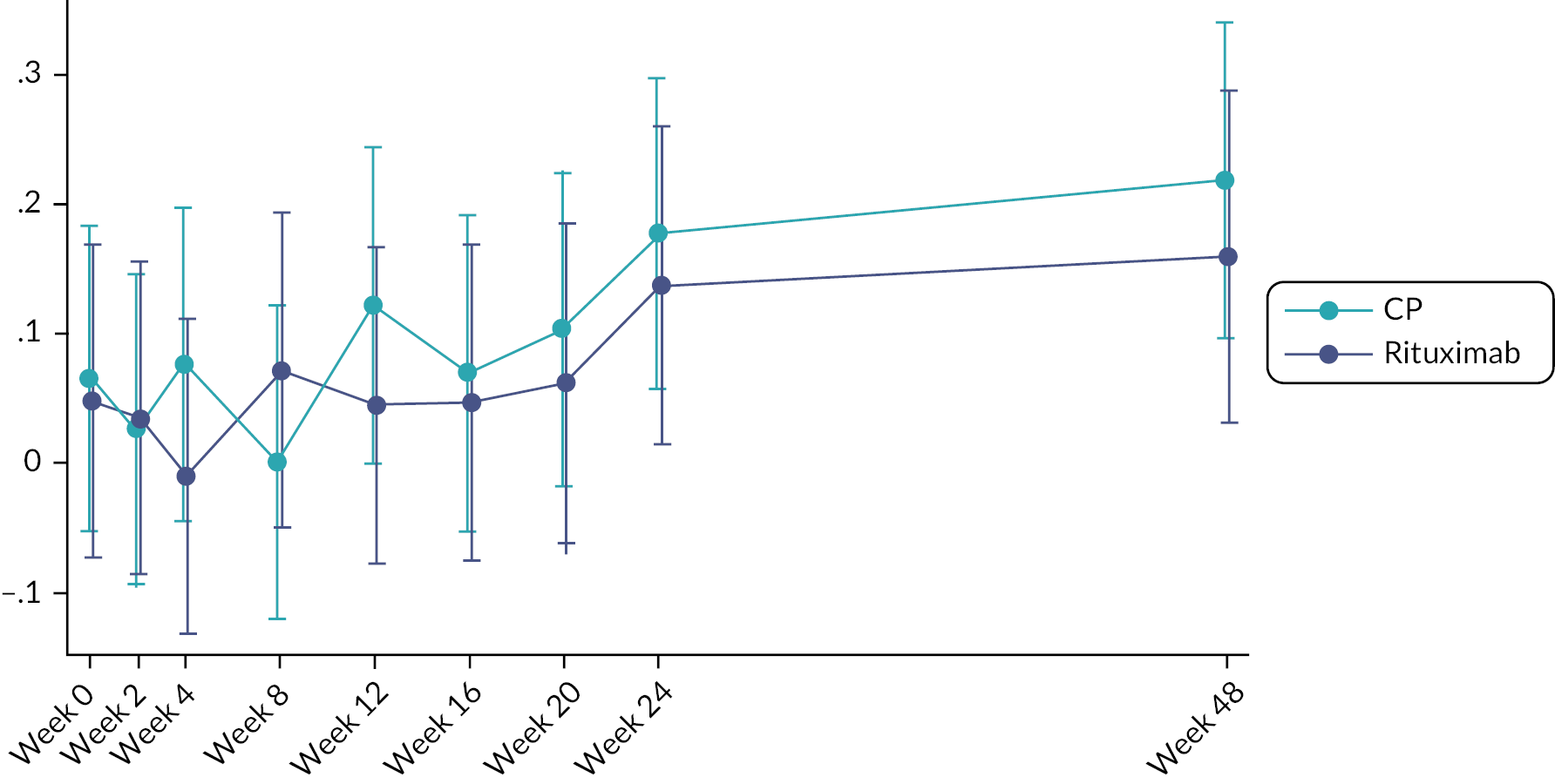

The primary outcome for the study was change in FVC measured in ml over 24 weeks. Spirometry was measured at baseline and at every subsequent visit (weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24) according to the standards outlined in the guidelines from the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society. 45 Sites were encouraged to undertake spirometry at the same time (plus or minus 1 hour) at each visit to minimise the effects of diurnal variation on FVC measurements. The Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) predictive equations were used to calculate the predicted normal and percentage predicted values for FVC. 46

Twenty-four weeks was chosen as the time point for the primary outcome measure on the basis that this was the point in time at which the effect of the investigational drugs alone could best be determined. After 24 weeks, subjects were permitted to start other immunosuppressant agents and thus interpretation of later time points is confounded by this variable use of immunosuppressants other than CP or RT.

Secondary outcomes

A range of physiological, QoL and biomarker measures were assessed as secondary end points for the study.

Questionnaires

Short Form 36

The Short Form 36 (SF36) questionnaire is a validated 36-item tool describing health-related QoL. It measures each of the following eight health domains: physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional and mental health. From these eight subscales two component scores are derived: a physical health component score and a mental health component score. It also includes a single item that assesses perceived change in health status over the past year. The higher the scoring, the better health and functioning. Short Form questionnaire – 36 items (SF-36) was measured at baseline, 24 and 48 weeks.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, 5-level version

EuroQol-5 Dimensions is a well-established and validated instrument which evaluates five dimensions of QoL which include mobility, self-care, usual activities (e.g. work, study, housework, family or leisure activities), pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension is answered on a five-level scale. The questionnaire encompasses a visual analogue scale (VAS) numbered 0 (worst imaginable health) to 100 (best imaginable health) by which respondents can report their perceived health status. EQ-5D was measured at baseline, 24 and 48 weeks.

St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire

St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) is a respiratory disease-specific instrument designed to measure impact of respiratory symptoms on overall health, daily life and perceived well-being. It was initially developed for individuals with chronic obstructive airways disease, but it has subsequently been validated in other respiratory conditions including ILD. 47 It includes 50 items and scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more limitation. SGRQ was measured at baseline, 24 and 48 weeks.

King’s brief interstitial lung disease

King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease (K-BILD) is a 15-item self-completed validated questionnaire describing health status during the past 2 weeks in responders with (ILD). 48 It covers three domains (psychological, breathlessness and activities and chest symptoms) and the score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores denoting best health status. K-BILD was measured at baseline, 24 and 48 weeks.

Scleroderma Health Assessment Questionnaire

Scleroderma Health Assessment Questionnaire (SHAQ) is a disease-specific tool measuring disease status and changes in disease status over time and it is composed of the standard Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and additional VAS scales to measure symptoms specific to scleroderma and overall disease severity. SHAQ was measured in individuals with scleroderma at baseline, 24 and 48 weeks.

Physiological measures

Lung function

In addition to the measurement of FVC as described for the primary outcome, FVC was also measured at 36 and 48 weeks. Gas transfer was measured at baseline, 24 and 48 weeks according to the standards outlined in the guidelines from the ATS and European Respiratory Society (ATS guidelines). The diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLco) was obtained and the percentage predicted values were obtained using the predictive equations provided by GLI. 49

Forced vital capacity and DLco are both assessed in the routine clinical management of individuals with ILD. Both measurements are used as determinants of treatment response and/or disease progression.

6-minute walk test

The 6-minute walk test is performed by asking subjects to walk as far as possible, using a 30 m track, in 6 minutes. During the test, distance walked, oxygen saturations and subjective breathlessness are all recorded. The test was conducted on room air, according to AST guidelines. 50 In subjects with ILD both 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and evidence of oxygen desaturation have been shown to be prognostically important.

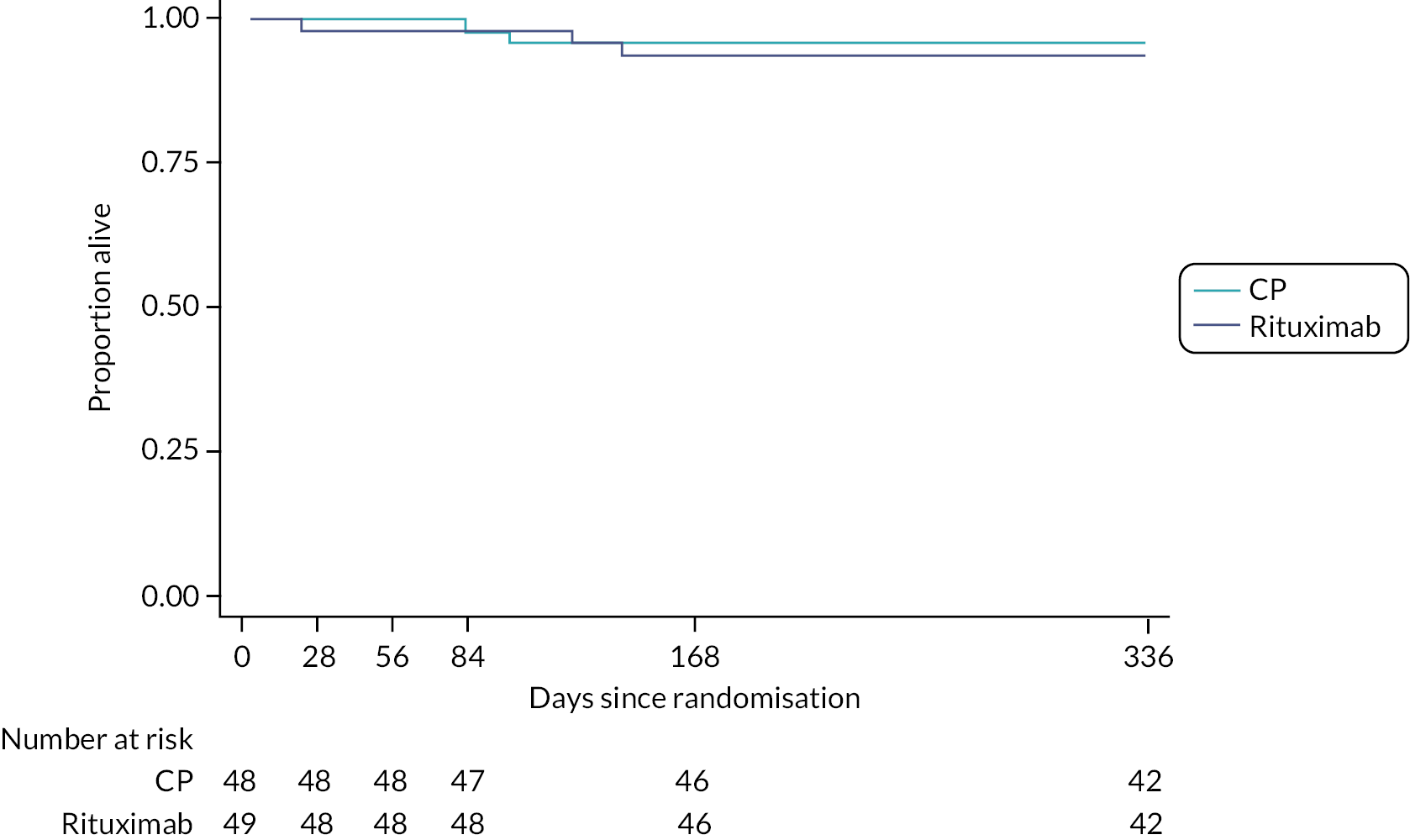

Death

For patients who died during the course of the trial sites were asked to provide information regarding date and cause of death. Prior to unblinding deaths were adjudicated to determine whether the cause of death was related to the underlying CTD or associated ILD. All-cause and disease-related deaths were analysed separately.

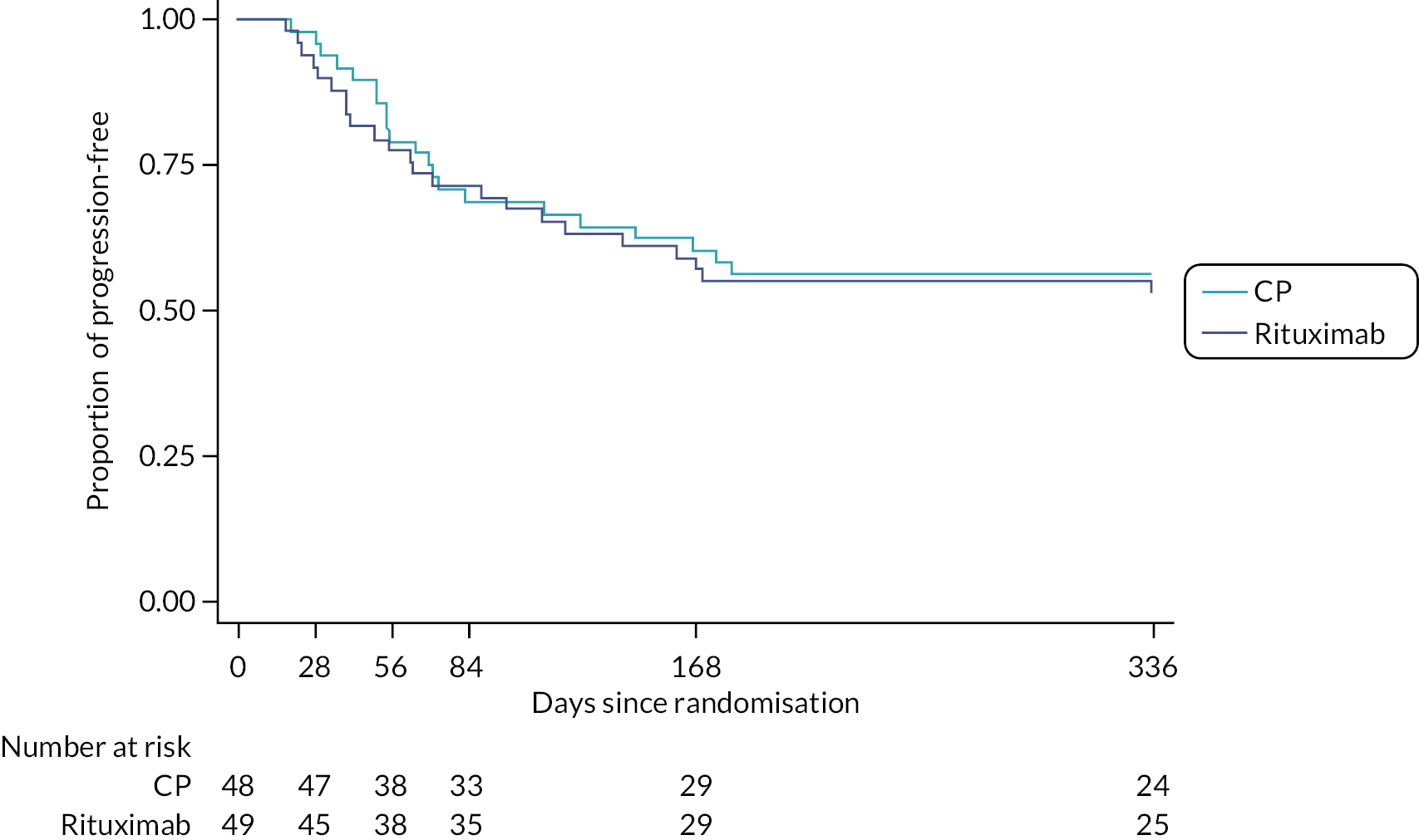

Disease progression and treatment failure

Disease progression was determined to be the time of first occurrence of either; (1) >10% decline in FVC from baseline (day 0), (2) lung transplant, (3) death or (4) treatment failure (as defined by the need for open-label rescue therapy with either RT or CP at any point during the 48 weeks of the study). Time to disease progression and time to treatment failure were analysed separately.

Skin thickening

In the subgroup of subjects with systemic sclerosis skin thickening was measured using the mRSS at baseline and then weeks 12, 24, 26 and 48. mRSS was assessed using the method described by Rodnan et al. as further clarified by Khanna et al. 51 Skin thickness was estimated by palpation in 17 defined body areas on a 0–3 scale giving a total score of between 0 and 51. Wherever possible, the protocol required that the same investigator made the assessment of mRSS at each study visit.

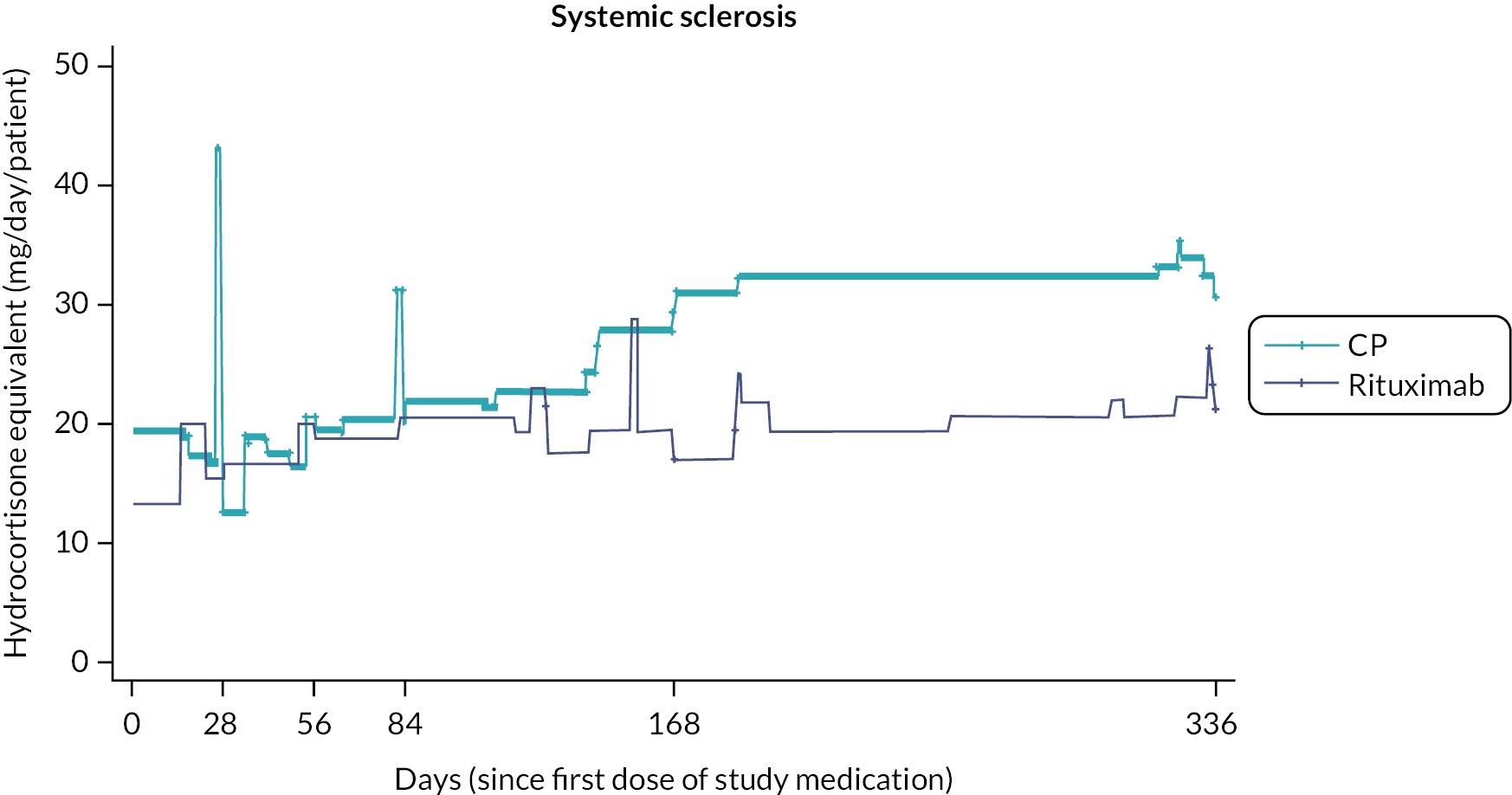

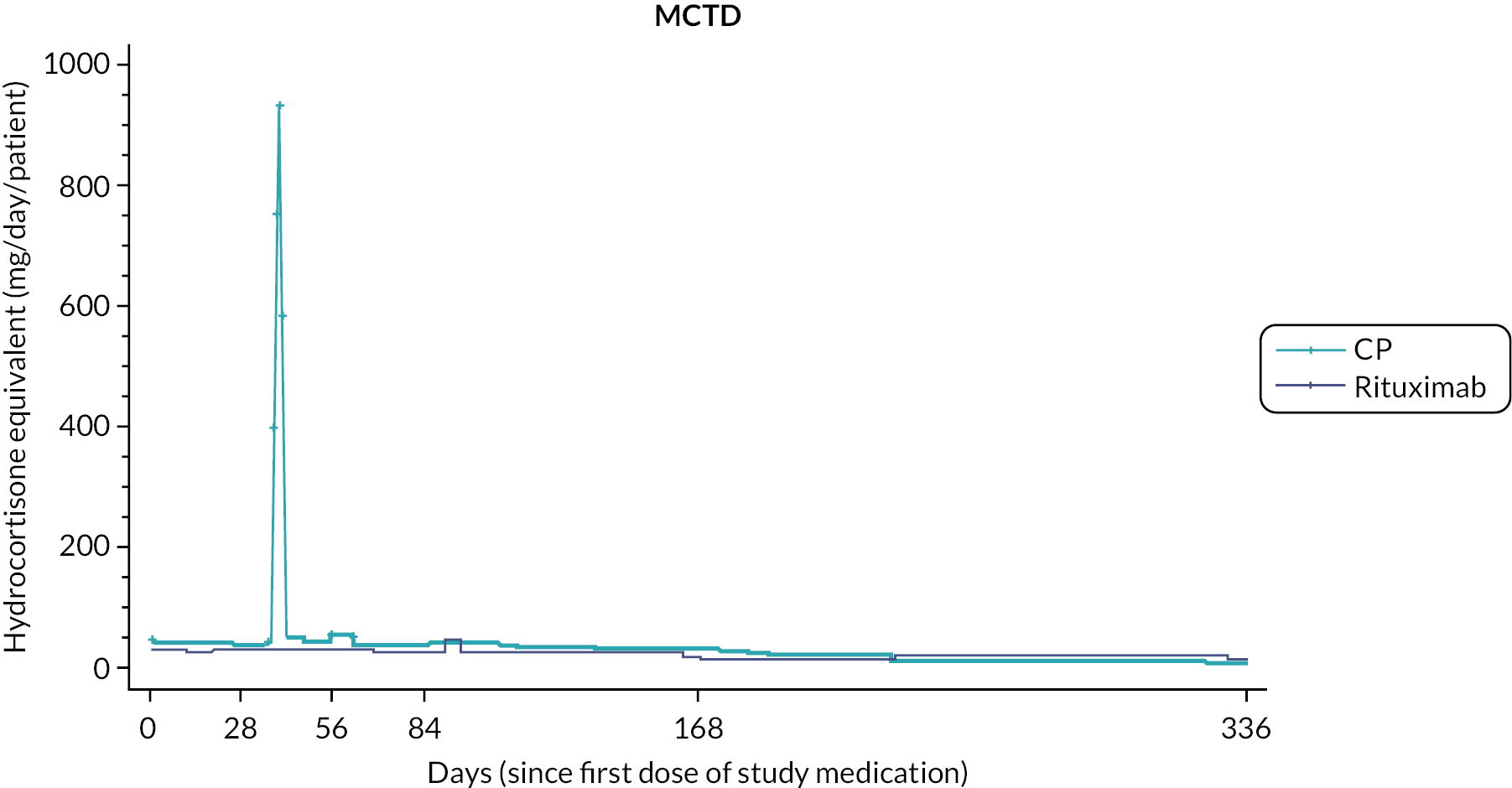

Corticosteroid usage

Prior studies comparing RT to CP in other disease settings have suggested that the requirement for rescue corticosteroids differs between treatment regimens. To assess corticosteroid use, detailed information, including formulation, dose and duration of treatment, with any corticosteroid medication was captured at each study visit. To enable comparison of different corticosteroid regimens all doses were converted to the equivalent dose of hydrocortisone prior to the final analysis.

Physician global assessment of disease activity

At each visit, the PI was asked to provide a gestalt assessment of overall disease activity on a 10 cm visual analogue scale.

Healthcare utilisation and cost-effectiveness analysis

To assess the costs to the NHS associated with RT and CP, a prospective healthcare utilisation and cost-effectiveness analysis was undertaken. Subjects were asked to keep diaries to record all healthcare interactions including primary care services, hospitalisation and outpatient attendance. Participants were asked to provide information on both the frequency and duration of healthcare interactions. Costs were also calculated for grade 3 and 4 AEs.

Biomarkers

Lymphocyte subsets were analysed, according to standard clinical practice, at baseline and 6 months. Plasma, serum, whole blood (for DNA) and PAXgene tubes (for RNA analysis) were collected at each blood draw to enable assessment of experimental anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic biomarkers such as CA125, C3M, pro C6, CCL18 and YKL40.

Safety

Vital signs (temperature, weight, pulse, blood pressure, oxygen saturations, oxygen status, respiratory rate) and the findings from physical examination were recorded at each study visit. Blood samples for laboratory tests (full blood count, urea, electrolytes, liver function tests) and urine for urinalysis were collected at every infusion visit (baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20)

Pharmacovigilance

The Sponsor provided all sites with the Sponsor’s pharmacovigilance standard operating procedure (SOP) for recording and reporting of AEs; this complies with UK Regulations and patient version guideline reporting requirements, applicable to all Clinical Trials of Investigational Medicinal Products (CTIMPs). The study complied with Health Research Authority safety reporting procedures (URL: www.hra.nhs.uk/approvals-amendments/managing-your-approval/safety-reporting/; accessed 3 September 2021).

Pharmacovigilance definitions were adapted from the European Commission guidance (2011/C 172/01) titled, ‘Detailed guidance on the collection, verification and presentation of adverse reaction reports arising from clinical trials on medicinal products for human use’. AEs were defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a clinical trial participant who is administered an IMP and which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with this treatment [i.e. any unfavourable or unintended change in the structure (signs), function (symptoms) or chemistry (lab data) in a patient to whom an IMP has been administered, including occurrences unrelated to that product]. All study subjects were reviewed by the PI or designee and asked about AEs at each study visit (day 0, weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24 and 48). Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic some of the safety assessments were undertaken by telephone or video call in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. All AEs were assessed by the local PI or delegate as to whether they met the criteria for a serious adverse event (SAE) as defined in the protocol and Sponsor’s SOP. SAE definitions included any AEs which:

-

resulted in death or:

-

were life-threatening (placed the patient, in the view of the investigator, at immediate risk of death)

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation (hospitalisation is defined as an inpatient admission, regardless of length of stay; even if it is a precautionary measure for observation; including hospitalisation for an elective procedure, for a pre-existing condition)

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity (substantial disruption of one’s ability to conduct normal life functions)

-

consisted of a congenital anomaly or birth defect (in offspring of patients or their parents taking the IMP regardless of time of diagnosis).

All SAEs/serious adverse reactions (SARs) (including those which were expected) had to be reported in the eCRF by the investigator/or designee within 24 hours of their becoming aware of the event. The eCRF sent a notification of each SAE report to the Sponsor who reviewed the report within two working days of receipt. All SAEs, whether related or unrelated to the treatment were recorded in the hospital notes and eCRF. The Sponsor had access to SAEs via the eCRF.

All SAEs were assessed by the local PI for their severity (mild, moderate or severe) and relatedness (Definitely, Probably, Possibly, Unlikely and Not related). SAEs deemed to be definitely, probably or possibly related to the trial IMP were categorised as SARs. The Sponsor prepared the Development Safety Update Report (DSUR) in collaboration with the CI in accordance with regulatory requirements. The CI reviewed all SAEs reported in the database and confirmed the assessment of relatedness and expectedness. The Sponsor and CI also assessed all SARs for expectedness against section 4.8 of the SmPC (MHRA-approved reference safety information). No suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSAR) were reported in this trial.

Monitoring

The trial was monitored according to a monitoring plan developed in accordance with Sponsor SOPs and based on the trial risk assessment. Monitoring was conducted to ensure that the RECITAL study was conducted, recorded and reported in accordance with the protocol, SOPs, GCP and the applicable regulatory requirements. Monitoring included but was not limited to, checks on consent forms, source data verification (SDV), investigator site file and pharmacy file, local procedures, delegation logs, IMP storage and accountability and IMP destruction.

Quality control procedures at clinical sites included formal in-person site initiation training, electronic case report form (CRF) review and the periodic checking of essential documents, ISFs and pharmacy site files (PSFs).

In addition to reviewing the CRF data, the monitor/manager:

-

monitored SAE/R narratives against patient source data

-

discussed study progress with the investigator and other site staff

-

reviewed the ISF for completeness

-

tracked protocol deviations/violations

-

tracked patient progress in the study

-

reviewed any changes in site staff or facilities

-

reviewed the drug accountability records in pharmacy and checked drug supplies.

Following monitoring, a report was written and shared with the investigator team to ensure that the team understood the findings of the report and actions recommended by the Sponsor. The Regulatory Compliance Manager was responsible for all monitoring undertaken by the study monitor and study manager. The findings were presented to the Clinical Research Oversight Committee (Clin-ROC) to inform the committee of all quality assurance/quality control activities undertaken by the research and compliance team.

On-site monitoring was performed at all 11 recruiting sites between 2015 and 2020. The on-site monitoring visits, in addition to activities performed remotely, involved SDV of a sample of patients at the site, checks to ensure documentation were performed according to GCP, a review of the clinic notes to check for unreported notable or serious events, a pharmacy monitoring visit and investigator site file and PSF review.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the close-out visits were undertaken by sending all sites a ‘Self-Monitoring Form’ to enable Sponsor to monitor study activities remotely.

The trial statistician performed risk-based central statistical monitoring and produced a study report prior to all DMC meetings and guided the committee through the report. Usually, the Chair of the DMC reported its recommendations in writing to the TSC within 2 weeks of the meeting.

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis plan (SAP) was produced and agreed with the TSC and DMC prior to analysis (see the project webpage www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/11/116/03). Deviations from the SAP were recorded in the SAP deviation document. A summary of the planned analysis strategy for the primary and secondary outcomes can be found below.

Primary efficacy analysis

-

Analysis of the primary outcome was by modified intention to treat. In other words, data were included in respect of all subjects who met all the entry criteria for the trial and had been randomised and received at least one dose of study drug. The data was analysed according to the initial randomisation groups with no changes made in respect of subsequent withdrawals or crossovers.

-

The hypothesis to be tested was that RT is superior to CP. The study was to be considered positive if statistical significance at the level of 0.05 (two-tailed) was achieved.

-

To test the hypothesis above and estimate the difference in FVC at week 24 (together with 95% confidence interval), a three-level hierarchical (mixed/multilevel) model with unstructured correlation matrix and adjusted for baseline FVC and CTD type (stratification factor) treating the primary outcome as an interaction term between treatment and visits, including at week 24 was used.

Representing FVC in mL as FVCiv (in ml) for patient I at visit v with treatment (RT or CP) t(i), the FVCiv is modelled as the sum of four components:

-

baseline FVC: represents the estimated FVC at baseline. This term comprised an individual level random effect which was drawn from a distribution parameterised using the associated centre-level random effect. Hence unexplained variations in the FVC measures were split into three components corresponding to the three levels of the model, that is the variation attributable to the centre (between centre variation) and the individual (between individual variation), as well as the residual variation (within individual variation).

-

CTD diagnosis stratum (categorical) used for randomisation was added as a covariate.

-

visit: represents the visit number as a categorical variable.

-

treatment: a binary variable representing treatment arm.

-

Interaction term: this represents a coefficient that captures the changes in FVC at each visit between the arms. The magnitude of change at 24 weeks and its 95% confidence interval will be calculated to answer the research question.

-

No other baseline covariates were added as no substantial imbalances were revealed between the arms.

The Stata code used for the primary outcome was:

mixed changeFVC i.CTD i.week i.Arm#i.week || SITENAME: || SUBJECTNUMBERSTR:

Secondary efficacy analysis

-

Analysis of secondary efficacy outcomes was also performed by modified intention to treat.

-

Change in continuous physiological variables between baseline and 48 weeks were assessed by similar multilevel model as described for the primary outcome.

-

Categorical change in physiological variables was measured using chi-squared tests under the null hypothesis of no difference between the treatment groups.

Mortality, treatment failure and progression-free survival were measured using Kaplan–Meier estimates. A log-rank test was used to compare treatment groups and a Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine hazard ratios (HRs) for survival analyses.

Sample size

Previous studies of intravenous CP in SSc demonstrated a 1% decline in FVC at 12 months, with a coefficient of variation of 7.8%. Our observational data and a previous non-randomised study of RT (used as rescue therapy in those failing treatment with CP) suggested improvements in FVC at 6–12 months of between 9.5% and 20% compared to baseline. Using 1 : 1 randomisation, a sample size of 52 patients in each group gives a 90% power to detect a 5% difference (approximately 140 ml) between groups at 24 weeks in the change in FVC (as measured in ml) with a significance level (alpha) of 0.05 (two-tailed). Anticipating a dropout rate of 10% our target recruitment was 58 patients in each arm of the study. On the basis of data derived in other interstitial lung diseases 5% change in FVC is associated with change in long-term prognosis and can therefore be considered a clinically meaningful difference between the two groups. Given the number of individuals treated with CP at units participating in the study, this number was considered feasible to deliver within the planned trial timelines.

Primary efficacy variable

-

Change in FVC (expressed in ml) at week 24.

Secondary efficacy variables

-

Change in DLco at 24 weeks.

-

Change in health-related QoL scores (SGRQ, SF-36, K-BILD).

-

Change in Global Disease Activity Score (GDAS).

-

Change in 6MWD over 48 weeks.

-

Change in FVC and DLco at 48 weeks.

-

Absolute categorical change of %FVC at 24 and 48 weeks (decrease by >5%, increase by >5% and change within <5%).

-

Absolute categorical change of %FVC at 24 and 48 weeks (decrease by >10%, increase by >10% and change within <10%).

-

48-week change in FVC.

-

Disease-related mortality (adjudicated by steering committee at close of study).

-

Overall survival.

-

Progression-free survival [i.e. avoiding any of the following: mortality, transplant, treatment failure (see below) or decline in FVC > 10% compared to baseline].

-

Treatment failure (as determined by need for transplant or rescue therapy with either open-label CP or RT at any point until 48 weeks).

-

Total corticosteroid requirement over 48 weeks.

-

Change from baseline in SpO2 at 24 and 48 weeks.

-

Healthcare utilisation during study period (visits to primary care, unscheduled hospital visits, emergency admissions).

-

Scleroderma-specific end points (change in scleroderma HAQ, mRSS).

Safety variables

-

Vital signs (temperature, weight, pulse, blood pressure, oxygen saturations, oxygen status, respiratory rate).

-

Physical examination (skin, lungs, cardiovascular, abdomen).

-

Laboratory tests (blood counts, urea, electrolytes, liver function tests, urinalysis).

-

Adverse and SAEs.

-

Discontinuation of RT or CP due to intolerance or side effects.

Exploratory variables

-

Change in lymphocyte subsets in relation to efficacy outcomes.

-

Change in plasma protein levels following therapy and in relation to markers of disease activity (FVC, DLco, QoL, global disease scores).

-

Outcome in relation to underlying CTD.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

A cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted to estimate the costs and outcomes associated with using RT versus CP to treat patients with CTD-ILD in the RECITAL study. Data on health resources used, such as primary care service, hospitalisation, outpatient, oxygen, their frequencies and durations were collected from patient diaries as reported during the RECITAL clinical trial. The average frequencies of resources used were calculated by dividing the number of visits by the number of patients who used the service, as reported in the RECITAL diary. The proportion of patients who used a specific healthcare service was calculated in an intention-to-treat analysis, dividing the number of patients who used a particular healthcare service by the total number of patients randomised for each treatment arm.

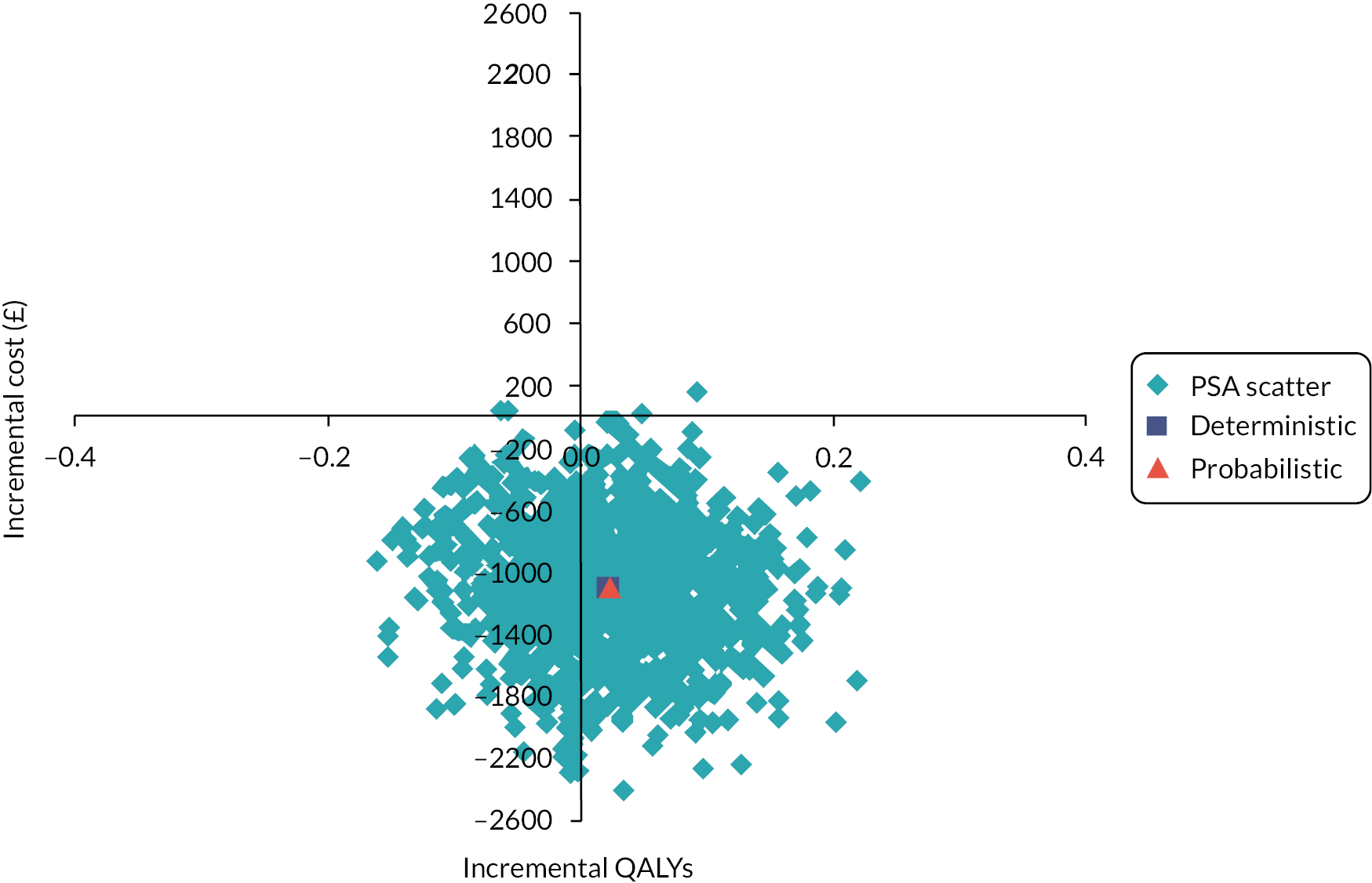

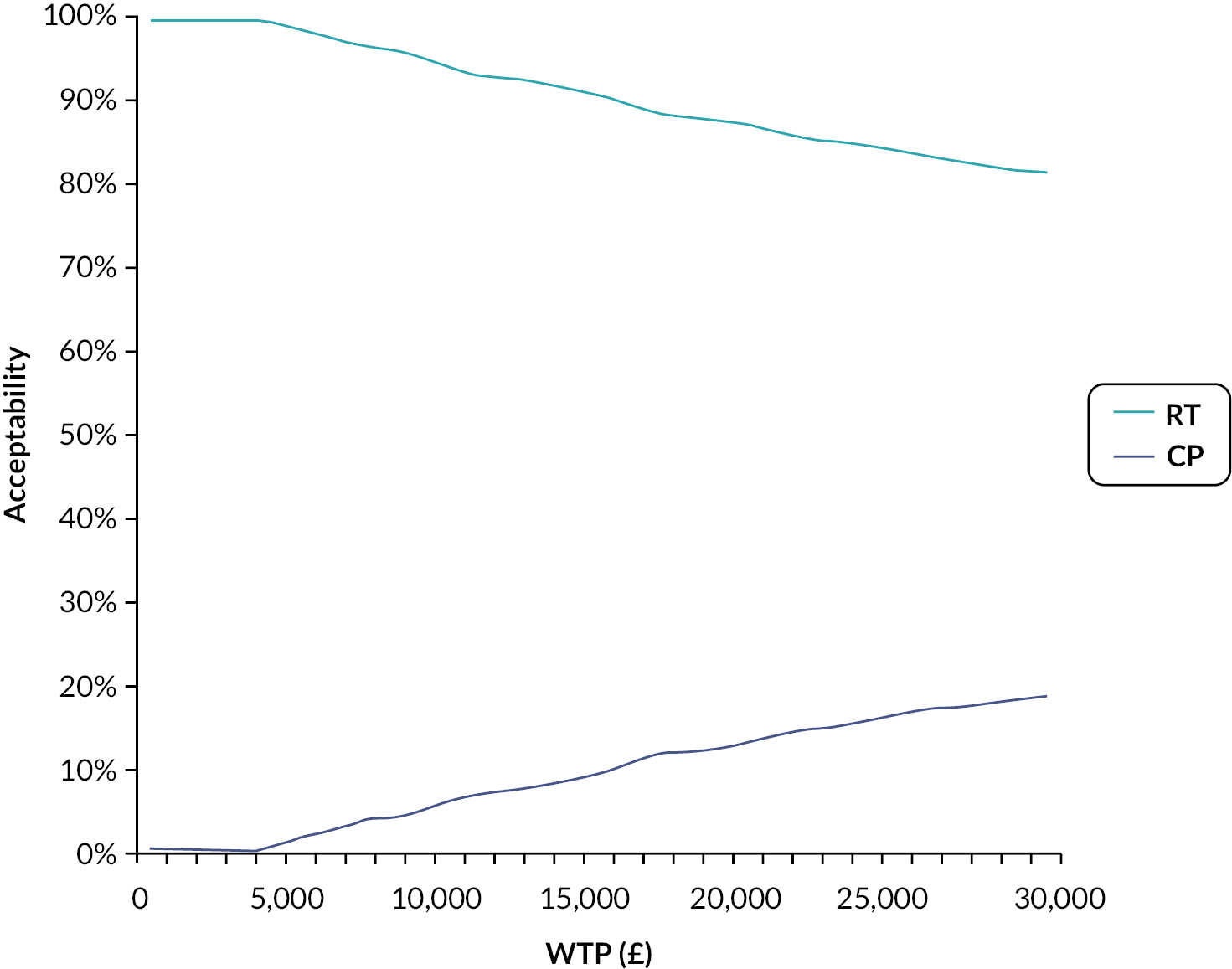

We calculated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) to compare the costs and effectiveness of RT versus CP. This was calculated by the difference in costs divided by the difference in effects of both technologies. A willingness to pay (WTP) threshold of £30,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained was assumed in this analysis (based on the commonly accepted thresholds used by the UK NICE). A discount rate on the cost and effects was not applied due to the temporal framework as our analysis did not exceed 1 year. The uncertainties around the input parameters were assessed by carrying out probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA), incremental net monetary benefit (INMB) and cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC).

Model input parameters

Resources use

The probabilities of requiring a healthcare service among the patients with CTD-ILD were derived from clinical trials whenever feasible (see Table 3).

| Resource used | Parameters | % patients using the resource | Frequency (mean) | Duration mean (minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide – CP | ||||

| Primary care services | Community and social services visits | 10 | 2.6 | 60 |

| Dentist | 4 | 2 | 30 | |

| GP | 54 | 2.56 | 15.54 | |

| Nurse | 34 | 4.53 | 13.38 | |

| Occupational therapy | 2 | 1 | 20 | |

| Optician | 2 | 1 | 45 | |

| Phlebotomist | 4 | 2 | 7.5 | |

| Physiotherapist | 10 | 1.4 | 36.43 | |

| A&E | Hospital A&E | 34 | 2.35 | - |

| Hospital outpatient | Hospital outpatient | 72 | 7.83 | - |

| Hospital inpatient | Hospital inpatient | 2 | 1 | - |

| Telephone calls | GP | 16 | 1.88 | - |

| Nurse | 12 | 2 | - | |

| Ambulatory oxygen | Ambulatory oxygen | 36 | - | - |

| AEs | Chest infection | 6 | - | - |

| Febrile illness | 2 | - | - | |

| Lung infection | 10 | - | - | |

| Pulmonary oedema | 2 | - | - | |

| Flu (Influenza A) | 2 | - | - | |

| Non-cardiac chest pain | 2 | - | - | |

| Rituximab – RT | ||||

| Primary care service | Community and social services visits | 2 | 12 | 60 |

| Dentist | 2 | 1 | 30 | |

| GP | 51 | 2.5 | 15.24 | |

| Nurse | 20 | 6.3 | 23.98 | |

| Occupational therapy | 2 | 6 | 55 | |

| Phlebotomist | 2 | 4 | 5 | |

| Physiotherapist | 6 | 4.67 | 48.93 | |

| Urgent care | 2 | 1 | 15 | |

| Palliative care | 2 | 2 | 45 | |

| A&E | Hospital A&E | 25 | 1.62 | - |

| Hospital outpatient | Hospital outpatient | 59 | 5.2 | - |

| Telephone calls | GP | 20 | 1.4 | 12.75 |

| Nurse | 10 | 2 | 7.22 | |

| Ambulatory oxygen | Ambulatory oxygen | 20 | - | - |

| AEs | Lung infection | 11.8 | - | - |

| Community-acquired pneumonia | 2 | - | - | |

| Dyspnoea | 2 | - | - | |

| Sepsis | 2 | - | - | |

| Urinary tract infection | 3.9 | - | - | |

| Worsening ILD and consolidation infection | 2 | - | - | |

Costs and utility values

All costs were estimated using the NHS perspective, therefore, only direct medical costs were accounted for and expressed in Great British pounds (£). QALYs were derived from the utility values [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)] extracted from RECITAL Clinical Trial and collected at 24 and 48 weeks. The primary outcome was cost-effectiveness, as defined by Great British pound costs, QALYs (or effectiveness), ICER and INMB. A strategy was considered cost-effective if it was: (1) more effective and less expensive (dominant strategy); (2) more effective and more expensive with an ICER < £30,000.

Model assumptions

In the formulation of the key assumptions, we made conservative estimates to avoid favouring intervention. Key assumptions of the model were: we assumed only grade 3 and 4 AEs (moderate and severe) and all hospitalisation required to treat AEs were non-elective short stay (day-case) to account for the total cost of the AE; we included the main treatment options reported in the RECITAL diary as alternatives to treat the reported AEs; we assumed that AEs occurred once; CP dosage was calculated assuming an idealised patient with a weight of 70 kg; one-way sensitivity analysis was carried out assuming either a 10% increase or decrease in input parameters. We examined the main assumptions in a sensitivity analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

The robustness of the outcome was assessed by sensitivity analyses. One-way sensitivity analyses were performed based on the parameters with the highest level of uncertainty (including all costs and utility values). These analyses consisted of varying each key parameter, assuming either a 10% increase or decrease in input parameters. Besides that, the impact of the uncertainties around the key parameters on the ICER was assessed through 1000 PSA using Monte Carlo simulation. PSA was carried out with all parameters being simultaneously varied in pre-specified ranges using pre-set distributions (gamma for cost and beta for utility values) (see Table 4).

| Resource used | Parameters | Unit cost (£) | Cost (£) per item | Total cost per category | Distribution | Source | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs | |||||||

| Drug | CP, 600 mg (CP) | 15.22 | 5062.29 | 5062.29 | Gamma | British National Formulary (BNF) (NICE), 2021 | Every 4 weeks for a total of six doses |

| Primary care services | CP – Community and social services visits | 51/hour | 663.00 | 6569.38 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 138 | Social worker (adult services): 45 (£51) per hour (costs including qualifications given in brackets). Assume 1-hour session |

| CP – Dentist | 133/hour | 266.00 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 130 | NHS dentist (performer-only): £105 per hour; £133 per hour of patient contact | ||

| CP – GP | 255/hour | 4557.11 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 126 | GP – with qualification cost: £255 per hour of patient contact (including direct care staff costs) | ||

| CP – Nurse | 42/hour | 721.18 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 124 | Nurse (GP practice): £38 (£42) per hour (costs including qualifications given in brackets) | ||

| CP – Occupational therapy | 49/hour | 16.33 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 141 | Community occupational therapist (local authority): £45 (£49) per hour (costs including qualifications given in brackets) | ||

| CP – Optician | 255/hour | 191.25 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 126 | We assume the same salary as the GP to estimate the unit cost for an optician | ||

| CP – Phlebotomist | 20/hour | 10.00 | Gamma | PSSRU (2015) p. 173 | Clinical support worker nursing (community): £20 per hour | ||

| CP – Physiotherapist | 34/hour | 144.51 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 151 | Physiotherapists/oTs (Band 4) | ||

| A&E | CP – Hospital A&E | 212/episode | 8480 | 8480 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 106 | A&E: £212 total cost per user |

| Hospital outpatient | CP – Hospital outpatient | 135/episode | 38,070 | 38,070 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 87 | Outpatient attendances: £135 weighted average of all outpatient attendances. We assumed the weighted average of all outpatient attendance costs because there are several reasons for outpatient reported in the diary |

| Hospital inpatient | CP – Hospital inpatient | 3366/episode | 3366 | 3366 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 87 | Non-elective inpatient stays (long stays): £3366 |

| Telephone calls | CP – GP | 8.41/e-consultation | 126.15 | 149.07 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 128 | GP telephone calls: £8.41 average cost per e-consultation |

| CP – Nurse | 1.91/e-consultation | 22.92 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 128 | Nurse face-to-face contacts: £1.91 average cost per e-consultation | ||

| Ambulatory oxygen | CP – Ambulatory oxygen | 91.02/2 weeks | 1638.36 | 1638.36 | Gamma | Whitty et al. (2020) | The average cost for ambulatory oxygen for 2 weeks was estimated to be £ 91.02 (95% CI £ 77.83–104.21) per participant |

| Adverse events | CP – AEs | - | 31,003.03 | 31,003.03 | Gamma | Calculated | AE cost was calculated by accounting the AE treatment cost + hospitalisation (day-case) |

| Drug | RT, 1 g | 349.25 | 35,623.50 | 35,623.50 | Gamma | BNF (NICE), 2021 | At baseline and repeated at 14 days |

| Primary care services | RT – Community and social services visits | 51/hour | 612.00 | 6946.91 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 138 | Social worker (adult services): 45 (£51) per hour (costs including qualifications given in brackets). Assume 1-hour session |

| RT – Dentist | 133/hour | 66.50 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 130 | NHS dentist (performer-only): £105 per hour; £133 per hour of patient contact | ||

| RT – GP | 255/hour | 4210.05 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 126 | GP – with qualification cost: £255 per hour of patient contact (including direct care staff costs) | ||

| RT – Nurse | 42/hour | 1052.52 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 124 | Nurse (GP practice): £38 (£42) per hour (costs including qualifications given in brackets) | ||

| RT – Occupational therapy | 49/hour | 269.50 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 141 | Community occupational therapist (local authority): £45 (£49) per hour (costs including qualifications given in brackets) | ||

| RT – Phlebotomist | 20/hour | 6.67 | Gamma | PSSRU (2015) p. 173 | Clinical support worker nursing (community): £20 per hour | ||

| RT – Physiotherapist | 34/hour | 388.18 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 151 | Physiotherapists/oTs (Band 4) | ||

| A&E | RT – Hospital A&E | 212/episode | 8480 | 8480 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 106 | A&E: £212 total cost per user |

| Hospital outpatient | RT – Hospital outpatient | 135/episode | 21,060.00 | 21,060.00 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 87 | Outpatient attendances: £135 weighted average of all outpatient attendances. We assumed the weighted average of all outpatient attendance costs because there are several reasons for outpatient reported in the diary |

| Telephone calls | RT – GP | 8.41/e-consultation | 117.74 | 136.84 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 128 | GP telephone calls: £8.41 average cost per e-consultation |

| RT – Nurse | 1.91/e-consultation | 19.10 | Gamma | PSSRU (2020) p. 128 | Nurse face-to-face contacts: £1.91 average cost per e-consultation | ||

| Ambulatory oxygen | RT – Ambulatory oxygen | 91.02/2 weeks | 910.20 | 910.20 | Gamma | Whitty et al. (2020) | The average cost for ambulatory oxygen for 2 weeks was estimated to be £ 91.02 (95% CI £ 77.83 to 104.21) per participant |

| AEs | RT – AEs | - | 24,097.69 | 24,097.69 | Gamma | Calculated | AE cost was calculated by accounting the AE treatment cost + hospitalisation (day-case) |

| Utility | |||||||

| Parameters | Value | Distribution | Source | ||||

| CP – EQ-5D at week 24 | 0.308 | Beta | RECITAL Clinical Trial | ||||

| RT – EQ-5D at week 24 | 0.330 | Beta | RECITAL Clinical Trial | ||||

| CP – EQ-5D at week 48 | 0.633 | Beta | RECITAL Clinical Trial | ||||

| RT – EQ-5D at week 48 | 0.637 | Beta | RECITAL Clinical Trial | ||||

Trial oversight committees

An independent DMC undertook interim review of the trial’s progress including updated figures on recruitment, data quality and main outcomes and safety data. More specifically the DMC:

-

assessed data quality, including completeness (and by doing so encouraged collection of high-quality data)

-

monitored recruitment figures and losses to follow-up

-

monitored compliance with the protocol by participants and investigators

-

monitored evidence for treatment differences in the main efficacy outcome measures

-

monitored evidence for treatment harm (e.g. toxicity data, SAEs, deaths)

-

decided whether to recommend that the trial continues to recruit participants or whether recruitment should be terminated either for everyone or for some treatment groups

-

suggested additional data analyses for the monitoring purposes of DMC

-

advised on protocol modifications suggested by investigators or the Sponsor (e.g. to inclusion criteria, trial end points or sample size)

-

monitored compliance with previous DMC recommendations

-

considered the ethical implications of any recommendations made by the DMC

-

assessed the impact and relevance of external evidence.

The committee met by teleconference every 6 months or at least annually for the duration of the study and comprised:

-

Dr Andrew Wilson – Chair – University of East Anglia

-

Dr Clive Kelly – Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Gateshead (to May 2019 – retired)

-

Dr Harsha Gunawardena – North Bristol NHS Trust, Southmead

-

Dr Ashley Jones – Centre for Medical Statistics and Health Evaluation, University of Liverpool.

The TSC provided overall supervision for the trial and considered reports from the TMG, the trial team and the DMC. The roles and responsibilities were set out in the TSC Charter.