Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 16/61/18. The contractual start date was in February 2018. The final report began editorial review in April 2022 and was accepted for publication in August 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Metcalfe et al. This work was produced by Metcalfe et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Metcalfe et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Subacromial spacer balloons

Shoulder pain is a common and disabling problem. The prevalence of shoulder pain in UK adults is approximately 16%, with rotator cuff disease accounting for 70–85% of this. 1–3 Surgery for rotator cuff disease has increased considerably; nearly 30,000 annual cases in 2009–10 in the UK, when this disease was last formally studied. 4 Individuals with a symptomatic rotator cuff tear typically present with pain, restricted movement and loss of strength and function, and the condition is associated with substantial expense to society through treatment costs and loss of work (both paid and unpaid). 5–8

The term ‘rotator cuff’ refers to the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor muscles and associated tendons around the shoulder, which when intact, function to keep the humerus centred on the glenoid as the shoulder moves, providing a stable fulcrum for normal glenohumeral joint motion. 9,10 A rotator cuff tear can result in loss of this stabilising function and lead to pain. The exact cause of pain is unknown but may be due to mechanical impingement between the humerus and the acromion, impingement of torn or loose tissue in the joint or biological causes such as bursitis or synovitis. 10,11

Rotator cuff repair is a widely accepted treatment for symptomatic rotator cuff tears. 12,13 However, there are multiple factors which influence whether a tear can be repaired, including the size of the tear, its chronicity, fatty infiltration of the muscle (atrophy) and the ability to bring the torn end back to its original site without excessive tension. Some tears cannot be surgically repaired (in which case they are called irreparable tears), and these can be difficult to manage.

Treatment for symptomatic irreparable rotator cuff tears includes physiotherapy, injections, arthroscopic debridement (with or without biceps tenotomy), partial repair, muscle transfers, interposition grafts and even shoulder replacements, typically reverse shoulder arthroplasty. 14–17 Arthroscopic debridement is commonly used and benefit has been demonstrated in case series studies. 18,19 However, it remains a controversial option and there are few randomised controlled trial (RCT) data on its use in the irreparable tear population. 18–20

The InSpace® (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) subacromial balloon spacer received a Conformité Européenne (CE) mark in 2010. In 2013, the device was introduced into UK orthopaedic practice as a potential treatment option for people with irreparable rotator cuff tears. 21 At the start of our study, the cost was approximately £1250 per implant. Its introduction was underpinned by case series evidence. In May 2016, an interventional procedure guidance document was published by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which found that there was very limited evidence for its use. Therefore, NICE recommended that the device should be restricted to use in the context of research only and a research recommendation was made to assess its effectiveness. 22 It received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance in the United States in July 2021, with approximately 29,000 devices having been implanted outside the United States prior to this date. 23

The InSpace balloon is a saline-filled balloon made of biodegradable (dissolvable) synthetic material. It is inserted above the main glenohumeral joint of the shoulder at the end of an arthroscopic debridement after an irreparable tear has been identified. It is simple to deploy and typically adds less than 10 minutes to the procedure. 21,24 The balloon cushions the humerus, preventing it from pressing on the acromion above it when the deltoid is active and during abduction of the arm, potentially reducing pain. It may also assist in the biomechanics of the shoulder, resisting proximal migration of the humerus under deltoid activity. It is thought the InSpace balloon begins to deflate from 3 months, during which time it is thought to allow and improve rehabilitation of the remaining rotator cuff and deltoid, so that when it has dissolved the biomechanics of the shoulder are maintained.

The safety of the device was established in rodents. One adverse event was recorded: a fibrosarcoma thought to be unique to rodents. 25 Proof of concept was established in a series of 24 irreparable cuff tears in Slovakia in 2012, with five-year follow-up results published in 2016. 26,27

The InSpace balloon has been used in a number of centres across the UK. At the time of starting this study, data had been presented in three conference abstracts, totalling 61 cases. 28–30 These case series studies demonstrated improvements in outcomes from baseline. Complications such as balloon displacement and non-cyst forming synovitis were reported in a small number of cases (3 of 61). One retrospective non-randomised study of 23 participants (12 with the balloon) showed an improvement in outcomes compared with debridement alone. 31

Reviews in 2019–20 found between 10 and 20 studies of the InSpace balloon, all case series. 32–36 The largest of these reviews included 619 participants (513 analysed; in some studies people with complications were excluded from analysis). 32 Many case series have documented encouraging clinical results but some studies have reported poor results or cases of inflammation and pain and have concluded that comparative data are needed.

One 2021 case series study37 following 51 people who underwent balloon placement found that after a mean follow-up of 3 years, shoulder function scores improved substantially after balloon spacer insertion (measured using the Constant score). 38,39 The authors reported limited need for revision surgery, with five participants undergoing reverse total shoulder replacement, one latissimus dorsi tendon transfer and high participant satisfaction. 37 In contrast, a different case series published in 2021, followed up 22 participants for almost 3 years. 40 The balloon spacer was found to be effective in a minority of participants in the medium term, as despite an improvement in Oxford Shoulder Scores (OSS) (23.6 vs. 29.6; p < 0.02), six participants converted to reverse total shoulder replacement at a mean time of 11 months post balloon insertion, with a mean deterioration of 1.1 on the OSS, while a further six participants with the balloon still in place demonstrated either a deterioration on the OSS or an improvement less than the minimal important difference – reported as 6.0 points. 41

Prior to starting our study, we undertook a systematic review (search date September 2016) and meta-analysis of randomised trials in rotator cuff pathology. 42 We found 57 trials (n = 4542), mostly of repair, but no trials using the InSpace balloon. The review found improvements in outcome for rotator cuff tears treated surgically, with conservative care and with acromioplasty. 42 Therefore, benefits compared with baseline found in case series may not be unique to the InSpace balloon. The effectiveness of the balloon in comparison to nonoperative care or acromioplasty is not known. It could still be a substantial improvement or may be of no benefit. 20 The device is costly but there is no evidence that it is effective clinically. If the device is effective, then it would relieve pain and improve function for patients with a disabling condition that currently has few good alternative treatments and it should be recommended for widespread use. However, if the device is ineffective or harmful, alternative approaches should be sought.

One other blinded randomised trial funded by the manufacturer (previously OrthoSpace, now Stryker) has been undertaken in the United States comparing partial cuff repair with a subacromial balloon spacer (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02493660). 43 It should be noted that partial cuff repair is not a technique that is often used in the UK and is not an appropriate comparator in a UK context but is more appropriate in the United States.

A non-inferiority, prospective, single-blinded, multicentre RCT was conducted by Verma et al. 43 to compare the outcomes of arthroscopic subacromial balloon spacer implantation with partial repair in participants 40 or more years of age who had full-thickness massive rotator cuff tears. A summary of 12-month results has been posted on a trials registry but results have not, at the time of writing, been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Participants’ baseline and follow-up data were collected to identify a non-inferiority margin of 10% difference in the proportion of responders in a composite outcome measure. This composite outcome was defined as participants who had improved from baseline on both the Western Ontario Rotator Cuff (WORC) score (≥ 275 points) and American Shoulder and Elbow Society (ASES) score (≥ 6.4 points) at 6 weeks and had maintained the improvements at 12 months without subsequent secondary surgical intervention or serious adverse device effects. Of the 184 randomised participants, 176 (88/group) completed 12-month follow-up.

At 12 months, 45 (51.1%) participants in the spacer implant group and 35 participants (39.8%) in the partial repair group had reached and maintained the primary composite end point, corresponding to an 11.43% unadjusted mean advantage for the spacer implant group. However, this composite outcome should be taken in context, as it is likely to be difficult for people who have had partial cuff repair to achieve improvements by 6 weeks as many would still be in an early postoperative recovery phase. 44,45 Both groups improved between baseline and follow-up in all WORC and ASES scores but there were no differences observed between groups in WORC and ASES data reported so far. Six participants (n = 3 balloon spacer; n = 3 partial repair) required secondary surgery; two in each group undergoing reverse shoulder arthroplasty and one participant in each group undergoing shoulder arthroscopy. 43

Trial designs in new surgical procedures

The safe introduction of new surgical procedures is essential to the delivery of high-quality surgical care. Innovative procedures may result in a step-change improvement in treatment but can also bring new risks and substantial costs. Major harm can occur when a well-meant intervention is used widely across the health service before it is formally and thoroughly evaluated. 46,47

Pharmaceuticals undergo rigorous clinical trials before being introduced but this is not always true for surgical procedures, which are often introduced on the basis of cadaveric testing or small case series data only. 48 There is a need to develop new processes and methodology to introduce surgical procedures safely, using early RCTs to determine whether a treatment is likely to be safe, clinically effective and cost-effective prior to widespread uptake. 48

To rigorously assess new surgical procedures, large multicentre RCTs which produce reliable and statistically precise evidence may be undertaken. However, these studies typically need to recruit over extended periods. 47,49 Large pragmatic surgical trials are expensive (typically £1.5–2 million or more) and can take five years or more from award to completion, as for example the Wound management of Open Lower Limb Fractures (WOLLF), Fixation of Distal Tibia Fractures (FixDT) and Ankle Injury Management trials, even disregarding the time taken over feasibility and pilot studies. 49–51 Costly, ineffective or unsafe treatments may be used for many years before they are removed from practice. There is thus a requirement for trial designs to determine efficiently and rapidly whether an intervention is ineffective or even harmful but also to demonstrate superiority if the intervention is a genuine improvement on standard care. Improvements in the efficiency of undertaking trials of surgical interventions would provide earlier answers to crucial clinical questions, providing benefits to patients and making better use of health-care resources.

Adaptive trial designs are becoming increasingly popular and their use has been encouraged by major scientific journals, the US FDA and National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) panels. 52–54 This design allows for prospectively planned modifications, such as stopping the study or discontinuing an intervention, based on emerging findings as the trial proceeds, while preserving the scientific validity and integrity of the trial. This more flexible strategy typically reduces costs and shortens timescales, without compromising the integrity, statistical power or rigour of the study. 52,55–57 Efficiency savings in terms of cost and time can be substantial (a 40% reduction in sample size in one study) without a loss in power or increase in false-positive error rate. The use of adaptive designs which are flexible in their sample size may also avoid the delay associated with prolonged pilot or feasibility studies, as they can be incorporated into the trial without delaying the main study. 58,59 Yet, despite the potential benefit of reducing the number of people exposed to a procedure that may be unnecessary or even harmful, adaptive designs remain rare in surgical trials. 52,57,60

In this trial, we applied these design principles to a multicentre clinical trial of a new surgical procedure for rotator cuff tears. We have termed this trial design REACTS (Randomised, Efficient, Adaptive Clinical Trials in Surgery). Subacromial spacer for Tears Affecting Rotator Cuff Tendons (START) is the first study using this new statistical adaptive design approach for the assessment of a new surgical procedure. The statistical principles are laid out in a 2019 methodology paper. 61 Further evaluation of the REACTS studies was also undertaken in a range of other trial settings, with the aim of establishing this trial design as the future standard for assessing new surgical procedures. In the future such an approach, if successful, could be used before a new procedure is introduced into widespread clinical practice. This would reduce costs to funders but more importantly it will ensure that high-quality evidence is delivered more rapidly to improve patient care and outcomes.

Aim

Our primary clinical aim was to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness and safety of a subacromial InSpace balloon for patients with symptomatic irreparable rotator cuff tears. 22 Methodologically, the primary aim was to develop and implement appropriate statistical tools to allow an efficient adaptive clinical trial design. 61

Chapter 2 Main trial methods

Trial design

We conducted a participant- and assessor-blinded, adaptive, multicentre RCT with a parallel economic analysis. The setting was secondary care across the UK. The study compared arthroscopic debridement using an InSpace balloon with arthroscopic debridement alone and was designed using the REACTS framework (see Figure 1). We have published a detailed description of the protocol elsewhere. 62

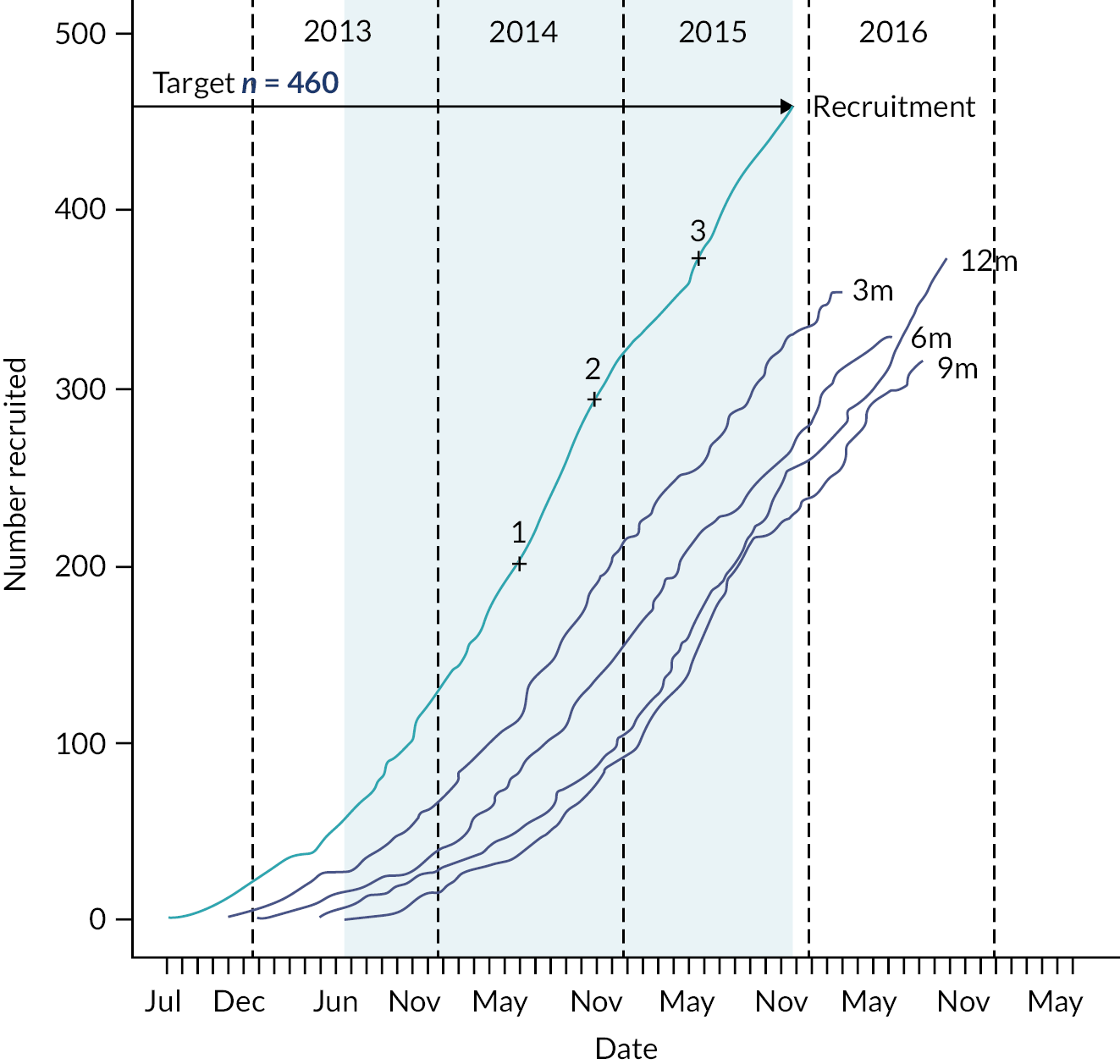

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram describing the planned trial methodology.

Patient and public involvement

Patient involvement has been central to the design, delivery and interpretation of the study and the results; this involvement will continue as we disseminate the findings. Initially, we engaged with multiple people who had previously undergone rotator cuff surgery to learn about and understand their experiences. Their insights were reassuring about the need for a trial and helped establish the design of the study, especially the choice of primary and secondary outcomes and the design of all participant facing materials. We engaged with patients during development of the study materials and trialled our study forms with a number of patients before they were used in the study.

One of the co-authors of the report has shoulder problems previously treated surgically and represents the patient view in trial management meetings, while two other patients sit on our steering committee. We will produce patient and public focused summaries of the research and disseminate this widely.

Objectives

Primary clinical objective

Our primary clinical objective was to quantify and make inferences on observed differences between arthroscopic debridement using an InSpace balloon with arthroscopic debridement alone 12 months after surgery, using the OSS as the primary outcome measure. 63,64 A 12-month time point was selected based on our meta-analysis of outcomes for randomised trials which found that shoulder scores typically reach a plateau at 12 months after any intervention for a rotator cuff tear. 42 Although we are collecting 24-month scores, they do not provide sufficient additional value to justify the increase in costs and delay in the trial result that would be required had they been used as the primary outcome.

Secondary clinical objectives

Our secondary clinical objectives were to:

-

quantify and make inferences on observed differences between the two intervention groups on the following measures; all were assessed at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months:

-

Perform an economic analysis to assess the comparative cost-effectiveness of the two interventions (see Chapter 5).

-

Perform a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) substudy to compare the acromiohumeral distance (AHD) on MRI scans in a sample of participants with and without the balloon at 8 weeks and at least 6 months after treatment. This was to assess the proposed mechanism of action of the InSpace balloon while still inflated (8 weeks) and to determine any persistent effects following deflation (after 6 months).

Methodological objectives

The methodological objectives of the study were to:

-

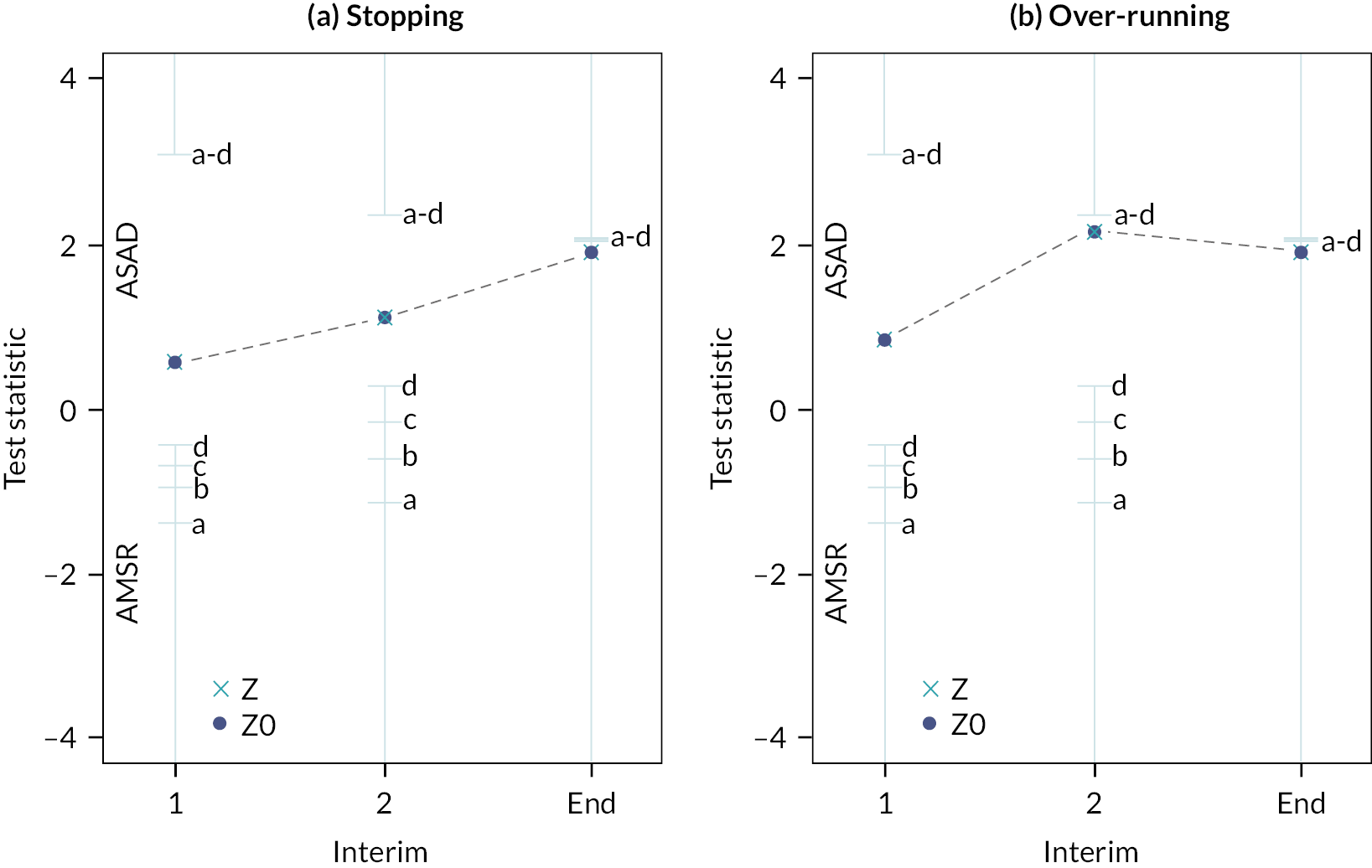

develop and implement appropriate statistical tools for an efficient adaptive clinical trial design, with the potential to stop early either for futility or efficacy, using outcome data available at 3, 6 and 12 months61

-

compare the use of frequentist and Bayesian design and analysis on the conduct and interpretation of an adaptive surgical clinical trial with reference to decision-making by data monitoring committees (DMCs) during the study and by clinicians, commissioners and other stakeholders at the conclusion of the trial

-

explore the challenges of supporting adaptive design decision-making with net benefit and expected value of information approaches to health economic analyses.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The Oxford Shoulder Score

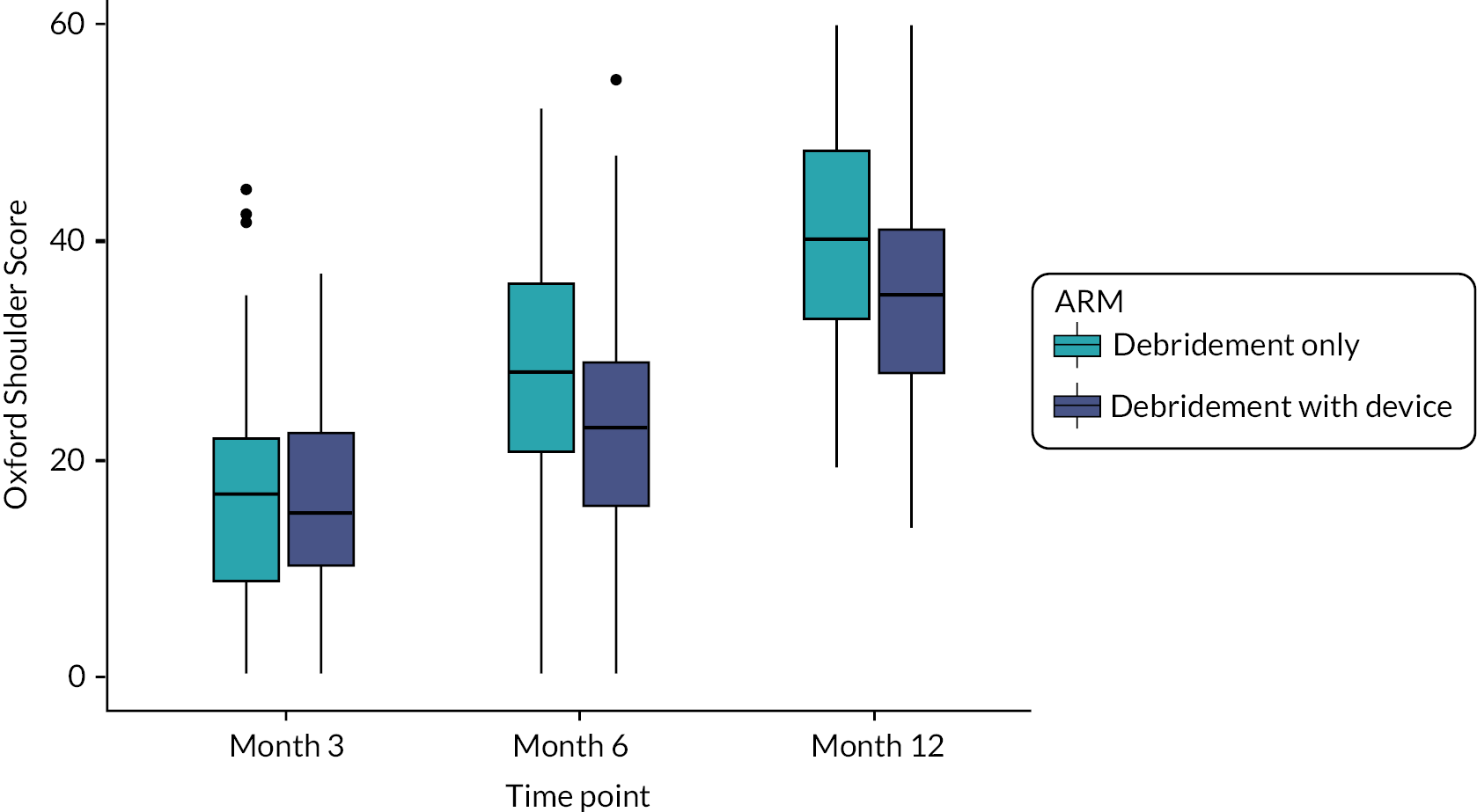

The OSS is a patient-reported outcome measure with 12 questions which has been well validated to assess the degree of pain and disability caused by shoulder pathology. It is simple to complete and has proved to be valid and reliable in determining the outcome from shoulder surgery. 41,68 It is a well-known measure and has also been used in previous high-impact randomised trials of shoulder surgery. 69 A higher score (0–48) corresponds to a better outcome. 63,64

Originally, the planned primary outcome for the study was the Constant score. 38,39 This was chosen as it had been widely used in shoulder trials, is well accepted by surgeons, and has good reliability and responsiveness. 42 However, in light of the COVID-19 outbreak in March 2020, the trial management group (TMG) decided to change the primary outcome to the OSS. As the Constant score requires face-to-face contact to measure and it is usually taken in hospital clinics, it would have exposed participants to unnecessary risk during the height of the pandemic. The decision was agreed by both the trial steering committee (TSC) and DMC as well as the NIHR prior to the change. The OSS correlates well with the Constant score; both assess shoulder pain and function, are similarly responsive and have comparable effect sizes in rotator cuff pathology. 41,63,64,68,69 More details on the effect of changing the primary outcome can be found in the power calculation and sample size section below.

Secondary outcomes

The Oxford Shoulder Score at baseline, 3, 6 and 24 months

-

The Constant score at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months: the Constant score consists of four variables that are used to assess shoulder function. The subjective variables are pain and activities of daily living (sleep, work, recreation/sport), which give a total of 35 points and the objective variables are ROM and strength, which give a total of 65 points. Each component can be reported separately or can be combined to give a score out of 100. A standardised protocol for the objective component of the score was developed based on the work of Moeller et al.,70 with training provided for all sites. 38,39

-

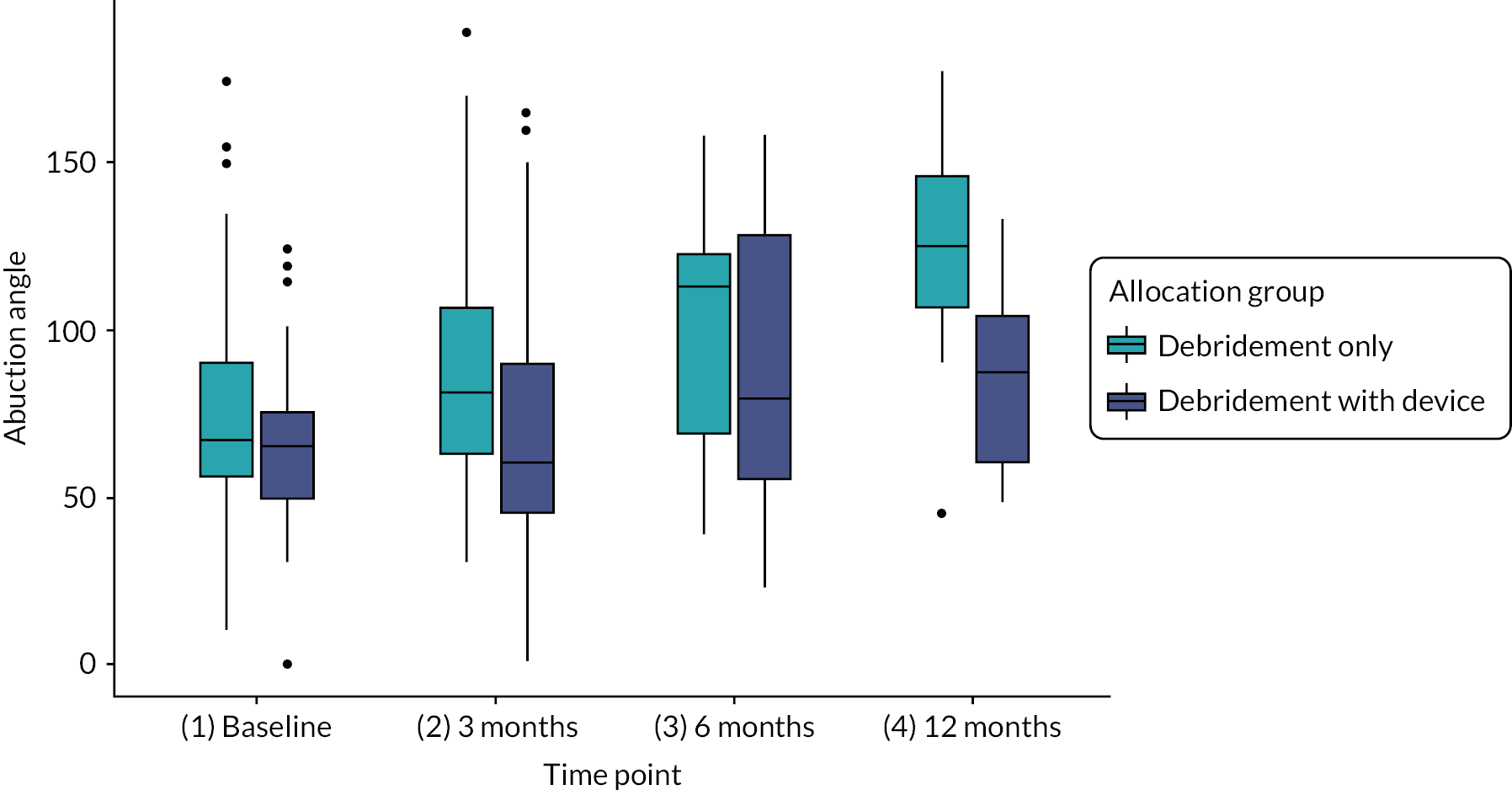

Range of pain-free movement in abduction and flexion of the shoulder at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months measured using a 12.5-inch long-arm goniometer.

-

Strength of shoulder in the scapular plane at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months measured using a supplied IsoForceControl EVO2 dynamometer (Herkules Kunststoff, Switzerland).

-

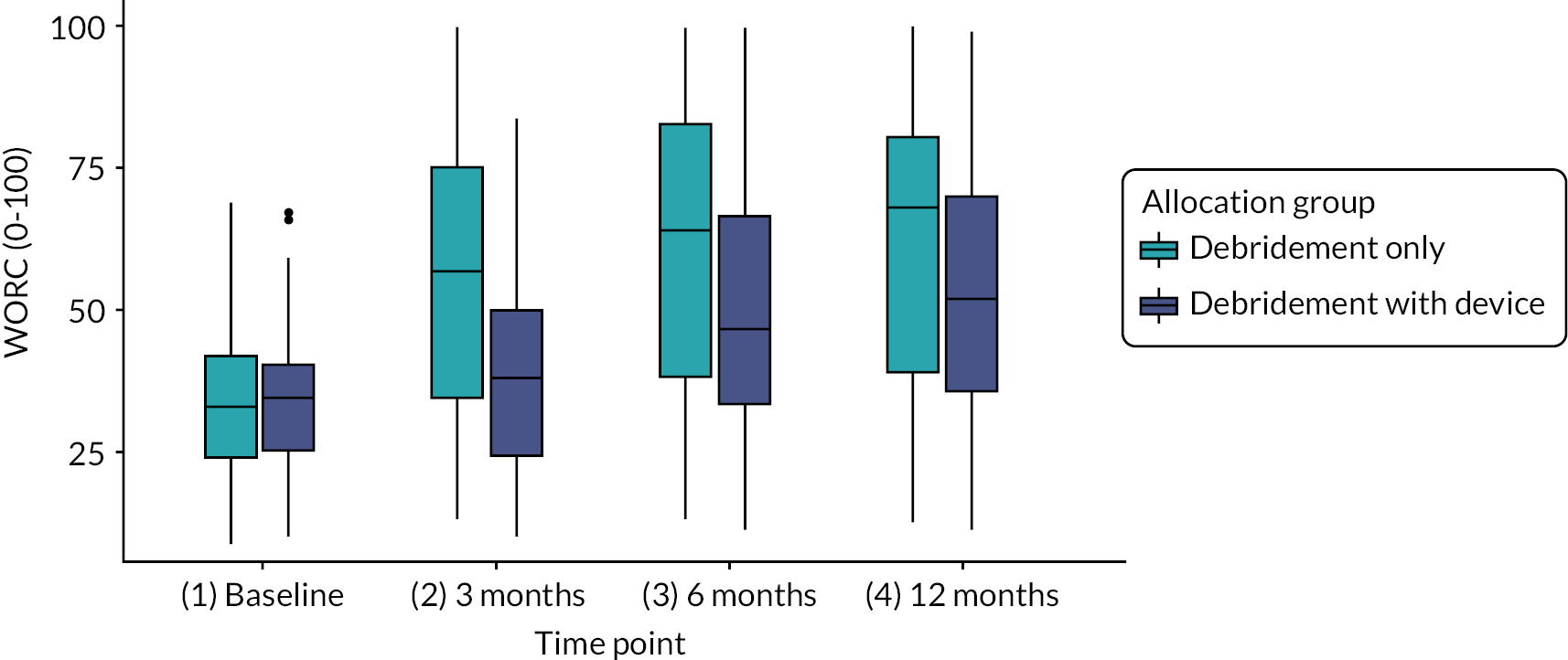

WORC index at baseline, 3, 6, 12 and 24 months. 65 The WORC is a condition-specific self-reported instrument to assess ‘quality of life’ (QoL). It comprises 21 items incorporating five domains: physical symptoms, sports/recreation, work, lifestyle and emotions. Item scores are recorded on a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 0 to 100 (100 mm VAS). Individual domain scores can be summated for a total score (range 0–2100). Higher scores represent poorer QoL. 65 To present this in a more easily accessible and reproducible format, the VAS lines were modified into 11-point numerical rating scale lines (1-cm intervals labelled as 0-10). Item scores were then summed and reported as a percentage of maximum total score.

-

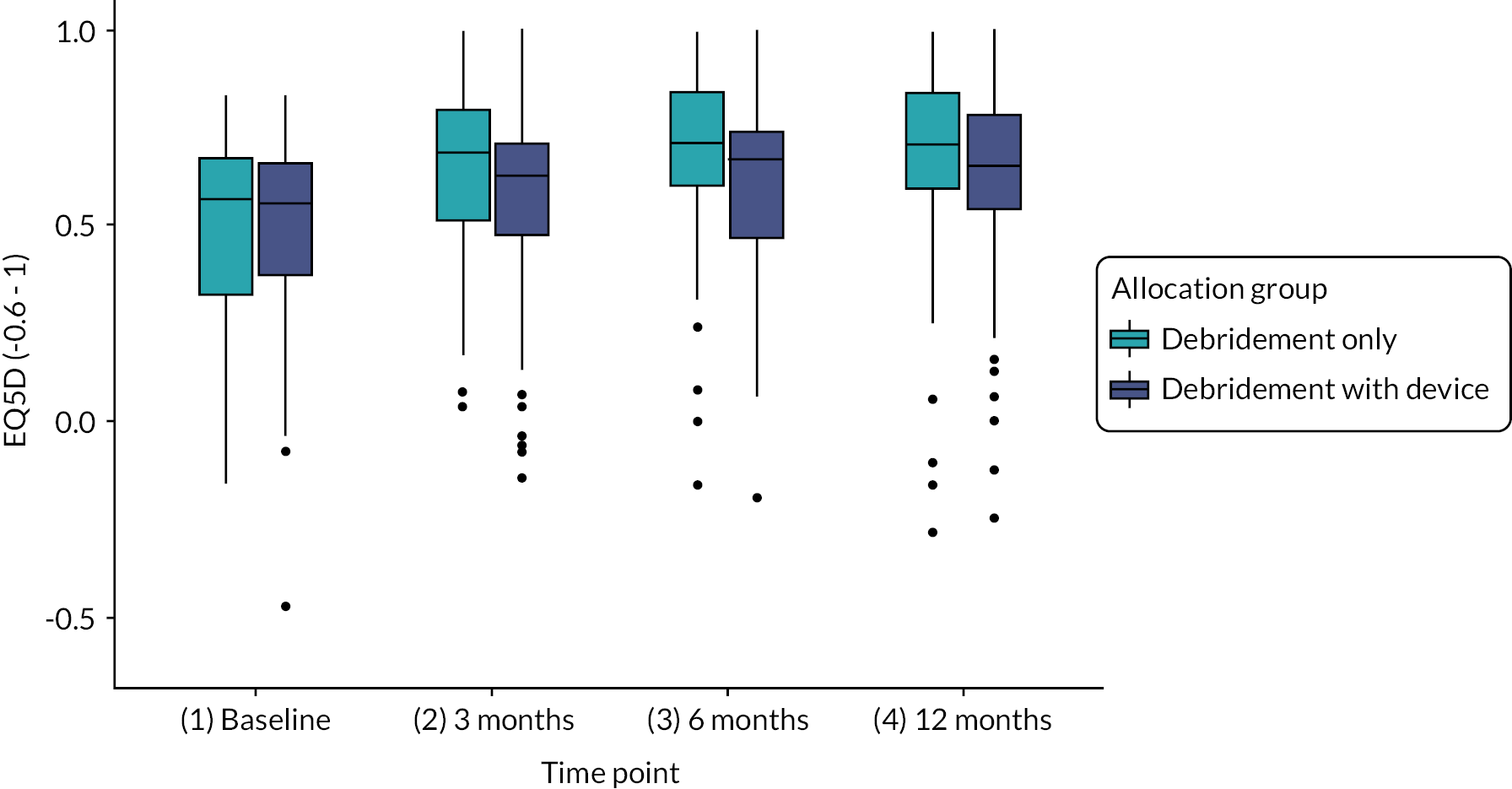

Health utility assessed using EQ-5D-5L at baseline, 3, 6, 12 and 24 months. 66,67 The EQ-5D-5L is a validated, generic health-related QoL measure consisting of five dimensions each with a five-level answer possibility. Each combination of answers can be converted into a health utility score using the UK crosswalk value set. It has good test–retest reliability, is simple for participants to use and gives a single preference-based index value for health status that can be used for broader cost-effectiveness comparative purposes.

-

Health-care resource use at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months. The primary analysis focused on direct intervention and health-care/personal social services (PSSs) costs, while wider impact (societal) costs were included within a sensitivity analysis. Relevant resource-use questionnaires were administered to participants at baseline and all follow-up points to collect resource-use data associated with the interventions under examination.

-

Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) score was collected at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months. This was collected using a simple seven-point scale assessing the participants’ perception of improvement. 71

-

Analgesia use (drug, and approximate frequency) collected at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months.

-

MRI scans (a planned substudy of 56 patients, 6 weeks and at least 6 months postsurgery): see the ‘MRI substudy’ section.

-

Adverse events were collected from site reports sent directly to the trial office when they occurred throughout the first 12 months of each participant’s follow-up, and from participant’s 3, 6 and 12-month questionnaires.

Note that the patient-reported outcome measures (OSS, WORC, EQ-5D-5L, PGIC) collected at 24 months will be published separately so as not to delay publication of the primary 12-month outcome data.

As an exploratory analysis, baseline shoulder radiographs performed as part of standard care were collected and the shortest AHD was measured according to the method described by Kolk et al. 72 Measurements were performed independently by two blinded observers, a professor of radiology and a consultant orthopaedic surgeon, and a mean of their two scores was used as a final value.

Setting and participants

Participant identification, screening and withdrawals

Potential participants were identified by the attending clinical team in intermediate or secondary care clinics, or from surgical waiting lists. The attending clinician confirmed each patient’s eligibility for the study based on clinical assessment and standard care preoperative imaging for each site (e.g. MRI or ultrasound).

All potential participants meeting study entry criteria were checked for eligibility and their details recorded on a screening log. Potential participants suitable for inclusion and willing to be approached were given verbal and written information about the study by a suitably trained member of the research team, were given adequate time to consider the information and were invited to ask questions and discuss the study further prior to informed consent being obtained. Trial procedures including baseline assessments were not undertaken until the consent form was signed and dated by the participant.

All participants provided informed, written, signed and dated consent. As there was a delay of a number of weeks before randomisation (the waiting list for surgery), people entering the study still had the option to withdraw before treatment commenced if for any reason, they changed their mind. Any new relevant information arising during the trial was discussed with the participants and, where applicable, continuing consent was obtained using an amended consent form.

Sites agreeing to take part in both the main study and the additional MRI substudy were provided with a combined main and substudy patient information sheet and consent form.

Eligibility was also confirmed by the operating surgeon intraoperatively and participants were excluded (withdrawn) at this stage if it was discovered that the rotator cuff tear was repairable. These excluded participants were informed by letter that they were no longer taking part in the study. Baseline data were, however, retained to explore any differences between those who were deemed ineligible intraoperatively to those who were randomised. Participants randomised into the study were allowed to withdraw from follow-up at any time, without prejudice and without any effect on their current or future care.

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible to be included in the trial if they met the following inclusion criteria:

-

Rotator cuff tear deemed by the treating clinician to be technically irreparable. Multiple factors apart from size can influence whether a tear can be repaired (i.e. chronicity, retraction of the tendon ends and fat infiltration in muscle). However, patients with tears thought to be technically repairable, such as a small tear, but considered unsuitable for repair due to age or comorbidities, were not eligible for this study.

-

Experiencing intrusive symptoms (pain and loss of function) which in the opinion of the treating clinician warrants surgery.

-

Had undergone unsuccessful nonoperative management, as determined by the treating clinician.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were considered ineligible if they met any of the following criteria:

-

Advanced glenohumeral osteoarthritis on pre-operative imaging (in the opinion of the treating clinician). This was interpreted as Kellgren–Lawrence grade 3 or 4 changes on routine preoperative radiographs73 or the MRI equivalent if radiographs were not available.

-

Subscapularis deficiency,1 defined as a tear involving more than the superior 1 cm (approximately) of the subscapularis, if repaired, or any tear that is not repaired.

-

The treating clinician determines that interposition grafting or tendon transfers are indicated.

-

Pseudoparalysis (an inability to actively abduct or forward flex up to 20 degrees), as determined by the treating clinician.

-

Having any unrelated, symptomatic ipsilateral shoulder disorder that would interfere with strength measurement or ability to perform rehabilitation.

-

Other neurological or muscular conditions that would interfere with strength measurement or ability to perform rehabilitation, in the opinion of the treating clinician.

-

A previous proximal humerus fracture that could influence shoulder function, as determined by the treating clinician.

-

Previous entry into the present trial (i.e. other shoulder).

-

Unable to complete trial procedures.

-

Age under 18 years.

-

Unable to consent to the trial.

-

Unfit for surgery as defined by the treating clinician.

Randomisation

Participants were randomly allocated on a one to one basis to the two treatment groups via a central computer-based randomisation system provided by Warwick Clinical Trials Unit (WCTU), independent of the study team. A minimisation algorithm was used to determine participant allocation, using site, sex (used rather than gender as we were interested in the structural effect), age group (< 70 and ≥ 70 years) and cuff tear size (as assessed by the operating surgeon, ≥ 3 or < 3 cm, commonly used as the definition between small/medium and large/massive cuff tears) as factors, with a random element included to provide a 70% chance that the participant would receive the treatment that minimises imbalance, to ensure unpredictability.

Randomisation was performed by theatre staff, after intraoperative findings were checked (including cuff tear size) and eligibility confirmed. To maintain blinding, staff used an online system in a separate room (a 24-hour back-up automated telephone system was also available). Participants were randomised strictly sequentially at site level. Allocation concealment was maintained by the independent randomisation team who were responsible for the generation of the sequence and had no role in the randomisation of participants beyond this.

Trial interventions

Standard arthroscopic debridement (control)

The control group were randomised to arthroscopic debridement of the subacromial space with removal of inflamed tissue (bursectomy) and unstable remnants of the torn tendon, limited bone resection of the acromion, retention of the coracoacromial ligament and biceps tenotomy (if not already torn). The anaesthetic (general or local) was decided by the anaesthetist. Surgeons were permitted to use their normal surgical technique within the confines described in a trial-specific surgical guideline, available on the Warwick Research Archive Portal (http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk).

Standard arthroscopic debridement plus insertion of InSpace balloon (intervention)

Those allocated to the intervention underwent the same arthroscopic debridement as the control group plus insertion of the InSpace Balloon by a subspecialty trained shoulder surgeon. The recommended surgical technique was followed for sizing, insertion, and deployment of the balloon, as documented in the surgical manual. The content of the surgical manual was confirmed with the manufacturers (OrthoSpace at the time) prior to interventions starting in the study, to ensure the study followed recommended techniques.

For both groups, fidelity was assessed with an operative record form, arthroscopic photographs (posterior and lateral portal photographs after debridement for both groups, and a photograph from the posterior portal just before balloon inflation in the balloon group to demonstrate balloon position). In addition, the number of physiotherapy visits for each participant was also documented in both groups.

Rehabilitation

The postoperative rehabilitation programme was developed during the set-up phase of the trial. The process involved collecting current NHS rehabilitation protocols from participating sites, manufacturer protocols, scoping the literature and ratification among a panel of expert physiotherapists. As with the surgical technique, a copy was forwarded to the manufacturer, OrthoSpace, prior to starting interventions to ensure that the study did not conflict with manufacturer’s recommendations. A physiotherapy trial manual was produced and followed, to standardise rehabilitation progression and is available from: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/med/research/ctu/trials/startreacts/links/healthlinks/physiotherapy_manual_v2.2_10072018.pdf.

Postoperative rehabilitation for both groups was blind to treatment allocation and included standardised postoperative information, home exercises and the offer of a minimum of three face-to-face physiotherapy appointments. Additional physiotherapy was arranged at the discretion of the trial sites.

Blinding

Participants and assessors were blinded to treatment allocation; only the surgical teams at the time of the operation were aware of the allocation. Theatre staff were asked not to mention or discuss the balloon and to communicate the allocation in writing – that is, by using methods such as holding up a piece of paper on which the allocation was clearly written.

For those participants who were awake during surgery, drapes were used to obscure their view and arthroscopic screens were positioned in such a way that they were unable to see the procedure. Although the incisions required for the two procedures are similar one (the lateral portal) needs to be slightly larger to insert the balloon; 1.5 cm as opposed to 1 cm. Therefore, a 1.5-cm incision was used for all participants and, due to the very small change from standard care, was very unlikely to have any negative effects on any participant. Incisions were, therefore, the same for both groups and there was no external way in which the participants could detect the presence or absence of the balloon.

A standard recommended operation note template was provided to all sites and adjusted to fit local operation note systems to ensure that operation notes could be blinded and to prevent accidental unblinding (e.g. in any discharge information or during postoperative physiotherapy. The details of the operation related to the balloon were recorded in a secure online form easily accessible to the surgeon.

Although unblinding was unlikely, an unblinding plan was produced for use by NHS staff in emergency situations such as overnight admission for suspected postoperative infection. Using a predefined web-based system and two-way secure verification procedure performed using e-mail, staff used a link inserted in the operation notes to access a code to unblind the allocation group, which was only sent to an active NHS e-mail address. The trial team requested a full explanation of the clinical circumstances and the need for access to data for audit and monitoring purposes from the person performing the unblinding, and the principal investigator for the site was informed.

Participants were also asked at the 12-month time point, after collection of the primary outcome, if they were aware of their allocation.

Adverse events, adverse device effects and serious adverse device effects

Adverse events, serious adverse events (SAEs), adverse device effects and serious adverse device effects were defined using standard accepted criteria. An unanticipated serious adverse device effect was defined as an adverse effect which, by its nature, incidence, severity or outcome, was not identified in the risk analysis report. Adverse events were recorded for any participant where it was thought there may be a relationship between the event and the trial interventions or the condition being studied (in this case, any shoulder condition or related to the anaesthetic). These included device-specific deficiencies or complications such as balloon migration, which was recorded if it was identified by clinical teams during their normal practice.

All SAEs, serious adverse device effects and unanticipated serious adverse device effects occurring from the time of randomisation until 12 months post-randomisation were communicated to the sponsor within 24 hours of the research staff becoming aware of the event. All events were followed up until resolution or a final outcome was reached.

For participants lost to follow-up at or beyond the 12-month time point, their general practitioner was contacted and a short form requesting any information or health record that could be an adverse event was requested, as well as confirmation of the current contact details of the participant.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were carried out using R version 4.0.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). 74

Power and sample size

Initial sample size calculations were based on the Constant score, with a target difference of 10 units, as widely used for other trials and a standard deviation (SD) of 20, giving a moderate standardised mean difference of 0.5. 20,27,75,76 In anchor-based studies the estimated target difference for the OSS is 6 with an SD of 12 being observed in multiple studies. 41,68,69,76 For an expensive invasive procedure of this nature, a smaller standardised mean difference was considered unlikely to be worthwhile. Therefore, a moderate standardised mean difference of 0.5 was considered appropriate. For a power of 90% and a (two-sided) type I error rate of 5% a study with a conventional fixed design (i.e. with no possibility of stopping early), assuming an approximate normal distribution for the score data, would require 170 participants.

The design characteristics and required sample size for the planned adaptive design were assessed and estimated in a large simulation study (see below). 61 We anticipated correlations between time points (based on Karthikeyan et al.)76 and effect sizes to be equivalent between the Constant score and OSS; thus, these simulations remained valid, despite the change of primary outcome. 68,76 The simulations showed that an adaptive design that allowed the possibility of early stopping for efficacy and/or futility, was feasible for the START:REACTS study.

Based on an assumed modest correlation between 3-, 6-, and 12-month OSS equal to 0.5, and an SD of 12 for both 3- and 6-month scores, the simulations for the selected adaptive design indicated that follow-up data from a maximum of 188 participants would be needed to detect a six-point difference in the OSS between treatment arms with 90% power and 5% (two-sided) type I error rate. Allowing for 15% lost to follow-up, while attempting to keep this below 10%, a maximum study sample size of 221 was calculated.

Primary outcome analysis

All data have been analysed and reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines. 77,78 A detailed statistical analysis plan and a data-sharing plan were agreed with the DMC prior to any formal analyses being conducted. 79

The primary analysis investigated differences in the OSS 12 months after surgery between the two treatment groups on an intention-to-treat basis following the methods, test statistics and boundaries described by Parsons et al. 61 To preserve the integrity of the study, the exact boundaries used for testing were specified in an adaptive charter known only to the study team and independent DMC. In brief, if the study recruited to target, Parsons et al. ’s61 methods would be used to calculate the boundaries. As the study stopped early, testing proceeded using boundaries calculated by the deletion method for over-running analysis,80 with inferences following directly from widely used methods for unbiased estimates and confidence intervals (CIs) in group sequential trials. 80–82

Secondary outcome analyses

Descriptive statistics of all outcome measures data (i.e. the OSS, WORC, EQ-5D-5L, PGIC and analgesia usage) at each time point were constructed.

Adjusted estimates of treatment group differences (with 95% CIs) for the OSS at 12 months post-randomisation were calculated using a mixed-effects model including a random effect for the recruiting centre and fixed effects for variables of interest including patient age, sex and size of tear. Estimates of efficacy for the other outcome measures followed this approach to analysis. Adverse and SAEs were analysed using Fisher’s exact test. Patient-reported change in symptoms and the PGIC were analysed using adjusted proportional odds ordered regression models.

Owing to the low level of missing data in the primary outcome, no imputation was undertaken.

Exploratory analyses

To assess the impact of changing the primary outcome measure from the Constant score to the OSS, we assessed the relationship between the two scores by fitting a simple linear model between the two outcomes at each time point.

Based on discussions with clinicians at sites, proximal humeral migration on a preoperative X-ray was used by some shoulder surgeons to understand the severity of the rotator cuff tear. 83,84 Explanatory models were used to assess the relationship between acromiohumeral position and the OSS data in the trial. The routine clinical images at baseline (X-rays and MRIs) were used to measure AHD for all participants recruited (registered) into the study. To assess the effects of AHD on the primary outcome, AHD was added as an additional confounder in the adjust mixed-effects model (described above).

Subgroup analyses

Prespecified subgroup analyses were undertaken to assess whether there was evidence that the intervention effect differed with respect to:

-

the size of the rotator cuff tear as measured at the start of surgery, defined as large or massive cuff tear (≥ 3 cm) or moderate to small tear (< 3 cm)

-

sex (male or female)

-

age (≥ 70 or < 70 years).

These variables were selected as they are either important to the function of the intervention (cuff tear size) or to interpretation (sex and age). The subgroup analyses followed the methods described for the mixed-effects model for the primary analysis, with additional interaction terms incorporated into the mixed-effects regression model to assess the level of support for these hypotheses. The study was not powered to formally test these hypotheses, so they are reported as exploratory analyses only, and are secondary to the analysis reporting the main effects of the intervention in the full study population. 85

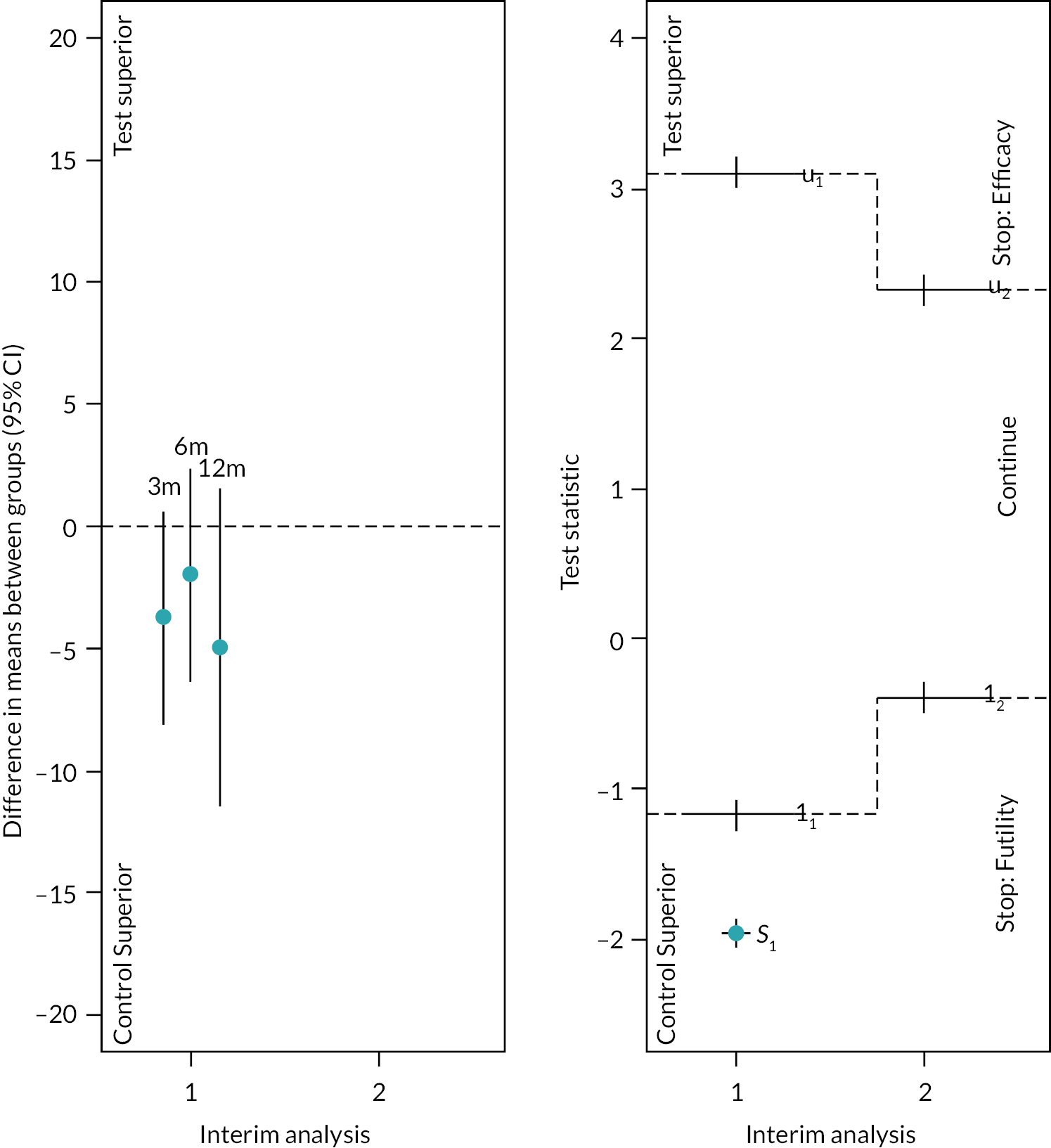

Interim analyses

Interim analyses were only undertaken following the principles laid out by Parsons et al. 61 Details of the timings and settings for the interim analyses were kept confidential so as not to prejudice the outcome of the trial based on the decision to stop the study or proceed but were recorded in the DMC meeting minutes and on date-stamped internal documents. The decision to stop the study early for efficacy or futility was not planned to be communicated outside of the DMC closed meeting. However, the TSC requested to view the interim analysis report before accepting the DMC’s recommendation to close randomisation.

Initial simulation study

A 3-month work package was undertaken at the start of study to develop appropriate methodological tools, implement a series of simulation studies using synthetic data to understand the properties of the selected design and its sensitivities to model assumptions and, in collaboration with the study DMC, agree futility and efficacy stopping boundaries. 61

Study end points for the OSS were at 3, 6 and 12 months. For the adaptive design, the 12-month primary outcome would have been too late to be used for determining futility before the study finished recruiting, and therefore, available early and late outcome data were used to determine early stopping.

A 3-month outcome was chosen, particularly as the balloon degrades after this time, with the predictive strength of the model strengthened further by the addition of 6- and 12-month outcomes. A decision to stop for futility would only be considered when there was sufficient confidence (based on this comprehensive simulation work) using all available 3-, 6- and 12-month data. A decision to stop because of clear evidence of efficacy was also considered in the modelling but especially strong evidence of efficacy (and the relationship to later outcomes) was required for early stopping.

Boundary setting

Futility stopping boundaries based on early and late observations of a single study end point with a final analysis adjusted for futility stopping have been suggested previously by Stallard. 58 Methodology developed previously by the group for two time points was extended to three time points (and also made more general) to allow the totality of observed data at planned interim analyses to be used to inform study progress (e.g. stopping).

Results from our systematic review suggested a strong association between early and late outcomes based on data from trials of interventions for rotator cuff tears. 42 A strong positive correlation between 3- and 6-month outcomes and 12-month outcomes indicated that information on the former early outcomes were strongly indicative of later outcomes, and consequently intervention efficacy or futility.

Sequential stopping boundaries were constructed that allowed stopping for futility or stopping to reject the null hypothesis (efficacy), with interim analyses determined by the results of the simulations and agreed with the TSC and DMC. 86 It was agreed that the stopping boundaries would be binding. Stopping boundaries for safety were also agreed and set as a separate criterion for early stopping.

Simulated data that replicate the metric properties of the primary outcome were then used to explore the characteristics of the design and sensitivities to likely treatment effect sizes and correlations between early and late outcomes. The aim was to understand changes in study power and rates of early stopping for a range of likely treatment effect sizes. The results of these simulation studies were presented to the TSC and DMC, and rules were agreed such that it was clearly defined as to when interim analyses should happen, what the thresholds were for early stopping, and how decisions should be communicated within the study team.

Preliminary simulations indicated that a single interim analysis using 3-month data on 53 patients per arm with the probability of early stopping under the null hypothesis set to 50% would result in only a small reduction in power to 88% for modest correlations between 3- and 12-month data. Given the findings of our systematic review of a good relationship between early and late outcomes in trials of interventions for rotator cuff tears42 and the fact that correlations were improved by considering all of the available time points, there is likely to be little loss of power.

As we expected correlations between time points (based on Karthikeyan et al.)76 and effect sizes to be equivalent between the Constant score and the OSS, these simulations remained valid, despite the change of primary outcome score. 68

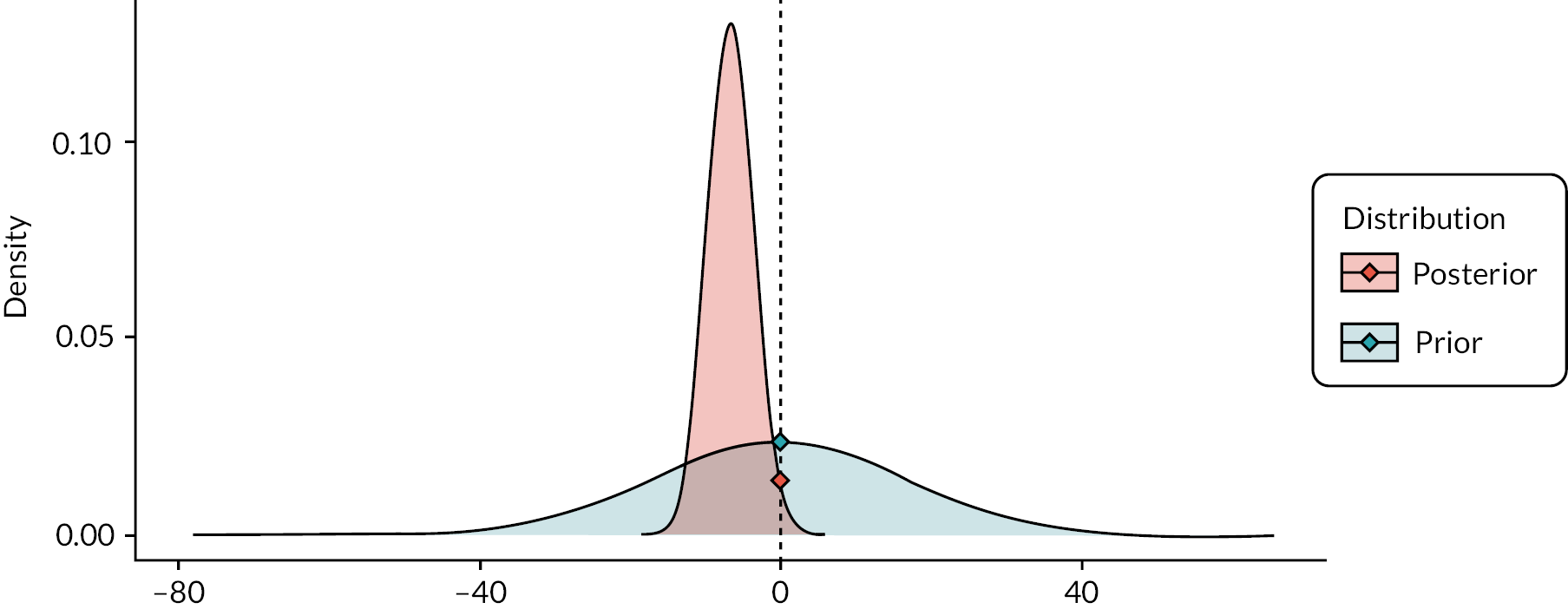

As with the primary analysis, the interim analyses were performed using a frequentist approach although a Bayesian framework was explored as a substudy (see Chapter 8).

Changes to the protocol

As described above, the planned primary outcome for the study was originally the Constant score. 38,39 However, in light of the COVID-19 outbreak in March 2020, the TMG decided to change the protocol to use the OSS as the primary outcome.

Various other changes were made to the original protocol throughout the duration of the trial. These include:

-

To insert the balloon, the ‘lateral portal’ incision was slightly larger – 1.5 cm as opposed to 1 cm. To ensure blinding to study allocation, we used a 1.5-cm incision for all participants.

-

For surgeons unable to attend a training session in person we suggested that they either read the surgery manual or watch an online surgery video.

-

As eligibility was confirmed intraoperatively, patients found to be ineligible at randomisation were informed that they were no longer taking part in the study by letter.

-

The number of sites taking part increased to 16–20 from the initial proposed amount.

-

We conducted two pilot studies for the MRI substudy (MRI pilot and shoulder muscle function pilot) prior to conducting the main substudy. This was to confirm that the design of the main substudy was robust enough to achieve the objectives set out.

-

There were concerns that participants who were lost to follow-up may have had safety events that we could miss. For that reason, we decided to contact the participants’ general practitioners for those who were considered lost to follow-up at 12 months to request information in regards to adverse and SAEs.

-

We used minimisation for randomisation rather than permuted random blocks based on a simulation exercise which demonstrated a high risk of major imbalance in the study arms with random permutated blocks. The randomisation process was changed to minimisation with a random factor, with a 70% weighting towards balance across the whole study.

-

The isometer was deleted from the secondary objectives and replaced with a dynamometer, which was used for the strength measurements at 3, 6 and 12 months.

-

Images were collected at baseline from previous imaging of the shoulder to assess in a secondary exploratory analysis whether imaging findings (especially proximal migration of the humerus) predicts outcome after surgery.

-

Planned sample size increased from 212 to 221 due to recalculation to increase the power in the study after discussions with the DMC.

-

We changed the time point for the first MRI in the substudy from 6 to 8 weeks, with the window between −2 and + 4 weeks. This was to ensure that participants had longer to recover from surgery before their first MRI.

-

The time window for the 3-month follow-up decreased from −6 to −2 weeks to ensure that participants had longer to recover before they returned for the 3-month follow-up.

-

Study participants whose postoperative pain interfered with their rehabilitation programme could be referred for a steroid injection (with or without local anaesthetic in the shoulder region).

Chapter 3 Main trial results

Participants

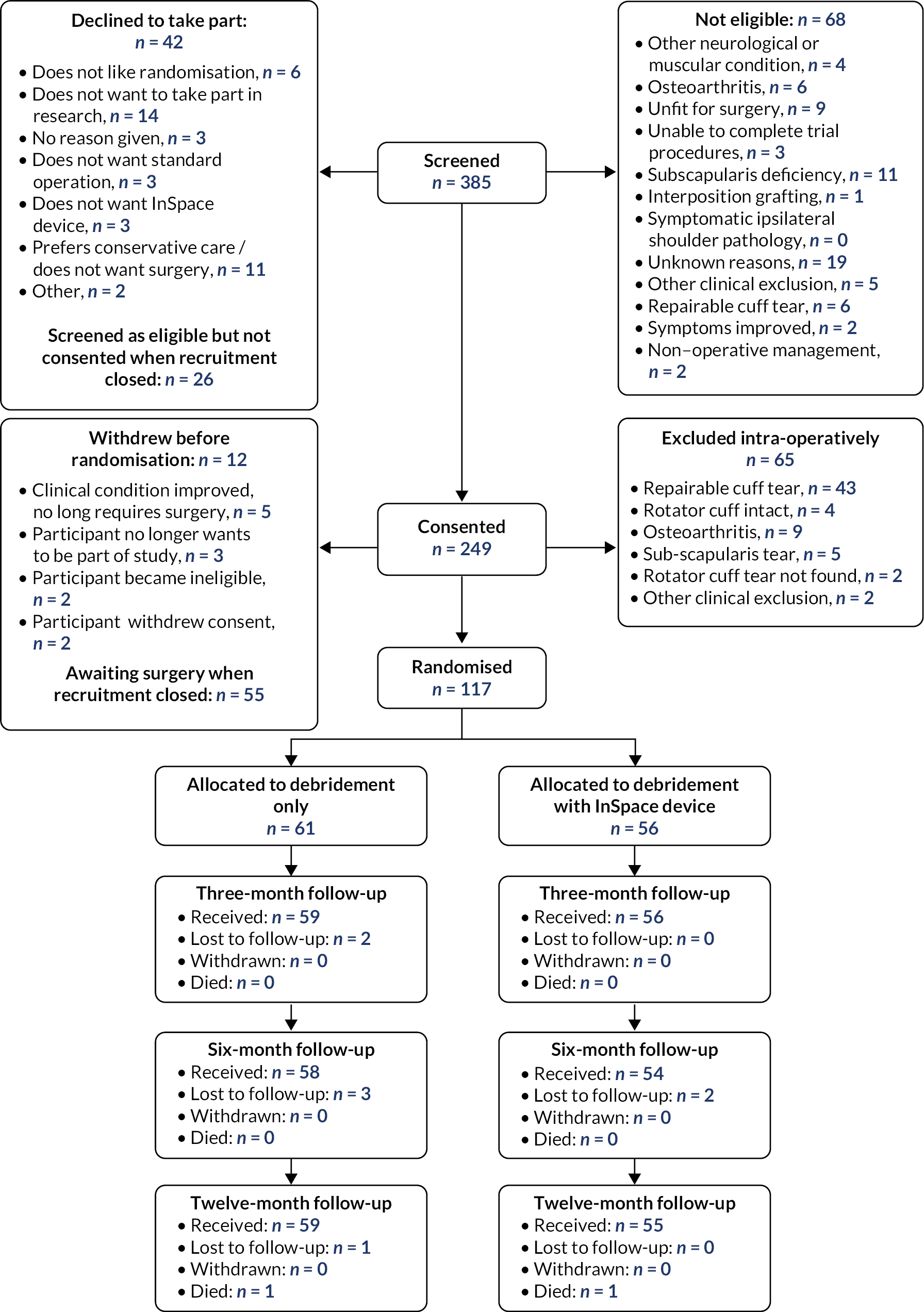

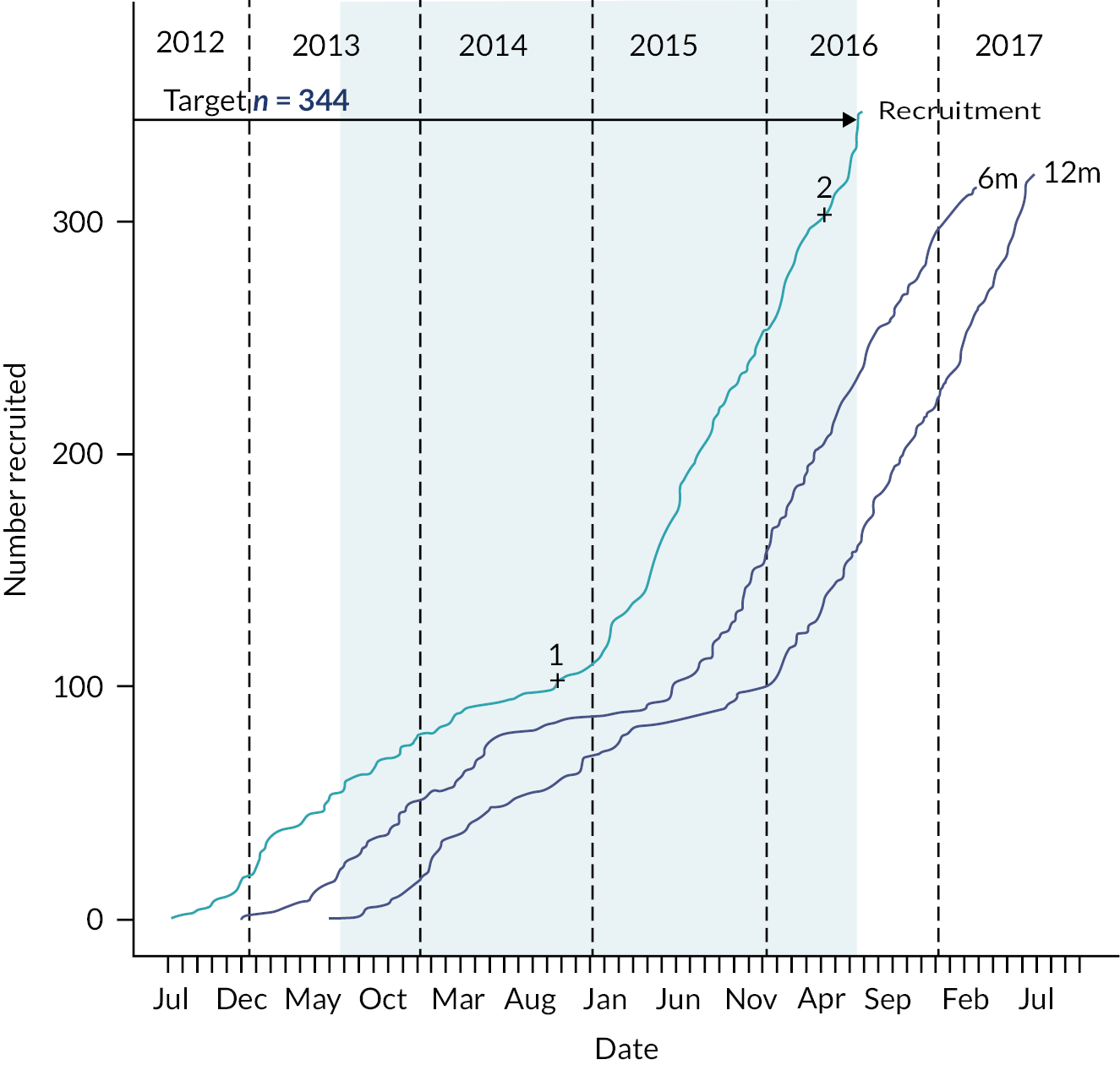

Between 1 June 2018 and 30 July 2020, we identified 317 eligible people and 249 (79%) consented to participate. A total of 117 participants were randomised into the study when recruitment was closed; 61 (52%) participants were randomised to receive arthroscopic debridement surgery alone, and 56 (48%) participants were randomised to receive arthroscopic debridement with the InSpace balloon (see Figure 2). On the 30 of July 2020, recruitment and randomisation were stopped after the futility boundary had been crossed at the first interim analysis. Stopping rules and observed data at the first interim analysis are given in Appendix 1.

FIGURE 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram.

Baseline statistics

Baseline variables were well balanced (see Table 1), although there were more male than female participants (n = 67 : 50), and slightly more under age 70 years in the InSpace balloon group. The mean age of the study participants was 67 years; 79 (68%) participants had injured their right shoulder, with 63% having their dominant shoulder affected. Mean duration of symptoms or pain was five years and 68% reported past trauma or injury may have caused the tear. Five participants had rotator cuff tears of less than 3 cm in the control group and one in the intervention group. The mean tear sizes were very similar between groups (debridement-only, mean 4.3 cm; debridement with InSpace balloon, mean 4.2 cm).

| Baseline statistics | Debridement-only (n = 61)a |

Debridement with InSpace balloon (n = 56)a |

All randomised (n = 117)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline details and demographics | Age (years) – mean (SD) | 67.3 (9.0) | 66.4 (7.6) | 66.9 (8.3) | |

| Age group (years), n (%) | Under 70 | 33 (54) | 36 (64) | 69 (59) | |

| Sex, n (%) | Female | 28 (46) | 22 (39) | 50 (43) | |

| Rotator cuff tear size, n (%) | Large (≥3 cm) | 56 (92) | 55 (98) | 111 (95) | |

| Medium/small (<3 cm) | 5 (8) | 1 (2) | 6 (5) | ||

| Right shoulder affected, n (%) | 42 (69) | 37 (66) | 79 (68) | ||

| Left or right-handed, n (%) | Left | 10 (16) | 5 (9) | 15 (13) | |

| Right | 51 (84) | 50 (89) | 101 (86) | ||

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | ||

| Dominant or non-dominant shoulder affected, n (%) | Dominant | 38 (62) | 36 (64) | 74 (63) | |

| Non-dominant | 22 (36) | 18 (32) | 40 (34) | ||

| Missing | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 3 (3) | ||

| Baseline PROM mean, - (SD) | OSS | 21.7 (9.4) | 23.1 (8.5) | 22.4 (9.0) | |

| Constant score | 33.6 (13) | 29.9 (13.4) | 31.9 (13.2) | ||

| WORC | 34.4 (14.2) | 33.7 (13.1) | 34.1 (13.6) | ||

| EQ-5D-5L | 0.501 (0.258) | 0.486 (0.247) | 0.494 (0.251) | ||

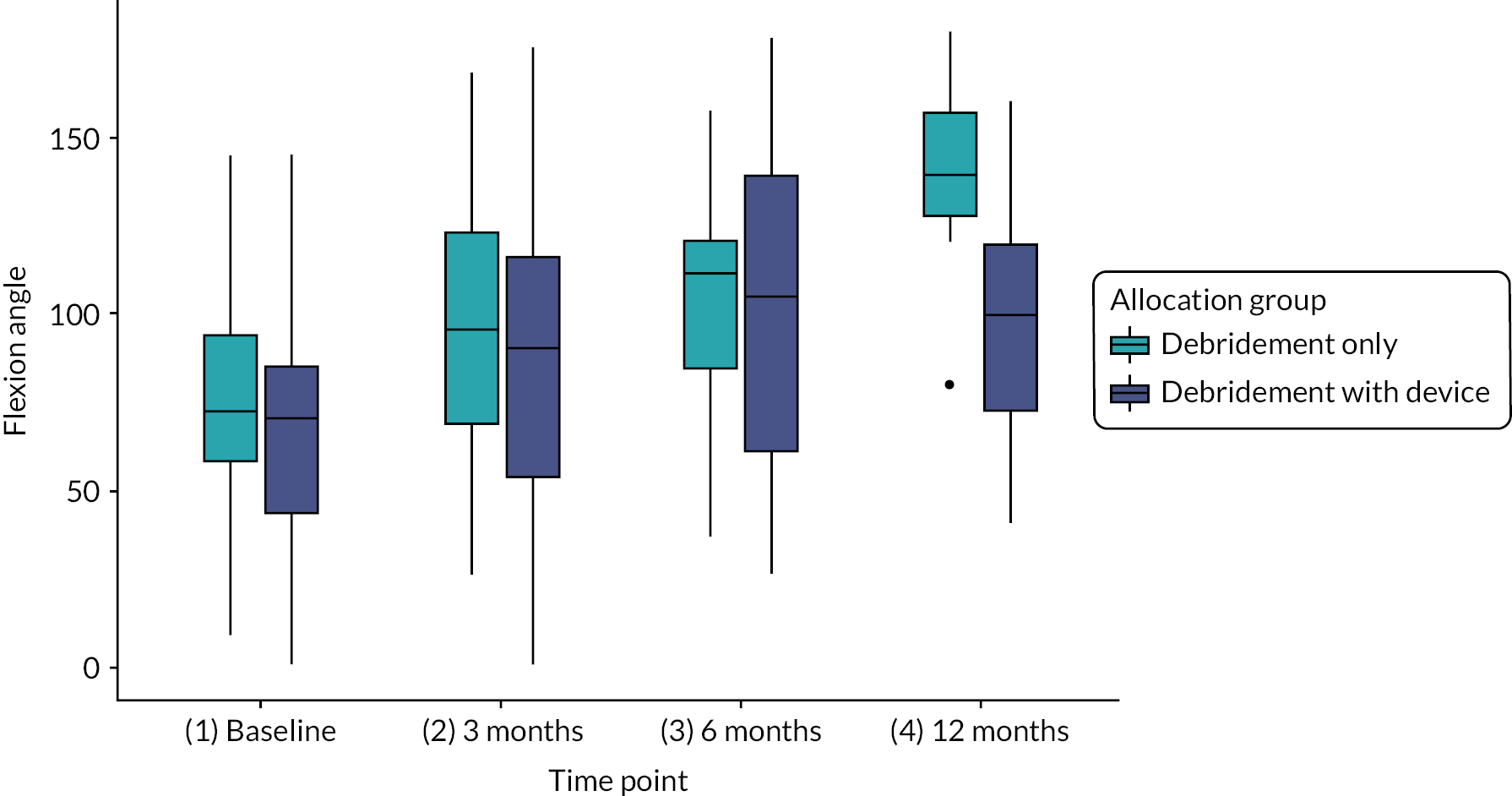

| Pain-free range of motion, mean (SD) (n = 109) | Abduction angle (degrees) | 76.3 (32.8) | 63.9 (22.2) | 70.5 (28.9) | |

| Flexion angle (degrees) | 74.1 (25.1) | 67.8 (29.8) | 71.1 (27.4) | ||

| Symptom duration in years – mean (SD) | 4.3 (6.2) | 5.5 (7.1) | 4.9 (6.7) | ||

| Other medical conditions, n (%) | 53 (87) | 45 (80) | 98 (84) | ||

| Participant smokes, n (%) | 4 (7) | 5 (9) | 9 (8) | ||

| Participant has diabetes (all type II), n (%) | 9 (15) | 9 (16) | 18 (15) | ||

| Participants has unilateral or bilateral symptoms, n (%) | Unilateral | 43 (71) | 39 (70) | 82 (70) | |

| Received previous physiotherapy treatment, n (%) | 42 (69) | 44 (79) | 86 (74) | ||

| Previously received steroid injection, n (%) | 34 (56) | 36 (64) | 70 (60) | ||

| Number of steroid injections taken | Median (range) | 2 (1–6) | 2 (1–10) | 2 (1–10) | |

| Previously had surgery on shoulder, n (%) | 16 (26) | 9 (16) | 25 (21) | ||

| Surgery details | Anterior-posterior tear size (cm) | Mean (SD) | 4.3 (1.3) | 4.2 (1.3) | 4.2 (1.3) |

| Mediolateral retraction from GT attachment (cm) | Mean (SD) | 4.3 (1.0) | 4.0 (1.0) | 4.1 (1) | |

| Biceps tendon intact, n (%) | 38 (62) | 39 (70) | 77 (66) | ||

| Subscapularis torn, n (%) | 12 (20) | 14 (25) | 26 (22) | ||

| Subscapularis tear size (cm) | Mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.4) | |

| Subscapularis repaired, n (%) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 4 (3) | ||

Primary outcome: Oxford Shoulder Score

Response rates were very high across the follow-up time points. Twelve-month primary outcome data were obtained from 114 of the 117 participants (97%). Of the three instances of missing primary outcome data, two participants had died (neither trial related) and one could not be contacted. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the OSS at each time point.

| Follow-up point | Statistic | Debridement-only (n = 61) |

Debridement with InSpace balloon (n = 56) |

All randomised (n = 117) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Received, n (%) | 61 (100) | 56 (100) | 117 (100) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 21.7 (9.4) | 23.1 (8.5) | 22.4 (9.0) | |

| 3 months | Received, n (%) | 59 (97) | 54 (96) | 113 (97) |

| Missing, n (%) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 4 (3) | |

| Mean (SD) | 30.4 (11.2) | 25 (10.4) | 27.8 (11.1) | |

| 6 months | Received, n (%) | 58 (95) | 54 (96) | 112 (96) |

| Missing, n (%) | 3 (5) | 2 (4) | 5 (4) | |

| Mean (SD) | 33.3 (10.4) | 28.5 (11) | 31 (10.9) | |

| 12 months | Received, n (%) | 59 (97) | 55 (98) | 114 (97) |

| Missing, n (%) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (3) | |

| Mean (SD) | 34.3 (11.1) | 30.3 (10.9) | 32.4 (11.2) |

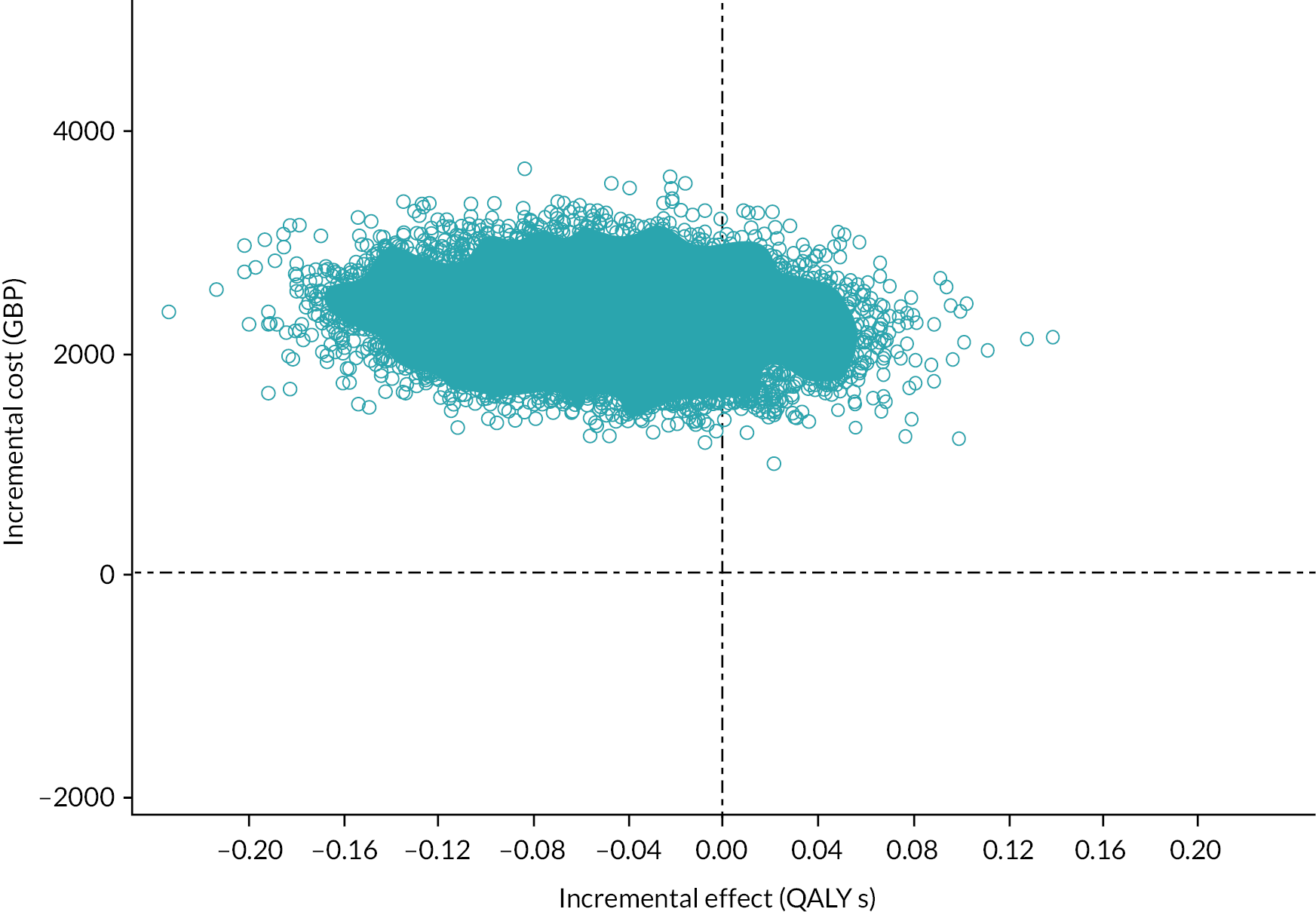

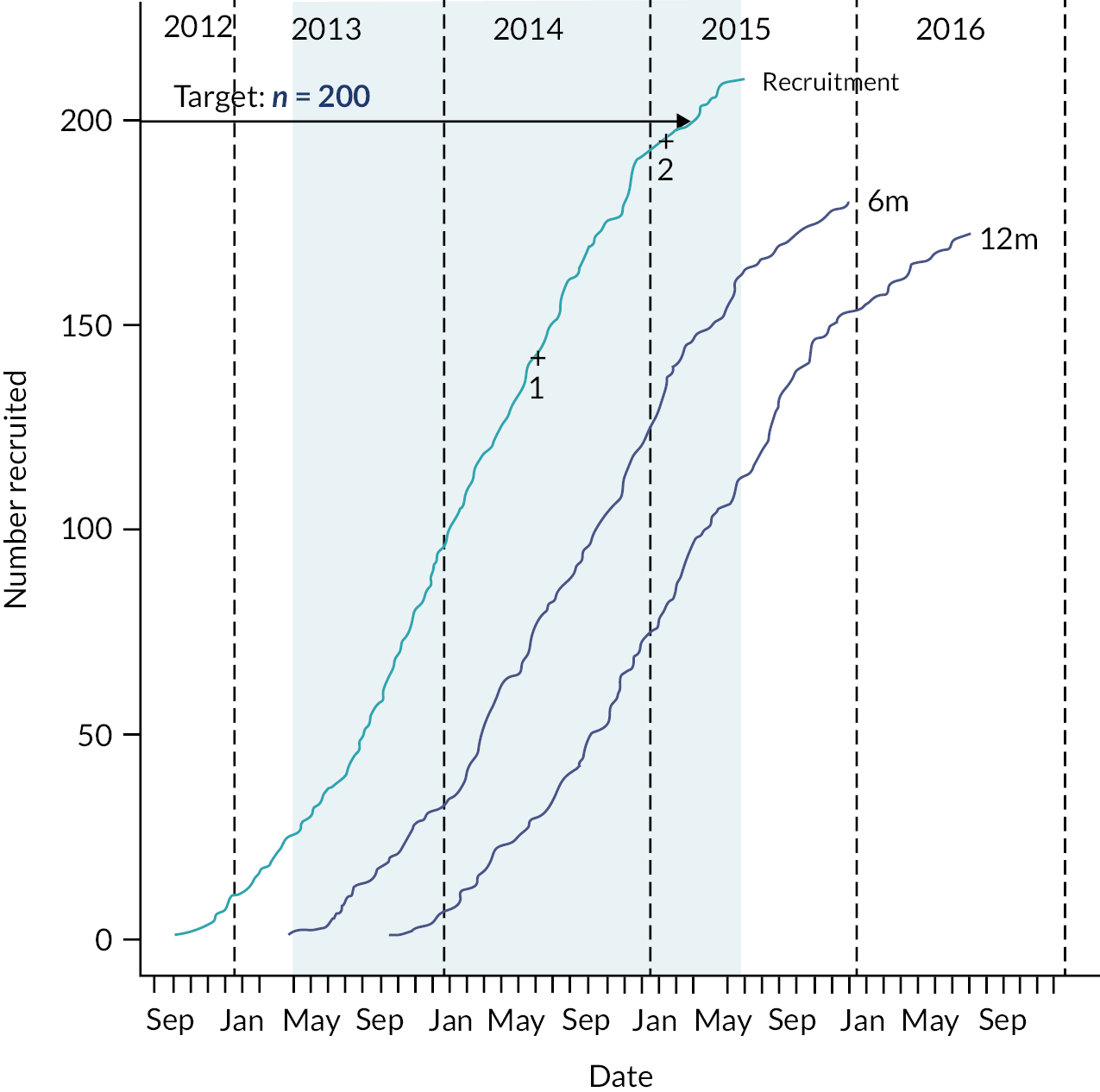

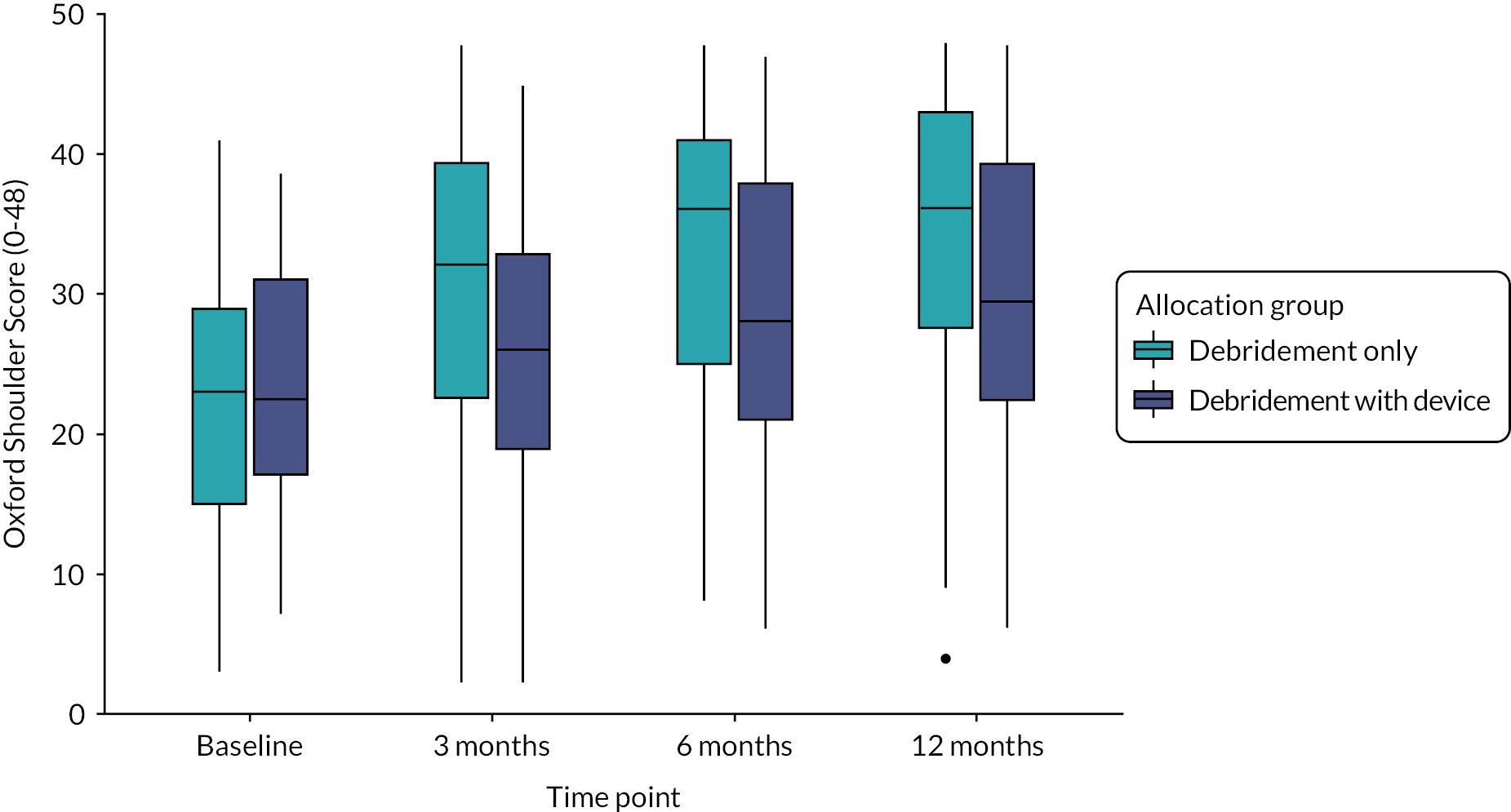

Figure 3 shows the mean OSS score at each time point and the two allocation groups. Scores improved compared with baseline in both groups. The debridement-only group had a relatively quicker recovery and higher scores at each of the follow-up time points.

FIGURE 3.

Oxford Shoulder Score means and 95% confidence intervals for each time point.

Primary efficacy analysis

In the primary intention-to-treat analysis, the mean (unadjusted) difference in the OSS at 12 months was −4.2 points (95% CI −8.2 to −0.26; p = 0.037), favouring debridement only. This estimate of the effect of the intervention is smaller than our target difference of six points, however, this difference is included in the 95% CI. It should also be noted that this was a target for a worthwhile benefit, and we had not specified what might be a meaningful harm.

Secondary efficacy analyses

The secondary prespecified efficacy analysis was a model adjusted to account for the baseline OSS, sex, tear size and age group. The results are shown in Table 3. A similar treatment effect was observed to the primary analysis, with the groups which received the InSpace balloon having worse outcomes than the group which received arthroscopic debridement alone (effect −4.2, 95% CI −7.8 to −0.6; p = 0.026). This difference was smaller than the target difference of six points. The baseline OSS score was the only other statistically significant variable, showing that those participants whose disability and pain were worse at baseline also had worse outcomes at follow-up. That is, there was an additional gain of 0.57 points (95% CI 0.4 to 0.8; p < 0.001) at follow-up for every point increase in the baseline OSS.

| Fixed effect variables | Coefficienta | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | Debridement-only | 0 |

– |

0.026 |

| Debridement with balloon | −4.2 | (−7.8 to −0.6) | ||

| Baseline | OSS score | 0.6 | (0.4 to 0.8) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | Male | 0 | – | 0.598 |

| Female | −1.1 | (−4.9 to 3.0) | ||

| Tear size | Large | 0 |

– | 0.349 |

| Medium or small | 4.0 | (−4.4 to 12.3) | ||

| Age group (years) | < 70 | 0 | – | 0.778 |

| ≥ 70 | 0.6 | (−3.2 to 4.4) | ||

Secondary outcomes

The Constant score

Further details of the Constant scores can be found in Appendix 1.

The Constant score had high levels of missingness due to the difficulty of obtaining data during the lockdown due to COVID-19. Insufficient data were collected to allow for the planned linear regression model to be calculated. However, as earlier time points were less affected, some inferences could be made on the 3- and 6-month data. The collected data showed that the debridement-only group had better outcomes at these early time points.

Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index

Further details of the WORC scores can be found in Appendix 1. Here it can be seen that the effect of the InSpace balloon again has a reduction on function (mean −8.4 points, 95% CI −16.7 to −0.1; p = 0.055), following the results of the OSS. Similarly, to the adjusted OSS model, smaller tear size and higher ages were associated with non-significant increases in function. Female sex was also associated with an in increase in function, but this was small (mean 1.5, 95% CI −7.3 to 11.1; p = 0.74).

EuroQol Five Dimension Five-Level score

Further details of the EQ-5D-5L scores at each time point can be found in Appendix 1. No terms were found to be statistically significantly associated with health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The InSpace balloon was associated with a small non-significant decrease on overall HRQoL (mean −0.056, 95% CI −0.15 to 0.03; p = 0.239). The older age group was associated with an increase (0.015, 95% CI −0.08 to 0.12) while female sex (−0.007, 95% CI −0.10 to 0.09) and smaller tear sizes (−0.059, 95% CI −0.28 to 0.15) were associated with reductions in HRQoL, although all these differences were non-significant.

Patient Global Impression of Change

Participants were asked to report how much better or worse their shoulder felt 12 months after their surgery as well as if there was any change in their activity limitations, symptoms, emotions, and overall QoL. Details are shown in Appendix 1. There were no statistically significant differences in either overall change (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.3 to 1.2) or in PGIC (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.3 to 1.1); although both questions favoured the arthroscopic debridement alone group.

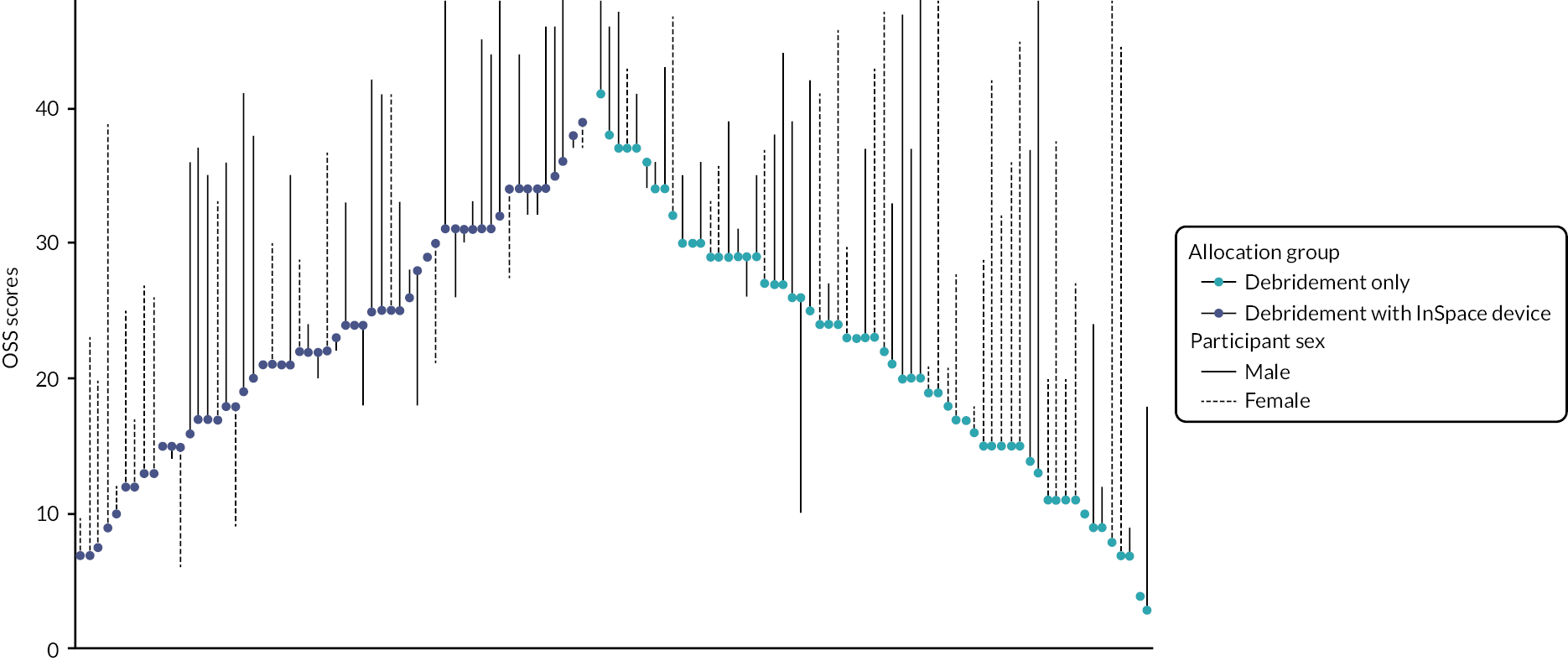

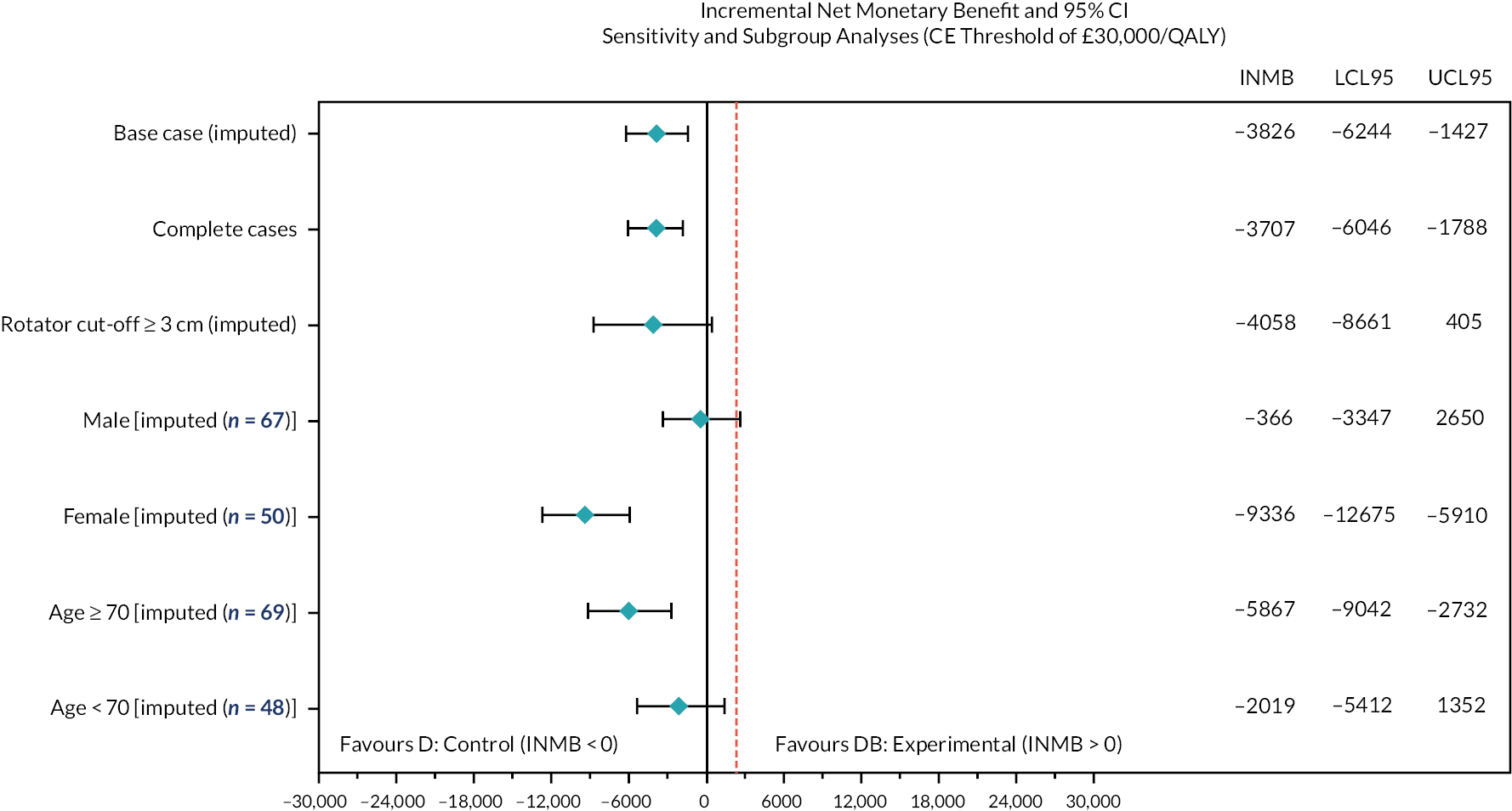

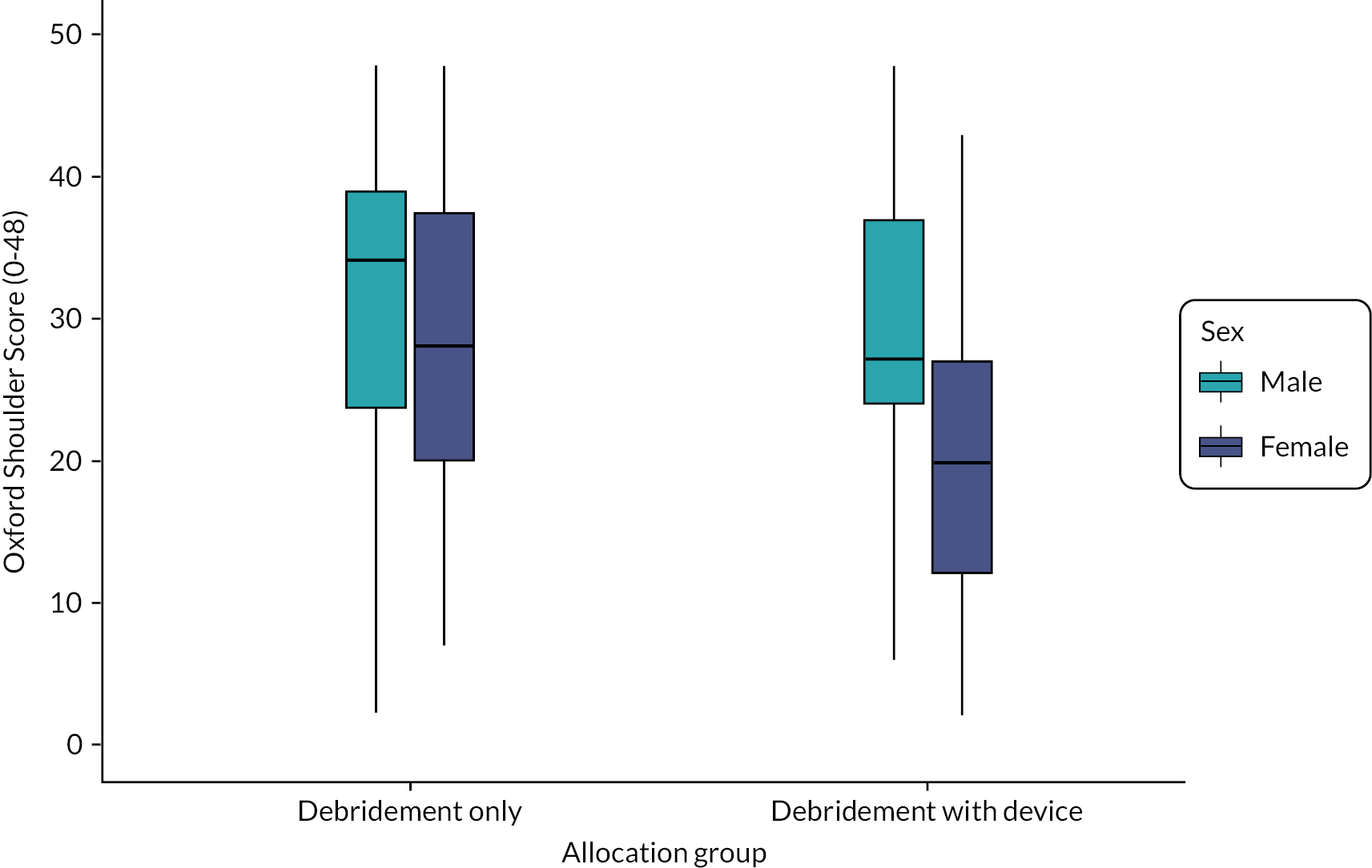

Subgroup analyses

Descriptive statistics and details of the models for each of the pre-specified subgroups (age group, tear size and sex) can be found in Appendix 1. The results of each of the three subgroups are summarised visually in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of the adjusted effect of the allocation group on 12-month OSS for each pre-planned subgroup. Blue circles denote the adjusted mean difference, grey whiskers the 95% CI. Values left of zero favour the arthroscopic debridement group.

When including an interaction term for age and allocation group, the model remained broadly consistent with the secondary effect analysis (interaction effect for InSpace balloon and 70 years and over −5.3, 95% CI −12.1 to 2.38). This was also the case for tear size (interaction effect for InSpace balloon and small tears 6.8, 95% CI −14.9 to 28.8). Note that because of the small number of small to medium tears, the marginal effects of tear size could not be estimated.

Participant sex was found to be an important confounder (interaction effect for InSpace device and female sex −9.5, 95% CI −16.5 to −2.6). Females in the InSpace balloon allocation group had a decrease in function, larger than the worthwhile difference, when compared with males. Figures depicting this effect can be found in Appendix 1.

To further investigate this effect, we constructed a waterfall plot (see Figure 5). This allows us to inspect visually the effects of baseline and 12-month OSS, allocation group and participant sex. Here, it can be seen that while females tended to have lower scores at baseline, those allocated to receive debridement-only typically had larger gains than those who received the InSpace balloon. Most participants reported better function at follow-up than at baseline, although a larger number of people declined in function in the balloon group compared to baseline.

FIGURE 5.

Waterfall plot of 12-month OSS score by sex and allocation group. Scores have been ordered by baseline score (highest at centre) and allocation group (debridement-only on right-hand side). The coloured dot denotes the participant’s baseline score, which is joined to the participant’s 12-month OSS by a line (solid for males, dashed for females).

Safety data

Overall, 20 participants reported a total of 28 adverse events. Numbers were similar in the two groups (n = 9 : 11; see Table 4). There were six serious adverse events, four in the debridement with InSpace balloon group and two in the debridement-only group. Three serious adverse events were considered unrelated to the surgery and three were considered related: two (one in each group) for persistent pain or disability at 12 months (defined as requiring continuing secondary care review) and one for further surgery, a reverse shoulder replacement in the debridement with device group.

| Adverse events | Debridement-only (n = 61) | Debridement with InSpace balloon (n = 56) | Total (n = 117) |

p-values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant experienced any AE (n, % of total participants in group) |

9 (15) | 11 (20) | 20 (17) | 0.624 | |

| AEs per participant, n (% of total participants with AEs) |

1 | 7 (78) | 9 (82) | 16 (80) | 0.592 |

| 2 or more | 2 (22) | 2 (18) | 4 (20) | 1 | |

| Total reported AEs (n) | 11 | 17 | 28 | 0.134 | |

| Exacerbation/persistence of shoulder pain or restrictive ROM, n (% of total AEs in group) | 5 (46) | 6 (35) | 11 (39) | 0.756 | |

| Injection into the shoulder region, n (% of total AEs in group) | 1 (9) | 3 (18) | 4 (14) | 0.348 | |

| Adhesive capsulitis, n (% of total AEs in group) | 0 | 2 (12) | 2 (7) | 0.227 | |

| Persistent muscle soreness or muscle injury, n (% of total AEs in group) | 0 | 1 (6) | 1 (4) | 0.479 | |

| Other, n (% of total AEs in group) | 5 (46) | 4 (24) | 9 (32) | 1 | |

| Related events – SAE category | |||||

| Participants experiencing ≥ 1 SAE, n (% of total participants in group) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 3 (5) | NA | |

| Total reported SAEs (n) | 1 | 2 | 3 | NA | |

| Hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, n (% of SAEs in group) | 0 | 1a (50) | 1 (33) | NA | |

| Persistent or significant disability/incapacity, n (% of SAEs in group) | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 2 (67) | NA | |

| Was related SAE expected: Yes, n (% of related SAEs in group) | 1 (100) | 2 (100) | 3 (100) | NA | |

| Related to InSpace balloon, n (% of total in group) | NA | 2 (100) | 2 | ||

| Unrelated events – SAE category | |||||

| Participants experiencing ≥ 1 SAE, n (% of total participants in group) | 1 (2) | 2 (4 | 3 (3) | NA | |

| Total reported SAEs (n) | 1 | 2 | 3 | NA | |

| Hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, n (% of SAEs in group) | 0 | 1 (50) | 1 (33) | NA | |

| Persistent or significant disability/incapacity (n, % of SAEs in group) |

1 (100) | 1 (50) | 2 (67) | NA | |

Sensitivity and exploratory analyses

Effects of COVID-19

We undertook a sensitivity analysis to assess if COVID-19 could have affected the primary analysis. Data from participants who had completed the 12-month primary outcome before the first lockdown were compared with the remaining participants; 25 participants had completed their 12-month primary end point prior to the first UK lockdown (20 March 2020) and 89 participants were followed up during/after the COVID-19 lockdown period. The results of this analysis (see Appendix 1) confirm that COVID-19 did not significantly change the collected OSS or EQ-5D-5L scores at 12 months, nor did it affect the completion rates. However, since there was a major impact on collecting the 12-month Constant score (97.8% missing during or after COVID-19), this score could not be assessed.

Acromiohumeral distance and rotator cuff pathology

Since more participants than expected were excluded intraoperatively, we did additional exploratory analyses to explore whether there were differences in the pathology between the two groups at registration, prior to surgery. Hence, these analyses should be interpreted with caution and may not be generalisable.

While baseline OSS and Constant scores were both greater in the repairable cuff tear group, these differences were small and not statistically significant (OSS mean difference 2.1, 95% CI −5.0 to 0.9; Constant score mean difference 3.8, 95% CI −1.2 to 8.9). The difference in AHD was statistically significant with those which had a repairable cuff tear having a significantly larger AHD than those with a non-repairable tear (mean 1.1, 95% CI −0.11 to 2.1; p = 0.034). Full details of these analyses can be found in Appendix 1.

Acromiohumeral distance and Oxford Shoulder Score at 12-month follow-up

Including AHD into the adjusted efficacy model showed that the OSS improved by approximately 0.47 points for every 1 mm increase in the AHD; however, this was not a statistically significant result (95% CI −0.3 to 1.2; p = 0.236). The effect of the allocation group remained broadly similar to the main analyses, favouring the debridement alone group.

Relationship between the Oxford Shoulder Score and the Constant score

The original primary outcome was the Constant score (see above). As the study design was dependent upon the observed correlations at each follow-up pint, Pearson’s correlation coefficient between this outcome and the OSS were calculated to confirm that it was a suitable alternative. The OSS is scored between 0 and 48, hence we rescaled scores to a 0–100 range to allow direct comparison to the Constant score (range is 0–100). These results (see Appendix 1) suggest that the Constant score has a strong association with the OSS at each time point.

Chapter 4 Discussion of main trial results

Clinical discussion

We set out to test the effectiveness of a new surgical procedure, the InSpace subacromial balloon spacer, for people with irreparable rotator cuff tears. The study was blinded and the comparator was an otherwise identical procedure without the balloon. A futility boundary was crossed and the study stopped with 117 participants recruited as the result of a planned interim analysis. Arthroscopic debridement was found to be superior to arthroscopic debridement with the InSpace device, based on the OSS 12 months after surgery. Given that the only difference between the two interventions was the device itself, it is highly unlikely that the balloon provides any meaningful benefit, and it could be harmful.

Secondary outcomes were in agreement with the primary outcome. Although these were mostly not significant, there was a consistent pattern of change in favour of debridement-only. Significant differences were noted for some of the objective measures such as strength and ROM, although numbers for these measures at later time points were limited due to the pandemic, so these should be treated with caution. Safety data showed no differences between interventions, although as there were few adverse events, the sample size was much too small to detect any meaningful difference in this regard.

The target difference for the OSS this study was six, based on previous anchor-based studies and used in other multicentre trials. 41,68,69,76 While the point estimate was lower than this, the target difference was contained within the CI and the CI excluded zero. Minimum clinically important differences (MCIDs) are typically determined to measure benefit, they are less likely to be relevant in the setting of negative results. It may be difficult to justify using any intervention that shows statistically significant worse results on the primary outcome compared with control, no matter how small the point estimate of the difference.

In the subgroup analyses, a strong effect of sex was observed, with poor results for the device in females. We strongly caution against the use of the device in females but, even in males it is unlikely that the device provides any benefit. There was no other significant association found in the subgroup analyses, although an association with age (older people having worse results) could not be ruled out.

The lack of influence of baseline AHD on outcome should reassure surgeons that there is not a latent subgroup related to radiographic disease severity.

A blinded multicentre trial of the InSpace device compared with partial rotator cuff repair was conducted by Verma et al. 87 and was reported shortly after our study, in April 2022. This was a company-funded trial (by OrthoSpace, subsequently purchased by Stryker) and contributed to the device being awarded FDA marketing approval in the United States in 2021. The eligibility criteria were different to ours, principally as the study was focused on people with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears (over 5 cm or two or more tendons torn). However, in our study, tear size did not appear to influence the result. The study reported non-inferiority of the balloon compared to partial cuff repair, with similar outcomes across most domains at the primary outcome time point of 2 years. 43 A small improvement in the secondary outcome of ROM was seen in the balloon arm, although some differences were present at baseline, and any discrepancy in this might be related to stiffness after partial repair. Partial rotator cuff repair is rarely used in the UK in this condition and the evidence for its use is limited to case series data, with mixed results reported. 44,45,83 The trial did not directly test the effect of the balloon, as we have in the present trial.

Apart from the direct clinical impact, the findings of our study also demonstrate the critical importance of randomised trials in the early evaluation of surgical devices and techniques, before they are introduced into widespread clinical practice. The InSpace device had been used in around 29,000 cases in Europe at the time of the 2021 FDA approval, largely on the basis of case series data alone, most of which has only been published in the last few years. 23 Case series are unable to demonstrate a true benefit as a comparator is needed. We have previously shown in a meta-analysis that outcomes for people with a rotator cuff tear improve over time regardless of the treatment given, and, therefore, an improvement in patient outcome from baseline does not mean that a treatment is effective.

There was no clear pattern in the safety data and this is also an important observation. Monitoring of safety data alone cannot be used to ensure that a product is not causing harm. Such information may only be evident in a robust evaluation of clinical outcomes, such as a clinical trial reporting patient-focused outcomes.

This study identifies a deficiency in the current process for introducing new surgical devices and procedures. One solution to this would be to apply the IDEAL criteria more stringently to the introduction of new procedures, allowing registered prospective development studies and randomised trials in approved centres, but only allowing a product or technique to be more widely available when convincing proof exists that it is likely to be of benefit. 88,89 This would be a marked change to current practice but would protect patients from potential harm and prevent the health service from incurring unnecessary expense.

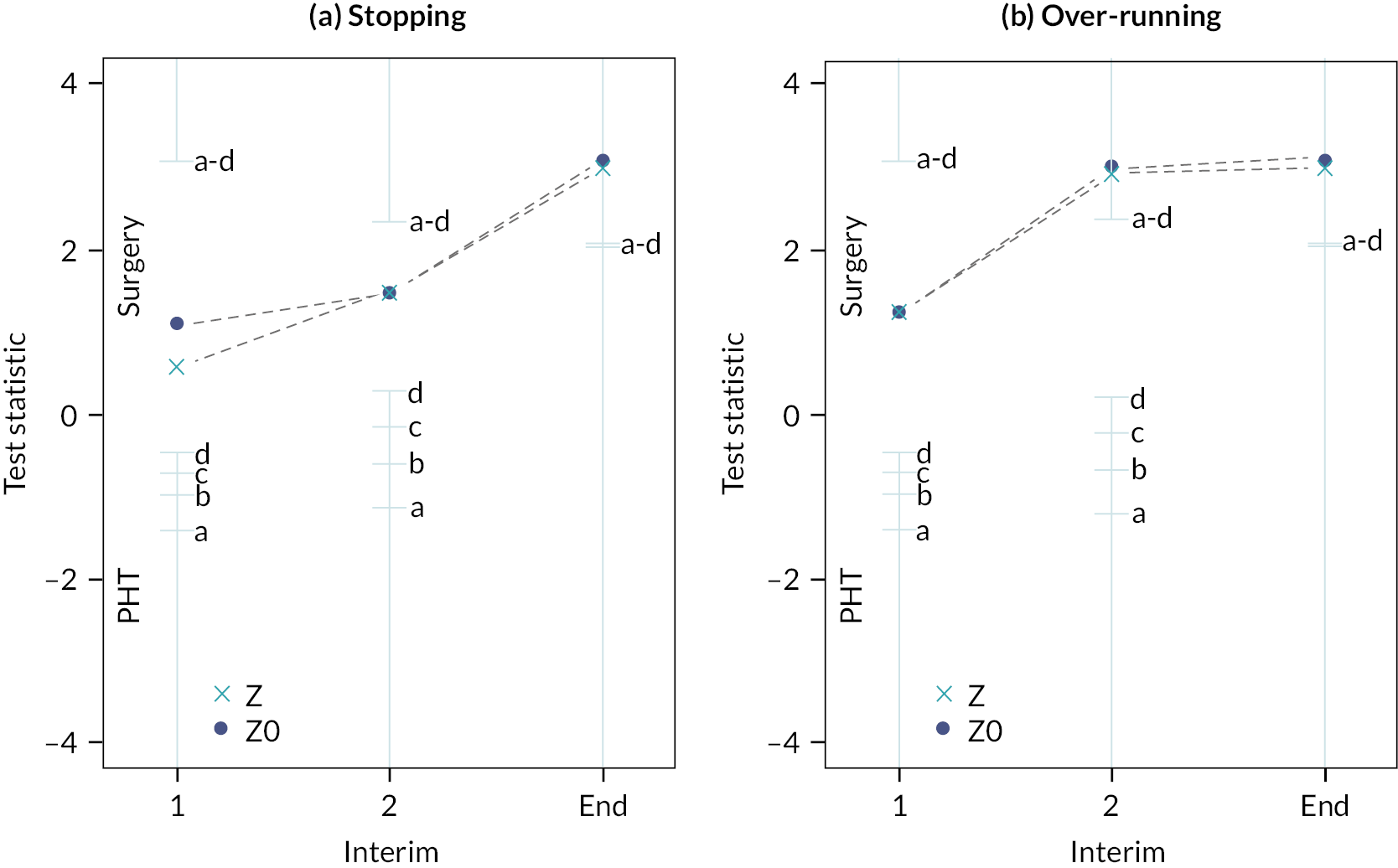

Adaptive design methods

In this study, we have successfully implemented a novel adaptive group sequential randomised trial, using the correlation between early end point data and the primary outcome to inform stopping decisions at two planned interim analyses. The correlations between time points were higher than expected and due to the pandemic, we continued to accrue outcome data for a 3-month period while randomisations were paused. As a result of these factors, the emerging data enabled us to stop recruitment early with robust data in what would have otherwise been a very challenging time. Assuming that we continued with the rate of recruitment that was observed prior to March 2020, the study would have taken an additional 11 months to recruit the full sample size, although it is likely that recruitment would have been further delayed by the effects of the pandemic on elective surgery. This highlights the value of the novel methodology by not only saving on research costs but also by providing much earlier impact for patients and the health service, improving patient outcomes and saving money.

Having successfully implemented this novel methodology in one study, we recognise the need for ongoing work to establish this as a technique for future use and to convince clinicians, trials methodologists and research funders that the methods could be used more widely. To address this, we undertook a large simulation study using data from multiple previous high-impact randomised trials; this work is reported in Chapter 7.

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations which should be considered. As the study stopped early, CIs remained wide for the secondary outcomes and a larger sample size may have provided more precise estimates. The study was designed to determine if the device was effective or not, which was consistently answered by both the primary and secondary outcomes. Even if a larger sample size demonstrated further evidence of harm, the implications of the findings would remain that the device is not recommended in this population. A larger sample size would have exposed more people to risk, but it is highly unlikely that the overall findings of the study would change. The study was not designed to have adequate power for subgroup analyses, either at 117 or 221 participants, and it is unlikely that the clinical conclusions would have been changed had these analyses been formally powered. While the device could be of benefit in a different population, our eligibility was focused on the most commonly used indications for the device both in the UK and internationally. Because of the pandemic, we were not able to collect objective measures for many of the participants, especially at 12 months, although the objective outcomes we did take in the study were consistent with the primary outcome and significant differences were observed in favour of debridement-only, although with a very small amount of data.

This study was not designed to determine the effectiveness of arthroscopic debridement for people with an irreparable rotator cuff tear. It is commonly used in the UK for this indication and provided an appropriate comparator in this study. Given the results presented here, there is need for a future trial of arthroscopic debridement compared to alternative surgical procedures, placebo, or a non-surgical intervention. There is also a need for additional RCTs of other treatments, as there is a lack of evidence for all available treatment options for irreparable rotator cuff tears at present.

Conclusion

We implemented a novel group sequential, blinded, multicentre randomised trial in people with irreparable rotator cuff tears and found that arthroscopic debridement was superior to an otherwise identical procedure performed with the InSpace device. We do not recommend the InSpace balloon spacer in this population.