Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number 16/117/04. The contractual start date was in September 2018. The draft manuscript began editorial review in March 2023 and was accepted for publication in November 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 O’Doherty et al. This work was produced by O’Doherty et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 O’Doherty et al

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and context

Evidence suggests that one in five women and one in 25 men in England and Wales have experienced sexual violence and abuse since the age of 16 years. 1 Sexual violence is defined as any sexual act, or attempt at a sexual act, or an act directed at a person’s sexuality, involving coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship with the subjected individual. It includes, but is not restricted to, rape, sexual assault, child sexual abuse (CSA), sexual harassment, rape within marriage and relationships, forced marriage, so-called honour-based violence, female genital mutilation, trafficking, sexual exploitation and ritual abuse. 2 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, fewer than one in six victims of rape reported to the police. In the year ending September 2022, the number of sexual offences recorded by the police (199,021) was the highest level recorded within a 12-month period, and showed a 22% increase when compared with the number of offences recorded by the police for the year ending March 2020. 3

Sexual violence and abuse is a serious public health concern, for which the range of immediate and long-term physical and mental health effects are well-documented. 4,5 Physical health consequences for women include unwanted pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), painful sex, chronic pelvic pain and vaginal bleeding. 5,6 For men, these include genital and rectal injuries and erectile dysfunction. 7 The mental health effects of sexual violence are substantial. The incidence and severity of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is common among women and men who have experienced sexual violence and abuse. 8,9 Other mental health consequences include anxiety, depression, self-harm and suicidality, alcohol and drug abuse as well as eating disorders. 4 Furthermore, experiencing mental health problems is associated with an increased risk of other long-term health conditions including hypertension, cardiovascular disease and gastrointestinal problems. 10 The significant health burden of sexual violence and abuse has wider economic costs to society, reaching more than £12 billion per year (2015/16). 11

Although a wealth of evidence underpins the substantial negative effects of sexual violence and abuse, much less is understood about the longer-term health and well-being outcomes for survivors. In light of this, there has been a call for dedicated longitudinal research on the health effects of sexual violence. 4 Notably, a recent 3-year follow-up study in South Africa reported that women survivors were 60% more likely to acquire human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in that time compared with control group women who had not been raped. 12 However, the longitudinal exploration of survivor’s health and well-being remains limited. More broadly, there are key gaps in sexual violence research with men survivors13 and survivors who have a disability. 14 Additionally, there is a lack of research that has examined sexual violence and abuse exposure and chronic mental health problems, and comorbidity of health outcomes15 and understanding sexual health and well-being outcomes beyond measuring STI acquisition only. 16

Why is research on sexual assault referral centres needed?

Providing accessible and an evidence-based response to survivors is critical. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that an initial response should include providing survivors with medico-legal and health services at the same time through holistic care, in the same location and preferably by the same health practitioner. 17 In the USA, many states now offer Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner programmes or Sexual Assault Response Teams to provide the recommended services. This type of support has been modelled in Australia, Canada and the UK. 18 In England and other parts of the UK, investment in sexual assault referral centres (SARCs) has grown considerably, especially as a ‘best practice’ response for survivors after incidents of sexual assault or rape. 19 Sexual assault referral centres are intended to coordinate all of the care and support needs for survivors of any age and gender, regardless of whether the survivor is a recent or non-recent victim, and to support survivors with the opportunity to make a police report if they choose to do so. As highlighted in the National Service Specification for SARCs,19 which outlines the aims and service standards of SARCs, the core services provided at SARCs include crisis emotional support by dedicated crisis workers, a forensic medical examination (FME; or nurse-led examination) to enable the collection of evidence needed to prosecute alleged perpetrators, provision of emergency contraception and HIV post-exposure prophylaxis, referral to sexual health centres and other healthcare services, referral for mental healthcare needs such as counselling and to an Independent Sexual Violence Advisor (ISVA), particularly if navigating the criminal justice system (CJS). Thus, SARCs operate within a wider landscape of Sexual Assault and Abuse Services (SAAS), across several systems and government organisations including health, social care and criminal justice partners. As stated in the Specification, an effective SARC does not simply provide services to survivors, but rather helps them understand what options are available and facilitate their choices with care.

There are approximately 50 SARCs in England, including a number of specialist paediatric sites. 20 While NHS England (NHSE) is responsible for the commissioning of the public health element within SARCs, the police and/or police and crime commissioners are responsible for commissioning forensic medical examination services. SARCs operate with considerable variation in areas where they are located, such as in hospitals or community settings, and the organisational model in which their services are delivered, for example, individual SARCs can be led by the police, private organisations, the NHS or charities. 19,21 To date, little is known about how effective and cost-effective SARCs are in addressing the physical and mental health outcomes for child and adult survivors. There is also a lack of evidence about whether the varying models in which SARCs operate has an effect on their effectiveness to support survivors. There are sparse data focusing on survivors’ access to mental health care after reaching a SARC18 and how service users of ethnic minority backgrounds, as well as sexual and gender minority communities, might experience care and support from SARCs.

Research objectives

Aims

-

To evaluate the evidence for psychosocial interventions for survivors of sexual violence and abuse.

-

To examine SARC models of service delivery by exploring work practices, workforce and technology factors and the integration of SARCs in the broader context of a health and community response to sexual violence and abuse.

-

To undertake a 1-year follow-up study in a cohort of survivors of sexual violence and abuse to explore the effect of different SARC models of service delivery, access to health care and other SAAS on PTSD, depressive symptoms, quality of life (QoL), substance misuse, violence re-exposure, sexual health and costs.

-

To identify the effect of delivering post-crisis trauma-focused counselling interventions in the voluntary sector compared with the NHS on health and other outcomes.

-

To engage young SARC service users (age range: 13–17 years) and explore impacts of exposure to sexual violence and abuse on their lives and quality of care and support from SARCs.

-

To draw on the cohort sample using maximum variation sampling to ensure a broad range of subgroups represented, supplemented by a community sample and to conduct a qualitative investigation of the experiences at SARCs and outcomes of SARCs and barriers and facilitators to access.

Research questions

-

For individuals who have experienced sexual violence and abuse, do psychosocial interventions reduce PTSD and other poor health outcomes? What are providers’ experiences of delivering such psychosocial interventions? What are the experiences of survivors and supporters in accessing such psychosocial interventions?

-

What are the implications of four inter-related aspects of SARCs – the everyday work they do, the workforce, the technology and the organisation – for the delivery of SARC services? What is the work of SARCs including the types of interventions delivered? Who is the SARC workforce? What are the technologies that enable SARCs to get work done? What is the organisational context of SARCs and to what extent are SARCs embedded within the overall response by statutory and voluntary sector organisations to the needs of survivors of sexual violence and abuse?

-

What are the health and cost trajectories of those who attend SARCs? How can these be compared for different SARC models of service delivery and access to health and SAAS?

-

What is the effect of receiving post-crisis counselling in the voluntary sector when compared with that provided through the NHS?

-

What are the experiences of children and young people (CYP) of receiving care and support from SARCs?

-

What are the experiences of access to SARCs by survivors from marginalised or minority populations?

Chapter 2 Project governance

Project steering group

A Study Steering Committee (SSC) independently chaired by Professor Roger Ingham had oversight of the multidisciplinary evaluation of sexual assault referral centres for better health (MESARCH) project. The Committee held 10 sessions at 6-monthly junctures over the project lifecycle, used to gather progress updates from the project team including review of the 6-monthly progress reports submitted to the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and the funder’s response. These sessions assessed adherence to the study protocol and discussed amendments; assessed barriers to progress; enabled access to guidance and the range of expertise available through the members, who linked us with resources and networks; and enabled space for problem-solving, reflection and celebrating the ‘big’ and ‘small’ achievements of the project. The membership is listed in our protocol22 and included two members of our Lived Experiences Group/patient and public involvement (PPI) (see Patient and public involvement) and at least one representative was in attendance at all Committee sessions. The NIHR was notified of meeting minutes and actions arising from meetings with the SSC and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC; see Ethics). The SSC was also available to provide independent advice as required outside of the scheduled SSC meetings.

Ethics

Oversight and approvals

Approvals were granted by research ethics committees and the Health Research Authority before any data collection. Approval dates and reference numbers are provided in the Ethics Statement at the end of the report. In addition, five NHS SARC sites and one onward referral NHS agency confirmed site capacity and capability. Amendments to the study protocol and documentation were discussed with the SSC, and approval was sought and obtained from the relevant ethics committees. These amendments are outlined in V3.3 of the protocol. 22 The DMEC met on three occasions over the project course with the purpose of monitoring data collection and analyses across all studies, risks to the project and making recommendations on the ethical considerations where appropriate.

Ethical considerations

We now outline key ethical considerations that were made across the studies that involved primary data collection (SARC process evaluation, cohort study, embedded qualitative study and the CYP’s study). In the presentation of findings and quotes, we have ensured that participants are not identifiable. Where we had permission to use direct quotes from participants, we have used pseudonyms (chosen by participants or the research team) or quotes have been attributed to an unidentifiable label. In addition to the project team receiving regular training for conducting interviews with survivors of sexual violence and abuse, we developed a safety protocol drawing on safety and distress protocols from our previous published work, and based on the expertise of the MESARCH team, members of our Lived Experiences Group (LEG) and SSC, staff at Coventry Rape and Sexual Abuse Centre, and informed by the Charter of Survivors Voices. 23 The safety protocol outlined different procedures the project team would follow in relation to key risks. The procedures are as follows:

Promoting the safety of participants

Project team interviewers were trained to ensure that if a person expressed a concern about their current safety or well-being, then they were ready to ask about safety and support the interviewee or participant to seek the help they need. Equally, the interviewer was trained to enquire and respond if there was a concern based on other cues, such as behaviours of the respondent or indirect expressions of fear or worry or risk of self-harm or suicidality, as well as environment cues such as background noise or activity. Interviewers were trained in revisiting the contract set out at the beginning of the research about exceptions to maintaining confidentiality. The safety protocol also outlined an approach to discuss safety planning with a participant when they disclosed information and processes for recording disclosures of risk. As part of monitoring the safety and well-being of participants, we used a RAG (red, amber, green) system of different categories (see Appendix 1, Table 22). The ‘red’ category incidents involved considering whether we had to break confidentiality to promote safety through mandatory reporting. The decision to break confidentiality did not occur in the project.

Responding to a participant’s distress

We were mindful that there could be situations where a participant could be distressed at any stage of the research. This occurred during 5–10% of interviews. The researchers informed participants that the research could be concluded at any time and were prepared to signpost them to local or national services or connect them with their crisis worker, ISVA or Children and Young People’s Independent Sexual Violence Advisor (ChISVA) for further support. Although we did not ask participants to share details about the nature of the sexual abuse they experienced, the questions included in the interviews were carefully developed to avoid blaming or stigmatising language. Interviewers were mindful of triggers that could cause distress or embarrassment. Interviewers also reminded participants that they could choose which questions they felt comfortable to answer. Researchers were also trained in responding to participants experiencing a flashback during participation in the research and in monitoring whether negative effects were arising directly from the study over time.

New disclosures and data being subpoenaed by the criminal justice system

The project was committed to not jeopardising any criminal proceedings. We explained to participants before the research interviews and throughout the research process that if their case was going through the CJS, then there was a possibility that the project could be asked to provide information submitted by a participant to the research if requested by the courts. If participants had a live case and chose to talk about the incident(s), researchers were trained to remind participants of the commitments of the research and offered to direct the discussion to another part of the interview. New (first) disclosures or disclosures of new information about a live case would require the team to pass on the information to the police; however, we had no instance of having to take this action.

Maintaining safety for researchers

It was important that researchers made their role clear to participants that the purpose of the study was intended for research and not for treatment, signposting them to appropriate services and responding to safeguarding concerns and disclosures appropriately. The researchers communicated with participants and potential participants using their professional details and names, through the project phones and by email rather than providing any personal contact details. The research team was also prepared to respond to potential instances where a participant might frequently contact the project team and/or request to speak with a specific team member. We had no instances of this occurring.

During COVID-19, remote interviews continued to be conducted as researchers worked from home. To support staff members involved in contacting participants and conducting interviews, all communication and planned calls continued to be documented in a shared calendar and tracking system so that all project team members were aware of when contact occurred. The staff members continued to have weekly check-ins and regular opportunities for debriefing. In March 2021, LEG representatives and SSC members recognised the growing effects of conducting the research on those interviewing participants and engaging with data including screening a large number of studies for evidence reviews. The LEG and SSC recommended the introduction of regular supervision for staff members. In response, external clinical supervision was implemented every 6 weeks from May 2021 to ensure the staff members were well supported throughout the project.

Data management

A comprehensive data management plan was developed for our studies involving data collection. We regularly monitored our processes regarding where and for how long personal data and anonymised data sets were stored, as well as who had access to these data. To manage the personal data and safety notes of participants in our 1-year cohort study, a secure tracking system was developed for use by staff members who were interviewing participants, enabling accurate recording and tracking of participants’ personal data (such as their contact details), when they were due follow-up interviews, and information about safety concerns (this included the RAG system) and any actions implemented.

Patient and public involvement

Background

Patient and public involvement refers to involving patients, members of the population directly or indirectly affected by the target problem and/or members of the public in the research process. In MESARCH, we worked with survivors of sexual violence and abuse. While a research context could be empowering and beneficial to survivors in their recovery from trauma,24,25 negative engagement could lead to re-traumatisation. 23 The use of PPI to shape how research with survivors is carried out can lead to high-quality practice and positive experiences for participants. However, previous research suggests that there is considerable scope for improving the quality of PPI in sexual violence and abuse research. 23,26,27 Our research aimed to advance practice in this area.

Methodology

Drawing on principles of co-production, we worked in partnership with those with lived experience of sexual violence and abuse, referred heretofore as ‘the MESARCH LEG’. MESARCH reflects the shift to research being carried out collaboratively with members of the public who share decision-making rather than models of lay consultation and tokenistic involvement. 28,29 Several theoretical positions underpinned our approach. First, we value a multiplicity of knowledge and have afforded great weight to experiential knowledge within the research process thus creating opportunities for epistemic justice, a concept coined by philosopher and feminist Miranda Fricker30 where voices that are often silenced or marginalised are amplified. Second, building and maintaining strong relationships with the LEG was central to our approach to lived experience involvement, premised on theories of relational engagement, dialogical ethics and an ethics of care, and reflecting the significance of the human and socially interactive element of engagement. 31–33 Lastly, drawing on the concepts of citizenship and democracy, the active and meaningful involvement of those with lived experience of sexual violence and abuse in our research promotes the empowerment of survivors. 34 This is particularly relevant in relation to involving survivors of sexual violence and abuse who will have experienced disempowerment through abuse, communities and institutions. To ensure good practice in involving survivors of abuse and trauma in our research, we worked closely with Survivors’ Voices (a survivor-led organisation that harnesses the expertise of people affected by abuse), drawing on their Charter, which details principles and good practice for good survivor engagement in research. 23 We were also guided by the Rape Crisis National Service Standards, adapting a set of quality service standards to meet the needs of survivors of sexual violence and abuse. 35 These principles provide a framework against which we have monitored the extent to which our research is trauma-informed and achieves authentic survivor focus.

Methods

Our LEG was supported by a dedicated public engagement officer to enable a co-design and co-production approach across the project. LEG members were recruited through survivor support groups, delegates at conferences, participants on related research studies and recommendations from other researchers. Over the lifecycle of the project, the group included 11 members participating at different times and brought 794 hours of expertise into the project. Members of the LEG were diverse across sex, age, ethnicity, sexuality, education, employment and life opportunities. They brought a wide range of professional and lived expertise as well as various engagement with the CJS, NHS, therapies and third-sector services. We consistently worked to expand diversity as members moved on and new members joined, recognising the association between diversity and gains being achieved across the research.

The involvement of the LEG in the project was guided by a terms of reference document that was co-produced and regularly reviewed. Involvement was enhanced through formal meetings (8) administered through the lead university, participation of two LEG members in SSC meetings (10) to provide a lived experience perspective and contribute to the oversight of the project, and ongoing communication through other means as and when it was required. The work of the LEG was fully resourced by the NIHR covering people’s time, travel, childcare expenses and conference attendance. We also engaged with survivor support groups, organisations led by survivors, specialist sexual violence and abuse organisations and key stakeholders to further embed PPI across the project.

Patient and public involvement activity across the project lifecycle

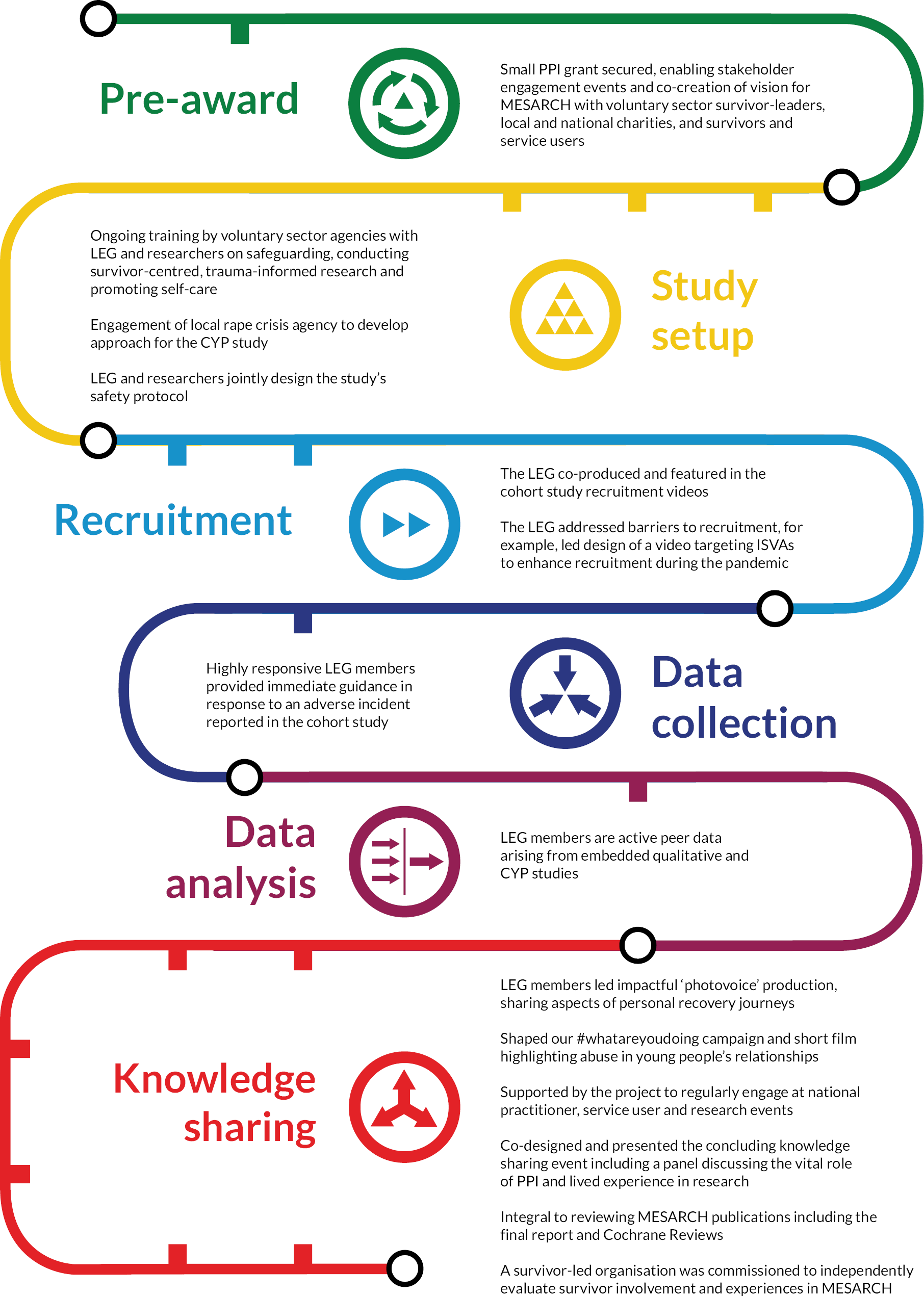

Patient and public involvement was embedded across all aspects of the project, from its design and delivery to the interpretation and sharing of the findings (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Embedding lived experience and ‘experts-by-experience’ across the MESARCH project. CYP, children and young people; ISVA, independent sexual violence adviser; LEG, lived experiences group; PPI, patient and public involvement.

Pre-award

We held a stakeholder event to integrate perspectives from a wide array of third-sector organisations and administered a survey, in collaboration with a charity that supports survivors of sexual trauma, to gather views on research aims and methods. The results shaped our choice of primary outcome, use of incentives and plan for examining post-crisis care. We secured a PPI grant, which enabled us to co-create a vision for the project with survivors and service users; we built partnerships with the charity sector; and we created a leadership team to include survivorship alongside academic and practice-based experience.

Study set-up

From the outset and throughout the project, high-quality training that met gaps in skills and knowledge for teams was critical. The research team and LEG participated in five bespoke training sessions delivered by survivor-led organisations, specialist sexual violence organisations and members of the LEG. The training sessions addressed safeguarding issues; deepened the ability to understand trauma and respond in a research setting; enhanced the research skills of the LEG to enable them to work effectively with the research team; and promoted well-being and self-care. We worked with the LEG and sexual violence and abuse charities to optimise not only how we engaged with target service users and survivor participants but also the quality of participation experiences. This included developing and refining the safety protocol (see Ethics), the interview schedules for the cohort study and embedded qualitative study and the participant facing documentation. Initiation of the CYP study led to connecting with a local sexual violence and abuse charity where the young people (age range: 13–24 years) worked with us to design and develop the methods for the CYP study through a series of workshops.

Recruitment

There are particular challenges to reaching survivors for research purposes, even where that research offers the prospect of improved health and well-being through psychosocial interventions to the individual. 36 When the research is ‘observational’, there is a less apparent benefit to participation. Extensive groundwork and reflection was needed to co-produce a narrative for engagement with survivors and draw people safely and ethically to the research. The LEG was central to identifying and resolving moral questions and dilemmas about the undertaking the research, in addition to some of the more pragmatic details of connecting with survivors safely, and achieving participation and retention rates needed from a scientific viewpoint. Our recruitment videos, co-designed and featuring LEG members, are a good example of a practical response to mitigating the challenges brought about by research in this sphere (see http://mesarch.coventry.ac.uk/join-1000-voices-for-change/). LEG members actively used their collective voice to reduce barriers ISVAs might have faced in referring people to this study (e.g. Is MESARCH safe? Is it in the interest of my clients?).

Data collection

Having hugely influenced the content of interviews and the areas we assessed (e.g. adding suicidality, self-harm and eating problems outcomes and helping to select appropriate measures), the LEG worked towards closely monitoring how participants were experiencing the interviews and were active in resolving problems (see Ethics for details of adverse events).

Data analysis

Although the contribution in this arena was not quite as developed as that in others (because of the analysis tending to come late in the project lifecycle), LEG members have been integral to analysis for our CYP study (see Chapter 7) and our diverse survivor voices work where we tried to engage those hardest-to-reach (see Chapter 8). In these activities our LEG colleagues have fulfilled the definitions of peer or co-researchers, meaning they worked jointly and in partnership with researchers on research tasks using their lived experience to inform their work. 37,38

Knowledge sharing

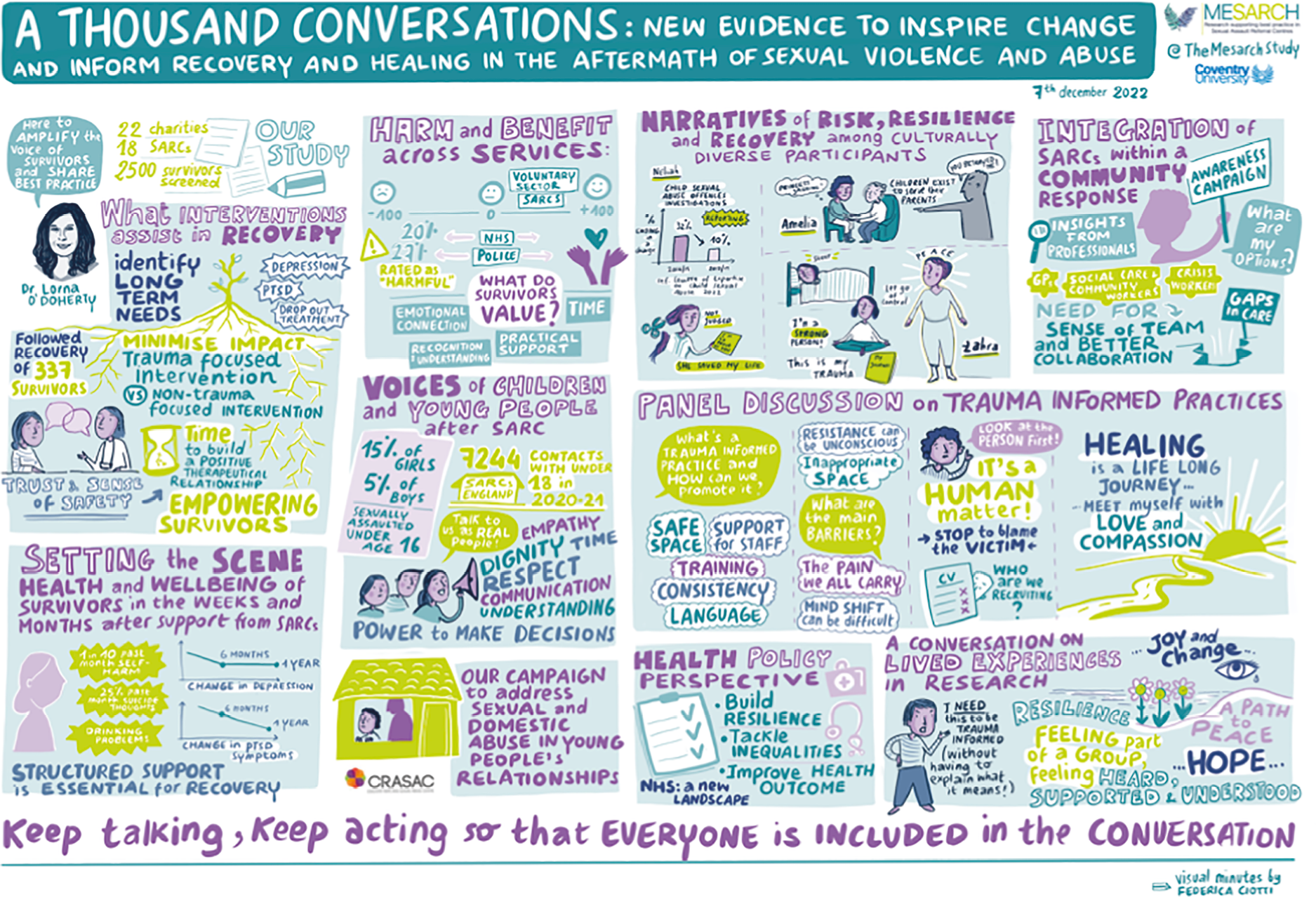

The LEG has been heavily involved in sharing knowledge and insights gained from the research, for example, shaped plain language statements across outputs such as our Cochrane Reviews (see Chapter 3). Other examples include a fully-supported LEG-led production in the form of ‘photovoice’ where members presented photos to convey recovery journeys (https://vimeo.com/547572348/2709483bd8). The end of our project knowledge-sharing event (7 December 2022; see Figure 2) was co-designed and co-delivered by the LEG and researchers (http://mesarch.coventry.ac.uk/whats-our-project-creating/). The LEG also shaped our ‘#whatareyoudoing’ campaign highlighting the problems of sexual and domestic abuse in young people’s relationships39 partly funded by NIHR as part of MESARCH, and raised this work as important at the NHSE survivor forum.

FIGURE 2.

Visual minutes from the MESARCH knowledge-sharing event.

Impact and evaluation of PPI

The overall impact of the LEG/PPI work summarised in Figure 1 on the research has been tremendous and is understood to explain the low incidence of adverse events and known harms arising from the research. This expertise was also part of operational success. There were also direct and unanticipated positive benefits for the LEG members themselves as captured in the testimony of one member (see Appendix 1, Box 43). LEG members also told us that being part of the group has contributed to recovery by enabling safe exposure to triggers. The conversations and interactions (online, by email, in person and in-print) that were part of the everyday work of the project normalised talking about sexual violence and abuse. Members have also commented on how being involved in MESARCH and being heard by MESARCH amplifies individual voices and provides a platform for creating change and being part of influencing better responses to others affected by abuse. PPI also enhanced the research team’s confidence to undertake this work, deepening our understanding in relation to trauma and abuse, and our LEG members’ commitment to the project was hugely motivating for overcoming the challenges encountered during the project. Our work with the PPI group has also inspired future research around understanding long-term physical health outcomes for survivors of sexual violence and abuse, and influencing the implementation of trauma-informed practice across the NHS (considering clinical services beyond mental health); building a toolkit of methods for doing better research in this field; and growing the evidence base on novel interventions for survivors that reflect survivors’ individual needs and preferences.

In an effort to identify any gaps in our PPI provision in MESARCH, we commissioned an independent, survivor-led organisation to evaluate it. 40 A summary of the conclusion reached by Survivors’ Voices is provided in Box 1.

In the MESARCH team approach, we found key features of trauma-informed research: careful attention to creating a safe environment, genuine care for survivors and a commitment to authentic and empowering involvement that amplified the voices of survivors.

Using the evaluation tools of the Survivor Charter and Involvement Ladder, we have gathered clear evidence of trauma-informed practice in the approach of the MESARCH team. This enabled and supported survivors to make a vital contribution to the project, as both participants and co-producers, centering lived experience at the heart of the research. Key strengths were a strong attention to creating a safe environment and demonstrating genuine care for survivor well-being, built on trustworthy relationships. Their commitment to authentic engagement, involving survivors as both participants and co-producers, empowered survivors and researchers. This meant the team could successfully amplify the voices of survivors, bringing the validity and impact of lived experience to trauma, abuse and violence research.

Chapter 3 Evidence synthesis

We conducted two complementary Cochrane Reviews to synthesise the evidence of the effects of psychosocial interventions on mental health and well-being for survivors of sexual violence and abuse. The term ‘psychosocial’ used in this research refers to ‘interpersonal or informational activities, techniques, or strategies that target biological, behavioural, cognitive, emotional, interpersonal, social, or environmental factors with the aim of improving health functioning and well‐being’. 41 This includes the types of interventions that may be offered to survivors by SARCs and by other services in the voluntary sector, the NHS or privately. The first review combined published randomised trials from various parts of the world that examined the effects of interventions designed to support adults in the aftermath of rape, sexual assault or abuse. The second review combined qualitative studies of adult and child survivors of sexual violence and abuse to develop a picture of service users’ (and family members’) experiences of interventions, as well as the perspectives of the professionals who delivered them.

The reviews are referred to as published articles that include detailed descriptions of the methodologies used, 73 studies analysed across both reviews and the findings. 36,42

Our findings underscore the importance of access to psychosocial interventions in the aftermath of sexual violence and abuse as a range of psychosocial interventions were effective at improving the mental health and well-being of survivors in the short term. These include traditional trauma-focused approaches such as those recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance43 [e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and Eye Movement Desensitisation Reprocessing (EMDR)], which showed the strongest effects for mental health; non-trauma-focused approaches; and several emerging areas such as Reconsolidation of Traumatic Memories (RTM), trauma-sensitive or trauma-informed yoga, Lifespan Integration and cognitive training (e.g. neurofeedback). Although survivors said that they often found interventions difficult, they also appreciated that they needed to work through trauma, which, they said, resulted in a wide range of benefits. These included positive effects on their physical health, mood, understanding of trauma, and interpersonal relationships, and enabled them to re-engage with a wide range of valued life domains.

Survivors highlighted a range of features associated with the context in which interventions were delivered that had an impact on how they accessed and experienced interventions. This included organisational features, such as staff turnover, that could influence survivors’ engagement with interventions; the setting or location in which interventions were delivered; and the characteristics of those delivering the interventions. Therefore, listening to survivors and providing appropriate interventions at the right time for individuals can make a significant difference to their health and well-being. These findings provide support for NHSE’s aim to provide lifelong support for survivors of sexual violence and abuse, with SARCs being a vital option as a first point of care. Our Cochrane Reviews have been translated for a range of audiences and are accessible here: www.coventry.ac.uk/research/areas-of-research/centre-for-intelligent-healthcare/mesarch/.

Chapter 4 Process evaluation of sexual assault referral centres

Background

NHS England’s strategic direction for SAAS was launched in 2018 and aimed to advance the support to victims and survivors of sexual violence and abuse across England enabling people to recover, heal and rebuild their lives. 44 SARCs are a vital first point of care within this strategy. Service Specification 30 identifies the core services that should be delivered within SARCs including assessment, FMEs, and health and well-being interventions. 19 Nevertheless, SARCs in England vary considerably in the types of organisations that lead them, the staff members who work within them, and the care and support services that they provide. SARCs are further differentiated based on whom they support with some providing care to adults, some to children and others to survivors of all ages. Within this context, we know very little about how staff experience this work and its variation, although we do know that this work can have an emotional toll. 45 Furthermore, while rates of access to SARCs in England and service users’ characteristics have been reported elsewhere,46 understanding about survivors’ experiences of SARC services has been limited. One small study reported that SARCs were experienced as a safe haven, calming and welcoming, and where survivors felt supported and understood. 47 In light of these gaps, the first aim of this study was to identify key issues and concerns associated with the work of SARCs, their workforce and the use of technologies. SARC service delivery was severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which also witnessed shifts in the type and incidence of sexual violence and abuse. Given that our research coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic period, we were able to examine the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on SARC service delivery and document the innovation that occurred. These findings are reported elsewhere.

Sexual assault referral centres act as an initial point of contact; therefore, it is vital that the care and support provided to survivors of sexual violence and abuse is of the highest possible standard and that there is continuity of care beyond SARCs. SARCs in England sit within a large and complex network of organisations and professionals that reflect the widespread needs of survivors at different stages, receiving referrals from these organisations and professionals, and referring SARC clients to them. While inter-agency and inter-professional collaboration has been explored for some years across professions such as social work,48 knowledge regarding collaboration across professionals in the SAAS context is limited. A small amount of relevant research has been conducted in the USA,49–51 but only one example has been described in a European context,52 and none in England. Furthermore, survivors’ perspectives have been largely absent in this research. 51 Therefore, a second aim of this research was to explore the integration of SARCs in the broader context of a health and community response to sexual violence and abuse, drawing on perspectives of both professional and service user stakeholders.

Methods

Study design overview

The main component of this study was a process evaluation of SARCs. A process evaluation is broadly recognised as a method that seeks to understand the work of an intervention, how that intervention is delivered and its effect, alongside contextual factors that may affect outcomes. 53 In completing this process evaluation, we undertook qualitative investigation of professional and survivor voices regarding SARC service delivery and integration of SARCs within the SAAS pathway. From the mapping of all SARC sites in England, we identified several diverse sites to undertake the qualitative enquiry. Data used to map SARCs were collected between March and July 2019. These data were supplemented with national SARC indicators of performance (SARCIPs) data supplied by NHSE54 and gathered from SARCs between April 2018 and April 2019. Data were collected from professionals and survivors participating in the qualitative study between July 2019 and July 2021. We also drew upon qualitative data gathered with survivors as part of the linked cohort study (see Chapter 5) between September 2019 and May 2022.

Changes to protocol

We planned to use Normalisation Process Theory, an effective approach when exploring a new intervention or service. 55 However, when it came to applying Normalisation Process Theory to our data, the services, staff and integration of SARCs were not newly implemented. Therefore, we sought an alternative theoretical approach to capture the importance of effective integration between different organisations and professionals, and drew upon theory related to inter-professional collaboration.

Theoretical approach

Bronstein’s theory of interdisciplinary collaboration48 has been applied extensively across other fields and in two studies exploring integration within Dutch and United States (US) models of SARC provision. 49,52 Coordination and collaboration have been hypothesised to be linked with the effectiveness of Sexual Assault Responses Teams in the USA. 50 These studies point to the theory’s relevance to capturing interdisciplinary collaboration and integration for SARCs in England. Bronstein defines interdisciplinary collaboration as a process that facilitates the achievement of goals that cannot be achieved by individual professionals. 48 Bronstein’s model comprises five components: interdependence, newly created professional activities, flexibility, collective ownership of goals and reflection on process. Interdependence refers to the dependence between and reliance upon different professionals in working together to achieve their own goals and requirements. Newly created professional activities are collaborative acts, programs or structures that can help achieve more than that if undertaken independently by professionals. Flexibility captures deliberate acts of role blurring in which professionals working together can achieve greater efficiency and effective working. Collective ownership of goals relates to a shared responsibility among professionals to achieve goals with a commitment to client-centred care. Finally, reflection on process relates to professionals acknowledging their collaborative roles and evaluating how to effectively achieve and strengthen these relationships. Bronstein argues that inter-professional collaboration can be affected by several characteristics including professional role (e.g. clear and well-defined roles), structural characteristics (e.g. manageable workloads), personal characteristics (e.g. how collaborators perceive each other) and history of collaboration (e.g. prior experiences of collaboration). Previous research has highlighted challenges to inter-professional collaboration, for example, perceived power imbalances and different professional focus/orientations between staff members;49 these challenges will be explored in the context of this research.

Sampling, recruitment and participants

We mapped SARCs across England using data collected from SARC managers through an online survey (36/48 sites returned data) and SARCIPs data. We produced a data set, which allowed sampling of sites for the qualitative process evaluation and the cohort study (see Chapter 5).

Using this data set, we recruited a stratified random sample of seven SARCs from all 48 sites, with strata defined according to service delivery model (police-led, NHS-led, charity-led or private sector); size (small, medium and large) and level of integration of services (on-site, embedded ISVA service or not).

At each site, we invited a range of professionals based at the SARC to participate in an audio-recorded interview. We also approached professionals external to the SARCs whose organisations were part of inward and onward referral pathways. We recruited directly through the UK Association of Forensic Nurses to ensure representation of Forensic Nurse Examiners (FNEs) within the sample. We also invited survivors who had attended these SARC sites through the staff. We undertook 72 interviews with professionals (see Appendix 2, Table 23). Five interviews were conducted with survivors initially. We subsequently recognised the wealth of qualitative data being gathered as part of our cohort study in reference to accessing care at SARCs (see Chapter 5). The qualitative data from our cohort study provided data from a further 293 survivors who accessed 21 SARCs including the eight SARCs where we undertook the in-depth evaluation of SARC services.

Analysis

Thematic analysis (TA) was the chosen process for analysing the two sources of data: in-depth interviews with survivors and professionals (n = 77) and data arising from asking open-ended questions about care during the baseline cohort study interviews (n = 293). Specifically, Braun and Clarke’s Reflexive TA approach was applied. 56–58 This method adopts a flexible and organic approach to coding and subsequent theme development, and it is considered theoretically independent. Primarily, inductive coding was undertaken, being led by the content of the data, with semantic coding used (the data are considered to represent the explicit meaning of the data). The standard TA method was followed including familiarisation and initial code development, clustering of codes to initial preliminary themes, theme development and subsequent finalising of the thematic themes. 56 Coding was undertaken by four members of the team, and during the initial coding phase, regular meetings were undertaken to inform, develop and refine the coding book. Once all the initial coding was completed, one team member checked all codes for quality purposes and to ensure that the data fitted to the code label. This process also refined codes into preliminary themes. The analysis then focused on key themes that explained the research questions in ensuring that these themes were distinct and closely aligned to the data.

Results

Overall, and as set out in the qualitative data presented in Chapter 5, survivors identified accessing SARCs as a positive approach in their recovery journey. Recovery journeys are rarely linear or uniformly positive, but survivors relayed that their encounters with SARCs (and other specialist services) fulfilled what survivors want from services and professionals in the aftermath of abuse. 59,60 In light of the experiences of professionals as well as those of SARC service users, the following sections explore key issues, concerns and strengths associated with the environment and organisational characteristics of SARCs, examining the ‘work’ they do, the workforce, technologies used, and finally SARC integration within the wider community response to sexual violence and abuse. The sections also pay particular attention to the interdisciplinary collaboration across profession(al)s within SARCs, and between SARCs and other agencies, focusing specifically on the key elements of Bronstein’s model.

What is the work of SARCs including the types of interventions delivered?

Sexual assault referral centres provide a vital early or the first point of care for survivors and providing a frontline response to survivors constitutes the majority of their work. There is a standard care offering at SARCs based on Service Specification 30. 19 In the research, survivors focused on the elements of core services that were salient for them. Crisis support was strongly valued by participants – the emotional support, information and options presented, and the referrals made. ‘[SARC staff] tried their hardest not to cause me any more distress, of course there was distress and it was uncomfortable, but not their fault’ – the FME is an extremely demanding experience, and for one participant, akin to ‘having a post-mortem while you were still alive’. ISVA support, which may be provided directly through SARCs, was also highly valued, particularly in relation to practical support through investigative and criminal justice proceedings and the techniques to support recovery. Counselling, increasingly offered through SARCs, was considered a largely positive experience, although wait-lists to access counselling, and the restrictions on the number of sessions meant that some survivors ‘felt I was getting somewhere and then it has to stop, I didn’t think it was good enough that it stopped’.

Another core function of SARCs is access to other services; SARCs opened a range of referrals for clients. However, drawbacks were ‘I was getting bombarded with a lot of people calling me … I had five or six agencies calling me the day after, my phone didn’t stop ringing’ and the consequence of this as ‘I had to keep going over and over my story’. It was highlighted how survivors find it difficult to navigate the services and suggests the value of SARC and ISVAs working closely to assist this understanding: ‘I think victims and survivors find it really difficult to understand the landscape of what’s going on out there in terms of the case, who’s providing what’. (ISVA service delivery manager)

While service specifications set out the core areas of delivery for SARCs,19 variation arose with different leadership models, commissioning arrangements, geography and the needs of the local community. Participants commonly identified typical journeys through SARC services. They also noted divergence from primary routes. Access needs and how people engaged with the services varied with individuals’ circumstances (e.g. specific or complex needs, location); the time since the trauma occurred (e.g. non-recent abuse or CSA); and external factors such as being on wait-lists for therapeutic care and the status/progression of criminal justice proceedings. The research also documented the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw a step-change in access and service provision and witnessed clear evidence of collaboration within and between the services as commented on by this FNE: ‘you can’t deliver a service like this without being a close-knit team’.

While standard care requirements are set out for SARCs by NHSE, there is much scope for additional work to enhance provision and access. The research documented examples of SARC teams working creatively to ensure that their services could accommodate the range of needs of clients from different communities/locally including those whose access to services had been delayed, non-linear or complicated by different factors. One police officer demonstrated reflection on process in how they worked with their local SARC: ‘I attend the SARC a lot because if there’s been an operational issue, even though it may be north of the county, I will get invited, and then [SARC manager] and I and others will sit down and go, “ok, how can we deal with [this], what can we do going forward to make sure that this doesn’t happen again?”’ Teams developed new initiatives such as in-house emotional support or counselling; acting as a holding contact point while clients awaited access to other SAAS and other forms of care (e.g. community mental health, longer-term counselling); and enabling video interviewing/live link technologies. SARC staff expressed a commitment to clients, ‘we’re here, checking in, or there’s always someone here twenty-four seven … people do call us and say, “I’m suicidal” or ‘I don’t know where to turn to, I haven’t heard from this person”’. They wanted to ensure that their services could support people at any point after sexual violence and abuse, and they saw a role for being a point of contact for survivors of CSA and informing survivors about options for reporting and referrals to ISVA and third-sector support. SARCs expressed that efforts should be made to address public perception that SARC support means police involvement. They demonstrated how self-referral to services was fostered and also noted the ongoing difficulties for self-referring survivors in terms of physically reaching their services in some areas of the country (by contrast, those who report to the police are usually transported to SARCs by police officers). SARC staff operated in line with trauma-informed care; professionals were keen to see that choice was exercised in key areas such as reporting mechanisms as noted by this crisis worker: ‘I think it’s really important to allow people that opportunity to validate what’s happened to them … to try and re-balance, regain some power in a situation where they’ve felt powerless and to have that choice’. Staff highlighted the longer-term storage of forensic data and anonymous submissions to police intelligence as an underutilised service.

In terms of people’s access, there was widespread endorsement of anonymous locations and for sites where survivors can provide alternative reasons for being there (e.g. hospital site). The staff members were aware that co-location with police forces was challenging for survivors. SARC buildings ranged from purpose-built to adapted, and survivor-centred design features were strongly supported. One such example was entering and exiting the space through alternative doors to signal the beginning and end of the SARC journey (at services where clients generally do not return for other care and support). Staff reported a range of issues with SARC estates from lack of physical and confidential spaces for client support and administrative work and shared entrance/common corridors. Forensic rooms were perceived as overly clinical and suggestions were made by professional and survivor participants to address this through features such as wall/ceiling decorations. The staff members reported efforts to ensure that the SARC was welcoming CYP, that furniture was comfortable and that coverings provided to survivors were appropriate (e.g. participants cited instances of gowns being transparent). SARC teams expressed concerns about reaching clients in remote areas. The shift to greater use of digital services and remote care in response to the COVID-19 pandemic had the effect of mitigating some of the geographical barriers affecting survivors’ access to SARCs and ISVA care. Many survivors also identified a preference for remote contact with providers, feeling ‘more relaxed’ and that ‘the distance of a telephone call is better for me’ when talking about difficult topics.

Who is the SARC workforce?

Across service delivery models, staff roles generally seen at SARCs were SARC manager/deputy and an administrative member/team, crisis workers and FMEs/FNEs. Flexibility in roles at SARCs was common ‘my role covers a lot of areas’, for example, managers and administrators trained as crisis workers. Depending on the degree of integration at the site, ISVAs enacted their roles in flexible ways, as core staff at a SARC; employed by the voluntary sector but co-located at a SARC; with largely visiting/remote role; or based physically at a voluntary sector organisation. Thus, many models could be drawn upon to suit the landscape, for example, some sexual health services have ISVAs. NHS SARCs tended to employ clinical staff directly, whereas private sector SARCs made greater use of staff banks. With SARCs increasingly offering short-term psychosocial interventions, counsellors were also integrated into the staff of SARCs, frequently on a part-time/co-located basis. Finally, several roles were noted to lend themselves to specialisation, with some sites training crisis workers and ISVAs to specialise in the care of particular groups, for example, CYP, individuals with learning disabilities. Within the scope of the current research, we focus on two prominent workforce issues: (1) the nature of the crisis worker’s role and related training and (2) challenges to effective interdisciplinary SARC teams.

The crisis worker’s main purpose is to support clients of the service. However, the role involves a diverse range of task and balancing the sensitivities of cases and needs and expectations of vulnerable clients with the constraints of what can be provided:

One morning I might be helping with a forensic medical, and in the afternoon we might be doing call-ups for email enquiries, and reaching out to people that have accessed that way. I think it’s an incredibly difficult role to learn, if I’m honest, because it’s so varied and wide. There are some repetitions within it that are very quick and easy [to learn] … but there’s other stuff that makes it much trickier, like around geographical location. So understanding what services are purchased in relation to paediatric FMEs in a geographical location, which means that if somebody is ringing from [name of city] and they [want to] come in, do we see them or not? Or there’s understanding and learning what the service offers outside of the area as well as in the area.

Crisis worker

Without prior experience of the region, crisis workers’ practice might suffer. Training varied from across sites with most involving formal learning components, for eample, safeguarding, and a period of shadowing: ‘my first client interaction that I shadowed, it was kind of a steep learning curve because it’s not like anything else’ (crisis worker).

Shadowing, and training more broadly, was noted to be variable and rely on standards set by providers. The crisis worker’s role has not attracted much attention within the research literature beyond the toll it places on individuals,45 an issue also recognised in our research. While the role was consistently valued by service users for whom the crisis worker is the first SARC professional they encounter, ‘I found it helpful that I received emotional support from [the crisis worker] when I got there because it was scary and going with the police’ (survivor), professional participants viewed the role as lacking incentivisation (e.g. opportunities for progression).

‘When a client or when a victim is at the SARC and you’ve got [private company who run forensic services], and you’ve got the police, and you’ve got a crisis worker, surely all three agencies should be working together because we’re supporting that one person’. (SARC manager) – meeting the client’s needs was a shared goal for staff at SARCs and there was frequent reference to ‘we are quite a tight knit group’ (ISVA). However, in terms of the challenges to effective interdisciplinary SARC teamsthe nature of staff contracts was a common workforce concern (subcontracting of SARC roles, on-call/zero hours contracts, staff employed by different providers). A crisis worker participant contrasted the scenario of where FNEs are employed directly by SARC and the experience of working with FNEs/FMEs contracted on an on-call basis: ‘the other doctors, you only see them every now and then, so you don’t really build up the same rapport with them, and obviously they all work slightly different … try and suggest the way that you would do it normally, just to try and make it easier and quicker, because obviously we want to put the victims first, so we want to make it easier for them … I do think that it’s so much better when you work together’. Implicit here is that placing survivors ‘first’ requires effective teams and staff who are familiar with each other and the setting. While all participants agreed that consistency in staffing was important for team-working and reducing isolation, flexible contracting was desirable for some professionals balancing other livelihoods and commitments. SARC managers did have particular concerns about crisis workers in this regard: ‘[crisis workers] do an amazing job but I think they do just feel a little bit disconnected from the service’.

Despite the workforce concerns that were voiced across the staff members and SARCs included in the study, we found very high levels of intra-SARC interdependence, particularly among crisis workers and FNEs. There was strong recognition of the importance of clear communication and inter-professional respect, supporting each other to reduce the impact of their work, and a commitment to providing an integrated service to the client. Simple examples such as gathering information from their clients together and sharing information between professionals as appropriate benefited clients in not having to repeat information or re-tell about their experiences and evidenced newly created professional activities. Collective ownership of goals in pursuit of client-centred care represents a key aspect of effective interdisciplinary collaboration. 48 Reflecting the impact of this care, one survivor commented: ‘I felt safe with the doctor, I felt safe with [crisis worker name] who was in the room. I didn’t feel that anything bad was gonna happen’.

What are the technologies that enable SARCs to get work done?

This section focuses on two key issues: (1) use of remote/digital services in providing care and (2) challenges emerging in information sharing across the services. The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that SARCs used digital technologies to facilitate service delivery, including triaging of clients before they attended the SARC. Staff reported that they carefully determined the appropriateness of remote care for different clients. Some benefits to triaging were realised in that clients spent less time at the SARC once they arrived. Survivors reported both positive and negative responses to the increased use of digital technologies, highlighting the need for developing remote services as part of a suite of options and tools. The second key issue related to information sharing. Different IT systems for different organisations meant that SARC staff members spent considerable time making manual referrals through online systems or secure email systems, which added considerably to workload:

I referred a lady to adult social services because I felt her needs would be met with [social care provider]. But I couldn’t go direct with [social care provider]; I had to go through adult social services, and they have to make the referral. And I was told on that phone call that “somebody would be contacting you.” And today, I’ve not had a contact, and it’s been about two weeks, so that’s something that I am going to have to chase up. So that is quite time consuming.

ISVA

This work, described by one SARC staff member as their ‘nagging work’, was frequently highlighted with regard to sharing information with partner organisations. Survivors experienced interruptions or delays in access to onward care:

I haven’t received any care, I got told I’d have sexual health screening, that hasn’t been sorted or anything, I had to go to the doctor’s about getting an examination done, they were supposed to help sort that out, but they didn’t.

Survivor

To what extent are SARCs embedded within the overall response to the needs of survivors of sexual violence and abuse?

The most important external partnerships for SARCs included the police, sexual health, ISVAs, third sector and social care. For example, our data suggested well-established and collaborative relationships between SARC staff and police officers. Single point-of-contact officers in police forces worked directly with SARC managers to develop pathways for survivors and training by SARCs to ensure police officers understood local provision and access. Collaboration with third-sector organisations was more challenged: ‘with any multi-agency working, we all seem to work parallel with each other quite often and not come together at the top to deliver’ (crisis worker). There was a strong sense that collaboration was driven by individual senior members of staff at the SARC and/or the partner organisation and involved local implementation. Positive relationships at senior levels trickled down and fostered positive cross-working, seen to ultimately benefit survivors. Examples of cross-working included co-delivery of training and sharing of resources and space. Professionals expressed a wish for change. For some, implementing a more consistent SARC model was the answer, with more services under ‘one-roof’ such as integrated ISVA and sexual health services. Others recognised existing high-quality provision in these areas within their communities and that pathways and relationships should be strengthened. Another example was Achieving Best Evidence interviews, with some believing these should be conducted consistently at SARCs while others saw SARCs as a place solely for acute crisis care and considered that survivors may not wish to return to these locations. Participants pointed out that SARCs have all evolved in different ways in the communities they serve and, in expressing how the sector needs to develop in the future, emphasised the need for simplification and better approaches to supporting clients with complex needs.

The role of SARCs is vital, but there was real concern about the invisibility of SARC services. Survivors relied on the police and others to learn about SARCs, ‘I wouldn’t have known about them if it hadn’t been for the detective’ (survivor). In response to the lack of public awareness about SARCs, there were several examples of teams initiating outreach services in their communities, often targeting groups seen to experience even greater barriers to receiving help (e.g. men, minority communities). Gaps in knowledge about service provision by SARC extended to important professional groups: ‘there are so many more people that need to know about the SARC’ (crisis worker). GPs were identified as a professional group lacking awareness of SARC services, with referrals from GPs being infrequent. This SARC manager talked about the difficulties of engaging with GPs:

Probably in defence of GPs, they have just got so much demands on their time and they don’t have free time, so we’ve put on training events especially for GPs. We do the open days, we try and target GPs … some of them are just not aware of what we’re doing, they’re really out of date, the information that they are giving clients.

From the perspective of a survivor: ‘GPs have got such little understanding …. They don’t take it in. And then they’re like, we don’t know who you can speak to … they just don’t know what the right support is’.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This work highlights the excellence in care and support being provided within SARCs, as such, the value of SARCs in the provision of care and support to survivors is supported. The contribution of SARC provision to the care pathway, extends beyond provision of forensic services, importantly fulfilling an early role in coordinating care for survivors. However, this research also documents the challenges that SARCs, and the SAAS sector as a whole, experience in addressing survivors’ needs. Drawing on 77 interviews (72 professionals, 5 survivors) and 293 survivor responses, the novelty of this qualitative enquiry is evident in the breadth of participants spanning both inward and onward referral routes, as well as SARC staff themselves, along with the voices of survivors in sharing about the care and support they received.

In addressing the first aim of this work, findings have highlighted key issues and concerns associated with the work of SARCs, their workforce and the use of technologies. In doing so, this research documents the high level of dedication of SARC staff and captures their commitment to client-centred care and an ethos consistent with trauma-competent practice. 60 This commitment of professionals at SARC was further evidenced in their response to the COVID-19 pandemic, where they effectively utilised technology to ensure that care could be continued while enabling greater flexibility and choice for survivors. Appreciating several distinct roles are involved in producing the range of care and options for survivors, our findings emphasised crisis workers as vital to a survivor’s care journey at SARC. Attention to the crisis worker role is fundamental in further developing the workforce of SARCs.

We found evidence of effective interdisciplinary collaboration spanning across Bronstein’s five components of interdependence, newly created professional activities, flexibility, collective ownership of goals and reflection on process both within SARCs and across the sector. Despite being hampered by the complexity of how different services are contracted, SARC staff worked hard to achieve cohesive teams and ensure that an excellent service is provided for their clients. We saw many examples of work that reflected good quality inter-professional collaboration, specifically inter dependence and collective ownership of goals in delivering client-centred care. Matthew and Hulton called for research to identify whether there is a link between effective SARC collaborative practice and survivors’ experiences of SARC services. 51 This research answers that call with our findings showing high levels of effective inter professional collaboration found between SARC staff (specifically between crisis workers and FMEs/FNEs), and subsequent positive endorsement of SARCs by survivors.

However, there were factors that can hamper inter-professional working within SARC settings. The ways in which professional roles at SARC are commissioned can lead to short-term teams and unstable working hours of staff, whereby collective ownership of goals in pursuit of client-centred care is difficult to achieve. In comparison, consistent teams enabled strong inter-professional working and evidenced best practice. This generated cultures of transparency and respect, more compassionate support and offered a high-quality experience of care for survivors.

Across the sector, and moving beyond the SARC setting, the second aim of the research was to explore the integration of SARCs in the broader context of a health and community response to sexual violence and abuse. In doing so, our research gave a positive picture of interdisciplinary collaboration across the wider sector across criminal justice, health and third-sector organisations. Professionals across these sectors clearly engaged in collective ownership of goals48 in recognising the importance of effective, and cohesive care and support for survivors. This runs counter to US research where research noted cross-system coordination being non-existent or lacking consistency, with subsequent challenges to the effectiveness of SARC provision and integration. 61 However, barriers remain, primarily in the form of inefficient communication systems for sharing information. Effective information sharing systems were highlighted as being critical to enabling strong inter-professional working and importantly contributed to efficient working practices, reducing the workload burden of SARC staff.

However, this study has demonstrated challenges to optimising the access to and fully realising the benefits of SARC services, specifically relating to the invisibility of SARCs. SARCs need to be more apparent as a care option for those in crisis, particularly if the person experienced rape, sexual assault or abuse recently. This includes wider community awareness (e.g. families, workplaces, friends of survivors) given patterns of disclosure in personal/social networks. 62 It is paramount that public awareness of SARCs is prioritised, for example, through investment in public awareness campaigns. This is particularly important for groups of survivors who are underrepresented at SARCs and experience barriers to accessing them. NHSE made efforts to address this problem with a campaign in 2022 targeting specific groups including black and Asian women, men, and survivors from lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and/or queer (LGBTQ+) communities with a focus on youth across these groups. A broader campaign was also run in South-East England targeting all ages.

Strengths and limitations

The study’s originality resides in the breadth of the experiences brought to bear on questions about the role and effectiveness of SARC services, with input from 35 SARC professionals and 37 stakeholders outside of SARCs as well as the voices of 293 survivors who have accessed 21 SARCs in England. While prior work49–52 has explored aspects of the work captured, this study benefited from the large-scale nature of data collection which allowed triangulation of experiences of multiple informants. There were important gaps in representing those inside SARCs (medical examiners). The study also lacked GPs and social workers, two professional groups that are integral to early intervention in sexual violence and abuse.

Implications for health care

Enhancing the visibility of SARCs among professionals

The findings highlight the need for awareness-raising work to be continued and further developed, in reaching survivors across all parts of England. However, gaps in awareness of SARCs, specifically highlighted in GPs, critically need to be addressed. For example, current heavy GP workloads may mean that more traditional methods of awareness raising in professional groups at a local level will not be effective. Instead, more thought should be given to developing collaborative relationships at higher levels (e.g. Integrated Care Boards, British Medical Association, General Medical Council, Royal College of General Practitioners), with a clear pathway to facilitating GPs and SARCs to develop local collaborative relationships. In summary, survivors need to be able to make informed and empowered choices about their crisis care and thereafter. Professionals being able to signpost survivors to SARCs provides survivors the option to benefit from specialist knowledge and referral pathways, at minimum. Our findings also suggested that the physical visibility of SARCs needs further attention, for example, Walker et al. 47 recognised a need to balance accessibility and discretion in locating SARCs.

Valuing and developing collaboration

In other words, strong collaborative relationships between SARC staff and other agencies translated into high-quality care and support for survivors. As highlighted in the National Service Specification, SARCs are a mainstream provision, linked to other care pathways and must achieve strong partnerships across health and social care, the specialist sexual violence and abuse services in the voluntary sector and the CJS. However, the effectiveness of this collaboration and partnership was affected by two issues. Firstly, the nature of relationships between SARCs and their partner organisations frequently relied on individual relationship building. Bronstein highlights personal characteristics as a factor that can strengthen inter-professional collaboration, where professionals who view each other with trust, respect, understanding and engage in informal communication can engage in much more successful collaborations. 48 We interviewed many professionals who exemplified this good practice, in the way in which they worked with other individuals. This translated into effective and efficient working that assisted over-burdened service delivery. However, the sustainability of these benefits is threatened by staff changes. Decision-makers may want to consider how relationships between agencies can be developed sustainably.

Secondly, inefficient information sharing substantially increased the workloads of professionals. There is a need for significant financial investment which simplifies information sharing. uncovered a bestWhile it is unlikely that a simple solution exists, decision-makers need to consider how IT interfaces between organisations could be facilitated and also promote reflection on/reviews of referral pathway processes that may be unnecessarily complex. This is particularly key given that it has an impacton survivors when their care is disrupted, delayed or stopped due to issues with information sharing.

The commissioning process for SARC staff and the contracting of SARC services (and services in the wider sector) did not always support staff to collaborate effectively. We consider that a secure workforce should be an aim for commissioners in this area. Our work has not uncovered a best practice model to achieve this (e.g. one SARC model of staffing that should be promoted), and we also recognise that commissioning processes and local existing services means that it is not practical to recommend wholesale change of commissioning processes. However, at a local level, two key aims should be focused upon. The first is that commissioning should be undertaken more collaboratively across all relevant sectors (e.g. public health, criminal justice, local government) so that there is more coherence to the way in which services are contracted across local regions. Secondly, commissioners and integrated care boards should review these structures, and specifically, the processes between organisations with a view to simplification and to reduce barriers that aggravate workloads.

Recommendations for research

Given the gaps in including informants from social work and general practice, future research could examine the specific challenges these professional groups perceive in participating in a community response to sexual violence and abuse. Furthermore, while this research has identified excellent practice in relation to collaboration, continued research attention is needed to evaluate these practices to ensure that this captures the complexity of how SARC services are delivered both nationally and internationally. Overall, we hope to have highlighted the dedication and creativity of staff delivering client-centred care and support in the SAAS sector, which was reflected in survivors’ experiences of high standards of care across the sector.

Chapter 5 Health and well-being of survivors after accessing sexual assault referral centres

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from O’Doherty et al. 63 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

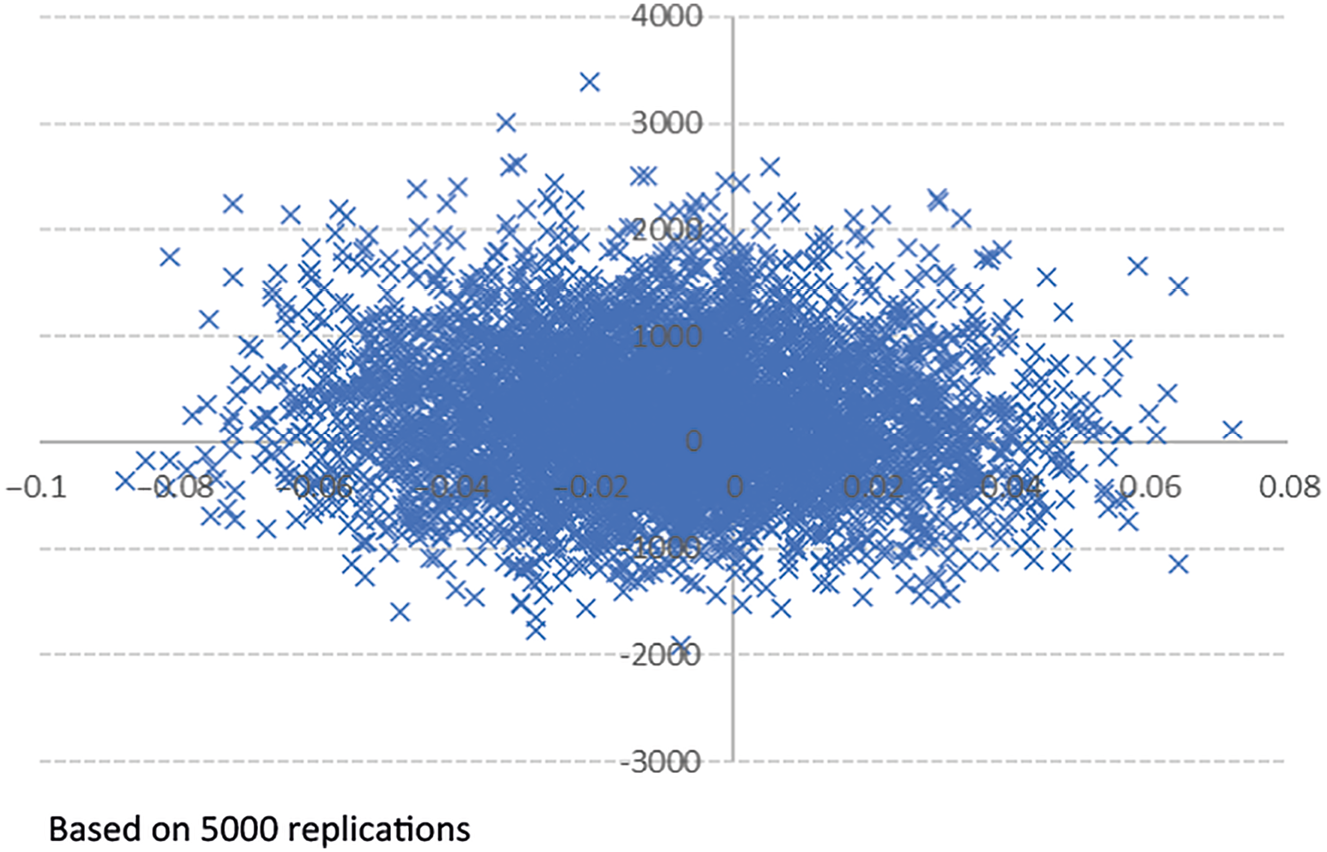

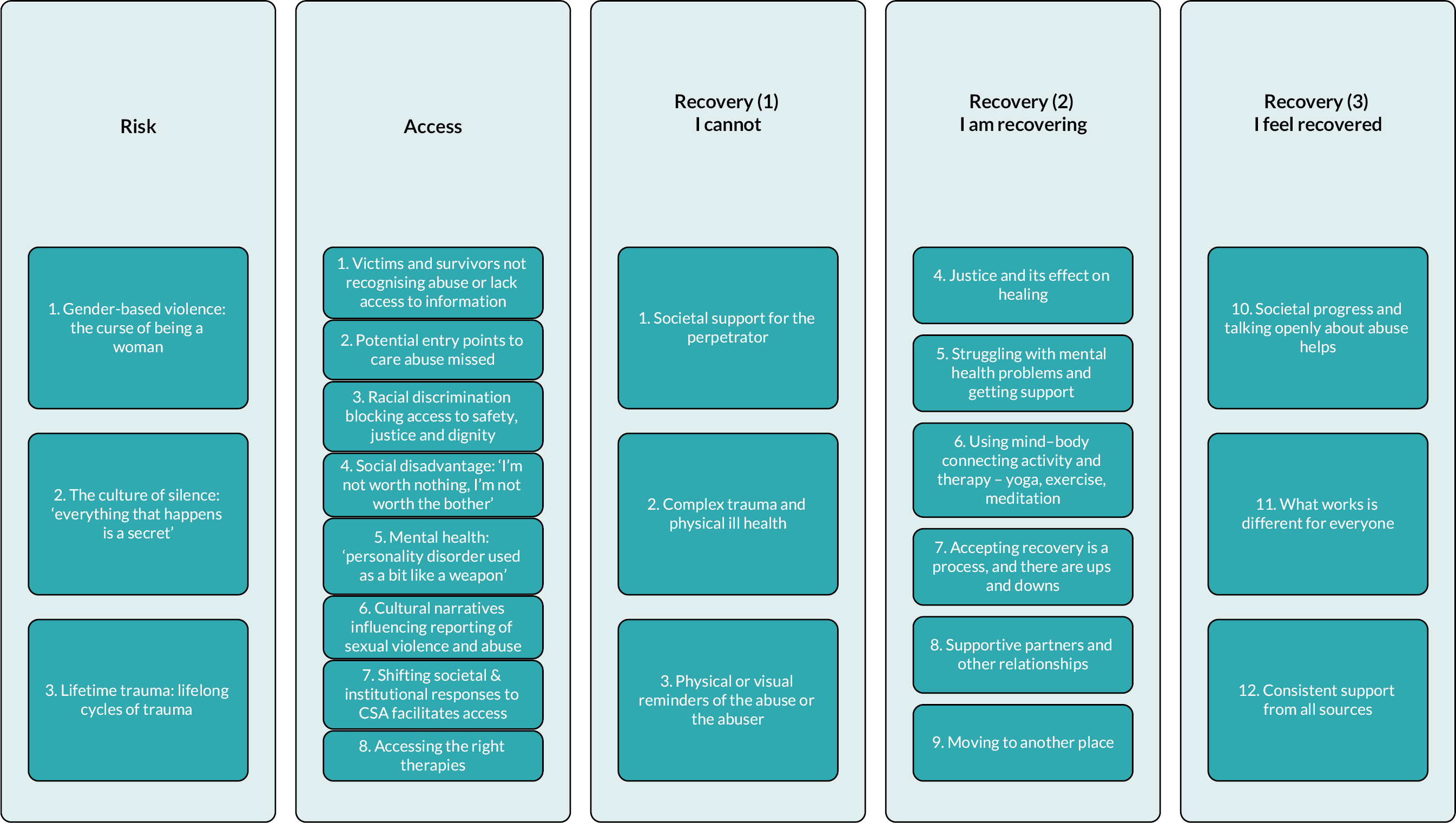

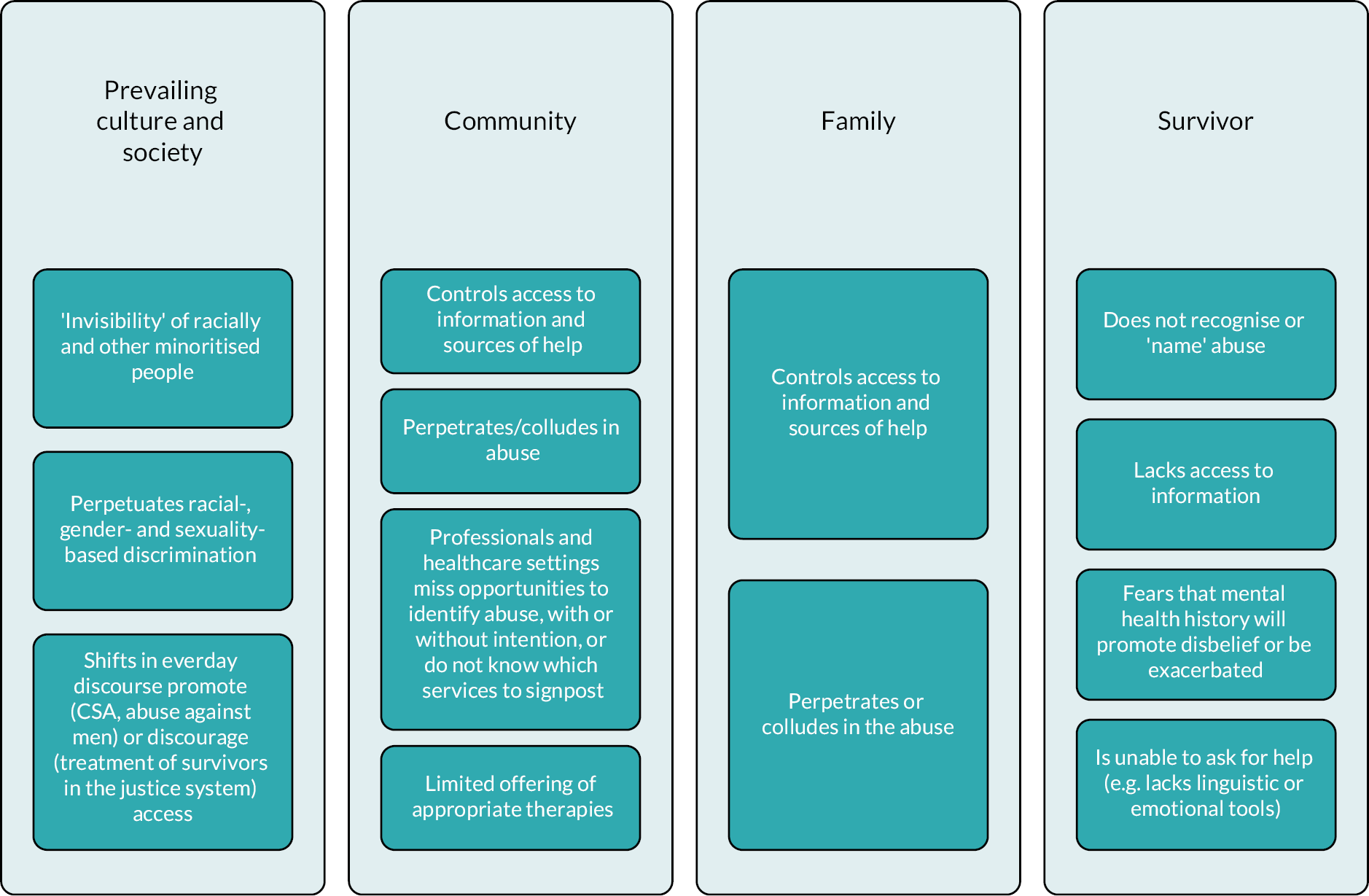

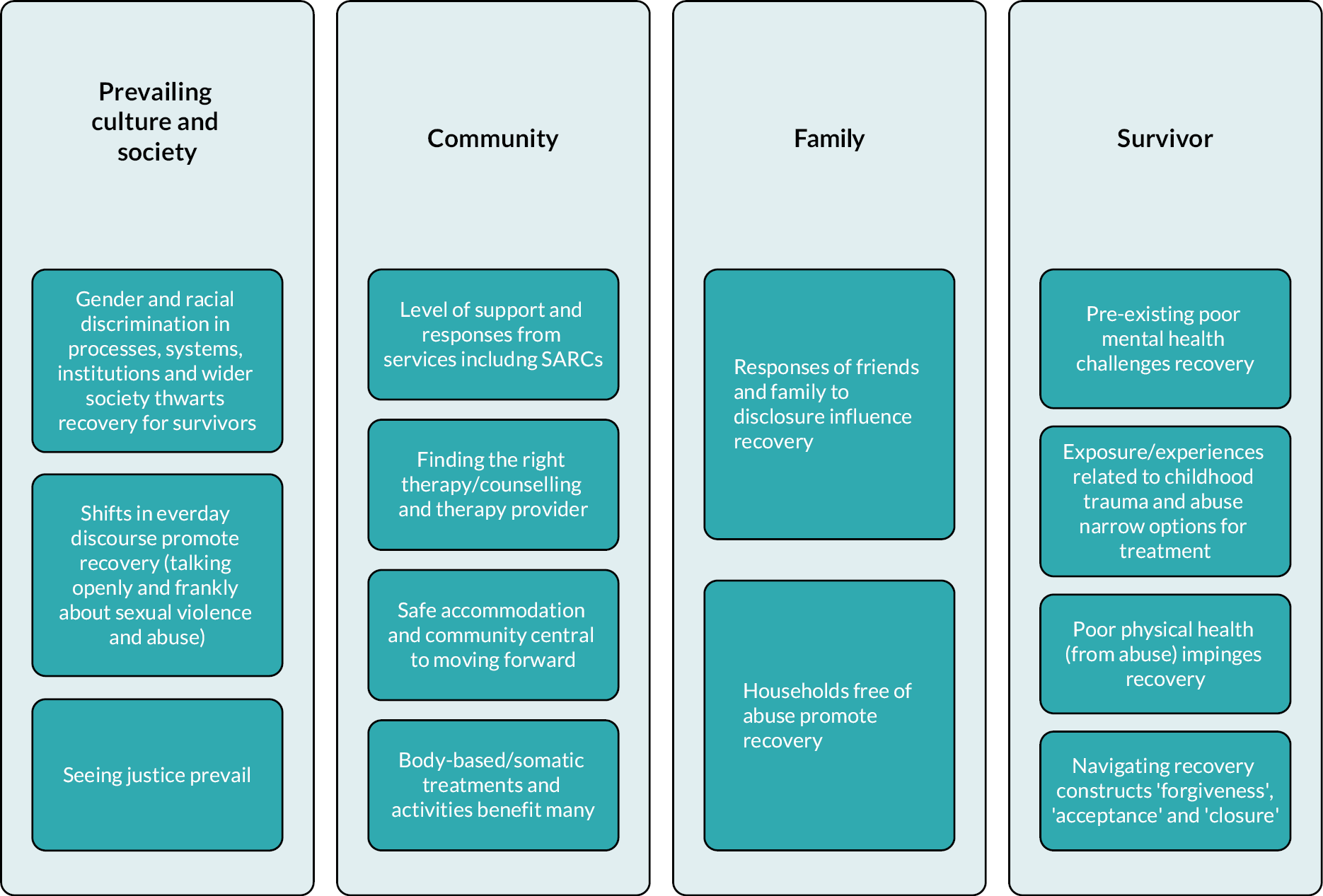

Background