Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/1002/34. The contractual start date was in June 2010. The final report began editorial review in July 2012 and was accepted for publication in November 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Coombs et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Increasing pressure from technological developments and changes in legislation and government policy has meant that change can be regarded as a continuous feature of the contemporary health-care environment. 1 The ability of health-care managers or organisations to adapt and respond to change engendered by these stimuli is vital if they are to succeed in such an environment. Whether at the level of the individual or the organisation, change typically involves not only the learning of new behaviours, ideas or practices, but also giving up, or abandoning, some established ones. Despite both of these elements being equally important to change, there has been a significantly greater academic focus on processes of learning and acquiring new knowledge and practices than on processes of abandoning or giving up established knowledge and practices. 2 The objective of this study is to make a contribution to addressing this neglect through undertaking a detailed examination of individual-level processes of abandoning or giving up knowledge, which is more formally defined as unlearning.

The concept of individual unlearning

The capability to unlearn is important as the inability to give up or abandon knowledge, values, beliefs and/or practices can produce a rigidity in thinking and acting, and can create a blinkered outlook, limiting a health-care manager's or organisation's adaptability. 3 This can occur when existing views are never questioned or challenged, for example through the use of ‘defensive routines’. 4 The inability to question what may have been successful organisational norms, values, practices and knowledge can create what have been referred to as ‘competency traps’,5 in which useful competencies become outdated through never being challenged, revised or abandoned. Thus, the ability of health-care managers or organisations to unlearn established knowledge, behaviours or values can be a significant catalyst to and facilitator of change.

The analysis developed in this report builds from and extends the work of Tsang and Zahra,2 who developed a conceptual analysis of organisational-level unlearning processes. Tsang and Zahra 2 concluded their article by suggesting which areas of knowledge on unlearning are still limited and which require development (p. 1454). One key area where knowledge is particularly limited is the dynamics and character of individual-level processes of unlearning, and how they connect to and interact with organisational learning and unlearning. Individual-level processes of unlearning represent a neglected topic in an under-researched field, in which analysis has been relatively limited. Our concern here is to take a first step towards addressing this gap in knowledge.

Rushmer and Davies6 argue that distinctions can be made between three separate types of individual unlearning. The first type of individual unlearning that they identify, which they label fading, refers to the slow gradual process of unlearning that can occur over time, when particular skills and capabilities are forgotten through a lack of usage. This form of unlearning is typically not experienced as being significant or challenging for people, and because of the gradual way that it occurs people may not be conscious that they are experiencing it. The second type of individual unlearning identified by Rushmer and Davies is labelled wiping. This represents a more significant, deliberate and conscious form of unlearning. Wiping is a form of unlearning focused relatively narrowly on a particular practice, or activity, in which a person consciously unlearns through making deliberate efforts to give up a particular way of thinking/acting, as a precursor to changing these beliefs/practices. Rushmer and Davies argue that this process of unlearning may be initiated by some external catalyst, such as a change initiative, which places demands on people to change their ways of working and/or thinking. The third form of individual unlearning identified by Rushmer and Davies is deep unlearning. Deep unlearning represents a radical form of unlearning that typically occurs rapidly and unexpectedly, and is experienced by people as significant as it brings into question some basic assumptions and values. Because of these characteristics this form of unlearning can produce significant emotions (fear, confusion, etc.) in the people who experience it. Rushmer and Davies argue that some external catalyst, such as an event whose characteristics or outcomes are unexpected, initiates deep unlearning. A key difference between this form of individual unlearning and wiping is the speed at which the change is made and the emotional impact associated with the experience. Deep unlearning is argued to be a fast process involving high emotional impact for the individual experiencing the unlearning.

Context of the study

The central focus of this study was on examining the extent to which health-care managers engage in processes of individual unlearning. A typical catalyst for individual unlearning is processes of change that require the adaptation of working practices. 2 The pace of change in the NHS in recent years has been significant. For example, Greener7 talked about how the ‘pace and scope of change’ was ‘intense’ (p. 206). Thus, as a result of the amount of ongoing change in the NHS, all health-care managers are likely to have experiences of individual unlearning, in which they have had to adapt their work practices and routines as a result of change. Further, individual unlearning may also be experienced by health-care managers who have undergone a significant role transition, such as would happen when a clinician moves into a managerial role. For example, a clinician moving into a clinical management position may need to adapt the way he or she uses knowledge to act and make decisions, as anecdotal evidence suggests that clinical and managerial decision-making processes are underpinned and supported by different knowledge bases. Clinicians moving into managerial roles thus arguably need to engage in processes of individual unlearning to effectively adapt how they act and make decisions in the new managerial roles they occupy. The lack of research on the topic of individual unlearning means that there is a limited understanding of how frequently health-care managers experience it or the type of events/circumstances that trigger it. Therefore, in this study we also investigated the triggers to individual unlearning with all participating health-care managers.

This research was also concerned with understanding the barriers to and enablers of individual unlearning that exist. Although individual unlearning has the potential to be an important component in the processes of learning and change, research suggests that there are many barriers to unlearning at both the individual and the team/organisational level, which means that learning from mistakes, failure and crisis often does not happen. 8 Similar observations can be made regarding enablers to individual unlearning. For example, Becker9 argues that, to enable staff to have a positive attitude to change and consequently to unlearning, managers need to demonstrate commitment, make the case for change, involve staff in planning and provide reassurance. Other examples of enablers include having secure but challenging conversations with trusted colleagues,6 and the informal support of colleagues and managers9,10 and mentors. 10 The small amount of research on unlearning6 and learning from failure that has been carried out in the health sector suggests that this is a work context in which the barriers and enablers to unlearning can be significant. However, our understanding of the key barriers to and enablers of different forms of unlearning remains sketchy.

Existing research also suggests that NHS managers with clinical and non-clinical backgrounds may have a different approach to issues such as accountability, use of guidelines and finance. It has been argued that these differences are a result of each discipline's training, beliefs and experiences. 11 Similarly, there is evidence to suggest that clinicians and managers have different priorities concerning health-care delivery: clinicians tend to prioritise patient care, whereas managers focus more on cost. 12 Research by Guven-Uslu13 suggests that these different mindsets influence how managers with a clinical background are likely to approach decision-making compared with those without clinical experience. Given the increased emphasis that is being given to encouraging clinicians into leadership and managerial roles,14 these different mindsets are likely to become increasingly more significant to the efficient running of the NHS. Therefore, the individual unlearning processes associated with significant change, such as changes in role, may also have implications for the way that health-care managers review and reflect on their decision-making processes, and ultimately how they make future decisions.

Thus, there is a need for more research to understand the nature of individual unlearning in the health-care environment. The main aims of this study were to examine whether or not health-care managers engage in processes of individual unlearning, and the individual- and/or organisational-level barriers that may inhibit effective unlearning and learning from occurring or facilitate it. It also explored the implications of individual unlearning for managerial decision-making in the health service.

This study investigates these aims through an examination and synthesis of the academic literature concerning the processes of individual unlearning, and capturing and analysing health-care managers' experiences of individual unlearning. The study utilised a case study approach, investigating experiences of unlearning in two different types of NHS trust (an acute trust and a mental health trust). A case study-based approach represents a suitable methodology for the investigation of individual unlearning because, as outlined, individual unlearning is a relatively neglected and unexplored aspect of learning and change processes, and qualitative case studies provide an effective way to conduct exploratory research, which can give rich, qualitative insights into managers' experiences of individual unlearning. 15,16

Within each organisation, the main source of data was face-to-face, one-to-one, semistructured, qualitative interviews with a range of health-care middle managers. The purposive sample participants varied in terms of clinical/non-clinical background, type of department/unit and length of time as a manager. A total of 29 health-care managers were interviewed across both sites, which captured a total of 57 episodes of unlearning and 28 episodes of fading. The participants were also invited to attend a workshop to hear about initial findings and to comment on those findings.

Contributions

Although this original exploratory study is relatively small in scale, with the data drawn from 29 health-care managers from two NHS trusts, it still provides a number of important contributions. First, we have developed the concept of individual unlearning. We argue that individual unlearning is a distinctive type of learning, involving a conscious decision to give up knowledge, values or behaviours. However, this abandoned knowledge is not permanently lost but put to one side, and it remains retrievable for future use. Using this conceptualisation of unlearning, we argue that the category of fading proposed by Rushmer and Davies6 is more akin to a process of unintentional forgetting rather than unlearning. Indeed, fading may not enter individuals' consciousnesses unless they are invited to identify lost skills or capabilities. Therefore, as unlearning requires conscious and intentional action, it is questionable whether or not fading can be conceptualised as unlearning.

Second, we conceptualise two distinct types of individual unlearning and their differentiating features and dynamics. The first type of unlearning (behavioural) is triggered by a deliberate process of change that has been externally imposed. We argue that behavioural unlearning has a bidirectional relationship with organisational change and that an individual's attitude to change may shape his or her attitude to unlearning. A significant weakness in the unlearning literature is its neglect of people's attitudes to unlearning, an area that must be considered when attempting to understand individual behavioural-type unlearning processes. The second type of individual unlearning (cognitive) is triggered by an unexpected external event that questions some basic assumptions of the individual. We argue that it is important to recognise that the cognitive unlearning process is emotionally challenging, but may not occur suddenly or produce an instant change in behaviour.

Third, we develop a new typology that distinguishes between four separate types of individual unlearning, as shown in Table 1. Previous research on unlearning6 proposes that each type of individual unlearning is linked to a different type of catalyst. Thus, using Rushmer and Davies'6 labels, change events are the catalyst for wiping (behavioural unlearning), whereas individual experiences are the catalyst for deep unlearning (cognitive unlearning). However, during the course of data collection it became apparent that this distinction between catalysts was questionable, as the catalysts for both wiping and deep unlearning included both individual experiences and change events. Thus, our analysis suggested that, although the distinction between unlearning types was useful, as was the distinction between types of catalyst, Rushmer and Davies' typology could be improved through a recognition that specific catalysts were not associated with each type of unlearning. This led us to reconceptualise their typology (see Table 1). This was carried out by combining Rushmer and Davies' two types of unlearning, which results in a typology that distinguishes between four separate types of individual unlearning.

In addition, with two exceptions,6,17 the literature on this topic defines unlearning as the conscious and intentional abandoning of skills, behaviours and values, whereas fading equates to forgetting and is unconscious and unintentional (see Chapter 2, Types of individual unlearning and the nature of individual unlearning processes, Fading). De Holan and Phillips18 take this further by distinguishing between memory loss or accidental forgetting and unlearning, which is intentional. In our view, lack of conscious action means that fading is more akin to unintentional forgetting than unlearning, hence the exclusion of fading from the typology.

| Catalyst of unlearning | Type of unlearning | |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioural unlearning (wiping) | Cognitive unlearning (deep unlearning) | |

| Individual experience | Behavioural unlearning initiated by individual experience | Cognitive unlearning initiated by individual experience |

| Change event | Behavioural unlearning initiated by change event | Cognitive unlearning initiated by change event |

Another way in which we reconceptualised Rushmer and Davies' typology6 was by relabelling wiping as behavioural unlearning and deep unlearning as cognitive unlearning. The reason for doing this was to create labels for the unlearning types that were more explicit and clear regarding what was being unlearned, as supported by our empirical data analysis. In this new typology, ‘behavioural unlearning’ refers to the individual unlearning of specific behaviours such as practices, activities or routines, which have no (or limited) impact on people's underlying knowledge, values and assumptions. As in Rushmer and Davies' model,6 behavioural unlearning, like wiping, does not have a significant affective impact. Deep unlearning, which is relabelled ‘cognitive unlearning’, is emotionally charged as it involves giving up or abandoning more deeply held knowledge, values and assumptions. In making this distinction, we further found that, although behavioural unlearning may be restricted to this domain, cognitive unlearning is likely to be accompanied by or lead to behavioural unlearning. However, it must be emphasised that the typology was developed from the data analysis and informed by a review of the relevant literature and that Rushmer and Davies' unlearning typology was the initial perspective utilised to differentiate between different types of unlearning.

Fourth, our study also considers the influence of unlearning on health-care managers' decision-making, a variable that has not been examined in other unlearning studies. Our study provides evidence to suggest that individual unlearning can impact on some health-care managers' decision-making processes. This impact involves managers moving away from an idea imposition process of decision-making to a discovery-led process of decision-making. The discovery-led process has been argued in the literature to be more successful and, therefore, the findings from this study suggest that there may be a relationship between health-care managers who engage with individual unlearning and improvements in decision-making.

Fifth, our study involved a type of research data not previously utilised in this domain – qualitative interview data – which give insights into how individual health-care managers understand the changes that their unlearning experiences have produced.

Structure of the report

In the following chapter we review in more detail the literature concerning unlearning. The chapter clarifies and develops the unlearning concept before reviewing the academic literature on unlearning. The types of individual unlearning are discussed along with the nature of the individual unlearning process. The chapter also provides a summary of recent change in the NHS, which provides the context for the study. The chapter concludes with the research questions that the study investigated.

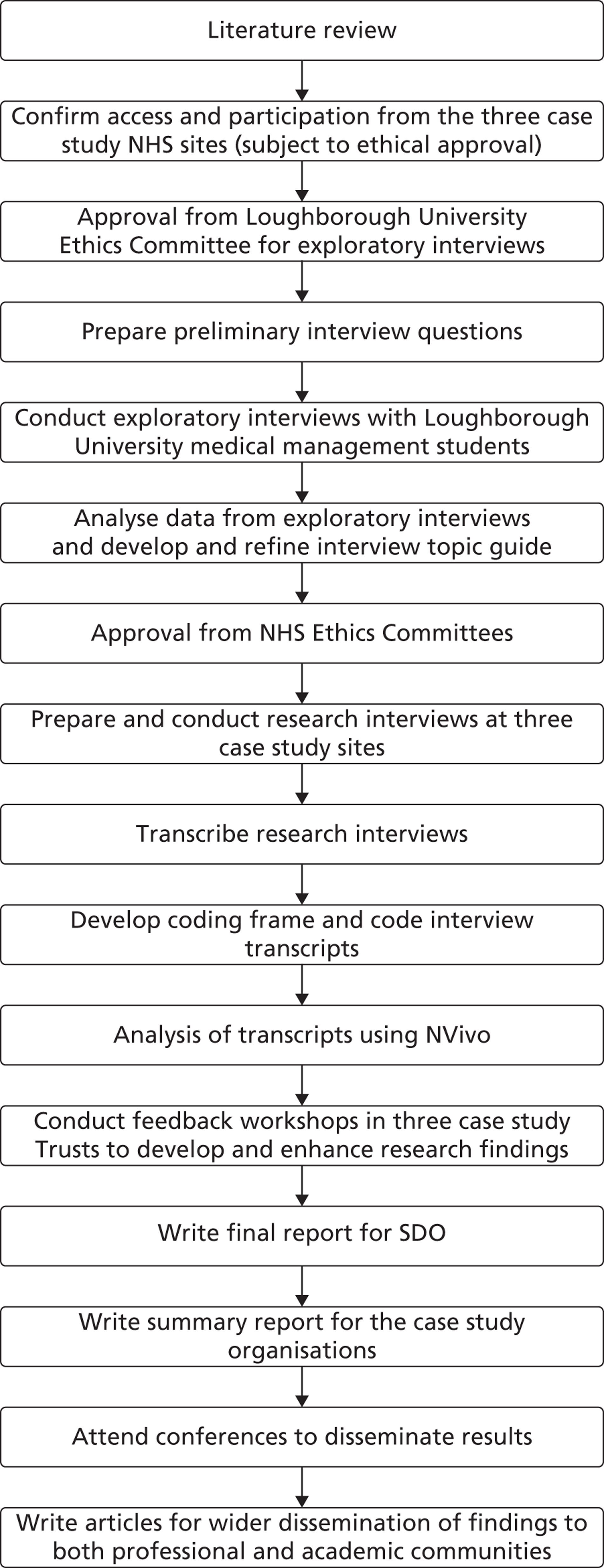

Chapter 3 discusses the key methodological considerations for the study. The choice of research strategy, selection of case study sites and processes of data collection and analysis are explained. The chapter also provides a description of the case study sites.

Chapter 4 presents the findings of the study and reflects on the research objectives presented at the end of Chapter 2. It is divided into six main sections. Episodes of individual unlearning and fading describes the nature of unlearning and fading episodes and the ways in which health-care managers experience unlearning and fading. Barriers to individual unlearning and Enablers of individual unlearning and fading report, respectively, the barriers to and enablers of unlearning and fading that were identified by participants. The impact of individual unlearning and fading on managers' decision-making reports the influence of individual unlearning on decision-making and the changes that participants had made in relation to the different types of unlearning experienced. The influence of health-care setting and professional background on health-care managers' individual unlearning and fading reports the analysis examining whether health-care context or the professional background of participants differentiated participants' experiences of individual unlearning and fading. Finally, Workshop findings provides a summary of the key findings from the workshop conducted at each case study site.

Chapter 5 discusses the key findings of the report in relation to the study research objectives and the existing literature. It also provides a discussion of the relationship between learning, unlearning and change that became evident during the course of the study. Finally, conclusions, limitations, recommendations for future research and implications for practice are presented in Chapter 6.

Chapter 2 Background

Introduction

This chapter draws on a range of literature to suggest that the process of individual unlearning may have particular features. The analysis of individual unlearning presented here is based on a review of the contemporary academic literature on unlearning, but to help address themes that are relatively unexamined by this literature it also draws on a wider body of work on learning and change. After the chapter unpacks and defines the concept of unlearning, it presents the details of the literature search that was conducted. Following this is a large section that differentiates between two different types of individual unlearning, and which suggests that each type of individual unlearning may have its own distinctive features and dynamics. The final two sections summarise recent changes in the UK health-care sector and present the research questions of the study.

Clarifying and developing the unlearning concept

Thus far, ‘unlearning’ has been very broadly defined as abandoning or giving up knowledge, ideas or behaviours. This is in contrast to ‘learning’, which has been defined as increasing one's capacity to take effective action through the addition of new skills or knowledge. 19 However, to fully understand the concept of unlearning it is necessary to define it in greater detail. Although unlearning can be traced back to the 1950s, until recently it has been largely neglected in the literature on learning and knowledge management. Akgün et al. 20 trace the origins of unlearning to literature on learning and cognitive psychology published in the 1950s and 1960s. Another perspective on unlearning emerged in the 1950s, which explored ‘unlearning . . . the inherent dominative mode’ in relation to Western thinking about the ‘other’ (p. 376). 21 The ‘other’ referred to how people in the West view people or perspectives they regard as non-Western. Unlearning in this context concerned Westerners trying to think beyond their own perspective to take account of others. 21 Indeed, some educational literature22 applied Williams'21 meaning to understand how trainee teachers could unlearn their attitudes to ethnic minority and working-class young people. Similarly, Mavin et al. 23 utilise unlearning in the same sense and suggest that an unlearning process is necessary to challenge the unquestioned and unchallenged gender-blind and male-biased character of the academic business and management literature.

In the business and management literature unlearning tends to be linked to one or more of organisational learning, change and memory,2,8,9,20 knowledge management24,25 or human resource management. 26 However, some authors draw on more than one discipline, relate unlearning to individuals and/or groups and locate the concept in the disciplines of education and learning2,22,27 or psychology. 26

If unlearning involves the giving up or abandonment of knowledge, values or behaviours, it needs to be acknowledged that this can happen both unconsciously and deliberately. The unconscious or accidental giving up of something is typically referred to as forgetting, as it occurs over time through particular knowledge or behaviours becoming unused and eventually forgotten. 6,17 This process of forgetting contrasts with deliberate unlearning, which involves a process of consciously choosing to abandon or give up particular knowledge, values or behaviours. As with Tsang and Zahra,2 the assumption here is that unlearning is a conscious and intentional process and, as such, is distinct from forgetting. De Holan and Phillips18 agree about the deliberate nature of unlearning, although they do not distinguish in the same way as others between forgetting and unlearning. Indeed, for them, ‘managed unlearning’ is one of four modes of forgetting old knowledge.

A second area of difference in the unlearning literature relates to whether or not the knowledge or behaviours being given up are obsolete, outdated and in some way inferior to new knowledge or behaviours that are subsequently acquired. As highlighted in Table 2, a number of articles make this assumption. 24,28,29 Thus, for example, Srithika and Bhattacharyya28 define organisational unlearning as ‘the identification or removal of ineffective or obsolete knowledge’ (p. 68). However, making such a value judgement regarding the inferiority of the knowledge to be abandoned is unnecessarily restrictive and judgemental. Thus, similar to Tsang and Zahra,2 we suggest that it is more appropriate to define unlearning simply as abandoning or giving up knowledge or behaviours without making any judgement on the status of the knowledge or behaviours being unlearned.

In considering individual unlearning, an issue that is typically neglected is what happens to the knowledge or behaviours that people unlearn. It is important to acknowledge that what is unlearned is not permanently lost by people such that they are unable to think or act in the way that they had done previously. Arguably, the only ways that particular capabilities could become permanently lost are through some type of medical or neurological intervention (drugs, surgery, etc.), through developing an illness or having an accident (such as having a stroke or a car accident that results in brain injury) or through lack of use over a long time period. Thus, the type of deliberate individual unlearning considered here does not involve the permanent loss of something, but instead involves a person putting particular values, knowledge or behaviours ‘to the side’ and consciously choosing not to continue using them. Thus, individual unlearning in this sense is not necessarily permanent because, either consciously or unconsciously, people may at some point in the future begin to reuse that which they had previously abandoned or unlearned. An example of this would be when someone changed how he or she undertook a task by returning to do it in a way that had been previously abandoned.

The final issue in developing the concept of unlearning is how it is relates to learning. Tsang and Zahra2 consider that unlearning may precede learning, occur simultaneously with learning or occur independently of learning. However, the dominant perspective regarding the relationship between the sequencing of unlearning and learning is that unlearning is a unique stage and is a prerequisite to, and a precursor of, learning. 20,26,30–32 For example, Cegarra-Navarro et al. 30 define unlearning as ‘the elimination of obsolete knowledge’, which is regarded as a necessary precursor to learning, or ‘the creation and absorption of new knowledge’ (p. 901). However, an alternative way to conceptualise the relationship between unlearning and learning is to consider unlearning as a distinctive type of learning. 33 This is the perspective utilised by Argyris and Schön,34 who argued that ‘we may also speak of the particular kind of learning that consists of “unlearning”: acquiring information that leads to subtracting something (an obsolete strategy, for example) from an organisation’s existing store of knowledge’ (pp. 3–4).

In summary, in examining individual unlearning this section suggests that individual unlearning should be conceptualised as a distinctive type of learning. It involves a conscious process of choosing to give up knowledge, values or behaviours. No value judgement should be made regarding the value or status of what is abandoned, and that what is unlearned is not permanently lost to people and may be utilised again at some point in the future.

Reviewing the academic literature on unlearning

Although Tsang and Zahra2 conducted a partial review of the unlearning literature, their central focus was organisational-level unlearning rather than individual unlearning. Their review identified 34 separate pieces of work. However, they do not specify the boundaries of the search that was conducted to produce this list, with it including book chapters and journal articles published over a wide time frame.

Because of the multidisciplinary nature of the interest in the topics of learning and unlearning, we searched several management (Business Source Complete, Emerald), psychological (PsycINFO), health (MEDLINE) and education [Education Resources Information Center (ERIC)] electronic databases for English-language articles that were published between January 2000 and March 2012. We searched for articles that had ‘unlearning’ in the title, abstract or keywords. Additionally, we searched for articles on ‘abandoning behaviour or knowledge’ and ‘giving up behaviour or knowledge’. This search generated over 330 articles. From these sources we concentrated on those published in peer-reviewed scientific journals, leaving 261 articles. After removing duplicate search results we examined the abstracts of these articles and excluded studies that reported on animal-based, psychological or memory experiments. We also excluded personal viewpoint and unreferenced opinion articles, leaving approximately 100 articles. After a first round of reading of the collected articles, we selected those articles that investigated the topic of unlearning, either theoretically or empirically. This led to the exclusion of articles that used the term ‘unlearning’ in the abstract or title, but which were not fundamentally concerned with investigating it as a topic. Although the focus in this article is fundamentally on individual-level unlearning, our initial review included all articles on unlearning, whether they were focused on individual-, team- or organisational-level unlearning (see Tables 2 and 3). We also searched the reference lists of all sources collected and performed citation searches, which resulted in the addition of several relevant articles.

A total of 34 articles2,3,6,9,10,20,22–26,28–32,37–49 were identified for analysis (Table 2). An initial observation from the list is that < 35 relevant articles were identified in a time period of over 10 years, which highlights the extent to which the concept of unlearning is neglected and underdeveloped. This neglect is in stark contrast to the considerable level of interest in the topic of learning since the mid-1990s. 5,35,36

In terms of how the literature defines unlearning (see Table 2, column 2), although many authors develop their own particular form of words, what is noticeable about the way that unlearning is defined (also found to be the case by Tsang and Zahra2) is the striking degree of homogeneity that exists. What is common to these definitions is that unlearning involves ‘abandoning’, ‘eliminating’, ‘rejecting’, ‘discarding’ or ‘giving up’ something – with that something being particular values, assumptions, knowledge or behaviour at the individual level, and knowledge, assumptions or routines at the organisational level.

In terms of the type of unlearning examined, as Table 3 highlights, there has been a greater focus on organisational or group or team unlearning (21 articles2,3,20,23,24,26,28,31,37,40,42–44,46,47,50–54) than on individual-level unlearning (16 articles6,9,10,22,23,25,26,29,30,32,37–39,41,45,48). In this context, group or organisational unlearning, as with organisational learning, refers to norms, assumptions, behaviours and routines that are collectively shared and understood. 20,24 Although a few articles look at multiple levels of unlearning,37 or the inter-relationship between different levels of unlearning,38 the vast majority of articles focus on one level of unlearning alone.

| Author | Definition of unlearning | Topic | Details of empirical study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cegarra-Navarro et al.39 | Unlearning defined as ‘the changing of beliefs, norms, values, procedures and routines’ (p. 234) | How organisational context can counteract the negative effects of counterknowledge and facilitate individual unlearning | Survey of 164 small- and medium-sized enterprises in the Spanish construction industry |

| Wong et al.40 | Presents multiple definitions used by others – no clear definition | Develops and tests conceptual model to study effect of unlearning on the relationship between organisational learning and organisational success | Survey of 200 professionals in consultant offices and contractor firms in Hong Kong |

| Cegarra-Navarro et al.41 | No formal definition of unlearning | How organisational context facilitates individual unlearning of technology knowledge in a health-care environment | Survey of 117 nurse managers and medical managers |

| Cegarra-Navarro et al.42 | No formal definition of unlearning | How organisational context facilitates unlearning and influences organisational performance | Survey of 263 Spanish metal industry firms |

| Lee43 | Team unlearning defined as ‘ability . . . to change beliefs and routines to address rapidly changing environments’ (p. 1843) | Studies role of challenge and hindrance stressors on team unlearning | Survey of 200 new product development teams based in three science parks in Taiwan |

| Lee and Sukoco44 | Organisational unlearning defined as ‘actively reviewing and breaking down the organisation's long-held routines, assumptions, and beliefs’ (p. 412) | Studies role of team reflexivity and team stress on unlearning and product innovation | Survey of 200 new product development teams based in three science parks in Taiwan |

| Low45 | Presents multiple definitions used by others – no clear definition | Explores the antecedents of individual unlearning | Three focus groups with a total of 25 educators |

| Pighin and Marzona46 | Unlearning defined as ‘throwing away concepts learnt in the past to give space for possible new learning’ (p. 59) | Examines role of unlearning for business process re-engineering based on the reorganisation of information systems | Single case study |

| Zahra et al.47 | Uses Tsang and Zahra's2 definition of organisational unlearning: ‘the discarding of old routines to make way for new ones, if any’ (p. 324) | How organisational context may influence unlearning and entrepreneurial capability | None – conceptual article |

| Becker9 | ‘A process of releasing old ways’ (p. 252) | Examines factors that facilitate and inhibit unlearning during a change process | Survey of people involved in change in one Australian company |

| Casillas et al.24 | Organisational unlearning defined as per Cegarra-Navarro and Mayo37 as eliminating ‘ineffective and obsolete knowledge and routines’ (pp. 162–3) | How organisational unlearning affects internationalisation | Survey of 103 Spanish small- and medium-sized enterprises |

| Cegarra-Navarro et al.30 | Individual unlearning defined as ‘the elimination of obsolete knowledge’, which is regarded as a necessary precursor to learning (‘the creation and absorption of new knowledge’) (p. 901) | How organisational context facilitates individual unlearning | Semistructured interviews with nine staff in a Spanish regional hospital |

| Cegarra-Navarro et al.48 | Individual unlearning defined as in Cegarra-Navarro et al.30 | How unlearning affects knowledge of the business environment | Survey of 127 Spanish hospitality companies |

| Conner22 | Unlearning defined as ‘any time when prospective teachers describe instances or ways in which they come to recognize and rethink previously held views and attitudes’ (p. 1171) | Role of unlearning in changing perspectives and attitudes of low-income urban youth | Interviews with and survey of 21 prospective educators |

| Yildiz and Fey49 | Use Tsang and Zahra's2 definition of organisational unlearning: ‘the discarding of old routines to make way for new ones, if any’ (p. 450) | Develops theoretical model regarding the role of organisational unlearning in knowledge transfer processes | None – conceptual article |

| Srithika and Bhattacharyya28 | Organisational unlearning defined as the ‘identification and removal of ineffective or obsolete knowledge’ (p. 68) | How appreciative inquiry (a particular type of organisational development intervention) can facilitate the process of organisational unlearning | None – conceptual article |

| Becker10 | Presents multiple definitions used by others – no clear definition | Examines factors that facilitate and inhibit unlearning during a change process | Qualitative case studies of change in three Australian companies (23 interviews) |

| Tsang and Zahra2 | Organisational unlearning defined as ‘the discarding of old routines to make way for new ones, if any’ (p. 1437) | Developing understanding of the concept of organisational unlearning | None – literature review |

| Tsang50 | Organisational unlearning defined as ‘the discarding of old routines to make way for new ones’ (p. 7) (does not have the ‘if any’ element of definition in Tsang and Zahra2) | How organisational unlearning affects knowledge transfer processes | Interview-based study of a number of technology transfer joint venture initiatives |

| Akgün et al.51 | Unlearning defined as ‘changes in beliefs and routines in the organisation’ (p. 207) | How environmental turbulence affects team unlearning and team unlearning affects team performance | Survey of 197 firms in north-east region of the USA |

| Akgün et al.20 | Individual and organisational unlearning defined as ‘eliminating memory’ (p. 797) | Develops understanding of the unlearning concept through linking it to the literature on change and organisational memory | None – conceptual article |

| Fotaki31 | Unlearning defined as ‘the absence of in-depth questioning of predominant paradigms’ (p. 1063) | Lack of learning by UK and Swedish governments in relation to patient choice regarding health care | None – conceptual article |

| Rebernic and Sirec29 | Abandoning ‘obsolete tacit knowledge’ (p. 406) | The problems and challenges related to managing and unlearning tacit knowledge | None – conceptual article |

| Cegarra-Navarro and Sanchez-Polo38 | Definition of individual unlearning not clearly specified | The effect that individual unlearning had on organisational relearning | Survey of 130 small- and medium-sized enterprises in the Spanish telecommunications sector |

| Cegarra-Navarro and Dewhurst25 | Individual unlearning defined as a ‘process in which obsolete and misleading knowledge is rejected’ (p. 50) | How organisational context facilitates individual unlearning | Survey of 139 Spanish optometrists |

| Akgün et al.3 | Team unlearning defined as ‘changes in beliefs and routines’ (p. 73) | How the business environment affects team unlearning, as well as some consequences of this | Survey of 319 new product development teams in the USA |

| Becker et al.26 | Unlearning defined as ‘the process by which individuals and organisations acknowledge and release prior learning (including assumptions and mental frameworks) in order to accommodate new information and behaviours’ (p. 610) | The extent to which different types of organisation take account of unlearning in human resource development interventions | Survey of 70 Australian human resource and operational managers |

| Cegarra-Navarro and Moya37 | Individual unlearning defined as ‘the capacity of individuals to reflect on their performance in order to identify and promote actions that will result in improved performance’ (p. 162) | How individual and group unlearning contribute to organisational performance | Survey of 139 Spanish optometrists |

| Rushmer and Davies6 | Individual unlearning defined as ‘getting people to stop doing things’ (p. 10) | Developing the concept of unlearning by examining processes of unlearning and distinguishing between different types of unlearning | None – conceptual article |

| Rampersad52 | No formal definition of unlearning | Developing analysis that regards change as fundamentally involving learning and unlearning | None – conceptual article |

| Mavin et al.23 | Defines unlearning as ‘raising and challenging taken for granted assumptions’ (p. 572) | The ‘gender-blind’ and male-biased nature of management education | None – conceptual article |

| Sheaffer and Mano-Negrin53 | Defines unlearning as ‘systematically rethinking and overhauling prescribed procedures, programmes, policies, and strategies underlying flexible corporate vision’ (p. 581) | Assesses the extent to which companies' unlearning capability predicts their crisis preparedness | Survey of 130 chief executive officers or vice-presidents for human resource management in Israeli firms |

| Sinkula54 | Organisational unlearning defined as ‘process by which firms eliminate old logics and make room for new ones’ (p. 255) | Develops a conceptual model to map how organisational unlearning is linked to organisational performance | None – conceptual article |

| MacDonald32 | Transformative unlearning regarded as a complex, challenging and lengthy process; about giving up established practices/knowledge/assumptions that may be linked to sense of identity | Develops understanding of the character, dynamics and emotional challenges of ‘transformative unlearning’ | Detailed reflection on personal experience |

| Author | Individual or organisational unlearning | Aspect of unlearning examined (antecedent, process or consequences) |

|---|---|---|

| Cegarra-Navarro et al.39 | Individual | Antecedent |

| Wong et al.40 | Organisational | Consequences |

| Cegarra-Navarro et al.41 | Individual | Antecedent |

| Cegarra-Navarro et al.42 | Organisational | Antecedent |

| Lee43 | Team | Antecedent |

| Lee and Sukoco44 | Organisational | Antecedent |

| Low45 | Individual | Antecedent |

| Pighin and Marzona46 | Organisational | Antecedent |

| Zahra et al.47 | Organisational | Antecedent |

| Becker9 | Individual | Antecedent |

| Casillas et al.24 | Organisational | Consequences |

| Cegarra-Navarro et al.30 | Individual | Antecedent |

| Cegarra-Navarro et al.48 | Individual | Consequences |

| Conner22 | Individual | Antecedent |

| Yildiz and Fey49 | Organisational | Consequences |

| Srithika and Bhattacharyya28 | Organisational | Process |

| Becker10 | Individual | Antecedent |

| Tsang and Zahra2 | Organisational | Process |

| Tsang50 | Organisational | Consequences |

| Akgün et al.51 | Team | Antecedent and consequences |

| Akgün et al.20 | Organisational | Antecedent and process/types of unlearning |

| Fotaki31 | Organisational | Consequences |

| Rebernic and Sirec29 | Individual | Consequences |

| Cegarra-Navarro and Sanchez-Polo38 | Individual | Consequences |

| Cegarra-Navarro and Dewhurst25 | Individual | Antecedent |

| Akgün et al.3 | Team | Antecedents and consequences |

| Becker et al.26 | Individual and organisational | Antecedent |

| Cegarra-Navarro and Moya37 | Individual and team/group | Consequences |

| Rushmer and Davies6 | Individual | Process/types of unlearning |

| Rampersad52 | Organisational | Process |

| Mavin et al.23 | Individual and group | Consequences |

| Sheaffer and Mano-Negrin53 | Organisational | Antecedent |

| Sinkula54 | Organisational | Consequences |

| MacDonald32 | Individual | Process |

Another difference in the focus of the reviewed articles was whether they examined the antecedents, process or consequences of unlearning. The largest proportion of articles (n = 183,9,10,20,22,25,26,30,39,41–47,53) examined the antecedents of unlearning, with unlearning facilitated by the organisational context,9,25,30 environmental turbulence51 and organisational size. 26 A total of 133,23,24,29,31,37,38,40,48–51 of the reviewed articles examined the consequences of unlearning, with unlearning argued to be related to a diverse range of processes and outcomes including knowledge transfer processes,49,50 processes of internationalisation,24 the non-academic impact of academic scholarship,33 organisational performance37,54 and health-care policies. 31 Finally, only 62,6,20,28,32,52 of the 34 articles examined the character and dynamics of unlearning processes.

Table 3 also reveals that of the 34 articles reviewed only two6,32 focused on individual processes of unlearning. These are the articles by Rushmer and Davies6 and MacDonald. 32 Further, of these two only MacDonald32 presents any empirical evidence, which was a reflection on personal experience. Thus, to say that there is a conceptual and empirical gap in knowledge with regard to the process of individual unlearning is an understatement.

The following utilises the work of MacDonald32 and Rushmer and Davies6, as well as some other literature on learning and change, to consider the character and dynamics of the process of individual unlearning. In so doing it is suggested that distinctions can be made between different types of individual unlearning.

Types of individual unlearning and the nature of individual unlearning processes

As has been outlined thus far, distinctions can be made between individual- and organisational-level unlearning, and between the unlearning of values/assumptions, beliefs, skills, knowledge and/or behaviours. A number of authors go beyond these distinctions to construct distinctive categories of unlearning. 6,51,54 For example, Akgün et al. 51 develop a typology that links differences in the nature of the business environment to the character of organisational unlearning. Sinkula54 on the other hand distinguishes between the unlearning of axiomatic knowledge and the unlearning of procedural knowledge. Here, axiomatic knowledge is defined as fundamental unquestioned beliefs and values, and procedural knowledge is considered to be equivalent to Argyris and Schön's34 concept of ‘theory in use’, referring to the tacit knowledge that shapes the way that people act.

However, the categorisation proposed by Rushmer and Davies6 is the most relevant to individual unlearning as they propose a useful distinction between three possible separate and distinctive types of individual unlearning: fading, wiping and deep unlearning (Table 4). Each type of unlearning is argued to differ in respect of catalyst, intentionality, speed and impact. First, fading or routine unlearning occurs gradually over time through lack of use. It is regarded as neither significant nor challenging for people. Indeed, fading may not enter individuals' consciousness unless they are invited to identify lost skills or capabilities.

| Category | Fading | Wiping | Deep unlearning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst | Lack of use | Imposed change event | Unexpected individual experience |

| Level/type of impact on individual (identity, values, knowledge, behaviour) | Minor and unproblematic | Mainly behavioural, but may involve abandoning knowledge | Typically significant – not only behaviour/knowledge questioned but also values and/or identity |

| Speed of unlearning | Slow | Variable, but not necessarily sudden | Sudden |

| Extent of emotional impact/challenge | Minimal | Variable, but not necessarily significant | Typically significant |

Wiping is the second category of individual unlearning identified by Rushmer and Davies. 6 The catalyst for wiping is a change initiative external to the person. Wiping can be defined as a process of unlearning that results from a deliberate process of change that has been externally imposed, for example a change initiative or a change in job role. Wiping is deliberate, conscious and more significant than fading, and is typically focused on a relatively narrow practice or activity, with a person consciously making deliberate attempts to give up a particular way of thinking and acting as a precursor to changing his or her beliefs and practices.

Parallels between wiping and categories of unlearning developed by other authors can be discerned. For example, wiping is similar to ceasing a particular behaviour and making incremental change8 and to intentional forgetting of new or existing knowledge. 18 The notion of wiping is reinforced and extended by other categories such as ‘operational level unlearning’, whereby performance routines (enacted by individuals) and ostensive routines (codified systems) are discarded as a result of evolutionary, continuous, incremental change. 2 Wiping is also similar to ‘adjustive unlearning’, in which incremental changes in beliefs are accompanied by fundamental changes in routine, and to ‘operative unlearning’, which involves small-scale changes in beliefs and routines. 51

The third category of individual unlearning proposed by Rushmer and Davies6 is deep unlearning. This radical form of unlearning is argued to occur rapidly as a result of an external event whose characteristics and/or outcomes are unexpected, and which bring into question some basic assumptions. Characteristically, it has a significant impact on the individuals who experience it, leading them to question their values and beliefs, and possibly their frame of reference. As a consequence, deep unlearning may be accompanied by challenging emotions such as anxiety, fear and confusion. Thus, in contrast to wiping, deep unlearning is more likely to involve the unlearning of values and assumptions.

Like wiping, the notion of deep unlearning is echoed elsewhere. Baumard and Starbuck8 talk about challenging core beliefs and Tsang and Zahra2 characterise deep unlearning as discarding values and norms as a result of episodic, discontinuous change. Deep unlearning is also similar to reinventive unlearning and formative unlearning identified by Akgün et al. 20,51 Reinventive unlearning occurs when an organisation changes both beliefs and routines in response to a changing and highly unpredictable environment, whereas formative unlearning occurs when new beliefs structures are combined with incremental routine change. Finally, there are similarities between deep unlearning and what MacDonald32 defines as transformative unlearning (see Deep unlearning).

Finally, linking back to the idea that unlearning represents a distinctive type of learning, it can be suggested that, although wiping has parallels with single-loop learning (incremental learning or change in which basic assumptions remain unchallenged), deep unlearning can be equated more with double-loop learning (learning or change in which existing assumptions and values are questioned and reflected on).

The above definitions and descriptions provide only a brief overview of the general character of fading, wiping and deep unlearning processes. Thus, to develop a fuller understanding of the dynamics and character of the processes of fading, wiping and deep unlearning it is necessary to consider them in more detail. The definitions suggest that there are significant differences between the ways that people experience and understand fading, wiping and deep unlearning, and in the process dynamics of fading, wiping and deep unlearning. Therefore, it is useful to consider each separately, which is presented in the following three subsections.

Fading

Rushmer and Davies6 argue that unlearning could be considered as a process that will automatically occur when the factors that sustain the original learning are removed. Schein55 refers to unlearning as the forgetting curve, which suggests that some past learning will simply fade away over time. Rushmer and Davies6 propose that, with simple behavioural actions, this passive replacement can be seen as moving down the unlearning curve. They give an example of a health-care professional comprehending a new, altered, mandatory health form. The professional may first puzzle over the new layout and in completing the form may make errors through an erroneous habitual response. However, Rushmer and Davies argue that, as the health-care professional continues to complete the form, familiarity and confidence are gained with the new layout. The old way of completing the form recedes, discomfort and previous expectations fade and forgetting takes place.

However, as unlearning requires conscious and intentional action it is questionable whether or not fading should be conceptualised as unlearning. A lack of conscious action suggests that fading is more akin to a process of unintentional forgetting, rather than unlearning. Even authors who use the term ‘forgetting’ in their definitions of unlearning18,30 identify intentionality or purposefulness as defining characteristics of unlearning. We could not find any other studies that conceptualise passive unlearning, possibly because of the difficulty of investigating the concept. Without longitudinal study it would be very hard to gather data on learning that had been unintentionally forgotten, as by definition the participant could struggle to identify it. For this study we decided to continue to use the fading category for the purposes of empirical testing and fulfilling our original project proposal. This allowed us to examine the concept of fading and the value of this element in Rushmer and Davies'6 categorisation.

Wiping

In terms of the relationship between unlearning and change, the dominant perspective in the unlearning literature is that unlearning is a facilitator of change. 2,9,10,23,31,38,50 Although this may be true in relation to wiping (see Table 4), it also needs to be acknowledged that the relationship works in the opposite direction, with external change acting as the prime catalyst for wiping. Thus, in the context of wiping, the primary reason why people engage in unlearning is because it is perceived as being a necessary element of a specific organisational change initiative. This is articulated explicitly in a textbook on change,56 which, in talking about the importance of change for contemporary organisations, says that ‘people are being required to unlearn old ways and develop new competencies’ (p. 7).

Although much of the unlearning literature suggests that the relationship between unlearning and change is close, it has considered only unlearning as being a facilitator of change and has not examined the relationship between unlearning and change in any detail. Consequently, the literature provides limited insight into how change can be a facilitator of wiping, or how individuals experience the character and dynamics of the process of wiping.

The most useful article for considering the bidirectional relationship between unlearning/wiping and change is the conceptual article by Akgün et al. 20 In talking about the relationship between unlearning and change it refers explicitly to Lewin's57 three-stage model of change. This very simplified and much criticised model of change suggests that change happens through the sequential processes of unfreezing, change and refreezing (see Akgün et al.,20 pp. 800–1; Hayes,56 p. 52). Akgün et al. assume that unlearning and learning together constitute the second stage in Lewin's model. This conceptualisation of the wiping/change relationship, with unlearning being at the centre of change, highlights the bidirectional nature of the change/wiping relationship. However, the focus of Akgün et al.'s20 article is on organisational-level unlearning/wiping and, thus, it does not provide insights into the character and dynamics of individual-level unlearning/wiping.

Tsang and Zahra2 also examine the relationship between learning, unlearning and organisational change. They distinguish between different types of change (continuous and episodic) and suggest that each type of change will involve a distinctive form of unlearning. They define continuous change as change that is incremental and gradual in character. By contrast, episodic change is typically discontinuous and infrequent and is greater in scope than continuous change. Episodic change can also be linked to a process of double-loop learning in which basic assumptions are challenged. Thus, in relation to the types of unlearning considered here, continuous change can be linked more to wiping, whereas episodic change can be linked more to deep unlearning.

As wiping is so closely inter-related with processes of organisational change, it is useful to refer to some change-related concepts. In this context, if organisational change provides the catalyst for wiping/unlearning, people's attitude to unlearning is likely to be closely linked to and virtually inseparable from their attitude to the change process that precipitated it. Thus, if people do not regard the changes being undertaken as favourable they are unlikely to have a positive attitude to any unlearning that flows from the change. Equally, if the opposite is the case and people do regard change as necessary and important, they are likely to have a more positive attitude to any unlearning it precipitates. Although Tsang50 does not explicitly use the concept of resistance to change, the reluctance to unlearn and learn that he found in relation to the knowledge transfer processes that were examined can be argued to constitute resistance to change.

The concept of resistance to change is useful when considering people's attitudes to change and unlearning. The change literature suggests that, because of the uncertainty caused by change, resistance is common. A key theme in the change literature is concerned with anticipating, managing and minimising any potential resistance to change. 56 Although some of the unlearning literature touches on the topic of resistance to change,47,52 people's attitudes to unlearning are neglected. This neglect may be because of the assumption that people will embrace wiping-type unlearning relatively willingly. However, this assumption represents an important omission because people's attitude to unlearning is likely to be shaped by their attitude to change. Thus, to understand the character and dynamics of individual-level wiping-type unlearning processes it is fundamentally necessary to take account of people's attitudes to the changes that precipitated them.

Deep unlearning

In examining how individuals experience deep unlearning and the process through which it unfolds, few of the unlearning articles reviewed are relevant. Of the six articles2,6,20,28,32,52 that focus on the process of unlearning (see Table 3), only two examined processes of deep unlearning,6,32 with the other four concerned with individual and organisational unlearning, which is more equivalent to wiping. In tentatively outlining a model for the dynamics of the process of deep unlearning this section draws on MacDonald's32 empirical and conceptual work and links it with some wider, relevant literature on learning.

MacDonald32 suggests that the process of what she labels ‘transformative unlearning’, which has much in common with deep unlearning, has three distinctive but overlapping steps. The key features of transformative unlearning that resonate with deep unlearning are that it involves questioning, reflecting on and giving up some core values, assumptions, knowledge and practices, and also that this process is deeply emotional and challenging for people to undertake. Similar to the mainstream perspective in the unlearning literature, MacDonald conceptualises unlearning as a necessary precursor to learning, and that both together are interlinked components of change. Finally, the catalyst for transformative unlearning is a process of change that brings a person's pre-existing values, assumptions knowledge and practices into question.

The first stage in MacDonald's model is receptiveness, in which a person accepts the possibility that there are perspectives and viewpoints that challenge his or her assumptions and that he or she is prepared to consider these perspectives. Following this is the second stage of recognition, which is the process through which a person acknowledges the veracity of these alternative viewpoints, and the limitations that exist in his or her own perspectives. Finally is the process of grieving, which she suggests is the emotional core of transformative unlearning, whereby a person comes to terms with ‘the loss of prior ways of seeing – the loss of fundamental assumptions which until now had brought certainty and security’ (p. 174). It is only after these three stages of the transformative unlearning process have been undertaken that a person is able to effectively change and learn new assumptions, knowledge and practices.

MacDonald's32 model can be illustrated by summarising the example she uses, which involves her own experiences as a practising nurse in relation to changes in the recommended sleeping position for infants following research on cot death, or sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). In the 1970s and 1980s, the generally accepted and unquestioned practice was that babies were put to sleep in the prone position (lying on their front with the head to the side). This was a practice that MacDonald not only recommended to young mothers but also used with her own children. However, research in the early 1990s into the causes of SIDS suggested that putting infants to sleep in a supine position (lying on the back or side) reduced the risk of SIDS. Being aware of and reading this research represented the process of receptivity for MacDonald. However, this process was not quick or easy as it challenged ideas and practices she had taken for granted her whole working life. As more research emerged in the early to mid-1990s on the causes of SIDS, and as MacDonald read more of it, she entered the recognition phase in which she started to accept the validity of the new perspective on infant sleeping positions and began to accept the need to change her own assumptions and practices. This process was facilitated by dialogue with other nurses who were also going through the same process. However, before she was able to comfortably and fully accept the need for this change, MacDonald suggests that it was necessary to go through a process of grieving in which she came to terms with the fact that current research and advice suggested that her previous knowledge and practices had their limitations. This was argued to be the most emotional aspect of the unlearning process as it ‘touched the emotional core of my identity as a nurse’ (p. 174). As with the process of recognition, this process of grieving was facilitated by dialogue and communication with others.

Although this model of the process of transformative unlearning has resonances with Rushmer and Davies'6 concept of deep unlearning, it also differs from it in two key respects. First, the catalyst for transformative unlearning was external change rather than some specific incident or experience. Second, a more significant difference was the timescale over which transformative unlearning occurred. Although Rushmer and Davies suggest that deep unlearning involves a sudden and rapid realisation of the need for change, and an equally sudden process of change, in MacDonald's model transformative unlearning was a slow process that occurred over a period of years. As both transformative and deep unlearning involve the emotionally challenging process of unlearning fundamental assumptions and values, they represent comparable forms of unlearning. However, what MacDonald's perspective highlights is that not all deep unlearning occurs through the sort of sudden Archimedean epiphany which produces an instantaneous change in behaviour. Although particular events may lead people to question their values and assumptions, it may take more time for behavioural change to follow.

Two other process models of learning from the learning literature also have potential relevance to understanding the character of deep unlearning processes. First is Garud et al.'s58 narrative model for learning from what they call ‘unusual experiences’. Unusual experiences are defined as ‘situations that bear little or no resemblance to the types of experiences that have occurred in the past’ (p. 587). Although Garud et al. talk of learning rather than unlearning, there is the potential that, in making sense of unusual experiences, people's assumptions, values and practices may be brought into question and a process of individual unlearning may be undertaken, in which certain values and/or behaviours are abandoned and changed. However, although the narrative model that they develop for how people make sense of unusual experiences may have some relevance to understanding the dynamics of individual unlearning processes, a major limitation of their framework is the lack of consideration given to emotional issues. Despite acknowledging that making sense of unusual experiences involves reflecting on basic assumptions, and that dialogue with others in doing so may result in contrasting perspectives, issues of emotion are not considered. For this reason, Garud et al.'s model is not considered appropriate for understanding the dynamics of the process of deep unlearning.

A final very general model that is relevant for understanding the process of deep unlearning, which has some synergy with MacDonald's model, is the process of organisational inquiry outlined by Argyris and Schön,34 which takes inspiration from the work of the pragmatist philosopher John Dewey. Similar to deep unlearning, and Garud et al.'s58 unusual experiences, the catalyst for a process of inquiry is the experience of doubt, which is defined as the experience of a ‘problematic situation’, triggered by a mismatch between the expected results of action and the results actually achieved. Such experiences, they argue, inhibit continued action and encourage a process of reflection/inquiry aimed at resolving the doubt. Thus, the start of this process of inquiry can be considered equivalent to the initial stage of receptiveness in MacDonald's32 model, with the objective of resolving the sense of doubt that has been experienced, providing the primary catalyst to this receptiveness. The process of inquiry outlined by Argyris and Schön34 is relatively generic and lacking in detail but it involves combining reflection and action as well as an active process of dialogue with others. The ultimate aim of this process of inquiry is doubt resolution, whereby the mismatch that was experienced is made sense of. Arguably, this process of inquiry is equivalent to both the receptiveness and the grieving stages of MacDonald's model. Once the process of inquiry has resulted in the doubt that was experienced being resolved, this makes it possible for learning and change to occur, whereby people adapt their knowledge and actions to take account of the recently experienced mismatch.

Overall, therefore, MacDonald's three-stage model of dealing with transformative unlearning provides a useful template for understanding how people experience and make sense of what is referred to here as deep unlearning. However, as the only empirical illustration of this model is MacDonald's reflections on her own experience, further research is necessary to empirically test and evaluate this model before its validity can be established. As has been revealed by reviewing the literature on individual unlearning types, change can feature as the catalyst to individual unlearning and unlearning can trigger further change. Therefore, the following section briefly reviews the literature concerning individual-level transitions in change theory.

Reviewing the literature concerning individual-level transitions in change theory

When examining individual attitudes to and experiences of change there are two main literatures of relevance: resistance to change and emotion/attitude to change. The following reviews each of these literatures and considers how they may relate to individual unlearning.

Organisational change has been studied from many perspectives with the use of many methods. 59 In their literature review, Armenakis and Bedeian60 identified five themes in the change literature: content issues, which deal with the substance and nature of a particular change; contextual issues, which deal with forces and issues that exist in an organisation's internal and external environment; process issues, which examine the actions taken to implement change; criterion issues, which focus on outcomes from organisational change efforts; and affective and behavioural reactions to change. It is the last category that is of most interest to this study.

Resistance to change is a concept that is frequently discussed in conjunction with the unfreezing stage of Lewin's57 change model. It is often presented as a negative barrier to change, defined as a restraining force acting to maintain the current state of equilibrium. 61 Traditional approaches to resistance to change frame compliant behaviours as non-resistant and non-desirable behaviours as resistant. The early solution presented to overcome resistance was to increase employee participation. 62 However, Lawrence63 argued that this was an oversimplified solution to resistance and that change had both technical and social characteristics. It was a lack of attention to the latter that often led to resistance to change. Lawrence's view was that attitudes were important in how managers think about resistance to change and that expecting resistance to change from employees often delivered resistance.

In his review of the literature Foster59 observes that other scholars have conceptualised resistance to change as an emotional reaction rather than a purely behavioural one. For example, Argyris and Schön64 discussed resistance in terms of defensive routines and frustration, and Kanter65 refers to feelings of uncertainty and loss of control in understanding individual responses to change. Klarner et al. 66 argue that the literature concerning emotions during change can be divided into two parts. First, some studies in change management focus on employee behaviour as a result of emotions evoked during change. Second, other studies have used psychological stage models to explain the relationship between emotions and employee behaviour during change. Both of these parts are considered briefly below.

It has been argued that emotion drives the adaptive behaviour of employees in response to change. 67 This adaptive behaviour involves learning new strategies and being resilient to setbacks. 68 Several studies have considered the behavioural outcomes of employees who show either positive or negative emotions. It has been argued that failure to emotionally adapt to change leads to resistance among employees. 69 For example, resistance can lead to withholding of participation during change events. By contrast, Avey et al. 68 found that positive emotions could help individuals cope and could create support for the change. Positive emotions were found to increase the level of commitment and emotional engagement to the organisation, even in times of disruption. 70 However, Piderit71 has argued that dichotomising individual responses to change as either altogether negative or altogether positive is an unhelpful oversimplification. Piderit71 proposes that conceptualising resistance to change as multidimensional would help account for the possibility of ambivalence or mixed feelings towards change, and presents a tripartite attitudinal model of resistance to change that includes three components: emotional (affective), intentional (behavioural) and cognitive. She concludes that the term ‘resistance to change’ is inaccurate and unhelpful, and does not provide the best framework for understanding organisational change implementation. Ford et al. 72 add that, by assuming that resistance is necessarily bad, change agents have missed potential contributions that could help build awareness and momentum and eliminate unnecessary or counterproductive elements, increasing the likelihood of successful implementation of change. Both Piderit71 and Foster59 conclude that studies at the individual level would be better served using the term ‘response to change’. Further, Klarner et al. 66 argue that studies on emotions during change treat change as a snapshot event but would be better served by characterising change as a process, with the result that emotions could evolve during change. Klarner et al. 66 add that studies often focus on single change but neglect to consider the repetitive nature of change that occurs in many organisations and that emotion should also be examined as a continual construct.

Studies in human resource management and organisational behaviour have also attempted to use psychological stage models to explain the relationship between triggers for employee emotions, coping behaviours and change outcomes. 66 It has been argued that the trigger for the change process can produce strong emotions as well as the change itself. 73 Other studies have looked at the relationship between employee emotions and coping behaviour during change. Smith and Lazarus74 advocate psychological appraisal theory to explain this relationship, with the employee engaging with an appraisal process that considers the implications of the change for his or her personal goals and well-being. The appraisal process shapes the individual emotional response, which is translated into specific coping behaviour. These coping strategies can influence the organisational change outcome. 75 Positive employee emotions towards change can increase engagement, affecting the emotions of other team members. 76 By contrast, resistance to change is demonstrated by disengagement, which can hamper effective change. 68 Klarner et al. 66 contend that these stage models suffer from the same deficiencies as those of change management studies that have examined emotion. The studies tend to consider emotions as either positive or negative rather than considering multiple possible emotions during change. They treat change as a snapshot event and fail to consider how emotions may evolve during a change process, with different events during a change process triggering different emotions. Consequently, they call for more studies that consider the evolving character of emotions during a change process, as well as studies that consider employees' emotions during repeated change.

Reflecting on the literature presented in this section suggests synergies between individual unlearning and individual transitions from change. Several studies have proposed that a catalyst to unlearning can be an organisational change event. 2,6 Therefore, individual unlearning may be part of the adaptive behaviour process that employees experience as a result of change. Employees may be required to give up or abandon some previous strategies or knowledge as well as learning new ones, and this abandonment may trigger strong emotions. MacDonald32 argues that the unlearning process can involve giving up some core values, assumptions, knowledge and practices, which can be challenging and deeply emotional for people to undertake. Similarly, studies of individual transitions during change have found that employees report feelings of uncertainty, loss of control and frustration and enact defensive routines. 64,65 Positive emotions have been found to increase commitment and engagement with change, but may also demonstrate an increased willingness to engage with individual unlearning, seeing it as an opportunity to refresh old thinking and knowledge. Therefore, it is possible that employee emotions during change may also influence their engagement with unlearning processes, which may explain how employees respond and adapt to change.

Emotion has also been linked to decision-making processes, the main outcome of interest for this study, and the following section reviews the decision-making literature in relation to individual unlearning.

Reviewing the academic literature on decision-making

In reviewing the literature concerning individual decision-making and decision-making processes we examined the learning, knowledge management and organisational behaviour fields. By searching for literature published from 2005 we identified 29 articles that considered learning and decision-making in the article title, but we found none of these articles to be directly relevant to this study. Similarly, since 2005, 11 articles had been published that included knowledge management and decision-making in their titles, but these also did not provide any further insights for this study. Neither field provided any new material regarding unlearning and decision-making. However, searches in the organisational behaviour field were more successful, especially concerning work psychology, which is most relevant to this study because of its focus on the individual. Consequently, the following discussion draws heavily from this discipline.