Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 10/1007/22. The contractual start date was in July 2011. The final report began editorial review in April 2013 and was accepted for publication in August 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

None.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Tuffrey-Wijne et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Section 1 Introduction

Chapter 1 Background to the study

Introduction

The safety of patients with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals has been a subject of growing interest and concern in recent years. It follows a number of high-profile reports of poor care and avoidable harm, including avoidable deaths in this patient population. 1–3 This has resulted in a range of recommendations and strategies for promoting better and safer health-care delivery to people with learning disabilities. 4,5

This study explored the factors that affect the implementation of such strategies in six NHS acute hospitals in England; in particular, the cross-organisational, organisational and individual influences that have a bearing on this. It was not an audit or mapping of current practice, although the study included an investigation of the extent to which the six study sites had put relevant strategies in place. Rather, the aim of this study was to understand the systems and processes that either helped or hindered the implementation of these strategies. Through exploring examples of good practice, as well as examples of practice that could be improved or was suboptimal, the study aimed to identify both the key determinants and the key barriers to successful implementation. It aimed to understand how the degree of success with which the strategies were implemented may be linked to safer hospital environments for people with learning disabilities. It also explored to what extent this could be generalised to other vulnerable patient groups.

Definition and prevalence of learning disability

Definition

The term ‘learning disability’ covers a wide spectrum of impairments. In the White Paper Valuing People, the Department of Health6 states that learning disability means the presence of:

-

a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn new skills [impaired intelligence; intelligence quotient (IQ) below 70], with

-

a reduced ability to cope independently (impaired social functioning).

These impairments start before adulthood, with a lasting effect on development.

The White Paper points out that presence of a low IQ is not in itself a sufficient reason for deciding that an individual should be provided with additional health and social care support. An assessment of social functioning and skills should also be taken into account. Many people with learning disabilities also have physical and/or sensory impairments.

The definition covers adults with autism who also have learning disabilities. It does not include:

-

those with a higher-level autistic spectrum disorder, who may be of average or even above average intelligence – such as some people with Asperger syndrome

-

all people with ‘learning difficulties’, which is more broadly defined in education legislation

-

people whose impaired intelligence and/or impairments in social functioning (even if they are lifelong) have been acquired during adulthood, for example those with dementias or brain injuries.

Prevalence

There are no definitive figures for the prevalence of learning disabilities. The presence of learning disabilities is not recorded in the decennial census of the UK population, and no government department collects comprehensive information on the presence of learning disabilities in the population. The Department of Health6 estimated that around 2.5% of the population in England have learning disabilities, most of whom (85%) have mild learning disabilities. Emerson and Hatton7 suggest that 3% of children and 2% of adults have learning disabilities. The number of people with learning disabilities is set to rise by 1% per year. 6 It is estimated that, between 2011 and 2030, there will be a 14% increase in the number of people with learning disabilities aged ≥ 50 years using social care services, and a 164% increase of those aged ≥ 80 years. 8

Health inequalities

The health status of people with learning disabilities has been well described. They have poorer health than the general population, with a much higher prevalence of certain conditions and diseases, which often go undiagnosed. 9–13 These differences in health status are, to an extent, avoidable and can therefore be described as health inequalities. The health inequalities, as described in the following section, are substantial. 14–17

Access to health care

Most people with learning disabilities have greater health-care needs than the general population. Common health problems include respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, mental illness, epilepsy, physical and sensory disability, being underweight, obesity, oral health problems and cancer. 14,18 People with learning disabilities experience more admissions to hospital than the general population. 19

Valuing People Now,20 which sets out the government policy and a 3-year strategy for people with learning disabilities, specifies the objective that all people with learning disabilities should get the health care and support they need to live healthy lives.

The Disability Rights Commission,17 established by an Act of Parliament to stop discrimination and promote equality of opportunity for disabled people, carried out a formal investigation into the health inequalities experienced by people with learning disabilities. Focusing on primary care, the Commission found that there were several reasons for health inequalities, of which social deprivation was only one. People with learning disabilities were less likely to access health promotion or screening programmes. They also experienced ‘diagnostic overshadowing’, that is reports and symptoms of physical ill health were viewed as being inherent in the person’s learning disability and so not investigated or treated. 14 Primary care services often remained inaccessible and unresponsive to people with learning disabilities, as they had not put into place effective adjustments (including policies and procedures) to change this.

In a progress report, the UK government – in recognition of the finding by the Disability Rights Commission that people with learning disabilities often receive a poorer quality of service from the NHS – pledged that it would use progress in relation to this particularly vulnerable group as a way of testing whether its approach to tackling health inequalities was working. 21

Premature deaths

The Department of Health22 quotes figures drawn from Hollins et al.,23 estimating that people with learning disabilities are 55 times more likely to die prematurely than the population as a whole if they are < 50 years of age; for those > 50 years of age, the figure is 58 times more likely. Hollins et al. also found that the majority of deaths were due to respiratory disease, which accounts for only 15–17% of deaths in the general population.

Hoghton et al. 24 assert that:

. . . health inequalities are the result of the interaction of several factors including increased rates of exposure to common ‘social determinants’ of poorer health (e.g., poverty, social exclusion), experience of overt discrimination and barriers people with learning disabilities face in accessing health care.

p. 5. Reproduced with permission from Hoghton M, Turner S, Hall I. Improving the Health and Wellbeing of People with Learning Disabilities: An Evidence-Based Commissioning Guide for Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). London: IHAL, Royal College of General Practitioners and Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2012

Issues around premature or avoidable death were highlighted poignantly in Mencap’s Death by Indifference report,1 detailing the case histories of six people with learning disabilities who died in hospitals from avoidable conditions. In the report investigating these deaths, the Health Service Ombudsman for England2 highlighted distressing failures in the quality of health and social care and found that patients with learning disabilities were treated less favourably than others, resulting in prolonged suffering and inappropriate care. When relatives complained, they were left drained and demoralised, and with a feeling of hopelessness. One of the cases investigated was that of Martin Ryan, aged 43 years, who had severe learning disabilities and no speech. Martin died after he went without food for 26 days while in hospital following a stroke; by the time staff realised what was happening, his condition had deteriorated and his life could not be saved. The Ombudsman concluded that:

. . . had service failure not occurred it is likely the patient’s death could have been avoided.

HC 203 I-VIII, p. 142

The Ombudsman recommended that all NHS care organisations in England should:

. . . review urgently the effectiveness of the systems they have in place to enable them to understand and plan to meet the full range of needs of people with learning disabilities in their areas.

HC 203 I-VIII, p. 12. 2 We acknowledge The National Archives as custodian of this document

A 3-year confidential inquiry into premature deaths of people with learning disabilities (CIPOLD), investigating the deaths of 247 people with learning disabilities within five primary care trusts (PCTs) in England, reported its findings during the final month of this study. 3 It found that people with learning disabilities died, on average, 16 years sooner than people in the general population. Twenty-two per cent of people with learning disabilities in CIPOLD were < 50 years of age when they died, compared with 9% of the general population. Forty-two per cent of the deaths were considered to be premature. The most common reasons for this were delays or problems with diagnosis or treatment, and problems with identifying needs and providing appropriate care in response to changing needs. A similar proportion of deaths in a control group of 58 adults without learning disabilities were premature, but these were largely due to lifestyle factors such as smoking or alcohol, rather than poor-quality health care.

Healthcare for All

The independent inquiry into access to health care for people with learning disabilities (2008)

The evidence from Mencap’s Death by Indifference report1 and other inquiries led to an independent inquiry into access to health care for people with learning disabilities, set up by the Department of Health. Its report, Healthcare for All, was published in 2008. 4 The inquiry found that the cases highlighted in the Death by Indifference report1 were by no means isolated. There was:

. . . convincing evidence that people with learning disabilities have higher levels of unmet need and receive less effective treatment, despite the fact that the Disability Discrimination Act and Mental Capacity Act set out a clear legal framework for the delivery of equal treatment . . . witnesses described some appalling examples of discrimination, abuse and neglect across the range of health services.

p. 7. 4 Reproduced with permission from Michael J. Healthcare for All: Report of the Independent Inquiry into Access to Healthcare for People with Learning Disabilities. London: Aldridge Press; 2008

Several reasons for such evidence of unsafe and unlawful treatment were highlighted, including cross-organisational, organisational and individual influences. The report concluded that:

. . . the evidence . . . suggests very clearly that high levels of health care need are not currently being met and that there are risks inherent in the care system. People with learning disabilities appear to receive less effective care than they are entitled to receive. There is evidence of a significant level of avoidable suffering and a high likelihood that there are deaths occurring which could be avoided.

p. 53. 4 Reproduced with permission from Michael J. Healthcare for All: Report of the Independent Inquiry into Access to Healthcare for People with Learning Disabilities. London: Aldridge Press; 2008

The report sets out 10 clear recommendations for service planners, providers and practitioners to improve this unacceptable situation.

Healthcare for All recommendations

Four out of the 10 recommendations fall within the responsibility of acute care service providers and are the focus of this study:

All healthcare organisations including the Department of Health should ensure that they collect the data and information necessary to allow people with learning disabilities to be identified by the health service and their pathways of care tracked.

Recommendation 2, p. 114

All trust boards should demonstrate that they have effective systems in place to deliver effective, ‘reasonably adjusted’ health services for those people who happen to have a learning disability. This ‘adjustment’ should include arrangements to provide advocacy for all those who need it, and arrangements to secure effective representation on PALS [Patient Advice and Liaison Service] from all client groups including people with learning disabilities.

Recommendation 10, p. 114

Family and other carers should be involved as a matter of course as partners in the provision of treatment and care, unless good reason is given, and trust boards should ensure that reasonable adjustments are made to enable them to do this effectively. This will include the provision of information, but may also involve practical support and service co-ordination.

Recommendation 3, p. 114

Section 242 of the National Health Service Act 2006 requires NHS bodies to involve and consult patients and the public in the planning and development of services, and in decisions affecting the operation of services. All trust boards should ensure that the views and interests of patients with learning disabilities and their carers are included.

Recommendation 9, p. 11. 4 The above quotations are reproduced with permission from Michael J. Healthcare for All: Report of the Independent Inquiry into Access to Healthcare for People with Learning Disabilities. London: Aldridge Press; 2008

Starting points for this study

This study was undertaken in response to a call from the then National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) programme, now the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HS&DR) programme to investigate the factors affecting patient safety in health-care organisations. The starting points for the study were the above four Healthcare for All4 recommendations, as well as three particular patient safety issues for people with learning disabilities: medication errors, preventable deterioration and misdiagnosis.

Structure of the report

The report has four main sections: Introduction (see Chapters 1–3), Literature review (see Chapter 4), Results (see Chapters 5–11) and Conclusions (see Chapters 12–14).

Section 1: Introduction

Chapter 1 provides the background and rationale for the study, the national context, a definition of ‘learning disability’ and an overview of the structure of the report.

Chapter 2 sets out the study aims and theoretical framework.

Chapter 3 provides a description of the study methods, the participants and the research team. It also sets out the major challenges encountered in carrying out the research.

Section 2: Literature review

Chapter 4 provides an updated literature review, conducted during the course of the study, with a focus on the specific lines of inquiry in the study and in the light of national developments during the study period. This gives an important context for the study results.

Section 3: Results

Chapters 5–8 report on the findings in relation to the four recommendations of Healthcare for All,4 as follows:

-

Chapter 5 explores ways of identifying patients with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals and tracking their pathways of care.

-

Chapter 6 looks at providing reasonably adjusted hospital services.

-

Chapter 7 discusses the involvement of carers as partners in care.

-

Chapter 8 examines how patients and carers may be involved in service planning and development.

Chapters 5–8 each include an empirical subframework of the cross-organisational, organisational and individual factors that affect the safety of patients with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals.

Chapter 9 reports on the findings in relation to the learning disability liaison nurse (LDLN) role in NHS hospitals.

Chapter 10 reports on the findings in relation to specific patient safety issues faced by patients with learning disabilities.

Chapter 11 reports on the results of stage III of the study, which focused on the extent to which the study findings are generalisable to other vulnerable patient groups. This includes a brief review of the literature.

Section 4: Conclusions

Chapter 12 summarises the main findings and explores some of the main themes. It integrates the results and empirical subframeworks, resulting in an empirical framework of factors that promote or hinder a safer environment for patients with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals.

Chapter 13 discusses the implications of the study results for health-care services.

Chapter 14 provides recommendations for further research.

Chapter 2 Study aims and theoretical framework

Rationale for the aims and objectives

Knowledge gaps

As has been described (see Chapter 1), there have been a range of initiatives and examples of good practice with regards to implementing the changes recommended in Healthcare for All4 in order to promote the safety of patients with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals. However, it has been reported that such good practice examples are patchy. The extent to which these initiatives are effective in promoting safer care, and the factors that promote effective long-term change, are poorly understood. In particular, it is not clear:

-

which particular organisational and management structures contribute to the safer care of patients with learning disabilities

-

how effective ‘change agents’ (such as LDLNs) are in promoting safer care for people with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals

-

how patients with learning disabilities and their relatives can be effectively engaged in improving safety in hospitals

-

which contributions to patient safety can be effected within individual NHS acute hospitals, and which require a wider approach (for example through regulatory bodies).

Implementing the recommendations requires changes in both the organisation of systems and services, and staff practice. The examination of these issues at organisational, group and individual level is essential in order to understand how change may be facilitated with regard to learning disability practice. Without a clear understanding of these issues, improved safety for patients with learning disabilities in hospitals is likely to remain haphazard.

The purpose of this study was not to perform an audit of NHS acute trusts in relation to their performance against targets or the implementation of policies and systems to improve safe care of patients with learning disabilities. Rather, its purpose was to understand the processes of implementation and the factors that influence the effectiveness of the measures.

Healthcare for All4 concludes:

The evidence shows a significant gap between policy, the law and the delivery of effective health services for people with learning disabilities.

p. 53. Reproduced with permission from Michael J. Healthcare for All: Report of the Independent Inquiry into Access to Healthcare for People with Learning Disabilities. London: Aldridge Press; 2008

There is a lack of knowledge about how to translate hospital policy and guidelines into effective practice and improved services. This study was set up to address that knowledge gap. It aimed to understand the extent to which evidence of good practice in promoting safety for patients with learning disabilities is driven by (a) policy and its communication downwards through the health service organisation and/or (b) bottom-up initiatives originating from new patient/practitioner partnerships, innovative teams and charismatic leaders.

Defining cross-organisational, organisational and individual influences

In the context of this study, cross-organisational influences are those that affect the care of patients with learning disabilities across multiple NHS acute hospitals. This may include influences from primary care, secondary care and social care settings. They are imposed by the external policy context, by the structure and delivery of the NHS as a national organisation or by the interface between different health-care organisations and structures. They encompass decisions made at a regional or national level. Cross-organisational influences on patient safety issues cannot be addressed by NHS acute hospital trusts in isolation.

Organisational influences comprise the policies and systems adopted by individual NHS acute trusts which ultimately affect the resources available and local working conditions. It is at the level of organisational influences that NHS acute hospital trusts have a unique power to address patient safety issues within their organisations.

Individual influences are related to the way in which individual staff and staff teams can affect the care and safety of patients with learning disabilities. They are reflected, for example, in ward culture and staff attitudes. Individual influences also comprise factors inherent in the population profile of patients with learning disabilities and their carers, over which NHS hospitals will have little control.

Study aims

Aims

The primary aim was to describe the cross-organisational, organisational and individual factors in NHS hospitals that promote or compromise a safe environment for patients who have learning disabilities.

The secondary aim was to develop guidance for NHS acute trusts about the implementation of successful and effective measures for promoting a safer patient environment.

Research questions

-

What systems and structural changes have been put in place in NHS acute hospitals to prevent adverse outcomes for patients with learning disabilities, in particular with regards to specific safety issues (medication errors, misdiagnosis and preventable deterioration), and to recommendations 2, 3, 9 and 10 of Healthcare for All?

-

How successful have these measures been in promoting safe practice? In particular:

-

What cross-organisational, organisational and individual factors have been barriers and enablers in implementing the Healthcare for All recommendations for patients with learning disabilities in a sample of six NHS hospitals?

-

What are the examples of effective, replicable good practice at these six sites?

-

-

To what extent can the findings and learning from question (2) be generalised to other vulnerable patient groups?

With regards to the third question, the study aimed to identify which factors affecting patient safety are likely to be unique to the presence of learning disability, and which are due to general vulnerability and communication problems. This will enable the identification of findings that are transferable to other vulnerable patient groups.

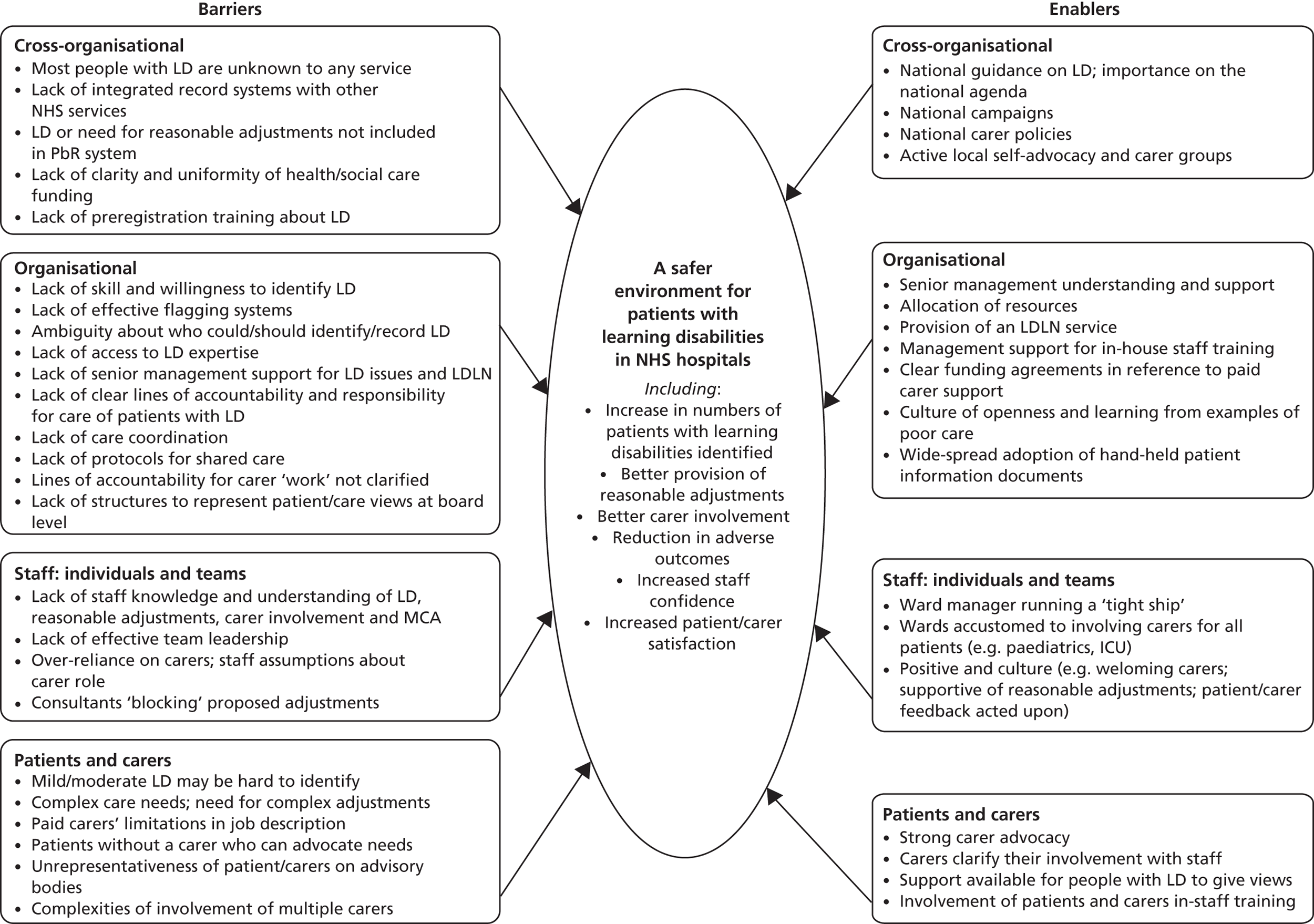

Theoretical framework

This study took a systematic approach to an empirical identification of the factors that affect the implementation of strategies to promote a safer environment for patients with learning disabilities in hospitals, and in particular the implementation of recommendations 2, 3, 9 and 10 of Healthcare for All,4 as well as patient safety issues that had been identified in consultation documents by the Care Quality Commission (CQC)25 and the Department of Health26 (no longer available). A theoretical framework was developed for understanding the range of factors that might impact on such implementation in NHS hospitals. This framework was based on the literature summarised in Chapter 1, as well as the wide-ranging insights and experience of the multidisciplinary research team and the research advisory board.

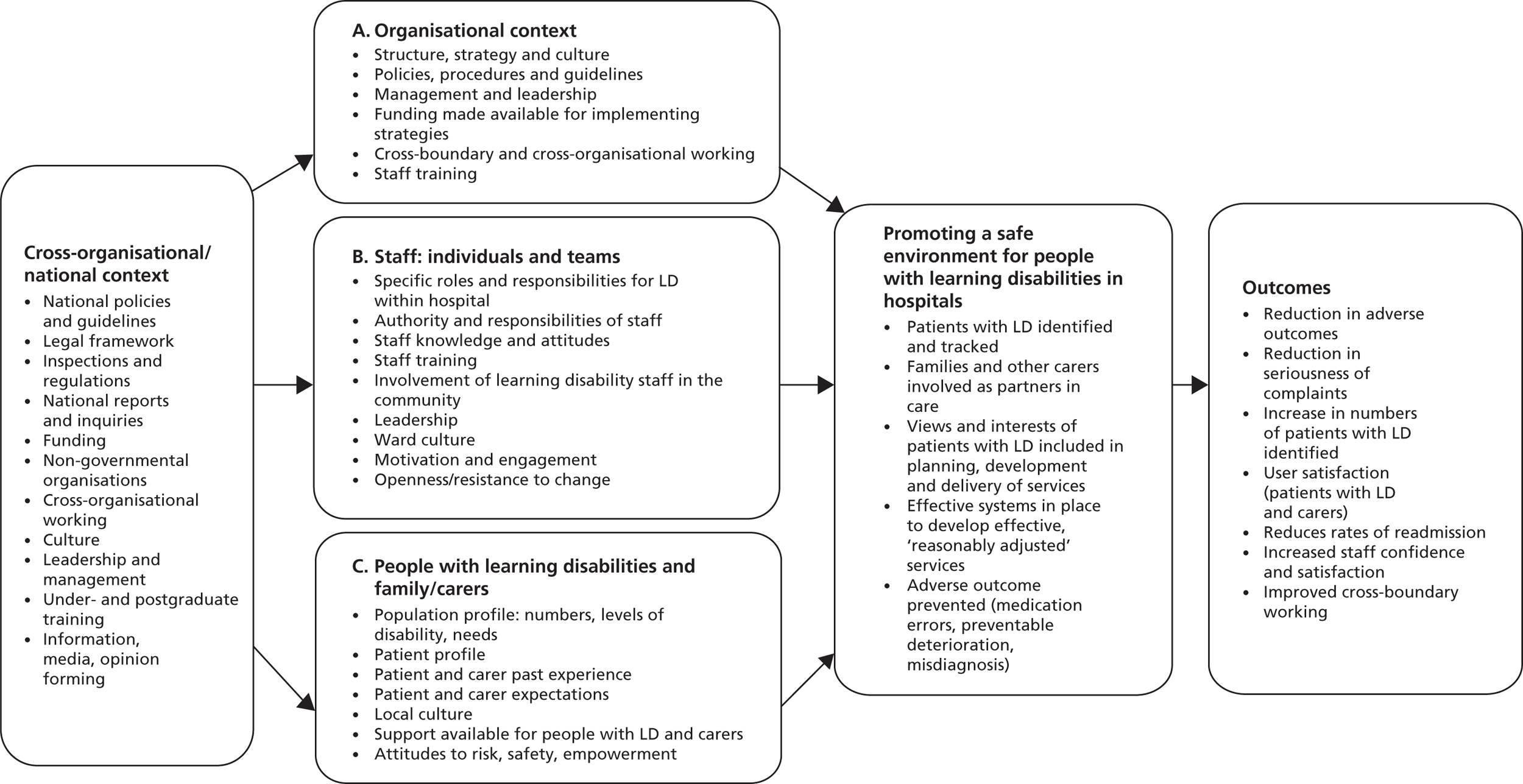

The theoretical framework identifies potential barriers and facilitators to improving safety for patients with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals in a number of domains: cross-organisational, organisational and individual. Organisational and individual domains are indicated in boxes A, B and C of the theoretical framework (Figure 1). Each box contains a number of factors within each domain that might be anticipated to function as barriers to or facilitators of promoting a safe environment for people with learning disabilities in NHS acute hospitals.

FIGURE 1.

Theoretical framework identifying factors that affect the promotion of a safer environment for patients with learning disabilities. LD, learning disabilities.

In addition, the framework identifies a number of outcomes that might be associated with effective patient safety measures for patients with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals. These outcomes are largely derived from the research team’s interpretation of Healthcare for All,4 and other reports and literature described earlier.

After testing and further developing the theoretical framework over the course of the study, it will be re-presented in Chapter 12 as an empirical framework for promoting the safety of patients with learning disabilities.

Research framework

From the theoretical framework flows the research framework (Table 1), where specific research questions are asked within each domain (A, B and C). The research methods, described in Chapter 3, are derived from this research framework.

| Research Focus | A. Organizational context | B. Staff individual and teams | C. People with LD and carers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation 3 | |||

| All health-care organisations, including the Department of Health, should ensure that they collect the data and information necessary to allow people with learning disabilities to be identified by the health service and their pathways of care tracked | A1. What are the policies, procedures and systems for identifying patients with LD? A2. On admission, what data and information are collected from patients with LD? A3. What are the policies, procedures and systems for tracking their pathways of care? A4. What do senior managers see as the barriers to and facilitators of collecting the necessary information? |

B1. Are staff on hospital wards aware of the need to identify and track patients with LD? B2. Do staff on hospital wards know the policies, procedures and systems for tracking patients with LD? B3. Do staff on hospital wards identify and track patients with LD? B4. How are staff on hospital wards alerted to the fact that a patient has LD? B5. Have LD staff (both within and outside the hospital) been asked to assist with providing the necessary information to enable people with LD to be identified and their pathways tracked? |

C1. Are patients with LD and their families/carers aware of the requirement for hospitals to identify their needs and track their care pathways? C2. Have patients with LD and their families/carers been asked to provide the necessary information? C3. Are patients with LD and their families/carers able and happy to provide the necessary information? |

| Recommendation 2 | |||

| Family and other carers should be involved as a matter of course as partners in the provision of treatment and care, unless good reason is given, and trust boards should ensure that reasonable adjustments are made to enable and support carers to do this effectively. This will include the provision of information, but may also involve practical support and service co-ordination | A5. What policies and reasonable adjustments are in place to enable and support families/carers to be involved as effective partners in care provision? A6. Does the hospital have guidelines on the provision of information for carers, practical support and service co-ordination? A7. Is there a culture among senior managers that encourages partnerships with families/carers? |

B6. Are staff on hospital wards aware of any policies or the need to make reasonable adjustments to enable and support families/carers to be involved as effective partners in care provision, including care and discharge planning? B7. In what ways are families/carers involved as partners in care provision by staff on hospital wards? (Is there provision of information, practical support and service co-ordination?) B8. Is there a culture among staff on hospital wards that encourages partnerships with families/carers? |

C4. Do families/carers feel that they have been supported and included as partners in care provision, including care and discharge planning? C5. Have families/carers been provided with information and practical support? C6. Are families/carers satisfied with the care provided by the hospital? |

| Recommendation 9 | |||

| Section 242 of the National Health Service Act 2006 requires NHS bodies to involve and consult patients and the public in the planning and development of services, and in decisions affecting the operation of services. All trust boards should ensure that the views and interests of people with learning disabilities and their carers are included | A8. What policies and systems have been put in place by the hospital to ensure that the views and interests of patients with LD and their families/carers are included in the planning, development and delivery of services? A9. Are people with LD and their families/carers represented on advisory and decision-making bodies within the hospital? A10. Is there a culture among trust board members and other senior managers that encourages inclusion of the views and interests of people with LD and their families/carers in the planning, development and delivery of services? |

B9. How are staff on hospital wards made aware of the views and interests of patients with LD and their carers? B10. Have LD staff (both within and outside the hospital) been invited to offer the necessary support to ensure that the views and interests of patients with LD and their carers are included? |

C7. How have the views and interests of people with LD and their carers been included? C8. Do people with LD and their families/carers believe that their views and interests are taken into account by the hospital? C9. If people with LD and their families/carers are represented on advisory/decision-making bodies, what has been their experience? |

| Recommendation 10 | |||

| All trust boards should demonstrate that they have effective systems in place to deliver effective, ‘reasonably adjusted’ health services . . . This ‘adjustment’ should include arrangements to provide advocacy for all those who need it, and arrangements to secure effective representation on PALS from all client groups including people with learning disabilities ‘Reasonable adjustments’ in this context are described in the literature and include:

|

A11. What systems have been put in place by the hospital to ensure reasonable adjustments are made? A12. What do senior managers understand by ‘reasonably adjusted services’? A13. What funding has been made available to ensure that reasonable adjustments are made? A14. What are the arrangements for provision of advocacy to all those who need it? A15. What partnerships are in place with other agencies who have a remit to support patients with LD? A16. Are there professionals within the hospital with a specific remit to promote the delivery of effective, reasonably adjusted health services? |

B11. What do individual staff members and teams understand by ‘reasonable adjusted services’? B12. How do individual staff members and teams ensure that they deliver effective, reasonably adjusted services? B13. Are individual staff members aware of the specific needs of patients with LD, and do they know how to ensure those needs are met? B14. Do individual staff members know how to arrange advocacy for patients who need it? B15. Have LD staff (both within and outside the hospital) been asked to assist with ensuring that hospital services are reasonably adjusted? |

C10. Do patients with LD and their families/carers feel that the patient’s individual needs have been met? C11. Was the patient given information in a way he/she could understand? C12. Did staff allow enough time in their care of the patient? C13. Were patients provided with advocacy when they needed it? |

| Safeguarding and safety: prevention of adverse outcomes | |||

With specific focus on:

|

A18. What measures are in place to ensure the safe administration of medication to patients with LD, including giving clear information about medicines to the patient? A19. What measures are in place to avoid preventable deterioration and misdiagnosis for patients with LD? A20. What systems are in place for monitoring adverse outcomes and complaints involving patients with LD? |

B17. Are individual staff and staff teams aware of the measures to ensure safe administration of medication to patients with LD? B18. Are individual staff and teams aware of the measures in place to avoid preventable deterioration and misdiagnosis for patients with LD? B19. Are individual staff and teams aware of the systems in place for reporting adverse outcomes? B20. Are adverse outcomes involving patients with LD reported by staff? |

C15. Do patients with LD and their families/carers think they have been given understandable information about medicines, including medicines to take home? C16. Do patients with LD and their families/carers think that preventable deterioration was avoided? C17. Do patients with LD and their families/carers feel they received an accurate and timely diagnosis? C18. Do patients with LD and their families/carers know how to make a complaint? C19. What adverse outcomes and complaints involving patients with LD or their families/carers have been recorded within the hospital during the data collection period? |

Chapter 3 Research design and methods

Study design

The theoretical and research frameworks posed a number of different research questions best addressed using a range of methods at a number of levels of enquiry. This was a complex study which integrated qualitative and quantitative methods and involved three stages, followed by a period of data synthesis. The study lasted 21 months (from July 2011 to March 2013).

Stage I consisted of mapping the systems and structural changes within each hospital site (related to research question 1).

Stage II (the main stage) was related to research question 2, and comprised a range of methods, including interviews, surveys and observation.

Stage III involved synthesis of the data, including synthesis with the literature on other vulnerable patient groups. In addition, structured feedback was gathered from clinical and patient safety leads in other vulnerable patient groups, to assess generalisability (research question 3).

The full research protocol can be found in Appendix 2.

Sampling

Selection of hospital sites

A purposive sample of six hospital sites was selected for the study. (The original research proposal and initial recruitment involved five study sites. Soon after the start of the study, site D was withdrawn and site F recruited. Site D was later re-included in the study, making a total of six sites.) A brief profile is shown in Table 2. Selection was made according to the following three criteria, which were likely to impact on the implementation of the strategies under investigation:

-

A range of urban/rural and sociodemographic environments were represented, and a range of hospital sizes (the number of staff per hospital was between 3000 and 6000; number of beds was between 450 and 900).

-

Hospitals selected had shown active engagement with issues around safety for patients with learning disabilities, based on the hospital’s record since 2008 in prioritising the safety of patients with learning disabilities. The selected study sites had a range of recent or more long-standing implementation plans for the recommendations in Healthcare for All. 4

-

Contrasting examples were sought of the use of a LDLN service. Three hospitals employed a LDLN; two hospitals worked closely with LDLNs based in primary care who had an explicit remit to provide a LDLN service at that hospital; and one hospital did not have a LDLN service. As terminologies and job titles for this role varied across study sites, for the sake of uniformity and anonymity the term LDLN is used throughout this report, and the gender of the LDLN has been assigned female in all quotes and descriptions.

| Hospital | Type | Area | Learning disability liaison nurse |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Teaching | Urban | Hospital based |

| B | District general | Urban | Community based |

| C | District general | Urban | None |

| D | District general | Urban/rural | Hospital based |

| E | Teaching | Urban/rural | Hospital based |

| F | District general | Rural | Community based |

Collaborators

The research team worked with a collaborator at each site, whose role it was to promote and support the study within their organisation and to provide access to participants (staff, patients and carers). These initially consisted of two Directors of Nursing, two Deputy Directors of Nursing and two LDLNs. During the course of the study, four of these collaborators left their posts and new collaborators had to be found. In some cases, this caused delays to data collection.

The study site collaborators were an integral part of the study. The initial group of collaborators were involved in the design of the study protocol. Throughout the study period, the group of collaborators met five times in order to discuss progress and any difficulties with data collection, and provided advice on ways in which the protocol could be adapted in order to cope with any difficulties that had emerged.

Participants

A wide range of staff, patients and carers participated formally in the study through surveys, telephone and face-to-face interviews, participant observation and expert panel discussions (n = 1249 after exclusions). An overview of these participants is given in Table 3, and full details are given in Appendix 3. Sampling methods for each participant group are described under the relevant sections below (see Data collection). In addition, the researchers kept field notes of conversations and observations at the hospital sites, adding further informal participants.

| Data collection | Hospital site | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | ||

| Stage I informants (strategic managers) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 11 |

| Interviews with people with learning disabilities | 9 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 33 |

| Tracer patientsa | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 19 |

| Carer survey | 35 | 12 | 2 | 19 | 8 | 12 | 88 |

| Carer interviews | 10 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 37 |

| Staff interviews | 12 | 9 | 8 | 14 | 10 | 15 | 68 |

| Staff survey | 253 | 76 | 81 | 133 | 296 | 151 | 990 |

| Panel discussion | 11 | 10 | 9 | – | – | 12 | 42 |

| Total | 335 | 124 | 108 | 183 | 327 | 211 | 1251b |

During the course of the study the researchers also spoke to staff, patients and carers involved in hospital trusts throughout England that were not part of the study. Whilst these are not specifically reported here, the insights gained from such ‘shadow hospital trusts’ informed the final analysis.

Data collection

Stage I

Stage I took place from August to September 2011. The aim of this stage was to map the systems and structural changes that had been put into place at the six hospital sites, with regards to research question 1. A questionnaire was developed and sent by e-mail to the collaborators at each site, who either filled it in themselves or nominated someone else within the trust who was well placed to answer the questions (n = 11). This was followed up by a telephone interview to clarify and complete the answers with some informants (n = 6).

Documents relating to all relevant policies, procedures and systems were examined. This included any systems for flagging or identifying patients with learning disabilities; any patient-held information documents currently being used at the trust; relevant carer policies; systems or arrangements in place to provide reasonable adjustments (specifically, whether trusts provided accessible information and met individual communication needs); and any specific arrangements in place to allow family and carers to make a complaint. Documents relating to particular patient safety issues including medication errors, preventable deterioration and misdiagnosis were also examined.

Stage II

Stage II was related to research question 2 and took place from October 2011 to September 2012. This stage formed the main part of the study and was concerned with examining the effectiveness of the measures identified in stage I. The wide range of methods, sampling strategies and data collection tools are set out below.

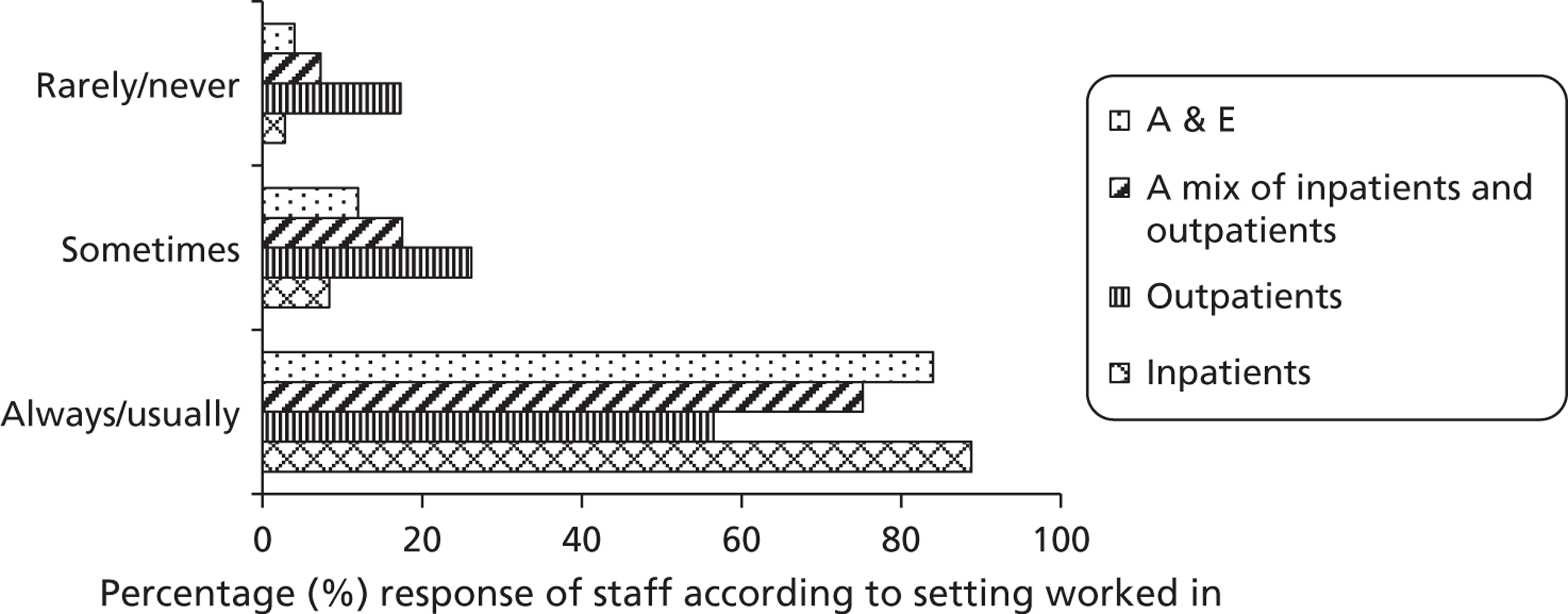

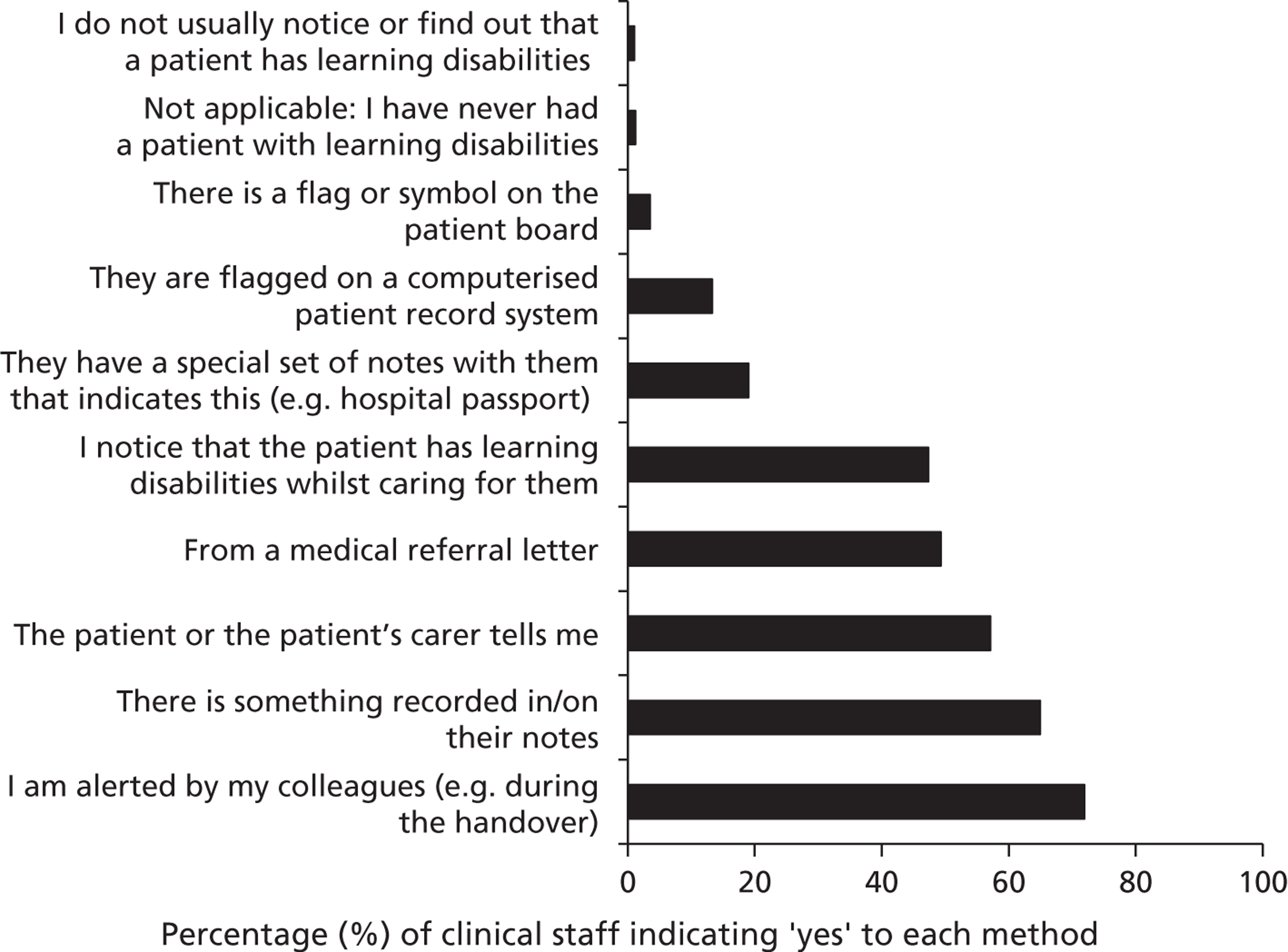

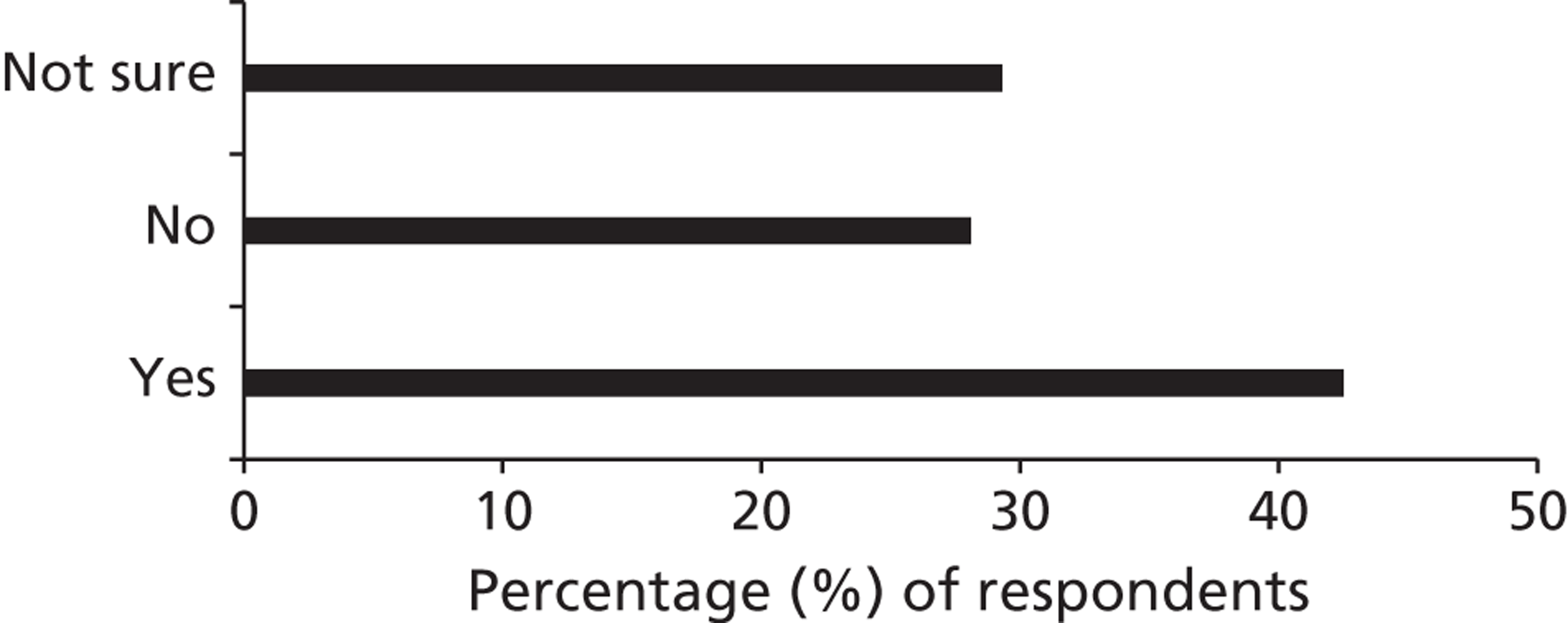

Survey for staff

An electronic questionnaire was distributed to all clinical staff. This was a deviation from the original research protocol, which stipulated that paper questionnaires would be distributed to all clinical staff on only three selected wards per hospital. The collaborators suggested that an electronic questionnaire to all staff would be easier to administer. The research advisory board agreed that this was an improvement on the protocol, as it would yield more a comprehensive data set. Questions were designed according to the theoretical framework within the study protocol, taking into account the findings from stage I, qualitative data gained from staff interviews conducted in the early part of stage II and with reference to existing literature. LimeSurvey software version 1.86 (open source) was used to design and host the electronic questionnaire. Details of the questions asked along with corresponding basic descriptive results are listed in Appendix 4.

Endorsement

A strategic manager at each collaborating site was asked to endorse the staff survey. At three sites this was the Director of Nursing or Deputy Director of Nursing and at three sites this was the Chief Executive. Links to the clinical staff electronic questionnaire were sent to all clinical staff via e-mail with the accompanying endorsement.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

‘Clinical staff’ were defined as qualified or unqualified staff who care for or have a caseload of patients [e.g. nurses, health-care assistants (HCAs), doctors, allied health professionals (AHPs) and others]. The definition of ‘clinical staff’ acted as an initial screening question; participants were requested to exit the questionnaire if they indicated that they were not clinical staff. Where relevant to the interpretation of the results, only participants who indicated that they had cared for a patient with learning disabilities at their current hospital were included in the analysis; those who had never cared for a patient with learning disabilities, or who were not sure if they had cared for a patient with learning disabilities, were excluded (this information was supplied in answer to question 5 of the questionnaire). The exclusion criteria applied to the reporting of each question are documented throughout Appendix 4.

Survey response

A total of 1018 questionnaires were returned. Four of these responses were excluded as they had been completed by people who had indicated that they were not clinical staff. A further 24 questionnaires were returned completely blank and were therefore excluded from the analysis, leaving 990 usable questionnaires.

Response rate

Human resources departments at each site were requested to provide a breakdown of the numbers of clinical staff employed in each staff group (medical and dental, qualified nursing and midwifery, AHPs, HCAs, other support staff and other clinical staff) for the relevant time period. This allowed calculation of the percentage response rate from each site (Table 4). Differences in the response rates at each site are likely to be due to differences in the methods of distribution. For example: site E had a much more targeted approach to distribution; ‘clinical staff’ definition may differ between sites; and some figures exclude those on leave (sick/maternity) and those working 0-hours contracts, whereas others do not.

| Site | Number of questionnaires returned | Approximate % response ratea |

|---|---|---|

| A | 265 | 5.3 |

| B | 79 | 2.7 |

| C | 84 | 4.1 |

| D | 139 | 4.0 |

| E | 298 | 14.9 |

| F | 153 | 6.7 |

Survey representativeness

The survey response is likely to be biased towards those who have an interest in the subject matter; for example, almost a quarter (24.7%, 214 out of 866) indicated that someone in their family or close social circle had learning disabilities. It is also likely to be biased towards professionals who are comfortable with online surveys and who are able to spend some time completing the survey during work hours. The response rate seems low; however, there was a good spread of clinical staff groups across the six study sites, and using the online method, the number of questionnaires returned was higher than anticipated in the original protocol.

Interviews with staff

Semi-structured face-to-face interviews were held with hospital staff (n = 68). The interview schedule for ward staff included a tracer scenario27 designed to assess staff knowledge of policies, procedures, structures and issues related to learning disability. Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. They were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Senior managers

For the purpose of this study, and throughout this report, the term ‘senior manager’ refers to managers with hospital-wide responsibilities for patient care. This includes, but is not limited to, (Deputy) Directors of Nursing, Medical Directors and Directors of Patient Safety. All Directors of Nursing and Medical Directors were invited to participate and to suggest one further senior manager with hospital-wide responsibilities (n = 27).

Clinical staff

At each hospital site, three wards were selected in which to conduct staff interviews. Selection criteria specified that these should be (1) a medical assessment ward or similar; (2) a ward selected by the collaborator as having a relatively high number of people with learning disabilities; and (3) the ward that had received the highest number of complaints (all complaints, not specifically related to people with learning disabilities), excluding accident and emergency (A&E) departments (which, at most sites, had the highest number of complaints). On each of these wards, the ward manager or sister was interviewed and asked to select two further ward nurses for interview (n = 31). This selection was partly purposive (to ensure a range of responsibilities and experience was included) and partly convenience (interviews were held with nurses available on the day of the researcher’s visit).

In addition, hospital staff with specific responsibilities for implementing learning disability policies were purposively selected for interview. This included, for example, the LDLNs and matrons who were responsible for a group of wards. Community learning disability nurses who had strong links with the hospital were also interviewed.

Sampling people with learning disabilities and carers

Inclusion criteria for people with learning disabilities were: (a) the presence of a learning disability, (b) age ≥ 16 years and (c) having been an in- or outpatient at the hospital during the 12-month stage II data collection period. Inclusion criteria for carers required being a family or paid carer of an adult (aged ≥ 16 years) with learning disabilities admitted to the hospital during the data collection period.

The theoretical definition of learning disability (see Chapter 1) is not easily operationalised in practice. Few people, for example, have a known IQ value. For the purpose of this study, we included any patient who had been identified by the hospital as having learning disabilities.

The extent to which patients and carers could be included in the study depended on the ability of the participating hospitals to identify patients with known learning disabilities. The sampling of patients with learning disabilities and their carers was further limited by the fact that many have never been formally identified as having learning disabilities and are unknown to health and social care services. The researchers’ efforts to identify patients and carers for the purpose of this study, and the lessons learnt, form part of the findings (see, in particular, Chapter 5).

The sampling strategy for people with learning disabilities and carers had to be adjusted during the study. The original protocol stated that all patients with learning disabilities identified within the hospital during the 12 months of stage II would be given information about the study and invited to contact the research team if they wished to take part in a face-to-face interview; their carers would be given a questionnaire and the option to take part in a telephone interview. The aim was to purposively select patients for face-to-face interview to ensure a range of abilities and hospital experiences, and to continue sampling until saturation of data had been reached (i.e. no new themes, issues or topics arising from the interviews). It was anticipated that this would be approximately 60 patients (10 per hospital). It was further estimated that around 600 carer questionnaires would be distributed and that around 50 carer interviews would be conducted.

The collaborators were asked to ensure that this happened. In practice, the task of distributing the study information sheets to carers (see below) and patients with learning disabilities fell to the LDLNs within the hospitals. They found this difficult to do, partly because they did not usually carry the study information sheets with them when seeing patients and carers, and partly because they felt that at the point of contact, the hospital experience was complicated and anxiety-provoking enough for the patient without any added information about a research study. To support recruitment of patients and carers, a flyer was distributed to a number of hospital wards. Five months into stage II, no patients had been recruited and only 18 carer questionnaires had been returned. The sampling strategy was changed in two ways: (1) following the patient’s discharge, carers were sent study information and a questionnaire, as well as study information to pass on to the person with learning disabilities (two people with learning disabilities were recruited in this way); and (2) a hospital open day was hosted at each study site, and people with learning disabilities living locally were invited to come and be interviewed. Information about these days was distributed among hospital staff, community learning disability teams and community residential and advocacy organisations. Twenty-three people with learning disabilities were recruited this way. Carers or supporters who came with the person were offered a carer questionnaire and an opportunity to be interviewed if they had supported a person with learning disabilities attending that hospital within the data collection period. Six carer interviews were held during the open days. One person with learning disabilities was interviewed during a stakeholder feedback conference.

In addition, the original protocol stated that all people with learning disabilities who were members of advisory/decision-making bodies or patient representation groups within the hospital, and all those who had made a formal complaint themselves, would be invited for face-to-face interview (estimated n = 15). In practice, only seven people with learning disabilities who were on advisory bodies were referred to the research team and invited to be interviewed (all took part). The research team was not aware of any patients with learning disabilities who made a formal complaint during the data collection period.

In total, 33 people with learning disabilities took part in an interview (32 face-to-face interviews and one telephone interview at the interviewee’s express request). Despite the collaborators and/or LDLNs being sent over 1000 carer questionnaires to distribute, only 94 questionnaires were returned.

The recruitment problems stemmed in great part from the difficulty all hospitals had in correctly identifying patients with learning disabilities (see Chapter 5). At one hospital with an active LDLN, 35 carer questionnaires were returned; at a hospital without a LDLN, only two carer questionnaires were returned.

Despite the carer and patient participant numbers being only around half the projected total, the research team and research advisory board believed that data saturation had been achieved by the end of the study.

Carer survey and carer interviews

Data collection tools for carers were developed with the support and advice of a carer representative on the research advisory board.

Survey

The carer questionnaire, including responses, can be found in Appendix 5. Six of the 94 completed carer questionnaires did not meet the inclusion criteria (four were concerned with people with learning disabilities aged < 16 years and two were completed not by carers, but by patients with learning disabilities themselves), leaving a total of 88 usable questionnaires. Of these, 54 (61.4%) were from paid carers and 34 (38.6%) were from family carers, mostly parents.

Interviews

All those who indicated that they were willing to be interviewed (n = 48) were contacted. A total of 37 semi-structured carer interviews were conducted, either by telephone (n = 26) or face to face (n = 11). Interviews were either audio recorded and transcribed verbatim (n = 18), or the interviewer wrote a summary of the interview immediately afterwards and sent it to the interviewee for verification, additions and approval (n = 19).

Interviews with people with learning disabilities

Interviews with people with learning disabilities were conducted by one of the two coresearchers who had learning disabilities themselves, with the support of one other researcher following several practice and training sessions. The coresearchers helped with the development of the data collection tools as well as the development of study information and consent sheets (see Appendix 6).

There were three different data collection tools:

-

Talking Mats™ (Talking Mats Ltd, Stirling, UK), a communication resource that helps people with communication difficulties to express their views. 28 Participants were asked to place specifically developed pictures on different sections of a mat to indicate ‘Like’, ‘Not sure’ or ‘Do not like’ (see Appendix 7). A set of neutral pictures was offered to start the session, in order to introduce the participants to the use of Talking Mats™ and to make them feel at ease.

-

An interview schedule using pictures and stories about other people attending hospital (see Appendix 8). Many people with learning disabilities find it easier to express their views through the use of story-telling. 29

-

An interview schedule consisting of a list of questions about the interviewee’s own hospital experiences (see Appendix 9).

The decision whether to use (b) or (c) in addition to (a) was taken by the supporting interviewer. Flexibility was used to allow for individual communication needs and comprehension. Interviewees could have their own supporter with them during the interview if they wished. Whether or not to use tape recording was agreed with each interviewee.

Tracer patients

‘Tracer patients’ were included with the aim of establishing how policies and procedures worked in practice, how the patients’ specific needs were met, and how their safety was ensured. The following data were collected: participant observational data (generally, two episodes of 2 hours); interview(s) with the patient if he/she had verbal understanding and ability; interview with a carer or carers; and interviews with hospital staff involved in the patient’s care. The patient’s hospital records and notes were studied. If the patient lacked the capacity to give informed consent, the research team identified and consulted someone who was not the patient’s professional care worker, to establish whether the patient should take part; this was in line with legislation in England under the Mental Capacity Act 2005. 30,31 Data consisted mostly of researchers’ field notes.

The original protocol stated that 30 tracer patients in total would be selected on the wards where staff interviews were held (see above). In practice, it proved extremely difficult to recruit tracer patients this way, for the following reasons: many wards did not have a suitable patient with learning disabilities within the data collection period; hospital staff (usually the LDLN nurse who was involved in selecting tracer patients) deemed the potential participant unsuitable for the study (for example, because the hospital stay was already stressful and complicated); or patients moved around the hospital or were discharged before researchers were able to complete information and consent procedures. The sampling base was extended to all inpatients, but despite much researcher effort, only eight tracer patients were recruited into the study.

Monitoring of records

The research team set out to monitor the following data throughout stage II:

-

the extent to which hospitals were able to identify and track patients with learning disabilities, by asking them to provide, as far as they were able, numbers of patients with learning disabilities accessing hospital services; where in the hospital the patient was admitted; length of stay; and readmissions to hospital within 7 days of discharge

-

all adverse incidents that involved patients with learning disabilities and/or their families/carers (not limited to serious incidents)

-

all complaints involving patients with learning disabilities and/or their carer(s).

The difficulties with these aims are set out in Chapter 5 (identifying and tracking patients) and Chapter 10 (monitoring adverse incidents and complaints).

Stakeholder feedback conferences

Towards the end of stage II, a stakeholder feedback conference was held at four of the six study sites (at the other two study sites, a convenient time when potential attendees were available could not be arranged). Stage ll participants at that site and local stakeholders were invited to attend; delegates included hospital staff, community learning disability staff, families, paid carers and people with learning disabilities. Attendance ranged from poor (with only two delegates) to moderate (around 30 delegates). The preliminary findings were presented by the research team and feedback was invited through discussion workshops. This was an additional way of testing the researchers’ interpretations around facilitators and barriers in promoting a safe environment for patients with learning disabilities in hospitals.

Stage III

Stage III was related to research question 3, and took place from November to December 2012. It was hypothesised that the factors associated with success and failures in dealing with patients with learning disabilities are likely to be similar for any vulnerable group with ‘non-standard needs’. A small number of questions on the differences and similarities in dealing with other vulnerable patient groups were part of the interview schedules in stage II.

At the end of stage II, the emerging findings were summarised in a discussion document alongside an emerging empirical framework.

Stage III consisted of synthesis of the emerging study findings with existing literature, which was searched for congruence with these findings in relation to other specific vulnerable patient groups, in particular patients with dementia and patients with mental health problems.

Expert panel discussions

Each hospital was invited to take part in an expert panel discussion, where the research team met with the hospital’s senior managers and senior clinicians who had a responsibility for patients with learning disabilities or for other vulnerable groups. Four of the hospitals were able to organise such a discussion, involving a total of 42 staff (see Appendix 3 for a breakdown of these participants).

The discussion document was presented to the panel by the principal investigator and a focused discussion was held to establish participants’ views on the generalisability of the emerging findings to other vulnerable patient groups. The discussions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

This study consisted of six detailed local case studies followed by a stage of data synthesis and generalisation. A comparative case study approach enabled the identification of generic features of change as they were indicated across contrasting areas. Comparison between the six sites, in particular when taking differences between samples into consideration, provided insight into where the barriers to and facilitators of the safety of patients with learning disabilities have generic importance.

Qualitative analysis

All qualitative data (including face-to-face interviews, telephone interviews, ethnographic data from tracer patients and data from open-ended questionnaire questions) were collated and analysed together in order to aid data synthesis. All qualitative data were entered into NVivo 9 (QSR International, Southport, UK), a computer software programme for managing qualitative analysis. 32 The initial common analytical coding framework was based on the research framework (see Table 1). Data analysis took place throughout the data collection period and involved coding subsamples of the data and weekly discussions with the core research team about emerging findings and possible new analytical codes. Members of the wider research team (research advisors) joined these discussions approximately once a month. Data sets that did not fit into the framework, or were difficult to synthesise, were used to generate new themes and refine the coding framework throughout the data collection period. Themes emerging from all three levels of inquiry (organisational, staff, and people with learning disabilities/carers) were compared and accommodated within the framework, ensuring that any commonalities or differences (for example, between different stakeholder groups, wards or hospital sites) were highlighted in the analysis. Meetings were held with specific stakeholder representatives on the research advisory board to discuss emerging findings in relation to relevant topics. This included meetings with Vanessa Gordon (Associate Director of Patient Safety, NHS Commissioning Board), the family carers on the research advisory board (for the purpose of involving carers) and the coresearchers and advisors with learning disabilities. The emerging findings were also discussed with experts outside the research team and research advisory board, including Sir Jonathan Michael (chairperson of the independent inquiry and author of Healthcare for All4). A final analytical framework was agreed by the research team in the final month of stage II.

Quantitative analysis

The quantitative data in this study consisted of semi-structured questionnaires with carers and with clinical staff. Data were analysed using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) Statistics 19 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics have been used as follows: continuous data have been described with mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values, and categorical data with frequencies and percentages. The online staff questionnaire survey had some missing data as a result of people dropping out of the survey prior to completion. Where these data are presented, only the sample of people known not to have dropped out up to that specific question is included as the denominator in calculating the descriptive statistics.

Data synthesis

The number of qualitative and quantitative data generated by the study was extremely large. During the stage of data synthesis, the research team looked for congruence and incongruence between qualitative and quantitative findings. In particular, the team looked for instances of incongruence between policy and practice. Special attention was paid to specific examples of both good and poor practice in relation to the safety of patients with learning disabilities, and the identification of the specific cross-organisational, organisational and individual factors that had a bearing on these examples. This resulted in a final empirical framework of factors that affect the promotion of a safer environment for patients with learning disabilities.

It must be noted that in this report many examples of good and poor practice are highlighted. This does not reflect the quantitative incidence of such examples (which this study did not aim to elicit), but rather, it reflects the study focus of aiming to understand how and why good or poor practice occurs.

Ethical issues

Ethical approvals

The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Services (NRES). Three substantial amendments were submitted to NRES during the course of the study, to include the sixth study site and to reflect altered sampling strategies. All were approved (Research Ethics Committee reference 11/LO/0428). Local research approval was obtained at each participating trust.

Ethical issues

Vulnerability of people with learning disabilities

This study included data collection involving vulnerable adults. The research team had long-standing expertise in conducting research involving participants who have learning disabilities in sensitive areas including death, dying, bereavement and abuse, and have gained international recognition in this area. 33

The research team believed that ethical considerations for this study needed to be given attention above and beyond any requirements of research ethics committees. Therefore, a range of steps were taken in order to safeguard all informants from undue harm in accordance with the principal of beneficence. Particular attention was paid to obtaining informed consent from research participants with learning disabilities, using a range of accessible study information materials, and to ensuring sensitivity to the various ways in which people with learning disabilities may express withdrawal of consent.

Anonymity

It became clear during the course of the study that the sensitivity of the subject area was a major challenge. Both before and during the study period, a range of NHS trusts across England had been publicly ‘named and shamed’, in particular through Mencap’s Death by Indifference report and follow-up report. 1,34 It was important to emphasise to the participating sites throughout the study that the results would be reported anonymously and that confidentiality would be protected.

For this reason, the study sites are described in this report in general terms only, pseudonyms are used throughout, and identifying details altered where they do not affect the essence of the data. Unless it is necessary for understanding local differences, particular data have not been attributed to particular study sites.

Project management

The study was hosted by the Division of Population Health Sciences and Education at St George’s, University of London. It was conducted by a broad research team and supported by a research advisory board with a wide range of knowledge, skills, experience and expertise. This included investigators and advisors with academic skills, but also those with personal experience of having learning disabilities, caring for someone with learning disabilities, accessing NHS hospital services and working in NHS hospital settings including senior management. In order to ensure that the research was relevant to all informant and stakeholder groups, as well as academically sound, this collaboration between service users, clinicians and academics was crucial throughout the research process, from developing the original proposal to reporting its findings. All members of the research and advisory teams contributed in the areas where their expertise was most relevant, both in terms of topic area (for example: patient safety issues; organisational change; understanding the role of the learning disability nurse; other vulnerable patient groups) and in terms of research design (for example: design and administration of electronic and paper questionnaires; analysing and synthesising data from multiple sources; recruitment of participants).

The research advisory board had an independent chairperson, Sir Leonard Fenwick, an NHS trust Chief Executive, and met five times during the course of the study. Individual members of the research advisory board provided ad hoc expertise to the research team as needed. The role of the research advisory board included ensuring that the protocol was followed; ensuring that the project was kept within budget and that deadlines were met; and providing advice and support to the research team with regards to emerging barriers and ethical issues.

Full details of the members of the research team and research advisory board are given in Appendix 1.

Section 2 Literature review

Chapter 4 Literature review

Introduction

At the start of the study and throughout the study period, the initial literature review was updated and expanded to incorporate the specific issues addressed in the study. This chapter provides important context for the findings reported in Chapters 5–10. It presents an overview of national developments, inquiries and reports that affected the course of this study, as well as a more detailed literature review around the following aspects of the study: identifying patients with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals; providing reasonably adjusted services; involving carers as partners in care; and patient safety issues for people with learning disabilities.

Progress and national developments since Healthcare for All

The study follows four recommendations of Healthcare for All,4 but it was not conducted in isolation of events. Following another of Healthcare for All’s recommendations, the time-limited CIPOLD was set up and this published its final report in March 2013. 3 Furthermore, a learning disability public health observatory, the Improving Health and Lives Learning Disability Observatory (IHAL), was established as a 3-year project in 2010. 35 This has published a range of documents, data and reports on health inequalities and the progress that health and social care services are making in addressing these. 14,24,36 It includes a wide range of good practice examples, but also evidence that people with learning disabilities remain disadvantaged when accessing health services. The evidence from CIPOLD in particular is highly relevant in relation to this study; this is further discussed in Chapter 12.

In 2010, Mencap launched its campaign Getting it Right When Treating People with a Learning Disability, providing guidance for health care services. 5 It invited NHS hospitals to sign up to a charter of pledges to ensure that a range of reasonable adjustments were made (see Reasonable adjustments for people with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals). In 2012, over 200 health-care organisations had signed up, and Mencap reported excellent examples of good practice. However, Mencap claimed that the NHS continued to fail people with learning disabilities, leading to avoidable deaths, and in 2012 published a follow-up report in which it concluded that not enough progress had yet been made in addressing the health inequalities experienced by people with learning disabilities. 34

The issue of discrimination and abuse of people with learning disabilities within health and social care services was kept in the headlines through the disclosure in May 2011 of appalling criminal abuse practices at Winterbourne View, a care home for people with learning disabilities, and the subsequent Department of Health review. 37 This highlighted a widespread failure to design, commission and provide appropriate services for people with learning disabilities, and an unacceptable tolerance of people with learning disabilities being given the wrong care.

During the time this study was conducted, the NHS experienced one of the largest-scale structural changes in its history, with the transfer of commissioning responsibility from PCTs to clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and the new NHS Commissioning Board, and responsibility for public health moving from the NHS to local authorities. Pressures on NHS services have increased. Although NHS funding has stayed broadly level in real terms since 2010, hospitals are dealing with a growing population, increasing numbers of older people, people with complex care conditions and people with dementia needing hospital treatment. The CQC reported that NHS services struggled to make sure they had enough qualified and experienced staff on duty at all times (with 16% of NHS hospitals being understaffed), and also struggled to make sure staff were properly trained and supervised. 38

It is important to remember that the first core value underpinning the NHS, as set out in its constitutions, remains a commitment to providing:

. . . a comprehensive service, available to all irrespective of gender, race, disability, age, sexual orientation, religion, belief, gender reassignment, pregnancy and maternity or marital or civil partnership status.

p. 3. 39 We acknowledge The National Archives as custodian of this document

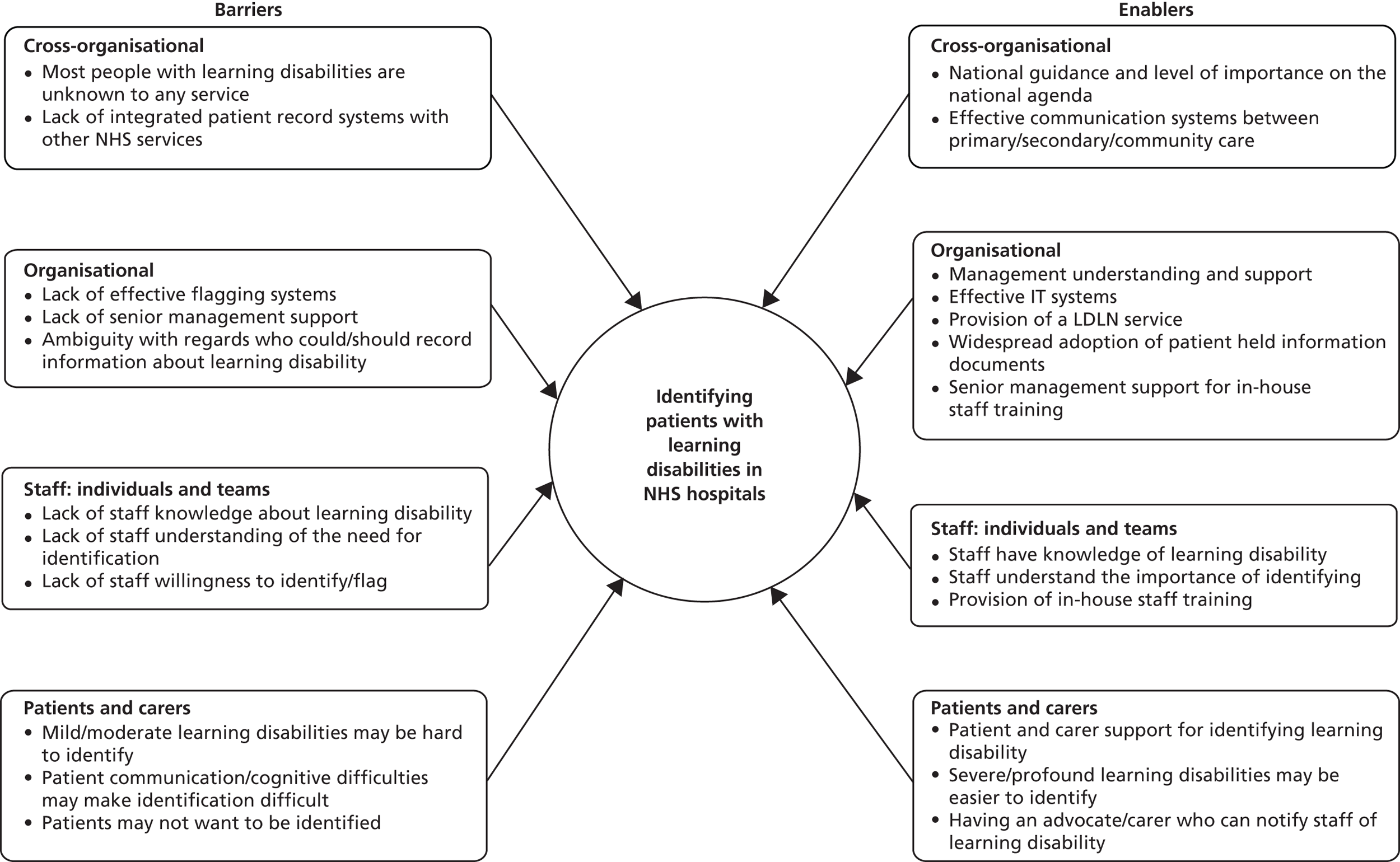

Identifying patients with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals

Healthcare for All4 states that:

. . . chief among the obstacles to delivering and evaluating the effectiveness of health services for people with learning disabilities is a lack of information about them . . . it is difficult for services to prepare properly or make the necessary ‘reasonable adjustments’ if patients’ communication and other special needs are unknown.

p.36. Reproduced with permission from Michael J. Healthcare for All: Report of the Independent Inquiry into Access to Healthcare for People with Learning Disabilities. London: Aldridge Press; 2008

The report recommended that health-care organisations should ensure they collect the data necessary to allow people with learning disabilities to be identified by the health service. This was accepted by government and a pledge was made in the White Paper Valuing People Now to work towards better systems for general practitioners (GPs) to identify people with learning disabilities and share that information with other NHS sources. 20

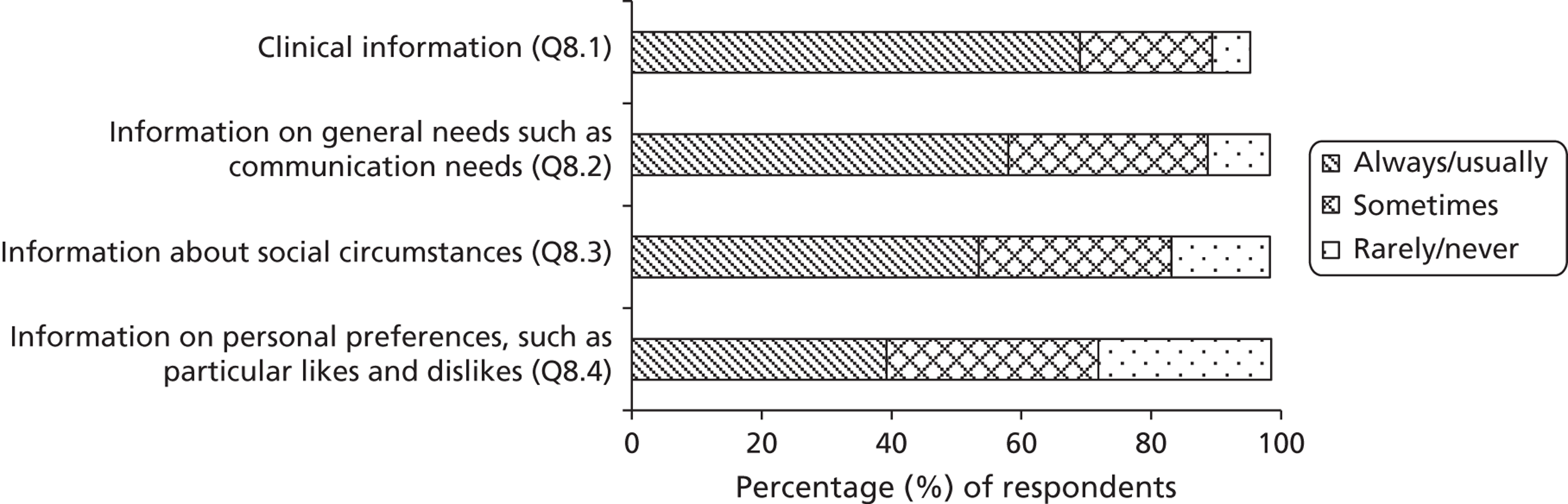

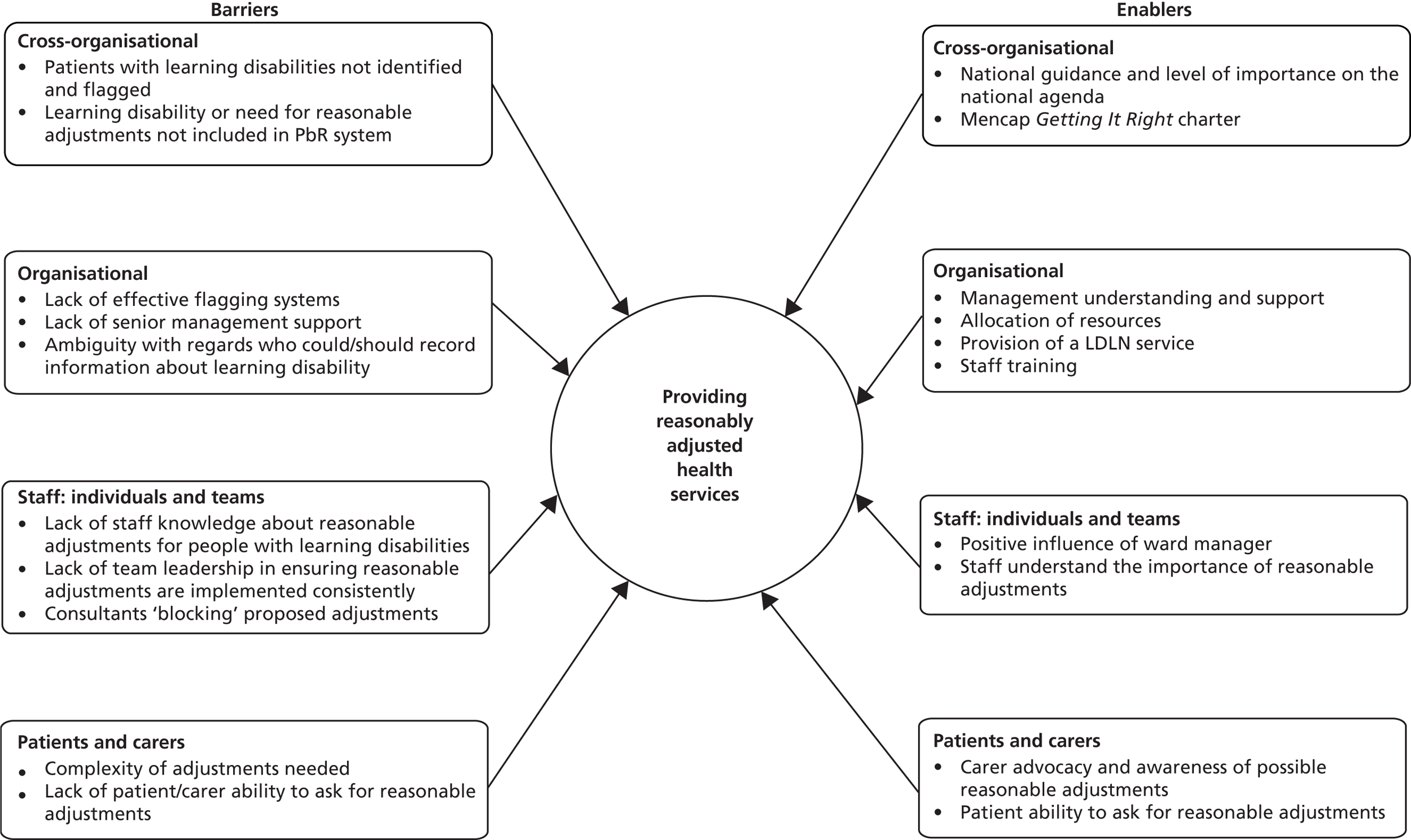

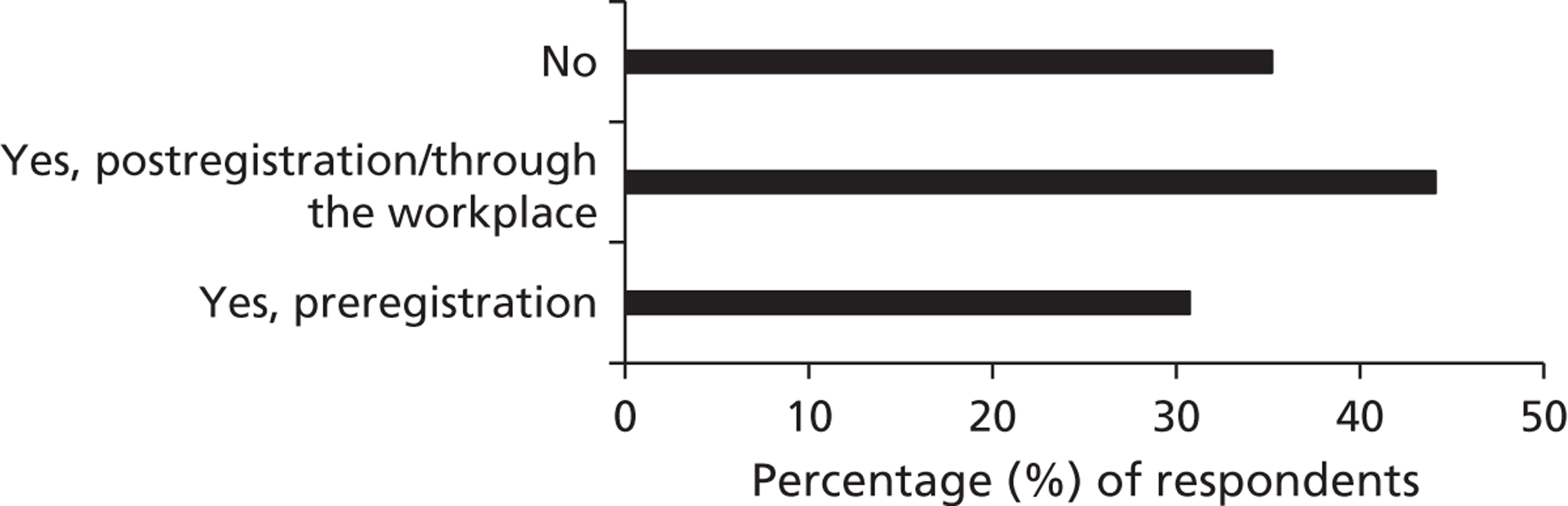

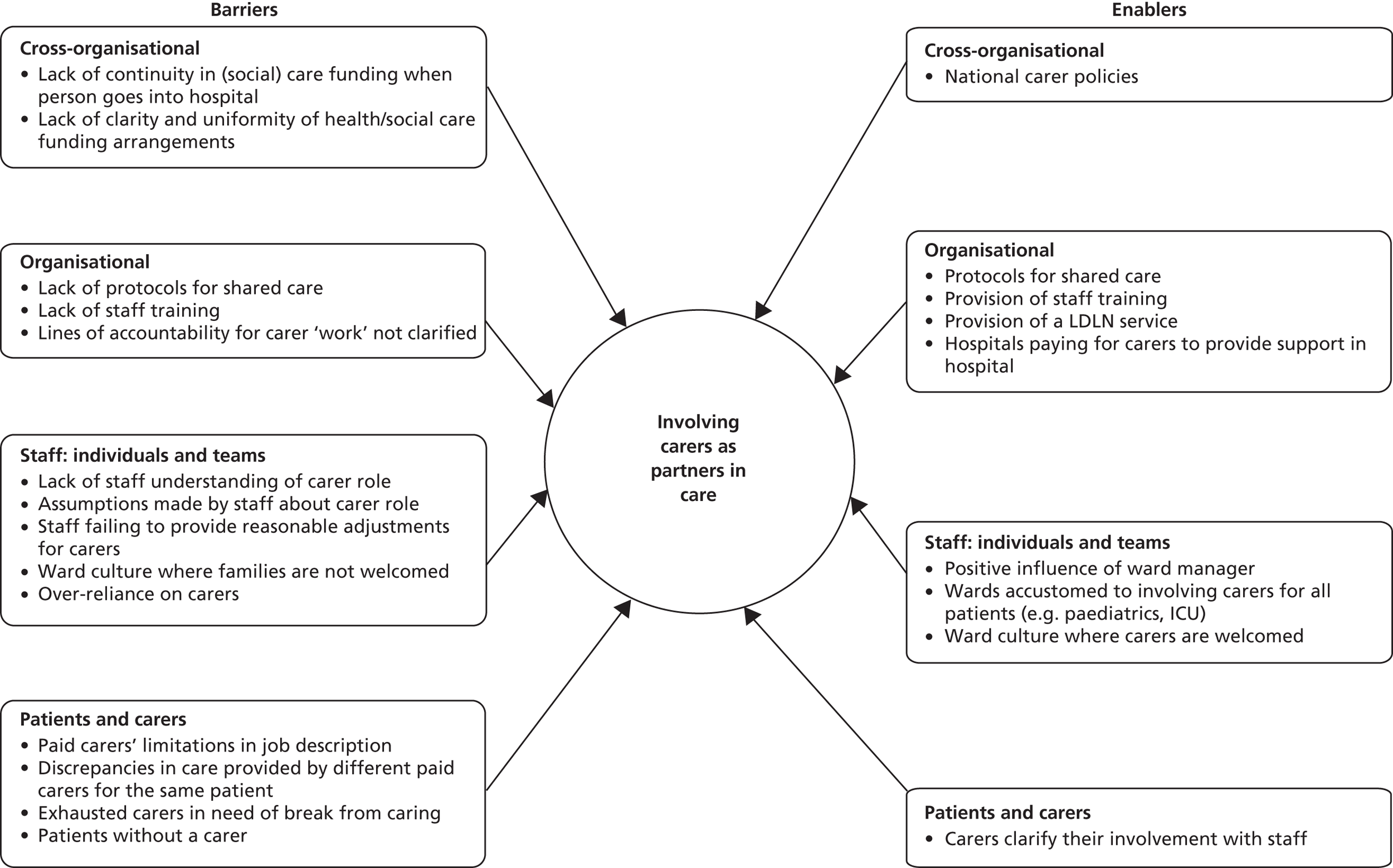

General practitioner practices have been given guidance by the Department of Health to carry out annual health checks for people with learning disabilities, which come with financial entitlements. This has encouraged GP practices to identify their populations of patients with learning disabilities. However, despite investments in a major overhaul in NHS information technology (IT) systems,40 the aim to achieve effective sharing of patient information between different NHS services through fully integrated electronic patient records by 2010 has not been achieved. The implementation of summary care records is still under way; around one in three people in England have one. 41 Summary care records contain key medical information, such as medication and allergies, made available across England to NHS staff involved in treating the patient. Mencap supports the summary care records in principle, observing that there would be a benefit if people with learning disabilities were able to add key information about their needs that they wanted clinicians to know, for example, information about how they communicate, or contact details for their carer. 42