Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/136/45. The contractual start date was in June 2017. The final report began editorial review in June 2021 and was accepted for publication in March 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Ramnarayan et al. This work was produced by Ramnarayan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Ramnarayan et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Over recent decades, evidence linking higher volume to better outcomes has led to the centralisation of specialist services, such as cancer surgery, perinatal care and trauma. 1–3 Prior to 1997, the care of critically ill or injured children (aged < 16 years) in the UK was quite fragmented. 4 In 1997, based on expert opinion and scientific evidence, the UK Department of Health and Social Care recommended that paediatric intensive care (PIC) services be centralised. 4 Dedicated regional paediatric intensive care units (PICUs) were established, and specialist paediatric critical care transport teams (PCCTs) were set up to transport critically ill children from general hospitals to PICUs. PCCTs act as ‘mobile intensive care’ teams. PCCTs travel to general hospitals and start PIC, ensuring that specialist expertise is not delayed until the patient reaches the PICU. 5

Currently, only 25 (12%) of the 215 acute hospitals in the UK where children may first present when they are critically ill have a PICU. Consequently, children presenting to hospitals without a PICU require transfer to a hospital with a PICU, which can be located at a median distance of 32 km away [interquartile range (IQR) 14–57 km]. 6 The use of PCCTs (rather than non-specialist teams) for the interhospital transport of critically ill children improves the odds of their survival by 42%. The majority (≈ 85%) of interhospital transports of critically ill children in the UK are currently performed by PCCTs. 7

Variations in current service provision

Each year in England and Wales, nearly 5000 critically ill children are transported by PCCTs to receive care in an appropriate location, such as a PICU. National audit data from the Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network (PICANet) reveal wide variations in the timeliness of access to PIC in these patients. 7 First, the median time taken for PCCTs to reach critically ill children at general hospitals ranges from 1 hour to 4 hours, reflecting considerable differences in how soon a critically ill child can expect to start receiving PIC. During the winter surge period, some children may wait up to 12–24 hours for the PCCT to arrive. Second, there is variation in the time taken by PCCTs to transport children into the admitting PICU, reflecting differences in how soon a critically ill child can start receiving definitive care (e.g. surgery) available in a specialist centre only. Similarly, PICANet data indicate that there is considerable variation in the care provided to critically ill children by PCCTs prior to PICU admission, in terms of the seniority of the transport team leader [e.g. consultant, junior doctor or advanced nurse practitioner (ANP)], critical care interventions performed by the transport team (e.g. intubation or central venous catheterisation and delivery of vasoactive drug infusions) and the frequency of critical incidents (e.g. accidental extubation) occurring during transport.

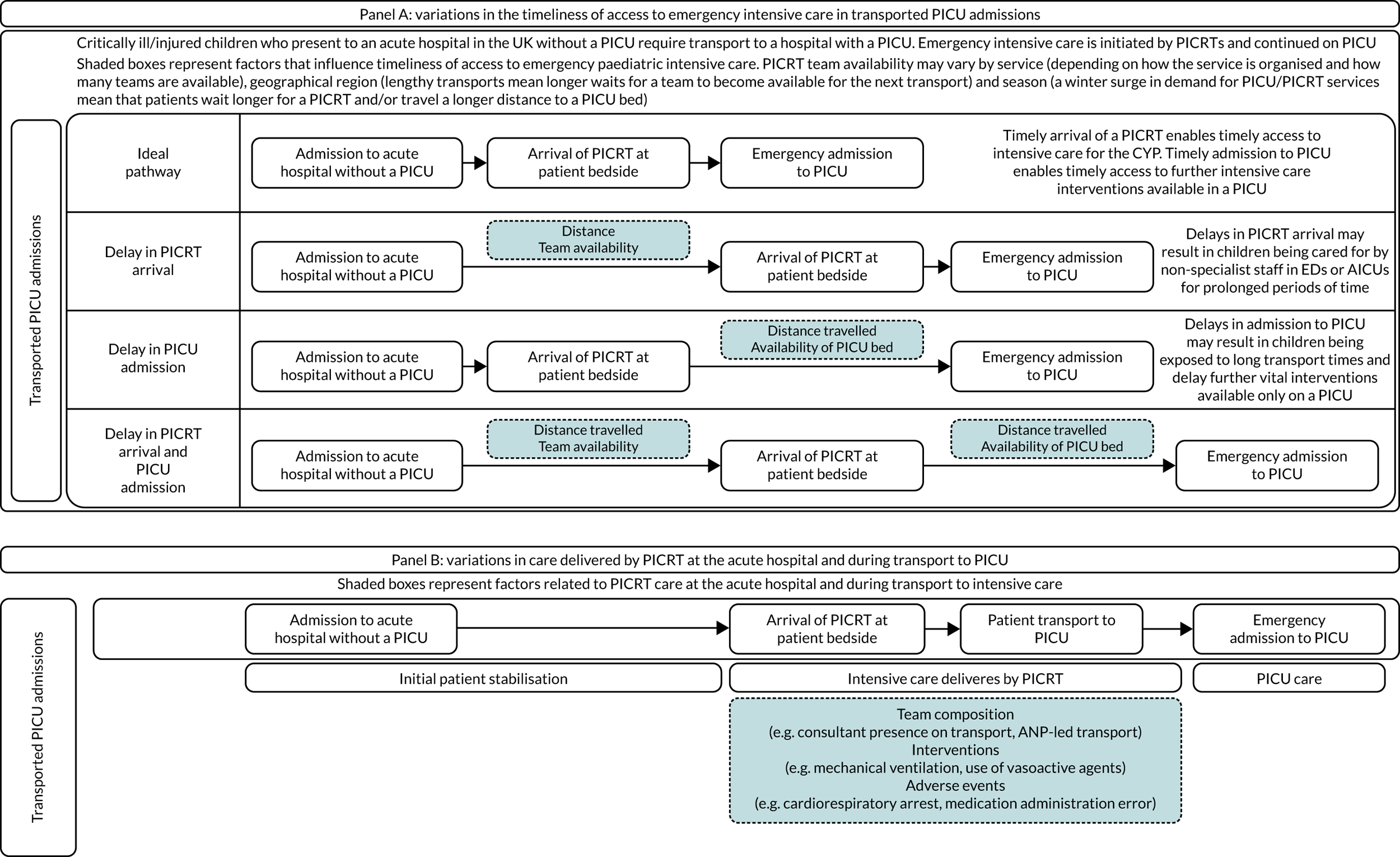

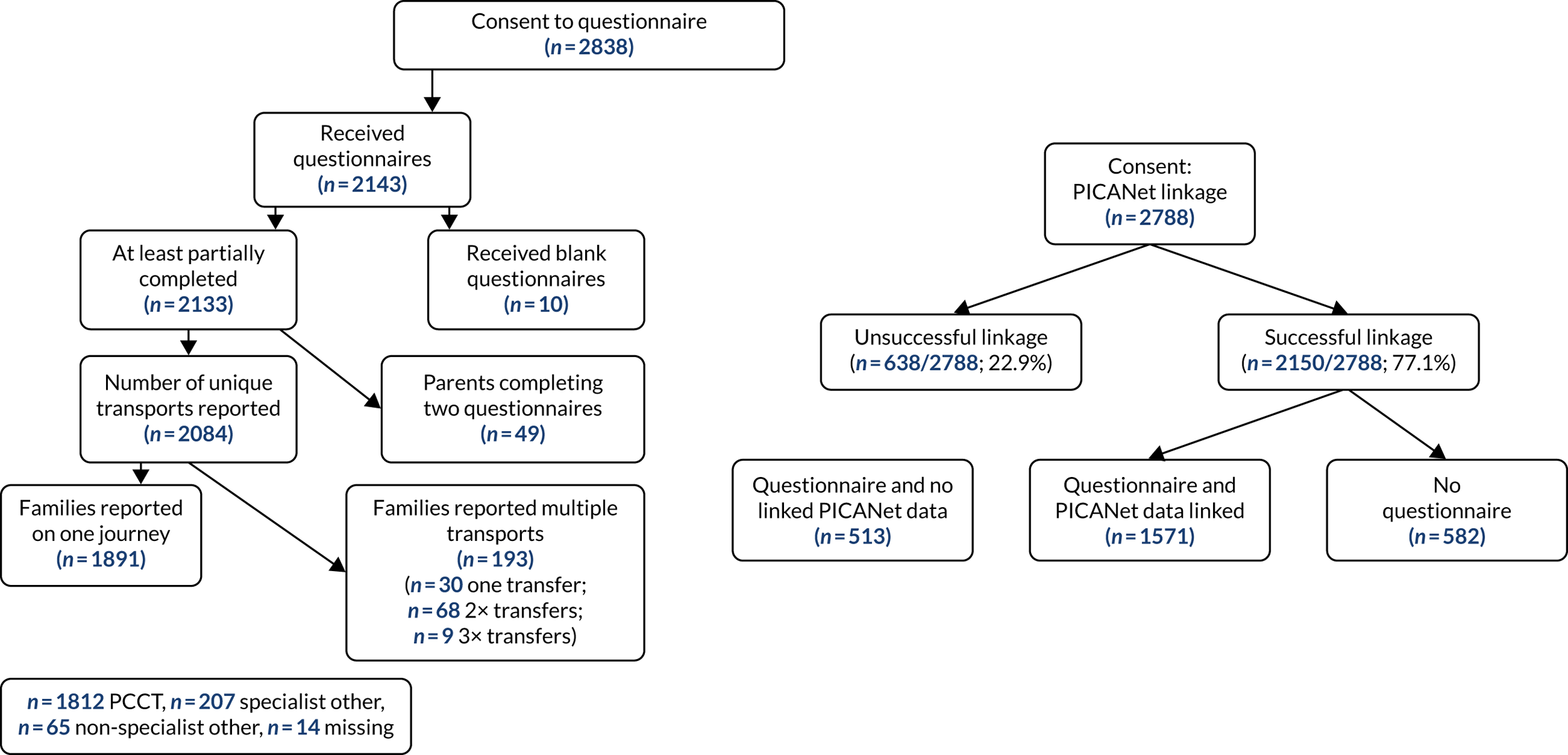

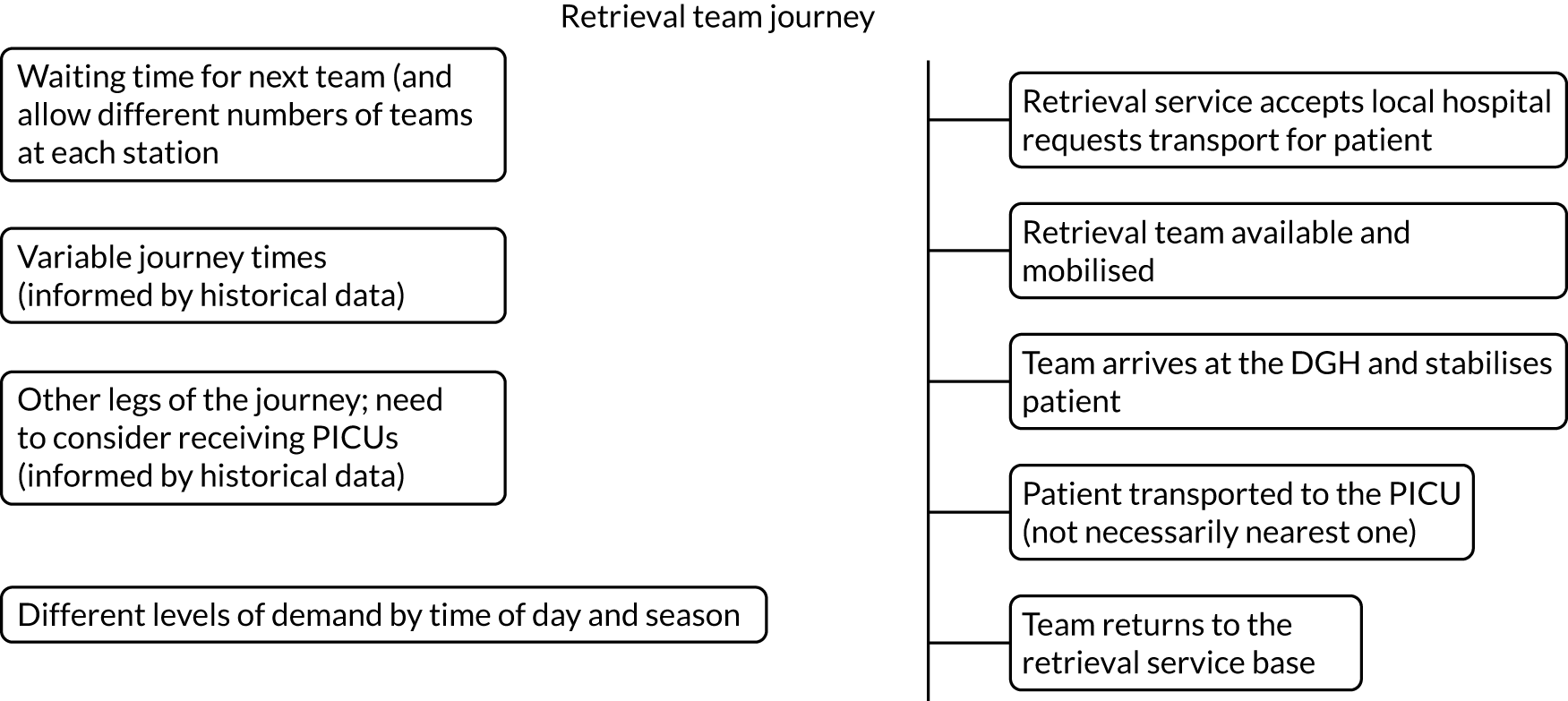

Common reasons for delays in timeliness of access to emergency PIC and variations in care provided by PCCTs are graphically shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Reasons for variation in timeliness of access to emergency PIC and care provided by PCCTs. CYP, children and young people; PICRT, paediatric intensive care retrieval team.

We do not know if these differences in timeliness of access to PIC and care delivered during stabilisation and transport by PCCTs matter in terms of clinical outcomes and patient experience, and it is also unclear what their impact on health-care costs is. This lack of scientific evidence has led over the years to the evolution of different models of PCCT provision, the development of national standards based on expert opinion rather than scientific evidence and has contributed to the lack of progress in improving care at the crucial interface between secondary and tertiary paediatric care.

Impact on patient outcomes and experience

Transported children represent one-third of all PICU admissions (and half of all emergency admissions). Yet, compared with the two other main patient groups (i.e. planned admissions and emergency admissions from within the same hospital where the PICU is located), transported children have the poorest clinical outcomes. Transported children’s PICU mortality is nearly double that of planned PICU admissions (8% vs. 4%) and higher than for internal emergency admissions (6%), and they have a significant risk of long-term complications and considerable associated health and social care costs. 6 It remains unclear whether or not this is solely because transported children are much sicker than other groups of critically ill children, or whether or not the timeliness of access to PICU expertise and the quality of care delivered by PCCTs prior to PICU admission may have an additional influence on clinical outcomes. From a family perspective, parents of sick children have described the process of PICU retrieval as the ‘the worst journey of their lives’ and demonstrate evidence of psychological trauma long afterwards. 8–10

Rationale for the study

Evidence is urgently required to enable understanding of if and how delays in access to PIC and variations in the quality of care provided during acute stabilisation and transport affect clinical outcomes and patient experience. National audit data relating to the referral and transport of critically ill children have been collected by PICANet since 2012. These data clearly show national differences in the timeliness of access to PIC (i.e. time taken by PCCT to reach the patient bedside) and in the care delivered by PCCT during transport (i.e. team composition, interventions performed and frequency of critical incidents). As the primary means through which critically ill children at general hospitals access PIC in an emergency, it is plausible that variations in PCCT provision compromise equity of access and may adversely affect their clinical outcomes and patient experience. Over the past decade, in the absence of scientific evidence, the development of PCCT services and national quality standards have been guided by expert opinion.

Provision of early high-quality acute care has been shown to improve clinical outcomes in specific diseases, such as paediatric sepsis and head trauma. 11,12 It is unclear how these findings apply to the vast majority of critically ill children who require stabilisation and transport to a PICU by PCCTs. From a wider NHS perspective, centralisation of specialist acute care has occurred in several NHS services, such as stroke, trauma and specialist paediatrics. 13,14 The findings from our research can provide evidence that can be generalised to evaluate other such centralisations, and this is especially relevant to questions relating to the trade-off between timeliness of access to acute care and provision of high-quality cost-effective specialist care.

Study aims

-

To understand if and how clinical outcomes and experiences of critically ill children transported to PICU are affected by national variations in timeliness of access to PIC and care provided by PCCTs prior to PICU admission.

-

To study the relative cost-effectiveness of current PCCT services and to use mathematical modelling to evaluate whether or not alternative models of PICU/PCCT service delivery can improve clinical and cost-effectiveness.

-

To generate evidence for the development of future clinical standards.

Study objectives

-

To perform a quantitative analysis using linked routinely collected data to study the association between timeliness of access to PIC and clinical outcomes in a national cohort of critically ill children transported to PICU.

-

To perform a quantitative analysis using linked routinely collected data to study the association between care delivered by PCCTs and clinical outcomes in a national cohort of critically ill children transported to PICU.

-

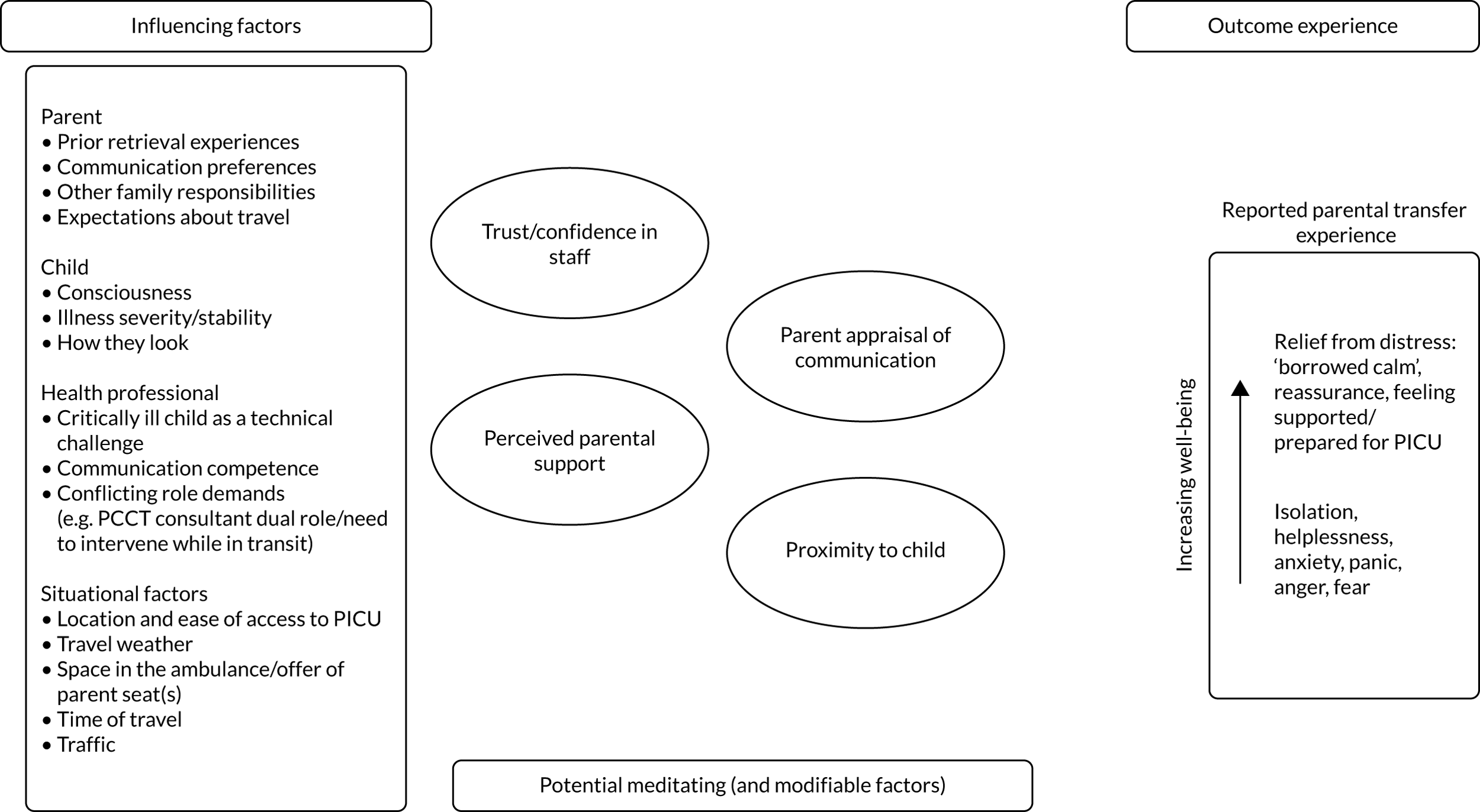

To explore, using qualitative methods (i.e. individual interviews and workshops) and questionnaires, the experiences and perspectives of a purposively sampled national cohort of parents of transported critically ill children and young people (CYP), and, if and where feasible, to use innovative methods to explore the experiences of transported critically ill CYP.

-

To explore, using qualitative methods (i.e. individual interviews and workshops), the experiences and perspectives of a purposively sampled national cohort of clinicians from a range of settings (e.g. acute general hospitals, PCCTs and PICUs) and service managers/NHS commissioners.

-

To perform cost-effectiveness analyses of PCCT provision for critically ill children, comparing different service models currently in use.

-

To use mathematical modelling and location–allocation optimisation methods to explore whether or not alternative models of service delivery for PICU/PCCT services can improve clinical outcomes while remaining cost-effective.

-

To synthesise study findings to inform the development of evidence-based national standards of care and information resources for families and clinicians.

Chapter 2 Overview of methods

Study design

The study design was a multiworkstream mixed-methods design. There were four linked workstreams and a final workstream that involved stakeholder workshops to draw together findings from the other workstreams.

Workstream A

-

A quantitative analysis of national PICANet data linked to routine administrative data [Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)], death registrations [Office for National Statistics (ONS)] and adult critical care data [case mix programme (CMP)].

Workstream B

-

A qualitative and questionnaire study involving interviews of parents of critically ill children transported to PICU (and children themselves, where feasible), interviews with clinicians working in PICUs, PCCTs and acute general hospitals, as well as service managers/commissioners, and questionnaires to collect feedback from parents of transported children.

Workstream C

-

A health economic evaluation of the costs and value for money of different models of PCCTs to identify cost-effective models of service delivery.

Workstream D

-

Mathematical modelling, including the use of location–allocation optimisation, to explore the potential clinical and cost impact of alternative models of service and geographical locations where PCCTs could be based.

Workstream E

-

Workshops involving key stakeholders (i.e. CYP, parents, clinicians and service managers/commissioners).

Integration of workstreams

We adopted a mixed-methods approach with a convergent triangulation study design whereby quantitative and qualitative data were collected concurrently, with equal weight being given to both workstreams. At the interpretation stage, we integrated findings from the qualitative and questionnaire study (of how national variations in the timeliness of access to emergency intensive care and care delivered by PCCTs affect patient/family experience) with findings from the quantitative study (of how clinical outcomes are affected by national variations) to generate complementary views of paediatric retrieval. Uniquely, the qualitative study gathered rich narrative detail from patient experiences and clinician perspectives that cannot be obtained from quantitative analysis of routine data alone. Integration was facilitated by regular discussions between the study team members at monthly study meetings. Further integration of study findings from the health economic evaluation and mathematical modelling were attempted at the workshop stage, although this was not completed as proposed because of changes in study conduct during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Salient issues faced). The dependencies between the workstreams and what was achieved during the study are shown in Appendix 1.

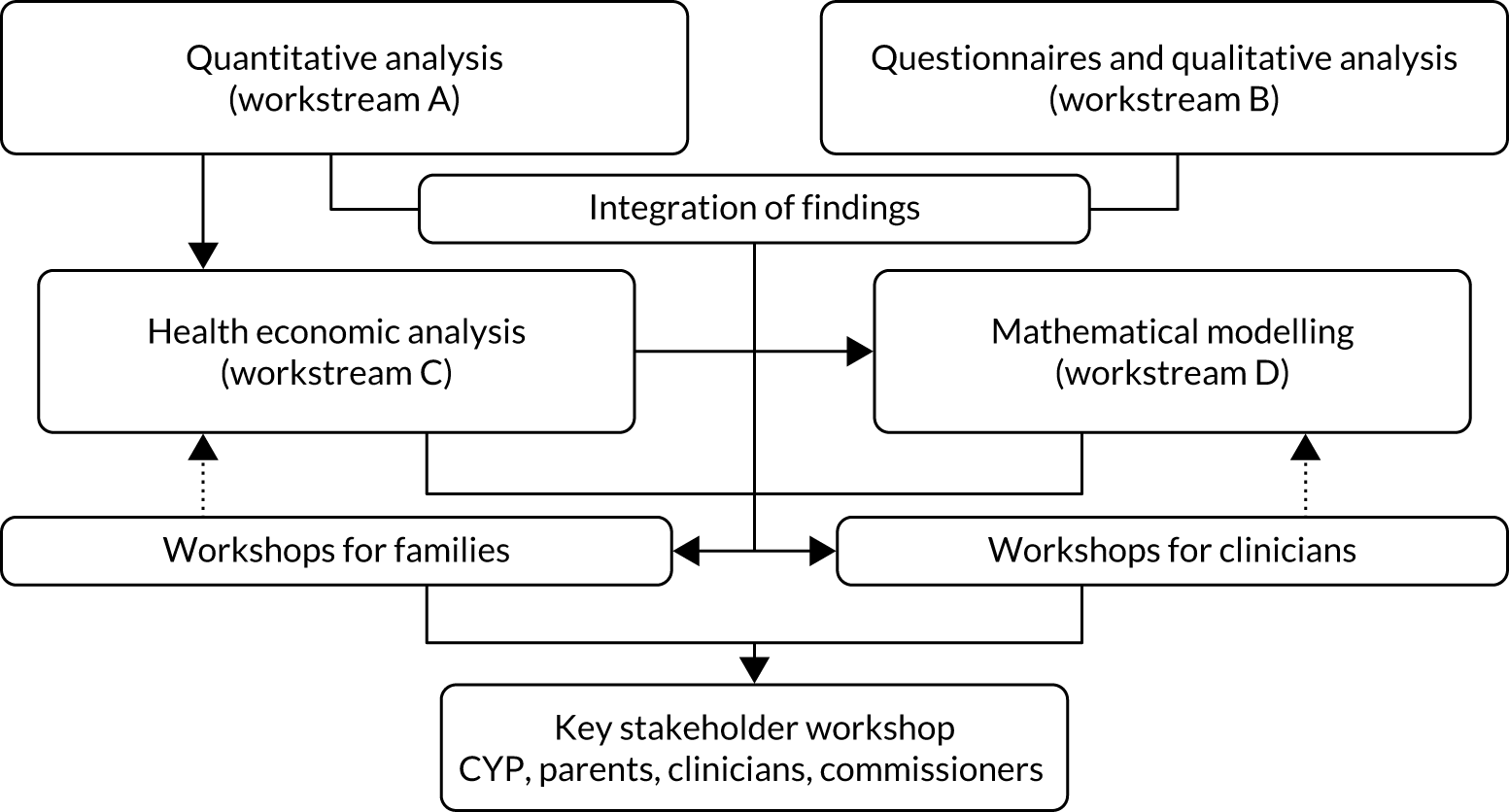

The overall study design is displayed in Figure 2, including points at which where findings are integrated.

FIGURE 2.

Study design and relationship between workstreams.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the DEPICT (Differences in access to Emergency Paediatric Intensive Care and care during Transport) study was provided by the Health Research Authority and the National Research Ethics Service – London Riverside Committee (reference 17/LO/1267). Approval for the use of patient-identifiable information without patient consent was provided by the Health Research Authority Confidentiality Advisory Group (reference CAG 0129). Relevant approvals were also provided by NHS Digital for data linkage and access to HES and ONS data.

Patient and public involvement

Two members of the public (ME and AP) were co-applicants on the proposal for the DEPICT study and were active members of the Study Management Group, contributing to the study design, operationalisation of the protocol and interpreting emerging findings. Matthew Entwistle and Anna Pearce critically reviewed patient information sheets (PISs) and consent forms and helped design the study questionnaires and interview topic guides. Anna Pearce was also part of the interview panel to recruit the qualitative researchers for the study. In addition, an independent lay member (Dermot Shortt) was part of the Study Steering Committee and provided input into the study conduct as it progressed and helped with the interpretation of emerging findings.

Salient issues faced

The COVID-19 pandemic had an adverse impact on the DEPICT study and necessitated the following changes to study procedures:

-

The DEPICT study data set, including the HES data, was held on secure servers at the University of Leicester (Leicester, UK). With the advent of the pandemic, all workstream A analyses had to be performed remotely using virtual private network (VPN) access. However, the HES data set was too large to manipulate effectively over VPN and, therefore, two specific secondary outcome measures [i.e. total length of stay (LOS) in hospital and hospital re-admission after PICU discharge] were unable to be studied. However, we feel that the absence of these outcomes does not detract from the importance of our findings.

-

The health economic analysis relied on the Cambridge team accessing workstream A data at Leicester. However, restrictions on physical access to the university since lockdown in March 2020, and inability to get remote access for honorary researchers, resulted in significant challenges. The full impact of COVID-19 on workstream C is detailed in Chapter 5.

-

The workshops for parents and clinicians were unable to be held as planned. One workshop for clinicians and parents was held in March 2020 just prior to lockdown, but was poorly attended. The methods for this workshop were planned beforehand; however, owing to the poor attendance, we were unable to draw meaningful conclusions. The final stakeholder workshop was changed to a virtual dissemination event in November 2020, making it difficult to collect systematic feedback to refine study conclusions.

Chapter 3 Workstream A: quantitative analysis

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Seaton et al. 15 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

The centralisation of PIC in the 1990s led to a reduced number of PICUs across the UK. In turn, this meant that critically ill children often presented at hospitals without the facilities to care for them, meaning that they needed to be transported to a hospital with a PICU. In more recent years, there has been a centralisation of the PCCTs rather than transports undertaken by ad hoc created teams from locally sourced staff. Therefore, children may now have to wait longer to be transported to PICU to receive care, but the trade-off is that this care will be provided by specialist teams.

Targets have been set surrounding access to care, for example the Paediatric Critical Care Society (London, UK) recommends that PCCTs should aim to arrive at the bedside of the child within 3 hours of the request to transport them to a PICU. However, these targets have been selected using expert consensus, rather than evidence-based research. To the best of our knowledge, no one has assessed whether or not these targets impact on outcome for children or whether or not they should be changed. Similarly, there is no guidance surrounding the way in which care is provided by the PCCT, for example what the level of the seniority of the staff leading the transport should be.

In this chapter, we will investigate the impact of the time taken to reach a critically ill child and whether or not the care and the PCCT impact on the outcome.

Aims and objectives

Workstream A has two broad questions to investigate:

-

Does timeliness of access to PIC impact on the outcomes of critically ill children? (For brevity, we refer to this as the ‘time-to-bedside’ work.)

-

Does care delivered by the PCCT, including the team composition, the stabilisation approaches and the occurrence of critical incidents, impact on the outcomes of critically ill children? (For brevity, we refer to this as the ‘models of care’ work.)

Methods

Children aged < 16 years who were admitted for PIC in England and Wales were included in this workstream. More detail about the cohort will be provided in Chapter 3, DEPICT study cohort. No data collection or study recruitment was undertaken as part of workstream A, as we made use of routinely available data that are collected by organisations that have permission to collect information about care received in health-care settings without explicit patient consent. We applied for Research Ethics Committee (reference 17/LO/1267) and Confidentiality Advisory Group (reference CAG0129) approvals to allow us to link together these data sources. In addition, we obtained permission from the appropriate organisations for use of their data [e.g. Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) for PICANet and NHS Digital for HES/ONS].

The data set for workstream A is formed from linking the following data sets.

PICANet collects information about the referral, transport and admission to PICU of all critically ill children in the UK and Ireland (note that we only used data from England and Wales). Data relating to the child’s demographics (e.g. age, sex), their clinical condition [e.g. Paediatric Index Mortality 2 (PIM2) score, diagnoses], events that occur during their transport to PICU (e.g. vehicle accidents) and the clinical interventions and support they receive (e.g. ventilator support) are captured. Data were required to be entered into the PICANet data system within 3 months of the event occurring. Information about the data extracted from PICANet can be found in Appendix 3.

The Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC) collects information about all admissions to general adult intensive care units. Similar to PICANet, information is collected about patients’ demographics and the care they receive. We extracted information about children (aged < 16 years) receiving care in general adult intensive care units who were subsequently transported to a PICU.

The ONS collects information from death certificates, including date and cause of death.

The Patient Episode Database for Wales (PEDW) and HES collects information about care, treatment and interventions received in hospital settings [i.e. wards and emergency departments (EDs)].

Data linkage

There were two separate data linkages in workstream A. First, linking of the PICANet referral, transport and admissions data sets. This linkage was undertaken by Sarah Seaton, with support from the PICANet team at the University of Leeds (Leeds, UK). Second, linking of the PICANet, ICNARC, HES and ONS mortality data. The linkage of all data sets was undertaken by NHS Digital under direction from Sarah Seaton and the DEPICT team.

PICANet linkage

The data related to a child’s referral, transport and subsequent admission to PIC are stored in three separate databases:

-

Referral data contains limited information relating to the hospital and clinical team requesting the transport. Referral data include information about whether or not the child was being ventilated at the time of referral.

-

Transport data contains information on the child’s transport, including demographic information about the child, all times associated with the transport, medical interventions received by the child and critical incidents that occurred during the transport.

-

Admission data contains information on the child’s admission to PICU, including demographic information, diagnoses and care they received during their time in PICU.

Copies of data collection forms used by PICANet can be found at www.picanet.org.uk/data-collection/ (accessed 21 June 2022).

All data sets contain personally identifiable data (e.g. name, date of birth, NHS number), but there is no in-built linkage between the data sets. Personally identifiable data can vary between data sources even when related to the same child. This variance can be accidental (e.g. typographical errors, such as spelling a name multiple ways) or can be due to updating of data (e.g. a transport of a child named ‘baby girl’ who on admission to PICU had been given a name by the family).

The PICANet system uses an algorithm to allocate individual children a unique pseudo-anonymised patient identifier (ID). The system identifies children who have been admitted previously (e.g. by looking for the same NHS number and other identifiable characteristics) and then allocates the same patient ID. Some children have multiple transport and admission events over a period of time.

The patient ID algorithm uses a probabilistic matching approach to consider several unique identifiers (e.g. NHS number, date of birth) for each child, before assigning the patient ID. Therefore, theoretically, the same child should be allocated the same patient ID for all their transport and admission events, although it is possible for one child to be allocated two different patient IDs if differing identifiable data are available for each record. In our linkage we, therefore, used a combination of both the patient ID and the original personally identifiable data.

Linkage was undertaken by the PICANet team at the University of Leeds, which has permission to hold the personally identifiable data. To facilitate the linkage, Sarah Seaton was provided with an honorary research fellow position at the University of Leeds.

Attempts to link between the transport and admissions data sets followed a hierarchy (if matched via any approach, then no further match attempts were made). There are four initial ‘rounds’ or ‘steps’:

-

The same patient ID in both data sets (i.e. transport and admissions data sets). The admissions data set to indicate that the child was a retrieval/transfer. The destination/admission PICU to match (i.e. transport and admissions data sets). The date and time of arrival at unit (i.e. transport data set) and admission (i.e. admissions data set) to match within ± 1 hour.

-

The same patient ID in both data sets (i.e. transport and admissions data sets). No indication from the admissions data set that the child was a retrieval/transfer. The destination/admission PICU to match (i.e. transport and admissions data sets). The date and time of arrival at unit (i.e. transport data set) and admission (i.e. admissions data set) to match within ± 1 hour.

-

The same NHS number, family name (and alternative family name) and date of birth in both data sets (.e. transport and admissions data sets). The admissions data set to indicate that the child was a retrieval/transfer. The destination/admission PICU to match (i.e. transport and admissions data sets). The date and time of arrival at unit (i.e. transport data set) and admission (i.e. admissions data set) to match within ± 1 hour.

-

The same NHS number, family name and date of birth in both data sets (i.e. transport and admissions data sets). No indication from the admissions data set that the child was a retrieval/transfer. The destination/admission PICU to match (i.e. transport and admissions data sets). The date and time of arrival at unit (i.e. transport data set) and admission (i.e. admissions data set) to match within ± 1 hour.

Following these initial four rounds, further rounds were repeated with increasing levels of flexibility in the matching of the difference in time between the date and time of arrival (i.e. transport data set) and admission (i.e. admissions data set):

-

In rounds 5–8 repeat steps 1–4, but relax the time difference to ± 2 hours.

-

In rounds 9–12 repeat steps 1–4, but relax the time difference to ± 6 hours.

-

In rounds 13–16 repeat steps 1–4, but relax the time difference to ± 12 hours (this is to account for errors in use of the 24-hour clock).

-

In rounds 17–20 repeat steps 1–4, but relax the time difference to ± 24 hours (this is to account for errors in the recording of the date).

We also undertook a manual review of the remaining unlinked data to ‘force’ a match if it was apparent that there was another reason that the records had not linked. In reality, ≈ 92% of all successful matches were obtained in step 1. Subsequent steps (i.e. steps 2–4) added minimal records, but provided assurance we had been as thorough as possible.

We tried and abandoned two additional approaches, which we document here for future researchers:

-

We attempted a match with no time restriction placed on it (i.e. any admission event at any date or time could match with a transport event of the same child from any date or time). Theoretically, we could link events that were several years apart in time. However, this provided only a small number of additional matches and hugely compromised data quality.

-

To ensure that we captured instances of the same child where the patient ID may have failed to allocate the same patient ID, we also investigated a match with same family name, postcode and date of birth. Although this identified a small number of additional matches (which we reviewed manually), this more often falsely identified sets of twins as if they were the same child. Care should be taken when using this approach.

Beginning with the transport data (as all children needed to have a transport record to be in our study), our match rate success between transport and admission data sets was ≈ 97%. We followed a similar process for matching the transport data with the referrals data set and achieved a match rate success of ≈ 96%.

The entire PICANet linkage took approximately 3 months of work to develop, check and implement. We have provided the detail here in the hope that this helps future researchers working to link this and other similar data sets.

NHS Digital linkage

NHS Digital was sent personally identifiable information about the unplanned (emergency) admissions of children aged < 16 years from PICANet and ICNARC. NHS Digital compared the data sets and informed us of any matches (using NHS number and other personally identifiable data) between the data sources and added in information related to hospital care (HES), ED attendances (HES) and mortality (ONS). The data flow for NHS Digital can be found in Appendix 2. We followed a similar approach with the data from NHS Wales (PEDW).

We faced significant delays with the NHS Digital data, beginning the process in spring 2018, submitting for review with NHS Digital in summer 2018, receiving approval in October 2018 and receiving the first download of data in late 2018. These data were re-supplied in February 2019 because of issues during the ICNARC data upload process. We were required to design and undertake a data destruction process approved by both NHS Digital and the University of Leicester.

However, on receipt of the revised data, it was clear that there were issues with data completeness and after detailed investigation during summer 2019 it became clear that we had not received the hospital data of children aged < 1 year (a large portion of our cohort) due to an oversight by NHS Digital. We contacted NHS Digital and the issue was confirmed. We were in the process of amending and updating our data-sharing agreement and so the corrected data were supplied in November 2019.

Despite these delays, we continued the aspects of workstream A that relied on the PICANet data and linked mortality data (unaffected by the outlined issues), and we have been able to produce two papers with only one outcome omitted,15,16 which we would have ideally included (i.e. re-admission to hospital within 1 year of discharge from PICU). In mid-2019, we had begun analysis of the HES data in collaboration with our colleagues from workstream C (health economics), which led to the identification of the issue with the unsupplied data. However, in November 2019, on receipt of the revised data, we had only limited time to begin analysis before the nationwide lockdown in early 2020 prevented continued work. A VPN at the University of Leicester allows substantively employed staff with the correct equipment to continue work on research projects while maintaining required data security, and we were able to continue the main analysis via this route. However, the HES data set was too large to access in this way because of the speed of personal home WiFi and so work related to this will be completed when we can physically access our offices again (after September 2021). Workstream C colleagues were unable to access the University of Leicester VPN, but support was provided from their colleagues working on workstream A.

DEPICT study cohort

Children were eligible for inclusion in the DEPICT study if they were aged < 16 years and transported as an emergency (non-elective) to an NHS PICU between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2016. Children were included if their PICANet transport record linked to a corresponding PICU admission. Children with missing referral data were excluded. If a child was transported multiple times during the DEPICT study, then we included their final transport only. Specific exclusions were applied for missing data for each specific aspect of the research.

Time-to-bedside methods

Inclusion and exclusion

Children were included as outlined in DEPICT study cohort, that is, they were transported to an NHS PICU in England and Wales in 2014–16 as a result of an emergency (non-elective) situation. Children were excluded if there was missing information about ventilation status at referral or if it was not possible to calculate time to bedside. Time to bedside is the difference between the time it was agreed that the child required transport to PICU and the time when the team arrived at the child’s bedside. For the secondary outcomes of LOS and length of invasive ventilation (LOV), additional exclusions were made if there were missing data.

Time to bedside statistical methods

Summary statistics were reported as counts/percentages for categorical variables or median/range or mean/standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. To investigate the impact of time to bedside on 30-day mortality, logistic regression models with clustered standard errors for the PCCT were fitted. Key confounders were selected a priori via discussion with the clinical members of the Study Management Group and were age of the child, PIM2 score,17 clinical diagnosis (based on PICANet diagnostic groups), ventilation status at referral (yes/no not indicated/no advised to intubate), number of transport requests from the collection hospital during the study (categorised as < 50 requests, 50–99 requests or ≥ 100 requests) and whether or not the child was receiving critical care around the time of the transport request (collected from intensive care or receiving care in a general intensive care unit in the 2 days preceding transport, yes/no).

Variables were included regardless of any statistically significant association with mortality (as the DEPICT team had made the decision not to focus on statistical significance in workstream A). Time to bedside was categorised as ≤ 60 minutes, 61–90 minutes, 91–120 minutes, 121–180 minutes and ≥ 181 minutes. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated alongside the (adjusted) probability of mortality by time to bedside. Logistic models were also fitted with secondary mortality end points of death on PICU, death within 2 days, death within 90 days and death within 1 year following PICU admission.

Clinical subgroups of children were selected a priori for investigation with regard to mortality, including children admitted with cardiac/neurological conditions, children with a low/high PIM2 score (low: PIM2 ≤ 0.10; high: PIM2 > 0.10) and children transported to PICU in summer/winter (summer: June/July/August; winter: December/January/February).

The outcomes of LOS and LOV were highly skewed (most children had a short LOS/LOV) and, therefore, negative binomial models were used with the same adjustments as the primary analysis. The expected (adjusted) LOS and LOV were estimated and presented graphically by time to bedside.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were performed on our primary analysis investigating the outcome of mortality analyses. First, we assessed the impact of using categorical variables to model age and the PIM2 score by re-fitting our analyses using fractional polynomials. Fractional polynomials allow more flexible parameterisations of continuous variables, compared with including them as linear terms,21 and are sometimes favoured over categorisation like that used here, which, although simpler to interpret, can lead to a loss of data/power. 22

Second, we investigated the impact of using the final transport for children transported multiple times by repeating the analysis using their first transport in the DEPICT study time window. Finally, the impact of missing data was investigated by re-fitting the model with different scenarios for these.

Models of care methods

Inclusion and exclusion

Children were excluded if there was missing information about ventilation status at referral or if they had missing or implausible time data (defined as > 24 hours) for the time to bedside, time spent at the bedside or the total time taken to reach the PICU. In the analysis of team composition, children were excluded if they had missing data about the team leader of the transport. In the analysis of secondary health-care outcomes, children were excluded if they had missing data for LOS or LOV.

Models of care statistical methods

Summary statistics were reported as counts/percentage for categorical variables and median/range for continuous variables. Adjustments were selected a priori and included time to reach the bedside, age of the child, PIM2 score, clinical diagnosis, ventilation status at the time of referral and whether or not the child was receiving critical care around the time of the transport request.

Team leader

Transports are led by the most senior member of staff, who can be:

-

a junior doctor

-

an ANP

-

a consultant.

We undertook the following three comparisons regarding the team leader using logistic regression models with mortality as the outcome: (1) consultant compared with not a consultant, (2) junior doctor compared with ANP and (3) comparison of all three options. We also considered LOS and LOV using negative binomial models.

Prolonged stabilisation by the paediatric critical care transport team compared with short stabilisation

We investigated key clinical interventions provided to the child, including the provision of intubation and re-intubation (i.e. airway procedures); central venous access, arterial access and intraosseous access (i.e. vascular access procedures); and initiation of vasoactive infusions. Clinical interventions were provided either by the referring hospital prior to the arrival of the PCCT or when the PCCT was in attendance.

We compared the scenario where the PCCT spent substantial time preparing the child for transport (i.e. prolonged stabilisation, defined as two or more interventions provided while the PCCT were in attendance) compared with short stabilisation (i.e. two or fewer interventions provided by the PCCT). For outcomes relating to mortality, we used logistic regression models. For LOS and LOV, we used negative binomial models.

Number and types of interventions

We investigated the impact of the total number of interventions received by the child (from the referring hospital and while the PCCT were in attendance) and the percentage of interventions that were provided while the PCCT was present. We investigated mortality using logistic regression and considered the impact of interventions on our secondary outcomes of LOS and LOV via use of negative binomial models.

Critical incidents

We investigated instances of critical incidents involving the child, vehicle or an equipment failure that occurred during the transport and affected the child’s care, including whether or not these incidents affected the adjusted odds of mortality. Critical incidents involving the child were accidental extubation, required intubation in transit, complete ventilator failure, loss of medical gas supply, loss of all intravenous access, cardiac arrest and medication administration error. Vehicle incidents included accidents and breakdown. We fitted logistic models to adjust for characteristics of the child for each type of incident and investigated the odds of mortality within 30 days of admission to PICU.

Model fit

Model performance for our mortality analyses was assessed using the AUC, Hosmer–Lemeshow test and Brier score.

Reporting conventions

Emphasis is on the clinical importance of the observed trends, associations or differences. p-values and statistical significance are not reported in line with the DEPICT study protocol. 23 CIs are reported throughout.

Findings

DEPICT study cohort

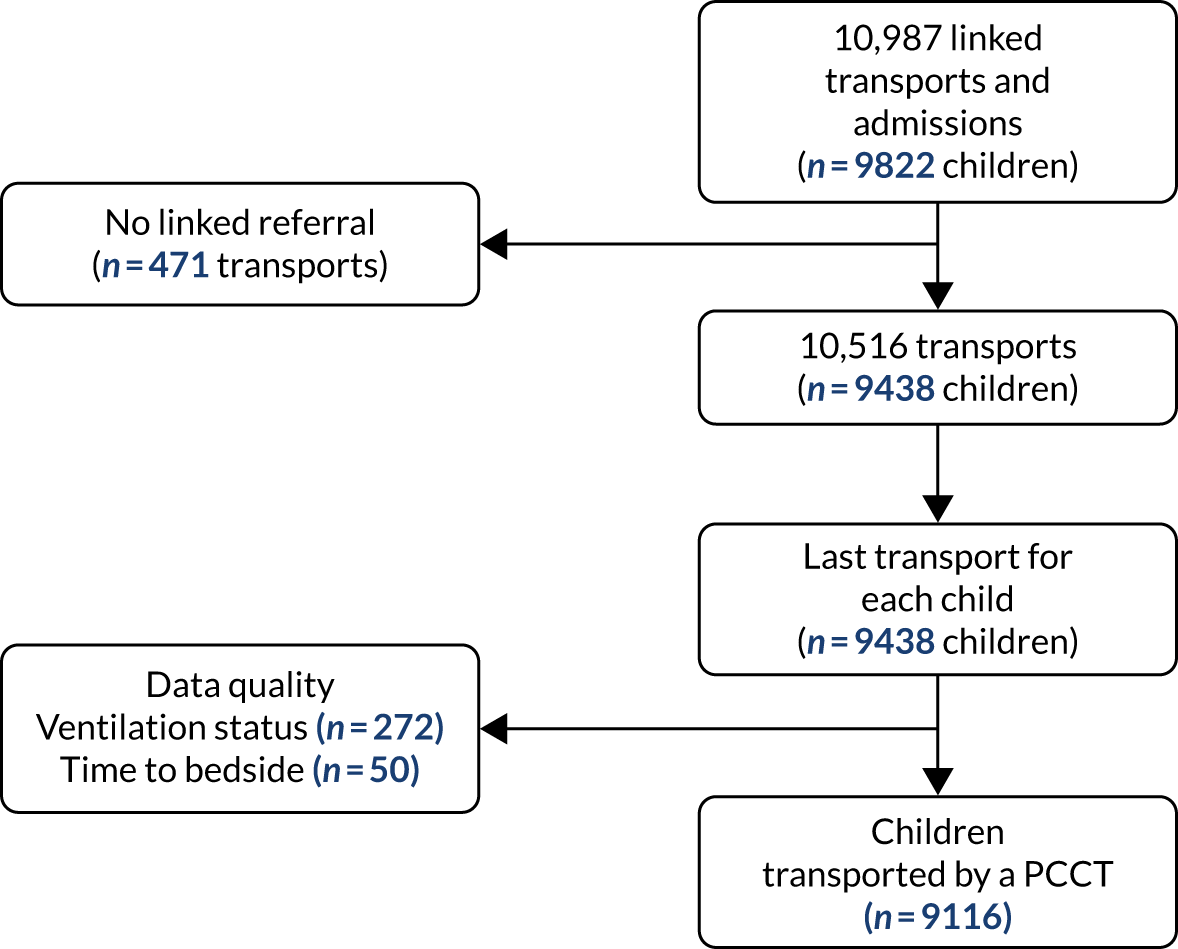

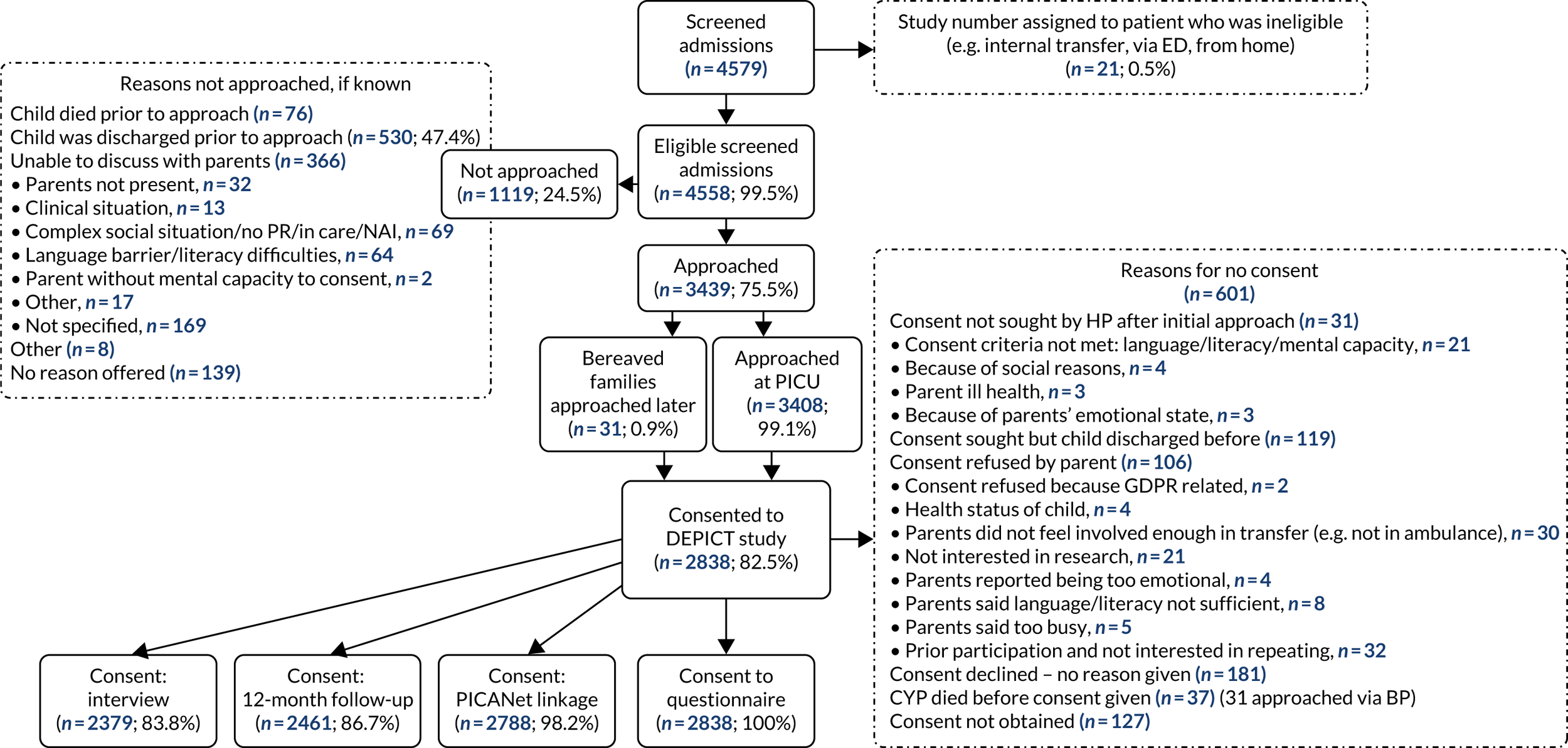

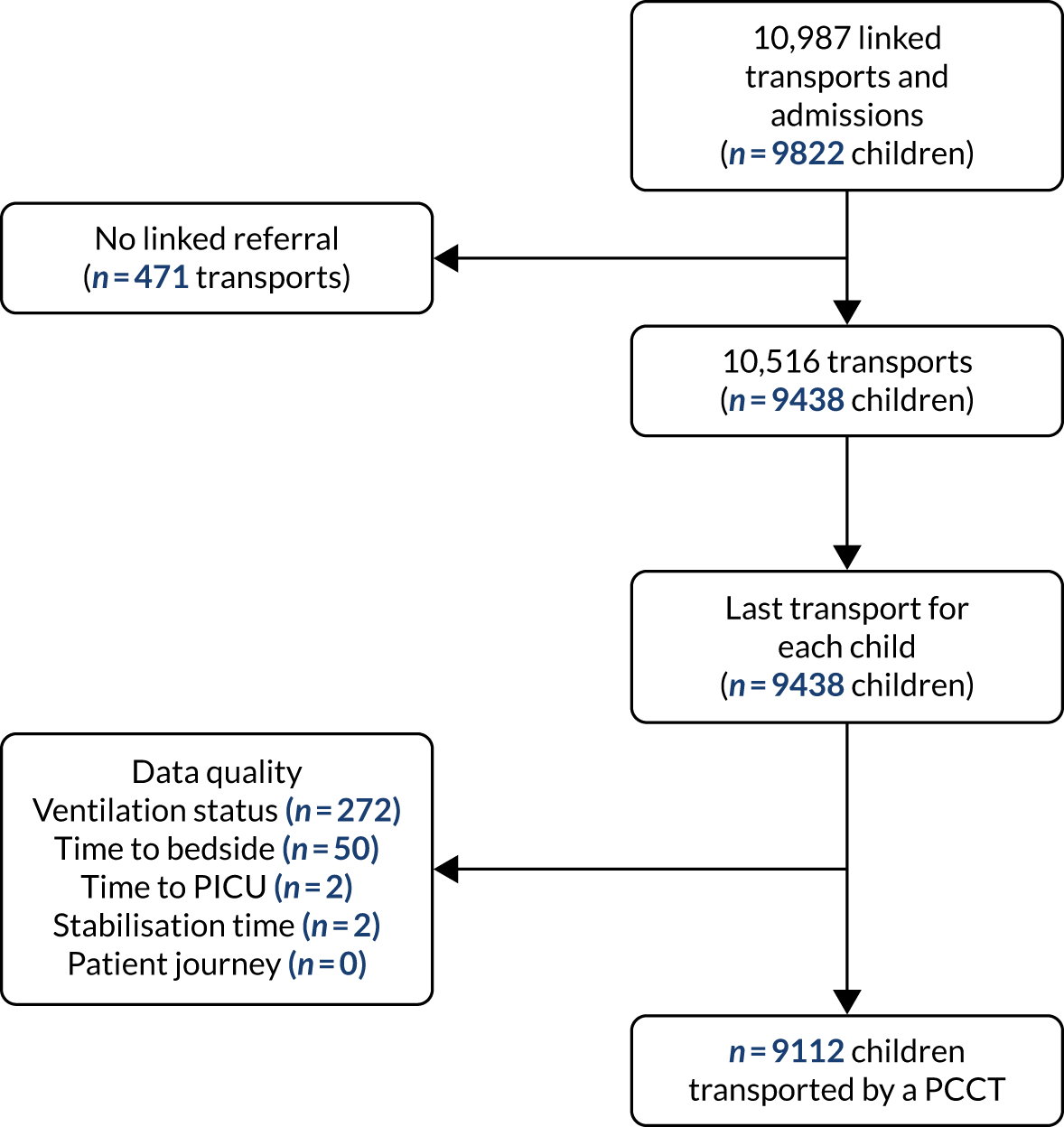

There were 10,987 emergency transports by a PCCT of children aged < 16 years with a linked admission record to a PICU during the study. Transports not linked with a corresponding referral event were excluded (n = 471, 4.3%), leaving 10,516 transports (Figure 3). For children with multiple transports, we used the latest transport, providing 9438 transported children. Additional exclusions were made for missing data in each section of our work, as outlined in the flow chart (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Time to bedside flow chart. Reproduced from Seaton et al. 16 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Time-to-bedside results

Inclusion and exclusion

Additional exclusions were made for children whose ventilation status at the time of referral was missing (n = 272) and children with missing or implausible data (defined as > 24 hours) for the time to bedside (n = 50), leaving 9116 children in the primary analysis (see Figure 3). Summary statistics for the included children can be found in Table 1. Approximately half of the children were aged < 1 year at the time of transport, and the most common reason for admission was respiratory problems. The median LOS in the PICU was 5 (mean 7.5) days.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 9116) | Arrived at the bedside in ≤ 60 minutes (N = 2654) | Arrived at the bedside in 61–180 minutes (N = 5271) | Arrived at the bedside in ≥ 181 minutes (N = 1191) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), n (%) | ||||

| < 1 | 4669 (51.2) | 1371 (51.7) | 2685 (50.9) | 613 (51.5) |

| 1 to < 5 | 2438 (26.7) | 682 (25.7) | 1437 (27.3) | 319 (26.8) |

| 5 to < 11 | 1174 (12.9) | 344 (13.0) | 679 (12.9) | 151 (12.7) |

| 11 to < 16 | 835 (9.2) | 257 (9.7) | 470 (8.9) | 108 (9.1) |

| Sex of child, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 5183 (56.9) | 1552 (58.5) | 2962 (56.2) | 669 (56.2) |

| Female | 3932 (43.1) | 1102 (41.5) | 2308 (43.8) | 522 (43.8) |

| Unknown | 1 (< 0.5) | 0 | 1 (< 0.1) | 0 |

| PIM2 score (%), n (%) | ||||

| < 1 | 1039 (11.4) | 314 (11.8) | 625 (11.9) | 100 (8.4) |

| 1 to < 5 | 4089 (44.9) | 1104 (41.6) | 2409 (45.7) | 576 (48.4) |

| 5 to < 15 | 2985 (32.7) | 845 (31.8) | 1710 (32.4) | 430 (36.1) |

| 15 to < 30 | 579 (6.4) | 220 (8.3) | 305 (5.8) | 54 (4.5) |

| ≥ 30 | 424 (4.7) | 171 (6.4) | 222 (4.2) | 31 (2.6) |

| LOS in PICU (days), median (10th, 90th) | 5 (2, 14) | 5 (2, 15) | 5 (2, 14) | 5 (2, 15) |

| LOS in PICU (days), mean (SD) | 7.5 (13.2) | 7.5 (15.1) | 7.4 (11.6) | 8.2 (15.2) |

| Child received multiple transports during the time window of DEPICT, n (%) | 775 (8.5) | 206 (7.8) | 459 (8.7) | 110 (9.2) |

| Parent accompanied the child in the ambulance, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 6974 (76.5) | 2188 (82.4) | 3966 (75.2) | 820 (68.9) |

| No, parent not present | 432 (4.7) | 135 (5.1) | 237 (4.5) | 60 (5.0) |

| No, parent declined to accompany | 1150 (12.6) | 233 (8.8) | 713 (13.5) | 204 (17.1) |

| No, parent not permitted to accompany | 385 (4.2) | 41 (1.5) | 259 (4.9) | 85 (7.1) |

| Unknown | 175 (1.9) | 57 (2.2) | 96 (1.8) | 22 (1.9) |

| Collection area, n (%) | ||||

| PICU | 259 (2.8) | 88 (3.3) | 127 (2.4) | 44 (3.7) |

| GICU | 731 (8.0) | 45 (1.7) | 430 (8.2) | 256 (21.5) |

| NICU | 822 (9.0) | 332 (12.5) | 374 (7.1) | 116 (9.7) |

| Theatre/recovery and theatre | 1978 (21.7) | 392 (14.8) | 1328 (25.2) | 258 (21.7) |

| X-ray/CT/endoscopy/A&E | 2773 (30.4) | 1084 (40.8) | 1464 (27.8) | 225 (18.9) |

| Ward/HDU/other intermediate area | 2536 (27.8) | 710 (26.8) | 1539 (29.2) | 287 (24.1) |

| Other/unknown | 17 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | 9 (0.2) | 5 (0.4) |

| Diagnostic group, n (%) | ||||

| Respiratory | 4355 (47.8) | 1102 (41.5) | 2591 (49.2) | 662 (55.6) |

| Cardiovascular | 1310 (14.4) | 477 (18.0) | 681 (12.9) | 152 (12.8) |

| Endocrine | 219 (2.4) | 65 (2.5) | 133 (2.5) | 21 (1.8) |

| Haematology/oncology | 153 (1.7) | 56 (2.1) | 78 (1.5) | 19 (1.6) |

| Infection | 820 (9.0) | 261 (9.8) | 484 (9.2) | 75 (6.3) |

| Neurological | 1505 (16.5) | 403 (15.2) | 907 (17.2) | 195 (16.4) |

| Trauma and accidents | 338 (3.7) | 121 (4.6) | 184 (3.5) | 33 (2.8) |

| Other | 416 (4.6) | 169 (6.4) | 213 (4.0) | 34 (2.9) |

| Ventilated at time of referral call, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 3814 (41.8) | 1129 (42.5) | 2109 (40.0) | 576 (48.6) |

| No (not indicated) | 2886 (31.7) | 911 (34.3) | 1652 (31.1) | 323 (27.1) |

| No (advised to intubate) | 2416 (26.5) | 614 (23.1) | 1510 (28.7) | 292 (24.5) |

| Size of acute hospital (based on transport requests in the DEPICT study time window), n (%) | ||||

| Small (< 50 requests) | 2274 (25.0) | 635 (23.9) | 1308 (24.8) | 331 (27.8) |

| Medium (50 to < 100 requests) | 3802 (41.7) | 1118 (42.1) | 2129 (40.1) | 555 (46.6) |

| Large (≥ 100 requests) | 3040 (33.4) | 901 (34.0) | 1834 (34.8) | 305 (25.6) |

| Receiving care in a critical care setting at collection organisation, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 1951 (21.4) | 479 (18.1) | 1022 (19.4) | 450 (37.8) |

| No | 7165 (78.6) | 2175 (82.0) | 4249 (80.6) | 741 (62.2) |

| Mortality, n (%) | ||||

| Died within 2 days of admission | 278 (3.1) | 105 (4.0) | 153 (2.9) | 20 (1.7) |

| Died in PICU | 571 (6.3) | 200 (7.5) | 316 (6.0) | 55 (4.6) |

| Died within 30 days of admission | 645 (7.1) | 226 (8.5) | 357 (6.8) | 62 (5.2) |

| Died within 1 year of admission | 949 (10.4) | 331 (12.5) | 520 (9.9) | 98 (8.2) |

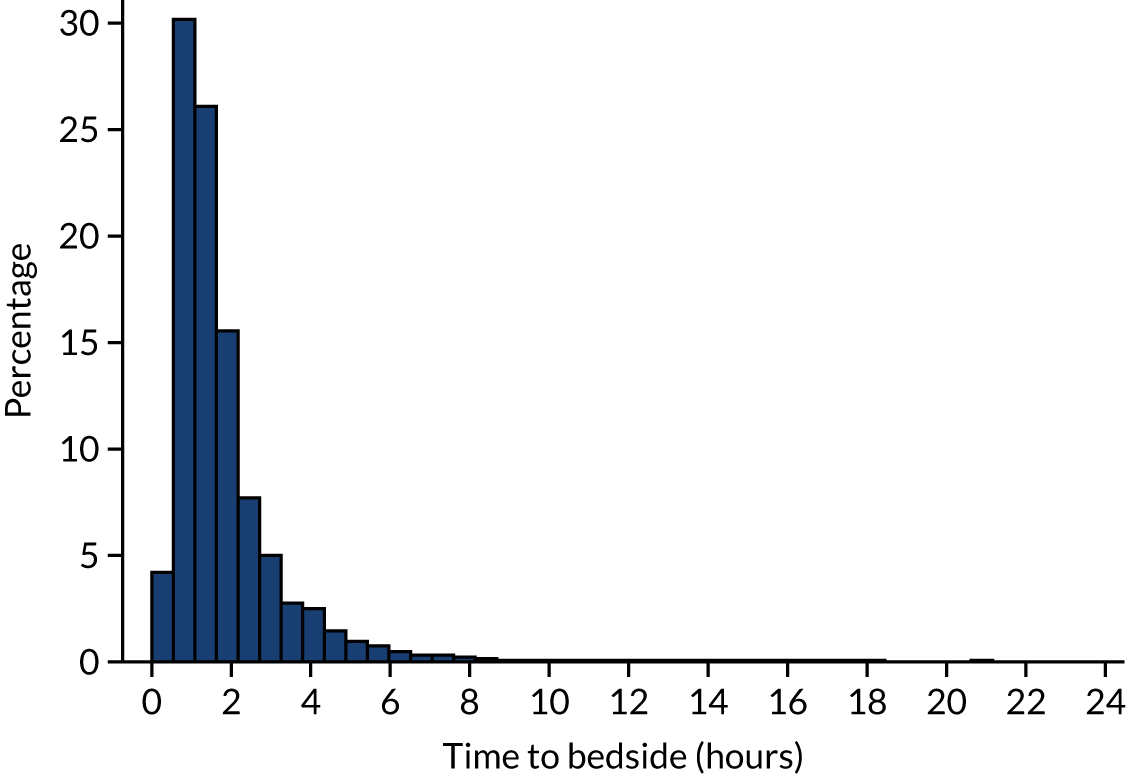

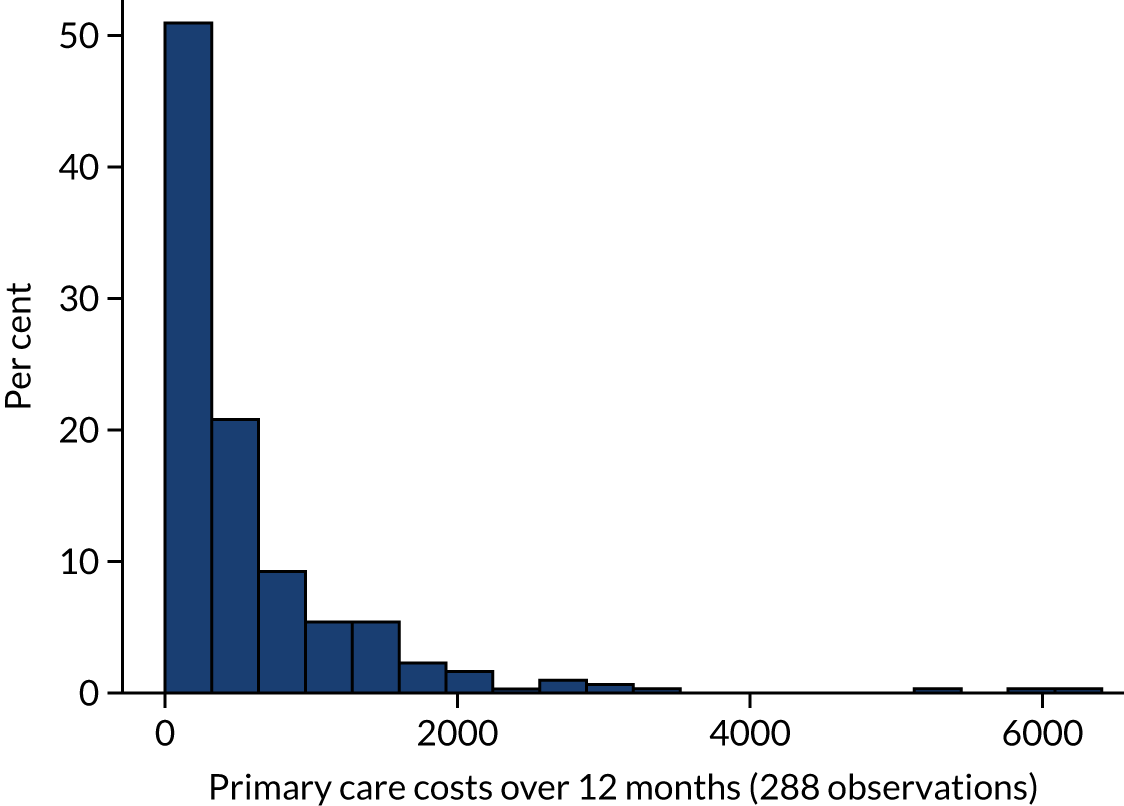

The target set by the Paediatric Intensive Care Society is to reach the bedside of the child within 3 hours of it being agreed that the child requires emergency transport to a PICU. This target can be relaxed to 4 hours when the child is being referred from a more remote location. However, further issues may prevent teams from meeting this target, for example the team being busy on other transports, poor weather and a long distance to travel to the referring hospital. Despite this, most (> 85%) of the children were met by the PCCT in < 3 hours (Figure 4) and very few children were left waiting for > 4 hours. We restricted our analysis to children whose time to bedside was < 24 hours; however, in reality, no child waited longer than ≈ 21 hours for a PCCT to arrive at their bedside.

FIGURE 4.

Histogram of time taken to reach the bedside of the child by the PCCT. Reproduced from Seaton et al. 16 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Time to bedside: mortality

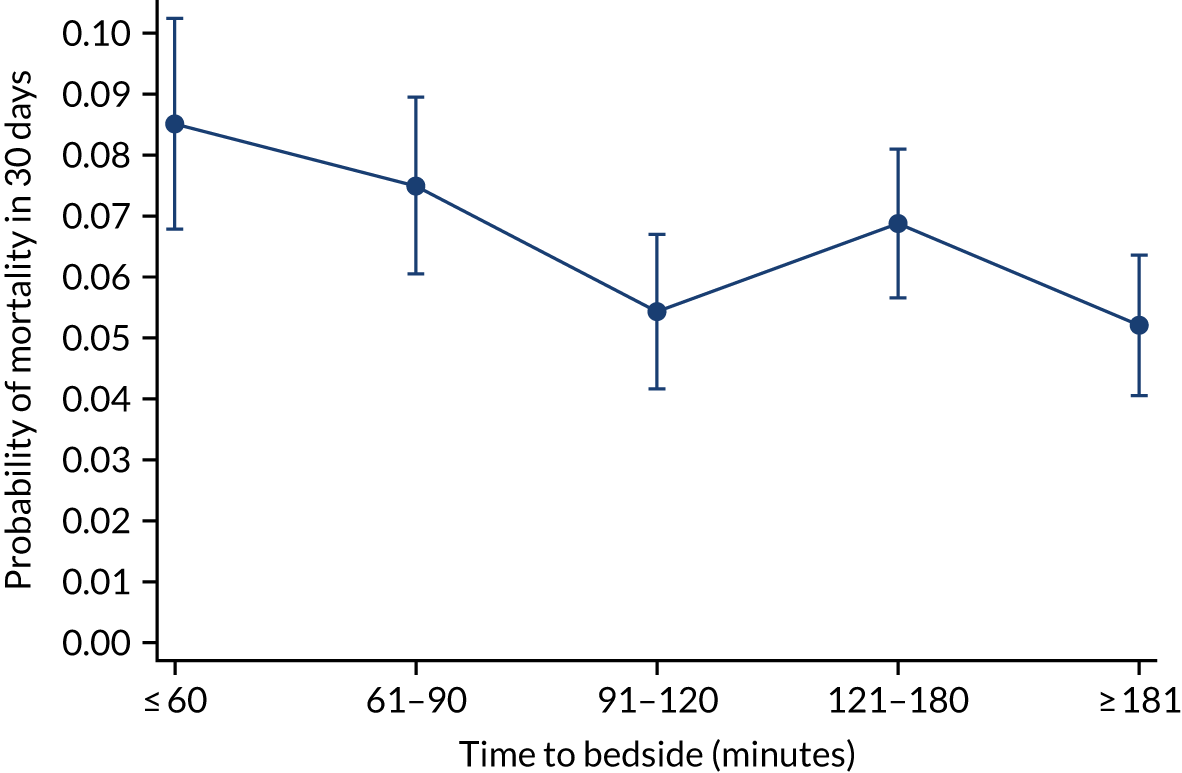

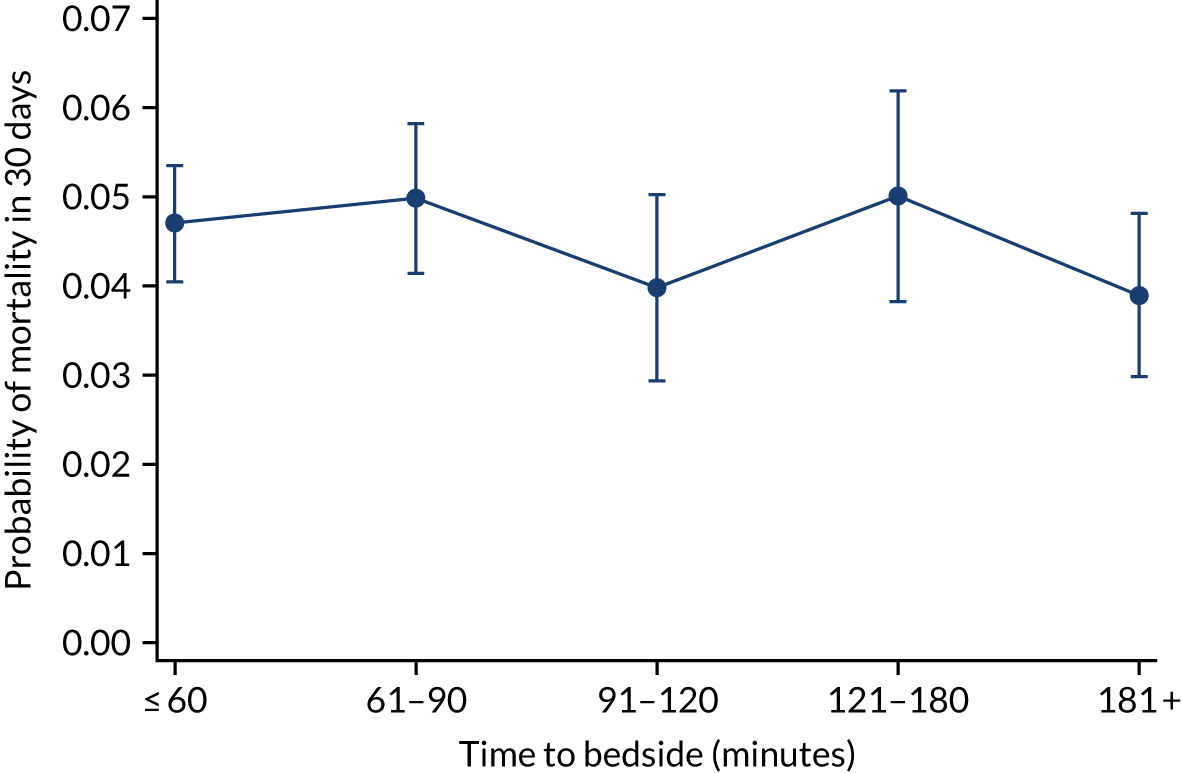

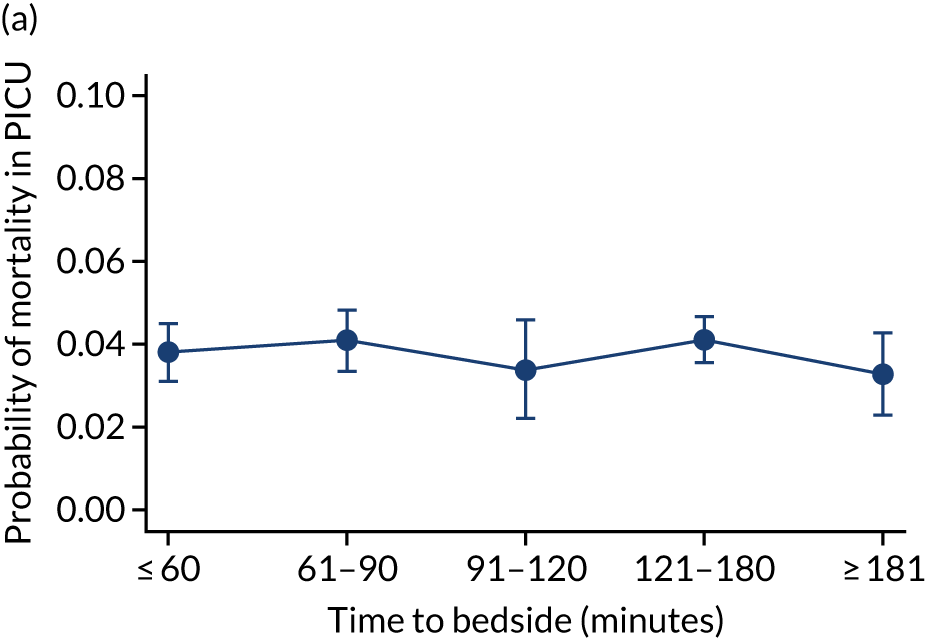

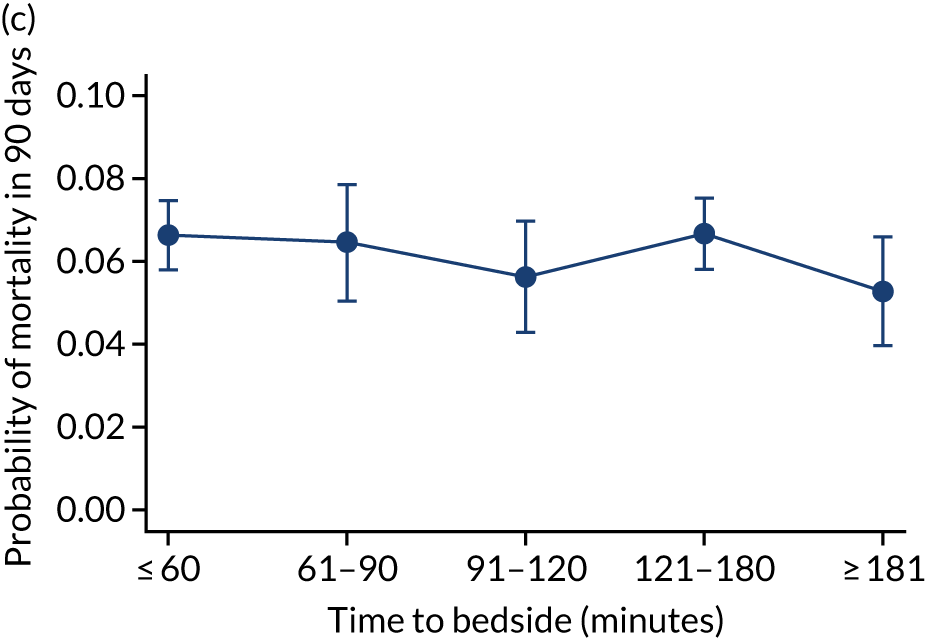

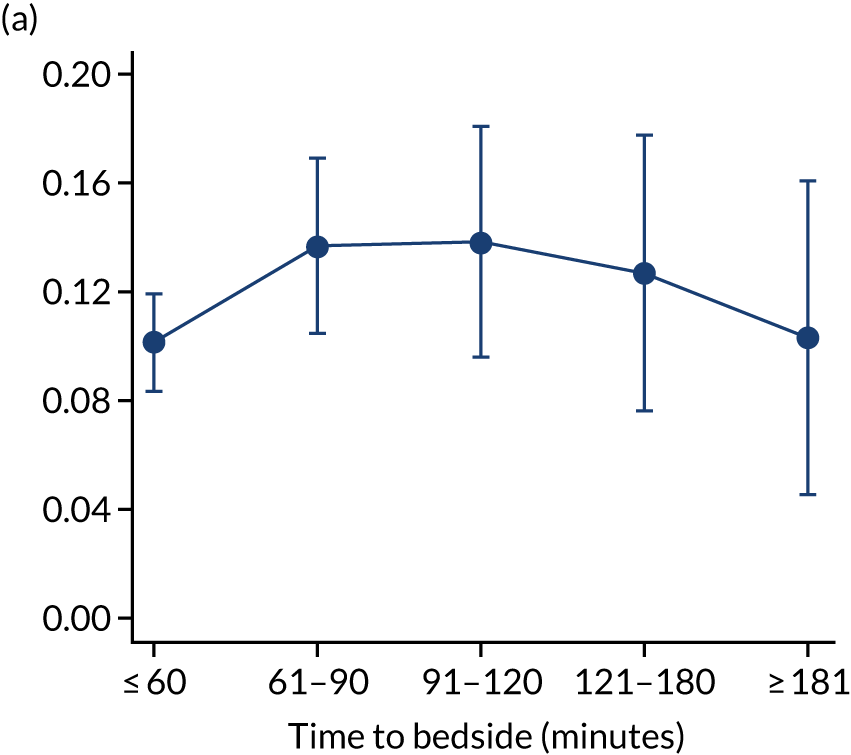

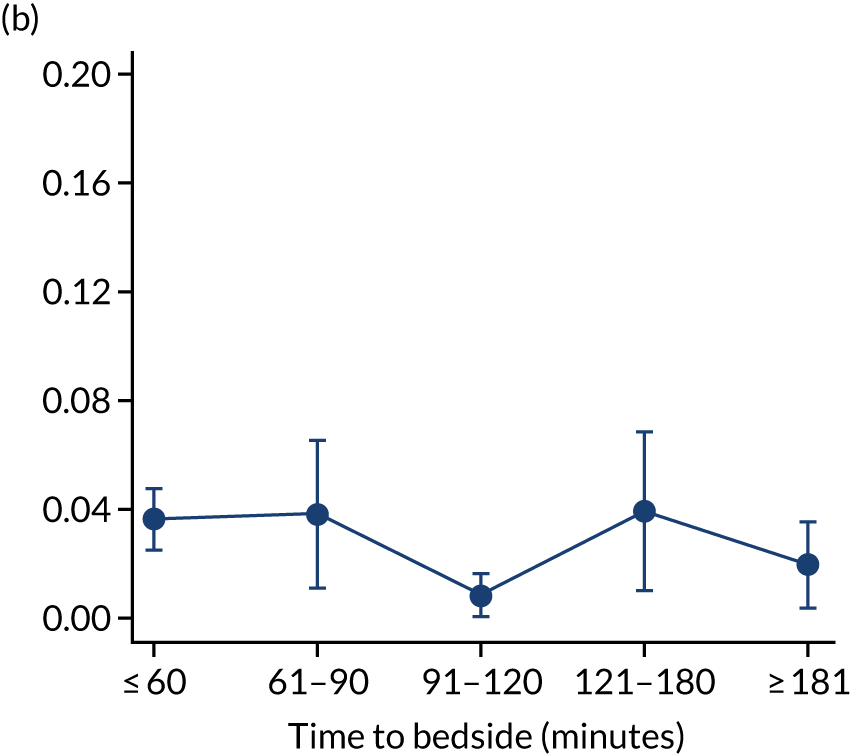

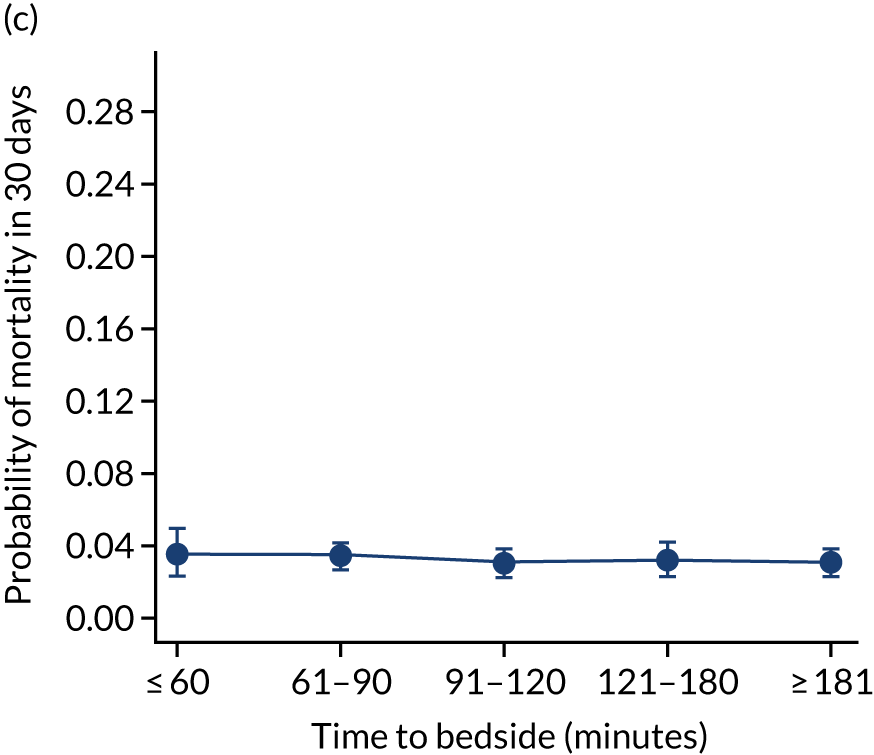

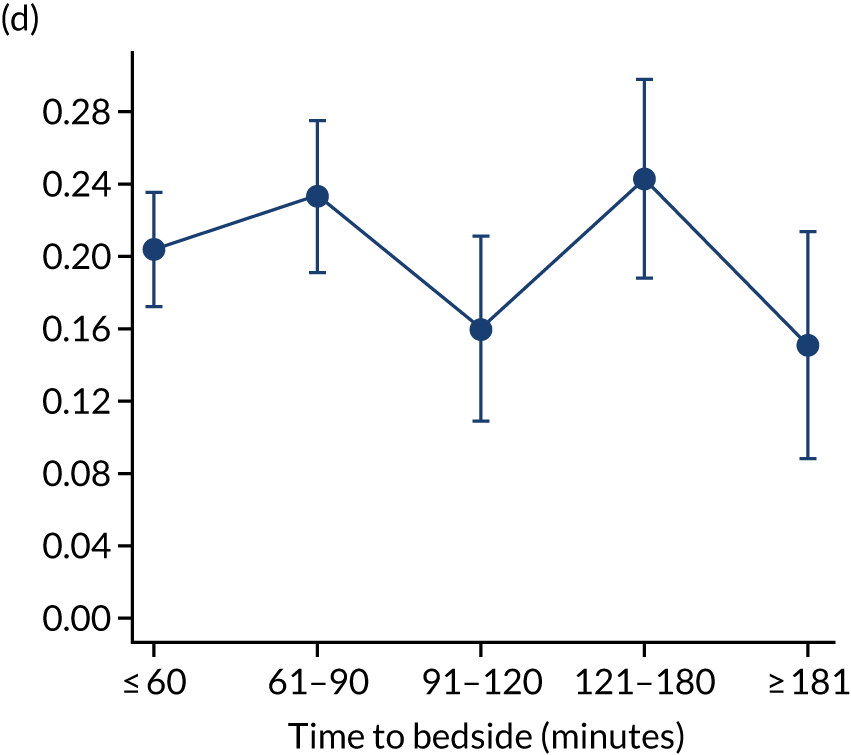

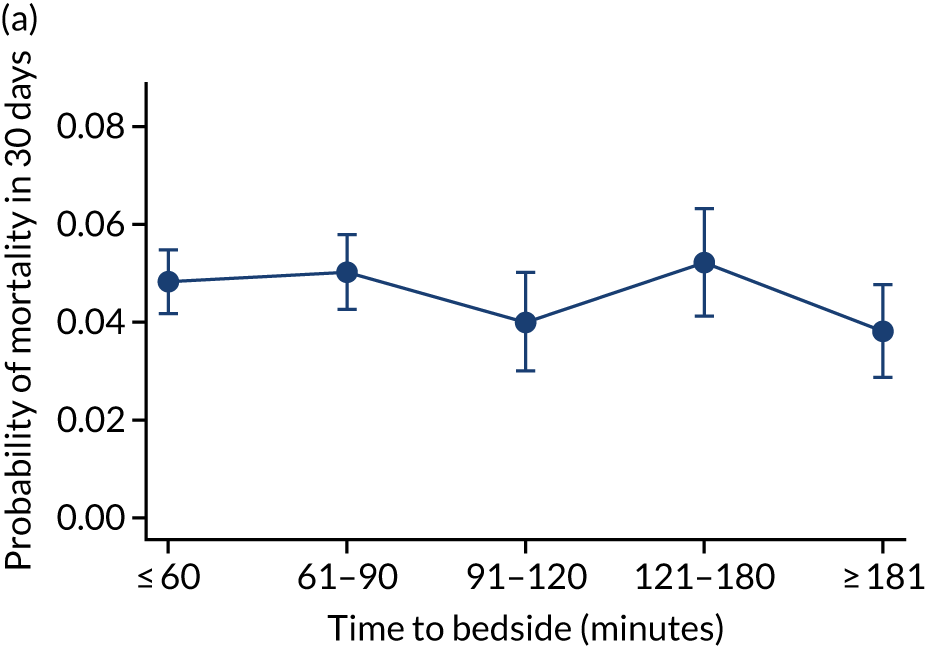

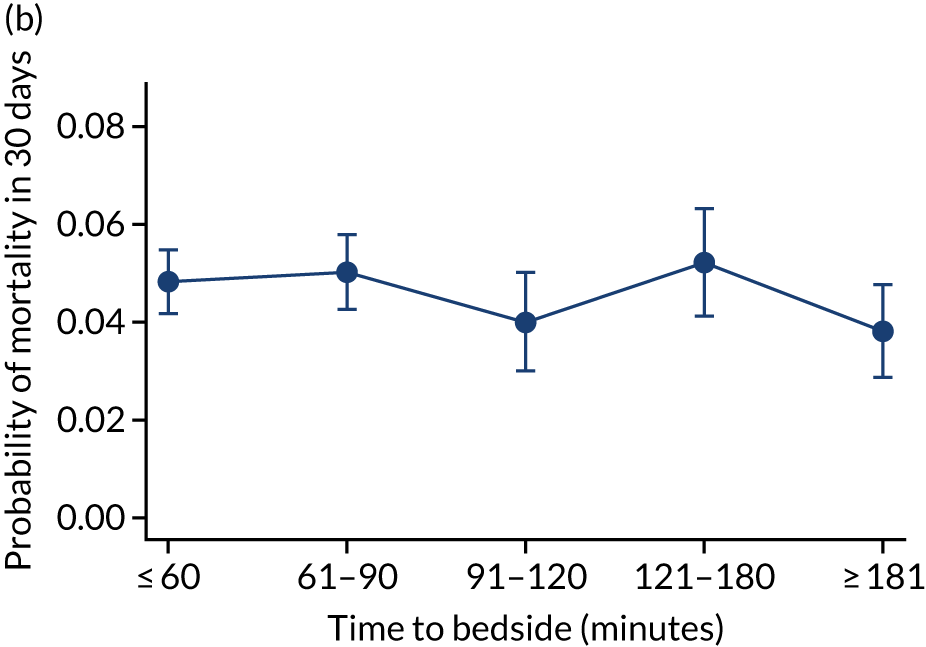

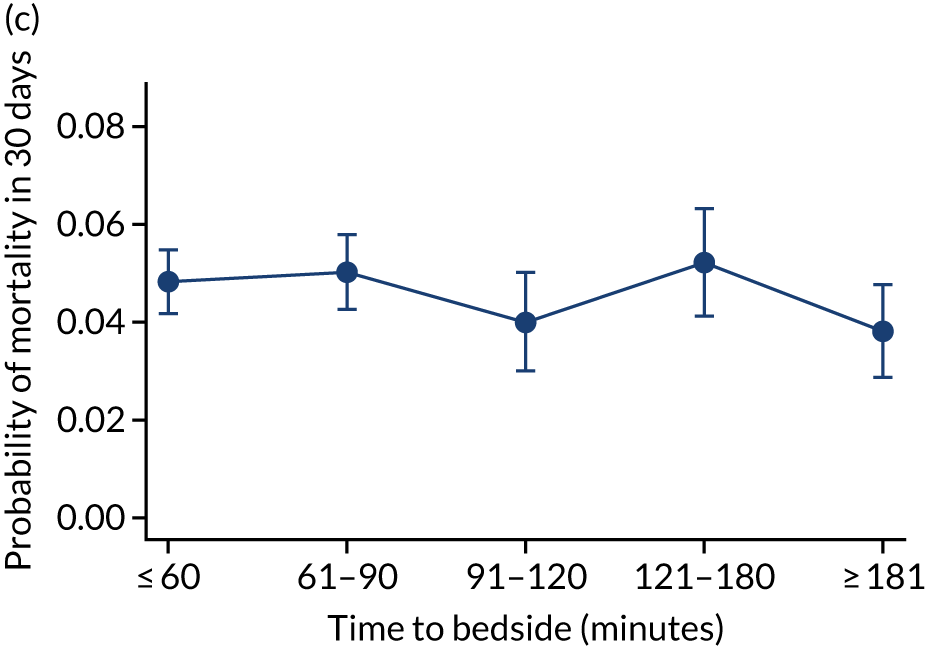

We investigated the impact of time to bedside on our primary outcome of mortality within 30 days of admission to PICU. Before adjustment, as time to bedside increased the probability of mortality 30 days after admission to PICU decreased (Figure 5) and this is likely to reflect that the children who are most critically ill, and have the highest probability of mortality, are not left waiting long periods of time for a PCCT to arrive. We fitted a logistic regression model that adjusted for age of the child, PIM2 score, diagnosis, receiving critical care, size of collection unit and whether or not the child was being ventilated at the time of the referral for PICU. We used clustered standard errors for the transport teams. After adjustment, there was no association between time to bedside and mortality within 30 days of admission to PICU (Table 2 and Figure 6). Similar relationships were seen for our alternative mortality end points of died during admission to the PICU, died within 2 days of admission, died within 90 days of admission and died within 1 year of admission (Figure 7).

FIGURE 5.

Unadjusted probability of mortality within 30 days of admission to PICU by time to bedside.

| Characteristic | Mortality in 30 days | |

|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | |

| Time (minutes) to arrive at bedside | ||

| ≤ 60 | Baseline | Baseline |

| 61–90 | 1.06 | 0.87 to 1.31 |

| 91–120 | 0.84 | 0.66 to 1.08 |

| 121–180 | 1.07 | 0.91 to 1.26 |

| ≥ 181 | 0.82 | 0.66 to 1.02 |

| Age (years) | ||

| < 1 | Baseline | Baseline |

| 1 to < 5 | 0.96 | 0.79 to 1.16 |

| 5 to < 11 | 1.40 | 1.11 to 1.77 |

| 11 to < 16 | 1.24 | 0.94 to 1.64 |

| PIM2 (%) | ||

| < 1 | Baseline | Baseline |

| 1 to < 5 | 2.22 | 1.17 to 4.23 |

| 5 to < 15 | 3.61 | 1.98 to 6.60 |

| 15 to < 30 | 11.31 | 5.77 to 22.19 |

| ≥ 30 | 34.47 | 18.22 to 65.20 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Respiratory | Baseline | Baseline |

| Cardiovascular | 2.41 | 1.62 to 3.57 |

| Endocrine | 2.73 | 1.85 to 4.05 |

| Haematology/oncology | 2.59 | 1.26 to 5.33 |

| Infection | 1.73 | 1.22 to 2.47 |

| Neurological | 1.28 | 0.76 to 2.16 |

| Trauma and accidents | 1.31 | 0.94 to 1.83 |

| Other | 1.81 | 0.96 to 3.44 |

| Ventilated at referral | ||

| No (not indicated) | Baseline | Baseline |

| Yes | 1.37 | 1.19 to 1.57 |

| No (advised to intubate) | 0.94 | 0.79 to 1.12 |

| Collection unit size | ||

| Small | Baseline | Baseline |

| Medium | 1.12 | 1.01 to 1.24 |

| Large | 1.04 | 0.88 to 1.23 |

| Receiving critical care | ||

| No | Baseline | Baseline |

| Yes | 1.06 | 0.90 to 1.25 |

FIGURE 6.

Adjusted probability of mortality within 30 days of PICU admission by time taken to reach the bedside while holding other variables in the model at the mean value. Reproduced from Seaton et al. 16 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

FIGURE 7.

Adjusted probability of mortality (a) in the PICU; (b) in 2 days; (c) in 90 days; and (d) within 1 year of admission against time taken to reach the bedside while holding other variables in the model at the mean value. Reproduced from Seaton et al. 16 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Subgroup analyses

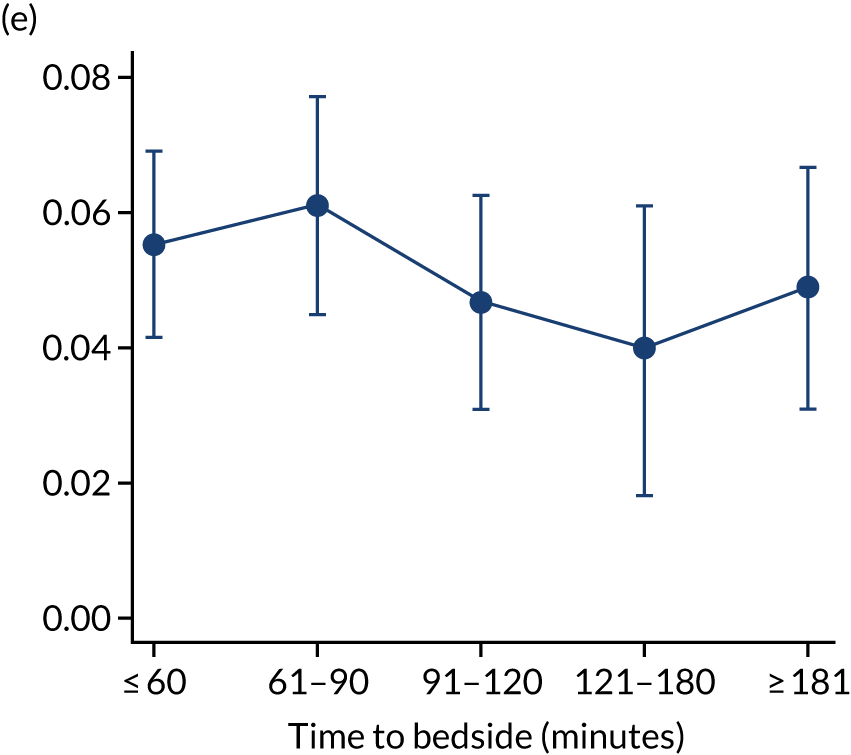

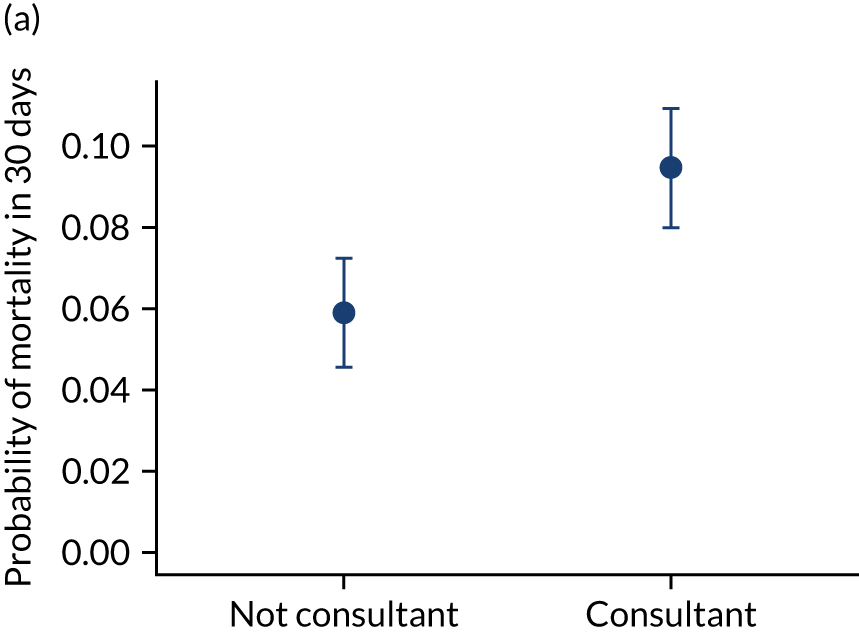

We made a priori decisions about clinically important subgroups to investigate further to see if the impact of time to bedside differed within them. The clinical subgroups selected were children admitted with cardiac/neurological conditions, children with a low/high PIM2 score (low: PIM2 ≤ 0.10; high: PIM2 > 0.10) and children transported to PICU in summer/winter (summer: June/July/August; winter: December/January/February). The analysis was fitted to each of these subgroups rather than via use of statistical interactions, and, therefore, our sample size was much reduced in our subgroup analyses, evidenced by the wider CIs and indicated in Figure 8. However, in each of our subgroups, we saw a similar lack of association between time to bedside and mortality within 30 days of admission to PICU (see Figure 8) and this suggests that the time taken by the PCCT to arrive at the bedside of the child is not associated with mortality for any of our subgroups.

FIGURE 8.

Clinically important subgroups and time taken to reach the bedside on mortality within 30 days of admission to PICU. Other adjustments are as in the primary analysis and those variables are held at the average value. (a) Children admitted with cardiac conditions (n = 1310); (b) children admitted with neurological conditions (n = 1505); (c) children with a low PIM2 score (n = 7511); (d) children with a high PIM2 score (n = 1605); (e) children transported to PICU in summer (n = 1777); and (f) children transported to PICU in winter (n = 2814). Reproduced from Seaton et al. 16 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

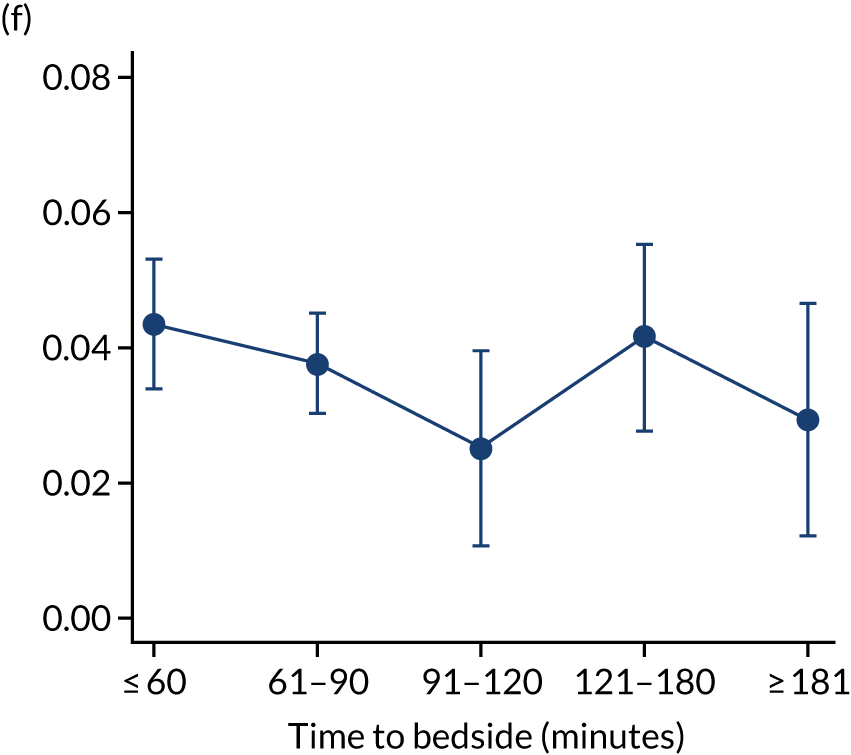

Length of stay/length of invasive ventilation

In addition to investigating the impact of time to bedside on mortality, we considered other important health-care resource outcomes, including LOS and LOV on PICU. For this analysis, we excluded children with missing data relating to LOS (n = 0) or LOV (n = 1).

We fitted negative binomial models for each outcome. After adjustment, as time to bedside increased the LOS increased slightly from 7.17 days to 7.58 days (Figure 9) and this suggested a small association between time to bedside and the child’s LOS in PICU. However, the LOV remained static as time to bedside increased (change from 5.01 days to 5.09 days).

FIGURE 9.

Time to bedside and (1) expected LOS; and (b) expected LOV estimated while holding other variables at their average values. Reproduced from Seaton et al. 16 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Model fit

The model fit of our mortality analyses was assessed using the AUC,18 Hosmer–Lemeshow test19 and Brier score. 20 All models had good fit (Table 3), with high values for the AUC, non-significant results for the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and low values for the Brier score. Similarly, despite smaller sample sizes, we noted good model fit for our subgroup analyses.

| Model | AUC | Hosmer–Lemeshow test | Brier score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality analyses | |||

| Mortality in 30 days of admission to PICU | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.056 |

| Mortality in PICU | 0.80 | 0.57 | 0.050 |

| Mortality in 2 days of admission to PICU | 0.84 | 0.65 | 0.026 |

| Mortality in 90 days of admission to PICU | 0.76 | 0.96 | 0.069 |

| Mortality in 1 year of admission to PICU | 0.75 | 0.51 | 0.082 |

| Subgroup analyses (all mortality in 30 days) | |||

| Cardiac diagnoses | 0.77 | 0.36 | 0.072 |

| Neurological diagnoses | 0.85 | 0.34 | 0.065 |

| Low PIM2 score | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.065 |

| High PIM2 score | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.081 |

| Winter | 0.80 | 0.33 | 0.058 |

| Summer | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.058 |

Sensitivity analyses

Modelling covariates as fractional polynomials

We chose to categorise time taken to arrive at the bedside into meaningful groups according to the current target and because few children waited longer than 4 hours for the PCCT to arrive. In our primary analyses, we also categorised age and PIM2 score and, to investigate the impact of this, we re-fitted our models using fractional polynomials for age and PIM2 score. We explored the conclusions of our primary analysis (i.e. mortality in 30 days) and the results remained consistent (see Appendix 4), with no increasing or decreasing trend observed as time to bedside increased. Our conclusions for other mortality end points and unrepresented outcomes also remained unchanged, and this indicates that our results are robust despite any decisions that we made about how to model certain covariates.

Using the first transport

Approximately 9% of children (see Table 1) in the final DEPICT study cohort had more than one transport included during the time window of the study. Those children with only one transport may have had other transports prior to 2014 or after 2016, which we did not include. We decided to undertake our analysis using the final transport of the child during the time window of the study. We investigated the impact of this decision by repeating our analyses using the first observed transport (see Figure 8). The adjusted probability of mortality was reduced, which was as expected, as children who are transported more than once during the DEPICT study time window have to survive the first transport to receive subsequent transports, and their outcome is attributed to the final transport. However, the lack of association between time to bedside and mortality 30 days after admission to PICU remained consistent (i.e. we saw no increasing or decreasing probability of mortality as time to bedside increased). Our results remained unchanged when analysing the first, instead of the final, transport.

Missing data

To investigate the impact of missing data, we examined the children with missing information concerning their ventilation status at the time of referral, as we believed this to be a key confounder between time to bedside and mortality. In addition, ventilation status at the time of referral was the only variable included in our adjustment with substantial missing data. We re-fitted the analysis three times, assuming that (1) all missing data belonged to children who were ventilated at the time of referral call, (2) all children were not ventilated and (3) all missing data were for children where advice was given to ventilate the child. In all scenarios, the lack of relationship between time to bedside and mortality remained consistent (see Appendix 5).

Time to bedside: conclusions

We saw no evidence to suggest any association between time to bedside and mortality at our primary end point (i.e. died within 30 days of admission to PICU) or any other time point. Our models had good fit and a robust sensitivity analysis indicates that our results are not affected by missing data or modelling decisions. We observed limited evidence of an increasing LOS as time to bedside increased, but no evidence of a similar relationship with LOV. A subset of the results in this section have been published in BMC Pediatrics15 and Intensive Care Medicine. 24

Models of care: results

To investigate the models of care provided to critically ill children around the time of transport, we considered the following three areas: (1) team composition (specifically the choice of team leader), (2) approaches to stabilisation and (3) the occurrence of critical incidents.

Inclusion and exclusion

Exclusions were made for children whose ventilation status at the time of referral was missing (n = 272), for children with missing or implausible data (defined as > 24 hours) for the time to bedside (n = 50) or time to PICU (n = 2) and for children with a missing stabilisation time (n = 2). A total of 9112 children were included in the primary analysis (see Appendix 6). Summary statistics are provided in Table 4. The median time spent at the bedside of the child in the referring hospital preparing them for transport (i.e. stabilisation time) was 105 (IQR 56 to 191) minutes, and as the number of interventions provided by the PCCT increased so did the median stabilisation time (hence the phrase ‘prolonged stabilisation’).

| Characteristic | Total (N = 9112) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) of the child, n (%) | |

| < 1 | 4668 (51.2) |

| 1 to < 5 | 2436 (26.7) |

| 5 to < 11 | 1174 (12.9) |

| 11 to < 16 | 834 (9.2) |

| Sex of child, n (%) | |

| Male | 5181 (56.7) |

| Female | 3930 (43.1) |

| Unknown | 1 (< 0.1) |

| PIM2 group (%), n (%) | |

| < 1 | 1039 (11.4) |

| 1 to < 5 | 4087 (44.9) |

| 5 to < 15 | 2983 (32.7) |

| 15 to < 30 | 579 (6.4) |

| ≥ 30 | 424 (4.7) |

| Diagnosis of the child, n (%) | |

| Cardiovascular | 1309 (14.4) |

| Endocrine | 219 (2.4) |

| Haematology/oncology | 153 (1.7) |

| Infection | 820 (9.0) |

| Neurological | 1504 (16.5) |

| Trauma and accidents | 338 (3.7) |

| Respiratory | 4353 (47.8) |

| Other | 416 (4.6) |

| Time to bedside (minutes), median (10th, 90th centile) | 83 (42, 208) |

| Time at bedside (minutes), median (10th, 90th centile) | 105 (56, 191) |

| Journey time to PICU (minutes), median (10th, 90th centile) | 50 (25, 100) |

| Stabilisation time by number of interventions delivered by PCCT, median (10th, 90th centile) | |

| None | 90 (50, 150) |

| One | 125 (80, 200) |

| Two | 157 (100, 241) |

| Three | 180 (110, 279) |

| Four or more | 207 (135, 315) |

| Grade of team leader, n (%) | |

| Consultant | 3028 (33.2) |

| Junior doctor | 4726 (51.9) |

| ANP | 1342 (14.7) |

| Unknown | 16 (0.2) |

| Critical incidents, n (%) | |

| Child incident | 121 (1.3) |

| Vehicle incident | 55 (0.6) |

| Equipment failure | 333 (3.7) |

| Any incident | 496 (5.4) |

| Died in 2 days of admission to PICU, n (%) | 278 (3.1) |

| Died in PICU, n (%) | 571 (6.3) |

| Died in 30 days of admission to PICU, n (%) | 645 (7.1) |

| Died in 1 year of admission to PICU, n (%) | 949 (10.4) |

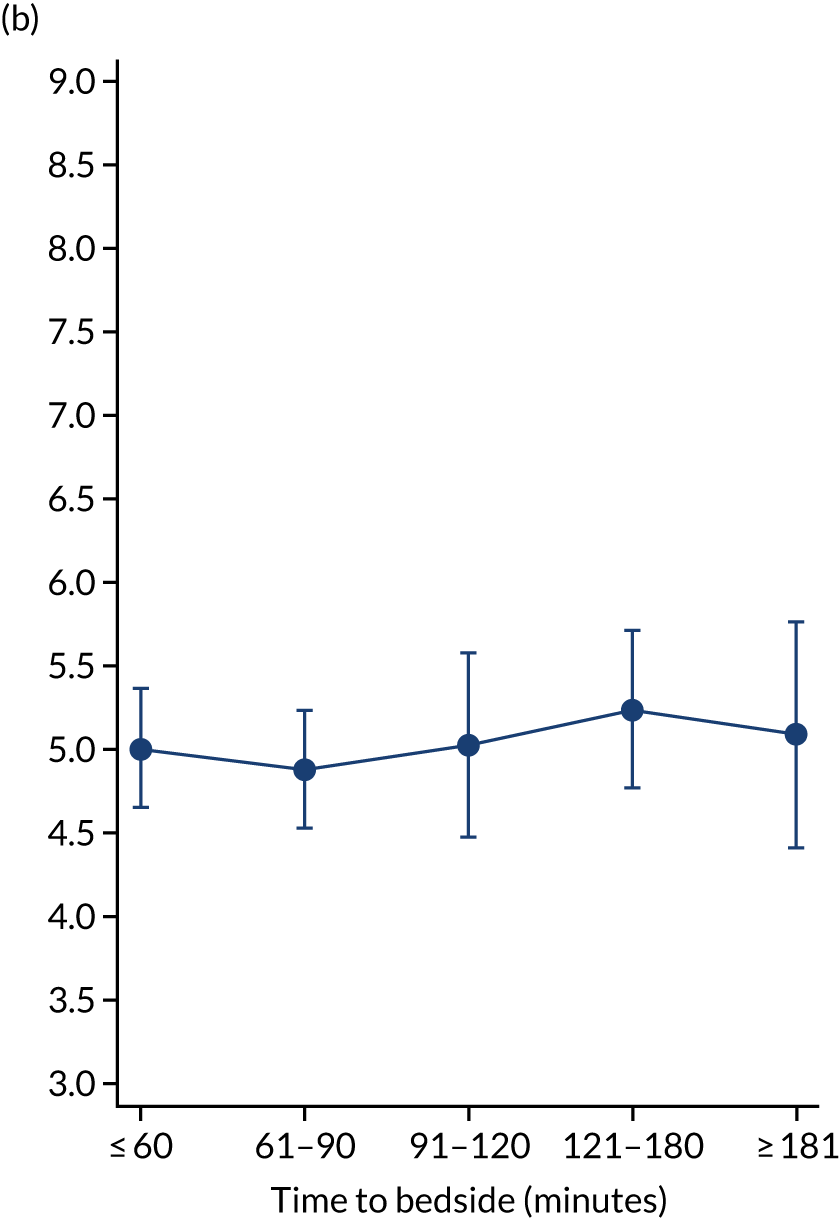

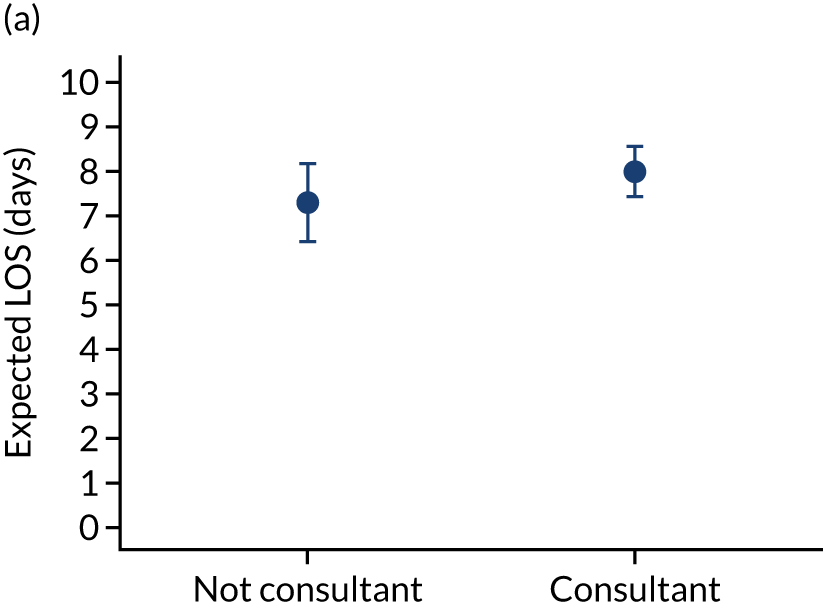

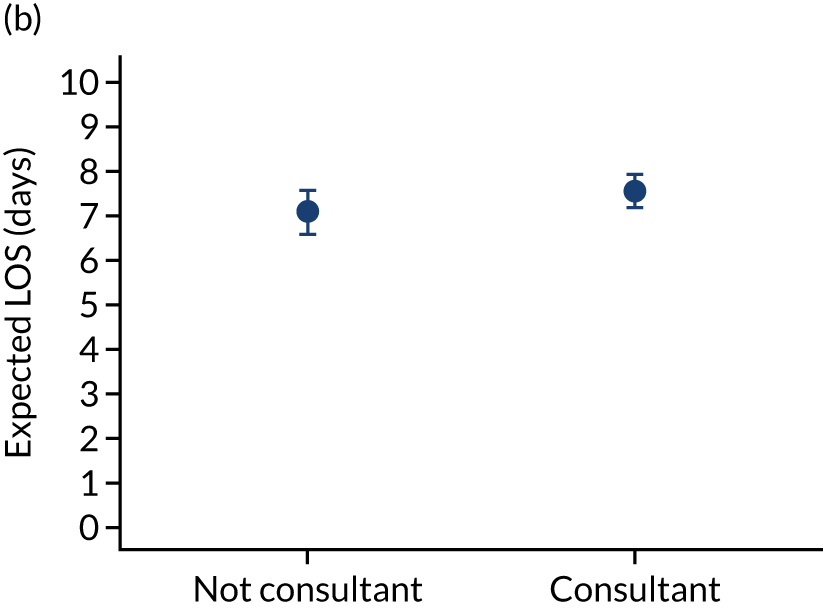

Models of care: team leader

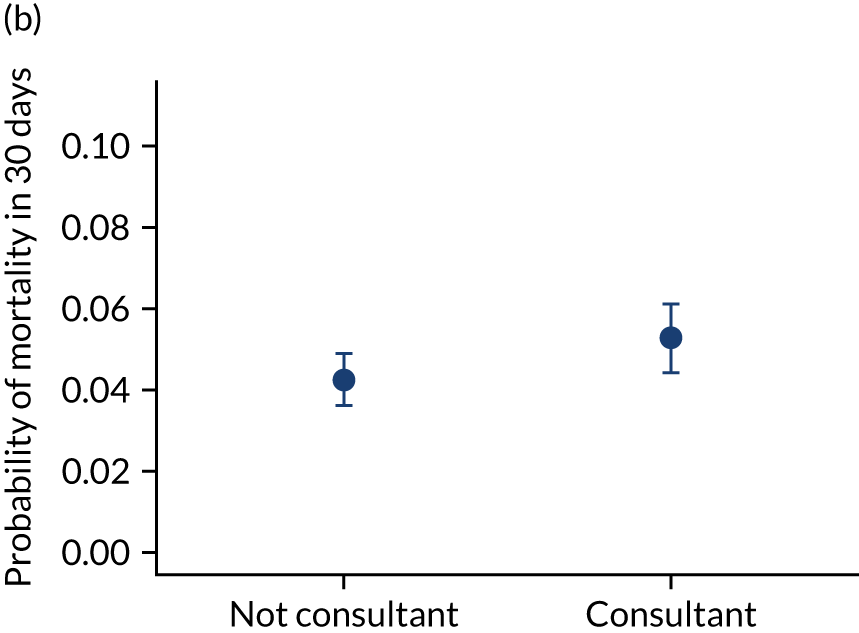

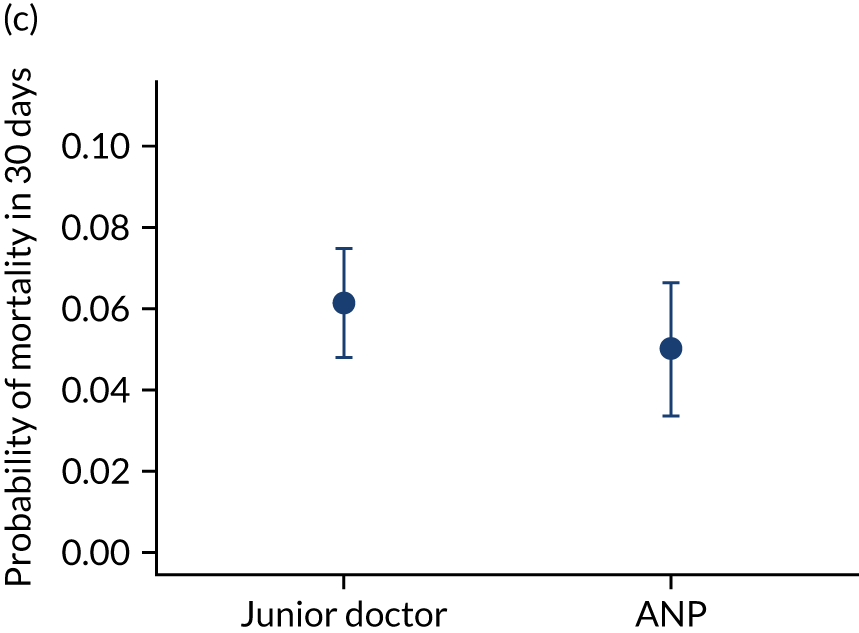

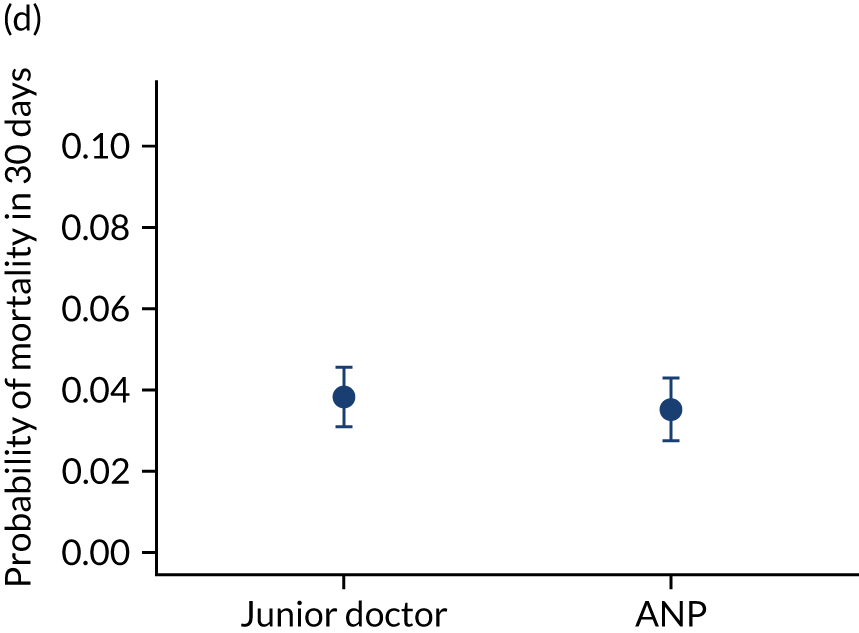

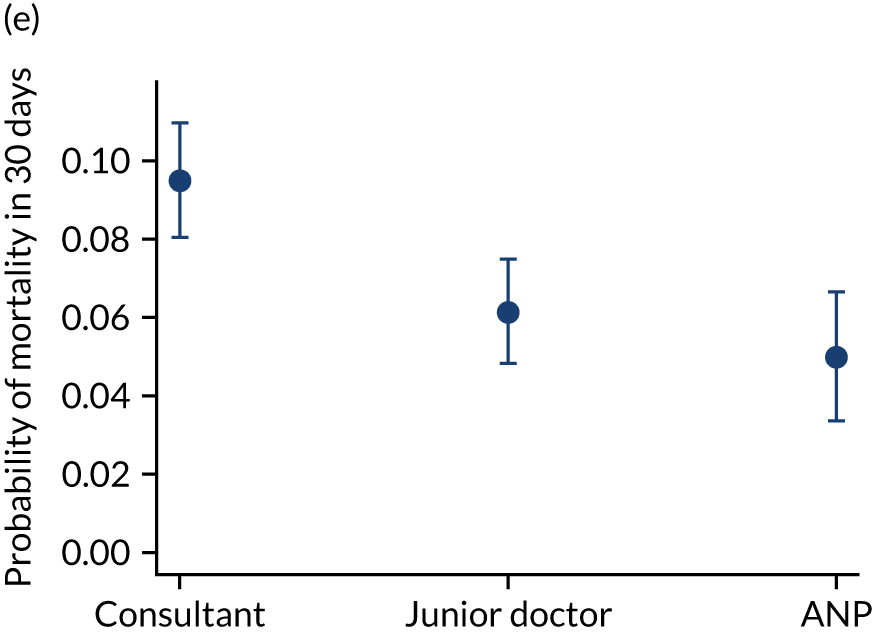

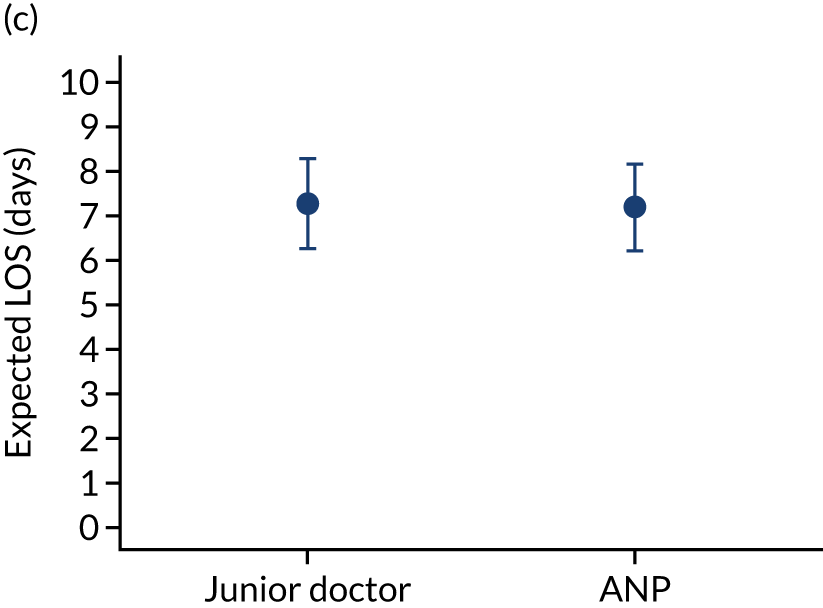

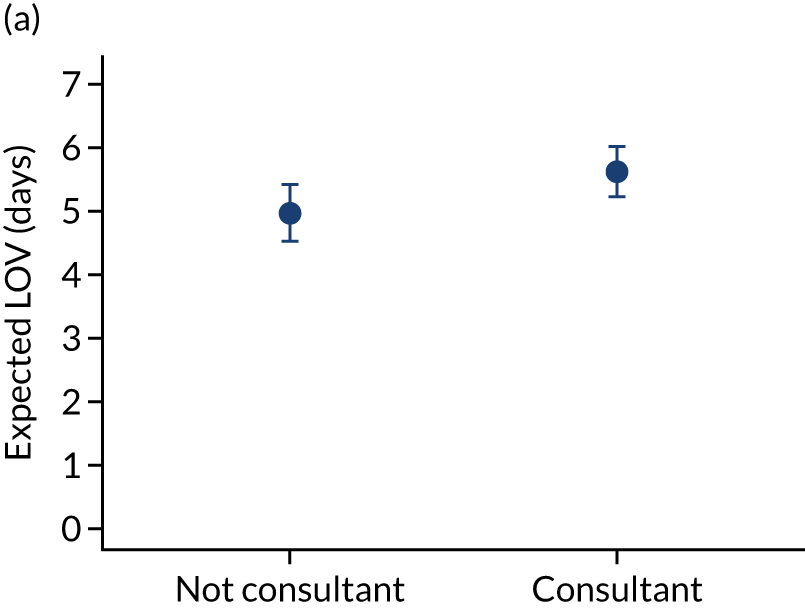

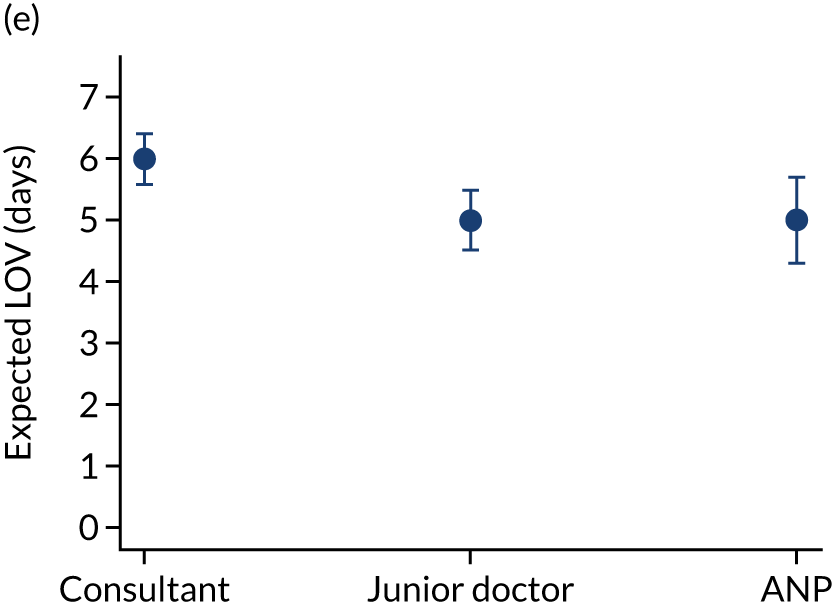

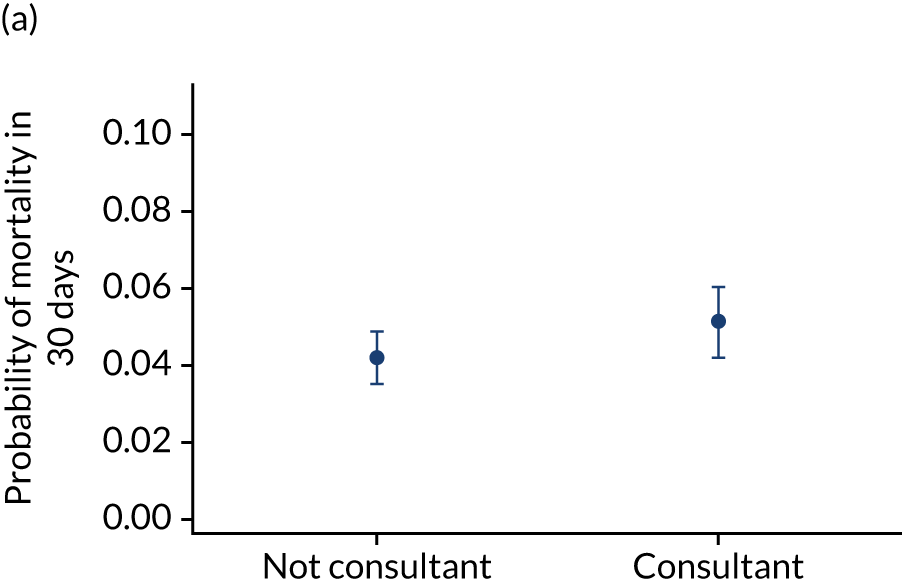

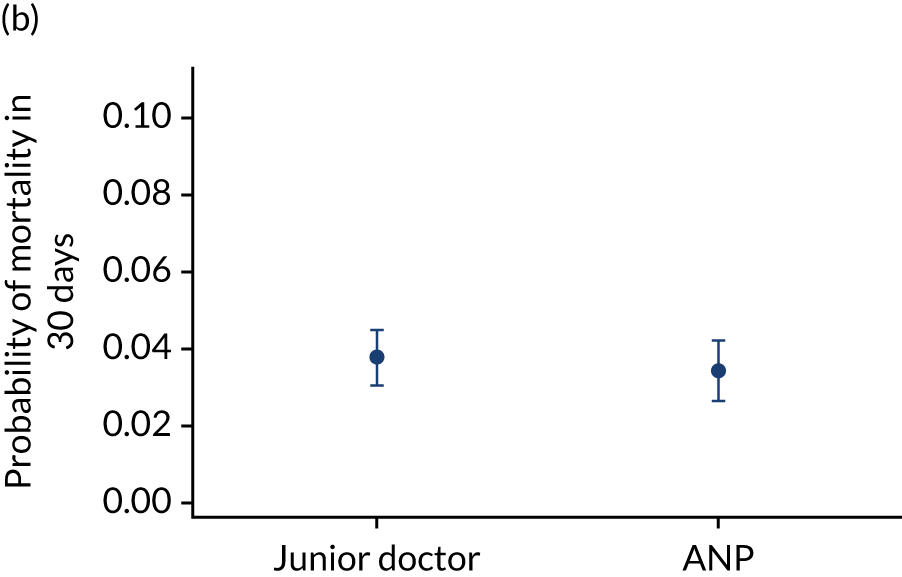

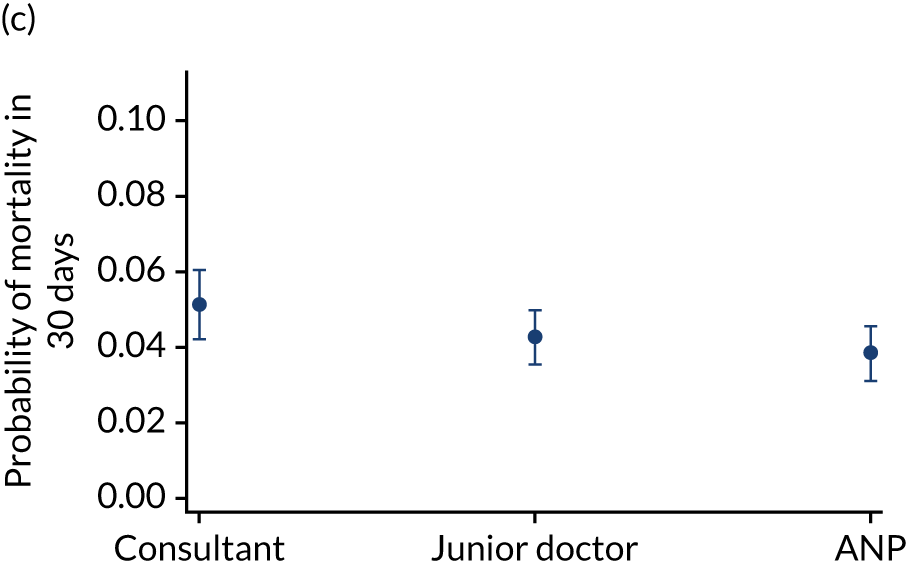

Additional exclusions were made in this section of the analysis for children with missing information about the team leader of the transport (n = 16) (see Table 4). Before adjustment, consultant-led transports had the highest probability of mortality (consultant 0.095 vs. not a consultant 0.059) (Figure 10). After adjustment, consultant-led transports still had the highest mortality, although the difference was substantially diminished (consultant 0.053 vs. not a consultant 0.043) (see Figure 10).

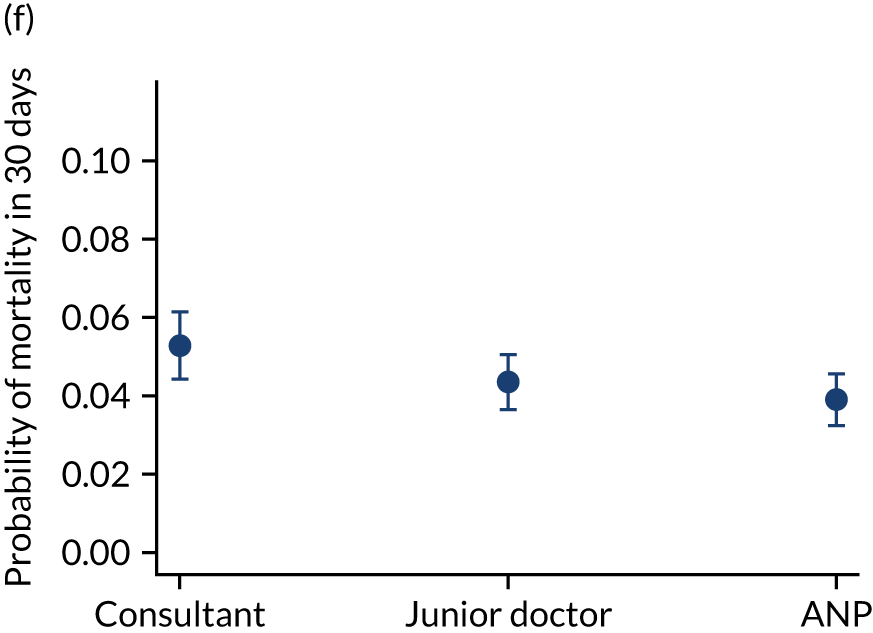

FIGURE 10.

Team leader and adjusted mortality 30 days after admission to PICU (while holding other variables at their average values). (a) Consultant vs. not a consultant (n = 9096) unadjusted; (b) consultant vs. not a consultant (n = 9096) adjusted; (c) ANP vs. junior doctor (n = 6068) unadjusted; (d) ANP vs. junior doctor (n = 6068) adjusted; (e) all team leaders (n = 9096) unadjusted; and (f) all team leaders (n = 9096) adjusted. Reproduced from Seaton et al. 15 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

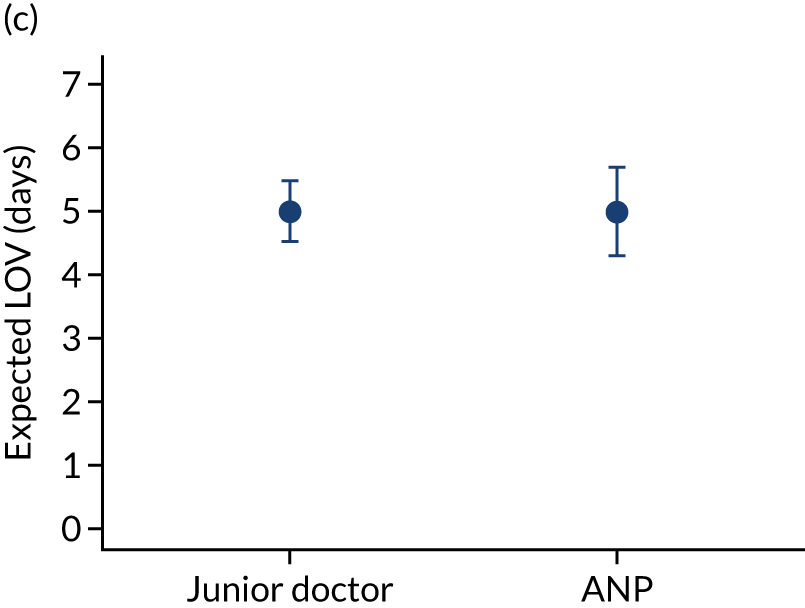

There were no differences between transports led by ANPs and junior doctors when considering adjusted mortality 30 days after admission to PICU (ANP 0.035 vs. junior doctor 0.038) (see Figure 10). Similar results were seen for our secondary mortality outcomes of died in PICU and died in 90 days of admission. All models investigating mortality had good model fit (Table 5).

| Model | AUC | Hosmer–Lemeshow test | Briers score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Team leader: mortality in 30 days | |||

| Consultant vs. not a consultant | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.056 |

| ANP vs. junior doctor | 0.79 | 0.49 | 0.048 |

| All three team leaders | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.056 |

| Team leader: mortality in PICU | |||

| Consultant vs. not a consultant | 0.80 | 0.17 | 0.05 |

| ANP vs. junior doctor | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.04 |

| All three team leaders | 0.80 | 0.31 | 0.05 |

| Team leader: mortality in 90 days | |||

| Consultant vs. not a consultant | 0.76 | 0.18 | 0.07 |

| ANP vs. junior doctor | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.06 |

| All three team leaders | 0.77 | 0.84 | 0.07 |

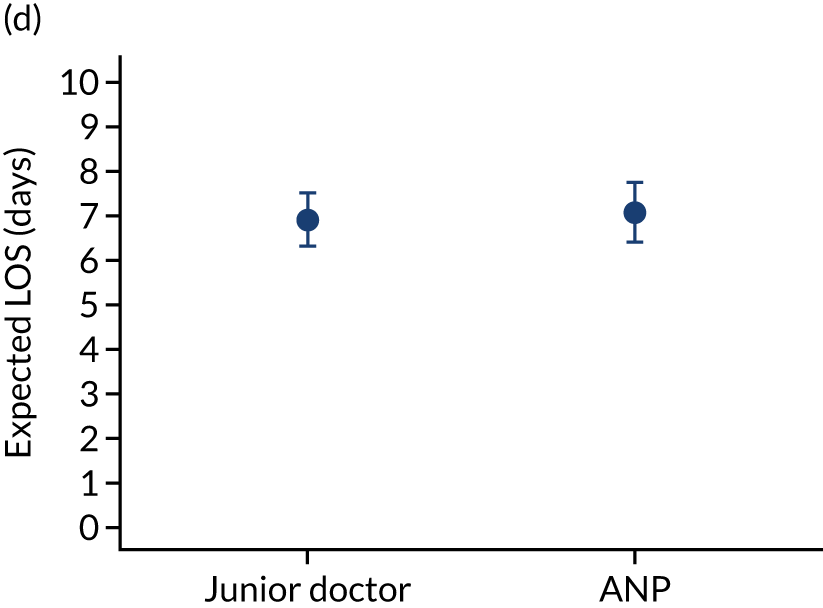

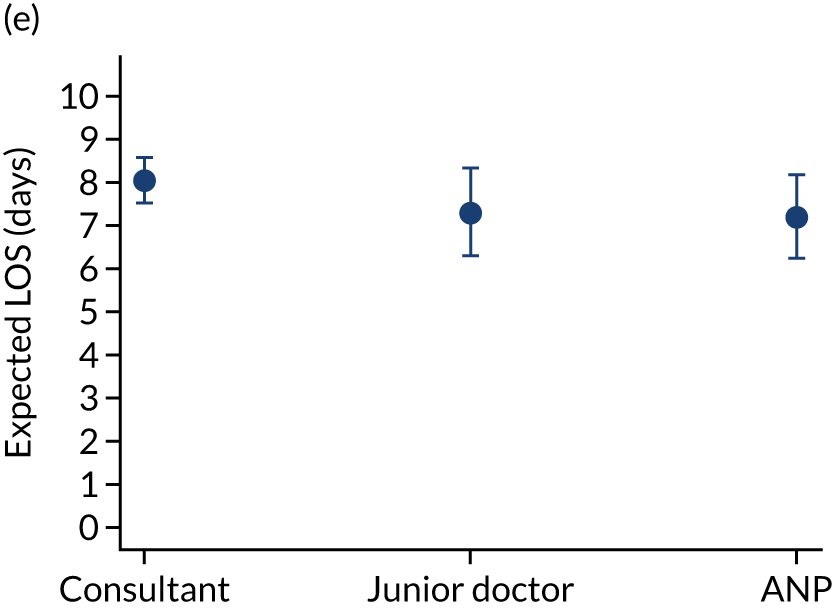

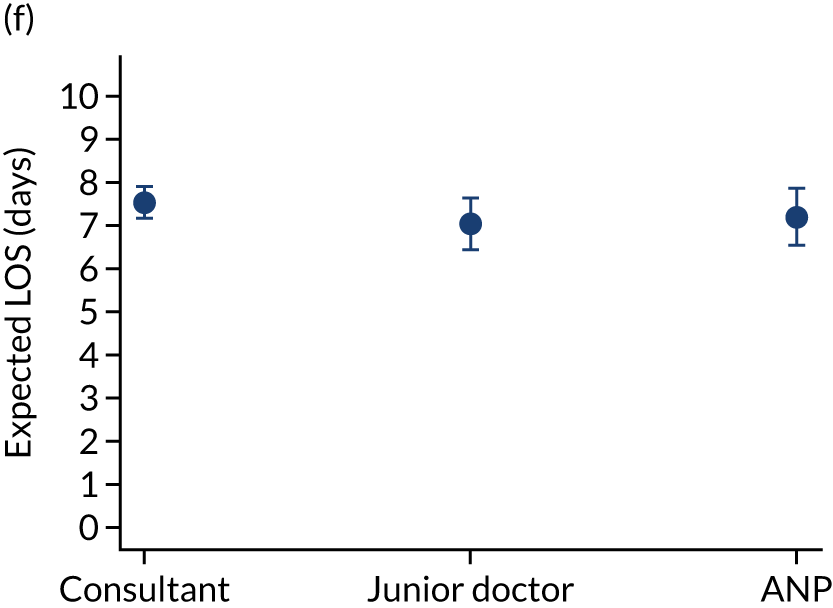

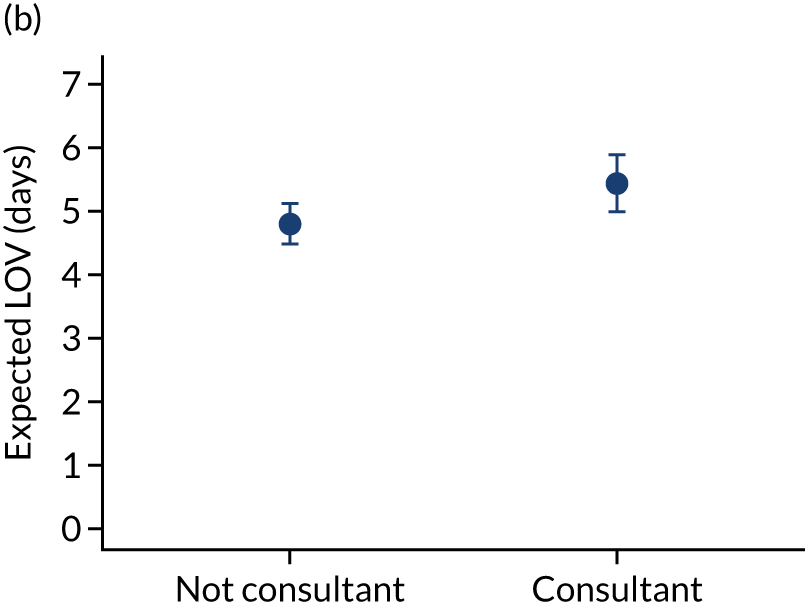

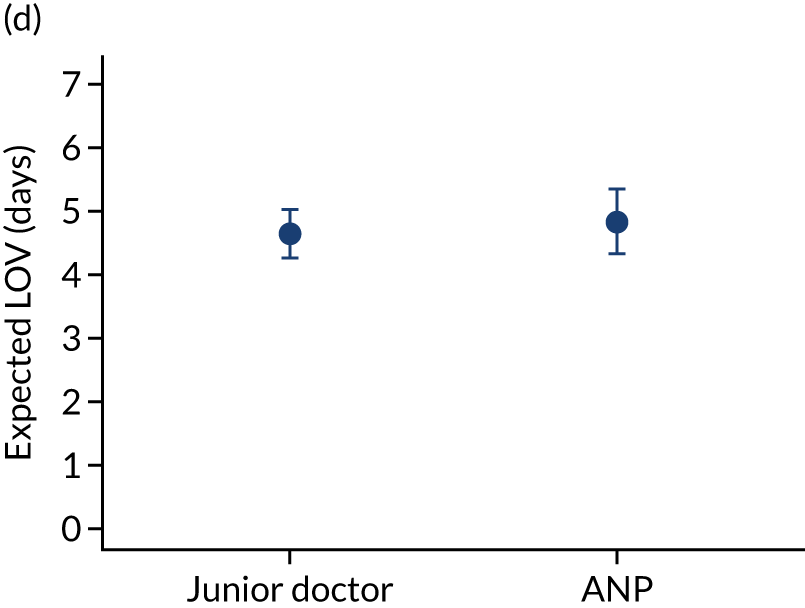

When investigating our secondary outcomes of LOS or LOV, children were excluded if they had missing LOS or LOV data, leading to the exclusion of one additional child from the LOV analysis. There were no substantial differences in the adjusted expected LOS by the seniority of the team leader. In the analysis where we directly compared all three types of team leader, the adjusted expected LOS was 7.55 days, 7.05 days and 7.22 days for consultants, junior doctors and ANPs, respectively (see Appendix 7). We did observe small differences in LOV in our three-way comparison, that is, consultant-led transports had the highest expected LOV (5.45 days) and junior doctors had the lowest expected LOV (4.77 days) (see Appendix 8).

Sensitivity analyses and model fit

All models in our team leader analysis had good model fit (see Table 5). To investigate the impact of any modelling decisions, as before, we re-fitted our primary analysis (i.e. mortality in 30 days of admission to PICU) allowing fractional polynomials to model age and PIM2 score. We compared the results from this sensitivity analyses with the results of our original adjusted analysis (see Appendix 9) and observed no noticeable changes to our conclusions.

To investigate the impact of missing data, we inputted values for the only variable in our analysis that had substantial missing data, namely whether or not the child was ventilated at the time of referral call. We assumed, in turn, that missing data represented children who were ventilated, children where it was indicated they should be ventilated and children who were not advised to be ventilated. We re-fitted the three models that investigated the impact of team leader on mortality within 30 days (i.e. the primary analysis), mortality while in the PICU and mortality in 90 days and our conclusions remained unchanged for each of these assumptions.

Models of care: stabilisation approaches

For the primary outcome, there was a marked difference in the unadjusted mortality between children who had received prolonged stabilisation and those who had not (0.137 vs. 0.060) (Table 6). Previously (see Table 4), we demonstrated that as the number of interventions delivered by the PCCT increased, so did the median stabilisation time, therefore, we refer to this as ‘prolonged’ compared with ‘short’ stabilisation. After adjustment, the difference was reduced substantially (0.059 vs. 0.044) (see Table 6), although differences did remain. Differences were seen in mortality at other time points between the children who had received prolonged stabilisation and those who had not, but differences were reduced markedly following adjustment (see Table 6).

| Stabilisation | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability | 95% CI | Probability | 95% CI | |

| Mortality in 30 days | ||||

| Short stabilisation | 0.060 | 0.051 to 0.069 | 0.044 | 0.039 to 0.048 |

| Prolonged stabilisation | 0.137 | 0.122 to 0.151 | 0.059 | 0.040 to 0.079 |

| Mortality in PICU | ||||

| Short stabilisation | 0.051 | 0.041 to 0.061 | 0.035 | 0.030 to 0.039 |

| Prolonged stabilisation | 0.135 | 0.123 to 0.147 | 0.056 | 0.036 to 0.076 |

| Mortality in 90 days | ||||

| Short stabilisation | 0.075 | 0.063 to 0.087 | 0.059 | 0.052 to 0.066 |

| Prolonged stabilisation | 0.158 | 0.143 to 0.174 | 0.079 | 0.055 to 0.103 |

| Expected number of days | Expected number of days | |||

| LOS | ||||

| Short stabilisation | 7.28 | 6.63 to 7.93 | 7.04 | 6.65 to 7.42 |

| Prolonged stabilisation | 9.15 | 8.12 to 10.19 | 8.47 | 7.56 to 9.39 |

| LOV | ||||

| Short stabilisation | 5.09 | 4.68 to 5.50 | 4.84 | 4.53 to 5.15 |

| Prolonged stabilisation | 6.74 | 5.88 to 7.59 | 6.18 | 5.33 to 7.02 |

Differences were apparent for LOS in PICU, for which adjustment differences of more than 1 day were noted between the two groups of children (short stabilisation 7.04 days vs. prolonged stabilisation 8.47 days) (see Table 6). Similarly, differences remained after adjustment for the expected LOV between the two groups (short stabilisation 4.84 days vs. prolonged stabilisation 6.18 days) (see Table 6).

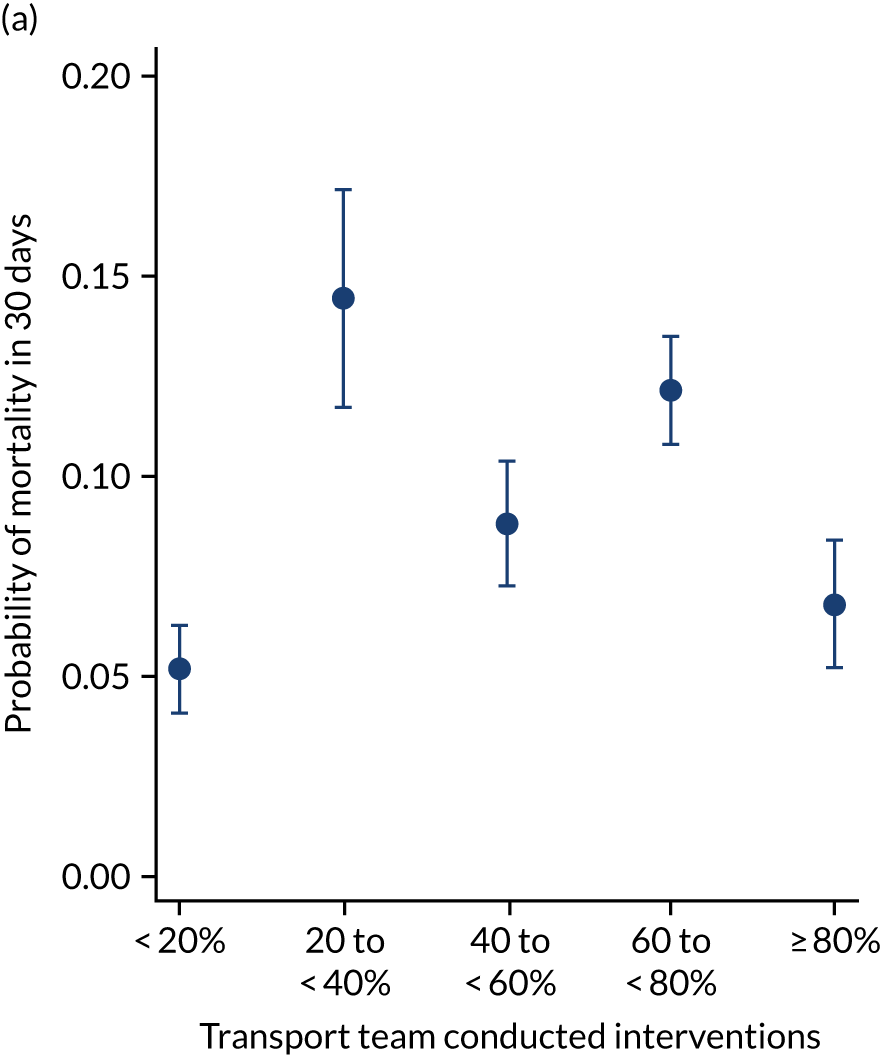

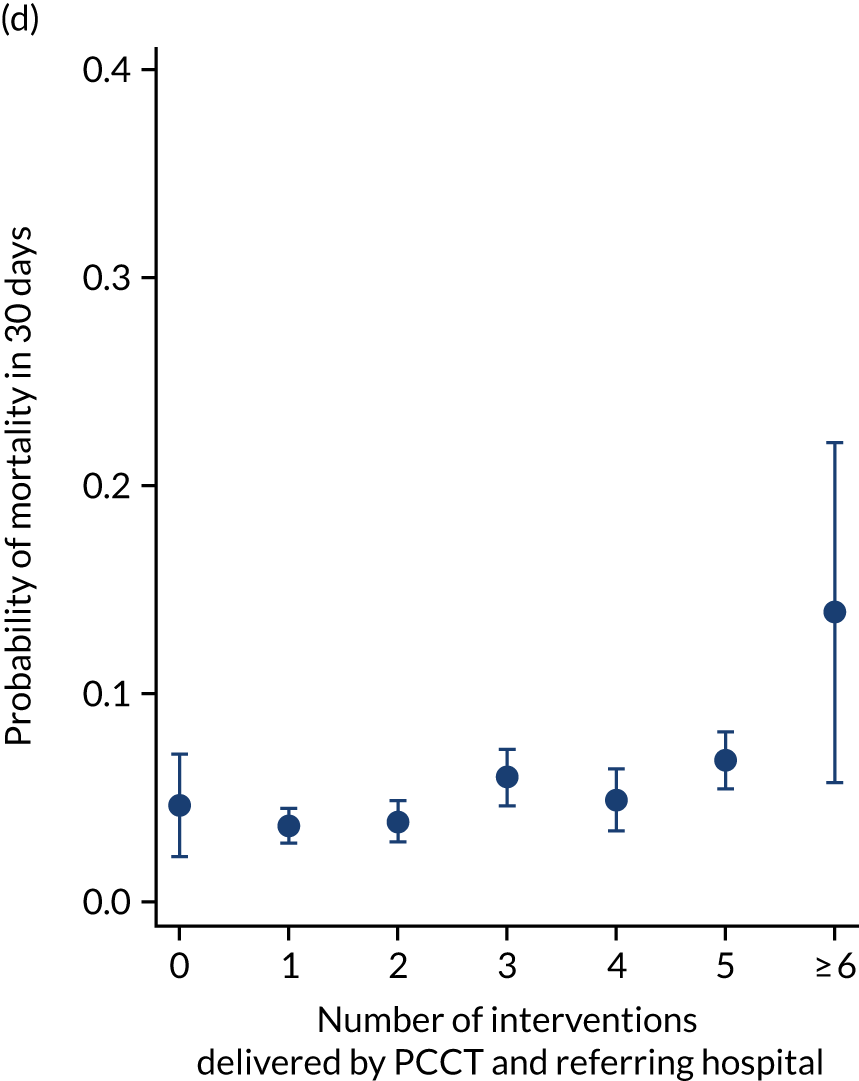

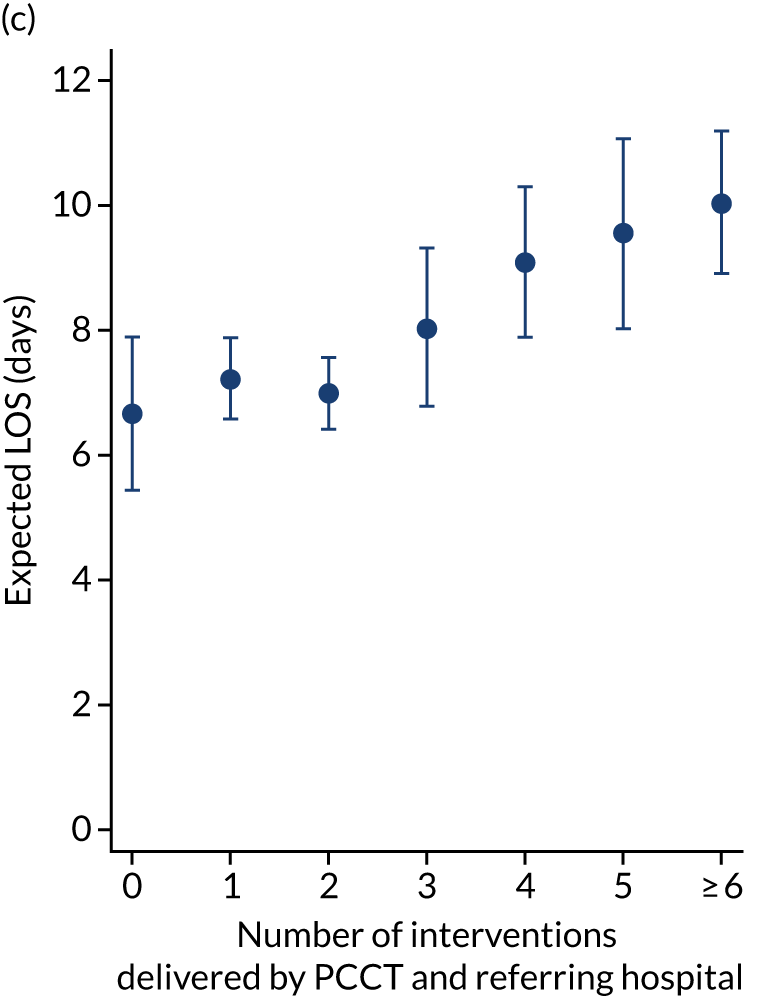

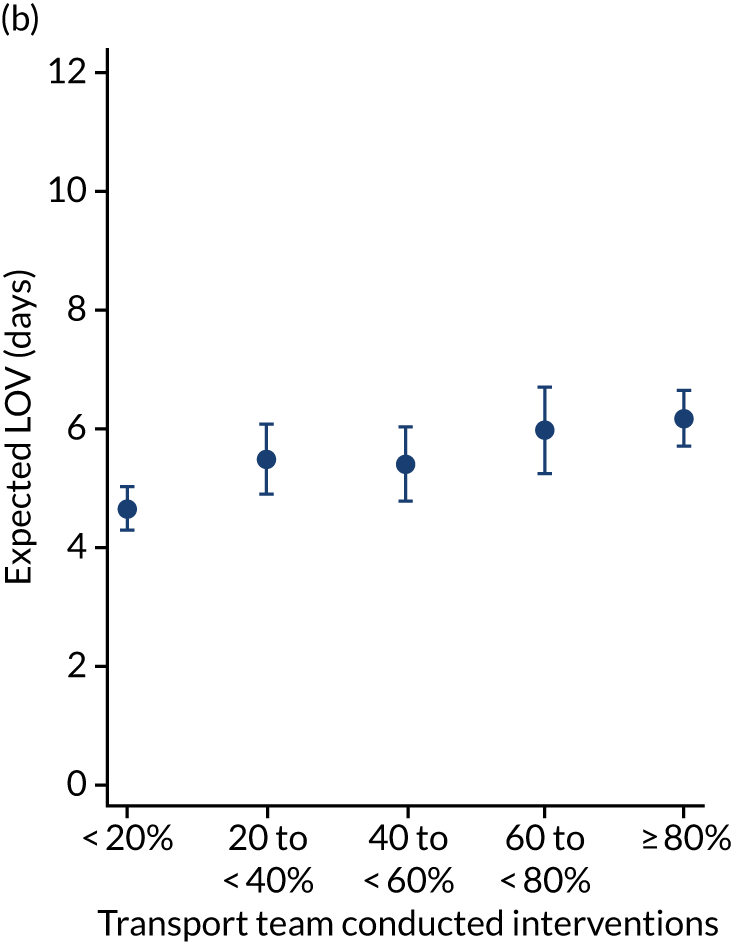

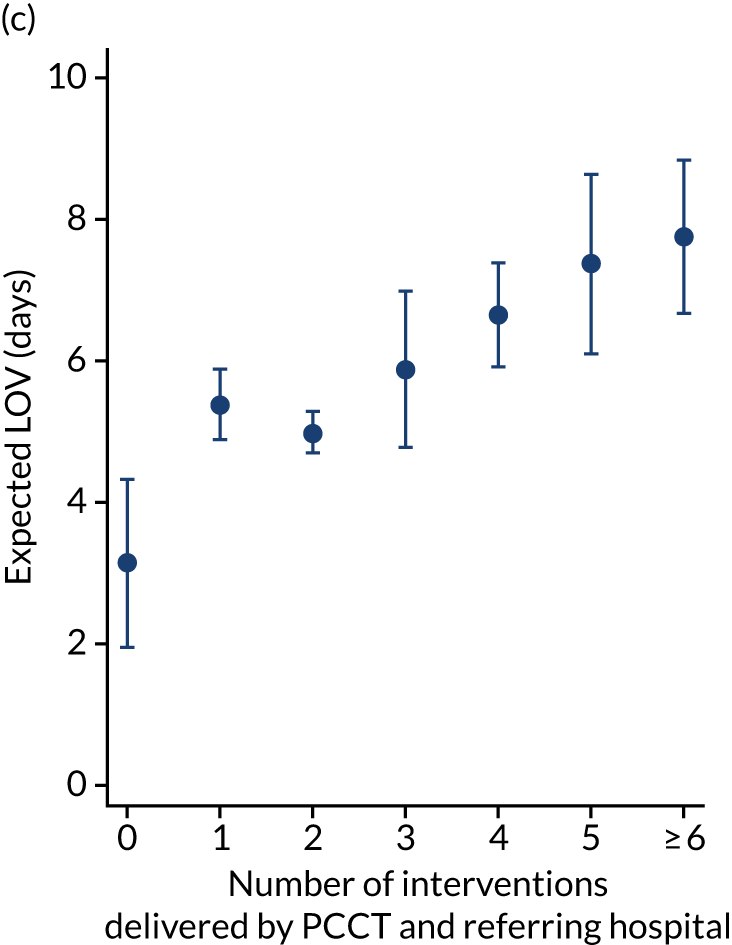

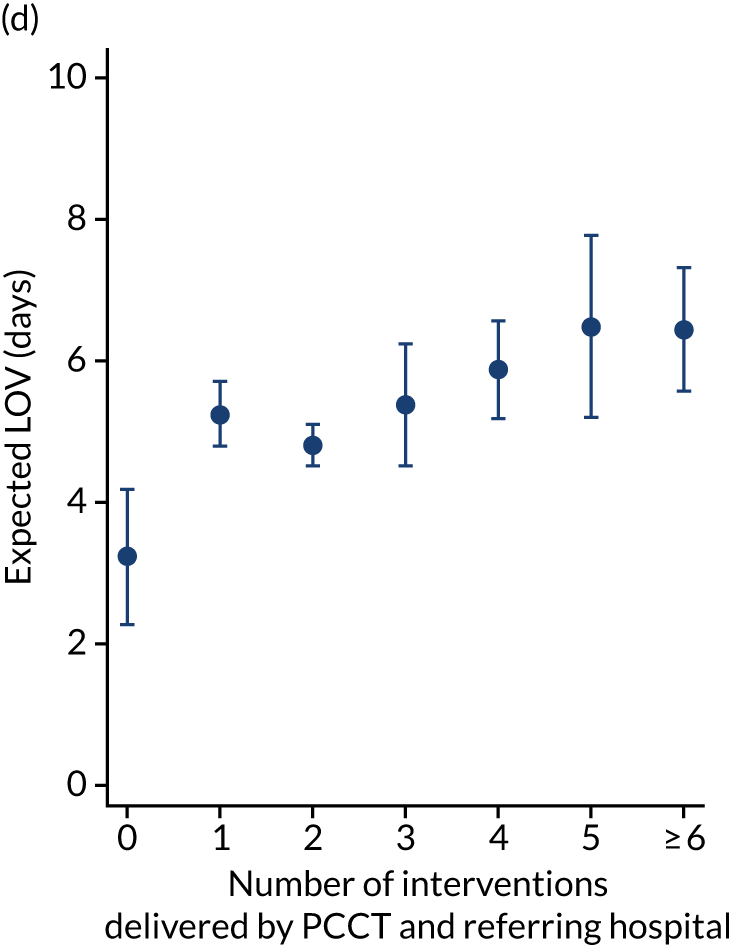

As an alternative way of considering the impact of stabilisation we considered the percentage of interventions conducted by the PCCT and the total number of interventions received by the child (Figure 11). There appeared to be no relationship in the unadjusted or adjusted analysis between the percentage of interventions that were delivered by the PCCT and mortality. When considering the total number of interventions provided to the child both by the referring hospital and the PCCT, the unadjusted probability of mortality at 30 days increased markedly as the number of interventions increased (see Figure 11). After adjustment, the trend was markedly diminished, although there was still an increase in mortality in the children receiving the most interventions, again, potentially indicating that the number of interventions was another proxy of the sickness of the child that was not entirely captured by the other variables in our adjustment.

FIGURE 11.

Total number of interventions delivered by PCCT and referring hospital and the percentage that were delivered by the PCCT. (a) Percentage of interventions delivered by the PCCT unadjusted; (b) percentage of interventions delivered by the PCCT adjusted; (c) total number of interventions delivered by PCCT and referring hospital unadjusted; and (d) total number of interventions delivered by PCCT and referring hospital adjusted. Reproduced from Seaton et al. 15 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

To explore the impact of stabilisation further, we estimated the adjusted change in time spent at the bedside of the child in the referring hospital (i.e. preparing the child for transport), according to interventions that the PCCT delivered (Table 7). For example, after adjustment for characteristics of the child, children who required intubation from the PCCT took on average 35.9 minutes longer to stabilise (95% CI 32.7 to 39.1 minutes) than those who did not require the PCCT to intubate them (see Table 7).

| Characteristic | Minutes change in stabilisation time (minutes) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention conducted while PCCT in attendance | ||

| Specified intervention not provided | Baseline | Baseline |

| Intubation | 35.9 | 32.7 to 39.1 |

| Central venous access | 41.4 | 37.8 to 44.9 |

| Arterial access | 26.2 | 23.2 to 29.2 |

| Intraosseous | 41.8 | 34.3 to 49.2 |

| Vasoactive infusion | 22.2 | 19.1 to 25.4 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| < 1 | Baseline | Baseline |

| 1 to < 5 | –1.2 | –3.8 to 1.3 |

| 5 to < 11 | 3.0 | –0.3 to 6.2 |

| 11 to < 16 | 6.5 | 2.7 to 10.2 |

| PIM2 group (%) | ||

| < 1 | Baseline | Baseline |

| 1 to < 5 | 11.5 | 8.1 to 15.0 |

| 5 to < 15 | 18.8 | 15.1 to 22.5 |

| 15 to < 30 | 29.4 | 24.1 to 34.7 |

| ≥ 30 | 29.1 | 23.1 to 35.1 |

| DEPICT diagnosis | ||

| Respiratory | Baseline | Baseline |

| Cardiovascular | –15.5 | –18.8 to –12.2 |

| Endocrine | –3.0 | –9.8 to 3.7 |

| Haematology/oncology | –10.5 | –18.5 to –2.5 |

| Infection | –5.8 | –9.6 to –1.9 |

| Neurological | –11.4 | –14.5 to –8.4 |

| Trauma and accidents | –9.2 | –14.8 to –3.7 |

| Other | –15.0 | –20.0 to –10.0 |

| Ventilated at referral | ||

| No (not indicated) | Baseline | Baseline |

| Yes | 7.1 | 4.5 to 9.6 |

| No (advised) | 1.2 | –1.6 to 3.9 |

| Receiving critical care | ||

| No | Baseline | Baseline |

| Yes | 7.9 | 5.3 to 10.6 |

| Constant | 84.5 | 81.0 to 88.0 |

All models investigating our primary outcome of mortality had good model fit (see Appendix 10).

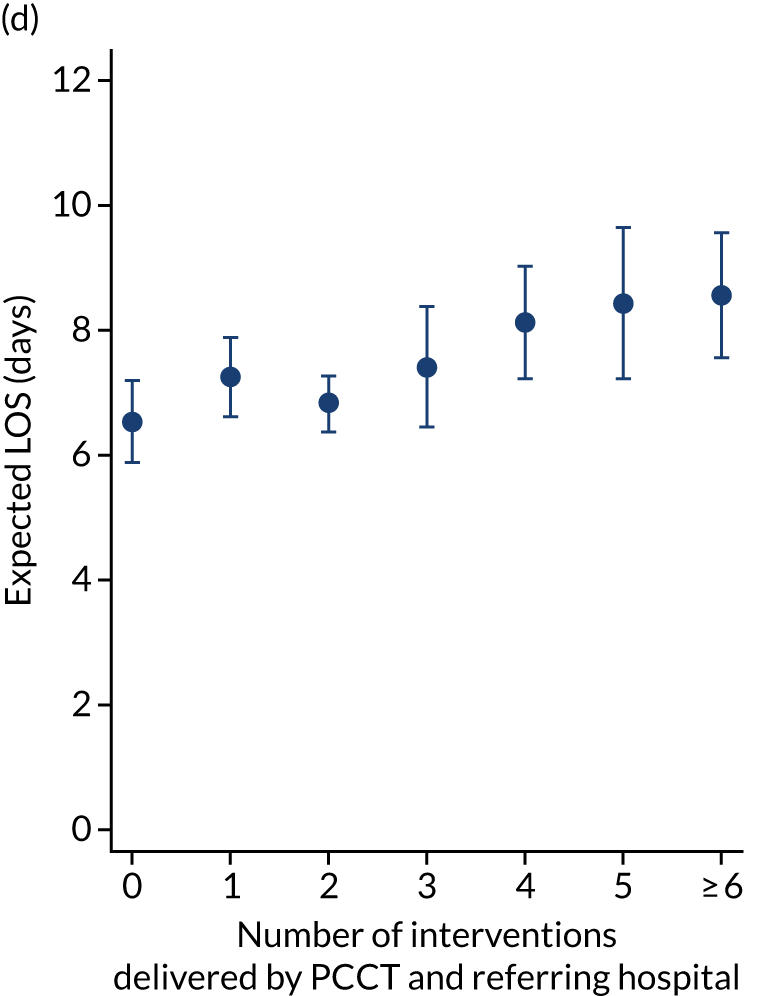

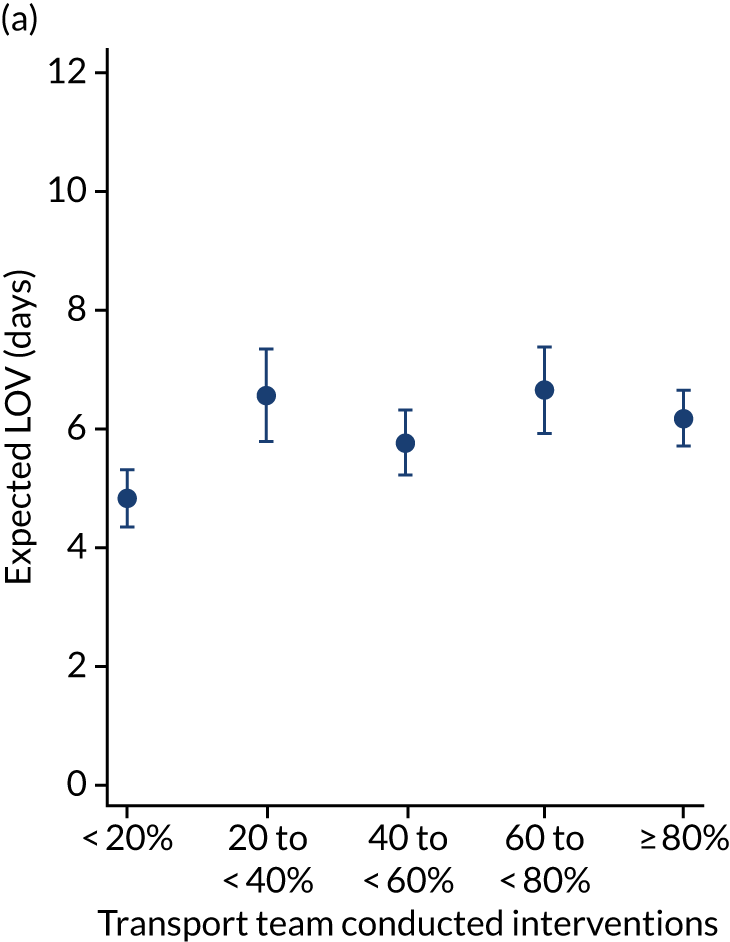

There were more apparent relationships when considering our secondary outcomes of LOS and LOV. The adjusted LOS increased as the percentage of interventions delivered by the PCCT increased (from 6.9 to 8.3 days) (see Appendix 11). Similarly, the adjusted LOS increased as the total number of interventions increased (from 6.5 to 8.6 days) (see Appendix 11). The adjusted LOV increased as the percentage of interventions delivered by the PCCT increased (from 4.7 to 6.4 days) (see Appendix 12).

Sensitivity analyses

To investigate the sensitivity of our results we re-fitted our primary analysis (see Table 6) using fractional polynomials for age and PIM2 score (see Appendix 13). We observed minimal differences and, therefore, concluded that our results were robust to the decisions made about the modelling of confounders. We also reproduced the adjusted analysis, using fractional polynomials, of the impact on mortality of the total number of interventions and the percentage delivered by the PCCT. Our conclusions remained unchanged.

Models of care: critical incidents

We considered the following three forms of critical incidents: (1) critical incidents involving the child, (2) critical incidents involving the vehicle and (3) critical incidents involving the equipment. Critical incidents due to equipment failures were the most common (n = 333, 3.7%) reason for critical incidents and those involving the vehicle were least common (n = 55, 0.6%) (see Table 4).

Before adjustment, there were elevated odds of mortality for all types of incidents except those involving the vehicle, although these incidents were the least common. After adjustment, the odds of mortality were reduced, but still remained high, most noticeably for incidents involving the child (OR 3.07) compared with those who did not experience a child incident (Table 8).

| Category of critical incident | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Any critical incident (baseline: no incident) | 1.96 | 1.46 to 2.65 | 1.60 | 1.05 to 2.45 |

| Incident involving the child (baseline: no child incident) | 4.29 | 2.68 to 6.85 | 3.07 | 1.48 to 6.35 |

| Incident involving equipment (baseline: no equipment incident) | 1.37 | 0.92 to 2.02 | 1.15 | 0.75 to 1.74 |

| Incident involving the vehicle (baseline: no vehicle incident) | 0.76 | 0.28 to 2.06 | 0.47 | 0.23 to 0.96 |

Discussion

Centralisation of paediatric intensive care unit care

The centralisation of PIC, which began with PICUs in the 1990s,4,25–27 has now also been introduced within the PCCTs that operate throughout England and Wales. In England and Wales, there are now 25 NHS PICUs that are served by nine PCCTs based at 11 geographical sites. Centralisation allows for a focusing of expertise and the development of specialist skills in a small number of sites. However, the consequence of this is that children may have to travel further, or wait longer, to receive access to the specialist care that they require. In other clinical areas, provision of early high-quality care is known to improve outcomes. 11,28

Internationally, a single-centre study from Canada29 identified that children who were transported long distances (> 350 km) by non-specialist teams had longer LOS in PICU and hospital. However, distance from the hospital did not affect outcomes in studies where a specialist team was used6,30 and this suggests that centralisation may not have led to detrimental outcomes for children who have to, potentially, wait longer for their care. However, no one, to the best of our knowledge, has investigated the impact of the centralisation of PIC on the outcomes of critically ill children in the UK in detail and on a larger scale. Despite this lack of evaluation, standards have been created in the UK for PCCTs to achieve, using expert consensus as there is a paucity of evidence-based research. The Paediatric Critical Care Society31 states that PCCTs should aim to reach the bedside of a critically ill child within 3 hours of the request for them to be transported to PICU and this can be relaxed to 4 hours when the child is being collected from a remotely located hospital. The NHS England Quality Dashboard also reports how frequently teams depart their base within 30 minutes of accepting a child for transport. 32

As well as the lack of evidence surrounding centralisation of care, currently no national guidance exists about the selection of a transport team leader for PCCTs, or whether or not transports should be triaged to different team leaders depending on the sickness of the child. Therefore, over the years, PCCTs have evolved dynamically in response to the resources available, with some PCCTs having the majority of transports led by consultants, whereas in other PCCTs consultants are triaged for sicker children only. Any triaging of team leaders in the UK is carried out in an informal manner, rather than via use of transport risk scores (as in other countries). 33

There is variation in the composition of teams used across the country, most notably some areas make use of ANPs, whereas others do not,7 but the impact of this has been unclear. Within neonatal transports, research suggests that nurse-led transports had similar outcomes to those led by junior doctors. 34,35

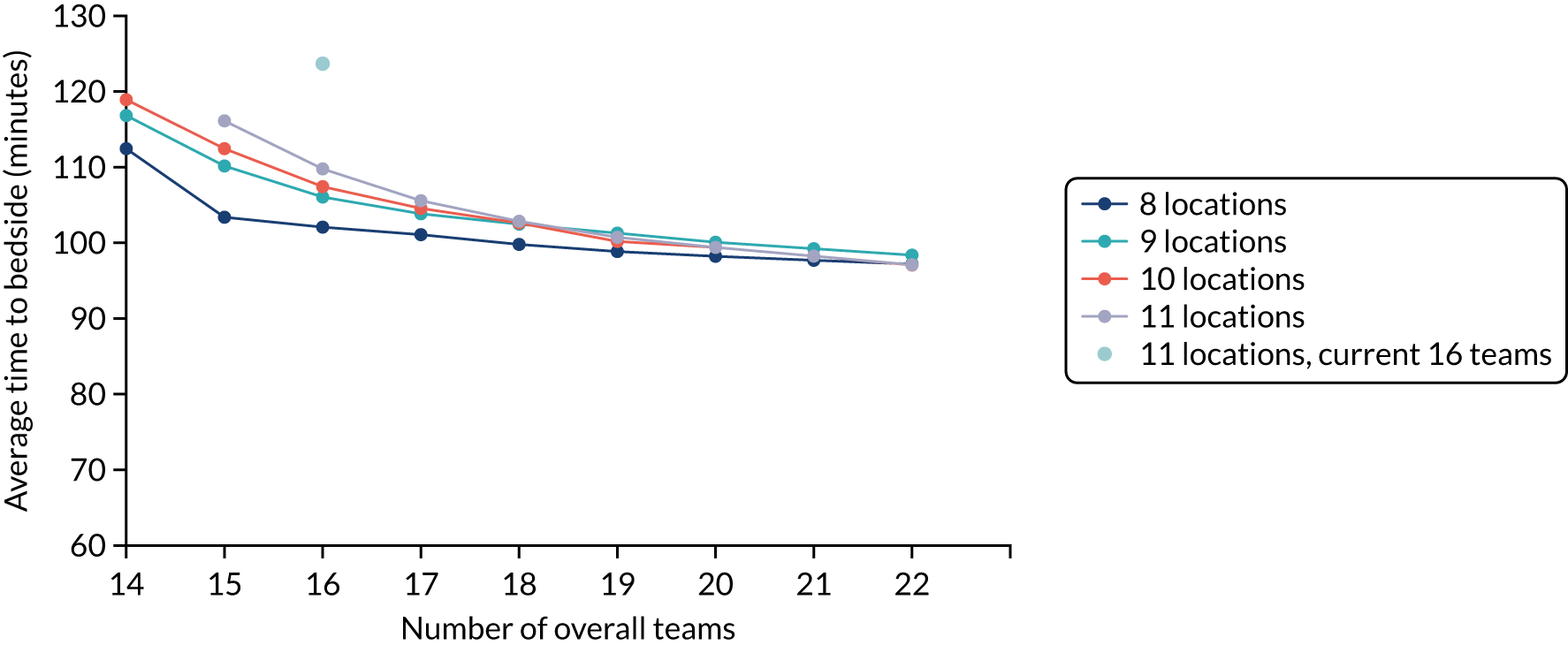

As well as the importance of selecting the appropriate team composition for the transport, there is no guidance surrounding different approaches to stabilising the child, with two broad approaches being commonplace: (1) taking time to stabilise the child before transport or (2) ‘scoop and run’. Previous research from a single London site has suggested that there is no association between the time spent stabilising the child before transport and short-term mortality in 24 hours. 36 We also considered the impact of critical incidents while the child was being transported to the PICU.