Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number 17/09/08. The contractual start date was in October 2018. The draft manuscript began editorial review in May 2022 and was accepted for publication in April 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Pryjmachuk et al. This work was produced by Pryjmachuk et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Pryjmachuk et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

This study arose from a successful application to a 2017 National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) commissioning call on research to improve services for children and young people (CYP) with common mental health problems (CMHPs). 1 Originally scheduled for 3 years beginning late 2018, it was extended for 7 months because of unanticipated delays caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

The study is linked to another study funded from the same call, ‘Queer Futures 2’ (QF2),2 which focuses on mental health services for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer (LGBTQ) young people. The NIHR asked the two studies to collaborate. This was facilitated through: our research associates (Fraser, Lane) having regular contact with QF2’s three research associates; this study’s chief investigator (Pryjmachuk) being a QF2 coinvestigator; representatives from the two studies sitting on each other’s study advisory group (SAG); and ensuring there was as little duplication as possible regarding the populations and services relevant to each study.

Background

Children and young people’s mental health

Over the last decade or so, CYP’s mental health has been a growing public health concern both nationally3–6 and internationally. 7 In 2004, around 1 in 10 CYP in England were estimated to have a mental disorder, that is, a mental health problem sufficient to warrant professional intervention. 8 In 2017, the time of the commissioning call, these estimates rose to one in eight CYP in England. 9 The most recent estimates, published in 2021 and covering the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, suggest around one in six CYP in England may have a mental disorder. 10 Moreover, data from NHS Digital11 indicate a near doubling (92%) in referrals to children’s mental health services in England from December 2017 to December 2021 and a 62% increase in contacts with children’s mental health services during the same period.

Within adult mental health, CMHPs are defined as a range of emotional disorders – notably depression, anxiety and anxiety-related disorders like panic, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – affecting a significant proportion of the population, hence the label ‘common’. 12 In adult mental health, CMHPs can be contrasted with ‘serious mental illness’ (SMI). SMI covers more disabling disorders affecting fewer people, for example, schizophrenia. This is not to say CMHPs cannot lead to serious difficulties but, where this is the case, a qualifying label is often added to the disorder’s name to indicate it may be more an SMI than a CMHP. Compare, for example, mild-to-moderate depression (CMHP) with severe depression (SMI).

Regarding CYP’s mental health, the commissioning brief largely reflected the demarcation between CMHPs and SMI seen in adult mental health with emotional disorders (depression and anxiety-related disorders) being included and psychoses excluded. However, the brief outlined a somewhat extended view of CMHPs including behavioural disorders, substance misuse, self-harm, gender identity disorders and emerging personality disorders. It also excluded learning disability, autism and eating disorders from its definition of CMHPs. This stance on CMHPs is in line with the latest English prevalence data:9,10 emotional disorders (anxiety and depression) remain the most prevalent (common) disorders among CYP; self-harm and suicide attempts among those with a mental disorder are relatively common, affecting 25% of such CYP; and gender identity problems increase the risk of developing a mental disorder. Though excluded from the brief, it seems eating disorders are becoming more common with prevalence rates in England in 11- to 16-year-olds doubling from 2017 to 2021. 10

Importantly, this study focuses on services for CYP experiencing, rather than diagnosed with, CMHPs; this allowed for greater inclusivity because not every CYP exhibiting signs and symptoms of a CMHP necessarily has a diagnosed mental health problem.

Mental health services

The seminal 1995 report Together We Stand13 led to the establishment of the de facto model for UK children’s mental health services, the so-called ‘tiers’ model. This model specifies four tiers of service provision according to clinician-perceived needs of CYP and their families. Tier 1, reflecting non-specialist, universal services, is concerned largely with mental health promotion and mental ill-health prevention. Tiers 2–4 reflect formal mental health services [i.e. ‘Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS)’], with Tiers 2–3 mostly equating to outpatient services. Tier 4 (very specialised services) mostly equates to inpatient services.

The tiers model has dominated UK service provision for at least two decades. However, for more than a decade, it has become increasingly clear that it has not met the needs of most CYP experiencing mental health problems. Numerous reports and reviews, including a 1999 Audit Commission report,14 the independent CAMHS review of 2008,15 the 2013 Chief Medical Officer’s report,3 the English Children’s Commissioner’s 2016 ‘lightning’ review6 and reports from the Welsh National Assembly in 20144 and 201816 have consistently described UK children’s mental health services as fragmented, unco-ordinated, variable, inaccessible and lacking an evidence base. Moreover, providing more money for existing services has not necessarily solved these concerns given that the financial responses to crises in children’s mental health identified in 1999 and 2008 did not result in any wholesale improvements in the quality of, or access to, services in subsequent reports or reviews. More recently, there have been attempts to transform services using initiatives such as the ‘Choice and Partnership Approach’ (CAPA),17 a CYP’s version of the adult Improving Access to Psychological Therapies’ programme (CYP-IAPT)18 and ‘THRIVE’,19 a putative alternative to the four-tier model. However, little is known about the effectiveness of these initiatives nor the effectiveness of service models in CYP’s mental health in general. Our previous NIHR work on self-care support in CYP’s mental health20 found factors like choice, child-centredness and staff flexibility to be more important than a service’s theoretical stance or a particular service model. Moreover, we found a service predicated on seemingly effective, evidence-based interventions may not necessarily be effective in itself, that is, specific interventions are often emphasised in services at the expense of important secondary service characteristics like accessibility, child-centredness and the ‘fit’ with individual CYP.

Study rationale

Given that little is known about the effectiveness of, and implementation complexities associated with, service models for CYP experiencing CMHPs is in itself a justification for the study. That services for CYP experiencing CMHPs are often early intervention services additionally strengthens this study’s value, as does exploring how services might be accessed and navigated.

Intervening early with CYP experiencing CMHPs helps prevent milder mental health problems becoming more severe during childhood, an important consideration, given the link between CYP’s health and well-being and educational attainment. 21 More significantly, intervening early can help prevent the continuation of problems into adulthood and the associated costs and burdens of treating adult mental health problems. Half of all adult mental health problems begin before age 14 and 75% before age 18,22 so there are clear benefits in identifying what constitutes an effective children’s mental health service.

The disparate factors associated with accessing and navigating services for CYP experiencing CMHPs have not been synthesised into a coherent model of effective and acceptable service provision. In reviewing the international literature and exploring specific services in England and Wales, we have been able to examine the accessibility of services for CYP experiencing CMHPs and how they are navigated and so identify what it is about services that seems to work and what CYP and their families think about services.

Study overview

Aim and objectives

The study’s overarching aim was to develop a model of effective, high-quality service design for CYP experiencing CMHPs by identifying services available to this population group, the barriers and enablers to access, and the effectiveness (including cost effectiveness) and acceptability of those services.

This aim was operationalised via several study objectives:

-

to systematically search, appraise and synthesise the international literature on services for this population group in order to (1) build evidence of the effectiveness and acceptability of current service provision and (2) assist with objective 2

-

to develop a descriptive typology of services for this population group using the literature referred to in objective 1 and a survey of service provision in England and Wales

-

through primary research, to explore the barriers and enablers that CYP and their families experience in accessing and navigating services

-

to identify the key factors influencing effectiveness and acceptability in order to build an evidence-based model of high-quality service provision for this population group

-

to estimate provider and user costs/benefits associated with different service models

-

to make evidence-based recommendations to the NHS about future service provision.

Design

The study combines evidence syntheses with primary research, using a sequential, mixed-methods design we have used in previous NIHR studies. 20,23 This design is useful for contrasting systematic syntheses of secondary research/policy data with primary data from service users and service providers. Such primary data can offer insights into help-seeking behaviour, access barriers and facilitators and why services underpinned by notionally effective interventions do not always have their intended outcomes.

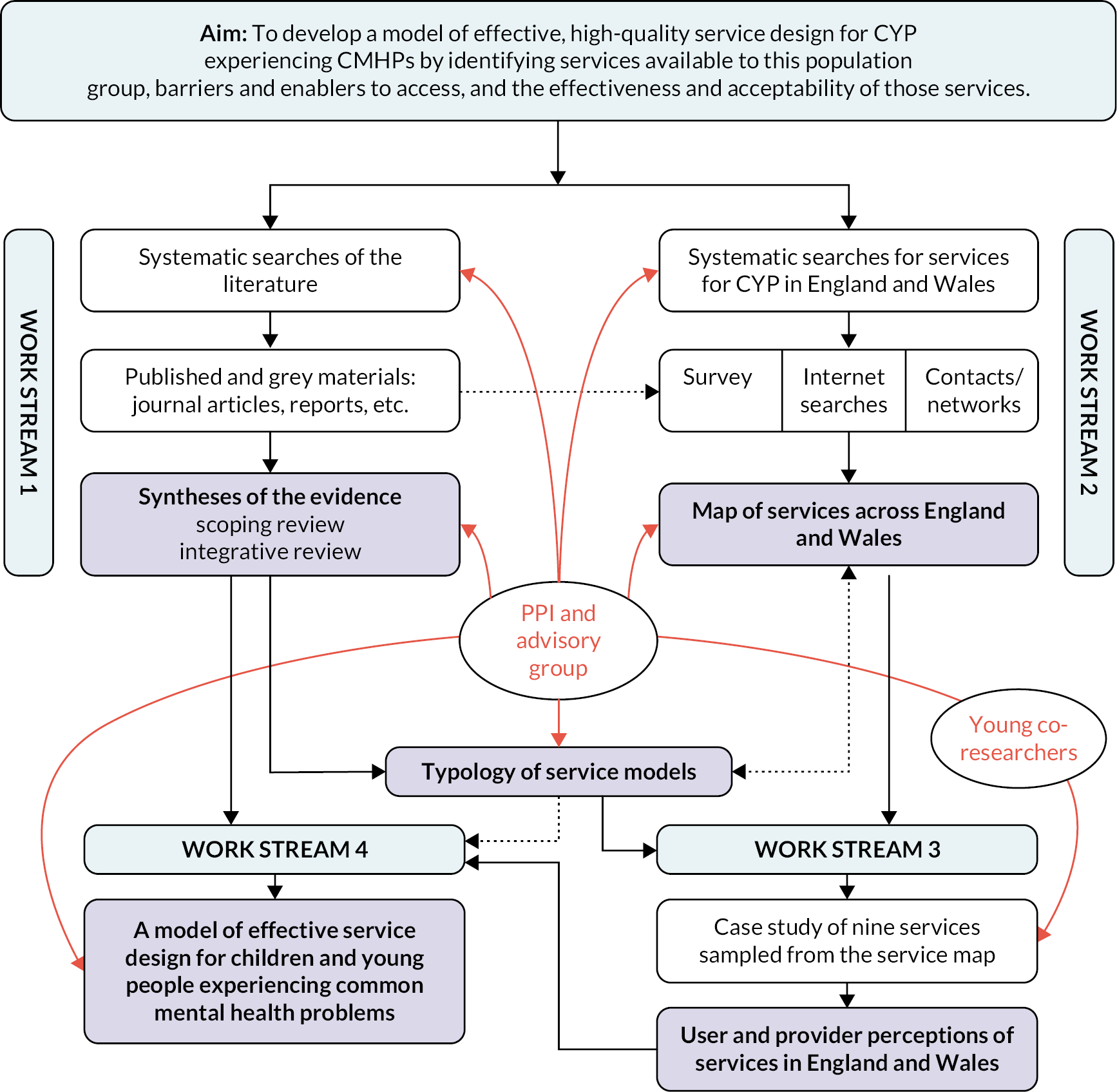

Table 1 outlines how the study’s four work streams map onto the study’s objectives as well as listing specific research questions underpinning each work stream. The flow chart in Figure 1 illustrates how the four work streams interconnect.

| Work stream | Objectives | Research questions |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Literature reviews | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 | What does the international literature say about the types of services available for CYP experiencing CMHPs? What is the international evidence for the effectiveness, cost effectiveness and acceptability of these services? |

| 2: Service map | 2, 4, 6 | What out-of-hospital services are available in England and Wales for CYP experiencing CMHPs? What are the characteristics of these services? |

| 3: Case study | 3, 4, 5, 6 | What are the barriers and enablers that CYP and their families and carers experience in accessing and navigating services for CYP experiencing CMHPs in England and Wales? What factors determine whether a service is perceived as viable, accessible, appropriate and cost-effective? |

| 4: Model development | 4, 6 | In what ways might the key factors associated with access to, navigating, and receiving help from these services be synthesised into a model (or models) of effective and acceptable, high-quality service design for CYP experiencing CMHPs? |

FIGURE 1.

Study flow chart. PPI, patient and public involvement.

In Work Stream 1, we conducted two literature reviews: a scoping review and an integrative review. To make sense of the fragmented, variable and often unco-ordinated services described in the literature, a typology of service models for CYP experiencing CMHPs was derived from the scoping review data.

In Work Stream 2, we mapped service provision for CYP experiencing CMHPs in England and Wales using an online survey together with desk research that involved internet searches and following up leads provided by relevant networks we knew of. In using our typology to categorise services identified in Work Stream 2, we were able to both validate the typology and establish a sampling frame for Work Stream 3.

In Work Stream 3, we paid several ‘young co-researchers’ (see Chapter 2) to assist the study’s substantive researchers in data collection and analysis. We collected data from nine case study sites reflecting the various service models in our typology. We collected quantitative and qualitative data from key stakeholders in each site to further explore issues such as accessibility, acceptability and (perceptions of) effectiveness. We also collected, where possible, data on resource use and associated costs.

In Work Stream 4, the research team, young co-researchers and SAG collaboratively synthesised the data from the other work streams into a model illustrating the key factors associated with, and which underpin, high-quality service provision for CYP experiencing CMHPs.

Report organisation

Chapter 2 describes the study’s patient and public involvement (PPI). Chapter 3 outlines the methods underpinning Work Stream 1, the literature reviews. Scoping review findings are reported in Chapter 4, alongside our definitive service model typology. So that the service provision profile reported in the literature could be contrasted with service provision in England and Wales, the service mapping (Work Stream 2) methods and findings are reported next in Chapter 5. In Chapter 6 (integrative review findings), evidence for the various service models within our typology is outlined. Chapter 7 provides an overview of the methods for, and findings from, Work Stream 3, the collective case study. Chapter 8, focusing on Work Stream 4, outlines how data from the other work streams were synthesised into a model of high-quality service design for CYP experiencing CMHPs. Chapter 9 discusses the implications of our model for service design and delivery in CYP’s mental health. It also outlines the study’s strengths and limitations, concluding with some recommendations for commissioning, practice and research colleagues.

Chapter 2 Patient and public involvement

This chapter outlines how PPI permeated the study. To ensure the study remained relevant to those accessing and providing services, we involved young people and parents/carers, as well as those who commission and provide mental health services throughout the study, from its inception through to dissemination.

Patient and public involvement also led to the study receiving an informal, short title of ‘Blueprint’. In conducting the study, we tended to use Blueprint to refer to the study rather than using its formal, long title.

Involvement during study development

Patient and public involvement influenced the study’s development in several ways. A director of Common Room (Neill), a young people’s consultancy led by lived experience, was a study co-applicant. Through Common Room, young people with lived experience of mental health issues provided constructive advice on initial study design, further fine-tuned the study proposal and helped co-write the study protocol.

In disseminating findings from our previous NIHR study on self-care support in CYP’s mental health,20 we held a priority-setting stakeholder event using James Lind Alliance principles24 in early 2015. At this event, CYP, parents/carers, service user groups and researchers identified several research questions that influenced the study’s development, including ‘what characteristics facilitate engagement in mental health services?’ and ‘how can the NHS develop and commission accessible, flexible and child-centred services?’ Around the same time, at a research planning meeting held in Manchester, young service users and parents provided critical comments about, and endorsed, the mixed-methods design we subsequently employed in this study.

Research team members felt the study findings would have more validity and credibility if young people were actively involved in the research – that is, data collection and analysis – rather than merely providing advice and guidance. Consequently, for the study’s fieldwork (primary research) aspects, six ‘young co-researchers’ were employed to work alongside the study’s two research associates.

Involvement during study delivery

Study advisory group

The study was guided by a SAG (see additional files www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/09/08; accessed 26 March 2024), which included young service users and parents/carers of CYP who had accessed services. Its membership, drawn from across England and Wales, additionally included representatives from children’s mental health services, social care, education, the third sector, academia and NHS service commissioning. We appointed two co-chairs to oversee planned six-monthly meetings: a mental health nursing academic with significant research and clinical experience in CYP’s mental health; and a young person with experience of both mental health services and PPI activities.

Prior to our first SAG meeting, we held a separate induction and training session for the PPI SAG members, delivered by the Manchester research associate (Fraser) who had extensive experience of PPI work in a previous NIHR programme grant. 25 This session included an introduction to the study and its research methods as well as a general introduction to PPI. We provided all PPI members with a copy of a research methods handbook designed specifically for PPI contributors. 26

At the SAG’s successful inaugural meeting in March 2019, we generated a list of potential short names for the study since the SAG considered the study’s formal, long title unwieldy. Shortly after this meeting we were saddened to hear of the unexpected death of our young person co-chair (see Dedication). A few months later, we organised a celebration of her life which was well attended by friends, family and former colleagues. Moreover, in recognition of her PPI contributions, we nominated her for a (posthumous) University of Manchester PPI award, which we – and her family – were delighted to hear she won. At our second six-monthly SAG meeting, we discussed whether we should appoint another young person co-chair: the SAG unanimously agreed we should. We subsequently appointed a new young co-chair who saw the study through to its completion.

The COVID-19 pandemic meant we had to modify our originally planned PPI engagement strategies. We had planned to hold all six SAG meetings in Manchester. We met in person for the second meeting in September 2019 but our third scheduled meeting, due March 2020, coincided with the initial pandemic lockdown period and had to be cancelled. Subsequent SAG meetings during 2020–1 were held remotely via videoconferencing which impacted on attendance and engagement. Our final SAG meeting (April 2022) was held as a hybrid in-person/remote meeting to accommodate requests for both options and, though overall attendance was reasonable, in-person attendance was low.

Throughout the pandemic, we maintained regular contact with our SAG via videoconferencing, e-mail and newsletters. While SAG engagement drop-off was observed among both PPI and service provider representatives, continued engagement with young person members was particularly difficult. We tried on several occasions to invite additional young people to the SAG with limited success since only one new young person was appointed. To address this gap, and to ensure we got substantial young person feedback on our final Work Stream 4 model (see below), our Common Room coinvestigator (Neill) facilitated access to another group of young people.

Despite the challenges above, we held six SAG meetings as planned and there has been SAG input into every stage of the study. Our SAG helped us define ‘common mental health problems’ for the purposes of the research and advised on inclusion/exclusion criteria for the literature search (see Chapter 3). In Work Stream 2 (see Chapter 5), the SAG used their networks to help publicise the mapping survey across England and Wales. SAG members also publicised our study website and Twitter feed and helped us refine the draft model typology emerging from Work Stream 1. Prior to submitting documentation for Work Stream 3’s ethical review, young person, parent and professional SAG members helped us refine the style and language of our participant information sheets, consent forms and topic guides. In Work Stream 4, SAG members provided feedback on our final model. We will continue to draw on SAG members’ expertise as we disseminate our findings.

Common Room

Following involvement in the study’s design and application stages, Common Room engaged with young people within its network to provide us with guidance on information and publicity about the study. Common Room facilitated a young person discussion group to determine an informal, short study title/name. As outlined earlier, suggestions were made at our inaugural SAG meeting, but we felt young people should have the final say. We made it clear that titles on the SAG shortlist should not constrain them; they could choose their own if preferred. In the end, the young people settled on a SAG shortlist option: ‘Blueprint’.

Common Room’s young people also provided feedback on initial designs for the study website. We had also planned to work with Common Room to recruit and employ Work Stream 3’s young co-researchers, but an organisational change within Common Room prevented us from pursuing this. However, we had contacts at a mental health research charity, the McPin Foundation (‘McPin’), that had substantial experience of supporting lived experience co-researchers and they agreed to facilitate our young co-researchers into post. McPin also provided a PPI representative for the study steering committee (see additional files www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/09/08; accessed 26 March 2024) required under NIHR governance regulations.

Common Room also facilitated a group of six young people, aged 13–23 years and all with lived experience of mental health services, to provide feedback on our preliminary Work Stream 4 model (see Chapter 8).

In addition, two young people provided feedback on draft versions of this report’s Plain language summary.

Young co-researchers and McPin

As noted earlier, we wanted young people with lived experience to work collaboratively with us as co-researchers during Work Stream 3’s data collection and analysis phases. We chose to work with young adults (aged 18–25 years) because there were fewer bureaucratic challenges in employing those over 18 years; their lived experiences would, nonetheless, still be relatively recent.

In recognising there could be inherent power issues in working with young co-researchers, we specified that our young co-researchers would have equal status as research team members and that renumeration would match typical pay for junior university research assistants. However, we were also cognisant that the young co-researchers would need supporting, both pastorally and in terms of research training. Given McPin’s extensive experience in supporting and training young people in advocacy, co-production and consultation, McPin were ideally placed to help us ensure the co-researchers’ expertise by experience was recognised and valued in a supportive and nurturing environment.

Due to their expertise in working with young people in similar roles, McPin provided mentorship in addition to being the formal employer. This helped us overcome bureaucratic challenges in trying to recruit and employ co-researchers via the host universities or contracting NHS trust. Using their extensive experience of training and working collaboratively with service user researchers, research team members Fraser, Neill and Bee designed a bespoke 2-day co-researcher induction and research methods training package. Our decision to train and work collaboratively with young co-researchers was commended by the NHS Research Ethics Committee that reviewed our application for the Work Stream 3 fieldwork.

We worked with McPin to advertise the co-researcher roles having agreed a cohort of up to six young people would best suit the study’s timeline. Six co-researchers would also prevent the role being burdensome for one or two researchers since the roles were expected to involve travel to several case study sites across England and Wales. We were also keen to provide opportunities for involvement in real-world research to as many young people as possible, within the funding available. A cohort approach would also accommodate any holiday, sickness or study periods.

We received 27 applications for the roles and were due to interview shortlisted candidates in March 2020, but these plans (and our April 2020 training plans) had to be cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. When it became clear that travel restrictions would not be lifted for some time, we sought ethical approval to adapt the study to accommodate remote data collection procedures. Consequently, we revised the co-researcher job description to emphasise remote data collection and asked previous applicants to indicate if they still wished to be considered. Twenty-two applications went forward for review and eight were shortlisted for (online) interview. Six candidates were offered a position and all accepted. We assigned three co-researchers to the University of Manchester and three to Cardiff University.

We adapted our bespoke induction and research methods training for online delivery and delivered the training over five sessions during autumn 2020. Contractual delays (between the universities, the contracting NHS trust and McPin) and governance delays (regarding NHS research passports) – also partly down to the pandemic – prevented the cohort from being involved in data collection until early 2021. The co-researchers subsequently worked with the study’s two research associates (Fraser, Lane) to co-interview CYP, parents/carers and service providers during remote video calls. We also delivered a remote qualitative analysis training session to support their involvement in data interpretation during Work Stream 3’s analysis phase. During this phase, the co-researchers helped us contextualise the data by assisting with the development of frameworks and the identification of themes.

The co-researchers co-designed and recorded a video version of the CYP participant information sheet to support recruitment of CYP participants to the case study interviews. This was used by case study sites to introduce the study to potential participants, and we received positive feedback on the accessibility of this medium compared to written document alternatives.

The co-researchers helped coproduce Work Stream 3’s findings, provided useful feedback on Work Stream 4’s final model and they will be involved in dissemination. We have received considerable interest from the wider research community about our collaborative approach to co-researching. As part of our dissemination plan, a co-authored paper capturing this journey and reflecting on the successes and challenges of this approach has been published. 27

Reflections on the study’s patient and public involvement

We set out to achieve meaningful PPI and to ensure the views of our PPI partners permeated each stage of the study. We met several challenges along the way, not least the impact of a global pandemic, but we also achieved successes and believe we have met the PPI goals specified in the original funding application.

Successfully collaborating with experts by experience takes time and resources and should be viewed as a journey throughout a study’s lifetime. Put simply, to do PPI well takes time and money and we are grateful to the NIHR for enabling us to provide the dedicated resources and financial support to cover our PPI partners’ time and expertise.

Working with McPin has been extremely valuable. Importantly, McPin helped provide a supportive and nurturing environment for the young co-researchers. Our decision to employ a cohort of six co-researchers proved sensible as all were able to set their own pace while gaining valuable real-world research experience. Taking a cohort approach allowed us a more flexible and nuanced approach to co-researcher involvement. For example, some were more comfortable with co-interviewing and wanted a lot of opportunities to be involved in data collection. Others were happier with a more reflective and analytical approach, focusing more on data analysis. All six co-researchers have used their experiences to move into new roles or further study. Four are pursuing research careers, two of which are health focused; the other two are studying to become healthcare practitioners.

In hindsight, although PPI costs would have increased, it might have been better to have had the co-researchers in post from the study’s inception rather than a year or so into the study. This would have enabled involvement in pre-fieldwork activities such as devising topic guides or applying for ethical review.

We finish this chapter with some co-researcher reflections:

I have learnt so much whilst working on Blueprint. This was my first experience of interviewing people and conducting qualitative research. I have since been able to take on many other mental health related roles that I do not think I would have been able to do had it not have been for the Blueprint Project. It improved my confidence tenfold.

[Blueprint] didn’t ask for any formal qualifications, instead focussing on experiences and qualities of candidates. Furthermore, one essential criterion was ‘personal experience of living with a mental health problem’. I personally found this hugely refreshing and welcoming. In the past, I have always felt the need to hide my mental health difficulties, particularly regarding employment for fear of being seen as unreliable or less able to work. The fact that the Blueprint project recognised that people with mental health difficulties have a lot to give in terms of lived experience, and provide an important perspective was extremely inclusive … it made me feel welcome, included, and valid.

My experience … has been overwhelmingly positive. The researchers at Cardiff and Manchester universities as well as McPin have helped to make the experience rewarding (in terms of knowledge gained for myself), productive (in terms of knowledge shared with the research team) and enjoyable (with little of the ‘burden’ people with lived experience typically feel in the world of work).

Chapter 3 Literature reviews methods

This chapter focuses on the methods underpinning the scoping and integrative reviews conducted in Work Stream 1. Since a single search underpinned both reviews, the methods for both are reported here. The scoping review findings are reported in Chapter 4 and the integrative review findings in Chapter 6.

In the agreed protocol (see additional files www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/09/08; accessed 26 March 2024), we stated that we would conduct four interconnected literature reviews on services for CYP experiencing CMHPs: (1) a descriptive review of service models; (2) a review of the effectiveness of these service models; (3) a review of their acceptability; and (4) a cost-effectiveness review. A protocol for these reviews was published in PROSPERO in August 2018, reference CRD42018106219. 28 However, in implementing the study, we amended our Work Stream 1 plans slightly: the descriptive review was refashioned as a scoping review, and we combined the effectiveness, cost effectiveness and acceptability reviews into a single integrative review.

Scoping and integrative reviews

A descriptive review is fundamentally the same as a scoping review. We shifted to the latter term because of calls for consistency in the health research field. 29 Scoping reviews are similar to systematic reviews: both are conducted using transparent and systematic processes. However, while the main purpose of a systematic review is to summarise the available literature in order to answer a focused question, a scoping review is useful where there is a need to clarify a concept (in our case, ‘service models for CYP experiencing CMHPs’) and/or identify key characteristics or factors relating to that concept. 30 Since scoping reviews focus on the literature’s breadth (scope) rather than depth, there are fewer restrictions on the types of literature than can be included compared to systematic reviews: documents do not have to be peer-reviewed, the literature can be ‘grey’ and document quality may be less important. Thus, scoping reviews often include a larger volume of literature than systematic reviews and, unlike systematic reviews, formal quality assessment of included documents is generally not required. 29–31

A principal outcome of a scoping review is a map of the available literature;30,31 indeed, where that map is presented visually, scoping reviews have been called ‘evidence maps’ or ‘evidence and gap maps’. 29,32–34 Since a typology is a form of map, a scoping review is an ideal vehicle for achieving one of the study’s principal outcomes: a descriptive typology of services for CYP experiencing CMHPs.

The integrative review was originally planned as discrete effectiveness, cost effectiveness and acceptability reviews. However, given the heterogeneity of research designs employed in the included studies, the variability in the outcomes of the effectiveness studies (such that meta-analysis was unfeasible), the overlap between the types of evidence available in each included paper and the very limited cost-effectiveness data, we made a pragmatic decision to combine the effectiveness, cost effectiveness and acceptability reviews into a single integrative review. An integrative review still meets the study aims and objectives outlined in Chapter 1.

Integrative reviews allow for the simultaneous inclusion of experimental and non-experimental (or quantitative and qualitative) research so that a particular phenomenon can be understood more fully. 35 They also provide opportunities for insight on a particular topic (in our case, services for CYP experiencing CMHPs) by synthesising knowledge across different ‘communities of practice’,36 whether these communities reflect different disciplines or different research traditions. Our integrative review is essentially a mixed-methods systematic review designed to answer specific questions about which services for CYP experiencing CMHPs work and what those delivering and receiving services think of them.

Methods

Review questions

The literature reviews address research objectives 1 and 2 and these research questions:

-

What does the international literature say about the types of services available for CYP experiencing CMHPs?

-

What is the international evidence for the effectiveness, cost effectiveness and acceptability of these services?

The first research question underpinned the scoping review; the second, the integrative review. The scoping review was also used to finalise a definitive typology of services for CYP experiencing CMHPs (see later in this chapter). Together with the service map (Work Stream 2; see Chapter 5), this definitive typology also provided the sampling frame for our subsequent case study research (Work Steam 3; see Chapter 7).

Search strategy

A Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes and Study Design (PICOS) formulation37 was used to frame the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the reviews (see Appendix 1). To identify and classify service models and find empirical evidence supporting different models, and because little was known about the breadth of service models for CYP experiencing CMHPs, we needed to conduct as broad a search of services for this population group as possible. Consequently, only the population (P) and intervention (I) elements of PICOS were used to devise the search strategy (see Appendix 2).

Since both reviews were focused on the same population (CYP experiencing CMHPs) and same ‘intervention’ (services for this population group), a single search was conducted. Search terms were established from combinations of the research team’s knowledge of, and expertise in, children’s mental health services, specific models and/or services mentioned in the commissioning brief and SAG contributions. The research team and SAG were aware of some literature that had attempted to categorise services, both in CYP’s mental health and in broader healthcare provision. This literature influenced both the ‘intervention’ search terms and a preliminary typology. Detail about the literature influencing this preliminary typology is provided later in this chapter.

Full searches were conducted using a variety of search platforms to access relevant bibliographic databases (see Appendix 2). Searches were limited to documents published from 1 January 1995 onwards as 1995 can be considered a watershed in UK children’s mental health service delivery, being the year in which the seminal report Together We Stand13 was published. No other limiters were applied.

The searches were conducted in May 2019. Additional documents (obtained from screening the reference lists of relevant literature reviews, citations in included documents and the research team’s networks) continued to be added to the literature pool until the end of 2020. The searches were not updated at a later point because the scoping review’s primary objective was the development of a typology (which was subsequently endorsed by the research team and SAG). Moreover, according to a recent consensus paper on updating systematic reviews,38 searches do not need updating if the findings or credibility of a review are unlikely to change, which was the case for both the scoping and integrative reviews.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

A single set of PICOS inclusion/exclusion criteria was used for both reviews (see Appendix 1), although some PICOS elements were irrelevant for the scoping review and for the acceptability data within the integrative review. The criteria were developed with SAG advice and fine-tuned after some preliminary engagement with the literature.

Several exclusions merit further brief discussion. Firstly, gender identity issues were excluded because they were a focus of the parallel QF2 study. Documents relating to services for gender identity issues were, however, passed onto the QF2 team. Secondly, during screening it became clear that many potentially relevant US documents were focused on CYP with ‘serious emotional disturbance’ (SED; sometimes ‘severe emotional disorder’), a concept which does not map well onto CMHPs. Serious emotional disturbance is not a formal diagnosis but rather a legal administrative term used by US state and federal agencies to identify CYP with high needs. 39 Sometimes documents describing SED populations clearly mapped onto our inclusion/exclusion criteria, for example, by further defining SED as including those with depression or anxiety (included) or those with complex needs at risk of an out-of-home placement (excluded). However, many documents did not delineate SED further. Consequently, following discussions with our SAG, we agreed to exclude SED unless there was further explicit reference to an included condition. Thirdly, relevant literature reviews were not included unless they described service models in sufficient detail, in which case they were included in the scoping review. Reference lists of reviews were, however, screened for potentially relevant documents. Any such documents not already identified by the search were added to the pool of literature for eligibility assessment. A final issue related to the study’s focus which was services for CYP experiencing CMHPs and not interventions or treatments for this group. As outlined earlier, a principal objective of the study was to produce a service model typology using information gleaned primarily from the scoping review. During initial screening we realised that to do this, we would need to distinguish between documents describing services (included) and documents merely describing treatments or interventions, for example, cognitive–behaviour therapy or parenting programmes (excluded). We scoured the generic healthcare management literature and asked colleagues in one of our affiliated business schools if they knew of any clear criteria for defining ‘service model’, but both our search of the generic healthcare management literature and responses from our business school colleagues only reinforced our views that the concept was somewhat ‘fuzzy’. We had further discussions at one of our SAG meetings and agreed some criteria that might define a service model for the purposes of this study (Box 1).

-

Purpose: to improve access or quality of care, provide discrete pathways through services and/or reduce costs

-

Target: to meet the needs of a population or population subgroup (e.g. CYP with mental health problems or CYP with depression)

-

Structure: requires defined standards, a framework, a standard operating procedure or guiding principles against which performance can be audited

-

Processes: complex system where the sum of the parts (e.g. staff, culture, interventions, funding) is greater than the whole

-

Outcomes: are system-wide or population level as well as individual level

Service model, intervention or feature?

In determining whether a document described, or provided evidence for, a particular service model, we met several challenges during screening. One significant challenge, mentioned above, concerned discriminating between interventions and services/service models. The English IAPT40 initiative illustrates how interventions and service models might overlap. In its original iteration, IAPT was predicated on cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) (an intervention), but IAPT is more than an intervention: it has specific operating procedures covering staff training, levels of intervention (stepped-care), outcome measures and quality assurance and thus we would categorise IAPT as a service model. However, many of the documents we examined were not as straightforward as the IAPT example and, while the criteria outlined in Box 1 helped, reviewers had to make independent judgements as to whether a service model or an intervention was being described, with disagreements being resolved by discussion or referral to a third reviewer. The second significant challenge with some service descriptions was whether what was being described in the document was, indeed, a service model or something more akin to a characteristic or feature of the service. Some examples we had to work through which ended up as ‘features’ of a model were telepsychiatry, open access, case management, integrated care and consultation-liaison. As with the service model/intervention dilemma we encountered, judgements within the research team mostly resolved any model/feature dilemmas that arose. The features we ultimately identified (see Chapter 4) were thus determined through extensive discussion among the research team with additional SAG feedback.

In hindsight, the challenges we encountered here are unsurprising. Most service models we identified had several interacting components, required those delivering or receiving the services to change their behaviour and were often designed to elicit a range of outcomes – traits that are typical of complex interventions. 41,42

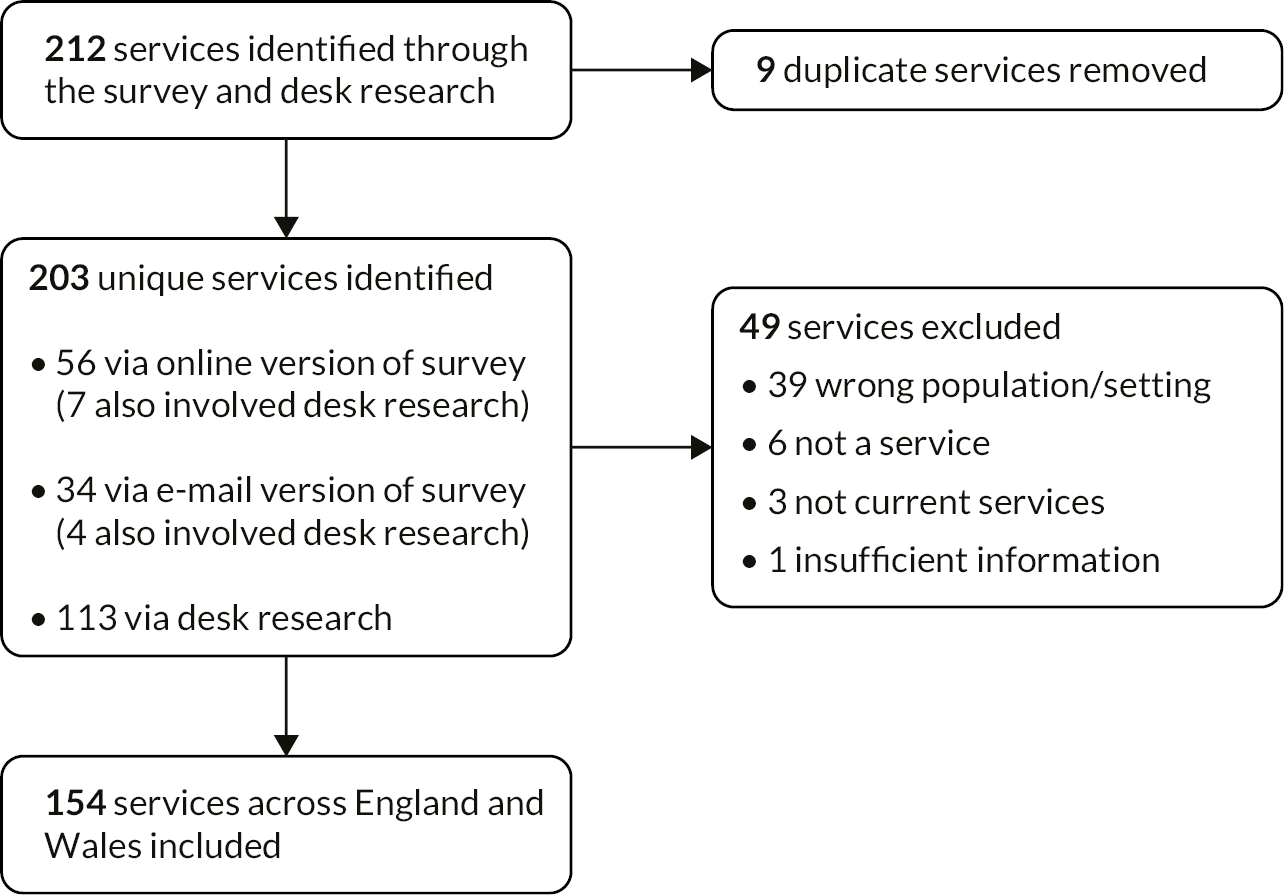

Search results, screening and document selection

The aggregate results from the databases and resources searched totalled 87,928 records which were exported into Endnote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). After automatic and further manual deduplication in Endnote, 39,396 records remained. Given screening this many records manually would be unwieldy, research team members Pryjmachuk and Fraser used a two-stage, semi-automatic rapid title/abstract screen (using Endnote’s search function) to both screen in relevant, and screen out irrelevant, records (see Appendix 3). Stage 1 screening-in, determined largely by using terms from the original search strategy, resulted in 6412 of the 39,396 records being retained. Stage 2 screening-out involved rapidly reviewing record titles in Endnote for irrelevant terms (some, like eating disorders and psychosis, were predetermined by the commissioning brief) and then using those terms to find further irrelevant records. For Stage 2 screening-out (but not Stage 2 screening-in), individual record titles were manually inspected prior to exclusion to reduce the risk of missing potentially relevant records. Of the 6412 records retained, screening-out led to a further 1691 removals, leaving 4271 records. These records were exported to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd, Melbourne, Australia), an online review management tool, for title and abstract screening against the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

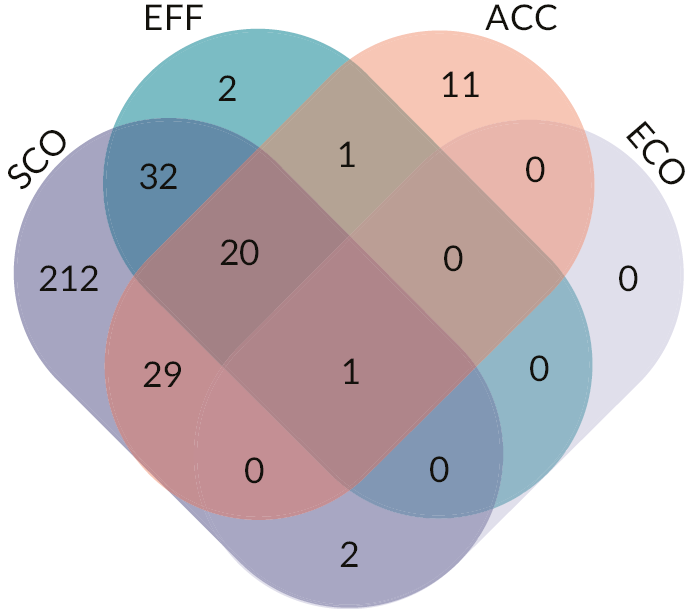

Screening was conducted independently by two reviewers. For consistency (particularly regarding service/intervention discrimination), research team member Pryjmachuk screened all Covidence records with Evans, Fraser, Kirk or Lane as a second reviewer. Disputes were settled by a third reviewer. Following screening, 839 of the 4271 records were identified as potentially relevant and flagged for full-text retrieval. A further 220 unique documents were identified as potentially relevant from other sources (relevant literature reviews, citations in included documents and the research team’s networks), of which 191 were retrieved for full-text review. In total, 1030 full-text documents were assessed for eligibility against the inclusion/exclusion for each of the two reviews, and 310 documents in total were included in one or both reviews. Many documents met the eligibility criteria for both the scoping and integrative reviews (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

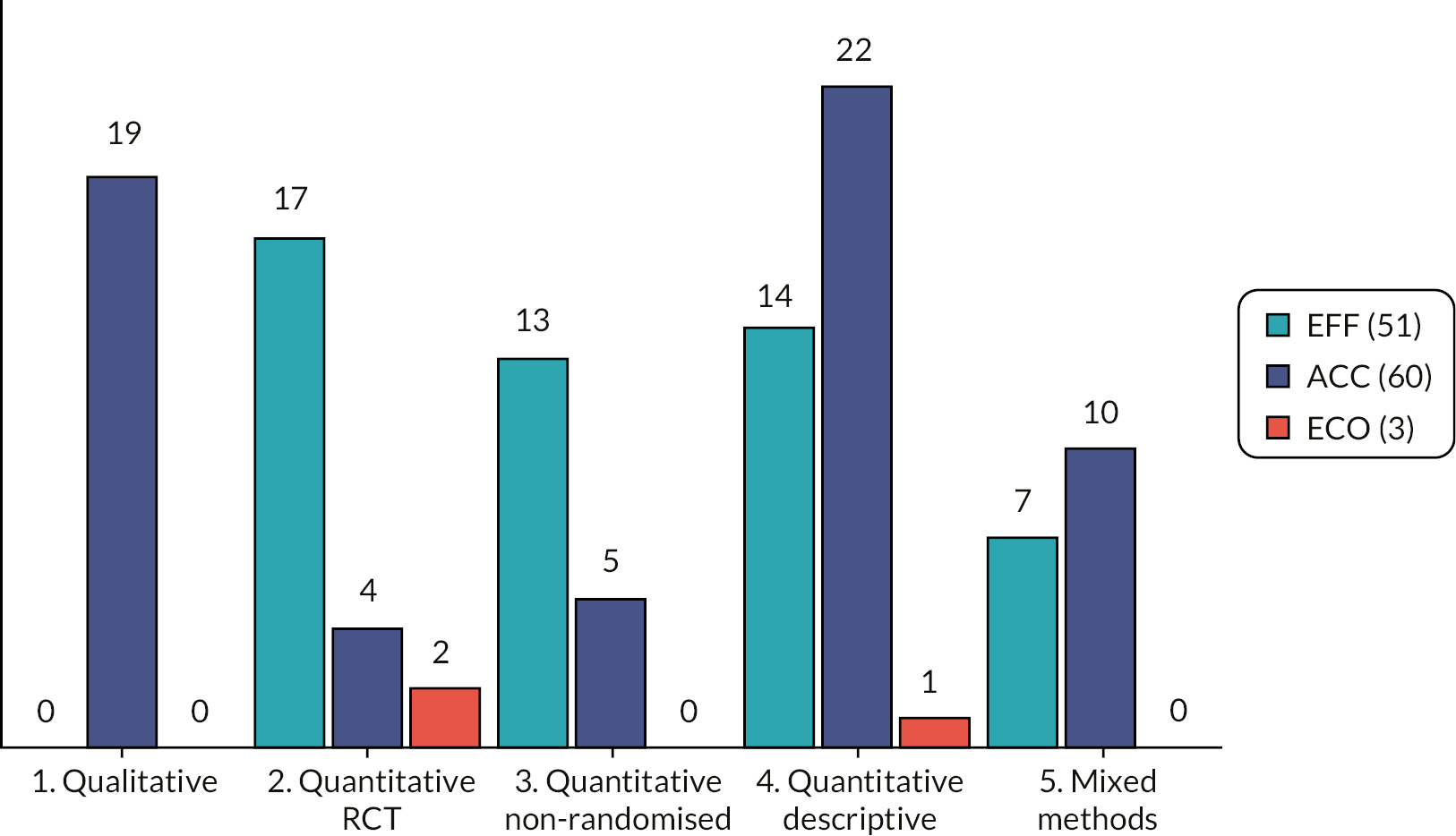

Venn diagram of documents included in each review. SCO, scoping review; EFF, ACC, ECO, respectively, effectiveness, acceptability and economic elements of integrative review. Total included documents = 310; SCO included = 296. EFF + ACC + ECO (integrative) included = 98 (EFF included = 56; ACC included = 62; ECO included = 3). Diagram produced using the tool available at http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/.

Two hundred and ninety-six documents were included in the scoping review, 84 of which contained empirical evidence and were thus also included in the integrative review. An additional 14 documents containing empirical evidence but an insufficient service description to be included in the scoping review meant 98 documents were included in the integrative review. Of these 98 documents, 56 provided effectiveness data, 62 acceptability data and 3 economic (cost-effectiveness) data.

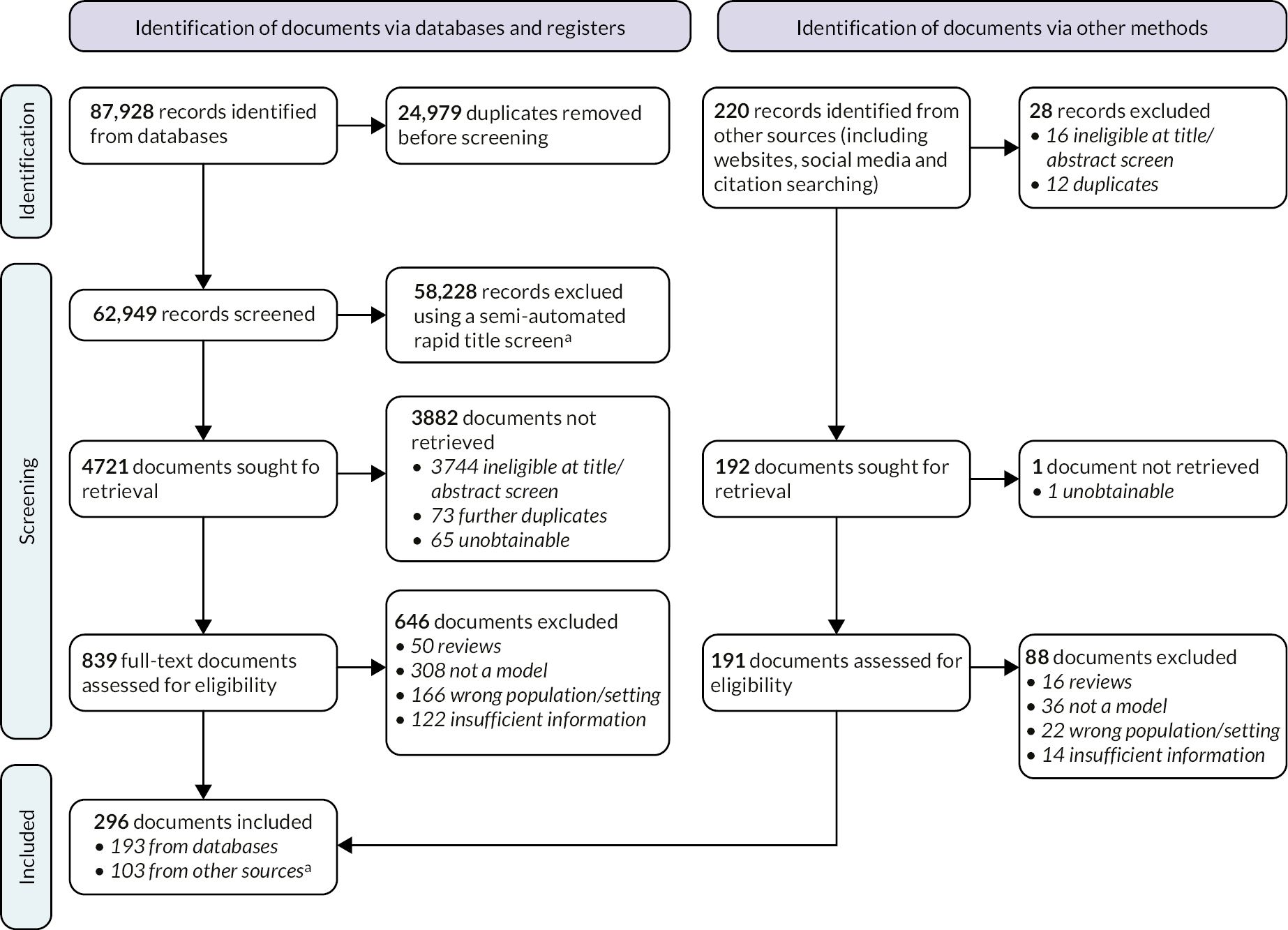

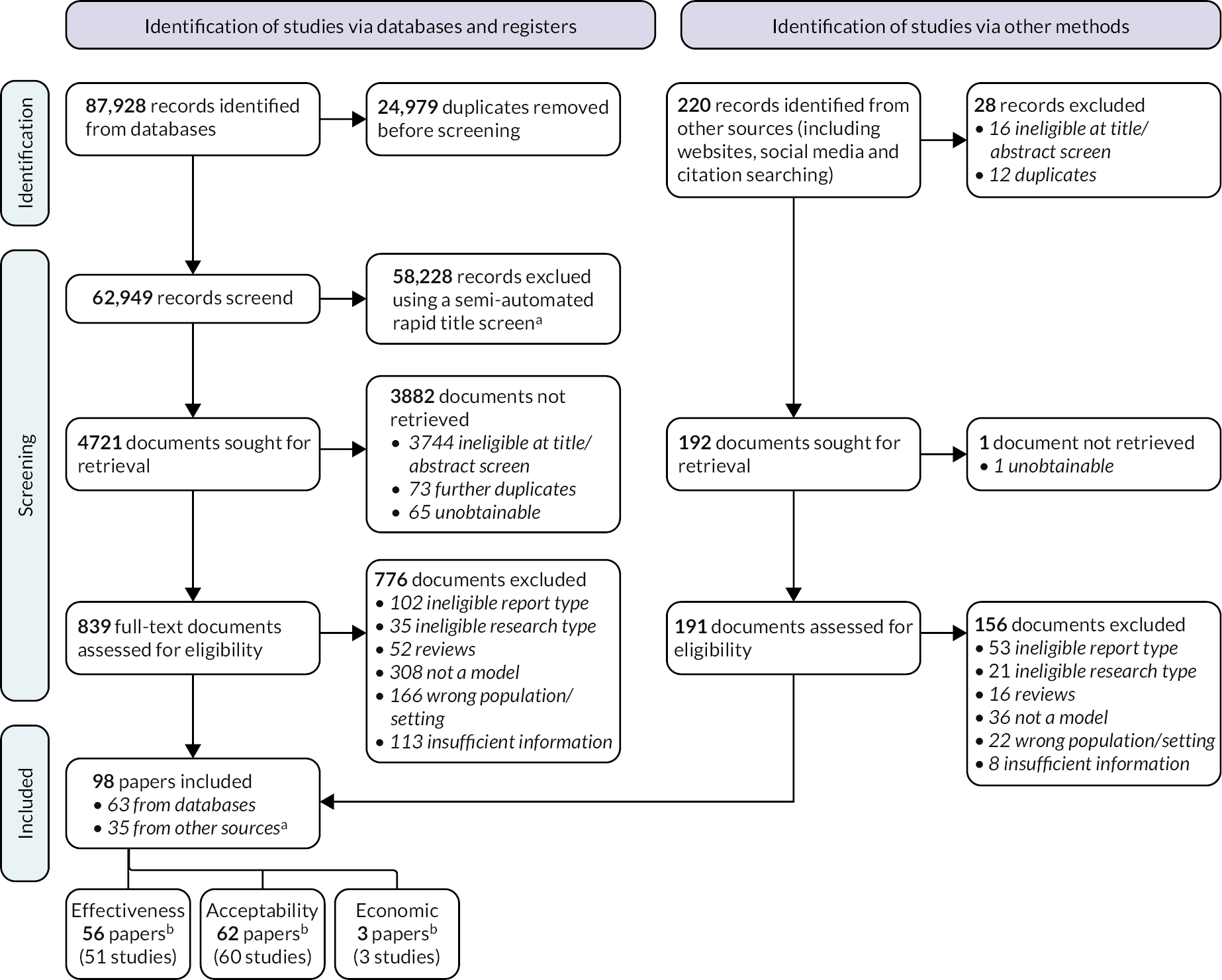

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 202043 diagrams for the scoping and integrative reviews are presented, respectively, in Figures 3 and 4.

FIGURE 3.

PRISMA 2020 for the scoping review. (a) Eighteen of the 103 included other sources reports were picked up via the databases but incorrectly screened out during the semi-automated rapid title screen.

FIGURE 4.

PRISMA 2020 for the integrative review. (a) Eight of the 35 included other sources documents were picked up via the databases but incorrectly screened out during the semi-automated rapid title screen. (b) Total papers exceeds 98 as some papers provided a combination of effectiveness, acceptability and economic (cost-effectiveness) data.

For both reviews, documents were excluded because they: (1) were literature reviews (though reference lists were screened); (2) did not describe or evaluate a service model or the document contained insufficient information for reviewers to be sure a service model was being discussed; or (3) were targeted at the wrong population. For the integrative review, additional reasons for exclusion included ineligible document type (e.g. thesis, conference abstract or book chapter) and ineligible research type.

Several documents identified via other methods and subsequently included (18 out of 103 for the scoping review; 8 out of 35 for the integrative review) were picked up by the original database searches yet missed by the semi-automated rapid title screen. Some potentially relevant documents (66 in total) were unobtainable because document supply services could not access physical library resources at the time because of COVID-19 restrictions.

A note on document and report identification labels

For the reviews, we have used the syntax (first listed author) (publication year) to identify a specific document or report, for example, ‘Asarnow 2005’ or ‘Lim 2017’. Studies reported in more than one paper are identified by a combination of their component papers, for example, ‘Asarnow 2005/Asarnow 2009’. Despite a similar appearance, these IDs are not in-text citations like those used in Harvard-style referencing systems; they are thus not listed in this report’s reference list. Instead, the full references of documents and reports included in the reviews are listed in Appendix 4. Where an included document or report is cited in this report, the standard Vancouver-style convention of superscript numbers has been used and that document/report does, indeed, appear in the reference list.

Data extraction

Non-English documents were translated prior to extraction. The 310 documents eligible for either of the reviews were extracted using a data extraction sheet devised in Microsoft Excel (see additional files www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/09/08; accessed 26 March 2024). This data extraction sheet was used for both reviews. For the scoping review, data extraction of all 296 included documents was completed only by Pryjmachuk, though Evans and Fraser checked a 10% sample of extractions for accuracy with both demonstrating high levels of agreement. For the integrative review, Pryjmachuk again extracted all 98 papers, but this time each paper was also extracted independently by either Evans, Fraser, Kirk or Lane (plus Camacho for any economic papers). For each paper, the two data extractions were compared by Pryjmachuk and any discrepancies resolved by discussion or (rarely) referral to a third reviewer.

Quality assessment

As mentioned earlier, scoping reviews typically do not include a quality assessment and so no scoping review documents were quality assessed. For the integrative review, we anticipated included studies would incorporate a wide variety of research methods, so we employed the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; version 2018)44 as our single quality appraisal tool. MMAT was embedded into our data extraction sheet (see additional files www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/09/08; accessed 26 March 2024). MMAT has five categories of study design: (1) qualitative; (2) quantitative randomised controlled trial (RCT); (3) quantitative non-randomised; (4) quantitative descriptive; and (5) mixed methods. For each study design category, appraisers consider a set of five specific questions, answering ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘can’t tell’ to each. To be considered a mixed-methods study (MMAT category 5), the data from the different research elements needed to be integrated. Where it was not, we used the approach of Scott et al. ,45 assessing each element individually and choosing the lowest quality rating to represent the study.

Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool discourages calculation of an overall quality score; so, we have presented MMAT results for the included studies in ‘raw’ format, colour-coding appraisers’ agreed judgements as green for ‘yes’, orange for ‘can’t tell’ and red for ‘no’. We also provide information about the MMAT study design category and the study type or methods used (see Report Supplementary Materials 1–3). When presented in tabular format (see Appendix 5; discussed further in Chapter 6, integrative review findings), the reader can get a visual representation of the included literature’s overall quality and so draw their own conclusions.

Scoping review mapping: service model typology

As mentioned earlier, literature in a scoping review tends to be mapped rather than synthesised. The resultant map from our scoping review is essentially our typology of service models for CYP experiencing CMHPs. We used an iterative process to develop our service model typology starting with existing (pre-search) knowledge of relevant literature we and our SAG were aware of (Table 2). These sources gave us a preliminary (version 1) typology – an initial list of service model types – which in turn informed the search strategy outlined earlier.

| Source | Context | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Jensen 199646 | Mental health care for CYP | Identifies several different services: clinic-based outpatient services; family preservation; therapeutic foster care;a day treatment; intensive case management; family support; inpatient hospitalisation;a systems of care |

| Bower and Gilbody 200547 | CMHPs in adults in primary care | Identifies four models of quality improvement in primary care: (1) training primary care staff; (2) consultation-liaison; (3) collaborative care; (4) replacement/referral |

| Schmied et al. 200648 | CYP with ‘high needs’ | Identifies four broad approaches: (1) therapeutic foster care;a (2) residential care;a (3) Multisystematic Therapy (MST); (4) service co-ordination and integration (includes case management, wraparound and systems of care) |

| Biggins 201449 | Home-based treatment in CYP’s mental health | Identifies four types of home-based treatment: (1) preservation; (2) treatment foster care;a (3) intensive case management and wraparound; (4) adult mobile crisis teams applied to CYP |

| McDougall 200850 | Tier 4 CAMHS in England | Identifies alternatives to inpatient care: day patient care; home-based treatment; case management; multisystemic treatment; multidimensional treatment foster carea |

| Kurtz 200951 | Tier 4 CAMHS in England | Similar categorisation to McDougall 2008 but with family preservation added |

| Shepperd et al. 200952 Lamb 200953 |

Alternatives to inpatient care in CYP’s mental health | Eight approaches identified: (1) MST; (2) intensive home-based crisis intervention (homebuilders); (3) intensive home treatment; (4) intensive specialist outpatient treatment; (5) day hospital; (6) case management; (7) therapeutic foster care;a (8) short-term residential carea |

| Shailer et al. 201354 | Young people with serious mental health problems in New Zealand | Identifies several community-based approaches: standard CAMHS; treatment foster care;a MST; strengthening families; auxiliary supports; out-of-home placements |

| Kwok et al. 201655 | Alternatives to inpatient care in CYP’s mental health | Five alternatives identified: (1) MST; (2) day patient; (3) specialist outpatient; (4) intensive home treatment; (5) supported dischargea |

| Social Services Improvement Agency 201556 | CYP with mental health/substance misuse/behavioural issues | Potential service models identified included: multidimensional treatment foster care;a strengthening families; MST; homebuilders |

| Houses of Parliament POST 201757 | CYP’s mental health | Classified services into four broad groups: (1) whole system models; (2) school-based models; (3) community-based models; (4) other models |

During the screening process (reading titles/abstracts and reading full-text articles for inclusion), we had periodic research team discussions about the classification of emerging model types, which led to further refinements and a more developed typology (version 2) once screening was complete. We used version 2 of the typology to initially code services in our service map (see Chapter 5). Once coded, the service map provided the sampling frame for Work Stream 3’s case study sites. The data extraction process for the scoping review led to some further (relatively minor) modifications to the typology. This modified typology (version 3) was endorsed by the SAG and is our final typology, described in detail in Chapter 4.

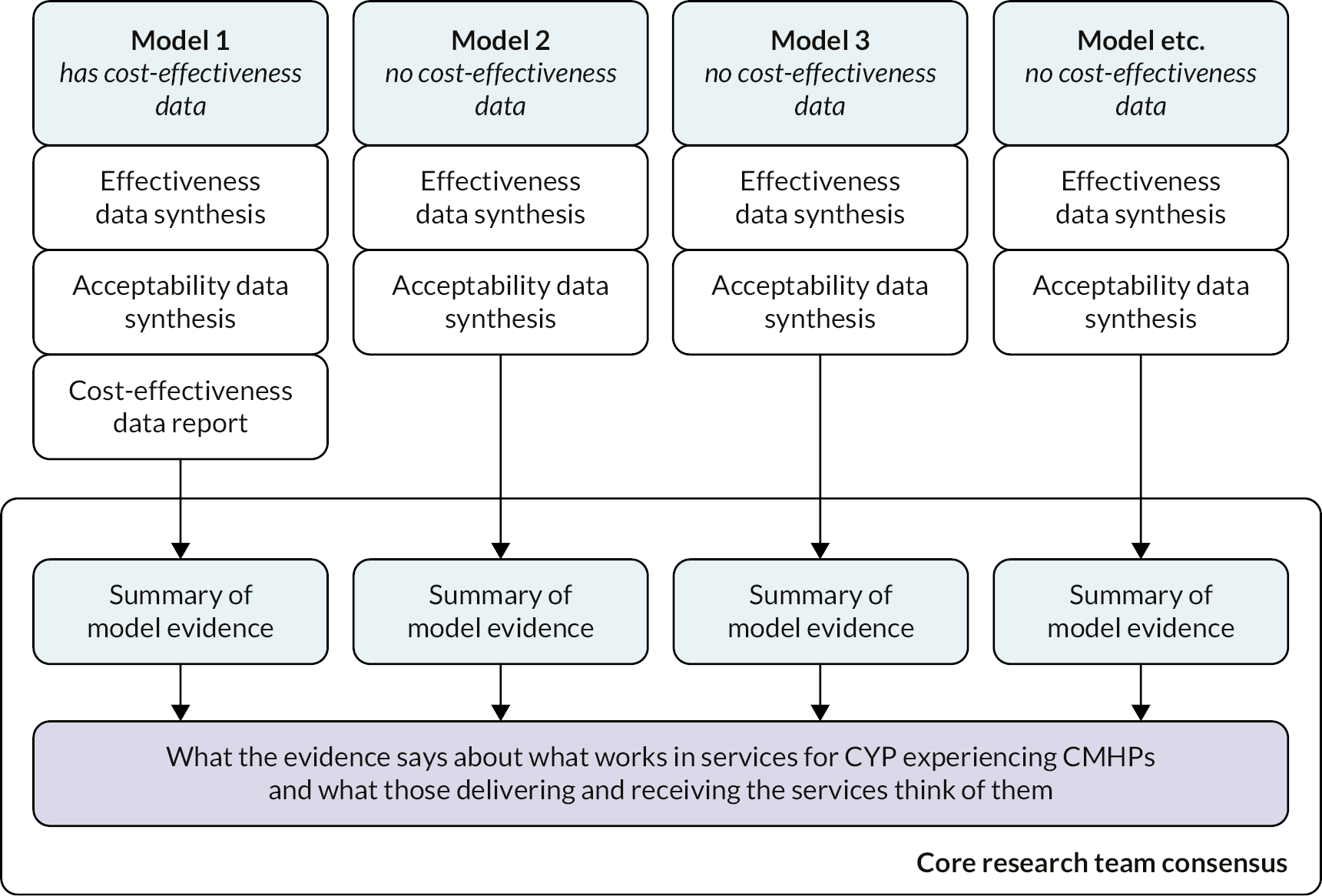

Integrative review synthesis

The integrative review’s synthesis method is based on the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating (EPPI)-Centre’s mixed-methods approach,58 whereby the different data sources (effectiveness, cost effectiveness and acceptability) are first analysed separately but subsequently compared and contrasted. Driving this approach was an intention to identify whether any of the specific models in the typology were more effective and acceptable than others, primarily to inform funders, commissioners and providers of services.

Following independent extraction by two reviewers, there was a comprehensive set of 98 combined data extraction sheets, each containing data relevant to effectiveness, cost effectiveness, acceptability or any combination of these. Key information from the data extraction sheets was then collated into separate summary tables for each of the three data sources (see Report Supplementary Materials 1–3).

The heterogeneity of the research designs and outcomes in the effectiveness studies meant that meta-analysis was unfeasible and so a narrative approach to synthesis was taken. The key effectiveness findings within each typology model group were synthesised by Pryjmachuk to provide an effectiveness evidence overview for each model group. A similar approach was taken for the acceptability studies. Quantitative synthesis for the cost-effectiveness studies was unfeasible since only three studies were included. Instead, cost-effectiveness data for the three studies were reported within the respective typology model group, after any aggregate effectiveness or acceptability data had been discussed.

For each model group, once the three data sources had been independently considered, the data were combined to summarise the effectiveness, acceptability and cost effectiveness of each model.

As a final stage in the integrative review synthesis, all of the data from across the various models were discussed among the core research team (Evans, Fraser, Kirk, Lane, Pryjmachuk) for a consensus on what the evidence says about what ‘works’ in services for CYP experiencing CMHPs and what those delivering and receiving such services like or dislike about them. The integrative review synthesis process is schematically outlined in Figure 5. The integrative review findings are reported in Chapter 6.

FIGURE 5.

Integrative review synthesis process.

Chapter 4 Scoping review findings and service model typology

This chapter presents the scoping review findings, starting with a descriptive overview of the body of included literature, after which we introduce our definitive typology of service models for CYP experiencing CMHPs. We also discuss some ‘features’ of services described in the included literature; in particular, we explore whether specific features are associated with specific service models.

Descriptive overview of included literature

The main inclusion criterion for the scoping review was a sufficiently detailed service description that enabled categorisation into one (or more) of the model types in our preliminary typology or into some new model type. Using this criterion, we identified 296 documents and extracted 342 service descriptions from those documents. Some documents described multiple services and some services were described in multiple documents.

Publication trends

Figure 6 outlines publication trends across time for the included documents. Data for 2019 and 2020 are incomplete because of the search date and cut-off date for inclusion. Since the search was conducted in May 2019, there are only partial data for 2019. The search was not repeated (for reasons outlined in Chapter 3) though additional documents were included up until the end of 2020 which explains the small number of 2020 documents. The trendline indicates a general increase in publications with notable peaks around 2003, 2009 and 2016–7.

FIGURE 6.

Included documents by publication year. (a) No date available for two documents.

There is no clear explanation for the peaks in Figure 6, though one explanation may be that (academic) interest in health topics wax and wane according to political priorities and/or public concerns and the availability of any associated funding, either for service development or research.

Country

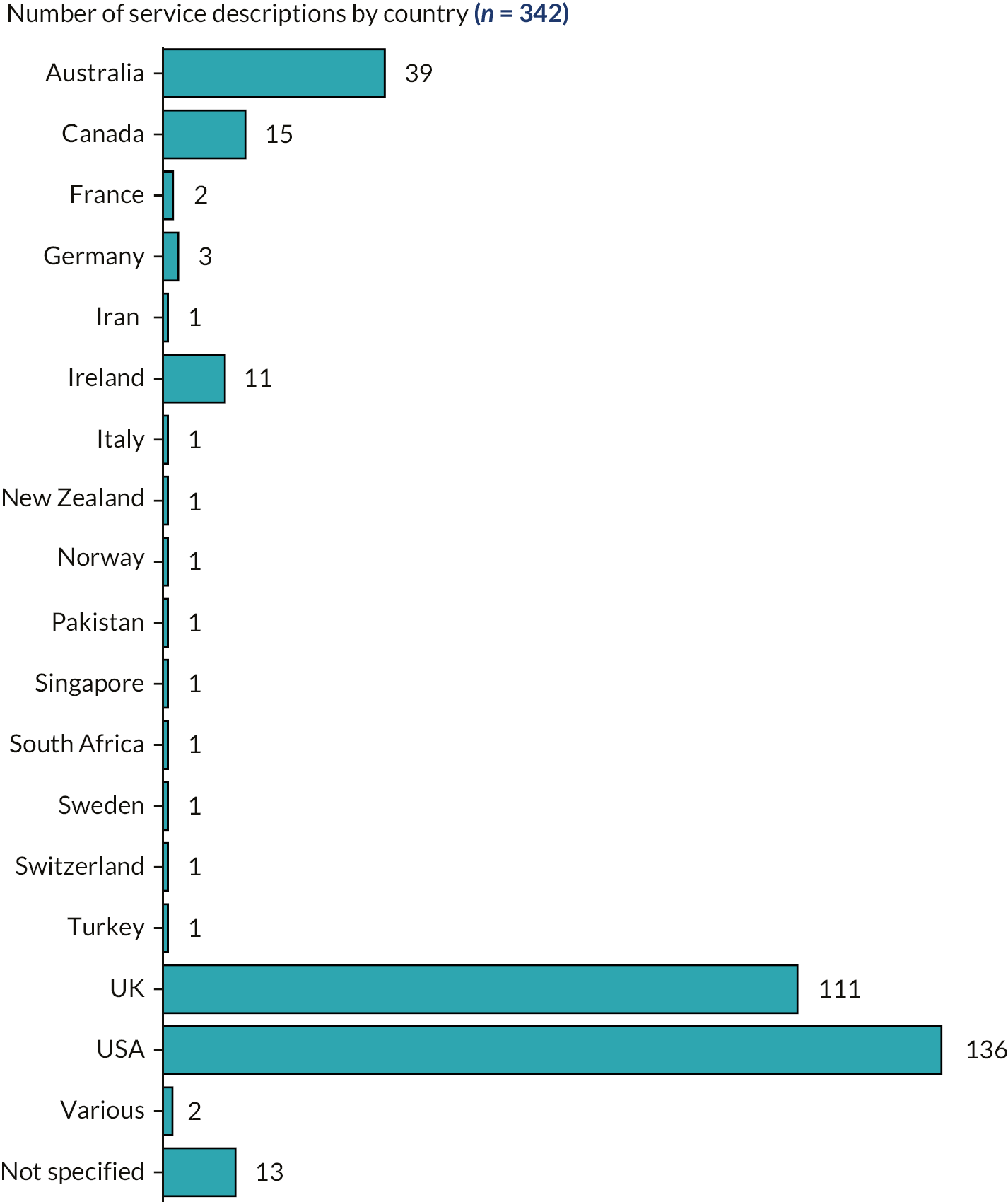

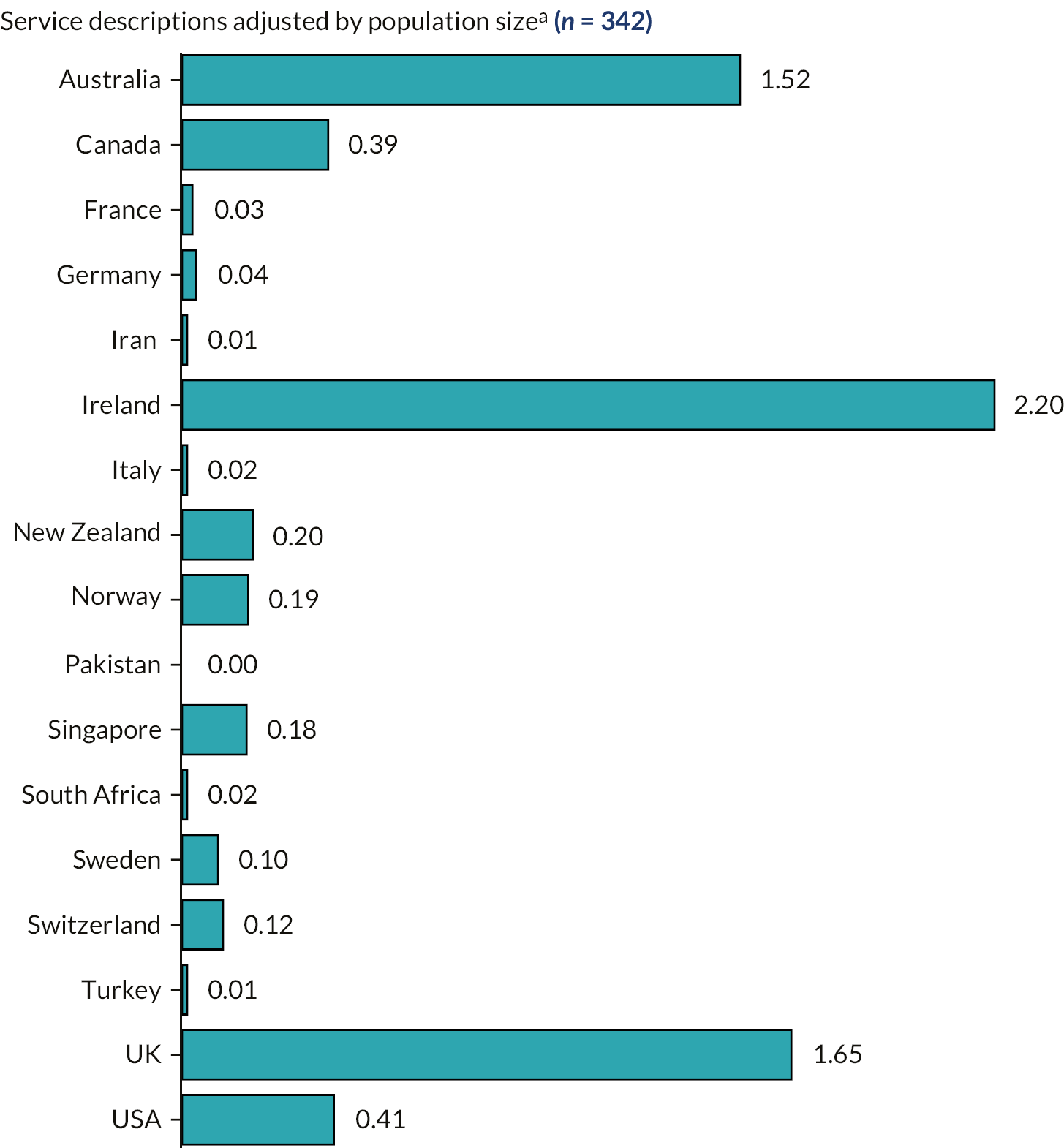

Figure 7 illustrates that more than 90% of services originated from the ‘Anglosphere’ (USA, UK, Australia, Canada and Ireland). Interestingly, if the numbers of service descriptions are adjusted for population size (using 2020 World Bank data59), Ireland punches above its weight in terms of population size while the USA punches below it (Figure 8).

FIGURE 7.

Service descriptions by country.

FIGURE 8.

Service descriptions by country adjusted by population. (a) Equal to number of services described/population size in millions.

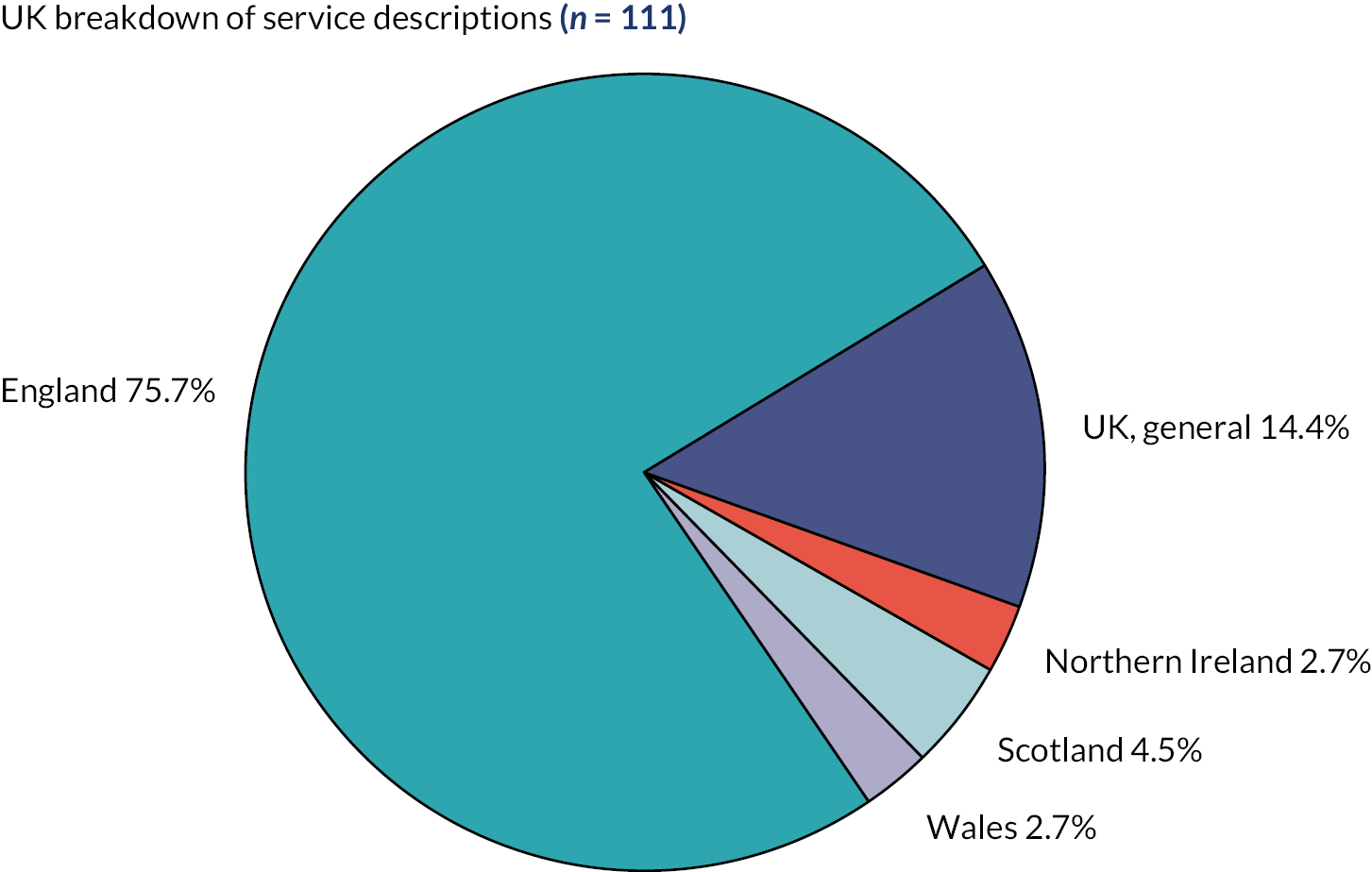

UK services

Regarding the UK services described, most emanated from England with a sizeable minority (14%) having a presence across the whole UK. Relatively few services were unique to Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

Service descriptions by UK constituent nation.

Document types

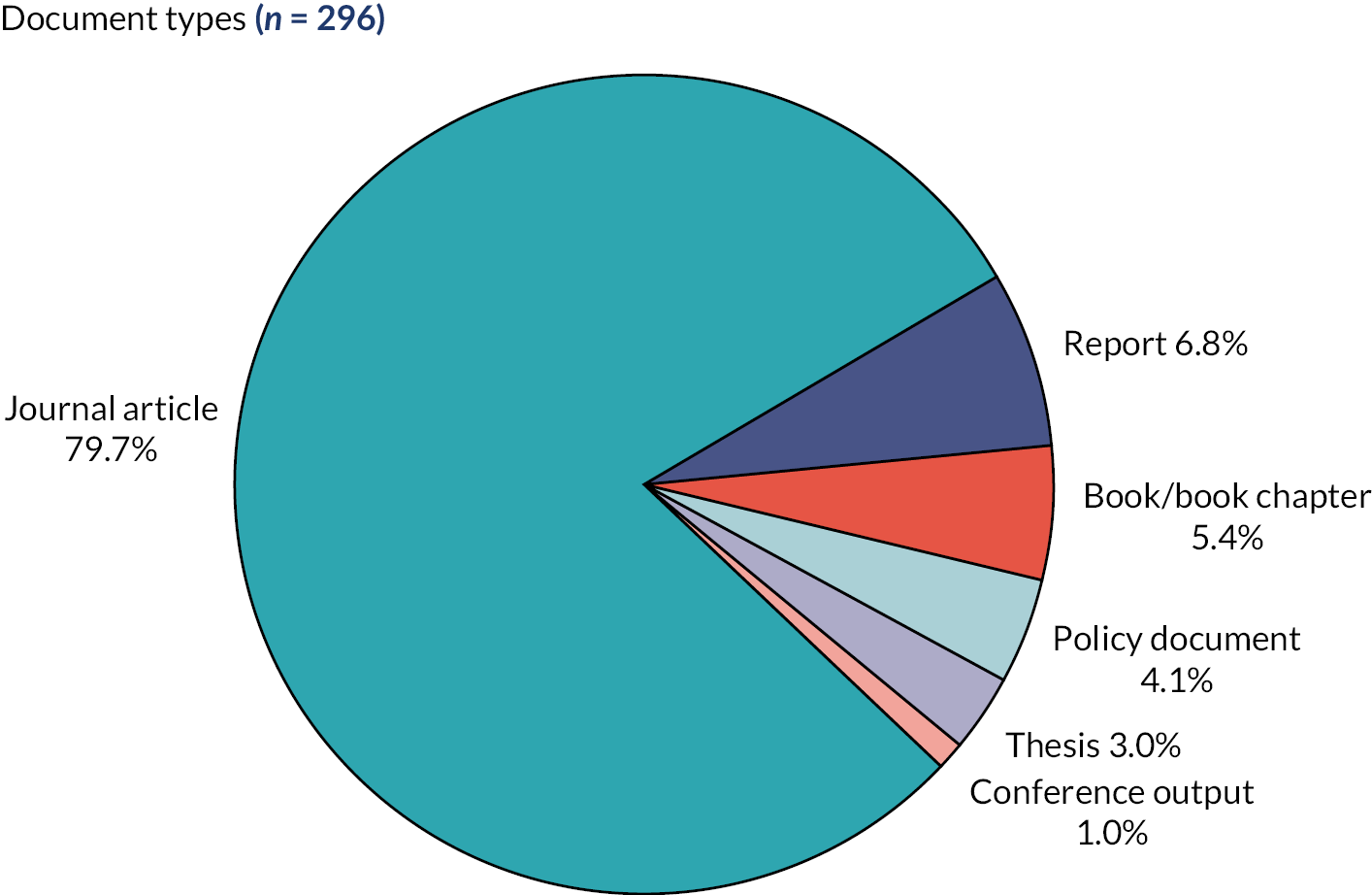

Most (80%) of the 296 documents were journal articles (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Included document types.

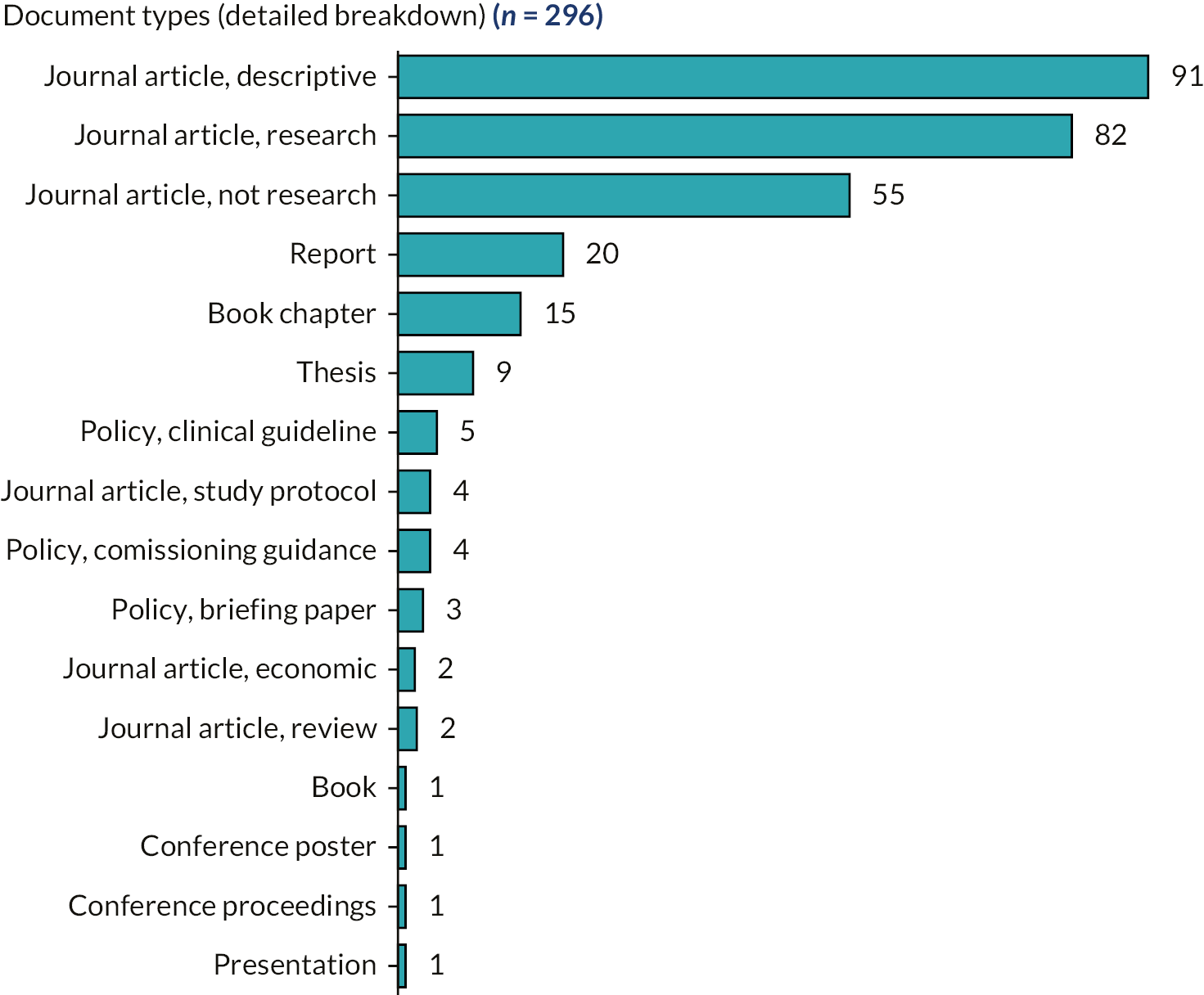

A significant proportion of journal articles were descriptive or they reported research that was ineligible for the integrative review (Figure 11).

FIGURE 11.

Detailed breakdown of document types.

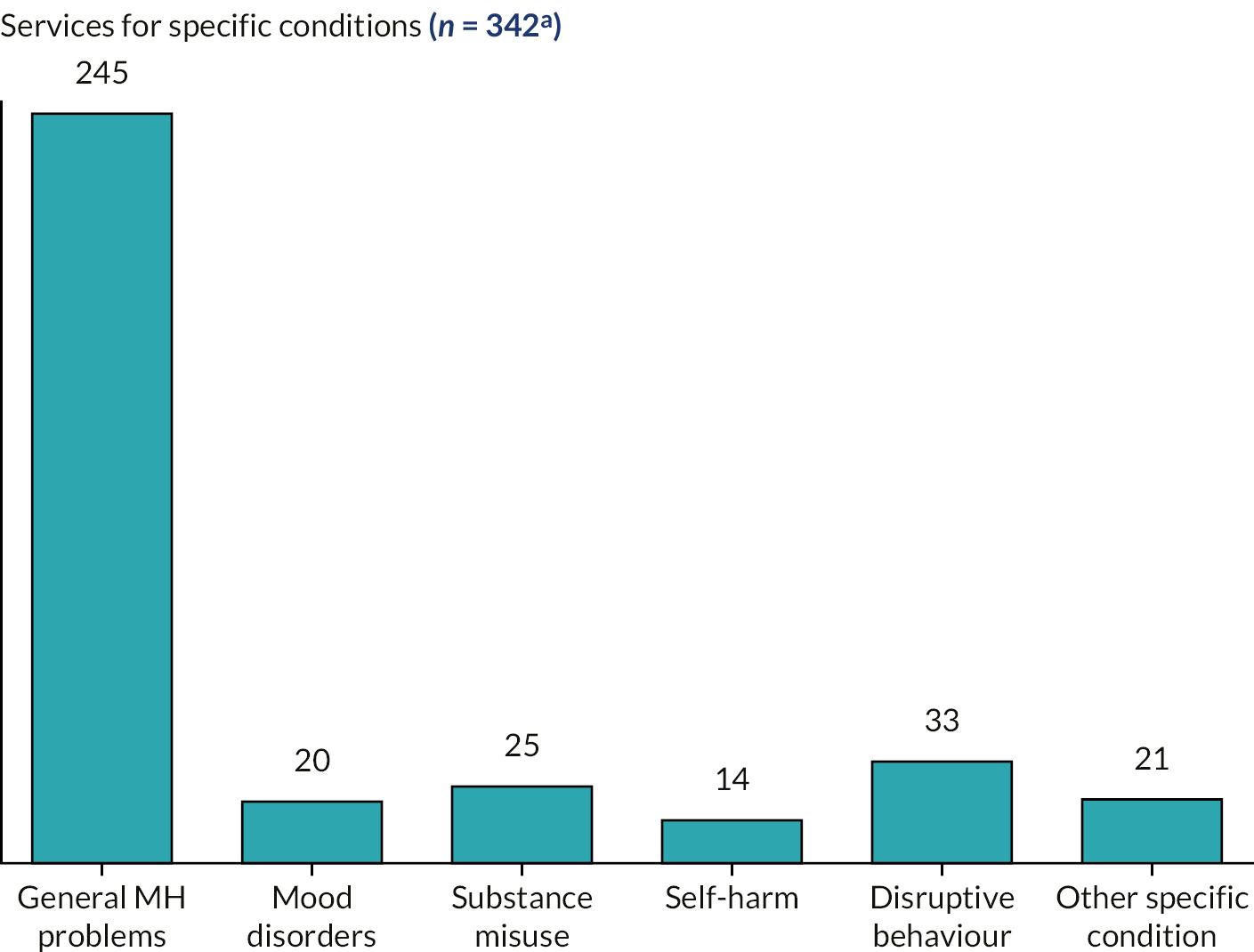

Services for specific conditions

Most identified services were targeted at CYP with general mental health problems (Figure 12). A minority targeted specific conditions such as anxiety and depression (mood disorders), substance misuse, self-harm and disruptive behaviour disorders.

FIGURE 12.

Services for specific conditions. (a) Total > 342 as some services cover multiple conditions.

Service model typology

Our final service model typology, derived from the scoping review and the knowledge and expertise of the research team and SAG, is presented diagrammatically in Figure 13. We identified 17 model types in six principal model groups (A–F). In addition, seven potential models seemed less rigid and more flexible than models in groups A–F, in that they tended to provided ‘scaffolding’ to services through a structured framework and often coexisted with models in groups A–F. Hence, our seventh group (G) is a group of (service transformation) frameworks rather than models.

FIGURE 13.

Typology of service models. NGO, non-governmental organisation.

Although the typology presents six discrete model groupings and a group of service transformation frameworks that cut across the six model groupings, real-life service provision often operates within a mixture of models and frameworks. Thus, the boundaries between models can overlap or be somewhat fuzzy (we revisit this point in Chapter 5). The arrowed lines in Figure 13 demonstrate some of the major relationships between the models. For example, there are links between in/outreach models (D), specialist CAMHS (A and B) and non-specialist CAMHS (C) – those providing in/outreach services are often experts drawn from specialist or non-specialist CAMHS and those providing in/outreach usually need to liaise with CAMHS. Another example relates to ecological models (E): ecological models assume any formal or informal mental health services a CYP receives are also part of their ecology.

Within each main model grouping are several submodels. Again, these are represented as discrete models, but in reality, they often overlap and/or are closely connected to one another. For example, the difference between school-embedded (B2) and schools outreach services (D2) is down to whether the staff providing the service are permanently located in the school (perhaps employed by the school) or whether the service is peripatetic, being provided by ‘visiting’ experts.

A detailed description of the typology models follows shortly; before this, it is worth exploring some additional characteristics of the services described in the included documents and how these services map onto our typology.

Distribution of services across models

The 342 service descriptions extracted from the 296 documents were subsequently categorised into one or more of the 24 different service models/frameworks within the seven broad groupings A–G. For reasons outlined earlier, many services could be categorised across multiple models/frameworks; however, to simplify analyses, a primary category was agreed for each service description during data extraction (Figure 14).

FIGURE 14.

Model distribution by primary category. ARC, availability, responsiveness and continuity.

The model grouping with the largest number of included documents (113) was in/outreach (D), followed by community-embedded specialist CAMHS (B; 89 documents) and service transformation frameworks (G; 54 documents), although a significant number of these (20) focused on a single framework, systems of care (G1). There were relatively few included documents for specialist CAMHS (A), community-embedded non-specialist CAMHS (C), ecological models (E) and demand management models (F).

Features associated with models

In Chapter 3, we mentioned the challenges we had in determining whether what was being described was a service, an intervention or a feature. Documents describing what we agreed to be interventions were excluded because of our focus on services. We did, however, record information about the features of a service when extracting data as we thought such information might be useful for model building in Work Stream 4. Features we extracted data about are listed in Table 3.

| Feature | Brief description |

|---|---|

| The service … | |

| X1 transitions | refers to the transition between childhood and adulthood; is often accessible between ages 18 and 25 years |

| X2 trauma informed | focuses on trauma and/or employs trauma-informed approaches |

| X3 family work | emphasises the importance of working with the family and not just the CYP |

| X4 intervention protocol | uses specific interventions (e.g. CBT, parenting), delivered according to a strict protocol |

| X5 interagency working | emphasises the importance of interagency or interdisciplinary working |

| X6 transdiagnostic | does not use clinical diagnosis, providing instead support focusing on (self-reported) problems or symptoms |

| X7 digital/remote | is delivered wholly or partially via digital (e.g. online) or remote (e.g. telepsychiatry) means |

| X8 task-shifting | has elements normally delivered by highly trained specialists delivered instead by associate specialists, parents or peers |

| X9 self-management | is predicated on the CYP/family learning how to self-manage problems |

| X10 shared decision-making | explicitly mentions shared decision-making or co-production |

| X11 care pathway | is explicitly underpinned by a care pathway |

| X12 early intervention | explicitly identifies as an early intervention service |

| X13 triage | has triage as a critical component |

| X14 integrated care | explicitly identifies as integrated care |

| X15 information and advice | has the provision of information and advice as an explicit function |

| X16 crisis care | provides care for CYP in crisis |

| X17 consultation-liaison | offers consultation with service users and/or liaison with other professionals |

| X18 peer work | uses parents and/or CYP with lived experience (paid or volunteer) to provide aspects of the service |

| X19 case management | uses a case manager (or similar) to manage/co-ordinate care |

| X20 open access | has few, if any, barriers to access (e.g. drop-in services, self-referral) |

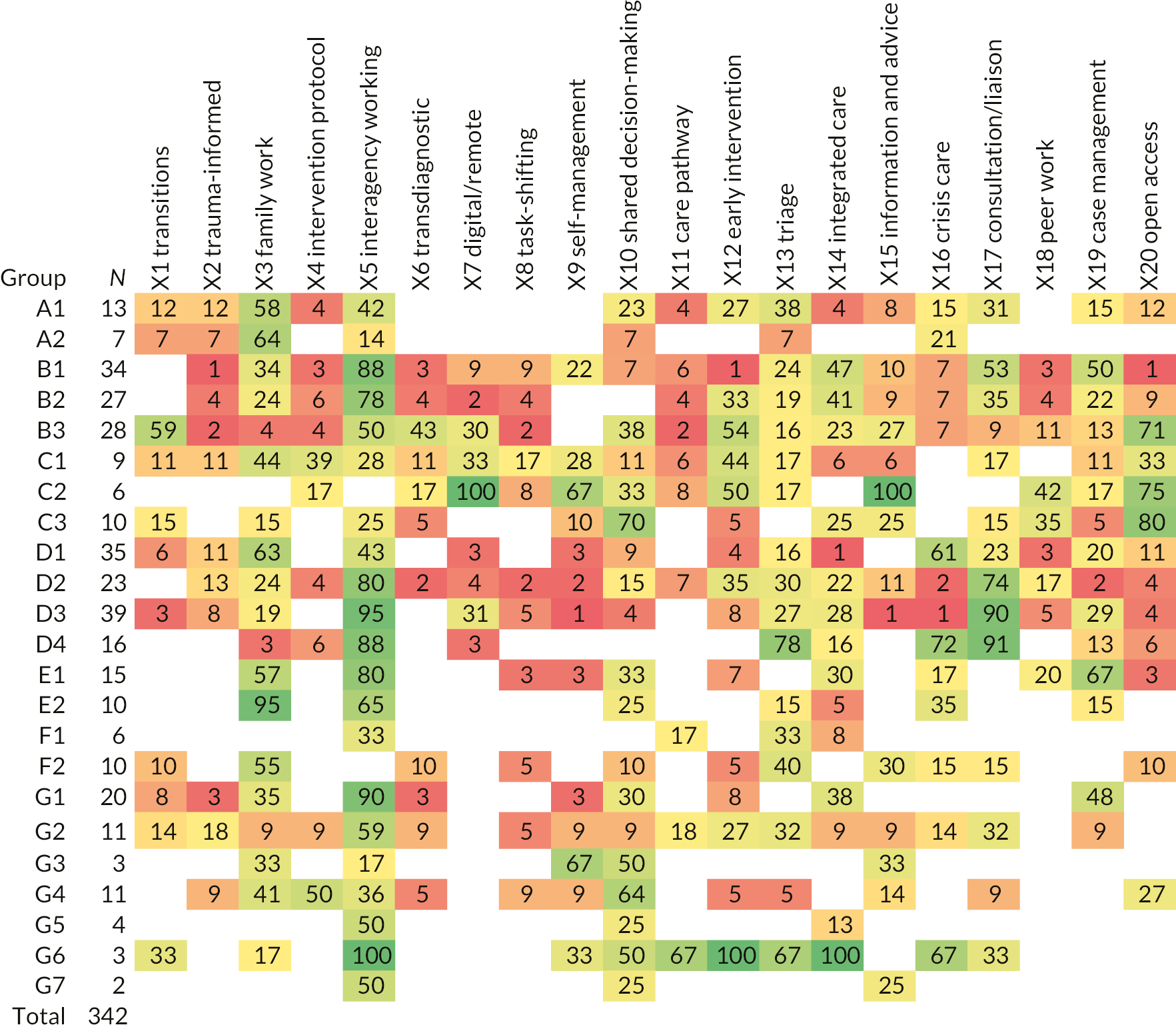

We mapped the features reviewers identified during data extraction across the various models to see if specific features were associated with specific models. To do this, we used a crude methodology of scoring 1 if a feature was evident in the data extraction for the service, 0 if it was not and 0.5 if, after discussion, the reviewers thought it ambiguous. The 342 extraction records from the 296 documents were grouped by primary model type and for each model type we counted the number of references to each feature (by totalling the 1, 0 and 0.5 scores), dividing the total by the number of extractions to produce a percentage of extractions mentioning that feature.

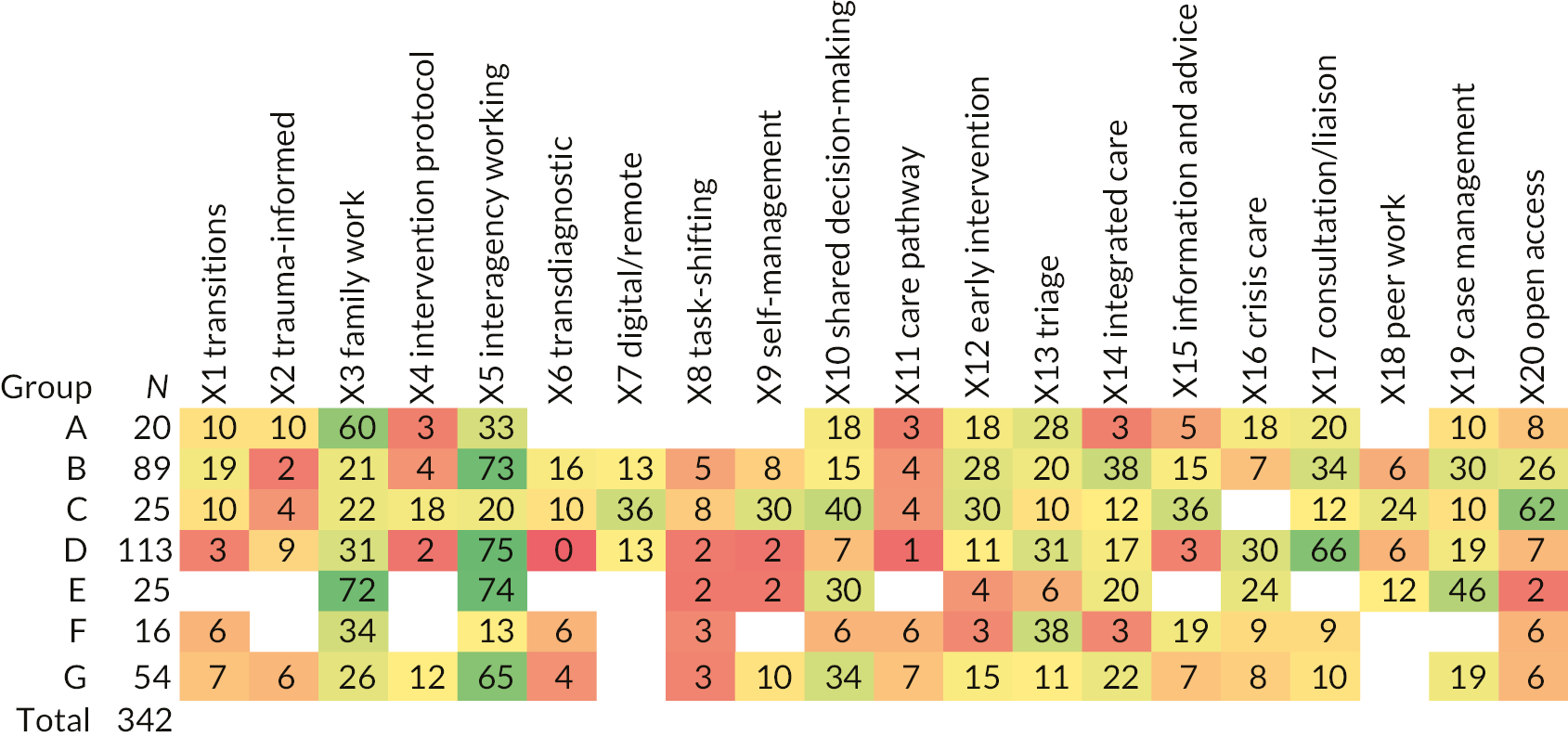

We have presented ‘percentage mentioning feature’ information as ‘heatmaps’ in Figure 15 (submodels) and Figure 16 (overall model groupings). By looking at higher percentages (greener cells), it is possible to get a sense of which features are associated with which models.

FIGURE 15.

Heatmap of features by model subgroupings. Numbers in coloured boxes indicate percentage of service descriptions mentioning feature.

FIGURE 16.

Heatmap of features by major model groups. Numbers in coloured boxes indicate percentage of service descriptions mentioning feature.

In the submodel analysis (see Figure 15), there were relatively few extractions for some model groups. There were no more than seven extractions for specialist CAMHS day care (A2), digital service (C2) and organisation-level demand management (F1), so any claims regarding features for these models should be treated with caution. In addition, since there were no more than four extractions for (i)THRIVE (G3), availability, responsiveness and continuity (ARC) (G5), formal partnerships (G6) and Evergreen Canada (G7), we have not speculated on features for these frameworks.

If an arbitrary rate of 50% or more of extractions mentioning a feature is used to signify a moderate association and an arbitrary rate of 75% or more a strong association, it is reasonable to argue that certain features seem to be associated with certain models. These associations are discussed shortly when we describe the models in detail but, before this, it is worth discussing several features rarely mentioned in the extracted service descriptions: trauma-informed (X2), transdiagnostic (X6), task-shifting (X8), care pathway (X11), integrated care (X14) and peer work (X18). Since a decision on identifying these as features was taken early in the screening process, it may be no services with these features subsequently appeared as we progressed through screening and data extraction. The absence of some, however, is surprising, notably integrated care and peer work.

Integrated care is important because it has been, for several decades, a central policy objective of many healthcare systems worldwide. 60 Though there is confusion in the literature,60,61 integrated care generally refers to attempts to provide holistic services to populations by asking providers to work together and collaborate or through creating single organisations to deliver integrated services. The literature is unclear as to which disparate entities require integration:61 there could be ‘vertical’ integration, such as the integration of primary, secondary and tertiary care or the integration of mental and physical health care, or there could be ‘horizontal’ integration such as the integration of health and social care (and perhaps even education where CYP are concerned). Two other features are closely aligned with integrated care – interagency working (X5) and case management (X19) – and it might be the confusion around what integrated care is means it is represented in these two features rather than as a specific, unique feature.

Peer work (X18), often seen as powerful adjunct to mental health service provision,62 featured in relatively few documents. We are unsure why but perhaps what seems a good idea is blocked by bureaucratic and organisational barriers in (often state-controlled) public health systems. Peer work was most frequently mentioned (though it did not meet the 50% threshold) in digital/remote (C2) and non-governmental organisation (NGO)-derived community hub (C3) services, services having more operational flexibility because they tend to be provided by the non-statutory sector.

Theoretical underpinnings

Only around one-third of services (29%) specified they were underpinned by theory. The most common theories cited were socioecological theory (27 services) and CBT (16 services). Services citing socioecological theory were largely ecological (E) services, while services citing CBT were mostly collaborative care (B1) or primary care mental health (C1) services. These observations are relatively unsurprising and will be discussed further as we consider each model in turn.

Model descriptions

Each model type is described in detail in this section, together with some examples of services categorised within that model type. For a full list of services identified in the scoping review, grouped by model type (see Appendix 6).

Group A: specialist Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services

Specialist CAMHS is the incumbent service model in many countries. It encompasses ‘standard’, institutionally based, medically (psychiatry) oriented CAMHS. In the UK, it is sometimes referred to as ‘statutory CAMHS’. It is a baseline against which other models can be compared and is frequently used as ‘usual care’ in effectiveness studies. Importantly, ‘specialist’ in this context is used to distinguish between mental health care delivered by mental health specialists and mental health care delivered by generalists like school nurses or general practitioners (GPs).

Specialist CAMHS comprises three components: outpatient services; day patient services; and inpatient services. While these can be considered models in their own right, the literature sometimes considers specialist CAMHS as an integrated whole. This may reflect variability in service delivery and organisation since the three components are sometimes provided by the same organisation and sometimes by separate organisations. Outpatient CAMHS (A1), often referred to as ‘clinics’ in the literature, may be based in hospital or community settings. In community settings, outpatient CAMHS may morph into a group B (community-embedded specialist CAMHS) model, for example, when an outpatient service moves out of a hospital setting into a setting such as a health centre or school. While many outpatient CAMHS are generic (A1a), clinics targeted at specific conditions (A1b) such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (included in the study’s remit) or eating disorders (excluded) are fairly common. Specialist CAMHS day care (A2) is also known as day hospital or partial hospitalisation. Inpatient care (A3) was outside of our remit.

Heatmap analyses found family work (feature X3) was moderately associated with all aspects of specialist CAMHS, suggesting most group A services target families rather than just CYP.

There were 20 service descriptions in total for group A, 13 for outpatient CAMHS (A1) and 7 for CAMHS day care (A2). Group A services were found in many countries. Examples of generic A1 services include Child Mental Health Clinic (Syed 2007, Pakistan), Innovative Tier 2 Service (Worral-Davies 2004, UK) and Norwegian Outpatient CAMHS (Bjørngaard 2008). Examples of specialist A1 services include ADHD Specialty Clinic (Campbell 2014, USA; McGonnell 2009, Canada), AtR!sk for emerging personality disorder (Kaess 2017, Germany) and Transcultural Child Psychiatry Team (Measham 2005, Canada).

Day services (A2) identified all included ‘day’ in their names, for example, a Turkish Day Clinic (Çakin Memik 2010), Day Service for Adolescents (Gatta 2009, Italy) and Extended Day Treatment (Vanderploeg 2009, USA).

Group B: community-embedded specialist Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services

B and C models are community-based, rather than hospital-based or institutionally based, services in which key mental health staff are embedded (‘co-located’) within, rather than being ‘visitors’ to, the service. Where key mental health staff visit a service, we classified it as an in/outreach (D) service. What distinguishes B from C models is the key mental health staff in B models are those drawn from traditional specialist CAMHS (e.g. psychiatrists, psychologists and mental health nurses), whereas C models tend to draw staff from less medically orientated professions like counselling and youth work.

We identified 89 group B service descriptions in total: 34 for collaborative care (B1), 27 for school-embedded mental health services (B2) and 28 for psychiatry-derived community hubs (B3).

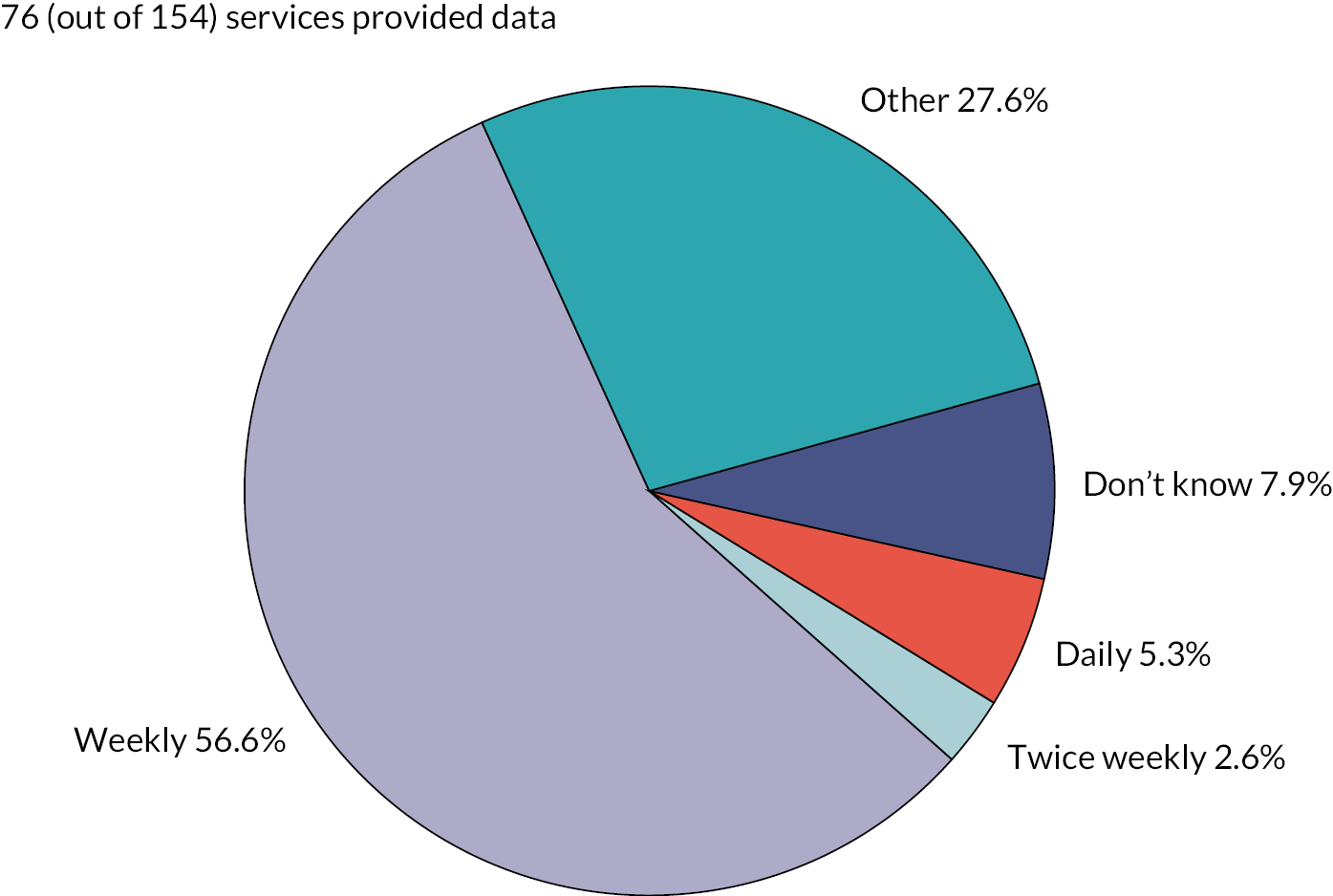

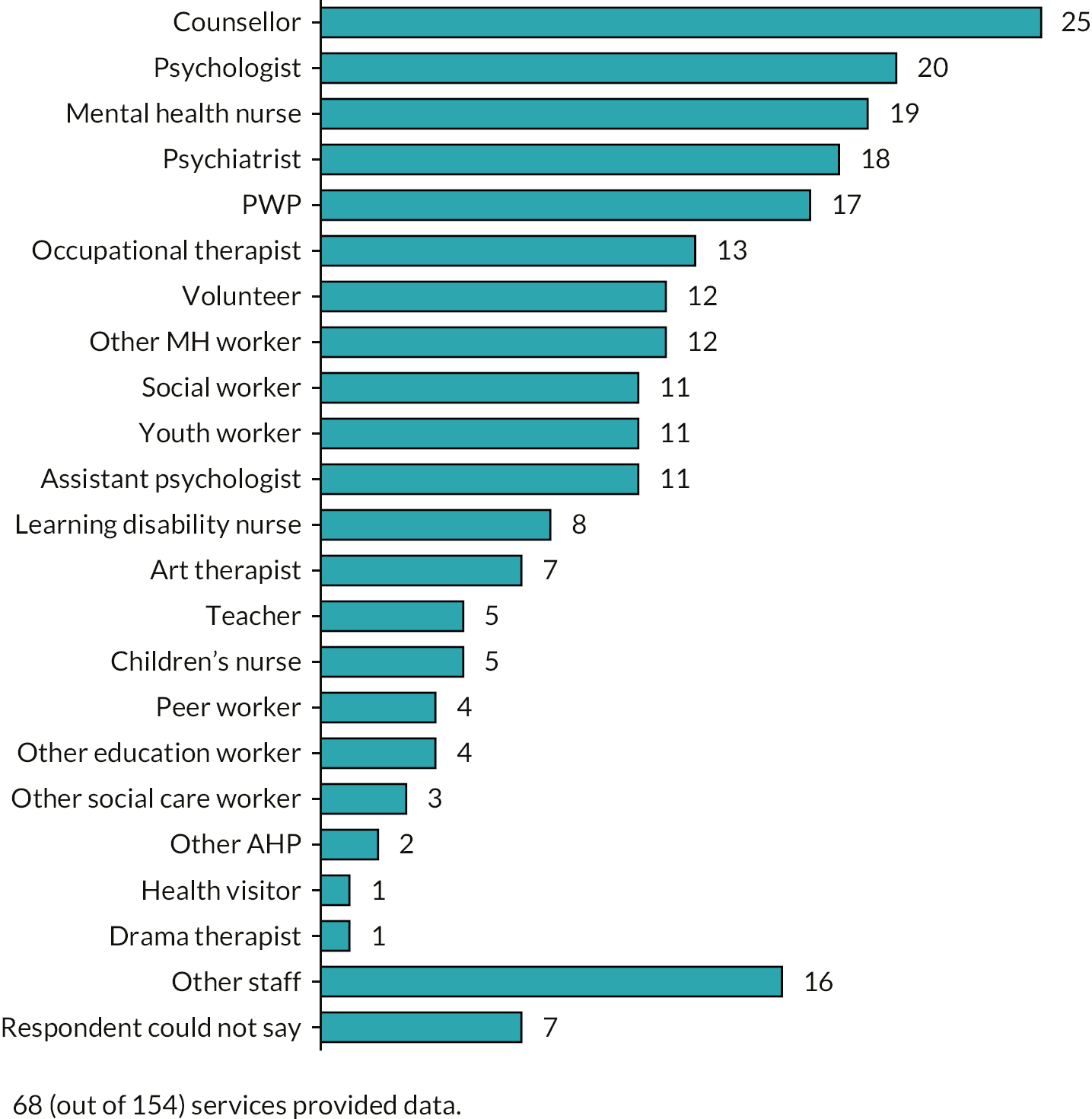

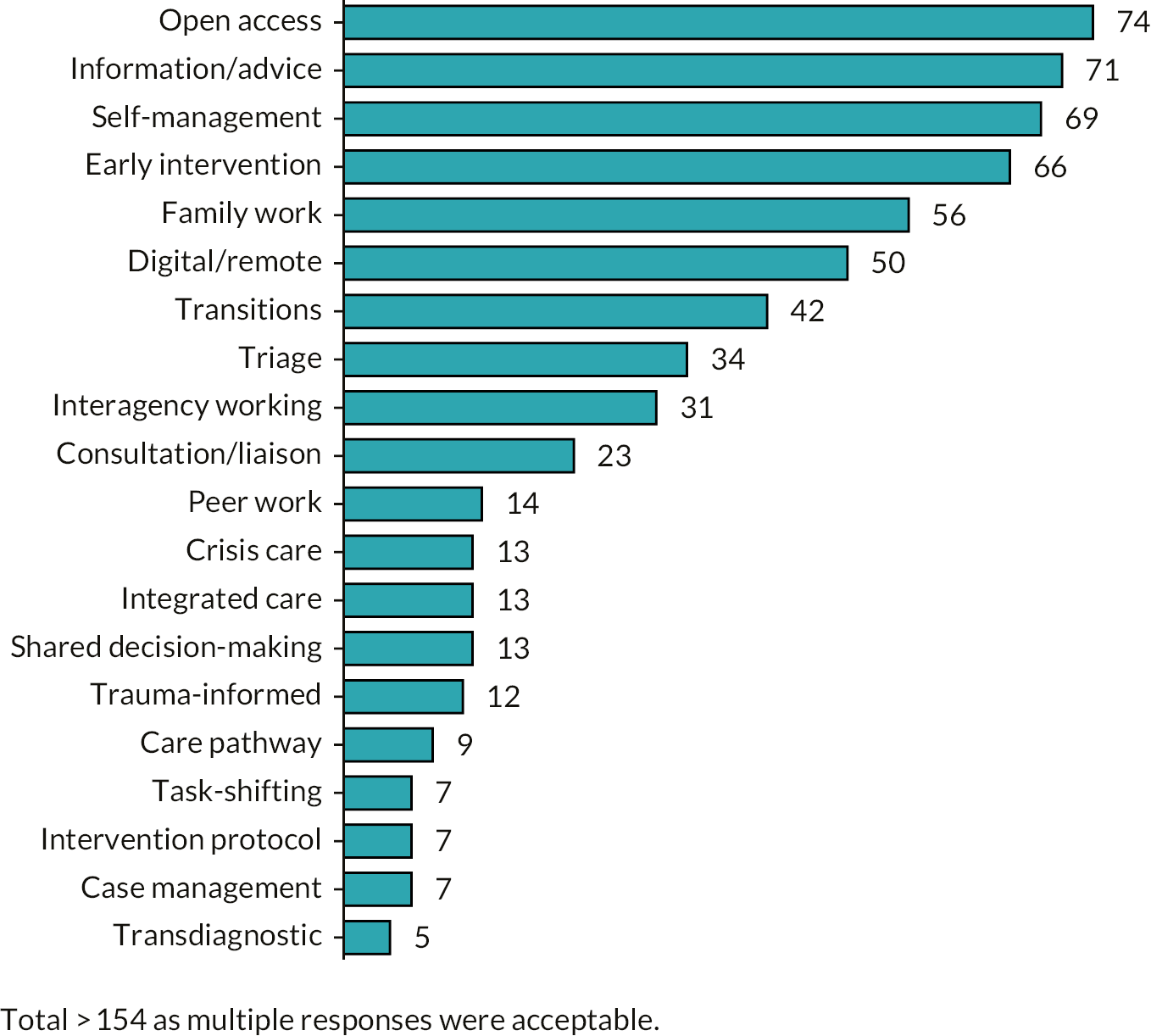

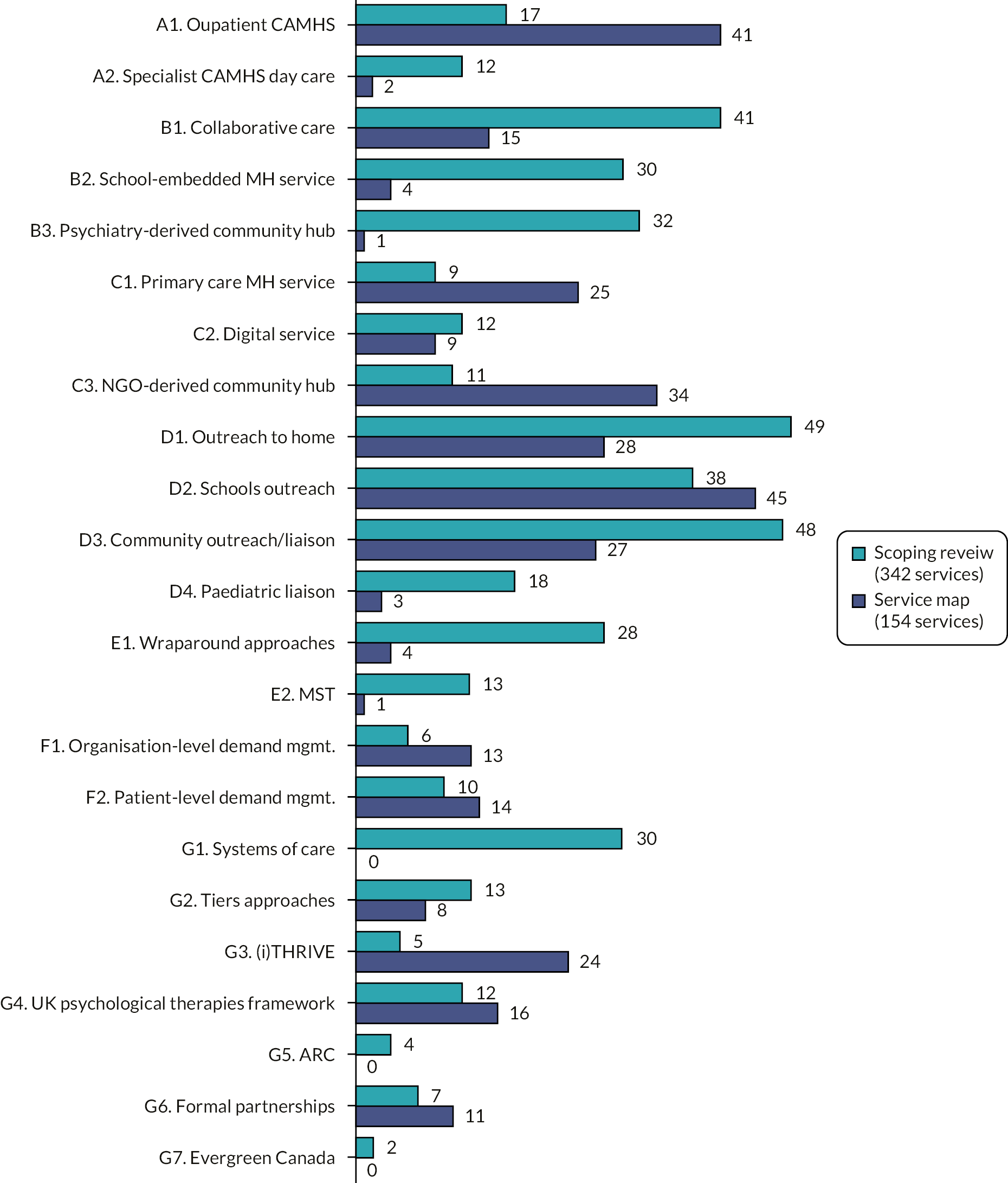

B1 collaborative care