Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number HSDR NIHR130298. The contractual start date was in January 2021. The final report began editorial review in January 2023 and was accepted for publication in April 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Glasby et al. This work was produced by Glasby et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Glasby et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Policy context

Transforming care so that people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people can receive support at home rather than in inpatient units, secure settings or assessment and treatment units (ATUs) is a key priority, which has significant implications for people’s quality of life as well as for public finances. Over the last decade, there have been a series of abuse scandals and significant public anger at such service models, often provided out-of-area and in the commercial sector at significant expense and with poor outcomes. A key aim of the ‘Building the Right Support’ and ‘Transforming Care’ programmes was to enhance community capacity, thereby reducing inappropriate hospital admissions and length of stay. 1,2 Despite this, some 2185 people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people were hospital inpatients at the end of January 2020, 58% of whom had a hospital stay of over 2 years. 3 In spite of significant policy pledges, progress has been painfully slow, with multiple missed deadlines. In 2012, the Department of Health4 was clear that:

By 1 June 2014 we expect to see a rapid reduction in the number of people with challenging behaviour in hospitals …. By that date, no-one should be inappropriately living in a hospital setting. (p. 22)

This was accompanied by a ‘concordat’ signed by the Department and some 50 partners:5

The abuse of people at Winterbourne View hospital was horrifying. Children, young people and adults with learning disabilities or autism … have for too long and in too many cases received poor quality and inappropriate care …. Too many people are ending up unnecessarily in hospital and they are staying there for too long …. [Our] actions are expected to lead to a rapid reduction in hospital placements for this group of people by 1 June 2014. People should not live in hospital for long periods of time. Hospitals are not homes. (p. 5)

When this target was not met, NHS England (NHSE) and partners2 (2015, p. 6) re-iterated their commitment to driving real change:

In February 2015, NHS England publicly committed to a programme of closing inappropriate and outmoded inpatient facilities …. Overall, 35–50% of inpatient provision will be closing nationally with alternative care provided in the community …. In three years we would expect to need hospital care for only 1300–1700 people where we now cater for 2600. This will free up money which can be reinvested into community services, following upfront investment.

As part of these national programmes, there have been a series of linked developments, including a national service model, a new financial framework, guidance for commissioners, model service specifications and the creation of 48 ‘Transforming Care Partnerships’ to re-shape services and reduce inpatient beds by up to 50% (www.england.nhs.uk/learning-disabilities/care/). Independent panels also conduct Care and Treatment Reviews (CTRs), with guidance suggesting that reviews should take place every 6 months for people in non-secure hospitals, every 12 months for people in secure hospitals, and every 3 months for children and young people in hospital. 6 More recently, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC)7 announced a series of additional measures:

All 2,250 patients with learning disabilities and autism who are inpatients in a mental health hospital will have their care reviewed over the next 12 months …. As part of the review, the government will commit to providing each patient with a date for discharge, or where this is not appropriate, a clear explanation of why and a plan to move them closer towards being ready for discharge into the community …. The government is also committing today to a further reduction of up to 400 inpatients to be discharged by the end of March 2020. For those in long-term segregation, an independent panel … will be established to oversee their case reviews to further improve their care and support them to be discharged back to the community as quickly as possible.

Despite all this, long-standing challenges remain (see Box 1). Moreover, many more recent actions seem very similar to previous initiatives, with no indication as to how these might be expected to achieve different outcomes second time round. As Hatton8 argues:

So what do I think are the lessons we can learn from the kind of ‘push’ that has already happened at least once, towards the end of Transforming Care in March 2019, and that policy announcements say are going to happen again?

Based on this evidence, the new initiatives announced … are unlikely to have the transformative effect claimed for them.

This has provoked widespread concern from disability rights campaigners:9

Measures introduced … to address the scandalous treatment of autistic people and people with learning difficulties in mental health hospitals are strikingly similar to failed government measures announced seven years ago …. [This] drew a furious response from disabled activists, who called for an end to meaningless government apologies and promises that fail to stop abuse in institutions.

In 2020, the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) announced that it was launching a legal challenge in response to alleged breaches of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR):10

Today we have launched a legal challenge against the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care over the repeated failure to move people with learning disabilities and autism into appropriate accommodation. We have longstanding concerns about the rights of more than 2000 people with learning disabilities and autism being detained in secure hospitals, often far away from home and for many years …. We have sent a pre-action letter to the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, arguing that the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) has breached the ECHR for failing to meet the targets set in the Transforming Care program and Building the Right Support program … Following discussions with the DHSC and NHSE, we are also not satisfied that new deadlines … will be met. This suggests a systemic failure to protect the right to a private and family life, and right to live free from inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Despite a subsequent government action plan,11 the EHRC have remained highly critical, with a subsequent press release (2022)12 reiterating long-standing concerns:

Every day a person is detained in hospital unnecessarily is a day too many. It is therefore unacceptable, more than a decade after action was first promised, that hundreds of people with autism and learning disabilities are still being kept as in-patients when they could be receiving community care. In too many cases, patients are also subject to restraint and segregation, which can worsen their conditions and make it increasingly hard for them to go home. In extreme cases, there could be significant violations of human rights. The DHSC’s plan to address these concerns has been delayed two years by Covid, and we are pleased it has finally been published. However, it does not go far enough …. The EHRC is exploring how best to use its legal powers to help patients and their families. This may include action in the courts.

There have also been similar debates in other nations of the United Kingdom (UK), with the publication of Scotland’s ‘Coming Home’ Implementation report,13 and critical responses from organisations such as Inclusion Scotland and C-Change Scotland:14

In February of this year the Scottish Government published the Coming Home Implementation Report detailing the proposed response to the critical issue of learning disabled and autistic people spending long periods of time in hospitals and inappropriate out of area placements.

Whilst we appreciate the Government’s focus on this issue and the intention to address it, we are gravely concerned about the process for compiling the report, and the proposals outlined within it ….

In 2022 it is not enough to write the words ‘nothing about us without us’ and publish a report that did not engage with disabled people. It is not good enough to cite human rights based approaches and fail to ensure the participation of the very people the report is about …. We believe the Scottish Government can and should do better. A critical first step would be ensuring real and meaningful engagement of disabled people and their families in any proposals to resolve these, and the other concerns, detailed.

Why this research is needed

All this matters because:

-

Hospitals, although potentially needed by some people for specific periods of time, are not designed to support people to lead an ordinary a life, and few people would want to live there if they could genuinely choose.

-

There has been a series of horrific care scandals in such settings, from Panorama investigations at Winterbourne View/Whorlton Hall to the death of Connor Sparrowhawk and the Justice for Laughing Boy campaign. 15–17 The distress that this has caused to individual people and families is immeasurable, and there are harrowing accounts of abuse, neglect, deaths and widespread deprivation of human rights. 18–20 These stories have been told in the mainstream media (see e.g. Birrell21–23), but with families also increasingly taking to social media (e.g. the 7 Days of Action campaign,24 #CloseATUs, or Bethany’s Dad). This has led to a raft of official reviews; an investigation by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights;25 a highly critical report by the Children’s Commissioner for England;26 campaigns and policy recommendations by groups such as Mencap,27 the National Autistic Society,28 the Voluntary Organisations Disability Group (VODG)29 and the Centre for Welfare Reform;30 highly critical research (e.g. Brown et al. 31); and widespread criticism from voluntary and advocacy organisations such as Autistic UK, People First and Changing Perspectives (see e.g. Pring9).

-

Such services are very expensive, with average weekly and annual costs of £3500 and £180,000 per person. 32,33 This creates a vicious circle whereby funding is sucked into institutional forms of care, leaving less money for community services and leading to even more people being admitted.

While we focus on England, similar issues have been highlighted by the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland,34 with one-third of patients waiting for discharge, sometimes for months or years. In Wales, a national review on behalf of the Chief Nursing Officer identified 256 people in long-stay settings, many of whom had ‘spent significant periods of their lives in hospital care, with some having been inpatients since reaching adulthood’ (Mills et al. 35, p. 179). Hatton36 also provides further cross-UK analysis.

Mencap32 warns of ‘a domestic human rights scandal’, pointing to:

-

‘Almost 2300 children and adults with a learning disability still detained in inpatient units.

-

Over 2500 restrictive interventions e.g. physical restraint in one month – over 820 of which were against children.

-

Average time in an inpatient unit away from home … is almost 5 and a half years.

-

8 years after Winterbourne View …, Government has not delivered on promise to “Transform Care”’.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC)37 suggests that

Thirteen of the 39 people that we visited were experiencing delayed discharge from hospital, and so prolonged time in segregation, because there was no suitable package of care available in a non-hospital setting …. Three of the people had been discharged from hospital previously but then readmitted when the placement could not meet the person’s needs. Staff and advocates have told us that the cost and question of who will fund an alternative placement can delay discharge. In one example a suitable property in the community, that would meet the person’s needs, could not be found for the budget available. Members of the expert advisory group have suggested that there may be conflicting incentives in the system for commissioning care and treatment for this group of people. (p. 20)

The Children’s Commissioner for England26 (pp. 1–2) concludes:

I am concerned that the current system of support is letting many children down and does not meet obligations under the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child …. Hospital admission may rarely be the right thing to do for children …. But it must always be in a child’s best interests and as part of a managed process with clear timescales and a focus on keeping the length of stay as short as possible. This is clearly not happening at the moment and we have a system which is costing millions, yet is letting these children down.

The House of Commons/House of Lords Joint Committee on Human Rights (p. 3)25 sets out a ‘pathway to detention’ which is entirely ‘predictable’:

It begins from before diagnosis. A family grows worried about their child. They raise concerns with the GP, and with the nursery or school. It takes ages before they get an assessment and yet more time passes before they get a diagnosis of autism. All that time they struggle on their own with their worries and without help for their child. This pattern continues throughout childhood as families are under-supported and what little help they have falls away when the child reaches the age of 18. Then something happens, perhaps something relatively minor such as a house move or a parent falls temporarily ill. This unsettles the young person and the family struggles to cope. Professionals meet to discuss what should happen, but parents are not asked for their views. Then the child is taken away from their home and the familiarity and routine which is so essential to them. They’re taken miles away and placed with strangers. The parents are desperately concerned. Their concerns are treated as hostile and they are treated as a problem. The young person gets worse and endures physical restraint and solitary confinement – which the institution calls ‘seclusion’. And the child gets even worse so plans to return home are shelved. The days turn into weeks, then months and in some cases even years. This is such a grim picture, yet it has been stark in evidence to our inquiry …. We have lost confidence that the system is doing what it says it is doing and the regulator’s method of checking is not working. It has been left to the media … to expose abuse. No-one thinks this is acceptable.

How this fills gaps in the literature

Despite significant national debate, very little previous research has engaged directly with people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people or their families to understand the issues from their perspective (see Chapter 3). In research into older people’s hospital admissions and discharge, there has been a similar failure to consider the lived experience of older people and families – and a previous National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) study (‘Who Knows Best’)38–40 is believed to be the first research to meaningfully consider these issues from the perspectives of older people themselves. Whilst professionals often see the individual at a particular point in time (often in a crisis), it is only the person and their family who have a longitudinal sense of how their story has unfolded: their informal networks; their contacts over time with formal services; their experience of hospital; the different options considered; and what has ultimately helped/hindered in securing desired outcomes. Failing to take into account this lived experience is not only morally wrong, but also deprives us of a major source of expertise with which to improve services. Similarly, there has been little consideration of the perspectives of front-line staff, who are being asked to practise in very different ways in a difficult environment, arguably without the support needed to do this well. Again, this mirrors much of the literature around older people’s hospital admissions/discharge, where the tacit knowledge/practice knowledge of front-line staff is largely overlooked (see Chapter 7 for discussion of insights from the broader hospital discharge literature).

Seeking to make a similar contribution in services for people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people, this study addresses four main gaps in the literature (see Chapter 3 for further discussion):

-

While older people’s delayed discharges are frequently debated,41,42 the large numbers of people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people in long-stay settings when they no longer need to be is seldom framed as a ‘delayed transfer of care’ in the same way, is not counted as such in national datasets and is not researched to the same extent. This means that insights from other user groups are not applied to services for people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people, and that we lose an opportunity to improve policy/practice.

-

Most literature on older people’s delayed discharges neglects the lived experience of older people and their families, and most studies in learning disability services focus on information from ward censuses or researchers/clinicians working from medical notes. Even where agencies have sought to review services from multiple perspectives, they have seldom been able to involve people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people in meaningful ways, often lacking the time to get to know people well or to find ways to work effectively with people who do not communicate verbally. Elsewhere, there are powerful stories from family members, but some reports seem to fail to talk to the person themselves (e.g. National Autistic Society28). This is now starting to change, with agencies such as the CQC citing the stories of Adam, Jane, Rachel and John in their review of segregation (p. 20)37 or NHSE setting out Martin’s story (www.youtube.com/watch?v=VC1kQUkVUzM), and with a growing understanding of the importance and power of collating local learning about personal journeys in other service settings (see e.g. CQC43). However, this remains the exception rather than the norm, and has struggled to penetrate many aspects of long-stay settings.

-

Previous research neglects the tacit knowledge of front-line staff, and says little about how workers experience their roles, how delays impact upon them, what support they need and practical steps forward from a staff perspective. While our main aim is to better understand and value the lived experience of people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and their families, an important secondary aim is to understand and value staff experience.

-

Much of the debate is essentially negative in nature (identifying problems, but seldom proposing practical ways forward). In contrast, this study will produce good practice guidance written from the perspective of people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and their families and will develop a free online training video, so that our contribution is more solution-focused.

Aims and objectives

Against this background, the University of Birmingham and the rights-based organisation Changing Our Lives conducted a joint study to better understand the experiences of people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people in long-stay hospital settings, their families and front-line staff – using this knowledge to create practice guides and training material to support new understandings and new ways of working. Our aims were to:

-

review the literature on the rate/causes of delayed hospital discharges of adults with learning disabilities and/or autistic people from specialist inpatient units, NHS campuses and ATUs (referred to as ‘long-stay hospital settings’ as a shorthand);

-

more fully understand the reasons why some people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people are unable to leave hospital, drawing on multiple perspectives (including the lived experience of people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and their families, and the tacit knowledge of front-line staff);

-

identify lessons for policy/practice so that more people can leave hospital and lead a more ordinary life in the community.

Achieving these aims in such service settings required in-depth work, and a unique set of skills and experiences. The University of Birmingham provides expertise around national research into health and social care policy priorities (including working to evaluate the national Building the Right Support programme), commissioning, people’s experiences of health and social care, and the implementation of new service models. Changing Our Lives brings extensive experience of working alongside people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people in long-stay and other settings to help them leave hospital and lead an ordinary life. They are also experts in working with people with a label of ‘challenging behaviour’ and people who do not communicate verbally.

In 2021, the NIHR asked us to consider extending the original research to include additional perspectives from social care (provided this was achieved within the timescales of the initial study). When our proposal was accepted in early 2022, we were able to supplement the original design by including the experiences of social workers, advocates and social care providers who support people as they leave hospital.

Chapter 2 Methods

Literature review

We conducted a formal review of the literature, identifying rates of delayed discharge for people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people in long-stay hospital settings, the methods used to identify such rates and the solutions proposed. This adopted the approach used in previous Department of Health/NIHR research into delayed transfers of care44 and the appropriateness of emergency admissions. 45 Studies were included if they reported original empirical data on rates of delayed discharge and were published from 1990 onwards (the year of the passage of the NHS and Community Care Act). An initial search was conducted by literature-searching specialists at the Health Services Management Centre (HSMC) Knowledge and Evidence Service (so that our search drew on detailed knowledge of the specific search terms utilised in each database and was therefore as broad and inclusive as possible at this initial stage). We searched the following databases (see Box 2 for sample search terms):

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts

-

Health Management Information Consortium

-

MEDLINE

-

Scopus

-

Social Policy and Practice (including CareData, Social Care Online and AgeInfo)

-

Social Science Citation Index

-

Social Services Abstracts

The reference lists of articles included in this study were also searched, and an additional search of the ‘grey’ literature was undertaken via the websites of:

-

CQC

-

Centre for Welfare Reform

-

Challenging Behaviour Foundation

-

Children’s Commissioner for England

-

Department for Health and Social Care

-

EHRC

-

Health and Social Care Scotland

-

House of Commons/House of Lords Joint Committee on Human Rights

-

Learning Disability England

-

Learning Disability Wales

-

Mencap

-

Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland

-

National Audit Office

-

National Autistic Society

-

NHSE

-

Northern Ireland Assembly

-

Northern Ireland Audit Office

-

Scottish Commission for Learning Disability

-

Scottish Government

-

Scottish Learning Disability Observatory

-

Social Care Wales

-

Tizard Centre

-

UK Parliament

-

VODG

-

Welsh Audit Office

-

Welsh Government

-

Welsh Parliament

This also included a general Google search, using variants of terms such as ‘learning disabilities’, ‘delayed discharge’ and ‘hospital’, scanning at least 10 pages of search results for each of these combinations.

All abstracts identified were read independently by two members of the team (Glasby, J./Ince) and discussed in team meetings before inclusion. Alongside research studies, we included the most recent formal review for each of the four nations of the UK (rather than include all bulletins in an ongoing series of reports, for example, we included the most current reviews at the time of the search).

Included studies were summarised using the criteria for assessing the quality of material generated from diverse study designs proposed by Mays et al. ,46 extracting data on: rates of delayed discharge; the methods used to calculate these; the extent to which there has been engagement with people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and their families, and with front-line staff; and the barriers/solutions identified. Specifically excluded were: material published and/or based on data collected prior to 1990; local inspections where findings had been summarised in a national report; additional articles reporting findings from studies already included in the review; admission to non-long-stay settings; and the admission of people with mental health problems (unless the person had learning disabilities and mental health problems). This initial review was designed to set the scene for the subsequent study, summarising the rate of delayed discharge identified in previous studies; the methods used to calculate such rates; the extent to which there has been engagement with people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people, families and front-line staff in conducting such research; the causes of delays; and potential solutions put forward.

Learning disabilities – People with learning disabilities; Learning disability; Learning disabilities; Learning disorders; Learning difficulties; Intellectual disability; Intellectual development disorder; Mental disorders; Mental impairment; Developmental disabilities; Autism; Autism Spectrum Disorder; Child & adolescent mental health; Autistic spectrum; Language development disorder; Mental handicap

Long-stay hospitals – Long-stay hospitals; Long stay patients; Mental health hospitals; Long stay units; Secure settings; Secure units; Medium secure units; Forensic; Psychiatric secure units; Segregation; Secure accommodation; ATUs; Assessment and treatment units; Treatment facilities; Hospitalization/hospitalisation; Hospitals; Hospital units; Hospitals, special; Hospitals, psychiatric; NHS in-patient; Child and adolescent mental health; CAMHS; Psychiatric units; Custodial institutions; Patient institutionalization; Assessment units; Inpatients; Institutionalization/institutionalization; Forensic psychiatric units; Hospital patients; In patients; Learning disability hospitals; Intellectual disability in patient units

Delayed discharge – Delayed discharge; Delayed hospital discharge; Delayed transfer of care; Appropriateness of stay; Blocked beds; Hospital stay duration; Discharge planning; Patient discharge; Hospital discharge; Timely discharge; Treatment duration; Length of stay; Hospital patients; Bed availability; Patient transfer; Long term care; Bed availability; Future plan; Shift of care

Case-study research

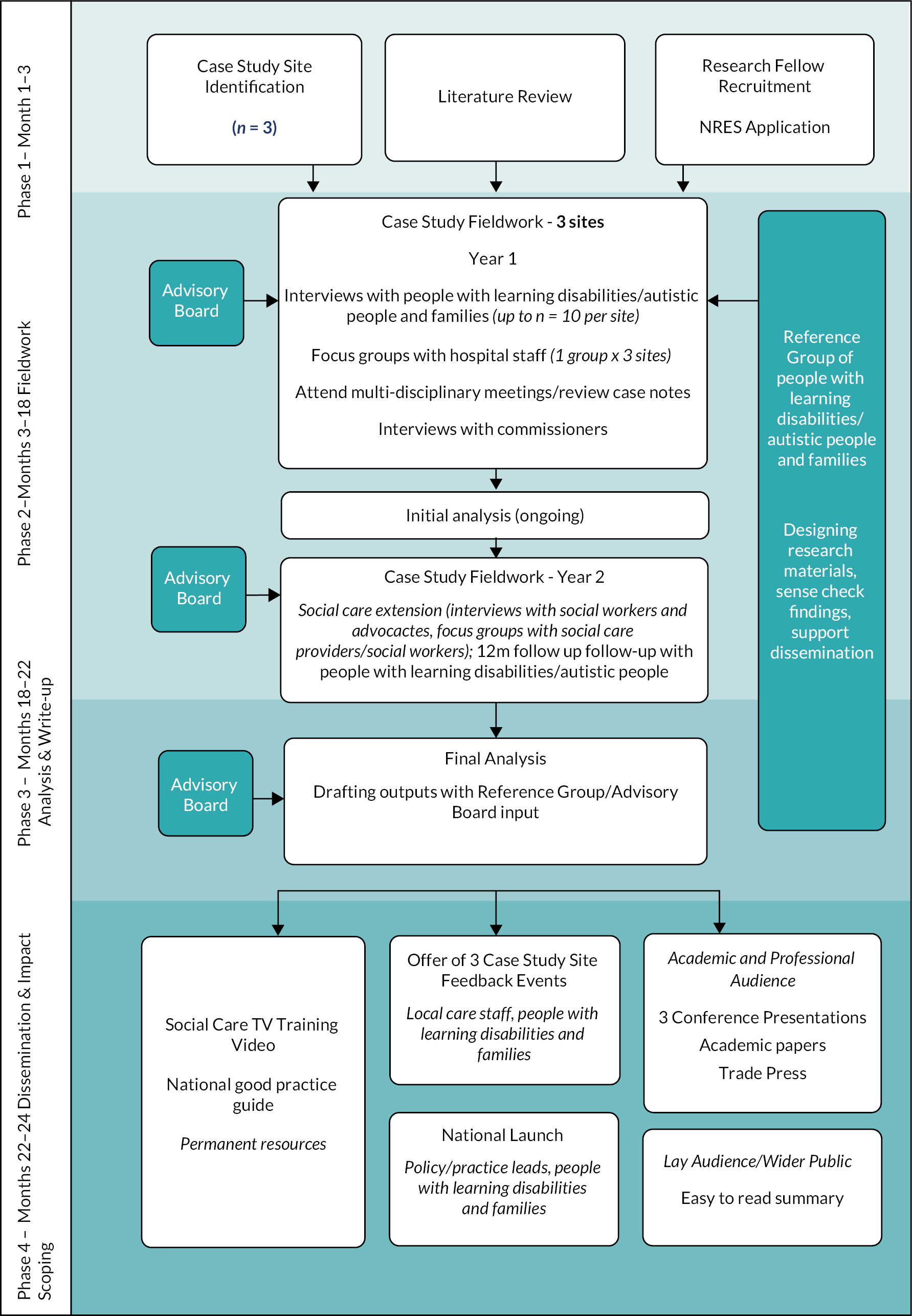

We worked with three long-stay hospital sites from across the country in order to conduct (see Figure 1 for an overview and Appendices 2 and 3 for all research materials):

-

in-depth work with up to 10 people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and their families to understand their journey through services over time, their experience of long-stay hospital provision, the kinds of lives they would like to be living, and the barriers that are preventing them from leaving hospital;

-

focus groups with hospital staff (one group per site), with scope for individual interviews if a key person could not attend the focus group;

-

interviews with commissioners working with the people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people taking part in the research.

FIGURE 1.

Why are we stuck in hospital? (Overview).

As part of a social care extension funded by NIHR part-way through the study, we supplemented our initial study with interviews/focus groups with the social workers supporting our participants and/or from the networks of advisory board members, as well as national focus groups with social care providers and interviews with advocacy organisations who support people in hospital.

Topic guides and a sample introductory letter/information sheet/consent form are set out in Appendices 2 and 3. While the latter had very minor changes in wording for the different groups taking part (e.g. a ‘declaration form’ rather than a ‘consent form’ for consultees), they were all written in an accessible style, and we have included the materials for people with learning disabilities as an example, rather than include all documents with only minor variations.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The study focused on people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people (aged 18 or over) in long-stay hospital settings (and included a family member, hospital staff and a commissioner for each person with a learning disability and/or autistic person who agreed to take part). With our subsequent social care extension, we later included a social worker for each person, as well as broader groups of social workers, advocacy organisations and social care providers who support people coming out of long-stay hospital (either working on a regular basis with our case-study sites or via partners’ national networks). While the definitions of ‘learning disability’ and ‘autism’ are seldom set out in national policy documents, we adopted definitions provided by the Valuing People White Paper (p. 14)47 and the National Autism Society (www.autism.org.uk/about/what-is.aspx):

-

‘Learning disability’ includes the presence of: ‘a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information, to learn new skills (impaired intelligence), with; a reduced ability to cope independently (impaired social functioning); which started before adulthood, with a lasting effect on development. This definition encompasses people with a broad range of disabilities’.

-

‘Autism’ is ‘a lifelong developmental disability which affects how people communicate and interact with the world’.

When defining ‘long-stay settings’ for people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people, our study followed the technical guidance issued by NHS Digital (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-collections-and-data-sets/data-collections/assuring-transformation) to define the long-stay settings which are the subject of its monthly statistical reports (as part of the Transforming Care programme):48

The collection will consider in-patients receiving treatment/care in a facility registered by the Care Quality Commission as a hospital operated by either an NHS or independent sector provider. The facility will provide mental or behavioural healthcare in England. Record level returns will reflect only in-patients or individuals on leave with a bed held vacant for them. This should include patients of …:

People not included:

The guidance from NHSE’s National Clinical Director for Learning Disability, regarding whether a patient should be included if they have a ‘primary diagnosis of Learning Disability’ only, is as follows: ‘For our purpose whether or not a person is recorded as having a primary diagnosis of LD is not relevant, and should not be used as a criterion for inclusion in this data collection. If a person is in specialist hospital bed (either MH or LD) and that person has a Learning Disability or Autism, then that person should be included in the Assuring Transformation data return.’

Our sample was therefore up to 30 people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people, with additional interviews/focus groups undertaken with a family member, care staff, a social worker and a commissioner relating to each person, and advocacy organisations and social care providers working to support people coming out of long-stay hospitals (either working with our three case-study sites, or recruited national via the networks of membership organisations such as VODG, Care England and Learning Disability England). There were no additional inclusion/exclusion criteria for these groups, other than that hospital staff and commissioners are closely involved in the care of the 30 people taking part, and that advocacy organisations/social care providers/social workers are either active in our case-study sites, working directly with our participants or volunteered to take part via national networks of Advisory Board members.

Case-study selection

Case studies were selected to include each of the main current service models and sectors (at least one ATU, one forensic unit, one NHS inpatient unit and one independent provider). These sites also included people with experience of long-term seclusion and segregation, and people with experience of the criminal justice system. While choice of sites was to some extent opportunistic (depending in part on willingness to grant access), we sought sites from different areas of the country and based in different localities in terms of factors such as affluence, ethnicity and rurality. Participating wards included a mix of male/female provision and a mix in terms of levels of security. Participants included a mix of people with learning disabilities and autistic people, some people with experience of the criminal justice system, and some people with experience of long-term seclusion and segregation. People also came from different health and social care systems across the country, and many had been in a number of different hospitals over many years (see below for further details). While all participants were aged 18 or over, some were young adults who were also reflecting on some experiences from before the age of 18. While some people came from minority ethnic communities, our sample was largely from a white UK background (see Chapter 7 for further discussion).

Clinical engagement

Having secured NHS research ethics and local approvals, we worked with lead clinicians in each site to seek their professional opinion as to who could consent to take part, and who might need a ‘consultee’ (usually a family member) under the Mental Capacity Act. This is an approach which we adopted in our ‘Who Knows Best’ research into older people’s experiences of emergency hospital admissions, and it was helpful in ensuring local ownership of the research and providing additional clinical expertise and insight (above and beyond the clinical experience of the research team). These leads gave our introductory letter to everyone on the ward, so that only members of the direct care team initially approached potential participants in the first instance. The introductory letter had a reply slip to confirm that the person was interested in finding out more and potentially exploring participation, and this was returned to the research team by the local lead.

Working with people and families

We chose a research team which is skilled at working with people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and their families in long-stay settings, at working sensitively and ethically with issues of capacity/consent, and at designing accessible information. Making sure that we followed local/national COVID guidance around hospital visitors, we based ourselves in one or two wards/units per site, interviewing all people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people (or consultees) who agreed to take part. Subject to permission and depending on family circumstances, we also carried out an online interview of a family member. Our research team was experienced at working in situations where the person and their family have different views about what is best, or where there are tensions between families and care staff – and we made sure that our interviews enabled people to tell their stories and share their experiences, rather than our having to agree one single version of ‘the truth’ (thus allowing for multiple perspectives, rather than one person’s viewpoint potentially dominating).

Our approach differed according to the ward and people we were working with. In some sites, we were able to base ourselves on the ward for several days, getting to know the service in question, minimising potential disruption and allowing people to approach us if and when they felt comfortable to do so. People could then talk to the researcher direct and agree a time when they felt able to be interviewed. Where it was not possible/permitted to have such open access to the ward, a more formal approach to organising the interviews was adopted (e.g. working with care staff who would work with people on the ward to agree times to meet). People living on one ward also wanted to invite us to their regular ‘patients’ council’ before individuals decided whether or not to take part. In all instances, we were extremely aware of the difficult circumstances people were experiencing and were as flexible as possible to ensure we spoke to people at a time that worked best for them, often returning to see someone on multiple occasions if they did not feel like speaking to us on a given day. We also spoke to ward staff, familiarising ourselves with people’s preferred style of communication before beginning conversations.

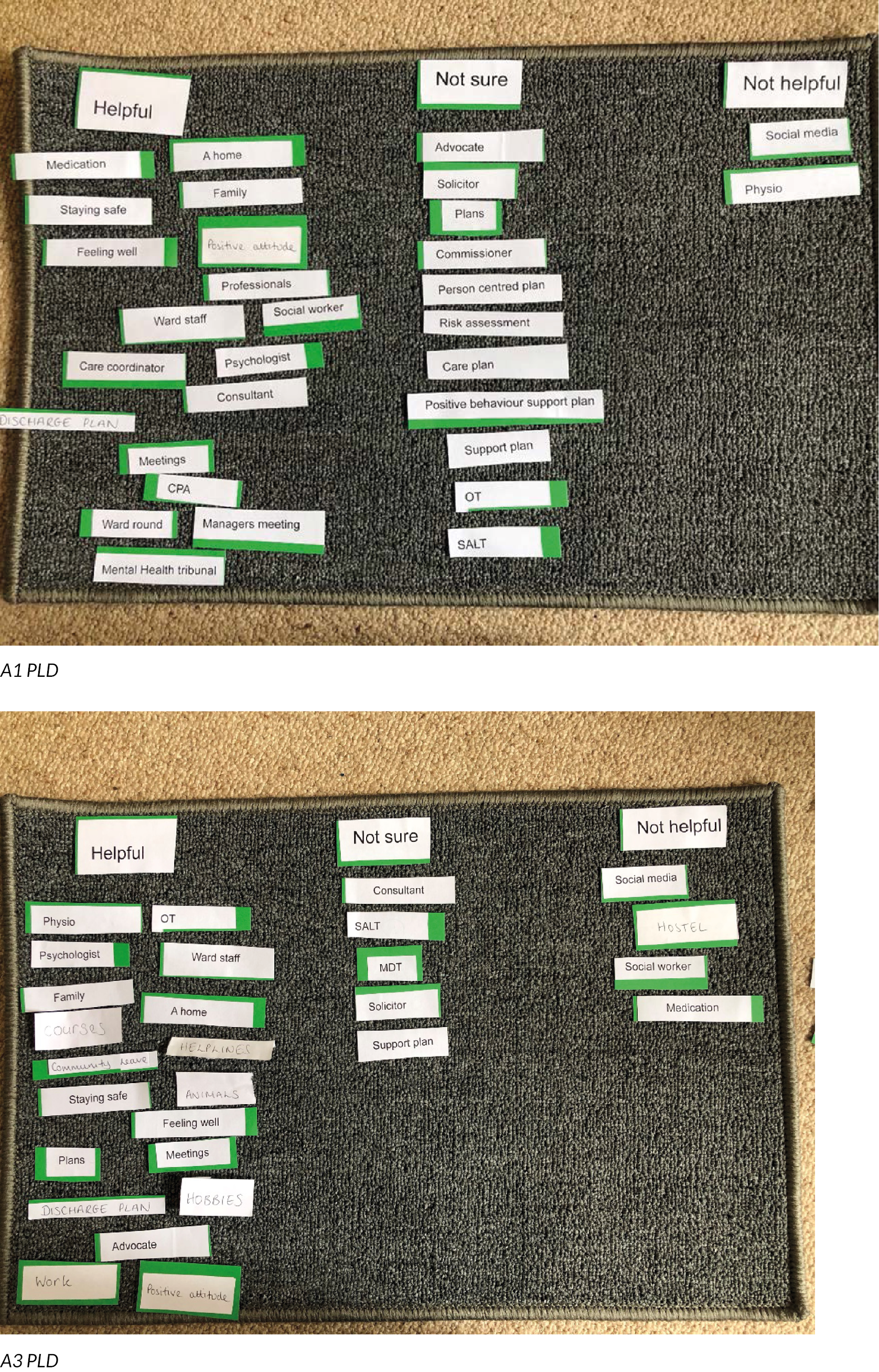

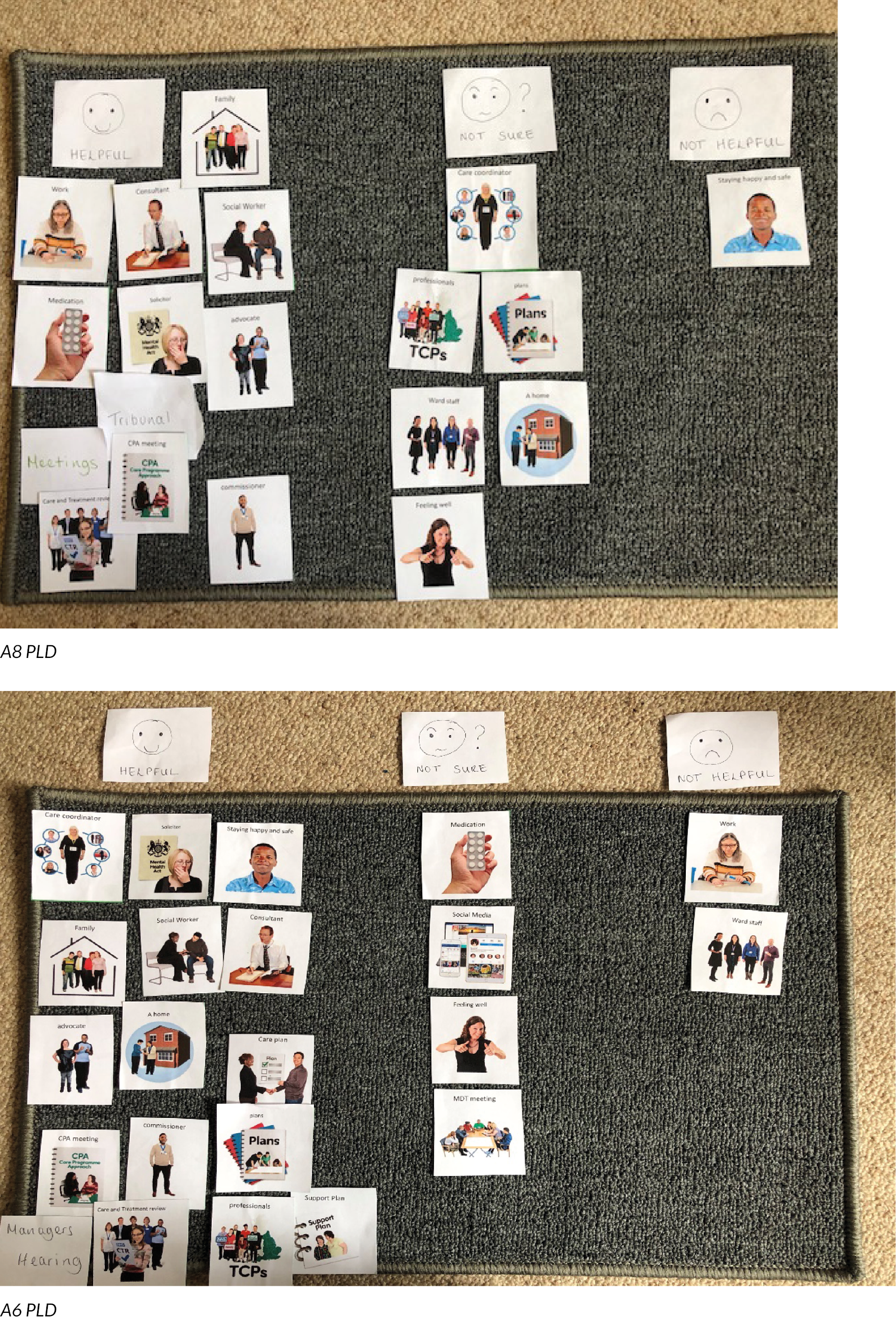

During these interactions, which sometimes took place over several visits, we asked people about why they thought they are in hospital/still in hospital; how they felt about it; what they wanted their life to be like/why they thought their life isn’t currently like that; and what would help them, or others, leave hospital more quickly. Where we had spoken to people early enough in the project, we then repeated this 12 months later to get a sense of what had changed (or not) over time. Where people did not communicate verbally, we used other forms of communication, such as ‘talking mats’ (see Box 3) and art, utilising whatever communication mechanisms the person preferred. With permission from the participant, we also interviewed their family, attended multidisciplinary review meetings and reviewed hospital case notes.

We designed a ‘talking mat’ to be used in the discussion around what was helpful in moving people on. First of all, people from our Reference Group talked about what had helped them leave hospital. These suggestions were then incorporated into the talking mat, with each suggestion represented in a picture. People taking part in the research were offered each picture in turn and asked to place it on a different place on the mat, depending on whether they thought that element helpful for moving on, not helpful or not sure. There were also some blank cards so that people could add their own suggestions.

The talking mat worked particularly well in capturing the views of a participant with selective mutism. Here, the researcher sat on the floor with the mat and the pictures. As each one was held up in turn, the person used their foot to point to where they wanted it to be put on the mat.

For those who did not wish to use pictures, the same ideas were presented in words and the person sorted them into piles, according to what they found helpful and not helpful.

Even where people communicated verbally and were felt by staff to be fully able to take part in interviews, we found that the use of talking mats could help people structure their thoughts, express clear views and preferences and take a more active part in the discussion.

For practical examples from our research, see section What helps below. For information on talking mats more generally, see www.talkingmats.com/.

Staff perspectives

Hospital staff

For staff perspectives, we carried out a focus group of hospital staff in each site. These explored how staff experience their work; how delays impact upon them; what support they would like; key causes of delays; and practical steps forward from a staff perspective. When engaging with staff, we sought to include front-line members of the immediate ward/care team (e.g. support workers and nurses on the unit), as well as members of the wider clinical team (psychologists, psychiatrists, physios, OTs, social workers etc.). Focus groups were particularly helpful here, as they enabled people from different professional backgrounds to interact and, wherever possible, reach a degree of consensus around key issues. To guard against the dangers of front-line staff feeling unable to speak freely, we also offered the opportunity to have an individual interview if this would help them to feel more comfortable contributing their views and experiences. While we were intending to carry out focus groups face-to-face, COVID restrictions meant that these took place online.

In addition to these focus groups/interviews, we also reviewed each person’s case file and observed a series of multidisciplinary decision-making meetings relating to as many of our participants as possible. These were designed to help us better understand people’s journey through services and the local context – so were more for background/preparatory purposes, than to collect or report new data.

Interviews with commissioners

Once the person with a learning disability had consented to take part, the hospital care team contacted commissioners with an introductory email, information sheet and consent form. Interviews took place by telephone or online (Teams/Zoom).

Interviews/focus groups with additional social care participants

Having received agreement from NIHR that we could extend the study to include additional social care perspectives, we carried out online interviews with social workers allocated to each of our participants. In one site, the provider had in-house social care staff who helped co-ordinate discharge from the hospital perspective, so we interviewed them as well as social workers based in local authorities. We also carried out online interviews/focus groups with advocacy organisations and social care providers supporting people to leave hospital (recruiting both those active in our case-study sites, and from organisations which are part of our Advisory Board/their memberships). Because of the diverse nature of our Advisory Board, this meant that we included a range of organisations providing statutory advocacy (e.g. Independent Mental Health Advocates) to a whole ward, site or geographical area; potentially smaller organisations that work with particular individuals in a very person-centred and bespoke way; and a mix of local, regional and national providers across the voluntary, community and private sectors. Our interviews with social workers were also supplemented by national focus groups with social workers connected to the British Association of Social Workers (BASW) work around ‘homes not hospitals’.

Data analysis

Interviews/focus groups were recorded using an encrypted recorder (after obtaining security clearance to use such devices in locked settings) and transcribed by a professional transcription company. The research team also kept detailed records of their time on the ward, insights from case notes and observations from review meetings, building up an in-depth picture of what the person’s life was like, what kind of outcomes they were seeking, what sort of support might work best for them, barriers to leaving hospital, and possible ways forward. These notes were hand-written and were made as soon as possible after each visit (given that pens were not allowed in some sites). Where the person taking part did not want the interview recorded or the discussion could not be transcribed due to the nature of the person’s speech/communication, we drew in detail on such notes (making sure that these were much more extensive than in situations where notes were only really accompanying the formal transcript of the interview).

Data were analysed using the framework approach,49 identifying key themes from the data and constantly checking back to refine emerging themes and to ensure that these continued to represent the data. 50 Initial codes were developed (by Ince, in discussion with Glasby, J./Glasby, A.) after team meetings to share emerging informal themes (which were also sense-checked with our Advisory Board and Reference Group). Final codes were then agreed by consensus in regular team meetings, with two members of the team (Ince and Konteh) each independently coding the same initial six interviews and meeting to compare their experiences and the outcomes of this process. After this was found to be yielding a consistent approach, the remaining transcripts/notes were coded by one researcher only (Ince or Konteh), but with regular team meetings and a half-day analysis workshop to take stock of key themes and compare back with the original data. In later chapters, we label each quote with a letter for the case-study site (A, B, C) and according to whether the participant was a person with a learning disability (‘PLD’), family member, commissioner, social worker or advocate. Thus, for example, A6 PLD would be the sixth person with a learning disability and/or autistic person we interviewed in site A. Focus groups with hospital staff, care providers or social workers are labelled as ‘Provider focus group 1’ etc.

While we were sensitive to the possibility of very different views being expressed by different professionals in our hospital focus groups in particular, the overall themes that emerged tended to be very consistent, with the focus groups easily reaching a shared consensus. The main exception to this was around rates of delayed hospital discharges (see Different professional perspectives). Thus, quotes reported from focus groups are similar to quotes from interviews, typically representing a shared view from participants.

In our main findings chapters (see Chapters 4–6), we tend to highlight a key finding, then provide more detailed quotes to illustrate the issues at stake. Because we are focused on people’s lived experience and the practice knowledge of staff, we include longer quotes than may sometimes be the case in other types of research to maintain the richness and detail of people’s responses.

Drawing on lived experience and working with policy/practice partners

To ensure that our research was informed by lived experience, we worked with a Reference Group of people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and their families to co-design our approach, sense-check findings and support dissemination. We recruited this group from initiatives such as the Sandwell Learning Disability Parliament (people with learning disabilities working together to improve local services), people with previous experience of leaving long-stay hospitals and people from previous Changing Our Lives projects such as Sky’s the Limit (supporting young people with complex needs to lead ordinary lives away from institutional settings). To make sure that this was a diverse group, we also built on a leadership development programme which Changing Our Lives runs on behalf of young adults with learning disabilities and from black and minority ethnic communities. Reference Group members were reimbursed for any expenses, paid for their time at INVOLVE rates, and received appropriate support for the tasks in which they were involved.

While we had initially intended to facilitate a national group on a face-to-face basis, COVID restrictions meant that we started by working with people one-to-one. Although this had not been our original plan, it enabled people from all across the country to take part (including from some very isolated health and social care communities, who might have found it difficult to be a member of the group if it was meeting in a single, central location). After starting one-to-one, we later brought a series of smaller groups together in order to begin moving from individual to more collective perspectives, with a mix of online and face-to-face meetings. Early on, our focus was on how we could describe the aims of the research to people in an accessible manner, and ways of making sure that people really understood that their participation might not mean that they themselves could leave hospital – but might benefit others. Later on, the role of the Reference Group was to sense-check emerging findings, and to help explain key themes in ways that would be as accessible as possible to people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people. Members of the Reference Group also contributed directly to our policy and practice outputs (e.g. being interviewed as part of our training video, helping to design an easy-read summary, narrating video summaries etc.).

We also worked with a national Advisory Board, chaired by a disabled person, to help secure access to case-study sites, advise on the development of policy/practice outputs and support dissemination. This included senior representation from the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE), Think Local Act Personal (TLAP), NHS England/Improvement (NHSE/I), Learning Disability England, VODG, the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS) and the Challenging Behaviour Foundation, as well as senior clinical, legal and academic experience (see Appendix 1). As we extended the study to include additional social care perspectives, representatives joined from BASW and Care England. Advisory Board members were also offered the opportunity to jointly badge our proposed outputs in order to maximise impact.

Dissemination and anticipated impact

We sought to plan how we would work with our findings and embed them in policy/practice from the outset, committing to:

-

hold a national launch, inviting key national policy/practice leads, people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and families to an event which sets out findings/explores key implications;

-

summarise findings in an easy read version for people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people;

-

offer a feedback event to each case-study site, involving local staff, people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and families;

-

create a short but attractively produced guide to tackling delayed discharges, drawing in particular on the experiences of people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and their families; this may be jointly badged with partners from our Advisory Board, and will be sent to every Director of Adult Social Services/NHS Chief Executive in England;

-

produce a free training video for ‘Social Care TV’ (online resources used by SCIE to reach care staff who may not otherwise have access to formal training opportunities);

-

disseminate via articles in the trade press, academic papers and relevant academic/practice conferences.

Part-way through the project, we won additional funding from the University of Birmingham’s ESRC Impact Accelerator Account to work with a local gallery (The Ikon) to commission a leading artist to produce an original installation/exhibition to amplify the voices of people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people from our study (Murray;51 see also www.ikon-gallery.org/exhibition/why-are-we-stuck-in-hospital and our project webpage for more details).

Ethical issues and approvals

We sought research sponsorship from the University of Birmingham’s Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee, ethical approval from a Health Research Authority Research Ethics Committee, and local R&D approval from case-study sites. The research team was experienced at conducting complex health and social care research in difficult environments, at working sensitively and ethically with issues of capacity/consent in ways which enable people who are seldom heard to take part in research, and at working at the pace of individuals with particular communication needs. We conducted the research in a way that valued the voices and experiences of people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people, their families and front-line staff, whilst also recognising the need to minimise potential distress, be respectful of the complexities of life in long-stay settings and ensure safety for everyone involved (e.g. in situations where people may have behaviour that is labelled as challenging services).

All participants were given information about the research (including in accessible formats) and we regularly checked that they understood the aims of the study, consented to take part and were clear on key rights. In particular:

-

participation is voluntary, with no negative consequences from not taking part;

-

people may withdraw at any time prior to the completion of our final report without giving a reason – if they choose to withdraw, their data will not be used;

-

we would have to contact social services if we had any safeguarding concerns (NB this did not transpire in practice).

We did this on an ongoing basis in situations where capacity might fluctuate, checking back over previous conversations, understandings and agreements each time we met. After completing an initial reply slip to signal potential willingness to take part, participants received a more detailed information sheet, and were asked to sign a consent form at the time of interview. Where a lead clinician assessed someone as unable to consent to take part in the research, they approached a consultee on the person’s behalf. In the case of families, consultees, care staff and commissioners, the introductory letter, information sheet and consent form were given by the local lead clinician or a relevant member of the care team, and people who wanted to take part replied to the research team. Part way through the study we sought an amendment to our ethical approval for the research team to contact commissioners directly, given that invitations from hospital staff had not yielded many responses and mindful of the fact that these were senior managers who we felt would feel comfortable declining to participate if they did not wish to take part.

To make sure our research was safe, we:

-

completed university risk assessments;

-

ran training for the research team around being safe in long-stay settings, handling difficult conversations, behaviours that can escalate/de-escalate anger/frustration, and principles of safe practice;

-

consulted with case-study sites around any individuals or parts of the ward we should avoid and any known ‘triggers’ for people on the ward, taking any advice given (e.g. it may not be appropriate for a female researcher to be with a particular person on their own);

-

ensured we were inducted into local procedures around how to respond if there is a serious incident and where exits are and how to exit a locked area safely;

-

spent time on the unit/ward so that people got to know us gradually and are not made nervous by the presence of ‘strangers’ asking questions;

-

undertook ‘managing aggression’ training (which was a requirement for access to one of the sites).

Any recordings were made with an encrypted recorder, with data transferred to password-protected university computers and uploaded to university servers at the earliest opportunity. The recording was then deleted from the audio recorder. Interviews and focus groups were transcribed by a professional transcription company from a list of approved university suppliers, with a confidentiality agreement in place. Where an interview was not audio-recorded (e.g. if the person did not communicate verbally), we made detailed hand-written notes, transferred these to a password-protected computer as soon as possible and destroyed the notes. All data were kept on password-protected university laptops, on university servers or (for manual files) in a locked office at the University. When Changing Our Lives staff made any computer notes or were working on draft reports, they were working with anonymised data and transferred any materials to university servers at the earliest opportunity, deleting these files. Data transfer took place using secure university systems (known as ‘BEAR Data Share’). Personal data were destroyed at the end of the project (24 months), with any other data to be destroyed after 10 years. The document linking personal data to anonymised findings was kept on a password-protected university computer.

Success criteria and potential barriers

In designing this research, we were mindful of potential risks/barriers (many of which are reasons why similar research has not previously been undertaken) and had active plans in place to mitigate these (see Tables 1 and 2). In both tables, the nature and experience of the research team, the complementary nature of the skills of Changing Our Lives and the University of Birmingham, senior support from members of our Advisory Board and our prior experience of the NIHR ‘Who Knows Best’ study were key aspects of our approach.

| Selected (top 5) risks/barriers | Mitigating factors/steps |

|---|---|

| Difficulty recruiting case-study sites in challenging policy/practice context | Active support of Advisory Board (especially NHSE and Learning Disability England); strong profile and links of research team; ability to work in challenging/sensitive settings; anonymisation of case-study sites to prevent reputational risks |

| Difficulty recruiting people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and families | Experience of working with people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and families in long-stay settings; strong networks/practice links; support from active and senior Advisory Board; ability to work in sensitive, ethical ways, taking time to build trust and relationships; support of Reference Group in designing appropriate materials |

| Difficulty recruiting care staff/commissioners | As above |

| Complexities of engaging people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people in research (especially where people do not communicate verbally or have behaviour that challenges services) | Skilled/experienced research team. Changing Our Lives in particular has been selected as a partner for this research due to its long-standing/in-depth track record in this regard |

| Risk of violence/aggression towards research staff | See above (under ‘ethical approvals’) for practical steps around ensuring safety |

| Success criteria | How these will be delivered/met |

|---|---|

| Identification of skilled/experienced research team | Already assembled/set out in the initial proposal |

| Appointment of high-quality Research Fellow with experience of working with people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people | Successful track record of research team in previous studies; networks of applicants/Advisory Board |

| Securing research sponsorship (UoB), ethical approval (HRA) and local R&D approval | Experienced team comfortable working with issues of capacity/consent and in long-stay settings, with strong track record of securing ethical approval in timely fashion in previous studies |

| Creation of high-profile/influential Advisory Board (chaired by a skilled facilitator who is also a disabled person) and Reference Group of people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people and families | Advisory Board already assembled, with senior commitment from key national bodies, chaired by Siraaj Nadat BEM. Reference Group to be assembled from the Sandwell Learning Disability Parliament, people with previous experience of leaving long-stay hospitals and people from previous Changing Our Lives projects such as Sky’s the Limit (supporting young people with complex needs to lead ordinary lives away from institutional settings) |

| Three case-study sites signed up to the research, achieving the proposed number of participants | See above for approach to recruiting case-study sites and working with people/families/staff |

| Collection of proposed data within project timescales | See above for details of project management, roles and responsibilities, as well as online CVs (for details of prior successful delivery) |

| Quality of data analysis | See above for approach to data analysis, and see online CVs for prior track record of research team |

| Launch of high-quality outputs (academic and policy/practice) | See above/online CVs for practical examples of impactful policy/practice outputs and high-quality academic outputs |

| Delivery of project on time/to budget | See online CVs for details of prior successful delivery |

Chapter 3 Literature review

Overview of included studies

There were a very limited number of outputs which met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 2 and Table 3). Considering this is such a long-standing policy priority, this topic seems to be significantly under-researched, with existing claims to knowledge limited to a handful of very context-specific studies and national monitoring exercises (many of which have a number of methodological limitations). Overall, 13 research studies met our criteria (of which one – Thomas et al. 52 – came from the reference list of a study that had been identified in the initial searches – Beer et al. 53), together with five national reviews (see Figure 2). Of the 13 studies, 11 were based on bed census or retrospective case-note analysis and did not include qualitative data. Three of the 13 tested a hospital discharge protocol54–56 and often dealt with delays in a more indirect/implicit manner (e.g. the protocol seemed to significantly reduce delays, hence implying that there were significant delays before the project). Only five of the research studies involved front-line practitioners such as nurses or doctors in the research. Settings included both open and secure wards, large hospitals, small rehabilitation units, ATUs, whole Trusts, single wards and national overviews.

FIGURE 2.

Overview of included studies.

| Authors and date | Population/setting | Length of stay or delay (where included) | Rate of delayed discharge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander et al. (2011)60 | 138 patients in a 64-bed forensic service over a 6-year period | Median length of stay for the discharged group was 2.8 years (1025 days), 75% staying for less than 5 years | Of 61 patients who were still inpatients, 36 (59%) were considered ‘difficult to discharge long-stay’ patients |

| Beer et al. (2005)53 | 200 inpatients across 20 low secure units (8 were for people with learning disabilities) in the South Thames region | 66 (33%) people were inappropriately placed; of these, 60 needed less security | |

| CQC (2020)61 | In-depth reviews of 66 people as part of inspection visits to a wide range of mental health and learning disability services | Discharge prevented due to lack of community services for 60% of the 66 people they met | |

| Cumella et al. (1998)57 | 21 patients admitted for more than 3 months to an acute admissions facility in North Warwickshire | Mean length of stay beyond treatment needs estimated at approximately 6 months | 18 out of 21 people (86%) |

| Devapriam et al. (2014)54 | 16-bed specialist learning disability inpatient unit for people with learning disabilities | 29% (14 out of 49 people) | |

| Dickinson and Singh (1991)62 | Specialist ‘mental handicap hospital’ in London | Average length of stay for ‘new long-stay’ cohort was over 2 years | 57 (55%) of 104 admissions were deemed ‘new long-stay’ patients (resident for over 12 months) |

| Kumar and Agarwal (1996)63 | ‘Mental handicap hospital’ in south of England | 68.4% (188/275 people) considered suitable for discharge to a small home with minimal supervision; 72 (26%) suitable for discharge, but some difficulties in management likely | |

| MacDonald (2018)64 | All but one Health and Social Care Partnerships in Scotland | More than 22% over 10 years; 9% for 5–10 years. Many people didn’t answer, but 13 people were delayed for 1 year+, and 10 people who were delayed had placements costing over £150,000 p.a. Only 51% had active discharge plans | 67 people |

| Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland (2016)34 | All 18 hospital units in Scotland – 104 people’s records (half of those in Scottish services) | 50% over 3 years; just over 20% over 10 years | Nearly one-third of current inpatients (32%) across Scotland were delayed discharges |

| Mills et al. (2020)35 | 256 patients with learning disabilities in units managed directly by, or commissioned by, NHS Wales (across 55 units) | Mean (all patients) – 5.2 years current admission; 53% over 2 years; 19% over 10 years. 18% of current costs (5.994 million) could be reinvested in community services if all people who could be transitioned were transitioned | 80 (54%) people could be considered for transition |

| Nawab and Findlay (2008)55 | Small nine-bed ATU in Lanarkshire | 74% of all admissions = 1 week to 3 months; 20% = more than 3 months; 5% = more than a year | 11% (18) considered delayed discharge |

| Oxley et al. (2013)58 | Two small inpatient units (total of 12 beds) in London (1999–2001 vs. 2009–2011) | Mean length of stay: period 1 = 198.6 days (6 months); period 2 = 244.6 days (9 months) | 67% (40/60) in period 1; 59% (24/41) in period 2 |

| Palmer et al. (2014)65 | All of Northern Ireland’s learning disability hospital inpatient population, mostly at Muckamore Hospital Belfast | Average length of stay 6.2 years (includes short stays of days or weeks – so some must be very long) | No rate of delay reported, but on 31 March 2014, 24 of 30 people from the Delayed Discharge List (people admitted for assessment and treatment) devised in 2011 were still not resettled; and in March 2015, 49 people on the Priority Transfer List (long-term inpatients over 12 months) still required resettlement |

| Perera et al. (2009)66 | All 15 Health Boards in Scotland (range of settings) | Nearly half (47.9%) had been inpatients for more than 5 years | 68 (17.52%) had delayed discharges |

| Taylor et al. (2017)56 | Offenders with learning disabilities in an 18-bed locked rehabilitation unit in Northeast England | See ‘rate of delayed discharge’ column for changes in length of stay | This is an evaluation of a discharge protocol, so no rate of delay given. However, the mean length of stay reduced by over 60% from 39 months (3 years 3 months) to 14 months (1 year 2 months) during the project (implying a degree of delay). The rate of discharge was 7, 6 and 8 people over the first 3 years of the study, jumping to 16 discharges following use of the protocol (again implying previous delays) |

| Thomas et al. (2004)52 | 102 offenders with learning disabilities in all high-security hospitals in England | Mean = 10.26 years; median = 8.5 years | 32 (31%) did not need this level of security (different professionals disagreed on another 16 patients) |

| Washington et al. (2019)59 | Two 21-bed ATUs in North England | Mean admission length = 151 days | Just over 50% (36/70) experienced delayed discharge |

| Watts et al. (2000)67 | Learning Disability Trust in Northeast England | At follow-up 16 months later, 23 of the 44 patients identified as delays remained in hospital | 44 (18%) out of 247 patients were delayed |

Rates of delay

Rates of delay varied significantly depending on location, setting, population studied and methods adopted (see Table 3). However, it is impossible to compare rates between different studies, given a wide range of definitions of ‘delay’, as well as a number of implicit definitions and/or proxy measures (see Table 4).

| Authors (date) | Definition |

|---|---|

| Alexander et al. (2011)60 | ‘Difficult to discharge long-stay’ group = stay longer than median for discharged group (2.8 years) |

| Beer et al. (2005)53 | Being in an ‘inappropriate’ placement – i.e. needing different levels of security |

| CQC (2020)61 | No formal definition: implied in relation to length of stay, length in segregation, readiness for transition |

| Cumella et al. (1998)57 | ‘Bed blockage’ – appropriate for discharge but not able to be discharged |

| Devapriam et al. (2014)54 | Medically fit for discharge but they are unable to leave hospital because arrangements for continuing care have not been finalised (p. 211) |

| Dickinson and Singh (1991)62 | ‘New long-stay’ patient – resident over 12 months |

| Kumar and Agarwal (1996)63 | Nurses asked whether ‘the patients could be discharged and managed in the community with minimal support or were likely to require prolonged inpatient treatment’ (p. 64) |

| MacDonald (2018)64 | A hospital inpatient who is clinically ready for discharge from inpatient hospital care and who continues to occupy a hospital bed beyond the ready for discharge date (p. 11) |

| Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland (2016)34 | We regard them as being kept in hospital when this is recognised as no longer the best place for them to be living (p. 18) |

| Mills et al. (2020)35 | Implied: readiness for transition |

| Nawab and Findley (2008)55 | Clinically fit for discharge but cannot move on from the unit for other reasons (p. 91) |

| Oxley et al. (2013)58 | A delayed transfer occurs when a patient is ready for transfer from a general and acute hospital bed but is still occupying such a bed (p. 37) |

| Palmer et al. (2014)65 | Identified as ready for discharge but there is nowhere for them to go (p. 35) |

| Perera et al. (2009)66 | When a patient, clinically ready for discharge, cannot leave the hospital because the other necessary care, support or accommodation for them is not readily accessible and/or funding is not available (p. 167) |

| Taylor et al. (2017)56 | Inpatients that are clinically fit to leave hospital (p. 144) |

| Thomas et al. (2004)52 | Implied as people who could move to a lower level but remain at higher security than needed |

| Washington et al. (2019)59 | When the original aims of the admission had been met and the length of stay exceeded the recommendations of the Learning Disability Senate (p. 28). The Learning Disability Professional Senate (2016) stipulated specifically that 75 per cent of admissions should be discharged within 3 months and 90 per cent should be discharged within 6 months (p. 25) |

| Watts et al. (2000)67 | Ready for discharge and able to cope in the community with appropriate support, but could not be discharged (p. 179) |

The highest rate of delay was 86% (18 of 21 patients) reported by Cumella et al. 57 in an acute admissions unit intended for shorter stays. Similarly, Oxley et al. 58 and Washington et al. 59 found almost 63% and over 50% of patients delayed in similar ATU settings. These very high rates are due to the expectation that these settings are not intended for stays of longer than a few months, but often ended up with people resident for years, sometimes becoming de facto long-stay settings. On the other hand, Nawab and Findley55 reported only 11% of patients as being delayed.

This was also an ATU, but here 74% of people stayed less than 3 months, suggesting considerable variation, either in service model and/or performance.

In studies of secure settings, rates of delay were reported differently – often based on the appropriateness of the setting or level of security for the patient’s needs. These rates were still very high: for example, 32% of patients in a low-security unit needed less security,53 while a similar proportion of people could be considered for transfer in a high-security setting. 52 In the medium-secure setting explored by Alexander et al. ,60 59% of people were considered ‘difficult to discharge long-stay patients’ (i.e. with a longer median length of stay than those discharged).

In studies based in general wards or a range of different service settings, rates of delay were still significant, ranging from around 18%66,67 to 29%54 and 32% in one of the reviews conducted in Scotland. 34 In CQC’s review across England, 60% of discharges were delayed due to problems finding community placements:

A lack of suitable care in the community prevented discharge for 60% of people we met. Most people in long-term segregation needed bespoke packages of care in the community, but this was difficult to achieve.

(CQC, 2020, p. 29)61

Those reporting proxy measures of delayed discharges identified even higher rates: Kumar and Agarwal63 found 68.4% of people were considered ‘suitable for discharge’ (but still in hospital), while Mills et al. 35 found 54% of people across Wales ‘could be considered for transition’.

A small number of studies also report the extent of delays: MacDonald64 found 67 people in ‘out of area’ placements (i.e. not within the local authority where they lived) across Scotland were considered to have delayed discharges, one-third of them for over a year. In Northern Ireland, Palmer et al. 65 found that of 30 people on a delayed discharge list, only 6 had been discharged between 2011 and 2014, leaving 24 people still delayed in hospital (and a further 25 new admissions since 2011 also delayed). Devapriam et al. 54 also noted the extent of delays at different stages of the discharge process, with the majority of people being delayed for an average of 4 months – but for one patient over 2.5 years – at the first stage of assessment and identifying a suitable placement.

Throughout these studies, there is no consistency as to how delays are defined (see Table 4), making it impossible to meaningfully compare results and gain an overview of delayed discharges across the UK. The majority of studies adopt either an explicit or an implicit definition that sees a ‘delayed discharge’ as occurring when a person stays in hospital after they have no clinical need to remain. However, studies in secure settings often focus on whether someone could be transferred to a less-secure setting (even if they remain an inpatient), and national reviews suggest that some people discharged from hospital are actually transferred to other hospitals (not really a ‘discharge’ at all in lay terms). Some studies use the terminology ‘difficult to discharge’60 or assume that lengths of stay exceeding a particular limit indicate a delay by default. 59,60,62,67 These varying interpretations generate important questions about subjectivity and perspective: in whose view is a person ready to move on? Who assesses whether the level of restriction is appropriate or what length of stay is excessive for different settings, and on what basis (see below for further discussion)?

Broader length of stay

Lengths of stay are sometimes reported either as context or as a proxy for delays, and in different ways. Some studies report the proportion of people staying for different lengths of time, while others report mean or median lengths of stay, and some a combination (see Table 4). Oxley et al. 58 also reported a longitudinal change in length of stay, with median stays increasing from 6 to 9 months across 4 years. Length of stay ranged significantly between settings – for example, ATUs or similar settings had shorter lengths of stay than secure settings, ranging from weeks55 to median stays of 3–6 months. 58,59 What is notable, however, is the large proportions of people staying for many years: secure settings reported a large number of people staying more than 5 years, including 42% of people staying over 5 years and 11% over 10 years in a medium-secure setting,60 mean lengths of stay in a locked rehabilitation unit of over 6 years (for those now discharged, Taylor et al. 56) and mean lengths of stay of over 10 years in a high-security setting. 52 In studies reporting across a range of settings, more than half of people were often staying more than 5 years. 35,65,66 In Scotland, the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland34 found around 70% of people staying longer than 3 years. Where lengths of stay are reported as an average, of course, the inclusion of a number of short-stay settings means that some people experience very lengthy inpatient stays, sometimes reaching into decades.

‘Explaining’ delayed discharge

The range of reasons given for delayed discharges are shown in Table 5, and cover those associated with individual characteristics as well as those pertaining to the discharge process and wider system. In many ways, this is similar to Glasby’s41 review of delayed hospitals discharges from general hospitals, which explored individual, organisational and structural issues at stake, and argued for the need to work across multiple levels at the same time.

| Authors (date) | Reasons for delayed discharge – characteristics | Reasons for delayed discharge – process/system issues |

|---|---|---|

| Alexander et al. (2011)60 | More criminal sections and restriction orders; history of fire-setting; having suffered abuse; diagnosis of personality disorder; history of substance misuse | |