Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/145/06. The contractual start date was in June 2017. The final report began editorial review in November 2020 and was accepted for publication in June 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Benger et al. This work was produced by Benger et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Benger et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and objectives

Overview

In this chapter, we set out the background, context and aims of the general practitioners working in or alongside the emergency department (GPED) study. We show how GPED has developed in response to increasing emergency department (ED) demand and how it relates to previous initiatives, drawing on a range of published literature. A taxonomy of GPED models, developed with the other research team undertaking related work and supported by the same funding call, is described, and this has also been published. 1 By considering the key determinants of GPED, we identify a lack of clarity and consistency regarding the expectations of GPED and the effects it will have on patients, staff, the ED and the wider health-care system. The central roles of streaming and governance are briefly considered before we set out the aims and objectives of the research, the expertise of the study team and the structure of this report.

Background and policy context

Health-care systems across the globe are facing unprecedented challenges. This is particularly apparent in urgent and emergency care, which is experiencing steadily increasing demand. 2 In 2019, attendances at EDs in England reached record levels; 2018–19 saw an increase of 4.4% compared with 2017–18, and an increase of 21% since 2009–10. 3

Although attendance numbers decreased dramatically in March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic (decreasing by 29.4% in March 2020 compared with March 2019), the proportion of patients requiring admission reached its highest ever level. 4 COVID-19 required the NHS to change its approach to managing demand, for example by reducing capacity in EDs to accommodate social distancing on the assumption that all patients might have COVID-19. 5 Despite an uncertain future, the Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) and other authors have stated that EDs need to be transformed to avoid returning to previous experiences of crowding and to provide the best care for patients. 6,7

High levels of attendance result in high occupancy, which is often referred to as ‘crowding’. Crowding occurs when there are insufficient resources to adequately meet patient demand. 8 ED crowding can undermine patient safety, clinical outcomes and quality of care because of increased waiting times9–11 and delayed service delivery,12 with associated increased mortality13 and reduced patient and clinician satisfaction. 14

Waiting times to be seen and treated in England also reached record levels during 2019. Only 79.8% of patients were seen and discharged, admitted or transferred within 4 hours of arrival in December 2019, which was the lowest recorded performance since the ‘4-hour target’ was introduced in 2004. 15

Alongside an acknowledgement that overall ED attendances are increasing, one hypothesis is that more patients are attending the ED either ‘inappropriately’ (i.e. with medical conditions that are not sufficiently urgent to require ED care) or for routine care that could be better delivered elsewhere. It has been estimated that between 15% and 40% of patients attending the ED could be treated in general practices,16–18 particularly children17,19 and those aged 16–44 years. 20,21 However, the lack of a standardised definition of ‘inappropriate’ can be problematic. Using criteria developed by a panel of experts from the RCEM, Morris et al. 22 found that the proportion of avoidable attendances was 19.4%, lower than previously reported. 16

Explanations for avoidable ED attendances include the convenience of access, a sense of anxiety on the part of a patient or carer about the severity of the patient’s condition, a lack of self-care skills,23 the availability of prompt and effective care and access to hospital-based investigations within the ED, a lack of awareness of alternatives to the ED,18 patient dissatisfaction with their own primary care provider24 and a belief that the ED is the correct place to source health care. 25 In a qualitative metasynthesis, Vogel et al. 26 identified four reasons that patients visit the ED over primary care:

-

perceived urgency of the medical condition

-

barriers to accessing primary care

-

advantages of the ED

-

fulfilment of medical needs and quality of care in the ED.

Similarly, a team from the University of Sheffield27,28 identified six mechanisms that explain why patients make clinically unnecessary use of emergency and urgent care:

-

need for risk minimisation

-

need for speed

-

need for low treatment-seeking burden

-

compliance

-

consumer satisfaction

-

frustration in accessing general practitioner (GP) appointments.

Some authors believe that this is exacerbated by reduced access to primary care. 2 However, others report that poor access to GP services does not appear to influence patient attendances to the ED29 and this issue remains unresolved.

Many initiatives have been introduced in the UK to address this challenge, including telephone advice and guidance (NHS Direct/NHS 111) and the provision of alternative facilities, such as walk-in centres and urgent treatment centres, at which patients can access primary care for non-urgent conditions. 2 In addition, over the past decade, EDs across the UK and Europe have implemented a range of new models of care co-locating general practice services in or alongside the ED. By 2015, some form of general practice co-location existed in 43% of UK EDs. 18

Rationales for introducing GPs in or alongside the ED, in addition to addressing the rising demand in attendance, include bringing vital primary care skills and expertise into the ED, reducing admission and investigation rates, improving patient care and reducing costs. 30 However, there is a lack of clarity regarding the mechanism(s) through which these benefits might be achieved, and the hypotheses that underpin the deployment of GPs in the ED are often vague and unclear. 31

In 2014, four Medical Royal Colleges produced 13 recommendations to improve urgent and emergency care. 32 The first of these was that ‘Every emergency department should have a co-located primary care out-of-hours facility’ (copyright © The Royal College of Emergency Medicine, Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health and Royal College of Surgeons). 32 This recommendation was echoed in 2015, when a review of urgent and emergency care in the NHS in England proposed that selected patients should be directed or ‘streamed’ to an alternative health-care provider who could better meet their needs to reduce ED attendances. 33 However, the RCEM reported in 2015 that ‘less than half of EDs in the UK have fully implemented co-located primary care out-of-hours facilities and a third have no co-located primary care facility at all’ (copyright © The Royal College of Emergency Medicine). 34

In 2017, these recommendations were translated into policy. In March 2017, the Next Steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View was published and set out a ‘comprehensive plan to reduce the growth in minor cases that present to A&E [accident and emergency] departments’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.; URL: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/). 35 An accompanying statement said that ‘[e]xperience has shown that onsite GP triage in A&E departments can have a significant and positive impact on A&E waiting times’. 36

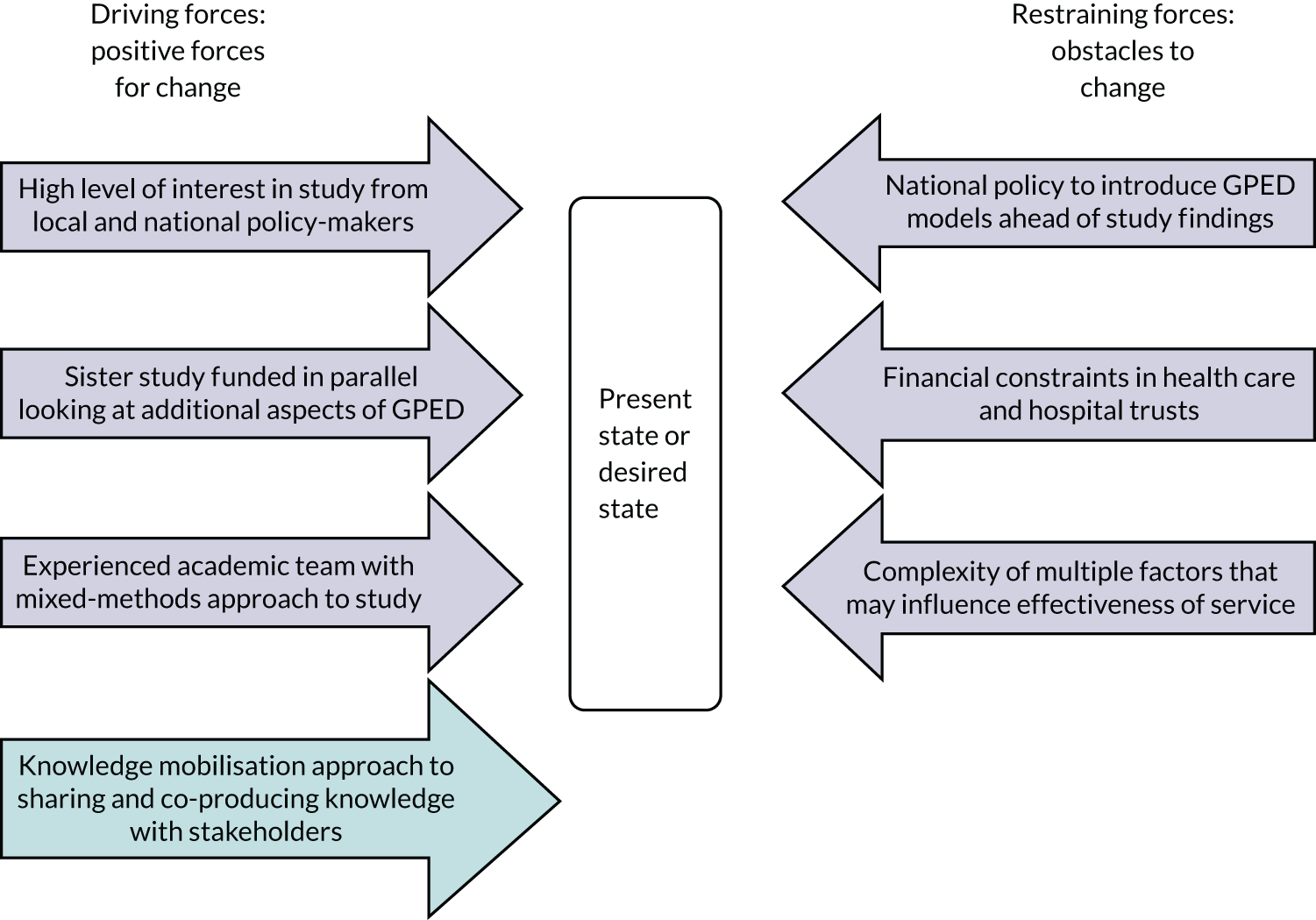

To support this intervention, the UK government announced a capital fund of £100M in the Spring Budget 201737 to which hospitals in England could apply to support or introduce GPED. 36,38 This announcement occurred at the same time as our team was awarded funding to complete the research that is reported here, and this initiative has influenced our study and our findings significantly.

Although the UK government and NHS leaders have proposed the adoption of front-door streaming and co-located care, data to support the benefits of GPED are limited.

Some evaluations of early adopters in the UK and Europe suggested that situating GPs in the ED has the potential to be a promising innovation39 that may reduce resource use40,41 and increase patient satisfaction. 42 Carson et al. 30 reported that the proportion of cases seen by GPs varied and that clinical and operational governance was often disjointed. In a survey of patients, Bickerton et al. 43 found that, although co-located care offered patients a greater range of health-care provision, it also increased the risk of duplication of services and repeat attendance. Similarly, evaluations of nurse-led walk-in centres co-located with the ED found ‘no evidence of any effect on attendance rates, process, costs or outcome of care’. 44 More recently, in a relatively small study, Uthman et al. 45 found that GPs who saw patients in the ED used fewer resources without increasing reattendance and referred more patients to follow-up services. In addition, service users appreciated simplified health-care provision from a single point of access, although this required clear communication between health service staff and patients. 46

Critiques of GPED’s ability to address high levels of ED occupancy include the arguments that eligible patients are often quick and easy to manage, do not breach the ‘4-hour target’ and do not contribute to crowding. 30,47 A recent realist review concluded that, despite GPs in ED being associated with a reduction in process time for non-urgent patients, this does not necessarily increase capacity to care for the sickest patients. 48 The main cause of ED crowding was perceived be because of congestion in the flow of sicker patients into the hospital and a lack of beds, rather than absolute attendance numbers. 49 In addition, GPED may encourage patients to present to the ED with a primary care problem, thereby increasing attendance numbers. 47,50

Several recent reviews have examined GPED in more detail. In a rapid review, Fisher et al. 51 concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support policy or local system design. In an update of Fisher et al. ’s51 rapid review, Turner et al. 52 reported that ‘the evidence base to support development of this model of care was weak and based on poor quality studies’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). These findings were supported by a narrative review by Ramlakhan et al. ,50 which recommended a robust evaluation to inform future policy.

A 2012 Cochrane review53 concluded that there was insufficient evidence regarding GPED to make recommendations for policy or practice. However, the review was based on three non-randomised studies that did not assess patient safety or outcomes and were judged to be of low quality. An updated review54 in 2018 still found insufficient evidence from which to draw conclusions for practice or policy.

Based on current evidence, the most recent guidance55,56 from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) concluded that there was insufficient evidence to reach a recommendation on co-located GP units. NICE found inconclusive evidence that such units reduce the demand on the ED or improve clinical or economic outcomes. 55,56

Providing a reliable solution that applies across the complex range of ED services is challenging and requires adaptation to the specific context. Nevertheless, co-location of GPs in or alongside the ED (i.e. the GPED intervention) remains a preferred option. 57

To date, the consequences for the NHS workforce, both GPs and hospital staff, have not been well considered. It is not clear what the impact is for GPs, who are already under considerable pressure, and GPED may not be the best use of their time and skills. It is also unclear how GPED might have an impact on existing primary care services that are themselves experiencing a steadily increasing demand, with particular challenges in recruitment and retention, and how the additional costs of employing GPs, which may exceed the employment costs of other types of staff, will be met. 58–61

Some of the apparent impact of GPED on EDs may simply be relabelling of the same work, with no real benefits for patients or the NHS. Furthermore, any improvements reported may be attributable to employing additional senior medical staff rather than the fact that they are specialist primary care practitioners. 62 Co-located GP services may stimulate an increase in demand at hospital sites, transferring the problem of overcrowding from EDs to co-located GP urgent care centres (UCCs).

In response to these challenges, and the lack of reliable evidence, this study is one of two commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) [the other being Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR) project 15/145/04; URL: https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/15/145/04 (accessed October 2021)] to evaluate the clinical effectiveness, safety, patient experience and system implications of the different models of GPED.

Taxonomy of GPED models

Departments that were early adopters of GPED were pioneers in the design and execution of co-located GP services. These EDs provided a blueprint for those that followed, with some used as exemplars. Foremost among these was Luton and Dunstable Hospital (L&D) (for more information on the L&D model, which was included as one of our case study sites, see Chapter 3).

There are several models currently in use without any evidence regarding which is the most effective and efficient model of care. 30 An evaluation of 13 EDs in the north of England found that sites varied considerably with regard to their models of care. 59

In 2010, three types of service were identified in a published taxonomy: off-site GP services, a service co-located with the ED and GPs fully integrated with the ED team. 30 It should be noted that the primary purpose or intention of these models may differ; for example, off-site and co-located services may be implemented to move a cohort of patients with problems suitable for general practice out of the ED altogether (potentially reducing the recorded number of ED patients) and integrated GPs may be intended to improve the care and experience of ED patients.

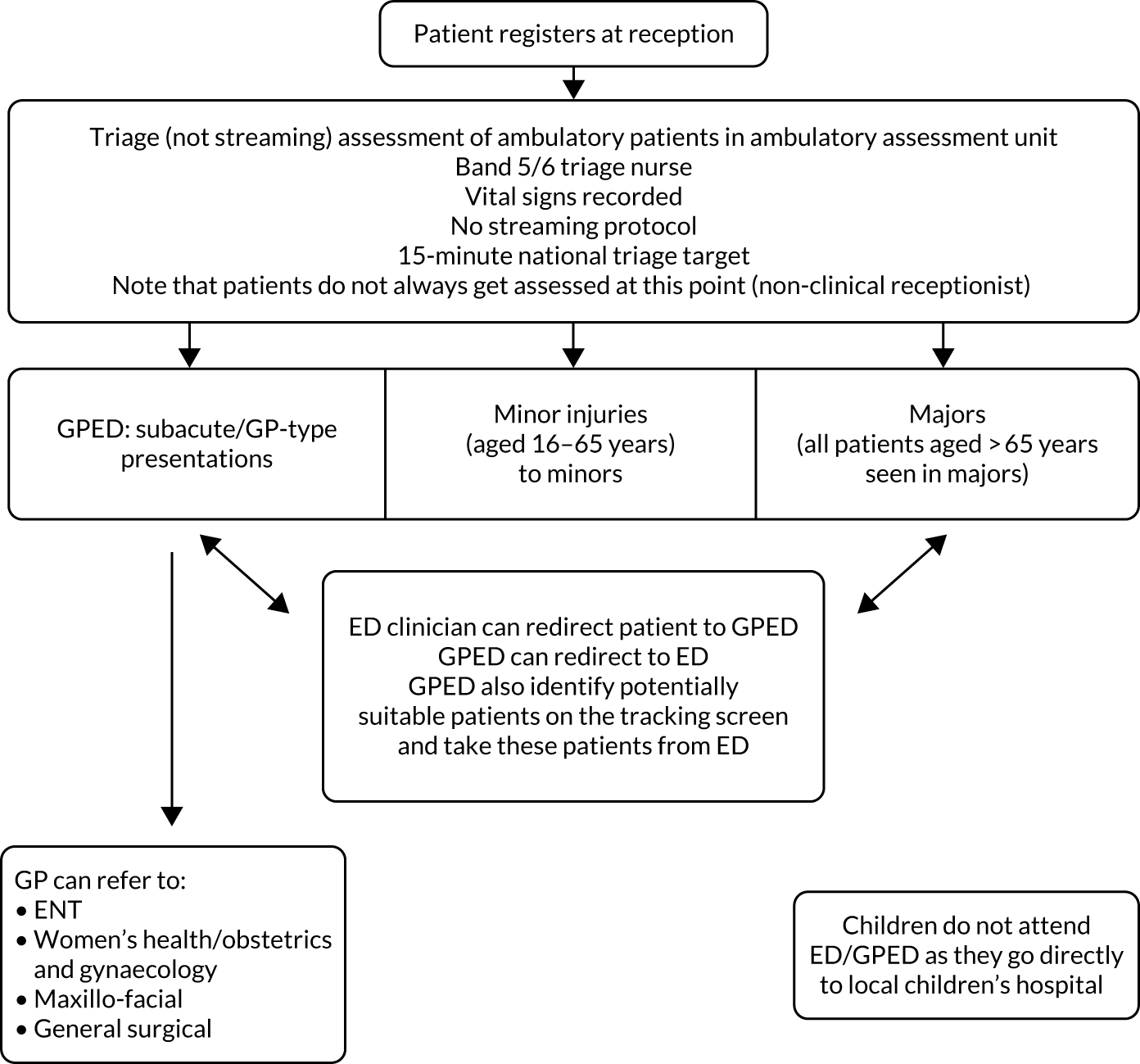

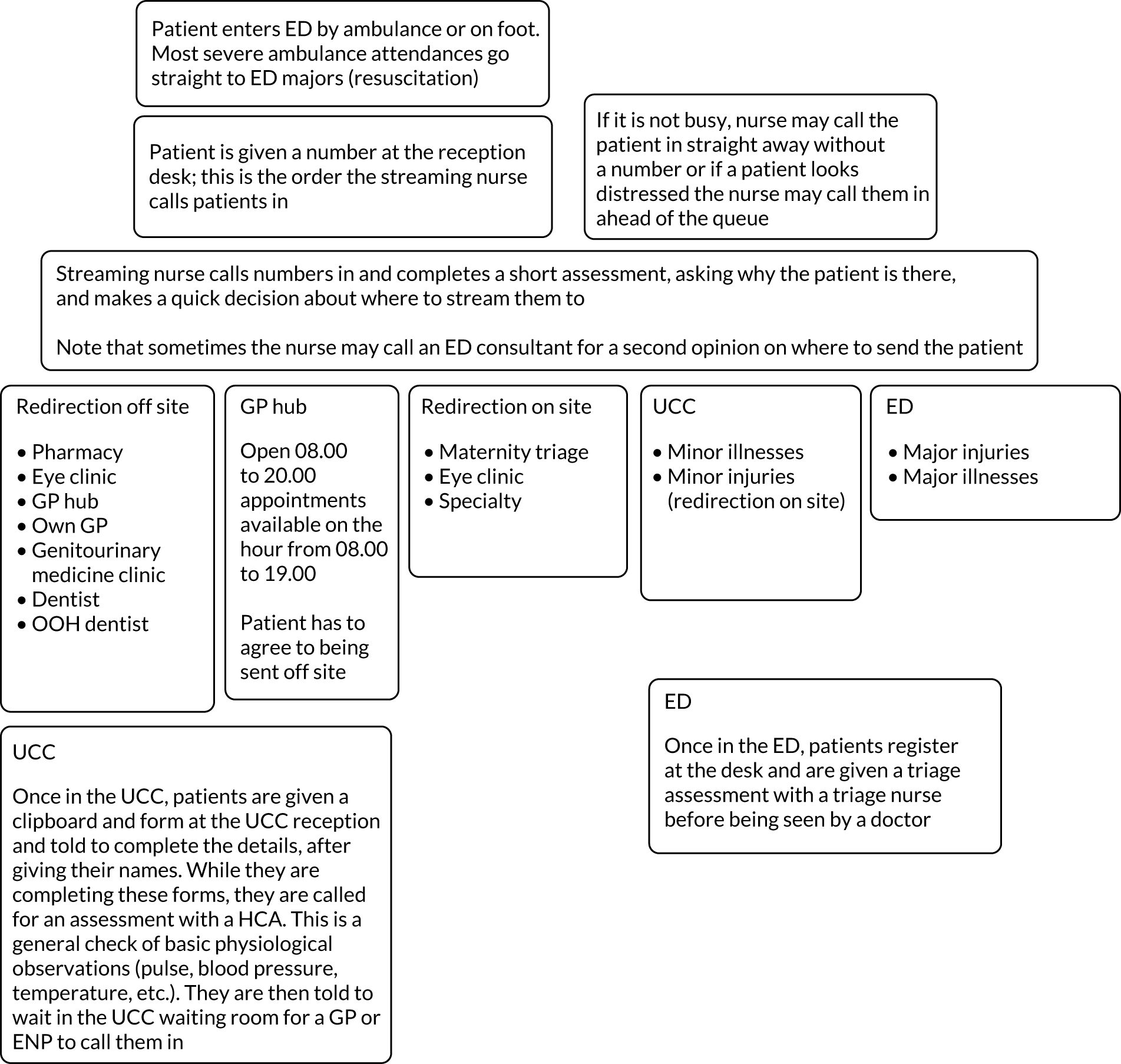

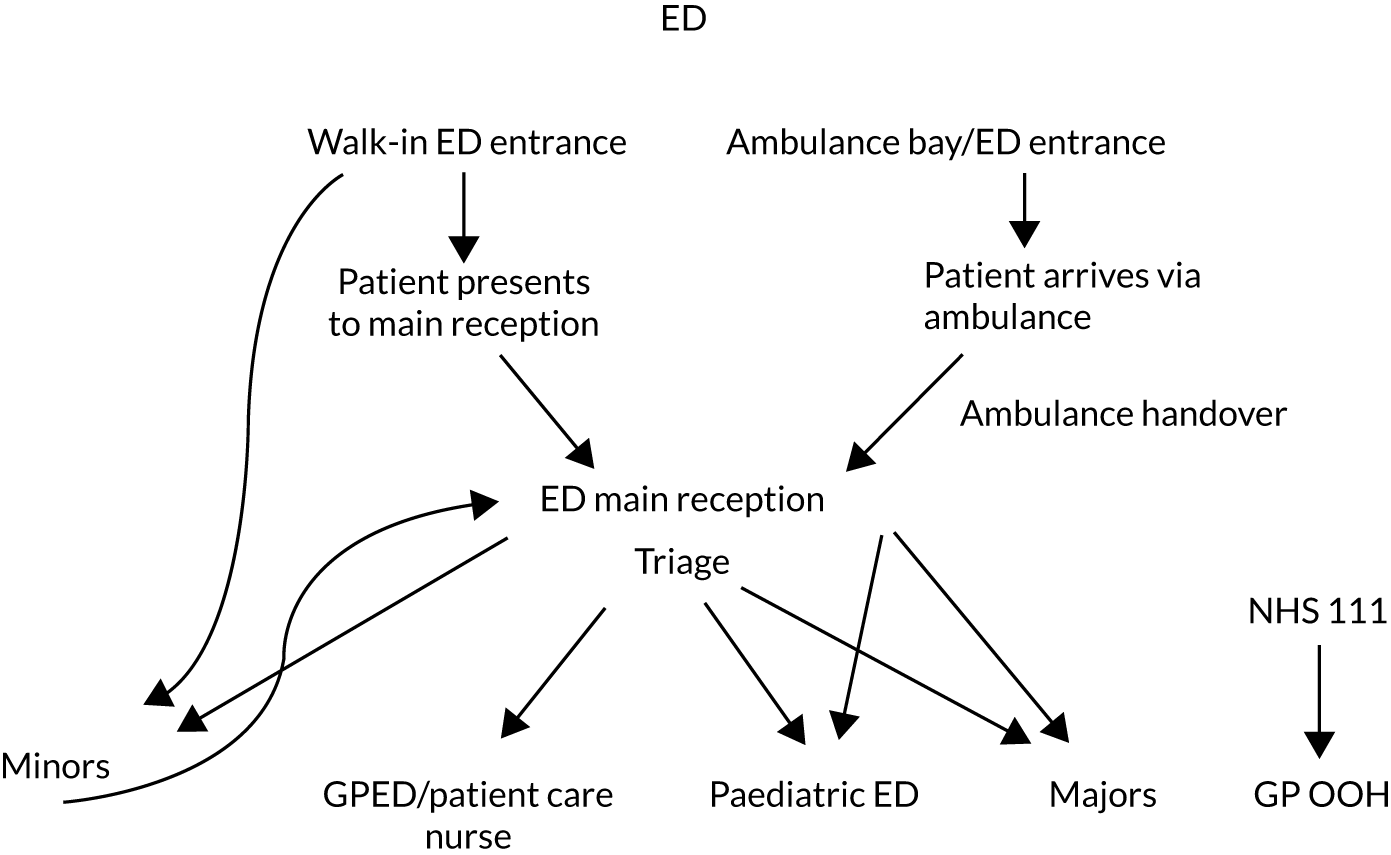

In 2017, in a study of 13 EDs in the north-west of England, Ablard et al. 59 described three distinct models: primary care services embedded within the ED, co-located UCCs and GP out of hours (OOH). In a concept paper published jointly by our study team and the other NIHR-funded team described above,1 a four-model taxonomy was described (Figure 1).

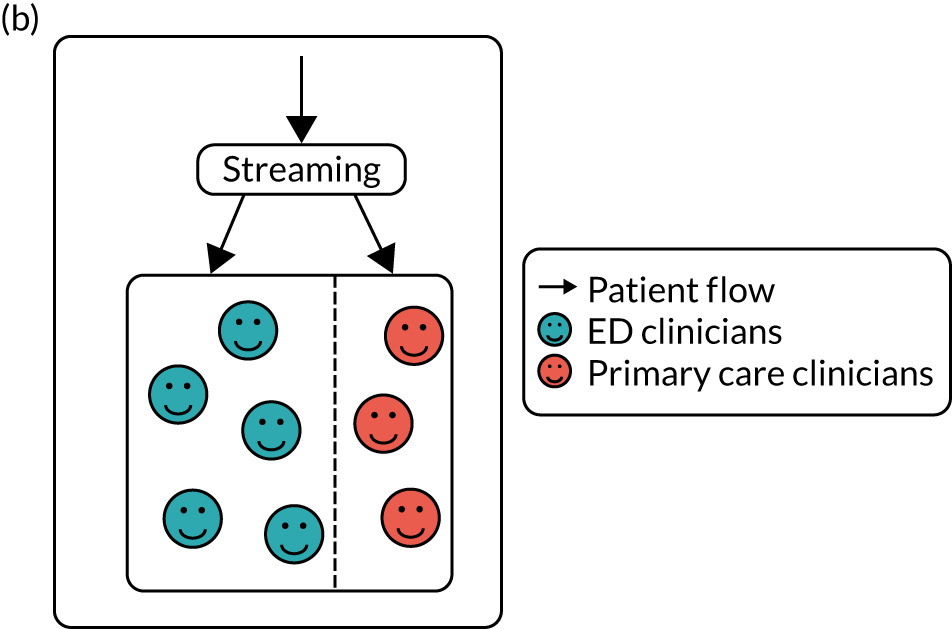

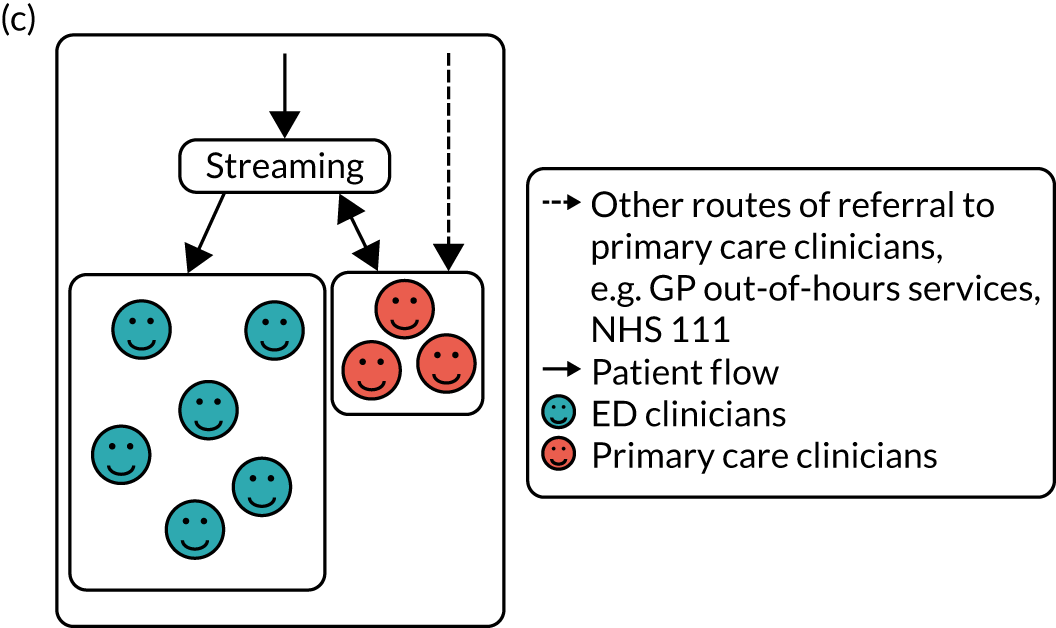

FIGURE 1.

Taxonomy of GPED. (a) Inside – integrated; (b) inside – parallel; (c) outside – on site; and (d) outside – off site. Reproduced with permission from Cooper et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

The four models are based on whether access to the GP service is inside the ED (patients access a primary care service within the ED) or outside the ED (patients access a primary care service that is distinctly separate from the ED). GP services located on a hospital site with no links to an ED are not included in this taxonomy:

-

Inside – integrated: the primary care service is fully integrated with the emergency medicine service.

-

Inside – parallel: there is a separate primary care service within the ED for patients with primary care problems.

-

Outside – on site: the primary care service is elsewhere on the hospital site.

-

Outside – off site: the primary care service is off site (may include telephone advice via NHS 111, or pharmacies, dentists, opticians, UCCs or registered in-hours or OOH primary care services).

Although this describes the structural location of the GPED service, there is still considerable variation in the way that GPED models operate across sites.

Factors influencing the implementation of GPED

This study was designed to examine the impact of GPED and the relative clinical effectiveness of the most common models of GPED currently in use. It is therefore important to recognise that these models can differ quite substantially. This might reflect the rationale for introducing GPED; local demands from both service users and community health-care provision; and practical issues, such as geographical space, financial constraints, and governance and managerial responsibilities.

Expectations and hypotheses of the use of GPED

There appear to be several implicit hypotheses that underpin GPED initiatives, including the following potential benefits: (1) reduced pressure on the ED, freeing resources to concentrate on those patients who are the most ill and injured and reducing waiting times; (2) improved outcomes for patients, assuming that the treatment of less seriously ill patients by GPs rather than hospital doctors will be associated with better risk management, reduced resource use and a lower chance of unnecessary hospital admission; (3) improved efficiency; and (4) redirection of patients into more appropriate services, improving patient experience, providing patient education and reducing future ED attendances for those patients with less serious conditions, thereby allowing EDs to concentrate on those with serious and urgent conditions. 31 However, little is known about whether or not these hypotheses are shared across different stakeholder groups or individuals and what underpins these beliefs.

Streaming of patients suitable for GPED

Central to the effective implementation of GPED services is the identification of patients suitable for redirection. Despite the promotion of ‘front-door clinical streaming’ to address increasing demands on urgent and emergency care,35 limited accompanying guidance has been provided. Initially, the NHS circulated advice based on the model used by L&D hospital,63 which is an ‘outside: on-site’ model with a primary care service on the hospital site, but distinctly separate to the ED. This was followed by a brief additional document,64 building on guidance produced by the RCEM. 65

This guidance emphasises the importance of a high-quality assessment and identifies three main objectives:

-

improving safety

-

identifying ‘acuity’ (the severity and urgency of a patient’s illness) to ensure that the most time-critical patients are treated by the right service within appropriate time frames, and that appropriate prioritisation occurs for the remaining patients

-

improving efficiency in the system to ensure that patients do not wait unnecessarily for investigations or diagnostic decision-making.

Clearly, patient safety is paramount, and this requires a trained clinician to enact clear streaming protocols. This can be undertaken by a range of personnel, such as senior ED nursing staff, emergency nurse practitioners (ENPs), primary care nurse practitioners and GPs.

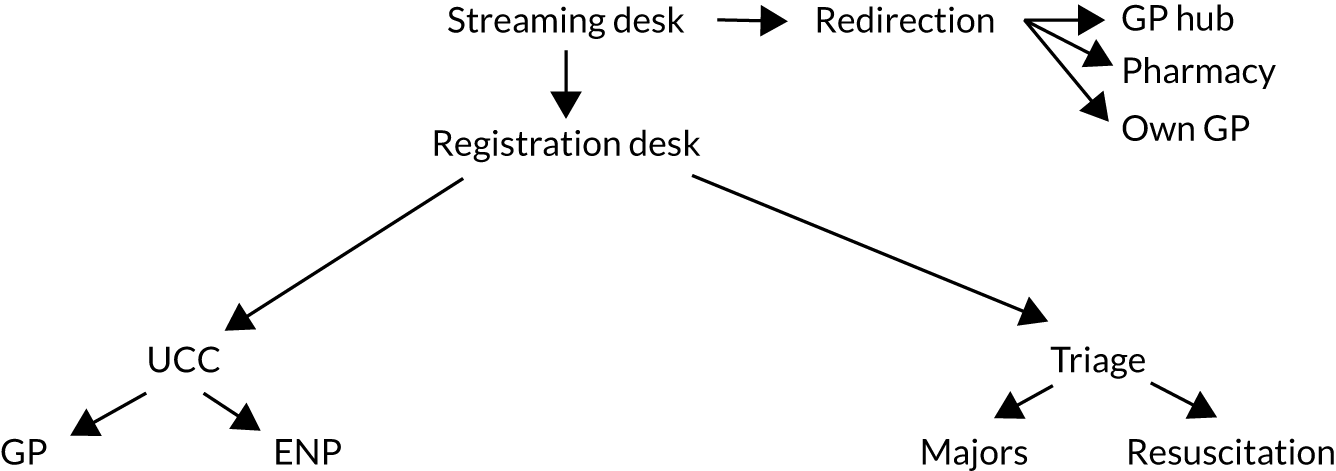

Selecting patients who are appropriate for redirection can occur via streaming or triage. Streaming is described as a brief assessment of the patient, often based on strict protocols, and may occur either prior to or following registration (the point at which demographic information is collected and the patient is identified). Streaming seeks to identify which specific service or practitioner group (stream) best meets the patient’s needs. Triage is a more comprehensive assessment and is usually completed post registration. It seeks to determine the patient’s acuity and, therefore, the order of priority in which patients should be seen. Both processes require an experienced member of clinical staff. The choice as to whether streaming and/or triage is employed is likely to depend on the availability of non-ED services, demand and case mix. Patients suitable for GP care are more likely to be streamed to this service, whereas patients waiting for treatment in an ED are more likely to undergo triage. Limited assessment followed by direction off site may increase clinical risk; a more thorough assessment is required when longer delays to reassessment or definitive care are anticipated. Differences in the choice of triage or streaming, and in the type of clinician undertaking these roles, further complicate the different GPED models in operation, in addition to the four structural location types described in the taxonomy (see Figure 1).

GPED governance

Although the RCEM recommends that the ‘front door’ of the ED is managed by the ED,65 the implementation of GPED requires providers of primary care and secondary care to work together. The method of GPED governance varies considerably and can include GPs employed by a primary care provider, GPs employed by a Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) and GPs employed by the acute hospital trust.

These differing governance systems can influence decisions relating to when the service runs, who decides how it is run, and the risk assessments and thresholds that are deemed acceptable. As such, the employing agency will be responsible for who they recruit and the relevant training that is provided. To our knowledge, the influence of GPED governance has not been explored to date.

Study aim

We aimed to explore the effects of GPED on patient care, the primary care and acute hospital team, and the wider urgent care system, and to determine the effects of different service models of GPED.

Study objectives

Ascertaining the current provision of GPED

Objective 1

Objective 1 was to map and describe current models of GPED in England by drawing on multiple sources, such as survey data, interviews and routinely available information.

Exploring the impact of GPED on emergency department performance

Objective 2

Objective 2 was to use the retrospective analysis of routinely collected ED attendance data [from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data set66], collection of local data and non-participant observation to determine the impact of GPED on patient processes and outcomes, including overall attendances, attendances in different components of the local urgent care system, waiting times, emergency admissions, reattendances and mortality.

Objective 3

Objective 3 was to use the retrospective analysis of HES data66 to assess the impact of GPED on the case mix of admitted patients by exploring admission rates, including the number and proportion of short-stay and zero-day admissions, subject to an examination of coding behaviour by hospital trusts, and any changes that may undermine the reliability of this measure.

Exploring the impact of GPED on the local workforce

Objective 4

Objective 4 was to use a mixed-methods approach, including workforce surveys (WFSs) and interviews, to explore the impact of GPED on GPs, including turnover, absence, satisfaction, well-being and attitudes to and scope of practice.

Objective 5

Objective 5 was to use a mixed-methods approach, including WFSs and interviews, to explore the impact of GPED on the working patterns and roles of other health-care professionals (HCPs) in the ED, including training, workload, skill-mix and expertise.

Exploring the impact of GPED on the local community

Objective 6

Objective 6 was to use a mixed-methods approach, involving secondary data analysis and qualitative techniques, to explore the impact of GPED on local urgent care services; the wider system, including primary care (e.g. demand for in-hours and OOH GP appointments); and the interface between services, including patient flow.

Exploring the impact of GPED on service users

Objective 7

Objective 7 was to use interviews and non-participant observations to assess the impact of GPED on patients and carers.

Resource utilisation and costs of care

Objective 8

Objective 8 was to explore the costs and consequences of care at ED sites with and without GPs in or alongside the ED, and compare the costs of different service models.

Objective 9

Objective 9 was to use interviews with managerial and clinical leaders, the analysis of HES data66 (where available) and a prospective mixed-methods case study to prospectively evaluate the current promotion of GPED models of care through collaboration with sites that received capital funding to implement GPED. This objective was added after project initiation in response to the capital funding initiative announced by the UK government in spring 2017. 37

Report structure and overview of study plan

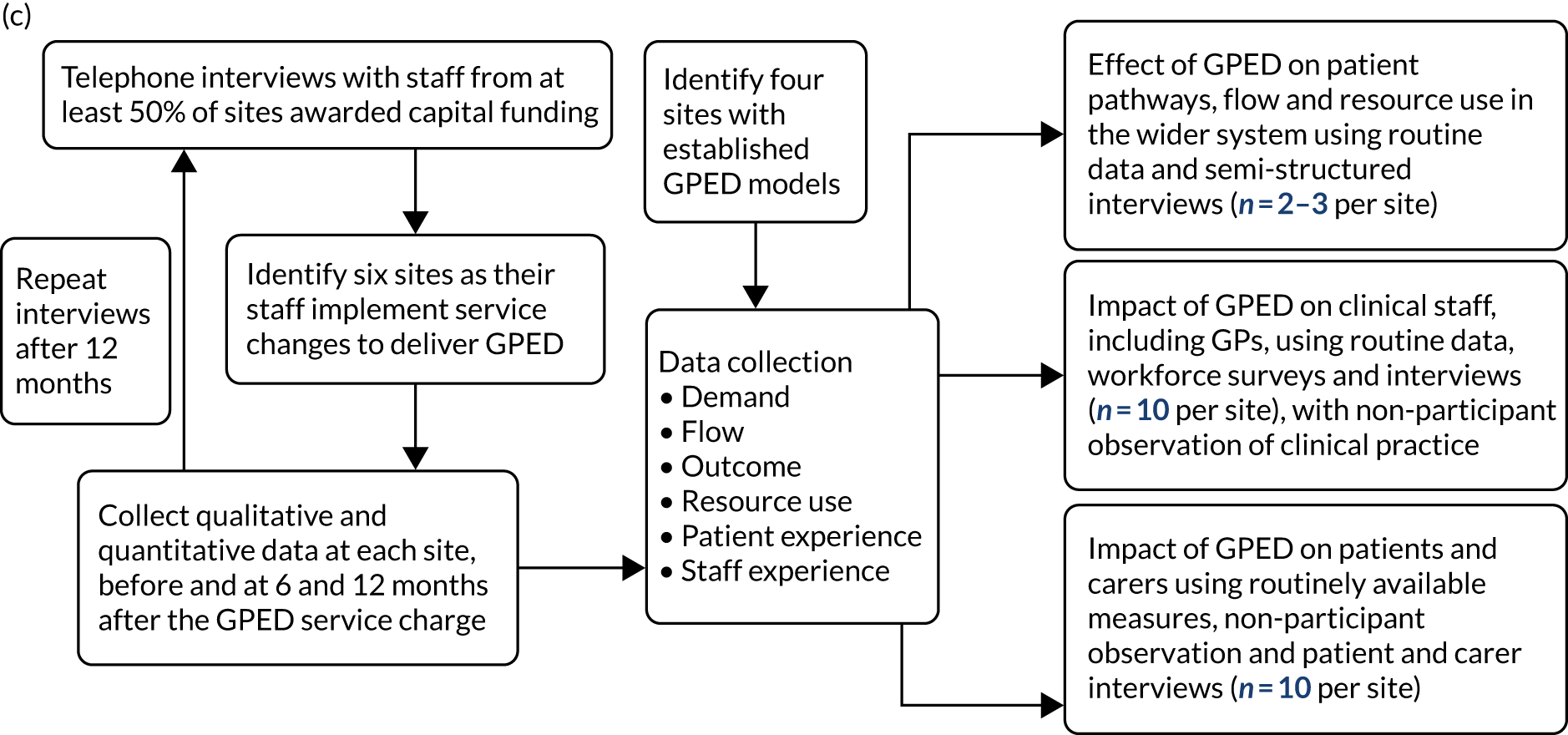

This was a mixed-methods study, comprising three work packages (WPs).

Work package A mapped, described and classified current models of GPED in all EDs in England. This classification was based on an updated taxonomy (see Figure 1) created in collaboration with the other NIHR-funded study to ensure consistency of terminology and, therefore, the comparability of findings. Our research team interviewed key national and local system leaders, staff and patients to identify the domains of influence and hypotheses underpinning GPED, and the potential mechanisms for benefit and disbenefit. We examined these further through WPs B and C.

Work package B used a retrospective analysis of routinely available HES data. 66 This was complemented by a detailed mixed-methods analysis in 10 case study sites. Our primary outcome measure was originally planned to be the number of ED attendances; however, in practice, this proved impossible and the changes that we made to the protocol as a result of this and other challenges arising during the study are considered further in the Chapter 2. Additional outcome measures included waiting times, admission rates, zero-day admission rates, reattendances, patient satisfaction and mortality.

In WP C, we reported a detailed mixed-methods analysis in 10 case study sites that were about to implement (six sites) or had already implemented (four sites) a new GPED model of care. In each of the 10 case study sites, we used survey and interview techniques to collect and synthesise quantitative and qualitative data to ascertain the views and experiences of GPED from staff working across the case study sites and from patients and carers attending the service.

The findings of all study WPs are reported in Chapter 3 and discussed in Chapter 4. The conclusions and implications for future research and policy are mapped out in Chapter 5.

Summary

In this chapter, we have set out the background of and context for GPED initiatives in England. We have described an underpinning taxonomy of GPED models of care and noted uncertainty regarding the anticipated impact of GPED at all levels of the system. ED streaming and models of GPED governance are identified as key determinants of success. We have stated our study aims and objectives and described the structure of the report that will follow.

Chapter 2 Methods

Overview

In this chapter, we set out our research methods and show how these addressed each of the nine study objectives. We describe the protocol changes that were required as the research progressed, and the reasons for these modifications. Of particular note is the fact that we found GPED to be more widely adopted than we had anticipated, highly variable within and between sites, and extremely sensitive to local context. For each of the three WPs, we describe our approach to data sampling/recruitment, collection and analysis. GPED has effects across multiple levels of the health-care system and, therefore, we have adopted an approach that recognises macro levels, meso levels and micro levels of influence. The chapter concludes with a description of our approach to mixed-methods data synthesis, the ways in which patient and public involvement (PPI) have contributed to and enhanced this research and our approach to knowledge mobilisation.

Study design

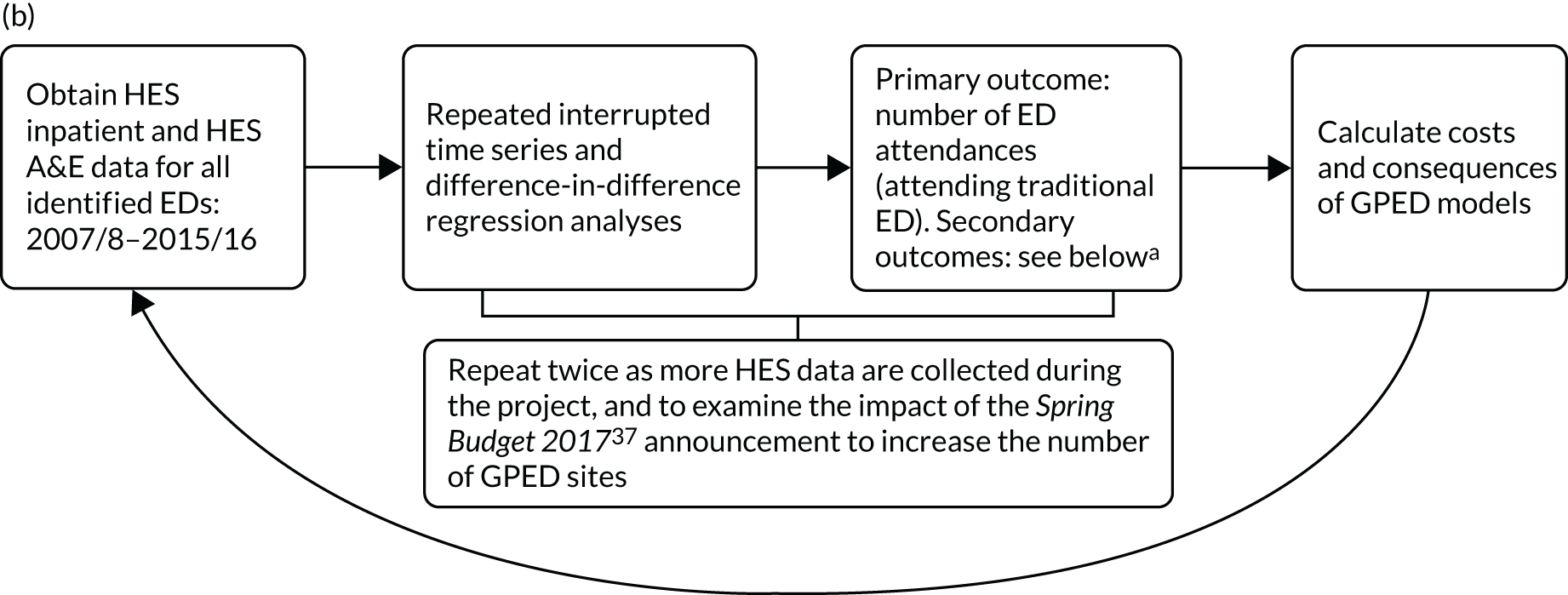

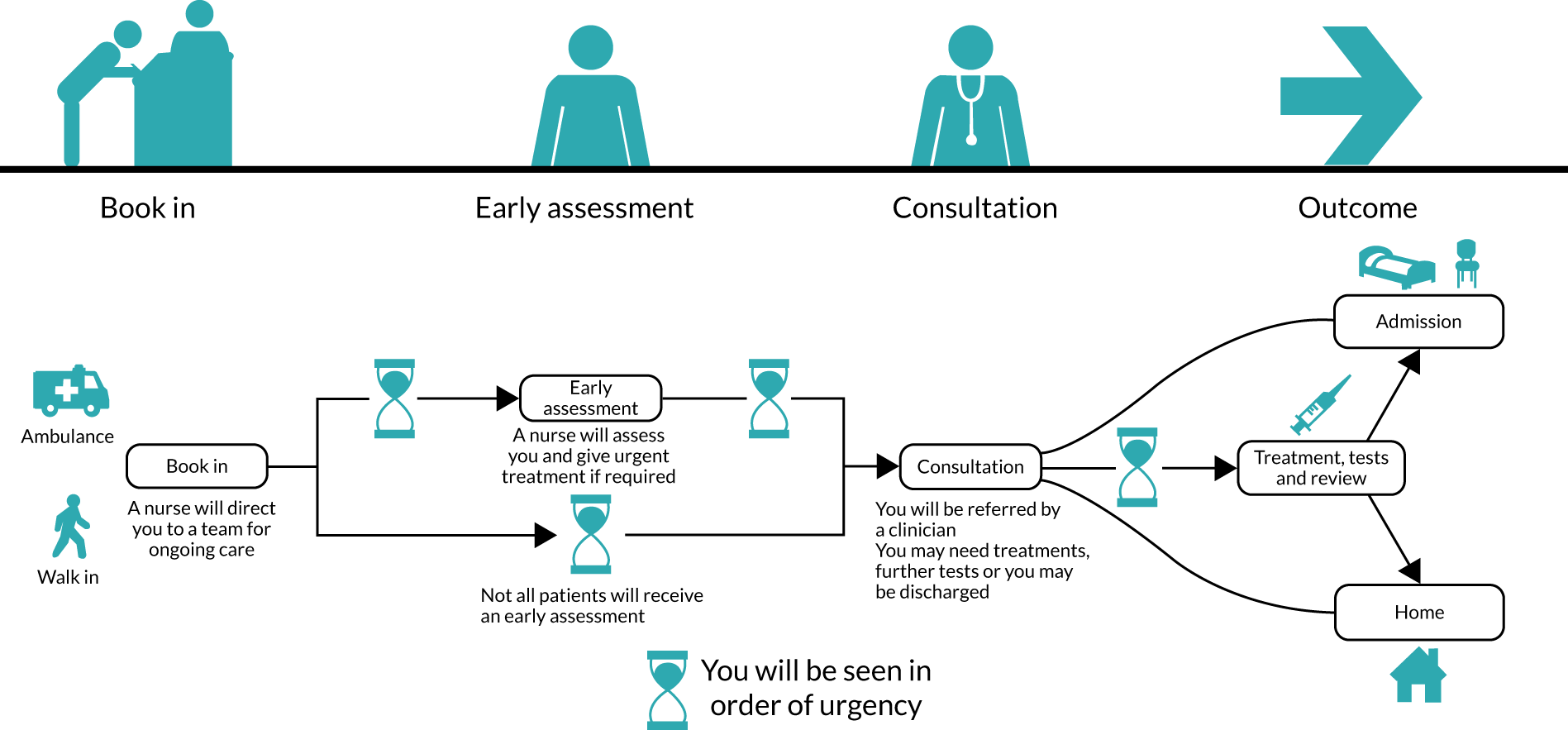

As described in Chapter 1, this study adopted a mixed-methods approach with three WPs. The links between the nine study objectives and the three WPs are shown in Table 1. Each WP is described in more detail below and is illustrated in Figure 2.

| Objective | WP |

|---|---|

| 1: to map and describe current models of GPED in England (drawing on multiple sources in WP A) | A |

| 2: to determine the impact of GPED on patient processes and outcomes, including overall attendances, attendances in different components of the local urgent care system, waiting times, emergency admissions, reattendances and mortality (from retrospective analysis of HES data66 in WP B, collection of local data in WP C and non-participant observation in WP C) | B and C |

| 3: to assess the impact of GPED on the case mix of admitted patients by exploring admission rates, including the number and proportion of short stay and zero-day admissions, subject to an examination of coding behaviour by hospital trusts, and any changes that may undermine the reliability of this measure (from retrospective analysis of HES data66 in WP B) | B and C |

| 4: to explore the impact of GPED on GPs, including turnover, absence, satisfaction, well-being and attitudes to, and scope of, practice (through a mixed-methods approach, including WFSs and interviews in WP C) | C |

| 5: to explore the impact of GPED on the working patterns and roles of other HCPs in the ED, including training, workload, skill-mix and expertise (through a mixed-methods approach, including WFSs and interviews in WP C) | C |

| 6: to explore the impact of GPED on local urgent care services; on the wider system, including primary care (e.g. demand for in-hours and OOH GP appointments); and on the interface between services, including patient flow (through a mixed-methods approach using secondary data analysis and qualitative techniques in WP C) | B and C |

| 7: to assess the impact of GPED on patients and carers (through interviews and non-participant observation in WP C) | C |

| 8: to compare resource utilisation and costs of care at ED sites with and without GPs in or alongside the ED, and to compare the costs of different service models (through economic analysis in WP B) | B |

| 9: to prospectively evaluate the current promotion of GPED models of care through collaboration with sites that have bid for capital funding to implement GPED, conducting interviews with identified system leaders and measuring changes in the above parameters over time and as implementation proceeds (through the baseline and 12-month interviews in WP A; the analysis of HES data,66 where available, in WP B; and a prospective mixed-methods case study approach in WP C) | A, B and C |

FIGURE 2.

General practitioners working in or alongside the ED: efficient models of care – flow diagram. (a) WP A: mapping different models of GPED in England; (b) WP B: retrospective quantitative analysis of national data – costs and consequences; and (c) WP C: prospective and retrospective mixed-methods evaluation in 10 case study sites. a, Includes 4-hour performance, unplanned ED reattendance within 7 days, patients leaving the ED without being seen, emergency hospital admission, zero-day admission, length of stay, re-admission to hospital within 28 days and in-hospital mortality. CQC, Care Quality Commission.

Ethics and research governance permissions

This research study was approved by:

-

East Midlands – Leicester South Research Ethics Committee (reference: 17/EM/0312)

-

University of Newcastle Ethics Committee (reference: 14348/2016)

-

Health Research Authority (HRA) (Integrated Research Application System: 230848 and 218038).

Changes to the study protocol

The study protocol has been published previously. 31 However, some important changes were required as the study progressed in response to ongoing research activity and the emerging findings.

Work package A

The WP A database (WP A1) proved much more challenging to construct than had been anticipated. We agreed with colleagues leading the complementary study, based at Cardiff University, that we would pool the information collected by both teams regarding service provision at each ED site. However, the data that our team collected were not always consistent with the Cardiff team’s survey findings. Different data sources sometimes conflicted, and it could be difficult to be certain regarding the type of model that was in place. Furthermore, key informants found it hard to recall previous service models or dates of change, and this was exacerbated by a rapid turnover in the managerial staff responsible for GPED in participating hospitals.

As the research progressed it became apparent that, contrary to previously published literature,34,67 almost every ED in England had some sort of pre-existing GPED service, and that the models in place tended to vary quite considerably over time and in response to service developments, local initiatives and workforce availability. Even within a single site, GPED usually operated for part of the working week only, and the nature of the service could vary over weeks and months or even within a single day. This made it hard to align sites with the agreed taxonomy or complete an analysis based on the type of GPED model in place. To address this, we created a three-level hierarchy of information sources (level 1, direct observation or interview; level 2, survey return; level 3, documentary or publicly available information), and included sites in our quantitative analysis only if we were confident regarding the type of model that was in use. As a result, the maximum number of sites that we could include in the WP B HES analysis was 40, when we had hoped to exceed 100.

We had originally intended to construct a series of hypotheses underpinning GPED from the initial interviews with system leaders (WP A2) to identify a set of expectations of GPED that could be tested in our research. However, it became apparent that by interviewing system leaders we risked overlooking the views of more local managers, as well as health-care staff, patients and carers. Therefore, we combined WP A2 with the interviews conducted in WP C to generate a fuller range of hypotheses from the perspective of all stakeholders across the system. This approach, however, highlighted that, for any specific issue, views regarding the likely effect of GPED could be profoundly contradictory, with some respondents postulating ‘positive’ effects but others predicting ‘negative’ outcomes. We therefore revised our approach to identify eight core ‘domains of influence’, alongside the anticipated effects of GPED on each, accepting that the predicted effects were sometimes contradictory.

Work package B

Our original aim, as outlined in the study protocol,31 was to compare the clinical effectiveness of different GPED models identified in WP A with a no-GPED model, and then to explore associated costs and consequences. Routinely collected hospital data do not identify the treating physician, and it is therefore not possible to compare outcomes for patients treated by GPs with those treated by usual ED staff. Furthermore, a successful GPED service may improve patient flow, which has positive effects on patients who are not seen by a GP but attend a hospital with GPED services. We had therefore planned two statistical analyses at hospital level: (1) a repeated interrupted time-series analysis of monthly hospital-level data that compared outcomes before and after the introduction of a GPED service, and (2) a difference-in-difference regression approach, with closely matched non-GPED sites as controls. Both methods rely on a clearly defined intervention point for all hospitals that have implemented a GPED service.

As described above, following completion of the initial mapping of different GPED models (WP A1), we found our planned analytical approach to be impossible for two reasons. First, it became clear that the vast majority, if not all, of type 1 EDs already included some form of GP care. It was therefore not possible to use a matched-control difference-in-differences approach. Second, we found that hospitals could not identify a reliable ‘intervention point’, which ruled out an interrupted time-series approach. GP services in EDs have evolved over time, and hospitals were unable to provide detailed retrospective information about the initial recruitment of GPs working in an ED setting, including the date on which a specific arrangement became operational.

These factors necessitated an early reconsideration of our analysis plans and, in consultation with the Study Steering Committee (SSC), we decided to implement a cross-sectional approach rather than a longitudinal approach. Therefore, we analysed data from hospitals with a well-established and clearly defined GPED service (level 1 in our WP A1 hierarchy) during the financial year April 2018 to March 2019. Instead of comparing GPED and control EDs over time, we used the presence of a GP in the ED as the intervention. A total of 40 of these hospitals were able to provide information about the hours (during weekdays and weekends) that a GPED service was (in principle) available, and there was substantial variation in operating hours among hospitals. This facilitated two different analytical approaches that involved comparing outcomes between patient groups who (1) attended the same ED, but at slightly different hours of the day, so were/were not exposed to GPED; or (2) attended different EDs at the same hour of the day which operated/did not operate a GPED service at that time. Both approaches have different strengths and weaknesses; however, by triangulating the results obtained under different approaches, we were able to increase our confidence in the validity of the observed results.

In our protocol,31 the planned primary outcome of WP B was intended to be the volume of patients attending the ED of each hospital. This reflected an assumption that GPED would ‘stream’ patients away from traditional ED attendance. WP A1 and early exploration of HES A&E data66 established that this is not necessarily the case; depending on hospital data-recording practices, the model of GPED and other local factors, it became apparent that GPED patients are often still entered into HES A&E data. 66 Therefore, we were unable to differentiate between patients seen by a GP and those seen by usual ED staff; as a result, our rationale for volume being a primary outcome did not hold. We considered adopting an alternative primary outcome, for which performance against the ‘4-hour wait standard’ was the most promising candidate. However, as this was not specified in our protocol, and to avoid any risk of bias from post hoc decision-making, we present the results of our quantitative analyses ranked equally, without an identified primary outcome. Nevertheless, we have retained volume of attendances in our indicator list, in case GPED affects the overall volume of patients attending the ED. 47,50

The issues with our primary outcome measure also changed our approach to the costs and consequences analysis. Again, as we had anticipated that GPED systems would redirect patients from ED to primary care interventions, we had planned to attach unit costs to any reductions in ED attendances and compare these with estimated costs of a GPED service (mainly the salary costs of GPs). As GPED and traditional ED attendances are not separately coded, this is not possible with routine data. Our exploration of costs and consequences was therefore adjusted to assess whether or not there are resource consequences of the range of performance indicators we observed, and to value any significant changes using Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2019. 68 This was supplemented by a qualitative exploration of resource use and costs.

Work package C

Originally, it was our intention to explore the impact of GPED at 10 case sites. These sites were to be purposively selected to ensure that our analysis included ‘established’ sites, where GPED had been embedded for some time, and ‘prospective’ sites where the ambition was to use capital funding to introduce GPED. As described in our published protocol,31 10 case sites were purposively selected on this basis. However, it became clear during data collection that a GPED service had been implemented to some extent at all sites for some time. Therefore, we have not classified sites as prospective or established in our analysis, as any distinction on this basis would be artificial. Instead, we have explored the history of GPED at each site, which provided important context for understanding how the service was operationalised. This has also offered insights into national variation, as well as developed an understanding of how context had an impact on the perceived ‘success’ of each GPED model.

We had planned to use the taxonomy that was developed through WP A1 to not only structure our analysis, but also to allow us to compare the clinical ‘effectiveness’ of different GPED models. However, substantial heterogeneity in terms of both the length of time that sites had been operating a GPED model and the way that the policy was interpreted resulted in a wide range of implemented models. These complex contexts did not always fit easily into the broad categorisations outlined in the WP A1 taxonomy, limiting the value of any comparisons across and within the taxonomy.

We visited each ‘prospective’ case site at three time points, and had originally planned to treat the data as a longitudinal qualitative data set, from which we would explore how GPED was implemented at sites that had received capital funding and the impact of these changes on patient care, urgent care and the wider health-care community over time. However, the fact that GPED had been introduced in some form at all sites for different lengths of time meant that any changes resulting from capital funding were generally more gradual and subtle, making it difficult to analyse our data longitudinally. This finding was further reinforced in the findings from WP A3, in which interviews with staff from sites that had received capital investment to implement GPED often identified less change than expected over the 12 months following a funding award.

As a result of the different GPED models and time periods for which they had been in use, it could be argued that we were, in effect, evaluating the impact of different ‘interventions’ across an unknown time frame. This made any comparison of GPED by site or time point irrelevant. For transparency and to highlight the complexity associated with analysing our data at the case-site level, we have created a series of pen portraits for each of the 10 case sites that were included in the WP C analysis. These are detailed accounts of the GPED model and key findings at each site. We will refer to these pen portraits throughout this report. (The pen portraits for each site and for each time point are included in Appendix 3. This allows readers to explore each of our key qualitative themes by case site should they wish to do so.)

We had originally planned to collect data from the primary and urgent care systems surrounding our WP C case study sites to quantitatively evaluate the effect of GPED on the wider health-care system. However, it proved exceptionally difficult to obtain primary and community data, even with the assistance of the SSC. After considerable effort, we were able to obtain some quantitative data from four of our case study sites; however, these data were found to add little to the HES data that were already available. As a result, our views on wider system effects are largely based on the qualitative data collected from each case study site in WP C.

The difficulties that we encountered in distinguishing established case study sites from prospective ones also had implications for the analyses of the WFS in WP C. It was initially planned that analyses of established and prospective sites would be conducted separately and, in the case of prospective sites, there would be repeated administrations of the survey to staff members to determine whether or not perceptions of the new service changed over time and in the context of implementation. However, following our recognition of the lack of distinction between prospective and established sites, we decided that it would be preferable to combine data from surveys of established sites, as well as data from the baseline time point for prospective sites, which were viewed as comparable and appropriate for cross-sectional analyses. For example, the same survey items regarding work pressures, job satisfaction and turnover intentions were included in surveys administered to staff in both established and prospective sites, and data from these survey respondents could be readily pooled. This approach mirrors the protocol changes that were required in WP B in that we opted to convert our approach from a longitudinal to a cross-sectional design.

Summary of changes to the study protocol

Overall, we found that the reality of GPED was much more complex and variable than we had anticipated. Models varied between and within sites and changed frequently in response to a variety of factors, of which national policy and funding represented only one component. This made classification and comparison particularly challenging, both within and between sites. We adapted our data collection, analysis and interpretation to reflect this reality, moving away from a longitudinal approach towards a more cross-sectional one. We explore the implications of this observation further in the later sections of this report.

Work package A: mapping different models of GPED and interviews with key informants to understand the hypotheses that underpin GPED and the experience of implementing these models of care

Introduction

Before commencing the mixed-methods evaluation of the impact of GPED and the differential impact of alternative GPED models, it was necessary to develop an understanding of current practice and the rationale that underpins GPED initiatives. WP A was designed to (1) map and classify current models of GPED (WP A1) and (2) understand the rationale that underpins GPED (WP A2). With the announcement of £100M in capital funding to support the implementation of GPED in all EDs in England,37 we added a third objective: (3) identify how a sample of EDs planned to implement GPED and determine the extent to which these plans were realised over the subsequent 12 months (WP A3).

Work package A had four main purposes:

-

to map, classify and report the current models of GPED, describe how these changed following the provision of capital funding and examine whether or not the implemented models were associated with observable characteristics of the EDs

-

to understand the hypotheses that underpin GPED implementation (in combination with data from WP C)

-

to support the analysis of routinely available (HES) data66 that was required in WP B

-

to identify potential case study sites for WP C.

Work package A addressed objectives 1 and 9.

Database population (work package A1)

Data were collected regarding the GPED model(s) used (if any) in all 177 type 1 EDs (consultant-led 24-hour services with full resuscitation facilities) in England. Sources included a combined interview study (described below), an online survey conducted by our research team at the University of the West of England (UWE) and an online survey conducted by Cardiff University [the parallel research team funded by NIHR; URL: https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/15/145/04 (accessed October 2021)]. This was supplemented by data sourced from public websites and NHS England, direct enquiry to individual sites and relevant data available from other researchers with an interest in this subject area, as well as data collected in WP C (from case study sites). The team assigned a level of confidence to each piece of information according to the three-level hierarchy described previously (see Work package A).

Data were collected at two time points, September 2017 and December 2019, and collated in a single database. Models were classified into one of four types according to a taxonomy developed iteratively with the team led by Cardiff University and funded by the same research call: inside – integrated; inside – parallel; outside – on site; and outside – off site (see Figure 1). 1

Alongside data classifying these GPED services in accordance with the agreed taxonomy, details of the service configuration (e.g. the times GPED was active and the number of GPs present) and the date of commencement of any service change(s) were also collected. This was supplemented by routinely available HES data66 and hospital site demographics, including annual ED attendances, the percentage of the area served by the ED that was classified as rural and the associated deprivation score. 69

We conducted a simple comparison of group means analysis to identify significant differences in hospital site demographics by the type of model used.

Interviews with national-level system leaders (work package A2)

Sampling and recruitment

Senior policy-makers and service leaders in selected commissioner and provider organisations, as well as NHS England, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and RCEM, were contacted by e-mail on up to two occasions inviting them to participate in a semistructured telephone interview.

Data collection

Detailed study information was provided and verbal consent was obtained. The aim was to explore the participant’s views of GPED, the potential advantages and disadvantages of this service configuration, and the mechanisms and hypotheses that underpin it.

Semistructured interviews, supported by a topic guide (see Appendix 1), provided some flexibility in the questions that were asked, allowing the interview to be adapted to the background and knowledge of the participant. During these interviews, participants were asked about their current role and its relation to GPED; the background to GPED and its main aims; perceptions of GPED and stakeholder involvement; models of GPED and likely effects on the ED, general practice, patient care and experience; and potential unintended consequences. When permission was given, the interview was audio-recorded and the researcher took notes. The interview recording was then transcribed verbatim by an independent transcription service. Interviews were conducted between December 2017 and January 2018.

Interviews with site-level system leaders (work package A3)

Sampling and recruitment

We identified the sites at which it was planned and not planned to implement GPED with capital funding provided by the Chancellor’s Spring Budget 2017 announcement. 37 For all 177 type 1 ED sites (defined as a consultant-led 24-hour service with full resuscitation facilities and designated accommodation for the reception of A&E patients) that were awarded capital funding to support the introduction of GPED, we sent an e-mail invitation to a managerial or clinical leader to participate in a structured telephone interview. We anticipated that recruitment of service leaders would be challenging, so to maximise our response rate each ED was sent three reminder e-mails by the project manager and/or the chief investigator.

Data collection

To ensure a systematic approach to data collection, structured telephone interviews were carried out with ED managers or clinical leads. Detailed study information was provided and verbal consent was obtained. Interviews were supported by a topic guide (see Appendix 1), designed to identify the local context and determine their planned model, expected benefits and wider impacts. Participants were asked a range of questions relating to hospital site demographics (e.g. annual attendance), the interviewee’s role in implementing GPED, challenges in the ED, perception of GP buy-in, barriers to and risks of GPED, patient perception of GPED, expected impact of GPED on ED and patient care, the current and proposed GPED model, the background to GPED introduction, the expected impact of GPED and perceptions of whether or not staff value GPED. In addition, the interviewees were asked what models of GPED had been adopted previously in their ED; the model of GPED they were using currently (when relevant), according to the described taxonomy; the times that GPED was active; and the number of GPs working at any given time. This information was then added to the WP A1 database. When permission was given, the interview was audio-recorded and the researcher also took notes. These interviews were not transcribed; instead, the researchers produced a matrix in which details of the responses were recorded.

All of those who received capital funding and were interviewed were contacted again 12 months later to review progress against their originally stated expectations, assess how successful the implementation of GPED has been and understand the extent to which the aims of the new GPED model had been achieved. For the repeat interviews, the approach to data collection was identical to that described above.

Analysis of work package A data

We conducted a simple descriptive analysis on the provision of GPED according to the three-level taxonomy and a comparison of group means analysis to identify significant differences in hospital site demographics by the type of model used.

The interview data from WPs A2 and A3 were combined with relevant WP C data and analysed collectively. (For further details of this analysis, see Work package C: detailed mixed-methods case studies of different GPED models, consisting of non-participant observation of clinical care; semistructured interviews with staff, patients and carers; and workforce surveys with emergency department staff.)

Work package B: quantitative analysis of national data to measure the clinical effectiveness of GPED using retrospective analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics

Introduction

The purpose of the quantitative analysis was to provide empirical evidence on the impact of GPED on patient flow in EDs and patient health outcomes using routinely collected health-care records for hospitals in England. WP B addressed objectives 2, 3, 6, 8 and 9.

Data sampling

This section describes the data sources and the steps that were taken to define the analysis samples.

Hospital Episode Statistics

The HES A&E data set66 contains routinely collected electronic health records for all attendances at type 1–4 EDs in England. We extracted data on all patients attending type 1 (i.e. 24 hours, 7 days per week, consultant led) EDs during the study period 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019. Each observation pertains to an individual attendance and there may be more than one attendance for a given patient. The HES A&E data set66 provides information on the sociodemographic characteristics of the patient, including their unique (encrypted) NHS number, age, sex, ethnicity and the level of deprivation in their residential neighbourhood [as measured by The English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 201569 score]. It also records the reason for attendance and which, if any, treatments or diagnostic procedures were performed by ED staff. Because the reason for attendance was found to contain limited diagnostic information, this variable was not used in the analysis. For each attendance, the HES A&E data include the hospital code, as well as the exact date and time of arrival and discharge from the ED. 66 Finally, we extracted information on the discharge destination and used this to flag patients who were admitted to a hospital ward from the ED.

More detailed information on the clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of patients admitted to a hospital ward are available in the HES Admitted Patient Care (APC) data set. 66 We extracted information on all patients admitted to an English NHS hospital as an emergency [i.e. the variable ADMIMETH (admission method) takes on one of the following values: 21–28, 2a–c] during the study period. For each patient, we recorded the encrypted NHS number, as well as the dates of admission and discharge.

The two samples were combined to create a single data set, in which each observation pertains to a full care episode (i.e. from arriving at the ED to discharge from either the ED or the hospital ward). This was achieved in several steps. First, the data samples were merged using the patients’ encrypted NHS numbers as a key. Any admission records without at least one corresponding ED attendance record were excluded from the data set. This situation may arise if, for example, a patient is admitted directly to the hospital ward at the request of their community GP (i.e. the patient bypasses the ED and is therefore not subject to GPED). Second, in some cases, a unique merge could not be achieved because the same patient attended the ED more than once or was admitted to hospital on multiple occasions on the same day. To identify the relevant pairs of observations that comprised a care episode, we excluded any matches where

We did not enforce an exact match in dates (i.e. a difference of zero) because of issues around recording in instances in which the patient left the ED shortly before midnight and was admitted after midnight. When a patient was identified as being transferred to a different provider from an ED and a matching inpatient record was observed (in terms of encrypted NHS number and date), outcomes were attributed to the ED that the patient attended.

Mortality data

Information on the date of death for all patients who attended the ED during our study period was obtained from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). We used these data to construct indicators of 30-day mortality, calculated from the day of ED attendance.

GPED model and opening hours

Information on GPED opening hours and the type of GPED model that was operational in hospitals during the study period was collected during WP A (see Data collection). For each hospital, we established the start and end time of the GPED service on each day of the week as some hospitals operate their GPED model on different schedules during the week than on weekends. Complete data were available for 40 hospitals where we were confident which GPED model was in place (level 1 in our WP A1 information hierarchy). Hospitals with missing GPED hours information were excluded from the analysis; a comparison of all hospitals with the 40 analysed in our sample is shown in Appendix 2, Table 23.

Outcome measures

We investigated the impact of GPED on a range of different measures of ED performance and patient outcomes. All outcome measures are defined at the patient level except volume of activity, which was measured at the provider level. Detailed specifications for each outcome measure, as well as the relevant HES variables used in their calculation, are shown in Table 2.

| ID | Outcome | Definition | Level of measurement | Missing (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Attendance < 4 hours | = 1 if the time from admission to discharge (depdur) in an ED was < 4 hours | Patient | 0.79 |

| 2 | No unplanned reattendance | = 1 if the patient does not reattend an ED within 7 days of discharge or that reattendance is planned (aeattendcat = 2) | Patient | 4.18 |

| 3 | Treated | = 1 unless the attendance was unplanned (aeattendcat = 1 or 3) and the patient left before being treated (aeattenddisp = 12) | Patient | 14.43 |

| 4 | Necessary attendance | = 1 if an attendance was ‘necessary’, defined as not meeting any of the following criteria for being unnecessary:

|

Patient | 0.00 |

| 5 | 30-day survival | = 1 if date of death of the patient was at least 30 days after ED attendance | Patient | 1.42 |

| 6 | Admission to ward | = 1 if patient was admitted as an inpatient following ED attendance (aeattenddisp = 1 or 7 and admimeth = 21–28, 2a–d) | Patient | 1.48 |

| 7 | Attendance not ending in same-day discharge | = 1 if patient attendance ended in discharge home or admission overnight (admitted = 0 or admitted = 1, and dischargedate – admissiondate > 0) | Patient | 0.00 |

| 8 | Volume of activity | Count of attendances per hour of day and day of week | Provider | 0.00 |

Statistical analysis

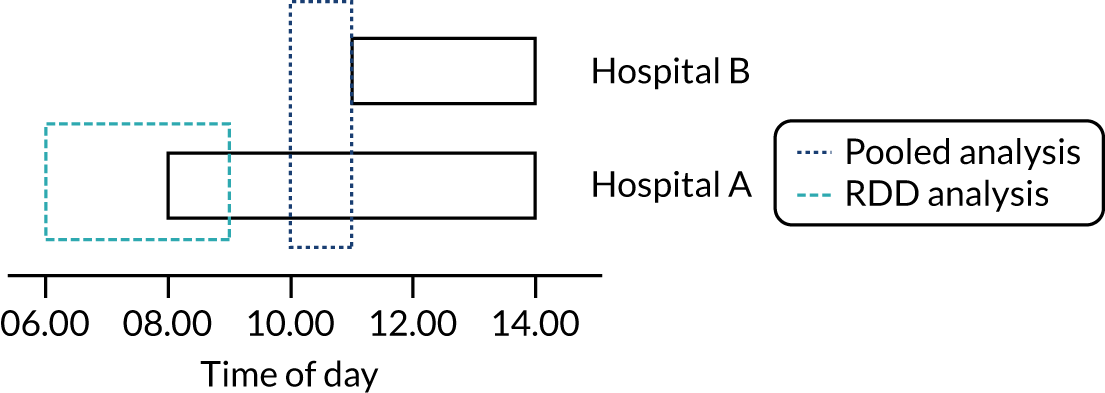

Each outcome was analysed separately and two alternative methodological approaches were considered: (1) a pooled analysis of all ED attendances to hospitals reporting GPED start and end times, in which differences in GPED opening hours across hospitals were used to separate the effect of GPED from the general effects of time of day; and (2) a regression discontinuity design (RDD) in which outcomes for patients attending the same ED shortly before or after the GPED service starts are compared to identify hospital-specific effects of GPED. Figure 3 provides a stylised representation of these analytical approaches.

FIGURE 3.

Stylised representation of alternative methodological approaches to quantify the impact of GPED using variation in GPED service opening hours.

All analyses use a critical value of α = 0.05 to determine statistical significance. No adjustment was made for multiple testing.

Pooled analysis

Our main approach was to pool data on all patients treated in English NHS hospitals in a single regression model and to use differences in GPED service availability across hospitals and times of day to identify the impact of GPED on outcomes. Nearly all hospitals for which we had data from WP A operated a GPED service for a specific, continuous subset of hours within each day, but the specific hours differ across providers. For example, a service might begin at 08.00 and end at 23.00 in one hospital, but run from 12.00 to 18.00 in another hospital. We quantified the effect of GPED by comparing outcomes for patients arriving at a given hour of the day in hospitals that (1) operate a GPED service at that time (the ‘treatment group’) or (2) do not operate the GPED service at that time (the ‘control group’).

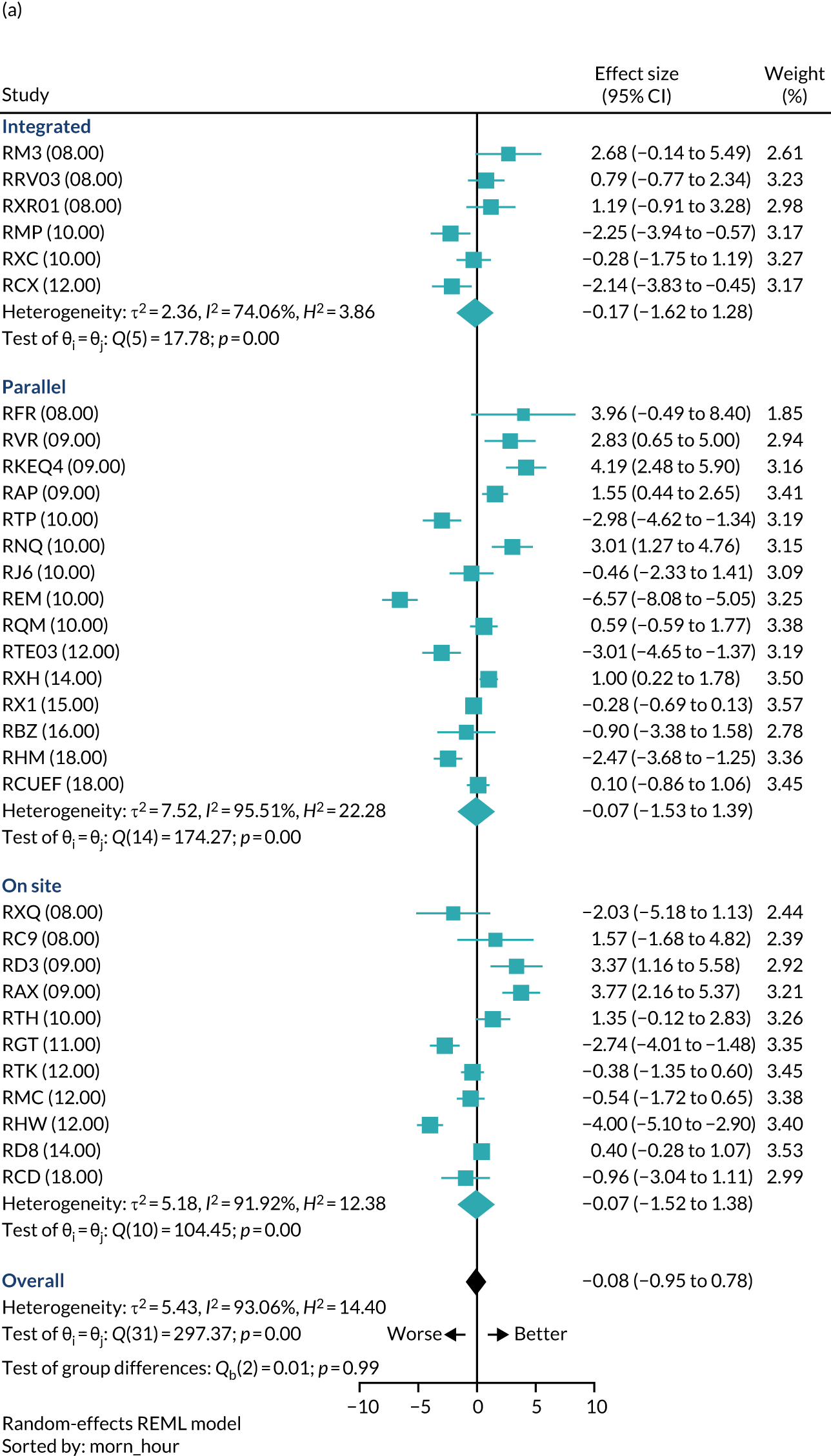

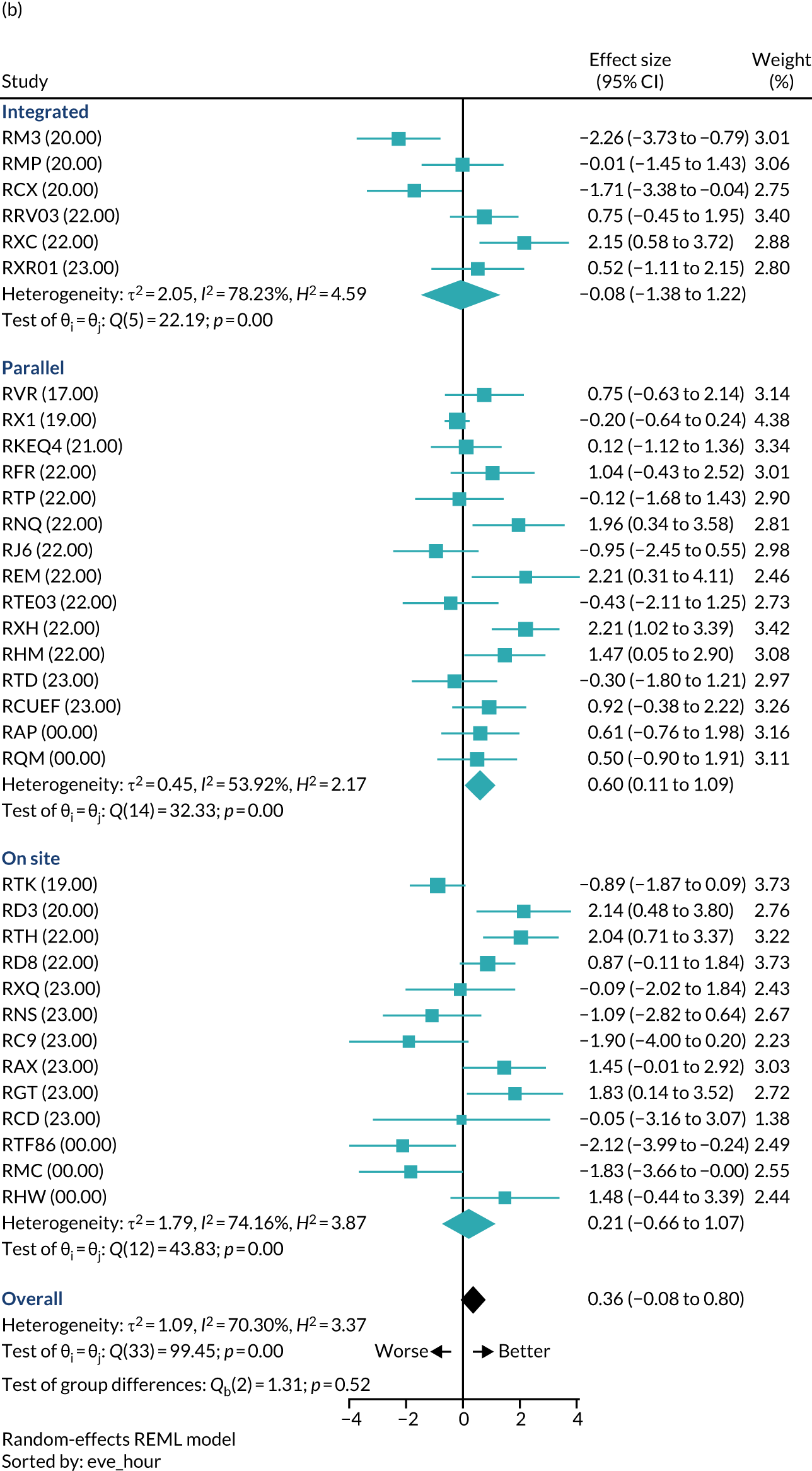

We estimated separate ordinary least squares (OLS) (outcomes 1–7, i.e. linear probability models) and Poisson (outcome 8) panel data regression models for each outcome. Our main variable of interest was a binary indicator for whether or not the hospital operated a GPED model at the hour of the day when the patient attended the ED (yes/no). We also analysed the impact of different GPED models (inside –integrated, inside – parallel, and outside – on site; these models are referred to as ‘integrated’, ‘parallel’ and ‘on site’, respectively, in the rest of the report) by including a set of interaction terms between the GPED model and the binary indicator of service availability. All models controlled for hospital and hour-by-day of week fixed effects, month of year and, in the case of the OLS models, additional patient characteristics, such as their age (in 5-year bands), sex and socioeconomic deprivation profile, which may have acted as confounders. The hospital fixed effects captured time-invariant differences in performance across EDs that reflect hospital-specific factors, such as management quality, building infrastructure and the quality and availability of substitute health-care services within the local health economy. The hour-by-day fixed effects captured difference in service availability and patient acuity over the course of the day that follow a common pattern across all hospitals in England. For ease of interpretation, all regression coefficients are presented as average marginal effects on the original scale of the outcome variable. The estimates’ quantities refer to either percentage point changes in the likelihood of an event (for OLS models) or changes in the counts of events (for the Poisson model).

The scope of this pooled analysis was limited to hours of the day when there was variation in GPED service availability across hospitals. Patients attending EDs during hours of the day when all/none of the hospitals operated a GPED service contributed to the identification of hospital fixed effects and the influence of case-mix characteristics, but did not contribute to the statistical identification of the effect of GPED services on outcomes.

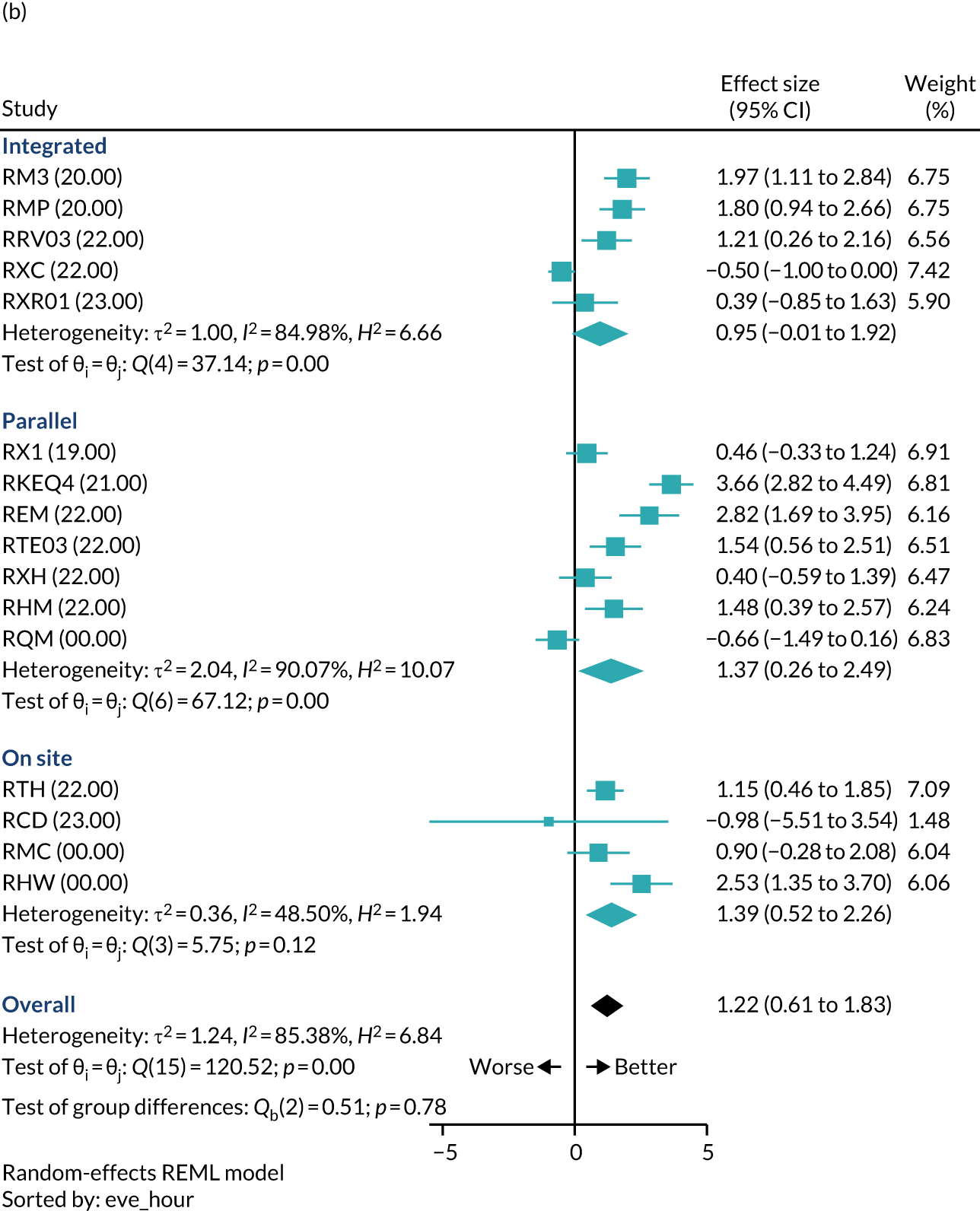

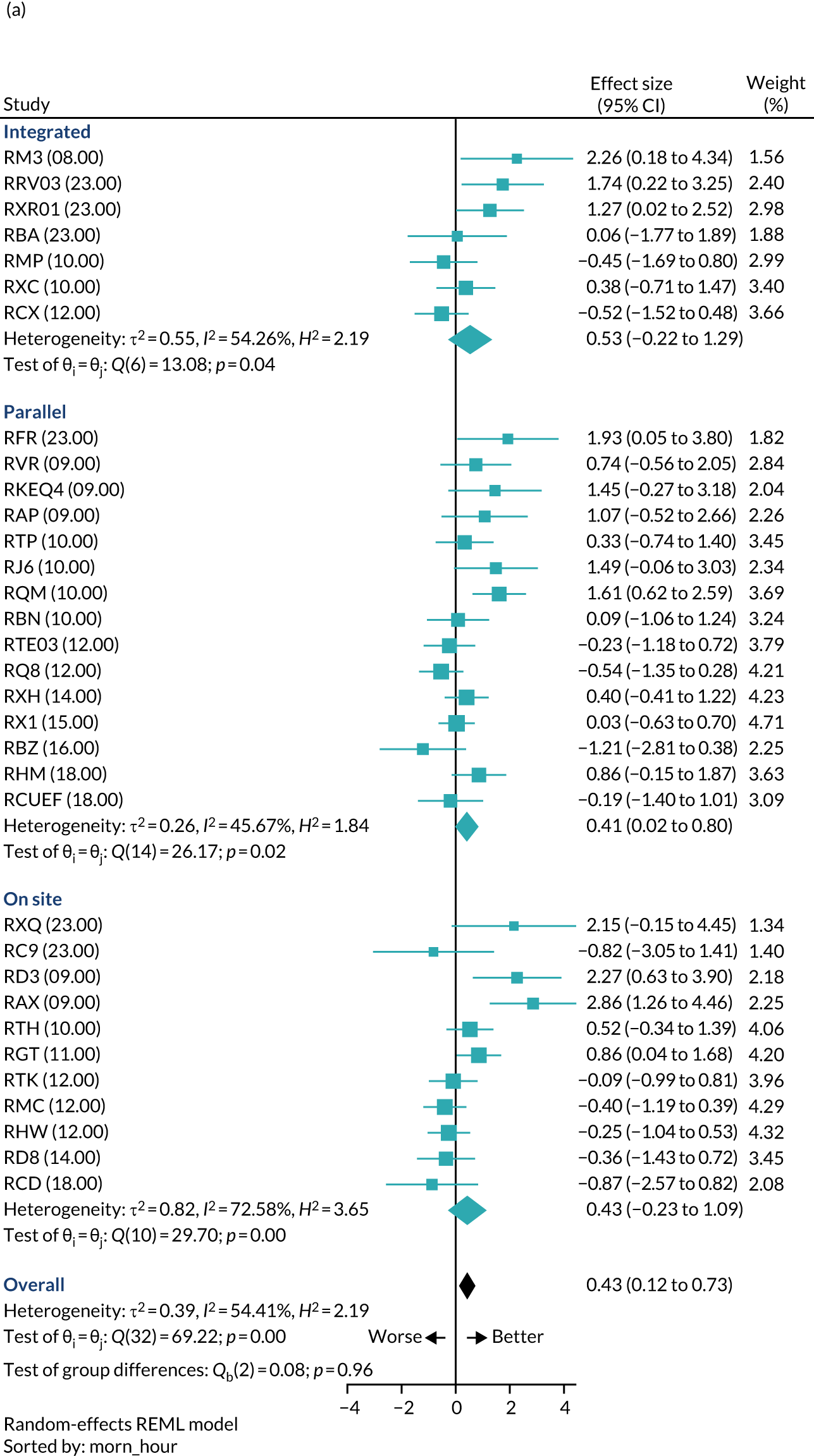

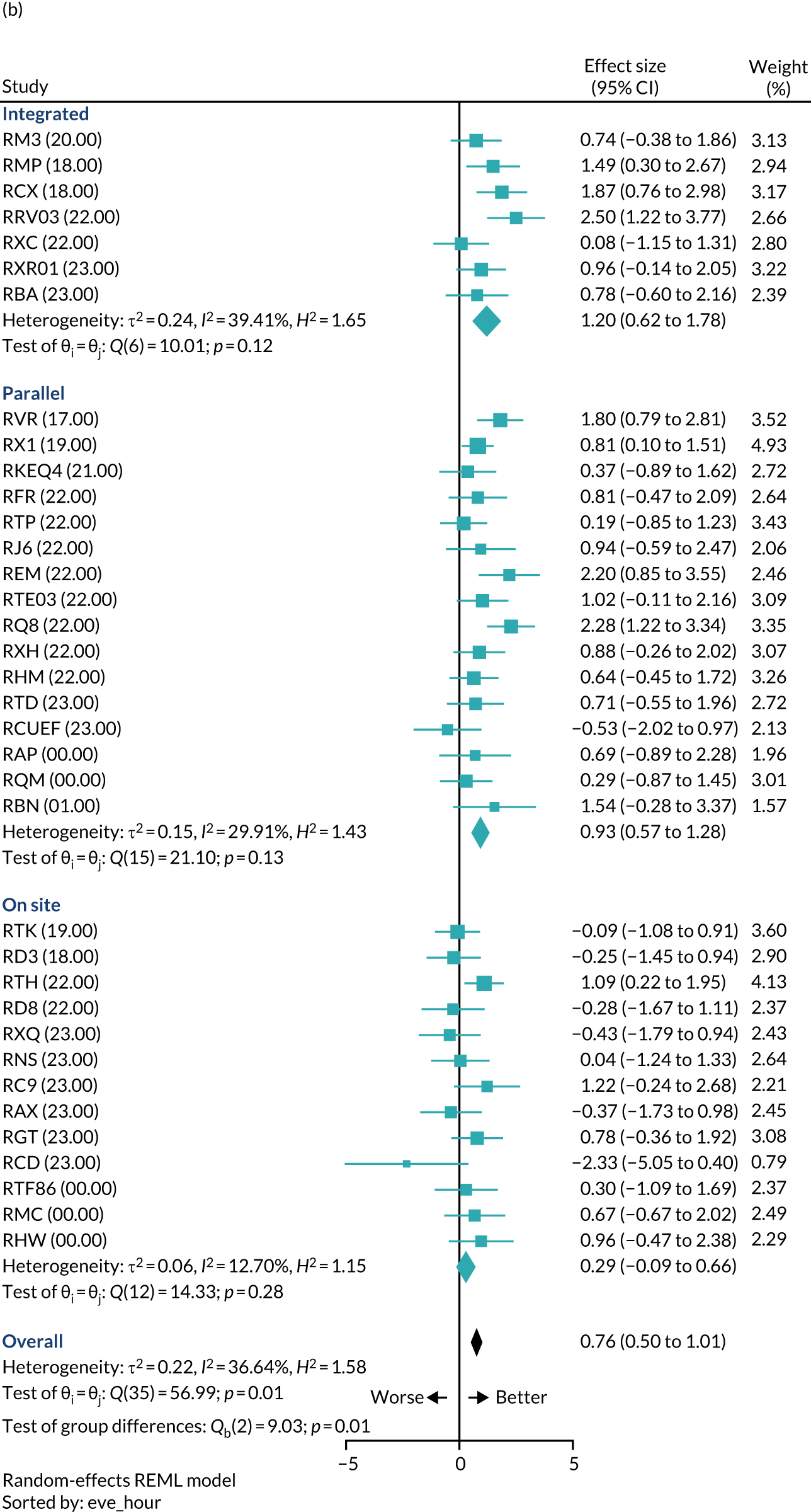

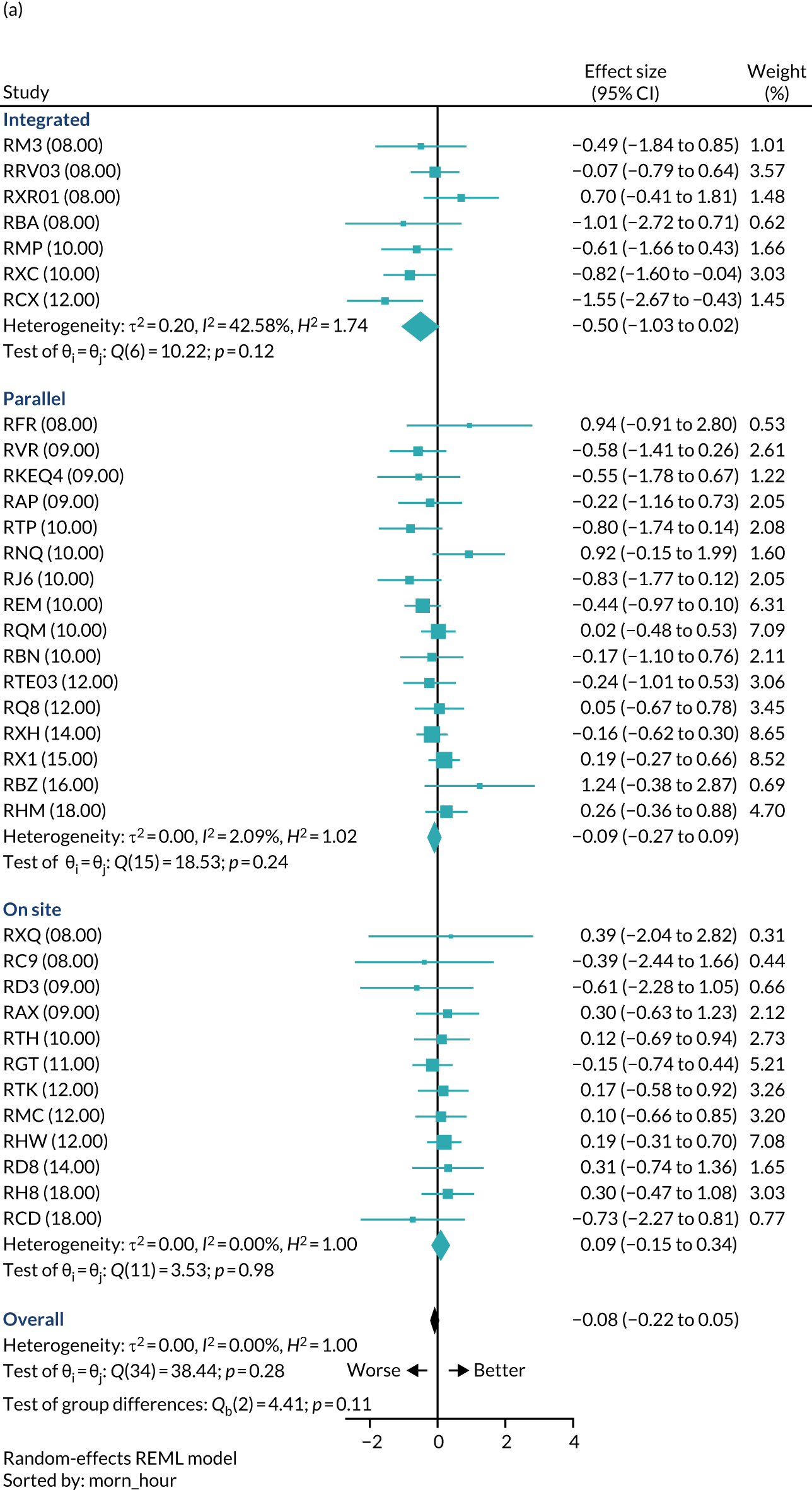

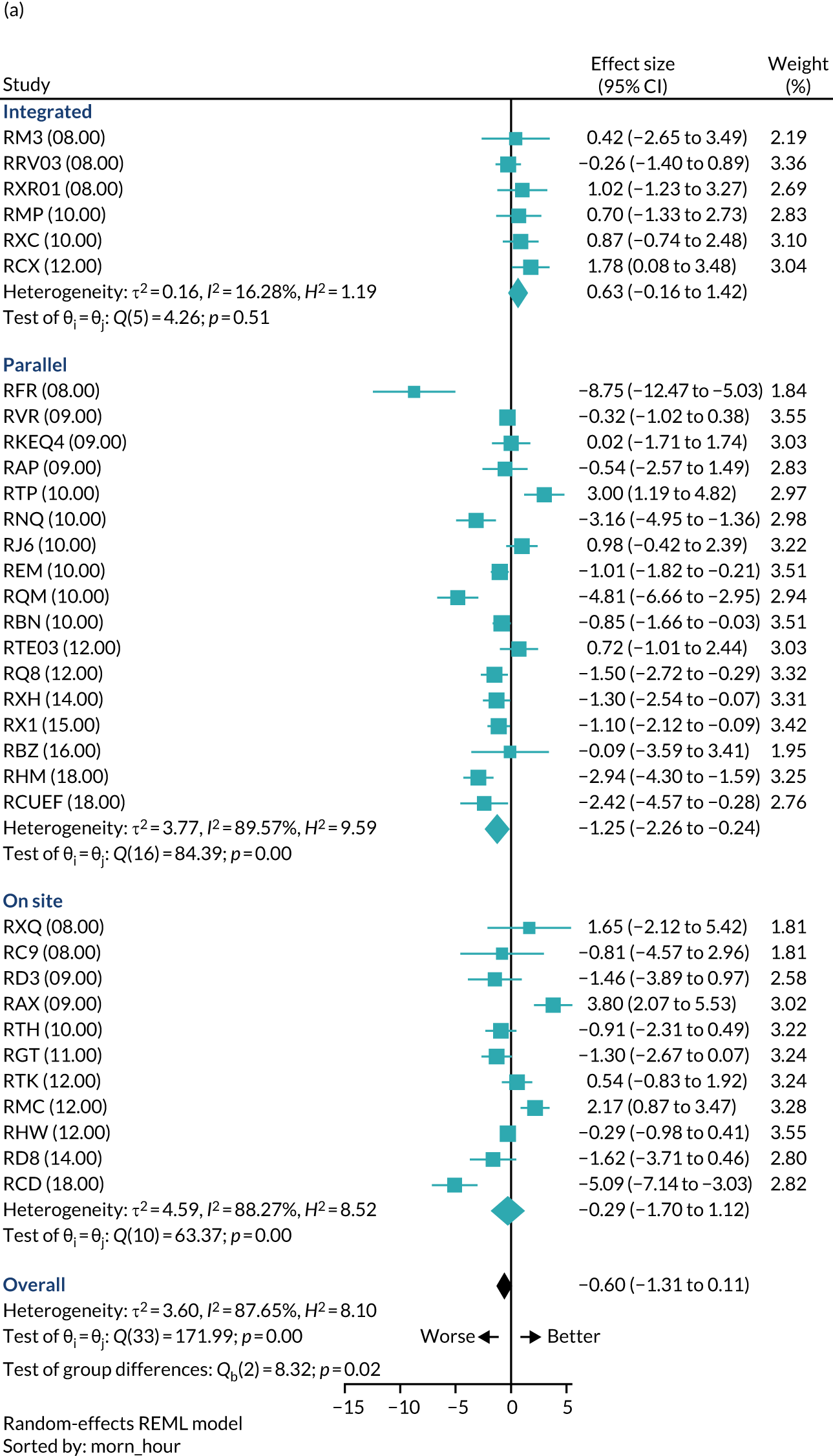

Regression discontinuity design

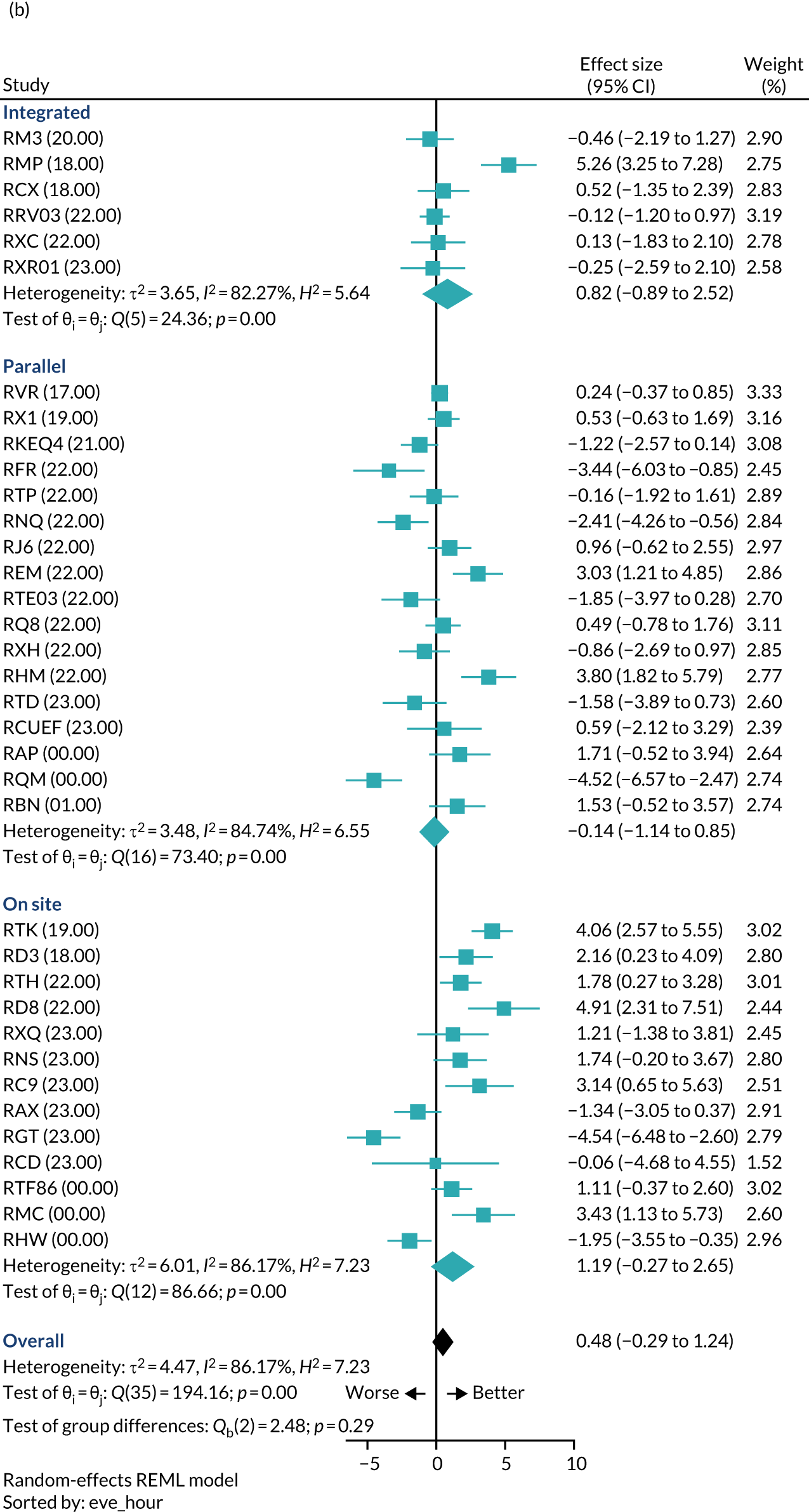

The pooled analysis estimated the average effect of GPED, calculated over all hospitals and hours of the day in our sample. To explore potential heterogeneity in the clinical effectiveness of GPED services across hospitals, we used a RDD that permits estimation of hospital-specific effects. In each hospital, there are some patients who attend the ED while the GPED service is in operation, whereas other patients arrive before or after those core hours and, therefore, are not treated by a GP. Patients attending at markedly different times of the day are likely to be systematically different in terms of their observed and unobserved characteristics, which precludes a direct comparison of outcomes for patients attending when the GPED service is operational with outcomes for patients attending at other times. However, we assumed that the exact arrival time of patients at the ED is exogenously determined (e.g. by the time of onset of their medical problem) and is not affected by the availability of GPED services. This implies that patients arriving shortly before or shortly after the time GPED starts are, in effect, randomly allocated to the control and treatment groups within the same hospital. The same principle holds for patients arriving shortly before (treatment group) and after (control group) the end of GPED each day. Consequently, we expect patients in both groups to have, on average, similar observed and unobserved characteristics so that any differences in outcomes between groups are unlikely to be biased by confounding. Put another way, the GPED start/end times create discontinuities in treatment allocation that the RDD exploits to obtain hospital-specific estimates of the effect of GPED on the relevant set of outcomes.

Under random allocation, the difference in outcomes between patients in the treatment and control groups can, in principle, be established using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. two-sample t-tests for continuous variables). However, residual imbalances in observed patient characteristics across treatment groups may remain, in which case inference can be further improved through regression adjustment. We therefore estimated the effect of GPED on outcomes 1–6 using logit regression models that include an indicator for treatment status and adjust for a set of observed patient characteristics. The volume of activity was not analysed with the RDD approach, as ED demand is known to fluctuate rapidly over the course of the day, so comparisons of volume across adjacent time intervals are not valid. As same-day discharge (outcome 7) is defined as discharge from an inpatient setting on the same calendar day as admission, time of ED attendance is strongly related to the probability of same-day discharge. Therefore, this outcome was also not analysed, as results would provide a partial picture only, strongly driven by the distribution of times when GPED starts and ends. We estimated separate models for each hospital and for each outcome around the start and end of GPED under the assumption that the effect of GPED may be partly driven by the hour of the day it was in operation, that is the effect at the start and end of the service may not be symmetrical. This resulted in up to 80 hospital- and time-specific estimates per outcome. We then summarised these estimates, with associated measures of uncertainty, using forest plots and random-effects meta-analysis, with subgroups defined by the type of GPED model in place (integrated, parallel and on site).

Some patients who arrive outside GPED opening hours may still be treated by a GP, for example because they are required to wait in the ED before being seen and a GP begins their shift in the meantime. These patients would be misclassified as belonging to the control group rather than the treatment group. We therefore excluded patients arriving during the hour before the start of GPED. Similar adjustments were applied around the GPED end time. These adjustments (described as 1-hour ‘doughnut holes’) may weaken the argument of random allocation and we tested for differences in observed characteristics of treated and control patients with a series of logit models, in which treatment status is used as the outcome variable and patient characteristics are used as covariates. Assuming that patients in both groups are similar in terms of observable variables, we would expect the overall explanatory power of these models, represented by the R-squared statistic, to be low. A cut-off value of 0.05 was used to exclude hospitals that showed poor balance, and, therefore, evidence of non-random treatment allocation, from the analysis. Based on this rule, three hospitals were excluded, leaving a sample of 37 hospitals.

Exploring the potential for cost savings

We explored the potential net cost savings from GPED using a simple and conservative approach. We used results from the WP A1 survey of EDs to ascertain the average hours that a GP service is in operation in English EDs and (if possible) the number of GPs present. We used salary and associated costs and the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2019 to value GPs’ time. 68 These figures constitute the cost of operating a GPED service to the average hospital. We assumed that GPs are an addition to the existing workforce, rather than a replacement for ED staff, such as consultants. This assumption is based on our research results, in that we found GPs were almost universally engaged as an extra workforce. In a small number of sites, particularly where an integrated model was in place, GPs occasionally filled a gap in the ‘middle grade’ (registrar) ED roster, but in no cases were GPs specifically employed to replace ED consultants, and we did not identify settings where the number of ED staff had been reduced as a direct result of GPED.

To calculate the cost savings to commissioners resulting from the availability of GPED services, we used national tariffs for hospital care and multiplied these by the estimated changes in relevant outcomes obtained as part of the quantitative analysis of routine hospital data. Specifically, we focused on outcome measures that have resource implications (i.e. changes in attendances, reattendances and emergency hospital admissions, including zero-day admissions). We did not cost changes in the number of patients who left without being seen, as these would still trigger payments to providers.

These relatively crude quantitative estimates of the costs of operating a GPED service and the cost savings resulting from it were then compared to establish a net impact on NHS costs. For ease of interpretation, we express all figures as costs and cost savings per calendar year. Our costing study was further supplemented by qualitative data from our case study sites, where cost implications were considered in interviews with GPs, ED managers and other staff.

Our calculations constitute a cost–consequence analysis. We did not attempt to perform a formal economic evaluation that compared costs and health benefits of GPED as information on changes in patients’ health-related quality of life are not routinely collected in ED settings and the impact of GPED on mortality was found to be negligible.

Work package C: detailed mixed-methods case studies of different GPED models, consisting of non-participant observation of clinical care; semistructured interviews with staff, patients and carers; and workforce surveys with emergency department staff

Introduction

GPED has effects across multiple levels of the health-care system. Therefore, we completed a multimethods study consisting of interviews with policy-makers (macro level), service leaders (meso level) and health professionals and patients (micro level); and observations of clinical practice, as well as the distribution of quantitative surveys to the GPED workforce (Table 3). WP C addressed objectives 2, 4–7 and 9.

| Macro level | Meso level | Micro level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National-level leaders | Site-level system leaders – time 1 | Site-level system leaders – time 2 | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | |

| Total number of participants | 10 | 57 | 26 | 124 health professionals; 94 patients/carers | 20 health professionals (13 had participated at time 1) | 82 health professionals (24 had participated at time 1/time 2); 54 patients/carers |

| Period of data collection | December 2017 to January 2018 | August 2017 to September 2018 | February 2018 to February 2019 | November 2017 to December 2019 | June 2018 to October 2018 | November 2018 to December 2019 |

| Number of EDs represented | N/A | 64 | 30 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Interview type | Semistructured telephone interviews | Structured telephone interviews | Structured telephone interviews | Semistructured face-to-face and telephone interviews | Semistructured face-to-face and telephone interviews | Semistructured face-to-face and telephone interviews |

| Other data collected | 83 periods of observation; 373 WFSs completed | No other data collected | 59 periods of observation; 87 WFSs completed | |||

| Aim | In-depth understanding from key informants | Broad perspective from a wide range of emergency settings | Broad perspective from a wide range of emergency settings | In-depth understanding from a small number of case sites | In-depth understanding from a small number of case sites | In-depth understanding from a small number of case sites |

| Job roles represented | NHS England, DHSC, CCGs, GPs, NHS trusts, NHS Improvement, RCEM | Chief executives, chief operating officers, clinical leads, lead nurses and ED managers | Chief executives, chief operating officers, clinical leads, lead nurses and ED managers | GPs, ED doctors (juniors, registrars, consultants) and nurses (streaming, triage, minor injuries) | GPs, ED doctors (juniors, registrars, consultants) and nurses (streaming, triage, minor injuries) | GPs, ED doctors (juniors, registrars, consultants) and nurses (streaming, triage, minor injuries) |

The macro level refers to national policy and wider social norms and in this report is based on interviews conducted with 10 key informants (WP A2) that aimed to gain detailed insights as to why GPED was implemented from a carefully targeted group of policy-makers. The meso level is the organisational level and involved a large number of structured interviews with ED managers and clinical leads (combined with the system leader interview data collected in WP A3) to gain a broad service-wide understanding of what EDs throughout England expected from GPED. Lastly, the micro level refers to the individual level and is based on semistructured interviews, along with a WFS, administered during in-depth visits to 10 selected ED case sites throughout England. The interviews and the WFS were intended to obtain a detailed understanding of health professional and patient perceptions of the impact of GPED. Adopting a macro-level, meso-level and micro-level approach enabled us to gain a detailed, but also service-wide, understanding of the impact of GPED on the urgent care system, primary and acute hospital teams, and patient care. 70–73

Sampling and recruitment

Macro level

Key informants were identified strategically, as described in Interviews with national-level system leaders (work package A2).

Meso level

Managerial or clinical leads were identified and invited to interview. Further details are given in Interviews with site-level system leaders (work package A3).

Micro level

Data were collected from 10 case study sites, which were selected purposively to ensure maximum variation according to GPED model, duration of using GPED, geographical location, deprivation index and ED volume (A&E attendances).

Sampling of staff, patients and their families was opportunistic by the research team, occurring while the team were undertaking on-site data collection. Care was taken to ensure that a range of health professionals representing different staff groups and grades, who had varying levels of involvement in introducing GPED and who undertook different roles within GPED models, were interviewed. Key informants at each site, such as ED leads and/or medical directors, were also interviewed.

We invited staff members at WP C case sites to complete a WFS and adopted multiple strategies to maximise recruitment. For example:

-

We prioritised survey distribution when conducting on-site data collection for WP C, which allowed the research team to promote the survey while on site. Paper and electronic versions of the survey were distributed to account for staff preference and local variation.