Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR135643. The contractual start date was in October 2021. The final report began editorial review in June 2022 and was accepted for publication in November 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Smith et al. This work was produced by Smith et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Smith et al.

Introduction

Background

Rapid evaluation is used in a wide range of fields to ensure research findings are provided to evidence users in a timely, responsive and rigorous manner. 2 In health and social care, such studies are typically commissioned by policy-makers, senior managers, service providers and others keen to understand in as close to real time the ways in which service interventions are being designed, implemented and experienced. This reflects the complexity and fast pace of health and social care practice and policy needs, and the need to provide early yet rigorous evidence-based insights into how a new service is working (or not), whether it is ready to be rolled out further and how it might be altered and improved for the next phase.

There is often a particular policy window that is open and for which rapid evaluation research is sought to inform decision-making or policy review. 3 Professor Sir Chris Whitty underlined this point about the importance of providing timely, rigorous evidence synthesised from a range of disciplines relevant to the particular policy question as follows: ‘An 80% right paper before a policy decision is made it is worth ten 95% right papers afterwards, provided the methodological limitations imposed by doing it fast are made clear’. 4 Many evaluations of health and social care interventions therefore increasingly rely on rapid approaches and formative research designs (composed of iterative processes and research designs where the findings are shared as the study is ongoing in a more rapid fashion than in non-rapid studies), reflecting this quicker pace of modern policy-making and service innovation, all lent further impetus by the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. 5

It is important to acknowledge that evaluation and rapid evaluation are part of the wider community of health services and applied research, and many of the issues faced are common to the broader field, with rapid working bringing certain aspects and challenges particularly to the fore. 6 As we set out below, the toolkit of methods used within rapid evaluation are frequently those of applied health services research, sometimes adapted or enhanced to enable or mitigate the rapid approach. However, we also discuss various definitions of rapid evaluation which indicate how it is increasingly considered to be a distinct practice.

This essay draws primarily on the experience of two National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded rapid evaluation teams over the period 2018–23 – the Birmingham RAND and Cambridge Rapid Evaluation (BRACE) team and the Rapid Service Evaluation Team (RSET) from University College London and the Nuffield Trust – in undertaking a total of 19 evaluations of a diverse range of health and social care interventions. Where appropriate, the essay also draws on wider literature and experience of rapid evaluation to help contextualise and extend the analysis. Appendix 1 sets out details of the projects completed by the two teams and examples from these evaluations are used throughout this essay to support and deepen the insights distilled. The essay is organised using the ‘evaluation pathway’ and includes:

-

defining rapid evaluation;

-

balancing rigour and rapidity;

-

selecting, scoping and co-designing rapid evaluations;

-

engaging with stakeholders;

-

determining when a rapid approach is not appropriate;

-

mixed, quantitative and qualitative methods in rapid evaluation;

-

teams and skills for rapid evaluation; and

-

lessons for the conduct of rapid evaluation.

The overall aim of the essay is to synthesise practical learning from the experiences of two NIHR-funded rapid evaluation teams with a particular focus on the methodological challenges and operational realities of undertaking this form of research in a complex and fast-moving environment. The distinctive nature of this rapid evaluation research is also examined, including the importance of thorough scoping in partnership with stakeholders, the need for significant senior supervision and management of multiple projects and teams, and wide dissemination of project outputs.

The emerging field of rapid evaluation

The interest in rapid research across UK health and social care is mirrored globally by transnational organisations such as: the World Health Organization with their development of methods for rapid evaluation and evidence synthesis to inform decision-making and the design of rapid advice guidelines for public health emergencies;7,8 the Global Evaluation Initiative’s rapid evaluation programme, which is coordinated through the World Bank Independent Evaluation Group and the United Nations Development Programme Independent Evaluation Office; and the Better Evaluation platform’s toolkits on rapid evaluation. 7–10 Several health care and planning departments around the world have also set up their own rapid evaluation teams, such as the Centre for Evaluation and Research Evidence in the Victorian Department of Health in Australia; the Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation in South Africa; and the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 11–13 The scale of international activity related to the development of rapid evaluation approaches highlights their heterogeneous nature and applicability to study of health and social care interventions.

In UK health and social care, this increased interest in rapid evaluation methods and practice was evidenced by a funding call in 2017 from the NIHR to establish two rapid service evaluation teams. This resulted in the commissioning for five years of the RSET and BRACE teams. A third evaluation team based at the University of Manchester was commissioned by the NIHR in 2022, and there are plans for others based on specific sectors such as social care and technology-enabled services. Other national and local rapid evaluation teams are funded by different means. For example, the Rapid Research Evaluation and Appraisal Lab (RREAL) maintains links with academic institutions such as University College London while operating as a rapid response team providing services directly under contract to public sector, charitable, non-governmental and commercial organisations. 14 Furthermore, the NIHR-funded rapid evaluation teams work in close collaboration with the rapid evidence synthesis centres that are also funded by the Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR) Programme of the NIHR. 15,16

What is rapid evaluation?

Despite these developments in this emerging field of research, challenges remain about how to define, design and implement rapid evaluations. For example, there are numerous ways to define rapid timeframes, just as with what is meant by evaluation. 17,18 Indeed, rapid evaluation is a term that is much used but is less often well described and understood, and hence is subject to multiple and sometimes confusing definitions.

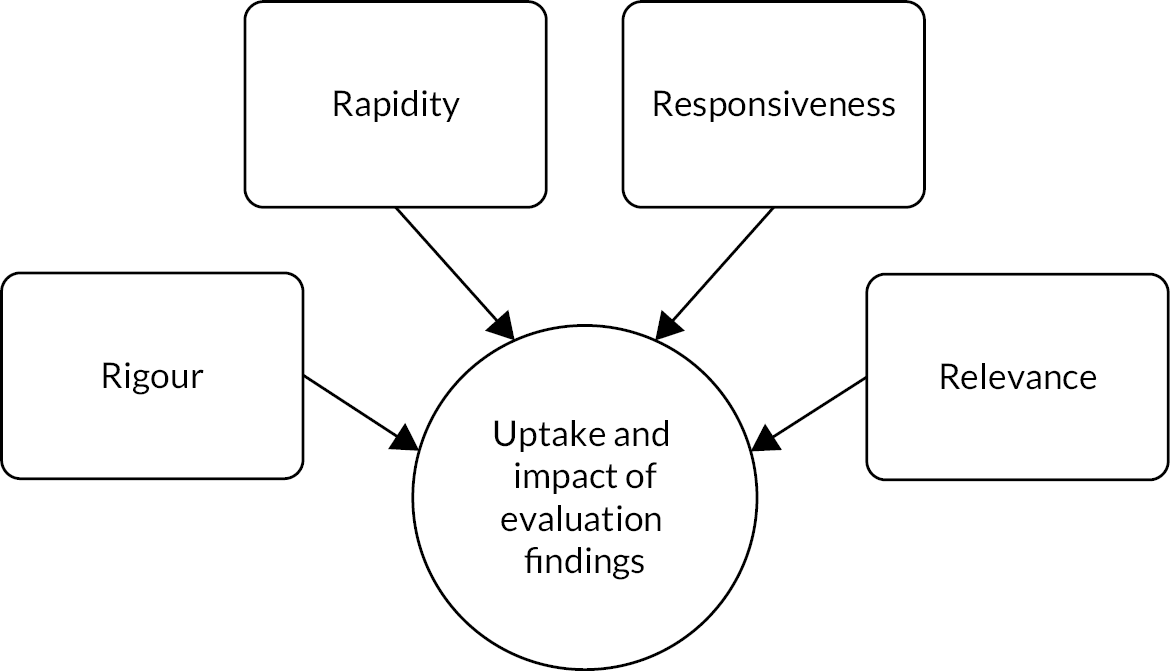

Riley and colleagues argued that for evaluation studies to have an impact on health care organisation and delivery, they would need to align to the 3 Rs, namely be rapid, responsive and relevant. 1 In this chapter, drawing on the experience of five years of the two NIHR-funded rapid service evaluation teams, we add to the 3 Rs a fourth R of rigour, and analyse our experience of how such research approaches can be used to balance rigour, responsiveness, relevance and (of course) rapidity in providing evidence for policy and practice (Figure 1 overleaf).

Within the overall conceptualisation of the 4 Rs there are various typologies that articulate specific aspects of rapid evaluation practice and can assist researchers in making decisions about when and how to apply rapid evaluation methods. For example, drawing on the experience of the two NIHR-funded teams, this timescale-focused typology has proved helpful to frame how ‘rapid evaluation’ is defined:

-

Rapid can be evaluating an intervention at an early stage in the innovation process (essentially early evaluation).

-

Rapid can mean an evaluation project with a short overall timescale.

-

Rapid may mean that the evaluation study is mobilised more quickly.

-

Rapid can mean that findings are shared quickly, through a short timescale or cycles of formative feedback within a longer evaluation.

The timescales for a particular study may be driven by the needs of policy-makers and/or practitioners, for example, to inform specific decisions to be made at national or local levels. This was particularly the case during the COVID-19 pandemic. Within this timescale-based approach, there will likely be a need for the creation of ‘rapid-learning research systems’ that bring together researchers, funders, practitioners and community partners to ask relevant questions and then seek to answer them using rigorous, efficient and innovative evaluation designs. 1 A particular challenge for such rapid-learning research systems is how they can deliver evaluation findings in ways that maximise their utility for decision-making and implementation and are sufficiently nuanced to take account of complex and perhaps conflicting stakeholder demands. This was a particular feature of the RSET and BRACE joint evaluation of remote home monitoring using pulse oximetry during the COVID-19 pandemic, as set out in Box 5 and in Sidhu et al. ’s analysis of learning networks and rapid evaluation. 19

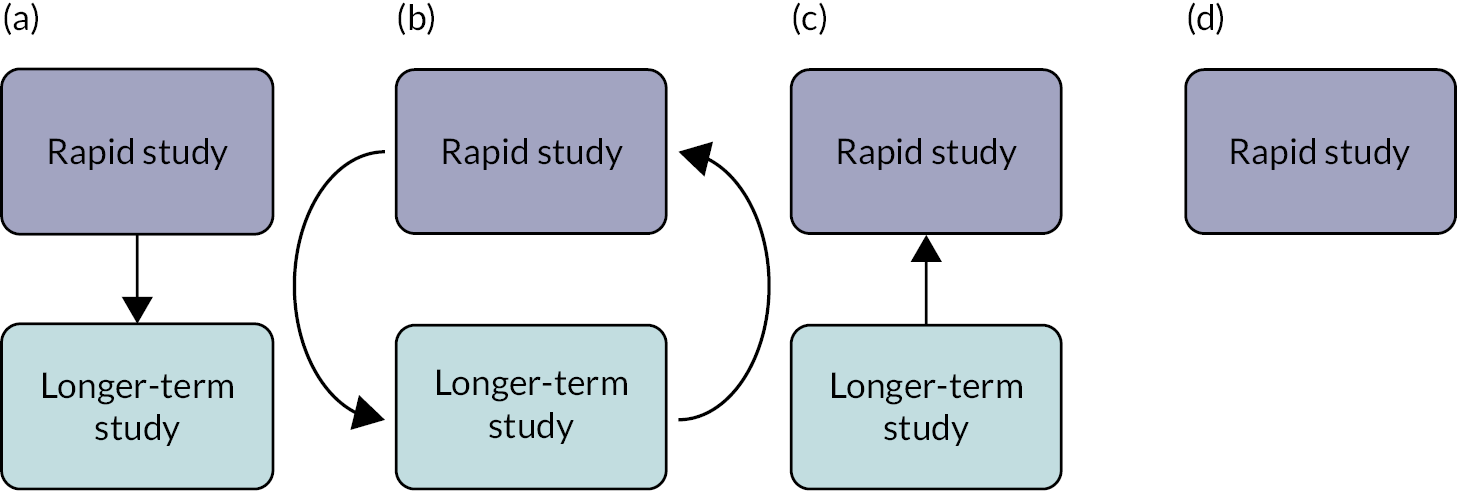

A second typology that has proved important for the two NIHR rapid evaluation teams was developed by Vindrola-Padros and focuses on the ways in which rapid evaluation is ordered and used in relation to other types of studies. 20 This relational-based typology is set out in Figure 2 overleaf, and asserts that a rapid evaluation can be: (a) the precursor to a longer study; (b) the follow-up to a longer-term study; (c) a nested study within a longer-term evaluation; or (d) a stand-alone research project. Examples of rapid evaluations which were the precursor to a longer study include the joint RSET-BRACE evaluation of remote home monitoring using pulse oximetry for COVID-19 patients (see Box 5) and the RSET evaluation of pre-hospital video triage for suspected stroke patients (see Box 7).

In a scoping review that sought to clarify approaches falling within the category of rapid evaluation in primary research, Norman et al. from the University of Manchester reviewed 352 papers and identified four main approaches that they suggested as useful preliminary categories for understanding rapid evaluation, and this methodology-based typology is as follows:

-

Use of a methodology designed specifically for rapid evaluation.

-

Increasing rapidity by doing less, or using a less-time intensive methodology.

-

Use of alternative technologies and/or data to increase the speed of an existing evaluation method.

-

Adaptation of methods from a non-rapid evaluation. 21

These typologies are not exhaustive but are offered as an illustration of the wider discussion about different ways to define, plan and undertake rapid evaluation research. This diversity of definitions of rapid evaluation is mirrored in the range of research designs used in this field. Researchers committed to rapid working have been experimenting with different research designs to carry out studies in short timeframes or integrate feedback loops so findings can be shared regularly and promptly. Examples of such designs include real-time evaluations, rapid feedback evaluations and rapid cycle evaluations, and may include the use of methods such as rapid assessment procedures (RAPs), rapid appraisals, rapid ethnographic assessments and rapid ethnographies. 22–24 More details of these and methods used in rapid evaluation are set out on pages 15–23. 5

Rapid evaluation can therefore be characterised by its timescale in being rapid as opposed to slower, which can mean a study of anything from a few days to many months. Rapid evaluations undertaken by RSET have ranged from 2 to 12 months. 5,25 The RSET evaluation of the special measures regime took 12 months and informed the development of a new regulatory framework, the Recovery Support Programme, to replace the special measures regime. 26,27 Rapid evaluations undertaken by BRACE have ranged from 2 to 31 months. Phase one of the RSET/BRACE evaluation of remote home monitoring using pulse oximetry for COVID-19 patients was completed in two months in order to inform the national roll out of these services (see Box 5). The BRACE evaluation of the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Trailblazer Programme started in October 2019 and finished in May 2022, but data collection was paused for most of 2021 due to COVID-19. The evaluation supported the national roll out of mental health support teams in schools and colleges. 28

Rapid evaluation also tends to be based on larger teams to enable more ground to be covered in a shorter amount of time (e.g. for teams of qualitative researchers to undertake fieldwork in parallel); necessitates an early and thorough scoping stage to co-design research questions; and incorporates regular feedback to evaluation stakeholders. 2,29,30 It is, however, important to note that there is no overall consensus about these dimensions, in what is an emerging and evolving field of research methodology.

Balancing rigour and rapidity

Short timeframes risk being associated with evaluations that might appear to be rushed, less rigorous and lacking sufficient engagement with theory. 2 However, rapid evaluations may engage with theory. For example, our study of remote home monitoring services for patients with COVID-19 used burden of treatment theory to analyse patient experiences and exposed the caring burden placed particularly on some patients and their families/friends in engaging with these services. 31 When undertaking rapid evaluation, there are inevitable trade-offs to be made about the breadth and depth of data collected and some services, interventions or contexts may prove more amenable to rapid evaluations than others. 17 A focus on rapid working may therefore potentially impede a research team’s ability to:

-

grasp fully the nature and influence of contextual factors;

-

access a sufficiently wide range of perspectives;

-

engage sufficiently with evaluation stakeholders;

-

explore the impact of an intervention in a longitudinal manner;

-

analyse data fully and/or triangulate different data from different sources;

-

delve deeper into emerging issues or unexpected findings;

-

sense-check emerging findings;

-

have sufficient data (e.g. enough qualitative observations) to answer the research question with a sufficient degree of certainty; and

-

measure longer-term outcomes.

A particularly significant risk with rapid evaluation is the danger of early assessment, where judgements may be made before an innovation has had a chance to succeed and hence may increase uncertainty in the research findings. From the combined experience of the BRACE and RSET evaluation teams in 19 studies (see Appendix 1), this can be mitigated by: careful attention to scoping an evaluation and determining the precise research questions and focus of the study; a thorough and ongoing approach to co-design and collaborative working with stakeholders; the use of rapid feedback loops that include caveats about any uncertainty in the findings; having a skilled and diverse team of researchers with sufficient senior oversight and support; and working with a carefully crafted and regularly updated dissemination strategy. These issues are explored in detail in subsequent sections of this essay.

Gaps remain in the applied health services research community’s understanding of the value and use of rapid evaluations in comparison to longer-term studies. Some authors have identified an intrinsic tension between speed and trustworthiness, arguing that rapid approaches need to address issues of validity and data quality to gain greater adoption in the evaluation landscape. 2 These assumptions can influence how evaluation findings are viewed by evidence users and ultimately whether and how they will be applied in policy and practice. 2 This essay offers practice-based insights from the NIHR-funded BRACE and RSET teams into how rapid evaluations can be scoped, undertaken and disseminated in ways that are as rigorous, responsive and relevant as possible, thus ensuring that they are ‘quick and clean’ and credible to those who commission and need the evidence from such studies.

Selecting, scoping and co-designing rapid evaluations

Identifying and prioritising topics

While much of the literature and learning on rapid evaluation focuses on project scoping, data collection and analysis, there is also potential for rapidity in how topics for evaluation are initially identified and prioritised. The work programmes of the two NIHR rapid evaluation teams included both responsive studies (i.e. where topics were proposed by the funder) and evaluations of service innovations identified by the teams themselves.

Both teams undertook rigorous horizon-scanning processes in their initial months to map priority areas and issues in health and social care, describe key knowledge gaps and identify service innovations that might be promising candidates for rapid evaluation. This involved a combination of activities, including: structured literature searches; reviews of policy documents and relevant reports (e.g. on service innovations in health and social care, including in key areas such as digital innovation); website scans; and consultation with stakeholders in the field of health and social care policy, innovation and research (including, e.g. members of local Academic Health Sciences Networks). Topic recommendations were also sought from the teams’ respective advisory and patient and public involvement (PPI) bodies and their wider policy, practitioner and research networks. Both the BRACE and RSET teams compiled a database of potential evaluation topics, which were updated as new topics were identified through ongoing horizon scanning, this being carried out more informally after the initial phase. Examples of rapid evaluation studies where topics were identified through these horizon-scanning processes are shown in Table 1 overleaf.

| Study | How was topic identified? | If evaluation not pursued, why not? |

|---|---|---|

| Innovations in outpatient services | Broad topic identified by RSET Stakeholder Advisory Board. Evaluation of PIFU identified by RSET researchers as emerging policy. Detailed evaluation identified in conjunction with PIFU team at NHS England. | |

| Hospitals managing general practice services | Topic identified by the BRACE team as an innovative emerging model for primary care organisation and management. The focus within the second phase evaluation on outcomes for patients with long-term conditions stemmed from a set of thematic priorities identified by the BRACE Health and Care Panel at a prioritisation workshop. | |

| Buurtzorg community nursing | Approached by West Suffolk clinical commissioning group. | Ultimately, the decision not to proceed with an evaluation was based on the very small scale of the new scheme and given its uncertain future funding, further doubt about timescales for amassing enough data to proceed. |

| Redthread Youth Violence Intervention Programme | Approached by the Redthread programme. | |

| Pre-hospital video triage of potential stroke patients | Approached by local stroke consultants who had led the two pilots in North Central London and East Kent in early 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The clinicians concerned had longstanding relationships with members of the RSET team, having collaborated on previous NIHR-funded work. | An initial approach by East Kent was not progressed in 2018/19. This was because their original pilot had only run for a few weeks and had limited data. |

In 2019 the teams were also asked by the NIHR to rapidly identify and produce a shortlist of priority innovations to evaluate in adult social care and social work, to inform the NIHR’s commissioning priorities in this area. Working closely with an adviser from the James Lind Alliance, a process for rapid identification and prioritisation of social work and care innovations was developed. 32,33 This process – which is set out in Box 1 – produced a shortlist of twenty innovations in adult social care and social work in a little over three months, two of which were subsequently evaluated by the rapid evaluation teams. 34,35

The process was undertaken by the BRACE and RSET teams, facilitated by a James Lind Alliance adviser, between August and November 2019.

Step 1: Identification of innovations. Emails were sent to 182 individuals or organisations in the social work and social care field, including people who use adult social care services, carers, frontline professionals, service providers, commissioners, national organisations, think tanks and researchers. The email asked people to nominate innovations in adult social work and/or social care that they thought would benefit from being evaluated. A total of 158 innovations were put forwards.

Step 2: Development of shortlisting criteria. A set of selection criteria was developed for use in shortlisting innovations. The criteria included that innovations: met an agreed definition of a ‘service innovation’; focused on social care/social work outcomes (not just health-related outcomes); were assessed as being amenable to rapid evaluation; and were not already the subject of current or prior evaluations.

Step 3: Grouping and sifting of innovations. The selection criteria were applied to the nominated innovations to produce a longlist. This process was undertaken by two researchers and any disagreements about the application of the criteria were resolved by a third researcher. A meeting was held with members of the research team and topic experts to finalise a shortlist of 20 innovations, with priority given to innovations that most fully met the selection criteria.

Step 4: Prioritisation of innovations. An in-person workshop was held with 23 participants, including people who use adult social care services, carers, practitioners, providers, commissioners, researchers and key national organisations. The design of the workshop was based on the James Lind Alliance’s consensus development model (Crowe et al. 2015), and three rounds of prioritisation resulted in a ranked list of the 20 shortlisted innovations. 36

For further insights into approaches to setting priorities in health and social care research, see the reporting guideline for priority-setting of health research from Tong et al. 37

Scoping a rapid evaluation

In all types of evaluation, a preparatory or scoping phase to clarify its purpose and the research questions is critical to success. 38 This can be more challenging in rapid evaluation, as there may be considerable pressure on researchers to start data collection and produce findings as quickly as possible. 20,39 As explored below, while scoping may need to be undertaken quickly, it must not be rushed or compromised. Indeed, where the timescale for a study is short, it is possible that scoping the evaluation questions and approach may take longer than data collection and analysis.

Scoping is undertaken to inform decisions about study design and delivery, to ensure that an evaluation is warranted, feasible, timely, relevant and promises findings that will be useful to intended evidence users. It also serves to familiarise researchers about the innovation and its context. Many of the purposes of scoping are analogous to those of a formal evaluability assessment, although in the experience of the BRACE and RSET teams the latter is not a common feature in rapid evaluation studies, tending more often to be employed where long-term or resource-intensive evaluations are proposed. 40 Furthermore, consideration may be given to using theory of change approaches when scoping and designing a rapid evaluation. 41 Scoping is therefore best approached as a process of open and intensive inquiry guided by the key questions derived by the NIHR rapid evaluation teams (see Box 2 overleaf), rather than through a pre-determined set of activities or methods.

Defining the focus: Is the intervention sufficiently well defined, for example in terms of its aims and how these are expected to be achieved? For theory-based approaches, scoping can inform a draft programme theory, to be tested out or developed as the study progresses.

Evaluation purpose: What is the main purpose of the study? What questions do stakeholders want the evaluation to answer?

Establishing evidence gaps: What is already known about the intervention or service in question? Are there other evaluations planned or under way, and what is their focus?

Evaluability: Is the intervention or service ready to be evaluated? Where an outcome evaluation is proposed, has sufficient time passed for desired outcomes to appear?

Stakeholder engagement: Who are the main stakeholders, and how will they contribute to and support the delivery of the evaluation?

Evaluation feasibility: Can sites, participants and/or data be accessed in the timeframe available? What data are already being collected about the intervention and will they be available to researchers? What other challenges might arise, and could they be mitigated?

Evaluation utility and timing: Will the findings be used and, if so, how? When and how should findings be shared to maximise their usefulness?

When seeking to answer these scoping questions, researchers are likely to gather information to inform more detailed methodological considerations at the design stage, for example about sampling approaches and sizes, methods of recruitment of sites and participants, relevant theoretical or conceptual frameworks, and (where appropriate) potential comparator control groups. While careful planning helps researchers to design evaluations that meet the 4 Rs as described above (rapidity, responsiveness, relevance and rigour), scoping questions may need to be re-visited periodically once a study is under way and, if necessary, approaches revised. A key purpose of scoping is to enable researchers to assess whether a rapid evaluation is appropriate and feasible. Scoping work may sometimes result in a decision not to undertake a rapid evaluation, although, as is discussed in more detail below, this outcome does not necessarily indicate the end of all research activities.

Scoping of a rapid evaluation typically includes tasks such as rapid evidence assessments, documentary analyses, data reviews and identification of standardised measures or validated tools. But scoping is not just a research activity, it also initiates a process of relationship-building and engagement, as illustrated in Box 3, which describes the scoping work undertaken for an evaluation of women’s health hubs by the BRACE Centre.

Women’s health hubs are a model for delivering integrated and holistic care for women’s reproductive and sexual health needs. 42 Scoping for an evaluation of hubs was undertaken in three and a half months and included:

-

An initial meeting with leads from the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) – who requested the evaluation – to understand the context for the request and evidence needs.

-

A rapid review of policy and evidence on women’s health hubs and related hub models.

-

Preliminary mapping of hubs to start to determine how many had been set up, where and when.

-

Interviews with 10 key stakeholders, including hub leads, national policy-makers, and representatives of key professional and women’s health organisations.

-

A consultation session with a group of women with lived experience of women’s health issues to explore their views about and priorities for the evaluation.

-

Establishing stakeholder and women’s advisory groups through which the team would secure advice and guidance throughout the study.

-

Discussions with university research governance and ethics colleagues to clarify which research approvals would be required.

-

A stakeholder workshop to share findings from the scoping work and agree the priority questions and areas of focus for the evaluation.

The scoping work concluded that it was too soon to assess the impact of women’s health hubs and the team proposed an early, implementation-focused evaluation including a package of work to scope the feasibility and design options for a longer-term impact evaluation. A key challenge to emerge from the scoping work was the lack of consensus about what a ‘hub’ was – preliminary work suggested that there were many different types of hub models, with varying structures, purposes and target populations. In response to this, the research team, in discussion with stakeholders, agreed that a key goal of the early evaluation would be to map the range of models and approaches and explore the local contextual factors that shaped how models had been designed, the services provided and the commissioning arrangements underpinning them. The study protocol is available on the NIHR Funding and Awards: Women’s Health Hubs web page. 43

Engaging with stakeholders

Working in close collaboration with evaluation stakeholders increases the likelihood that studies produce evidence that is relevant and actionable – this form of partnership approach is now widely expected by health service research funders and commissioners. This emphasis on researchers working in collaboration with the intended users or beneficiaries of research is also a response to the growing recognition that:

simple linear and often uni-directional models of knowledge transfer, and strategies to bridge the gap between the supposed different ‘cultures’ of research partners, have had limited impact. 44

Encouraging stakeholders to play a role in research processes is intended to foster greater ownership of the study and the evidence produced, while maintaining the independence of the research team, its analysis and conclusions. In addition to potential benefits in terms of enhancing awareness of and use of findings from the research, this ownership can also support rapidity – for example, when stakeholders help expedite access to research sites and participants. 45 Through regular communication with service, policy and patient stakeholders, researchers are also likely to pick up information about actual or planned changes to the intervention or service, or in the wider context, which might suggest the need to adapt the evaluation activities or tools to ensure the continued relevance of study findings. 30 However, building and maintaining relationships with stakeholders takes time and energy, so needs to be built carefully into timescales for a rapid study.

Both BRACE and RSET established multi-stakeholder consultative groups (BRACE’s Health and Care Panel, RSET’s Strategic Advisory Board), whose membership included NHS and social care system leaders, managers, clinicians and other practitioners, voluntary sector organisations, health services researchers, and patients and the public. These groups enabled swift access for both teams to advice and support at critical stages of project design and delivery, and in crafting outputs for dissemination of findings. In addition, access to specialist topic and methods knowledge was secured for individual projects, for example through the creation of project advisory groups, appointment of specialist advisers, or arrangements for engaging with existing networks or communities of practice.

Engagement of this nature involves careful and sustained dialogue and negotiation, rather than being a simple information-gathering exercise. The more constrained a study is in terms of available time or resources, the more tightly defined its focus and research questions will have to be. Difficult decisions will need to be made about what is in scope and which issues or questions are to be excluded. These are ultimately value-based decisions and therefore stakeholders have an important role to play. Furthermore, there may be tensions between the commissioners of an evaluation wanting ‘an answer’ and the study providing more nuanced or uncertain findings. This will prove easier to negotiate where effective engagement has been established early in the evaluation process with regular feedback and sharing of emerging insights.

Rapid patient and community involvement and engagement

A key challenge for researchers is to balance methodological considerations with the interests and priorities of the different groups involved, including patients and the public. Stakeholder preferences for a particular study design or for the measurement of certain outcomes may not prove feasible, requiring careful management of expectations. 17 This raises a question about how sufficient engagement can be achieved where timescales are restricted, especially for groups – such as patients and the public – where the best practice advice is to approach relationship-building as a long-term process.

Rapidity is undoubtedly a challenge to PPI. Trust and relationship-building underpin effective collaborations between researchers and patients and the public, and it is widely held that these take time to achieve and should not be rushed. 46 There is a risk that if PPI is undertaken quickly, it might exclude groups that face barriers to involvement and/or for whom tailored approaches are required, and researchers may lack the time to consider and address imbalances of power experienced by different groups to ensure equitable participation. 47 This does not mean, however, that involvement is unfeasible in rapid evaluations. Established PPI panels or groups offer researchers a means by which to engage and consult quickly, where good working relationships and agreed ways of working may already be in place. The two NIHR-funded rapid evaluation teams created bespoke PPI groups to rapidly secure advice while scoping and delivering studies. For example, these groups advised on the development of evaluation questions and identification of areas of focus; reviewed draft protocols, recruitment and research tools; commented on interim and emerging findings to ensure that analysis took account of patient and public perspectives; and proposed ways of disseminating studies to patient and public audiences.

Where more specialist input was required, engagement with people who had specific lived experiences was additionally sought. This was most often through liaison with existing service user or community groups, which enabled teams to quickly access a wider range of perspectives (including seldom-heard groups) than would have been possible had specialist PPI groups been recruited from scratch and at speed. For example, for a BRACE evaluation of mental health support teams in schools and colleges, the study team worked closely with the University of Birmingham Institute for Mental Health’s Youth Advisory Group, a diverse group of 18- to 25-year-olds with lived experience of mental health issues. Members of the Youth Advisory Group designed the recruitment process and research materials for focus groups with children and young people (including writing the script for an engaging and understandable video to use when recruiting school children to focus groups, in place of the usual participant information sheet), were trained and supported to co-facilitate these groups, and were involved in the analysis and writing up of findings, as well as advising on other elements of the study. But it should be noted that this type of engagement can be challenging to do rapidly, given the need to be sensitive to individuals’ needs and circumstances. In the case of the mental health support teams’ evaluation, the co-production of focus group research with the Youth Advisory Group took around nine months from preparing an application for ethical review through to completion.

Another example of where rapid PPI influenced the approach to an evaluation was with the study of telefirst access to general practice by people living with multiple long-term conditions. The lead researcher met with five members of the BRACE PPI panel, all of whom live with long-term conditions, in two online workshops. This led to a critical review by the evaluation team of the analysis plan for the study, in particular to include hearing problems as a specific category in the data analysis. In similar vein, this PPI engagement led to a decision not to have mental health problems as a separate analytical category as there might be situations where people with mental health problems would find telephone triage easier or harder, and this distinction could not be incorporated into the analysis framework. 48

The growing use of video-conferencing technology has reduced the need to travel and therefore enables PPI groups to be convened at much greater speed. In so far as it helps to overcome some of the practical barriers to participation, such technology could potentially lead to more inclusive and diverse contributions to evaluation projects. Conversely, it risks further marginalising some groups from involvement processes where they lack technology access and/or skills. 49 Researchers must also be realistic about what can be achieved. Some involvement methods, such as co-production, encourage the sharing of power and responsibility and so may be more valued. But it is unlikely that the conditions for genuine co-production can be fostered where timescales are short. 50 Arguably, meaningful rapid consultation is preferable to poorly conceived and rushed co-production.

The willingness of patients and the public to contribute to rapid evaluations should not be underestimated, even despite the limitations to involvement described above. Patients and public participants are often frustrated at what they perceive to be the slow pace of research. The BRACE and RSET centres’ experience is that PPI participants are generally very responsive to requests to contribute within short timescales and find this refreshingly different, especially when they understand why there is a need to work quickly in a context of co-design and partnership and are able to see the results of their input in a relatively short space of time.

Undertaking rapid evaluation in an inclusive manner

A central concern for both the BRACE and RSET teams was to ensure that our approach to rapid evaluation was appropriately inclusive, attending carefully to different dimensions of equality and diversity in how we scoped, undertook, analysed and disseminated our projects. Both teams recognised that this area of our activity was constantly in need of challenge and learning, and we explored this in our respective BRACE and RSET mid-point reviews that were highly formative in nature, and again when drawing together learning for this report.

A core aspect of our approach to equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) was in the composition of evaluation teams, where we sought where possible to have a balance amongst colleagues of gender, ethnicity, professional or disciplinary background. This challenged us to ensure that there was always sufficient senior and experienced leadership, supervision and support within the team for an evaluation, including in respect of induction and integration into a project and wider evaluation centre team, giving swift and funded access to any training needed and ensuring that effective mentoring and line management was in place. Six-monthly whole-day facilitated development meetings of the wider BRACE team helped support this inclusive approach, along with regular team meetings for each evaluation project. To support this inclusive and developmental approach, the RSET team met on a monthly basis to discuss progress with projects and other issues relating to the work, and project meetings were held weekly or fortnightly. Additionally, following the mid-point review, project leads met with all RSET researchers on a one-to-one basis to review progress, and identify and overcome any barriers for individuals.

In recruiting people to our respective stakeholder engagement panels, EDI was a key consideration. For example, the BRACE Health and Care Panel sought to engage people of a diverse range of professional and patient/carer backgrounds, from across the four nations of the UK, different sectors of health and care, and attending to protected characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, age and disability. A similar approach was taken in relation to RSET’s Stakeholder Advisory Board and when establishing our respective patient and public involvement groups. For some evaluation studies, bespoke patient and public involvement was put in place in order to ensure fully inclusive project scoping, supervision and review. For example, for the Mental Health Trailblazers evaluation we worked with the University of Birmingham’s Institute of Mental Health Youth Advisory Group to specifically co-design recruitment and consent materials so that these were accessible and engaging to a wide range of children and young people, with a video ‘information sheet’ used to support literacy issues. For the RSET study on peer support social care in prison, we worked with the organisation EP:IC, an independent research, evaluation and consultancy collective in social and criminal justice, to recruit a panel of people with lived experience of prison and either providing or receiving peer supported social care. Within this project, feedback from panel members was used to inform study design, data collection tools (e.g. ensuring questions around safeguarding were included) and analysis.

Both teams sought always to select case study sites within evaluation projects that enabled us to explore each service innovation in a range of settings serving populations with differing needs. For example, for hospitals managing general practice, sites in urban, rural and coastal settings were selected and a similar approach was taken for the selection of site for the evaluation of remote home monitoring of COVID-19 patients, this sampling being guided by considerations of dimensions such as inequalities, rurality, ethnicity and deprivation.

Determining when rapid evaluation may not be appropriate

A fundamental purpose of scoping is to decide whether an intervention or service can and should be evaluated rapidly. Ultimately, the answer to this question depends on how ‘rapid’ is understood in the context in question. That said, there are some warning signs which indicate that a rapid approach may be less appropriate or that more extensive preparatory work is required before a study can get under way (Box 4).

-

When there is already substantial evidence about the intervention and resources for further evaluation cannot be justified. In such a case, a rapid evidence synthesis could be proposed.

-

When there is no compelling reason why the study should be undertaken rapidly and limited rapid evaluation team capacity would be better invested elsewhere.

-

When there is substantial disagreement among stakeholders, for example about the aims of the intervention or about what is required from an evaluation, albeit scoping work may include facilitation of consensus among stakeholders.

-

When there are clear signs that stakeholders are unlikely or unwilling to engage in the evaluation process or with the evaluation findings.

-

When any national or local approvals required cannot be secured within the time or resources available for evaluation.

-

When there are clear signs that researchers will not be able to access sites, participants or data required for evaluation within the time or resources available.

-

When the quantitative requirements of the evaluation are unlikely to be met, even through seeking to predict outcomes from existing or rapidly acquired evidence.

-

When researchers are being asked to cut corners in a way that might compromise the rigour of the research or ethical standards.

-

When the evaluation questions require a longitudinal or sequenced design.

Where researchers and their stakeholders decide against a rapid evaluation, this does not necessarily signal the completion of all research activities. Scoping work itself often yields important substantive insights that can inform ongoing implementation or delivery of the intervention or service, and so the focus may switch to disseminating the outputs from scoping. Researchers may work with intervention or service leads on activities that could support later evaluation. This could include, for example, developing a theory of change to articulate how the intervention or service is intended to work and specify desired outcomes; or defining metrics, doing power calculations and setting up systems for ongoing routine data collection. In some cases, a rapid evaluation may be undertaken but with a tighter scope than was originally proposed, so that the study focuses only on questions and data collection and analysis activities that the scoping work indicated would be feasible within the timeframe available.

An example of scoping work leading to a decision not to proceed with rapid evaluation was where the RSET team decided to abandon an evaluation of a community nursing initiative in West Suffolk based on a Dutch model of decentralised management and decision-making – the Buurtzorg model. 51 Ultimately, the decision not to proceed with an evaluation was based on the very small scale of the new scheme and, given its uncertain future funding, concerns that there would not be sufficient time to amass enough data to proceed. In the event, the scheme did engage with the King’s Fund and a local HealthWatch group to undertake some limited evaluation of staff and patient experience. 52,53

The quantitative analysis proposed by an evaluation should reflect the data that are available and the evaluation should have sufficient flexibility built in to accommodate any uncertainty about data availability, as was the case when scoping the RSET evaluation of Redthread Youth Violence Intervention Programme. 54 What is available may not be the best or most detailed data and good quality aggregate data may therefore be considered sufficient. However, the data may fall well short of being able to address some or all of the key quantitative questions – for example, collection of local routine data may have only just started or data quality may be poor. Under these circumstances it may be sensible not to progress any further, or to evaluate the data processes themselves and advise on how to organise these to enable future evaluation.

Methods for rapid evaluation

Overview of methods

The methods used for rapid evaluation are typically those employed in other evaluation research, albeit often adapted or combined to suit the rapid approach. While there has been considerable discussion in the methodological literature about qualitative methods within rapid evaluation,7,20,23 there has been rather less examination of rapid quantitative analysis, yet this is an emerging field and rapid evaluation studies are increasingly mixed methods in nature, or on occasion purely quantitative.

Mixed methods in rapid evaluation

As with all health services research, studies will often require a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods to answer complex questions in nuanced ways that encompass a range of perspectives, such as staff and patient experience, patterns of service utilisation, impact on waiting times or learning about the process of implementation. 6 Stakeholders will typically want to know the answer to questions such as: how will it work, what will the implementation issues be, and what advice can be given about how best to proceed? This has been the case with many of the projects undertaken by the NIHR-funded rapid evaluation teams, including COVID-19 Oximetry @home which is described in more detail in Box 5 overleaf. Other BRACE or RSET studies using mixed methods have included:

-

Mental Health Trailblazer schemes in schools [BRACE, with the Policy Innovation and Evaluation Research Unit (PIRU)]. 28

-

Special measures regime (RSET). 55

-

Reduction in Youth Violence Intervention Programme (RSET). 56

-

Acute hospitals managing general practice services, phases 1 and 2 (BRACE). 57

The specific mix of methods will depend on issues such as the nature of the service innovation, its stage of implementation, the evaluation questions, availability of data for tracking, ease of access to key stakeholders for interviews, time available for local and national research governance processes necessary for fieldwork involving patients, and the number of researchers available to staff the project.

In non-rapid applied health services research studies, there is typically a sequential approach whereby qualitative methods may be used to explore issues raised by quantitative analyses, such as the reasons for a change in patterns of service utilisation or an apparently slow take-up of a new initiative. Likewise, initial qualitative work may raise questions that require examination using quantitative data, such as establishing whether a change in service described in research interviews has led to actual shifts in use of local services. With rapid working, sequential application of methods will often not be possible, and there will be a need for simultaneous study of different aspects of a service innovation. The time available to compare and synthesise insights from different data collection activities is likely also to be limited yet will be even more important where timescales are compressed. It is in the selection of an appropriate blend of research methods, the execution of a multi-method study through close and intensive team working with sufficient senior oversight, and then the analysis and synthesis of these different sources of quantitative and qualitative data that a rapid research team particularly brings its expertise and insights to bear.

The study took place in two phases. Phase one was completed in two months and focused on implementation and costs of services established during the first wave of the pandemic, and a systematic review. These findings informed the national roll out of these services. Phase two, conducted during the second wave and completed in one year, evaluated effectiveness, cost, implementation, patient and staff experience and behaviours (delivery and engagement), impacts on inequalities and differences in the mode of remote monitoring (technology-enabled vs. analogue services).

Methods used for phase twoWe used the following methods to evaluate the COVID-19 remote home monitoring services.

To explore impact and effectiveness (e.g. hospitalisations and mortality) of these services across England, we used routinely available data, hospital administrative data and aggregated or other information produced by the services.

To explore costs of setting up and running these services, we used a survey tool to collect aggregated data on patient numbers, staffing models and allocation of resources from 26/28 sites.

To explore implementation, staff experiences of delivering services, patient experiences of receiving and engaging with these services, impacts on inequalities and differences in the mode of remote monitoring, we conducted:

-

Surveys across 28 sites in England. We received responses from 292 staff and 1069 patients and carers.

-

Interviews with 58 staff and 62 patients and carers across 17 of these sites.

-

Interviews with five national leads.

Using mixed methods was a strength of this evaluation because it enabled the study team to triangulate data from multiple sources to build a comprehensive understanding of the development, coverage, implementation, effectiveness and cost of services. For example, we were able to explore possible reasons for low patient enrolment, as demonstrated by national quantitative data, using the survey and interview findings. This enabled the team to develop balanced conclusions that took the different findings into account.

One challenge of using mixed methods in this rapid study was that the quantitative and cost elements relied on data completeness. For example, we were only able to carry out effectiveness analyses for organisations that had complete data.

Further information about the study is available from Fulop et al. (in press). 58

Quantitative methods in rapid evaluation

Formal quantitative evaluation studies often rely on various conditions to be satisfied, as set out in Box 6, and these can take time to be fulfilled and may conflict with the needs of rapid evaluation. It is important to note that some of these constraints can also be present within qualitative evaluations, underlining the increasingly intertwined nature of qualitative and quantitative methods within health services research and evaluation. 21

-

The time for the service to be implemented.

-

The time needed for sufficient individuals to be exposed to the service/innovation.

-

The time from exposure to outcome.

-

The time for data owners to collect and curate data.

-

The time for researchers to request and receive data.

-

The time for researchers to analyse data and produce findings in a useful format.

If the primary aim of a rapid evaluation is to start the research quickly, then there are possible ways of overcoming some of the barriers set out in Box 6, for example by ensuring that some of the information governance processes are completed in advance. If the aim is more focused on rapid results, then there are means of shortening or overlapping these steps while maintaining a robust analysis. 59 However, this can only be achieved up to a certain point or within specific situations. For example, it may not be possible to speed up implementation of the service innovation and if it is going to take some years for the full impact to be observed, there is little option for reducing that time.

In the meantime, the new service may evolve, with changes being made as implementers notice what seems or does not seem to be working, or in response to wider policy. In such a scenario, the service implementation is not stable which has implications for how to interpret quantitative findings and understand what can be carried forward to other settings. 60 Furthermore, if too long is spent waiting for the right time to evaluate a service innovation, there is a risk that it emerges as ineffective and costly when this could have been foreseen earlier. Even more significantly, a service may fail when this could have been prevented, which makes the need for carefully considered rapid evaluation even more important. 60

Within a rapid evaluation study, it may therefore be useful to reassess carefully the purpose of quantitative analysis and keep an open mind about methods. Rather than embarking on a comprehensive assessment of service- and cost-effectiveness, the aim of quantitative analysis may be more about guiding decision-making on how the service is implemented, understanding how effective and costly it is likely to be and addressing shorter-term measures of safety and equity. 18,61,62 At the same time, assessments can be made of data quality within the monitoring of the new service, data collection processes and pathways to facilitate a robust evaluation in the future. This all represents valuable analysis which affirms the important role of quantitative expertise within rapid evaluation teams.

Routine quantitative data for rapid evaluation

It can take several months to obtain individual patient-level data and such delays can be a major barrier to any evaluation, whether rapid or otherwise. If there are plans to use the same data for multiple projects (e.g. routine NHS hospital activity data contained in Hospital Episode Statistics), it may be preferable to have a data-sharing agreement that covers them all. For example, within the NIHR RSET and BRACE teams, the Nuffield Trust and RAND Europe respectively have a data-sharing agreement with NHS Digital that permits use of Hospital Episode Statistics for all rapid evaluations undertaken for the life of the NIHR grant funding those teams. A similar arrangement is also possible within Trusted Research Environments or data safe havens, which are single secure environments in which researchers can access sensitive data. It should be noted that for large national routine datasets like Hospital Episode Statistics there is a time lag of a few months for data being made available, which can preclude evaluation in real time. Uncleaned versions of data may be available more quickly (e.g. Secondary Uses Service data are the uncleaned version of Hospital Episode Statistics), but there is an inevitable trade-off in quality.

The aims of a rapid evaluation may, however, be sufficiently served by aggregated data rather than data at individual patient level. Aggregated data can be accessed more quickly and may even be already in the public domain. For example, the RSET evaluation of the Quality Special Measures Regime used published data on quality indicators, such as achievement against the 4-hour accident and emergency target or cancer waiting times, to assess its impact. 63 The BRACE evaluation of the impact of telephone triage on access to primary care for people living with multiple long-term health conditions used published data from the English GP Patient Survey and from Understanding Society, a nationally representative survey of households in the UK. 48,64,65

Many organisations collect their own data, either at individual level or aggregated, which can be available in near real time, but quality and completeness of such data can be variable. For example, the RSET/BRACE evaluation of the COVID Oximetry @home intervention used new routine data that were collected by sites about numbers of people enrolled onto the programme which, for many sites, were unusable because they were incomplete. 66 If there are existing routine data sets, they may be preferable to bespoke collections where there is no added disruption to care management processes and hence a lower risk of poor quality. 67

Embracing uncertainty from rapid quantitative analysis

There will inevitably be a trade-off between time available for quantitative analysis of a service innovation and the certainty of the evidence that results. Rapid evaluation will lead to a greater range of uncertainty about likely outcomes, but it is important to embrace this and support decision-makers in accounting for such uncertainty. 68 It can be useful to explore the relationships between uncertain outcomes and the assumptions that are made. For example, an evaluation of different strategies for reopening schools after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK explored the relationships between different assumptions about the effectiveness of contract tracing and isolation on disease transmission. 69 In some cases, the range of possible outcomes may be too broad to be useful. On the other hand, it is possible that, despite the uncertainty, analysis of quantitative data can show the likelihood of a poor outcome to be low and with relatively little impact on cost. Conversely, the chances of a poor outcome may be considered too great for a service to continue. The key questions may be not so much ‘does it work?’ but ‘could it work?’ and ‘when could it work?’

Quantitative approaches

In some situations, robust observational studies are possible within a rapid evaluation, particularly if there are sufficient data, benefits are likely to be seen early and processes for data collection and analysis are established in advance. However, this is not always going to be possible and is not always needed, and quantitative methods have particular value in providing timely feedback to inform ongoing or rapid decision-making. The overriding aim is to make the best use of what is available within the time frame while being clear about limitations and the range of uncertainty.

With this in mind, existing quantitative methods that may be adapted for use within rapid evaluation studies include: an analysis of short-term outcomes; extrapolating prior or early evidence to predict longer-term outcomes; and real-time monitoring of process and outcome measures for continual feedback (Table 2). In our experience with RSET and BRACE, the opportunity to use all of these methods has not arisen, although they are planned as recommendations for further evaluation work with at least two ongoing RSET projects. These methods will now be examined in turn.

| Effective use of short-term outcomes | Extrapolating outcomes from short-term observations and existing evidence | Continuous monitoring | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summary | Measuring outcomes that can be observed over the course of an evaluation. | Using what is known to provide best estimates of future outcomes under ranges of assumptions and scenarios. | Ongoing monitoring of outcomes or processes making use of the latest observations as soon as they become available. |

| When to use | If short-term outcomes are relevant or there are interim outcomes that can lead to relevant findings (e.g. by extrapolation). To assess safety. |

When important outcomes are not likely to be observed over the period of an evaluation. For planning new services and evaluating multiple options. |

To identify potential problems as soon as possible. For reassurance that outcomes are on track. |

| Methods | Observational study methodologies. | Mathematical modelling. | Sequential monitoring of time series. Statistical process control. |

| Key considerations | Sample sizes. Comparators/counterfactuals. |

Decision support. Making use of the range of uncertainty in predictions. Model calibration and validation. Sensitivity analysis. |

Setting appropriate thresholds to signal potential concerns or evidence of improvement. |

Effective use of short-term outcomes in rapid evaluation

With some services, the major impact would be seen quickly, for example, where the aim is to reduce the need for people who are already ill to be admitted to hospital, as in the RSET and BRACE teams’ evaluation of pulse oximetry monitoring at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. 20,66

Where major effects are not likely to be realised over the course of an evaluation project, or counterfactuals are not easy to establish, it may be useful to focus on outcomes that can be assessed rapidly; for example, the performance of a service including its safety and how far its take-up is equitable. For the RSET evaluation of the Redthread Youth Violence Intervention Programme, the team focused on comparing characteristics of young people eligible for the programme who engaged with it against those who did not engage. This provided insight into any potential problems with reaching certain populations. 54 Also, several early studies of remote monitoring of COVID-19 patients using pulse oximetry were not able to robustly indicate effectiveness. Non-biased comparator populations were not easy to acquire, and some studies relied on retrospective comparisons, but analyses were sufficient to establish that the home monitoring service was likely to be safe. 70

Other approaches to making effective use of short-term outcomes might focus on interim endpoints. For example, to evaluate rapidly the effectiveness of a new diagnostic service for people with suspected cancer it is not feasible to wait for people to die to assess mortality – both ethically and because of the length of time required. Instead, it would be more practical to assess the stages of cancer being detected in the new service and use this to assess how quickly people are being diagnosed. This may be enough to influence decision-making about the service’s future, although, if required, mathematical models of stage-dependent cancer progression can then be used to predict the likely impact on life years gained. 71

Extrapolating outcomes from existing evidence

Another quantitative approach that can be adapted for rapid evaluation studies is the use of modelling to extrapolate the impact of a service, using available evidence and/or early data from the running of a new service to predict possible outcomes. The primary aim of such models is to inform decision-making, sometimes even before a new service has been established, and they are particularly well suited to evaluating several hypothetical alternatives. Moreover, once a service is up and running, modelling can be used to provide early feedback on possible outcomes and identify where changes might prove most beneficial.

Quantitative researchers regularly evaluate long-term outcomes such as quality-adjusted life years, for which they apply modelling techniques to produce a range of estimates. Another classic example is the queueing model, where an understanding of the layout of the system, patient or client arrival rates and service times can be used to predict waiting times and cost, and applied to advise on the optimal layout of the system or service (e.g. how many receptionists or health care assistants to add at different times of the day). 72

These approaches have been adopted in evaluations of health care interventions73,74 which are informed by assumptions about the dynamics of a process, existing evidence and early quantitative observations. Indeed, longer-term extrapolation can be from short-term or interim findings. The cancer service example already described above is one example of this. Sensitivity analysis is crucial: central estimates for outcomes are less important than the range of uncertainty that comes from evaluating different assumptions and scenarios because such uncertainty can be used to assess the risk associated with different decisions. Since modelling can produce results quicker than long-term follow-up and examine more alternatives than an observational study, it can be a valuable approach to use within a rapid evaluation. Modelling per se is not always a rapid process as it can be both complex and time-consuming. Evaluators should carefully consider the most appropriate modelling approach within a rapid evaluation.

Continuous monitoring

Continuous monitoring can also be used within rapid evaluations to track the implementation of a new health or social care intervention. In such cases, rather than wait for enough data to become available to perform a single evaluation, analysis can be ongoing using, for example, sequential monitoring techniques. 75 These techniques could be applied in (or close to) real time with appropriate alerting rules for when evidence suggests a service is not working as hoped or, worse, appears to be unsafe. Such approaches are commonly used in drug and vaccine safety surveillance76 and the monitoring of health care outcomes. 77,78 They are also widely used by health systems for quality improvement. 79,80 For the provision of evidence, sequential analysis of data has been shown to have greater statistical power than analyses undertaken at the end of a data collection process. 81

Qualitative methods in rapid evaluation

Qualitative analysis is critical for exploring the context of a new service, barriers to and enablers of its implementation, and the views of patients and health care professionals about how well the innovation is working, or not and how it might be improved. The range of qualitative methods for data collection within rapid evaluation is not substantively different from those commonly used in longer-term qualitative studies, for example interviews, observations, focus groups, surveys and documentary analysis. In seeking to work more rapidly, it is typically the application of qualitative research methods that is different from longer-term studies, for example, by reducing time frames to collect and analyse data, or undertaking data collection and (at least some) analysis in parallel. This presents both opportunities and risks, as is explored below and summarised in Table 3 overleaf. As with quantitative data collection and analysis within rapid evaluation, there are trade-offs to be made between time available for fieldwork and analysis, certainty and/or richness of data gathered, and reporting findings early and frequently while accepting they may be incomplete or emergent.

| Shorter timeframes for data collection | Simultaneous data collection and analysis | Speeding up qualitative data analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summary | Adaptations to collect data within shorter timeframes. | Analyse fieldwork data during the process of data collection. | Reduce the amount of time required for qualitative data analysis. |

| When to use | When there is limited time for data collection and there are existing groups that are relevant for the study. | To share emerging findings as the study is ongoing, identify gaps during data collection, maintain consistency across researchers. | When findings can be identified from audio-recordings or notes (without having to transcribe a full dataset). |

| Methods | Focus groups in naturally occurring settings such as team or board meetings (selected purposively), using group interviews, adopting remote technology for interviews or observations, single site visits for different research activities. | RREAL RAP sheets, daily researcher memos or data summaries. | Bypassing transcription and analysing data directly from recordings. Using voice-recognition software to transcribe interviews. |

| Key considerations | Participants might not engage in discussions related to the research and focus on the original meeting instead. Loss of face-to-face nuance and some richness of insights. Risk of researcher overload with multiple data collection activities. |

RREAL RAP sheets (see Appendix 2 for an example) are suitable for qualitative studies that use a thematic approach in analysis but might not be appropriate for narrative or discourse analysis. | In-depth analysis might be limited. This approach might not be appropriate for all types of qualitative data analysis. Can transcribe later and return to data for subsequent papers. |

Shorter time frames for qualitative data collection

Some authors have reported using adaptations during the process of data collection to work within shorter timeframes. 29,82 For example, fewer interviews or focus groups may be undertaken, with the evaluation team being clear with project stakeholders of the downsides this may entail in terms of breadth or depth of insights. One way of mitigating this risk in rapid evaluation is to use a larger team of researchers to undertake interviews and/or observations in an intensive short period of time, using a common database to store notes and recordings, having dedicated research capacity to thematise and analyse these data, and scheduling regular research team workshops to discuss findings and identify gaps and insights. This was an approach that was used by BRACE and RSET to positive effect during the evaluation of remote home monitoring using pulse oximetry during COVID-19 (see Box 5). The advantages and disadvantages of deploying a larger team of researchers are discussed below in the section on teamwork and skills.

Other adaptations of qualitative methods for rapid working include, for example, the use of ‘naturally’ occurring groups for focus group discussions, where researchers request a slot of time within an extant meeting or group, using this time to conduct a focus group discussion within research permissions and protocols, rather than organising a specific and separate data collection session. This clearly has the advantage of economising on effort for the research team and is likely to increase convenience and reduce burden for respondents. Downsides include people being in ‘meeting mode’ rather than focused on research, there being other interpersonal dynamics at play within the group setting, a possible reticence to share views in front of colleagues (and more so than in a usual focus group), and the research team having less time to explore issues in depth. Another option is to conduct group interviews at a case study site rather than arrange one-to-one discussions. This enables more people to be interviewed more quickly, although entails some trade-off of data richness and diversity, as people will likely have less chance to share and develop their own views with the research team and may feel some degree of constraint in the group setting.

Technology can prove very helpful when seeking to shorten the time taken with specific research methods, for example in enabling the use of remote video conferencing such as Zoom or Microsoft (MS) Teams for conducting research interviews, which offers more flexibility of scheduling and location for the discussion, saving on travel times and costs. Recording of the interview can also be more straightforward when using these modalities and during the pandemic researchers have gained valuable experience in collecting and storing data in this way. There are as ever trade-offs to consider, including the two-dimensional nature of the interaction, the researcher being less able to take stock of wider contextual issues (which are known to be an important aspect of qualitative interviewing) or spot non-verbal cues, and the risk of a respondent not being as ‘present’ as they might be for an in-person discussion. 83 Similar issues will be raised by virtual observation of meetings, something that was much easier to undertake during the COVID-19 pandemic. There are, however, important specific considerations to be made when planning the observation, recording and analysis of virtual meetings and the conduct of online interviews, including ethical approvals, data storage and confidentiality. 84

Time frames for collecting qualitative data can also be reduced by using different methods simultaneously, for example by using a single site visit to collect documents, undertake interviews and carry out observations of meetings or other activities. This offers significant economy of time and possibly resources but does pose the risk of researchers experiencing overload of information, losing some attention to context and complexity of data, and missing some of the benefit to be gained by multiple visits and experiencing a range of organisational or service dynamics and issues over time. As ever, it is vital that researchers keep a careful note of their methods, reflect with evaluation stakeholders on the efficacy of approaches taken and use innovations in data collection as an opportunity to explore improved ways of undertaking studies in the complex and fast-moving context noted in the background to this essay.

Compressing the timescales for undertaking qualitative research does risk some potential unconscious bias towards engaging with easy-to-reach or -engage groups, therefore limiting the perspectives gained. Using existing workplace meetings in place of arranging a research focus group is one example where this might occur. As noted in the earlier discussion of PPI, experience has shown that researchers need to build a particular degree of trust and dialogue with some groups before they can effectively engage them. 85 This is especially true of groups that are seldom heard, whose experiences of marginalisation (from society and research processes) may have resulted in cynicism and distrust. 86 Where this is the case, it is important for rapid evaluation teams to ensure that they include researchers with specialist skills and connections into particular communities, or with trusted intermediary groups such as voluntary sector organisations.

Simultaneous data collection and analysis