Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/116/25. The contractual start date was in May 2018. The final report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in July 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Jones et al. This work was produced by Jones et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Jones et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Introduction

The overall aim of this study is to better understand the introduction of a new role in NHS England that is designed to support workers to speak up about ‘anything that gets in the way of providing good care’ (© National Guardian’s Office. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 1 These roles are called Freedom to Speak Up Guardians (FTSUGs). We were interested to find out how FTSUG roles are being implemented in acute trusts and mental health trusts and whether or not FTSUGs are helping workers to ‘speak up’ about their concerns.

Background to ‘speaking up’ in the NHS

Employees who ‘speak up’ or ‘raise concerns’ about problems with health-care services have traditionally been referred to as ‘whistleblowers’. The terms whistleblowing/whistleblower, raising concerns and ‘speaking up’ are commonly and interchangeably used in the health-care literature, policy and the media. This report refers to speaking up and raising concerns, referring to whistleblowing and its derivatives only where others use those terms.

Although speaking up makes an important contribution to delivering safe care, NHS workers who raise concerns have not always been listened to or treated well. 2 The public inquiry into appalling patient care failings at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust, eponymously referred to as the ‘Francis Report’,3 found that workers’ concerns were often ignored, and that those speaking up were mistreated by colleagues. The report also concluded that the unnecessary and avoidable suffering of patients was primarily caused by serious failure on the part of the trust board, who ‘did not listen sufficiently to its patients and staff or ensure the correction of deficiencies brought to the Trust’s attention’ (© The Stationery Office. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 3

The issues identified in the Francis Report, however, were not unique to Mid Staffordshire or isolated to the early 2000s. Since the 1960s, several reports and inquiries4 have described the difficulties experienced by health-care workers attempting to speak up and how the many and varied concerns raised were missed, misunderstood or ignored by those responsible for assuring safety and quality across the NHS. 5,6 The failure to listen to and protect workers speaking up has been described by the House of Commons Health Select Committee as a stain on the reputation of the NHS. 7 Nonetheless, these issues are not exclusively found in the NHS because health-care employees globally report mistreatment and indifference as a result of raising concerns. 8–10

The introduction of Freedom to Speak Up Guardians

The events at Mid Staffordshire had a profound impact on health-care policy in England. 11 One of the many government responses to the Francis Report was the commissioning of a review of culture and practice around raising concerns in the NHS, the Freedom To Speak Up (FTSU) review, also referred to as the ‘Francis Review’. 12 The review refers to speaking up as a patient safety issue and confirmed many of the worries previously identified, finding widespread reluctance to speak up among some workers, rooted in a sense of futility. It also refers consistently to the detriment experienced by some who raise concerns and outlines that concerns raised about workplace incivility should be viewed as patient safety issues:

. . . wherever there is a reference to ‘raising concerns’, ‘speaking up’ or ‘whistleblowing’ it should be considered to refer to the raising of a concern relevant to safety or the integrity of the system. I include in this concerns about oppressive behaviour or bullying and dysfunctional working relationships, which I consider to be safety issues.

Francis12 © Francis R, 2015. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.0

In addressing these significant challenges, the FTSU review set out 20 principles to guide the development of ‘a consistent approach to raising concerns . . . whilst leaving scope for flexibility for organisations to adapt them to their own circumstances’ (© Francis R, 2015. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.0). 12 A single ‘overarching Principle’ states that every NHS organisation should ‘foster a culture of safety and learning in which all staff feel safe to raise concerns’ (© Francis R, 2015. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.0). 12

Principle 11 (‘Support’) proposed the introduction of the flagship FTSUG role in all NHS England trusts and foundation trusts, supported by the National Guardian for Freedom to Speak Up and the National Guardian’s Office (NGO) (see The role of the National Guardian’s Office). The FTSUG role was founded on three interlinked objectives to ensure that:

-

NHS employees are not victimised for raising concerns

-

speaking up is part of the normal routine business of any well-led NHS organisation

-

NHS organisations, both individually and collectively, learn from employees who speak up.

The FTSU review12 further proposed that the responsibility for driving, maintaining and monitoring progress in effecting culture change rested with the board. Responsibilities were outlined for a designated non-executive director (NED) and executive lead for FTSU, which ensured that support was available to all workers speaking up, and facilitated open discussions, reflective practice and shared ownership of problems and solutions.

Implementing the review’s proposals, the government mandated that each organisation providing health care in England should appoint one or more Guardian13 to act as a point of contact for anyone with ‘a concern about risk, malpractice or wrongdoing (they) think is harming the service’ (© NHS Improvement, 2016. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 14 FTSUG roles had to be funded from organisations’ own resources, with the NGO funded via a centrally allocated budget of £950,000 per annum. At commencement of data collection for this project (October 2018), over 500 FTSUGs had been appointed.

The FTSU review12 clearly states a preference for flexibility in the role’s implementation and local adaptations to fit with each organisation’s perceived needs. A universal job description, which was produced by the NGO for the FTSUG role,15 provided numerous and broad guidance, expectations, principles and outcomes for the role. The job description is discussed and analysed in detail in Chapters 4–6.

In broad terms, the role of the FTSUG is intended to be an independent, impartial and objective role, serving as a highly visible contact for any worker with a concern, while also ensuring that concerns are responded to appropriately. The independence of FTSUGs is a recurring theme in many of the NGO’s documents and guidance; however, this refers to cultivating independence of thought, and from the hierarchy within the NHS trusts, rather than in procedural terms. For example, the guidance stresses that FTSUGs should function within existing procedures and processes, serving as an additional route only where concerns raised through the organisation’s existing channels do not gain traction. 14 However, FTSUGs are also entrusted to open a line of communication between workers, senior managers and the board, offering a route to speaking up outside the direct line management and formal human resources (HR) options. Having to navigate these discipline-specific, professional and procedural boundaries places the FTSUG in a potentially precarious position. FTSUGs are also potentially vulnerable as employees of organisations that they must hold to account when practices are contrary to the Francis vision12 of open and transparent culture in which speaking up is a consistent and normalised feature of everyday practice.

The role of the National Guardian’s Office

The NGO was established in April 2016 as an independent non-statutory body that was tasked with normalising speaking up and leading effective cultural change, but was not concerned with historical cases and the instigation of speak-up investigations. The NGO is jointly sponsored by the Care Quality Commission (CQC), NHS England and NHS Improvement, and its Accountability and Liaison Board includes senior representatives from the sponsoring bodies. Three years after its establishment, additional funding was allocated to the NGO to support its work to integrate FTSU in primary care, including the appointment of regional leads to spearhead this work.

The NGO provides resources for Guardians and the organisations in which they are situated; for example, guidance on recording cases and reporting data for Guardians,16 and FTSU guidance for boards. 17 Training materials and events for Guardians are also disseminated, in addition to national guidelines on FTSU training for organisations. The NGO also arranges an annual FTSU conference and co-ordinates regional FTSUG networks. Data, annual reports, survey reports, responses to consultations and other publications are archived on the NGO’s website. The NGO also obtains feedback from FTSUGs on its own performance. Respondents to the 2019 Guardian’s survey18 were asked to rate how supportive they perceived the NGO to be, on a scale ranging from zero (‘not at all’) to 10 (‘fully’). The average score was 6.5, indicating that perceptions of support had dropped from the previous year’s score of 7.1.

In June 2017, a 12-month pilot scheme for case reviews was undertaken by the NGO, during which the NGO considered referrals for case reviews by current and former workers in NHS trusts and foundation trusts who were unsatisfied with speaking-up procedures and response to concerns. Following a review, the trusts involved were expected to implement the recommended improvements, which would then be monitored by the regulators. Publication of the findings encouraged learning to be shared across the FTSUG network, which many Guardians interviewed in work package (WP) 2 described as useful. Following an evaluation of the pilot scheme, the case review process seems set to continue.

Measuring and monitoring speaking up in the NHS

As is discussed at length in Chapter 4, FTSUGs submit non-identifiable data to the NGO about speaking up in their organisation. Data are collated every 3 months and are published in the NGO’s annual report. The 2019/20 report19 indicated that 16,199 FTSU cases were raised with Guardians, an increase from 12,244 cases in the previous year. Many concerns (23%) included an element of patient safety/quality, while 36% included an element of bullying/harassment.

In addition, the NGO, working with NHS England, devised a ‘FTSU Index’, which was described as a ‘key metric’20 by which organisations can monitor their FTSU culture, comparisons can be made between trusts and good practice can be shared. The FTSU Index is a compound measure that is calculated as the mean of responses to four questions from the previous year’s NHS staff survey, rounded to one decimal place. The index has risen nationally from 75.5% in 2015 to 78.7% in 2019, leading the NGO to declare that the NHS has much to celebrate. 20 The index is utilised by the NGO as an indicator of potential areas of good practice and concern on matters of FTSU culture in organisations. Information is shared with stakeholders, including CQC, NHS England and NHS Improvement, to inform various aspects of their work to normalise speaking up. FTSU is also inspected within the CQC ‘Well Led’ domain; those trusts exhibiting higher scores on the index are more likely to be rated ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ by the CQC.

However, drawing meaningful comparisons and definitive conclusions from FTSU data is fraught with difficulties. Despite NGO guidance, the collection of FTSU data is beset with problems of accuracy and consistency, as discussed in Chapter 4. There is also a fundamental question, possibly unanswerable, of what a rise or fall in the number of speak-up cases realistically signifies. Caution is also advisable regarding the contribution of FTSUG roles to upwards or downwards trends in data when we consider that this novel role was implemented locally without specific requirements over delimitation of remit, responsibilities and accountability structures. A further degree of localness is added because speaking up is highly situational and context dependent, and the work of FTSUGs is superimposed on to existing organisational procedures and protocols. These inherent issues could be positive in the sense that FTSU’s adaptation to the local environment, interwoven practices and operational contingencies could allow the Guardian role to evolve alongside the necessary changes in organisational culture. However, as an unprecedented intervention in the context of the NHS, or health-care internationally, and having no requirement for uniformity, the implementation of the Guardian role was always likely to vary across England.

Report structure

In Chapter 2, the aims and objectives are presented alongside the methods used to address these. Chapter 3 presents a literature review of speak-up interventions in health care. The results of telephone interviews undertaken with FTSUGs regarding the implementation of the role are presented in Chapter 4, which subsequently contributed to the design of data collection in case sites. In-depth exploration of the implementation and work of FTSUGs and the impact of FTSU more generally are presented in the findings from six case site reports in Chapter 5, and cross-case findings in Chapter 6, both drawing on non-participant observations, analysis of documents and interviews with FTSUGs and FTSU stakeholders. Finally, we summarise and discuss our findings and present our conclusions in Chapter 7.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter reports the study aims and objectives, the research questions and the methodological approach used to address these. The aims of the study were twofold: (1) to map varying approaches to implementing and configuring FTSUG roles in acute and mental health trusts, and (2) to gain insights into benefits and drawbacks of different FTSUG implementation models on speaking up and responding to workers’ concerns.

The study objectives were to:

-

assess the scale and scope of the deployment and work of FTSUGs

-

assess how the work of FTSUGs is organised and operationalised alongside other relevant roles with responsibilities for workers’ concerns

-

evaluate the comparative effectiveness of different types of FTSUG roles in supporting ‘Freedom to Speak Up’

-

identify barriers to, facilitators of and unintended consequences associated with the implementation of FTSUG roles.

Finally, the following research questions were addressed:

-

How are FTSUGs being variously deployed, managed and held accountable for their work?

-

How is the work of FTSUGs defined and negotiated in relation to the work of others who also deal with workers’ concerns?

-

Do different implementation models for the FTSUG role affect the ‘Freedom to Speak Up’, both in the ways that workers raise concerns and in how these concerns are responded to?

Overview of theoretical approaches and work packages

This section opens with a discussion of the theoretical frameworks that informed the study’s design, followed by a detailed overview of the relevant WPs. For the purposes of this investigation, we conceptualise the FTSUG role as a complex intervention. 21 Complex interventions are conventionally defined as difficult to implement because they consist of several interacting and interlocking components spanning a number of organisational levels, from the macro level (national policy organisations and regulators) to the meso level (individual trusts) and the micro level (individual employees, teams and wards/units). 22 These organisational levels have also been described as ‘nested’, simultaneously sitting above and below (and interacting with) other systems of different scale. 23

Given the complex nature of the FTSUG role and the contexts within which the role was implemented, as outlined in Chapter 1, Normalisation Process Theory (NPT) offered an appropriate framework to guide the study. 24,25 NPT assists researchers to identify factors that promote or inhibit the routine incorporation of complex interventions, such as FTSUGs, into everyday practice. NPT consists of four main components, or generative mechanisms, that help to identify the social processes underpinning the implementation of complex interventions (Table 1). 25

| NPT generative mechanism | Explanation of the mechanism and how it may be enacted in the context of FTSUG work |

|---|---|

| Coherence or sense-making | Sense-making work undertaken individually and collectively to operationalise the FTSUG role. The ‘success’ of this depends on the perceived workability and integration of the various elements of the new role into everyday practice |

| Cognitive participation | The incorporation of FTSUGs within the workplace depends on relevant individuals’ capacity to resource, cooperate and co-ordinate their actions |

| Collective action | The FTSUG role will be more disposed towards normalisation into practice if there is individual and collective intention and commitment to operationalising the role in practice |

| Reflexive monitoring | The appraisal work that people do to assess and understand the ways that the FTSUG role affect them and others around them |

In simple terms, NPT proposes that practices are embedded in social contexts as the result of people working, individually and collectively, to implement them. For example, if those involved in the implementation of FTSUGs can identify coherent arguments for adopting the role, are engaged in the process of implementation, are able to adapt their work processes to utilise FTSUGs (or FTSUGs adapt to fit in with existing practices) and judge FTSUGs to be valuable once they are in use, then FTSUGs are more likely to become embedded in routine practice. The introduction of FTSUGs cannot, therefore, be considered a discrete intervention that works in the same way regardless of the organisational context. Instead, FTSUG roles are likely to be designed and used in different ways depending on prevailing institutional arrangements.

A limitation of NPT is that it does not (and cannot) cover all phenomena of interest. 25 Accordingly, we also draw on insights from other relevant theories, such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). 26 The CFIR provides terms and definitions for constructs that allow researchers to clearly and consistently articulate factors that potentially affect implementation outcomes. Particularly useful are CFIR insights into the influence of factors from the outer setting (e.g. policy or regulatory recommendations) and how they are often mediated through changes in the inner setting of organisations, such as changes in personnel or resources that affect, positively or negatively, the implementation of the FTSUG role implementation.

Work package 2: telephone interviews with Freedom to Speak Up Guardians working in acute hospital and mental health trusts

Work package 2 addressed the research aims, objectives and questions by providing an in-depth understanding and national picture of how FTSUGs are selected/recruited, deployed and organised within their organisations. To this end, we conducted semistructured telephone interviews (n = 87) with FTSUGs working in acute hospital trusts and mental health trusts. Participants were asked the same set of questions about their variable characteristics, such as their age, sex and nature of employment (e.g. hours allocated), as well as the work systems within which they were embedded. FTSUGs were also asked how they monitored FTSU within their organisation, such as the staff group and the demographics of those speaking up, and whether or not workers experience detriment following speaking up. The questions were informed by the findings of the literature review and existing concepts that had influenced some of our previous work on this subject (see standalone document 1 WP2 interview schedule; see https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/16/116/25/#/documentation). 2,4,27–29 For example, interview questions regarding the coherence and clarity of new work processes and boundaries, the monitoring of change, and the availability of resources to support the implementation were informed by the literature review.

Freedom to Speak Up Guardians were identified and purposively sampled from the NGO register of FTSUGs. Initial contact with FTSUGs was made by e-mail and a telephone interview was arranged with those volunteering to participate. FTSUGs were recruited from each of the 10 (at the time) NHS England regions (see standalone document 2; see https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/16/116/25/#/documentation) and worked in the following type and size of trusts:

-

23 out of 54 mental health trusts in existence at the time

-

64 out of 135 acute trusts in existence at the time

-

42 from small organisations (< 5000 staff)

-

35 from medium organisations (5000–10,000 staff)

-

10 from large organisations (> 10,000 staff).

We also interviewed FTSUGs from organisations with different CQC overall ratings, as shown in Table 2, which also shows the numbers of FTSUGs contacted, a 34% overall response rate and that a large percentage of FTSUGs responding were interviewed.

| WP2 recruitment stage | CQC rating, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | Good | Requires improvement | Inadequate | ||

| Contacted | 36 | 123 | 82 | 14 | 255 |

| Responded | 15 (42) | 55 (45) | 29 (35) | 8 (57) | 107 (42) |

| Interviewed | 14 (39) | 44 (36) | 23 (28) | 6 (43) | 87 (34) |

Interviews were audio-recorded, which allowed subsequent review to clarify any confusion or inaccuracy. Data analysis, which was aided by NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK), took place concurrently with data collection. Initially, descriptive statistics and bar charts were produced to help to visualise the ‘shape’ of the data, for example summarising categorical variables, such as sex and professional background. These steps helped to identify interesting or anomalous features and proved useful in generating cross-tabulations of the relationships between these characteristics and other variables.

Thematic qualitative analysis, which followed a recognised six-step process,30 proceeded with in-depth familiarisation of the interview transcripts followed by inductive coding and thematic analysis, which identified the range of respondents’ views about their experiences of organisational commitment to the role, including barriers to and enablers of role normalisation. FTSUGs’ accounts of their work were also situated within the NPT generative mechanisms (see Table 1), generating insights that were revisited during case studies.

Once data were grouped into qualitative themes, we revisited the quantitative findings to establish whether a theme (or its dimensions) applied to only a particular group or whether it was a more general theme. Implications for fieldwork in WP3, such as the emergence of issues or problems that were not initially anticipated, were discussed and our field methods were modified accordingly. For example, we became increasingly aware that many FTSUGs were employed in substantive roles that they undertook alongside the FTSUG role. Fieldwork was, therefore, arranged to minimise researchers’ exposure to sensitive or confidential information unrelated to the project.

Methodological rigour was ensured through standard procedures of reflexivity, transparency and auditability. 31 Initial coding and emergent themes were developed within and then across the two teams based in Cardiff and London. Research associates at each site (JB and CB) individually undertook the initial analysis, overseen by the chief investigator (AJ) and Mary Adams and Jill Maben, who reviewed a further proportion of all transcripts to ensure inter-rater consistency/reliability. Emergent and final themes were regularly discussed and agreed with all members of the research team during three-weekly team meetings (face to face initially and online following COVID-19 workplace and travel restrictions). Additional insights into emergent findings were provided by public involvement members and the project advisory group (PAG), thus ensuring rigour was maximised at each step of analysis and across the data set.

Work package 3: six organisational case studies

We purposefully sampled four acute trusts and two mental health trusts, initially identifying potential case study sites from our analysis of WP2 data. However, although we contacted several trusts from each CQC band and different ‘types’ of FTSUGs (full time, part time and undertaking another role or not), ultimately we could recruit only trusts that volunteered to take part. Eight trusts agreed to take part. An additional seven trusts expressed an interest but did not participate, citing organisational pressures, or following further discussion with senior colleagues. Following consultation with the PAG, the final six sites were selected because they provided a range of CQC ratings, sizes and types of FTSUGs deployed (e.g. part or full-time), which best addressed the research aims and objectives.

Three months were spent at each case site shadowing FTSUGs, followed by 1 month undertaking preliminary within-case and tentative cross-case consolidation. Case sites were divided equally between Carys Banks and Joanne Blake, who undertook the large majority of data collection and were supported and supervised by Mary Adams, Aled Jones and Jill Maben, who also undertook visits to case sites and undertook short periods of observations. Three-weekly online whole-team meetings provided Carys Banks and Joanne Blake with the opportunity to present updated progress reports to other team members and to compare and contrast case site activities and the overall management of data collection. Case studies focused on exploring whether or not and how the role had been normalised alongside other local roles and initiatives overlapping with FTSU, in addition to understanding how FTSUGs were working in relation to their social and physical settings. CQC inspection reports and the NGO ‘Speak-Up Index’ provided useful historical and contemporary insights into speaking-up cultures within organisations. Planning for the case studies also drew on the findings of the literature review (see Chapter 3), especially the key finding that the implementation of speaking-up interventions is best understood within the wider context that they occur.

Purposive sampling was again used within the case sites to identify key informants, documents and stakeholders who were involved in the oversight and delivery of the FTSUG role, and any related speak-up initiatives. Prior to data collection, an initial visit to each site was arranged with the FTSUG to discuss plans for data collection, including how the FTSUG’s activities could be shadowed without the researcher’s presence being intrusive. With this in mind, an activity planning document (see Appendix 1) was completed in conjunction with the FTSUG, including information on FTSU-relevant events/meetings and key individuals who may subsequently be recruited for interview.

An initial 2-week introductory and orientation period helped to establish rapport with FTSUGs and other staff, and enabled an early sense of the Guardian’s work and FTSU in each organisation. Thereafter, data were concurrently generated at two sites using the following methods:

-

Overt non-participant observations of:

-

the FTSUG role in practice, for example delivering ‘speaking-up’ training and advice to workers, participating in walk-rounds and attending meetings within the trust (e.g. board meetings and operational meetings)

-

face-to-face meetings and/or telephone or e-mail activities with workers wanting to speak-up or with workers who had already spoken up to the FTSUG

-

meetings to review concerns with colleagues, such as line managers and NED/executive leads for FTSU.

-

-

Descriptive free-text fieldnotes were recorded during and/or following each observation event, either while in the field or soon after being in the field. These were written up in Microsoft Word® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and collated at the completion of data collection at each site alongside relevant documentation, and summarised prior to analysis to identify the most relevant content in relation to FTSU.

-

Relevant organisational policies, internal communications and reports carried out by FTSUGs were recorded.

-

Trust board reports on concerns raised by workers were also collected.

-

Semistructured interviews were conducted with the following individuals:

-

FTSUGs – two interviews: one when fieldwork commenced and one towards the end of the data collection period

-

employees who had raised concerns via the FTSU service

-

key stakeholders closely involved in the implementation and ongoing deployment of the FTSUG role, including board members, executives, NEDs, directors or assistant directors of HR, organisational development (OD) and staff-side chairpersons

-

employees who had not spoken-up to the FTSUG.

-

Up to 20 interviews at each site were tentatively predicted, with the final number (Table 3) being slightly short of this. The final number of interviewees (n = 109) tallies with our purposive sampling strategy, which meant that the data saturation point was reached when key participants (listed above) at each case site were interviewed. We were very encouraged by the range of staff at all sites who dedicated time for the interviews, often despite very busy schedules. The data generated proved to be rich and contributed greatly to our understanding of the implementation of the role.

| Case sites (n) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

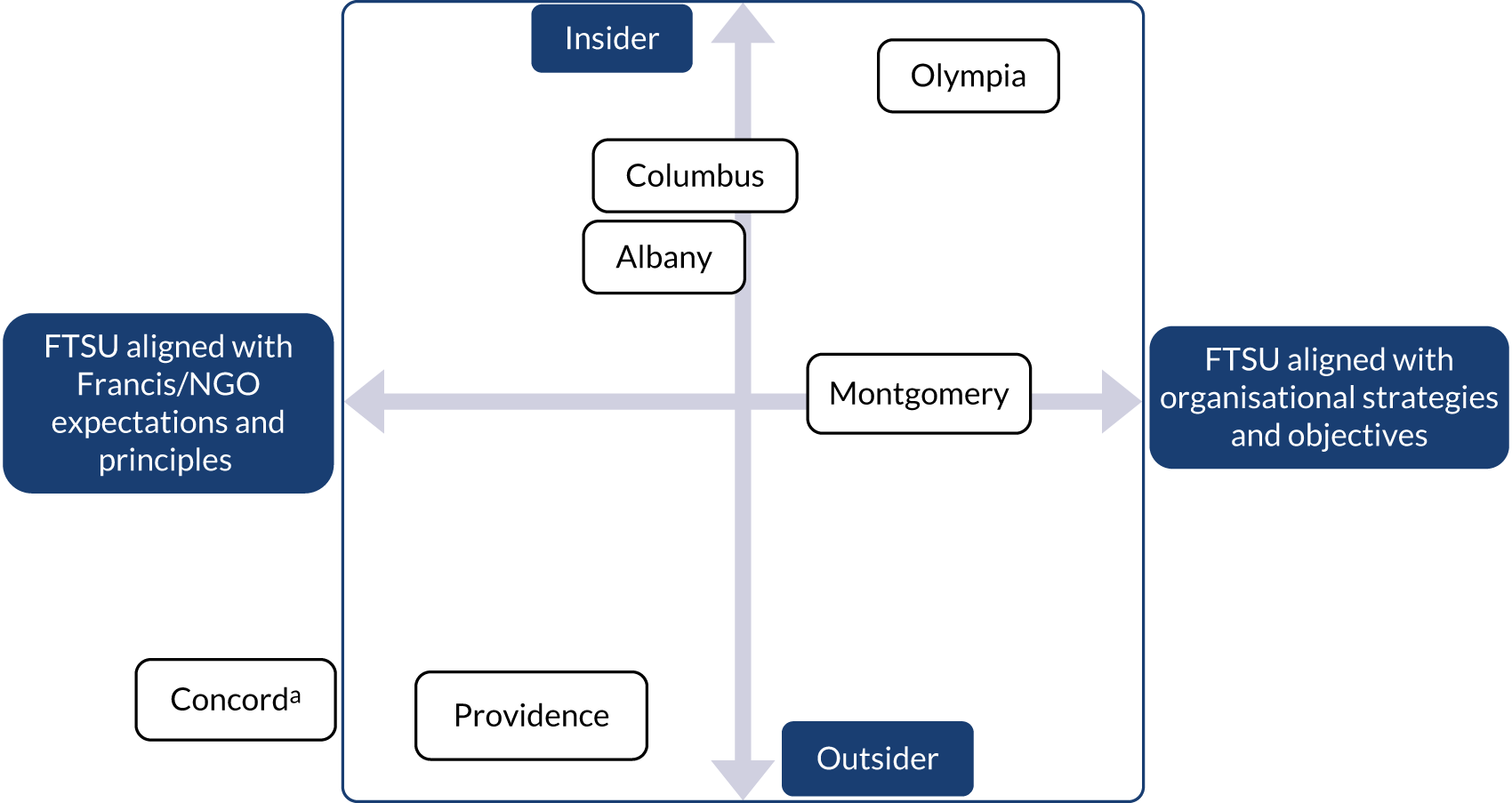

| Albany | Olympia | Montgomery | Columbus | Providence | Concord | |

| Number of interviews undertaken | 19 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 16 | 19 |

Central to our conduct throughout the study was sensitivity to the demands of the FTSUG role and the potential for the researchers’ presence to influence speaking up by workers. During observation periods, the researcher removed themselves if it appeared that the FTSUG was being approached by someone with a concern or if the FTSUG or employee requested that the researcher withdraw (see Research ethics). The main objective during observations was for the researcher’s presence to be unobtrusive and to alter practices as little as possible.

Although the data collection phase is presented here separately from data analysis, in practice the two phases were intertwined. A software package (NVivo 12) assisted with the storage of transcribed interviews and other documents, as well as the thematic analysis of data in a process underpinned by the same approach to methodological rigour outlined in Work package 2: telephone interviews with Freedom to Speak Up Guardians working in acute hospital and mental health trusts. An inductive ‘data condensation’28 process, foreshadowed by research aims/objectives/questions, was used to select, focus, simplify and abstract data from the range of field data and interview transcripts. Each case study was individually analysed prior to cross-case analysis. To integrate and aggregate findings across cases, a series of NPT thematic charts were developed for each case study. Further exploration of the charted themes was then undertaken to map and understand the range of views and experiences across each site. Established theory and research into speaking up and organisational culture, in addition to our own expertise and the perspectives from the PAG/patient and public involvement (PPI) team members, all contributed to the interpretation of the qualitative findings.

Telephone interviews with national stakeholders (n = 7)

Semistructured telephone interviews were undertaken by Daniel Kelly and Aled Jones with national stakeholders. These individuals were purposively sampled from roles and organisations involved on a national level in establishing, liaising with or oversight of the FTSUG initiative, or had worked in organisations that had a direct interest in FTSU (e.g. trade unions or patient safety campaign groups). Individuals were initially identified from organisational webpages or from previous contact with or awareness of the research team and PAG members. If agreeing to participate, interviewees were recruited and interviewed and the data analysed in the same manner as described in WP2.

Research ethics

All study work packages were approved by the School of Healthcare Studies, Cardiff University, Research Ethics Committee reference HCARE/14082018.

Patient and public involvement in the research

From the outset, PPI was integral to the development, design and overall conduct of this project, shaped by the awareness that PPI involvement should be both meaningful and relevant. A group of four PPI members initially participated during the study design phase. Two of the PPI group continued to contribute directly to all WPs throughout the study via the PAG and other activities, such as the following:

-

contributing to preparation for data collection and data analysis activities, such as reviewing emerging findings and development of later findings

-

informing the preparation and accessibility of dissemination materials

-

participating in future workshops and other dissemination events and activities, such as authoring and providing a PPI perspective to training materials for NHS employees

-

playing a significant role in setting future research priorities and, overall, helping us to not lose sight of why the research is important and how the research might positively influence practices from a PPI perspective.

Details of the PPI and PAG members can be found in the Acknowledgements.

Summary

This chapter has set out the research design and the approaches taken towards data generation and analysis, which were underpinned by NPT. The empirical elements of the study were set across two phases: WP2 comprised telephone interviews with FTSUGs working in acute trusts and mental health trusts in England, and WP3 comprised six in-depth case studies of the implementation of FTSUGs at four acute trusts and two mental health trusts. Input from relevant external stakeholders was interwoven throughout in the form of contributions by PPI members and a dedicated PAG.

Chapter 3 Literature review

Introduction

A systematic narrative review of the literature was conducted for two purposes:

-

to identify and examine international research reporting on strategies or interventions promoting ‘speaking up’ practices in the workplace

-

to critically appraise and map key concepts and tensions to inform the development of research tools and to inform interpretation of primary research findings.

A version of the review was published in January 2021. 32

Review question and methodology

The review question was ‘What workplace strategies and/or interventions have been implemented to promote speaking up by health-care employees?’. Consistent with the study’s theoretical orientations (see Chapter 2), the review was underpinned by recent writing on complex adaptive systems in health care. 33,34 A previous scoping review35 identified that this topic area embraces diverse theories and methods across numerous contexts and is, therefore, unsuitable for systematic review approaches involving the formal weighting of independent bodies of evidence. Instead, an acknowledged and widely used systematic narrative review approach was used to ‘tell the story’ from within the literature36 and to deepen the understanding of the review question by interpretation and critique. 37

Searching and screening

Searches were undertaken to include findings on studies of international speak-up interventions designed for workers in all areas of health-care practice and all health-care settings, including education. Grey literature, statutory interventions and regulatory interventions were not reviewed because they were unlikely to contain empirical research reporting the outcomes of speak-up interventions in the workplace (Box 1 gives further information on search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria).

-

Speak*-up OR ‘Speak* up’ AND employee* OR staff OR student* AND train*OR teach* OR educat* OR evaluat* OR implement* OR interven* OR tools OR strateg* OR “pilot test*” OR ‘pilot-test*’

-

Whistle-blow* OR Whistleblow* OR whistle

-

‘raising concerns’ OR ‘raise concerns’

-

‘employ* voice’

-

‘voice concerns’ or ‘voicing concerns’

Databases used: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Social Policy and Practice, ASSIA and Web of Science™ (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA).

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaInclusion criteria: English-language journal articles published in 2008–18 inclusive, reporting any empirical research on interventions designed to promote speaking up or improve teamwork, communication or work culture where speaking up was identified as an outcome.

Exclusion criteria: editorials, reviews, theoretical papers, methodological papers, discussion papers and anything not published in English. Books, book chapters, theses, conference papers and any empirical papers were all excluded where there were no data reported.

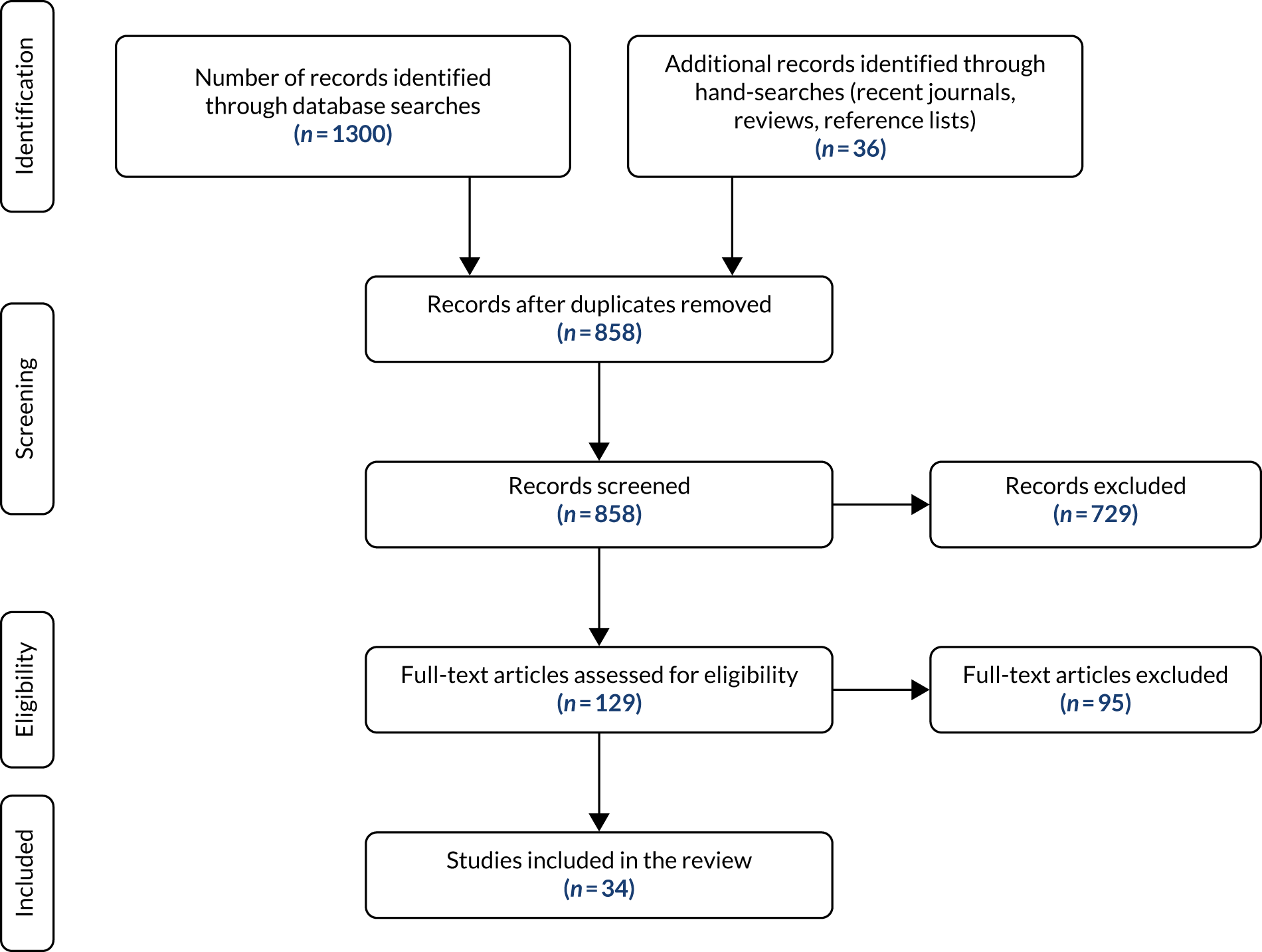

The searches identified 1300 citations, with a further 36 records identified via searches of reference lists or search updates. After eliminating 478 duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 858 records were screened for relevance by Aled Jones and Joanne Blake. Of these, 729 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (e.g. editorials or viewpoint articles rather than empirical research), leaving 129 articles for full-text review. Following full-text review, a total of 34 papers were included in the final review, as shown in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart (Figure 1). Joanne Blake and Aled Jones undertook data extraction, which enabled data analysis and synthesis (see the following section).

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow chart of the paper screening process.

Data analysis

The team’s prior experiences of researching the topic area and undertaking narrative reviews38,39 indicated that an inclusive review of the research would help to identify a range of evidence that best represented the complexities and ambiguities associated with the topic. Although the emphasis was mostly on including rather than excluding papers, the relevant Critical Appraisal Skills Programme frameworks guided the appraisal of papers and resulted in the exclusion of some studies owing to a lack of key information, such as research ethics approvals or data analysis approaches. The review findings were subsequently themed and synthesised by Joanne Blake and Aled Jones, with particular reference to authors’ accounts of the effectiveness of interventions and contextual factors, such as implementation barriers or facilitators. Other members of the team critically reviewed and contributed to the iterative process of identifying themes and synthesising the literature.

The remainder of this chapter describes the types of study design and interventions reported. This is followed by interpretation and synthesis of the findings, taking into account contextual factors40 identified within the studies that influence (for better or for worse) the implementation of employee speaking-up initiatives.

Results

The final 34 publications originated from Europe, Asia and North America, comprising studies using quantitative (n = 23), qualitative (n = 5) and mixed-method (n = 6) methodologies. Three types of intervention feature in the included papers: educational initiatives (n = 5), workplace/workforce training initiatives (n = 17) and workplace initiatives (not involving formal or overt training, or educational input) (n = 12). Interventions were designed as either ‘stand-alone’, focusing on only improving the act of speaking up,41–59 or ‘bundled’ initiatives,60–72 in which speaking up was targeted within a multifaceted intervention aimed at improving teamworking62 or clinical protocols65 (Table 4).

| Type of intervention | Methodology | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Qualitative | Mixed methods | ||

| Educational initiatives: speak-up learning interventions undertaken within universities with undergraduate students | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Workplace initiatives: interventions undertaken within workplaces not involving formal training or educational input | 6 | 5 | 1 | 12 |

| Workplace/workforce training initiatives: mostly voluntary, occasionally mandatory enrolment of employees onto formal training courses, often involving simulated practices and/or teamworking interventions | 14 | 0 | 3 | 17 |

| Total | 23 | 5 | 6 | 34 |

Quantitative approaches were as follows:

-

randomised controlled trials of speak-up interventions, for example simulations41,42 and training programmes60

-

quasi-experiments of speak-up educational interventions for registered nurses and health-care students43,61

-

post-course surveys following safety communication training62 and a speaking-up action exercise44

-

pre- and post-implementation surveys of interventions, including executive walk rounds (EWRs);45–50 various team-based communication tools for use by trauma resuscitation teams, by interventional ultrasound teams, by theatre/anaesthesia teams and during infection prevention practices,51–54,63–67 and an educational intervention and an educational course for nursing students. 68

Qualitative approaches were as follows:

-

interdisciplinary team development using focus group interviews and auto-ethnography55

-

communication and decision-making using observation, audio-recorded meetings and individual interviews69

-

infection prevention using individual interviews70

Mixed-methods approaches were as follows:

-

speak-up teaching and learning activities using a survey, a focus group and individual interviews58

-

a patient safety course for medical students using a survey and written vignettes71

-

an intervention to prevent faculty mistreatment of medical students in learning environments using surveys and focus groups72

-

workplace patient safety initiatives using qualitative interviews, observations and surveys,59,73 including routine hospital data. 74

The following sections discuss indicative conclusions about the effectiveness (or otherwise) of the interventions. Given the large array of interacting and emergent factors that influence whether or not interventions in complex systems are successfully implemented, it is unsurprising that the studies reviewed could not be apportioned into a neat binary of effective or ineffective interventions. 33,34 Instead, the effectiveness of most of the interventions reviewed was indeterminate, that is, some aspects of an intervention resulted in the desired changes but other aspects did not. As a number of others have recently noted,75–77 the success or failure of interventions within complex adaptive systems is rarely ‘all or nothing’; more typically, interventions are partially fulfilled. Based on these insights and informed by narrative reviewing guidance,36 we divide the results into an overview of interventions that were effective, ineffective or indeterminate, followed by a section that synthesises the results to draw new insights and conclusions based on the body of evidence.

Intervention effectiveness

There was significant variation between papers on whether or not and how intervention effectiveness was defined. Some studies lacked pre-implementation baseline measures,44,62 whereas others evaluated effectiveness from self-reported perceptions of intervention participants. 46,50,53 Notably, few studies evaluated change in speaking-up practices within clinical practice contexts, with the majority of interventions undertaken in simulated clinical environments or classrooms.

Many studies reported inconclusive results, and no specific characteristics of interventions and implementation approaches were associated with more positive implementation outcomes. The heterogeneous nature of the interventions and outcomes measured contributed significantly to this. However, in those studies reporting only positive outcomes, it was notable that several involved interventions informed by and targeting multidisciplinary teamworking,42,63–66 although two studies were undertaken with uni-disciplinary teams. 43,72 Although the details of the intervention design are not fully discussed by the study authors, these findings echo previous studies that suggest that increased multidisciplinarity in planning and decision-making is positively associated with successful implementation. 26 A summary of the type and design of the interventions and their overall effectiveness is presented in Table 5, and these are further discussed in the following thematic overview and cross-study synthesis of researchers’ explanations of why, or how, their speak-up interventions were implemented successfully (or not).

| Intervention type | Description | Summary of findings |

|---|---|---|

| Effective interventions | ||

| Workplace/workforce training (standalone) | Team-based communication or teamwork improvement training (with content including ‘speaking up’ skills)63–66 | Pre- and post-implementation survey: statistically significant changes in likelihood to speak up scores |

| Assertiveness-based team training course vs. effective team training course42 | Pre- and post-implementation survey: statistically significant changes in likelihood to speak up scores with assertiveness-based team training | |

| Small-group, multifaceted educational intervention (including personal reflection and peer-support – nursing workforce)43 | Statistically significant change in mean speaking up scores (‘post test’) | |

| Educational (bundle) | Awareness-raising of medical students about processes for speaking up and handling concerns about mistreatment by faculty members during clinical placement plus system for anonymous reporting with timely response and awareness-raising of all participants in learning environment (e.g. administrators and faculty members)72 | Self-reported awareness of speaking up policies and procedures increased from 67% to 100%; stigma of speaking up declined but fear of reprisal remained a major concern for students |

| Indeterminate/partially effective interventions | ||

| Workplace (stand-alone interventions) | Staff forum for team members to speak up about safety concerns69 | Reported success in only 7 out of 25 sites. Difference explained by key leader (physician or practice manager) of the intervention: their engagement in the improvement project and their encouragement/discouragement of discussions within the teams |

| Structured hospital ward-based team debriefing policy (to encourage speaking up about clinical and administrative challenges)55 | Reported increase in confidence that the team could speak up and concerns aired; however, some areas of speaking up were ‘off limits’ (e.g. disputes over legitimacy of some concerns and delving into performance of another team member) | |

| Surgical checklist (as intraoperative communication tool during surgery)67 | Nurses and anaesthesiologists surveyed were significantly more likely to speak up to team members with this tool. However, follow-up interviews raised concerns with perceived intimidation in teams and the possibility of non-deployment of checklists by surgeons not supportive of intervention | |

| EWRs as a means of improving speaking up between senior leaders and ward staff45–50,56,57,78 (developed by the IHI in the early 2000s) | EWRs were intended to provide a structured opportunity for staff to directly communicate concerns during executive visits to clinical areas. Some evaluations noted that staff felt more at ease when discussing errors and reporting safety concerns.46,47,50 Collection of 6 years of longitudinal data by one study50 showed a marked increase from 30% to 90.5% of EWR participants agreeing that their reporting of incidents had increased, and that 96% of issues raised were resolved. Concerns about the fidelity of the IHI model have been reported,57 with some studies unclear about the benefits of local adaptations or derivations from the IHI EWR model. Deviations may result in a culture of ‘checking up’, rather than listening to staff speaking-up about their concerns.57 Some studies report the limited engagement of senior management in the intervention, and with the concerns of front-line staff47 | |

| Workplace (bundled) | Hospital-based, infection-risk prevention initiative including speaking up fostered by interdisciplinary and collaborative adverse event investigations and by interdisciplinary care work (e.g. patient rounds)70 | There were more speaking-up opportunities in hospitals with better infection prevention outcomes (where retrospective learning events were seen as collaborative rather than interrogative). Especially for nurses, interdisciplinary care processes facilitated speaking up where physicians valued collaborative, interdisciplinary care interventions |

| Hospital intervention to improve workplace culture and speaking up (interventions included workshops, forums and online resources)74 | Significant changes in ‘culture scores’ across all hospitals (baseline to 24-months later). Four out of 10 hospitals had no statistically significant or marked qualitative changes in culture. Staff in the six (out of 10) hospitals in which changes were significant reported no fear in speaking up; there were greater decreases in mean risk-standardised mortality rates in these organisations | |

| Patient safety training for medical interns and staff (error communication technique training, presentations by senior staff on their own speaking-up experiences), including speaking-up training to senior team members52 | Post-training self-rated scores of interns showed significant improvement in knowledge and attitudes; no reported effects on behaviours | |

| ‘Empowerment’ workshops for nurses (with specific content on speaking up)60 | Post training, self-reported scores indicated improvements in ‘communication openness’; views of punitive response to errors did not change significantly | |

| ‘Ethical Action Exercise’ with third-year medical students; tasked with one speaking-up intervention during clinical placement44 | Of 111 students completing the exercise, 86% found speaking up difficult. A total of 12 students reported negative reactions | |

| Educational (blended) | Didactic and varied interactive classroom programme for students in professional training (social work) to support students to speak up more to staff during clinical placements plus prompt card to guide students on a six-step speaking-up approach58 | Post-course interviews showed self-reported increase in confidence and support of the prompt card, but the six-step speaking-up approach was expected to be too difficult to implement in practice |

| Ineffective interventions | ||

| Workplace/workforce training (standalone) | ‘Conversational skills’ improvement workshop with anaesthesiologists41 | No significant differences between intervention and control group subjects. Speaking-up behaviours deeply rooted and difficult to change by education alone |

| Educational (standalone) | Inter-professional (undergraduate) training using ‘Crucial Conversations’ to promote psychological safety during error disclosure61 | Ineffective, significantly as a result of ‘negative attitudes towards such inter-professional conversations’61 |

Thematic overview and synthesis of the factors affecting the implementation of interventions

Undertaking thematic analysis within a narrative review entails working with and reflecting directly on the main ideas and conclusions across studies. These will now be discussed under the following themes: Theme 1: workplace culture – hierarchical and interdisciplinary factors and the implementation of speak-up interventions, and Theme 2: Psychological safety and the implementation of speak-up interventions.

Theme 1: workplace culture – hierarchical and interdisciplinary factors and the implementation of speak-up interventions

Definitions of workplace culture routinely refer to an organisation’s hierarchical form(s); its division of labour by organisational locations, departments, units, the sets of roles, tasks and jobs, and the technologies used. 79 It is widely accepted, therefore, that any attempt at nurturing a culture of speaking up in the workplace has to take into account wider organisational factors, including the inter-related issues of workplace histories, power, norms and hierarchies. 27 Indeed, the implementation of speak-up interventions was often explained by researchers as being contingent on the enduring and mostly adverse influence of pre-existing workplace cultures, hierarchies and interdisciplinary tensions.

For example, Balasubramanian et al. 69 described how lead physicians and office managers, who are accustomed to chairing and managing team meetings, refused to relinquish control of meetings to subordinate colleagues during workshops that were designed to encourage speaking up about workplace problems. As a result, team members who attempted to introduce discussion in a less hierarchically mediated way eventually ‘gave up in the face of this tag team opposition’. 69 Even in teams in which lead physicians encouraged team-led discussion, airing problems that might be perceived as encroaching into a physician’s territory were proscribed. Similar interdisciplinary and hierarchical tensions were described by others,55 who explained that regardless of a general sense that ‘things had changed for the better’,55 deeply rooted hierarchical and cross-disciplinary tensions persisted, which resulted in certain clinical concerns, such as clinicians’ performance, remaining off-limits.

A further hierarchical issue that was identified as both an enabler of and a barrier to successful implementation of speak-up initiatives was the perceived support of medical leaders for the intervention. 51,53,55,63,69,70 Robbins and McAlearney70 described how nurses were more likely to implement a speaking-up intervention when physicians ‘clearly valued and encouraged this input’. 70 Ironically, it seems that entrenched interprofessional, hierarchical and cultural attitudes within organisations were insoluble barriers to the successful implementation of interventions designed to tackle such attitudes.

Although workplace cultures and hierarchies were often invoked as contextual explanations for unsuccessful implementation and intervention outcomes, researchers rarely considered pre-existing cultural and hierarchical issues within the wider society. There were, however, two notable exceptions.

Roh et al. 71 described how Korean national culture proved an insurmountable barrier to medical students speaking up about senior doctors’ transgressions. National cultural norms strongly reinforced workplace hierarchies where ‘less powerful people expect their superior to tell them what to do, with dependency on many formal rules or informal customs’. 71 Unsurprisingly, following an educational intervention, low confidence in speaking up to seniors persisted among students, possibly resulting from students ‘feeling confused or even shocked’71 because implementation of the educational package challenged long-standing national cultural norms. Similarly, Oliver et al. 58 acknowledged that the design of their educational programme had not reflected how ‘structural inequalities faced by students of non-hegemonic identities influenced the difficulty of speaking-up’. 58 As one student commented, ‘I am a racialized young woman, and a difficult conversation is just different for me than it is for a cisgendered white male’. 58

There is a dearth of literature focusing on the influence of wider societal intolerances, such as racism or homophobia, on speaking up within health care. This is particularly relevant given the heightened social awareness of barriers to speaking up owing to international social justice movements, such as ‘Black Lives Matter’ and ‘#metoo’. With the exception of the two studies discussed above,58,71 researchers position workplace cultures as existing in isolation from broader societal culture. However, they are not alone, as disregarding the dynamic interplay between the wider socioeconomic-political system and the local organisational setting is a known limitation of many studies and systematic reviews. 40,80 Similarly, others conclude that national cultures have a greater impact than organisational cultures on policy implementation and innovation, but are ‘often overlooked’. 81 Furthermore, although health-care teams often consist of workers from multiple ethnic and cultural backgrounds, the question of speaking up within culturally diverse teams is also overlooked in the literature.

Not representing this level of interconnectivity can threaten the transferability of research findings and of policy recommendations in the future. As a result, future research and reviews should provide detailed descriptions of the context(s) and setting(s) in which studies are carried out and acknowledge the potential for setting–context interplay.

Theme 2: psychological safety and the implementation of speak-up interventions

Psychological safety, an important and conceptually sound construct that is often cited within health policy82 and organisational learning literature, is defined as ‘a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject, or punish someone for speaking-up’, stemming ‘from mutual respect and trust among team members’. 82 A prevailing ‘theory of change’ in the studies reviewed was that the implementation of speak-up interventions would enhance psychological safety, which would result in more staff raising concerns. 41,47,49,50,55,61,63–65,72 However, not all studies proceeded to report the direct effects of their interventions on psychological safety and speaking up. Of those that did,47,49,55,69 the majority reported improved psychological safety in terms of colleagues’ confidence to speak up, while others had little effect41 or more variable success. 42

Negative repercussions for psychological safety were reported when interventions created an expectation of mutual respect among staff, only for this not to materialise. This was particularly apparent in the EWR literature,56,57,71 in which promises made by senior leaders to respond to the concerns of front-line employees were subsequently broken.

The results of some studies41,51,53,55,58,63,69–71,74 also expose a more intricate relationship between psychological safety and mutual respect. For example, ensuring or enhancing mutual respect between workplace colleagues is a prerequisite of psychological safety,82 which unsurprisingly was regularly targeted by many interventions. However, mutual collegial respect can sometimes unintentionally evolve into a barrier to speaking up when manifested as a form of deference to colleagues, based on long-standing professional hierarchical norms or sociocultural customs. 41,51,53,55,58,63,69–71,74

To summarise, we do not question the premise that psychological safety and related values, such as mutual respect, are fundamentally important in optimising conditions for speaking up. However, those designing and implementing interventions to enhance psychological safety need to be cognisant of a fine line between mutual respect and less helpful deference between colleagues, and the difficulties of finding the ‘sweet-spot’ of neither too much nor too little mutual respect.

Discussion

This review demonstrates that health-care researchers internationally are attempting to address difficulties that are associated with speaking up in health care. A disparate range of research designs, academic and professional disciplines, and perspectives informed the studies, including medicine, nursing, social work, human factors, sociology and psychology. Some significant limitations were identified across the papers reviewed. For example, there was very little evidence of researchers critically reviewing and building on extant studies when preparing and designing new projects, with many of the flaws of previous study designs being overlooked. Similarly, researchers rarely placed their findings within broader local, national or transnational policies and contexts. The body of knowledge is, therefore, piecemeal and limited in impact.

The small-scale nature of most studies may be explained by the fact that research funding was seldom declared. Relatively poorly funded research can also result in implementation studies that often fall short of truly understanding how complex socioprofessional systems work. 33 This is evident in many of the papers reviewed, which reflect implicit mechanistic or cognitive-rationalist assumptions about the nature of speaking up. Researchers consistently overlooked how otherwise well-conceived individual components of training interventions (e.g. improved communication skills) are often usurped in practice by complex inter-relationships with pre-existing contextual issues, such as sociocultural relationships, workplace hierarchies and perceptions of speaking up.

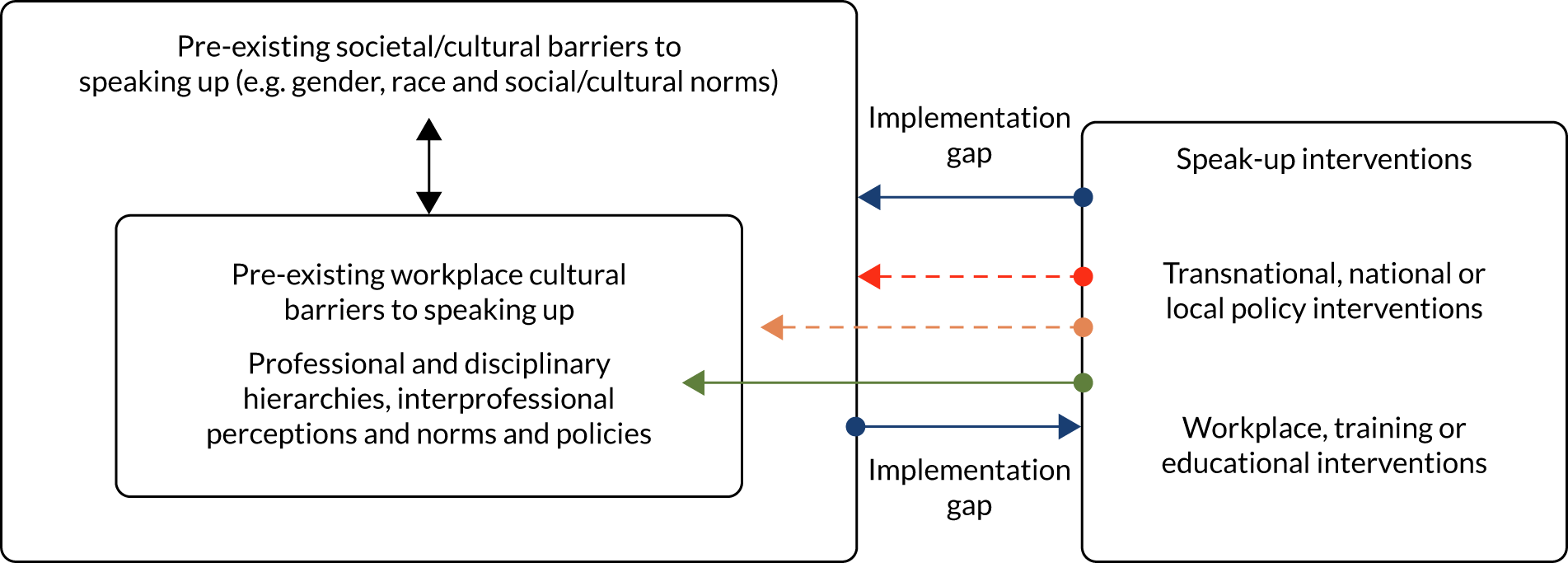

Figure 2, informed by complex systems thinking perspectives and implementation models such as the CFIR,26 presents a nuanced and intersectional model of the forces described that speak-up interventions had to contend with. The model takes into account pre-existing and entrenched inner forces (workplace barriers) and outer sociocultural forces, many of which are present in the NHS and relevant to the implementation of FTSUGs. An intersectional approach refers to the complex ways in which multiple issues (e.g. race, sex and cultural norms) routinely interact to influence everyday experiences of people receiving and working within health care. 83

FIGURE 2.

Iterative model of intersectionality of pre-existing workplace and societal barriers to and their effects on speak-up interventions. This model takes account of the intersectionality of pre-existing societal and workplace culture, which forms a formidable barrier (blue arrows) to the implementation of speak-up interventions in practice. Some interventions successfully bridge the gap (green arrow), others bridge but the effect is variable or weak (amber arrow) and others fail to bridge the gap (red arrow).

There are few certainties within the complex realities of modern health-care practices;84 however, a significant theme in the literature is the global pervasiveness and dominance of workplace cultures that were inimical to speaking-up interventions. Implementing speak-up interventions was reported as immensely challenging work in the USA, Republic of Korea, Islamic Republic of Iran, Canada and England. Regardless of their location, health-care researchers and policy-makers who are interested in improving employee’s freedom to speak up will have to overcome pre-existing complex societal and workplace norms, which are often long standing in nature.

To the best of our knowledge, this narrative review is the first to locate the evidence within broader health systems and a policy context, and to adopt a complex systems perspective that is currently lacking within systematic review literature. 40 Doing so results in a better understanding of ‘speaking up’ as an action that has emergent and dynamic properties within a ‘messy’ system, rather than as fixed entities and stable properties. We problematise certain aspects of psychological safety that have been left unexplored in other reviews;85 in particular, we discuss the concept of mutual respect and how the closely related issue of deference can be a significant barrier to speaking up. Furthermore, we have shown how the complex interplay between societal/cultural values and societal/cultural norms affect speak-up intervention, although this was largely unexplored within the evidence reviewed.

-

Additional academic papers may have been published during the long process of peer reviewing and publishing this report.

-

Studies were conducted in higher-income countries, and the factors influencing speaking up may be different in lower- and middle-income countries.

-

The papers reviewed were published in English-language journals, excluding studies published in other languages.

-

The search strategy may have missed relevant studies that used different sets of terms or different words in the title or abstract.

Summary and conclusions

While noting the limitations of the review (Box 2), the review presents a critical overview of factors that could assist policy-makers and researchers when developing interventions to support speaking up in the health-care workforce. We recommend that future developments are based on a meaningful collaboration between a range of stakeholders from diverse cultural backgrounds and workplaces, including researchers, policy-makers, service users and practitioners. One enabler of meaningful collaborative working is adequate research and development funding to properly resource various stakeholders, meetings and equipment. We also recommend, therefore, that speaking-up research (and related engagement and research impact activities) be prioritised in the allocation of research funding.

Recommendations for future research include the need to consolidate and build on existing knowledge and to better situate studies within complex local and national contexts and culturally diverse workforces. In addition, more studies of speaking up in health care within low- and middle-income countries would address a significant gap in the literature and provide better understanding and solutions to meet the demands therein. Our review findings can facilitate the implementation of new policies as it surfaces conditions that may counter efforts to create more open speak-up cultures in health care. However, there is unlikely to be a one-size-fits-all approach to creating such a culture.

Chapter 4 Telephone interviews with Freedom to Speak Up Guardians

This is the first of three chapters presenting empirical findings. This opening chapter focuses on findings from national telephone interviews undertaken with FTSUGs (also referred to as Guardians), followed by findings from in-depth case studies (see Chapter 5) and a final chapter consisting of cross-case findings (see Chapter 6).

The following research objectives are addressed in this chapter:

-

assess the scale and scope of the deployment and work of FTSUGs

-

assess how the work of FTSUGs is organised and operationalised alongside other relevant local and national roles with responsibilities for managing concerns

-

identify barriers to, facilitators of and unintended consequences associated with the implementation of FTSUG role.

As outlined more fully in Chapter 2, interviews (n = 87) were undertaken with Guardians working in acute trusts and mental health trusts across NHS England. The following sections provide insights into the demographic details of the FTSUGs interviewed, how they were appointed and the effects of implementation decisions, particularly regarding time and resource allocations, on the work of FTSUGs. The availability of resources is considered to be a tangible and an immediate indicator of organisational commitment and readiness to implement an intervention. Indeed, the level of dedicated resources is positively associated with implementation, but is not necessarily sufficient to guarantee success. 26 Being unprepared or unrealistic about the effort required to implement change has also been shown to demotivate and anger staff. 86

Freedom to Speak Up Guardian: one title, many roles

The age, ethnicity and sex of the Guardians who were interviewed closely mirror the NGO annual survey results,18 with Guardians mostly consisting of white women (n = 75) aged 45–64 years (n = 58) (see Appendix 2). Although the FTSUGs who were interviewed ranged from entry-grade professionals (band 5: £25,000–30,000) on the NHS ‘Agenda for Change’ pay scale to very senior managers (earning > £100,000 with board-level responsibilities), most Guardians (n = 44) interviewed were working at middle-ranking management bands 7 and 8a.

Surprisingly, given the extensive and challenging remit of the FTSUG role, as outlined in Chapter 1, the majority of Guardians (n = 55) who were interviewed were allocated ≤ 2 days to undertake the role, with most allocated ≤ 1 day (n = 44); only 11 out of 87 worked as full-time Guardians (see Appendix 3). Furthermore, most Guardians (n = 59) undertook the FTSUG role alongside a range of clinical (e.g. nurse specialist, radiographer and physiotherapist) or non-clinical (e.g. HR or OD practitioner) roles, whom we refer to as ‘adjunct’ FTSUGs. The remaining 28 Guardians who were interviewed occupied no other role within the trust and were appointed as part-time or full-time FTSUGs; we refer to them as ‘stand-alone’ Guardians.

From the outset, it is clear that there is much variation in terms of both those undertaking the role (their seniority, disciplines and skills) and the implementation decisions related to the role. At one extreme of implementation variation are the full-time ‘stand-alone’ FTSUGs, who are supported (as will be demonstrated later in the chapter) by administrative staff, external supervision and an independent budget. At the other extreme is the ‘adjunct FTSUGs’, who are allocated no time, or any supporting resource, while undertaking the role alongside a substantive full-time role.

The effects of such implementation variation on the practical fulfilment of the role are considerable, and an attempt to unpick this is the focus of much of this report. Nevertheless, a fundamental point to consider at this stage of the report is that the role title ‘Guardian/FTSUG’ has rather inexact and ‘fuzzy boundaries’,87 which makes precise ‘like-for-like’ comparisons across trusts difficult. The origins of such variation are embedded within the FTSU report,12 which offers little implementation guidance for trusts other than ‘Boards should decide what is appropriate for their organisation’ (© Francis R, 2015. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.0). 12 The assumption that trust boards know what is ‘appropriate for their organisations’ requires further scrutiny given the evidence that points to significant contrast between NHS senior managers’ perceptions of raising concerns and the problematic realities encountered by workers. 88

The following extracts from the telephone interviews demonstrate that pre-implementation decisions within some trusts were often poorly thought-out or were based on assumptions that proved unsustainable once the FTSUG role was implemented:

Implementing the role was a bit of a kneejerk reaction. Not enough thought went into although full of good intentions. Lots more work than expected and not enough time to do it.

r64

When I started I was told by senior management to expect only one or two concerns a year. In reality the number is very different.

r08

Although the NGO produced guidance for the FTSUG role,15–17 which is discussed at length in Chapter 6, the prevailing approach adopted during the role’s implementation was for boards to decide what was appropriate. Throughout this chapter, and elsewhere in the report, we return to the various NGO guidance as we track the implementation of the FTSUG role through different local organisational structures, systems and processes.

To summarise, there was little in the way of shared understanding and coherence across trusts about how to implement the role. Variations in time and banding allocated to the role could be the result of some boards carefully and optimally tailoring the role to fit the conditions ‘deemed appropriate for their organisation’. However, there is also evidence of knee-jerk implementation of the role and unrealistic expectations, with marked differences in implementation across organisations of similar size, function and CQC rating. Nonetheless, the majority of trusts believed that it was feasible and appropriate to appoint one person, allocated little or no extra time alongside a substantive role, to address the challenging prospect of supporting cases of speaking up, while simultaneously building a trust-wide culture of openness. The following comment neatly summarises the views of many FTSUGs:

Speaking-up is couched as an issue and solution which concerns organisational culture but it’s certainly not possible for one individual to change culture of one organisation that is part of a complex system.

r06

Selection and appointment of Guardians

Ensuring the careful selection and appointment of FTSUGs would appear to be particularly important, given the contested nature and long-standing problems of speaking up in the NHS and the ambitious culture change remit associated with the new role. The only reference made to selecting and appointing FTSUGs in the FTSU review, however, states that the person should be appointed by the organisation’s chief executive officer (CEO) to act in a genuinely independent capacity.

Trusts chose very different approaches to appointing Guardians, varying from open and democratic approaches to closed and obscure selection processes that favoured those already known to decision-makers. Most Guardians (n = 54, 62%) were appointed following a formal and competitive recruitment process, culminating in a selection interview:

I applied following an external advert. It was the most stringent process and toughest interview I’ve ever been through. Very senior people interviewing.

r36

Some trusts deployed a democratic/participative recruitment process that involved employees in initial recruitment decisions, such as the following process in which employees’ views also informed implementation decision-making:

Staff were asked did they want an internal candidate, did they want it bolted-on to an existing role or to be a substantive role. The board agreed to go with whatever decision was made, which was an externally appointed person in a full-time role.

r33

Interestingly, whenever the broader workforce was consulted, their decision was for a full-time FTSUG role to be externally advertised and appointed following a formal interview process. On each of these occasions, an external applicant was appointed.

By contrast, other trusts (n = 33, 38%) opted to appoint Guardians via closed, informal and opaque recruitment processes, often following a personal approach from a senior manager or a board member:

The trust secretary suggested I submit an expression of interest. I then met with them and the board chair and they offered me the role.

r85

I created the job following a discussion with the CEO. I wrote the job description and was seconded to set up the role and remained when it became a substantive post.

r45

Several respondents reported being ‘tapped on the shoulder’ (r32) as a direct result of their current or previous roles within the organisation. Those working in ‘patient complaints’ or ‘staff liaison’ roles were often approached because they were regarded as offering ‘a good fit, they said I was already talking confidentially to staff and raising concerns with senior managers’ (r74).

Others described how they were informed when interviewed for a substantive role or soon after appointment that the remit of their new role included being the Guardian. A newly appointed director of nursing explained that she was unexpectedly ‘advised that I was the Guardian on my second day’ (r35). Importantly, none of these unexpected and retrospective appointments was allocated any time to undertake the role.