Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HSDR Rapid Service Evaluation Team, contracted to undertake real time evaluations of innovations and development in health and care services, which will generate evidence of national relevance. Other evaluations by the HSDR Rapid Service Evaluation Teams are available in the HSDR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR132703. The contractual start date was in August 2020. The final report began editorial review in March 2022 and was accepted for publication in July 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Fulop et al. This work was produced by Fulop et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Fulop et al.

Chapter 1 Context

Background

In December 2019, a new form of coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was identified in Wuhan in China. 1 The SARS-CoV-2 virus causes an infectious disease, which is referred to as ‘COVID-19’. 2 In January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak to be a ‘public health emergency of international concern’. 3 COVID-19 has been responsible for millions of deaths and hospitalisations worldwide. 4 The WHO has reported that, globally, there have been 761,071,826 confirmed cases and 6, 879,677 deaths (as of 22 March 2023). 5 COVID-19 cases have continued to fluctuate since January 2020. For example, since January 2020, England alone has experienced three waves of the COVID-19 pandemic (wave 1: March to May 2020, wave 2: October 2020 to February 2021, wave 3: began in July 2021 but has been complex to track and is therefore currently difficult to estimate when the end date was). 6

COVID-19 is characterised by some common symptoms including a fever, a continuous cough, tiredness and loss of taste and/or smell. 2 In wave 1, there was a lack of knowledge of COVID-19 and treatment options compared with later waves. During the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions on travel, social interaction and access to public spaces, known as a ‘lockdown’, were introduced worldwide. For example, within the UK, individuals were asked to stay at home (with the exception of critical workers, e.g. health-care professionals, food retail workers) and to socially distance from others. 7 To minimise spread of the disease and increase capacity of health-care services, many routine health-care appointments were cancelled across the NHS or delivered remotely,8–11 and parts of the workforce were redeployed.

COVID-19 is an acute disease with differential effects on the population. Diagnosis of COVID-19 can have many health, mental health, economic and social impacts on individuals. While many individuals develop mild to moderate illness, for some the disease can be life-threatening. 2 COVID-19 has been responsible for thousands of deaths and hospitalisations in the UK. 6 As at 2 March 2023, the UK had reported 209,396 COVID-19 deaths. 5 In particular, some groups have been shown to have worse mortality and outcomes from COVID-19 – for example, older adults, those with significant medical comorbidities, males, those living in more deprived areas, black and Asian ethnic groups, and those working in certain occupations (such as taxi/bus/coach drivers, retail assistants, construction workers, social care workers and nurses). 12

Patients with COVID-19 may present with ‘silent hypoxia’ (very low oxygen saturations, often without breathlessness). 13,14 Patients may not be aware that they have low blood oxygen saturations, which may lead to delays in patients being escalated and admitted to hospital, presenting with more serious advanced symptoms of the disease. This has resulted in some patients needing invasive treatments and/or being admitted to intensive care units (ICUs), with a higher likelihood of mortality. 15,16

To deliver better and more personalised care to people in their own homes, services which enable patients to self-manage their health and care at home (e.g. remote home monitoring) have been identified as a priority within the NHS @home programme17 and the NHS Long Term Plan. 18 Prior to the pandemic, remote home monitoring models have been used to monitor and provide care for patients with chronic health conditions [e.g. heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, kidney disease, cancer]. 19–21 However, the COVID-19 pandemic enhanced and accelerated the need for health-care services to use technology in care delivery. 22

To reduce pressure on hospitals and infection transmission, and to ensure that patients with COVID-19 receive appropriate care in the right place and are appropriately escalated as early as possible, COVID-19 remote home monitoring models using pulse oximetry were developed and implemented in many different countries during the pandemic,23–32 and are now recommended by the WHO. 33 The type of remote monitoring varies, in relation to the frequency of monitoring, mode of monitoring and recording (analogue or technology enabled), referral criteria and the inclusion of pulse oximetry. 23–32

Within remote monitoring models, patients take readings at home and submit these to a health-care professional in another location for review. 34 Pulse oximeters are small devices that can be placed on a person’s finger and used to measure blood oxygen levels. Pulse oximeters were used as previous research indicates that oxygen saturation may predict outcomes such as mortality and admissions to ICUs. 35 Patients, or their carer, measure blood oxygen saturations with a pulse oximeter (together with other measurements, e.g. temperature) at home. They record these readings in one of two ways: (1) recording readings on a paper diary and providing readings via telephone (analogue), or (2) recording and submitting readings using digital technology such as smartphone applications (apps), automated telephone or text (technology enabled). Once patients have submitted readings, a health-care provider reviews these readings elsewhere, escalating care when necessary. 32,36

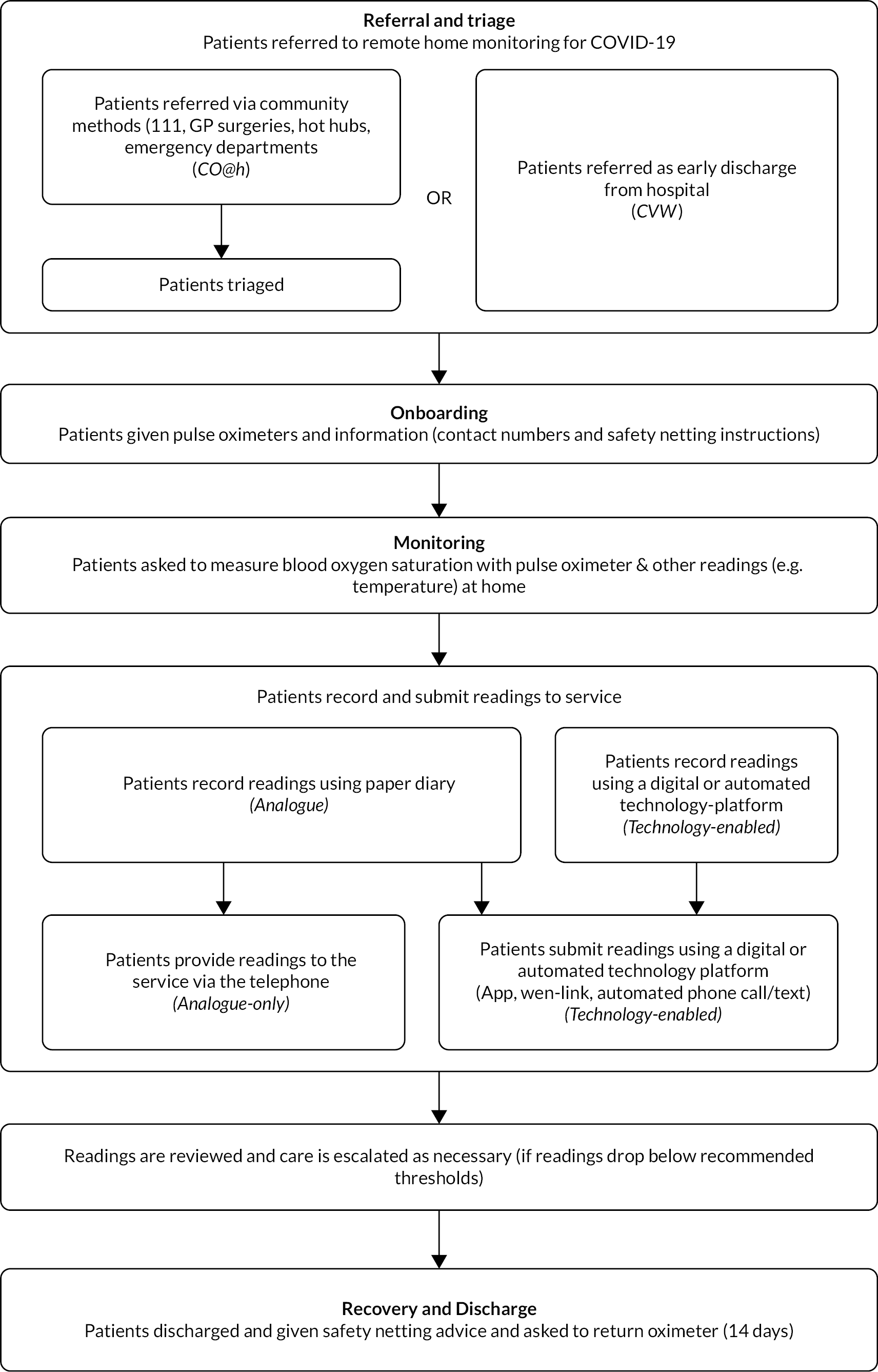

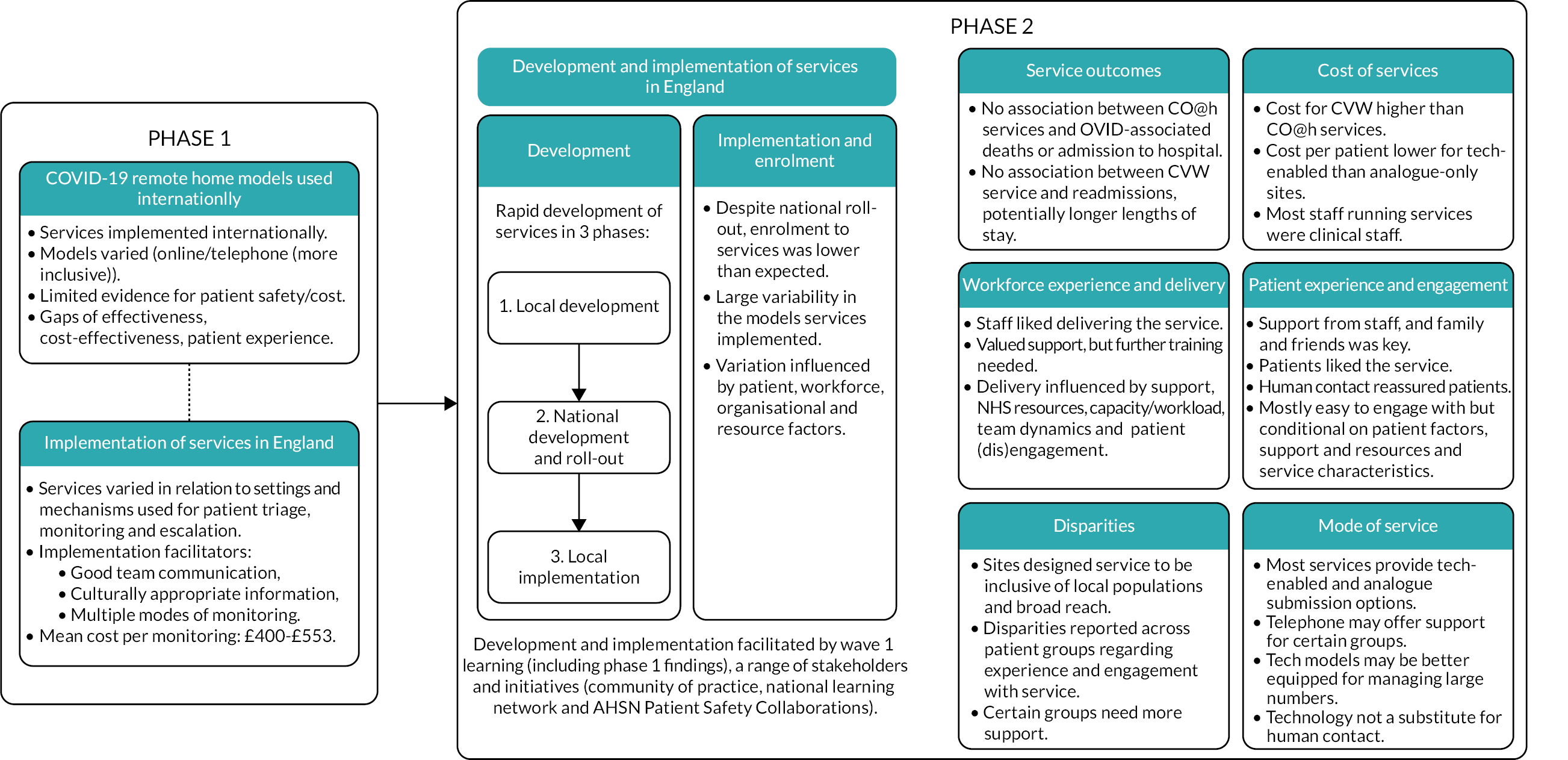

In England, during the first wave of the pandemic, COVID-19 remote home monitoring models (pre-hospital and early discharge models) using pulse oximeters were implemented in a number of areas. 36 During 2020, NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHSEI) purchased and distributed them to clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) throughout England. NHSEI purchased 706,000 oximeters across waves 1 and 2 (Zofja Zolna, NHS England, 2020 personal communication). These pulse oximeters were European Conformity (CE) marked, as recommended by Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) guidance,37 and were available to local sites within three days through an ordering system set out in the standard operating procedure (SOP). In November 2020, NHSEI launched a national roll-out of COVID Oximetry @home (CO@h) services. 38 Patients were referred within the community to the CO@h service (e.g. via general practices (GPs), COVID-19-specific community clinics, called ‘hot hubs’, and emergency departments). In addition, in January 2021, NHSEI launched a national roll-out of ‘COVID virtual ward’ (CVW) models, whereby patients were referred on to services upon being discharged from hospital early. 39 CVW models aimed to reduce pressures on hospitals by enabling early discharge and continuation of recovery at home. The national model of COVID-19 remote home monitoring, advocated by NHSEI, was for self-monitoring and self-escalation (with reference to clinical judgement), based on their learning from wave 1. 38,39 Self-monitoring and self-escalation refer to patients (or carers, where appropriate) monitoring their own readings and escalating their own care as necessary, with an option for prompts or check-in calls to take readings on certain days. This differs from remote home monitoring models whereby patients (or carers) submit readings to providers who monitor these readings remotely. NHSEI supported the national roll-out and local implementation of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services, including providing financial support for primary care to establish and implement COVID-19 remote home monitoring services,40 resourcing NHS Digital to supply data to COVID-19 remote home monitoring providers to identify people who may benefit from these services,41 and the commissioning and funding of Academic Health Science Network (AHSN) patient safety collaboratives. This study included both CO@h and CVW models. Collectively, throughout this report, we refer to these services as remote home monitoring for COVID-19 patients (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

A summary of remote home monitoring for COVID-19 services.

In addition, NHS user experience (NHSX) supported the implementation of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services through facilitation of the use of technology-enabled platforms. In the initial stages of roll-out (during wave 1), NHSX helped to pilot sites to use technology-enabled platforms as part of their CO@h and CVW services by signposting services to technology companies (however, it was up to local sites to decide whether the technology offered by these companies met their needs). In wave 2, NHSX funded and supported the implementation and evaluation of technology-enabled solutions for COVID-19 remote home monitoring services.

Despite previous research on the use of remote home monitoring models for other chronic health conditions,19–21 there is a lack of studies exploring models of care developed to implement remote home monitoring across different health-care contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to explore the implementation of remote home monitoring models within the context of a pandemic as it is likely that this context differs in relation to health-care pressures, patient needs and uncertainties. There is also a lack of studies evaluating the effectiveness and implementation of remote home monitoring models for patients with COVID-19, including in-depth analyses of patients’ and staff’s experiences of receiving and delivering care. This mixed-methods evaluation of remote home monitoring models in England aimed to address this gap by exploring the impact of the implementation of COVID-19 remote home monitoring models [on length of stay (LOS) in hospital, re-admission and health outcomes], the costs of implementing these models, the experiences of patients with remote home monitoring, staff involvement and experiences of delivering care and the processes used to implement these models at national and local levels. The study had a particular focus on inclusivity of these services and potential impact on inequalities.

Study aims

Phase 1

The phase 1 study comprised:

-

an international rapid systematic review of remote home monitoring services for patients with COVID-1932

-

a rapid study of implementation of remote home monitoring services for patients with COVID-19 during the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic in England (mixed methods). 36

The rapid systematic review aimed to analyse the implementation and impact of remote home monitoring models for patients with COVID-19.

The empirical implementation study aimed to develop a conceptual map of remote home monitoring models, to explore the experiences of staff implementing these models during the COVID-19 pandemic, to document impact of services, to understand the use of data for monitoring progress against outcomes, and document variability in staffing and resource allocation.

Phase 2

Building on phase 1, we conducted a multisite, mixed methods national evaluation involving 28 purposively selected COVID-19 remote home monitoring services (October 2020 to November 2021).

This evaluation aimed to explore effectiveness, costs, implementation and experience (staff/patients) of COVID-19 remote home monitoring, and comprised four workstreams:

-

effectiveness

-

cost analysis

-

national survey of implementation and staff and patient experience

-

in-depth case studies of implementation and staff and patient experience.

Research questions

Phase 1

Systematic review:

-

What are the aims of remote home monitoring models?

-

What are the main components of these models?

-

What are the patient populations considered appropriate for remote monitoring?

-

How is patient deterioration determined and flagged?

-

What are the expected outcomes of implementing remote home monitoring?

-

How have these models been evaluated?

-

What are the benefits and limitations of implementing these models?

Implementation study:

-

What were the conceptual models guiding the implementation of remote home monitoring models during the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

What were the processes that acted as barriers and facilitators in the design and implementation of pilots of these models during wave 1 of the pandemic?

-

What were the expected outcomes of the virtual wards implemented during wave 1 of the pandemic?

-

What data were collected by pilot sites and how has it helped them monitor progress against their expected outcomes?

-

What quantitative evidence did the sites use from national and international experiences of these models to help inform clinical management decisions?

-

How were resources allocated (including staffing models) to implement the remote home monitoring pilots during wave 1 of the pandemic?

-

What are the lessons learned from implementing remote home monitoring models during wave 1 of the pandemic? Can some of these lessons be used for planning care delivery for winter 2020–21?

Phase 2

-

What was the impact of remote home monitoring for patients with COVID-19 on mortality and use of hospital services? (workstream 1)

-

What were the costs of setting up and running CO@h and CVW models? (workstream 2)

-

What were the factors influencing delivery and implementation of remote home monitoring for patients with COVID-19? (workstream 3)

-

What were the experiences and behaviours (i.e. engagement, use of other services) of patients receiving remote home monitoring for patients with COVID-19? (workstream 3)

-

Were there potential impacts of remote home monitoring for patients with COVID-19 on existing health inequalities? (workstream 3)

-

What were the experiences of staff delivering remote home monitoring for patients with COVID-19? (workstream 3)

See Chapter 2 for protocol deviations.

Structure of this report

-

Chapter 1 (context) outlines the rationale for this evaluation

-

Chapter 2 (methods) presents the design and methods used (phases 1 and 2). Detailed methods are presented within each findings chapter.

-

Chapter 3–11 (findings) outline the findings.

-

Chapter 3 – phase 1

-

Chapter 4 – implementation study (workstream 3 and 4).

-

Chapters 5 and 6 – effectiveness study (workstream 1).

-

Chapter 7 – cost analysis (workstream 2).

-

Chapters 8 to 11– patient and staff experience findings (workstreams 3 and 4).

-

-

Chapter 12 (discussion and conclusion) – key findings, strengths and limitations, implications/lessons learned and future research.

Other related evaluations

Two other evaluations of remote home monitoring models for COVID-19 were commissioned alongside this evaluation, conducted by: (1) Institute of Global Health Innovation, National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Patient Safety Translational Research Centre, Imperial College London and, (2) the Improvement Analytics Unit (IAU; a partnership between the Health Foundation and NHSEI). Both evaluations investigated the impact of the CO@h service on mortality and hospital service use. 42–45 Imperial College London also examined inequalities in the enrolment of eligible patients on to the CO@h service and conducted quantitative evaluations of differences between technology-enabled and analogue pathways. 46

The Birmingham, RAND and Cambridge Evaluation Centre (BRACE) and Rapid Service Evaluation Team (RSET) also investigated the use of pulse oximetry in care homes across England and completed a mixed-methods rapid evaluation using an online national survey sent to all care homes in England and qualitative interviews with staff from six care homes acting as case study sites (see Sidhu et al. 47).

Working with stakeholders

Throughout the evaluation, the team worked with a range of stakeholders at national and local levels (phase 1: community of practice, phase 2: NHSEI, NHS Digital, NHSX, community of practice, national learning network and Clinical advisory group).

Chapter 2 An overview of the methods used in the COVID-19 remote home monitoring evaluation

This chapter outlines the methods used in phase 1 and phase 2 of the evaluation. Individual chapters provide further details.

Phase 1

This phase was developed as a result of a 4-week scoping exercise including initial scoping of the literature, discussions with a small number of sites, documentary analysis and discussions with colleagues at Public Health England (PHE) and NHSEI.

Methods

Setting

In England, within health-care organisations (trusts/CCGs) who delivered remote home monitoring services for COVID-19 patients (including CO@h and CVW models). The evaluation took place between July and September 2020.

Procedure

Systematic review

A rapid systematic review of virtual ward models (led by primary and secondary care) was conducted. The systematic review followed the method proposed by Tricco et al. 48 (see Chapter 3).

Implementation study

A rapid multisite implementation study which combined qualitative and quantitative approaches. Interviews were conducted with staff across eight sites in England. Additionally, we collected data on impact, costs, and staffing models (see Chapter 3).

Ethical approval

This phase received ethical approval from the University of Birmingham humanities and social sciences ethics committee (ERN_13-1085AP37) and was categorised as a service evaluation by the Health Research Authority (HRA) decision tool and University College London/University College London Hospitals (UCL/UCLH) Joint Research Office.

Phase 2

The protocol was informed by phase 1 and developed with input from our clinical advisory group (colleagues at PHE, NHSEI, NHS Digital and NHSX), and with other research teams working in this area.

Methods

Setting

In England, within health-care organisations (trusts/CCGs) that delivered remote home monitoring services for patients with COVID-19 (including CO@h and CVW models). The evaluation took place between October 2020 and November 2021 (data collection took place between February and June 2021, but the patient survey retrospectively included January 2021).

Design

A rapid multisite study combining qualitative and quantitative approaches to analyse the implementation and impact of remote home monitoring services for patients with COVID-19. The design of phase 2 built on phase 1 methods and findings and consultation with our clinical advisory patient and public involvement (PPI) groups and the 70@70 nurses. Specifically, findings from phase 1 informed focus on outcomes and patient experience, and the sampling approach.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was divided into two separate protocols:

-

Covered workstreams 1 and 2 and the staff elements of workstreams 3 and 4, received ethical approval from the University of Birmingham humanities and social sciences ethics committee (ERN_13-1085AP39) and was categorised as a service evaluation by the HRA decision tool and UCL/UCLH Joint Research Office (January 2021).

-

The patient experience study (survey and case study interviews – workstreams 3 and 4) was reviewed and given favourable opinion by the London-Bloomsbury Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 21/HRA/0155: Feb 2021).

The study team was aware of the sensitive nature of this research for organisations and individuals, and has experience in conducting research on similar sensitive topics. The team maintained the independence of the research, followed an informed consent process, and maintained the anonymity of participants and organisations.

The patient experience study was categorised as an urgent public health study. The primary and local clinical research networks supported the team to get local approvals and participant identification centre agreement sign off at each site.

Theoretical lens

We analysed remote home monitoring models using different theoretical lenses. We explored remote home monitoring models within the social and political context in which they are designed and implemented (including the clinic and home), the multiple realities, assumptions and values that play a role in their implementation, the organisational structures that shape experiences of receiving and delivering care and the sociopolitical issues that frame development, diffusion and use of technology. 49 This lens went beyond an analysis of remote home monitoring solely as a technological innovation to consider dimensions such as: self-management, accountability and clinical responsibility, ‘personalised care’, inequalities in access to care and ‘caring at a distance’. 50–52

Furthermore, we used a framework with a sociotechnical lens that incorporates non-adoption, abandonment and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of technologies for health and social care (see Chapter 11). This includes expected and necessary changes/adaptation to staff working practices and the context for widespread use of the technology. This framework (informed by theory and evidence) describes the barriers to successful uptake of innovations and provides a guide to the type of issues that should be considered by evaluators. 53

Procedure

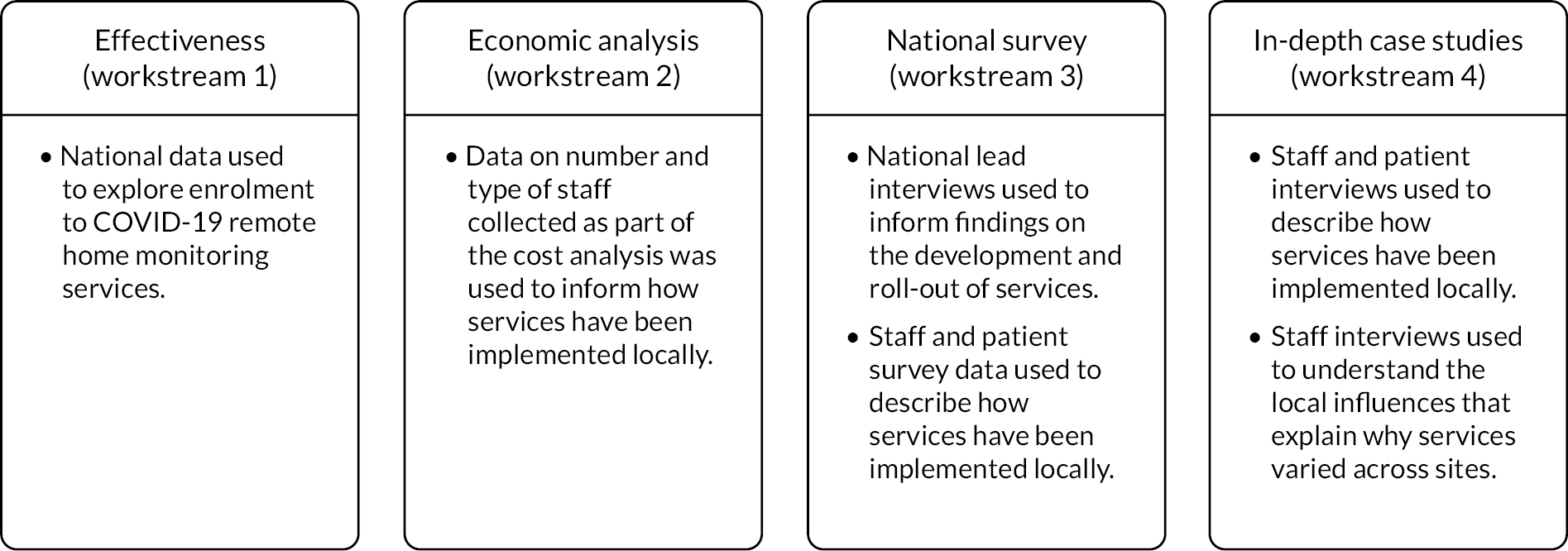

The evaluation consisted of four workstreams (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Overview of the methods for each workstream.

Workstream 1: the clinical effectiveness of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services

Workstream 1 aimed to use combinations of aggregate population-level data and hospital administrative data to both describe and estimate the impact of the roll-out of remote home monitoring models for CO@h and CVW services.

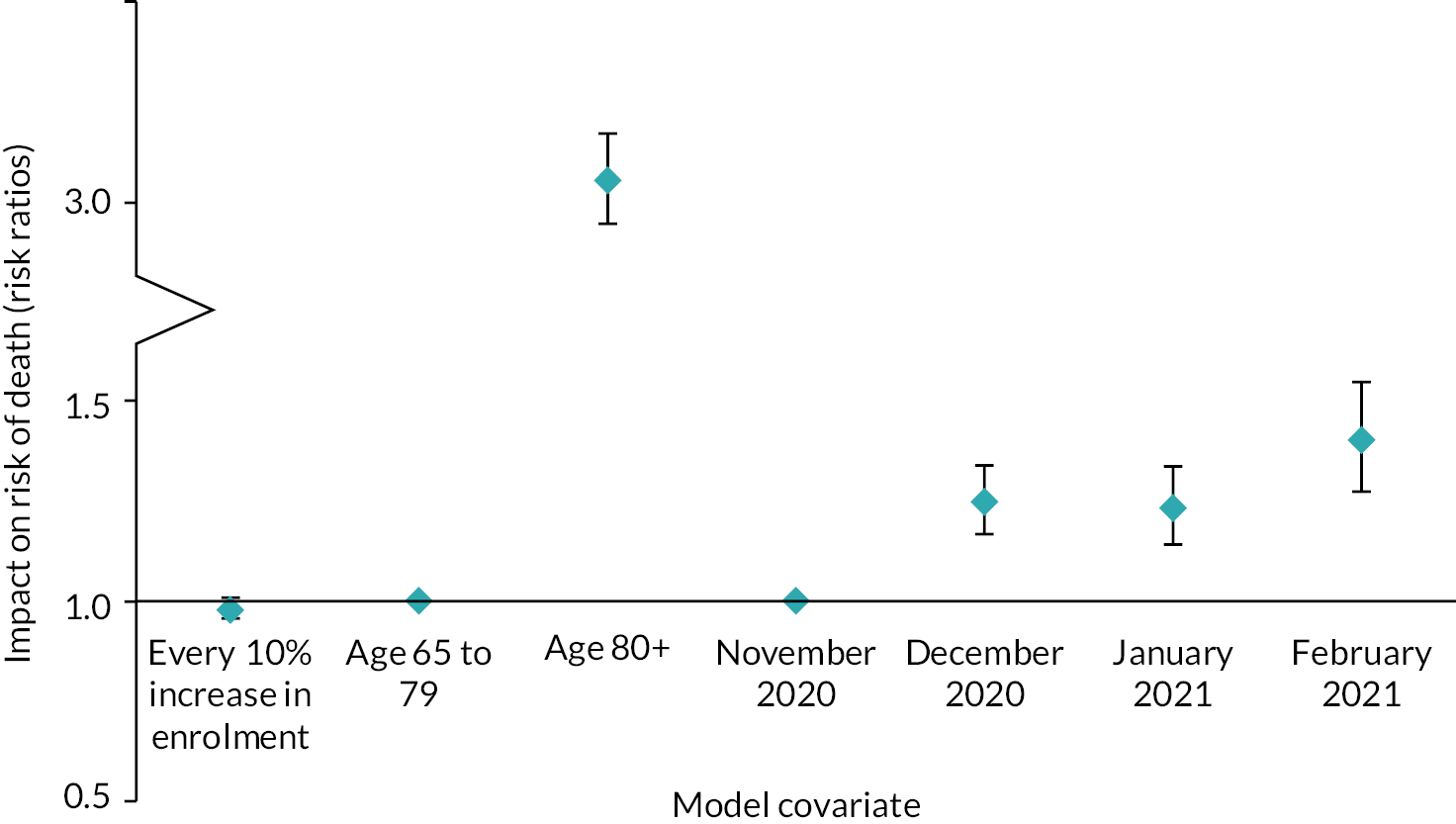

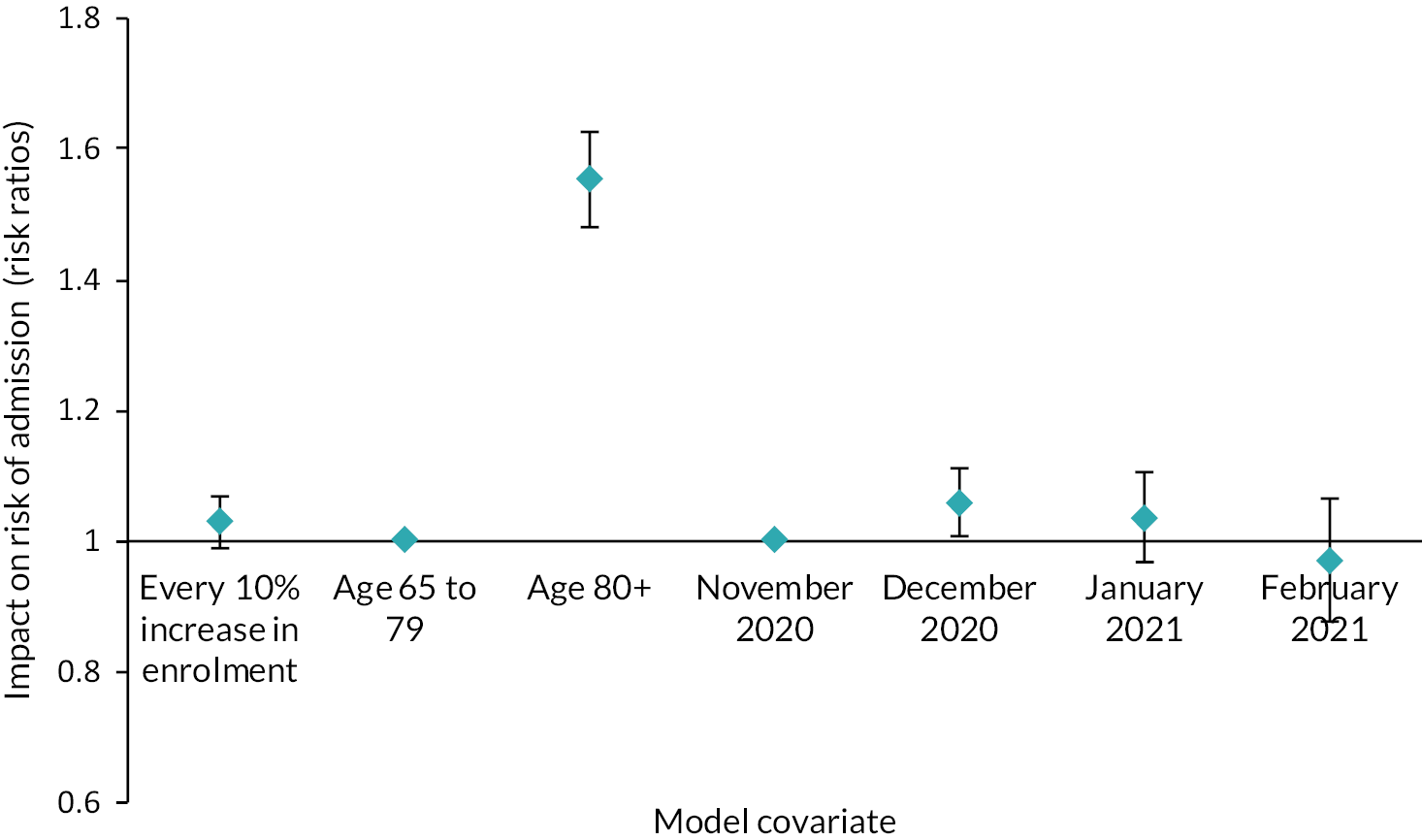

The study of the impact of CO@h on mortality and admissions was designed as an area-level analysis combining aggregated data from different sources. The aim was to use these data as time series to enable us to investigate ‘dose–response’ relationships between the evolving rates of enrolment to the services within each area and their outcomes, ‘enrolment rates’ being defined as the ratio of people enrolled on to services to the number of new cases each fortnight. For the in-hospital outcomes, we used an observational design relating in-hospital mortality and lengths of stay at an individual patient level to the rate of enrolment to CO@h services within the area at the time of admission.

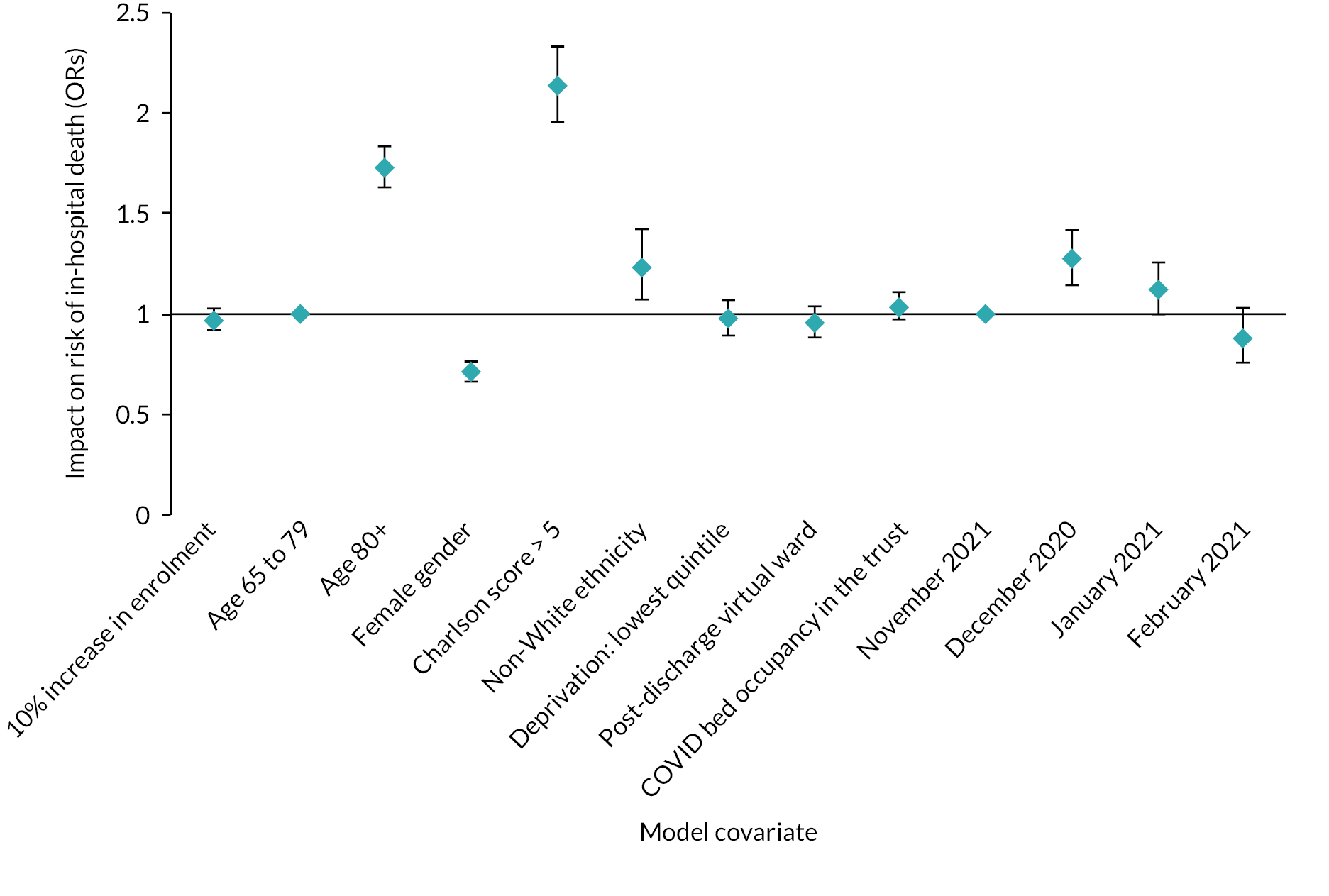

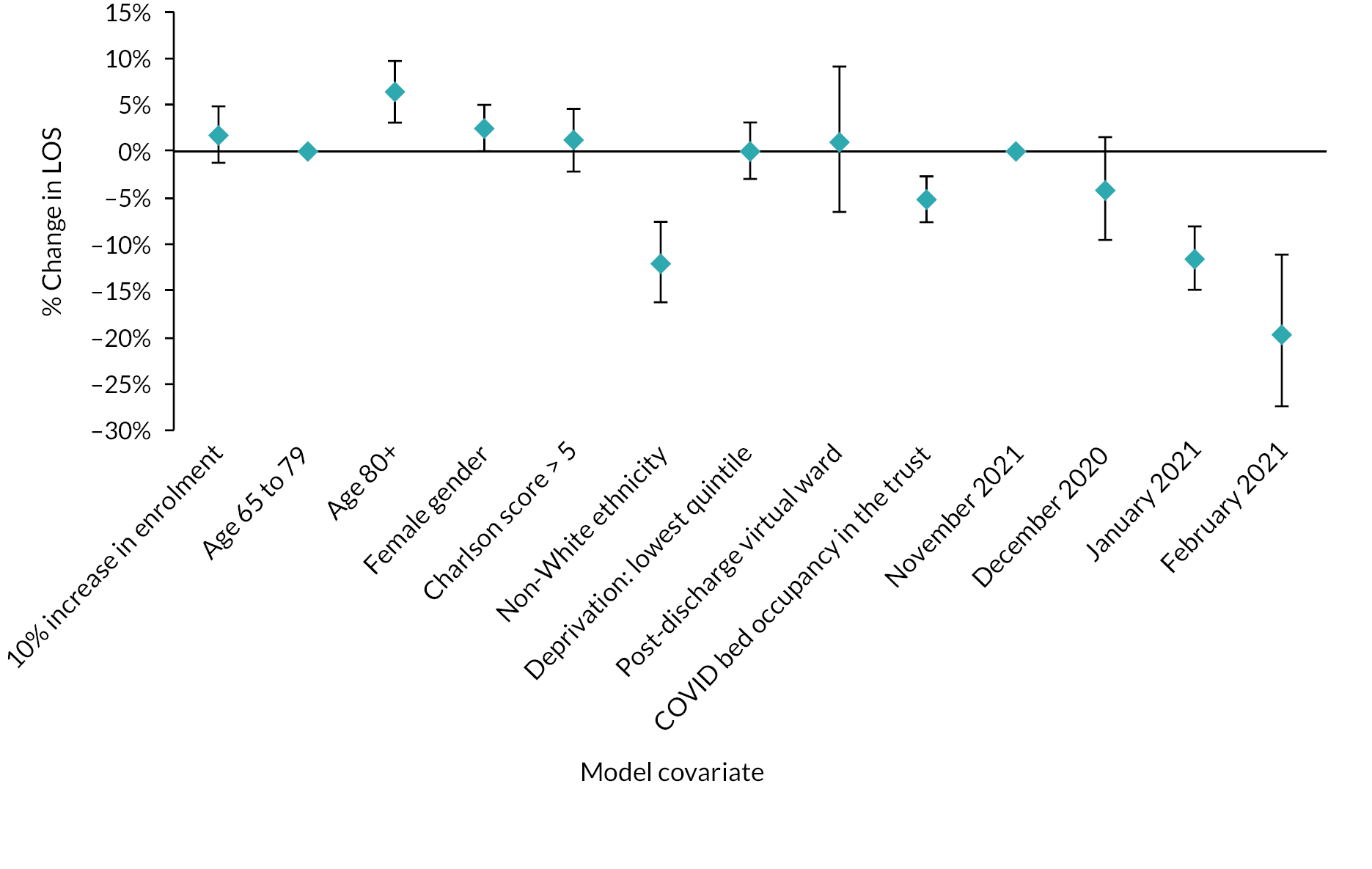

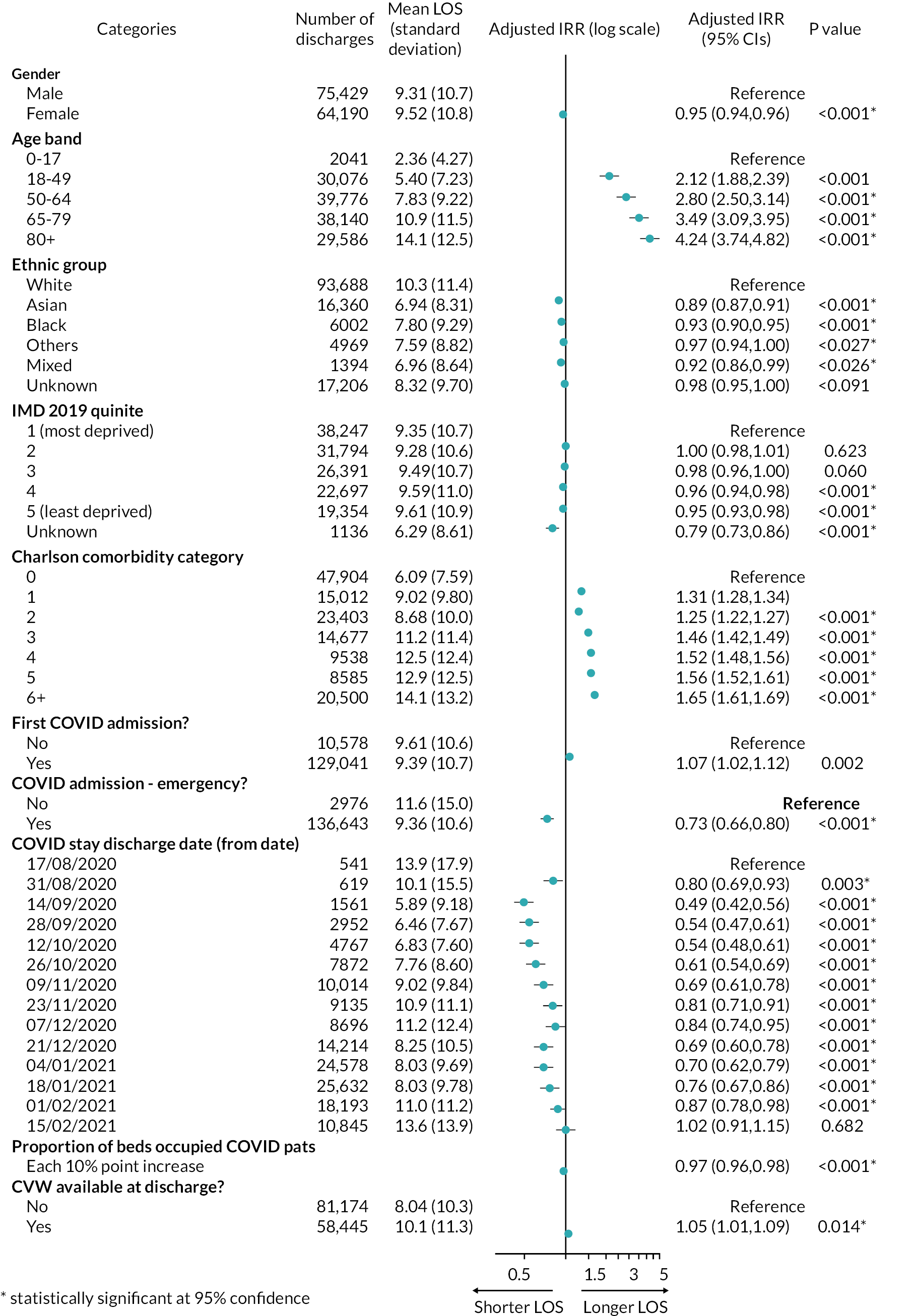

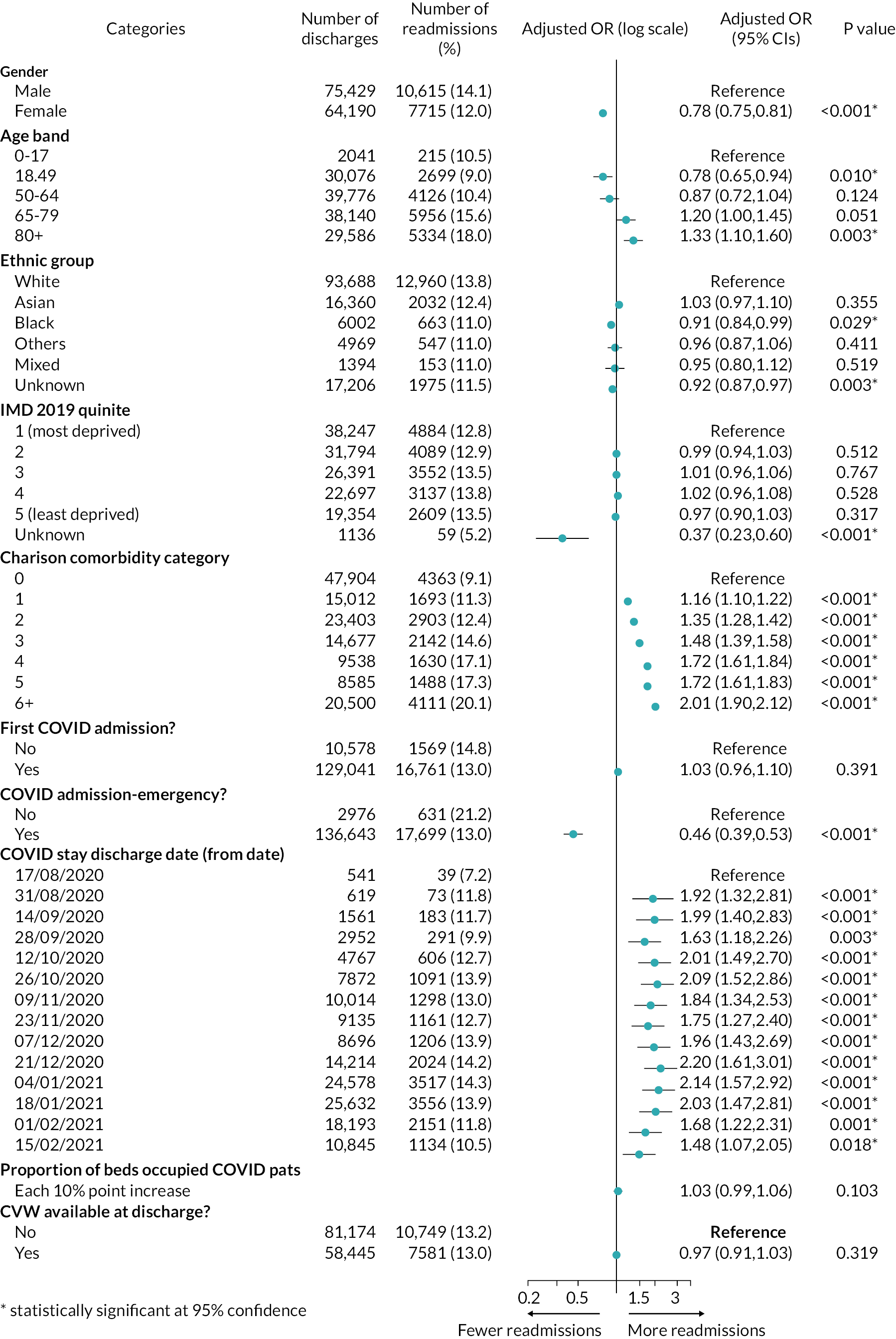

For the analysis of impact of virtual ward services, we designed an admission-level multivariate regression analyses for patients with COVID-19 being discharged from hospital. The aim was to examine the association between various factors – including the availability of a virtual ward – with the length of COVID-19 inpatient spells, and likelihood of subsequent COVID-19 readmissions.

We evaluated the CO@h service across the CCG areas in England (N = 37) where we judged there was complete data on numbers of people enrolled on to services (onboarded) between 2 November 2020 and 21 February 2021. The study population included anyone aged 65 years or over with a laboratory-confirmed positive test for COVID-19 and any hospital admission within that age group for COVID-19 or suspected COVID-19.

For the virtual ward study, we extracted information from inpatient Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data on all individuals discharged alive from any of 123 English hospital trusts where there had been a confirmed or suspected COVID-19 International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10) primary diagnosis code recorded during the stay. We included all patients discharged between 17 August 2020 and 28 February 2021, a period covering the beginning, the peak, and the start of the decline of England’s second COVID wave. Where a patient had two or more relevant inpatient stays, all stays were included in our analysis.

For our analysis we used data from a number of sources (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

For CO@h we analysed four main outcomes: mortality from COVID-19, hospital admissions for people with confirmed or suspected COVID-19, in-hospital mortality for these admissions and their lengths of stay. Because we were using population-level data, we first calculated enrolment rates for CO@h over time and then used multivariate regression models to investigate relationships between levels of enrolment and outcomes.

To analyse outcomes for patients admitted to hospital, we used individual-level HES. Again, we used multivariate regression models relating enrolment rates to outcomes, adjusting for individual patient characteristics (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

For the CVW analysis we developed multivariate regression models to examine the impact of the availability of CVW on two outcomes: (1) the LOS of the COVID-19 inpatient stay, and (2) on subsequent readmissions for COVID-19. Our models adjusted for the following person, inpatient spell, and trust characteristics: age at admission, gender, ethnic group, Charlson Comorbidity Index category,54 whether the stay was the person’s first COVID-19 hospital stay, whether the inpatient stay was an emergency admission, Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) decile, the time period of the discharge date, hospital trust, and a trust-and-week-specific measure giving the proportion of all acute beds occupied by patients with COVID-19.

Further details are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Workstream 2: economic analysis

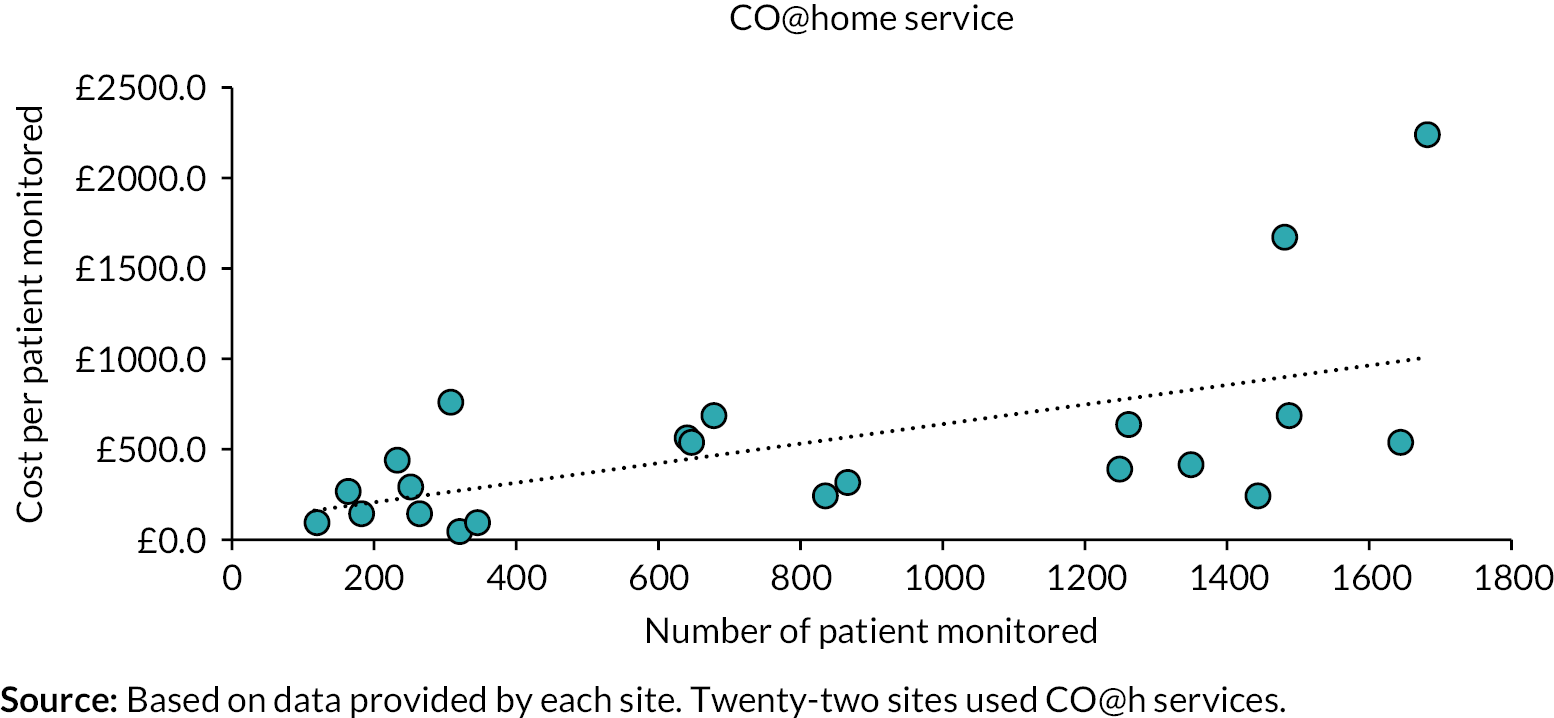

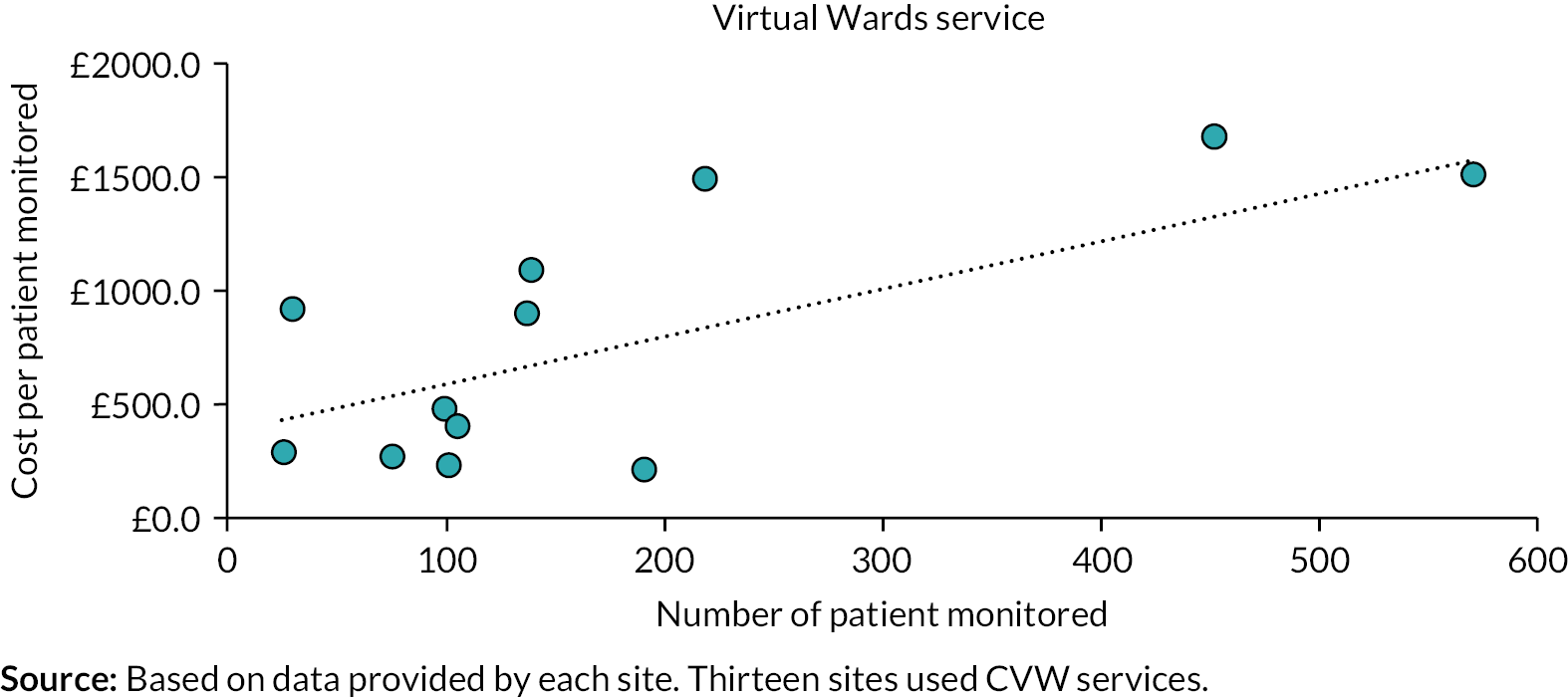

The aim of workstream 2 was to conduct a cost analysis of remote home monitoring that comprised an analysis of setting up and running remote home monitoring services for patients with COVID-19. As described in the study protocol, we originally planned to undertake a cost–utility analysis of remote home monitoring services for patients with COVID-19. 55 However, in the absence of any impacts on mortality or hospitalisation being demonstrated by the effectiveness analysis (workstream 1), a cost–utility was considered uninformative and our analysis focused only on analysing the costs of setting up CO@h and CVW services and mean running cost per patient monitored.

Remote home monitoring models were costed using data on staff (clinical and non-clinical) and non-staff resource use during the second wave. Contacts at each of the 28 sites (see workstream 3/4 for further details) were asked to complete a form in Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) (see Project website documentation – Study instruments) and 26 sites returned it electronically to the researchers. The data collection process was conducted between April and June 2021. Information was collected on staff (including the number of staff, their function/seniority and the number of hours worked) and non-staff resources used for setting up and running the sites (including information on the type and costs of digital monitoring platform used, oximeters, other medical equipment, etc.). We also collected information regarding the number of patients involved (triaged, monitored, deteriorated, escalated and deaths). The cost analysis was conducted separately for CO@h and CVW services.

Costs of setting up remote home monitoring services for patients with COVID-19 We calculated the costs incurred for setting up and running the CO@h and CVW models, also examining the variation by whether data submission was undertaken using technology-enabled with analogue modes versus analogue-only modes. The set-up costs were reported separately as mean costs per site. Note that the lifetime of the sites extends beyond the period observed in the study (e.g. some of the equipment, such as digital platforms and thermometers, can be used for longer than the study time) and therefore we did not calculate the mean set-up costs per patient or per unit of time. The running costs were calculated as mean costs per patient monitored and included the costs of staff (clinical and non-clinical) who were involved in running the services, and non-staff costs including costs of pulse oximeters (based on the number of patients monitored and assuming that 70% of pulse oximeters would be returned and reused) and other monthly expenditures related to maintaining the digital platforms. We adjusted the resources used and costs incurred per patient by applying weights based on the number of patients monitored by each service (CO@h and CVW) and the total numbers of patients monitored at each site. To investigate the effect of the type of service, data submission mode, seniority of full-time equivalent (FTE) staff and the total number of patients monitored factors on the mean running cost, we have used an ordinary least square regression model.

Technology-enabled versus analogue-only modes To explore the differences in staff, resources, types of patients and patient outcomes further between tech-enabled and analogue versus analogue-only data submission modes, additional data were collected from four of the 28 sites. All of these four sites used both tech-enabled and analogue data submission modes. We conducted an in-depth analysis of the time spent per patient for specific activities of the programme and calculated the cost per patient for all the activities. The mean cost for each activity per patient was calculated based on the time spent for each activity and staff working on each activity.

Workstreams 3 and 4: implementation and patient and staff experiences

The aim of these workstreams was to (1) understand the development of national COVID-19 remote home monitoring services and, (2) analyse the implementation of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services, and patient and staff experiences of care.

These workstreams included data from: staff surveys and interviews, patient/carer surveys and interviews, interviews with national leaders and documentary analysis of relevant national operating procedures (see Report Supplementary Material 1 for detailed methods).

Selection of sites Twenty-eight services were included in our national evaluation. To obtain maximum variation, we sampled services based on a range of criteria, including the setting (primary care or secondary care), type of model (pre-hospital, early discharge, both), mechanism for patient monitoring (paper-based, app, both), geographic location (across different areas of the country), timing of implementation (implemented since wave 1 of the pandemic or recently implemented) and involvement in the evaluation with the other evaluation partners (Imperial and IAU).

To conduct an in-depth analysis of implementation, staff and patient experiences, 17 of these sites were selected as in-depth case study sites using the aforementioned criteria. In four of these sites, we also conducted in-depth comparisons of technology-enabled versus analogue models (see Economic analysis above). These sites were identified by NHSX to ensure inclusion of different digital platforms.

Sites were recruited through an expression of interest process whereby we presented our study at local and national meetings and asked sites to express interest in participating. Clinical Research Networks facilitated the set-up of sites and local governance approvals. Some sites were identified through our phase 1 evaluation.

Staff (survey and interviews) We conducted a survey of staff involved in delivering COVID-19 remote home monitoring services in 28 services (including clinical leads, delivery staff and data staff). The study coordinator at participating sites distributed links to the online surveys to staff involved in delivering/leading services via e-mail.

For staff interviews, we purposively sampled staff involved in delivering services, leading services and data processes at each of the 17 sites. Potential participants were approached by staff at participating sites and were introduced to the researcher or asked to contact the researcher if they would like to take part. The researcher sent potential participants an information sheet. If they agreed to participate, they were asked to sign a consent form.

Patients and carers (survey and interviews) To take part in our evaluation, participants needed to be

-

18 or over

-

proficient in English (or one of Polish, Bengali, Urdu, Punjabi, French and Portuguese)

-

eligible to receive remote home monitoring services for COVID-19, and must also have been offered and received COVID-19 remote home monitoring services.

We were flexible within our sampling to consider both national and local eligibility criteria.

A total of 25 of the 28 sites agreed to run the patient survey. NHS staff from participating services sent the patient survey to patients and carers either via post, text or e-mail. Patients/carers completed the surveys and returned these to the researchers either electronically or via post.

For patient interviews, we aimed to purposively sample four to six patients or carers who received services or declined/disengaged from services at each of the 17 case study sites. We sampled using a range of criteria including age, gender, ethnicity, employment status, mechanism for onboarding, type of monitoring and outcomes. Potential participants were approached by staff at participating sites and were asked if they would be interested in taking part. Participants were then sent an information sheet by the researcher. If the patient/carer agreed to take part in the study, they were asked to sign consent forms and send them to the researcher ahead of the interview.

National lead interviews and documentary analysis To understand development of the national service and capture changes in design and implementation over time, we conducted interviews with national leaders who were purposively selected from different roles across organisations. We also analysed key documents (e.g. SOPs).

For the national lead interviews, national leads were contacted via e-mail and asked if they would like to take part. If happy to take part, they were asked to give their consent in advance of the interview. Researchers then arranged a convenient time for the interview.

Staff (survey and interviews) The staff survey was developed for this study. We developed different questions for different groups (service leads and staff delivering the service). The staff survey included questions about experiences delivering remote home monitoring services for patients with COVID-19. The questions were reviewed and piloted prior to use (see Project website documentation – Study instruments for survey questions).

We developed a topic guide for staff interviews. Different questions were developed for different groups: (1) service leads, (2) staff delivering the service, (3) data. The topic guide included questions about the service, experiences of delivering services and views on patient engagement (see Project website documentation – Study instruments for topic guide). Interviews at four of the 17 sites included think-aloud questions about using the technology.

Patients/carers (survey and interviews) The patient/carer survey was developed for this study. The survey included questions about experiences receiving remote home monitoring services for patients with COVID-19. The questions were reviewed and piloted prior to use (see Project website documentation – Study instruments for survey questions).

We developed a topic guide for patient/carer interviews. Different questions were developed for those who received the service, and those who declined or disengaged. The topic guide included questions on their experiences of receiving services and engagement (see Project website documentation – Study instruments for topic guide).

Survey and interview questions were informed by relevant service documentation,38,39 theoretical frameworks relating to social, political and technical contexts49–53 and behaviour,56 and previous literature on engagement. 57,58 Questions on demographic characteristics were informed by previous literature. 59–64

National leads (interviews) We developed a topic guide for national lead interviews. This included questions about the service, leadership and governance, data and implementation (see Project website documentation – Study instruments for topic guide).

Staff (survey and interviews) Staff were asked to follow an online link to complete the survey. The survey began with an information sheet and consent form. Survey sites were asked to keep a record of the number of surveys sent to determine response rates.

Interviews were conducted by one of six postdoctoral researchers (MS, CV, HW, LH, IL, JB); each site had a different lead researcher. Interviews were carried out via telephone or an online platform as preferred by the participant.

Patients/carers (survey and interviews) Patients were asked to complete the survey in one of two ways: (1) if monitored through use of a tech-enabled mode, patients/carers were e-mailed or texted the link to the online survey, or (2) if the patient was monitored using analogue methods, they received the survey in the post, together with a pre-paid envelope. Surveys were distributed at onboarding to the remote home monitoring service or discharge from the remote home monitoring service, depending on service procedures. The survey included an information sheet and consent form.

Interviews were conducted by one of six postdoctoral researchers (MS, CV, HW, LH, IL, JB); each site had a different lead researcher. Interviews were carried out via telephone or an online platform as preferred by the participant.

National leads (interviews) National lead interviews were conducted by four researchers (MS, CV, HW, NJF). Interviews were carried out via telephone or an online platform such as Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA) or Microsoft Teams (MS Teams) (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) as preferred by the participant.

Data management Surveys (patients and staff) Electronic surveys were transferred directly into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Surveys received via post were returned to the Nuffield Trust or UCL offices, stored securely in locked filing cabinets and inputted into REDCap by members of the research team. Data were securely stored on UCL’s Data Safe Haven portal.

Interviews (national lead, patients/carers and staff) All interviews were audio-recorded (with consent), transcribed verbatim, anonymised and stored securely.

Site characteristics Sites were characterised with respect to their population size,65 the proportion in urban versus rural areas,66 the proportion in the most and least deprived areas (with respect to national quintiles),67 and ethnicity. 68 For sites based on CCG areas we calculated these characteristics using publicly available data at lower-layer super output area (LSOA) level mapped to CCGs,69 while for trust-based sites we used data derived from inpatient HES admissions during the financial year 2019–20, in addition to web searches for the trust catchment populations.

Surveys (patients/carers and staff) Survey data were analysed using descriptive statistics, multivariate and univariate analyses on Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 25). Participating sites were provided with a report on the patient survey responses from their site compared with overall findings.

Interviews (national lead, patients/carers and staff) Data collection and analysis was facilitated through the use of rapid assessment procedure (RAP) sheets. 70 RAP sheets were developed per site to facilitate cross-case comparisons and per population (to make comparisons between subgroups). The categories used in the RAP sheets were based on the questions included in the interview topic guide, maintaining flexibility to add categories as the study progressed. RAP sheets were used to develop coding frameworks to explore themes and subthemes in more depth and identify example quotes. Further details on analysis methods are reported within each chapter (see Chapters 4 and 8–11).

Although our study was rapid, many steps were taken to ensure the transparency, rigour and robustness of our qualitative research methods. For example, our study used purposive sampling to recruit a large number of participants with a range of characteristics. In terms of analysis, our study used both rapid analysis methods (e.g. RAP),70 together with traditional qualitative analysis methods (e.g. in-depth coding of transcripts and development of themes and subthemes). Our study involved a range of experienced qualitative researchers, and our analysis was strengthened by continuous team discussions about the interpretation of our data. We also discussed findings with those providing the service and our clinical advisory group to sense check our interpretation. Additionally, our findings were triangulated with quantitative, economic and other qualitative analyses. Our methodological approaches are consistent with previous recommendations on conducting trustworthy, robust and rigorous qualitative research. 71–74

Integration

Data from all four workstreams were integrated to answer our research questions and to facilitate processes of triangulation. The study team met weekly throughout the study. We included findings from each workstream within our RAP sheet. We produced RAP sheets at site level and also at population level (including for subgroups of staff and patients). For example, findings on local barriers and facilitators to implementation and patient and staff experiences helped the interpretation of findings on outcomes, service use and costs. Quantitative data on resource allocation were understood in relation to qualitative data on staff experiences of planning and delivering services. Data from the case studies were used to explain the survey findings (representing experiences and trends at a national scale). In addition, emerging findings from this study were discussed in relation to those from the two other evaluation partners (Imperial and IAU).

Deviations from protocol

We planned to undertake a cost–utility analysis of the COVID-19 remote home monitoring services but in the absence of any impacts on mortality or hospitalisation, as demonstrated by the effectiveness analysis (see Chapters 5 and 6), the economic analysis only included the costs of setting up and running services (see Chapter 7).

We intended to conduct ‘think aloud’ sessions with patients who had used tech-enabled data submission from the four sites selected for in-depth analysis of tech-enabled platforms. However, patients did not have access to the platforms after discharge and recall of the use of these platforms during their illness was poor. Consequently, the ‘think aloud’ methodology was discontinued for patient interviews.

Patient and public involvement

Members of the study team met with service user and public members of the BRACE PPI group and health and care panel and patient representatives from RSET in a series of workshops. These workshops informed study design, data collection tools, data interpretation and to dissemination for phase 2. For example, patient-facing documents, such as consent forms, topic guides, patient survey and patient information sheets were reviewed by this group. Additionally, PPI members helped to pilot patient surveys and interview guides with the research team. We also asked some members of the public to pilot the patient survey.

Dissemination and formative feedback

Throughout the project, we regularly shared feedback with stakeholders on emerging findings and lessons learned. The study will inform clinical practice for COVID-19 but will also inform the use of remote monitoring models in other conditions and areas of the NHS. Dissemination has been facilitated through various existing and new networks. Findings have been and will be published in peer-reviewed journals.

Chapter 3 Capturing and informing early stages of design and implementation of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services (phase 1)

Overview

This chapter draws on two papers by Vindrola-Padros et al.,32,36 published in Lancet eClinicalMedicine: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100965 and https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100799. These are open access articles under the term of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

What was already known

-

Previous research has explored the use of remote home monitoring models for non-COVID-19 conditions.

-

COVID-19 remote home monitoring services were implemented rapidly around the world, but implementation processes were rarely documented.

What this chapter adds

-

The COVID-19 remote home monitoring services varied in relation to the health-care settings and mechanisms used for patient triage, monitoring and escalation.

-

Good communication within clinical teams, culturally appropriate information for patients/carers and the combination of multiple approaches for patient monitoring (app and paper-based) were considered facilitators in implementation.

-

We could not reach substantive conclusions regarding patient safety and the identification of early deterioration due to lack of standardised reporting and missing data.

Aims of the phase 1 evaluation

In July 2020, we began a rapid mixed-methods evaluation to identify the key characteristics of COVID-19 remote home monitoring models operating during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, explore the experiences of staff implementing these models, understand the use of data for monitoring progress against outcomes, document variability in staffing and resource allocation, document patient numbers and impact, draw out lessons learned for the development of models for the 2020–21 winter period and identify areas for further research. To achieve these aims, phase 1 was divided in two main workstreams: (1) a rapid review of the literature, and (2) a rapid mixed-methods evaluation to document implementation and identify the lessons learned during wave 1 of the pandemic. Findings from both these phases have been published,32,36 so we provide a summary here.

A rapid systematic review of the evidence

Remote home monitoring models have been implemented in the United States, Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, Ireland, China and UK, with some variation in the frequency of patient monitoring, modality (a combination of telephone or video calls and use of applications or online portals), patient admission criteria, staffing used for patient monitoring and level of clinical oversight and use of pulse oximetry. However, there is limited published literature on the models of care developed to implement remote home monitoring across different health-care contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic, the experiences of staff implementing these models and patients receiving care, the use of data for monitoring progress, resources required, as well as the impact of these models on clinical, process and economic outcomes. The aim of this review was to analyse the implementation and impact of remote home monitoring models for confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patients, identifying their main components, processes of implementation, target patient populations, impact on outcomes, costs and lessons learned.

Methods

Design

We followed an established rapid review method. 48 This method uses an adapted systematic review approach, with the aim to reduce time taken to carry out the review (e.g. using a large multidisciplinary team to review abstracts/full texts and extract data, having a percentage of excluded articles reviewed by a second reviewer, and using software for data extraction). 48

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement. 75 The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020202888, registered 6 August 2020).

Search strategy

We used a phased search approach. 48 This involved gradually adding search terms based on the keywords used in the identified literature (see Vindrola-Padros et al. 32 for search terms). We used the following databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL PLUS, EMBASE, TRIP, medRxiv and Web of Science (searches carried out by CV on 9 July 2020 and updated on 21 August 2020, 21 September 2020 and 5 February 2021). To identify additional publications, we manually screened reference lists of included articles. We removed duplicates.

Study selection, inclusion and exclusion criteria

One researcher (CVP) screened titles, with researchers cross-checking exclusions in abstract (KS) and full-text phases (KS/MS). Disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. To be included, studies needed to: (1) focus on monitoring of confirmed or suspected patients with COVID-19, (2) focus on pre-hospital monitoring, monitoring after emergency department presentation and step-down wards for early discharge, (3) focus on monitoring at home (excluding monitoring done while the patient is in health-care facilities), and (4) be published in English.

Data extraction and management

We analysed articles using a data extraction form developed in REDCap. We extracted data on design, populations, process, clinical outcomes and economic impact. The form was independently piloted by two researchers (CV/KS) and finalised. Data extraction was checked by three researchers (TG/CSJ/ST).

Data synthesis

The information entered in free text boxes was exported from REDCap and analysed using framework analysis. 76 We did not assess quality of studies.

Results

We present a summary of findings below (see Vindrola-Padros et al. for further information). 32

Search results

The initial search yielded 902 articles. After screening, 155 articles remained for full-text review. After full-text review (n = 11), identifying additional references from reference lists (n = 3) and updated searches (n = 13), 27 articles met the inclusion criteria (see Report Supplementary Material 332 for PRISMA flow chart).

Characteristics of included remote home monitoring models

Remote home monitoring models were implemented in different countries, including the United States (n = 11), UK (n = 9), Canada (n = 2), Netherlands (n = 2), China (n = 1), Ireland (n = 1), Brazil (n = 1), Australia (n = 1). Different study designs were used: descriptive studies (n = 12), evaluations (n = 6), observational studies (n = 7), feasibility study (n = 1), news feature (n = 1). See Vindrola-Padros et al. 32 for further details.

Aims and designs of remote home monitoring models

The primary aim of remote home monitoring models was to enable early identification of deterioration for patients self-managing COVID-19 symptoms at home (including those who had not been admitted to hospital as well as those who had been discharged).

A secondary aim of the models was to reduce the rate of hospital infection and demand for beds in the acute care sector (including preventing admitting those suitable for home management and discharging those admitted to hospital earlier with care from a remote team).

Most of the remote home monitoring models were led by teams in secondary care (n = 23), with some led by primary care (n = 3) and some led by both primary and secondary care (n = 2). Thirteen of the models functioned as pre-admission wards (preventing admission of patients to hospital) and five were designed for patients admitted to hospital who could be discharged and monitored at home (step down wards), and 10 were both (with separate pathways).

Patient populations appropriate for remote monitoring

Most of the models established broad criteria for patient eligibility, defining the patient group as adult (over 18 years) patients with COVID-19 symptoms (suspected and confirmed cases). Some models limited referrals to confirmed cases. Some models excluded certain groups (e.g. patients over 65 years with significant comorbidities, or pregnant women). The size of patient cohorts varied considerably (ranging from 12 patients to 6853; see Vindrola-Padros et al. 32 for further details).

Stages of remote home monitoring

The articles described five main stages in remote home monitoring for COVID-19: (1) referral and triage to determine eligibility (including recording patient demographics, clinical variables, health data for risk assessment and vital signs data, and in some cases a risk assessment); (2) onboarding of patient to remote home monitoring service (provision of information to patient and/or carer on monitoring process, mechanisms for escalation and self-care); (3) monitoring [including recording of observations, communication of the information via a paper-based system and telephone or digital technologies such as apps or online forms, inclusion of pulse oximetry (in some cases), assessment of the information by the medical team]; (4) escalation (if required according to pre-established thresholds); and (5) discharge from the pathway (once their symptoms improved or patient opted out of the pathway).

Expected outcomes

Outcomes of remote home monitoring models were grouped in three main categories: (1) process outcomes related to the remote home monitoring pathway (e.g. time from swab to assessment, time to escalation, ambulance attendance/emergency activation), (2) process outcomes related to secondary care (e.g. LOS) and (3) patient outcomes, including clinical outcomes such as emergency department attendance/reattendance, hospital admission, ICU admission, readmission, mortality, ventilation needs and experience (e.g. patient satisfaction).

Impact on outcomes

It was difficult to carry out an analysis of the impact of remote home monitoring across all examples because not all articles reported data on the same outcomes. In terms of clinical outcomes, mortality rates were low, admission or readmission rates ranged from 0 to 29%, and emergency department attendance or reattendance ranged from 4% to 36%. Six of the models reported data on patient feedback and indicated high satisfaction rates.

Information about remote home monitoring process outcomes was limited (n = 6 articles), but time, from swab to assessment ranged from 2 to 3.7 days and virtual LOS from 3.5 days to 13 days (see Vindrola-Padros et al.). 32

Economic impact

Very few of the selected studies for this rapid review provided a descriptive form of economic analysis. The amount spent per patient on remote monitoring varied by country and type of costs included in the analysis.

Strengths and limitations of review

The last search was carried on 5 February 2021, so any articles published after this date were not included. However, the inclusion of preprints helped to mitigate this issue. Although we employed multiple broad search terms, it is possible that we missed articles that did not use these terms. Owing to the variability in study designs and the descriptive nature of the articles we did not assess these articles for quality using standardised tools for assessment. However, we feel it is important to note that we found several cases of missing data and inconsistencies in the reporting of evaluations that would lead to low quality ratings.

Future research areas identified

The review highlighted that further research should focus on exploring patient experience, implementation, outcome evaluation and cost-effectiveness.

A rapid mixed-methods evaluation of the early implementation of remote home monitoring services

A number of remote home monitoring models were set-up during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in England with a high degree of variability in relation to the mechanisms implemented for patient assessment and triage, monitoring and escalation.

Despite previous research on the use of remote home monitoring models for other conditions and their widespread use during the COVID-19 pandemic, studies on their implementation and impact are rare. This study aimed to identify the key characteristics of these services, explore staff experiences, understand the use of data for monitoring progress against outcomes, and document variability in staffing/resource allocation.

Methods

Design

A multisite mixed-methods study that combined qualitative and quantitative approaches to analyse the implementation and impact of remote home monitoring models during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (July to September 2020) in England (see Vindrola-Padros et al.). 36

Sample and recruitment

We recruited staff with experience delivering these models across eight pilot sites in England. We purposively recruited sites to represent a range of characteristics including the type of remote home monitoring service, different population sizes, areas of the country and monitoring approaches (see Vindrola-Padros et al.). 36

Data collection

We conducted interviews with 22 staff. Most of these interviews were carried out by pairs of researchers. Interviews were conducted using a topic guide, were audio-recorded and lasted 30–60 minutes. We also collected data on staffing models and resource allocation (number of staff, their function/seniority, the number of hours worked, all other resources used in setting up and running pilots and associated costs).

Data analysis

Detailed notes from interviews were added to RAP sheets. 70 Multiple researchers cross-checked data to ensure consistency. The team met weekly to discuss emerging findings and develop themes. Set up costs were reported as mean cost per site, and for running costs, mean costs of patient were calculated for the pilot period (see Vindrola-Padros et al.). 36

Findings

We present a summary of findings below (see Vindrola-Padros et al. 36).

Models implemented

The models varied in relation to the health-care settings and mechanisms used for patient triage, monitoring and escalation. The main components of models were triage, admission to service (including provision of pulse oximeter), patient provides readings through phone calls or app, medical team monitor observations and escalate cases, and discharge at 14 days or when symptoms have improved.

Barriers and facilitators to implementation

Staff described high levels of patient engagement. Implementation was embedded in existing staff workloads and budgets. Implementation facilitators included: good communication within clinical teams, culturally appropriate information for patients/carers and the combination of multiple approaches for patient monitoring (app and paper-based).

Barriers to implementation included: unclear referral criteria and processes, difficulties carrying out non-verbal assessments over telephone, lack of culturally appropriate patient information, lack of administrative support and workforce availability.

Cost

The mean cost per monitored patient varied from £400 to £553, depending on the model. Mean costs were higher in pre-hospital than early discharge from hospital model.

Strengths and limitations

The study was limited in the sense that we could not determine the effectiveness of these models due to lack of comparator data.

Future research areas identified

We identified the sustainability of the models and patient experience (considering the extent to which some of the models exacerbate existing inequalities in access to care) as future areas of research.

Dissemination and use of findings

The findings from the rapid review and the rapid mixed-methods evaluation on the implementation of COVID-19 remote home monitoring models across eight sites in England were disseminated widely and used to inform decisions in relation to the roll-out of services during autumn/winter 2020–21. The main channels for the dissemination of findings included journal articles,13,32,36 blogs,77–79 a slide set80 and presentations (see Project website documentation – Dissemination).

Impact

A senior director at NHSEI provided the following feedback on how findings from phase 1 of our evaluation influenced the national roll-out of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services in England:

-

Setting very simple entry criteria [65 and over OR clinically extremely vulnerable (CEV)].

-

Ensured that we did not go down a tech-only or tech-first route.

-

Produced translations of all the patient facing guidance and an easy-read version at the outset. It is possible that we may have missed the importance of this point.

-

National SOP was focused on patient self-escalation and our workforce calculations were informed by this work.

-

Created a minimum standard for out-of-hours to ensure that the links were clear.

-

We required services to be established within two months and had confidence that we could encourage all CCGs to set up by 31 December.

-

Ensured that we were able to get pulse oximeters out to CCGs within three working days.

-

Provide CCGs with a feed of patients that have tested positive and identify people within the cohort (65 years and over or CEV).

Informing phase 2 of the evaluation

The findings from phase 1 of the evaluation were also used to inform the design of phase 2, including the selection of outcome measures, cost analysis and identification of key areas of focus such as: the sustainability of these models during the second and third waves of the pandemic, patient and carer experiences with the services and how these varied according to the type of model (including analogue vs. digital models), factors that could have created or exacerbated inequalities in health and access to care and the costs involved in delivering these services.

Chapter 4 The development and implementation of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services (phase 2)

Overview

What was already known

-

COVID-19 remote home monitoring services were implemented internationally during wave 1 of the pandemic.

-

During our phase 1 evaluation (wave 1 of the pandemic), some facilitators and barriers to COVID-19 remote home monitoring services were identified.

-

It is important to explore local variation to fully understand implementation and to identify factors that might explain variation in effectiveness and cost outcomes across service models.

What this chapter adds

-

Rapid development of national remote home monitoring services took place in three phases: (1) local development, (2) national development and roll-out, and (3) local implementation.

-

Patient enrolment to COVID-19 remote home monitoring services across England was lower than expected.

-

There was large variability in the models implemented for COVID-19 remote home monitoring services.

-

Variation was influenced by patient, workforce, organisational and resource factors, and the rapid and evolving COVID-19 situation.

-

These factors might help to explain variation in outcomes/effectiveness of different service models.

Introduction

It is important to understand the impact of local factors on adoption when implementing national policy initiatives81–83 as evidence suggests local factors affect service design,84–86 ability to meet service aims,87 sustainability of the service and can also hinder the accurate assessment of efficacy and cost-effectiveness. 57,81,83,84,88

To increase our understanding of how local conditions affect rapid implementation of national policy during a public health crisis89–92 and support future development and implementation of services,93–96 it is necessary to explore the development, enrolment rates and implementation of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services (see Research question 6, Chapter 1).

This chapter provides:

-

an overview of the development of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services including the national roll-out and the enrolment rates of the services

-

a description of how services have been implemented and used locally

-

an analysis of the local factors that help explain why the services varied across sites

-

a backdrop for findings presented in Chapters 5–11.

Methods

A summary of the methods is provided below; further details can be found in Chapter 2, Report Supplementary Material 1.

Sample and recruitment

Twenty-eight sites were recruited to our study. Sites were included from all regions across England, represented CCGs and trusts, varied in urban/rural, deprivation scores, ethnicity, and size (see Chapter 2, Report Supplementary Material 2).

Data collection

To identify when new services started and to estimate the proportion of new diagnosed cases who were onboarded (enrolment rates), we drew on a selection of data sources (see Report Supplementary Material 1), including Kent, Surrey and Sussex AHSN (KSS AHSN) data (see Chapter 6), bespoke onboarding data and data on diagnoses of COVID-19 provided by PHE (now the UK Health Security Agency).

To describe the development and roll-out of services we conducted interviews with national leads (see Chapter 2). To explore implementation, we conducted a documentary analysis of service documentation, surveys with patients and staff and interviews with patients, carers and staff, and a cost survey (see Chapter 2).

Data analysis

Survey and interview data

Inductive thematic analysis was used to analyse interview data inputted into RAP sheets. 70 Survey data were analysed using descriptive statistics (using SPSS, version 25). To allow for comparison, quantitative and qualitative data sets were mapped against the SOP components (referral, triage, onboarding, monitoring, discharge).

National data on enrolment

For the CO@h programme, we defined rates of enrolment as the proportion of new cases diagnosed who were onboarded. For each CCG, we estimated these rates by dividing the numbers onboarded each fortnight by the number of new cases of COVID-19 diagnosed in the same fortnight. We could only do this for CCGs where the onboarding data were judged to be complete, and to make this judgement we used a combination of management information provided by the programme and data collected by our own costing survey (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

For the CVW programme, data quality issues left us unable to use NHS situation reports (SITREPs) data on the number of patients with COVID-19 discharged from hospital to virtual wards. We were able, however, to carry out a limited analysis of enrolment rates for seven hospital trust-based sites by comparing the number of patients monitored on a post-discharge pathway (as reported in our costs survey, see Chapter 7) to the number of patients with COVID-19 discharged alive, according to national HES Admitted Patient Care (APC) data.

Findings

Within this section, the following findings are presented: (1) a summary of interview and survey data (n = 28 sites), (2) an overview of the development of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services (including (a) development of these services, and (b) coverage of these services nationally and rates of enrolment), (3) a description of the different typologies and implementation of services between sites, and (4) factors influencing the implementation of these services.

Participant characteristics

We received 292 staff surveys (39% response rate) across 28 sites and 1069 patient and carer surveys (18% response rate) across 25 sites (see Report Supplementary Material 2 for demographic characteristics). Interviews were conducted with national leads (n = 5), staff (n = 58 across 17 sites), and patients or carers (n = 62 across 17 sites). See Report Supplementary Material 2 for demographic characteristics.

An overview of the development of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services including the national roll-out and the uptake/coverage of the resultant service

Within this section, we first present an overview of the three phases of development and implementation of these services. Secondly, we present the uptake/coverage of the final service.

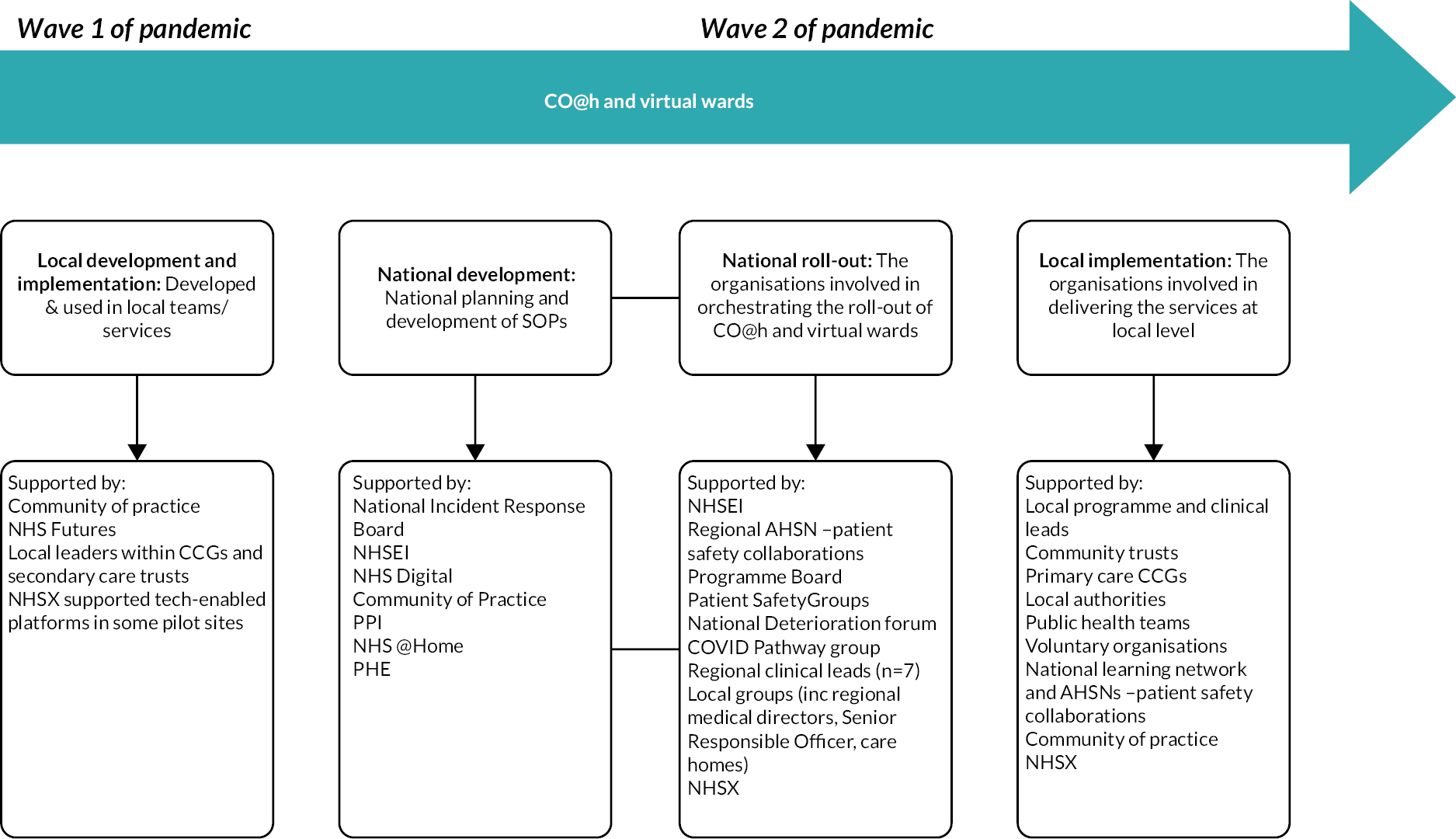

Development of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services

The development of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services occurred rapidly, in three stages: (1) local development and implementation, (2) national development and roll-out, and (3) local implementation (see Figure 4 for timeline and key groups involved in each phase).

FIGURE 4.

Development of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services.

Local development and implementation – wave 1 and the first use of pulse oximetry in patients’ homes

The use of oximetry to monitor patients with COVID-19 in their home began in wave 1 as several, initially disconnected, local services were established, motivated by attempts to mitigate silent hypoxia (very low oxygen saturations, often without breathlessness). Pulse oximetry was initially used to monitor patients in the community. 36 During phase 1, local clinical leaders within CCGs and secondary care trusts had identified a need for this service and were integral in facilitating the initial development, set-up and implementation of services, and instigated the development of an informal community of practice. NHSX supported a few of the pilot sites to use tech-enabled models by putting them in touch with tech companies. The local development and implementation of services gained interest from national stakeholders.

An evaluation of phase 1 was commissioned and conducted by researchers from NIHR RSET and NIHR BRACE (see Chapter 3). The purpose of this evaluation was to provide lessons for the ongoing development/roll-out of the services.

Two learning communities were set up prior to the national roll-out, to support local implementation: a community of practice and a national learning network.

The community of practice was an informal group, led by key national clinical and policy leads and attended by national and local clinical leaders for local services adopting these pulse oximetry services. The community of practice held regular online meetings (every couple of weeks) to share best practice quickly from national leads to local teams, and between local teams, offering mutual support and leadership. This community of practice grew rapidly.

A national learning network (the National Deterioration and COVID-19 Forum) was set up by the AHSN patient safety collaboratives to support clinical leads and provide resources to facilitate implementation of these services. The set-up of the national learning network was prompted through NHS @home17 (via the national team and regional medical directors). Additionally, regular webinars were held to share learning. 97 The learning network was hosted within the Future NHS collaboration platform (an online platform designed to help services to co-develop services, share materials and work together). 98

The conversations and shared learning from both these networks played a key role in shaping the basic pathway underpinning these services. These communities were set up to support local clinical leads and share experiences.

National development and roll-out

Between wave 1 and 2, there was a period of gathering evidence (research and clinical consensus), discussions around how services should be developed and development of safety netting guidance. This evidence included our evaluation findings from phase 1 (see Chapter 3).

During the summer and autumn of 2020, NHSEI began to develop SOPs for CO@h, with leadership and governance from the NHS @home team. The National Incident Response Board approved operationalisation and national roll-out of the CO@h service as the appropriate next step.

The SOP for CO@h38 (see Appendix 1, Table 24) that emerged was informed by the learning gained from previous services which provided care at home, experience gained from managing wave 1 in the community including the various pilots and case studies. It was shared through the NHS Futures website98 and the pre-existing evidence base. 32,36 It was intended that services would be inclusive by design and enabled by, but not dependent on, technology (to remain accessible to the most vulnerable patient groups).

In January 2021, a SOP for CVW (early discharge from hospital) was published and these services were rolled out. 39 Virtual ward models were designed to be run by acute trusts, with responsibility for services being with secondary care services39 (see Appendix 1, Table 24).

Following service development, the AHSNs were commissioned through the AHSN’s patient safety collaboratives to facilitate regional roll-out. 97 A programme board with all key stakeholders was established and met weekly to discuss a number of workstreams including data management, workforce/training, patient safety, operations, pathways, evaluation and oximeter distribution. The programme was monitored via comprehensive data collection for CO@h which aimed to track how the programme was developing/performing with a focus on using the data as shared learning. As part of this process any safety incidents were recorded, using patient safety groups where appropriate.

National roll-out of CO@h and virtual ward services was supported by 20 highly attended regional launch events, which included question and answer sessions. To support national roll-out, national clinical leads and seven regional clinical leads were funded to support local implementation. NHSEI agreed to purchase pulse oximeters. NHSEI purchased 706,000 oximeters across waves 1 and 2. These pulse oximeters were CE marked (as recommended by MHRA guidance)37 and were available to local sites within three days through an ordering system set out in the SOP. NHS Digital supported data management. 99 NHSX were a partner in the roll-out and implementation of tech-enabled platforms within COVID-19 remote home monitoring services. NHSX committed to supporting (funding) up to 50 organisations to use a tech-enabled model for CO@h and/or virtual ward models during wave 2 (sites bid for this funding and then chose and procured the platform they wanted to use). CO@h and virtual ward services were rolled out between November 2020 and February 2021.

Local implementation

NHSEI were integral in supporting the local implementation of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services, including providing financial support for primary care to establish and implement these services,40 resourcing NHS Digital to supply data to service providers to identify people who may benefit from these services41 and the commissioning and funding of AHSN support.

National leads described the importance of local leads assuming responsibility and accountability for their services, guided by the SOPs for CO@h and CVW.

While there was some variation in responsibility and accountability, local CCGs were primarily responsible and accountable for delivery of CO@h and secondary care trusts were responsible and accountable for delivery of CVW. Each local service had its own local governance and management structure, which were expected to minimise national input and allow local services to be more responsive to and reflective of the needs of local populations. This local governance was overseen and supported by the AHSNs. NHSX managed data reporting on tech-enabled deployment.

With local services responsible for the day-to-day running of CO@h and CVW, services allocated resources, designed staffing models, and distributed equipment and educational materials. The management teams particularly of integrated services (i.e. where CO@h was combined with CVW) consisted of colleagues drawn from across multiple settings including primary and secondary care, but also the ambulance service, mental health trusts, care homes, and patient safety collaboratives. The precise mix depended upon the scope of services within the local environment. Regional ‘clinics’ were established by the local AHSNs to facilitate regular engagement and support the initial set-up. Two-way relationships were developed between policymakers and strategic management and front-line NHS workers as a way of sense-checking the work completed. Significant support and buy-in from senior management within acute trusts and across CCGs helped to set up COVID-19 remote home monitoring services. There was, however, a need to have supportive local authority and public health teams to integrate CO@h and CVW services with existing ways of data sharing.

Throughout the national roll-out, local services were supported by the community of practice and the national learning network (as described earlier).

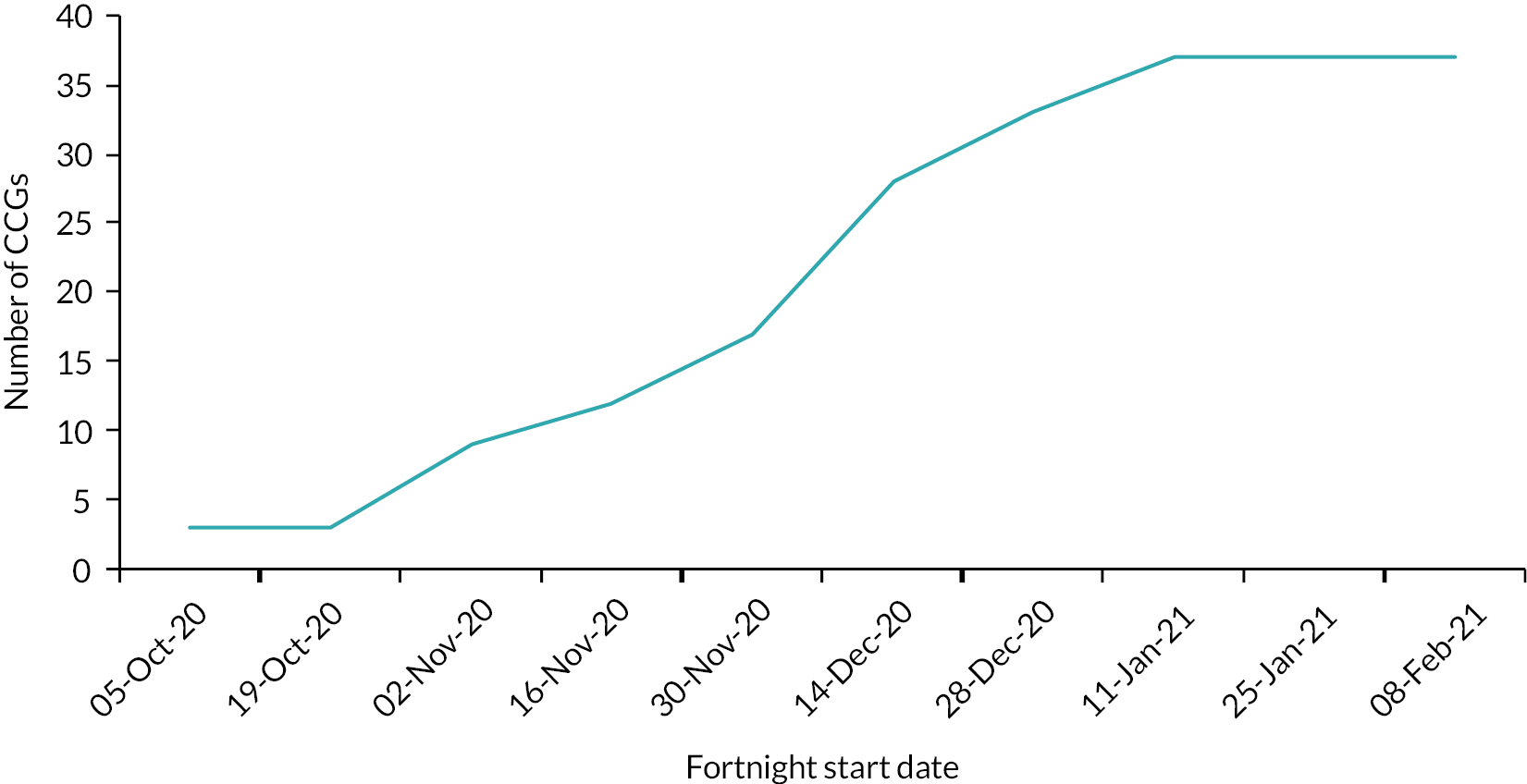

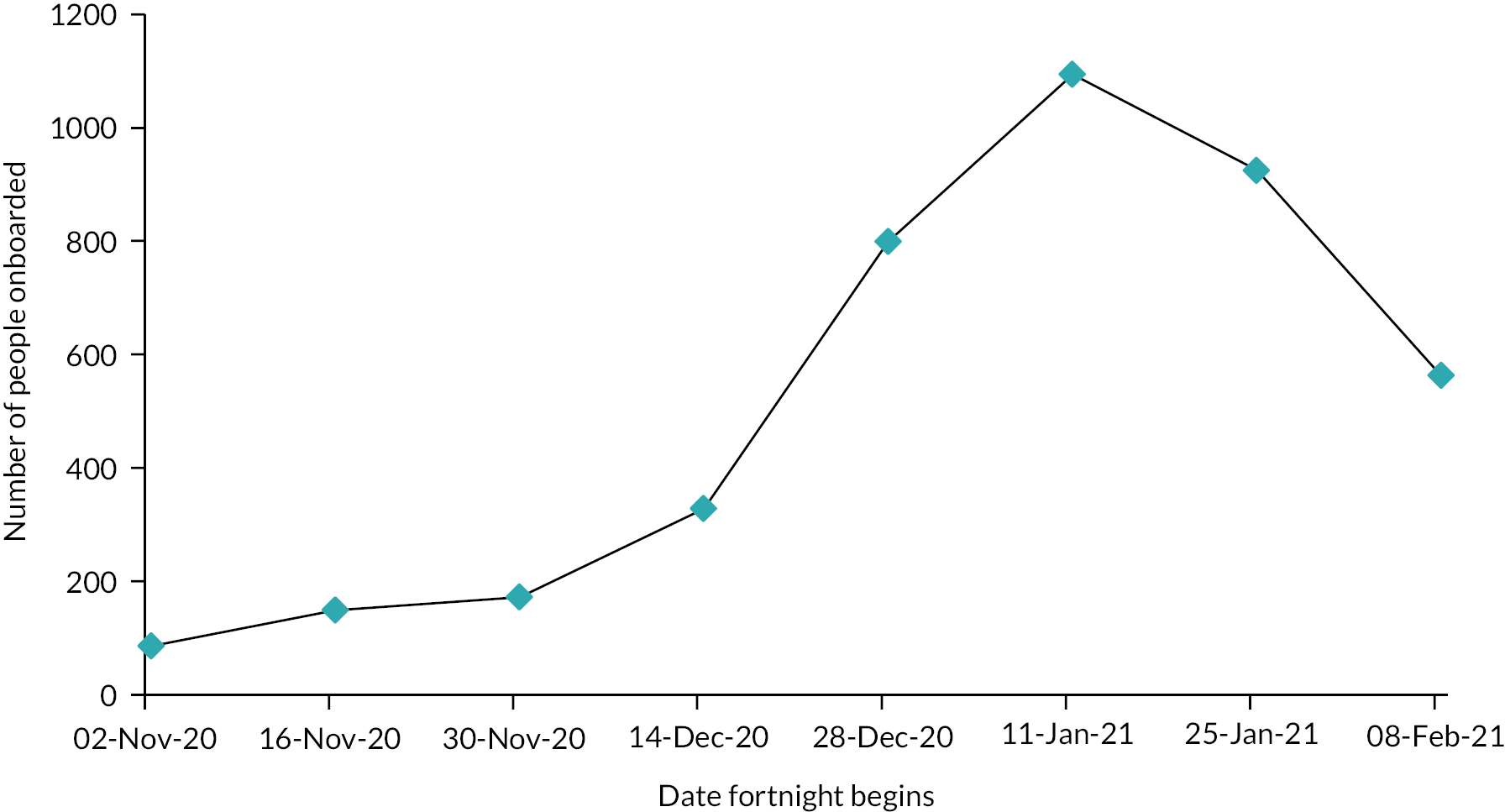

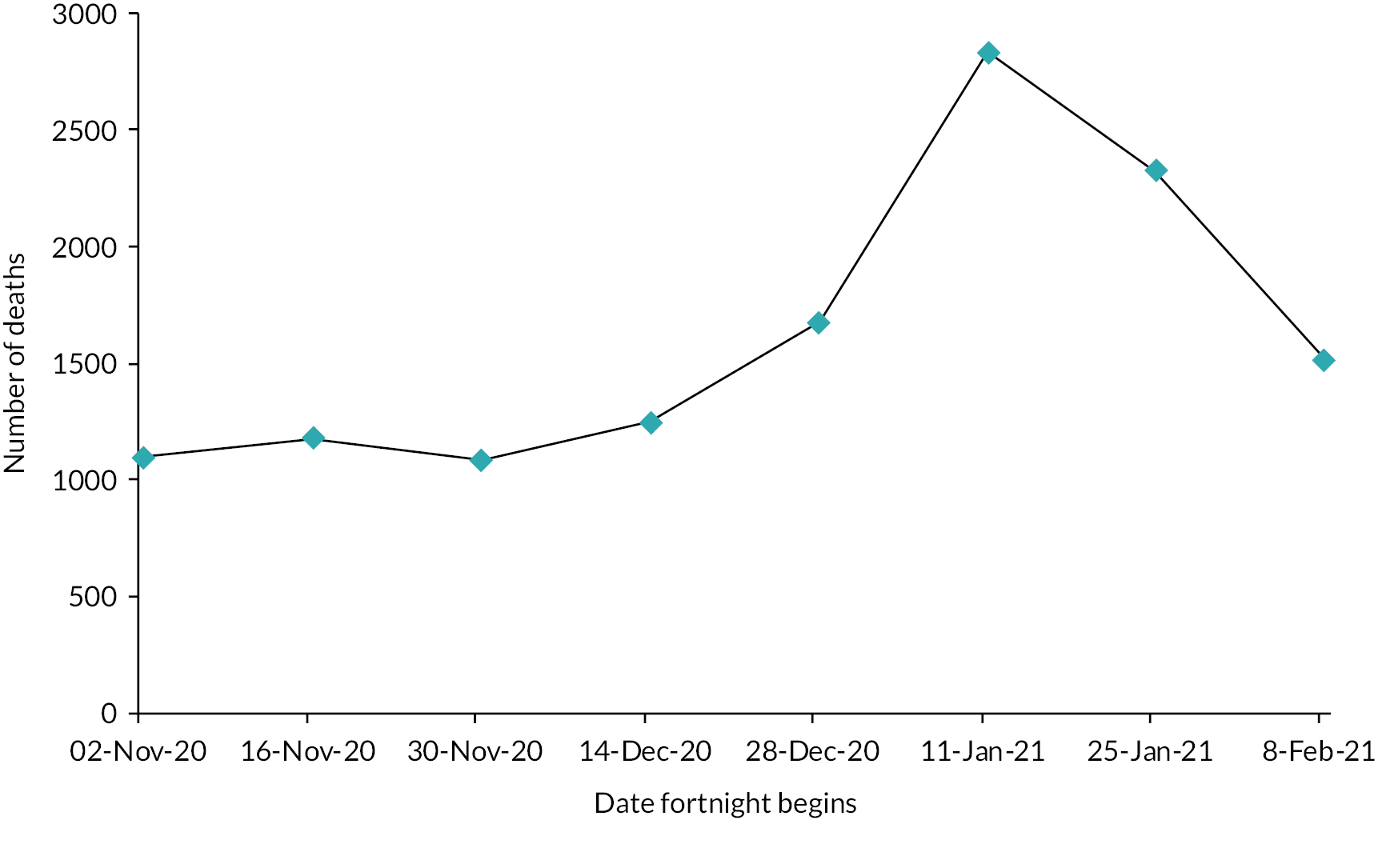

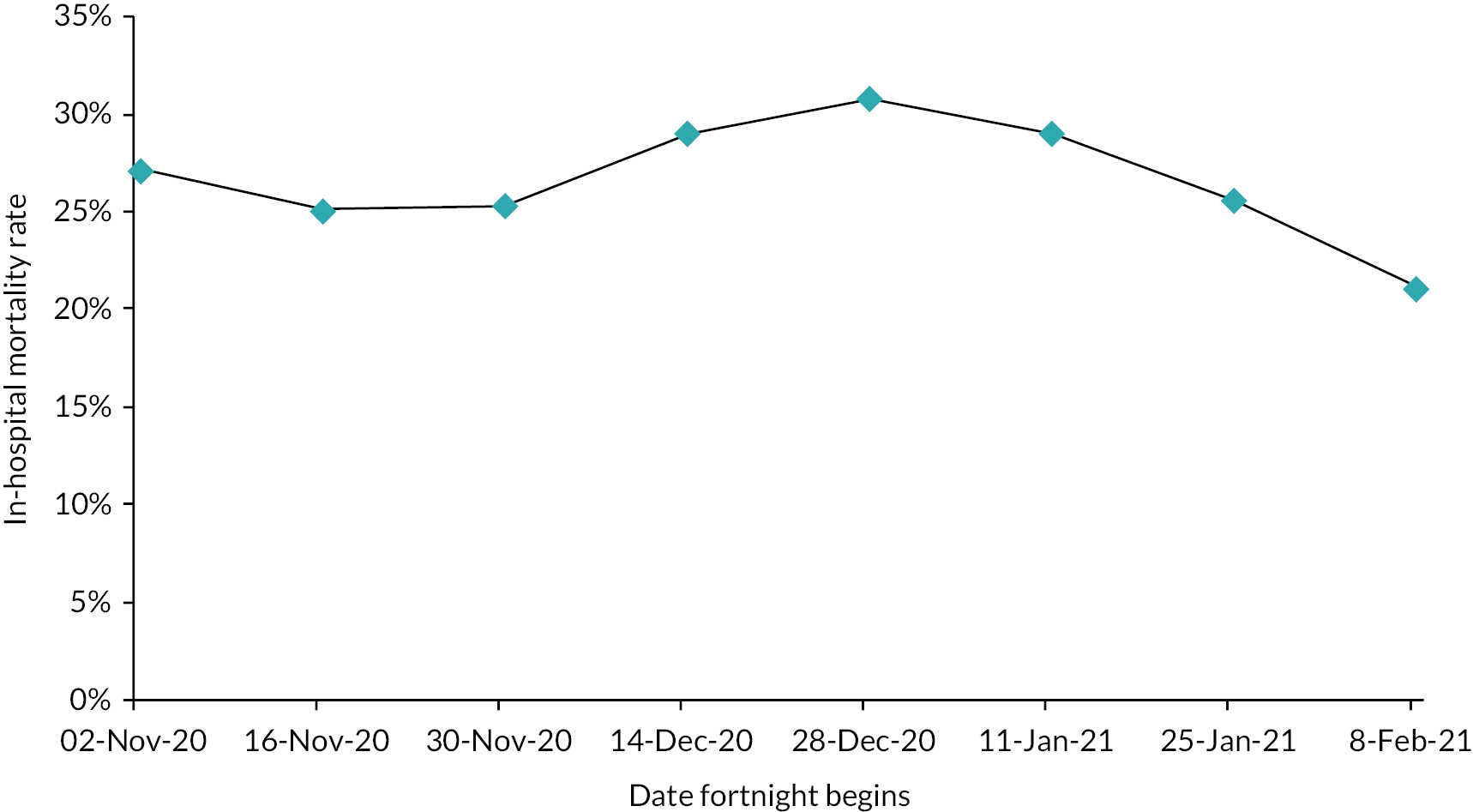

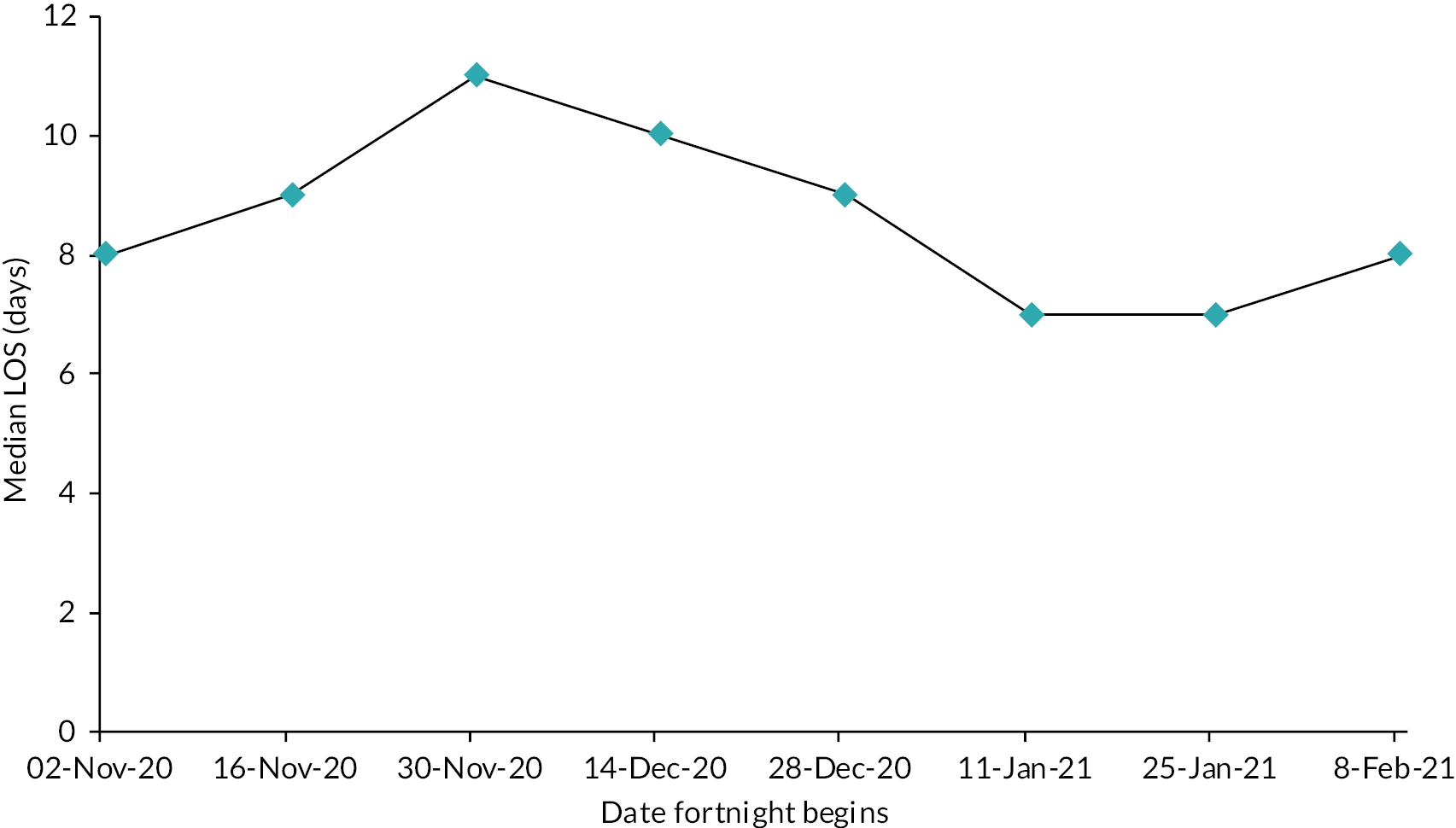

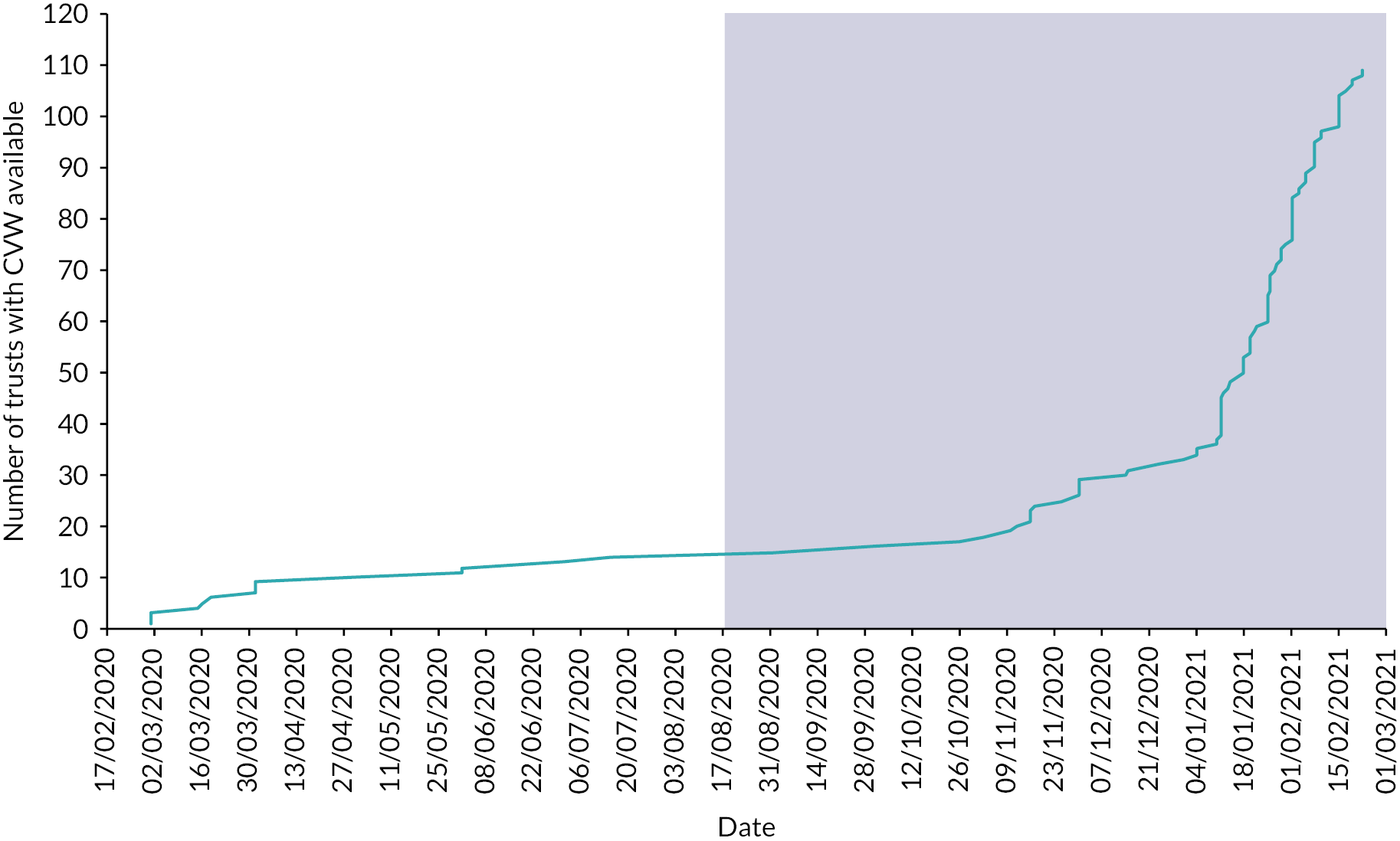

National coverage of COVID-19 remote home monitoring services and enrolment

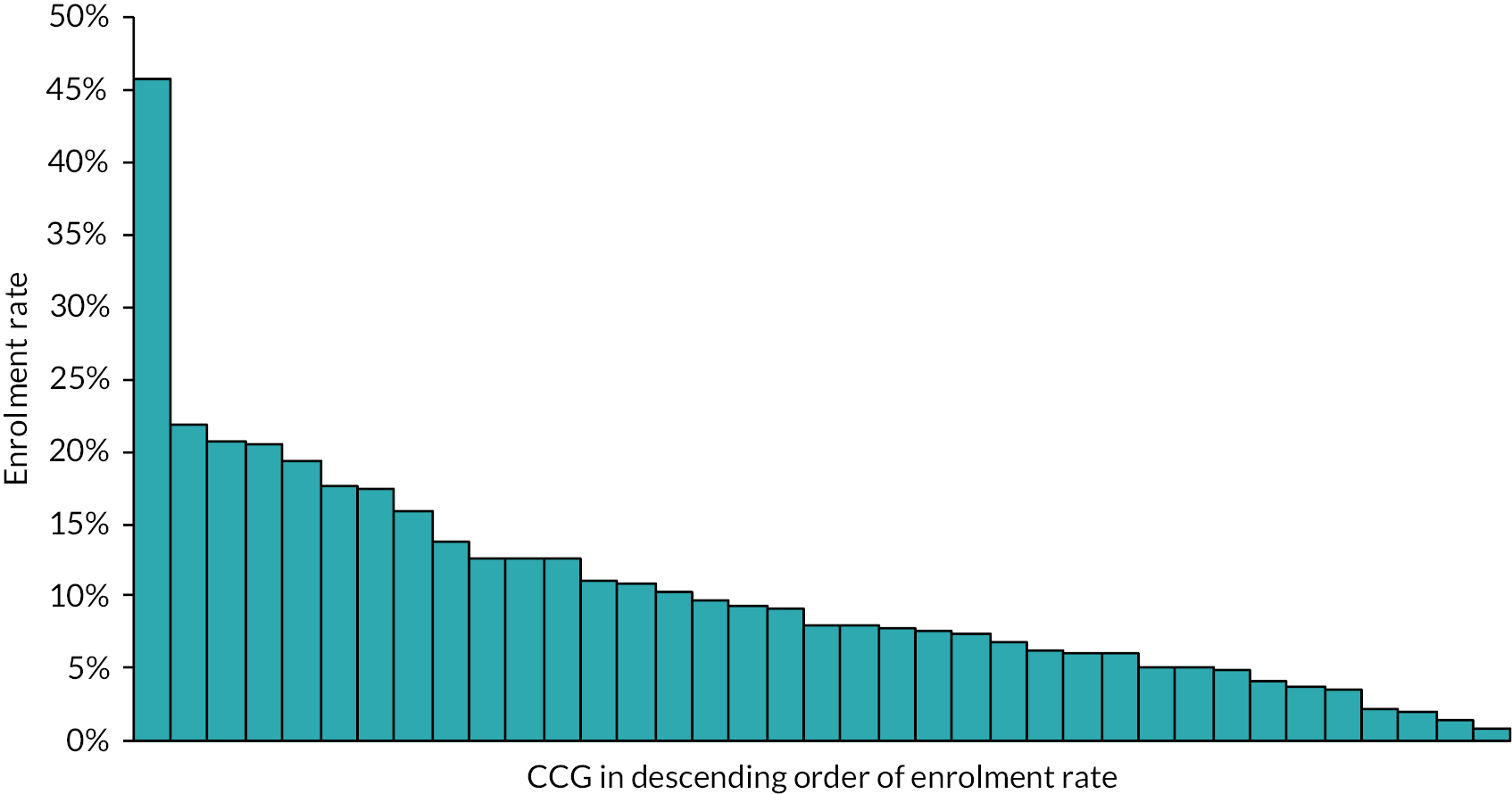

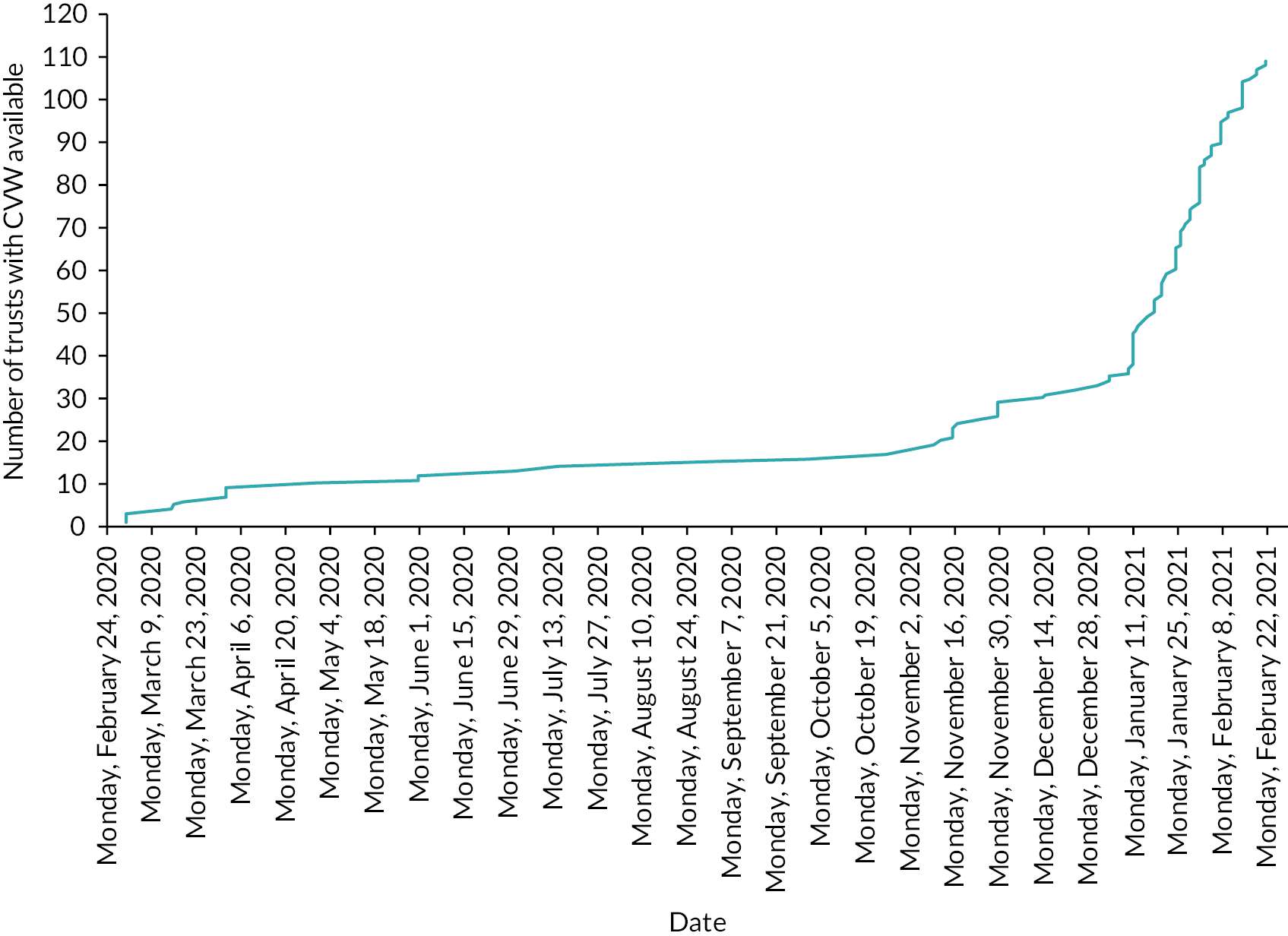

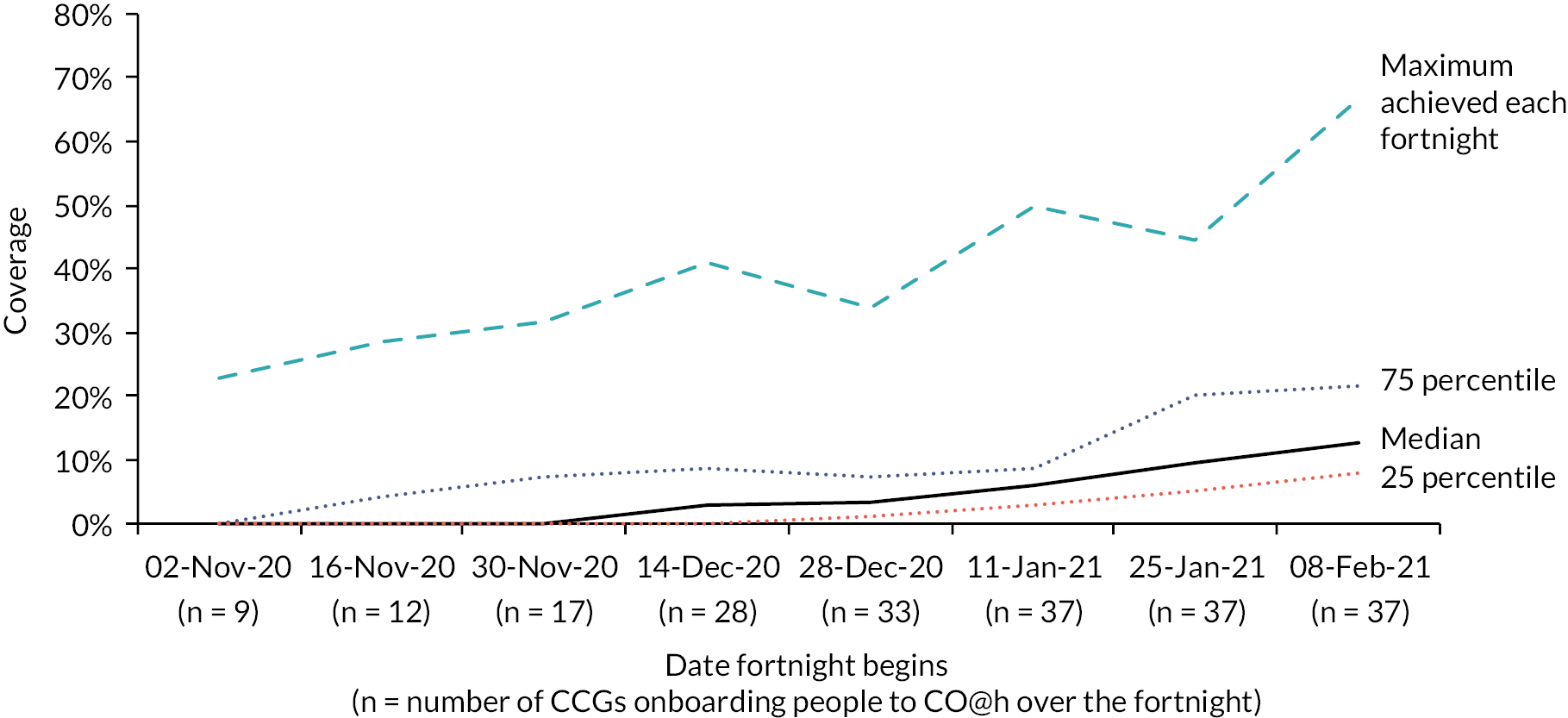

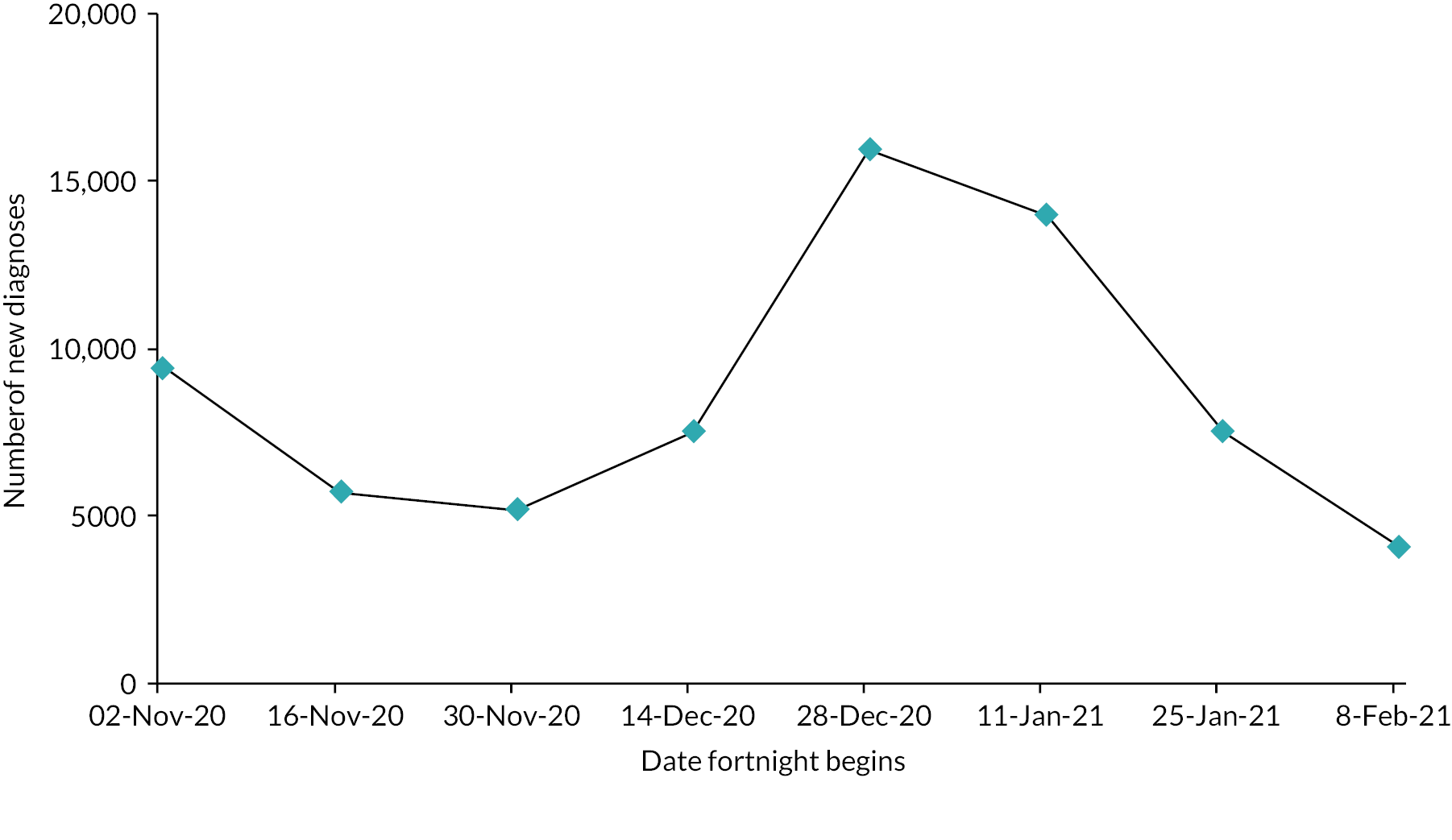

COVID Oximetry @home