Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR131800. The contractual start date was in September 2021. The draft manuscript began editorial review in June 2023 and was accepted for publication in March 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 McConnell et al. This work was produced by McConnell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 McConnell et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from McConnell et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death worldwide. 2 Heart failure (HF) characterises the final phenotype of many cardiovascular diseases3 estimated affect 64.3 million people worldwide in 2017. 4 Its prevalence is expected to rise due to the improved survival following an acute myocardial infarction associated with the availability of life-saving evidence-based treatments and due to ageing populations. 5,6 Patients with HF experiencing New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III or Class IV symptoms account for over 1 million hospitalisations per year in the USA and Europe. 7 Additionally, HF is the most frequent cause of hospitalisation among individuals aged > 65 years. 8 In 2012, HF was estimated to account for £22.5B of health expenditure globally; between 2012 and 2030, it is estimated that total costs will increase by 127%. 9 Integrating palliative care (PC) with routine management of HF has been shown to significantly reduce healthcare costs overall compared to usual care (without PC)10 and significantly reduce the number of hospital visits and duration of inpatient stays. 11,12 The National Audit Office review of end-of-life (EoL) care recommended PC for patients with HF, due to a potential cost savings by reducing utilisation of acute services. 13 An example of potential savings from integrating care is found in the work by Atkinson et al. 14 in Wales who set up a co-specialty PC and HF hospital-community service with a catchment population of approximately 445,000 people, with 350 to 400 HF admissions each year. Over the 5-year study period, the introduction of the integrated service resulted in an estimated average saving of at least £10,218.36 per referral; as year-on-year savings have increased, in 2020 this figure rose to £14,109.36 per referral. 14 Overall, it is estimated that the integrated service has saved approximately £2.4M over 5 years, with almost £1.3M saved in 2020 alone for that catchment area. 14

There is evidence of improved patient and informal caregiver outcomes when PC is integrated in HF management. A review of carers’ needs identified that integrated PC in HF management led to an improvement in satisfaction with care from both the patient and their informal caregiver. 15 Informal caregivers are typically defined as those who provide unpaid care to individuals with whom they have a relationship, that is family members or spouses. 16 Informal carers are crucial to facilitating independent living and supporting quality of life (QoL) for patients with HF, and therefore PC can address caregivers’ needs and help them care for their loved one. 17 Integrated PC in HF management can benefit QoL, symptom burden and levels of depression in patients with the condition. 18

Integrated palliative and HF care aims to achieve continuity of care by integrating administrative, organisational and clinical services that make up the patients care network. 19 Examples of integrated PC and HF interventions include collaborations and shared goal-setting between PC and clinical cardiology teams to ameliorate symptoms with PC goals, alongside HF management. 20 The addition of social-worker-led PC services alongside HF management21 improved the physical, psychological, social, spiritual and EoL outcomes of patients. In 2020, the European Association for Palliative Care Task Force22 concluded that the inclusion of PC within the regular clinical framework for people with HF provides improvement in QoL as well as comfort and dignity. This was echoed in a position paper by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)23 Heart Failure Association (HFA), which stated that many patients with HF would benefit from earlier integration of a palliative approach into the care provided by the multidisciplinary team (MDT) involved.

However, although two decades have passed since the first publication on the benefits of PC for patients with HF,24 the HFA Atlas identified only 10 out of 42 European countries with designated PC units for patients with HF. 23 The poor integration of PC into HF management can be explained by a number of factors, including uncertainty around the HF disease trajectory and complexities of communicating this uncertainty to patients and informal caregivers. 25–27 HF is an unpredictable illness, with periods of stability of symptoms, interjected with numerous exacerbations, and a gradual progression of the disease towards death. Many patients with HF overestimate survival,28 further adding to cardiology providers’ reluctance to initiate difficult conversations around prognosis. 27 This difficulty is further compounded by lack of patient and practitioner knowledge around what PC is and a general misunderstanding that PC is applicable only at EoL. 26,27,29,30 The fragmentation of inpatient and outpatient services also creates a barrier to the holistic need’s assessment required for an integrated PC approach. 31

Overview of existing evidence

Until recently, the lack of evidence from clinical trials demonstrating benefits of PC for people with HF posed an additional barrier. However, there has been an exponential increase in published literature since the turn of the century, increasing from 10 publications on average in 2000 to over 100 publications per year in 2017. 32 McIlvennan and Allen31 published a review summarising the evolving role of PC for patients with HF, along with the barriers and opportunities for its integration into routine practice. Findings from the review highlighted the need for evidence on how best to integrate PC and HF given the cultural and environmental differences in how PC services are delivered. 31 Three systematic reviews of PC interventions for patients with HF by Diop et al. ,33 Datla et al. 18 and Sahlollbey et al. 32 all highlighted the benefits of PC in HF management for patient-centred outcomes and reducing hospital utilisation. A recent scoping review examining elements of integrated PC in HF management34 identified the need for a multidisciplinary approach to integration, and for cardiology staff to champion the benefits of PC. This review also highlighted the need for research with robust theoretical underpinnings given the complex behaviour changes required for sustaining integrated care in practice. 34

A recent editorial35 exploring the phenomenon of inconsistent implementation of integrated PC and HF interventions proposed a realist approach could provide a sound theoretical understanding of the barriers and facilitators to routine implementation. Research to date has focused on trying to evidence effectiveness through a linear cause and effect approach, which fails to ignore the messy, non-linear world of real-life practice. 35 Datla et al. 18 also identified a lack of clear consensus around: (1) the core components of integrated PC and HF interventions; (2) the ideal configuration for the MDT; and (3) the most effective service provision model to ensure that generalist and/or specialist PC is tailored to patient needs. The issue of heterogeneity was further highlighted in a narrative literature review aimed at identifying the key characteristics of integrated PC and HF interventions. 36 Of the nine studies included, all integrated PC and HF interventions were implemented in different countries with different models of health service provision for citizens (USA, Sweden, Hong Kong), different settings (inpatient, outpatient and home-based), delivered by a heterogeneous mix of MDTs [HF physicians, HF nurses, general practitioners (GPs), community nurses, occupational therapists], using different modes of delivery (face to face, telemedicine), and involving different intervention components (symptom management, advance care planning). Therefore, we still do not know:

-

which intervention produces the best outcomes for patients and their informal carers (what works: specialist vs. primary care etc.)

-

when best to initiate PC (for whom; at what stage in the disease trajectory), or

-

the optimal delivery method (in what circumstances; required infrastructure, staff competencies etc.).

Rationale explaining why this research is important now

Globally the population is living longer than ever before. In 2022, there were 771 million people aged 65 years or over globally, three times more than in 1980 (258 million). 37 Globally, the older population is projected to reach 994 million by 2030 and 1.6 billion by 2050 ‒ a rise of 10% in 2022 to 16% in 2050. 37 Although we can celebrate this achievement in life expectancy, it comes with significant challenges for an already struggling healthcare service now and in the future. Older people have complex health needs, with on average 4.5 comorbidities. HF often dominates their physical and psychological needs,24 along with being the costliest aspect of their care due to high rates of hospitalisation and pharmaceutical, device, and surgical interventions as their HF progresses. 38–40 Older people with HF have undeniably had their needs overlooked, with calls for more attention to, and research for, this vulnerable group to ensure they receive appropriate, effective treatment and care. 31,41,42 The 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic HF highlighted the need for studies to determine specific options for PC within the treatment of HF. 43

Although we have some promising examples of integrated PC and HF interventions,20,21 there is heterogeneity in terms of countries, healthcare settings, delivery by mix of MDTs, modes of delivery and different intervention components. 44 Hence, this review is vital for identifying which model works best, for whom, or in what circumstances.

Aims and objectives

Aim

To understand how integrated PC and HF interventions may work in different healthcare settings for example inpatient/outpatient, and for which groups of people, so we can recommend strategies to maximise the potential for widespread implementation, reduce healthcare costs, and improve QoL for patients and informal carers.

Objectives

-

To conduct a realist synthesis (RS) to build an understanding of which integrated PC and HF interventions work best together, in which contexts and for which patients who have HF and informal carers

-

To co-produce implications with an expert stakeholder group, to maximise potential for widespread implementation through a user guide for healthcare providers and user-friendly summaries for patients and the public

Review questions

-

What are the mechanisms by which integrated PC and HF interventions work to produce their intended outcomes?

-

What are the contexts which determine whether integrated PC and HF interventions produce their intended or unintended outcomes?

-

In what settings are integrated PC and HF interventions likely to be effective?

Chapter 2 Review methods

This methods chapter is based on previously published work45,46 by our methodological expert, Geoff Wong (GW), the lead researcher on the Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) project (www.ramesesproject.org/) which developed realist review quality and publication standards and training materials (see Report Supplementary Material 1).We used a realist approach to understand and make sense of the complexity of integrating PC in HF management and to examine what works for whom, in what circumstances, how and why. Realist synthesis is a theory-driven approach for understanding existing diverse multiple sources of evidence relating to complex interventions. It is theory driven because it uses evidence to iteratively develop and test structurally coherent explanations (i.e. theories) of complex interventions. The review methodology followed Pawson’s47 five iterative stages for RS: (1) locating existing theories; (2) searching for evidence; (3) selecting documents; (4) extracting and organising data; and (5) synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions (Figure 1). The review project ran for 22 months, from September 2021 to June 2023. The RS protocol was published in BMJ Open1 and the review was registered on PROSPERO (number CRD42021240185).

FIGURE 1.

Project flow diagram using Pawson’s five iterative steps.

Stakeholder group

An international stakeholder group was recruited during the planning stages of this project to provide clinical management, clinical practice, academic, policy and service user expertise to guide programme theory refinement and development, and our comprehensive dissemination strategy. Our stakeholder group comprised 32 individuals, including medics, nurses and policy staff representing healthcare professionals involved in the delivery of PC and HF management; research clinicians in PC and HF at national/international level; policy and community groups; and patient and public involvement (PPI) partners. Stakeholder meetings (n = 5) lasted 2 hours (with the exception of the fourth meeting which lasted 3 hours to present and discuss implications) and took place at regular quarterly intervals throughout the project (Table 1). Meetings took place on the teleconferencing application Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA) to facilitate engagement from all stakeholder members, and also due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. All participants provided verbal consent for the recording prior to each meeting. Recordings were not used as a form of data, but to ensure accurate notetaking of stakeholders’ expert feedback and advice. Stakeholder meetings began with a short presentation to introduce and reacquaint stakeholders with the topic, review methods and issues for discussion. Discussions at the early stages were open-ended; however, the project team encouraged discussion around the ‘preliminary’ initial programme theory and key ideas from the initial literature searching to draw out our initial programme theory. Stakeholders also kept in regular communication with the project team through e-mail, adding any further comments or thoughts from the meetings, which were added to the initial programme theory. Stakeholders also provided relevant documents included within this review (n = 11). Later stakeholder meetings focused on actionable findings and the dissemination strategy.

| Date | Stakeholder attendees | Topics discussed | Examples of stakeholders’ contributions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 November 2021 | 14 stakeholder participants including nursing staff, consultants, PPI members and GPs | Stakeholders reminded about research topic and realist methods. Open discussion around preliminary initial programme theory, integrated PC in HF, contexts that work, outcomes and what matters for healthcare professionals (HCPs) and patients |

|

| 30 March 2022 | 12 stakeholder participants including cardiology and PC consultants, GPs, PPI members and researchers | Stakeholders were presented with the initial programme theory and the initial findings. Open discussion around what a clear pathway for integrated PC in HF would look like, the issues around terminology for PC, the culture within cardiology and education |

|

| 6 July 2022 | 14 stakeholder participants including specialist HF nurses, cardiology and PC consultants, PPI members and researchers | Stakeholders were presented with our emerging findings focused around three key areas: need for a clear pathway; the role of education; and the impact of wider and organisational issues |

|

| 12 October 2022 | 20 stakeholder participants including specialist HF nurses, cardiology and PC consultants, PPI members and researchers. This meeting also incorporated additional HF nursing specific feedback that was gained through an interactive question and answer session at the Irish Nurses Cardiovascular Association event. This event was attended by over 100 HF nurses, from undergraduate to clinical nurse specialists | Stakeholders were presented with key findings and associated implications based around education; buy-in; resourcing; and guidelines. In addition, identifying a future programme of work was discussed |

|

| 8 March 2023 | 12 stakeholder participants including specialist HF nurses, cardiology and PC consultants, PPI members and researchers | Stakeholders were presented with the final animation, followed by a detailed discission on the implications and dissemination plan. Additionally, the refined future plan of work was presented |

|

Patient and public involvement

Our PPI group were involved throughout the planning and execution of this project. The PPI group was recruited by TM during April 2020 from members of two established public involvement and engagement groups (Marie Curie PPI Research Voices Group London and British Heart Foundation PPI Network members). We received eight responses from PPI members, three of whom agreed to membership of our stakeholder group. At this initial stage their input was sought in relation to the importance of our proposed study, how we should focus on our review and our plain language summary.

During the review, we asked PPI stakeholder group members:

-

to help us to develop our initial programme theory

-

for their advice and feedback on our programme theory as it evolved

-

to consider our findings and implications from their varied perspectives

-

to provide input and support into our dissemination strategy and

-

to review and contribute to our materials, to ensure they met the needs of patients and the wider public.

Informal meetings were arranged with our PPI members prior to main stakeholder meetings (Table 1) to provide any support that was needed. For example, before the first stakeholder meeting, our PPI meeting focused on realist terminology, emphasising the importance of ensuring PPI voices were heard at meetings. This meeting also provided an opportunity for any other questions or concerns that our PPI members had about their role. We witnessed the value of having these informal meetings with our PPI members in the stakeholder group meetings. For example, in the first stakeholder meeting, PPI members made significant contributions to developing the programme theory. Their perspectives and opinions were welcomed by all stakeholders and illuminated real-world implications for service users in terms of what works, and what does not work when integrating PC with HF management. The strength of PPI involvement in this project is evident in the considered pieces provided for the website (https://palliatheartsynthesis.co.uk/blog/) and reflective pieces (see Appendix 4). The review methods adopted within this RS are outlined in the following section.

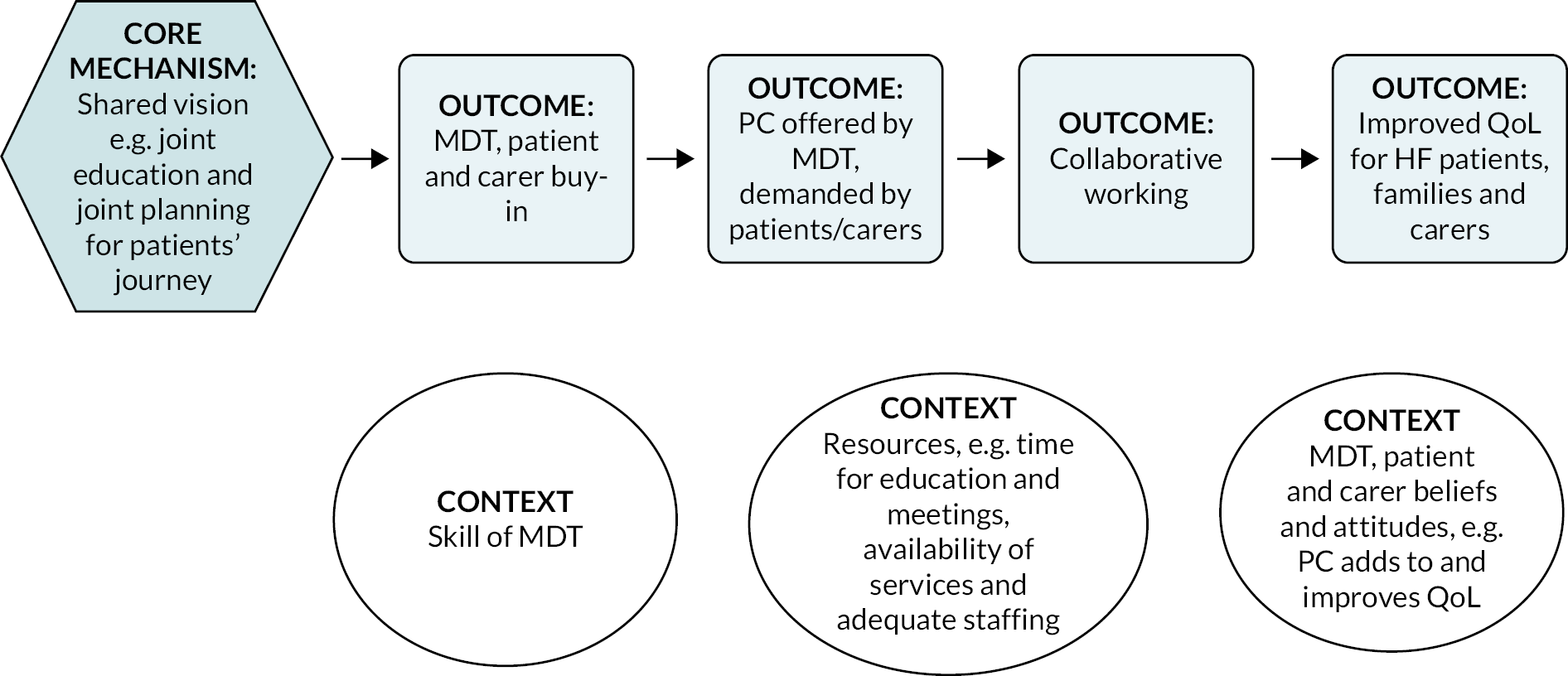

Step 1: locate existing theories

Within the first stage of the review, we conducted exploratory searches to locate key literature sources and to identify any existing theories that may be relevant. Exploratory searches were carried out on MEDLINE using key terms for PC and HF. The informal searches conducted within step 1 differed from the more formal searching that was carried out in step 2, as their purpose was to identify quickly a set of highly relevant documents. Thus, exploratory and informal search methods including citation tracking and snowballing based on known existing documents were also used. Drawing on the literature identified in the informal searches and the project team’s experiential and content knowledge, we developed a ‘preliminary’ initial programme theory to explain how integrated PC in HF management may work, and the core mechanisms which generate its outcomes (Figure 2). This preliminary initial programme theory was presented to our stakeholder group to facilitate discussion for the further development of our initial programme theory.

FIGURE 2.

Preliminary initial programme theory.

Refinement of the preliminary initial programme theory

Following the presentation of the preliminary initial programme theory at our first stakeholder group, we found that stakeholders focused on HCPs’ perspectives as providing key explanations for challenges around implementation of integrated PC in HF management. This indicated that we should narrow the scope of the synthesis to focus on HCPs’ perspectives on integrated PC. We still considered the importance of patient and informal caregiver perspectives; however, stakeholders emphasised the gatekeeping nature of HCPs to access integrated PC in HF.

Step 2: search strategy

Formal search

Our search strategies were designed, piloted and implemented by an information specialist with experience of carrying out iterative searches for RS ‒ Claire Duddy (CD), in collaboration with Clare Howie (CH) and TM.

For the main search, CH identified potential search terms using published search strategies from existing systematic reviews18,19,31–34 and by reading other relevant published research documents22–24,36,48–50 that were identified via earlier scoping searches and during protocol development. Other search terms were chosen based on suggestions of key documents and language used by our stakeholder group.

Claire Duddy used MEDLINE (via Ovid) to iteratively develop a search strategy, identifying a core set of free text and subject heading (MeSH) terms and then testing the effect of adding, removing and refining terms. We used existing sets of known relevant documents to benchmark the search strategy and assess the impact of making changes. These were documents that were cited in the protocol, and documents included in two recent systematic reviews. 18,34 Our overall aim was to reach an appropriate balance of sensitivity and specificity, such that the search strategy retrieved a range of relevant literature that was likely to contain data that could be used to refine and develop our initial programme theory, while minimising the retrieval of irrelevant literature. The final agreed strategy for the main search combined terms for HF with terms for PC and is outlined in full in Appendix 1.

In November 2021, CD conducted searches in the following databases: MEDLINE (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), PsycINFO (via Ovid), AMED (The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database via Ovid), HMIC (The Healthcare Management Information Consortium via Ovid) and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature via EBSCOhost) (see Appendix 1). We adapted the search strategy developed for MEDLINE for use in each database, adjusting the search syntax and subject heading terms as appropriate. All search results were exported to EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) reference management software and duplicates were removed using the ‘Find Duplicates’ function and additional manual checks by CD.

In addition to the database searches, we sought to identify additional academic and grey literature via several supplementary searching methods. We ran simplified versions of our search strategy in Google, OpenGrey and the NICE Evidence search website with the aim of identifying relevant grey literature. Results (up to the first 500 for Google and NICE Evidence) from these resources were screened ‘on screen’ to identify material that described PC for patients who have HF and new material was added to the EndNote library.

Although our protocol documented we may undertake forward citation searching, we judged the large volume of documents retrieved did not necessitate additional searching. We asked our stakeholder group and wider networks to suggest additional relevant literature that we should consider for inclusion.

Following the main search in November 2021, we set up an alert using Google Scholar to help us to identify any newly published relevant material. The alert used the terms ‘heart failure’, ‘palliative care’ and ‘end of life’. New results were collated by CD on a monthly basis until August 2022 and shared with CH, TM and Carolyn Blair (CB) who considered them for inclusion throughout the project.

Step 3: document selection

Inclusion criteria

We kept the initial inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review deliberately broad as we aimed to identify all relevant quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods and non-empirical documents relating to HF and PC.

The following inclusion criteria was applied:

The screening process was piloted by CH with a sample of 50 titles and abstracts to ensure the application of the inclusion criteria was suitable. Consistency checks were carried out by a second reviewer (TM) on a 10% random sample of the screening (title, abstract and full text) and the coding process for the main search. Very few inconsistencies were identified and, when identified, these were resolved through discussion.

We also included all documents from the stakeholders and the alerts that contributed to the evolving programme theory. Documents were screened initially by title and abstract, using the inclusion criteria detailed in Table 2. Following this process, 1066 documents met the initial inclusion criteria (January 2022). Selection was predominantly focused on whether documents were likely to contain data that would contribute to the refinement of the initial programme theory. Documents were organised according to perspective reported, that is whether they included data speaking to patient, informal caregiver, HCP perspectives related to PC in HF management (or no particular perspective). Discussions were held with Joanne Reid (JR), TM, CH, CD, Loreena Hill (LH) and GW to refine the inclusion criteria (25 January 2022). At this point, based on the initial programme theory and stakeholder discussions, it was decided to refine the inclusion criteria further to align with the focus of the review (see Chapter 2, Refinement of the preliminary initial programme theory).

| Categories | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Document types | All documents focused on PC for patients with HF |

| Study design | All study designs. Non-empirical data (e.g. from opinion/commentary pieces) which help direct/shape theory development |

| Types of settings | All documents about inpatient or outpatient or home-based care settings |

| Types of participants | All adult patients (18 years and over) with HF |

| Types of intervention | Any combination of PC strategies for the management of patients with HF |

| Outcome measures | All integrated PC- and HF-related outcome measures |

Documents that described HCPs’ perspectives on PC in HF were included for full-text screening. With the refinement of the inclusion criteria, 140 documents from the main search were found to provide data relating to HCPs’ experiences of PC in HF. All documents containing data thought to contribute to programme theory refinement were included.

Step 4: extracting and organising data

When document selection was completed, CH and CB uploaded the full texts of included documents into NVivo (Version 12, 2018) (QSR International, Warrington, UK) qualitative data analysis software, to assist with data management. Data extraction involved coding data within NVivo. Initial coding of the documents retrieved by the main search was undertaken by CH and 10% was independently checked by TM. Coding was both inductive (codes emerging through data analysis) and deductive methods (codes determined prior to analysis through initial programme theory and stakeholder discussions). The coding framework resulted from the analysis of the richest documents, which were documents that we judged had the most potential to inform the programme theory; within this review, these were mostly qualitative research documents. Examples of initial codes identified were ‘biomedical culture within cardiology’ and ‘terminology – understanding what PC is and is not’. We concurrently worked to identify ‘guiding principles’ and features underpinning the interventions, and relevant implications discussed mostly in policy documents, reviews and commentaries. The framework generated was applied to the rest of the documents and refined as the analysis progressed. For example, we identified relevant contexts when these mechanisms were likely to be ‘triggered’, such as a shared understanding (across patient, informal caregiver and HCPs) that PC in HF management positively contributes to optimised QoL. Such contexts and mechanism became ‘codes’.

The coding frame was based on the richest documents and then was conducted chronologically (CH), starting with the most current documents to identify any improvements in relation to implementation of integrated PC and HF overtime that could help direct/shape our programme theory. Alerts and stakeholder documents were then imported into NVivo, coded by CB and checked by JR. Regular team meetings throughout this phase focused on analysing the codes and their relationship to the developing programme theory. These regular team discussions and engagement with the data enabled and facilitated understanding of how emerging data may influence the refinement of our programme theory. Based on these discussions, additional coding was undertaken by CB and checked by JR. This then in turn led onto the realist analysis (step 5) to help explain and develop the final programme theory and context–mechanism–outcome configurations (CMOcs).

Data extraction was conducted on included documents from the main search (CH, 10% checked by TM), alerts (CB and JR) and stakeholder documents (JR) to capture descriptive categories captured within an Excel spreadsheet. These descriptive categories included participant characteristics (i.e. which type of healthcare professionals), study characteristics and implications provided. While we included an international evidence base within this review, we were mindful of the medico-legal context within the NHS and details on the county of origin of each included document are captured in the data extraction tables. The characteristics of the included documents are summarised in Appendix 2, Tables 37–40.

Step 5: synthesising and drawing conclusions

The analysis was driven by a realist logic. We sought to interpret and explain mechanisms, such as shared vision and provision of joint PC and HF education, in which integrated PC in HF management would occur (or not). We used the coding of the included documents within NVivo to draw relationships between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes, and to further develop our initial programme theory. To develop and refine the CMOcs, and the programme theory, we made judgements about the relevance and rigour of data extracted from the included documents following a series of questions that are commonly used in realist reviews. 46 Our data synthesis process was informed by the following questions (Box 1).

Are the contents of a section of text within an included document referring to data that might be relevant to programme theory development?

Judgements about trustworthiness and rigourAre the data sufficiently trustworthy to warrant making changes (if needed) to the programme theory?

Interpretation of meaningIf the section of text is relevant and trustworthy enough, does its contents provide data that may be interpreted as functioning as context, mechanism or outcome?

Interpretations and judgements about CMOcsWhat is the CMOc (partial or complete) for the data?

Are there data to inform CMOcs contained within this document or other included documents? If so, which other documents?

How does this CMOc relate to CMOcs that have already been developed?

Interpretations and judgements about programme theoryHow does this (full or partial) CMOc relate to the programme theory?

Within this same document are there data which inform how the CMOc relates to the programme theory? If not, are there data in other documents? Which ones?

In light of this CMOc and any supporting data, does the programme theory need to be changed?

Reproduced with permission from Papoutsi et al. 46 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text above includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

We followed a process of constantly moving from data to theory as we refined explanations for patterns of particular behaviours or outcomes. We attempted to frame these explanations at a level of abstraction that could encompass a variety of phenomena or behaviour patterns. We worked on identifying relationships between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes within and across different documents (e.g. mechanisms inferred from one document could help explain how contexts influenced outcomes reported in a different document). We regularly synthesised data from different documents to build CMOcs, as complete CMOcs could not always be found in the one document.

As described above, we identified ‘guiding principles’ and implications that underpin existing interventions. The juxtaposition of these ‘guiding principles’ (underpinning interventions and implications) with the ‘possible mechanisms’ identified allowed us to identify particular configurations of mechanisms and contexts that were more likely to be conducive, or hinder implementation of integrated PC in HF management. Additionally, this work helped to identify barriers to the effectiveness of implementing integrated PC into HF management. Within this review, the most self-explanatory example of this may be PC and HF specialisms working within silos and a consequential lack of shared learning and reciprocal partnership working to facilitate integrated PC within HF management.

Direct quotations from included documents coded within NVivo were collated and presented to help demonstrate/explain emerging CMOs and contribute towards the synthesis. These CMOcs were compared to and contrasted with our evolving programme theory to understand relationships between each CMOc and their place within the programme theory. As the review progressed, we iteratively refined the programme theory driven by interpretations of the data included in the literature, and by feedback received by our stakeholders.

In summarising, the evidence synthesis process was achieved using the below analytic processes:51

-

Juxtaposition of data sources: data reported in different documents were compared and contrasted.

-

Reconciling ‘contradictory’ or disconfirming data: when outcomes differed in seemingly comparable circumstances, further investigation was undertaken to find explanations for why different outcomes happened. This involved looking closer at what made up the context for different kinds of ‘problems’, to understand how the mechanisms triggered could explain different outcomes.

-

Consolidation of sources of evidence: when the findings from different documents had similarities, a judgement was made as to whether these similarities could adequately form patterns to inform the development of CMOcs and programme theory, or whether there were nuances that needed to be highlighted, and for what purpose.

The aim of the analysis was to reach theoretical saturation, that sufficient information had been captured to portray and explain the processes leading to the implementation of integrated PC in HF management and the mechanisms that can aid this implementation.

Use of substantive theory

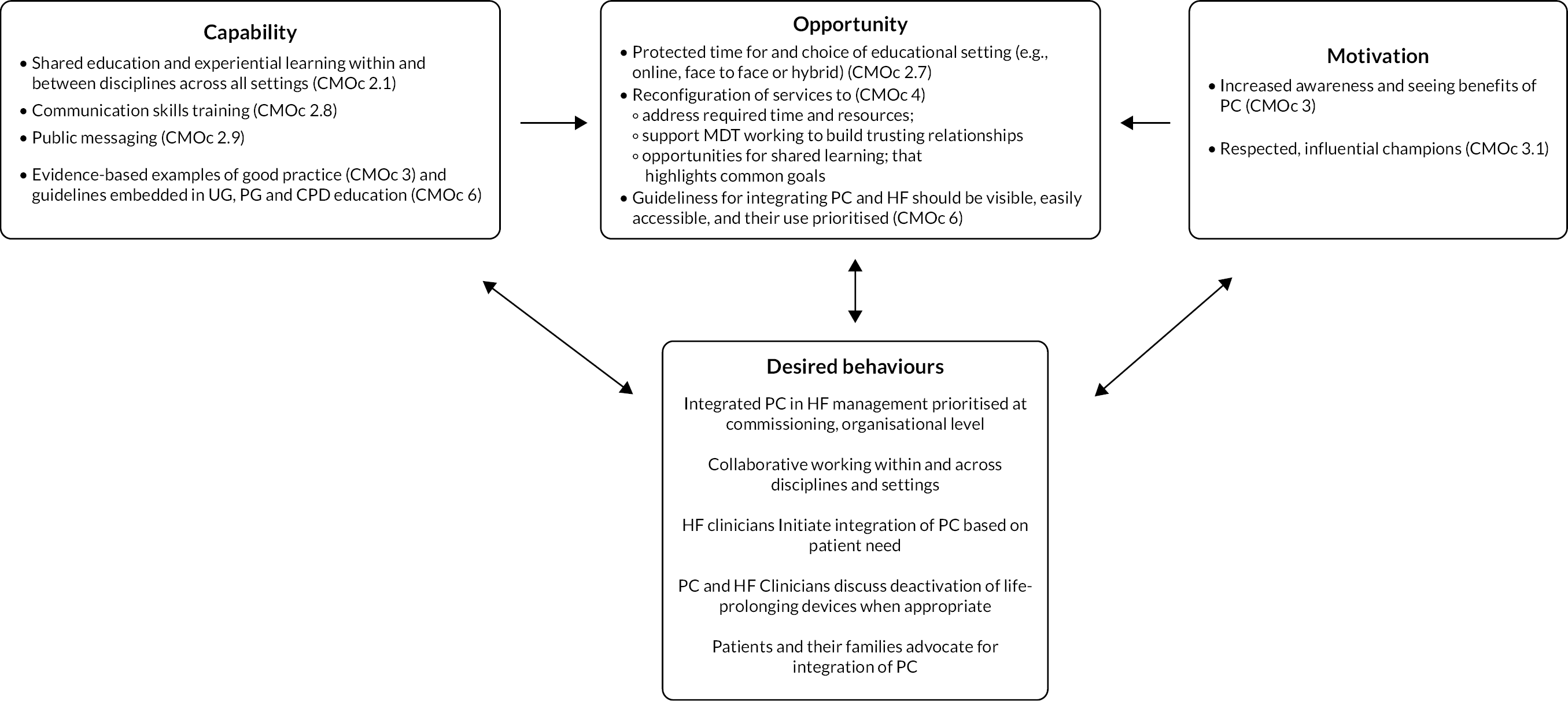

As realist syntheses are a form of theory-driven review, they commonly use existing theoretical frameworks (or substantive theories) to either provide analogy or as ‘lenses’ to help explain, for example, the underlying mechanisms behind our findings. Taking this into account, the use of substantive theory was discussed within our regular team meetings throughout this project. Based on the content expertise within the project team, a key theoretical framework that was considered at these meetings was the capability, opportunity, motivation, behaviour (COM-B) model. The COM-B model of behaviour presents three components required for any behaviour (B). These factors are capability, opportunity, and motivation,52 visually detailed in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

The COM-B model of behaviour.

Capability refers to having the knowledge, skills and abilities to engage in a behaviour, and is comprised of two areas: psychological capability and physical capability. Opportunity, within the context of the COM-B model, refers to the external factors needed to engage in a particular behaviour and describes two components: physical opportunity and social opportunity. Motivation refers to internal processes that influence behaviour and has two components: reflective and automatic motivation. This theoretical model was deemed particularly relevant to help frame our findings, as the successful implementation of integrated PC and HF can be largely explained by healthcare professional capabilities, opportunities and their motivation (or lack of) to integrate care.

Chapter 3 Results

Sections of this report have been reproduced with permission from McConnell et al. 53 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, providing the original author and source are credited. The text within this report includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Results of the review

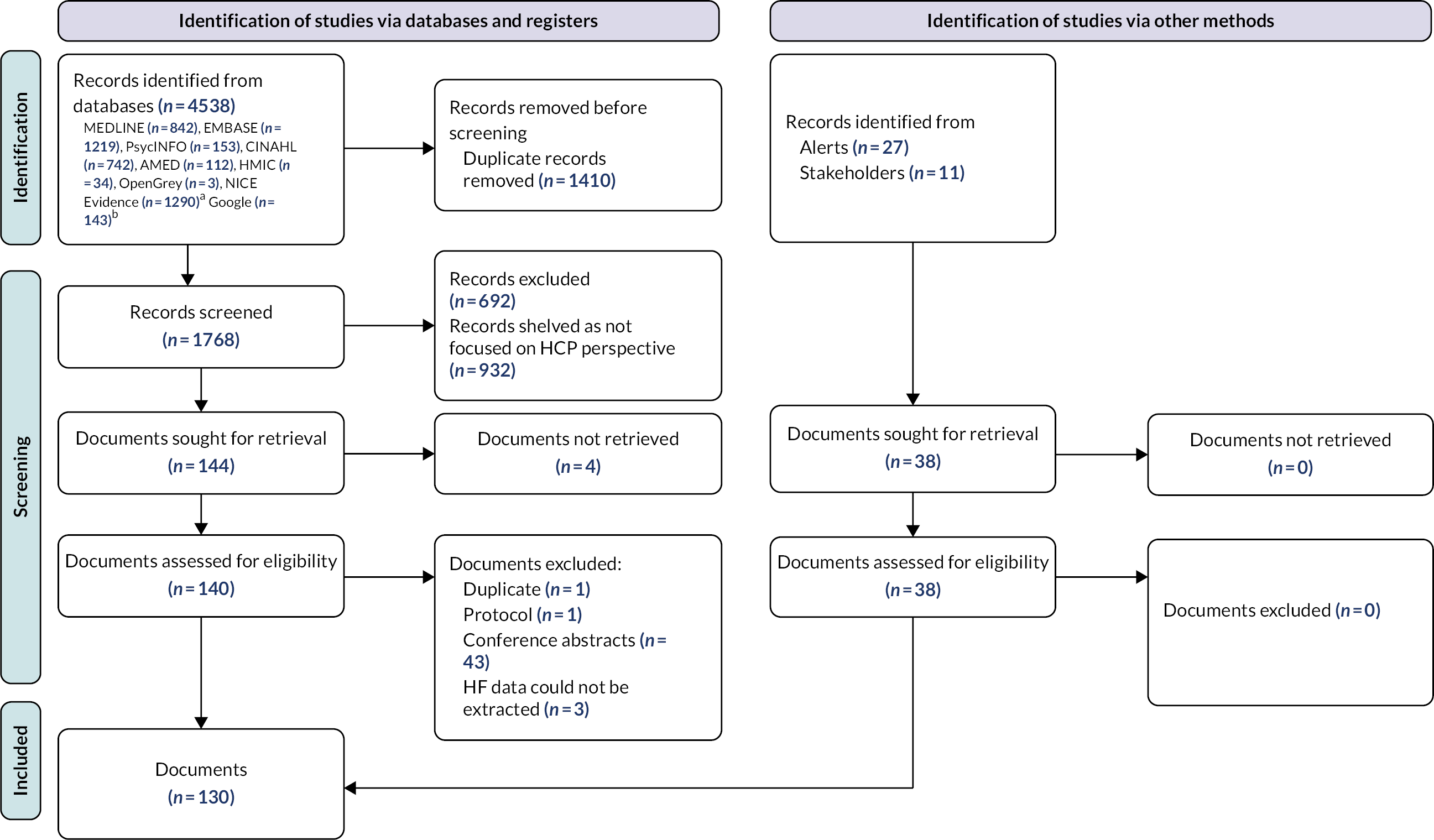

The Preferred Reporting of Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram54 reports the number of documents that were identified, included and excluded in the review (Figure 4). In total, 1768 records were identified through database searching and screened, with 1076 documents meeting the initial inclusion criteria. Given the large number of eligible documents, we consulted with our stakeholders during our first meeting held on 3 November 2021 (see Chapter 2, Stakeholder group) to agree on the most pertinent aspects of our preliminary programme theory to focus on so we could make the most substantial contribution to our programme theory. The background literature and our stakeholder group collectively emphasised the key role that HCP perspectives play in influencing whether or not PC is integrated within HF management. Therefore, we narrowed our inclusion criteria to documents focused more specifically on HCPs’ perspectives on PC in HF management. The number that met these narrowed criteria was 140, of which 48 were removed based on exclusion criteria. A further 38 documents were returned from alerts (n = 27) and stakeholder documents (n = 11). In total, 130 documents were included in the review (see Appendix 2, Tables 37–40). No discrepancies were identified during the 10% check of coding and data extraction from the main search.

FIGURE 4.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews. a NICE Evidence search (evidence.nhs.uk) is now retired. A total of 1290 hits were ranked by relevancy and the first 500 hits were screened ‘on screen’. b Google search (google.com) estimated 20,200,000 hits but only the first 143 were available and were screened ‘on screen’. Reproduced with permission from Page et al. 54 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text above includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Study characteristics

The majority of documents ‒ 36% (n = 46/130) ‒ were conducted in the USA and a smaller number ‒ 26% (n = 34/130) ‒ conducted in the UK. The majority of documents ‒ 37% (n = 48/130) ‒ focused on a combination of HCPs, patients and informal caregivers. A total of 6% (n = 8/130) of documents focused on physicians (of different specialties), 6% (n = 8/130) focused specifically on nursing staff, and a minority 1% (n = 1/130) focused on GPs. The date of publication ranged from 2000 to 2022, with the majority 69% (n = 90/130) of documents published between 2011 and 2021. The majority 66% (n = 86/130) of documents were research, including 29% (n = 37/130) qualitative work, 15% (n = 19/130) survey designs, with a small number (4%) of trials (n = 5/130) and 17% (n = 22/130) literature reviews. The majority 72% (n = 94/130) of documents focused on barriers and facilitators to PC in HF management. A small number of documents, 10% (n = 13/130), focused on aspects of integrated service design or tools to assist needs assessment. Appendix 2 provides a detailed overview of the characteristics of all included documents.

Summary of context–mechanism–outcome configurations

Table 3 contains a summary of the 6 CMOcs and 30 sub CMOcs uncovered from our review of the literature, in three main clusters.

| Cluster/CMOc | Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main CMOc | Sub CMOc | ||

| Cluster 1: culture change Understanding the impact of a biomedical culture |

|||

| CMOc 1 | When HF physicians and HF nurses work within a biomedical culture that equates PC with EoL care only (C), they are less likely to integrate PC early (O) because they do not think it is appropriate (M) | ||

| CMOc 1.1 | When HF physicians’ and HF nurses’ training focuses predominantly on biomedical interventions to prolong life (C), they can be reluctant to consider PC (O), because they perceive they have failed in their care of the patient by doing so (M) | ||

| CMOc 1.2a | When HF physicians and HF nurses experience discomfort with poor prognosis (C), they may use language to soften a diagnosis/prognosis (O) because they do not want to erode the patient’s hope for more curative treatments (M) | ||

| CMOc 1.2b | When HF physicians and HF nurses use language that they feel may soften a diagnosis/prognosis (C), patients may be less upset but also less aware of the seriousness of their illness (O) because they do not fully understand (M) | ||

| CMOc 1.3 | When HF physicians and HF nurses synonymise PC with EoL care (C), they are reluctant to discuss this with patients who have HF receiving active treatments (O), because they do not think the patient is at the end of their life yet (M) | ||

| CMOc 1.4 | When the health and QoL of a patient with HF is deteriorating (C), HF physicians and HF nurses are still reluctant to integrate PC (O), because they are concerned this will signal to the patient that they are giving up on them (M) | ||

| CMOc 1.5 | When HF physicians and HF nurses believe that PC is suitable only for people with cancer who have a more predictable prognosis (C), they are unlikely to discuss PC with patients (O), because they believe it will not be helpful (M) | ||

| CMOc 1.6 | When HF physicians are focused on exhausting treatment options to prevent patients from dying (C), they are less likely to accept the need for PC (O) or want to discuss it with patients (O) because they do not believe the two approaches (biomedical and PC) can be provided in parallel to alleviate patient suffering (M) | ||

| CMOc 1.7a | When life-prolonging devices are futile (C), HF physicians infrequently discuss deactivation (O) because they lack confidence discussing this with the patient and their informal caregivers (M) | ||

| CMOc 1.7b | When life-prolonging devices are no longer appropriate for patients who have HF (C), PC physicians and PC nurses are uncertain about how to discuss this with patients (O) because they lack the specialist knowledge to do so (M) | ||

| Cluster 1: culture change Achieving culture change, using educational opportunities to change the culture for PC in HF |

|||

| CMOc 2 | When HF physicians and HF nurses have exposure to educational strategies that teach and prioritise PC (C), they are more willing to provide generalist PC and know when to refer to or seek input from specialist PC (O) because they have greater knowledge and confidence in their abilities to do so (M) | ||

| CMOc 2.1 | When HF and PC physicians and nurses take part in joint education that focuses on effective partnership working and patient care-co-ordination across different care settings (C), they are better able to identify and address the PC needs of patients with HF earlier (O) because they can learn how to share and mobilise their different knowledge and skills (M) | ||

| CMOc 2.2a | When PC physicians and PC nurses assess suitability for PC and provide care based on prognosis (i.e. in a similar way to cancer patients) (C), patients with HF are less likely to receive timely needs-based PC (O) because their condition is so variable and unpredictable (M) | ||

| CMOc 2.2b | When those involved in the care of patients with HF across settings have access to and seek advice, support and education for any challenges they face in managing patients who have HF (C), patients with HF are more likely to get better care (O) because HCPs are more able to identify their PC needs (M) | ||

| CMOc 2.3 | When those working in HF have access to and attend education for any challenges they face in managing patients who have HF with PC needs (C), patients with HF are more likely to get timely PC (O) because HF physicians and HF nurses have better knowledge of when PC may be needed (M) | ||

| CMOc 2.4 | When HF physicians and HF nurses have access to, and attend UG, PG or ongoing PC education that focuses on the purpose and role PC can play in HF clinical practice (C), they are likely to better appreciate when PC is needed for patients (O) because of their increased understanding (M) | ||

| CMOc 2.5a | When HF and PC physicians and nurses take part in experiential learning with peer support and reflection (C), they develop better mutual understanding and relationship building between disciplines (O) because they come to appreciate their respective strengths and skills (M) | ||

| CMOc 2.5b | When physicians and nurses in HF and PC are given protected time and choice of educational settings (e.g. online, face to face or hybrid) (C), they are more likely to attend (O) because they are empowered to do so (M) | ||

| CMOc 2.6 | When HF physicians and HF nurses who find it challenging to discuss PC with patients who have HF are offered and attend suitable education in communication skills (C), they are more likely to raise this issue with patients and their informal caregivers (O) because they have the confidence and knowledge needed (M) | ||

| CMOc 2.7 | When patients with HF, who think that PC lacks relevance for them, are provided early on with individually appropriate information about the purpose and role of PC in HF (C), they are more likely to have a better understanding of when they might benefit from PC (O) because they have a better appreciation of it (M) | ||

| Cluster 1: culture change Winning hearts and minds, using leadership and examples of benefit to change the culture for PC in HF |

|||

| CMOc 3 | When service providers and users have sufficient appreciation about the benefits of PC (C), they are more motivated to advocate for integrated PC in HF management (O), because they understand its role in improving patient outcomes (M). | ||

| CMOc 3.1 | When a respected and influential HF clinician in an organisation consistently advocates for the benefits of integrating PC into HF (C), they are more likely to be able to overcome indifference and resistance to integration (O) because they are perceived to have authority and credibility (M) | ||

| CMOc 3.2a | When patients who have HF and their informal caregivers are able to directly experience the benefits of early integrated HF and PC (C), they are more likely to ask for it (O) because they have an appreciation of its value (M) | ||

| CMOc 3.2b | When HF physicians and HF nurses are able to directly see the benefits for their patients of early integrated HF and PC (C), they are more likely to implement it (O) because they have an appreciation of its value (M) | ||

| Cluster 2: practice change Facilitating practice change for example considering the impact of wider context and organisational issues on PC integration |

|||

| CMOc 4 | When HF and PC physicians and nurses have opportunities to work collaboratively with relevant professionals to provide integrated PC and HF management (C), they are better able to assess and address their patients’ PC needs (O) because they learn when and how to draw on each other’s skills and knowledge (M) | ||

| CMOc 4.1 | When well-functioning MDTs consist of a wider range of relevant professionals (C), the team has access to a wider range of expertise (O) because each brings unique perspectives and experiences (M) | ||

| CMOc 4.2 | When MDTs are well organised with clearly defined roles and responsibilities (C), it enables high-quality parallel planning and more effective decision-making across care settings (O) because members know what is expected of them (M) | ||

| CMOc 4.3 | When HF physicians and HF nurses caring for a patient with HF are able to identify the relevant staff member(s) who has the most frequent contact with the patient with HF (C), patients are more likely to be receptive to advice delivered by them (O) because they trust them (M) | ||

| CMOc 4.4 | When HF physicians and HF nurses work in a clinical hierarchy where important decisions around key aspects of patient care are made by those higher up the hierarchy (C), those further down the hierarchy (usually HF nurses) feel unable to discuss PC with patients (O) because they do not believe they have the permission to do so (M) | ||

| Cluster 2: practice change Facilitating improved practice by overcoming the organisational barriers to integration |

|||

| CMOc 5 | When organisations help staff to overcome the barriers to integration of HF with PC (C), staff are more likely to focus on its delivery (O) because they are enabled to do so (M) | ||

| CMOc 5.1 | When organisations help staff to overcome barriers to the integration of PC in HF management that are beyond their individual control (C), staff are more likely to focus on timely integration (O) because they are enabled to do so (M) | ||

| CMOc 5.2 | When HF physicians and HF nurses take the time early in the HF disease trajectory to learn from patients and their informal caregivers about their goals of care (C), they can provide them with more tailored care and make decisions together (O) because they have a better understanding of their needs (M) | ||

| CMOc 5.3 | When HCPs co-operatively and collaboratively utilise each other’s areas of expertise and information for the management of patients throughout their illness trajectory (C), the patient experiences greater continuity of care (O) because the information and care they receive is not fragmented or inconsistent (M) | ||

| Cluster 3: organisational change The need to embed clear, visible guidelines to integrate PC into HF management |

|||

| CMOc 6 | When guidelines outlining who should be doing what and when are clear, visible and implemented (C), then patients with HF have their PC needs assessed and addressed at the right time, by the right people (O), because staff have clarity over expectations and roles (M) | ||

| CMOc 6.1 | When HF physicians and HF nurses perceive that guidelines for the integration of HF and PC do not provide adequate clarity over roles and responsibilities (C), they are not likely to be guided by them (O) because they lack clinical relevance or ease of implementation (M) | ||

| CMOc 6.2 | When organisations have provided both guidelines and the time and resources needed to implement them (C), HCPs are more likely to follow them (O), because they have clarity of what their organisation expects of them (M) | ||

Overview of context–mechanism–outcome configuration synthesis

The following sections present the programme theory and its underpinning CMOcs and sub CMOcs in such a way as to be transparent as well as accessible. The CMOc synthesis is further illustrated in Appendix 3, Table 41. Each section starts with an overarching CMOc, or series of CMOcs (Tables 4–34) supplemented by an explanation of the evidence base which underpins the CMOcs – that is what works/or what does not work, for whom, and in what circumstances. Illustrative data (e.g. extracts from included documents) are included in boxes under the narrative for each subsection (Boxes 2–26) as a way of showing how we made our interpretations and inferences for each of the CMOcs. Although documents included within the review refer to various terms for stages of HF (e.g. chronic HF, advanced HF, congestive HF), for inclusivity we use the term HF throughout.

| CMOc | Description |

|---|---|

| CMOc 1 | When HF physicians and HF nurses work within a biomedical culture that equates PC with EoL care only (C), they are less likely to integrate PC early (O) because they do not think it is appropriate (M) |

Cluster 1: culture change

CMOc 1: understanding the impact of a biomedical culture

Overarching CMOc 1 highlights the ‘biomedical culture’ within cardiology, and the need and potential for this culture to be challenged before PC can be successfully integrated into HF management. 48,55–58 We deem this overarching CMOc to be one of the most important explanations of why certain HF physicians and HF nurses are less likely to work to support integration of PC. 48,55–58 The narrative below describes and explains the nuances of how this biomedical culture prevents timely access to PC. This includes the difficulties with terminology in HF and PC, covering common misunderstandings which impact perceptions of PC and hence when it is most appropriately integrated. 56,59–63 Due to the complexity of the HF, illness trajectory prognostication is evidently challenging, which can cause delays in timely PC integration. 29,61,63–66 Finally, we consider specific issues relating to life-prolonging devices, and the challenges these pose for HF physicians and HF nurses conducting PC conversations with patients and their caregivers. 62,67–70 The perspectives of key HCPs have been cited in the narrative that follows. It is however important to note that, despite differences in perspectives that are likely to occur within practice across the subspecialties in cardiology (i.e. electrophysiologists), the majority of sources do not necessarily distinguish between these different subspecialties, and therefore an accurate comparison of perspectives is not possible. Furthermore, given that international literature has been included in this synthesis, we are aware that the differences in medico-legal systems within countries may result in differing perspectives on care delivery.

CMOc 1.1: biomedical culture and fears of clinical failure

Cardiology is described as active and interventional,71 and as such, HF physicians are trained to treat patients’ cardiac conditions with urgent effect which has been very successful in terms of the marked reduction in deaths now following myocardial infarction (MI). However, the intense, fast-paced environment and expectations of cardiology do not naturally permit HF physicians time to reflect on palliative and/or EoL needs. 65,72 Rather the literature illustrates that HF physicians’ clinical focus is firmly set on the need for immediate medical action to prevent patients with HF illness progression or death. 57,67,73,74 Interpretation of the data shows that HF physicians are reluctant to engage with PC, as moving from a biomedical to more holistic PC focus is seen as medical failure. 48,55–58 The fear of medical failure is not restricted to physicians, it is also evident in a proportion of nurses (24%) when they are not able to change the natural progression of HF. 58 These feelings may be embedded with a reported discomfort with death, which is often incorrectly seen as synonymous with PC. 75 PC discussions are viewed as ‘taboo’ and perpetuated by moral discomfort and a biomedical approach. 56,59,60 Within the literature reviewed PC was predominantly aligned with EoL care29,76 and a determination to prolong life is perpetuated by the mindset that anything other than biomedical treatment means clinical failure. 55–57 Therefore, hospitalisation or aggressive treatment73 is considered less of a ‘defeat’ than ensuring PC is integrated earlier in the illness trajectory to improve QoL and relieve distressing symptoms. 77 There is a clear necessity to create more willingness and ease in discussing PC needs alongside medical care directed specifically at treating HF. Building skills which will help identify PC needs in patients with HF is also key, and this is addressed under CMOc 2.

| Sub CMOc | Description |

|---|---|

| CMOc 1.1 | When HF physicians’ and HF nurses’ training focuses predominantly on biomedical interventions to prolong life (C), they can be reluctant to consider PC (O), because they perceive they have failed in their care of the patient by doing so (M) |

-

Wotton et al. :78

Transition to palliative care was made difficult when physicians viewed this as having failed the patient.

-

Borbasi et al. :73

Medicine’s fixation with cure-at-all-costs might well be the reason why patients with ESHF (early-stage heart failure) are treated aggressively until the very end.

-

Green et al. :55

Some doctors suggested that cardiologists could be reluctant to take responsibility for a patient’s transition to a palliative approach because it could give rise to a sense of failure.

-

Green et al. :55

It’s a sort of mental barrier to some cardiologists … palliative care is a sort of admission of defeat that you can’t do anything more.

-

Ziehm et al. :48

Generally, physicians of all subgroups (cardiologists and general practitioners) described cardiology as a discipline which is not able to accept medical limits. This means that cardiology is perceived as prolonging non-palliative treatment because palliative care is seen as defeat.

-

Ziehm et al. :48

As a cardiologist you are taught very early that there is always a way and that everything can be done.

-

Ziehm et al. :48

Healthcare providers, especially physicians express also their feelings about PC in terms of losing the patients or experiencing a defeat when the patients die … based on ‘an inappropriate notion of ideal medicine’.

-

Ecarnot et al. :71

In cardiology, the end of life is generally quite sudden, and when it’s sudden and unexpected, we are very physically active and interventional, and we don’t really have the time to be asking ourselves all these questions.

-

Higginbotham et al. :57

There was a belief held amongst some of the doctors that recognizing dying was equivalent to failure and so they felt morally justified in continuing to provide medical intervention.

-

Singh et al. :58

35% (n = 11) of physicians … and 24% (n = 18) of nurses … agreed that they experienced a sense of failure when they were not able to change the natural progression of heart failure or slow clinical worsening.

CMOc 1.2a and 1.2b: terminology and misunderstandings of palliative care

Another barrier to integrating PC identified in the literature is around terminology. In the context of a biomedical culture where the focus is on saving lives, hearing the words ‘heart failure’ is described by HF physicians and HF nurses as a shock to most patients and informal caregivers. As a result, physicians and HF nurses sometimes adapt their terminology to, for example, a pumping problem to soften the diagnosis. 61–63 The justification for this approach is rooted in the physicians’ desire to prevent upset and discomfort with the emotional responses evoked by the word ‘failure’ (interpreted by patients as meaning their heart would stop abruptly). 61–63,79 As a result, the term ‘heart failure’ is avoided by some physicians, who feel it is too emotive or inappropriate for the patient to hear. 61–63,79 The issue with semantics is also present when discussing PC. 80 Findings consistently point towards the discomfort among HF physicians about discussing a term associated with EoL care with their patients. 64,80 The consequence is a lack of information being given to patients regarding HF severity and prognosis,81 hindering patient-centred, holistic care and hindering patient and family opportunities to make advance preparations, which impacts on the patient’s QoL. 62,80,82 As with the stigma around PC terminology, the diagnostic term ‘heart failure’ evidently incites difficulties in communication for HF physicians and HF nurses. Therefore, training in communication skills with patients and informal caregivers could help to more easily facilitate confident conversations which ensure that patients and informal caregivers are fully aware of the diagnosis and holistic care options.

| Sub CMOc | Description |

|---|---|

| CMOc 1.2a | When HF physicians and HF nurses experience discomfort with poor prognosis (C), they may use language to soften a diagnosis/prognosis (O) because they do not want to erode the patient’s hope for more curative treatments (M) |

| CMOc 1.2b | When HF physicians and HF nurses use language that they feel may soften a diagnosis/prognosis (C), patients may be less upset but also less aware of the seriousness of their illness (O) because they do not fully understand (M) |

-

Harding et al. :61

(Heart failure is) chronic and intractable … This long-term chronic deterioration is probably something we’re not terribly good at, particularly the psychosocial aspect.

-

Chattoo and Atkin:62

… it was interesting to note how one of the patients (in his late sixties), who had been treated by a cardiologist for a year, seemed shocked when the HFN (heart failure nurse) mentioned the term ‘heart failure’.

-

Chattoo and Atkin:62

The HFN remarked that cardiologists often introduced her as ‘the nurse who takes care of pumping problems’ or ‘nurse who will take care of your tablets’, without engaging with the diagnosis or her role.

-

Chattoo and Atkin:62

Healthcare professionals are often reluctant to talk about heart failure because of the implications of the words ‘heart failure’, and if they don’t have time to sit down with somebody and explain then it can be quite a frightening term to hear.

-

Stocker et al. :63

I mean, how would you … explain heart failure to someone? I don’t like the term heart failure because failure just sounds like you’re about to pop it which generally speaking they’re not.

-

Stocker et al. :63

It doesn’t always work that way in practice. If that patient is in shock or in denial or very upset still about the fact that they’ve got heart failure, because the term (palliative care) itself is a scary term.

-

Ament et al. :82

You have to help the patient to get the right information. Otherwise, you don’t know if the information they’re getting is giving them realistic expectations, because that’s where it starts. You have to know what they understand and what they can expect.

CMOc 1.3: the problems associated with terminology and misunderstandings of palliative care

| Sub CMOc | Description |

|---|---|

| CMOc 1.3 | When HF physicians and HF nurses synonymise PC with EoL care (C), they are reluctant to discuss this with patients who have HF receiving active treatments (O), because they do not think the patient is at the end of their life yet (M) |

As alluded to earlier in CMOc 1, integration of PC for patients with HF may be suboptimal due to limited knowledge and misperceptions of PC as a service reserved for those near death and not suitable for patients with chronic conditions like HF. 58,74,75,83 The evidence suggests PC is being inaccurately synonymised with EoL care and this attitude evidently informs whether and how early HF physicians integrate PC into HF management. 58,74–76,83 Given HF physicians’ self-perceived identity as life-savers84 and considering that PC is synonymised with EoL care, this paradigm does not naturally nor easily merge with the role of conducting PC conversations. PC is described as a ‘grey area’ which evidently incites a fear for HF physicians and HF nurses that post-conversation patients will have the perception that they going to die imminently. 82,85–87 Although time issues to initiate PC conversations is often blamed on inadequate staffing67,85 (expanded on in CMOC 4), the widespread reference to lack of time may actually hide a lack of confidence in HF physicians and HF nurses to conduct PC conversations, as has been suggested in the literature – respondents working in the hospital mentioned that they do not feel comfortable to make time for conversations with patients about PC needs. 88 HF physicians report not having adequate knowledge and feeling under-skilled, thus lacking in confidence in a palliative approach, which then makes them reticent to discuss PC. 63,82,85–88 The term ‘supportive care’ as a service name was viewed by HF physicians and HF nurses to be less synonymous with EoL and hospice; less prognosis dependent compared to the term ‘palliative care’; and is deemed more suitable to adopt in HF care. 64 The issue of rebranding is part of a current, larger debate among PC specialists, which has not been studied among HF physicians and patients with HF. 64 However, changing the name to ‘supportive care’ without adequate education around what this type of care involves may raise the same problems as those found for the term ‘palliative care’. What is necessary is to ensure that there is adequate PC education to improve knowledge in the underlying ethos and components of PC and how this can be integrated at all stages of HF illness trajectory. 58,64,74,75,83 The literature also highlights communication difficulties between the clinician and the patient in relation to the core aspects of PC,58,74,75,83 so whether or not PC is rebranded64 HF physicians and HF nurses require training to improve communication skills in order to accurately convey what PC means.

-

Kavalieratos et al. :83

When asked to describe eligibility and appropriateness criteria for palliative care (for which there are none, aside from patient need), cardiology and primary care providers used the terms ‘hospice’ and ‘palliative care’ interchangeably unless prompted for clarification.

-

Kavalieratos et al. :83

Interviewer: And, so in your mind, is there a distinction between palliative care and hospice care? Cardiologist: No. Not in my mind. Is there?

-

Schallmo et al. :75

The term ‘palliative care’ was often used interchangeably with end-of-life care and sometimes interchangeably in the same article. This led to confusion because the reader was unsure whether the author was referring to communication barriers of PC or hospice, or both.

-

Janssen et al. :74

… and at a certain moment you get to using the words ‘PC’. But it is so loaded because palliative is confused with terminal.

-

Singh et al. :58

… most healthcare professionals providing care to individuals with heart failure regard palliative care as an end-of-life approach.

-

Singh et al. :58

A high proportion of participants believed the service name ‘palliative care’ was a barrier to referral, synonymous with hospice, decreases hope and was viewed to be prognosis dependent, in comparison to the service name ‘supportive care’.

-

Bonares et al. :64

57.4% believed that their patients have negative perceptions of the term ‘Palliative Care’, and 44.1% (243 of 551) stated that they would be more likely to refer to SPC (specialised palliative care) earlier if it was renamed ‘Supportive Care’.

-

Bonares et al. :64

There is evidence that, among medical oncologists and patients with cancer, the term supportive care is received more favourably than palliative care. This has not been studied among cardiologists and patients with heart failure.

-

Bonares et al. :64

Referral frequency was associated with … less equation of palliative care with end-of-life care (P < 0.001).

-

Graham et al. :85

I need to be able to take the time to introduce it in a way that I don’t walk out of the room and they actually think ‘what the hell is he talking about – I’m gonna die so I need palliative care?’

CMOc 1.4: heart failure physicians and heart failure nurses’ fears in relation to giving up on patients

The presence of a biomedical culture within cardiology, combined with the stigma around the term PC as synonymous with EoL, also generates moral tension, as HF physicians feel that they have given up on patients with HF and their informal caregivers when they introduce PC. 57,88–90 As a primary care physician in an American qualitative study explains: ‘It’s that dance around giving up, the perception of giving up on them when you start talking about end‐of‐life in hospice and that sort of thing’. 67 The distress caused through fears of diminishing hope for patients when introducing PC is evidently closely linked to HF physicians’ misperception of PC and concerns of ‘walking away from’ or giving up on patients. 57,67,78,89 There is also dual pressure from HF physicians’ clinical perception of their role as ‘life-savers’84 and their possible (inadvertent) misconstruction of what patients and informal caregivers need and want that is holistic individualised care. 60,67 However, this attachment to their professional identity is in part understandable as evidence suggests that HF physicians are not the only group who view themselves as life savers. 90 Patients with HF and informal caregivers have an understandable confidence in cardiology teams’ competency to prolong life and many may have a resistance to PC through lack of understanding and misconceptions that it is EoL care only. Therefore, public health campaigns to help communicate a wider knowledge of the benefits of PC and regarding the integration of PC into HF management early in the illness trajectory may help provide more familiarisation and realistic expectations. Knowledge of PC and adequate time to provide continuity of care could also help to relieve undue pressure relating to HF physicians’ concerns about ‘walking away’ from patients and informal caregivers.

| Sub CMOc | Description |

|---|---|

| CMOc 1.4 | When the health and QoL of a patient with HF is deteriorating (C), HF physicians and HF nurses are still reluctant to integrate PC (O), because they are concerned this will signal to the patient that they are giving up on them (M) |

-

Kavalieratos et al. :83

… cardiology providers frequently discussed the ‘point at which you are unable to do more’ … the trigger to get (the palliative care service) involved was knowing that my patient was dying and that I didn’t have other medical options for them.

-

Ismail et al. :84

Important and underemphasised aspect of cardiology. We like to think of ourselves as life savers, is that possibly why we don’t address the end-stage heart failure issues so well.

-

Glogowska et al. :90

This curative culture is not exclusive to cardiologists. Patients … may have received many successful treatments over the span of their heart failure trajectory, so may also believe that the cardiologist will always be able to find a new treatment.

-

Shinall:56

The culture of medicine, designed to prolong life at all costs, had trouble accounting for the need to stop at some point, and providers acutely felt the clash between honoring a patient’s wishes and their own discomfort in stopping life support, which at times felt like murder.

-

Singh et al. :91

Yeah I think there’s probably a perception, a real perception of you know … we haven’t done our job.

-

Hutchinson et al. :67

[Patients] want to know that everything possible is being done. And they feel as if going home is like people giving up. (CARD6U)

-

Hutchinson et al. :67

… no one likes to get angry phone calls or be sort of accused of not taking the best care of their loved one, or giving up on them … when you start talking about end-of-life in hospice and that sort of thing.

-

Higginbotham et al. :57

Several doctors recognized that prolongation of life was not right but at times felt obliged to meet the treatment expectations of both the patient and their families.

CMOc 1.5: the complexity of the illness trajectory: delays to palliative care

A further barrier to integrated PC for patients with HF relates to complexity of the illness trajectory, which can follow an extremely variable clinical course with periods of stability interrupted by exacerbations that may rapidly lead to instability and ultimately death. 61,62,76,92 HF physicians and HF nurses point towards the various barriers that delays a PC conversation with patients with HF. Firstly, given the alternating phases of acute HF and phases of prolonged relative stability, HF physicians and HF nurses emphasise that it is very difficult to make a definitive prognosis. 61,66,86 The complexity in formulating a short- to medium-term prognosis is further compounded by HF physicians’ and HF nurses’ perception of patients’ readiness, or lack of readiness for PC conversations. 65,66,85 When twinned with the biomedical culture, and misunderstandings of PC this creates barriers to shared decision-making93 (expanded in CMOc 4) and ultimately a delay in timely PC conversations. Some HF physicians and HF nurses acknowledged that this delay in having PC conversations was suboptimal, and primary care physicians in particular highlighted how this can lead to the inequity of PC provision for patients with HF compared to those with a cancer diagnosis, where they would routinely discuss ‘prognosis’ and PC needs at the same time. 61 The evidence suggests that HF physicians and HF nurses mistakenly intertwine PC needs with an EoL prognosis29 and therefore opportunities to have PC conversations based on a patient needs, rather than on solid evidence that nothing more can be done from a life-prolonging treatment-only perspective, are missed. 61,63–66 Some HF physicians and HF nurses highlighted an awareness that they should discuss prognosis early (which in the literature also generally means discuss PC), ideally at the point of diagnosis. 56,67,71 However, they rarely did, as this was perceived as inappropriate (or ‘cruel’) and generated fears around causing excessive distress for patients; or perhaps, as previously noted in the literature, this masked their lack of confidence in having PC conversations. 63 This feeling of being under-skilled in discussing prognosis and PC issues led to a ‘trickling down’ of prognostic information and indirect and abstract communication about the progressive and terminal nature of HF. 63 While it is evident that HF physicians and HF nurses want to ensure patients have the best care possible, they are constrained by underpinning barriers including a lack of PC knowledge and confidence in communication skills. 25,66,82,85,86 There is clearly a need for education and training for HF physicians and HF nurses so they understand that PC for patients with non-malignant chronic illness such as HF should be based on patient need and not on their prognosis, and that PC can be integrated into any point of their HF management plan when symptoms are more problematic, and stopped when patients are feeling better. 29,61,63–66

| Sub CMOc | Description |

|---|---|

| CMOc 1.5 | When HF physicians and HF nurses believe that PC is suitable only for people with cancer who have a more predictable prognosis (C), they are unlikely to discuss PC with patients (O), because they believe it will not be helpful (M) |

-

Brännström et al. :86

As chronic heart failure (CHF) is an unpredictable disease it is more difficult to talk about existential issues with these persons than with those with cancer.

-

Harding et al. :61

Cardiac staff identified the unpredictable disease trajectory as a reason why future care options are not discussed.

-

Harding et al. :61

They can be really, really poorly, and then suddenly their heart seems to gain a bit more strength and they’re up and pottering about, so it’s very difficult to prognosticate, and I think that’s what’s often so uncertain and difficult.

-

Chattoo and Atkin:62

We propose that issues of meaning of illness and pain that seem so closely embedded within popular and professional understandings of cancer … are muted within the mechanical, clinical representations of heart failure as a ‘pumping problem’.

-