Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 15/74/01. The contractual start date was in February 2017. The final report began editorial review in May 2022 and was accepted for publication in February 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Gunn et al. This work was produced by Gunn et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Gunn et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which affects around 4% of the world population,1 accounts for around 1% of the 285 million consultations per year in primary care in England and Wales,2 which is approximately 2.8 million. Around one-third of these patients meet criteria for IBS with diarrhoea (IBS-D). Symptoms include frequent, loose or watery stools with associated urgency, which can severely limit socialising, travelling and eating out. This results in a reduction in quality of life (QoL) and loss of work productivity. When patients with IBS are asked to rank symptoms in order of importance, erratic bowel habit is rated first, followed by abdominal pain and, for those with diarrhoea, urgency. 3 This can often be associated with incontinence, which is socially debilitating, but often under-reported. 4 Current over-the-counter treatments for patients with IBS-D such as loperamide reduce bowel frequency, but do not improve abdominal pain5,6 and often lead to constipation. The lack of effective treatments results in frequent referrals to secondary care, and such patients have in the past been a significant proportion of gastroenterology outpatients. A previous meta-analysis showed that the 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonists (5HT3RAs) alosetron and cilansetron benefitted such patients, improving stool consistency, and reducing both frequency and urgency of defaecation. 7 However, these drugs had serious side effects, including constipation in 25% of patients and, rarely, ischaemic colitis (1 in 700). Alosetron was initially withdrawn and is now available in the USA, only through a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy and is not available in Europe. Cilansetron never came to market, while ramosetron, another 5HT3RA, is only available in Japan, where it is licensed for IBS-D with several good-quality trials confirming its benefit. 8,9

Ondansetron is a potent, highly selective 5HT3RA, which blocks 5HT3 receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. Penetration across the blood–brain barrier is limited, with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentration < 15% of plasma levels so central nervous system (CNS) adverse effects are few. Ondansetron was developed and is currently licenced for use in adults and children for the management of nausea and vomiting induced by cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiotherapy (mediated by local release of serotonin in the gut from enterochromaffin cells), and for the prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Constipation is an unintended side effect of ondansetron, which was first shown to slow colonic transit 30 years ago. 10,11 Ondansetron is widely used and unlike alosetron has not been associated with ischaemic colitis. We previously performed a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover pilot study of two 5-week periods of treatment recruiting 120 IBS-D patients randomised to receive either ondansetron [2 mg up to 8 mg three times a day (t.d.s)] followed by placebo, or placebo followed by ondansetron with washout period of 2–3 weeks. 12 The primary outcome measure for the study was the difference in average stool consistency in the last 2 weeks of treatment, which showed a highly significant improvement with ondansetron versus placebo. We also showed significant benefits for both urgency and stool frequency, with associated slowing of whole gut transit. 12 Despite having limitations, results of this pilot study were very encouraging, supporting our clinical experience of ondansetron’s benefits. Recently a novel formulation of ondansetron (Bekinda) comprising 3 mg immediate release and 9 mg slow-release has been shown in a 12-week randomised, placebo-controlled trial to improve stool consistency, though it was underpowered to show significant benefit for pain. Currently there is lack of understanding as to exactly how it works, nor can we predict the individual dose required for optimum effect, which varies widely. 13 One key effect we found, also seen with other 5HT3RAs,14 was a marked reduction in urgency, which may play an important role in improving QoL for patients with IBS-D. 15

Potential mechanisms of action of 5HT3 receptor antagonists

Transit

5-HT3 receptor antagonists slow transit,10,11 an effect we found particularly marked in the left colon of IBS-D patients and rectosigmoid region, but the underlying mechanism was unclear. 12

Tone and motility

An early colonic barostat study showed a reduction in the postprandial rise in colonic tone with ondansetron in both carcinoid syndrome patients16 and healthy volunteers,17 which would be predicted to slow colonic transit. Previous studies of the impact of 5HT3RAs on human colonic motility18–20 were however paradoxical in showing that the 5HT3RAs tropisetron, alosetron and cilansetron all increased periprandial frequency of colonic contractions, and mean amplitude of contractions in the left colon. We hypothesised that 5HT3RAs increase retrograde sigmoid motility, perhaps enhancing ‘brake’ function,21,22 which would be a novel mode of action.

Proteases

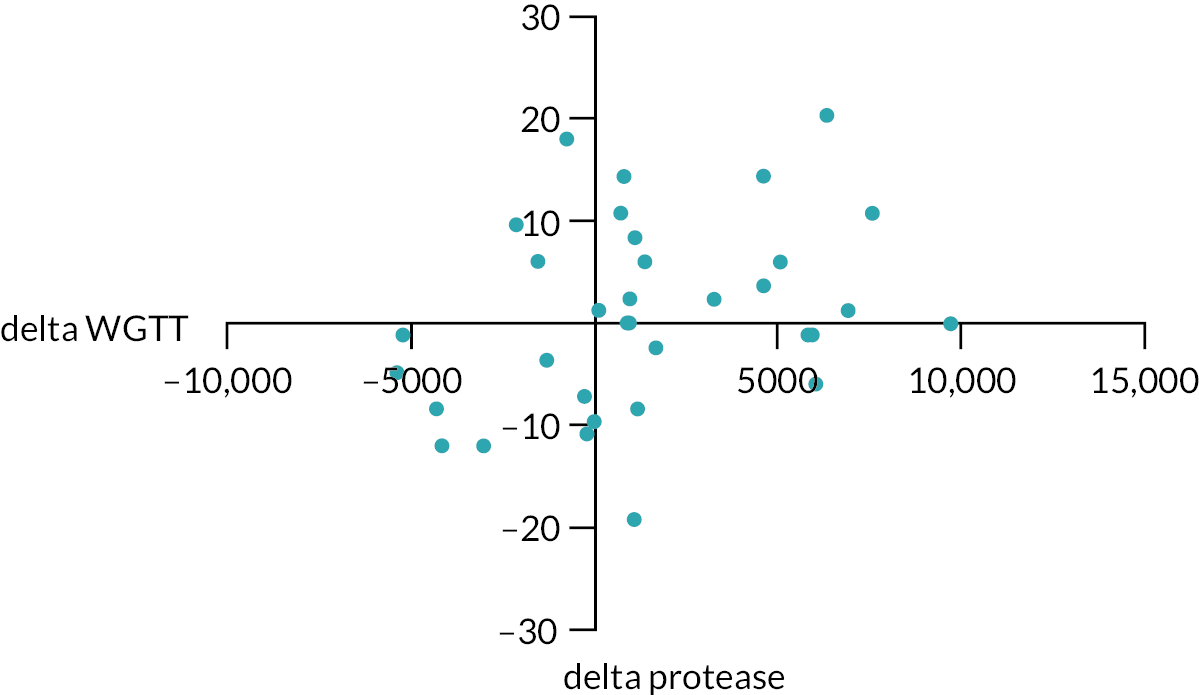

In our pilot study we showed the decrease in urgency associated with ondansetron use correlated directly with the reduction in faecal protease (FP),23 but whether this represents a true causal relationship, or just an epiphenomenon, is unclear. FPs have been shown to be increased in IBS-D and, at least in animal models, cause hypersensitivity to rectal distension via activation of protease-activated receptors type 2 (PAR2). 24 We have shown that most FPs are endogenous,23 representing pancreatic enzymes that have escaped degradation by colonic bacteria. We hypothesise that slowing gut transit with ondansetron reduces FP, by allowing time for bacterial degradation, and that this may contribute to the beneficial effects of ondansetron on urgency. Reducing faecal tryptase might improve the anal soreness that is commonly reported by patients with IBS-D.

Bile acids

Bile acids have also been shown to sensitise the rectum,25 and elevated faecal bile acids (FBAs) have been shown by several groups in patients with IBS-D. 26 Slowing transit may increase the time for bile acid deconjugation by colonic bacteria, and therefore enhance absorption, but how important this is in reducing rectal sensitivity, compared with the effects on FPs, is unclear.

Genetic factors altering sensitivity to 5HT3RAs

We have shown that individuals vary widely in their responsiveness to ondansetron, explaining why trials using fixed doses of 5HT3RAs result in severe constipation in around one in four patients. Meta-analysis gives a relative risk of constipation of 4.3 (3.3–5.6). 7 However, when patients were allowed to dose titrate we found that constipation was rare, occurring in only 9% of patients, most of whom responded to dose reduction and only 2% discontinuing ondansetron because of this. 12 However, the required dose of ondansetron ranged from 4 mg on alternate days to 8 mg three times a day (t.d.s. ). The reasons for this variation are unclear, but recent evidence suggests that responsiveness to 5HT3RAs might be linked to polymorphisms in the genes controlling 5HT synthesis. Serotonin availability in the rectal mucosa is thought to be determined by the activity of the rate-limiting synthetic enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase-1 (TPH-1), which produces serotonin in enterochromaffin cells. A recent small study showed TPH-1 messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) levels in rectal mucosa (and thus presumably serotonin synthesis rate) were approximately doubled in responders to another 5HT3RA, ramosetron, compared with non-responders, and that this was linked to the TPH-1 genotype. 27 TPH-1 rs211105 minor allele G was found in 44% of non-responders, but only 4% of responders, indicating that possessing the major allele increases responsiveness to the drug. It was also associated with worse diarrhoea, possibly because of the greater 5HT synthesis.

Objectives

The overall aim was to determine the efficacy and safety of ondansetron in patients with symptoms of IBS-D, in particular evaluating the effect on the characteristic abnormalities of stool consistency, frequency and urgency as well as abdominal pain, satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms, mood and use of rescue medication and to determine the effect of 12 weeks ondansetron over 1 month after discontinuation.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

A multisite, parallel-group, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial, with embedded mechanistic studies recruiting patients from primary and secondary care as well as the community.

Participants

Patients were screened using a standardised protocol to establish eligibility using the following criteria.

Inclusion criteria

These were as follows:

-

patients had to meet modified Rome IV criteria for IBS-D (see as previously published);

-

patients had to be aged ≥ 18 years;

-

patients should have completed standardised workup to exclude:

-

microscopic colitis (colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy with colonic biopsies);

-

bile acid diarrhoea (BDA) [Selenium homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) results of > 10%, C4 results of < 19 ng/ml or failed 1-week trial of a bile acid binding agent (colestyramine 4 g t.d.s. , colesevelam 625 mg t.d.s. or equivalent)];

-

lactose malabsorption (suggested but not mandated negative lactose breath hydrogen test, negative clinical challenge or failure to respond to lactose-free diet);

-

coeliac disease [tissue transglutaminase (tTG) or duodenal biopsy];

-

-

patients of childbearing potential or with partners of childbearing potential had to agree to use methods of medically acceptable forms of contraception during the trial and for 90 days after completion of trial medication;

-

for women of childbearing potential, a negative pregnancy test was performed within 72 hours of confirmation of eligibility;

-

weekly average worst pain score had to be ≥ 30 on a 0 to 100-point scale;

-

stool diary needed to show stools with a consistency of 6 or 7 on the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) for 2 or more days per week.

Modified Rome IV diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea

Must fulfil the following criteria for the past 3 months:

-

recurrent abdominal pain at least weekly;

-

pain is associated with two or more of the following criteria:

-

related to defaecation;

-

associated with a change in frequency of stool;

-

associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool;

-

-

symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis;

-

> 25% of abnormal stools are loose (BSFS 6 or 7) but < 25% are hard (BSFS 1 or 2).

Reproduced under creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Exclusion criteria

-

Gastrectomy.

-

Intestinal resection.

-

Other known organic gastrointestinal diseases [e.g. inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis)].

-

Unable or unwilling to stop restricted medication, including regular loperamide, antispasmodics (e.g. hyoscine butylbromide, mebeverine, peppermint oil, alverine citrate), eluxadoline, tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) doses > 30 mg/day or other drugs likely in the opinion of the investigator to alter bowel habit. These medicines should be discontinued for a 7-day washout period prior to registration.

-

Corrected QT (QTc) interval ≥ 450 milliseconds for men or ≥ 470 milliseconds for women [assessed within the last 3 months by electrocardiogram (ECG)].

-

Previous chronic use of ondansetron or contraindications to it.

-

Pulse, blood pressure (BP) and laboratory blood values outside the normal ranges according to the site’s local definition of normal [assessed within the last 3 months]. Note minor rises in alanine transaminase (ALT) (< 2 × upper limit of normal) will be acceptable, but the patient’s general practitioner (GP) will be informed if they remain elevated at the end of the trial.

-

Women who were pregnant or breastfeeding.

-

Patients currently participating in, or who have been in, a trial of an investigational medicinal product (IMP) in the previous 3 months, where the use of the IMP may cause issues with the assessment of causality in this trial.

-

Patients who had started or altered dosing of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or TCAs in the last 3 months, or who were planning to change the dose during the trial.

-

Patients currently taking and unwilling or unable to stop apomorphine or tramadol (which interact with ondansetron).

-

Patients with only stools of consistency 7 on the BSFS for 7 days a week.

Patients taking QT-prolonging or cardiotoxic drugs were reviewed by the local principal investigator (PI) to determine whether they were suitable for the trial.

Intervention

Participants were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis to initially receive either ondansetron 4 mg or matched placebo, one tablet daily. Both treatments were administered in oral doses which ranged from one tablet every third day to a maximum of six tablets daily for 12 weeks. The optimum dose was established by dose titration monitored closely by the research nurse using a standardised advice protocol in the first 2 weeks of the trial to avoid constipation, which at a standard dose occurs in one-quarter of patients. Patients were told to increase or decrease dosage every 2 days according to their stool consistency. If stools became hard or there was no bowel movement on day 2, they were asked to stop the drug for 1 day and recommence at a lower dose going from one tablet daily to one tablet on alternate days. If stools still remained hard or infrequent, they were asked to reduce to one tablet every third day. Continuing loose stools led to the advice to increase the daily dose by one tablet every 2 days, while constipation led to a reduction in dosage. Most patients had established a stable dose by 2 weeks. Patients were reminded to take their medication regularly on each trial visit, as well as during the phone calls within the 2-week titration period. Counts of any remaining IMP were done at visits 4 and 5.

Participant timeline

This is summarised in Appendix 1, Table 34 with details given below.

Visit 1

Potential trial candidates attended their first visit for registration and consent by the PI or delegate. If required, further tests to exclude diagnoses other than IBS-D were arranged. These included a SeHCAT scan, serum C4 level (Edinburgh centre only) or a 1-week trial of a bile acid binding agent to assess for bile acid malabsorption (unless done within the last 5 years), and a colonoscopy (unless done within 2 years, or 5 years if they also had a current normal calprotectin) to assess for microscopic colitis. Baseline serum blood tests, vital signs, demographics (date of birth, gender, ethnicity and smoking history) and an ECG were obtained. Current medications were reviewed, and those unable to discontinue drugs likely to alter bowel habit were unable to enter the trial. Patients on QT-prolonging drugs and cardiotoxic drugs were reviewed by the PI for suitability for the trial, as high-dose ondansetron may increase the risk of QT prolongation and arrhythmias. Eligible and consenting patients were registered and allocated a unique trial ID.

All patients were asked to complete a 2-week daily diary recording stool frequency, stool consistency for each stool (using the BSFS), worst abdominal pain (on a scale of 0–100), worst bowel movement urgency (on a scale 0–100) and if they had used loperamide that day. In addition, patients had the option to be sent two automated text messages each day, something most participants initially agreed to do. The first message asked the patient if they had passed a stool of consistency 6 or 7 on the BSFS. They had to reply with either a yes or no. The second text message asked what their worst abdominal pain score was that day. The patient could respond with a number from a scale of 0–100 (where 0 is no pain and 100 is the worst imaginable pain).

Visit 2

Two weeks later the patient returned to confirm eligibility. The diary was used to confirm they had stool consistency BSFS 6–7 for more than 2 days a week and did not meet the exclusion criteria of having only BSFS 7. They also had to have a weekly average worst pain score ≥ 30. For patient consenting to the whole gut transit study, Transit-Pellet capsules containing markers were dispensed and the abdominal X-ray appointment confirmed for the morning of visit 3. If the patient had consented to one or both mechanistic studies, appointments for baseline assessment were arranged prior to visit 3.

Visit 3

On visit 3, patients underwent a pregnancy test if applicable, whole gut transit assessment by abdominal X-ray (if consented), rigid sigmoidoscopy (if consented), completion of baseline questionnaire booklet [including IBS-SSS, Short-form Leeds dyspepsia questionnaire (SFLDQ), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Patient Health Questionnaire 12 (PHQ-12) and IBS-QOL questionnaires], and collection of stool, whole blood and serum samples (if consented). Patients were then randomised and given a 6-week patient diary and the trial medication in accordance with their blinded randomisation allocation. Patients were asked to record the following on a daily basis: stool frequency, consistency of each stool, worst abdominal pain experienced that day, worst bowel movement urgency, number of trial medication capsules taken and whether they had used loperamide that day. Every week the diary required them to respond to the question whether they felt that ‘they have had satisfactory relief from their IBS symptoms that week’. If they agreed, the patient continued to receive two text messages each day for the rest of the trial, asking if they had passed a stool of a consistency of six or seven that day, and what their worst abdominal pain was that day.

During the first 2 weeks, patients were contacted every 2 days by the local site team to discuss bowel habit. The dose of ondansetron or placebo was titrated as required. Additional guidance on dose titration was given to each trial site in a standard operating procedure, and to the patient in a dose titration instruction leaflet (see Report Supplementary Materials 1 and 2). A check for serious adverse events (SAEs) was performed during each telephone call. The steady dose to be taken forward for the remainder of the trial was mostly confirmed in week 2, although patients could alter this during the 12 weeks, if required, to avoid constipation.

Visit 4

At 6 weeks on the trial treatment, patients returned for their fourth visit. Diaries were collected, and the investigator asked whether any reportable adverse events (AEs) had occurred since the last visit. A pregnancy test was taken (if required) and concurrent medication reviewed to ensure these do not interfere with the trial medication. A further 6-week patient diary, trial medication and Transit-Pellet capsules (for use 6 days prior to visit 5) were dispensed. If the patient consented to mechanistic studies, appointments were confirmed and arranged as convenient between 8 and 11 weeks of treatment. Daily text messages continued for a further 6 weeks for those patients who agreed.

Visit 5

After 12 weeks on the trial medication, patients returned for visit 5. A pregnancy test was taken (if required), concurrent medication reviewed to ensure that these did not interfere with the trial medication and the investigator asked whether any reportable AEs had occurred since the last visit. Unused medication and completed patient diaries were collected. The plain abdominal X-ray to assess whole gut transit was performed for consenting patients. Serum and stool samples were collected for consenting patients, and all patients completed the 12-week questionnaire booklet, including the IBS-SSS, SFLDQ, HADS and IBS-QOL questionnaires. Patients were issued with a follow-up diary and continued to respond to text messages for a further 4 weeks.

Visit 6

Patients returned for the sixth and final visit, where the diary was collected, and the investigator asked about any reportable AEs since the last visit.

See Appendix 1, Table 34 for a breakdown of activities per visit.

Trial outcomes

Primary outcome measure

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-defined response in relation to abnormal defaecation and abdominal pain measured over 12 weeks post randomisation by patient diary and daily text message.

Definition: A FDA responder is a patient who records both a reduction in pain intensity and an improvement in stool consistency for at least 6 weeks of the 12-week treatment period, where:

-

reduction in pain intensity is defined as ≥ 30% decrease from baseline in weekly average worst daily pain;

-

improvement in stool consistency is defined as ≥ 50% decrease in the number of days per week with at least one loose stool [BSFS (21) 6 or 7)].

The two components to response (pain intensity and stool consistency) are also reported as individual outcomes.

Secondary outcome measures

Irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea symptoms measured by patient diary and daily text message over 12 weeks post randomisation and calculated for weeks 1–12 and for weeks 9–12:

-

abdominal pain (mean daily pain score, scored 0 = no pain to 100 = worst possible pain);

-

urgency of defaecation (mean daily urgency score, scored 0 = no urgency to 100 = worst imaginable urgency);

-

stool consistency (mean number of days per week with at least one loose stool; mean daily BSFS);

-

stool frequency (mean number of daily stools);

-

use of rescue medication (loperamide) over 12 weeks of treatment;

-

satisfactory relief assessed through answers to ‘Overall, have you had satisfactory relief from your IBS symptoms in the past week?’ Yes or No (measured by diary at the end of each week).

Self-reported symptoms, QoL and mood at 12 weeks post randomisation:

-

IBS symptom severity [measured by the IBS Severity Scoring System (IBS-SSS)];28

-

dyspepsia (using the SFLDQ);29

-

QoL and mood (IBS-QOL);30

-

HADS questionnaires;31

-

somatic symptoms [Patient Health Questionnaire 12 Somatic Symptoms (PHQ-12SS)] questionnaire. 32

Post-treatment (weeks 13–16 post randomisation) recorded in patient diary:

-

abdominal pain;

-

urgency;

-

stool consistency;

-

stool frequency.

Safety:

-

SAEs assessed throughout 12-week treatment period;

-

AEs assessed 4 weeks after the end of treatment to determine if there are any persisting effects.

Summary of any changes to the project protocol

A number of minor amendments were made; a summary of protocol changes can be found in Appendix 1, Table 35. There were no changes to end points or drug administration.

These minor amendments included:

-

raising the permitted calprotectin level to be < 100 ng/mg in view of new national recommendations;

-

allowing a 7-day trial of colestyramine to replace SeHCAT testing to exclude BDA to overcome the problem of long delays in SeHCAT testing;

-

simplifying the information sheets and including the new data on congenital malformations which became available during the trial;

-

adding GP surgeries within the East Midlands as Participant Identification Centres (PICs), October 2018 and January 2019;

-

allowing patients who have had a colonoscopy within 10 years to exclude microscopic colitis to be enrolled in the trial. The exclusion criteria have been amended to clarify that patients would need to stop taking high-dose TCAs to 19 July 2019;

-

allowing new adverts, July 2019;

-

both the treatment patient information sheet (PIS) and the treatment + tests PIS have been updated to reflect the new safety information regarding the use of ondansetron in pregnancy, October 2019;

-

the SMS Guidance for patients has been updated. A fully tracked document has been included for review. Changes have been made to this document to make it easier to understand and to add clarity on what is involved in this aspect of the study, October 2019;

-

an SMS messages flowchart has been added. Due to an oversight the content of the SMS messages has not been previously submitted for approval, October 2019.

Mechanistic methods

The trial aimed to evaluate the possible mechanisms underlying any changes in the primary and secondary end points. The hypothesis we wished to test was that ondansetron would slow transit, particularly on the left side of the colon, possibly by stimulating retrograde sigmoid contractions. We planned to measure whole gut transit at baseline and 12 weeks (n = 400), using radio-opaque markers and an abdominal X-ray as previously described by Abrahamsson. 33 All patients were offered the opportunity to take part in high-resolution manometry (HRM) studies to be performed at baseline and after 8–11 weeks of treatment at either Nottingham or the Royal London Hospital. We provided travel expenses and where necessary overnight stay for those who needed to travel to reach one of these centres though few required this. We also hypothesised that, like alosetron, a closely related 5HT3RA, ondansetron would relax the rectum as shown by increased compliance in the rectal barostat studies which were performed in Nottingham and the Royal London Hospital. Previous studies had identified abnormalities of FPs and bile acids in IBS-D which correlated with transit, so we planned to assess their correlation with symptoms at both baseline and week 12.

We attempted to collect faecal samples at baseline and week 12 for all patients to assess faecal water %, bile acids and protease.

Transit

Aim

To assess if ondansetron altered colonic transit significantly.

Methods

Patients were asked to take the transit capsules daily for Transit-Pellets method™ supplied by Medifactia AB Limited, Stockholm, Sweden. Pellets were taken starting 6 days before their planned visit 3. Patients were instructed to take one pill at approximately 9 a.m. each day apart from day 6 when there were two pills to take, one at 9 a.m. and the second pill at around 6 p.m. This adaptation of the standard Metcalf method is designed to deal with patients with very fast transit when pellets taken at 9 a.m. may well have left the colon leaving zero pills to count. This then would raise the question of whether any pills had been taken whereas taking the second later pill makes this much less likely. On visit 3 a plain abdominal X-ray was taken and used to count the number of pellets in each of three regions designated right colon, left colon and pelvic area as defined on the plain abdominal X-ray by a vertical line to tip of the fifth lumber vertebra spinal process and then tangential to either pelvic brim as shown below. Colonic transit calculations from plain X-ray (Figure 1) were as described by Chan et al. 1 and used by Garsed et al. 2

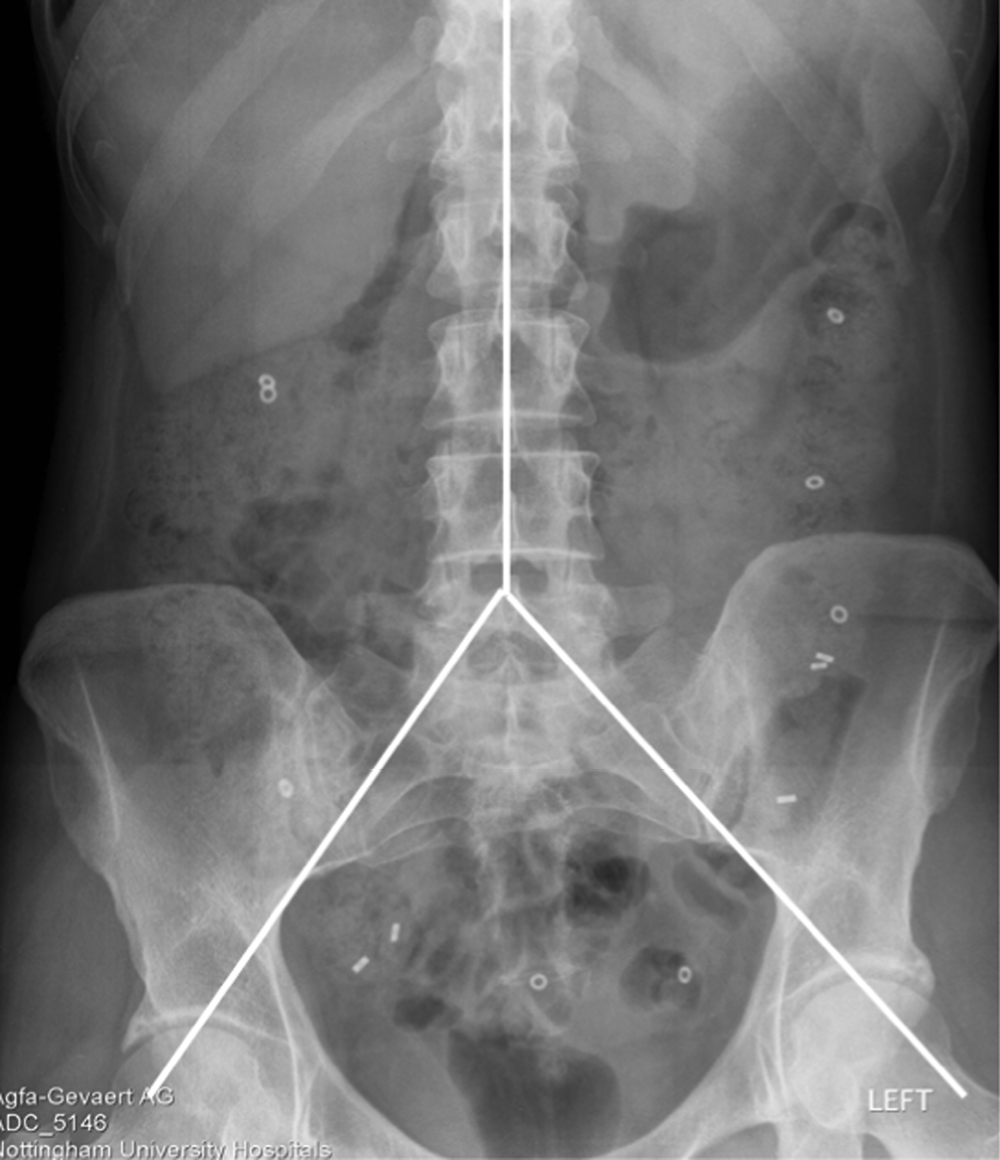

FIGURE 1.

Colonic transit calculations from plain X-ray. Whole gut transit (WGTT) was calculated from total pellets × 2.4 hours, so in this example of a patient on ondansetron with 21 pellets, WGTT = 50.4 hours.

Regional transit was calculated from the number of pellets in the right, left and pelvic areas × 2.4 so in the example right transit time = 2 × 2.4 = 4.8, left = 2.4 × 3 = 7.2 and pelvic = 16 × 2.4 = 38.4 hours.

High-resolution manometry

Aim

Our aim was to characterise for the first time, the motor patterns in IBS-D using high-resolution manometry (HRM). We also planned to assess if baseline readings would relate to symptoms and whether these would alter with treatment.

This was performed at baseline and after 8–11 weeks of treatment in Nottingham and the Royal London Hospital. Patients from other sites were also offered the opportunity to travel to either site; two patients accepted this offer. The methods followed those reported by Dinning et al. 34 and subsequently used by Corsetti et al. 35,36

Methods

After a 12-hour fasting period, all patients were admitted to the Motility Unit for bowel preparation with tap water enemas. They then underwent a colonoscopy-assisted positioning of the colonic HRM catheter (UniTip High-Resolution Catheter, Unisensor AG, Attikon, Switzerland). As the colonoscope was being withdrawn after having fixed the catheter with haemoclips, four biopsies were taken. The catheter consisted of 40 sensors spaced 2.5 cm apart. After allowing 1 hour for the recording to settle following the colonoscopy, colonic pressure recording was started and continued for 2 hours before consuming a standardised meal [Tomato & Basil Dolmio PastaVita (285 kcal, 3.9 g fat, 8.7 g sugars) and Ensure® TwoCal drink (399 kcal, 17.8 g fat, 9.2 g sugars)]. During the recording, the subjects were asked to score their feeling of abdominal gas, desire to evacuate gas, desire to defaecate and urgency to defaecate every 15 minutes. Both the investigator and patient were blind as to their treatment. The manometry files were sent via secure transfer to Dr Phil Dinning at the University of Adelaide for analysis using previously published methods. 21,37

Barostat assessment

This was performed at baseline in nine subjects and after 8–11 weeks of treatment in Nottingham and the Royal London Hospital; six of whom also underwent manometry. Patients from other sites were also offered the opportunity to travel to either site but only two patients accepted this offer.

Aim

To assess if ondansetron increases rectal compliance and decreases sensitivity (manifest as increased pressure thresholds for pain and urgency) compared to placebo.

Methods

Patients were asked to fast from midnight for morning slots, or from 8 a.m. for afternoon slots prior to the assessment. They were asked to bring their usual dose of the study drug for the 8–11-week visit. After taking the dose, there was a 60-minute delay before making any measurements. On arrival patients were given instructions on how to self-administer a 500 ml body temperature tap water enema. After defaecating, patients were asked to lie down on the bed in a semi-prone left lateral decubitus position in a relaxed fashion with the foot end of the bed elevated from horizontal by 15° to decrease the effects of abdominal viscera on the bag volume. Rectal sensitivity was then assessed 60 minutes after taking the trial medication using a dual-drive barostat (Distender series II, G & J Electronics, Toronto, ON, Canada) and a polyethylene bag (600 ml) fixed on the end of a double-lumen barostat catheter (MUI Scientific, Mississauga, ON, Canada). The catheter was inserted into the rectum so that the middle of the bag was located approximately 10 cm from the anal verge and taped securely to the buttocks. The barostat bag was then unfolded by transiently inflating it with 75 ml of air and subsequently deflating it completely but leaving it in situ. Rectal pressure/volume relationships were assessed during a phasic isobaric, ascending method of limits distension protocol (4 mmHg steps to maximum toleration; 1 minute distension period, with 1 minute rest period between distensions). This was followed by a random phasic distension protocol distending to 8, 16, 24 and 36 mmHg with subjects rating sensation of gas, urgency, discomfort and pain on a 0–10 visual analogue scale (VAS). The maximum pressure used was adjusted depending on established pain threshold to avoid excessive pain and pressure was immediately released if patients reported > 80 mm of discomfort or pain on the VAS, following which higher distensions were not administered. Once the series had been completed the bag was deflated and removed. All procedures followed the written standard operating procedure which was part of the protocol.

End points

Primary: Pain pressure threshold mmHg.

Secondary: Urgency volume threshold, urgency pressure threshold, pain volume threshold.

Stool biomarkers: faecal proteases and bile acids

Aim

Previous studies had identified abnormalities of FPs and bile acids in IBS-D which correlated with transit and urgency, so we planned to assess these along with transit to see if we could confirm these findings and see if these affected symptoms.

Methods

All patients were asked to provide stool samples to assess whether ondansetron reduces total FBA and tryptase concentrations, both active mediators which might correlate with urgency.

Faecal water was measured by simple drying of weighed faecal samples in a vacuum rota-evaporator (Jouan, RC10.22, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 400 °C until constant weight was achieved.

Proteases

Using previously reported methods, samples (reproduced under creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/)23 (1 g) of stool stored at –70 °C were thawed and mixed in 5 ml 50 mM Tris buffer, 150 mM NaCl, pH7.2. Turbid suspensions were clarified using a sequential combination of centrifugation [10 minutes, 3000 relative centrifugal force (RCF)] and filtration (0.2 μm). Particulate-free supernatants were archived (–70 °C) until required for various assays or protein characterisation procedures.

Quantitation of total protein

Total protein quantitation was performed using the Bradford method,38 modified for low volume and high throughput. Briefly, equal volumes of sample and reagent were mixed in 96-well microplates and, following 20 minutes incubation, absorbance measurements at 595 nm were used to quantitate by reference to bovine serum albumin calibrants.

Quantitation of total protease activity

Total FP quantitation was performed using the non-specific proteolysis of azo-casein. The endoproteolysis of this liberates azo-peptides into the supernatant which are quantitated by absorbance measurement at 440 nm subsequent to protein precipitation with trichloroacetic acid. Protease activity was quantitated against bovine trypsin calibrant and expressed as trypsin units. Protein concentrations ranged from 0.08 to 1.7 mg/ml and measured protease activities were normalised against these values and expressed as units of trypsin/mg protein.

Quantification of bile acids (LC–MS)

After thawing faecal sample, 0.5 g was suspended in 2 ml of 50% (w/v) acetonitrile and extracted by vortexing and sonication for 10 minutes. The suspension was centrifuged twice at 25,000 g for 20 minutes. Supernatants were transferred to sample vials and loaded onto a liquid chromatography mass spectrometer (LC–MS) system containing online solid-phase extraction (SPE).

At the beginning of each analysis, 50 µl of the sample were transferred to SPE column at a flow of 0.1 ml/min with the loading mobile phase, aqueous 5% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid and 0.02% trifluoroacetic acid.

The chromatographic separation was performed using a binary system with pumps (A) and (B) (Jasco, PU-2085 Plus) connected to a degasser (Alltech, degasser, Stamford, UK). The two systems were connected using a two-position, six-port valve, used to switch automatically from loading (position 1) to injection (position 2) after 9 minutes (Valvemate®, Gilson, Dunstable. UK). Samples were analysed on a Waters Ex-bridge C18 Column (Waters, 100 × 2.1 mm; 3.5 µm particle size, Waters, Wexford, Ireland), using a gradient program. Mobile phase (A) 5 mM ammonium acetate, 0.1% ammonium hydroxide, mobile phase (B) 100% acetonitrile. Initial composition was 80% (A) was reduced to 70% (A) over 30 minutes the further reduction to 65% (A) over the next 3 minutes. The eluent composition was held at 65% for 1.5 minutes before returning to 80% (A) initial condition over the next 1.5 minutes. Flow rate 0.2 ml/min.

High-performance liquid chromatography was coupled in series with the turbo ion-spray (ESI) source of the tandem mass spectrometer (Micromass, Manchester, UK). Electrospray ionisation was performed in negative mode with nitrogen as the nebuliser gas. Detection of individual bile acids was performed using selective-ion monitoring (SIM) mode. Additional structural information was obtained via tandem MS (MS/MS) fragmentation, with collision energies ranging from 15 to 30 electron volts. Data were acquired using software MassLynX (Waters, Wexford, Ireland).

The concentration of bile acids in the samples was determined on the basis of the peak areas of individual bile acids and external standards.

End points

Primary: FP in trypsin units/mg protein, primary and secondary bile acids mmol/l stool water.

Secondary: Concentrations of individual bile acids, namely, cholic, chenodeoxycholic, deoxycholic and lithocholic acid, ratio of secondary/primary bile acids.

Mechanistic outcome measures

-

Whole gut transit time (WGTT; in hours), assessed using radio-opaque markers and an abdominal radiograph at baseline and 12 weeks.

-

Pain pressure threshold, pain volume threshold, urgency pressure threshold and urgency volume threshold, assessed using a barostat prior to starting the trial and 8–11 weeks during the trial.

-

FBAs and proteases prior to starting the trial and at 12 weeks during the trial.

-

Number of high amplitude propagated contractions (HAPCs) fasted and postprandially, assessed by HRM at baseline and at a visit at 8–11 weeks during the trial.

-

Percentage time occupied by cyclical propagated contractions, assessed by HRM at baseline and at a visit at 8–11 weeks during the trial.

Sample size

Primary end point

Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome using titrated ondansetron trial (TRITON) planned to recruit 400 patients from up to 24 sites across England and Scotland. This would have provided 90% power at 5% significance to detect a 15% absolute difference between the randomised groups in the proportion of patients achieving the FDA-recommended end point39 of a weekly responder for pain intensity and stool consistency for at least 6 weeks of the 12-week treatment period. This difference (15%) was considered to represent the minimum clinically important difference since in practice over the last two decades new IBS drugs with a lesser margin of efficacy are rarely prescribed in the NHS. We assumed a placebo response rate of 17%, as recently reported12 using this end point and allowed for a 15% attrition rate.

Mechanistic studies

Whole gut transit

Our previous study using the same radio-opaque marker technique showed ondansetron increased WGTT by a mean [95% confidence interval (CI)] of 10 (6 to 14) hours. 12 Using 200 per group would have given us a 90% power to detect a change of 0.7 hours.

High-resolution left-sided colonic manometry

Previous studies with the closely related 5HT3RA alosetron showed an increase in motility index compared with placebo, with a mean [standard deviation (SD)] of 1.0 (1.2),19 indicating we would have a power of 80% to detect a standardised effect size of 1 with 17 patients. We aimed for 20 patients on each treatment to allow for dropouts, that is, 40 each undergoing 2 studies, a total of 80 HRM studies.

Rectal compliance and sensitivity

Previous studies with alosetron showed an increase in compliance from 5.9 (SD 1.3) to 9.8 (SD 1.2) ml/mmHg in 22 patients. 40 We aimed to study 40 patients on each treatment to calculate correlations with symptoms, which typically require much larger numbers than just showing a change in mean values.

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed on a 1 : 1 basis to receive either ondansetron or placebo, and each patient was allocated three bottles of trial medication, each with a unique IMP kit code. Minimisation was used to ensure treatment groups were well balanced with respect to the minimisation factors of registering site and whether the patient had undergone mechanistic assessments.

Blinding

The trial was double-blind, neither the patient nor those responsible for their care and evaluation (treating team and research team) knew the allocation or coding of the treatment allocation. This was achieved by identical packaging and labelling of both the over-encapsulated ondansetron and matched placebo. Each bottle of ondansetron/placebo was identified by a unique kit code. Randomisation lists containing kit allocation were generated by the safety statistician at the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) and sent to the clinical supply company that produced the kits and the code break envelopes. Management of kit codes on the kit logistics application, which was linked to the 24-hour randomisation system, was conducted by the CTRU safety statistician in addition to maintaining the backup kit-code lists for each site.

Access to the code break envelopes was restricted to the safety statistician and designated safety team. Code breaks were permitted in emergency situations, where treatment allocation knowledge was needed to optimise treatment of the patient. Unblinded interim reports provided to the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) were provided by the CTRU safety statistician and the reports were securely password protected.

Statistical methods: general considerations

All hypothesis tests were two-sided and used a 5% significance level. Methods to handle missing data are described for each analysis. Analysis and reporting were in line with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT). 41 As TRITON was a double-blind trial, the trial statistician was blinded to treatment group allocation throughout the trial, until the database had been locked and downloaded for final analysis. Only the safety statistician, supervising trial statistician, backup safety statistician and authorised unblinded individuals at the CTRU had access to unblinded treatment group allocation prior to final analysis.

Frequency of analyses

Outcome data were analysed once only, at final analysis, although statistical monitoring of safety data was conducted throughout the trial and reported at agreed intervals to the DMEC. Final analysis took place 16 weeks post–last patient randomisation.

End-point analysis

All analyses were conducted on the ITT population, defined as all patients randomised, regardless of non-compliance with the intervention. A per-protocol (PP) analysis of the primary end point was carried out to indicate whether results were sensitive to the exclusion of patients who violated the protocol (e.g. those patients randomised but subsequently found to be ineligible). Primary and secondary analyses were blind to random allocation. Outcome measures were analysed by regression models appropriate to the data type. Such analyses adjusted for randomisation minimisation factors: site, completion of manometry assessment and barostat assessment, as well as baseline values where applicable, age and gender. Baseline characteristics were summarised by randomised group.

Primary analysis

The primary analysis compared the proportions of patients achieving the FDA-recommended end point between treatment groups at 12 weeks post randomisation using a logistic regression model adjusted for minimisation factors, age and gender. The plan was that any missing data were assumed missing at random (MAR) and imputed for the primary analysis. However, complete case analysis was undertaken and those without sufficient data (n = 4) to evaluate the primary end-point were assumed to be non-responders. The potential impact of missing data would be small with only 5% of missing responses. Odds ratios and corresponding 95% CIs are presented.

Sensitivity analysis was planned to assess the impact of missing data on the treatment effect was performed. This was planned to include complete case analysis and alternatives to multiple imputation (e.g. pattern mixture modelling), if missing patterns suggested data were missing not at random. However, given the small overall sample size and only four participants with missing data (5%), this was not undertaken.

Secondary analyses

The proportions of patients with satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms at 12 weeks post randomisation was compared between the treatment groups using logistic regression models, adjusting for minimisation, baseline values, age and gender. Odds ratios and corresponding 95% CIs are presented.

Differences between the treatment groups for the continuous secondary end points at 12 weeks post randomisation were compared using linear regression models, adjusted for the minimisation variables, baseline where applicable, age and gender. These end points were urgency of defaecation over the last month, stool frequency over the last month, number of days per week with at least one loose stool (BSFS > 5) over the last month, average stool consistency, number of days rescue medication used over 12 weeks, abdominal pain score, HADS depression and anxiety scores, SFLDQ score, IBS-QOL score and subscales, PHQ-12 and IBS-SSS severity scores. Treatment estimates and corresponding 95% CIs are reported.

The differences between the treatment groups post treatment over weeks 13–16 post randomisation in the following end points: stool frequency, abdominal pain and urgency of defaecation were compared using linear regression model adjusting for minimisation factors, baseline values and relevant baseline factors. Treatment estimates and corresponding 95% CIs are reported. Any missing data are assumed MAR.

Exploratory analyses on the daily measurements (worst abdominal pain, loose stools, number of stools passed, consistency of stool, worst urgency and use of loperamide) were carried out, using repeated measures models, which incorporate correlation between measurements from the same patient.

SAS software version 9.4 was used in the analyses of primary and secondary end points.

Safety analyses

All patients who receive at least one dose of trial treatment were included in the safety analysis set. The number of patients reporting a SAE (up to 28 days after the last dose of treatment), and details of all SAEs, are reported for each treatment group. The number of patients withdrawing from trial treatment is summarised by treatment arm, along with reasons for withdrawal. All safety analyses performed prior to final analysis were undertaken by the safety statistician (rather than the trial statistician), thus ensuring that the trial team remain blinded.

Subgroup analyses

No subgroup analyses were planned.

Mechanistic studies

Mechanistic studies were analysed by the site research fellow, blinded to the intervention allocation under supervision of the chief investigator and local supervising PIs. The differences between treatment groups for changes in whole gut transit times, colonic motility measures (% time of cyclical retrograde contractions and HAPC frequency), rectal compliance and thresholds for urgency and pain measured using the barostat, FBA concentrations and faecal tryptase were assessed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for analysis of treatment and time effects and t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test and Wilcoxon matched pairs test for paired comparisons between normally and non-normally distributed variables, respectively. In addition, exploratory mediator analyses were planned to explore whether treatment effects, in terms of changes in urgency or pain, are mediated through changes in FBAs or protease using Spearman/Pearson correlation as appropriate.

Patient and public involvement

Both the grant application and the design of the study were assisted by our patient participation and involvement (PPI) group, which included patients with IBS-D who supported the original application and subsequently helped with the design of patient-facing documents.

Chapter 3 Clinical trial results

Site and patient recruitment

Recruitment strategies

A number of strategies were adopted during the trial to address the recruitment difficulties that were encountered. The initial plan had been to open 11 secondary care centres for recruitment, but it soon became clear that this would not be adequate to achieve the necessary numbers required to complete the trial. The source of patients varied widely by site (see Appendix 3, Table 37). As well as increasing the number of secondary care sites to 16, we utilised numerous other strategies to attract more patients to the trial.

We opened a number of secondary PICs. The secondary care PICs would identify potential participants from their clinics and refer them on to a recruiting centre for consideration for the trial. A total of six such PICs were opened.

A key issue in recruitment of patients within secondary care seemed to be changes in referral patterns over recent years. A trial in Yorkshire showed the value of screening patients with diarrhoea with calprotectin in primary care, reducing unnecessary colonoscopy and this has strengthened existing National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance42 on the use of calprotectin in primary care. Evidence from NICE suggests a substantial reduction in referral from primary care with recent onset diarrhoea (56% in Cannock Chase, Staffordshire, UK). 43 Patients are thus less likely to be referred into secondary care for investigation of diarrhoea but are being investigated and managed in primary care. We soon realised that we would need to widen our recruitment pool to include patients in primary care and also in the general population.

We set up a self-referral pathway to allow patients to refer themselves to a local recruitment centre to be considered for the trial. Advertising was used to increase awareness of the trial and interested patients could visit the TRITON trial website for further information. The website included a simple self-screening questionnaire to confirm whether the patient was broadly eligible for the trial (see Appendix 10, Figure 31). Potentially eligible patients could then contact one of the trial research fellows to obtain further information about the trial and discuss their suitability before being referred on to their local recruiting centre.

We used a number of strategies to reach patients outside the secondary care centres. We approached GP practices in the areas surrounding the recruiting centres to set them up as PICs. The practices were asked to perform a search of their patient database to identify any suitable patients for the trial. They would then mail out a letter and leaflet introducing the trial to the patient asking them to visit the trial website if they were interested. Between March 2019 and February 2020, a total of 26 GP practices were set up as PICs and mail outs were sent to a total of 1381 patients. Of all the patients screened, two were identified in this way and of these one was randomised into the trial.

Starting in October 2019, we advertised within GP practices and pharmacies using posters and leaflets. GP practices that agreed to participate as PICs were asked to display the promotional materials in their waiting rooms. We also approached the Clinical Research Networks to arrange for promotional materials (see Appendix 10, Figures 32 and 33) to be displayed in the waiting rooms of GP practices not involved as PICs, as well as pharmacies.

In addition, we instigated a publicity drive to increase awareness of the trial outside of clinical settings. To achieve this, we advertised in local press in the areas surrounding our recruiting centres. The first advertisement drive was in May 2019 and regular advertising continued until March 2020. This advert (see Appendix 10, Figure 34) consisted of a quarter page in colour in publications such as the Metro, Manchester Evening News and London Evening Standard.

In November 2019, a Communications Officer was appointed to assist with the advertising strategy for the study, being responsible for engaging with Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), TV, newspaper and radio, IBS charities and other patient forums to publicise the study. The trial Twitter account was used to engage with sites and improve awareness within trial teams in the hope that it would help attract more patients to the study. We actively encouraged staff at recruiting centres and collaborators to follow and retweet as well as using appropriate hashtags and tagging any relevant organisations in our tweets. We also advertised on social media, in particular Facebook (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) and Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA).

Professor Spiller and Karen Andrews (patient and public involvement representative) did an interview for the Mail on Sunday, which was the lead article on their health page on Sunday, 23 March 2019 and produced 3000 visits to our webpage and some 430 contacts of which approximately 10 entered the trial.

ContactME-IBS is a registry run through one of the TRITON recruiting sites, County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust. ContactME-IBS holds the contact information of approximately 2766 adults interested in hearing about, and taking part in, IBS research, of which 641 were suitable for TRITON having been identified as having IBS-D and associated pain (a key eligibility criterion). A mail shot to the 641 potentially eligible registry patients was sent in November 2019. Due to the nature of the registry setup, patients are mainly centred around areas where ContactME have had a drive to recruit GP practices, with 593 of the potentially eligible registry patients located in areas affiliated with TRITON secondary care sites, and 48 in areas without a suitable TRITON site.

Summary of patient identification method and screening approach is in Table 1.

| Identification method | Screened (n = 1582)a (%) | Clinic 41 (2.6%) (%) | Telephone call 20 (1.3%) (%) | E-mail/letter 15 (0.9%) (%) | Missing 1506 (95.2%)b (%) | Randomiseda (n = 80) (%) | Clinic 17 (21.3%) | Telephone call 3 (3.8%) (%) | E-mail/letter 3 (3.8%) (%) | Missingb 57 (71.3%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary care | 485 (30.7) | 41 (8.5) | 18 (3.7) | 11 (2.3) | 415 (85.6) | 58 (72.5) | 17 (29.3%) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | 39 (67.2%) |

| Primary care and pharmacies | 10 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (10.0) | 8 (80.0) | 4 (5.0) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0%) |

| Self-referral via website | 64 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (3.1) | 61 (95.3) | 12 (15.0) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.7) | 9 (75.0%) |

| Self-referral – other means | 34 (2.1) | 34 (100.0) | 4 (5.0) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0%) | |||

| Secondary PIC | 4 (0.3) | 4 (100.0) | ||||||||

| Primary care (invitation letter) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (100.0) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0%) | |||

| Patients on file | 951 (60.1) | 951 (60.1) | ||||||||

| Forwarded by CTRU | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | ||||||||

| Identified by bowel cancer charity | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | ||||||||

| Other | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | ||||||||

| Missing | 28 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.6) | 27 (96.4) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0%) |

Screening and recruitment

A total of 1582 potential participants were screened for entry into TRITON, across 13 hospital sites, including those referred to local sites by the Clinical Research Fellows (section Self-referrals below). Of these, 295 (18.6%) were found to be eligible for the study, 173 (58.6% of eligible) consented to take part in the study, 149 (86.1% of consented) were registered to the study, and 80 (53.7% of registered) were randomised to the study. Eligibility varied widely between centres from 10% to 90% with some being more efficient than others in deciding who to approach (see Appendix 3, Table 36). A detailed flow of these patients in the form of a CONSORT diagram can be seen in the supplementary document. A large proportion, 55.8% (882/1582), of screened patients were ineligible due to not meeting the Rome IV criteria. Of those who passed screening and were registered, insufficient pain scores were the largest single cause of being ineligible for randomisation (31/149). Overall, patients were screened over 28 months from March 2018 until June 2020.

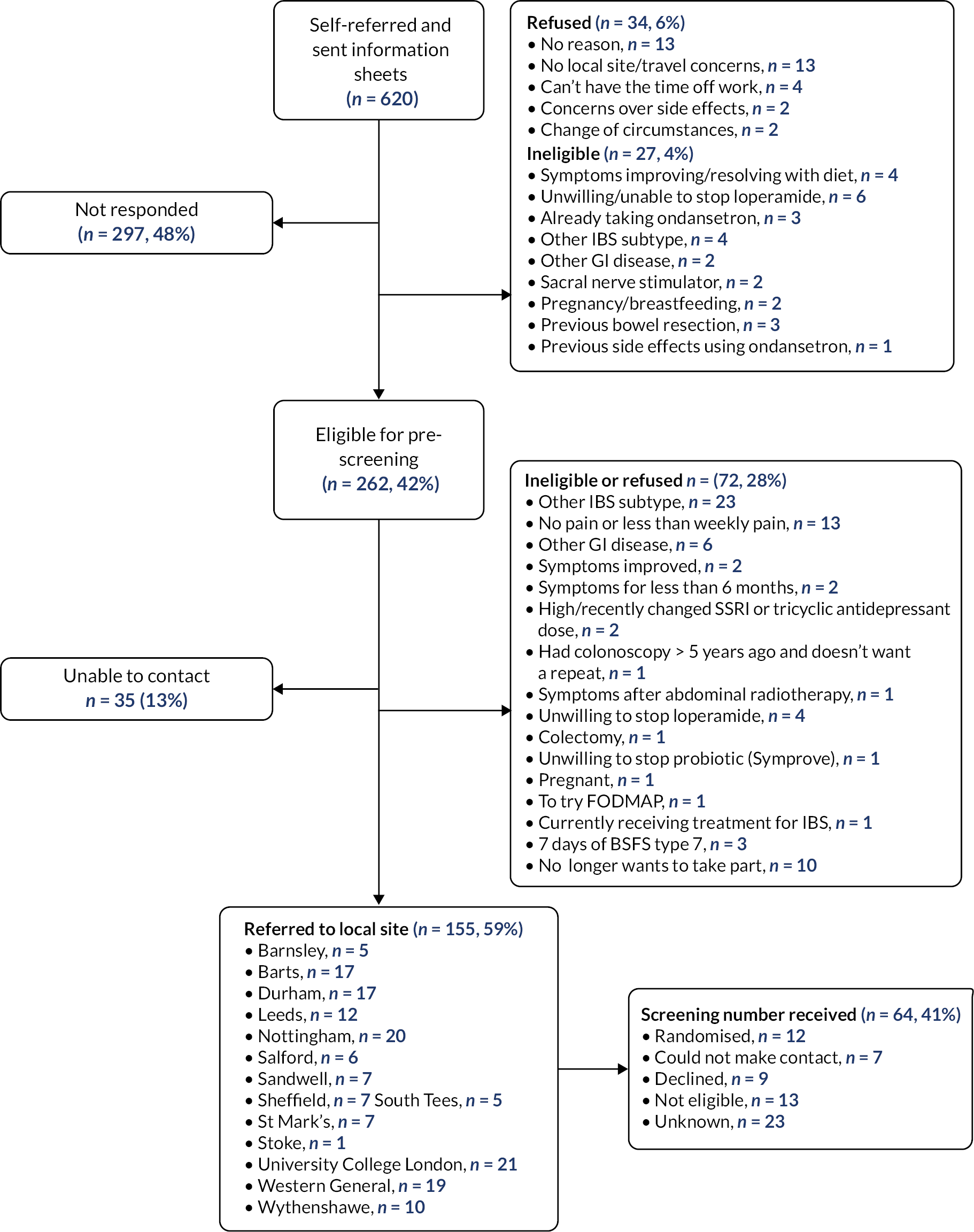

Self-referrals

A total of 620 people self-referred via the TRITON website (Figure 2) and were sent information sheets. Subsequently, 297 (47.9%) did not respond further. A total of 155 (25.0%) were referred onto a local site, having confirmed their interest in taking part in the TRITON study and fulfilled the initial eligibility checks.

FIGURE 2.

Self-referral flow of participants.

The trial Clinical Research Fellows responded to each patient’s e-mail, and 64 patients were screened through the formal screening process. Twelve patients were randomised using the self-referral route (see Table 1). Self-referrals were received and screened over 20 months from November 2018 until June 2020.

Screening characteristics

Characteristics of screened participants (age and gender) summarised by site are detailed in Table 2. One site in particular screened more potential participants than the others, 49.2% (778/1582) of the total; but most of these screening forms were missing age and gender data. The percentage who were eligible varied from 0.6% to 91.7% of those considered indicating that some sites were much more selective in who they approached. For those potential participants with screening data available, the mean age of those screened was 44.9 years old (SD 15.4), and 67.1% were female (523/780). Further screening information by site can be found in Appendix 3, Tables 36–38.

| Age (years) | Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Total (%) | Mean (SD) | Missing | Male (%) | Female (%) | Missing (%) |

| James Cook, South Tees | 38 (2.4) | 39.6 (12.5) | 0 | 13 (34.2%) | 25 (65.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| St James’s University Hospital, Leeds | 80 (5.1) | 43.5 (17.4) | 6 | 16 (20.0%) | 63 (78.8%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| Royal Hallamshire Hospital | 51 (3.2) | 48.1 (13.9) | 1 | 23 (45.1%) | 27 (52.9%) | 1 (2.0%) |

| Sandwell Hospital | 43 (2.7) | 45.2 (12.5) | 1 | 15 (34.9%) | 28 (65.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| University Hospital of North Durham | 23 (1.5) | 49.0 (11.8) | 4 | 6 (26.1%) | 16 (69.6%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Wythenshawe Hospital | 12 (0.8) | 47.4 (15.7) | 0 | 5 (41.7%) | 7 (58.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Royal Stoke University Hospital | 44 (2.8) | 43.6 (17.1) | 0 | 14 (31.8%) | 28 (63.6%) | 2 (4.5%) |

| Nottingham University Hospital | 58 (3.7) | 45.7 (18.2) | 4 | 25 (43.1%) | 32 (55.2%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Barnsley District General Hospital | 216 (13.7) | 46.8 (15.5) | 5 | 54 (25.0%) | 161 (74.5%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| St Mark’s Hospital | 11 (0.7) | 56.3 (12.1) | 2 | 6 (54.5%) | 5 (45.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Western General Hospital | 53 (3.4) | 43.8 (14.6) | 1 | 12 (22.6%) | 40 (75.5%) | 1 (1.9%) |

| Salford Royal Hospital | 16 (1.0) | 38.6 (15.5) | 0 | 6 (37.5%) | 10 (62.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Barts and London School of Medicine and Dentistry | 159 (10.1) | 43.0 (14.3) | 67 | 43 (27.0%) | 53 (33.3%) | 63 (39.6%) |

| University College London Hospital | 778 (49.2) | 42.1 (16.1) | 740 | 19 (2.4%) | 28 (3.6%) | 731 (94.0%) |

| Total | 1582 (100) | 44.9 (15.4) | 831 |

257 (32.9% of non-missing)

(16.2% of total) |

523 (67.1% of non-missing)

(33.1% of total) |

802 (50.7%) |

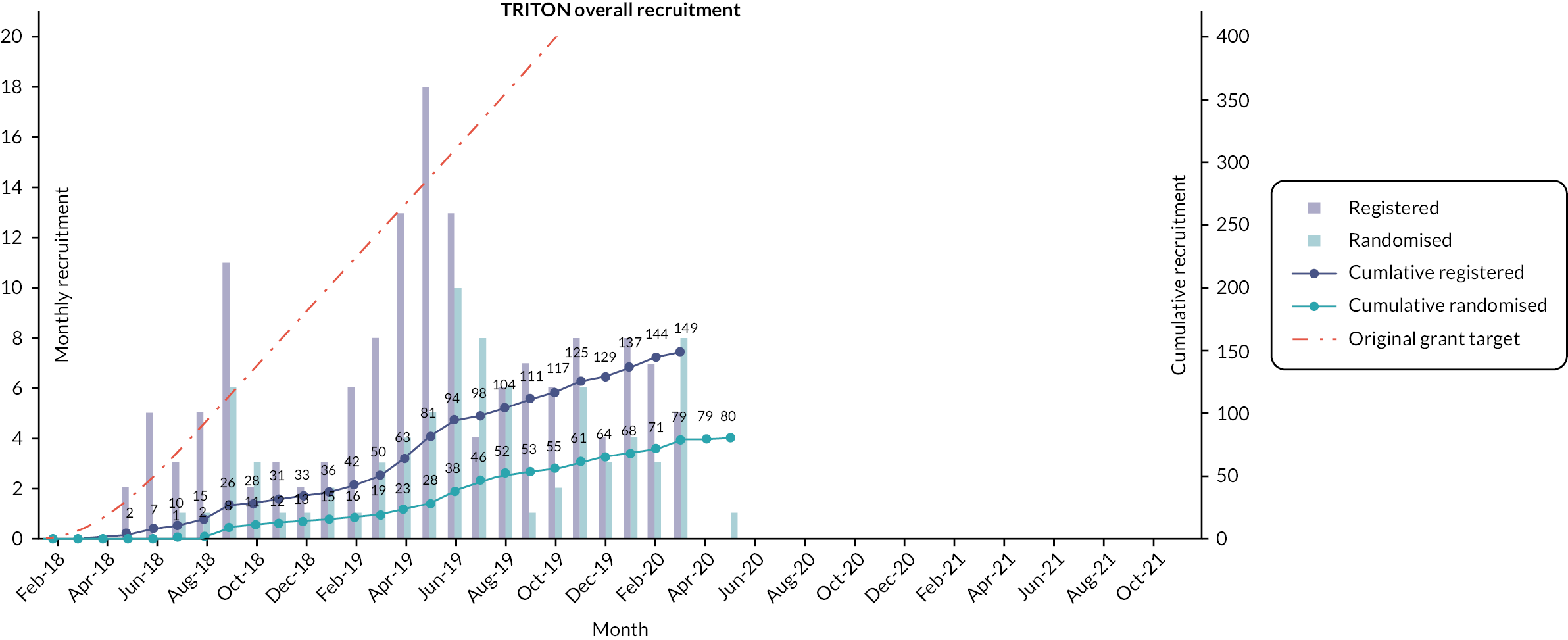

Randomisation and participant flow

Registration data by site are provided in Appendix 3, Table 39. Participants were randomised over 23 months from July 2018 until May 2020 (Figure 3). Thirty-seven (46.3%) participants were randomised to ondansetron and 43 (53.8%) to placebo (see CONSORT diagram). By the end of treatment at 12 weeks, six participants discontinued treatment, four in the ondansetron arm (one of these patients withdrew from follow-up) and two in the placebo arm.

FIGURE 3.

Overall recruitment.

Populations

Populations are summarised in Table 3.

| Randomised to | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Ondansetron (n = 37) | Placebo (n = 43) | Total (n = 80) |

| ITT | 37 | 43 | 80 |

| PP | 36 | 40 | 76 |

| Safety | 37 | 43 | 80 |

Intention-to-treat (ITT) population. All 80 randomised participants are included in the ITT population.

Per-protocol (PP) population. Four patients of the 80 randomised were removed from the PP population due to major protocol violations. One participant was taking a restricted medication (Buscopan), two participants’ abdominal pain scores in the pre-treatment diary were too low compared with the inclusion criteria, and one participant became pregnant while in the trial.

Safety population. All 80 participants received at least 1 dose of trial medication, and there were no cases of incorrect treatment taken, so all 80 randomised participants are included in the safety population in accordance with randomised allocation.

Baseline

At baseline, randomised participants were of a similar age to all screened participants, mean age 43.9 and 44.9 years, respectively. Overall, a higher proportion of males were randomised compared with the proportion of males screened; 41.3% and 32.9%, respectively. However, a high proportion of screening records had no age and sex data making comparisons uncertain (Table 4). In both arms, males and females reported similar non-gastrointestinal somatic symptoms associated with IBS measured by PHQ-12 (Table 5).

| Randomised | Screened | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Ondansetron (n = 37) | Placebo (n = 43) | Total (n = 80) | Screened (n = 1582) | Missing |

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 45.0 (15.7) | 43.0 (16.3) | 43.9 (16.0) | 44.9 (15.4) | 831a |

| Sex, N (%) | 802a | ||||

| Male | 16 (43.2%) | 17 (39.5%) | 33 (41.3%) | 257 (32.9%)b | |

| Female | 21 (56.8%) | 26 (60.5%) | 47 (58.8%) | 523 (67.1%)b | |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |||||

| White | 34 (91.9%) | 41 (95.3%) | 75 (93.8%) | – | |

| Black | 2 (5.4%) | 1 (2.3%) | 3 (3.8%) | – | |

| Asian | 1 (2.7%) | 1 (2.3%) | 2 (2.5%) | – | |

| Current smoker, N (%) | |||||

| Missing | 4 (10.8%) 1 | 5 (11.6%) 0 | 9 (11.3%) 1 | ||

| Number of years smoked/number of cigarettes/day listing | (8/12, 10/15, 12/7, 38/9) | (5/10, 10/5, 12/7, 18/7, 37/6) | |||

| Pre-treatment diary | Ondansetron (n = 37) | Placebo (n = 43) | Total (n = 80) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean pain score (SD) | 61.4 (19.7) | 55.2 (16.7) | 58.0 (18.3) |

| Mean days per week with loose stool (SD) | 5.9 (1.3) | 5.4 (1.2) | 5.6 (1.3) |

| Mean urgency score (SD) | 67.5 (19.6) | 60.4 (17.8) | 63.8 (18.9) |

| Urgency score missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mechanistic test undertaken | |||

| Barostat, N (%) | 8 (21.6%) | 10 (23.3%) | 18 (22.5%) |

| Colonic manometry, N (%) | 7 (18.9%) | 6 (14.0%) | 13 (16.3%) |

| Both mechanistic tests undertaken | 6 (16.2%) | 6 (14.0%) | 12 (15.0%) |

| PHQ-12 score | |||

| Male, N | 16 | 17 | 33 |

| Mean (SD) missing | 7.5 (4.63) 0 | 7.5 (3.54) 0 | 7.5 (4.04) 0 |

| Female, N | 21 | 26 | 47 |

| Mean (SD) missing | 10.3 (4.32) 0 | 9.6 (4.63) 0 | 9.9 (4.46) 0 |

During the pre-treatment period, participants randomised subsequently to ondansetron reported, on average, higher abdominal pain scores (61.4 vs. 55.2 mean pain score), slightly more days per week with a loose stool (5.9 vs. 5.4 mean days per week) and a higher urgency to defaecate score (67.5 vs. 60.4 mean urgency score) than those randomised to placebo (see Table 5). Pre-treatment diary scores by site are provided in Appendix 3, Table 40.

Table 4 shows that the participants were well matched for demographics across randomised treatment arms. Demographic data by site are provided in Appendix 3, Table 41.

As part of the trials mechanistic substudy, participants were offered a barostat procedure and a colonic manometry. Eighteen participants underwent a barostat and 13 a colonic manometry assessment. Of these, 12 undertook both manometry assessments (see Table 5). Mechanistic test uptake by site is provided in Appendix 3, Table 42.

Further baseline summaries including summaries across time points are in Summaries and analyses of the secondary outcomes.

Losses and exclusions after randomisation

Treatment discontinuation and withdrawals

Five participants discontinued treatment, four in the ondansetron arm (two were requested by the patient and two by the clinician) and one in the placebo arm (requested by the patient) (see Table 6 and Appendix 4, Table 43). One participant in the placebo arm withdrew due to pregnancy (see Appendix 8, Table 65).

| Ondansetron (n = 37) (%) | Placebo (n = 43) (%) | Total (n = 80) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of discontinued treatment (% of randomised) | 4 (10.8) | 1 (2.3) | 5 (6.2) |

| Requested by patient | 2 (50.0) | 1 (100.0) | 3 (60) |

| Requested by clinician | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (40) |

| Reason for discontinuation | |||

| Patient decision | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Patient’s health compromised | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Drug intolerance | 1 (25.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) |

| Othera | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

Seventeen participants, 10 in the ondansetron and 7 in the placebo arm, withdrew from one or more parts of the study data collection processes. All 17 withdrew consent for daily text messaging, and 3 participants in the ondansetron arm also withdrew from trial follow-up (Table 7).

| Withdrawal | Ondansetron (n = 37) (%) | Placebo (n = 43) (%) | Total (n = 80) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of withdrawn from any part of the study (% of randomised) | 10 (27.0) | 7 (16.3) | 17 (21.3) |

| Number of withdrawn consent for | |||

| Daily text messaging (% of withdrawals) | 10 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) |

| Use of previously obtained samples (% of withdrawals) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) |

| Optional main study assessments (% of withdrawals) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (17.6) |

| Trial follow-up (% of withdrawals) | 3 (30.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (17.6) |

Protocol violations and deviations

There were four major protocol violations: one participant took a restricted medication (hyoscine), two had abdominal pain scores in the pre-treatment diary too low to meet the inclusion criteria and one became pregnant during the trial. All four were removed from the PP population.

There were 12 participants that deviated from the protocol in terms of taking more than 2 loperamide doses a week in the treatment period, 5 in the ondansetron arm and 7 in the placebo arm (Table 8). Four of those five participants in the ondansetron arm deviated from the protocol during the pre-treatment, treatment and post-treatment periods. Two of the participants in the placebo arm deviated from the protocol in the pre-treatment, treatment and post-treatment periods.

| Unique participant | Ondansetron | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment | Treatment (weeks 1–12) | Follow-up (weeks 13–16) | |

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 | ||

| 5 | 12 | ||

| 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | 2 | 3 | |

| 8 | 2 | 8 | 2 |

| Placebo | |||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 | ||

| 4 | 1 | ||

| 5 | 5 | 3 | |

| 6 | 1 | ||

| 7 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| 8 | 1 | ||

| 9 | 5 | ||

| 10 | 1 | ||

| 11 | 1 | ||

| 12 | 1 | ||

| 13 | 2 | 2 | |

These participants were included in the ITT analysis and additional analysis was undertaken adding the use of loperamide as an independent variable in the primary analysis model, section Supportive and sensitivity analyses.

Clinical efficacy of the intervention

Analyses of the primary outcome

Analyses were conducted on the ITT population and all 80 participants were included in the primary analysis. There were 15/37 [40.5%, 95% CI (24.7%, 56.4%)] primary end-point responders in the ondansetron arm and 12/43 [27.9%, 95% CI (14.5% to 41.3%)] in the placebo arm. Four participants (two in each arm) did not provide sufficient data to calculate the primary end point and were therefore assumed to be non-responders. Multiple imputation was not used, as there were only 5% of missing responses the potential impact of the missing data would be small44 and the overall sample size was small.

Considering the individual components of the primary end point; there were 17/37 [46.0%, 95% CI (29.9% to 62.0%)] on ondansetron who were pain responders (i.e. met FDA criteria for reduction in pain intensity) and 16/43 [37.2%, 95% CI (22.8% to 51.7%)] on placebo. As regards stool consistency, 25/37 [67.6%, 95% CI (52.5% to 82.7%)] on ondansetron and 22/43 [51.2%, 95% CI (36.2% to 66.1%)] on placebo were stool consistency responders according to FDA criteria (Tables 9 and 10). There was no statistical evidence of a difference in the FDA-defined primary end-point responder rate between arms. The odds ratio from the logistic regression model, adjusted for the treatment group, minimisation variables (undergoing manometry or barostat), age and gender was 1.93 (95% CI 0.73 to 5.11, p-value 0.1869). Site was excluded from the model due to model convergence issues (see Table 10). Additionally, when assessing individual components of the primary end point, ondansetron had greater effect on stool consistency improvement than on pain intensity reduction when comparing between arms. However, none of these differences were statistically significant.

| Primary end point | Ondansetron (n = 37) | Placebo (n = 43) | Total (n = 80) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of primary end-point responders, N (%) | 15 (40.5%) | 12 (27.9%) | |

| Number of non-responders, N (%) | 20 (54.1%) | 29 (67.4%) | |

| Number of participants with insufficient data to evaluate primary end point, N (%) (treated as non-responders in ITT) | 2 (5.4%) | 2 (4.7%) | 4 (5.0%) |

| Pain intensity reduction responders, N (%) | 17 (46.0%) | 16 (37.2%) | |

| Stool consistency reduction responders, N (%) | 25 (67.6%) | 22 (51.2%) | |

| Number of available data weeks | |||

| Mean (SD) | 11.2 (2.1) | 11.3 (2.0) | 11.3 (2.0) |

| Median (range) | 12.0 (4, 12) | 12.0 (0, 12) | 12.0 (0, 12) |

| Number of weeks as a responder | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.3 (3.9) | 3.4 (3.9) | 3.8 (3.9) |

| Median (range) | 3.0 (0, 12) | 2.0 (0, 12) | 3.0 (0, 12) |

| Number of weeks as a non-responder | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.0 (3.9) | 7.9 (4.0) | 7.5 (4.0) |

| Median (range) | 7.0 (0, 12) | 8.0 (0, 12) | 8.0 (0, 12) |

| Analysis | Responders | Model output | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ondansetron (n = 37) | Placebo (n = 43) | |||||

| N (%) | (95% CI) | N (%) | (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | |

| 1. Primary end point | 15 (40.5) | (24.7 to 56.4) | 12 (27.9) | (14.5 to 41.3) | 0.1869 | 1.93 (0.73 to 5.11) |

| a. PP | 0.2493 | 1.78 (0.67 to 4.76) | ||||

| b. Sensitivity + loperamide use | 0.3076 | 1.68 (0.62 to 4.57) | ||||

| c. +interaction (treatment arm * loperamide use) | 0.3598a | 1.71 (0.54 to 5.40) | ||||

| d. +HADS anxiety score | 0.2026 | 1.96 (0.70 to 5.53) | ||||

| e. +HADS depression score | 0.0942 | 2.50 (0.86 to 7.31) | ||||

| 2. Pain intensity reduction | 17 (46.0) | (29.9 to 62.0) | 16 (37.2) | (22.8 to 51.7) | 0.3222 | 1.61 (0.63 to 4.12) |

| a. PP | 0.4229 | 1.47 (0.57 to 3.81) | ||||

| b. Sensitivity +loperamide use | 0.4976 | 1.40 (0.53 to 3.67) | ||||

| c. + interaction (treatment arm * loperamide use) | 0.3496a | 1.72 (0.55 to 5.35) | ||||

| 3. Stool consistency reduction | 25 (67.6) | (52.5 to 82.7) | 22 (51.2) | (36.2 to 66.1) | 0.0730 | 2.45 (0.92 to 6.52) |

| a. PP | 0.1042 | 2.28 (0.84 to 6.16) | ||||

| b. Sensitivity + loperamide use | 0.0647 | 2.60 (0.94 to 7.15) | ||||

| c. + interaction (treatment arma loperamide use) | 0.0595a | 3.13 (0.96 to 10.26) | ||||

Supportive and sensitivity analyses

Analysis of the primary outcome on the PP population supported the primary analysis result that there is no evidence of a difference in the treatment arms (see Table 10). Throughout the study (pre-treatment, treatment and follow-up), participants were allowed to use rescue medication (loperamide) no more than twice per week. Similar proportions of participants used loperamide during pre-treatment and follow-up (off-treatment) across arms, but a higher proportion used loperamide in the placebo arm during treatment; 39.5% (n = 17) compared with 18.9% (n = 7) in ondansetron (see Appendix 6, Table 48). Therefore, as part of the sensitivity analyses, use of rescue medication was added as an independent variable and the primary analysis model was repeated. The outcome of this analysis is consistent with the primary analysis finding that there is no difference in the primary end point of FDA-defined responder rates between the treatment arms. Additionally, loperamide use was added as an interaction term with the treatment allocation and the findings were again similar. The number of responders using rescue medication is summarised in Appendix 6, Table 49; higher proportions of both responders and non-responders in the placebo arm used loperamide. Sensitivity analysis including HADS anxiety and depression scores as independent variables in the primary end-point model supports the conclusion of no evidence of a statistical difference between the treatment arms (see Table 10).

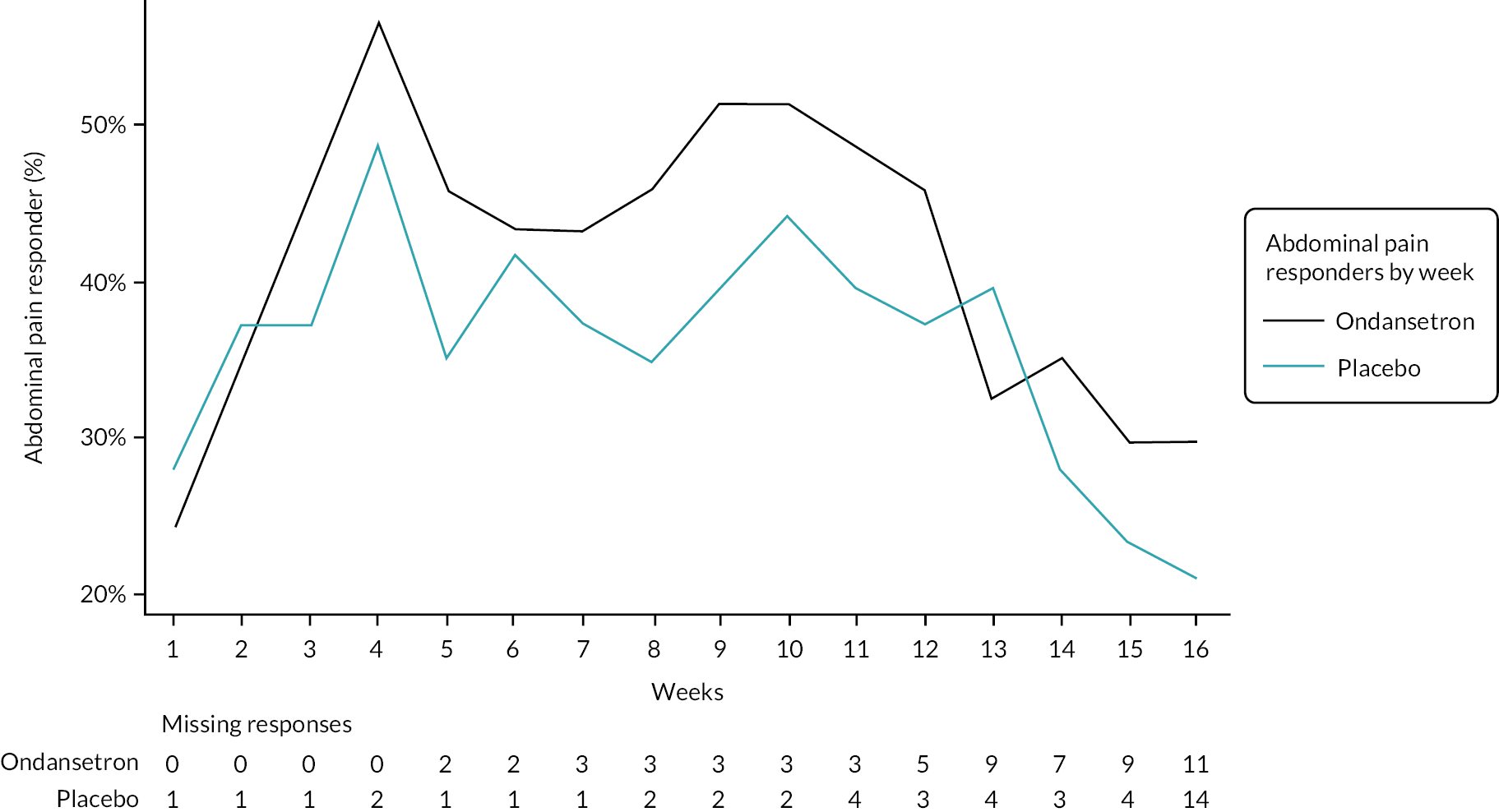

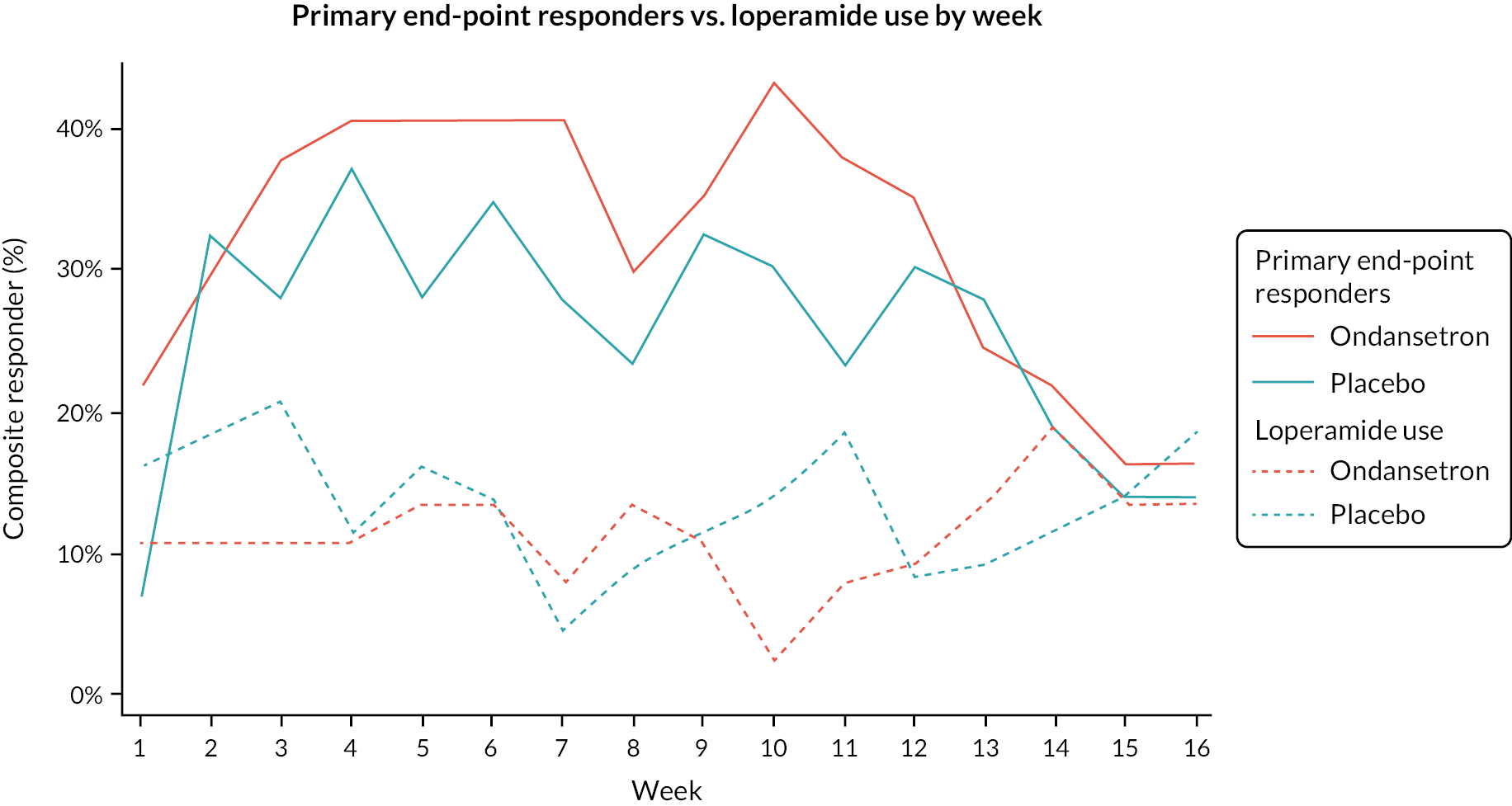

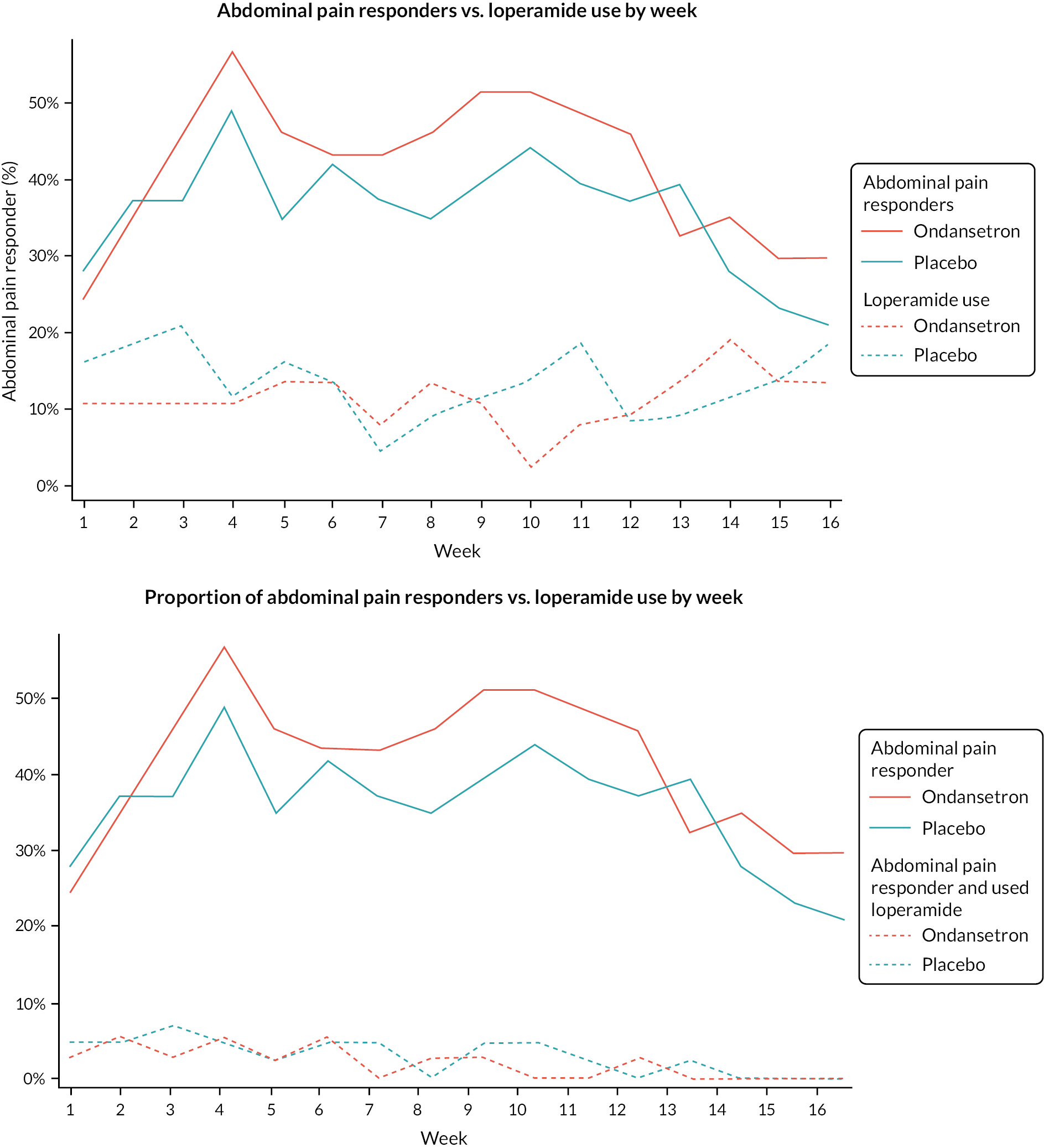

Summaries of overall responders and responders to individual components of primary outcome by week

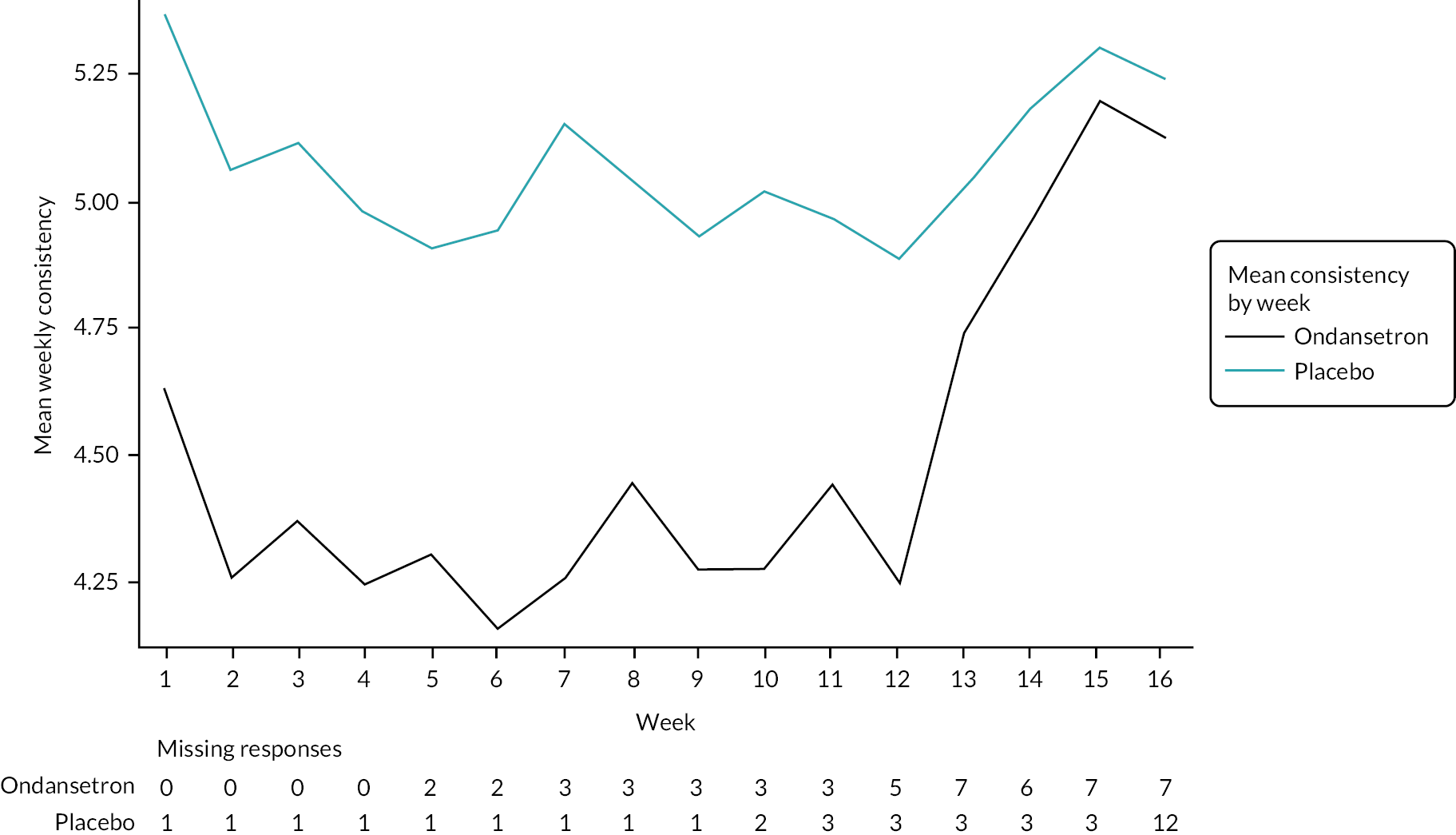

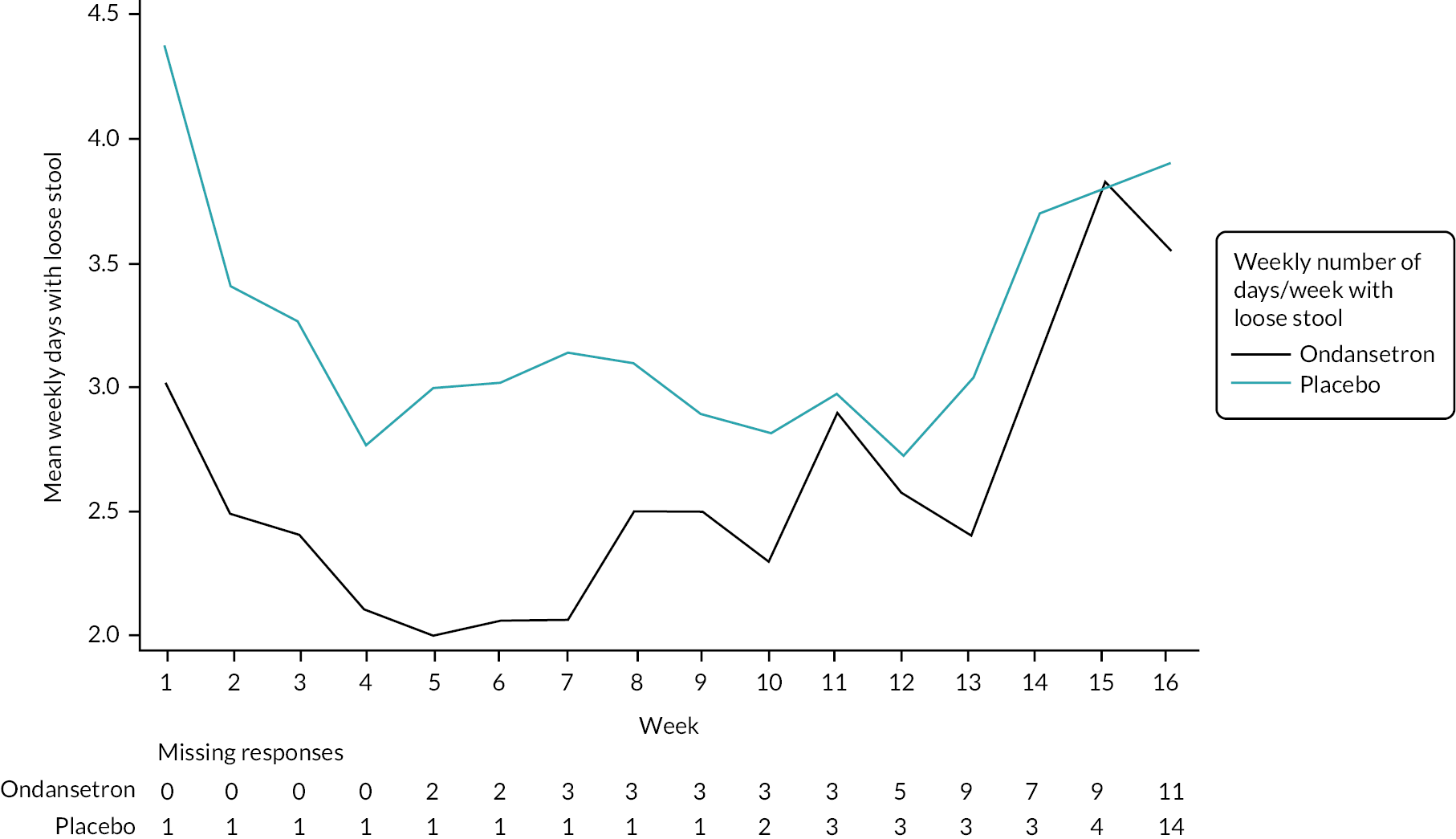

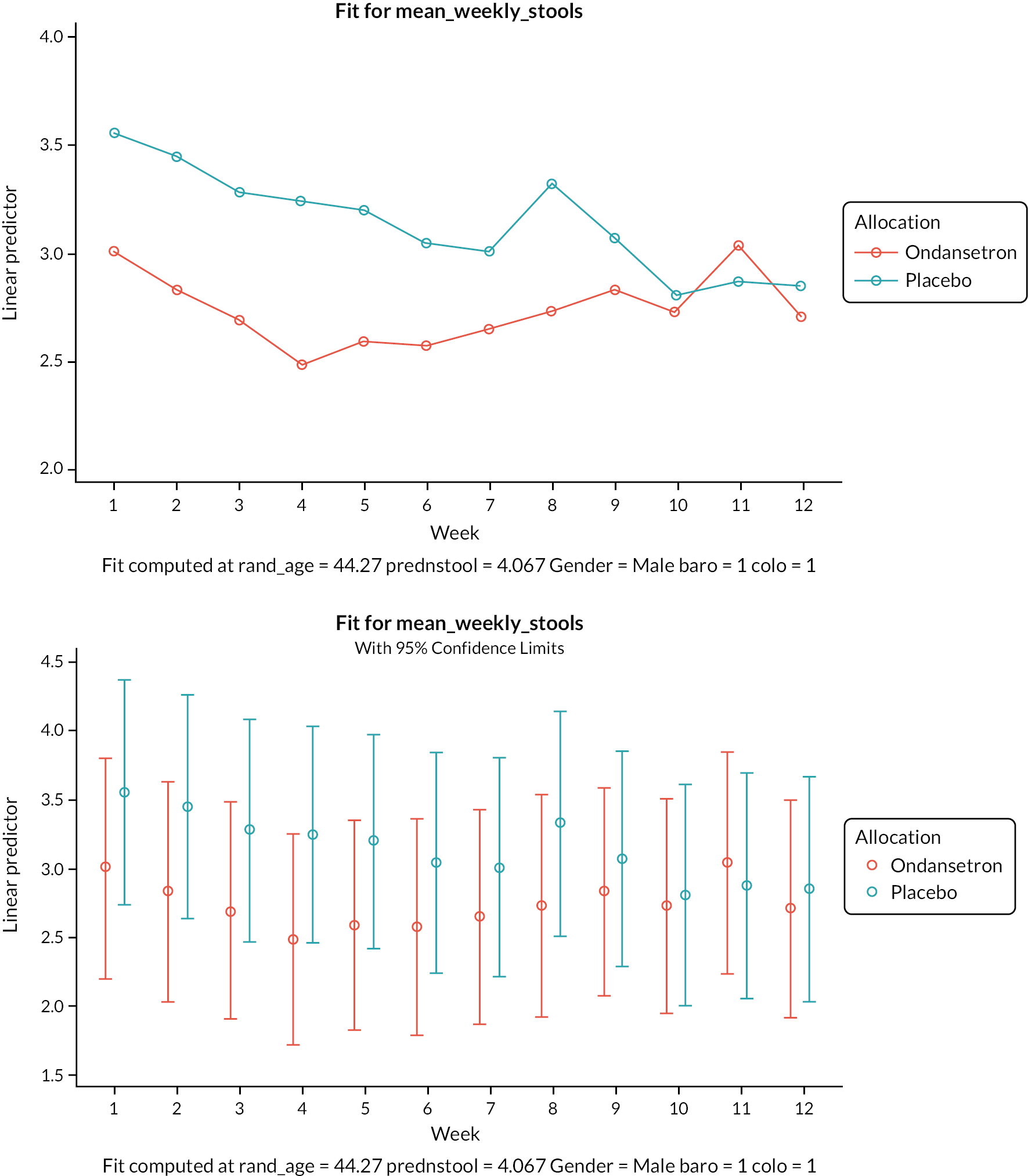

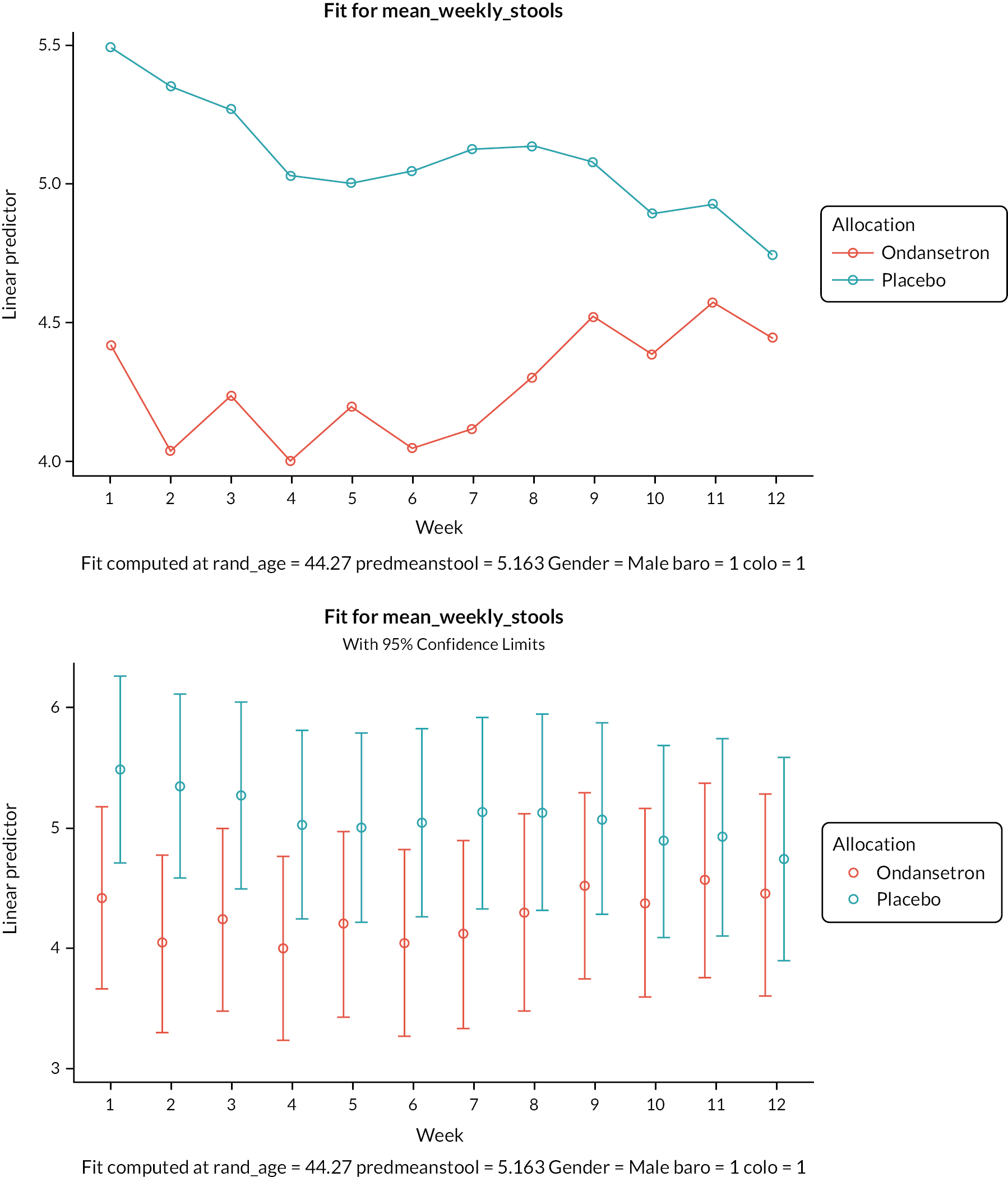

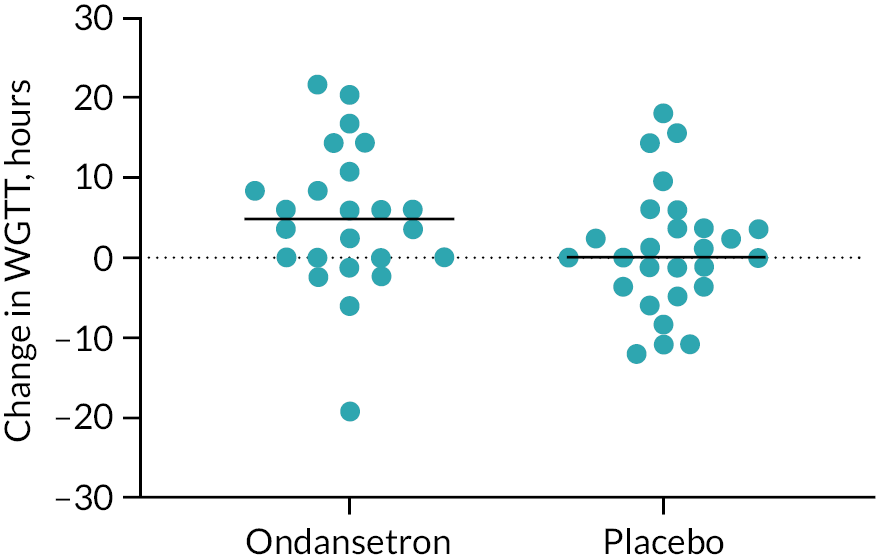

A graphical summary of responders by week is provided in Figures 4–6. Weeks 1–12 are the treatment weeks and weeks 13–16 are the post-treatment follow-up weeks. Based on those summaries, participant response increased during the weeks in treatment in both treatment arms and decreased in the follow-up period. The largest difference between treatment arms is in stool consistency; a higher proportion of participants in the ondansetron arm were responders compared with those in the placebo arm (see Figure 6). This effect was apparent already in the first week (see Appendix 7, Table 54).

FIGURE 4.

Overall responders by week.

FIGURE 5.

Weekly abdominal pain responders.

FIGURE 6.

Weekly stool consistency responders.

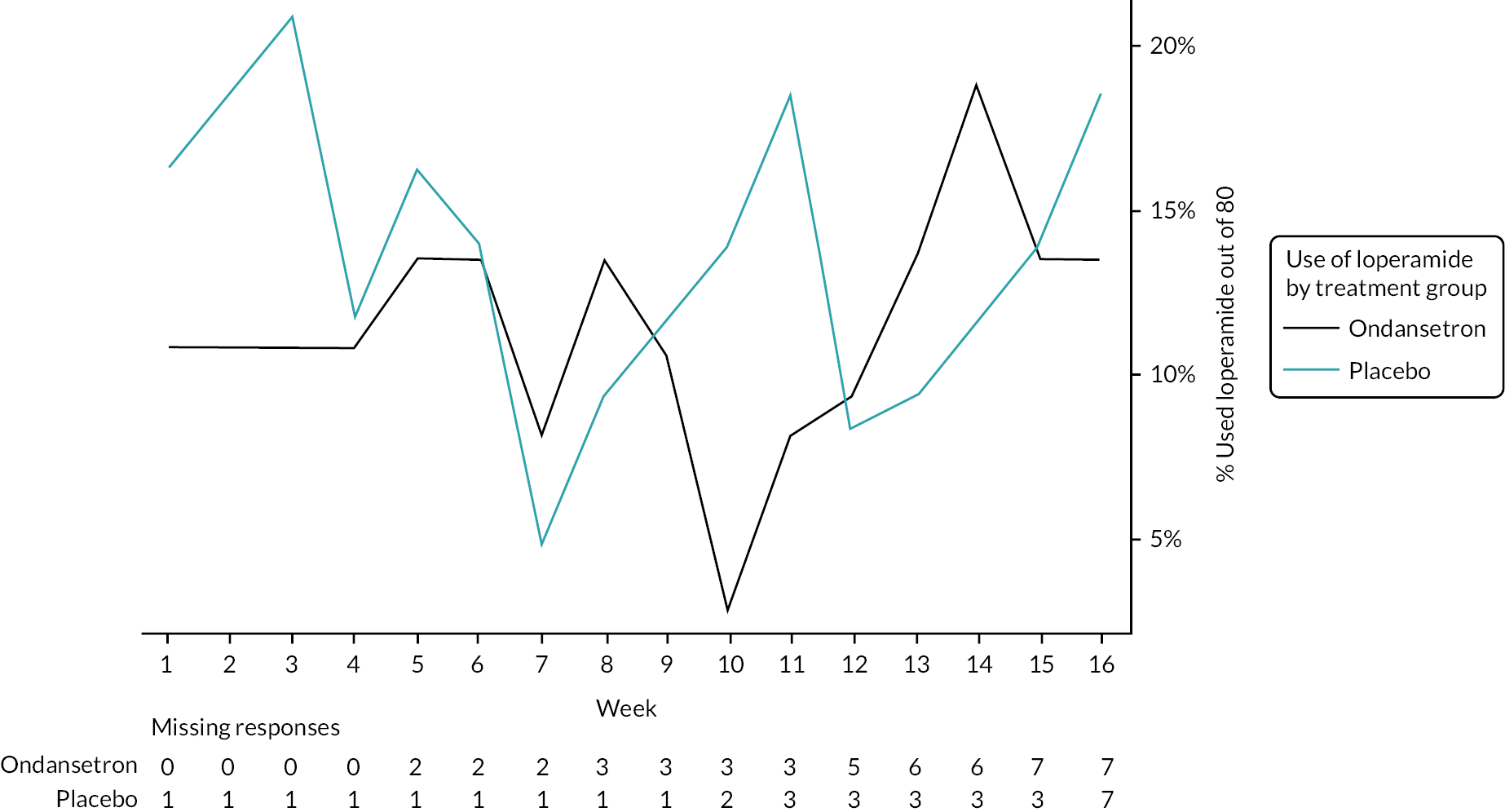

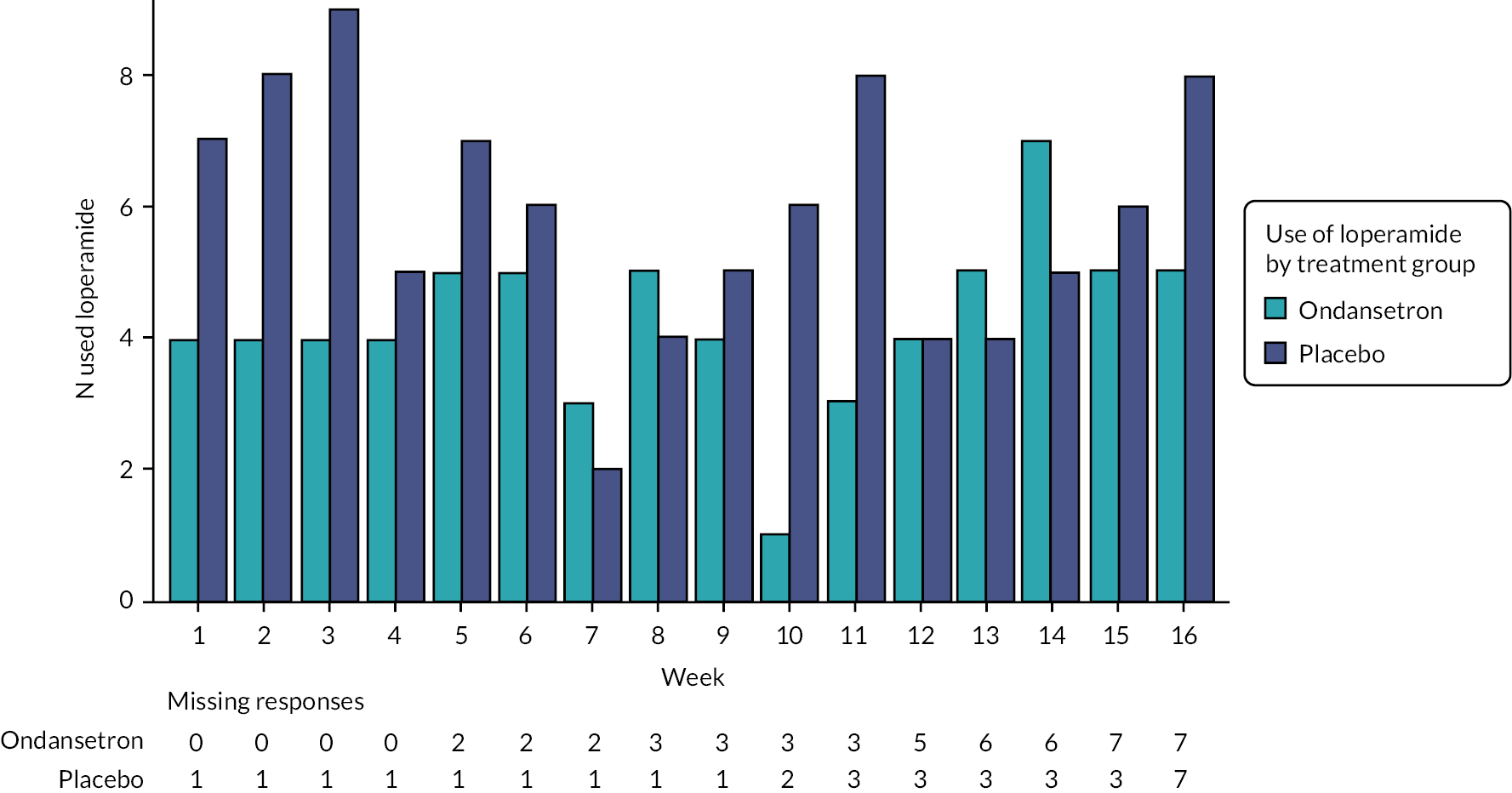

The number and proportion of participants using loperamide as a rescue medication by week are summarised in Figures 7 and 8. Additionally, the proportion of participants using loperamide was added to the figures to complement the sensitivity analyses. Tables summarising number and proportion of responders by week are in Appendix 7, Tables 52–56.

FIGURE 7.

Loperamide use (proportion of participants).

FIGURE 8.

Loperamide use (number of participants).

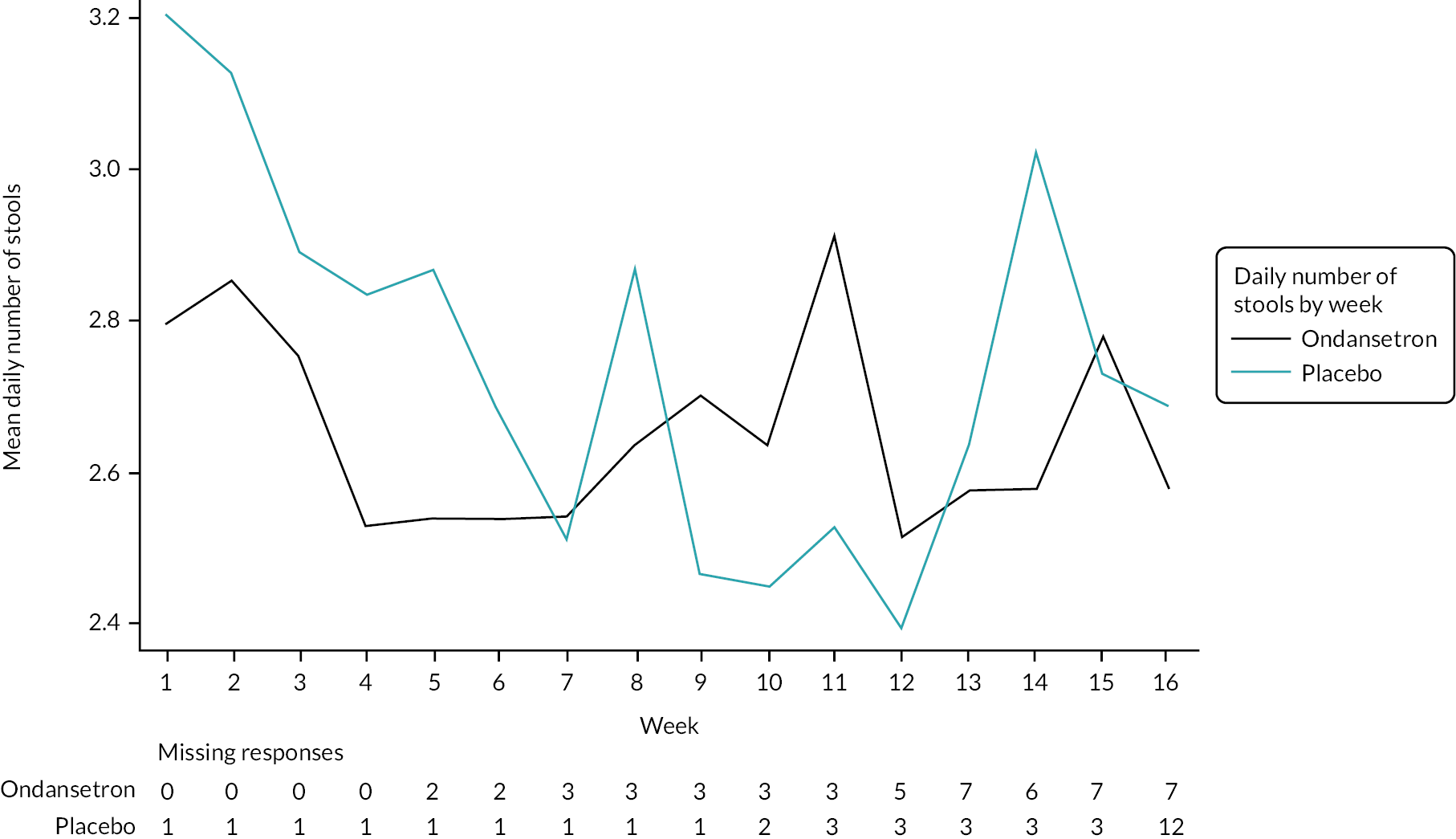

Summaries and analyses of the secondary outcomes

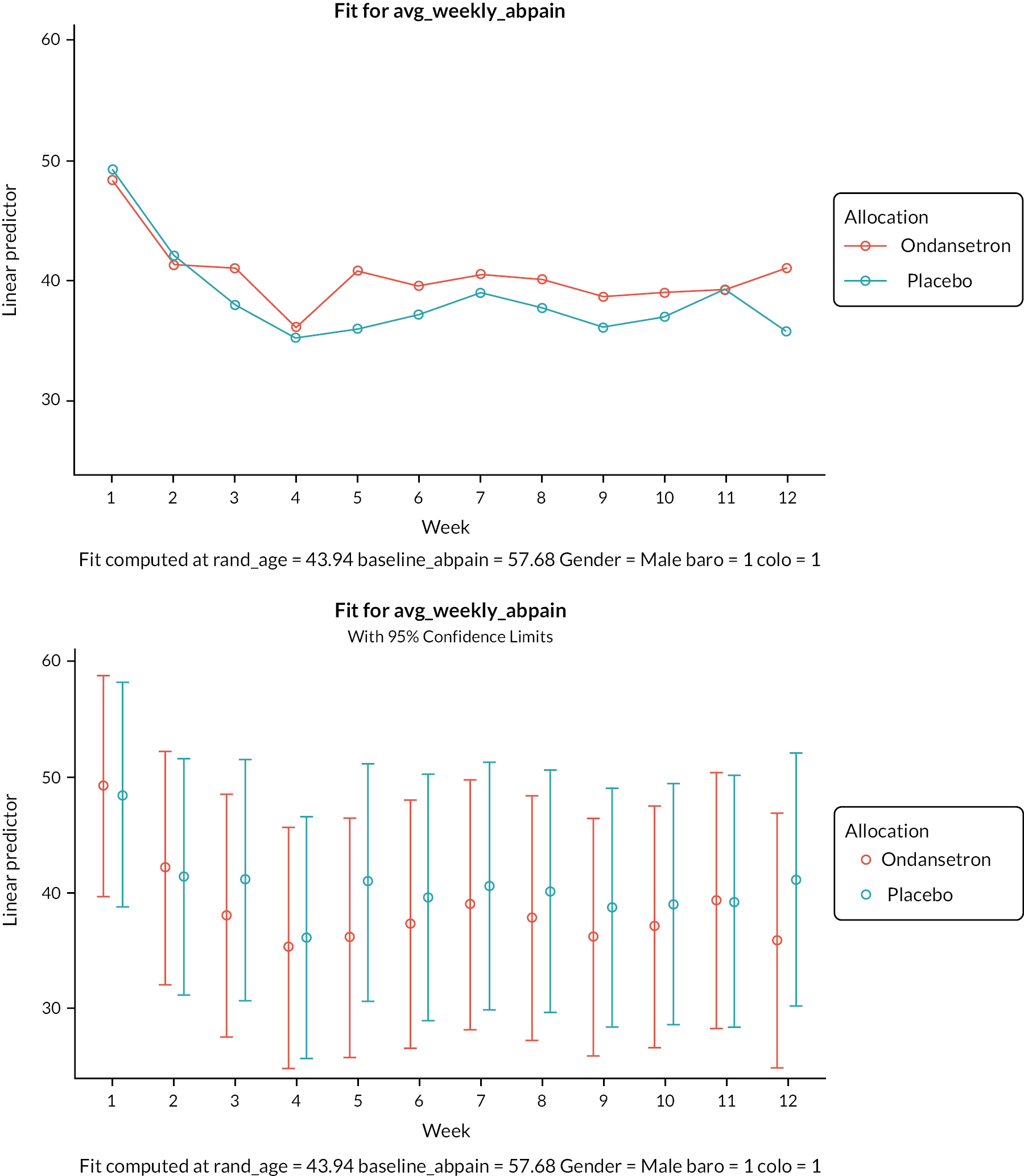

Abdominal pain

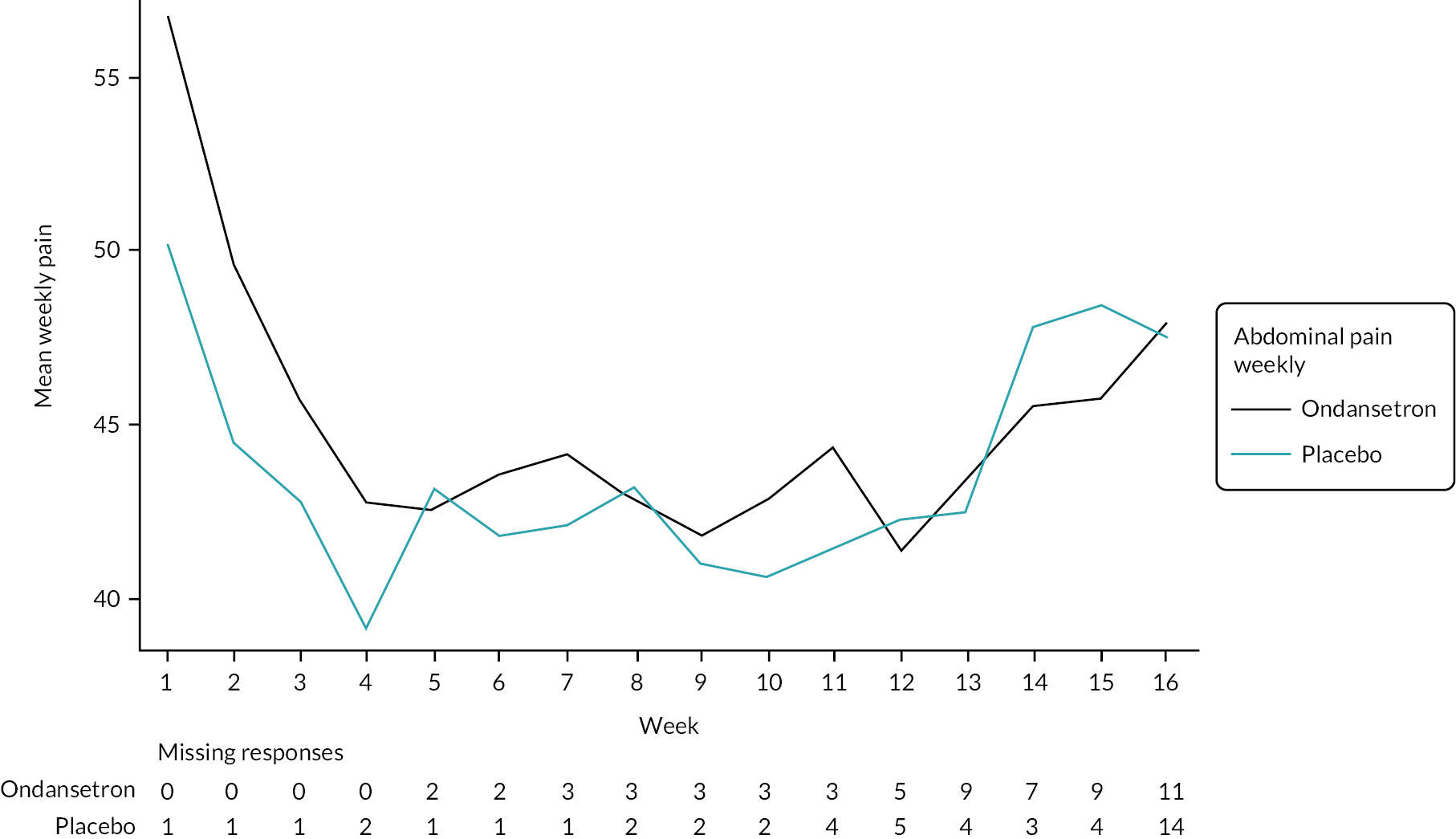

Mean abdominal pain scores were higher in the ondansetron arm prior to randomisation compared with placebo (see Table 5), but were similar across the treatment arms during the treatment and showed a similar increase in the follow-up period (Table 11), indicating a greater reduction in pain scores in the ondansetron arm during treatment (see Appendix 6, Tables 44 and 53). However, there was no evidence of a statistically significant difference in abdominal pain scores between the treatment arms during or after the treatment periods (Tables 12–14).

| Weeks 1–12 | Weeks 9–12 | Off-treatment weeks 13–16 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ondansetron (n = 37) | Placebo (n = 43) | Total (n = 80) | Ondansetron (n = 37) | Placebo (n = 43) | Total (n = 80) | Ondansetron (n = 37) | Placebo (n = 43) | Total (n = 80) | |

| Abdominal pain score (0–100) | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) missing | 44.6 (23.13) 2 | 42.6 (21.25) 1 | 43.5 (22.00) 3 | 42.7 (25.28) 3 | 41.0 (25.02) 4 | 41.8 (24.98) 7 | 47.4 (27.08) 10 | 46.2 (24.06) 4 | 46.7 (25.14) 14 |

| Median (range) | 44.2 (5.5, 100.0) | 47.3 (6.0, 81.9) | 46.4 (5.5, 100.0) | 44.0 (0.4, 100.0) | 44.6 (1.4, 81.5) | 44.5 (0.4, 100.0) | 47.3 (3.2, 100.0) | 48.0 (0.0, 91.5) | 47.7 (0.0, 100.0) |

| Urgency score (0–100) | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) missing | 44.2 (27.54) 0 | 45.1 (22.35) 3 | 44.7 (24.82) 3 | 40.7 (29.09) 5 | 43.4 (24.01) 4 | 42.2 (26.26) 9 | 48.0 (29.04) 10 | 50.9 (23.95) 6 | 49.7 (26.04) 16 |

| Median (range) | 38.9 (3.1, 100.0) | 47.3 (7.1, 81.6) | 44.9 (3.1, 100.0) | 37.2 (0.7, 100.0) | 46.2 (0.0, 78.2) | 44.3 (0.0, 100.0) | 45.7 (0.8, 100.0) | 53.8 (0.4, 85.5) | 51.5 (0.4, 100.0) |

| Analysis (linear models) – weeks 9–12 | Adjusted mean ondansetron | Adjusted mean placebo | Difference in adjusted means | SE | p-value | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | N analysed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain score (0–100) | 40.0 | 41.6 | –1.6 | 4.67 | 0.741 | –10.9 | 7.8 | 73 |

| Stool urgency (0–100) | 35.6 | 42.5 | –6.8 | 5.7 | 0.236 | –18.2 | 4.6 | 70 |