Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR130588. The contractual start date was in July 2022. The draft manuscript began editorial review in January 2023 and was accepted for publication in September 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Cantrell et al. This work was produced by Cantrell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Cantrell et al.

Background and structure of the report

In general terms, signposting means pointing people to sources of information, help or advice that they should find useful. The UK health and social care system is complex and many people are unaware of the diverse services available. This gives rise to a need for signposting from their first point of contact with the service (often a general practice) to other sources of information and support where appropriate. The resources signposted could be information about a specific condition, information about an online support group or details of support or activities offered by health and social care organisation and the voluntary and community sectors (VCSs). Many members of health and social care staff carry out signposting as part of their role and its importance has increased in recent years in conjunction with the development of social prescribing as an alternative or add-on to conventional medical treatment. The need for signposting also reflects how demand for many services exceeds the available supply, potentially leading to long waiting lists and frustration on the part of patients.

Against this background, it is important to consider how the concept of signposting has developed; it was defined in 2013 as ‘new roles and support for navigators, health trainers and advisers who help patients and service users understand, access and navigate community-based services that will improve their health’. 1

The diversity of approaches to signposting is illustrated by a survey of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) in England conducted in 2018–9. 2 Of the 195 CCGs approached for the survey, 162 provided usable data and 147 provided some form of ‘care navigation’ service in primary care. Services were delivered by existing practice staff, dedicated paid employees and volunteers in various combinations. Seventy-five different titles were used to describe the role, with ‘care navigator’ and ‘link worker’ being most common. Care navigators (CNs) are people who help patients to navigate the healthcare system from screening, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up for a specific medical condition. Link workers (LWs) can be based in primary care practices or community or voluntary organisation and help support people to access resources from their local community to address and support their health and social care needs. The majority of services were available to all adult patients (‘generic’ services), particularly when delivered by receptionists or other members of practice staff, but some were only available to those meeting particular criteria such as older people or those with a long-term health condition.

Another variable was the method of referral into, or contact, with the service, the most common being referral by a primary care or community health professional, followed by self-referral and at contact with a general practitioner (GP) surgery. 2 Signposting or care navigation can also be delivered through diverse channels: face to face, by phone or virtually or by technology assisted by humans or by technology that has been developed to undertake signposting.

Signposting can be one element within social prescribing. Social prescribing interventions with a clear signposting element will be included in the review, extracted data will focus on the signposting element.

This diversity of approaches suggests a need to investigate what is known about which works best and why. The topic was identified as an evidence gap by Health and Care Research Wales following a prioritisation exercise in 2020. The original research question was: ‘What approaches improve signposting to services for people with health and social care needs? What works best, for whom, in what circumstances and why? Are there any benefits from implementing options in combination’? A realist review approach3 was thus specified from the outset. Programme theories identified from a review of theoretical and empirical literature led us to develop questions and then synthesise the evidence from the distinct perspectives of the service user, the provider of signposting services and the commissioner or funder.

Experimental report format

This report uses an experimental format to optimise its usefulness to its target audiences. This audience-centric method of presentation seeks to minimise ‘academic formatting’ as requested by policy/decision-makers. 4,5 It starts by introducing the problems and then covers the findings from each of the three questions that the report is addressing. Each of the questions is introduced together with any subquestions. Information is then provided about the perspective the questions is being answered for, for example service user, provider of a signposting service and commissioner/funded of a signposting service. Findings from the literature are then presented together with the initial conclusions specific to that perspective supported by data extraction tables. The report then finishes with an overall conclusion and references.

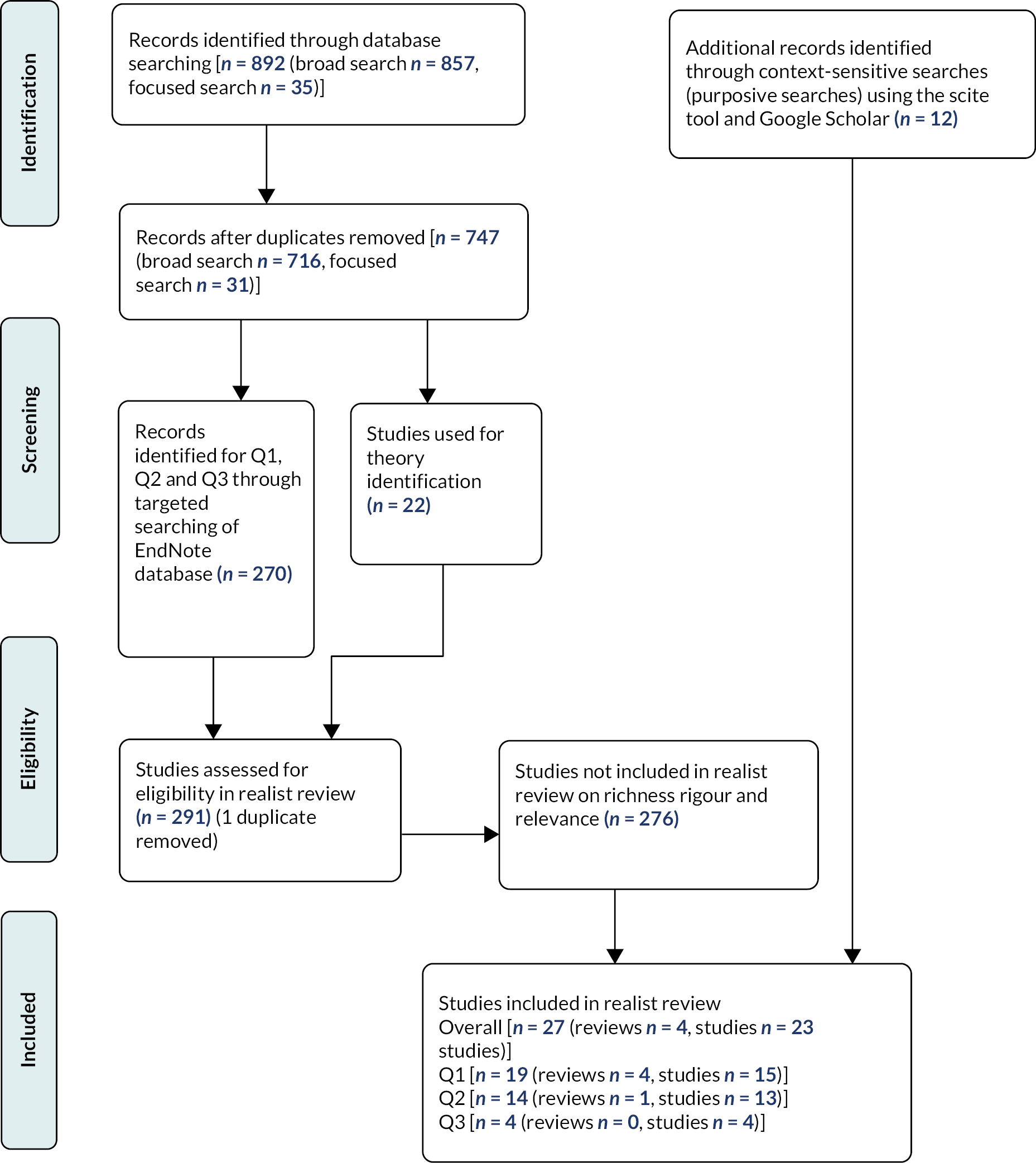

The report appendix provides supporting detail for the methodology. This experimental format thus seeks to optimise usefulness to the intended audience by providing the findings much earlier in the report. It recognises that a detailed research methodology is of comparatively less interest to primary audiences. Nevertheless, full methods are still provided for researchers with the time or methodological interest to require more from the report. Further details of the methodology can be found in Appendices. Appendix 1 covers the report methodology, the MEDLINE search strategy is reported in Appendix 2 and the document flow diagram for the review is detailed in Appendix 3, Figure 1. Appendix 4.The full date extraction of context-mechanism-ouctome (CMO) configurations in the programme theory signposting table, Report Supplementary Material 1.

Appendix 4, Table 12 provides details of the consolidated programme theory, and the data extraction tables are in Appendix 5, Tables 13–15. Full details of the realist review questions can be found in Appendix 6, and public and patient involvement in Appendix 7.

Statement of problem

Signposting is an informal process that involves giving information to patients to enable them to access external, usually non-clinical, services and support. 6 Signposting also includes self-referral, which often requires patients to contact health and support services by telephone or the internet. Signposting may also take place within clinical interactions or within more extensive social prescribing.

Typically, signposting is conceived as a brief activity – one of the ways it is distinguished from social prescribing or care navigation – perhaps comparable in duration to the GP consultation. Concern has been expressed that this may represent an inappropriate response for those with complex health and social care needs. Accompanying and competing narratives focus on diversion away from inappropriate utilisation of primary care or health service resources or on an improved joined-up service for service users, thereby improving the overall quality of care. The team at the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Evidence Synthesis Centre at the University of Sheffield was therefore asked to conduct a focused realist synthesis to explore how signposting services work, for whom and under what circumstances. In answering these questions, the research team concentrated on three complementary perspectives (service user, service provider and commissioner). Full details of the realist reviews questions are provided in Appendix 6. These three perspectives are captured in three complementary questions and considered in turn before integrating the three sets of findings below.

Research question 1 (service user perspective)

Question 1: What do people with health and social care needs require from a signposting service to believe it is a valuable and useful service?

Subquestions

To address this overarching question, the following subquestions were formulated:

-

What do people with health and social care needs require from a signposting service to believe it is a valuable and useful service?

-

What do people with health and social care needs require to be confident in accessing a signposting service?

-

Which aspects of signposting services help people with health and social care needs to engage with signposting services?

-

Which aspects of signposting services enable people with health and social care needs to be satisfied with the service provided?

Perspective

This question and subquestions take the perspective of the individual using signposting services. Service users may use a generic service designed to handle people with different conditions or circumstances or may use a service designed for people with a specific condition or situation (or their carers, families, etc.).

Findings for Question 1 (value and usefulness): service user perspective

Findings for Question 1 are organised under the four identified subquestions. A total of 19 items of evidence were reviewed including 4 reviews and 15 individual items reporting UK studies or service evaluations. Few items featured ‘signposting’ as the focus of the study or research question. Relevant literature included studies of navigator roles and social prescribing and qualitative studies of patient and receptionist interactions in primary care. The focus of the questions means that included items are mainly qualitative or mixed-methods studies. However, one quantitative study reported a correlation between patient satisfaction and ‘patient burden’ – the extent to which the patient had to ‘push’ themselves through their interactions to achieve appropriate options and choices. For data extraction table for Question 1, see Tables 1–4.

| Author (year) | Review year | Included country/countries | Type of review | Number of included studies | Review findings | Review implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bickerdike et al. (2017)7 | 2017 | UK | Systematic review | 15 evaluations | Mostly small-scale evaluations, limited by poor design and reporting and rated with a high risk of bias. Common design issues included lack of comparative controls, short follow-up durations, a lack of standardised and validated measuring tools, missing data and failure to consider potential confounding factors. Most evaluations presented positive conclusions | Current evidence fails to provide sufficient detail to judge either the success or value for money of social prescribing. If social prescribing is to realise its potential, future evaluations of social prescribing must use comparative designs and consider when, by whom, for whom, how well and at what cost |

| Chatterjee et al. (2017)8 | 2017 | Evaluation of UK social prescribing schemes | Systematised review | 86 schemes located including pilots, 40 evaluated primary research materials: 17 used quantitative methods (6 RCTs); 16 qualitative methods, and 7 mixed methods; 9 exclusively involved arts on prescription | Outcomes included increase in self-esteem and confidence; improvement in mental well-being and positive mood; and reduction in anxiety, depression and negative mood | Despite positive findings, the review identifies gaps in the evidence base and makes recommendations for future evaluation and implementation of referral pathways |

| Liebmann et al. (2022)9 | 2022 | Canada, Sweden, UK, USA | Qualitative meta-synthesis | 18 (19 papers) | Analysis identified three themes: increased sense of well-being, factors that engendered an ongoing desire to connect with others and perceived drawbacks of social prescribing. Themes illustrate benefits and difficulties people perceive in social prescribing programmes addressing loneliness and social isolation, with overall balance of more benefits than drawbacks | Given some unhelpful aspects of social prescribing, greater thought should be given to potential harms. Further qualitative and quantitative research is needed to better understand mechanisms and effectiveness and how different components of social prescribing might be best matched to individual participants |

| Mossabir et al. (2015)10 | 2015 | Sweden, UK | Scoping review | 7 | Mental health conditions and social isolation were most common reasons for referral to interventions. Referrals were usually made through general practices. Studies reported improvement to participants’ psychological and social well-being as well as decreased use of health services. Limited measures of participant physical health outcomes | Interventions linking patients from healthcare setting to community-based resources target and address participant psychosocial needs |

| Author (year) | Study year | Study country/countries | Study design | Study sample | Sample size | Population age | Population gender | Health condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bertotti et al. (2018)11 | 2018 | Hackney UK | Realist evaluation – focus groups and individual interviews | Two quantitative GP online surveys with GP surgeries, qualitative interviews with stakeholders, two learning events involving SPCs, commissioners, community organisation representatives and service users, and observations of sessions between SPCs and individuals | Seventeen patients using social prescribing services, three community organisations, three SPCs, commissioners and GPs | Not stated | Not stated | Social isolation, mild–moderate mental health problems, presenting with a social problem, or frequent attenders to GP/A&E |

| Brunton et al. (2022)12 | 2022 | England | Qualitative | Stakeholder staff | Thirty-four respondents in 17 semistructured interviews 1 focus group of 14 practice managers | Not stated | Not stated | N/A |

| Burroughs et al. (2019)13 | 2019 | Staffordshire, England | Feasibility study | Phase 1 older people and third-sector providers Phase 2 support workers Phase 3 study participants, support workers and GPs |

Six support workers – four actually worked with older people in intervention arm Intervention arm – 19 Usual care – 20 Overall randomised – 38 participants |

Participants (older people) – median age: Intervention arm – 73 years Usual care – 70 years Total – 71 years |

Participants (older people) – female sex, n: Intervention arm – 10 Usual care – 12 Total – 22 |

Older people with anxiety or depression |

| Carduff et al. (2016)14 | 2016 | South East Scotland, UK | Semistructured qualitative interviews | Carers, carer liaison and GP from each practice (total = 19) | Eleven carers who had received intervention from their practice and with the carer liaison and one GP in each practice (total = 19) | Mean age of 74 years (range 58–86 years), interviewed across participating practices | Of 83 carers, 55 (66%) female and 28 (34%) male | Carers for persons with dementia (40%), 16% carers for person with cancer and 16% for lung disease |

| Carstairs et al. (2020)15 | December 2018–January 2019 | Scotland | Exploratory study utilising semistructured interviews | Primary care patients and HPs from one UK NHS board | Patients (n = 14) and HPs (n = 14) from one UK NHS board | Health professionals aged 25–64 years Patients aged 25 to ≥ 65 years |

Health professionals seven female and seven male Patients eight female and six male |

Primary care patients referred for physical activity opportunities |

| Foster et al. (2021)16 | 2020 | UK | Included: (a) analysis of routine quantitative data (May 2017 – December 2019) (b) semistructured interviews and (c) SROI analysis | Interviews with 60 service users, LWs and volunteers | All service users n = 10,643 Subsample of service users with pre and post scores on the UCLA loneliness scale n = 2250 Subsample of service users with follow-up UCLA n = 101 |

Mean age = 65.5 years (SD: 19.3) | Female 5388 (65.8) Male 2802 (34.2) |

18 years or older referred from any source. No specific eligibility criteria for loneliness but service targeted at young parents, individuals with health and/or mobility issues, recently bereaved, retired or with children leaving home |

| Gauthier et al. (2022)17 | 2022 | Canada | Case study | ARC navigators | Sixty-six journal entries from 2 ARC navigators (NB and NN) | Not stated | Not stated | Navigators worked with vulnerable populations, for example those with frailty, chronic illness and mental health problems |

| Hammond et al. (2013)18 | 2009–11 | North West England | Ethnographic observation in North West England. Seven researchers conducted 200 hours of ethnographic observation, predominantly in reception of each practice | Seven urban general practices. Forty-five receptionists asked about their work as they carried out their activities. | Observational notes taken. Analysis involved ascribing codes to incidents considered relevant to role and organising these into clusters | Not stated | Not stated | General practice patients |

| Harris et al. (2020)6 | 2020 | Yorkshire and Humber region of Northern England | Qualitative – Semistructured interviews | Primary care team – GPs, nurses and health and social care workers (healthcare assistants and social prescribers) | Twenty-one members of primary care team | Not stated | Not stated | Three exemplars of common health problems: physical LTCs; common mental health problems; and medically unexplained symptoms |

| Hibberd and Vougioukalou (2012)19 | 2012 | UK | Three-phase evaluation (May–August 2010; September–December 2010 and January–March 2011). Questionnaires and focus groups | People with dementia and their carers who had contacted an adviser | Not stated. Total users 392 | Mainly in 70s and 80s | Not stated | People with confirmed diagnosis of dementia and their carers |

| Papachristou Nadal et al. (2022)20 | 2022 | South London UK | Qualitative one-to-one semistructured interviews within wider pilot intervention study | In-depth interviews conducted directly after end of the intervention | Sixteen participants were interviewed: 10 healthcare professionals 6 (of the 19 intervention group participants) participants with severe mental illness and diabetes | Age of the 19 participants in the intervention group Mean (SD) 45.8 (9.7) Median (minimum, maximum) 46.0 (25.0, 64.0) IQR (lower quartile, upper quartile)17.00 (35.00, 52.00) |

Gender of the 19 participants in the intervention group (%) Male 8 (42.1) Female 11 (57.9) |

People with type 2 diabetes and severe mental illness |

| Stokoe et al. (2016)21 | 2016 | UK | Qualitative conversation analysis of incoming patient telephone calls, recorded ‘for training purposes’ | Total number of receptionists 9(9) 9(8) 10(10) (number of receptionists audiotaped in brackets) | Three English GP surgeries | Not stated | Data from GP1, GP2, GP3 Total patients 5987, 7691, 10,943 Proportion appointments booked by phone 96%, 92%, 91%. Number of calls collected for study 613, 582, 1585 Number of calls selected for analysis [final number 150 (149) 150 (148) 150 (150)] |

Not stated |

| White and Kinsella (2010)22 | 2010 | UK | Evaluation | GPs, practice staff and patients | Twenty-two (including 12 patients) | Under 35 years 33% 36–65 years 48% Over 65 years 15% Not recorded/declined 4% |

Female 66% Male 34% |

Not stated (patients with mental health and social issues) |

| White et al. (2022)23 | 2022 | UK | Evaluation of social prescribing service (January 2019–December 2020) | Interviews and focus groups | Total participants: 57 key stakeholders; social prescribing managers, LWs, referrers (GPs and social work practitioners), clients, VCS agencies and groups |

Those aged 16 years and over | Not stated | Loneliness and isolation; anxiety; becoming healthy and active |

| Wildman et al. (2019)24 | 2019 | UK inner-city area in west Newcastle upon Tyne (population n = 132,000) ranked among 40 most socioeconomically deprived areas in England | Qualitative methods using semistructured follow-up interviews | Users of LW social prescribing service who had participated in earlier study | Twenty-four service users | Participants aged between 40 and 74 years | Eleven women and 13 men | People with LTCs living in socioeconomically disadvantaged region. Two-thirds of participants experiencing mental health and social isolation issues |

| Author (year) | Signposting context | Setting | Generic or specialist | Signposting features | By whom | Type of resources required | Length of interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bertotti et al. (2018)11 | Primary care | Twenty-three GP surgeries located in the London Borough of Hackney and the City of London | Generic | GP referral process; interaction with SPC; interaction with community/statutory organisations. To co-produce a well-being plan resulting from discussions about needs and aspirations of each patient and availability of local support services |

SPC | Eighty-five community organisations in borough which delivered physical activity classes, health advice, networking activities (e.g. lunch clubs), psychological support, art and other services | Up to six, 40 minutes long, sessions |

| Brunton et al. (2022)12 | Challenges of integrating signposting into general practice | Primary care | Generic | Integrating signposting into general practice | Reception staff as CNs Social prescribing LWs |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Burrough et al. (2019)13 | Primary care | General practice | Specialist | Older people received support for anxiety and depression and to attend a community group or usual care | Support worker employed by Age UK North Staffordshire | Training, support materials and manual | Three to six sessions, lasting 15 minutes to 4 hours Supervision time varied between 60 and 280 minutes per support worker |

| Carduff et al. (2016)14 | Primary care | General practices | Specific | Carers identified opportunistically, from register and through self-identification (poster) | Carer liaison | Carer toolkit including assessment form, fridge magnet with contact numbers etc. | Not stated |

| Carstairs et al. (2020)15 | Primary care | General practice | Specialist | Jog leaders and group members hosting ‘meet and greet’ sessions at practice could allow HPs to gain knowledge about this option. Provide opportunity to signpost patients to group members for more information, support and reassurance and to establish ‘buddy’ to start activity journey with | LWs | Access to resources advising on available option, and time to seek out this information is a critical barrier for HPs. To help overcome these barriers, HPs need up-to-date resources, and alternative connecting solutions that rely on an intermediary or resource including practice champions, LWs within practices, and community hubs | Not stated |

| Foster et al. (2021)16 | Social prescribing service across 37 different sites throughout the UK | Varies | Generic | Developing supportive relationship with service users, assessing their needs and providing person-tailored care | Paid LWs alongside volunteers | Access to appropriate community activities and services (signposting) such as craft groups, adult learning and leisure facilities | Support provided for up to 12 weeks |

| Gauthier et al. (2022)17 | Primary care | Generic | ARC navigators | Not reported | Navigator 1 logged 433 encounters [mean total duration per patient = 126 minutes (range: 6–466 minutes)] with 66% of encounters occurring via telephone (n = 284) Navigator 2 logged 1025 encounters (mean total duration/patient = 91 minutes) | ||

| Hammond et al. (2013)18 | Primary care | GP surgery | Generic | Face-to-face interactions | Receptionists | Knowledge of practice | Brief contact |

| Harris et al. (2020)6 | Primary care | Thirteen general practices | Generic |

|

GP: 12 (57%) Nurse: 7 (33%) Health and social care worker: 2 (10%) |

Information and self-help resources and peer and community support groups. Practical support – tangible services and aids; equipment provision, vouchers, books, self-monitoring diaries, completing forms and teaching practical skills to help patients use specific health-related equipment |

Brief consultations (< 15 minutes) |

| Hibberd and Vougioukalou (2012)19 | Community | Commissioned by Council’s Adult Social Care Services in partnership with NHS | Specialist | Face to face at home, telephone or e-mail. Referral to or contacting health or social services. Filling in forms. Practical support and advice. Information about clubs/activities | Dementia advisers | Detailed information about practical help (phone numbers etc.) and understanding of who and what to contact. Details of benefits and information about local services | Up to 2 hours mentioned |

| Papachristou Nadal et al. (2022)20 | Community | Community Mental Health Unit | Specialist | Referral to social and leisure resources and help with navigating health system | CN | Swimming, living well programmes, leisure centres or food clubs | Not stated but CN not only booked appointments but attended with service user |

| Stokoe et al. (2016)21 | Primary care | GP surgery | Generic | Telephone interactions | Receptionists | Help with appointments | Not stated but within usual primary care reception interactions |

| White and Kinsella (2010)22 | Primary care | GP surgery | Generic | Not described | Social prescribing health trainers | Signposting to other agencies and working with service users to find ways of coping with issues they are facing | Initially 1 hour |

| White et al. (2022)23 | Primary care | Based within GP practices and other locations including community centres | Generic | Separate social prescribing services available to support housing, debt and welfare benefits; such issues directed to separate in-house welfare service, and not dealt with directly by LWs, so excluded from data analysis | Social prescribing service co-delivered by two VCS organisations with support provided by LWs (four or five variously during evaluation) | Buddying to support clients on initial agency visits | Service offered short-term support but with need for flexibility to tailor duration of support to meet individual needs |

| Wildman et al. (2019)24 | Primary care | GP surgery | Generic | Highly personalised service to reflect individual goal-setting priorities and a focus on gradual and holistic change dealing with issues beyond health | LWs | Emotional support and ‘everyday reassurance’ for service users lacking self-esteem and experiencing anxiety; ‘instrumental support’ (e.g. filling out welfare benefit application forms); ‘informational’ support in identifying sources of help within wider community; and ‘appraisal’ support with decision-making and problem solving | Service users remain for up to 2 years or longer if required. During patient’s engagement, face-to-face contact is supplemented by telephone, e-mail or text contact. Meeting duration frequency increases or decreases according to need |

| Author (year) | Outcomes measured | Main findings | Key messages including limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bertotti et al. (2018)11 | Referral to SPC (stage one)

|

Data collection shows that beneficial outcomes for patients result from combination of multiple stages working together effectively. Realist evaluation approach enabled identification of three stages of interaction between the patient and three other stakeholders: the GP (stage one), the SPC (stage two) and community organisations (stage three) | SPCs pivotal to effective functioning of social prescribing service and responsible for activation and initial beneficial impact on users. There are significant potential benefits from social prescribing but also several challenges. ‘Buy-in’ from some GPs, branding and funding for third sector in context of social care cuts are some of the challenges that need to be thought about and overcome. The SPC is central to social prescribing and their role needs to be understood more clearly practically and conceptually |

|

|||

| Brunton et al. (2022)12 | Stakeholder views on challenges of integrating signposting into general practice | Three themes that highlight the challenges of integrating signposting into general particle were role perceptions, role preparedness and integration and co-ordination of roles | Key factors that affect signposting in practice are: clarity of role purpose and remit, appropriate training and skill development for role holders and adequate communication and engagement between stakeholders/partnership working Limitations: views of CNs from only 1/5 areas where they were working and their experience could be different to CNs working in different areas of Greater Manchester |

| Burroughs et al. (2019)13 | Participation in study did not impact on routine care, other than response to calls from study team about risk of self-harm. GPs not aware of work done by support workers (SWs) with patients |

Older people found sessions with SWs acceptable, although signposting to, and attending, groups not valued by all participants. GPs recognised need for additional care for older people with anxiety and depression, which they could not provide |

SWs recruited from Age UK employees can be trained to deliver an intervention, based on principles of BA, to older people with anxiety and/or depression. Training and supervision model acceptable to SWs, and intervention acceptable to older people |

| Carduff et al. (2016)14 | Development of an intervention model to identify, assess, support and refer carers. To evaluate if the intervention is feasible and acceptable | Eighty-three carers identified from four practices: 36 from practice registers, 28 by practice staff and 7 self-identified. Eighty-one carers received the pack and 25 returned the CSNAT form. Follow-up calls to discuss support were received by 11 carers and an additional 12 carers were referred/signposted for support. The qualitative interviews suggest carers valued the connection with their practices but found the paperwork in the toolkit burdensome | Carers did not describe need for intensive support, preferring smaller interventions. Feeling ‘connected’ was very important to the well-being of carers. They endorsed the provision of carer support being available in their community through their local GP practice. The approach this study used to identify and support carers was acceptable. The success of the intervention was dependent on engagement within the whole practice. Carers needed to be proactively identified by practices as they did not tend to self-identify or ask for help. Practices need to adopt a public health approach to raise carer awareness about support within their communities |

| Carstairs et al. (2020)15 | Barriers and facilitators for patient connection | Three methods of connecting patients to community-based groups identified: informal passive signposting, informal active signposting and formal referral or prescribing. Barriers and facilitators fell into five theoretical framework domains for HPs and two COM-B model components for patients. Patients liked their HP to connect them to resources on specific PA opportunities to consider and potentially follow up on. Patients described that connecting to tangible PA options is favourable instead of just being told ‘you should get more active’ given as they think it helps them towards implementing the changes |

HPs raising the topic of PA can help patients to justify, facilitate and motivate action to change. The workload for HPs associated with the different methods of connecting patients with community-based opportunities varied, and is central to implementation by HPs. Combining resource solutions and social support for patients can provide them with a larger range of PA options along with the information and support they require to connect with local opportunities |

| Foster et al. (2021)16 | Loneliness scores Return on investment |

The majority of service users (72.6%) felt less lonely after receiving support. The mean decrease in UCLA score −1.84 (95% CI −1.91 to −1.77) indicates an improvement. Improved well-being, increased confidence and life having more purpose were some of the additional benefits. Base-case analysis estimated a SROI of £3.42 per £1 invested in the service. Key aspects for the service were having skilled LWs and support tailored to individual needs. There were challenges though included utilising volunteers, meeting some service users’ needs in relation to signposting and sustaining improvements in loneliness. Nevertheless, the service appeared to be successful at supporting service users experiencing loneliness | This national social prescribing programme was found to help reduce people’s loneliness as well as improving their well-being and increasing their sense of purpose. The model achieves a positive net social value for money invested (£3.42 return per £1 invested). Key to the service success is having skilled LWs who deliver personalised support. Challenges to service delivery include using volunteers, signposting and sustaining improvements in loneliness |

| Gauthier et al. (2022)17 | Navigators learning experience | Reflective journal entries analysed using five framework categories

|

Experiences suggests that navigator education programmes should include learning opportunities from experiences of primary care, which could be testimonials from patients during training or initial supervised patient interactions. Supervision could help navigators with managing expectation, confidence building and help them start developing skills to apply person-centred care Limitations: limited generalisability firstly due to journal entries from only two navigators. Additionally, the navigators knew that the journals would be read by others which may introduce social desirability bias |

|

|||

| Hammond et al. (2013)18 | Receptionist attitudes and behaviours | Receptionists face difficult task of prioritising patients, despite having little time, information and training. They felt responsible for protecting patients who were most vulnerable; however, this was sometimes made difficult by protocols set by the GPs and by patients trying to ‘play’ the system | Framing receptionist–patient encounter as between the ‘powerful’ and the ‘vulnerable’ impairs a full understanding of the complex tasks receptionists perform and contradictions inherent in their role. Calls for more training, without reflective attention to practice dynamics, risk failing to address systemic problems, portraying them instead as individual failings |

| Harris et al. (2020)6 | Participants’ accounts showed that referral and signposting to external services and resources was most common SMS activity used across all three exemplar common health problems | From the interview analysis three categories and six subcategories, illustrating different self-management support activities across common health problems, were identified. Referral and signposting were frequently used to facilitate patient engagement with services and resources. Challenges were experienced by practitioners in balancing medical management and psychosocial support and motivating patients to engage with self-management | Digital repository of available community services and additional training in motivational interviewing would support practitioners and enable them to increase their confidence and skills in SMS across common health problems. Limited consultation time was a common obstacle but unclear exactly what the optimum duration and pattern of consultations should be. Recommendation from this research includes increasing awareness of practical support initiatives for people with common mental health problems and mediclally unexplained symptoms (MUS) and for healthcare commissioners the setting targets for management of physical LTCs |

| Hibberd and Vougioukalou (2012)19 | Service user perceptions Service provider perceptions |

Immediacy is very important. Service users feel able to recontact service at any time without restrictions. The service did not use answerphones which are off-putting for those with hearing or cognitive problems. Service users appreciated being listened to by someone who knew what they were talking about. Adviser independence from health and social services was appreciated making it easier to talk about problems and issues with services |

Can ‘oil the wheels’ within a longer pathway (often seen as disconnected). Some overlap, for example, with post-diagnostic counselling but not seen as an issue because of special need for reinforcement among this cognitively impaired population |

| Advisers particularly appreciated when service users feel frustrated, upset or vulnerable. Service users value (1) repeated back information and (2) review of action points at end of call. Written reminders sent as follow-up. Need for emotional support not just practical support. Relaxed environment also appreciated |

|||

| Papachristou Nadal et al. (2022)20 | Thematic analysis | From analysis of 19 participants, five main themes emerged regarding the care-navigator role: administrative service; signposting to local services; adhering to lifestyle changes and medication; engaging in social activities; further skills and training needed | Key findings emphasise benefits of care-navigator role in helping people with severe mental illness to better manage their diabetes, that is, through diet, exercise medication and attending essential health check-ups |

| Stokoe et al. (2016)21 | Published satisfaction survey scores | Analysis identified ‘burden’ on patients to drive calls forward and achieve service. ‘Patient burden’ occurred when receptionists unable to meet patients’ initial request did not offer alternatives to or did not summarise relevant next actions at the end of calls. ‘Patient burden’ frequency differed across the three GP services. Increased ‘patient burden’ was associated with decreased satisfaction scores on satisfaction survey |

Patients in some practices have to push for effective service when calling GP surgeries. Conversation analysis specifies what constitutes (in)effective communication. Findings can then underpin receptionist training to improve patient experience and satisfaction |

| White and Kinsella (2010)22 | Six of 12 patients signposted to another service or activity. Some patients primarily need space to discuss their troubles. Some are signposted to another agency after only one or two sessions with the SPHT; patients seen for three or more sessions are encouraged to develop a personal health action plan | In only 9 months, 484 patients were supported to cope better and improve their health. 51% of patients seen were referred to community-based service for support. 48% made personal action plan. 87% of those signed off had made changes that enabled them to cope better and improve their health |

Benefits for practices of the health trainer and social prescribing service:

|

| Patients seen were among the most vulnerable and disadvantaged they had mild mental health problems, relationship difficulties or were socially isolated. The service was valued very highly be patients – they really liked the friendly, informal approach, someone with time to listen and the support to develop with their own solutions to their difficulties |

|

||

| GPs and other practice staff liked having a service to refer patients with primarily social problems. There was some evidence that patients, who had seen a health trainer, visited their GP less with social problems |

|

||

| White et al. (2022)23 | Number of users referred to social prescribing service. Sources of referral to service. Thematic analysis of interview data |

Two thousand one hundred and ninety-nine users referred to social prescribing service (September 2017–August 2020). Sources of referral included self-referral (28%); social workers (20%); HPs (12.5%). Despite emphasis on social prescribing as a resource to help primary care manage demand, only 4.2% referrals were from GPs, a significant proportion (41.5%) were from two practices. The five themes identified from the qualitative data were: Theme One, Accessing Link Worker Support; Theme Two, How Link Workers Support Clients; Theme Three, Getting on: Accessing Support in the Community; Theme Four, Perceived Benefits of Social Prescribing; Theme Five, Working to Deliver Social Prescribing |

Key support included referral into and onwards from social prescribing services (in addition to signposting), longer-term LW support and buddying. Practitioner responses highlighted the balance between empowerment and dependency featured in practitioner responses. There is a need for good support and supervision for LWs to enable them to provide support while minimising client dependency. Further exploration is needed of why GP referrals were lower than expected and how referrals could be increased. Social workers were key referrers to social prescribing services suggesting a potential need to investigate in greater depth the role of social prescribing in UK social work practice |

| Wildman et al. (2019)24 | Service users’ perspective on social prescribing service | Participants reported reduced social isolation and improvements in their condition management and health-related behaviours. Findings indicated that, in this sample of people facing complex health and socioeconomic issues, longer-term intervention and support were required. | Highlights issues of interest to commissioners and providers of social prescribing:

|

Positive features of LW social prescribing for service users included:

|

From research perspective, diversity of improvements and their episodic nature suggest that evaluation of social prescribing interventions requires longitudinal quantitative and qualitative data | ||

| Requires strong, supportive relationship with an easily accessible LW in promoting sustained behaviour change. Highlights importance of LW continuity. A barrier for some participants was a lack of suitable and accessible voluntary and community services for onward referral |

What do people with health and social care needs require from a signposting service to believe it is a valuable and useful service?

People with health and social care needs in the UK carry a strong expectation that they will be seen by health professional staff, particularly by their GP. 12 Any attempt to direct them to non-clinical staff carries the risk that they will see themselves as being ‘fobbed off’. 12,25,26

Practice manager 2: So, the patient loses faith in the call handler because they think that [they’ve] just been fobbed off. ‘You can’t even get through to that doctor’s, and then when you do, she’s telling me that I need to go there, and then I’m phoning there again and then to be told that they’re fully booked up’. And then it gives us a bit of a bad…it’s not fair really. 12[6]

This phenomenon has been reported for patients who are directed towards self-care options,27 as well as for patients with psychosis being handled within primary care. 28 This means it is likely that the threat of being ‘fobbed off’ may exist for both users of generic signposting services and users of specialist signposting services. A patient who feels ‘fobbed off’ is more likely to re-present to the surgery within a short period of time27 in search of a response that they view as appropriate. Staff members involved in signposting have a small window of opportunity within which to counter this potential negative attitude. This contrasts with extensive social prescribing or social navigation options which report the build-up of trust over a sustained period of time.

It is significant, from the literature relating to LWs, that patients may be prepared to ‘trade’ the extra time, used to develop a full and accurate picture of their individual need taken by a LW against the clinical interaction with a GP or practice nurse. 24

There’s a huge difference [between a link worker and a nurse or doctor]. The practice nurse just wants to stick the jab in your arm, and let them get on with it, and that’s it. Doesn’t ever really have time to do the in-depth analysis of where you’re at and what you’re doing. The Ways to Wellness person has that concern. 24[6]

The implication of this statement is that signposting services, as individually configured for brief contact, cannot satisfy the need for ‘in-depth analysis’ as articulated here. Potentially, an alternative source of ‘capital’ that can be traded against clinical knowledge and expertise is the detailed knowledge of community resources which can be acquired through training, experience and a suitable directory or resource of activities and opportunities:

…it’s important to have someone there, who has a finger on the pulse, knows all these different things. Doctors can’t know everything and I mean, what they know obviously helps improve your health, but things like support in the community and things, I don’t think enough of them know about it. I don’t even know that the practice nurses know enough about it. 24[6]

A less tangible benefit but, nevertheless one valued by the service user, is the ability to link together an otherwise disjointed health and social care response; someone who “puts all the links together, which is a link worker in an intervention where ‘everything was involved’.”24

Although this benefit was described in the context of a LW, who fulfils many diverse roles, it can be transparently attributed to the signposting component with its focus on both ‘navigation’ and ‘joining up’.

An adequate response requires multiple expectations to be satisfied sequentially – that the one signposting will identify options efficiently, that these options will be available, that they will be feasible and that they will be appropriate to the needs of the individual. 12 These demanding requirements correspond to provision identified for Question 2, namely well-trained staff, supported by information resources, directories or lists of contacts, underpinned by an appropriately resourced community infrastructure and informed by a knowledge of the needs of the individual. A qualitative meta-synthesis9 highlights the matching of response to need as one of the persistent challenges of linking schemes, requiring further research and this appears to be equally true of a briefer signposting intervention where time to establish a full and accurate picture of complex need may be even more limited.

Within the limited contact time implied by active signposting, it is likely to prove challenging to build up the confidence of the user in the signposting service and trust of the service user in the service provider with whom they are in contact. One GP reports how trust between a GP and their patient is fundamental to them subsequently listening to their advice and trusting the recommended destination for the referral. 6 The relationship between GP and patient is at best an ambivalent one – trust can be built up over many years or lost speedily by a negative episode of care. While recognisable reception staff may have built up a comparable relationship with service users in their community, they represent only a small proportion of potential signposting contacts and so, in many cases, the relationship may equate to ‘cold calling’ requiring the build-up of trust from ground zero.

Trust can be built up within a signposting service through the quality of the initial response (achieved by staff training and experience), the quality of the advice and its appropriateness to the individual service user and the quality of the resources as subsequently accessed. 12 A paradox exists that repeat use may be a sign that the original need remains unfulfilled given that repeated contact works contrary to a programme theory of subsequent self-management. The value of the service is seen not when a user returns to the service for the same need, but when they have the confidence to return to the service for a different but related need, when they recommend the service to others in a similar situation or, in some cases, where they themselves volunteer to become part of the pathway either within the initial signposting service or in contributing to the community back-up response.

Signposting services are intended to build up service user self-esteem and confidence, thereby improving their self-direction and, in the case of chronic conditions, their resourcefulness and self-management. While this is undoubtedly evidenced in sustained social prescribing services,7,8,16,29 it is difficult to attribute this to a brief variant of the intervention, as in signposting. Intermediaries, whether those signposting or those in social prescribing roles, describe how building up of service user self-esteem and confidence may require extended time, multiple contacts or, commonly, both.

As identified elsewhere in this review, the quality of the community response may be determined by the level of resourcing received by the organisations to which the service user is referred. One way in which a signposting service may mitigate their dependence on community resource levels is through access to a wide range of service providers. For example, one evaluation describes how it referred just over half of its service users to other organisations, including literacy courses at colleges, volunteering and community allotments, line dancing and the local Citizen Advice Bureau. 22

What do people with health and social care needs require to be confident in accessing a signposting service?

Users of signposting services have varying levels of need. Two particular factors were identified as shaping the signposting response to users with different needs. First, those delivering the service may attempt to accommodate the needs of vulnerable service users. 18 This may be done by providing extra help – such as filling out forms – or by moving from being a service interface to becoming a patient champion. In some cases, this may involve actually making the decision for the service user when their capacity or confidence to make their own decision is thrown into question. Signposting services are particularly valued by those who are frustrated, upset or vulnerable. One evaluation report highlights how those being targeted by signposting services were those seen as being among the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, those with mild mental health problems and those with relationship difficulties or who were socially isolated. 23 Paradoxically, however, the extent and nature of these types of challenge may require more intensive involvement than just signposting, moving much more towards social prescribing. 23 As a general finding, those who superficially most likely to benefit from the extra support in navigation offered by signposting are also those who might benefit from more intensive forms of support. This not only makes it challenging to demark where signposting ends and social prescribing begins, but also means that the more time that is spent in establishing the service user’s needs, the more extensive the awareness of the full scale and complexity of their needs and thus the more intensive a response is required. A corollary may be resistance to pressures from those seeing themselves as entitled; assuming a gatekeeper role against those who might seek access to opportunities or resources at the expense of those who are more in need.

Second, signposting services may serve different functions for different age groups, even if they share the same apparent symptoms such as social isolation, depression or anxiety – younger service users may value initiation of opportunities, and therefore be more amenable to signposted activities, whereas older people’s loneliness is often entrenched, arising from diminishing social networks, attributed to the deaths of family/friends and a loss of functional ability to engage in activities. 16

Which aspects of signposting services help people with health and social care needs to engage with signposting services?

The evidence identifies three critical points in the signposting process with a bearing on engagement with signposting. First, the one signposting should be able to offer options. 21 Second, the ‘patient burden’ in seeking to progress, for the one using the service, should be kept to a minimum. 21 Third, the one signposting should summarise the suggested actions to confirm resolution and closure. 21 This feature is considered particularly important where the service user experiences cognitive difficulties as with those with memory problems or dementia. A written summary may be used to reinforce the agreed action. Significantly, offering options and summarising what has been agreed feature as important characteristics of medical receptionist interactions and communications generally, aside from a signposting role. However, fulfilment of these requirements has been found to be variable. An additional contingent requirement is a further loop whereby unsatisfactory or unacceptable options are rechannelled to acceptable alternatives. 21 Again, this is described as reducing ‘patient burden’. 21

Signposting services are primarily transactional, rather than relational, and, particularly if delivered by those identifiable from former or split receptionist roles, may create an expectation in speedy and brief resolution to avoid tying up the service for other users. In contrast, navigators document the importance of gaining and building service user trust. 17 Question 2 documents how this requires that navigators develop relationships with patients ‘actively listening and digging deeper’17 in order to tailor their response to patient needs and individual preferences. 10 It further notes how four included studies in a scoping review of linking schemes10 found that relationships with facilitators that were described as ‘being flexible, trustworthy, empathetic and accessible (Andersson 1985, Woodall and South 2005, Brandling and House 2007, White et al. 2010)’10(:480) encouraged service user engagement. Evidence is equivocal on the optimal balance between transactional and relational roles for a service as a whole and available data suggest that service users hold different individual preferences for these roles and these, in turn, may fluctuate according to the situation being encountered and the urgency of the response being required. Evidence suggests that access to requisite skills in questioning are needed for both services that aim to provide signposting or extensive social prescribing.

Signposting services may provide a misleading picture of their success when a service user, either intentionally or unintentionally, gives the impression that they plan to follow up on the suggestion but does not actually follow through. Service users describe how the ‘right’ advice may not have been timely for them, particularly, when they have multiple issues of competing priority with which to contend. In these cases, the otherwise apposite action may be deferred or even ignored all together. Evidence captures from signposting staff, specifically navigators, a note of hopefulness, that service users will respond positively to the direction being offered and will subsequently benefit, rather than secure expectation that they will do so. 17

Which aspects of signposting services enable people with health and social care needs to be satisfied with the service provided?

Service users may feel that a signposting service is merely a way to steer ‘them away from GP appointments, rather than steering them towards the most appropriate care’. 12 Service users may feel dissatisfied that they are being ‘managed’ by non-clinical staff who are not equipped to handle their situation. This very much depends upon the nature of the advice, for example, whether the referral is to community groups and activities or to other ‘more appropriate’ health services. This concern ties in to the reciprocal concern (Question 2) of staff involved in signposting being drawn into a clinical role. While the concerns of clinical staff may centre on safety,12 those of service users may focus on the perceived quality of the response.

Evidence suggests that service users may not initially identify what intervention they require. They may not be aware that a signposting service exists or that it can help them in relation to the specific issues that they face (the issue of ‘who will signpost to the signposters?’). Knowledge of available services and their roles is variable among potential referrers such as primary healthcare staff. Even if they access a signposting service, it may take time in order to elicit what they actually require, as well as to establish realistic expectations, both what can be achieved and what cannot be achieved by the service. One qualitative study evaluating a social prescribing service23 reports that ‘sometimes they just don’t know what they need and they need to talk, so it’s important to just listen … the questions that you ask them are important for getting out information’23(:6, e5110).

Mismatched expectations are potentially a source of dissatisfaction with a signposting service even when it closely fulfils its intended remit. A further issue relates to follow-up – expectations from the service can be shaped by previous experiences with the service so that repeat service users may feel more comfortable in accessing the service when they require ‘more of the same’ that they are in accessing a wider diversity of services that may or may not be offered by the signposting service.

Summary for value and usefulness of signposting: service user perspectives

Interpretation of the review brief became more challenging as our review team became sensitised to the nuances of signposting provision. Should we literally focus only on the signposting component in isolation? In which case, we could reasonably conclude that beneficiaries from signposting in isolation are likely to represent only a small proportion of service users, for whom the referral target is simply the missing piece in their route to self-management and resolution. In such a situation, a 2- to 5-minute intervention may be viewed as sufficient. Or is signposting to be considered as an adjunct that must always be backed up with more extensive social prescribing that provides for those for whom signposting will not be enough?

Two further complexities were identified. First, where signposting is prolonged beyond its brief 2- to 5-minute ‘dosage’, it may offer an opportunity to elicit more information on user need; therefore, increasing the likelihood that referral to more intensive services is required – effective, rather than efficient, signposting thereby potentially subverts its own programme theory of brief contact and referral onwards. This tension plays out against the two driving and competing narratives for signposting, namely the driver to deflect inappropriate non-health-related demands away from the health service, particularly primary care (‘to free up GPs’ time by directing patients to other sources of help’), and the driver to use signposting as a way to improve the quality of care through better integration and linking of services (‘to enable patients to be signposted at the first point of contact, to the “right” professional or service’). 12

Second, where signposting cannot be extended beyond its 2- to 5-minute duration, it may represent an inappropriate response to more profound needs, thereby functioning to cloak levels of actual need. This links to the need identified in a qualitative metasynthesis9 to evaluate potential harms of social prescribing which can be extrapolated to encompass equally the briefer interventions delivered by signposting.

Conceptually, the challenges presented by signposting services mirror, albeit on a wider scale, those posed by the creation of the NHS111 service as an alternative to urgent primary and secondary care. Service users require reassurance that the response that they are receiving is not of inferior quality, that the operatives with whom they are dealing are proficient, that the response is appropriate and that the eventual outcome that they receive is the best possible for their current situation. Similarly, signposting services may be seen to be equally vulnerable to high-profile accounts of occasional inappropriate response, evidenced in concerns from signposting staff about ‘stepping into clinical areas’ and patient safety. Such concerns may require that specialist signposting for high-risk groups, for example, for patients with psychosis, receive additional safeguards (whether this be training, expertise or procedures) for both signposting staff and their service users.

Initial conclusions for value and usefulness of signposting (service user perspective)

-

Although a distinction between brief signposting services and intensive extended social prescribing services is meaningful from the perspective of service funding and training and expectations on staff, this distinction is less useful from the perspective of service user need.

-

A small proportion of potential service users have their needs satisfied by the largely navigational brief intervention offered by signposting. A much larger proportion of service users will require extensive support, perhaps requiring an extended duration of contact or multiple episodes of contact or both.

-

A key issue is whether signposting and social prescribing, as two distinct levels of service provision, are delivered within a fully integrated service, whether they represent separate services with a fluid interface or whether they are loosely linked and largely dysfunctional.

-

A related key issue concerns the potentially diverse relationships between the signposting service and the opportunities or activities to which they direct the service users; these could be formally integrated within a common ‘scheme’, loosely confederated with minimal governance and quality control or opportunistically aggregated with little commonality of candidacy or expectation.

-

The signposting service operates as a ‘shop window’ for services, statutory or voluntary, on offer. Deficiencies in the signposting service may impact negatively on take-up of the available opportunities. Conversely, poor access to, resourcing of and delivery by, supporting services may reflect negatively on the credibility of the signposting service influencing numbers of repeat users or testimonials to the signposting service.

Research question 2 (service provider perspective)

What resources (training, directories/databases, credible and high-quality services for referral) do providers of front-line signposting services require to confidently provide an effective signposting service?

Perspective

Question 2 is from the perspective of the individual providing a signposting service. Many different people provide these services including volunteers, lay people, receptionists and various health professionals including GPs, physiotherapists, nurses and pharmacists.

Findings for Question 2 (required resources): service provider perspective

For Question 2, a total of 14 items of evidence were reviewed, 1 review and 13 individual items reporting UK, USA or Canadian studies or service evaluations. The findings from the included studies are discussed within themes. The data extraction tables follow the findings; see Tables 5–8.

| Author (year) | Review year | Included country/countries | Type of review | Number of included studies | Review findings | Review implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mossabir et al. (2015)10 | 2015 | Sweden, UK | Scoping review | Seven studies | Almost all interventions were facilitator-led, whereby the facilitator works to identify and link participants to appropriate community-based resources. Studies reported improvement to participants’ psychological and social well-being as well as decreased use of health services. Limited measures of participant physical health outcomes | Interventions linking patients from healthcare setting to community-based resources target and address participant psychosocial needs. Health professionals aid the referral of patients to the intervention and role of intervention facilitators is key to the interventions |

| Author (year) | Study year | Study country/countries | Study design | Study sample | Sample size | Population age | Population gender | Health condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bertotti et al. (2018)11 | 2018 | Hackney UK | Realist evaluation – focus groups and individual interviews | GPs, stakeholders, SPCs, commissioners, community organisation representatives and service users | Seventeen patients using social prescribing services, three community organisations, three SPCs, commissioners, and GPs | Not stated | Not stated | Social isolation, mild–moderate mental health problems, presenting with a social problem, or frequent attenders to GP/A&E |

| Brunton et al. (2022)12 | 2022 | England | Qualitative | Stakeholder staff | Thirty-four respondents in 17 semistructured interviews, 1 focus group of 14 practice managers | Not stated | Not stated | N/A |

| Burroughs et al. (2019)13 | 2019 | Staffordshire, England | Feasibility study | Phase 1 older people and third-sector providers Phase 2 support workers Phase 3 study participants, support workers and GPs |

Six support workers – four actually worked with older people in intervention arm Intervention arm – 19 Usual care – 20 Overall randomised – 38 participants |

Participants (older people) – median age: Intervention arm – 73 years Usual care – 70 years Total – 71 years |

Participants (older people) – female sex, n: Intervention arm – 10 Usual care – 12 Total – 22 |

Older people with anxiety and depression |

| Carstairs et al. (2020)15 | December 2018–January 2019 | Scotland | Exploratory study utilising semistructured interviews | Primary care patients and HPs from one UK NHS board | Patients (n = 14) and HPs (n = 14) from one UK NHS board | Health professionals aged 25–64 years Patients aged 25 to ≥ 65 years |

Health professionals seven female and seven male Patients eight female and six male |

Primary care patients referred for physical activity opportunities |

| Donovan and Paudyal (2016)30 | Northumberland Region, England | Qualitative | Pharmacy support staff from 12 HLP initiatives | Twenty-one pharmacy support staff | Age range < 30–69 years < 30 years: 4 40–49 years: 6 50–59 years: 8 60–69 years: 3 |

Female: 21 | Pharmacy customers | |

| Farr et al. (2021)31 | 2020 | England | Qualitative | Professionals and service users involved with implementing the THRIVE framework for CYP’s mental health | Eighty (CAMHS clinicians, commissioners, service leads, service users and their parents or carers. Participants from the wider referral pathway and implementation team were also included) | Not stated | Not stated | Mental health conditions referred to CAMHS |

| Gauthier et al. (2022)17 | 2022 | Canada | Case study | ARC navigators | Sixty-six journal entries from two ARC navigators (NB and NN) | Not stated | Not stated | Navigators worked with vulnerable populations, for example, those with frailty, chronic illness and mental health problems |

| Hammond et al. (2013)18 | 2009–11 | North West England | Ethnographic observation in North West England. Seven researchers conducted 200 hours of ethnographic observation, predominantly in reception of each practice | Seven urban general practices. Forty-five receptionists asked about their work as they carried out their activities | Observational notes taken. Analysis involved ascribing codes to incidents considered relevant to role and organising these into clusters | Not stated | Not stated | General practice patients |

| Harris et al. (2020)6 | 2020 | Yorkshire and Humber region of Northern England | Qualitative – semi-structured interviews | Primary care team – GPs, nurses and health and social care workers (healthcare assistants and social prescribers) | Twenty-one members of primary care team | Not stated | Not stated | Three exemplar types of common health problems: physical LTCs; common mental health problems; and medically unexplained Symptoms |

| Kennedy et al. (2016)32 | England | Qualitative | Community | Fifteen case studies of observations facilitator–participant interactions at intervention delivery and interviews with participants | Adults over 18 years, range from 43 to 76 years | Six female, nine male | Type 2 diabetes | |

| Komaromy et al. (2018)33 | 2011 (training CHWs for CARS program) 2015 (training CHWs for ‘Let’s move New Mexico’ family obesity prevention training programme) | USA | Training programme evaluation | CHWs attending CARS program CHWs attending ‘Let’s move New Mexico’ family obesity prevention training programme |

CARS training programme – 139 individuals have completed training programme ‘Let’s move New Mexico’ family obesity prevention training programme – 25 CHWs |

Not stated | Not stated | Patients with substance use disorders Families at risk of obesity |

| Toal-Sullivan et al. (2021)34 | 2017–8 | Canada | Evaluation (training programme) | Navigators attending ARC training programme | Programme piloted May 2017 – 13 participants: five experienced multicultural health navigators, four members of ARC research team, three university students and one ARC patient navigator Second implementation training programme with 11 participants comprising 5 multicultural health navigators, 4 members of research team and 2 ARC patient navigators | Not reported | Not reported | Navigators worked with vulnerable populations such as those with frailty, chronic illness and mental health problems |

| White et al. (2022)23 | 2022 | UK | Evaluation of social prescribing service (January 2019–December 2020) | Interviews and focus groups | Total participants: 57 key stakeholders; social prescribing managers, LWs, referrers (GPs and social work practitioners), clients, VCS agencies and groups |

Those aged 16 years and over | Not stated | Loneliness and isolation; anxiety; becoming healthy and active |

| Author (year) | Signposting context | Setting | Generic or specialist | Signposting features | By whom | Type of resources required | Length of interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bertotti et al. (2018)11 | Primary care | Twenty-three GP surgeries located in the London Borough of Hackney and the City of London | Generic | GP referral process; Interaction with SPC; Interaction with community/statutory organisations. To co-produce a well-being plan resulting from discussions about needs and aspirations of each patient and availability of local support services |

SPC | Eighty-five community organisations in borough which delivered physical activity classes, health advice, networking activities (e.g. lunch clubs), psychological support, art and other services | Up to six, 40-minute-long sessions |

| Brunton et al. (2022)12 | Challenges of integrating signposting into general practice | Primary care | Generic | GP referral process; Interaction with SPC; Interaction with community/statutory organisations. To co-produce a well-being plan resulting from discussions about needs and aspirations of each patient and availability of local support services |

Reception staff as CNs Social prescribing LWs |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Burroughs et al. (2019)13 | Feasibility of support workers employed by Age UK | Community | Specialist | Older people received support for anxiety and depression and to attend a community group or usual care | Support workers employed by Age UK North Staffordshire | Training Manual Support material Supervision |

Three to six sessions, lasting 15 minutes to 4 hours Supervision time varied between 60 and 280 minutes per support worker |

| Carstairs et al. (2020)15 | Primary care – GPs identifying patients who could benefit from jogScoltland | General practice | Specialist | Informal, active or referral to JogScotland. Jog leaders and group members hosting ‘meet and greet’ sessions at practice could allow HPs to gain knowledge about this option. Provide opportunity to signpost patients to group members for more information, support and reassurance and to establish ‘buddy’ to start activity journey with | GPs | Videos, leaflets | Standard GP appointment |

| Donovan and Paudyal (2016)30 | Pharmacy support staff views and attitudes on the HLP initiative | Primary care | Generic | Developing supportive relationship with service users, assessing their needs and providing person-tailored care | Pharmacy support staff | Knowledge of services, resources, community support | Brief consultation |

| Farr et al. (2021)31 | Improving access to mental health services against background of long waiting times and strict referral criteria | Four London boroughs | Specialist | Discussion with families and referrers of those not meeting CAMHS criteria | CAMHS staff, including STAR workers focusing on school outreach and signposting | Support from schools, local authorities and third sector/CVS | Variable |

| Gauthier et al. (2022)17 | Navigators’ experiences of assisting patients’ access to health and social resources in the community | Primary care | Generic | Navigators’ document their experience as a navigator through reflective journaling | ARC navigators | Not reported | Navigator NB logged a total of 433 encounters [mean total duration per patient was 126 minutes (range: 6–466 minutes)] with 66% of encounters occurring via telephone (n = 284) Navigator NN logged a total of 1025 encounters (mean total duration per patient was 91 minutes) |

| Hammond et al. (2013)18 | Primary care | Seven general practices | Generic | Face-to-face interactions | Receptionists | Knowledge of practice | Brief consultations – phone or in-person |

| Harris et al. (2020)6 | Primary care | Thirteen general practices | Generic |

|

GP: 12 (57 %) Nurse: 7 (33 %) Health and social care worker: 2 (10%) |

Information and self-help resources and peer and community support groups. Practical support – tangible services and aids; equipment provision, vouchers, books, self-monitoring diaries, completing forms and teaching practical skills to help patients use specific health-related equipment |

Brief consultations (< 15 minutes) |

| Kennedy et al. (2016)32 | Initial evaluation of a web-based tool GENIE consisting of network mapping, user-centred preference elicitation and needs assessment and facilitated engagement with resources | Community | Specialist | Facilitators guided participants through the GENIE process, an online tool to map social networks, and help participants to find and access relevant resources | Facilitators were local health trainers and CNs | Database of relevant resources and activities | GENIE process designed to take 30–40 minutes |

| Komaromy et al. (2018)33 | Evaluation of using Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) model for CHW training | Community | Specialist | Training and ongoing support | CHS training using ECHO model | Not stated | Not stated |

| Toal-Sullivan et al. (2021)34 | Evaluation of training programme for lay navigators | Primary care | Generic | Training for lay navigators in primary care | Lay navigators | Not stated | Twelve-module blended approach |

| White et al. (2022)23 | Primary care | Based within GP practices and other locations including community centres | Generic | Separate social prescribing services available to support housing, debt and welfare benefits; such issues directed to a separate in-house welfare service, and not dealt with directly by LWs, so excluded from data analysis | Social prescribing service co-delivered by two VCS organisations with support provided by LWs (four or five variously during evaluation) | Not stated | Service Offered short-term support but with need for flexibility to tailor the duration of support to meet individual needs |

| Author (year) | Outcomes measured | Main findings | Key messages including limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bertotti et al. (2018)11 | Referral to SPC (stage one)

|

Beneficial outcomes for patients result from combination of multiple stages working together effectively. Realist evaluation approach enabled identification of three stages of interaction between the patient and three other stakeholders: the GP (stage one), the SPC (stage two) and community organisations (stage three) | SPCs’ pivotal effective functioning of social prescribing service and responsible activation and initial beneficial impact on users. Social prescribing shows significant potential for benefit, but several challenges must be considered and overcome, including ‘buy-in’ from some GPs, branding and funding for third sector in context of social care cuts |

|

|||