Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR130995. The contractual start date was in February 2021. The draft manuscript began editorial review in March 2023 and was accepted for publication in November 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Gavine et al. This work was produced by Gavine et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Gavine et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Importance of breastfeeding

Breastfeeding has a significantly positive impact on multiple health outcomes across the lifespan. For children, this includes fewer deaths and hospital admissions for infectious diseases1–4 and reduced incidence of obesity, diabetes mellitus and dental disease. 5–7 Breastfeeding has been linked to improved educational and behavioural outcomes. 8–10 For women, breastfeeding is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease, breast and ovarian cancer and diabetes mellitus. 11–13 The impact of breastfeeding on health outcomes applies across settings and population groups, including in high-income countries (HICs) such as the UK. Globally, the scaling up of breastfeeding to near-universal level could prevent 823,000 deaths of children under 5 years old and 20,000 annual deaths of women from breast cancer. 14 To optimise population health, global and UK infant recommendations are that infants should be breastfed (or receive breastmilk) exclusively for about 6 months and that this should continue as part of a mixed diet until 2 years or beyond. 15,16

Increased breastfeeding has the potential to reduce healthcare costs. 17,18 In addition to the important effects on health for women and children, breastfeeding has wider health system and societal impacts, including cost savings for the NHS and environmental benefits. The cost to the global economy of not breastfeeding has been estimated at £242B, and, in the UK, estimates are that £23.6M in additional treatment costs could be saved each year by increased breastfeeding. 17 A further cost to the NHS is the increasing number of prescriptions for specialist formula to treat cow’s milk protein allergy. 19 The environmental impact of not breastfeeding (i.e. feeding with infant formula) is significant, for example from plastics and resources used by the dairy industry. 20,21 Therefore, significant health, societal and environmental gains are to be had from increasing breastfeeding duration and exclusivity.

UK breastfeeding patterns

The UK has low breastfeeding rates. Following the cessation of the quinquennial UK-wide Infant Feeding Surveys, comprehensive, robust data on breastfeeding rates are lacking. For England, the most recent data (2020/21 data), reported by NHS trusts, showed a 72% initiation rate and 49% prevalence of breastfeeding at 6–8 weeks. 22 The comparative figures were 60% initiation and 45% prevalence at 6–8 weeks for Wales (2016 data)23 and 65% initiation and 43% prevalence at 6–8 weeks for Scotland (2018/19 data). 24 In Northern Ireland (2020 data), the initiation rate was 62% and prevalence at 6 weeks was 40%. 25 Rates of exclusive breastfeeding are much lower in all four countries. Throughout the UK, there is a marked social gradient in breastfeeding rates whereby women from socioeconomically deprived groups, those with lower education levels and adolescent women are least likely to breastfeed. 26 For example, in Scotland (2018/19 data),24 breastfeeding prevalence at 6–8 weeks was 62% in the wealthiest quintile compared with 28% in the most deprived quintile. The differences were starker by mother’s age, with breastfeeding prevalence at 6–8 weeks of 58% among mothers aged 40 years and 13% among mothers aged under 20 years. 24 In the UK, women from non-white ethnic groups had higher rates of breastfeeding initiation, prevalence and duration than white women; rates of exclusive breastfeeding after 1 week were similar. 26 Women and babies from the most deprived backgrounds and younger mothers have most to gain from the health benefits conferred by breastfeeding. It has also been reported that around 80% of women in the UK stop breastfeeding before they intended, causing distress26 and potentially leading to poorer mental health. 27,28

Comparing breastfeeding rates between the four countries of the UK, and with countries internationally, is fraught with difficulty, as data are collected in different ways, at different time points and for different years. Nevertheless, rates of breastfeeding in the UK are consistently reported to be lower than those in other European countries. For example, in 2015, a survey of European countries found that breastfeeding initiation rates ranged from 80% in the Netherlands to 98% in Norway and that breastfeeding prevalence at 2 months ranged from 64% in the Netherlands to 89% in Norway (both outcomes were reported by 6 of 11 countries). 29 The exception is Ireland, which has similar rates to the UK with a breastfeeding initiation rate of 64%30 and breastfeeding prevalence at 3 months of 35%. 29

Breastfeeding support

In the UK, formal breastfeeding support, comprising practical, informational, emotional and social support may be provided by healthcare practitioners, voluntary organisations and peer supporters. Women may also receive informal breastfeeding support from families and friends. However, many women report feeling unsupported by healthcare providers and their social networks, especially in the early weeks following birth. 31 This was exacerbated by the impact of COVID-19 on breastfeeding support services, which were already being reduced. 32,33

There is evidence that women living in deprived areas face multiple barriers to breastfeeding and accessing appropriate breastfeeding support. Common barriers include pain, the perception that they do not produce sufficient milk to meet their baby’s needs,34 embarrassment about breastfeeding in public and negative societal attitudes to breastfeeding. 34,35 While these barriers affect all women, they can be particularly challenging in settings where family and friends lack knowledge and experience of breastfeeding. 35 Women from disadvantaged backgrounds may value particularly the experiential knowledge and skills adapted to local contexts provided by peer support. 36 However, survey data suggested that coverage of breastfeeding peer support across the UK was variable and not accessed by socially disadvantaged women. 33 Additional barriers for women from minority ethnic groups, for example Bangladeshi women, include diverse cultural influences of their heritage and their areas of residence in the UK37 and cultural stereotypes held by healthcare providers. 38 There is strong global evidence that, for healthy women and babies, breastfeeding support is effective at increasing partial and exclusive breastfeeding. 39–42 However, these reviews combine evidence from high-, middle- and low-income countries, with most of the HIC evidence coming from the USA. Interventions tested in trials are heterogeneous and generally undertheorised. The extent to which global evidence is transferable to the UK setting is unclear. Previous evidence from UK-based trials is limited and has not demonstrated efficacy of interventions. 43–45 Feasibility studies in the UK show that peer support interventions are acceptable46,47 but effectiveness has not been established.

Women with multimorbidities

The prevalence of maternal chronic conditions is rising,48 which is in part due to increasing maternal age and the improved management of long-term conditions (LTCs). 49 For instance, UK data show that 2.3% of women have been diagnosed with diabetes either prior to or during pregnancy,50 0.5% have a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease,51 0.5–1.0% have a diagnosis of epilepsy,52 18.4% have a postnatal diagnosis of anxiety53 and 11.4% have a postnatal diagnosis of depression. 53 Moreover, the rates of gestational diabetes in pregnant women in the UK range from 1.2% to 24.2% depending on maternal characteristics and diagnostic method,54 and this increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes 10-fold. 55

The prevalence of multiple long-term conditions (MLTC) in the UK is also rising, particularly among working-age adults. 56 Within a general adult population, the onset of MLTC happens 10–15 years earlier in those living in the most deprived areas than in those living in more affluent areas. 57 The MuM-PreDiCT study sought to identify the prevalence of multimorbidities specifically during pregnancy and reported that between 19.8% and 46.2% of pregnant women experience two or more LTCs. 58 LTCs were defined as conditions that had a significant impact on patients, and the specific 79 conditions included in the study were determined in consultation with stakeholders. 59 Unlike in the general adult population, it is not currently clear if the prevalence of MLTC is higher among women from areas of high socioeconomic deprivation. The MuM-PreDiCT study did not find higher odds of multimorbidities in women from areas of high socioeconomic deprivation or in any specific ethnic group. 58 Post hoc analysis explored whether this was being impacted by the health conditions used to define multimorbidity, as some conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety and polycystic ovarian syndrome, were higher in more affluent areas. 58 When a shortened list of conditions was used, socioeconomic deprivation was associated with multimorbidities after adjusting for maternal age and gravidity [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.30, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.08 to 1.57]. 58 However, this was no longer significant once body mass index (BMI) and smoking status were also adjusted for (aOR 1.05, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.27). MLTC were more common in mothers aged 45–49 years (aOR 1.8, 95% CI 1.0 to 3.20), and this remained significant when adjusted for other characteristics.

Living with MLTC can have a significant impact on mental well-being and can make engaging in other activities difficult. 60 Within the context of maternal health, experiencing a LTC during pregnancy is associated with mental health conditions in the postpartum period such as post-traumatic stress. 61 Mothers with LTCs are also more likely to experience other adverse determinants of health, such as intimate partner violence, smoking, living in poverty and a lack of educational qualifications. 62

There is some evidence for the management of single conditions during pregnancy and the postnatal period, for example diabetes,63 epilepsy,64 and depression,65 that is focused on the treatment modalities for that single condition. However, there is a complete lack of evidence on MLTC in mothers. Postnatal care, in particular, has been universally described as poor due to a lack of follow-up care and help for women to care for their babies. 66 Breastfeeding could present a challenge to women with MLTC, as is evidenced by significantly lower breastfeeding rates among women with single LTCs. 62,67 For instance, a study comparing UK women with lifelong limiting conditions found that breastfeeding rates at 3 months were lower in this group than among women without any conditions (25.6% vs. 33.4%);62 however, rates of initiation were similar. Data from Canada showed that although women with chronic diseases had similar odds of initiating breastfeeding, they were more likely to cease breastfeeding early than women in the general population (aOR 2.48, 95% CI 1.49 to 4.12). 68 Data from other countries also suggest that breastfeeding rates are lower among women with a range of specific conditions such as insulin-dependent diabetes (aOR 0.49, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.89), epilepsy (aOR 0.42, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.68)69 and rheumatoid arthritis (any breastfeeding at 3 months in women with rheumatoid arthritis = 26% vs. 46% of general population). There is currently a complete lack of evidence on breastfeeding rates in women with MLTC. 70

There are several reasons why women with LTCs may have additional difficulties breastfeeding, including a physiological delay in milk release to 72 hours after birth, an increased risk of early separation from the infant as a result of caesarean section and/or requirement for the infant to be placed in neonatal intensive care unit facilities, fatigue, and poor and inconsistent advice about the safety of medications. 68 Anecdotal evidence from the Breastfeeding Network has also identified a lack of joined-up care as a barrier to breastfeeding. As breastfeeding can confer significant health benefits to both mother and infant,14 there is a need for breastfeeding support interventions to provide effective support to all women that is tailored to their individual needs. 71

Economic impact

Breastfeeding in itself is considered a cost-effective intervention. 17,72 Increased breastfeeding has the potential to reduce healthcare costs. 17,18 In addition to the important effects on the health of women and children, breastfeeding has wider health system and societal impacts, including cost savings for the NHS and environmental benefits. The cost to the global economy of not breastfeeding has been estimated at US$570B (£396B) each year, with estimates indicating that 0.75% of gross national income in HICs is lost from not breastfeeding. 73 With a UK gross national income of £2505B in 2022,74 this equates to a value to the UK economy of £18.8B. For the UK health system, estimates are that £23.6M of additional treatment costs each year could be saved by increased breastfeeding. 17 This cost to the NHS is considered a conservative estimate, as a limited number of maternal and child-related illnesses were included in the analysis. A further cost to the NHS is the increasing number of prescriptions for specialist formula to treat cow’s milk protein allergy. 19 For example, an 800g tin of specialised formula (Aptamil Pepti® 1 powder, Nutricia, Trowbridge, UK) prescribed for cow’s milk allergy, which would feed a baby under 6 months old for 1 week, costs the NHS £19.72 at 2023 prices. 75 The environmental impact of not breastfeeding (i.e. feeding with infant formula) is significant. For example, plastics and resources used by the dairy industry have a cost in carbon dioxide emissions equivalent to 50,000–77,500 cars on the road each year and a water footprint of 4700 l/kg. 20,21 Therefore, significant health, societal and environmental gains are to be had from increasing breastfeeding duration and exclusivity. In choosing a breastfeeding support intervention to implement into a health system, policy-makers need to understand not only the evidence of effect and contextual factors that should be considered but also the evidence of cost-effectiveness. With pressure on NHS resources, service managers need to ensure that any investment yields a positive return both in the short term, with increased breastfeeding, and in the long term, with reduced health service resource use and subsequent cost savings.

Why this research is needed

There is a need to find out what works to support women in the UK to meet their infant-feeding goals, to breastfeed for longer, and to increase rates of exclusive breastfeeding. This involves understanding the characteristics and components of breastfeeding support interventions that are likely to be effective and cost-effective in the UK, as well as how to implement and evaluate such interventions. This is particularly the case for populations where breastfeeding rates are low, including young mothers, women of low socioeconomic status, those from marginalised groups, and those with multimorbidities. Although this has been a policy aspiration in the UK for several decades, there is a gap in evidence regarding effective interventions. At a time when the NHS is struggling to meet demand, and life expectancy is stalling, cost-effective public health interventions targeted to disadvantaged communities are vital.

Chapter 2 Research design including stakeholder engagement

Aim and objectives

The aim was to synthesise global and UK evidence to co-create with stakeholders a framework to guide the implementation and evaluation of cost-effective breastfeeding support interventions in the NHS.

Objectives

-

Update the Cochrane review ‘Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies’41 to identify effective breastfeeding support interventions (see Chapter 3).

-

Conduct a theoretically informed mixed-methods synthesis of process evaluations of UK-relevant breastfeeding support interventions (see Chapter 4).

-

Conduct an economic evaluation of interventions to enable women to breastfeed (see Chapter 5).

-

Conduct a systematic review to identify effective interventions that provide breastfeeding support for women with LTCs (see Chapter 6).

-

Conduct a mixed-methods synthesis of barriers to and facilitators of breastfeeding support in women with LTCs (see Chapter 7).

-

Conduct a systematic review of economic evaluations of breastfeeding support interventions for women with single LTCs (see Chapter 8).

-

Co-create a NHS-tailored implementation and evaluation strategy framework to address contextual barriers and inform transferability of cost-effective interventions to increase breastfeeding rates among healthy women and those with LTCs in the UK (see Chapter 9).

-

Contribute to methodological development of involving stakeholders in co-creation of systematic reviews and synthesising process evaluations to support the transferability and applicability of global evidence to local health service contexts (see Chapter 10).

Objectives 1–3, 7 and 8 were in the original proposal (referred to throughout this report as the main study). Objectives 4–6 were added when additional funding was awarded to address the needs of women with multimorbidities. The focus of objectives 4–6 is on single LTCs because of the lack of evidence relevant to multimorbidities. The primary focus of our work was support for healthy women to breastfeed, addressing inequities in health outcomes. This included women from diverse ethnic and socioeconomic groups. The work on MLTC was an add-on. However, we were also interested in multimorbidities as a contributing factor to health inequities. Objective 7 was modified from the original proposal to incorporate the findings of the additional work. To increase usability, we reframed the main output as a toolkit instead of a framework.

Study design

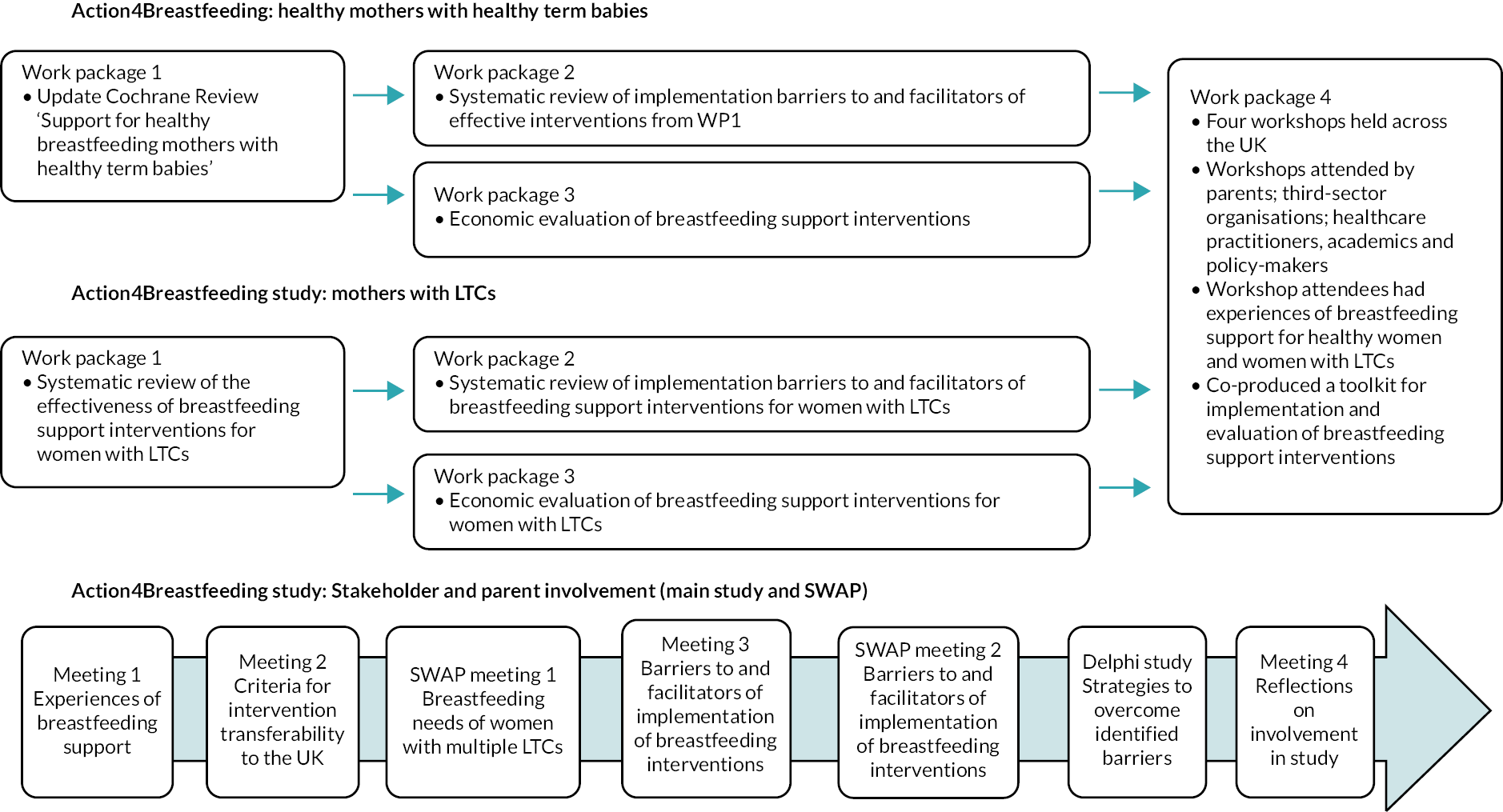

The study comprised evidence syntheses and economic evaluations with embedded stakeholder engagement, including patient and public involvement (PPI). We used principles of co-creation to ensure that study outputs were relevant to the NHS context. The main study comprised four interlinked work packages with a cross-cutting strand of stakeholder engagement and PPI, as shown in Figure 1. The main study took place over 2 years and the additional work took place over 9 months.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram.

The methods for each evidence synthesis are described in the relevant chapters. In this chapter we present our approach to stakeholder engagement and PPI.

Stakeholder and parent engagement: main study

To ensure joint ownership,76 our approach was ‘active involvement’, defined as ‘the contribution of any person who would be a knowledge user but whose primary role is not research’, throughout the process of evidence synthesis, including planning, production and dissemination. 77 Involvement and co-creation were essential to enhance the quality and relevance of the evidence syntheses. 78,79 Stakeholders and parents were involved in three ways: a co-investigator (PB) from a breastfeeding support organisation represented service user views; the stakeholder working group, parents’ panel and focus group discussions ensured that the experiences of breastfeeding women and service providers were represented in key decisions; and attendees at four workshops co-created the study outputs. Here we describe the participants, activities and outcomes of the stakeholder working group, parents’ panel and focus group discussions. See Chapter 9 for details of the workshops.

Participants

The stakeholder working group comprised 11 members representing third-sector organisations [Breastfeeding Network, Association of Breastfeeding Mothers, La Leche League, National Childbirth Trust (NCT)]; health professionals [general practitioner (GP), midwife, health visitor]; breastfeeding support workers; community breastfeeding support services; national infant-feeding networks; and national policy bodies. Two members also had roles with UNICEF-UK Baby Friendly Initiative. There were representatives from the four nations of the UK. Members of the stakeholder working group were selected to represent areas of high deprivation and/or ethnically diverse populations. For example, the health visitor covered deprived areas in Manchester; the midwife was from the north-east of England, where breastfeeding rates are low; the GP worked in inner-city Glasgow; and the community breastfeeding lead worked in an ethnically diverse area of London.

The parents’ panel comprised nine parents, seven mothers with recent and varied breastfeeding experience and two fathers whose partners had breastfed and who were members of a third-sector organisation. The mothers were recruited via a national third-sector organisation Facebook group. We acknowledge that this approach can lead to the recruitment of parents from higher-income and more educated backgrounds. One member of the parents’ panel was a Gypsy/Traveller, one of the most marginalised and deprived communities in the UK. For this reason, we supplemented the parents’ panel with focus group discussions.

Focus group discussions were held to reach parents from socially disadvantaged backgrounds who were less likely to participate in larger group meetings and who represented groups least likely to breastfeed. The participants were recruited via a not-for-profit organisation providing peer support (not specific to infant feeding) to parents living in economically deprived, ethnically diverse populations in West Yorkshire. Fifteen women participated in the focus group discussions.

Activities and outcomes

The stakeholder working group and parents’ panel each met four times and also participated in an online consensus-building exercise. The consensus-building exercise drew on modified Delphi study methodology. 80 All meetings were held virtually due to COVID-19 restrictions. Focus group discussions were held at three time points, with both a virtual and in-person option provided; there were six focus groups in total. Table 1 shows the main activities at each meeting. Between meetings, a newsletter was circulated to all members to update them on the progress of the study. At the fourth meeting, the stakeholder working group and parents’ panel reflected on their experiences of engaging with the study. Their views are included in Chapter 10.

| Meeting (number of participants) | Description of activity | Outcomes/impact on study |

|---|---|---|

| SWG 1 (11) | Getting to know each other and setting ground rules. Presentation of project and bite-size training on systematic reviews. Assessing the transferability of breastfeeding interventions to the UK (breakout discussions) | Early discussions of criteria for assessing transferability developed for SWG 2 |

| PP 1 (6) | Getting to know each other and setting ground rules. Presentation of project and bite-size training on systematic reviews. Reflections on personal experiences of breastfeeding support | Factors viewed as important to satisfaction with breastfeeding support influenced Cochrane review (review 1) meta-analysis (e.g. selection of outcome time points) |

| FGD 1 (8: 5 online, 3 face to face) | Topic guide covered personal experiences of breastfeeding support, and views of important components of support including who, where, when and how | Factors viewed as important to satisfaction with breastfeeding support influenced Cochrane review (review 1) meta-analysis (e.g. selection of outcome time points) |

| SWG 2 (7) | Interactive exercise to score and rank transferability criteria from the PIET-T process model81 | Top 3 ranked criteria (1, population’s acceptability of the intervention; 2, quality of the primary evidence available; 3, sustainability of the intervention) used to select examples of effective interventions from the Cochrane review (review 1) for discussion of implementation barriers and facilitators |

| PP 2 (4) | The PIE-T model explained. Results of the SWG ranking exercise presented. Discussion of the 12 highest-scoring criteria | Parents’ views of transferability criteria informed decision not to exclude any effective interventions, as any intervention could be transferred to the UK with adaptations and resources |

| FGD 2 (6: 3 online, 3 face to face) | Visual materials in plain language covering the key transferability criteria presented. Participants asked to discuss important factors to take into account when transferring interventions from another country to a UK setting | Discussions of barriers to and facilitators of accessing breastfeeding support and informed consideration of transferability |

| SWG 3 (6) | Five effective interventions from the Cochrane review (review 1) presented and discussed to identify implementation barriers and strategies | Identified barriers and facilitators included in the consensus-building exercise study |

| PP 3 (4) | Five effective interventions from the Cochrane review (review 1) presented and parents discussed positive and negative aspects, barriers to access and strategies to overcome the barriers | Identified barriers to access and strategies included in the consensus-building exercise |

| Consensus-building exercise 1 (10) | Respondents (SWG and PP) presented with 18 barriers (from previous meetings) and asked to recommend strategies from 10 themes from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) framework82 | For each barrier, strategy themes with > 70% consensus were taken forward to round 2. Due to lack of consensus on strategies, one barrier was excluded from round 2 |

| Consensus-building exercise 2 (8) | For each of the 17 barriers, respondents asked to rank in order of importance individual strategies from the themes that reached consensus in round 1 (34 strategies) | Due to low response rate (no parents responded) and lack of consensus, 34 strategies were taken forward to the workshops |

| FGD 3 (9: 6 online, 3 face to face) | Five effective interventions from the Cochrane review (review 1) discussed to identify implementation barriers and strategies | Identified barriers and facilitators compared with findings from SWG, PP and workshops to illuminate considerations that might be needed when adapting for communities with low breastfeeding rates |

Stakeholder and parent engagement (multiple long-term conditions)

Participants

The MLTC stakeholder working group comprised 12 members representing third-sector organisations [Breastfeeding Network, La Leche League, Lactation Consultants of Great Britain and the British Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Association] and a wide range of healthcare professionals (consultant physician, consultant psychiatrist, GP, pharmacist, health visitor, specialist midwife, infant-feeding co-ordinator and diabetes specialist nurse) involved with caring for women with MLTC who may breastfeed. Stakeholder working group members were from England, Scotland and Wales and were selected for their experience in supporting women with a wide range of long-term physical and mental health conditions to breastfeed.

One-to-one discussions with condition-specific experts including a consultant endocrinologist and an HIV breastfeeding specialist were also undertaken.

The MLTC parents’ panel comprised seven parents with MLTC and recent breastfeeding experience. Parents’ panel members were from across the four UK nations and had lived experience of a wide range of physical and mental health conditions, including diabetes, lupus, fibromyalgia, inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis, hypertension, kidney disease, connective tissue disorders, asthma, chronic fatigue syndrome, anxiety and depression. Parents were recruited via third-sector organisation Facebook groups.

Activities and outcomes

The MLTC stakeholder working group and parents’ panel met twice during the 9-month study. These meetings mirrored the first and third meetings of the main study stakeholder working group and parents’ panel. The first meeting of the parents’ panel was focused mainly on giving parents opportunities to tell their stories of breastfeeding alongside coping with multimorbidities. The first meeting of the stakeholder working groups was focused on participants’ experiences of providing breastfeeding support to women with MLTC and the barriers to and facilitators of providing support. In the second meeting, the stakeholder working group and parents’ panel discussed the same five effective interventions used in the main study, this time focusing on whether and how these interventions could be adapted to meet the needs of women with multimorbidities. The findings from the MLTC stakeholder engagement contributed to the workshop activities as described in Chapter 9.

Role of stakeholder engagement

The main purpose of the stakeholder working groups, the parents’ panel and the focus group discussion was to adapt the international evidence, that is, the findings of the reviews, to ensure relevance to the UK context and the NHS, and to coproduce the toolkit. The stakeholder engagement therefore influenced the interpretation and adaptation to the UK setting of the review findings rather than their methods. The exception to this was in influencing the decision on outcome time points and variables for the meta-regression for review 1.

Chapter 3 Effective interventions for breastfeeding support for healthy women with healthy term babies

Introduction

This chapter contains a summary of the methods and results section from the updated Cochrane review on breastfeeding support for healthy term women with healthy term babies. 83 The full review including table of characteristics, forest plots and risk of bias assessments is published in the Cochrane Library. 83 Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Wiley. Copyright © 2022 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Objectives

-

To describe types of breastfeeding support for healthy breastfeeding women with healthy term babies.

-

To examine the effectiveness of different types of breastfeeding support interventions focusing on breastfeeding support provided on its own or breastfeeding support in combination with a wider maternal and child health intervention.

-

To examine the effectiveness of the following intervention characteristics on breastfeeding support:

-

type of support (e.g. face to face, telephone, digital technologies, group or individual support, proactive or reactive)

-

intensity of support (i.e. number of postnatal contacts)

-

person delivering the intervention (e.g. healthcare professional, lay person)

-

to examine whether the impact of support varied between high‐ and low‐ and middle‐income countries.

-

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Inclusion criteria

Types of studies

All randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs), with or without blinding, were included. Cluster‐RCTs were also eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Participants were healthy pregnant women considering or intending to breastfeed their baby, or healthy women who were breastfeeding healthy babies. Healthy women and babies were considered those who did not require additional medical care. Studies of women requiring additional medical care (e.g. women with diabetes, women with HIV/AIDS, overweight or obese) were excluded. The inclusion criteria were amended in this update to include women undergoing caesarean section.

Types of interventions

We defined breastfeeding support as contact with an individual or individuals (either professional or volunteer) offering support that is supplementary to the standard care offered in that setting. Interventions could be delivered as standalone breastfeeding support interventions (breastfeeding only), or breastfeeding support could be delivered as part of a wider maternal and newborn health intervention (breastfeeding plus) where additional services are also provided (e.g. vaccination, intrapartum care, well-baby clinics).

‘Support’ interventions eligible for this review could include elements such as reassurance, praise, information, and the opportunity to discuss and to respond to the mother’s questions and could also include staff training to improve the supportive care given to women. It could be offered by health professionals or lay people, trained or untrained, in hospital and community settings. It could be offered to groups of women or one‐to‐one, including mother‐to‐mother support, and it could be offered proactively by contacting women directly, or reactively, by waiting for women to get in touch.

This update now also includes support provided via digital technologies as well as support provided over the telephone.

Support could involve only one contact or regular, ongoing contact over several months. Studies were included if the intervention occurred in the postnatal period alone or also included an antenatal component.

Types of outcome measures

-

Stopping any breastfeeding at 6 months postpartum.

-

Stopping exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months postpartum.

-

Stopping any breastfeeding at 4–6 weeks postpartum.

-

Stopping exclusive breastfeeding at 4–6 weeks postpartum.

-

Stopping any breastfeeding at 2, 3–4 and 12 months postpartum.

-

Stopping exclusive breastfeeding at 2 and 3–4 months postpartum.

-

Maternal satisfaction with care.

-

Maternal satisfaction with feeding method.

-

All‐cause infant or neonatal morbidity (including infectious illness rates).

-

Maternal mental health.

Exclusion criteria

Types of studies

Any study that did not involve the random allocation of participants was excluded (non-RCTs; quasi-experimental studies; one group before-and-after studies; cohort studies; case–control studies; case reports; or qualitative studies).

Types of participants

Studies that focused specifically on women or infants with additional care needs were excluded. For mothers this could mean coexisting medical problems (e.g. diabetes, HIV) or pregnancy-related complications (e.g. pre-eclampsia). For infants this could include preterm birth, low birthweight or additional care in a neonatal unit.

Types of interventions

Interventions taking place in the antenatal period alone were excluded from this review, as were interventions described as solely educational or promotional in nature.

Additional limitations

We did not exclude studies based on language or date of publication. Abstracts were eligible for inclusion if they provided sufficient information for data to be extracted. If they did not provide sufficient information, they were recorded as ongoing studies.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register was searched by its information specialist in May 2021. This includes results of searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (11 May 2021).

We also searched the reference lists of retrieved studies and the list of excluded studies from the previous version of this review to identify any studies that met the new inclusion criteria. 41

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group methods. Two review authors independently selected trials, extracted data and assessed risk of bias using Covidence software. 84 The certainty of the evidence was assessed by two reviewers using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. 85

We then assessed study trustworthiness using the new approach implemented by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group to identify and manage potentially untrustworthy studies. 86 All full texts meeting the inclusion criteria and studies included in the previous update of this review were evaluated against the following criteria.

Research governance

-

No prospective trial registration for studies published after 2010 without plausible explanation.

-

When requested, trial authors refuse to provide/share the protocol and/or ethics approval letter.

-

Trial authors refuse to engage in communication with the Cochrane review authors.

-

Trial authors refuse to provide individual patient data upon request with no justifiable reason.

Baseline characteristics

-

Characteristics of the study participants being too similar [distribution of mean (standard deviation) excessively narrow or excessively wide].

Feasibility

-

Implausible numbers (e.g. 500 women with severe cholestasis of pregnancy recruited in 12 months).

-

(Close to) zero losses to follow‐up without plausible explanation.

Results

-

Implausible results (e.g. massive risk reduction for main outcomes with small sample size).

-

Unexpectedly even numbers of women ‘randomised’ including a mismatch between the numbers and the methods, for example if they say no blocking was used but still end up with equal numbers, or they say they used blocks of four but the final numbers differ by six.

Any studies classed as potentially high risk for any of these criteria were referred back to the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group, who contacted the study authors for more information. If we did not receive adequate information, the study remained ‘awaiting classification’.

Data synthesis

We used methods outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for statistical analysis. 87 In this update of the review, we grouped interventions into two different categories for meta-analysis. The first group, ‘breastfeeding only’, were interventions that only contained breastfeeding support. In the second group, breastfeeding support was one part of a larger intervention that also aimed to provide other health benefits for the mother or her infant (e.g. vaccinations, new-baby care).

We used meta-regression to further assess statistical heterogeneity for the four primary outcomes when a sufficient number of studies were included in the analyses (i.e. at least 10 observations per characteristic modelled). 88 The following four categories were selected for the meta-regression in conjunction with stakeholders:

-

by type of supporter (professional vs. lay person, or both)

-

by mode of support (face to face vs. telephone support vs. digital vs. combination)

-

by intensity of support [low (fewer than four) vs. moderate (four to eight) vs. high (nine or more)]

-

by income status of country [high‐income country vs. low- and middle‐income country (LMIC)].

We performed sensitivity analyses based on risk of bias for allocation concealment and incomplete outcome data. Additionally, sensitivity analyses were conducted to investigate the effect of including cluster‐randomised trials where no adjustment was possible.

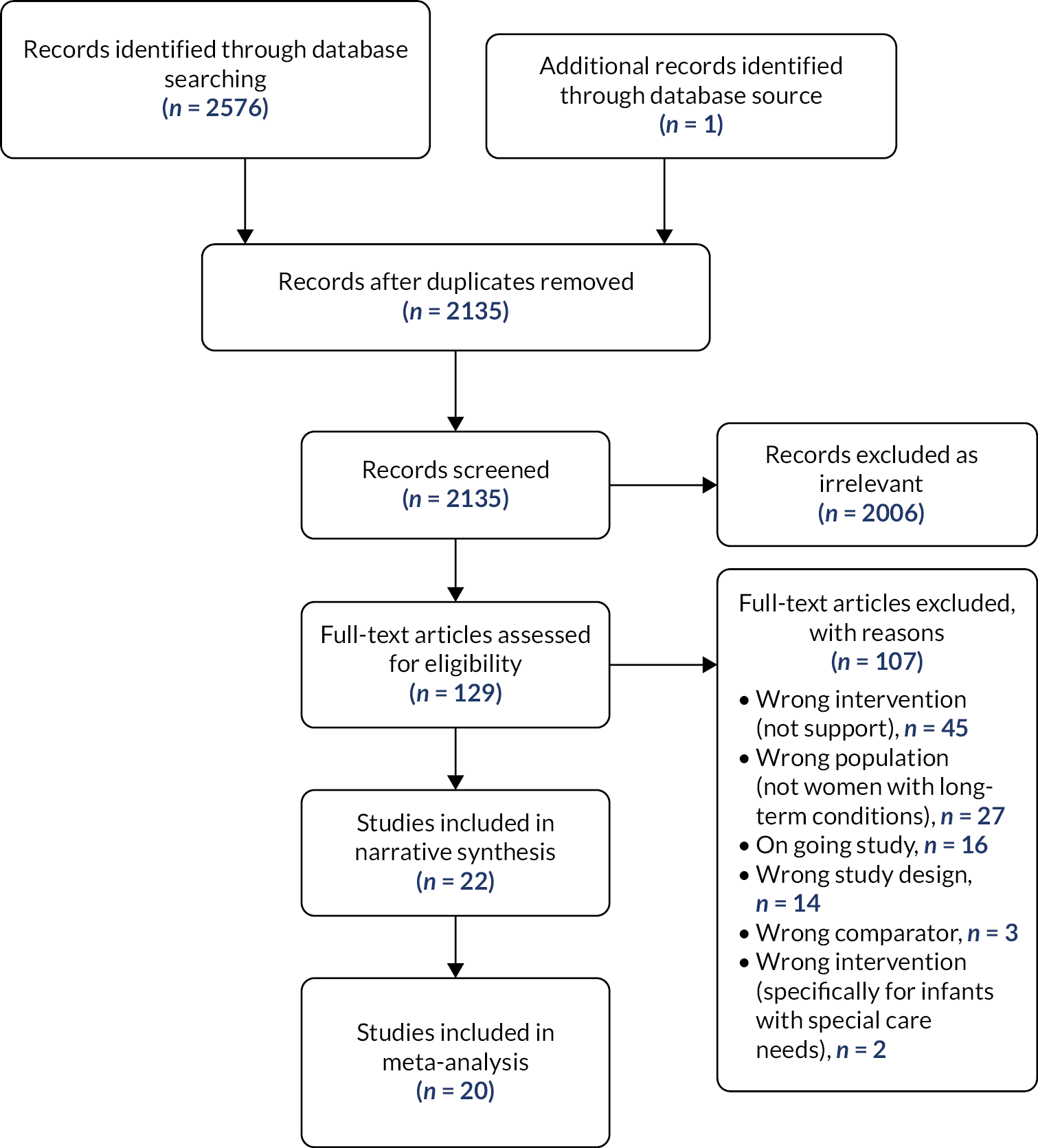

Results

A total of 590 trial reports were assessed for inclusion in this update (see Gavine et al. 83 for full details). This included 560 studies from the updated search, 16 trial reports that were awaiting classification in the previous version of the review, 8 studies that were ongoing in the last version of the review and 6 previously excluded studies that were reassessed due to the change in inclusion criteria. Of these, 72 met the inclusion criteria.

All studies (100 previously included and 72 newly identified studies) were assessed against Cochrane’s criteria for trustworthiness. Of the 100 previously included studies, we requested further information for 38, and of the new studies identified in this update, we required clarification for 43. In total, we received satisfactory responses for 27 studies. In total, 54 studies were reclassified to ‘awaiting classification’. The remaining studies were included, and this updated review includes 116 trials, of which 103 contribute data to the analyses.

In total, 249 studies were excluded with reasons (this comprises 139 reports from the updated search and 110 reports from previous versions of the review). The majority of studies (n = 136) were excluded as the intervention was not relevant to the review, for example interventions that were focused on education and/or promotion only and did not offer any support, interventions that were focused on other aspects of postnatal care, and antenatal-only interventions. We excluded any study that was not a RCT (n = 53). A further 49 studies were excluded because they did not focus on healthy mothers (e.g. coexisting medical conditions requiring additional care) or babies (e.g. preterm, low birthweight). Eleven studies were excluded because the comparator was not either standard care or an alternative non‐breastfeeding intervention. Finally, four studies were excluded as they were not research papers. For full details, see Gavine et al. 83 for characteristics of the excluded studies.

Description of included studies

This updated review includes 116 trials, of which 103 contribute data to the analyses. The 116 studies comprise 83 individually randomised trials and 33 cluster‐randomised trials. Most are two‐arm RCTs; however, 20 studies are either three‐ or four‐arm RCTs. In total, 125 interventions with more than 98,816 mother–infant pairs were included. See Gavine et al. 83 for further details and tables of characteristics.

Participants

Participants living in 42 countries are included in the review. Using the World Bank classification of countries by income, 21 of the new included studies in the review were conducted in HICs, 6 in upper-middle‐income countries, 16 in LMICs and 5 in low‐income countries (LICs). Participants were women from the general healthy population of their countries. However, 52 studies recruited women from groups at high risk of health inequalities or health inequities in their country. Most of these studies were conducted in HICs (n = 33). These included women defined as low-income or living in a disadvantaged area (n = 18), women with a non-white ethnic background (n = 9) and young mothers (n = 6).

Interventions

Of the 125 interventions included in the review, 91 interventions comprised only breastfeeding support components. The remaining 34 interventions aimed to increase breastfeeding rates as part of a multicomponent intervention, which aimed to improve other aspects of child health, such as vaccination rates, or sleep.

Women received breastfeeding support proactively in 85 interventions. In 32 studies, women had access to both proactive and reactive support, and in 6 studies only reactive support was offered. Just over half of the studies included an antenatal component.

Most interventions provided one-to-one support (n = 115). However, in 19 of these 115 interventions, additional group support was also available to women. Eight studies consisted of only group support and two studies provided support to partners. The majority of interventions were provided by professionals (n = 74). Thirty-five interventions were provided by a lay person (usually a peer supporter), and 14 had both lay and professional input. The majority of studies reported that the person providing the support had undergone training in breastfeeding (n = 97).

Face-to-face support was a component of the majority of interventions (n = 104). In 64 of the 104 interventions, face‐to‐face support was the only mode of support available. In 36 interventions, face‐to‐face support was complemented with telephone support. Telephone support alone was evaluated in 14 studies. Only five studies used fully digital approaches (e.g. social media, messaging services), and two studies used only two-way text messaging.

Intervention intensity was grouped as follows: low intensity (three or fewer contacts), moderate intensity (four to eight contacts) and high intensity (nine or more contacts). Twenty-one interventions were specified as low intensity, 41 were specified as moderate intensity, and 44 were specified as high intensity. The intensity of the remaining 19 interventions was not specified.

In 97 studies, the control groups were described as receiving the standard care for the study population. However, there are large differences in standard care provision both between and within countries. Thirteen studies compared the study intervention against either an active control arm or a control group that offered participants additional care to the standard care available to non‐participants. In six studies the care received by the control group is either not reported or unclear.

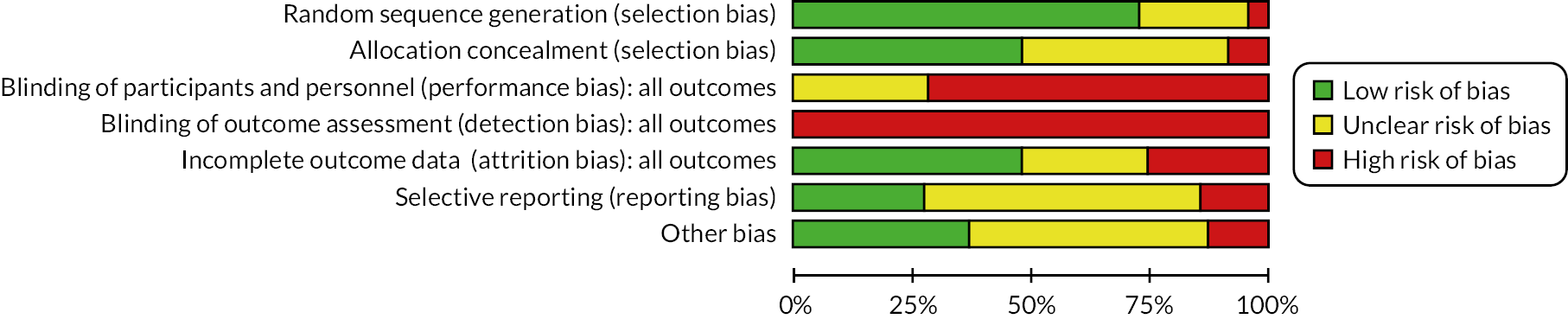

Risk-of-bias assessments

We considered that the overall risk of bias of trials included in the review was mixed. Blinding of participants and personnel is not feasible in such interventions, and, as studies utilised self‐report breastfeeding data, there is also a risk of bias in outcome assessment.

For full details of the risk-of-bias assessments, see Gavine et al. 83 A summary of the judgements is detailed in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Risk-of-bias graph: review authors’ judgements about each risk-of-bias item presented as percentages across all included studies (Gavine et al. 83).

Effects of interventions

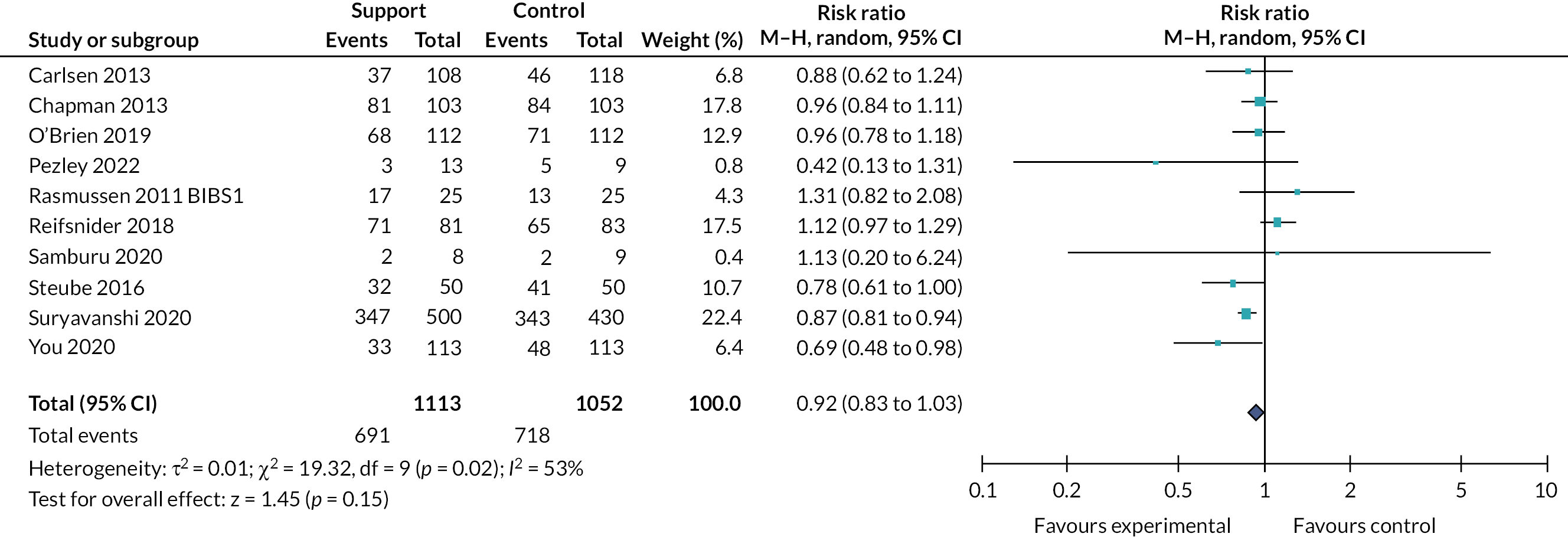

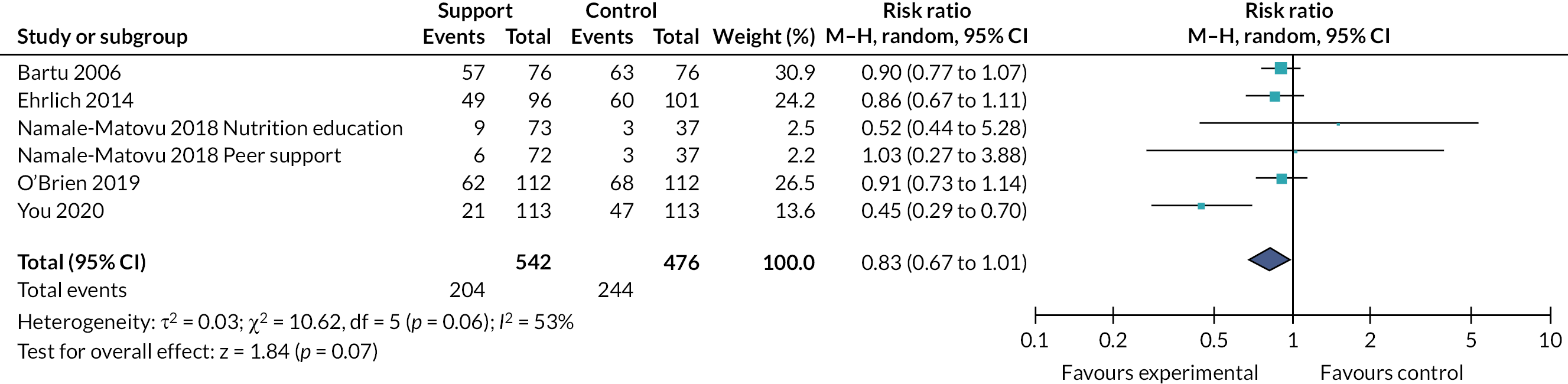

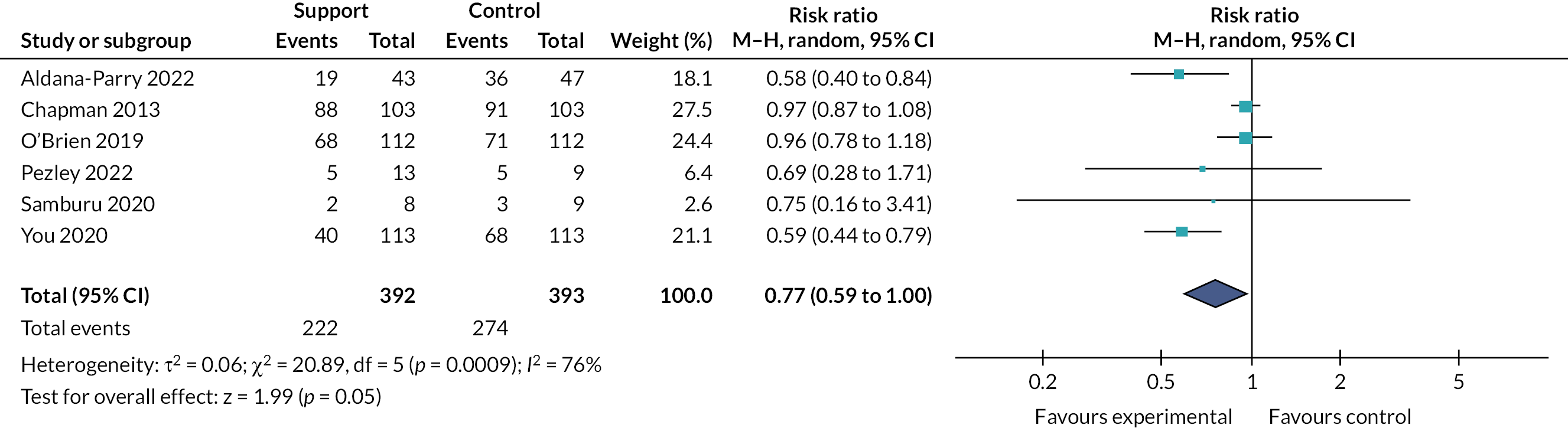

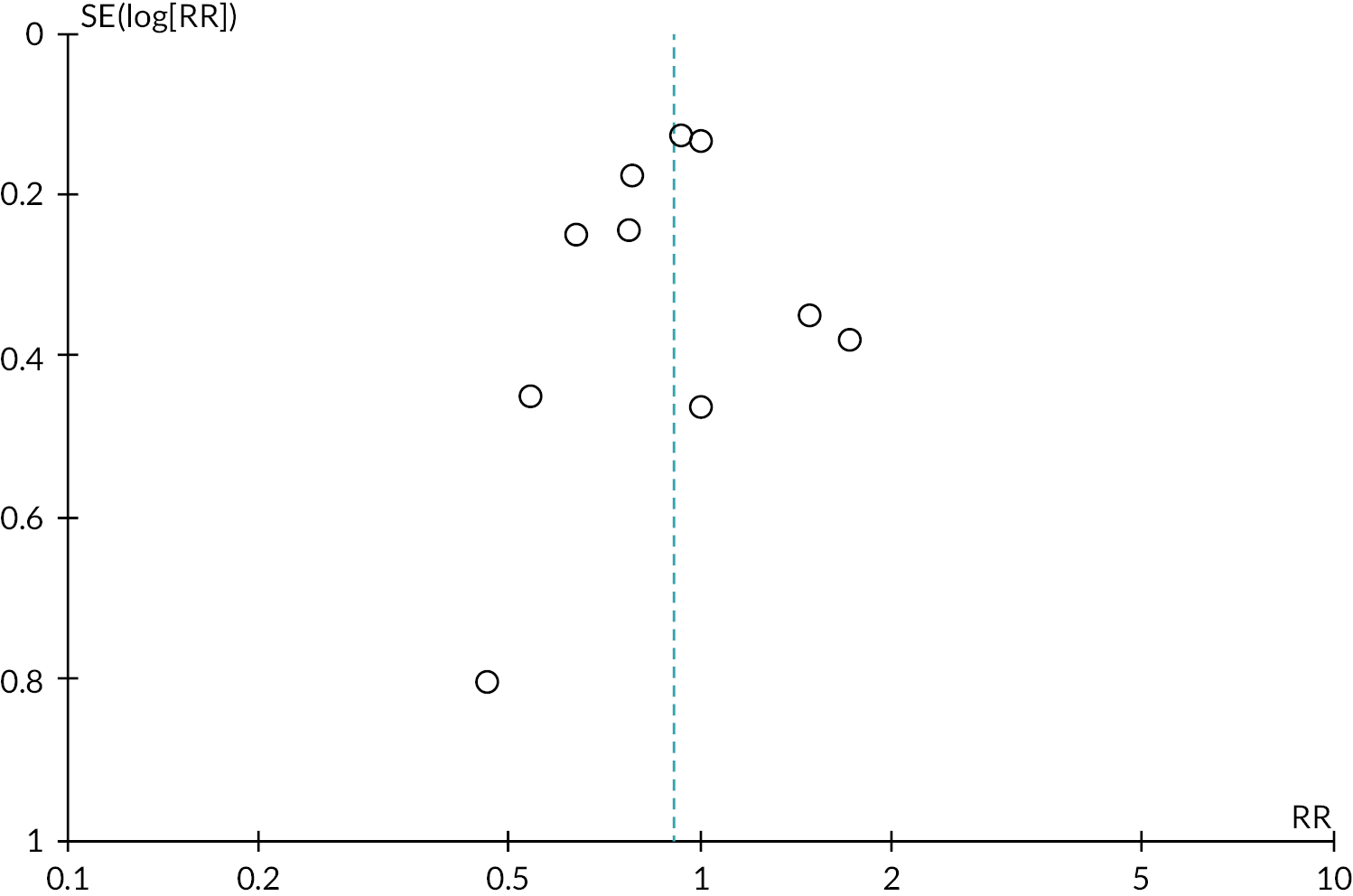

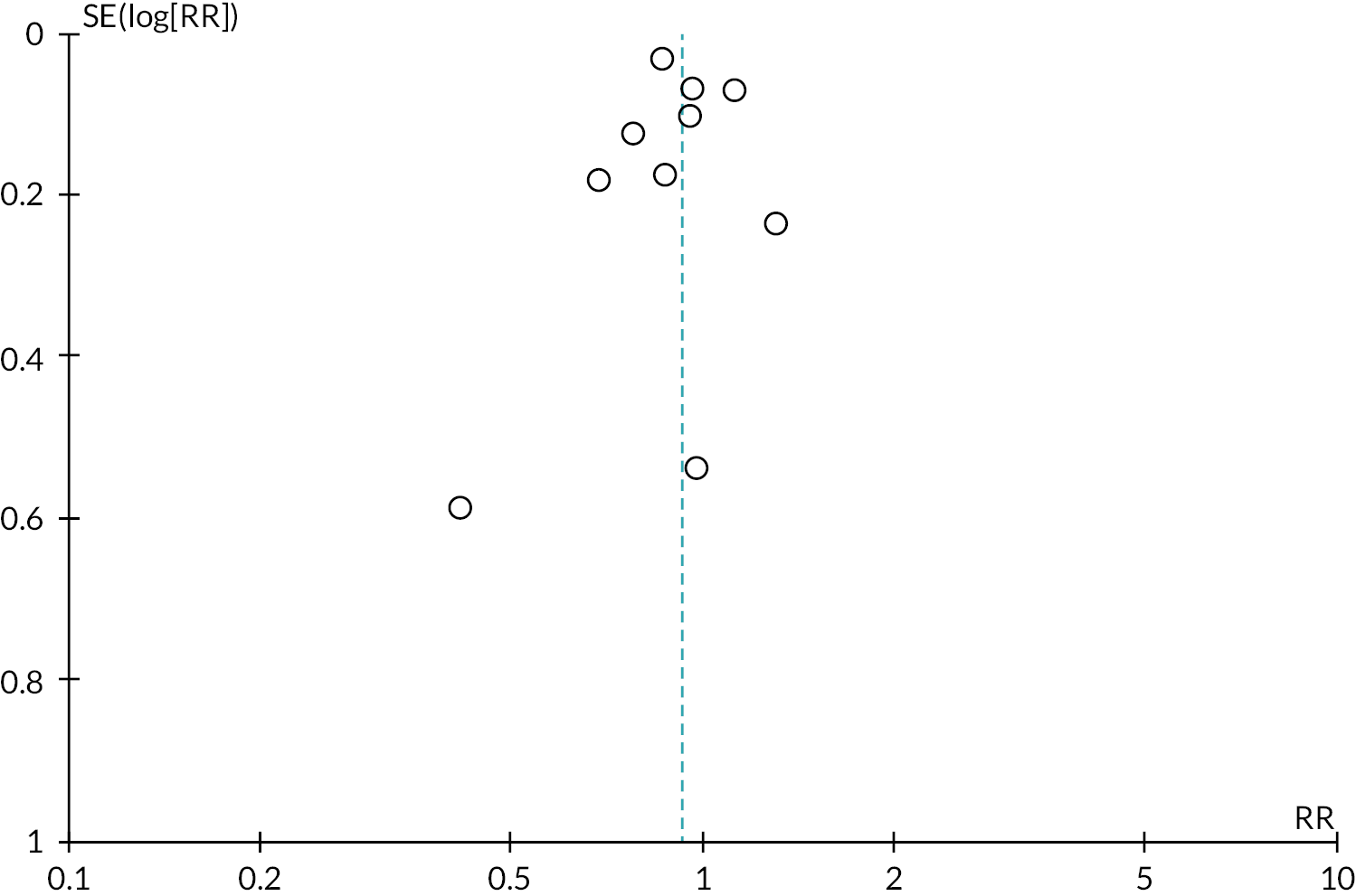

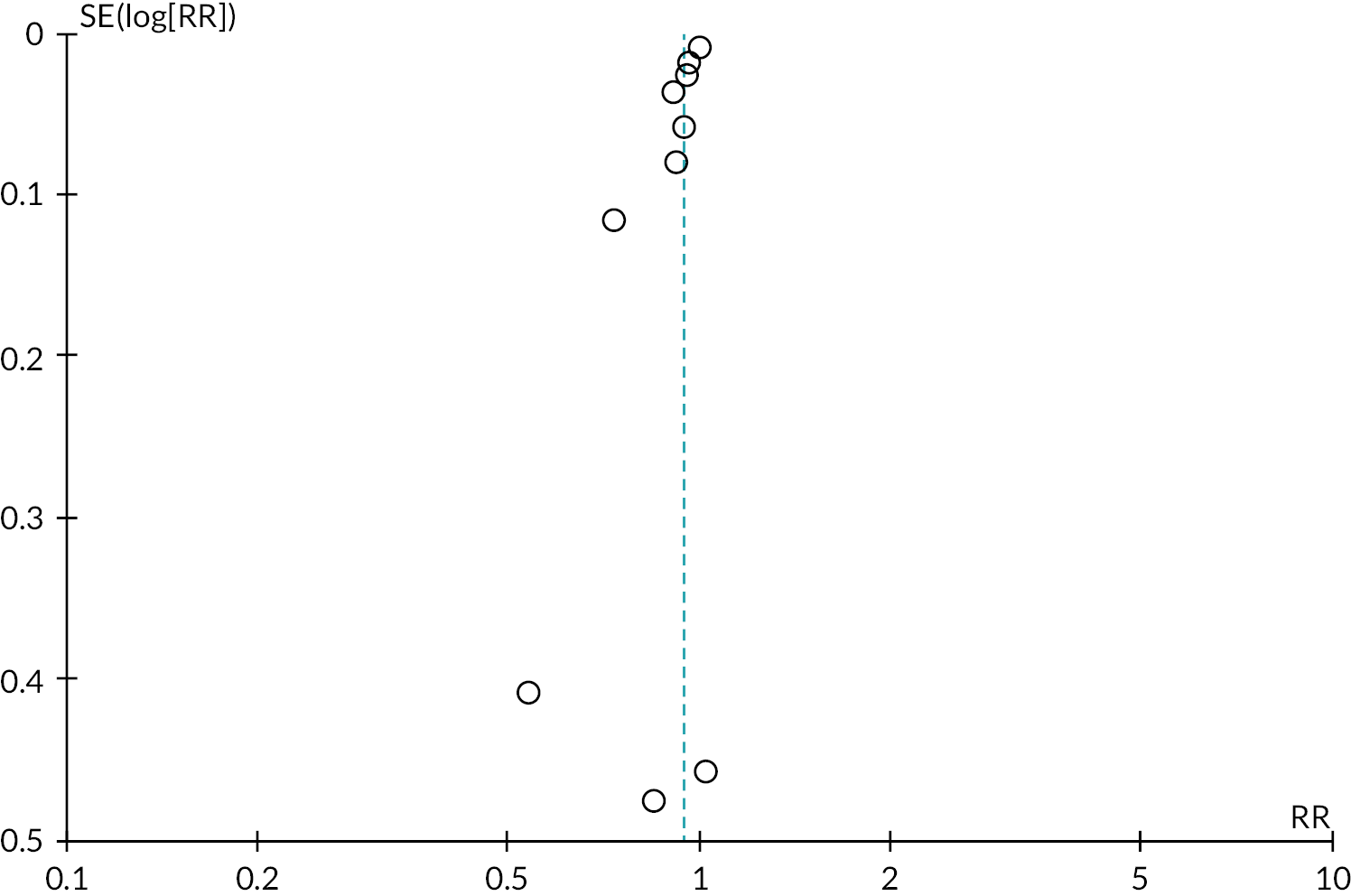

Tables 2 and 3 provide the summary of findings. For full details of effects of interventions, including forest plots and funnel plots, see Gavine et al. 83

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effectsa (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk with usual care | Risk with support | ||||

| Stopping breastfeeding (any) at 6 months | 600 per 1000 | 558 per 1000 (534 to 582) | RR 0.93 (0.89 to 0.97) | 14,610 (30 RCTs) | +++⃝ Moderateb |

| Stopping exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months | 847 per 1000 | 763 per 1000 (746 to 788) | RR 0.90 (0.88 to 0.93) | 16,332 (40 RCTs) | +++⃝ Moderateb |

| Stopping breastfeeding (any) at 4–6 weeks | 308 per 1000 | 271 per 1000 (244 to 299) | RR 0.88 (0.79 to 0.97) | 11,413 (36 RCTs) | +++⃝ Moderateb |

| Stopping exclusive breastfeeding at 4–6 weeks | 518 per 1000 | 430 per 1000 (394 to 466) | RR 0.83 (0.76 to 0.90) | 14,544 (42 RCTs) | +++⃝ Moderateb |

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effectsa (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk with usual care | Risk with support plus | ||||

| Stopping breastfeeding (any) at 6 months | 541 per 1000 | 508 per 1000 (492 to 524) | RR 0.94 (0.91 to 0.97) | 4879 (11 RCTs) | +++⃝ Moderateb |

| Stopping exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months | 685 per 1000 | 541 per 1000 (479 to 616) | RR 0.79 (0.70 to 0.90) | 7650 (13 RCTs) | ++⃝⃝ Lowb,c |

| Stopping breastfeeding (any) at 4–6 weeks | 433 per 1000 | 407 per 1000 (355 to 467) | RR 0.94 (0.82 to 1.08) | 2325 (6 RCTs) | +++⃝ Moderated |

| Stopping exclusive breastfeeding at 4–6 weeks | 542 per 1000 | 396 per 1000 (309 to 515) | RR 0.73 (0.57 to 0.95) | 2402 (6 RCTs) | +⃝⃝⃝ Very lowc,e |

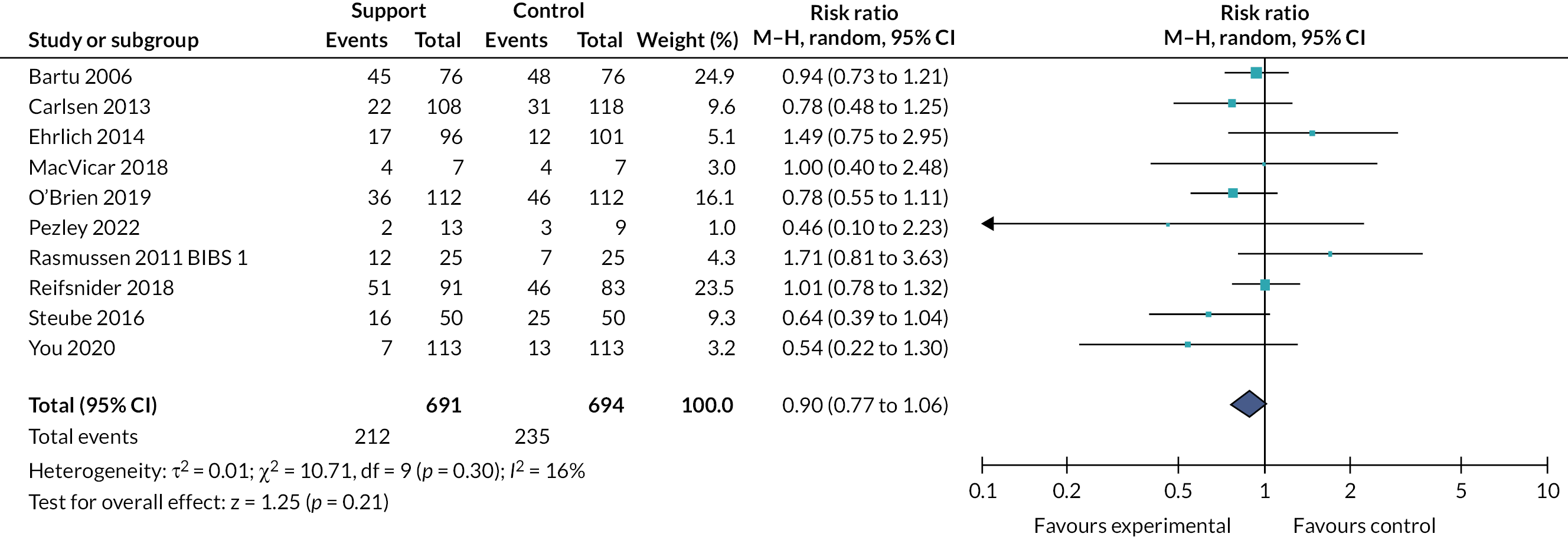

Primary outcomes

Moderate‐certainty evidence indicated that ‘breastfeeding only’ support probably reduced the number of women stopping breastfeeding for all primary outcomes: stopping any breastfeeding at 6 months [relative risk (RR) 0.93, 95% CI 0.89 to 0.97]; stopping exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.93); stopping any breastfeeding at 4–6 weeks (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.97); and stopping exclusive breastfeeding at 4–6 weeks (RR 0.83 95% CI 0.76 to 0.90). Sensitivity analyses excluding studies rated as being at high or unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment and incomplete outcome reporting found similar or more beneficial treatment effects.

The evidence for ‘breastfeeding plus’ was less consistent. For primary outcomes there was some evidence that ‘breastfeeding plus’ support probably reduced the number of women stopping any breastfeeding (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.91 to 0.97, moderate‐certainty evidence) or exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.90). ‘Breastfeeding plus’ interventions may have a beneficial effect on reducing the number of women stopping exclusive breastfeeding at 4–6 weeks, but the evidence is very uncertain (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.95). The evidence suggests that ‘breastfeeding plus’ support probably results in little to no difference in the number of women stopping any breastfeeding at 4–6 weeks (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.08, moderate‐certainty evidence).

We conducted meta‐regression to explore substantial heterogeneity for the primary outcomes using the following categories: person providing care, mode of delivery, intensity of support and income status of country. It is possible that moderate levels (defined as four to eight visits) of ‘breastfeeding only’ support are associated with a more beneficial effect on exclusive breastfeeding at 4–6 weeks and 6 months. ‘Breastfeeding only’ support may also be more effective in reducing women stopping exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months in LMICs than in HICs. However, no other differential effects were found and thus heterogeneity remains largely unexplained. The meta‐regression suggested that there were no differential effects regarding person providing support or mode of delivery; however, power was limited.

Secondary breastfeeding outcomes

Moderate‐certainty evidence indicated that ‘breastfeeding only’ support probably had a beneficial effect on the following: stopping exclusive breastfeeding at 2 months (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.89), any breastfeeding at 3–4 months (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.93) and exclusive breastfeeding at 3–4 months (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.89). Low-certainty evidence suggested that ‘breastfeeding only’ interventions may have a beneficial effect on the number of women breastfeeding at 9 months (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.97). However, low certainty evidence suggests that ‘breastfeeding only’ interventions have little impact on the number of women doing any breastfeeding at either 2 months (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.11) or 12 months (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.00).

‘Breastfeeding plus’ interventions probably had little to no impact on stopping breastfeeding for any of the secondary outcomes: any at 2 months (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.07, moderate-certainty evidence); exclusive at 2 months (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.03, very low-certainty evidence); any at 3–4 months (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.15, low-certainty evidence); exclusive at 3–4 months (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.00, low-certainty evidence); or any at 12 months (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.00, moderate-certainty evidence).

Non-breastfeeding outcomes

There were no consistent findings emerging from the narrative synthesis of the non‐breastfeeding outcomes (maternal satisfaction with care, maternal satisfaction with feeding method, infant morbidity and maternal mental health), except for a possible reduction of diarrhoea in intervention infants.

Chapter summary

The update of this Cochrane review on breastfeeding support for healthy term women identified 116 trials, of which 103 contribute data to the analyses. More than 98,816 mother–infant pairs were included. When ‘breastfeeding only’ support is offered to women, the duration and particularly the exclusivity of breastfeeding is likely to be increased. Support may also be more effective in reducing the number of women stopping breastfeeding at 3–4 months than at later time points. For ‘breastfeeding plus’ interventions the evidence is less certain.

There does not appear to be a difference in who provides the support (i.e. professional or non‐professional) or how it is provided (face to face, telephone, digital technologies or combinations). Indeed, various kinds of support may be needed in different geographical locations to meet the needs of the people within that locality.

Chapter 4 Systematic review of implementation research of effective breastfeeding support interventions for healthy women with healthy term babies

Introduction

The Cochrane review update undertaken in our review 1 confirmed that there is ample evidence to know that breastfeeding women need support to be available and to be provided, and that such support is likely to make a difference. Such an evidence base also suggests that one key research question for the future is to identify how such support can best be provided consistently across countries and settings.

Therefore, there is now a need to improve the evidence base around scaling up issues for breastfeeding support interventions, which will require a greater emphasis on implementation and quality improvement approaches rather than effectiveness studies. To enable further advances in this area, it will be fundamental to identify and synthesise available qualitative and process evaluation data on existing interventions. The overall aim of this review was to conduct a theoretically informed mixed-methods synthesis of process evaluations of breastfeeding support interventions identified as effective in review 1.

Objectives

-

To identify qualitative and quantitative data from process evaluation studies linked to breastfeeding support interventions identified as effective in review 1.

-

To synthesise the views and experiences of those involved in receiving or delivering breastfeeding support interventions identified as effective in review 1.

-

To identify the contextual factors (barriers/facilitators) affecting the implementation of breastfeeding support interventions identified as effective in review 1.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review is registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021229769).

Search strategy

We systematically searched six electronic databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus, PsycInfo, ASSIA, Scopus and Web of Science). Searches were conducted in March 2022 using combinations of index terms and free-text words relating to ‘breastfeeding support’ AND ‘implementation research’ (a sample search strategy for MEDLINE is provided in Appendix 1). No restrictions were applied on publication date and publication language. Reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews were scanned for eligible studies. Supplementary searches were conducted based on the name of interventions identified in Gavine et al. ,83 included articles’ authors, and forwards and backwards citation checking.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they reported findings of primary research exploring the views and experiences of any participants involved in either delivering or receiving any of the breastfeeding support interventions identified as effective in Gavine et al. ,83 including breastfeeding women and babies and their families, service providers, managers, commissioners and policy-makers.

Qualitative and quantitative studies, either standalone or in mixed-methods designs, were included. Studies reported any type of process evaluation outcome relating to the selected interventions, including any subjective participant-reported outcomes and constructs such as attitudes, views, beliefs, perceptions, understandings or experiences.

There were no restrictions on publication date or language of publication.

Exclusion criteria

Articles only reporting on impact evaluation results of breastfeeding support interventions (i.e. effectiveness of interventions) were excluded.

Studies that focused specifically on women or infants with additional care needs were excluded. For mothers this could mean coexisting medical problems (e.g. diabetes, HIV) or pregnancy-related complications (e.g. pre-eclampsia). For infants this could include preterm birth, low birthweight or additional care in a neonatal unit.

Studies relating to interventions taking place in the antenatal period alone were excluded from this review, as were interventions described as solely educational or promotional.

Selection process

Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts and relevant full texts against the predetermined eligibility criteria. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consultation with a third reviewer.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Data extraction was undertaken independently by two reviewers using a piloted data extraction form. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consultation with a third reviewer. The table of characteristics is presented in Appendix 2, Table 13.

Quality appraisal of included studies was conducted by two reviewers, using a self-developed tool derived from a set of criteria previously used in other National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded work to assess the quality of process evaluations. 89 Studies were not excluded based on the quality/adequacy of the reporting. Instead, the quality of studies was taken into consideration during data synthesis by exploring whether any particular finding or group of findings were dependent, either exclusively or disproportionately, on one or more studies classed as ‘low quality’ or ‘inadequately reported’. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion and the involvement of a third reviewer where necessary. See Appendix 2, Table 14.

Data synthesis

We adopted a mixed-methods synthesis approach. We first undertook two preliminary syntheses of quantitative (synthesis 1) and qualitative (synthesis 2) process evaluation studies, and then integrated qualitative and quantitative process evaluation data into a theoretically informed cross-study synthesis (synthesis 3).

For synthesis 1 we used narrative methods90 to synthesise quantitative findings from included process evaluations. Two reviewers independently assessed the tabulated characteristics of the included quantitative studies and agreed the criteria to organise the included studies. For synthesis 2 we used a data-driven approach to thematic synthesis91 to synthesise qualitative findings from included process evaluations. This involved three overlapping and interrelated stages: (1) line-by-line coding of findings from primary studies, (2) categorisation of codes into descriptive themes and (3) development of analytical themes to describe or explain previous descriptive themes. To ensure the robustness of the synthesis, various techniques to enhance trustworthiness were undertaken, including audit trail, multiple coding, reviewer triangulation and team discussions. Finally, for synthesis 3, we adopted a theory-driven approach to thematic synthesis91 to synthesise and bring together quantitative and qualitative findings from included primary studies. This synthesis was informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR),92 a comprehensive framework that characterises the contextual determinants of implementation and can be used to inform implementation theory development and verification of what works where and why across multiple contexts.

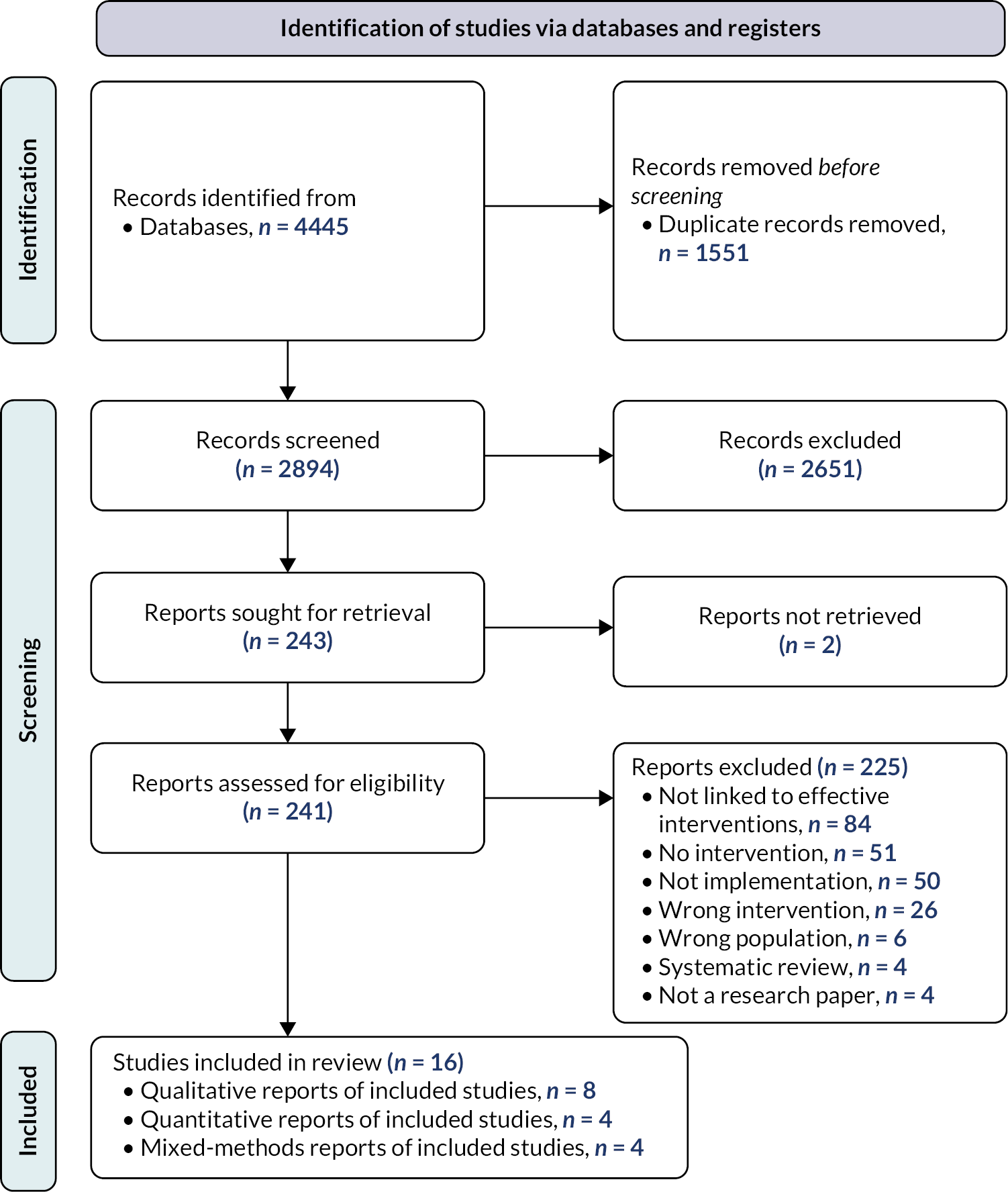

Results

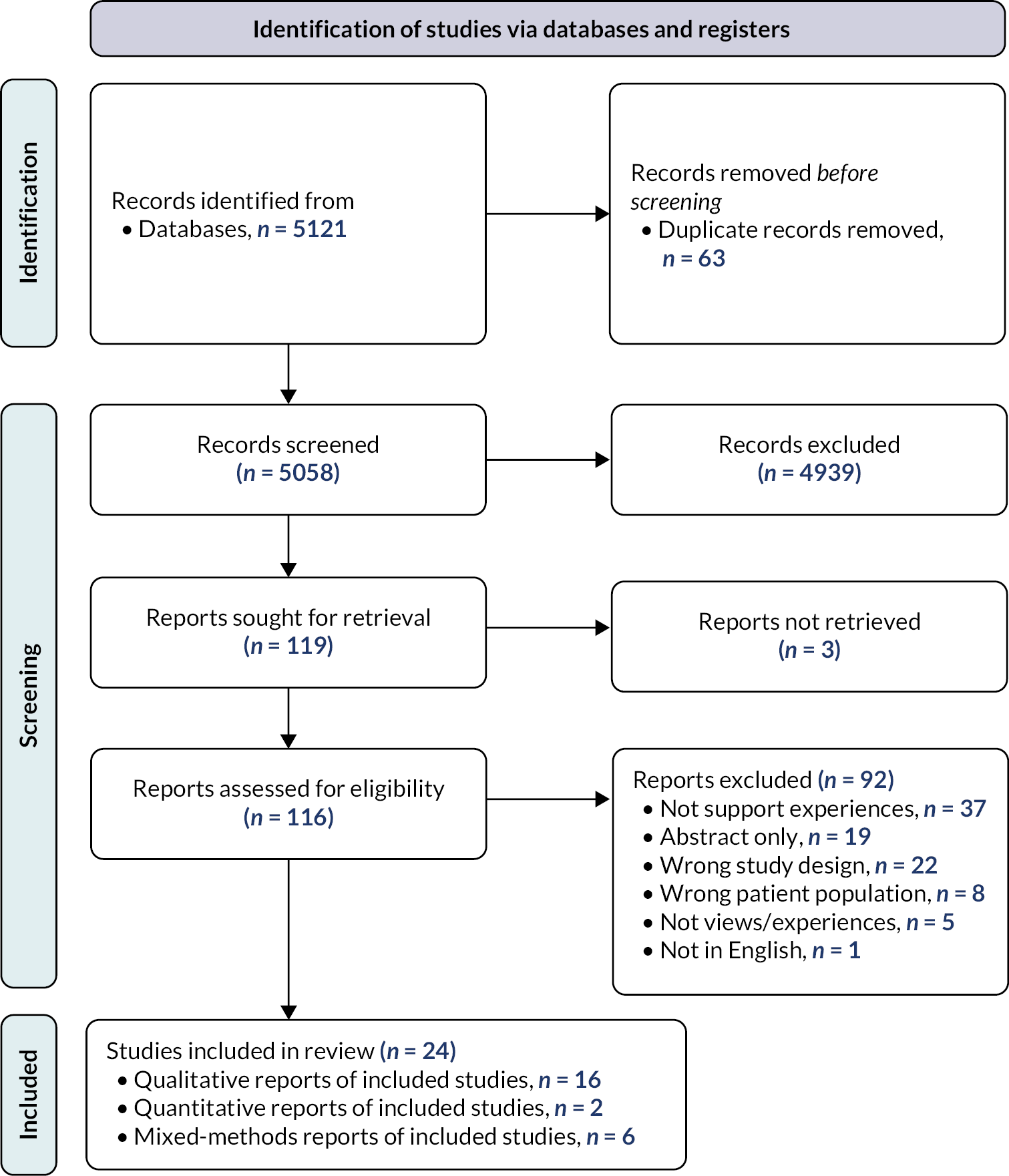

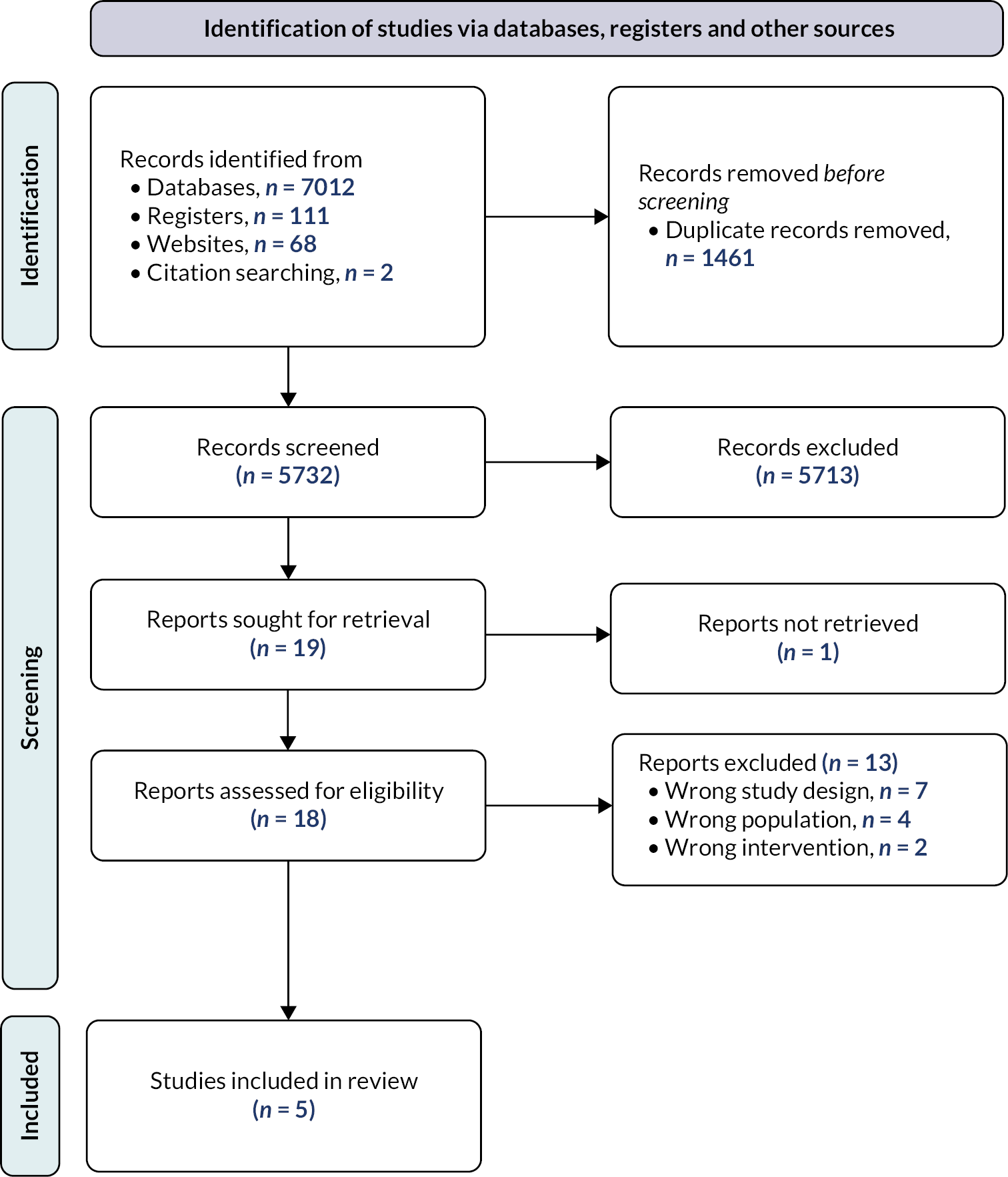

The searches identified 2894 records, which were assessed against the inclusion criteria. Title and abstract screening resulted in 243 records considered eligible or inconclusive. Full-text articles were then retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Two records could not be retrieved. Of the 241 records screened at full text, 225 were excluded. The main reason for exclusion was studies not being linked to an intervention identified as effective in review 1 (n = 84), followed by standalone studies that were not linked to any intervention (n = 51) and studies not involving implementation research and/or process evaluation data (e.g. pre-implementation or intervention development studies) from eligible interventions (n = 50). Other reasons for exclusion were studies linked to either interventions (n = 26) or populations (n = 6) not eligible for inclusion in review 1, and systematic reviews (n = 4) and other publication types not reporting primary research findings (n = 4). The remaining 16 studies were included in the final synthesis (Figure 3). The 16 studies are linked to 10 RCTs of effective interventions from review 1.

FIGURE 3.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Summary of included studies

A summary of key characteristics of the included studies is presented in Appendix 2, Table 13.

Twelve studies contributed qualitative data to the synthesis, comprising eight qualitative93–100 and four mixed-methods101–104 process evaluation studies; and eight studies contributed quantitative data to the final synthesis, comprising four quantitative105–108 and four mixed-methods studies. 101–104

Studies reported data from ten countries: nine from HICs (five in the USA, two in Australia and one each in Canada and the UK); and seven from LMICs (four in Uganda, two in South Africa and one in Pakistan). All of the studies from Uganda and South Africa were evaluations of aspects of the PROMISE-EBF RCTs. 109

Study settings included rural and urban areas and hospital and community facilities. In eight of the studies in HICs, the target populations were low-income or disadvantaged populations, or those living in areas with low breastfeeding rates.

Study samples ranged from 26 to 130 mothers, 12 to 254 peer counsellors, 13 to 28 healthcare staff and 2 to 409 other stakeholders, including supervisors, programme managers and co-ordinators, and unspecified key informants. Other forms of data included observations, diaries and daily activity logs.

Process evaluations included in this review were linked to effective interventions identified in review 1 (for details, see Appendix 2, Table 13).

The descriptions of linked interventions were coded against a taxonomy of behaviour change techniques. The most commonly identified behaviour change techniques related to social support, goals and planning, and feedback and monitoring. A summary of the behaviour change techniques identified across all the linked interventions is provided in Appendix 2, Table 15.

Quality appraisal

The quality of the 16 process evaluations was mixed (see Appendix 2, Table 14). Seven studies were judged to have made a fairly thorough attempt to increase rigour and minimise bias in sampling, data collection and analysis. 93,96,97,100,101,103,107 A further six studies were assessed to have taken at least a few steps to increase rigour of sampling, data collection and analysis. 94,98,99,102,104,105 For the remaining three studies, judgements for at least one element of sampling, data collection or data analysis were hindered by poor reporting. 95,106,108 All studies’ findings were judged to be at least fairly well supported by the data. The findings of three studies were judged to have limited breadth and/or depth. 93,106,108 In Andaya et al. ,93 the evaluation was based on exit interviews lasting 8–12 minutes. Chapman et al. 106 report only coverage of the intervention. Ridgeway et al. 108 do not report responses to open-ended questions in their survey. Seven studies were judged not to have privileged the perspectives of breastfeeding women. 94,97,98,102,104,106,108 Two studies were judged to have low reliability of findings94,95 and one study was judged to have low usefulness. 94,95

Stakeholders’ perceptions and experiences

Stages 1 and 2 of our mixed-methods synthesis resulted in the categorisation of primary quantitative and qualitative data from included studies into 86 descriptive themes. Building on these findings, further analytical work and team discussion was undertaken, and the initial descriptive themes were grouped around a resulting set of 18 factors affecting the implementation of effective interventions, which in turn informed our preliminary, data-driven synthesis conclusions. These revolved around the following three analytical themes:

-

that qualitative/quantitative monitoring data and feedback are provided for women and/or professionals to reflect on and evaluate the progress, quality and experience of implementing the new breastfeeding support intervention

-

that breastfeeding support needs of women/families served by the implementing organisation (including any barriers to/facilitators of meeting those needs) are known

-

that individuals involved in the new breastfeeding support intervention are appropriately trained, have confidence in their capabilities, and are able to execute the courses of action required to achieve the desired implementation/intervention goals.

For the final stage of our thematic synthesis, we mapped our descriptive and analytical themes against the domains of the CFIR. Our three analytical themes and subthemes aligned across five subdomains of the implementation process domain (assessing needs, assessing context, tailoring strategies, engaging, and reflecting and evaluating) of the CFIR framework.

Our final three overarching, theoretically informed analytical themes are described below. Table 4 shows the distribution of primary studies underpinning each analytical theme and their mapping against the relevant CFIR subdomains.

| Included studies (n = 16) (first author and year) | Implementation process (consolidated framework for implementation research) mapped sub-domains | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5B – assessing needs | 5C – assessing context | 5E – tailoring strategies | 5F – engaging | 5H – reflecting and evaluating | |||

| 1 – innovation deliverers | 2 – innovation recipients | 1 – implementation | 2 – innovation | ||||

| Theme 1: assessing the needs of those delivering and receiving breastfeeding support interventions | Theme 2: assessing the context and optimising delivery of and engagement with breastfeeding support interventions | Theme 3: reflecting and evaluating the success of implementing and providing breastfeeding support | |||||

| Ahmed 2012101 | • | • | • | ||||

| Andaya 201293 | • | • | |||||

| Bronner 2000105 | • | • | • | • | |||

| Chapman 2004106 | • | ||||||

| Cramer 2017102 | • | • | • | • | |||

| Daniels 201094 | • | ||||||

| Dennis 2002107 | • | • | • | • | |||

| Hoddinott 2012103 | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Nankunda 200695 | • | • | • | • | |||

| Nankunda 201096 | • | • | • | ||||

| Nankunda 2010104 | • | • | • | ||||

| Nkonki 201097 | • | • | |||||

| Rahman 201198 | • | • | • | ||||

| Ridgway 2016108 | • | • | |||||

| Rujumba 202099 | • | • | |||||

| Teich 2014100 | • | ||||||

Assessing the needs of those delivering and receiving breastfeeding support interventions

Included studies identified several implementation challenges relating to the needs, preferences and priorities of those delivering and receiving breastfeeding support interventions. Nine studies reported on issues from the perspective of intervention deliverers.

Some reported having to deal with feelings of frustration when running breastfeeding support services with low attendance rates. 102 This was a particular challenge for those running services located in small or rural areas. For those juggling a breastfeeding support role with healthcare provider roles, the pressure of the competing demands in the context of low attendance rates could make them feel like their time might have been better spent on other activities. 102

One key strategy reported to both identify and address the needs of breastfeeding support providers was through training. 94–96,98,103,105,107 Studies largely reported that intervention deliverers felt training prepared them well, in terms of both counselling skills and technical competence (e.g. being able to show how to breastfeed correctly). All of this was perceived as key to ensuring consistency in intervention delivery.

Other issues that could be addressed through training were to do with the practical expectations of undertaking the breastfeeding supporter role. Uncertainties about safety, transport and reimbursement while delivering support were among the most reported needs for those delivering community-based interventions,94,95 as well as around more complex issues, such as managing difficult scenarios or the interplay of cultural beliefs and breastfeeding practice. The last was particularly relevant to lay breastfeeding supporters delivering interventions at community level. They noted the importance of acknowledging that trainees themselves belong to a range of communities that might be systematically exposed to certain issues/inequities more than others (e.g. rural isolation, HIV prevalence in the community) and/or might hold cultural beliefs about breastfeeding or breastfeeding-related practices that could act as barriers. These should be identified and addressed in a culturally sensitive manner and without antagonising the communities, enabling lay providers to appropriately and inclusively support breastfeeding women from a range of communities. 94,95,97

Those in implementation leadership roles also emphasised the importance of effective management and supervision. This was reported as a key facilitator of some interventions,94,97 particularly to ensure that certain needs of intervention deliverers continue to be addressed beyond the provision of formal training. For example, for those engaged in interventions relying on peer, lay and/or volunteer supporters, there was an important need to provide them with ongoing emotional support, including mentoring and motivation.

Overall, the breastfeeding supporters felt that their role was important, satisfying and rewarding,15 with implications that were perceived to go beyond the specific breastfeeding support encounters to act as triggers of the wider support network of the breastfeeding women. 95,96

The needs, preferences and priorities of recipients of breastfeeding support interventions were echoed in five studies.

Breastfeeding women perceived the provision of support as positive, important and needed. 99,107 Key to this was being offered the opportunity to ask questions and being allowed to spend enough time to address any issues. 103,104 Also important was accessing support flexibly as needed, rather than having to fit support around fixed working hours or at times that might not be convenient (particularly if receiving support visits at home or after starting paid work after maternity leave). 101,103,104

Assessing the context and optimising delivery of and engagement with breastfeeding support interventions

Some studies reported a range of contextual factors affecting the implementation and delivery of breastfeeding support interventions. These included identification of appropriate settings and accessible, available spaces to deliver breastfeeding support;95,102 consideration of environmental factors that are considered breastfeeding promoting (and avoidance of those that are not) in the intervention delivery settings (e.g. use of breastfeeding promotion leaflets, posters and videos);105 and availability of and alignment with local policies and procedures, as well as with existing practices, in maternity care. 98,105 Studies also reported examples of tailoring implementation strategies to address barriers, leverage facilitators and optimise how breastfeeding support interventions fit the context. These included strategies to promote and encourage engagement, such as ensuring embeddedness within the community,95,96 addressing challenges to recruit breastfeeding supporters,102 favouring lay language;103 teamwork and positive interactions with other breastfeeding supporters and healthcare professionals;96,105 responsiveness of support content and language to address known barriers and common issues;100,103,106,108 and continuity/accessibility of interventions across the continuum of care. 93,103

Reflecting and evaluating the success of implementing and providing breastfeeding support

Included studies reported a broad range of reflective and evaluative accounts about the success of implementation processes and about how impactful breastfeeding support interventions were perceived by women.

Reports about the success of implementation focused on issues relating to key implementation outcomes such as satisfaction,103,104,107 fidelity,103 convenience101,103,104 or usefulness. 101,104,107 Other studies reported on the key drivers that enabled successful engagement between mothers and breastfeeding supporters,97,104,107 including elements of responsiveness/tailoring and content areas addressed in support encounters. 95,97,104,106,108 Some studies reported data on the views and experiences of enacting the role of breastfeeding supporter95,96,98,105,107 and breastfeeding supporter’s supervisor/lead,97,107 all of which documented positive perceptions by those undertaking and/or interacting with those roles. Other studies looked at factors affecting the scale-up of breastfeeding support interventions, including key barriers (e.g. stigma around exclusive breastfeeding, economic barriers and limited resources, health facilities, lack of supportive policies, low male involvement, negative sociocultural beliefs) and facilitators (e.g. promotion at health system level, engagement of professional associations and active collaborations with existing groups, the media and appropriate role models). 98,99

Some studies included reports of perceived meaningfulness and impact of breastfeeding support interventions from women’s perspectives, which can be considered reflective accounts that add to the existing body of evidence about the success of breastfeeding support interventions. Women perceived breastfeeding support interventions as beneficial to women, babies and the wider community;102 and helpful for improving breastfeeding knowledge,93 ensuring the early establishment of breastfeeding93 and enabling women to recognise feeding patterns and problems. 101 Breastfeeding supporters were perceived by women as allies who bolstered their confidence in their decision to breastfeed, particularly for those who were faced with a lack of encouragement from family or hospital staff. 93

The provision of practical information about breastfeeding mechanics and hands-on support were perceived as useful and enabled women to feel reassured and encouraged to continue breastfeeding. 93 The element of responsiveness in terms of support content areas afforded by breastfeeding support interventions helped make interventions meaningful for women in the context of their specific breastfeeding support encounters. 95,97,104,106,108 The most commonly reported issues addressed were reassurance, general breastfeeding information, supply and demand, breastfeeding positioning and attachment, feed frequency, normal infant behaviour, expressing and breast pump use, nipple pain/damage issues and not having enough milk. More interactive intervention components (e.g. monitoring systems, telephone-based support) were appreciated and seen as useful but perceived as a ‘mixed fit’ for breastfeeding support. Women saw these modes of support as an addition to rather than a replacement for face-to-face support. 101,103

Chapter summary

This review comprised 16 studies linked to 10 interventions identified as effective in review 1, which reported the views and experiences of those delivering or receiving breastfeeding support. The quality of the included studies was mixed, but all study findings were judged to be at least fairly well supported by the data.

The synthesis resulted in three overarching themes, theoretically informed by the CFIR: (1) assessing the needs of those delivering and receiving breastfeeding support interventions; (2) assessing the context and optimising delivery and engagement with breastfeeding support interventions; and (3) reflecting and evaluating the success of implementing and providing breastfeeding support.

Included studies identified several implementation challenges relating to the needs, preferences and priorities of those delivering and receiving breastfeeding support interventions. Breastfeeding supporter training was a commonly reported implementation strategy, which also enabled implementation teams to identify and address breastfeeding supporters’ needs. Included studies reported a range of contextual factors (e.g. alignment with local policies) affecting the implementation and delivery of breastfeeding support interventions as well as a range of tailoring strategies (e.g. community involvement, use of lay language, responsive support content/information) to address contextual factors. Reports about implementation success focused on issues relating to key implementation outcomes such as satisfaction, fidelity and usefulness.

Chapter 5 Health economic evaluation

Overview