Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as award number 11/30/07. The contractual start date was in February 2014. The final report began editorial review in November 2022 and was accepted for publication in May 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Bhandari et al. This work was produced by Bhandari et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Bhandari et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Many different diseases may damage the kidneys and most result in a progressive decline in kidney function with time, known as chronic kidney disease (CKD). Some patients with CKD may progress to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) requiring dialysis and/or kidney transplantation to prolong life and improve clinical outcomes. The progressive nature of kidney damage, irrespective of cause, is a major global challenge. Despite an increasing number of treatments that slow the decline of kidney function with time, the numbers of patient with ESKD will continue to increase.

Chronic kidney disease affects 9.1% globally and up to one in seven people in the UK. 1 The underlying common pathogenic process is progressive renal scarring as evidenced by tubulo-interstitial fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis, irrespective of the underlying causative disease, which most commonly is diabetes and/or hypertension. CKD has serious implications for those affected and is associated with a high prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) disease, early mortality and high economic cost. 1 The risk of adverse event (AEs) is directly related to the severity of the CKD; advanced CKD (stage 4 or stage 5) is associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk of death, and an up to 50-fold increased risk of kidney failure, as defined by requirement for dialysis treatment, compared to that of age-matched individuals with normal kidney function. 2–5 Furthermore, the presence of advanced CKD has a major negative impact on a range of other outcomes including quality of life. 6,7

A high proportion of the healthcare budget is spent on people with kidney disease. The most explicit example of this being the cost of dialysis treatment for ESKD, which is ~£32,000/year/patient. 4 This cost is in a patient group with poor health and poor quality of life, a 10–15%/year mortality risk and a substantial increase in hospitalisations. 1,5,6 The management of people requiring dialysis currently requires approximately 3% of the total NHS budget. 7 For CKD overall the economic costs are profound. A recent economic analysis, based on Public Health England data, projected that by 2025, CKD will cost £11.4 billion for every 1 million people with diabetes. Consequently, there are major benefits associated with slowing the progression of CKD to ESKD for patients, their families and for the healthcare systems in which they are managed. Treating high blood pressure (BP) is the most important intervention that can slow the progression of CKD. Some people with CKD, especially those with proteinuria, gain additional protection from angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). 8–11 There is also benefit of use post myocardial infarction and for other CV events, an important consideration given the high CV risk to this patient group. 12

There is some evidence that in people with advanced CKD estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR < 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2; stage 4 or stage 5) who are progressing towards ESKD and are receiving treatment with renin–angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors, discontinuing these drugs may lead to a stabilisation or improvement of kidney function and decrease or delay the need for dialysis treatment. 13 To date, the research on this has been limited to a small randomised single-centre trial in Asia,14 post hoc analyses in other studies,15,16 observational studies of RAS inhibitors across all eGFRs17 and analysis from registry studies. 18

A meta-analysis19 reporting an association between discontinuing RAS inhibitors and stabilisation of kidney function, however, also reported a potential increased risk of major CV events and death in people with low eGFR values in whom RAS inhibitors were discontinued. This was not supported by Registry data suggesting no benefit on kidney function. 20 Furthermore, Molnar and colleagues analysed a representative US veterans cohort with non-dialysis CKD consisting of 141,413 participants of which 26,051 had received treatment with RAS inhibitors. The population was 97% male with a mean age of 74.8 ± 19.8 years, with a mean [± standard deviation (SD)] eGFR of 52 ± 16 ml/minute/1.73 m2 and only 6% of patients in CKD stage 4 or stage 5 category. They found an association with reduced all-cause mortality in the RAS inhibitor group, but only 10% remained on treatment throughout all follow-up visits. 17 Cheng et al. , in a meta-analysis, separately evaluated the effects of RAS inhibitors on all-cause mortality, CV deaths, and major CV events in patients with diabetes mellitus. 21 In their final analysis of 20 eligible studies (with 25,544 participants), they found a 13% reduction in all-cause mortality [hazard ratio (HR) 0.87, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 0.98], 17% in CV death (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.99), 21% in CV events (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.95) and 19% in heart failure (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.93), in patients receiving ACEi compared to placebo. For studies where patients received ARBs, there were 11 eligible studies (with 17,334 participants), and there was significant association with a reduction in heart failure events (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.82), but not in other CV end points. Notably, there have been no clinical trials of the impact of RAS inhibitors on progression of kidney disease where patients are randomised at an eGFR of < 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2, and this remains a much-understudied cohort of patients in historical randomised clinical trials. 22,23

Clinical data

Irrespective of the underlying cause of CKD, the use of RAS inhibitors for the control of BP (hypertension is an almost universal complication and co-factor in the progression of CKD), and minimisation of urinary protein excretion (a surrogate for glomerular hypertension and risk of progressive CKD) has a central role in clinical practice in slowing the progression of CKD in patients with mild to moderate CKD. The rationale is that RAS inhibitors reduce intraglomerular pressure over and above the effect of these agents on systemic BP. High intraglomerular pressure through direct effects on the glomerular vasculature leads to changes in intraglomerular extracellular matrix and the development of glomerulosclerosis and tubule-interstitial scarring through proteinuria and other mechanisms.

Lewis and others demonstrated that RAS inhibitors reduced the doubling time of creatinine in patients with type I and type II diabetes over a 3-year period. 8–10 Further studies have shown that RAS inhibitors reduced the progression of kidney disease in patients with no diabetes. 14,24–27 Data from the HOPE, LIFE and ALLHAT studies have confirmed the benefit of ACEi use in mild CKD. 28–30 Ruggenenti et al. in an analysis of 322 patients with non-diabetic CKD at varying stages of disease randomly assigned to either ramipril or conventional treatment, found that the renoprotective effects were maximised when ACEi therapy was started earlier in the course of the disease [i.e. glomerular filtration rate (GFR) > 50 ml/minute/1.73 m2], but suggested that therapy should be offered to all patients with CKD, even those with a GFR between 10 and 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2. 15 In 2006, Hou et al. examined a Chinese population of 422 patients with non-diabetic CKD and placed them into one of two groups based upon their baseline serum creatinine levels. Patients in group 1 (serum creatinine between 133 and 265 µmol/l; n = 104) received 20 mg of benazepril per day and patients in group 2 (serum creatinine between 274 and 442 µmol/l) were randomised to 20 mg of benazepril per day (n = 112) or placebo (n = 112). Participants were followed up for a mean of 3.4 years. 14 The authors reported a statistically significant, 43% decrease in the composite end point of doubling of serum creatinine level, progression to ESKD, or death, in the benazepril group compared to placebo. In 2006, a Cochrane Review explored the use of RAS inhibitors in preventing the progression of kidney disease in patients with diabetes. 31 The review included 49 studies with 12,067 patients at all stages of kidney disease. It included studies that compared ACEi or ARBs to placebo and studies that directly compared ACEi and ARBs. The authors found that both ACEi and ARBs improved kidney outcomes (ESKD, doubling of creatinine, prevention of progression of microalbuminuria to macroalbuminuria, remission of microalbuminuria to normoalbuminuria). 31 Further, when compared to placebo, use of ACEi at maximum tolerated doses appeared to prevent death in patients with diabetic kidney disease [relative risk (RR) 0.78, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.98]. These mortality data were not found with ARBs. The authors however cautioned against the conclusion that RAS inhibitors prevent the progression of CKD and suggested that the beneficial initial effect seen may be due to their anti-proteinuric effects, and that there was little robust evidence of benefit in advanced CKD and that the conclusions were based mainly on composite end points.

These studies suggesting that RAS inhibitors are renoprotective, and potentially cardioprotective, in patients with CKD have led to guideline recommendations where the evidence base for RAS inhibitors in patients with mild to moderate kidney disease and with proteinuria and/or diabetes has been interpreted as also applying to advanced CKD. 32 However, the rigour of some of these studies, which did not dissect the renoprotective effects that are specific for RAS inhibitors from their antihypertensive effect, is now being questioned by many nephrologists.

A detailed assessment of published data from the REIN study indicated a limited effect of ACEi on GFR progression despite a large difference in composite end points including doubling of serum creatinine. 15,24 This may relate, in part, to the effects of ACEi on reducing glomerular capillary pressure and increasing glomerular blood flow through efferent arteriole vasodilatation, leading to a reduction in filtration fraction and hence proteinuria. ACEi should lead to increased peritubular circulation secondary to improved efferent arteriolar blood flow. However, the increase in peritubular capillary flow may affect proximal tubular transport of proteins and creatinine via effects on the organic cationic transporters, leading to increased tubular creatinine secretion, a fall in serum creatinine and hence an apparent rise in GFR. 33

While these principles may hold for mild to moderate CKD, the biological actions and clinical effects in advanced CKD are unknown. Renoprotection from RAS inhibitors may be lost in more advanced disease where significant ischaemic nephropathy is present and there is loss of peri-tubular capillary vasculature. This hypothesis is supported by reports in patients with CKD both with and without diabetes indicating that RAS inhibitors may accelerate kidney progression. 11,34 It is possible that in more advanced CKD the intrarenal haemodynamic effects of RAS inhibitors may decrease the time to ESKD. Furthermore, combined ACEi/ARB treatment has been shown in one large study to worsen kidney outcomes in patients at high CV risk. 35

A meta-analysis of nine randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (n = 9797 participants) of at least 6 months’ duration in adult patients with diabetes and non-dialysis-dependent CKD stage 3 to stage 5 examined single RAS inhibitor versus placebo or an alternative antihypertensive agent. 36 The authors found no difference between the RAS inhibitors group and control group regarding all-cause mortality (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.1), CV mortality (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.41) and AEs (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.25). There was, however, a trend towards a lower risk of the composite end point of need for KRT/doubling of serum creatinine (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.92) in the RAS inhibitor group versus the control group, but this was dependent on the selected outcome measure. 36 (Copyright © 2015, Oxford University Press)

Finally, initiation of RAS inhibitors therapy may cause acute reductions in eGFR, hyperkalaemia and episodes of acute kidney injury. 37,38 Therefore, it is unclear whether the risks may outweigh the benefits as CKD progresses to an eGFR < 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2 and whether RAS inhibitors should be discontinued at this level of kidney function. As discussed above, this group of patients is under-represented in clinical trials and this is one of a number of clinically important questions for patients with advanced CKD that have not to date been addressed by a RCT. 22 The particular importance of carrying out a rigorous clinical trial on RAS inhibitors in advanced CKD is the major uncertainty in this area, with data from observational studies raising concerns that some patients may sustain worse clinical outcomes if they continue RAS inhibitors when they progress to advanced CKD.

An observational study by Ahmed and colleagues reported that RAS inhibitor withdrawal in 52 patients with advanced CKD led to an overall mean increase in eGFR of 10 ml/minute/1.73 m2 over 12 months (16.4–26.6 ml/minute/1.73 m2), and an increase or stabilisation in eGFR in all but 4 patients. 13 A modest increase in BP was observed, but there was no increase in CV events. 13 Furthermore, data from a retrospective cohort study highlighted the challenges of RAS inhibitors in patients with CKD. 39 Evaluation of risk factors for adverse drug events found factors such as hyperkalaemia and kidney impairment as stated reasons for discontinuation of RAS inhibitors. 39 In this study, of 2225 outpatients administered an ACEi, 19% of the initial group discontinued ACEi therapy due to AEs.

The impact of RAS inhibitors on kidney outcomes in advanced CKD should always be considered through the prism of CV disease. The close interaction of kidney and heart is critical to survival and there is a huge array of traditional and kidney specific risk factors for CV disease that makes this a complex area of study. For example, the risk factors for poor CV disease outcomes in the general population and mild to moderate CKD are associated with better outcomes in advanced CKD. 40,41 Furthermore, CV events are more common in dialysis than pre-dialysis patients suggesting the increased importance of avoiding dialysis therapy, which accelerates CV risk. 42,43 There are no studies assessing the benefits of RAS inhibitors therapy in CV risk reduction in advanced non-dialysis CKD. Observational studies suggest lower CV risk at all levels of eGFR with the use of RAS inhibitors. 17,44 Several randomised controlled studies in dialysis patients have shown increased CV events with use of ACEi. 45,46 A prospective cohort study from Taiwan examined 28,497 patients with hypertension, a baseline serum creatinine more than 520 μmol/l, and receiving erythropoietin stimulating agents (ESA), and compared outcomes in those receiving RAS inhibitors with those not receiving RAS inhibitors. At a median follow-up of 7 months, 70.7% of the cohort were receiving long-term dialysis, with a HR of 0.94 (95% CI 0.91 to 0.97) for receipt of dialysis and a HR of 0.94 (0.92 to 0.97) for a reduced composite of death or dialysis in patients receiving RAS inhibitors. 47

Two observational studies reported differences in outcomes. In a study of 54,000 patients, Qiao and colleagues reported an increased risk of CV events and no impact on kidney function in those receiving RAS inhibitors. 20 They observed that continuing RAS inhibitors did not increase the risk of KRT (HR 1.19, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.65). However, there was a 20.4–45.3% discontinuation rate of RAS inhibitors across CKD stages 1 to stage 4 that after 5 years had increased to 46.8–83.7%.

A separate study examined 30,180 individuals registered in the Swedish Renal Registry, of which 10,254 were on RAS inhibitors of whom 1553 discontinued RAS inhibitors within 6 months. 18 The median age was 72 years, median eGFR 23 ml/minute/1.73 m2 (range 18–29) and median urinary albumin : creatinine ratio (ACR) 35 mg/mmol (6–156). The results of the study showed that the estimated 5-year mortality risk was 40.9% (95% CI 38.9 to 42.8) among those who continued RAS inhibitor therapy, and 54.5% (95% CI 48.5 to 61.2) among those who stopped RAS inhibitor therapy. This thus corresponded to an absolute risk difference of 13.6% (95% CI 7.0 to 20.3) in the number of deaths for every 100 individuals and a 5-year restricted mean survival time difference of −3.6 months (95% CI −5.4 to −1.8). The 5-year risk of major adverse CV events was 47.6% (45.9–49.4) in the RAS inhibitor continuation group and 59.5% (53.8–66.1) in the discontinuing group, with an estimated 5-year absolute risk difference of 11.9 (5.7–18.6) events for every 100 individuals, and a 5-year restricted mean survival time difference of −33 months (−5.3 to −1.4). The impact on 5-year kidney replacement therapy (KRT) was 36.1% (34.7–37.7) in the continue group and 27.9% (23.5–32.5) in the discontinue group, giving an absolute risk reduction of −8.3 (−12.8 to −3.6) KRT events for every 100 individuals, with a 5-year restricted mean survival time difference of 0.8 months (−0.8 to 2.5) suggesting a lower absolute KRT risk in those discontinuing RAS inhibitor medications.

The main limitations of these studies are the lack of available information on the decision to stop RAS inhibitor therapy (clinician-related, patient-related, AE-related or other) and the residual confounding associated with observational studies.

A UK study of primary care records showed that there was a 56.8% discontinuation of RAS inhibitors at 5 years after initiation for patients with kidney disease. 48 In a study of 122,363 patients who began RAS inhibitors, cardiorenal outcomes were worse in those with a creatinine increase of 30% or more since starting RAS inhibitors, with higher rates of ESKD, myocardial infarction, heart failure and death. This trend was also seen, to a lesser degree, in those with a smaller increase in creatinine values. 49,50

The Stockholm Measurements Study, an observational cohort study involving older participants, reported that 26% of those who had started a RAS inhibitors discontinued the medication within 6 months. 51 This intervention was associated with 12% (6.9–18.3%) and 7.1% (1.8–13.2%) higher absolute risk for death and major CV events, respectively, over a 3-year period of follow-up. Again, these data do not account for confounding factors, inherent with observational studies. A further population-based study of 78,000 adults with non-dialysis-dependent CKD stage 3 to stage 5 also found that discontinuation of RAS inhibitors in those with hyperkalaemia (defined as a serum potassium of > 5.5 mmol/l) was associated with a higher risk of mortality and CV events. 52 Hence, whether RAS inhibitors provide a benefit in advanced and progressive CKD remains unclear.

Rate of change of glomerular filtration rate in clinical trials

A 2018 scientific workshop convened by the National Kidney Foundation, US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency evaluated the evidence for rate of change in GFR (i.e. GFR slope) as an alternative end point for kidney disease progression in RCTs,53 and several recent studies and a meta-analysis have assessed CKD disease risk using kidney function loss as measured by rate of decline of eGFR (slope eGFR). 54,55 These studies have confirmed the utility of differences in eGFR slope as a surrogate for renal clinical outcomes as a means of assessing the impact of interventions with medication in clinical trials. 56–59 Inker et al. did a Bayesian individual patient meta-analysis of 47 studies with 60,620 participants and found that treatment effects on GFR slope from baseline to end of the study strongly predicted benefits on clinical outcomes. 54 The advantage of using this outcome is that it is a continuous variable which provides greater potential for discrimination of the ability of a novel therapy to demonstrate an effect on eGFR slope over time. Modelling analyses demonstrated that preservation of eGFR slope by ≥ 0.75 ml/minute/1.73 m2/year over 3 years [median HR and 95% prediction interval: 0.69 (0.47 to 1.00)] predicts a clinically relevant delay of CKD progression with at least 96% probability. 52

Kidney replacement therapy with dialysis remains an expensive and undesirable therapeutic option for patients with CKD and timing can impact mortality. 60 Mortality at 3 years is 25% and dialysis is associated with a poor quality of life. 61,62 Kidney transplantation, although associated with better clinical outcomes and quality of life, is not an option for many patients with ESKD, where significant comorbidity precludes transplantation, in particular for older patients (≥ 65 years old) who make up the majority with advanced CKD. There are few data on the effect of discontinuing RAS inhibitors on the CV event rate in this population. Indeed, no increased CV risk was noted in an observational cohort study from Ahmed et al. 13 but the potential risk of increased CV events needed further investigation in larger studies was an important consideration in trial design.

Summary

Trial evidence on the effectiveness and safety of RAS inhibitors discontinuation in advanced CKD is lacking; this is reflected in current guidelines which provide no specific instructions regarding RAS inhibitors in relationship to the severity of CKD. 63 The study by Ahmed et al. 13 suggests that withdrawal of RAS inhibitors in advanced CKD may be beneficial and based on the varied evidence; there is a need for a RCT for individuals with CKD who are receiving treatment with RAS inhibitors to compare the outcomes of a group who have RAS inhibitors to a group who continue.

Hypothesis

Does a strategy of discontinuing RAS inhibitor in patients with advanced (stage 4 or stage 5) progressive CKD lead to stabilisation of or improvement in kidney function over a 3-year follow-up period, provided good BP control is maintained with other agents, compared to a strategy of continuing RAS inhibitor?64 The trial population will comprise participants with advanced and progressive CKD (stage 4 or stage 5), where there is no evidence base for the efficacy of RAS inhibitors on slowing further progression of CKD.

Primary objective

Thus, to test whether discontinuing ACEi or ARB treatment, or a combination of both, compared with continuing on these treatments, improves or stabilises kidney function in patients with progressive stage 4 or stage 5 CKD based on assessment of kidney function using the modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) four-variable eGFR at 3-year follow-up, we carried out a multicentre open-label randomised trial in patients with advanced and progressive CKD.

Secondary objectives

To test whether in each of the randomised groups:

Clinical outcomes

-

The number of participants starting KRT or sustaining a > 50% decline in eGFR differs.

-

There is a difference in the time taken to reach ESKD or need for KRT.

-

Hospitalisation rates from any cause are different.

-

Participant quality of life and well-being [measured using the kidney disease quality of life (KDQoL)-SF™ v1.3 questionnaire] differs.

-

Participant physical function (measured using the 6-minute walk test) differs.

-

Withdrawal of these treatments does not cause excess harm (e.g. increased CV events such as heart failure, hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke) and is not associated with an increase in adverse effects.

-

Participant survival in each group is similar.

-

Cystatin-C levels differ.

-

BP control is the same.

Mechanistic outcomes

-

There is a change in urine protein excretion [urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio (uPCR)].

-

Discontinuation of ACEi/ARB affects haemoglobin concentration.

-

Discontinuation of ACEi/ARB affects the requirement for ESA.

The results of this trial will provide evidence as to whether RAS inhibitors should be discontinued or continued in patients with advanced and progressive CKD. The study also included assessment of clinically relevant parameters (e.g. anaemia) and clinical outcomes including hospitalisation rates, physical function and quality of life. It was also designed to report on CV events, for which evidence is currently lacking. It was designed to assess if the benefits stopping RAS inhibitors outweigh the risk. The study should provide robust evidence to direct future guidelines and, if the study does not give a definitive answer, provide the basis for a larger RCT with a hard end point (death).

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design and oversight

This was an investigator-initiated, multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label trial that compared discontinuing or continuing RAS inhibitor in patients with advanced and progressive stage 4 or stage 5 CKD. Details of the objectives, design and methods of the trial have been published. 64,65

Ethics approval and research governance

The protocol (Appendix) was approved by relevant health authorities and institutional review boards. Leeds East Research Ethics Committee approved the protocol (13/YH/10394).

The study was prospectively registered STOP ACEi EudraCT Number, 2013-003798-82 and ISTRCTN 62869767.

Trial oversight was provided by a Trial Management Group (TMG) chaired by the chief investigator (Sunil Bhandari). The Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit (BCTU) co-ordinated and managed the trial.

An independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) provided overall oversight and supervision on the conduct of the trial, and a data monitoring committee reviewed unblinded data to assess patient safety throughout the trial.

The trial was funded by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and the Medical Research Council (MRC) Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programme (11/30/07).

The trial was sponsored by Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.

The trial was adopted by the Comprehensive Clinical Research Network (CCRN) and the Comprehensive Local Research Networks (CLRNs).

The protocol is available on the trial website and as a supplement linked to the New England Journal of Medicine publication. 65 www.birmingham.ac.uk/stopacei (last accessed 9th November 2022).

Participants

Adults (≥ 18 years) with CKD stage 4 or stage 5 [eGFR < 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2, using the MDRD equation (MDRD175)], who were not receiving dialysis and who had not received a kidney transplant were eligible for participation provided the eGFR had declined by at least 2 ml/minute/1.73 m2 per year over the previous 2 years and they were receiving treatment with either an ACEi or ARB, or combination of both, for more than 6 months. Exclusion criteria included uncontrolled hypertension or a history of myocardial infarction or stroke within the previous 3 months. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed below. All participants provided written informed consent.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged ≥ 18 years (male or female).

-

CKD stage 4 or stage 5 (eGFR < 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2 using the MDRD equation) and must not have received a kidney transplant or be on dialysis therapy.

-

Progressive deterioration in kidney function (fall in eGFR of ≥ 2 ml/minute/year over previous 24 months) as measured by linear regression analysis [There was a requirement of a minimum of three measurements of eGFR to identify a > 2 ml/minute fall over 1 year to enter the trial. The loss in eGFR was expressed ‘per year’ so that over 12 months there must have been loss of 2 ml/minute or more, but over 24 months there must have been a total loss of 4 ml/minute or more. The last eGFR was within 3 months of randomisation. We recognise the limitations of eGFR due to intra- and interpatient variability in serum creatinine. Based on a reported intraindividual variation for serum creatinine of 4.3% and intralaboratory variation of 3.0%, a variation of 13% can be considered ‘real’ with 95% probability. The power function in the MDRD equation has a component of variability that increases the threshold for potential variation between two tests to 14.4%. Hence, a minimum of three eGFRs over 1 year or 6 over 2 years would be required to accurately identify a decline of ≥ 2 ml/minute/year in people with an eGFR < 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2. This optimised the eGFR slope against time. The eGFR slope was calculated using an Excel spreadsheet which allowed entry of the previous creatinine measurements or eGFR values with automatic generation of a slope and rate of GFR loss. This program was provided to all principal investigators (PIs) for centres participating in the trial. The measurements of eGFR were inserted into the table with the date of the measurements and this generates the linear line with automatic calculation of the change in GFR].

-

Treatment with either an ACEi or ARB or a combination of both for > 6 months with at least 25% of the maximum recommended daily dose on the day of consent.

-

Resting BP ≤ 160/90 mmHg when measured in accordance with British Hypertension Society guidelines in clinic or recent home BP reading within the previous month or a 24-hour ambulatory BP measurement within the last 3 months were acceptable.

-

At least 3 months of specialist kidney follow-up at the time of entry into the trial.

-

Written, signed informed consent to the trial.

Exclusion criteria

-

Aged < 18 years.

-

Uncontrolled hypertension (> 160/90 mmHg) or requirement for five or more agents to control BP.

-

Undergoing dialysis therapy.

-

Previous kidney transplant (functional).

-

Any condition which, in the opinion of the investigator, makes the participant unsuitable for trial entry due to prognosis/terminal illness with a projected survival of < 12 months.

-

History of myocardial infarction or stroke in preceding 3 months.

-

Participation in an interventional research study in preceding 6 weeks.

-

Pregnancy confirmed by positive pregnancy test or breastfeeding.

-

Inability to provide informed consent (e.g. due to cognitive impairment).

-

Immune mediated kidney disease requiring disease specific treatment.

-

Known drug or alcohol abuse.

-

Inability to comply with the trial schedule and follow-up.

Screening and eligibility

Eligibility was assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria and participants were then identified as described below.

Patients with CKD under the care of a nephrologist were reviewed regularly (e.g. every 3 months) in a hospital outpatient clinic. Potential participants in secondary care were identified by the research team at each of the recruiting centres (e.g. from medical records, clinical records, individual kidney unit databases or other local registries) and were invited to participate by letter. In some cases, the research nurse or responsible clinician for the potential participant introduced the study before providing the invitation letter and participant information sheet (PIS).

Members of the site staff screened for potential eligible trial participants using the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria had their eligibility assessed by medically qualified personnel with access to and a full understanding of their medical history.

Informed consent procedure

Potential participants were initially provided with a PIS (i.e. the current Main Research Ethics Committee (MREC) approved version on appropriately headed paper) and a covering letter explaining the trial to them and inviting them to participate in the trial. This was sent to them before their next clinic attendance. They had time to consider the trial and decide whether they wished to take part, and to discuss the trial with their family and friends. At their next clinic appointment, potential participants had plenty of time to discuss the trial further and to have any questions that they may have about the trial answered. The nature and requirements of the trial were carefully explained. This individual discussed the trial with them in detail and gave a comprehensive verbal explanation of the trial (explaining both the investigational and standard treatment options and highlighting any possible benefits or risks relating to participation). The investigator, or designated medically qualified personnel, explained that there was no obligation for a potential participant to enter the trial, that trial entry was entirely voluntary, and that it was up to the potential participant to decide whether or not they would like to join. It was explained that the potential participant could withdraw at any time during the trial, without having to give a reason and that their decision would not affect the standard of care they received. Throughout the study, participants were encouraged to ask questions and were reminded that they could withdraw at any time without their clinical care being affected. Any reasons for non-participation were recorded if the information was volunteered.

At the appointment (baseline assessment), the research nurse went through the randomisation form including the eligibility checklist. The participant and responsible clinician signed the informed consent form, and the responsible clinician performed a final confirmation of eligibility.

Randomisation procedures

After all eligibility criteria had been confirmed and informed consent had been received, the participants were randomised into the STOP-ACEi trial. Participants were randomised individually into the trial in a one to one ratio to either continue with their RAS inhibitors treatment or discontinue their ACEi and/or ARB treatment.

Randomisation and blinding

Patients were randomly assigned using a centralised internet-based system hosted at BCTU in a 1 : 1 ratio to either discontinue or continue RAS inhibitors. Minimisation was used to ensure balance between groups for the following variables: age (< 65 or ≥ 65 years), eGFR (< 15 ml/minute/1.73 m2 or ≥ 15 ml/minute/1.73 m2), diabetes (type I diabetes, type II diabetes or no diabetes), mean arterial pressure {MAP measured as [(2 × diastolic) + systolic]/3; < 100 or ≥ 100 mm Hg}, and proteinuria [protein-to-creatinine ratio (PCR) < 100 or ≥ 100 mg/mmol].

Telephone and online randomisation

Participants could be randomised into the trial via a secure 24-hour internet-based registered service (www.trials.bham.ac.uk/stopacei) or by a telephone call (telephone number 0800 953 0274) to the BCTU. Telephone randomisation was available Monday–Friday, 09:00–17:00. For the secure internet randomisation, each site and each researcher were provided with a unique log-in username and password in order to access the online system. Online randomisation was available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, apart from short periods of scheduled maintenance and occasional network problems.

Randomisation Notepads were provided to investigators and were completed and used to collate the necessary information prior to randomisation. All questions and data items on the Randomisation Notepad were answered before a Trial Number could be given. If data items were missing, randomisation was suspended, but could be resumed once the information was available. Only when all eligibility criteria and baseline data items had been provided was a Trial Number allocated.

With the participant’s prior consent, their general practitioner (GP) was informed.

Back-up randomisation

If the internet-based randomisation service was unavailable for an extended period of time, a back-up paper randomisation was also available at the BCTU. The randomisation list was produced using a random-length block design. In this instance, investigators rang the BCTU randomisation service (telephone number 0800 953 0274). This was not required during the trial.

Follow-up

Patients were followed-up every 3 months from randomisation to 3 years with a 3-month window for visits.

Intervention

Trial treatment

For those randomised to discontinuing RAS inhibitors, any guideline-recommended antihypertensive agent other than RAS inhibitors could be used to control BP. 66 Re-initiation of RAS inhibitors was permitted only as a last resort when other agents had failed or were not tolerated. For those randomised to continue RAS inhibitors, the investigator chose the agent and dose and could combine it with any other guideline-recommended antihypertensive agent to control BP. 66 In both groups, BP was controlled to target (≤ 140/85 mmHg) and monitored as recommended by UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Hypertension and CKD guidelines. 63,66

Stop group

These participants discontinued RAS inhibitors treatment from the point of randomisation onwards. If a participant was due to take an RAS inhibitor on the morning of the randomisation visit (i.e. before randomisation), this was taken as normal. To compensate for the loss of antihypertensive activity, additional antihypertensive treatment was allowed to be commenced. Any antihypertensives used in routine clinical practice were permitted to control BP throughout trial participation, but excluding ACEi or ARBs, except as a last resort. Any of the following alternative antihypertensives could be prescribed: calcium channel blockers, alpha- and beta-adrenoreceptor antagonists, hydralazine, minoxidil and thiazides or those deemed by the responsible clinician. It was acceptable to use aldosterone receptor antagonists (e.g. spironolactone) in the discontinue arm. The normal contraindications and safety precautions for use of these treatments were adhered to, as per routine care. We recommended that the Renal Pharmacy Handbook was consulted in combination with the British National Formulary due to the complex prescribing needs of patients with CKD. In all cases, it was considered best to commence treatment at low doses and then increase to a therapeutic level. The choice of antihypertensive depended on the other treatments being taken by the participant and was at the discretion of the responsible clinician.

Continue group

These participants continued on ‘standard’ care and continued their RAS inhibitor treatment. The choice and dose of RAS inhibitors were at the discretion of the responsible clinician.

Both treatment groups

In both groups, BP was controlled in participants in the trial to the target BP outlined by the NICE Hypertension guideline (clinical guideline number 127) and NICE CKD guideline (clinical guideline number 73). 63,66 The standard BP target was used (≤ 140/85 mmHg). Currently it remains unknown if there is an optimal BP for delaying kidney progression and it is not clear whether there is any advantage to hypertension control using RAS inhibitors for BP reduction. RAS inhibitors could be used if the clinical status of the participant required this at any time in the trial and was closely monitored, with the potential for the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) to close the trial should there be significant dilution of the trial groups. All participants remained in the study, irrespective of inability to control BP, as this could occur in normal clinical practice, but all efforts were made to optimise BP and any treatment given were recorded at the follow-up visit.

The monitoring of BP was consistent with the NICE CKD guideline. 66 As detailed home readings and 24-hour ambulatory BP readings were acceptable for the trial at baseline. Home readings or clinic BP readings were also acceptable at follow-up visits.

Between the 3-monthly visits, patients were monitored and managed in accordance with local practice for follow-up of any change of therapy. Any changes in medication or visits to a GP practice or hospital reported by the participant were recorded in the source data and reported on the case report form (CRF) for the next clinic visit.

Measurement of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and renin levels at baseline and at 1, 2 and 3 years were carried out as a measure of adherence in a selection of patients. It is recognised, however, that when a RAS inhibitor is discontinued the normal biological effect is a reduction in renin and angiotensin I and an increase in ACE activity but these effects only last up to 2 weeks and then return to basal levels.

Throughout the trial, investigators/responsible clinicians prescribed any concomitant medications or treatments deemed necessary to provide adequate supportive care to participants. Medication changes were recorded in the source data at each follow-up visit and reported in the CRF. In addition, the dose of ESA prescribed was recorded in the source data and reported in the CRF.

Adherence

We attempted to minimise the loss to follow-up in this study by (1) emphasising to participants the importance of their attendance at follow-up assessments even if they were no longer compliant with the intervention, (2) reducing outcome assessment appointments during the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), (3) using a reminder protocol with telephone contact and (4) providing travel remuneration (including, where necessary, taxi costs).

Data for adherence were collected at each follow-up visit to ensure that adherence was measured for each patient at each study time point up to needing dialysis or receiving a kidney transplant. When we were developing the statistical analysis plan, we considered incorporating a per-protocol analysis into the statistical protocol. However, since adherence was measured at each time point, it is therefore possible that participants were adherent at one visit, non-adherent at the following visit and then adherent again at later visits. Consequently, there was no straightforward way to compute an overall adherence measure for per-protocol analysis. We also discussed this with the data monitoring committee, and they agreed that it was best to just describe the level of adherence at each time point. It was noted that considering the length of follow-up and that the trial was open-label, the levels of adherence are in line with expectations when compared with large blinded CV trials which report 20–30% treatment non-compliance over shorter duration. Treatment non-compliance was commonly due to worsening renal function in the continue arm but, interestingly, this was also reported as a reason in the stop arm.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was kidney function at 3 years as calculated according to the MDRD175 four-variable eGFR. 67 Data for the primary outcome were censored at the initiation of KRT (dialysis or transplantation).

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcome measures included time until the development of ESKD (as defined by the local investigator according to criteria that included terminal palliative care or KRT); a composite of a decrease of more than 50% in the eGFR, the development of ESKD, or the initiation of KRT; hospitalisation for any cause; quality of life (as measured on the KDQoL 36-Item Short Form Survey, version 1.3); exercise capacity (as assessed by the 6-minute walk test); measures of cystatin C and BP; and CV events and death. At the time of this report, the transfer and processing of samples for cystatin C measurement had not yet occurred, so the results are not provided here. Secondary mechanistic outcomes included measures of haemoglobin and urinary protein excretion (PCR) and ESA requirements.

Quality of life

KDQoL-SF 1.3 is a disease-specific quality of life measure. The KDQoL-SF 1.3 questionnaire includes the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) as generic core plus symptoms/problems of kidney disease scales.

Safety and monitoring of the intervention

All adverse and serious AEs were recorded.

Statistical considerations

Sample size calculation

Limited data were available upon which to calculate the sample size for the STOP-ACEi trial. One observational study by Ahmed et al. 13 provided data on eGFR in 52 patients with advanced CKD in the 12 months prior to stopping RAS inhibitor treatment, at the point of stopping RAS inhibitors and 12 months after stopping (see below). These data were used for the basis of the sample size calculation.

To detect a minimum relevant difference (MRD) in eGFR between groups of 5 ml/minute/1.73 m2 (i.e. an effect size of 0.31, assuming a SD of 16 ml/minute/1.73 m2) with 80% power and alpha = 0.05, required 410 participants (205 per group) including a 20% attrition rate.

| Mean ± Std. error (SD) |

12 months before RAS inhibitors were discontinued | When RAS inhibitors were discontinued | 12 months after RAS inhibitors were discontinued |

| eGFR (ml/minute/1.73 m2) | 22.9 ± 1.4 (10.1) | 16.38 ± 1 (7.2) | 26.6 ± 2.2 (15.9) |

To err on the side of caution, the largest SD above was used to estimate the variability for the eGFR (i.e. a SD of 16 ml/minute/1.73 m2) for the sample size calculation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle and were adjusted for the minimisation variables and baseline values (where available). The ITT population included all randomised participants, with participants analysed according to the group to which they were randomised, regardless of what treatment (if any) they received. All available data for participants that were lost to follow-up or withdrew, or had died prior to completing the final trial follow-up, were included in the analysis. The reference group for all analyses was those who continued RAS inhibitors. The statistical analysis plan did not provide correction for multiplicity; therefore secondary outcomes are reported as point estimates and 95% CIs. Analyses were performed with SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and Stata software version 17 (Stata-Corp).

Full details of the analysis methods are provided in the Statistical Analysis Plan (Supplementary Appendix available with the New England Journal of Medicine paper). 65 The primary outcome was analysed using a repeated-measures, mixed-effects linear regression model (which included a time-by-treatment-group interaction term) to estimate the difference between groups in eGFR at 3 years. A compound symmetry covariance structure was assumed. Any measurements of eGFR made after starting dialysis or receiving a kidney transplant were excluded. To examine the impact of data that were not missing at random, sensitivity analyses (fitting pattern mixture and joint models) were performed for the primary outcome. We also repeated analyses for the primary outcome using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration 2009 (CKD-EPI 2009) and MDRD186 four-variable equations for eGFR.

Continuous secondary outcomes, such as BP, were analysed using the same methods as for the primary outcome, but data were not censored when KRT was started. Categorical (dichotomous) secondary outcomes were analysed using a Poisson regression model with robust standard errors (SEs) to estimate the RR and 95% CI, as the log-binomial model failed to converge. Time-to-event outcomes, such as time to ESKD, were analysed using a Cox proportional-hazards model to obtain a HR and 95% CI. Categorical (dichotomous) safety outcome measures [hospitalisations, serious adverse events (SAEs)] were summarised as the proportion of participants and percentages and compared using a chi-squared test.

Data collection for kidney outcomes did not distinguish between ESKD and KRT outcomes (i.e. they were coded the same, apart from the free-text entry).

Subgroup analyses

The minimisation variables in the randomisation process were diabetes [type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes (including insulin-treated type 2 diabetes), no diabetes], BP {MAP measured as [(2 × diastolic) + systolic]/3; < 100 or ≥ 100}, age (< 65 or ≥ 65 years), proteinuria (PCR < 100 or ≥ 100 mg/mmol), and eGFR measurement (< 15 or ≥ 15 ml/minute/1.73 m2).

Several a priori subgroup analyses were planned with respect to the above minimisation variables for the primary outcome. The analysis methods followed those of the primary outcome. To allow for the possibility of differential changes over time within subgroups, time by subgroup and the three-way interaction between treatment, time and subgroup were included in the model. Although all data were included in the regression models for the subgroup analyses, estimates of differences are only presented at 3 years. Given the well-known dangers of subgroup analyses, these analyses were treated as hypothesis-generating.

Safety analyses

Discontinuations from the intervention and permanent study withdrawals and their reasons were tabulated. Adherence was assessed where possible from the CRFs. The chief investigator reviewed all AEs submitted by PIs except those from their own unit. These were reviewed by another primary investigator on the TMG.

Cardiovascular event data (as part of the safety data) are summarised using descriptive statistics. The total number of patients with at least one event for each event type (i.e. heart failure, stroke, myocardial infarction) and total number of events for each event type is tabulated by treatment arm and overall.

Data monitoring and quality assurance

The trial was co-ordinated by a TMG, consisting of the chief investigator, Trials Management Team Leader and Senior Trial Manager and the senior and trial statistician. The Trial Manager co-ordinated the study and was accountable to the chief investigator. The Trial Office was responsible for randomisation, collection of data in collaboration with the research co-ordinator, data processing and analysis. A TSC was established to oversee the conduct and progress of the trial. The study’s funder, NIHR HTA formally appointed the chair and members after the nominations from the TMG. A charter was drawn up to describe membership, roles and responsibilities of the TSC. The Independent DMEC was an independent group of experts, consisting of a nephrologist, a lay member and a statistician, who monitored patient safety and treatment efficacy data while the clinical trial was ongoing; the primary mandate of this committee was to protect patient safety.

Chapter 3 Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement input into original intervention development

The planning and delivery of the STOP ACEi trial were facilitated by close engagement with people living with CKD and on RAS inhibition therapy. Patients contributed directly to both the development of trial materials [e.g. patient information leaflets (PILs) and consent forms] and the way the trial was conducted.

Two groups have been involved in the study design:

-

a focus group

-

a kidney user group.

At an early stage, the team co-developed the project with the assistance of a focus group. The focus group included patients, nurses and service users and was funded by a Yorkshire Public Patient Involvement (PPI) grant. They have met on four occasions to discuss trial design and assisted in the final development of the information leaflets to ensure they were appropriate and acceptable.

A renal user patient group, some of whom met the criteria for the trial, was gathered together during the running of the trial to assist in recommending ideas to promote recruitment to the trial and provide any observations or comments on the trial. The chief investigator regularly spoke with patients on their experience of the trial and advice on any further suggestions. He ensured that patients were content with the burden of baseline and 3-monthly follow-up assessments were acceptable to also. This feedback was extremely useful and was reassuring that patients were fully informed about the commitment required for the research and understood the main aspects of trial design.

Patient and public involvement input to the Trial Steering Committee

During the running of the trial a patient representative has served on the TSC. This was a patient with kidney disease. As a TSC member they played a vital part in project oversight and management of the trial and made recommendations that were taken forward to improve the running and conduct of the trial. They contributed to all the meetings they were able to attend and provided valuable input.

The results of the trial will be fed back to all patients in the kidney community via the investigators.

Chapter 4 Results

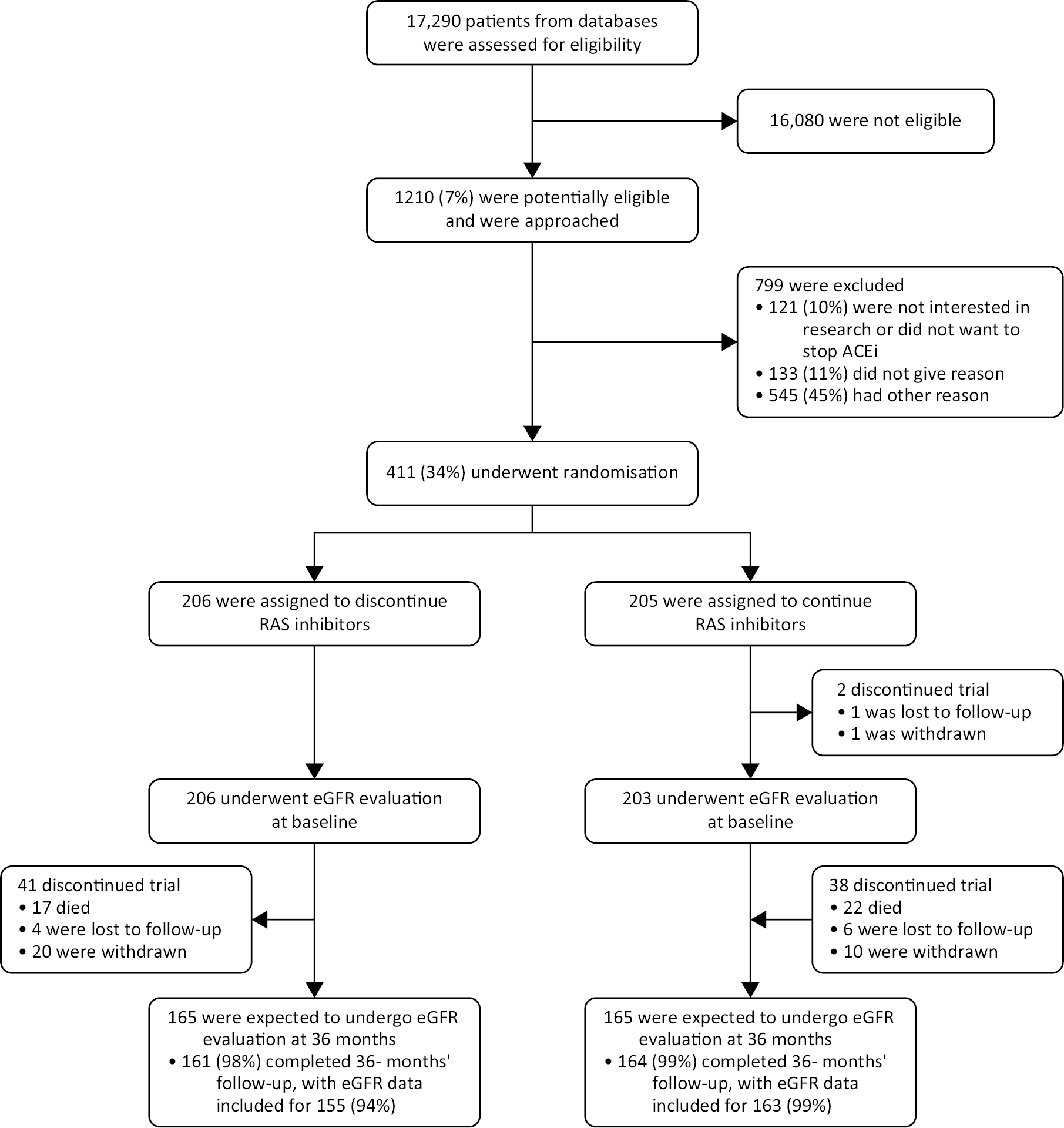

Recruitment

Between 11 July 2014 and 19 June 2018, 17,290 patients were screened at 39 participating centres in the UK and 1210 patients were invited to participate in the trial (see Figure 1), with 411 patients at 37 centres randomised into the trial; 206 to discontinue and 205 to continue RAS inhibitors. Follow-up continued until 19 June 2021. The median follow-up was 3 years [mean (SD) 2.7 (0.8) years].

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Details are shown regarding the screening, potential eligibility, randomised assignments and disposition of the trial patients. Among the patients who died during the trial, three had completed the 3-year assessment before death, so their data were included in the analysis. This factor explains the difference in the total number of deaths that were reported in the trial. ACE denotes angiotensin-converting enzyme, and RAS denotes renin–angiotensin system.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

Patient characteristics at baseline are shown in Tables 1–3. Median age was 63 years, 281 (68.4%) were men and 60 (14.6%) were non-white. The median eGFR was 18 ml/minute/1.73 m2; 118 (28.7%) had an eGFR of < 15 ml/minute/1.73 m2. The median level of proteinuria (PCR) was 115 mg/mmol (interquartile range 28–248 mg/mmol) and the median haemoglobin was 116 g/l (interquartile range, 107–125). Diabetes (either type 1 or type 2) had been diagnosed in 153 patients (37%), diabetic nephropathy in 87 patients (21%), hypertensive/renovascular nephropathy in 68; (17%), genetic diseases in 81 (20%), and glomerulonephritis in 76 (18%) to account for most cases of CKD (see Table 3).

| Baseline characteristics | STOP (N = 206) | Continue (N = 205) | Total (N = 411) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| N | 206 | 205 | 411 |

| Mean (SD) | 62.7 (12.6) | 61.4 (13.6) | 62.1 (13.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 63.3 (54.4–73.1) | 63.3 (50–71.6) | 63.3 (51.4–72.1) |

| Minimum–maximum | 28.8–90.6 | 28.3–85.8 | 28.3–90.6 |

| Age groupa | |||

| < 65 years | 116 (56.3%) | 110 (53.7%) | 226 (55%) |

| ≥ 65 years | 90 (43.7%) | 95 (46.3%) | 185 (45%) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 140 (68%) | 141 (68.8%) | 281 (68.4%) |

| Female | 66 (32%) | 64 (31.2%) | 130 (31.6%) |

| BMI | |||

| N | 205 | 202 | 407 |

| Mean (SD) | 29.9 (5.9) | 29.7 (6.4) | 29.8 (6.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 29.4 (25.4–33.6) | 29 (25.5–32.5) | 29.3 (25.5–33.2) |

| Minimum–maximum | 16.6–49.3 | 16–60.6 | 16–60.6 |

| Haemoglobin (Hb) (g/l) | |||

| N | 205 | 202 | 407 |

| Mean (SD) | 117 (15) | 117 (14) | 117 (15) |

| Median (IQR) | 116 (108–127) | 116 (107–124) | 116 (107–125) |

| Minimum–maximum | 58–161 | 87–169 | 58–169 |

| Serum creatinine (micromole/l) | |||

| N | 206 | 203 | 409 |

| Mean (SD) | 321.2 (107.8) | 314.6 (97.9) | 317.9 (102.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 299.5 (242–372) | 298 (243–367) | 299 (243–367) |

| Minimum–maximum | 152–796 | 140–690 | 140–796 |

| eGFR (ml/minute/1.73 m2) | |||

| N | 206 | 205 | 411 |

| Mean (SD) | 17.7 (5.4) | 17.9 (5) | 17.8 (5.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 18 (14–22) | 18 (14–21) | 18 (14–22) |

| Minimum–maximum | 6–30 | 7–30 | 6–30 |

| eGFR groupa | |||

| < 15 ml/minute | 58 (28.2%) | 60 (29.3%) | 118 (28.7%) |

| ≥ 15 ml/minute | 148 (71.8%) | 145 (70.7%) | 293 (71.3%) |

| Rate of decline eGFR (ml/minute/1.73 m2) | |||

| N | 206 | 205 | 411 |

| Mean (SD) | −6.0 (4) | −6.3 (4.7) | −6.2 (4.3) |

| Baseline characteristics | STOP (N = 206) | Continue (N = 205) | Total (N = 411) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin (g/l) | |||

| N | 205 | 202 | 407 |

| Mean (SD) | 39.9 (5) | 40.1 (4.1) | 40 (4.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 40 (37–43) | 40 (38–43) | 40 (37–43) |

| Minimum–maximum | 26–50 | 26–50 | 26–50 |

| C-Reactive protein (CRP), (mg/l) | |||

| N | 187 | 184 | 371 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.4 (7.6) | 7.2 (9.8) | 6.8 (8.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (2–7) | 4.9 (2–7.6) | 4.6 (2–7) |

| Minimum–maximum | 0–47 | 0–74 | 0–74 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/l) | |||

| N | 198 | 194 | 392 |

| Mean (SD) | 22.3 (3.4) | 22.2 (2.9) | 22.3 (3.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 22 (20–24) | 22 (20–24) | 22 (20–24) |

| Minimum–maximum | 13–32 | 14–31 | 13–32 |

| Potassium (mmol/l) | |||

| N | 206 | 202 | 408 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.9 (0.6) | 5 (0.6) | 5 (0.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 5 (4.6–5.4) | 5 (4.6–5.4) | 5 (4.6–5.4) |

| Minimum–maximum | 2.9–6.3 | 3.3–6.6 | 2.9–6.6 |

| Proteinuria (mg/mmol) | |||

| N | 206 | 205 | 411 |

| Mean (SD) | 178.6 (209.3) | 172.8 (198.9) | 175.7 (203.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 108.5 (26–236) | 117 (30–252) | 115.2 (28–248) |

| Minimum–maximum | 0.3–1209 | 1–1137 | 0.3–1209 |

| Proteinuria groupa | |||

| < 100 | 97 (47.1%) | 98 (47.8%) | 195 (47.4%) |

| ≥ 100 | 109 (52.9%) | 107 (52.2%) | 216 (52.6%) |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | |||

| N | 206 | 205 | 411 |

| Mean (SD) | 136.5 (12.9) | 136.3 (13.7) | 136.4 (13.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 136 (129–147) | 138 (126–147) | 137 (128–147) |

| Minimum–maximum | 99–160 | 98–160 | 98–160 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | |||

| N | 206 | 205 | 411 |

| Mean (SD) | 75.7 (9.2) | 76 (8.9) | 75.9 (9.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 77 (70–82) | 77 (70–82) | 77 (70–82) |

| Minimum–maximum | 40–90 | 45–90 | 40–90 |

| MAP | |||

| N | 206 | 205 | 411 |

| Mean (SD) | 96 (8) | 96.1 (8.5) | 96 (8.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 97.3 (91.7–102.7) | 97 (90.7–101.7) | 97 (91–102) |

| Minimum–maximum | 71.3–113.3 | 70.7–112.7 | 70.7–113.3 |

| MAP groupa | |||

| < 100 | 132 (64.1%) | 129 (62.9%) | 261 (63.5%) |

| ≥ 100 | 74 (35.9%) | 76 (37.1%) | 150 (36.5%) |

| Alcohol intake (units) | |||

| None | 88 (42.7%) | 94 (45.9%) | 182 (44.3%) |

| ≤ 20 per week | 103 (50%) | 96 (46.8%) | 199 (48.4%) |

| > 20 per week | 13 (6.3%) | 12 (5.9%) | 25 (6.1%) |

| Missing | 2 (1%) | 3 (1.5%) | 5 (1.2%) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never smoker | 86 (41.7%) | 100 (48.8%) | 186 (45.3%) |

| Ex-smoker | 97 (47.1%) | 80 (39%) | 177 (43.1%) |

| Current smoker | 23 (11.2%) | 23 (11.2%) | 46 (11.2%) |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Diabetesa | |||

| Type 1 | 9 (4.4%) | 11 (5.4%) | 20 (4.9%) |

| Type 2 | 66 (32%) | 67 (32.7%) | 133 (32.4%) |

| No diabetes | 131 (63.6%) | 127 (62%) | 258 (62.8%) |

| Baseline characteristics | STOP (N = 206) | Continue (N = 205) | Total (N = 411) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | |||

| White – English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British | 168 (81.6%) | 168 (82%) | 336 (81.8%) |

| White – Irish | 3 (1.5%) | 4 (2%) | 7 (1.7%) |

| White – any other white background | 0 (0%) | 8 (3.9%) | 8 (1.9%) |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group - white and black Caribbean | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group – white and black African | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group – any other mixed/multiple ethnic background | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Asian/Asian British – Indian | 5 (2.4%) | 8 (3.9%) | 13 (3.2%) |

| Asian/ Asian British – Pakistani | 5 (2.4%) | 3 (1.5%) | 8 (1.9%) |

| Asian/Asian British – Bangladeshi | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Asian/Asian British – Chinese | 2 (1%) | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| Asian/Asian British – any other Asian background | 2 (1%) | 3 (1.5%) | 5 (1.2%) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/black British – African | 8 (3.9%) | 3 (1.5%) | 11 (2.7%) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/black British – Caribbean | 5 (2.4%) | 4 (2%) | 9 (2.2%) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/black British – other | 3 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| Any other | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.5%) |

Prior cardiovascular events and risk factors

Clinically overt CV disease was not common in the participant population recruited to the trial (see Table 4). The prevalence of CV disease (a history of one or more of the following: myocardial infarction 9%, stroke 6%, heart failure hospitalisation 2%, atrial fibrillation 4%, or peripheral vascular disease 5%) varied, but was overall low at baseline. Just under half of the participants (45.3%) had never smoked, and 71% had hypertension at baseline.

| CV events at baseline | STOP (N = 206) | Continue (N = 203)a | Total (N = 409)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever had a major CV event | |||

| Hospitalisation for heart failure | 1 (< 1%) | 5 (2%) | 6 (1.5%) |

| Myocardial infarction (ST elevation) | 11 (5%) | 9 (4%) | 20 (5%) |

| Myocardial infarction (non ST elevation) | 8 (4%) | 8 (4%) | 16 (4%) |

| Stroke | 10 (5%) | 16 (8%) | 26 (6%) |

| Heart failure at baseline | 7 (3%) | 8 (4%) | 15 (4%) |

| Other CV disease or event (previous or current) | |||

| Angina | 9 (4%) | 17 (8%) | 26 (6%) |

| Coronary intervention (angioplasty) | 10 (5%) | 12 (6%) | 22 (5%) |

| Coronary intervention (coronary artery bypass) | 6 (3%) | 8 (4%) | 14 (3%) |

| Carotid intervention | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 4 (1%) |

| Hypertension | 147 (71%) | 147 (72%) | 294 (72%) |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 9 (4%) | 9 (4%) | 18 (4%) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 6 (3%) | 1 (< 1%) | 7 (2%) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 11 (5%) | 10 (5%) | 21 (5%) |

| Other CV condition | 20 (10%) | 18 (9%) | 38 (9%) |

Most participants (58%) were on three or more antihypertensive medicines; 268 (65.5%) were on a statin (see Tables 5 and 6). Forty per cent (163/411) were on oral bicarbonate supplements. The use of SGLT2 inhibitors was very low at < 1% and no patients were documented to be taking a potassium binder. Approximately 20% of participants were taking ESA therapy.

| Antihypertensive medications at baseline | STOP (N = 206) | Continue (N = 203)a | Total (N = 409)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACEi/ARB | |||

| ACEi | 99 (48%) | 123 (61%) | 222 (54%) |

| ARB | 104 (51%) | 77 (38%) | 181 (44%) |

| Both ACEi and ARB | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 6 (2%) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 137 (66%) | 132 (65%) | 269 (66%) |

| Loop diuretic | 67 (33%) | 66 (33%) | 133 (33%) |

| Thiazide diuretic | 11 (5%) | 13 (6%) | 24 (6%) |

| Thiazide-like diuretic | 4 (2%) | 9 (4%) | 13 (3%) |

| Potassium-sparing diuretic | 1 (< 1%) | 2 (1%) | 3 (1%) |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor agonist | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (< 1%) |

| Alpha-blocker | 65 (32%) | 66 (33%) | 131 (32%) |

| Beta-blocker | 63 (31%) | 69 (34%) | 132 (32%) |

| Methyldopa | 0 (0%) | 1 (< 1%) | 1 (< 1%) |

| Moxonidine | 2 (1%) | 6 (3%) | 8 (2%) |

| Hydralazine | 0 (0%) | 1 (< 1%) | 1 (< 1%) |

| Other antihypertensive | 4 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 7 (2%) |

| Number of antihypertensives taken by participant at baseline | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) |

| Minimum–maximum | 1–6 | 1–7 | 1–7 |

| Other concomitant medications at baselinea | STOP (N = 206) | Continue (N = 203)b | Total (N = 409)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statin | 134 (65%) | 134 (66%) | 268 (65.5%) |

| Fibrate | 4 (1.9%) | 5 (2.5%) | 9 (2.2%) |

| Ezetimibe | 13 (6.3%) | 7 (3.4%) | 20 (4.9%) |

| Digoxin | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (1.5%) | 4 (1%) |

| Nitrate | 5 (2.4%) | 10 (4.9%) | 15 (3.7%) |

| Aspirin | 65 (31.6%) | 62 (30.5%) | 127 (31.1%) |

| Clopidogrel | 12 (5.8%) | 9 (4.4%) | 21 (5.1%) |

| Warfarin | 8 (3.9%) | 12 (5.9%) | 20 (4.9%) |

| GLP-1 analogues/agonists | 3 (1.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 4 (1%) |

| Metformin | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Sodium glucose transporter 2 inhibitor | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Thiazolidinedione/glitazone | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (1.5%) | 4 (1%) |

| DPP-4 inhibitor | 16 (7.8%) | 22 (10.8%) | 38 (9.3%) |

| Sulphonylurea | 17 (8.3%) | 13 (6.4%) | 30 (7.3%) |

| Bicarbonate | 75 (36.4%) | 88 (43.3%) | 163 (39.9%) |

| Bisphosphonate | 1 (0.5%) | 4 (2%) | 5 (1.2%) |

| Phosphate binders | 15 (7.3%) | 15 (7.4%) | 30 (7.3%) |

| Calcium/vitamin D | 103 (50%) | 101 (49.8%) | 204 (49.9%) |

| Prednisolone | 4 (1.9%) | 5 (2.5%) | 9 (2.2%) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Ciclosporin | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Azathioprine | 2 (1%) | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| Tacrolimus | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Methotrexate | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 3 (1.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 4 (1%) |

| N (%) on ESA treatment | 38 (18.5%) | 43 (21.2%) | 81 (19.8%) |

Adherence to treatment

In the first 3 months, 180 (94.2%) participants who were randomised to stop RAS inhibitors were reported as being adherent compared with 179 (94.2%) participants who were randomised to continue RAS inhibitors. At 36 months of those who had not withdrawn from the trial, commenced dialysis, received a kidney transplant or died, 50 of 57 (87.7%) participant randomised to discontinue remained off RAS inhibitors compared with 53 of 69 (76.8%) participants randomised to continue on RAS inhibitors (see Table 7).

| Time point (months) | Adherence | STOP | Continue | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | N of participants completed follow-up | 191 | 190 | 381 |

| Non-adherent | 11 (5.8%) | 11 (5.8%) | 22 (5.8%) | |

| Adherent | 180 (94.2%) | 179 (94.2%) | 359 (94.2%) | |

| 6 | N of participants completed follow-up | 169 | 177 | 346 |

| Non-adherent | 16 (9.5%) | 19 (10.7%) | 35 (10.1%) | |

| Adherent | 153 (90.5%) | 158 (89.3%) | 311 (89.9%) | |

| 9 | N of participants completed follow-up | 151 | 161 | 312 |

| Non-adherent | 14 (9.3%) | 18 (11.2%) | 32 (10.3%) | |

| Adherent | 137 (90.7%) | 143 (88.8%) | 280 (89.7%) | |

| 12 | N of participants completed follow-up | 133 | 148 | 281 |

| Non-adherent | 15 (11.3%) | 22 (14.9%) | 37 (13.2%) | |

| Adherent | 118 (88.7%) | 126 (85.1%) | 244 (86.8%) | |

| 15 | N of participants completed follow-up | 117 | 126 | 243 |

| Non-adherent | 12 (10.3%) | 15 (11.9%) | 27 (11.1%) | |

| Adherent | 105 (89.7%) | 111 (88.1%) | 216 (88.9%) | |

| 18 | N of participants completed follow-up | 103 | 113 | 216 |

| Non-adherent | 11 (10.7%) | 16 (14.2%) | 27 (12.5%) | |

| Adherent | 92 (89.3%) | 97 (85.8%) | 189 (87.5%) | |

| 21 | N of participants completed follow-up | 99 | 102 | 201 |

| Non-adherent | 10 (10.1%) | 14 (13.7%) | 24 (11.9%) | |

| Adherent | 89 (89.9%) | 88 (86.3%) | 177 (88.1%) | |

| 24 | N of participants completed follow-up | 89 | 99 | 188 |

| Non-adherent | 11 (12.4%) | 16 (16.2%) | 27 (14.4%) | |

| Adherent | 78 (87.6%) | 83 (83.8%) | 161 (85.6%) | |

| 27 | N of participants completed follow-up | 80 | 90 | 170 |

| Non-adherent | 9 (11.3%) | 13 (14.4%) | 22 (12.9%) | |

| Adherent | 71 (88.8%) | 77 (85.6%) | 148 (87.1%) | |

| 30 | N of participants completed follow-up | 72 | 85 | 157 |

| Non-adherent | 8 (11.1%) | 19 (22.4%) | 27 (17.2%) | |

| Adherent | 64 (88.9%) | 66 (77.6%) | 130 (82.8%) | |

| 33 | N of participants completed follow-up | 61 | 74 | 135 |

| Non-adherent | 9 (14.8%) | 16 (21.6%) | 25 (18.5%) | |

| Adherent | 52 (85.2%) | 58 (78.4%) | 110 (81.5%) | |

| 36 | N of participants completed follow-up | 57 | 69 | 126 |

| Non-adherent | 7 (12.3%) | 16 (23.2%) | 23 (18.3%) | |

| Adherent | 50 (87.7%) | 53 (76.8%) | 103 (81.7%) |

Primary outcome

At 3 years, among the 411 patients who had undergone randomisation, the least-squares mean (LS-Mean) (± SE) eGFR was 12.6 ± 0.7 ml/minute/1.73 m2 in the discontinuation group and 13.3 ± 0.6 ml/minute/1.73 m2 in the continuation group [estimated adjusted mean difference: −0.7 ml/minute/1.73 m2 (95% CI −2.5 to +1.0; p = 0.42); with a negative value indicating the outcome favours continuing RAS inhibitors] (see Figure 2 and Table 8).

FIGURE 2.

Primary outcome plot of the LS-Means ± 95% CI over time for revised MDRD175 four-variable equation.

| Time point (months) | Summary statistic | STOP | Continue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR (ml/minute/1.73 m2) | 3 | Number of patients with data | N = 187 | N = 190 |

| Empirical mean (SD) | 17.1 (6.3) | 17.1 (5.8) | ||

| LS-Mean (SE) | 18.8 (0.3) | 18.8 (0.3 | ||

| 6 | Number of patients with data | N = 166 | N = 172 | |

| Empirical mean (SD) | 16.5 (6.3) | 16.8 (6.6) | ||

| LS-Mean ± (SE) | 17.58 ± (0.28) | 18.23 ± (0.33) | ||

| 9 | Number of patients with data | N = 148 | N = 157 | |

| Empirical mean (SD) | 16.6 (6.3) | 16.9 (6.2) | ||

| LS-Mean ± (SE) | 16.71 ± (0.31) | 17.51 ± (0.31) | ||

| 12 | Number of patients with data | N = 130 | N = 142 | |

| Empirical mean (SD) | 16.4 (6.4) | 16.7 (6.6) | ||

| LS-Mean ± (SE) | 16.12 ± (0.35) | 16.72 ± (0.35) | ||

| 15 | Number of patients with data | N = 117 | N = 122 | |

| Empirical mean (SD) | 16.3 (6.4) | 16.3 (6.3) | ||

| LS-Mean ± (SE) | 15.27 ± (0.36) | 16.22 ± (0.38) | ||

| 18 | Number of patients with data | N = 100 | N = 108 | |

| Empirical mean (SD) | 16.7 (6.8) | 17.5 (6.2) | ||

| LS-Mean ± (SE) | 14.96 ± (0.43) | 16.06 ± (0.40) | ||

| 21 | Number of patients with data | N = 96 | N = 99 | |

| Empirical mean (SD) | 16.5 (6.8) | 17.2 (6.4) | ||

| LS-Mean ± (SE) | 14.49 ± (0.47) | 15.67 ± (0.42) | ||

| 24 | Number of patients with data | N = 88 | N = 95 | |

| Empirical mean (SD) | 16.2 (7.4) | 16.7 (5.6) | ||

| LS-Mean ± (SE) | 13.57 ± (0.54) | 14.60 ± (0.39) | ||

| 27 | Number of patients with data | N = 78 | N = 87 | |

| Empirical mean (SD) | 16 (7.1) | 15.9 (5.6) | ||

| LS-Mean ± (SE) | 13.47 ± (0.53) | 13.92 ± (0.49) | ||

| 30 | Number of patients with data | N = 69 | N = 80 | |

| Empirical mean (SD) | 16.2 (7.4) | 16.2 (7) | ||

| LS-Mean ± (SE) | 12.84 ± (0.58) | 13.88 ± (0.63) | ||

| 33 | Number of patients with data | N = 59 | N = 66 | |

| Empirical mean (SD) | 16.1 (7.8) | 16.4 (6.5) | ||

| LS-Mean ± (SE) | 12.36 ± (0.64) | 13.55 ± (0.54) | ||

| 36 | Number of patients with data | N = 56 | N = 69 | |

| Empirical mean (SD) | 16.9 (8.1) | 16.7 (7) | ||

| LS-Mean ± (SE) | 12.56 ± (0.68) | 13.28 ± (0.60) |

There was no evidence that the treatment effect differed when the data were analysed according to the pre-specified subgroups (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome at 3 years.

Sensitivity analyses using pattern mixture models and a joint model gave similar results, as did the analyses using the two other eGFR equations (CKD-EPI 2009 and the MDRD186 four-variable equation) (See Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables S1–S4, Figs S1–S17).

Chapter 5 Secondary outcome analyses of study

Secondary outcomes

Of patients randomised to discontinue RAS inhibitors, 128 (62%) developed ESKD or had KRT (dialysis or transplantation) compared to 115 (56%) randomised to continue RAS inhibitors (adjusted HR 1.28, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.65) (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan–Meier curve by treatment group (stop or continue RAS inhibitors) for time to KRT or ESKD.

The number of participants with a > 50% decline in eGFR or starting KRT including ESKD was also similar [140 (68%) if RAS inhibitors were stopped vs. 127 (63%) if RAS inhibitors were continued (adjusted RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.22)] (see Table 9).

| Outcomes | STOP RAS inhibitors | Continue RAS inhibitors | Mean difference or RR or HR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome – LS-Mean ± (SE) at 3 years | −0.7 (−2.5 to 1.0); p = 0.42 | ||

| eGFR using revised MDRD175 four-variable | 12.6 ± (0.7) | 13.3 ± (0.6) | |

| Primary outcome sensitivity analysis – LS-Mean ± (SE) at 3 years | |||

| eGFR using CKD-EPI creatinine equation | 12.0 ± (0.7) | 12.8 ± (0.6) | −0.8 (−2.5 to 1.0) |

| eGFR using original MDRD186 four-variable | 13.4 ± (0.7) | 14.1 ± (0.6) | −0.8 (−2.6 to 1.1) |

| Primary outcome sensitivity analysis – pattern mixture models | |||

| eGFR using revised MDRD175 four-variable with: | |||

| Flat value five imputation for MNAR eGFR values | - | - | −0.5 (−1.7 to 0.7) |

| Flat value seven imputation for MNAR eGFR values | - | - | −0.4 (−1.5 to 0.7) |

| LOCF imputation for MNAR eGFR values | - | - | −0.4 (−1.5 to 0.6) |

| Primary outcome sensitivity analysis – joint model | |||

| eGFR using revised MDRD175 four-variable | - | - | −0.8 (−2.0 to 0.4) |

| Secondary clinical and safety outcomes | |||

| ESKD or KRT – number with outcome/total number (%) | 128/206 (62) | 115/205 (56) | 1.28 (0.99 to 1.65) |

| KRT or > 50% decline in eGFR – number with outcome/total number (%) | 140/206 (68) | 127/202 (63) | 1.07 (0.94 to 1.22) |

| Mortality – number with outcome/total number (%) | 20/206 (10) | 22/205 (11) | 0.85 (0.46 to 1.57) |

| Number with any hospitalisation – number with outcome/total number (%) | 135/206 (66) | 147/205 (72) | - |

| Total hospitalisations – total events | 414 | 413 | - |

| N with any SAE – number with outcome/total number (%) | 107/206 (52) | 101/205 (49) | - |

| Total SAEs – total events | 237 | 253 | - |

| Total CV events – total events | 108 | 88 | - |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) – LS-Mean ± (SE) at 3 years | 140 ± (2) | 140 ± (2) | 0 (−4 to 5) |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) – LS-Mean ± (SE) at 3 years | 76 ± (1) | 76 ± (1) | 0 (−2 to 3) |

| Distance (in metres) from 6-minute walk test – LS-Mean ± (SE) at 3 years | 394 ± (19) | 412 ± (9) | −18 (−57 to 22) |

| Secondary mechanistic outcomes | |||

| Haemoglobin (g/l) – LS-Mean ± (SE) at 3 years | 119 ± (1) | 119 ± (1) | 0 (−0.3 to 0.4) |

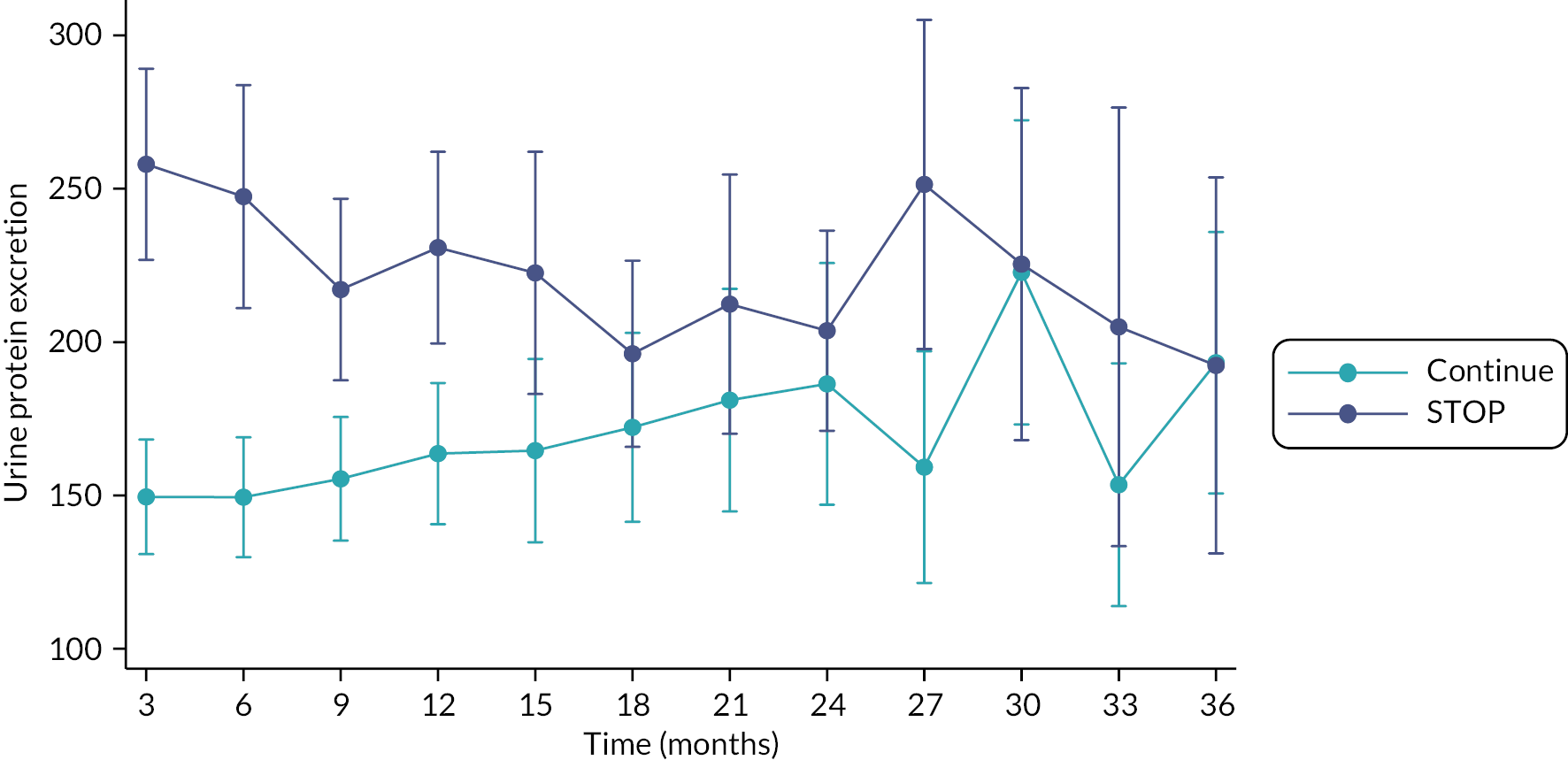

| uPCR (mg/mmol) – LS-Mean ± (SE) at 3 years | 192 ± (31) | 193 ± (22) | −1 (−76 to 74) |

| N with ESA treatment – number with outcome/total number (%) | 114/206 (55) | 112/202 (55) | 0.96 (0.81 to 1.13) |

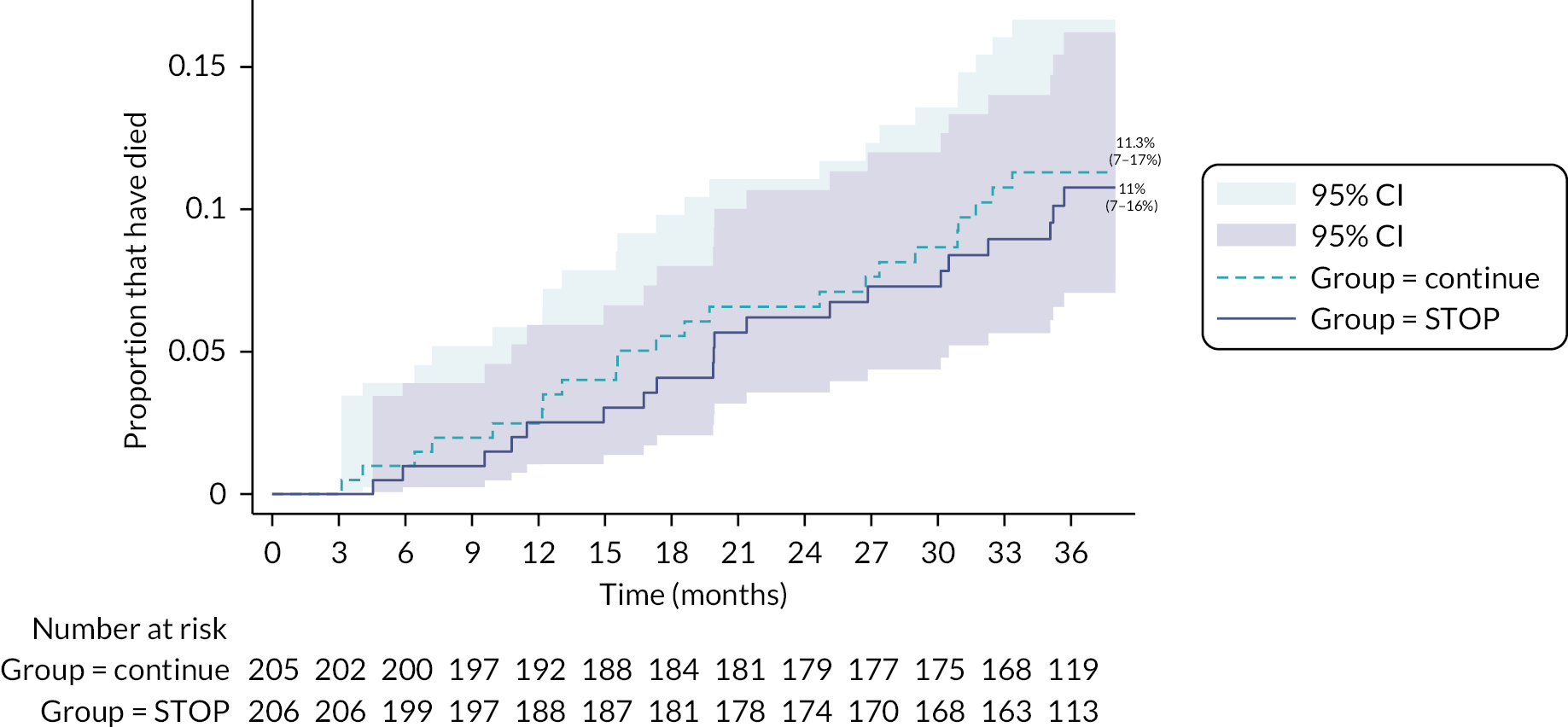

The number of hospitalisations for any reason (414 vs. 413) and CV events (108 vs. 88) were similar across the two groups (i.e. stop and continue respectively) (see Table 9). Twenty patients randomised to discontinue RAS inhibitors and 22 randomised to continue RAS inhibitors died (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.57) (see Table 9 and Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Kaplan–Meier curve by treatment arm for mortality.

Confidence interval widths have not been adjusted for multiplicity and may not be used in place of hypothesis testing. The mortality analysis was conducted using time to event analysis. For those patients who did not die, they were censored based on the date of their last follow-up assessment. Some patients in the trial completed the final 3 years’ time point slightly earlier than was expected consistent with the protocol visit window of ±6 weeks. Consequently, when computing the actual time (in months) between date of randomisation to the date of last visit, over 90 patients who completed their final 3 years’ visit had a computed censoring time in months of slightly < 36 months. This is then reflected in the graph as it is split into exact 3-monthly intervals and so for those patients that had a censoring time of < 36 months, they do not get counted as at risk at the 36 months’ time interval in the graph. We chose to estimate the actual time in months to censor patients on to reflect the analysis as accurately as possible.

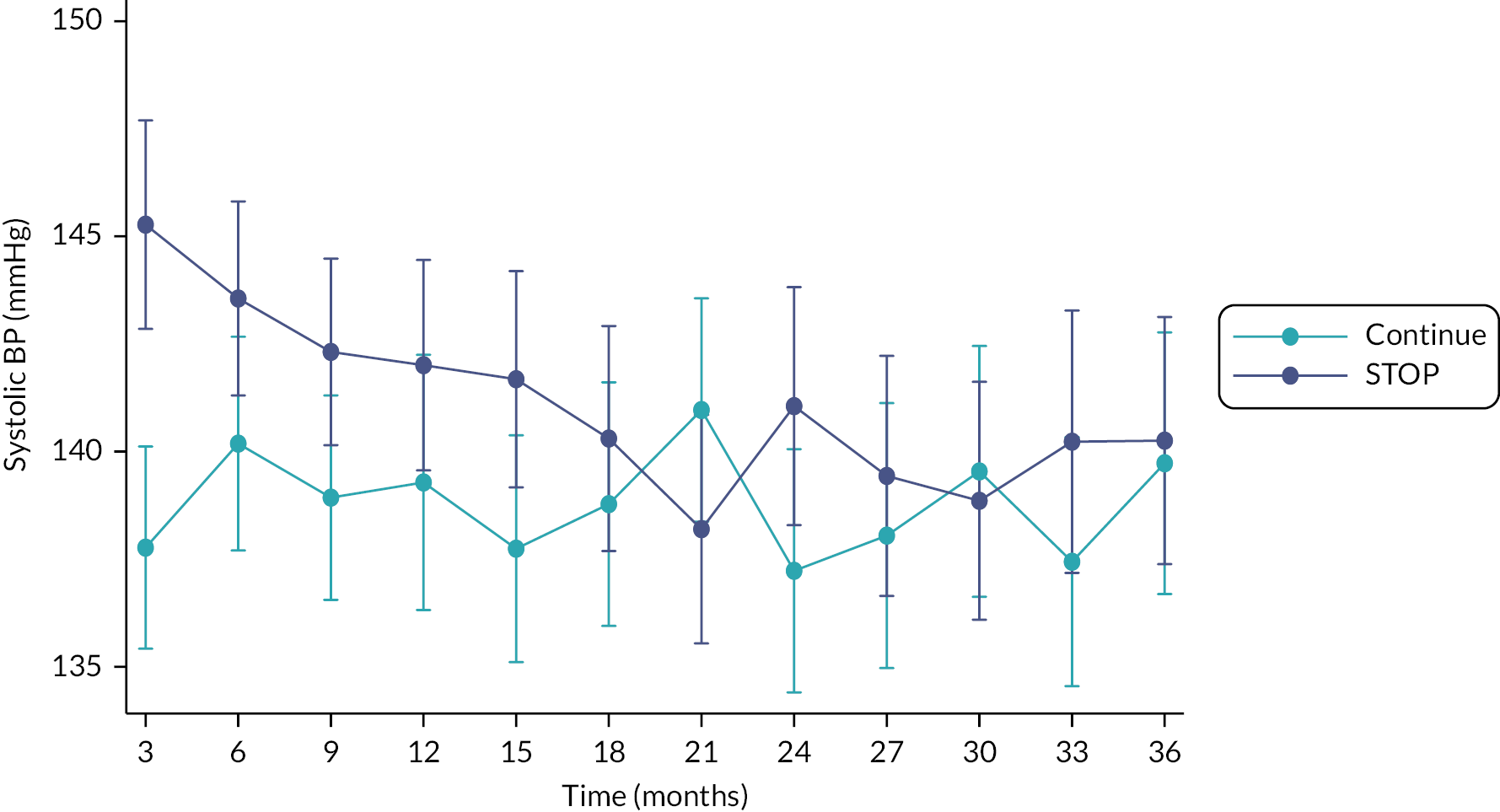

In the first 15 months after randomisation, both systolic and diastolic BP values were higher in those who were randomised to discontinue rather than continue RAS inhibitors. After this point, BP values were similar in the two groups. The difference in LS-Mean at 3 years for systolic BP was 0 mmHg, 95% CI −4 to 5 mmHg. The results were similar for diastolic BP; 0 mmHg, 95% CI −2 to 3 mmHg (see Figures 6 and 7). The number of antihypertensive medicines prescribed during the trial was similar between the two groups (see Table 10).

FIGURE 6.

Least-squares means plot over time by treatment arm for systolic and diastolic BP (mmHg).