Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 08/1809/233. The contractual start date was in January 2009. The final report began editorial review in August 2012 and was accepted for publication in January 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Bill Noble has received funding from an academic journal for board membership and has received funding from charitable organisations and the Department of Health to attend conferences. Jane Seymour has received funding from an academic journal for board membership, has undertaken consultancy for international bodies, has received grants from a range of UK and international funders and has received royalties from a UK publisher.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Gott et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Report structure

The report itself is presented in the following nine chapters, which are presented in the order the research took place. Below we outline the content of each chapter, along with selected published outputs arising from each chapter. A full list of our outputs is provided at the end of the report (see Appendix 6). Further publications are currently being prepared or are under review.

Chapter 1 provides the policy background to the study; presents the study aims and objectives; and provides an overview of the study design.

Chapter 2 discusses the role of the Palliative Care Studies Advisory Group, a group of service users that was established to support the project. Extracts of this chapter have been published as follows:

-

Palliative Care Studies Advisory Group. Service user involvement in research: a briefing paper by the Palliative Care Studies Advisory Group. Sheffield: University of Sheffield; 2012.

Chapter 3 presents two systematic reviews of the literature, which informed subsequent data collection and analysis. Extracts of this chapter have been published as follows:

-

Gardiner C, Ingleton C, Gott M, Ryan T. Exploring the transition from curative care to palliative care: a systematic review of the literature. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2011;1:56–63.

-

Gott M, Ward S, Gardiner C, Cobb M, Ingleton C. A narrative literature review of the evidence regarding the economic impact of avoidable hospitalisations amongst palliative care patients in the UK. Prog Palliat Care 2011;19:291–8.

-

Green E, Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C. Communication surrounding transitions to palliative care in heart failure: a review and discussion of the literature. Prog Palliat Care 2010;18:281–90.

Chapter 4 summarises findings from qualitative focus groups and interviews conducted with health-care professionals to explore their views of palliative care transitions within the acute hospital setting. Extracts of this chapter have been published as follows:

-

Gardiner C, Cobb M, Gott M, Ingleton C. Barriers to the provision of palliative care for older people in acute hospitals. Age Ageing 2011;40:233–8.

-

Gott M, Bennett M, Ingleton C, Gardiner C. Transitions to palliative care in acute hospitals in England: qualitative study. BMJ 2011;342:d1773 (republished as Gott M, Bennett M, Ingleton C, Gardiner C. Transitions to palliative care in acute hospitals in England: qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2011;1:42–8).

-

Gott M, Seymour J, Ingleton C, Gardiner C, Bellamy G. ‘That’s part of everybody’s job’: the perspectives of health care staff in England and New Zealand on the meaning and remit of palliative care. Palliat Med 2012;26:232–41.

-

Ryan T, Gardiner C, Bellamy G, Gott M, Ingleton C and nursing staff. Barriers and facilitators to the receipt of palliative care for people with dementia: the views of medical and nursing staff. Palliat Med 2012;26:879–86.

Chapter 5 presents the findings of the survey of palliative care needs and management conducted at the two study sites. Extracts of this chapter have been published as follows:

-

Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C, Cobb M, Seymour J, Ryan T, et al. Extent of palliative care need in the acute hospital setting: a survey of two acute hospitals in the UK. Palliat Med 2013;27:76–83.

-

Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C, Richards N. Palliative care for frail older people: a cross-sectional survey of patients at two hospitals in England. Prog Palliat Care 2013; in press.

-

Gott M, Gardiner C, Ingleton C, Cobb M, Noble B, Bennett M, et al. What is the extent of potentially avoidable admissions amongst hospital inpatients with palliative care needs? BMC Palliat Care 2013;12:9.

-

Gott M, Ingleton C, Gardiner C, Seymour J, Parker C, Ryan T. Prevalence and predictors of transition to a palliative care approach amongst hospital inpatients in England. J Palliat Care 2013;29:146–52.

-

Ingleton C, Gardiner C, Richards N, Seymour J, Gott M. Exploring education and training needs amongst the palliative care workforce. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:207–12.

-

Ryan T, Ingleton C, Gardiner C, Parker C, Gott M, Noble B. Symptom burden, palliative care need and predictors of physical and psychological discomfort in two UK hospitals. BMC Palliat Care 2013;12:11.

-

Ward S, Gott M, Gardiner C, Cobb M, Richards N, Ingleton C. Economic analysis of potentially avoidable hospital admissions in patients with palliative care needs. Prog Palliat Care 2012;20:147–53.

Chapter 6 considers the findings of the qualitative interviews conducted with patients meeting diagnostic and prognostic criteria for palliative care need. Extracts of this chapter will be published as follows:

-

Richards N, Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C. Awareness contexts revisited: indeterminacy in initiating discussions at the end of life. J Adv Nurs 2013; in press.

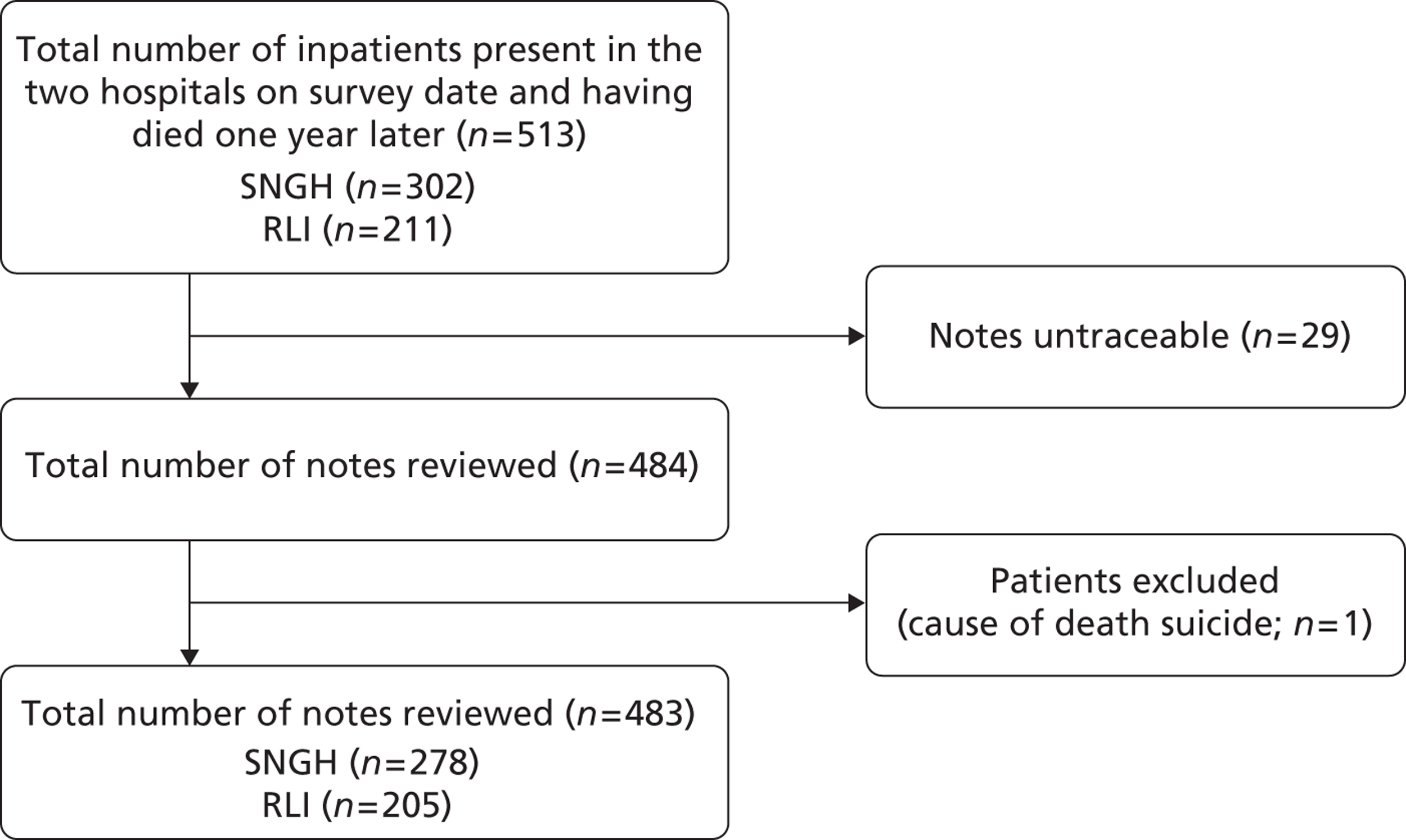

Chapter 7 presents the results of the retrospective review of case notes conducted for patients who were present in the hospitals at the time of the survey and who had died in the subsequent 12 months.

Chapter 8 provides a summary of information collected from focus groups convened with key health- and social-care professionals in the two study localities to explore their views of key findings.

Chapter 9 presents the final study conclusions within the context of the existing evidence base and discusses their implications for future research.

Extracts from the following articles have been reprinted with permission from SAGE:

-

Gardiner C, Gott M, Ingleton C, Cobb M, Seymour J, Ryan T, et al. Extent of palliative care need in the acute hospital setting: a survey of two acute hospitals in the UK. Palliat Med 2013;27:76–83 by SAGE Publications Ltd, All rights reserved. © Gardiner et al.

-

Gott M, Seymour J, Ingleton C, Gardiner C, Bellamy G. ‘That’s part of everybody’s job’: the perspectives of health care staff in England and New Zealand on the meaning and remit of palliative care. Palliat Med 2012;26:232–41 by SAGE Publications Ltd, All rights reserved. © Gott et al.

-

Ryan T, Gardiner C, Bellamy G, Gott M, Ingleton C and nursing staff. Barriers and facilitators to the receipt of palliative care for people with dementia: the views of medical and nursing staff. Palliat Med 2012;26:879–86 by SAGE Publications Ltd, All rights reserved. © Ryan et al.

Chapter 1 Background to the study

In this chapter we provide a brief background to the study, highlighting the rationale for undertaking research focusing on palliative care management for older people in acute hospital settings in England. The policy context relevant to the study is also discussed, with a particular focus on policy recommendations specific to the acute hospital setting. Finally, this chapter presents the study aims and objectives and gives an overview of the overarching study design.

Introduction

This report was prepared at a time of considerable challenge for those charged with planning the future provision of palliative and end-of-life care services. An almost twofold increase in the number of people dying globally is predicted over the next 40 years, with particularly dramatic rises expected in the proportion of people living to, and therefore dying in, their ninth and tenth decades. 1 Overarching these demographic trends are worries about the future funding of care in the face of a global economic recession2 and gradually emerging recognition that the mid-20th-century model of palliative care is no longer fit for purpose. Indeed, it is now widely acknowledged that older people, who will represent an ever-increasing majority of those requiring end-of-life care in the future, are the ‘disadvantaged dying’3 because they do not fit with classical 20th-century understandings of who needs palliative care and who delivers it. It is within this context that the World Health Organization has identified addressing the ‘substandard care’ that older people receive at the end of life as a key public health concern. 4 In England, improving palliative care provision for older people has been recognised as an NHS priority; however, there are still clear gaps in the evidence base needed to underpin much-needed improvements in service delivery and organisation.

The UK policy context

This project started shortly after the publication in England of a landmark policy document: the End of Life Care Strategy for England. 5 This is a national manifestation of a broader international trend towards resituating ‘palliative care’ within public health policy6 and human rights discourses. 7 Long-standing debates about whether such care should be ‘five star’ care for the few8 or whether its legitimate focus should be confined largely to dying cancer patients have now largely ceded to new debates about the relationship between ‘generalism’ and ‘specialism’ in palliative care;9 how to encourage widespread planning for incapacity;10 and how to aid transitions to palliative care in the face of the rapidly rising incidence of long-term conditions and the overall ageing of the population, which mean that clear designations of ‘terminal illness’ are increasingly rare. 11

Proposed fundamental changes to the NHS, in which primary care trusts (PCTs) will be replaced by clinical commissioning groups12,13 responsible for commissioning services in line with the needs of patients within localities, bring into sharp focus the urgent need to move beyond simple models of palliative care to ensure that patients approaching death are appropriately supported in complex care systems. 14 The National Council for Palliative Care15 has advised that each commissioning group has an end-of-life care lead, precisely because of this complexity.

Palliative care in acute hospitals

An area of particular policy priority recently has been the provision of palliative and end-of-life care in acute NHS hospitals. 16 A number of high-profile reports have concluded that a proportion of patients dying in these settings ‘experience very poor care’ (p. 1). 16 As 90% of people spend time in hospital in their final year of life17 and 56% of all deaths occur in this setting,18 this ‘proportion’ translates into a significant number of patients receiving poor care, the vast majority of whom will be older people. The proportion of deaths in institutionalised settings (including acute hospitals) has been predicted to rise by > 20% in the next 20 years. Although more recent data suggest that there may be the beginnings of a shift towards an increasing proportion of home deaths in the UK,19 the reality is that significant numbers of patients will continue to require care in hospital in their last 12 months of life. Ensuring high-quality palliative care provision in hospital must therefore be prioritised.

There is evidence that the extent of palliative care need amongst hospital inpatients is high. In a survey of palliative care needs in an acute hospital in Sheffield in 2001, medical and/or nursing staff identified that 23% of the 453 inpatients in their care had palliative care needs (according to a standard definition). 20 Three-quarters of these patients were aged > 60 years, with the greatest proportion aged between 81 and 90 years. Only 2% had received specialist palliative care input, and any palliative care that they were receiving was ‘generalist’ in nature (i.e. provided by health professionals with no accredited training in palliative care). A survey conducted in France in 1999 reported that only 13% of total hospital beds were occupied by palliative care patients. 21 A more recent study in 2011 reported that 9.4% of hospital patients in Belgium were identified as having palliative care needs. 22 However, both of these studies used the subjective judgement of ward-based medical and nursing staff to identify patients with palliative care needs, rather than using an objective measure.

Nevertheless, acute hospitals obviously do represent a significant site of palliative and end-of-life care management in England, as reflected in the growing body of policy guidance directed at these settings from professional bodies and the Department of Health (DoH). At the time of designing the study, palliative care policy and practice within acute NHS hospitals focused primarily on the period immediately before death. The Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP),23 promoted by the End of Life Care Programme24 for use on all acute hospital wards, remains the most widely adopted end-of-life care ‘tool’ within this setting. However, it has been increasingly argued that attention needs to be paid to palliative care needs earlier in the disease trajectory. 25,26 Geriatric medicine, for example, has promoted the concept of ‘continuous palliation’, a care approach incorporating palliative care from the point of diagnosis of a life-limiting illness onwards. 27

More recently the AMBER care bundle (see www.ambercarebundle.org; accessed June 2013) has been developed to support clinicians in decision-making about care and treatment of hospital patients who are at risk of dying in the next 1–2 months. Although some early audit data suggest that this initiative is successful in improving patient outcomes, at the time of preparing this report limited data were available on this initiative.

A focus on ‘transitions’ within the acute hospital context

In 2010 the General Medical Council (GMC)28 published guidance on end-of-life care that is particularly pertinent to the focus of the current study. This guidance states that doctors must ensure that death becomes an explicit discussion point when patients are likely to die within 12 months, and is in line with one of the central tenets of the End of Life Care Programme, namely that health professionals recognise when patients are likely to be entering the last year of life and ensure an appropriately managed transition to a palliative approach to care. 5 Midway through the current project, the National End of Life Care Programme29 published specific and comprehensive guidelines regarding how to manage palliative care transitions within the context of acute hospital settings. The guidelines advocate ‘good honest communication’, ‘advanced care planning’ and ‘access to tailored information’ as crucial for optimising the provision of palliative care in the hospital setting.

The following are identified as key steps in ensuring a well-managed palliative care transition: recognising when the patient is in the last 12 months of life, understanding that the patient has palliative care needs and building consensus within the clinical team as to how these should be addressed, effectively communicating the team consensus to patients and their families, and ensuring that patients are offered opportunities to express preferences for end-of-life care that are recorded and subsequently acted on.

It is within this context that the present study aimed to address the need to improve palliative care management within acute hospitals through a focus on ‘transitions’. For the purposes of this study we defined ‘transition’ as a change in the approach to a patient’s care from ‘curative treatment’ (in which the focus is on cure or chronic disease management) to ‘palliative care’ [in which the focus is on maximising quality of life (QoL)]. Transitions in care may or may not be associated with a change of care setting. The transition will not be complete or unproblematic in all cases. Indeed, many experts now recommend that curative and palliative approaches to treatment are adopted concurrently,30 particularly for older people31 for whom adopting a transition late in the disease trajectory can lead to ‘missed opportunities for palliation’ (p. 2). 29 How this process is managed within acute hospitals, however, remains unknown.

The extent to which a transition in care setting to the acute hospital corresponds to a transition in care approach is also unclear, although repeat hospitalisations have been identified as a trigger for moving to a palliative approach in certain conditions. 32

This study aimed to clarify these ‘unknowns’ by examining the extent and nature of palliative care transitions within the acute hospital setting. Adopting a proactive approach to palliative care management through a managed transition in care may result in several tangible benefits for both patients and the wider NHS. These include facilitating patient involvement in advance care planning (when desired) and enabling a proactive care plan to be developed. There is also evidence that many more people are dying in acute hospitals than would wish. 33 Not only does this result in people not having the death that they would have chosen, but it also incurs significant unnecessary financial costs for the NHS. Health-care costs are most significant in the last 3 years of life, with high rates of hospitalisation. As such, this study also explored the economic impact of potentially avoidable hospital admissions amongst patients nearing the end of their life.

Research aim and objectives

Research aim

To examine how transitions to a palliative care approach are managed and experienced in acute hospitals and to identify best practice from the perspectives of older patients and key service providers and commissioners.

Research objectives

-

To explore the extent and current management of palliative care need within acute hospitals.

-

To identify patient factors that are predictive of key aspects of palliative care need and, in particular, physical and psychological symptom load.

-

To examine the circumstances under which transitions to a palliative care approach occur within acute hospitals, with a particular focus on the influence of age and disease type on decision-making.

-

To explore how decisions to move to a palliative care approach are made and who is involved in decision-making.

-

To examine if and how information about a transition to a palliative care approach is communicated to patients and their families and how they are involved in decision-making.

-

To explore the perspectives of patients, service providers and commissioners regarding acute hospital admissions and discharges associated with a transition in care.

-

To identify those hospital admissions amongst people with palliative care needs that were avoidable but which occurred because of a lack of alternative service provision or support in the community.

-

To identify patient factors predictive of avoidable hospital admissions.

-

To quantify the cost of avoidable acute hospital admissions amongst those patients with palliative care needs.

Study design

The research aims were addressed using a mixed-methods approach informed by a pragmatic philosophy. 34 Mixed-methods approaches are recommended for the study of complex issues in which multiple but inter-related objectives are being addressed. In this study we used techniques of both complementarity (in which findings from one method are used to elaborate or clarify findings from another method) and development (in which findings from one method are used to inform the other method). 35 The study was conducted in the following phases:

-

phase 1: two systematic literature reviews were conducted to inform data collection and analysis

-

phase 2: exploratory focus groups and interviews were held with 58 key health- and social-care professionals to determine survey methodology

-

phase 3: a survey of palliative care need and management amongst inpatients at the two settings was conducted, which involved collecting information from patients, the key medical and nursing professionals responsible for their care, and patient notes

-

phase 4: in-depth interviews were conducted with 15 patients identified in the survey as having palliative care needs

-

phase 5: 12 months following the survey a review was conducted of the case notes of all hospital inpatients who were present in the two hospitals on the first day of the surveys but who died in the subsequent 12 months

-

phase 6: interviews and focus groups were convened with key health- and social-care professionals and service commissioners/planners to discuss the implications of the study in the two study settings.

Detailed methodological information about each study phase is provided in the relevant chapter.

Study settings

UK National Health Service

The UK National Health Service (NHS) was launched in 1948 and is the world’s largest publicly funded health service. With the exception of charges for some prescriptions and optical and dental services, the NHS remains free at the point of use for anyone who is resident in the UK, currently more than 62 million people. The Department of Health is responsible for the NHS, which is funded centrally from national taxation. NHS services in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales are managed separately. The NHS employs more than 1.7 million people. 36

Hospital settings

The settings selected for inclusion in this study were two acute NHS hospitals in England: the Sheffield Northern General Hospital (SNGH) and the Royal Lancaster Infirmary (RLI).

These settings were selected because they serve sociodemographically distinct populations. The RLI serves a predominantly white Caucasian semi-rural/remote rural population. By contrast, the SNGH services a largely urban, more economically disadvantaged and ethnically diverse area. A brief overview of the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patient populations and health services of relevance to the study is provided in the following sections to provide context to our findings.

Sheffield Northern General Hospital

The SNGH is the largest hospital campus within the Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, with approximately 1100 inpatient beds. The catchment population for tertiary referrals is 1.3 million and the local population is 500,000. The results of the 2010/11 national NHS Inpatient Survey37 placed Sheffield Teaching Hospitals in the top 20% of NHS trusts for patient satisfaction. As part of the national Transforming Community Services programme, adult community services, which were part of NHS Sheffield, became part of Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust from 1 April 2011.

Sheffield is predominantly urban, with 98% of the population classified as living in urban settlements. 38 The city has a diverse population both ethnically and socioeconomically, and the black and minority ethnic population in the city has increased significantly since the 2001 census, from around 11% of the total population to 17% in 2009. 39 The closing of the mining and steel industry in the 1980s has left Sheffield with a legacy of extreme socioeconomic variation; 31.8% of the population are classified as being in the most deprived quintile nationally. Life expectancy for people living in the wealthier suburbs is over 10 years more than for those living in poorer areas,40 where there are also high levels of health risk behaviours such as smoking and obesity. Correspondingly, Sheffield has a high incidence of socioeconomic health-related diseases such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. In total, 15.5% of the population are aged > 65 years. 38 These National End of Life Care Intelligence Network data reveal that 67% of deaths in Sheffield occur amongst people aged > 75 years and 36% amongst those aged > 85 years. Causes of death are in line with overall trends for England, with the top three leading causes being respiratory (34%), cardiovascular (29%) and cancer (28%). In terms of place of death, 57% of people are classified as dying in hospital, 18% in their own home, 17% in care homes and 5% in hospices, similar to the average figures for England. An average of 15.3 hospital days for admissions ending in death is reported. Total spend on end-of-life care per death and hospice services per death is higher than the national average at £2803 (national average £525) and £2047 (national average £1096) respectively.

In terms of palliative care provision, the SNGH houses an 18-bed specialist palliative care unit and St Luke’s Hospice, in the south of the city, has 20 beds. There is also a 24/7 on-call palliative care service available throughout the trust. On average, the service cares for 800 new patients per year.

Royal Lancaster Infirmary

The RLI is operated by University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust (UHMBT), which serves the population of South Cumbria and North Lancashire. The trust operates from three main hospital sites – the RLI, Furness General Hospital in Barrow and Westmorland General Hospital in Kendal – serving a population of circa 363,000, spread across an area of over 1000 square miles. It operates a range of acute and emergency services, including a 24-hour emergency department (A&E). End-of-life care intelligence data are provided by the PCT; data for Lancaster are therefore included within the wider Cumbria region. 41 In Cumbria, the population is slightly older than the average for England, with 20% aged > 65 years and 11% aged > 75 years. A 161% increase in the population aged > 85 years is predicted by 2033. Only 48% of the population are classified as living in urban settlements (compared with 81% for England as a whole) and > 99% are white (compared with 90% for England). The population is more affluent than the national average, with only 11% in the most deprived quintile. In total, 36% of deaths occur amongst those aged > 85 years. Place of death is mainly in line with national averages, although there is a slightly lower proportion of hospital deaths (52% in hospital) and a slightly higher proportion of home deaths (23%). In line with Sheffield and England as a whole, the top three leading causes of death are respiratory (31%), cardiovascular (33%) and cancer (28%). 41 The average number of bed-days per hospital admission ending in death is 12.5 (in line with the national average). The total spend on end-of-life care services and hospice services is below the national average at £498 and £359 respectively (compared with £1096 and £525).

Ethical approval

It is a requirement of all research involving NHS patients or staff that ethics approval is granted through the appropriate research ethics committee. National multisite ethical approval for this study was granted by Nottingham 1 Research Ethics Committee and, where required, from the National Information Governance Board (NIGB) Ethics and Confidentiality Committee (ECC). Research governance approvals were gained from the relevant NHS trusts and honorary contracts were issued to all members of the research team (n = 30).

A number of ethical issues were of particular importance. The main ethical issues with regard to the survey related to the discussion of sensitive issues with patients and the possibility of patients becoming distressed. The research team has considerable experience in palliative care research and extensive expertise discussing sensitive issues with patients. The methodology was developed following consultation with service users (see Chapter 2) and professional academics and clinicians to minimise patient burden. The NHS research ethics committee stipulated that the terms ‘palliative’ or ‘end of life’ were not used on any of the patient/carer study materials and were not mentioned verbally in interactions with patients or carers. This was to avoid the potential distress that use of these terms might evoke.

There were also ethical issues surrounding the inclusion of patients lacking the capacity to consent. Much research in palliative care has neglected to include the views and opinions of patients with dementia and other cognitive impairments and therefore we felt that it was imperative to include these patients to capture their perspectives. The core principles of the Mental Capacity Act 200542 informed the research methods so that patients lacking capacity could be appropriately protected but also be given the opportunity to participate. 10 In addition, the data collection team included researchers with specific and extensive experience in dealing with patients lacking capacity.

Ethical issues: the retrospective case note review (phase 6)

We were unable to obtain patient consent to collect data for the retrospective case note review as we were examining notes of patients who had died. Therefore, additional ethical approval was sought from the NIGB ECC under section 251 of the NHS Act 200643 for use of identifiable patient data without patient consent. We recognised this as an ethically contentious issue and as such undertook significant consultation with our service user group and experienced academics and clinicians to inform our application.

Amendments to the protocol

Amendments to the protocol are listed in full on the ‘Record of Reported Changes in SDO Project’ form and are summarised below.

The original protocol aimed to collect data from the general practitioner (GP) of every patient who participated in the hospital survey through a short telephone interview; however, this was not possible because of difficulties with the recruitment of GPs. Although the majority of patients gave consent for the research team to contact their GP, the response from GPs was extremely poor. After contacting approximately 200 GPs by telephone, only 25 agreed to participate. Therefore, data collection was ceased.

Patients were interviewed on only one occasion post discharge from hospital rather than on two occasions as detailed in the original protocol. This was because the majority of the patients interviewed were in poor health and extremely frail at the time of the interview and it was not felt appropriate to approach them a second time following a 6-month interval.

An extra phase of research (retrospective review of case notes) was added to the protocol following completion of the hospital survey. The original protocol aimed to collect data from the medical notes of all hospital inpatients at the time of the survey; however, this approach was not possible because of ethical restrictions preventing collection of data from patients unable or unwilling to providing consent. As objectives 7, 8 and 9 were dependent on collection of data from a complete population of hospital inpatients, the retrospective review was conducted.

The final focus groups held with NHS staff and managers to disseminate the results of the study did not involve any individual interviews, as stated in the original protocol. Although it was anticipated that senior clinicians and stakeholders would not wish to participate in group discussions and we would therefore offer individual interviews, these staff proved keen to discuss the implications of the research with their teams. Interviews were therefore not necessary.

Chapter 2 Service user involvement

The study was underpinned by service user involvement and collaboration. In this chapter we will showcase some of the work undertaken by our service user group and highlight the important role that it played in the success of the research project in terms of improving research methods, gaining ethical approval and outcomes for the study. We also highlight the future role for the group and its planned activities.

Service user involvement in palliative care research

It is now widely accepted that the involvement of consumers or service users can enhance research and practice in palliative care. 44 In line with other areas of health care, the importance of ensuring effective service user involvement in palliative and end-of-life care research is now widely acknowledged. However, user involvement within this context provides a number of unique challenges, particularly because of the potential vulnerability of the service user group in question. Our team has undertaken a significant body of work over the past decade developing models of effective and safe service user involvement in palliative and end-of-life care research. This has involved comprehensively reviewing the evidence base for service user involvement in health research more broadly and drawing implications for palliative care,45 stimulating debate about the theoretical context informing service user involvement in research46,47 and, most importantly, exploring the views of service users themselves about what optimum models of user involvement in palliative care research should constitute. 48–51 We drew on this previous work, in addition to our collective experience of facilitating service user involvement in research in multiple projects in the area of palliative and end-of-life care, to develop a strategy to ensure appropriate and effective service user involvement in the current study.

User involvement

From inception, a key goal of this study was to facilitate the curative involvement of service users in the research process. Service users have had a significant impact on the study from the design stages, through data collection and project management to dissemination. A dedicated service user group was set up in June 2009, which from mid-2011 has been known as the Palliative Care Studies Advisory Group (PCSAG). The group has provided ongoing support to the study and is now consulted by researchers from across the region on a wide range of palliative and end-of-life care projects.

Demand for the group’s input is such that members intend to continue their regular meetings and maintain their involvement in research, with support from our research team at the University of Sheffield.

Project development and design

Before the study was funded, a group of research partners from the Cancer Experiences Collaborative (CECo) was consulted regarding the preliminary proposal. The group provided important feedback, including outlining key ethical challenges from the perspective of service users, and this feedback was incorporated into the final version of the proposal.

Setting up a dedicated user group

Initial meetings of the project steering group identified a range of significant potential ethical challenges in the design of the study. As such, it was proposed that a dedicated group of service users, consumers and research partners be set up to provide consultation and feedback on all aspects of the project, but particularly to assist in identifying and managing ethical issues.

An initial User Consultation Day was arranged for June 2009. The aims of this full-day event were to provide an introduction to the project and generate feedback on some early issues; encourage involvement from a wide range of service users and consumers; and identify individuals who might like to continue to be involved with the project as part of a formal user group. The User Consultation Day was attended by 17 service users, carers and advocates with an interest in palliative and end-of-life care. Attendees were drawn from a range of local, regional and national organisations including the North Trent Cancer Research Panel, CECo, the Alzheimer’s Association, the Older Lesbian and Gay Association, Darnall Dementia and local care homes. Feedback from the day was excellent, and 16 of the attendees expressed an interest in continuing their involvement in the project through formal user group meetings.

Ongoing involvement of the user group

Following the successful User Consultation Day, members of the dedicated user group have met every 6 months to provide consultation to the project. Additional members have joined the group from an older carers research project at the University of Nottingham and from the volunteer service at the Nightingale Macmillan Unit at the Royal Derby Hospital. The group now has around 20 members, with 8–12 members attending each meeting.

The biannual meetings are chaired by Dr Gardiner or Professor Ingleton and have focused on designing materials for the study, discussing difficult ethical issues, providing feedback on findings and assisting in dissemination plans.

Motivations for getting involved

Many members were motivated to become involved because of personal experiences of health or social care, either their own care or that received by loved ones. The following quotes are illustrative of members’ motivations more generally:

As far as research is concerned, it doesn’t matter what the subject is, if you don’t have continual research into it you don’t move forward, you just stand still. This is why I’m prepared to take part. My thoughts are based on my experiences of looking after my wife. If by influencing research I can help somebody in the future, that’s all to the good. I can put something back into society in return for what I got out of it.

Ken Hall, member of the advisory group

It was at the time my wife was in hospital for the umpteenth time because she was ill over 13 years and I got talking to one of the sisters there and she sort of put my name down [laughing]. I really don’t know how it came about but she said would you be interested and . . . I thought I’ll have a go at it. But I’ve found it highly interesting, highly informative and I’m pleased I did.

John White, member of the advisory group

Well I decided to take part in the advisory group because I did have a personal issue. I was diagnosed with breast cancer, and I didn’t feel ill, and it seemed that I must be made very ill in order to get better and I wanted to question this. Why is cancer treatment so arduous, for one thing? And in the interview with my physician, why were my concerns about other health problems just totally dismissed? That wasn’t right, so now I try and bring that sort of perspective into groups I attend.

Also, at first I did think that the glamorous side of research – the expensive new drugs – was the be-all and end-all, but over the 8 years I’ve been involved in research groups, I find that this sort of research which helps patient comfort is much more important and perhaps people should recognise this.

Jacqui Gath, member of the advisory group

Another member of the group, Simon Cork, wrote a short piece about his motivation for and experiences of being involved in the group for a newsletter produced by the School of Nursing at the University of Sheffield. This short commentary is provided in Appendix 1.

Key contributions of the group to the study

The user group has made a number of important contributions to the project.

Commenting on whether research in this area is important

A discussion was had about the value and the merits that the group members found in the proposed research. Members gave examples of both positive and negative experiences of end-of-life care. It was emphasised that a good death should be seen as a success in medical terms. The group feedback was incorporated into the study’s application for ethical approval, and facilitated the approval process.

Developing project information leaflets for distribution to the public and assisting with distribution

The group designed and agreed content for a project information leaflet. Members encouraged a more positive style of language and pointed out areas in which more explanation about the research was needed. The group identified places where the leaflet could usefully be distributed (e.g. day centres, local council offices and Age UK) and many members were involved in distribution.

Identifying ethical problems with or concerns about the study

One of the most important contributions of the advisory group has been in negotiating the ethical challenges of the study. All ethically contentious issues were discussed with the group to inform the study design and to assist with applications submitted to the research ethics committees. The most ethically challenging issue related to gaining approval from a specialist ethics committee to undertake a retrospective medical case note review of patients who had died. An initial application made by the project researchers was rejected on the grounds of the contentious ethical issues. A dedicated meeting of the advisory group was held to gain detailed feedback on the issues raised, which was then incorporated into a revised application. Additional written support from one member of the group was also supplied and a second application to the ethics committee was approved. It is worth highlighting how crucial the input of the advisory group was in securing this ethical approval; without it it is extremely unlikely that a key component of the project would have been able to go ahead.

Commenting and providing feedback on the project website and suggesting content

The group agreed that a project website (see www.transitionstopalliativecare.co.uk; accessed June 2013) was a very good idea as it would help to disseminate information about the study to a wider audience, especially younger people. Suggestions for content included links to other related websites and regular updates on the input of the advisory group.

Contributing to dissemination and distribution of the research findings

To see the results of the research being implemented, the group was keen to play a part in disseminating findings from the study in different forums. Some wanted to do so informally through face-to-face encounters with their peers and with people they came into contact with on a regular basis: ‘That’s far more effective than reading it in a written report in the funder’s office.’ The group also agreed that it was important to see findings disseminated through the mainstream media.

Advising other research projects

In late 2010 the group was approached by a research group from the University of Nottingham and by a researcher at the School of Health and Related Research at the University of Sheffield. These researchers had become aware of the group and asked if members would consider providing advice to their projects. The group now provides consultation to a wide range of palliative care research studies from a range of universities. Projects that the group has offered advice to include a study exploring palliative sedation, a study on end-of-life care communication for patients with respiratory disease and a study on optimising hospital environments for palliative care. The group has also advised on a PhD research project and on a medical student’s research project, directly contributing to the success of these projects and to the awarding of educational qualifications.

The group has offered valuable feedback for researchers. People who use services are able to offer different perspectives on research from those of professional researchers. They can help to ensure that the issues that are identified and prioritised are important to them and therefore to health-care, public health and social-care services as a whole. For researchers, it is easy to get preoccupied with the more technical aspects of conducting research. The user group was able to remind the professionals of the overall purpose of the research – the ‘nuts and bolts’ as one member called it – and why it matters.

Future role for the user group

User group members have been keen to continue their involvement in research after the end of this study. The group, now titled the PCSAG, is working with researchers on palliative and end-of-life care in Sheffield, Nottingham and even as far away as New Zealand. This includes large- and small-scale projects, PhD projects and projects funded by universities, government departments and the third sector. This project has benefitted greatly from the involvement of the group and it is envisaged that other future projects can consult the group and benefit from its feedback.

To promote itself to academic institutions, health-care organisations and the third sector, the group has produced a briefing paper (Figure 1) outlining the background of the group and the important role that it can play in improving research methods and outcomes (see Appendix 2 for the briefing paper).

FIGURE 1.

Palliative Care Studies Advisory Group briefing paper: front cover.

A Service User Involvement in Research Showcase event was held in Sheffield on the 10 July 2012 and was facilitated by Dr Gardiner, Professor Ingleton and Professor Gott, on behalf of the PCSAG. The aim of this full-day event, which was evaluated positively, was to reflect on the role of patient and public involvement (PPI) in research. It focused on the activities and input of the PCSAG in addition to showcasing the role of PPI in other research areas. The showcase event was attended by a wide range of services users, advocates, academics and researchers. A number of presentations were made about service user involvement in research, and during breakout sessions delegates discussed ways in which to disseminate project findings. Delegates suggested publishing a short document describing project findings in a format appropriate for both users and professionals. This document will be produced following submission of this final report and will be disseminated to a wide audience as part of the project dissemination strategy.

Chapter 3 Exploring the transition from curative care to palliative care: a systematic review of the literature (phase 1)

To inform the study, two systematic reviews were conducted of the relevant health- and social-care literature. This chapter presents findings from the reviews and identifies the research evidence base in the following areas:

-

the transition from curative care to palliative care

-

the economic impact of avoidable hospitalisations amongst palliative care patients in the UK.

A systematic review of literature exploring the transition from curative care to palliative care

Background

The transition to palliative care can be a confusing and traumatic time for patients and their families, and may trigger fears of helplessness and abandonment. 52 Although traditionally a sharp transition point has signalled the beginning of palliative care, more recent therapeutic models have described an approach incorporating gradual transitions, emphasising palliative input and QoL considerations during the active phase. 53 A phased transition or simultaneous care approach recognises that treatment goals evolve and that concurrent curative and palliative care may be most appropriate. 25

A scoping review by Marsella54 identified three key elements that complicate the transition to palliative care. First is the nature of the transition and what it means to patients. Second, transitions can be difficult because of a lack of time to appropriately prepare patients and families. Lastly, a lack of information regarding the goals of palliative care can lead to confusion and complications. Schofield and colleagues55 undertook a literature review as the basis for outlining steps for facilitating the transition to palliative care. Although these steps provide useful recommendations, the authors acknowledge a paucity of research in the area and fail to address the impact of variations in health-care systems and resources in cross-national literature.

Evidence also suggests a lack of concordance with respect to triggers indicating the appropriateness of a transition to palliative care. Although policy guidelines advocate the use of the ‘12 months’ question as an indicator that patients may require palliative care input, recent evidence suggests that this question may not be appropriate for patients with non-cancer diagnoses. 56

The Gold Standards Framework (GSF)57 suggests the use of a prognostic indicator guide to identify patients predicted to be in the final 12 months of life who might be in need of palliative care. However, implementation is variable and the direct impact on patients and carers is not known. 58

Review methods

A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative literature was undertaken to explore evidence relating to transitions to palliative care in the UK. The review was undertaken in the following five stages: (1) search strategy, (2) inclusion criteria, (3) assessment of relevance, (4) data extraction and appraisal and (5) data synthesis using a descriptive thematic model.

Search strategy

The aim of the search was to identify a comprehensive list of published papers that met predefined inclusion criteria. Medical subject headings (MeSH) (‘palliative care’, ‘terminal care’, ‘hospice care’) and keywords (‘supportive care’, ‘end of life care’, ‘transition’, ‘continuity’) were identified and relevant databases were selected and searched in consultation with a health-care information management specialist. The following databases were searched for literature published between 1975 and March 2010: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (see Appendix 3 for the search strategies). The following journals were hand-searched for relevant articles: Palliative Medicine, Journal of Palliative Care, Supportive Care in Cancer and Journal of Advanced Nursing. Relevant references from bibliographies and through citation indices were followed up. Grey literature searches were conducted through the above databases, through consultation with expert colleagues from the wider study steering group (n = 10) and through internet search engines.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were developed by consensus within the research team. Literature had to refer to the transition from active or curative care to care incorporating a palliative approach. Literature also had to refer to an adult population (aged > 18 years) and be UK based (as variations in health-care systems and resourcing worldwide mean that the relevance of international papers to the UK is likely to be limited). All types of published literature were eligible for inclusion, including grey literature.

Assessment of relevance

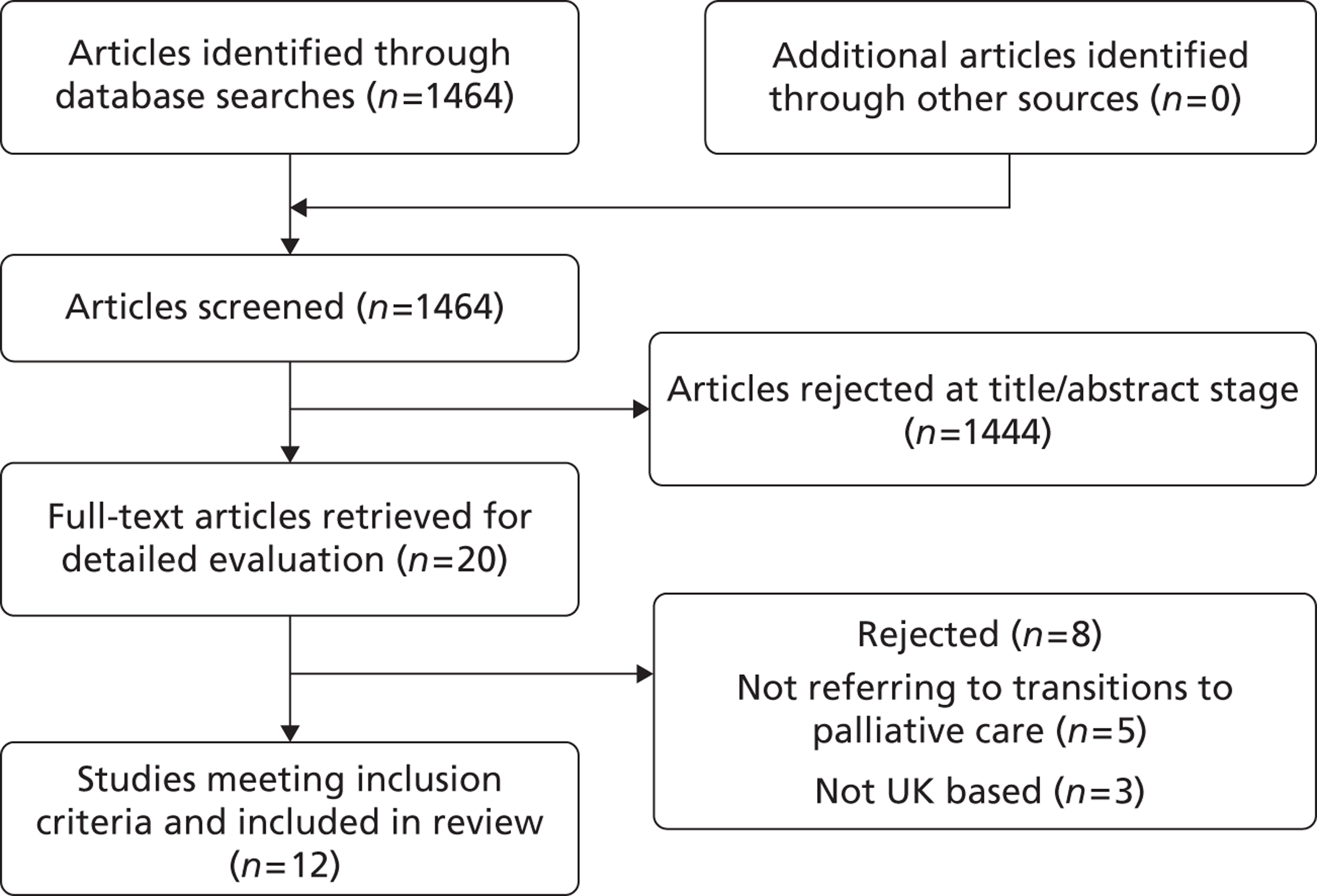

Study selection was conducted in a systematic sifting process over three stages: on the title, abstract and full text. Details of the study identification and selection process are shown in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart in Figure 2. At each stage studies were rejected that definitely did not meet the inclusion criteria. Each paper was independently assessed by CG and one of the other authors (CI, MG or TR); in cases in which there was disagreement between researchers, consensus was reached by discussion.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of included literature.

Data extraction, appraisal and synthesis

The review was conducted using a descriptive thematic method for systematically reviewing and synthesising research that employed different research methods and modes of analysis. The thematic approach was data driven and all data relating to transitions from curative care to palliative care were extracted from papers. A checklist adapted from Hawker and colleagues59 was used as the basis for extraction and appraisal. Double data extraction was performed independently on all included studies by two authors (CG and MG, TR or CI).

Quality assessment was carried out using a range of quality indicators of rigour,60 which varied by study type. A score was calculated for each paper based on the scores for each item on the checklist. Scores ranged from 9 (very poor) to 36 (good) and indicate the methodological rigour for each paper. As each paper was assessed by two researchers, a mean score for each paper was calculated. Because of the diverse nature of the included studies, statistical synthesis or analysis of study findings was not appropriate. Quality assessment for non-empirical papers was undertaken according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Narrative, Opinion and Text Assessment and Review Instrument (NOTARI) tool for assessment of expert opinion. This tool does not generate a score for methodological rigour and, although findings from non-empirical papers must be considered with caution, expert opinion papers are included in this review to minimise exclusion of relevant context.

Results

Of 1464 citations initially identified, 12 articles61–72 (relating to 11 studies) met the inclusion criteria. Articles that were excluded (n = 1452) were not relevant to the research aim or were not UK papers (Figure 2). One paper included both UK and European data and was included. 61 Eight of the included articles were qualitative studies of patients, carers or health professionals. 61–67,72 One study was a mixed-methods comparative cohort study,68 one a case study report,69 one a critical discourse analysis70 and one a non-empirical discussion piece. 71 Transition to palliative care was the main focus in only two of the included papers;61,72 the remainder referred to transition only as a minor theme or as a component of the discussion.

Most papers scored satisfactorily on assessment of methodological rigour, with no paper scoring < 28 out of a maximum of 36. One paper71 could not be scored as it was a non-empirical expert opinion piece; therefore, findings from this paper should be considered with caution. Details of the 12 papers and assessment scores are provided in Table 1.

The thematic synthesis of evidence led to the emergence of four main themes: (1) patient and carer experiences of transitions, (2) recognition and identification of the transition phase, and criteria for making transitions, (3) optimising and improving transitions and (4) defining and conceptualising transitions.

Patient and carer experiences of transitions

Of the 12 papers included in the review, nine61–68,72 provided evidence or discussion of patient and carer experiences of transitions. The overwhelming consensus was of fear and uncertainty when making the transition to palliative care. Larkin and colleagues61,72 reported how cancer patients described a variety of emotional responses reflecting fears and losses. Patients found transitions confusing because of mixed messages, poor communication and uncertainty. They described having limited knowledge about the purpose and timing of transitions, feeling uncertainty about who instigated the transition, having limited involvement in decision-making and, once transferred to palliative care services, feeling a sense of waiting for something to happen. Patients also reported that hospitals can provide unrealistic information about the level of service available for patients on transitioning to palliative care. This finding resonated with health professionals who reported that patients’ expectations may be unrealistic regarding the care that can be delivered.

Patient concerns were also identified in a qualitative study of lung cancer patients, who reported that they felt particularly unsafe in periods between curative treatment and follow-up appointments. 63 They also felt ill-prepared for discharge from curative care and detected inadequacies in interprofessional communication. Communication was also highlighted as an important issue in a qualitative interview study of patients receiving specialist palliative care. 64 Patients in this study described uncertainties about the extent and nature of inter- and intraprofessional communication and described having to relay information themselves between different professionals involved in their care. Patients and carers described continuity of care as a key component for improving the experience of transition to palliative care; continuity appears critical to satisfaction with care and services. However, it is clear that complexities may occur and continuity may be disrupted when many agencies are involved in providing care for an individual.

Recognition and identification of the transition phase

Recognition of the palliative care transition phase by health- and social-care professionals was identified as an important factor for facilitating optimum care. O’Leary and colleagues68 reported that early recognition of the palliative care transition point was key to ensuring that end-of-life issues were addressed. In a study by Bestall and colleagues,65 primary care professionals described how late recognition of palliative care need, and referrals at a late stage, could have a negative impact on patients and on their relatives during bereavement. However, it was acknowledged that a clear-cut transition to a palliative care approach was rare. Particular challenges exist when identifying the transition in non-cancer conditions such as heart failure, in which the episodic nature of the condition can lead to a delayed recognition of the palliative transition.

Four papers made suggestions for criteria to identify the transition to palliative care. 61,65,68,70 O’Leary and colleagues68 listed factors defining the palliative transition point in heart failure, including deterioration despite optimum support, increasing fatigue or functional dependence, low ejection fraction, recurring hospitalisations, emotional distress, carer fatigue and patient request. Bestall and colleagues65 explored reasons for referral to specialist palliative care for both cancer and non-cancer conditions and highlight a lack of standardised criteria in the UK to determine when a referral should be triggered. Referral criteria identified in this study included complex symptoms, problems with medication side effects, complex social or practical issues, carer burnout, and emotional distress. Health professionals discussed the use of referral criteria such as the Leeds Eligibility Criteria73 or locally developed guidelines, but most would have liked further guidance about when and how to refer patients to specialist palliative care. Cancer patients interviewed in a study by Larkin and colleagues61 described how a rapid deterioration resulting in loss of independence was a primary reason for a transition to palliative care. Some respondents reported that a decision to move to palliative care was based on an evaluation of their potential burden to others rather than on personal choice.

Optimising and improving transitions

The majority of studies acknowledged that the transition to palliative care could be improved. As early as 1978, researchers identified the importance of continuing care after the cessation of curative treatment. 69 However, only four papers made any specific recommendations or developed any guidelines for improving the transition. 62,67,68,70

O’Leary and colleagues68 discussed how the optimum transition should encompass planned and integrated transfer of patient information, the reiteration of patient preferences and the renegotiation of care goals. Recognition of the transition point was identified as key so that a collaborative care plan can be established, ensuring the most appropriate level of care. In addition, improvements to services such as respite and out-of-hours care were also identified as a requirement for optimum transition. 62 Kendall and colleagues67 developed recommendations for the care of patients with cancer in primary care after discussion with patient groups. Patients and carers outlined an important and unique role for primary care staff throughout the cancer trajectory. Continuity of care and an individualised approach were considered crucial to driving patient-centred care forwards. Recommendations given for managing the recurrence of cancer and the last weeks included letting patients express their concerns, helping with social and practical issues, respecting patients’ values and choices and supporting carers, frequently reviewing and co-ordinating care, and being flexible and responsive. Continuity of care was also highlighted as a crucial factor by patients and staff in a study by Patrick and colleagues. 62 Continuity appeared critical to overall satisfaction and was particularly important during the transition when many agencies were involved in an individual package of care. Researchers in critical care also identified individualised assessment as important, and again highlighted a need for comprehensive collaboration. 70 Although it is acknowledged that transitions in critical care may be very different from transitions in other care settings, many of the care goals and recommendations are similar.

Defining and conceptualising transitions

Defining the concept of a transition to palliative care remains a challenge. In health care, transitions may include changes in the place of care, the caregiver or the goals of care. However, transition in the palliative care literature goes further than just change in place or caregiver. It also relates to the personal meaning of life, life/role changes, perceptions of end of treatment, and likelihood of death. Understanding what this transition entails is necessary for facilitating end-of-life care. 68 A study by Larkin and colleagues61 explored the experiences and meaning of transition for a group of palliative care patients. Although they reported that the successful merging of the curative–palliative interface was beneficial for patients, they suggest that the concept of transition warrants further investigation. The authors describe how transition literature often describes overtly positive outcomes such as resilience, reconstruction, coherence, life purpose, sense of self, transcendence and transformation, whereas interview data from patients do not always match these descriptions. Transience is suggested as an alternative concept and is further explored in a second study. 72

| Author and year | Aim | Participants | Setting | Method | Relevant findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bestall 200465 | To explore the reasons why patients and families are

referred to SPC Assessment score = 31 |

13 patients referred to SPC (cancer and non-cancer diagnoses), 12 professionals working in SPC, 3 GPs, 6 community nurses | North Trent Cancer Network, England | Qualitative semistructured interviews and content analysis | Five key themes reported: reasons for referral to SPC, reasons against referral to SPC, timeliness of referrals, continuity of care, use of referral criteria. Currently no standardised criteria in the UK to determine when a referral to SPC should be triggered. Referral criteria outlined and include complex symptoms, use of referral guidelines. Development of referral criteria may aid transition to SPC |

| Jarrett 200964 | To investigate patients’ perceptions of IIPC in

a SPC setting Assessment score = 32 |

22 patients receiving SPC input (21 cancer patients and 1 multiple sclerosis patient) | Two SPC units, England | Qualitative in-depth interviews, grounded theory analysis of transcripts | Patients largely positive about IIPC when it occurred, some patients uncertain about extent and nature of IIPC, some patients described relaying information between different professionals or care locations and some patients and families very proactive to enhance IIPC and continuity of care |

| Kendall 200667 | To involve patients with cancer and their carers in

designing a framework for providing effective cancer

care in primary care Assessment score = 32 |

18 patients/carers with cancer and 16 professionals involved in cancer care | South-east and south-west of Scotland | Action research model involving two patient/carer discussion groups who met monthly over a year and interviews with professionals | Five key points during cancer trajectory have particular significance: diagnosis, treatment, after discharge, recurrence and the final weeks. Important role for primary care acknowledged throughout cancer trajectory. Support from primary care beneficial during transition from remission to recurrence to final weeks. Continuity of care and an individualised approach are crucial |

| Krishnasamy 200763 | To explore patients’ and family members’

experiences of care provision after a diagnosis of lung

cancer Assessment score = 31 |

23 lung cancer patients and 15 carers | Tayside, Scotland | Qualitative in-depth longitudinal interview study involving three interviews over a 6-month period | Four key domains of need apparent: pathway to confirmation of diagnosis; communication of diagnosis, treatment options and prognosis; provision of co-ordinated care; and support away from acute services including difficulties transitioning between services. Patients felt particularly unsafe in periods in between treatment and follow-up appointments and felt ill prepared for discharge or detected inadequacies in primary/secondary care communication. Many patients relied on relationship with their hospital consultant and found it difficult transitioning into palliative care |

| Larkin 200761 | To document palliative care patients’

experiences at the palliative–terminal

interface; to identify perceived supportive and

inhibitory factors; and to analyse common experiences in

the context of current palliative care development in

European terms as a means to inform

practice Assessment score = 30.5 |

100 advanced cancer patients | Palliative care centres in six European countries (UK, Ireland, Spain, Netherlands, Italy, Switzerland) | Phenomenological approach using semistructured interviews | Transition is a confusing time for patients because of mixed messages and poor communication and uncertainty; physical environment of the hospice offers a place of security to address this. Transition concepts fail to capture the palliative care experience fully and warrant further exploration. Transience is reported as an alternative concept, although more research is needed. Successful merging of curative–palliative interface is beneficial to patients. Clinicians need to ensure a seamless transition as proposed as a key construct of palliative care |

| Larkin 200772 | To support, define and consolidate the emerging concept

of transience and to critically appraise how far

qualitative approaches fit the examination of transience

as a concept and its potential importance to palliative

care Assessment score = 28.3 |

100 advanced cancer patients | Palliative care centres in six European countries (as above) | Qualitative conceptual evaluation using two case examples from interview data (see Larkin57) and a critical review of the literature | Transience is proposed as a preferred concept to transition in relation to palliative care. Transience encompasses attributes such as fragility, impermanence and stasis, which are not adequately explained by the transition concept. More evidence is needed before transience can be described as a well-defined and robust concept for palliative care but data from case studies support concept of transience |

| Murray 200766 | To identify and compare changes in psychological, social

and spiritual needs of people with end-stage disease

during the last year of life Assessment score = 35.5 |

24 patients with lung cancer and 24 with heart failure | Primary and secondary care in south-east Scotland | Data synthesis from two longitudinal, qualitative in-depth interview studies. Thematic and narrative analysis of transcripts | Characteristic social, psychological and spiritual trajectories were discernible. Lung cancer patients reported particular distress at transition points including after treatment – ‘returning to their old life’. They also experienced difficulties at relapse/disease progression – for some engaging in a battle with the cancer gave them some sense of purpose. In terminal phase patients had overwhelming uncertainty, panic attacks, etc. In heart failure, social and psychological deterioration ran in parallel with physical deterioration and were mediated by this. Spiritual distress fluctuated more and was modulated by other factors |

| O’Leary 200968 | To demonstrate whether the palliative care needs of

patients with advanced heart failure receiving

specialist multidisciplinary co-ordinated care are

similar to those of cancer patients deemed to have

specialist palliative care needs Assessment score = 28.5 |

50 heart failure patients (NYHA stage III/IV) and 50 cancer patients (newly referred to SPC) | Outpatient heart failure disease management clinic and SPC home service in England | Cross-sectional comparative cohort study using quantitative and qualitative methods to explore functional status, symptom burden, emotional well-being, QoL and information and communication needs | Heart failure and cancer patients similar in terms of symptom burden, emotional well-being and QoL. Heart failure patients should not be excluded from SPC services; however, many needs can be met at a specialist heart failure unit. Recognition of palliative transition point may be key to ensuring that end-of-life issues are addressed. Various factors defining the transition point in heart failure are listed. Understanding the concept of transition can facilitate end-of-life care |

| Patrick 200762 | To learn about the quality of local services from the

perspective of patients, carers and staff and to develop

an appropriate methodology for future

consultation Assessment score = 32 |

10 palliative care service users/carers and 9 staff | Palliative care services (hospice, community and hospital) in Kent, England | Semistructured interviews with patients and focus groups with staff. Content analysis of transcripts | Continuity of care important and complex when many agencies involved in an individual package of care. Continuity critical to participants’ overall level of satisfaction with the service provided. Staff had concerns that patients’ expectations are beyond what they can deliver. Hospitals give unrealistic expectations about the level of service in the community, e.g. out-of-hours and respite care services. More respite and out-of-hours medication services needed |

| Pattison 200471 | Discussion paper on the integration of critical care and

palliative care at end of life No assessment score (non-empirical paper) |

N/A | UK | Discussion paper drawing from several literature sources. | Discussion of the difficulties faced when patients transition from curative treatment to palliative care. Transition must not emphasize a dichotomy between cure and palliative care. Nurses can potentially be excluded from decisions regarding a transition and may not be in control when the change of goal takes place. Transitions can be fragmented & comprehensive collaboration is required, patients must not be reduced to a prognostic probability |

| Pattison 200670 | To explore written guidelines and documents for critical

care as evidence for the provision of end-of-life care

in critical care Assessment score = 34.2 |

N/A | UK | Critical discourse analysis of four key UK government critical care documents | Little clear guidance about how to provide end-of-life care in critical care. Transitions to end-of-life care in critical care are often discussed within the context of a transition in physical location; this defines a very definite transition point. In addition, patients can deteriorate very quickly and the transition from curative to palliative care may be rapid. Dying in critical care may infringe dignity. Transition away from interventions to comfort measures can improve dignity |

| Wills 197869 | Case study summary of the first year of a Macmillan

continuing care unit for patients with malignant

disease Assessment score = 17.5 |

71 cancer patients referred to the unit in its first year of opening | Continuing care unit at an acute hospital in West Sussex, England | Case study of routinely collected data | The unit has the unique ability to co-ordinate with community- and hospital-based services. Importance of continuing care after cessation of curative treatment acknowledged and achieved by regular home visits. As a consequence, good relationships were built up, inpatient duration was reduced and more effective episode care was made possible |

Conclusions

Recent UK policy has stressed the importance of managing and facilitating the transition from curative care to palliative care. This review of the literature suggests that, within a UK context, little is known about this potentially complex transition, and literature relating to the optimisation of the transition is sparse. As such, the review attempts to identify important issues for the conceptualisation and optimisation of transitions to palliative care. It is clear that such transitions can be a confusing and distressing time for patients and their families. They can leave patients and their families feeling abandoned and lacking a clear understanding of their future care and treatment options. Facilitating a sensitive transition is therefore imperative for improving the experiences of patients and their families at this difficult time.

The current review identified only four papers that include suggested criteria for identifying the transition to palliative care, and none has been formally evaluated or validated. Further indicators have recently been proposed by Boyd and Murray,30 taking into account a review of prognostic models and guidelines. They propose that clinical judgement informed by evidence, rather than more refined prognostic accuracy, is the key to an earlier identification of patients with palliative care needs. There is a clear need for further formal validation of proposed indicators if a model of best practice is to be identified. Internationally developed indicators such as the US National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization tool should also be considered. However, the organisation and resourcing of palliative care services in the USA and elsewhere may define a sharper transition to palliative care accompanied by an immediate cessation of curative care, thus reducing the appropriateness of US models for a UK health-care system.

Recommendations for optimising or improving the transition to palliative care are similarly sparse, despite recognition that patients and their families often experience a poor transition in their care. A key challenge is sensitively managing the often abrupt change in care provider, care location and care goal that has traditionally accompanied a referral to specialist palliative care services. The abruptness of these changes can lead to patients and their families feeling confused and abandoned, and recommendations highlight a need for collaborative working and continuity of care during the transition. 62,67,68 Evidence suggests that continuity of care is crucial to achieving a sensitive and well-managed transition. UK strategies currently place emphasis on improving the palliative care that is delivered by generalist providers (primary care teams, hospital staff, social-care services),30 who are often well placed, because of their long-standing relationships with patients, to provide high-quality palliative care whilst retaining continuity of care. However, it is likely that they will need support from specialist palliative care services and close collaborative working between care providers is necessary so that patients with a need for palliative input are identified whilst disease-modifying treatments continue.

Many patients may stand to benefit from better identification, assessment and management of the transition to palliative care. Research is required to further explore these issues, particularly in light of evidence which suggests that some patients may be reluctant to receive information relating to a poor prognosis or ‘bad news’. 74,75 A phased transition incorporating palliative care in parallel with disease-modifying treatments appears the most appropriate model for optimising transitions. This model is particularly relevant for patients with non-cancer disease, whose condition may be more slowly progressive, or with fluctuating trajectories. Within this phased transition, continuity of care and multidisciplinary collaboration are crucial. An agreed consensus of definition, and potential refinements to the concept of ‘transition’, may also be necessary to enhance consistency. Further research is required, taking into account UK policy and guidance, to maximise current resources and develop appropriate guidelines and care models for managing the transition from curative care to palliative care.

A narrative literature review of the evidence regarding the economic impact of avoidable hospitalisations amongst palliative care patients in the UK

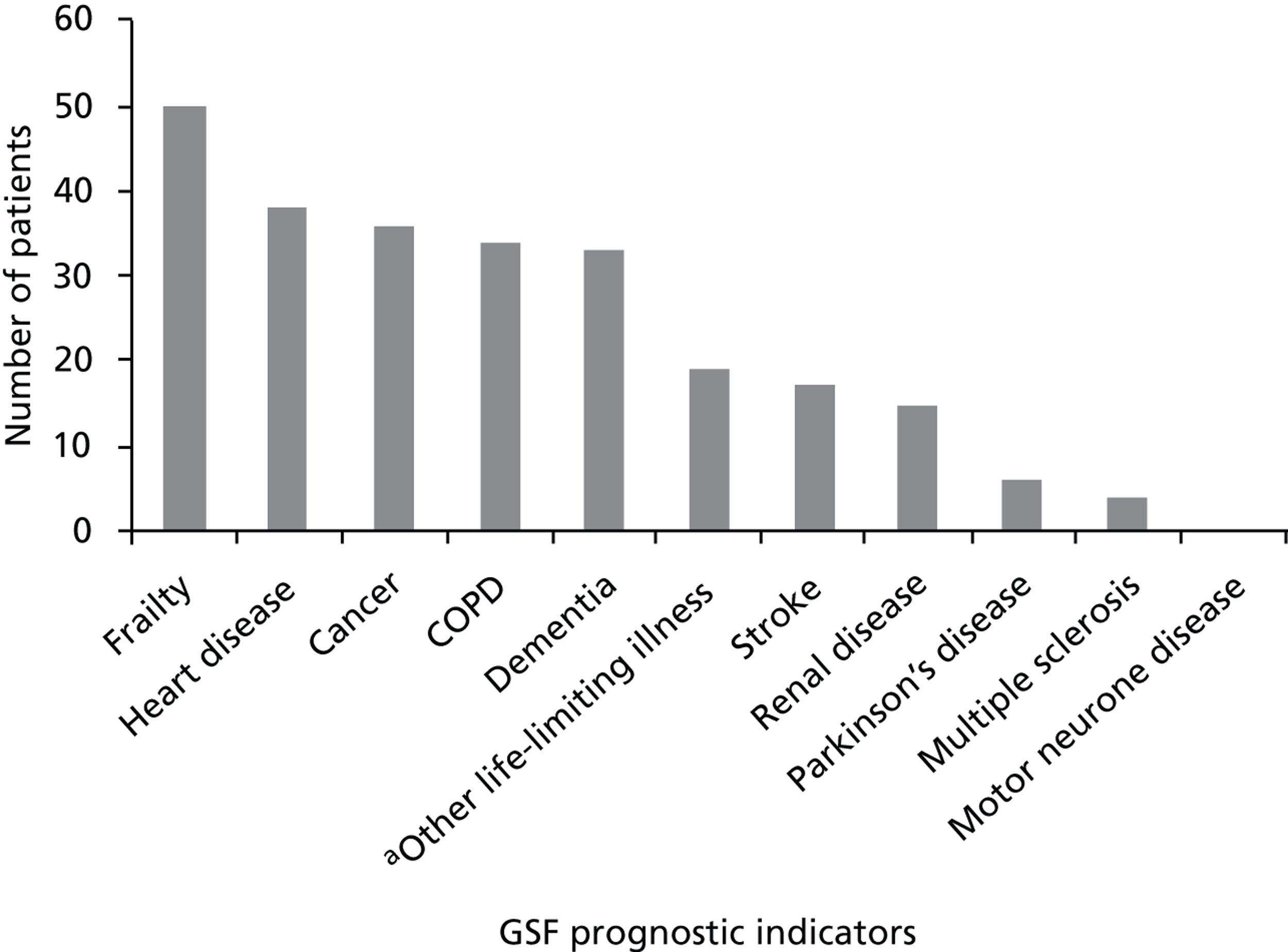

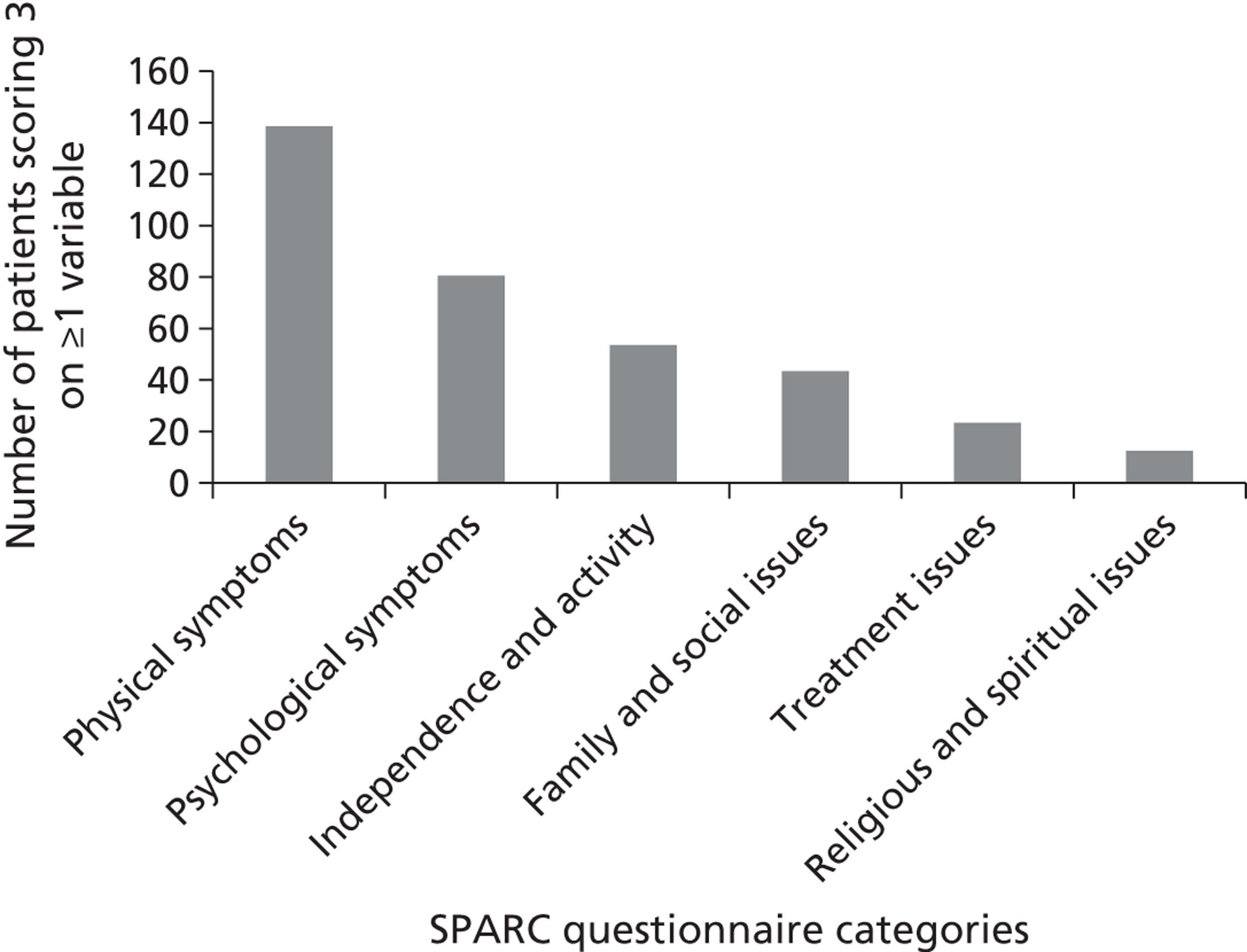

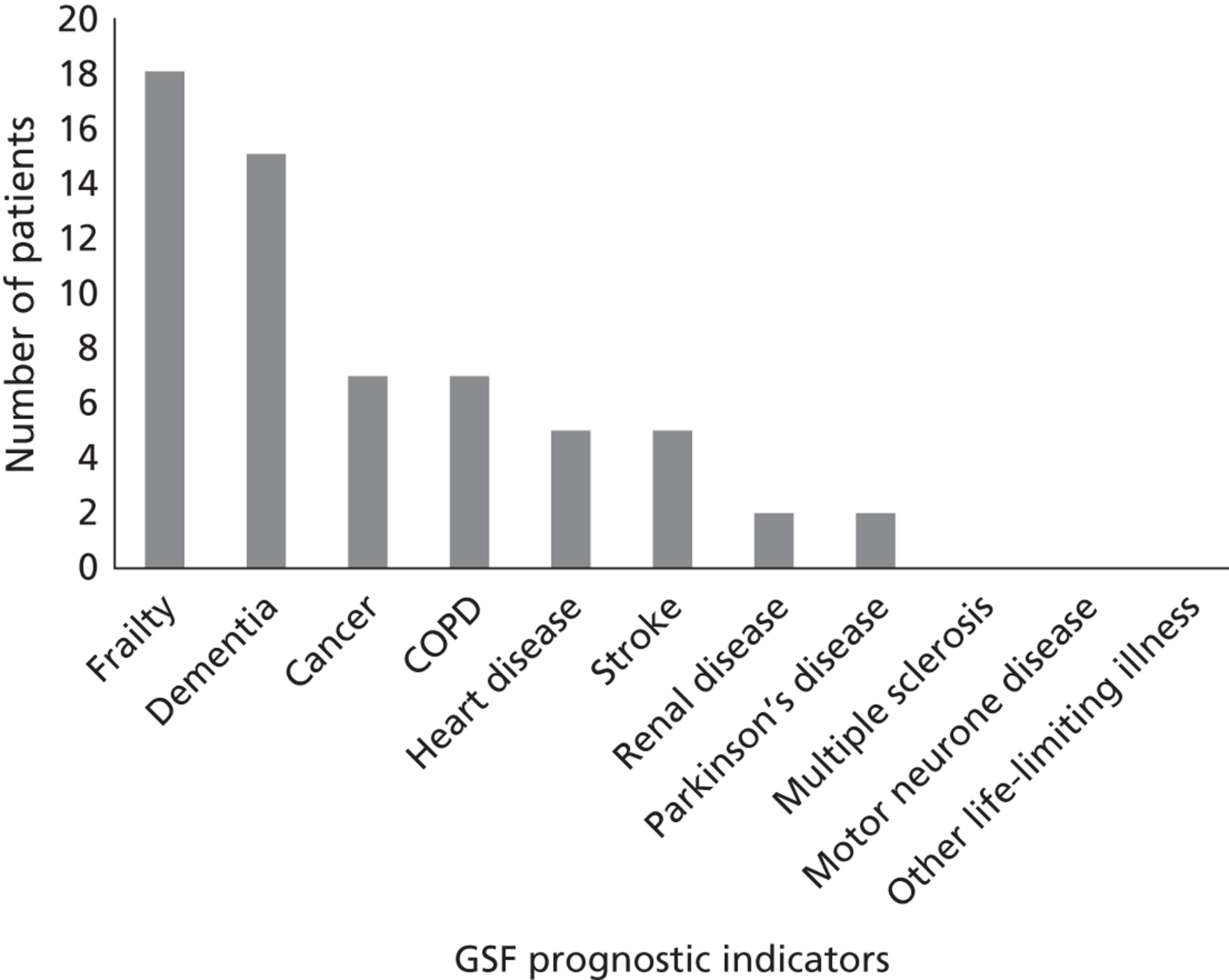

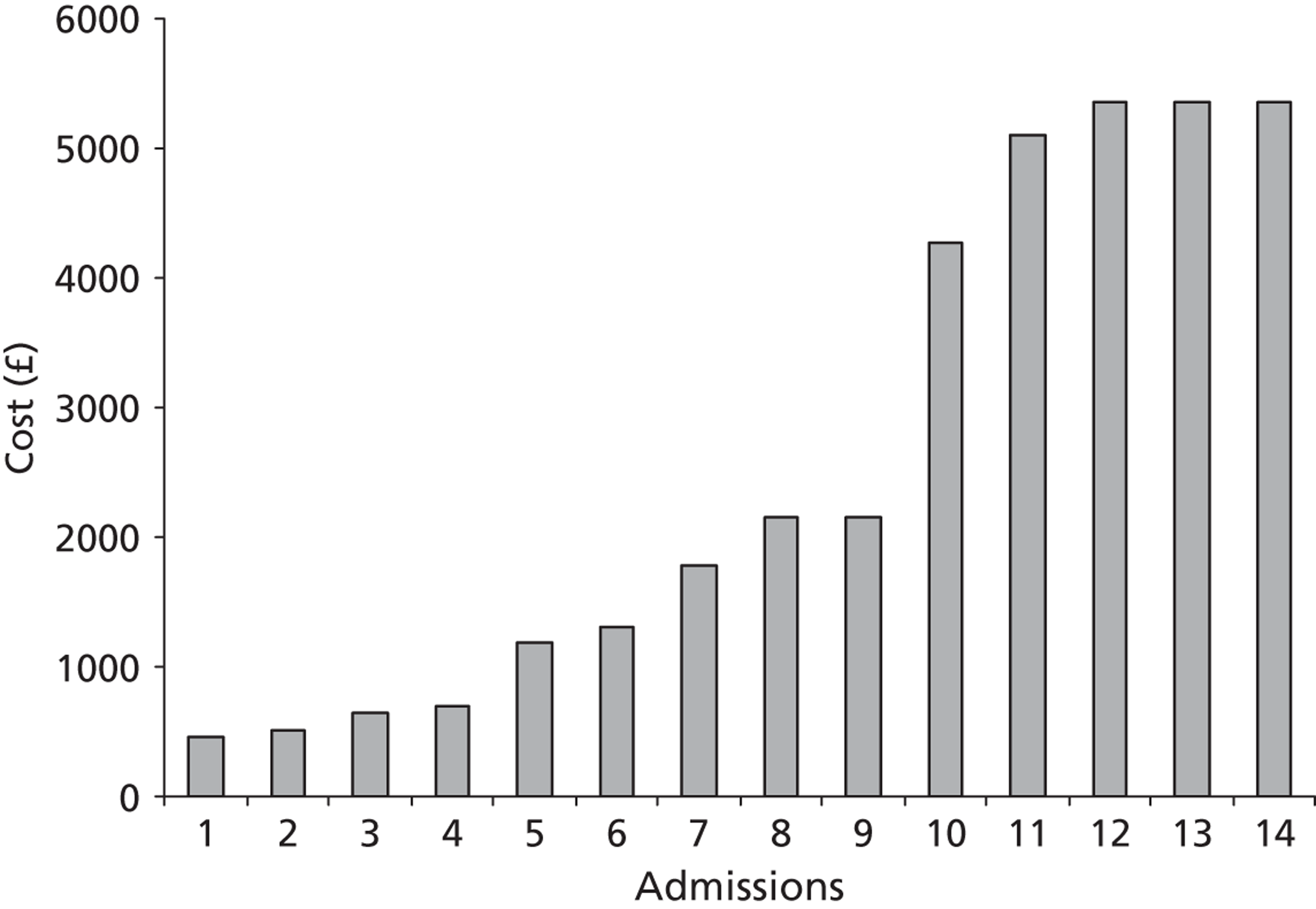

Background