Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR134314. The contractual start date was in January 2021. The final report began editorial review in April 2022 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Glasby et al. This work was produced by Glasby et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Glasby et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and context

Box 1 provides a summary of Chapter 1 of this report.

Summary of key points

-

The social care system in England is under significant pressure, and there are funding gaps and workforce challenges that make it difficult to keep up with rising demands. The exit of the UK from the EU, and the COVID-19 pandemic, have created additional pressures.

-

Technology has been suggested as one way to improve care and address pressures in the health and social care system. It was specifically highlighted as a priority within recent social care reforms as a way to support people living independently within their homes.

-

Sensor-based technology with artificial intelligence capabilities is one type of technology that may be useful in some contexts. There is evidence to suggest that this type of technology can potentially improve some aspects of care and care planning, although there are key gaps in evidence that need to be addressed.

-

The uptake and sustainability of technology is influenced by wider factors, including implementation processes, support available for front-line staff, and engagement with people who draw on care and support and their carers.

-

This study is based on scoping work identifying a key gap in evaluations of artificial intelligence in social care. It focuses on decision-making and implementation processes.

Social care in England

‘Social care’ is a term which refers to the practical assistance which is given to people with disabilities, people with mental health problems, people with learning difficulties, frail older people and unpaid carers to manage activities of daily living (getting washed and dressed, eating, going to the toilet, etc.) as well as support to have choice and control over their own lives. This can take the form of direct services (home care, day care, residential care, etc.), or a direct payment (where the person receives funding with which to design their own care and support, potentially employing their own personal assistants). It is funded and organised by local councils (known as ‘local authorities’ in England, sometimes known as ‘municipalities’ internationally), as well as by people who are funding and/or organising their own care, and direct services are delivered by a mixed economy of private, voluntary and public sector services.

Even prior to COVID-19, the social care system in England was under significant pressure. There is an increasing demand for support, with a total of over 1.9 million requests for adult social care in 2019/2020, a number which has increased by 120,000 since 2015–6. 1 A growing number of older people nationally, as well as increases in working-age adults with care and support needs, has contributed to this trend. In the same time period, the number of adults receiving long-term care has fallen,1 indicating growing unmet and undermet need. In recent years, it has been estimated that there are 1.2 million older people in England with unmet care needs. 2

Funding gaps are an important issue in social care. While spending increased in 2019–20 compared with previous years, this should be understood within a context of years of low funding/cuts followed by only a very modest increase from 2015 to 2020. Compared with 2010–11, spending in 2019–20 was higher in real terms, but lower on a per-person basis. Increasing demands and rising costs (even adjusting for inflation) have contributed to this funding gap, along with general financial pressures on local authorities that commission social care. 1 This highlights the need for innovation and renders the long-term sustainability of social care a pressing issue in policy and practice. 3

The social care workforce is also facing challenges. Adult social care is characterised by large numbers of unpaid carers, and workforce issues among paid carers, including high staff turnover and poor conditions. 2 The vacancy rate in social care decreased slightly in 2019–20 compared with 2018–9, although it was still high compared with 2012–3 and with the overall unemployment rate, potentially made worse by low pay, low status and poor levels of public understanding. 1 In order to meet projected demands for social care, a 2021 report estimated that an extra 627,000 social care staff would be needed, representing a 55% growth over the next decade. This far exceeds the growth in the social care workforce that has occurred over the past 10 years. 4 The exit of the UK from the EU may also impact on the social care workforce [16% of whom are non-British (7% from European Economic Area countries)], which relies heavily on migrant workers from EU and non-EU countries. 5

The fragility of the social care sector has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. 6 Social care workers are at an increased risk of infection and death from COVID-19, and the pandemic has likely exacerbated issues in social care around underfunding, unmet social care needs, the burden on unpaid carers, and widespread social and economic inequalities. 7 Although there were fewer requests for social care during the COVID-19 pandemic, we do not yet know what impact there will be in the long term (e.g. in terms of a ‘backlog’ of need to be addressed, an exacerbation of need that was temporarily unmet during lockdown, and/or the long-term implications for public finances). 1 The impacts of ‘long COVID’ are also still unclear and may impact social care needs in the future.

Digital technology in health and social care

As social care in England faces growing pressures, there has been a turn towards new technologies as a potential solution that might ease pressures across a number of public services and promote independence. While this has often focused more on the health service, there has been increasing awareness of the potential of digital technology for social care in recent years. 8 In 2018, the Health Secretary pledged £500 million to transform care technology within both health and social care. The announcement of this money included references to a ‘tech transformation’, with funding set aside for hospital- and home-based technology, electronic systems within the NHS, finding new technology with applications in health and social care, and driving culture change. 9

For people not from a technology background, the language used in different policy announcements and in the broader literature can often be confusing, with lots of different terms used, sometimes interchangeably. Before we explore recent policy and the underpinning evidence in more detail, Box 2 sets out some key definitions.

| Artificial intelligence (AI) | The intelligence demonstrated by a machine or software system which can learn and make decisions for itself. |

| Algorithm | A set of instructions, rules or procedures used by a software system to accomplish a set task. |

| Application programming interface | An interface that allows software programs/apps to communicate with one another regardless of how each application was originally designed. |

| Assisted living technology/assistive technology | Technology used as part of a range of services that help people maintain independence and improve a range of outcomes. It includes both telehealth (remote monitoring for clinical biomarkers) and telecare (e.g. alarms, sensors, reminders) designed to deliver health and social care services to the home. |

| Broadband | High-speed internet access in which a single cable can carry a large amount of data at once. |

| Clinical informatics | The application of data and information technology to improve patient and population health, care and well-being outcomes. It can be used to advance treatment and the delivery of personalised, coordinated support from health and social care. |

| Data | Any information stored on a computer that is not the computer code. It can be either structured or unstructured. Structured data (e.g. ‘patient records’) can be organised and used for multiple purposes, whereas unstructured data are normally used for a single purpose and includes documents, pictures, videos or sound recordings. |

| Data protection impact assessment | A process that helps organisations identify and minimise risks that result from data processing. DPIAs are usually undertaken when introducing new data processing systems, processes, or technologies. |

| Digital literacy | The ability to use digital technology and communication tools to seek, find, understand, and evaluate information. |

| Electronic health record | A comprehensive medical record of the past and present physical and mental state of health of an individual in electronic form. |

| GP Connect | A service that allows GP practices and authorised clinical staff to share and view GP practice clinical information and data between IT systems. |

| Graphical user interface | A computer program that enables a person to interact with different electronic devices using graphical icons, such as pointing devices (via a mouse). |

| Health and Social Care Network (HSCN) | A data network for health and care organisations which replaced the NHS network, N3. |

| Information governance | The overall strategy for securely and appropriately managing information/data. It provides a framework to bring together all the rules and guidance, whether legal or simply best practice, that apply to the handling of information. |

| Internet of things | The ability of everyday objects (rather than computers and devices) to connect to the internet. Examples include kettles, fridges, televisions and wearable technology such as smartwatches and fitness trackers. |

| Interoperability | The ability of computer systems or software to exchange and make use of information. |

| Machine learning | The development of computer modelling and algorithms that use data and learn from them to produce predictive models with minimal human intervention. |

| NHS Digital Social Care Programme | A framework developed to support front-line staff, people using services, and commissioners to maximise digital opportunities in health and social care. |

| NHSX | Unit within the UK government responsible for policy and best practice around technology, digital, and data within the NHS. This was absorbed into the NHS Transformation Directorate in 2022. |

| (Digital) platform | Includes both hardware (the device you are using) and software (the operating system you are using) on which applications can run. |

| Predictive analytics | The process of learning from historical data, statistical algorithms and machine learning techniques in order to predict future activity, behaviour and trends. |

| Remote monitoring | The process of using technology to monitor individuals in non-clinical environments, such as in the home, assisted living, or care home settings. It includes sensors and wearable devices. |

| Surveillance technology | Surveillance technology includes CCTV, cameras and microphones. |

| Telecare | Telecare services offer remote care, often for frail older people and people with cognitive or physical impairments, providing the reassurance needed to allow them to remain living in their own homes. Typically, a monitoring service is provided which will escalate alarm activations to a named responder or, if appropriate, the emergency services. |

| Telehealth | The use of electronic sensors or equipment that monitor people’s health in their own home/community (e.g. equipment to monitor vital signs such as blood pressure, blood oxygen levels or weight). These measures are then automatically transmitted to a clinician who can observe health status without the person leaving their home environment. |

| Use case | A use case identifies, clarifies, and organises system requirements. It is made up of a set of possible sequences of interactions between systems and users in a particular environment related to a specified goal. |

| Wearable technology (‘wearables’) | Electronic devices that can be incorporated into clothing or worn on the body as implants, or accessories that can send and receive data via the internet, often via smartphones. |

| Wi-Fi | A wireless network which enables computers and mobile devices to connect over a wireless signal to the internet without using wires or cables. |

The NHS Long Term Plan, published in 2019, promoted digitally-enabled care as one of its central tenets. In particular, the Plan mentions that technology can help automate some aspects of care, improve the quality of care and free up staff to do other tasks. The Long Term Plan also highlights that home-based monitoring equipment can play a key part in preventing hospital admission, and identifies AI-based technology as a practical solution to drive digital transformation in the NHS. 10 In line with this, the Government Digital Service and the Office for Artificial Intelligence have published recommendations for public sector organisations to: assess whether AI has the potential to assist services to meet the needs of their users; describe how the public sector may best use AI; support the safe, fair and ethical adoption of AI; and guide organisations on how to plan and prepare for the implementation of AI. 11

In the same year, NHSX was created to take forward digital transformation within the NHS, signalling further commitment to digitally-enabled care within the health and social care system. It was recently announced that NHSX and NHS Digital (a non-departmental body created in 2013 to support information, data and information technology (IT) systems within the NHS) will merge into NHS England. According to representatives from the Department of Health and Social Care, this merger will help to accelerate digital transformation within the NHS. 12 Digital Social Care was also created in 2019 to support and advise the social care sector on technology. 8

In 2019, Eric Topol led an independent review on how to prepare the health-care workforce to deliver digitally-enabled care. This review recognised that the deployment of AI and other technologies can free up more time to deliver care. Recognising the direction of travel towards digital health and social care, the review identified a need for improved digital literacy of staff and targeted support to implement digital technology. While other technologies are also discussed in the report, AI was highlighted as one of the central approaches to meeting the financial challenges of delivering high-quality care. 13

The most recent reform of adult social care, as reflected in the White Paper People at the Heart of Care, also pledged at least £150 million of additional funding to drive the adoption of technology and achieve digitisation to support independent living and improve the quality of care. 14 The paper also explores how technology fits into a broader 10-year vision for adult social care, setting out various commitments to accelerate the adoption of technology, ensure that individuals will be able to adapt their homes and access practical tools and technology to live independently and well in their homes, and ensure that staff working in social care will have the confidence to use technology to support care needs and free up time in social care. 14 The paper also mentions the potential for technology to be fully utilised to ‘enable proactive and preventative care and to support people’s independence’, including by using technology to identify risks, prevent incidents and ensure quick responses to care needs. 14 To achieve this, the White Paper identifies a need for practical guidance and training on technology and digital skills among the social care workforce, additional investment and funding models, and data infrastructure to support technology in care. 14

Although COVID-19 has caused additional pressures for the health and social care system in England, it has also accentuated awareness of the potential of technology to deliver or facilitate the delivery of care and support. 8,15 Since the pandemic, more people who draw on care and support have needed to receive care remotely, and more technology has been implemented across health and social care to allow care to continue as best it can, for both COVID and non-COVID patients.

AI-based technology for social care

One type of technology that may be particularly relevant for adult social care is sensors with AI capabilities. These can be thought of as a type of telecare, which includes technology and devices used to monitor people who draw on care and support, generate and analyse data about them, and connect them to or provide them with health and care services. 8

There are often said to be three generations of telecare, which increase in complexity. In the first, a button is pressed by the user during an emergency, and an alert is sent to a nominated individual via a telephone connection. Second-generation technologies do not rely on intervention by the user (i.e. by requiring the user to press a button). Instead, an automatic alert is sent when a potential breach to health and safety (e.g. a fall) is detected by the sensors. The third generation uses more innovative systems that focus on functionality, with the provision of remote support and lifestyle monitoring to pre-empt, detect and reduce problems relating to activities of daily living. This is the type of technology we are focused on in this evaluation, and we refer to it as ‘AI-based technology for social care’ or ‘new and emerging technology’. The aim of these technologies is to improve quality of life for people who draw on care and support and their carers (rather than exclusively providing reassurance to the person or their carer, or to ensure that help can be available after a fall, as was often the case with previous generations of technology). 16–18 They aim to maintain or increase independence by generating alerts when problems occur and by spotting emerging issues early to prevent problems or crises before they arise. 19–21

Other mechanisms by which AI-based technology for social care is intended to improve health and well-being can include better personalisation of care, greater control and choice for people who draw on care and support (whether at home or in care homes), and a reduction of costs for health and social care services. 22,23 There are also more novel applications of new and emerging technology in social care, such as interactive robots placed within people’s homes,24 although these are less well developed and less widely used in the UK.

While these technologies are not new in social care, technological advances are leading to the development of more sophisticated AI devices that use machine learning to identify patterns in people’s daily activity, recorded by multiple sensors around a person’s home. 3 Machine learning (or computational learning) is defined as ‘the set of techniques and tools that allow computers to “think” by creating mathematical algorithms [read as a set of instructions] based on accumulated data.’3, p. 6 The machine learning aspect of AI can allow such technologies to utilise data collected through sensors for offline learning with the aim of improving care.

Evidence around technology in social care

While it cannot replace personal care, technology has the potential to help people with care and support needs to live independent and active lives, and to assist those providing support. However, in order for technology to be successfully embedded into care, it needs to be ‘based on a persuasive evidence base; useful to those who are caring; and – first and foremost – help achieve the outcomes users desire’. 25, pg. 1

Research supporting the effectiveness of these types of technology in the context of social care is, however, mixed. A 2008 randomised controlled trial by the then Department of Health [the Whole Systems Demonstrator (programme)] aimed to explore the cost-effectiveness of technologies for health and social care. 8,20,26–29 The WSD evaluation did not look specifically at AI, which was less well developed at that time, yet findings from this study provide key learning relevant to other types of technology. The aim of the WSD evaluation was to provide local health and social care commissioners with knowledge on which to base investment decisions, and to provide suppliers of the technology with an understanding of potential business models. Results were mixed, and neither telehealth nor telecare was found to be cost-effective compared with usual care. 8,30 The trial identified barriers to the use and acceptance of telecare among people drawing on care and support, including concerns around a lack of technical competence to operate equipment, misunderstandings around what skills are needed to use technology, and fears associated with ageing and self-reliance with respect to using telehealth and telecare resources. 31 Despite early indications from the Department of Health that telehealth and telecare had resulted in reductions in emergency and elective admissions, bed-days, costs and mortality rates,32 it has been argued that the findings of the study were misinterpreted based on political pressure and that the actual findings of the study were less positive. 33

There are some indications that home sensors with AI technology may be effective in some contexts. A recent randomised controlled trial of an AI- and machine learning-based technology using home sensors for people with dementia (the Technology Integrated Health System study) found that the technology led to mental health and well-being benefits for people who draw on care and support, and that it prompted early intervention to avoid hospital admissions. Furthermore, the technology was well accepted by people drawing on care and support and carers. 34,35 However, some people raised concerns about the reliability and user-friendliness of the technology, highlighting internet connectivity issues and the need for more passive forms of data collection that do not require input from the person with dementia, who may become annoyed by having to use devices to collect data. 34 It is worth noting that this evaluation focused upon health rather than social care outcomes, specifically: urinary tract infection, agitation, irritation and aggression. 34,35

Despite these relatively positive results, other studies more focused on social care outcomes found that similar technology was not effective. A health technology assessment (the ATTILA randomised controlled trial) of another assistive technology for people with dementia who continue to live independently at home found that the technology did not allow people to live in the community for longer, nor did it decrease carer burden, depression or anxiety relative to a basic care programme. 36

What influences the success of technology in health and care?

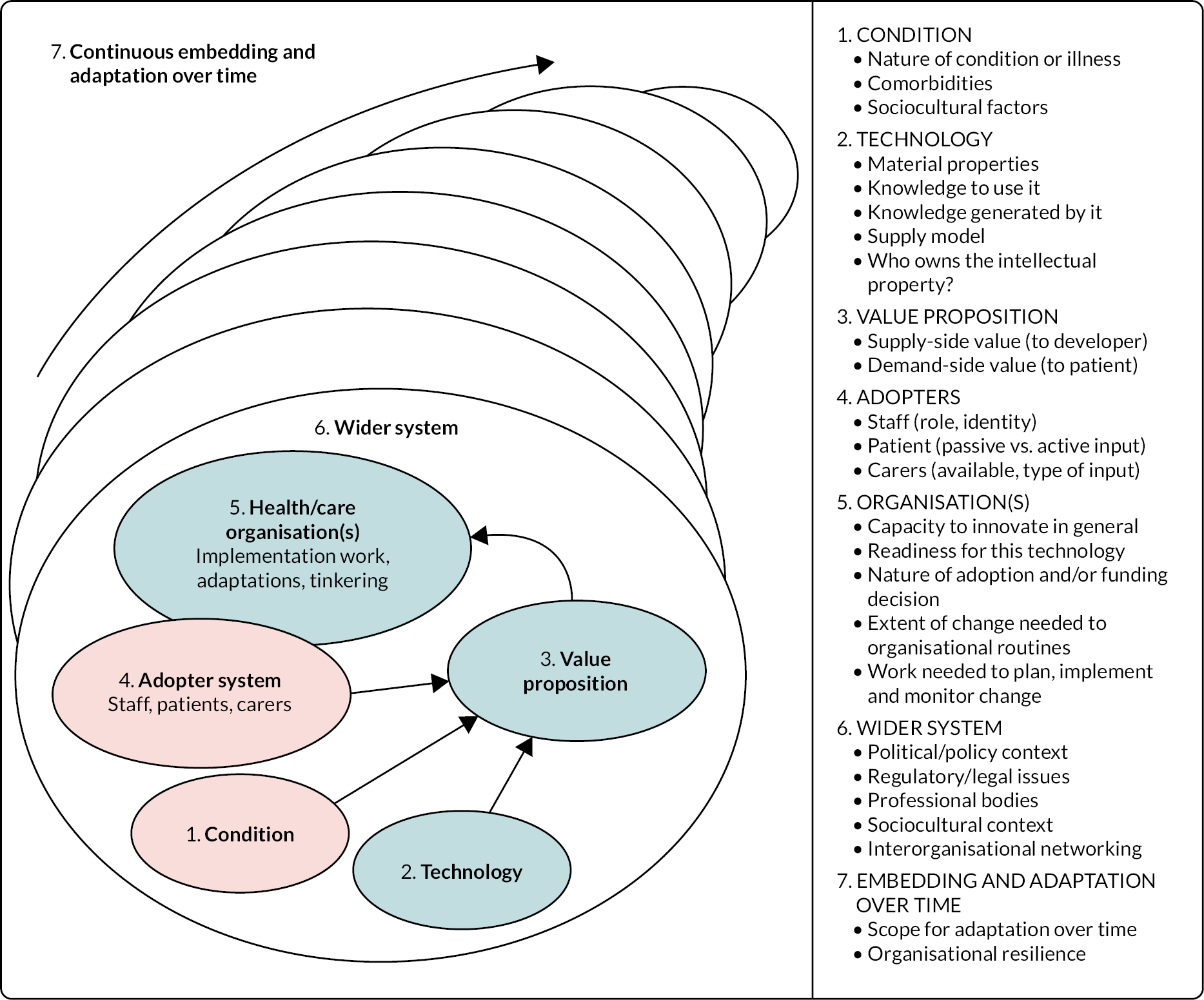

The wider literature around the adoption and implementation of technology in health and social care points to the importance of considering wider contextual factors and how these influence the success of technology. For instance, Greenhalgh et al. (2017) argued that many previous studies have tended to focus on the short-term adoption of simple innovations by individual adopters and on individual barriers and facilitators, failing to theorise the adoption of new technology. 37 In contrast, they propose a new framework for theorising and evaluating the adoption/non-adoption, abandonment and challenges to the scale-up, spread and sustainability of health and social care technologies: the NASSS (adoption/non-adoption, abandonment, scale-up, spread, sustainability) framework. This framework includes elements relating to: the condition or illness of the person/population; the technology itself; the value proposition in terms of what the technology will accomplish; adopters of the technology (e.g. patients, staff and carers); organisational considerations; elements of the wider system (e.g. policy, regulation); and how the technology is embedded and how the system around it is adapted over time (see Box 3). 37 This framework (informed by theory and evidence) describes the barriers to successful uptake of assistive technology innovations, and provides a guide to the type of issues that should be considered by commissioners and providers when deciding which technologies to adopt, as well as by researchers interested in evaluating the implementation of assistive technologies in health and social care. 37 Chapter 10 of this report draws on this framework (alongside insights from the ‘rational model’ of policy implementation) to draw out key learning from our findings.

The framework proposed by Greenhalgh et al. (2017) incorporates the following influences:

-

Condition (the nature of the condition or illness of users, comorbidities, sociocultural influences)

-

Technology (material features; type of data generated, knowledge needed for use, technology supply model)

-

Value proposition supply-side value (to developer), demand-side value (to patient)

-

Adopters for staff (role, identity), for users (simple vs. complex input), for carers (availability, nature of input).

-

Organisation (capacity to innovate – leadership etc, readiness for technology/change, nature of adoption/funding decision, extent of change needed to routines, work needed to implement change)

-

Wider system (political/policy, regulatory/legal, professional, sociocultural)

-

Embedding and adaptation over time (scope for adaptation over time; organisational resilience).

Greenhalgh et al. recommend that evaluators of assistive technologies for health and social care consider each of these groups of influences on the success of the implementation effort.

Reproduced with permission from Greenhalgh T. 37 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text above includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Copyright © 2023 Glasby et al.

The wider literature also points to some well-known problems associated with the adoption of new technologies. For example, there is often a mismatch between the value that developers of technology see in creating a business case and sales model for their products (the supply side), as opposed to the value that providers and decision-makers within the health and social care system (the demand side) expect from the technology in terms of benefits to people who draw on care, staff and the health and social care system. 38,39 Training needs have been highlighted as an issue in the increasing presence of AI-based technology in social care settings. For example, there is a need for training for staff in how to interpret the data collected by AI technologies. 3 There are also key considerations such as internet connectivity, particularly in certain parts of the UK, along with ethical questions and data privacy and security concerns, which need to be taken into account when commissioning technology for adult social care. 40

Lastly, the implementation process matters greatly in terms of how successful a digital technology may be in health and social care. Findings from the NHS England Test Bed programme suggest a number of key lessons in supporting implementation, adoption and spread of technologies in health and social care,41 as described in Box 4.

-

Dedicate sufficient time and resource to engage with end-users.

-

Co-design or co-production with end-users is an essential tool when implementing technology.

-

Identify the need and its wider impact on the system, not a need for a technology.

-

Explore the motivators and barriers that might influence user uptake of an innovation.

-

Ignore information governance requirements at your peril.

-

Don’t be afraid to tailor the innovation along the journey.

-

Ensure adequate training is built in for services using the technology.

-

Embedding the innovation is only half the journey; ongoing data collection and analysis is key.

-

Ensure there is sufficient resource, capacity and project management support to facilitate roll-out.

-

Recognise that variation across local areas exists and adapt the implementation accordingly.

Similar factors were identified in a report looking specifically at assistive technology in adult social care. This pointed to the importance of engaging people who draw on care and support and using language they can understand around assistive technology, engaging with staff to encourage culture shifts and greater acceptance of technology, ensuring that technology meets identified needs when commissioning it for social care, having clear protocols around the use of data, and ensuring that digital infrastructure will support technology. 42

Gaps in the evidence

It has been recognised that technology is not being used to its full potential in social care, with a range of stakeholders (from national voluntary organisations such as Carers UK to the government’s Industrial Strategy) identifying the need to increase investment in this area. 23,43 There are substantial gaps in understanding the use of emerging technologies to deliver public services, including for assistive technologies in health and social care. 3,19,20,44–46 Specifically, there is a lack of evidence on the expected or achieved impact of these technologies on people drawing on care and support and carers, hindering the wider use of technology in social care. 20 This lack of evidence has been acknowledged by commissioners of services, who have also expressed concern about this in terms of how to implement technology alongside existing systems, the potential impact on future service use, and cost-effectiveness. 20 In addition, although there is a wide range of devices and systems commercially available to support people with care and support needs, there is very little validated information to help select the most suitable technologies. 19

Research and evaluation of AI-based technologies for social care in the literature are underdeveloped and limited by methodological issues, and a call has been made for more robust research in this area. 3,20 The evidence base is characterised by gaps in knowledge across several themes, including the attitudes and perspectives of different stakeholders (people who draw on care and support, carers and care staff) and the impact on the broader workforce and services. Little is known about how the care workforce may be affected by the adoption of AI-based technology, or what is required from them to facilitate acceptance by people drawing on care and support and carers. 3 A lack of involvement of the social care workforce in the design and development of AI for social care has also been acknowledged as a barrier to its implementation. 3 The value of exploring the experience of people who draw on care and support and carers using qualitative methods has been acknowledged in the literature, for instance via input into the design and implementation of assistive technology. 47 However, research and evaluation specifically on the experiences and attitudes of people drawing on care and support and of carers towards AI-based technology is sparse,3 and there is a lack of evidence around the perspectives of technology providers and innovators and those commissioning care. Lastly, although there is a clear interaction and overlap between health and social care,28 most literature and empirical research on assistive technology focuses on health outcomes.

As a result, discourse on the promise of technological innovation (e.g. from policy-makers and technology companies) is contradicted by evidence showing a poor track record of assistive technologies. They are not widely used in social care currently as they often fail to be scaled up at a local level, or spread widely, and are not sustained in the long term at a system or organisational level. 37 This dissonance has been identified in the literature around remote care technologies for social care in the UK, pointing to the need to fill gaps in the evidence before promoting technology as a ‘silver bullet’ for existing challenges in social care. 48

Context for study

Interest from policy-makers, commissioners and care providers in developing and using technology for social care makes it a current priority for evaluation. 11,22,49 In July–November 2019, an NIHR-funded national prioritisation exercise was held, during which organisations and individuals with knowledge of adult social care and social work identified promising innovations. 50 As part of this, a prioritisation workshop using James Lind Alliance principles was held with 23 members, including people who draw on care and support, carers, care staff, researchers, commissioners and policy-makers. 51 This prioritisation exercise resulted in a shortlist of the top innovations which would benefit from a rapid evaluation, several of which related to new and emerging technology.

This study builds on the prioritisation exercise by evaluating how one example of new and emerging digital technology (a system of sensors with AI which we have anonymised using the name ‘IndependencePlus’) was implemented in case study sites across England. In particular, we focus on the decision-making process for and implementation of this technology, including consideration of the outcomes that local authorities/care providers are trying to achieve by adopting new and emerging technology, and the way in which this is experienced by people who draw on care and support, carers and care staff.

As a result of this scoping work, the resulting study seeks to answer the following core research questions:

-

RQ1. How do commissioners and providers decide to adopt new and emerging technology for adult social care? (Decision-making)

-

RQ2. When stakeholders (local authorities and care providers, staff, people who draw on care and support and carers) start to explore the potential of new and emerging technology, what do they hope it will achieve? (Expectations)

-

RQ3. What is the process for implementing technological innovation? (Implementation)

-

RQ4. How is new and emerging technology for adult social care experienced by people who draw on care and support, carers and care staff? (Early experiences)

-

RQ5. What are the broader barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of new and emerging technology in addressing adult social care challenges? (Barriers and facilitators)

-

RQ6: How has the COVID-19 pandemic influenced responses to the questions above? (Impact of COVID-19)

-

RQ7: How can the process of implementing new technology be improved? (Making improvements)

IndependencePlus

Below (see Box 5), we provide a brief overview of the features of the IndependencePlus technology that was piloted at case study sites involved in this study. While our study is not an evaluation of this specific technology, this is meant to provide context that will be useful in understanding this report and the study findings.

-

Sensors: Sensors placed in key locations in individual homes collect information about an individual’s daily activities, without video or audio recording. Information that is collected includes: opening and closing of doors; getting out of bed; opening the refrigerator; using the kettle; and flushing the toilet.

-

AI capabilities: Once data are collected on an individual for a sufficient period of time, a baseline can be established, allowing for automated processing of data indicating whether a measure has increased or decreased from the baseline, indicating potential improvement or decline of the individual drawing on care and support. To establish a baseline, continuous data collection is required over a period of time, which may be disturbed if sensors become disconnected or if they run out of battery.

-

Individuals living alone: Since the technology cannot distinguish between individuals within the living space, it is best used for individuals living alone, rather than in group living situations.

-

Connectivity and Wi-Fi: Individuals using IndependencePlus must have Wi-Fi connection for their data to be collected, and sensors must be plugged in or have a charged battery in order to operate.

-

Data dashboard: Data from sensors for each individual are displayed on a data dashboard. In case study sites, only social care workers had access to this data dashboard, although it could theoretically be made available to individuals drawing on care and support or their carers. Social care staff then needed to interpret the data, and understand what increases or decreases in different parameters meant for the individual person.

Part way through local pilots, IndependencePlus evolved the data it collected to include a range of health data (see Chapter 7 for further discussion of this development).

Chapter 2 Methodology

Box 6 provides a summary of Chapter 2 of this report.

Summary of key points

-

This study was conducted across two stages. Stage 1 took the form of scoping work to better understand new and emerging digital technologies for social care and the challenges and lessons learnt from previous research and evaluation efforts. Stage 2 involved evaluation of the implementation of new and emerging digital technology, using the example of IndependencePlus, through qualitative data collection.

-

The study has generated a number of lessons about the key things to consider when implementing new and emerging technology in social care.

-

However, significant recruitment challenges were faced during stage 2 of the research, particularly related to the pressures of COVID-19 on social care, as well as a range of other factors. This had significant implications for our research, and is discussed in detail at the end of this chapter.

To address the research questions outlined in Chapters 1 and 3, we undertook two stages of data collection, each of which is outlined in more detail below:

-

Stage 1: Scoping work to better understand new and emerging digital technologies for social care, with a focus on home sensors with AI technology, and the challenges and lessons learnt from previous research and evaluation efforts. This consisted of a rapid review of the literature, nine key informant interviews, three online project design groups and selection of potential case study sites.

-

Stage 2: An evaluation of new and emerging digital technology, using the example of IndependencePlus, through qualitative data collection and analysis from three case study sites (20 interviews), supplemented by three interviews and focus groups with care technology providers/innovators and regulatory bodies. The work in case study sites consisted of selecting and recruiting local authorities and care providers who had been exploring the potential of new and emerging digital technology, interviewing key stakeholders (seeking to include decision-makers and operational leads, care staff, carers and people who draw on care and support), reviewing documents from case study sites and, finally, analysis and synthesis. This was supplemented by interviews with technology providers/developers, and interviews with national organisations involved in developing policy for and regulating AI in social care. We had originally intended to hold local workshops with case study sites to sense-check emerging findings, but due to recruitment and engagement challenges (described later), this was not possible during the initial life of the project. However, we will offer this to our sites later in 2022 in case circumstances have changed sufficiently for this to be a helpful contribution.

Each of these stages will be outlined in further detail below. However, we encountered significant challenges in recruiting case study sites and participants to interview (partly due to the impact of COVID, but also due to the nature of the pilots themselves, which were all deemed not to have worked and were subsequently abandoned). We reflect on this at the end of the chapter.

Although we were interested in new and emerging digital technology generally, we collected data from sites that had chosen to use a specific type of technology – home sensors with AI technology –provided by a single technology company. This form of AI technology had been identified via the NIHR-funded prioritisation exercise as worthy of rapid evaluation (see below for further discussion), with various examples of new and emerging technology cited. In this report, we have anonymised the technology provider and sites in order to maximise learning about the decision-making and implementation process more generally, rather than to explore the effectiveness of a single technology or product. We therefore refer to this technology and the company providing it using the pseudonym ‘IndependencePlus’. All case study sites were also anonymised to guard against reputational risk in situations where local authorities or care providers have experimented with new ways of working and not been able to deliver desired outcomes – but still generated important learning that could benefit others. During our scoping work, a range of stakeholders felt that this was a helpful safeguard which would maximise their ability to share genuine learning, whether outcomes were perceived to be ‘positive’ or ‘negative’.

Stage 1: Scoping work

To inform our study design, the research team undertook scoping work to better understand new and emerging digital technologies for social care, with a focus on home sensors with AI technology. We conducted a rapid scan of the literature, nine key informant interviews and three project design groups with stakeholders, and selected our potential case study sites. Scoping work included an exploration of which questions we should ask stakeholders, which themes to consider, and how best to collect the data from care providers and commissioners, people who draw on care and support, carers and care staff. It also enabled us to explore the challenges and lessons learnt from previous research and evaluation efforts and develop our research questions. This work guided our approach to stage 2 of the work. The approach to the scoping work is outlined below, and the results are described in the following chapter.

Rapid scan of relevant evidence

As part of our scoping work, we conducted a rapid scan of international literature relating to the implementation of new and emerging digital technology within social care, as well as evidence from research and evaluations of home sensors with AI technology specifically. Unlike systematic reviews, rapid evidence scans do not involve systematic methods of searching or selecting articles and do not aim to produce an exhaustive or reproducible summary of a topic. Instead, this was a pragmatic scan of articles for the purpose of informing possible research questions and identifying tools and analytical frameworks for the study (to be developed and tested with our key informants and project design groups). It was carried out through Google searches (including Google Scholar), recommendations of articles from experts, and ‘snowballing’, where sources emerged through looking at references and citations of relevant sources. 52

Although the search was not intended to be comprehensive, we used search terms encompassing the following areas:

-

‘social care’

-

‘AI’ OR ‘artificial intelligence’ OR ‘preventative sensor technology’ or ‘machine learning’ or

-

‘sensors’ or ‘assistive systems’ or ‘telecare’.

Due to the informal nature of this rapid scan of the evidence, we are unable to provide exact search strings, the number of articles reviewed or reflections on the quality of the evidence, as would be required in a more formal or systematic review.

Key informant interviews

In total, nine interviews were conducted over several months in 2020 on the phone or online with research experts in the field and with decision-makers and operational leads (i.e. staff involved in the implementation of AI sensor technologies) from local authorities and care providers. Interviewees from local authority commissioners and care providers were selected on the basis that they had used IndependencePlus. Informants with research expertise in this area were also interviewed and were identified from relevant literature and through networks established within the research team. Interviews were semistructured, allowing a flexible approach in the topics covered. The topic guides can be found in the project documentation.

Online project design groups

The research team held three online project design groups with stakeholders in October 2020. Design group 1 involved four local authority commissioners and care providers who were decision-makers and operational leads with experience of using IndependencePlus. Design group 2 involved four people who draw on care and support, and carers. Design group 3 involved three people who draw on care and support, and carers. Attendees of the second and third groups were from the BRACE Health and Care Panel and the University of Birmingham Social Work Service User and Carer Contributor group. To avoid exclusion on the basis of an individual’s access to and proficiency or confidence with digital technology, individuals were asked if they would prefer to speak over the phone with a member of the research team, rather than attend the design meeting. Furthermore, one carer who was interested in contributing but was unable to attend the dates of the online project design groups was offered an individual interview, which took place over the telephone in October 2020. In these online project design groups for both groups of stakeholders, we asked participants about the type of questions and themes they thought we should ask in the evaluation and enquired about the practicalities of collecting data (particularly given the COVID-19 pandemic). This was to help us develop the topic guides for data collection and select appropriate and feasible methods in our evaluation.

Identification of case study sites

As part of the scoping work for this study, the research team created a list of potential case study sites. These were all of the local authorities and care providers in the UK known to be using IndependencePlus. We developed this list through e-mailing and then speaking on the phone or online with the organisations listed on the IndependencePlus website, which listed all their clients. We were aware of eight sites using IndependencePlus and had communication with five of these (three others did not respond), all of which provisionally stated an interest and willingness to participate in this study. These were three local authorities (i.e. councils with responsibility for adult social services, who assess people’s needs/eligibility and commission care and support services) and two care providers (public, private or voluntary organisations commissioned to provide care). Our process of obtaining case study sites was therefore pragmatic, with no selection based on any characteristics other than them using IndependencePlus and being interested in participating. These case study sites, however, cover both local authorities and care providers, a mix of urban and rural areas, and different groups of people who draw on care and support (e.g. older and younger ages, and a range of mental and physical health conditions). While we did not assess how similar or different these providers or councils are from other organisations providing social care, there is no reason to believe they are atypical in any significant way.

Stage 2: Evaluation of new and emerging digital technology

After conducting the stage 1 scoping work, stage 2 of the study focused on evaluating the implementation of new and emerging digital technology, using the example of IndependencePlus, through qualitative data collection and analysis from three case study sites, supplemented by interviews and focus groups with care technology providers/innovators. This stage of work consisted of recruiting case study sites, interviews with key stakeholders, and review of documents, each of which will be discussed here.

Recruiting case study sites

We formally invited each of the five sites identified from the stage 1 scoping work (three local authorities and two service providers) to take part in the evaluation. However, two sites were subsequently unable to take part due to a culmination of different reasons described later in the limitations section of this chapter. Therefore, we worked with three case study sites (one care provider and two local authorities). Table 1 provides an overview of each of the three case study sites.

| Case study site 1 | Case study site 2 | Case study site 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organisation type | Social care provider (charity; lots of services across the country) | Local authority (rural) | Local authority (urban with some rural areas) |

| Care setting | Care home with nursing services | Care in the communityb | |

| Number of service users who used IndependencePlus | 23 | 9 | 20–30 |

| Demographics of people using IndependencePlus | People with complex physical and sensory impairments | People with physical impairments, people with learning disabilities, people with mental health problems, older people, people with dementia | People with learning disabilities, people with physical impairments, people with dementia |

| Length of time of the IndependencePlus pilot | <12 months | 12 months | 12–18 months |

| Stated reasons for ending the pilot | Issues with technology making it difficult to use Change within IndependencePlus towards focusing on health data in response to COVID-19 |

||

Coordination and communication with case study sites

The team had already begun building relationships with the five potential case study sites that had expressed an interest in participating during the scoping work, through e-mail and telephone contact with decision-makers and operational leads, and through a scoping workshop. For the three case study sites that agreed to participate, these relationships were strengthened by the allocation of a member of the research team to each case study site and the identification of a lead contact at each case study site. We had regular and clear communication with case study leads and other local contacts to ensure that the relationship remained strong throughout the study – especially in such a difficult external policy and practice context.

Interviews with key stakeholders

Recruitment

Decision-makers and operational leads were recruited through the links made with case study sites during the scoping work. Interviews were undertaken between April and December 2021 (this is longer than initially intended due to the impact of COVID). Following each interview with decision-makers and operational leads, the local leads were asked to identify front-line staff, people who draw on care and support and carers who had experience of using the sensor technology (even if very limited) and who might be interested in taking part in a subsequent interview. We did not want this to enable local senior stakeholders to pick and choose who we approached, but it was designed to ensure that we did not invite someone to take part in inappropriate circumstances (e.g. if an older person had recently died). Inclusion criteria for people who draw on care and support, carers and care staff were:

-

having had the sensor technology set up in their home and having attempted to use it (for people who draw on care and support or their carers)

-

having had experience of implementation and delivering care through the use of sensor technology (for care staff)

-

having had experience of using the sensor technology for a range of social care needs (i.e. no particular user groups were excluded).

There were no limitations as to the perceived level of ‘success’ of the sensor technology used. We were interested even if the technology was abandoned, as we were keen to learn from a wide range of experiences of the use of technology (and suspected that there may be even greater learning for others in situations where the technology was not taken forward than in pilots that were felt to have had positive outcomes – albeit it can be difficult to get access to sites that perceive their innovation has not worked as they intended; see below for further discussion). In addition, there were no exclusion criteria related to the length of time for which the technology had been used, so that we could obtain varied experiences. The criteria for sampling people who draw on care and support were deliberately broad, to include anyone needing support with their daily living, and may include older people, people with dementia or mental health problems, people with physical impairments or learning disabilities, and family carers.

The local lead(s) passed information about the study to people who draw on care and support, carers and care staff, seeking permission for the research team to contact people interested in taking part or finding out more. Where permission was granted, a member of the team e-mailed or rang potential participants to describe the study and its aims in detail. Each participant returned a consent form prior to commencing the interview and was given 1–2 weeks to decide whether they would like to participate. Prior to commencing the interview, participants also had the opportunity to ask questions about the study and/or wider Birmingham, RAND and Cambridge Evaluation Centre (BRACE)-related work. It was made clear that participants could withdraw from the study at any time, without having to give a reason, and they were also given information about how to find out more about the study, or to raise concerns about its conduct.

At each of the case study sites, we aimed to conduct qualitative semistructured interviews with 2–3 decision-makers and operational leads, five staff with experience of working with IndependencePlus, and five people who draw on care and support or carers. However, we faced significant challenges in recruiting individuals to interview (for reasons described later in the limitations and caveats section). Partly due to this, the stakeholder groups were widened to include interviews with a series of technology providers/innovators supporting the development of care-related digital technology (this included an interview with IndependencePlus itself) as well as with respondents from national bodies which regulate care. The total number of interviews was 23 (with 24 individuals) and we were unable to secure any interviews with people who draw on care and support (see below for further discussion). One carer provided feedback in written form, which is included in the count of 23 interviews below. The breakdown of the interviews conducted is provided in Table 2.

| Case study 1 | Case study 2 | Case study 3 | Technology providers/innovators | Regulatory organisations | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision-makers and operational leads | 3 | 9 | 3 | - | - | 15 |

| Care staff, care providers and unpaid carers | 0 | 2 | 3a | - | - | 5 |

| Technology provider | - | - | - | 2 (1 = IndependencePlus) | - | 2 |

| Regulatory organisations | - | - | - | - | 1b | 1 |

| Total | 3 | 11 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 23 |

Within this report, interviewees are referred to using a code encompassing their case study site or role (e.g. technology provider) and a unique identifier. For example, the first interviewee from case study site 1 is referred to using the code ‘CS1 P01’.

Interview conduct

Topic guides were developed for the interviews: one for decision-makers and operational leads, another for staff, and a third for people who draw on care and support and carers (see the project documentation for topic guides). The themes and questions covered in the topic guides were informed by the stage 1 scoping work.

The interviews invited decision-makers and operational leads to reflect on how decisions were made about the adoption of IndependencePlus; the process of implementation; early experiences of its use (including potential costs and savings); and key learning points that could help others considering using these types of digital technologies.

Care staff and carers were asked about their practice/lived experiences of the implementation process; practical realities of the technology use; the extent to which the technology had enabled, improved or hindered daily activities; the extent to which the technology had increased or compromised feelings of choice and control; and how this type of technology (or the implementation of it) may be improved.

Interviews with stakeholders lasted 30–60 minutes and were conducted online using Microsoft Teams® or Zoom, with the option of telephone interviews also offered. Interviews were audio-recorded (subject to consent being given) and detailed notes were taken by the interviewer.

Review of case study and technology provider documents

Once an interview with a decision-maker or operational lead was completed, we asked whether they could identify any documents (not containing sensitive information) that could be shared with the research team. This was to help build a picture of the decision-making process, the implementation process and any challenges/successes. The documents shared by case study sites are outlined in Table 3. We reviewed these as background and contextual information.

| Case study 1 | Case study 2 | Case study 3 | Technology provider |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedback notes | IndependencePlus issues and solutions workshop notes | IndependencePlus COVID package | User survey |

| Staff survey | IndependencePlus risk register | Dashboard ideas | Matrix of different levels of intervention in different types of site |

| Technology strategy | Info sheet | ||

| IndependencePlus alerts |

Data analysis

Once we had completed the interviews, the team held a data workshop to discuss our provisional findings and identify themes.

Given the limited number of interviews per case study, and the similarity of themes arising from the interviews, the data from each case study were analysed together. Our analysis explored the desired outcomes of new and emerging technologies for social care; how these outcomes are expected to be achieved; and what resources, approaches and activities are supporting the implementation in practice. Thematic analysis of interview transcripts and documents provided by interviewees was conducted using guidance from Braun and Clarke. 53 We iteratively developed a coding frame (see the project documentation) using early interviews and discussion among the study team. 54 NVivo 12 qualitative analysis software was used for interview coding. Pilot coding of a small number of interviews was conducted independently by two researchers (SP and IL) and the team then met to agree on refinements to the coding framework and to add any additional emerging codes. The remaining interviews were then coded independently by four members of the research team (SP, IL, LH and DT).

In seeking to place our subsequent findings in a broader context, we drew on the NASSS socio-technical framework developed by Greenhalgh et al. (2017). This framework describes considerations such as the service’s capacity for innovation, the expected input/adaptation from care staff and the context for widespread use of the technology,37 and proved a helpful mechanism for making sense of our key findings. We also compared insights from our study with those of the ‘rational model’ of implementation set out in much of the literature (see Chapter 10). By considering both frameworks, we hoped to acknowledge the reality of complexity and uncertainty when implementing new and emerging technology, while also exploring some of the key headings or ‘stages’ that others might consider if planning future implementation.

Ethical approval and consent

The University of Birmingham research governance team identified this study as a form of service evaluation which did not require approval by the Health Research Authority (HRA) or an NHS Research Ethics Committee. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Birmingham Humanities and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee to conduct the stakeholder interviews (ERN_13-1085AP41, ERN_21-0541 and ERN_21-0541A). We sought and received an amendment to our initial ethical approval when later including interviews/focus groups with IndependencePlus and national technology providers/innovators.

Information sheets and consent forms were shared with potential participants, which set out the study aims, design, risks, benefits and who to contact if they had further questions. The information sheet also made clear that participants have a right to withdraw from the study at any point, without needing to give a reason. Information sheets and consent forms were shared with potential participants via e-mail. Of the 24 interviewees, 23 completed the consent form electronically and e-mailed it to the research team, and the other interviewee provided verbal consent having expressed a desire to consent verbally rather than via the consent form. At the start of each interview, the researcher confirmed that the interviewee was happy to proceed and to be audio-recorded.

Strengths, limitations and caveats

There are a number of strengths, limitations and caveats to note for this study, which are described here. Most notable are the challenges of engaging and recruiting case study sites and interviewees, which are outlined in the later subsection.

The research team considered whether to include multiple types of digital technology for social care, provided by a number of companies. We decided to have just one ‘exemplar’ digital technology used consistently across our case studies because, through our scoping work, it was evident that by keeping this constant, we could better establish what factors influence local decision-making and early experiences of implementation of new and emerging digital technologies. This decision was taken in conjunction with potential case study sites on the basis that different companies are constantly developing new technology, and that a helpful focus for this study would be on the underlying decision-making and implementation process rather than a direct evaluation of a specific digital technology. The use of IndependencePlus was therefore our sampling frame, making sure that the type of new and emerging technology being implemented was consistent across all sites. Had we included different technologies in different case study sites, there would have been too many variables to draw broader conclusions.

Interviews were conducted online to reduce the spread of COVID-19 and in line with government public health guidance. Benefits of online or video data collection have been acknowledged, including reduced travel time for researchers and the ease of scheduling a time that is suitable for interviewees. 55 There are, however, some drawbacks to conducting interviews online. For instance, it can be more difficult to build rapport or monitor how a participant is feeling. 56 Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the research team have been developing their skills in online and telephone interviewing with health and social care professionals, people who draw on care and support and carers. The team have in place some techniques and solutions for ensuring interviews are conducted appropriately and that participants feel comfortable, such as sending lay information and discussion topics ahead of time, spending more time on rapport-building prior to the interview, active listening, consideration of and planning for technical difficulties, and upholding good practice and regulations for security and confidentiality.

Some stakeholders may not have had a positive experience with the technology, and their dissatisfaction or frustration may make them less keen to participate, or they may have thought we were only interested in ‘success stories’. Therefore, we ensured that invitations to participate clearly outlined the aims and potential benefits of the study (e.g. learning from past experiences and providing local authorities and care providers with better information for future decisions – irrespective of the ‘success’ or otherwise of local pilots). We also spent significant time in our scoping phase working with key leads across our case study sites, reminding them that we were interested in lessons which would help other local authorities and care providers exploring new and emerging digital technologies in future – not just in whether or not the technology ‘worked’. We feel that this is a key feature of the current study, but we found that we needed to give ongoing reminders and provide significant reassurance to sites throughout, as they were not used to sharing learning from innovations which had been abandoned or not as successful as they had hoped. We believe that there is a significant methodological and ethical issue here. However, the sheer effort expended in helping sites to feel comfortable sharing lessons that did not feel positive to them (for the benefit of others) was substantial and needed to be sustained throughout the life of the project – and there are important practical lessons here, too.

Challenges in recruitment of sites and interviewees

As mentioned, negotiating access and subsequent data collection with the case study sites was very challenging during the pandemic. We attempted many different ways of supporting recruitment, such as multiple e-mail reminders/calls, flexibility in (re)scheduling interviews, and offering participants the opportunity to provide written feedback via e-mail (rather than taking time out for an interview). Throughout the study, we were in almost constant touch with sites, trying to form a judgement as to whether to persevere with data collection or to pause and recommence when service pressures reduced. During our scoping work, sites were adamant that they wanted to take part – both to share learning with others and to help them reflect on their own learning. However, the conduct of the study in the midst of a pandemic was extremely arduous for the research team and for sites, and we had to keep reflecting on whether we were persevering with the study in order to enable people to share their experiences or simply ‘making a nuisance of ourselves’ when people had more important priorities (and this was a constant source of discussion and reflection in our team meetings, and in interaction with local leads). The reality of conducting very topical research in adult social care during the pandemic was that many months could elapse without proposed interviews having taken place (with multiple slots scheduled, cancelled, rescheduled, paused, not taking place on the day, rebooked – and then eventually going ahead when pressures temporarily eased). We believe passionately that there is helpful learning from this study, but extracting the learning took much longer than planned, and required significant perseverance, commitment and flexibility on behalf of everyone involved. We remain incredibly grateful to participants for nonetheless making the time to share key lessons with others, at possibly the most difficult time in the modern history of adult social care.

In addition to those mentioned, other significant engagement challenges existed due to a culmination of multiple factors:

-

The five initial sites we approached adopted the technology on a pilot basis, but experienced significant difficulties, and all stopped using it. We believe that there is important learning for others from these experiences, but it meant there was less incentive for sites to engage, given that they had often moved on in practice. Relatedly, care staff perceived several of the pilots to have failed and, in some senses, to have ‘wasted’ their time. While this is a significant finding in its own right, it also made recruiting additional participants difficult.

-

On occasion, there were politically contentious or difficult topics to work through with staff (e.g. negative attitudes towards the technology provider) – which again makes the learning valuable, but also made it difficult to recruit participants.

-

The timing of the prioritisation exercise and the subsequent commissioning/scoping of the project meant that these pilots were run some time ago, and things had often moved on significantly at a local level.

-

The technology was designed to be unobtrusive and to exist largely in the background, so people drawing on care and support (many of whom were older people, including some with dementia) did not recall the pilot.

-

It can be difficult to engage technology providers in such research, given that a number of the pilots were perceived to be unsuccessful, and given a number of issues around commercial confidentiality.

-

As discussed above, the research took place when adult social care was under unprecedented strain due to the COVID-19 pandemic – with significant additional pressures falling on staff whose role is technology-related (who often had to drop all other work and focus solely on adapting to the pandemic). Participating sites have been very generous with their time and very passionate about sharing their experiences – but we spent significant time building relationships and had to change plans instantly if more important priorities suddenly emerged locally. The team gave potential participants multiple opportunities to participate, made participation as quick and unobtrusive as possible, and informally chased and prompted as much as was appropriate in the context – but any more would have placed undue pressure on sites in a very challenging context, and would not have felt ethical.

Despite this, the study has generated significant learning about the key things to consider when making decisions about and implementing new and emerging digital technology, and has produced some practical guidance and learning that future organisations could find helpful when considering the adoption of AI-based technology. The later inclusion of the perspectives of technology providers is also an additional strength, often absent from the literature (see Chapter 1). As anticipated, the study fills key gaps in the literature, provides useful learning and works well within the context of the broader NASSS framework. It remains very timely given the potential benefits of new digital technology and the rapid changes which have been brought about by the pandemic – but progress was often painstakingly slow/hard-fought and the study was by no means easy to conduct.

Chapter 3 Results of the scoping exercise

Box 7 provides a summary of Chapter 3 of this report. The chapter presents the results of the scoping work which was conducted for this study, including all results from the rapid literature review.

-

The scoping exercise encompassed the first stage of this research and consisted of a rapid scan of relevant literature, nine key informant interviews and three online project design groups.

-

Key themes were fed into the design of stage 2 of the study. Given the challenges described in Chapter 2, it is possible that stage 2 may not have been feasible to complete without the insights and relationships developed during stage 1.

To inform our study design, the research team undertook scoping work to better understand new and emerging digital technologies for social care, with a focus on home sensors with AI technology. We conducted a rapid scan of relevant evidence, undertook nine key informant interviews, ran three project design groups with 11 stakeholders, and selected our case study sites. Scoping work included an exploration of which questions we should ask stakeholders, which themes to consider, and how best to collect the data from care providers and commissioners, people drawing on care and support, carers and care staff. This also enabled us to explore the challenges and lessons learnt from previous research and evaluation efforts and develop our research questions.

Rapid scan of relevant evidence

As part of our scoping work, we conducted a rapid scan of literature relating to the implementation of new and emerging digital technology, as well as evidence from research and evaluations of home sensors with AI technology specifically. We did this to clarify the research questions, develop research tools and identify appropriate analytical frameworks for the study. This was an informal process, using Google and Google Scholar searches, as well as ‘snowballing’ techniques, where sources emerged through looking at references and citations of relevant sources. 52 As mentioned in Chapter 2, due to the rapid and pragmatic nature of this rapid scan of the evidence, we are not able to provide exact search strings, the number of articles included in the rapid scan or a reflection on the quality of the evidence. This was a pragmatic step to inform the design of stage 2, and should not be understood as a systematic review of the literature.

From this informal/rapid scan we identified the studies and literature discussed in Chapter 1 of this report – many of which were categorised into three main themes (see Table 4). First of all, there was a widespread sense that technology in general was not being used to maximum effect in social care. In particular, there seems to be a lack of evidence around the implications of new and emerging digital technologies – hence why this topic emerged as such a priority for rapid evaluation in the national prioritisation exercise which led to the current study. Second, there can be significant difficulties in terms of selecting what technologies might be most appropriate within social care. There is apparently little in the way of guidance for those procuring digital technology and a lack of awareness of the needs and opinions of the people who are ultimately expected to benefit – those who draw on care and support. These challenges around choosing the most appropriate example of the technology are exacerbated by a rapidly changing marketplace populated by numerous smaller start-up companies that provide new and sometimes optimistically described technology. The final theme relates to the management of what can sometimes seem unrealistic expectations of the technology compared with the actual impact it can have on social (as opposed to health) care. The extent of these expectations is not aided by the lack of demonstrable evidence of the efficacy of much of this new technology.

| Key themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Understanding the functionality of digital technologies | Technology not being used to its full potential in social care |

| Gaps in understanding of new and emerging technology in particular | |

| Selecting appropriate digital technology | Little information to support stakeholders in selecting technology |

| Importance of the voices of people who draw on care and support and carers | |

| Fast pace of change of the technology market and challenges this poses to the use of technology for social care | |

| Managing expectations | A lack of evidence concerning the outcomes expected by key stakeholders (including commissioners and providers, people who draw on care and support and carers) |

| Predominance of health over social care outcomes |

Key informant interviews

We spoke to strategy and technology leads, commissioners and programme managers from across our case study sites. The interviews covered three key topics. First, we discussed the key areas that might be explored in our evaluation and the nature of the questions that should be asked of senior managers and care staff. Second, we discussed potential challenges and solutions when undertaking research of this kind. Third, we explored the practicalities of trying to collect data from a diverse workforce and a range of people who draw on care and support and carers, especially in a challenging policy context. This helped to ensure that stage 2 of our study was designed in such a way as to ask the right questions, generate helpful learning and ensure our methods of recruitment and data collection were practical and appropriate.