Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR128359. The contractual start date was in January 2020. The final report began editorial review in April 2021 and was accepted for publication in February 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Evans et al. This work was produced by Evans et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Evans et al.

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

One in six children aged 5–19 years in England has a probable mental disorder,1 and a recent National Assembly inquiry found a 100% increase in demand for mental health services in Wales between 2010 and 2014. 2 With resources stretched and young people often waiting lengthy periods to be seen, increasing numbers of children and young people (CYP) are seeking help or have had help sought on their behalf during mental health crises. During such periods of crisis, it is vital that effective and timely evidence-based care is provided. Crisis care for CYP has become a policy priority both nationally2,3 and internationally,4 with substantial funding allocated to the development of crisis services. 5 The needs of young people in crisis can be met through designated clinical services [e.g. local Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) teams and/or dedicated CAMHS crisis teams] and in emergency departments, but also through non-clinical services provided through a range of organisations.

In the UK, the landscape of crisis care delivery has shifted substantially in recent years, with particular investments being made in dedicated community crisis teams that aim to provide care close to home and avoid the need for hospital admission. 6 However, little is known about how these teams are organised and experienced, their effectiveness or how they are integrated within local systems, and concerns continue to be expressed regarding their adequacy. 7 In the context of local services, community crisis teams work alongside community CAMHS teams and sometimes other types of specialist CAMHS, such as those providing assertive outreach, emergency departments and paediatric wards. In the larger ecology of service provision, crisis responses are also provided through general NHS provision (e.g. in emergency departments, in schools and universities, by the police, through social services, via the third sector and through internet- or telephone-based counselling services).

Despite the prioritisation of crisis care for CYP, no up-to-date data are available on types of service responses and their organisation, the experiences of young people, their families and staff, and outcomes for CYP. Previous reviews have focused specifically on the provision of designated clinical services for those in mental health crisis,8–10 neglecting the diverse settings where young people are likely to access initial crisis support outside the mental health system (e.g. schools, online networks and social media, crisis helplines, emergency departments, third-sector organisations, the criminal justice system). However, given that CAMHS are unable to meet the needs of the large numbers of children in crisis each year, it is likely that (in the UK context) a substantial proportion of crisis responses occur outside NHS services. Non-NHS settings may be more frequent points of access to crisis support for young people, making it important to understand how these systems interact with designated mental health services, how these different response types are experienced by young people and their families and what their outcomes are. For example, a recent report11 revealed that the police account for the largest number of referrals to children’s services of 16- and 17-year-olds, whereas the second highest source of referral for those aged < 18 years is education. There have also been increasing reports of mental health problems and self-harm from teachers12 and from third-sector organisations in front-line contact with children and adolescents. 13

International policy guidance has consistently stressed the importance of a joined-up systems approach in providing support to CYP, advocating cohesive working between health, education, social services, youth work and the third sector. 4 Recent guidance from the National Assembly for Wales7 recommends that schools should form community hubs of cross-sector and cross-professional support for children’s emotional and mental well-being. Therefore, a research approach that isolates clinical responses to mental health crises would risk excluding valuable data. By including evidence from wider social contexts, broader lessons may be learned about what CYP experiencing mental health crisis find particularly helpful.

Why is the research important?

This project was designed to meet a priority health need about which there is expressed and sustained interest, that is the mental health of CYP between the ages of 5 and 25 years. This is an area of international importance4 and is a priority for future UK mental health research. 14 One in six (12.8%) children aged 5–19 years in England has a mental health difficulty,1 with services struggling to meet demand as need rises. 3,7 A particular concern is the provision of safe, accessible and effective care for young people who need urgent help during a mental health crisis. This is in the context of a significant number of CYP experiencing mental health crises each year, characterised by serious self-harm and/or other behaviours that present major risks to the self and/or others. There was a 68% increase in self-harm incidence among girls aged 13–16 years in England between 2011 and 2014. 15 There are a number of organisations that might respond to CYP at these times of mental health crisis, including children’s mental health services, hospital emergency departments, pastoral or counselling staff in schools, third-sector organisations and the police. The aim of this review was to investigate the evidence underpinning such responses. Since the development of the initial proposal for this study, the world has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Initial studies have found that the mental health of CYP has been affected by the stress associated with the impact of both COVID itself and lockdowns, particularly in CYP with specific additional vulnerabilities, such as those with pre-existing mental health conditions or those being quarantined because of infection/fear of infection. 16 However, this study predated the COVID pandemic and did not draw on any of the COVID-related literature.

In England, out-of-hours and crisis services for young people are a policy priority,3,17 with model service specifications including expectations that NHS trusts provide round-the-clock home-based crisis care. 18 InWales, crisis care is also a priority,19 with new CAMHS investment including money for urgent mental health interventions. 5,20 Intensive ‘hospital at home’ services have featured in Scottish guidance,21 and in Northern Ireland calls have been made for similar investments. 22,23 Responding appropriately to young people in crisis has also featured in recent national Crisis Care Concordats. 24,25 This is, therefore, a high-priority area that falls clearly within the remit of the Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme in addressing the four areas of quality, access, organisation and outcomes.

In the context of such high levels of need and in view of the urgency of this issue, it is vital that the care being provided to CYP in crisis is evidence based and effective. Evidence from this synthesis created knowledge of immediate use to NHS managers, practitioners, carers and others involved in the care of CYP. The project was designed to have an affect on services and practice by presenting its findings in accessible ways to health education and social services, the public, practitioners and educators.

Why is the research needed?

Despite the national and international prioritisation of crisis care for CYP, to our knowledge, no up-to-date data were available on the following aspects of the existing range of crisis responses: service organisation; effectiveness; and young people’s, their family members’ and staff members’ experiences. National guidance has been developed, stating what ought to be present in dedicated services of this type, drawing on what young people want. This includes care that is immediately accessible, provided by the right professional and is understandable. In addition, care should be provided in settings that are acceptable and not in hospital, whenever possible, and should be characterised by continuity. 6 However, we did not know how far these standards were being met and what their evidence base was. This contrasted sharply with what was known about crisis services for adults with mental health difficulties, which have been subjected to recent national audit26 and quality inspection27 and the evidence for which has recently been updated. 28,29

A number of alternative services provide responses for young people in crisis or distress outside the NHS. For instance, school and university counselling services (e.g. Place2Be school services) and online platforms provide online counselling and well-being support (including moderated peer-support forums, 7 days per week, until 10 p.m.) for CYP. Often these counselling services involve the integration of services across statutory and third sectors. 30 Given the increasing emphasis on cohesive working across systems, there was a need to consider the international evidence for all forms of crisis support provided across social, education and third-sector organisational contexts.

Initial search and the need for an evidence update

An initial search of the existing literature across MEDLINE and PsycINFO® was conducted to establish the feasibility of conducting a full systematic review of the relevant evidence prior to funding being agreed. Three systematic reviews were found that informed this study; however, these reviews also revealed a gap for a new updated review and synthesis. Shepperd et al. 31 brought together evidence for alternatives to inpatient mental health services for CYP and mapped current provision at the time. In this review,31 ‘crisis care’ was included alongside other types of non-hospital care for young people with ‘complex mental health needs’. Hamm et al. 10 limited their review to emergency department interventions, whereas Janssens et al. 8 reviewed the organisation of mental health emergency care for CYP, noting a lack of clarity around terminology. The authors of these three reviews, along with others,9 made a case for advancing the evidence base in a context in which descriptions of provision are unclear and research is both underdeveloped and of variable quality.

The Cochrane review of Crisis Intervention for People with Severe Mental Illnesses28 excludes CYP, but does, however, contain a helpful definition of ‘crisis services’:

Any type of crisis-orientated treatment of an acute psychiatric episode by staff with a specific remit to deal with such situations, in and beyond ‘office hours’. This can include mobile teams caring for patients within their own homes, or non-mobile residential programmes based in home-like houses within the community.

Murphy et al. 28

Although this definition emphasises clinical service provision by those ‘with a specific remit’ to deal with psychiatric crisis, we derived a broader definition of crisis care, which is inclusive of non-clinical environments. For this review, we considered a crisis service for CYP to be:

The provision of a service in response to extreme psychosocial distress, which for CYP may be provided in any location such as an emergency department, a specialist or non-specialist community service, a school, a college, a university, a youth group, or via a crisis support line.

Our search for evidence also uncovered additional studies of relevance, including evaluations in emergency departments. 32–34 In addition, our search extended to the National Institute for Health and Care Research database, where we uncovered National Institute for Health and Care Research-commissioned studies investigating mental health crisis services for adults (e.g. Paton et al. 29 and Lloyd-Evans et al. 35) and different ways of providing mental health care for young people (e.g. Tulloch et al. 36).

In conclusion, with one in six (12.8%) children aged 5–19 years in England having a probable mental disorder, the demand for services was increasing and growing numbers of CYP were seeking help during their mental health crises. New models of crisis services for CYP are continually being developed across the UK and internationally, and there was a need to consider the evidence for all forms of crisis support provided across social, education and third-sector organisational contexts, and how they interact with existing services. Therefore, an up-to-date evidence synthesis was required, taking into account new evidence published since the previous reviews,8–10 as well as incorporating UK-only grey literature relating to the organisation, provision and experience of mental health crisis responses for CYP.

Chapter 2 Working with stakeholders and defining parameters

This chapter describes the approach taken with stakeholders, including members of the public with personal experience of CYP experiencing mental health crisis and receiving care. Our engagement with patients and the public reflects commitments and experiences demonstrated in other studies on which members of this project team have worked (e.g. Hannigan et al. ,37 which provided an evidence synthesis into ‘risk’ for young people in mental health hospitals and which actively involved young people as stakeholders in shaping the study’s progress). Reporting of this section is completed with reference to GRIPP2-SF standards. 38 GRIPP2-SF standards require reporting of how public and patient involvement has informed all parts of a project, including its aim, methods and outcomes.

We worked with Liz Williams, who identifies herself as a carer of young adults with mental health issues, and Mair Elliot, who identifies herself as an expert patient, in the initial development of the project proposal. This is clearly an area of importance for people who want to access services for CYP in psychological crisis. Both Liz Williams and Mair Elliot have been co-investigators on this study and have contributed to several critical stages of the project where their expertise was most important, including the creation of search terms, selection of papers, synthesis and plan for the dissemination of findings. Discussions about the focus of the project were also held with clinical colleagues working in local CAMHS during the development of the proposal.

The project was supported by a Stakeholder Advisory Group (SAG), which was established during the project set-up phase. The SAG included professionals from a range of sectors that respond to CYP in mental health crisis, including professionals from an emergency department, a secondary school, social services and specialist CAMHS, parents with the lived experience of using mental health services for their family members and members of the third-sector organisation Place2Be (London, UK), which provides mental health support to children in schools. The SAG was independently chaired by Professor Michael Coffey from Swansea University (Swansea, UK).

The full membership of the SAG is found in Report Supplementary Material 1, and over the life of the study the combined project team and SAG met at three strategic time points (i.e. in person in Cardiff, and then via two further virtual meetings convened using videoconferencing because of the COVID pandemic restrictions). In the first meeting, the terms of reference (see Report Supplementary Material 2) were discussed and then agreed with the SAG, and the SAG were invited to review our search terms and assist with the generation of others, including identifying suitable databases and sources of UK-only grey literature. The notes of the meeting can be found in Report Supplementary Material 3. The second (virtual) meeting took place at the completion of evidence searching, providing an opportunity to share work in progress (see Report Supplementary Material 4). The final (virtual) meeting was scheduled towards the commencement of the whole-project synthesis and report-writing phase, with a focus on sharing preliminary findings and discussing plans for dissemination and maximising impact (see Report Supplementary Material 5). Following discussion during the first stakeholder meeting, the project title was changed from CAMHS crisis to child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) crisis.

Defining the project’s search parameters

At the first SAG meeting, candidate database search strategies and search terms developed by the project team for CYP were presented and discussed, and candidate definitions of the terms ‘crisis’ and ‘mental health’ were distributed and discussed at length with the purpose of refinement (see Report Supplementary Material 6). The decision was made not to search by specific services (e.g. schools, police) at this point and to have a four-arm search.

Arm 1: children and young people

The additional terms discussed at the SAG for this arm focused on trying to identify studies in which our population group may have been referred to by terms more related to setting than the terminology already identified as relevant to defining CYP. The SAG was concerned that CYP, particularly within educational, juvenile and other settings, may be missed. Additional suggestions that were discussed were the words and phrases ‘pupil’, ‘student’, ‘undergraduates’, ‘learner’, ‘apprentice’, ‘young offender’ and ‘adults aged 18–25 years’. A particular mention was made of adverse childhood experiences and whether or not this could be incorporated into this arm. The suggestions were evaluated by an information specialist (EG) and reported back to the project team. The words that were included within the final search strategy were ‘pupil’, ‘student’ and ‘young offender’. Other terms were considered to be too broad (e.g. ‘learner’ and ‘apprentice’), problematic to search given the constraints of the databases (e.g. ‘age 18–25 years’ and ‘minor’) or would already be retrieved through the use of existing key terms (e.g. ‘adverse childhood experiences’ and ‘children in care’).

Arm 2: crisis

At the outset, the decision was made not to search for specific crisis events, as it was felt that this potentially could have led to an endless list of presenting clinical situations and that certain crisis events, not thought of, could be missed. Our strategy was to use the keywords ‘crisis’ or ‘crises’ in arm 2 and ‘mental health’ or ‘psych*’ in arm 3. However, when the search strategy was being tested to ensure that all recognised relevant papers were being retrieved, Elizabeth Gillen found that several already-identified key papers were missing. This was because these papers used the term ‘rapid response’ and ‘suicide’ to define the crisis event with no mention of the terms ‘crisis’ or ‘mental health’. After discussion at a later project team meeting, it was felt that the terms ‘suicide’ and ‘self-harm’ were so synonymous with a crisis that they should be included as specific examples in the mental health arm. The term ‘rapid response’ was then added to arm 2.

Arm 3: mental health

The general use of a mental health arm was discussed at length, as the SAG was concerned that this could make the search very medicalised and that the project needed a strategy to ensure the retrieval of non-health sector articles. It was recognised, however, that without this third arm the search would be unwieldy. A discussion followed that, although in practice episodes of crisis happen in many sectors, it is likely that any write-up of research undertaken in the area would refer to mental health in some capacity and so this arm was included and expanded on, as detailed above. To address the concerns, and to increase the sensitivity of our search, a fourth arm was introduced that encapsulated alternative terminology that could be used to define a mental health crisis, which could then be combined with arm 1 to provide us with a second search methodology.

Arm 4: mental health and crisis

Positional operators were used within our new arm 4 to retrieve articles using alternative terminology to describe a mental health crisis. The terms discussed with the SAG included the terms ‘severe’, ‘extreme’, ‘intense’, ‘emergency’, ‘critical incident’, ‘urgent’, ‘distress’ and ‘trauma’. ‘Trauma’ was removed, as it was felt that this term would retrieve too many irrelevant records related to physical trauma. Following further discussions, it was decided to proceed with four of these terms (i.e. ‘emergency’, ‘critical incident’, ‘urgent’ and ‘distress’) in proximity to the terms ‘mental’ and ‘psych*’. Trials combining this new arm with arm 1 showed the strategy to be successful in increasing the sensitivity of our search, pulling in alternative literature, without excessively compromising precision or making the search unmanageable.

Finding UK-only grey literature

Websites to search, which had already been identified by the project team, were circulated (see Report Supplementary Material 7), and in the first meeting SAG members were invited to identify additional online sites.

Feedback from young people

One member of the project team (RL) met with young people from the Advice Leading to Public Health Advancement (ALPHA) group. The ALPHA group is a research advisory group that works for the Centre for Development, Evaluation, Complexity, and Implementation in Public Health Improvement (School of Social Sciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK). The ALPHA group comprises young people aged 14–25 years who provide advice to health-based researchers. The purpose of meeting with members of the ALPHA group was to obtain advice from these young people about search terms, UK organisations and services, and sources of support available to them, and to determine the most suitable methods of sharing the findings from this evidence synthesis. Table 1 presents the breakdown of the 11 participants by age and gender.

| Participant age (years) | Gender | |

|---|---|---|

| Male (n) | Female (n) | |

| 14 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 0 | 1 |

| 16 | 0 | 1 |

| 17 | 1 | 3 |

| 18 | 1 | 2 |

| 19 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | 0 | 2 |

The activity was broken up to tasks. Task 1 was about generating further search terms. For this task, we split the ALPHA members into two groups. We asked each group to spend 10 minutes at each station discussing the topics, then moving onto the next station until all four stations have been met with both groups. We used this technique as it allows for ALPHA members to have open discussions in their group and work collaboratively to answer the questions. It also allows for the other group to analyse the previous group’s findings, either by agreeing and providing further feedback or by disagreeing and providing suitable alternatives. Table 2 and Figures 1 and 2 contain a summary of the key points discussed at each station.

| Station | Findings |

|---|---|

Describe the following terms and how they may affect someone:

|

Physical structure and chemical make-up of the brain can affect mental health (e.g. people with adverse childhood experiences are more disposed to mental disorders, as their brain has changed to adapt to their environment) |

| General attitude, good and bad, emotional well-being, logical thinking and ability to think clearly, emotional responses, ability to cope | |

| A point where you need to heal, danger, inability to do or solve, feeling trapped, isolating yourself, panic attacks | |

| Stops your ability to function, cause distress, negative effect on well-being, psychological, emotions | |

| Anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorder, schizophrenia, psychosis, multiple personality disorder, body dysmorphia, substance abuse | |

| Suffering in any way: mental and physical, impairment of function, chronic stress, relationship breakdown, isolating yourself | |

| What places do young people go when they are in crisis? |

|

| What resources do young people use when in crisis? |

|

| Suggestions on where to look for grey literature? |

|

FIGURE 1.

Responses for what places do young people go when they are in crisis.

FIGURE 2.

Responses for what resources do young people use when in crisis.

As a part of this study and evidence synthesis, the study team wanted to know the most suitable methods and approaches for sharing these findings. The findings were to be aimed and CYP and parents/carers to provide advice or guidance on services to access at time of emotional crisis. For this second task, we asked ALPHA members to remain in the same groups and answer the following questions:

-

Who should we share this information with?

Responses: teachers, local authorities, helping, parents, in school counsellors, NHS and young people.

-

What information to include?

Responses: specific relatable information tailored for the correct audience (e.g. posters in school for young people); main study findings with accessible information, including useful services and more specific services.

-

Where should this information be shared?

Responses: these posters can be in hotspot areas in the schools, such as back of toilet doors. If feasible, targeted adverts on Instagram (Meta Platforms, Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) or Facebook (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA).

-

Why do we need to share this information?

Responses: increased awareness and use of services; young people will feel comfortable knowing where they can go to access information.

-

What is the best approach for sharing this information?

Responses: ParentMail (IRIS Software Group Ltd, Slough, UK), ParentPay (IRIS Software Group Ltd, Slough, UK), posters at school, animation video to showcase main findings, parents evening, e-mail/letter and social media.

We asked ALPHA members whether or not it was a good idea to present the findings from this systematic review in an animation video format. We received a mixed response to this question, as some ALPHA members thought that it was a good idea and a useful way of sharing the information, whereas others were unsure. Some ALPHA members felt that there are too many information animation videos and producing another one would not have the desired impact and, therefore, suggested using a different platform for sharing this information, such as either a poster or a whole-school approach.

Chapter 3 Methods and description of included reports

The methods used in this evidence synthesis and the materials finally included are described in this chapter. The protocol for the evidence synthesis was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO CRD42019160134) at the commencement of the project. For the purposes of this review, guidance for undertaking reviews in health care published by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination39 was followed. To incorporate stakeholder views, methods informed by the EPPI-Centre (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre)40,41 were used. To ensure rigour, the reporting of this evidence synthesis follows the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews) statement. 42

Aims and objectives

The aim of this project was to synthesise international evidence relating to the organisation and effectiveness of services that respond to CYP in crisis, and the evidence relating to the experiences of people using and working in these services.

Detailed objectives were to critically appraise, synthesise and present the best-available international evidence. Specifically, we looked at:

-

the organisation of crisis services for CYP aged 5–25 years, across education, health, social care and the third sector

-

the experiences and perceptions of CYP, their families and staff with regard to mental health crisis support for CYP aged 5–25 years

-

determining the effectiveness of current models of mental health crisis support for CYP

-

determining the goals of crisis intervention.

Inclusion criteria

We used PICOS/PiCo framework to guide the inclusion criteria on population (P), intervention/phenomena of interest (I), comparators (C), outcome (O), study design (S) and context (Co).

Population

This evidence synthesis considered all relevant evidence specifically relating to support for CYP (aged 5–25 years) in emotional/mental health crisis.

For the purposes of the current study, CYP will included individuals within the age range of 5–25 years. A number of mental health services for CYP in the UK and internationally now cater for this age range. Imposing an age limit of 18 years would, therefore, have risked excluding valuable studies concerning those aged 18–25 years.

Intervention and phenomena of interest

This evidence synthesis considered all relevant evidence on the:

-

organisation of services relating to crisis support

-

effectiveness of current models/interventions that provide support to CYP in mental health crisis

-

views and experiences of CYP, families and staff

-

goals of services.

Building on the definition used in Crisis Intervention for People with Severe Mental Illnesses,28 for this proposed review a crisis response for CYP was defined as follows:

The provision of a service in response to extreme psychosocial distress, which for children and young people may be provided in any location such as an emergency department, a specialist or non-specialist community service, a school, a college, a university, a youth group, or via a crisis support line.

Comparators

No comparators were used in the study.

Outcomes

The following outcomes were considered: the organisation of crisis services and their effectiveness (i.e. all outcomes as described across the primary studies), the experiences of CYP and their families, and the goals of crisis services.

Context

All records were considered with regard to the organisation of crisis services, their effectiveness and the experiences of CYP and their families in any setting, including virtual.

Study design/types of evidence

Types of evidence sought included both quantitative and qualitative research, and UK-only grey literature. Reports published in the English language since 1995 were considered.

Exclusion criteria

The following exclusion criteria were used:

-

usual care provided at emergency departments with no specific mental health component

-

standard CAMHS care

-

under-fives

-

CYP not in mental health crisis

-

evidence relating to adult mental health services, where there is no designated provision for young people

-

evidence relating to general/non-crisis/long-term support

-

studies that included participants who are children and adults, but the average age of the participants was > 25 years

-

crisis was a group crisis experience, such as a mass shooting or stabbing in an educational establishment or a natural disaster

-

care not at actual point of crisis.

Developing the search strategy

The focus of the search strategy was to achieve high sensitivity without overcompromising precision and making the search results unwieldy. To ensure that all relevant literature was obtained, a comprehensive search strategy was designed. The search strategy took into consideration the discussions around the research question during the first combined project team and SAG meeting (see Chapter 2).

Preliminary searching

Preliminary database searching using MEDLINE and PsycINFO were carried out as part of an initial scoping exercise undertaken during preparation of the proposal for funding, with material from this drawn for Chapter 1. The preliminary keywords that were used to inform these searches included ‘child’ OR ‘adolescent’ AND ‘CAMHS’ OR ‘mental health’ AND ‘crisis’. This search strategy was further developed, taking into account relevant synonyms and alternative spellings. The text words contained in the title and abstract and the index terms used to describe the articles retrieved were then analysed and used to develop more comprehensive and detailed searches.

Comprehensive searching

The preliminary search terms were presented and discussed at the first combined project team and SAG meeting (see Chapter 2). As a result of this process, Elizabeth Gillen developed a comprehensive search strategy.

As a means of testing and refining this search strategy before applying it across multiple databases, records retrieved across MEDLINE and PsycINFO were first screened by Deborah Edwards to ensure relevance and to assess that the strategy was neither too broad nor too narrow.When the project team was satisfied with the search strategy, the strategy was then tailored across all databases, with searches run from database inception and undertaken between February and April 2020 (updated in January 2021). The final search strategies are displayed in Appendix 1.

The 17 databases searched were:

-

MEDLINE ALL (on the Ovid platform)

-

PsycINFO (on the Ovid platform)

-

EmCare (on the Ovid platform)

-

Allied and Complimentary Medicine Database (on the Ovid platform)

-

Health Management Information Consortium (on the Ovid platform)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

-

Education Resources Information Center (on the ESBCOhost platform)

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (on the ProQuest platform)

-

Sociological Abstracts (on the ProQuest platform)

-

Social Services Abstracts (on the ProQuest platform)

-

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database (PQDT) Open (on the ProQuest platform)

-

Criminal Justice Abstracts (on the National Criminal Justice Reference Service)

-

Scopus

-

Web of Science (WoS)

-

OpenGrey

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

-

Electronic Theses Online Service (EThOS).

To identify UK-only grey literature documents, a number of supplementary searches were undertaken. Members of the SAG advised the project team as to which relevant websites to search (see Chapter 2). (A full list of the websites searched, along with the search terms utilised, can be found in Report Supplementary Material 8.) Members of the SAG were also asked to inform the research team of any other reports they were aware of that might be relevant to the evidence synthesis.

Searches were also conducted using Google as described by Mahood et al. 43 The first 10 pages of each Google output were screened using the terms:

-

young people, mental health crisis

-

children, mental health crisis.

To identify published reports that had not yet been catalogued in electronic databases, recent editions of Pediatric Emergency Care, Psychiatric Services, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention were hand-searched. These journals were selected because of the large number of outputs identified in database searches from these journals. Reference lists of included studies were scanned and forward citation tracking was performed using WoS.

Primary research records retrieved from database searches

All records retrieved from the 17 database searches were imported or entered manually into EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and duplicates were removed. The total number of hits retrieved for each database is displayed in Table 3.

| Database searched | Number of references retrieved |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE ALLa | 11,756 |

| PsycINFO | 10,077 |

| EmCare | 4447 |

| HMIC | 663 |

| CINAHL | 5210 |

| AMED | 191 |

| ERIC | 1940 |

| ASSIA | 1037 |

| Sociological Abstracts | 701 |

| Social Services Abstracts | 564 |

| Scopus | 10,593 |

| WoS | 9277 |

| Cochrane | 872 |

| OpenGrey | 220 |

| EThOS | 320 |

| PQDT Open | 116 |

| Criminal Justice Abstracts | 10 |

| Total | 57,994 |

Primary research records identified from supplementary searching

All primary research citations identified as potentially relevant from the supplementary searches (see Table 4) were entered manually into EndNote. A total of 31 records were identified.

| Source | Number of citations |

|---|---|

| Reference lists of included studies | 23 |

| Forward citation tracking of included studies | 7 |

| 0 | |

| SAG | 0 |

| Organisational websites | 1 |

| Hand-searching | 0 |

| Total | 31 |

Removing irrelevant records

The next stage was to remove irrelevant records by searching for keywords within the title using the search feature within the EndNote software. The keywords used to identify papers that did not meet the evidence synthesis inclusion criteria were agreed by the project team. The results for each keyword were screened by Deborah Edwards to ensure that they were, in fact, irrelevant before removing them. All records that remained at the end of this process were exported as an XML (extensible markup language) file and imported to Covidence™ (Melbourne, VIC, Australia).

Examples of the types of keywords that were used were as follows:

-

asthma

-

armed

-

abortion

-

adult*

-

baby

-

cancer

-

child abuse

-

cultural crisis

-

culture

-

diabetes

-

disaster

-

economic crisis

-

epilepsy

-

fertili*

-

financial crisis

-

first aid

-

gun

-

HIV/AIDS

-

hostage

-

hurricane

-

infant

-

maternal

-

migrant

-

military

-

mother*

-

neonat*

-

politic*

-

postpartum

-

predictor*

-

prison

-

refugee

-

screening

-

soldier

-

sexual abuse

-

validity

-

war.

Title and abstract screening

Two members of the review team independently assessed each record for relevance using the information provided in the title and abstract and the software package Covidence. A third reviewer resolved any disagreements. The full texts of all records that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, or in cases in which a definite decision could not be made based on the title and/or abstract alone, were retrieved.

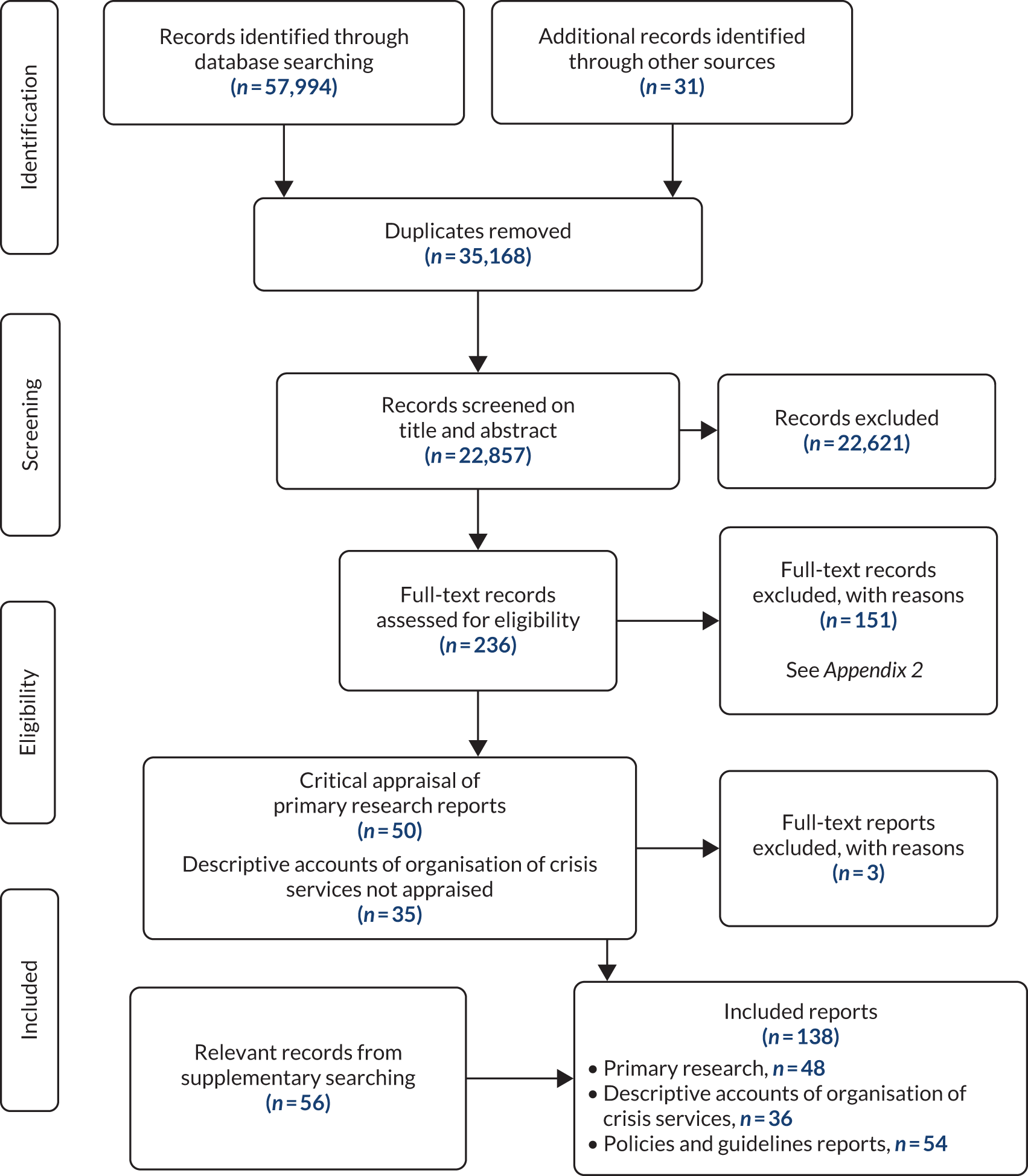

Full-text screening

A purposely designed form was used to screen each retrieved report. The form was piloted on 10 reports before being used independently by two reviewers to complete the full-text screening. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. All English-language items relating to the objectives were included at this stage. Figure 3 shows the flow of records through each stage of the evidence synthesis process in the PRISMA flow chart. 42

FIGURE 3.

A PRISMA flow chart.

UK-only grey literature identified from supplementary searching

Sixty-nine literature records were identified as being potentially relevant from across all supplementary searches (see Table 5) and these records were all entered manually into EndNote. The UK-only grey literature identified was read by two members of the project team and considered against the topic inclusion criteria, with disagreements resolved as above. Thirteen records were excluded (see Report Supplementary Material 9), leaving a total of 56 records being assessed as relevant to the evidence synthesis (see Appendix 3).

| Source | Number of citations |

|---|---|

| Organisational websites | 64 |

| 5 | |

| SAG | 0 |

| Total | 69 |

Reports included in the evidence synthesis

One hundred and thirty-eight reports were included in the evidence synthesis and consisted of primary research (n = 48), descriptive accounts of the organisation of crisis services (n = 36) and UK-only grey literature (n = 54).

Quality appraisal

The methodological quality of all the research reports was assessed following searching and screening using a design-specific checklist (see Table 6). Alternative tools, which reflected the specific design and methods used in individual research outputs, were used as necessary when suitable Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools were not available. This was independently undertaken by two reviewers and any disagreement was resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

| Study design | Checklist |

|---|---|

| RCT | CASP checklist for RCTs:44 11 items (‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘can’t tell’) |

| Quasi-experimental study | JBI checklist for quasi-experimental studies (non-randomised experimental studies):45 nine items (‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’, ‘not applicable’) |

| Prospective cohort study | Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Methodology Checklist 3: Cohort Studies:46 14 items (‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘can’t say’, ‘does not apply’) |

| Retrospective cohort study | Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Methodology Checklist 3: Cohort Studies:46 eight items (‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘can’t say’, ‘does not apply’) |

| Descriptive cross-sectional study | SURE checklist:47 12 items (‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘can’t tell’) |

| Qualitative study | CASP checklist for qualitative studies:44 10 items (‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘can’t tell’) |

Based on critical appraisal, the following three reports48–50 were excluded:

-

A qualitative study by Rossi and Cid48 was excluded because the data analysis was not sufficiently rigorous and it was concluded that there were insufficient data to be able to extract from.

-

A quasi-experimental study by McBee-Strayer et al. 49 was excluded because overall assessment of the quality of the study was rated as ‘unacceptable’.

-

A quasi-experimental study by Blumberg50 was excluded because the overall assessment of the quality was rated as ‘unacceptable’.

The descriptive accounts of organisation/models of crisis services and the UK-only grey literature were not subjected to quality appraisal.

For the CASP, Joanna Briggs Institute and Specialist Unit for Review Evidence checklists, an overall score is generated reflecting the number of items answered ‘yes’. For Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Methodology Checklist 3: Cohort Studies,46 the overall assessment reflects how well the study has sought to minimise the risk of bias or confounders. The final ratings are classified as high quality (described as the majority of criteria met with little or no risk of bias and the results are unlikely to be changed by further research), acceptable (described as most of the criteria met with some flaws in the study and an associated risk of bias, and the conclusions may change in the light of further studies) or low quality (described as either most of the criteria not met or significant flaws relating to key aspects of study design, and conclusions are likely to change in the light of further studies).

The authors46 of the checklist suggest that retrospective designs should not receive a rating higher than acceptable, as they are generally regarded as a weaker design.

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis

When multiple research reports from the same study were identified (i.e. 47 research reports covering 40 research studies), data were extracted and reported as a single study. The demographic data were extracted directly into tables based on study design following guidance from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 39 The data extracted included the aim of the research, nature of the crisis, type and location of treatment, participant details, recruitment, age, gender, ethnicity, intervention or programme, data sources, outcomes and outcome measures. This process was conducted by one of the team of reviewers (JC, NE or RL), with each being responsible for a different study design, and then this process was independently checked for accuracy and completeness by a second reviewer (DE). A record of corrections was kept.

The full texts of all the reports and the electronic versions of all UK-only grey literature were uploaded into the software package NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to aid the extraction, analysis and synthesis of the content. The data analysis and synthesis for each of four objectives was conducted separately and is presented as separate chapters.

The first objective was to critically appraise, synthesise and present the best-available evidence on the organisation of crisis services for CYP aged 5–25 years, across education, health, social care and the third sector. To answer objective 1, a narrative approach was employed that involved the development of thematic summaries,40,51,52 synthesising the data relating to the organisation of crisis services from primary research, descriptive accounts and UK-only grey literature documents. Thematic summaries are ‘summaries of findings of their included studies that have been arranged into themes’. 53 Natural groups of studies that investigated the same areas were brought together into meaningful sections and the final thematic summaries were written by one researcher and checked by a second. This objective is presented in Chapter 4.

The second objective was to explore the experiences and perceptions of CYP, their families and staff with regard to mental health crisis support for 5- to 25-year-olds. A thematic synthesis53 was performed on qualitative data extracted from primary research studies, wider research reports and stakeholder consultations with service providers and/or young people and their families (which were part of a wider body of work). Using NVivo, inductive data-driven codes, led jointly by Rhiannon Lane and Deborah Edwards, were generated through line-by-line reading of each document in line with each of the research objectives. The codes were then grouped into themes and subthemes by one researcher (RL) and checked by a second (DE). The confidence in the synthesised findings from the qualitative research to address objective 3 was assessed by two reviewers (DE and NE) using the CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) approach. 54,55 This objective is presented in Chapter 5.

The third objective was to determine the effectiveness of current models of mental health crisis support for CYP. Owing to the heterogeneity of the included intervention studies, meta-analyses could not be performed and so thematic summaries, as described above, were conducted. Outcome data were extracted as they were presented across the primary research reports using NVivo. The purpose of this was to group data for each outcome and not to code the extracts in any detail. The confidence in the synthesised findings from the quantitative data was assessed by two reviewers (DE and JC) using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach. 56 This objective is presented in Chapter 6.

The fourth and final objective was to determine the goals of crisis intervention. To address this objective, thematic summaries, as described above, were employed to bring together data across the primary research, descriptive accounts of the organisation of crisis services and UK-only grey literature documents that related to the goals of crisis services. This was led by Ben Hannigan and was checked by Deborah Edwards and Nicola Evans. This objective is presented in Chapter 7.

Description of reports

Forty-eight reports, covering 42 research studies, were deemed suitable for inclusion in the evidence synthesis. Demographic information on the characteristics of included research studies is displayed in Appendices 4–9. Thirty-six additional reports, covering 39 descriptive accounts of the organisation services, were also included (see Report Supplementary Material 10).

Country of origin

The majority of the research reports were conducted within the USA (25 studies across 30 reports32,34,57–84), followed by Canada (eight studies across nine reports85–93), the UK (n = 394–96) and Australia (n = 291,92), and one study from each of the following countries: Ireland,97 the Netherlands,98 New Zealand99 and Sweden. 100 The descriptive accounts of the organisation of crisis services were mainly from the USA (19 descriptions across 15 reports33,101–114) and Canada (n = 10115–124). Three reports125–127 were from Australia and one report from each of the following countries: Germany,128 Switzerland,129 the Netherlands130 and the UK. 131

Study designs and methods

For the research studies, there were 31 quantitative studies (reported across 37 reports32,34,57–69,71–75, 77–89,92,93,98,132) and 11 qualitative studies. 70,76,90,91,94–97,99,100,133 The quantitative studies included a prospective cohort study (n = 132), retrospective cohort studies (n = 1234,62,65–68,71,72,74,75,87,89), quasi-experimental studies (four studies across six reports82,83,86,92,93,132), randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (four studies across eight reports57,61,64,78–81,84) and descriptive cross-sectional studies (n = 1058–60, 63,69,73,77,85,88,98).

Participant characteristics

Participants across the research studies were:

-

CYP experiencing, or who had experienced, a crisis (31 studies across 34 reports32,34,58–63,65–75,77,82–84,86,87,89,91–95,97,98,100,132)

-

CYP experiencing crisis and their family members (two studies across six reports57,64,78–81)

-

family members/parents of CYP experiencing crisis (n = 276,88)

-

caregivers and siblings of CYP experiencing crisis (n = 190)

-

family and close friends bereaved by suicide of a CYP (n = 1133)

-

youth counsellors (n = 1134)

-

staff members from project sites (n = 194)

Participant group sizes for CYP ranged from two134 to 253262 participants. One qualitative study91 had a large number of participants (n = 1449), but data from only one-third of these participants were analysed.

Some studies did not identify the ages of the CYP, labelling them as adolescents,34 young people,134 child psychiatry patients,71 elementary school students77 or high school students. 60,69,73,77 Three studies71,94,100 included young people aged > 16 years only (i.e. 16–24 years,100 16–25 years94 and 18–25 years70).

The majority of research studies included a mix of male and female CYP. One study included only males58 and a further study (across two reports) included only females. 82,83 A further seven studies34,66,71,77,90,94,99 did not report gender.

Outcomes across effectiveness studies

Symptoms of depression

Levels of depression were reported in three studies (across four reports57,78,82,83) and were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory,82,83 the Brief Symptom Inventory,78 the anxiety and depression subscale of the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL),78 the Hopelessness Scale for Children of the Youth Self-Report Scale78 or the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). 57

Psychiatric symptoms

Psychiatric symptoms or symptomatology was addressed in three studies (across four reports64,79,87,98) and were measured using the Global Severity Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory,64,79 the functioning subscale on the Childhood Acuity Psychiatric Illness Scale (CAPI)87 or the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales for Children and Adolescents (HoNOSCA). 98

Behaviour

Three studies (across four reports57,61,64,79) investigated internalising and externalising behaviour using the CBCL. The internalising behaviours measured reflected mood disturbance (including anxiety and depression) and social withdrawal. The externalising behaviours reflected conflict with others and violation of social norms.

Psychosocial functioning

Psychosocial functioning was investigated in four studies (across five reports61,64,79,86,87) and was measured using the Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale,61 the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS),86 youth and/or caregiver reports on the social competence subscales of the CBCL,61,64,79 youth reports on the antisocial friends and conventional involvement of friends subscale of the Family, Friends, and Self Scale (FFS)64,79 and through tracking school attendance. 64,79 Greenham and Bisnaire87 measured the levels of functioning of those with psychiatric symptoms using the functioning subscale on the CAPI.

Hospitalisation rates

Nine studies (across 12 reports32,64,68,74,75,79,80,84,86,89,92,93) investigated the effectiveness of a number of different crisis-based interventions or assessment processes on hospitalisation rates. These interventions/processes were explored at the time of the crisis,68,86 within 72 hours of the crisis,75 within 30 days of the crisis,68,89 at 1-month follow-up,84 at 2-month follow-up,86,93 at 3-month follow-up,32 at 6-month follow-up,86,93 up to 1-year follow-up64,79,80 or at an unspecified time frame. 74,92

Costs

Costs were addressed in seven studies. 58,65,67,72,74,81,93 The types of analysis that were conducted included cost savings (n = 658,65,67,72,74,93), cost-effectiveness (n = 281,93), cost-efficiency74 and opportunity costs. 67 Five studies58,65,67,72,74 reported significant cost savings and one study93 found no significant differences. Of the studies reporting cost savings, four58,67,72,74 out of the five58,65,67,72,74 studies reported that these savings were reflective of reduced lengths of stay (LOSs).

Discharge destination and referral pathways

The destination to which CYP were discharged or referred on to was reported across 11 studies,32,58,59, 61,63,65,74,85,87,92,98 and are reported as follows:

-

home (biological or foster family) or the residence they were previously living in (n = 5;58,59,61,74,87 and, when reported, the percentage of those discharged ranged from 65%65 to 86%61)

-

residential treatment facilities (n = 2;59,65 2%65 and percentage not reported59)

-

outpatient mental health services (n = 3;32,63,98 and, when reported, the percentage ranged from 43%32 to 90%63)

-

hospital/inpatient psychiatric units (n = 10;32,58,59,61,63,65,74,85,87 and, when reported, the percentage ranged from 8%61 to 35%32)

-

no further specialised treatment needed (n = 2;85,98 with the percentage ranging from 16.7%98 to 82%85)

-

other services, which included outpatients or other psychiatric facilities (n = 1;65 12.2%65).

Emergency department visits post discharge

Repeat emergency department visits post intervention were addressed in nine studies32,34,62,66,72,74,75,86,89 at the following time points post discharge: within 72 hours,74,75 within 1 month,32 within 30 days,66,89 within 6 months,86 within 12 months34,72 or within 18 months. 62

Family functioning/empowerment

Six studies (across seven reports33,61,64,79,82–84) addressed family functioning or empowerment. This was measured using the Family Adaptation and Cohesion Scales – Version II (FACES II),61 the Family Adaptation and Cohesion Scales – Version III (FACES III),64,79,82,83 caregiver self-reports on the Global Severity Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory,64,79 the Family Empowerment Scale84 or the Conflict Behaviour Questionnaire. 57

Length of stay

Two studies59,87 provided descriptive information regarding LOS across the inpatient crisis programmes/interventions and ten studies58,65,67,71,72,74,75,86,89,132 investigated the impact of a variety of interventions on LOS.

Completed suicide and suicide attempts

Four studies32,57,78,86 investigated the incidence of attempted or completed suicide at different follow-up points post intervention.

Suicidality

Five studies (across six reports32,57,82,83,86,87) reported on levels of suicidality measured using the Harkavy–Asnis Suicide Scale (HASS),57,82,83 the risk factors subscale of the CAPI,87 the Spectrum of Suicidal Behaviour Scale (SSBS)86 and the Reasons for Living Inventory for Adolescents. 84

Post-discharge use of services/resources

Four studies (across six reports57,82,83,86,89,93) investigated the effects of interventions on resources and/or patient treatment accessed post discharge.

Self-esteem/self-concept

Three studies (across five reports61,64,79,82,83) investigated the impact of the intervention on levels of self-esteem64,79,82,83 or self-concept. 61 The instruments used included the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale,82,83 the self-esteem subscale of the FFS64,79 and the Piers–Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale. 61

Impulsivity

One experimental study (across two reports82,83) investigated the impact of the intervention on levels of impulsivity using the Impulsiveness Scale.

Satisfaction with mental health crisis services/programmes

Aspects of satisfaction with mental health crisis services/programmes were reported in nine studies64,74,75,77,84,85,88,92,132 and one organisational report. 96 Five studies64,74,84,92,132 looked at client satisfaction defined as satisfaction with the mental health crisis service/programme by patients, their parents or guardians, which was measured using Lubrecht’s Family Satisfaction Survey (LFSS),64 the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire,61 a telehealth satisfaction survey74 or satisfaction questionnaires developed specifically for the studies. 92,132

Health-care staff satisfaction with mental health crisis services/programmes

Four studies74,75,85,96 investigated health-care staff satisfaction with the service. Satisfaction was measured with a telehealth satisfaction survey74 or with satisfaction questionnaires developed specifically for the studies. 75,85,96

Satisfaction with clinicians who delivered the mental health crisis service/programme

Satisfaction with the clinicians who delivered the mental health crisis service/programme was explored in two descriptive cross-sectional studies. 77,88 Satisfaction was measured using a satisfaction questionnaire developed specifically for the study77 or using an adapted version of the Quality of Care Parent Questionnaire. 88

Results of quality appraisal

Randomised controlled trials

The methodological quality of each of the four RCTs (reported across eight reports57,61,64,78–81,84) was judged against the relevant 11 quality criteria used in the CASP checklist and each is summarised in Table 7. Five reports64,78–81 reported on different elements of the same multisystemic therapy (MST) intervention and were appraised as one study. Only one study57 scored highly, answering ‘yes’ to all the questions on the checklist. Two studies61,84 did not provide enough information to determine if true randomisation had taken place (question 2), stating that randomisation had been performed, but no further details were provided. In one study,61 not enough information was provided to determine whether or not all participants had been accounted for at the end of the trial (question 3). Two studies57,84 blinded recruitment and assessment staff (question 4). For one study,64,78–81 the experimental and control groups were not treated identically because of the nature of the intervention and control (question 6). All of the studies reported results for all the outcomes (question 7). Only one study57 reported confidence intervals (CIs) with regard to the precision of the estimate of the treatment effect (question 8). Owing to the way the sample was recruited, it was difficult to say whether or not the results were generisable across two studies (question 9). 61,64,78–81 It was not evident whether or not the benefit of the intervention was worth the harms and costs in one study57 (question 11).

| Study and country | Location of intervention | Type of intervention | Question | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |||

| Asarnow et al.;57 USA | ED | Crisis services/interventions initiated within the ED | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Evans et al.;61 USA | Home | Home- or community-based programme | Y | CT | CT | N | N | Y | Y | N | CT | Y | CT |

| Henggeler et al.,64,79 Huey et al.,78 Schoenwald et al.80 and Sheidow et al.;81 USA | Home | Home- or community-based programme | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | CT | Y | Y |

| Wharff et al.;84 USA | Paediatric ED | Crisis services/interventions initiated within the ED | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

Quasi-experimental studies

The methodological quality of each of the four quasi-experimental cohort studies (reported across six reports82,83,86,92,93,132) was judged against the nine quality criteria used in the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist and each is summarised in Table 8. When multiple reports existed for the same study, these were appraised as one study. Three studies82–83,86,92–93 scored highly, with one pilot study132 included that had a lower score. For one study,92 there were some differences between the study group and matched comparison group (question 2). Another study86 did not delineate between the control group and the experimental group in terms of loss to follow-up (question 6), but, overall, this was low (3% at 2 months and 8% at 6 months). For one other study,132 all carers who were able to be contacted took part in the survey and differences between groups were taken into account in the analysis.

| Study and country | Location of intervention | Type of intervention | Question | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |||

| Roberts et al.;92 Canada | Telepsychiatry suite in remote EDs | Telepsychiatry | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Rotheram-Borus et al.;82,83 USA | ED | Crisis services intervention initiated within the ED | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Greenfield et al.86 and Latimer et al.;93 Canada | Paediatric ED and then outpatient department | Outpatient mental health programme | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Nagarsekar et al.;132 Australia | Paediatric ED | Assessment approach with the ED | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Cohort studies

The methodological quality of each of the 13 cohort studies32,34,62,65–68,71,72,74,75,87,89 was judged against the relevant quality criteria derived from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Methodology Checklist 3: Cohort Studies46 and each is summarised in Table 9. All 13 studies were judged to be of acceptable quality, indicating that some flaws in the study design were present with an associated risk of bias. For two studies,34,67 it was not possible to determine if the two groups being studied were from the same source population and for a further one study74 the two groups were from different populations (criterion 2). The retrospective cohort study conducted by Maslow et al. 66 did not have a comparison cohort (criterion 2). Four studies66,75,84,89 did not identify any confounders and in one further study34 it was not possible to determine this information (criterion 13). Only three of the studies62,68,75 provided CIs as part of the statistical analysis (criterion 14). Although the study by Greenham and Bisnaire87 was a retrospective study, 89.8% of parents/guardians gave informed consent for the use of their clinical information for research purposes. Three studies34,71,89 utilised both retrospective and prospective samples, with the retrospective data used as the control group.

| Study and country | Location of intervention | Type of intervention | Criterion | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | Rating | |||

| Wharff et al.;32 USA | PED | Crisis services/interventions initiated within the ED | Y | Y | Y | N/A | 55.4% | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | A |

| Greenham and Bisnaire;87 Canada | Inpatient unit | Inpatient care | Y | N | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N | A |

| Fendrich et al.;62 USA | Community | Mobile crisis service | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Y | A |

| Holder et al.;65 USA | PED | Implementation of a dedicated mental health team in the ED | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N | A |

| Mahajan et al.;67 USA | PED | Implementation of a dedicated mental health team in the ED | Y | CS | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N | A |

| Rogers et al.;72 USA | Inpatient unit | Inpatient care | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N | A |

| Uspal et al.;75 USA | PED | Implementation of a dedicated mental health team in the ED | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | N | Y | A |

| Lee et al.;89 Canada | PED | Assessment approach with the ED | Y | Y | Y | N/A | 11% | CS | Y | N/A | Y | Y | Y | N/A | N | N | A |

| Martin;68 USA | Community | Mobile crisis service | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Y | A |

| Thomas et al.;74 USA | Telepsychiatry suite in remote ED | Telepsychiatry | Y | N | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N | |

| Maslow et al.;66 USA | Outpatient clinic | Outpatient mental health programme | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | N | N | A |

| Reliford and Adebanjo;71 USA | PED | Telepsychiatry | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N | A |

| Greenfield et al.;34 Canada | Outpatient clinic | Outpatient mental health programme | Y | CS | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | CS | N | A |

Descriptive cross-sectional studies

The methodological quality of 10 descriptive cross-sectional studies58–60,63,69,73,77,85,88,98 was judged against the 12 quality criteria used in the Specialist Unit for Review Evidence tool47 and each is summarised in Table 10. Five studies60,63,69,73,77 failed to clearly state the study design. All studies addressed clearly focused questions apart from one73 in which it was unclear. All studies selected participants fairly and all provided details on participant characteristics, apart from Walter et al. 77 who provided details of students attending schools in general rather than of those in crisis. Two studies63,98 did not provide adequate details of their methods of sampling and in a further two studies77,85 it was unclear whether or not the outcome measures were appropriate. One evident weakness of most studies was description of statistical methods, which was good in only four studies. 77,85,88,98 Results were well described in all 10 studies. 58–60,63,69,73,77,85,88,98 One study77 failed to provide information on participant eligibility. No studies reported any sponsorship/conflict of interest and three studies60,63,73 failed to identify limitations.

| Study and country | Location of treatment | Type of treatment | Question | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |||

| Michael et al.;69 USA | High school | Assessment approach with educational settings | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Sale et al.;73 USA | High school | Assessment approach with educational settings | N | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| Capps et al.;60 USA | High school | Assessment approach with educational settings | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| Walter et al.;77 USA | Elementary and high school | Assessment approach with educational settings | N | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Baker and Dale;58 USA | RTC | Crisis programmes | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Baker et al.;59 USA | RTC | Crisis programmes | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Dion et al.;85 | Canada Psychiatric ED at a children’s hospital | Crisis services/interventions initiated within the ED | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Lee and Korczak;88 Canada | PED | Outpatient mental health programmes | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Gillig;63 USA | Outpatient clinic | Adolescent crisis service | N | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| Muskens et al.;98 the Netherlands | Home | Home-based programme | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Qualitative studies

The methodological quality of each of the 11 qualitative studies70,76,90,91,94–97,99,100,133 were judged against the 10 quality criteria used in the CASP qualitative checklist44 and are summarised in Table 11. Only one study100 discussed whether or not the relationship between researcher and participants had been adequately considered, indicating an overall weakness in reporting this concept. Across four studies,90,91,96,99 not enough information was provided to state definitively whether or not the research design was appropriate to the aims of the research (question 3). The recruitment strategy was unclear for two studies91,94 (question 4). Three studies76,96,97 did not state whether or not they had ethics approval (question 7). Six studies90,91,94–97 failed to identify whether or not the data analysis was sufficiently rigorous, with a lack of in-depth description (question 8).

| Question | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study and country | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Bolger et al.;97 Republic of Ireland | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Haxell;99 New Zealand | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | Y | CT | Y | Y |

| Idenfors et al.;100 Sweden | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Garcia et al.;94 UK | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | N | Y | CT | Y | Y |

| Liegghio and Jaswal;90 Canada | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | Y | CT | Y | Y |

| Liegghio et al.;91 Canada | Y | Y | CT | CT | Y | N | Y | CT | Y | Y |

| Narendorf et al.;70 USA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Nirui and Chenoweth;133 Australia | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Walter et al.;76 USA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| NICCY;95 Northern Ireland | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | CT | Y | Y |

| RCEM;96 UK | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | N | CT | Y | Y |

Chapter 4 Organisation of crisis services

This chapter addresses the first objective, which was to present the best-available evidence on the organisation of crisis services for CYP aged 5–25 years, across education, health, social care and the third sector.

An overview of the different types of crisis services/responses that have been described across the included literature was presented to the SAG at the second meeting (see Report Supplementary Material 4). After discussion, it was decided to categorise the different types of crisis services/responses as follows: triage/assessment-only approaches, digitally mediated support approaches, and intervention approaches and models (see Report Supplementary Material 11).

Triage/assessment-only approaches

Twenty-three reports60,67,69,71,73,74,85,88,89,110,115–117,119–121,123,124,130,132,136,227 described different triage/assessment-only approaches for CYP experiencing crisis (see Report Supplementary Material 11) and three UK-only grey literature documents95,135,141 each presented a case example. Approaches included CYP presenting in crisis to the following types of services: emergency departments, educational settings, telephone triage and out-of-hours mental health emergency services.

Emergency departments

Eight reports89,110,115–117,119,123,124 described mental health assessment tools for paediatric emergency department clinicians, which included the HEADS-ED,110,116,117 HEARTSMAP89,119,123,124 and a Mental Health Assessment Triage Tool. 115 Four reports88,120–122 described urgent follow-up models after initial assessments had taken place at the emergency department. Two reports67,85 described the addition of involving trained mental health workers within a medical emergency department setting. Another report132 described Kids Assessment Liaison for Mental Health (KALM), which sought to build extra capacity for an emergency department medical officer to complete the assessment and to link with an on-call psychiatrist regarding an assessment and management plan. A further two reports71,74 described videoconference-based psychiatric emergency consultation programmes (i.e. telepsychiatry). One further report110 described the enhanced care co-ordination model for all CYP aged 0–21 years presenting with mental health concerns. The model involves a comprehensive needs assessment, a review of the CYP’s current use of services, and a package of medical and behavioural health follow-up with support for the family. 110

A case example95 described a 24 hours per day, 7 days per week (24/7), service that used a model in which the crisis response home treatment team worked together with Rapid Assessment Interface Discharge professionals. CYP were assessed by mental health practitioners in emergency department within 2 hours and then linked with onward support. 95 Another case example135 described a crisis service that provided assessments in the emergency department within 4 hours and appropriate follow-up care, which was available beyond normal office hours. The aim of the service was to prevent admission, and support could be provided for up to 6 weeks. 135

Educational settings

Four reports60,69,73,136 investigated CYP who presented within educational settings, of which three60,69,73 explored the use of the Prevention of Escalating Adolescent Crisis Events (PEACE) protocol within US high schools. This protocol involved an in-school facility in which high school-aged children could be assessed by psychology services before referral on to appropriate mental health services. The fourth report136 presented an urgent evaluation service for students, which aimed to provide ambulatory psychiatric evaluation within school hours, offering same-day assessment, co-ordination of care and linkage to the emergency department within the same hospital if required.

Telephone triage

Two reports102,110 described crisis telephone services within the USA in which onward referrals were made to appropriate services. One case study110 described a triage approach that responded to CYP presenting with mental health crises. This allowed for all referrals to access care via a single point of access telephone number between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m. The response time was determined by the location of the CYP and so ranged between 4 and 24 hours. Further assessment was carried out by either a consultant or the crisis team.

Out-of-hours mental health services

One report130 described an out-of-hours mobile crisis team for child care/custody protection services, as well as mental health-care providers in the region. One case study130 described a street triage model that enabled police officers to seek immediate consultation, advice or face-to-face support from a specialist mental health practitioner in making an assessment between 6 p.m. and 2 a.m. about anyone they encountered with an apparent mental health crisis. This triage model was for all ages and was not specifically for CYP. The aims of this model were to reduce the use of Section 136 Mental Health Act 1983137 and to provide more appropriate response to people’s mental health needs. (In England and Wales, Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983137 refers to powers that police have to move a person from a public space, when they appear to be suffering from mental disorder, to a place of safety.)

Digitally mediated approaches

Six reports99,101,104,109,118,127 described the organisation of digitally mediated approaches for CYP who were experiencing crisis (see Report Supplementary Material 12). One further UK-only grey literature document138 presented two case examples describing digitally mediated approaches. Approaches included telephone support/counselling services, text-based support/counselling services, telephone and text support/counselling services and online mutual-help groups.

Telephone support/counselling

One report101 described a telephone-based approach for CYP experiencing crisis, with which follow-up, emergency support and telephone tracing for those feeling suicidal were made available. The case example138 described Childline139 and the Samaritans,140 which provide support for people in mental health crises, particularly those who feel suicidal, with Childline in particular aimed at CYP aged < 19 years. Although both Childline139 and the Samaritans140 offer support via telephone and e-mail, Childline139 also has a live webchat facility.

Text-based support/counselling