Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/70/73. The contractual start date was in March 2017. The final report began editorial review in April 2021 and was accepted for publication in January 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Annandale et al. This work was produced by Annandale et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Annandale et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

This report presents findings from a study funded by the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme. The study’s broad aim was to identify and describe key situated interactional practices of decision-making that take place during labour in midwife-led units (MLUs). Understanding how decisions are made in clinical practice is important because women’s retrospective accounts of birth show that greater involvement in decision-making is associated with greater postnatal satisfaction and well-being, and decreased anxiety. 1–5 Drawing evidence together, Hodnett5 showed, almost 20 years ago, that when women evaluate their childbirth experience the ‘influences of pain, pain relief, and intrapartum medical interventions on subsequent satisfaction are neither as obvious, as direct, nor as powerful as the influences of the attitudes and behaviours of the caregivers’. 5

This basic finding has been replicated over time,6–9 and the need for effective, sensitive and inclusive communication is enshrined in policy guidelines. For example, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines10 recommend the following:

Treat all women in labour with respect. Ensure that the woman is in control of and involved in what is happening to her . . . establish a rapport . . . ask her about her wants and expectations for labour, and be aware of tone and demeanour, and of the actual words used . . .

However, despite the evidential and policy drivers, there are challenges to implementation in practice. 11 A critical issue in addressing these challenges is the dearth of evidence concerning how interactions actually happen during labour. 12 As Pilnick13 observes, ‘The potential implications of these interactional processes [. . .] are immense, since . . . “good” practice is ultimately achieved through interaction rather than through policy or regulation’. 13

Accordingly, at the core of this study is fine-grained analysis [using conversation analysis (CA)] of the interactions that took place between women, health-care practitioners (HCPs) and birth partners (BPs) during 37 video-recorded or audio-recorded labours. Recordings took place in two MLUs in the UK, where midwives are the lead HCPs caring for pregnant people who are (1) defined as low risk for pregnancy or birth complications and (2) have opted for midwife-led care.

Midwife-led care refers to the autonomous care by midwives of pregnant persons who present to maternity services as low risk for complications. 14 During the intrapartum period, midwife-led care takes place in units staffed and managed by midwives, although referrals to obstetric-led care occur should complications arise. Notions of normality and risk, therefore, underpin the distinction between midwife- and obstetric-led care. 15 Midwife-led care is associated with facilitating, when appropriate, the normality of birth as a spontaneous physiological process and, therefore, less intervention. 16,17 Emphasis is placed on midwives’ professional expertise and women’s embodied and agentic capacities to manage labour. This does not mean, however, that risk surveillance is absent from midwife-led care,15 nor that pregnant people and midwives are not engaged in decision-making. Those people with low-risk pregnancies have many options for their care during labour and birth, including (but not limited to) choices around pain relief, vaginal examinations (VEs) and management of the third stage. These are routine (likely not medically urgent) decisions of the kind that might be relevant to any labouring person in any context. The routine and widespread nature of these decisions during labour and birth make it particularly important to understand how they are managed in practice. Accordingly, decision-making in MLUs forms the focus of our research.

The two key research questions were:

-

What communication strategies (e.g. open questions, option listing, requests) are used by HCPs, women and their BPs to initiate decision-making?

-

What responses are made relevant by these strategies (e.g. an open question makes relevant a narrative response and a request makes relevant a granting/declination; see Chapter 2, Conversation analysis)?

Addressing these questions provides an understanding of interactional practices for managing decision-making and how far it is shared between HCPs and labouring people. In keeping with CA, which is the leading methodology for analysing talk-in-interaction, decision-making is treated here as a visible and practical set of interactional activities (as opposed to internal cognitive processes).

The study had four objectives:

-

To create a rich data set based on recordings of people giving birth in MLUs. We collected data via (1) antenatal questionnaires (ANQs) surveying women’s expectations and preferences for birth, (2) intrapartum video-/audio-recordings of labour and births, and (3) postnatal questionnaires (PNQs) about women’s experiences of, and satisfaction with, decision-making during labour.

-

To contribute to the evidence base for shared decision-making through a fine-grained analysis of the verbal and non-verbal details of interactions that take place in real time during birth, specifically how decisions are initiated, who initiates them and how different ways of initiating decisions are responded to. Using CA, the primary analytic focus was on how talk is used (by all parties) to encourage or discourage involvement in decision-making over the course and events of a birth.

-

To assess whether or not women’s actual experiences reflect their antenatal expectations and whether or not there is an association between interactional strategies used (by all parties) during labour (particularly the extent to which decisions are shared) and women’s later reported level of satisfaction. In this way, we could assess whether or not satisfaction is related to definable aspects of care in MLUs.

-

To disseminate findings to health-care providers and service users to contribute to translating existing Department of Health and Social Care and NHS policy directives on sharing decision-making into clinical practice.

Our study primarily focuses on decisions made during the intrapartum period. However, we recognise the importance of decision-making during the antenatal period and have included antenatal surveys of women’s expectations and wants. We know that women do not, on the whole, enter MLUs without having given some thought to their preferences around key aspects of their care during labour and women may also develop written birth plans. Birth plans are an important method for inviting participation in decision-making and for personalising care. 18,19 However, the effectiveness of birth plans at translating antenatal preferences into intrapartum practice is variable19 and relies on the contingencies of actual intrapartum events,20 as well as the flexibility of HCPs (who might also be subject to clinical contingencies). 21 Once in labour, a woman may face numerous decisional moments that might or might not have been foreseen and that have to be acted on in the moment. 11,22 For these reasons, it is vital to understand how decision-making occurs in real time during labour and birth.

A note on the terminology of birthing persons

All of the people in labour who participated in our recordings appeared to identify as women (as evidenced by the uncontested gendered pronouns by which others referred to them). Accordingly, when referring to our data set, we use the term ‘women’ to refer to people in labour. In common with broader maternity-related literature and policy documents, we also often use the term ‘women’ to refer to persons who labour when discussing labour and birth more generally. However, we recognise that this language does not include those who experience pregnancy and labour without identifying as women (e.g. trans-men and gender non-binary persons). Therefore, when discussing labour and birth beyond the context of our specific data set, we also use more gender-neutral terms, such as ‘labouring person’ or ‘service user’. Our use of this dual language aims to acknowledge the complexities involved in gendering people who give birth.

Choice and participation in decision-making in the NHS

The NHS firmly advocates service user choice. 23 Nevertheless, choice is a disputed concept, particularly in its application to health-care services. 24–26 Successive policies characterise service users as self-determining consumers,27,28 but both service users and HCPs are constrained in a range of ways relative to commercial encounters. For instance, although service users have the right to refuse care, they do not have the right to demand particular treatments and/or investigations. 29 HCPs have a duty to act in the best interests of service users and cannot simply agree to their choice if doing so would cause harm. In this sense (as well as others), the consumer choice model works imperfectly in health care. Nevertheless, respect for service user autonomy can act as a corrective to the long-standing perception of paternalism within medical encounters,30–32 in which HCPs might assume authority and afford service users little or no say in what happens to them. However, there remains a possibly inescapable (although perhaps narrowing) asymmetry between HCPs and service users in terms of medical and institutional knowledge, expertise and skill. 33 Where there is low health literacy or self-efficacy, the choice agenda risks placing an onerous burden on service users. 34,35

Shared decision-making is an approach to health care that attempts to occupy the middle ground between consumerism and paternalism by recognising, respecting and incorporating both HCPs’ and patients’ domains of expertise in medical encounters. 36,37 Therefore, shared decision-making is designed to counteract potentials for both consumerist patient abandonment and paternalist coercive action, and is seen as, ‘the pinnacle of patient-centred care’. 38 However, a range of conceptual39–42 and practical barriers43–45 have resulted in a limited and inconsistent implementation of shared decision-making in practice. 46–48 Barriers include (variable) patient ambivalence about their role as decision-makers45,49 and HCP concerns about, or experience of, time and resource constraints (including human resources). 44,50

A focus on involving women in decisions relating to intrapartum care has been a long-standing principle of UK maternity policy (and elsewhere). 10,51,52 These policies are clear that service users benefit from active engagement in decision-making. However, as noted above, fine-grained analyses of how decisions are initiated and managed in interactions between HCPs, labouring people and BPs is under-researched. Maternity care provides an ideal context to study the implementation of participatory approaches to decision-making because, relative to other aspects of health-service delivery, service users are, for the most part, healthy and able to function without complication. 53 In this sense, pregnancy and birth ought not to routinely provide agentic barriers to enacting informed choice in care decisions.

Decision-making during labour and birth

Although its history overlaps with the development of the choice/shared decision-making agenda in the NHS, policy emphasis on involving women in decision-making during labour has also been shaped by a distinct and long-standing critique of the medicalisation of childbirth.

Medicalisation of birth and its critique

The medicalisation of birthing practices over the nineteenth and particularly twentieth centuries is well documented. 54–56 Childbirth practices transformed from a ‘natural’ physiological, domestically located event, accompanied by an often lay female attendant, to a mainly ‘medical’ event, taking place in an institution, accompanied by a hierarchy of trained professionals and potentially involving multiple medical and technological procedures. In the UK, for example, homebirth was reasonably standard until the 1920s, when a shift towards hospital birth began, rising to around 65% by the 1950s. 57 In the 1970s, the Peel Report58 recommended that, on the grounds of safety, all births should take place in a hospital. By the 1980s, less than 1% of births took place at home and, since then, homebirth rates have remained consistently low (the figure for 2018 was 2.1%). 59

The factors that contributed towards and maintain medicalisation are complex and multifaceted,60 but include (1) the emergence and proliferation of biomedicine in general and in obstetrics in particular;61 (2) a focus on maternal and fetal risk;15,62–64 and, relatedly, (3) the development of technologies that enable a preventative approach by permitting a range of measurements and an assessment of body functions and processes. 65–67 Taken together, these factors of medicalisation are often associated, although in variously contested ways,68 with achieving safer childbirth. 69

For some women, having access to a medicalised setting offers reassurance and might be a key component for their satisfaction levels and feeling in control. 70–73 However, medicalisation has also occasioned resistance from feminists, midwives and childbirth activist groups [e.g. the National Childbirth Trust (London, UK), the Association for the Improvement of Maternity Services (Surrey, UK) and the Association of Radical Midwives (Northumberland, UK)]. The advancement of (male) biomedical authority is historically gendered and arguably disempowers women both as birthing subjects74,75 and as midwives61 by pathologising childbirth (and the pregnant body more broadly), bringing it under medical surveillance and intervention. 76,77 Although birth is generally safe in the UK, the focus on risk has intensified64,78 and has become normative so that most people give birth not only in hospital but also under obstetric-led care. 79,80 This can be explained in multiple ways, but might relate to the perceived risks of birth. 2,81–83

In the latter part of the twentieth century, mounting resistance to medicalisation went some way to reopening discussions about the normal physiology of birth, women’s bodily capabilities and midwives’ essential skills. 62 One response to the medicalisation of birth – variously called ‘humanist’60 or ‘feminist’,20 or identified by its features (e.g. woman-centred84–86) or by its central (but contested)87 association with midwife-led care88–90 – is more akin to ideas about shared decision-making adopted in the NHS more broadly. In this multifaceted approach, which, for the sake of consistency, we will call midwife led, the potential for normality (variously conceptualised)91 is promoted in an attempt to rebalance medical authority over women and midwives. Women are viewed more holistically, as more than birthing bodies, and there is recognition of the inter-relationships between psychological, emotional, social, cultural and physiological aspects of birth. 70,75,92,93 In this approach, midwives are the lead professionals and work in partnership with women to establish and support their needs and preferences, ‘being ‘with women’ as opposed to being ‘with institution’94 (see also Fottler et al. 95). There is also recognition that the process and experience of birth matters, not just the outcome. 96,97 Being involved in decision-making, having choice and feeling in control are positively associated with women’s reporting of high levels of satisfaction and positive birth experience,18,98–100 which has implications for postnatal well-being of mother and baby. 101,102

In the UK, critique of the medicalisation of childbirth culminated in the publication of the ground-breaking Changing Childbirth report,103 which reversed the Peel Report’s58 recommendation for 100% hospital births, acknowledged the psychosocial aspects of birth and promoted woman-centred care through supporting choice, control and continuity of carer (i.e. the so-called ‘three Cs’). 51 These ideas continue to resonate and are visible in subsequent maternity care policies. 52,104 However, realising the ideals of the ‘three Cs’ has been challenging. 87,105

Challenges of involving women in decision-making

Despite persuasive evidence that the choice and control that accompany engagement in decision-making are beneficial, women’s accounts suggest that there is considerable variation in the extent to which they report being included in decision-making during birth. 106–112 Indeed, the most recent Care Quality Commission report113 shows that 22% of women surveyed in 2019 said that they were only sometimes (18%) or never (4%) involved in decisions. Other studies report highly variable optionality around different types of clinically routine decisions,112 especially where this concerns personally sensitive/invasive procedures, such as VEs and fetal monitoring. 114

Villarmea and Kelly11 ask why involving women in decisions during labour is ‘so good in theory yet seemingly so difficult in practice’. 11 They11 suggest that there is a tension between individualising decisions and the broader organisational context of decision-making, and argue that it is possible that what sounds theoretically possible at the level of individual women might not be deliverable in the reality of a busy, under-resourced unit/ward. For example, the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) (London, UK)115 reports that, in 2019, the NHS was short of the equivalent of almost 2500 full-time midwives. However, Villarmea and Kelly11 suggest that these organisational issues might be inappropriately augmented by a stereotype that women in labour lack full capacity because of the deleterious effects of pain and tiredness. 116,117

Whatever the reasons for the inconsistent implementation of policies that promote the inclusion of labouring women in decisions, most existing studies have relied on women’s (and HCPs’) retrospective accounts that are variously removed from the actual experience and may, therefore, be subject to a range of biases. 118–120 Ethnographic observations121–124 have provided valuable insights into more situated practice, but tend to gloss the details of interaction (for exceptions see Jordan93,125 and Korstjens et al. 126). Moreover, one scoping study on collaboration and communication in maternity care found that few studies have researched both women/partners and HCPs. 12 To investigate the subtleties of discussions among women, partners and HCPs, a fine-grained analytic approach is needed. This approach will enable the examination of the specific context in which decision-making is ultimately accomplished. As a consequence of the reliance on retrospective data and the lack of specific focus on actual instances of interaction, only general recommendations for effective practice are usually offered. For example, Better Births52 requires that:

Women should be able to make decisions about their care during pregnancy, during birth and after their baby’s birth, through an ongoing dialogue with professionals that empowers them. They should feel supported to make well informed decisions through a relationship of mutual trust and respect with health professionals, and their choices should be acted upon.

However, there is little specific guidance on exactly how HCPs can facilitate this involvement in decision-making.

Conversation analysis: real-time decision-making in health-care interaction

Conversation analysis is a theoretically and methodologically distinctive approach to studying precisely how talk-in-interaction works on the micro level in everyday practice. CA uses audio-recordings and video-recordings of authentic interactions in real time (and associated transcripts) to enable direct observation and fine-grained analysis of not only what is said but also how it is said (e.g. emphasis, breathiness and evidence of hesitation), when and by whom. The key methodological advantages of CA are that it does not rely on recall and that it investigates interactional conduct at a fine level of detail that people cannot easily articulate (e.g. in a research interview) and, indeed, of which they are largely unaware.

A focus on the detail of communication matters because, as noted above, talk-in-interaction is central to the activity of medical health care. 127 By focusing on the details of authentic interactions, CA can expose and interrogate the micro-level realisation of interactional challenges faced by HCPs and patients. Examining the precise wording that HCPs use reveals features that can affect interaction in ways that might not be open to speakers’ intuitions. For example, a small change in question format from ‘is there anything else you want to address today’ to ‘is there something else you want to address today’ elicits significantly more reported concerns from patients. 128

A small number of CA studies have explicitly addressed shared decision-making. 129 However, conversation analysts do not begin with a particular model of decision-making, but rather try to inductively understand how agency in decision-making gets differentially distributed through the process of interaction. By examining health-care interactions, conversation analysts have identified a continuum of HCP approaches to opening decision-making that are more or less authoritative, ranging from those that are more ‘unilateral’ or ‘presumptive’ to those that are more ‘bilateral’ or ‘participatory’. 130–132 Collins et al. 130 define these dimensions in the following terms:

In ‘bilateral’ approaches, the practitioner talks in a way which actively pursues patient’s [sic] contributions, providing places for the patient to join in, and building on any contributions the patient makes . . . In ‘unilateral’ approaches the practitioner talks in formats less conducive to patient’s [sic] participation: e.g., the scene for the decision is already set; the decision is presented as ‘made’. 130

That is, turns are designed to convey levels of authority and involvement in decision-making. A presumptive or unilateral format (e.g. ‘I am going to . . .’) informs a recipient that something has already been decided and does not actively invite an interactional response and, therefore, makes resistance or negation more difficult. This format conveys (claims) a speaker’s authority over the decision. In contrast, a participatory or bilateral format (e.g. ‘what are your thoughts about . . .’) actively encourages recipient involvement in the decision. Of course, recipients may avoid the constraints of a turn, and other CA studies have shown the ways that patients can influence decision-making by, for example, resisting recommendations133–135 or by introducing their own agendas. 136–139 Taken together, these findings highlight the ways that health-care decisions are negotiated as joint social activities between service users and HCPs,140 as well as the subtle ways that agency may be enacted or constrained in interactions.

Conversation analytic studies in the context of labour and birth

In the main, CA studies of decision-making have focused on consultations between HCPs and patients in a range of primary and secondary care settings, that is, contexts in which decision-making is chiefly concerned with events or procedures that will likely be enacted outside the consultation (e.g. treatment, testing or referral decisions). Exceptions include analyses of surgical practice141 and physiotherapy sessions,142 and performing obstetric ultrasound scans. 143 In the context of maternity care, CA studies have examined antenatal appointments144–147 and genetic counselling,13,148,149 as well as calls to a homebirth helpline. 150,151 Very few studies have examined interactional practices of situated decision-making in the fast-moving, time-limited context of childbirth. There are three exceptions (all based in obstetric-led care): Jordan125,152 and Bergstrom et al. ,153,154 which both focus on the (transition to) second stage of labour, and our own pilot study155 conducted on analyses of extracts from the British television show One Born Every Minute (OBEM) (Dragonfly, London, UK). 155

Jordan152 (recorded in the USA in the mid to late 1980s) focuses on the ways that a labouring woman’s embodied knowledge and expertise is subjugated to the doctor’s technical expertise, such that she has to wait for his assessment of her cervix before being permitted to push. For example, as she waits for the doctor to come, a nurse instructs the woman to resist what her body is telling her to do, saying, for example, ‘It won’t be long. It’ll feel better for you to push. But in the meantime, I don’t want you to, okay?’. 152 When the doctor does the examination, he announces his verdict to the nurse (‘she can push’152) and the nurse speaks to the labouring woman (‘you can push’152). Bergstrom et al. 154 extended findings about the interactional realisation of an apparent ‘don’t push’ rule that applies until there has been some objective assessment of the readiness of the cervix. This study was based on analyses of three (of 23) video-recordings of the second stage of labour (including the one analysed by Jordan) in which the camera just happened to be switched on before second stage had been officially declared. In a different report on the whole data set of 23 recordings, Bergstrom et al. 153 describe the sequential structure of conducting VEs and suggest that these are accomplished as a ‘ritual’ that transforms an intimate act into a socially acceptable act.

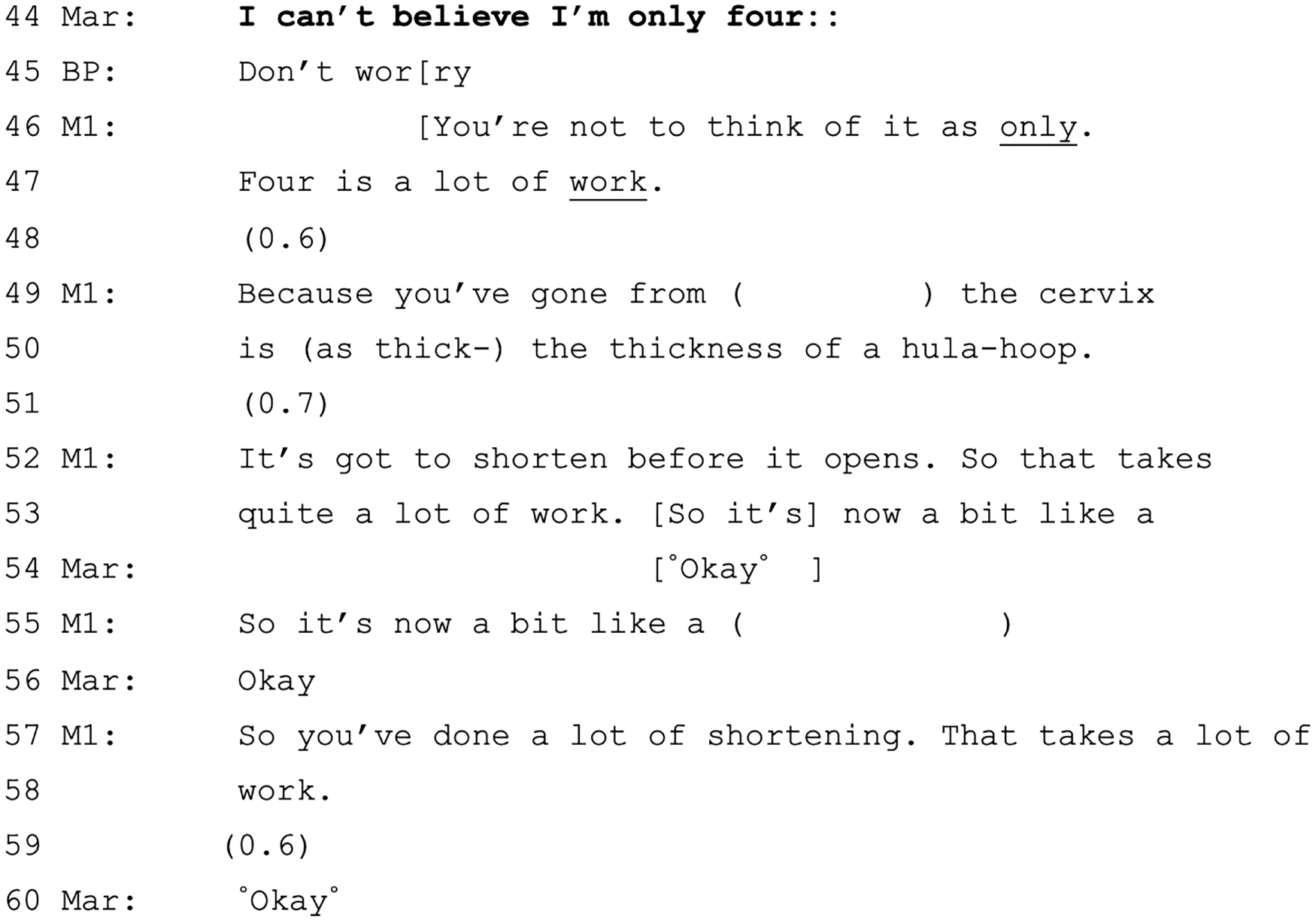

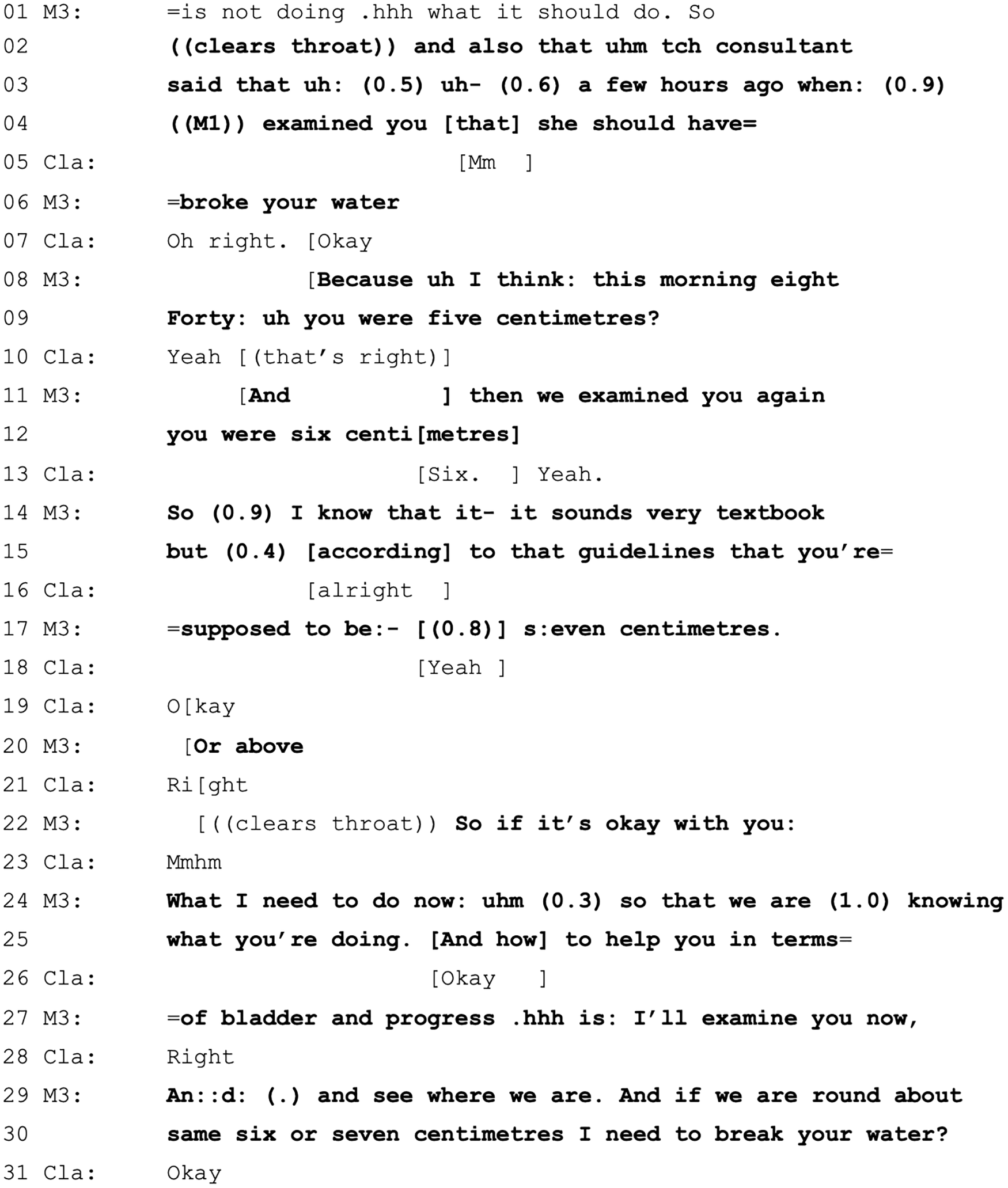

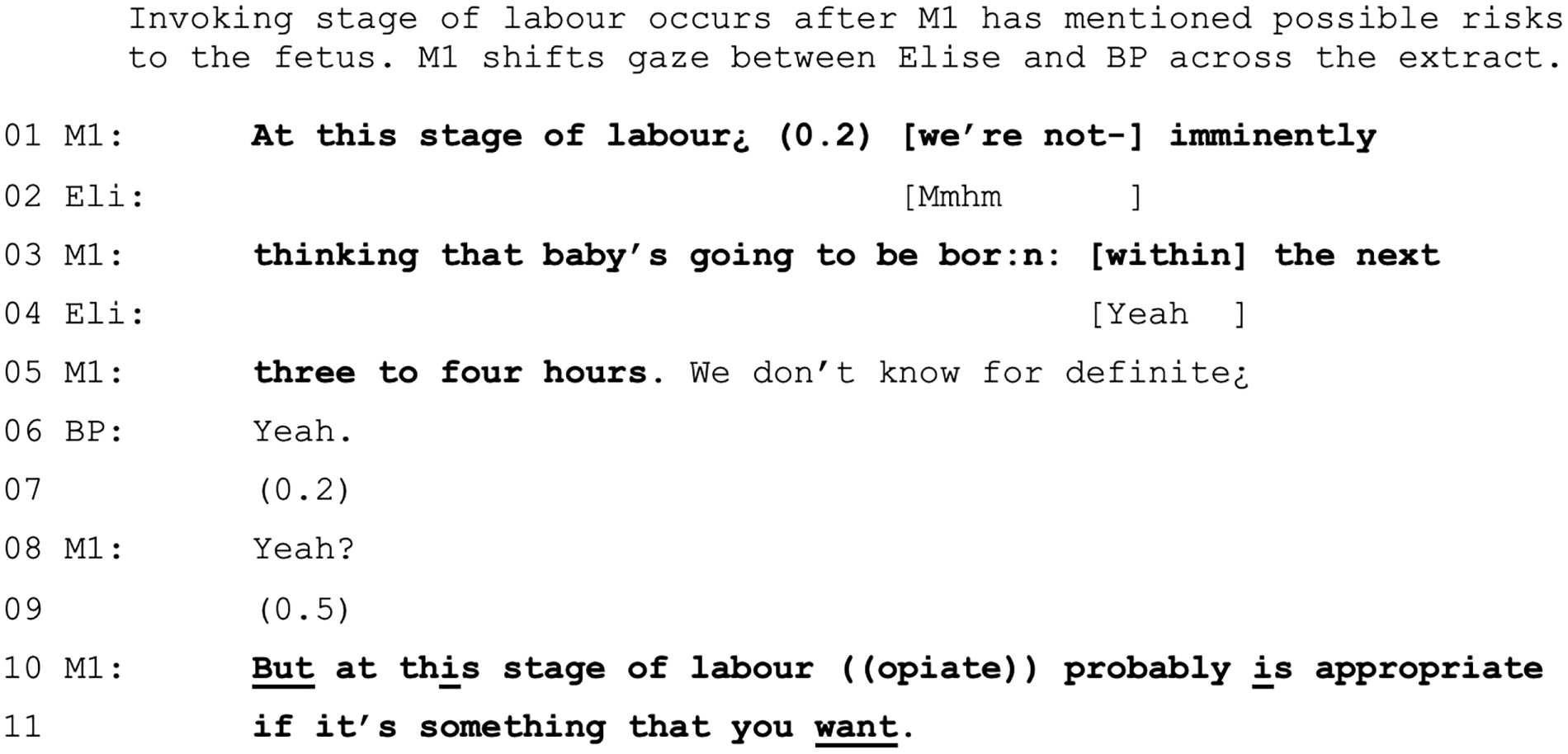

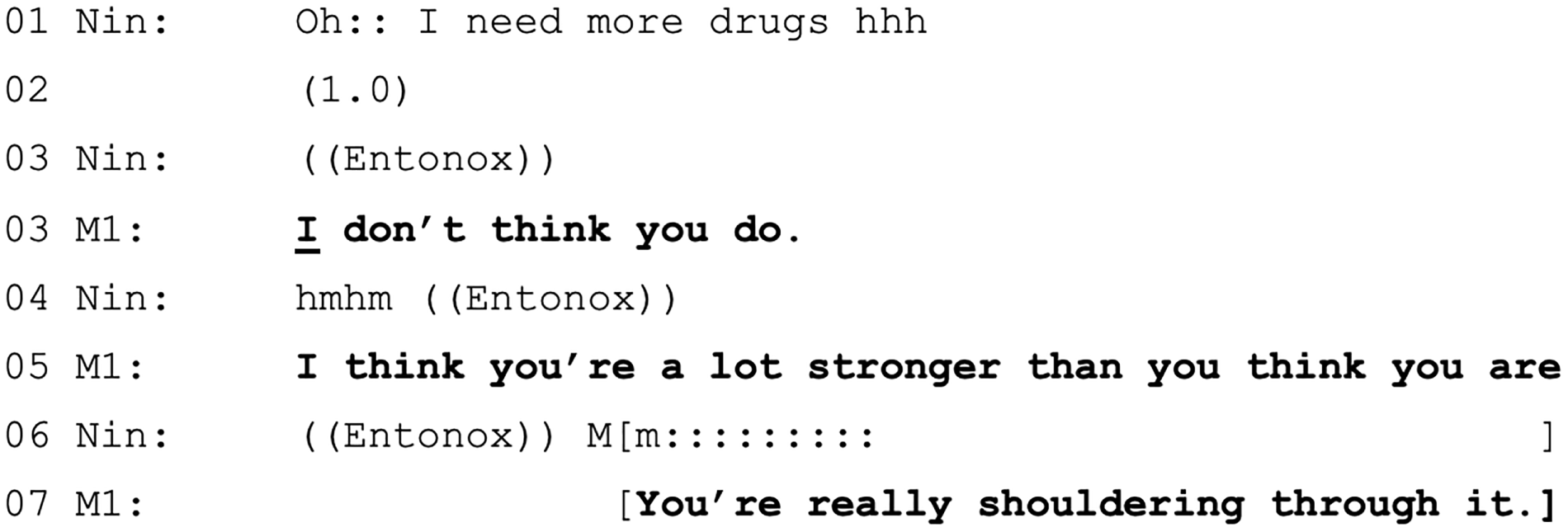

More recently, in preparation for the current project, we conducted a pilot study of decision-making in labour based on data from the television programme OBEM (an observational documentary series shown in the UK on Channel 4). We transcribed, in detail, the interactions between HCPs, women and BPs for 26 births taken from the first three series (broadcast between 2010 and 2012). We considered a spectrum of decisions, including investigative/monitoring activities (e.g. VEs and fetal monitoring), pain management decisions and decisions for assisted or surgical deliveries. HCPs used a range of interactional practices that varied the ‘optionality’ afforded to the participant in the responding turn. For example, there were omissions (e.g. implementing a decision without discussion), directive pronouncements (e.g. ‘you need to . . .’ and ‘we are going to . . .’), propositional constructions (e.g. ‘do you want to do . . . ?’ and ‘why don’t you . . . ?’) and open questions (e.g. ‘what is your plan for pain relief?’). Two phrases were routinely deployed: ‘we need to . . . ’ and ‘we’re going to . . . ’. These assertive formulations were used in both situations of risk [e.g. ‘Uhm. We will need to take you (down) to theatre to deliver the baby. Baby doesn’t like this after you’ve pushed’] and in routine activities [e.g. ‘Now what I need to do uhm (2.5) find out how dilated you are’]. Overwhelmingly, women agreed to these decisions; however, when they did not, it was interactionally effortful for them to decline.

The OBEM data afforded fascinating insight into interactional practices for managing and negotiating decision-making during birth and provided good grounds for conducting this type of research. However, these data were not ideal for conversation analytic purposes because they are heavily edited to be produced as a 1-hour television programme. Therefore, our findings were based on a less than optimum data set for these purposes and could not represent the range of decision-making practices used either across the specific births shown or across the labour wards that were filmed. Therefore, we needed to produce a bespoke data set based on unedited recordings of the birthing event as it happens to more completely track nuanced interactions as they occur across the (perhaps many) hours of labour. It is this novel data set that forms the basis of the current report.

Inductive coding of interactional data based on conversation analysis

As outlined above, qualitative analysis, using CA, is at the heart of our analyses and enables us to explore how talk is used (by all parties) to encourage or discourage involvement in decision-making over the course and events of a birth (study objective 2). However, as interactional practices are definable and can be categorised in clear ways,156,157 it is also possible to design and apply a coding frame to quantify the interactional practices that take place during labour and birth. Nonetheless, extensive inductive conversation analytic work is first necessary to ensure that quantitative coding is thoroughly underpinned by observed nuanced interactional realities. This means that influential and effective coding systems, such as the Roter Interaction Analysis System,158 are not suitable for our purposes because, although they can be used flexibly, they ultimately rely on application of pre-established categories.

The reward of combining conversation analytic work with quantitative coding is that it permits exploration of distributional159 and comparative156 research questions (for illustrative studies, see Robinson and Heritage160). Examples of both distributive and comparative research of this kind are illustrated in a recent NIHR-funded study of decision-making in neurology consultations reported by Reuber et al. 161 Using CA, the authors had previously identified HCP practices for constructing a decision as a choice (or not) for patients. 162 In their follow-up study, Reuber et al. 161 developed a novel coding scheme (on which ours is modelled; see Chapter 2, Quantitative coding and analysis of interactional data) to facilitate extensive and nuanced coding of instances of HCPs’ use of recommendations, option lists (i.e. when HCPs provide a menu of options from which patients might select) and what they called ‘patient-view elicitors’ (PVEs) (i.e. a range of HCP turn designs that invite patients to express a preference). The coding scheme captured the qualitative data relating to how turns were initiated and responded to, as well as any follow-up discussions in pursuit of a decision. These internal-to-consultations data were next combined with data collected external to the consultation (via questionnaire), such as patient satisfaction and perception of whether or not choice had been offered. The final combined data set facilitated both distributional and comparative analyses. For example, the three focal practices (recommendations, option lists and PVEs) were not evenly distributed, with recommendations being the most common approach to decision-making overall. Furthermore, the frequency with which each practice was employed depended on the type of decision being made. Decisions relating to investigations and tests tended to involve recommendations, whereas treatment and referral decisions were relatively more likely to include option lists and PVEs. In comparing the consequences of the three practices, one striking finding was that recommendations consistently led to agreement with a proposed course of action, whereas PVEs were more likely to lead to rejection and option lists to postponement of a decision.

An important implication of Reuber et al. ’s161 findings (discoverable primarily from the distinctive methodological approach) is that the guidelines concerning patient choice are not routinely being enacted (at least in the context of neurology). Moreover, the tendency to accept recommended courses of action (as opposed to those offered as optional or as dependent on patient preference) sets up a possible conflict between what might be seen as a duty of care and a responsibility to provide patient choice. When the HCP has compelling clinical grounds for favouring a particular course of action, a recommendation is more likely than either of the choice-implicative formats to achieve acceptance. Therefore, previous work suggests that patient choice tends to be reserved for decisions for which clinical outcomes may be less contingent on patient preference.

In the present study, the quantitative coding of interactions enabled us to explore (1) the extent and distribution of different practices (objective 2) and (2) relationships between these practices and women’s postnatally reported levels of satisfaction with their experiences (objective 3). This analysis builds on Reuber et al. ’s projects,161,162 but with important adaptations to include decisions initiated by women and their BPs. In the context of labour and birth, with long-standing debate about the empowerment of maternity service users, we did not think it was appropriate to exclude analyses of the decisions that they might initiate.

Much existing research about decision-making in the intrapartum period excludes BPs (for related exceptions, see Hildingsson163 and Thies-Lagergren and Johansson164). There are understandable reasons for this, given that people in labour and their HCPs are the ratified decisional parties (except in certain critical situations in which the person is unable to consent for themselves and their BP is also their next of kin). However, as we showed in our analysis of data from OBEM,155 BPs do participate in decisional discussions and their role should not be neglected. 165

As a consequence of including analyses of decisions initiated by HCPs, labouring people and their BPs, in comparison with Reuber et al. ,161 we identified a broader range of initiating formats in relation to a broader range of decision types. This is not surprising given the very different context for the research. The extensive nature of our data and findings (which also includes data from interviews and surveys) cannot be easily summarised in a single report. We have necessarily had to compromise on the depth and breadth of what it is possible to include and have chosen to focus on key areas of decision-making during labour and birth. Through our analysis of these key areas, we illustrate the full range of interactions that were observed.

Unpacking ‘satisfaction’

As already highlighted at various points, previous studies have indicated that women’s perceptions of their involvement in decision-making are associated with postnatal satisfaction. A key objective of this study is to understand this relationship more precisely by exploring whether or not there are associations between women’s reported levels of postnatal satisfaction and the ways that decision-making actually unfolds through interaction (as explored by our inductive coding of the interactional data). In this way, we aim to determine whether or not satisfaction is related to definable aspects of practice in the MLU.

Conceptualising satisfaction

Satisfaction is a deceptively simple concept, but attempts to measure it are complex, multidimensional and often poorly defined. 1,119,166 In discussion of how satisfaction should be conceptualised, two approaches dominate:166–168 (1) the fulfilment approach, which sees satisfaction as determined by the outcome of the experience (e.g. a healthy baby), and (2) the discrepancy approach, which treats satisfaction as arising from (in)congruity between what was expected and what actually happened. 1,169 The latter approach was used by Christiaens and Bracke1 and is summarised as follows:

Satisfaction is a state of mind reflecting the evaluation of the birth experience as a whole compared to several antenatal values and expectations. If expectations are met, the corresponding values and beliefs are affirmed. If not, conflicts arise, which may bring about distress.

Christiaens and Bracke1

In the present study, we also take the discrepancy approach, collecting data about our participants’ expectations antenatally (at 35 weeks) and asking them whether or not they were met postnatally (at 6 weeks). These data will be related to measures of satisfaction related to aspects of their care (i.e. being listened to by staff, views taken into account and the decisions made). Uniquely, we are also able to relate satisfaction to what happens in decision-making during labour.

Structure of the rest of the report

Chapter 2 describes our methods and analytic approaches. Chapter 3 presents key findings from the questionnaires and the coded interactional data to address research objective 3. Thereafter, analytic chapters address research objectives 1 and 2 by exploring decision-making in four common specific contexts: fetal monitoring (see Chapter 4), progress (see Chapter 5), pain relief (see Chapter 6) and third-stage decisions (see Chapter 7). Finally, Chapter 8 presents our conclusions, discusses the implications of our findings and suggests avenues of future research.

Chapter 2 Methodology

Introduction

The principal focus of the study was CA and subsequent coding of recordings of labour and birth, with additional methods (i.e. questionnaires and interviews) being used to supplement this analysis and address our research objectives. Through these mixed methods, we explored decision-making during labour and birth in MLUs at two English NHS trusts.

Recordings of labour and birth

Recordings of labour and birth were analysed using two approaches. First we adopted a qualitative approach, using CA to explore how decision-making takes place. The focus of the CA was on how talk was used (by all parties) to encourage or discourage women’s involvement in decision-making over the course and events of labour and birth. Second, quantitative codings of the recordings of labour and birth were analysed. Each recording was coded to quantify the number of types of interaction that took place during decision-making (i.e. how decisions were initiated, who initiated them and how different ways of initiating decisions were responded to). The coding frame was derived inductively from the qualitative CA.

Antenatal and postnatal questionnaires

Antenatal questionnaires and PNQs surveyed women’s expectations, experiences and satisfaction with labour and birth. These questionnaires made it possible to compare women’s antenatal expectations with what actually happened during labour, as captured by the recordings and as reported by women. In combination with the quantitative coding of the recordings of labour and birth, the PNQ was also used to determine whether or not there is an association between interactional strategies used during labour and women’s postnatally reported level of satisfaction.

Semistructured interviews with midwives and obstetricians

Semistructured interviews with midwives and obstetricians were conducted at each research site and analysed using thematic analysis. These interviews (1) supported local study implementation (by exploring perceptions of recording feasibility) and (2) explored HCPs’ perceptions of factors that facilitate, or constrain, women’s involvement in decision-making during labour.

Owing to the innovative nature of the study, concerns were expressed by colleagues, reviewers and service user groups (SUGs) about its feasibility. These concerns included whether or not women and HCPs would agree to the recording of labours and births and whether or not it would be possible to generate high-quality recordings suitable for CA. Key to addressing and overcoming these concerns was an extensive period of planning and service user consultation (see Patient and public involvement). Critical ethics issues resolved through this planning process included:

-

concerns about the intimate nature of the recordings and ensuring that those in labour had control over, and felt comfortable with, this process

-

managing the sensitivities of initial approach and follow-up during the period of participation (i.e. from 20-week scan to 6 weeks post partum) because of the potential for miscarriage, stillbirth or neonatal death to occur within this time frame

-

managing consent for recordings involving multiple participants

-

navigating HCPs’ concerns about the potential use of recordings in litigation.

These issues were addressed through our recruitment and consent procedures, which we outline in this chapter. Given the sensitive nature of the data, participant anonymity is paramount. Accordingly, all participants and study sites have been given pseudonyms throughout this report.

Ethics approval was granted by the National Research Ethics Service Committee for Yorkshire and the Humber (South Yorkshire) following a meeting on 23 March 2017. Approval was confirmed by the University of York Economics, Law, Management, Politics and Sociology Research Ethics Committee. The protocol underwent Health Research Authority-approved substantial and non-substantial amendments (see Pregnant people) to produce the final methodology reported in this chapter. The study was accepted as part of the NIHR’s Clinical Research Network Portfolio of studies (and received a ‘green’ red-amber-green rating for recruitment).

Given concerns about feasibility, the study was designed with a 12-month pilot phase, with review points at 4 and 12 months. Owing to a delay in the start of recruitment (waiting for all research and development approvals to be in place at trust level), the final review point for the pilot was moved from 12 months (February 2018) to 16 months (June 2018). At the end of this 16-month period, feasibility had been established and the study was approved by NIHR to progress to the main phase.

In what follows, we provide an overview of our two study sites, moving on to describe the data collection and analytic procedures for each of the three forms of data source (i.e. recordings of labour, questionnaires and interviews) described above. We conclude the chapter by reflecting on the role of patient and public involvement (PPI) in the study, and how this positively shaped the design and conduct of our research.

The study sites

There are four settings for labour and birth in the English NHS: (1) home, (2) freestanding midwifery units, (3) alongside midwifery units and (4) obstetric units (OUs). ‘Freestanding midwifery units’ are at a geographical distance from an OU and, therefore, vehicle transfer is required if complications arise during labour. The more common ‘alongside midwifery units’ provide midwife-led care in a setting adjacent to, or in the same building as, an OU. 52

We collected data in alongside MLUs at two NHS trusts in England between April 2018 and October 2019. Sites were selected to enable access to a population of participants diverse in ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES). Site A is a very large, purpose-built unit that includes an OU and an alongside MLU. This MLU is adjacent to the OU and, therefore, depending on the clinical scenario, doctors may attend the unit when called on. In 2020, approximately 6200 babies were born at site A (OU and MLU figures combined). Site B contains a medium-sized alongside MLU, which is located on a separate floor to the OU. Doctors do not attend to women on this unit (except in certain emergency situations) and, instead, women who develop complications are transferred to the OU. In 2020, approximately 4500 babies were born at site B (OU and MLU figures combined).

Rather than conducting a comparative analysis of practice, our aim in selecting MLUs A and B was to include examples of midwife-led care from two units considered sufficiently similar that major differences in interactional practices of decision–making would not be expected. These similarities were confirmed through the HCP interviews and recordings of labour. Semistructured interviews explored HCPs’ perceptions of the factors that shape decision-making, enabling us to consider the impact of potential organisational differences between MLUs A and B (e.g. site-specific practices; see Semistructured interviews with health-care practitioners). These interviews revealed no differences in accounts of the factors that shape decision-making and, indeed, pointed to the shared set of professional resources (national clinical guidelines) that govern practice in this context. Similarities were further verified through our CA and coding of interactional practices during labour and birth, and the analytic patterns identified were observed at both sites. On this basis, the data gathered at both sites were pooled for the purpose of analysis and analytic generalisation. 170

Recordings of labour and birth

The recordings of labour and birth enabled us to study real-time interactions. Recordings took place in the MLUs only and were stopped if women were transferred to another location for obstetric-led care (women were informed of this possibility on the information sheet).

Data collection

There were three groups of participants for each recording: (1) individuals (aged ≥ 16 years) with a healthy singleton pregnancy expected to labour spontaneously and give birth vaginally at term, (2) their BPs and (3) HCPs (i.e. clinical staff at each site). Although we did not ask participants about their gender identity, those recorded all had names conventionally assigned to females and were gendered as women (and accepted this gendering) during interactions with BPs and midwives. Accordingly, each woman was given a ‘female name’ pseudonym (see Appendix 1). These pseudonyms were selected on the basis that no other consented participant shared this name and that it had the same number of syllables as the original name (which is important to retain for CA purposes). Birth partners are referred to as ‘BP’ plus numbers (e.g. BP1) in the order of their appearance in the recordings. HCPs who were recorded were given pseudonyms based on their professional role and order of appearance in recordings (e.g. M1, M2, Doc1 and Doc2). As the number of male midwives at each site is very small, we refer interchangeably to all midwives in our analysis as female or using the gender-neutral ‘they/them’ to preserve anonymity.

All participants were informed that only the research team would see the un-anonymised footage, and each participant was given the option of choosing in what form the anonymised data could be shared publicly (i.e. as an anonymous transcript, as anonymised video clips, as anonymised audio clips and/or as anonymised photographs). When participants in the same recording selected conflicting ‘levels’ of consent, anonymity was prioritised and the option providing the highest level of anonymity was adhered to. For example, if one participant agreed that anonymised transcripts, photographs and video clips could be shared, but another only agreed to transcripts, then only the anonymised transcripts would be shown publicly. Below we describe the data collection procedures for each group of participants involved in the recordings and provide an overview of the recordings collected.

Pregnant people

Recruitment

Research midwives screened and approached eligible pregnant people to provide details of the study at the 20-week scan appointment (after the scan had been completed, at which point it was felt that they would be less anxious) or at antenatal appointments thereafter. Pregnant people also had the option of self-referring into the study at any point after their 20-week scan appointment, for example by responding to study information on posters (see Appendix 2). The information provided addressed all three aspects of the study in which people were being invited to participate, namely the recording of labour and the two questionnaires (i.e. the ANQ and the PNQ). It made clear that whether or not recording ultimately took place was dependent on a number of contingent circumstances (e.g. availability of equipment and staff agreement).

Those people who were certain that they wanted to participate following the research midwife’s initial approach had the option of providing consent then and there. Alternatively, the research midwife followed up those people who expressed interest in the study with a telephone call and arranged to take consent face to face in their home (or other location of their choosing), remotely via Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) or telephone, or at another antenatal appointment. Consent was reconfirmed verbally on arrival in labour. Women in labour were instructed to identify themselves as a study participant when they contacted the MLU and both MLUs also used systems to flag up study participation on patient records.

There were no existing data available from the trusts on which to base estimates of recruitment figures (i.e. how many women would have to be recruited into the study to achieve the original study target of 50 recordings of labour and birth). The rationale for a sample size of 50 women, as specified in the study protocol, was to allow for a diverse range of participants to take part while producing data that would be manageable for the conversation analytic work. Assuming a 60% conversion rate from consented women into recorded labours, we had anticipated that we would need to recruit 85 women to the study. However, in the initial months of the pilot phase, it became clear that we would have to revise these targets because the conversion rate proved much lower than anticipated (closer to 20%). Therefore, we gained NIHR and Health Research Authority approval for the following:

-

To lower the target number of recordings to a target number of 20–30 on the basis of advice from experts in CA who confirmed that this would remain a powerful qualitative sample for the purpose of our research objectives. This change was approved by our Study Steering Committee.

-

To recruit a larger number of participants than originally anticipated (estimated n = 150) to achieve this target.

-

To extend the study recruitment period.

-

To increase the points of potential recruitment into the study by enabling pregnant people to be recruited at any antenatal care appointment after the 20-week scan appointment and/or to self-refer into the study. The original protocol described recruitment only at the 20-week scan appointment and up to 35 weeks of pregnancy.

Characteristics of the recorded sample of women

The study successfully recruited and consented 154 women (site A, n = 111; site B, n = 43), producing 37 recordings for analysis. From the outset, given their different patient populations, it was not anticipated that the two sites would recruit equal numbers.

Table 1 shows that only 24% of the consented women went on to be recorded. This figure includes women who were admitted to the MLU but who were later transferred to the OU (in which case only the MLU part of their labour was recorded). A further 18% of consented women laboured/gave birth in the MLU but were not recorded. This occurred for a number of reasons, including insufficient time to set up the camera before starting care because women were in advanced labour on admission (n = 8), the fact that no midwife who had consented to the study was on duty (n = 8), user error in setting up the camera (n = 7) and other reasons that could not be determined (n = 5). Nearly half (49%) of the sample of consented women (all of whom were anticipating labouring and giving birth in the MLU) were not admitted to the MLU at any point and, therefore, were not recorded. This is higher than reported in the NHS Patient Survey Programme’s 2019 Survey of Women’s Experience of Maternity Care,113 which found that 22% of those planning to labour and birth in a MLU, instead, entered an OU. In the present study, this occurred for a range of clinical reasons during pregnancy or at the point of admission, which made women ineligible for midwife-led care. Finally, there was a small group (13%) of women who did not enter the MLU for other reasons, for example because no birthing room was available on the MLU or because they had moved to another area or had withdrawn from the study after initially consenting (applying to only five women). Notably, all withdrawals of consent occurred prior to labour commencing and there were no instances where a woman withdrew her consent following recording.

| Site | Labour/birth in MLU, n (%) | Labour/birth took place in OU: not recorded, n (%) | Other: not recorded, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recorded | Not recorded | ||||

| A | 30 (27) | 19 (17) | 52 (47) | 10 (9) | 111 (100) |

| B | 7 (16) | 9 (21) | 24 (56) | 3 (7) | 43 (100) |

| Total | 37 (24) | 28 (18) | 76 (49) | 13 (9) | 154 (100) |

In summary, contrary to concerns expressed by reviewers and commentators that people would not want to have their labours recorded, people were willing to take part. The key challenge concerned the high proportion of people who, although intending to give birth in the MLU, became ineligible to do so because they developed complications in pregnancy or on admission that meant that it was recommended that they give birth on the OU.

We aimed to recruit as diverse as possible a sample of women by SES and ethnicity. SES was measured using the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD),171 an area-based measure of relative deprivation based on household postcode (see Appendix 3 for details of the IMD). The IMD ranks areas in deciles from 1 (most deprived) to 10 (least deprived). Our respondents fell in all deprivation deciles, indicating some level of diversity, but a mean score of 6.30 and skewness of –0.89 indicates that there was a larger percentage of participants from least deprived areas. The sample was overwhelmingly white, with 97% of participants identifying as such. The proportions of women of different ethnicities who were approached by the research midwives were broadly similar to the proportions of women of different ethnicities who gave birth at each trust during the study recruitment period (see Appendix 4 for ethnicity figures, although note that these figures cannot be directly compared, as the numbers are calculated at trust level only and incorporate women who birthed in OUs as well as MLUs). The predominantly white make-up of the recorded sample (see Chapter 3) seems primarily explained by the comparatively smaller potential recruitment pool of ethnic minority women and that, in general, members of these groups who were approached were less likely to give their consent to participate in the study. We reflect on the implications of this as a study limitation in the discussion (see Chapter 8, Limitations).

Comparison of recorded and non-recorded samples

As explained, all of the women who consented to the study were intending to give birth in MLUs. Likelihood ratio chi-squared and Mann–Whitney U-tests were conducted, as appropriate, to explore if there were significant differences between the recorded (n = 37) and non-recorded samples (n = 87 or fewer). The demographic and satisfaction information are derived from ANQ and PNQ responses and, therefore, total numbers do not always add up to 154 due to full or partial missing data in participants’ ANQ and/or PNQ responses (see Questionnaires for more information on ANQ and PNQ data collection and the satisfaction variables).

Tables 2–5 show that there were no significant differences between the recorded and non-recorded samples in terms of ethnicity, parity, SES or any of the aspects of satisfaction. This provides evidence that the two samples are, to a large extent, equivalent. It should be remembered that, although the recorded sample of women all laboured for a period of time in the MLU, they did not necessarily give birth there (i.e. they may have been transferred to an OU). Therefore, these data should not be taken to represent relative satisfaction between women who received care in the MLU and those who received care elsewhere. Rather, theses data are presented here only to assess the characteristics of the recorded sample compared with the consented sample.

| Sample | Ethnicity, n (%) | Total, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Mixed/multiple ethnic group | Asian/Asian British | Black/African/Caribbean/black British | Other | ||

| Recorded | 36 (29.3) | 1 (0.8) | 37 (100.0) | |||

| Non-recorded | 80 (65.0) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (1.6) | 1 (0.8) | 86 (100.0) |

| Total | 116 (94.3) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (2.4) | 2 (1.6) | 1 (0.8) | 123 (100.0) |

| Sample | Parity, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First baby | Subsequent baby | ||

| Recorded | 22 (19.0) | 12 (10.3) | 34 (100.0) |

| Non-recorded | 55 (47.4) | 27 (23.3) | 82 (100.0) |

| Total | 77 (100.0) | 39 (100.0) | 116 (100.0) |

| Sample | n | Mean rank |

|---|---|---|

| Recorded | 37 | 60.19 |

| Non-recorded | 87 | 67.93 |

| Total | 124 |

| Question | n | Mean rank |

|---|---|---|

| How satisfied were you that you were listened to by staff?a | ||

| Recorded | 32 | 45.77 |

| Non-recorded | 62 | 50.84 |

| Total | 94 | |

| How satisfied were you that your views were taken into account by staff?b | ||

| Recorded | 32 | 49.59 |

| Non-recorded | 62 | 46.42 |

| Total | 94 | |

| How satisfied were you with the decisions that were made?c | ||

| Recorded | 31 | 52.61 |

| Non-recorded | 61 | 43.39 |

| Overall satisfactiond | ||

| Recorded | 31 | 50.81 |

| Non-recorded | 61 | 44.31 |

Birth partners

Birth partners received information at 20 weeks or thereafter (via women, who were asked to pass study information sheets to anyone likely to attend the birth). In instances in which it was not possible to obtain consent from a BP prior to labour (e.g. because a different person attended the birth than originally planned), MLU staff verbally confirmed consent for recording. MLU staff noted when a recording took place in a logbook and indicated if there was a need for research midwives to obtain retrospective written consent from the BP. If written consent was not given, or could not be determined (i.e. because of a lack of response), BP footage was edited out of the recording, and this was necessary in three recordings. A total of 158 BPs consented, of whom 43 featured in recordings.

Health-care practitioners

Health-care practitioners at both sites were briefed in writing and at meetings, and were given opportunities to provide written consent to opt in to the study. Anticipating that HCPs were likely to be concerned about the potential use of recordings in litigation (owing to high rates of litigation in this field of health care, leading to the UK’s most expensive clinical negligence claims172), we sought advice from the sponsor’s contracts manager and made clear the status of these data in our information sheets. Specifically, we informed participants that all research material, irrespective of its nature, could potentially be used if requested to corroborate a complaint and that, in these circumstances, it would not be possible to maintain confidentiality. In addition, participants were informed that in the highly unlikely event that poor practice was observed on the recordings, the research team would have an ethical and legal obligation to follow institutional procedures for reporting this. However, if care was given according to usual best practice standards, then accurate recording would be an advantage if care was to be questioned subsequently.

Project information posters were placed around both study locations to ensure that non-clinical staff (e.g. cleaners and administrators) were aware of the study. Recording signs were used to indicate if recording was in progress inside a room and these highlighted that no footage of staff would be used in the study unless written consent was given. Where staff who had not previously consented entered to provide care during labour, we contacted them subsequently to ask for their retrospective written consent. If consent was not given, then their footage was edited out of the recording. A total of 121 HCPs consented (site A, n = 104; site B, n = 17), of whom 74 were recorded.

Procedure for recording labour and birth

Each participating unit was provided with a mobile Smots™ camera (Scotia UK plc, Edinburgh, UK), a stand-alone recording device (independent of the research or health-care team once set up) that provides high-quality video-/audio-recordings in clinical settings. Data were recorded to a securely located bespoke encrypted laptop via a secure intranet connection, which was separate from the hospital intranet [and later uploaded to a military-grade password-protected hard drive, returned to the University of York (York, UK) and uploaded to its secure server].

Women and their BPs were advised in the consenting process that they could position the camera and could switch it on/off (or to request that others do so) at any point. In switching the camera off, our procedures prioritised the woman’s consent. Therefore, HCPs could not switch the camera off without the woman’s consent (unless there was a medical emergency) and BPs were encouraged to switch the camera off only with the woman’s consent whenever possible. Our preference was to capture video data to be able to observe non-verbal interactions; however, women had the option of choosing audio-only recording. Of the 37 recordings, 24 (65%) were video-recordings and 13 (35%) were audio-only recordings. Women were recorded ideally as soon as the first stage of labour was established until the end of the third stage of labour (i.e. after delivery of the placenta). In practice, some recordings began during the latent stage of labour and in several recordings the camera was switched off immediately after the baby was born, meaning that the third stage was not recorded. The total recorded time was 166 hours and 56 minutes (for further detail of recording parameters, see Appendix 5).

Data analysis of recordings

Recordings of labour and birth were analysed through two approaches. CA was used to develop an in-depth qualitative understanding of how decision-making is carried out during labour and birth. The insights developed from this analysis informed the development of a standardised coding scheme through which a quantitative coding of the interactional data was conducted.

Conversation analysis

In intrapartum care, midwives and women are engaged in a range of context-specific activities, such as discussing options for care and investigations. It is the analysis of how these activities are accomplished that formed the basis of our analyses. Therefore, we adopted an ‘action-based’ approach to understanding communication in care, derived from the micro-analytic tradition of CA. A fundamental CA insight is that talk is highly organised and that there is, as the founder of the approach Sacks173 suggests, ‘order at all points’. Therefore, talk is suitable for systematic analysis. CA focuses on participants’ objectively observable conduct, based on detailed analysis of actual interactions, and avoids claims about interactants’ internal (and unobservable) intentions, cognitions or desires.

Conversation analysis is predicated on the understanding that talk is used to perform social actions (i.e. to ‘do’ things). Of relevance here, actions might include offering (e.g. ‘would you like X’), requesting (e.g. ‘please can I have X’) and recommending (e.g. ‘I think we should give you some X’). However, a long-standing CA finding is that first actions (like those just illustrated) set up a relevant next action for recipients to respond,174–176 that is, actions are packaged in pair-related sequences, comprising a first pair part (from speaker A) and a second pair part (from speaker B), known as adjacency pairs. A request, for example, sets up a conditional responsive slot for a recipient to grant or decline. If the request is not followed by a relevant next turn, then the second pair part is relevantly missing and the adjacency pair is incomplete. 176

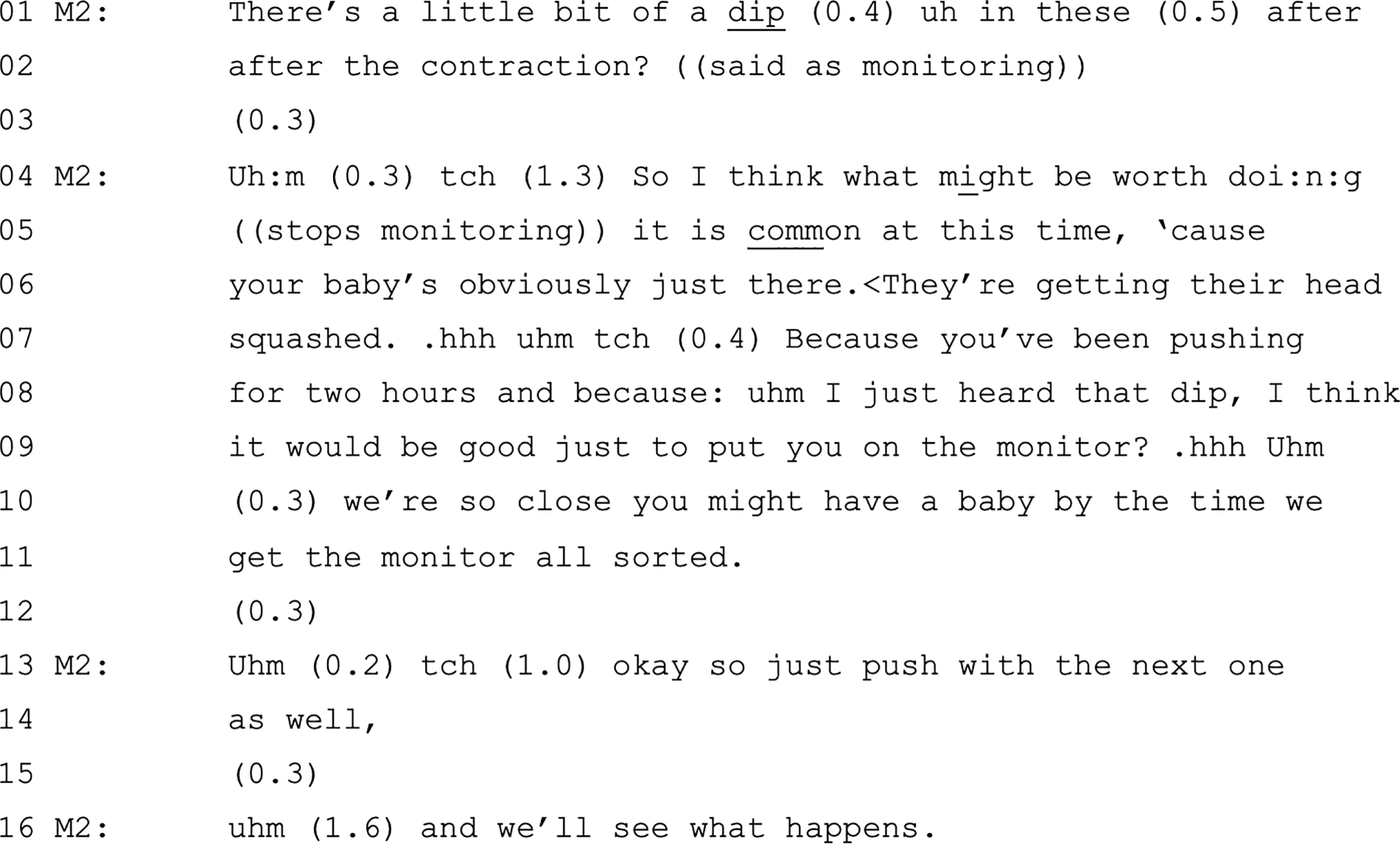

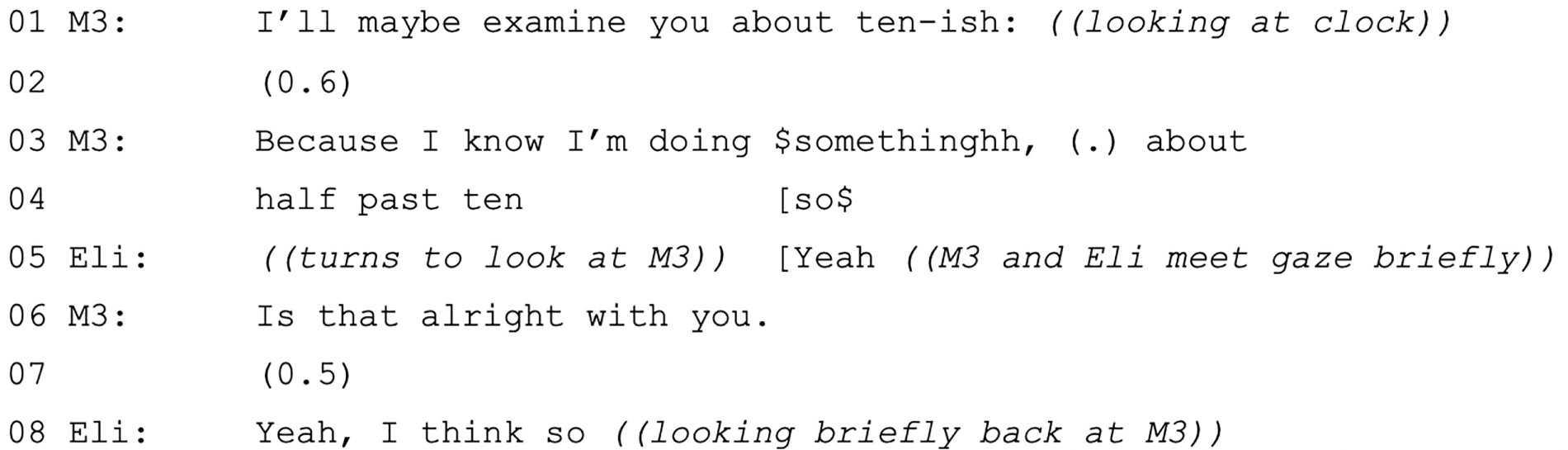

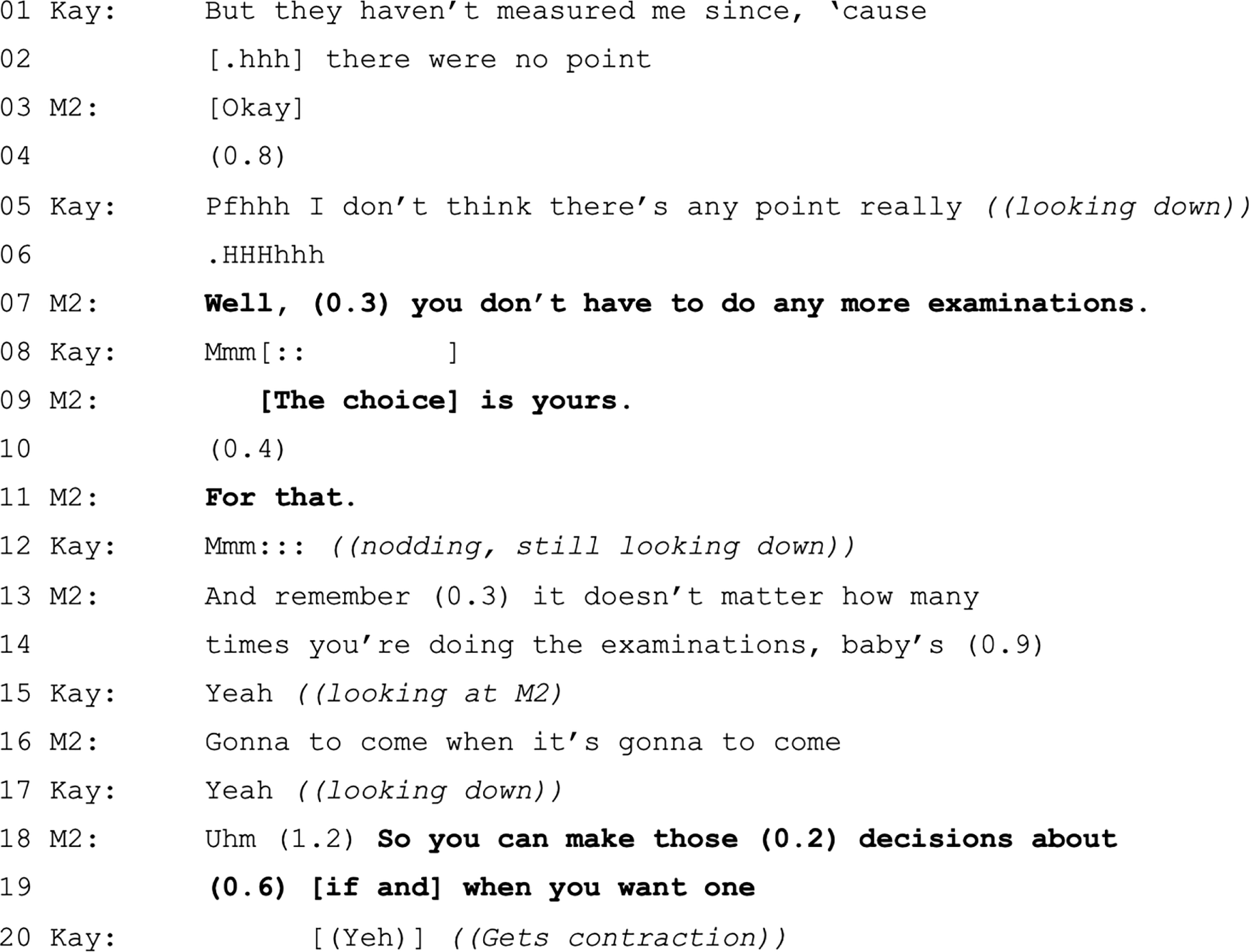

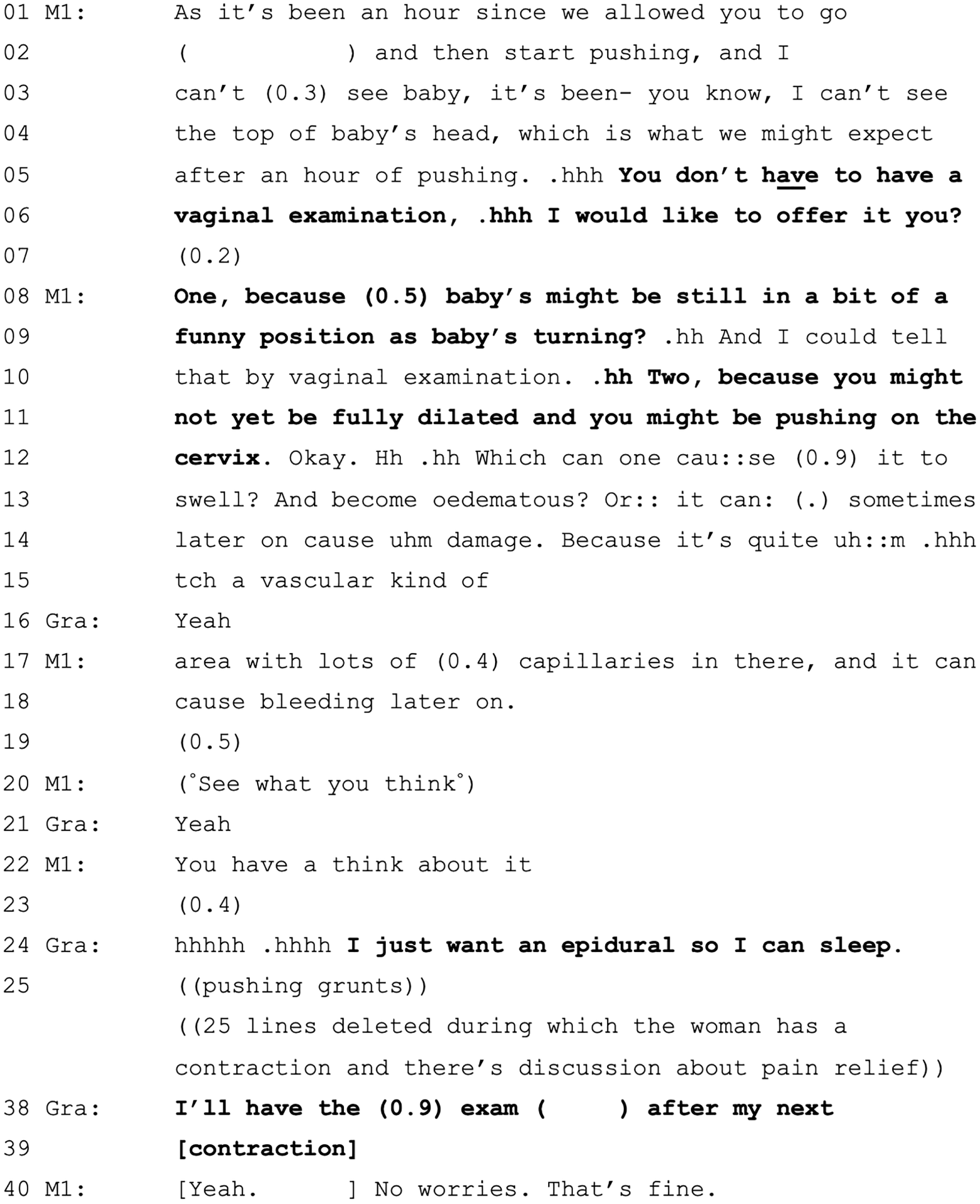

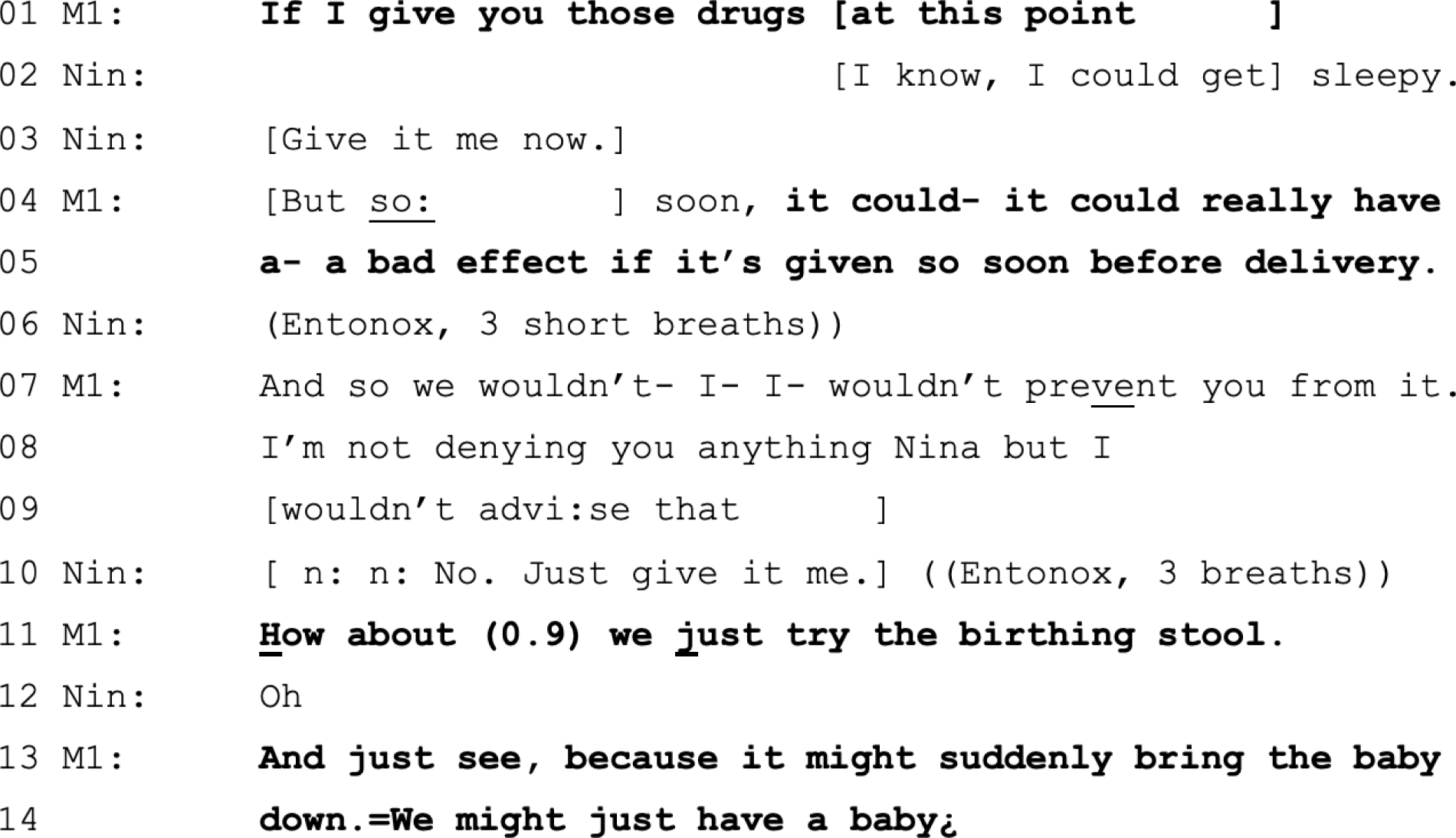

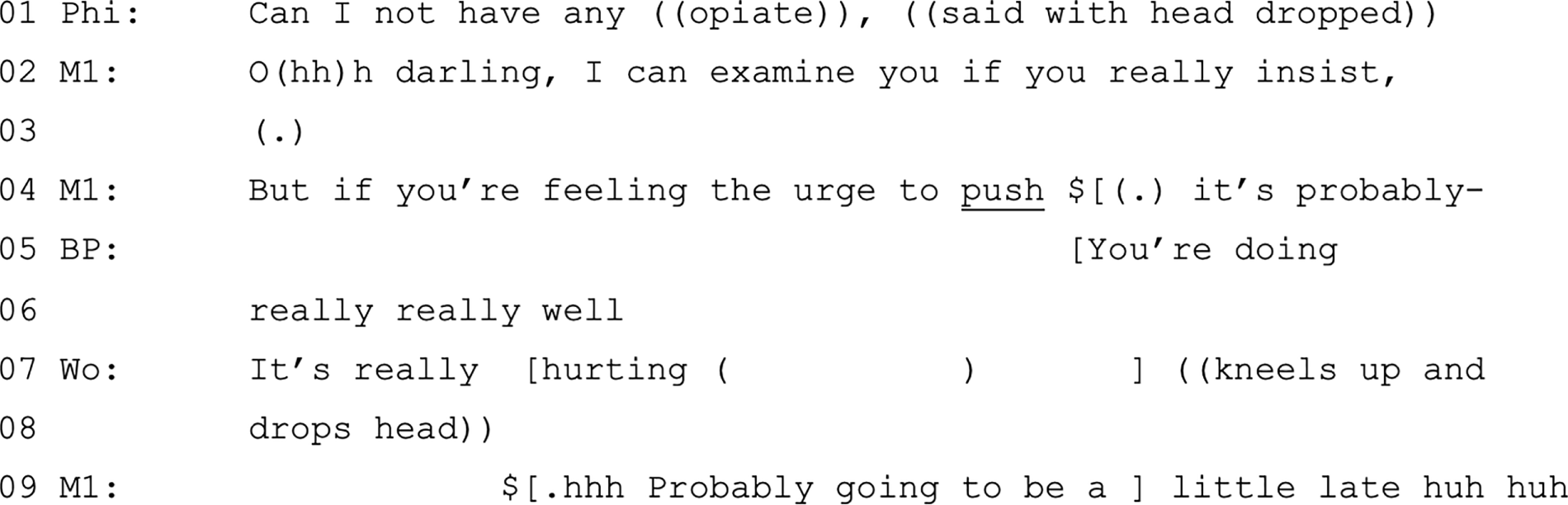

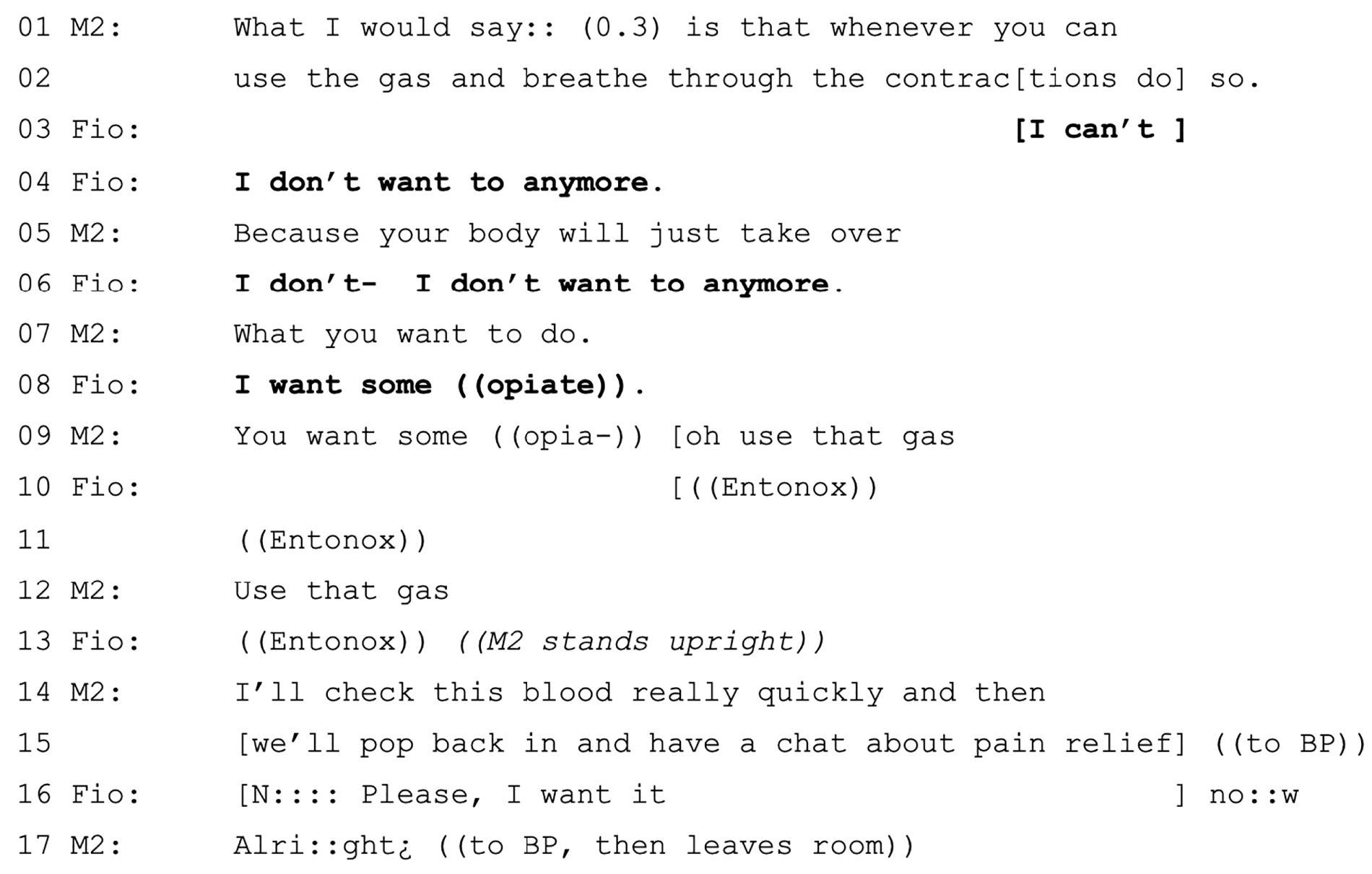

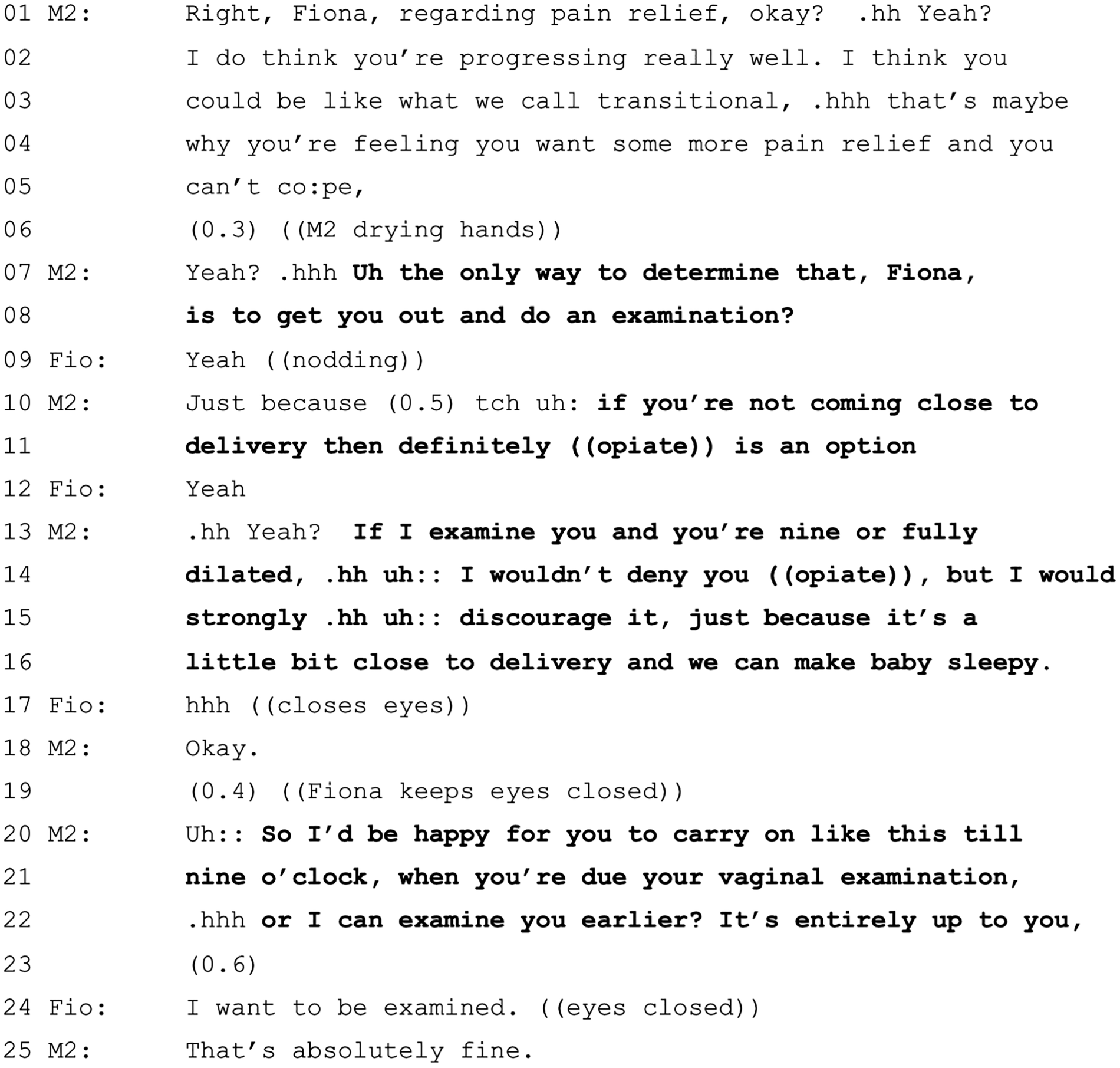

Therefore, the provision of a type-related second pair part is normative in that if it is missing then the speaker of the first pair part regularly pursues a relevant response. 176 Therefore, the basic two-part sequence might be expanded in various ways, as illustrated in Figure 1. In Figure 1 (which is just one way in which a request sequence might be expanded), we see that the recipient of the request remains silent after the first request and the first speaker then pursues a response by reissuing the request, which is again met with silence, prompting a second pursuit, to which the recipient does respond (here, declining the request).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic illustration of expanding a request sequence in talk.

Accordingly, turns at talk do not occur merely serially, but are structured by reference to one another, ‘in some before and after relationship’. 177 The organisation of adjacency pairs, however, does not imply that speakers have little option in selecting responses, as a range of relevant next actions is possible. 178,179 A request might, for instance, be relevantly followed by acceptance, declination or some form of hedge that defers the granting. Therefore, the production of any particular relevant response is always a selection by the respondent from alternatives. However, these alternatives are not equivalent, as some responses are ‘preferred’ over others. 178 Preference refers not to ‘personal, subjective, or “psychological” desires or dispositions’,178 but, instead, to a distinction between preferred responses that ‘forward’ the action of the initiating turn (e.g. granting a request) and dispreferred responses that ‘block’ it (e.g. declining a request), regardless of what the individual responding personally wants. 180 Put more simply, it is interactionally more straightforward to provide a preferred response.

Preference is oriented to in the grammatical and lexical design of turns and in their timing. Therefore, relative to preferred responses, which tend to be immediately and straightforwardly delivered by the respondent, dispreferred responses tend to be delayed, and contain markers of hesitation, as well as accounts for why the preferred response cannot be provided179 (e.g. in turning down a request, speakers do not ‘just say no’). 181 Speakers of initiating actions (i.e. talk) might also encode something of their expectation relating to the ease with which action might be progressed. For example, in making a request, a speaker might convey something about both their entitlement to ask and the burden that fulfilling the request might have for the recipient. 182 Therefore, modal requests (e.g. ‘can you . . . ’) display an entitlement to ask and an expectation of ease of granting, whereas ‘I wonder if . . . ’ displays low entitlement and some expectation that granting the request might be burdensome for the recipient. Recipients (and speakers generally) have agency in talk, but they are constrained by the way the initiating actions are formulated.

Therefore, doing CA requires paying systematic attention to the organisation of turns at talk, the relationship between turns, the ways that turns are designed to build the action they are producing, and how dimensions, such as entitlement and other contingencies, are conveyed and managed. As outlined in Chapter 1, CA in the context of health care has illustrated how talk can be organised in ways that either invite or discourage patient participation in decision-making. Our analysis focuses on illuminating these aspects of interaction in MLUs to facilitate an understanding of the extent to which decisions become jointly negotiated (or ‘shared’) and whether or nor they are initiated by particular participants in the interaction.

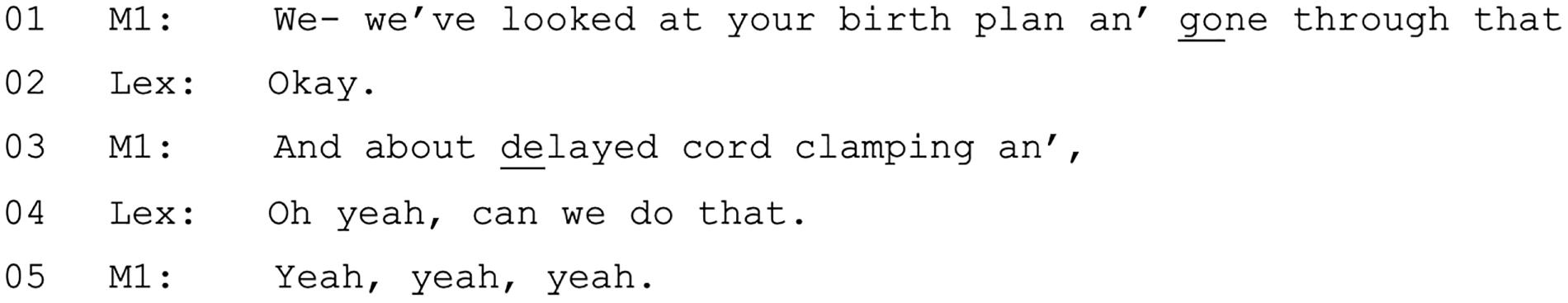

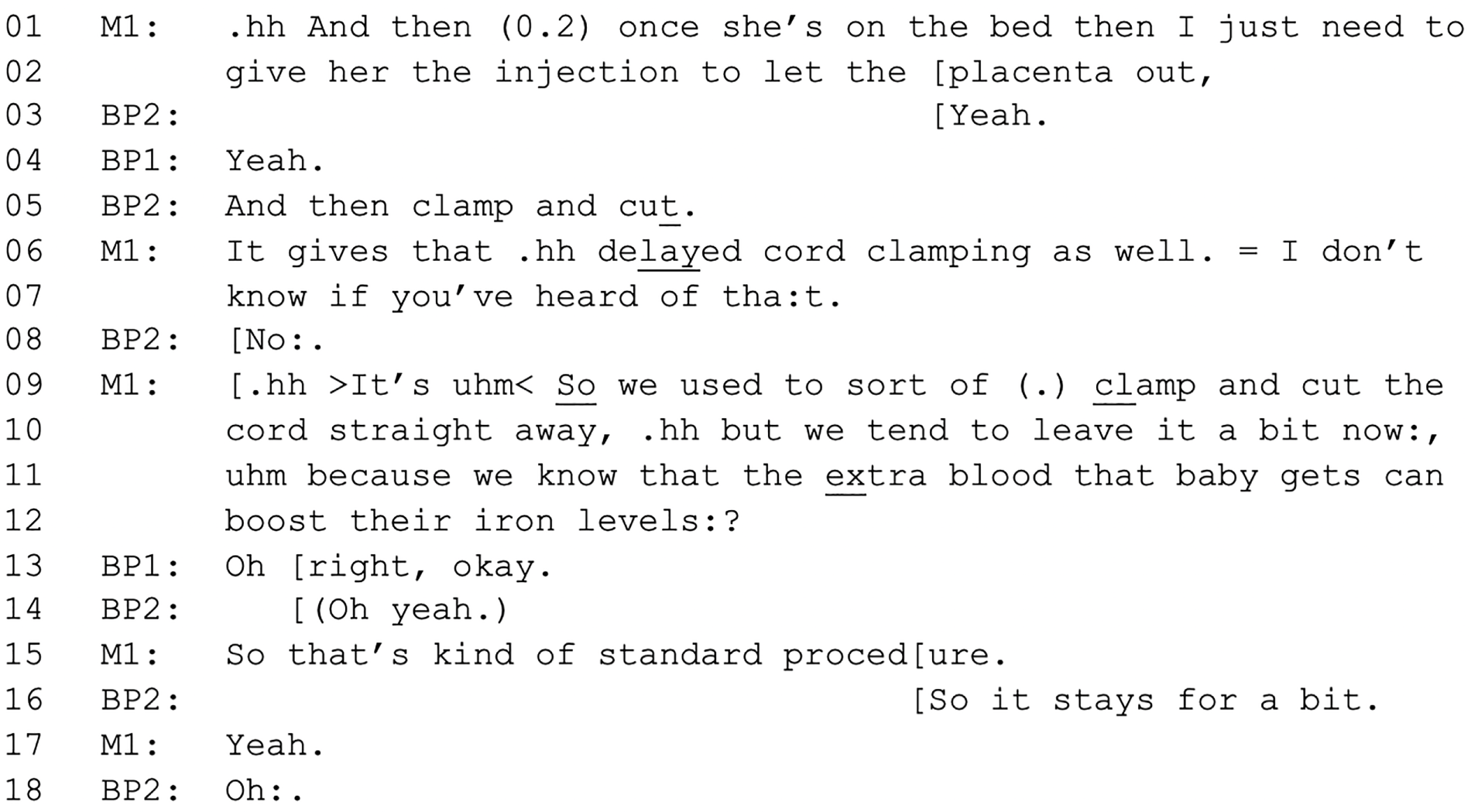

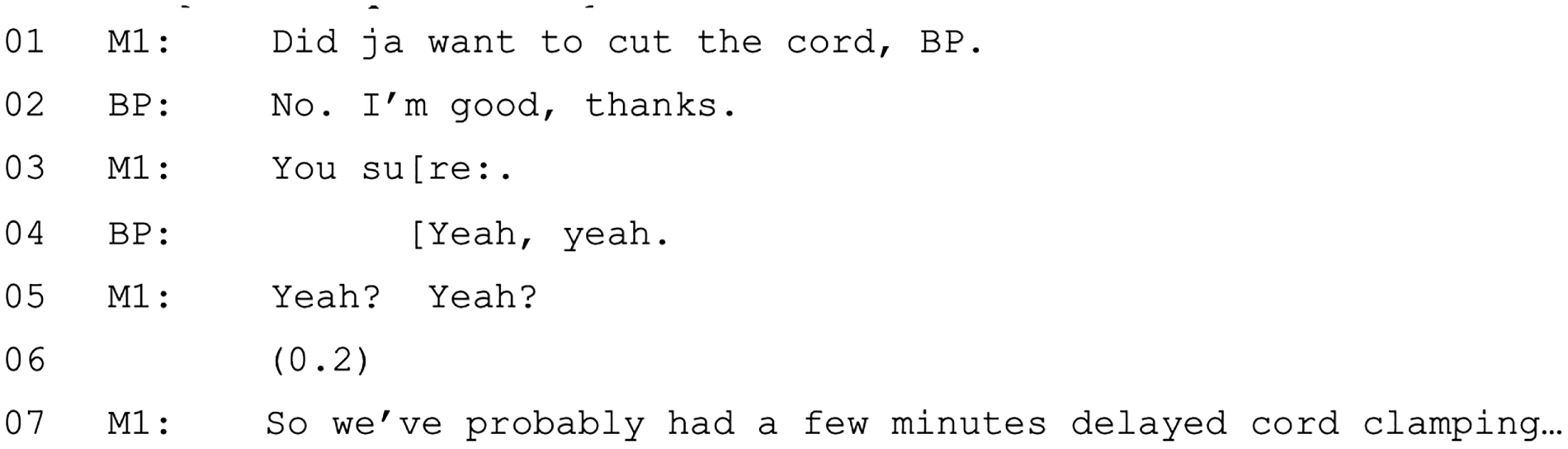

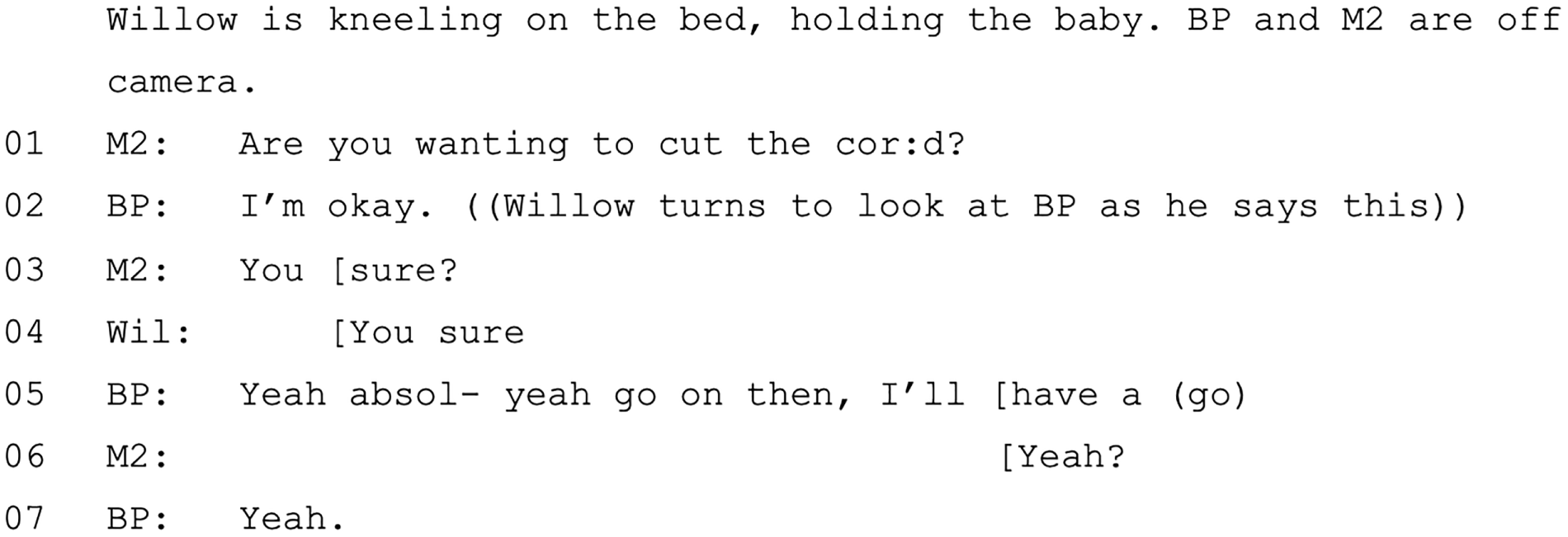

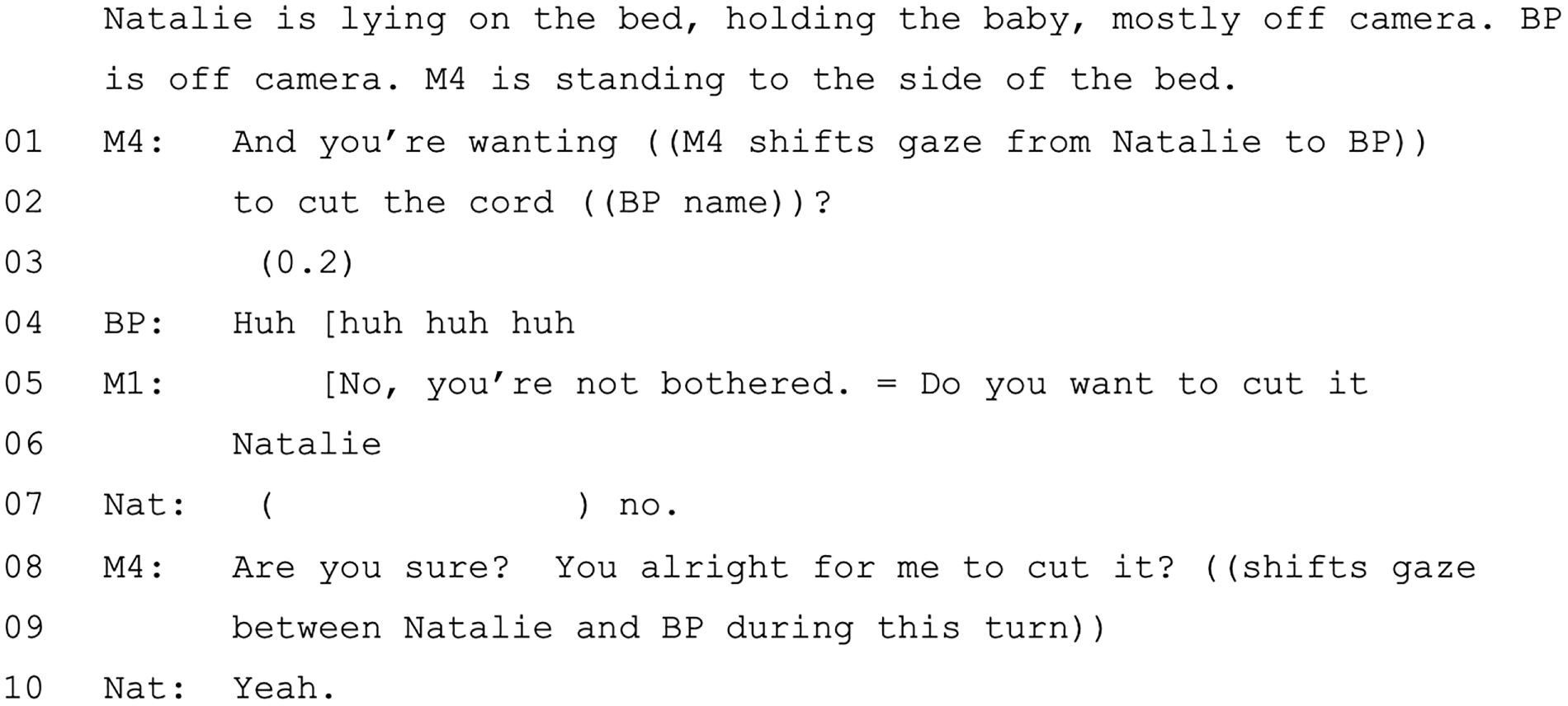

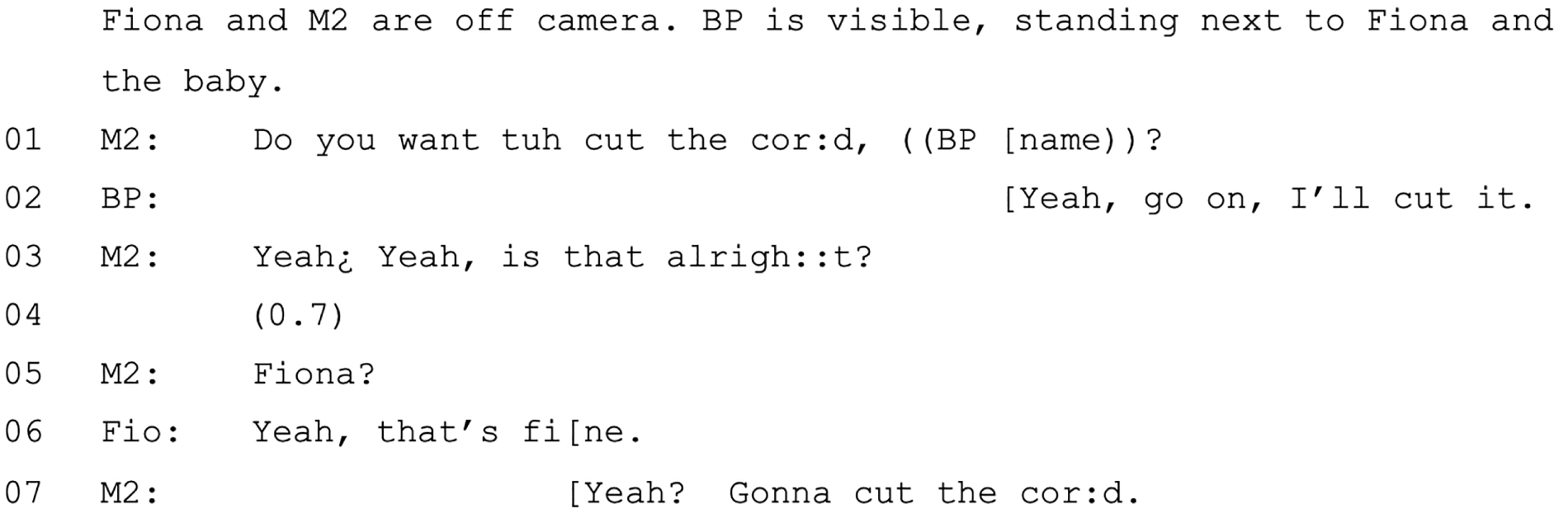

Given the breadth and depth of data and the intensive nature of conversation analytic work, we were necessarily selective in the topics we focused on for the purposes of this report. A key finding of our preliminary analysis (subsequently verified by the quantitative coding of the data) was that the way decisions are initiated appears to be contingent on what kind of decision is being made (e.g. monitoring and pain relief). To elucidate these differences, we elected to explore decisions about monitoring, VEs, artificial rupture of membranes and pain relief, and ‘third-stage’ decisions relating to delivery of the placenta and cord clamping/cutting. These were decisions that we asked about in the questionnaires and were initiated in ways that were either relatively constraining (e.g. monitoring and VEs) or more participatory (e.g. pain relief and third-stage decisions) with respect to women’s agency. These topics form the basis of Chapters 4–7 of this report.

The interactions between HCPs, women and BPs were identified and edited for verbatim transcription (i.e. for budgeting purposes, we did not generally send whole recordings to the transcriber). Data concerning the decision types outlined above were selected from the professionally transcribed verbatim transcripts and re-transcribed using the conventions of CA (known as Jeffersonian transcription;183 see Appendix 6 for CA transcription conventions).

The data, plus the associated transcripts, were then examined in detail for how decisions were initiated and responded to so to establish how far decision-making was shared (research objective 2). Where possible (i.e. where we had video), our qualitative CA included embodied actions (e.g. gaze and head movements). Given the mix of audio-only recordings and video-recordings, a focus on these non-verbal features has not been possible across the data set. However, in the title of each of the data extracts presented in the CA chapters (see Chapters 4–7), we include information about whether the extract is based on audio or video, and, if the latter, whether or not the participants were on camera.

Quantitative coding and analysis of interactional data

Development and application of the coding scheme

In creating the coding scheme to generate quantitative data, we were committed to carrying out the necessary act of data reduction (for quantitative analysis) without sacrificing CA’s sensitivity to interaction. 156 Although informed by existing formal coding frameworks (see Stivers et al. 132 and Reuber et al. 161), the coding scheme was primarily developed through an iterative bottom-up process in which we drew on the CA from the study to adequately capture what was going on in the interactions.

Inspired by Reuber et al. ’s161 use of an online questionnaire to ‘extract’ quantitative data, the coding scheme comprised a codebook (see Appendix 7) and an online data extraction form constructed using Qualtrics® software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA). The coding scheme was developed and refined through an iterative process. The first step was an extensive data familiarisation process that involved three members of the team (LB-J, CJ and VL) watching and listening to an opportunity sample of recordings (i.e. as recordings were completed, transcribed and subject to preliminary CA). Following this, the coding scheme was developed through a process of trial and error, whereby definitions of interactional practices (derived from the CA) were produced, and where we considered the different ways in which participants could immediately respond to the different decisional practices and how best to capture the often extensive decision-making sequences that occurred. Multiple versions of the coding scheme were developed and the coding team met frequently to discuss the coding process, the success of the coding scheme in providing valid descriptions of real interactional practice and any disagreements. After each meeting, a new version of the codebook and data extraction form was constructed, taking into account discussions and any agreed changes before the independent coding process started again. Through the application of this iterative process, a final coding scheme was developed that would allow for the identification of interactional phenomena identified in the CA, while allowing the classifications to be reliably applied between coders.

The coding scheme was designed so that, when applied, the following could be coded for each recording:

-

The stages in labour when the recording started and ended, together with length and format (i.e. audio-only, video or mixed) of recording.

-

All decisions about the key aspects of care asked about in the ANQs and PNQs (described in Data analysis of recordings). There were 12 categories of decision, including, for example, pain relief, fetal monitoring, manual (not visual) VEs, position for first stage, position for birth and active/physiological third stage.

-

For each decision identified, we recorded who it was initiated by (i.e. midwife, doctor, labouring woman or BP).

-

Decisions were commonly made through extended sequences and, therefore, to track decision-making across time we followed Reuber et al. ’s161 methodology, and made a distinction between a decision and the decision points that constituted it. Each decision could have any number of decision points that represented the chain of decision-making relating to that decision. This was carried out so that our coding retained the sequential order of decision points and so that it was possible to compare first decision points with later ones within a single decision. Each decision point was classified as one of 11 types, including pronouncements, recommendations, requests, offers, open questions and indecipherable. Note that, following our pilot work and that of Reuber et al. ,161 we maintained a distinction between the strongly directive recommendations (pronouncements) and those that contained a proposal.

-

We coded the immediate recipient response to each decision point. Coders selected one of 11 response types, including ‘no audible response’, ‘acknowledges’, ‘agrees/accepts/aligns/selects option’ and ‘disagrees/rejects/denies/misaligns’ (misalignment refers to not going along with a proposed course of action).

-

For each decision point, we also recorded the specific section of transcribed text that constituted the decision point.

-

When all decision points for a single decision had been coded (i.e. the decision was complete and there were no further initiating turns for that decision), we coded whether or not the possible course of action was pursued, agreed and acted on, agreed but not acted on, or abandoned.

-

For each decision, we assessed the level of ‘sharedness’ and ‘balance’ in decision-making by selecting one of seven categories on an ordinal scale. Researcher-based judgements were made for each separate decision according to who led the decision-making process and to what extent the other party had some say in the decision-making. For these purposes, we combined midwives and doctors into the category ‘HCP’ and women and BPs into the category ‘birth party’. Decisions were coded as (1) unilateral HCP, (2) HCP led but birth party had some say, (3) HCP led but birth party had most say, (4) equal balance between HCP and birth party, (5) birth party led but HCP had most say, (6) birth party led but HCP had some say or (7) unilateral birth party.

However, some exceptions applied (see Appendix 7). For example, we coded only those decisions that were asked about in the questionnaires, and only on occasions when decisions were discussed between HCPs and women and/or BPs (i.e. not decisions that were discussed only between HCPs or between women and BPs).

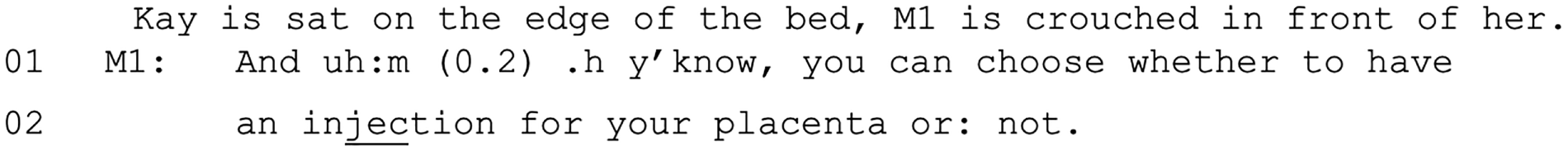

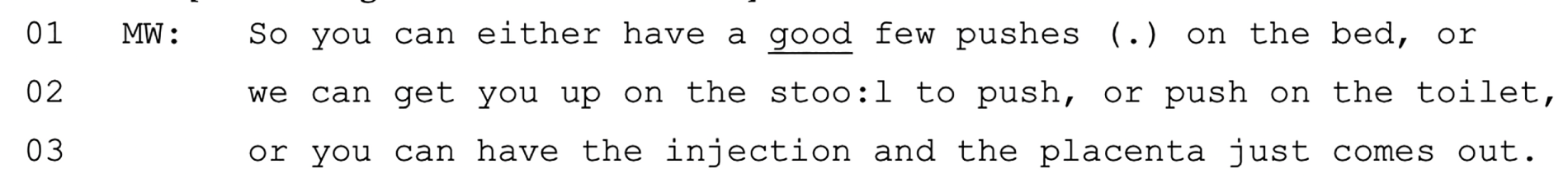

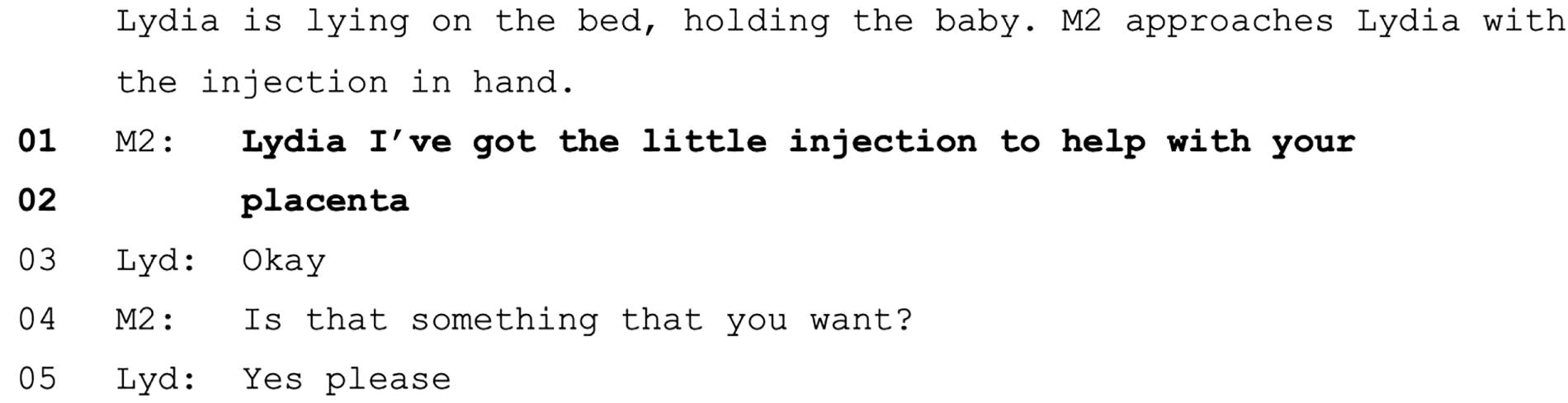

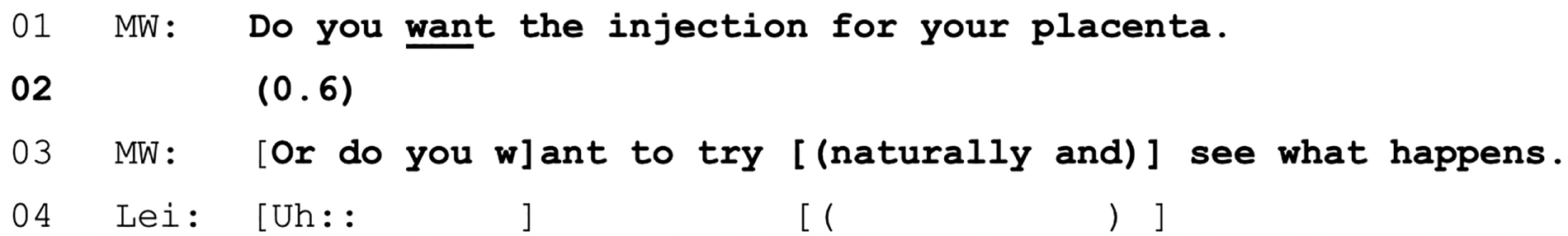

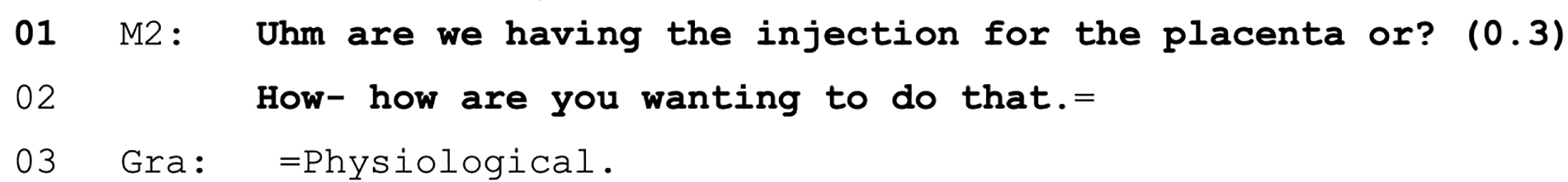

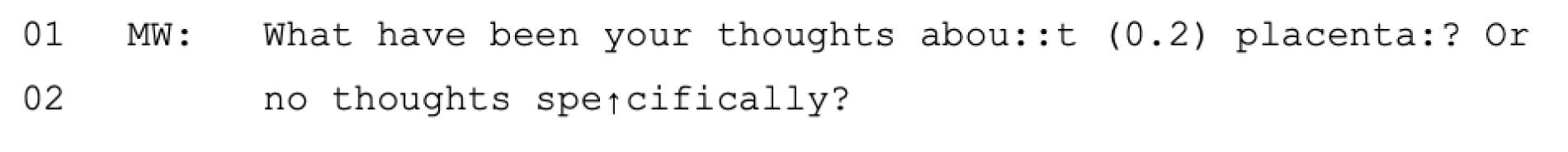

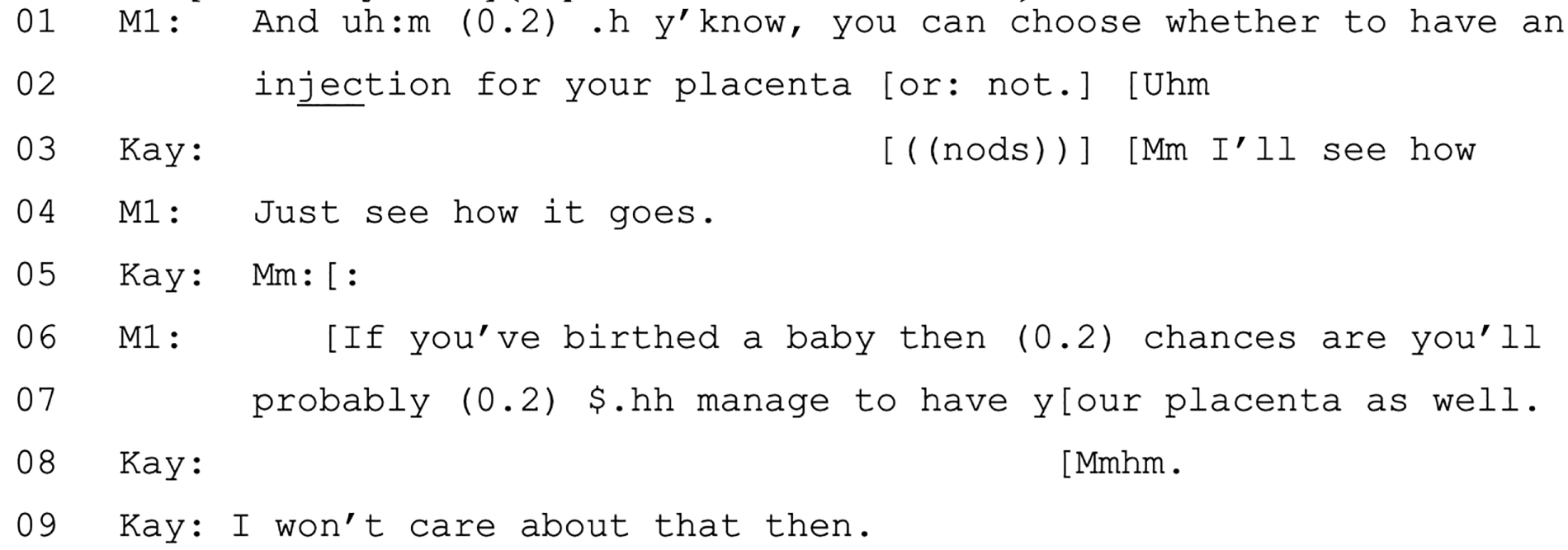

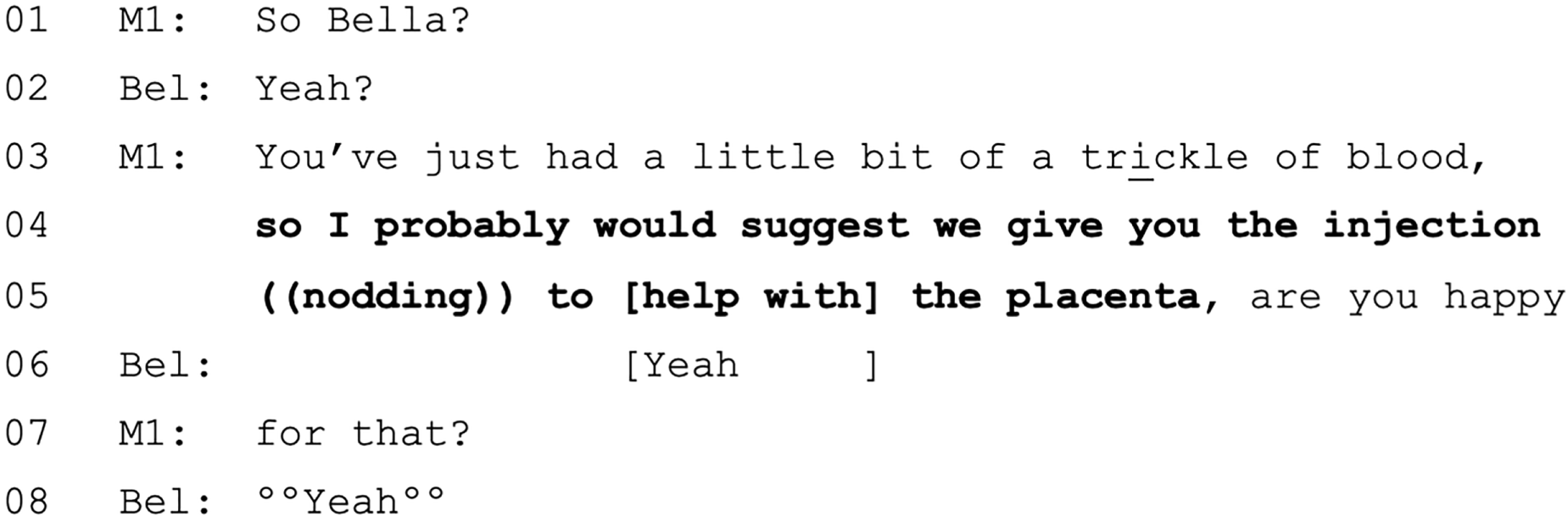

Table 6 provides our codebook definitions for each interactional practice that could constitute a decision point, with examples. For ease of reading, full Jeffersonian transcription notation is not used here, but was used to conduct the CA work. As can be seen from the definitions, our codebook was heavily influenced by the CA work in that it captures the ways in which initiating turns can vary the dimensions of entitlement and decisional domain. 132

| Format | What is conveyed | Example |

|---|---|---|

| No verbal initiation (just do it) | Conveys entitlement, but there are always embodied actions that women might notice and resist | Monitoring without asking/informing |

| Pronouncements | Something is going to, needs to or will happen. High entitlement/ownership, expects agreement | [Midwife] said she examined you about 8:40? So I’ll examine you about 12:40 |

| Instruction/command/demand | A decision is initiated as a directive to the other party to do something, high entitlement and expectation of agreement | Get up and walk about. You will have your baby |

| Recommendation/suggestion/proposal | Endorses a course of action, expects agreement, but leaves some room for the other to decide | I’m just wondering about examining you really, to be honest. I’m just, I’m not getting a clear picture really. So I just think it might just be helpful |

| Request | A decision is initiated in a way that asks the other to grant something. Might convey entitlement to ask, but decisional domain is with the other | Please can I have some pethidine? |

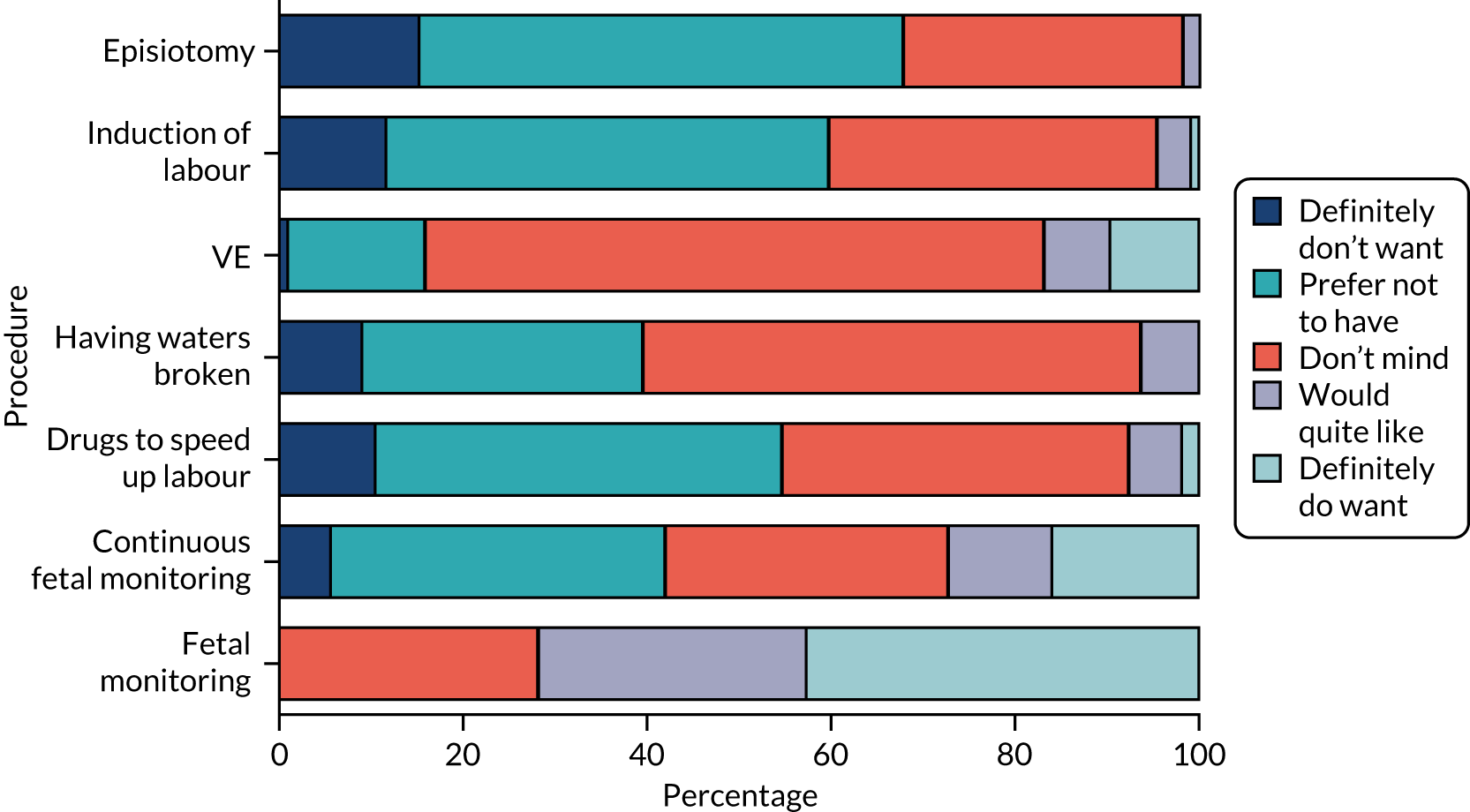

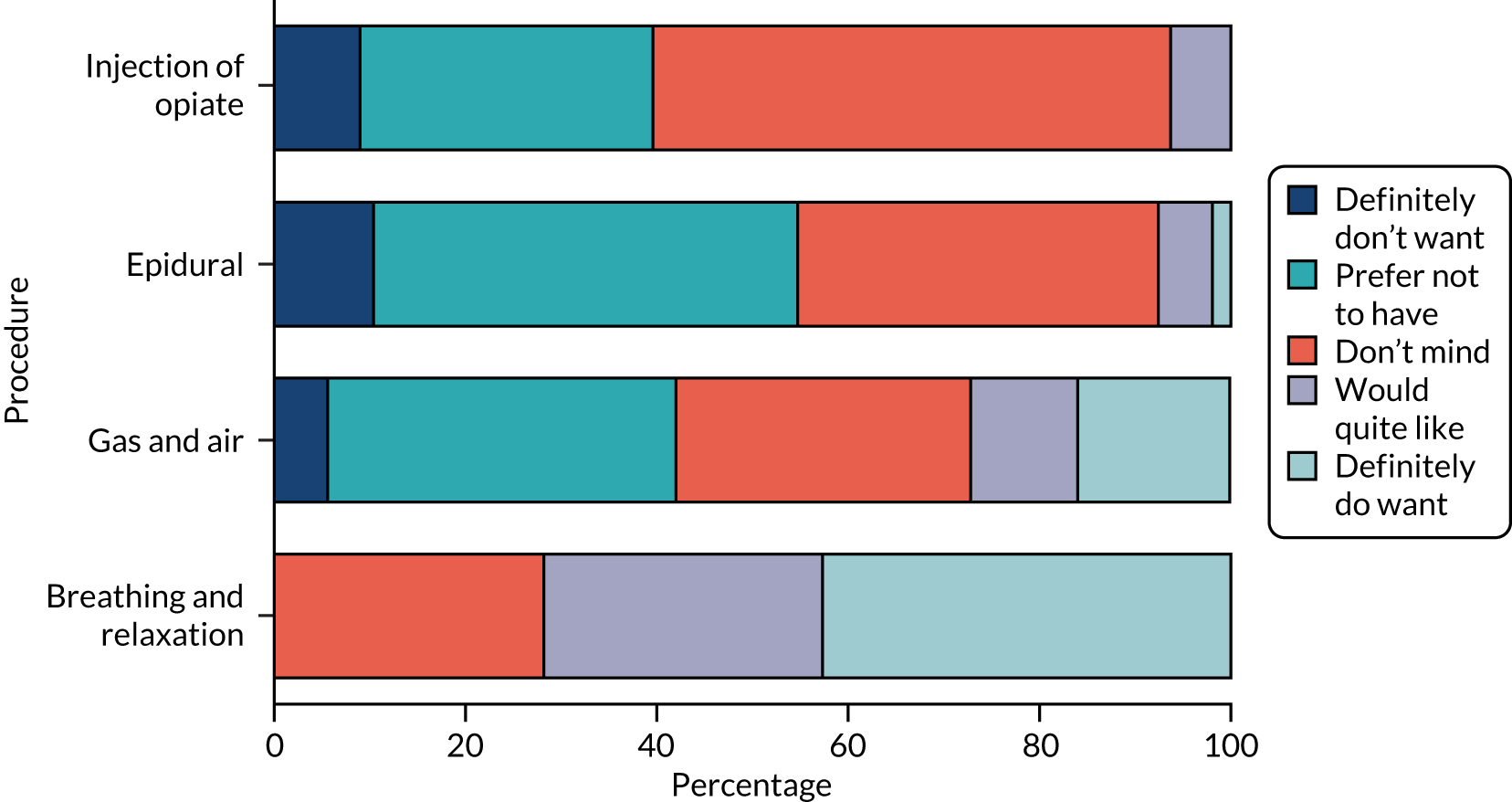

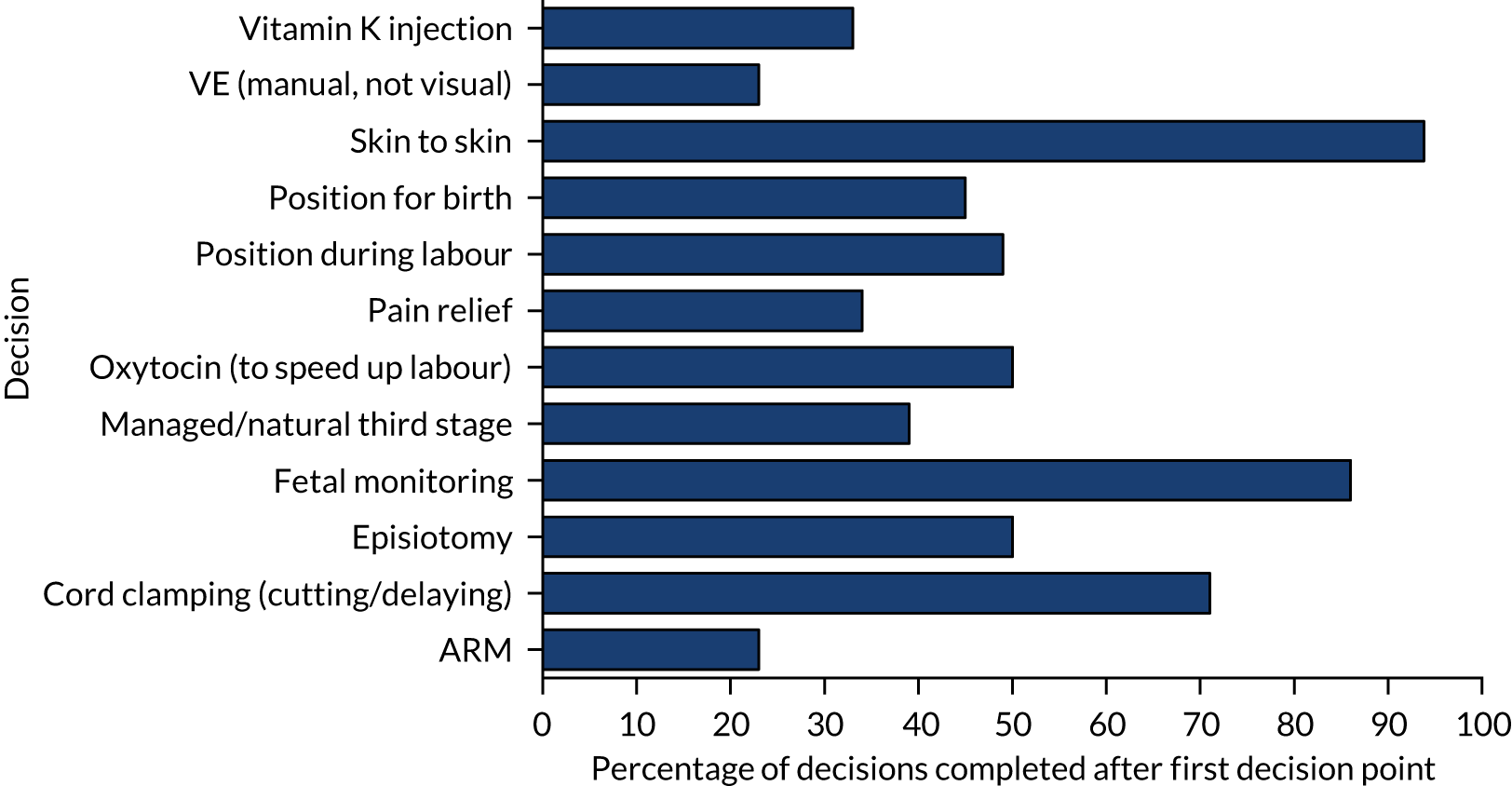

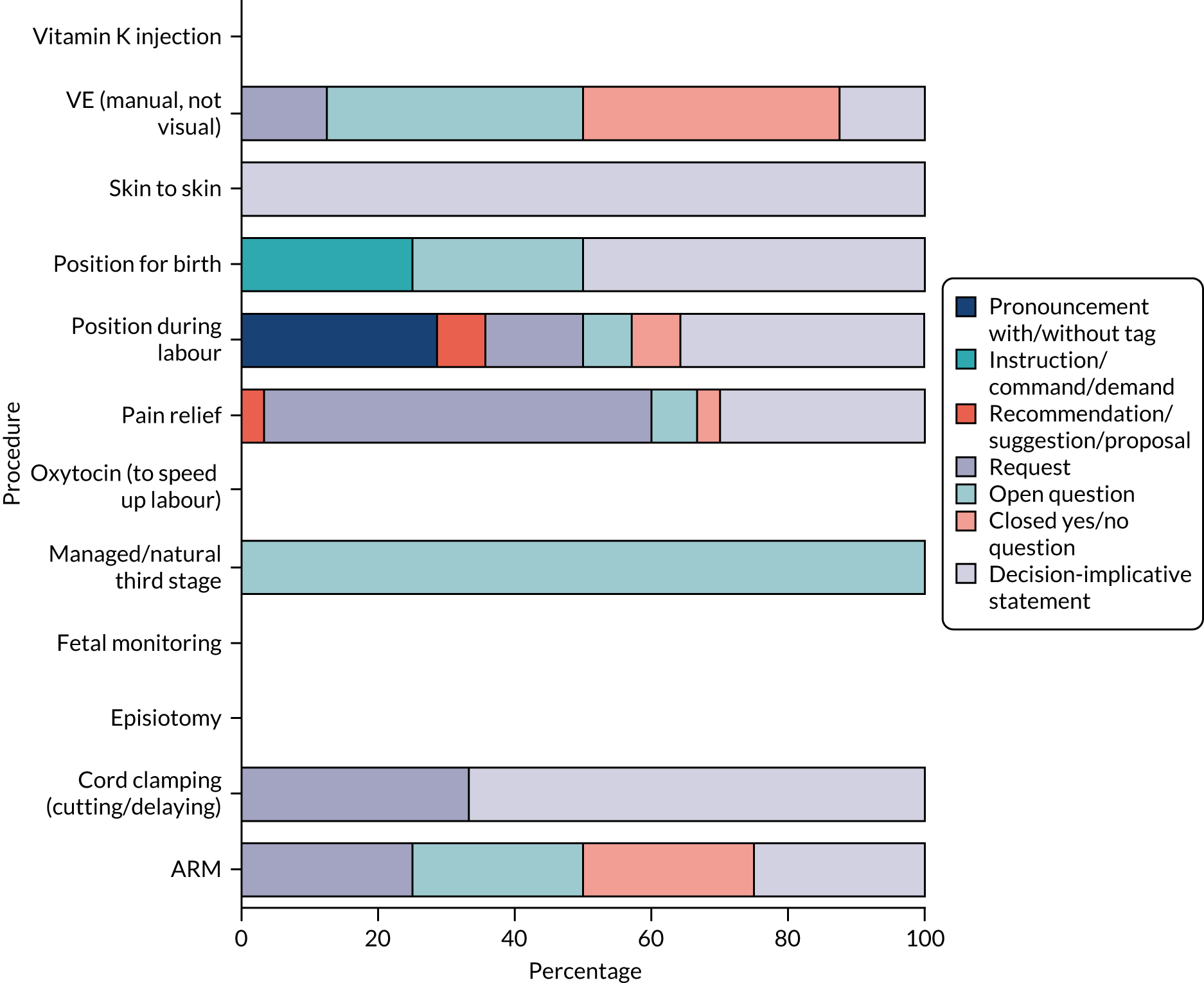

| Offer | A decision is initiated in a way that self has the right/possibility to enact on behalf of the other but is seeking the other’s view/permission | I could offer you some codeine as well if you wanted that |