Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR132269. The contractual start date was in October 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in June 2022 and was accepted for publication in March 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Varese et al. This work was produced by Varese et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Varese et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

What is the problem being addressed?

Responding to major incidents that impact on health and social care services is a challenging area in which to deliver services and evaluate outcomes, but guidance indicates the importance of pre-planning for these incidents, including a mental health response. 1 The ‘Resilience Hub’ approach is an innovative service model, originally developed in response to the 2017 Manchester Arena bombing,2 that could also address the urgent mental health needs of keyworkers affected by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. This system of care was designed not only to respond to the immediate needs of young people, adults and emergency response workers affected by the bombing, but also as an adaptive system of response that could be redeployed when the situation demanded, ensuring that expertise in large-scale mental health screening and trauma management could be sustained and expanded for responding to future crises. This adaptable service initiative can be flexed as needed, and while each large-scale trauma event will bring its own challenges and nuances, certain principles and understanding of processes to manage large-scale trauma can be vital to manage the system-wide challenges that emerge in the face of such emergencies. 3 Therefore, when the COVID-19 pandemic arose, local expertise and infrastructure were in place in Greater Manchester to provide large-scale mental health screening and support, and the Hub was adapted to support NHS, social care, ambulance service staff and some COVID-specific staff teams within fire and police services throughout the COVID-19 crisis. Broadly informed by the Greater Manchester Resilience Hub approach, similar services (i.e. variedly known as ‘Resilience Hubs’ or ‘Staff Mental Health and Well-being Hubs’) has been since set-up across various UK regions to respond to the mental health impact of the pandemic in these keyworker groups. As yet, no research has been conducted to evaluate the support offers of these novel NHS services.

Why is this research important?

During previous pandemics, mental health complaints have been found to be a common response, both within the general public4 and especially among health and social care keyworkers. 5 Previous work has also indicated the impact of a pandemic on front-line staff such as those found during the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak where 549 respondents reported symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) over a 3-year time frame. 6 Findings for the current pandemic are no different. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses which looked at the prevalence of mental health difficulties amongst front-line health care workers during COVID-19 found high levels of stress, anxiety and depression, highlighting the need for urgent action. 7–10 While the literature consistently finds evidence of immediate mental health impacts,11 the more long-term impacts such as burnout still require further attention. 12

Observational studies from countries most affected in the early stages of the pandemic were quick to highlight that keyworkers were at significant risk of adverse mental health outcomes due to a range of distinctive risk factors, including long working hours, risk of infection and fear of infecting family members, shortages of personal protective equipment, loneliness, physical fatigue and separation from families. 13 A meta-analysis14 found that at least 20% of keyworkers reported symptoms of depression and anxiety. Certain professional and demographic groups were highlighted as being disproportionately affected, for example, female keyworkers and nursing staff. 13 There is also recognition that keyworkers who belong to ethnic minorities may have been particularly affected,15 as well as keyworkers exposed to work circumstances conducive to ‘moral injury’, that is psychological distress that results from actions, or lack of, that violate a person’s moral or ethical code; for example, having to make difficult decisions about which patients can access life-saving equipment in times of critical shortage. 16

The large-scale impacts of policy to manage the pandemic, such as lockdowns, led to significant changes in healthcare utilisation. Despite considerable variation, research and official data suggested significant reductions in healthcare utilisation across a wide range of physical healthcare services. 17–20 Evidence also suggested that secondary mental health services experienced a reduction in service utilisation during lockdown,21 with reduced admissions observed for all service types, except children and adolescent mental health services, psychiatric intensive care units (ICUs) and intellectual disability acute beds. Other studies highlighted the reductions in referrals to primary care mental health services, psychological therapy and all secondary care mental health teams apart from early intervention in psychosis (EIP) services. 22 These reductions are a plausible result of public health messages (e.g. ‘stay home, save the NHS, save lives’) and policies required in order to ensure that the increased demand in other parts of the system, most notably ICUs,23 could be sustained at the height of the pandemic.

At an early point in the pandemic, the NHS Clinical Leaders Network24 issued an urgent call for action to ensure that NHS organisations prioritise initiatives to enhance mental health resilience and support provision for staff involved in patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to this, funding was announced to support the mental health of these staff, aiming to provide a proactive approach, rapid clinical assessments and onward referral and care navigation. As highlighted by other commentators, support was needed for everyone who had a direct clinical or caring responsibility,25 and the importance of supporting the social care sector in such initiatives was recognised, given the likely deleterious impact of the pandemic on this broad keyworker group (e.g. nursing homes staff). This is a sector where low pay and zero hours contracts have left that part of the system struggling with staff shortages and an estimated vacancy rate in 2019–20 of 7.3%, thereby in an already weakened state heading into the pandemic. 26

UK mental health services offer evidence-based psychological therapies, but what was missing was a way to identify keyworkers who most need support from these services, and help them to access support in a timely manner. 3 Consequently, both nationally and internationally, there were numerous recommendations to establish, scale-up and evaluate effective and timely systems for monitoring the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak among keyworkers, and facilitate access to appropriate psychosocial support for those who most need it. These recommendations, informed by extensive research in disaster mental health,27 particularly highlighted that response efforts should include: (1) proactive outreach approaches to encourage open communication about and disclosure of the mental health difficulties, therefore addressing possible reluctance amongst certain professional groups about disclosing vulnerability even when experiencing significant distress; (2) timely early detection and screening for mental health problems; (3) the importance of identifying and effectively treating milder mental health presentations before they evolve into more complex and enduring mental health issues; (4) the provision of tailored support according to individual needs, including ‘lower intensity’ support (e.g. psychoeducation; access to support hotlines and remote advice/support) as well as direct provision of psychological support to any healthcare workers who might need higher-intensity interventions. 27–32

The model described earlier and developed in Greater Manchester was highlighted as a potential exemplar of how this mental health support might be achieved. Several Hubs began set-up in 2020. While there was some variation in terms of how these Hubs operated, their central functions were aligned to the proactive approach, and rapid clinical assessments and onward referral were defined as being key characteristics of service delivery.

In autumn 2020, 38 further Hubs (also known in some regions as ‘Staff Mental Health and Well-being Hubs’) were commissioned by NHS England and established as pilots across England. NHS England provided guidance for Hubs,33–35 detailing, for example, expectations around the service model, such as proactive outreach, team-based working, rapid clinical assessment and ensuring access to evidence-based psychological care where required.

Research objectives

This research distils the learning from our evaluation of four Resilience Hubs in the North of England. To better protect the anonymity of Hub clients and staff considered in this project, the participating Hubs are here referred to as Site A, Site B, Site C and Site D. The research primarily pertains to two central functions of the ‘individual support’ offered by Resilience Hubs that were either already operational or at an advanced stage of set-up at the time of commencing the research (i.e. October 2020): (1) the provision of mental health screening to in-scope keyworkers; (2) facilitation of access to psychosocial support for NHS, social care and emergency response keyworkers. The exact support offers provided by these Hubs considerably evolved over the course of the pandemic in response to both local needs, ongoing learning and national guidance. One of the most significant changes was the expansion of the reach and volume of ‘team-based support’ provided to teams and organisations in their geographical footprint. While this offer is described in several components of the research (e.g. our health economic analyses), the project did not aim to formally evaluate team support offers.

As the project was set up and funded as part of an urgent National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) call issued in early stages of the COVID-19 crisis to maximise ‘recovery and learning’ from the pandemic, a full clinical and cost-effectiveness evaluation of the Resilience Hub model using a controlled design was deemed unviable. Rather, the project employed a mixed-method approach combining observational quantitative, qualitative and health economic data to address the four main objectives listed below. After outlining the patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) work that underpinned our research in Chapter 2, and a detailed ‘service mapping’ exercise to better contextualise the support offers provided by the four participating Hubs and the processes needed to deliver the services in Chapter 3, we describe the methods and findings of research activities addressing the principal aims of the project in Chapters 4–7.

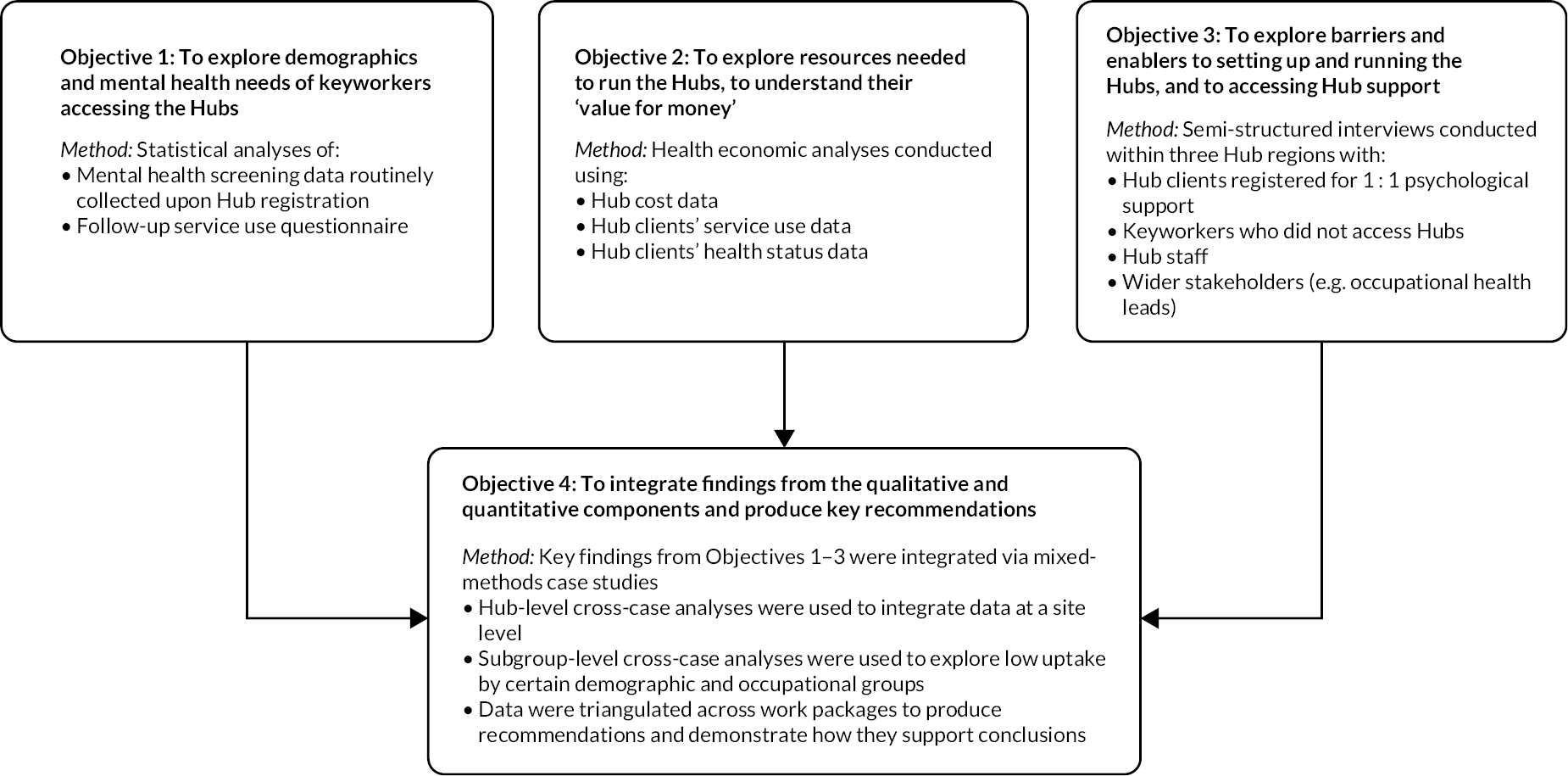

The four principal objectives of the project are summarised in Figure 1 and described below.

FIGURE 1.

Research objectives.

Objective 1: To provide findings to model service demand and guide future adaptations to the Resilience Hub approach to suit contextual needs and inform evidence-based commissioning, we aimed to conduct a quantitative analysis of routine demographic, occupational, and mental health screening data collected by the Hubs for keyworkers who accessed individual psychological support. These analyses aimed to consider:

-

sociodemographic and other keyworker characteristics associated with mental health presentations requiring higher levels of support

-

sociodemographic and other keyworker characteristics associated with lower levels of support access and uptake

-

specific exploration of points 1 and 2 for different keyworker groups, for example, different occupational and professional groups, and people from ethnic minority groups.

To address Objective 1, in Chapter 4, we report the findings of quantitative analyses conducted on routine screening data collected by the Hubs on a combined sample of 1973 Hub clients, alongside analyses of service use data collected from a subsample of Hub clients (N = 299) as part of a survey deployed approximately 5–8 months following Hub screening.

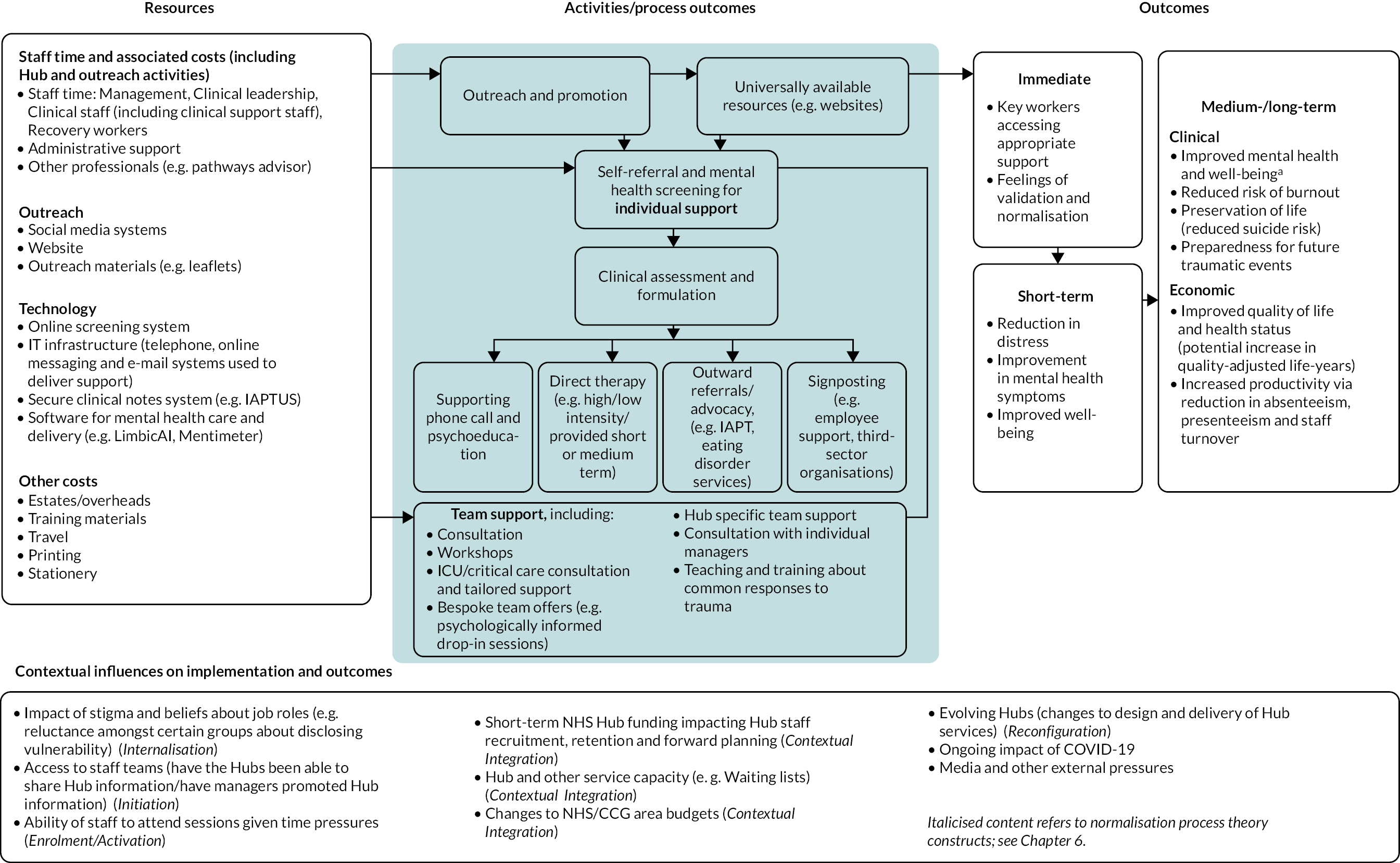

Objective 2: Conduct a health economic analysis, to explore the cost and health benefits associated with the set-up, use and management of Resilience Hubs.

To address Objective 2, in Chapter 5, we report analyses of costing data provided by the participating Hubs as well as analyses of health status and service utilisation data from Hub clients who completed the abovementioned service use survey, alongside a logic model developed to illustrate the potential benefits associated with Hub support.

Objective 3: To identify barriers and enablers relevant to the repurposing of the Hub model to respond to novel crises, and the implementation of the Resilience Hub model, we aimed to conduct a qualitative interview study with multiple relevant stakeholder groups at three sites (A, B and D).

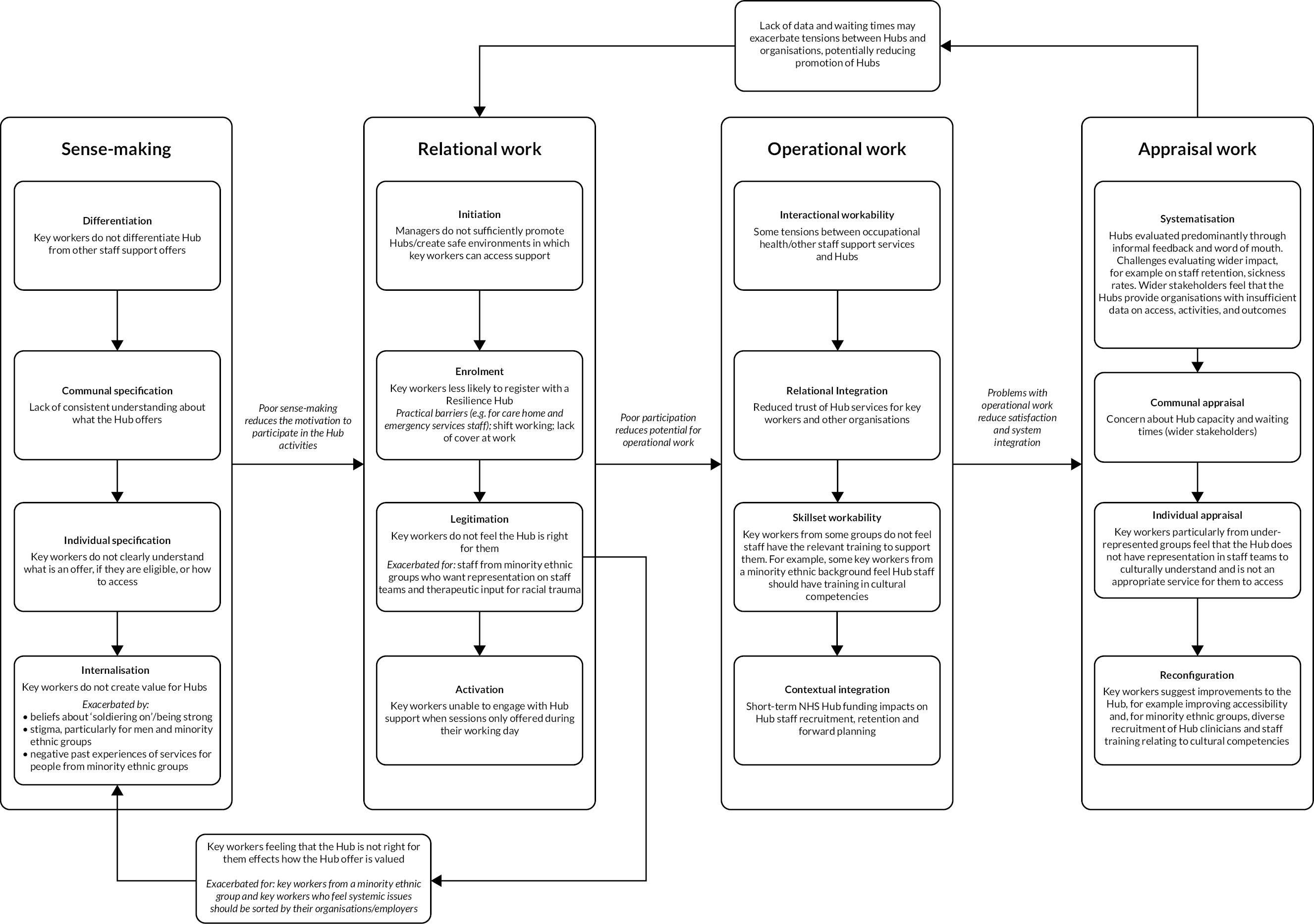

To address Objective 3, in Chapter 6, we report the findings of in-depth qualitative interviews guided by normalisation process theory (NPT) and Sekhon’s Acceptability Framework, conducted with 14 members of Resilience Hub staff, 19 Hub clients who accessed individual Hub support, 20 keyworkers who had not accessed Hub support, and 10 wider stakeholders who were involved in the provision of support for staff within the health and care system (e.g. occupational health leads; HR directors).

Objective 4: To integrate and triangulate findings from the above qualitative and quantitative components, we aimed to produce mixed-method case studies.

These are presented in Chapter 7, and a combined discussion of the findings of all components of the research, alongside key clinical, service and research recommendations emerging from this programme of work are outlined in Chapter 8.

Chapter 2 Stakeholder/patient and public involvement and engagement

Overview

This chapter describes the PPIE activities for the study. In this research, ‘members of the public’ involved in stakeholder engagement were health and social care staff who either had accessed Hub support or did not access Hub support but would have been eligible to do so. This chapter aims to describe the PPIE activities while considering the recommendations of transparent reporting of PPIE in health service research. 36 In developing this project, the research team consulted front-line staff and Hub staff from two sites (Sites A and D) about the research teams’ proposed and PPIE strategy.

Methods

Definition of patient and public involvement and engagement and stakeholder engagement

PPIE in research is defined as an active partnership between researchers and patients and potential patients of health and social care services. 37 While there is typically a distinction made between the perspectives of the public and those who have a professional role in services, the nature of this study meant that we involved the perspectives of health and social care staff who would have been eligible for Hub support. To diversify the perspectives, we received through PPIE consultations, we carried out wider stakeholder engagement with health and social care staff in addition to consulting our formal staff consultation group.

Staff consultation group

In the first 2 months of the project, Hub clients at Site D who had given consent to being contacted for research purposes were e-mailed an invitation to be a part of the advisory group for the study. Further invitations were sent to clients and healthcare staff of Sites A and B to invite new members to join the group.

A core advisory group was set up, and around six members regularly attended the meetings. The group preferred to be called a ‘Staff Consultation Group’ rather than a PPIE group, as members considered themselves to be staff who care for patients, not the patients themselves. The Staff Consultation Group met virtually every 2 months, for on average 90 minutes, with frequent additional tasks (e.g. feedback on research materials, findings) also taking place between meetings. During the final 6 months of the study, the group agreed to meet monthly to review and discuss emerging study findings.

Meetings were arranged and chaired by the research team’s PPIE lead (KM). Members of the research team who attended the meetings included the study’s project manager (KA), and a research assistant (RA). The study’s health economist (GS), and health economics research associate (AR) and other RAs also attended meetings on an ad hoc basis to discuss specific aspects of the research with the group.

Efforts to diversify the staff consultation group

After the first meeting, a short, anonymous demographics form was sent to group members. While the group was diverse in terms of some characteristics (e.g. job role, sector, age and disability), all group members identified as being white women, although not all White British. This was most likely a result of initially approaching those accessing a Hub for support, amongst whom men and people from ethnic minority communities were under-represented (see Chapter 4).

The staff consultation group and the research team worked to diversify the group. Actions taken included targeted emails to Hub clients in under-represented groups, specifically highlighting that we sought to involve people who identified with a range of different demographic groups. RAs from each site also contacted local NHS Trusts’ ‘BAME Networks’ and equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) leads, who provided advice around the wording of invitation e-mails. RAs attended network meetings for consultation, advice and promotion of the study.

For example, as part of this work, the RA at Site B also attended local BAME Network and EDI network meetings. At this meeting the RA introduced the Hub offer, the research study, and the need to diversify the Staff Consultation Group. These networks sent out information and invitations to be a part of the group via network meetings during online sessions and through the network mailing list. Other engagement included informal virtual meetings and e-mail correspondence with colleagues in EDI positions and NHS staff with a passion for reducing health inequality. The RA attended five BAME Network meetings and met informally with others outside the BAME Network (three monthly meetings with a smaller group of three stakeholders from December 2021 to February 2022; additional individual meetings with potential stakeholders who were interested in the research; meeting with champions in the community who worked with voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) organisations to seek advice around engaging with under-represented communities).

Following these engagement efforts, two new regular members joined the Staff Consultation Group, one being from a white non-British background, and other from a minority ethnic group. However, the group nevertheless remained all women. Much of the involvement from people from minority ethnic communities was conducted in an informal manner due to the barriers with research engagement discussed in Equality, diversity and inclusion.

Other stakeholder engagement

Various stakeholders were also invited to make suggestions for the best ways to gather, interpret and disseminate research findings from the study. Stakeholders consulted included the study’s Project Steering Committee, and a regional BAME Network, and Site D’s Expert Reference Group, comprising of primary care, social care, VCSE and well-being leads from across the system. These groups shared several innovative methods that could be used, which were incorporated into the study’s impact and dissemination plan.

Involvement of the Staff Consultation Group across the research

Throughout the study, the Staff Consultation Group advised the research team on crucial aspects of the research from study set-up to data collection, to reviewing study findings. Further details of how the Staff Consultation Group contributed to the research at various stages can be found in subsequent chapters for each research objective. At the end of the project, the Staff Consultation Group reviewed and commented on study findings and two members of the group reviewed and amended the Plain language summary.

Chapter 3 Service mapping

Overview

The aim of this chapter was to describe, compare and contrast the models used by the Hubs, the interventions they provide, and detail an in-depth categorisation of the processes needed to deliver the services. 38

Methods

A service mapping template was developed from four different tools to capture relevant elements of service provision (available from the authors upon request). These tools included:

-

Section A (introductory questions) and Section D (service inventory) of the European Service Mapping Schedule,38,39 a widely used service mapping tool. Sections B and C were not included as these sections relate to counting large numbers of services, so were not informative for the current project.

-

The template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist,40 to provide an in-depth explanation of the interventions provided by the Hubs.

-

A checklist for describing health service interventions41 to provide additional contextual information, including organisational information, patient group, workforce and staffing.

Procedure

The template was completed by Hub RAs at each site. Sources of information included business cases, Hub websites and meetings with clinical leads and managers within each Hub. Information from each Hub was then integrated to compare and contrast features across the sites. The document was then reviewed by site leads (i.e. individuals with leadership or management responsibilities within each Hub) for accuracy. Data were collected between March 2021 and March 2022, capturing a snapshot in time of the Hubs’ services, while recognising possible future change.

Results

Geographical regions

The four Hubs were based in different geographical regions within England. Table 1 gives estimates of the number of eligible staff within each site region.

| Site | Health and social care staff within site regions (excluding staff from private organisations) |

|---|---|

| Site A | 126,000 |

| Site B | 165,000 |

| Site C | 129,000 |

| Site D | 180,000 |

The Hubs were set up as collaborations between several NHS trusts within their respective localities. Each site is hosted by one NHS Trust, with some local variations.

Goals

The initial goal of the Hubs was to offer timely psychological support to health and social care staff who had been psychologically affected by the pandemic. The aim was to support individuals, teams, organisations and the wider health and care system. This aim was operationalised through the provision of psychological support for individuals, and individual and team-based support for managers, leaders, and staff teams. The function of the Hubs continued to evolve, broadening beyond the pandemic, for example, providing support following local incidents.

Funding

Each of the Hubs was funded by NHS England and Improvement (NHSE and I), with some variation in local funding arrangements.

Target population

All Hubs opened to NHS and social care staff who lived or worked within the respective Hub regions; variations are described below. Some variations to Hub eligibility included staff outside of the NHSE and I national scope for Hubs, including education staff, and emergency services staff other than ambulance staff. Eligibility as defined by NHSE and I also changed over time, whereby Hubs were initially set up to support staff affected by the pandemic. Latterly, this remit changed to include all staff within in-scope groups, regardless of the cause of difficulties. 33 Table 2 details groups in scope at each site.

| Site A | Site B | Site C | Site D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over 18 (health and care staff) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 16–17 years (health and care staff) | ✓ | Not in scope | ✓ | ✓ |

| Family membersa | ✓ | Not in scope | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ambulance service | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Police/fire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ (if involved in specific COVID-related health and care duties) |

| Education | ✓ | Not in scope | Not in scope | ✓ (if responsible for well-being) |

| 3rd sectorb | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| VCSE | ✓ | ✓ (if local authority commissioned) |

✓ | ✓ |

Site D was also open to staff who work in the VCSE sector, family members (including direct, extended or chosen family members from any region in the UK), ambulance staff and fire service and police officers involved in COVID-19-specific duties. Different workstreams were available for emergency services personnel and individuals working within complex safeguarding teams.

Sites A and C were open to all emergency services and VCSE staff, and immediate family members of healthcare staff who live or work in the respective Hub region. Site A also supported staff from education. Site B was also open to all emergency services, third-party organisations and voluntary organisations who had been commissioned by local authority. Although the Hubs were predominantly set up for people who had been affected by COVID-19, Site C and Site D opened to staff regardless of the cause of their difficulties. In contrast, Sites A and B supported staff whose difficulties were caused by or exacerbated by COVID-19.

Several of the Hubs opened to different occupational groups in a phased approach to avoid overwhelming Hub services. Site A opened to all staff in December 2020; Site C did not have a staged offer; however, a reduced version of the service opened in November 2020 to enhance existing occupational health and psychology services. Site C was opened on a larger scale to support individuals and teams in February 2021. Site B opened initially to NHS critical care staff in February 2021, broadening to all NHS staff in March 2021, followed by social care in July 2021 and emergency services in August 2021. Site D initially opened to screening and referrals from managers/leaders for health and care staff and targeted groups (e.g. staff working on COVID wards and care home staff) in May 2020, and was advertised to all health and social care staff, and their families in November 2020.

Model summary

All Hubs operated an outreach and screening model to support clients, although there were variations in the implementation of this overarching model. Each of the Hubs had an online self-referral system. Self-referral forms include mental health screening, demographic and occupational information, which inform subsequent clinical assessment. Subsequent psychological support differed across the Hubs and is outlined below (see Services offered by the Hubs).

The Hubs discharged clients following completion of support or treatment. Clients could re-refer to these Hubs if needed, and there was no limit on how many times a client could re-refer. Initially most of the support was provided virtually, but due to demand and easing of restrictions, all Hubs expanded their offer to provide face-to-face support when appropriate. At the time of data collection, the Hubs were open Monday–Friday, but offered some evening appointments if required.

Staffing

Staffing skill mix was similar across the Hubs, representing a ‘top-loaded’ model with a higher number of senior clinicians compared with non-qualified staff such as assistant psychologists (APs). Table 3 illustrates the breakdown of staff at the time of data collection, according to agenda for change (AfC) banding, demonstrating this staffing model. Band six members of staff correspond generally to qualified clinicians. Common skill mix across the Hubs’ teams included: clinical psychologists (CP); psychological therapists; mental health practitioners; cognitive–behavioural therapists; APs and administrators. Most staff was employed via secondment from their usual employment, or via fixed-term contracts.

| Service | Percentage of Band 6 staff or higher |

|---|---|

| Site A | 78.51% |

| Site B | 67.04% |

| Site C | 73.96% |

| Site D | 74.17% |

Similar rationales underpinned this staffing model across Hubs. More senior staff were employed due to an anticipated need for organisational working, for example, working with teams, as well as a need for staff experienced and accredited in trauma-focused interventions, to deliver NICE-recommended trauma therapies such as eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR). 42 Furthermore, clients who required therapeutic input and presented with a range of difficulties and more complex needs required more senior clinicians. Finally, each Hub’s triage assessment and treatment planning was led by psychological formulation; ensuring a collaborative approach to explain difficulties and make sense of them while acknowledging the individual’s strengths and resources,43 necessitating experienced clinicians skilled in psychological formulation. However, Site B’s staffing was based on a ‘two-pronged model’, which included a high number of senior therapists as well as APs. In addition to the above need for senior staff, the sizeable workforce of APs was responsible for low+intensity interventions (see Self-help and psychoeducation and Low-intensity interventions), co-facilitating workshops, developing resources, regional mapping of available services and outreach.

Staffing numbers, AfC banding and roles across the Hubs as whole-time equivalents (WTEs) in post at the time of data collection are outlined in Table 4. Of note, this information does not necessarily reflect the staffing levels originally planned in the business cases of the Hubs (e.g. due to difficulties in appointing certain NHS posts) and may therefore underestimate the staffing resources forecasted to deliver planned Hub support at each site.

| Role | AfC banding | Site A | Site B | Site C | Site D | Staff group44 | Role code44 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical leadership | 9 | 0.4 | – | – | – | STT | S2L |

| Clinical leadership | 8d | – | – | – | 0.45 | STT | S2L |

| Clinical leadership | 8c | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.5 | STT | S2L |

| Clinical leadership | 8b | – | 1.8 | – | 0.9 | STT | S2L |

| Service lead | 8b | – | – | – | 0.3 | A and C | G1 |

| Clinical/principal psychologist | 8b | – | 1.2 | 2.0 | – | STT | S2L |

| Operational/service manager | 8a | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.5 | A and C | G1 |

| Clinical psychologist/psychological therapist/practitioner | 8a | 4.4 | 3.2 | 1.0 | 2.9 | STT | S2L |

| Strategic engagement lead | 8a | – | 1.0 | – | – | A and C | G2 |

| Pharmacist/non-medical prescriber | 8a | 0.6 | – | – | – | STT | S2P |

| Assistant service manager | 7 | – | – | 1.0 | – | A and C | G2 |

| Clinical psychologist/psychological therapist | 7 | 3.3 | 6.3 | 2.9 | 1.9 | STT | S2L |

| Advanced practitioner | 7 | – | – | 2.0 | – | STT/N | S1U/N4D |

| Business manager | 6 | – | 1.0 | – | – | A and C | G2 |

| Research associate | 6 | 0.4 | – | – | – | A and C | G2 |

| Trainee clinical/counselling psychologist | 6 | – | 1.8 | 0.6 | – | STT | S8L |

| Mental health nurse | 6 | – | – | – | 0.6 | N | N4D |

| Research assistant | 5 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | A and C | G2 |

| Trainee assistant psychological practitioner | 4 | 1.0 | – | – | – | STT | S8M |

| Assistant psychologist | 4/5 | – | 7.0 | 5.6 | 2.1 | STT | S5L |

| Pathways advisor | 4 | – | 0.8 | – | – | A and C | G2 |

| Administrator | 5 | – | – | – | 0.5 | A and C | G2 |

| Administrator | 4 | 0.4 | – | 1.0 | – | A and C | G2 |

| Administrator | 3 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | A and C | G2 |

| Total WTEs | – | 13.9 | 26.6 | 19.9 | 12.15 |

Staff training and induction was arranged according to staff needs. Staff at each of the Hubs received training in electronic patient records systems, ongoing continuing professional development training and sessions on specific areas of concern, such as Long COVID, working with critical care staff, or specific mental health difficulties.

Services offered by the Hubs

Outreach

Each of the Hubs used outreach to promote the services and increase uptake of individual and team support. The Hubs offered presentations to staff teams to promote Hub support, how to self-refer and invite staff to ask questions. The Hubs’ team-based interventions were also used to disseminate to staff teams, regular meetings with acute trusts, stakeholders, social care and local authority, and through e-mail contacts between organisations. Common methods of outreach included distribution of flyers, banners and business cards, information packs distributed throughout care homes and meetings with leads of partner organisations. Other methods of promotion included social media (Site B), promotional items (e.g. branded stationery, well-being pack; Site B and D) and slots on local media platforms (all sites).

Site D used a locality system whereby Hub clinicians were assigned to specific workforces/areas within the region. Site A launched a branding and communications campaign across a wide range of partnership organisations.

Site B employed a full-time Strategic Engagement Lead to direct and manage communications and outreach across the region. Stakeholders were invited to a monthly Partnership Engagement Forum to gain stakeholder engagement and support targeted outreach. A monthly newsletter was disseminated across the region’s networks at the local and strategic levels to reach as many staff as possible. Site D and B’s critical care leads participated in close planning with the regions critical care network to direct critical care specific outreach and promotion.

Outreach activities were conducted by each Hub to target specific staffing and demographic groups that had lower uptake of Hub support. Targeted outreach included visiting and providing materials to care homes (Sites B, C and D), producing information for care homes (Sites A and D), gathering direct e-mail addresses for care home staff, ambulance staff and hospices to promote the offer (Site C; Site D), developing bespoke social media graphics for different groups (Site B; Site D), promoting workshops or facilitated peer support (FPS) sessions for care home staff (Sites B, C and D) and men’s mental health (Site C; Site D). Meetings with NHS Trusts Equality Leads took place to promote the Hubs and target health and care staff from minority ethnic backgrounds (Site C; Site D), as well as creating links with race equality networks (Sites B, C and D). A race equality campaign was implemented to attempt to reach more staff within this group (Site B). Webinars were also conducted with the local Council of Mosques (Site A). Face-to-face check-ins were delivered with critical care staff within the region (Site D) and links made with the ambulance service Suicide Prevention Lead to attempt to increase the uptake from this group (Site B). Meetings with representatives from emergency services also took place (Site A), and further meetings were held with representatives from critical care units to identify how best to spend specific funding to support critical care staff (Sites A and D).

Website resources

Each Hub had a website, providing information about services, eligibility, psychoeducation materials and downloadable self-help resources and short webinars. The websites also provided details of other mental health services/charities available to staff, as well as crisis helplines for emergencies. Individuals could self-refer on each Hub’s website. Site A’s website also included testimonials from Hub clients to promote and normalise the service. Staff accessing Site B’s website could book onto peer support groups and well-being workshops, as well as sending feedback, testimonials and suggestions to the Hub.

Self-referral and mental health screening

At each Hub, prospective clients were encouraged to self-refer online, although other options were available. Mental health screening formed a part of the self-referral process, although this process varied across Hubs. Screening at each Hub included measures of post-traumatic stress [International Trauma questionnaire (ITQ) or PTSD Checklist for the DSM-5 (PCL-5)],45,46 depression Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9),47 anxiety Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)48 questionnaire and social and occupational functioning [work and social adjustment scale (WSAS)]. 49 Sites A, C and D also included a measure of problematic alcohol use alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT). 50 Each Hub collected demographic and occupational information from prospective clients, and on occasions additional screening measures not covered at other Hubs. The use of specific screening measures across Hubs is summarised in Table 5, and the measures are described in detail in Routinely collected measures.

| Site A | Site B | Site C | Site D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and occupational questions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| PHQ-9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| GAD-7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WSAS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| AUDIT | ✓ | No | ✓ | ✓ |

| ITQ | No | No | ✓ | ✓ |

| PCL-5 | ✓ | ✓ | No | No |

| Smoking/drug use | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ (since September 2021) |

✓ (since May 2021) |

| Questions around the impact of COVID-19 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

At Site A, online mental health questionnaires were presented as a tool for keyworkers to assess their own mental health and receive immediate feedback on their score, with the option to self-refer to the Hub after feedback. In contrast, completion of mental health screening within Sites C and D acted as a self-referral into the service, with immediate feedback provided via e-mail. Within Site B, individuals completed a brief self-referral form, and following acceptance of the referral by the Hub, clients were sent the mental health screening measures to complete prior to clinical assessment.

Assessment

Self-referral and mental health screening data were used to inform subsequent clinical assessment of keyworkers’ difficulties, to determine support and interventions offered by the Hubs.

At the time of data collection, Sites C and D offered an assessment phone call following the completion of screening questionnaires. Clients at Site C were offered either a rapid or a full assessment, dependent on the outcome of an initial review of screening scores. Within Site D, dependent on the initial presentation of the individual’s needs, the assessment was provided by any member of the clinical team, typically lasting between 30 and 60 minutes. The aim of this assessment was to gather information about the individual’s difficulties, construction of a collaborative formulation and quickly ascertain how the service could offer evidence-based support to manage those difficulties. Clients at Sites A and B were offered a full 60–90-minute formulation-based clinical assessment from a qualified clinician [a cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), therapist or CP] via video consultation as standard.

All Hubs offered an in-depth formulation-led assessment. Where Hubs offered shorter assessments as standard, in-depth assessments were offered dependent on clinical need. The aim of the in-depth assessment (60–90 minutes, with the potential to extend to a further session) was to develop a psychological formulation-led characterisation of individuals’ difficulties, and to inform support and treatment planning. For example, at Site D, a panel was used to decide whether a full assessment was clinically necessary or would expedite access into therapy. Site D also provided facilitated assessments into services where an agreement had been made, to prevent clients from re-telling their story. These assessments follow a pre-determined clinical framework developed by the Hub and are conducted by senior clinicians. If risk was a concern (e.g. a score of 2 or 3 on item nine of PHQ-9), duty clinicians at the Hubs ascertained the level of distress and facilitated support and/or access to appropriate services.

Onward referrals

There was variation across sites in the extent to which onward referrals were made following screening and assessment, versus direct provision of therapy within the Hubs. As one of the earlier sites to set up, the aim of Site D’s staff well-being work was to be proactive and preventative. As such, there was a focus on team and system support to reduce the number of clients requiring individual intervention. If deemed clinically necessary, onward facilitated referrals were typically made to maximise usage of already commissioned services, and fewer clients seen within the Hub for formal therapeutic work. Site D therefore facilitated a high number of outward referrals into other appropriate services, in addition to psychosocial support. When mainstream commissioned services were exhausted, or there was a clinical rational the Hub utilised its own therapy resource for those with complexity and clinical risk otherwise unmet. The site used an outreach and clinical advocacy model to ensure individuals received appropriate levels of support and offered evidence-based psychologically informed advice, self-help support and psychoeducation. Site C adopted these same principles and at the time of data collection facilitated approximately 60% of referrals to other services. Site B adopted the same principles, utilising regional mapping and waiting time check-ins to establish whether locally commissioned offers could be considered ‘timely’ to ascertain the most appropriate source of psychological support for that client, taking into account timeliness of available local support against risk of deterioration. As a result, Site B had an approximately even split between in-house intervention and onward referral.

By contrast, upon set-up of Site A, a scoping exercise of local services concluded that during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, waiting times were significant; therefore, their intervention model was designed to provide in-house therapy provided directly by the Hub. Therefore, a small number of onward referrals were made to other services where appropriate.

Site B also provided a pastoral care pathway involving engagement with community, charity and third-sector organisations to offer an alternative model of care for interest-based support. A dedicated pathways advisor signposted keyworkers to appropriate support groups and activities, such as therapeutic singing, martial arts or music groups.

Interventions for individuals

Self-help and psychoeducation

Self-help and psychoeducation were offered at each Hub to provide support for low-level mental health needs. This involved providing materials, explanations of difficulties and signposting to other services. Self-help and psychoeducation were used to help the individual to manage their difficulties and offer advice on how to access further support if required. If an individual’s needs or levels of distress were significant, they may have been offered an alternative intervention to address those needs.

Sites C and D offered supported self-help and psychoeducation following every referral into the Hub. This was offered via telephone by APs or qualified clinicians, where required. Site C predominantly offered an assessment with a further two supporting phone calls to agree the treatment pathway, with the potential for further self-help and psychoeducation offered subsequently. However, within Site D, there was no maximum number of sessions of self-help and psychoeducation offered as this was dependent on the individual’s needs and goals at that time. Site B had a heavily front-loaded website containing substantial self-help and psychoeducational resources. These were signposted during assessment, or clients could be allocated to a low intensity in Hub intervention (see Low-intensity interventions).

Low-intensity interventions

Sites A, B and C provided a lower-level intervention for less complex difficulties, which was more formally structured than the self-help and psychoeducation offered at Site D. Low-intensity interventions typically involved a specific number of sessions based on low-intensity CBT principles, for example, guided self-help/psychoeducation, skill-building and relaxation exercises. At Site A, these were delivered by qualified psychological practitioners, APs and trainee associate psychological practitioners, typically over 6 sessions, with a maximum of 12 sessions. Individuals could be ‘stepped up’ to high-intensity therapy if clinically necessary. In addition, low-intensity sessions were used to support individuals waiting on the high-intensity waiting list at Site A. At Site B, low-intensity interventions were delivered by APs. These consisted of manualised, semistructured, psychoeducational and CBT skills-based sessions on topics such as sleep, anxiety, or panic, usually offered for four to eight sessions. Following low-intensity interventions, clients were subsequently offered higher-intensity interventions if required, signposted to other services, referred elsewhere, or discharged from the Hub.

Therapy

Direct therapy was offered by all Hubs. The rationale for providing direct therapies was similar across Hubs, including, for example, significant waiting times at local services; particular types of complexity (e.g. concerns around confidentiality; previous negative experiences in services) and circumstances in which clients’ presentations fell between gaps in services [e.g. difficulties that were too complex for improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) services, but not sufficiently complex or enduring for community mental health team, support].

High-intensity therapy was delivered by CBT Therapists, EMDR therapists and consultant practitioners and CPs, and modalities included, for example, CBT; cognitive analytic therapy (CAT); compassion focused therapy; acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT); and trauma-focused interventions such as trauma-focused CBT and EMDR. This usually consisted of approximately 12 sessions at each Hub, but could greatly exceed this.

One difference across Hubs was that, at Sites B and D, the delivery of high-intensity therapies was further divided into ‘Step 3’ and ‘Step 4’ interventions (with Step 2 representing lower-intensity interventions), dependent on the complexity of the client’s difficulties. Step 3 therapy (usually 8–12 sessions) consisted of ‘straightforward’, single modality, problem-specific interventions, for example, CBT for low mood, EMDR for single-incident trauma. Step 4 therapy (20+ sessions) consisted of integrative, formulation-driven therapy or EMDR for complex difficulties. Both were delivered by CBT or EMDR therapists, CPs, or other similar qualified clinicians.

Two Hubs also offered group-based interventions. Site C’s 7-week bereavement support group helped individuals dealing with loss and grief in the workplace, delivered by clinicians trained in bereavement support or group analysis. A 6-week mindfulness group was also offered to help reduce stress and learn new skills, delivered by a Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapist. Site C also provided a nine-session peer support group for people experiencing Long COVID.

Pharmacological intervention

Individuals could receive pharmacological advice or support following psychological assessment at Site A. Pharmacological intervention was delivered by pharmacists, and included, for example, psychoeducation around medication, new prescriptions relating to mental health and medication reviews. Individuals could attend an initial appointment to discuss medication advice, follow-up appointments if medication was prescribed, and monthly medication reviews. Following discharge from the Hub, prescriptions were continued with the client’s GP. Site C offered support around medication from an associate nurse consultant, which included offering psychoeducation, advising individuals regarding non-medical prescribing and liaison with GPs.

Support for teams

A wide range of team-based interventions was offered across the Hubs, developed to support to the needs of managers, team leaders and help support the psychological safety of the health and social care system. Clinical leads, CPs or other psychological practitioners delivered team-based support across Hubs. Team-based interventions were bespoke to teams’ needs as determined through an initial consultation and formulation, and could be made up of a combination of different interventions.

While there were variations across sites, all sites provided consultation with managers and team leaders to help identify difficulties faced by teams and provide bespoke solutions. Team-based work incorporated trauma-informed approaches, signposting to supportive resources, reflective and resilience-based sessions, self-care workshops, training for teams and organisational strategy support, as well as direct support for managers as needed.

Workshops were provided virtually and face-to-face where appropriate across the Hubs. These were delivered by qualified clinicians with experience in supporting teams and organisations, and focused on different emotional well-being, self-care, psychological first aid and validation of the team’s difficulties. Examples included sessions on burnout, ‘containing the containers’, moral injury and psychological self-care. Furthermore, FPS was also offered by some Hubs to provide a safe reflection space for teams to come together to discuss relevant topics/difficulties.

Teams could engage with multiple aspects of team support provided by the Hubs, determined through initial and ongoing consultation with managers and teams. An example of this is outlined in Box 1.

A team manager contacted the Hub for support, and details of the Hub offer were sent to all services within the remit in the Hub’s region (promotion of the offer). An initial discussion was offered to the team manager, and discussion was had around support offered by the employer to identify the current difficulties (consultation). The manager provided the Hub with e-mail addresses of their employed staff, who were sent information on screening/self-referral and the Hub’s offer (outreach).

Face-to-face workshops were offered to this and other teams within the region to offer solutions and build psychological safety (workshops). The Hub joined the team’s ‘diversity and inclusion group’ to ascertain potential barriers that may have prevented some staff groups from accessing the Hub. A group of ward managers then requested a facilitated peer support session to provide validation of experiences and an opportunity for reflection (facilitated peer support).

Following this, the team experienced a death within their service, which resulted in the Hub re-promoting the offer and providing an explanation on colleagues re-engaging with the Hub without having to ‘re-register’ or complete questionnaires. Staff members were signposted to a bereavement service to provide more specialised support in this area (onward referral). Further consultation, promotion of the offer and a face-to-face workshop were provided. The team were also able to contact the Hub for support for additional difficulties.

Additional support for critical care staff

Critical care departments experienced high demand and were exposed to high numbers of patient deaths in the pandemic. Critical care staffs were therefore identified as a group likely to have been significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and all Hubs offered support by senior clinicians to this client group. Three of the Hubs utilised additional available funding to provide and co-ordinate support for this group, determined according to the number of ICU beds taken up with COVID-19 patients. The Hubs co-ordinated to provide broadly similar support across the services, differences in their methods of input are described below.

Within Site D, enhanced support was offered, including team and individual support, consultation, training and support for Professional Nurse Advocates to develop their skills, promotion of the general offer and more enhanced resources and ‘check-ins’ for Band 7 and Band 6 staff to help reflect and resolve difficulties. Each critical care unit had a senior clinician as an account manager and had the opportunity for onsite presence.

Site A similarly offered team well-being sessions for ICU staff as well as contributing to training consultations and supervision for key staff members. Site A also planned to assist these staff groups to enhance their well-being packages for example, team rooms and garden units.

Site B developed bespoke well-being resources for critical care staff and focused on promoting the offer to ICU staff. Drop-in sessions were also provided to some hospital sites to provide space to identify difficulties and access initial support with signposting.

Site B and Site D also joined a new critical care forum, which aimed to share learning and updates from supporting critical care staff to further improve the level of support.

Chapter 4 Quantitative analyses (Objective 1)

Overview

The analyses presented in this chapter considered screening data collected by the participating Hubs (N = 1973) as well as mental health service use data collected via an online survey in a subsample of Hub clients (N = 299). The aims were to identify keyworker characteristics associated with greater likelihood of mental health and functional difficulties that may benefit from mental health support, evaluate the extent to which keyworks accessed mental support following Hub input, explore keyworker characteristics associated with differential access to mental health support following Hub input, and gather data on keyworkers’ satisfaction with the support received by the Hubs.

Method

Participants

One thousand nine hundred and seventy-three individuals were included in the analyses of Hub screening data. All participants (1) were over 18 years of age, (2) completed screening at one of the Hubs and (3) consented for their data to be used for research purposes. Out of this sample, 900 participants had consented to be contacted for research purposes and were eligible for completing the follow-up survey deployed 5–8 months following the completion of the Hub screening measures. In total, 299 individuals completed the service use questionnaire that is 33.2% response rate across sites, with 77 participants in Site A (40.5%), 29 (29.9%) in Site B, 46 (27.5%) in Site C and 147 (33.0%) in Site D.

Routinely collected measures

Despite local variation in the screening information collected (see Chapter 3), the four Hubs routinely collected comparable data on the following domains.

Depression

Symptoms of depression were measured using the 9-item version of the PHQ-9. 47 This questionnaire asks participants to rate on a four-point Likert scale (0 = ‘not at all’ to 3 = ‘nearly every day’) the extent to which they have struggled with common symptoms of depression in the previous 2 weeks. PHQ-9 scores are added to compute a total score ranging from 0 to 27, with scores between 0 and 4 indicating ‘no depression’, 5–9 indicating ‘mild depression’, 10–14 ‘moderate depression’, 15–19 ‘moderate-to-severe depression’ and 20–27 ‘severe depression’. For the purposes of the present analyses, ‘caseness’ on the PHQ-9 was defined as scores suggestive of at least moderate depression.

Anxiety

Symptoms of anxiety were measured using the brief GAD-7,48 a self-administered tool that is frequently asking participants to rate on a four-point Likert scale (0 = ‘not at all’ to 3 = ‘nearly every day’) the extent to which they were bothered by common symptoms of anxiety in the previous 2 weeks. The total score can range between 0 and 21, with scores between 0 and 4 indicating ‘no anxiety’, 5–9 ‘mild anxiety’, 10–14 ‘moderate anxiety’ and scores ≥ 15 indicating ‘severe anxiety’. GAD-7 ‘caseness’ in the present analyses was defined as scores suggestive of at least moderate anxiety.

Post-traumatic stress symptoms

At two of the Hubs (Sites A and B), post-traumatic symptoms were assessed using the PTSD Checklist for the DSM-5 (PCL-5),46 a self-report questionnaire comprising 20 items corresponding to the DSM-5 symptom criteria for PTSD. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale (0 = ‘not at all’; 4 = ‘extremely’). A total PTSD severity score (ranging between 0 and 80) can be obtained by summing the items’ scores, and used to identify individuals with probable diagnosis of PTSD (i.e. individuals with severity scores ≥ 31). At the remaining Hubs (Sites C and D), post-traumatic symptoms were assessed using the ITQ. 45 The ITQ is a self-administered questionnaire assessing PTSD symptoms and additional features of complex PTSD (CPTSD) known as ‘disturbances in self-organisation’ (DSO) experienced by respondents in the previous month. It comprises 18 items rated on a five-point Likert scale (0 = not at all; 4 = extremely). The ITQ was scored to provide both a dimensional PTSD symptom score (i.e. a total post-traumatic stress score computed using six items assessing core PTSD symptoms including avoidance, hyperarousal and intrusions) and according to the standard ITQ diagnostic algorithm to identify probable International Classification of Disease – 11th Revision diagnosis of PTSD or CPTSD (via endorsement of specific PTSD and DSO items in conjunction with self-reported impact of symptoms on the person’s functioning). 45 For the purposes of the reported caseness analyses, any individual meeting ITQ criteria for PTSD on the PTSD subscale, irrespective of their CPTSD status, were regarded as having a probable diagnosis of PTSD.

Problematic alcohol use

Three Hubs (Sites A, C and D) collected data on harmful alcohol use using the AUDIT,50 a self-report questionnaire comprising 10 items rated on a five-point Likert scale (0–4). The AUDIT total score can range between 0 and 40, with scores between 0 and 7 indicating ‘low risk’, 8–15 indicating ‘hazardous drinking’, 16–19 ‘harmful drinking’ and scores ≥ 20 indicating ‘possible dependence’. In our analyses, AUDIT ‘caseness’ was defined as scores suggestive of at least hazardous drinking.

Social and occupational functioning

The WSAS49 is a brief measure comprising five items rated on a nine-point Likert scale (0 = ‘not at all’; 8 = ‘very severely’) to assess impact of mental health difficulties across multiple day-to-day tasks/domains. The total score can range between 0 and 40, with scores between 0 and 10 indicating functioning levels expected in non-clinical populations, between 11 and 20 indicating ‘significant’ impairment in functioning, and scores > 20 indicating ‘moderately severe or worse’ functional impairment. For the present analyses, WSAS ‘caseness’ was defined as scores suggestive of at least significant functional impairment.

The Hubs also collected data on a range of Hub clients’ characteristics relevant to the planned analyses, including the following.

Demographic data

Information was available on Hub clients’ age, gender, ethnicity, disability status (i.e. whether they self-reported having a disability) and sexual orientation.

Occupational and work environment characteristics

Although there was considerable variance across sites, the Hubs routinely collected information pertaining to Hub clients’ work setting, for example, whether the person worked in hospital settings (ICU/Critical care, Nightingale, A and E, Other Ward/Service, Across Hospital Site) or other setting (Primary care including GP Practices, Education, Emergency Services, Residential Care, Community Care, Local Authority, Voluntary/Charitable Sector, Other), and in what role.

Pre-pandemic mental health concerns

All Hubs collected information on whether the person was concerned about their emotional well-being/mental health before COVID-19.

Impacts of COVID-19

All Hubs collected information on common impacts of COVID during the acute phase of the pandemic. These covered whether the person had been impacted by COVID-19 in any of the following ways: (1) seconded to a different post; (2) moved to work in a different location; (3) undertaking new tasks within usual role; (4) been ill with confirmed COVID-19 (recovered at home); (5) been ill with confirmed COVID-19 (including being in hospital); (6) family member been ill with confirmed COVID-19 (recovered at home); (7) family member been ill with confirmed COVID-19 (included being in hospital); (8) experienced family/close friend bereavement; (9) suffered financial loss within the household.

Service use questionnaire

A service use questionnaire (SUQ) adapted from previous health economic research by the project team51 was developed to capture information on: (1) what level of support participants received from the Hubs, and their overall satisfaction with the support provided by the Hubs; (2) which mental health support services (if any) keyworkers accessed or were currently on waiting-list for following their registration with the Hubs; (3) to what extent keyworkers accessed these services as a result of Hub support. Additional health economic information collected as part of the SUQ is described in further detail in Chapter 5. A copy of the SUQ is available in Report supplementary material 1.

Procedures

All individuals screened by the Hubs were routinely asked to provide consent for their anonymised data to be used for research purposes, and whether they would like to be contacted for further follow-up research. Relevant data for all consenting Hub clients were extracted from the Hubs’ electronic patient records systems, cleaned, and anonymised by RAs based at each Hub. The data were compiled into a central database managed by the study statisticians, who performed quality checking and relevant re-coding/cleaning ahead of the planned analyses.

All keyworkers who consented to be contacted regarding follow-up research were sent an e-mail invitation to complete the SUQ (and additional measures relevant to the planned health economic analyses reported in Chapter 5) via a bespoke online survey deployed between 5 and 8 months following their Hub registration. Participants received up to four reminders over a 2-month period until they declined involvement or completed the survey. To minimise the impact of digital inequality, keyworkers who reported not having reliable access to an e-mail at Hub screening or completed the Hub screening measures over the phone were contacted by their respective Hub RAs using an alternative contact method (e.g. mobile phone) and given the opportunity to complete survey using alternative means (e.g. over the phone with support of the Hub RA). Data collected via the survey underwent data cleaning and recoding in preparation for statistical analysis by researchers based at the University of Manchester Biostatistics Collaboration Unit and in the Manchester Centre for Health Economics.

Analysis

For each site, and across sites, we numerically summarised data on participant demographic and occupational characteristics, and reported COVID-19 impacts and pre-pandemic emotional well-being concerns. Due to considerable differences in how occupational and work environment data were recorded across sites, occupational information was recoded so that data from all sites could be compared. Participants were allocated to seven mutually exclusive occupational categories: NHS; Primary care; Social care; Emergency services; Education; VCSE; Local authority; and other. We further defined a subgroup of NHS workers, namely those working in ICU or Critical Care (including Nightingale workers) and those in clinical and non-clinical roles, to explore the potential relative risk associated with these more specific NHS keyworker groups.

Data from mental health screening questionnaires were summarised numerically as total scores and used to determine the number of participant meeting threshold for clinically significant difficulties across the assessed domains. A series of logistic regression models, adjusted for site due to the multisite nature of the data, were conducted to examine the association between each candidate predictor and ‘caseness’ on each mental health screening outcome variables. In addition, for all scales, we conducted a series of supplementary analyses using linear regression to examine the associations between candidate predictors and mental health screening data using the scales’ dimensional/continuous scores (the findings of these analyses are available in Appendix 1, Part 3, Tables 37–57 and are broadly consistent with the caseness analyses reported in the main body of the report).

To evaluate whether these relationships varied across the sites, all models were refitted with an interaction between predictor variables and site. The interaction was assessed using a Likelihood Ratio Test for logistic regression models, and a F-test corresponding to an analysis of variance in linear regression models in our supplementary analyses. Owing to the large number of tests performed, p-values should be considered nominal; significant associations are best interpreted as exploratory. To offer some protection against spurious findings arising from multiple testing, we used a significance threshold of p < 0.001 for interaction analyses to identify potential differences across Hubs. A final set of analyses was conducted using proportional odds ordinal logistic regression analyses, adjusted for site, to identify potential predictors of an aggregate measure of ‘overall severity’ (low, moderate, high) across the various standardised screening measures collected by the Hubs. This was defined by the highest severity categorisation received on any of Hubs screening questionnaires (see Appendix 1, Part 1, Table 29 for further detail on this derived variable).

For the analyses of SUQ data, access to mental health support following screening and satisfaction with support were summarised numerically by Hub. Logistic regression models, adjusted for site, were used to examine the relationship between screening questionnaires and whether an individual accessed mental health support because of the Hubs. Due to the low numbers, these relationships were not compared across sites.

Results

Demographic and occupational characteristics

The demographic characteristics of included Hub clients are displayed in Table 6.

| Site A (n = 475) |

Site B (n = 367) |

Site C (n = 400) |

Site D (n = 731) |

Total (N = 1973) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.6 (10.6) 0% missing |

38.8 (11.4) 3.0% missing |

42.3 (11.2) 0% missing |

41.9 (11.4) 0% missing |

41.1 (11.2) 0.5% missing |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White British | 433 (91.4) | 327 (91.6) | 367 (92.4) | 586 (88.5) | 1713 (90.6) |

| Other white | 12 (2.5) | 13 (3.6) | 11 (2.8) | 29 (4.4) | 65 (3.4) |

| Black | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (1.0) | 7 (1.1) | 13 (0.7) |

| Asian | 20 (4.2) | 10 (2.8) | 6 (1.5) | 29 (4.4) | 65 (3.4) |

| Mixed | 6 (1.3) | 4 (1.1) | 6 (1.5) | 8 (1.2) | 24 (1.3) |

| Other | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.6) | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.5) | 10 (0.5) |

| Missing/not stated | 0.2% missing | 2.7% missing | 0.8% missing | 9.4% missing | 4.2% missing |

| Gender | |||||

| Woman | 401 (84.4) | 309 (86.3) | 331 (82.8) | 612 (84.2) | 1653 (84.3) |

| Man | 73 (15.4) | 47 (13.1) | 63 (15.8) | 96 (13.2) | 279 (14.2) |

| Identified in another way | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 19 (2.6) | 24 (1.5) |

| Missing/not stated | 0% missing | 0% missing | 1% missing | 0.4% missing | 0.6% missing |

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Heterosexual | 420 (90.1) | 307 (89.0) | 318 (94.6) | 587 (92.3) | 1632 (91.5) |

| Identified in another way | 46 (9.9) | 38 (11.0) | 18 (5.4) | 49 (7.8) | 151 (8.5) |

| Prefer not to say/left blank | 1.3% missing | 6.0% missing | 16.0% missing | 13.0% missing | 9% missing |

| Disability status (Yes) | 64 (13.5) | 30 (8.2) | 72 (18.0) | 29 (4.0) | 195 (10.9) |

Overall, the demographic characteristics of Hub clients were similar across Hubs. The average age of clients was 41.1 years [standard deviation (SD) = 11.2], ranging from 38.8 years at Site B to 42.3 years at Site C. The available ethnicity data indicated that clients were predominantly from White British backgrounds (between 89% and 92%), with only 5–6% of participants being from ethnic minority backgrounds; 1–2% White Irish and 2–3% from other white backgrounds. In terms of gender and sexual orientation, between 83% and 86% of Hub clients identified as women, and between 80% and 88% identified as straight/heterosexual. Self-reported information on disability status was more variable, ranging between 4% at Site D and 18% at Site C. Of note, these differences may be artefactual and due to variances in how questions on disability status were framed at different Hubs. In particular, at Sites B and D, items to confirm lack of a disability (i.e. ‘none’) were embedded within an extensive, alphabetically ordered list of potential disabilities, which may have led to high levels of missingness (80.4% and 67%, respectively). It is therefore considered likely that nearly all the missing responses at these sites are from people without a disability, and disability data were analysed accordingly in subsequent analyses.

In terms of occupational background (Table 7), NHS employees represented the largest occupational group. A sizable minority of these NHS employees (30% of all NHS participants at Site A, 18% at Site D, 12% at Site B Hub and 10% at Site C) worked in ICUs, including the decommissioned Nightingale hospitals. Only a relatively small proportion of Hub clients reported working in social care settings (between 4% at Site B and 8% at Site D) or in ‘blue light’ services (between 1% at Site B and 12% at Site C).

| Site A (n = 475) |

Site B (n = 367) |

Site C (n = 400) |

Site D (n = 731) |

Total (N = 1973) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS | 289 (60.2) | 315 (87.0) | 222 (57.8) | 312 (44.0) | 1138 (58.9) |

| Primary care | 31 (6.5) | 15 (4.1) | 20 (5.2) | 66 (9.3) | 132 (6.8) |

| Social care | 18 (3.8) | 13 (3.6) | 26 (6.5) | 59 (8.3) | 116 (6.0) |

| Emergency services | 20 (4.2) | 3 (0.8) | 45 (11.7) | 30 (4.2) | 98 (5.0) |

| Education | 14 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 9 (1.3) | 24 (1.2) |

| VCSE | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 13 (3.4) | 36 (5.1) | 51 (2.6) |

| Local authority | 17 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | 15 (2.1) | 36 (1.9) |

| Othera | 84 (17.5) | 16 (4.4) | 54 (14.1) | 182 (25.7) | 336 (17.4) |

| Missing | 0% missing | 1.4% missing | 4% missing | 3% missing | 2.1% missing |

Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 and pre-pandemic mental health concerns

Table 8 shows a breakdown of the COVID-19 impact questions included in the Hubs’ screening tools.

| Question | Site A (n = 475) |

Site B (n = 367) |

Site C (n = 400) |

Site D (n = 731) |

Total (n = 1973) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you been impacted in any of these ways by COVID 19? | |||||

| Ill with COVID-19 (recovered at home) | 147 (30.9) 0% missing |

84 (23.2) 1.4% missing |

144 (36.8) 2.3% missing |

204 (28.7) 2.9% missing |

580 (29.9) 1.5% missing |

| Ill with COVID-19 (including being in hospital) | 19 (4.0) 0% missing |

10 (2.8) 1.4% missing |

23 (6.0) 4.8% missing |

12 (1.7) 5.2% missing |

64 (3.3) 2.9% missing |

| Family member ill with COVID (recovered at home) | 119 (25.0) 0% missing |

68 (18.8) 1.4% missing |

136 (35.0) 2.8% missing |

187 (26.77) 4.2% missing |

511 (26.5) 2.1% missing |

| Family member ill with COVID (including being in hospital) | 37 (7.8) 0% missing |

14 (3.9) 1.4% missing |

39 (10.1) 3.8% missing |

60 (8.7) 5.3% missing |

150 (7.8) 2.7% missing |

| Suffered financial loss within the household | 84 (17.7) 0% missing |

33 (9.1) 1.4% missing |

84 (21.4) 2.0% missing |

152 (21.5) 3.3% missing |

353 (18.2) 1.6% missing |

| Undertaking new tasks within usual role | 245 (51.63) 0% missing |

173 (47.8) 1.4% missing |

193 (49.1) 1.8% missing |

409 (58.3) 4.1% missing |

1021 (52.7) 1.9% missing |

| Seconded or redeployed to a different post | 116 (26.2) 6.9% missing |

46 (12.7) 1.4% missing |

48 (12.2) 1.8% missing |

109 (16.2) 8.1% missing |

319 (17.0) 5.2% missing |

| Moved to a different work location | 153 (34) 5.3% missing |

61 (16.9) 1.4% missing |

105 (26.7) 1.8% missing |

253 (36.4) 4.9% missing |

572 (30.1) 3.7% missing |

| Bereavement | 71 (14.9) 0% missing |

44 (12.2) 1.4% missing |

65 (17.1) 4.8% missing |

168 (23.8) 3.3% missing |

348 (18.0) 2.2% missing |

| Were you concerned about your emotional well-being before COVID? | |||||

| Yes | 170 (36.3) | 169 (46.9) | 136 (34.0) | 276 (38.3) | 754 (38.6) |

| Unsure | 102 (21.8) 0% missing |

57 (15.8) 1.9% missing |

64 (16.0) 0% missing |

124 (17.2) 1.5% missing |

347 (17.8) 1.0% missing |

Mental health and functional screening data

Table 9 displays descriptive statistics pertaining to the mental health and functioning screening tools used by the Hubs.

| Site A (n = 475) |

Site B (n = 367) |

Site C (n = 400) |

Site D (n = 731) |

Total (n = 1973) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 score | 14.4 (5.5) | 13.8 (5.9) | 13.2 (5.9) | 11.4 (6.3) | 12.9 (6.1) |

| None | 21 (4.4) | 15 (4.6) | 27 (6.8) | 117 (16.0) | 180 (9.3) |

| Mild | 73 (15.4) | 76 (23.3) | 94 (23.6) | 185 (25.3) | 428 (22.2) |

| Moderate | 141 (29.7) | 94 (28.9) | 117 (29.3) | 186 (25.4) | 538 (27.9) |

| Moderately severe | 149 (31.4) | 78 (23.9) | 94 (23.6) | 159 (21.8) | 480 (24.9) |

| Severe | 91 (19.2) | 63 (19.3) | 67 (16.8) | 84 (11.5) | 305 (15.8) |

| Missing | 0% missing | 11.1% missing | 0% missing | 0% missing | 2.1% missing |

| GAD-7 score | 12.3 (4.9) | 12.6 (5.4) | 16 (5.5) | 10.2 (6.1) | 11.4 (5.7) |

| None | 28 (5.9) | 17 (5.2) | 44 (11.0) | 153 (20.9) | 242 (12.5) |

| Mild | 121 (25.5) | 91 (28.0) | 102 (25.6) | 207 (28.3) | 521 (27.0) |

| Moderate | 146 (30.7) | 84 (25.8) | 124 (31.1) | 164 (22.4) | 518 (26.8) |

| Severe | 180 (37.9) | 133 (40.9) | 129 (32.3) | 207 (28.3) | 649 (33.6) |

| Missing | 0% missing | 11.4% missing | 0.3% missing | 0% missing | 2.2% missing |

| PCL-5 score | 36.6 (16.6) | 34.3 (16.7) | – | – | 35.6 (16.7) |

| PTSD present | 293 (61.7) | 180 (55.4) | 473 (59.1) | ||

| Missing | 1.0% missing | 11.4% missing | – | – | 5.0% missing |

| ITQ score | – | – | 8.8 (6.3) | 8.2 (6.5) | 8.4 (6.4) |

| PTSD present | 40 (10.0) | 56 (7.7) | 96 (8.5) | ||

| Missing | – | 0.3% missing | 0% missing | 0.1% missing | |

| CPTSD present | – | – | 97 (24.5) | 147 (20.4) | 244 (21.6) |

| Missing | 1.0% missing | 1.6% missing | 1.4% missing | ||

| AUDIT score | 5.7 (5.8) | – | 5.0 (5.1) | 5.2 (5.0) | 5.3 (5.3) |

| Low risk | 351 (73.9) | 322 (80.5) | 564 (77.2) | 1237 (77.0) | |

| Hazardous | 88 (18.5) | 63 (15.8) | 131 (17.9) | 282 (17.6) | |

| Harmful | 18 (3.8) | 5 (1.3) | 23 (3.1) | 46 (2.9) | |

| Possible dependence | 18 (3.8) | 10 (2.5) | 13 (1.8) | 41 (2.6) | |

| Missing | 0% missing | – | 0% missing | 0% missing | 0% missing |

| WSAS score | 18.9 (8.3) | 17.5 (7.9) | 17.9 (9.5) | 15.1 (9.3) | 17.0 (9.0) |

| Subclinical | 65 (13.7) | 55 (16.9) | 77 (19.3) | 213 (29.1) | 410 (21.2) |

| Significant | 213 (44.8) | 152 (46.6) | 170 (42.5) | 311 (42.5) | 846 (43.8) |

| Moderately severe or worse | 197 (41.5) | 119 (36.5) | 153 (38.3) | 207 (28.3) | 676 (35.0) |

| Missing | 0% missing | 11.2% missing | 0% missing | 0% missing | 2.1% missing |

| Overall severity | |||||

| Low | 24 (5) | 23 (6.3) | 29 (7.3) | 128 (17.5) | 204 (10.3) |

| Moderate | 104 (21.9) | 71 (19.3) | 128 (32.0) | 230 (31.5) | 533 (27.0) |

| High | 347 (73.1) | 232 (63.2) | 243 (60.8) | 373 (51.0) | 1195 (60.6) |

| Missing | 0% missing | 11.2% missing | 0% missing | 0% missing | 2.1% missing |