Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/1002/14. The contractual start date was in October 2010. The final report began editorial review in December 2012 and was accepted for publication in May 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Salway et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

Although the volume of enquiry into the mobilisation and utilisation of research evidence within the health sector is growing rapidly, there remain important gaps in our understanding about which strategies work to encourage greater and more appropriate use of research evidence and how and why specific approaches might work. In particular, our understanding of knowledge utilisation processes within the policy context is far weaker than our understanding of knowledge utilisation processes within the clinical practice environment. 1 The current project responded to this gap in understanding by exploring the health-care commissioning cycle – an increasingly powerful determinant of the health services on offer and the care that patients receive – and by explicitly focusing on an area that has so far been overlooked, namely the mobilisation and utilisation of evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality.

The study’s broader goal was to support the commissioning of health services that better meet the needs of black and minority ethnic (BME) people and thereby help reduce ethnic inequalities in health-care access, experiences and health outcomes.

The project was novel and ambitious in bringing together three complex and contested areas of investigation: ethnicity, evidence use and commissioning. We found no previous studies that had sought to engage in detail with this particular focus, but instead drew on a wide range of related literature that explores particular aspects of this arena.

Ethnic diversity and inequality in health and health care

England has long been recognised as a multiethnic society and the diversity of the population is growing rapidly both in terms of the range of ethnic identities represented and the proportion of the population who identify as other than white British (around 20% of the total population in the 2011 census2). Ethnicity is a complex and contested ‘biosocial’ concept, a form of group identity that draws on notions of shared origins or ancestry, but which commonly invokes aspects of sociopolitical hierarchy as well as cultural commonality and shared biological features. 3 Ethnic identity influences the health of individuals and groups through a variety of mechanisms including direct and indirect discrimination; differential access to health-promoting resources; cultural practices; migration; and some genetic or biological factors. 4 Not surprisingly, therefore, mortality and morbidity patterns across ethnic groups are complex. Nevertheless, substantial evidence indicates that minority ethnic groups suffer disadvantage across a range of indicators. 4,5 Furthermore, a large body of evidence documents lower satisfaction with health services among minority groups than among the white British majority6,7 as well as poorer access,8–10 poorer quality of care and worse outcomes in several areas of service provision. 11–13 Inaccessible services, unmet need, poor patient–provider communication, inappropriate diagnoses and treatment, and negative service experiences remain common. 14,15 Therefore, rather than mitigating the disadvantages that many minority ethnic people experience in wider society, health services may often make things worse.

Despite a significant volume of national policy and guidance over many years, as well as several focused initiatives, progress towards health-care services that effectively meet ethnically diverse needs has been disappointing. 16 The Commission for Equality and Human Rights’ [previously the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE)] formal investigation into the Department of Health (DH), and Nigel Crisp’s 10-point action plan response,17 highlighted the need for significant improvement in this area.

Earlier research has sought to illuminate the factors operating at organisational and individual level that support or hamper progress towards cultural competence within health-care organisations. Several studies highlight the way in which education and training programmes designed to address gaps in professional knowledge require wider, systems-based approaches to achieve desired shifts in practice. Kripalani et al. 18 notes the importance of clear support from senior staff in terms of signifying priority and modelling desired behaviour; Yamada and Brekke19 identify the need for attention to organisational factors influencing practice; and Shapiro et al. 20 suggest that practice-based learning and models of good practice are needed alongside training courses. These findings point to the embedded nature of practitioner assumptions and behaviours and the need to challenge ‘tacit knowledge’ through new learning that is context specific, has a link to action and is informed by experience. 21 Other research highlights the significance of systems in the development of culturally relevant interventions and the importance of practitioner self-awareness. 19

Analyses that situate the formulation of health-care policy and practice within the wider sociocultural context of contemporary Britain are also helpful. It has been argued that UK policy relating to ethnic diversity lacks coherence and suggests at best ambivalence towards minority ethnic groups and uncertainty regarding the form that multicultural Britain should take. 22,23 Atkin and Chattoo24 argue that strategies for addressing disadvantage in health-care provision are undermined as providers and managers struggle to reconcile conflicting messages regarding minority ethnic populations and their needs and entitlements. It is increasingly argued that progress towards more culturally competent health services requires practitioners and organisations to examine value bases; expose stereotypes, prejudices and ethnocentrism; challenge power relationships and oppressive practices; and work in true partnership. 25 It is noteworthy, however, that, although such models often emphasise the importance of community consultation and local intelligence data, they are commonly silent on the role of other types of evidence, including research evidence. Similarly, recent policy documents and initiatives aimed at supporting commissioners and managers to address ethnic diversity and inequality pay little attention to how research and other types of evidence might be mobilised and utilised in this endeavour (see, for example, materials from Race for Health26,27).

Evidence use in health-care policy and practice

The study’s premise was that progress towards better services for minority ethnic populations is, at least in part, hampered by limited and inappropriate evidence use. Better use of research evidence alongside other types of evidence and knowledge should help to overcome persistent shortcomings in the design and delivery of health care for our ethnically diverse population. However, there is a need to understand more about the current patterns of evidence use, the barriers to and supports for the mobilisation and utilisation of evidence of different types, and how the critical and effective use of evidence might be enhanced.

The growing body of studies exploring knowledge mobilisation and utilisation within the health policy-making arena, some with an explicit focus on health inequalities, provided some useful insights to inform our enquiry. Much of this work draws on broader theoretical perspectives that view policy-making as a process of collective interaction between diverse stakeholders, in which both the identification of, and responses to, problems are viewed as socially situated and constructed. 28–30 These contributions highlight the distinctive nature of evidence utilisation in policy formation (at both strategic and service design levels) compared with the clinical practice context. 1,31 Kelly and Swann32 note the way in which evidence syntheses within public health can offer only ‘scientifically plausible frameworks for action’ (p. 270) and not prescriptions for specific intervention, as decision-making requires judgements based on knowledge of local context, including prevailing practices, organisational structures and commitment and engagement of key actors. Similarly, Elliot and Popay’s33 investigation of evidence use by NHS managers revealed that research was felt to offer clarity and to contribute to decision-making, but rarely to provide simple, clear-cut answers. Other work confirms that health-care policy-makers work with a ‘mixed economy’ of evidence, piecing together information from diverse sources in their decision-making. 1,34

Blackman et al. 35 look particularly at policy-making related to health inequalities and identify this area as a ‘wicked problem’ that cuts across traditional organisational boundaries and whose complexity limits the scope of evidence-based action. ‘Wicked problems’ tend to carry with them greater scope for debate around what should be done and how it should be achieved and more room for disagreement on what counts as robust and relevant evidence. They suggest that policy-making in relation to ‘wicked problems’ tends to be less a technical exercise and more a process of dialogue and argument with power relationships clearly in evidence. Exworthy et al. 36 highlight similar factors that may complicate the knowledge-into-action process relating to the health inequalities agenda, including the multiplicity of agencies and the diffuse nature of responsibility. Although this past research exploring the utilisation of evidence within the health inequalities context is an important backdrop to the present study, there is a need for enquiry that specifically focuses on ethnic diversity and inequality. Mir and Tovey’s37 study begins to explore these issues and shows that whether managers act on research and other knowledge is shaped by resources, organisational culture and particularly the absence of substantial disincentives. However, there is a need for further systematic study, particularly because of the significant additional issues that arise in terms of the generation and application of a research evidence base in this area.

Past work has highlighted some of the current inadequacies in availability of evidence relating to ethnicity and health. The poor collection, analysis and reporting of service-level ethnic monitoring data has been identified as a particular impediment to action for several decades,38,39 although there has been recent notable progress in some service areas. 40 A lack of evidence about specific ways in which practice guidelines should be modified to improve health outcomes for minority ethnic populations19,41 and omission of these populations from studies of evidence-based treatments42 have been highlighted. The lack of evidence on the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of cultural competence interventions may result in these being seen as an extra burden, particularly in the context of staff shortages and financial restrictions. 43 The need for better mobilisation of evidence to improve understanding of the links between ethnicity and health among health-care managers and practitioners has also been repeatedly highlighted. 44 As the volume of research on ethnicity and health expands, so too do concerns regarding quality, its potential role in stereotyping and stigmatising ethnic minorities, and its limited benefit to minority ethnic populations. 45 Critically appraising and applying research evidence on ethnicity and health presents significant challenges and demands particular competencies. 3 Issues include the need to interrogate conceptualisations of ethnicity that erroneously present ethnic ‘groups’ as stable or discrete entities and/or fail to address its multifaceted nature; question whether research adequately addresses the concerns of minority ethnic people; recognise the limited analytical potential offered by crude administrative ethnic categorisation; and carefully consider how evidence can best be synthesised across contexts when concepts and categorisations vary widely. 46,47 Clearly, then, there are some significant challenges relating to both the quantity and quality of available evidence that are likely to impact importantly on how managers access and apply evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality. To date, these have not been explored in any detail.

Related work in the broad area of health inequalities highlights a number of factors related to the characteristics of research evidence and research products that have relevance to the focus of the present study. Exworthy et al. 36 suggest that the multifactorial nature of inequalities, the paucity of evidence of effective interventions and the need for upstream and long-term investments all complicate the knowledge-into-action cycle in health inequalities policy. Pettigrew et al. 1 found that policy-makers charged with the health inequalities agenda commonly perceive the lack of locally relevant evidence and evidence on the distributional effects of interventions to be problematic. More generally, Greenhalgh et al.’s48 major review of innovation diffusion in health-care organisations identifies a number of key attributes of successful innovation that are rarely applicable to the evidence base on ethnic diversity and inequality, including evidence of clear benefits and cost-effectiveness, low complexity, ease of adaptation and low risk or uncertainty. Indeed, utilisation of the research evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality is likely to be compromised by the predominance of grey literature, the lack of evaluative studies, the lack of studies that consider the distributional effects of interventions by ethnicity and the lack of consideration of ethnicity within influential evidence syntheses [e.g. Cochrane reviews, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance]. 19

Notwithstanding weaknesses in the evidence base that need to be filled, there is nevertheless a substantial body of evidence of the scale and nature of the health disadvantage suffered by BME groups, as well as evidence that identifies generic ways in which health services could be modified to better meet the needs of minority ethnic patients (such as the provision of adequate interpretation facilities and enhanced cultural competence among health-care providers). 49,50 Furthermore, in some service/disease areas the quality of the research evidence base could lend itself to more specific, instrumental use by commissioners in pursuit of improved outcomes for minority ethnic groups, such as evidence-based diabetes interventions. 51 However, although a growing number of studies seek to identify factors that shape whether research evidence impacts on policy or practice,30,52 to date none has specifically engaged with the issue of ethnic diversity and inequality. More needs to be understood regarding the factors that support or inhibit the use of evidence in this context, including how evidence is presented and conveyed to decision-makers; what is regarded as evidence or knowledge; how the quality and relevance of evidence is assessed; when evidence is regarded as necessary; how easily evidence of different types can be accessed, appraised, synthesised and adapted to the local context; and how decision-making is achieved in the face of significant evidence gaps.

Commissioning

The term ‘commissioning’ is peculiar to the UK health system, with terms such as ‘strategic purchasing’ or ‘planning and funding’ used elsewhere. A useful definition of commissioning is provided by Woodin:53 ‘the set of linked activities required to assess the healthcare needs of a population, specify the services required to meet those needs within a strategic framework, secure those services, monitor and evaluate the outcomes’ (p. 203). Since 2002, primary care trusts (PCTs) have had responsibility for commissioning most local health services, including primary care and public health interventions, with some specialist services and national programmes being commissioned at regional or national level. The election of the coalition government in 2010 has been followed by radical restructuring of the NHS, with clinical commissioning groups [CCGs, led by general practitioners (GPs) with support from other clinicians and commissioning managers] now taking up the reins for most local health-care commissioning. Despite these changes, a continued aspiration for an enhanced role of commissioning in reshaping health services is clearly evident. Government policy continues to emphasise the proactive and strategic nature of commissioning, which should involve both transformational (reshaping the configuration of services) and transactional (custodianship of the budget, contract monitoring) elements. 54 The government’s aspiration for an evidence-driven commissioning infrastructure that drives up the quality and efficiency of health services is clearly evident in the QIPP (Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention) transformational programme, with its range of resources to assist commissioners in their role, including comparative expenditure data, benchmarking of quality indicators and a growing number of detailed disease-focused commissioning toolkits. Key competencies for commissioners increasingly place knowledge management centre stage. World-class commissioning (WCC) competencies included critically mobilising and utilising research and best practice evidence; effectively garnering local intelligence and promoting engagement to assess needs; and turning information into knowledge and action for service reconfiguration that improves access, quality and outcomes. 55 And although the language of WCC has been shelved with the change in government, more recent policy guidance continues to highlight the central role of evidence and ‘intelligence’. 54 The role of public health in the commissioning cycle, particularly through the profiling of health needs of local populations and the synthesising of wider research evidence, is recognised as important,56 and public health teams are expected to continue to provide a ‘core offer’ to CCGs in support of health-care commissioning even once they have been relocated to local authorities.

As such, commissioning remains a key arena within which the mobilisation and utilisation of evidence of different types takes place, with the potential to importantly impact on the shape and content of health-care services. 57 To date, however, commissioning has received relatively little attention within health services research, and evidence use within commissioning has not been explored in any depth. Early investigation by the King’s Fund58 suggested that a lack of timely and high-quality information undermined effective practice-based commissioning. McCafferty et al. 59 explored the development and implementation of WCC and concluded that inappropriate and poor-quality data, a lack of robust information systems and a lack of capacity to generate data and interpret knowledge were considerable obstacles. McDermott et al. 60 looked at the commissioning of stop-smoking services and found that evidence-based guidelines on effective interventions were inconsistently drawn on by commissioners and that in fact services were often not specified by commissioners in very much detail. Clearly, these few studies paint only a very partial picture of evidence use within commissioning, and none has focused on the needs of multiethnic populations.

Goal, aims and objectives

Although research to date has helped to describe the complexity of the processes involved in, and the very wide range of factors that can act as barriers to, evidence mobilisation and utilisation,48,52,61 as yet little has been done to identify effective routes to shaping or enhancing the process in real-life policy-making contexts. There is a need to move towards identifying routes of intervention to effectively shift embedded values, beliefs, structures and practices that serve to undermine the contribution of evidence. The present study aimed to contribute to this general need and to generate specific understanding in an important area that has not to date been the focus of enquiry.

Goal

To support the commissioning of health services that better meet the needs of BME patients and thereby help reduce ethnic inequalities in health-care experiences and health outcomes.

Aim

To enhance the critical use of research evidence alongside other forms of knowledge by managers within the PCT commissioning cycle.

Objectives

Theoretical

-

To develop a theoretical model of knowledge utilisation that explicates the emotional, ideological and political dimensions through the example of ethnic diversity and inequality.

-

To contribute to the theoretical literature that addresses mechanisms for enhancing the critical use of research evidence by managers in complex decision-making environments.

-

To contribute to the theoretical literature that addresses mechanisms for enhancing the cultural competence of health-care services by integrating an understanding of the role of knowledge(s) mobilisation.

Empirical

-

To describe, across a range of commissioning contexts, how managers seek out, appraise and apply research evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality alongside other forms of knowledge.

-

To identify factors (at evidence, individual and contextual levels and their interfaces) that support or inhibit the critical and effective use of research evidence within the commissioning cycle and thereby identify promising routes of intervention.

Operational

-

To develop practical diagnostic, evaluative and change management tools for use by individual managers, teams and organisations to (1) assess and promote critical reflection on current competencies and practice with respect to utilisation of evidence on ethnic diversity and inequality, (2) identify actions to strengthen competencies and good practice and (3) support specific elements of the knowledge utilisation process.

-

To educate researchers and research funders regarding the current limitations of the evidence base and how they might generate research products that are more appropriate and accessible for managers charged with the task of commissioning services for multiethnic populations.

-

To strengthen links between university researchers and managers and contribute to the development of a shared commitment to enhancing research evidence utilisation for enhanced organisational performance.

Chapter 2 Methodology and methods

Conceptual framework

Recent reviews have highlighted the diverse streams of theoretical literature on knowledge utilisation processes. 52,62 They also call for more research within health-care contexts to draw on these traditions and thereby become more explicitly theory based. 48,63

Recent work that seeks to integrate micro-, meso- and macro-level conceptual frameworks and articulate the interplay between these levels is also useful here. 48 So too are frameworks that emphasise the complex and contested nature of research evidence as well as the messy, diverse and convoluted pathways that often link research evidence to policy-making and practice. In this, Davies et al.’s64 notion of ‘knowledge interaction’ is attractive as it captures the way that multiple actors engage with varied sources of evidence to craft policy-making within the context of competing drivers. Empirical work based on such holistic models seems more likely to identify fruitful avenues for intervention to enhance effective evidence use, particularly compared with that focusing on pieces of the jigsaw in a more piecemeal fashion. We therefore conceptualised evidence mobilisation and evidence utilisation within the commissioning cycle as resulting from dynamic interactions between diverse evidence sources alongside variation in individual agency and organisational rules, structures and processes. This was further situated within the wider health-care setting and its current restructuring agenda, themselves situated within the broader sociopolitical context of multicultural Britain.

Within this comprehensive multilayered framework, our focus on ethnic diversity and inequality demands that we foreground four specific issues. First, we draw on Weiss’s65 insights regarding the varied ways in which research evidence might emerge and be used within policy-making: as empirical findings (be they direct or instrumental), as ideas or challenges to current thinking (i.e. conceptually) or as briefs or arguments for action (be these persuasive or symbolic). We also recognise the often inherently contested and political nature of research and other evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality. Reviews of past work suggest that the direct use of evidence in policy-making is generally the exception rather than the norm. 66,67 They also note the limited progress that has been made to date in modifying services to meet the needs of BME populations. 44 For these reasons we were particularly mindful of the potential importance of the indirect influences of evidence.

Second, at the level of individual actors and their interface with knowledge sources, we draw on sociocognitive perspectives68,69 that emphasise the importance of the ‘thinking subject’ and the ‘mental models’ that guide people’s ‘sense-making’. Although the crucial role of policy-makers as receptors of knowledge is widely recognised,30,69 sociocognitive models look beyond technical skills and resources to values, assumptions and worldviews. We suggest that the ways in which individual commissioners understand the nature of ethnicity and associated inequalities will be central to how they seek out, appraise and apply different types of knowledge within their work. These perspectives fit closely with the work of Hunter,70 Husband71 and Gunaratnam and Lewis,72 all of whom highlight the need to explore the ‘felt dimension’ of health-care policy-making and practice within the multiethnic, post-Macpherson setting. As Hunter70 argues, in exploring the role of those in policy-making positions, we must ‘consider these individuals as emotional as well as relational actors’ (p. 150). For example, professional anxiety and uncertainty about cultural competence can be disempowering to professionals and detrimental to care. 73

Third, within the organisational context, we seek to expose the taken-for-granted ‘ways of being and doing’ that operate and how these interact with research and other forms of evidence. We view the health system and health-care organisations not just as mechanical structures that provide health care but rather as culturally embedded and politically contingent,74 as purveyors of wider societal norms and values. 75 These ideas fit with Lam’s76 notion of ‘social embeddedness’ – the recognition of the interconnections between individual managers (micro), their organisational context (meso) and the wider societal context (macro) within which these operate. This means that, although evidence utilisation processes might be characterised as anarchic and unpredictable, there are nevertheless ‘deep structures’, including racialised hierarchies, that shape and constrain these processes in persistent ways.

Fourth, within the layer of the wider context, we pay particular attention to the influence of stakeholders beyond commissioning organisations, particularly service users, the public and their representatives. Given commissioning’s strong generic focus on consultation and ‘knowing communities’, and our particular focus on ethnic equality, we seek to understand not only the ways in which these external stakeholders represent additional, perhaps conflicting, sources of knowledge (such as patient preferences, or public notions of entitlements), but also the ways in which they access, appraise, interpret and present research evidence to the commissioning tasks independently.

Notwithstanding our choice of a multilayered theoretical model that is sufficiently sophisticated to allow understanding of the complex processes of evidence mobilisation and utilisation, our underlying assumptions are that these processes can be understood; causes and effects can be identified; and steps can be taken to modify these processes to build on strengths and mitigate weaknesses.

Methodological overview

The theoretical framework outlined in the previous section, together with our review of the relevant empirical literature presented in Chapter 1, directed our methodological approach in a number of ways.

First, we adopted an explicit integrated knowledge translation model for the conduct of the study,77 bringing university researchers and PCT managers to work together in a collaborative team throughout the entire research process: developing research questions, shaping methodology, generating and interpreting data and disseminating findings in accessible formats. Past work has indicated that sustained and intense interaction between users and researchers increases the likelihood that research findings will be utilised. 78 Given the complex and potentially challenging focus of the present study, such collaborative working was deemed crucial to ensure that the project was successfully completed and had both reach and impact.

Second, we adopted a broad and inclusive understanding of ‘evidence’ and did not seek to offer respondents any kind of definition. We also recognised that ‘research evidence’ comes in many different guises and might perform many different tasks that are potentially useful within commissioning for multiethnic populations. These could include alerting commissioners to issues for consideration; describing patterns of ill health by ethnicity; explaining the underlying causes of differentials between ethnic groups in key outcomes; evaluating the effectiveness of alternative approaches to reducing ethnic inequalities; developing appropriate indicators for monitoring service implementation; and so on. As there remain significant gaps in the research evidence base relating to ethnicity and health (see Chapter 1), and as the commissioning task inevitably involves identifying approaches that are feasible and acceptable within a specific local context, we also recognised that many other sources of evidence would feature heavily within commissioning work. We therefore chose not to draw any clear distinction between the concepts of ‘knowledge’ and ‘evidence’ and to view research as just one source within a complex ‘mixed economy’ of knowledge. 1,34 During data generation we allowed respondents to be guided by their own mental models of ‘evidence’ and ‘knowledge’ and to use a range of related terms – such as ‘data’, ‘information’, ‘intelligence’ and ‘insight’ – as they saw fit.

Third, we combined detailed case study investigation in particular sites with key informant interviews and workshops that engaged with a wider spread of respondents. The case study approach excels at understanding complex, multifactorial real-life situations and allowing the integration of data on a number of levels alongside a detailed contextual analysis of events and relationships. 79,80 This type of approach was needed to capture the dynamics of the whole system, allowing the examination of individual and institutional actors and exploring their values, ways of working and skill sets in relation to evidence. Respondent narratives were seen both as a representation of the personal attitudes and perspectives held by each set of key actors and as a window into the complex processes operating within the commissioning arena. Nevertheless, combining interviews with observational and documentary evidence was important to develop a more holistic picture than is possible from interviews alone. Meanwhile, the use of broader data-generation methods before and after the case study work allowed us to engage with a wide range of commissioning contexts in order to generalise theoretical understanding and develop research products with wider relevance and transferability.

Fourth, we aimed to describe how well research evidence was being used, not just whether it was used at all. Given our focus on improving the cultural competence of health-care provision for BME groups, the ultimate test of how well research evidence is used is whether it leads to modifications in policy and practice that improve levels of access and satisfaction and service outcomes for minority ethnic users. Tracing the use of evidence to such outcomes or benefits was, however, beyond the scope of the current study. Instead, we examined the intermediate steps in this process, looking at whether and how commissioners and other actors within the commissioning arena accessed varied sources of evidence; critically appraised and selected evidence; synthesised evidence across sources and methods; adapted and presented evidence in appropriate formats; integrated research evidence with other knowledge sources; explicitly articulated assumptions, priorities and values underlying the assessment of different knowledge sources; and translated syntheses of integrated knowledge into commissioning products and processes (such as service specifications, business cases, care pathway models, tenders, provider contracts and performance management indicators).

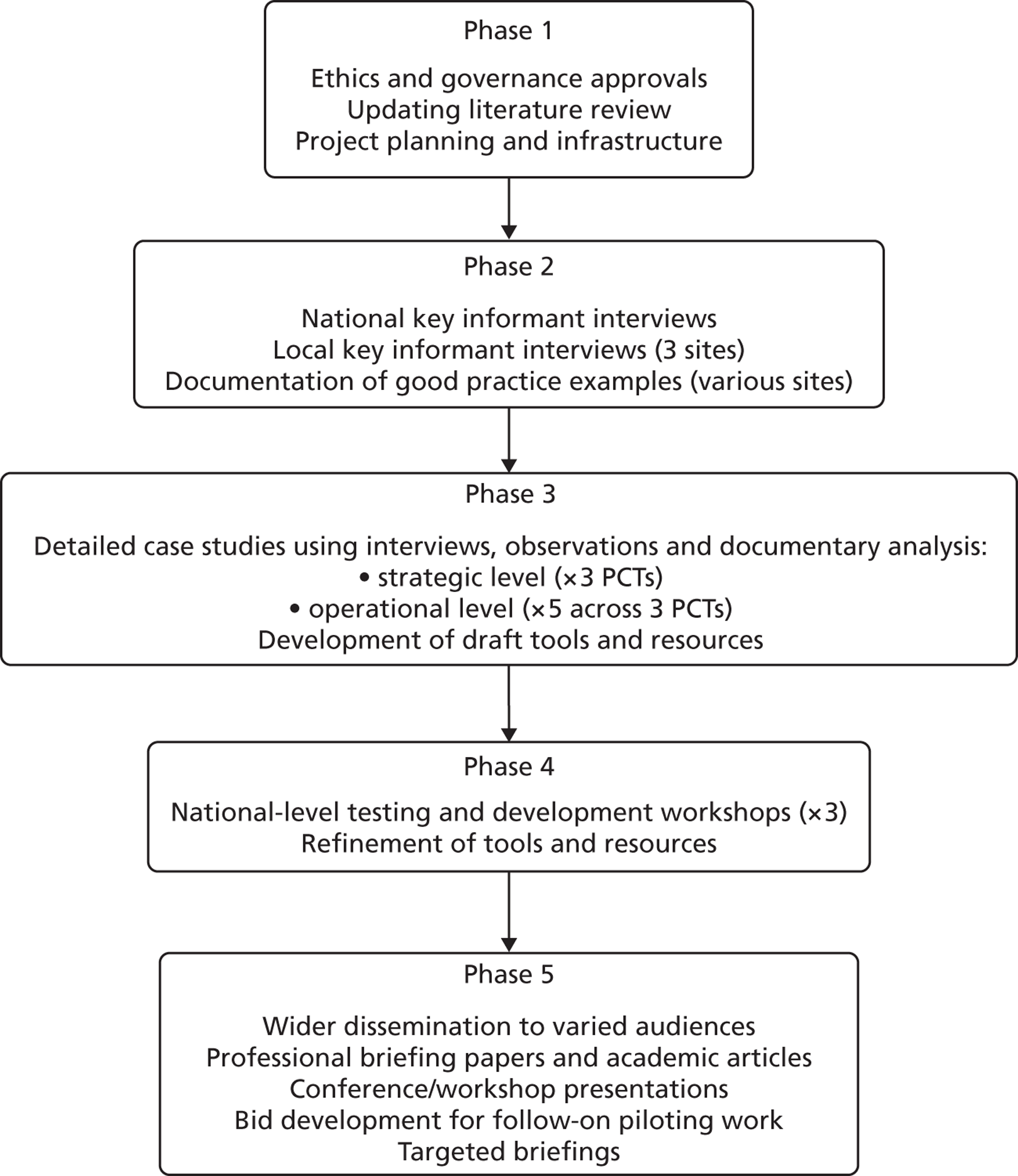

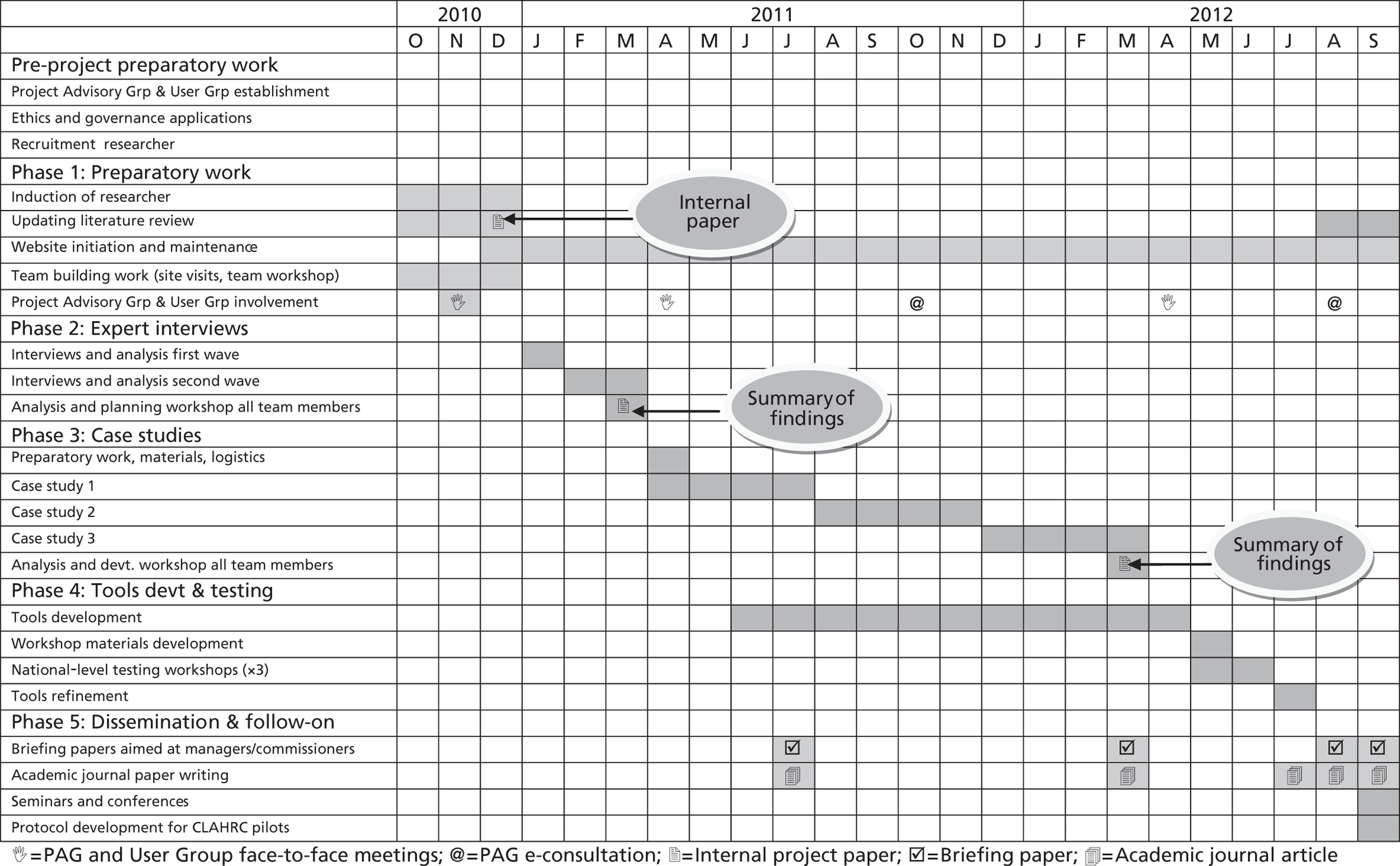

Figure 1 illustrates the five phases of the project.

FIGURE 1.

Project phases.

Research questions

Three broad research questions were identified to guide the empirical components of the study. Each broad research question was broken down into a set of more detailed questions that indicated our intention to explore five inter-related ‘levels’ that make up the evidence mobilisation and utilisation process: evidence, individual managers, commissioning teams, organisational settings and the wider context.

Research question 1: how does a focus on ethnic diversity and inequality shape the knowledge mobilisation and utilisation process within the health services commissioning context?

-

What characteristics of research evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality influence how it is received by managers (e.g. source, method, (un)certainty, relevance, concepts/theory)?

-

What mental models of ‘how research evidence should be used’ are managers working with?

-

To what extent is the accessing and application of information relating to ethnic diversity and inequality part and parcel of broader evidence-gathering exercises for commissioning or rather a distinct exercise?

-

What factors prompt managers to seek out research (and other types of evidence) relating to ethnic diversity and inequality (e.g. policy directives, new priorities, external audit, stakeholder inputs, signs of service failure)?

Research question 2: how does organisational context shape the mobilisation and utilisation of knowledge relating to ethnic diversity and inequality?

-

How often, and at what stages, do managers apply research evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality in their commissioning tasks?

-

How are commissioning teams constituted and organised? How does this impact on evidence use?

-

Who is seen as holding expertise and insight in relation to ethnic diversity and inequality? Why?

-

To what extent do PCT commissioning organisations have explicit models, structures, processes and objectives that support the mobilisation and utilisation of evidence? Do these consider ethnic diversity?

-

In what ways does managerial behaviour support and encourage, or deter, the explicit consideration of research evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality within commissioning teams?

-

In what ways do the available infrastructure and resources support and encourage, or deter, the explicit consideration of evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality within commissioning teams?

-

How do national, regional and organisational policy priorities inter-relate to shape the mobilisation and utilisation of evidence in this area?

Research question 3: how can individual, team and organisational competencies be effectively enhanced to support the critical use of research evidence for the commissioning of services that better meet the needs of a multiethnic population?

-

How competent are managers to (1) identify and access, (2) critically appraise and synthesise and (3) adapt and apply evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality?

-

What expectations do managers have of, and what problems do they encounter with, the evidence base?

-

What individual-level factors facilitate or hinder the mobilisation and utilisation of research evidence in this area (e.g. knowledge/awareness, skills and experience, ‘mental maps’, autonomy, authority, personal biography)?

-

What areas of capacity development would likely improve the individual- and team-level competencies required for the mobilisation and utilisation of research evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality?

-

How does research (and other) evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality currently find its way into the commissioning process – through which actors and which routes? How can these be supported?

-

Who are the key actors and what are the key organisational settings and processes that present barriers against enhanced mobilisation and utilisation of evidence?

-

What factors in the wider societal and broader NHS context must be buffered against, or can be drawn on, to support the routine, critical use of research evidence in commissioning for multiethnic populations?

-

What characteristics of the form, content and delivery of interventions in support of enhanced mobilisation and utilisation of research evidence are likely to increase relevance and utility?

Phase 1 development

Literature review

Before the start of the project an extensive literature review was undertaken to guide the development and methodology of the project. It was important for this to cover not only academic papers and research, but also national policies, guidelines and toolkits relating to commissioning, evidence use and ethnicity. This was updated throughout the project and a RefWorks® (version 2.0; ProQuest LLC, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) database maintained. Considering the evolving nature of the NHS commissioning infrastructure during the period of this study, the research team also attempted to keep up to date with articles in the media, policy directives and information from colleagues.

Project teams

The project was a collaborative endeavour involving two universities and three PCTs. Each PCT had one mid-level manager assigned to the project as a co-researcher and one senior staff member designated as a champion for the project. The champions and one of the co-researchers were engaged in the development of the initial proposal, identifying the research questions and shaping the study design alongside the academic researchers. The named co-researchers in two of the sites were unable to take up the role on the project, a reflection of NHS restructuring and the long time between proposal development and funding. However, once the project was under way, two new co-researchers were appointed and all three co-researchers subsequently engaged in all aspects of the project work alongside the university researchers, including the national-level work (phases 2 and 4) and local case study work (phase 3) that focused on their own organisations. The champions were also engaged in the project, particularly in one of the sites, although their senior roles necessarily meant that they did not have day-to-day involvement, providing input instead at key junctures of the project.

To assist in the development and delivery of the project, three project teams were created to manage and guide the research. The project management group comprised university researchers and PCT-based co-researchers. This group met regularly to design research tools, co-ordinate data collection, provide updates on emerging themes and findings, complete analysis and produce project outputs. This was also the core operational research team, with most members directly engaged in data generation, analysis and reporting. The research team included individuals identifying as white British, British Pakistani and Pakistani, both male and female, across both the academic and PCT researchers. Team reflections during the course of the project did not reveal any significant concerns regarding the influence of researcher ethnicity on the data generated. We did, however, wonder whether the significance of racism might have been more salient had we had a more ethnically diverse research team.

The project advisory group had a wider strategic role in guiding the development, analysis and outputs of the project and linking the project to relevant developments. The group met three times during the project period. This group was formed of senior academics engaged in health inequality and ethnicity at a national level, as well as senior stakeholders from the partner PCTs and individuals from the NHS and third sector with extensive experience of commissioning and health-care policy.

Finally, a user guidance group was convened, comprising representatives from community organisations and third-sector providers engaged specifically with ethnicity and health. Although the end-users of the project are considered to be commissioning managers and other stakeholders involved in health-care commissioning rather than service users, input from organisations directly involved in representing and providing services for minority ethnic communities was considered important. This helped to ground the project towards improving service delivery and prevent the findings from becoming too abstracted. Organisations and individuals were chosen who had previously been engaged in commissioning and who were able to share experiences from service provider and user perspectives.

Selection of primary care trust study sites

Three PCTs were recruited as partner organisations for the study. The intention was that these organisations would form the sites for the in-depth case study work and engage in the project as full partners – in keeping with our integrated knowledge translation model. 77 The PCTs were therefore chosen on the basis of both theoretical and practical considerations. It was important for the sites to reflect a degree of variation in relation to our topic of focus, but it was also important that the organisations would be active partners, willing to invest staff time and engage in reflection on the study findings and their implications for policy and practice. Sites were therefore chosen across South and West Yorkshire where the research team already had strong ties to practice and where relevant work was already under way. A regional focus was also felt to offer the possibility of useful sharing and learning between PCTs. The sites were chosen to have PCTs covering urban areas with significant but contrasting minority ethnic populations, where it was anticipated that there might be a variety of commissioning activities as well as available data and a range of awareness on ethnicity-specific issues. Sheffield, Leeds and Bradford were chosen as sites that fit these criteria, each with different ethnic demographics and organisational structures for health and social care.

Bradford, with its history of immigration from the Indian subcontinent, has long recognised itself as a multiethnic city, with 36% of its population identifying themselves as belonging to an ethnic group other than the white British majority in the 2011 census. 2 In contrast, Sheffield and Leeds had much smaller minority ethnic populations of around 19% and their public services have only recently started to engage seriously with the needs of these communities. Nevertheless, all three cities have experienced high levels of inward migration in recent years and now have well-established as well as newer minority communities. At the time of the study design, all three PCTs were engaged in achieving WCC targets and engaged in work on meeting the needs of BME groups, and all had staff members who were willing and interested to actively engage in shaping the project.

During the study period, Bradford and Airedale PCT and Leeds PCT clustered to form NHS Airedale, Bradford and Leeds. As this initially had little impact on day-to-day commissioning work, the restructuring did not reduce the amount of relevant work being undertaken. However, it did provide opportunities for co-researchers to contrast and reflect on different organisational practices as their functions and management structures were amalgamated.

Although the PCTs formed the focal point of the research, we also explored partnership working and engaged with other key stakeholders across the three cities, including local authorities and third-sector provider organisations.

NHS restructuring

Between the submission of the project proposal to funders and the commencement of the project in October 2010, the new coalition government released their White Paper81 on the NHS, which became the Health and Social Care Act 201282 in March of that year. During this long period of debate, in which the Bill was substantially redrafted, there was great uncertainty as to how the NHS would be restructured. However, it was clear from an early stage that commissioning structures would change significantly.

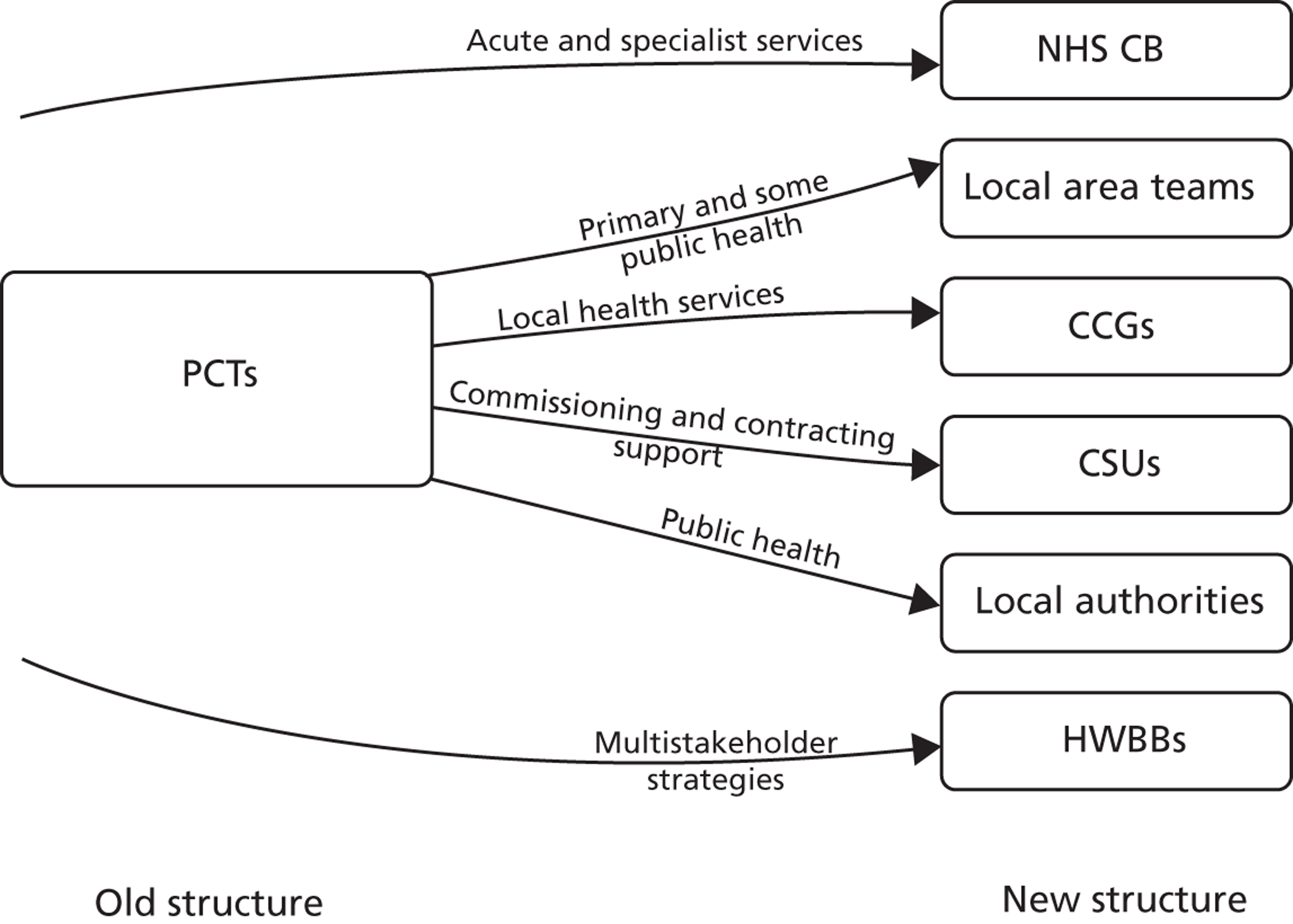

Central to this was the abolition of PCTs and the establishment of CCGs led by GPs with support from other clinicians. Although some former PCT staff transferred their employment directly to the new CCGs as commissioning managers, others transferred to separate commissioning support units (CSUs), providing commissioning and contracting support to the CCGs. Meanwhile, the public health function of PCTs was transferred to local authorities. Strategic health authorities were also abolished, with a new national body called the NHS Commissioning Board (NHS CB) established with responsibility for commissioning primary care and specialist health services through a network of local offices. Health and well-being boards (HWBBs) were established as local partnerships bringing together the CCGs, local authority, patient and public representatives and other stakeholders as the primary mechanism for setting local health and well-being strategies (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Simplified representation of role shifts from PCTs to new organisations in post-2010 commissioning structures.

Despite these emerging changes, the project retained its focus on PCTs and continued to pursue the original set of research questions, as it was agreed with the Health Services and Delivery Research programme that they retained relevance and value regardless of how commissioning work might be organised in the new NHS. However, three adjustments were made to our methodology. First, explicit questions were added to the key informant interviews to elicit respondents’ opinions and concerns about how evidence and minority ethnic health would be considered in the new commissioning arrangements. Second, the project team deliberately devoted less time in the case study work to comprehensively documenting existing structures within and across the local organisations, focusing instead on functions and processes that were likely to persist following structural transition. Third, we extended our original plan for phase 2 to include the documentation of a number of ‘good practice’ examples. Fourth, the project team kept up to date with developments and designed the analysis and outputs to reflect the changing structures, aiming to ensure that findings were framed in a way that would be applicable, and provide guidance, to the new commissioning teams.

Ethics and governance

Ethical approval was obtained from Nottingham Research Ethics Committee 2 and specific research permission was gained from each of the PCTs that were the main focus of the study. Standard procedures for ensuring informed consent and protection of research data were maintained. The main area of concern related to the difficulty of ensuring complete anonymity given that the identity of the case study sites would be public knowledge – a common issue in this type of health services research. During consent, participants were given the option to review any use of quotes from their interview before publication, or to express their right to have their contributions attributed to them.

Pilot interviews

Before undertaking the main data collection, as described below, a series of informal pilot interviews (n = 6) were undertaken with experts in the field of health-care policy and/or health inequalities. The interviews were very loosely structured and aimed to generate ideas about how the phase 2 interviews might best be structured, complementing the literature review work. These interviews suggested the need to adopt an open-ended and wide-ranging approach to generation of the main data, rather than focusing too narrowly on issues relating to ethnic diversity and inequality. This was felt to be important for three reasons: first, to allow respondents the opportunity to shape their responses and highlight the issues that they felt to be important, particularly because the pilot interviews suggested (and the later fieldwork confirmed) that many commissioning actors do not have a particular interest or expertise in ethnic equality issues; second, to ensure that any claims made for factors operating in relation to our focus on ethnic diversity and inequality were informed by an understanding of factors that shape (and, importantly, constrain) evidence use and commissioning work more generally; and third, pilot interviews alerted us to the potential danger that our findings and subsequent tools could lack relevance to and credibility for end-users unless they were well grounded in a broader understanding of day-to-day commissioning realities.

Phase 2 methods

The purpose of phase 2 was threefold: (1) to gain insights, from a broad range of perspectives, into the key characteristics that facilitate or hamper progress towards evidence utilisation in pursuit of reduced ethnic health inequalities (particularly as these relate to the wider sociopolitical setting and the health policy context); (2) to document elements of good practice that illustrate how progress on this agenda can be made (particularly as there were widespread concerns about loss of expertise and learning during transition); and (3) to inform the shape and focus of the phase 3 case studies.

National key informant interviews

Interviews with selected informants aimed to collect a broad range of perspectives on key characteristics relating to NHS management, the research evidence base, the PCT commissioning context and the wider sociopolitical setting that facilitate or hamper progress towards evidence utilisation in pursuit of reduced ethnic health inequalities. In-depth qualitative interviews with experts have been used successfully to examine the structure and functioning of health-care policy-making at national levels83 and, specifically, to examine evidence use in health. 84

Sampling

Respondents were selected for their broad experience and associated ability to provide a rich perspective on the evidence–practice interface within health-care policy-making. Most also had a particular interest or expertise in equality and diversity (E&D) or health inequalities issues. Respondents recruited included senior staff working in DH directorates, strategic health authorities, public health observatories, national third-sector policy-focused stakeholder organisations and universities.

Participants were identified initially by networks of association with the research team and project advisory group members. Snowball sampling85 was used to expand the number of participants by asking interviewees for recommendations of other key informants who the research team should contact. The aim was to interview around 20 national key informants. Respondents were contacted by e-mail and/or by telephone, informing them about the project and providing them with a participant information sheet. There was a high participation rate, with only three people declining to participate because of the pressure of work.

Data generation

A semistructured interview guide was prepared to assist the different researchers in covering a similar range of topics in each interview while still allowing for opportunistic and individual-specific questions. The topics included in the guide covered professional background and experience; commissioning structures, networks and processes; the impact of commissioning; the role of evidence and knowledge in commissioning; barriers to and opportunities for commissioning to address ethnic health inequalities; and how participants anticipated the new commissioning structures might impact on their work and the field.

The team followed Hunter’s70 advice regarding the use of reflexive, narrative approaches that emphasise dialogue within the research context, as ‘prior and on-going relationships with professional participants make it difficult and indeed undesirable for researchers to maintain silence’ (p. 149). This assisted in accessing more implicit understandings and discussion of sensitive topics that might not easily have been articulated within the interview setting. In following the COREQ (COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research) guidelines for qualitative research,86 interviewers were encouraged to reflect on their position and relationship with the interviewee, and how this might impact on how participants reflected on each of the questions posed.

Most interviews were audio recorded with the respondents’ consent and these recordings were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber with substantial experience in NHS research. All identifiable names and places were subsequently anonymised within these transcripts.

Basic profile information about each interviewee’s current and previous roles, experience, age group, sex and ethnicity were recorded. Participants also indicated whether they wished quotes taken from their interviews to be anonymised or attributed, and if they wished to see the context of any quotes used in project reports before publication. This information was collated into a database (Microsoft Access 2010; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), with each interviewee given an anonymised code.

To provide context and permit reflexivity for these interviews, interviewers also prepared a short memo immediately after each interview to record the location and any interruptions that might have impeded discussions; their perceptions on key messages and the flow of the interview; whether participants were hesitant to discuss any particular topics; and any pre-existing relationship between the interviewer and interviewee. This contextual information was considered during analysis to record factors that might affect how the interview was interpreted, and to provide background to other researchers who were not present during the interview.

Good practice examples

During the pilot interviews, concern was expressed that cuts and efficiency savings to the NHS, particularly to PCTs, were leading to reductions in capacity amongst E&D staff and the potential for loss of learning and experience in meeting the needs of minority ethnic health populations. We therefore undertook to select and profile 10 examples of promising practice on how evidence had been used to inform commissioning for specific projects on minority ethnic health. The aim of this strand of work was to capture the expertise and experience of staff involved in overcoming specific barriers in this area and to collect positive examples of how projects had been moved forward to completion. Researchers used interviews with key staff alongside documentary analysis to develop a brief narrative of how each piece of work had been undertaken, and to identify any transferable learning on how evidence on ethnicity might best be used to influence commissioning.

A purposeful sample of examples from different areas of health work was selected following recommendations of good practice from key informant interviews and an open call for suggestions on the minority-ethnic-health JISCMail network (see www.jiscmail.ac.uk/lists/minority-ethnic-health.html). A copy of the good practice guide can be found on the project website (see www.eeic.org.uk/mcs).

Local key informant interviews

In addition to the national-level interviews, a number of key informants were identified and interviewed during phase 2 in each of the three focused case study sites. These interviews generated similar data regarding the wider policy and organisational context of commissioning work and formed an essential first step in the case study work. As such, they provided background information and identified areas that would provide examples of ongoing commissioning work. Engaging with local stakeholders early on during the project also proved very useful for establishing the later phases of the project.

Sampling

Respondents were selected on the basis of their extensive local experience and ability to provide a broad perspective on local structures and processes as well as on national level drivers and context. The PCT co-researchers were particularly important in identifying potential respondents. The response rate was high and the final sample included senior and mid-level staff from various directorates within the three PCTs, the local authorities and third-sector organisations.

Data generation

Data generation employed the same topic guide as for the national-level interviews although more emphasis was given to eliciting local examples and illustrations of the wider policy context. Again, the majority of interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Phase 3 methods

In contrast to some case study designs, we did not select our study sites, or our operational case study examples within these sites, to be exemplars of good practice in terms of research utilisation. Given the emergent nature of commissioning practices, particularly in relation to ethnic diversity and equality issues, such an approach was neither feasible nor appropriate. Instead, the case studies were intended to provide sufficient variation to be able to compare and contrast commonalities and differences and thereby gain analytical purchase.

Case studies

To further explore and extend thematic findings from the key informant interview stage, detailed case studies were undertaken over several months to examine commissioning in depth. A case study approach allows for the examination of behaviours and phenomena while explicitly embedding exploration within a specific context. 87 A suite of data collection methods was used, including participant observation, interviews, and documentary analysis to collect data at operational group, individual and strategic levels. In our original protocol we stated the intention to convene formal focus group discussions with commissioning staff. However, in practice this proved difficult as respondents’ work commitments made it difficult to identify extended periods of time when they could come together for the research and consequently they preferred us to piggyback our data generation onto their existing work schedules. This meant that we opted for more observational periods, although we also engaged in some guided group discussions, particularly around emerging findings, allowing for useful respondent validation.

Observational work often adopted an ‘observer as participant’ model88 in which researchers were present in commissioning meetings as part of a team, asking prompting questions and, in some cases, engaging and contributing to discussions when relevant. Participants were regularly reminded of the researcher’s role as a research observer. Individual participant interviews allowed the questioning of commissioning actors away from group settings and provided important background information that was not available from observing operational group meetings. Interpretive documentary analysis89 was employed to identify and synthesise key themes from relevant documents. This analytical approach enabled us to identify different layers of explicit and implicit meaning within these documents and link these to themes from the interviews and observational work. Drawing on the experience of researchers focusing on diversity and equality issues, we sought to ‘follow documents around’90 and tap into both official and private discourses to uncover taken-for-granted ‘rules’ and convoluted pathways of influence. As such, the formal data-generation methods were complemented by many informal opportunities and by regular reflection on the part of PCT co-researchers.

Strategic and operational case study foci

In line with Black’s31 distinction between ‘governance policy-making’ (i.e. the level at which strategic agendas are set) and ‘administrative policy-making’ (i.e. the operational level), the case study work engaged with both distinct levels of commissioning activity. Therefore, the operational-level case studies profiled a condition- or issue-specific commissioning work stream, whereas the strategic-level case studies examined commissioning work undertaken by senior staff and strategic groups.

Local participants from the key informant phase were asked to suggest areas of ongoing commissioning that, although not necessarily ‘best practice’ in terms of evidence use or consideration of ethnicity, might illuminate common practices, barriers or enablers. The ongoing NHS restructuring meant that options for observing active commissioning work were reduced. Nevertheless, relevant areas of commissioning were identified at each site and case study work was completed as originally planned (see Chapters 4 and 5).

Data generation

Once each case study area had been identified and the teams therein had consented to involvement in the project, researchers, co-researchers and some participants undertook informal mapping exercises to identify key actors, partners and processes involved in the work. A timeline for each case study was produced as a prompting tool and to show how individuals, agendas and partnerships had changed over time, leading to the current structure of commissioning work.

Individual interviews used the same procedures detailed earlier for key informant interviews but employed a revised topic guide that enabled the collection of more specific detail while still allowing cross-comparison with earlier phases of data collection.

As noted above, observational work was undertaken in both formal and informal settings, with researchers participating to a greater or lesser extent in the ongoing discussions and interactions. In the case of the more formal observational sessions, including meetings of groups and teams, the researchers took detailed written notes during and immediately after each observation period, using a standard template. The template prompted the researcher to record information relating to commissioning processes in general, as well as evidence use and ethnicity (see Appendix 2). Whenever possible, direct verbatim quotations by participants were noted alongside a more general description of the interactions and discussion, and relevant supporting material (such as documents circulated before, during or after the meeting) was compiled alongside the observational notes. Relevant information provided by the more informal observational opportunities, such as witnessing corridor conversations, was recorded by the researchers at suitable opportunities using a series of research memos, again using the same thematic codes to organise the material.

Interpretive documentary analysis was conducted on items presented or discussed at meetings and other background reports and materials using a standard template (see Appendix 2). These reports/materials were given to researchers by members of the group or accessed online when applicable. Although relevant documents varied in each case study, strategic documents included:

-

minutes of board meetings/strategic team meetings

-

strategic statements and organisational aims/values

-

joint strategic needs assessments (JSNAs) and other needs assessments

-

evidence presented/utilised

-

research and development plans or policy

-

health inequality action plans

-

national policy documents

-

policy-level equality impact assessments.

Templates used across the case study work prompted researchers to be alert to a range of relevant factors and processes, including how evidence was presented as part of the process (including consideration of its source and how it was received), who raised issues of ethnicity (and how related debates were framed), who was taking responsibility for evidence and ethnicity and how commissioning was changing (see Appendix 2).

Analysis, synthesis and integration of data

Key informant interviews

An ongoing process of analysis was used involving a coding scheme developed and iteratively adjusted during the first interview period, based on theory-derived topics and concepts from pilot interviews. This analysis schema was piloted and refined by all researchers and PCT-based co-researchers in dedicated workshops used to clarify themes and ensure consistent coding across the sites and researchers (see Appendix 2).

Microsoft Excel and Access were used to organise these codes (around 120 grouped into 10 broader themes) into a practicable framework,91 with summary descriptions and direct quotes extracted and used to populate the codes for each interview. This approach allowed researchers to read a topic-by-topic summary of each interview by reading the framework horizontally, or examine a particular coded theme by reading vertically across all of the interviews to explore commonalities and contrasts.

Coding of transcripts was undertaken by the team member who conducted the interview, with around 20% of transcripts checked by a second member of the team to ensure that themes and codes were being completed consistently. The two researchers with most capacity on the project read the coding for all transcripts. After transcription and coding were completed, team members engaged in a series of analysis workshops to discuss, challenge and refine interpretations.

Case studies

Producing an integrated analysis of the rich data generated through the range of methods used in the diverse case study was challenging both practically and theoretically. Data from the interviews, documentary analyses and observational work were all systematically organised and indexed against the coding framework that was developed for the key informant interviews. Regular analysis sessions were held involving university researchers and PCT co-researchers to engage in the inductive and interpretive identification and testing of emerging themes. Internal briefing documents were prepared and circulated during the generation and refinement of theory to ensure transparent links between data and emerging claims (see Appendix 2 for an illustration of the theme document used to link phase 2 emerging findings to the phase 3 work). In line with the theoretical model described earlier, the overarching approach to the analysis was informed by critical ethnographic perspectives, in that we attempted to synthesise the traditional ethnographic focus on the subjective meanings and beliefs of respondents with the insights gained from a broader structural analysis. 92

Analysis of case study material was first carried out at a ‘within-case’ level. The researcher/co-researcher pairs who had undertaken the bulk of data generation in each site worked together to produce the analysis. Detailed narrative templates were prepared separately for both the strategic- and operational-level case studies conducted at each site, detailing the holistic ‘story’ of each of these case studies. Following this stage, thematic templates were next prepared for each case study. The focus here was on integrating, and triangulating, data across each of the domains of analysis (evidence, individual, team, organisation and wider context) in order to describe the diverse factors that shaped evidence utilisation and to identify any enabling factors that support evidence use. Appendix 2 includes the templates that were used for the operational-level case studies by way of illustration; similar templates were also used systematically for the strategic-level work.

Once templates had been completed for the within-case analyses we moved on to the cross-case analysis. This involved a systematic comparison across the three sites to identify relational and substantive patterns. Cross-case analysis work was initiated through a series of face-to-face team workshops in which a structured process of review and reflection on the case-specific templates was followed. The standard templates encouraged all researchers to interrogate their material against a common analytical framework and allowed team members to readily engage with the claims and supporting materials emerging from all three study sites. Subsequently, draft integrated analysis documents were produced and an iterative process of review and refinement involving all research team members was used to draw the data together across the sites into a more general set of claims and findings.

Tools development

A key project aim was to develop a series of tools and resources to support the critical and effective use of evidence on ethnic diversity and inequality within commissioning. Tools development was firmly grounded in the research findings and also involved structured inputs from potential end-users. Chapter 7 provides an overview of some of these tools and details the process of tools development.

Chapter 3 The wider context: findings from national key informant interviews

Introduction

This chapter draws on the 19 national-level key informant interviews, detailed in Table 1. These interviews were expected to generate information in response to research questions 1 and 3, detailed below, with a particular focus on the wider policy context and organisational factors that direct and shape commissioning work, and the place of evidence use within this arena.

| Characteristics | National key informants |

|---|---|

| Sector/organisationa | Two DH, two senior GPs, two strategic health authority, two academics, two public health observatory, one local government (LGID), eight national third sector |

| Sex | Nine female, 10 male |

| Ethnicity | Nine white British, 10 other |

| Total | 19 |

Research question 1: how does a focus on ethnic diversity and inequality shape the knowledge mobilisation and utilisation process within the health services commissioning context?

-

What factors prompt managers to seek out research (and other types of evidence) relating to ethnic diversity and inequality?

-

To what extent is the accessing and application of information relating to ethnic diversity and inequality part and parcel of broader evidence-gathering exercises for commissioning or rather a distinct exercise?

-

What characteristics of research evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality influence how it is received by managers?

Research question 3: how can individual, team and organisational competencies effectively be enhanced to support critical use of research evidence for the commissioning of services that better meet the needs of our multiethnic population?

-

What factors in the wider societal and broader NHS context shape the routine, critical use of research evidence in commissioning for multiethnic populations?

-

How does research (and other) evidence relating to ethnic diversity and inequality currently find its way into the commissioning process – through which actors and which routes?

-

Who are the key actors and what are the key organisational settings and processes that present barriers against enhanced mobilisation and utilisation of evidence?

The bulk of this chapter is devoted to describing these wider contextual issues. However, in practice, many of the key informants also offered important insights into micro-level factors operating at the level of individuals and teams. We have noted these where relevant, although most were explored in greater detail through the case study work, which is presented in Chapters 4 and 5.

As noted in Chapter 2, our data collection did not focus narrowly on patterns of ethnicity evidence use but also solicited a wider range of information on commissioning structures and processes, and evidence use more generally. Key informant interviews were therefore loosely structured to allow respondents the opportunity to shape their responses and highlight the issues that they felt to be important. In particular, we did not offer any precise definition of ‘evidence’ but encouraged respondents to think broadly about the varied types of evidence (or knowledge) that play a part in commissioning work, with formal research evidence being just one aspect of this bigger picture.

Exploring generic commissioning drivers, structures and processes was important as these were likely to fundamentally shape the demand for evidence of different types as well as the access to, and use of, evidence within commissioning work. Further, an understanding of the more generic landscape was felt to be important in ensuring that any claims made for factors operating in relation to our focus on ethnic diversity and inequality were informed by an understanding of processes that shape and constrain evidence use in commissioning work more generally.

For this reason the findings in the present chapter are organised into three main sections: general findings relating to (1) evidence-informed commissioning and (2) ethnic diversity and inequality within English health-care policy and practice, followed by findings relating more specifically to (3) use of evidence on ethnic diversity and inequality in commissioning. Although research evidence did feature in respondents’ narratives, they also discussed a wide range of other types of evidence, reflecting the fact that these may often feature more prominently within commissioning work.

Respondents have been identified by their current broad role and sector but most had varied backgrounds giving them experience of different aspects of commissioning and evidence mobilisation processes. People in director-level roles have been identified as ‘senior managers’. More specific titles have been avoided to preserve anonymity.

Evidence-informed health-care commissioning: rhetoric and reality

What is health-care commissioning? What kinds of models are used?

The key informants varied in how closely they had been involved in commissioning work, yet all had sufficient exposure to commissioning organisations to provide useful commentary on the general features of commissioning structures and processes.

All respondents recognised commissioning as a complex set of activities, the intention of which is to shape health services to better meet population health needs:

I think, my sense is that commissioning actually covers a lot of different sorts of activities, but broadly speaking it’s the process of understanding the health needs of a population, and planning and procuring services to meet those needs. But within that, you know, there’s a lot of different sorts of functions, and different kind of patterns about how that might be carried out.

Third-sector manager and analyst

However, the consensus was that there was wide variation in the ways in which PCTs have been organised and commissioning work has been achieved in practice. Some respondents drew distinctions between PCT and local authority commissioning, but most felt that there was also important variability in approach and quality within each of these commissioning arenas.

To an extent, such variability might be considered to reflect an appropriately responsive system, in that no single model of commissioning might be suitable for all circumstances. Nevertheless, there was also a sense in the respondents’ reports that there remains a lack of clarity in terms of what ‘good commissioning’ might look like and significant contestation of roles and responsibilities within the commissioning arena. Moreover, although all respondents felt that commissioning should be an important lever for health-care redesign and improvement, most also expressed the feeling that the transformational potential of commissioning remains largely unrealised. For this reason it is important to examine the scope of variation described, with three distinct inter-related areas of variation evident.

First, respondents felt that there was important variation in the extent to which people in commissioning roles saw their job as one of transforming services to better meet needs as opposed to ensuring robust control of contracts and budgets (the so-called ‘transactional’ elements). Our respondents indicated that they felt that the former aspects were very important but were, in practice, not always emphasised: