Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/09/31. The contractual start date was in November 2018. The final report began editorial review in February 2021 and was accepted for publication in October 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Wilson et al. This work was produced by Wilson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Wilson et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a serious mental health condition characterised by a pervasive pattern of emotional instability, interpersonal dysfunction, disturbed self-image and impulsive behaviour, including self-harm. 1 BPD is associated with severe and persistent functional impairment2,3 and a suicide rate 50 times higher than that of the general population. 4 It is estimated that up to 80% of individuals with BPD self-harm and 75% attempt suicide,5 and BPD symptoms are among the best prospective predictors of self-harm in young people. 6

Borderline personality disorder is a developmental disorder, with symptoms usually first evident during adolescence. 7 Approximately 3% of children and young people present with BPD symptoms. 8,9 Left untreated, the symptoms of BPD adversely affect the young person’s capacity to meet developmental milestones, such as establishing independent social networks, forming stable relationships and developing academic, occupational and independent living skills, precipitating lifelong disability. BPD is predictive of poor educational achievement,10 unemployment and dysfunctional employment. 11

Growing research interest in adolescent BPD10 has spurred the development of the first wave of evidence-based treatments for BPD symptoms in young people: cognitive analytic therapy (CAT), dialectical behaviour therapy for adolescents (DBT-A) and mentalisation-based treatment for adolescents (MBT-A). These interventions have been demonstrated in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to result in improvements in clinically important symptom domains, including self-harm, suicidal ideation and mood disturbance. 11–13 However, despite these promising findings, BPD treatment is still not routinely accessed by young people and the availability of evidence-based treatments for BPD in adolescents is poor. 10

Implementation of evidence-based treatments for adolescent BPD in routine clinical practice has been hindered by the expensive, highly specialised nature of the clinical resources required to deliver these treatments. 14 Furthermore, current mental health service models often require young people to meet institutional requirements to receive treatment rather than provide treatment in a way that suits the needs of young people. 15 Consequently, those experiencing the most severe and complex mental health difficulties are both less likely to access services16 and less likely to receive evidence-based interventions when they do. 17 The severe and complex nature of BPD makes this group particularly vulnerable to the barriers to treatment such service models impose.

Therefore, late intervention is currently the norm, with specialist treatments being offered to only a small minority of individuals with a chronic disorder. Young people with BPD symptoms often access treatment only once they reach a state of chronic psychosocial dysfunction and frequent mental health crises. 18 This late intervention model comes at substantial personal, social and economic cost, both to young people and their families and to health services. 19

Therefore, there is an urgent need for interventions that are more accessible to facilitate early access to treatment for young people presenting with BPD symptoms. The nature and severity of BPD symptoms mean that interventions that rely on regular clinic attendance or self-directed digital delivery are likely to have low uptake and completion rates. 14 Instead, utilising opportunities to deliver early interventions in contexts that are accessible to young people through working in partnership with universal services is a promising strategy.

Study rationale

As outlined above, there is a pressing need for accessible interventions to address the growing prevalence of BPD symptoms, including self-harm, among young people. 20–22 Currently available evidence-based interventions for adolescent BPD symptoms are not able to be delivered at scale within the NHS context because of their high clinical resource requirements. CAT for adolescents with BPD symptoms comprises 16 individual sessions delivered over approximately 26 weeks. DBT-A comprises twice-weekly sessions (individual therapy and a multi-family skills training group) delivered over a period of 12–16 weeks, with between-session telephone coaching. MBT-A involves weekly individual sessions and monthly family sessions over a 1-year period. CAT, DBT-A and MBT-A must all be delivered by qualified mental health professionals with additional specialist training and supervision. As a result of the relatively long treatment durations and the highly trained practitioners needed to deliver these therapies, few young people with BPD symptoms can access appropriate treatment at present.

The challenge of delivering early intervention for BPD can be met only by moving away from complex, resource-intensive psychotherapies towards brief interventions that can be delivered by non-specialists in accessible settings. 14 The Brief Education Supported Treatment (BEST) intervention has been designed to overcome these barriers to implementing early intervention for BPD symptoms through an innovative, cross-sector approach. Based on a treatment package developed by the Norfolk Youth Service,15 the intervention distils key elements of existing evidence-based interventions for adolescent BPD into a brief practicable format. The package promotes understanding difficulties using a mentalising approach and the development of self-care strategies to enable young people to manage distress.

Prior to the current study, this treatment package was delivered in secondary mental health services only. Owing to limited funding for children and young people’s mental health services and high and increasing demand, thresholds for access to secondary care were high. As a result, few young people with BPD symptoms were able to access the treatment package, and often only after they had been experiencing symptoms for many years. Therefore, we aimed to adapt the treatment package to enable it to be delivered within schools and colleges to facilitate earlier intervention.

Schools and colleges can play an important role in the emotional health and well-being of young people and are well placed to identify those with mental health problems. 16 Increased recognition of the potential of schools and colleges as settings for early intervention has led to an expansion of school-based mental health interventions in many high-income countries. 17 In the UK, mental health provision has traditionally been delivered within the health service. However, recent policy developments23,24 have led to an increased role of schools and colleges in the provision of mental health services for young people.

It is critical that the development of these new services is evidence informed to ensure that the maximum benefit is gained from scarce public resources. Many studies have found school-based interventions to have positive effects on young people’s mental health. 17,25 A recent network meta-analysis26 found little evidence that school-based interventions for the prevention of anxiety and depression are effective. However, a meta-analytic review of indicated school-based interventions found some evidence that these interventions are effective in reducing elevated depression and anxiety symptoms,27 although there is considerable variability in effect sizes reported.

At present, education and health services are too often disconnected, and schools and colleges report receiving inadequate support to meet the needs of pupils experiencing mental health problems. 28 A 2017 survey29 found that a majority of secondary teachers felt they needed further support to identify mental health issues (62%) and provide appropriate support (68%). Similarly, in a survey of 105 colleges in England,30 only 18% reported that referrals to secondary mental health services were responded to in a timely manner and 74% had referred pupils with mental health problems to accident and emergency (A&E) during the previous academic year.

Maximising opportunities for joint working between education and mental health services is vital if we are to meet the needs of the most vulnerable young people. This approach is in line with Children and Young People’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (CYP IAPT) and THRIVE principles, which advocate applying psychological approaches in a range of settings and contexts. 29,31 Public and patient involvement (PPI) work during the development of the study indicated that school and college staff and young people would like to be able to access mental health interventions within educational settings.

Since the conception of this study, the UK government has committed to providing access to mental health support within schools and colleges through funding the creation of new mental health support teams (MHSTs). 32 Signalling a commitment to the expansion of school- and college-based mental health provision initially proposed in a 2017 Green Paper,23 the key priorities for the NHS in England set out in the NHS Long Term Plan24 included the roll-out of MHSTs to between one-fifth and one-quarter of the country by the end of 2023.

The BEST intervention model involves training members of a school or college’s pastoral team to deliver an adapted version of the treatment package developed by the Norfolk Youth Service. School and college staff members then work alongside a mental health professional to co-deliver the intervention to young people enrolled at their school or college who have been identified as experiencing BPD symptoms. This co-delivery model was intended to maximise engagement and facilitate continuity of care by utilising the young person’s existing support networks. Furthermore, we hypothesised that working alongside a mental health professional to deliver the intervention would reduce the anxiety often experienced by education staff supporting young people with BPD symptoms by empowering them with the tools to offer effective support.

At the commencement of the study, the adapted treatment package had yet to be delivered in a school or college setting. Therefore, an intervention piloting and refinement phase was needed before commencing the feasibility trial to enable us to ensure that the intervention was suitable to be implemented within the context of schools and colleges. Following this intervention refinement phase, we planned to conduct a feasibility RCT to assess the feasibility of a future trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the refined intervention. This feasibility RCT was also intended to inform the design of any future effectiveness trial by answering questions about the suitability of the proposed outcome measures and the extent to which contamination of the control arm could be limited in an individually randomised study. A cluster randomised design was initially considered because of the possibility of contamination occurring with schools and colleges. However, owing to concerns about our ability to retain the engagement of schools and colleges randomised to treatment as usual (TAU), and the increased sample size and thus resources a cluster randomised trial would require, establishing the feasibility of limiting contamination in an individually randomised design was an important objective.

If proven effective in a future definitive trial, the BEST intervention could be implemented nationally, transforming the treatment of BPD symptoms by making early intervention the norm. This has the potential to produce substantial long-term benefits to individuals, society and the NHS by reducing the number of young people who develop entrenched psychopathology associated with chronic functional disability. As the intervention is designed to be delivered by non-specialists in BPD, the existing mental health workforce could be upskilled to deliver the intervention, supervised by a relatively small number of more specialist practitioners, making the intervention potentially highly scalable.

Aim and objectives

The aim of the study was to finalise the BEST intervention and inform the design of a future trial of its clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. To meet this aim, we planned to achieve the following objectives.

Objective 1

To refine the BEST intervention to maximise the likelihood that it can be successfully implemented within the context of educational settings (schools and colleges).

Objective 2

To assess the feasibility of evaluating the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the refined BEST intervention in a future RCT.

The factors we planned to consider in assessing feasibility were:

-

our ability to recruit participants to time and target

-

our ability to retain participants in the trial post randomisation

-

the acceptability and suitability of the proposed outcome measures and feasibility of identifying all costs and resource use that are relevant to the intervention

-

the ability of staff to deliver the intervention with fidelity to the model

-

the degree of contamination of the control arm (i.e. the extent to which participants randomised to the control arm received elements of the trial intervention)

-

the acceptability of the intervention from the perspective of staff and young people.

Research overview

The study was reviewed by Yorkshire & The Humber – South Yorkshire Research Ethics Committee (18/YH0416) and confirmation of Health Research Authority approval was received on 7 November 2018. The study was conducted in two stages, corresponding to the two objectives outlined above.

Stage 1: intervention refinement

The first stage of the study was intended to allow for refinement of the intervention and study processes to maximise the likelihood of their successful implementation. This preliminary stage of the study comprised two components: (1) a rapid evidence synthesis of barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of indicated mental health interventions within schools and colleges, and (2) a pilot of the intervention within three educational settings (one school and two colleges). Learning from the evidence synthesis and findings from the pilot were combined to enable us to finalise the intervention manual and resources, refine the practitioner training workshop and amend study procedures in preparation for the feasibility RCT.

Stage 2: feasibility randomised controlled trial

This second stage of the study comprised a feasibility RCT in which eligible young people were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive either BEST plus TAU or TAU alone. Participants were assessed pre-randomisation and followed up at 12 and 24 weeks using a battery of validated self-report and interviewer-rated measures. The feasibility RCT was accompanied by a detailed mixed-methods process evaluation exploring the acceptability of the intervention, fidelity of implementation across educational settings and contamination of the control arm.

Patient and public involvement

Three young people with relevant lived experience and one parent/carer representative acted as advisors to the study. Our advisors reviewed all participant-facing study documents to ensure that the format and language used were appropriate. Based on the feedback of our young advisors, rather than preparing separate participant information sheets for young people under 16 years and those over 16 years as originally intended, we created an ‘easier to read’ and a ‘detailed’ version of the information sheet, both of which were provided to all young people. Our parent-carer representative gave feedback on the information provided to the parents or carers of potential participants, and our protocol for approaching parents/carers to gain informed consent was based on her advice.

Our young advisors were influential in refining the intervention in preparation for the feasibility trial, providing feedback on the proposed amendments and suggesting changes to the wording and format of the manual worksheets. For instance, rather than referring to tasks to be completed in between sessions as ‘homework’, we presented these as suggestions of things to practice.

A young advisor also contributed to the training workshop for practitioners, sharing his personal experience as a young person with BPD symptoms and how he felt he could have been better supported within school. Furthermore, young advisors provided valuable advice on the recruitment strategy and helped to prepare promotional materials. One young advisor and our parent-carer advisor were members of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) to ensure that PPI perspectives were represented in study oversight.

Chapter 2 Evidence synthesis

This chapter is adapted with permission from Gee et al. 33 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Aim and research question

It has been suggested that the fidelity of implementation of school-based interventions may be crucial to their effectiveness. 34 Furthermore, effective mental health interventions are often not successfully adopted and sustained, in part because of insufficient consideration of compatibility with the organisational contexts in which they will be used. 35 Therefore, it is important to understand factors influencing the implementation of mental health interventions within schools and colleges to create a final intervention that can be successfully implemented and sustained.

To maximise the relevance of the findings to the implementation of the BEST intervention and facilitate a meaningful synthesis, we focused the review on indicated interventions for adolescents experiencing symptoms of an emotional disorder within high-income countries. Emotional disorders (e.g. anxiety, mood, post-traumatic stress) are the most prevalent mental health conditions during adolescence and, although rates of behavioural disorders (e.g. hypokinetic, conduct) have remained broadly stable, rates of emotional disorders among young people in England have increased by around 50% since 2004. 36 ‘Indicated’ interventions refer to those interventions delivered only to pupils identified as experiencing symptoms of a disorder.

The aim of the rapid evidence synthesis was to bring together the available evidence on barriers to and facilitators of successful implementation of indicated interventions within schools and colleges. The evidence synthesis intended to address the following research question: ‘What are the barriers to and facilitators of to the implementation of indicated psychological interventions for adolescent emotional disorders delivered within schools and further education or sixth form colleges located in high-income counties?’.

Methods

Design

A rapid evidence synthesis is a type of systematic review in which components of the systematic review process are simplified, omitted or made more efficient to produce the information required for a specific purpose within a limited time period. 37 To ensure completeness and quality, we retained core features of the systematic review process, including publication of the protocol, a comprehensive literature search, and duplicate study selection and data extraction. The key simplification we made to the review process was the omission of formal assessment of the scientific quality of the included studies. This was considered less relevant to the aims of the review because the transferability of findings related to barriers to and facilitators of implementation of an intervention is not necessarily dependent on the validity of the study design used to examine its effectiveness, risk of bias or other factors commonly assessed as part of determining study quality. In addition, we limited the scope of the review by including only English-language publications and studies conducted in high-income countries.

The protocol was registered with the PROSPERO registry prior to implementation of the search strategy (CRD42018102830).

Search strategy

We searched eight electronic databases [EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycInfo®, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), British Nursing Index, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) and British Education Index] from inception to 15 November 2018. To identify potentially eligible articles missed by the electronic search, we hand-searched a list of records retrieved as part of a recent related systematic review27 and contacted key experts in the field.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) the study had an interventional design; (2) participants were aged 10–19 years at the time of recruitment; (3) all participants were presenting with elevated mental health symptoms or psychological distress; (4) the intervention studied was a psychological intervention (i.e. based on psychological theory as evidenced in a manual or other supporting material) designed to reduce symptoms of an emotional disorder; (5) the intervention studied was delivered wholly or partly within an institution whose primary function was education; (6) the study was conducted in a high-income country (as defined by the World Bank38); and (7) the report included information on barriers to and/or facilitators of the implementation of the intervention.

We included studies with any interventional design, that is any study that involved the implementation of an intervention. Purely observational studies of interventions that were already part of routine practice were excluded. Studies of universal interventions delivered to all pupils were outside the scope of this review. Studies of integrated indicated–universal approaches were eligible for inclusion only if separate findings were reported on the implementation of the indicated component. The focus of this review was on the implementation of interventions in schools and (sixth form/further education) colleges; therefore, studies of interventions delivered within universities or other higher education institutions were excluded.

Study selection

Study selection was carried out with the aid of Covidence systematic review software (Melbourne, VIC, Australia). After duplicate records were removed, the titles and abstracts of all articles identified by the literature search were independently reviewed by two reviewers. All disagreements between reviewers were discussed as a team and consensus decisions were reached. The full texts of articles deemed potentially relevant were obtained and assessed for eligibility by two researchers. Reviewers assessed eligibility independently and all disagreements regarding eligibility or conflicts in criteria for exclusion recorded were discussed by the two reviewers concerned and, if consensus not reached, resolved by a third reviewer. A flow diagram of the selection process was maintained as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance. 39

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted by two reviewers and cross-checked to ensure accuracy. Contextual information was recorded using a piloted data extraction spreadsheet. The following information regarding the study sample was recorded: lower and upper age, gender (percentage female) and criterion for elevated mental health symptoms or psychological distress. In addition, the following information about the intervention was recorded: name, brief description, planned contact hours, whether parents or carers were involved and whether the intervention was delivered by staff members internal to the school or external facilitators. Included articles were imported into NVivo software version 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) where barriers and facilitators were synthesised as described below. Post hoc, we extracted details of the participant identification and referral processes employed in each study.

Data synthesis

A thematic synthesis40 of factors reported to affect intervention implementation was conducted with the aid of NVivo (version 12) qualitative data analysis software. Included papers were imported into NVivo and sections of the text describing barriers to or facilitators of implementation, including both quoted original data and author interpretation, were coded using an inductively developed coding structure. Coding of all included studies was completed by Briony Gee and independently by one other member of the review team. Discrepancies in coding were discussed by the two reviewers concerned and consensus interpretations were researched in all cases.

Codes generated inductively were first organised into descriptive themes that aimed to summarise the barriers and facilitators reported, staying close to the primary studies. The next stage of the analysis involved developing analytic themes by structuring and interpreting the descriptive themes according to the selected theoretical framework. This stage of the analysis aimed to ‘go beyond’ describing the findings of the included studies to generate new understandings of the factors influencing successful implementation of indicated school-based mental health interventions. A suitable framework was selected a posteriori with the aid of Nilsen’s taxonomy of implementation science theories, models and frameworks. 41 The theoretical framework was selected only after the generation of initial descriptive themes to ensure that, as far as possible, the analytic themes developed were data driven rather than reflecting the review team’s prior assumptions.

Durlak and Dupre’s ecological framework for effective implementation42 is premised on the view that a multilevel ecological perspective is necessary for understanding successful implementation. It is a determinant framework41 that aims to understand influences on implementation outcomes by specifying individual, organisational and community-level factors that act as implementation barriers and enablers. This framework was deemed to be an appropriate organising concept for the current review because schools and colleges are dynamic and complex social organisations, and thus the implementation of new practices within them is influenced by factors on multiple interacting levels. 43

A sensitivity analysis was conducted in which only studies of interventions found to be effective were retained. Studies in which there was no evidence that the intervention was effective in improving the primary outcome or that did not report a group-based statistical analysis of intervention effectiveness were removed from the thematic synthesis to explore whether or not implementation issues differed by study outcome.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

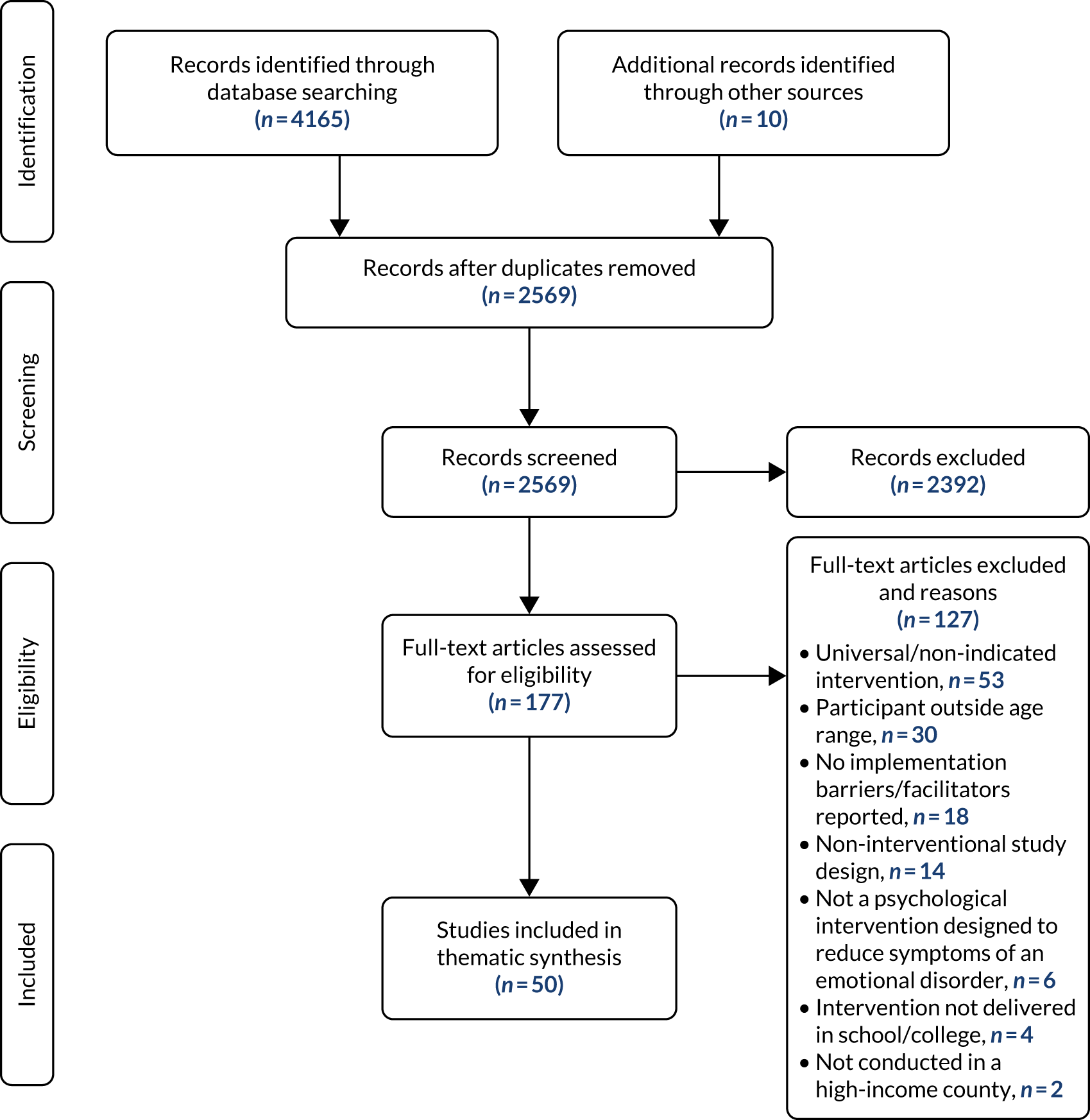

Our electronic searches returned 2559 unique study records. In addition, 10 studies were identified through hand-searching and correspondence with experts. The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA diagram illustrating study selection process.

We identified 50 unique papers that met the inclusion criteria (Table 1).

| Author(s) | Year | n | Lower age (years) | Upper age (years) | % female | Presenting problem | Identification methoda | Intervention type | Parental involvement | Internal/external delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bei et al.44 | 2013 | 10 | 13 | 15 | 100 | Sleep problems | A | Mindfulness | No | Both |

| Bernstein45 | 2010 | 4 | 11 | 18 | 100 | Anxiety | C | CBT | Yes | Internal |

| Berry and Hunt46 | 2009 | 46 | 12 | 15 | 0 | Anxiety | C | CBT | Yes | External |

| Burke et al.47 | 2017 | 7 | 10 | 11 | – | Anxiety | C | CBT | Yes | Unclear |

| Butler-Hepler48 | 2013 | 59 | 11 | 14 | 71 | Depression | A | CBT | No | Both |

| Chu and Weissman49 | 2009 | 35 | 12 | 14 | 60 | Either depression or anxiety | C | BA | No | External |

| Chu et al.50 | 2016 | 35 | 12 | 14 | 71.4 | Either depression or anxiety | A | BA | No | Both |

| Cooley et al.51 | 2004 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 80 | Anxiety | A or C | CBT | No | External |

| Cooper et al.52 | 2010 | 27 | 13 | 15 | 77.8 | Depression | A | Humanistic counselling | No | External |

| Crisp et al.53 | 2006 | 27 | – | – | 74 | Depression | C | CBT | No | External |

| Drmic et al.54 | 2017 | 44 | 13 | 15 | 14 | Anxiety | C | CBT | Yes | Both |

| Ehntholt and Smith55 | 2005 | 26 | 11 | 15 | 34 | Psychological difficulties as a result of trauma | C | CBT | No | External |

| Feldman56 | 2007 | 29 | 11 | 13 | 44.8 | PTSD | A | CBT | Yes | Both |

| Fitzgerald et al.57 | 2016 | 127 | 15 | 18 | 57.5 | Anxiety | A | Attention bias modification | No | Unclear |

| Gartenberg58 | 2017 | 2 | 15 | 15 | 50 | Anxiety | C | CBT | No | External |

| Ginsburg and Drake59 | 2002 | 12 | 14 | 17 | 83.3 | Anxiety | A | CBT | No | External |

| La Greca et al.60 | 2016 | 14 | 13 | 18 | 79 | Either depression or anxiety | A | IPT | No | External |

| Hunt et al.61 | 2009 | 260 | 11 | 13 | 43 | Anxiety | A | CBT | Yes | Internal |

| Jaycox et al.62 | 2009 | 76 | – | – | 51.3 | PTSD | A | CBT | No | Internal |

| Kaplinski63 | 2007 | 49 | 14 | 18 | 63.3 | Depression | C | CBT | No | External |

| Lamb et al.64 | 1998 | 41 | 14 | 19 | – | Depression | A | CBT | No | External |

| Liberman and Robertson65 | 2005 | 33 | 15 | 17 | – | Schizotypy | A | CBT | No | Unclear |

| Listug-Lunde et al.66 | 2013 | 16 | 11 | 14 | 37.50 | Depression | A | CBT | No | Both |

| Livheim et al.67 | 2014 | 98 | 12 | 18 | 82.70 | Depression | C | ACT | No | Both |

| Masia et al.68 | 2001 | 6 | 14 | 17 | 50 | Anxiety | C | CBT | No | External |

| Masia-Warner et al.69 | 2005 | 35 | 13 | 17 | 74 | Anxiety | A or C | CBT | Yes | Both |

| Masia-Warner et al.70 | 2016 | 138 | 14 | 16 | 68 | Anxiety | A or C | CBT | Yes | Both |

| McCarty et al.71 | 2011 | 67 | 12 | 13 | 55.6 | Depression | A | CBT | Yes | Unclear |

| Melnyk et al.72 | 2014 | 16 | 14 | 17 | 56 | Anxiety | C | CBT | No | External |

| Messinger et al.73 | 2011 | 8 | 11 | 13 | 62.5 | Anxiety | A | CBT | No | External |

| Morsette et al.74 | 2012 | 57 | 10 | 15 | 56 | PTSD | A | CBT | Yes | Internal |

| Mowatt75 | 2017 | 16 | 13 | 15 | 68.80 | Depression | C | CBT | No | External |

| Mufson et al.76 | 2004 | 63 | 12 | 18 | 84 | Depression | A | IPT | No | Internal |

| Oros77 | 2016 | 6 | 14 | 17 | 100 | BPD | A | DBT | No | External |

| Pass et al.78 | 2018 | 32 | 11 | 18 | 68.75 | Depression | B or C | BA | Yes | External |

| Pearson79 | 2017 | 3 | 11 | 12 | 0 | Anxiety | C | CBT | Yes | External |

| Rickard et al.80 | 2016 | 47 | 11 | 17 | 36 | General social/emotional problems | C | CBT | Yes | Internal |

| Riley81 | 2012 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 50 | Psychological distress as a result of loss/change | C | Grief education | No | External |

| Robinson et al.82 | 2015 | 21 | 14 | 18 | 81 | Suicidal ideation | B | CBT | No | External |

| Rohde et al.83 | 2014 | 378 | 13 | 19 | 68 | Depression | A | CBT | No | Internal |

| Ruffolo and Fischer84 | 2009 | 60 | 11 | 18 | – | Depression | B or C | CBT | No | Internal |

| Schoenfeld and Mathur85 | 2009 | 3 | 11 | 12 | 0 | Anxiety | C | CBT | No | External |

| Scotti86 | 2014 | 7 | 14 | 18 | 100 | Eating disorder | C | DBT | No | External |

| Stasiak et al.87 | 2014 | 34 | 13 | 18 | 41 | Depression | A | CBT | No | External |

| Stein et al.88 | 2003 | 126 | – | – | 56 | PTSD | A | CBT | No | Both |

| Stein89 | 2011 | 126 | – | – | 56 | PTSD | A | CBT | No | Internal |

| Stice et al.90 | 2011 | 306 | 14 | 19 | 100 | Eating disorder | A | Dissonance intervention | No | Internal |

| Woods and Jose91 | 2011 | 83 | 13 | 15 | – | Depression | A | CBT | No | Internal |

| Young et al.92 | 2010 | 57 | 13 | 17 | 59.7 | Depression | A | IPT | Yes | External |

| Young et al.93 | 2016 | 186 | 12 | 16 | 66.7 | Depression | A | IPT | Yes | External |

Included studies were published over a 20-year period between 1998 and 2018. Most included studies were of indicated interventions for young people with symptoms of depression (n = 17), anxiety (n = 16), post-traumatic stress disorder (n = 5) or either depression or anxiety symptoms (n = 3).

The majority of studies were of interventions described as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or CBT based (n = 35). Half the included studies (n = 25) were of interventions delivered by an external facilitator, 11 were delivered by an internal school-based staff member and 10 by both internal and external personnel. The remaining studies (n = 4) did not report whether those delivering the intervention were internal or external to the school.

Although studies of interventions delivered within sixth form and further education colleges were eligible for inclusion, no such studies were identified. As all included studies were of interventions delivered within schools, the results of the thematic synthesis below are specific to school-based interventions.

Thematic synthesis

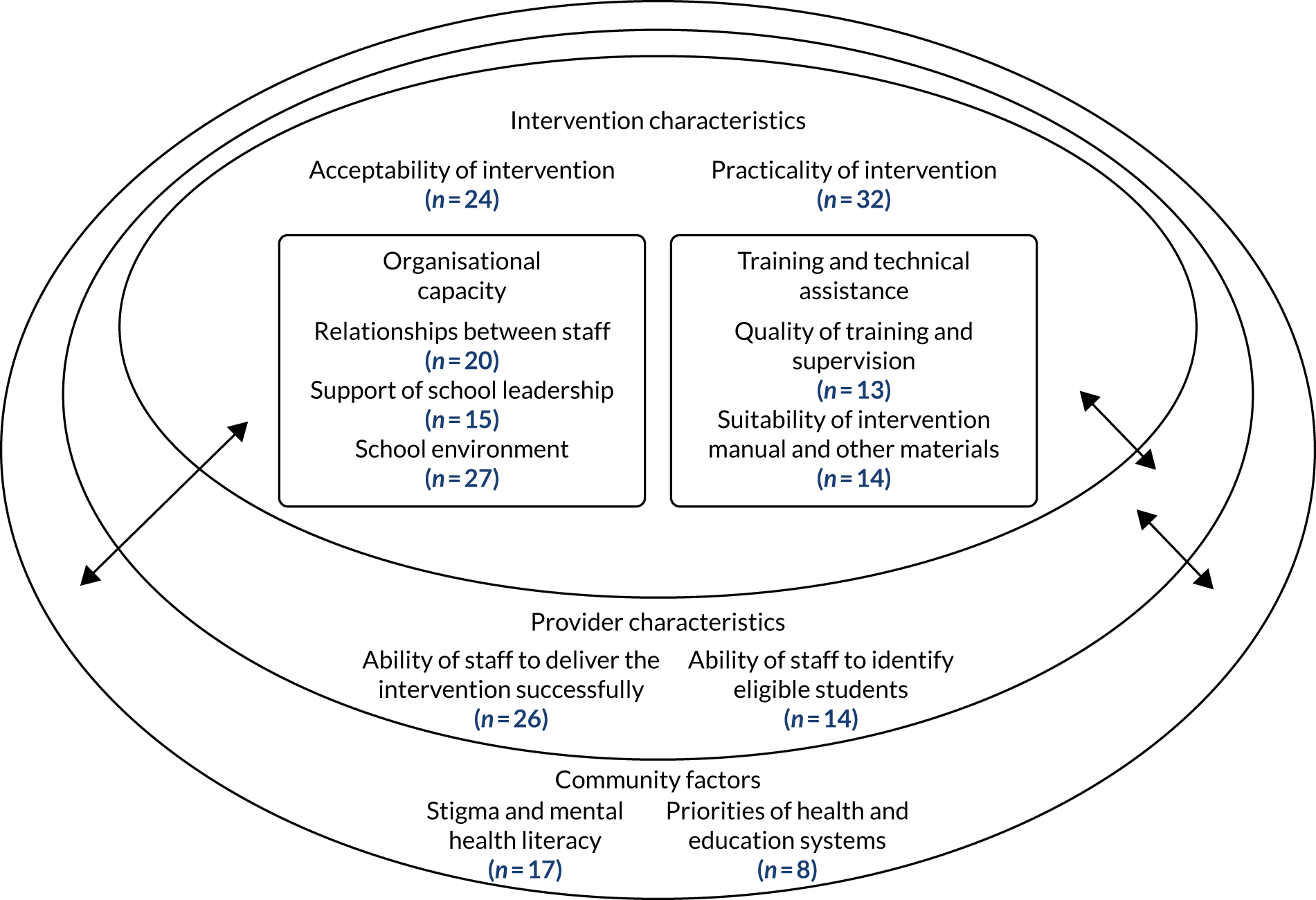

Eleven analytic themes were developed (Figure 2): two related to intervention characteristics (acceptability, practicality); three related to organisational capacity, that is practices, processes and culture of the structures through which the intervention is implemented (relationships between intervention facilitators and school staff, support of school leadership and school environment); two related to training and technical assistance (quality of training and ongoing supervision, and suitability of the intervention manual and other materials); two provider characteristics (ability of staff to deliver the intervention successfully and ability of staff to identify eligible students); and two community-level factors (stigma and mental health literacy, and priorities of health and education systems).

FIGURE 2.

Diagram of factors reported to influence the successful implementation of school-based indicated interventions for adolescents with symptoms of an emotional disorder.

The number of the included studies that contributed to each analytic theme is given in brackets next to the name of each theme below. Quotations from primary papers to be presented alongside the findings were selected based on how clearly they exemplified the themes.

Intervention characteristics

Acceptability (24 studies)

Intervention acceptability was noted as important to attendance and engagement, and hence to successful implementation. Acceptability reflects the extent to which people delivering or receiving an intervention consider it to be appropriate, based on anticipated or experienced cognitive and emotional responses to the intervention. Characteristics identified as influencing the acceptability of interventions included whether or not it was experienced as helpful, enjoyable, developmentally appropriate and well designed, and the format of delivery. High acceptability was achieved through ensuring that the intervention matched the needs and preferences of participating adolescents by focusing on issues important to their lives and presenting material in an interactive, appealing and accessible but mature way.

Many of the school-based interventions studied were delivered in a group format. This was sometimes identified as contributing to high acceptability through capitalising on the developmental priority given to peer relationships during adolescence. Key perceived benefits of group delivery were the sense of belonging and mutual support, and the social connections fostered through participating in activities with other young people experiencing similar difficulties. For instance, Riley81 reported that ‘pupils favoured group over individual input due to feelings of reduced isolation, opportunities to make friends, normalisation of feelings, learning from others, building confidence and supporting each other’.

However, group delivery was also frequently identified as a barrier to implementation through contributing to a lack of acceptability for some students. A group was viewed as an unsuitable therapeutic setting for some young people, because of either behavioural issues (e.g. some groups included students who were unable to work appropriately in a group48) or young people not feeling comfortable disclosing personal experiences in front of peers (‘the group setting was inhibiting for some students, especially given that they knew one another relatively well’;66 ‘students did not want to talk about their fears in front of peers’54). This created problems conducting intervention sessions as planned and ensuring that the intervention was meaningful for all group members.

Practicality (32 studies)

The intervention feature most frequently reported as affecting the success of implementation was the extent to which the intervention could be flexibly deployed to cause minimal disruption to school routines. Restricting the length of sessions to single class periods, structuring the programme of sessions around the school term, scheduling sessions to minimise interference with academic activities and allowing for breaks in intervention delivery because of exam periods and other school events were commonly reported adaptations required for successful implementation within the school setting.

Certain intervention components were noted as being problematic to implement within a school setting. Parent/carer involvement was consistently noted as desirable but challenging to achieve. In some studies, components of the intervention involving parents/carers were noted to have been removed or reduced owing to resource limitations or concerns about the feasibility of organising sessions for parents/carers within the school setting. Studies that sought to involve parents/carers in sessions commonly reported disappointing attendance.

A further intervention component recurrently identified as posing challenges to implementation was exposure to feared activities, objects or situations. The school setting was noted to facilitate some types of exposure work; for instance, Masia et al. 68 in their study of an intervention for social phobia noted that the school setting enabled the intervention facilitators to set up in vivo exposure exercises within the schools. However, other researchers encountered barriers to conducting exposure therapy within a school setting. These included practical difficulties arranging exposure to infrequent, unpredictable or inaccessible events or objects; difficulties planning appropriately idiosyncratic exposure hierarchies in a group setting; resistance from adolescents; and lack of confidence among intervention facilitators not experienced in the use of exposure.

Some studies reported the group format as contributing to an increase in practicality through making more efficient use of available resources. This was recognised as particularly important in communities with limited access to mental health resources. 66 However, difficulty identifying a sufficiently homogenous group of students within a single school for group delivery to be appropriate was also discussed. Moreover, a study by Oros77 highlights the risk of iatrogenic harm as a result of inappropriate group composition. They recommend that participants are screened more carefully before being included, as they had observed that peer contagion may play a part in making some participants’ symptoms worse.

Organisational capacity

Relationships between intervention facilitators and school staff (20 studies)

Positive relationships between individuals delivering the intervention and other staff members were frequently cited as important facilitators of successful implementation. When the intervention was facilitated by staff external to the school, effective communication with school staff and efforts to integrate into school systems were seen as particularly important. Effective collaborations between external providers and school staff were sometimes supported by establishing a reciprocal partnership in which external staff members contributed their time and expertise to school activities beyond the intervention itself.

Maintaining positive relationships with teaching staff not involved in the implementation of interventions was sometimes cited as a challenge. For instance, Scotti86 reported that, although young people and their parents perceived a school-based intervention to be both acceptable and beneficial, teachers found that having students attend sessions during the school day was unacceptably disruptive. Scheduling sessions outside the normal school day minimised this disruption but it was more difficult to deliver the intervention with fidelity as attendance was sporadic and treatment adherence was poor. 86 Therefore, securing ‘buy-in’ from teaching staff and maintaining positive relationships between intervention facilitators and teachers is important to support successful implementation.

Support of school leadership (15 studies)

The support and involvement of senior school leaders were frequently cited as key facilitators of successful implementation. Support at the appropriate level within the school hierarchy ensured that necessary resources were made available, and positively affected support for implementation of the intervention within the wider school system. For instance, Drmic et al. 54 reported the vital importance of the involvement of a member of the school leadership team as an ‘opinion leader’ who was ‘intimately involved in all aspects of the implementation project’ and ‘was able to garner support/interest from key stakeholders’. Conversely, when interventions were implemented without the clear endorsement and direct input of a school’s senior leadership team, interventions were more difficult to implement and sustain. For instance, Pass et al. 78 reported that ‘we had to withdraw resources from one school where the senior leadership were not involved, and a major staff restructuring led to loss of pastoral leads who had been the main contacts for the therapy team’.

School environment (27 studies)

Logistical issues associated with delivering psychological interventions within the school environment were the most commonly reported barrier to implementation. Difficulties scheduling sessions within the constraints of school timetables were frequently reported. Kaplinski63 commented that they had not anticipated how regularly scheduled sessions would be interrupted or cancelled as a result of, for example, fire alarms and school assemblies. Lack of appropriate spaces within schools in which to conduct sessions was also a barrier.

The extent to which the wider school environment was conducive to good mental health and provided a suitable setting for therapeutic work was also noted as important to the successful implementation of interventions. For instance, Ehntholt et al. 55 reported that two schools participating in a study of a group intervention for children with post-traumatic stress symptoms ‘were far from ideal environments for the establishment of therapeutic groups . . . it was difficult for the children to genuinely relax during the sessions due to the school’s loud, chaotic environment’.

However, encouragingly, staff participants in a study by Butler-Hepler48 commented that, following the implementation of the intervention, the climate within the school appeared to be healthier, and teachers were more willing for students to have counselling, suggesting that the implementation of psychological interventions within schools has the potential to positively affect the school environment. Therefore, there is the potential for successful implementation to initiate a virtuous cycle.

Training and technical assistance

Quality of training and ongoing supervision (13 studies)

The need for high-quality training of intervention facilitators and supervision from appropriately experienced and qualified experts to support fidelity of delivery was emphasised in several studies. Although the importance of training and supervision was consistently endorsed, it appears that more intensive training and supervision are likely to be required for interventions delivered by staff with relatively little experience of delivering psychological interventions.

More informal support from others facilitating the intervention was also sometimes identified as important for successful delivery. For instance, Ruffolo and Fischer84 found that ‘the mentorship supervision model supported the school-based social workers in connecting with each other and providing each other ongoing support’. However, the authors noted that protecting staff time to participate in supervision was challenging and would require sustained funding and leadership support.

Suitability of intervention manual and other materials (14 studies)

The provision of an intervention manual that was clear and easy to follow, and good-quality supporting materials such as workbooks and resources to support homework exercises, was identified as a facilitator of successful implementation. Several authors suggested that well-structured, highly manualised interventions may be more easily mastered by novice facilitators, enhancing treatment fidelity. When interventions employed technology to facilitate delivery, it was important that these were well designed, with user-friendly interfaces to maximise acceptability and engagement.

Provider characteristics

Ability of staff to deliver the intervention successfully (26 studies)

Although some interventions studied were delivered by members of the research team or other external specialists, many of the interventions involved training existing school-based staff with diverse professional backgrounds to deliver a manualised programme. Skilled facilitation of interventions was noted as crucial to successful implementation and in all studies in which this was reported on, trained school-based professionals were found to be able to deliver the interventions with acceptable fidelity. However, the findings of some studies suggest that school-based professionals, who were often less experienced in delivering manualised interventions for emotional problems, were less able to implement the interventions as planned than specialist mental health staff. Although delivery of interventions by external specialist might therefore seem to be supported, some authors of studies of interventions that relied on external providers expressed concern about the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of this delivery model.

Ability of staff to identify eligible students (14 studies)

There were also some concerns raised about the feasibility of procedures used to identify students for whom interventions would be suitable. Although school-wide screening and other comprehensive recruitment strategies co-ordinated by the research team were reported to be successful in identifying eligible young people, these were acknowledged to be unlikely to be sustainable outside the research context. Although recruitment strategies relying on referrals from school staff members were often reported to be effective, the capacity of school staff to identify students who could benefit from an intervention was raised as a concern by some study authors. For instance, Pass et al. 78 described how ‘feedback from school staff suggested that many lacked confidence in identifying students with depression symptoms and had very little protected time to consistently manage the referral process’.

Community factors

Stigma and mental health literacy (17 studies)

The impact of stigma on implementation was considered by several study authors. The potential for stigma by peers within the school community was a concern for some young people and their parents. This finding might partially explain the lower than anticipated student uptake and difficulties obtaining parental consent for participation reported by many studies.

However, not all studies found stigma to be a barrier to implementation. For instance, Crisp et al. 53 asked participants to complete a self-report measure of their perceptions of barriers to treatment. Items assessing potential barriers related to stigma (e.g. ‘My friends thought I was stupid for going to therapy’ and ‘I felt uncomfortable about going to sessions at school’) were consistently rated as never or rarely a problem. Several authors reported that participating in a school-based intervention was viewed as less stigmatising than accessing conventional mental health treatment.

Priorities of health and education systems (eight studies)

The need to align the priorities of the health-care and education systems to facilitate successful implementation of school-based mental health interventions was alluded to by a number of studies. Lack of adequate resource allocation for services to support mental health and well-being within schools, arguably a symptom of low prioritisation of these issues, was also identified as a barrier to effective implementation.

Sensitivity analysis

Themes remained broadly similar when studies in which there was no evidence of effect on the primary outcome or that did not report statistical analysis of intervention effectiveness were removed. There was a change of more than 5% in the percentage of included studies that contributed to two of the themes: practicality was reported as affecting the implementation of fewer of the interventions found to be effective than the complete set of included interventions, and quality of training and ongoing supervision was reported as a facilitator of implementation by only the subset of studies of interventions found to be effective.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to identify and synthesise factors reported in the literature to influence the implementation of indicated interventions for adolescent emotional disorders delivered within schools and colleges. The thematic synthesis resulted in 11 analytical themes that brought together findings from 50 primary studies. Themes encompassed characteristics of the interventions, training and support, organisational factors and community-level factors that have been identified as affecting implementation.

The findings of this review support the view that delivering indicated mental health interventions within a school context presents many challenges and that implementation is influenced by factors on multiple interacting levels. The most frequently reported challenges were logistical in nature. Practitioners delivering interventions in a school setting must be aware of and prepared to work within the constraints imposed by school calendars, timetables and the physical school environment. It is important that those designing school-based mental health initiatives select interventions that can accommodate such constraints and consider whether or not all components of an intervention are feasible to deliver within the school context. However, which interventions can practicably be delivered within the school context will depend on factors at the organisation and community level.

Having intervention champions at an appropriately senior level within the school is crucially important if intervention delivery is to be prioritised and appropriate resources made available. Senior leadership support was reported to be influenced by the extent of competing priorities, and thus it is important that both the health-care and education systems maintain a shared focus on the emotional health of young people. UK schools have faced criticism for focusing on academic achievement at the expense of mental health and well-being. 94 However, recent proposals to include emotional and mental well-being in the education inspection framework95 might increase the priority given to mental health initiatives in future. Close collaboration between the Department of Health and Social Care and the Department for Education in the production of the Green Paper on transforming mental health provision for young people96 sets an important precedent of joint working with the potential to have an impact on implementation at the local level.

Studies included in the review evaluated interventions delivered by a wide variety of professionals, including external providers, and existing school-based staff. Although there is some evidence that external personnel can deliver interventions with higher fidelity than internal school-based staff, reliance on external facilitation was accompanied by some challenges. For instance, it was noted that external facilitators must make particular efforts to establish effective communication with school staff and to integrate into school routines. Authors also raised concerns about the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of reliance on external facilitators.

This potential tension between fidelity and sustainable implementation might be partially addressed by appropriate supervision and ongoing support. The quality of training and support is likely to be particularly important when intervention facilitators are less experienced in delivering evidence-based interventions. Furthermore, it appears that well-structured, highly manualised interventions may be easier for less experienced practitioners to implement with fidelity and so should be preferred within service models involving provision of interventions by practitioners with limited training in delivering psychological interventions.

For an indicated intervention to be successfully implemented it is important to have appropriate mechanisms to identify young people experiencing the symptoms targeted. As indicated in Table 1, the main identification strategies employed by studies included in the review were referral by school staff members, identification through screening or a combination of both strategies. A recent review97 of school-based identification methods concluded that universal screening may be the most effective method of identifying children experiencing mental health difficulties. However, studies included in the current review raised concerns about the sustainability of this approach for indicated programmes. Therefore, ensuring that school staff members who might act as ‘gatekeepers’ have appropriate training and capacity to identify students who could benefit from an indicated intervention is likely to be essential. This training must be ongoing to account for staff turnover and to ensure that knowledge and skills are maintained. As the feasibility of school-based identification of mental health difficulties was not the focus of this review, we direct interested readers to a review by Soneson et al. 98 for a fuller discussion of this issue.

Although there is evidence that targeted school-based interventions have larger and more durable effects on mental health outcomes than do universal approaches,25 concerns have been raised about potential stigma. A recent review of qualitative research found that some students are apprehensive about engaging with targeted school-based mental health interventions because of fear of negative stigma-related consequences. 99 Stigma has also been found to be one of the most commonly reported barriers to accessing school-based treatment in quantitative research. 100,101

Corroborating these concerns, the current review identified a number of studies that reported fear of potential stigma as a barrier to implementation. However, stigma was not universally viewed as a barrier: there was evidence that some young people view school-based interventions as less stigmatising than conventional mental health treatment and that acceptability of the indicated interventions was generally reported to be high. Studies directly exploring young people’s experiences of receiving school-based metal health support are scarce,99 and therefore there is a need for further research to fully understand acceptability.

Limitations

Although studies of interventions delivered within sixth form and further education colleges were eligible for inclusion, no such studies were identified. Therefore, we are unable to reach any conclusions about how to deliver mental health support in such colleges. In the UK, colleges educate and train more than two million people each year, and over two-thirds of all 16- to 18-year-olds are enrolled at a college. 102 There are substantial differences between schools and colleges that are likely to have an impact on the implementation of mental health interventions. For instance, colleges tend to be less formal environments than schools with less structured timetables and greater student independence. Therefore, there is a need for further research on the delivery of mental health interventions within this context to inform UK policy.

The scope of the current review was limited to studies conducted in high-income countries. This was necessary to facilitate meaningful synthesis as the factors affecting the implementation of interventions in low-resource contexts are likely to differ in important ways from the factors that affect the implementation of similar interventions in contexts in which greater resources are available. However, there are promising school-based mental health interventions delivered in low- and middle-income countries17 and understanding the factors that have an impact on the implementation of these interventions in these contexts is undoubtedly important.

The sensitivity analysis conducted post hoc was intended to provide an indication of whether or not the implementation barriers and facilitators reported differed according to the effectiveness of the interventions concerned. The results of this analysis indicate that the inclusion of studies of interventions not found to be effective did not have a substantial impact on the themes identified. However, there are several factors that complicate the interpretation of this analysis, including the use of inconsistent definitions of effectiveness across studies and the lack of systematic measurement and reporting of barriers and facilitators. Therefore, it is not possible to draw conclusions regarding whether or not implementation barriers and facilitators actually differed or to infer that the presence or absence of a particular factor is linked to effectiveness.

The findings of this review must be interpreted with some caution owing to the quality of the evidence regarding implementation synthesised. Although we did not formally assess the quality of included studies, because this would not necessarily relate to the quality of the information on implementation, we noted that most coded sections of the text describing barriers to or facilitators of implementation were from author interpretation rather than objectively collected process data. Implementation is a topic that has received relatively scant attention in comparison with effectiveness and, for this reason, it was rarely a primary focus of eligible studies. As a result, implementation factors were often captured informally and therefore the data lacked richness. Future research should employ formal process evaluation and implementation science designs. It has been argued that one of the most critical issues in mental health services research is the gap between what is known about effective treatment and what is provided in routine care. 35 If this gap is to be bridged, it is important that researchers give increased attention to factors affecting implementation and design studies accordingly, incorporating process evaluation and implementation science approaches.

Implications

The findings of this review have important implications for those with a role in planning and implementing school-based mental health initiatives (Box 1). Recent UK policy proposals23 include the creation of new MHSTs based within schools and colleges and the introduction of designated senior leads for mental health in each setting. MHSTs will offer direct support to young people experiencing mild to moderate mental health difficulties, supervised by NHS mental health professionals. There is the potential for this model to offer an effective solution to the tension between fidelity and sustainability highlighted by this review; learning from the current evidence will be important to realising this potential.

-

Involve young people and education professionals in the selection of psychological interventions to be delivered within schools to ensure that they are acceptable and practical to deliver in this context. Group interventions are efficient and often acceptable but do not meet the needs of all young people. Provision should be made for those who require individual support.

-

Carefully consider the best method of identifying young people who could benefit from indicated interventions. If whole-school screening is not feasible, staff will need training and support to enable them to identify and refer suitable students.

-

Ensure that those delivering interventions receive high-quality training and ongoing supervision.

-

Plan for the inevitable logistical challenges associated with the constraints of the school calendar, routines and environment.

-

Identify an (appropriately trained and supported) intervention champion at a senior level in each school to promote buy-in from other staff members and to develop a school culture that prioritises mental well-being.

-

Health and education policy should be designed to promote a shared focus on the emotional health of young people across sectors.

The findings of this review indicate the need to ensure that the curriculum for the workforce who will be trained to work as part of the new MHSTs is designed with input from young people and education professionals. This will help to ensure that the interventions this new workforce are trained to deliver are acceptable to young people and can practicably be delivered in educational settings. Interventions are more likely to be implemented successfully if they are well structured, manualised and delivered by staff who receive high-quality training and supervision.

Designated senior leads for mental health will be well placed to encourage genuine and committed ‘buy-in’ from all aspects of the system, including senior leaders, governors, teaching staff and parents/carers. However, changing whole-school culture is no small task. It will be important that leads are appropriately supported to fulfil this role. This might include the creation of forums for designated senior leads to share good practice, and the co-production of a school and college mental health charter to support cultural change.

There is a danger that the creation of new school-based services will add further complexity to a system that is already fragmented and which in turn could lead to the creation of more treatment silos. 103 We must avoid this and instead use these developments as an opportunity for greater joint working and system alignment.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that those involved in the implementation of school-based mental health interventions should ensure that they select appropriate interventions, consider logistical challenges and provide high-quality training and supervision to enable staff to deliver interventions with fidelity. Furthermore, it is important to consider the structural and environmental support required for successful implementation to ensure that potential benefits are maximised.

Chapter 3 Intervention piloting and refinement

Description of prototype BEST intervention

Background

In Norfolk, following Future in Mind recommendations,22 child and adolescent mental health service (CAMHS) transformation and the development of local transformation plans (LTPs) encouraged services to develop innovative practices. Norfolk LTP priority areas included responding to the rise in reported self-harm and suicidal acts in young people and improving access to mental health support. It was recognised that mental health services for children and young people must be designed around their needs. Therefore, system leaders have been working to develop strong relationships between NHS mental health services and educational settings to facilitate improved collaboration.

The Norfolk Youth Service is a pragmatic, assertive and ‘youth-friendly’ service for young people aged 14–25 years that transcends traditional service boundaries between CAMHS and adult services. The service was developed in 2012 in collaboration with young people and partnership agencies and is based on an engaging and inclusive ethos. The service is recovery oriented and evidence based and aims to satisfy recent policy commitments to extend mental health provision for young people to those up to the age of 25 years. The challenges of engaging and supporting young people with early symptoms of BPD has been a key area of work for the Norfolk Youth Service. This work has been ongoing since the development of the youth service and has resulted in several innovative approaches to working with early symptoms of BPD in adolescence. This work has included collaboration with, and learning from, specialist services worldwide, including the Orygen (Orygen Youth Health, Parkville, VIC, Australia) service.

Part of the work of the Norfolk Youth Service has been to produce and deliver a treatment package for young people with BPD symptoms that distils fundamental elements of evidence-based interventions for adolescent BPD into a brief (three to six sessions) practicable format. This package was designed to be delivered within secondary mental health services. However, because of long waiting times and high thresholds for treatment as a result of increasing demand for mental health support, the team recognised that many young people with BPD symptoms did not access secondary services until they had reached crisis point. Therefore, the need to adapt the treatment package to enable it to be delivered outside specialist services to facilitate earlier intervention was identified.

Theoretical underpinnings

The BEST intervention was developed to address issues apparent in the delivery of evidence-based interventions for adolescent BPD symptoms, including difficulties of access to specialist services that provide such treatments, problems engaging young people in treatment, early treatment drop-out and lack of resources available to deliver lengthy interventions. Therefore, the intervention takes account of issues specific to engaging with an adolescent population and providing interventions tailored to this group.

The development of the intervention utilised knowledge from attachment theory, which identifies how patterns of relating are established in the context of early attachment relationships. In-depth psychological therapies that aim to identify unhelpful patterns of relating to others and work to establish new healthier patterns of relating (such as MBT-A or CAT) have been demonstrated as effective with young people. 1 However, as previously mentioned, there are also many difficulties in engaging young people in this form of treatment early enough and for a sustained period.

The BEST intervention draws from relational elements of attachment theory to support the young person to identify unhelpful patterns of relating and to work towards the development of more helpful strategies. This is supported through enhancing the relationship with an identified member of staff at the young person’s school or college, thus nurturing relationships that are already established and part of the young person’s everyday life, eliminating the need for additional specialist support from sources external to the young person’s current support network.

Drawing from MBT-A,2 the BEST intervention recognises that adolescents with BPD symptoms are those most vulnerable to mentalisation failure. Mentalisation refers to the ability to make sense of the subjective states and mental processes of self and others. It is known that a decrease in the ability to mentalise leads to an increase in emotional arousal. The initial phase of MBT-A involves formulation and crisis planning. The BEST intervention mirrors this phase and aims to develop a shared understanding of the presenting difficulties, identify difficulties of mentalisation and develop a crisis plan for managing periods of distress. The staff training element of the intervention aims to increase staff’s ability to mentalise during incidents of distress or conflict, thus supporting the young person to restore their own ability to mentalise. A recent systematic review of MBT interventions for children and families confirmed that these interventions support mentalising and reflective functioning skills. 104

The BEST intervention also incorporates elements from DBT-A. 4 This approach aims to support young people to achieve behavioural control and stabilisation through promoting the understanding of symptoms, the development of positive coping strategies and crisis planning. The BEST intervention makes use of resources for developing positive self-care coping strategies delivered within DBT-A.

Furthermore, the BEST intervention draws on theory from developmental psychology and neurodevelopmental research. Findings from neurodevelopmental research5,6 have informed current understanding of changes in emotional regulation and social cognition during adolescence. The intervention uses this evidence as the basis for educating professionals and young people about the difficulties they are experiencing, as well as to inform the structure and content of sessions.

Outline of prototype intervention

The BEST intervention is a brief, manualised treatment package designed to be co-delivered by a mental health professional working together with a member of staff from the young person’s school or college. Therefore, the intervention addresses several challenges faced by young people experiencing BPD symptoms and those working to support the young people. The approach is designed to:

-

tackle the confusion and anxiety experienced by the young person experiencing BPD symptoms by providing psychoeducation and strategies for the self-management of symptoms

-

contain the anxiety often experienced by educational staff supporting a young person with BPD symptoms by increasing their understanding of these symptoms and empowering them with tools to offer effective support

-

respond to evidence of the need for treatment strategies to focus on early intervention by providing support that, while drawing from existing evidence-based interventions, is delivered in a format that can be implemented consistently by staff without specialist training.

The BEST treatment package is delivered over up to six sessions lasting approximately 1 hour each, over a treatment window of 8 weeks. The sessions cover three manualised components delivered over the six sessions, supported by a resource pack (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/170931/#/documentation; accessed 6 April 2022).

The first component of the intervention focuses on education about emotional instability: how it relates to early features of BPD, why it can happen and what helps with managing it. This component also looks in detail at typical early features of BPD and allows the young person to reflect on which of these symptoms are relevant to them and the ways in which they are affected by them. The key message in this component is one of education to reduce confusion and anxiety about distressing symptoms. This component is delivered by working through a psychoeducation leaflet about emotional instability and early features of BPD. This leaflet can then be taken away by the young person to be discussed further at the following session, with their reflections.

The second component of the intervention incorporates co-development of a maintenance cycle to help the young person understand what factors are maintaining the current difficulties, and thus identify areas for change. Feedback received from service users has indicated that they do not want to receive interventions that give the impression of ‘box ticking’ and that are not tailored to their unique individual experience. The formulation is used to validate the experience of the individual and provide a framework for the intervention, increasing its meaning and purpose for the young person. This individualised approach aims to encourage engagement and motivation.

The third component builds on areas for change identified in the development of the maintenance cycle. This incorporates the co-development of a crisis plan to support with managing periods of distress. Crisis plans will focus on the development and use of self-care strategies to support emotional regulation. This component introduces self-care distress tolerance strategies, including techniques for sensory self-soothing, grounding and distraction. Introduction of these strategies will be supported by completion of worksheets, which the young person can take away to support ongoing practice. Crisis plans will also incorporate the development of appropriate pathways for accessing additional support when needed to support the young person with managing their distress in a helpful way and to develop positive help-seeking behaviours.

The content of each of the six sessions is summarised in Table 2.

| Session | Objective | Key activities |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | For the young person to be able to recognise different emotions and their effects |

|

| 2 | For the young person to understand the concept of mentalisation |

|

| 3 | For the young person to be familiar with the features of emotional instability/BPD |

|

| 4 | For the young person to understand why the ability to mentalise sometimes breaks down and the consequences of this |

|

| 5 | To help the young person plan ways of managing difficult emotions |

|

| 6 | For the young person to reflect on their crisis plan |

|

Co-delivery

Every session is co-delivered by a trained member of pastoral staff from the young person’s school or college (referred to during the project and in this report as education practitioners) and a clinician working as part of local NHS-funded mental health services (referred to as mental health practitioners) working together. The role of the mental health practitioner is to support the education practitioner in maintaining adherence to the intervention and in monitoring and managing risk issues. The education practitioner was an ongoing point of contact for the young person between treatment sessions.

Co-delivery of the BEST intervention allows treatment to be delivered within a setting that is accessible to the young person and removes the need to access specialist services. As well as the benefits of a setting known to the young person, co-delivery also means that the intervention utilises an ongoing relationship that the young person has with school staff. Schools and college staff currently feel inadequately supported to meet the needs of pupils with mental health problems. 28 Leaving school and college staff to provide support to pupils experiencing BPD symptoms without professional advice is likely to result in suboptimal outcomes for young people and may build resistance to later interventions for those who go on to meet the thresholds for specialist CAMHS. Co-delivery of the intervention was intended to contain anxiety experienced by educational staff by reducing the confusion and anxiety that often surrounds young people with BPD who self-harm, increasing their understanding and empowering them with tools, knowledge and skills to offer effective support.

All staff (both education and mental health practitioners) attended a 1-day training workshop prior to delivering the intervention with young people. The purpose of the workshop was to prepare practitioners to co-deliver sessions and, in the case of education practitioners, provide ongoing support to participants from their institution. The 6-hour workshop introduced relevant theory, covered the practicalities of delivering sessions and equipped practitioners with skills to enhance their ability to mentalise during incidents of distress or conflict.

Supervision

Supervision for both education and mental health practitioners delivering the intervention was provided by supervisors trained in the delivery of MBT-A who had extensive experience of working with young people with early features of BPD within a CAMHS setting. Supervision was used to support the use of a mentalising approach within sessions and to support adherence to the treatment package. Supervision was provided in group format at least fortnightly during the intervention phase. At the end of each session, the co-facilitators rated their adherence to the intervention using the fidelity checklist and completed session notes, which were reviewed by the supervisor.

Pilot methods

Design