Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HSDR Rapid Service Evaluation Team, contracted to undertake real time evaluations of innovations and development in health and care services, which will generate evidence of national relevance. Other evaluations by the HSDR Rapid Service Evaluation Teams are available in the HSDR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/138/31. The contractual start date was in October 2018. The final report began editorial review in July 2020 and was accepted for publication in September 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Smith et al. This work was produced by Smith et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Smith et al.

Chapter 1 Context

Primary care networks are groups of general practices that were brought together across England in 2019 to hold shared budgets and develop new services in response to national policy that was intended to bring about better integration of health care within local communities.

Primary care networks were to build on the many pilots of new ‘vanguard’ models of integrated health care that had been developed as a result of the NHS Five Year Forward View. 2

Primary care networks offer the possibility of significant levels of additional funding for general practice through a compulsory, formal and incentivised model that differs from many predecessor schemes of collective primary care.

There were (as at May 2020) 1259 PCNs in England, serving populations ranging from 20,000 to well above the 50,000 suggested in policy. 3

Primary care networks sometimes build on prior general practice collaborations and are often supported by the organisational infrastructure of the extant collaborations. Other networks are brand new entities in the process of becoming established and working out how best to source their management support.

The research took place in a rapidly changing policy and service context: initially as a result of the implementation of The NHS Long Term Plan4 and subsequent professional challenge to the PCN policy and contractual proposals, and thereafter as a result of the global COVID-19 pandemic emerging in early 2020.

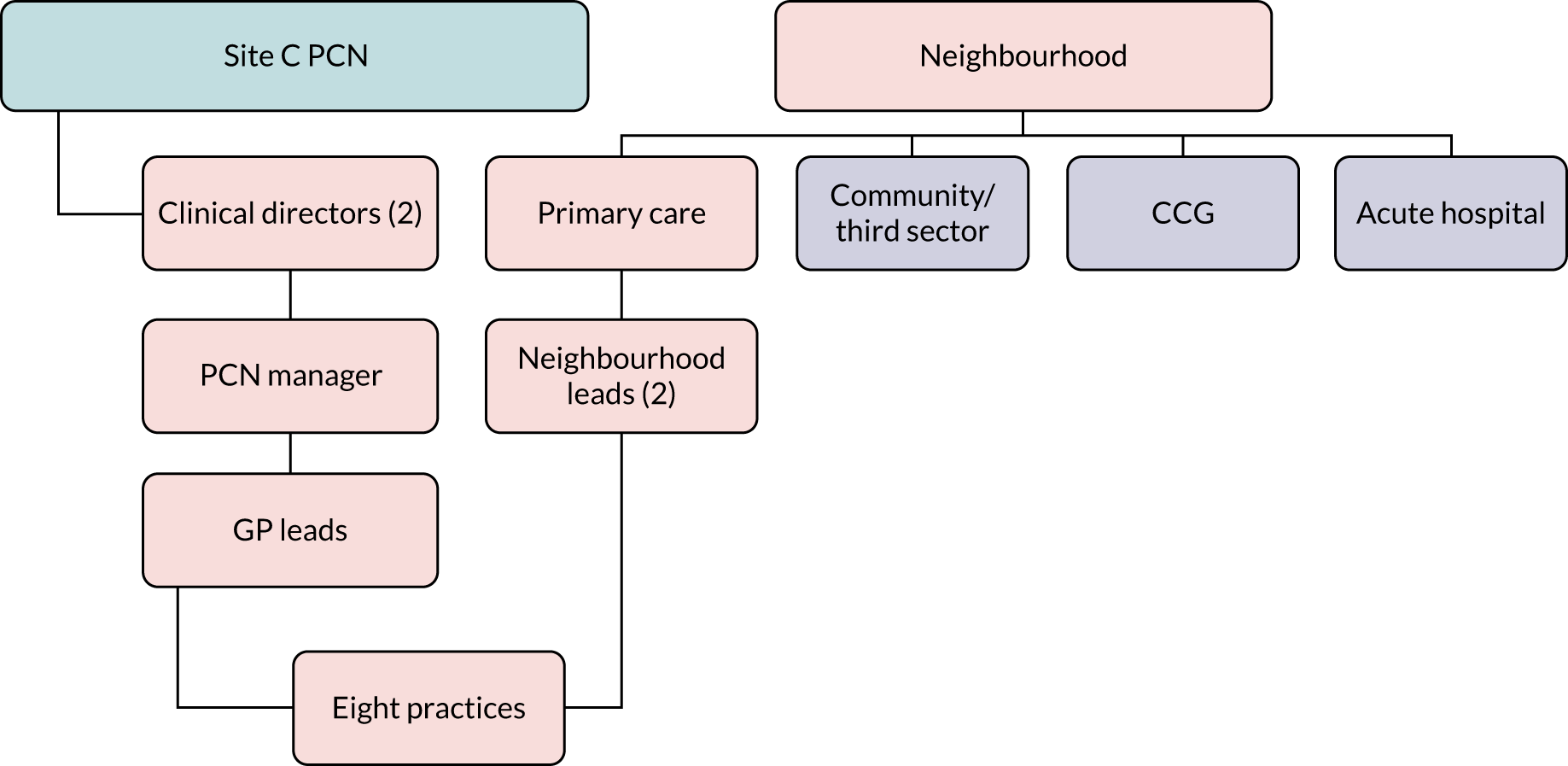

PCN, primary care network.

Parts of this report have been reproduced from Parkinson et al. 1 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Introduction

The aim of this rapid evaluation study was to provide early evidence about the implementation of primary care networks (PCNs) in the NHS across England, with a particular focus on understanding what has helped or hindered their progress, how they operate in relation to pre-existing collaborations in general practice (GP), and exploring issues for rural as compared with urban PCNs. The detailed research questions (RQs) for the study are set out in Chapter 2.

Primary care networks are groups of GPs that were brought together in 2019 to hold shared budgets and develop new services in response to national policy intended to bring about better integration of health care within local communities. The study entailed a review of existing international research evidence about collaborations within GP and then, based on identified knowledge gaps, case study research to examine the nature, functioning, potential and shortcomings of PCNs. The research took place in a rapidly changing policy and service context – initially as a result of the implementation of The NHS Long Term Plan4 and subsequent professional challenge to the PCN policy and contractual proposals, and thereafter as the global COVID-19 pandemic emerged.

The findings from this rapid evaluation study are intended to inform NHS England and Improvement’s (NHSE&I’s) and the primary care community’s future planning and guidance for PCNs. Our analysis of these findings forms the basis of recommendations for how the sustainability of PCNs can be assured and how they might develop in the future, including in the context of the significant changes taking place in primary health care and GP as a result of the COVID-19 global pandemic.

Policy context

General practice is one of the main first points of contact that patients have with the NHS and acts as a gateway that connects people to specialist care at treatment centres, hospitals, mental health services and community health-care services. NHS GP has until recently had high approval ratings among patients and the public,5 and is considered important and cost-effective in that it enables health outcomes to be improved and health inequalities to be addressed while helping to contain costs in the wider health system. 6,7

In its Five Year Forward View strategic plan,2 published in 2014, NHS England (now NHSE&I) identified the need for new models of care that increasingly require collaboration across a range of health and social care services and providers. Related to this, it was asserted that GPs needed to work together (and with other primary care practitioners and services) in a more systematic, sustained and organised manner. 2 The 2016 General Practice Forward View8 built on the NHS Five Year Forward View,2 describing how the NHS needed to change to make sure that sufficient and sustainable primary health care could be provided. The NHS Five Year Forward2 view also noted that GPs needed to be flexible and ready to change, including by adapting to evolving health needs (in particular, those of an ageing population living with multiple complex conditions) and the opportunities presented by new technology. The context for these plans was one of GP in the UK being under considerable strain, as evidenced by the Commonwealth Fund’s 2019 survey9 of primary care physicians, in which just 6% of UK general practitioners reported feeling ‘extremely’ or ‘very satisfied’ with their workload (the lowest of all countries surveyed), and 49% reported wanting to reduce their clinical hours in the next 3 years.

The NHS Long Term Plan,4 published in January 2019, confirmed that spending on primary and community health services was to be at least £4.5B higher in 5 years’ time to ‘fund expanded community multidisciplinary teams aligned with new primary care networks based on neighbouring GP [general practitioner] practices’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). Subsequent guidance10 published by NHS England and the British Medical Association (BMA) later in January 2019 confirmed the requirement for all GPs in England to form local ‘primary care networks’ (PCNs) covering patient populations of 30,000–50,000 by July 2019, ‘so that no patients or practices are disadvantaged’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government License v3.0).

Primary care networks were to build on the many pilots of new ‘vanguard’ models of integrated health care that had been developed as a result of the Five Year Forward View,2 and these new networks were advocated by NHS England to be ‘an essential building block of every Integrated Care System’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government License v3.0). Those vanguard models of care entailed pilots of significant integration of GP and community health services; hospital, mental health, community and primary care; GP and social care (particularly in providing support to residential care homes); and services focused on particular clinical conditions such as cancer. The funding for these vanguard schemes ended in March 2018, and early and interim assessment of their progress concluded that their long-term impact and sustainability was unproven. 11,12 Our evaluation of the early implementation and progress of PCNs took place in the context of these prior vanguard schemes; in some sites the work of the networks was building on aspects of those schemes and the joint working in health and social care that had underpinned the vanguard projects.

General practice collaborations in the NHS in England

Collaborations in GP, also sometimes known in international health policy as ‘organised general practice’ or ‘managed primary care’, have emerged in many health systems over the past three decades. 13 PCNs represent the latest incarnation of such collaborations in the NHS in England.

In 2017, the Nuffield Trust and the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) undertook a survey of all GPs across England, to establish the pattern and frequency of collaborative working across practices. 14 Eighty-one per cent of respondents reported that their practice was already working in collaboration with other local GPs, this having been at 73% in the prior iteration of the survey in 2015. 15 The primary reasons given for working collaboratively were to improve access for patients to GP; to transfer more health services into the community; to strengthen financial and organisational sustainability of GP; and to improve staff experience, training and education. The survey results also emphasised that:

-

Working at scale in collaborative arrangements was broadly accepted as the future for GP in England.

-

There were many forms of GP collaboration across the NHS, with GP federations being the most commonly reported (see Table 1 for an explanation of GP federations).

-

In almost all cases these collaborations had emerged from within GPs rather than being mandated in national policy.

-

GPs were often part of more than one collaboration.

-

These collaborations varied in size, with > 50% having > 100,000 registered patients.

-

Networks varied in focus and motivation for collective working, with smaller groups tending to prioritise practice sustainability, staff experience and patient access. Larger groups tended to prioritise patient access and transferring services to the community.

-

Time and work pressures were considered the main barrier to collaborations achieving their aims. 14

Table 1, drawing on the work of Rosen et al. ,16 sets out the main GP collaboration models in England in place in 2019, and thus provides important contextual details about the pre-existing GP collaborations from (or alongside which) new PCNs have formed. The interplay of pre-existing GP collaborations and PCNs formed a core aspect of this evaluation study (see Chapter 2, Methods). The collaboration models in Table 1 vary considerably. For example, super-partnerships represent a formal merger of practices and have a board of directors to oversee the collaboration, together with a shared contract that binds all practices together. GP federations can be either informal or formal in the way they are set up and members work together, and they can take a variety of legal and contractual forms. Networks are typically informal in nature, coming together around a set of specific issues, such as enabling extending the opening hours of GP or a 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, out-of-hours service, or to inform the planning of local services. 16

| Collaboration model | Key characteristics |

|---|---|

| Informal network | Networks (described as ‘informal networks’ here to distinguish between them and ‘primary care networks’ as set out in The NHS Long Term Plan4) are one way in which GPs can collaborate. There are no formal ties between the practices; instead, they rely on informal discussions, meetings and co-operation. All practices in such a network keep their own contracts and funding sources, and no particularly tangible objectives are typically set |

| Multisite practice organisation | These organisations are very formal in nature and there is one core company or group of directors holding one GP contract for all practices within that management framework. The goals of each practice, therefore, should be in alignment with those of the organisation as a whole. Funds are held in the central hub of the organisation and disseminated to practices for specific purposes |

| Super-partnership | Similar to multisite practice organisations, super-partnerships represent mergers of previously independent GPs into a single new organisation. The governance for super-partnerships is complex. Practices may choose either to manage each of their contracts separately, although activities and goals are shared and aligned across all participating practices, or to draw up a new GMS contract and appoint an executive board to oversee the work of all participating practices. In the latter case, funds will be redistributed in accordance with any new processes in place |

| Federation | Federations are more formal than networks but less formal than multisite practice organisations and super-partnerships. In federations, participating GPs maintain responsibility for their own contracts. However, some additional legal agreements might be pursued and put into place to carry out joint activities. An executive board function typically exists to oversee the federation; however, each practice may set its own goals and objectives and these may not necessarily align with those of the organisation as a whole |

| PCH | The PCH model was created by the NAPC building on the Health Care Home from the USA.17 An integrated care model, it has four key characteristics that need to be met for a collaboration to be categorised as a PCH: (1) the partnership must span across primary, secondary and social care; (2) there is a strong element of personalised care with the aim of improving the health of the population as a whole; (3) all funding is channelled through one central budgetary system between all stakeholders in the collaboration; and (4) it covers a population of 30,000–50,000 registered patients across collaborators |

| Hubs | Hubs often emerge as part of existing collaborative relationships among different GPs that are already in place and are usually focused on delivering extended access to GP care. Their aims and objectives can differ depending on local population needs; however, a core feature is that they provide same-day urgent appointments to registered patients. For example, this can been done by having a shared triage system to point patients to the most appropriate route of care. In addition, they may offer out-of-hours care. More recently, COVID-19 primary care hubs have been formed18 |

Along with different models of collaborative working, GP collaborations also vary in terms of how they are set up geographically. Although GPs can group together based on geographical proximity (as is the case for PCNs), some collaborations are not geographically contiguous; rather, they are regional or national multipractice organisations that are geographically dispersed. 19 Notably, some types of collaborations may go by more than one name (federation, super-partnership, primary care group, etc.) but may share common characteristics in terms of the functions performed. 20

The nature and extent of these prior GP collaborations is important context to the implementation and development of PCNs, as many collaborations have continued to operate alongside new networks, often providing management and infrastructure support. It has been noted in prior analysis21 that GP collaborations can bring opportunities for smaller practices that have struggled to tailor services for patients living with complex needs in both rural and urban areas. It is of note that the prior collaborations in place as PCNs were established are largely ones that evolved from within general practice and primary care (as opposed to being mandated in national policy), and are typically considered to be ‘owned’ by local practices and practitioners (or may indeed be formally owned by them). By contrast, PCNs have been mandated in national policy, and the issue of general practitioners’ sense of ownership of and belonging to the new networks is explored in the research reported here.

Primary care networks

Primary care networks are the latest attempt on the part of the NHS in England to engage GP (and other primary care practitioners and teams) in bringing about a range of service changes intended to support local populations living with ever more complex long-term conditions, and reduce the reliance of such people on inpatient hospital care. Previous similar policy initiatives have included GP fundholding, total purchasing pilots (TPPs), personal medical services (PMS) schemes and primary care groups. 22 Furthermore, with PCNs there is a desire to use this more collaborative approach as a means to strengthen the sustainability of GP, including in respect of its workforce and financial health.

Primary care networks are distinct from previous collaborations in terms of the context in which they are being implemented. Almost half of general practitioners in the NHS in England are employed on a salaried or sessional basis (as opposed to having equity ownership of the practice), and a majority are women (many of whom work part-time and/or wish to have portfolio careers, as do some of their male colleagues). 23 Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant shortfall had been seen in the availability of general practitioners and other health professionals (including community and practice nurses) at a time of rising demand for services. Furthermore, the sustainability of GP is a key current concern, in respect both of securing sufficient workforce and of matching supply of services to growing patient demand. 9

Primary care networks are particularly noteworthy in that they offer GPs the possibility of significant levels of additional funding, and in that there is a contractual basis to this. Hence, PCN working has a formal, incentivised and compulsory feel to it in comparison with many predecessor schemes of collective primary care. Unsurprisingly, given the PCN approach outlined above, with additional funding on offer from NHSE&I to develop new services for local patients, almost all GPs have joined a PCN,24 although the extent to which this is an enthusiastic and committed move is explored within this evaluation. In late 2019, NHSE&I ran a consultation about the service specifications to underpin the PCN contract, which resulted in major concerns on the part of GP about the pace, scope and scale of what was expected. 25 Subsequent revisions to the PCN service specifications in early 2020 extended the timescale for networks to take on responsibility for some services, such as early cancer diagnosis. Once the COVID-19 pandemic emerged in the UK in March 2020, a decision was taken to defer the implementation of some PCN services set out in national specifications, although the Enhanced Healthcare in Care Homes scheme26 was brought forward to start in May 2020, causing further consternation in the primary care community. 27

Primary care networks commenced on 1 July 2019 as required by NHS England and Improvement and in 2020 there were around 1250 networks across England covering populations of approximately 30,000–50,000 patients,28 a size that is consistent with the primary care home model (National Association of Primary Care). Each PCN holds a Directed Enhanced Services (DES) contract as a formal agreement across the constituent practices, with one practice typically holding this on behalf of those within the network. The DES contract provides funds for the network to operate new services that are specified by NHSE&I as noted in the previous paragraph.

These services provided by a PCN are being phased in over a period of 3 years with social prescribing and practice-based pharmacy being the first to be implemented, followed by enhanced health services for care homes. The intention was to provide a total of £1.8billion in funding through PCNs by 2023–24, including resource to operate the networks and help pay for additional primary care staff. For this latter aspect – paying for additional staff – the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme was introduced by NHS England and Improvement in 2019 and its early progress has been evaluated for the Department of Health and Social Care by the King’s Fund. 29

These PCNs sometimes build on prior GP collaborations and are often supported by the organisational infrastructure of the extant collaborations. Other networks are brand-new entities in the process of becoming established and working out how best to source their management support. For this latest iteration of GP collaborations in the English NHS, there is much to be learnt from examining research evidence on the nature and speed of implementation and the development and impact of previous primary care organisations dating back to the early 1990s, in particular those that were brought together to hold shared contracts to deliver health services for a local population.

In the next chapter, we describe the methods used for this rapid evaluation of the implementation and early development of PCNs, what helped and hindered their progress, how they worked with the GP collaborations that were already in place as the new networks were formed and what this means for future development of PCNs. Following this, we set out the findings of our rapid evidence assessment (REA) of GP collaborations, using this to frame questions for exploration in the case study research that is presented and discussed in subsequent chapters.

Chapter 2 Methods

The overarching purpose of this evaluation was to produce early evidence of the development and implementation of PCNs introduced into the NHS in England in July 2019. The evaluation had a particular focus on seeking to understand how practices entered into collaborations, why some collaborations stall or fail, and if and how the experience of rural collaborations may differ from that of urban examples.

We completed a qualitative cross-comparative case study evaluation comprising four work packages:

-

a REA

-

a stakeholder workshop with leading academics, policy experts, and patient/public representatives to share findings from the REA and shape REAs for case study work

-

interviews with key stakeholders across case study sites alongside observations of strategic meetings, online surveys and analysis of key documents

-

analysis of findings from work packages 1–3 to develop a set of lessons for the next stage of development of PCNs in the NHS in England, for dissemination to policy-makers, practitioners and representatives of patients, carers and the public.

We undertook a multifaceted sampling process to select four case study sites, based on identifying appropriate primary care collaborations through clinical commissioning groups that had not been previously evaluated.

A content analysis approach to documentary reviews and observations was undertaken. Data analysis for interviews was informed by a framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multidisciplinary health research. Our analysis was guided by theoretical and policy literature on collaborations of GPs.

Aims and research questions

The overarching purpose of this evaluation was to produce early evidence of the development and implementation of PCNs introduced into the NHS in England in July 2019, to inform subsequent policies and support that was to be provided for these new collaborations. The evaluation therefore sought to identify the forms of GP collaboration previously used in primary care in England, the reasons for GPs to enter (or not) into collaborations, and evidence about the impact of PCNs and prior GP collaborations, along with any barriers to or facilitators of progress.

The evaluation had a particular focus on seeking to understand the rationale behind why and how practices entered into collaborations, the potential influence of prior collaborative working on PCNs, and if and how the experience of rural collaborations may differ from that of urban examples. The findings from the evaluation are intended to feed into NHSE&I’s planning and implementation guidance for PCNs and inform proposals for longer-term study of PCNs.

To address our aims, we sought to answer the following evaluation questions:

-

What was the contextual and policy background within which PCNs were introduced?

-

What were the pre-existing forms of GP collaborative working across primary care in England?

-

How have new PCNs been implemented in a sample of urban and rural settings?

-

How do new PCNs relate to pre-existing GP collaborations?

-

-

What are the rationales and motivations for GPs to enter into GP collaborations, including new PCNs? In particular, what role do financial incentives play in facilitating or inhibiting collaboration? What are the expected outcomes for PCNs?

-

What evidence exists about the positive or negative impacts associated with different experiences of establishing GP collaborations, and how do these relate to newly formed PCNs?

-

What appear to be the barriers to and facilitators of effective collaboration across GPs, with respect to both to whether or not collaborations were successful and to whether or not collaborations achieved an impact?

-

What does the analysis of prior experience of GP collaborations, and the early implementation of PCNs, suggest in terms of the likely progress of PCNs in the NHS in England, including in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated challenges?

General approach

We completed a mixed-methods cross-comparative case study evaluation30–32 comprising four work packages [(WPs) Table 2]:

-

a REA

-

a stakeholder workshop with leading academics, policy experts and patient/public representatives, to share findings from the REA and shape REAs for case study work

-

interviews with key stakeholders across case study sites alongside observations of strategic meetings, online surveys and analysis of key documents

-

analysis of findings from WPs 1–3 to develop a set of recommendations for the next stage of development of PCNs in the NHS in England, for dissemination to policy-makers, practitioners and representatives of patients, carers and the public.

| WP | Description | Research questions |

|---|---|---|

| 1: a REA | An overview of published evidence to distil prior learning and inform the development of propositions to be tested through comparative case studies of new primary care collaborations/networks | 1.1, 3 |

| 2: stakeholder workshop |

A workshop led by members of the study team for relevant stakeholders (e.g. academic and policy experts in the field, PPI representatives), in which initial findings from the REA were shared and discussed The aim of this workshop was to clarify evidence gaps and evaluate questions of particular relevance to emerging policies on PCNs and thus inform the next steps for WP3 |

1.1, 2, 3 |

| 3: comparative case studies of four PCNs (minimum of two in rural settings) | Interviews with those involved in the conceptual design and implementation of PCNs in their sites and exploration of relationships with any prior GP collaboration in the case study site; analysis of key documentation (both internal and publicly shared); non-participant observation of strategic meetings; and an online survey to collate information on challenges associated with collaborative working and to measure early impacts | 1.2, 1.3, 3, 4 |

| 4: analysis of findings from WPs 1–3 to develop a set of recommendations for the next stage of development of PCNs in the NHS in England | Share and discuss findings generated from data collection from WP3 | 1, 3, 4, 5 |

| 4: dissemination to policy-makers, practitioners and representatives of patients, carers and the public | Develop recommendations for commissioners, providers and policy-makers through academic outputs, virtual meetings with policy-makers, blogs, podcasts and online media | 1, 3, 4, 5 |

Work package 4 was originally designed to be a number of face-to-face case study-specific workshops, as well as round table discussion with key experts. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020 onwards), the study team, following guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR) programme, suspended data collection and focused on the analysis and writing-up of findings. NHS colleagues at case study sites were made aware that they were no longer expected to comment on or respond to our communication (May 2020). We were, however, able to use digital slide decks to share and discuss with policy experts, academics and staff at our case study sites in autumn 2020/winter 2021 (n = 3) to share and discuss emerging findings (academic outputs available online and possibly in the form of blogs and executive summaries), and to ensure their applicability to the next stage of development of PCNs.

Protocol sign-off

The study topic was identified and prioritised for rapid evaluation by NIHR HSDR after receiving a request from NHS England (in 2018) in respect of PCN planning and implementation. This varies from the approach to the identification of innovation usually adopted by the Birmingham, RAND and Cambridge Evaluation (BRACE) Centre, which involves horizon scanning.

An initial topic specification (first stage protocol) was prepared (September 2018) and, once approved, was used as the basis for writing the full research protocol (March 2019), which drew on the findings of the initial REA (WP1) and workshop (WP2). The full research protocol was revised further (October 2019) as PCN implementation shifted with regard to policy changes.

Ethics approval

An application for an ethics review to the University of Birmingham’s Research Ethics Committee was made by the project team and approval was gained in May 2019 (ERN_13-1085AP34). The project team received confirmation from the Health Research Authority (HRA) that this study was to be categorised as a service evaluation and therefore approval by the HRA or a NHS Research Ethics Committee was not required. At each case study site, we approached relevant local research and development offices to register our service evaluation, and received confirmation that all were content for the evaluation to proceed in their local area.

Work package 1: rapid evidence assessment

A REA followed a systematic approach, in line with guidance on literature reviews in health care,33 but the scope of the search was restricted to key search terms and review criteria to allow for a focused review of the literature within a limited time frame. 34 The REA aimed to synthesise the body of evidence on GP collaborations across primary care drawing on UK and international literature.

Searches were undertaken in two stages on 21 September 2018. First, the study team completed a search for reviews and evidence summaries published during the period 1998–2012, inclusive, to account for the breadth of published literature. Second, a search was then undertaken of all published literature (including primary research studies and reviews) from the year 2013 until September 2018 using key search terms in titles and abstracts. Searches were undertaken in PubMed® (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA), Ovid® (Wolters Kluwer, Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands) MEDLINE® (National Library of Medicine), Web of Sciences™ (Clarivate™, Philadelphia, PA, USA) [Social Sciences Citation Index™ (Clarivate) only] and Scopus® (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) (restricted to the following subject areas: medicine, social sciences, nursing, multidisciplinary and health professions) for literature published in the English language and containing selected search terms (Box 3), which were then adapted to other publication databases. Forward and backward citation searching of relevant articles were undertaken to ensure that key articles had been identified through our search strategy. Search terms were developed in collaboration with an experienced health services research librarian (Rachel Posaner of the University of Birmingham).

((“Primary care*” OR “primary health care*” OR “general practice” OR “GP*” OR “family physician*” OR “family doctor*” OR “primary care*” OR “family health team*”) AND (“collaborat*” OR alliance OR “primary care network*” OR network* OR “super-partnership*” OR “super partnership*” OR “superpartnership*” OR “federation*” OR “multi-site practice organi*” OR “ multi site practice organi*” OR “multisite practice organi*” OR “cooperat*” OR “co-operat*” OR “cluster*”) AND (“effective*” OR “efficien*” OR “success*” OR “valu*” OR “impact*” OR “cost*” OR “econom*”) AND (“review*”))

OR

((“collaborat*” OR “alliance” OR “primary care network*” OR “network” OR “super-partnership*” OR “super partnership*” OR “superpartnership*” OR “federation*” OR “multi-site practice organi*” OR “multi site practice organi*” OR “multisite practice organi*” OR “cooperat*” OR “co-operat*” OR “cluster*”) AND (“primary care*” OR “primary health care*” OR “general practice” OR “GP*” OR family physician*” OR “family doctor*” OR “primary care*” OR “family health team*”) AND (“economies of scope” OR “at scale” OR “scope” OR “cost*” OR “economies at scale*”) AND (“review*”))

OR

((“primary commissioning” OR “independent practice assessment” OR “community health organi*” OR “independent practice organi*” OR “independent practitioner organi*” OR “health care home” OR “community-oriented primary care” OR “community-owned primary care” OR “community health trust”) AND (“review*”))

These are the search terms for 1998–2012, inclusive, for the BRACE primary care collaborations REA (restricted to review only); 2013 onwards includes all the same terms but drops the term “review*”.

The year 2013 was considered of particular importance to GP collaborations in the NHS in England given the introduction of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) in April of that year, replacing primary care trusts (PCTs) as the bodies responsible for commissioning most NHS services for their local populations. CCGs have all the GPs in a geographic area as members and are governed by boards comprising general practitioners, other clinicians (including a nurse and a secondary care consultant) and lay members. Thus, since April 2013, GPs in England have been required to collaborate for purposes of commissioning secondary and tertiary care services for their registered populations, but have not been required to collaborate to provide health-care services. Our REA and evaluation were, therefore, restricted to collaborations for service provision rather than collaborations for commissioning. The evidence review was registered with PROSPERO before screening began (PROSPERO protocol registration number CRD42018110790).

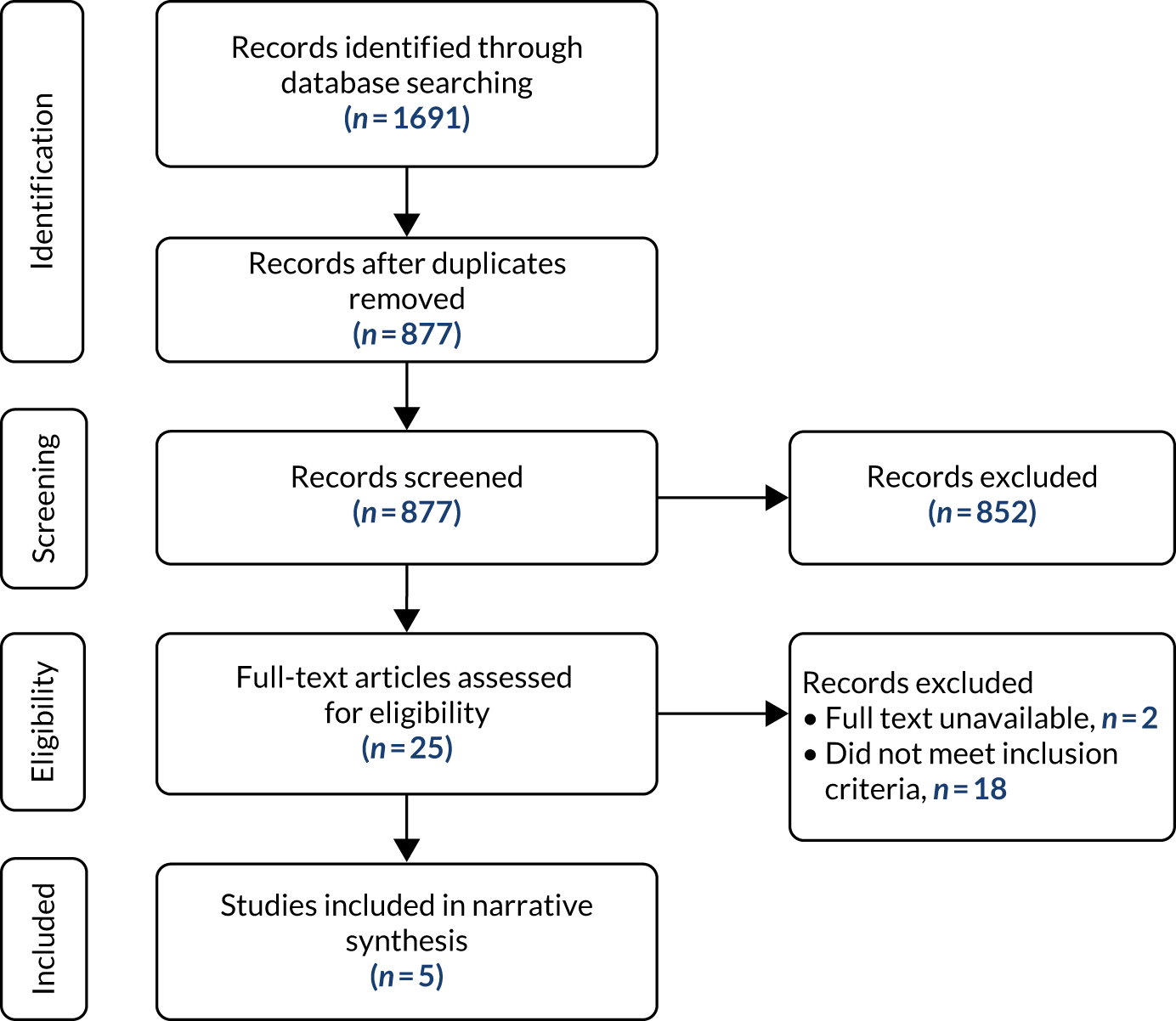

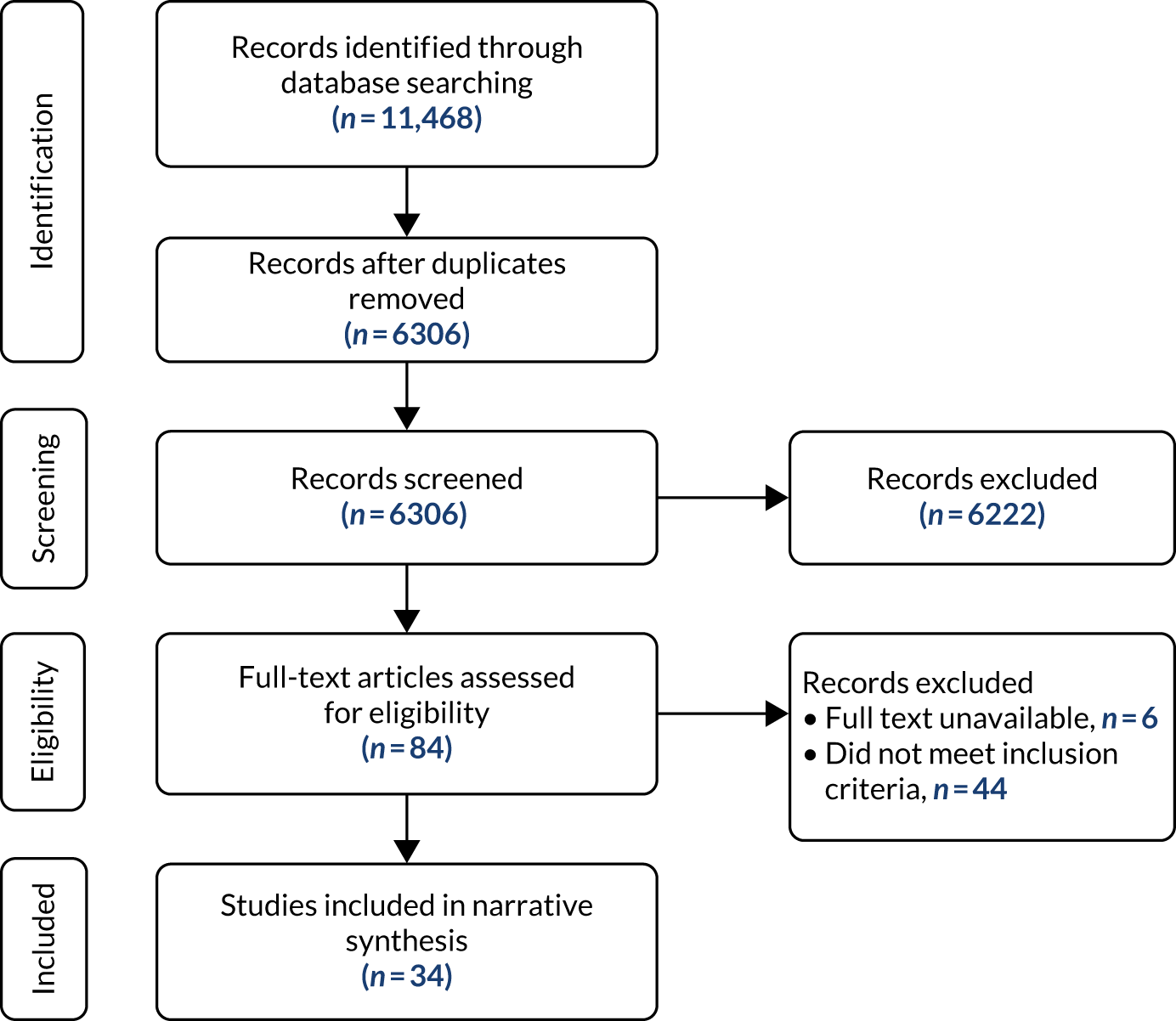

Five review articles and 34 peer-reviewed primary research studies were eligible for inclusion. In addition, we identified 16 grey literature publications, bringing the total number of included publications in this REA to 55. We present these numbers using an adapted version of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram35 in Figures 1 and 2.

FIGURE 1.

A PRISMA flow diagram of screening decisions: 1998–2012, inclusive (reviews only).

FIGURE 2.

A PRISMA flow diagram of screening decisions: 2013–18, inclusive (all methodologies).

In summary, the REA included both scholarly (academic) literature and grey literature (i.e. reports and articles not submitted to a peer-reviewed journal) that described and evaluated models of GP collaboration in the UK and internationally, including demographics of GP collaborations, impacts of primary care collaborative working, and any reported barriers to and facilitators of implementing these arrangements.

Although we aimed to be inclusive in our approach to the REA and capture an accurate representation of the body of literature published on collaborations, there were some limitations of the review:

-

Defining ‘collaboration’ was challenging given the numerous ways that it was described in the literature and the associated terms attached to it. Despite this, we believe that we captured relevant publications to provide a sufficient overview of evidence relevant to the objectives of this study, as the reviewers erred on the side of inclusion when screening the titles, abstracts and full texts when there was doubt about the relevance of a publication after discussion.

-

We found that in several cases a particular collaborative model, in particular the GP federation in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, was discussed in more than one paper. 36,37 Consequently, there is a risk of over emphasising that model.

-

We found little evidence of measured outcomes and costs to back up the expected impacts of collaborations. Examples of such outcomes that may be desirable to measure include the incremental costs/savings associated with collaboration, measures of staff satisfaction and changes in patient health outcomes.

Work package 2: project design stakeholder workshop

A half-day project design workshop38 was held in November 2018 and involved, in addition to the research team, primary care policy officials from NHSE&I, a patient representative (from the BRACE Health and Care panel, a source of advice from the health and care sector that acts as a sounding board in relation to the choice, design, delivery and dissemination of rapid evaluations conducted at BRACE) and academics with experience of researching primary care organisations and policy experts in the field (n = 12). The aim of the workshop was to discuss the findings of the REA (WP1), to help identify gaps in the literature, and thereby identify and agree the appropriate focus of evaluation questions for the case studies in WP3. Furthermore, the results of the REA were consolidated into a slide set and working paper at this stage, providing vital resources for the evaluation team to shape the data collection strategy for case study sites.

A structured agenda was prepared in advance of the workshop and included time for plenary discussions, presentations of findings from the REA (also shared with participants in advance) and smaller group discussions. Members of the study team took detailed notes during the workshop, which were used to further develop and refine the case study design (WP3). Notes from the workshop, including proposed detailed evaluation questions and confirmed evidence gaps, were shared with all participants following the workshop. For more information on this, see Report Supplementary Material 1.

Results from the workshop highlighted a number of evidence gaps that could be addressed throughout the evaluation. Participants felt that it was important to understand how ‘participation’ in a collaboration is understood and how ‘success’ within a primary care collaboration would be defined.

Participants at the workshop also felt that a key unexplored area was experiences of primary care collaborations in rural, as opposed to urban, areas to better understand regionally specific challenges in primary care. First, questions were raised with regard to how PCNs can cater for different types of rural and coastal populations, where the population is older than the national average, with subsequent implications for demand on health and care services as well as for the workforce. Second, good innovation and practice were felt to be too often based on urban examples of primary care delivery, with relatively little being known about whether or how easily such learning is transferable to rural settings.

Notably, the study team was encouraged to steer away from case study sites that had already been well evaluated. Finally, attendees were keen for the evaluation to include an exploration of what management and organisational development skills/capacity are needed to make a collaboration work and from where collaborations are drawing these skills and capacity.

Following the project design workshop, the study team continued to communicate and share preliminary learning from the evaluation with key stakeholders and policy experts in attendance to acknowledge and incorporate learning from other national evaluations/research happening in parallel, and ensure that data collection remained responsive to emerging insights captured by policy experts. Thus, the study team, throughout the duration of the rapid evaluation, held regular teleconference meetings with policy experts from NHSE&I, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), The Health Foundation (London, UK) and senior academics in primary care policy research at the University of Manchester (Manchester, UK).

Work package 3: comparative case studies of four primary care collaborations

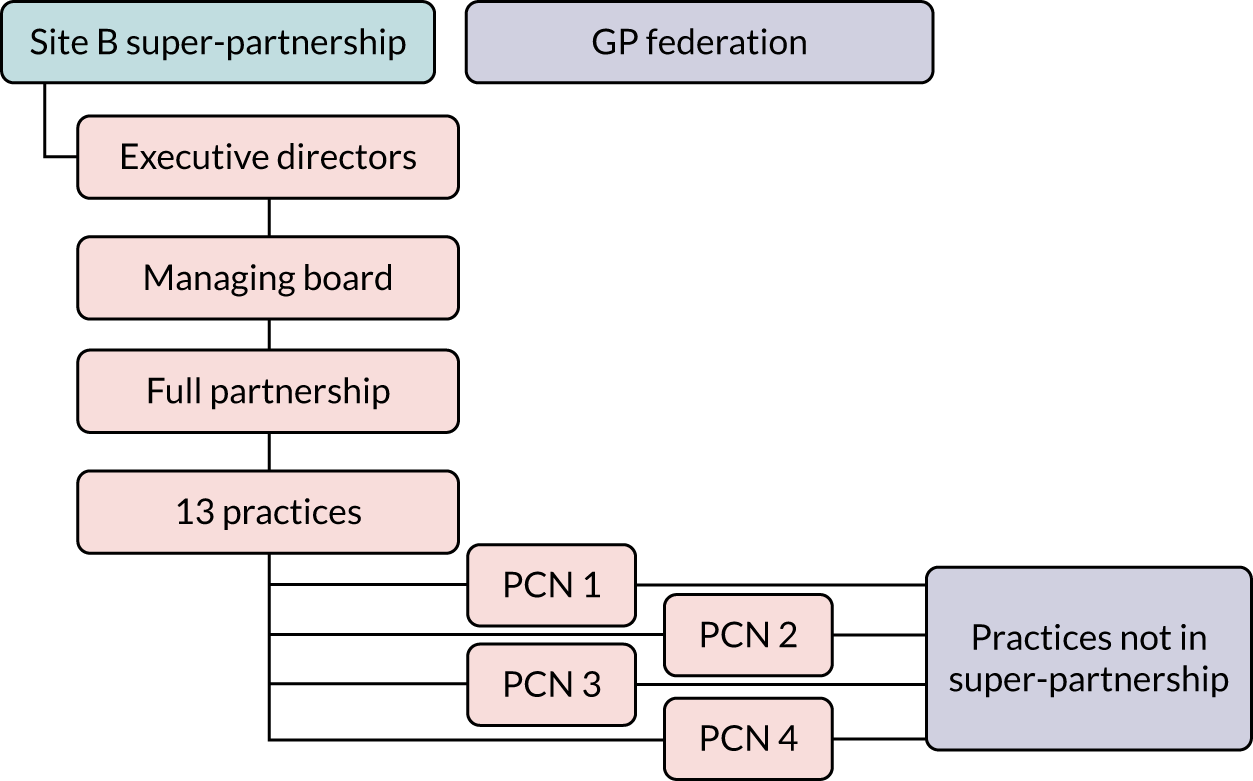

We conducted comparative case studies of four primary care collaborations in England (three PCNs and one GP super-partnership comprising several PCNs). This work package involved three phases:

-

case study selection and site recruitment

-

data collection at four case study sites

-

analysis and reporting.

These phases were undertaken between April 2019 and April 2020. Given that our evaluation began in September 2018, our initial search for case study sites was focused on primary care collaborations [e.g. GP federation, primary care home (PCH), 24-hour access hub or GP super-partnership] rather than having a sole focus on PCNs. However, after the implementation of NHSE&I’s PCNs model in July 2019, and discussion with the NIHR HSDR secretariat, the research team’s focus turned to recruiting PCNs as case study sites (unless the team was already in the process of recruiting another form of primary care collaboration).

Phase 1: case study selection and site recruitment

Sampling strategy

We undertook a multifaceted sampling process to select four case study sites, based on identifying appropriate primary care collaborations through CCGs that had not been previously evaluated and varied with respect to:

-

rural or urban setting [based on the 2011 rural–urban classification (RUC) of CCGs in England39]

-

collaborations facing significant challenges compared with those that were operating without significant operational complications.

With the support of the University of Birmingham Health Services Management Centre’s Knowledge and Evidence Service team, two members of the research team (AH and MS) carried out a search of three online non-academic databases – GPOnline, Pulse and the Health Service Journal (January 2018 to April 2019) – to identify well- and poor-performing primary care collaborations using the following terms: “collaboration” OR “alliance” OR “primary care network*” or “network*” OR “super-partnership*” OR “super partnership*” OR “superpartnership*” OR “federation*” OR “multi-site practice organisation*”.

However, from the search results, it remained difficult to identify primary care collaborations but easier to ascertain CCGs encountering challenges with the delivery of primary care. In addition, at the time of identifying potential case study sites (May 2019), there was no definitive database/source detailing the existence of primary care collaborations in England. Therefore, the research team obtained an anonymised list of all responses from the Nuffield Trust and RCGP’s Collaboration in General Practice survey14 to identify CCGs to approach, and contacted a number of experts in the field to support the identification of collaborations that may be interested in taking part in our evaluation (May 2019). From July 2019, the study team primarily focused on recruiting PCNs for its case study sites. Our inclusion/exclusion criteria are detailed in Table 3.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

Rural or urban setting (based on the 2011 RUC of CCGs in England) Collaborations facing significant challenges compared with those who were operating without significant operational complications Informal networks, multisite practice organisations, super-partnerships, federations, PCH (pre July 2019) or a PCN (post July 2020) Collaborations either active or that have ceased to be operational in the past 12 months Collaborations consisting of any number of collaborators/GPs (pre July 2019) or that meet PCN model specifications (post July 2019) |

Collaborations that have already been the focus of research or evaluation within the previous 2 years |

Case selection and site recruitment

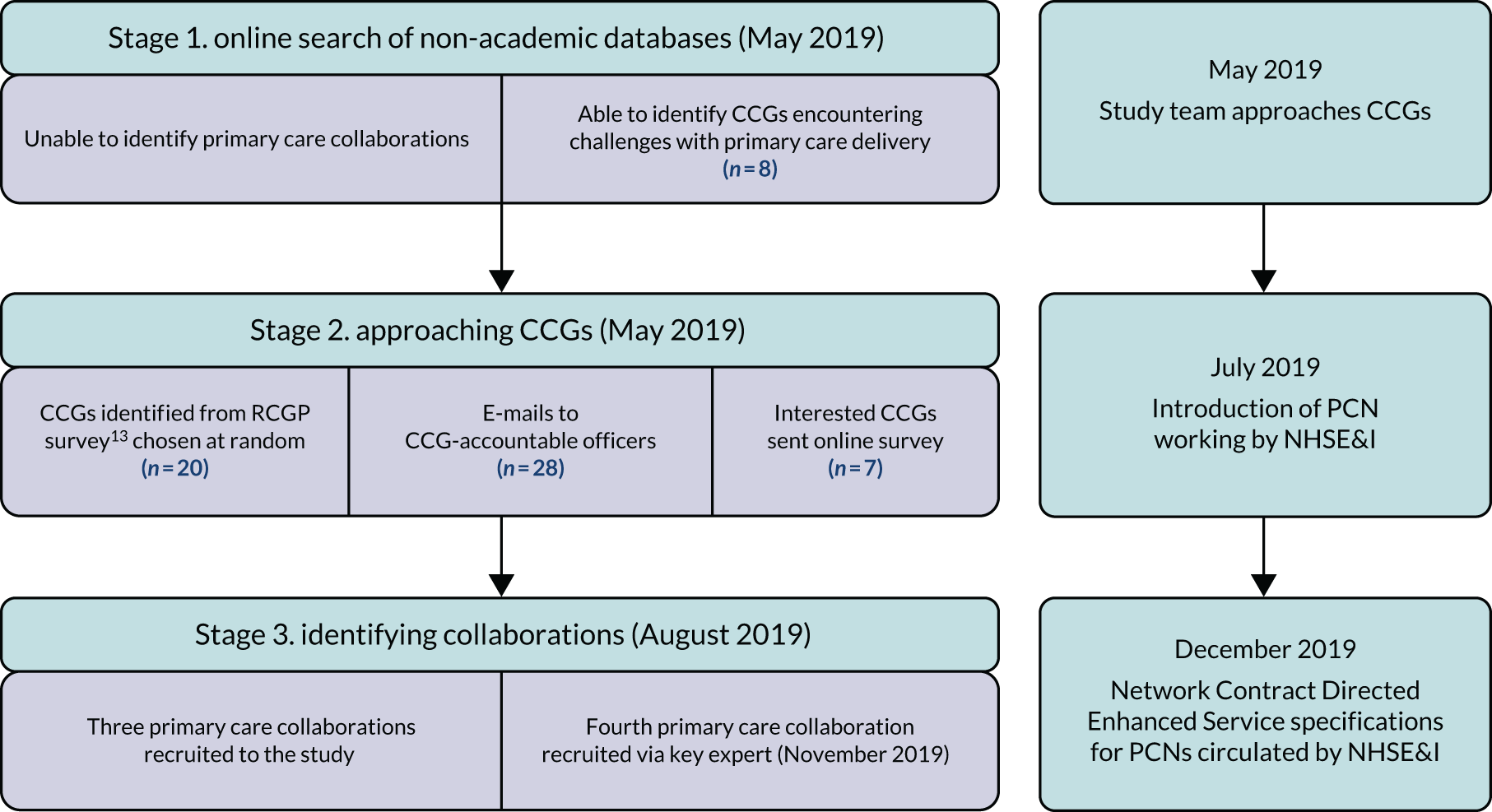

Amelia Harshfield and Manbinder Sidhu identified eight potential CCGs (seven of which were urban and one of which was rural) from online searches. Of the CCGs that responded to the 2017 RCGP survey,14 the total number classified as rural was 28, whereas the total number classified as urban was 133 (based on the 2011 RUC of CCGs in England). The study team took an executive decision to approach 28 rural and urban CCGs in England in May 2019 [comprising eight collaborations identified from online searches (rural, n = 1; urban, n = 7) and 20 CCGs identified from the 2017 RCGP survey14 chosen at random (rural, n = 10; urban, n = 10) based on resources and to begin data collection in a timely fashion].

The study team sent e-mail correspondence directed to CCG accountable officers (or their equivalent) on behalf of the principal investigator (JS) (with a follow-up e-mail sent 4 weeks after the initial invitation). The e-mail was accompanied by an information sheet and a reply form asking the CCG to name all operational/non-operational primary care collaborations (from the previous 12 months) in their area, and was followed up with a telephone conversation between Amelia Harshfield or Manbinder Sidhu and the primary care lead at the CCG. Seven of the 28 CCGs invited responded expressing a willingness to know more about the evaluation with the possibility of taking part.

To support the identification of primary care collaborations via CCGs, the study team disseminated a short online survey (see Appendix 1) to those groups that had responded to our initial approach, asking them to provide details about their primary care collaborations and whether pre-existing collaborations were now PCNs or how they were part of the local emerging network configuration. The survey was pilot tested with two policy experts prior to circulation.

By August 2019, only three primary care collaborations that met our inclusion criteria, from three different CCGs, were committed to taking part in our evaluation (two PCNs and one GP super-partnership). All three primary care collaborations were recruited as our case study sites. Our fourth case study site (a PCN), which met our inclusion criteria, was recruited directly via a key expert employed by a GP super-partnership in England (November 2019). Figure 3 summarises our sampling process.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of case study site sampling.

Phase 2: data collection at four case study sites

The study team followed Johl and Renganathan’s40 phased framework for responsible engagement with organisations and gatekeepers, which includes ‘pre-entry’, ‘during fieldwork’, ‘after fieldwork’ and ‘getting back’ phases. The use of this framework helped the study team to establish a communication plan to build gatekeeper trust and support for the project. A gatekeeper was defined as a person based at our case study sites who could act as an intermediary between a researcher and potential participants with the authority to deny or grant permission for access to potential research participants. 41

Potential participants for interviews were identified, when possible, via a stakeholder mapping exercise with a gatekeeper at each site. Individuals were purposively sampled for maximum variation42 with regard to knowledge of impacts and enablers of, and barriers to, GP collaboration in their area. When stakeholder mapping was not possible, the team incorporated both snowballing and convenience sampling methods to identify interviewees. 43

The gatekeeper helped the team by forwarding documents for analysis and arranging interviews with participants. Communication with gatekeepers across case study sites was often challenging given the changing policy landscape of primary care during late 2019 (such as Brexit planning, NHS financial and workforce challenges, and the scope and pace of PCN policy implementation, as discussed in Chapter 1). Although the research team established significant rapport with gatekeepers, it was difficult to engage clinical and non-clinical staff responsible for delivering front-line primary care health services during a period of policy turbulence, which was made more difficult with the rise of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our data collection involved four components: stakeholder interviews, non-participant observation of meetings at PCN or GP collaboration executive board level, document review and an online survey.

Stakeholder interviews

Interviewees included CCG staff (related to the set-up and implementation of PCNs), GPs in collaboration lead roles, practice managers (PMs), pharmacists, and those in roles focused on the financial and operational management of collaborations/PCNs. Depending on the size of the primary care collaboration/PCN, the evaluation team planned to complete 10–15 interviews across each case study site or until data saturation had been reached. 44

All interviewees received an information sheet (by e-mail or in person) and were given time to make a decision with regard to participation and to ask questions about the process. Participants signed a consent form prior to participating in the interview, including whether or not they consented to the recording of the interview. Participants were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time (without giving a reason) and were given information about how to find out more about the study or raise any concerns about its conduct.

Individuals participated in a semistructured interview with either one or two members of the study team, either in person or via telephone, and interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. A topic guide was developed and used during interviews (see Appendix 2), although the semistructured nature of the interviews allowed interviewers to deviate from the topic guide based on the interviewee’s knowledge, experience and previous responses. The topic guide contained questions relevant to understanding barriers to and facilitators of PCNs (and/or larger collaborative working within which PCNs exist), operational challenges associated with establishing and running the PCN/collaboration, and the early successes/impacts achieved at each case study site.

Interviews were audio-recorded (all participants gave consent) and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service. These transcriptions were anonymised and kept in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the Data Protection Act 2018. 45

In total, we interviewed 25 participants across four case study sites. Table 4 provides a description of those we interviewed.

| Site | Description of staff | Number of staff (interview numbers) |

|---|---|---|

| A | Primary care clinical | 4 (1–4) |

| Primary care non-clinical | 5 (5–9) | |

| B | Primary care clinical | 3 (10–12) |

| Primary care non-clinical | 3 (13–15) | |

| CCG | 2 (16 or 17) | |

| C | Primary care clinical | 4 (18, 20–22) |

| Primary care non-clinical | 2 (23 or 24) | |

| CCG | 1 (19) | |

| D | Primary care non-clinical | 1 (25) |

| Total | 25 |

Non-participant observation of meetings

We observed meetings (at an executive and managerial level where operational and clinical deliveries were discussed) between key stakeholders at case study sites to gain a deeper understanding of how the collaboration was operating and what priorities and challenges it was addressing. These interactions were recorded on an observation template based on the agenda for the meeting, as well as using sociograms (i.e. visual representations of relationships between individuals in a given setting) when possible (at meetings with fewer attendees) to map the nature of interactions within the meeting. 46 This observation template can be found in Report Supplementary Material 2.

Participant information sheets and written consent forms were circulated in advance or on the day of the meeting to all attendees. Prior to each observation, a member of the study team provided a verbal explanation of the project and its aims and gave attendees an opportunity to ask questions. Individuals who did not consent were omitted from recorded observation notes. Two participants from different case study sites requested that their comments be omitted from observation notes. During meetings, team members were seated appropriately to record observations but remain unobtrusive to the discussion.

Throughout the evaluation, being able to attend meetings proved to be challenging for staff in three of the four case study sites; for example, meetings were regularly rescheduled at short notice and the study team often had limited access to high-level strategic meetings. Thus, collaborations were selective with regard to the nature of meetings they allowed the evaluation team to attend. In addition, it was sometimes difficult to gain access to meetings at which staff from individual practices expected that they might divulge information that may represent their primary care collaboration in a negative manner. Therefore, such concerns had a significant impact on the number of observations that were completed (n = 9), despite extensive efforts on the part of the evaluation team working with case study gatekeepers.

Document review

Members of the study team gathered documents describing and containing data on the nature of primary care collaborations, and the priorities and aims, challenges and objectives, activities, set-up, operation, staff involvement, and costs and outcomes of collaboration. These were used to contextualise the development and functioning of the collaboration/PCN and to provide a historical perspective. Documents were sourced through case study gatekeepers and included:

-

material related to the structure of the collaboration/PCN

-

infrastructure and governance arrangements and charts

-

agendas and minutes of collaboration/PCN board and other meetings

-

local communications materials.

Data were extracted from source documents using a structured Microsoft Excel® Version 2108 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) template, which is available in Report Supplementary Material 3. The research team summarised information from documents that informed the writing of our context (see Chapter 1) and case study summaries (see Chapter 4).

Online smart survey

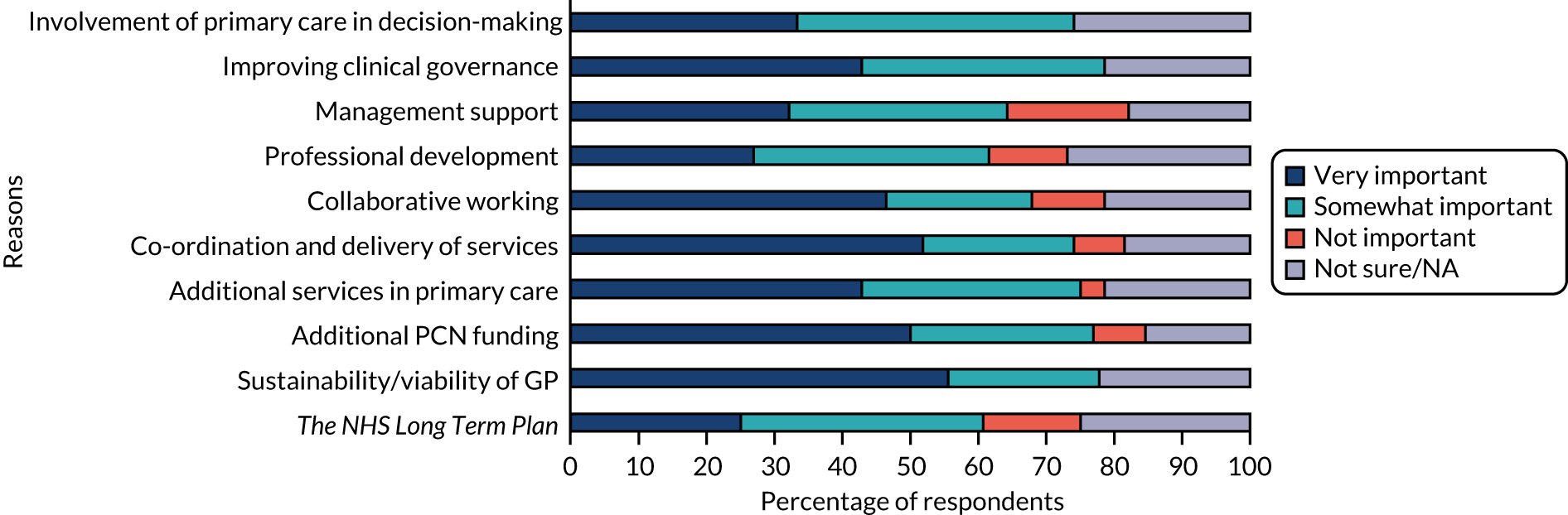

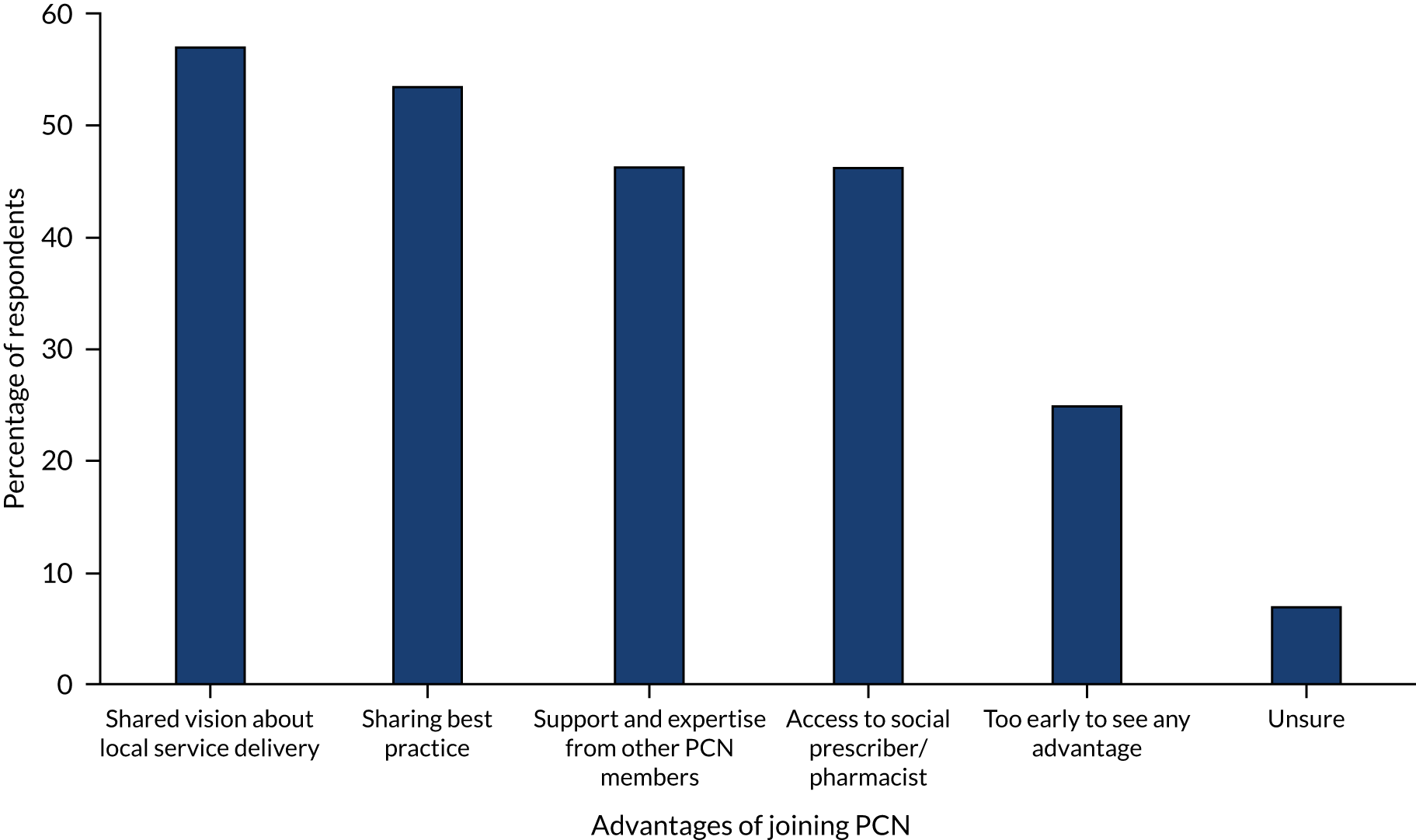

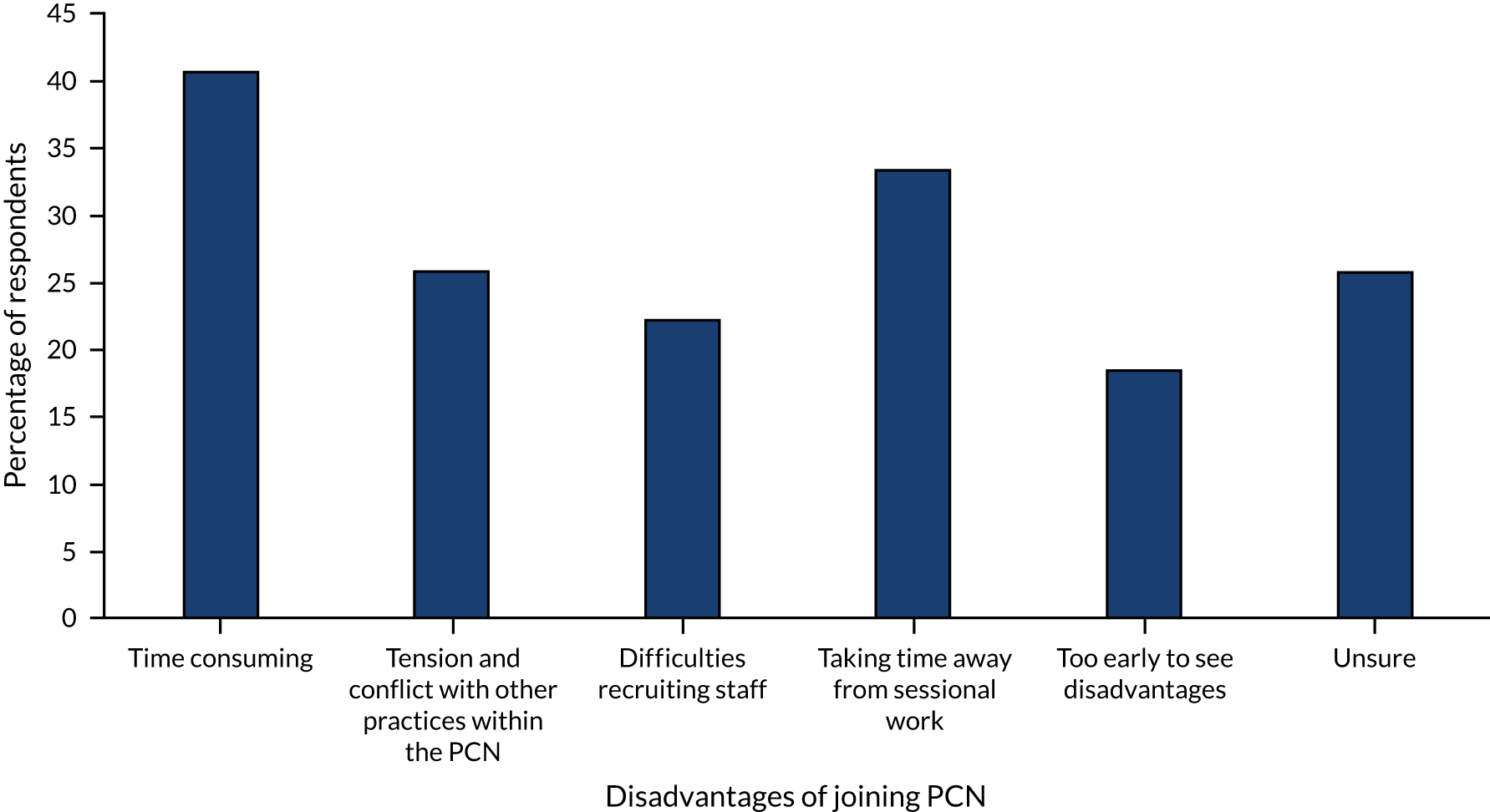

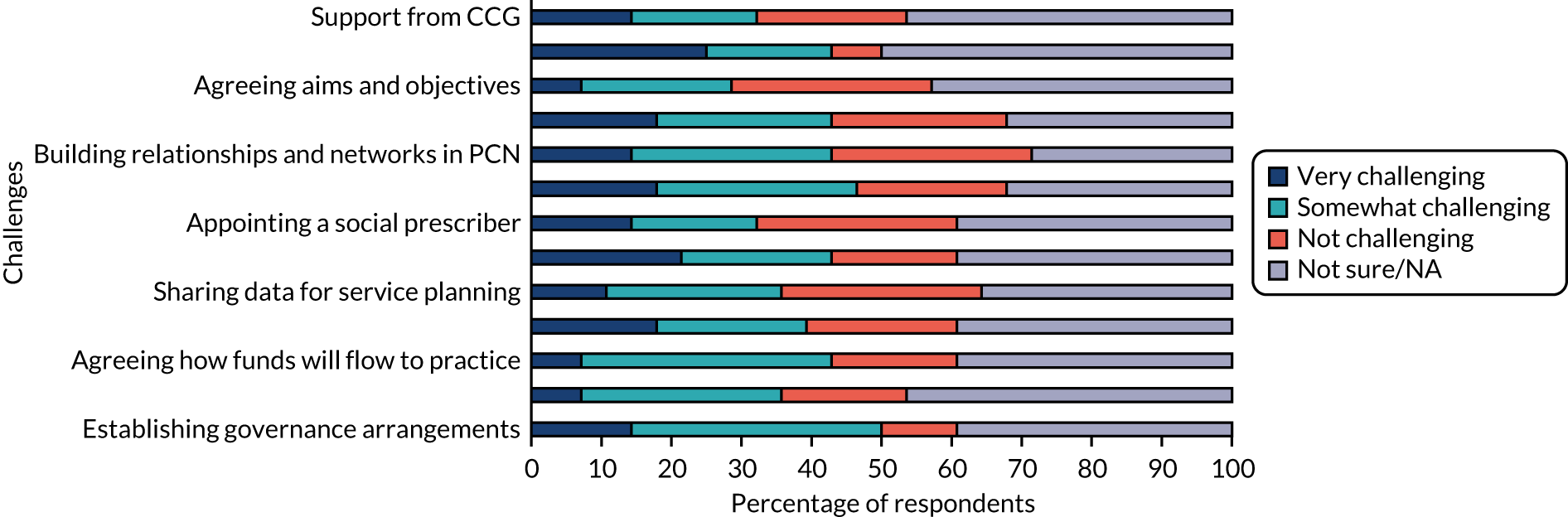

Throughout data collection, members of the evaluation team across all four case study sites struggled to arrange and complete interviews with clinical staff working in primary care (who were time limited), although other non-clinical staff were more available for interviewing. Therefore, in January 2020, the research team designed a short online survey (taking no more than 10 minutes to complete; see Appendix 3) to supplement data collected from interviews and observations, as well as to gather further data from general practitioners, nurses, PMs and newly introduced staff members recruited via the implementation of NHSE&I’s PCN model (i.e. social prescribers, pharmacists). Prior to circulation, a draft version of the survey was piloted with two senior and experienced general practitioners who were external to the case study sites to ensure that questions were appropriate to our evaluation questions, and to check for ease of comprehension and completion. Once redrafted following their comments, the survey was distributed across case study sites via gatekeepers (February–March 2020). A breakdown of survey responses from each site and characteristics of participants is provided in Tables 5 and 6. The results are discussed in Chapter 5, and additional information on survey responses is available in Appendix 5, Tables 8 and 9.

| Site | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| A | 2 |

| B | 14 |

| C | 4 |

| D | 8 |

| Total | 28 |

| Role | Number of respondents |

|---|---|

| Primary care clinical staff | 17 |

| Primary care non-clinical staff | 4 |

| Primary care organisational management-related staff | 3 |

| Other (community-based health-care providers/leaders) | 4 |

| Total | 28 |

Phase 3: analysis and write-up

Between January and April 2020, the insights gained through interviews, documents, non-participant observations and the online survey were analysed for each case study site.

We took a content analysis approach to documentary reviews and observations, hence, an iterative process of reading appropriate primary care literature and engaging in interpretation. To aid in the process of analysing and interpreting the data, the core evaluation team (MS, SP and JS) undertook an online data analysis half-day workshop in March 2020 followed by regular weekly online video calls (March–April 2020). These meetings had to take place online, as the COVID-19 pandemic was under way during the majority of phase 3, and the evaluation team was working from home as per government guidance.

Our analysis was guided by theoretical and policy literature on collaborations of GPs and in particular the framework developed by Smith and Mays,22 seeking to identify and understand the following:

-

objectives underpinning a collaboration

-

measures (or proxy measures) of the impact of a collaboration

-

degree of success in ‘tipping the balance’, that is shifting policy attention away from more traditionally powerful elements of health systems, such as acute hospitals, towards primary health care (in this case the local PCN area and overarching CCG)

-

the role played by primary care collaborations in strengthening primary care services and influence. 13

Data analysis for interviews was informed by the Gale et al. 47 framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multidisciplinary health research. This method of analysis is a highly systematic method of categorising and organising data while continuing to make analytical and interpretive choices transparent and auditable. Hence, the aim for the project team was to facilitate comparison across the case studies.

There are seven stages to analysis within the framework approach:47

-

transcription

-

familiarisation with the interview

-

coding

-

developing a working analytical framework

-

applying the analytical framework

-

charting data in a framework matrix

-

interpreting the data.

Data analysis and early interpretation of emerging findings was led by Amelia Harshfield (November 2019 to February 2020). However, Amelia Harshfield was on maternity leave from March 2020 onwards and Sarah Parkinson led data analysis and writing up of the findings, with input from Judith Smith and Manbinder Sidhu throughout.

Stage 1: transcription

All interviews across the four case study sites were transcribed verbatim through a professional outsourced transcribing company; a single organisation, specialising in transcribing health-related qualitative interviews, was used for all interviews.

Stage 2: familiarisation with the interview

Members of the project team (AH and MS) established familiarity with the data by reading two transcripts (or one-page summaries of transcripts) from each case study site and discussing emerging findings and areas of interest (which warranted further probing in subsequent interviews) and was discussed during telephone weekly meetings (November 2019 to February 2020). During meetings, team members were able to reflect on, discuss and share preliminary thoughts and impressions of early findings. This in turn led the evaluation team to construct detailed case descriptions for each of the four sites (see Chapter 4).

Stage 3: coding

Stages 3 and 4 (coding and developing a working analytical framework) of analysis occurred in tandem. The study team applied a deductive approach, having first developed an initial coding framework focusing on specific areas of interest identified from our REA and primary care policy literature, as well as interview guides and an initial reading of interview transcripts and field notes. Second, two researchers (SP and MS) independently coded the one interview transcript to ensure that no important aspects of the data were missed. The qualitative data analysis software package NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to undertake coding.

Stage 4: developing a working analytical framework

After piloting the initial coding framework and revising it based on the coding of an initial transcript, an analytical coding framework was agreed by all project team members (see Appendix 4). The analytical coding framework differed from the initial framework in that it had fewer codes, and these were more grounded in relation to the study REAs. Once agreed, all remaining interview transcripts were coded (n = 24). The codes in the final analytical framework were categorised under the following broad themes, namely general information (including the nature of primary care collaboration, governance and pragmatic information with regard to implementation, e.g. stakeholder involvement); description of, and reasons for, developing a collaboration/PCN; understanding and measuring impact (e.g. service delivery, financial and organisational); goals/metrics; what had gone well and poorly since the introduction of PCNs; and future steps.

Stage 5: applying the analytical framework

The working analytical framework was then applied by indexing (the systematic application of codes from the agreed analytical framework to the whole interview data set) by two project team members (SP and MS). Manbinder Sidhu coded data from two sites where he had collected data to build on existing levels of immersion. However, Sarah Parkinson coded data across all four sites to build a wider encompassing understanding of the data. Each code (n = 140) was shortened in name (if possible) for easier application. Data from observations and document analysis were discussed in data analysis meetings (March and April 2020) with regard to supporting emerging findings from interview data.

Stage 6: charting codes

As opposed to traditional methods of charting data (summarising data from each transcript by category of code), the project team took a novel rapid approach of a single researcher reading all content (from interviews across each site) under each code. The summary of codes was discussed at a second data analysis online video half-day workshop attended by team members (April 2020). Divergent interpretations with the coded data were resolved, and theoretical engagement with the coded data was undertaken, through discussions during the workshop among study team members. As a result, the evaluation principal investigator (JS) wrote a critical summative narrative paper of our findings and their relevance to policy literature, which was checked by Sarah Parkinson and Manbinder Sidhu. This overarching narrative paper helped team members to understand the scope and relevance of their findings, and supported the team in working out how best to write up themes in a coherent and integrated manner. No data were recoded following the second data analysis workshop.

Stage 7: interpreting the data

The critical summative narrative paper was circulated to wider team members (SP and MS) for comments (April 2020). The narrative was further refined with some outstanding queries remaining, with the intention that these would be resolved during the writing of Chapter 6. In addition, refinements to the narrative summary paper supported the interpretation of data across the four case study sites, interrogating theoretical concepts relational to our evaluation questions and mapping connections across our themes. Once all members of the project team agreed on the summative narrative, writing up of findings commenced. The project team circulated a summary of findings (digital slide deck) to each case study site providing an opportunity to give comments [i.e. member validation48 (June 2020)]. These comments were acknowledged and incorporated into findings.

Summary of analysis

We have provided a transparent account of our adapted framework analysis model suitable for rapid evaluation in which we detail significant discussion and contributions of project team members. Our approach supported engagement with the data in a timely fashion while iteratively returning to the literature to create a summative narrative paper. In the following chapter, we present a summary of our findings from the REA. A summary of Chapter 2 is given in Box 3.

Follow-up interviews on the COVID-19 response

Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, data collection for this evaluation concluded in March 2020, at which point only limited information about the response of each case study site to the pandemic was available. To help fill some of these gaps, the research team contacted the gatekeepers at each site in June 2020 for a short 30-minute semistructured telephone interview on collaborative responses to COVID-19 through PCNs. Gatekeepers were contacted by e-mail, at which point the study team also sent preliminary findings and the case study site description (see Chapter 4) to check the text for accuracy. This member validation process allowed the study team to check the factual accuracy of information about each case study site.

Three follow-up interviews were conducted with representatives from sites B, C and D. The interviews addressed the following questions:

-

What changes to service delivery have been made across your PCN since the beginning of the pandemic? Has any support or guidance been received from NHSE&I, CCG, local foundation/acute trusts? Success stories?

-

How has PCN policy helped/hindered primary care delivery during this period? (Organisational/managerial/leadership/governance issues.)

-

What has been the impact on staff? (Clinical and non-clinical.)

-

What changes do you think will continue beyond the pandemic and why?

The information from these interviews is summarised at the end of Chapter 5.

Chapter 3 Lessons from the evidence

The REA sought to answer the following questions:

-

What are the forms of organisational collaboration used in GP?

-

What are the reasons for GPs to enter into collaboration, or not?

-

What are the perceived facilitators of, or barriers to, effective GP collaborations?

-

What evidence is there of positive or negative impacts (both intended and unintended) brought about by collaborations in GP?

There are many diverse models that GPs adopt to collaborate with one another and different approaches taken to developing services. Forty-seven different ways of describing a GP collaboration were identified and the population covered by a GP collaboration ranges from < 1000 people to > 500,000 people.

In an English context, reasons to collaborate in various types of arrangements have included to hold budgets and bid together for contracts; to commission services for a local population as part of national policy on primary care-led commissioning; to deliver a wider range of services for patients; to strengthen practices’ resilience by providing better primary care management and better staffing resources; and to enable better access to care for patients by extending opening hours of GPs.

The main factors reported in the literature to have an impact on the progress of GP collaborations, and of particular relevance to the development of PCNs, can be summarised within four themes: management and leadership, engagement of general practitioners and the wider primary care team, strategic direction and objectives, and relationship of the GP collaboration with the wider health and care system.

Impacts claimed for GP collaborations included enabling the delivery of high-quality health care; introducing new specialist services in primary care settings; providing direct access to diagnostic facilities for general practitioners, hence avoiding unnecessary outpatient referral; pooling resources to avoid duplication of effort; and a sense of overwhelming workload in respect of understanding what is required to participate in the collaboration.

Rapid evidence assessment

Given the > 30-year history of development of GP collaborations in the UK and internationally, and the existence of a significant body of research and evaluation, it was considered important to undertake a rapid assessment of this evidence to inform this evaluation of the early implementation of PCNs. A major review of the evidence relating to large-scale GP was undertaken by Pettigrew et al. 21 at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in 2016. Therefore, the evidence assessment for this evaluation of PCNs focused primarily on more recent literature (2013–18), using 55 publications from the UK context and from all high-income countries (as defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development49), as well as examining reviews and syntheses of prior research (1998–2018). Full details of the methods for the REA are given in Chapter 2.

The REA sought to answer the following questions:

-

What are the forms of organisational collaboration used in GP?

-

What are the reasons for GPs to enter into collaboration, or not?

-

What are the perceived facilitators of, or barriers to, effective GP collaborations?

-

What evidence is there of positive or negative impacts (both intended and unintended) brought about by collaborations in GP?

Forms of organisational collaboration in general practice

The traditional model of GP in the UK, in common with many other developed countries, is of small, privately owned partnerships operating under a contract with the publicly funded national health system. Over the past three decades, there has been an international move towards more organised and collective GP, largely based on horizontal integration across practices, and typically involving practices working in networks, federations or more formal mergers in super-partnerships. 19,20,50 In some of these arrangements, dedicated management and organisational support are put in place centrally, and formal entities that are owned and operated by groups of practices are established.

The REA offered insights into the diverse models that GPs adopt to collaborate with one another and the different approaches taken by GP collaborations when developing services. Forty-seven different ways of describing a GP collaboration were identified in this evidence assessment, including those summarised in Table 1 in Chapter 1 that reflect the policy context of GP collaborations in the UK.

The evidence review revealed that, in the international context, the population covered by a GP collaboration ranges from < 1000 people through to > 500,000 people. In 2017, 28% of GP collaborations in England covered a population of < 50,000 people and 31% covered a population of > 200,000. 15 In the research literature, there is frequent analysis of the size of GP collaborations and discussion about the advantages and disadvantages of different scales. Many of these discussions conclude that, rather than be overly prescriptive about a particular size or structure for GP collaborations, policy-makers should seek, where possible, to allow organisational form to follow function21,51,52 and that there are perils in a national policy or funding body mandating a specific size or form. 13,53 In the case of PCNs, size and form have been mandated (albeit implementation has in practice allowed more flexibility), with the justification being that this builds on the National Association of Primary Care’s suggestion of a population of 30,000–50,000 people being appropriate for the PCH model of care. 17

Reasons for general practice collaboration

Collaborative GP is most frequently associated with a desire to strengthen and extend the provision of primary care and community-based health and care services, along with enabling financial, workforce and organisational efficiencies. 20,24,50 In some countries, and particularly in England, networked and collaborative primary care has tended to be focused on engaging GP in the purchasing or commissioning of wider health services (as in GP fundholding, TPPs, PCTs and, more recently, CCGs). Research into different iterations of primary care commissioning has, however, shown that they tend to focus mainly on developing local primary care service provision and networking, rather than planning and purchasing a wider range of community and secondary care services. 22 PCNs have been established primarily to focus on extending the provision of local health and care services, and are commissioned and funded to do this by NHSE&I. There is an aspect to the work of PCNs that is arguably about commissioning (the assessment of local health needs, and then developing services to meet those needs) but this is within a context of service specifications set out by NHSE&I.

In the international context, primary care physician-led and -owned groups have typically emerged as a means to hold contracts with funders or insurers, or to deliver a range of health-care services that seek to keep quality high while containing costs. 13,53,54 Although examples of GP collaborations in countries such as New Zealand, Canada and the USA have often been able to demonstrate some success in meeting these goals, evaluation studies have found that primary care organisations often underestimate the complexity and scale of the management capacity required, and pay insufficient attention to the time and support needed to engage local health-care professionals in the new service delivery arrangements. 54–56 The vital importance of infrastructure and management support to primary care-led organisations is also reported in studies of community-owned and -led services, including in New Zealand57 and the UK. 58

General practitioner collaborations have often focused on working together to provide a range of new health services. Some GPs may start collaborating to bid for contracts to offer these services, or assume budgets to provide them, whereas others may start collaborating for different reasons (e.g. to have greater influence in the local or regional health system, to fend off a perceived threat to GP independence or provide training and development support for primary care teams) and find that as part of their collaborative process they then start introducing new services. The latter happened with primary care groups in the NHS,50 physician groups in California54,55 and independent practitioner associations in New Zealand. 13,53

In the English context, GPs have entered into various collaborative arrangements over the past 30 years, citing different reasons for doing so. These reasons include to hold budgets and bid together for contracts,19,59 to commission services for a local population as part of national policy on primary care led commissioning,20,51,60 to deliver a wider range of services for patients,16,36 to strengthen practices’ resilience by providing better primary care management and better staffing resources,61 and to enable better access to care for patients by increasing opening hours,3,62 among others. 21 Unsurprisingly, these collaborations vary in form, functions, staffing arrangements and culture. It is often difficult to divorce the commissioning aspect of a GP collaboration from its role in developing service provision (and, as noted above, there are elements of this overlap within PCN policy), given that many commissioning collaborations moved to focus on the provision of care within primary and community services. 20,51,63 A summary of reasons for forming a GP collaboration is set out in Box 5.

To improve and extend service provision for patients in primary care including, for example, practice-based physiotherapy, specialist asthma and diabetic care, pharmacy-led medication reviews in GP or care homes, dementia cafés and carer support, and intensive home support for people living with multiple complex conditions. 14,19,21,36,61,64–74

To engage general practitioners and their teams in local care planning and purchasing. 21,50,51,60

To encourage greater integration of local health services, including through the development of effective multidisciplinary teamworking. 3,19,20,61

A response to governmental mandate or recommendation, including to take on responsibility for commissioning or purchasing certain local health services. 3,13,15,36,61,62,66,70,75–78

To enable GP to gain greater influence in the local or regional health system. 21,50,51,53,60

To improve the sustainability and resilience of GP. 19,61,79–82

To reduce costs and become more cost-effective. 65,68,83–86

To increase, recruitment, retention, job satisfaction or staff experience within primary care. 14,68