Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/144/29. The contractual start date was in July 2017. The final report began editorial review in April 2022 and was accepted for publication in November 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final manuscript document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Spilsbury et al. This work was produced by Spilsbury et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Spilsbury et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

In England and Wales, an estimated 425,000 older people live in circa 18,000 care homes. 1 The care home population represents the oldest and most vulnerable groups in society. Older people are entering care homes later, approximately 70% are living with cognitive impairment2 and 76% requiring assistance with mobility. 3 People now living in residential homes (care homes without nursing) would likely have been in nursing homes (care homes with nursing) 5–10 years ago. Nursing homes today provide care once delivered in acute hospitals. 4–7 This is due to increase in chronic progressive conditions that require more intensive care and resources, changes in the role of care homes to manage acute patients following a hospital admission (step-down care) and to prevent an admission to hospital (step-up care). 8 Care homes deliver end-of-life care for many. 9,10 This complex mix of residents shapes the type and level of care and services required. Change will continue as the social care system responds to financial constraints and reduced healthcare support to care homes.

Staffing is the largest operating cost for care homes11 and the quality of care provided within care homes is contingent on the nursing and direct care support workforce – a resource that homes struggle to recruit and retain. 12,13 The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has exacerbated the pre-existing effects of the variation in staffing between and within homes. 14 This study was commissioned in part due to the lack of understanding about factors influencing variations in direct care staffing and turnover, and the impact on residents and relatives, staff and healthcare resources. Previous studies commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) focused on the interface between care homes and the healthcare inputs needed for equitable and optimum care. 15 Our study is unique in that its focus is on direct care staff employed within the care home and the ways in which deploying this workforce and its skill mix impact on quality. This study was commissioned at the same time as a study on the relationship between workforce employment conditions and training, Care Quality Commission (CQC) quality ratings and the health- and care-related quality of life of care home residents. 16

At the time of reporting – 2 years after the first cases of COVID-19 were detected in the UK – there is increasing recognition of the pivotal role of care homes in supporting older people and meeting their long-term needs in ways that reflect their preferences for care and support. 17 Understanding how best to provide care and support for residents through effective use of human resources in homes is societally and politically important. Ensuring quality for care home residents is the subject of ongoing international debate involving the public, policy-makers, commissioners, providers, clinicians and researchers. 4,18 The government recognises the role of social care staff and the need to recognise, reward and invest in development of this workforce. 19

We consider below the care home context and its workforce, the concept of quality for this setting and previous studies of the staffing–quality relationship.

Care homes and the direct care workforce

Care homes are not part of the NHS; they are independent organisations, including for-profit chains, not-for-profit third-sector organisations and privately owned homes or companies with only a small number of homes. 20 Care in this sector is funded through a mix of self-funding, means-tested support from local authorities and continuous healthcare funding from the NHS. Over one-third of people living in care homes pay (in full or in part) for their own care; others are supported by public funding (local authority, NHS continuing care or through some combination of local authority, charity and NHS support). 21 Self-funding residents are reported to pay higher fees compared to those funded by local authorities and this price differential is perceived by many as unfair and predicted as unsustainable for future care provision. 20,22

Care homes in England (the context for this study) include homes with nursing (or nursing homes), without nursing (or residential homes), or both (dual registered homes). There is considerable overlap in dependency levels and care needs among residents in care homes with and without nursing. 5 However, important differences exist in the workforce in different types of care homes.

In homes with nursing care, registered nurses (RNs) are employed around the clock to supervise care delivery which is mainly provided by a large workforce of non-registered care staff, also known as care support staff or care assistants (CAs). RNs in these homes will provide clinical care and support and liaise with other healthcare professionals on behalf of residents. In care homes without nursing, the workforce comprises only social care staff. The NHS provides healthcare input (including nursing care) on an ‘as required’ basis. Registered NHS nurses may be involved in supporting specialist care for residents in both types of care homes (e.g. palliative care). Care staff in either of these settings (with and without nursing or dual registered) are employed at different levels (e.g. as CA, senior CA or nursing assistant). While not registered with any professional body (e.g. the Nursing and Midwifery Council), many of these social care staff possess vocational qualifications or have completed the Care Certificate. 14 In recent years (from 2019), the nursing associate role has been introduced into the sector. 23 Nursing Associates work alongside RNs, taking on some clinical skills previously undertaken solely by RNs.

The most recent Skills for Care report provides a detailed profile of the care home workforce (2020/21):14

-

there are 470,000 direct care staff in care homes with and without nursing;

-

there are 31,000 RNs in care homes with nursing;

-

there has been a significant decrease (33%) in number of RNs in the sector since 2012–3;

-

there are high turnover rates of RNs and care support workers;

-

vacancy rates are high in the sector with the highest vacancy rates for registered managers;

-

the majority of the workforce identify as female (82%) and were more likely to work in direct care roles (83%) than in managerial roles (79%);

-

over one-quarter (27%) of workers are aged 55 years and over;

-

the social care workforce is more diverse (21% ethnic minorities) than the general population (14%).

Staffing profiles and establishments vary across provider organisations due to funding arrangements and geographical location. This variation means studying care homes and those who work in them is complex.

Quality in care homes

Quality – as a concept – is similarly complex: it is contested and dynamic. Several formulations are both possible and legitimate and individual stakeholder perspectives shape its definition. In the care home context, these perspectives include residents, relatives, care home staff, NHS staff, provider or commissioning organisation, regulatory bodies and policy-makers. The ways in which quality is measured, monitored and reported in care homes is a topic debated internationally and difficulties arise because of the diverse range of views, values, expectations and preferences held by these different key stakeholders.

In England, care home quality is regulated by the CQC. CQC conduct inspections and award publicly available ratings of care homes. Quality ratings are based on inspectors’ assessment of evidence gathered using five key lines of enquiry (KLOEs): ‘safe’, ‘effective’, ‘caring’, ‘responsive’ and ‘well led’ (see Appendix 1). Inspectors use four sources of information: (1) CQC’s ongoing relationship with the provider; (2) ongoing local feedback and concerns; (3) pre-inspection planning and evidence-gathering; and (4) the inspection visit. An overall rating is aggregated from ratings for each of the KLOEs, with ratings awarded on a four-point scale: ‘outstanding’, ‘good’, ‘requires improvement’ or ‘inadequate’. 24 In 2021, 85% of residential homes and 78% of nursing homes were rated as good or outstanding. 22 The frequency of CQC inspection visits varies depending on a care home’s rating, but care homes may be inspected at any time. 24 Local authorities and commissioners ensure that care homes they work with are fulfilling their statutory and contractual responsibilities, but this information is not publicly available.

Understanding the staffing–quality relationship in care homes

Two dimensions of quality need to be considered in this context: quality of care and quality of life. While the nature and characteristics of the care home workforce, and their approaches to care, are likely major determinants of quality, research into the staffing–quality relationship is comparatively scarce – when compared to acute health care. There is some evidence that care home staff have an impact on satisfaction. 25,26 The measurement of quality in homes (with an emphasis on staffing) has predominantly focused on clinical outcomes: pressure ulcer prevalence, falls or medication errors. Evidence, mainly from North America, suggests ‘inadequate’ staffing levels in care homes reduce quality and that the numbers – rather than skills – of workers improve quality. 17,27 These findings must be treated cautiously as they are drawn mainly from cross-sectional studies, are inconsistent, involve non-contemporaneous data sets and assume staffing and quality are linearly related. Most extant longitudinal studies which have attempted to address these limitations have been conducted in North America. 27,28 There are no previous studies on the relationship between nurse staffing and quality in English care homes. Previous analyses of care homes in England found quality was positively correlated with staff retention and a significant negative relationship with job vacancies;29 and that a deficiency in staffing could lead to care home closure. 30 More recently, Towers et al. 16 identified that improving working conditions (such as wages and training) and reducing staff turnover are associated with increased quality and outcomes for care home residents.

Our mixed-method (QUAL-QUANT) parallel design study builds on existing work and addresses some of the methodological challenges associated with understanding the staffing–quality relationship, using a theoretical framework31 to understand quality through structures, processes and outcomes.

Chapter 2 Study aim and objectives

The aim of the Staffing Relationship to Quality in care homes (StaRQ) mixed-methods study was to investigate the most effective workforce models of nursing and care support in care homes for the sustained benefit of residents, relatives and staff.

Study objectives were to:

-

describe variations in the characteristics of the care home nursing and support workforce [work package (WP) 1];

-

identify the dependency and needs of residents and relatives in care homes and their association with care home staffing (WP2, WP3);

-

examine how different care home staffing models (including new roles) impact on quality of care, resident outcomes and NHS resources (WP1, WP2, WP3);

-

explain how care home workforce (numbers, skill mix and stability) might meet the dependency and needs of residents (WP1, WP2, WP3, WP4);

-

explore and understand the contributions of the nursing and support workforce (including innovations in nursing and support roles) in care homes to enhance quality of care (WP1, WP4);

-

translate methods used for modelling the relationships between staffing and quality to provide a platform for sector-wide implementation (WP5).

Chapter 3 Methodology and methods

Donabedian’s theoretical framework31 of quality (focusing on structures, processes and outcomes) framed our understanding of the relationship between care homes’ workforce and quality for residents. Structure is the (relatively) stable features of the organisation that affect its ability to deliver care and services. Process is the interactions between provider and consumer; what is done for and with residents by the provider. Outcomes are those end results attributable to antecedent care.

Quality is complex, contested and dynamic; several definitions are possible and legitimate. Individual perceptions, values, expectations and preferences in the care system all shape the concept. The care home system includes residents, relatives and care home staff, as well as external health and social care providers: NHS staff, commissioning organisations, regulatory bodies and policy-makers. Quality is further complicated as homes must address both quality of care and quality of life. Our mixed-method (QUAL-QUANT) parallel design study was designed to address the complex nature of quality; it was viewed broadly, and our five interlinked WPs – involving literature reviews, quantitative analysis, documentary analysis and qualitative fieldwork – sought to unpick structures, processes and outcomes from a variety of perspectives.

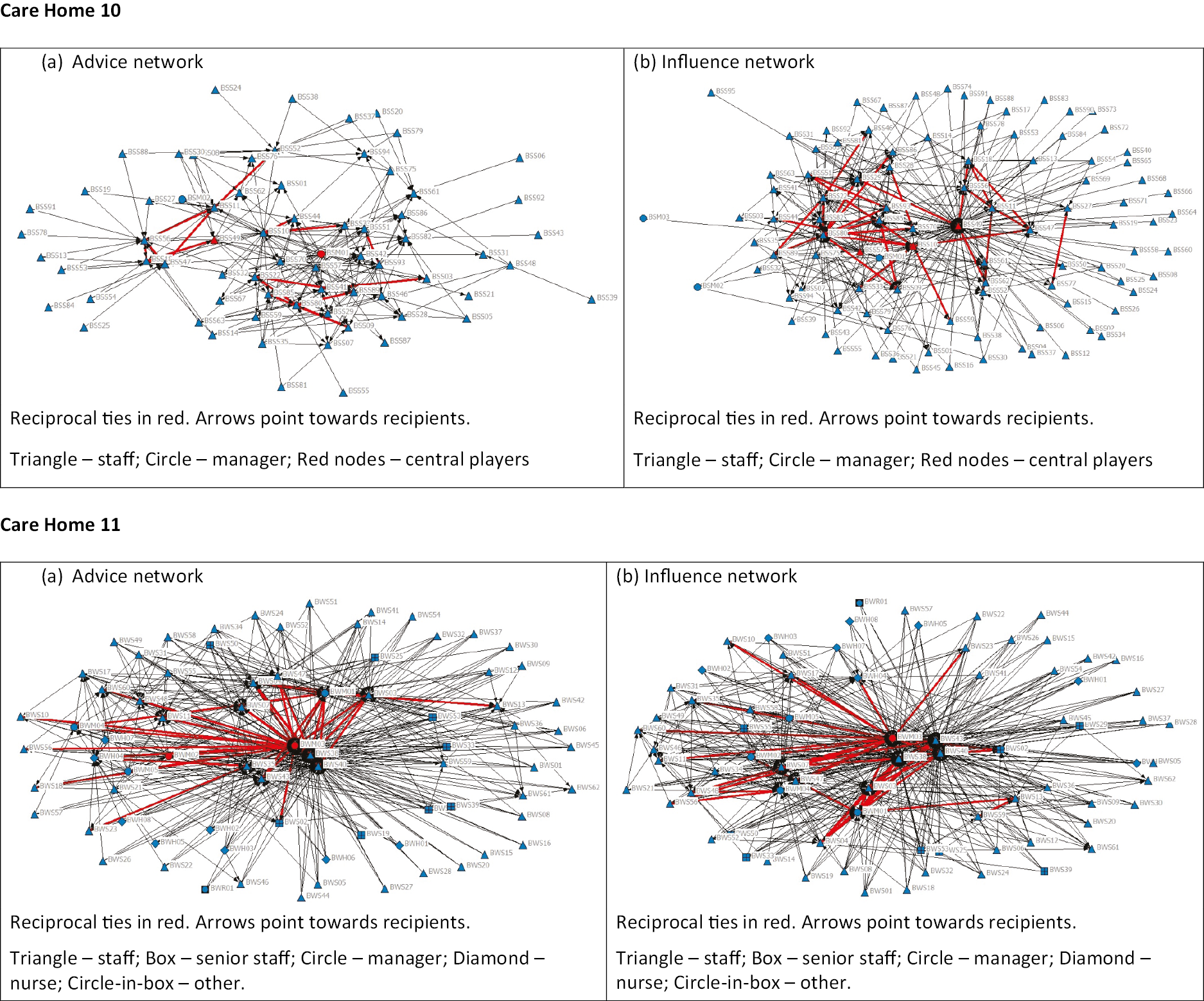

Work package 1 highlights the care home workforce context for quality by (1) reviewing descriptive research into the roles and responsibilities of RNs and CAs and (2) a realist review generating and outlining theories of how and why workforce is related to quality in care homes. In WP2 and WP3 we used routinely collected measures of staffing and examined (longitudinally) the relationship of these to measure of quality (outcomes). WP3 also examines the costs of quality – to care home providers the wider impacts of variable quality on the health and social care system. In WP4 we analysed CQC inspection reports of homes rated outstanding or inadequate, to develop understanding of how (1) care homes ensure a workforce to support people living in care homes and (2) the workforce enhances quality for residents. WP5 constitutes an important translational phase; we explore the advice and influence networks between home staff and ‘readiness’ for implementing innovations.

Our study was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, deviations from our original protocol were necessary (see Appendix 2). We used alternative methods wherever possible to address our original study objectives.

Work package 1: determining the characteristics of the care home workforce and understanding quality

Two literature reviews were conducted.

Work package 1i: roles and responsibilities of the care home workforce linked to quality

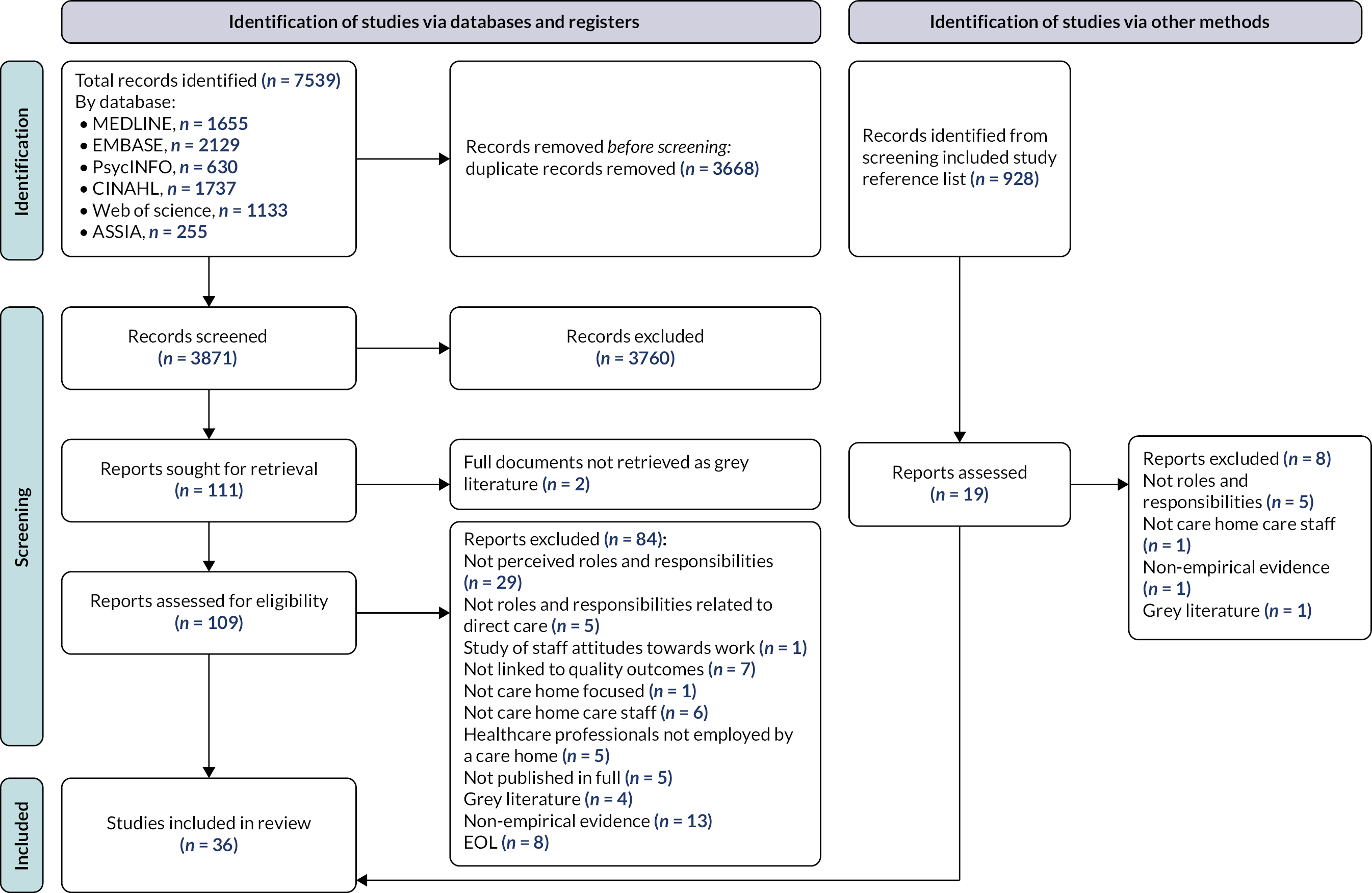

A systematic review synthesised studies of care home staff (RNs and CAs) perceptions of their role. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO. 32

Data sources

Search strategy and information sources

A search strategy was developed with an information specialist in February 2021 (see Appendix 3). Text words and subject headings (where available) were used. Limits applied to the search included a date limit (2010 onwards) and English language. This date restriction was applied to ensure the evidence reflected the current practice of staff in care homes. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE I ALL (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), APA PsycINFO® (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), Web of Science (all databases, Clarivate) and Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (ProQuest). The database search identified 3871 records.

Study selection

Search results were imported into Rayyan (https://rayyan.qcri.org/). Two reviewers (RD, KH) independently screened all titles and abstracts, assessing against the inclusion/exclusion criteria (Box 1). This process ensured the criteria were consistently applied. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion (RD, KH) or by including a third reviewer (KS). The full articles of included papers (n = 109) were retrieved, and two reviewers (RD, KH) confirmed study eligibility (n = 25). The reference lists of included studies were also screened: 11 additional studies were included. The review includes a total of 36 studies (see Appendix 4).

Inclusion criteria – studies needed to meet all of these criteria to be eligible:

-

staff employed by the care home (RNs and care staff)

-

staff describing their roles and responsibilities related to general day-to-day care and life for residents to live well

-

links established between roles and responsibilities and residents’ quality of care or quality of life

-

reporting original research

-

published in full, and in English between 2010 and 2021

Exclusion criteria – the study focus was on:

-

the care home manager, who has a broader role than direct care for residents

-

staff employed in care homes but who do not provide direct care for residents (e.g. housekeeping or catering staff)

-

healthcare professionals who are not employed by a care home but who may visit the care home to provide care for residents (e.g. RNs working for community nursing teams)

-

temporary staff employed by agencies who intermittently work in a care home

-

staff experiences and attitudes towards their work

-

end-of-life care

-

non-empirical (such as opinion or discussion articles) published prior to 2010

Data extraction

Data on author, year, study location, study aim, study rationale, theoretical framework, research question, participant characteristics, study setting and data collection and analysis methods were extracted. The review question guided extracting data from the results and discussion sections of included studies. Results of interest were staff perceptions of their roles and responsibilities that contributed to quality: we were interested in both quality of care and quality of life because of the care context. Links between roles and responsibilities and qualities could be explicit or related to concepts indicating quality. For example, relationships or dignity were considered indicators of quality of life and identifying and recognising deterioration in residents were indicators of quality of care. Data were extracted and organised for results using three worksheets in Microsoft Excel to extract data for studies focused on (1) CAs, (2) RNs and (3) both CAs and RNs. Data were extracted by one reviewer (RD or KH) and checked by the other (RD, KH). Discrepancies were discussed with a third reviewer (KS). Included studies were those where authors made explicit links between staff responsibilities and quality of care and life, or made links to a concept or concepts.

Quality assessment of studies

Studies were quality assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). 33 Two reviewers (RD and KH) independently screened and assessed methodological quality. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (KS). We did not exclude studies based on quality assessment, but we were able to appraise the quality of evidence available to address our question. See Appendix 5.

Data analysis

We used content analysis:34 this approach supports analysis of large amounts of text data. There were four stages to our analysis: (1) familiarisation with the data; (2) organising data into meaning units; (3) coding data to higher level themes; and (4) refining higher level themes. One researcher (RD) iteratively coded data relating to roles and responsibilities and quality of care and life. Coding was developed for different roles: RNs and CAs. Organising data in this way supported comparative analysis so that we could identify similarities, differences and patterns in roles and responsibilities. We ensured an audit trail of the review process to enhance transparency. A team of three researchers was used for analysis and interpretation.

A narrative synthesis of our analysis is presented in Chapter 4.

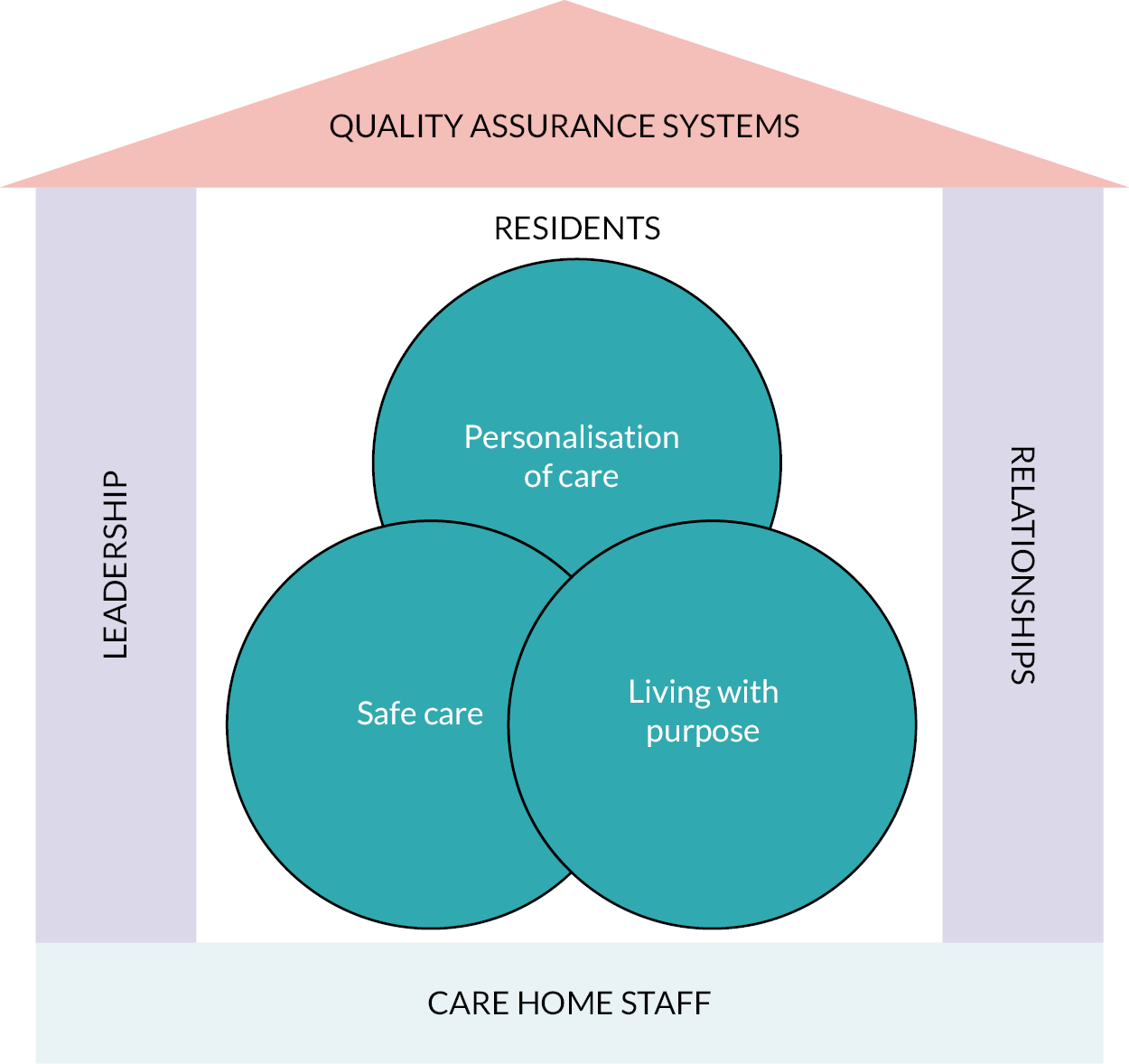

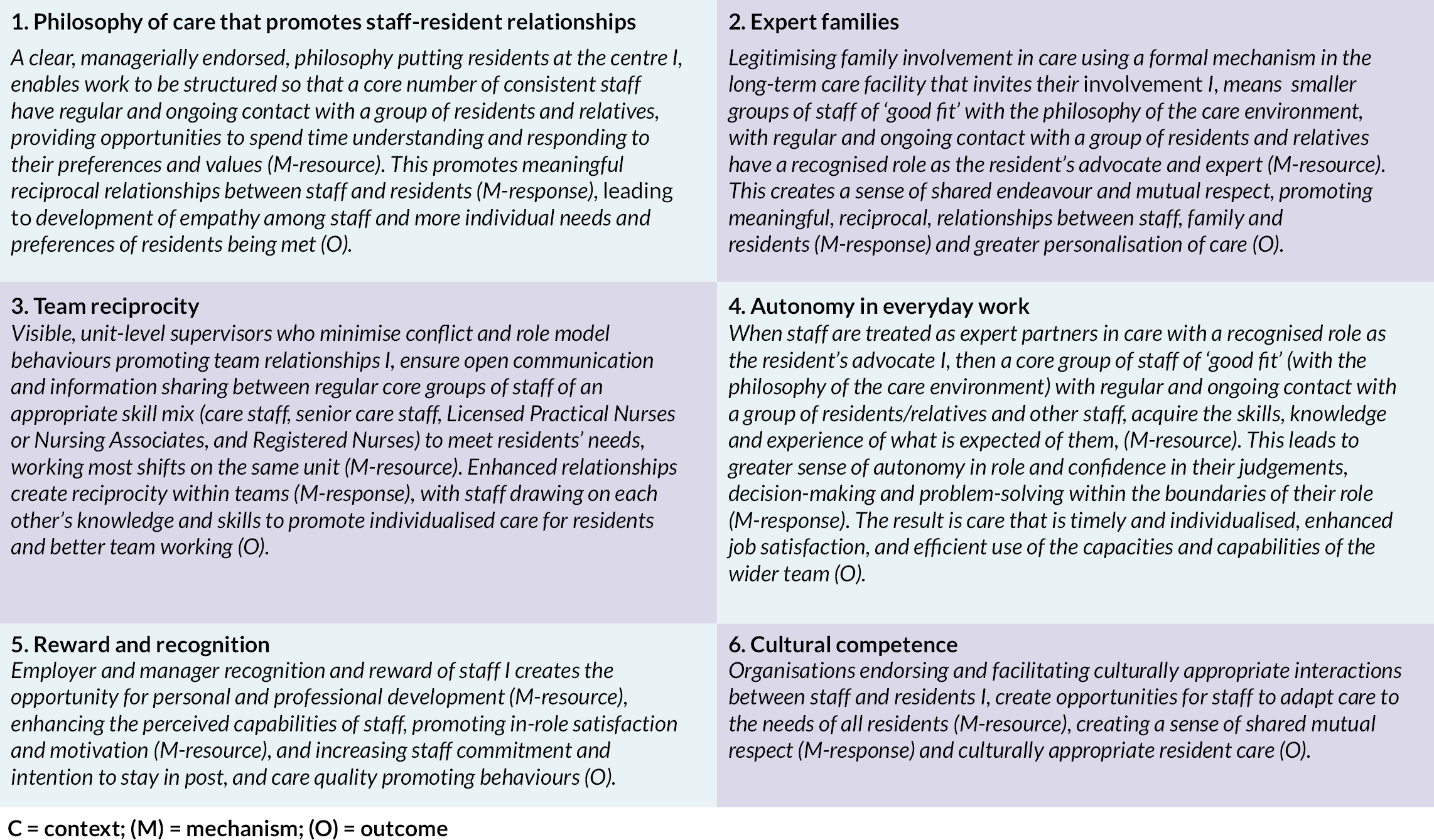

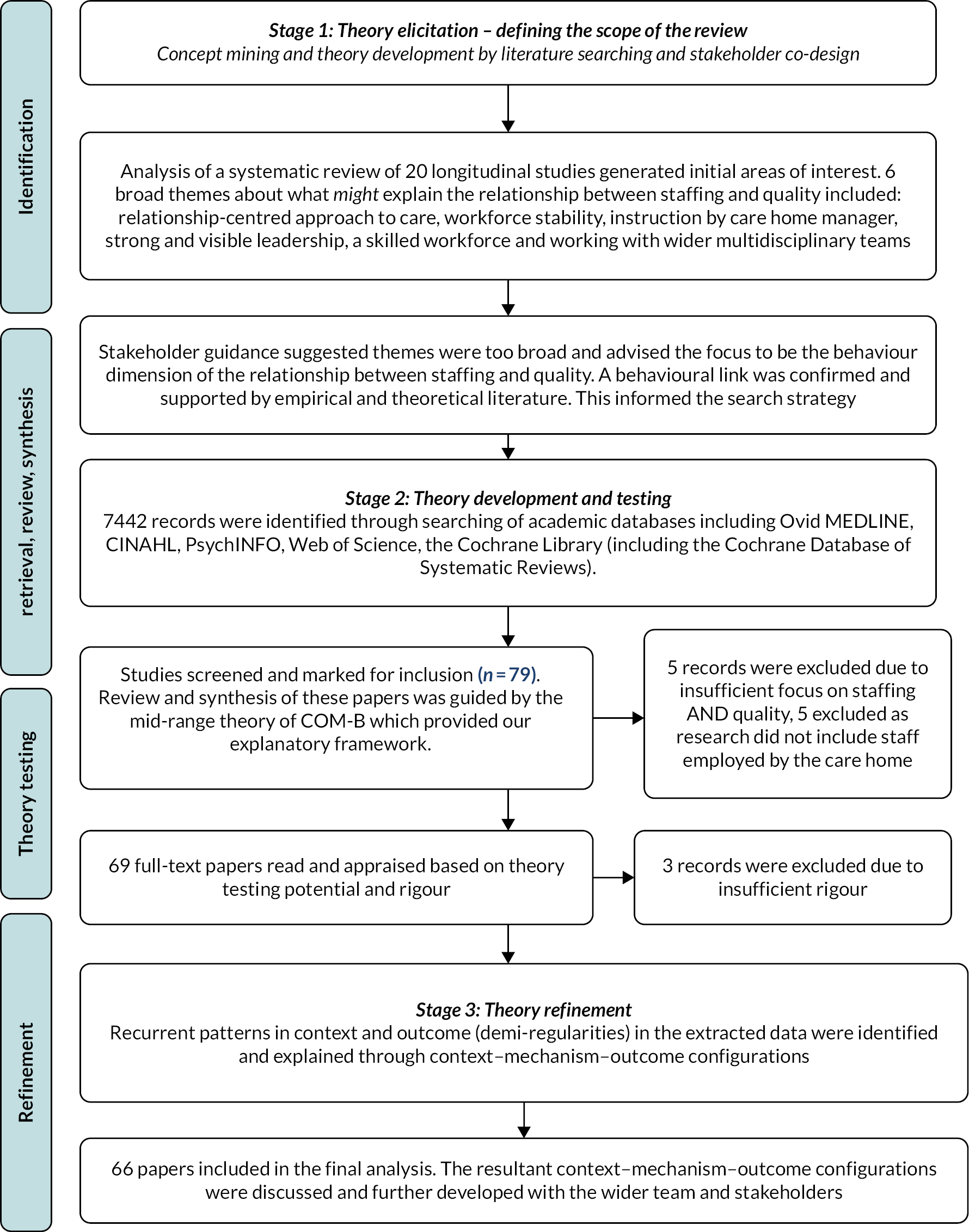

Work package 1ii: care home staff behaviours for promoting quality of resident experience

Our realist review developed evidence and theory-based explanations of how care home staff promote resident quality of care and quality of life, why and in what circumstances. 35,36 Theories were developed in three stages: (1) elicitation, (2) development and testing and (3) refinement. Consultation with residents, relatives, staff, providers, commissioners, regulators and policy-makers ensured sense-checking of our theories and improved our explanation and analysis. 37,38 See Appendix 6 for review process.

The review protocol was registered with the Research Registry (registration number 1062: https://tinyurl.com/mxt8s2h6). RAMESES reporting standards guided our review processes. 36 Our methods have been published by Elsevier Ltd, Crown Copyright © 2021;39 permission is granted by Elsevier for use in this report.

Stage 1: theory elicitation

Defining the scope of the review: concept mining and initial theory development

This stage provided the structure and framework for exploring and synthesising diverse research. 40 First, the most recent systematic review of the relationship between staffing and quality27 was used to develop preliminary explanations by identifying key concepts and theories. Six ‘If–Then’ statements41 derived from the included studies, were further mined to develop ideas and assumptions about how and why staffing influences quality (see Appendix 7). We used these statements to articulate programme theories containing possible social rules, values or sets of interrelationships38 that might limit or trigger programme mechanisms and their linked outcomes.

In line with Pawson et al. ,40 our programme theories were iteratively scrutinised and agreed with stakeholders to refine review scope. We had two stakeholder groups: (1) care home residents and relatives (n = 5) and (2) care home managers (n = 7). Each group met three times during the review period. In the first meeting, residents and relatives directed us towards one area: how everyday human interactions that occur between staff and residents shape residents’ experiences of care. In the words of stakeholders, ‘how staff made residents feel’. Care home managers confirmed the importance of this link. Staff behaviours became a key concept (theory area) linked to ‘quality’.

Mapping staff behaviours against research-reported staffing model characteristics and quality outcomes42–44 confirmed the working hypothesis. By way of illustration, in one qualitative study, behaviours such as ‘getting to know the resident’ and ‘treating residents like their mum or dad’, generated resident ‘joy’ and ‘satisfaction’. 45 These behaviours became the focus for our review and theory development.

To frame our review and help isolate key behaviours and associated triggers, we used Michie et al. ’s COM-B theory. 46 COM-B suggests behaviour results from three interacting components in people or teams: capabilities (the psychological or physical abilities of people to enact behaviours); opportunities (the physical or social environment that enables behaviours); and motivations (reflective and automatic mechanisms that activate or inhibit behaviour). Using COM-B and bespoke data extraction forms we coded data from studies on staffing and quality as capabilities, opportunities, motivations or behaviours. Demi-regularities, or patterns, then provided the basis for context–mechanism–outcome configuration development. 35 By the end of stage 1, our review questions had evolved to become:

-

What staff behaviours influence care home residents’ experience of quality?

-

What influences the behaviour of care home staff?

-

What impact does the interaction between staff behaviours and context have on care home residents’ experience of quality?

We sense checked our review questions in stakeholder meetings where the importance of the multilayered relationships staff had with those they care for and work with and how these relationships influence staff behaviours and quality as experienced by residents was highlighted.

Stage 2: theory development and testing

Search, appraisal, extraction and synthesis of evidence

This stage involved systematically searching, appraising, extracting and narratively synthesising evidence to test and develop emergent programme theory from stage 1. 40

Search strategy

With an information scientist, we designed an inclusive search strategy to maximise data for extraction around three central concepts – long-term care facilities, staffing and quality – and searched a range of databases from inception to November 2019 (see Appendix 8). To minimise the risk of missing eligible studies we additionally: (1) consulted experts from the research team members’ networks; (2) forward citation matched; and (3) scanned reference lists of identified papers.

Selection and appraisal of documents

Search results were saved, managed and duplicates removed using EndNote. Titles and abstracts of the retrieved papers were screened for inclusion by the study team (KH, KS, CT, BH, AA, DV).

Studies were included if they:

-

addressed the relationship between staffing models and quality (quality of life and/or quality of care);

-

took place in a care home context;

-

explicitly focused on quality or, implicitly, accounts of quality similar to our working model of quality based on ‘how staff make people feel’;

-

addressed capabilities, opportunities, motivations and/or behaviours.

Studies were excluded if they:

-

did not focus on staffing AND quality;

-

were not research, that is unsystematic approach to inquiry;

-

were not conducted in care homes;

-

if they focused on external providers – this work has already been done. 47

Study quality was assessed qualitatively for:

-

relevance – degree of contribution to theory building and/or testing; and

-

rigor – whether the method used to generate the data was credible and trustworthy. 36

Studies were included if they contributed to the initial programme theory of stage 1. Full-text papers marked for inclusion were retrieved and read in full by (KH and KS). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with members of the wider research team (CT, BH, AA, DV) and with reference to the review framework and emergent programme theory. 40 Sixty-six studies were included in this review.

Data extraction

Data on staff behaviours and triggers (capability, opportunity, motivation) and their interaction in care home settings were extracted. KH and KS double-extracted data from over a third of the included papers (n = 25; 38%). This was done in three stages: KH and KS both extracting from five papers then discussing, followed by two further rounds (with 10 papers in each round) with discussion. Piloting and double extraction from a sample of papers were used to promote consistent and comprehensive data extraction. KH extracted data for all included papers. Data from author explanations and discussions can help make explicit in what context, which mechanisms lead to which outcomes48 and so were included.

Stage 3: theory refinement

In this final stage, we refined context–mechanism–outcome configurations and examined supporting evidence in three researcher-led discussions during November to December 2019 with our stakeholder groups which included: residents and relatives (group 1) and care home managers (group 2), and our Study Steering Committee (SSC) members (including representatives from provider organisations, policy-makers, regulators, methodologists and members of the public). Stakeholders were invited to comment critically on the resonance, relevance and gaps in our theories. Revision of context–mechanism–outcome configurations after each discussion led to the final set of refined context–mechanism–outcome configurations (presented in Chapter 4).

Work package 2: modelling relationships between staffing and quality at a national level

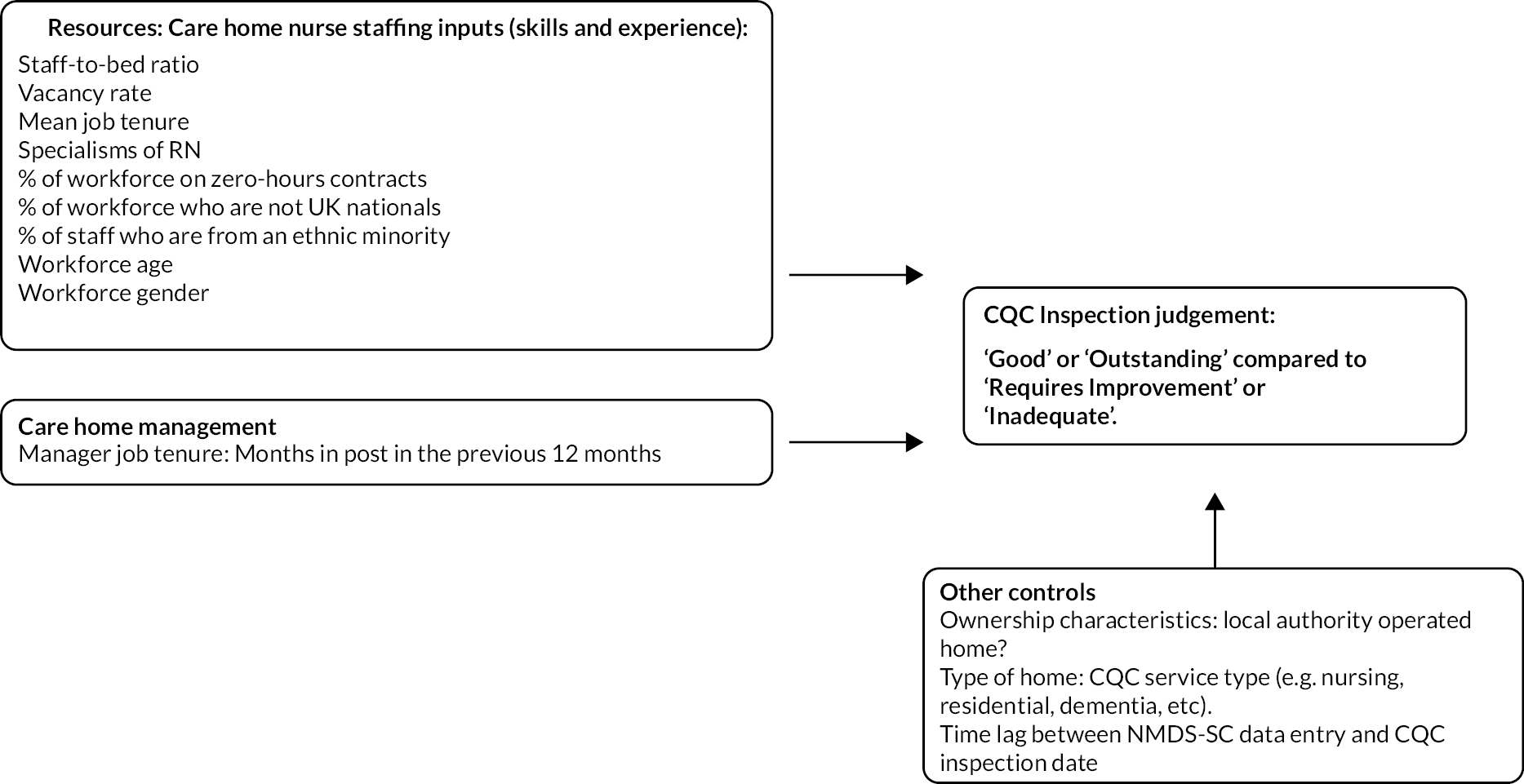

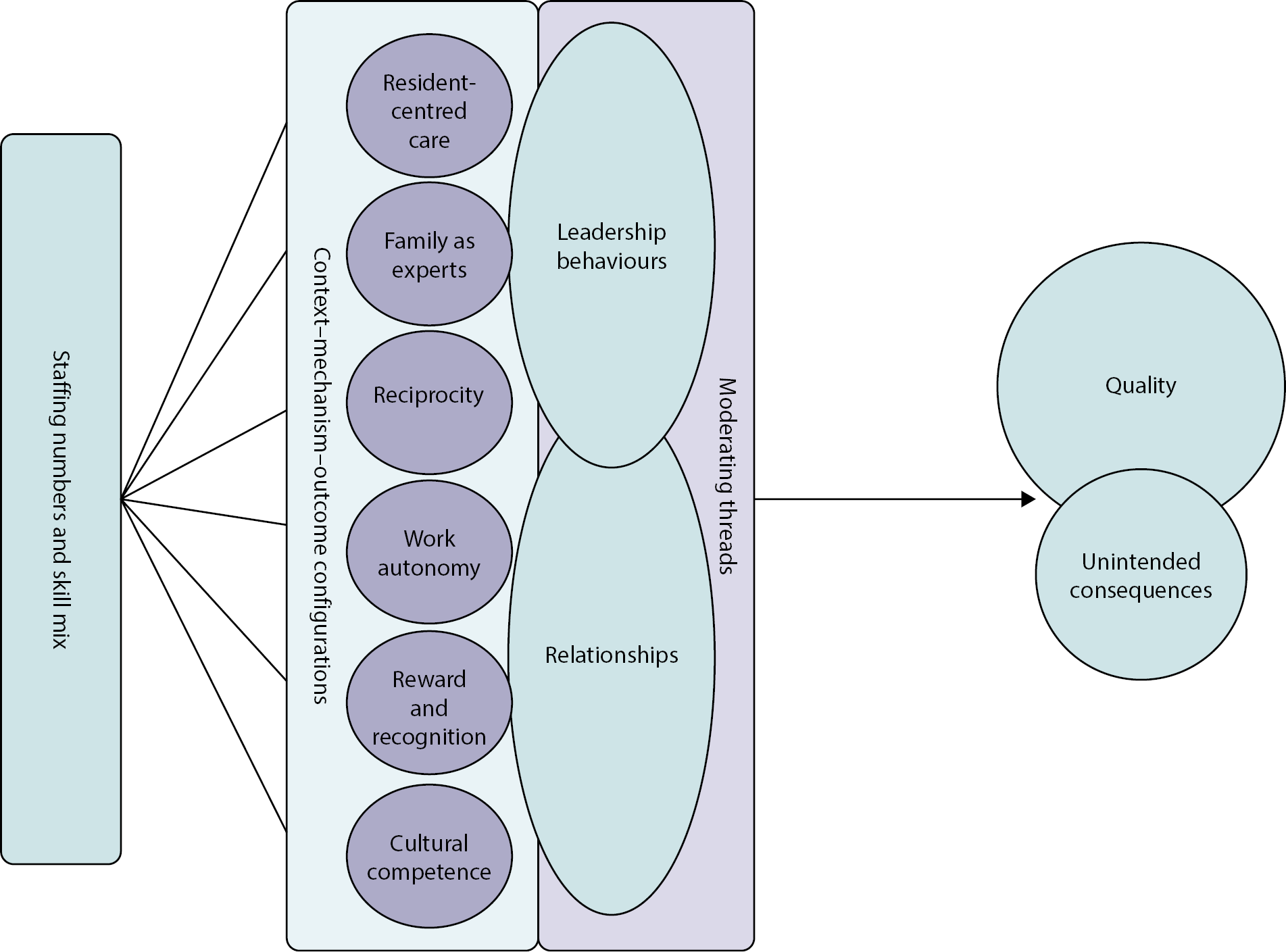

This was a cross-sectional observational study of a subpopulation of English care homes providing workforce data to Skills for Care for the National Minimum Data Set for Social Care (NMDS-SC) in the period September 2014–July 2017: the NMDS-SC was replaced by the Adult Social Care Workforce Data Set (ASC-WDS) in August 2019. CQC inspection judgements about care quality (see below) were modelled as functions of the staffing resources of the homes while accounting for organisational characteristics of the home operator (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The relationship between workforce characteristics and care quality outcomes in the NMDS-SC.

Measuring care quality

All care homes in England are subject to regular inspection by the CQC, with the precise timings of inspections dependent on a risk-based model developed by the CQC using data regularly reported to it by care homes. CQC inspectors make judgements about whether care homes (with and without nursing) are (1) safe, (2) effective, (3) caring, (4) responsive and (5) well-led (see Appendix 1). The results of their judgements are reported as being inadequate, requiring improvement, good or outstanding, with a judgement using this scale for each of the five categories and an overall judgement. 49 In practice, over 75% of inspection judgements are ‘good’, with around a fifth requiring improvement and much smaller numbers in the ‘outstanding’ and ‘inadequate’ categories. 22

This inspection method assesses care quality through expert professional judgements informed by data analysis and relatively short audit visits to care homes. Whether this approach accurately conceptualises and measures care quality is debatable, but we took a pragmatic view that CQC inspection judgements tell us something useful and interesting about the care quality that homes provide. In particular, we are interested in relationships between the CQC measure of care quality and care homes’ staffing establishments. Is there evidence of different approaches to staffing establishments and do different approaches lead to different outcomes? Our approach was novel because existing studies of relationships between staffing and care quality focus on clinical indicators. These may be sensitive to the quality of nursing care50,51 but miss broader conceptions of care(r) quality.

Data sources

The study draws on NMDS-SC data from September 2014 to July 2017. It includes records from 5028 individual care homes in England, in the CQC-regulated activities category of ‘accommodation for persons requiring nursing or personal care’ which reported that they provided services to older people. This is approximately 50% of care homes for older people regulated by the CQC: 36% of homes (n = 1785) in the data set were care homes with nursing, the remainder (n = 3243) without nursing (residential care). Data are collected through care home operators making voluntary returns, detailing aspects of their workforce and home characteristics, to Skills for Care. Substantially incomplete records, and/or records that contained obvious data entry errors, were excluded from our analysis.

Participation in the NMDS-SC is voluntary. While the data set covers a high proportion of English care homes, it may not be representative of the whole sector. Internal analysis from Skills for Care52 suggests independent care home operators are less likely to participate than local authority-run homes (24% of homes in our data set are operated by local authorities). Homes in London and the South East are less likely to participate, while homes in the North East are more likely to participate. Larger multihome operators are more likely to participate than smaller operators. Care home operators who do not participate, or who participate but provide incorrect or substantially incomplete data may also differ from those included in our analysis in important but unobservable ways. However, it is worth highlighting that CQC inspection scores did not differ substantially between care homes that submitted data to the NMDS-SC and those that did not.

The data should be thought of as a population data set (where the population is all care homes that participate in NMDC-SC without significant amounts of missing data and date-entry errors) rather than a sample. Results will not necessarily generalise to care homes that do not participate in the study, but the analysis is still of value because of the large proportion of English care homes that participate. Skills for Care extracted data from the NMDS-SC data set that included measures of care home and workforce characteristics (Box 2).

Workforce measures

-

Total staff (including non-care staff)

-

Percentage of staff who are on permanent contracts (as opposed to staff provided by an employment agency or on temporary contracts)

-

Percentage of staff on zero-hours contracts (i.e. where staff are not contracted to work a specific number of hours a week but are called into work when they are needed)

-

Percentage of posts that are unfilled (vacancy rate)

-

Average staff job tenure

-

Percentage of staff who are full-time

-

If a care home with nursing, the specialism of the RN working in the home (four categories: community nursing, older people, adults, mental health)

-

Number of months that the registered manager had been in post in the year prior to the most recent inspection

Care home characteristics measures

-

Number of resident beds (including occupied and unoccupied beds)

-

Staff-to-bed ratio was computed from data on staff and bed numbers

-

Whether the home was operated by a local authority or independent operator

-

Whether the home provides specialist dementia care

-

Whether the home provides nursing care

-

Dates on which care homes provided data to the NMDS-SC

Data on each home’s latest CQC inspection scores along with the date of the inspection were added to this data set. CQC scores are reported in Table 1. The time between data entry into the NMDS-SC and the date of the CQC inspection was calculated and included in the analysis to control for measurement error arising from changes to staffing between data entry and inspection (the median gap between data entry and inspection was 2 months with half of all inspections within 7 months of data entry). Table 1 reports the distribution of CQC scores among homes in the sample.

| All (%) | Care homes without nursing (%) | Care homes with nursing (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| Good | 72.8 | 67.8 | 74.8 |

| Requires improvement | 23.5 | 27.6 | 21.9 |

| Inadequate | 1.8 | 2.6 | 1.5 |

| Number of observations | 5028 | 1785 | 3243 |

Note that 72.8% of homes were judged to be good, with just 1.9% judged outstanding, 23.5% requiring improvement and 1.8% inadequate. Residential care homes without nursing care were slightly more likely to be in both the outstanding and require improvement category than homes with nursing care. This lack of variation in our key outcome measure has implications for our analytical approach which we explain below. Descriptive statistics for all these measures are reported in Table 2. The data set also contain data on CQC service type (e.g. dementia, learning difficulties, mental health) as some homes reported providing care to residents in more than one CQC category (i.e. not just to older people). These variables were not used in the analysis reported below (because preliminary analysis found no relationship between them and CQC scores) but they are reported for information.

| Variable | Nursing and residential homes | Care homes with nursing | Residential homes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | |

| CQC rating (good + outstanding) | 0.747 | 0.435 | – | 0.698 | 0.459 | – | 0.766 | 0.423 | – | |||

| Number of beds | 37.331 | 20.684 | 48.194 | 23.457 | 33.067 | 18.164 | ||||||

| Total number of staff (headcount) | – | 36.000 | 31.000 | – | 52.000 | 34.000 | – | 24.000 | 24. | |||

| Staff-to-bed ratio | 1.230 | 0.554 | – | 1.310 | 0.546 | – | 1.183 | 0.537 | – | |||

| Proportion of staff who are on permanent contracts | 0.918 | 0.098 | 0.906 | 0.095 | 0.924 | 0.099 | ||||||

| Vacancy rate | 0.021 | 0.085 | 0.021 | 0.08 | 0.021 | 0.086 | ||||||

| Staff tenure (years) | 4.451 | 2.605 | 4.010 | 2.185 | 4.624 | 2.763 | ||||||

| Proportion of workforce who are employed full time | 0.528 | 0.240 | 0.583 | 0.21 | 0.507 | 0.248 | ||||||

| Proportion of workforce on zero-hours contracts | – | 0.00 | 0.078 | – | 0.023 | 0.1 | – | 0.00 | 0.067 | |||

| Specialism of RN – older people (yes, proportion) | – | – | 0.331 | 0.406 | – | – | – | |||||

| Specialism of RN – adults | 0.232 | 0.349 | ||||||||||

| Specialism of RN – learning difficulties | 0.026 | 0.127 | ||||||||||

| Specialism of RN – mental health | 0.060 | 0.171 | ||||||||||

| Specialism of RN – community care | 0.003 | 0.028 | ||||||||||

| Specialism of RN – other | 0.005 | 0.039 | ||||||||||

| Workforce age | 43.643 | 4.544 | 43.339 | 3.998 | 43.747 | 4.757 | ||||||

| Proportion of workforce who are female | 0.866 | 0.102 | 0.847 | 0.087 | 0.875 | 0.107 | ||||||

| Proportion of workforce with a disability | – | 0.00 | 0.018 | – | 0.00 | 0.017 | – | 0.00 | 0.02 | |||

| Proportion of workforce who are not UK nationals | 0.026 | 0.088 | 0.045 | 0.11 | 0.016 | 0.073 | ||||||

| Proportion of workforce who are ethnically white | 0.925 | 0.21 | 0.629 | 0.135 | 0.944 | 0.174 | ||||||

| Number of months that a manager was in post in the 12 months prior to inspection | 12.000 | 0.00 | 12.000 | 1.0 | 12.000 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Months between NMDS-SC data entry and CQC inspection | 2.000 | 7.0 | 2.000 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 6.0 | ||||||

| Proportion of homes operated by local authorities | 0.235 | 0.403 | – | 0.221 | 0.347 | – | 0.254 | 0.413 | – | |||

| NMDS service flag (care homes with nursing, proportion) | 0.355 | 0.478 | 1.000 | 0.000 | – | |||||||

| CQC service type: dementia (proportion) | 0.653 | 0.476 | 0.674 | 0.469 | 0.648 | 0.477 | ||||||

| CQC service type: children 0–18 years of age | 0.002 | 0.047 | 0.003 | 0.053 | 0.001 | 0.044 | ||||||

| CQC service type: learning disabilities | 0.111 | 0.314 | 0.074 | 0.262 | 0.124 | 0.329 | ||||||

| CQC service type: mental health | 0.175 | 0.38 | 0.183 | 0.387 | 0.170 | 0.376 | ||||||

| CQC service type: people who misuse drugs and alcohol | 0.012 | 0.11 | 0.013 | 0.115 | 0.012 | 0.111 | ||||||

| CQC service type: people detained under MHA | 0.01 | 0.101 | 0.016 | 0.115 | 0.009 | 0.097 | ||||||

| CQC service type: people with an eating disorder | 0.009 | 0.095 | 0.011 | 0.105 | 0.009 | 0.096 | ||||||

| CQC service type: physical disabilities | 0.362 | 0.481 | 0.481 | 0.5 | 0.313 | 0.464 | ||||||

| CQC service type: sensory impairment | 0.184 | 0.388 | 0.192 | 0.394 | 0.180 | 0.384 | ||||||

| CQC service type: whole population | 0.002 | 0.042 | 0.002 | 0.047 | 0.002 | 0.044 | ||||||

| CQC service type: younger adults | 0.216 | 0.412 | 0.295 | 0.456 | 0.181 | 0.384 | ||||||

| CQC-regulated activities: accommodation for persons requiring nursing or personal care | 1.0 | 0.017 | 1.000 | 0.0 | 1.000 | 0.019 | ||||||

| CQC-regulated activities: nursing care | 0.001 | 0.034 | 0.003 | 0.058 | – | |||||||

| CQC-regulated activities: personal care | 0.026 | 0.158 | 0.016 | 0.126 | 0.028 | 0.167 | ||||||

| CQC-regulated activities: assessment or medical treatments | 0.349 | 0.476 | 0.898 | 0.302 | 0.116 | 0.321 | ||||||

| N observations (locations) | 5028 | 1785 | 3243 | |||||||||

Table 2 provides some insight into between home variations in care home workforce. The average number of beds per home was 37, with homes that provided nursing care typically larger (mean beds = 48) than residential homes (mean beds = 33). The median number of staff employed was 36 (52 in homes with nursing; 33 in homes without nursing. Note that we focus on total staff employed as our main measure of staffing because in preliminary analysis including more detailed measures of staffing by job grade prevented our multilevel models from converging; in our judgement the total staff measure was the best way of balancing parsimony with model performance). The interquartile ranges for this measure were quite large: 34 for homes with nursing and 18 for homes without nursing, suggesting significant variation in numbers of staff employed in different homes. The mean staff-to-bed ratio was 1.23 (1.31 in homes with nursing and 1.18 in homes without nursing). On average, 2% of posts were vacant, but with a relatively high standard deviation suggesting a significant proportion of homes with large numbers of vacancies. Mean staff tenure was 4.5 years. On average, 53% of staff were employed in full-time posts. Mean staff age was 44 years. Over 85% of the workforce were female. Around 8% were from ethnic minorities and 2.5% were not UK nationals.

The NMDS-SC has a number of strengths and weaknesses compared to the extant literature. The data cover a high proportion of care homes in England (although as discussed above, results cannot necessarily be generalised to the total population of care homes). It includes measures of aspects of staffing likely to be important for care quality that have not been present in many previous studies, specifically the extent to which a home uses temporary staff, the role-related experience of staff and the proportion of jobs unfilled and detailed measures of staffing by job grade. Key factors likely to have a causal impact on care quality, specifically the acuity of resident care needs and occupancy levels, and many characteristics of the home (e.g. whether it is run for profit, whether it is a purpose-built facility) are not captured by the data set. These limitations need to be kept in mind when considering the results of our analysis below.

Data analysis

Latent profile analysis

To examine whether it was possible to discern any patterns in variations in staffing between homes and whether different care home staffing models might be associated with care quality we first examined whether it was possible to detect distinct home/staffing models. Specifically, we attempted to see if it was possible to identify homes with similar workforce characteristics (e.g. similarities/differences in staff-to-bed ratios, patterns of staff experience or temporary staffing use). To do this, we used latent profile analysis (LPA) using the R package tidyLPA. 53,54 LPA is a type of modelling that uses Expected Maximisation algorithms to find maximum likelihood parameters of the statistical model, assuming that it is derived from unobserved latent variables. 55 LPA is a data-driven approach pertinent to a research design in which a number of clusters is not assumed in advance. However, this analysis did not provide any evidence of distinct care home staffing models.

Next, we used multilevel logistic regression to test for relationships between the workforce characteristics described in Table 2 and CQC scores to examine whether differences in workforce characteristics were associated with differences in CQC assessments of quality.

Multilevel logistic regression

We originally planned to treat CQC inspection scores as an ordinal measure of quality. However, 75% of CQC ratings were reported as ‘good’ (see Table 1). However, preliminary analyses suggested that ordered logit analysis was technically inappropriate because the proportional odds assumption was violated. Further confusion matrices derived from ordered logit models found that these models failed to correctly predict both inadequate and outstanding homes. Therefore, we split the CQC score variable into homes rated ‘inadequate’ or ‘requires improvement’ in one category and ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ in the other and proceeded with logit analysis on this binary outcome.

Local authorities in England act as commissioners and funders of social care for residents and have statutory responsibilities to promote the efficient and effective operation of a market for care services in their locality and must foster workforce development and continuous improvements in service quality. 56 Further, around a fifth of homes in the data set were directly operated by local authorities. Therefore, to account for variations in approach taken by local authorities in managing these homes and in fulfilling their statutory duties, we took a multilevel approach. Where homes are clustered within local authorities, we fitted multilevel logistic regression models using R software environment for statistical programming and data visualisation. The main effects were estimated by multilevel (hierarchical) logistic regression. This is a nested model: care homes represent level one and local authorities with social care responsibilities level two.

Multilevel (hierarchical) regression was appropriate because CQC inspection ratings varied significantly by local authority – as evidenced by the intraclass correlation (ICC) score in regression outputs (ICC score captures the proportion of variation in CQC scores that is due to differences between local authorities). Conditional and marginal R-squared show the proportion of variance explained by fixed effects only and the entire model, respectively. We fitted three separate models. The first is for all homes for older people (nursing and residential), the second is for homes that provide residential care only, and the third is for homes that provide nursing care. This is because relationships between workforce characteristics and quality may differ in these different contexts.

Cost–benefit analysis

Our initial study protocol outlined a planned cost analysis to estimate the additional staffing costs needed to bring about improvements in inspection scores. However, because the size of the relationship between additional staffing resources and increased chances to a good or outstanding inspection score were so small, the results of such an analysis would not be meaningful in any practical sense, as the additional staffing costs needed to bring about small improvements in quality evaluations would be so large that it would not represent a realistic or feasible intervention. We have therefore not included a cost–benefit analysis in WP2.

Work package 3: modelling relationships between staffing, quality, outcomes and resource use at an organisational level

This study sought to answer two questions: Are adverse events for residents more likely when a lower proportion of care is provided by nurses; and is the lower level of nursing input the likely cause of greater risk of these adverse events for residents? To answer these questions, we need to understand why skill mix changes over time. We analysed routinely collected longitudinal data from a single care home provider over 42 months. The data were more fine-grained: staffing, planned and actual hours worked by CAs and RNs, and data on resident and home characteristics. We utilised nurse-sensitive indicators of care quality as our outcome measures (see Data sources).

Study setting

The setting was a care home owner operator with 134 homes with and without nursing in England, a total of 7,624 resident beds, and an average occupancy rate of 86.5% (interquartile range = 13.75). The average share of residents with nursing needs was 66.1% (interquartile range = 42.4). Around 20% of residents were in dedicated dementia care units. Around a fifth of residents paid for their care, with funding from local authorities or the NHS via clinical commissioning groups constituting the remainder.

The study period was December 2014–May 2018 (42 months). The unit of analysis of the study is the care home month, so there were 5628 (134 × 42) care home month observations in the study. Because we used routinely collected administrative data, essential for business, there were no missing values.

Care home staffing arrangements and skill mix: implications for our study

This care home provider’s target nurse staffing levels were (relatively) fixed: one or two nurses per shift depending on the number of available nursing beds in the home. Home occupancy rarely drops to radically reduced nurse staffing levels. However, carer shifts may reduce as occupancy rates decline – lower occupancy rates increase skill mix. As occupancy rates, particularly low occupancy, may be the result of confounders (including care quality) that impact risk of adverse events. To counter this, we controlled statistically for occupancy.

Skill mix falls if there are shortages of nurses and rises when shortages of carers occur because of staff illness or unfilled vacancies. The provider tried to avoid being short of nurses by using (temporary) agency staff – but this was not always possible. We included measures of nurse and carer shortages in the analysis to identify any increased risk to residents that results from short-term staffing shortages as opposed to increased risk due to inadequate staffing establishments.

For a given level of skill mix, processes of care may change if demands on staff time increase or staff must adjust to a shift in care context. For example, in care homes with nursing, new resident admissions increase demands on nurses because they require nurses to assess residents’ needs, then develop and monitor the effectiveness of care plans until residents become settled into the home. The use of agency nurses as a result of unfilled vacancies or staff illness will substitute nursing staff who know residents and their care needs with nurses without home-specific experience, risking a change in care quality. To test whether these factors affected our measures of care quality, we included a measure of the proportion of care hours provided by agency nurses in a given home/month and the average number of weekly admissions as a proportion of the total beds in the home.

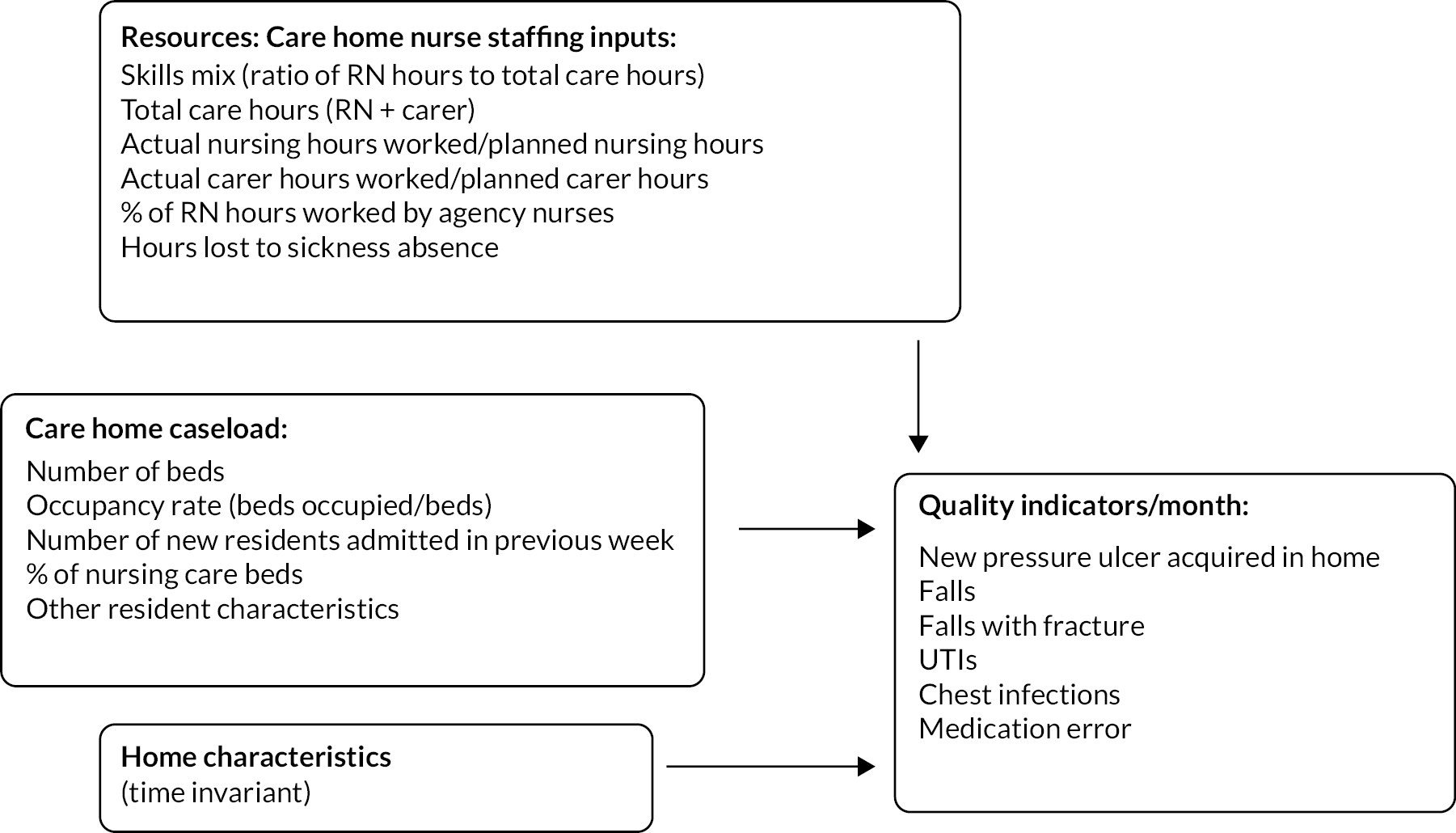

Finally, skill mix will change as resident care needs change. Skill mix falls as resident care needs increase – residents need more personal care and carer hours increase but nursing hours remain constant. Increased resident care needs may increase the risk of resident adverse events because greater care needs are likely associated with poorer health and more frailty. In interpreting our analysis, a lower skill mix and greater risk of adverse events could be caused by inadequate nurse staffing but could also be caused by unobserved changes to resident-specific risks influencing skill mix. We used the econometric method of growth mixture modelling (explained below) to control for medium-term unobserved changes to resident care needs influencing trajectories of nurse-sensitive indicators of care quality over time and skill mix. We could not control for short-run changes in resident care needs resulting in month-to-month fluctuations in care workers’ hours and therefore skill mix. See Figure 2 for our theoretical reasoning.

FIGURE 2.

The relationship between staffing and care quality outcomes at the care home/month level.

Data sources

Measures of quality

Quality outcomes were operationalised using nurse-sensitive indicators of care quality. Nurse-sensitive indicators of care quality investigated were: pressure ulcers developed in the care home; falls; falls that result in a fracture; urinary tract infections (UTIs); and chest infections. We also examined reported medication error rates as a broad measure of care quality. These measures all represent adverse incidents within the care home. All outcome measures were transformed to a ‘rate per occupied bed per care-home month’. See Table 3 for statistical description of measures. All these indicators constituted relatively rare events. The most common falls occurred at a rate of ~one per five occupied beds a month. Falls resulting in a fracture were much less common: ~1 per 335 occupied beds per month. Chest infections occurred at rate of ~1 per 20 occupied beds per month, UTIs 1 per 14 occupied beds per month, pressure ulcers 1 per 100 occupied beds per month and medication errors 1 per 62 occupied beds per month. We discuss the limitations of these data sets in Chapter 5.

| Mean | SD | Median | IQR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes (rate per occupied bed per month) | ||||

| Pressure ulcers | 0.01 | 0.021 | 0 | 0.009 |

| Falls | 0.197 | 0.181 | 0.151 | 0.201 |

| Falls with fracture | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0 | 0 |

| UTIs | 0.069 | 0.082 | 0.044 | 0.103 |

| CI | 0.051 | 0.07 | 0.029 | 0.072 |

| Medication errors | 0.016 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.018 |

| Staffing characteristics | ||||

| Total monthly care hours per occupied bed per month (RN + carer) | 124.52 | 31.10 | 122.482 | 35.481 |

| Skill mix: proportion of monthly care hours provided by RNs | 0.203 | 0.093 | 0.225 | 0.101 |

| Agency nurses (proportion of monthly care hours provided by agency nurses) | 0.047 | 0.07 | 0.019 | 0.067 |

| Proportion of planned RN hours per month actually worked | 0.982 | 0.116 | 0.973 | 0.123 |

| Proportion of planned carer hours per month actually worked | 1.001 | 0.134 | 0.99 | 0.136 |

| Total care hours (RN + carer) lost to sickness absence per month | 0.051 | 0.036 | 0.043 | 0.046 |

| Control variables | ||||

| Total number of beds | 56.611 | 25.838 | 52 | 29 |

| Occupied beds (average per week) | 48.377 | 22.137 | 44.25 | 25.275 |

| Occupancy rate (average per week) | 0.865 | 0.122 | 0.9 | 0.138 |

| Admissions as a proportion of total beds (average per week) | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.02 | 0.022 |

| Resident characteristics (measures at a single point in time, April 2018, only) | ||||

| Proportion of residents with nursing needs | 0.661 | 0.323 | 0.714 | 0.424 |

| Proportion of residents in dedicated dementia units | 0.198 | 0.254 | 0.053 | 0.344 |

| Proportion of residents in dedicated dementia units who also exhibited challenging behaviour | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0 | 0 |

| Proportion of young disabled residents | 0.049 | 0.147 | 0 | 0.022 |

| Proportion of residents with learning difficulties | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0 | 0 |

| Proportion of residents with Parkinson’s disease | 0.007 | 0.017 | 0 | 0 |

| Proportion of residents with Huntington’s disease | 0.002 | 0.018 | 0 | 0 |

| Proportion of residents receiving end-of-life care | 0.055 | 0.076 | 0.031 | 0.076 |

| Proportion of residents with other specific care needs | 0.045 | 0.088 | 0.013 | 0.048 |

Measures of workforce

We calculated total care hours (nurses and carers), carer hours and nurse hours per occupied bed per month and a skill mix variable – the proportion of care hours provided by RNs per occupied bed/month. The median number of total care hours per occupied bed per month was 122.5 (interquartile range = 35.5). The median percentage of these hours provided by RNs (skill mix) is 22.5% (interquartile range = 10%). If nurses are off sick or there are unfilled RN vacancies, the care home provider would seek to cover shifts using RN provided by agencies. The median percentage of care hours provided by agency nurses per month was 1.9% (interquartile range = 6.7%). We also have measures of whether nurse and carer hours were at or below their planned levels. We used this to calculate the proportion of planned hours worked each month, providing a combined measure of staff absence due to uncovered shifts arising from sickness and absence. The median percentage of planned hours worked for RN hours worked is 97.3%, although an interquartile range for this variable of 12.3% indicates that shifts where nurse staffing was below target were not uncommon. For carer hours worked as a proportion of planned carer hours worked, the median is higher, 99%, although the interquartile range is slightly larger at 13.4%. See Table 3.

Control variables

Other variables included in the analysis measure aspects of time-varying, home case load, that is changes to demand for care that could therefore affect the processes of care, specifically (see Table 3): (1) ratio of average weekly new residents admitted to available beds (median = 0.02, interquartile range = 0.022); (2) number of occupied beds (median = 44.3, interquartile range = 25.3) and the total number of beds (occupied and unoccupied, median = 52, interquartile range = 29).

We computed the proportion of beds occupied per month (median = 0.9, interquartile range = 0.138) and included this in the regression modelling instead of separate measures of number of beds occupied and total beds. The care home provider shared data constituting proxy measures of potential need: the proportion of residents who were elderly, receiving specialist dementia care and exhibiting challenging behaviours, younger residents with disabilities, receiving specialist care for Parkinson’s or Huntington’s disease and residents receiving specialist end-of-life care. The data were from a single time point (April 2018) and included to examine whether their inclusion affected results.

Data analysis

We estimated a number of different regression models with the indicators of care quality as dependent variables. First, we used simple pooled, cross-sectional ordinary least squares (OLS) models as a more easily interpretable benchmark to assess the results of more complex models against. Next, we fitted models with care home fixed effects to control for time-invariant omitted variables (i.e. home specific structures of care). These models also included time effects to control for variables that are constant across care homes but tend to vary over time, for example gradual changes to home caseload.

Finally, we specified multilevel growth models (growth mixture modelling with a random intercept) that account for different trajectories of outcomes between care homes. For example, unobserved processes of care changed over time due to (unobserved) changes in home caseload. The ICC was used to illustrate the proportion of total variation in nurse-sensitive outcomes of care quality due to differences in home-specific trajectories over time (except the models with falls with fracture where the ICC score was low). The difference between conditional (variance explained by fixed effects only) and marginal (variance explained by the entire model) R2 shows – our preferred – mixed effects models outperform models with separate fixed and time effects. Marginal effects were calculated from the results of the growth mixture models to use as an input into our cost–benefit analysis of changing skill mix.

We used models with lagged and lead measures of key variables to test whether staffing in previous months might explain nurse-sensitive indicators of care quality in future months – a form of sensitivity analysis. Results were not statistically significant. Exploration of non-linear relationships between the outcome variables, total staffing and skill mix using squared terms for skill mix and other workforce measures, also yielded small and statistically non-significant results and these analyses are not reported. Although note that regression analysis is typically only able to detect non-linear relationships if the non-linear relationship follows a very specific functional form, there may therefore be non-linear relationships we are unable to detect with these methods. 57

We shared results of our preliminary analyses with quality and operational managers from the care home provider who provided the data in order to sense check our results against their experiences. This did not result in any significant changes to the analysis.

Cost–benefit analysis

The cost perspective taken in the analysis was, as far as possible, that of the NHS (with costs presented in 2019–20 prices). This is where most notable healthcare services for outcomes associated with staffing are likely to take place, although not exclusively. The NHS will also bear costs of nursing time, although these costs are shared by multiple stakeholders. The financing of nursing hours in care homes is complex including NHS, local authority and private funding, as is the provision of healthcare services to this population. 58–61 Regardless of this, the aim was to present indicative estimates of NHS cost savings that would arise from positive changes to workforce attributes. Unit costs are summarised in Table 4.

| Cost variable | Unit cost (£) | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing time (skill mix) | 39.23 | Per hour | Curtis and Amanda62 |

| Medication errors | 3.07 | Per error | Elliott et al.70 |

| Falls with fractures | 4247.00 | Per event | Franklin and Hunter71 inflated using indices provided by Curtis and Amanda62 |

| UTI | 337.00 | Per event | Derived from NHS Reference Costs, Hospital Episodes Statistics and ONS population estimates85–87 |

In the absence of any care home-specific nursing unit costs, data from Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) Unit Costs of Health and Social Care were used to determine costs of nursing hours. 62 These estimates were derived from Agenda for Change pay scales and other indirect costs, including overheads and were assumed to be broadly indicative of appropriate unit costs. This gave an hourly cost for a Band 5 community-based nurse of £39.23, equating to a cost of £23,460 per month or £281,520 per year for an average home.

We next needed to estimate treatment cost savings for falls with fractures, UTIs and medication errors. To do this, a series of pragmatic literature reviews were conducted to identify unit costs. Literature was consulted rather than immediately piecing together assumed resource use and nationally available unit cost sources for two reasons: either they were not directly measurable healthcare costs, but rather an impact of some causative events (medication errors, fall with fractures), or to attempt to gather costs that reflected the average severity and resource use of these events over an appropriate time horizon (ideally to resolution) in an appropriate population (UK care home residents).

Data sources and analysis

Searches were performed in December 2020 using PubMed, supplemented by Google Scholar and citation snowballing, date restricted to 10 years or 2010 to present (as of December 2020), with search terms: Cost of medication errors in care home UK and Cost of medication errors in the UK. For other searches, ‘medication errors’ was replaced with the appropriate outcome of interest: ‘falls’ and ‘UTIs’.

Sources were chosen to inform the cost calculations on the basis of a series of suitability criteria. Data were preferred if they were UK specific, relevant to a care home population, in appropriate units to match the outcomes as defined in the analysis, and contemporaneous. In the event that competing sources were identified, consideration was given to factors such as the nature of the evidence, including sample size and study design. Only sources that were considered as potentially suitable are referred to in the summary provided here. While it is recognised that these methods do not guarantee that all the potentially relevant literature will have been identified, it is expected that sources of most relevant cost data will have been encountered.

Cost of medication errors

The search identified a relatively small literature relating to the costs of medication errors. 63–70 Of these, only one estimated the prevalence and burden (in terms of healthcare resource use and deaths) in care home settings. 70 This study utilised several other studies to produce aggregate-level estimates of the Cost of medication errors to the NHS. In the base case, the authors estimated that 237,287,788 ‘definitely avoidable’ adverse drug events occurred annually, at a cost of £98,462,582 (mean of £0.41 per error). Including ‘probably avoidable’ adverse drug events increased this to £728,462,837 (£3.07 per error). While these estimates were not without limitations, they came close to fitting the requirements of this study (UK, contemporary, most comparable population, able to derive a ‘per error’ cost). The price year for which costs were presented was not clear in the publication and so no inflation indices were applied.

Cost of falls resulting in fractures

Six studies of interventions or trials designed to reduce falls in older people that included cost–benefit analysis were identified. 71–76 Only one of these studies, which was in non-care home setting, included UK-specific cost estimates of a fall74 while another presented costs in British Pound (GBP) but was based on Australian resource use estimates. 71 Franklin and Hunter71 presented age-group specific cost estimates for minor (£427.84 for 75- to 89-year-olds) and major falls (£4014.52) in the UK (2016–17 GBP), the major distinction being the requirement for hospital admission. While it might be assumed that this correlates with fractures, the study did not specifically distinguish between falls resulting in fracture. Two other studies also considered a UK setting but presented mean costs of fractures for each arm or associated costs, but not mean cost per fall resulting in a fracture. 75,76 Two further studies77,78 estimated the costs of managing falls in older adults living in the community but it was difficult to ascertain how costs cited related to falls specifically. Guidelines produced by the National and Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK were identified which costed falls based on PSSRU unit cost data. 79,80 However, the care home data did not distinguish between underlying cause of fracture, or site of fracture, so it is unclear how suitable these data were.

Therefore, none of the sources offered costs that were both reflective of the institutional setting or country (UK specific). The study by Franklin and Hunter71 did (at least) present estimates that were broadly consistent with the characterisation required (fall with fractures vs. major falls) and stratified for an older population (75–89 years old). It was assumed that a fall resulting in a fracture would likely lead to a hospital admission in an older frail population. These costs were inflated to 2019–20 prices (£4247) using NHS cost of inflation estimates. 62

Costs of urinary tract infections

Searches for sources of costs of UTIs did not yield many publications. Of studies identified three referenced costs, however it was not possible to isolate the cost per UTI from them. 81–83 A study by Pickard and colleagues82 suggested an increased cost of £547.63 for patients undergoing catheterisation who experienced a UTI. One study considered an economic perspective of UTIs and measured direct costs to the Italian health service in women with cystitis and a history of UTIs (mean annual cost of €229 per woman). A quality improvement project aimed at reducing UTI related to dehydration in care homes was identified. 84 The authors suggest that the project was effective and state that every avoided hospital admission would lead to a cost saving of £1300, but the study did not directly collect resource use/cost data.

In the absence of a suitable source, a cost was estimated based on the proportion of clinically significant UTIs that lead to hospitalisation. Secondary care costs are likely to significantly outweigh any costs associated with antibiotic treatment. Further pragmatic searches were performed but did not yield usable data. An estimate was computed (Table 5) based on UK population estimates (2020) and estimates of the incidence of clinically significant UTI in adults aged 70 years and over in the UK to derive a denominator and hospital episode statistics (2019–20) to derive a numerator. 85–87 It was estimated that in 2019–20, approximately 21% of clinically significant UTIs led to hospitalisation in those aged 70 years and above. A unit cost derived from NHS Reference Costs (2018–9) was weighted using 21% to derive a mean cost per UTI (Table 6),88 equating to an average treatment cost of £337.

| Population | UTI rate/100 person years | UTI (men) |

UTI (women) |

Admission (men) |

Admission (women) |

% UTI w/admission | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||||||

| 70–74 | 3,363,906 | 3.05 | 10.96 | 50,696 | 186,512 | 10,632 | 15,337 | 11 |

| 75–79 | 2,403,759 | 6.13 | 14.34 | 72,808 | 174,379 | 13,947 | 20,117 | 14 |

| 80–84 | 1,726,223 | 6.13 | 14.34 | 52,286 | 125,227 | 18,755 | 27,053 | 26 |

| 85–89 | 1,049,866 | 10.54 | 19.8 | 54,677 | 105,160 | 19,005 | 27,414 | 29 |

| 90 and over | 609,503 | 10.54 | 19.8 | 31,743 | 61,051 | 16,331 | 23,558 | 43 |

| 262,208 | 652,330 | 78,670 | 113,479 | 21 | ||||

| HRG code | Description | Activity | Unit cost (£) | Weighted cost (£) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA04H | Kidney or UTI, with Interventions, with CC Score 12+ | 2145 | 6014 | 49 |

| LA04J | Kidney or UTI, with Interventions, with CC Score 9–11 | 3042 | 4668 | 54 |

| LA04K | Kidney or UTI, with Interventions, with CC Score 6–8 | 4411 | 3836 | 65 |

| LA04L | Kidney or UTI, with Interventions, with CC Score 3–5 | 4105 | 3000 | 47 |

| LA04M | Kidney or UTI, with Interventions, with CC Score 0–2 | 2261 | 2475 | 21 |

| LA04N | Kidney or UTI, without Interventions, with CC Score 13+ | 8560 | 3051 | 100 |

| LA04P | Kidney or UTI, without Interventions, with CC Score 8–12 | 45,706 | 2210 | 386 |

| LA04Q | Kidney or UTI, without Interventions, with CC Score 4–7 | 89,469 | 1536 | 526 |

| LA04R | Kidney or UTI, without Interventions, with CC Score 2–3 | 51,153 | 1078 | 211 |

| LA04S | Kidney or UTI, without Interventions, with CC Score 0–1 | 50,630 | 738 | 143 |

| Total activity | 261,482 | – | – | |

| Weighted unit cost | 1602 a | |||

| Cost per UTI | 337 b |

Work package 4: understanding the contributions of the care home workforce to enhance quality

This was a documentary analysis of CQC inspection reports – one mechanism used in the sector to assess quality. We aimed to explore:

-

how staffing structures and/or workforce models (numbers, skill mix and stability) influenced quality; and

-

care processes involving care home staff associated with quality and explain the relationship between staffing and quality.

We used document analysis89 to elicit meaning, gain understanding and develop empirical knowledge. 90 This is the first published systematic analysis and synthesis of regulatory reports to explore the relationship between staffing and quality. It represents a novel approach for understanding and explaining quality in this context by synthesising data usually viewed and reported for single homes in isolation.

Data sources

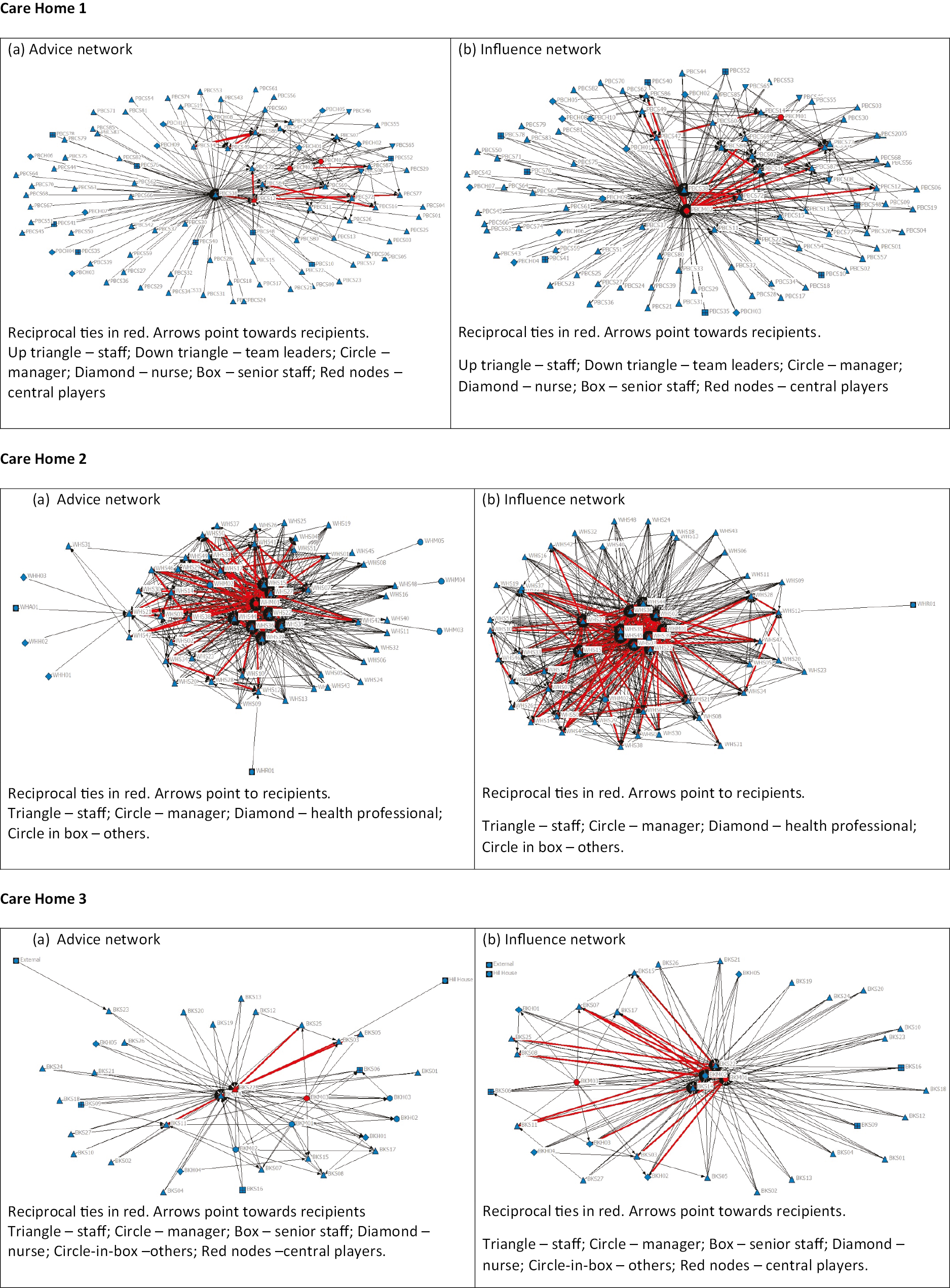

Publicly available CQC inspection reports91 were the data. Our two-stage sampling approach started with CQC reports (n = 125) for our care provider partner from WP3. We included reports from homes rated outstanding (n = 8) or inadequate (n = 2) (Table 7). We piloted our data extraction methods on these 10 care home reports and then (in stage 2) extended the sample to homes from other providers rated as outstanding or inadequate.

| Care home ID | Type | Location | Size | Resident mix | CQC rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care Home 1 | Dual registered | London | 42 beds | Treatment of disease, disorder or injury, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 2 | Dual registered | East Midlands | 55 beds | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, physical disabilities, treatment of disease, disorder or injury, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 3 | Dual registered | South East | 49 beds | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, dementia, treatment of disease, disorder or injury, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

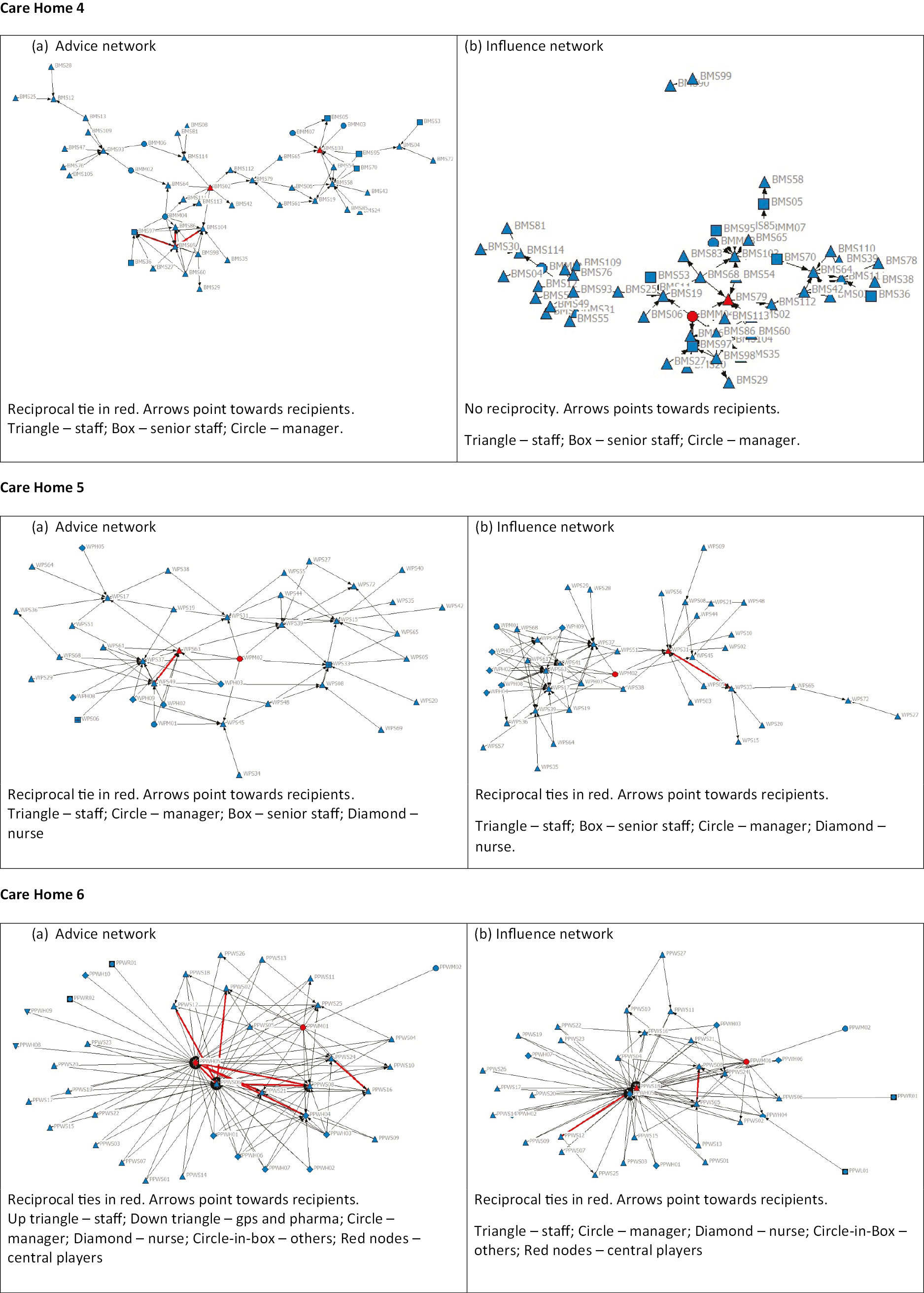

| Care Home 4 | Dual registered | South West | 56 beds | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, dementia, treatment of disease, disorder or injury, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 5 | Dual registered | South West | 49 beds | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, treatment of disease, disorder or injury, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 6 | Dual registered | North East | 59 beds | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, dementia, physical disabilities, treatment of disease, disorder or injury, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

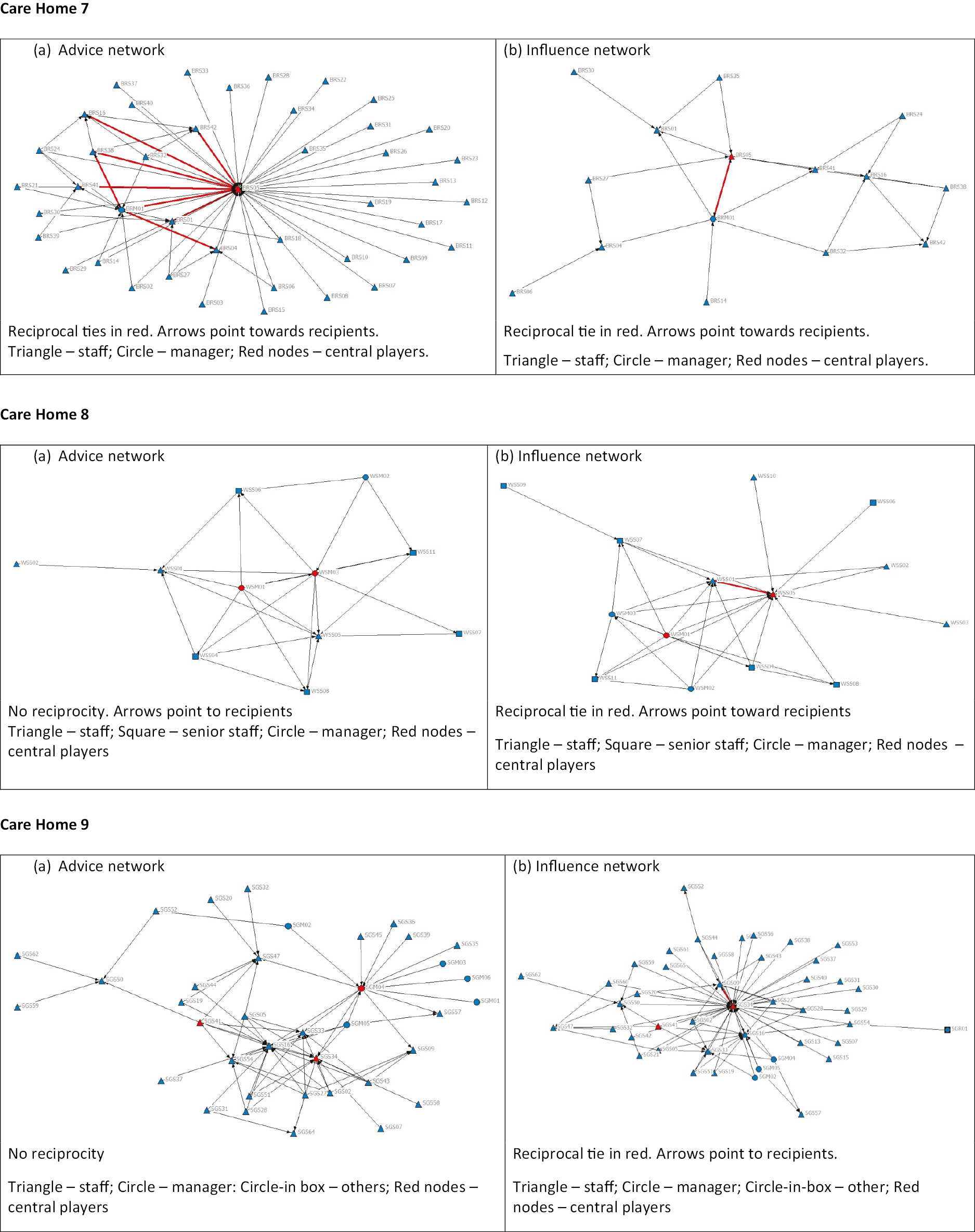

| Care Home 7 | Dual registered | East of England | 40 beds | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, physical disabilities, treatment of disease, disorder or injury, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 8 | Dual registered | London | 52 beds | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, treatment of disease, disorder or injury, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 9 | Residential care | East | 35 beds | Dementia, caring for adults over 65 years | Inadequate |

| Care Home 10 | Dual registered | North West | 78 beds | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, dementia, treatment of disease, disorder or injury, caring for adults over 65 years | Inadequate |

Of the 1066 care homes in England rated as outstanding and 277 rated as inadequate on the CQC website in January 2021 (www.cqc.org.uk/search/services/care-homes), we purposively (Box 3) sampled 20 CQC reports (10 rated as outstanding and 10 as inadequate). Purposive sampling criteria were chosen as ownership, care home size, geographical location influence home structures (numbers/mix of staff, pay, occupancy, resident mix) and organisational processes – impacting on quality and resident experience. Table 8 describes our final 20 care homes in stage 2 and Appendix 9 details our criteria for purposive sampling.

-

Care home ownership: Care home services are mostly supplied by independent care providers, made up of a mix of both for-profit and not-for-profit businesses, but with some local authority provision.

-

Size of the provider organisation: Care home provider organisations vary in size. The vast majority are small providers with around 4000 owning just one home. There are six large care organisations each owning over 100 homes in their portfolio. On a national basis, these six providers have a combined share of 11% of all care homes.

-

Geographical location: There are regional, as well as urban and rural, variations in the CQC reports of quality in care homes. 22

-

Individual care home size: Small care homes (1–10) beds are more often rated as ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ than larger care homes (50+ beds). 22

| Care home ID | Type | Size of provider organisation | Ownership | Location | No of beds | Resident mix | CQC rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care Home 11 | Dual registered |

Large | For-profit | Northeast | 43 | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, dementia, treatment of disease, disorder or injury, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 12 | Dual registered |

Large | For-profit | Northeast | 29 | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, dementia, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 13 | Residential care |

Large | Not-for-profit | Hull, Yorkshire and Humber | 87 | Accommodation for persons who require personal care, dementia, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 14 | Dual registered | Large | Not-for-profit | Southwest | 71 | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, dementia, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 15 | Dual registered | Large | Not-for-profit | Hull, Yorkshire and Humber | 34 | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 16 | Residential care | Medium | Not-for-profit | Southeast | 22 | Accommodation for persons who require personal care, dementia, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 17 | Dual registered | Medium | For-profit | Southeast | 71 | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, dementia, physical disabilities, treatment of disease, disorder or injury, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 18 | Dual registered | Small | For-profit | Northwest | 64 | Accommodation for persons who require nursing or personal care, physical disabilities, treatment of disease, disorder or injury, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |

| Care Home 19 | Residential care | Small | For-profit | West Midlands | 24 | Accommodation for persons who require personal care, dementia, caring for adults over 65 years | Outstanding |