Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR128349. The contractual start date was in September 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in February 2023 and was accepted for publication in September 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Allen et al. This work was produced by Allen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Allen et al.

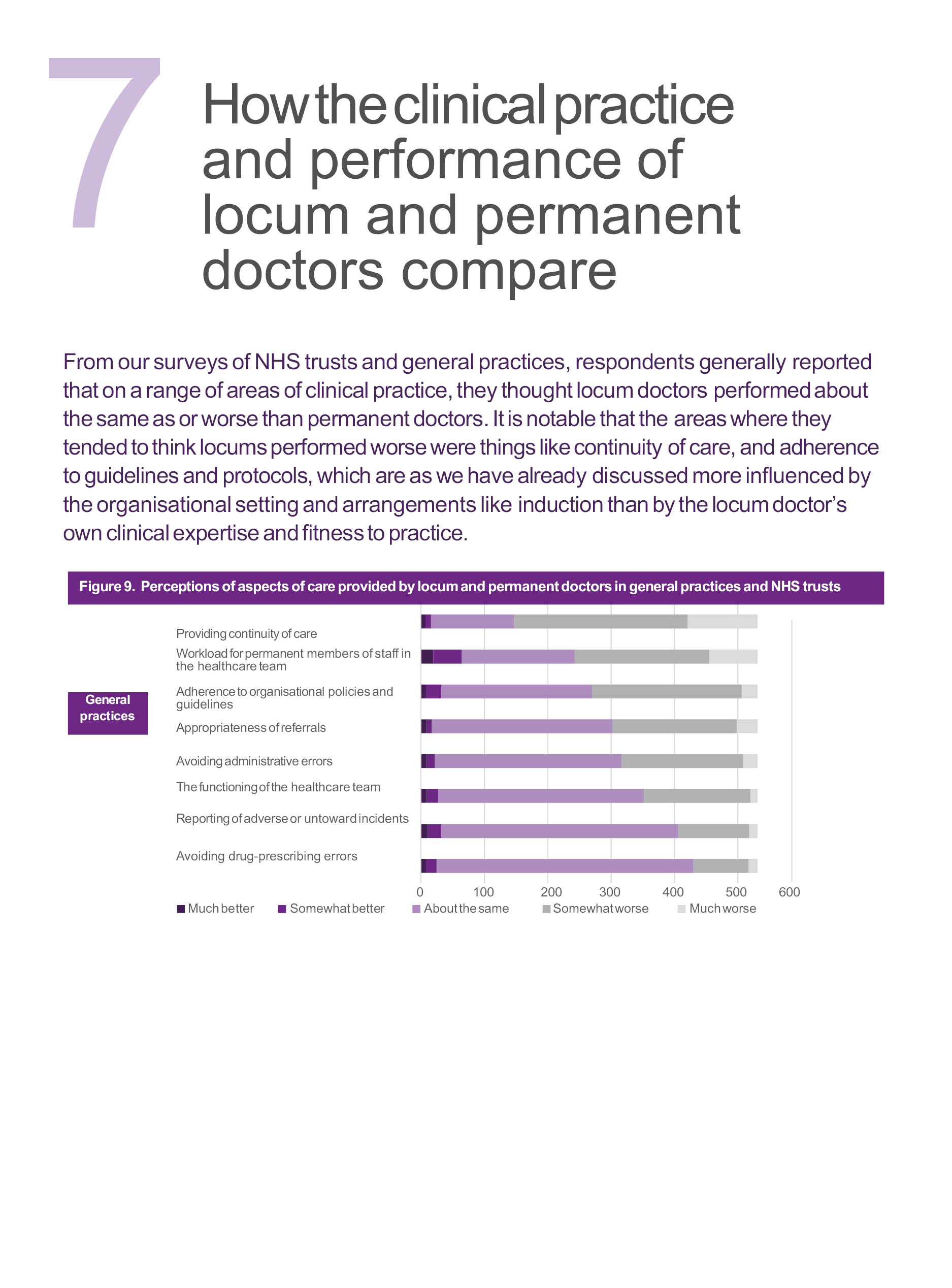

Chapter 1 Background

The overall aim of this research on temporary doctors (generally termed locums) was to provide evidence on the extent, quality and safety of medical locum practice and the implications of medical locum working for health service organisation and delivery in primary and secondary care in the English NHS.

The use of locum doctors in the NHS is widely believed to have increased, and there have been widespread and sustained concerns among policy-makers, healthcare providers, professional associations and professional regulators about the quality/safety, cost and effective use of locum doctors. There was little prior research on locum practice/performance or working arrangements to confirm those concerns or to inform the development of working arrangements for locums which would assure safety and the quality of care.

Locum doctors in the National Health Service in England

The numbers of doctors working as locums in the NHS in England are thought to have grown substantially over the last decade, although there has been surprisingly little empirical data published on the NHS medical workforce to substantiate this trend. Nevertheless, between 2009 and 2015, the use of locums in NHS hospitals was reported to have almost doubled1 and between 2015 and 2019 the number of locums working in primary care was reported to have increased by 250%. 2 In 2018, 8810 doctors were registered with the General Medical Council (GMC) as working primarily as a locum, representing 3.6% of all registered doctors, though it is believed that many other doctors undertake some locum work alongside more conventional permanent employment. 3

Locum doctors are essential for maintaining continuity of service and providing flexibility in service capacity and provision. Healthcare organisations use them to cover gaps in rotas due to unplanned absence or recruitment and retention problems, and also to fill service gaps in underserved or shortage specialties and areas. However, rising locum numbers and particularly the associated increase in cost have led to a growing concern among policy-makers, employers and professional associations about locum use. 4–6 Medical agency staff were estimated to have cost the NHS £1.1 billion in 2015–6,7 and a locum pay cap was introduced in 2015 to curb expenditure. 8

Before undertaking this research, we had already undertaken an international review of the empirical and ‘grey’ literature on locum doctors and the quality and safety of patient care,9 in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, including a comparative analysis of the use of locums in five countries. Our analyses showed that locums were regarded as necessary, as they allow healthcare organisations to maintain adequate staffing levels and flexibility, but also potentially problematic, in that their use may have adverse effects on continuity of care, patient safety, team functioning and costs. This literature also suggested that there was often a lack of robust systems for managing/overseeing locum doctors including inadequate pre-employment checks and induction, unclear line management structures, poor supervision and reporting of performance, and a risk that locums with performance problems move from organisation to organisation.

National Health Service Employers, NHS England and NHS Improvement have all produced guidance on locum working and employment for NHS organisations, locum agencies and locums themselves. 10–12 However, evidence suggests that some basic requirements (such as adequate induction and familiarisation with organisational systems and procedures) are often lacking, communication, especially about locum performance between organisations and locum agencies, is poor, and locum doctors often are not included in or given access to systems for clinical governance and professional development. 13–15

Some insights into these issues arose from the introduction of medical revalidation in the UK from 2012 onwards. Revalidation requires all doctors to demonstrate that they are up to date and fit to practise through participating in regular, annual appraisals and securing a 5-yearly revalidation recommendation to the GMC from a senior doctor in their employing organisation [known as a responsible officer (RO)]. Research on the implementation of revalidation highlighted the lack of robust arrangements for clinical governance for locum doctors. 14 Locums had difficulties in arranging annual appraisals and collecting the portfolio of supporting information about their practice that was required for revalidation [e.g. patient and colleague feedback, details of adverse events and complaints/compliments, records of continuing professional development (CPD) etc.]. As a result, their rates of deferral were higher than for any other group of doctors apart from trainees. 16 A review commissioned by the GMC highlighted a number of concerns and recommended that the GMC and UK health departments should reform the arrangements for overseeing locum doctors. 16

Theoretical context

Internationally, there has been an increasing shift towards non-standard forms of work such as temporary work17 and more people have ‘portfolio’ careers which involve them working for shorter periods or concurrently across different organisations, often without a conventional employment relationship. 2

This research is grounded in three main existing bodies of literature/theory: that related to temporary workers in organisations and the causes/consequences of precarious employment;18–20 the wider literature on the sociology of the medical profession and particularly theories concerned with restratification and intraprofessional hierarchy and the nature and construction of professional identity;21–23 and theories concerned with social identity and intergroup relations, group identity and behaviours. 24,25 The peripatetic nature of locum working may mean that locums practise on the periphery of healthcare organisations and of the profession, and may consequently have a weaker connection to organisational and professional norms and values. This raises questions about how locum doctors’ professional autonomy and identity are constructed and legitimised relationally, how group identities and intergroup relationships are constructed and enacted and the nature of intraprofessional group relationships and behaviours.

Our earlier qualitative research on the experiences of and attitudes towards locum doctors, involving interviews with locum doctors, locum agency staff and representatives of healthcare organisations who use locums,15 showed that locums were often perceived to be inferior to permanently employed doctors in terms of quality, competency and safety. Despite their relatively high occupational status as medical professionals, locum doctors experienced many of the difficulties seen in research on temporary workers in other sectors, such as marginalisation, stigmatisation and limited access to opportunities for training and development. Our findings suggested that the treatment and use of locums could have important potential negative implications for team functioning and patient safety.

The quality and safety of locum doctors

Some high-profile examples of locum failures in care over recent years have contributed to widespread concerns about the quality and safety of locum doctors. 26–29 Locum doctors are often perceived negatively by patients,4 other healthcare professionals5 and NHS leaders. 6 They are often regarded as less professional30 or as untrustworthy ‘outsiders’ who lack commitment and have poor intentions towards the organisation. 31,32

However, empirical evidence that locum doctors provide care which is of a lower quality or less safe than permanent doctors is very sparse. 9 But we do know that locum doctors are more likely to be the subject of complaints, more likely to have those complaints subsequently investigated and more likely to be subject to sanctions by the GMC. 33

Locum doctors may present a greater risk to quality and safety because they often work in unfamiliar teams and settings, and are less likely to receive proper oversight and necessary support from colleagues and employing organisations. 33 The presence of locums in the work environment has been described as an ‘error-producing condition’. 34 On the other hand, the shift towards locum working may represent a wider societal change in attitudes to careers and work–life balance and may provide employers with greater flexibility in staffing and greater externality of perspectives from locums who work across multiple organisations, while it may give locums reduced work pressures/risk of burnout, increased autonomy and new career opportunities/flexibility.

Our recent review found only eight empirical studies comparing locum and permanent doctor practice and performance (three of which were from the UK), generally with small sample sizes and weak methodologies. The most substantial study we identified was from the USA and compared 30-day mortality, costs of care, length of stay and 30-day re-admissions for a random sample of 1,818,873 Medicare patients treated by locums or permanent physicians between 2009 and 2014. There were no significant differences in 30-day mortality rates between patients treated by locums compared with permanent doctors. However, cost of care and length of stay were significantly higher when patients were treated by locums. Furthermore, in subgroup analyses, significantly higher mortality was associated with treatment by locums when patients were admitted to hospitals that used locums infrequently, perhaps due to hospitals being unfamiliar with how to support locums. Only locum doctors who provided 60 days or more of care were included in the analysis, meaning that shorter-term locums, who might have had less opportunity to become familiar with the organisation, may have been excluded. 35 Overall, we concluded that there is limited empirical evidence to support the many commonly held assumptions about the quality and safety of locum working.

Conceptual framework

Our recent international review of the literature on locum working9 identified eight key factors through which locum working may affect the quality and safety of patient care and which may also provide the basis for mechanisms or interventions designed to improve the quality and safety of locum working. These factors are summarised in Table 1, and we have used this framework to structure and guide our research and analysis.

| Theme | Theme description |

|---|---|

| Governance and patient safety | Locums are on the fringes of governance. Gaps in the oversight of locums continue to be a patient safety risk for example background checks. The short-term nature of locum work means that locums are less likely to take part in clinical governance activities, such as audits and CPD. |

| Policies, procedures and continuity of care | Locums are less likely to be aware of contextual issues and local policies and procedures that are relevant to providing safe and effective care, especially if they do not receive adequate induction and briefing when they take up a locum role in a new/unfamiliar organisation. Locums are not prepared for practice in the same way as permanent staff – for example, inductions are often poor or absent, meaning locums are unable to carry out their duties safely and efficiently. Other risks include not knowing how to escalate concerns, and being placed in challenging environments where staffing is an issue. Procedures may be less likely to be carried out when a locum is on duty. The use of locums presents a patient safety issue and may have a negative impact on continuity of care. |

| Impact on the healthcare team – scope of practice | Locums (particularly short-term locums) can place burden on other members of the healthcare team, such as nurses and junior doctors, who could be expected to perform outside of their scope of practice to compensate for a locum’s lack of contextual/local knowledge/competencies. |

| Impact on the healthcare team – workload | Locum working can increase workload for other members of the healthcare team, for example, extra support for the locum who is unlikely to be familiar with policies and protocols and patients returning to see their regular doctor. |

| Information exchange – patients | The quality and quantity of patient information may be reduced when locums are employed, as locums are less likely to be familiar with the patient group and how to report and hand over information about patients to other healthcare professionals. |

| Information exchange – locum practice | The quality and quantity of information exchange about locum doctor practice are poor, meaning that potentially relevant information about locum practice may not be shared with their regulator, employing agency or organisation where they are employed. |

| Professional isolation and peer support | Locums may become professionally isolated and may be less likely to establish/maintain their professional networks and to have good informal networks of peers to turn to for advice, support or social interaction. |

| Professional motivation and commitment | Locums’ moral purpose and vocational commitment are often called into question, and it is suggested that they may be more motivated by financial rewards/incentives than other doctors, and less committed to medicine as a vocation. |

Research aim and research questions

The overall aim of our research was to provide evidence on the extent, quality and safety of medical locum practice and the implications of medical locum working for health service organisation and delivery in primary and secondary care in the English NHS. Our three main research questions were:

-

What is the nature, scale and scope of locum doctor working in the NHS in England? Why are locum doctors needed, what kinds of work do they undertake and how is locum working organised?

-

How may locum doctor working arrangements affect patient safety and the quality of care? What are the mechanisms or factors which may lead to variations in safety/quality between locum and permanent doctors? What strategies or systems do organisations use to assure and improve safety and quality in locum practice? How do locum doctors themselves seek to assure and improve the quality and safety of their practice?

-

How do the clinical practice and performance of locum and permanent doctors compare? What differences in practice and performance exist and what consequences may they have for patient safety and quality of care?

Chapter 2 Overview of the study

The research aim and questions outlined at the end of the last chapter of this report were addressed through four main work packages. In this section, we provide a brief description of each work package and how it relates to the remaining chapters of the report. We also describe some important aspects of the research process including our project advisory group and patient and public involvement (PPI) arrangements and provide details of ethical approval for the research.

Overview of work packages and the structure of this report

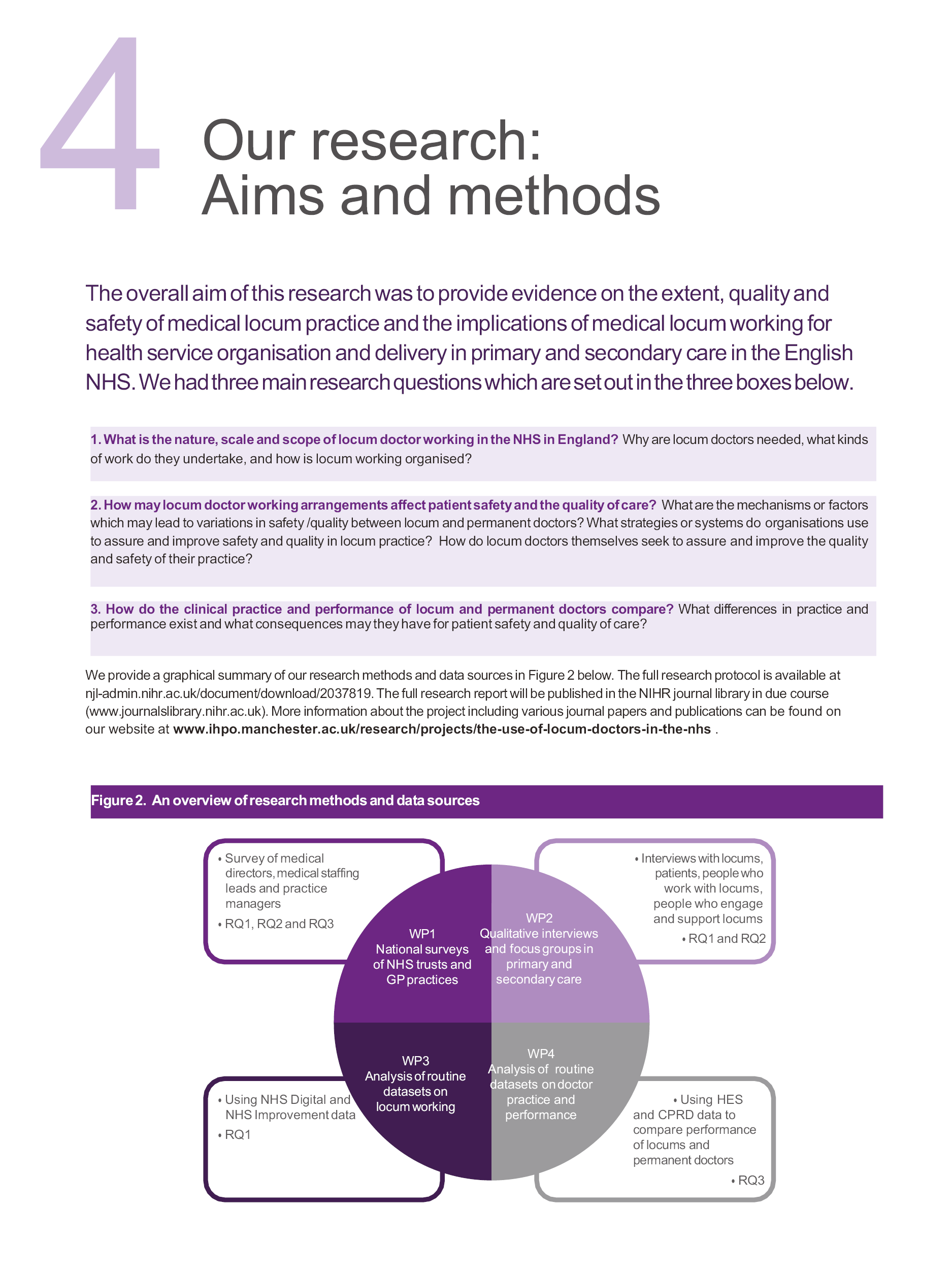

The study was organised into four main work packages designed to address the three main research questions outlined above, as follows:

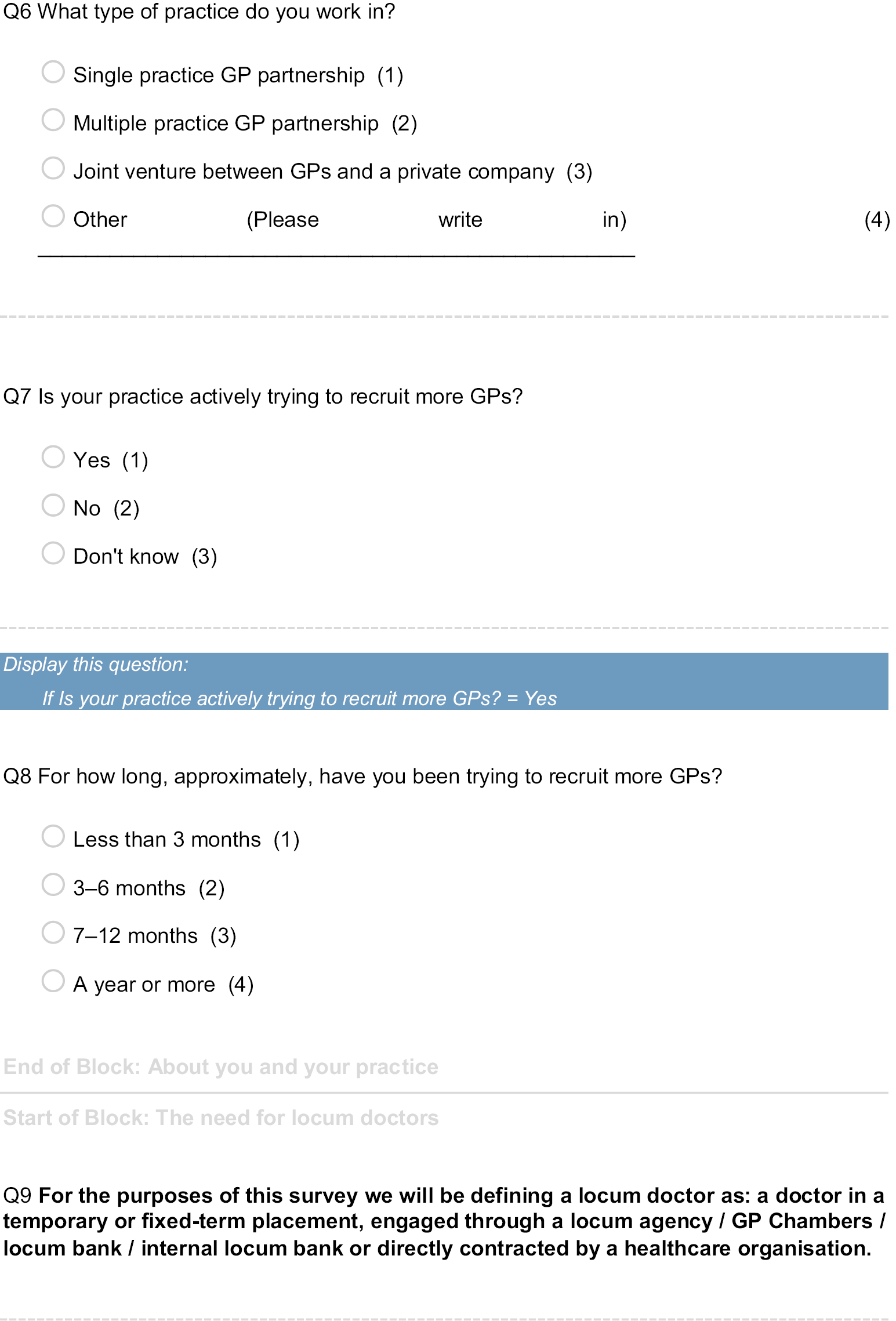

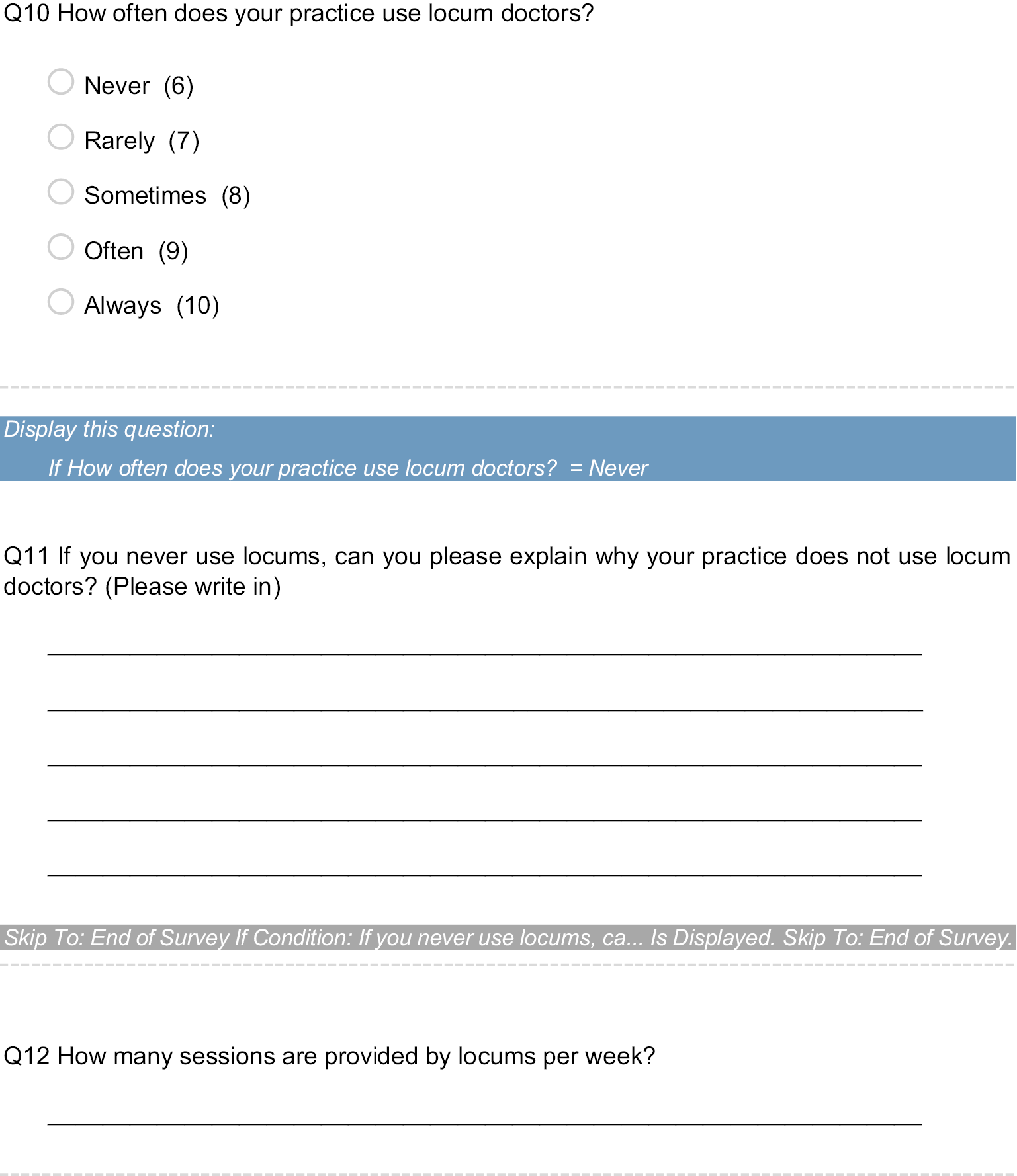

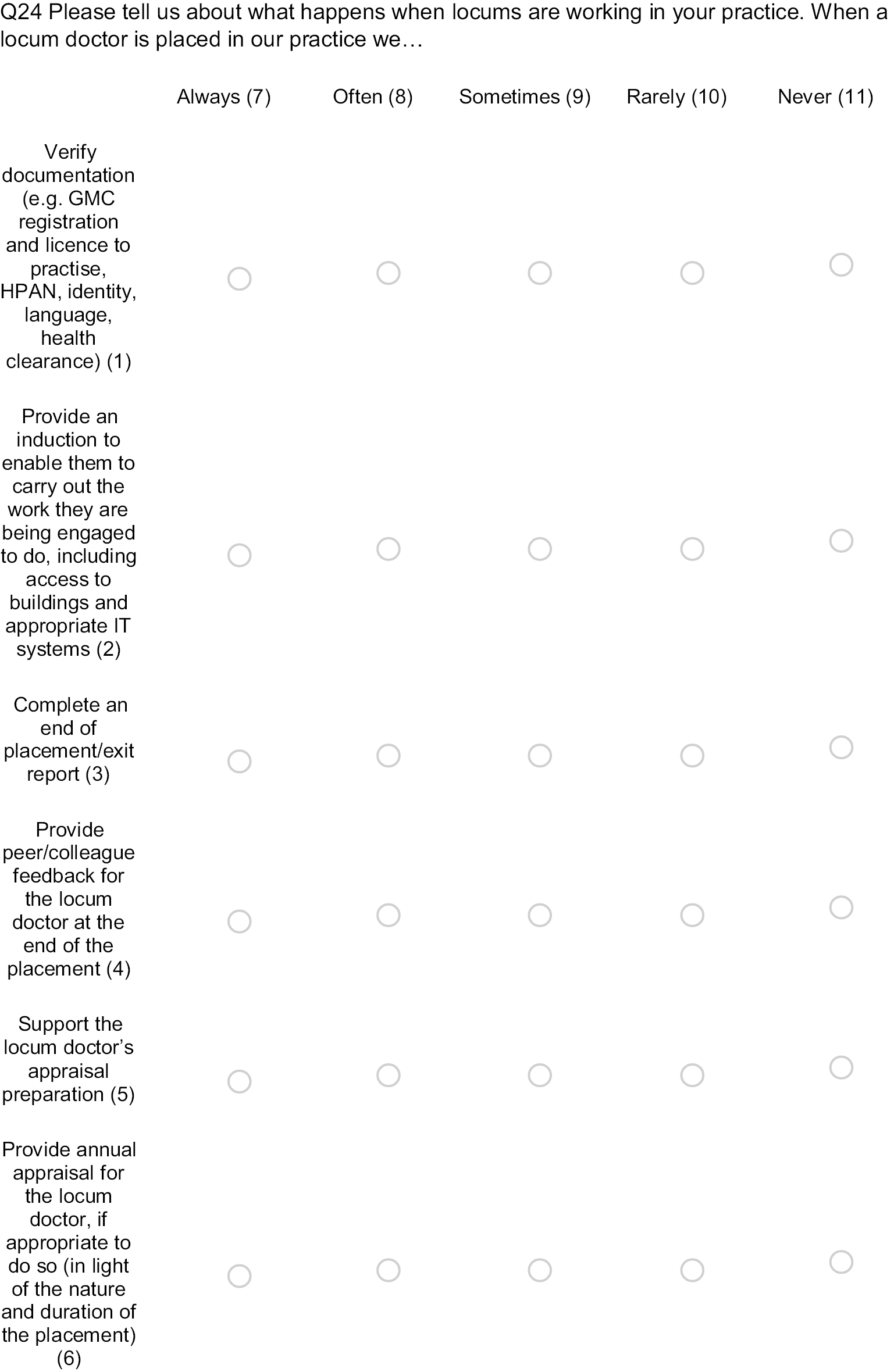

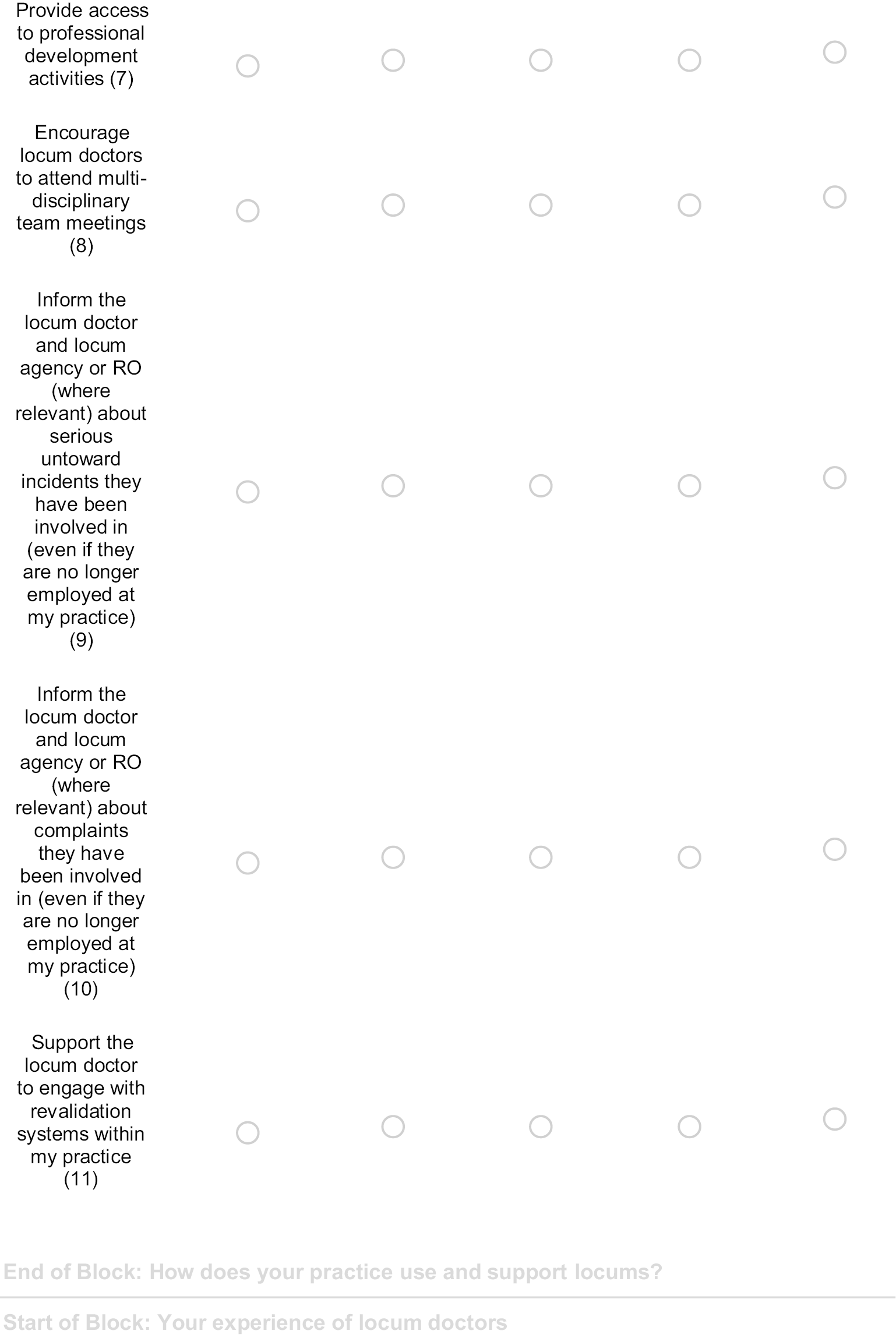

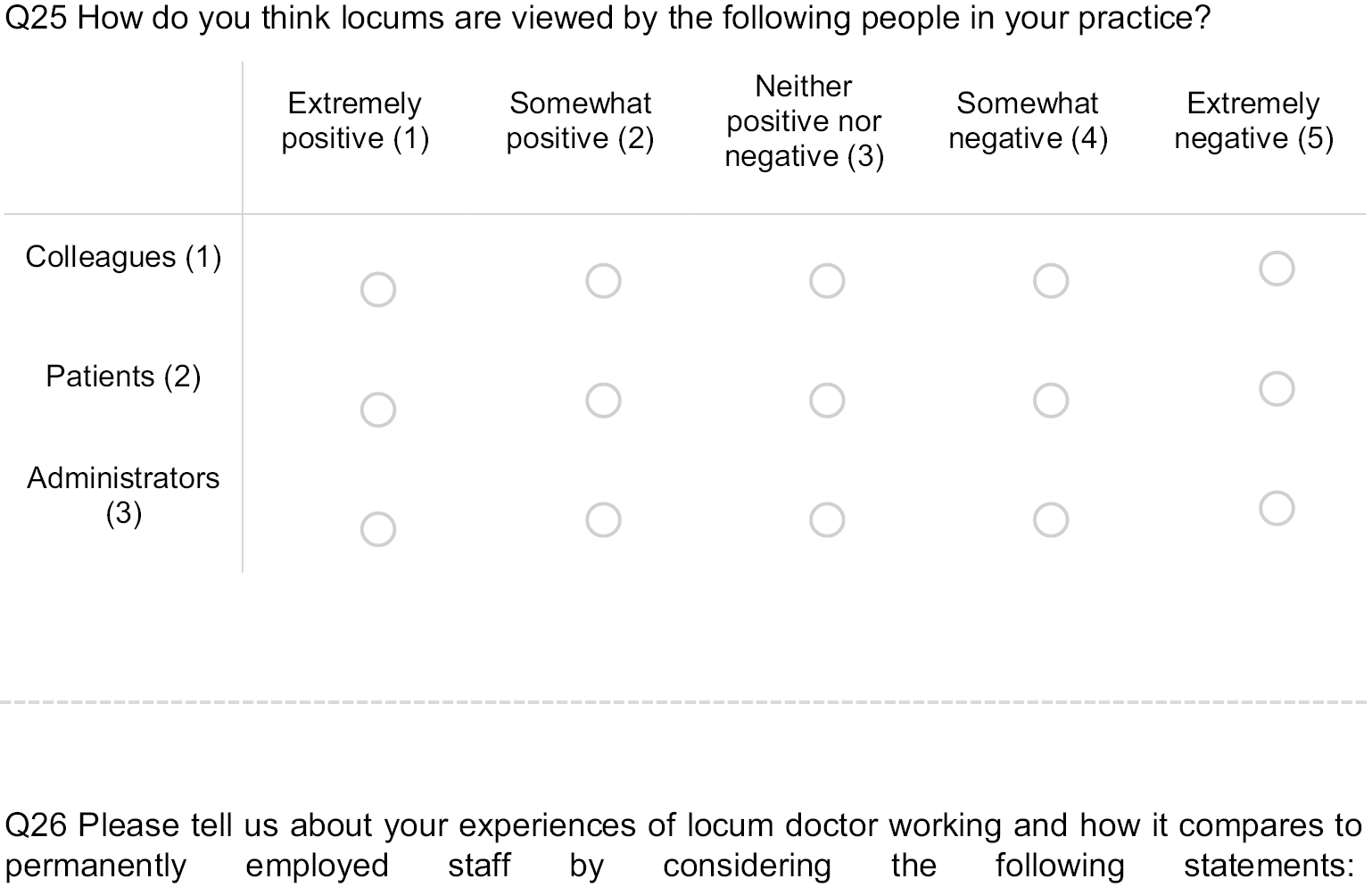

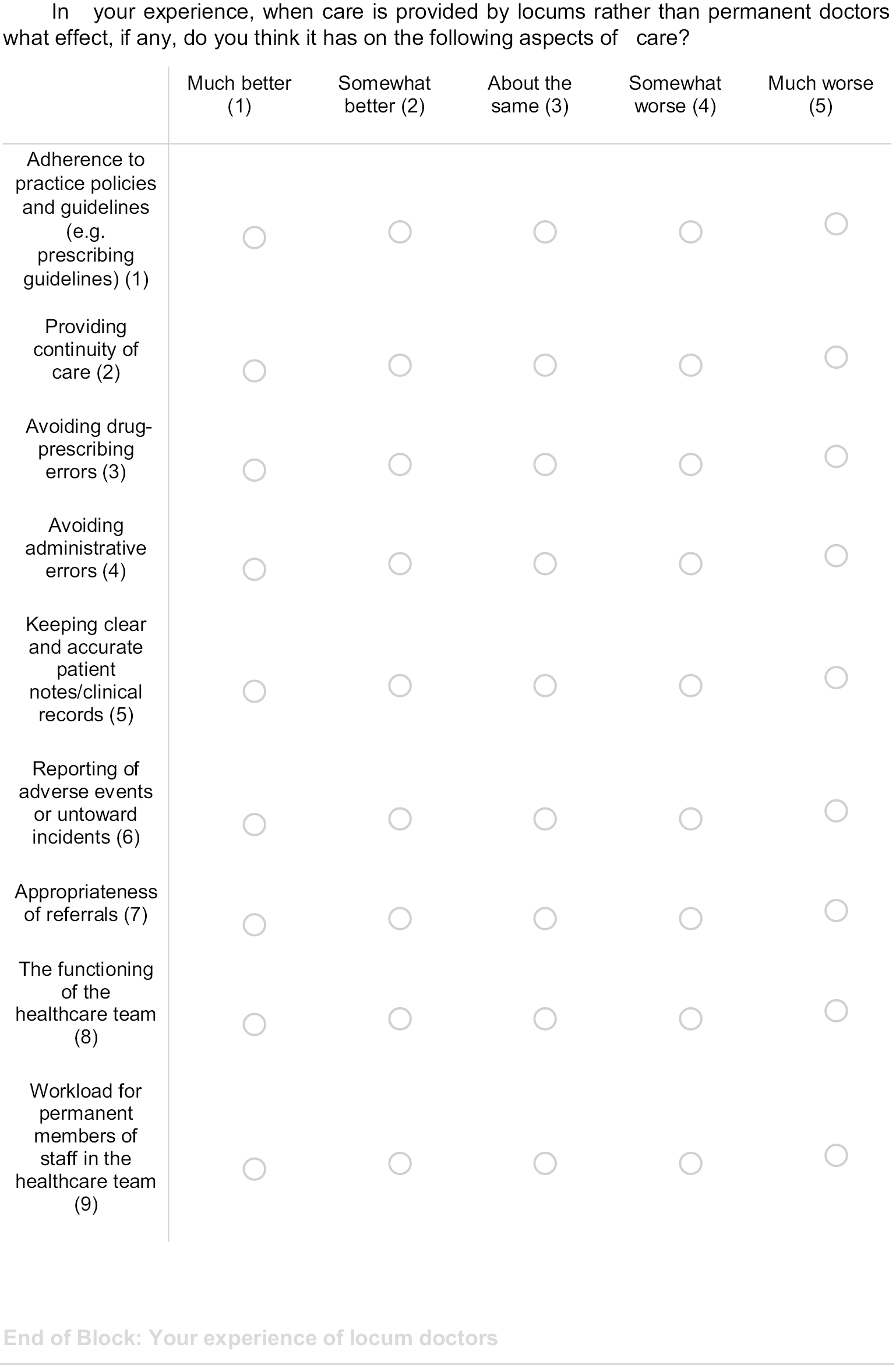

Work package 1 (addressing research questions 1 and 2) involved a survey of medical directors/medical staffing leads in NHS trusts in England and a survey of general practices in England. The two surveys examined the nature, scale and scope of locum doctor working, why locums were needed, what work they undertook and how their work was organised, and sought views on the performance of locum doctors and a range of issues concerning governance and oversight of practice. The findings from these two surveys are reported in Chapters 5 and 6 of this report.

Work package 2 (addressing research questions 1, 2 and 3) involved a combination of semistructured interviews and focus groups conducted across 11 healthcare organisations in both primary and secondary care in the NHS in England. We developed and used three interview schedules (for interviews with locum doctors; people who worked with locums in healthcare organisations; and patients and members of the public). The findings from this work package are reported in Chapters 7 and 8 of this report.

Work package 3 (addressing research question 1) involved the collection and analysis of existing routine quantitative data sets on locum doctor working in the NHS in England. We used quarterly workforce returns from all general practices in England to NHS Digital to examine locum working in primary care. We used weekly locum usage returns from all NHS trusts in England to NHS Improvement to examine locum working in secondary and community services. The findings from this work package are reported in Chapters 3 and 4.

Work package 4 (addressing research question 3) involved the collection and analysis of existing, routine quantitative data sets on doctors’ practice/performance which identify whether doctors are locum or permanent staff and so allow us to compare the practice/performance of locums and permanent doctors. We used the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) linked to Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) to examine these issues in primary care. We sought to undertake a similar analysis in secondary care, using electronic patient record (EPR) data from two NHS hospitals: Salford Royal Hospital and the Bradford Royal Infirmary. However, we encountered a number of problems both in securing data extraction from the two hospitals' EPR systems and in identifying locum and permanent staff activity in the data sets, which severely limited our ability to examine these issues in secondary care. The findings from this work package are reported in Chapters 9 and 10.

Project advisory group

We convened a project advisory group which met regularly throughout the research and provided a valued sounding board for the research team as we developed and undertook fieldwork and data analysis and reported on our findings. We are very grateful to all members of the project advisory group, which was chaired initially by Dr Paul Twomey, medical director for NHS England in the northern region, and then after his retirement by Dr Yasmin Khan who succeeded him in that position.

Patient and public involvement

We established a PPI forum with four patient members. The chair of our PPI forum was also a member of our project advisory group. The PPI forum were involved regularly in project design and planning, and gave us feedback and guidance on research materials and outputs (e.g. study protocol, participant information sheets, survey tools, interview schedules, emerging findings). Our PPI group coproduced our patient interview schedule, two members of our PPI forum led the patient focus groups and all were involved in analysis of patient interviews. We are grateful to our PPI group and their input throughout our project. We hope they will continue to provide invaluable support for developing strategies for sharing the findings of the research with the wider community and the public.

Ethical approval

The study sponsor was the University of Manchester. The study received ethical approval from the Health Research Authority on 8 December 2020 [Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) project ID: 278888; Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference: 20/NW/0386].

Chapter 3 The use of locum doctors in general practices in England: analysis of routinely collected workforce data

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from Grigoroglou et al. 36 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Aims

In this chapter, we quantify general practice locum use in England for the period 2017–9 as an aggregate and by Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) by age group, country of qualification and gender, for the entire general practitioner (GP) locum workforce of England and we make comparisons with other types of GPs (partners who share ownership and leadership of a practice; salaried GPs who work in a practice for a fixed salary; registrars who are GP in training; and GP retainers who are supported by NHS England to stay in practice often with caring or family responsibilities). We also examine which practice and population characteristics explain variability in locum use at the general practice level for the whole primary care population of England.

Methods

Data

We accessed several data sources to extract individual-level information on full-time equivalent (FTE) working hours (1 FTE = 37.5 hours/week), type of GP (i.e. locum GP, GP partner, salaried GP, GP registrar, junior GP and GP retainer), type of locum GP (i.e. long-term of infrequent locum) and GP characteristics (age, gender, country of qualification). General practice-level information was extracted on population age and gender, quality of care, morbidity burden, patient satisfaction, rurality, deprivation, single-handed practices and healthcare regulators rating for each general practice in England. Definitions and sources for all data are provided in Appendix 1.

Practitioner-level information from NHS Digital was extracted from practices at the last day of each reporting quarter, with 12 quarters available between 31 December 2017 and 30 September 2020. We restricted the time period window, as there were differences in the methodology used by practices to report locum data prior to December 2017. For the period of analysis, some practices did not provide valid or complete records, and this resulted in some data being recorded as missing or estimated. Even though we excluded these records from the analyses, coverage was very high with approximately 95% of all practices providing valid workforce data in December 2019. FTE for locum GPs was derived as an average of the total number of hours worked in each month over the reporting quarter. 37

From NHS Digital,38 we obtained information on achievement indicators for all long-term conditions in the UK’s Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), which we used to calculate morbidity burden and performance for each general practice in our data set. The QOF is a national pay-for-performance scheme in primary care that was introduced in 2004 with the aim to improve quality of care and linked financial awards to performance on achievement indicators. Lower-layer super output area (LSOA)-level deprivation, as measured by the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2019,39 was available for all LSOAs (geographically defined neighbourhoods of 1500 people on average) and we assigned LSOA deprivation scores to practices based on the practice’s postcode. The IMD is a relative measure of deprivation for all 32,844 LSOAs in England where each LSOA is assigned a score on a continuous scale (i.e. 0–100) and a higher score corresponds to greater deprivation. We extracted data on patient satisfaction for all practices from the GP Patient Survey, data on rural/urban classification based on practices’ location40 and practice overall inspection ratings from the Care Quality Commission (CQC). All data were matched on practice unique identifiers [i.e. organisation data service (ODS)] and year. Data were publicly available and did not require ethical board review.

Statistical analysis

We plotted total locum FTE against total FTE for all types of GPs over time for the whole of England. We used violin plots to compare the age and FTE distribution of locums and other GP types, and by gender. We plotted cumulative FTE by gender and country of qualification for all GP types. We calculated the average rate of general practice locum use in 2019 defined as total locum FTE as a proportion of the total GP FTE and visualised geographical variation in locum use at the CCG level with the use of spatial maps.

We used mean-dispersion negative binomial models with robust standard errors to model locum FTE, with fixed-effect predictors for region (as categorical, to account for between-region variations) and time (as continuous, to account for time trends). We used the natural logarithm of the annual total GP workforce FTE count as offset. We control for several practice characteristics in all models: deprivation, practice CQC ratings, the proportion of practice’s female population, the proportion of practice’s patients aged over 65 years, single-handed practices, rurality, QOF performance, QOF morbidity burden, patient satisfaction and practice workload defined as list size over total GP FTE. We used one set of negative binomial regression models to investigate the relationship between locum FTE and practice and population characteristics over time (2018–9) and one set of models to investigate the relationship cross-sectionally (2019).

Stata v16.1 was used for the principal data cleaning, management and analyses. For the two primary sets of analyses, we used the nbreg command with the exposure option and the incidence rate ratio (IRR) specification. Practices with < 1000 patients were omitted from the regression analyses because these practices are opening, closing or serving specific populations.

Results

Variation in locum use

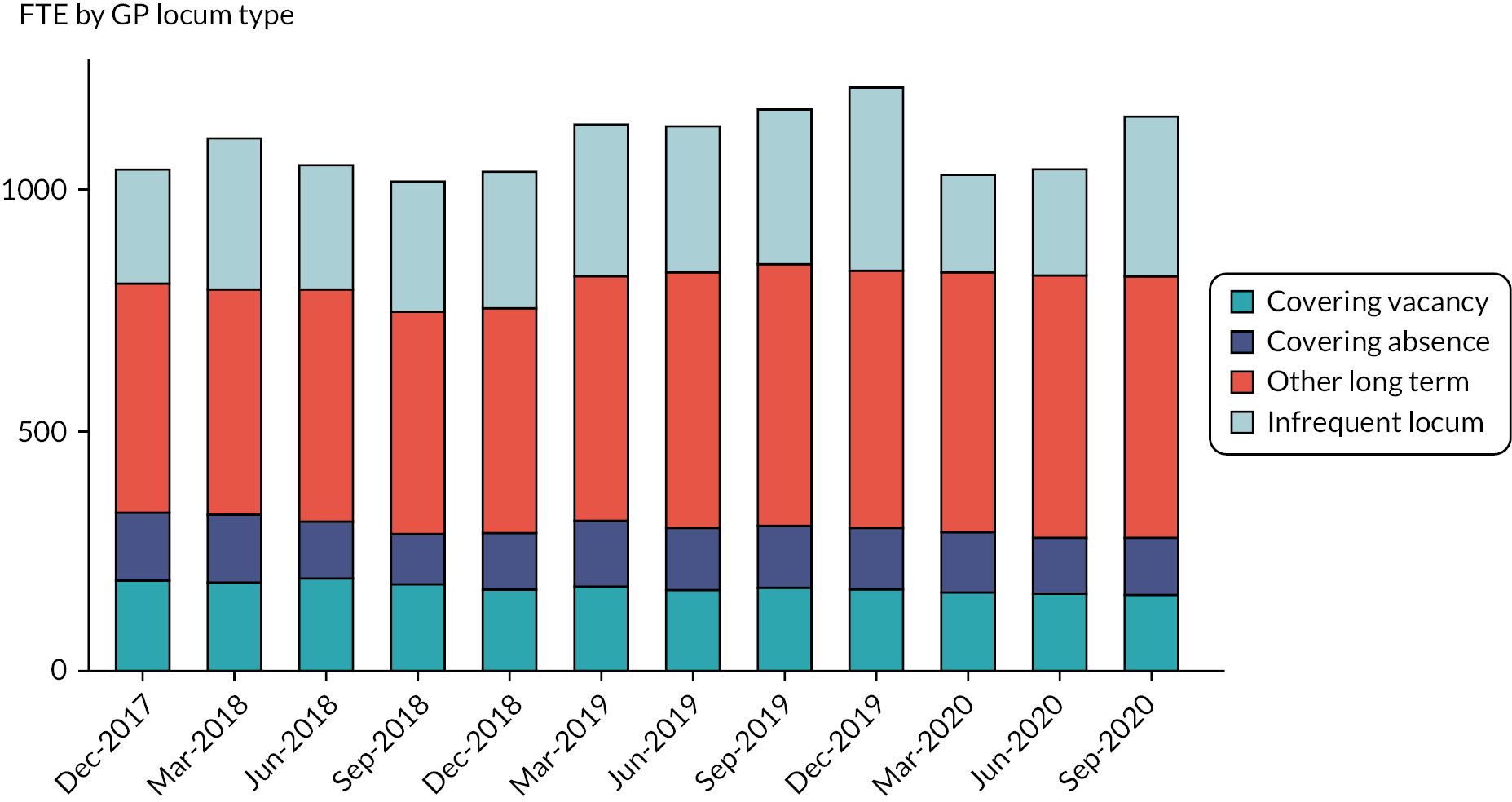

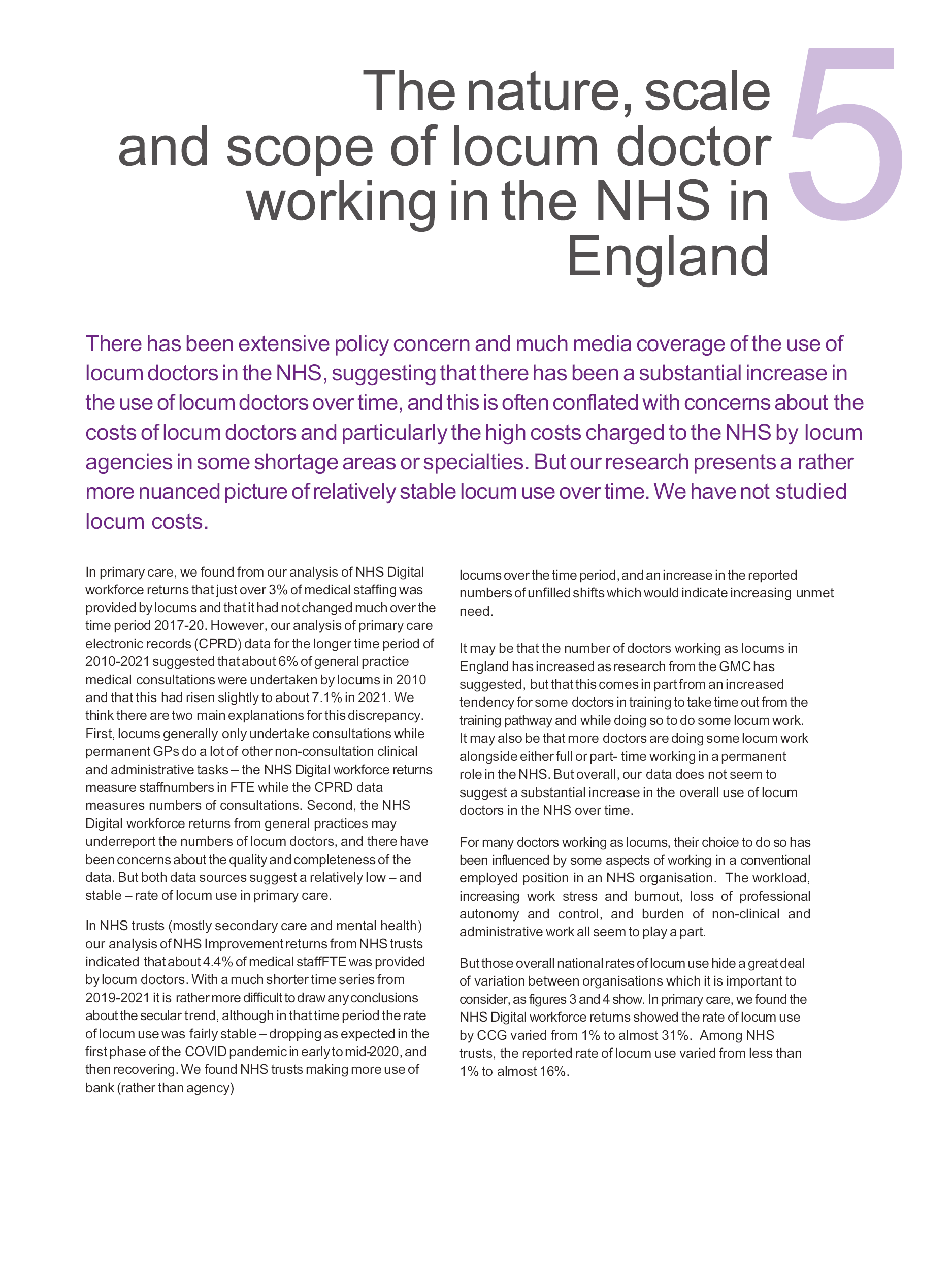

Over time, reported mean locum use in England varied from 3.15% (1045.8 FTE) in December 2017 to 3.31% (1157 FTE) of total GP FTE in September 2020 (Figure 1). The proportion of practices that reported at least some locum use varied from 37.4% and 40.8% in 2018 and 2019, respectively. Most locums (74%) worked in long-term positions compared with infrequent locums (26%) (Figure 2). Long-term locum use remained stable over the study period, though there was a substantial 47% reduction in infrequent locum use between the first and the second quarter of 2020, indicating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

FIGURE 1.

Variation in FTE by GP type over time, December 2017–September 2020.

FIGURE 2.

Variation in locum type over time, December 2017–September 2020.

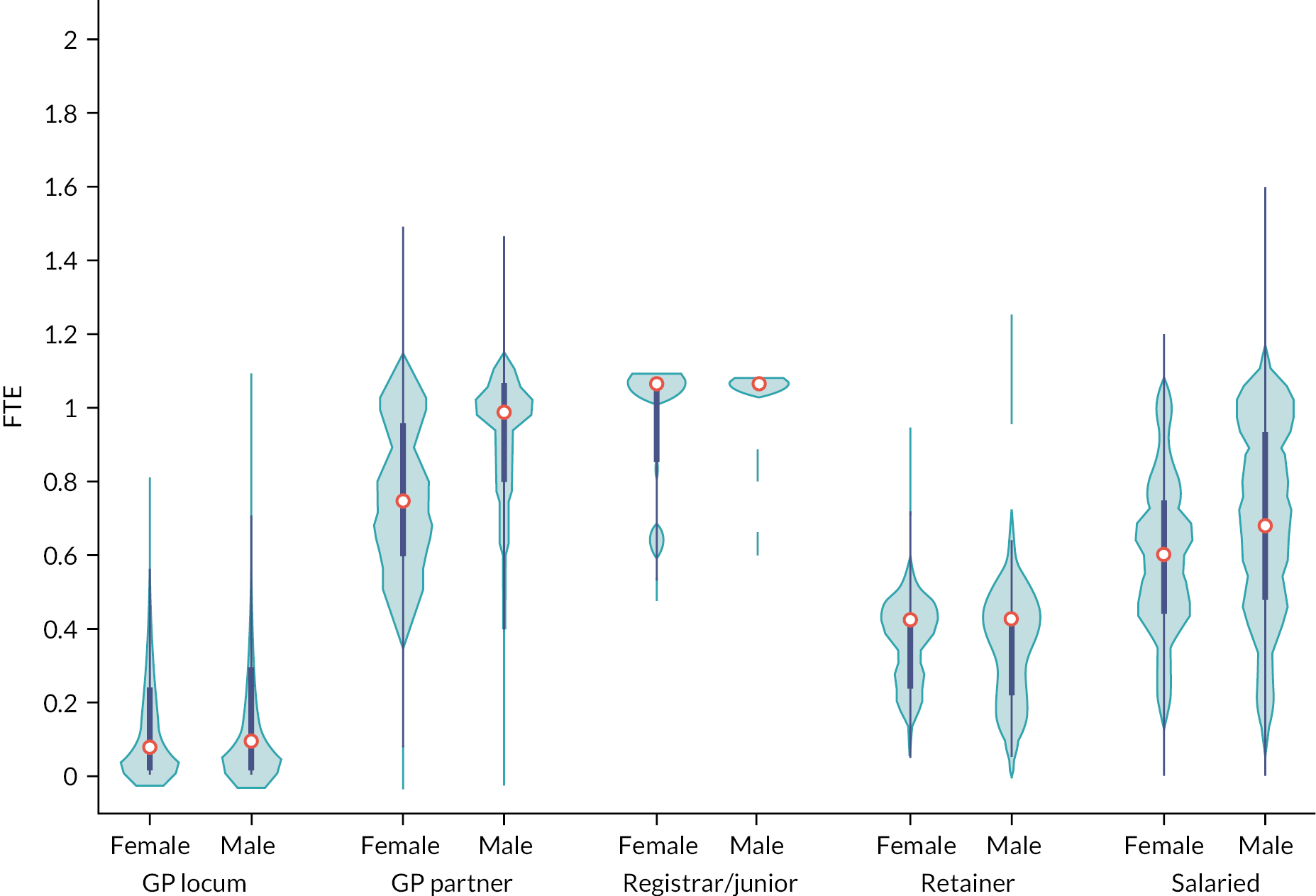

Violin plots depicting the FTE distribution of locums and other types of GPs are presented in Figure 3. Median locum FTE in December 2019 was 0.09 FTE (0.7 sessions in a practice where 1 FTE = 8 sessions) and we observed a similar distribution in FTE for both male and female locums in contrast to other GP types (e.g. GP partners/salaried GPs) where we observed large variation in the distribution of FTE between genders.

FIGURE 3.

Full-time equivalent distribution of GPs in December 2019, by type and gender.

Locum characteristics

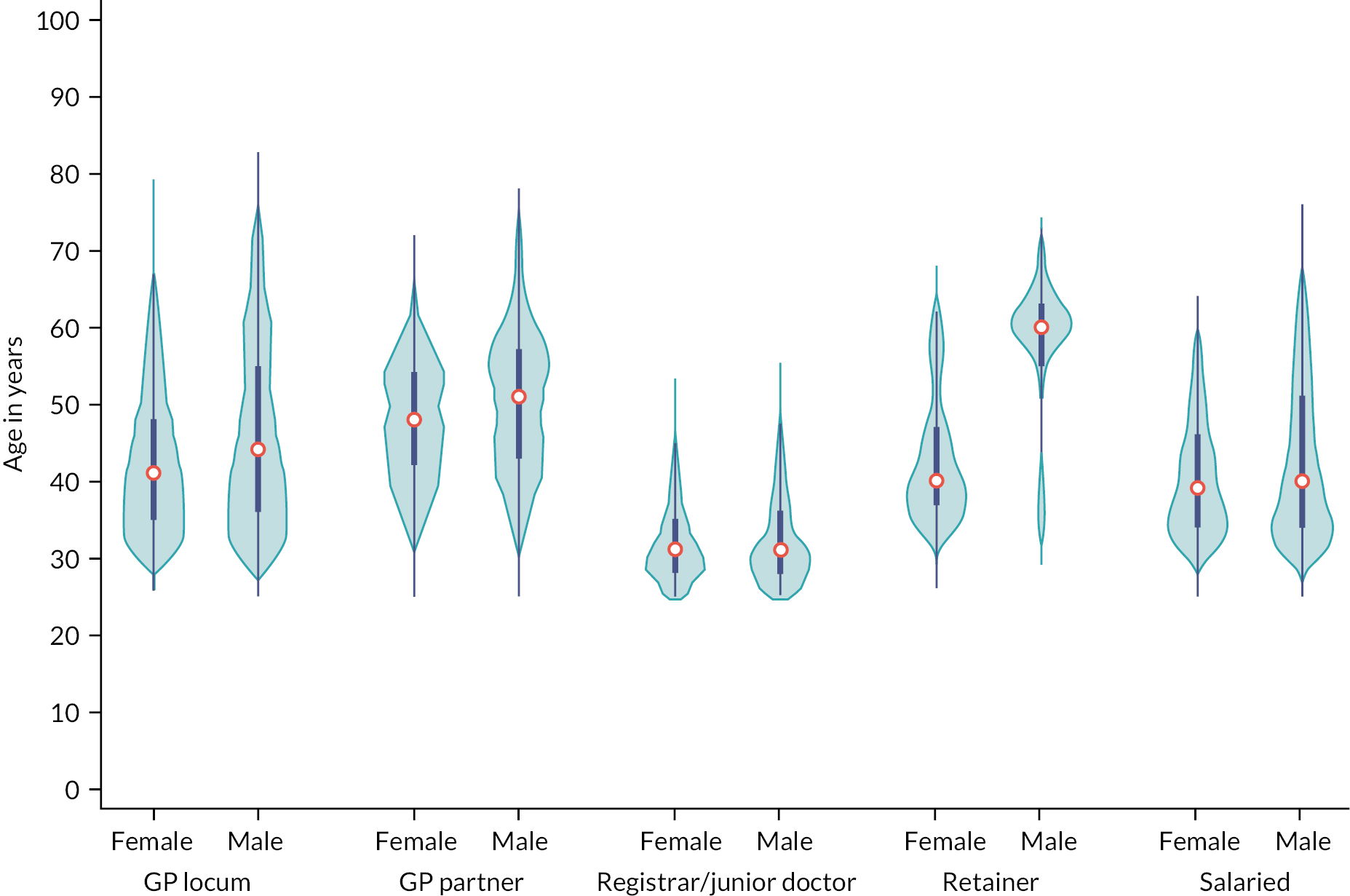

Locum workforce characteristics in terms of age are presented in Figure 4. In December 2019, the age distribution of locums shared similar characteristics with the age distribution of both male and female salaried GPs. Median age of female locums was 41 years [interquartile range (IQR) 35–48] and median age of male locums was 44 years (IQR 37–55). The median age for GP partners, junior doctors, GP retainers and salaried GPs was 49, 31, 42 and 39 years, respectively.

FIGURE 4.

Age distribution of GPs in December 2019, by type and gender.

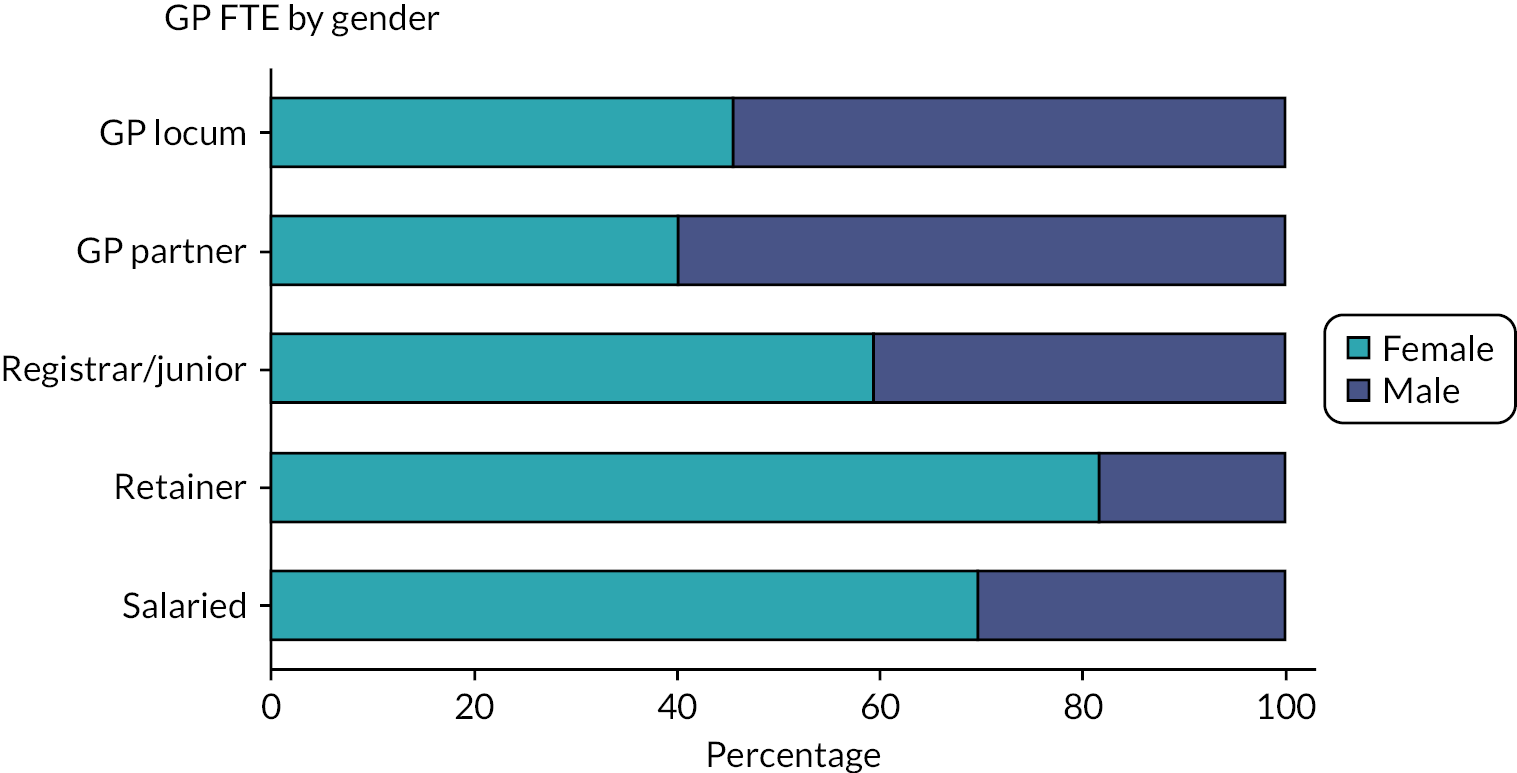

Locum workforce characteristics in terms of gender are presented in Figure 5. Male locums accounted for 54.5% of total locum FTE. This was similar to GP partners who were mostly males (60%) but in contrast to registrars/junior doctors (40.6%), GP retainers (18.5%) and salaried GPs (30.5%) who were mostly females.

FIGURE 5.

Gender breakdown by GP type, December 2019.

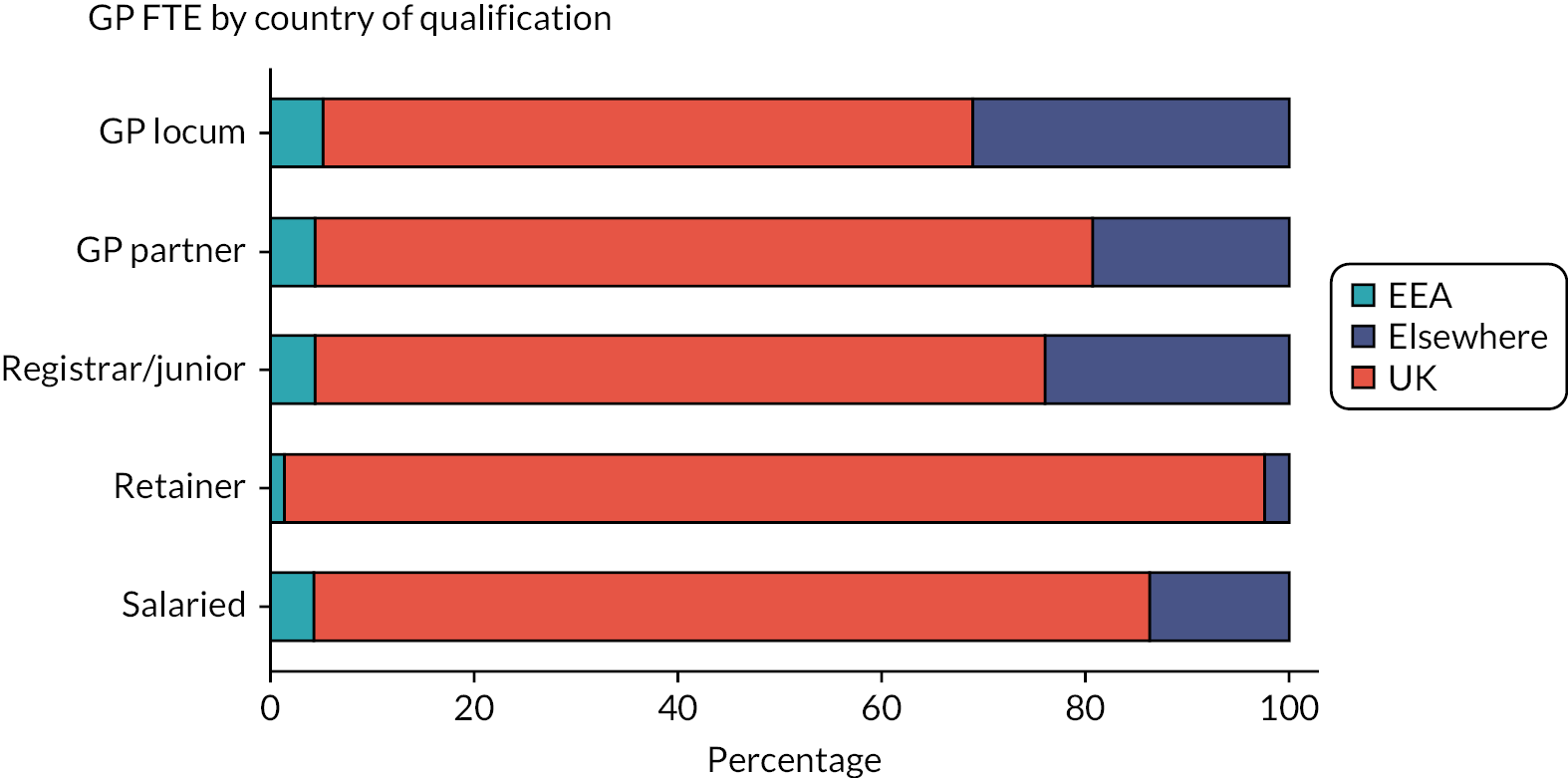

Locum workforce characteristics in terms of country of qualification are presented in Figure 6. Most locums obtained their degree in the UK (63.8%), although this proportion was smaller compared with other types of GPs (82% for salaried GPs and 76% for partner GPs).

FIGURE 6.

Country of qualification breakdown by GP type, December 2019.

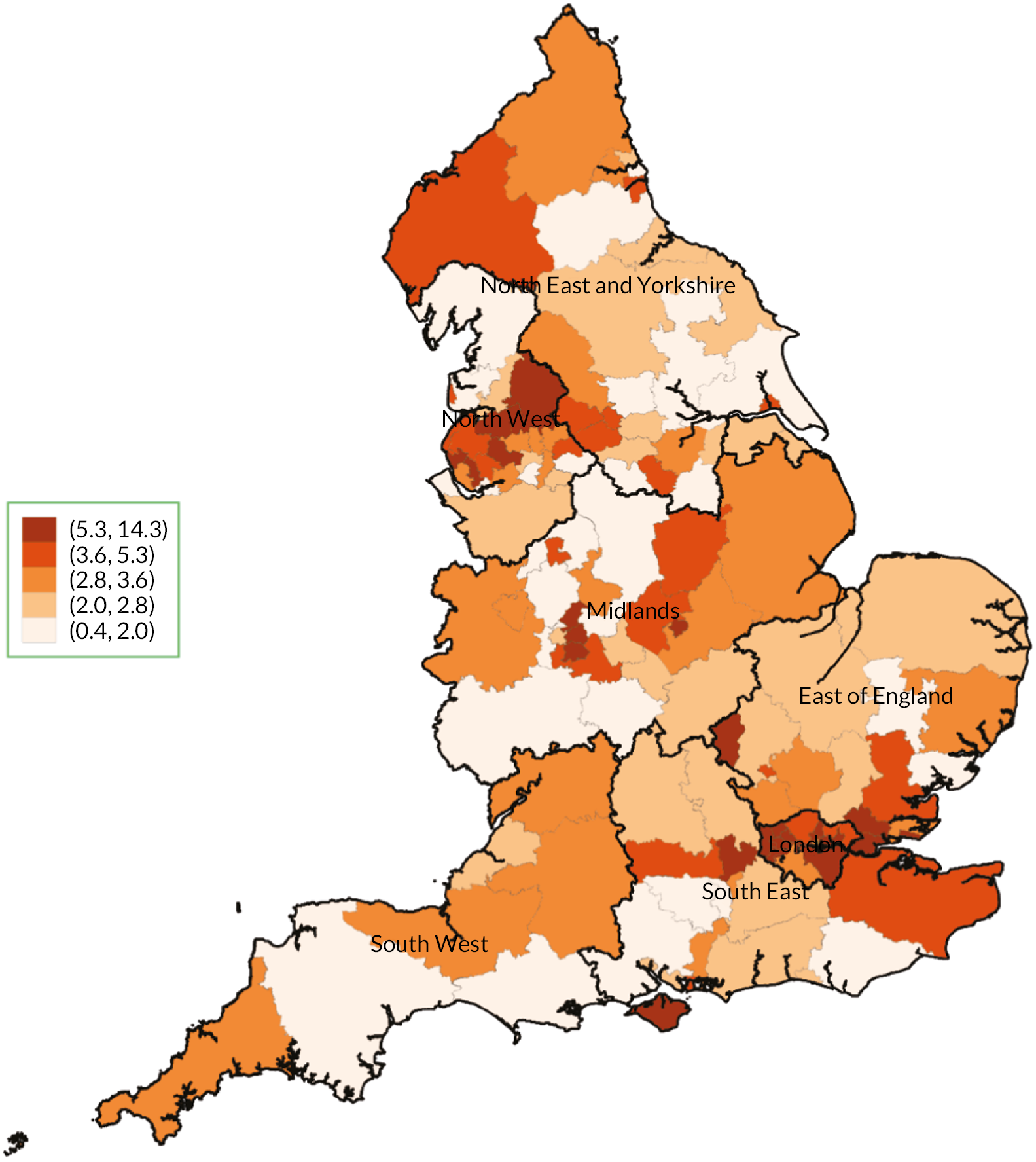

Geographic variation of locum use

We present variability in mean locum use at the CCG level across regions in 2019 in Appendix 1, Figure 28, with dark-shaded areas indicating higher locum use and light-shaded areas indicating lower locum use. Locum use varied substantially between regions (from 0.4% to 13.7%) with locum use accounting for 2.5% of total GP FTE in the North East and 7.4% in London. Descriptive statistics on locum FTE, population size estimates, number of practices, census information, deprivation and QOF population achievement for all English regions in 2019–20 are reported in Table 2. In Table 24, Appendix 1 we provide a table with 10 CCGs with the highest use of locums and 10 CCGs with the lowest use of locums in 2019.

| England | North East and Yorkshire | South West | East of England | North West | South East | Midlands | London | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locum GP FTE, yearly mean (95% CI) | 192.1 (125 to 259.2) | 136.9 (118.9 to 154.8) | 137.8 (130.2 to 145.3) | 155.1 (147.1 to 163.2) | 165.1 (159.6 to 170.7) | 165.6 (152.5 to 178.6) | 254.8 (234.3 to 275.4) | 329.5 (323.5 to 335.5) |

| Total GP FTE, yearly mean (95% CI) | 4564.1 (1967.4 to 6639.6) | 5457.9 (2754.6 to 8154.1) | 3628 (1849.7 to 5396.3) | 3718.0 (1911.5 to 5497.5) | 4408 (1805.9 to 6983) | 4869 (2238.4 to 7471.5) | 6317.2 (2937.3 to 9699.3) | 4471.7 (1696.9 to 7254.1) |

| Locum use (%)a | 4.2 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 4 | 7.4 |

| General practice population | 57,653,853 | 8,788,992 | 5,477,907 | 6,692,664 | 7,057,650 | 9,178,676 | 10,780,976 | 9,676,986 |

| Practices, n | 6422 | 991 | 539 | 655 | 951 | 856 | 1268 | 1162 |

| Single-handed practices, n | 693 | 73 | 5 | 59 | 119 | 52 | 120 | 107 |

| Practice list size, median (IQR) | 7522 (4692–11,124) | 7708.8 (4913.3–10,884.5) | 8760.8 (5996.8–12,481.5) | 8997 (6065–12,868.5) | 6410.3 (4212.3–9315.8) | 9845.3 (6367.4–13,180) | 7333.5 (4591.8–10,829.6) |

7311.5 (4858–10,554) |

| IMD 2019,b median (IQR) | 21.9 (12.5–35.5) | 29.3 (15.7–46.8) | 18.2 (11.4–26) | 16.6 (9.2–24.5) | 32.5 (17.3–52.8) | 14.2 (7.6–22.5) | 25 (14.3–39.8) | 22.1 (13.6–30.7) |

| Practice female pop, median (IQR) (%) | 3778 (2315–5611) (50) | 3851 (2428.5–5437.8) (50) | 4392.5 (3035.8–6365.5) (50.1) | 4529 (3018.3–6510.8) (50.3) | 3165.8 (2088–4686) (49.4) | 4956.4 (3228.6–6670.6) (50.3) | 3639.3 (2250.3–5441.9) (49.6) | 3617.3 (2380.3–5248.5) (49.5) |

| QOF data | ||||||||

| Population achievement, %, median (IQR) | 82.2 (79.7–84.4) | 83.1 (80.8–85) | 82.6 (80.1–84.3) | 82.5 (80.1–84.6) | 82.6 (80.2–84.7) | 81.8 (79.4–83.9) | 82.5 (79.8–84.6) | 80.6 (78–83.2) |

| Morbidity burden %, median (IQR) | 67 (55–77.3) | 75.7 (67.1–83.2) | 73.2 (64.9–80.4) | 64.8 (56.3–73) | 74.2 (65.5–82.2) | 64.2 (56.5–73.5) | 71 (62.4–79.4) | 50.6 (43.2–57.2) |

| Rural, % | 15.4 | 17.2 | 32.5 | 27.1 | 5.3 | 21.4 | 18 | 0.1 |

Results from regression analyses

After adjusting for practice and population characteristics, large variability in locum FTE between regions persisted (Table 3). Using Midlands as the reference category, practices in London had the highest locum FTE [IRR = 1.369, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.180 to 1.588], and practices in the North East and Yorkshire had the lowest locum FTE (IRR = 0.711, 95% CI 0.626 to 0.843).

| Model A, analyses over time, sample size = 12,545 practice X year observations | Model B, cross-section analyses, sample size = 6117 practices | |

|---|---|---|

| Rurality (0 = urban, 1 = rural) | 1.250 (1.095–1.428) | 1.300 (1.085–1.559) |

| IMD 2019 | 1.002 (0.999–1.006) | 1.005 (1.000–1.009) |

| QOF practice performance | 1.005 (0.991–1.017) | 1.009 (0.991–1.026) |

| Single-handed practice | 4.611 (4.101–5.184) | 4.618 (3.928–5.428) |

| QOF morbidity burden | 1.384 (0.963–1.991) | 1.255 (0.801–1.996) |

| Percentage of female population | 0.967 (0.959–0.981) | 0.970 (0.946–0.994) |

| Proportion of practice population aged ≥ 65 years | 0.970 (0.950–0.984) | 0.971 (0.958–0.988) |

| Practice workload (total GP FTE/list size) | 1.001 (1.001–1.002) | 1.001 (1.001–1.002) |

| CQC ratings (reference group is Outstanding) | Reference group | Reference group |

| Inadequate | 2.108 (1.370–3.246) | 2.687 (1.451–4.974) |

| Requires improvement | 1.229 (0.949–1.592) | 1.198 (0.822–1.744) |

| Good | 1.343 (1.103–1.637) | 1.267 (0.947–1.696) |

| Year (reference year is 2018) | Reference year | – |

| 2019 | 1.055 (0.970–1.148) | – |

| Constant | 0.041 (0.011–0.142) | 0.020 (0.004–0.111) |

Care Quality Commission ratings appeared to be a strong predictor of locum FTE, where practices rated as having inadequate (IRR = 2.108, 95% CI 1.370 to 3.246) and good services (IRR = 1.343, 95% CI 1.103 to 1.637) had higher locum FTE than practices that were rated as having outstanding services. Single-handed practices had substantially higher locum FTE (IRR = 4.611; 95% CI 4.101 to 5.184) compared with group practices. For practices in rural locations, locum FTE was 25% higher than for practices located in urban areas (IRR = 1.250; 95% CI 1.095 to 1.428). Practices with a higher proportion of female population had 3.3% lower locum FTE (IRR = 0.967; 95% CI 0.959 to 0.981) than practices that had a higher proportion of male population. A larger patient population in the over-65 age group was associated with 3% lower locum FTE (IRR = 0.970, 95% CI 0.950 to 0.984). Finally, patient satisfaction was very weakly associated with locum FTE, while deprivation, QOF quality of care, QOF morbidity burden and practice workload did not appear to have any discerning effect on practice locum FTE. Partial results from the overtime and cross-section regression models are reported in Table 3 and the full results are reported in Appendix 1, Table 25.

Discussion

Summary

This work describes a methodological approach to capture and monitor the scale and scope of the GP locum workforce in English primary care. Our findings suggest that between December 2017 and September 2020, the proportion of GP locum work in the NHS has remained relatively stable, despite widespread perceptions that the number of locum GPs has risen. 3 Regarding regional variation and the characteristics of locums, we describe the intensity of locum use in general practice and how this varies across regions, as well as important information about the composition of the GP locum workforce. We identified substantial geographical variation in locum use between and within regions suggesting differences in the distribution of locums in England. Our comparisons of locums with other GP types showed that locums were more mobile, younger males of whom most had qualified in the UK, although a large percentage had qualified elsewhere. Most locums were employed in long-term positions and on average they did relatively few sessions. Our regression analyses showed that practice characteristics such as rurality, CQC ratings and whether the practice was single handed were stronger predictors of higher locum FTE than population characteristics.

Strengths and limitations

This analysis was conducted at the population level and allowed us to quantify and examine the scale and characteristics of the GP locum workforce compared with other types of GPs for the first time across general practices in England. We explored whether variation in practice and population characteristics explain variability in locum FTE to account for different health needs across different practice populations. The study has national scope and comprehensive coverage of the primary care population (95% of all general practices).

We used publicly available routinely collected data from NHS Digital. However, other databases on workforce report different estimates on the number of locum GPs. The GMC register and the National Association of Sessional GPs estimate approximately 17,000–18,000 GPs with a locum licence in England in 2017,3,41 while the NHS Digital data report only 5040 employed locum GPs in December 2017. There may be several reasons why these differences exist, one being that the NHS Digital data show a picture of the actual GP workforce at each time point rather than the prospective workforce that other databases report. Locum headcounts may overestimate locum use as some locum GPs may also be simultaneously permanently employed.

Second, the GP workforce data collected by NHS Digital have been subjected to changes in data sources and methodology over the years and also include estimates for practices where data are incomplete or have not been submitted. We restricted our time period to exclude data prior December 2017 when the infrequent locum category was first reported in the collection and excluded estimates for those practices that did not submit valid data. Third, the locum data are believed to be under-reported when compared with other types of GPs, mainly due to the infrequent locum category for which reporting may be lower than long-term locum data. In September 2020, NHS Digital switched from quarterly to monthly data collections of the GP workforce data; however, the transition to monthly collection led to a decrease in the number of FTE for infrequent locums. For this reason, the data collections were reverted to quarterly to allow practice managers to report infrequent locum data in time. 37

Interpretation of findings

Previous international evidence shows that the numbers of locums continue to rise,3,42,43 but our findings suggest that this may not be the case for GPs in England. Previous reports from the GMC and the National Association of Sessional GPs showed that the proportion of GPs with a locum GP contract had increased from 30% to 39% of all licensed GPs from 2013 to 2016 and was equivalent to approximately 18,000 GPs in 2018. 3

One recent study examined the geographical variation in the distribution of the GP workforce, including GP locums, across the 13 Health Education England regions using data from NHS Digital but did not make specific comparisons between locums and other types of GPs. 44 Our comparisons can provide a review of the locum workforce at a more granular level which is also particularly relevant to NHS organisations (e.g. CCGs). To our knowledge, no other studies to date have examined contextual factors and their association with locum use in general practices.

The accurate monitoring of the GP workforce may help policy-makers and commissioners to understand current challenges in primary care, including capacity and composition of the GP workforce and inform workforce planning. This can be particularly useful to meet local healthcare needs with sufficient resources for training and deployment of GPs which will help ensure that the targets set out in the NHS long-term plan are met. 45 For example, this research highlights elevated locum GP employment in practices in rural areas and those with inadequate CQC inspection ratings. These types of practices may face substantial challenges in recruiting and retaining permanent GPs and we could hypothesise that relatively high and sustained levels of locum use may be an indicator of wider problems which are affecting recruitment and retention.

Furthermore, this work lays the foundation for future analysis of other existing routine primary care data sets that contain information on service utilisation and patient outcomes. Additional work is needed to identify whether there exist differences in the clinical practice and performance between locum doctors and permanent doctors and also what consequences these may have for patient safety and quality of care. Future work should also aim to identify career intentions of locum GPs and what factors influence the choice to work as a locum. Furthermore, it will be important to understand what implications these career intentions and the observed locum workforce characteristics have on future workforce planning. As more data become available, the impact of COVID-19 on the use of the GP locum workforce should be examined.

Locum GPs have an important role in the delivery of primary care services, particularly in the delivery of out-of-hours care and in helping to address short-term workforce shortages. Despite expectations that locum GP numbers are rising, we found that locum use in primary care has remained stable over time though the use of locums seems to vary substantially across different practice types and areas of the country.

Chapter 4 The use of locum doctors in National Health Service trusts in England: analysis of routinely collected workforce data and electronic patient records

Aims

In this chapter, we use data from NHS Improvement to quantify and describe locum use, and its variation, for all acute, ambulance, community and mental health NHS trusts in England from January 2019 to December 2021. We describe the rate at which NHS trusts were able to fill locum shifts and whether NHS trusts find their locum workforce via their own NHS staff banks or via locum agencies. We explore regional variations for these measures and identify NHS trusts with the highest and lowest locum usage in 2019. Finally, we examine whether some NHS trust and population characteristics explain variability in locum use at the trust level.

Methods

Data

National Health Service trust temporary staff employment data

In England, NHS Improvement is responsible for setting out rules which trusts are expected to follow on temporary staff expenditure. The rules have a strong focus on providing support to trusts to reduce their expenditure and to move towards a sustainable model of temporary staffing. To fulfil this responsibility and support trusts, NHS Improvement collects information from all NHS trusts on their employment of temporary staff. These data are not published and were secured for research through a bespoke data-sharing agreement.

We analysed data on locum use for all NHS trusts in England between January 2019 and December 2021. Data record the weekly number of shifts that were filled by bank or agency locums for each acute, ambulance, community and mental health trust in England. A shift is defined as the period between the doctor commencing and finishing their work, but the duration of shifts is not collected. Bank staff are defined as staff who are usually sourced in-house or from temporary staff banks such as NHS Professionals, which is the largest of these banks supplying temporary staff to NHS trusts. 46 Agency staff are defined as staff who are not on the payroll of the NHS organisation offering employment and are sourced from a third-party agency.

National Health Service Improvement data record information on the number of shifts filled by temporary staff in all staff groups, but we focus on the medical and dental group which includes the aggregate number of shifts, done by all doctors and dentists. The data contain the total number of shifts that were filled by bank staff, the total number of shifts filled by agency staff and the total number of shifts requested by each trust in every reporting week, grouped for doctors and dentists. A detailed table of all the variables in the NHS Improvement data is provided in Appendix 2.

National Health Service trust characteristics

We collected monthly data on all trusts’ substantive employees represented as FTEs and trust annual job turnover data for the medical and dental staff group using the NHS Workforce Statistics database. 47 Trust type information and trust overall inspection ratings were obtained from the CQC, which rates NHS trusts as outstanding, good, requiring improvement or inadequate. 48 Trust-level deprivation was derived using hospital admissions data from NHS Digital and aggregating inpatient postcode deprivation for each trust. 49 Trust-level vacancy rates were obtained in the form of advertised FTE roles for medical and dental staff, available from the NHS Vacancy Statistics from NHS Digital. 50 These trust characteristics were linked to temporary staffing data using unique trust identifiers and are discussed in detail in Appendix 2.

Outcome measures

Locum intensity

Our primary outcome measured locum intensity for each NHS trust in every reporting week. To calculate locum intensity, we combined bank and agency shifts to obtain the total number of shifts reported at trust level in every reporting week. We adjusted this weekly total by the size of the permanent medical and dental workforce in each trust, specifically, the total number of locum shifts was divided by permanent doctor FTE, including dentists (i.e. FTE of NHS and Community Health Hospital Doctors, Consultants, Associate Specialists, Specialty Doctors, Specialty Registrars, Foundation Doctors/Postgraduate Doctors) to give the locum intensity. The annual mean locum intensity was calculated over 12 months of data. A locum intensity of 0.25 indicates that the trust-filled 0.25 locum shifts per week per FTE permanent doctor. We report locum intensity in this way because we do not know the length of the reported locum shifts and therefore cannot directly convert them into FTE. If we assume that one FTE permanent doctor typically works five shifts per week and that shift length for permanent doctors and locum doctors is broadly equivalent, then a locum intensity of 0.25 means that 5% of medical staffing in that week was provided by locums.

Proportion of agency shifts

Our second outcome measured trusts’ reliance on agency staff, which are more costly than bank staff. We divided the number of agency shifts by the total number of filled shifts for every trust in every reporting week. An annual mean proportion of agency shifts was then calculated for each trust over 12 months of data.

Proportion of unfilled shifts

Our third outcome measures shifts that the trust was unable to fill. The total number of shifts requested by each trust in every week was provided by NHS Improvement. The number of filled shifts was subtracted from the number of shifts requested to obtain the number of unfilled shifts for each trust in each week. We calculated the proportion of unfilled shifts by dividing unfilled shifts by shifts requested. An annual mean proportion of unfilled shifts was calculated for each trust over 12 months of data. Trusts occasionally reported a higher number of shifts filled than requested. In these cases, we adjusted the number of shifts requested to reflect the number of total shifts filled in that week. These adjustments were made 811 times out of 11,450 (7.1%) trust-week observations in 2019.

A worked example of the algorithm that we used in each calculation is illustrated below:

-

To obtain the mean locum intensity for Manchester University NHS Foundation trust in 2019, we combined the number of bank and agency shifts to calculate the total number of filled shifts out of the number of shifts requested. For every reporting week in 2019, we divided the total number of shifts that week by the permanent doctor FTE reported for the month in which that week fell. For example, in the week commencing 7 January 2019, Manchester University NHS Foundation trust reported 205 agency shifts and 283 bank staff shifts. We divided the total number of shifts (i.e. 488) by the reported permanent doctor FTE in January (i.e. 4378.8) to obtain a locum intensity value of 0.11, suggesting that for every one full-time doctor, the trust had 0.11 locum doctor shifts that week. That would equate to 2.2% [(0.11/5)*100] of care provided by locums in that week if we assume five shifts per FTE.

-

We calculated the proportion of shifts filled by agency staff by dividing the total number of agency shifts by the total number of all shifts (agency and bank) for each trust in every reporting week. For example, the proportion of agency shifts for Manchester University NHS Foundation trust in the week commencing 7 January 2019 was (205/488)*100 = 42%.

-

We also had information on the number of shifts that each trust requested in every reporting week. For the same week, Manchester University NHS Foundation trust requested 574 bank and agency shifts but failed to fill 86 of these giving an unfilled rate of 15% [(86/574)*100].

Our analysis data set contained information on locum intensity, proportion of agency shifts, proportion of unfilled shifts and trust characteristics for 229 acute, mental health, ambulance and community health trusts in 2019. Of these, three acute trusts and one ambulance trust did not report data on monthly doctor FTE, and one acute trust and seven ambulance trusts reported zero weekly locum returns in every reporting week. Eight ambulance, one acute, one mental health and one community trust reported zero agency shifts in every reporting week. We also explored variation in the three outcomes over time, with 224 and 221 trusts reporting bank and agency shift data to NHS Improvement, in 2020 and 2021, respectively.

Analysis

National Health Service trust temporary staff employment data

Our first set of analyses was descriptive, and we used ordered bar charts to show the distribution of locum intensity, proportion of agency shifts and proportion of unfilled shifts for all trusts in 2019–21. Violin plots showed the geographic variation in each outcome across regions. We used spatial maps to illustrate the distribution of each outcome across all Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs), local partnerships aiming to improve health and quality of care in the areas they serve. Analysis from 2019 to 2021 uncovered whether trusts reported changes over time in locum intensity, proportion of agency shifts and proportion of unfilled shifts, a period including a majority of the COVID-19 pandemic in England.

Our second set of analyses was inferential and employed three mean-dispersion negative binomial regressions to model locum intensity, proportion of agency shifts and proportion of unfilled shifts in 2019. Each model used robust standard errors with fixed-effects predictors for region (as categorical, to account for between-region variation). Our dependent variables were: the mean number of total shifts (offset: natural logarithm of annual mean total permanent doctor FTE); the mean number of agency shifts (offset: natural logarithm of the annual mean total shifts); and the mean number of unfilled shifts (offset: natural logarithm of annual mean total shifts requested). Our choice of negative binomial models over standard Poisson models was based on the presence of overdispersion in the three outcomes. We controlled for CQC inspection rating, trust type (NHS general acute trusts, NHS specialist trusts, mental health trusts and ambulance trusts), trust size (quintiles of trust permanent doctor FTE), turnover and vacancy rates and regional effects.

The final data set consisted of 197 trusts out of 229 trusts in 2019 with complete data for all covariates (8.6% of missing data). We performed a sensitivity regression analysis excluding 25 ambulance and community trusts as these trusts tend to employ very small numbers of doctors relative to acute and mental health NHS trusts. The exclusion of ambulance and community trusts allowed us to examine the effects of deprivation, which could only be measured for acute and mental health NHS trusts. Stata v16.1 was used for the principal data cleaning, management and analyses. We used the nbreg command with the exposure option.

Results

Overall locum use

In 2019, total unadjusted locum use for all trusts in England was 2,004,485 shifts, of which 909,029 (45.3%) were bank shifts and 1,095,455 (54.7%) were agency shifts. Trusts requested 2,316,302 shifts with a trust mean of 208 per week [standard deviation (SD) = 258.3]. The completeness of the data was good with 99% of all trusts reporting at least some locum use in any week.

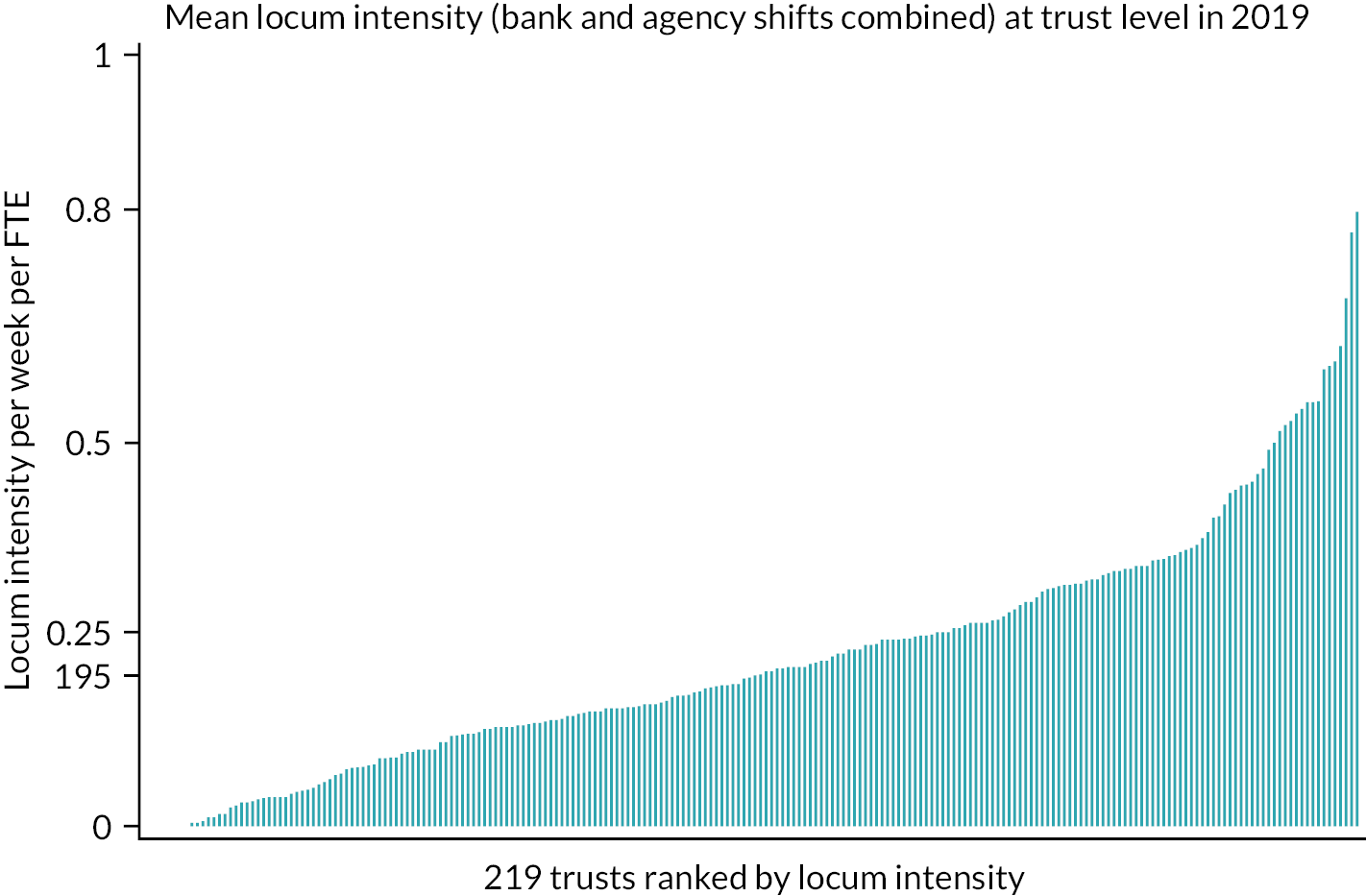

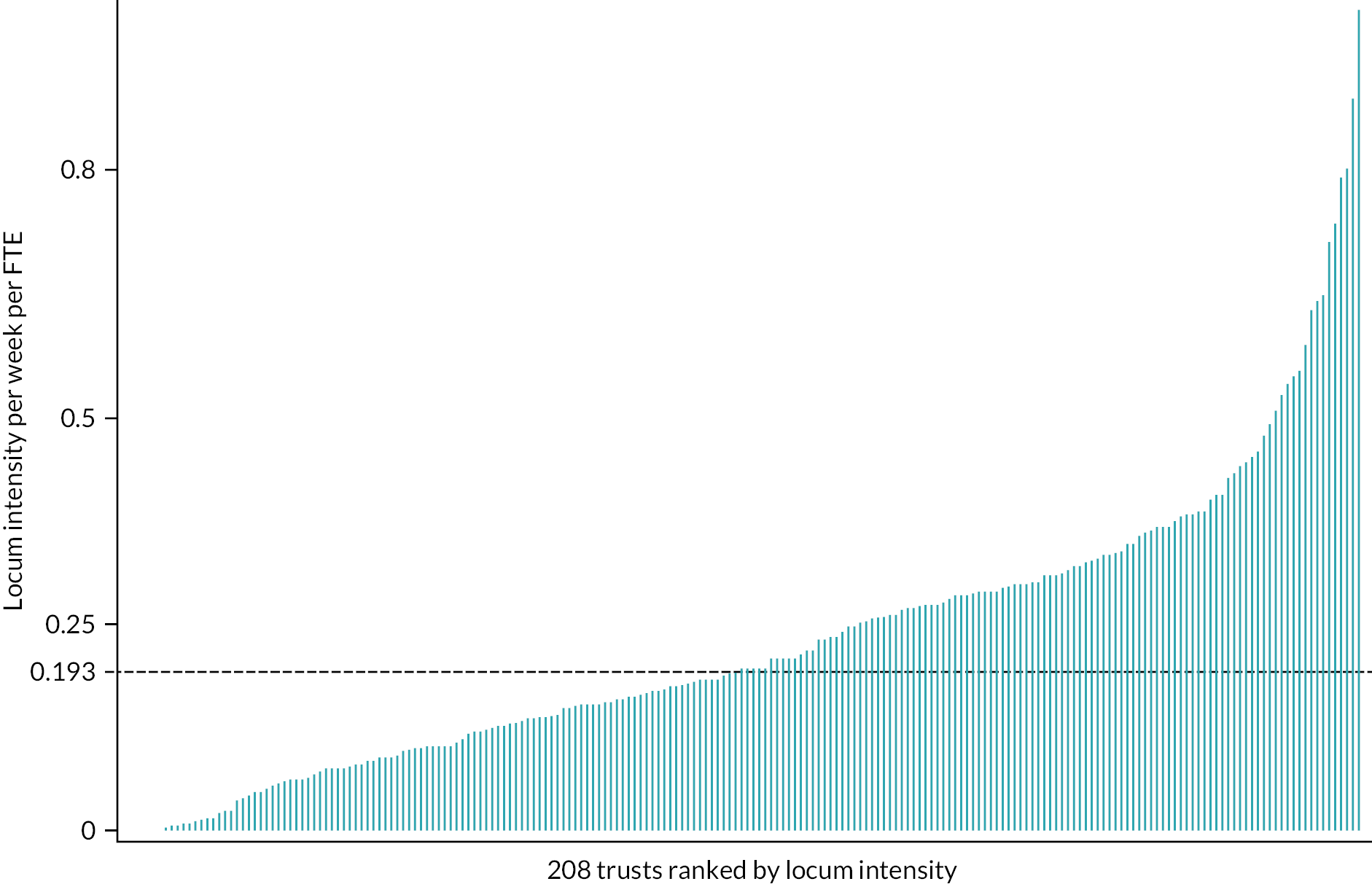

Locum intensity

Figure 7 plots the ranked mean locum intensity in 2019 for 219 NHS trusts in England showing significant variation in locum use across trusts. Mean locum intensity was 0.22 (SD = 0.16) (median = 0.195; 25th–75th centile = 0.11–0.31), indicating 0.22 locum shifts per permanent doctor FTE. Assuming five shifts per FTE, the locum intensity is equivalent to 4.4% of medical staffing provided by locums (25th–75th centile = 2.2–6%). Four ambulance trusts, three acute trusts and one community trust were not included in this analysis as they reported very low or zero permanent doctor FTE and therefore adjustments in their locum intensity could not be performed. The ranked rates of locum intensity in 2020 and 2021 are presented in Appendix 2, Figures 29 and 32. We report the 10 trusts with the highest and lowest reported locum intensity in 2019 in Appendix 2, Table 26.

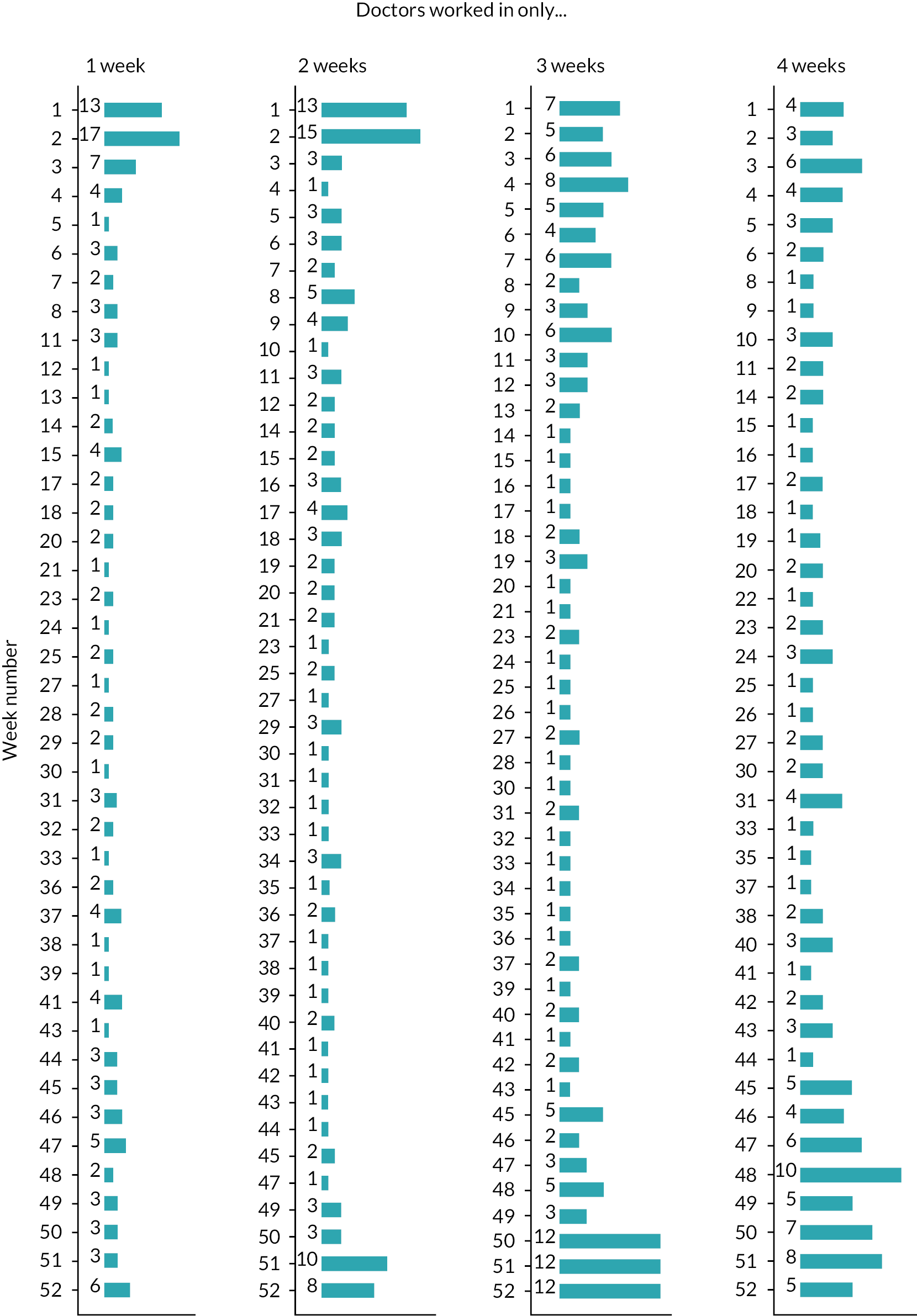

FIGURE 7.

Locum intensity in 2019, NHS trust level.

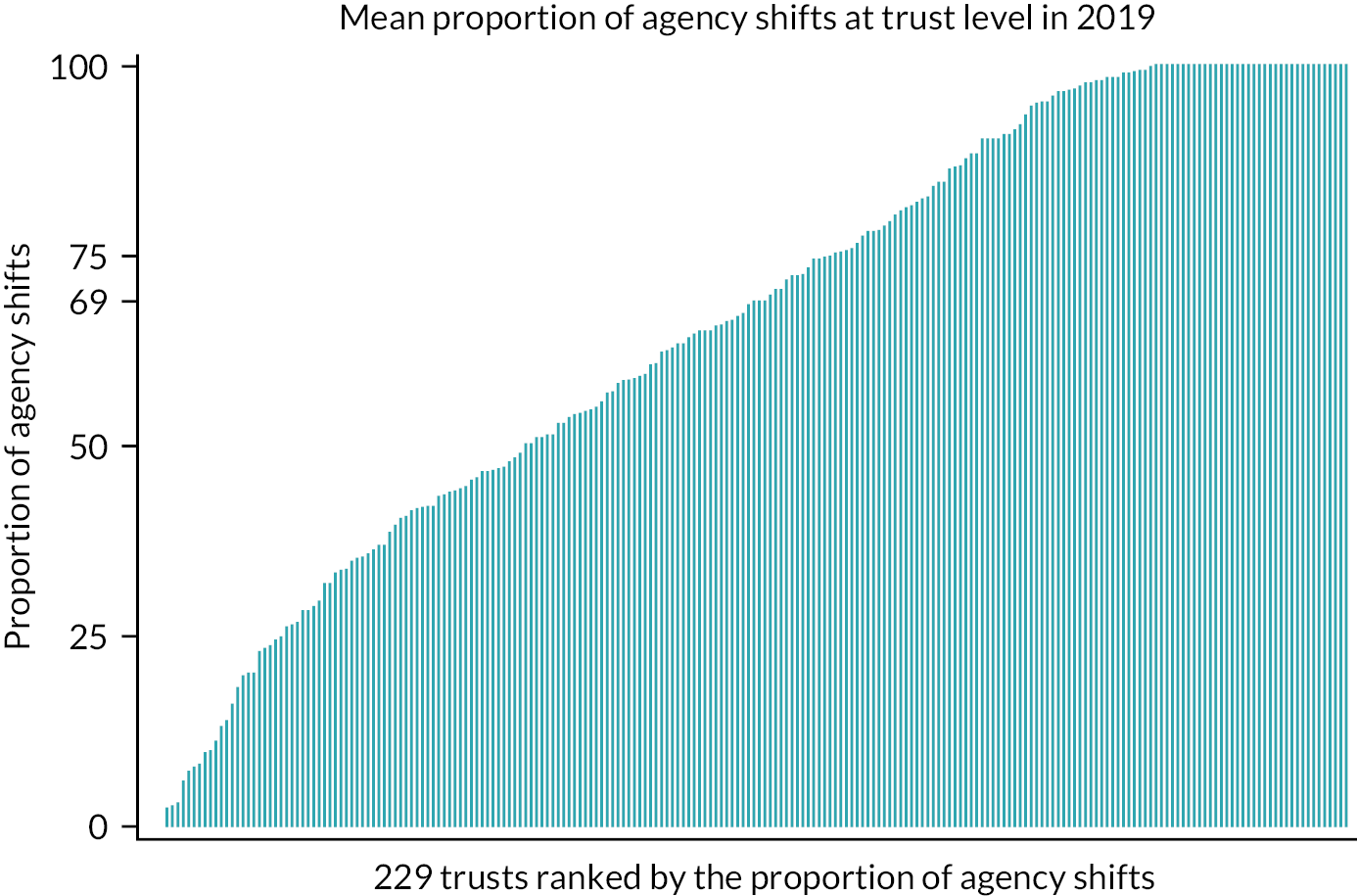

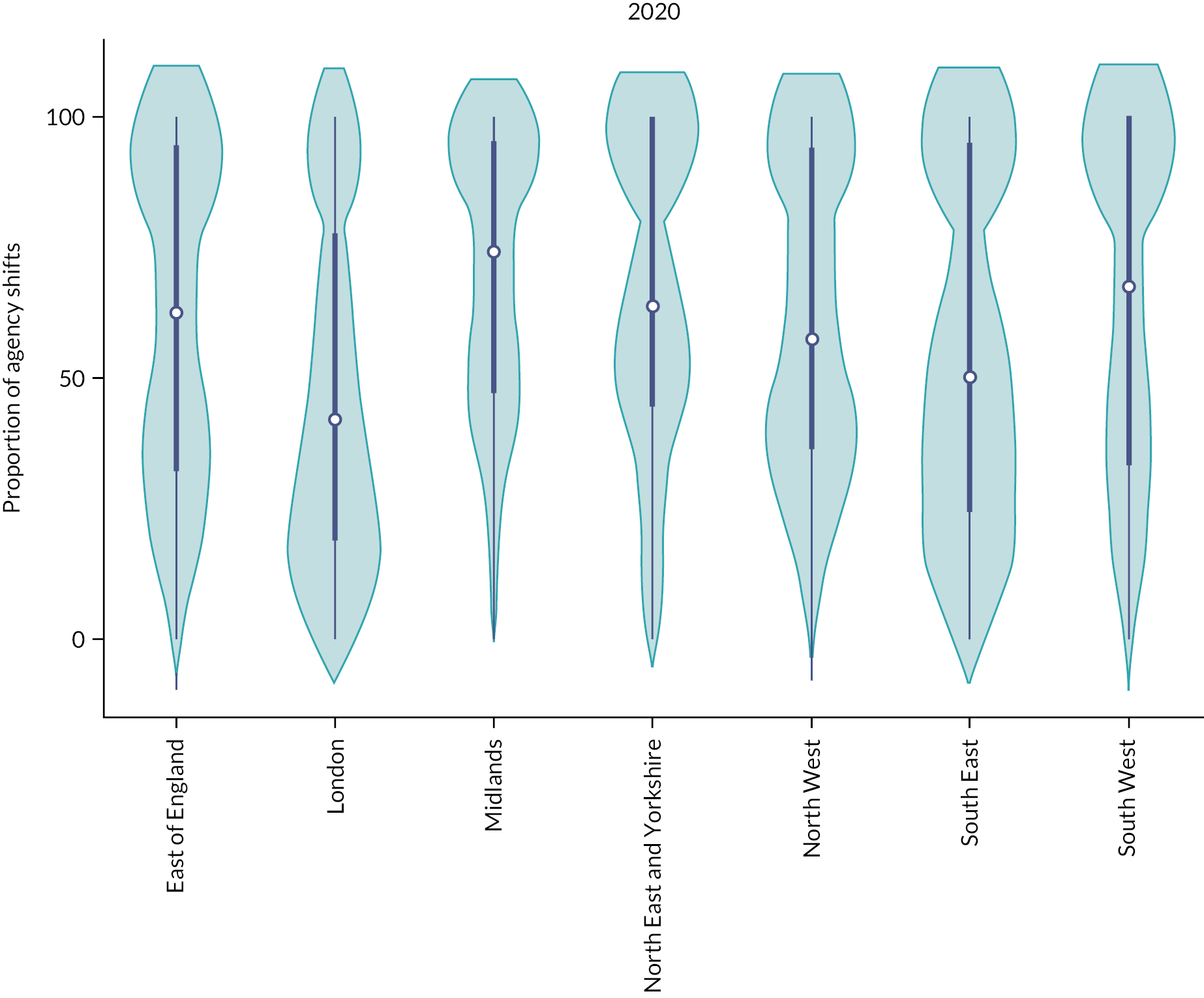

Proportion of agency shifts

The proportion of locum shifts filled by locum agency staff (rather than from staff banks) ranked from low to high at the trust level is depicted in Figure 8. The use of agency shifts varied substantially across trusts in 2019 with a mean of 66.1% (SD = 28.5%; median = 68.9%; 25th–75th centile = 43.5–95.8%). Half of trusts51 reported 100% of shifts filled by agency staff at some point in 2019, of which 24 trusts reported that shifts were filled entirely by agency staff in every week. Eight ambulance, one acute, one mental health and one community trust reported zero agency shifts in every reporting week in 2019. We present the ranked proportion of agency shifts for 2020 and 2021 in Appendix 2, Figures 30 and 33.

FIGURE 8.

Proportion of agency shifts in 2019, NHS trust level.

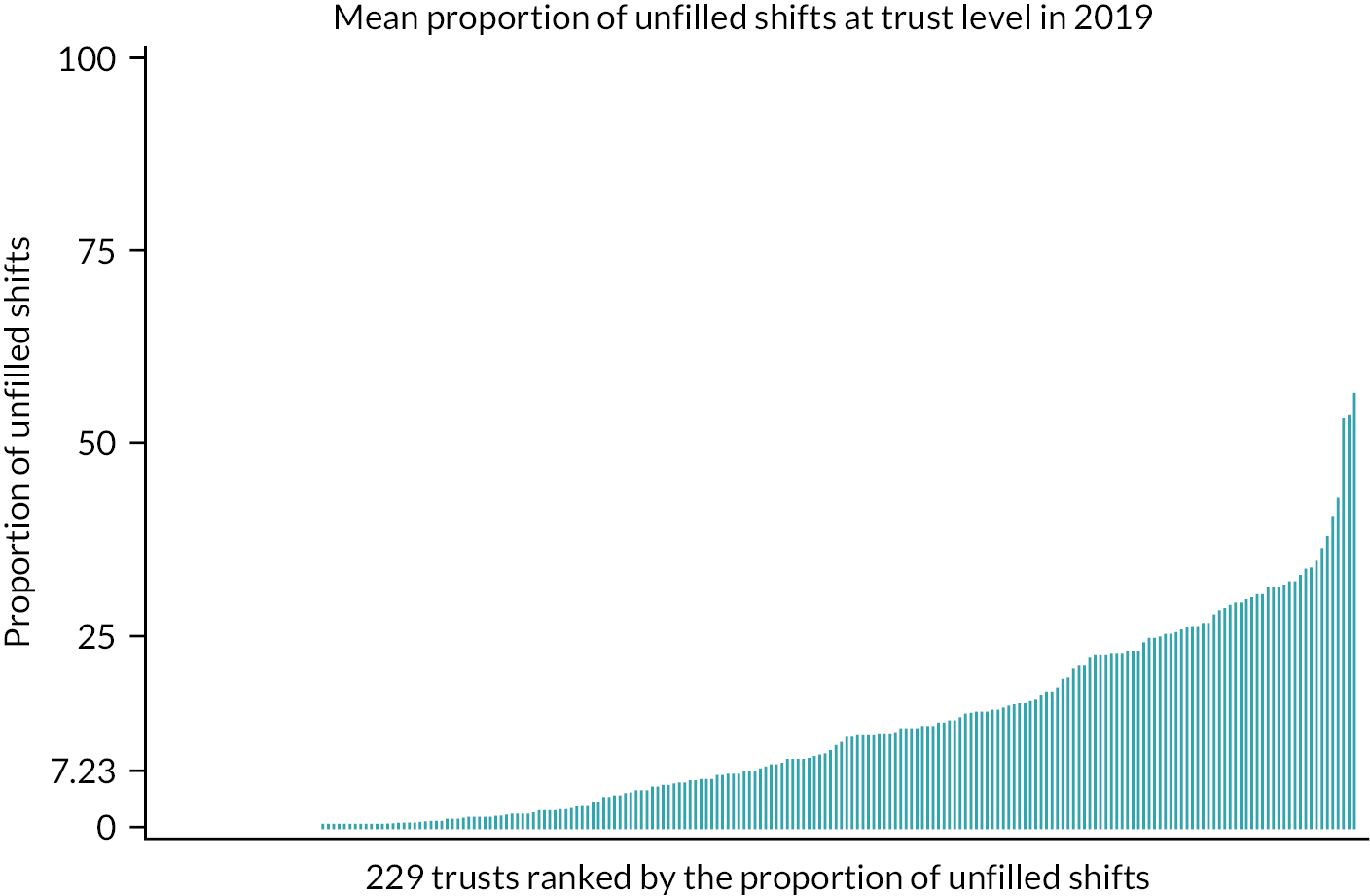

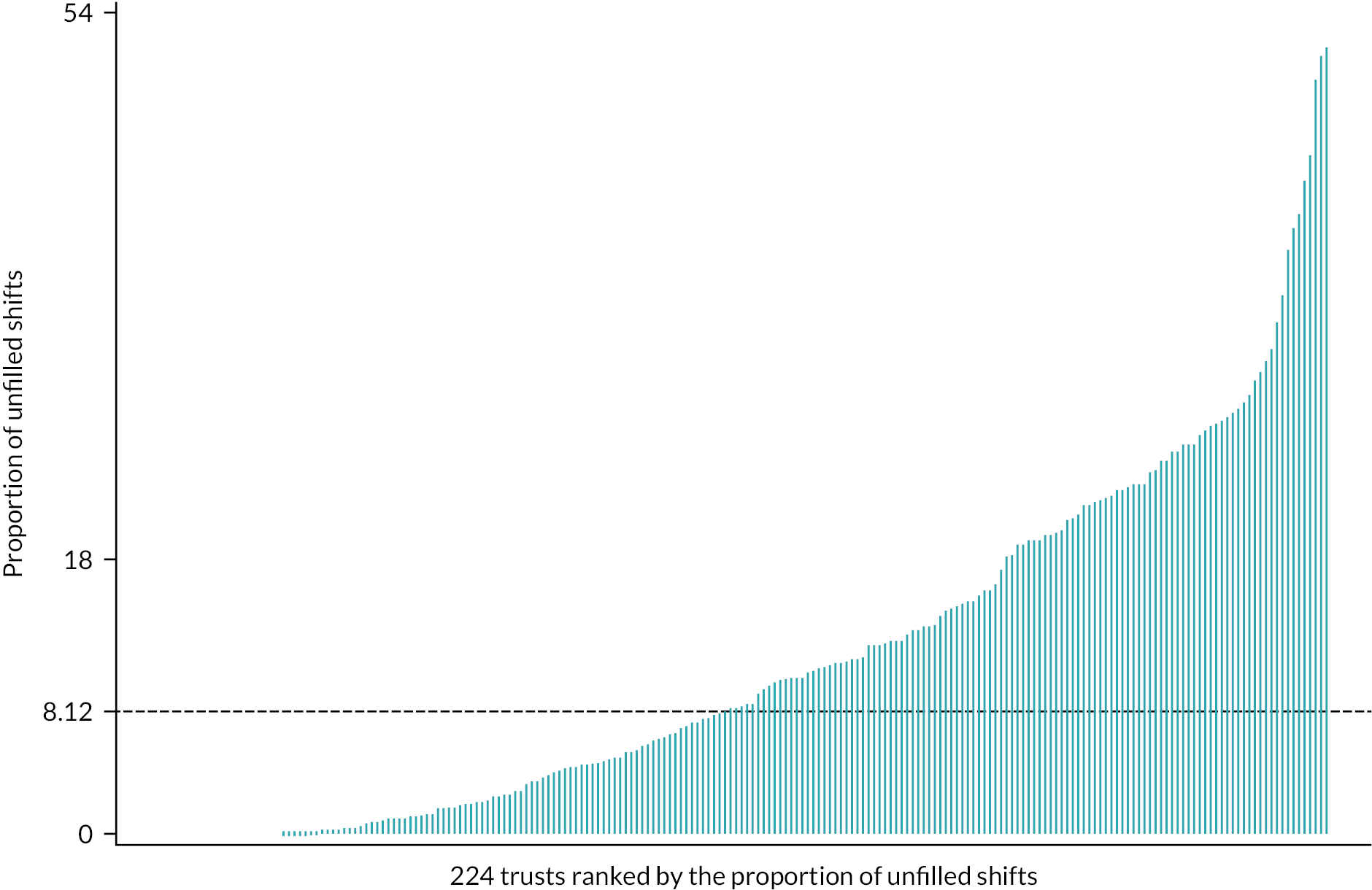

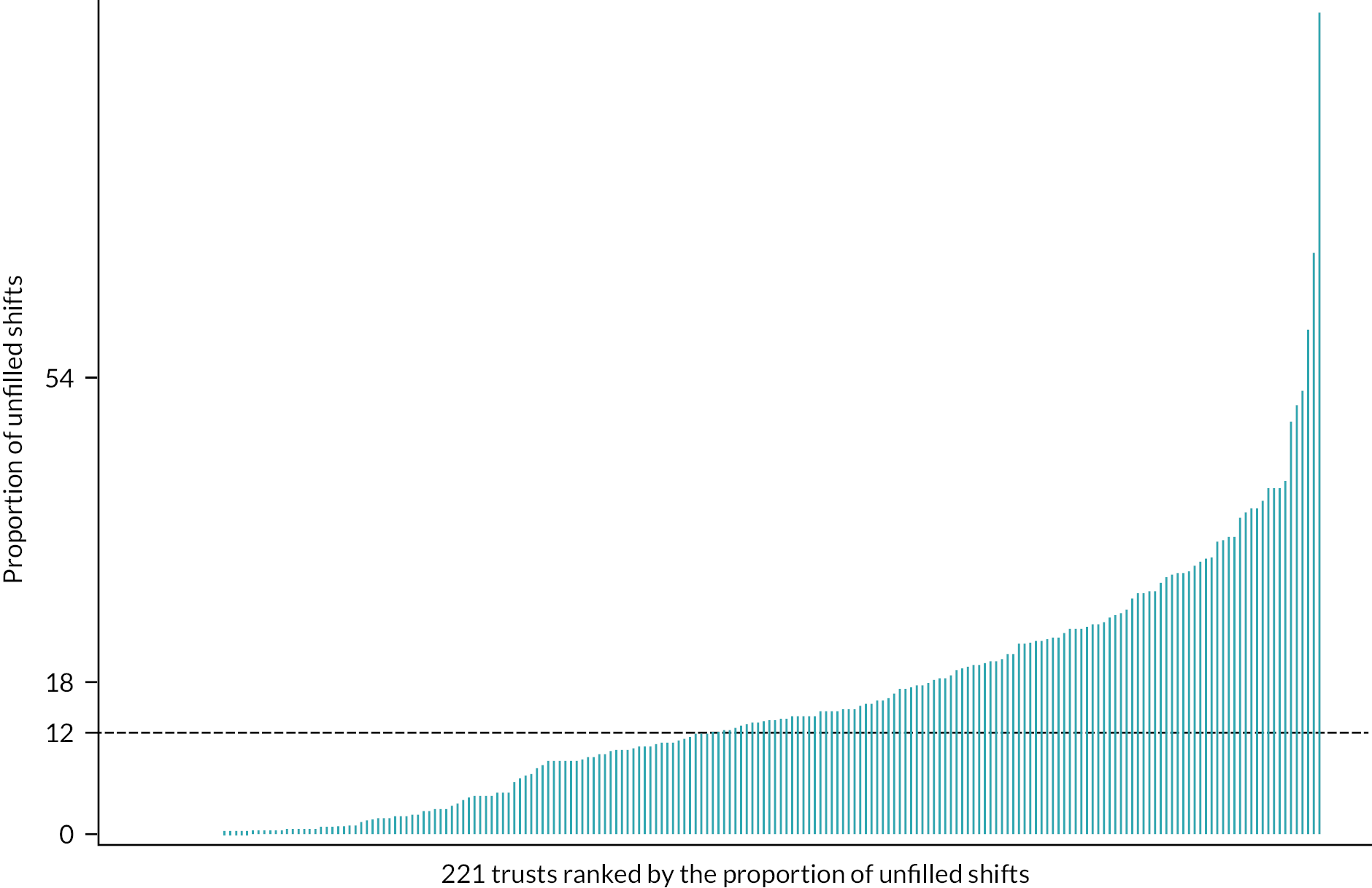

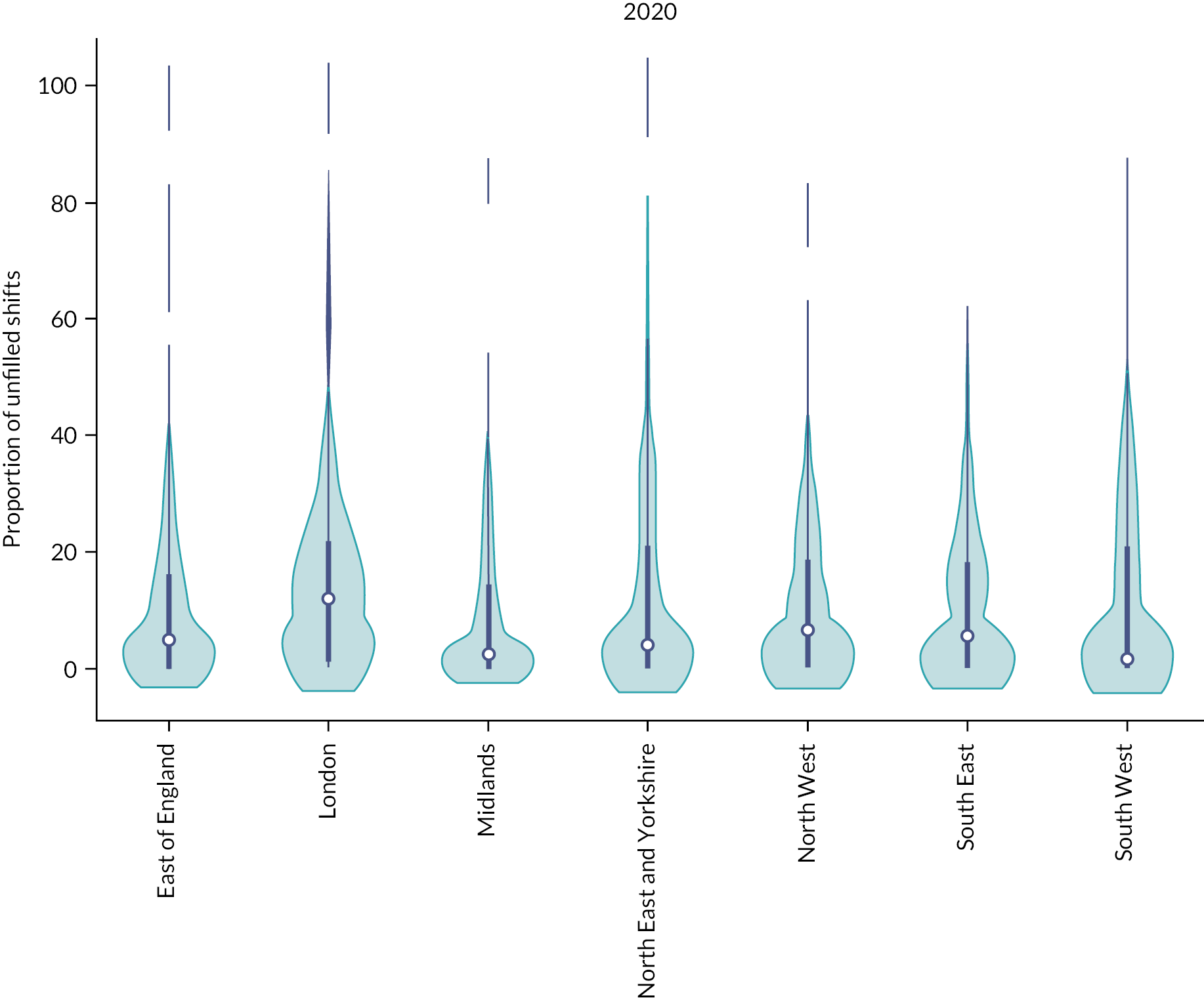

Proportion of unfilled shifts

In Figure 9, trusts are ranked from low to high on their proportion of unfilled shifts. Overall, trusts were able to fill the majority of their requested shifts either via bank or agency staff, but we observed substantial variation. The mean proportion of unfilled shifts was 11.3% (SD = 11.9%; median = 7.23%; 25th–75th centile = 0–18.1%). Seven ambulance and one acute trust did not request any shifts at any point in 2019. The ranked proportions of unfilled shifts for 2020 and 2021 are presented in Appendix 2, Figures 32 and 34.

FIGURE 9.

Proportion unfilled shifts in 2019, NHS trust level.

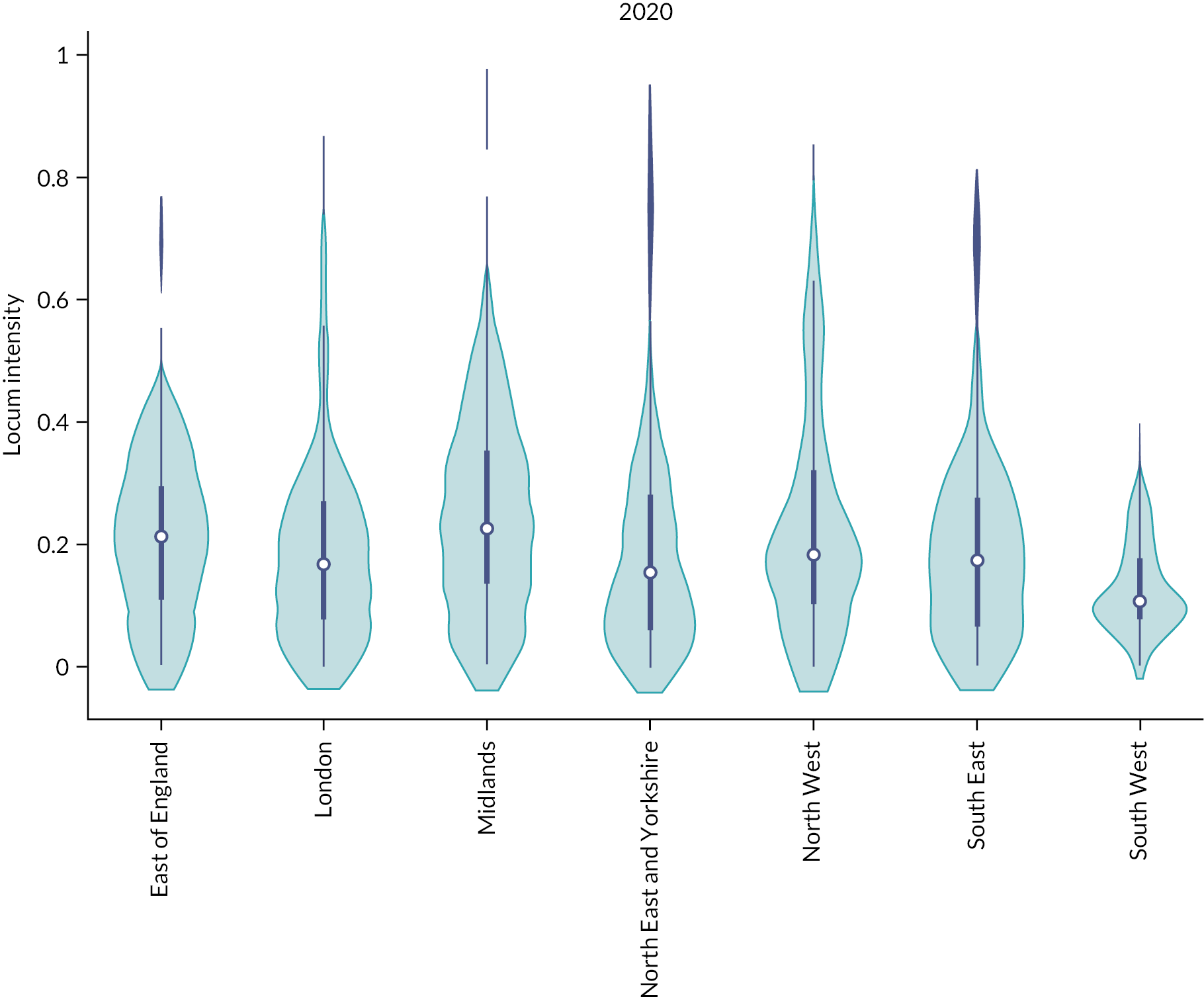

Regional variation in locum use

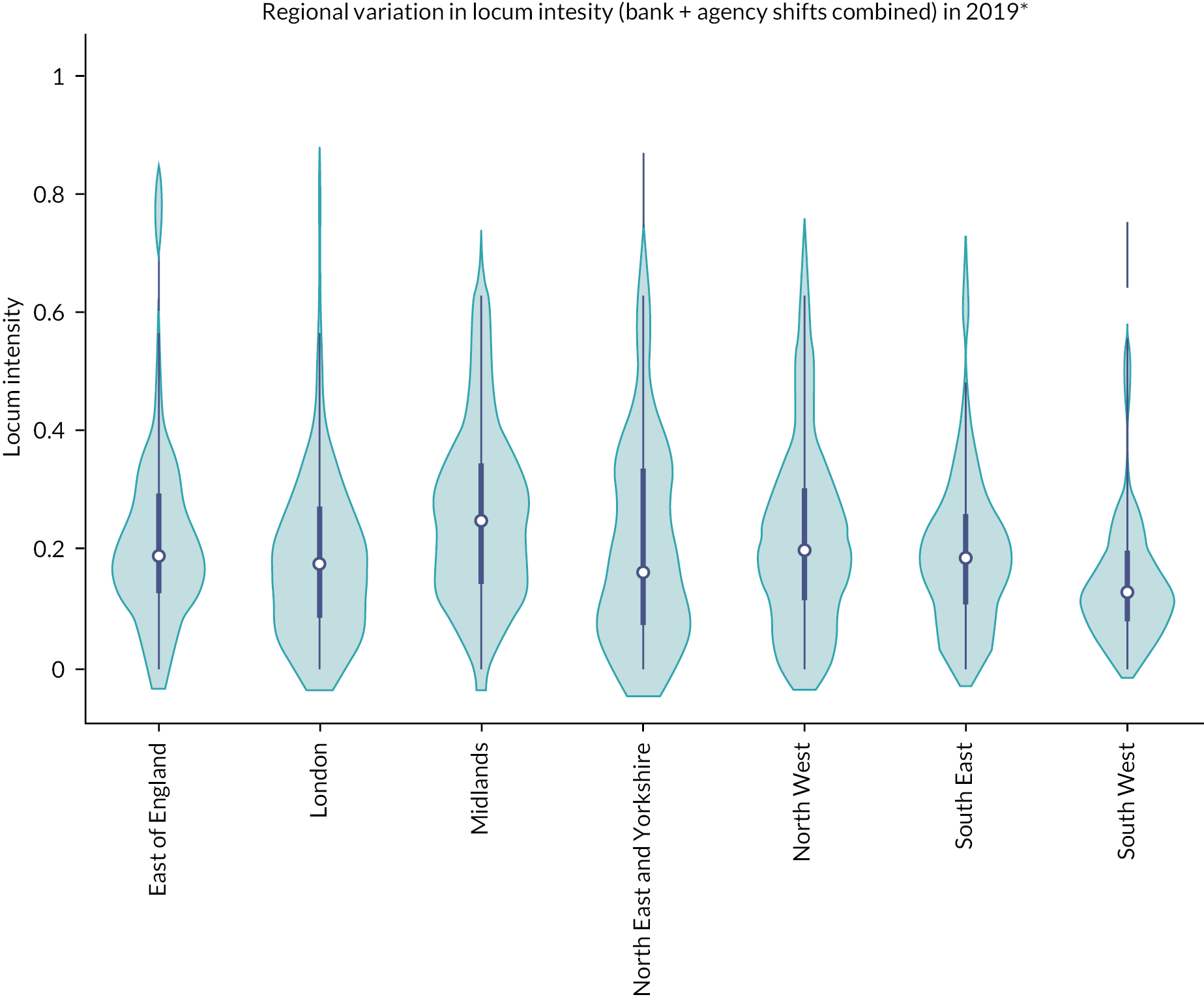

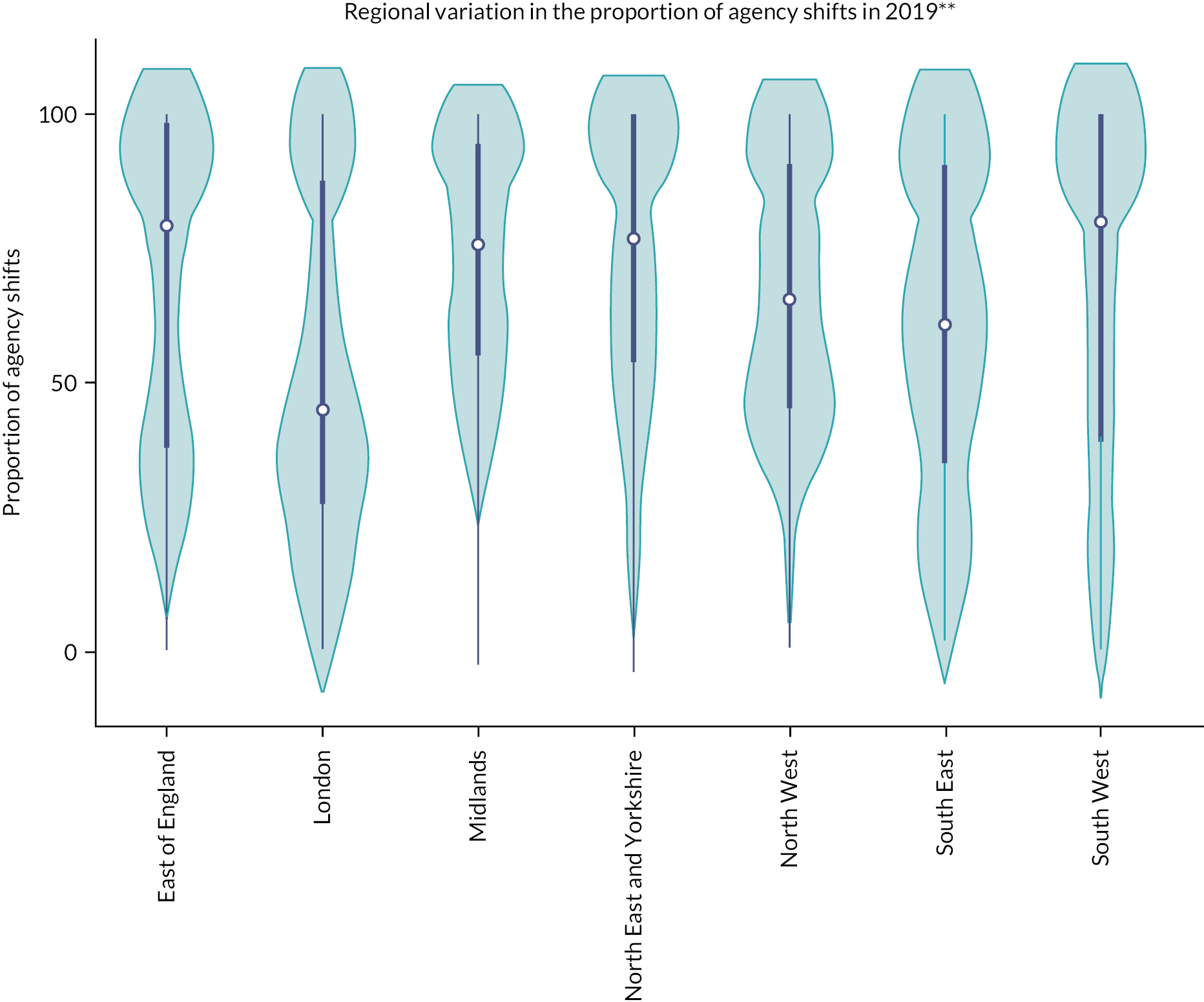

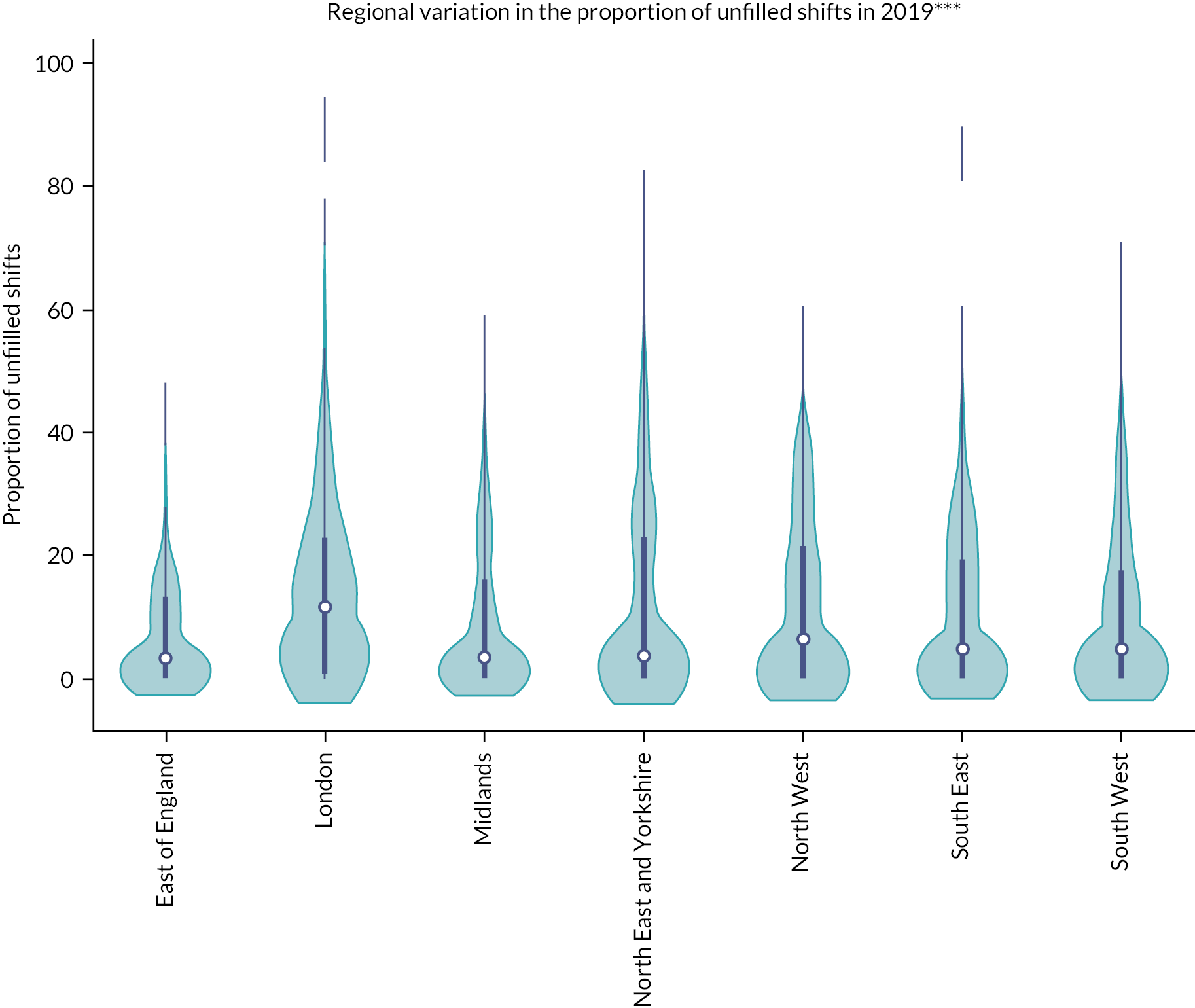

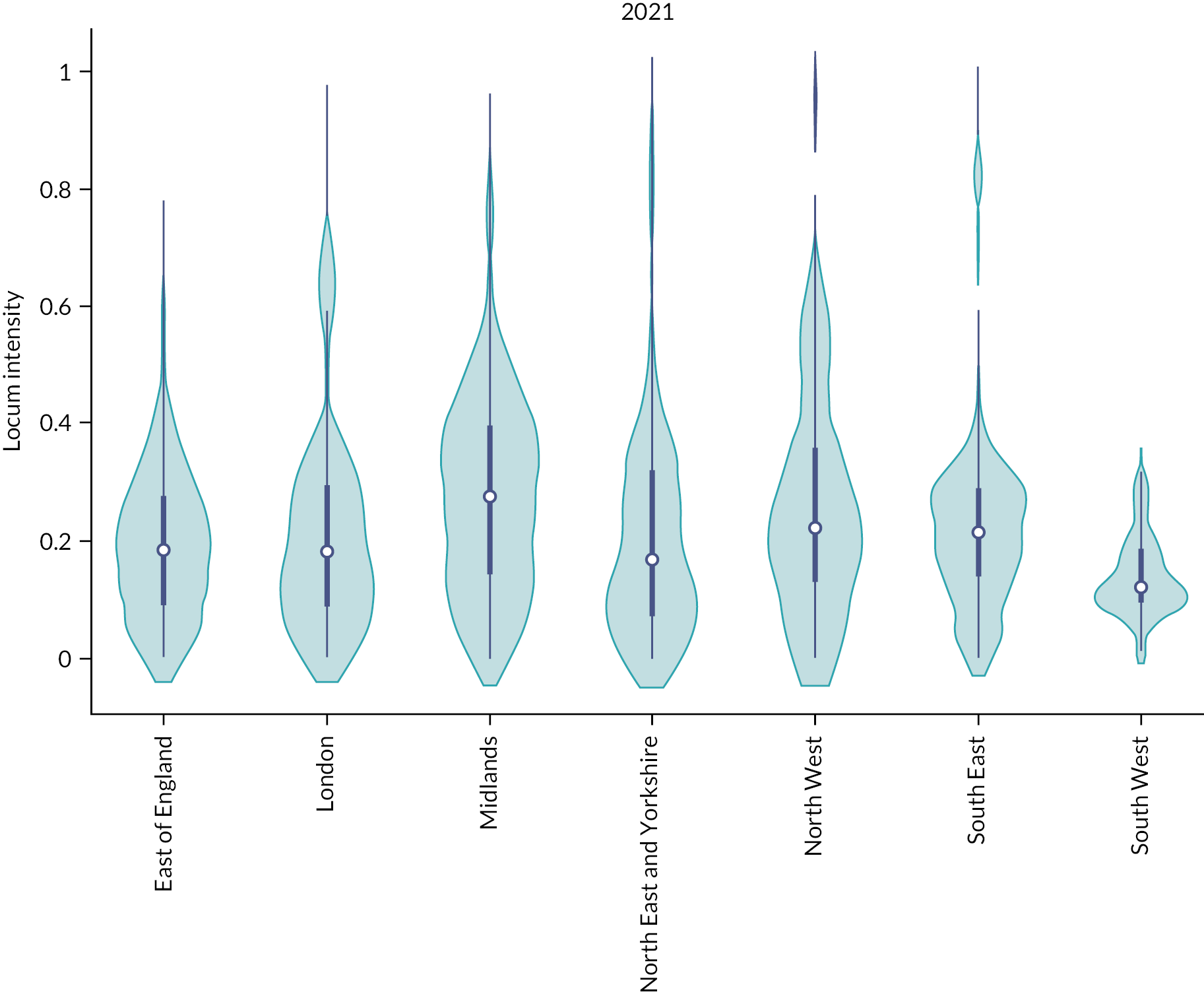

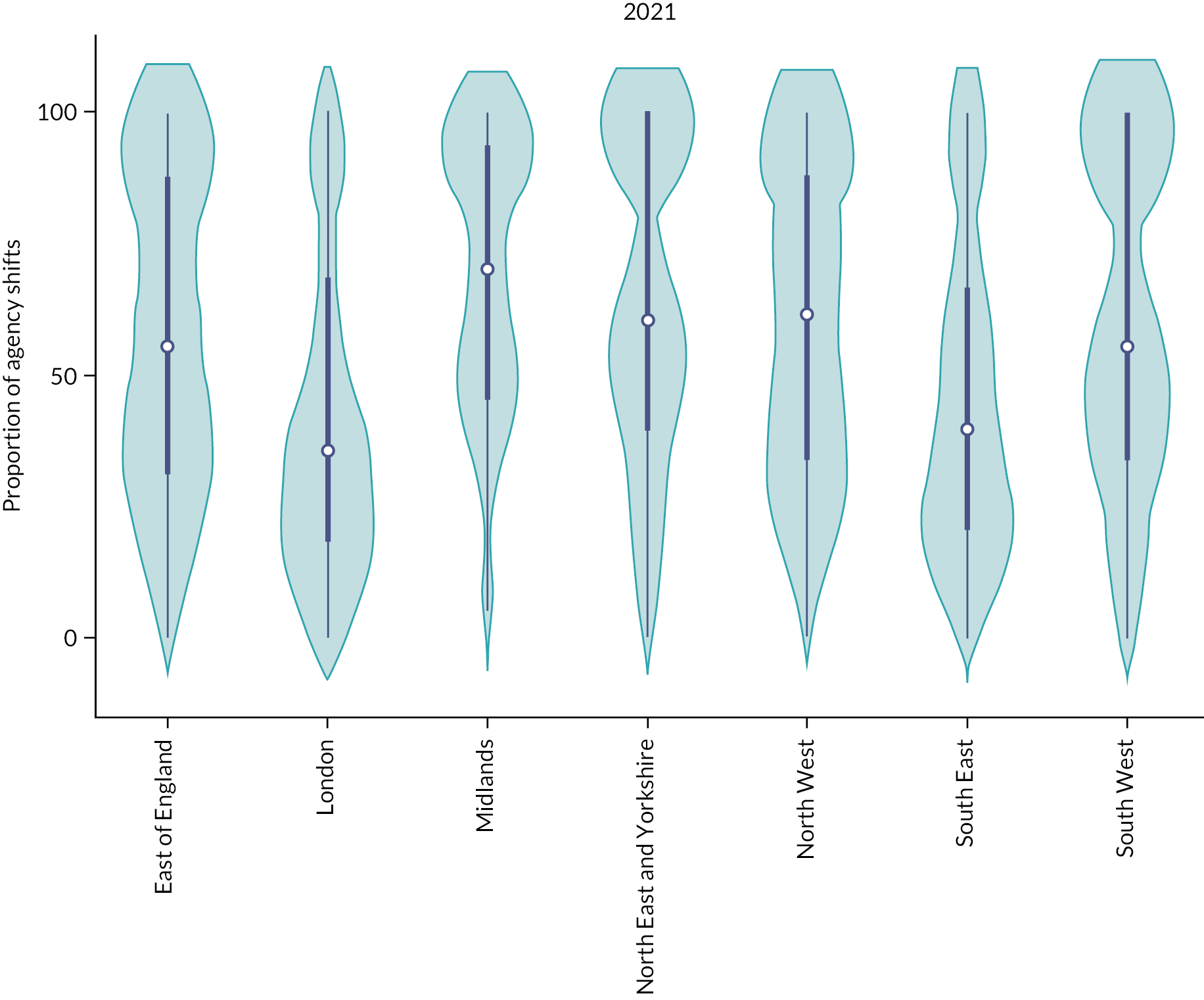

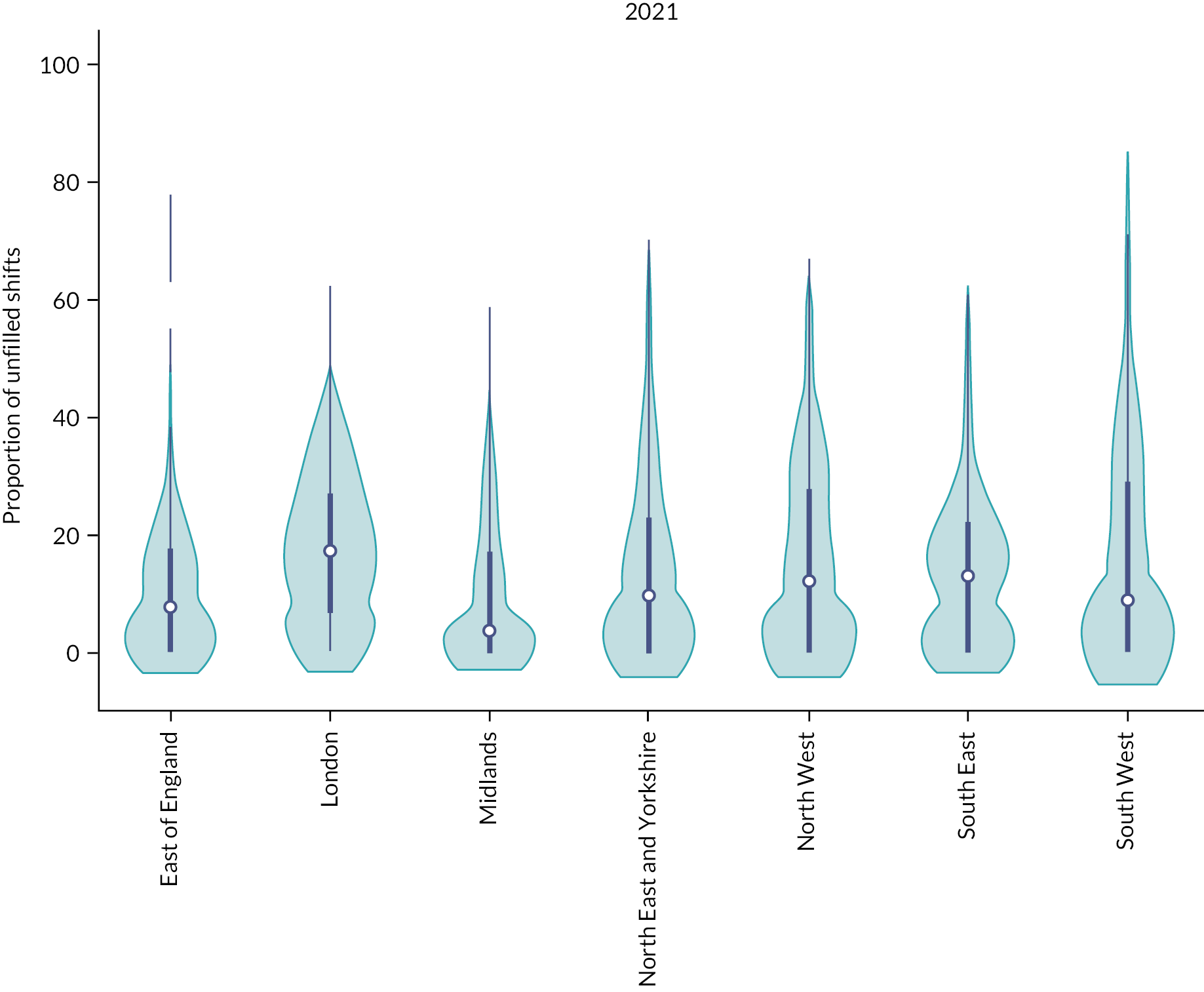

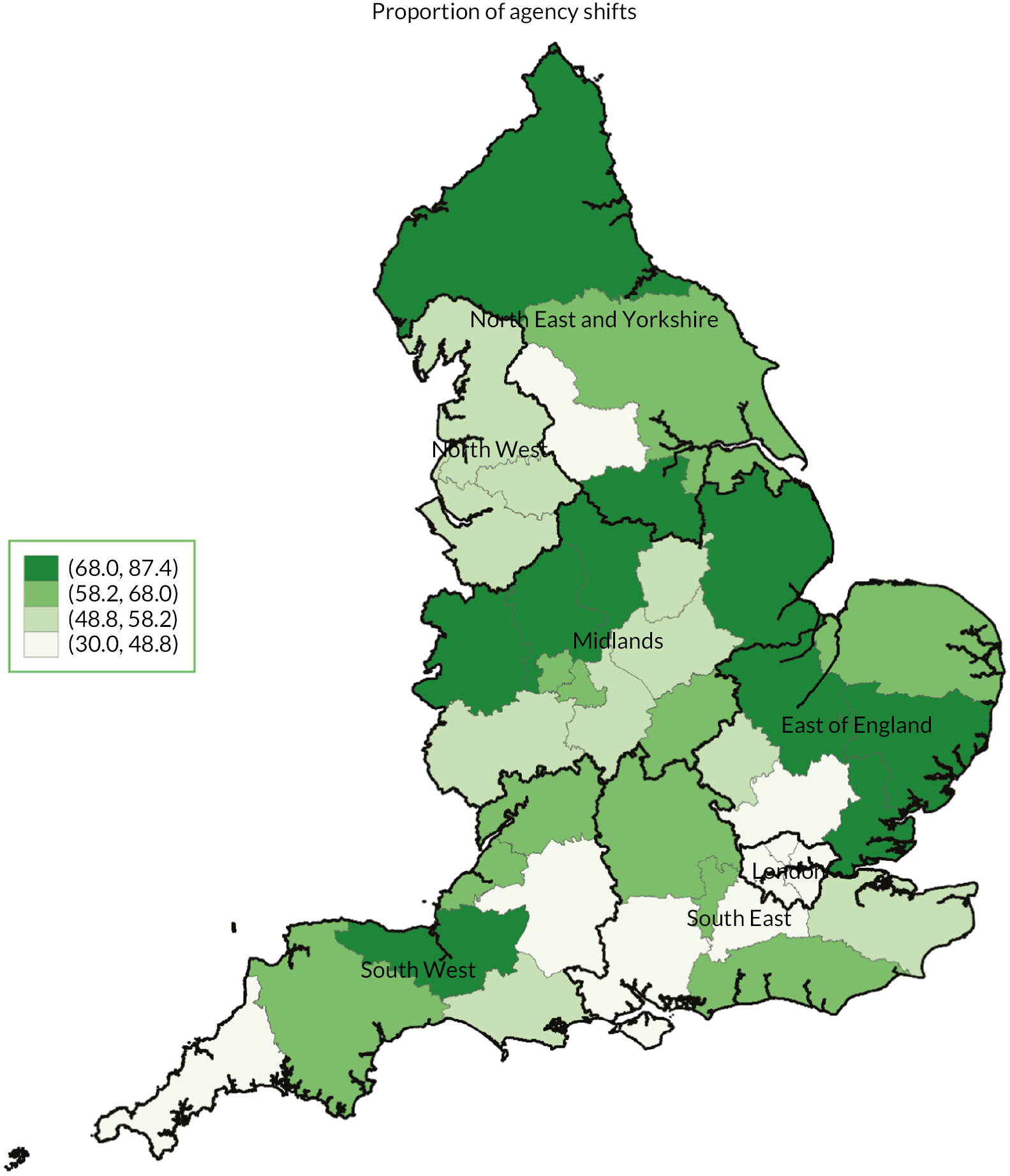

In Table 4, we present descriptive statistics on outcomes and trust characteristics at the regional level for 2019. Figure 9 shows regional variation in outcomes at the trust level in 2019. At the regional level, median locum intensity varied substantially from 0.13 in the South West of England to 0.26 in the Midlands (Table 4 and Figure 10). We also observed large variation in the proportion of agency shifts across regions. Trusts in London filled the lowest proportion of shifts using agency staff with a median of 44.8%, while trusts in the East of England filled the highest with a median of 78.1% (Table 4 and Figure 11). Trusts in the East of England filled requested shifts more successfully with unfilled shifts of 3.25%, whereas trusts in London had unfilled shifts of 11.6% (Table 4 and Figure 12). Regional variation for the three outcomes in 2020 (Figures 35–37) and 2021 (Figures 38–40) is presented in Appendix 2.

FIGURE 10.

Regional variation in locum intensity, 2019. Figure includes data from 222 NHS trusts in 2019, adjusted for permanent doctor FTE.

FIGURE 11.

Regional variation in the proportion of agency shifts, 2019. Figure includes data from 229 NHS trusts in 2019.

FIGURE 12.

Regional variation in the proportion of unfilled shifts, 2019. Figure includes data from 229 NHS trusts in 2019.

| East of England | London | Midlands | North East and Yorkshire | North West | South East | South West | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locum intensity | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.13 |

| Proportion of agency shifts (%) | 78.1 | 44.8 | 75.6 | 74.7 | 65.3 | 60 | 77.9 |

| Proportion of unfilled shifts (% of requested shifts) | 3.25 | 11.6 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 6.5 | 4.8 | 5 |

| Full-time doctor FTE | 803.3 | 869.1 | 569 | 715.5 | 612.6 | 1013 | 701.1 |

| Trust types | |||||||

| NHS general acute trusts (n) | 16 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 17 | 17 |

| Acute – NHS specialist trusts (n) | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 1 | – |

| Mental health trusts (n) | 4 | 10 | 12 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| Community health (n) | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 5 | – |

| Ambulance service (n) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

We investigated spatial variation within and between regions using spatial maps at the STP level (see Appendix 2, Figures 41–43). Substantial variability was observed for all three outcomes both within and between regions. High levels of locum intensity were concentrated in the Midlands, the North East and Yorkshire and the North West. The South East and South West ranked among the lowest in terms of locum intensity. High proportions of agency shifts were observed in areas in the Midlands, the East of England and the North East and Yorkshire. London had by far the lowest proportion of agency shifts. The proportion of unfilled shifts was high in areas in London, the Midlands and the South West and low in the East of England.

Results from regression analyses

The regression analyses results using the three different outcomes are presented in Table 5. The results are reported as IRRs for the coefficients of interest. Sensitivity analyses, where we excluded ambulance and community trusts and examined the effects of deprivation on our three outcomes were nearly identical to the results from the main analyses. Deprivation did not appear to have any discernible effect on any of the three outcomes. The results from the sensitivity analyses are provided in Appendix 2, Table 27.

| Locum intensity | Agency shifts | Unfilled shifts | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trust-level aggregate FTE (reference group is quintile 1) | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group |

| Quintile 2 | 0.784 (0.527 to 1.676) | 0.945 (0.734 to 1.218) | 0.936 (0.449 to 1.952) |

| Quintile 3 | 0.496 (0.299 to 0.825) | 0.937 (0.675 to 1.301) | 1.848 (0.735 to 4.645) |

| Quintile 4 | 0.611 (0.349 to 1.072) | 0.883 (0.617 to 1.264) | 1.878 (0.704 to 5.011) |

| Quintile 5 | 0.347 (0.187 to 0.644) | 0.796 (0.530 to 1.195) | 2.447 (0.826 to 7.251) |

| Trust type (reference group is NHS general acute trust) | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group |

| NHS specialist trust | 0.285 (0.174 to 0.468) | 1.510 (1.086 to 2.100) | 0.233 (0.091 to 0.598) |

| Mental health trust | 0.966 (0.628 to 1.486) | 1.576 (1.198 to 2.073) | 1.062 (0.508 to 2.221) |

| Ambulance service | 55.43 (20.56 to 149) | 0.033 (0.008 to 0.147) | 3.894 (0.453 to 33.14) |

| Community service | 1.443 (0.780 to 2.670) | 0.962 (0.641 to 1.445) | 1.360 (0.471 to 3.930) |

| CQC ratings (reference group is good and outstanding) | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group |

| Inadequate and requiring improvement | 1.495 (1.191 to 1.877) | 1.044 (0.907 to 1.201) | 1.193 (0.789 to 1.804) |

| Trust-level substantive doctor turnover rates | 1.015 (1.009 to 1.021) | 1.001 (0.997 to 1.003) | 0.995 (0.987 to 1.003) |

| Trust-level vacancy rates (FTE) | 1.000 (0.999 to 1.001) | 0.999 (0.999 to 1.001) | 0.999 (0.997 to 1.001) |

| Region (reference region is London) | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group |

| South West | 0.575 (0.361 to 0.915) | 1.447 (1.098 to 1.907) | 0.687 (0.316 to 1.493) |

| South East | 0.701 (0.472 to 1.041) | 1.349 (1.047 to 1.736) | 0.524 (0.252 to 1.092) |

| Midlands | 1.041 (0.714 to 1.520) | 1.425 (1.126 to 1.804) | 0.548 (0.276 to 1.086) |

| East of England | 0.813 (0.533 to 1.240) | 1.525 (1.167 to 1.993) | 0.402 (0.182 to 0.890) |

| North West | 1.045 (0.705 to 1.550) | 1.327 (1.035 to 1.701) | 0.855 (0.412 to 1.773) |

| North East and Yorkshire | 0.754 (0.495 to 1.150) | 1.449 (1.120 to 1.875) | 0.575 (0.269 to 1.230) |

| Constant | 0.030 (0.152 to 0.601) | 0.436 (0.283 to 0.671) | 0.117 (0.038 to 0.357) |

| Sample size | 220 | 214 | 214 |

Locum intensity

Results indicate that in 2019 trust size was a strong predictor of locum intensity. Using quintile 1 (i.e. small trust size) as the reference group, our results showed significant reductions in locum intensity for medium and very large trusts with IRRs of 0.496 (95% CI 0.299 to 0.825) for quintile 3, and 0.347 (95% CI 0.187 to 0.644) for quintile 5. As an example of interpretation, comparing quintile 1 and quintile 3 suggests a locum intensity 50.4% lower for the medium size trusts. NHS specialist trusts had a 71.5% lower locum intensity (IRR = 0.285; 95% CI 0.174 to 0.468) than NHS general acute trusts. Ambulance service trusts had 55 times higher locum intensity than NHS general acute (IRR = 55.43; 95% CI 20.56 to 149). However, this result is an artefact of the very low numbers of permanent doctors employed by ambulance trusts when compared with other trusts. CQC ratings were strongly associated with higher locum intensity with trusts rated as inadequate or required improvement having 49.5% (IRR = 1.495; 95% CI 1.191 to 1.877) higher mean locum intensity than trusts rated good or outstanding. Staff turnover rates had negligible effects on locum intensity (IRR = 1.015; 95% CI 1.009 to 1.021). Trusts in the South West had 40.25% lower locum intensity than trusts in London (IRR = 0.575; 95% CI 0.361 to 0.915).

Proportion of agency shifts

National Health Service specialist trusts and mental health trusts had 51% (IRR = 1.510; 95% CI 1.086 to 2.100) and 57.6% (IRR = 1.576; 95% CI 1.198 to 2.07) higher proportion of agency shifts than NHS general acute trusts. Ambulance service trusts had 96.7% lower proportion of agency shifts (IRR = 0.033; 95% CI 0.008 to 0.147) than NHS general acute trusts. Trusts in the East of England had the highest proportion of agency shifts compared with trusts in London (IRR = 1.525; 95% CI 1.167 to 1.993).

Proportion of unfilled shifts

National Health Service specialist trusts had 76.7% higher proportion of unfilled shifts when compared with NHS general acute trusts. Trusts in the East of England had 59.80 lower rates of unfilled shifts when compared with trusts in London (IRR = 0.402; 95% CI 0.182 to 0.890).

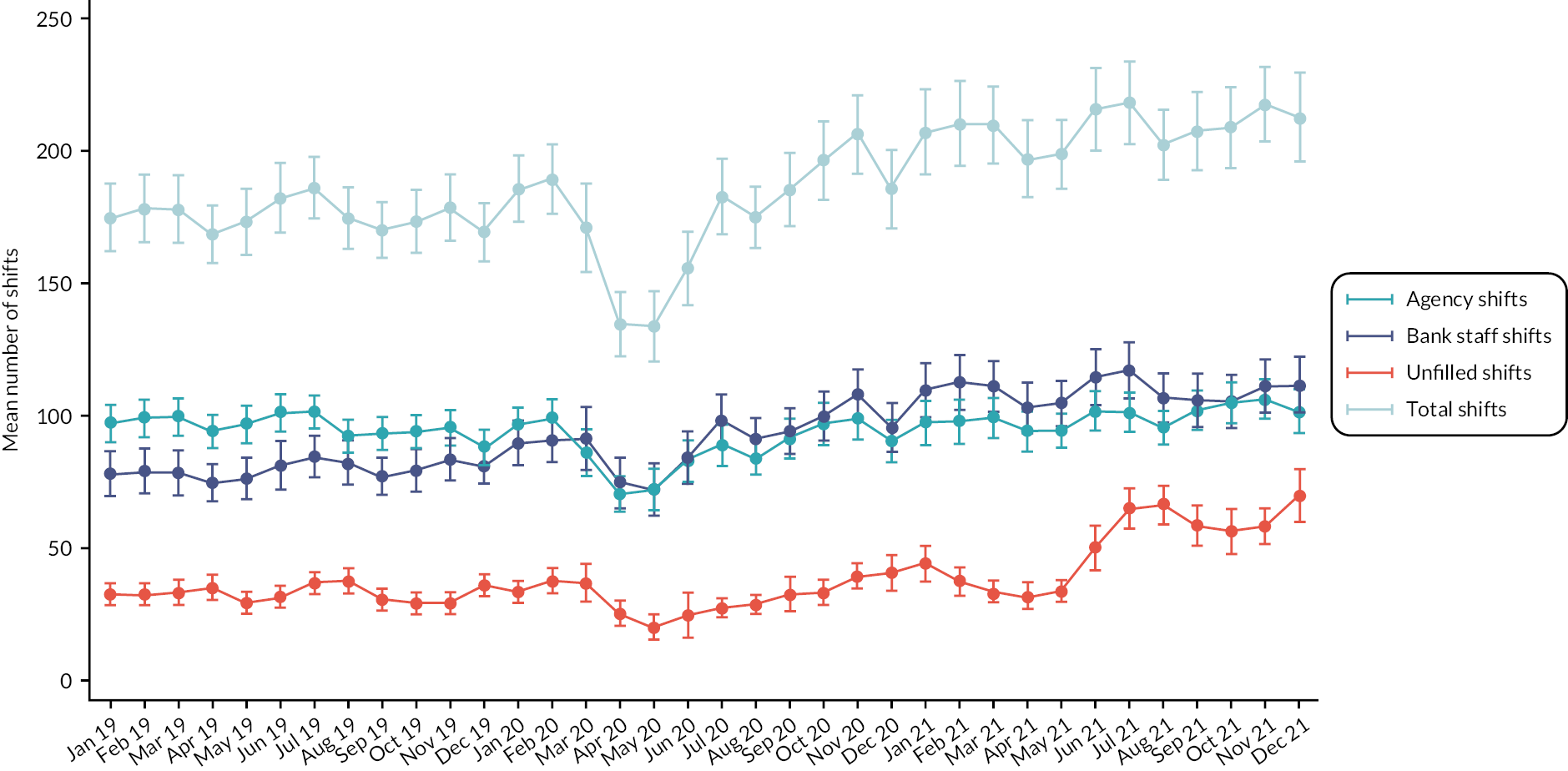

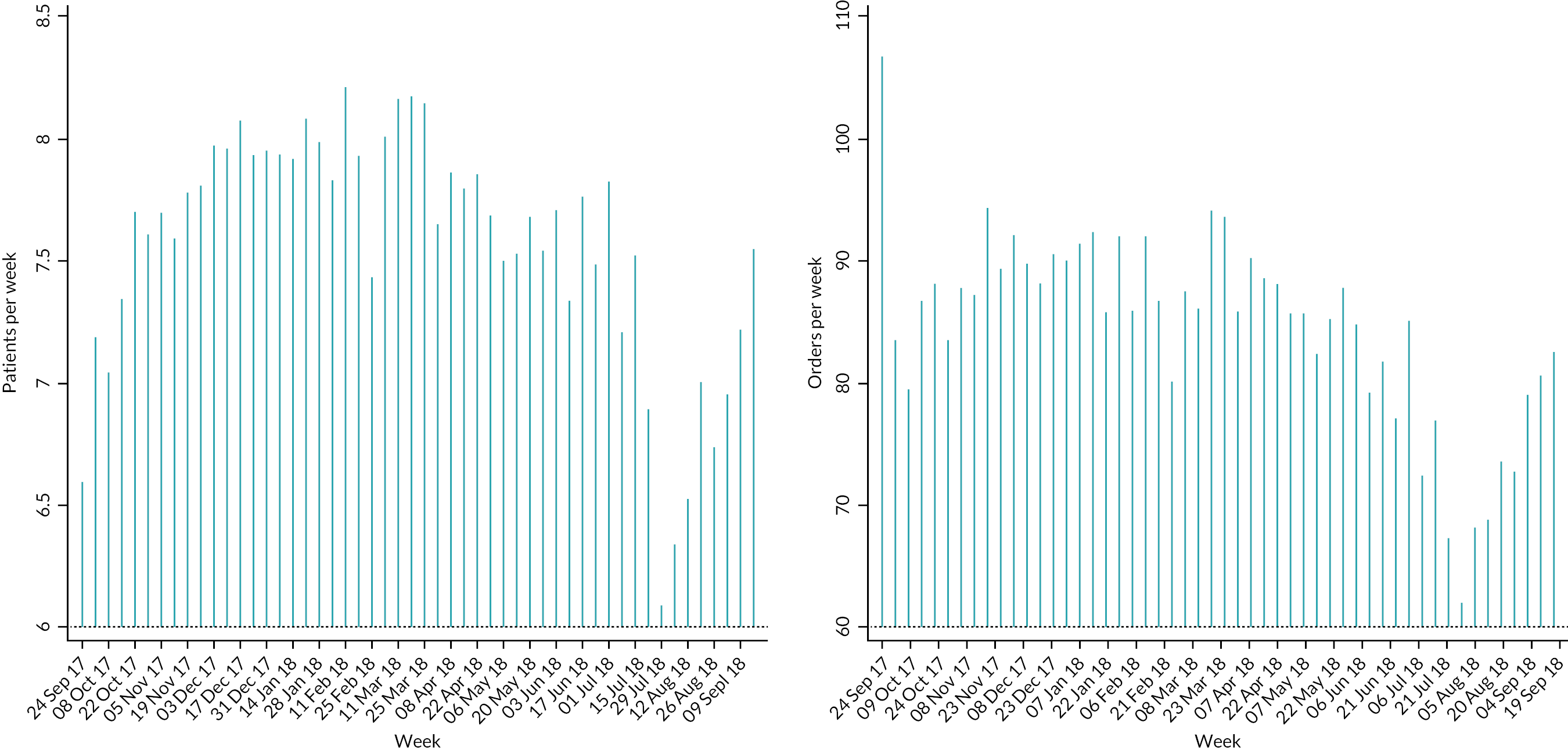

Locum use during the COVID-19 pandemic

Figure 13 shows the mean agency, bank, unfilled and total shifts per week at the trust level in 2019–21. Over time, the trust-level mean was 188.5 shifts per week (SD = 205.8), of which 95.2 (SD = 108.6) were agency shifts and 93.3 (SD = 135.8) were bank staff shifts and the mean of unfilled shifts across all trusts was 38.5 (SD = 85.2). Pre pandemic, we observed a small variability in the mean number of agency, bank and unfilled shifts. In March 2020, there was a steep decline (approximately 18%) in agency and bank shifts per trust as very few trusts reported locum use between March and April. In the third quarter of 2020, we observed an increase (approximately 15%) in agency and bank shifts per trust. In 2021, there was a steep steady increase in the mean number of unfilled shifts from 33.9 to 50.1 (47.8% increase) between May and June, which was sustained throughout 2021 and reached a peak of 69.2 unfilled shifts per trust in December 2021.

FIGURE 13.

Variation in mean number of locum shifts over time, 2019–21.

Discussion

Summary

This study provides evidence on the extent of locum use and factors associated with locum use in NHS trusts in England for the period 2019–21. Our findings show that, on average, 4.4% of medical staffing in NHS trusts in 2019 was provided by locum medical staffing. Trusts with lower CQC ratings, acute trusts and smaller trusts had higher locum intensity. We observed moderate variability in locum use across regions and greater variability in the proportion of shifts filled by agency locums. During 2021, the proportion of shifts that were unfilled reached a 3-year high. Our findings can help inform NHS organisations about the extent of their locum use and can provide important information about the effective planning of the NHS workforce.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is the national scope and coverage of every NHS trust of England. For the first time, using routinely collected data on locum use, we quantified the extent of locum use, sourced from agencies or banks, across all NHS trusts for the period 2019–21. We also explored whether trusts were able to cover sufficiently for staff shortages and identified drivers of locum use at the trust level for the whole of England. We reveal the impact of COVID-19 on locum use in NHS trust. Our analyses allowed us to control for measured trust and population characteristics.

However, this study has some important limitations which should be considered when interpreting the key findings. First, the NHS Improvement data do not reveal information on locum use by specialty and there may be substantial variations across specialties which we could not identify. Second, although NHS Improvement collects data on the number of locum shifts, it does not collect the shift duration or locum FTE which would allow a more straightforward comparison with permanent doctor FTE. We had to assume that shift lengths for permanent and locum doctors were broadly equivalent in order to estimate the proportion of medical staffing provided by locum doctors. Third, there may also exist variability in locum use between locums of different types (e.g. infrequent or long-term locums) or durations apart from the agency/bank categories, which has been observed in general practice. 36 Some locums may be employed for several months52 often to cover a vacancy which has not been filled, while others may cover short-term absences such as illness for as little as one or two shifts and we did not have that information. Fourth, the data set has no information on how well NHS trusts use their locum workforce such as the provision of adequate induction, training, supervision and feedback in accordance with National Health Service England (NHSE) guidance. Prior work15 suggests that locum performance is driven more by organisational attributes such as these than by the characteristics of the locum doctors themselves.

Interpretation of findings

The use of locum doctors is important because of the high level of spending it entails and because of concerns about the quality and safety of locum staffing arrangement. 9 Our study shows that the actual level of locum use, as a proportion of overall medical staffing, is relatively low on average, but varies considerably, with some trusts having much higher use of locums and some trusts relying overly on more expensive agency locums rather than using staff banks.

Some of this variation may be explained by organisational characteristics. For instance, larger trusts may be more able to cover workforce gaps within their own staff without needing locums, and specialist/tertiary trusts may find it easier to recruit and provide attractive workplaces compared with general acute trusts. Mental health trusts may face particular staffing shortages, which may explain the high level of agency locum use.

Our results show significantly higher locum intensity in trusts with worse CQC ratings (inadequate or requires improvement). It may be that these trusts find it harder to recruit and fill workforce gaps, but it could also be hypothesised that sustained high levels of locum use may impact quality and safety and hence affect CQC ratings.

The introduction of the first UK lockdown brought significant reductions in the numbers of both bank and agency locum doctors employed across NHS trusts, due to cancellations in elective care. However, shortly after, trusts started employing more locums likely in an effort to tackle excessive workload and increasing demand for healthcare services during the pandemic. Furthermore, in 2021, we observed an increase in the mean number of shifts filled by bank compared with the previous years and this was accompanied with a stable trend in agency shifts and an increase in the number of unfilled shifts. This suggests that trusts were meeting the increased demand with bank staff, which is in line with the new agency rules enacted by NHS Improvement in 2019 that aim to reduce reliance on agency staff. 53 Despite the increase in the mean number of total shifts, trusts appeared to be less able to fill the number of shifts they were requesting over the second half of 2021. This may suggest a persisting high workload for permanent doctors that trusts were unable to address with the use of locum doctors over that period.

Chapter 5 The use of locum doctors: findings from a national survey of National Health Service trusts in England

Aims

This chapter explores the use of locum doctors in NHS trusts in England through a national survey of NHS trusts. Locum working has benefits for individual doctors and organisations but there are concerns about the impact of locum working on continuity of care, patient safety, team function and cost. 9,54,55 The aim of this study was to conduct a national survey of NHS trusts to explore locum work, and better understand why and where locum doctors were needed; how locum doctors were engaged, supported, perceived and managed; and any changes being made in the way locums are used.

Methods

Questionnaire design

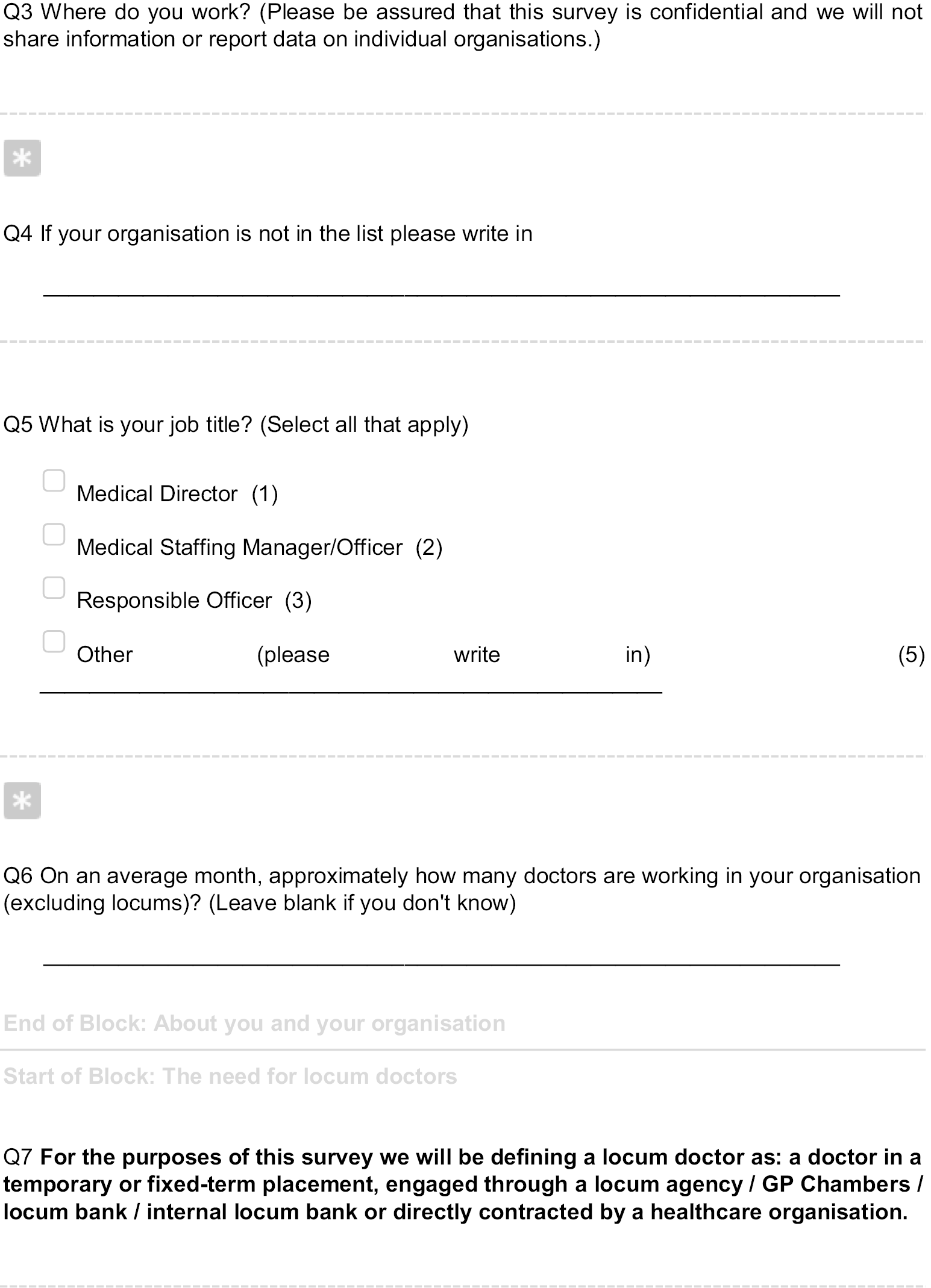

The survey was developed with input from stakeholders including a medical director, a research director, a senior leader in medical staffing, the chair of our PPI forum, a GP locum and a managing director of a locum agency. Drafts of the survey were sent out via e-mail and stakeholders responded with comments, and where possible in-depth discussions were conducted with stakeholders to gain further feedback. The research team discussed the comments received and made appropriate changes.

The study was approved by the Health Research Authority – National Research Ethics Service England, and the initial page of the survey stated that by completing the survey participants were agreeing to take part in the study.

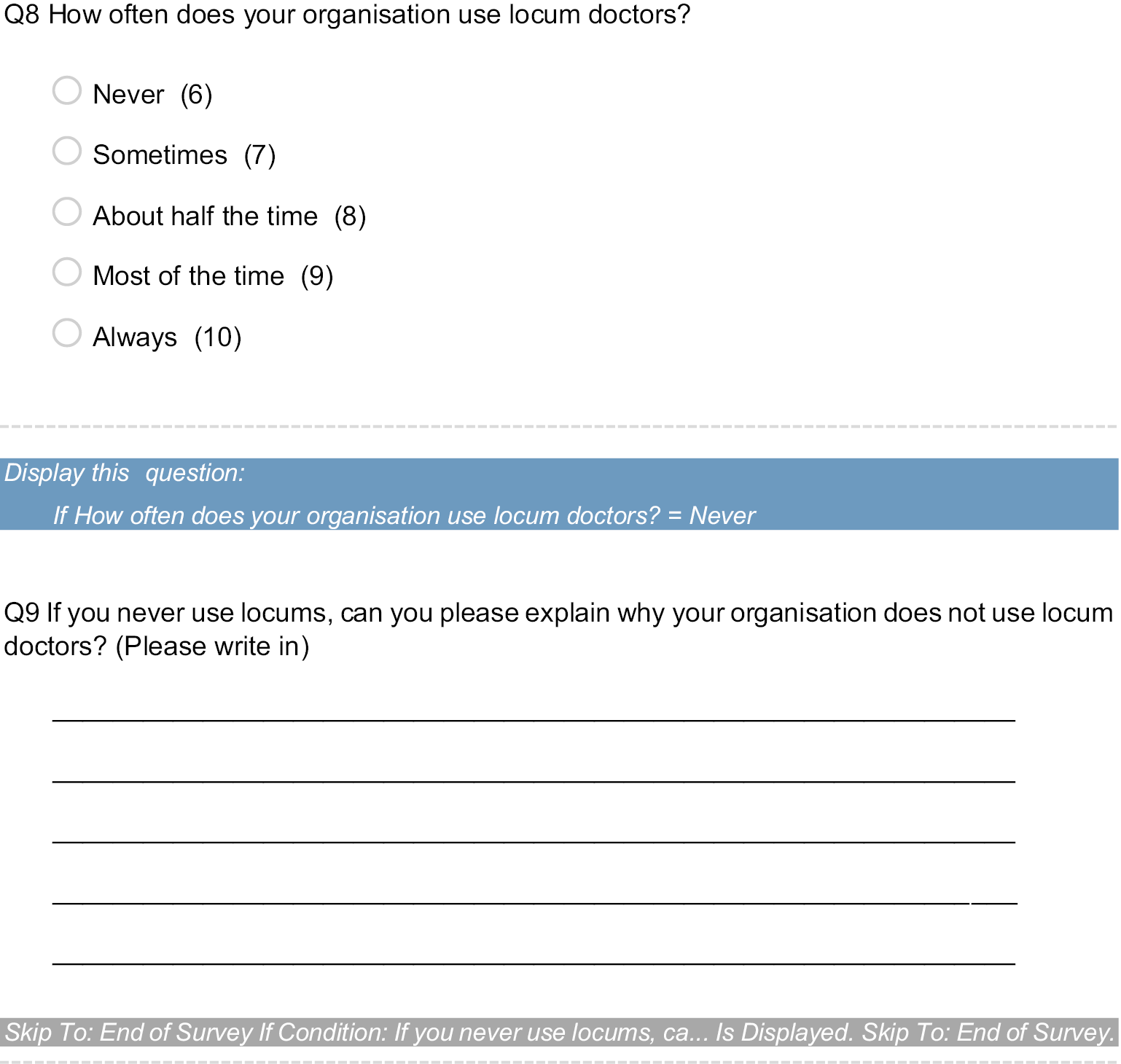

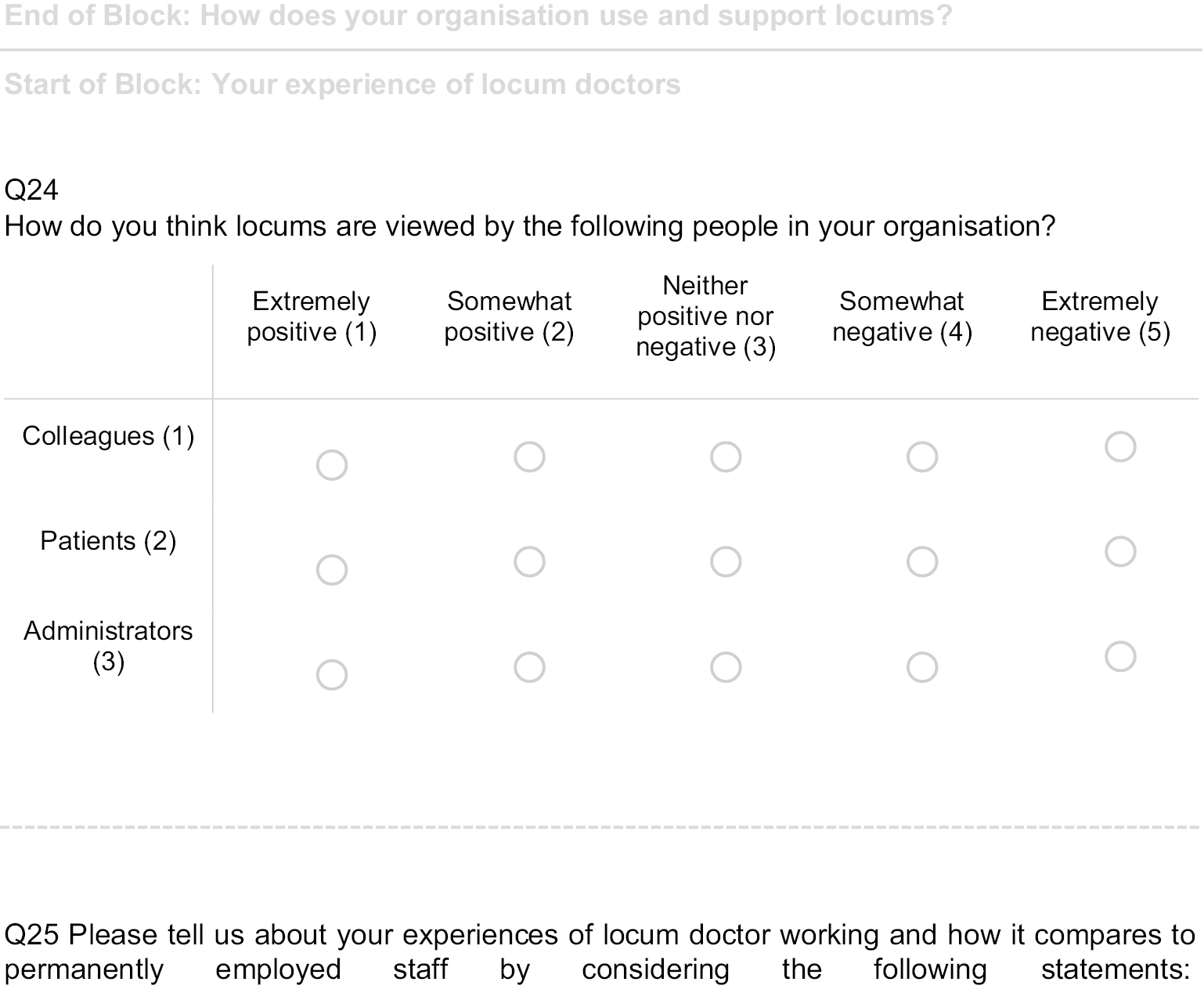

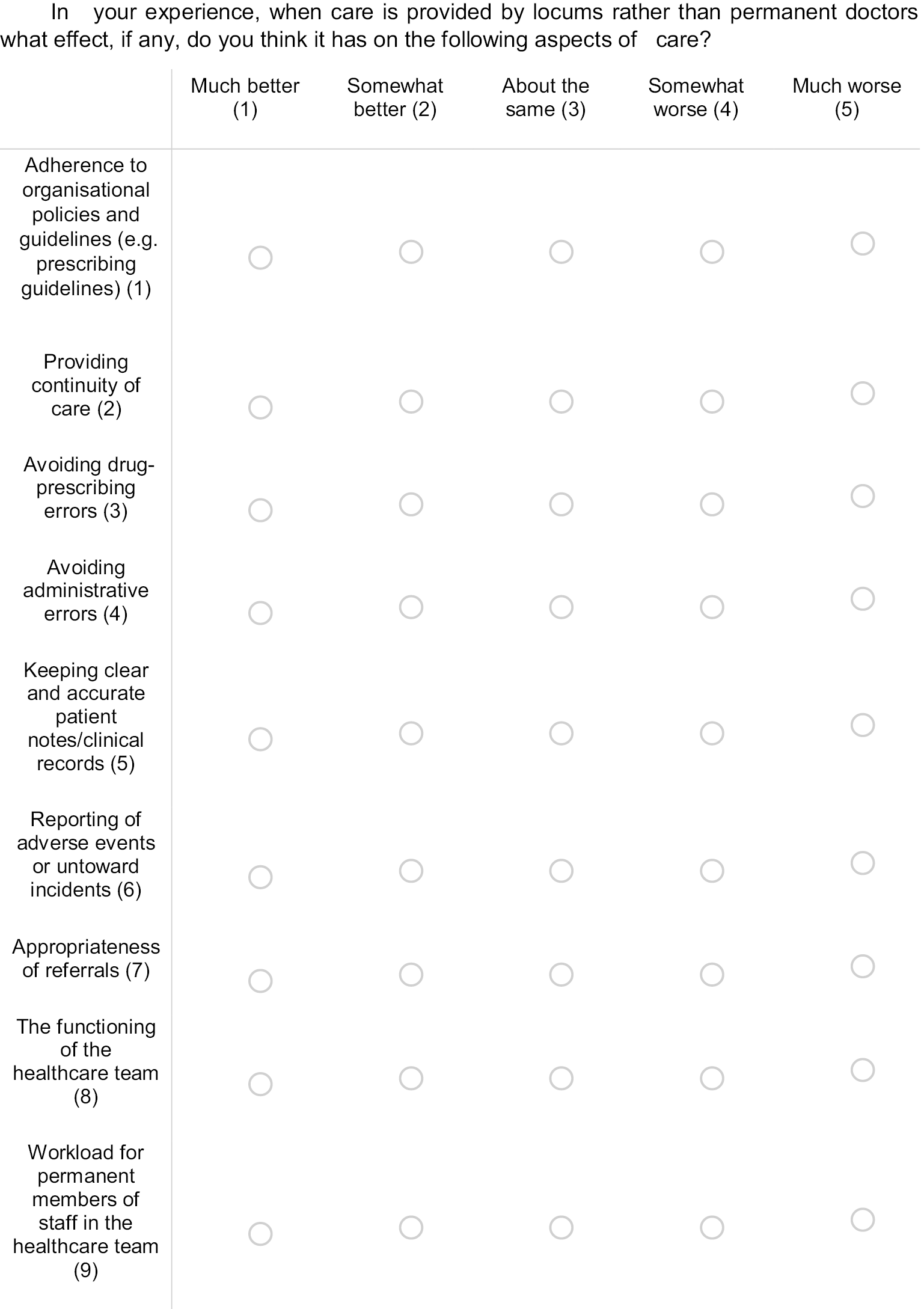

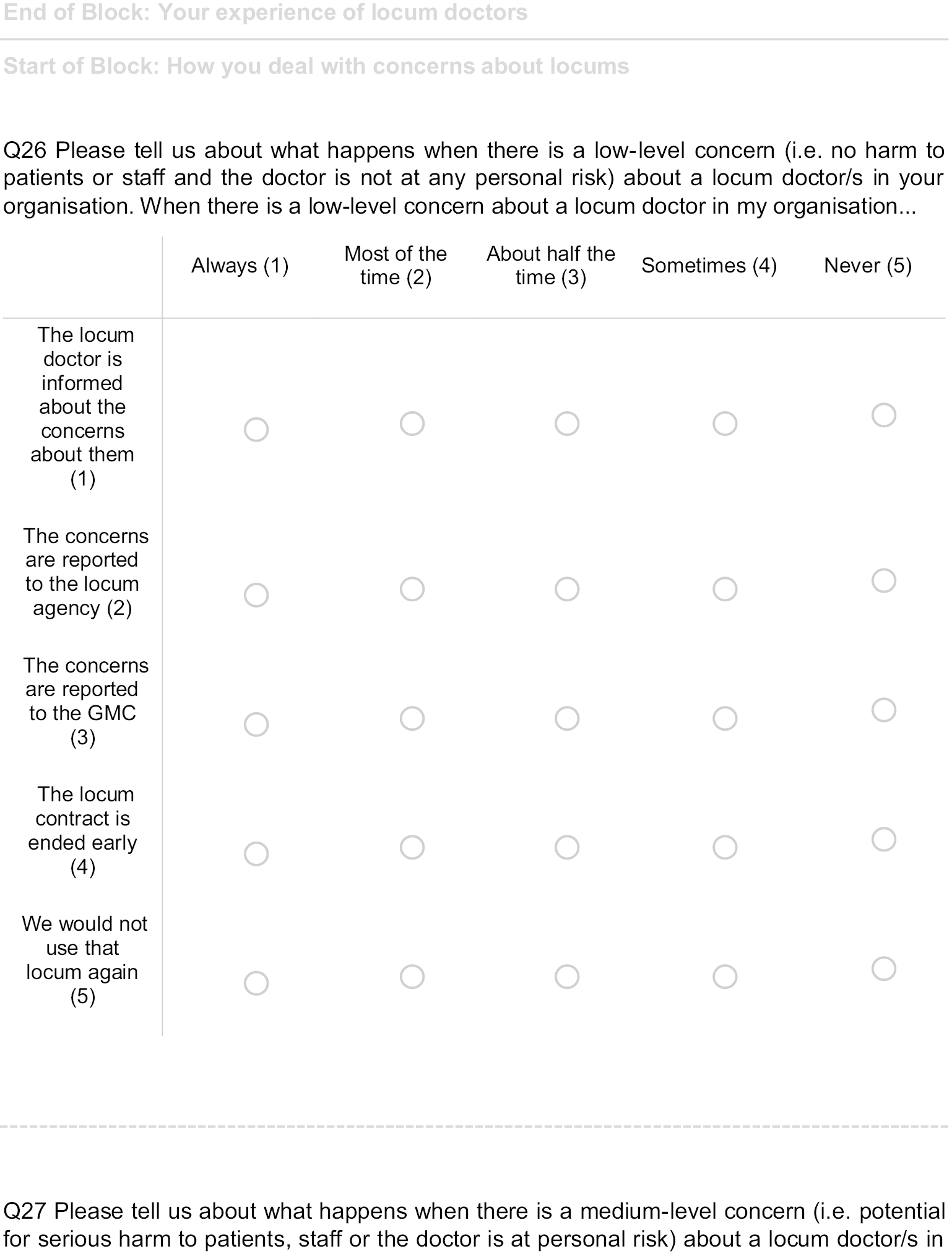

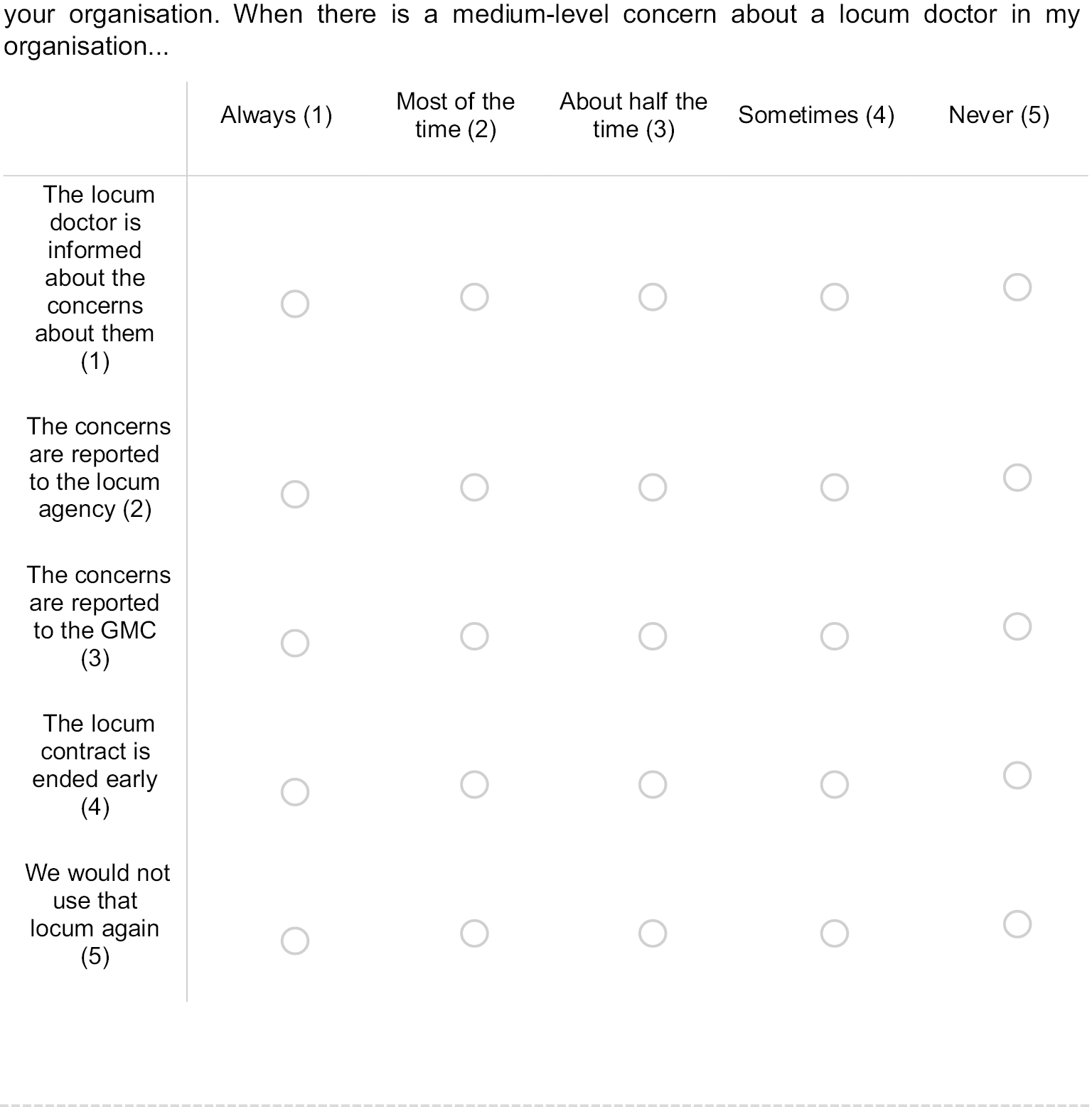

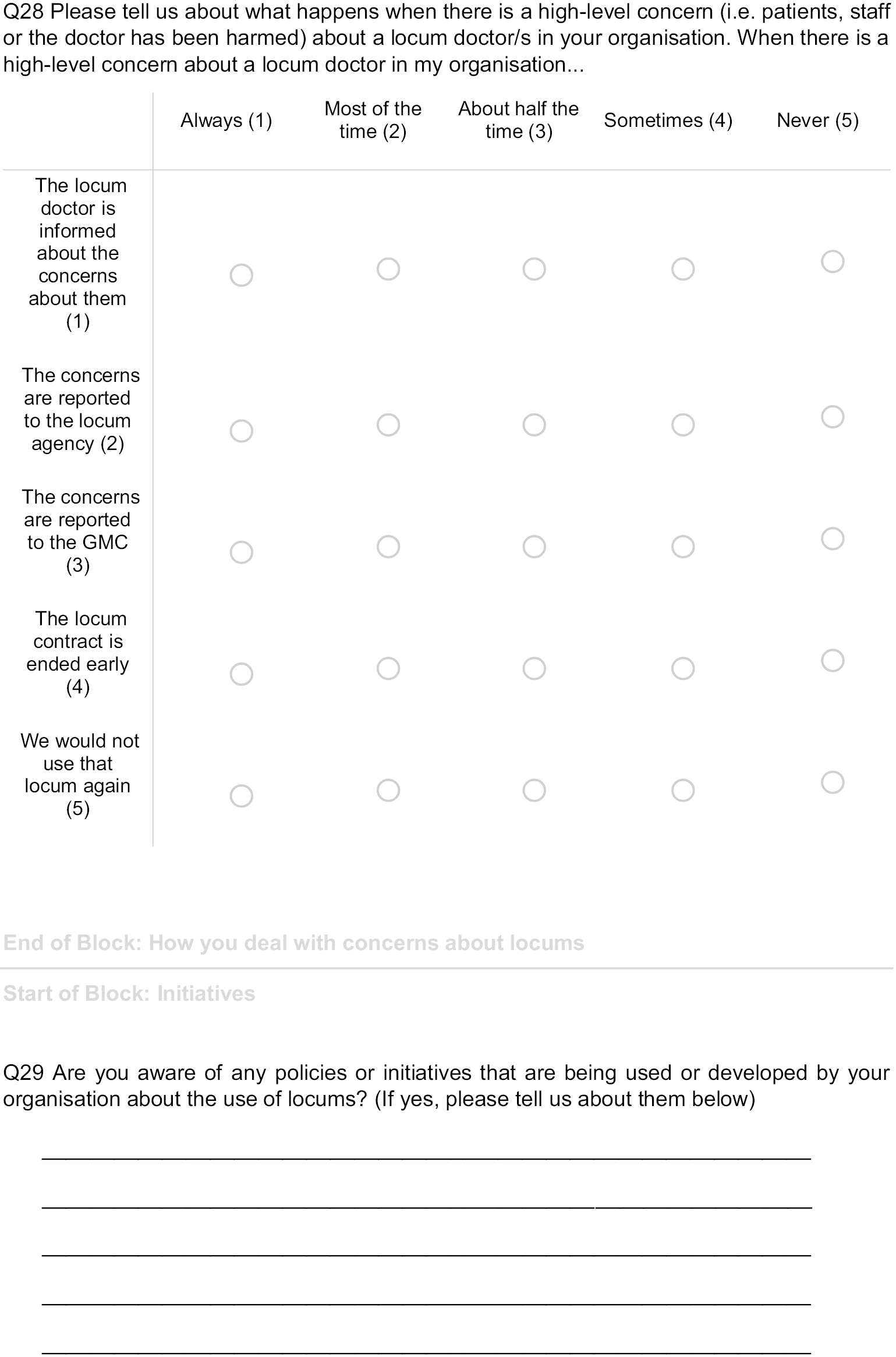

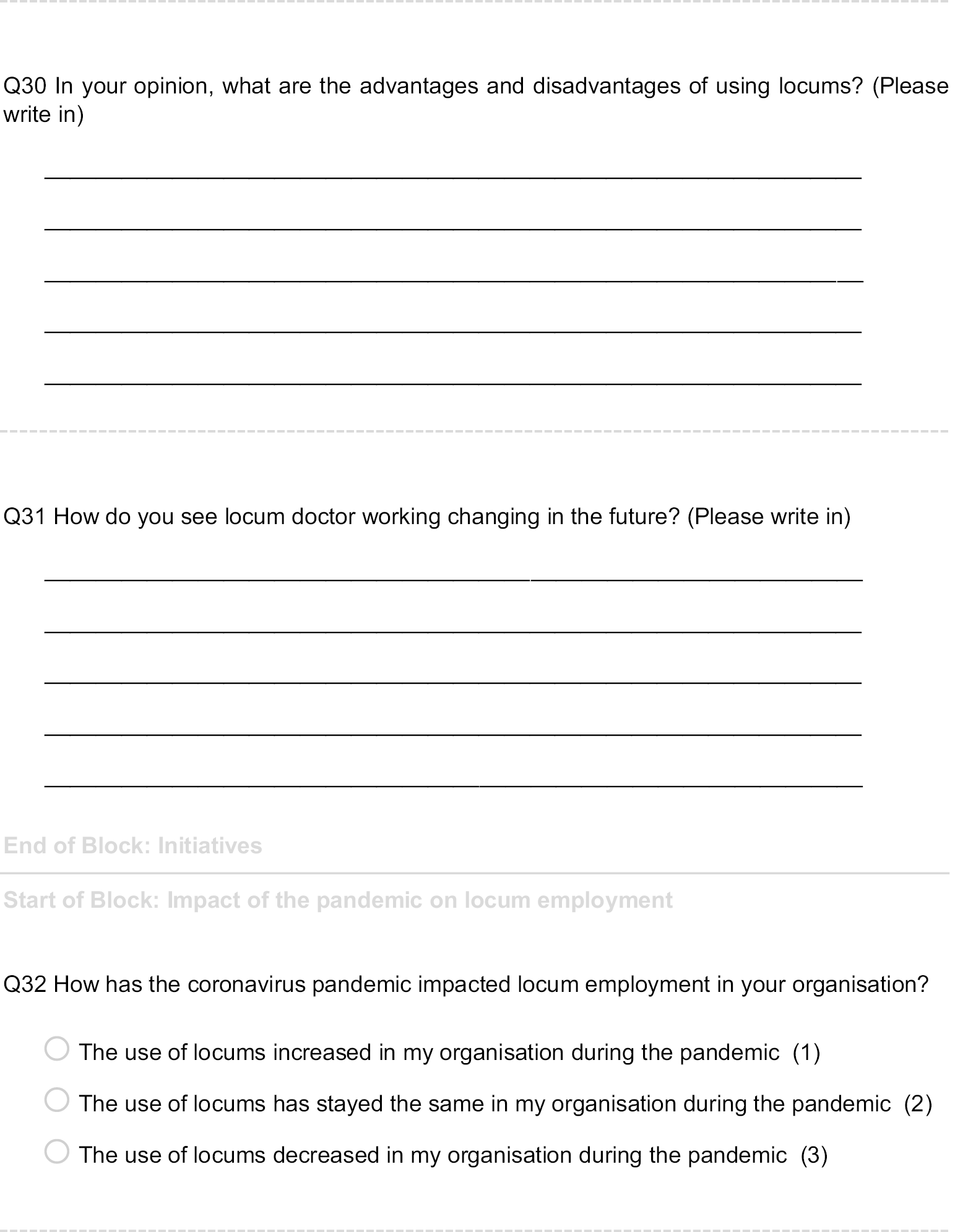

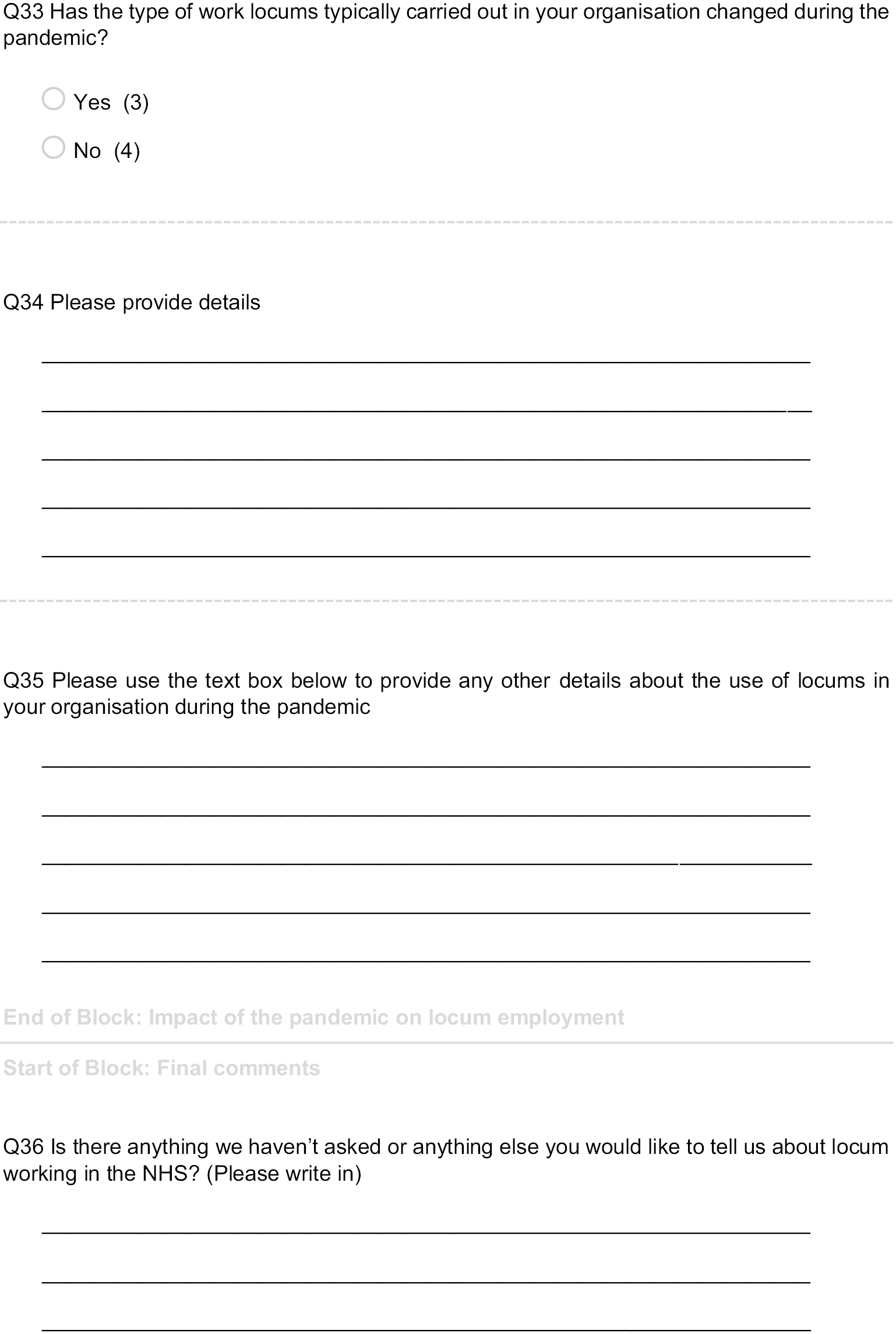

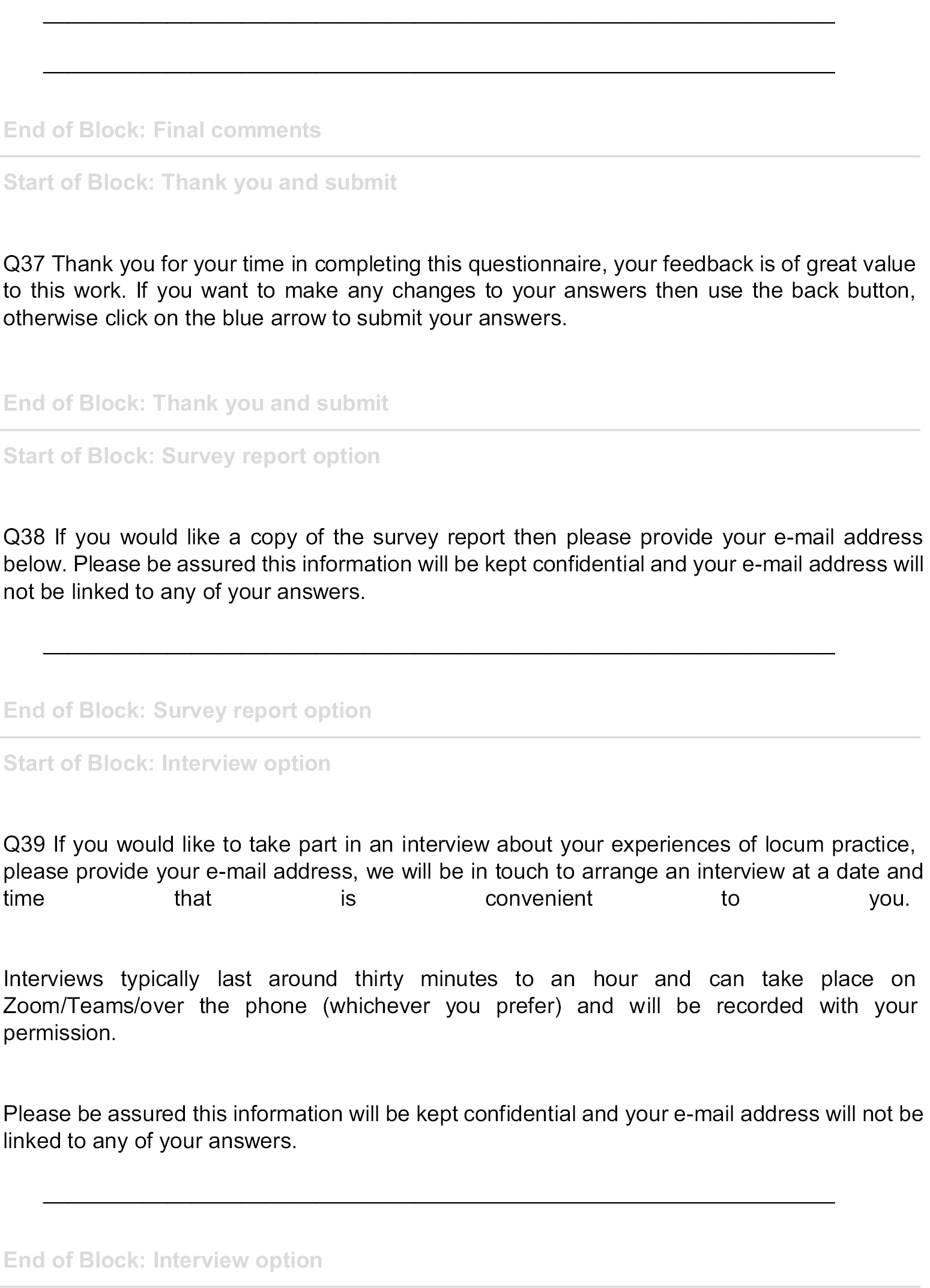

An 89-question custom-built online open survey56 was generated using Qualtrics software. 57 We collected information about why locums were needed, how locums were recruited, supported, perceived and managed, how the work of locums compared with permanent doctors, experiences of locum agencies, familiarity with the NHSE guidance for supporting locums and how concerns about locums were dealt with. We also sought the views of NHS trusts about the advantages and disadvantages of locum work and how they see locum doctor work changing in the future. A copy of the survey is provided in Appendix 3.

For the purposes of this survey, we defined a locum doctor as a doctor in a temporary or fixed-term placement, engaged through a locum agency, internal locum bank or directly contracted by a healthcare organisation.

Survey distribution

This was a survey of 191 NHS trusts in England. Prior to distribution, we e-mailed ROs to make them aware of the research and to encourage engagement. A RO is accountable for the local clinical governance processes in their particular healthcare organisation, focusing on the conduct and performance of doctors. RO duties include evaluating a doctor’s fitness to practise, and liaising with the GMC over relevant procedures. 58 The survey was initially sent to trust ROs in England and periodic reminders were sent to non-responders. Due to a low initial response rate, we contacted non-responding trusts by telephone to identify appropriate contacts at each trust. The survey was then sent to each of the contacts provided, which included R&D departments, medical staffing departments and medical directors. The electronic link to the survey was active for 7 months between June and December 2021 to allow trusts the time to respond during the pandemic.

Survey analysis

We analysed numeric and Likert scale data from survey respondents using frequency tables. Comparisons between NHS trusts who responded to the survey and all other NHS trusts in England were performed using t-tests. Since most survey responses were not normally distributed, non-parametric tests were used. Differences were investigated using Mann–Whitney U-tests.

Three free-text questions were analysed using thematic analysis;59,60 these questions asked about the advantages and disadvantages of locum agencies, the advantages and disadvantages of locums and the future of locum work. Employing an inductive approach – coding and theme development – involved identifying patterns of shared meaning across responses and was driven by the content of the comments rather than a priori themes. The written responses mostly consisted of short sentences which provided additional contextual detail to the quantitative questions. The written responses were read and reread to become familiar with the content, and notes were made of any potential codes for each question by identifying recurring words or units of meaning. 61 Responses to the three free-text questions were combined and mapped into overarching themes which encompassed the main issues highlighted in the data (a list of these themes and illustrative quotes are shown in Table 9). One further free-text question, which asked for opinions about the NHS England and Improvement guidance about supporting locum doctors, was not included in the thematic analysis as it was specific to the guidance. Illustrative comments are included to provide contextual detail to the quantitative question asking about trusts familiarity with the guidance.

Respondent characteristics

We surveyed a total of 191 NHS trusts and we received 98 usable responses (response rate 51%); of these, 89 completed the whole survey and 9 answered half or more of the questions. The responses included 66 (67%) acute hospitals, 26 (27%) mental health and 6 (6%) community health providers. The survey was completed by 35 (36%) Medical Directors and/or ROs (including Deputies and Associates), 54 (55%) medical staffing (e.g. Temporary Staffing Manager, Head of Medical Workforce), 3 (3%) clinical staff and 4 (4%) other roles (e.g. Medical Human Resources Business Partner). One respondent did not complete the question about their job role. Compared with all other trusts in England, there was no significant difference in CQC ratings, reported extent of locum usage, permanent doctor FTE or deprivation, suggesting the responses were broadly representative of NHS trusts generally.

Results

The need for locums

How often trusts use locums

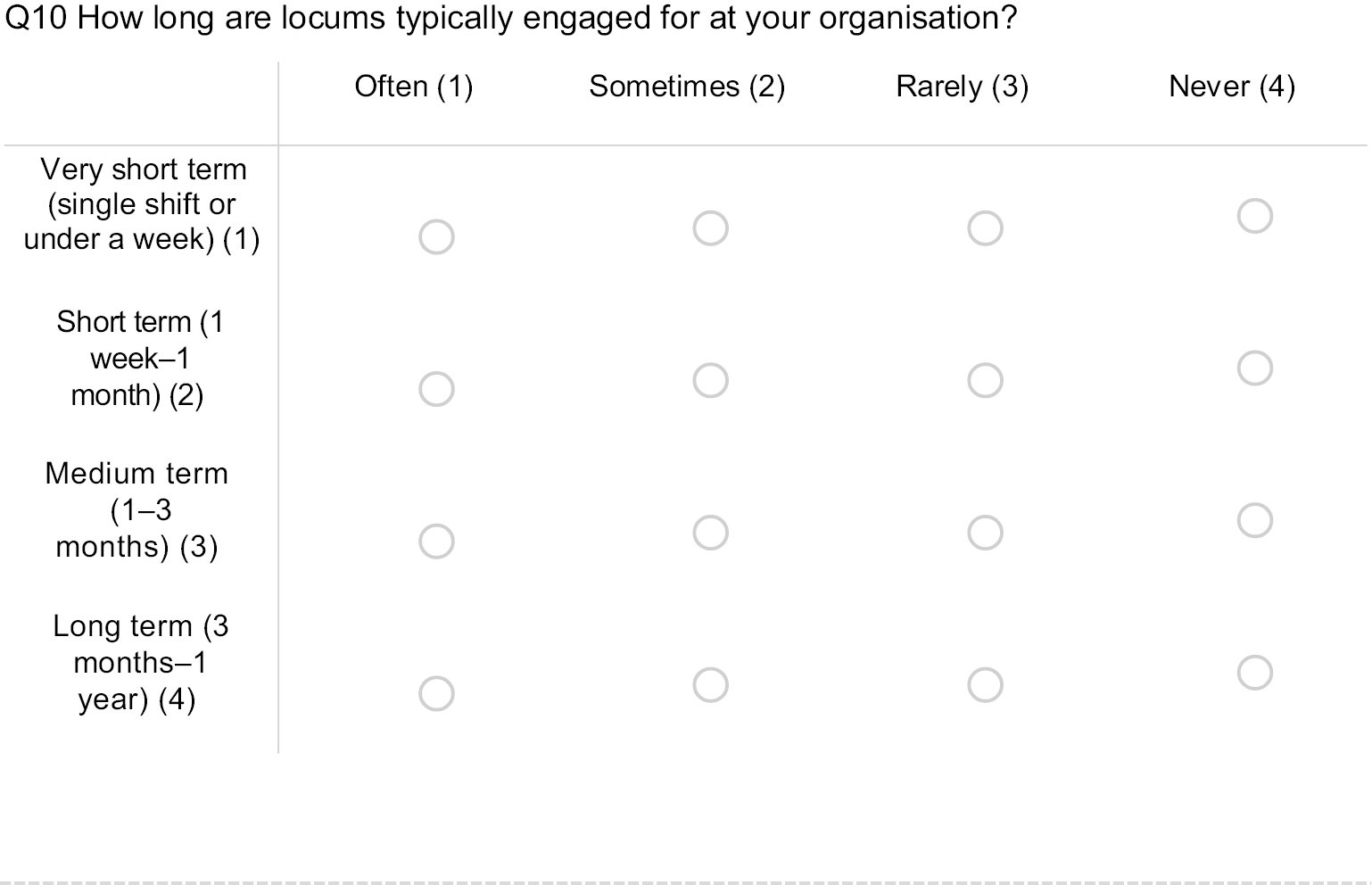

Over three-quarters of trusts always or most of the time used locums and only one trust reported that it made no use of locums. We asked trusts how long locums were typically engaged for at their organisation. Trusts used locums for all different engagement lengths, but locums were most frequently needed for medium-term (1–3 months) and long-term (3 months–1 year) lengths of time, and less frequently short term (1 week–1 month). Acute trusts used locums more frequently for very short (one session to under a week) and short-term lengths of time compared with mental health trusts (p < 0.001) and community health providers (p < 0.001).

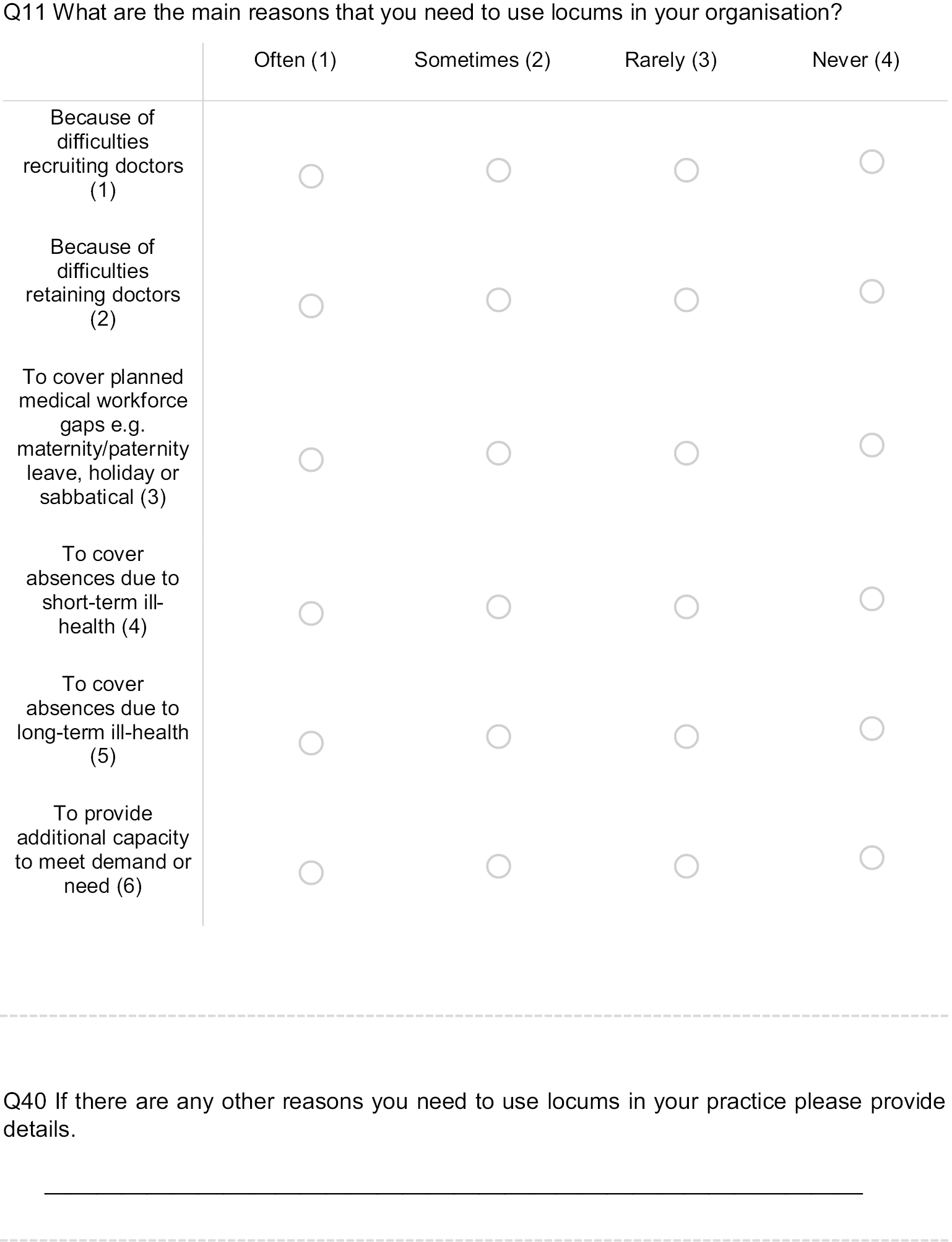

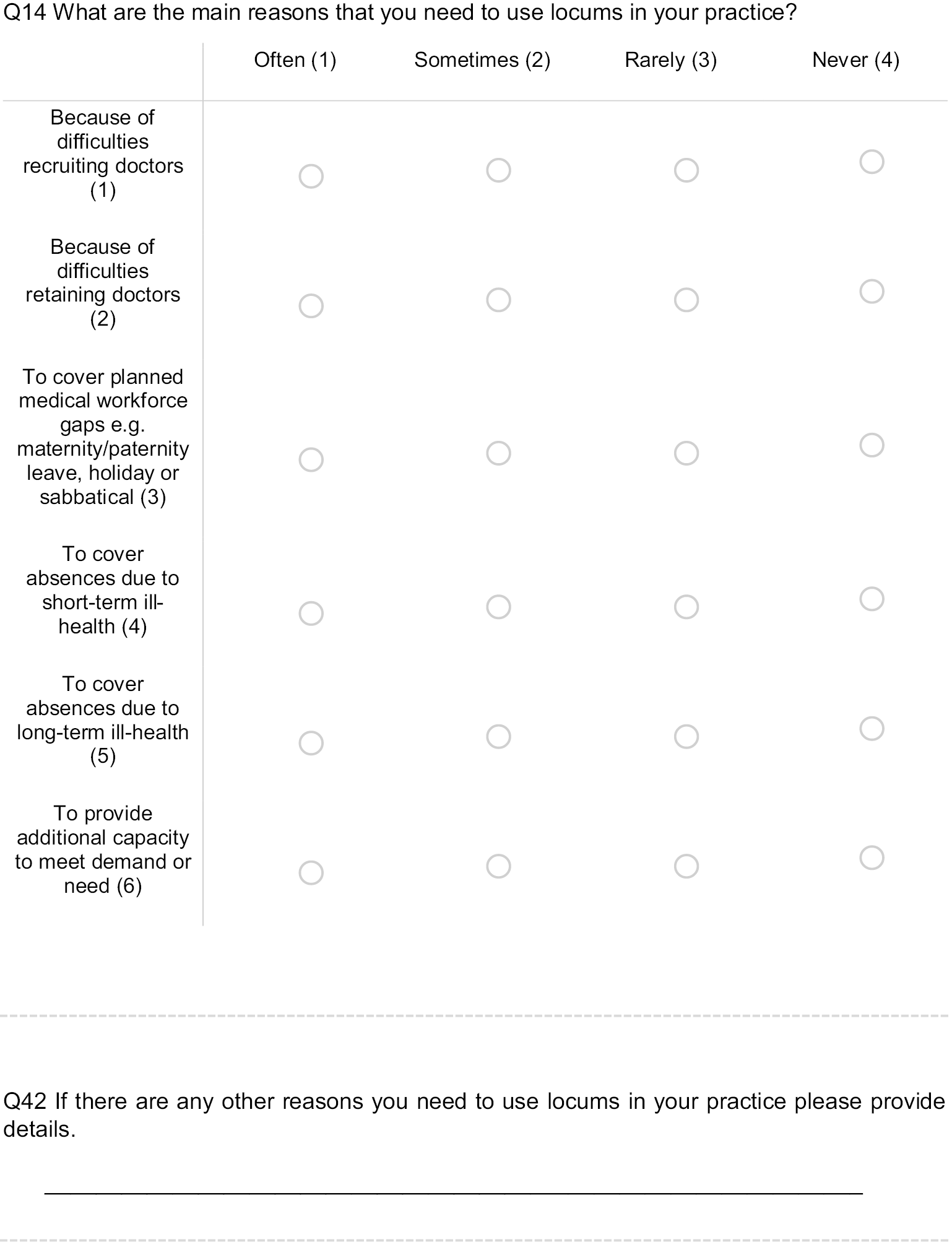

Reasons for locum use

Trusts reported the main reason for using locums was because of difficulties recruiting doctors (Table 6). Acute trusts needed locums to cover planned medical workforce gaps more frequently compared with community health provider trusts (p = 0.008), to cover absences due to short-term ill health more frequently compared with mental health providers (p = 0.002) and to provide additional capacity to meet demand or need more frequently compared with mental health trusts (p < 0.001) and community providers (p = 0.021).

| Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | Σ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust typea | |||||

| Because of difficulties recruiting doctors | 69 (71.1) | 21 (21.7) | 6 (6.2) | 1 (1.0) | 2.25 |

| Because of difficulties retaining doctors | 12 (12.4) | 38 (39.2) | 39 (40.2) | 8 (8.3) | 1.12 |

| To cover planned medical workforce gaps, for example maternity/paternity leave, holiday or sabbatical | 28 (28.9) | 52 (53.6) | 15 (15.5) | 2 (2.1) | 6.88* |

| To cover absences due to short-term ill health | 43 (44.3) | 31 (32.0) | 22 (22.7) | 1 (1.0) | 8.20* |

| To cover absences due to long-term ill health | 25 (25.8) | 50 (51.6) | 20 (20.6) | 2 (2.1) | 4.03 |

| To provide additional capacity to meet demand or need | 34 (35.1) | 38 (39.2) | 21 (21.7) | 4 (4.1) | 16.40** |

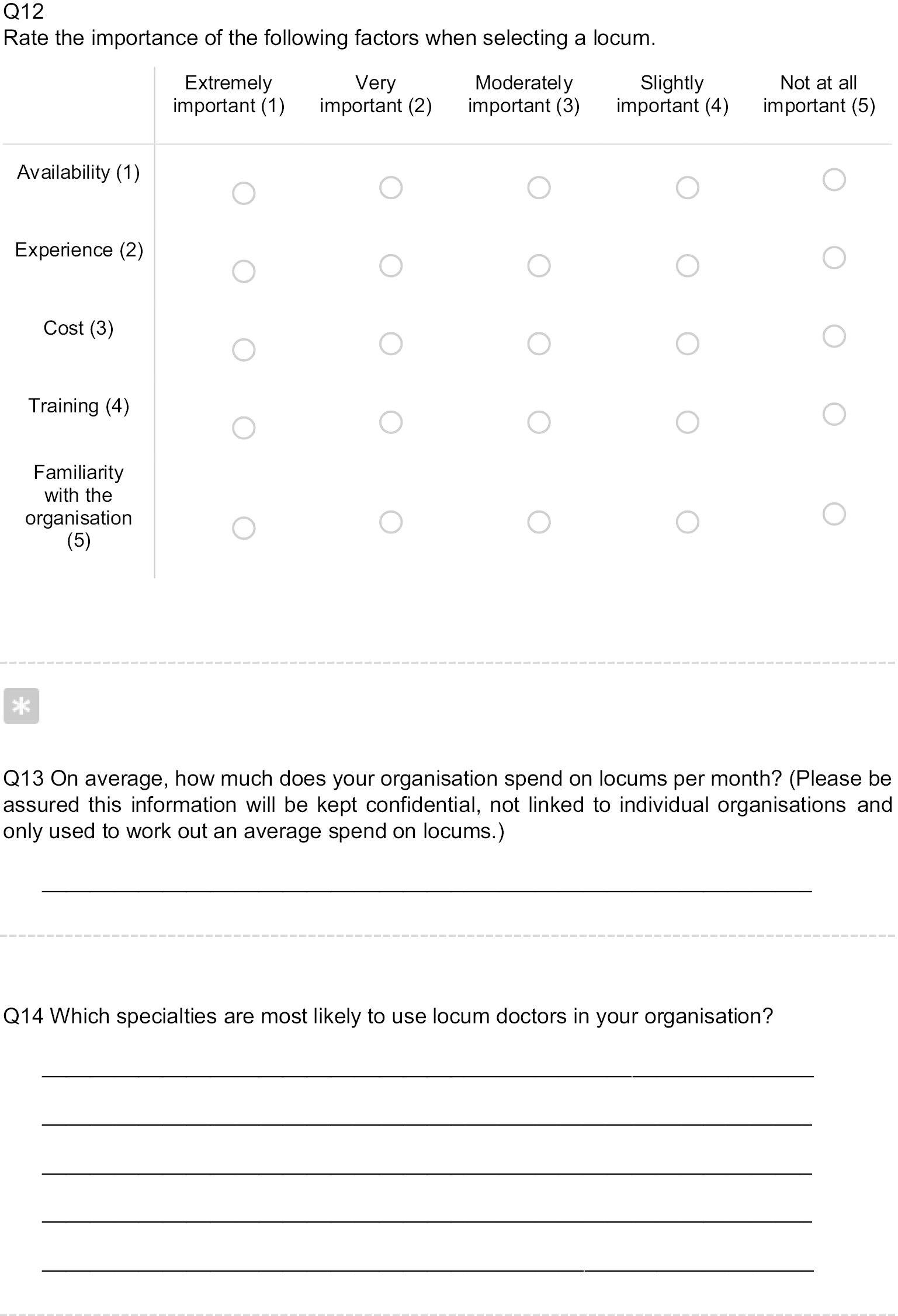

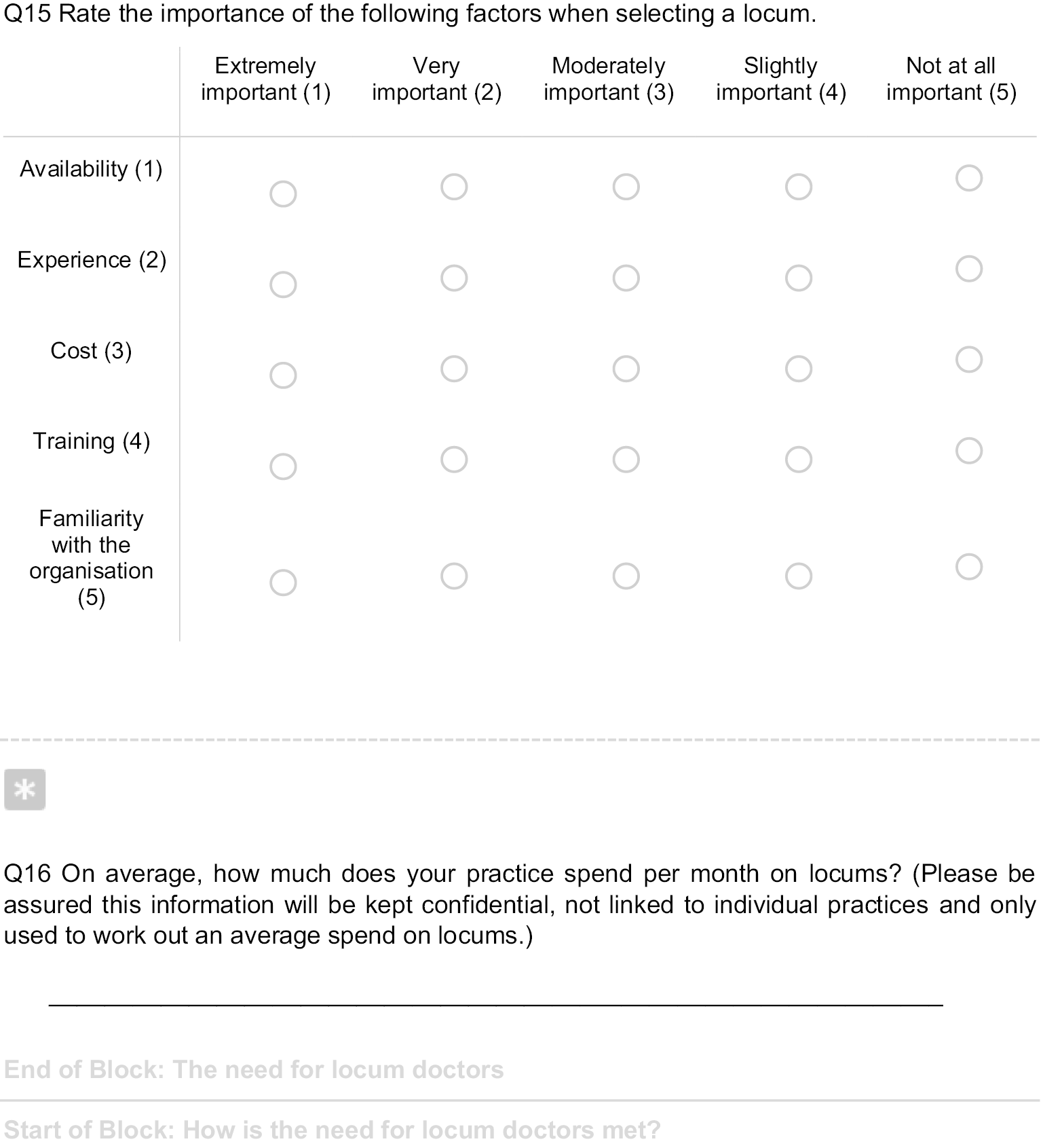

Factors important to trusts when selecting locums

Most trusts felt that all factors (availability, experience, cost, training and familiarity) were at least moderately important when selecting a locum with greater importance placed on availability and experience and less importance placed on cost and familiarity with the organisation.

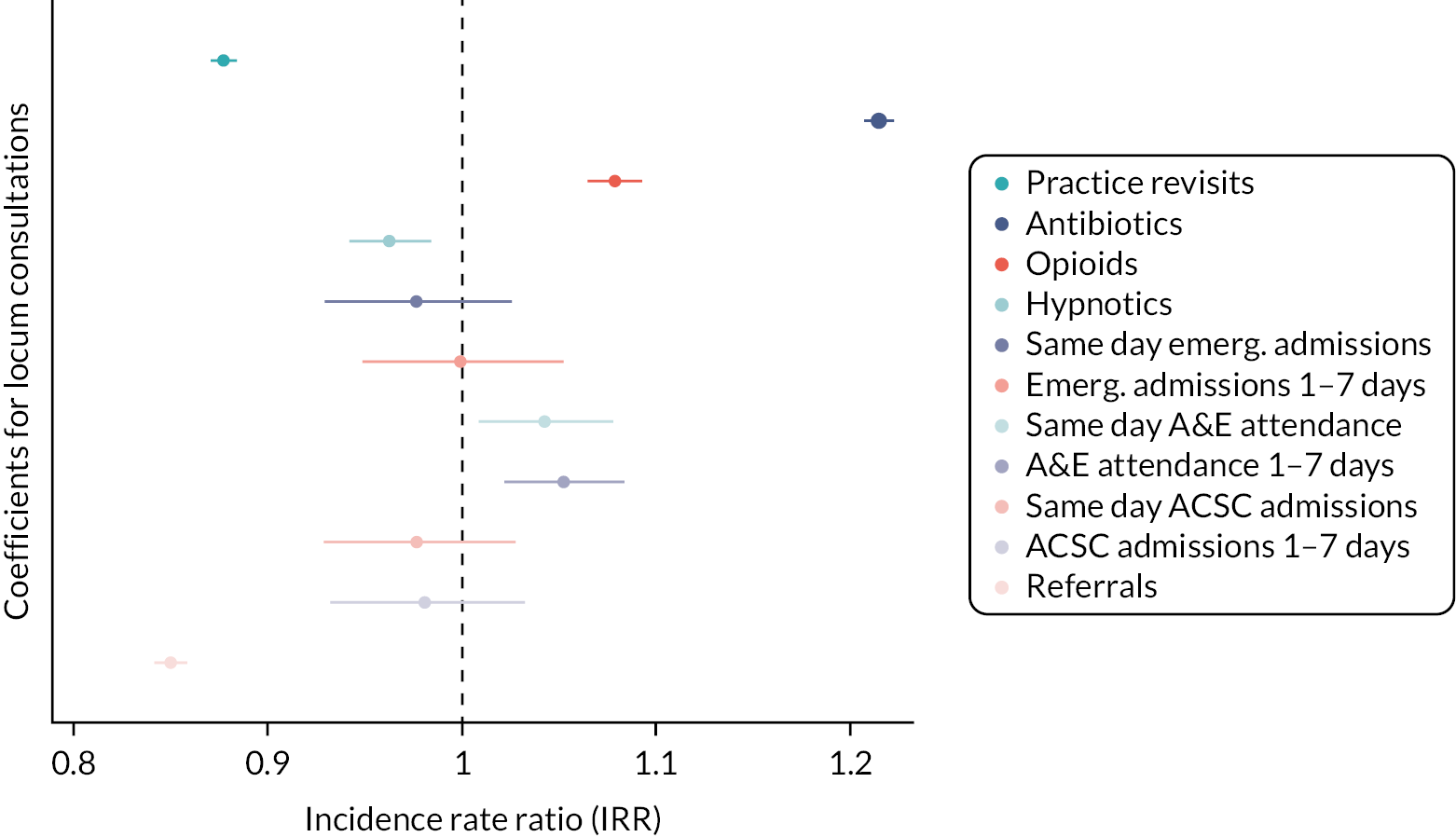

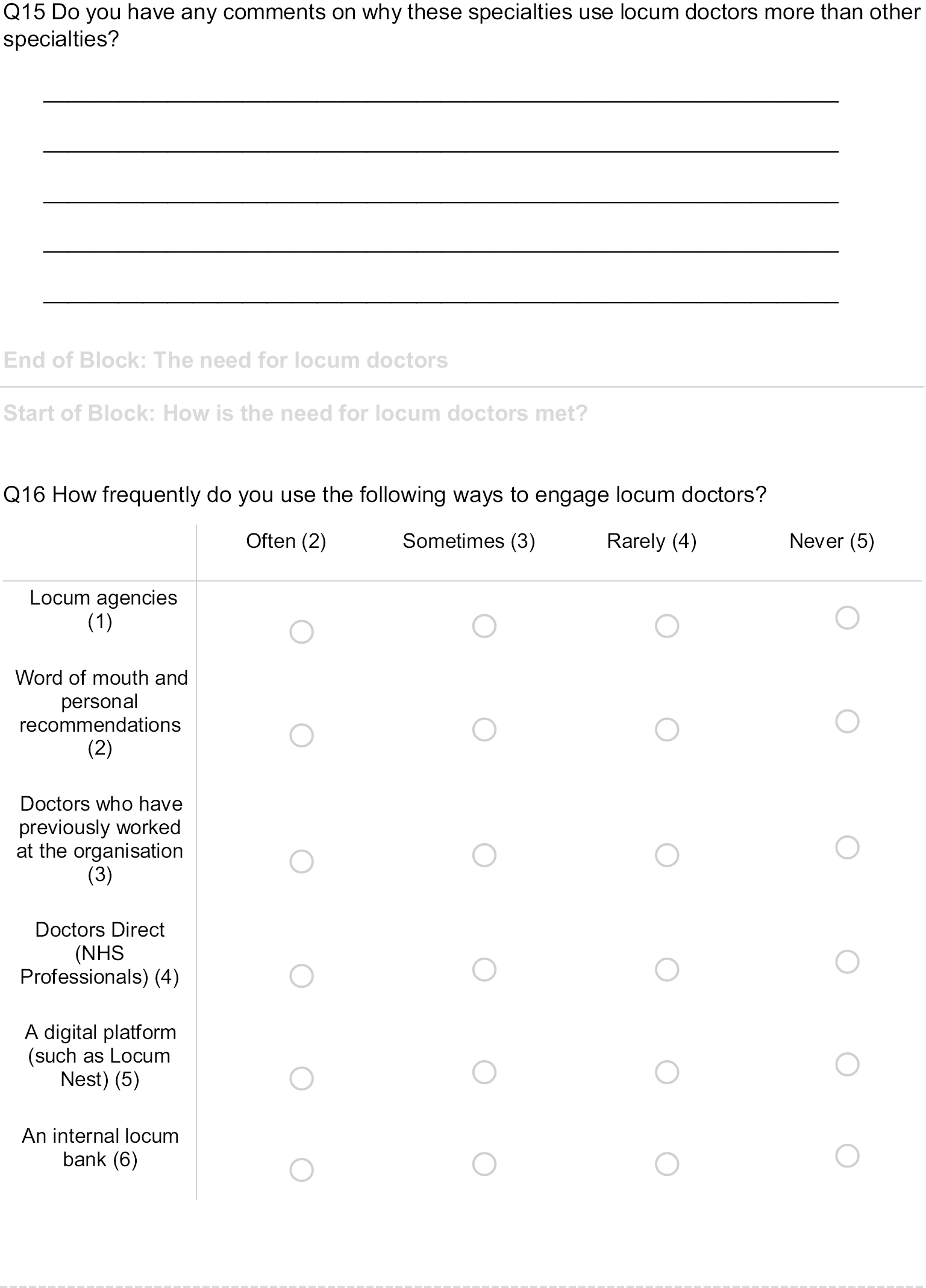

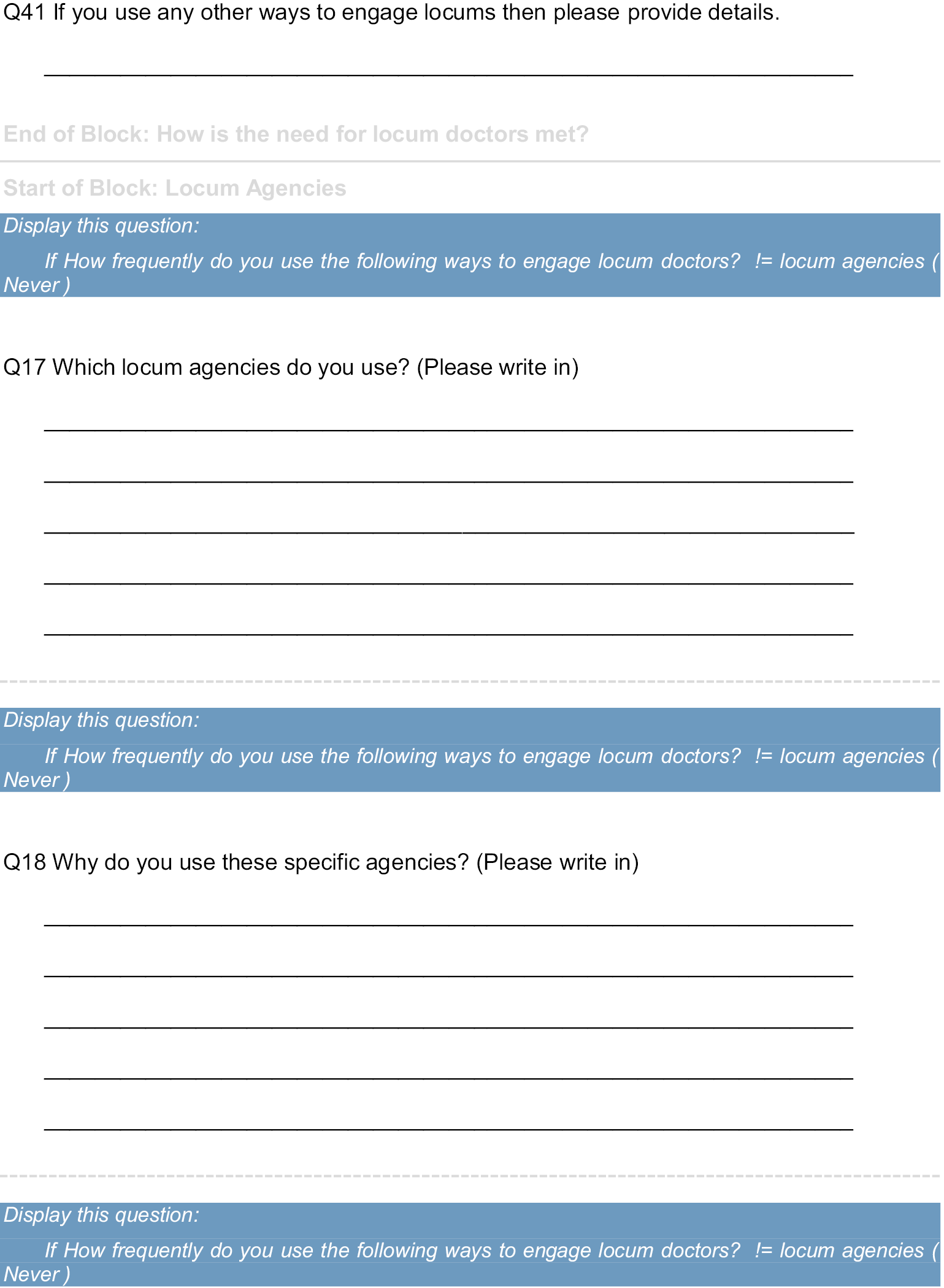

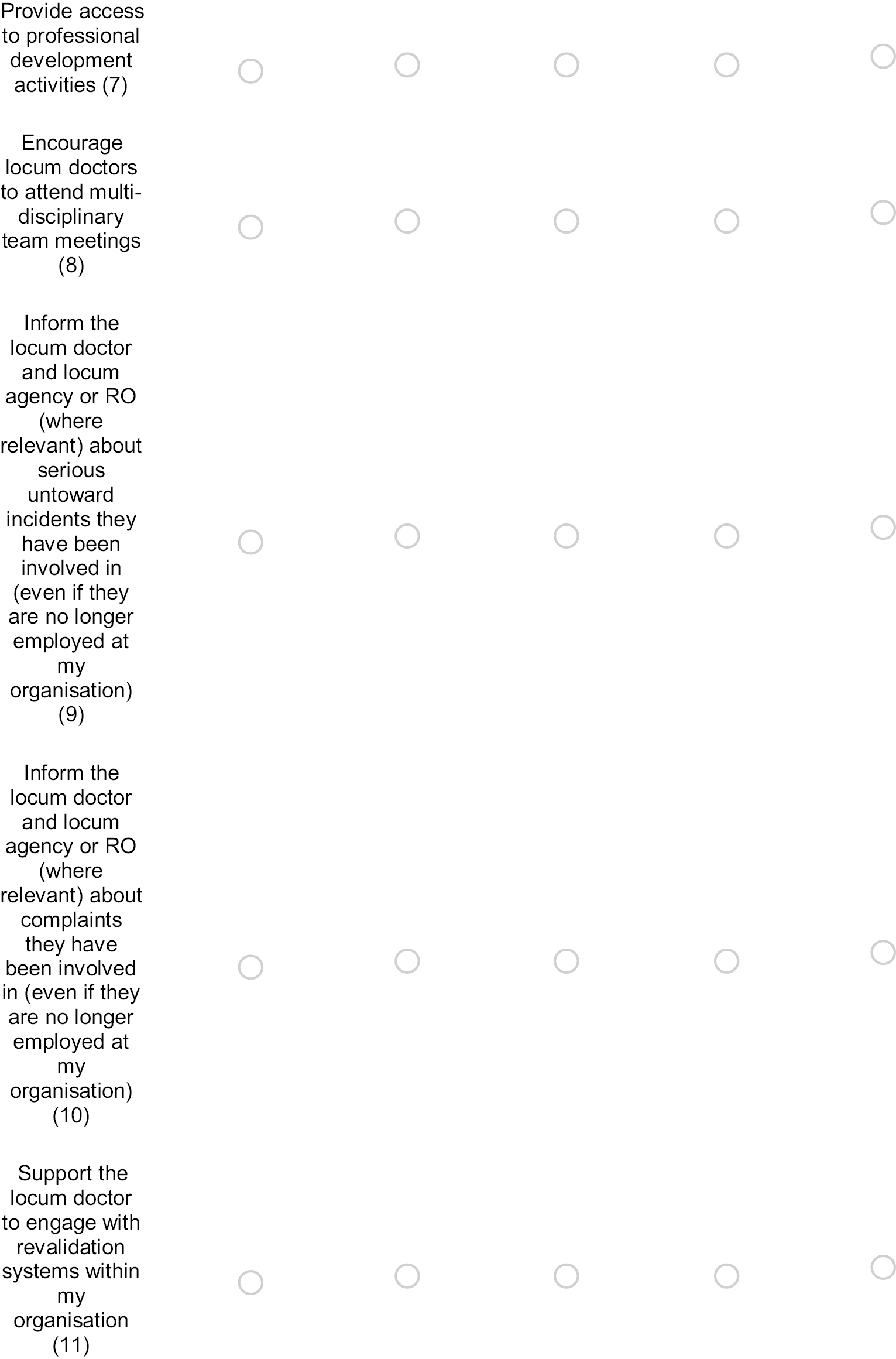

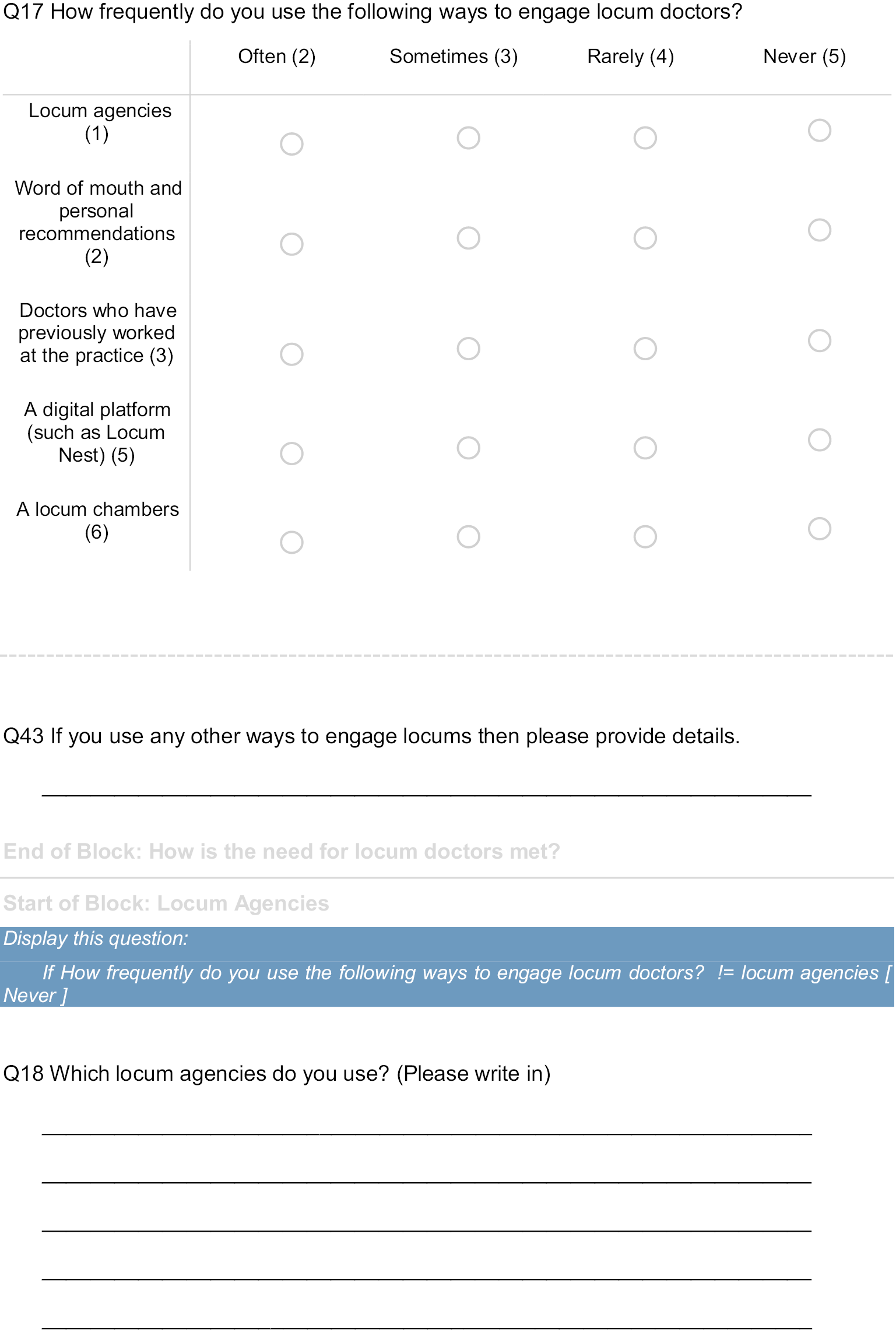

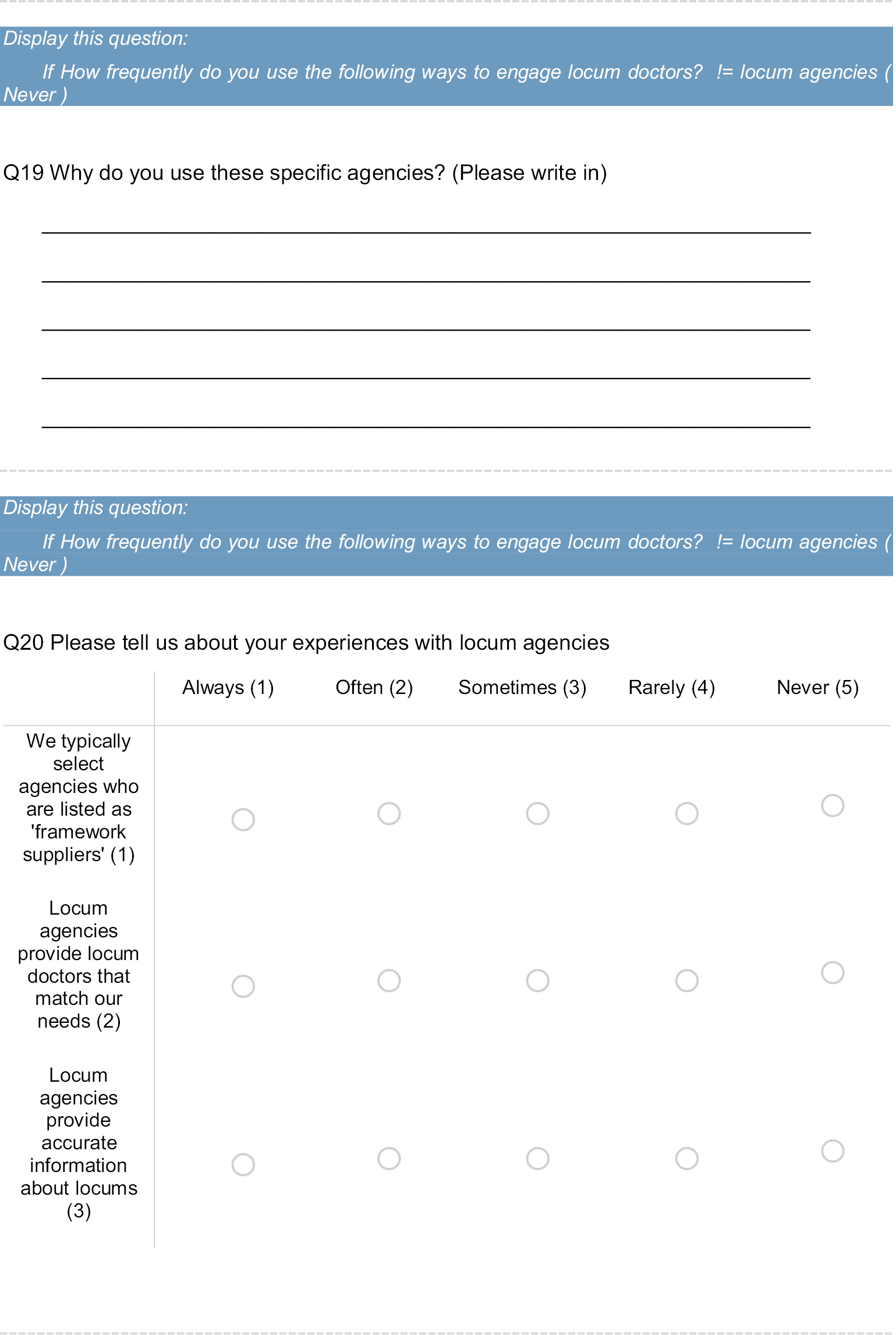

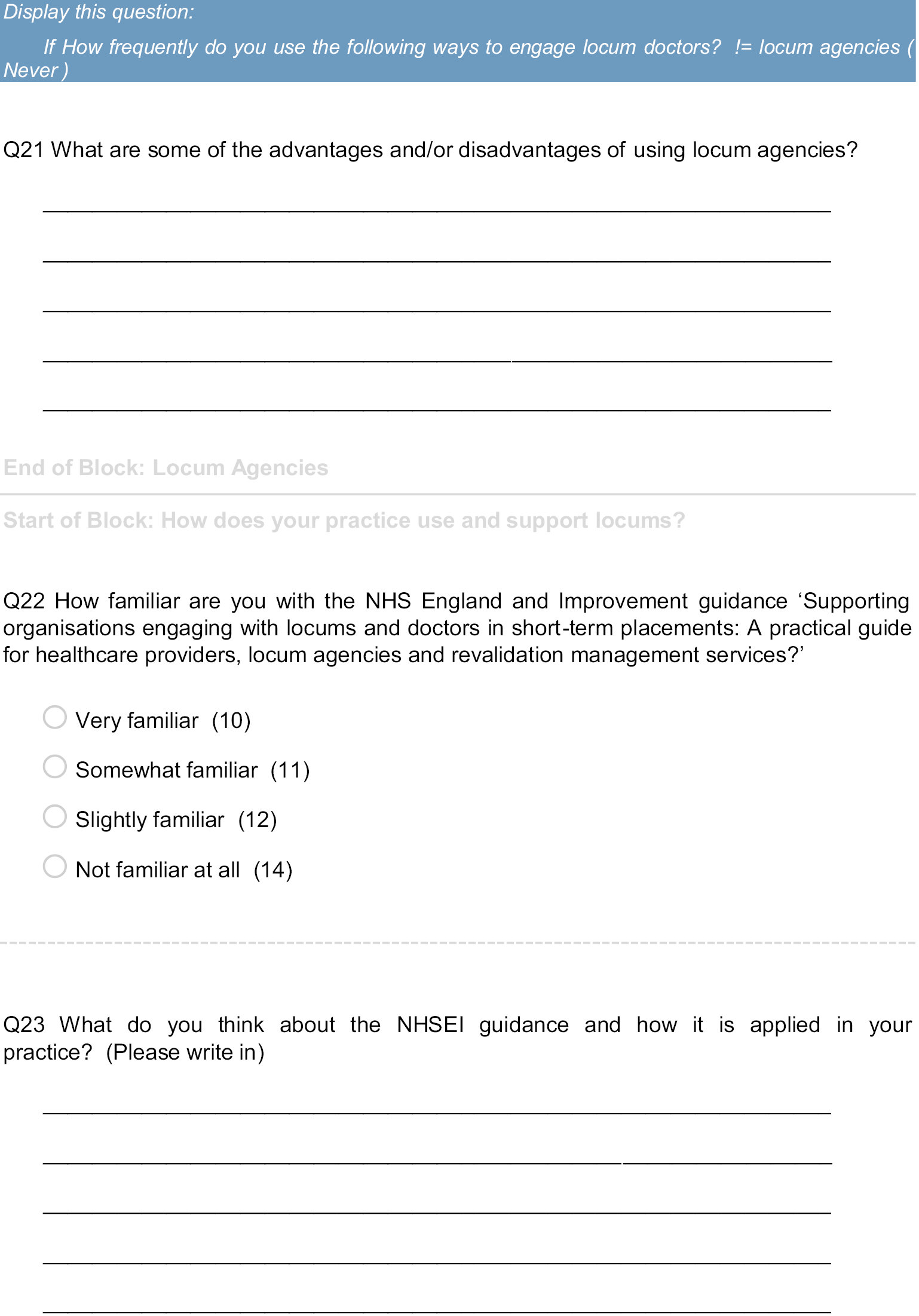

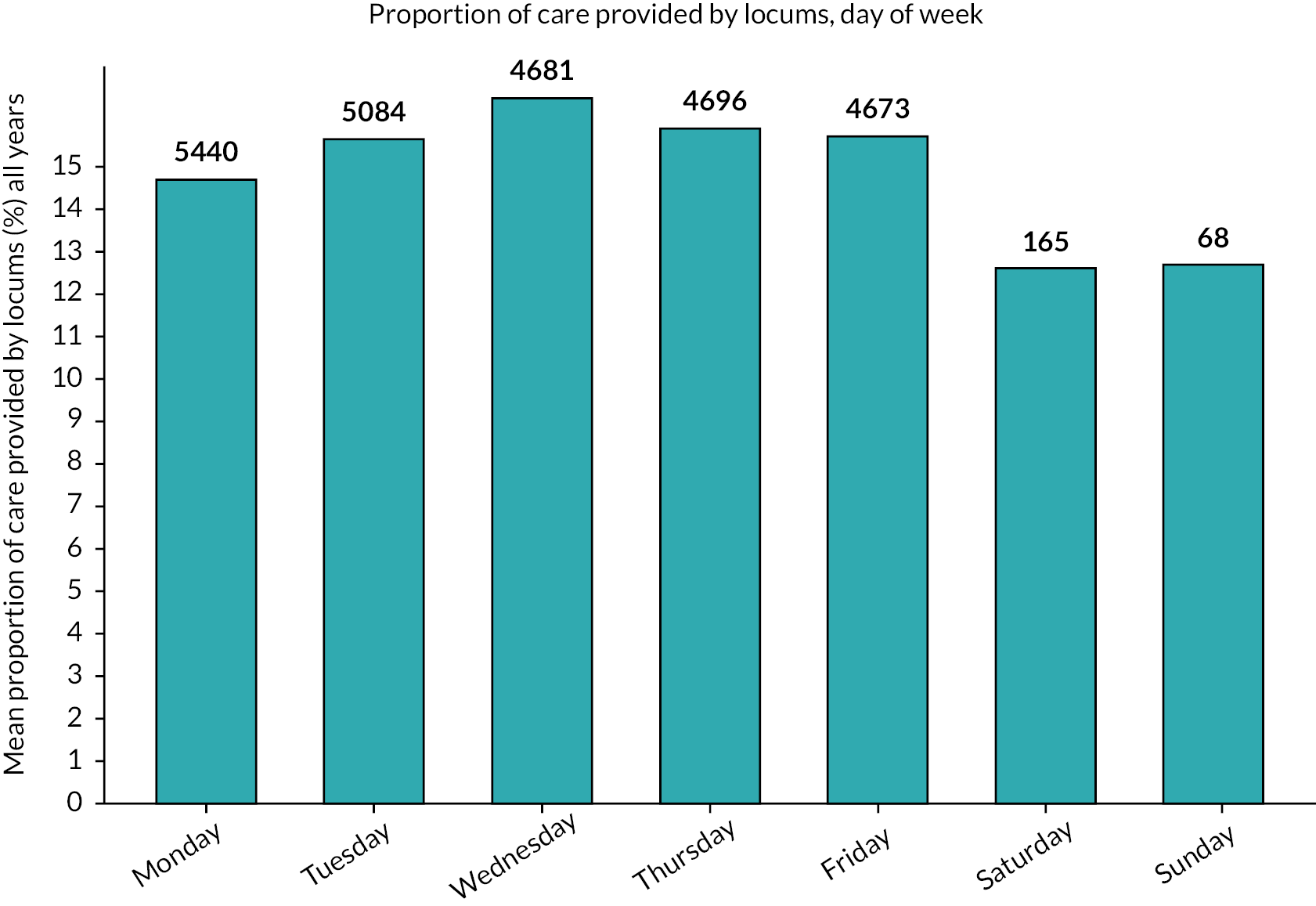

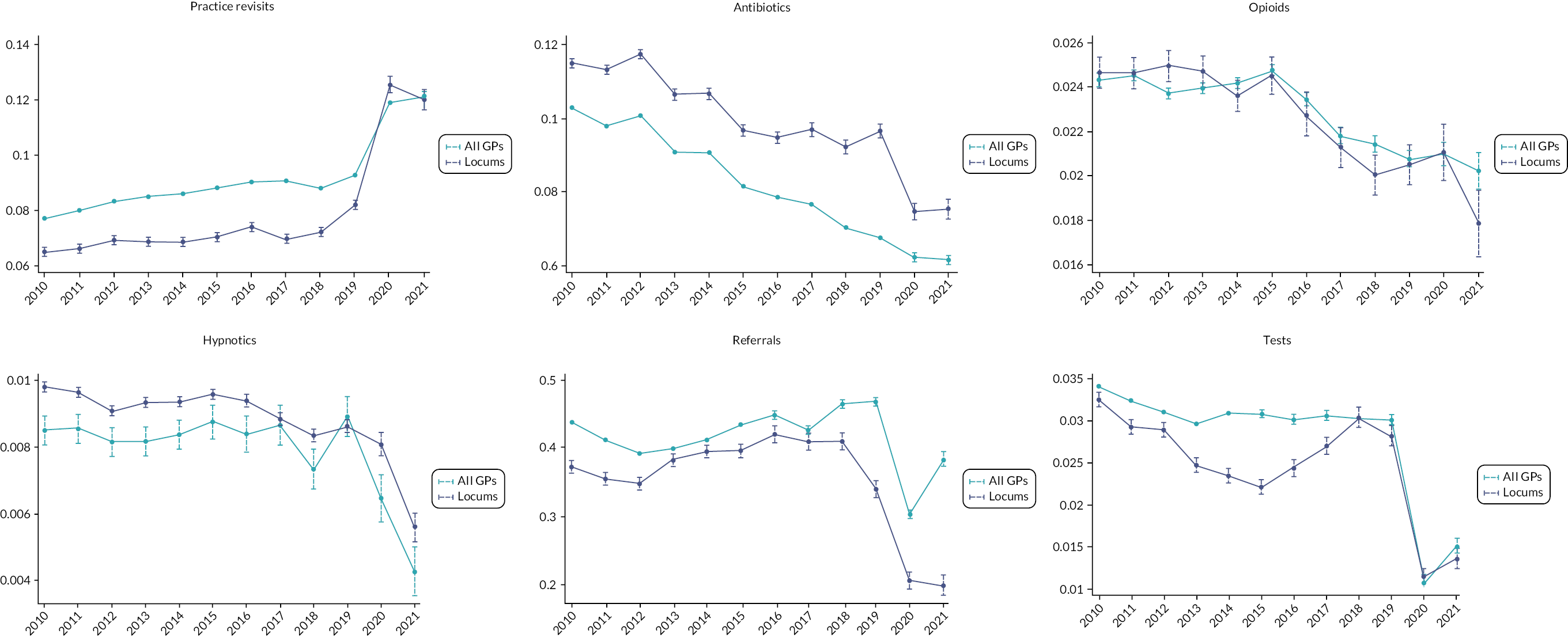

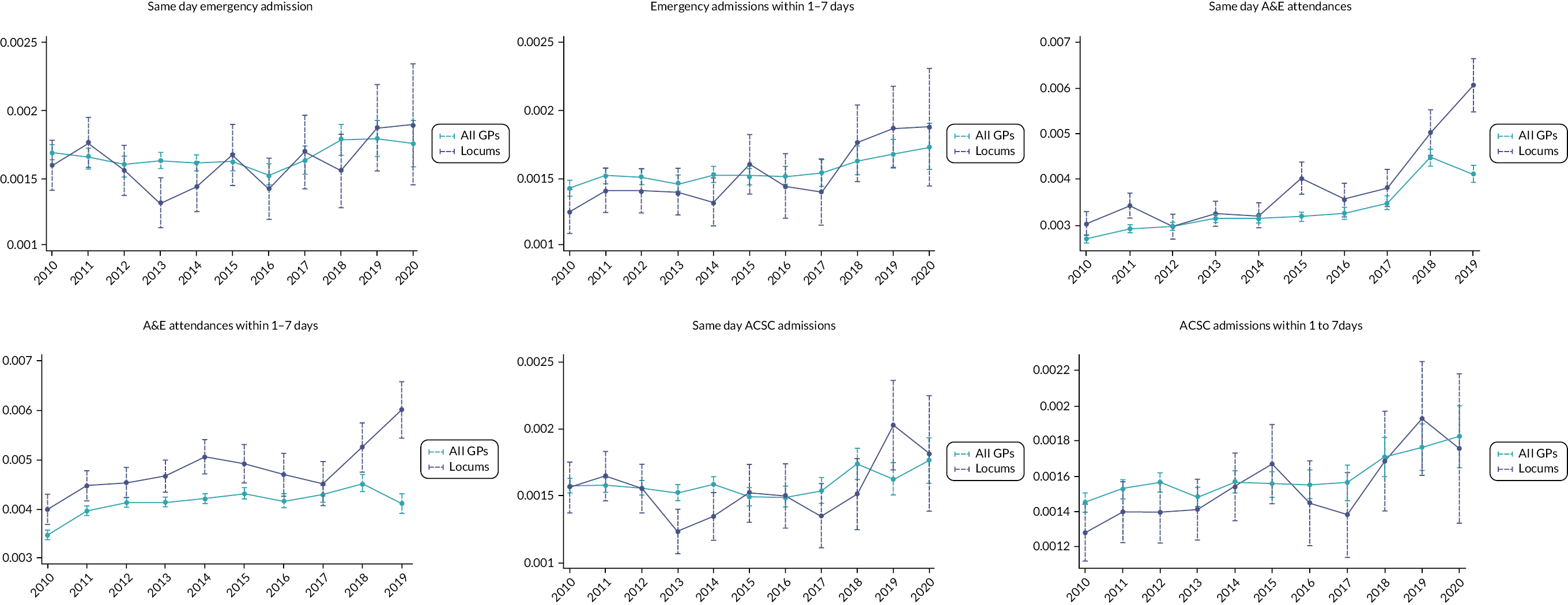

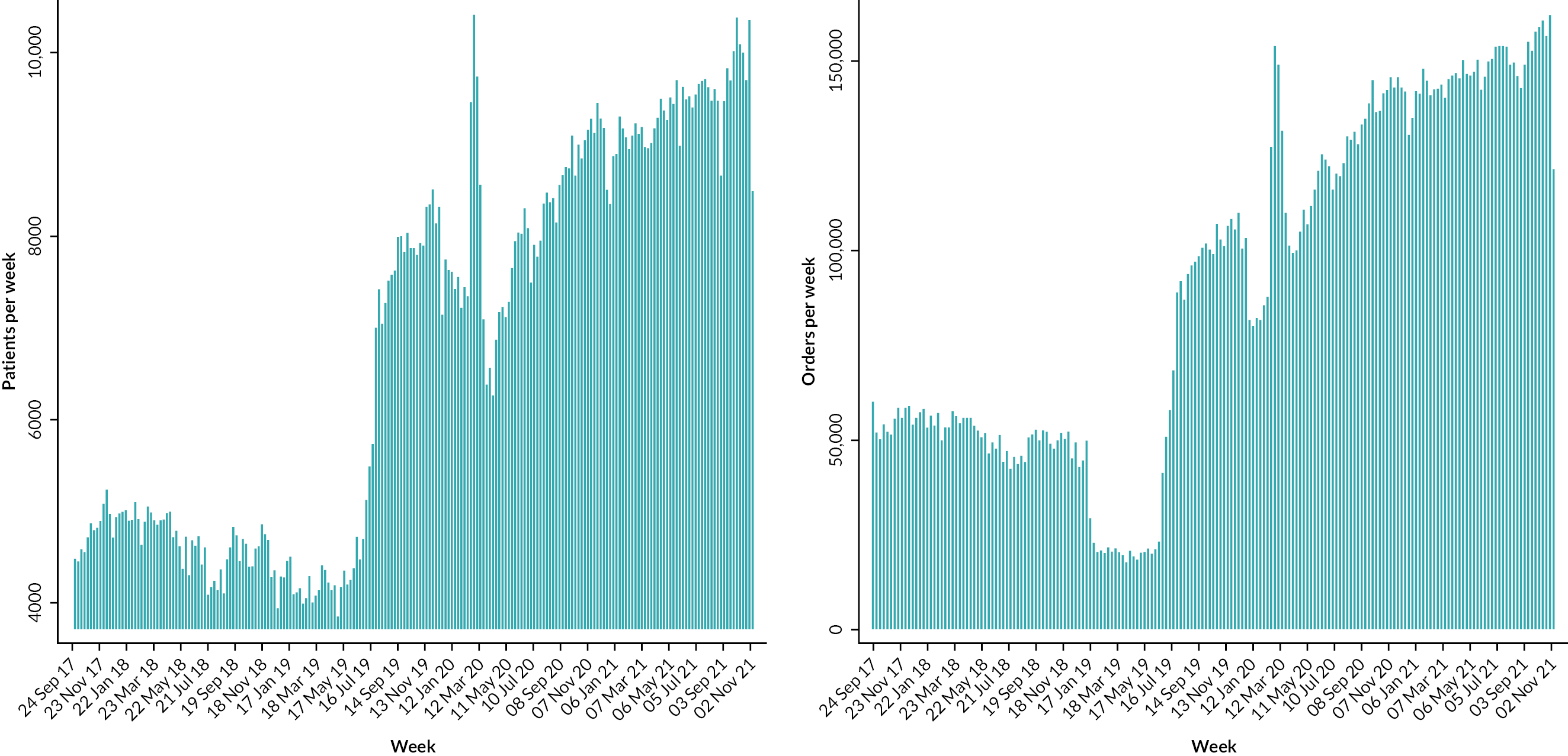

How the need for locum doctors is met