Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR129645. The contractual start date was in January 2021. The draft manuscript began editorial review in April 2023 and was accepted for publication in January 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Brimblecombe et al. This work was produced by Brimblecombe et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Brimblecombe et al.

Chapter 1 Context

Policy and practice

Research in relation to young and young adult carers has focused on estimating their prevalence and the outcomes of caring on them. 1 Aside from the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia, few countries have developed policy in relation to young carers. 2 However, some countries, primarily in the Global North, are beginning to increase their awareness of, and support for, young carers (e.g. Canada, New Zealand and Western Europe). Studies based in these countries indicate that comparatively, the role of a young carer is similar across countries and continents. 3 What does vary widely, according to local circumstances, are the tasks and responsibilities of a young carer, which may include domestic tasks, nursing or personal care, management of household or finances, care of siblings or emotional support,4 and the support offered to young carers to mitigate the negative impacts of these tasks and responsibilities. Yet few studies have the voices and perspectives of young carers at their centre, and there is a knowledge gap when it comes to understanding what young carers believe would be most helpful to them in terms of support.

An ongoing controversy concerning the needs of young carers may be a leading cause of this knowledge gap. Because of the ethical concerns of children and young people providing care, providing support for them can suggest an acceptance of their role as a carer. 4 This conflicts with ‘western constructions of childhood,’2 which do not ascribe regular caregiving responsibilities to children.

In England, young carers were first legally acknowledged in the 1995 Carers’ (Recognition and Services) Act5 and, since then, a series of laws and policies have referred to young and young adult carers. (See Appendix 1, Table 7; ‘Key legislation and policy affecting provision for young carers in the UK’ for more detail.) Following several revisions, the current definition used by the Department of Health in the 2014 Care Act6 and 2014 Children and Families Act,7 Section C.6, describes a young carer as follows: ‘a person aged under 18 years, who provides or intends to provide care for another person (of any age), except where that care is provided for payment, pursuant to a contract or as voluntary work.’ Individuals aged 18 years and above are legally considered to be adult carers in the UK; however, in much research and practice, the term ‘young adult carer’ is used frequently to describe a person with caring responsibilities who is between the ages of 16 and 25 years. 8,9

The 1989 Children Act10 placed a duty on local authorities to assess the needs of young carers in their area. Until this point, policy-makers, researchers and welfare professionals in the UK had failed to recognise and account for young carers2 and it was not until The 2004 Children Act11 and 2004 Carers (Equal Opportunities) Act12 that local authorities were given responsibility to proactively identify young carers in their area. These Acts also encouraged the adoption of a whole-family approach to need assessments across adult and children’s services. 13

Following this, the 2014 Children and Families Act7 alongside the 2014 Care Act6 created rights for young carers and their families to be identified, receive an assessment (the Carer’s Assessment of Needs on the first point of contact, and the Transition Assessment if a young carer is turning 18 and has previously received a Carer’s Assessment of Needs) and be supported using a whole-family approach. These Acts stipulated that services working with adults or children with care needs should identify young carers through their work with other family members. Moreover, local authorities were encouraged to join up the work of children’s services and adult services, so that young carers and young adult carers could benefit from service collaboration.

Another part of the 2014 Care Act (Section C.23)6 that impacted provision for young carers was that it required local authorities to consider ‘replacement’ care. This is the option of allowing the young carers’ needs for support to be met by providing services to the care recipient. Under the 2014 Care Act, local authorities are required to prevent a caring role having a negative impact on a young carers’ wellbeing and as such, ‘replacement’ care could reduce caring responsibilities or mitigate potential harm by reducing the young carer role. 6

Statutory guidance accompanying the 2014 Care Act13 acknowledged the possible short-, medium- and long-term effects of caring responsibilities for young people and further outlined how caring roles may impact the development of a child or young person. However, defining what care responsibilities are inappropriate or excessive is a complex and culturally contextualised process. 14 Even if one were to consider a base line for the role of ‘young carer’, many children in the UK undertake domestic and caring responsibilities. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the point at which children are considered to be young carers.

Young carers are an ongoing priority for health and social care policy and practice in England. For example, the 2019 National Health Service (NHS) Long Term Plan15 includes access to preventative health services and support for young carers. Young carers and the organisations that support them have also expressed need for better, more easily accessed services for themselves and the person they support. 16,17 The 2022 Health and Care Act18 introduced measures that aim to support carers further, such as legislating for carers’ involvement when decisions are made around developments to services, and young carers are named as a target population cohort in the NHS England Core20PLUS5, a national approach to support the reduction of health inequalities at both national and system level and improve care for children and young people. 19

Currently, preventing the negative consequences of care provision on young people’s health and wellbeing is a high priority for health and social care policy and practice. Costs associated with the negative consequences of providing care are high,20 and limited resources within health and social care sectors heighten the need to target services and provide appropriate and equitable support. Inequalities in care provision, care need and the impacts of care provision on health make this relevant to current emphases in health and social care practice on reducing health inequalities. 15 In England and Wales, an estimated 5.0 million usual residents aged 5 years and over provided unpaid care in 2021,21 and support for young carers is a key priority in health and social care long-term plans,15 reflecting the expectation that support for carers will remain highly and increasingly important in the future. Appropriate, acceptable and easily accessed support for young carers and the people they care for is therefore likely to remain core to the future needs of the NHS and the social care sector.

Review of the evidence

Impacts on young people of providing care

Previous research has shown that providing care has multiple impacts on young people, including their health and wellbeing,4,22,23 education4,24,25 and employment prospects. 4,20,26 This creates substantial associated costs to individuals, the government and the NHS. 20 Transition into adulthood can be a particular challenge for young carers because their caring responsibilities may be a barrier to employment, vocational training or further education. 27 However, and despite the increased rights to support described above, there are knowledge gaps on how to best support young carers and prevent these impacts. 22 This is especially the case for young adult carers aged 16–25 years; carers and care recipients who currently under-access services and people from underserved population groups such as ethnic minorities families. 28

What is good or not good about existing services? What can be improved?

Recent research findings have illustrated some of the problems with support that is currently available for younger carers and some of the ways in which support has been successful. 24,27 Qualitative research with young carers has shown that they value opportunities for respite. 29 By providing fun and meaningful activities, young carers can experience hiatus from their caring responsibilities and serious concerns. 30 However, when asked how services can best support them, young carers have identified that better support for the person they care for is, or would be, most useful. 4,29

As such, some scholars have highlighted the benefits of services that provide a whole-family approach to support. Ronicle and Kendall, in their 2011 research report, concluded that whole-family approaches had been helpful in reducing the proportion of young people taking on inappropriate caring responsibilities. 31 Moreover, Carers Trust, which supports 24,000 young carers in the UK each year, has noted how young carers and their families have spoken about the benefits of family support workers, who act as a main contact and liaison with several services that young carers and families use. 32 Similarly, Whitley and Wooldridge,33 in their evaluation of Sheffield Young Carers Family Project, found that the 90 families involved in the project indicated a positive experience. They appreciated the one-to-one intervention from family support workers due to the high quality of support provided and their dedicated and proactive nature. On top of this, whole-family social activities (such as group support and parent networking events) were beneficial. For young carers, they offered the opportunity to do fun and exciting activities; for cared for people, these activities facilitated them to speak to other families with a young carer, increasing their informal support networks and reducing isolation. The combination of dedicated family support and opportunities for social activities was a feature that was unique to the programme. As such, demand was high, with more than 30 families on a waiting list for involvement. 33

Outside of the UK, Schlarmann et al. (2011)34 have highlighted the benefits of Germany’s first young carers project, Supakids. Taking a whole-family approach, participants felt that the project allowed them to be ‘as they are’ and meet others in similar situations. Moreover, the service provided a first port of call for a variety of problems, providing a break from life at home. However, as Hafting and colleagues emphasise in their 2019 study, taking a whole-family approach is necessary but not sufficient when identifying young carers in Norway. 35 They found that this was because parents felt ambivalent about revealing information about family matters, which can prevent young carers from receiving further support, while general practitioners (GPs) felt ambivalent about bringing up this potentially sensitive topic of conversation with adult care recipients. Subsequently, services focusing on adults (such as substance misuse services) must recognise their responsibility for the wellbeing of a client’s child or children. 36

Few studies focus on support for young carers provided at schools and educational institutions; however, Eley’s 2004 report provides insight through interviews with 11 young carers in Scotland. Young people in this study felt ambivalent about disclosing their role as a carer for fear of unwanted intrusion in their family life, or reactions from teachers who would consider their caring responsibilities to be an ‘excuse’ for absence or poor performance. As such, although young people were reluctant to be identified, they felt frustrated by their teachers’ lack of awareness. 37 Young people may also yearn for normalcy, impacting their willingness to disclose their identity. 38

An evaluation of the Young Carers in Schools Programme (YCSP) by the charity Coram39 provides insight into the benefits this England-wide initiative offers. Firstly, the introduction of the initiative in schools resulted in increased identification of young carers, which led to an increase in referrals to local agencies and community-based carers services. This gave the young carers opportunities outside of school that they otherwise would not have accessed.

According to respondents of the survey (78% of which were leaders for young carers within schools, and 15% of which were support workers, school managers and family liaison officers), greater awareness of the needs of young carers through the YCSP helped staff to be more flexible and understanding, helping young carers to manage their schoolwork and have a more fulfilled student experience. Schools reported an improvement in academic engagement and attainment, with a higher motivation to learn.

Participants in Coram’s survey also reported that young carers appeared to benefit from participation in group activities and access to a supportive peer group. They reported that young carers were demonstrating widespread improvements in wellbeing, happiness and confidence. 39 The benefits of peer support have also been highlighted by other studies in the UK and Austria, which have investigated the experiences of young carers supporting parents with mental illness. 40,41

Strengthening the resilience of young carers through psychoeducation and support groups has been a benefit identified by Gettings et al. ,42 whose longitudinal feasibility study investigated methods of audio-conferencing to facilitate support groups for siblings of people with a neurodevelopmental disability in the UK. Young carers involved in the study stated how they felt more prepared, as they gained a better understanding of their siblings’ neurodisability. Moreover, the group provided a space where young carers could share difficult thoughts and feelings and reduce their isolation.

The method by which these programmes are delivered could have a major influence on how successful they are in supporting young carers. Although eHealth is becoming a more accessible and reliable means by which vulnerable individuals may seek support and information,43,44 for young adult carers in the UK, in-person support was reported as preferable in the past,8 although this may have changed in the intervening years. Online interventions may include the benefit of anonymity,45 but internet literacy and access can be barriers preventing individuals from reaching the information and help they require, as well as having the potential for being overheard. Moreover, young people involved in previous studies have noted the importance of services in youth-friendly formats46 as well as professional and responsive workers. 47

Studies in the United States (US) and Australia have also suggested that access to skill-building and targeted education programmes may be beneficial for young carers, providing them with the opportunity for self-efficacy and proficiency in the care they provide. 48–50 For example, the YCare protocol piloted by Kavanaugh and colleagues aimed to provide supportive training for young carers, ages 8–16 years. Participants in this study reported a significant increase in their confidence to complete caring tasks correctly, and many noted the benefit of meeting peers in a group training environment. 50

In summary, the literature fails to capture the service landscape for young carers in the UK from the perspective of young carers themselves. Although existing studies have indicated some benefits of particular programmes – such as a whole-family approach, or provision of respite opportunities for young carers – these do not give us a comprehensive idea of how young carers think services could be improved; particularly as many studies are based outside of the UK, are focused on a small geographical area, and/or predate the current rights for young carers and the more recent rise in young carer voluntary sector support organisations. 51

What additional support is needed

Financial support is a prominent area highlighted in the literature, as many young carers have unmet financial needs. In 2013, a longitudinal study of young carers in England found that the average income of a young carer’s family was on average £5000 less than a family with no young carer. 52 Moreover, the study found that young carers were more than four times as likely as non-carers to be in families where no-one was in paid work. Qualitative research with young carers often found that they were aware of the financial constraints their families faced. 29 More recently, Vizard and colleagues53 examined child poverty outcomes among young carers in the UK from 2005 to 2015 and found that in the wake of the financial crisis, recession and the onset of austerity, young carers have fared worse than other young people who did not have caring responsibilities. As such, this strongly suggests that young carers and their families face difficulties directly aggravated by poverty.

One contributing factor of lower family income is the difficulties young carers face with study and employment. Young carers are not included in the list of vulnerable groups who can apply for the 16–19 Bursary Fund, although individual higher education institutions may be willing to give young carers a discretionary bursary. The lower age limit for receipt of a carer’s allowance is 16, which excludes young carers below this age. The benefit also requires the person cared for to be in receipt of a disability-related benefit and for the carer to be providing 35 hours of care per week or more. For those who do qualify, there is an earnings limit for receipt of a carer’s allowance of £132 per week. The benefit specifically excludes carers in full-time education or those who study for more than 21 hours per week. Subsequently, in their interviews of young carers in the US, Keigher and colleagues54 found that young carers unable to seek employment may risk illegal activity (such as drug dealing) or other unstable jobs to make ends meet. 54

Young carers in school or college in the UK have also identified areas in which they require further support, including difficulties making friends who understand their caring role;55 challenges meeting the needs of a course or their homework;56 and bullying. 25 Young carers may also be more likely to miss and be late for school than their non-carer peers. 57 In light of this, as Becker and Becker8 suggest, young carers require the support and understanding of teachers – and from the education system more generally. Of course, although raising awareness and sharing information about young carers among staff and other students may be helpful, Bostock58 reminds us that this needs to be done according to the wishes of the young person, as some are more comfortable with their sensitive information being shared than others.

Another significant unmet need highlighted in the literature is communication within and between support services. Because many services work in isolation, this can lead to delays, miscommunication and the added stress of young carers and their families having to repetitively tell their stories to a wide number of services. Moreover, as Becker and Becker8 have indicated, there is a gap between support offered by youth services and adult services. As such, some young adult carers have suggested that the creation of an interdisciplinary and interprofessional network would aid communication between services in the UK. 59 Leading researchers in the field are also calling for a new agenda for policy development, one that champions greater awareness of the need for interdisciplinary and multi-agency working. 4

With regard to services for the care recipient, which could help reduce caring responsibilities, several studies point to difficulties they may face as a result of shortcomings within the healthcare services for care recipients. For example, according to young carers, they may not be included in decisions regarding the provision of care, or discussions between healthcare professionals and the care recipient. 56 The inclusion of young carers in this way can provide them with education and knowledge to support them in their role as a carer, and furthermore, it can instil confidence that the care recipient is well supported. 50

Turning to studies based outside of the UK, Hamilton and Adamson60 have suggested that identifying gaps in service provision may be difficult for young carers in Australia, as they may have limited time away from their caring responsibilities. Moreover, Moore and colleagues found that many of the young carers in their Australian study reported that the level of care they provided was downplayed either by themselves, their families or the services they accessed. 47 This may be due to stigma attached to the role of a young carer, particular family dynamics, or inadequate needs assessments by local service providers. Smyth and colleagues61 have also highlighted how young carers may not identify as such and therefore remain ‘hidden’ to services and support providers. As such, unidentified support needs may be prevalent among young carers and their families. In light of this, Moore and colleagues recommend a service approach that focuses on the impact of the responsibilities that young carers have, with an understanding that there are multifaceted issues behind these impacts. On top of this, as the needs of care recipients, young carers and their families change, services need to evolve and adapt to ensure an adequate provision of care, delivered at a pace that suited them. 62 This may be relevant to young carers in the UK who have found that their level of caring responsibilities has increased since the COVID-19 pandemic. 63

Through their interviews with young carers and young adult carers in Switzerland, Leu and colleagues45 have emphasised that there should be greater inclusion of the needs of young carers in emotional support and prevention programmes for children and adolescents with ill parents or siblings. From studies speaking to young carers and young adult carers in contexts outside of the UK, services to meet this need could include links to, and communication with, other people with similar experiences29,45,47 or advice from professionals on how to support themselves and practise self-care. 45 Two key components of these relationships, for young carers, is the feeling of trust in the person(s) they are talking to47 and that there is continuity within these relationships, whereby a stronger connection can be built. 62

Overall, studies have identified some of the unmet needs of young carers in the UK but offer little insight with regard to what this support may look like, or how services may be improved. Although it has been suggested that families with young carers may face financial difficulty, the literature, as of yet, has failed to fully investigate young carers’ perspectives about these issues.

Barriers to support

Research literature identifies numerous factors that may prevent young carers and their families from accessing support. These can be grouped into three overlapping categories: first, barriers of communication at the service level; second, barriers of identification (at both the personal and service level); and third, barriers of design, organisation and delivery of services.

Barriers of communication at the service level

Speaking to both young carers and service providers in the UK, Wayman and colleagues16 reported that many young carers did not realise that there were services available to support them nor how to access them. This may be because communication methods do not take into account the diverse needs of young carers, providing information suitable for their age, language abilities, disability (and communication needs), cultural beliefs or understanding. 16,64

Professionals (such as GPs and social workers) may fail to keep young carers informed about the person they care for. 65 Subsequently, young carers have indicated that this can make learning about the needs of a care recipient more challenging, and it can also restrict their ability to identify appropriate support services. 16

Barriers to identification

As previously mentioned, in many contexts the term ‘young carer’ may be one that young people do not identify with, or their role may not be recognised by their families. 29,61,64,66 For instance, young carers may regard their caregiving roles as usual household chores;65,66 for others, ‘young carer’ could have connotations of being a victim, or a ‘do-gooder’, which contrasts with the way that young people see themselves. 29

In the UK, some young carers may only recognise their role following their engagement with services. 67 Moreover, Obadina68 has highlighted that there may be stigma attached to the label of ‘young carer’, or a reluctance of young people and their families to self-identify due to a fear of unwanted intervention from services, fear of being judged, or family break-up. For some, it may harbour feelings of being different to other young people. 69

In their analyses of services accessed by young carers in Wales, Thomas et al. highlighted how identifying young carers may sit outside the remit of professionals, whose priority is the care recipient,56 and there may also be difficulty for some groups of young carers to be recognised as such. Butler and Astbury,69 for example, found that young carers in Cornwall were an ‘invisible population’ often overlooked by services. They noted a low referral rate to new young carers services in the area from GPs and schools, which they suggest is illustrative of a lack of recognition of young carers and their needs. This issue of identifying young carers was highlighted most recently by Warhurst and colleagues,70 whose study found that UK school staff found difficulty in identifying young carers who did not offer information about their caring responsibilities. 70

Barriers at service level – design, organisation and delivery

In a 2022 independent evaluation commissioned by NHS England, young carers noted that services for young carers were inconsistent across the country. 71 This inconsistency may leave many young carers struggling to access sufficient support.

Several studies based in Australia and the UK have highlighted that for individuals with specific needs, mainstream support services for young carers and their families may not be appropriate. First, young carers in a study by McDougall et al. 46 illustrated how mental health services may not be aware of the experiences of young carers and the difficulties they face, so may not be able to provide appropriate support or advice. Second, because young carers have competing responsibilities, they may have little (or no) time to engage with services and support available to them,60 particularly if they have a mental or physical illness or a disability. Third, as highlighted by Shah and Hatton’s UK study,72 services may have a lack of understanding of cultural needs of young carers and their families, including language, dress and etiquette and this may lead to reluctance of families to engage with such services.

In terms of accessing services, barriers at the service level include the cost of services and the transport to reach them, which may be restrictive for families. 60,73 Moreover, as there is no integrated pathway to support, professionals may fail to share information about young carers with other services, which can slow down referral processes and prevent young carers from accessing other resources. 29 A high turnover of staff may also affect access to services, as knowledge of the situations of young carers and their families may be lost through regular transition. Additionally, a high staff turnover can deter service users from accessing services, as they may be reticent to sharing and repeating sensitive and personal information. 16

Young carers and their families may feel discouraged from using services again if they have had previous negative experiences. This may include long waiting lists, unwelcoming environments or a low standard of service. 46 Families may feel frustrated or unable to communicate with service providers16 and these experiences may also inform their advice to others in their local community, who may be deterred from approaching services.

Overall, the literature focusing on barriers at the service level for young carers suggests that a lack of knowledge of young carers and their needs may lead to problems when accessing services. Although many of the studies in this area are UK-focused, many were written at least a decade ago, hence more up-to-date knowledge is required to understand the current experiences of young carers.

Conceptual framework

We drew on a number of theoretical and conceptual frameworks to inform the study. In considering both carer and care recipient views on service acceptability, we adopted Twigg and Atkin’s ‘dual perspective’: that caring takes place in a relationship, that there is a multiplicity of needs and that needs sometimes conflict. 74 We also utilised Purcal et al. ’s 2012 analytical framework which classifies three different possible aims of service support: (1) prevention of a child or young person taking on the caring role or working towards reducing or removing care by the child if that is already taking place; (2) assistance (supporting the carer to carry out their caring); and (3) mitigation (providing help to the young person which addresses negative impacts on them of their caring role). 75 This framework is closely related to Twigg74 and Twigg and Atkin’s76 typology of the ways in which the statutory care system engages with unpaid carers.

In exploring the barriers experienced by young carers and the people helped by them to getting the support they say they need, value and find helpful, we drew on and adapted Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use (BMHSU). 77,78 The BMHSU was originally developed to assess and understand under-access in healthcare use, and inequalities in access, for which it has been widely used. 79 It has also been used, although to a lesser extent, in studies of social care. 80,81 Other adaptations of the model have added aspects such as competing priorities (see e.g. Lederle review, 2021) or a greater emphasis on psychosocial factors. 80,82 In the BMHSU, barriers are termed ‘inhibiting’ and ‘impeding’ factors. 79 Individual impeding factors in the models include material circumstances; competing priorities; self-determination (privacy, dignity, independence, willingness to seek or receive help) and psychosocial factors such as fear, mistrust or nervousness. Contextual factors in the model include care policy; care financing (which affects availability, affordability, resources and staffing) and service organisation (e.g. accessibility, approachability, degree of specialisation, integration and communication). A further component of the BMHSU is ‘health literacy’, or in the study ‘service and support literacy’. Depending on the stance taken, whether that be a medical model or public health model perspective, ‘health literacy’, a key component of various iterations of the BMHSU, can be seen as being an individual-level barrier (e.g. individual knowledge, competencies and confidence); an organisational or other contextual-level barrier (e.g. ability of provider and/or governments to provide appropriate and accessible information and to communicate well about available support and services and how they work); or a combination of both. 83 Other components of the model can also be seen also have individual or contextual aspects or both. For example, cost of a service as barrier could be attributed to lack of affordability and/or lack of materials resources.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

The overarching research question was ‘What are the barriers to young and young adult carers accessing carer support services and/or services for the recipient of care, and what interventions and support services are acceptable to these groups and the persons they look after?’

The aims and objectives were to explore the following questions:

-

What types, components or features of services and other support are seen as helpful, valued and acceptable to young people who look after someone at home and the people they support? Conversely, what is found to be less or unhelpful?

-

What additional support is perceived as needed?

-

What are the barriers experienced by young and young adult carers in seeking and accessing services for themselves or the person they support?

-

What are the barriers and facilitators for practitioners in providing support and services perceived as valued, helpful, and needed by young and young adult carers and the people they support?

Chapter 3 Methodology

Engagement, recruitment and outreach

The focus of the research was on young and young adult carers and the people they support. These groups have historically been less likely to access services and other support than others with similar levels of need. 84 Many young carers do not identify as such because of, for example, fear of authorities, lack of engagement with any service or reluctance from families and/or young carers to be identified or labelled because of stigma, guilt and shame and/or because they feel it is not of benefit to their situation, so are unknown to services. 61 We aimed to include particularly marginalised groups of young carers and the people they care for, such as young carers of, and people with, stigmatised conditions such as severe mental illness. People with mental ill health and/or their carers are less likely to seek or access support than people with other conditions68,85 and people with mental illness supported by a young carer are even less likely to be receiving support than people supported by an adult carer. 86 Because of this focus, we initially intended to do pre-focus group/interview engagement activities, for example information meetings to explain the research and address any concerns or questions. These could be linked to existing events. However, because of COVID-19 restrictions during most of the fieldwork period, existing groups were not meeting in person, or at all, nor holding events and it was not the right time or method to attend any online events, so we changed the recruitment strategy accordingly.

In the study, we worked closely with collaborating organisations in four localities. These were young carers organisations that had already done extensive engagement and outreach within their areas and helped us recruit from among the young carers and care recipients they were or had been in contact with, many of whom were from the more marginalised populations in their areas. The young carers organisations also helped recruit from the wider body of organisations and groups within their localities, although not as widely as initially planned.

The engagement and recruitment strategies for the project included:

-

Co-development of recruitment materials and methods with young carer, care recipient and practitioner advisors

-

Young carers project workers’ direct involvement in study recruitment

-

Project workers in each locality working with young carers, care recipients and marginalised groups helping with recruitment and providing support for study participants

-

Providing clear information and reassurance during recruitment and data collection about confidentiality, anonymity and the information being gathered for research purposes only

-

Aiming to ensure that process, format and content of focus groups/interviews were as inclusive as possible. We were flexible about timing of focus groups and interviews. We arranged accessible focus group and interview venues (with options for interviews online or by phone) and arranged transport as needed. Transport was especially important for people with mobility issues and people living in areas where public transport is limited and transport costs high, but in practice the majority of participants in all localities attended by taxi, suggesting this was important to their attendance and inclusion.

Research design

The philosophical approach informing this study is that understanding what support is helpful, less helpful and needed and the barriers to support requires the perspective of those with lived experience,87 in this case the young and young adult carers and the people they support. The study had an in-depth qualitative methodology utilising focus groups, workshops and in-depth semistructured interviews. An explanatory rather than confirmatory framework was needed because not enough was known about experiences of those not receiving services to be able to explore these issues in a survey-type approach. 87 A qualitative approach was well suited to answering the research questions around barriers; what aspects of support are or would be acceptable; and to understand experiences and motivations and how these relate to interactions with, and intentions towards, services. The semistructured approach allowed us to be flexible in how we went about seeking answers to these questions.

While pragmatic considerations (convenience and preferences of individual participants) guided who took part in focus groups, and who took part in interviews, these two methods of data collection had different aims. Both addressed experiences with services, barriers to services use, and what good service provision looks like. However, the focus groups aimed to uncover, or allow to develop, shared understandings within the group, whereas the interviews aimed to encourage more in-depth exploration of personal circumstances, trajectories and experiences. Previous research has found that focus groups may be more effective than face-to-face interviews and questionnaires because people have often not thought about how they feel on the issues to be discussed and opinions may not be formed in isolation. 88 The focus group format can feel less threatening or challenging for some participants89 and younger carers may respond better in group settings. 90,91 However, some potential participants may have been unwilling or unable to join in a focus group and so were offered the option of face-to-face or telephone interviews. In practice, the vast majority of participants in the study chose to take part in a focus group rather than an interview (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Ethics and informed consent

Ethics approval for the focus groups and interviews was granted by the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) Ethics on 21 May 2021 (Ref. 1247).

1. Confidentiality and data security

We adhered to the 2018 Data Protection Act as well as General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) guidance related to the security of information. Completed paper materials (consent forms) are stored in locked filing cabinets in secure offices at the LSE. Access is by the research team. Interviews were transcribed by a professional transcription service, also adhering to GDPR guidelines, and data have been anonymised. Interview recordings and transcripts are held on a secure folder on the LSE servers accessed from password-protected computers in secure offices at the LSE. Information sheets explained that information would be kept confidential. The exception to confidentiality was that if the participants in interviews or focus groups raised concerns of serious risk of harm to participants or others. In this event we had a policy to aim to talk to the person and potentially take further action as required (see also Safeguarding below). This was also explained in the participant information sheets.

2. Safeguarding

We had in place robust safeguarding procedures for the study, developed with relevant experienced organisations and based on previous materials. This included situations where safeguarding issues might be disclosed and covered both the research and advisory processes. LSE also has a safeguarding procedure. Each key collaborating organisation had its own extensive safeguarding procedure which we and they also adhered to. Researchers carrying out the focus groups and interviews were Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) checked and had training and experience in conducting research with vulnerable adults and children. Project and support workers also had DBS checks.

Participant information sheets and advisory group information sheets explained the limits to confidentiality (i.e. that everything they told us would be confidential unless they told us something that indicated that they or someone else was at risk of harm, in which case we would discuss this with them before telling anyone else if possible). This was reiterated at the beginning of interviews, focus groups and advisory group meetings and conversations. If potential harm was disclosed, we followed our and others’ procedures. Participant information sheets also included helplines and information about what to do if a participant felt that they or someone they know was at risk of harm. Information sheets were available in age-appropriate versions.

3. Raising potentially sensitive topics

We took a number of measures developed in previous research which carried out interviews with vulnerable children and young people, adapted and built on for this project. These measures were based on our experience of conducting research on potentially sensitive subjects and were refined in conjunction with young carer advisors and with input from Health Research Authority (HRA) research ethics. Focus group facilitators/interviewers have extensive experience and expertise in this area. Experienced support workers were available during and after focus groups and interviews in case anything came up that the young people needed to discuss or wanted additional support with.

4. Consent

We sought informed consent from participants. We followed the HRA guidance on seeking consent for research from children. 92 If the participant was aged under 16 years, we sought assent from the young people themselves and consent from their parent/guardian. For participants aged 16 years or older, we sought consent directly from them. Information sheets to inform consent were distributed. These explained the purpose and nature of the research; what taking part involved and the potential benefits, risks and burdens; confidentiality; anonymisation of data and the voluntary nature of participation. Consent was also discussed with participants before the focus group/Interview began covering key points from the information sheet and consent taken either verbally or in person depending on the format. We liaised with project workers to get informed consent from parents/guardians before the focus group/interview but final consent, taken at the focus group/interview, was from participants. The child could refuse consent even if their parent had agreed consent and this was made clear to both parties. Participants were informed and reminded of the option to withdraw at any point including during the interview/focus group. Information sheets to inform consent were available in age-appropriate versions.

Sampling

The inclusion criteria for the study for young and young adult carers were that they be aged between 9 and 25 years and providing unpaid care. We also aimed to recruit a smaller number of care recipients; the inclusion criteria for care recipient participants were that they be aged 16 years or older and cared for by a young carer (not necessarily a young carer involved in the study). We recruited participants in four different localities in England. The four areas included different young caring situations and marginalised groups and represented different types of geographical and sociodemographic areas within England. All four areas are also internally diverse. Young carers who, at least on some level, identify as such, were common to all four sites, allowing a spread of experiences to be studied. Each locality also had in place strategies and networks to contact ‘hidden’ young carers, another marginalised group, again allowing a range of experiences to be gathered. The additionally marginalised groups in each area varied according to historic and sociodemographic context. These groups were identified by the young carers and other organisations in each locality. They were also, in the main, from population groups known to experience additional barriers to services more generally. Collaborating organisations recruited care recipients to take part through their existing networks, including parent groups, and contact lists for parents of young carers involved in their events and activities, and parents receiving one-to-one support. Siblings who were recipients of care were generally not included in these networks, and because of pandemic-related restrictions on the outreach activities we were limited to approaching potential participants via these organisations.

The four localities are described below:

Locality 1

Large city in the North of England; approximately a fifth of the population is from ethnic minority backgrounds; range of socioeconomic circumstances, with several areas with high levels of deprivation.

Locality 2

County in the South of England with a mix of rural areas, towns and cities. Lower than national average proportion from ethnic minority backgrounds; range of socioeconomic circumstances, with several areas with high levels of deprivation.

Specific additionally marginalised groups: young people providing care and the people they care for who experience stigmatised conditions, such as severe mental ill health and/or substance misuse.

Locality 3

Rural county in the North East of England; high proportion of people from White British backgrounds; range of socioeconomic circumstances, with high levels of deprivation in many areas.

Specific additionally marginalised groups: young people providing care and the people they care for who are rurally isolated; caring for/experiencing severe mental ill health, in some cases with substance misuse.

Locality 4

Coastal area in North West England with high area deprivation, below-average high household income, and much higher-than-average child poverty.

Specific additionally marginalised groups: young people providing care and the people for whom they care who experience stigmatised conditions, such as severe mental ill health and/or substance misuse.

Locality 4 was added to the study part-way through in response to a call for additional workstreams focusing on mental ill health and particular regions that have high mental health needs but are historically underserved by research activity on the topic.

Data collection

We discussed specific approaches to data collection with public advisors, the study steering group, and collaborating organisations in developing the project and before and during data collection. Research materials were also developed together with the project advisors, including information sheets and topic guides. We adapted and refined methods in response to local area circumstances, age, situation and number of participants, and in compliance with COVID-19 regulations at the time. Fieldwork commenced in June 2021 and during that time there was a range of COVID-19 procedures in place that varied geographically and organisationally. This included use of face masks, ventilation and spacing.

Focus groups

Focus groups were co-facilitated by two of the research team and project workers and aimed to discuss participants’ experiences with services, features of services and support needed and barriers to seeking support (research questions 1, 2 and 3). Focus groups were carried out in person, with one exception. Informed consent was sought to audio record the sessions, with assurances of confidentiality. Ground rules such as keeping confidentiality within the group were discussed and agreed with participants, the research team, and project or support workers. Topics for discussion included what aspects of services and other support participants had found helpful, less helpful and could be improved; what additional support was needed: what needs it would meet, what features it would have, and how and by whom it would be delivered; and barriers to getting the support that is needed.

Focus groups took about 2 hours including a break for food, usually pizza. We used a range of methods for the focus groups, co-developed with practitioners and young carer advisors and informed by the available literature. 93 This enabled a range of ways (verbal, visual, written, group, individual) for young carers to talk about their experiences. 93 Data collection methods included group and paired discussions, use of flipchart and stickers, drawing, writing and annotation. Data collection methods were designed to be engaging and interactive. We adapted methods and format according to the age, number and vibe of each group. For example, ice breakers and interim and closing activities were different for different age groups; these were often chosen by the co-facilitators from the care organisations. We also somewhat adapted activities depending on the nature and size of the group. Differences included the degree to which we worked with people individually, or held smaller group discussions within the larger group. The researchers took fieldnotes throughout.

We began the groups with icebreaker activities before we started on the topics and tasks. Following these activities, we began by working as a group to develop a list of all the different types of services and other support that young carers (or care recipients) come into contact with. Participants called out different people or services involved with them and their family, with prompts as needed from the research team (e.g. ‘Is there anyone that comes to your house? Anyone that you see at school? Anyone you see at other places? Anything you do for fun that is important to you?’). The research team made a list on a flipchart that the whole group could see. Some discussion about experiences with these services took place during the making of the list. Once we had the long list of services, we then took participants up to the flipchart, usually in pairs. Each participant had their own set of coloured stickers and during the discussions at the flipchart they were asked to rate services they had been in contact with, using stickers of different colours. The colours indicated whether the service or support had been good, ok but could be better, or bad. For ‘bad’ it was further suggested that this might mean they recommended other young carers to avoid this service. For the parent groups, we used coloured pens rather than stickers and did the rating activity as a group.

This rating exercise then led to discussion with the pair at the flipchart, or sometimes a single person, about what was helpful and unhelpful about services. This was done as a group for parents, though parents also shared information and views individually, for example during a break or while people were working alone on the ‘ideal world’ task. We were able to follow up these ratings with questions like, ‘so you gave this one a bad rating – could you tell me about that?’ The chart was annotated with key points by the researcher at the flipchart. The researcher also took notes, especially where information was personal and not appropriate to record on the flipchart. When points were added to the flipchart, this was discussed with the participant (‘shall I write that down’?). While some participants were at the flipchart, the remainder carried on with other activities, described below.

To explore additional unmet need, participants were guided to individually, or with the research team, annotate a simple representation of a young carer and the person they care for, with their views of the support they or someone else in their situation would receive in an ‘ideal world’, and which currently unmet needs it would help meet. Specifically, they were asked to consider what sort of things would help support young people who look after someone at home. We explained that this could include both help for the young carer and for the person they cared for. Researchers discussed the activity with the young people while they were doing it, asked prompts, and took notes. This was initially going to be a group activity. COVID-19 rules meant we could not do it this way, but we found that participants individually annotating the diagrams with the research team or support workers worked well for participants and gave them options for individual work and discussions. In later sessions, when restrictions were reduced, some participants completed the task in pairs, but each still completing their own sheet.

To explore barriers experienced by young carers and the people they supported, we asked participants to individually, in pairs, or with the research team, write on coloured bricks their views and experiences of barriers to support. Researchers prompted as needed. Each pair or individual then read out two barriers for others in the group to comment on, add to, agree or disagree with, facilitated by the research team.

We finished with a summary and synthesis activity. In this, the research team attempted to summarise key points made in the session by presenting what we understood to be the aspects and components that made up a good and not-so-good support or service, and what additional support was needed. We asked participants to indicate whether they agreed, disagreed or were not sure by holding up green, red and yellow cards, respectively. Participants could also add to the summary verbally or in written form. This gave participants an opportunity to consider whether we had listened properly; had understood correctly; and to establish areas of consensus and dissensus. To end the group, we held a ‘cool down’ activity unrelated to the study topics and reminded participants of the availability of the research team and the attending support workers after the group and the information sheet with helplines.

One-to-one, in-depth semistructured interviews were carried out where participants preferred this alternative. Interviews explored individual experiences of services, needs and barriers to finding or accessing services and other support (research questions 1, 2 and 3). Interviews took place variously by phone, in person in a place convenient and accessible for the participant, and online.

We carried out a total of 21 focus groups across the four areas, one online and the remainder in person. Two focus groups were carried out with adult care recipients and 19 with young carers. There were approximately 6–8 participants per group. The number of participants per focus group was based on typically suggested optimum size94 and on our previous experience holding focus groups with young people. For practical reasons, some groups were bigger or smaller than this in practice. The combined number of participants enabled us to cover a range of experiences, allowing the emergence of principle and subthemes, while remaining manageable within the project. The final sample numbers were determined by the continuing emergence of new themes, or where saturation of themes appears to be reached, as well as practical considerations. We also carried out two in-person interviews with care recipients and eight phone or online interviews with young carers. Focus groups and interviews for young carers and for care recipients took place separately from each other. The resultant sample was 150 participants, of which 17 were care recipients. Participants were aged 9–25 years with a range of caring and life circumstances and sociodemographic characteristics, including ethnicity, gender and social class. Forty of the carer participants were aged 9–11 years, 57 were aged 12–15 years, and 36 were aged 16–25 years. Where known, 25 cared for a sibling, 46 for a parent and 2 for another relative. Some cared for more than 1 person. Reasons for needing care, where known, were mental ill health (N = 26), physical ill health (N = 19), substance misuse (N = 8) and other (N = 5). Other included dementia, neurodiversity and learning disability. Many of the people cared for had more than one care need, for example mental and physical ill health. Care recipient participants were aged 16 years or older and had a range of physical and/or mental care and support needs. All care recipient participants were parents of the young person who cared for them. Although the inclusion criteria for care recipient participants potentially allowed for siblings to take part, in the event only parents were included. This was due to the existing networks and contacts of the collaborating young carers’ organisations; siblings tended not to be involved with the organisations in the same way that parents were. There were in addition ethical concerns from organisations about inviting sibling care recipients to participate, due to the need to identify their sibling as a carer and around ambiguities in who were the care recipients within the family.

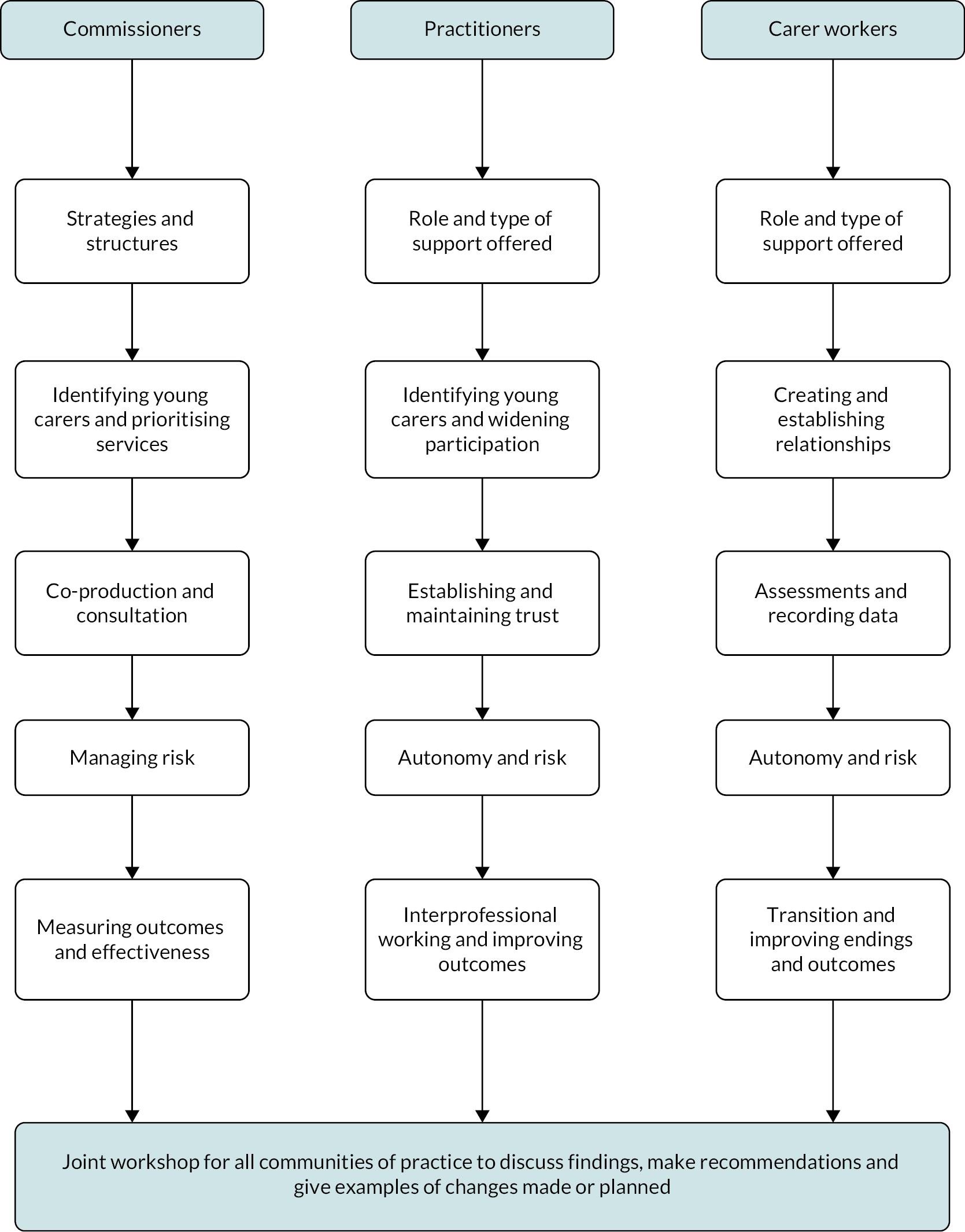

Practitioner workshops

We held workshops for practitioners from each of the four study areas. The initial plan was to hold them in person by locality, but we decided to hold them online for flexibility and ease of taking part for participants. This method also meant we could include practitioners from different locations in the same workshops. In the workshops we discussed selected key findings from the focus groups and interviews and explored the applicability of the findings to practice, barriers to putting the findings into practice, and any facilitating factors, or examples from practice where there had been successful approaches addressing the issues under discussion. We wanted to find out how the findings related to current service provision from the perspective of service providers and commissioners. The aims were: (1) to help inform study recommendations and (2) to address research question 4: ‘What are the barriers and facilitators for practitioners in providing support and services perceived as acceptable and appropriate by young carers and the people they support?’

Three workshops were held with 19 practitioners from schools, colleges, young carers organisations, voluntary sector services, mental health services, the NHS, adult social care and social care commissioners (Table 1). The first workshop was attended by five practitioners, the second by eight and the third by six. Each session lasted 90 minutes. We recruited practitioners through local young carer collaborating organisations in the four localities which contacted their wider networks to invite people to the workshops. The choice of types of service to invite was informed by findings from the focus groups and interviews, and by discussion with project advisors and collaborating organisations. A mix of practitioners from different service types was included in each workshop; the full list of the practitioner job roles and service types of those who took part is shown in Table 1.

| Job role | Service type |

|---|---|

| Support worker | Youth development agency |

| Community engagement manager | Young carers support charity |

| One-to-one worker | Young carers organisation |

| One-to-one worker | Young carers organisation |

| Youth participation officer | Young carers organisation |

| Senior practitioner and designated safeguarding lead | Young carers organisation |

| Development manager | Young carers organisation |

| Health development worker | Young carers organisation |

| Young carer practitioner | Voluntary sector family charity |

| Tutor/mentor | Sixth form college |

| Tutor/mentor | Sixth form college |

| School counsellor | Primary school |

| Associate director, engagement and experience | NHS |

| Assistant service manager | Multi-agency support team, local authority |

| Early-help coordinator | Local authority |

| Commissioning officer | Local authority |

| Commissioning officer for children and young people’s mental health | Local authority |

| Key worker | Family centre and advice hub, local authority |

| Managing director | Counselling, psychotherapy and supervision provider |

Following discussion among research team members and with project advisors, we chose the following key themes (aspects of valued or wished-for support), from the analysis of focus groups and interviews, to discuss in the workshops:

-

Signposting and linking to support

-

On-call and ongoing support/changing your mind

-

Support that reduces the young person’s caring responsibilities

-

Support that considers the whole family

-

Someone who listens and understands/building relationships and trust

For each theme we first briefly presented the research findings then invited discussion. At the first two workshops we discussed themes 1–4. For the third workshop theme 1 was replaced with theme 5, as we felt theme 1 had been well covered.

We followed up the presentation of each theme with questions on a slide to prompt discussion, but practitioners were keen to address the issues raised and discussion flowed easily. We were interested in hearing from practitioners on the following types of questions:

-

How does/might this work in practice?

-

What does/would get in the way of you providing that support?

-

What would help address these difficulties?

Chapter 4 Analysis

Overall approach

Transcripts and field notes from the focus groups, interviews and workshops were organised and coded by researchers with the help of NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software. 95 Analysis of the focus groups and interviews with carers and care recipients took place prior to the practitioner workshops, so that preliminary results could be discussed with the advisory groups and used to inform workshop discussions. The analysis approach was largely deductive and inductive thematic analysis. 96,97 We set out with particular research questions in mind, seeking to discover what acceptable intervention or support looked like, and for who, how this related to what was currently on offer, and what the barriers to access were. Initial codes and themes were also informed by the theoretical frameworks described above. Coding also took place inductively, with categories not pre-set but drawn from the data, allowing the development of themes which had not been anticipated. Within this broad framework, the approach taken varied by the specific research question the analysis was seeking to answer.

What is good or not good about existing services? What can be improved?

The material for analysis of this research question consisted of the annotated flipcharts, notes written by both participants and researchers during the session, notes made by researchers after the session, and transcripts. Material relating to a single focus group or interview was added to a single file and entered into NVivo. The dataset consisted of 21 focus group files and 10 interview files.

In this analysis we aimed to understand how young carers, and their parents, experienced the services and support they received. The analysis focused on seeking answers to the research question: ‘What makes support helpful, how can it be improved?’ We examined what was considered good or not good about existing services, and where it was felt improvements could be made. Material relating to gaps in services, needs that were perceived as not being addressed by services and barriers to accessing services were coded and analysed separately.

For this section of the analysis, material was coded both by the type of service being referred to, and thematically by the aspects of services and support that was considered helpful or unhelpful. The presence or absence of a particular aspect of support was at first coded together (e.g. person was non-judgemental/person was judgemental), partly because views were not always easily categorised as positive or negative, but also because reviewing the different aspects together allowed a more nuanced analysis. Later stages could then pick out and separate recurring themes related to what made a support helpful or less helpful. While some aspects of support were specific to a particular type of service (e.g. care workers in the home), there were also many themes which cut across different service types (e.g. ‘listening and understanding’). Material was coded both in relation to specific service types, so that themes which related to specific service types could be identified, and across service types, to identify cross-cutting themes. The initial themes constituted findings about what aspects of support were valued; what made support valuable and appreciated; what made support unhelpful, or not wanted; and how existing support could be improved. Material within codes was reviewed and code categories were further subdivided or combined as the thematic analysis proceeded. Files were named for the location, age range and other distinguishing features of each group or interview so that context was always apparent. Material within each code retained the link to the original file so that the broader context of excerpts could be reviewed as needed to enhance understanding.

Additional support needs

Analysis of additional support needs began with familiarisation with the data, including reading and rereading the interview transcripts. An initial coding framework was then developed, structured around the conceptual frameworks75,76 and the research question: ‘What additional support is perceived as needed by young and young adult carers aged 9–25 years and the people they support in England and what needs would it meet?’ Initial themes were reduction or removal of caring responsibilities; mitigation and improvement of negative impacts of caring; and assistance with caring role. Each theme had two initial subthemes: (1) the need the support would address and (2) the mode by which it would address it.

We then gathered all data relevant to each theme, including counterexamples and exceptions. Themes were adapted as required in response to the data, and deductive and inductive analysis then used to identify subthemes within the initial themes. Themes and subthemes were iteratively reviewed in relation to the extracts coded and not coded to each theme and subtheme. Iterations of analysis were also informed by discussions on initial themes and subthemes with young carer and practitioner advisors.

Barriers experienced by young carers in seeking and accessing services for themselves or the person they support

After initial familiarisation with the data, an initial coding framework was developed, structured around the conceptual framework77,78 and the research question: ‘What are the barriers experienced by young carers and the people they support in seeking and accessing services and support?’ The initial coding frame had the following overarching themes and subthemes: (1) individual barriers; and subthemes: material circumstances, competing priorities, self-determination and psychosocial; and (2) contextual barriers; and subthemes: care policy and care financing and care organisation.

As above, we then collated all data relevant to each theme, including counterexamples and exceptions. Themes and subthemes were adapted as required. For example, in the conceptual models that informed this analysis (e.g. Andersen’s BMHSU), health literacy has been variously conceived as an individual or as a contextual determinant. In the analysis it became clear that this had both individual and contextual aspects, so subthemes for ‘service and support literacy’ were created under both of those overarching themes with text coded accordingly. Deductive and inductive analysis was subsequently used to identify additional themes and further subthemes within the initial themes. As above, themes and subthemes were iteratively reviewed in relation to the extracts coded and not coded to each theme and subtheme. Iterations of analysis were also informed by discussions on initial themes and subthemes with young carer and practitioner advisors.

Practitioners workshops

Workshop discussions were transcribed verbatim and entered into an NVivo database. The transcripts were coded thematically in three ways. One researcher coded the three transcripts inductively, considering emergent themes. A second researcher coded the transcripts specifically to look for recommendations for practice. A third researcher interrogated the project, using both sets of coding and the original transcripts to develop themes in response to the five highlighted themes from the analysis of young carer and cared-for parent focus groups and interviews, which had guided the practitioners workshops, and other themes relating to the overall research question around which the practitioners workshops were devised: ‘What are the barriers and facilitators for practitioners in providing support and services perceived as acceptable and appropriate by young carers and the people they support?’

Cost analysis

The aim for this part of the analysis was to report economic evidence that could inform the recommendations developed in consultation with young carers and practitioners, which were themselves based on the findings. Economic evidence in this area is extremely rare. We wanted to explore what economic evidence was available and identify possibilities for how future research might be conducted to examine the costs and (economic) benefits of interventions that are supporting young carers.

Based on the recommendations developed for the study, we conducted a targeted, exploratory review of the literature – both academic articles and online reports from the UK social care sector – to identify economic information concerning some of the interventions that were covered by some of the recommendations. We focused on interventions that were likely to be suitable for potential economic analysis, that is that had substantial costs, outcomes and consequences attached to them. We summarised interventions from all sectors that we identified as most relevant, excluding areas that were very broad and where it was unclear what kind of resources the implementation or delivery would involve. We first used our own knowledge, and consultation with experts, to gather key literature. We also used the Economics of Social Care Compendium (ESSENCE) database (https://essenceproject.uk/glossary/). Following this, we undertook a search on Google Scholar for relevant documents published over the last two decades, focusing mainly on studies, reports and articles based on a UK context. We also undertook a general Google search for relevant grey literature, including annual reports from third-sector organisations and undertook snowballing searches of the literature. We extracted data pragmatically focusing on information about the cost, net savings and other considerations relevant for economic analysis.

We held a 1.5-hour online workshop with 10 service managers or chief executives of local voluntary sector provided services in England, policy and practice leads at voluntary sector organisations concerned with providing services and advocating for young carers, as well as local authority commissioners. This included leads of a national network concerned with sharing information and good practice evidence on young carers. All individuals had specific expertise and focus of their work with young carers. The objectives of the workshop were to discuss the findings from the review, including their relevance to the young carers field, identify evidence gaps and discuss what economic research might need to be conducted.

Chapter 5 Results

What is good or not good about existing services? What can be improved?

In the following section, we present results of the analysis relating to research question 1: ‘What types, components or features of services and other support are seen as helpful, valued and acceptable to young people who look after someone at home and the people they support? Conversely, what is found to be less or unhelpful?’ The findings mainly reflect the views of the young and young adult carers who made up the majority of the sample. Where views are those of the care recipients, this is indicated in the quote annotation.

As explained previously, this analysis draws principally on the section of the focus groups and interviews where we discussed the services and supports they had come into contact with. In the focus groups we created, together with participants, a list of services and supports young carers and care recipients were involved with, and then rated and discussed those services. Material from the other sections of the groups and interviews was also brought into the analysis where relevant to the research question.

The themes are presented in two sections. The first section sets out the themes that are specific to a particular service types (these types being: Support for the care recipient; Young carers groups; Mental health services; and Support in schools) while the second section presents themes with relevance across service types (under the broad top-level themes outlining what is helpful or unhelpful): Finding, and linking to other sources of support; Listening and understanding; People you can trust/confidentiality; Involving the young carer in decisions about support; Proactive, persistent or intrusive (a balanced and flexible approach to individual and changing preferences and needs); and the strong recurring theme of the level of each type of support received being ‘Not enough’.

Table 2 shows a list of the services mentioned by participants in the focus groups. The labels largely reflect the language participants used, although some categories have been combined. The purpose of the table is to show the range of services and supports under discussion. Participants did not necessarily know the role or profession of the person they encountered. For example, they were often unclear whether someone who visited them at home was a social worker or had a different role.

| Service | Young carers (N focus groups in which mentioned) | Parents (N focus groups in which mentioned) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| School and college-based support | |||

| Young carers group/lead at school | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Person at school/pastoral/SENCO | 13 | 1 | 14 |

| Time-out room/card at school | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Family engagement/support worker | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Teachers | 19 | 0 | 19 |

| School counsellor | 11 | 0 | 11 |

| Other students | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Free school meals/breakfast club | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| After-school clubs/activities for young carer | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| ‘Worry box’ | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| School behaviour team | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| School nurse | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Pupil premium | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| University lecturer | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| University counsellor/wellbeing services | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Young carers and carers groups | |||

| Young carers/carer centre groups and services | 16 | 1 | 17 |

| Parent group by young carers organisation | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mental health | |||

| Mental health worker/Therapist for young carers | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Mental health worker/Therapist for care recipient | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| CAMHS for care recipient (sibling) | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| CAMHS for young carers | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| Family counsellor | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Crisis team | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Social care and related | |||

| Social worker for care recipient | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| Paid carers | 13 | 1 | 14 |

| Council carers | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Social worker for young carer | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Family support worker | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Family social worker | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| Social services | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Multi-agency support team worker | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Home adaptations/equipment | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Respite carers | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Health and related | |||

| Hospital | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| GP/doctor | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| Social prescriber | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| District nurse | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Pharmacist | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Occupational therapist | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Physiotherapist for young carers | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Speech and language therapist for care recipient | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Drug and alcohol support for care recipient | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Autism services for care recipient | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Autism/ADHD services for young carers | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Other sources of support/services in contact with | |||

| Family | 16 | 0 | 16 |

| Friends | 11 | 0 | 11 |

| Neighbours | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Pets | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Trips | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Welfare benefits | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Charities/community support/volunteers | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Clubs/activities for care recipient | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Clubs/activities for young carers | 10 | 1 | 11 |

| Support at work for young carers | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Case worker | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Transport for care recipient | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Helplines and online communities/support | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Police | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Adult learning | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Peer support | 1 | 1 | |

| Citizens Advice Bureau | 1 | 1 |