Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/99/19. The contractual start date was in September 2019. The final report began editorial review in October 2022 and was accepted for publication in February 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final manuscript document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Cavallaro et al. This work was produced by Cavallaro et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Cavallaro et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from the published papers by Cavallaro et al. 1 and Cavallaro et al. 2 These are open-access articles distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given and an indication of whether changes were made. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Chapter outline

This chapter describes the context of adolescent pregnancy and the health visiting services available in England. It briefly describes the implementation of the Family Nurse Partnership (FNP) in England and reviews the literature on its effectiveness. It concludes with a description of the rationale for the present study and study objectives.

Adolescent pregnancy and adverse outcomes

Each year, approximately 3% of babies (~16,000 in 2020) are born to mothers aged < 20 years in England and Wales. 3 Adolescent mothers are more likely to experience adversity, be less engaged with education and employment and have rapid repeat pregnancies compared with older mothers. 4–7 For their children, young maternal age is associated with a higher incidence of preterm birth, low birthweight8,9 and a greater risk of child maltreatment and associated adverse long-term consequences, including poorer physical health and social, emotional and cognitive outcomes. 10–12 These adverse maternal and child outcomes of adolescent pregnancy, due to social adversity, disruption to education and employment and child-rearing practices, are of major importance to public health research and the NHS. 13,14 Programmes supporting adolescent mothers, such as the FNP, are therefore likely to remain a priority for the NHS and local authorities (LAs). 15

Understanding how best to target services to the most vulnerable mothers is key to improving the health of these mothers and their children. Evidence to help improve targeting is being called for by service providers, who need to understand the value of interventions in the context of their target populations and local services in order to inform commissioning and justify spending. 16

The Family Nurse Partnership and early years health visiting in England

Health visiting in England is delivered as part of the Healthy Child Programme. All families with children should receive a minimum of five visits from 28 weeks of pregnancy until the age of two and a half. 17,18 These mandated assessments allow health visitors to identify families in need of additional support and offer more intensive support, including additional health visitor contacts and referrals to other, more intensive, programmes. This model of proportionate universalism, an approach combining universal service provision accessible to all with more intensive services proportional to the level of need, has been recommended as key to reducing health inequalities in the UK. 19

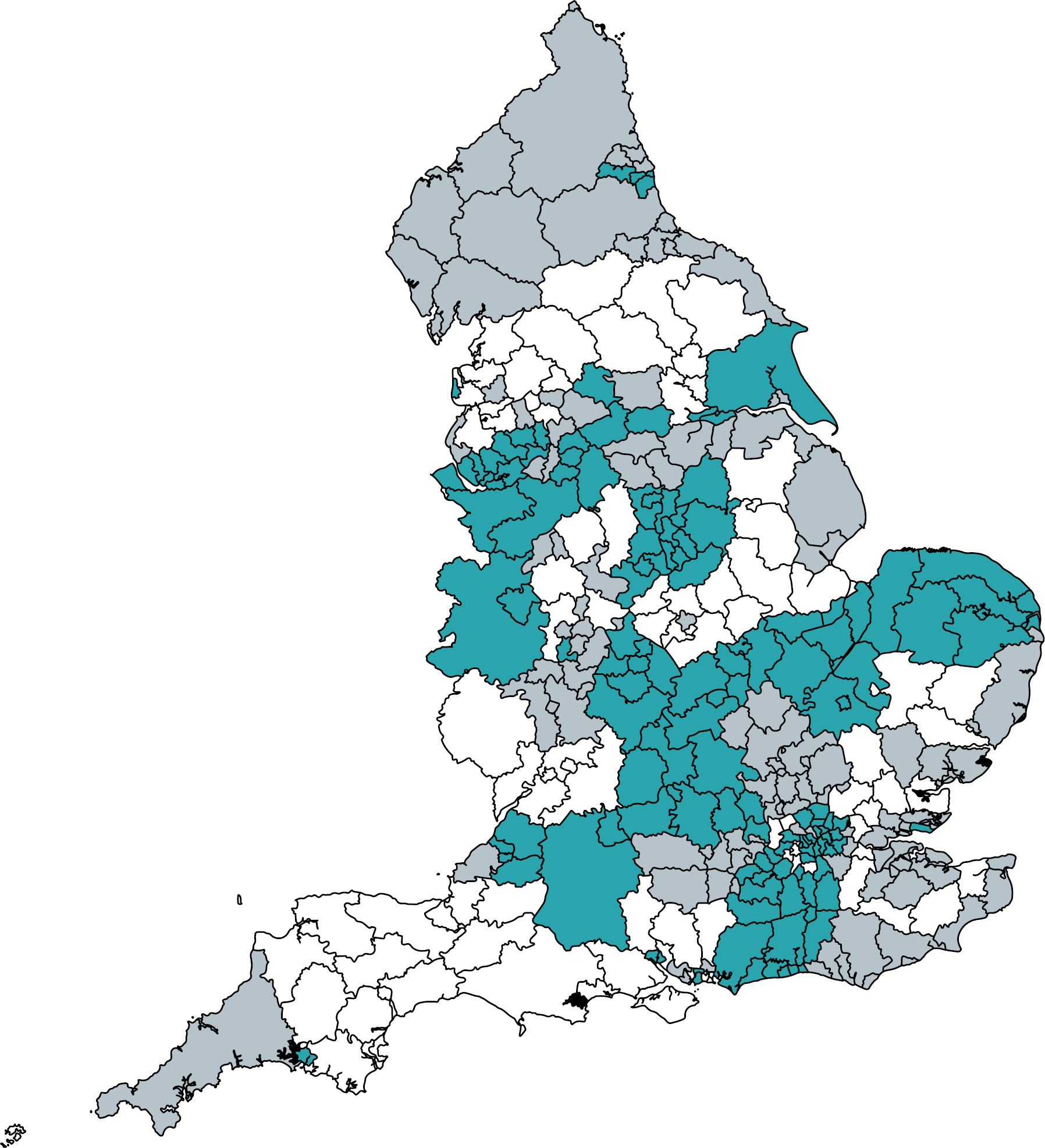

Several intensive health services aiming to reduce inequalities between adolescent and older mothers have been trialled; of these, FNP, an intensive home visiting programme supporting young first-time mothers, has a strong evidence base from several randomised trials in the USA and is recommended within the UK government’s Healthy Child Programme. 19,20 Mothers enrolled in the FNP receive up to 64 home visits by a dedicated Family Nurse from early pregnancy until the child’s second birthday. The FNP aims to improve birth outcomes, child health and development and promote economic self-sufficiency among young mothers. 21 Although a randomised trial of the FNP in England found no evidence of benefit on smoking in pregnancy, birthweight, hospital admissions before age 2 or second pregnancy within 2 years, improved cognitive development outcomes were reported, and there remains strong support for the programme locally (see Literature review – evidence of effect of Family Nurse Partnership programmes on maternal and child outcomes). 20–23 The Building Blocks 2- to 6-year follow-up reported no evidence of effect on maltreatment outcomes but evidence of improved school readiness, measured by a Good Level of Development in the early years foundation stage profile (EYFSP) and improved educational achievement at Key Stage 1. 24 The FNP has been commissioned in > 130 English LAs since 2007 (Figure 1).

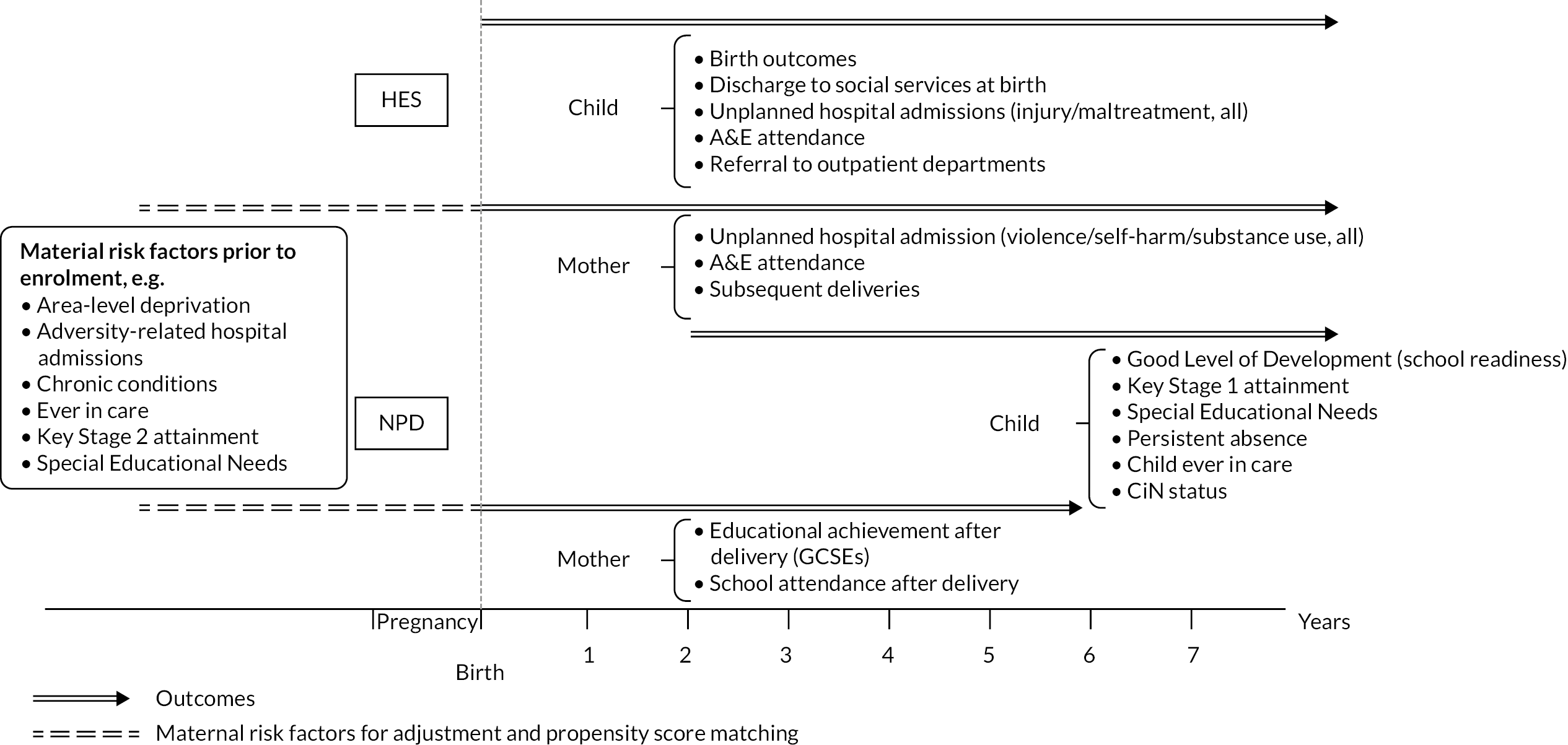

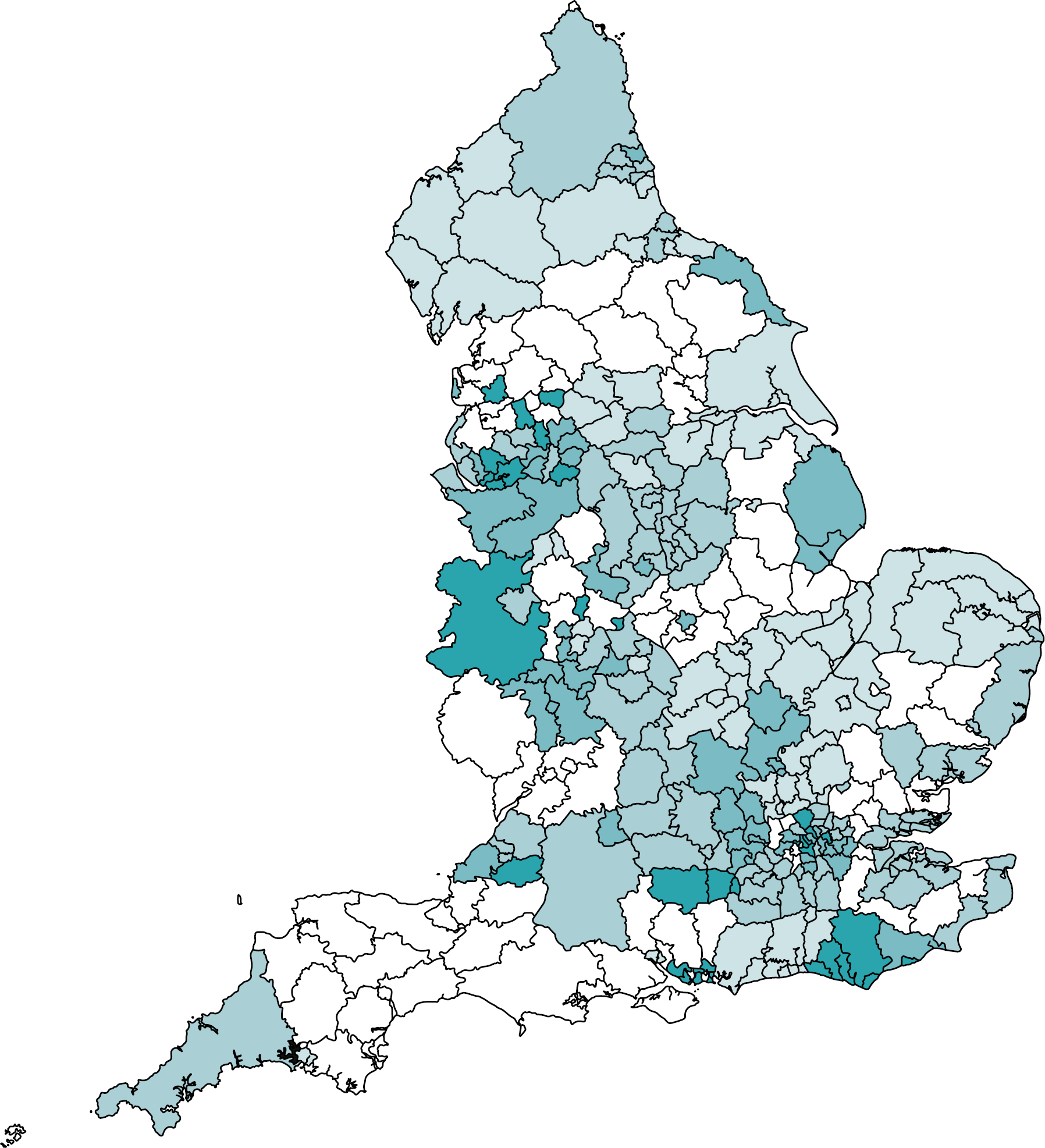

FIGURE 1.

Family Nurse Partnership site activity status in March 2019 among all FNP sites active during the study period (2010–9), by English LA.

Literature review – evidence of effect of Family Nurse Partnership programmes on maternal and child outcomes

Review approach

We conducted a literature review of the effect of FNP programmes on maternal and child outcomes using a combination of PubMed searches for ‘FNP’ or ‘Nurse Family Partnership’ (the original programme name in the USA) and identifying additional references through manual review of reference lists of previously identified papers from the USA, UK and other trials.

The evidence base for the FNP spans multiple countries and includes randomised controlled trials as well as a few non-randomised studies. Findings from this review were synthesised by the country in which the research was conducted, given differences in context and the importance of context (usual care) for the effect of interventions.

USA randomised trials

Most of the literature on the effectiveness of the FNP stems from three randomised trials of the Nurse Family Partnership (NFP) conducted in the USA by David Olds and colleagues, including over 20 peer-reviewed articles. The trials were conducted in Elmira, New York (enrolment 1978–80), Memphis, Tennessee (enrolment 1990–1) and Denver, Colorado (enrolment 1994–5). A wide range of maternal and child outcomes were examined, with up to 20 years of follow-up.

Overall, the evidence from the three USA trials indicates a positive effect on some – but not all – maternal and child health and educational outcomes. Often, the positive effect was observed in a subsample of particularly vulnerable mothers but not in the entire cohort. The Elmira trial found a one-third reduction in all accident and emergency (A&E) admissions among children up to age 2 and ages 2–4; however, no effect was observed on all hospital admissions ages 2–4. 25,26 Although a reduction in mean A&E and hospital admissions for injury/maltreatment of 55% was reported in the second year of life, no such effect was detected for injury/maltreatment in ages 0–1 or 2–4. No effect was observed on this outcome for up to 2 years in the Memphis trial. 27 The Elmira trial was the only NFP trial to examine child abuse/maltreatment reports and found a 40% reduction in such reports up to age 15 (although this benefit was not evident before the age of 4 years). 26,28

All three USA trials examined the effect of the NFP on child development and educational achievement. Results were mixed in the Elmira trial, with no effect up to age 4 for the whole sample and no effect on intellectual functioning at age 3 or 4 among children identified as maltreated. 26,29 There was no difference in intellectual functioning at age 3 or 4 among children of women smoking ≥ 10 cigarettes per day at enrolment; however, they did have higher intelligence quotient (IQ) scores (4.86 points on average) at this age than children of smoking mothers in the control arm. 30 The evidence in favour of a positive effect of the FNP was stronger in the Memphis and Denver trials, although these effects were concentrated in the subgroup of mothers with low psychological resources at enrolment (composite score including mental health, sense of mastery and intelligence scores), and even among this group, the positive effects were limited to only a few outcomes by age 6 and/or age 9 in the Denver trial. 31–36 Child mortality was only examined in the Memphis trial, which found no evidence of effect up to age 19 for all-cause mortality but a reduction in preventable-cause mortality in the NFP arm (0% vs. 1.6% in one control group, p = 0.04). 37

The effect of the NFP on maternal outcomes was weaker than on child outcomes. The Elmira trial found evidence of a 50% reduction in child abuse perpetration reports up to 15 years after giving birth. 28,38 There was evidence of 0.5 fewer subsequent births 15 years after the first birth among unmarried women of low socioeconomic status only in the Elmira trial but no evidence at 18 years in the Memphis trial or at 4 years in the Denver trial. However, there was evidence that NFP increased the subsequent birth interval by 5–28 months in all three trials (among the unmarried, low-socioeconomic subgroup in Elmira only). 32,34,38,39 There was no evidence of an effect on maternal educational qualifications beyond 6 months31,34,40,41 or on experience of domestic violence in the three trials (weak evidence of a decrease in the Denver trial). 28,34,42 Evidence was mixed regarding the effect on drug use or impairment. 34,38,42 The effect of NFP on maternal mortality was only examined in the Memphis trial, with no evidence of a difference in all-cause mortality but weak evidence of a 1% reduction for mortality from external causes at 20 years. 37

A more recent trial of 5670 Medicaid-eligible nulliparous pregnant mothers recruited between 2016 and 2020 in South Carolina found no evidence of an effect on birth outcomes (preterm birth, low birthweight, small for gestational age and perinatal death). 43

England Building Blocks randomised trial

One randomised controlled trial of the FNP (the Building Blocks trial) was conducted in England, enrolling approximately 1600 expectant mothers in 2009–10. 44 The Building Blocks trial found no evidence of effect on the four primary outcomes – smoking in late pregnancy, birthweight, second pregnancy within 24 months of first birth and rates of A&E attendance or hospital admissions within 24 months of birth. Some secondary outcomes suggested small positive impacts of the FNP in the first 2 years of life, including maternally reported child cognitive and language development. Safeguarding concerns recorded in primary care records were higher for mothers enrolled in the FNP.

Results for follow-up to age 6 showed no difference for most maltreatment outcomes between the trial arms, including referrals to social services, children referred as Children in Need (CiN), duration for which children were assessed as in Need, children with a child protection plan (CPP) or who were Looked After. 24 However, children in the FNP arm spent on average 2 months less time in care than children in the usual care arm. There was no evidence of a difference in children not attending a hospital outpatient appointment, attending A&E for injury or ingestion or being admitted to hospital for the same causes.

Nonetheless, there was evidence of FNP’s impact on some – but not all – child development and educational outcomes. There was no difference in Special Educational Needs (SEN) provision up to age 6 or educational attendance for ages 2–4. Children of FNP mothers were more likely to achieve a Good Level of Development at school entry (age 5) than in the usual care arm, with a greater beneficial impact on total point score (across 17 learning goals) observed for children of younger mothers. At Key Stage 1, children in the FNP arm were more likely to reach the expected level for reading; no other differences were observed for Key Stage 1 outcomes. The beneficial effects of the FNP were stronger among boys than girls (reading and writing), among younger mothers at enrolment (mathematics and writing) and among mothers not in employment, education or training at the time of enrolment (writing).

Other randomised trials in Germany, the Netherlands and Canada

Several other trials have been conducted in high-income countries. The VoorZorg trial in the Netherlands, enrolling in 2007–9, reported a reduction in child abuse/maltreatment reports by age 3 in the FNP arm, as well as a reduction in some types of interpersonal violence at 32 weeks of pregnancy and 24 months after birth. 45,46 A trial of a FNP-based model in Germany (Pro Kind) reported improved child development among high-risk women only, but no evidence of a difference in subsequent births within 2 years. 47 The follow-up trial evaluating outcomes at age 7 reported fewer behavioural problems in children, less child-abusive parenting, fewer maternal mental health problems and higher maternal life satisfaction in the intervention arm. 48 Some positive effects on mother–daughter interactions were also reported for a small subsample who agreed to participate in video recording. 49

One randomised controlled trial in Canada has not yet published results on primary outcomes but has reported preliminary findings on a number of secondary outcomes, with a reduction in prenatal cannabis use and a modest reduction in cigarette use in smokers associated with the intervention but no reduction in rates of prenatal cigarette and alcohol use. 50

Non-randomised studies in Australia, Scotland and the USA

Non-randomised studies in the USA and Australia have reported reduced preterm births, child maltreatment, infant death and subsequent births among FNP participants compared with controls, as well as higher high school attainment and different patterns of A&E attendance. 51–56 These studies adjusted for confounders through propensity score matching, frequency matching and entropy balancing, although due to limited maternal characteristics, the potential for residual confounding remains. The Australian study compared participants to eligible women who were not referred to and never participated in the programme, thereby also being subject to likely residual confounding. One prospective cohort study in Scotland has not yet reported results. 57

Other evidence

A randomised controlled trial of group FNP in England, administering 44 FNP sessions to groups of 8–12 expectant mothers, found no evidence of effect on parenting or maternal sensitivity or on secondary outcomes [except for a higher proportion of mothers breastfeeding at 6 months, odds ratio (OR) 3.2; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.99 to 10.6]. 58

Synthesis

The available evidence on the effectiveness of the FNP is summarised in Appendix 1.

The three USA trials of FNP showed mixed but overall positive impacts on child health and development outcomes and some maternal outcomes, similar to the more recent Netherlands trial. These results contrast with the Building Blocks trial in England, which showed no evidence of impact of FNP on most child outcomes, with the exception of some cognitive outcomes. There are two main contributing explanations for the difference in results observed in England compared with the USA and the Netherlands: first, there are likely important differences in usual care contexts between different countries. The social safety net is likely to be stronger in England than in the USA, with better access to services for adolescent mothers not enrolled in FNP (including the minimum five mandated health visiting contacts, universal health care free at the point of care, services provided through free Children’s Centres, etc.), which may explain the lack of association for most outcomes in England. For example, the mothers in the control arm of the Building Blocks trial received an average 16 health visiting contacts up to the child’s second birthday. Nonetheless, the usual care group in the Netherlands trial probably had access to similar or better levels of care than in England, with 9–11 home visits before the child’s second birthday, as well as support from child welfare and mental health organisations,59 indicating that there are important factors (beyond access to services) shaping the effect of FNP.

Second, there are notable differences in the eligibility criteria for FNP in England compared with other countries. The main eligibility criterion for enrolment in FNP in England is maternal age: adolescents who are aged up to 19 at last menstrual period (LMP), and who are first-time mothers, are eligible for enrolment as long as they live in a LA with a FNP site and are enrolled before 28 weeks of pregnancy. From November 2016, a few FNP sites extended their eligibility criteria to enable enrolment after 28 weeks gestation and among mothers aged 20–24 at LMP with other markers of vulnerability, recognising that mothers in these groups could also benefit. 60 Eligibility criteria for the Building Blocks trial (nulliparous, age ≤ 19, living in the catchment area of a local FNP team, < 25 weeks of pregnancy)44 are therefore aligned with the practice in English FNP sites at that time. Young age is the main eligibility criteria for FNP in England, based on the ease of identifying the youngest adolescent mothers, associations between adolescent motherhood and social adversity, disrupted education and employment13,61 and other factors contributing to poor birth and health outcomes among their children. 5,6,62

In contrast, additional socioeconomic criteria such as unemployment, low educational level or low income are used in combination with maternal age in other countries,27,35,63 based on logic models of how the original NFP was expected to provide benefits. 64 As a result, the population of young mothers enrolled in trials in other countries are a more selected and vulnerable group than in England, who may stand to benefit more from the FNP (as evidenced by greater effectiveness in socioeconomically deprived groups demonstrated in the USA trials). 32,36,38

Rationale for the present study

Usual care available to adolescent mothers is likely to have declined between the Building Blocks trial study period and after the introduction of austerity measures in England – in particular, health visitor budgets have decreased since responsibility for commissioning health visiting services shifted from the NHS to local government in England in 2015. 65 Furthermore, evidence from the USA trials suggests that the youngest, most disadvantaged mothers are likely to benefit most from FNP. 22 Adequately powered subgroup analyses are needed to examine whether some groups of families benefit from FNP more than others. In addition, constrained conditions under which trials are conducted often do not match the complexity of real-world implementation of programmes. 66

Linkage of existing administrative records provides a cost-efficient means of evaluating services as they are implemented in the real world by bringing together data from different sectors on a range of outcomes. They also allow for a sufficiently large sample size for subgroup analyses. Our population-based study aims to use longitudinal linked observational data between the health, education and social care sectors to evaluate the effects of FNP on outcomes of eligible mothers and their children up to age 7 to generate evidence on the factors that may influence effectiveness and programme engagement (including participant characteristics, setting, provider and programme delivery). 67,68 Evaluating outcomes for approximately 30,000 FNP families and up to 1 million controls built on the results of the Building Blocks trial24,44 will provide increased statistical power to detect smaller differences, differences in rarer outcomes and subgroup differences for which the Building Blocks trial was underpowered. Use of these data for the real-world evaluation of FNP is important and necessary to inform the targeting and commissioning of services by generating evidence on which groups of mothers and their children benefit from the real-world implementation of FNP in England.

Research aims and objectives

We aimed to evaluate the real-world, ongoing implementation of FNP in England on the outcomes of mothers participating in FNP and their children. Specifically, our objectives were to:

-

determine the rate of and characteristics associated with enrolment in FNP among young mothers across LAs in England

-

determine the effect of FNP on maternal and child outcomes, including identifying which families benefit the most from FNP

-

identify contextual and programme factors that might influence the effects of FNP.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from the published papers by Cavallaro et al. 1 and Cavallaro et al. 2 These are open-access articles distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given and an indication of whether changes were made. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Chapter outline

This chapter begins with a description of the study participants and data sources. It then describes the data linkages and manipulations performed for this study: linkage of FNP data to Hospital Admissions Data [Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)], creation of the cohort of FNP mothers and controls, creation of the child cohort and linkage of the FNP-HES mother and baby cohort to education and social care records [National Pupil Database (NPD)]. Lastly, it defines the outcome and exposure variables used, and the analyses conducted, in this study.

Study design and participants

We created a retrospective cohort of all first-time mothers aged 13–19 years at LMP with live births in England between 1 April 2010 and 31 March 2019 and their first-born child(ren), using individual-level, linked, longitudinal data from routinely collected hospital, education and social care records. We also constructed a similar cohort of all first-time mothers aged 20–24 at LMP because some FNP sites implemented modified inclusion criteria to include young mothers up to this age. The cohort was created through linkage of hospital records (HES), education and social care records (NPD) and FNP programme data for mothers and their children. Our approach built on previous linkage of education and health records and validated methods of linking hospital records for mothers and babies. 69–71

Data sources

Hospital Episode Statistics – Hospital Admissions Data

Hospital records for mothers aged 13–24 years and their children in England were extracted from records of births and deliveries in HES. HES is a data warehouse containing details of all hospital admissions (from 1997), outpatient appointments (from 2003) and A&E visits (from 2010) at NHS hospitals in England. 72 HES data have been extensively used in research. In addition to the birth record, we linked information from hospital admissions and A&E attendances for mother and child (including up to 11 years before delivery for the mother; see Appendix 2, Figure 16).

Information captured in HES includes administrative data [including admission dates, NHS trust, general practitioner (GP) code]; demographic information (including age, sex, ethnicity) and clinical information (diagnoses and procedures). A unique ‘Hospital Episode Statistics Identifier (HESID)’ is assigned to enable episodes of care for the same individual to be combined (this has recently changed to a ‘Token Person ID’). Diagnoses are coded by professional coders in hospitals using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes (International Classification of Disease, version 10); procedures are coded using Office of Population, Censuses and Surveys Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures, version 4 codes (OPCS-4). 73,74 Based on previous methodological work, we linked delivery records for mothers and birth records for their children within HES to create a mother–baby HES cohort. 69

National Pupil Database – education and social care data for mothers enrolled or not in Family Nurse Partnership and their children

The HES cohort of mother–baby pairs were linked to education and social care records from the Department for Education for both mothers and children in FNP and comparison groups (including information before delivery for mothers). Information on assessments, attainment and progression at each Key Stage is available for all pupils in state schools in England, alongside eligibility for free school meals (FSM), information about SEN provision and information about absences and exclusions. NPD, including social care data, has been extensively used in research. 75

For both mothers and their children in the cohort, we linked HES data to the following NPD databases:

-

The Spring School Census (formerly PLASC), the Early Years Census, the Pupil Referral Unit (PRU) Census and Alternative Provision – including pupil-level information from 2002 (for the School Census) for pupils aged 2–19+ on SEN, FSM eligibility and information about absences and exclusions.

-

The CiN Census – including information on referrals to children’s social services, assessments carried out upon these children and whether the children became the subject of a CPP, from 2008. 76

-

The Children Looked After (CLA) return – including information on all Looked After children and recent care leavers in England, from 2005. 77,78

For mothers only, we linked to Key Stages 2 and 4 data, which include teacher assessments and/or test results in Year 6 (age 11) and Year 11 (age 16). We also linked to Key Stage 5 data (Year 12–13, ages 17–18) but did not use these data due to small numbers. For children only, we linked to the Early Years Census and EYFSP. These data include whether the child achieved a Good Level of Development at school entry (age 5), which we used as a proxy for school readiness, as well as Key Stage 1 assessment data (age 7).

A Unique Pupil Number (UPN) is used by the Department for Education (DfE) for linkage of CLA and CiN with the NPD. The UPN is usually assigned at first entry to a maintained school or nursery, typically around the age of 4–5. Therefore, it is not possible to link the NPD to CLA or CiN data for children who receive social care services only before they enter nursery/school or for some adopted children (who can be provided with a new UPN). 79 It is not mandatory to return UPN in CLA or CiN beyond age 16. UPN was replaced by an anonymised Pupil Matching Reference in the data that we had access to.

Family Nurse Partnership information system – Family Nurse Partnership service data for mothers enrolled in Family Nurse Partnership

The HES cohort was linked to the Family Nurse Partnership information system (FNP IS) to obtain information on participation in FNP for mothers who were enrolled in FNP. The FNP IS supports the implementation of the FNP programme in England, originally provided by NHS Digital under contract to the FNP National Unit on behalf of Public Health England. Data are reported in real time and are used locally by FNP teams and nationally by the FNP National Unit to monitor programme delivery and support quality improvement.

Data collected in the FNP IS include information from the mother and child collected at enrolment (by 28 weeks gestation at the latest, including mother’s age, marital status, living arrangements, education, employment, social care); 36 weeks gestation (including maternal health, alcohol, drugs and smoking); birth (including birthweight and gestational age) and at regular intervals until 24 months after birth (including child health and development, social care and other maternal baseline variables). Information on each visit is also collected (including date, length of visit, family nurse seen and referrals to other services). The FNP IS became functional in 2009, and data quality was reported to be high from 2010 onwards. FNP data have been used in previous research. 80

The FNP IS contains maternal and child identifiers at enrolment/birth: name, sex, date of birth, postcode, GP code and NHS number. When mothers graduate from the FNP (mostly at the child’s second birthday, but sometimes earlier), pseudonymised data are retained only by the FNP National Unit, and identifiers are held solely on secure servers at NHS Digital.

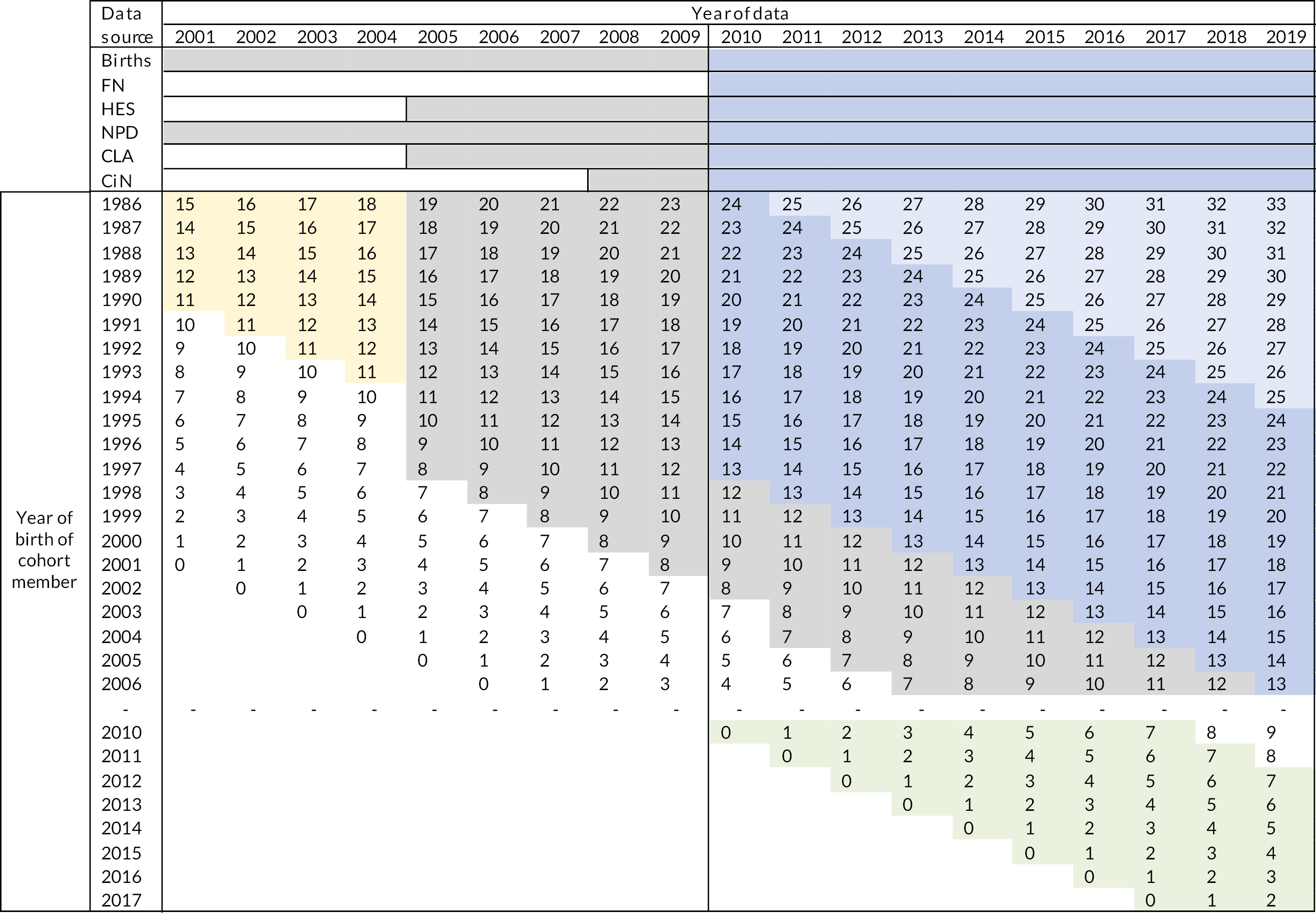

The time span covered by each data source (including look-back, study and follow-up periods) is described in Appendix 2, Figure 16.

Linkage Family Nurse Partnership-Hospital Episode Statistics

Linking mothers enrolled in Family Nurse Partnership to Hospital Episode Statistics

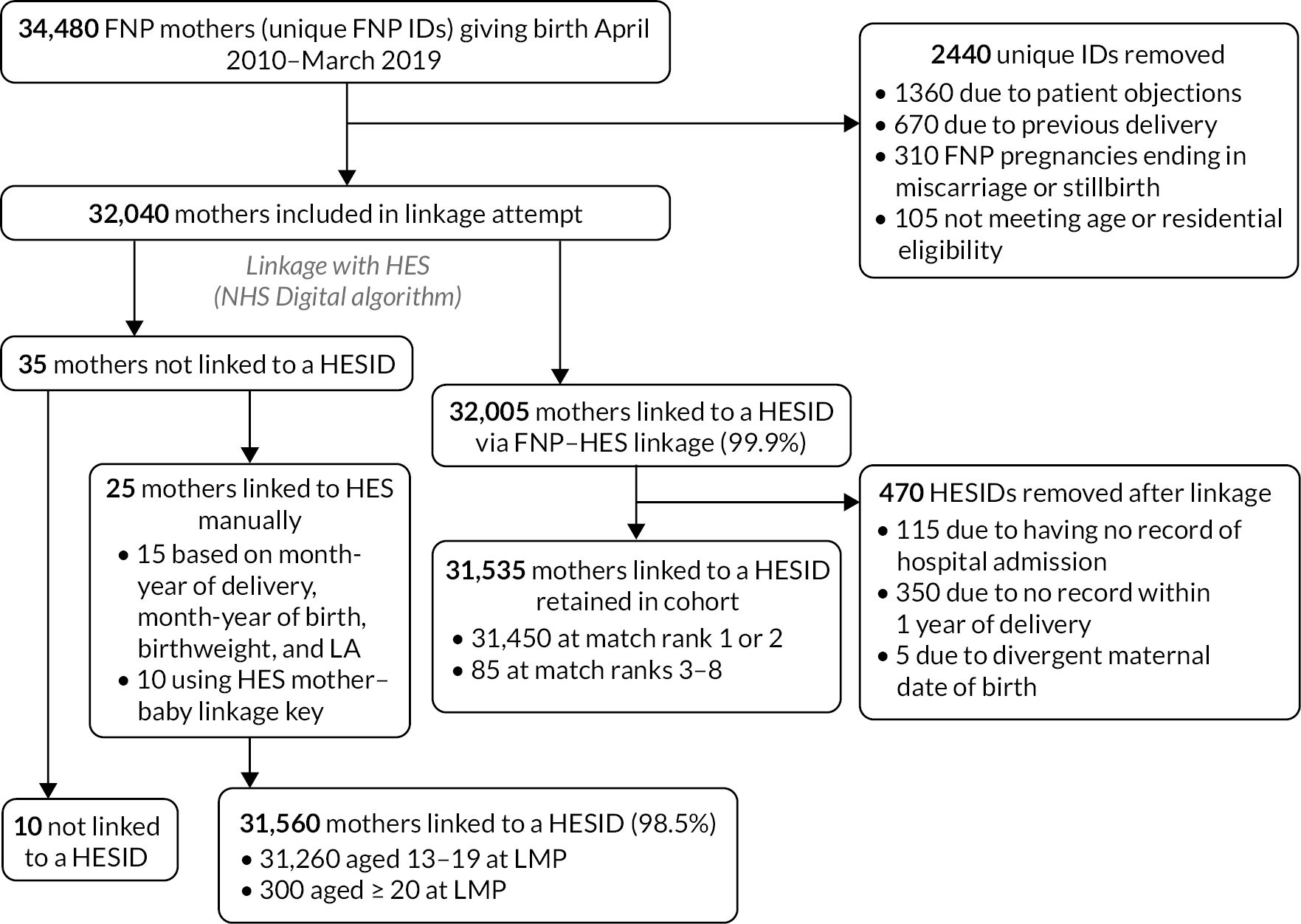

Linkage between data from the FNP IS and HES was conducted using deterministic linkage via NHS Digital (see Appendix 2, Tables 21 and 22). Of the 32,040 mothers in our FNP cohort who gave birth between April 2010 and March 2019, 31,560 (98.5%) were linked to a record in HES.

Characteristics of unlinked mothers

Appendix 2, Table 24, describes the characteristics of the 31,560 FNP mothers who linked to a HESID and the 480 FNP mothers who either did not link to a HESID (n = 10) or who linked to a likely incorrect HESID and were subsequently excluded (n = 470). Compared to mothers who linked to a HESID, unlinked mothers seemed to be a slightly more vulnerable group: they were less likely to be living with their mother (with or without their partner present) or to have any GCSEs at enrolment and more likely to have missing data. They had a lower mean number of FNP visits (26, compared with 35 for FNP mothers who linked to a HESID). They were more likely to be of black, South Asian or mixed/other ethnicity and living in London.

Description of linkage quality

Of the 31,560 FNP mothers included in our linked study cohort, 31,450 (99.7%) linked to HES via the FNP-HES linkage key at match rank 1 or 2, indicating high-quality links. Only 0.3% (n = 85) of mothers linked at match rank > 2, indicating less-certain links. Twenty-five mothers (< 0.1%) were linked to HES manually (see Appendix 2, Figure 17).

To check for potential false matches between FNP and HES, we assessed the agreement between information recorded separately in both data sources for all FNP mothers in our cohort who linked to at least one HES admitted patient care (APC) record (see Appendix 2, Table 25). Agreement between both data sources was generally high.

Identification of local authorities and enrolment dates for each Family Nurse Partnership site

Mothers aged 13–19

There is a complex history of FNP sites in England, with site openings, closures, mergings and splits throughout the study period. In addition, the catchment area of FNP sites may have changed over time (e.g. a site may have been decommissioned for one LA in its catchment area but continue to operate in another).

We used FNP IS data to identify the first and last month-year in which expectant mothers aged 13–19 at LMP were enrolled in each FNP site based on the enrolment dates recorded in each participant’s record. We calculated start and end dates separately for each lower-tier LA in each FNP site in order to allow for changes in catchment area over time. We used the lower-tier LA recorded in FNP participants’ HES records because FNP IS records only upper-tier LA of residence at enrolment. Lower-tier LA was also used to identify the catchment area for each FNP site (e.g. the Hampshire FNP site included only a subset of lower-tier LAs in Hampshire). Inconsistencies were resolved through detailed consultation with the FNP National Unit, including consultation of site records. Nonetheless, some misclassification in catchment areas or activity dates remains likely, particularly before the FNP became commissioned by LA in October 2015, when Primary Care Trust level commissioning (with potentially non-overlapping boundaries compared with LAs) meant slight changes in catchment areas may have occurred at this time.

Activity dates and lower-tier LAs included in the catchment area for 122 FNP sites are included in Appendix 2, Table 26).

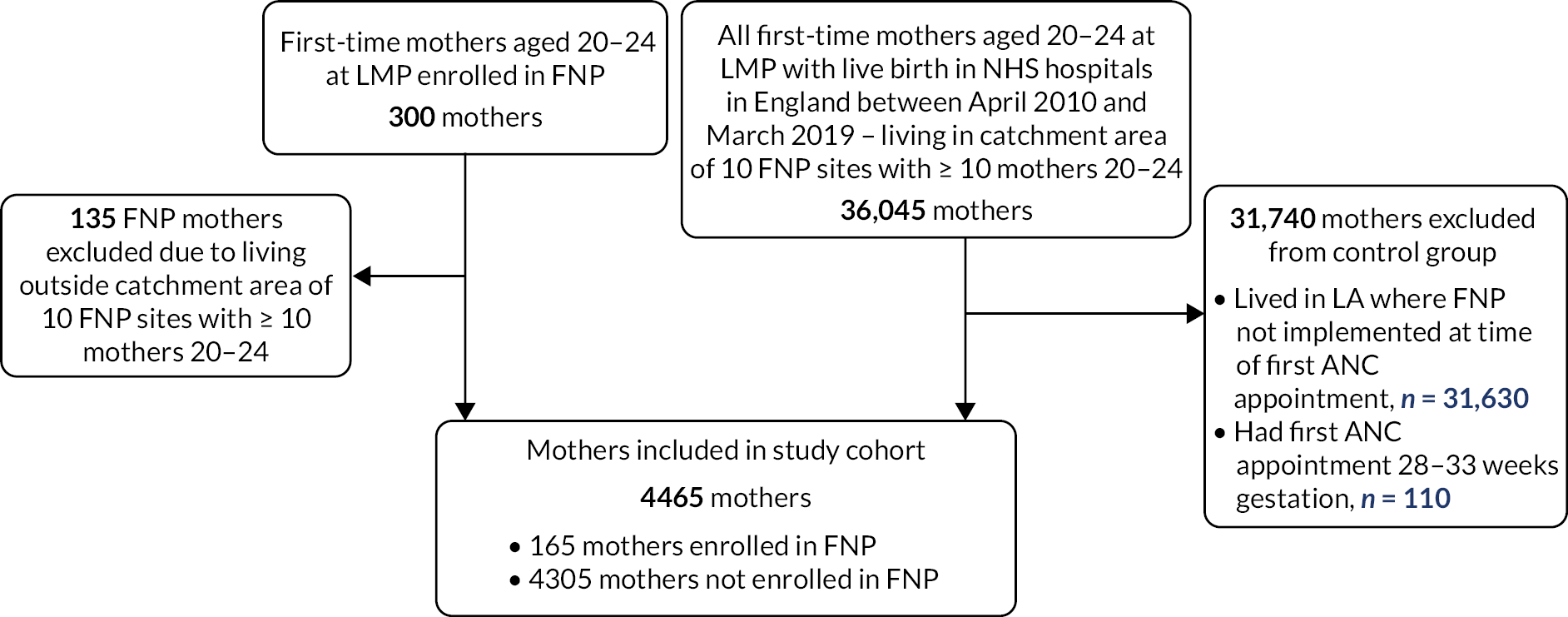

Mothers aged 20–24

As some sites had changed their eligibility criteria during the study period to allow some mothers aged up to 24 to be enrolled, we also planned to include mothers aged ≥ 20 in our analysis. We used FNP IS data to identify LAs that had extended their eligibility criteria to allow for recruitment of older mothers. We classified LAs as having extended criteria if at least 10 mothers aged 20–24 at LMP and giving birth up to 31 March 2019 were enrolled in the FNP. As with mothers aged 13–19, we defined site activity dates as the first and last month-year in which mothers aged 20–24 were enrolled in each site. We did not calculate different activity dates for lower-tier LAs in each site due to small sample sizes and because all but one site only included one lower-tier LA in their catchment area; see Appendix 2, Table 27).

Description of Hospital Episode Statistics cohorts

Mothers aged 13–19

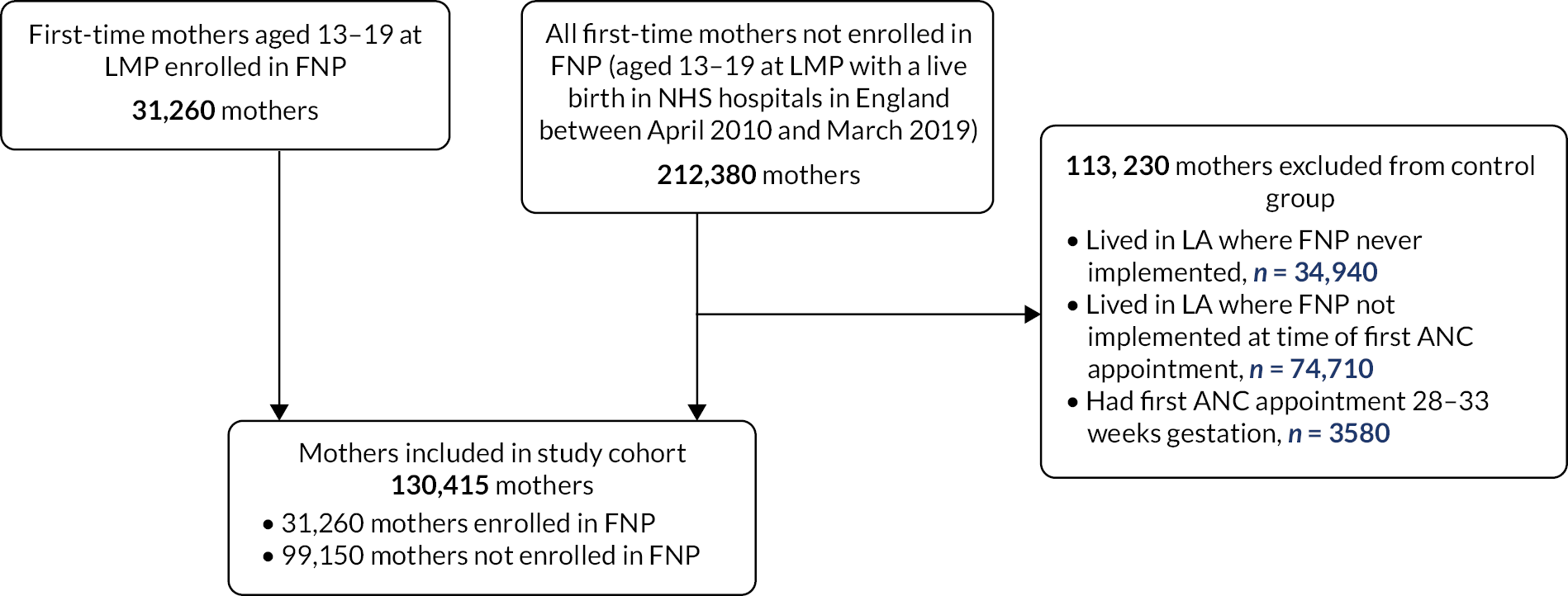

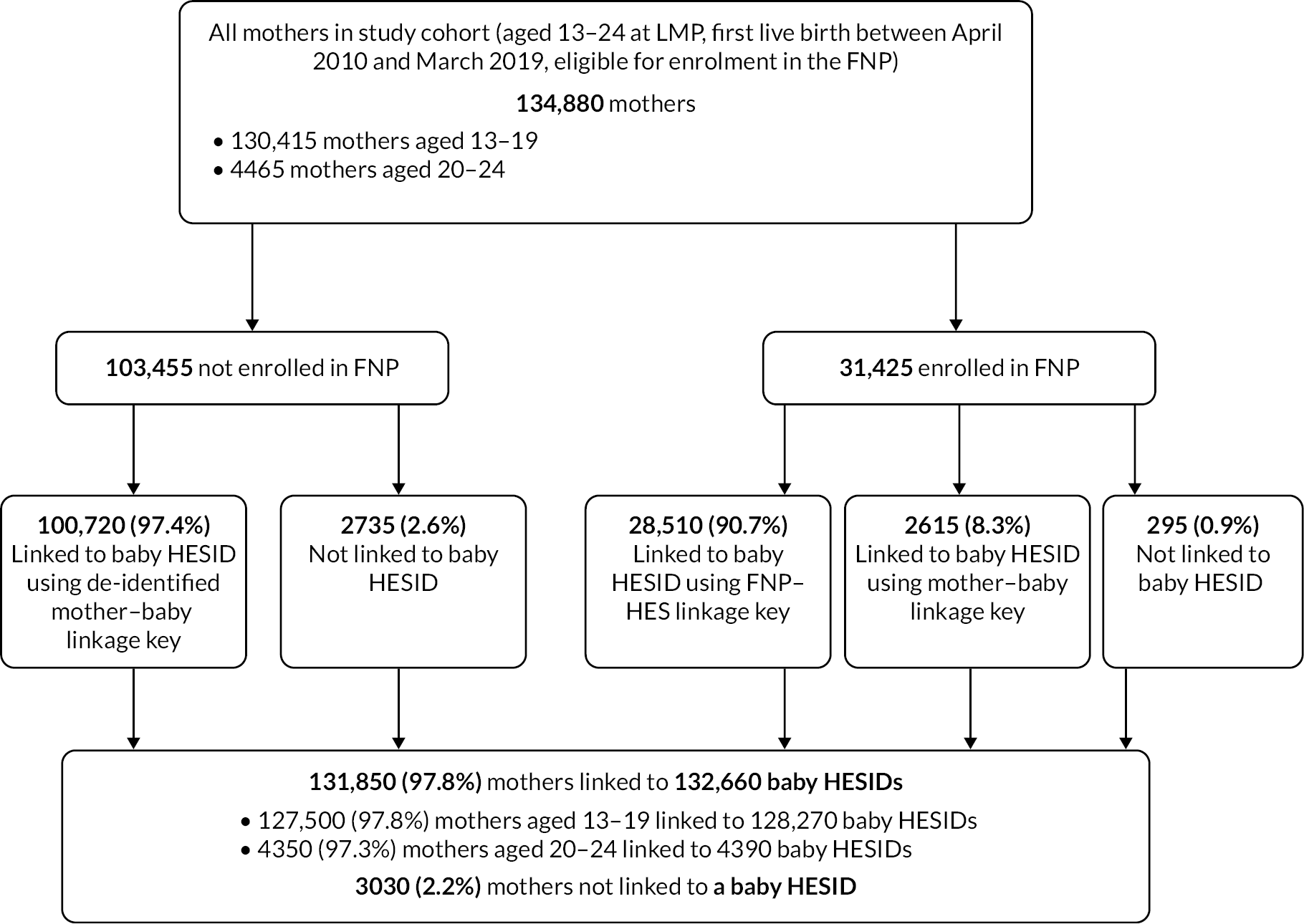

This study cohort included all 130,415 mothers aged 13–19 at LMP who had their first live birth between 1 April 2010 and 31 March 2019 and whose first antenatal booking appointment as recorded in HES (or estimated date of 28 weeks gestation, if missing) occurred on a date when the FNP was active in their LA of residence (Figure 2). Of these, 99,150 (76%) were never enrolled in FNP.

FIGURE 2.

Identification of FNP participants and comparison group among cohort of mothers aged 13–19. Note: numbers have been rounded to the nearest 5 in accordance with NHS Digital’s statistical disclosure rules for subnational analyses; totals may not be equal to the sum of component categories. ANC, antenatal care.

Date at LMP was estimated by subtracting gestational age at birth from the date of childbirth or subtracting 40 weeks (the median gestational age at birth among mothers aged 13–19 in our cohort) from the date of childbirth for the 13% of mothers with missing gestational age at birth. Mothers whose antenatal booking appointment occurred between 28 and 33 weeks gestation were excluded as they would not have met the eligibility criteria for the FNP (see Figure 2). This means we may have excluded a small number of eligible mothers within the few sites that allowed enrolment after 28 weeks from November 2016. Since we observed a spike in the number of mothers with a recorded gestational age at booking appointment of 33 weeks or more, we considered these to be data errors (6% of mothers) and recoded them to 28 weeks so that they could be retained within the cohort.

The creation of the study cohort of mothers aged 20–24 is described in Appendix 2, Figure 18.

Identification of Hospital Episode Statistics child cohort

We used two linkage keys to identify the children of mothers included in the study cohort: first, a FNP-HES mother–baby linkage key provided by the FNP IS, and second, a mother–baby linkage key based on a previously developed algorithm using de-identified HES data. 69

Among the 31,425 FNP mothers in our cohort, 31,260 aged 13–19 and 165 aged 20–24 years, 31,125 (99%) were linked to a baby HESID (see Appendix 2, Figure 18). Among the 1025 mothers in our cohort with multiple births, 80 (78%) had at least two recorded baby HESIDs, 220 (21%) had only one recorded baby HESID and 5 (0.5%) had no recorded baby HESIDs. Where only one baby HESID was recorded for a multiple birth, the identified child was retained in the child study cohort.

Hospital Episode Statistics – National Pupil Database linkage

Description of linkage

Linkage of all mothers and children in the study cohort to NPD education modules was performed by the DfE, following extraction of identifier information (including full name and postcode history) by NHS Digital. DfE used a matching algorithm requiring agreement (full or ‘fuzzy’) on names, date of birth and postcode; matching to NPD was not completed for names and date of birth only or on names and postcodes only (see Appendix 2, Table 28). Subsequent linkage to social care data was performed by DfE via the Pupil Matching Reference number.

Linkage of maternal Hospital Episode Statistics records to National Pupil Database

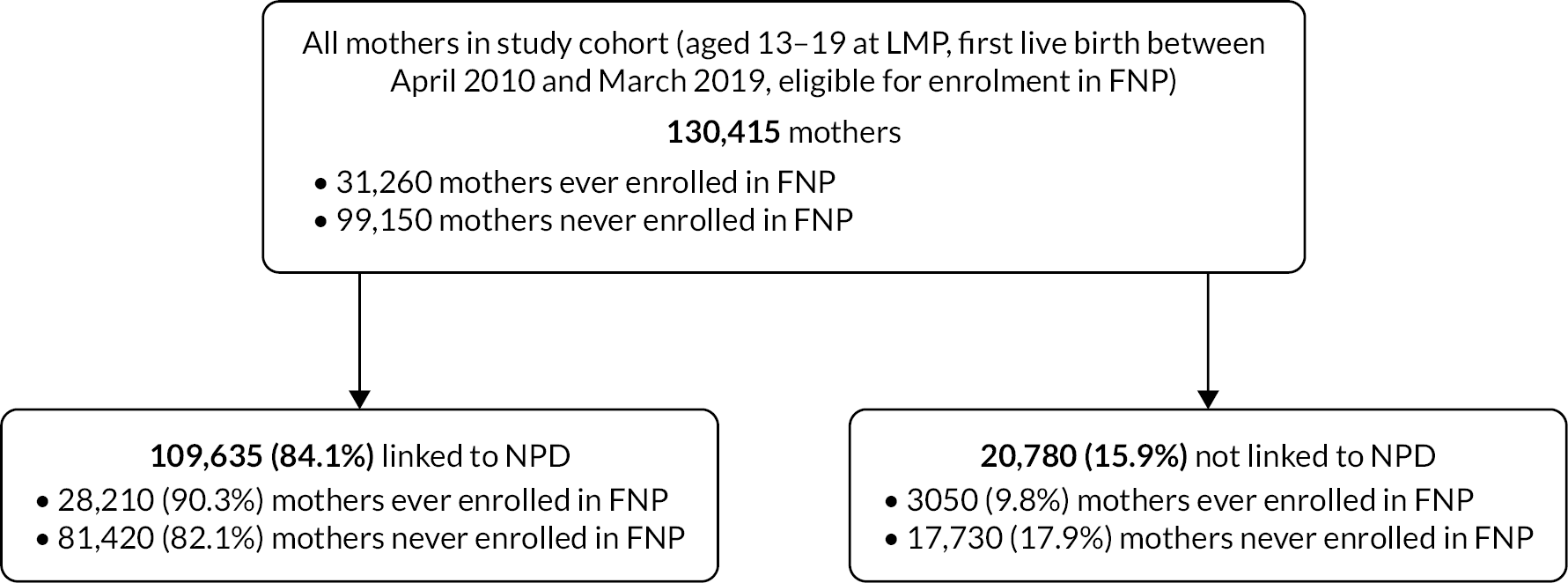

Of the 130,415 mothers aged 13–19 included in the study cohort, 109,635 (84.1%) were linked to a record in NPD (Figure 3). Mothers who were enrolled in FNP were slightly more likely to link (90%) compared with mothers who were not enrolled (82%). Overall, 98% of linked mothers linked at match strength 1, indicating fully confident matches.

FIGURE 3.

Description of linkage of the NPD and HES – mothers in cohort. Note: numbers have been rounded to the nearest 5 in accordance with NHS Digital’s statistical disclosure rules for subnational analyses.

Linkage of child Hospital Episode Statistics records to National Pupil Database

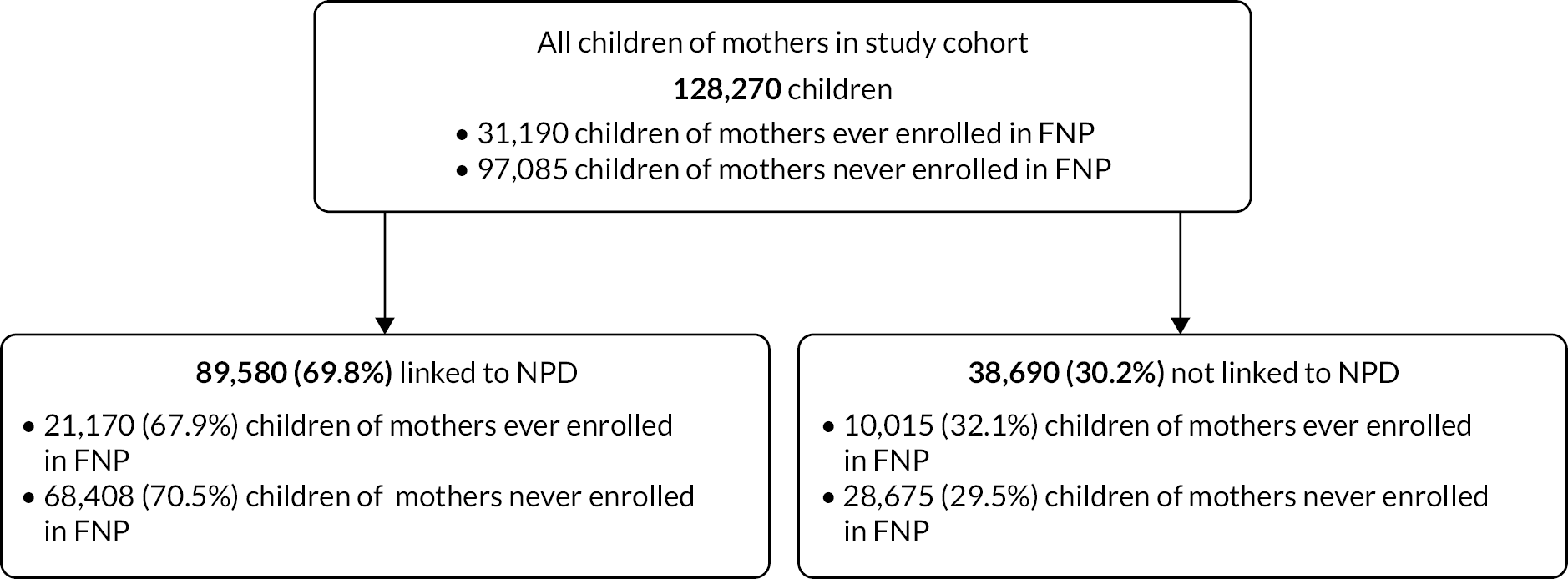

Among 128,270 children of mothers aged 13–19, 89,580 (69.8%) were linked to a record in NPD (Figure 4). Children born to FNP mothers were slightly less likely to link to NPD (68%) than those born to mothers not enrolled in FNP (71%). Overall, 97% of linked children linked at match strength 1, indicating fully confident matches.

FIGURE 4.

Description of linkage of the NPD to HES – children in cohort. Note: numbers have been rounded to the nearest 5 in accordance with NHS Digital’s statistical disclosure rules for subnational analyses.

Characteristics of unlinked mothers and children

There were some differences in the characteristics of mothers in the study cohort who were and were not linked to NPD (see Appendix 2, Table 29). Mothers who did not link to NPD were much less likely to be of white ethnicity (65% vs. 87% among all mothers who linked) and more likely to live in the most deprived quintile (52% vs. 47%) and to have reached 20 weeks of pregnancy at antenatal booking appointment (8% vs. 5%). However, unlinked mothers were less likely than linked mothers to have vulnerability indicators relating to a history of hospital admissions – those related to mental health, adversity and chronic conditions, as well as A&E attendance.

The FNP data gave more insight into the characteristics of those who did and did not link (see Appendix 2, Table 30). FNP mothers who did not link to NPD were more likely to be living alone or in care at enrolment and to attend their antenatal booking appointment after 10 weeks of pregnancy. However, they were less likely to be recorded as CiN, having a CPP or being a child in care during pregnancy.

There were also some differences in the characteristics of children in the study cohort who did and did not link to NPD (see Appendix 2, Table 31). Children who did not link to NPD were more likely to be born from 2016 onward, less likely to have a mother of white ethnicity and slightly more likely to live in less deprived areas.

Definition of outcome variables

Study outcomes and data sources for this study are described in Figure 5 and Table 1. We selected outcomes for the FNP evaluation based on the FNP logic model,64 with some caveats outlined below.

FIGURE 5.

Family Nurse Partnership evaluation – data sources and outcomes.

| Domains | Outcomes | Years after birth | HES | NPDa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child outcomes (up to age 7) | ||||

| Indicators of child maltreatment |

Unplanned hospital admissions for any injury or maltreatment-related diagnosisb | 0–7 | ✓ | |

| Discharge to social services at birth | 0 | ✓ | ||

| CLA | 4/5–7 | ✓ | ||

| CiN status | 4/5–7 | ✓ | ||

| CPP | 4/5–7 | ✓ | ||

| Healthcare use | Unplanned hospital admissions (any diagnoses) | 0–7 | ✓ | |

| A&E visits (any diagnoses) | 0–7 | ✓ | ||

| Referral to outpatient departments (uptake and non-attendance) | 0–7 | ✓ | ||

| Education | School readiness measured by a Good Level of Development in EYFSP at school entry (reception)86 | 5 | ✓ | |

| Achieved expected levels at Key Stage 1 assessment | 7 | ✓ | ||

| SEN provision | 5–7 | ✓ | ||

| FSM (eligible, applies for and receives) | 5–7 | ✓ | ||

| Persistent absence (absent for ≥ 10% possible sessions) | 5–7 | ✓ | ||

| Maternal outcomes (up to 7 years following delivery) | ||||

| Maternal adversity | A&E attendances (any diagnoses) | 0–7 | ✓ | |

| Unplanned hospital admissions (any diagnoses and for violence, self-harm or drug/alcohol abuse)87 | 0–7 | ✓ | ||

| Reproductive outcomes | Subsequent deliveries within 18 months of index birth | 0–2 | ✓ | |

| Education | Key Stage 4 assessmentc (5 A*–Cs at GCSE or equivalent) | 0–2 | ✓ | |

| School attendance after birthd | 0–2 | ✓ | ||

Indicators of child maltreatment

We assessed the effect of FNP on indicators of child abuse and neglect, as measured by the percentage of mothers whose baby was discharged from hospital to social services at birth, whose child had at least one unplanned hospital admission for injury or maltreatment-related diagnoses or who died (up to age 2 or 7) or whose child was ever recorded as a Child in Need, as having a CPP, or being a Child Looked After (at age 4–5 years). ICD-10 code lists for injury or maltreatment-related diagnoses were based on previously published lists81,82 and are included in Appendix 3. As the UPN for linking education and social care data is usually assigned at school entry, social care data for children only involved with social care prior to school entry cannot be linked. Therefore, we only examined CPP, Child in Need and CLA status after school starting age (4–5 years). Thresholds for CiN status vary across the country: only assessments that have been ‘accepted’ are recorded within the data. The CiN data exclude some disabled children (those who are not receiving services from LAs) and children who are receiving support from LAs through early help services. 83 We did not have the primary need code in our data, and some children referred to social care services will be referred for reasons other than child maltreatment (e.g. child disability).

The potential for surveillance bias to distort the effect of early life interventions on child maltreatment has been extensively discussed, and nurse home visiting has been shown to result in increased contact with nurses, potentially leading to lower thresholds for referral to social care services for families enrolled in FNP than families who are not enrolled. 29,44,45 This bias in ascertainment of maltreatment may dilute or reverse the association between FNP participation and maltreatment. Conversely, it has also been hypothesised that a nurse’s closeness to participants may delay reporting of suspected maltreatment. 45 We examined CiN referral source, aiming to determine whether the proportion of referrals initiated by health visitors differed between children of mothers enrolled and not enrolled in FNP.

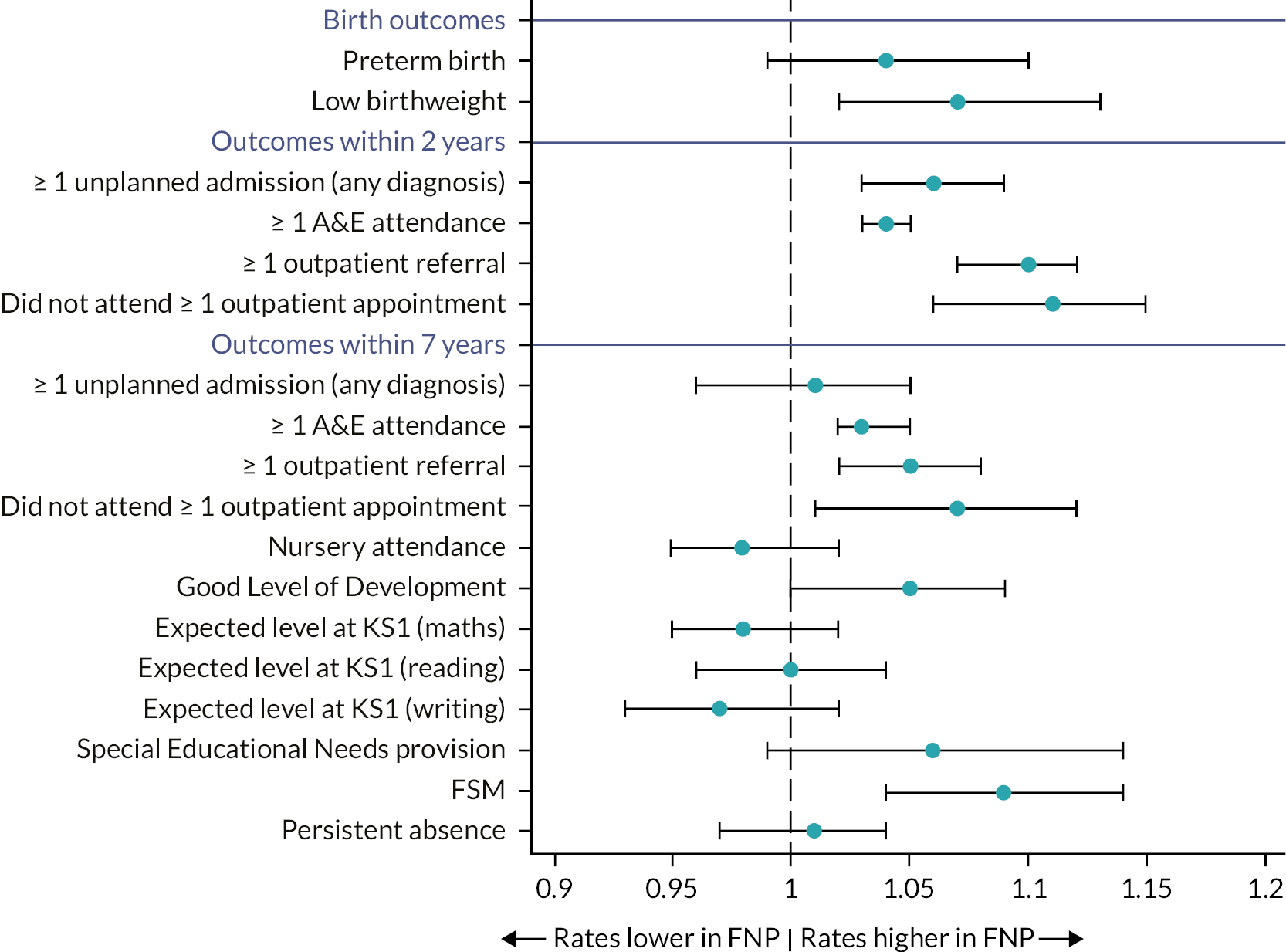

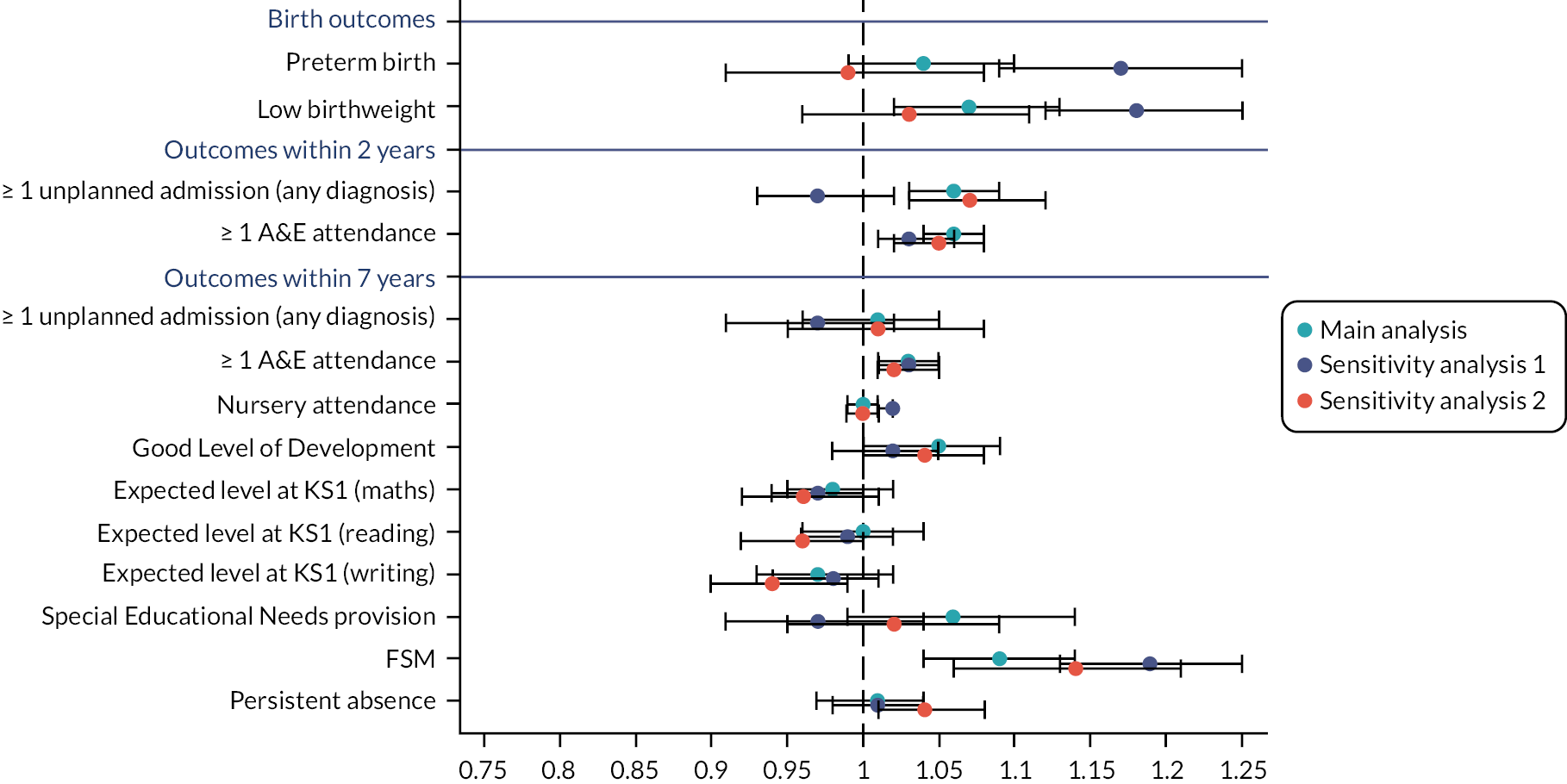

Child health, developmental and educational outcomes

We firstly described rates of preterm birth (< 37 weeks of pregnancy) and low birthweight (< 2500 g) between groups. We also described A&E attendance and unplanned hospital admissions for any diagnosis. These were reported as descriptive outcomes since the direction of effect could be interpreted positively or negatively (FNP participation might reduce the need for emergency care or alternatively increase appropriate care seeking). Nonetheless, they represent important outcomes for understanding the effects of FNP on care-seeking behaviour.

For children reaching school age, we examined the effect of the FNP on school readiness as measured by the percentage of each group achieving a Good Level of Development as recorded within the EYFSP (level 2 + across the combined five areas of learning at school entry) at age 5, persistent absence (absent for ≥ 10% of possible school sessions), achieving expected levels at Key Stage 1 (age 7) for Mathematics, Reading and Writing and recorded as having SEN provision. We also examined FSM eligibility (pupils are recorded as eligible if a claim for FSM has been made by them or on their behalf by their parents). We also calculated the percentage of children in each group recorded in the EYFSP as having attended nursery.

Maternal outcomes

For mothers, we evaluated unplanned hospital admissions for adversity-related reasons (violence, self-harm and drug/alcohol abuse) or for mental health-related diagnoses after delivery (see Appendix 3). As with child outcomes, A&E attendance and unplanned hospitalisations for any diagnoses were reported as descriptive outcomes. We also examined the effect of FNP participation on subsequent pregnancies within 18 months of the first live birth. We examined subsequent births within 18 months (rather than pregnancies within 24 months as measured in the Building Blocks trial) because 18-month birth intervals are associated with the highest risks of adverse outcomes for women and babies. 84,85 Amongst mothers who had not previously had the opportunity to take GCSEs (i.e. were < 16 at the start of the academic year in which they reached 20 weeks of pregnancy), we evaluated the percentage in each group who achieved 5 A*–C grades including English/Maths at GCSE level (or equivalent), in the 2 years after delivery. We did not evaluate A-level outcomes as these data were available for < 1% of mothers. Amongst mothers who would still have been school age in the year following the academic year in which they reached 20 weeks of pregnancy (i.e. those aged < 15 at the start of the academic year in which they reached 20 weeks of pregnancy), we evaluated the percentage in each group who were enrolled in school up to Year 11 during the 7 years following birth. We did not evaluate school outcomes past Year 11 or the proportion of mothers sitting GCSEs after Year 11, due to small numbers.

Follow-up cohorts

Outcome data were available for up to 7 years after delivery, but eligibility for each outcome depended on the child’s age. We therefore described outcomes (1) at birth, (2) in the 2 years following delivery and (3) in the 7 years following delivery. We describe the cohorts used for each set of outcomes in Table 2.

| Follow-up cohort | Number of mothers | Number of children | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 13–19 years | 20–24 years | Total | 13–19 years | 20–24 years | |

| Birth outcomes (Births 2010–9) |

134,880 | 130,415 | 4465 | 132,660 | 128,270 | 4390 |

| FNP mothers | 31,425 | 31,260 | 165 | 31,350 | 31,190 | 165 |

| Non-FNP mothers | 103,445 | 99,150 | 4305 | 101,300 | 97,085 | 4230 |

| 2-year follow-up (Births 2010–7) |

110,555 | 110,555 | – | 108,675 | 108,675 | – |

| FNP mothers | 25,690 | 25,690 | – | 25,630 | 25,630 | – |

| Non-FNP mothers | 84,860 | 84,860 | – | 83,040 | 83,040 | – |

| 7-year follow-up (Births 2010–2) |

27,250 | 27,250 | – | 27,015 | 27,015 | – |

| FNP mothers | 4385 | 4385 | – | 4375 | 4375 | – |

| Non-FNP mothers | 22,865 | 22,865 | – | 22,640 | 22,640 | – |

Definition of exposure variables

The main exposure of interest in this evaluation was enrolment in the FNP, regardless of the number of FNP visits received. Enrolment in the FNP was identified by linkage of a mother in HES to a FNP IS record.

The main maternal risk factors in this study are described in Table 3. We used 20 weeks of pregnancy as the reference point since 93% of all mothers attend an antenatal booking appointment by this stage. 88 We selected exposures based on maternal vulnerability risk factors known to be associated with poor infant outcomes and available within HES delivery records: maternal age, ethnic background and area-level deprivation [Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) quintile]. 89 We also considered maternal unplanned hospital admissions in the 2 years prior to 20 weeks gestation: mental health-related admissions (excluding self-harm and substance misuse); adversity-related admissions (violence, self-harm or substance misuse) and chronic condition admissions were identified based on published lists of ICD-10 diagnostic codes (see ICD-10 code lists for maternal hospital admissions related to adversity, mental health and chronic conditions). 87,89–91 Having at least one A&E attendance and repeated A&E attendances within 2 years prior to 20 weeks gestation was also considered as a risk factor. We also considered risk factors recorded in social care and education data. Seasonality of birth (quarter-year) was included based on evidence from the Building Blocks trial of associations, for example, with Key Stage 1 attainment. 24

| Maternal risk factor | Categorisation |

|---|---|

| Date of delivery | Year/quarter-year |

| Maternal age at birth | 13–15, 16–17, 18–19, 20 years |

| Ethnicity | White, black, South Asian, mixed/other or unknown |

| Area-level deprivation at birth | Quintile of the IMD |

| Region of residence | South-East, London, North-West, East of England, West Midlands, South-West, Yorkshire and the Humber, East Midlands, North-East |

| Gestational age at booking | < 10 weeks, 10–20 weeks, 20 + weeks |

| History of hospital attendances in the 2 years before 20 weeks of pregnancy: | Unplanned hospital admissions for adversity-related diagnosesa Unplanned hospital admissions for mental health-related diagnosesa Any hospital admission for chronic condition-related diagnosesa Any A&E attendance Repeated A&E attendance (4 + A&E attendances) Did not attend ≥ 1 outpatient appointment |

| History of Social Care contacts before 20 weeks of pregnancy | Ever had a CPP Ever a CLA |

| Educational risk factors before 20 weeks of pregnancy | Ever recorded as having SEN provision Ever recorded as having FSM (eligible, applies for and receives) Ever in the most deprived IDACI decile Ever excluded from school, in a PRU or alternative provision Ever persistently absent (≥ 10% of possible sessions) Achieved expected levels at Key Stage 2 Mathematics/Englishb Achieved 5 A*–Cs at GCSE levelc |

Analyses

Descriptive analyses

We described maternal risk factors at the time of pregnancy, previous health and educational risk factors (see Table 3) and pregnancy outcomes for all mothers in our cohort according to enrolment in FNP. We further described maternal risk factors at enrolment and during pregnancy among mothers enrolled in the FNP (using risk factors collected in FNP IS, such as living arrangements and intimate partner violence).

Enrolment rate and maternal risk factors associated with enrolment in the Family Nurse Partnership (Objective 1)

We restricted the enrolment analysis to mothers giving birth between April 2010 and March 2017 for those aged 13–19 at LMP in order to use the same cohort for Objectives 2 and 3 (ensuring at least 2 years of follow-up for all mothers and their children in the cohort). We calculated enrolment rates as the percentage of FNP participants among eligible first-time adolescent mothers living in a LA with an active FNP site at the time of first antenatal appointment before 28 weeks of pregnancy, including by site and maternal risk factor (see Table 3). We also calculated the percentage enrolment for all first-time adolescent mothers in England (including areas not offering the FNP). Multilevel logistic regression models with mothers nested within FNP sites were used to calculate crude and adjusted ORs of enrolment. Multivariable models included all maternal risk factors; multicollinearity was assessed using Spearman correlation coefficients. To examine variation in maternal risk factors for enrolment, we stratified the analysis by site characteristics: we classified FNP sites with enrolment rates in the top quartile as ‘high-enrolment sites’ and those with enrolment rates in the bottom quartile as ‘low-enrolment sites’. We stratified the multivariable models according to high-/low-enrolment site, region and financial year of delivery and tested for interactions between these strata and each maternal risk factor. We explicitly classified mothers not linking to NPD as ‘unlinked’ in relevant variables to retain them in the models.

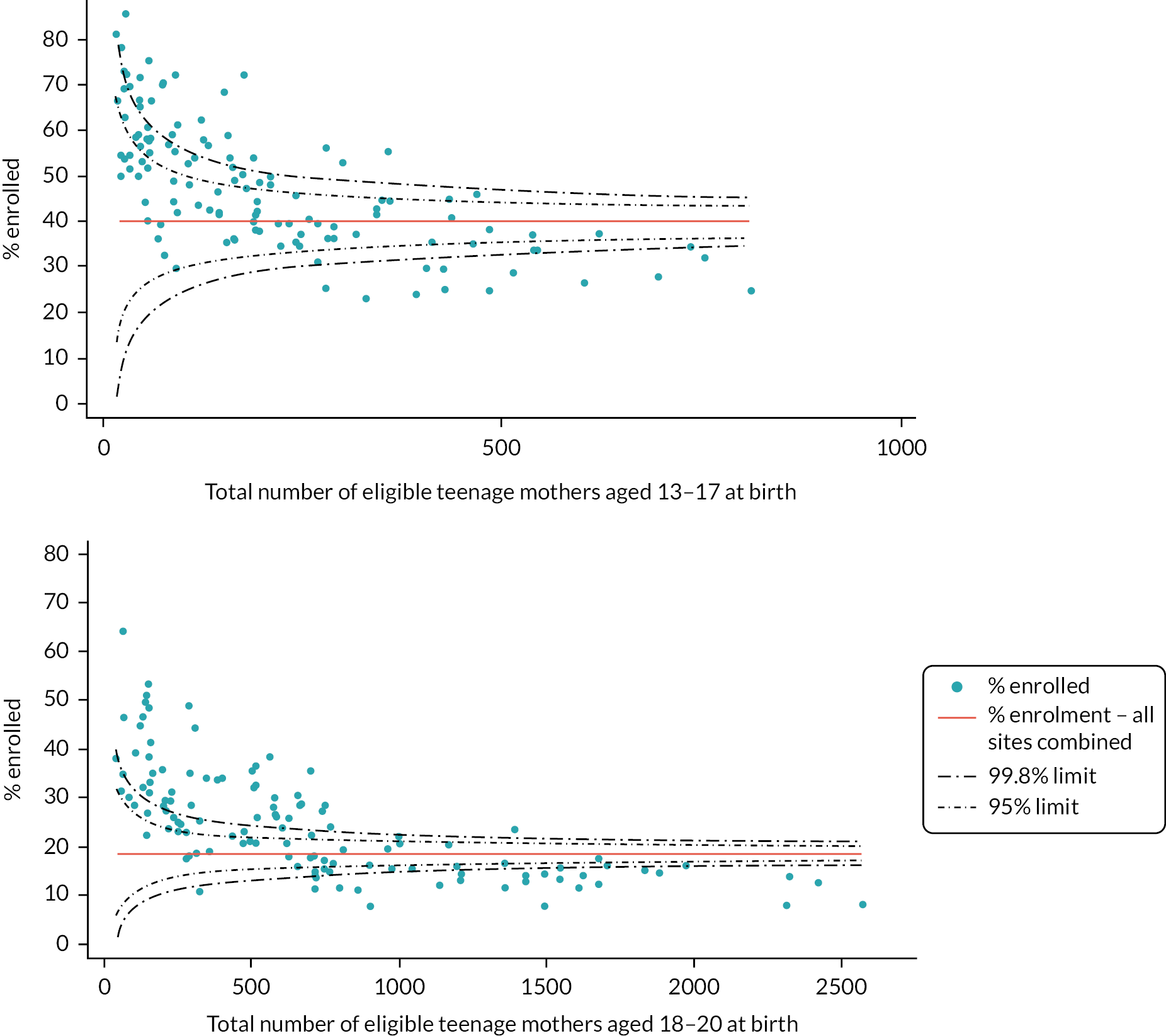

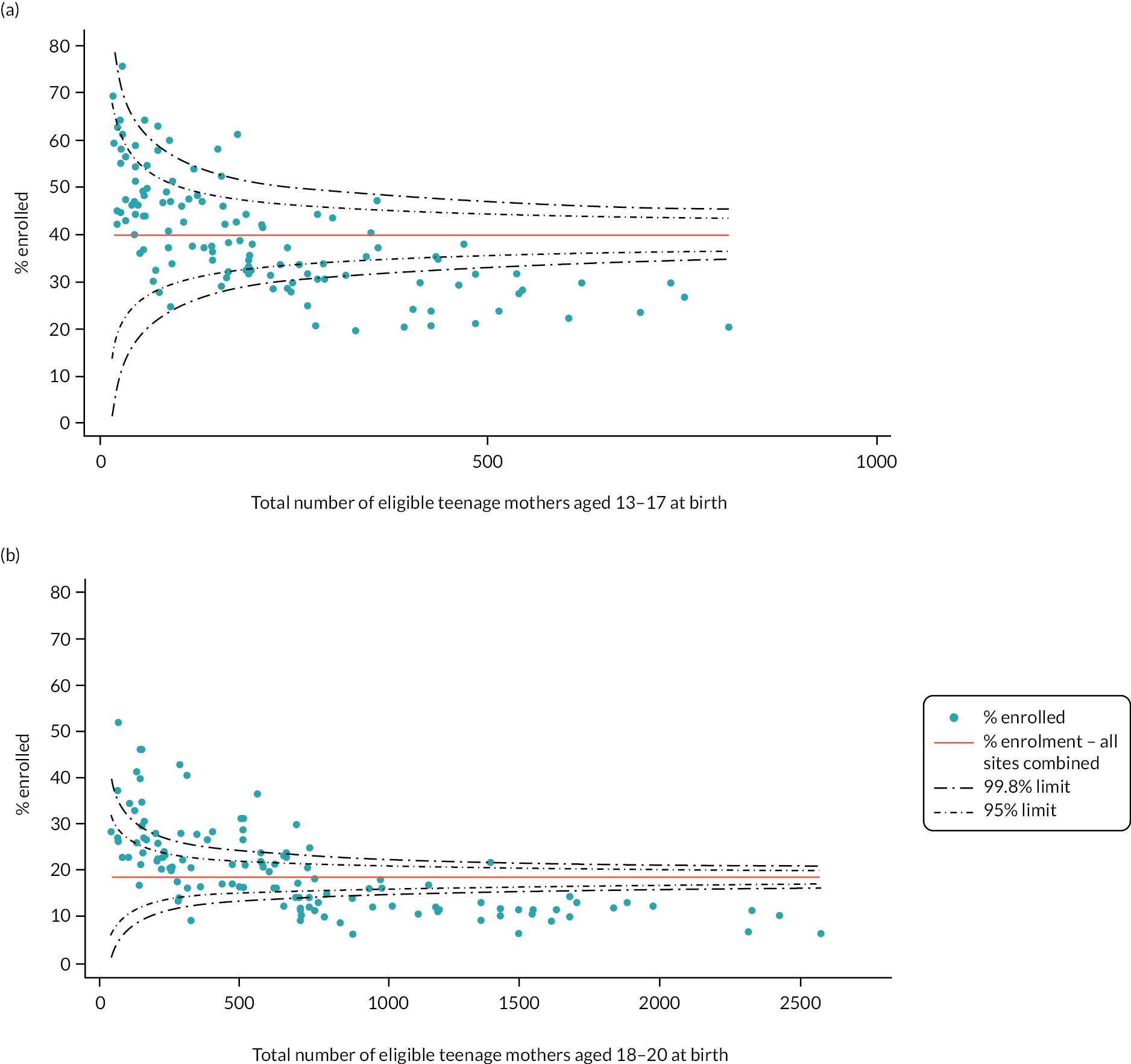

Lastly, we built crude and adjusted funnel plots of the percentage enrolled in each FNP site according to the size of the eligible adolescent mother population, separately for mothers aged 13–17 and 18–20 at childbirth, to assess the extent to which variation in enrolment rates across sites was likely to be due to chance. The outer limits on the plots define the range of percentages that are within three standard deviations (SDs) of the national average. If the observed variation was due to chance alone, we would expect only one in 500 sites to have a percentage that is outside these limits.

We conducted a secondary analysis for first-time mothers aged 20–24 at LMP living in LAs with FNP sites enrolling these older mothers. We used the FNP data to identify LAs that had extended their eligibility criteria as those where at least 10 mothers aged 20–24 at LMP and giving birth up to 31 March 2019 were enrolled in the FNP. We included mothers whose first antenatal appointment (or estimated date of 28 weeks gestation, if date missing) occurred from the month of enrolment of the first mother aged 20–24 in the local site.

We calculated the percentage enrolment as the percentage of FNP participants among the eligible study cohort, by site and across all sites. Multilevel logistic regression models of mothers nested within FNP sites were used to calculate crude and adjusted ORs of enrolment (adjusting for all risk factors). The two least-deprived IMD quintiles were grouped to account for smaller numbers. Sample size of FNP participants was too small for analyses stratified by time, region and high/low enrolment in this age group.

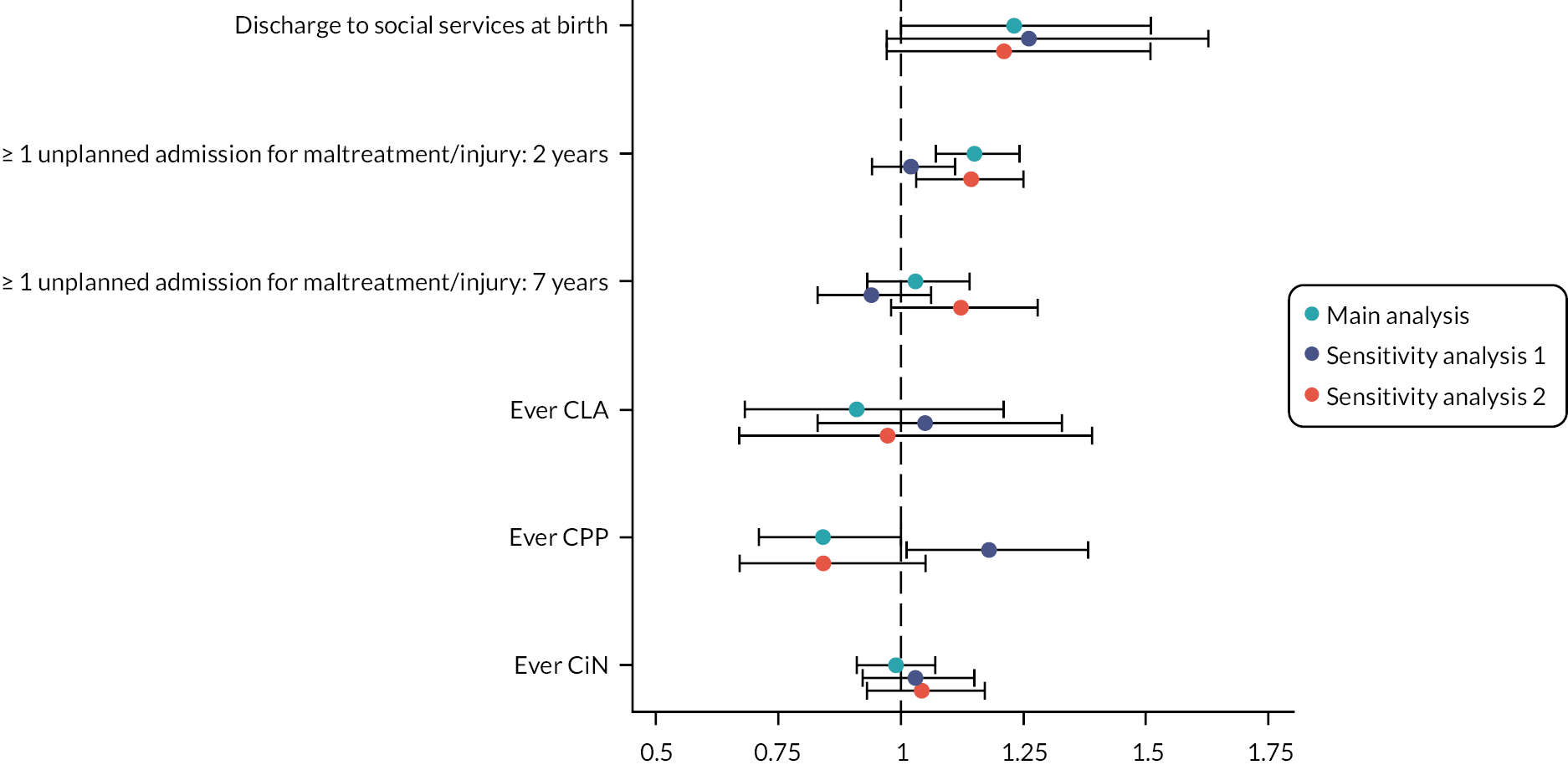

Effect of the Family Nurse Partnership on maternal and child outcomes (Objective 2)

We firstly described the outcomes of interest according to maternal risk factors and enrolment in the FNP.

We then compared outcomes for mothers ever enrolled in FNP, and their children, versus those never enrolled, using two analysis strategies to account for measured confounders related to FNP enrolment and outcomes. Propensity score matching aims to minimise bias, while adjustment for confounders aims to minimise variance.

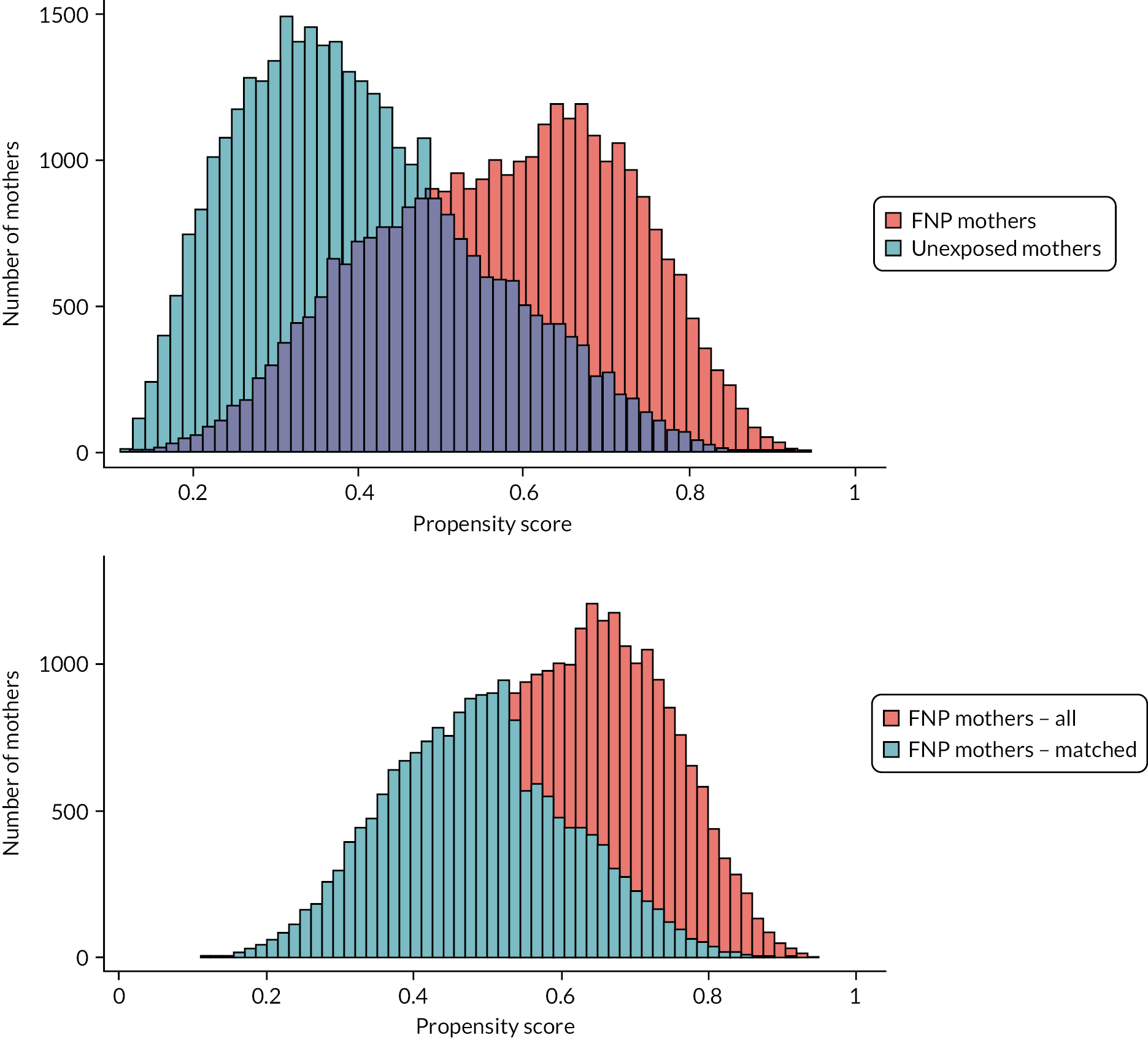

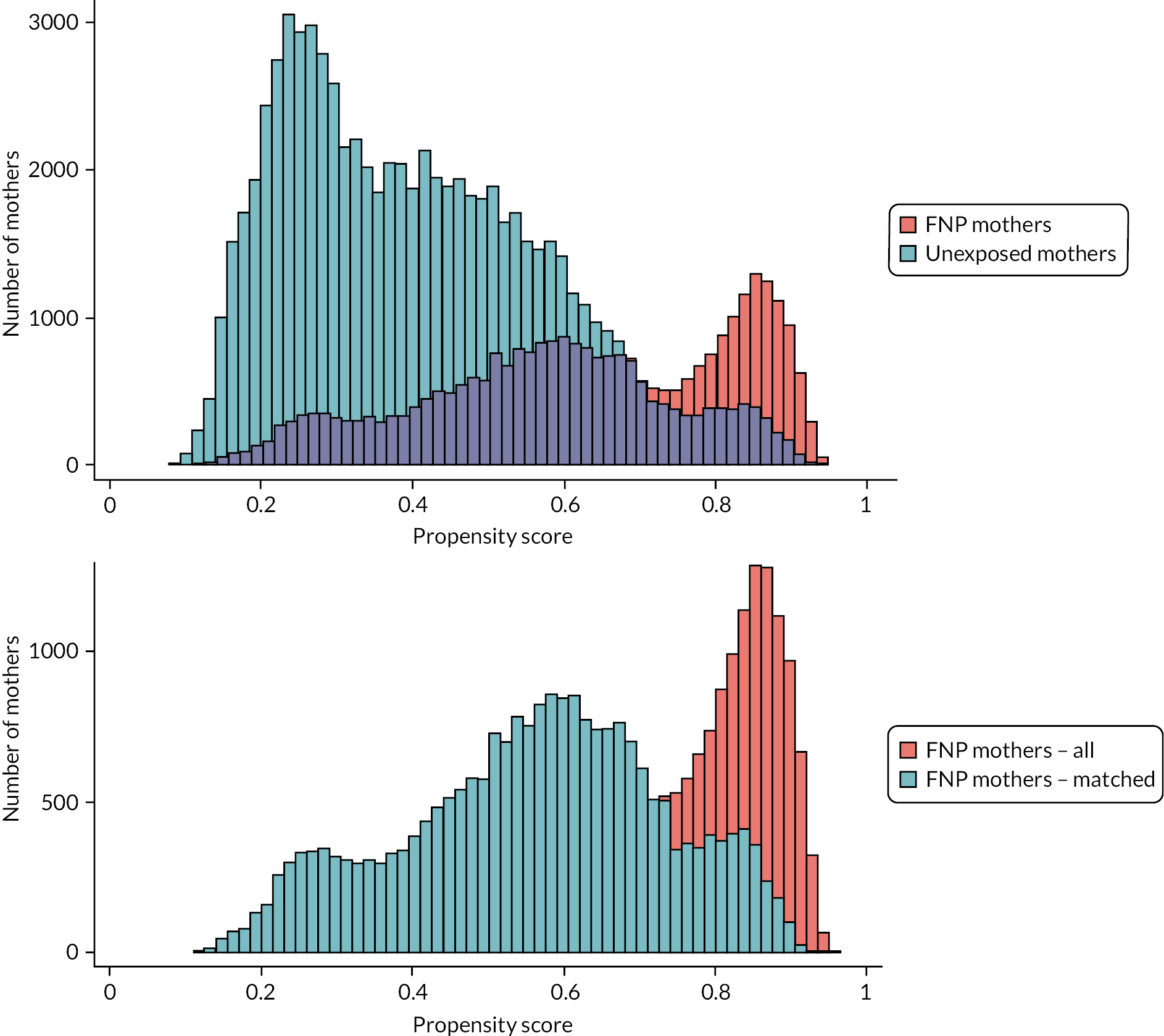

Propensity score matching

Propensity score matching is a quasi-experimental approach to evaluation that is used in contexts where a randomised controlled trial is not possible. Randomisation ensures that intervention and control arms are comparable at baseline. In observational data, however, intervention and control groups are often not comparable at baseline (e.g. due to family nurses prioritising the more vulnerable mothers for enrolment). Propensity score matching aims to mimic the randomisation process by ensuring that groups being compared have similar baseline characteristics by matching mothers with similar underlying needs who were or were not enrolled in the intervention.

To derive propensity scores in this study, we first constructed regression models with FNP participation as the outcome based on all available pre-enrolment maternal characteristics. 92 The predicted probability of enrolment from the model (the propensity score) reflects the probability of each mother in our cohort being enrolled in the FNP, taking into account, for example, maternal age, deprivation and history of mental health conditions. Mothers with similar propensity scores in the control and intervention arms were then matched to create balanced groups for analysis.

We explored both logistic and probit models for propensity score generation and chose the model that provided the best fit. Since we know that drivers of enrolment in the FNP vary by area, we used a multilevel structure to allow for clustering of mothers (level 1) within sites (level 2), allowing intercepts to vary for each site. 93 We included as predictors all available maternal characteristics associated with enrolment up to 28 weeks gestation (at which point the vast majority of mothers have been enrolled) listed in Table 3, as well as additional risk factors (including ‘did not attend’ hospital outpatient appointments within 2 years before 20 weeks gestation and year and quarter-year of childbirth). We explored interactions, as we hypothesised that predictors of enrolment might vary according to maternal age and by year of delivery (based on our results for Objective 1).

Since there was some missing data on maternal predictors of enrolment (e.g. ethnicity and educational/social care predictors for the mothers who could not be linked to NPD), we explored two options for handling missing data in the propensity score model. First, we explicitly modelled the missing data categories (i.e. ‘Unknown’ ethnicity and ‘Not linked to NPD’). Secondly, we used a missingness pattern information approach. 94 This means that we separately calculated propensity scores for the group of mothers with complete data (including all maternal variables as predictors), the group of mothers with missing data on both gestational age at booking and educational/social care variables (excluding these variables as predictors) and the groups of mothers with complete data on educational/social care variables but missing gestational age at booking (and vice versa). Matching takes place on the entire cohort using the propensity scores that have been derived in this way. Using the missingness pattern information approach, we assume that none of the following scenarios apply: (1) maternal/child outcomes affect missingness of the confounder; (2) outcome and missingness have shared unmeasured common causes and FNP enrolment, and missingness have shared unmeasured common causes and (3) the confounder and FNP enrolment both affect missingness, and the confounder is associated with outcome in the subgroup with missing data. 94 Our final strategy for handling missing data was determined by comparing the balance between FNP and non-FNP mothers in our matched cohort.

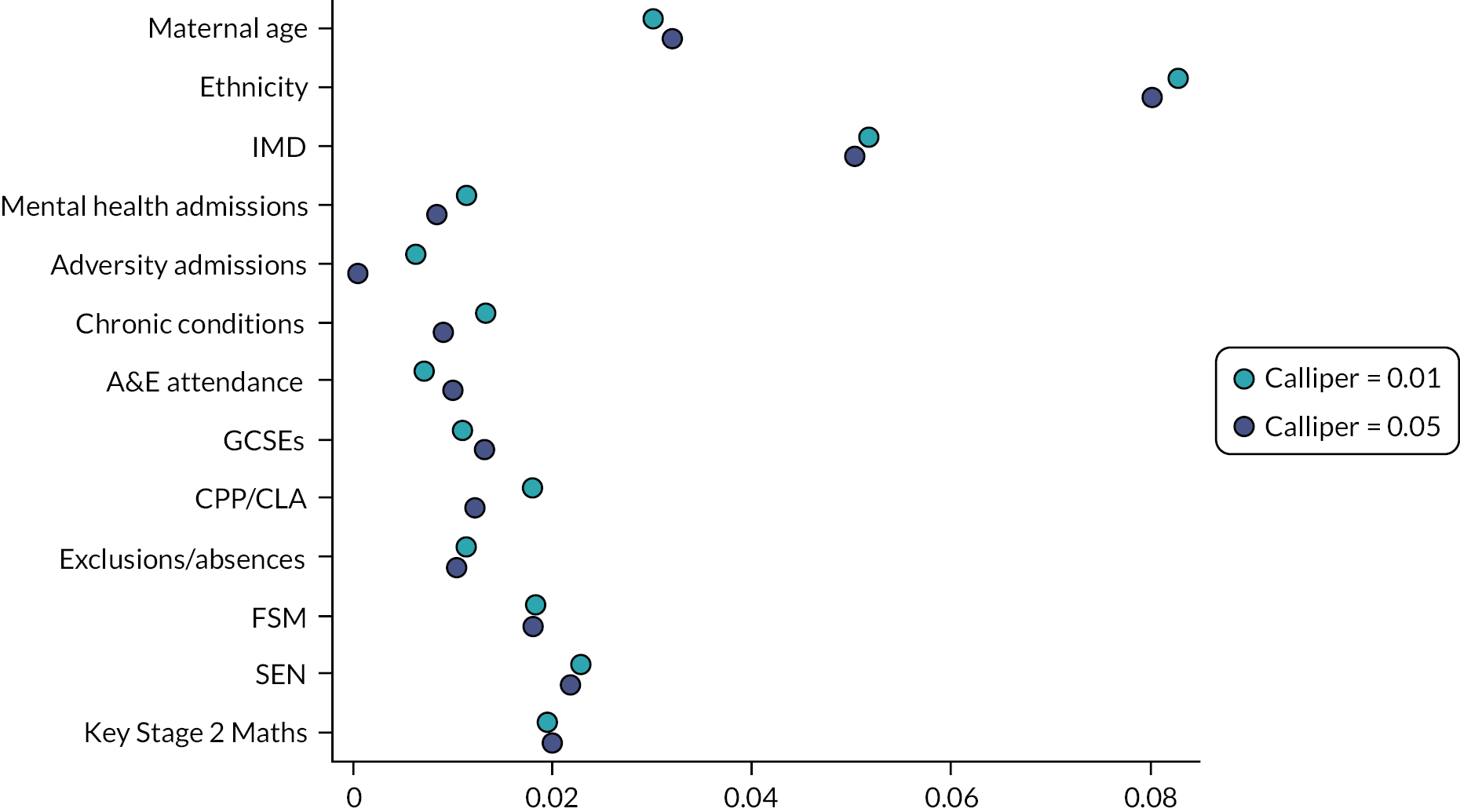

Once propensity scores had been generated for each enrolled and non-enrolled mother, matched groups were formed by matching mothers enrolled in the FNP to eligible non-participants within the same FNP site area with a similar propensity score. We explored using both nearest neighbour matching and calliper matching with a range of calliper widths. The selected approach was determined by inspecting the overlap in the distribution of propensity scores between mothers who were and were not enrolled in FNP and the balance of risk factors in the matched cohort. 92 To check the balance, we used standardised differences (effect sizes of 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8 are considered to be small, medium and large effect sizes, respectively). 95 We also inspected the coverage of the matched cohort in terms of the number of FNP mothers for whom a match could be found.

We explored one-to-one matching both with and without replacement, assuming that matching with replacement would minimise exclusion of mothers in the higher propensity score range. In order to determine which strategy to use, we inspected the number of times each non-FNP mother was selected as a match. We did not conduct propensity score analysis for mothers aged 20–24 due to small numbers and differing eligibility criteria and geographic range. The matching process was conducted separately for each follow-up cohort (i.e. for mothers with 2 years of follow-up and for mothers with 7 years of follow-up) to allow for equal numbers of FNP and non-FNP mothers in each group. Where mothers had given birth to multiple babies, we randomly selected one child per mother to analyse; this allowed us to keep balanced numbers in each group.

The effect of FNP was estimated by evaluating outcomes for mothers who received the intervention (i.e. who were enrolled in FNP) compared to the outcomes the same mothers would have experienced had they not received the intervention (in causal language, the average effect of the treatment on the treated). This effect was estimated as the difference in outcomes between matched groups. To estimate this difference, we calculated relative risks (RRs) with 95% CIs based on generalised linear models. We used a doubly robust approach, meaning that within the matched cohort, we adjusted for maternal risk factors. RRs presented from the propensity score analysis are therefore adjusted RRs.

All analyses were conducted in Stata V17. 96

Subgroup analyses

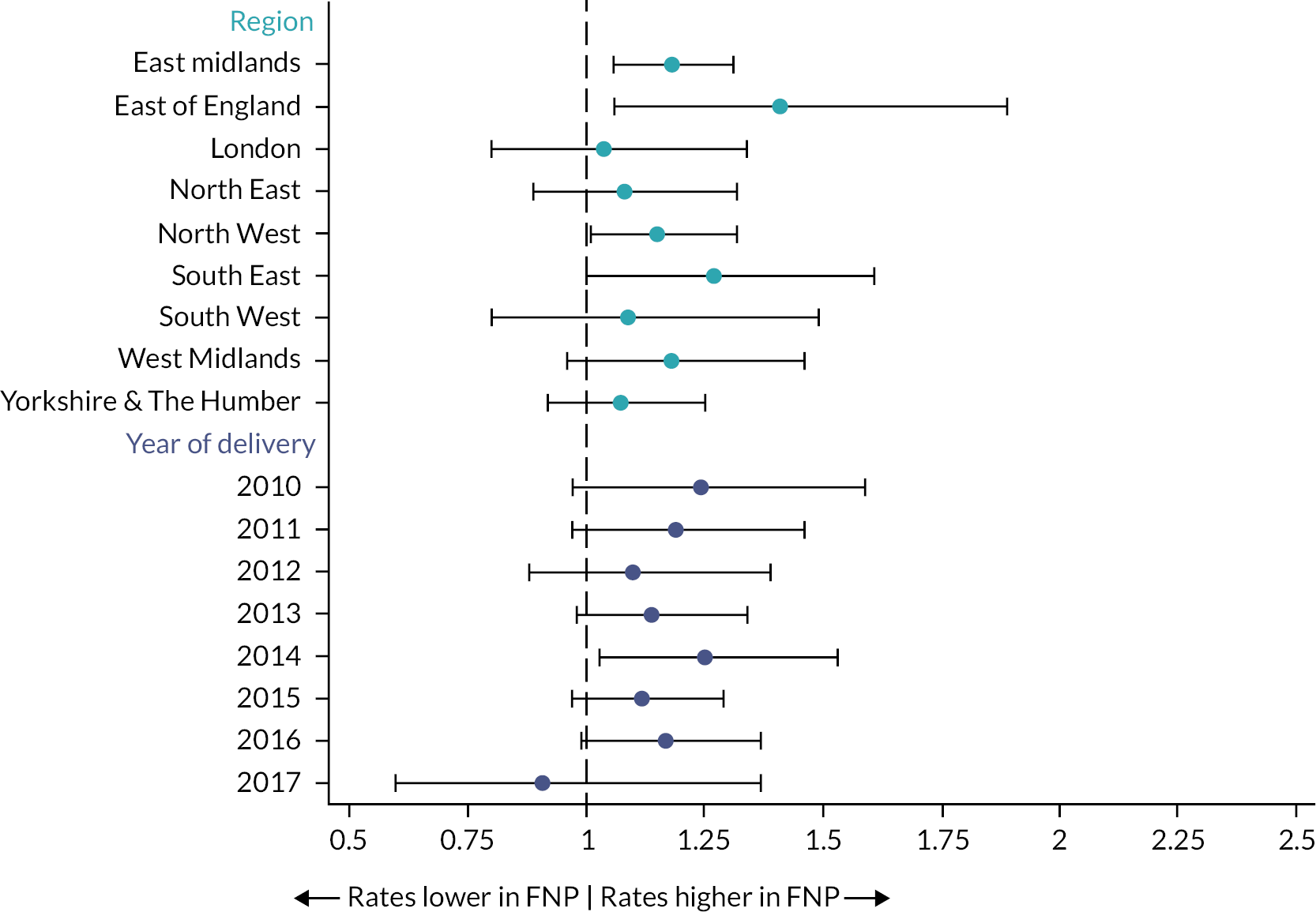

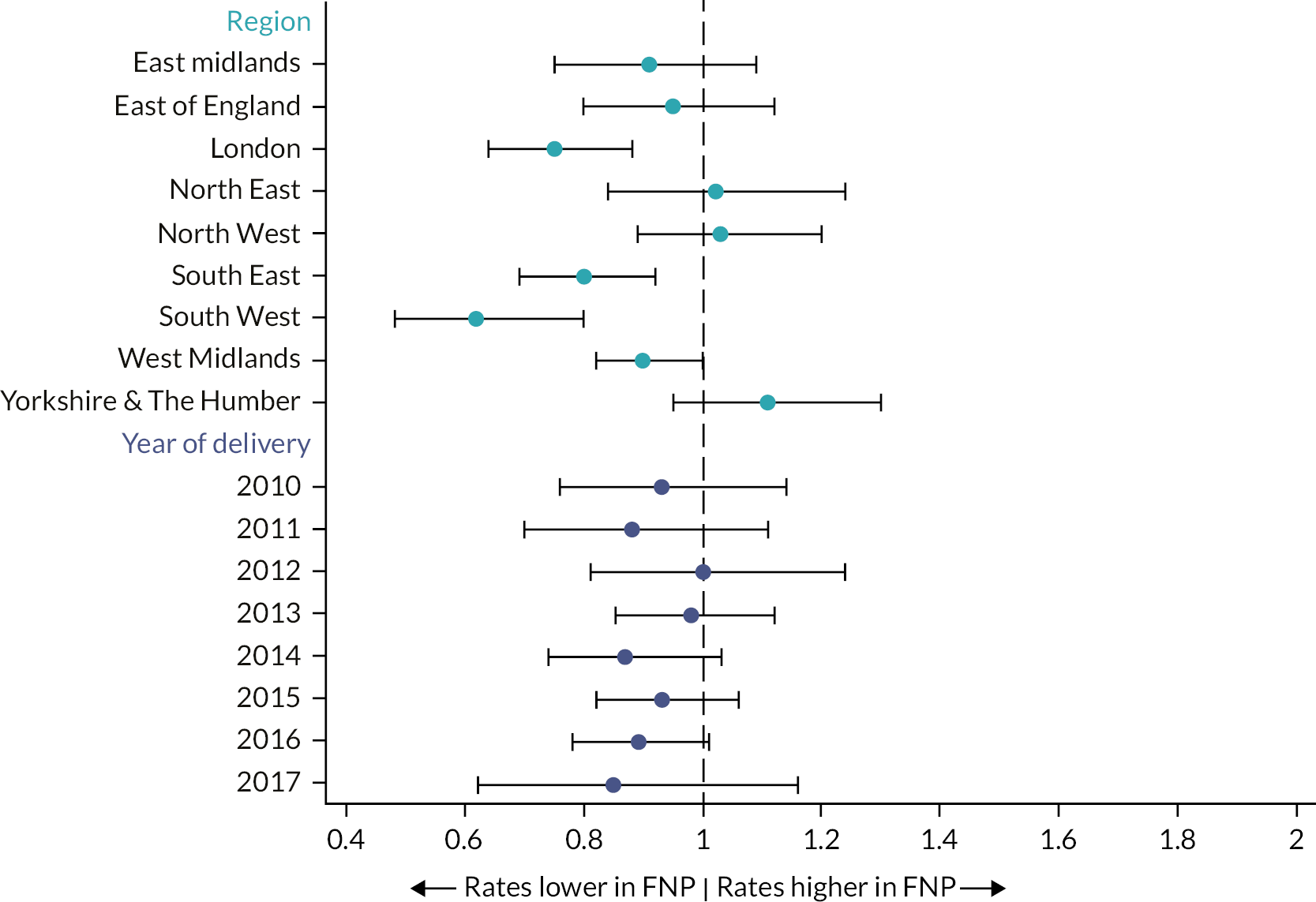

Interactions were used to investigate effect modification for selected outcomes according to maternal age, area-level deprivation, ethnicity, maternal history of adversity and mental health conditions, and maternal history of social care, based on previous evidence suggesting the youngest and most disadvantaged mothers are most likely to benefit from the FNP. We also explored interactions by year of delivery and region. We then presented RRs for each stratum of maternal exposure. Outcomes selected for evaluation were those with sufficient numbers to be analysed in subgroups: child unplanned admissions for maltreatment or injury up to age 2, a Good Level of Development at age 5 (school readiness), maternal unplanned admissions for any diagnosis in the 2 years following birth and subsequent births within 18 months.

Sensitivity analyses

In the main analysis, we restricted matching within the same LA and time period in which FNP was offered within that LA (i.e. to eligible, unenrolled mothers). 97 Secondary analyses relaxed this restriction, aiming to achieve more closely matched groups (with potentially smaller numbers matched) by matching:

-

within the same LA but in different time periods, allowing matches to eligible families before FNP was offered in that LA

-

within the same time period but in different LAs, allowing matches to eligible families in LAs that did not offer FNP.

Multivariable regression

We conducted unmatched regression analyses using generalised linear models to estimate RRs, adjusting for all maternal risk factors listed in Table 3. Models of best fit for each outcome were selected based on AIC.

Contextual factors associated with benefitting from Family Nurse Partnership (Objective 3)

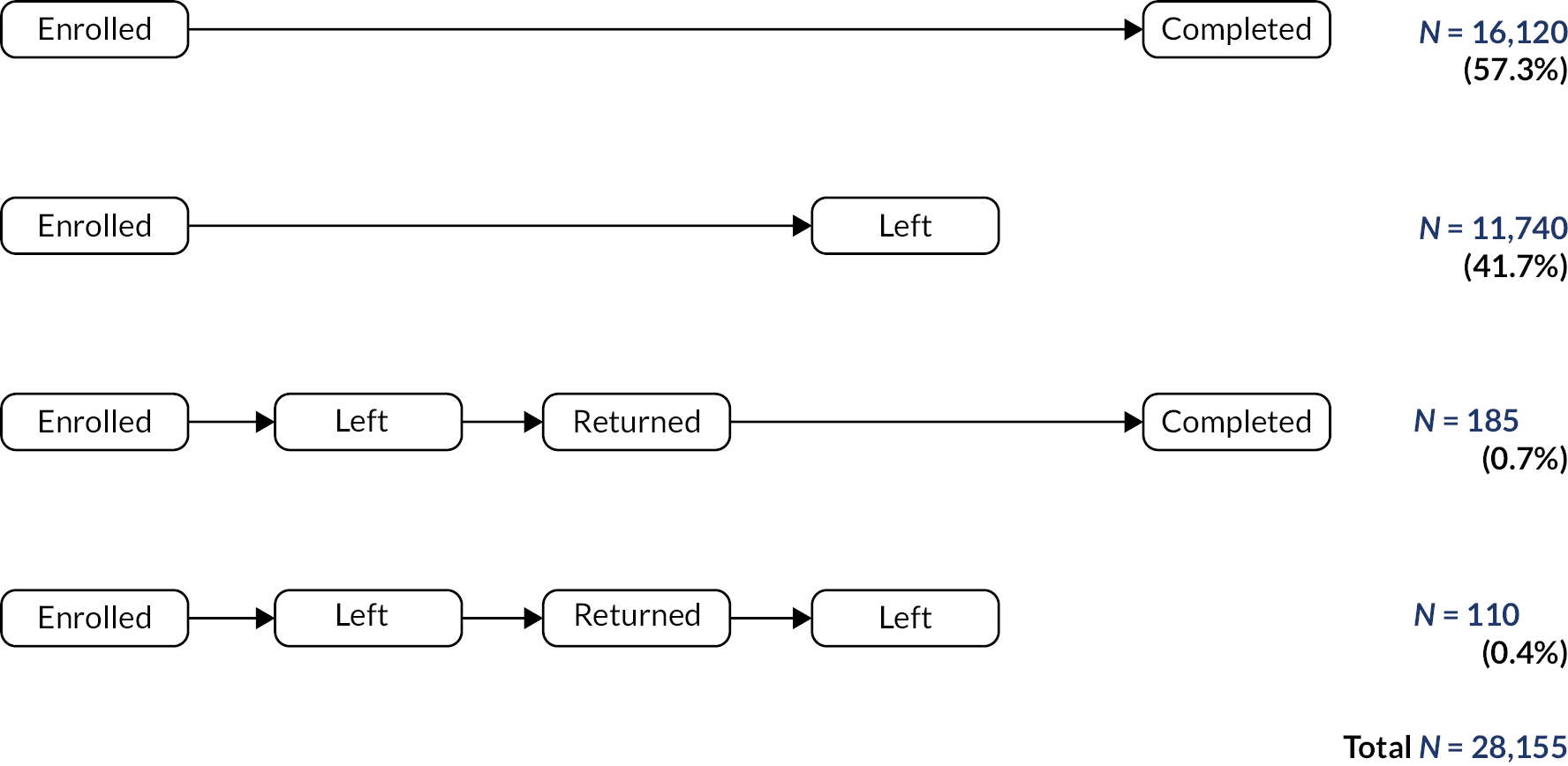

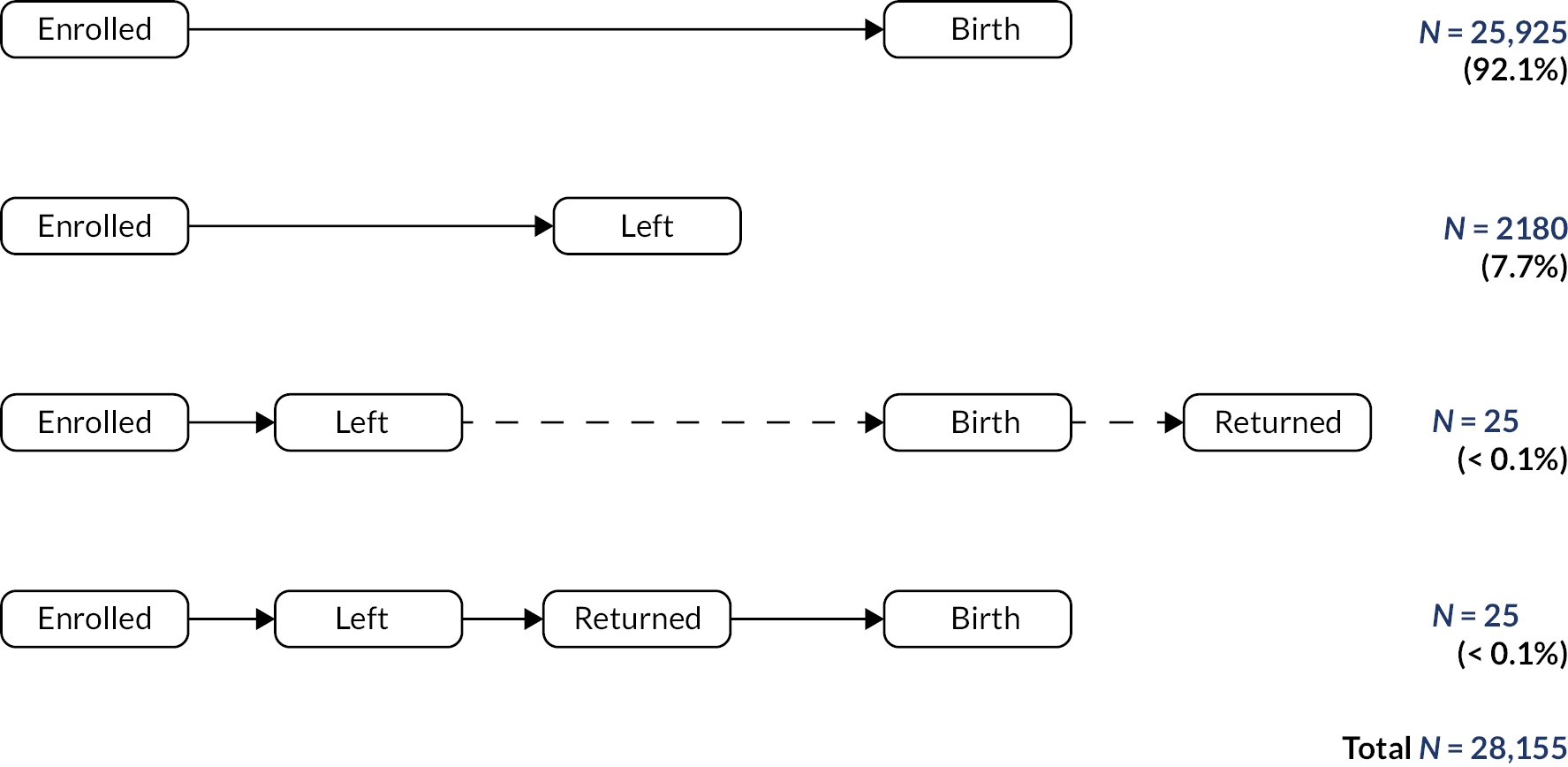

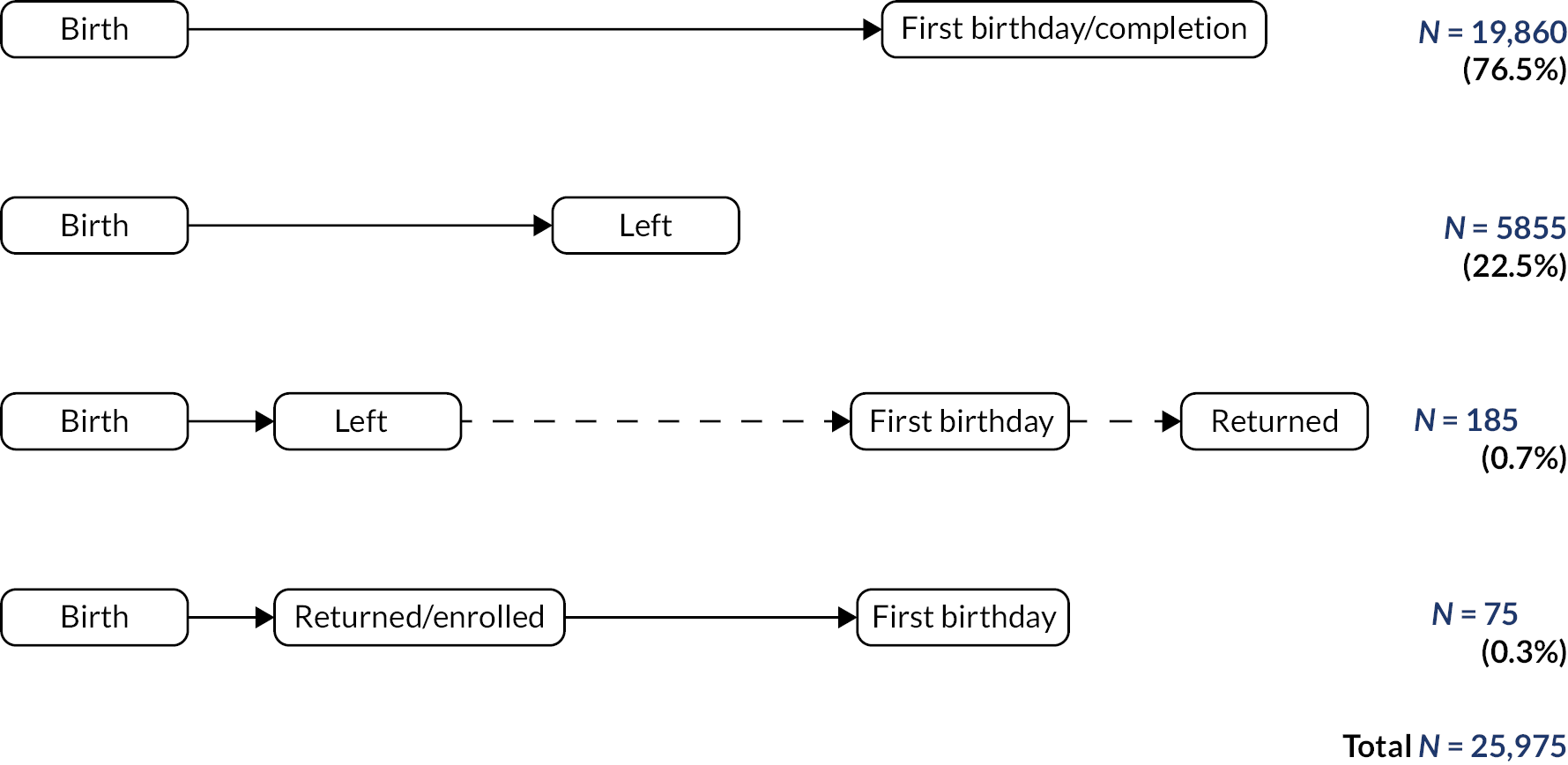

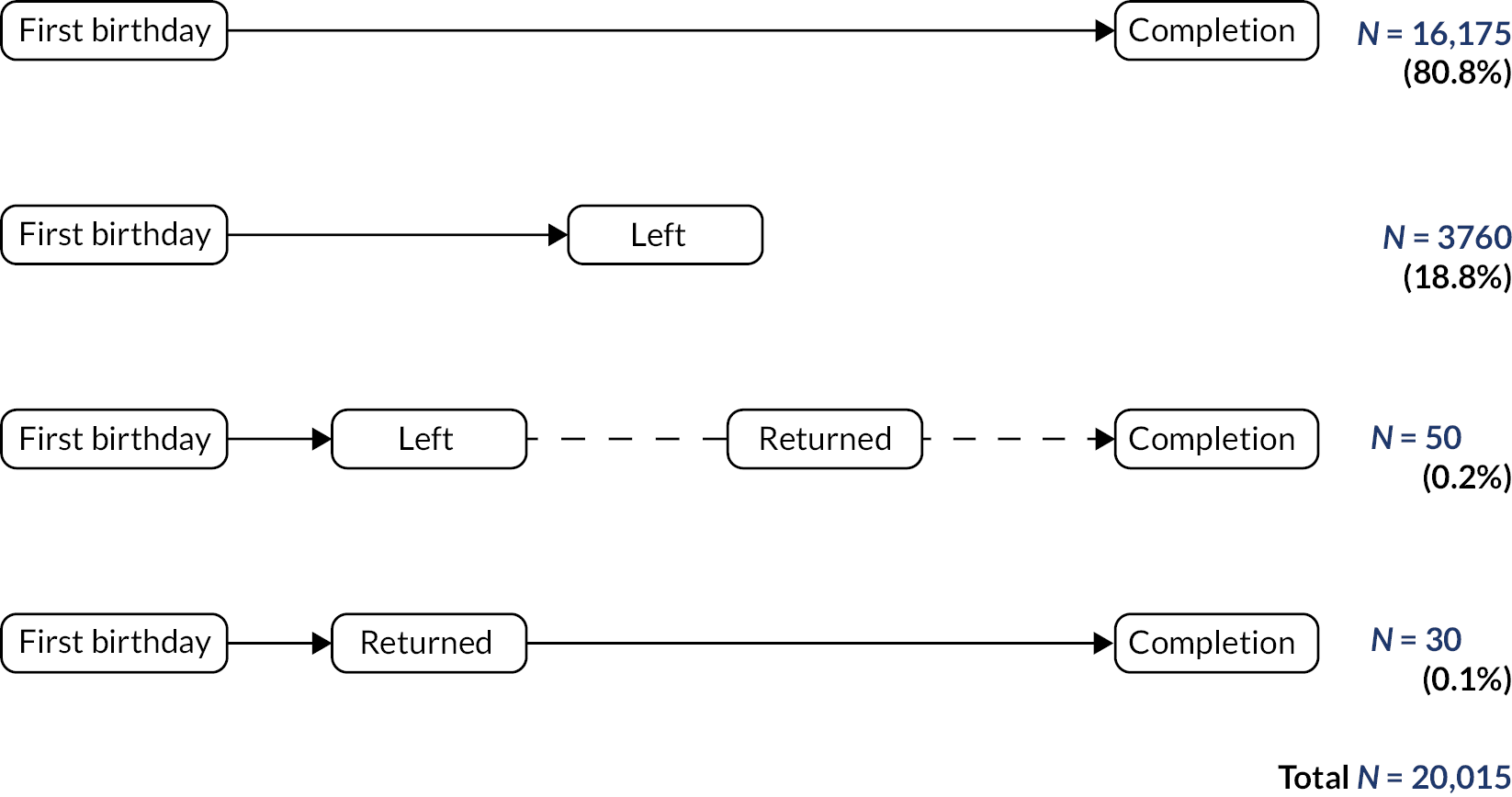

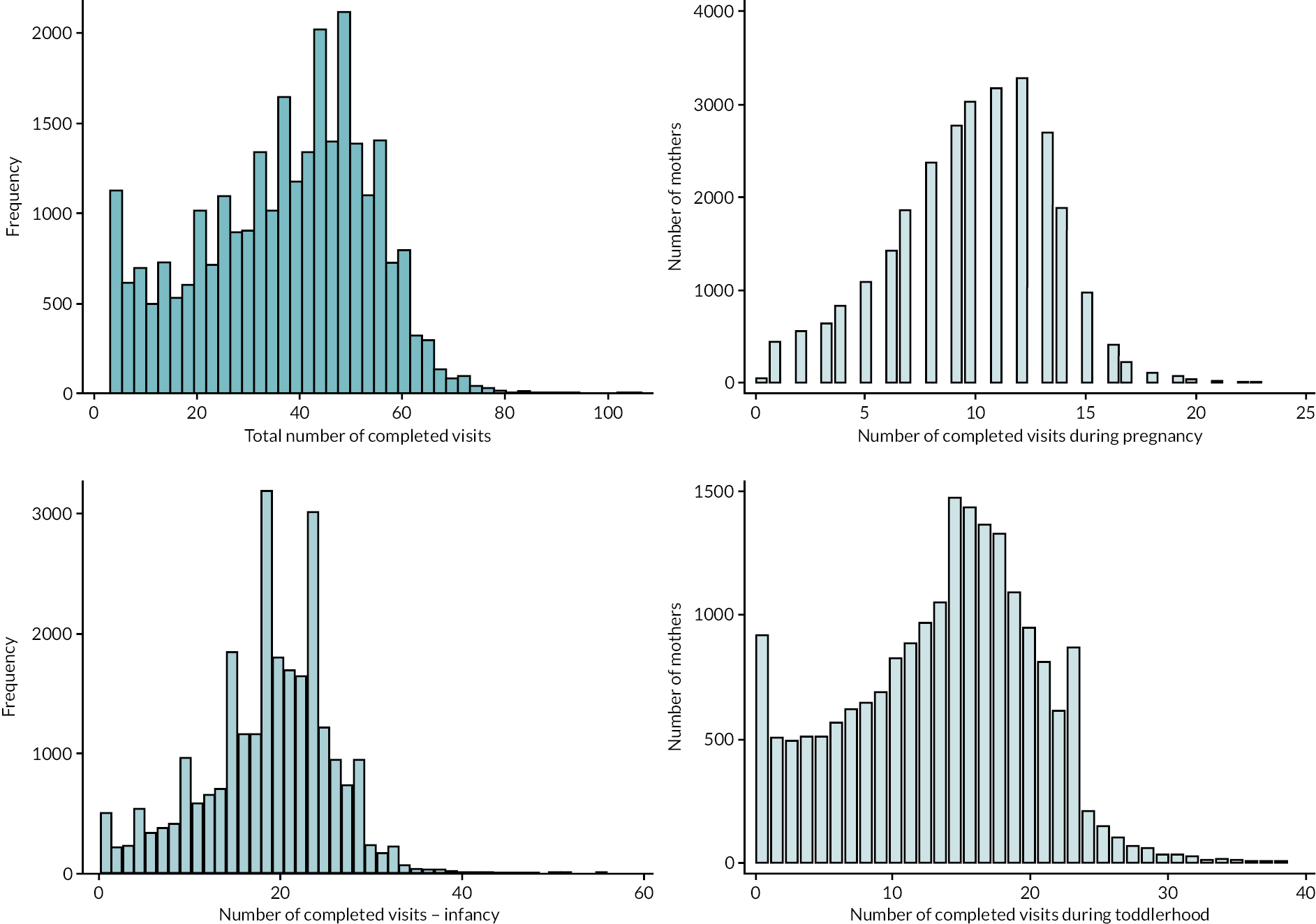

Description of attrition, fidelity targets and dosage in the Family Nurse Partnership

Since we knew that a small number of mothers who enrolled in the FNP did not receive any visits and that some received only a small number of visits, we described attrition, mean visit length and total time spent engaging with the programme. We defined dosage in the FNP among enrolled mothers by calculating the number of completed visits relative to FNP fidelity targets (Table 4). For this analysis, we first restricted the cohort to FNP mothers aged 13–19 who had linked with HES and who gave birth before the end of January 2018 (we had information on visits until January 2020), allowing 2 years for mothers to complete the programme.

| Programme phase | Frequency of visits (maximum) | Target percentage of visits | Attrition targeta |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy | Weekly for first 4 weeks, then every fortnight until birth (maximum = 14, for those enrolled at the target 16 weeks of pregnancy) | 80% or more | < 10% |

| Infancy (up to the child’s first birthday) | Weekly for first 6 weeks, then fortnightly in infancy (maximum = 28) | 65% or more | < 20% |

| Toddlerhood (child age 1–2 years) | Fortnightly for first 10 months, then monthly in toddlerhood (maximum = 22) | 60% or more | < 10% |

We calculated the proportion of visits completed as the actual number of visits completed divided by the expected number of visits for each mother. Some mothers may choose to leave the programme early (e.g. if they are returning to work and no longer have time for the visits or if they feel they will no longer benefit from visits). We, therefore, determined the expected number of visits by calculating the actual time spent in the programme using dates of enrolment, dates of completion and any leaving and returning dates recorded. We then determined the number of visits that should have occurred within this period based on the frequency of visits for each stage of the programme described in Table 4. 98 This was repeated for each programme stage (pregnancy, infancy up to the child’s first birthday and toddlerhood from age 1–2 years). This means that a mother who left early, but who had received all her visits before her leaving date, would be categorised as having 100% expected visits completed. The very small proportion of visits recorded as being < 15 minutes (0.2%; 2145 out of 1,010,890 visits, of which 565 visits were in the pregnancy stage, 960 in the infancy stage and 620 in the toddlerhood stage) were retained within this analysis. Further information on the data cleaning for this analysis is provided in Appendix 4.

Participant, programme and nurse characteristics associated with dosage in the Family Nurse Partnership

We first described individual and programme characteristics associated with dosage in the FNP, according to maternal risk factors prior to enrolment included in Table 3 and additional risk factors recorded in FNP IS (e.g. engagement of partner or parent in the FNP visits and nurse characteristics) and FNP site- or LA-specific characteristics. We evaluated which risk factors were associated with meeting the fidelity target (see Table 4) for each stage of the programme.

To evaluate the impact of these factors on dosage in the FNP, we modelled whether or not fidelity targets were met according to individual and programme characteristics. We repeated this analysis for each stage of the programme.

Effect of contextual factors and dosage on outcomes

To determine whether meeting fidelity targets and other contextual factors (i.e. individual and programme characteristics) were associated with selected outcomes, we compared outcomes according to whether each mother had met the fidelity target for each stage of the programme, for example, comparing outcomes for mothers who had completed the target number of visits in pregnancy with those who were enrolled but did not complete the target number of visits (see Table 4). We included variables for each stage of the programme, meaning that we compared outcomes for mothers who met the fidelity target for toddlerhood with those who were present at toddlerhood but did not meet the target and with enrolled mothers who had left before toddlerhood. Outcomes included in this analysis were those included in the subgroup analysis for Objective 2: child unplanned admissions for maltreatment or injury up to age 2, a Good Level of Development at age 5 (school readiness), maternal unplanned admissions for any diagnosis in the 2 years following birth and subsequent births within 18 months. As with the multivariable regression used in Objective 2, we used generalised linear models with a multilevel structure to allow for mothers nested within FNP sites. We included maternal risk factors and nurse/programme characteristics as covariates, as we expected these to be related to both engagement and outcomes.

Qualitative analysis

Following feedback from the Study Steering Committee and from the Family Nurses with whom we discussed the findings from this study, we decided that qualitative analysis describing the experiences of family nurses and parents would provide additional context to the quantitative analysis included in this report. This qualitative work is ongoing, but we report initial findings from the first three interviews in boxes within relevant results sections.

The interviews were semistructured and took place virtually during October and November 2022. The interviews were video recorded, transcribed and analysed by a researcher under supervision at the University of Kent. The interviewees comprised a parent (Annie), a FNP supervisor (Betsy) and a FNP nurse (Carol). Annie has two children, now aged 11 and 7, and resides in South-West England. The practitioners are employed by a LA in the same region.

A thematic analysis was completed which broadly followed the approach documented by Braun and Clarke. 100 This included reading and rereading the interview transcripts, coding each segment of each transcript, using the codes to generate themes; reviewing and revising the themes, providing distinct ‘… definitions and names for each theme’ and collating a concise summary to illustrate participants’ lived experiences.

Changes from protocol

We were unable to evaluate mortality in this study due to the large discrepancies between recording of deaths in the different data sources. Date and cause of death were obtained from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) via routine linkage between HES and civil registration (deaths) data performed by NHS Digital. In-hospital deaths are recorded in HES. For mothers enrolled in FNP and their children, deaths are also recorded in the FNP IS. Of the 115 child deaths recorded in the FNP data, < 10 were captured in the ONS mortality data and 60 were captured in HES. There were < 10 child deaths captured in the ONS data and 25 in HES that were not recorded in the FNP data. Due to the small numbers involved, small differences in the numerator could substantially alter inferences; therefore, we do not report mortality for children or mothers.

To further assess the robustness of findings to the analysis approach and to evaluate any potential differences in results due to the use of real-world data, we had planned to use our cohort to replicate findings observed in the Building Blocks trial, by deriving trial outcomes for a group of families in the administrative data cohort who were similar to those enrolled in the trial. Since Building Blocks recruited between June 2009 and June 2010 (and our cohort starts with births in April 2010), we were unable to replicate the trial cohort exactly, but we had planned to conduct a supplementary analysis restricted to mothers aged 13–19 who delivered between April and June 2010 in the 18 Building Block sites (see Appendix 2, Table 26). Only 185 mothers who were enrolled in the FNP gave birth within one of the Building Blocks sites between April 2010 (when our data began) and June 2010 (when recruitment in the Building Blocks trial ended). Since the usual care context began to change around this time period (due to a reduction in the health visiting workforce and a move away from GP attachment), evaluating outcomes for mothers meeting the Building Blocks criteria, but during later years, would not have been appropriate. 65 Therefore, we did not perform a sensitivity analysis for this group. We had planned to conduct propensity score analysis for the group of mothers aged 20–24 at LMP but did not due to small numbers. We had planned to conduct multiple imputations as a sensitivity analysis for the multivariable regression analysis but chose not to due to the large amount of other results from sensitivity analyses presented. We included some additional outcomes (FSM and CPPs in the child) that were not described in the original protocol. 1

Chapter 3 Results

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from the published papers by Cavallaro et al. 1 and Cavallaro et al. 2 These are open-access articles distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given and an indication of whether changes were made. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Chapter outline

This chapter begins with a description of the study cohort, providing a comparison of the characteristics of mothers who were and were not enrolled in the FNP. We then present the findings from Objective 1, which aimed to determine which groups of adolescent mothers receive FNP across LAs in England. For Objective 2, we describe child and maternal outcomes for the study cohort, providing an unadjusted comparison of outcomes for those who were or were not enrolled in the FNP (and according to maternal risk factors). We then present findings from the propensity score analysis (with sensitivity analyses) and from our multivariable logistic regression analysis. We show findings for subgroups according to maternal risk factors. Lastly, we present results from Objective 3, which aimed to evaluate the contextual factors associated with benefiting from the FNP.

Description of study cohort

Description of mothers in study cohort

Mothers who were enrolled in FNP were strikingly different from those who were never enrolled (Table 5). FNP mothers were younger, more likely to be admitted to hospital for adversity-related diagnoses or to attend A&E in the 2 years prior to 20 weeks of pregnancy and more likely to have their booking appointment after 20 weeks of pregnancy. FNP mothers were also more likely to have been in care or have a CPP, more likely to be recorded as having SEN provision, FSM and be in the most deprived quintile according to Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI), more likely to have been excluded or be persistently absent and less likely to achieve 5 A*–Cs at General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) level (but more likely to have achieved expected levels at Key Stage 1). Further information on the FNP cohort for mothers aged 13–19 based on data from the FNP IS is provided in Appendix 5, Table 33. Similar patterns were seen for mothers aged 20–24 (see Appendix 5, Tables 34 and 35).

| All mothers | Mothers enrolled in FNP | Mothers never enrolled in FNP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 130,415 | 100 | 31,260 | 100 | 99,150 | 100 |

| Maternal age at delivery (years) | ||||||

| 13–15 | 2685 | 2.1 | 1450 | 4.6 | 1235 | 1.2 |

| 16–17 | 26,065 | 20.0 | 10,370 | 33.2 | 15,690 | 15.8 |

| 18–19 | 72,465 | 55.6 | 15,805 | 50.6 | 56,660 | 57.1 |

| 20a | 29,205 | 22.4 | 3635 | 11.6 | 25,565 | 25.8 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 109,820 | 84.2 | 26,330 | 84.2 | 83,485 | 84.2 |

| South Asian | 3695 | 2.8 | 670 | 2.1 | 3030 | 3.1 |

| Black | 4650 | 3.6 | 1470 | 4.7 | 3180 | 3.2 |

| Mixed/other | 6840 | 5.2 | 1685 | 5.4 | 5155 | 5.2 |

| Unknown | 5410 | 4.1 | 1110 | 3.5 | 4300 | 4.3 |

| Area-level deprivation (quintile of IMD) | ||||||

| Least deprived | 6810 | 5.2 | 1445 | 4.6 | 5360 | 5.4 |

| 2 | 10,410 | 8.0 | 2305 | 7.4 | 8105 | 8.2 |

| 3 | 17,855 | 13.7 | 4115 | 13.2 | 13,735 | 13.9 |

| 4 | 32,550 | 25 | 7890 | 25.2 | 24,660 | 24.9 |

| Most deprived | 62,630 | 48 | 15,340 | 49.1 | 47,290 | 47.7 |

| Unknown | 160 | 0.1 | – | – | – | – |

| History of admissions/attendances with diagnoses within 2 years prior to 20 weeks of pregnancy | ||||||

| Adversity (violence, self-harm, substance misuse) | 5475 | 4.2 | 2295 | 7.3 | 3185 | 3.2 |

| Mental health (exc. self-harm/substance misuse) | 3340 | 2.6 | 1400 | 4.5 | 1935 | 2.0 |

| Repeat A&E attendances (≥ 4) | 21,105 | 16.2 | 6860 | 21.9 | 14,245 | 14.4 |

| Total linked to NPD (social care and education risk factors before 20 weeks of pregnancy available) | 109,360 | 83.9 | 28,145 | 90.0 | 81,210 | 81.9 |

| Ever excluded, in PRU or alternative provision | 32,945 | 25.3 | 10,560 | 33.8 | 22,390 | 22.6 |

| Ever recorded as persistently absent in a term | 40,600 | 31.1 | 15,090 | 48.3 | 25,510 | 25.7 |

| Ever in care | 6955 | 5.3 | 3235 | 10.3 | 3720 | 3.8 |

| Ever had recorded CPP | 3885 | 3.0 | 1990 | 6.4 | 1895 | 1.9 |

| Educational attainment (GCSEs)b | 100,270 | 76.9 | 23,785 | 76.1 | 76,485 | 77.1 |

| Achieved 5 A*–C GCSEs inc. Eng/Maths | 19,920 | 18.4 | 3975 | 14.2 | 15,945 | 19.8 |

| Total linked to Key Stage 2 data | 104,375 | 80.0 | 27,010 | 86.4 | 77,360 | 78.0 |

| Achieved expected level at Key Stage 2 (Maths) | 56,930 | 43.7 | 14,175 | 45.3 | 42,755 | 43.1 |

| Total linked to NPD Census (FSM, SEN available) | 108,365 | 83.1 | 27,995 | 89.6 | 80,365 | 81.1 |

| Ever recorded as having SEN provision | 56,475 | 43.3 | 17,150 | 54.9 | 39,325 | 39.7 |

| Ever recorded as having FSM | 61,315 | 47.0 | 18,525 | 59.3 | 42,795 | 43.2 |

Objective 1 – which groups of adolescent mothers receive Family Nurse Partnership across local authorities?

Parts of this section have been reproduced from the published paper on FNP enrolment by Cavallaro et al. 2 This is an open-access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given and an indication of whether changes were made is given. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Key messages

-

Only 23.2% (95% CI 23.0% to 23.5%) were enrolled in the FNP (25,680 of 110,520 eligible mothers).

-

Enrolment rates varied substantially across 122 sites (range: 11–68%), and areas with greater numbers of first-time adolescent mothers achieved lower enrolment rates.

-

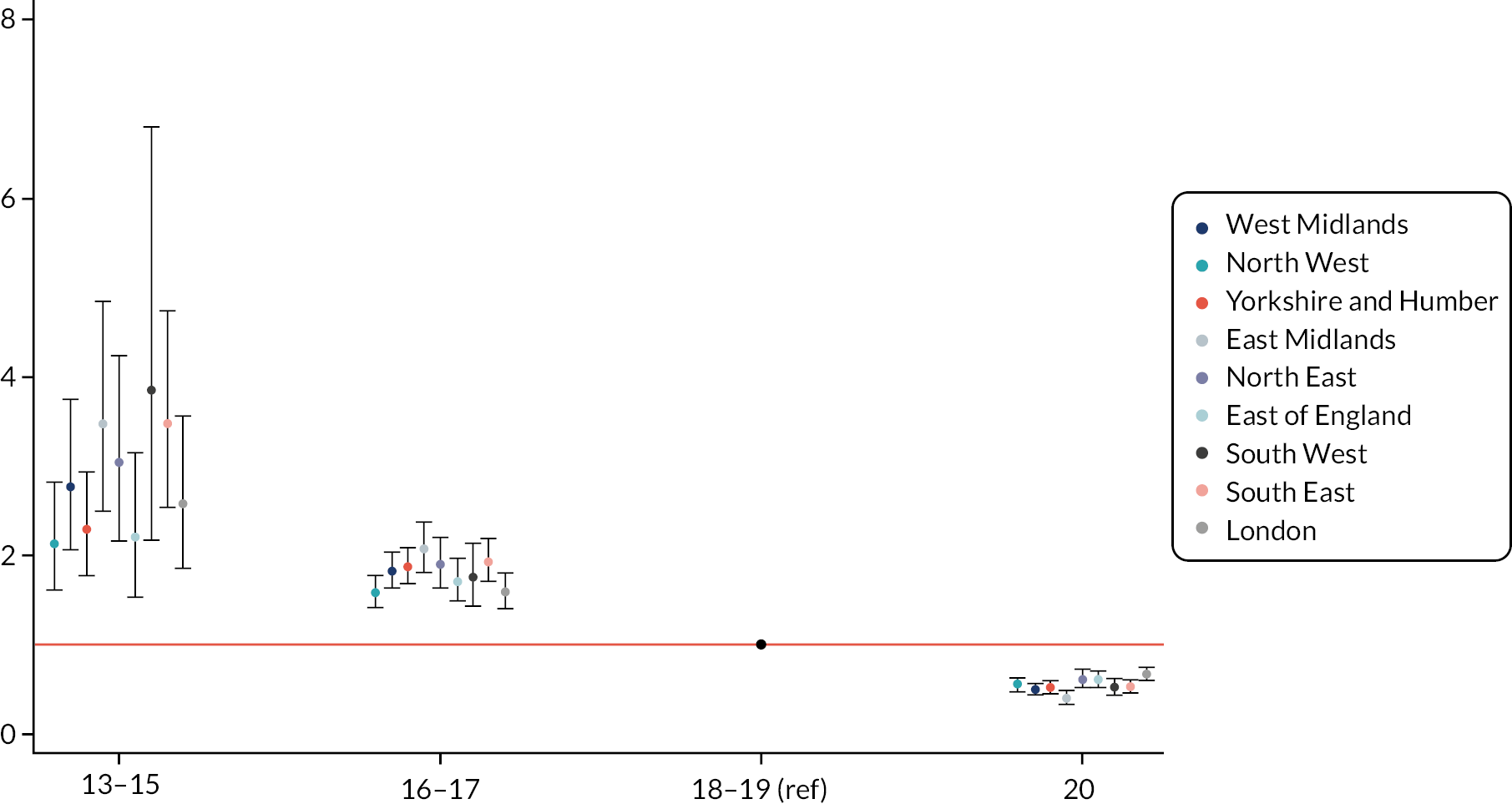

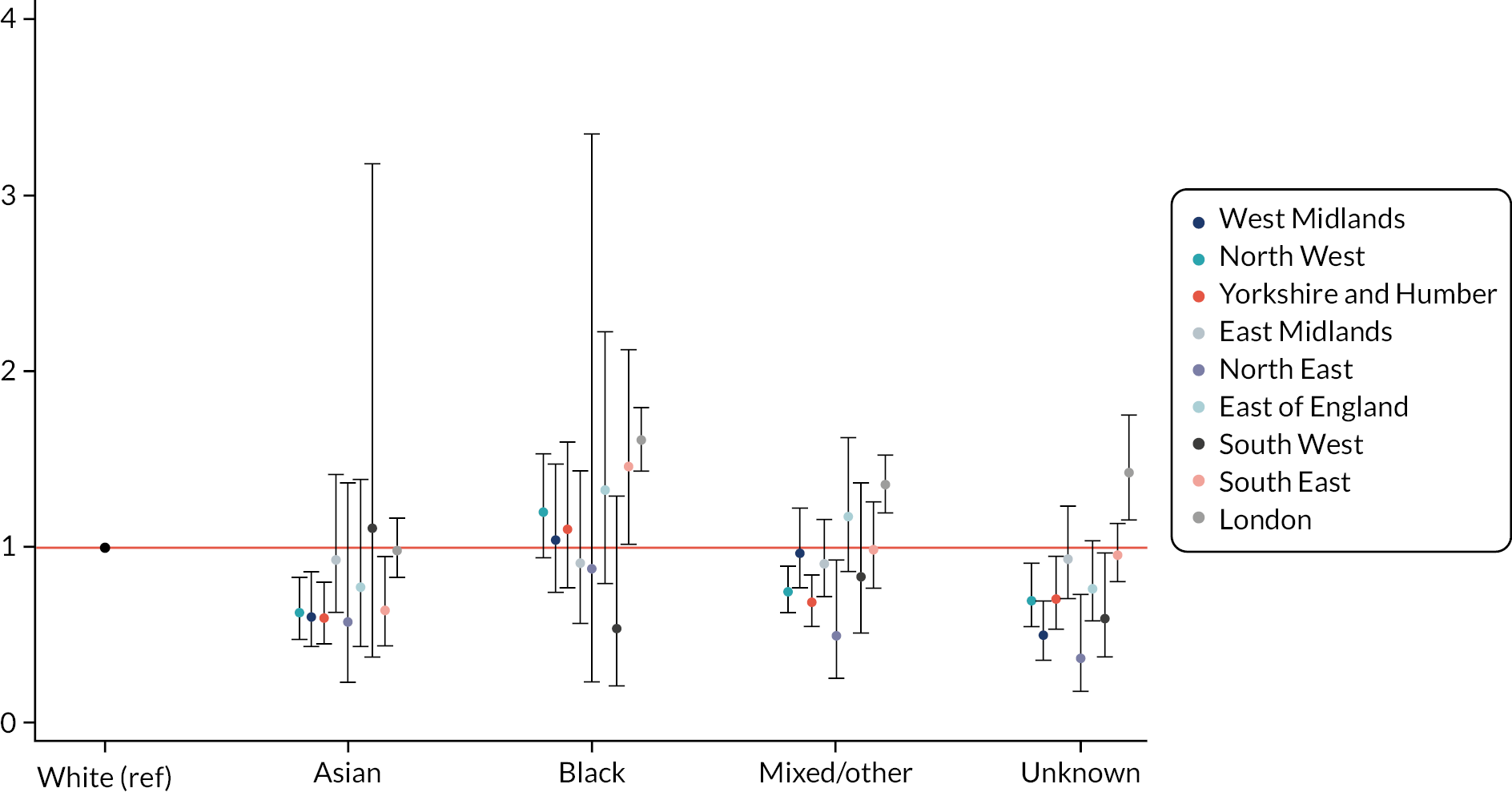

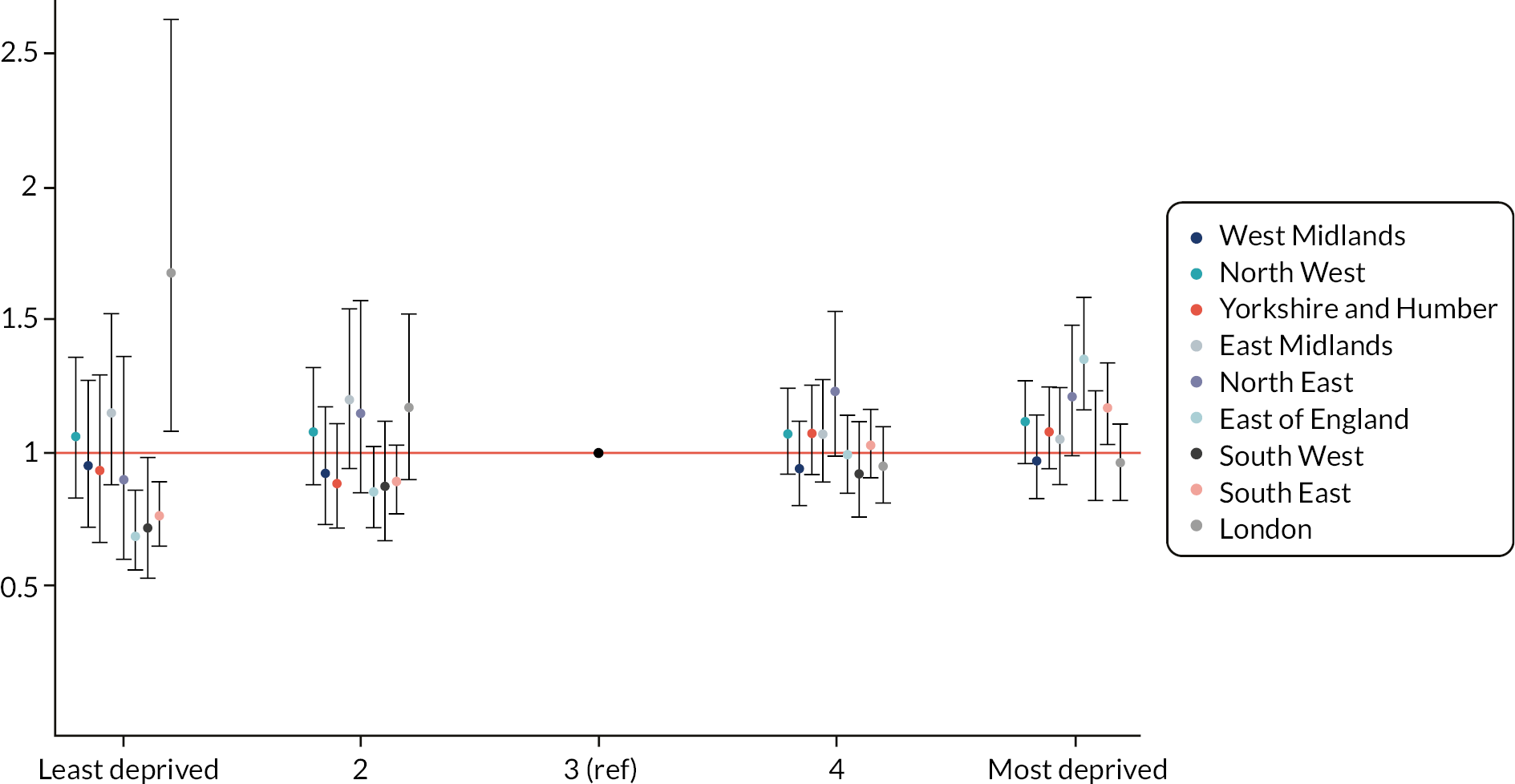

Mothers aged 13–15 were most likely to be enrolled (52%; adjusted OR 2.65, 95% CI 2.39 to 2.94 compared with 18- to 19-year-olds) but accounted for only 2% of all eligible mothers.

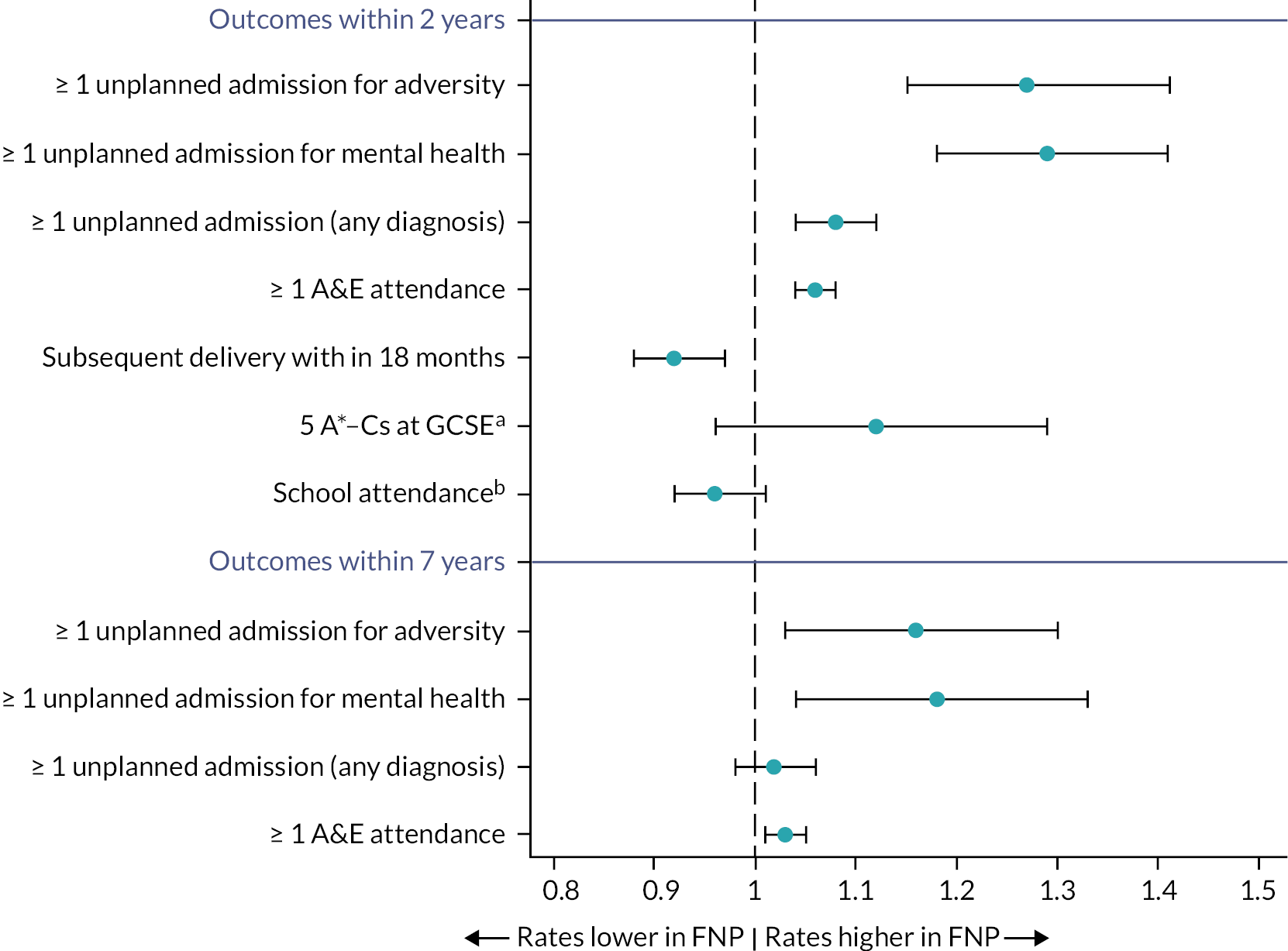

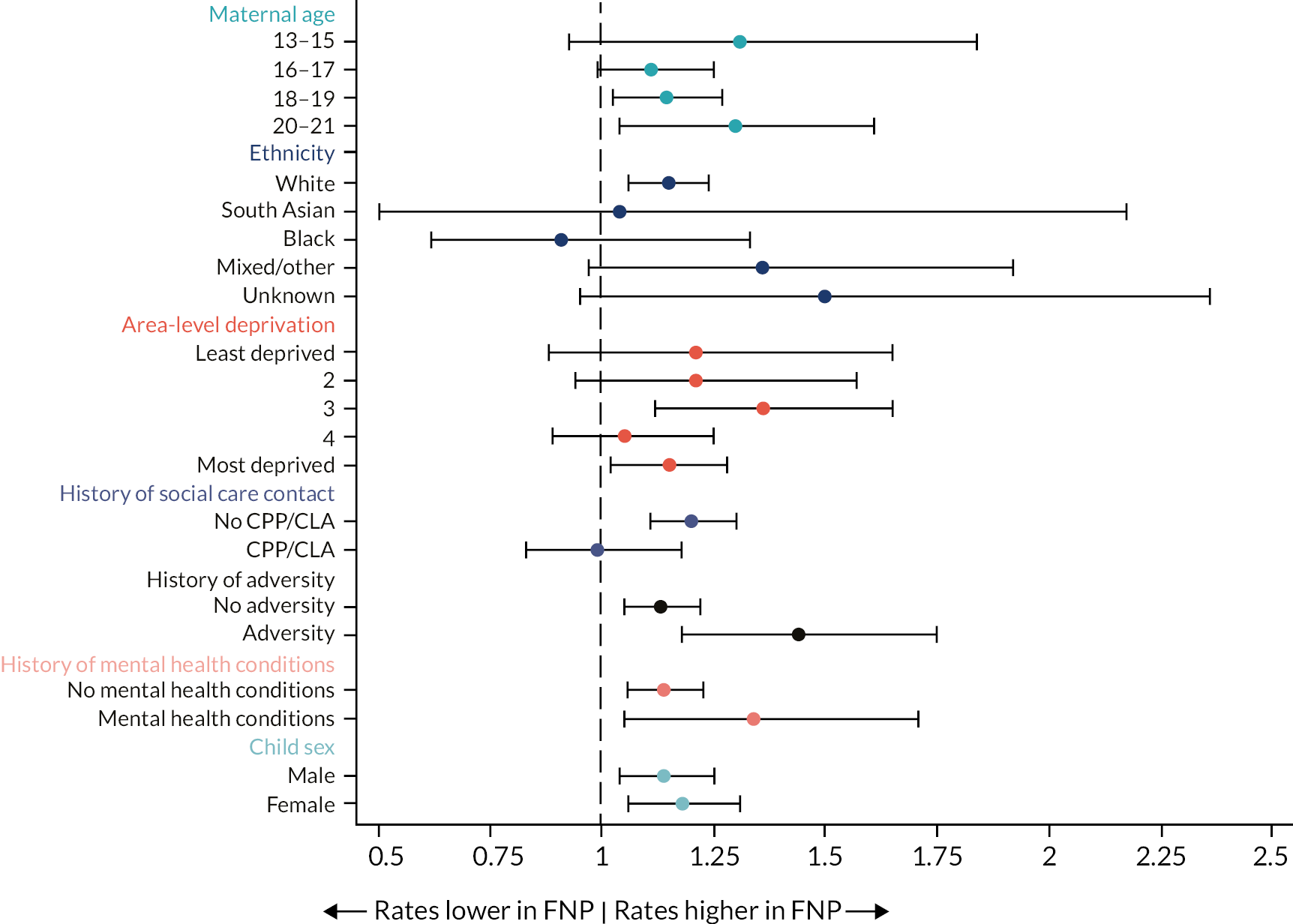

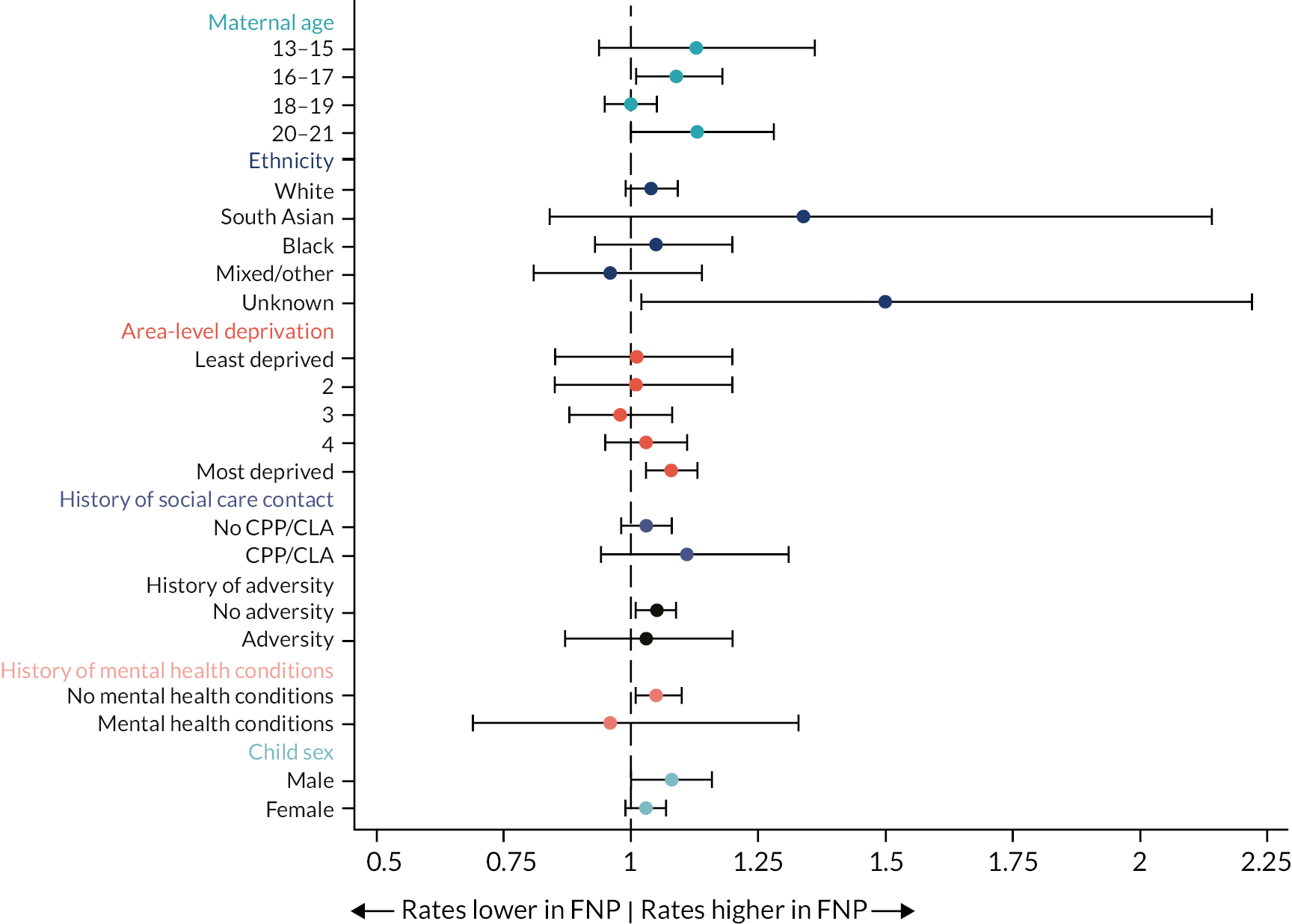

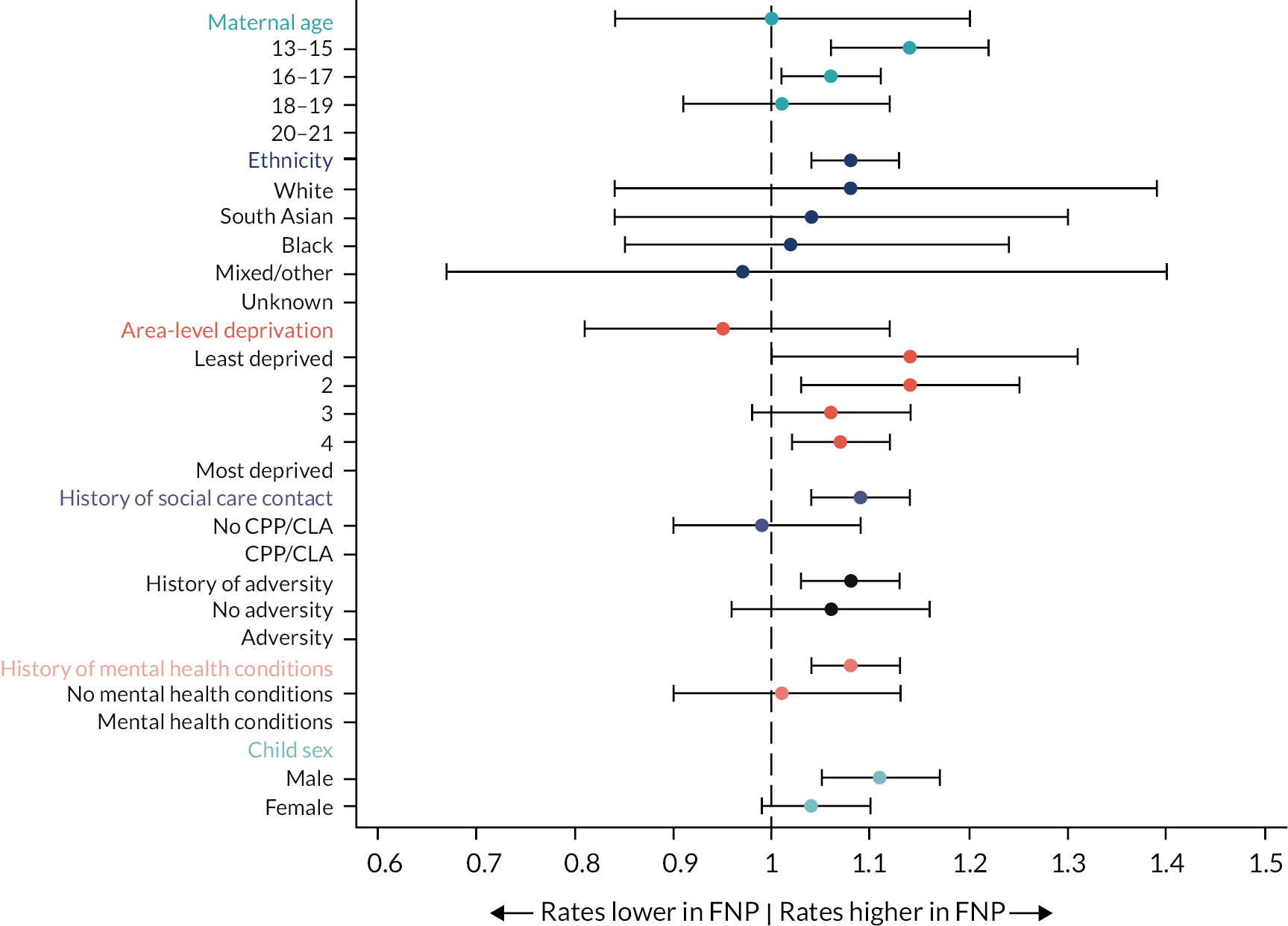

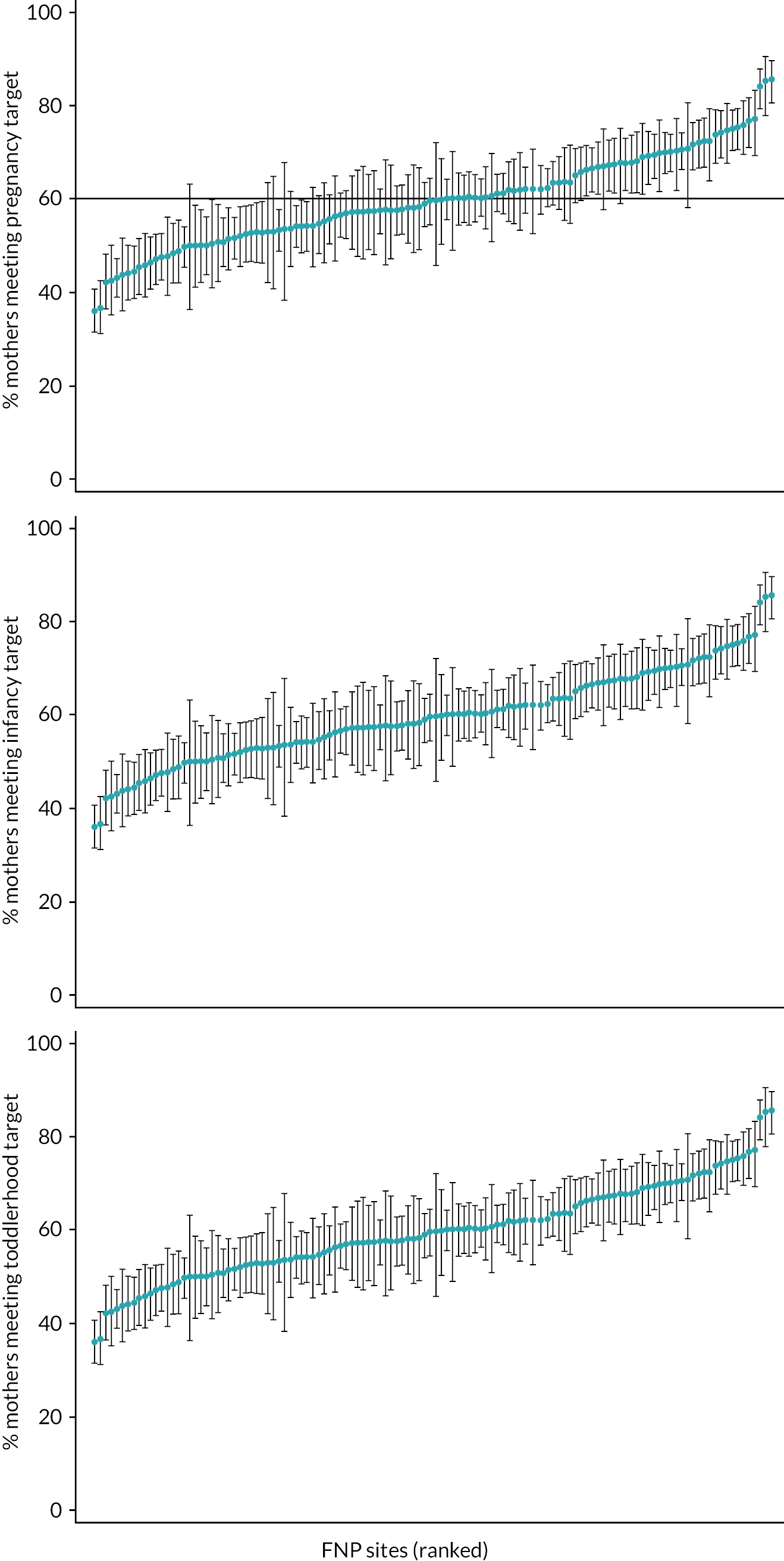

-