Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number 16/138/31. The contractual start date was in January 2021. The draft manuscript began editorial review in December 2022 and was accepted for publication in July 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Newbould et al. This work was produced by Newbould et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Newbould et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Box 1 provides a summary of Chapter 1 of this report.

Summary of key points

-

In England, the National Health Service (NHS) Long Term Plan endorsed digital ambitions for primary care, promising that patients would be able to choose digital-first options. The 2019 GP contract also included requirements for online consultations by April 2020 and video consultations by April 2021.

-

Digital First Primary Care is when a patient’s first contact with a GP is via a digital route. Digital First Primary Care might be accessed by a patient online, through a computer or a smartphone.

-

Approaches vary by provider, but the principles remain the same: a patient inputs their symptoms and concerns through a digital platform and then is given an appropriate response, which could include guidance for self-care, a suggested telephone, video or face-to-face practice appointment.

-

At the time of scoping for the project, in 2019, uptake of digital primary care was modest across England. The COVID-19 pandemic saw a rapid change in modes of service delivery in general practice, with all GP surgeries having to rapidly adapt their services to provide non-face-to-face consultations. At the time of writing, it is reported that under a third of consultations were remote.

-

There have been various shifts in policy focus in England in relation to the use of digital approaches during the pandemic. Initially, there was a directed shift to appointments via telephone or, to a lesser extent, video. As restrictions began to ease, this position changed with the increased use of face-to-face appointments.

-

These changes have taken place amidst an extremely challenging climate for general practice in England with workforce shortages and increased workloads.

What is Digital First Primary Care?

This rapid evaluation has conceptualised Digital First Primary Care as described below:

Digital First Primary Care is when a patient’s first contact with primary care is through a digital route, either through a laptop or smartphone. The patient enters details of the issue which they wish to consult a health professional about, either by completing a form or by entering a free-text narrative. The patient will then be contacted by the practice, usually on the same day, about their issue.

Practices which use this approach also provide a mechanism for access for those unable to use the digital route. Patients telephone the practice and a member of practice staff enters the information into the digital interface and the request is dealt with by the practice in the same way as it would be if the patient entered the information digitally.

Most practices enable patients to order repeat medication online; we would not define this as Digital First Primary Care, as the purpose of contact is not to see or speak to a health professional, rather to obtain medication.

The term, Digital First Primary Care, originated from an NHS programme during the COVID-19 pandemic where it was defined as follows:1

Digital First Primary Care is the name of a programme which supports the transformation of primary care by promoting the implementation, understanding and improvement of digital tools within general practice. 1

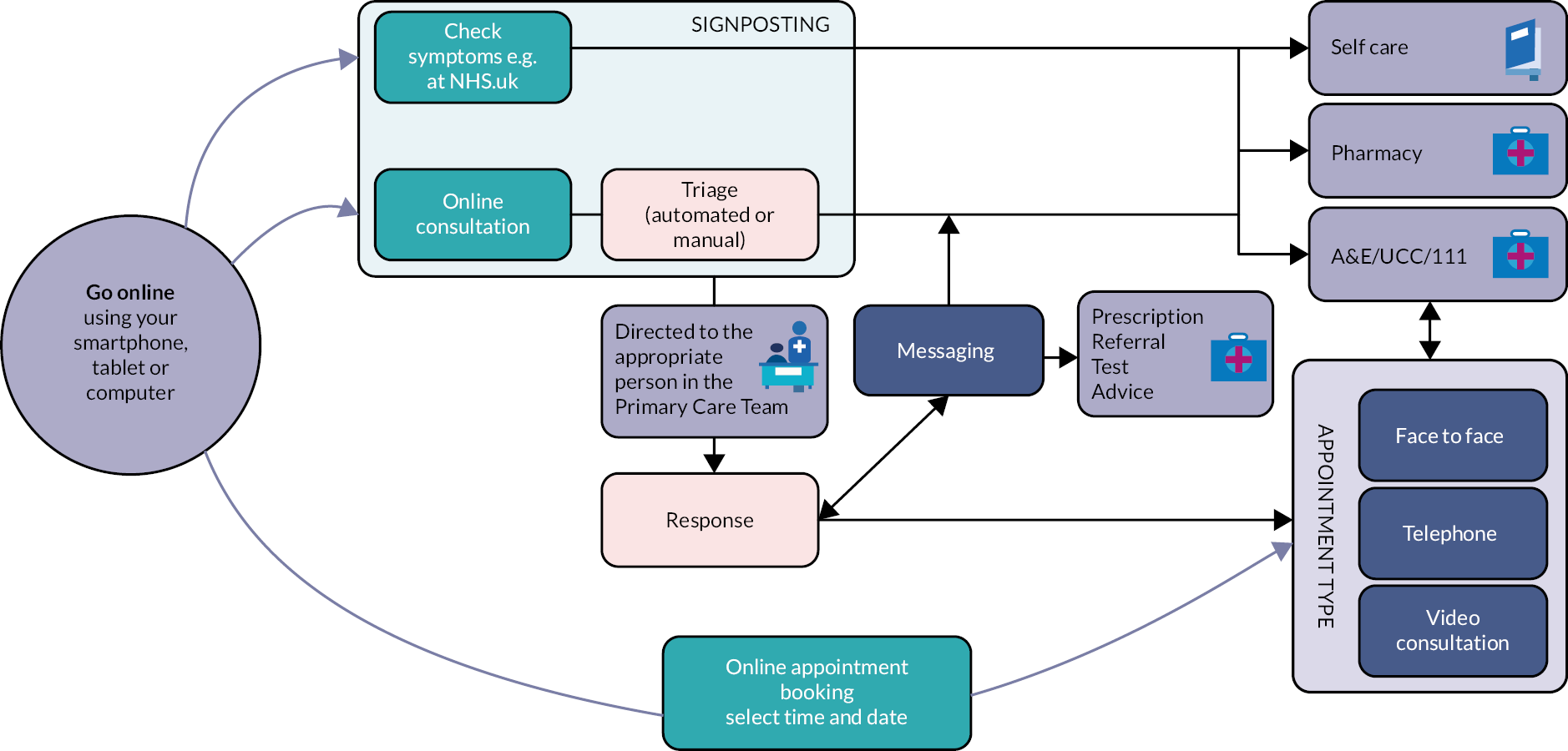

Figure 1, produced by NHS England, outlines the various patient pathways, from when a patient first contacts their practice digitally to the holding of a consultation. 1

Most general practices offer Digital First Primary Care by purchasing the approach from a commercial provider, although practices may also create the approach themselves. The design of Digital First Primary Care platforms varies by commercial provider, although the main principles are the same. The patient inputs their symptoms and concerns through a digital platform, such as a computer or smartphone, either via a set of questions within a digital algorithm or through a free-text submission. Once the information is entered, the patient is then given an appropriate response, which could be from a staff member within the practice or automatically generated by the algorithm for example an online message. This response could, for example, offer guidance for self-care, advice to attend an accident and emergency service (if the problem is deemed to be a serious one that cannot wait), a message back from a professional or a suggested telephone, video or face-to-face appointment with a general practitioner (GP) or other member of the practice team. Most models enable swift responses from practices back to patients, usually on the same day, and if a consultation is required, this is usually on the same day too. These approaches have been advocated by NHS England to enable clinicians to prioritise the care of patients in the most need. 2

Digital First Primary Care can, therefore, lead to a conventional general practice consultation style, such as a telephone consultation or face-to-face consultation, or a less traditional consultation, such as the health professional messaging the patient. Yet, the consultation is framed by the information the health professional receives ahead of the consultation, submitted through the digital route. Digital First Primary Care approaches may also enable practices to more easily provide video consultations.

Table 1 outlines the principles of the Digital First Primary Care consultation as compared to a traditional general practice system.

| Traditional appointment system | Digital First Primary Care | |

|---|---|---|

| First contact with the practice | Telephone or in-person at GP reception | Through digital platform |

| Triage and assessment | N/A (patient booked directly for appointment by reception team) | Either through digital algorithm or reviewed by health professional and digital message from the practice; patient may be referred to other services, such as self-care or pharmacy |

| Contact with health professional | Telephone or in-person | Message from health professional (digital), telephone consultation, face-to-face consultation or video consultation with health professional from the practice |

Accessing services via a digital route may mean that a patient’s experience of care differs from that of a patient accessing the practice via an alternative route, such as by telephone or by visiting a surgery. For example, messages about a person’s care might be exchanged between the patient and professional or the clinician may conduct the consultation having prior written information from the patient, for example discussing a patient’s diabetes having already received their blood-sugar readings via message, which would not be possible if the patient had not accessed care digitally.

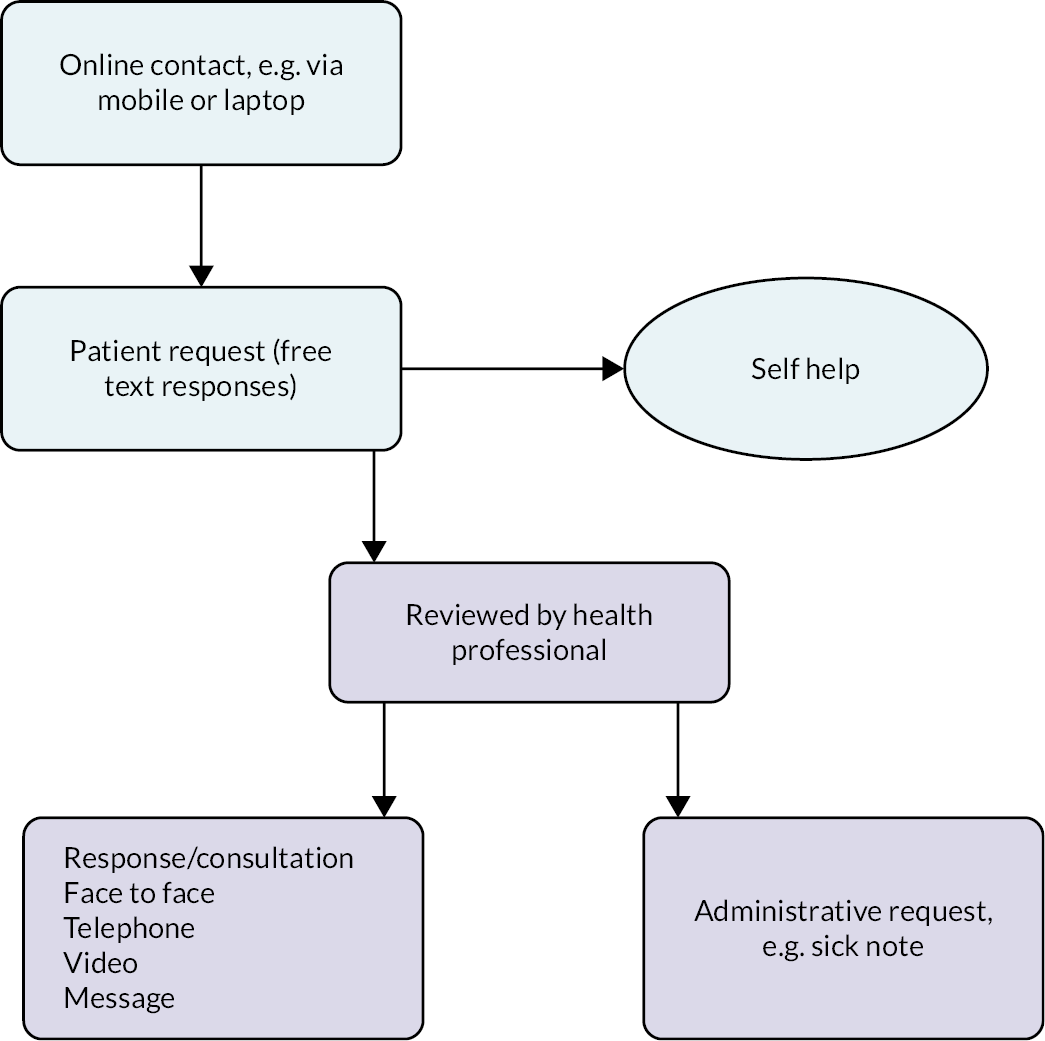

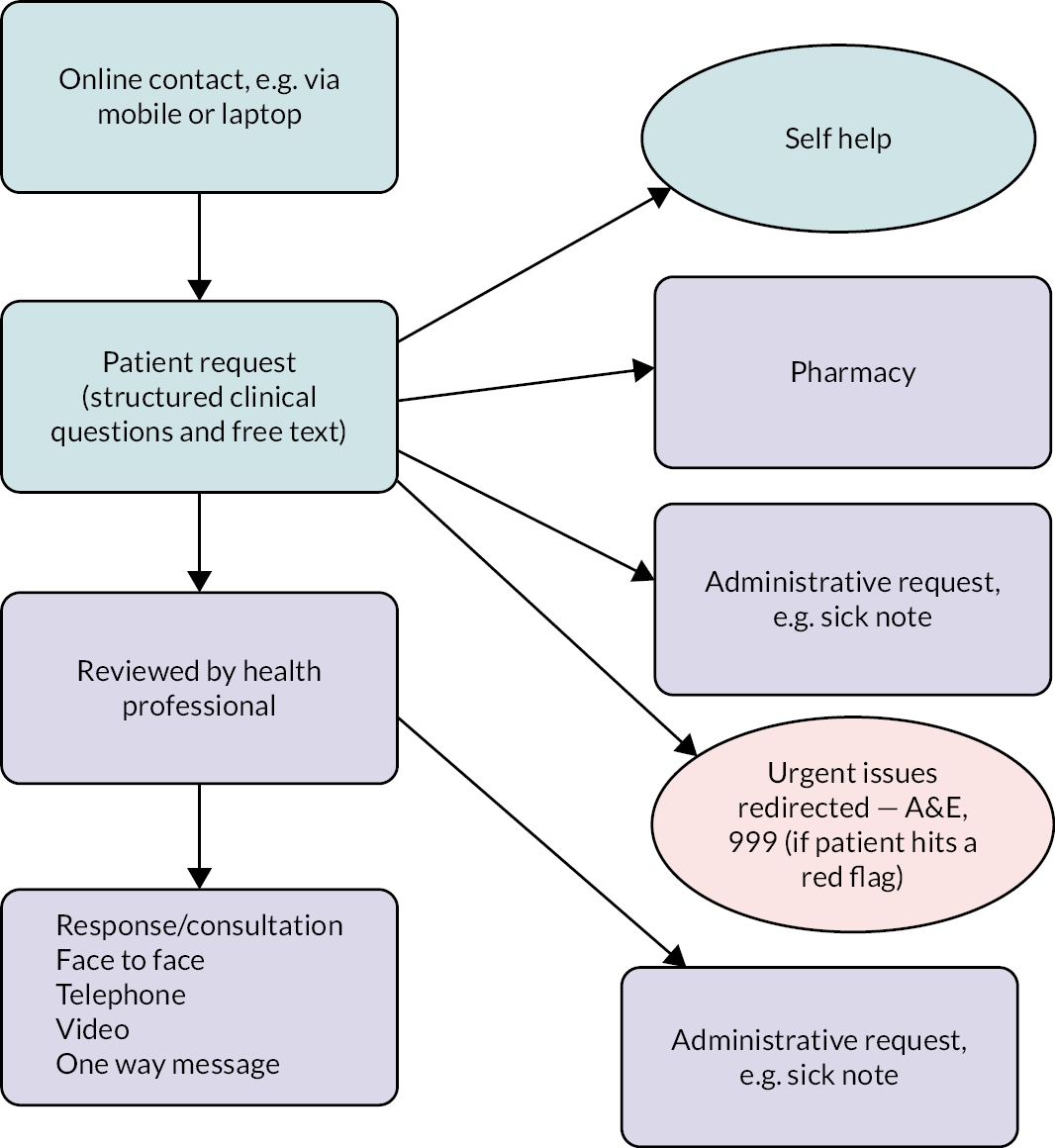

The exact nature of the Digital Frist Primary Care patient pathway depends upon the provider used, but most use either a free-text approach or an algorithm approach, Figures 2 and 3 illustrate examples of patient pathways from initial contact with the practice to the outcome, using two different approaches to Digital First Primary Care.

FIGURE 2.

Example of a Digital First Primary Care patient pathway: free-text approach.

FIGURE 3.

Example of a Digital First Primary Care patient pathway: algorithmic approach.

A ‘free-text approach’ (see Figure 2) is where a patient enters the nature of their problem in the system in their own words. The patient then receives an automated response to say they will hear back from the surgery. The response is then reviewed by a healthcare professional and the response is either dealt with by the administrative team at the surgery, for example a sick note, or a response is provided by a health professional in the form of a message or consultation, by a variety of means.

An alternative approach is an algorithm approach (see Figure 3) where the patient completes an online form which asks a series of questions. The form gives the patient options to choose from, for example the part of the body that the problem is in, the duration of time they have had it. After the query has been submitted a response is automatically generated and immediately sent to the patient. This could include self-help, if the problem is deemed as not requiring a primary care health professional, or to contact a pharmacist. If the problem is considered urgent, a message is sent telling the patient to dial 999 or attend an accident and emergency department immediately. Alternatively, patients are sent a message to say a health professional from the practice will contact them.

It should be noted that the figures outline examples of ‘typical’ patient pathways for patients using these Digital First Primary Care approaches; however, the ways in which the systems have been implemented and are used in practice may vary across general practices. For example, they may have different staff responsible for dealing with requests within a practice or some practices may use messaging or photos more than others.

English policy context

Scoping for this project began in July 2019, at a time when general practices throughout England were struggling with rising demand from patients with complex health needs, more work being transferred from secondary to primary care and increasing difficulty in recruiting and retaining GPs. 3,4 The General Practice Forward View (2016) aimed to help GP practices reduce and better manage their workload and the increased use of digital technologies was advocated. 4 The digital ambition for primary care was further endorsed in the NHS Long Term Plan (2019), which set out a target that, within the next 10 years, the NHS would offer a ‘Digital First’ option in primary care for most patients,5 with the aim that this would enable ‘longer and richer face-to-face consultations with clinicians where patients want or need it’. 5 More specifically, the plan set out a milestone that every patient in England would be able to access a Digital First Primary Care offer by 2023/24. 5 The 5-year framework for GP contract reform also reflected this policy shift towards digital approaches, including a requirement that practices should ensure that all patients have the right to Digital First Primary Care, including online consultations, by April 2020 and consultations via video by April 2021, with the aim to provide this access as quickly as possible. 6

Despite the increasing policy shift towards digital approaches, most GP surgeries were not operating in this way in early 2020, with an analysis of primary care data suggesting that 13–15% of consultations were conducted remotely in January 2020. 7 Wider studies suggest that factors such as a lack of training, inadequate technology and concerns about issues such as inequity of access, safety and workload limited the use of alternative approaches to face-to-face consultations, as well as low patient uptake in practices where digital approaches had been adopted. 8–10

The impact of COVID-19 on Digital First Primary Care

The COVID-19 pandemic saw a rapid change in modes of service delivery in general practice, with all GP surgeries having to rapidly adapt their services to provide non-face-to-face consultations, which could be supported by digital platforms. At the time of scoping for this project in 2019, the uptake of digital primary care was modest across England. In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, general practices had to quickly adapt their ways of working to reduce footfall in GP surgeries, protecting patients and staff from infection. 11

It was noted by providers that there was a dramatic increase in the adoption of Digital First approaches in primary care in response to COVID-19, although there are no publicly available data. Data are available, however, on the use of other forms of consultation. An analysis by The Health Foundation suggested that remote consultations increased from < 20% to > 50–60% of all consultations at the peak of the first national lockdown. 7 This trend appears to have continued, with further analysis conducted by the Health Foundation demonstrating that March 2021 saw the highest number of telephone appointments ever, at 11.4 million compared to 3.5 million in March 2019. 12 More recently, in 2022, the British Medical Association (BMA)13 reported that the ratio of face-to-face versus remote appointments has changed alongside the waves of COVID-19. In 2022, under one-third of consultations were remote, with September having the highest number of face-to-face appointments since before the pandemic. 14

When looking at specific types of digital approaches, evidence from the Health Foundation examining data from practices using one specific provider, suggested that patient preference for consultation via SMS/online messaging increased from 26% of requests before the pandemic to over a third in 2020 and 2021 and that a telephone consultation was the most popular patient preference. 15 While the majority of requests were initiated online (rather than by telephone or in person) before the pandemic, this continued to rise from 60% in June 2019 to 71.8% during 2021. 15 In addition, between March and June 2020, the use of video by patients to communicate with GP surgeries increased 50-fold compared to before the pandemic,11 although, compared to other forms of digital communication, the use of video was low and this remains the case more widely, accounting for around only 0.6% of consultations at the time of writing. 14

The impact of COVID-19 on policy and guidance in England

There have been various shifts in policy focus in relation to the use of digital approaches during the pandemic. In March 2020, all practices were written to by NHS England informing them that ‘all practices are now being advised to change face-to-face appointments booked online to triage appointments via telephone or video’. 16 Then, in a speech delivered in late July 2020, the then Health and Social Care Secretary, Matt Hancock, specified that ‘from now on, all consultations should be teleconsultations unless there’s a compelling clinical reason not to’. 17 To support this, NHS Digital provided guidance to practices about approved online consultation suppliers that could be used immediately, to enable practices to swiftly implement digital approaches.

As the easing of COVID-19 restrictions started to take place, a shift in policy and media narrative towards the availability and delivery of face-to-face appointments was noticeable. 16–18 Digital First Primary Care systems were widely procured and adopted at practice and system level during COVID-19 and made available via a Digital First Online Consultation and Video Consultation (DFOCVC) framework. A policy objective (from the NHS Long Term Plan) was therefore expedited by COVID-19. Yet, the use of online consultation and video systems remains highly variable across general practices in England due to population demographics, practice contexts and staff digital skills.

Further guidance was issued to practices in May 2021 detailing that video, online and phone consultations could be maintained, but that GP practices should ensure they offered face-to-face appointments and that patient preferences for face-to-face care should be respected,16 reversing the previous position of offering telephone or online triage before face-to-face appointments.

Later in 2021, this was followed by a plan from NHS England and NHS Improvement designed to improve access to GP appointments for patients. 17 The plan acknowledged longstanding issues around patients access to care and the subsequent need for changes in access as a result of COVID-19 and highlighted emerging challenges for practices in achieving an ideal blend of face-to-face and remote appointments. In response to these challenges, the plan laid out a range of actions to be taken to support general practice and improve access. This included a new £250 million Winter Access Fund in England, which detailed that practices that were deemed to not be providing appropriate levels of face-to-face care would not be able to access the additional funding and instead offered support to improve. 17

More recently, 2022/23 priority and operational planning guidance from NHS England and NHS Improvement asked healthcare systems to support primary care networks (PCNs) and practices to deliver the commitment to ensure that all patients have the right to be offered Digital First Primary Care by 2023/24, which would enable them to reach the right service, whether remotely or face-to-face. 18

During summer 2022, a new Digital Health and Care plan was published by the Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England, which set out priorities for digital transformation, consolidating previous commitments and ambitions. This included the development of the NHS app and website to support patient access to services, and the use of digital to support the management of long-term conditions. This noted that patients would not have to use digital services: for those who cannot or prefer not to access services digitally, traditional services would stay in place. 19

More widely, the multiple changes in emphasis and policy throughout this period were not well received by GPs. Following the guidance to return to offering face-to-face appointments, the BMA GP committee chair stated that: ‘NHSE and the Government owe practices a huge debt of gratitude, not a public rebuke for ultimately doing what they were instructed to do’ while the Chair of the Royal College of GPs explained that ‘it needs to be down to individual GP practices to be able to decide how they deliver services, based on their knowledge of their patient population’. 20

While some of the changes may only have been thought to be temporary – in place to support primary care to be able to continue providing patient care during the pandemic – it is likely that Digital First Primary Care approaches will be used to a greater extent than before the pandemic, with a blend of approaches supported in government policy. In the future, practices will likely offer a range of options and will operate in different ways, linked to their practice circumstances, set-up and the needs of their practice population. Notably, the term ‘Digital First Primary Care’ is a term that continues to evolve, as do the digital approaches adopted in general practice, such as the use of online consultations and triage systems.

Patients with multiple long-term conditions in England

In England, approximately a quarter of adults (depending on which conditions are included) have two or more long-term conditions. 21 People with multimorbidity are higher users of healthcare services, with estimates suggesting that their care needs account for over half of NHS costs, and they often have a lower quality of life and poorer life expectancy. 21,22 Continuity of care is particularly important in this patient group, given their frequent interactions with the health service. Continuity of care can help to reduce the number of times a patient needs to re-tell their story, improve relationships and trust with healthcare providers and give patients greater involvement in their own care. 23

The 2022 GP Patient Survey included questions related to digital use, and the data can be broken down by patients with long-term conditions and individuals with caring responsibilities. 24 While nearly two-thirds of both groups found it easy to use their GP practice website to find information or access services, over 40% of both groups had not used online GP services (e.g. booking appointments, ordering repeat medication or having an online consultation). Almost no patients from these groups (1–2%) had an online consultation for their last appointment, although over 40% had spoken to someone on the phone. 24

The issue of multimorbidity is prominent and is receiving consideration in NHS policy and guidance. Throughout the NHS Long Term Plan,5 multimorbidity is a key theme, with aims for the NHS to be more joined-up in its care, breaking down barriers to support people with long-term conditions. The recent Health and Care Act (2022) built on this,25 introducing significant changes to how health services are organised and delivered to support the delivery of more integrated and co-ordinated care. This is of importance in addressing challenges for those with multimorbidity who often require support from multiple organisations simultaneously, and should enable organisations to meet patient needs in a more joined up way.

The recent stocktake of primary care in the English NHS, in the form of the Fuller review,26 set out a vision for integrating primary care and bringing together general practice with other parts of the system to improve patient care. The vision was centred around three essential offers, one of which referred explicitly to providing more proactive, personalised care, including to those with multiple long-term conditions. 26 It highlighted that digital- and technology-based approaches offered solutions in providing access to and delivery of care for those who wish to use it, potentially freeing up more time for face-to-face support for those who need it most. 26

More widely, multimorbidity was also identified as a major strategic priority for the NIHR in 2021,27 with the Academy of Medical Sciences in 2018 calling for more research to address the challenge. 28

Context within English general practice at the present time

The changes described have taken place amidst an extremely challenging climate for general practice in England, with workforce shortages and increasing workload which were apparent even before the pandemic. The number of full-time equivalent, fully qualified GPs has fallen since 2015 yet GP appointment numbers are higher than they were before COVID-19,29 and the average number of patients GPs are responsible for has risen. 13 A provider poll carried out in August 2022 showed that 90% of the primary care providers who responded agreed or completely agreed that they were finding it difficult to recruit staff. 30 Yet the number of healthcare professionals in total (excluding GPs) has increased by over 6000 during the last year, in line with the government’s target to increase the number of health professionals working in general practice. 5,31 This could be linked, in part, to the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme, introduced in 2019 as part of the GP contract framework, to support the recruitment of 26,000 additional staff working in general practice by 2023/24 and aid an increase in the number of annual appointments in general practice. 32,33

Relatedly, the latest GP work–life survey highlighted that a third of GPs plan to leave direct patient care within 5 years, with GPs reporting the greatest stress from a range of factors including increasing workloads, long working hours and increasing patient demands. 34 Further, as a result of the pandemic, primary care professionals have been working in an uncertain and ever-shifting environment,35 and the impacts of COVID-19 on primary care were considerable,12 with the whole system now seeking to recover.

More widely, these pressures have been accompanied by negative media coverage and a narrative that general practice is ‘closed’, and less willing to see patients face-to-face. A statement from the chair of the BMA’s GP committee discussed ‘anti-GP’ rhetoric in the media following a media campaign about GP face-to-face appointments in England. 36 This was supported by a recent study, which found that newspaper coverage of remote consulting was highly negative, that remote consultations had become associated with poor practice and that some papers were ‘leading the war’ on general practice. 37

Aims of this study

This rapid evaluation originally had one distinct aim: to understand the experiences of those with multiple long-term conditions of Digital First Primary Care, from the perspectives of patients, their carers and healthcare professionals. However, due to recruitment challenges and a lack of uptake to the study from general practice, largely due to COVID-19 pressures, the focus instead was amended to the experiences of healthcare professionals and stakeholders. As a result, minor amendments were made to the research questions.

As a result of the scoping work, where relevant literature on the use of Digital First Primary Care by patients with multiple long-term conditions was engaged with and a workshop with patients [members of the BRACE patient and public involvement (PPI) group] was held, four research questions were identified by which to address this aim. 1

-

What is the experience of Digital First Primary Care for health professionals and stakeholders (including academics, policy makers and Digital First Primary Care providers), both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

What is the impact of Digital First Primary Care on the nature of consultations, from the perspective of health professionals and stakeholders, for patients with multiple long-term conditions and their carers? This includes aspects of communication, timeliness of care and continuity of care.

-

What, if any, are the advantages or disadvantages of Digital First Primary Care for health professionals when providing care for patients with multiple long-term conditions?

-

What lessons can be learnt from staff and stakeholders for future service delivery for patients with multiple long-term conditions in primary care? Are there individual groups within the community where there is particular learning for future service provision?

While in Chapter 1 we have set out a definition of Digital First Primary Care, it should be noted that, within the literature and during interviews with health professionals and stakeholders, firm distinctions and definitions were often not used.

Chapter 2 Locating the study within the wider literature

Box 2 provides a summary of Chapter 2 of this report.

Summary of key points

-

We explored key literature related to the use of Digital First Primary Care, including for patients with long-term conditions.

-

Digital First Primary Care has been subject to much research over the last decade, starting with research into telephone triage and moving towards the assessment of digital approaches as these became more commonly used.

-

While these studies identified positive aspects of using Digital First Primary Care, such as patient convenience, other evidence is mixed across studies, for example relating to GP workload.

-

While Digital First Primary Care has been the focus of much recent research, this has often not included a specific exploration of how digital approaches impact patients with multiple long-term conditions. Studies that have included patients with multiple long-term conditions specifically have identified some positive experiences of using Digital First Primary Care. However, challenges do exist, such as digital literacy, impersonal interactions and difficulties picking up on non-verbal cues. It is likely that the type, number and complexity of long-term conditions influence patients’ use and experience of Digital First Primary Care; however, there is very little research into this area.

To locate this study within the existing research and evidence on the use of Digital First Primary Care by patients, specifically those with multiple long-term conditions, we have reviewed the literature relating to this topic. Due to the complexities in the definition of Digital First Primary Care, noted in Chapter 1, a broad and inclusive approach was taken when examining the wider literature. At the start of the study, we undertook an initial pragmatic and rapid review of the relevant studies (see Box 3 for further information). While we acknowledge that there is a large literature base on the use of digital approaches in healthcare (including for specific conditions), we focused on key literature to provide context to our study, rather than providing a full systematic review of the literature.

-

Search terms used: digital, Digital First Primary Care, digital triage, COVID-19, long-term conditions and multi-morbidity.

-

Search engines used: PubMed and Google Scholar.

-

Additional searches: the reference lists of identified articles were screened for further potentially interesting references.

-

Years searched: 2011–present.

-

Searches conducted: at three points during the study (start, middle and towards the end).

-

Inclusion criteria: articles detailing the use of Digital First Primary Care in a general practice setting, either pre, during or after the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly those related to multiple long-term conditions.

-

Exclusion criteria: Articles not in the English language, studies conducted outside of the UK.

-

The findings from the identified literature were written-up in a thematic way to identify context and learning that applied to each of the research questions.

Here, we present a brief overview of the key literature related to the use and impact of Digital First Primary Care for patients (including those with long-term conditions) and healthcare professionals.

Impact of Digital First Primary Care on patients

Digital First Primary care could impact patients in a range of ways, as identified by multiple studies on this topic. Here, we discuss the impacts on patients in general and later in this section we discuss its use and impacts specifically for patients with multiple long-term conditions.

Some studies found that patient satisfaction could be high with regards to digital methods of engaging with GP practices; patients valued having multiple routes to communicate with their practice and appreciated the convenience of digital engagement (e.g. no need to travel and ability to minimise the amount of work missed). 38–43 However, other studies found more mixed evidence in relation to patient satisfaction, which could be due to differences in the digital literacy of patients and the complexity of the patient’s issue (see later). 43–45 The method of data collection for studies which explored this issue can also be a challenge (e.g. collecting data online only may skew data collection towards the views of the digitally literate, who may have more favourable views). 40

There was mixed evidence on how comfortable and confident patients felt discussing their symptoms remotely. One study found that patients had concerns around whether they could communicate their symptoms effectively remotely,40 but another found that patients may feel more confident doing this remotely. 44

There were some challenges identified in the literature for patients using digital methods of engagement with their practice. These included concerns over privacy/confidentiality, language barriers, a less holistic assessment of the patient, a heightening of inequalities, less continuity of care and the reduced quality of patient–clinician interactions. 43,44 There could also be issues with staff phoning patients at different times than they had originally specified. 42,44 One study found that one of the key issues raised by patients was the importance of respecting their time and understanding how appointments fit in with their lives. 42

Digital First Primary Care specifically for patients with long-term conditions

Few studies have been conducted that include an exploration of how Digital First Primary Care has been used specifically by patients with long-term conditions, highlighting variations in its uptake, benefits and challenges. While the focus of our study is on multiple long-term conditions, very little literature was identified in relation to this group of patients. Therefore, here, we summarise the findings from key studies exploring the use and impact of Digital First Primary Care both for patients with single and multiple long-term conditions.

The evidence is mixed as to the uptake of Digital First Primary Care for patients with multiple long-term conditions. A 2018 study found that patients with multiple long-term conditions showed higher rates of accessing alternatives to face-to-face consultations (although this group has a higher use of any type of consultation in general) than those without multiple long-term conditions. 9 However, an evaluation of Babylon GP at Hand, a primary care practice in North West London that offered Digital First approaches to primary care, found that users were likely to be healthier and that patients with more complex needs were less likely to use the service (with only 29% of users reporting that they had a long-term condition). 46 The low number of patients with long-term conditions using the service was speculated by the authors to be due to a cautionary note sent to potential users stating that those needing more frequent face-to-face appointments would need to travel to a surgery which may not be local to them; this may well have deterred those with long-term conditions from using the service.

Studies have found some benefits for patients with long-term conditions when utilising Digital First Primary Care approaches. Both the evaluation of Babylon GP at Hand and a study that explored the use of remote primary care consultations for people with dementia (and their carers) found that there was quicker access to care. 46,47 A 2021 rapid literature review exploring how patients and healthcare professionals experienced remote consultations found that they allowed for better monitoring of patients than in-person appointments. This was found to be particularly beneficial for patients with long-term conditions who could more conveniently complete tasks such as medication adjustments from home. 44 The study of patients with dementia also noted the benefits of the reduced risk of contracting and transmitting infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, when engaging remotely with primary care,47 which is particularly beneficial as patients with long-term conditions are often at high risk of worse outcomes from infectious diseases.

The literature also highlights the challenges patients with long-term conditions may face when engaging with their practice digitally. There may be difficulties in accessing care digitally for those with long-term conditions. For example, a 2021 rapid literature review found that staff reported a reduction in cases of certain chronic conditions, which may mean that these conditions were not being managed as well as they should. 44 In addition, a 2022 Nuffield Trust report found potential issues for patients with more complex health conditions as the availability of online support can increase demand for GP services overall, often for minor illnesses that do not require GP input, meaning less availability of consultations for patients with long-term conditions. 38 Other barriers to using remote consultation approaches were mentioned in the study exploring the views of dementia patients/carers, although many of these could apply to all patients, not just those with long-term conditions. These included interactions feeling impersonal, challenges with technology, hearing/memory challenges, the inconvenience of GPs not calling at the arranged time and difficulty in voicing concerns and in healthcare professionals picking up on non-verbal indicators of health (particularly physical health). 47

It is likely that the type, number and complexity of long-term conditions will influence patients’ use and experiences of Digital First Primary Care. For example, the evaluation of Babylon GP at Hand found that experiences varied according to the type of long-term condition, with patients with physical mobility problems reporting worse experiences and those with breathing problems reporting better experiences. 46

Impact on primary care staff

Primary care practice staff are also impacted by the introduction of Digital First Primary Care approaches and have opinions about its use. Here, we describe some of the benefits and challenges healthcare professionals may face when supporting patients both with and without long-term conditions.

Some studies found staff to be positive about the introduction of a new digital system, feeling confident in patients using it and that it could complement existing services. 38,39,41 As with patient impact, there is also the benefit of reduced transmission of infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, due to less footfall in the practice. 44 Some of the benefits of remote consulting were found to be prioritising patients with poorly controlled conditions, greater control over the working day for GPs and patients being more direct in describing their issue and raising fewer problems during phone consultations. 48 Video consultations were thought to be particularly useful for dynamic patient assessments, assessing children, training patients/carers in at-home procedures (e.g. wound care) and connecting with elderly/vulnerable patients. Using text messaging was thought to be effective for fitness to work notes, prescription information and risk assessment questionnaires for patients with long-term conditions. 48

There are also some important concerns from the perspective of staff, such as uncertainties about integrating new digital systems with existing processes and greater difficulties in healthcare professionals making clinical decisions when consulting remotely. 39,44 A challenge of the new ways of triaging patients included reaching out to vulnerable patients, for example those without a carer or homeless patients. 49

Studies have found mixed evidence on whether staff workload changes as a result of introducing digital systems,44,45 although many do note an increased staff burden and unintended consequences on workload in primary care or elsewhere. For example, one study found that most e-consultations resulted in phone or face-to-face appointments, which GPs felt duplicated their workload. 8 A 2019 rapid evidence review found that, while there was some evidence that Digital First services could reduce the burden on primary care, this differed across studies, depending on the outcomes of interest and the type of digital approach used. 50 In a 2021 mixed-methods study which explored GPs’ experience of triaging patients during the pandemic, GPs reported that telephone triage took longer than expected and felt similar to conducting a remote consultation, and this may result in confusion for the patient as to the purpose of the triage call. There may also be a risk of over-referring for face-to-face appointments (rather than remote) due to concerns over missing something a patient may be presenting with. 49 The Nuffield Trust published a report in 2022 on the practical challenges related to remote consultations and identified that remote consultations took longer than face-to-face consultations and there were greater referrals to other services. 38

There are also some concerns over patient safety. For example, studies identified challenges in picking up non-verbal cues from patients when conducting remote consultations, difficulties in building trust and rapport during shorter remote consultations, feelings of fatigue due to dealing with higher clinical risk, potential problems with missed or delayed diagnoses and safeguarding issues. 38,48,49 A longitudinal exploration of remote consulting during the pandemic found that telephone consultations required additional (and careful) questioning as complex cases which previously would have been seen in person were being managed by phone. 48

Summary

In summary, while Digital First Primary Care has been subject to previous research, this has often not included a specific focus on patients with long-term conditions. In particular, there is a significant gap in understanding its use and impact for patients with multiple conditions and the views of carers. For those studies that do include patients with multiple long-term conditions, this is often a secondary consideration rather than the core focus of the study (as outlined in this chapter). In addition, most studies focused on experiences of remote consultations as opposed to exploring the entire Digital First Primary Care pathway, starting from the initial (digital) contact with a GP practice. Therefore, our study is well placed to fill this gap in understanding and evidence from the perspective of healthcare professionals and stakeholders on the use of Digital First Primary Care specifically for patients with multiple long-term conditions.

Chapter 3 Methods

Box 4 provides a summary of Chapter 3 of this report.

Summary of key points

-

The original aim of this rapid evaluation was to understand the experiences of those with multiple long-term conditions of Digital First Primary Care from the perspectives of patients, their carers and healthcare professionals. Due to pressures within the general practices recruited, largely due to COVID-19, it was not possible to recruit patients and carers to the study. Instead, the study focused on the experiences of healthcare professionals and stakeholders. We completed a qualitative evaluation comprised of four linked work packages (WPs):

-

WP1. Locating the study within the wider context, engaging with literature, as well as co-designing the study approach and research questions with patients.

-

WP2. Interviews with health professionals working across general practice and expert topic stakeholders from policy organisations, academia and policy.

-

WP3. Analysis of data, generation of themes and testing findings with patients.

-

WP4. Synthesis, reporting and dissemination

-

-

We undertook a purposive sampling strategy to select general practices from two digital providers, GP federations and super-partnerships to identify NHS members of staff. A convenience sampling approach was used to recruit stakeholders.

-

Despite not applying an explicit theoretical framework, our analysis was guided by empirical literature on Digital First Primary Care both pre and post the COVID-19 pandemic.

General approach

Original approach

The original aim of this study was to understand the experiences of those with multiple long-term conditions of Digital First Primary Care from the perspectives of patients, their carers and healthcare professionals.

Our general approach to meet this aim was a qualitative evaluation comprised of four WPs: (1) contextually embed the study within the relevant literature and co-design the study with patients; (2) conduct interviews with NHS staff and patients and carers; (3) analysis of data; and (4) synthesis of learning and reporting.

Modified approach

General practices did not have the time, resources or capacity to recruit patients to the study, so we were unable to conduct interviews with patients/carers.

Following the initial study conception, the team reviewed and refined the research questions with respect to the on-going challenges and changes occurring in general practice and more widely. For example, our research questions were not only amended due to recruitment challenges, but also to include the topic of COVID-19. Table 2 illustrates the adaptation of the research questions for the study.

| Research questions at conception of the study (2019–2020) | Research questions addressed in the current study |

|---|---|

| Question 1: What is the experience of Digital First Primary Care for patients with multiple long-term conditions, their carers and health professionals? | Question 1: What is the experience of Digital First Primary Care for health professionals and stakeholders (including academics, policy makers and Digital First Primary Care providers), both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic? |

| Question 2: What is the impact of Digital First Primary Care on the nature of consultations for carers/patients with multiple long-term conditions and health professionals, which includes aspects such as the health professional(s) spoken to, timeliness of care and continuity of care? | Question 2: What is the impact of Digital First Primary Care on the nature of consultations, from the perspective of health professionals and stakeholders, for patients with multiple long-term conditions and their carers? This includes aspects of communication, timeliness of care and continuity of care. |

| Question 3: What, if any, are the advantages or disadvantages of Digital First Primary Care for patients with multiple long-term conditions and their carers? | Question 3: What, if any, are the advantages or disadvantages of Digital First Primary Care for health professionals when providing care for patients with multiple long-term conditions? |

| Question 4: What lessons can be learnt from staff, patients’ and carers’ views for future service delivery for patients with multiple long-term conditions in primary care? Are there individual groups within the community where there is particular learning for future service provision? | Question 4: What lessons can be learnt from staff and stakeholders for future service delivery for patients with multiple long-term conditions in primary care? Are there individual groups within the community where there is particular learning for future service provision? |

Protocol sign-off

The study topic was identified and prioritised for rapid evaluation in 2019 through the BRACE Centre’s approach to identifying innovations through horizon scanning. An initial topic specification (first stage protocol) was prepared (September 2020) and, once approved by NIHR HSDR, was used as the basis for writing the full research protocol (March 2021, published on the NIHR HSDR webpage), which drew on the findings from mapping the published and grey literature alongside stakeholder and PPI engagement (WP1). A revised protocol, version 3.0, was published following amendments to the approach.

Ethical approval

An application for ethical review to the University of Birmingham’s Humanities and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee was made by the project team and approval was obtained in August 2021 (approval number ERN_13-1085AP43, ERN_21-1233). The project team received confirmation from the Health Research Authority (HRA) that this study was to be categorised as a service evaluation and therefore approval by the HRA or the NHS Research Ethics Committee was not required. In addition, clarification was sought from the Head of Research Governance and Integrity at the University of Birmingham, who confirmed that the project should be categorised as service evaluation.

The methods used in the first, second and third WPs are described in the following paragraphs.

Description of the methods used to engage with patients from the BRACE Patient and Public Involvement group

A workshop with patients (five members of the BRACE PPI group) was held online in September 2020 to shape the research questions and share learning from the literature on the introduction, implementation and use of Digital First Primary Care services. During the workshop, members expressed a wish that the study team focus more on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the roll-out of Digital First Primary Care services, and on the impact of greater digital use in general practice more generally and how this affects access to and continuity of care. As a result, the authors ensured the interview topic guides for participants were amended to include these areas.

Focus on patients with multiple long-term conditions

Our evaluation focused on people living with multiple long-term conditions, forming part of the BRACE Centre’s overarching analysis of service innovations and how they are experienced by and impact on people living with multiple long-term conditions. 51 We used the definition from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) which defines multimorbidity as ‘the presence of two or more long-term health conditions which can include’:

-

Defined physical and mental health conditions, such as diabetes or schizophrenia.

-

Ongoing conditions, such as learning disability.

-

Symptom complexes, such as frailty or chronic pain.

-

Sensory impairment, such as sight or hearing loss.

-

Alcohol and substance misuse. 52

As part of this evaluation, we considered how any comorbidities a patient with multiple long-term conditions has may influence their use and experience of Digital First Primary Care (e.g. fatigue caused by the health condition or treatment side effects).

A note on the logistical challenges of recruiting GP practices

Throughout the duration of this study, we faced significant challenges in recruiting GP practices. This resulted in a change to the original protocol to enable the completion of the study. This section describes the challenges faced and subsequent changes to the research protocol. The project was initially conceived as a 6-month project but, ultimately, was completed over a period of 22 months due to a pause (during the pandemic) and challenges to recruitment.

The original aim of the study was to recruit six GP practices, conducting interviews with one to two GPs, one to two other healthcare professionals and three patients per practice (12–24 staff interviews and 18 patient interviews in total). While we recruited more than the intended practices to the study (8 in total), there were significant challenges with recruitment, and it took much longer than expected (8 months). Most practices did not respond to repeated recruitment requests, hence, we lack reasons for non-participation. Those who did respond mentioned the significant workload, staffing pressures and demand challenges they were facing (often related to COVID-19), which meant that they felt they the lacked capacity to participate. We attempted multiple methods of recruitment to bring GP practices on board, including at least weekly e-mail and telephone reminders. We also attempted to recruit practices via multiple sources, including direct contact from the research team (contacting 179 practices in total), recruitment via an open invitation from a Digital First Primary Care provider to all practices using their service, as part of their monthly newsletter, a purposeful approach via a GP super-partnership to all practices in their group and direct contact to practices who had participated in previous research studies known to the research team (see further detail later in this chapter).

To encourage recruitment, we offered flexibility in the timing and length of interviews and offered support in conducting the patient database search to identify patients/carers to approach to take part in an interview. Given the cited pressures on primary care, we had to reflect on when the right point was to stop contacting individual practices as we did not want to pressurise already-stretched staff. We also had to decide when to try alternative recruitment methods (the initial aim was to just recruit via direct researcher contact rather than via providers/super-partnerships) to ensure that we kept to the timelines for the study. For the practices recruited to the study, we were unable to recruit patients/carers for interviews as practices were unable to dedicate the resources needed to conduct the patient database search, despite offers of payment of service-support costs to participating practices. One practice was able to conduct the search but was unable to find the time for a GP to review the list of patients, a requirement before the letters could be posted. COVID-19 presented particular challenges in this respect; in previous studies the PI had been able to attend practices and help staff to prepare envelopes and stick on stamps. The lack of patient/carer views on Digital First Primary Care is a significant limitation of this study and it is important that this is the focus of future research studies (see Discussion and conclusions).

To mitigate some of these recruitment challenges, we made an amendment to our research design to include interviews with key Digital First Primary Care stakeholders, such as policy makers, think tanks, third sector organisations, academics, Digital First Primary Care providers and health professionals working in other roles [such as within Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs)/integrated care systems]. This helped to address gaps in knowledge about the development and implementation of Digital First Primary Care and provided a better understanding of the challenges of making digital policy-related changes within primary care. As several of the stakeholders were also practising health professionals, it also enabled the views of professionals from a greater number of practices to be included in the study.

As it appears that Digital First Primary Care is here to stay,53 it is important that we understand how its use impacts the care received by different patient groups, including those with multiple long-term conditions. Given the limited exploration of this topic in the literature so far, the authors have added to current understanding in this area and provide lessons for future practice (see Discussion and conclusions).

Sampling and recruitment of general practices delivering Digital First Primary Care

Two commercial providers of Digital First Primary Care (Provider A and Provider B) agreed to participate in our study and assist with the identification of practices using their approach. At the time of writing this report, we were unable to locate publicly available information to determine how many commercial providers were providing Digital First Primary Care services in England and how many practices and GPs were using these services.

Providers varied in the approach they were happy to take in terms of recruitment, so it was necessary for the research team to be flexible. One provider (Provider A) supplied the study team with a list of practices operating a Digital First approach for 6 months or more for the research team to contact directly. Provider B preferred a different approach, by which they sent recruitment material to a randomly selected sample of 150 practices using their Digital First approach on behalf of the research team. Due to recruitment challenges, the research team also contacted a super-partnership which shared recruitment material across their 45 practices. Practices across the super-partnership used both Provider A and B’s Digital First Primary Care platforms.

Our initial approach was to use a maximum variation sampling strategy to identify general practices, 54 for example with varied list sizes, locations (urban or rural) and including areas of high deprivation and with ethnic diversity. However, due to the recruitment challenges outlined, it was necessary to adopt a convenience sampling strategy.

Two study team members (MS and LH) approached all 179 practices from the list provided by Provider A as well as interested practices from the super-partnership via (1) an electronic invitation via e-mail sent to practice managers (or central practice e-mail addresses if the practice manager e-mail was unavailable) explaining the purpose of the study and their potential involvement, followed up by (2) weekly telephone calls to arrange meetings with primary care staff to discuss the study, concluding with (3) a final e-mail reminder for practices who had not responded within the 6–8 week timeframe. Despite approaching 179 practices for Provider A, only 2 were recruited.

For Provider B, an e-mail invitation was drafted by the research team and sent to a sample of randomly selected practices by the provider. Practices interested in taking part in the study were asked to get in contact with a member of the research team to arrange interviews. Initially, 50 invitations were sent out, followed by another 100. However, no practices were recruited via this method. Due to these recruitment challenges, the research team approached a GP super-partnership, whereby an e-mail invitation was sent out to the 45 practices in the partnership on behalf of the research team. This approach was successful and resulted in five practices being recruited to the study. In addition, members of the research team approached practices they had recruited to other research studies to see if they would like to take part in the study. This resulted in one further practice being recruited to the study. This meant a total of eight practices were recruited. All practices within our sample were using Digital First Primary Care in some capacity prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. A summary of the practice recruitment is provided in Table 3. Due to the challenges with recruitment, it took place over an 8-month period (January to August 2022) to ensure that we recruited enough practices to collect sufficient data.

| Recruitment source | Total number of practices invited | Number recruited | Provider |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provider A contact list: contacted directly by researcher | 179 | 2 | Provider A |

| Provider B-led recruitment: newsletter from provider | 150 | 0 | – |

| GP super-partnership-led recruitment: partnership e-mail on behalf of researchers | 49 | 5 | Either current or previous Provider B user |

| Practices involved in previous research: approached by researchers | 3 | 1 | Provider B |

| Total | 381 | 8 | – |

Sampling and recruitment of patients and carers

To identify patients with multiple long-term conditions, practice staff (and central administrators as part of the super-partnership) were asked to run a search of patient records to identify suitable patients. The research team worked with practices to refine their search depending on the clinical system used. The following inclusion criteria were used:

-

Aged 18 years and over.

-

Living with at least two long-term health conditions (in accordance with NICE guidance).

-

Have accessed Digital First Primary Care services recently.

The practices were asked to send invitations to up to 100 patients at a time who met the above search criteria in order to recruit up to four patients per practice. The intention was for practices to send a study invitation on behalf of the research team and the patients/carers to return a form to the research team if they wanted to participate in an interview. However, due to capacity challenges in the recruited practices, seven of the practices were unable to develop and run a patient search on their database. In the eighth practice the patient search was conducted but GP staff were not available to review the list of patients, a requirement of the study, within the timeframe of the project.

Other approaches to recruit patients and carers to this project, outside of general practice, were considered by the BRACE team in consultation with the steering group and PPI group. However, due to COVID-19 and pressures within other organisations, and the time constraints of the project, this was not possible.

Recruitment of health professionals and expert stakeholders

The study team invited any primary care clinician and allied health professional who was involved in using the Digital First Primary Care approach when managing patients living with multiple long-term conditions for an interview. A senior clinician or practice manager was identified across each practice to act as a gatekeeper to identify relevant staff to take part in interviews. A gatekeeper was defined as a person who could act as an intermediary between a researcher and potential participants with the authority to deny or grant permission for access to potential research participants. 55,56 The gatekeeper facilitated the identification of key individuals involved in the design, implementation, governance or use of Digital First Primary Care platforms for patients with multiple long-term conditions.

Staff were provided with a participant information sheet (see project documents) and completed interviews online (MS Teams/Zoom). Each respondent was provided with the participant information sheet in advance (see project documents). Interviewees had the opportunity to ask questions about the study and signed a consent form (see project documents) prior to participating in the interview, including whether they consented to the recording of the interview. Participants were informed that they were entitled to withdraw from the study at any time and were given information about how to find out more about the study and how to raise any concerns about its conduct.

The evaluation team originally planned to complete 2–4 interviews across each practice (1–2 GPs and 1–2 other health professionals, 12–24 interviews total). However, due to the previously mentioned recruitment and capacity challenges within primary care, 14 interviews were conducted with staff. These were held with 10 GPs and 4 nurses. The interviews lasted between 20 and 60 minutes.

Expert stakeholders were defined as participants that had regional or national level expertise in Digital First Primary Care, including those who may have critical oversight at a level beyond individual practices, for example GP federations and CCGs, decision-makers at a national level, those who work in academia, policy think tanks or commercial companies. The sampling was purposive, identifying participants with topic knowledge of Digital First Primary Care from the groups outlined. Potential participants were identified from the scoping of the published literature, grey literature, policy documents and organisations identified during the scoping work. Snowball sampling was also used – at the end of each interview, participants were asked ‘is there anyone else with topic knowledge in this area that you think we should speak to?’. E-mail invitations to participate in an interview, with information sheets, were sent to 30 contacts, 14 interviews were conducted with 15 participants. No explicit declines were received. The interviews lasted 30–75 minutes.

Fieldwork was completed in parallel across general practices and expert stakeholders (March to September 2022) by three members of the research team with experience of undertaking interviews and qualitative data analysis (lead by JN with MS and LH). JN, MS and LH were responsible for all communication and data collection; a small number of recordings of interviews completed by LH and MS with primary care staff for were reviewed by JN.

A topic guide for use with NHS staff was developed, adapted (as a result of changes to theresearch questions) and used by researchers as an aide-memoire during the interviews (see Appendix 1). The main themes covered by the topic guide were: reasons for implementing and using a digital platform; staff training (if any); the benefits and drawbacks of Digital First Primary Care; the impact on managing patients living with multiple long-term conditions; the impact on practice workload and staff satisfaction levels. A topic guide for stakeholders was developed covering similar topics with specific questions on their perceptions about the benefits and drawbacks of Digital First Primary Care for patients and submitted as an amendment for ethical approval.

The interviews were audio-recorded (subject to consent being given), transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service, anonymised and kept on the University of Birmingham’s research data server in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation 2018 and the Data Protection Act 2018.

The study did not formally aim to achieve data saturation, but participant samples were regularly reviewed during the data collection phase, while a purposive approach was taken to target specific stakeholders that were under-represented (i.e. nurses).

Characteristics of sites and participants

Eight practices were recruited representing a broad variation across locations, ethnic diversity, practice size, proportion of patients aged ≥ 65 years and level of deprivation (see Table 4). The reasons for declining participation included COVID-19 pressures and a lack of capacity due to staffing challenges. The researchers conducted fieldwork with practices from April to August 2022.

| Practice ID | Size (small < 6000 patients; medium 6000–12,000 patients; large ≥ 12,000 patients) |

Location | Percentage of non-White British patients by practice (%) | Percentage of patients ≥ 65 years old registered with practice (%) | Deprivation (1 = high, 10 = low) | Specific example of digital facilitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Medium | Rural | 1.4 | 31.6 | Low (score = 8) | One of several practices that is part of a vertical integration set-up with the local acute hospital. Using Provider A, introduced pre pandemic. |

| B | Large | Semi-rural | 7.2 | 17.1 | Low (score = 8) | Part of a nationwide super-partnership. Using Provider B, introduced pre pandemic alongside other digital platforms. |

| C | Large | Urban | 5.5 | 20.1 | Low (score = 10) | Part of a nationwide super-partnership. Using Provider B, introduced pre pandemic alongside another digital platform. |

| D | Large | Rural | 22.1 | 17.2 | High (score = 2) | Part of a nationwide super-partnership. Previously used Provider B but had moved away from it in favour of another digital platform. |

| E | Large | Rural | 3.7 | 27.3 | Low (score = 9) | Part of a nationwide super-partnership. Previously used Provider B but had moved away from it in favour of another digital platform. |

| F | Large | Rural | 15.3 | 16.5 | High (score = 2) | Part of a nationwide super-partnership. Previously used Provider B but had moved away from it in favour of another digital platform. |

| G | Medium | Urban | 55.5 | 8.3 | High (score = 3) | Using Provider B, introduced pre pandemic alongside another digital platform. |

Description of practice staff interviewed

We invited 19 potential participants and interviewed 10 GPs and 4 nurses across 8 practices (see Table 5). The interview lengths ranged from 30 to 75 minutes. The interviews were conducted via video conference or telephone.

| Characteristics | Number of participants (total = 14) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 6 |

| Male | 8 | |

| Role in practice | GP | 10 |

| Nurse | 4 | |

Description of stakeholder interview participants

In total, 15 stakeholders were interviewed, across 14 interviews, between June and September 2022. The interview lengths ranged from 28 minutes to 1 hour.

In summary, we took an empirically led approach to the data collection and analysis for this rapid evaluation, including repeated discussion across the whole project team and PPI members. Our approach supported engagement with the data in a timely fashion while simultaneously keeping abreast of ongoing developments with Digital First Primary Care in general practice by speaking to stakeholders. In the following chapter, we present our findings in relation to the context in which Digital First Primary Care has been implemented and its benefits and challenges for patients living with multiple long-term conditions, from the perspective of our participants.

Analysis and interpretation

Data analysis

Between April and September 2022, the data gathered through interviews were analysed. To aid the process of analysing and interpreting the data, the team (JN, MS, LH, KD) held twice-monthly video call meetings for the duration of the project to discuss the project’s progress and emerging findings. Furthermore, the team undertook four online half-day workshops (September 2020, August 2022, October 2022 and November 2022). The purpose of these meetings was to discuss the data in the context of findings from mapping the relevant literature (WP1), identify any unexplored gaps in the data and develop a theoretically informed line of argument to answer the research questions.

The interview analysis was informed by the Gale et al. framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. 58 This method of analysis is a systematic method of categorising and organising data while continuing to make analytical and interpretive choices transparent and auditable. There are seven stages to the analysis.

-

Transcription of interviews.

-

Familiarisation with the interview/observation/documentary material.

-

Coding.

-

Developing a working analytical framework.

-

Applying the analytical framework.

-

Charting data in a framework matrix.

-

Interpreting the data.

Stage 1. Transcription. All interviews with staff and expert stakeholders were transcribed verbatim through a professional, outsourced transcribing company.

Stage 2. Familiarisation with the material. The members of the study team established familiarity with the data by each reading three transcripts (one each conducted by JN, MS and LH) and discussing their learning at twice-monthly meetings, while the data collection was still ongoing (April to September 2022). During meetings, the team members were able to discuss and share their preliminary thoughts and impressions of the early findings.

Stage 3. Coding and Stage 4. Developing a working analytical framework. Stages 3 and 4 of the analysis took place in tandem. The study team applied a deductive approach, having developed pre-defined codes focusing on the specific areas of interest identified from our scoping of the relevant literature. These were reviewed, refined and added to. NVivo 12 was used to assist with the coding of data. An analytical coding framework was agreed upon (September 2022) by all study team members (see Appendix 2). The codes were categorised under broad themes.

Stage 5. Applying the analytical framework. The working analytical framework was then applied by indexing (KD, MS, LH) across all interview transcripts, that is the systematic application of codes from the agreed analytical framework to the whole dataset and subsequent transcripts using the existing categories and codes. Stakeholder and staff interviews were treated as one dataset.

Stage 6. Charting codes. The team developed a narrative-led framework based on the summaries of each code (once the analytical framework had been applied to all transcripts) to ensure that all the research questions were answered. This process was led by two researchers within the project team (MS, LH) with input from the other team members. The narrative-led framework was structured according to the research questions. As a result, codes were merged to develop preliminary themes.

Stage 7. Interpreting the data. The project team held an analysis workshop in August 2022 to finalise the development of themes, which was followed by another workshop in November 2022 to refine interpretation following an internal review. The main purpose was to understand the application of Digital First Primary Care across primary care and identify differences across the data, incorporating theoretical concepts for the purposes of critique relational to our research questions and mapping connections across our themes. Once all members of the study team had agreed on the final themes, writing up of the findings commenced.

Analysis and reflecting on findings with key experts and patients

The study team completed their analysis across WPs, bringing together the key themes from the data collection across different stakeholder groups. This was achieved rapidly by holding a workshop (after data analysis and write up, in November 2022) to bring together the knowledge and data collected throughout the project. As a result, one researcher (JN) developed a set of draft lessons for policy makers concerning the future care of patients with multiple long-term conditions in primary care and recommendations for further research which were developed further with the whole team (LH, KD, MS) (see Discussion and conclusions).

These draft lessons and recommendations were tested with members of the BRACE PPI group. In summary, our approach supported engagement with the data in a timely fashion while retaining the wider context discussed within the interviews.

Chapter 4 Results

Box 5 provides a summary of Chapter 4 of this report.

Summary of key points

-

It is important to recognise the context in which Digital First Primary Care is implemented. Primary care continues to face significant sustained pressure due to higher patient demand combined with staff shortages and pressure from secondary care, leading to staff burnout.

-

The main reason practices introduced Digital First Primary Care was to manage patient demand and reduce the need for unnecessary face-to-face appointments. The COVID-19 pandemic saw the rapid introduction of Digital First Primary Care approaches (to reduce viral transmission), which was not always as well thought through as it may have been pre-pandemic.

-

The introduction of Digital First Primary Care was frequently cited by interviewees as leading to an increase in patient demand. To manage this, some practices reported reducing the time the system was available for use (e.g. closing it down over the weekend).

-

Health professionals and stakeholders reported that Digital First Primary Care provided some benefits to patients with multiple long-term conditions. This included being able to speak to a healthcare professional more quickly, reducing unnecessary face-to-face appointments and supporting patients’ preferences. However, they felt there could also be drawbacks for this patient group, including challenges with digital forms or algorithms, poorer quality interactions and relationships with healthcare professionals and concerns over patient safety. Mixed views were found on whether Digital First Primary Care helped to improve continuity of care.

-

The interviewees felt that Digital First Primary Care may be particularly useful for patients with certain types of long-term health conditions (e.g. diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, mental health conditions and hearing loss). Younger patients, those working full-time and/or those who do not have English as a first language (if translation is available within the system) could also benefit from Digital First Primary Care. Health professionals and stakeholders reported that patient groups who may benefit less from Digital First Primary Care included those who are older/frail and those who do not have access to digital technology (or the skills to use it).

-

The interviewees reported that carers of patients with long-term conditions may benefit from Digital First Primary Care as they can have greater communication with healthcare professionals and be more actively involved in the patient’s care. However, there are some concerns about confidentiality, privacy and consent when it comes to carers accessing medical information. Some participants also noted that carers can lose the added support and in-depth discussion that a face-to-face appointment provides.

-

With regards to healthcare professionals, Digital First Primary Care can offer advantages in terms of better information sharing and communication across staff and patients, improved relationships with patients and greater efficiencies and flexibility. However, others felt that Digital First Primary Care was detrimental to the clinician–patient relationship, creating some inefficiencies. There were also concerns raised over the confidence staff have in their own clinical decision-making when using Digital First Primary Care and the issue of increased (unmanageable) patient demand.

Wider context in which Digital First Primary Care is being implemented

As described in Chapters 1 and 3, the fieldwork for the evaluation was undertaken during an extremely challenging period for general practice. Here, we will briefly discuss the points raised by the interviewees related to the wider context in which Digital First Primary Care was being implemented. While this is not exclusively relevant to patients with multiple long-term conditions, these contextual challenges will particularly impact patients who see a GP more frequently, which includes those with multiple long-term conditions.

Workforce recruitment and retention challenges within primary care were frequently mentioned by participants. Staff shortages and difficulties filling vacancies were a key issue across general practice in relation to both clinical and non-clinical staff, with shortages of working GPs highlighted as a particular issue. The interviewees reflected on how the number of GPs was falling, with fewer entering primary care and some retiring or leaving for other reasons. This challenge aligns with national data from the BMA, who note that the number of GPs in England has grown very little since 2015. 13 Linked to this, a reliance on locums in the absence of being able to recruit permanent staff to practices was reported by participants.

So if you go pre-COVID, there were a range of things that were making life more difficult for GPs. The population was getting older. The population was increasing. The number of GPs was decreasing.

Interview 7, researcher