Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/52/04. The contractual start date was in December 2017. The final report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in October 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Waring et al. This work was produced by Waring et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Waring et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The context: the politics of major system change

The implementation of change in health and care systems is notoriously difficult. 1–4 Change processes are often protracted and wasteful of scarce resources, and can result in variable, dysfunctional or unintended outcomes. Research within the field of implementation science, together with complementary insights from political science, management studies and organisational sociology, shows that a vast array of contextual and procedural factors influence change processes, including the availability and distribution of resources, incentives and opportunities, local cultures, regulatory pressures, leadership styles, communication patterns, public opposition and professional attitudes. 3–11

Although sometimes overlooked within implementation frameworks or subsumed within other contextual factors, a large body of social science research shows that change processes can be significantly complicated by the ‘micropolitics’ or ‘organisational politics’ of care services. 3,4,12–14 This is the idea that people often hold different and competing preferences and interests about change, which become manifest through particular behaviours or strategies as people seek to influence (or resist) the change process in line with their preferences and interests. 4,15,16 It also recognises that organisations are shaped by informal lines of power and influence, in the form of cliques or networks, which function alongside more formal structures of authority. This is exemplified by the abilities of health-care professionals to subvert or corrupt change that is seen as challenging their underlying interests or institutional jurisdiction. 12,16–20

Reflecting on these ideas, Langley and Denis12 describe how the micropolitics of health-care improvement stem from competing value systems that can lead to conflict around change processes. They suggest that change often involves winners and losers, and, therefore, it is important to consider the distribution of benefits and costs that influence how people respond to change. Further highlighting the political challenge of health-care improvement, Bate et al. 3 describe the importance of ‘. . . securing stakeholder buy-in and engagement, dealing with conflict and resistance, building change relationships, and agreeing and committing to a common agenda for improvement’. 3 Bate et al. 3 also describe the importance of ‘politically credible leaders’ who can broker between competing interest groups and manage political processes.

To clarify our understanding of ‘organisational politics’ or ‘micropolitics’, it is important to acknowledge that this study is concerned less with the formal or big ‘P’ politics of government policy-making, statutory institutions or formal governance structures, and more concerned with the informal or small ‘p’ politics of interpersonal influence, ‘soft power’ or the localised strategies that shape the everyday organisation of care. It is accepted that these two domains are interconnected and, in many ways, overlap. For example, political decisions made during formal policy processes frame the microlevel politics of policy implementation. At the same time, it is important to recognise that micropolitical behaviours are not confined to the local level of policy implementation but also exist in the ‘corridors of power’ in the ‘heart’ of policy-making. For this study, however, the primary methodological and analytical focus is the micropolitics located in the local and regional organisation and governance of services, rather than the national arena of policy-making (accepting that these two perspectives are clearly connected).

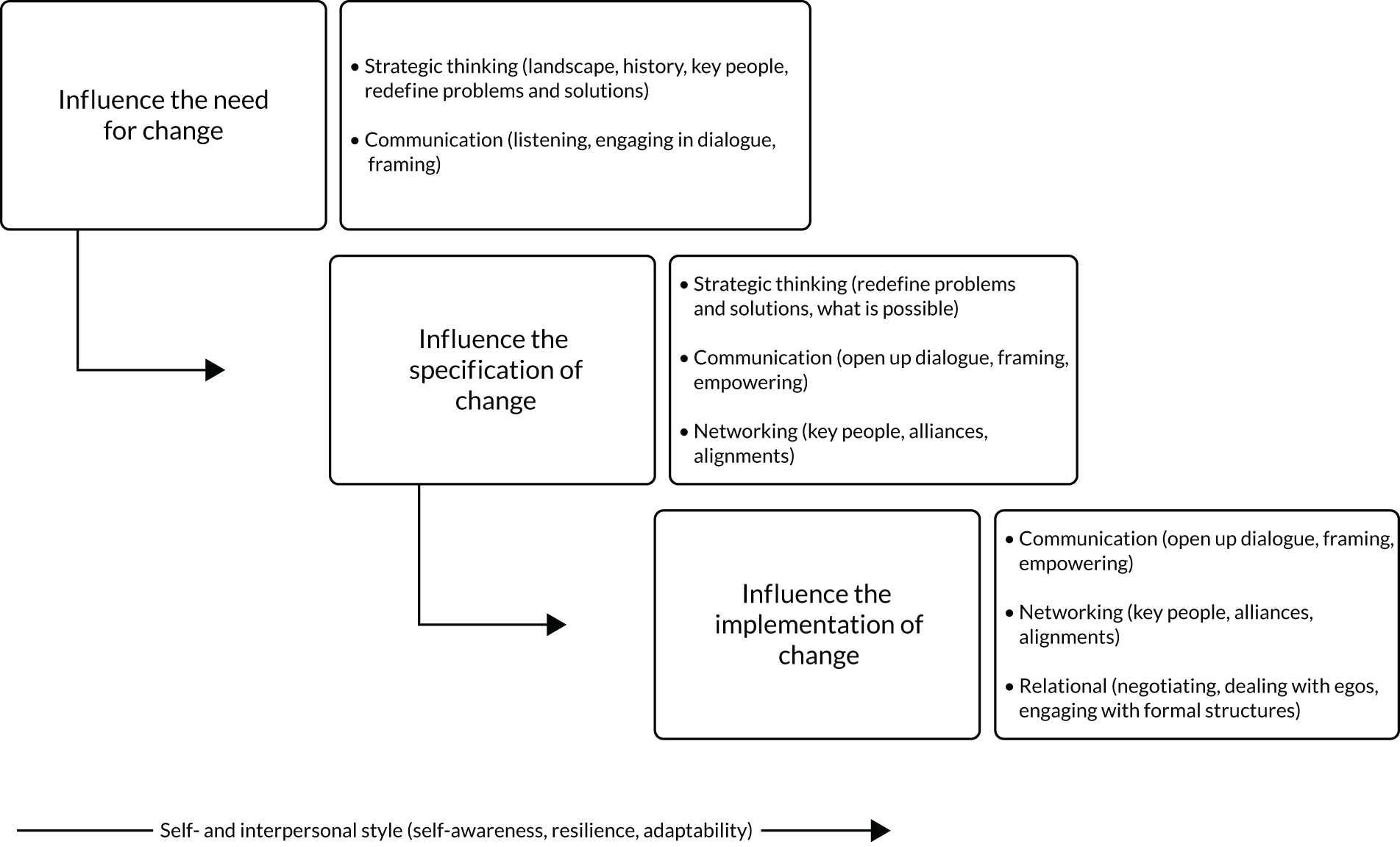

Taking stock of these ideas, the study investigated how health and care leaders can and do address the political challenge of change, by focusing in particular on the distinct skills, strategies and actions that are required to recognise and mediate the interests and behaviours that underlie the organisational politics of health service change. Although designated ‘leaders’ clearly have a significant role in this regard, for example chief executives or clinical directors, the study focused more broadly on change ‘leadership’ or the idea that change is a process undertaken by many ‘change agents’ working together in a distributed or co-ordinated way,21 rather than necessarily by a designated leader or role-holder. For this reason, this study was concerned with producing a more explicit and empirically developed understanding of the political skills, strategies or actions used by people as they seek to engender (or stymie) change.

In developing its focus, the study considered the distinct political challenges of implementing large-scale change or ‘major system change’ within health and care services. 9,22 If research suggests that the implementation of change within organisations is complicated by ‘organisational politics’, it can be reasonably assumed that the implementation of change across multiple interconnected organisations is likely to be even more complicated by ‘system politics’. Major system change has become a prominent feature of contemporary health-care reform as policy-makers try to redesign services in more co-ordinated ways to better meet the needs of people and communities. 9,23,24 In broad terms, this involves changing the way that multiple care organisations work together to provide a more integrated care service, to improve care outcomes, to share and optimise scarce resources and to realise aggregate health benefits for communities. Although there is no agreed definition, Best et al. 9 suggest ‘large-system transformation’ might be understood as:

. . . interventions aimed at coordinated, systemwide change affecting multiple organizations and care providers, with the goal of significant improvements in the efficiency of health care delivery, the quality of patient care, and the population-level patient outcomes.

Best et al. 9

In other words, large-scale transformation involves changing not only the way that individual organisations work, but also the distribution of roles and responsibilities among multiple organisations and how these organisations work together as a complex interconnected system. Prominent cases of major system change include, for example, the reconfiguration of specialist services for cardiac, stroke or major trauma care and, more recently, the introduction of regional Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs) across the English NHS. 10,22,25–27

As might be expected, the implementation of major system change can be challenging and involves co-ordinating a complex system of relationships and interdependencies. There is growing recognition that the implementation of change, especially large-scale change, rarely happens in a linear or planned way; rather, the dynamic properties of most complex systems mean that change happens in unpredictable and unintended ways. 28 Such complexity requires particular forms of ‘system leadership’ capable of dealing with the dynamic demands of care systems. In their review of the literature of large-scale service transformation, Best et al. 9 propose five ‘simple rules’ for change:

-

Engage individuals at all levels, with senior leaders shaping the vision while distributing the responsibilities for change to individuals and teams.

-

Establish continuous feedback loops through validated measures that allow for collective reassurance.

-

Attend to history and draw on learning opportunities from similar processes.

-

Engage physicians through facilitation, incentives and alignment with regulatory systems.

-

Involve patients and families as the ultimate beneficiaries of change, as opportunities for learning and to validate change.

These ‘rules’ speak to the ‘micropolitics’ of major system change, but they do not offer a developed or specific account of how ‘system politics’ affect change processes nor what system leaders can do about it.

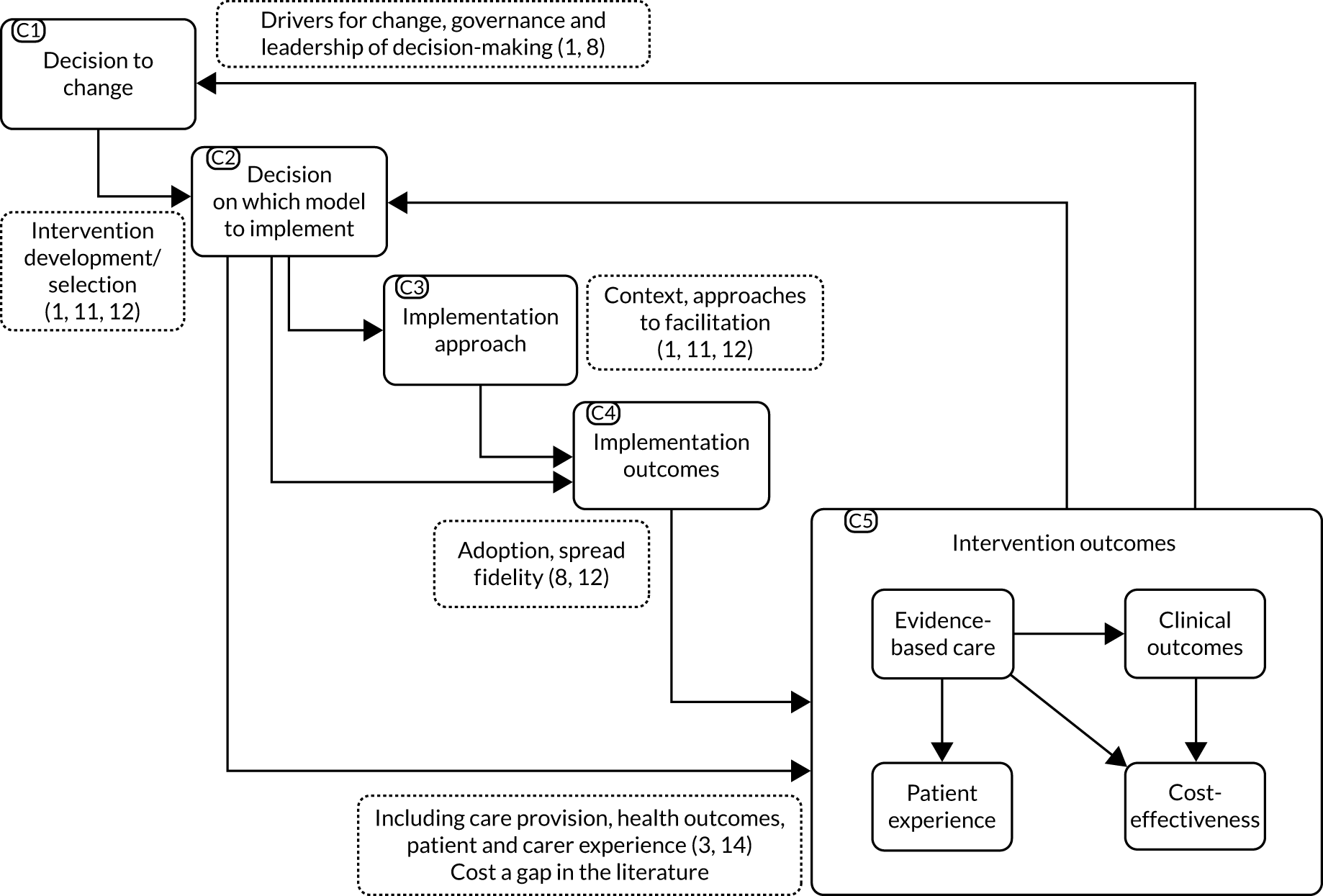

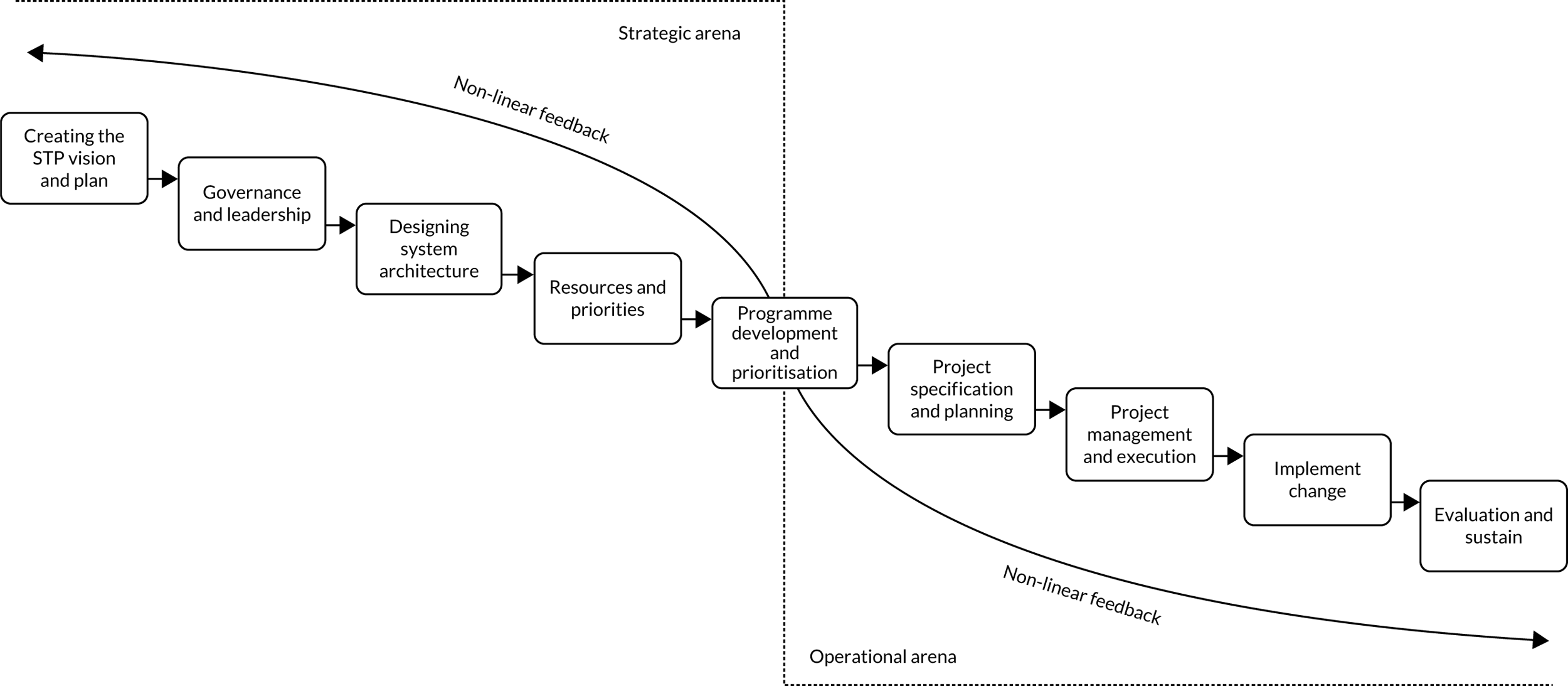

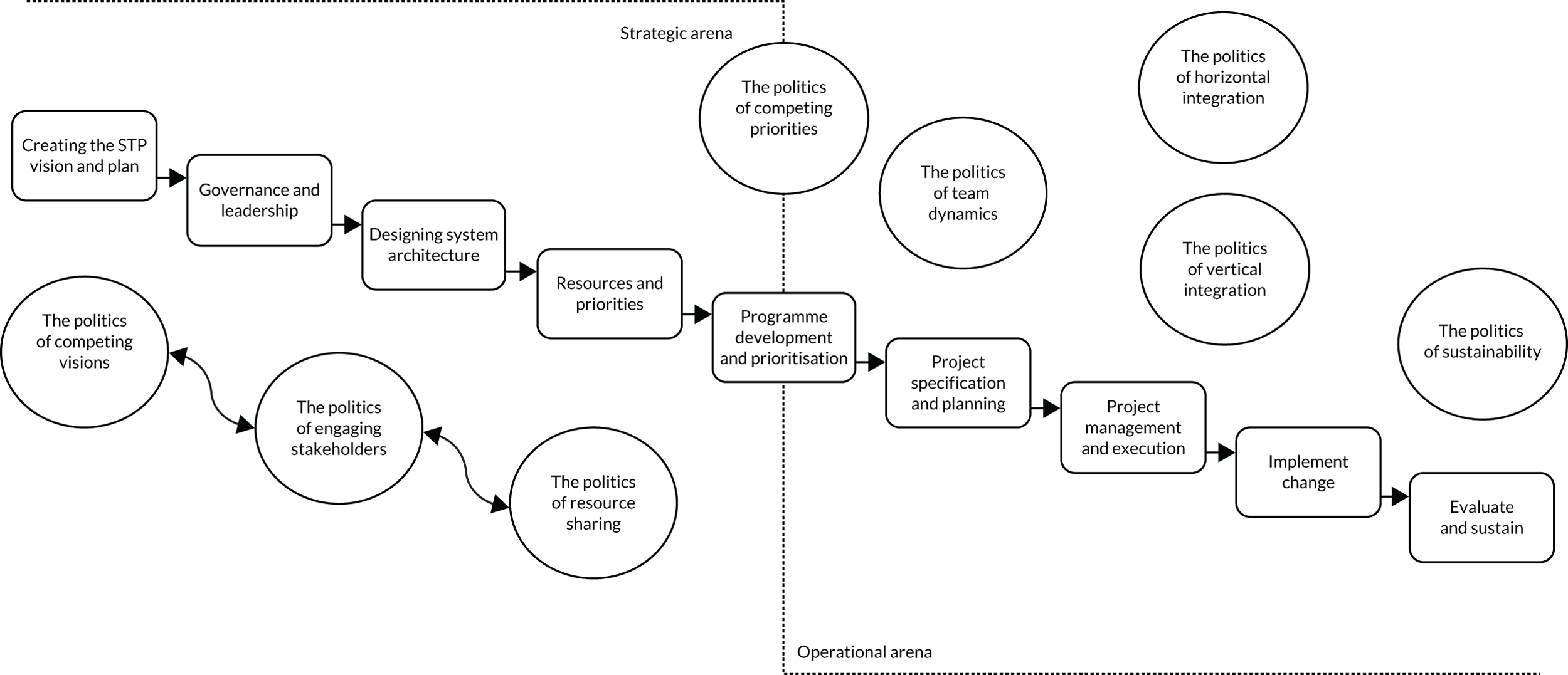

The application of these ideas to the reconfiguration of strokes services elaborates the challenges faced by system leaders. 2,22,29 In particular, Fulop et al. 2 examine the implementation of change across a series of linked stages (Figure 1), in which the implementation process ultimately shapes the implementation outcomes. Significantly, each stage represents a particular site for decision-making around which actors often disagree and, hence, each stage becomes a site for ‘system politics’ and political action. This research shows how the different approaches taken by leaders to reconcile competing preferences and priorities influence the resultant configuration of change and outcomes for patients.

FIGURE 1.

Implementation model with key decision points. Reproduced with permission from Fulop et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

A recent review of the literature on major system change identified a number of underdeveloped dimensions in the mainstream literature. 30 Of relevance here, the review identified the hidden politics of system change, in which issues of ideology and power are elided through an emphasis on technical evidence and planning. Building on this idea, there is a need for more direct and developed consideration of the way that ‘system politics’ shape the implementation of system change and the scope for leaders to manage with and through these politics.

As noted above, STPs are a prominent contemporary example of major system change. 27 They grew out of a long-standing agenda for more integrated care, especially between the health-care and the social care sectors. The need for integration has, arguably, accelerated following the Health and Social Care Act31 of 2012, which saw continuing calls for service integration but also increased fragmentation, with the emphasis on market mechanisms and the dissolution of regional-level strategic bodies for service planning. 32 In 2014, the NHS Five Year Forward View25 set out a renewed vision for integrated care, describing health-care systems that were centred on patients, people and communities. The ‘new models of care’ emphasised the role of primary care and encouraged multicare providers to expand services and tackle difficult issues. 25 By 2015, collaborative groups were invited to form ‘Vanguards’ to expedite the formation of these new care models and, drawing on the experiences of the Vanguards, the report Delivering the Forward View: NHS Planning Guidance27 introduced the idea of STPs to lead the development of regional-level service integration. The main themes addressed by the 44 STPs include redesigning primary care, prevention and early intervention, improving mental health, improving productivity, workforce development, changing the role of acute and community hospitals, and enhanced integration of health care and social care.

As with any form of major system change, the implementation of STPs has been complicated and constrained by a range of factors. 33 A significant issue has been the ambiguity of the statutory basis of the STPs, especially their position and function within (or rather, in-between) the prevailing NHS and social care regulatory landscape. STPs have relied on so-called ‘system leadership’ to nurture and guide collaboration among various regional organisations and bodies. Additional complications, which further add to the political challenges of change, include the extent and forms of public, professional and patient involvement, especially where STP plans have been developed at considerable pace. 34 For this reason, the continuing evolution of STPs, and now integrated care systems (ICSs), provides a prominent focus for investigating both the ‘system politics’ of change and the political skills, strategies and actions needed to engender change.

The challenges and opportunities of organisational politics

This study was informed by a well-developed, but also fragmented, literature on ‘organisational politics’ found across management studies, organisational sociology, social psychology, and public policy and management. Across these disciplines, it has long been recognised that organisations are complex ‘political arenas’ in which actors utilise a variety of interpersonal strategies to advance their personal or organisational interests. 35–44 In their influential analysis of bureaucratic organisations, Crozier and Freidberg45 challenged the assumption that order is realised through hierarchical structures, arguing instead that actors within a ‘relational system’ utilise various strategies to influence the organisation of work.

Influenced by pluralist political theories,46 organisational scholars have developed an extensive body of research demonstrating the strategies and tactics used by organisational actors when seeking to maximise their personal or professional interests in the organisation of work. 36,38,40,42,47 These interests often come to light during periods of change, when the distribution of roles and resources is disrupted. 4,47,48 Mintzberg39,44 describes how these interests are expressed through various ‘political games’ or strategies, such as ‘alliance-building’, ‘budgeting’ or ‘insurgency’. As suggested by Clegg et al. ,49 ‘strategy, once conceived, struggles to come into being through the processes of micro-politics’. Kotter and Schlesinger48 note that strategic change is often difficult because people fear that it will threaten established ways of working and vested interests. For this reason, managers need to pay closer attention to the interests that drive organisational politics and the resultant lack of trust that forms between ‘camps’. In overcoming these politics, they suggest that managers need to educate employees and communicate the rationale for change; engage and involve people in change processes; and, if necessary, find the inducements and incentives to secure support. Such ideas provide the foundations for Kotter’s eight-step approach for realising episodic change. 50 Although organisational politics can be seen as self-serving (so-called Machiavellian) behaviour, a growing body of research shows that it can have a more constructive influence. 41 For example, the competing interests of stakeholders need not result in destructive conflict, but can be a source of innovation as people forge a degree of shared understanding out of their differences. 51,52

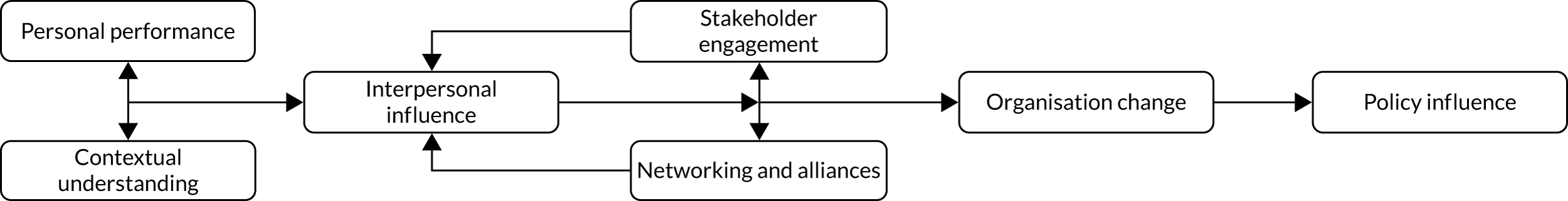

Research within the field of management studies suggests that, given the inherently political character of organisations, those people leading strategic change should develop and use particular political ‘strategies’, ‘behaviours’ and ‘skills’. Political skills enable leaders, first, to recognise and understand conflicting interests within the workplace and, then, to mediate those interests and build constructive coalitions in support of desired change. For Pfeffer,38 political skill involves ‘strategies’ to control the agenda, build coalitions and use experts; the use of ‘language’ to frame ideas and persuade others; and the control of ‘resources’. 38 As described in Chapter 3, the concept of political skill has been developed substantially by the US scholar Gerald Ferris and colleagues,53 among others,51 who describe it as a person’s:

. . . ability to effectively understand others at work, and use such knowledge to influence others to act in ways that enhances one’s personal and/or organizational objectives.

Ferris et al. 53

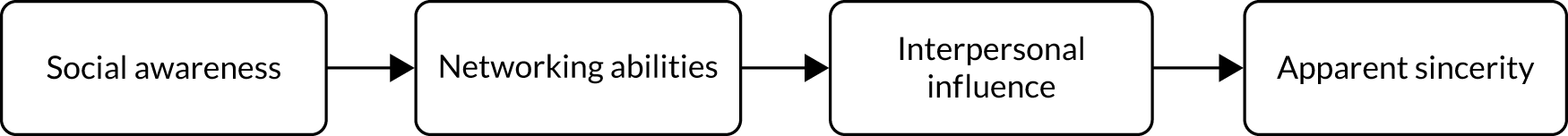

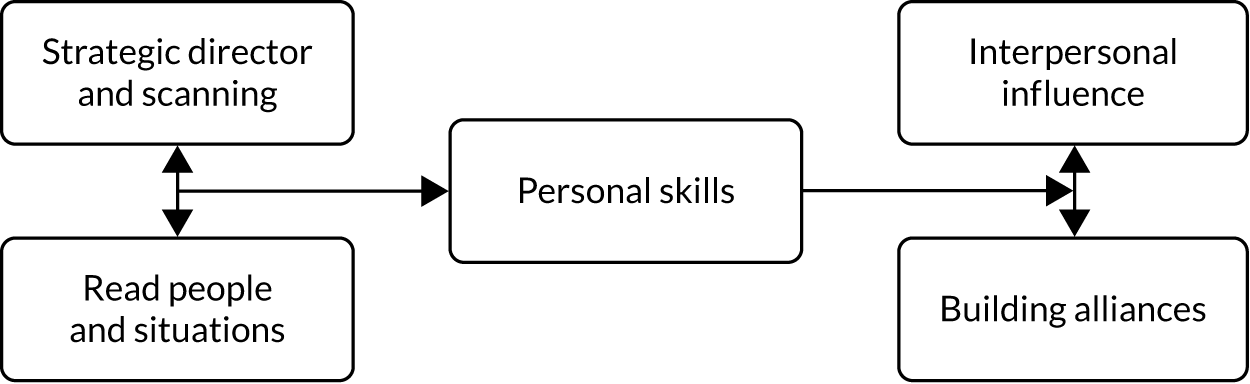

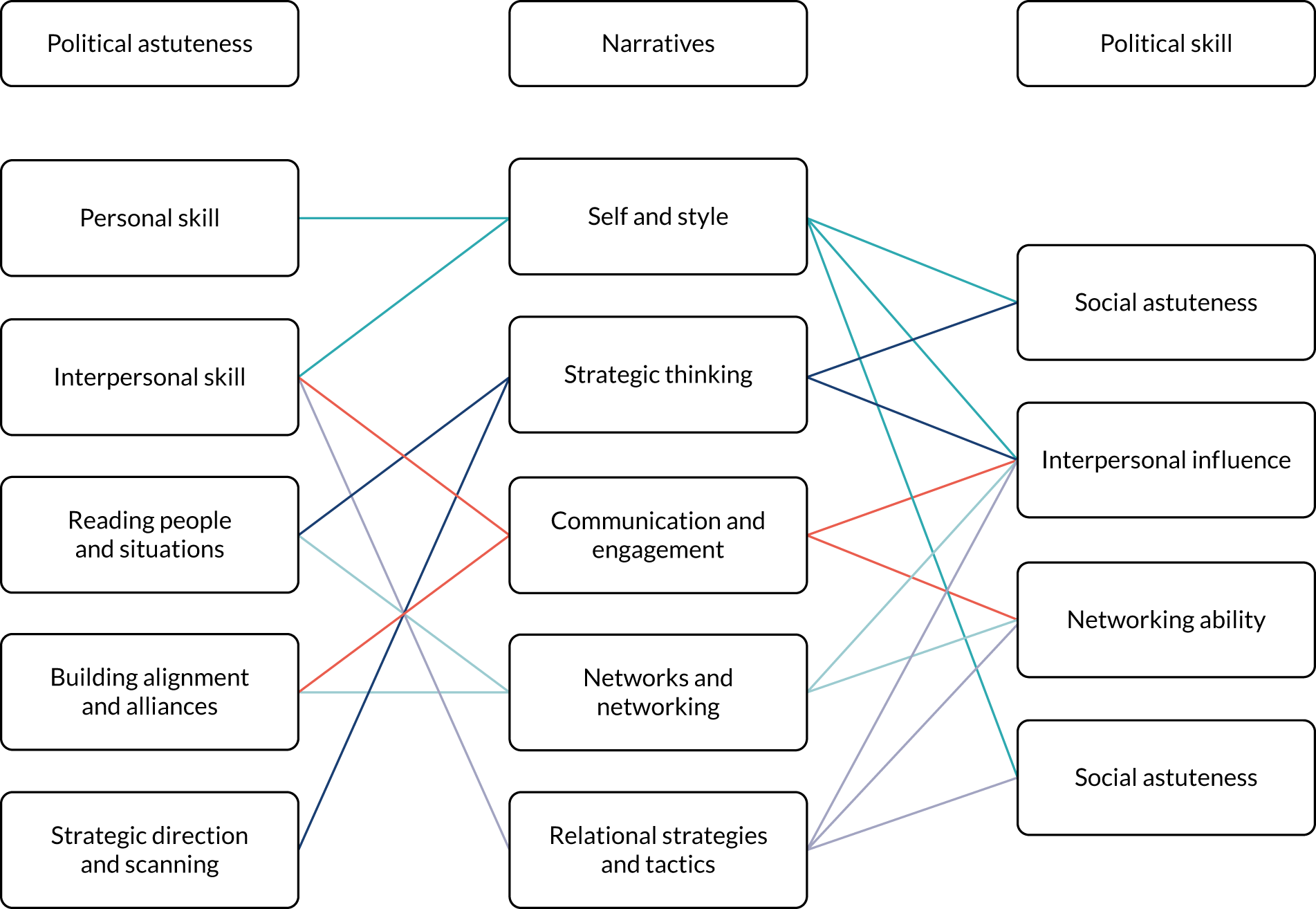

This is specified along the dimensions of ‘social astuteness’, ‘interpersonal influence’, ‘networking ability’ and ‘apparent sincerity’ to explain how individuals can influence others to realise their personal or organisational goals. The idea that leaders can develop and use political skill when seeking to implement organisational change was the primary point of departure for this study. Specifically, the study aimed to understand how health and care leaders can acquire, develop and use such skills for the implementation of major system change. Before developing this focus, it is important to briefly acknowledge wider debates on politics and power that further inform this study and provide the basis for lines of analysis that differ from the more mainstream ideas found in management studies.

Clarifying the concepts of organisational politics and power

It is far beyond the scope of this report to summarise the extensive literature on social power. However, the close connection between the terms ‘politics’ and ‘power’ requires some clarification, especially given that the terms are often used together in the wider health services research and policy literature. As noted, these terms are typically used to refer to forms of influence and power that operate beyond the statutory or formal institutions of government or policy-making, and instead focus on the informal relations of influence and power that are dispersed throughout and across the organisation of public services. 54 For some, micropolitics is a form of ‘soft’ interpersonal power,35,37,42 whereas for others it reflects ‘deeper’ ideological or structural interests. 17,55,56 For the purpose of this report, four perspectives are highlighted as relevant to the study of organisational politics in health and care services.

The first perspective treats power as an individualised resource or behavioural capability that usually resides within an individual and that is enacted over others through episodic forms of influence, persuasion or coercion. This can be through direct interpersonal influence or indirect forms of agenda setting or opportunity framing. This view is common within the predominant conceptualisations of political skill found within the management studies literature,53,57 in which ‘person A’ influences ‘person B’ based on their political skills. The second view develops this episodic viewpoint by attending not only to the capabilities or skills of individuals, but also, more importantly, to the relational interplay between social actors. From this point of view, social life is organised through the ‘interactive order’ that emerges from the relational patterns through which people make sense of themselves and others. 58–61 The third perspective focuses on the relative position of actors within a wider social field of relations. 62,63 This recognises that people hold variable and unequal positions within social settings, which is reflected, for example, in their access to certain roles, resources and relations, and also their acquired preferences, dispositions or viewpoints. These condition or shape a social actor’s inclination and opportunities to act or engage in both change processes and organisational politics. This dispositional power is derived less from an individual’s skills or abilities and more from the structured opportunities to act reflective of their acquired dispositions and forms of social, cultural economic and symbolic capital. 63 The fourth perspective sees power as more systemic, ideological or discursive. Rather than residing in people, power flows through the relationships between people, and these structured relationships are reflective of broader structural interests or ideological imperatives. On one level, this represents a hegemonic form of power55 in which actors may not be entirely conscious of the interests that structure their lives. On another level, it suggests that the ‘micropolitics’ of everyday life are shaped or constituted by broader social and political discourses that are manifest in bodies of knowledge, social institutions and other apparatus of governing. 64

These different perspectives span the structure/agency divide within the social sciences for which, at extremes, research emphasises either the voluntaristic behaviours of autonomous actors or the determinism of social structures, institutions and ideologies. 65 Without reducing analysis to either structure or agency, this study developed an integrative view of organisational politics in which the different forms of power and influence co-exist across different analytical dimensions while still being connected and influencing each other, and without reducing analysis to one over the other. For the study of health-care organisation, this means paying attention to the structural interests that shape health policies,17 the institutionalised forms of power associated with certain professions,66 and the prevailing biomedical and economic rationalities that constitute modern health care. 67 It also means recognising that health-care professionals not only engage in interpersonal relations from the discursively constituted social positions within the field of health-care organisation, but also can act both within and beyond these positions in their day-to-day episodic interactions and negotiations with others. 68,69

It is worth recognising from the outset that, although the literature on organisational politics often recognises that power and influence operate across and between multiple dimensions, the literature of political skill and, to some extent, political astuteness tends to focus on the more behavioural aspects of political influence. That is, it focuses on the capacity for individuals to exert influence over others, typically based on their particular skills or abilities. Although this influence is seen as inherently relational and interactive, the unit of analysis often remains the individual, which means that the contribution or contingencies of wider social and ideological factors can be downplayed or overlooked. This study took the concepts of political skill and astuteness as its primary conceptual and analytical focus because these afforded a discrete empirical focus from which to contribute to the health services research literature on the implementation of change, and also because they offered a more focused and practical basis for informing leadership development. This meant, however, that some of the wider conceptions of power and politics were not directly or explicitly operationalised or applied in the conduct or reporting of this study, primarily for the purpose of analytical clarity.

The need: acquiring and developing political skill

With growing recognition that the implementation of change in health-care services is complicated by organisational politics, there is commensurate interest in the need for health and care leaders to acquire and use political skills to better understand and navigate these politics. To some extent, these ideas appear to be shaped by the wider management literature, but there remains a significant lack of research and theory considering what political issues are involved in the implementation of major system change and what types of political skill or ‘political astuteness’ are required to manage ‘system politics’. Such evidence could then inform existing leadership development programmes or offer a more critical analysis of system change.

The pedagogical literature on workforce development suggests that the acquisition and development of leadership skills occur through a combination of at least three forms of learning. 70 First, through participation in formal education and training programmes, in which abstract concepts or methods are taught in the classroom or simulated environments. Second, through mentoring, coaching and action-learning in which learners are guided through individual and group reflection on ‘real-world’ challenges. 71 Third, through experiential and reflective learning in the context of taking actions in relation to ‘real-world’ situations. 72 To date, however, there has been limited research on how health and care leaders acquire and develop political skill or astuteness. Research suggests that formal training and real-world experience are both important. Hartley et al. ’s73 research with public managers in the UK, Australia and New Zealand finds that political skills are often acquired in a haphazard and sometimes painful manner. More evidence is required to both understand and meet the development needs of current and future leaders to acquire and use political skill (or astuteness) when leading major systems change.

In the English NHS, a number of established leadership programmes aim to enhance the capabilities of the health-care workforce to implement strategic change. The NHS Leadership Qualities Framework,74 developed in the mid-2000s, describes 15 aspects of leadership clustered around ‘personal qualities’, ‘setting direction’ and ‘delivering the service’. 74 This framework recognised the importance of ‘political astuteness’ in terms of (1) the capacity to understand the climate and culture of the organisation; (2) knowing who the key influencers are and how to involve them; (3) being attuned to national and local strategies; and (4) understanding the interconnected role of leadership. 74 The subsequent Healthcare Leadership Model75 included nine dimensions and again highlighted the need for leaders to understand the culture and politics of health care, including the informal chain of command. This suggests ‘successful innovation involves the exercise of political astuteness’ (© NHS Leadership Academy, 2013),75 including the cultivation of relationships and the building of coalitions among competing interests. However, the more recent NHS framework for improvement and leadership development – Developing People: Improving Care76 – gives less explicit attention to the importance of political skill. In various places, these capabilities are addressed in relation to ‘system leadership’, which involves building relationships and shared goals across organisational boundaries to help implement new service models. However, there is limited recognition of the need for service leaders to manage both the formal and the informal politics of health-care and social care services when implementing strategic change.

Although political skill is acknowledged across these frameworks, there is little evidence about how it is best acquired or how it can contribute to effective change. Many of the attributes are poorly specified or subsumed within other broader behavioural competencies. Even when there is explicit reference to political astuteness, there is limited evidence on which these qualities are based, and no explanation about how the concept has been adapted to the NHS context. With the pressing need to implement major strategic changes across the NHS, especially efforts to better integrate care services, there is a need to better understand the acquisition and contribution of political skill and to use that knowledge to inform the design and content of new learning and recruitment resources for service leaders and other change agents.

Study aims and objectives

The overall aim of this study was to produce a new empirical and theoretical understanding of the acquisition, use and contribution of leadership with ‘political astuteness’, specifically in the implementation of major health system change, from which to inform the co-design of materials and resources for the training, development and recruitment of current and future service leaders.

The study had six objectives:

-

identify key theories and frameworks of political astuteness within the social science literature and apply these to recent evidence of health system change to understand how service leaders can constructively create a ‘receptive context’ for change

-

understand the perceptions, experiences and reported practices of service leaders, and other change agents, about their acquisition and use of political astuteness in the implementation of health system change, taking into account differences in professional background, age, gender, ethnicity, geopolitical context and change context

-

understand how recent recipients of NHS leadership programmes think about, have acquired and make use of political astuteness to inform the development of new training resources

-

revise existing theoretical models of political skill and astuteness with reference to the wider social, cultural and relational context of health system change, from which to develop new theoretical propositions

-

investigate how political astuteness is used constructively by service leaders to create a ‘receptive context’ for implementing major health system change

-

work with providers of NHS leadership training, NHS recruitment agencies and patient and public involvement (PPI) groups to co-design recruitment and learning materials that support the acquisition, use and development of political astuteness for existing and future health-care leaders.

Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows. Chapter 2 describes the study design and methods. The following four chapters describe each of the study’s workstreams, including the findings of the two narrative reviews (see Chapter 3), the findings of the interview study (see Chapter 4), the findings of the in-depth case study research (see Chapter 5) and the development and co-design of learning resources and materials (see Chapter 6). Chapter 7 returns to the original research aims to make the final conclusions.

Chapter 2 Research design and methods

Introduction

This chapter describes the research design and methods used to address the study aims and objectives. It draws heavily from, and elaborates on, the published study protocol77 and also describes the challenges and changes in study design and practice encountered over the course of the study. The study comprised four linked work packages (WPs), each addressing a particular research objective. The findings produced through these activities are presented and discussed in subsequent chapters.

Work package 1: narrative reviews of the literature

The purpose of WP1 was to carry out two literature reviews: the first to identify key theories and frameworks of political skill, and associated terms, within the wider social science literature, and the second to apply the learning from this review to the health services research literature to understand how service leaders use such skills to create a ‘receptive context’ for change.

Review 1: a ‘review of reviews’

A preliminary scoping review showed that a number of recent systematic literature reviews on the concept of political skill had been published in the last 10 years. 43 For this reason, a ‘review of reviews’78 was carried out to (1) identify and synthesise the main theories and frameworks, (2) clarify the conceptual and theoretical assumptions informing these frameworks, (3) identify the different methodological approaches and (4) determine how political skill is both acquired and used in different strategic contexts.

Search specification and strategy

The preliminary scoping review found that the study of political skill can involve a range of closely related terms and concepts, such as ‘astuteness’, ‘intelligence’, ‘nous’ and ‘savvy’. Candidate search terms were reviewed in consultation with experts in the fields of organisational studies, public management, political science and sociology, as well as through the analysis of recently published reviews. The selected search terms and Boolean operators were ‘political skill’ or ‘political astuteness’ or ‘political savvy’ or ‘political acumen’ or ‘political nous’ or ‘political intelligence’ or ‘political leadership’ and ‘systematic review’ or ‘narrative review’ or ‘synthesis’ or ‘review’. These terms were used to search the following databases: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus, Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), MEDLINE® (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA), ProQuest® (ProQuest LLC, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) Social Science, PsycInfo® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA), PubMed® (National Library of Medicine), Scopus® (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and Web of Science™ [Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA; including Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (Clarivate Analytics)]. Finally, study advisors recommended manual searches of journals, including Academy of Management Review, International Journal of Management Reviews, Organisation Science and Political Quarterly.

Extraction and analysis

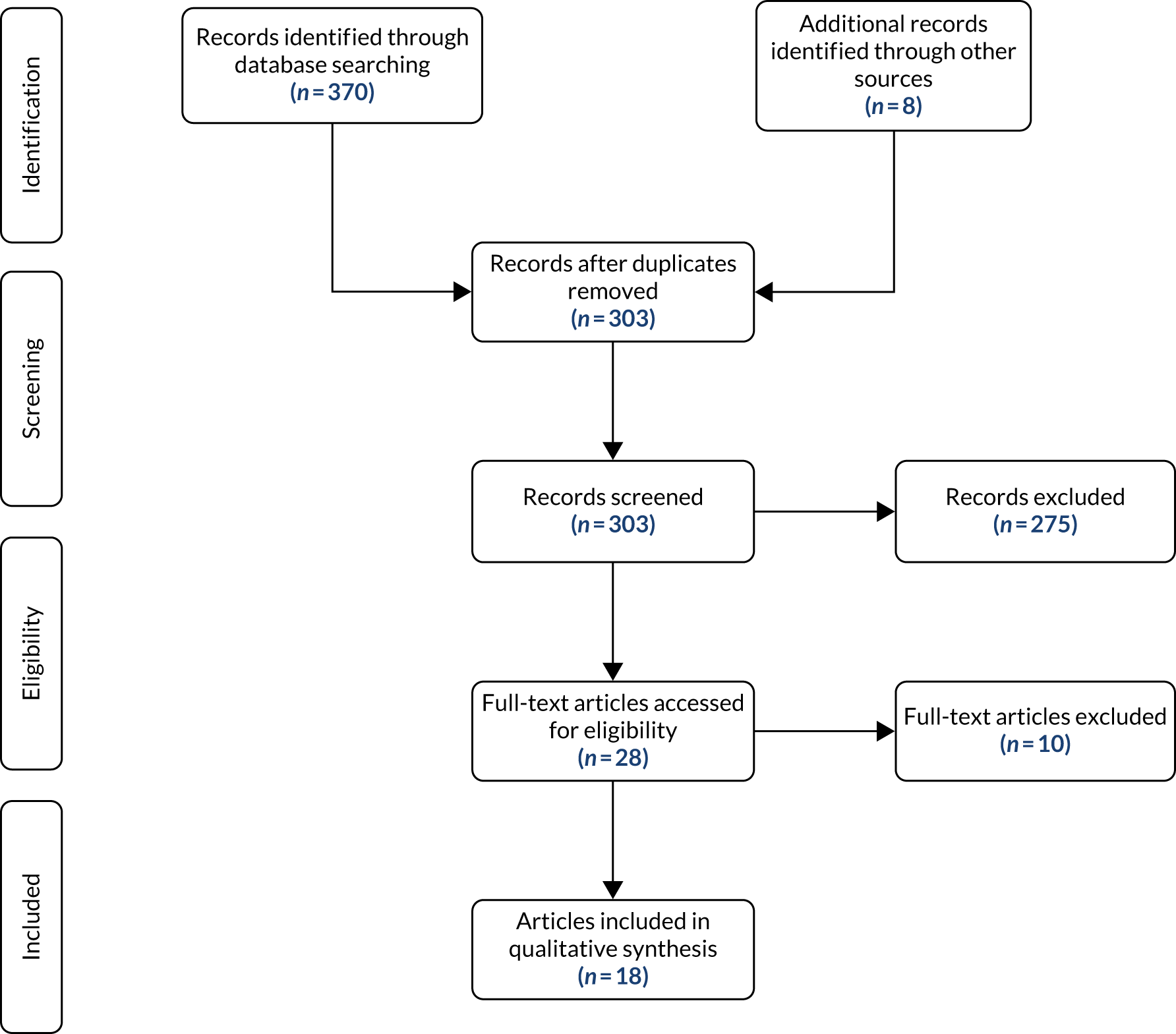

In total, the searches identified 303 sources (after duplicates were removed). These were screened (title and abstract review) by Jenelle Clarke, Simon Bishop and Justin Waring, excluding 275 sources. In line with our study design, for papers to be included they needed to relate directly to the concepts of political skill, astuteness or an associated term, as outlined above. Given that this was designed as a review of reviews, it excluded all primary research papers or empirical studies and included only narrative or systematic reviews of these concepts. Although the inclusion criteria may appear broad, in practice the searches returned a majority of studies that did not relate specifically to the theoretical concept of political skill or related concepts, and many cases addressed more general notions of politics or did not represent reviews of the literature. Three authors (JW, JC and SB) reviewed all of the titles and abstracts, made comments on a spreadsheet and met in person to go over the results. Two authors (JC and JW) independently reviewed 28 articles, excluding a further 10. Independent selections were reviewed and disagreements were deliberated (with SB). Selected publications were extracted and summarised using a standardised template, including authors, date, review method, number of sources, inclusion criteria, quality assessment, disciplinary perspective, theoretical background, empirical focus and review themes or findings (see Appendix 1). 79

Given the diversity of disciplinary, theoretical and methodological approaches within the literature, a narrative synthesis approach was taken to describe and interpret the main themes. 79 This involved a close reading of selected papers to summarise relevant themes and subthemes and, importantly, to interpret the reviews in terms of their contribution to prevailing disciplines, theories or debates.

Review 2: a review of ‘political skill’ in health services research

The second review aimed to understand how the concept of ‘political skill’ or associated concepts have been used in the health services research literature, especially research investigating the implementation of organisational and system change. The review investigated (1) how the concept is defined and operationalised in the health service research, (2) what methods of enquiry are used to study political skill, (3) what the concept contributes to the study of organisational change in health services and (4) to what extent the concept offers distinct or novel analytical insight into the wider social science literature. Unlike the first review, this was inclusive of primary sources and was not limited to review papers.

Search strategy

Search terms were identified in consultation with expert advisors in the fields of health services research, public policy and management, organisational studies and medical sociology. The search terms and Boolean operators were ‘political skill’ or ‘political astuteness’ or ‘political savvy’ or ‘political acumen’ or ‘political nous’ or ‘socio-political intelligence’ or ‘political leadership’ and ‘health’ or ‘healthcare’ or ‘health service’ or ‘health policy’ or ‘health policies’. A systematic literature search was undertaken using seven databases: MEDLINE, Web of Science, PsycINFO, ProQuest Social Science, PubMed, CINAHL Plus and Scopus. The searches were run between October and November 2018.

Selection criteria included any study written in English that described or applied the concept of political skill (or related terms) within a health-care context, including empirical and theoretical papers and prominent grey literature. No time restrictions were applied. Manual searches were carried out of identified bibliographies for further sources and literature recommended by domain-relevant experts (see Appendix 2).

Extraction and analysis

In total, 1718 records were identified (after duplicates were removed). Jenelle Clarke, Simon Bishop and Justin Waring independently screened the results (titles and abstract review), excluding 837 papers. Two authors (JC and JW) independently reviewed 96 articles (full text), excluding a further 35, with 62 identified for inclusion; disagreements were deliberated with Simon Bishop.

A standardised template was used to summarise and extract relevant data. 79 Characteristics included the full citation, method of study, disciplinary perspective, theoretical background, phenomenon of interest with regard to the change agenda or political issues, context for the study, methodological position, analytical approach, key findings, interpretation and explanation related to the study of change, and theoretical contribution. Narrative analysis of the papers was conducted thematically, with particular attention to how the concept of political skill has been used to explain health-care change.

Work package 2: narrative interview study

The purpose of the interview study was to investigate the perceptions, experiences and reported practices of service leaders and other change agents (broadly defined as people involved in leading the change process) about the acquisition and use of political skill in the implementation of health system change, taking into account differences in professional background; sociodemographic factors, such as age, gender and ethnicity; the geopolitical context; and the change context.

Methodological approach

The interview study followed a narrative approach to investigate how people experience and make sense of their lives in the form of stories. 80,81 The telling of stories involves organising experiences in ways that make them comprehensible to the narrator and the audience through forms of ‘emplotment’, that is, when events are connected together in a way that conveys meaning and order. These stories reveal underlying assumptions, beliefs and values. The interpretation of these stores surfaces the meanings that actors hold while still recognising that these stories are being told to a particular ‘audience’ for a given purpose. 80–84

Sampling and recruitment

Sampling aimed to investigate service leaders’ experiences of acquiring and using political skill within and across different care sectors (health and social care), organisational types (primary care, acute and community), strategic and operational arenas (senior management and delivery teams), professional backgrounds (medicine, nursing and pharmacy), career stage and regional contexts. A purposive sampling approach was adopted in which participants were recruited on the basis of exploring one or more of these differences. 85 In addition, people were recruited who were currently participating or had recently participated in leadership training programmes, to investigate how aspects of political skill are addressed in current training programmes.

An initial sampling frame was populated by members of the research team based on existing research connections and knowledge of prominent service leaders and professional representatives. In addition, opportunistic sampling of service leaders occurred during research engagement activities, for example conference attendance. Over 80 people were identified, all of whom were categorised to inform representative sampling decisions in terms of their professional background, occupational role, organisational affiliation and geographical location. All of the identified people were contacted in writing to seek their participation, resulting in 50 participants.

Two strategies were used to identify and recruit people enrolled on, or who had recently completed, leadership training programmes. First, and following attendance at the 2018 Health Services Research UK annual conference, contact was made with the professional network for NHS leadership and management trainees, who issued an invitation on behalf of the study to over 40 people, from whom five people were recruited. Second, the academic leads for two postgraduate leadership development programmes distributed a similar letter of invitation to their respective learner cohorts. This resulted in three people agreeing to participate in interview, while eight learners from one programme offered to take part in a focus group. In total, 16 ‘trainees’ were recruited.

In total, 66 people participated in either qualitative interviews (n = 58) or a focus group (n = 8). In terms of demographic composition, the sample included 37 females and 29 males: 59 were white British, four were Asian or British Asian and three were black or black British. In terms of career experience, the sample was categorised into three groups: 10 people with < 10 years of experience, 23 people with 11–20 years of experience and 33 people with > 20 years of experience. It was not possible to determine the career length for 12 participants because the information was not given or they had multiple career changes. Of the 16 ‘trainees’ recruited for interview or a focus group, six were within the first 10 years of their career, with the other 10 being in established professional positions (eight in quality improvement and two in general management).

Participants were recruited from different health and care settings, although the majority were based in the acute hospital setting. Five were significantly involved in STP leadership and had ‘dual roles’ both with their primary NHS employer and in the management of a STP. Three people were recruited from the social care sector and one from the police services on the basis of having a significant role in health-care planning (Tables 1 and 2).

| Role | Participants (n) |

|---|---|

| Regional-level director | 3 |

| Quality/service improvement | 18 |

| External relations/communications | 1 |

| Local authority management | 2 |

| Primary care leadership | 1 |

| Medical leadership (hospital/regional) | 5 |

| Management (general) | 17 |

| Nursing leadership | 6 |

| Research leadership | 2 |

| Patient/public | 3 |

| Voluntary | 5 |

| Police leadership | 1 |

| Non-executive | 3 |

| National-level leader | 3 |

| National-level service improvement | 4 |

| Total | 66a |

| Setting/sector | Participants (n) |

|---|---|

| Acute or specialist hospital | 30 (n = 2 also STP) |

| Primary care | 1 |

| Specialist service network | 3 |

| Research | 5 |

| Quality improvement agency | 5 |

| Commissioning | 3 (n = 1 also STP) |

| Ambulance | 1 |

| Local authority/social care | 3 |

| STP (employed by other organisation) | 5 (n = 3 dual roles) |

| National (NHS England/Improvement) | 4 |

| Voluntary sector | 5 |

| Police | 1 |

| Public representative/organisation | 3 |

| Medical trainee | 3 |

| Total | 66a |

Data collection

Narrative interviews invited participants to reflect on and talk about their experiences of organisational politics and political skill in the context of their involvement in health service change. A preliminary interview topic guide was developed to mirror the research objectives. This was piloted independently by three of the study team with the first seven participants, with feedback provided by the participants leading to revision of the topic guide (see Appendix 3). A total of 48 interviews were carried out face to face at a location chosen by the participants and 18 interviews were carried out over the telephone. All interviews were recorded with the consent of participants and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis and reflections

Narrative analysis aimed to interpret how participants make sense of their experiences through story-telling, linking individual accounts to shared systems of meaning and cultures. Narratives were ‘read’ for their content (what they talk about) and form (how they talk it). An important reflection is that many participants appeared to see the interview exchange itself as a ‘political act’, and forms of attribution bias were clearly present in the narratives. Importantly, the narrative approach is less concerned with determining the ‘facts’ of a given situation and more with the perceptions and meanings of participants. For Josselson,82 this requires a degree of suspicion on the part of the researcher to interpret meanings or assumptions that might be disguised or layered under more explicit statements.

In practical terms, data analysis followed a ‘step-wise’ approach to interpretative data analysis. 86–88 This involved (1) familiarisation with data through close reading, (2) generating initial codes through the systematic tagging of data, (3) constant comparison of codes to assure internal coherence, (4) axial coding to identify second-order codes and to elaborate overarching themes, and (5) reviewing themes in the light of the wider literature.

Data analysis started with all members of the study team closely reading at least two transcripts to identify ‘interesting’ narratives of political skill to guide subsequent coding. Three members of the team (JW, BR and SB) then coded the data through close reading and open coding of transcripts. Codes were subject to regular review to clarify interpretation and internal consistency. ‘Second-order’ codes were developed incrementally through the categorisation and grouping of codes. These were then further aggregated in the form of overarching themes. In these later stages, themes were simultaneously related back to the research literature to confirm or challenge existing research and theory. Overall, in excess of 100 detailed stories were identified that described experiences of organisational politics and examples of political skill.

Work package 3: in-depth qualitative case studies

The purpose of WP3 was to investigate how political skill is used constructively when implementing major system change. This involved applying and refining concepts and propositions developed through the preceding WPs to the study of political skill ‘in action’.

Methodological considerations

Work package 3 involved a qualitative case study approach. Case study research aims to produce a detailed description and analysis of a given ‘case’, which in many studies is representative of a broader phenomenon, but in others can be a rare, extreme or deviant case. 89,90 For health services research, case studies are especially relevant when seeking to understand how policy interventions are implemented in real-world settings. 91 Case study research is especially suited to the study of organisational politics because it provides fine-grained contextual understanding of how people interact and influence each other over time. 92

The initial study design proposed taking an ethnographic case study approach, with the aim of producing an immersive interpretative account of change processes. 93–95 It was recognised early within the study, however, that it would be challenging to carry out sustained in-depth fieldwork across multiple subcase study sites (i.e. the anticipated nine change projects). Specifically, the ability of two field researchers, even with the support of the wider study team, to carry out immersive longitudinal field observations tracking the ongoing development of nine different cases became unfeasible, even when field work was staggered across different time periods. The scheduling of field work was further complicated and compressed by the challenges and delays of case recruitment. For this reason, research was informed by the methodological principles of ethnography, especially developing an in-depth and interpretative understanding, but with greater reliance on time-limited observations of key events and greater use of interview and documentary data. 96

Sustainability and Transformation Partnership selection and recruitment

The study was designed to investigate change within three regional STPs as prominent examples of major system change. Given that STPs are made up of diverse portfolios of system change, the study intended to focus on three ‘subcases’ or system change ‘projects’ within each selected STP.

A preliminary desk review of all 44 STPs (completed during proposal development) identified key STP characteristics in leadership arrangements, strategic priorities and thematic areas for system change, such as urgent care, integrated care and mental health. Based on this desk review, three ‘candidate’ STPs were purposively selected during the initial application stage from Greater London and the Midlands to investigate differences in (1) geographical location and profile (demographic make-up, number of cities/towns and urban/rural features); (2) the number of large and specialist service providers; and (3) the profile of service transformation projects (with the intention of exploring both similar and different initiatives across the regions). Although these three sites were initially supportive of participating in the research, two of these later withdrew support and the research experienced significant challenges in recruitment, leading to both delays and variation in sampling and selection, the reasons for which are indicative of the organisational politics of health and care systems.

First, it was often difficult to determine where approvals should be sought within the STP governance structures and which body had statutory responsibility to approve research participation. Even when senior STP leaders were supportive of the research, managers from constituent NHS organisations could be less supportive, or vice versa. Although project teams or middle-level STP leaders were often supportive of the research, it took as long as 6 months to work through the various governance layers to find the group to authorise the research. Second, two of the candidate STPs experienced unanticipated changes in senior leadership, making it difficult to secure access. With one STP, the research team had many meetings with senior leaders over a 6-month period and eventually gained approval from the executive group; however, three members of this group then left their posts and the newly appointed leaders withdrew support for the study on the grounds that the recent leadership changes were ‘too sensitive’. Third, although STP leaders were highly interested in the study focus, they were often apprehensive about bringing to light ‘sensitive’ political issues during ‘live’ transformation processes. These recruitment challenges speak directly to the organisational politics of the STP agenda.

Given these challenges, STP recruitment was protracted and challenging. Following the planned approach, three candidate sites were approached through existing research networks, for example the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs).

After 6 months of discussions with STP leaders, two of these candidate sites withdrew support: one because of the aforementioned leadership changes and the other because of perceived political sensitivities. After nearly 6 months of discussions, one site in the Midlands agreed to participate. Another candidate site in Greater London was approached and, following another 6 months of negotiations, approval was granted. In parallel, all STPs in the Midland regions were contacted in writing to invite them to participate. Following a further 6 months of discussions, one STP agreed to participate. Because of the challenges around recruitment of STPs, case study data collection was delayed by over 6 months in two sites and by over 1 year in the other. The recruited STPs’ case study sites are summarised in Table 3, and the STP regions have been given pseudonyms to protect the anonymity of participating sites. Shortly after commencing fieldwork with this third site, field research was paused because of the COVID-19 pandemic (the impact of this is discussed in The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic).

| Regional characteristics | STP case 1 (Blue) | STP case 2 (Green) | STP case 3 (Red) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 1.2 million | 1.1 million | 1 million |

| Geographical footprint | Three medium-sized towns (c. 150,000 people) and villages, on edge of Greater London | One medium-sized city (c. 350,000), several towns and rural villages. Areas of high deprivation and wealth | One medium-sized city (c. 250,000), several large settlements (c. 100,000) and numerous smaller villages. Mix of dense urban and sparsely populated rural areas. Areas of high deprivation and low wealth |

| Demographic features | 0.7% among the most deprived in the UK. Predominantly white population, around 90%, which is higher than the average in the UK, but there is also an established traveller population | One-third of the population is an ethnic minority. Life expectancy is lower than the UK average. Substantial inequality. Problems with access to care and variety of quality of care. Large number of people dying from long-term conditions | Around 97% white British in the county but diverse cultural population in the main city. Ten-year gap in life expectancy between most deprived and most affluent areas. Rising ageing population. Over 20 areas in the county are among the poorest in the UK |

| NHS trusts | Six, including ambulance | Four, including ambulance | Five, including ambulance |

| Commissioning bodies | One merged CCG | Six CCGs then one merged CCG | One merged CCG |

| Primary care networks | 24 | 20 | 15 |

| Other NHS services | Community health social enterprise | Community health services social enterprise | Private community interest company |

| Local authorities | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Strategic objectives |

|

|

|

| Programme priorities |

|

|

|

Subcase transformation project: selection

The study design proposed to select three ‘subcases’ of system change within each selected STP. This was based on the assumption that the politics of system change would vary between the more ‘strategic arenas’ of high-level STP leadership and the more ‘operational arenas’ of system change. Informed by the preliminary desk review, common system transformation domains were identified, including urgent care, health and social care integration, and resource prioritisation. However, during STP recruitment, senior leaders asked the research team to focus on transformation projects that they regarded as priority issues, which were accepted as subcases on the basis of being a necessary compromise to support research access. Nevertheless, the selection of subcases took into account the difference in the focus of transformation, especially whether they were focused on the strategic or the operational levels of change, and how each project contributed to the overarching STP priorities. As described below, each subcase offered a distinct analytical focus for the study.

The recruited STPs’ subcase study areas are summarised in Table 4. Study names have been modified to protect the anonymity of teams.

| STP case 1 (Blue) | STP case 2 (Green) | STP case 3 (Red) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformation project focus | STP system architecture plan | Integration of primary and acute service | Integration of specialist pharmacy services | Merger of CCGs | Prioritisation for urgent care transform | Implementing personal health budgets | STP vision and mission | Workforce development |

| STP level | Strategic | Thematic programme | Operational project team | Strategic | Thematic programme | Operational project team | Strategic | Strategic |

| STP domain | Children’s, families and maternity | Placed/locality services | Medicines | Commissioning | Urgent care | Mental health | STP wide | STP wide |

| Analytical focus | Sharing vision and resources | Organisational (vertical) integration | Professional (horizontal) integration | Consultation processes | Mediating competing priorities | Reading the political landscape | Mediating interests | Sustaining change |

Selection and recruitment of individual participants

The recruitment of individual participants was also purposive, based primarily on a person’s direct or indirect involvement in system change and with the intention of exploring variations within and across project activities. 85 Participants were identified and recruited through three techniques. First, a review was undertaken of publicly available STP documentation that identified people involved in STP governance and project management, that is from organograms. Second, people were identified as potential participants during observational research, that is based on involvement in project work. Third, participants recommended speaking with others to pursue particular lines of enquiry as a form of ‘snowball’ sampling. All participants were provided with the study participant information sheet and gave written consent.

The study protocol anticipated recruiting representatives of patient groups involved in and affected by the proposed service transformations. A surprising finding was the limited involvement of patient or public groups in ‘day-to-day’ project activities. Most projects involved some formal public or patient representative from a recognised charity or advocacy group, and most of these people participated in the study. However, there was little wider service user or public engagement, which then limited the scope to involve such people in the research.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

It is important to acknowledge the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fieldwork. By the end of February 2020, data collection at the Greater London STP (Blue) was nearing completion and data collection at one Midlands STP (Green) was progressing well, with two subcase studies completed and the third under way. The second Midlands STP (Red) had agreed to participate and data collection was under way with senior system leaders and introductory meetings had been held with project teams. Following the introduction of the first UK ‘lockdown’ in March 2020, and in accordance with NIHR guidance, data collection for WP3 was paused, with activity focused on completing data analysis and preparing WP4.

At this time, it was decided to conclude data collection with the Greater London site. The Midlands STPs were contacted to discuss the ‘pause’ and to agree ways to restart the research in due course. One month into the pause, the research team was contacted by the lead of the project team for personal health budgets (STP Green) with the news that this project had been terminated. They reported that, owing to the pandemic, funding for the initiative was no longer available and members of the project team had returned to their primary ‘jobs’ to respond to COVID-19. Sufficient data had been collected up this point to provide important learning about the challenges of project set-up, from which a case report was developed. This concluded data collection at the first Midlands STP (Green).

Following the end of the first lockdown, the second Midlands STP (Red) was contacted to discuss recommencing the study. At this time, it was communicated that data collection could not recommence until the autumn owing to a backlog of work and new challenges associated with the pandemic. Further contact was made with the STP in early September to discuss data collection. At this time, the ‘cancer care’ project team indicated that they could no longer take part in the study owing to excessive work demands. Data collection with the ‘transforming the patient journey’ and ‘workforce development’ project teams was rescheduled for October to December. By the time that data collection was about to recommence, there was an increase in COVID-19 cases and hospital admissions and, subsequently, in November, a second lockdown. At this point, the ‘patient journey’ project team withdrew from the study owing to unprecedented work demand. The overarching STP leadership agreed to continue involvement in the research with the ‘workforce development’ and ‘system architecture’ project teams. However, as a result of the second lockdown and additional pressures on the service, data collection was further delayed and relied primarily on remote interviews carried out between December 2020 and February 2021. One of the advantages of in-depth qualitative work is that it enables collection of a large number of data in various forms and, therefore, when data collection was possible, there is sufficient data to meet the study objectives.

Data collection

The in-depth case study research involved a combination of qualitative methods, including semistructured interviews and group interviews, focused observations and shadowing, ‘in site’ ethnographic interviews and documentary analysis.

Interviews and focus group

Semistructured interviews were the primary method of data collection. Consistent with WP2, these took a narrative approach with the aim of exploring participants’ reflective experiences of change processes. Unlike the preceding WP, these interviews were able to explore multiple participants’ perspectives of a shared issue, thereby enabling greater understanding of the relational interplay between people. An interview topic guide was used to ensure that broadly common themes were investigated, but with considerable scope to allow participants to shape the conversation. The topic guide was designed based on the thematic findings of WP2, examining (1) the controversies of change; (2) the people involved and their interests; (3) the political skills, strategies and actions; and (4) the settlements.

As described above, interviews were carried out with people involved in ‘high-level’ STP governance and more operational system change. A small number of participants were interviewed on more than one occasion to investigate their experiences of change over time. With the restrictions brought about by COVID-19, the majority of later interviews were carried out using video-conferencing. With the time constraints owing to the pandemic, focus groups with the senior members of the second Midlands (Red) STP were organised to investigate change over time. In total, 73 people took part in 83 interviews (Table 5).

| STP case 1 (Blue) | STP case 2 (Green) | STP case 3 (Red) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic STP leadership |

|

|

|

| Project team 1 | Integrated ‘place’:

|

Urgent care:

|

Workforce development:

|

| Project team 2 | Medicines optimisation:

|

‘Personalised’ mental health care:

|

|

| Project team 3 | ‘New-born’ project

|

CCG reconfiguration

|

|

| Total | n = 26 participants | n = 32 participants (n = 40 interviews) | n = 15 participants (n = 17 interviews) |

Observations and ‘in situ’ interviews

Non-participant observations were carried out to develop in-depth understanding of the politics and political skill of system change. As described above, it was impractical to carry out in-depth participant observations across multiple case study projects. Instead, a more focused approach was taken, in which field researchers observed a sample of key senior leadership meetings for each STP and transformation project team. These observations focused on understanding how controversial issues were manifest in group settings, how people acted and interacted in relation to these issues and, in particular, the political skills and strategies used to influence change. The observations enabled the identification of people who could be invited to participate in an interview.

As part of the observations, many people were engaged in informal ‘in situ’ conversations about change processes. These took place within meetings, but more often in post-meeting discussions. These ethnographic-style interviews were useful for clarifying observations. In addition, five people agreed to be shadowed as part of their project work. This involved spending sustained periods of time with an individual while they participated in project meetings, met with other individuals or discussed key elements of the change process. These observations were usually arranged to take place before or after a scheduled project meeting, and lasted between 2 and 4 hours. In total, 23 meetings were observed over 49 hours (Table 6). As noted above, the impact of the pandemic meant that direct observations were not possible for much of the data collection for STP 3, with almost complete reliance on online technologies for data collection. Although such technology facilitated data collection for interviews and workshops, it reduced the scope for first-hand observations of both formal meetings and the more opportunistic in situ observations usually available in field research. For this reason, STP 3 has relatively less of this type of data to inform analysis.

| STP case 1 (Blue) | STP case 2 (Green) | STP case 3 (Red) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic STP leadership | Four STP board meetings (8 hours) | One STP board meeting (1 hour) | Two project meetings (2 hours) |

| Project team 1 | Integrated ‘place’

|

Urgent care

|

Workforce development

|

| Project team 2 | Medicines optimisation

|

Mental health

|

|

| Project team 3 | Maternity and new-born project

|

CCG reconfiguration

|

|

| Total | 11 meetings (22 hours) | 14 meetings (22 hours) | Three meetings (5 hours) |

Documentary data collection

Data collection involved collecting a large number of documentary and online sources for each STP and project team. Documentary sources provided important contextual understanding for each case study to inform sampling decisions, as well as primary data about how system change processes were reported, from which aspects of organisational politics could be ‘read’.

Desk research was carried out for each candidate and selected STP case study sites. This involved the collection and review of online documentary resources and other publicly available materials, including:

-

public strategy documents

-

public information provided in websites

-

public information available in downloaded documents

-

organograms

-

public information videos.

When research access was secured, additional documentary information was requested from project leads, including:

-

project plans and proposals

-

logic models

-

meeting agenda and minutes.

Data analysis

Data analysis involved three complementary approaches that moved from ‘within’-case to ‘cross’-case analysis, and then re-engaging with the analysis that was undertaken in preceding WPs.

First, data from each case study STP and transformation project were analysed with the intention of producing individual case reports. As with earlier WPs, an empirically grounded and interpretative approach was followed. 86–88,95 Specifically, case study data were open coded and summarised by Justin Waring and Bridget Roe by identifying common and distinct features: project/service focus, project maturity, project team members and stakeholders, significant issues or controversies, observed or reported actions and interactions, and project outcomes.

Second, a ‘rich’ descriptive account was produced for each STP and subcase. Following Stake,89 case reports were organised to give (1) an entry ‘vignette’ to set the scene and provide relevant background information, (2) a narrative account of the case that described the people involved and issues addressed, (3) a detailed account of the key or defining issues of the case, and (4) assertions or interpretations of the account relevant to the study objectives. In preparing these case reports, the thematic analysis from the preceding interview study was used to inform analysis in terms of the ‘controversies’, ‘protagonists’ and, in particular, the types and forms of ‘skills, behaviours and practice’. Data analysis showed that each transformation project experienced a range of political controversies, but that each was defined by a small number of key controversies at different stages of the change process.

The third stage involved cross-case analysis with the aim of identifying and explaining common and unique features,85,90 specifically how certain types and patterns of political skill were used around particular controversies. Preliminary cross-case analysis involved comparative ‘process mapping’ to understand how each case evolved over time, comparing ‘where’, ‘when’ and ‘why’ events occurred, ‘who’ was involved and ‘what’ they did. 90 From this, a ‘composite’ synthesis was developed of the ‘system change processes’, building on the existing literature on major system change. 2 Each case report was then reanalysed to illustrate a significant controversy within this composite picture of system change (see Chapter 5, Figure 9). For instance, some case reports illustrate the political issues experienced earlier in project planning or prioritisation, whereas others illustrate issues experienced later in project implementation or closure.

Work package 4: co-design learning materials and resources

The purpose of WP4 was to co-design learning and recruitment materials that support the acquisition and development of political skill and astuteness for health-care leaders. WP4 involved a number of linked activities informed by the earlier WPs.

Activity 1: a review of the literature on the acquisition and development of political skill

Activity 1 was undertaken as part of WP1 and involved a review of the literature to identify and summarise research on the acquisition and development of political skill. The selected review papers were further analysed to identify and categorise the methods and approaches for supporting the acquisition and development of political skill. In addition, a manual search was undertaken of prominent textbooks and monographs on political skill and leadership development (that would have been missed in the earlier search). This resulted in a total of 24 research papers and five monographs. The review summarised the main methods of acquiring and developing political skill, the pedagogic features of these methods, and the reported positive and negative features in terms of delivery, experience and learning.

Activity 2: qualitative interviews with service leaders

Activity 2 was undertaken as part of WP2 and involved carrying out narrative interviews with health and care leaders to understand their experiences of acquiring and developing political skill over their careers. As reported above, 66 participants took part in these interviews, including 16 people who were undertaking or had recently undertaken formal leadership education or training. All participants were invited to reflect on significant learning events and situations, including formal training and more everyday encounters. Participants were also invited to offer recommendations for how future leaders might learn and develop these skills.

Activity 3: a pragmatic review of training and development literature

Activity 3 involved a pragmatic review of frameworks, tools and learning resources that are specifically designed to support the acquisition and development of political skill or related capabilities. This review involved a pragmatic search of well-established leadership development agencies, university courses, professional press and other leadership development frameworks.

The pragmatic review started by carrying out interviews with four experts in leadership development to discuss the emerging study findings and to understand how current leadership programmes address the theme of political skill. Informed by these interviews, an online search was carried out of health and care leadership development agencies, including the NHS Leadership Academy (Leeds, UK), The King’s Fund (London, UK), The Health Foundation (London, UK) and the Institute for Health Improvement (Boston, MA, USA), and the online archives of agencies, such as the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (Coventry, UK). An additional online search was undertaken of commercial and non-commercial leadership development frameworks, including sources in the field of international development.

The identified frameworks, tools and resources were reviewed and categorised by Bridget Roe and Justin Waring, summarising (1) the express purpose of each tool or resource, (2) the originating source or underpinning theory, (3) key constructs about pedagogy or change, (4) the method of delivery and (5) the evidence base. Practical considerations were also recorded, such as the time needed for delivery, acceptability and actual or potential adaptation. A shortlist of candidate approaches and tools was created based on (1) the clarity and relevance of pedagogy, that is do they have a developed understanding or theory of learning; (2) alignment with the study’s empirical themes; and (3) feedback and recommendations from the preliminary workshops. The candidate list was then further reviewed and deliberated with study advisors in the light of the study findings.

Activity 4: workshops

Activity 4 involved facilitating a series of workshops to iteratively develop learning resources and materials. The workshops were initially planned to take place after the completion of data collection; however, following discussion with the study’s scientific committee, the workshops were configured to take place alongside the early WPs to inform the extrapolation of learning.

An initial set of three workshops was carried out in conjunction with WP1 to explore the perceived learning needs for health-care leaders to acquire and develop political skill and to consider how existing leadership programmes address these needs. An ‘educator workshop’ took place that involved seven people recruited through university networks, including representatives from Health Education England and the NHS Leadership Academy, three university-based providers of leadership education and two workforce development leaders from different NHS trusts. This workshop focused on the contribution of existing leadership development frameworks to service leaders’ acquisition of political skill. A ‘practitioner’ workshop was carried out with 12 health service leaders working in the area of quality improvement, who were recruited through a regional quality improvement network. This workshop explored participants’ understanding of organisational politics and recommendations about how political skills could be addressed in leadership development programmes. An ‘expert advisor’ workshop was carried out with four research experts (including organisational studies, public policy and management, and leadership research) and four relatively senior NHS executives to develop a greater understanding of the conceptual aspects of organisational politics and political skill. All three workshops were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

A fourth workshop was carried out in conjunction with WP2 to clarify the emerging analysis from the interview study. This workshop was organised as a dedicated session of a national Q Community knowledge exchange event. The Q Community is a network of people who are actively engaged in improving the quality of care services. It is supported by The Health Foundation, in conjunction with NHS England, and hosts various developmental events. The study team were invited to facilitate a workshop on ‘Harnessing Political Astuteness’ at a Q Community event on 13 November 2019. Nearly 60 delegates participated in the workshop, which explored their views about organisational politics, the impact on service improvement and how people can learn to use political skills in improvement work. These views were recorded through the use of flip charts, Post-It® notes (3M, Saint Paul, MN, USA) and other verbal summaries.

A fifth workshop was organised to review and appraise the shortlist of ‘candidate’ tools and resources that had been identified through the pragmatic scoping review of leadership development frameworks. Workshop participants included five specialists in knowledge exchange, capacity development and implementation science, who were recruited through the NIHR CLAHRC infrastructure. Participants were asked to review the identified tools and to consider their relevance and application to health-care services. Through this workshop, the candidate list of learning tools and resources was appraised, with recommendations offered on how the tools and resources could be adapted for use with health and care leaders. In addition, the workshop discussed the design, content and use of a complementary ‘workbook’.