Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number 17/51/08. The contractual start date was in February 2019. The draft manuscript began editorial review in July 2022 and was accepted for publication in October 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Holti et al. This work was produced by Holti et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Holti et al.

Chapter 1 Overview of the improving care for trans adults project

Context

The adult trans population has significant and distinctive health and well-being needs, which the NHS currently struggles to meet. Throughout this report we use the term trans to refer to the diverse people whose gender identities do not correspond to how they were assigned at birth or in early life. The term includes non-binary people.

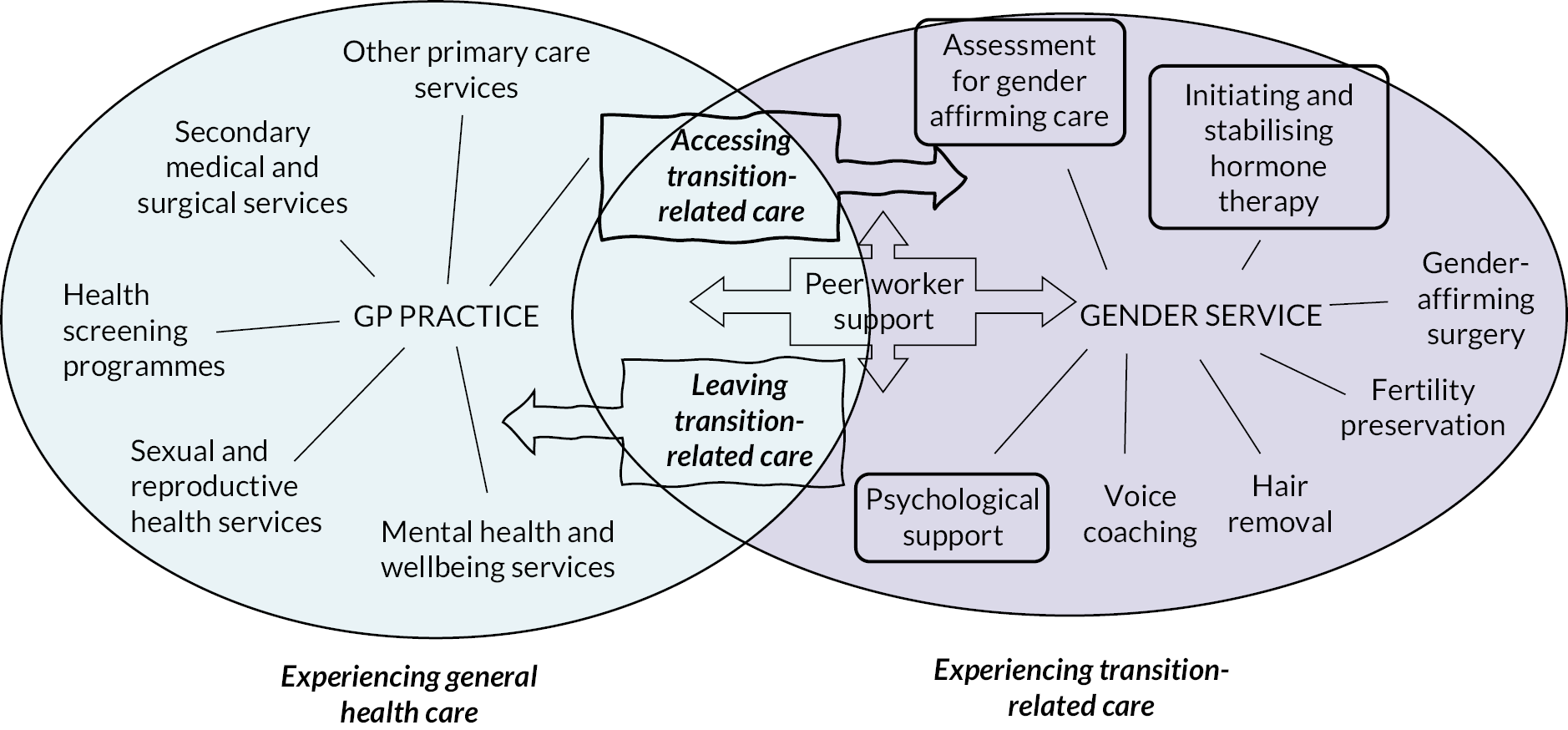

This research concerns improving the range of NHS health services that trans adults need. These include services intended to support people who are making a medical transition, and many other services relevant to wider aspects of physical and mental health and well-being. Not all trans people need to make a medical transition, and transition can take many different forms. However, issues of co-ordination arise between different aspects of transition-related care, and between transition-related care and general health care.

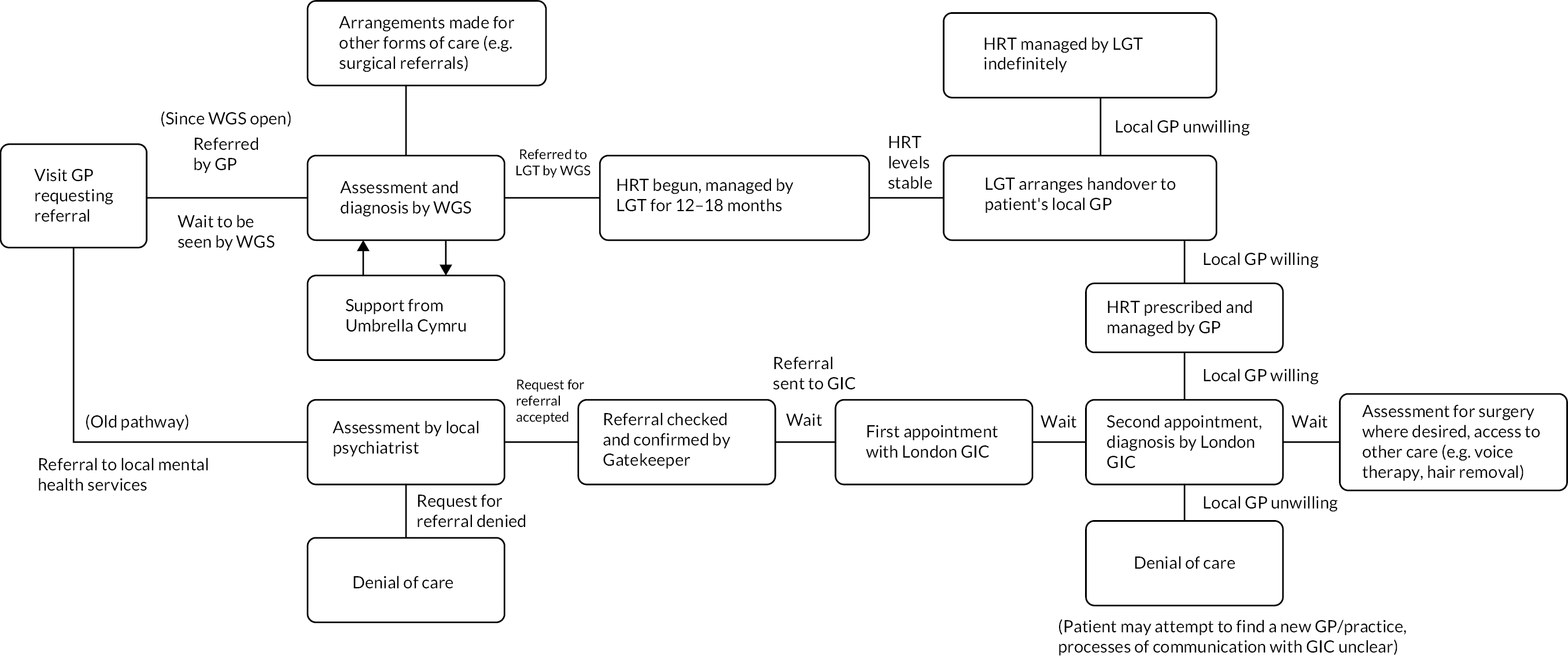

Currently, trans people over 17 who need to make a medical transition can seek care at one of the UK’s 10 specialist NHS Gender Identity Clinics (GICs), sometimes also known as Gender Identity Services (GISs). As we shall see, people experience very long waits to be seen. Since 2020, NHS England (NHSE) has also funded three pilot primary care gender clinics, providing most of the same transition care options.

Transition-related care is also likely to involve other NHS services. These may include a trans person’s own general practitioner (GP), practice nurse and local pharmacies, in prescribing, dispensing, administering, monitoring and managing long-term hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Various surgical specialists may be involved, with the NHS offering ‘top surgery’ for trans people who were assigned female at birth (AFAB), and genital reconstruction surgery for AFAB people and people assigned male at birth (AMAB). The NHS also offers some voice coaching and hair removal services.

Many trans people require the support of NHS mental health services, because of the prevalence of poor mental health, attributable to the minority stigma trans people face.

In the 2021 UK Census, 262,000 people (0.5% of returns) indicated that their gender was ‘different from their sex registered at birth’. 1 Waiting lists for the GICs in England have grown significantly in recent years, apparently due to a combination of significant increases in demand and relatively static capacity. Waiting lists totalled over 2300 in 2015, with a total clinic population at that point of 6000 (which can be estimated as ˂ 5% of the trans population). Waiting times for first appointments at that point varied between 9 and 64 weeks. 2 Following temporary reductions in their capacity during the coronavirus disease discovered in 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the majority of GICs are at the time of writing reporting 4- to 5-year waits, with the largest GIC alone reporting over 11,000 people waiting. 3

Because of barriers to accessing NHS care they need within an acceptable timescale, many trans people in the UK, who can afford to, turn to private providers of hormone therapy and gender-related surgery, within the UK and abroad. Many also access private provision of procedures important to their transition which are not offered by the NHS, such as facial feminisation surgery.

The need for better co-ordinated care across services and specialisms and over time was recognised by the House of Commons Women and Equalities Select Committee Report on Transgender Equalities. 4 This concluded that ‘The NHS is letting down trans people’,4 referring to overly complex referral pathways and lack of joint working between primary care and specialist services, particularly over long-term hormone therapy. The Medical Director for Specialist Services in NHSE raised explicit concerns about long waiting times at GICs, systemic failings in the care that trans people receive, and a pervasive lack of cultural awareness among NHS staff. 5 Whether their healthcare needs were associated with a medical transition or not, it was apparent that trans people typically experience serious barriers to receiving appropriate and well-integrated care. 6

This research has sought to build on initiatives to improve care and its integration, including those involving third-sector lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex, plus (LGBTQI+) organisations working in partnership with primary care organisations or with GICs. It has also sought to explore how lessons about effective integration of trans health care can best be implemented in the context of an NHS still coping with the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the remainder of this chapter, we set out the research aims and objectives and review the main guidelines that shape the current provisions, as well as the relevant existing literature on experiences of trans health care and related topics. The following chapter then summarises the research design and methodology.

Research aims and objectives

The aims of this collaborative research were:

-

To analyse empirically the current realities and derive conceptually informed future possibilities as to how various NHS services and third-sector organisations can work together effectively to address the needs of trans adults at different stages of their lives.

-

To disseminate this analysis and its implications for wider learning, improving the effectiveness of specialist and non-specialist services in meeting the needs of trans adults.

The overall objective was to produce guidance material and online educational materials for trans people who use services, commissioners and staff in specialist and generalist services, so that they can better understand and shape cost-efficient and integrated provision.

The research questions (RQs) were:

-

What is the range of models recently used in the UK for providing integrated care for meeting the specific health and well-being needs of trans people?

-

Which factors make services more or less accessible and acceptable to the variety of trans adults who need them?

-

In the different integrated service models, how effective are the different aspects of services and their interaction in meeting the needs of people at different stages of their gender transition and at different ages?

-

What lessons emerge as to how models for providing integrated care can be successfully implemented and further improved in meeting the needs of trans people, within limited resources and continuing constraints resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic?

Guidelines shaping the current system of care

As institutions, GICs serve multiple functions – medical and legal – in terms of regulating trans identities and access to health care. They provide a key route to accessing a diagnosis of ‘gender dysphoria’ through the NHS, which leads to various gender-affirming treatments. The same diagnostic criteria, applied within a GIC by a certified member of the Ministry of Justice’s panel of gender specialists, provide the basis for subsequent signing off for gender-affirming surgery as well as the application for a Gender Reassignment Certificate (GRC).

The criteria for and approach to diagnosing and creating treatment plans are set out in four main places.

-

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association (APA). This is widely influential internationally in terms of providing lists of symptoms to be used in mental health diagnoses. The latest version of this DSM-57 espouses the aim of moving away from the pathologising category of ‘gender identity disorder’ present in DSM-4. 8 It offers a set of criteria for the diagnosis of ‘gender dysphoria’, which is seen as the distress that can result from having a gender identity different from the sex assigned at birth. DSM-5 lists symptoms such as ‘a strong desire to be of the other gender’ [sic] alongside ‘clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning’. 8 It also requires these symptoms to be present on a stable basis, for at least 6 months.

-

The International Classification of Diseases, ICD-11. 9 This is generally understood within psychiatry as closely related to the DSM. The latter is seen as providing more detailed guidance on diagnostic criteria for conditions identified in the former. ICD-11 replaces the term ‘transsexualism’ used in ICD-1010 with ‘gender incongruence’, and situates this as a condition relevant to sexual health, rather than mental health. The criteria for applying it to a person are cast in terms of ‘a marked and persistent incongruence between an individual’s experienced gender and the assigned sex, which often leads to a desire to “transition”, in order to live and be accepted as a person of the experienced gender’. There is no requirement to identify a state of distress as in DSM-5. This is based on a body of evidence that distress in trans people is related to minority stress, rather than to being trans in itself. 11

-

The Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Good Practice Guidelines for the Assessment and Treatment of Adults with Gender Dysphoria. 12 These guidelines briefly introduce the concept of gender dysphoria in terms of a state of ‘distress associated with the experience of one’s personal gender identity being inconsistent with the phenotype or the gender role typically associated with that phenotype’ (p. 12),12 but also acknowledge that the terminology and criteria are under review by the ICD. The guidelines stress the need for respect for patient autonomy in decision-making on treatment, based on informed consent (p. 28). 12 They also emphasise that clinicians should adopt a patient-centred approach and customise treatment plans around individual circumstances and needs, specifically mentioning non-binary people (p. 19). 12 The guidelines refer to being informed by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care,13 which advocate patient-centred assessment and treatment. Alongside these collaborative features, the guidelines recommend that assessment conversations should explore whether there is history of ‘mental disorder’, childhood or adolescent cross-dressing with ‘possible erotic accompaniment’, and current relationship status. The latter appears to be a reference to the theory of ‘autogynephilia’, whereby trans women’s identities can be a by-product of sexual orientation. This theory has been severely critiqued as stemming more from anti-trans ideology than any evidence. 14 The guidelines fail to clarify how any of these lines of inquiry might affect the assessment of gender dysphoria, other than a statement that suspension of gender treatment ‘can only occur where there is evidence that a mental health condition is giving rise to a misdiagnosis of gender dysphoria or renders the patient untreatable until their condition is reasonably well controlled’ (p. 23). The guidelines further clarify that mental health conditions can ‘more usually’ be treated in parallel with ‘the gender treatment process’ (p. 23).

-

The Service Specifications for GICs for Adults (Non-surgical Interventions). 15 These specify that entering the NHS treatment pathway is dependent on an assessment that results in a diagnosis of gender dysphoria, while grounding this in the definition of transsexualism in ICD-10 as ‘a disorder characterized by a strong and persistent cross-gender identification’. The specification states that this assessment will normally take the form of two clinician sessions, conducted several months apart, with the second carried out by a doctor or clinical psychologist (p. 24). 15 It also refers to assessments and interventions being ‘personalised and based on shared decision-making, with service flexibility and reasonable adjustments to the delivery of care to match the individual’s needs and circumstances’ (p. 3). 15 It further stresses the importance of informed consent, including provision of full information about the possible risks of treatment (p. 7),15 but such considerations are clearly meant to apply after the diagnostic decision has been made.

Literature review

Experiences of trans health care

There is a limited body of existing literature that directly concerns the organisation and delivery of trans health care, with some UK-based studies. Some strands within this are relevant to the research reported here. These concern the dynamics underlying inadequate and poorly integrated care for trans people, which need to be overcome.

A first strand of literature concerns trans people’s experiences of health care in general, and the common negative experiences that lead people to delay or avoid accessing health care when they need to. A large-scale five-country survey of healthcare experiences revealed that more than half of the trans people surveyed delayed accessing health care in general, because of previous experiences of being misgendered or treated disrespectfully by clinicians, administrative staff or receptionists. 16 A qualitative study of trans individuals in Canada brings out some of the dynamics behind and consequences of such patterns. It concluded that trans adults often feel either explicitly or subtly discriminated against by health services, yet are expected to educate clinicians about transition-related matters and remain positive despite lack of recognition of their needs and everyday experiences of exclusion. 17 This was seen as linked to poorer overall health outcomes for trans people.

A second strand concerns experiences of transition-related health care. In the UK, as in many countries, trans people must go through a process of psychological evaluation, leading to a diagnosis of gender dysphoria or gender incongruence, before they can access gender-affirming treatment, such as hormone therapy or surgeries. One relatively small study of patient satisfaction ratings within an English GIC indicated high rates of satisfaction. 18 This satisfaction rating was, however, focused on the experience of the GIC itself, rather than the overall experience of transition-related care from different sources over time. A rather different picture emerges from a range of qualitative studies which bring out the difficulties and stresses that trans people face in their healthcare encounters.

In an analysis of qualitative survey data of trans users of mental health services and GICs, Ellis et al. 19 concluded that practitioners tend to be poorly informed about trans issues and the realities of trans people’s lives and that intrusive questioning and restrictive treatment pathways all contributed to actually having a negative impact on mental health and well-being, particularly in the context of the minority stress trans people experience in everyday life. A focus-group-based study of the experiences and transition-related needs of non-binary people attending a GIC concluded it was necessary to adapt GIC clinical assessment approaches to affirm rather than question a person’s gender identity and provide space for a non-binary person to explore and articulate their goals for treatment, taking account of the person’s likely pervasive experiences of transphobia and social isolation. 20

An in-depth study of the experiences of 14 trans people in Sweden concluded that they found the process of clinical evaluation needed to access gender-affirming medical treatment problematic. This was because of the length of time they had to wait and the lack of support while doing so, and clinicians appearing not to be familiar with important aspects of trans experience. Some trans people experienced themselves as paradoxically expected to take some elements of initiative with their medical transition – for example, through ordering hormones from abroad, in order to be judged by clinicians as sufficiently committed to transitioning to receive medical support. 21

A third important strand of literature concerns trans people’s experience of mental health care. A review of evidence suggests that the trans population carries a higher than average prevalence of common mental health conditions as well as suicidality. 22 Other studies indicate that the experience of receiving mainstream psychological therapies can be a difficult, unsatisfactory and even a fearful one for many trans people, often because clinicians can appear reluctant to engage with, or even recognise, a trans identity. 23,24 Therapists may imply that a trans identity is problematic, rather than focusing on the mental health difficulties that result from the transphobia to which trans people are subjected. In reaction to this, some clinicians in the UK and USA have advanced models for meeting the needs of trans clients more effectively,25–27 within a framework of affirming trans identities, while recognising the impact of minority stigma.

A further strand of literature relevant to this study critiques established models for accessing gender-affirming treatment through a process of psychological diagnosis. Several authors describe the emergence of clinical practice based on an informed consent model (ICM). 28,29 Ashley et al. 28 identify a variety of ICMs. The common element is that the focus of assessment shifts from diagnosis of gender dysphoria to that of clarifying treatment goals and ensuring the trans person concerned has a full understanding of the likely benefits and the medical risks, as well as the capacity to give their informed consent.

We did not study an example of an ICM in the research reported here. However, as reported in Chapter 4, the future desirability of ICMs emerged frequently during the interviews with trans people. In later chapters, we will explore the relevance of literature on ICMs to our findings on improving the integration of care for trans adults.

Wider literature on person-centred, co-ordinated care

The research reported here also builds on wider health policy and organisational studies literature to enable critical evaluation and learning from attempts to improve the integration of care for trans adults.

A first area concerns co-ordinated or integrated care. These closely related concepts have many different definitions referring to a wide variety of initiatives in designing and delivering health and social care (HSC) services. 30 However, most commentators agree on some core principles, which reflect the different perspectives of policy-makers, commissioners, service managers, clinicians and service users or patients. In any particular initiative to provide integrated care, based on the work of Lloyd and Wait,31 the following concerns are reflected to a greater or lesser extent:

-

Service users requiring several distinct branches of medical or social care benefit from experiencing seamless or ‘person-centred’ care, rather than a fragmented experience of separate attendances at different services, each lacking a full understanding of what others are doing.

-

Clinicians and other service professionals often want to improve their interdisciplinary co-ordination around cases, improving outcomes and preventing errors.

-

Managers want to improve the efficiency of services, removing duplication – for example, in the form of similar clinical or administrative work being carried out with the same person in different places.

-

Commissioners or policy-makers aspire to align the incentives of different services focusing on the needs of the same group of people, provide a more holistic system of care and improve clarity as to who is accountable for achieving health outcomes.

What these principles mean in practice, however, and the processes, methods and tools suitable for achieving them, depend greatly on context. 30,32

Second, there are strong connections between co-ordinated or integrated care and innovations in ‘person-centred’ approaches to health care, as well as user involvement in the shaping and delivery of care. 33 A large body of evidence indicates that improved patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes are strongly related to a person-centred and co-ordinated approach to health care. 34 Clear and full communication of clinical options to service users or patients, their involvement in decisions about their care and continuity in the clinical and support personnel working with them all have positive effects. A related body of work elaborates the social, clinical and resource effectiveness of users being involved, either as individuals or collectively, in the design and delivery of the services they need. 35 Ideas of user-led approaches to service design are relevant to understanding innovations in health services for trans people, given the role of third-sector organisations in advocating for and involving members of trans communities in shaping services.

Overall, we take from the literature on healthcare innovation the notion of person-centred, co-ordinated care as a useful conceptual guide for assessing the acceptability of current services for trans adults. These ideas are equally relevant for assessing progress resulting from initiatives to improve integration of care.

Chapter 2 Research design, data collection and analysis

The overall research design was a multicomponent and mixed-methods study of current realities and initiatives to improve health care for trans people, leading to the identification of areas for improvement and production of educational materials. The empirical research took place over a period of two and a half years, from March 2019 to September 2021, with a 6-month pause during the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, from March to October 2020.

The research followed the plan and detailed procedures set out in the study protocol, revised in the light of the pandemic during 2020, with all subsequent interviewing – the vast majority of the data gathering in the project – carried out remotely. 36 Changes to the plan are noted below. Data collection plans obtained research governance approval from the Health Research Authority (IRAS 262467).

We describe below the methodological approach for each of the four main research work packages (WPs), to demonstrate the rigour of this qualitative research against the ‘Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research’ in the healthcare sector published by O’Brien et al. 37 In keeping with these, we first summarise the composition and stance of the research team on key issues in researching trans health care, to make transparent the perspectives brought to interpreting research data.

Research team and project community

The core Improving Care for Trans Adults (ICTA) research team comprised nine white people:

-

four investigators, three cis men and one cis woman, all with established academic posts, and part-time on the project, all over 50;

-

two full-time research fellows, both trans and non-binary, employed on fixed-term contracts at the Open University, in their late 20s and early 30s;

-

three part-time co-researchers, all trans, one woman, one man and one non-binary person, employed by third-sector LGBTQI+ project partners, all aged between 25 and 40.

As described under WP 2 below, the core team was supplemented between June 2021 and January 2022 by two part-time trans researchers, who were Black, non-binary and in their 20s. An external organisation was engaged to provide an online platform for the national survey of trans healthcare experiences also described below.

The research benefited from extensive involvement of the ICTA patient and public involvement (PPI) group, all trans people, led by a non-binary person in the role of PPI lead, who met regularly with the research team. The PPI lead and group commented on the content of research instruments and participant information sheets, as well as on sampling priorities, interim analyses and report drafts. The whole project had a focus on health inequalities and equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI). The PPI group played a vital role in keeping such concerns foregrounded, repeatedly advocating steps to increase participation from marginalised groups of trans people. This report includes a statement from the PPI group (see Patient and public involvement group statement: patient and public involvement on improving care for trans adults project), which identifies the challenges the group experienced in taking up its role in relation to the research team as a result of how the project was organised. These included difficulties in influencing the research team to give enough attention to trans participation in general and to the involvement of the most marginalised trans voices of Black people and people of colour. In the final stages of the project, with permission from the funder, the PPI lead was also engaged for some additional hours as a researcher to assist with analysis of data as a part-time member of the research team because of their knowledge of the mental health provision for trans people.

Research team assumptions and standpoints

Team members shared a recognition that the most important interests to be served by the project were those of trans people and trans communities. They also held a commitment to advancing the rights of trans people in society and within healthcare systems, given that most health care internationally has historically failed to see trans identities as part of normal human diversity. For most of the last century trans identities were either ignored, regarded as deviant or treated as a form of mental illness. 38 In the current century, medical frameworks no longer classify being trans as a mental health condition,9 but most institutions in society enact cisnormativity in terms of expecting people to be cisgender, and are often harmfully transphobic as a result. 39 This may take a less overt form, such as treating trans people as outside of social norms and not deserving of recognition or welcome. Frequently, however, transphobia takes the form of overt and harmful aggression, including outright denial that a trans person’s gender identity is different to that assigned at birth.

A related shared perspective was that trans people carry unique experience and knowledge of how they are marginalised in a variety of ways within current UK society, and how this affects their lives, including their encounters with health services. The accounts of trans people are thus a vital source of insight and analysis into how health services function and affect them, rather than mere sources of data. Hence our approach to interviewing trans people sought to bring out not only their experiences of health care, but also their views on what had given rise to these experiences and how care could be improved in the future.

The active and effective involvement of trans people in roles other than informants was also a central element in seeking integrity in the research process. Early meetings of the research team acknowledged that its senior positions were all filled by cis academics with permanent university posts, with trans researchers and PPI group members on various kinds of fixed-term contract. The involvement of trans people in the PPI group, Steering group and Advisory Group in the analysis and interpretation of data was intended to give voice to a variety of trans perspectives on the interpretation of research data, while keeping in sight the overall goal of understanding how to improve health services for trans people and communities. We attempted to address the structural imbalance in terms of the roles of cis and trans team members by maintaining a culture of circulating drafts of outputs and responding to all comments made. In the final chapter of this report, we reflect on the difficulties that emerged, however, in achieving meaningful trans participation – trans colleagues were often placed in the position of commenting on work done rather than collaboratively shaping it from an earlier stage.

A final perspective central to the research process concerned researchers being reflexively aware of their assumptions and experiences of trans health care so that they were both open to and critically aware of what was emerging from data being collected or analysed. While the harmful impact of cisnormativity and transphobia is likely to be found in trans people’s accounts of their experience of health services, researchers needed to be open to identifying care practices that break with previous norms and understand how these have improved service-user experience. At the same time, researchers considered critically ways in which cisnormative assumptions remained present and could still have harmful consequences. They considered how far trans people’s more positive accounts of services may have been shaped by their awareness and stoical acceptance of poor care provided by many NHS services, as concluded by the House of Commons report already referred to. Trans people may be understood as sometimes ‘settling’ for questionable aspects of care.

While it is possible to set out perspectives shared across the team, there were also recurrent interpretative tensions. These arose in particular from gaps in the understanding of cis members of the team as to the wider history and context of trans health care. Such tensions were often about the extent to which a new service model should be seen as beneficial, because alongside a helpful aspect it preserved practices that compromised the dignity or rights of trans people. To an extent, such tensions were resolved through productive debate. While we have taken a clear stance on many conclusions and recommendations in this report, our interpretations of data in some areas remain unresolved, as is apparent from the PPI lead statement included in this report. We do not seek to gloss over such unresolved issues and also do not see them as undermining the scientific quality of our work. They are an inevitable aspect of researching a contested and politicised field such as trans health care.

Work Package 1: desk research on current arrangements across the United Kingdom

This addressed RQ1, broken down into two related RQs:

-

What range of models/approaches exists for the provision of health and well-being services to trans adults?

-

What examples are there of initiatives to improve the integration of healthcare services oriented to trans adult care?

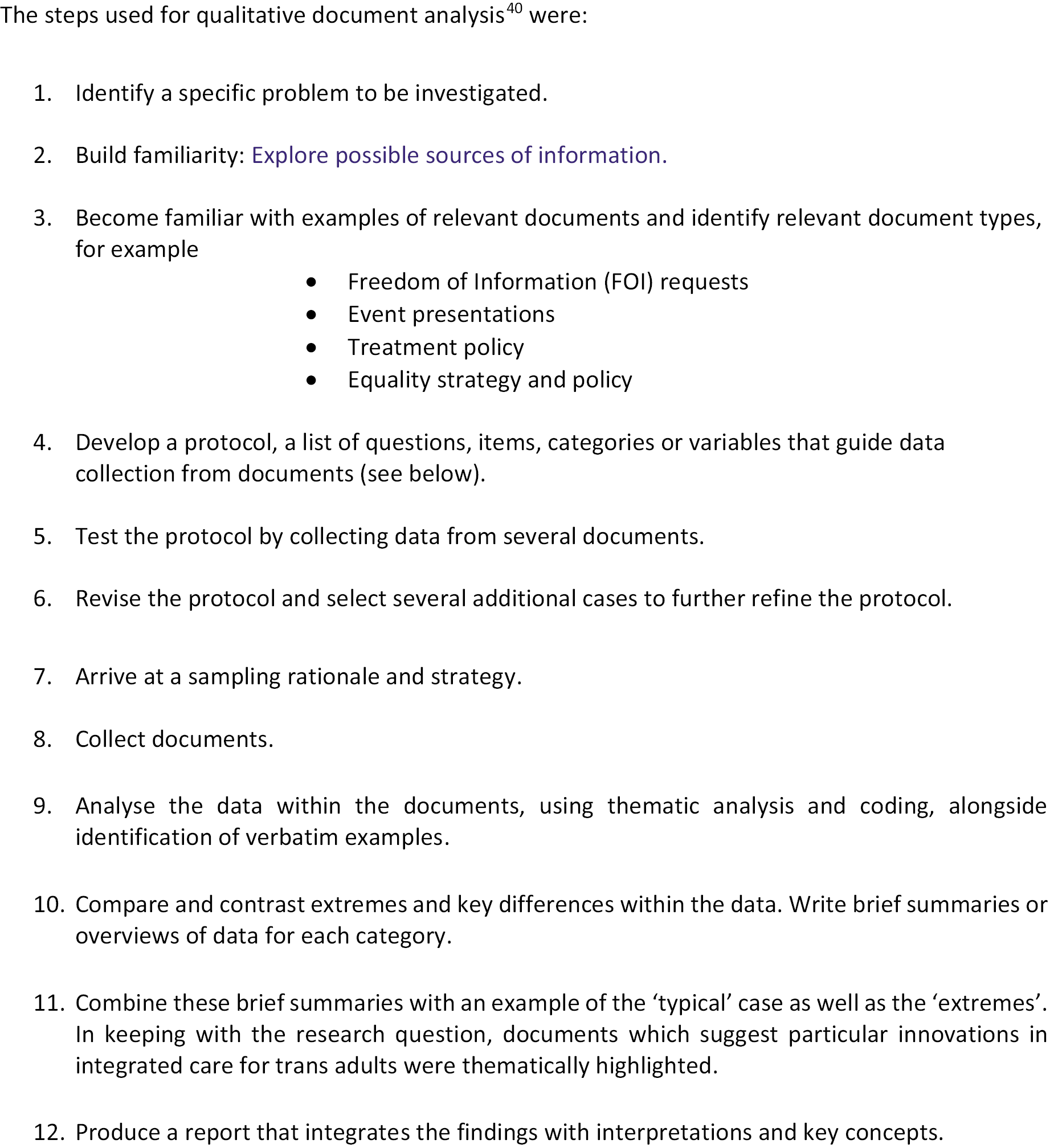

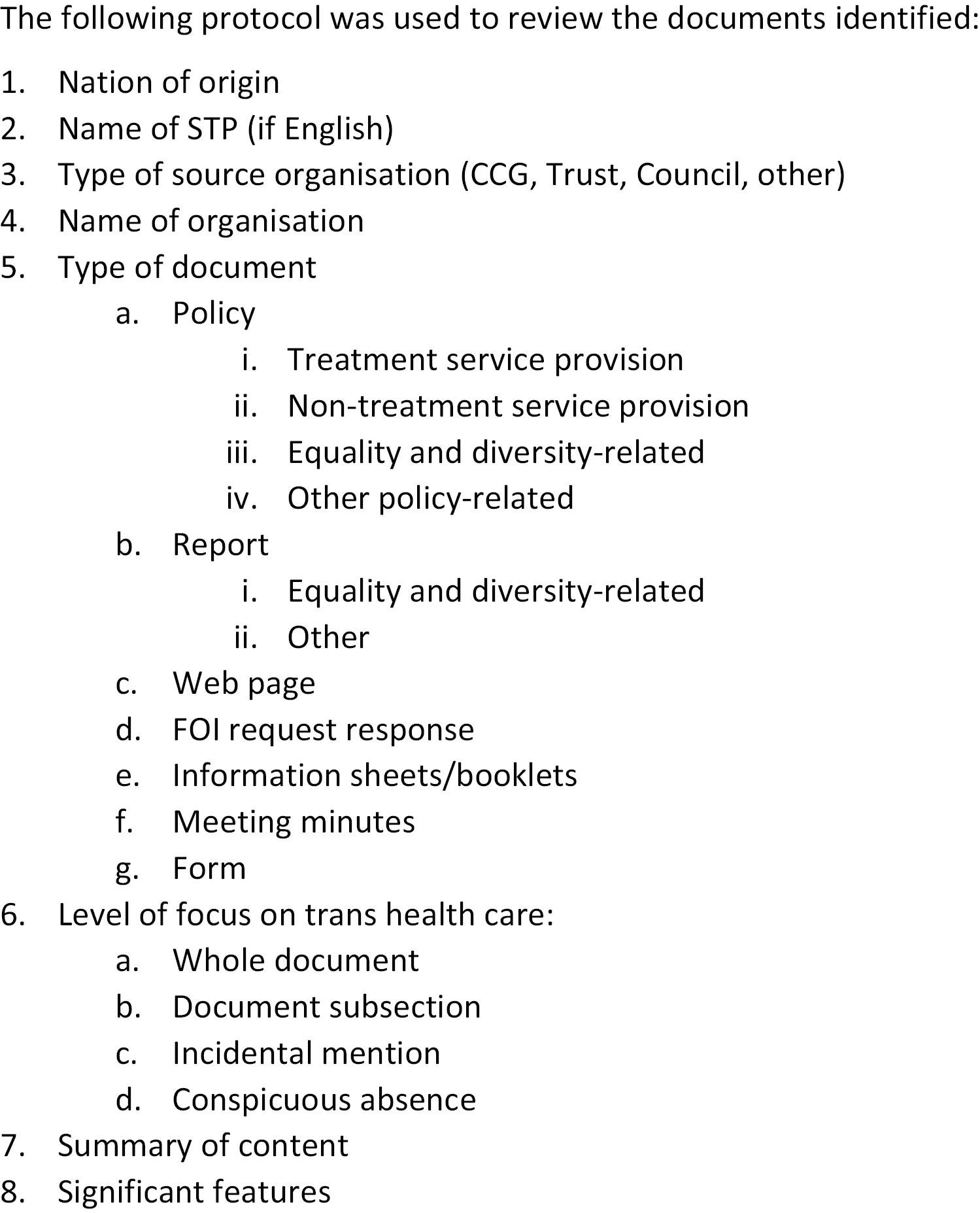

Researchers adapted a process for qualitative document analysis (QDA), as detailed by Altheide and Schneider,40 to review available documents across the UK concerning the current range of policies and services relevant to trans health care. This involved developing a strategy for sampling relevant documents, and developing a protocol for reviewing their content, which provided a basis for thematic analysis.

Appendix 1 summarises the QDA process and the protocol used to review documents. This WP was completed during the first year of the project and led to an interim project output. 41 It also informed the selection of initiatives to improve care researched empirically in WP 3.

Beginning with the English context, relevant policy documents were obtained from the websites of one NHS Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) from each of the 44 Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs) across England. Six STPs were then selected for more detailed consideration, with their constituent CCGs and provider organisations searched for documentation on trans healthcare policies and relevant services:

-

Birmingham and Solihull STP

-

Kent and Medway STP

-

Northumberland, Tyne and Wear, and North Durham STP

-

Somerset STP

-

Greater Manchester HSC Partnership

-

Sussex and East Surrey STP

The first four were chosen to represent different kinds of region. The last two were chosen because the cities of Manchester and Brighton (which respectively sit within these STPs) are known to contain services which may offer positive examples of integration and awareness of trans health care. In addition, researchers collated documents related to the gender dysphoria pathways as they exist in each of the four nations, and good practice guidance specifically related to trans health.

Following a review of the information available from NHS organisations in the selected areas, it was decided that further investigation into services provided by third-sector organisations was required due to the role which they may play in the integration of care. Materials from the websites of third-sector organisations within these areas were selected according to the criterion that they exemplified instances of collaborative working or service provision around health care. Social spaces for trans people were excluded as they are typically not a direct collaboration between third sector and local authorities. The benefits they can have to a trans individual’s well-being are significant, but these groups generally tend to affect this through personal advocacy and community building, rather than working with structures of health care.

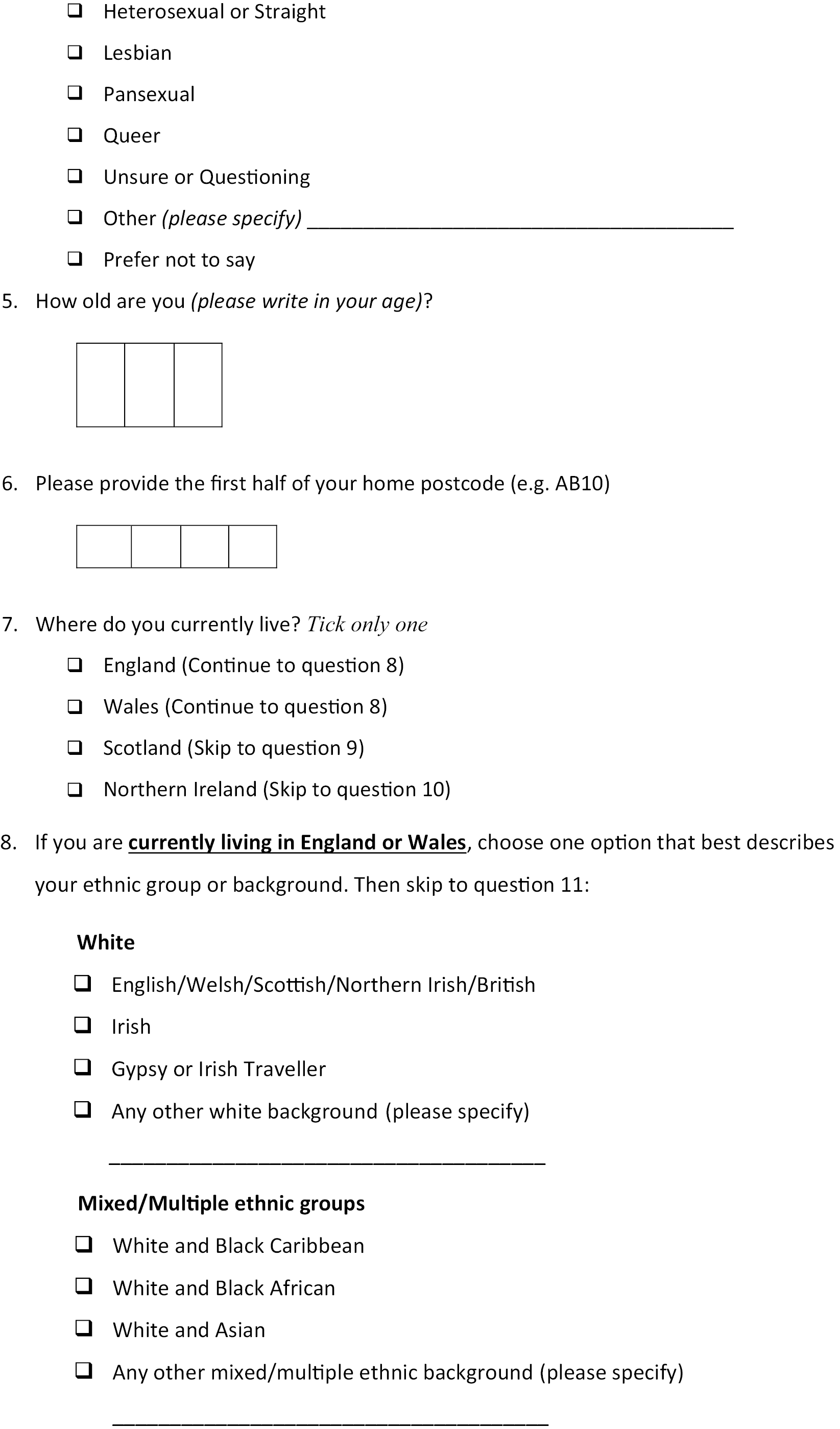

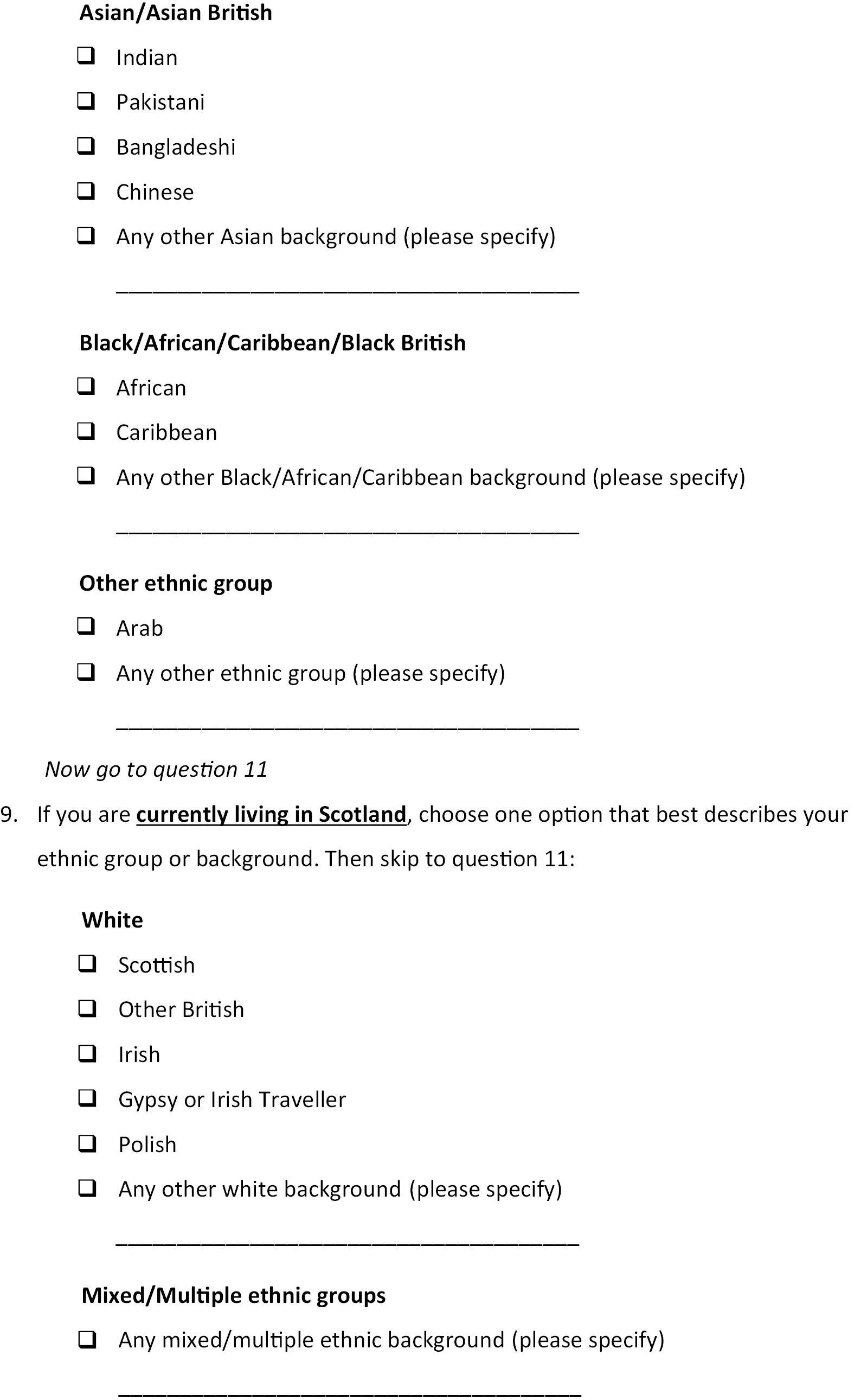

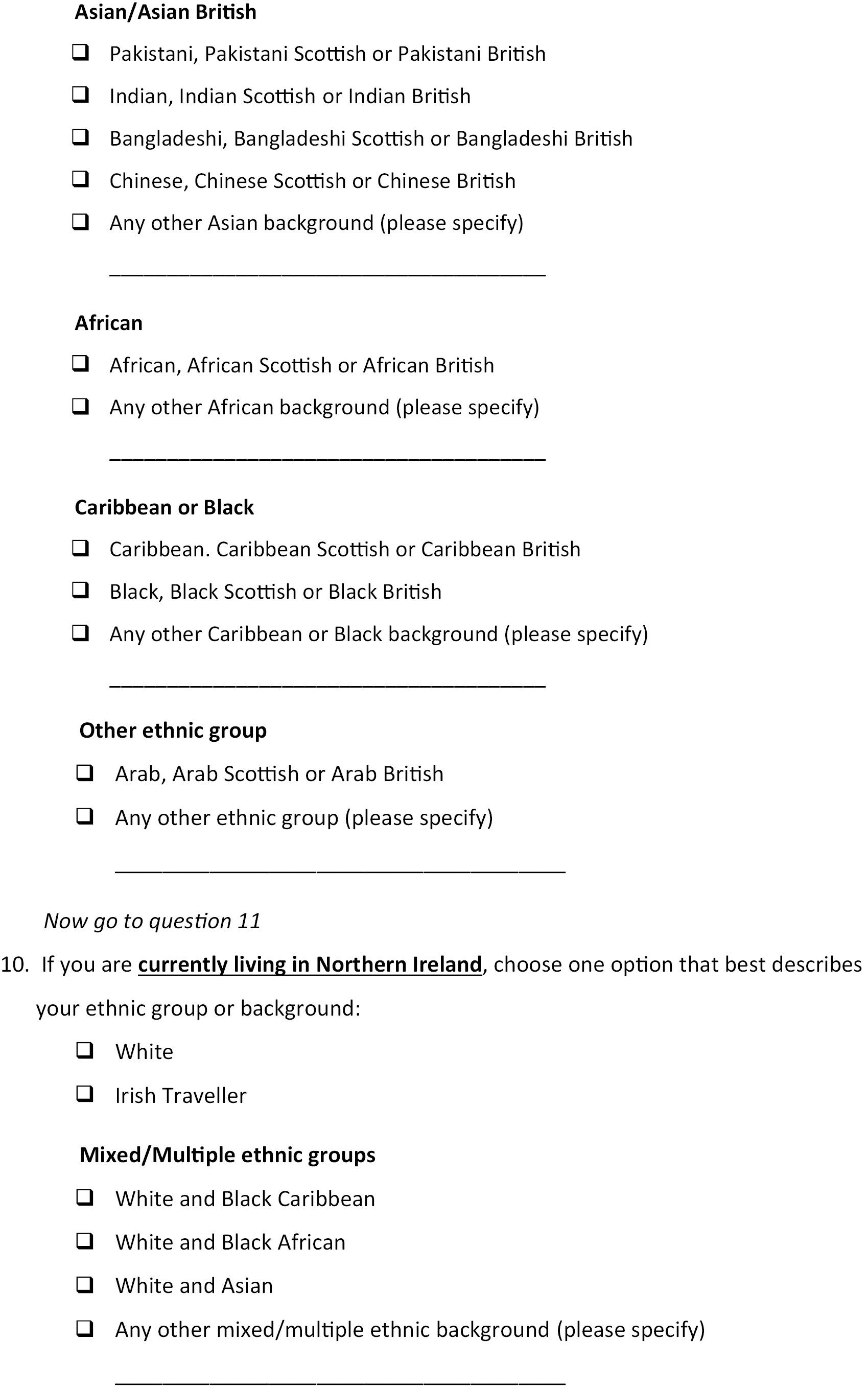

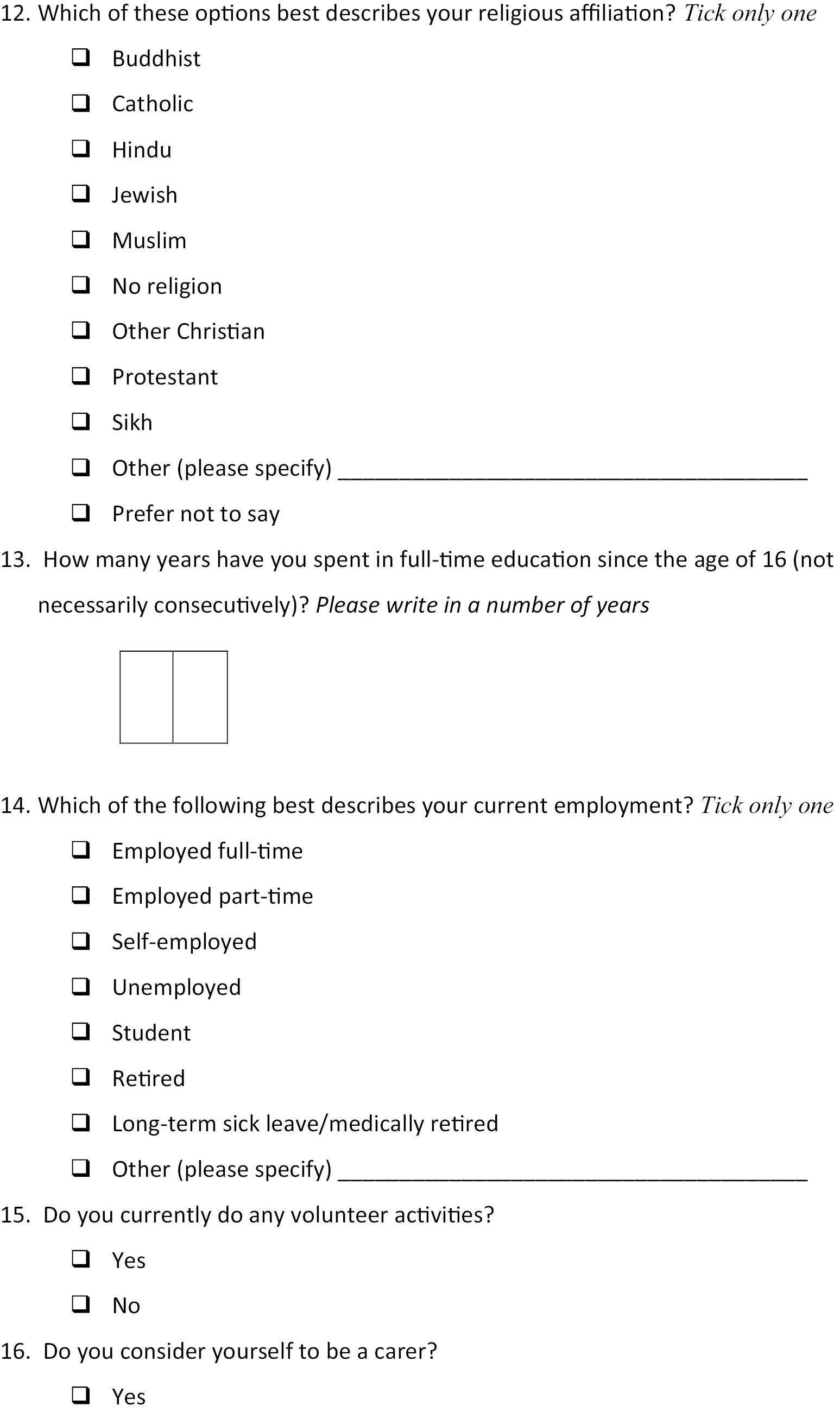

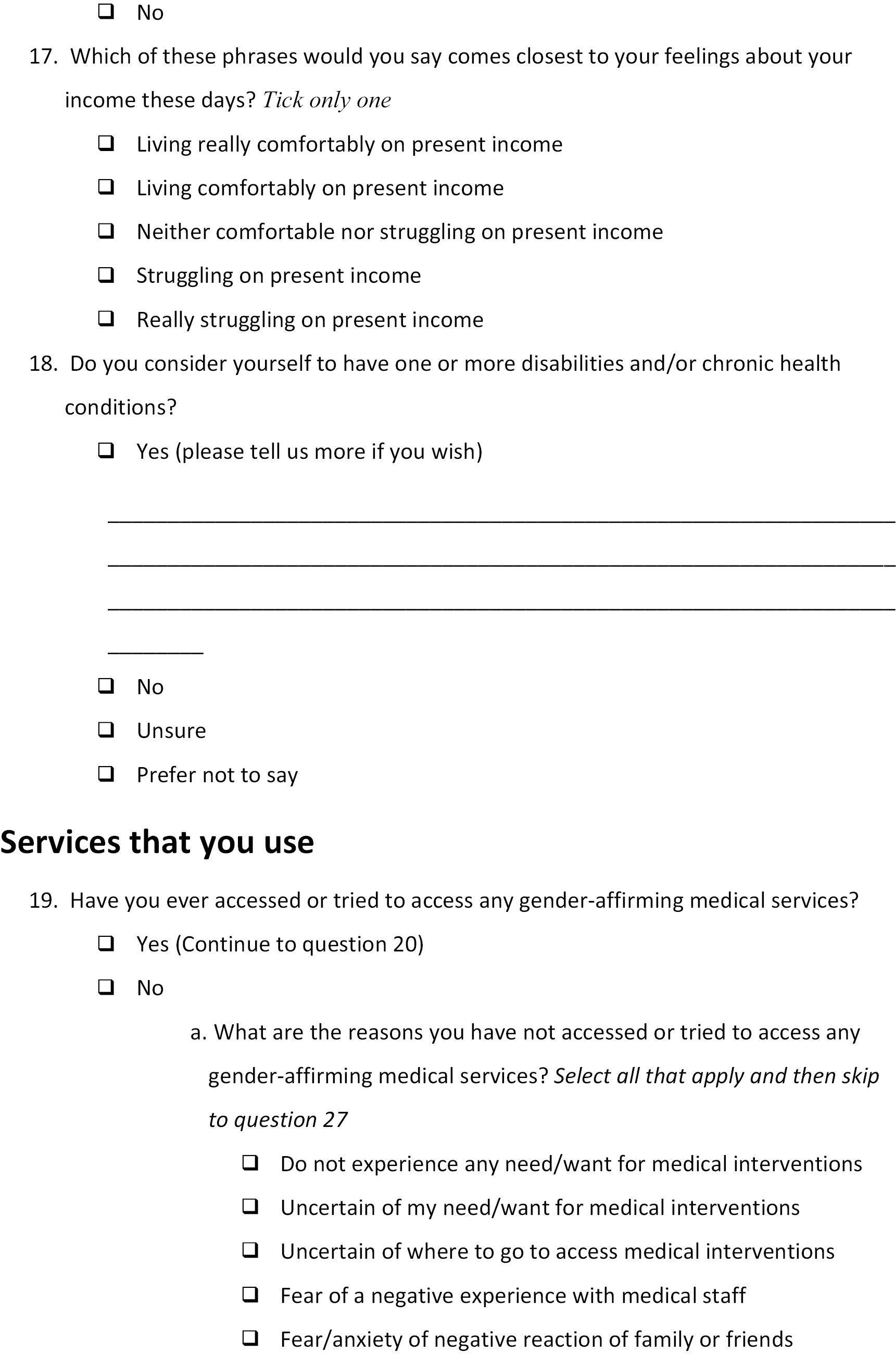

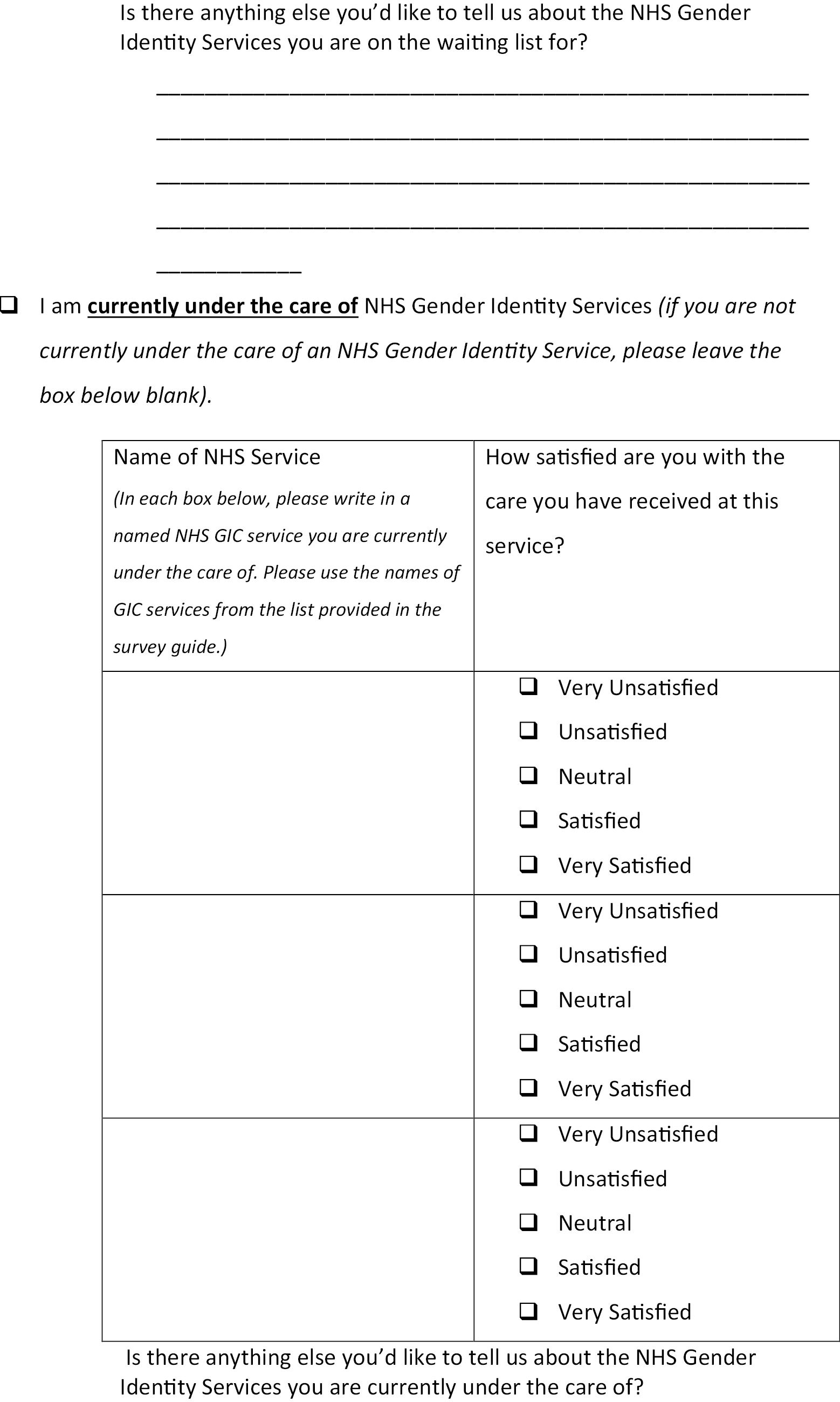

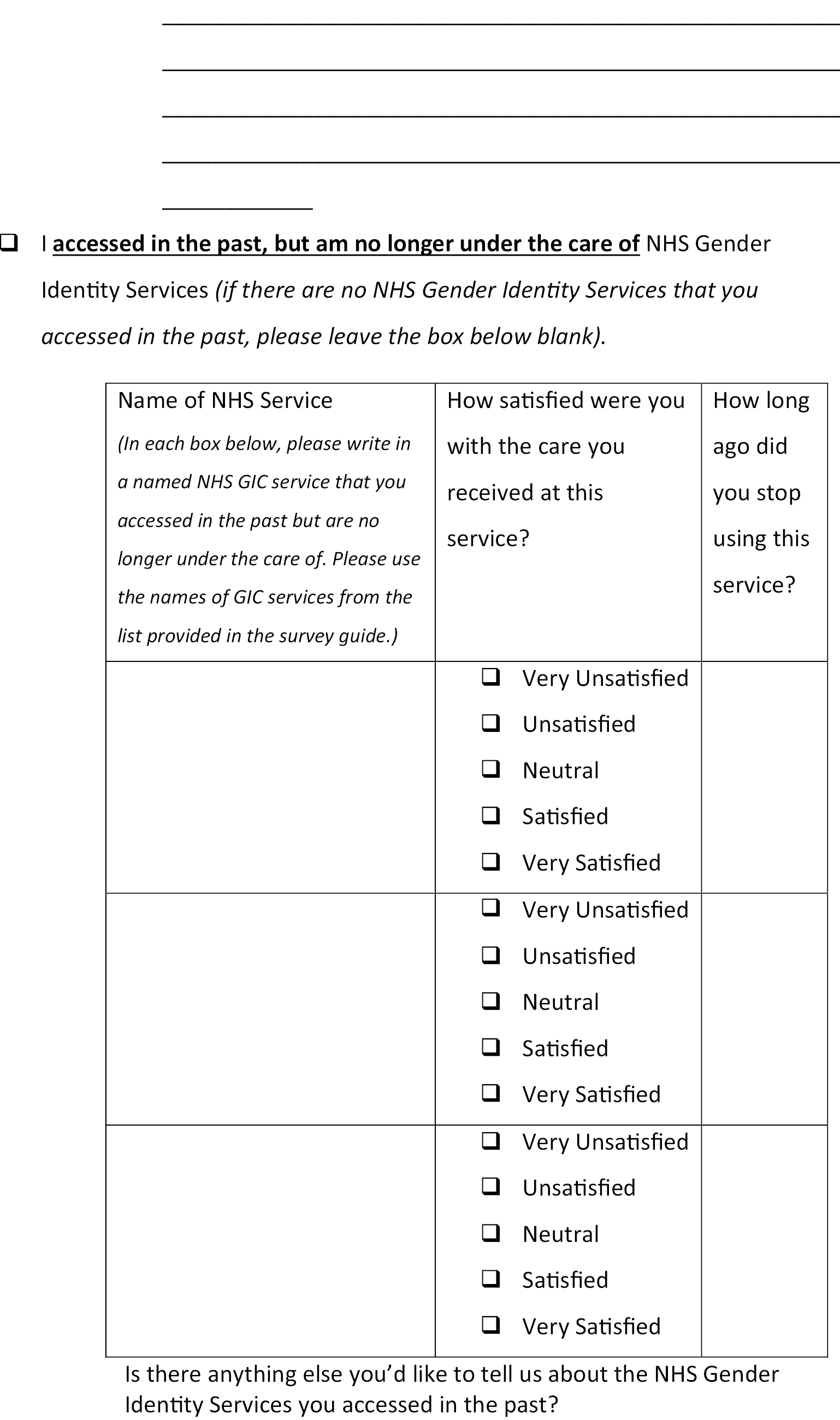

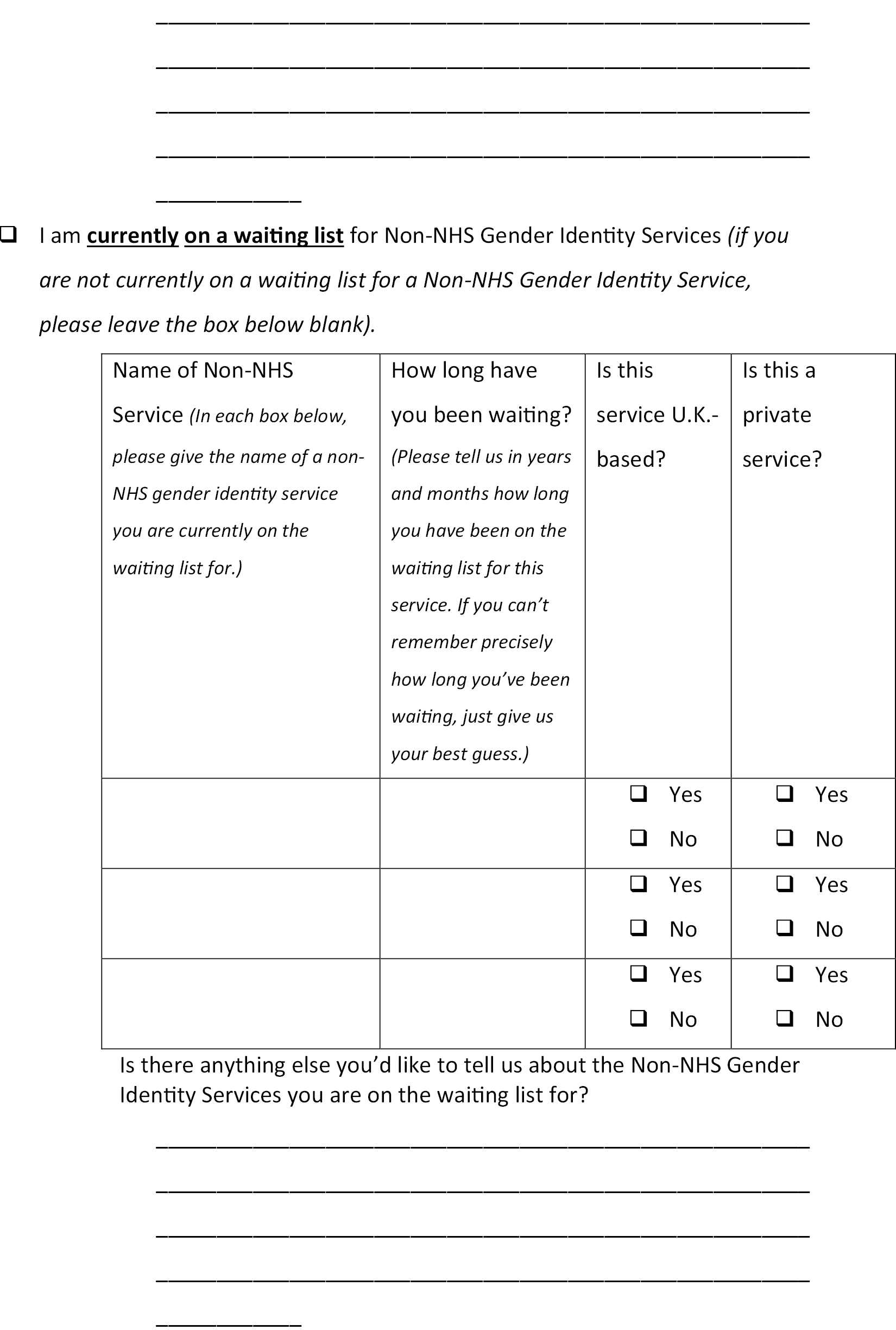

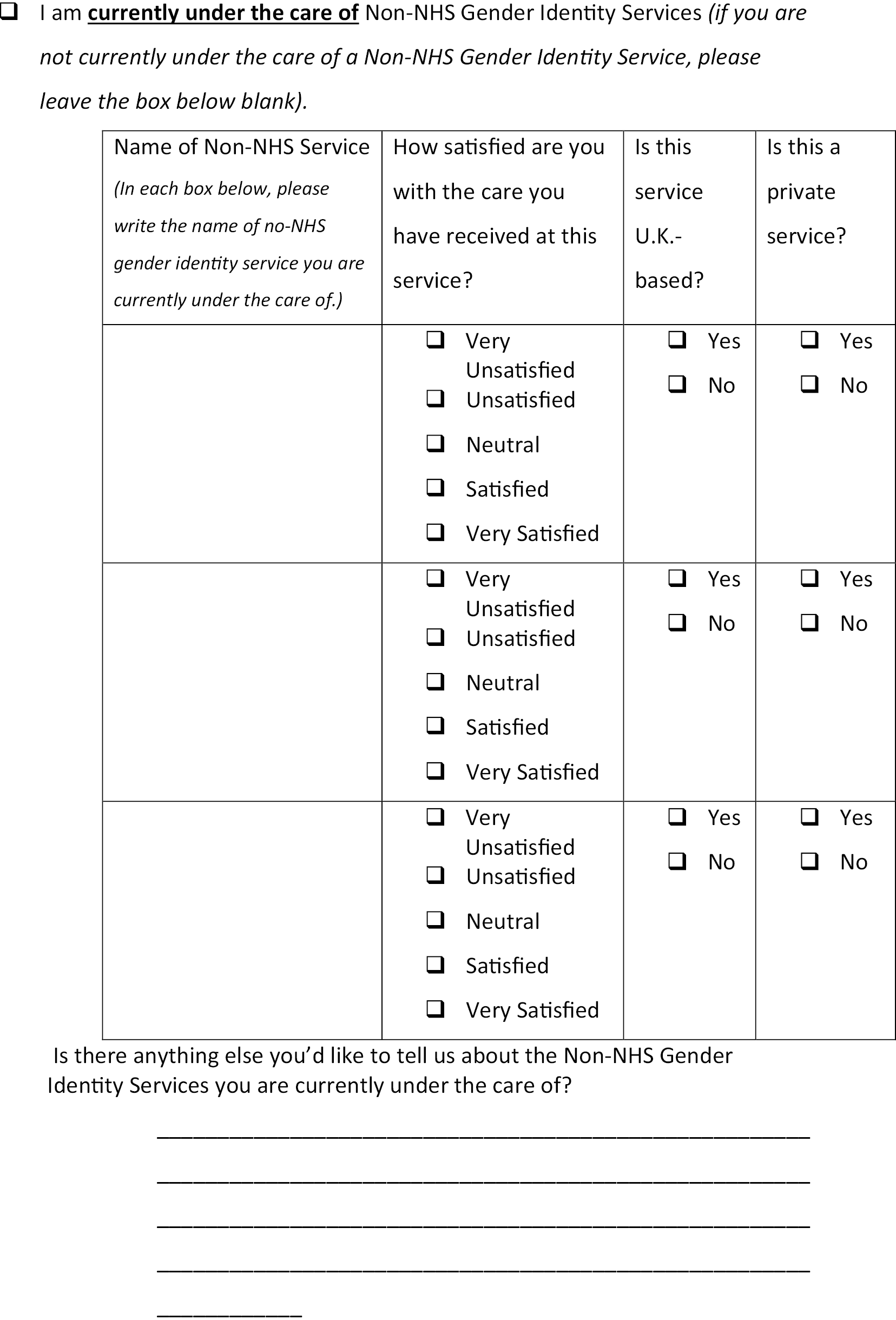

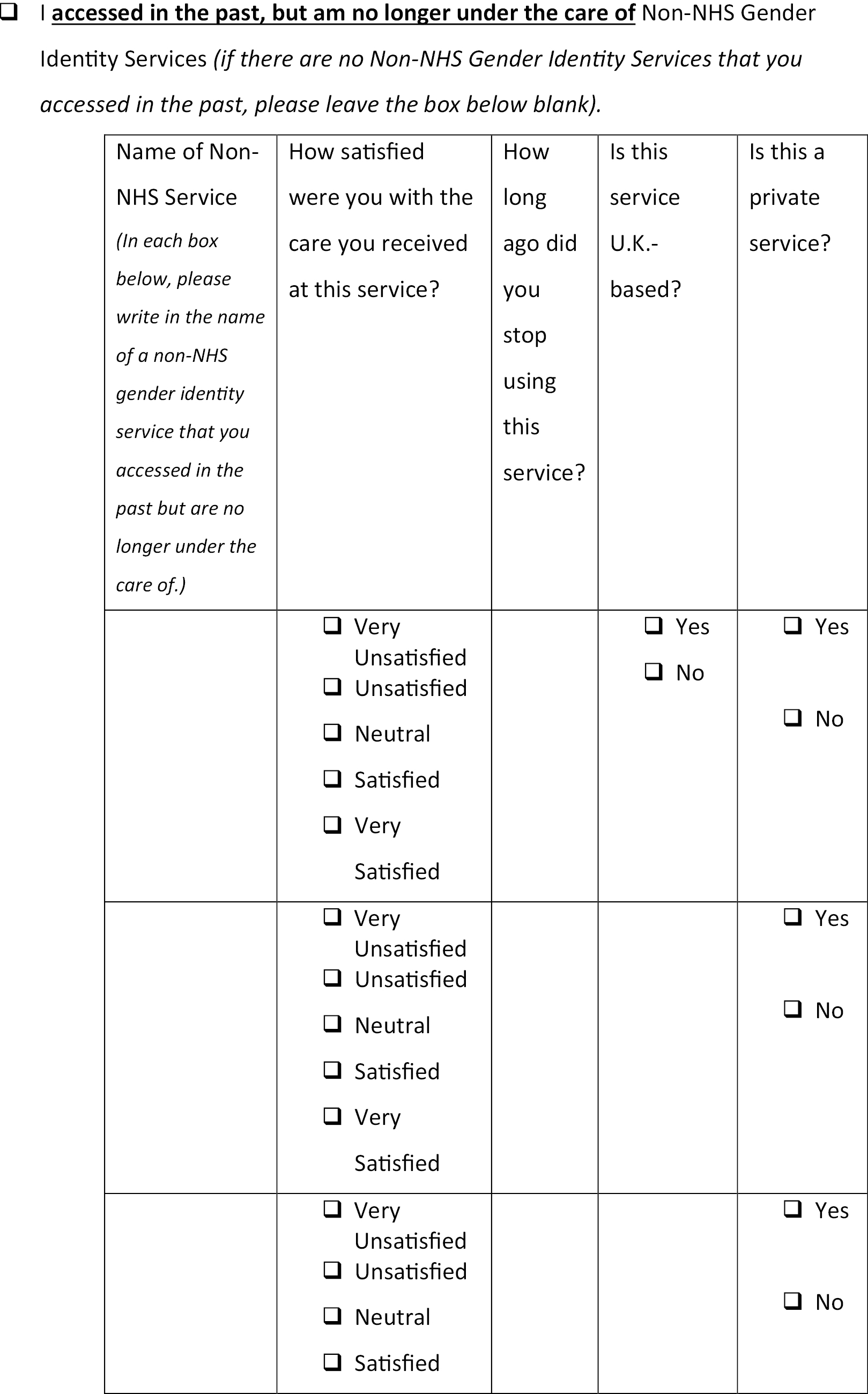

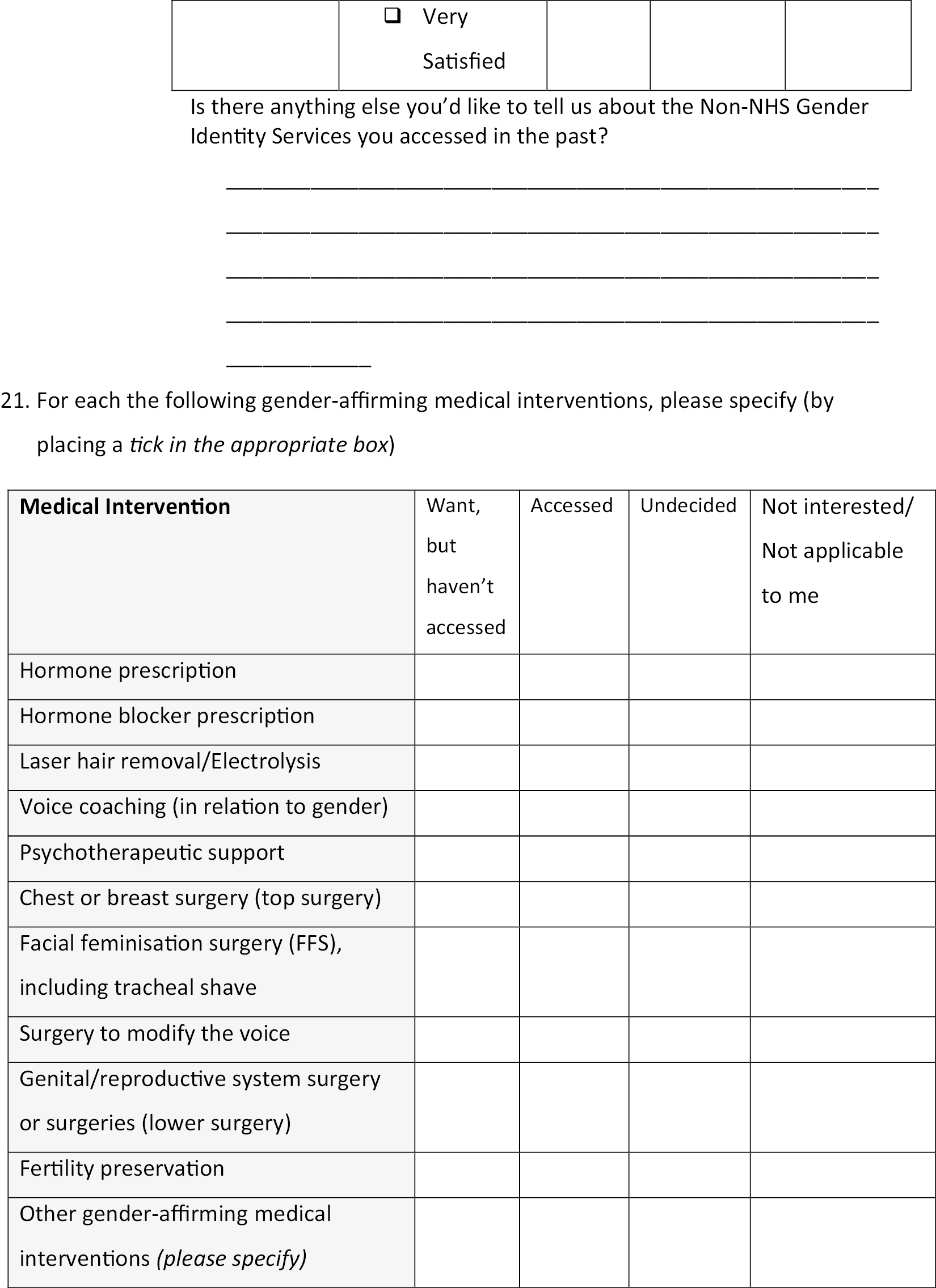

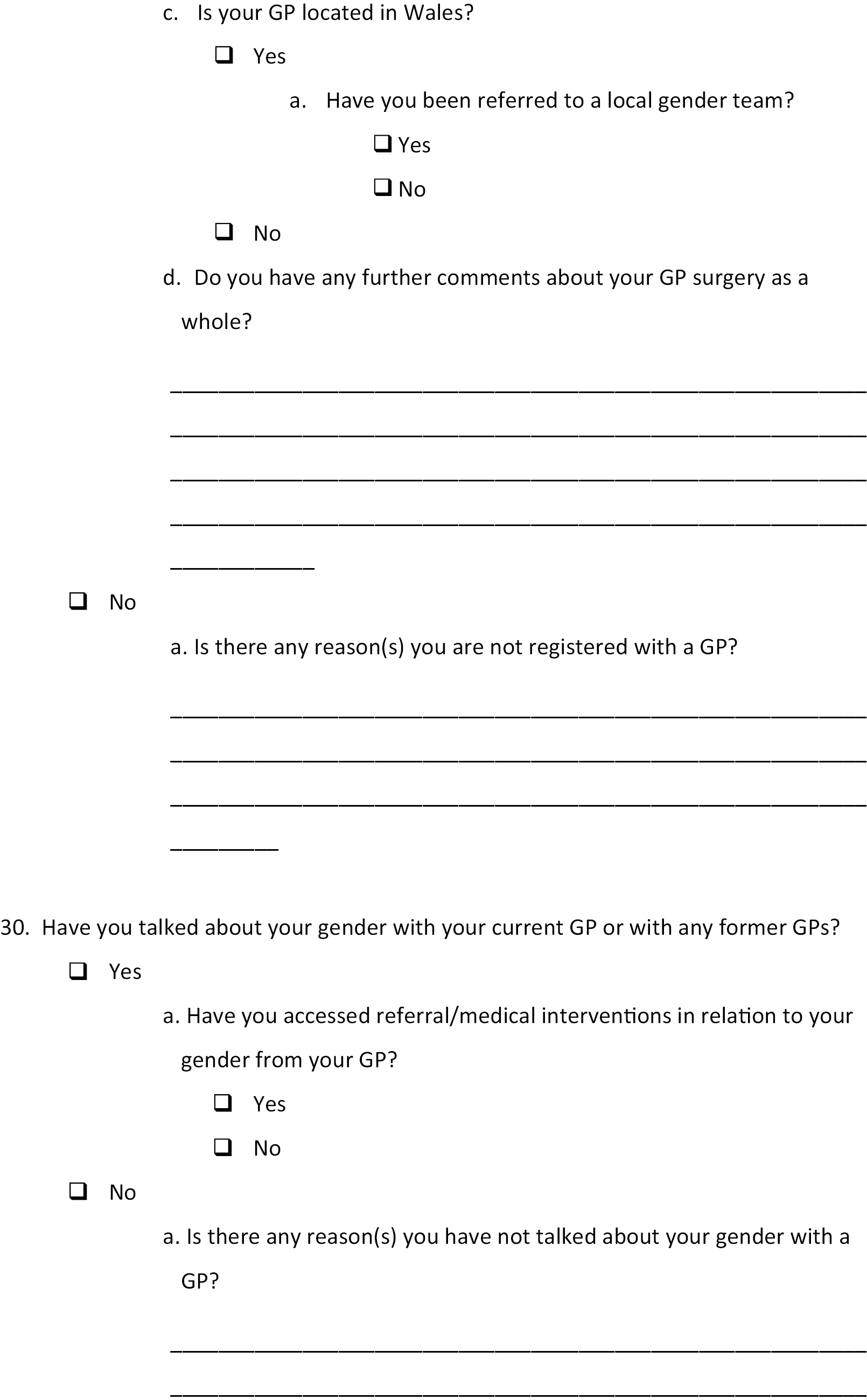

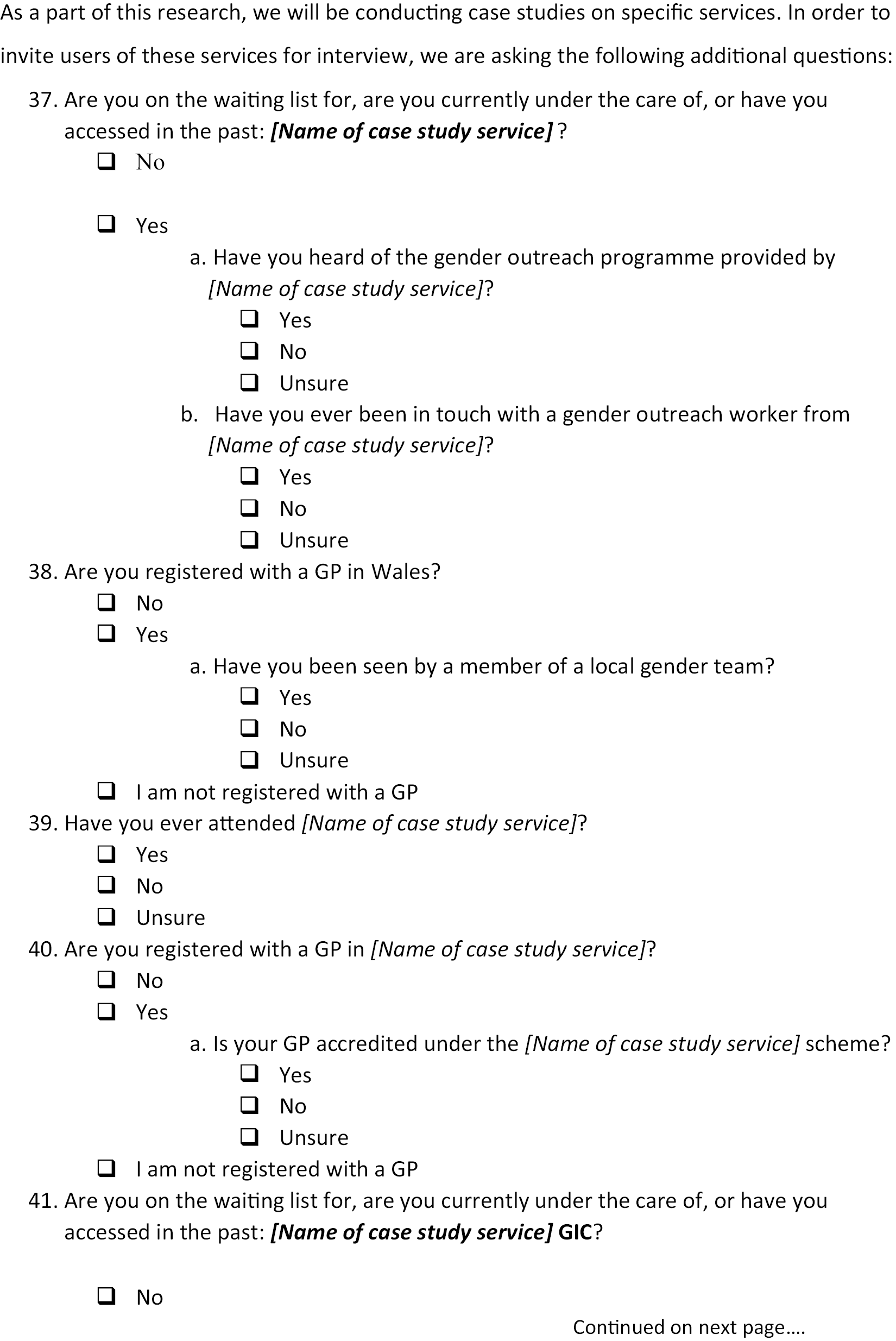

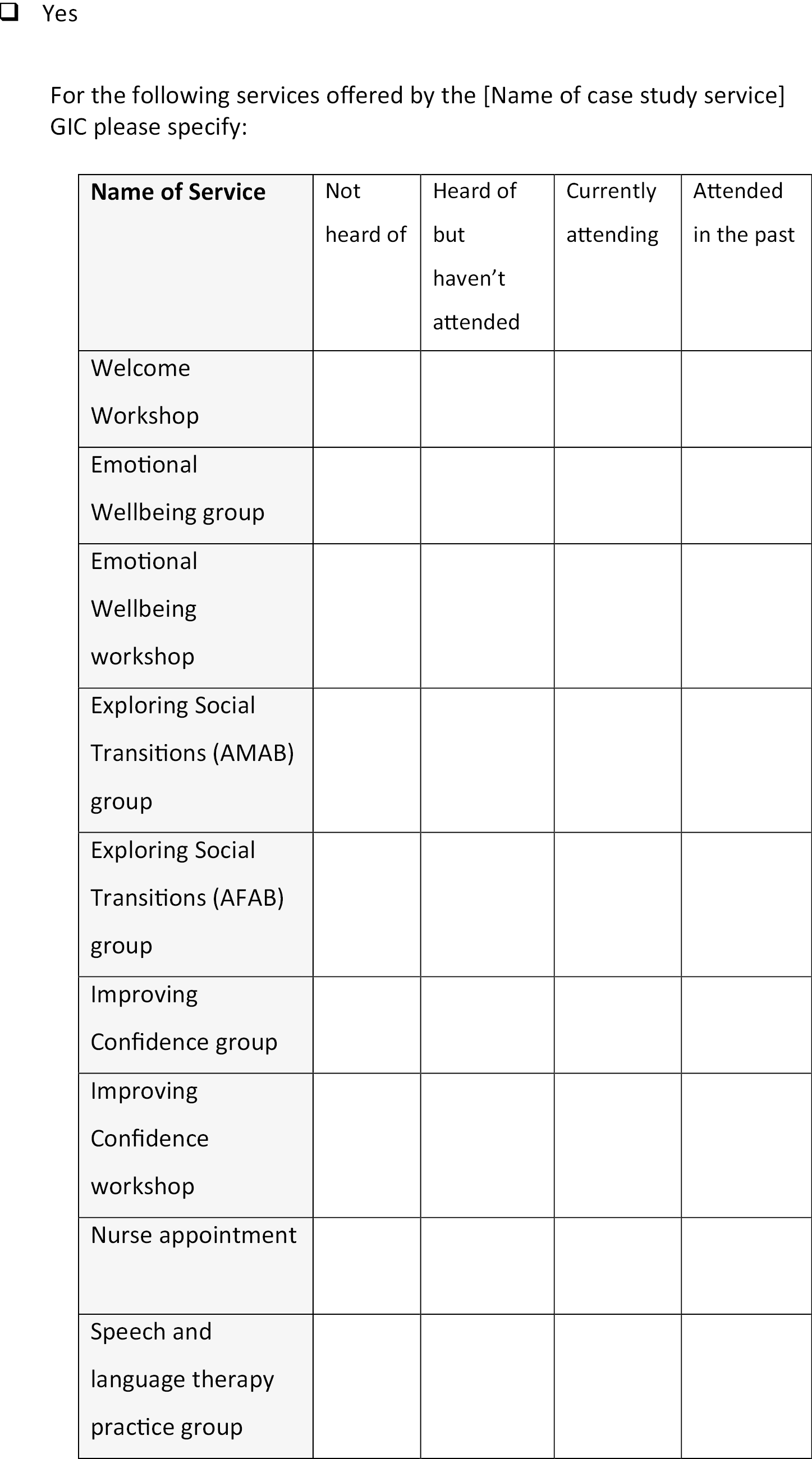

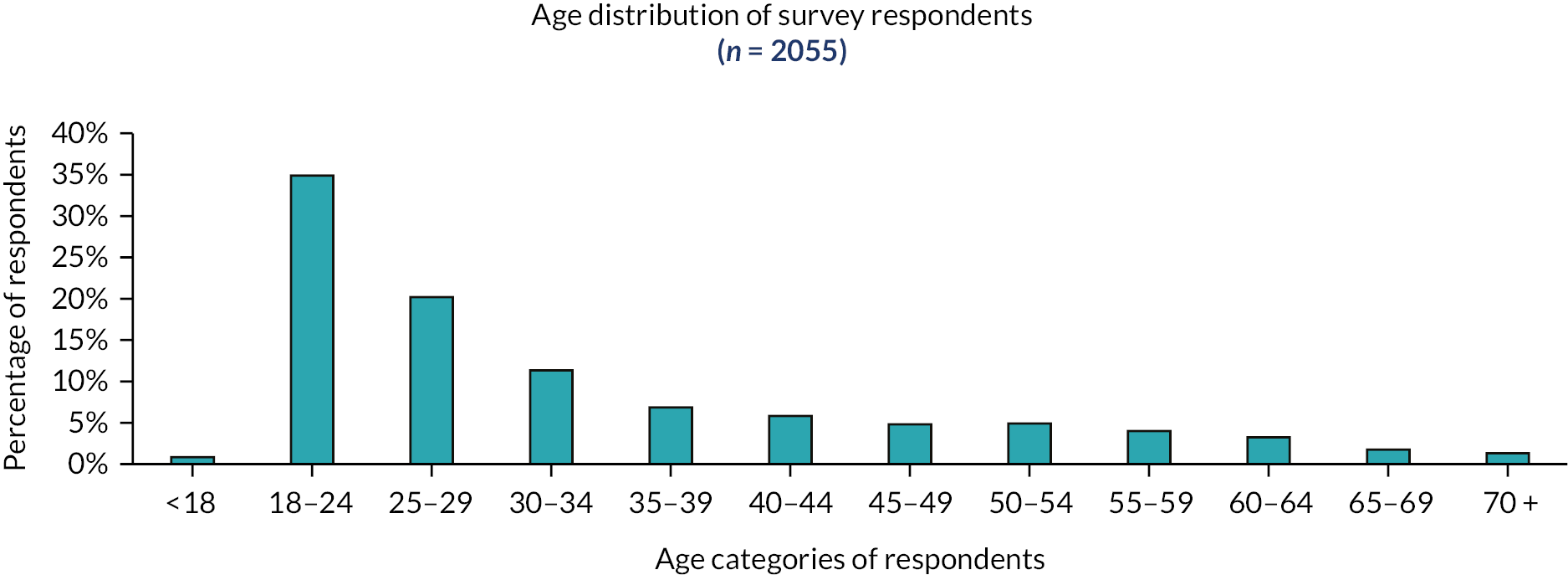

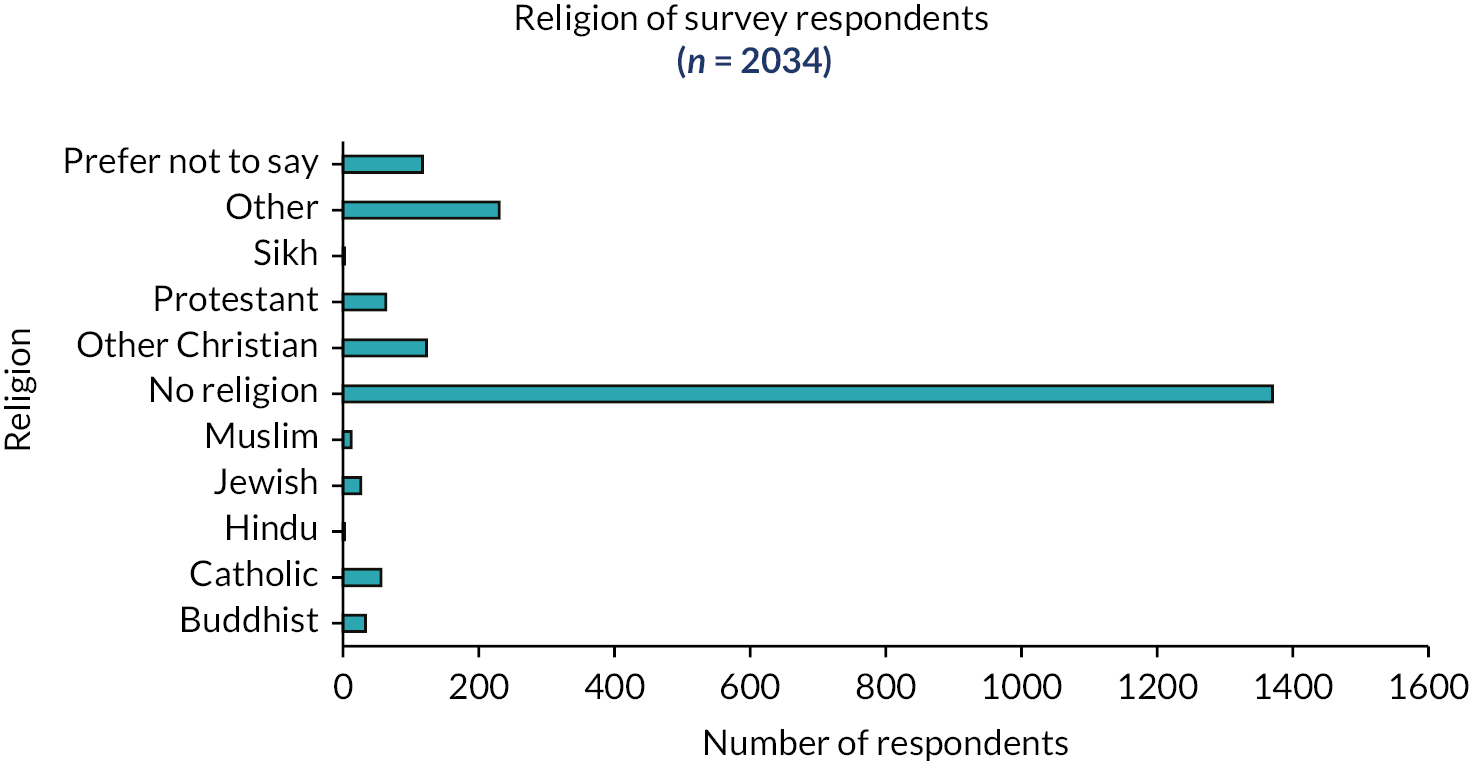

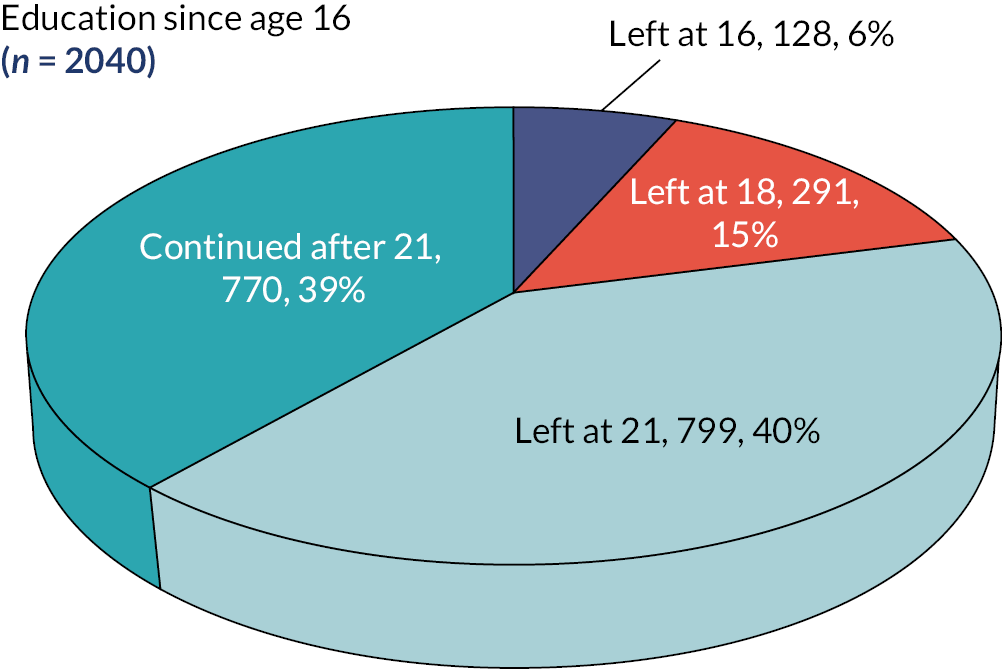

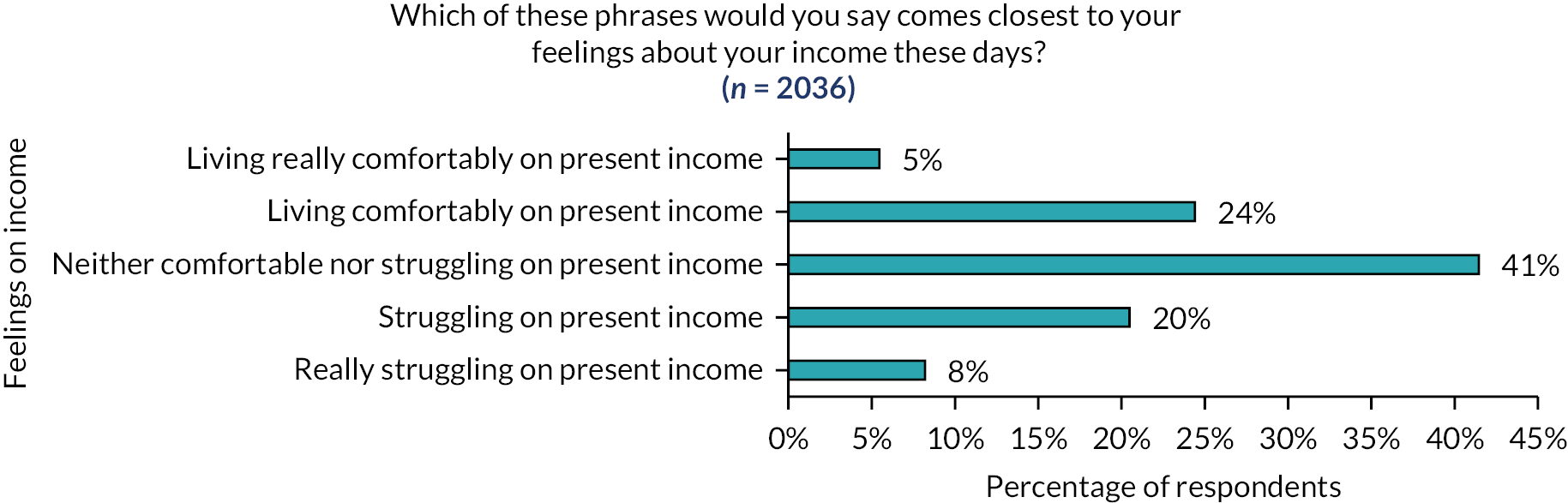

Work Package 2: an investigation of factors associated with service use and non-use

This addressed RQ2, concerning what makes services more or less accessible or acceptable for trans adults. An initial online and paper screening survey was used to gather data on demographics and service use across the UK, and received over 2055 responses, compared to a target of 500. The paper version of the survey appears in Appendix 2, as does a summary of the response data. The survey was promoted widely by project partners and through LGBTQI+ networks and organisations. Response options included offering to be interviewed, with over 800 people putting themselves forward. Researchers used data on demographics and service use to construct five purposive subsamples, to be invited for individual qualitative interviews. The underlying rationale was to identify groups more likely to experience social exclusion or stigma in everyday life, and who were also more likely to experience difficulties in accessing and receiving health care. The experience of these groups would be an indication of the priorities for improving services to make them more inclusive and more effective in addressing health inequalities.

In discussion with the PPI group, the following groups were identified as priorities for subsamples of trans service users:

-

older people and trans ‘elders’ (e.g. historic transitioners)

-

disabled or chronically ill people

-

people with low income or educational qualification

-

people living in rural areas

-

Black people and people of colour

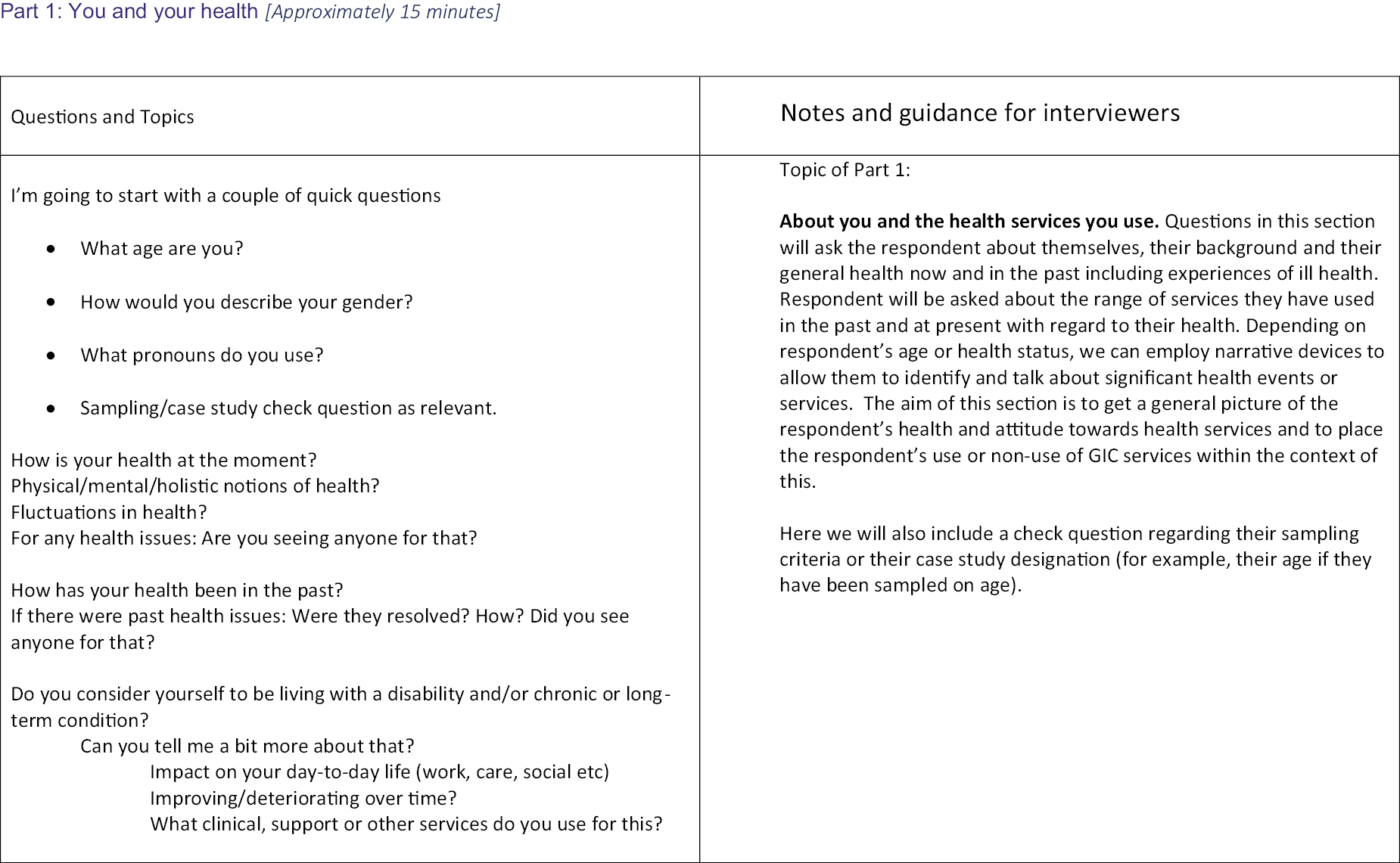

The individuals invited within each subsample were selected to give diversity in factors such as gender, location (according to the Office of National Statistics postcode classification of rurality) and age. When the last two were being sampled for, diversity was sought in other respects. The list of survey respondents to be contacted for each subsample was identified by researchers prior to accessing their names or personal details. Researchers then invited respondents for interview. This gave rise to a total of 65 interviews, lasting between 1 and 3 hours. Most were carried out by trans researchers. The first 10 were conducted face-to-face, immediately before the onset of pandemic restrictions, in early 2020. All the remainder were carried out online from September 2020 to mid-2021. The interviewer guide appears in Appendix 3.

The interview offers from trans adults resulting from the survey included relatively few Black people and people of colour. The survey was kept open for several months and additional targeted recruitment attempted, but with the continuing pandemic, recruitment of these groups remained low. The research team engaged two trans Black researchers, who recommended recruiting people to focus groups rather than individual interviews, because this would be perceived as a more supportive environment within which people could talk about their experiences. These researchers recruited focus groups and worked with the research team to adapt the interview protocol to a group context. A further amendment to the favourable research ethics opinion was obtained. Twenty-three people attended across eight online focus groups for trans Black people and people of colour (TBPoC), each lasting between 1 and 3 hours. Each group was audio-recorded, transcribed and the transcriptions anonymised. The total national sample of service users participating in this WP was thus 88 trans people, of which 65 were interviewed and 23 attended focus groups.

Across all the subsamples, individuals were invited for interviews because their survey response indicated relevance to a particular subsample. However, most interviewees had social characteristics or experiences that were relevant to more than one subsample. Many were treated during data analysis as belonging to more than one subsample. In analysing each subsample, the experiences of each interviewee were analysed primarily in terms of aspects relevant to that subsample – for example, that they were disabled, but also bearing in mind that they were a Black person or living on a low income. These intersectional aspects of their experience then featured in the analysis of other subsamples where they were also included.

Table 1 summarises the numbers of service users from the national sample who provided data within each subsample, indicating how many in each were also included in other subsamples.

| Subsample | No. of interviews | No. also in other subsamples |

|---|---|---|

| Older trans people and trans ‘elders’ | 28 | 24 |

| Trans people with low income and/or low educational qualifications | 16 | 13 |

| Trans people with chronic illness or disabled | 27 | 23 |

| Trans people living in rural areas | 17 | 17 |

| Trans Black people and people of colour | 16 (plus 23 focus-group participants) | 11 |

Table 1 indicates the substantial overlap in membership across subsamples. It shows that interviewees were in fact considered and incorporated within the analysis of all subsamples for which they had relevant characteristics. Of the total of 65 people in the national sample of individual interviews, 23 were included in 2 subsamples, 11 in 3, and 1 in 4. Just under one-third of those interviewed, 22 participants, featured in a single subsample. The transcriptions of the focus groups with the 23 Black people and people of colour were also not included in any of the analysis under other subsamples. This was because the focus groups took place at the very end of data collection and the analysis of other subsamples was largely complete.

The use of subsamples thus allowed firstly an analytical focus across a group of individuals on common characteristics that potentially made accessing or using health care challenging. Second, through interpreting data from individuals within two or more subsamples, researchers sought to capture the intersectional implications of combinations of social positions or perspectives.

In terms of data analysis procedures, interview and focus-group audio-recordings were transcribed, checked for fidelity and anonymised. The transcripts relevant to each subsample were then analysed thematically,42 as distinct groups of transcripts. A subteam of at least two researchers analysed each subsample, one of these a co-researcher from a third-sector partner organisation. At least one member of each subteam was trans.

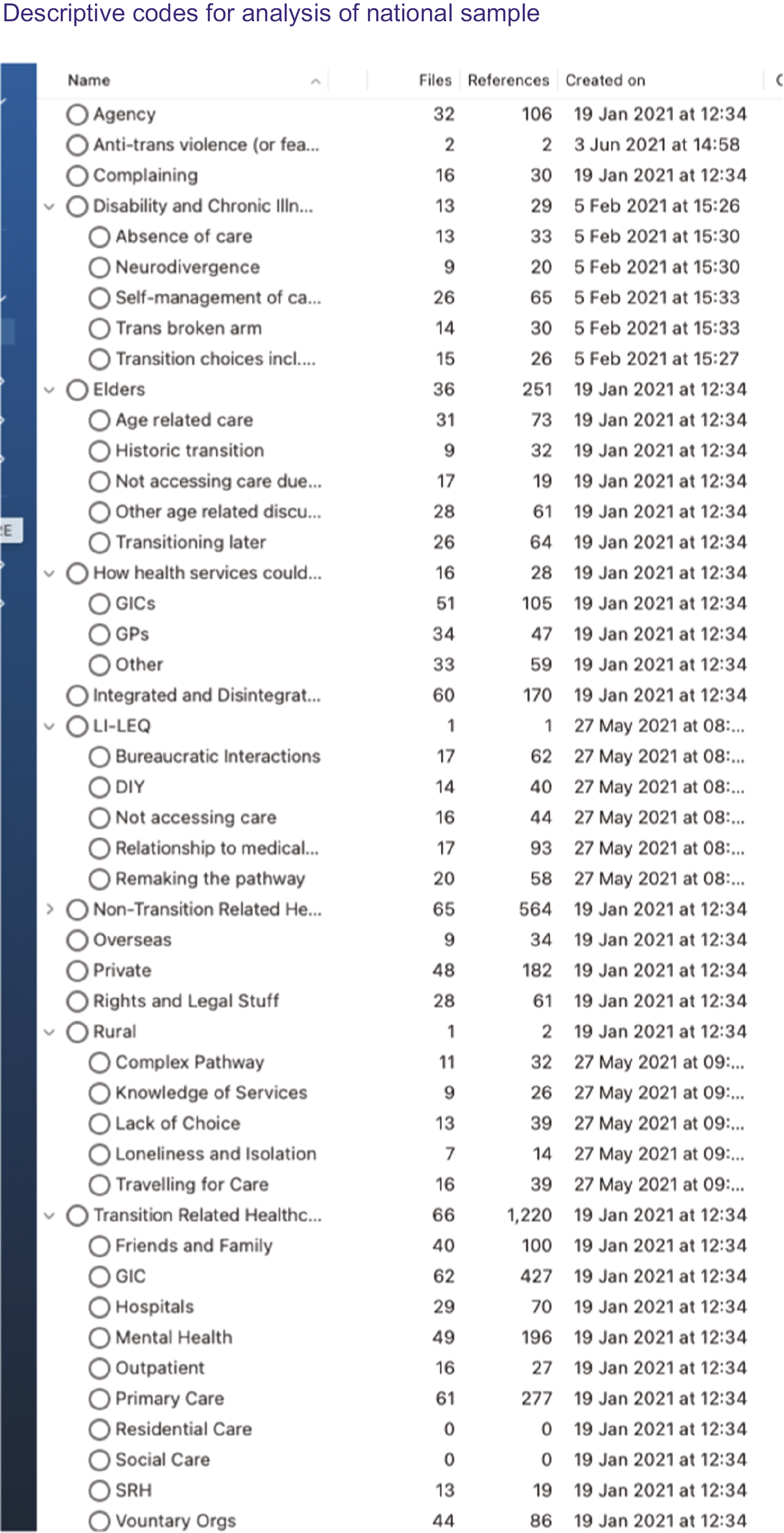

For each subsample, each researcher on the subteam first of all read all of the transcripts and then coded each one independently, corresponding to Phases 1 and 2 of thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke. 42 Codes were entered using NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) qualitative analysis software. A coding frame, adapted for each subsample, prompted identification of text relevant to RQ2 (factors affecting the accessibility or acceptability of services), using a set of codes corresponding to different categories of service-user experience. These descriptive codes were generated by the whole research team and then refined within each subteam, based on everyone reading an initial set of transcripts and sharing views on the aspects of service-user experience that were relevant to the RQ. The codes were thus inductively generated while also informed by the experience and perspectives in particular of the trans members of the research team. Appendix 3 shows the codes generated across the NVivo database of interviews, encompassing the five subsamples. It shows codes that were applicable to all subsamples, as well as those that were used to identify aspects of experience distinctively relevant to each subsample.

Codes were discussed and reviewed at regular subteam meetings. Researchers coded independently, using local copies of the database of interview transcripts for the subsample. Coding from the different researchers working on the subsample was then amalgamated by uploading and merging these local copies. Since the purpose of this stage of the analysis was to identify text relevant to different and well-specified aspects of service-user experience, there was little contention over differences in how text was coded. Some differing perceptions about the relevance of a portion of text to a code were discussed and resolved at subteam meetings, but quantitative measures or calculations of inter-coder reliability were not seen as necessary or meaningful, given the clarity with which codes could be formulated. Such measures and calculations can also be seen as at odds with the nature of an interpretative methodology. 43

One of the subteam members then led on further interpretation of the data as categorised under the codes for each subsample. This corresponded to Braun and Clarke’s Phases 3, 4 and 5 of thematic analysis (‘Searching for themes’, ‘Reviewing themes’ and ‘Defining and naming themes’). 42 The researcher refined and combined codes to produce a set of themes that captured the range of user experiences and topics revealed within the subsample, and produced a draft report on these themes. Particular attention was paid to interpreting data from individuals on positive or negative aspects of their care in the context of wider experiences they reported of coming out and living as a trans person, taking account also of the range of social positions or identities they held and social context. The researcher producing the initial draft was trans for four of the five subsamples. A Black researcher produced the draft of the report on the experiences of trans Black people and people of colour (TBPoC).

Draft subsample reports were then discussed and refined collaboratively by the wider team, resulting in each subteam producing a revised subsample report. Summaries of the refined subsample reports appear in Chapter 3, with the resulting themes appearing as the subheadings in the sections devoted to each subsample. In this phase of analysis, researchers compared the experiences described under each theme with those found in related research within the literature, sometimes drawing on concepts from other research to illuminate or explain the data. This stage of analysis thus combined inductive refinement of themes with use of relevant concepts or theories, such as theories of minority stress and microagressions,22,44 ideas of transnormativity38 concerning how trans identities have been regulated and controlled by cis-dominated medical professions, and analyses of how health inequalities are produced within LGBTQI+ populations through mechanisms that make services difficult or unattractive to access. 45 The idea of intersectionality46 also played a role in bringing out how trans people’s experiences of health care need to be differentiated depending on which other marginalising social categorisations, such as non-white ethnicity, they are subject to. Such concepts set the analysis of data in the context of wider social processes reported elsewhere. Combining inductive refinement with the application of concepts and comparison with findings from other research is recognised as a rigorous methodology for qualitative data analysis. 37,43

Work Package 3: case studies of initiatives to improve integration of care

This was initially planned to comprise six case studies of initiatives to improve aspects of the integration of care for trans adults, based on qualitative interviewing of service users and staff involved. This was to address RQ3, concerning the effectiveness of different aspects or features of services in improving care, and contribute to answering RQ4, concerning the lessons learnt for improving care.

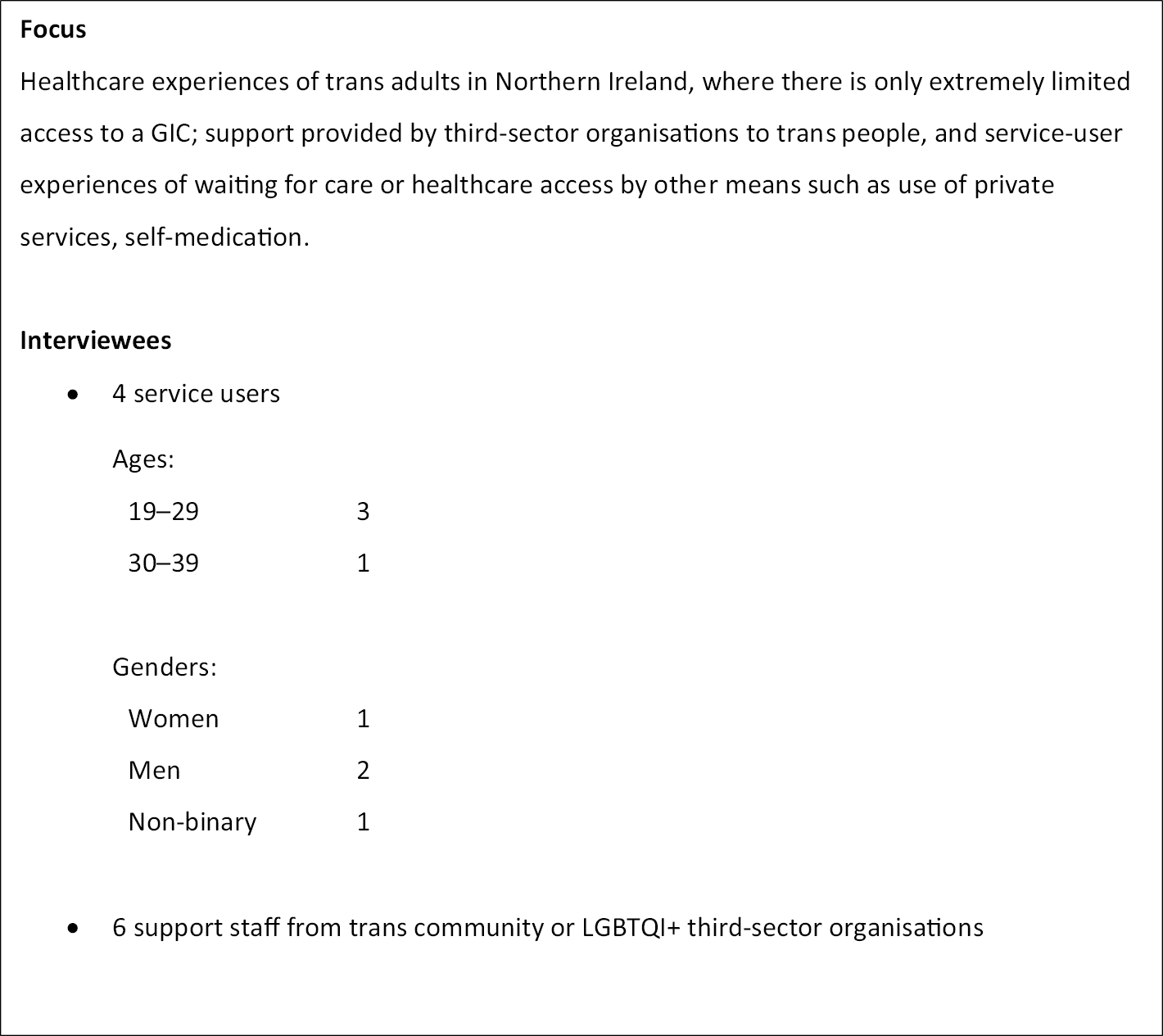

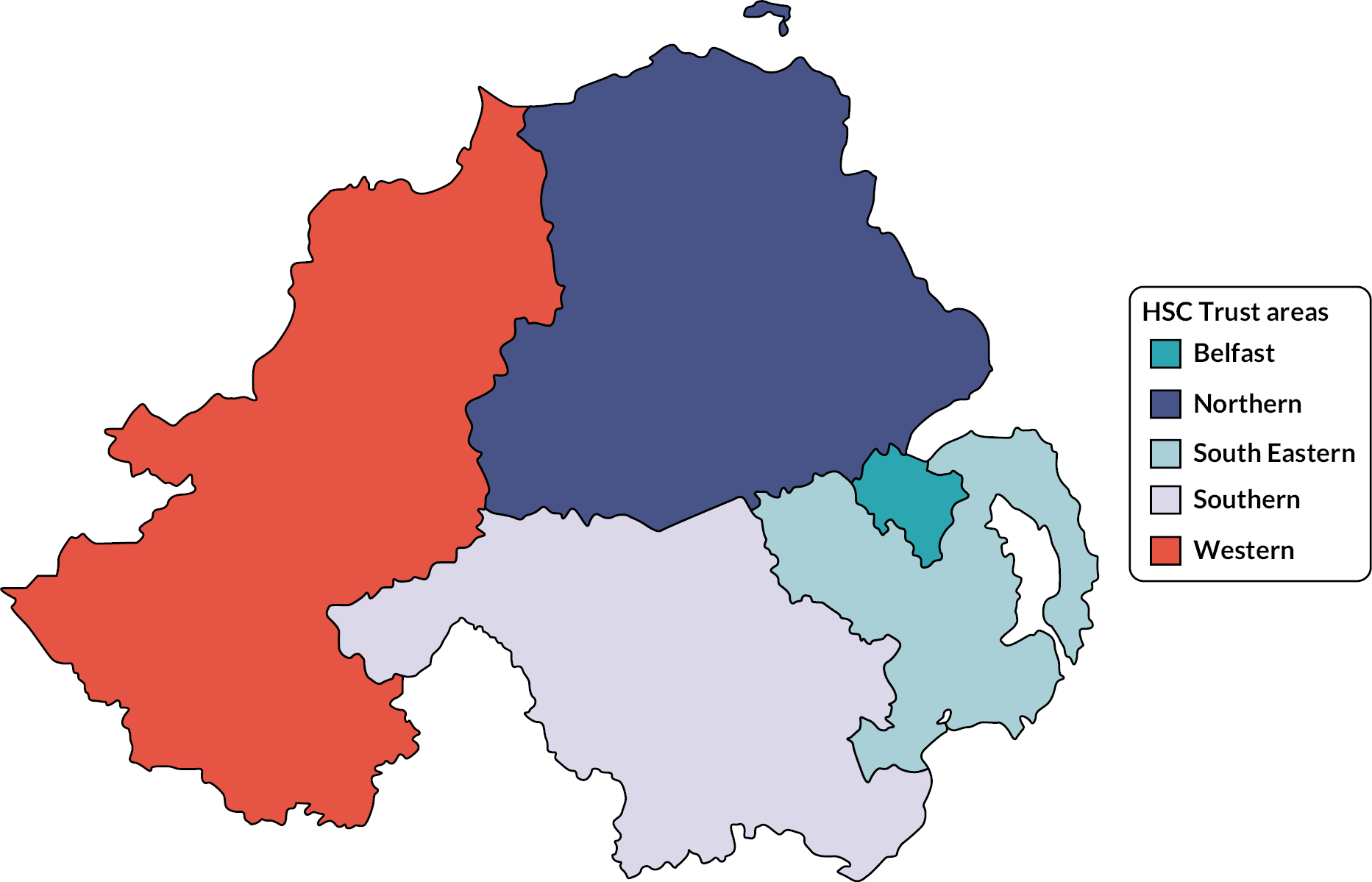

Four such case studies of service improvement or innovation were completed. In collaboration with the study steering group, two case studies of initiatives to improve care were replaced with two case studies of a different kind. One focused on the experiences of trans service users with mental conditions in using health care, as well as the views of third-sector mental health professionals on the current state of mental health services in supporting trans adults. The second focused on service-user and third-sector experiences of trans health care in Northern Ireland, where the low level of resourcing of a single specialist gender service has meant that it has not seen any new patients for several years.

The reasons for these changes were partly difficulties in gaining research access and local ethics and governance approvals to study NHS services during the pandemic, beyond the four case studies already approved. However, the significance of the topics studied in the new cases was also a major factor. The propensity of stigma-related mental health concerns in the trans population means that it is important to study how people experience relevant services and how they might be improved. The effective absence of an NHS specialist gender service in Northern Ireland means that it is important to understand how trans people needing care and third-sector organisations that support them are coping and what can be learnt from this in terms of making future care more acceptable and integrated.

In the four case studies of service improvement, the research team worked with a key staff contact within each service provider to agree the scope of the case study and identify which staff had been involved in the initial conceptualisation, design and implementation of the initiative to improve the integration of care for trans adults. The cohort of service users with experience of the innovation was also identified. Participant information sheets were then created and submitted for local ethical and governance approval. Staff were then invited to participate in interviews because of their role and experience relevant to the initiative being studied. Service users were invited to participate based on their having completed the national screening survey of trans adults’ healthcare experiences (see Work Package 2: an investigation of factors associated with service use and non-use), and indicated that they had used the services being studied and were willing to be interviewed. A service provider involved in one of the case studies mailed out details of the study to service users, indicating they could participate in the national survey if they were interested in being interviewed.

In Case Studies 5 and 6, staff interviewees were all third-sector professionals, recruited through an initial collaboration between the research team and an agency active in promoting services for trans people. In Case Study 5, this was a LGBTQI+ organisation active in promoting health care for trans people in Northern Ireland. In Case Study 6, this was an agency that provided mental health support for trans people. In both cases, the research team did not attempt to recruit NHS organisations or staff as research participants. This was partly because the need for these two cases emerged at a late stage of the overall project and there was insufficient time to secure NHS ethical and governance approvals. However, it was also because the scope of these particular case studies was to understand the experience of service users rather than that of NHS staff.

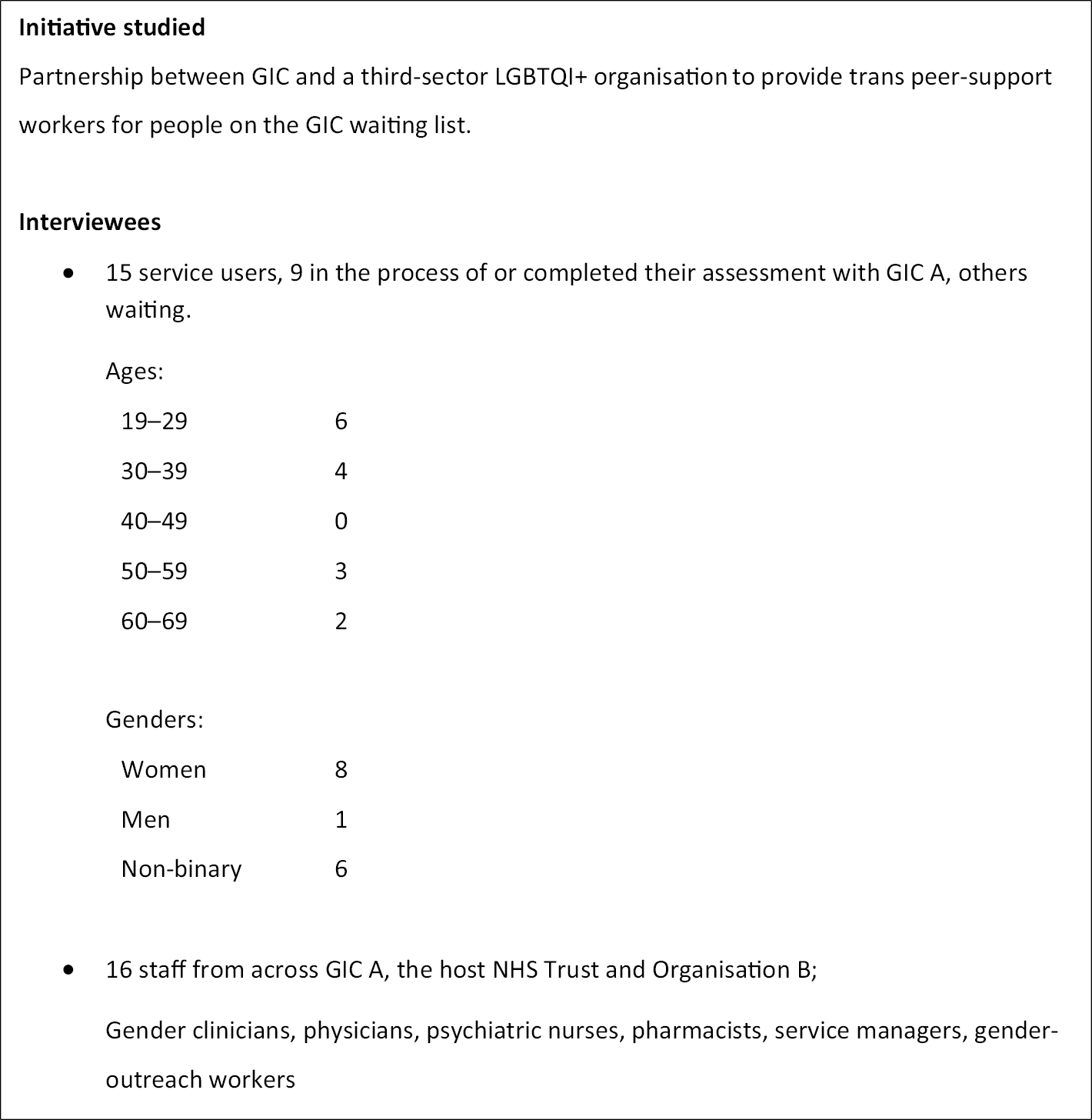

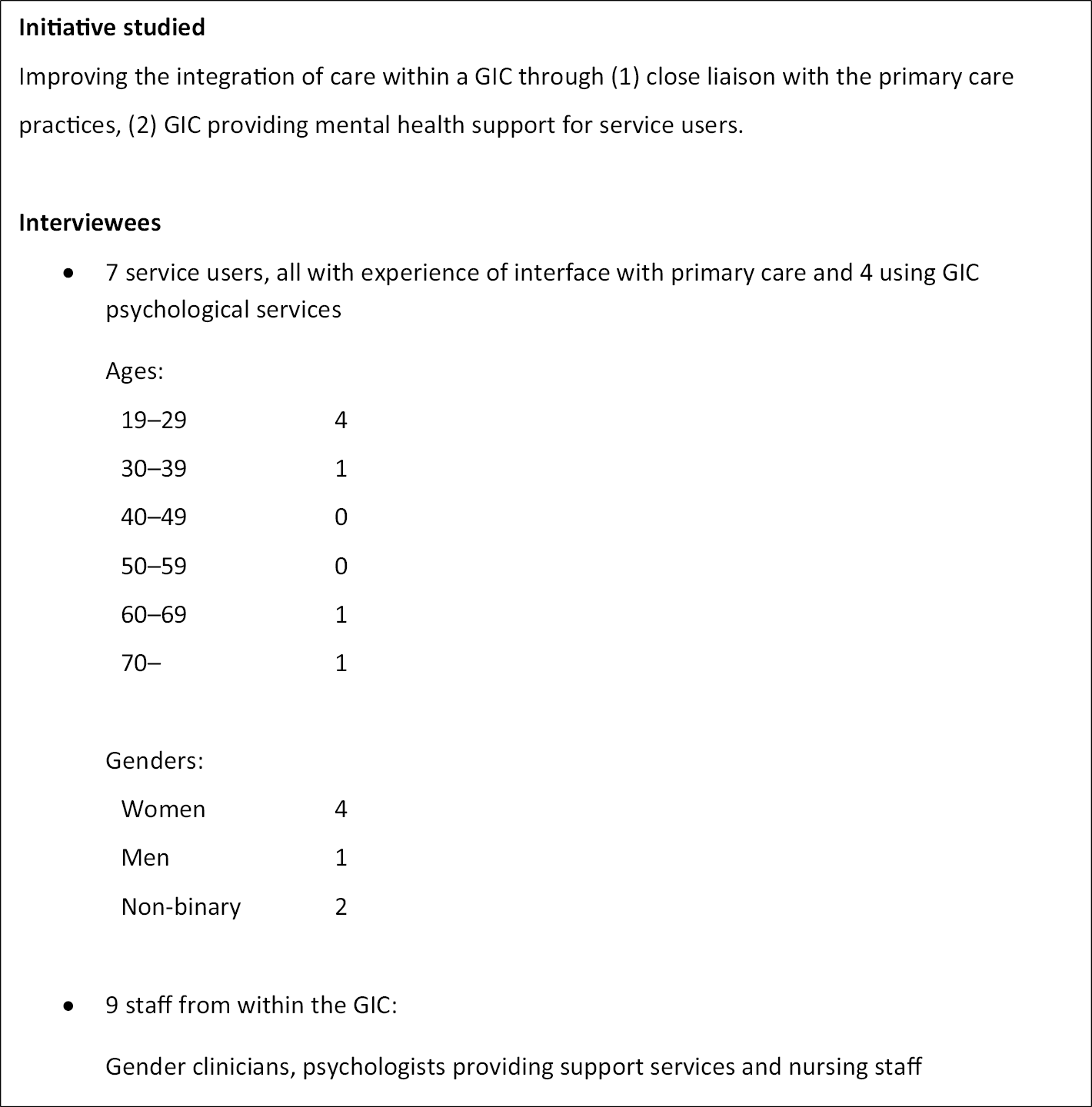

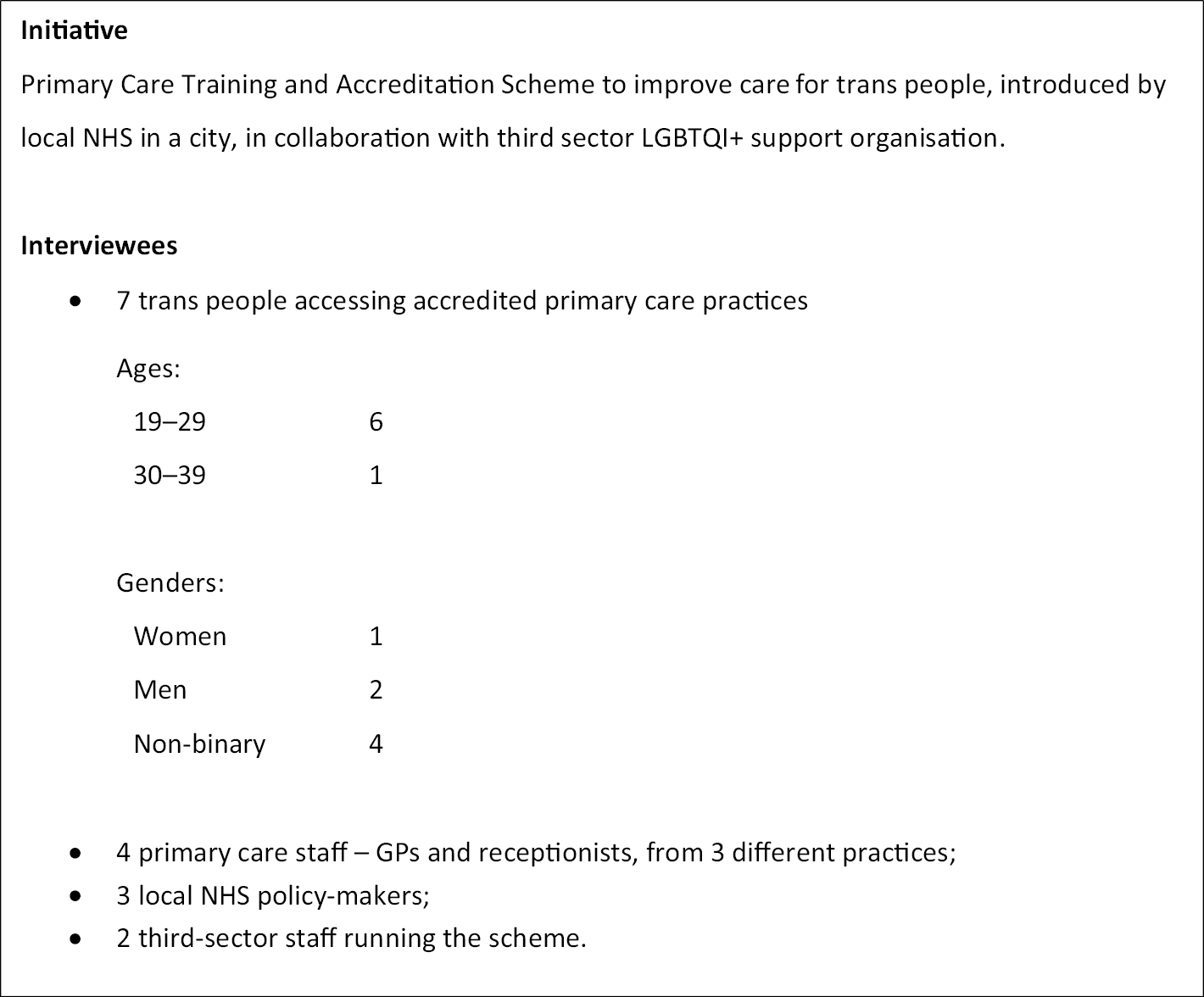

Table 2 shows the numbers interviewed in each case. The majority were carried out by video conference, apart from 15 staff interviews on Case Study 1 and 2 on Case Study 2 carried out face-to-face, all before the onset of the pandemic in March 2020. In each case, in the context of the pandemic there were limited numbers of service users offering to be interviewed so there was no scope for selection – the research team accepted the offers made and interviewed as many people as possible. The samples for each case were not held to be representative of the total population of service users for a particular service, rather to illustrate a variety of experiences.

| Case study | Staff | Service users |

|---|---|---|

| Case 1: Third-sector gender-outreach workers attached to a GIC | 16 | 15 |

| Case 2: Primary care liaison and psychology services within a GIC | 9 | 7 |

| Case 3: Primary care training and accreditation for trans health care | 9 | 7 |

| Case 4: The Welsh Gender Service | 8 | 10 |

| Case 5: Experiences of trans health care in Northern Ireland | 6 | 4 |

| Case 6: Healthcare experiences of trans adults with mental health conditions | 7 | 2 (plus 72 recruited elsewhere) |

| Totals | 55 | 45 |

The additional 72 service users whose interviews were analysed for Case Study 6 were recruited either in one of the other case studies or as part of the national sample of service users in WP 2. For both categories of research participant, their consent to participate included the provision that their data could be used for multiple kinds of analysis within the project. All service users included in the Case Study 6 analysis indicated the presence of a mental health condition in their survey response or during their interview. Of these 72, 56 came from those recruited for interviews in WP 2 (the vast majority of the 65 interviews already described), and the remaining 16 from those interviewed within other case studies. Two interviewees were recruited from the responses to the screening survey specifically for the mental health case study, because they had indicated extensive experience of psychiatric services.

Table 3 shows the numbers of interviewees among the total of 46 recruited across the case studies who met the criteria for being included within the analysis of one or more of the subsamples already described under WP 2, as well as the figure already given for those included in the mental health case study. Data on their experiences of health care were analysed within the context of these subsamples, as well as from the perspective of revealing the impact of innovations or circumstances that were the focus of the case study through which they had been recruited. As in WP 2, this approach to analysing experiences from more than one perspective was intended to recognise and reveal the intersectional nature of trans lives. Table 3 also indicates again the numbers already given in Table 2 for the national sample participants within each subsample. The final column then shows the resulting total number of participating service users within each subsample. The make-up of the participating service users in Case Study 6, Trans people living with mental health conditions, appears as an additional sixth row in the table, because in many respects this case study was more akin in its purpose to the subsamples recruited under WP 2. The emphasis was on understanding user experiences in relation to the accessibility and acceptability of services (RQ2), rather than studying the results of attempts to innovate (RQ3).

| Subsample | Interviews included from across case studies | Interviews included from the national sample | Focus-group participants | Total participants providing data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older trans people and trans ‘elders’ | 5 | 28 | 0 | 33 |

| Trans people with low income and/or low educational qualifications | 7 | 16 | 0 | 23 |

| Trans people with chronic illness or disabled | 16 | 27 | 0 | 43 |

| Trans people living in rural areas | 5 | 17 | 0 | 22 |

| TBPoC | 0 | 16 | 23 | 39 |

| Case Study 6: Trans people living with mental health conditions | 18 | 56 | 0 | 74 |

Within the population of 46 service users recruited across the case studies, just under half, 22 people, were not included in any of the other subsamples or Case Study 6 for analysis. Twelve people featured in one of the groups listed in Table 3, as well as in one of Case Studies 1–5. Four people featured in two groups, five people in three groups, and two people in four groups. One person fitted criteria for inclusion in five groups, that is four subsamples as well as Case Study 6, in addition to the case study where they were recruited.

Distinct, but overlapping, research subteams took responsibility for the interviews in each of Case Studies 1–5. Each subteam contained trans and cis researchers, with the trans researchers carrying out most of the interviews with service users, as well as carrying out some staff interviews. Appendix 4 contains typical topic guides for staff and service-user interviews. As described in the study protocol, interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and transcriptions then anonymised. Interviews with staff typically lasted between 1 hour and 90 minutes. Interviews with service users were between 1 and 3 hours long.

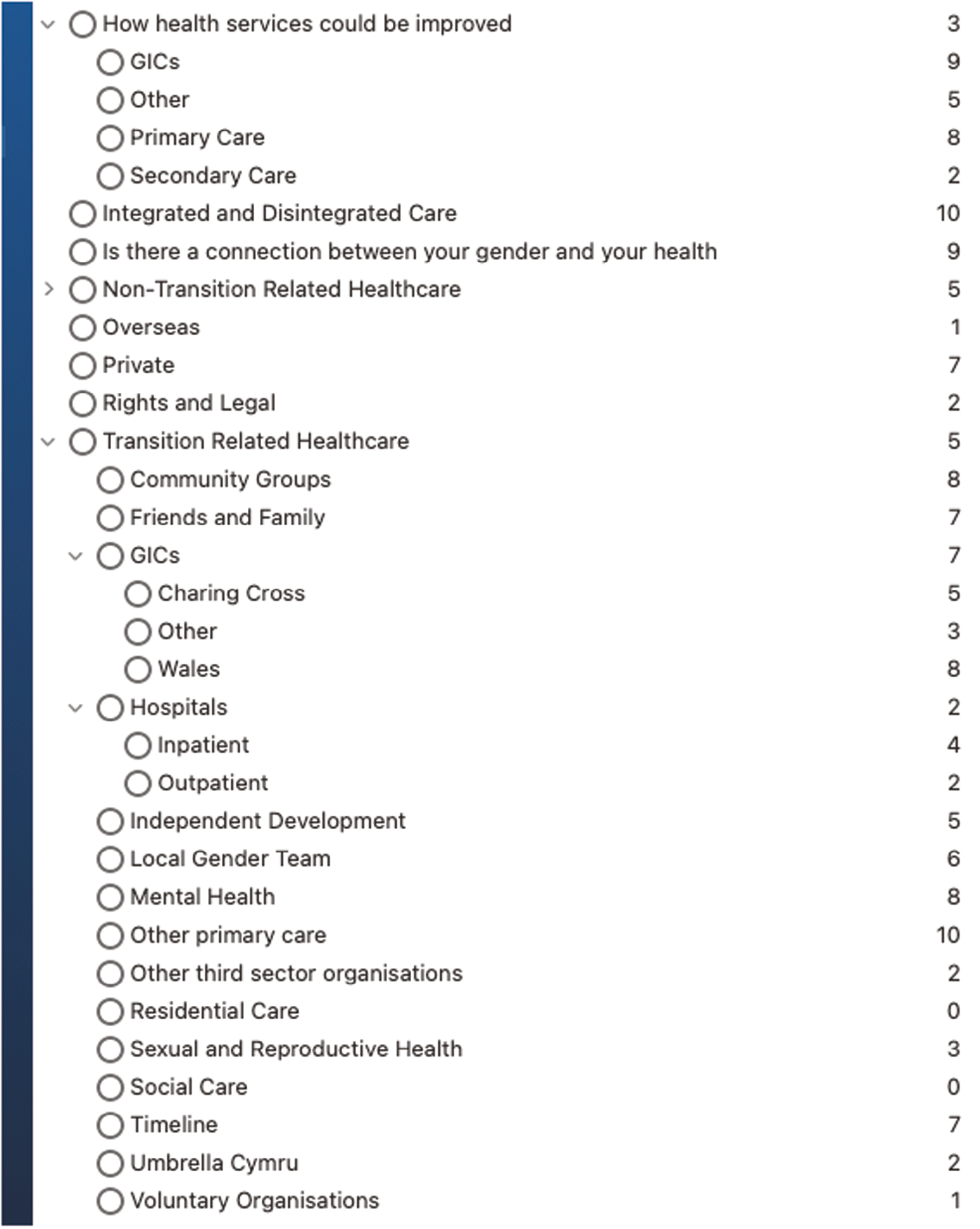

Case study data analysis was primarily based on these interviews, but also involved some analysis of service documents, such as policies and progress reports. As in WP 2, thematic analysis42 was used to summarise and interpret staff and service users accounts of changes to care practices, the extent to which achievements and benefits resulted, and the issues or challenges encountered. As in WP 2, there were two overall stages of the analysis carried out within each case. In the first phase, each staff and service-user transcript was coded independently by two different researchers on the case study subteam, at least one of whom was trans. The descriptive codes used allowed identification of text relevant to different aspects of RQ3, for example the motivations for the new care practices being studied, the practices themselves, the benefits, issues or difficulties encountered, as well as views on their overall effectiveness and the implications for future service development.

Appendix 5 shows the descriptive codes used in NVivo for staff and services user transcripts in one of the case studies. The coding frames were different because staff and service-user interviews contained data relevant to different as well as overlapping aspects of the overall case. For example, staff could be expected to provide most of the data on the reasons behind an initiative to improve care. When analysing service-user transcripts, researchers were careful to code accounts of benefits or shortcomings of care experienced only after absorbing the totality of a transcript and the wider personal history it contained. Researchers saw it as important to interpret an individual’s experiences of benefits, issues and difficulties with a current service in the context of their wider experiences of life or health care over time.

Descriptive codes were then merged and compared by a research team member responsible for producing a second-order analysis of each case in the form of a draft case study report. As in WP 2, differences between coders concerning the initial descriptive coding were noted and discussed where necessary, but mostly seen as helpful indications that additional text could be seen as relevant to understanding the impact of attempts to improve care (i.e. RQ3). Second-order analysis mainly took the form of inductively refining and combining descriptive codes to identify themes that adequately summarised the range of views across informants on the rationale for the innovation being studied, the practices that emerged, and the achievements, shortcomings and challenges encountered, as well as the implications for further service development. In the study of services in Northern Ireland and the mental health case study, the themes identified focused on the range of service-user experiences, rather than the course of an innovation. In three cases, the author of the draft was the PI, a cis man, and in one other case authorship was shared between a cis woman Co-I and a non-binary researcher. In the other two cases, the author was a trans researcher, in one case a woman and in the other a non-binary person.

As in WP 2, second-order analysis authors drew to some extent on concepts from existing related research in arriving at a set of themes to summarise the data, alongside inductive development. In the mental health case study, frameworks for understanding the relationship between mental health, microagressions and marginalisation22,44 were brought to bear. For Cases 1–4, concepts from institutional theory47 proved useful in structuring the analysis. These concepts concerned the process by which new service logics come into being, as clinicians and service designers seek to break with some aspects of existing services and perpetuate others. Existing literature has drawn attention to the role of interdisciplinary networks of health professionals joining with user communities to share a moral ethos about service priorities that challenges existing services. Such networks can then advocate and develop innovative practices. 48

For Cases 1 and 2, draft reports were fed back for validation to the interviewees, as a presentation, for discussion, in online workshops. Separate workshops for staff and service users were held for each case. Points of accuracy and interpretation were incorporated into subsequent drafts. Reports were fed back to key participants in Cases 3–5, with a request to correct issues of accuracy.

The analyses of all the cases in this report present anonymised data, including direct quotations from participants, preserving participant confidentiality. Most of the case analyses do not identify the services involved or their geographical setting, other than in very general terms. However, following discussions with key participants in Cases 4 and 5 (concerning services in Wales and Northern Ireland respectively), we did not attempt ‘geographical anonymisation’ for these cases. The configuration of social context and healthcare delivery issues in these cases would have made anonymisation of the setting involved difficult and arguably impossible. As in the other cases, anonymised quotations from participants are attributed only in terms of the speaker’s generic role and have been scrutinised so that they do not contain any clue as to the speaker’s identity.

Across WP 2 and WP 3, an important methodological element was the interviewing of trans service users by trans researchers, although cis researchers also undertook such interviews. Trans researchers were often able to identify where follow-up questioning could lead to fuller data. This, however, put trans researchers in the position of hearing accounts of care that placed them at risk of vicarious trauma or retraumatisation due to their own experiences. The trans researchers requested and were provided with a trans-led supervision forum, where they could process this impact on them.

Work Package 4: synthesis of findings and implications for improving practice

This addressed RQ4, concerning the lessons learnt for improving health care for trans adults. This included the development and comparison of analyses of the five purposive subsamples and the six case studies.

The drafts of case reports were first discussed and further developed within the research team. Authors worked to an extent inductively, refining and combining themes to represent the data succinctly but comprehensively, while also drawing on concepts from existing literature identified above under WP 2 and WP 3. In addition, ideas of integrated or co-ordinated care30,32 and person-centred care33,49 played a key role in conceptualising deficiencies in care reported and in analysing attempts to improve it.

During this stage, the project team discussed and agreed the structure of this final report, with the findings in two parts. Chapter 3 combines the analyses of the five subsamples within the national sample in WP 2 and Case Study 6 from WP 3, concerning experiences of trans people with mental health conditions, to reveal the dynamics of problematic and often poor care received by the majority of people in our sample. Chapter 4 then presents the remaining five case studies from WP 3 to analyse the extent to which attempts to improve and better integrate care have addressed the deficiencies described.

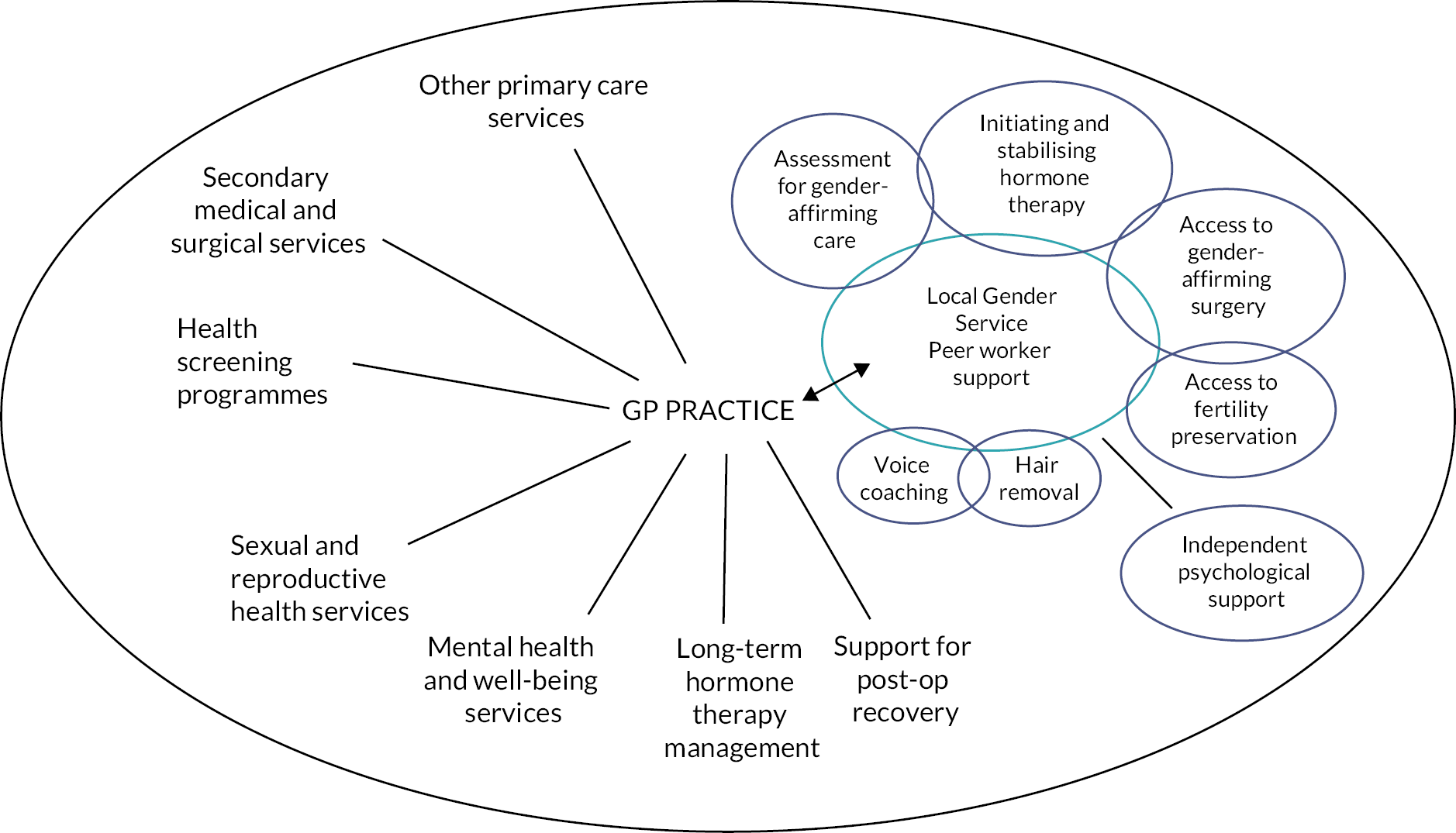

Chapters 5 and 6 then draw out the implications. In particular, two trans researchers within the team led on conceptualising a possible trajectory for the future of trans health care, based on three distinct underlying paradigms or models. The first paradigm involved improving the established model based on formal diagnosis of gender dysphoria as the gateway to gender-affirming treatment being available only through specialist gender services. The second and third paradigms involved progressively more integration of gender-affirming care within primary care and a diminishing role for specialist diagnosis. Developed versions of the paradigms appear in Chapter 6 and Appendix 9.

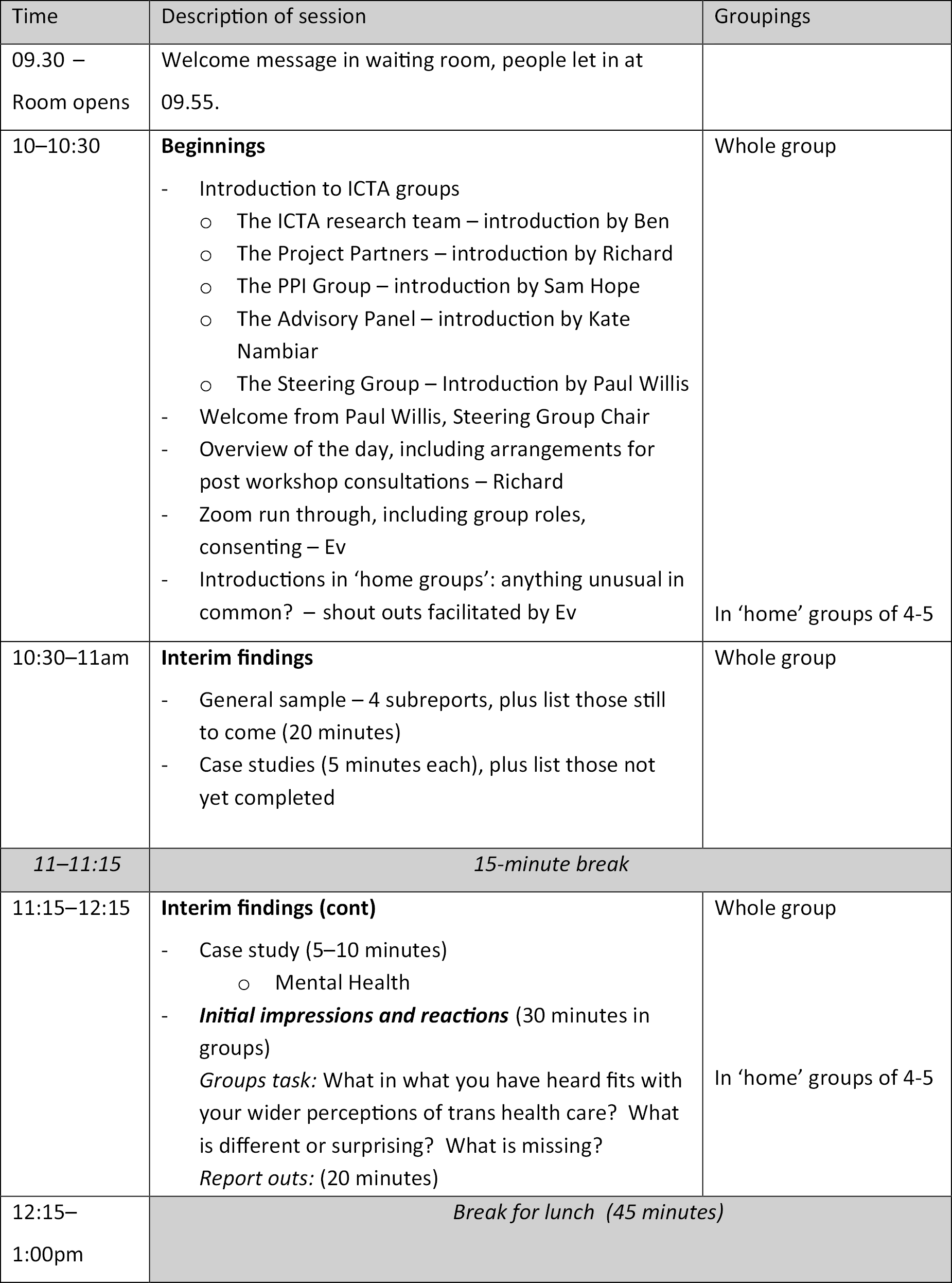

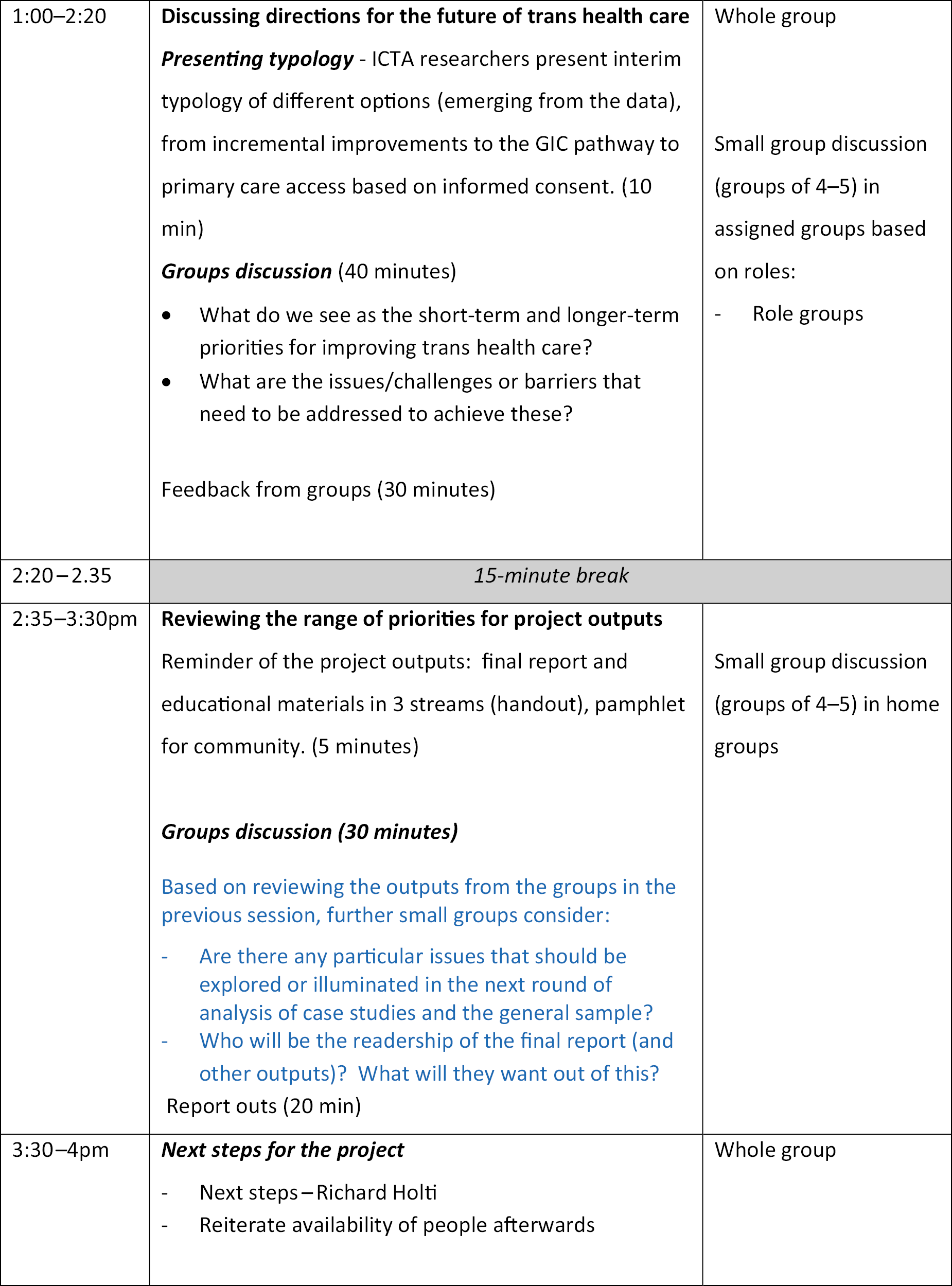

A day-long online workshop of the ICTA project community, comprising the research team, the study steering group, the advisory group and the PPI group played a key role in debating the emerging analysis. A total of 32 people, 21 of whom were trans, took part.

Leading up to it, trans members of the project team aired concerns that their perspectives and, in particular, conclusions that were critical of current services would be diluted in the final drafting of project outputs by their senior colleagues, to avoid alienating NHS project partners. A key purpose of the workshop was to ensure that a wide variety of trans voices were present among the stakeholders contributing to analysis. In structuring the workshop, the research team sought to balance presentations of draft findings, including the idea of the three paradigms, with focused small group discussions. The design intent was that there should be ample space for trans people to formulate and express views and statements about project outputs in groups that did not include representatives of NHS services.

The workshop design appears in Appendix 6. Participants were each pre-allocated to two different small groups of four or five people that met at different points during the day to discuss various presentations or topics. One set of groups was based on role: service users, primary care staff, mental health staff, GIC staff and third-sector staff. So trans people were either in a service-user group, or another grouping based on their professional role. The other set of groups comprised mixed ‘home groups’, which first met at the beginning of the day and were intended for participants to work together with others in different roles. Small group and plenary discussions were recorded, either through the online meeting software, or by note-takers. Anonymised examples of small group outputs are included in Appendix 6. The discussions and outputs from the workshop indicated broad agreement with the idea of representing possible futures of trans health care in terms of the three paradigms, and contributed to clarifying their content.

Following the workshop, the PI made arrangements to extend the duration of funding of the PPI group until the end of the writing-up period after the conclusion of the research contract, so that drafts of Chapters 5 and 6 were reviewed by this group of trans people. The two trans research fellows had both moved on to new posts by the time of final drafting and submission of this report but contributed their time to review drafts out of goodwill.

Such inputs were important in identifying possible gaps or negative impacts on equality issues in rationales for service improvement within case studies. For example, PPI group members foregrounded the data on the mental health burden on trans people of extended assessments, and the dangers of additional assessment being seen as necessary for people who already experience multiple forms of marginalisation, such as neurodivergent people or people with mental health conditions.

Clinical leads were also asked to comment on drafts of the case studies they were involved in. In response to feedback, the research team refined some case reports to focus more precisely on the learning from the intended service innovation, rather than the entire service. Revised case reports also differentiated the accounts of experiences of the relatively small number of service users interviewed, bringing out their range and relating them to personal histories and contexts. Service-user accounts thus served to illustrate different ways that individuals responded to the innovation studied, rather than claiming to represent user satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the service in general. NHS project partners were not involved in the shaping of the analysis in Chapters 5 and 6 of this report, although they, together with the study steering group, were given the opportunity to comment on Chapter 6.

Project outputs

All of this work provided the basis for project outputs and their dissemination. In addition to this report, the project has produced online educational materials for GPs, psychological therapists and members of the public, in particular trans people and their supporters. The materials concern rationales and practical issues involved in achieving improved integration of care for trans people. They are available free of charge from late 2024.

Chapter 3 Healthcare experiences of trans people

Introduction

This chapter focuses on the healthcare experiences of trans (including non-binary) people. It presents data relevant to RQ 2, namely:

Which factors make services more or less accessible and acceptable to the variety of trans adults who need them?

Additionally, the analytic focus is on exploring the extent to which participants experienced care as (1) person-centred and (2) co-ordinated.

The chapter reports on the experiences of six (overlapping) subsamples within the ICTA national sample of interviewees: people with mental health concerns or conditions, older trans people and trans ‘elders’ (those who transitioned years or decades ago); disabled or chronically ill people; people with low income or low educational qualifications; people living in rural areas; and TBPoC. The six subsamples were drawn from the 65 interviews and 8 focus groups (with 23 people) conducted for the national sample; the analytic group also included 24 of the 46 service-user participants interviewed for the case studies, giving a total sample of 111 people included across the 6 subsamples. The first subsample was the largest, in fact including all but 9 of the 65 interviewees, as shown in Table 3 in the previous chapter. It revealed themes that are fundamental to understanding the experience of the other groups, given this extensive overlap in membership. We therefore begin with the findings from this subsample, to set the context for the others that follow. Table 6 in Appendix 7 shows the demographic breakdown of each subsample, including by gender. The chapter concludes with a summary of the findings regarding the healthcare experiences across the subsamples.

People with mental health concerns or conditions

Prevalence of mental health difficulties

The original ICTA research plan did not call for a case study focused on mental health. The decision to conduct one came about as a result of the researchers noticing the high levels of mental health disclosures among the participants. This suggested the value of a focus on trans adults’ experiences of mental health and mental health treatment.

The responses to the survey used to recruit interviewees showed that, from a total sample of 2055:

-

23% (481) had accessed/were currently accessing transition-related psychotherapeutic support, of which:

-

262 or 54% accessed private psychotherapy

-

158 or 33% accessed NHS psychological therapies

-

61 or 13% accessed both NHS and private psychotherapy

-

-

11% (232) reported being on a waiting list for such support

-

21% (431) would have liked to be able to access such support.

In other words, half the survey respondents had accessed or wanted to access psychotherapy support for their transition journey.

From the same sample, in the 2 years prior to completing the survey:

-

26% (535) had accessed/were currently accessing NHS psychotherapeutic services for non-transition-related reasons.

-

28% (585) had accessed/were currently accessing third-sector/private psychotherapy for non-transition-related reasons.

-

18% (376) have been under the care of Community Mental Health Teams in the previous 2 years.

These data suggest a high level of felt need for psychotherapeutic support in this population (over one in four participants) but also a high level of engagement with community mental health services, given estimates of population average caseloads for adult community care of 100,000 people of 1632 (1.6%) according to an NHS report for 2019–20. 50 The finding of high levels of mental health felt need and service usage in this population corresponds with prior research. 19,51

The interview data analysed below resulted from 74 interviews with trans people, all included because they talked about experiencing mental health difficulties which included commonly reported experiences of anxiety and/or depression as well as reports of having been suicidal in the past. Additionally, participants reported mental health difficulties including personality disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, bipolar depression, and trauma-related mental health concerns. A number of participants reported neurodiversity (e.g. autism, dyslexia and dyspraxia).

Non-healthcare-related contributors to mental health

An initial analysis was conducted to examine what the interview data suggest participants understand or perceive as non-healthcare-related contributors (positive or negative) to their mental health. The key finding was that a variety of contextual factors create significant mental health burden for trans people, including loss of relationships and negative work experiences as a result of transitioning, threat of anti-trans violence and experience of microaggressions, and the inter/intrapersonal impacts of living in a trans-hostile society. One participant commented, ‘I mean like in the 80s your white hetero males used to throw stones at me, threw bottles at me, call me a poof all that sort of thing. I got beaten up a couple of times.’ There were also accounts of violence that were more recent, such as an experience of being physically attacked in a workspace. One participant talked about experiencing ‘stones (thrown) through the window’ of their house and being harassed by a group of teenagers on the street outside it.

This analysis also explored how participants attributed their mental health difficulties. Some attributed these to gender incongruence, but it was more common that they talked about mental health difficulties as linked to not transitioning and mental health improvements to transitioning:

My mental health is the bit that I’ve struggled with, and it’s been a definite benefit to that … for me transition has been only beneficial from a health perspective. Because if we’re talking about it, is ill health limiting then the thing that was limiting me was my mental health, which has improved.

Overall, the findings accord with a contextual or social understanding of the higher rates of mental health difficulties within trans populations. This understanding aligns with the ‘minority stress model’,52 a theoretical and explanatory framework that suggests that mental health disparities for trans people are largely explained by the stressors caused by living in a transphobic social context, such as harassment, discrimination and targeted violence. 11

Experiences of general health care

A second analysis focused on how participants understood relationships between their mental health and their experiences of general (neither transition-related nor mental health-related) health care. ICTA participants’ accounts suggested that positive experiences of health care were associated with encounters that were free of transphobic microaggressions, and supportive of trans patients’ medical transition. Conversely, negative experiences of health care were associated with experience of transphobic microaggressions, which are known to damage well-being. 44,53,54 Examples of microaggressions included being misgendered, deadnamed, subject to cisnormative or transphobic assumptions (e.g. about sexual history), health professionals being overly curious/questioning about trans status/experience when transness is not medically relevant, and medical staff making presumptions about trans health/identity that effectively dismiss a trans person’s knowledge of themselves. To exemplify this, one participant talked about their distress at being deadnamed:

I know walking into A&E that they’ve looked at my name, they’ve looked at my records, they’ve got me down as male and Mr [name] on the system and yet the staff have turned around and said to a nurse, oh this lady over here. And I’m like you have Mr [name] in front of you on the screen, you literally have it in front of you on the screen with a male marker, I’d already confirmed that that’s me, and yet you’ve still misgendered me and that’s [sigh] – I find those sort of situations difficult.

Participants also talked about their experiences of not receiving appropriate or (in the patient’s view) satisfactory health care, which contributed to stress and hence negative mental health. Often this was due to healthcare professionals’ lack of understanding of trans healthcare needs – for example, in one account a GP making a medically inappropriate and (for the patient) very damaging decision to stop a participant’s HRT. There were also accounts of non-transition specialist health services simply not providing health care to trans patients on the basis that they did not have a protocol for them. One participant described having urgent surgery cancelled because:

The surgeon said that they had no policy on how to treat transgender patients and then after time I was then informed that he would no longer be dealing with me and he would be passing me on to another hospital.

This person was subsequently treated without issue by another service.

The impact of repeated negative experiences of health care was a wary or anxious attitude towards seeking medical care, which is likely to contribute to health inequalities for this population, and might lead to self-exclusion from healthcare settings. Overall, there was evidence of iatrogenic harm in general healthcare settings that was trans-specific, that is beyond the level of iatrogenic harm experienced in the general population. Prominent issues concerned healthcare professionals’ apparent lack of training or cultural competence in working with trans patients, and transphobia in the form of doubting and undermining trans identity.

Experiences of transition-related health care

The third analysis examined how participants understood relationships between their mental health and their experiences of transition-related (GIC) health care. The accounts of waiting to access medical transition health care clearly suggest that a multiyear waiting list has a significant and detrimental impact on trans people’s mental health. As one participant said: ‘Waiting with gender dysphoria that long can be crippling. As I’m sure you’ve heard from others, it’s crippling.’ Another participant stated:

[The waiting list]’s so absolutely soul destroying for everybody going through it. It takes so long and everyone is so emotionally fed up of it and exhausted by the whole thing. That even if you consider yourself to be pretty resilient and if you think of yourself as a resilient person and that your mental health is strong it still gets exhausting and the wait is just interminable.

This finding is in line with other research on the negative impact of waiting to access health care. 55,56

Participants’ accounts of the experience of diagnosis within GICs suggest that for some the experience is positive and validating. For others, however, the experience is intrusive, uncomfortable/distressing and potentially destabilising or even re-traumatising, where patients were made to go over historic trauma without a trauma-informed support structure in place to manage potential risk. To exemplify, one participant described the questions they were asked as invasive and the experience as ‘deeply humiliating’: