Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 08/1819/221 The contractual start date was in August 2008. The final report began editorial review in August 2012 and was accepted for publication in December 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Mason et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

There have been a number of changes made recently by the government to improve the working conditions of NHS staff based on evidence that improved working conditions can improve staff well-being and in turn improve the quality of patient care. However, the evidence of a direct link between the well-being of staff and the quality of patient care within health care is limited. More evidence is required about which characteristics of working in the NHS influence staff well-being and which aspects of well-being influence patient care.

This study aims to evaluate the well-being of foundation doctors and compare this with the quality of care provided to patients attending the emergency department (ED). Key aspects of well-being that may influence quality of care include motivation, job satisfaction and confidence. Measures of these factors will have the potential to be developed into a tool that may be utilised more widely for doctors throughout the NHS.

Policy context and literature review

NHS policy context

The health and well-being of NHS staff has been of great interest to policy-makers in recent years, with a growing acknowledgement that good levels of health and well-being are likely to have benefits for organisations and patients. The role of organisations in contributing to the health and well-being of staff is recognised as key, with support structures aimed at improving the health of staff likely to positively influence staff retention, sickness absence, productivity and also, potentially, patient satisfaction and quality of care. 1,2

The publication of two major reports has increased the focus on health and well-being in the UK workplace and NHS organisations. 3,4 The Black review3 examined the health of the UK working-age population with a focus on the large-scale problem of sickness absence and reduced productivity (including the role of common mental health conditions). There is evidence that reduced well-being is one of the major causes of reduced productivity for individuals in work. Alongside this, a growing literature links morale and job satisfaction with health outcomes and performance. Although individuals may differ in the importance they attach to issues such as salary or level of responsibility, this review identified key job-related characteristics that influence well-being at work, such as employee autonomy and adequate social support. Good management and leadership also play a vital role in promoting well-being and improving performance. 3

Following on from the Black review,3 the Boorman review4 examined issues of health and well-being in the NHS workforce. The focus on staff well-being is explained by the continuing high rates of sickness absence in the NHS, with over 10 million sick days lost annually, equivalent to 45,000 whole-time equivalent staff,5 with over one-quarter of absences caused by stress, depression and anxiety. The NHS review of health and well-being4 found links between the well-being of staff and key performance indicators such as patient satisfaction and trust performance, with trusts with lower rates of sickness absence and turnover more likely to score highly on indicators of patient satisfaction and quality of care. The report4 recommended that organisations develop strategies and provide services to NHS staff to prevent and treat sickness, including work-related stress, anxiety and depression, and that management be assessed on their contribution to staff health and well-being.

These reports are consistent with pledges made in Lord Darzi’s 2008 report6 regarding the need for a broader commitment to health and well-being in workplaces and the recognition that the health and well-being of NHS staff was an important component of the commitment of the NHS to provide high-quality care. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance has also been produced,7 which recommends a strategic approach by employers to the well-being of staff. This includes ensuring that job design, selection, recruitment, training and appraisal promote well-being and that assessment of the well-being of employees is undertaken to identify areas for improvement.

Although the link between staff development, motivation and well-being and patient care is recognised as important,8,9 the impact of staff stress, depression and other aspects of well-being on patient care has been generally under-researched. Evidence demonstrating a link between indicators of well-being and indicators of patient safety, experience and quality of care is rare and has primarily been collected in nurse settings in the USA. There is also a lack of good-quality evidence from data collected longitudinally. 10

Training doctors in the NHS

Training and appraisal have been identified in the literature as important elements of appropriate people management, impacting on knowledge and skills, job satisfaction and well-being, which in turn may influence patient outcomes. 11 Previous studies have demonstrated relationships between the quality and extent of training and appraisal and the well-being of staff and better patient care. 12–16 Recently, postgraduate medical training has undergone changes in response to long-standing criticism of its suitability in a modern, patient-centred NHS. A report by the Chief Medical Officer17 highlighted a number of perceived problems with the job structure, working conditions and training opportunities in postgraduate medical education, with the balance between medical training and service provision weighted too heavily in favour of providing for service delivery at the expense of a well-structured and well-planned training programme for postgraduate trainees [senior house officers (SHOs)]. SHO training placements were perceived as short term and stand-alone and not part of a clearly structured training programme.

These issues called into question whether doctors were being appropriately trained to meet the demands of a modern, patient-centred NHS. 18 Postgraduate training was also criticised for failing to provide more trained specialists for a consultant-led NHS. 2 The report recommended the introduction of a new programme-based system of postgraduate training [foundation training (FT)] that would provide broad-based specialty experience and flexible training arrangements.

Foundation training

The new model of FT was piloted in 2004 and introduced nationally in 2005. The model introduced a fixed 2-year Foundation Programme to address the perceived deficiencies of the previous postgraduate training grades (pre-registration house officer and SHO). Postgraduate training was structured around a formal programme with a national curriculum and structured assessment of clinical competencies (see Appendix 2).

The first year of FT (foundation year 1 or F1) focused on developing the skills and competencies learned during undergraduate medical training. The completion of core competencies was required during F1 to achieve full registration with the General Medical Council (GMC). The second year of FT (foundation year 2 or F2) was designed to enable doctors to become functioning members of the health-care team, competent in the management of the acutely ill patient and with key skills in team working, time management and communication with both professionals and patients.

Foundation training generally consisted of 4-month placements in a variety of specialties to give postgraduate doctors sufficient experience of different areas of medicine. Modernising Medical Careers (MMC) also provided a clear structure for post FT with ‘run-through’ specialist training following on from FT. 19

As well as introducing new structural arrangements, FT changed the delivery of training within placements. For the first time doctors were explicitly required to demonstrate competency to practise through the completion of a range of specific assessments (see Appendix 2). These assessments were based on a new Foundation Curriculum. 20 The Foundation Programme also required the designation of educational supervisors (ESs) and clinical supervisors (CSs), charged with ensuring that foundation doctors were meeting their educational and training goals.

The well-publicised problems with selection processes in the early stages of MMC reform led to an inquiry into MMC, which also examined FT. 21 The inquiry highlighted a number of areas of concern with the FT model, including the insufficient breadth of clinical experience in foundation placements; a lack of flexibility in programmes; and the length of programme placements. This contributed to a perception that foundation doctors were not reaching appropriate levels of clinical responsibility compared with their SHO predecessors. The report also recommended greater clarity about expectations of the role of F2 doctors in the health-care team and what their service contribution should be.

A more recent evaluation of the Foundation Programme reported improvements including a well-defined curriculum, trainees exposed to a wider range of medical specialties and implementation of a comprehensive programme of trainee assessment. 22 However, the report stated that the programme still lacked an articulated purpose, found that there was confusion over the role of the F2 doctor and questioned the ability of placements to accurately reflect the current and future needs of the NHS. Further, the assessment process placed excessive loads on ESs and there were safety and quality issues in the learning environment.

Reduced hours of working and the European Working Time Directive

As well as changes to the structure of postgraduate training, there has been a major change to the conditions of work for postgraduate foundation doctors. The New Deal for junior doctors, published in 1991,23 highlighted the need for improved working conditions for this workforce group primarily focused on working hours. It was widely acknowledged that excessive hours of practice amongst foundation doctors was a risk to patients. In 2003 the working week was limited to 56 hours and the European Working Time Directive (EWTD)24 further limited the hours that medical staff could work to a maximum of 48 hours. This was implemented in stages with the 48-hour limit enforced by law in 2012.

Health service staff motivation and well-being

High levels of stress among health-care professionals has been recognised as a problem for some time. A review of doctors’ stress levels found that between 28% and 30% of doctors had above-threshold levels of stress compared with about 18% of the general population. 16 A survey of over 11,000 NHS staff5 found staff reporting high levels of stress and that they did not consider that senior managers took a positive interest in their health. Some studies have also reported high levels of depression amongst doctors. 25,26

Studies have also reported higher levels of stress among doctors (both consultants and junior doctors) working in emergency medicine (EM), with above-threshold scores for around half of the respondents from each group. 27,28 These levels of stress are again higher than might be expected among the general population. 29 However, the impact of stress, depression and well-being on patient care has been generally under-researched. 10

Foundation doctor well-being

There is a limited literature examining the well-being of doctors in training. One study looked at levels of psychological distress in SHOs working in the ED. 27 SHOs were selected from six EDs in London and received questionnaires to measure psychological outcomes and coping strategies. Over half of respondents scored above the threshold for psychological distress on the General Health Questionnaire. 30 Higher levels of anxiety and depression were related to a venting style of coping (such as expressing negative feelings) whereas lower scores for these outcomes were associated with a more active coping style (such as devising strategies to cope with stressors). Another study followed junior doctors for 3 years after their graduation from medical school finding that first-year postgraduates reported levels of depression of 29%, dropping to 10% by their third postgraduate year. 26

Foundation doctors and quality of care

Studies evaluating the impact of foundation doctors on the quality of patient care have evaluated the following outcomes: (1) numbers of patients seen; (2) reattendance of patients in the ED; and (3) confidence and competence in managing conditions.

A prospective observational study compared the productivity (numbers of patients seen) of F2 doctors and SHOs working across two EDs in Scotland. 31 Both groups demonstrated a significant rise in productivity between the first and last months of their attachments. There were no significant differences in productivity between the two groups of doctors over the 12-month study period. However, there were concerns about a reduction in the percentage of patients seen by junior doctors overall and an increased need for senior review of patients. Further analysis by Armstrong et al. 32 investigated the number of patients seen by all junior doctors (SHO/F2) over a 3-year period. The study found a 4% decrease in the number of patients seen by junior doctors in this period. In addition, there was a significant reduction of 16.6% in the number of patients seen per hour (an indicator of work rate).

A study at an inner-city ED in England also found no significant differences in the mean number of patients seen by F2 doctors and SHOs over a 12-month period. 33 Individual doctor performance had a greater influence on the number of patients seen than type of doctor (either F2 or SHO), with a small number of F2 doctors seeing considerably more patients than their SHO colleagues.

A study by Whiticar et al. 34 compared reattendance rates of patients to the ED over a month in 2006 by grade of doctor assessing the first presentation. Junior doctors (SHOs and F2 doctors) had higher reattendance rates (2.83% vs. 2.32%; p = 0.52) than middle-grade doctors and nurse practitioners (although the result was not statistically significant).

Croft and Mason35 assessed levels of confidence in foundation doctors’ management of common minor clinical presentations in an inner-city ED. Foundation doctors’ confidence in treating minor injury patients was identified as a problem, and a lack of exposure to minor injuries during daytime hours was cited by doctors as a possible cause.

A further study36 evaluated junior doctors’ experience in performing practical procedures in an ED. Two cohorts were measured: trainee doctors in the ED in June 2005 and June 2006. The study found that doctors in the later cohort reported significantly less experience in each procedure.

One study37 measured SHO and pre-registration SHO knowledge of basic acute care in 12 topics. A total of 185 junior doctors from six UK hospitals were included in the study. This study found that knowledge was poor across a range of basic acute care topics and that junior doctors were poorly prepared to identify and treat critically ill patients.

Overall, these studies raise questions with regard to foundation doctors’ confidence and performance in the ED which require further investigation.

NHS staff motivation, well-being and patient care

There is limited evidence of a direct association between factors that affect performance and outcomes in health care, which would be important to take into account when studying a changing workforce. In one study,15 which sought associations between organisational practice and clinical outcomes, it was possible to demonstrate a linkage between good human resources practice (such as appraisal and training) and effective teamwork and reductions in measures of patient mortality. A further study in a non-health care setting demonstrated that organisational climate (e.g. skill development, concern for employee welfare) was significantly associated with productivity and profitability, and that the relationship was mediated by employee job satisfaction. 38 There is an increasing literature on links between patient safety and organisational culture and climate, with a range of tools and interview methods proposed. 39

The link between staff development, motivation and well-being and the influence of these factors on patient care is recognised as important. 8,9 In one review of the literature,10 a significant linear effect was found between levels of nurse stress and burn-out and patient outcomes (patient satisfaction, medication errors and patient falls). However, the cross-sectional designs of the studies and lack of control of confounding variables (such as doctor sickness absence)40 limits the usefulness of these findings. 10

Few studies have evaluated the consequences of well-being for foundation doctors in terms of confidence, competence or patient outcomes. A study of SHOs working in 27 hospitals evaluated the relationship between psychological distress and confidence in performing clinical tasks. 41 The questionnaire was administered four times during the 6-month rotation. Overall, confidence levels in carrying out a range of practical and clinical tasks (recorded on a visual analogue scale) increased significantly between the first and fourth months of the SHO training rotation. SHOs with higher psychological distress scores at the end of months 1 and 4 had lower confidence scores. Factors associated with greater psychological distress were organisational, such as workload, certain clinical presentations and consultation issues such as communication.

Summary

The changes to postgraduate medical training (including uncertainties over future direction) and restrictions on working hours impact directly on postgraduate foundation doctors in training. These changes have also occurred at a time of rising demand for health care, with greater demands on staff in terms of providing care in services that are increasingly performance driven. It is important to consider how these major changes have influenced the well-being and motivation of foundation doctors and also the consequent impact on quality of care.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

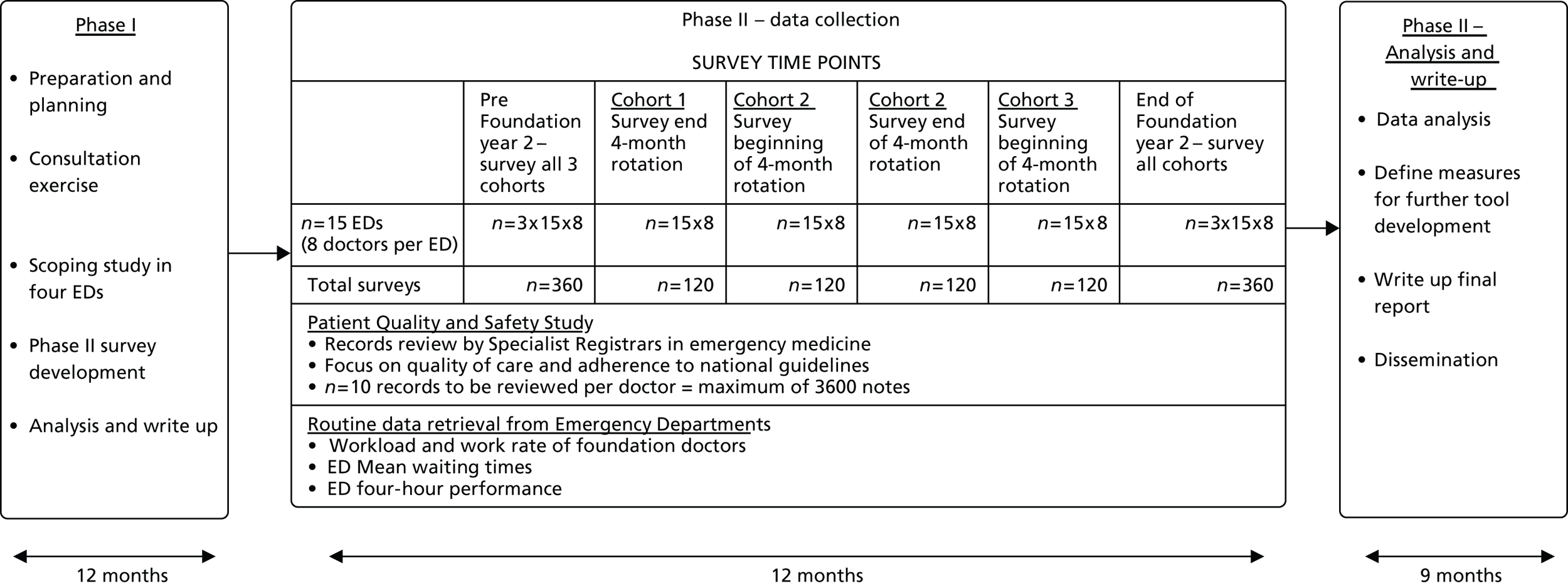

The study was conducted in two phases and used a mixed-methods approach across multiple sites to achieve the following aims and objectives.

Aims

-

To describe the current arrangements for the delivery of FT in England.

-

To identify how the experiences of F2 doctors training in EDs influence their well-being and motivation.

-

To evaluate how the well-being and motivation of F2 doctors in EDs is associated with the quality of patient care.

-

To identify key measures of F2 doctor well-being and motivation that are associated with quality of patient care. Key measures that are identified may underpin the development of a tool to monitor well-being and motivation during training.

Objectives

Phase 1

-

To conduct a national and regional consultation exercise with training stakeholders to:

-

describe the national strategic view of the aims of delivering FT, with a particular focus on the role of training in supporting the well-being of doctors

-

assess how the national view is implemented on a regional basis through the postgraduate deaneries and identify any regional variation to implementation within the specialty of EM

-

undertake a scoping exercise to identify factors contributing to the well-being of F2 doctors in training within up to four EDs to develop measures to inform a quantitative evaluation of foundation doctors in phase 2 of this study.

-

Phase 2

-

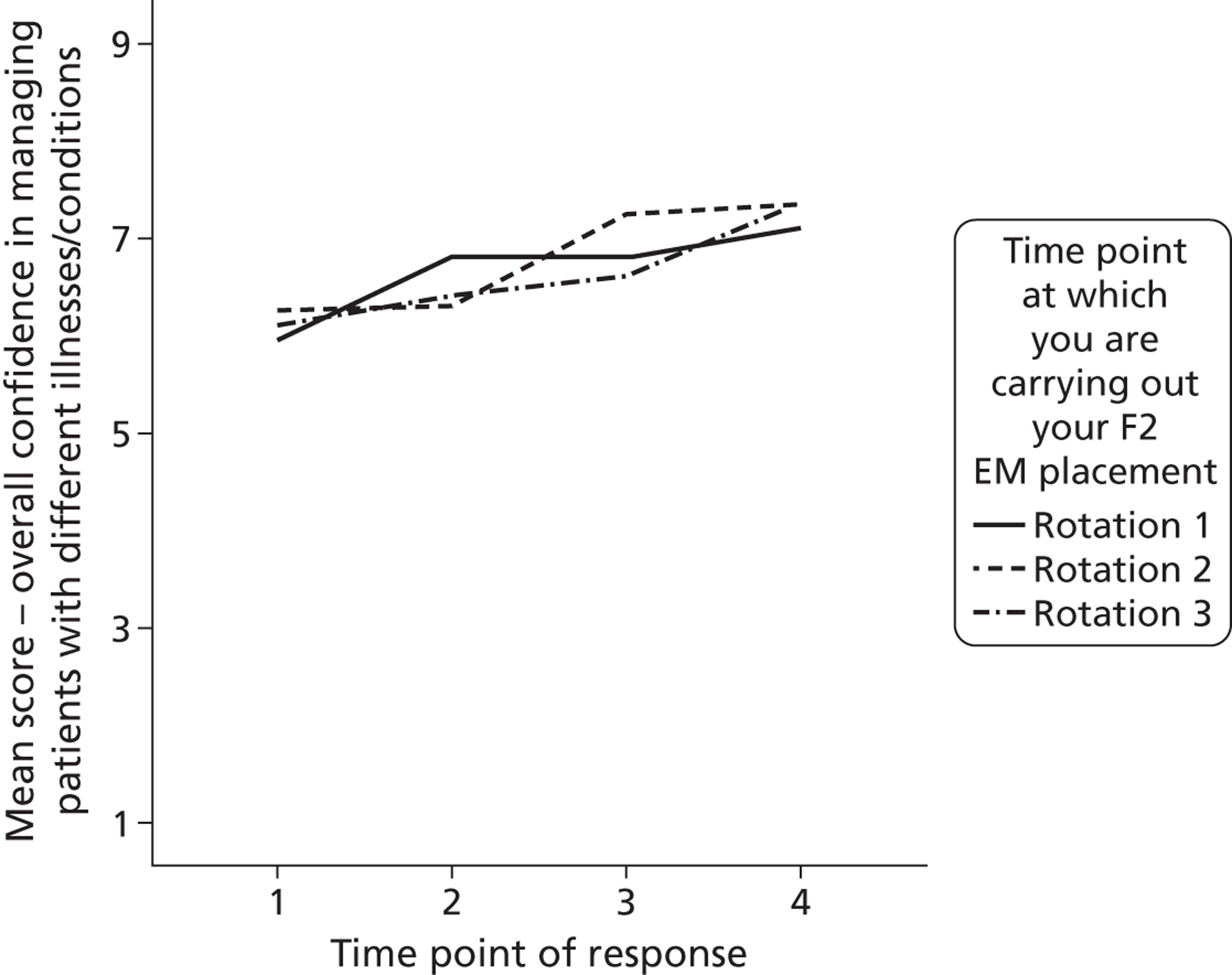

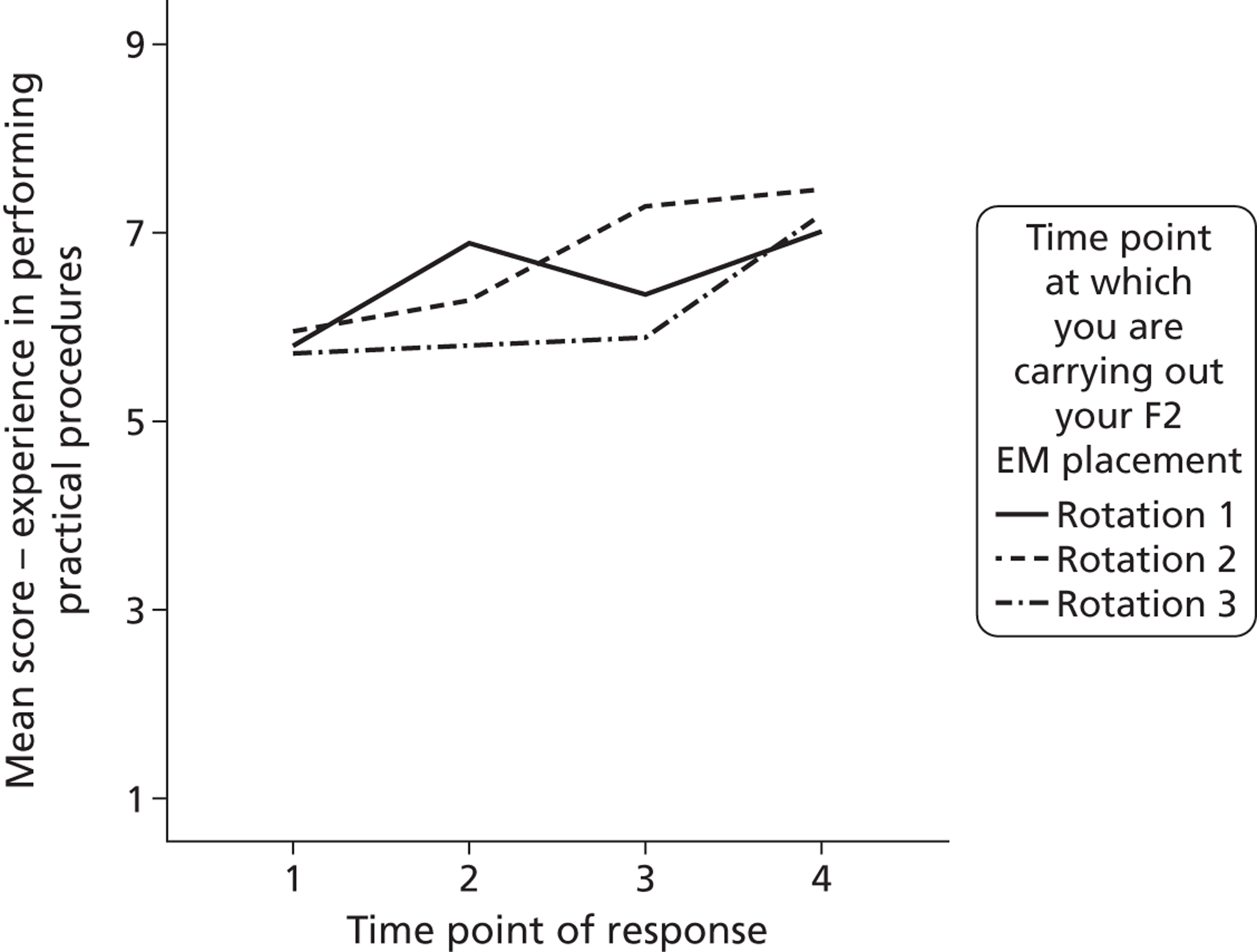

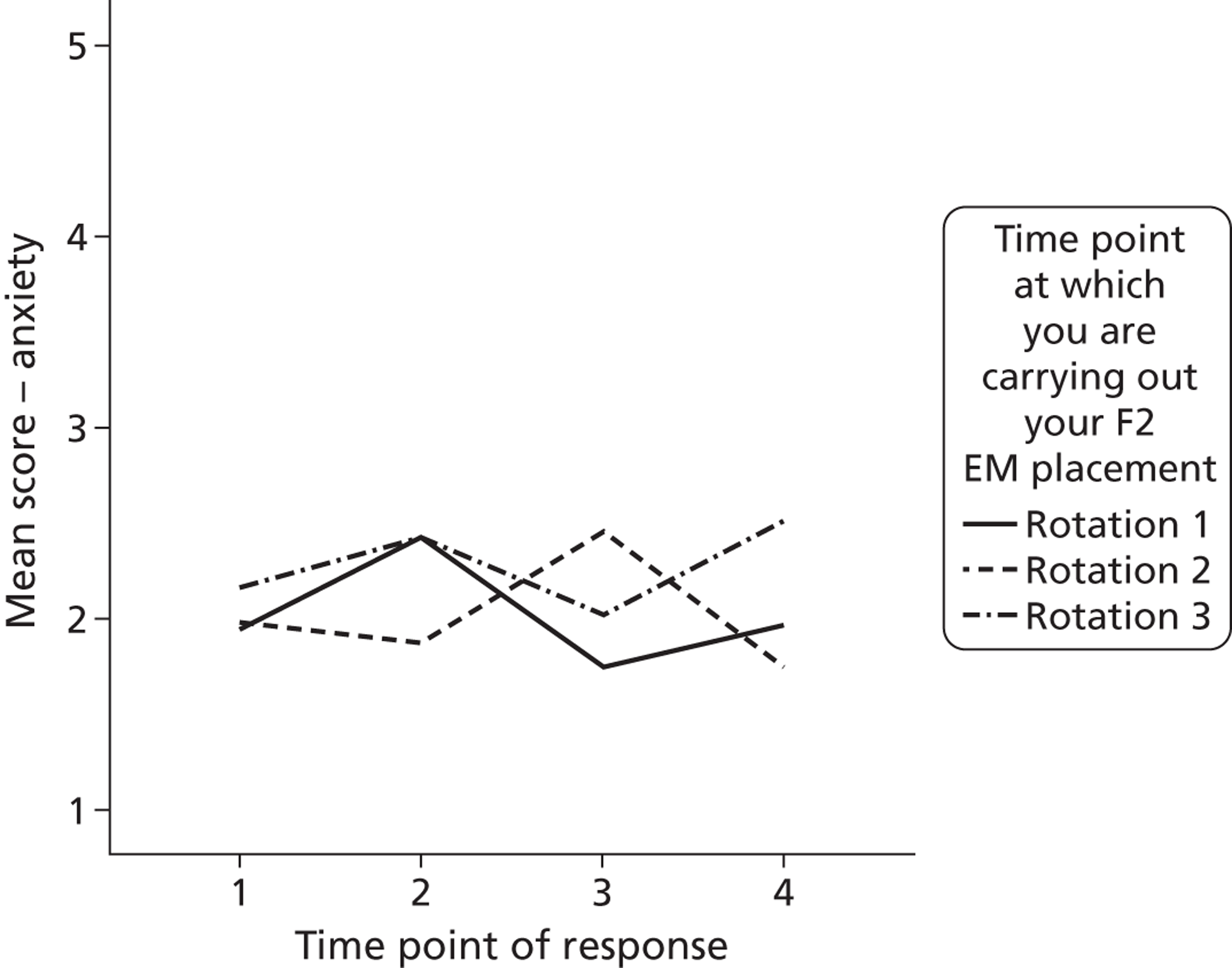

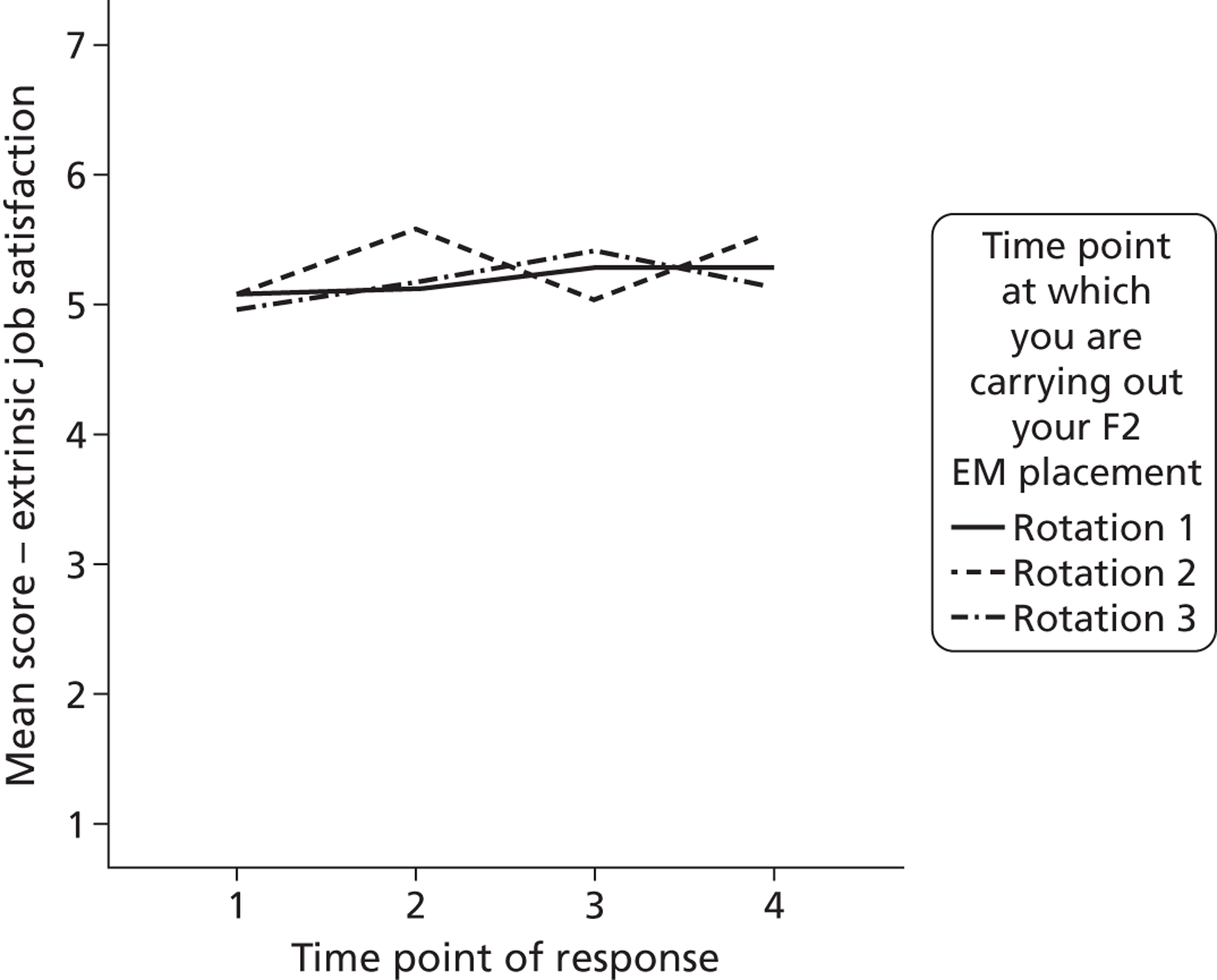

To undertake a longitudinal study using a structured survey to assess F2 doctors in terms of their well-being, motivation, confidence and competence at four time points over a 12-month period.

-

To conduct a survey at four time points (at the end of F1 and then after each F2 placement) to assess the level of and change in F2 doctor well-being, motivation, confidence and competence. One of these placements will be in EM and the impact of this placement can be assessed in relation to the study outcomes.

-

Assess patient safety and quality of care by F2 doctors by reviewing the clinical records of patients receiving emergency care from F2 doctors and evaluating routine ED data to link workload and mean time with the patient for each of the participating F2 doctors.

We will examine the findings from phase 2 to:

-

evaluate whether there is a relationship between F2 doctor well-being and motivation and patient care

-

identify best-practice models of F2 doctor training, which might be generalised and implemented across the NHS to promote a healthy and productive foundation doctor workforce

-

provide a starting point for the development of a tool that can be used to monitor the well-being, motivation and training of doctors in EM and other specialties.

Chapter 3 Phase 1: consultation exercise and scoping study

Introduction

A consultation exercise with national and regional postgraduate education stakeholders (PESs) and a scoping study with training leads (TLs) and F2 doctors in the ED were undertaken using qualitative methods to examine FT from multiple perspectives at the national, regional, trust and foundation doctor levels.

Aim and objectives

The aim of the consultation exercise and scoping study was to describe the current arrangements for the delivery of FT in England.

The objectives were to:

-

describe the national strategic view of the aims of delivering FT, with a particular focus on the role of training in providing for the well-being of F2 doctors

-

assess how the national view was implemented on a regional basis through the postgraduate medical deaneries (PMDs) and identify any regional variation to implementation within the specialty of EM

-

identify factors contributing to the well-being of F2 doctors within up to four EDs. The data collected were to inform the development of measures to be used in a quantitative evaluation of F2 doctors in the phase 2 longitudinal study.

Methods

Ethical and governance arrangements

Ethical approval for phase 1 was received in May 2009 (ref.: 09/H1307/27).

Approvals from non-NHS organisations and research governance approvals from participating NHS trusts were obtained between June and November 2009.

Consultation exercise

To understand the strategic aims, national structure and implementation of FT, national and regional stakeholders from key postgraduate educational organisations involved in the delivery and implementation of FT were interviewed by telephone or videoconference. A semistructured interview schedule was designed around the aims and objectives of the study, with a particular focus on identifying potential variation in the implementation of FT and provision within training of an appreciation of the well-being and motivation of F2 doctors (see Appendices 3 and 4 for interview schedules).

A letter of invitation and information sheet about the Evaluating the Impact of Doctors in Training (EDiT) study were given to interviewees in advance, along with the interview questions. Written, informed consent was received from each participant before the interview (see Appendices 6–8 for the letter of invitation, information sheet and consent form respectively).

Scoping study

A scoping study involving interviews with TLs and focus groups with F2 doctors was carried out in four EDs to evaluate the impact of training in the ED on both F2 doctors and other health-care staff. The four EDs were selected from 15 EDs recruited for the phase 2 longitudinal study. There was a particular focus on well-being and motivation of F2 doctors in order to develop measures to inform the quantitative evaluation in the phase 2 longitudinal study.

Interviews took place with TLs in EDs. A semistructured interview schedule was designed to assess the training role of doctors, the impact of training on staff, the well-being of training doctors and the quality of care (see Appendix 5). An Information sheet and interview questions were given to interviewees in advance (see Appendix 7). Written, informed consent was received from each participant before each interview.

Focus groups were held with four groups of foundation doctors in their ED placement (mainly F2 doctors, although some F1 doctors were present in two groups). A semistructured schedule (see Appendix 9) was also designed for the focus groups, which included issues around well-being, confidence, competence and ED training experiences. Written, informed consent was received from each individual before the focus groups.

Data analysis (consultation exercise and scoping study)

Three researchers were involved in the analysis of interview and focus group data in order to gain multiple perspectives and insights into the data collected and ensure inter-rater reliability. Interviews and focus groups were not recorded to maintain anonymity of the participants; however, data collected from all participants in the consultation exercise and scoping study comprised thematic accounts and reflections from each of the researchers,42 the content of which was validated with the participants to gain a full understanding of meaning. 43

One researcher produced templates for the four participant groups, aggregating themes at the group level for (1) national PESs, (2) regional PESs, (3) emergency department training leads (EDTLs) and (4) F2 doctors in the ED primarily by using the interview/focus group questions as a priori coding. 44,45 Each template was then examined by the other two researchers, checking for inter-rater reliability to reduce any potential bias. Agreement was high (92%), with issues of terminology being the main areas of correction; any areas of misunderstanding or possible bias were corrected on each template.

Individual templates derived from the interviews and focus groups were also reviewed by the three researchers for salience (agreement of themes across stakeholders) and difference (individual perspectives that add value to the enquiry) and key overall themes were derived for each group of participants. A summary template was then produced to bring together the similarities and differences between key themes across the groups (Table 1).

| National stakeholders | Regional stakeholders |

|---|---|

|

|

| TLs in NHS trusts | F2 doctors |

|

|

Results

Sample achieved

Consultation exercise

A total of 10 interviews were undertaken, three with national PESs and seven with regional PESs, between November 2008 and February 2009. Interviews lasted for approximately 60–90 minutes. The national PES interviews were with representatives of three national bodies involved with planning FT. The regional PESs were from four deaneries and foundation schools (FSs).

Scoping study

The scoping study took place between November 2009 and February 2010. Eight interviews with EDTLs were carried out across four EDs. The group comprised six consultants (two F2 TLs, four CSs or ESs) and two nurse practitioner tutors. The interviews lasted for approximately 60–90 minutes.

Four focus groups were held with F2 doctors in three EDs. Two focus groups were held within a teaching hospital site (with seven and four participants) and the other two focus groups were held in two separate large acute trust EDs (with eight and six participants). The focus groups lasted for approximately 90 minutes. A further planned focus group in a smaller district hospital was cancelled on two occasions because of staffing pressures.

National stakeholder interview findings

In the following sections the numbers in parentheses indicate the numbers of participants agreeing with a particular statement. Statements without a number are the comments of one participant only.

Number of trainees and sufficiency

Two of the three PESs agreed that there were 7000 Foundation trainees in England and a further 800 in Scotland (2). All participants felt that the volume was sufficient as there is open access for places between trainees from the UK and trainees from other European countries (3). Additional places are required to allow non-European trainees to access the programme.

Strategic aims and national structure

All participants described the aims of FT as delivering a structured programme to provide a range of experiences to foundation doctors (3). The outcomes of the programme were designed to be common to all foundation doctors but these could be achieved in a variety of ways.

A clear national structure was described consisting of (1) a National Curriculum, (2) a national structure of FSs headed by the UK Foundation Office, comprising the directors of FSs who met with education leaders to maintain an overall strategy, (3) an Assessment Framework and (4) a national conference to share best practice (with deanery, foundation doctor and organisational representatives present) and a Foundation Programme website containing guides and review papers.

Two participants described the regulator of medical education as having overall responsibility for training (2). At the time of our interviews there was joint responsibility for F1 training between the GMC and the Postgraduate Medical Education Training Board (PMETB), with F2 training regulated completely by the PMETB. Various review groups (such as the Curriculum Group) met with Academy of Medical Royal Colleges representatives to discuss standards and assessment tools and recommend changes to the PMETB in the form of review documents. Since completion of the interviews the PMETB has merged with the GMC and the latter is now responsible for the regulation of all stages of postgraduate education and training.

Participants described a variety of approaches that are currently being used to manage the implementation of F2 training, such as stakeholder conferences (with deanery, foundation doctor and organisational representatives present) (2) and a website containing guides and review papers.

Variation in implementing foundation training at the regional level

Placements

Participants agreed that foundation doctors have six 4-month rotations managed by the deaneries (3).

Two of the three participants concluded that a uniform national implementation of FT was difficult to achieve, mainly because of regional variation within the UK in terms of local population health needs and different operating structures (2). Some deaneries have placements of varying length (from 4 months to 1 year), combining a variety of roles (2), and participants noted that variation was encouraged within the national framework as a way of producing innovation and a variety of placements (3): ‘For example, combining GP and acute medicine placements with leadership development (was unpopular with F2 doctors at first) can produce a rounded programme’.

It was noted that up to 15 trainees per year worked their F2 placements outside the UK. Participants felt that foundation doctors were reluctant to try new learning opportunities that reflected current job opportunities, preferring placements reflecting a more traditional understanding of a doctor’s role in acute medicine. Some programmes offered good future career taster sessions whereas others did not (2). Overall, the innovative placements would seem to be in the minority and were often unpopular with trainees until they were established in their use. However, although the governing body (PMETB) encouraged varied training experiences, one participant felt that it did not evaluate outcomes.

Evaluation of the well-being of foundation year 2 doctors in foundation training

It was noted that, although support for trainees was ‘attempted and well meaning’, little systematic evaluation of trainees’ well-being or motivation appeared to occur in practice. Participants felt that a good deal of time was spent discussing the few ‘doctors in difficulty’ within the training system (1–2% in total) and little time was spent evaluating the well-being or motivation of the ‘average’ trainee.

The former PMETB trainee survey asks questions of the trainees about themselves and the programme (e.g. how often they were forced to cope with problems beyond their competence or experience; their concern about the reporting of medical errors) (2). Further placement feedback forms and multisource feedback may offer some insights into whether problems had occurred in the workplace. A participant noted that ‘medical training can be “over nurturing” and the idea of FT was to bring some sense of the reality to trainees about work’.

Assessments

A key part of achieving curriculum competencies is demonstrated by assessments (2) (e.g. observations, case-based discussions; see Appendix 2). Participants described the assessment of training outcomes as variable, from both the trainees’ and the supervisors’ perspectives. PESs’ concerns were that ‘deaneries vary in their understanding of the assessment process’ and ‘constructive feedback is not always being given’. PESs felt that the trainees found the assessments to be ‘just form filling’.

Several comments focused on the need to change, for example ‘Assessments need to be tightened up and not be so woolly’. In particular, it should be ensured that assessments ‘demonstrate[d] the achievement of competencies’, assessments ‘need[ed] to be refined and simplified for both the assessor and the trainee’ and they ‘need to be thoughtful; and focused’. However, it was noted that the ‘PMETB feel that work-based assessments are better than academic assessments’.

Evaluation of foundation training

Participants were asked how F2 training is evaluated and the following comments were made:

Deaneries are judged on how they meet their standards by QAFP [Quality Assurance of the Foundation Programme] assessments and visits.

Evidence of trainees completing their assessments in the electronic portfolio. (2)

Post placement questionnaires.

The Sign-off of the FY2 year.

In response to whether postgraduate training of doctors was ‘fit for purpose’, two participants felt that it was moving ‘in the right direction’ and one that ‘there are a lot of things in the FT that work better than the old system’. Much of this positive change was to do with ‘work-based assessments’ (2). FT has reduced the variability in training by setting a specific curriculum, which has been ‘the driver for learning’.

However, challenges were acknowledged with regard to FT. All participants agreed that it was difficult to ‘balance the F1 and F2 years’ (3), with F2 lacking in clarity in comparison to F1, which leads to GMC registration (2). Other issues were changing the view that ‘teaching sessions are the only learning opportunities’, ‘varying placements across deaneries and in particular getting enough community placements’. It was also noted that not all placements are filled by foundation doctors and that some F2 doctors are not employed after FT or ‘do not get the job they want’ (this comment would seem to refer to a greater number of generalist community roles available than specialty placements).

Career development of foundation year 2 doctors

As FT is the step between medical school and specialist training, we wanted to evaluate the level of support that existed for trainees to help them decide on their future career. Career development is also an important facet of job satisfaction,46 in particular ‘using your abilities’. 47

Participants described a variety of career support resources provided in various programmes: taster sessions, career management sessions, specialist training advisors and web resources. Recently, a National Education Advice Forum had been set up to improve careers advice. There was a comment that ‘more sideways movement should be made in programmes, offering change and more choice’. There was concern that trainees ‘were slotted into work and miss the bigger picture’. However, it was noted that ‘taster sessions are not well taken up by trainees, possibly because it is difficult to get release from their placements’. It was also noted that ‘career development should be done in medical training: FY2 is too late’ and that a more positive attitude was required of F2 doctors: ‘there is more that we can do; but the trainee has been in the NHS for five to six years at this point and they should be able to put some effort in themselves’.

Future development and changes

Foundation training had been under way for 3 years when this project started and there had been several challenges to its establishment, most notably the Tooke report. 21 We wanted to examine participants’ views on the future developments to this programme.

Although participants acknowledged criticisms of FT, they felt that there was political support for the training (and 4-month placements) and that it would remain relatively unchanged (2). However, participants acknowledged that there were opportunities for development:

There will be a curriculum review in 2009 and this will give the opportunity to refine and improve specific outcomes.

The review will give us chance to pull back and standardise things across the four countries.

There is a need to resource trusts and recognise training and learning time . . . we need to understand the issues of placements; while they should be less about service and more about learning. I do not want doctors to become supernumerary.

The next focus will be post FT; and this will need to be done flexibly.

Regional stakeholder interview findings

The seven regional PESs in our study were involved in programmes that offered places for between 200 and 550 postgraduate doctors. The smallest programme started in 2008 and worked with nine trusts, expecting to expand in the following year. The largest programme worked with 24 trusts and 19 community placements.

Regional implementation of Foundation Programmes

All regional stakeholder participants described a national structured programme for F2 (7), with three 4-monthly placements (2). Each region had its own pattern of committees and liaison groups that managed deanery and placement arrangements, for example ‘there are 16 individual programmes in the local “health economy” for two years’.

Participants (2) observed that trainees were employed by trusts while continuing in the privileged position of having deanery support to continue their medical education.

Most participants described three 4-month placements that were either ‘constructed from scratch’ or were developed ‘after some transition arrangements’ (2). A variety of placements were described involving primary care (2) and ED (but not in every rotation, 2). The use of primary care placements varied from being ‘in every track’ to descriptions of ‘GP placements that are poorly supported’ (2).

It was noted that the two foundation years were rarely considered concurrently: there is ‘no coupling of F1/F2 limiting choice and flexibility of the trainee if they want to do a different rotation that fits their career path’. One participant noted that ‘we have some FY2s who spend the whole year abroad’.

Involvement of placement organisations in the planning of training

Six out of seven participants commented on formal (and informal) meetings between PMDs and trusts regarding the planning of placements (6). In two cases FSs were based in the trusts and close working relationships were described. However, this was not true in all cases:

There is local design of the rotation against minimum standards; we visit every two years. We don’t handle this at all well; the education community is separate from service delivery distancing the Trusts.

Trusts need to be involved more: we try to listen to them; but this is often swept aside by demands of evaluation.

Poor transfer of information between departmental procedures and foundation school procedures; such as poor prescribing.

Quality assurance

A variety of mechanisms designed by the PMETB (e.g. end-of-placement trainee survey, annual report) and local mechanisms (e.g. trust reports, significant events) were described. Annual or biannual formal visits to trusts were carried out by postgraduate medical education representatives. A wide range of data were collected (e.g. induction, rotas, career outputs, job evaluation survey tool, end-of-placement survey, serious incident reporting). Most participants felt that these mechanisms were adequate but that little synthesis occurred with the information, commenting (4):

QA [quality assurance] systems are difficult.

Yes, the mechanisms exist but there is a danger of information overload.

If quality issues are indicated trusts produce an action plan.

Postgraduate assessments and supervision

Electronic portfolio (e-Portfolio) use was noted by five participants, with three commenting on widespread use and others noting difficulty in implementation – ‘needing to make them more user friendly’ – and ‘some trainees being more engaged with computer technology than others’. Their use as ‘a quality assurance tool allowing the deanery to track activity’ was welcomed.

There were mixed views about the value of formal assessments. On the positive side participants felt that the tools were effective [especially the mini-Peer Assessment Tool (mini-PAT)] but that they needed to be applied effectively and not used as ‘tick-box’ exercises (2). Difficulties were noted, such as getting ‘a full spectrum of procedures’ and ‘senior clinicians’ time’ (2). Trainee strategies were noted, such as ‘leaving all the assessments to the end of a rotation’ and ‘getting friendly staff member to sign-off competencies’ (2).

Participants recognised the important supervisory roles of the ES and CS (5), noting:

Consultants find it difficult to give their time as an ES as it is not recognised in their job plan. (2)

A good ES knows their trainees well; others have only one meeting.

We rely on CS assessments to know about problems with ill health or progress.

The ES is a key role; we are working on this but it is a poorly understood role. (2)

ES role needs to be close and special relationship with a trainee to build their competency – we need time and resources to build this capacity.

The quality of assessment and supervision varied:

e-Portfolios are only used by some and the role of the ES is poorly understood. (3)

Some trusts have difficulty providing ESs.

Trainees and assessors do not understand the importance of the assessment process.

Some areas are more engaged with computer processes than others.

Induction programmes were criticised (2) either as ‘lacking’ (not containing sufficient information, typically about how the hospital worked at night) or for being held at inappropriate times: ‘best in August and worse in December’.

Participants were asked what criteria were used to sign off the end of an F2 placement. Although participants (6) offered similar criteria, emphases were different. Criteria listed were teaching attendance levels of at least 70% (2), satisfactory appraisals, multisource feedback (2), completed e-Portfolio of competencies (2), good reports from all placements, deanery guidelines for assessment and end-of-year review.

Evaluation of well-being of foundation year 2 doctors in foundation training

Regional stakeholders described the formal process of defining a F2 doctor ‘in difficulty’ (3) when significant problems were noted and an action plan put in place to manage health issues (‘often going back to what was happening in medical school’). Others (2) noted an informal monitoring process (from the ES/CS). A majority of participants (5) felt that there could be ‘better ways to monitor trainees and check to see if they are reaching their potential’.

Regarding the question of who assessed well-being, no clear pattern emerged in the view of the participants. Two participants stated that the role of identifying issues lay with the CS and relevant medical team, who then needed to inform the ES at the deanery. Other participants felt that identification of well-being issues should rest at the deanery level, either with ESs or with postgraduate managers. There was a major concern regarding the degree to which problems could be kept hidden from supervisors in general, as serious issues of well-being known to a trainee’s GP or occupational health would not be routinely communicated to supervisors.

In terms of motivation the majority of participants believed that the foundation experience of practising medicine after a long undergraduate tenure was a motivating factor. Further, the opportunity to be part of a functioning team in the ED, making decisions (2) and being given timely feedback (3), was also a motivating factor for F2 doctors.

When asked which aspects of work F2 doctors struggle with a variety of examples were given: poor or little supervision (2); antisocial shift patterns; having to prioritise and make quick decisions (2); ED workload; not being involved in decision-making in some supernumerary roles; and work that involves a high level of communication and delegation.

One participant gave an example of a local patient safety group as a formal route by which an issue of F2 doctor well-being was identified, with the group identifying a ‘serious incident’ relating to a particular trainee. The majority of stakeholders (5) did not believe that the impact of F2 doctor well-being on patient care was evaluated formally:

Not sure if this is considered.

Currently we get indirect reports from staff saying when they are not good with patients.

Evaluation of foundation training

When asked about the extent to which FT was providing doctors who are fit for purpose there was a varied response from participants. Four of the seven participants believed that F2 was delivering training at the level required, ‘offering proof of certain competencies’ and ‘providing more rounded individuals who communicate well’, and was better at identifying doctors in difficulty than the previous model of training. Three participants had concerns about the variation in ‘active’ supervision and assessment in the workplace (2) and the ability of F2 to adequately prepare trainees for specialty training (2).

In terms of the EM context, there was widespread recognition among the participants that the ED was a tough training specialty for F2 doctors. However, the elements that made it difficult were also its strengths, requiring doctors to see large numbers of acutely ill patients and make decisions about whether to send them home or admit them to hospital (3).

Daunting for trainees, they have to work in a big team which is good, deals with a large numbers of ill patients; and they get a lot of peer support.

Training is very good in ED; they are consistently good at induction and teaching parameters.

This was not the type of experience offered by many other specialties. EDs were seen to have good induction processes for trainees, enabling them to understand what was expected of them (2).

The confidence levels of trainees were low at the beginning of their placements and they were likely to be exposed beyond their competence initially. For the process to work smoothly good levels of senior and middle-grade support (2) were required in departments.

Career development of foundation doctors

Participants noted that career development in FT was under further development in the regions where they were based (4). One region was investing heavily in career development, appointing an associate dean for careers, offering mandatory training in career development, having specialist careers advisors with open appointment times and offering podcasts about different specialties. Another talked about ad hoc taster weeks for trainees to experience different workplaces. However, most activities (3) were described as being ‘work in progress’ or ‘under discussion’.

Some limitations in terms of career choice were acknowledged (3) but it was felt that some F2 doctors needed to have more realistic aspirations based on their abilities. However, there was a sense that F2 was too late to begin careers training and that the process should begin at medical school (2).

There was disagreement between participants over whether F2 doctors were being asked to select specialist training posts too early in their careers. One participant felt that F2 doctors were old enough to make good decisions, whereas another felt that decisions to enter a particular specialty were being made without sufficient experience in that area. However, there was agreement that careers advice needed to be given at an early stage (2).

Future developments and changes

Participants were asked about any developments in FT that they thought would happen in the future. It was acknowledged that there was a lobby for change (2) – to put F1 into the medical school curriculum and extend FT for a third year. Both were felt to be unnecessary as it was thought that the system needs time to ‘bed down’ and that there was little need to change too much as FT will develop well over the next 4–5 years (2). However, participants agreed that more (and better-quality) supervision needs to be provided (2), assessments need to be improved and more work needs to be carried out around career development for F2 doctors.

Training lead interview findings

The interviews with the eight EDTLs elicited information about the implementation of FT in the ED, including the role of F2 doctors in the ED, changes in training provision, the evaluation of the well-being and motivation of F2 doctors, preparation for the delivery of patient care, and assessments.

Delivery of foundation training received in the emergency department

Participants described the experiences of FT with five to 24 students in their departments. One of the TLs from a department that took a higher number of students (both Foundation Programme and undergraduate) described an increase in numbers that had happened 2 years before: ‘there are too many trainees in the department; it is difficult to provide support for them all’.

Three of the eight participants described an induction to the ED lasting around 3 days. The purpose of the induction was to introduce F2 doctors to the way that the departments were run and their protocols and procedures. One participant described the support available for induction including posters and CDs with learning materials and protocols (additionally on the intranet). Most commonly, ED teaching was organised as 1- to 2-hour weekly sessions (4) focusing on specific aspects of ED work such as breaking bad news, dealing with domestic violence, trauma training and training in specific clinical conditions, sometimes using external speakers. One TL described a mandatory skills training day to learn specific procedures used in the ED such as intubation and the use of neck drains. Another TL described training that was supported with online modules tracking teaching sessions. A third TL stated that F2 doctors were encouraged to attend 3-day life support training courses (adult life support and advanced trauma life support).

In addition, two participants described generic teaching days (or deanery days) held twice a month delivering material from the Foundation curriculum. These sessions were usually consultant led and covered areas of clinical governance and audit and were described as ‘rather didactic, and not geared to the ED role’. Another TL described ongoing work in their centre to establish mandatory training for F2 doctors.

Role in the emergency department and day-to-day working

Training leads were asked about the role of F2 doctors in their EDs. F2 doctors were described as being part of the ED, gaining hands-on experience (2) and working with a wide range of patients (2), and with various degrees of autonomy to make decisions. Activities were described as watching and progressing patients’ treatment with support and feedback from senior medical staff (2). One TL noted that in the first 4 weeks of an F2’s placement every patient was seen by a senior doctor until the F2’s confidence increased. Another TL noted: ‘F2s may not be able to work to the standard of junior doctors – they are less confident now’.

A variety of departmental working arrangements were described by participants. ED work was considered as experiential learning (3) that was supported by discussion with middle grades (24 hours), senior registrars and consultants (2) and assisted with guidelines and by reading. Learning on the job was supported in one centre by an allocated CS who held appraisal meetings with F2 doctors at least twice in their training rotation. One participant described a nurse practitioner-led service in which F2 doctors assessed the diagnoses made by nurse practitioners to give them experience of minor injuries cases. One TL noted that all patients in the ED were seen by a consultant and that ‘there was a service tension between what was done in training and what was done as the job’.

Changes in the way that the emergency department has provided training in recent years

When asked about changes to training participants focused on teaching, supervision, increased workload, issues caused by the EWTD and the reduction of placement length from 6 months to 4 months.

Two TLs noted that training (teaching) was ‘no longer geared to ED specifically’ and that previously practical procedures had been taught more formally (on a one-to-one basis) followed by supervision until the trainee grew in confidence. It was noted that medical school training had changed its focus from teaching to problem-based learning; although this was thought to be better it was acknowledged that ‘there is a greater variation in learning as a result’. Gaps in trainee knowledge were noted (2) resulting in staff having to ‘offer more support and development in the ED than before’ (e.g. in anatomy and physiology). One TL commented that some F2 doctors had never been exposed to acutely unwell patients before and that the trainees found this difficult to cope with.

Central to these issues of training was the need to provide additional senior support to facilitate F2 doctor learning (5). Although some TLs noted that there were more consultants in the ED now (2), enabling all F2 doctors to have supervisors, others noted that there were not enough senior staff to support their students (2) or that other medical staff and nursing staff were undertaking supervision. For example:

There is insufficient senior staff for close supervision; we are not giving what we should be giving in terms of education and training.

increased strain on the team in ED to support trainees; this increases the stress on senior doctors.

Coupled with the issue of increased supervision for foundation doctors is the issue of increased workload (2). This is summarised well by the following quote: ‘We are incredibly busy; the workload just gets higher and we are not broken yet but it is not far off – we just need more senior staff’.

Changes in the working pattern of doctors to shift-based work (associated with the EWTD) were seen to be interfering with access to teaching and training opportunities for F2 doctors (3). For example:

Some training time is lost; many miss two or three (teaching) sessions as they are off shift or on holiday or study leave. They only attend sessions if they are interested and if they miss them this leaves gaps in their knowledge.

The TLs thought that career development also suffered from shift working, with trainees being asked to look at different work options when they are off duty.

Although it was noted that F2 doctors were on employment contracts, it was felt that there was little reward or monitoring of F2 doctor performance (2): ‘there is no clear system to reflect how well trainees work: good trainees get frustrated’.

One TL noted that the ED had productivity measures (noting the number of patients seen by a foundation doctor) so that staff were aware of the confidence levels of various trainees.

There were several negative comments about the change in rotation length (from 6 months to 4 months). The shorter rotation was perceived as not being enough time for the trainee to learn how to do the job well (2): ‘They are just becoming competent when they leave.’

Lack of confidence in the clinical setting was particularly evident if this was the first F2 rotation. One TL noted that the reduction in rotation length had required different ways of working with F2 doctors (supervising all of the patient episodes in the F2 doctors’ first 4 weeks of working, as noted above).

Evaluation of well-being and motivation

There was some divergence in TLs’ views on how effectively F2 well-being was evaluated in the ED. Some participants felt that well-being was poorly evaluated (2) as interviews were no longer used in placement allocation, whereas others believed that systems such as multidisciplinary team feedback (mini-PAT) or more informal feedback from staff (such as nurses) identified doctors who were ‘struggling’ or ‘in difficulty’ (2). However, it was clear that there was no formal system by which foundation doctor well-being and motivation were evaluated. Although this was the case, TLs felt that if there were issues then staff working with the F2 doctor would notice (3), through observation or by an incident occurring or unfavourable reports being given in the multisource feedback. It was felt that senior medical staff or ESs would become aware of issues of well-being (3) during assessments (such as the mini-PAT), when examining e-Portfolio progress or in supervisory meetings. If workload monitoring is used this would also offer a strong indicator of poor performance.

Motivation

The TLs were asked what aspects of ED work the F2 doctors are motivated by and about the areas in which they struggle. The profile of a ‘keen’ F2 who wants to progress was clearly described (2): ‘they have carried out audit projects, they turn up bright and early, and they are more flexible about working longer hours’. Motivated F2 doctors usually see acute medicine as part of their career plan.

Less motivated F2 doctors were the ones who did not enjoy working out of hours with really sick patients (2) or who found it difficult to work with non-medical management cases (such as with older frail patients). Some lack motivation because of poor clinical knowledge (‘this may be a long-standing problem’) or because their previous experience of ED (as a medical student or an F1) was poor and/or they did not see this rotation as part of their career plan.

The potential impact of poor F2 well-being on patient care was less considered. However, patient monitoring (e.g. waiting times) and workload monitoring (2) were thought to be useful in detecting issues.

Is foundation year 2 training adequate preparation for the delivery of patient care?

When asked whether F2 training adequately prepares doctors for service-level roles, TLs described variation in trainee performance and confidence (4), with some F2 doctors ‘able to meet the demands placed upon them’ but others ‘unprepared and lacking in confidence’. F2 doctors were perceived (in comparison with SHOs) to take longer to become independent fully functioning doctors, to be more reluctant to take decisions and to work at a slower rate.

When asked to evaluate the ED experience for F2 doctors there were rather more negative comments (16) than positive (5). From a positive perspective the ED offers problem-based learning, ‘an intense experience where trainees have to think for themselves and take decisions’, ‘broad exposure to a range of medical disciplines’ and ‘challenging shifts demonstrating service delivery’; in addition, ‘senior cover is always available’.

From a negative perspective, rotation patterns were often antisocial (5) and, coupled with the EWTD, there are issues of missed teaching and other learning opportunities (2); foundation doctors ‘have had little prior experience of acutely ill patients’ and ‘are less used to decision-making in their previous placements’; and they have had less ‘hands-on experience’ with practical aspects of training, reducing their confidence (2). Trainees are not well prepared for service delivery (3), having previously been encouraged to ‘do their best’, without taking into account how long this makes a patient episode (2). In addition, TLs felt that, as it was a busy environment, it was difficult to offer sufficient supervision in the ED (2), which the trainees were needy for.

When asked how the training could be improved, most TLs were mainly in favour of a return to 6-month rotations (5), whereas some could see that a balance between breadth and depth of experience was needed (3). For example: ‘A return to six months is needed, but this may have a negative impact on the breadth of understanding associated with less service delivery.’

Participants’ comments about improvements to training mainly focused on teaching (5), in particular the inclusion of more specific training related to each placement (2) and less generic training content. The change of emphasis to problem-based learning, requiring an active learner, was noted: ‘big change from passive formal learning to active trainee seeking learning. We need a marker for the “active learner”.’ However, this approach was criticised as ‘motivation to learn is not as high as in the past; they (trainees) expect to be taught’.

TLs wanted to offer more supervision (3) but this was felt to be impossible in a service-led specialty. In summary, TLs were aware of the difference in context between the various Foundation placements, in which many F2 doctors were not required to make decisions and were supernumerary to service delivery; however, in ED, ‘trainees are vital to service delivery and we have no control over our rotas’.

Assessments

Participants were asked about the contribution of FT assessments to ensuring that doctors provided good-quality patient care. Overall, half of the participants (4) felt that the assessments were an improvement in the evaluation of the delivery of patient care and half (4) felt that there were issues that needed to be addressed with the assessments before they would be of value. The strengths of the assessments included ‘providing the opportunity for observation of trainees undertaking practical procedures’ (direct observation of procedures or DOPs), for example suturing, and providing the opportunity for ‘trainees and supervisors to discuss elements of care that were worrying a trainee’ (case-based discussions) and for clinical assessments with direct feedback to the trainee (2). However, it was noted that the benefits were case dependent.

The issues limiting the use of assessments were the need for open-ended assessment of experience (and less ‘ticking boxes’ or mundane superficial questions) (2) and lack of confidence that assessments (such as multisource feedback in which the trainee chooses the assessors) reflected ability (2). It was felt that assessments were also limited in their ability to identify doctors who were struggling with service delivery.

Focus groups with foundation year 2 doctors

Focus groups were held with F2 doctors who were on placements in four of the EDs participating in this study (25 F2 doctors in total). The focus groups discussed issues of confidence and competence, anxiety and general experience in EM.

Foundation year 2 doctor competence and confidence

Participants were asked what gave them confidence to deliver good patient care. There was strong agreement across the focus groups that positive feedback on their performance from senior colleagues (consultants and registrars ‘affirming that the appropriate clinical process had been followed’), previous experience of the clinical situation (‘previously seeing how to manage a case like a Colles fracture’) and apparent patient satisfaction (‘patient saying that they feel better after treatment’) gave them confidence in their abilities.

Further, participants from three of the four focus groups agreed that good learning experiences, such as ‘learning from near misses’, and appropriate teaching, such as ‘acquiring knowledge that was specific and useful in ED, such as what to do when a patient presents with a headache’, increased their confidence.

In addition, participants from two of the four focus groups agreed that knowing that your skills work well, peer support (‘checking questions with peers before approaching seniors’), teamworking (‘working as part of a team when doing formal assessments’) and acknowledgement by the referral team that a correct referral was made all enhanced their confidence.

F2 doctors were asked what things they worried about when they finished their shift. There was agreement that the main worry was about sending a patient home: ‘was I right’, ‘should I have referred’, ‘I worry less if they are referred because the patient is safe’.

In addition, participants from two of the focus groups worried about making decisions within the 4-hour target (‘compared to other specialties there is a small space of time to make a decision whether to admit or discharge a patient’), their own self confidence (‘I am anxious about discharging patients; if I can discuss this with a consultant I am reassured’) and correctly diagnosing the condition (‘did I get it right’, ‘was my judgement correct’).

Improving training for foundation year 2 doctors

Participants from all of the focus groups agreed that teaching could be improved in terms of content (‘more clinically relevant topics rather than health and safety’) and their availability (‘EWTD cuts down teaching time’, ‘shift working does not allow me to complete the minimum teaching requirement’).

Participants from three of the four focus groups felt that it was important that there were review sessions (‘about patients that were seen on a shift after the event; talking about whether they discharged or not’), opportunities to address the poor work–life balance of working in the ED (‘some rotas are awful’, ‘doing a difficult shift every day is very demanding and I would have to consider the lifestyle implications if I took this job on as a career’) and consideration of specific difficulties of working in the ED (‘not having enough staff on at peak times like bonfire night’, ‘not having protocols to follow’, ‘repetition of the same questions: “is the patient going to breach” and “what drugs are needed”‘).

There were also varying views on teamworking in the ED. One group felt that the ED experience was improved by the teamworking of doctors and nurses, whereas another group noted that teamworking varied depending on the time of day: ‘teamworking was more likely out of hours when there were less seniors around’.

There were varying views of the appropriate length of the ED rotation: two focus groups agreed that they were ‘glad of the extra choice that a 4-month rotation gave within their FT’ and one group (with some participants doing a 6-month rotation) felt that the longer rotation was a good thing and that some trainees had made an active choice to do this length of rotation, saying ‘there was more opportunity to learn about acute care’ and ‘it would be considered a “badge of honour” completing a six-month rotation in ED’.

Value of assessments

Participants from three focus groups gave a balanced view of the positive (3) and negative aspects (3) of the formal assessment process.

From a positive perspective participants agreed that formal assessments build on the type of assessment used in the last 2 years of their undergraduate training (such as DOPs, which helped them begin to interact with senior medical staff); working as part of a multidisciplinary team facilitated assessment; and they enjoyed the mini-clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX) as it offered the best feedback on their progress.

Negative aspects were that assessments assume that ‘all junior doctors are the same’; the process is flawed as ‘you only put in the e-Portfolio things that you have done well; not where you may have learned more from something that you have done badly’; and there seems little point in doing DOPs as ‘these are done as part of everyday practice’.

Emergency department environment

When F2 doctors were asked whether they enjoyed the ED environment there was a positive ‘yes’ response (4) because ‘it is unpredictable work where you need to pick up clues to understand the patient’s condition’ (2); participants felt that it is a good teamworking environment where they did not feel isolated (as they did in some surgical rotations); and there are opportunities to carry out a large variety of different sorts of work enabling a fast rate of learning: ‘You learn so much by doing things at a fast rate – having to make decisions – it is great experience for the future.’ However, these views were balanced by the ‘rubbish’ working hours.

Chapter 4 Longitudinal study

Aims and objectives

Aims

-

To measure levels of (and change in) F2 doctor well-being, motivation, confidence and competence over the period of their F2 training.

-

To measure the impact of placements in EDs on F2 doctor well-being, motivation, confidence and competence.

Objectives

-

To undertake a 12-month longitudinal study to assess F2 doctors’ experiences of working in terms of their well-being, motivation, professional identity, confidence and competence.

-

To implement a survey at four time points during the longitudinal study (at the end of the F1 period and then after each of the F2 placements). One of these F2 placements will be in the ED and the impact of this placement on F2 doctors’ experiences of working will be assessed.

Methods

Ethical and governance arrangements

Ethical approval for the phase 2 longitudinal study was received in September 2009 (ref.: 09/H1300/80).

Approvals from non-NHS organisations and research governance approvals from participating NHS trusts were obtained between November 2009 and June 2010.

Survey design

We used a ‘closed’ online survey design because in the phase 1 focus groups F2 doctors expressed a preference for online surveys rather than paper versions. F2 doctors were eligible for this study if they had a placement in the ED during their F2 rotations. The online survey was accessible via a portal on the EDiT study website,48 with eligible doctors sent a link taking them to the appropriate part of the website to access the survey (see Appendix 13 for a screenshot of the website). The EDiT website provided information about the study, such as news and updates, and also included an interactive element (a medical casebook quiz). The website was designed to be informative and attractive to potential participants and thus increase recruitment and retention over the period of the survey. Visitors to the website could examine the information provided without being obliged to complete the survey itself.

Participants

As the focus of the study was examining the impact of placements in the ED on the FT experience of F2 doctors, the sampling frame (eligible doctors) for the survey was all F2 doctors in England who had a placement in the ED as part of their F2 training year. Eligible doctors were identified following discussions with PMDs and EDs.

Sample identification

In the first instance, (August–September 2008) we identified all type 1 EDs (defined as consultant-led 24-hour service with full resuscitation facilities and designated accommodation for the reception of emergency patients) in England from the Department of Health website. 49 We identified and contacted 176 NHS trusts in England with type 1 EDs for expressions of interest. After our approach, 45 trusts responded and expressed an initial interest in taking part in the study. Further contact took place with ED leads after the initial approach and more detailed discussions about the requirements of the study were held. Finally, 28 trusts with 30 EDs agreed to participate as the study sites. Study contacts, including lead consultants, foundation consultant leads and research nurses, were identified in the 30 participating EDs.

Deaneries and foundation schools

All 14 PMDs were contacted (December 2008–January 2009) to identify expressions of interest in participation. The postgraduate medical dean and the foundation school director (FSD) were contacted in the first instance. Details about the study were provided and agreement to participate in the study was sought from each deanery. Agreement to participate was obtained from nine deaneries. The FSD from each of these nine deaneries was asked to identify key contacts within the schools (foundation school administrators; FSAs) to assist the study team with the identification of F2 doctors who would have a placement in the ED within their F2 training (2010–11). EDs of NHS trusts were included in the study only when the deanery also agreed to participate.

Eligible participants

After recruitment of participating EDs and deaneries, our total eligible F2 doctor sample consisted of 654 F2 doctors, training between August 2010 and August 2011. Each of these F2 doctors had a placement in one of the 30 EDs participating in the study.

Participant contact

For data protection reasons and reasons stipulated by the approving ethics committee, we could not be given the names/addresses of the eligible F2 doctors by participating deaneries and FSs; instead, approaches to the doctors were made by study contacts in FSs and EDs on behalf of the study team.

The initial approach to inform the eligible F2 doctors of the study was made by the relevant FSAs. An e-mail with an attached letter of invitation and participant information leaflet (see Appendices 14 and 15 respectively) was sent to the F2 doctors before the start of the study (May 2010). The e-mail notified the doctors that they could opt out of the study at any stage and receive no further contact regarding the study.

Recruitment and consenting

In July 2010 a further e-mail was sent by FSAs to those eligible F2 doctors who had not opted out after the initial approach. This e-mail provided a link to and study password for the online survey. After accessing the survey, potential participants were required to enter their e-mail address and the study password to proceed any further (ensuring that only eligible F2 doctors completed the survey). Participants were asked to enter an e-mail address that would be current throughout the study time period to enable the accurate matching of participants’ responses at further time points. When participants entered the correct password an online survey consent form was generated (see Appendix 16). Participants were unable to proceed with the survey until they had completed the consent form (following consent, F2 doctors were able to access the survey proper with their e-mail address generating a unique study ID that would identify them throughout the study).

Following the initial recruitment e-mail in July, the sample of F2 doctors (with the exception of consenting participants or those who opted out) were contacted at two further time points (August and September 2010) by FSAs as a reminder to participate in the study. If F2 doctors had consented to take part at the first time point (T1) they were then contacted at subsequent time points directly by the study team. Participants could enter the study at T2 if they wished (and were coded accordingly) but not at later time points.

Development of survey measures

In the first instance a pilot questionnaire was designed to measure a range of work-related outcomes and job-related characteristics by adapting well-validated scales. The questionnaire was piloted with a small sample of F2 doctors and following feedback some minor amendments were made to the final questionnaire (see Pilot study of questionnaire). The pilot questionnaire and the final questionnaire are provided in Appendices 17 and 18 respectively.

The content of the final questionnaire is detailed in the following sections.

Background demographic information

Baseline information was collected on sample age, sex, place of qualification, year of qualification, ethnicity and description of Foundation placements (e.g. specialty undertaken, trust). Details of the placements (specialty and trust) were cross-checked with equivalent placement information from the nine participating deaneries to ensure accuracy of reported information.

Individual characteristics

Baseline background information was collected on personality and coping characteristics using validated scales:

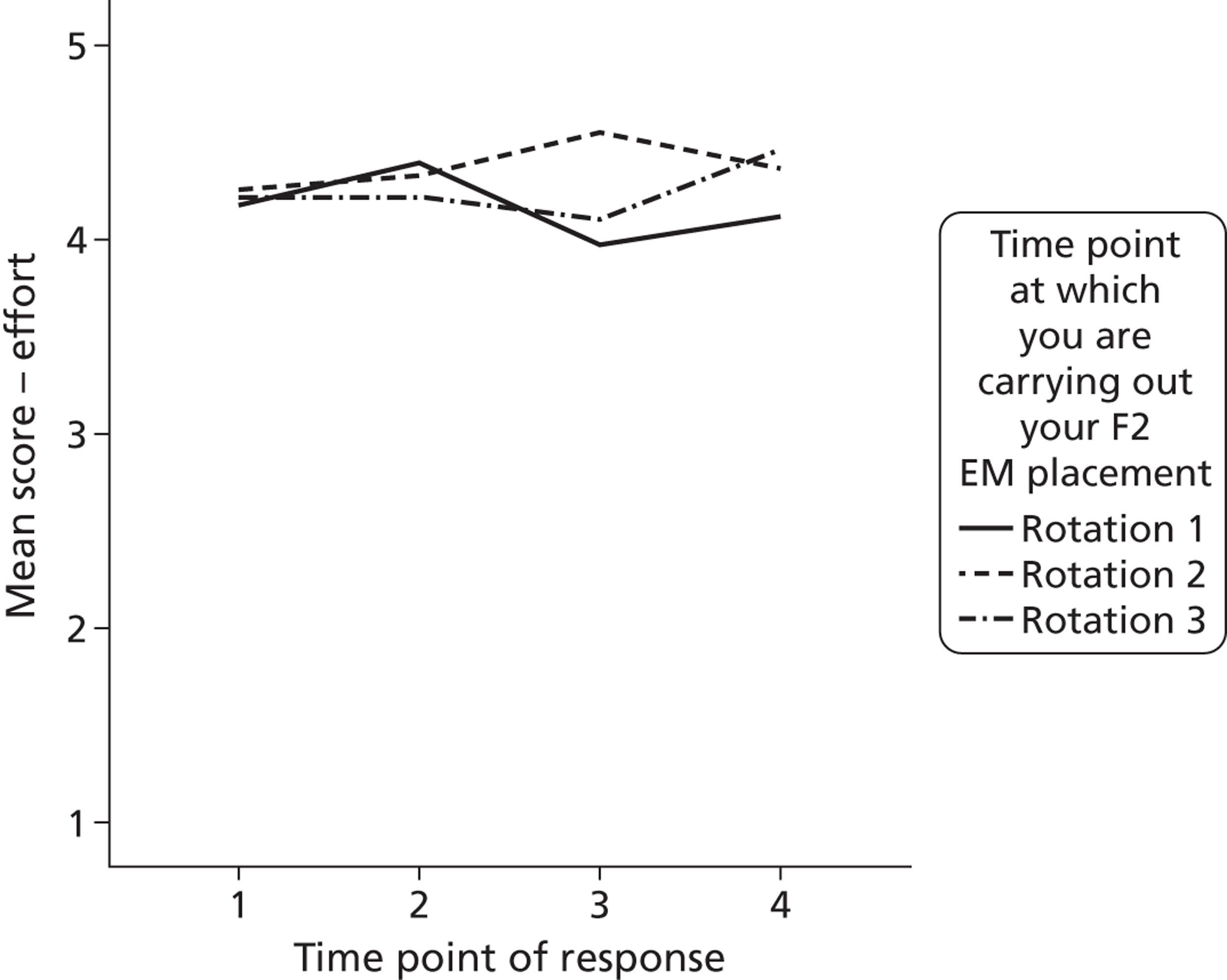

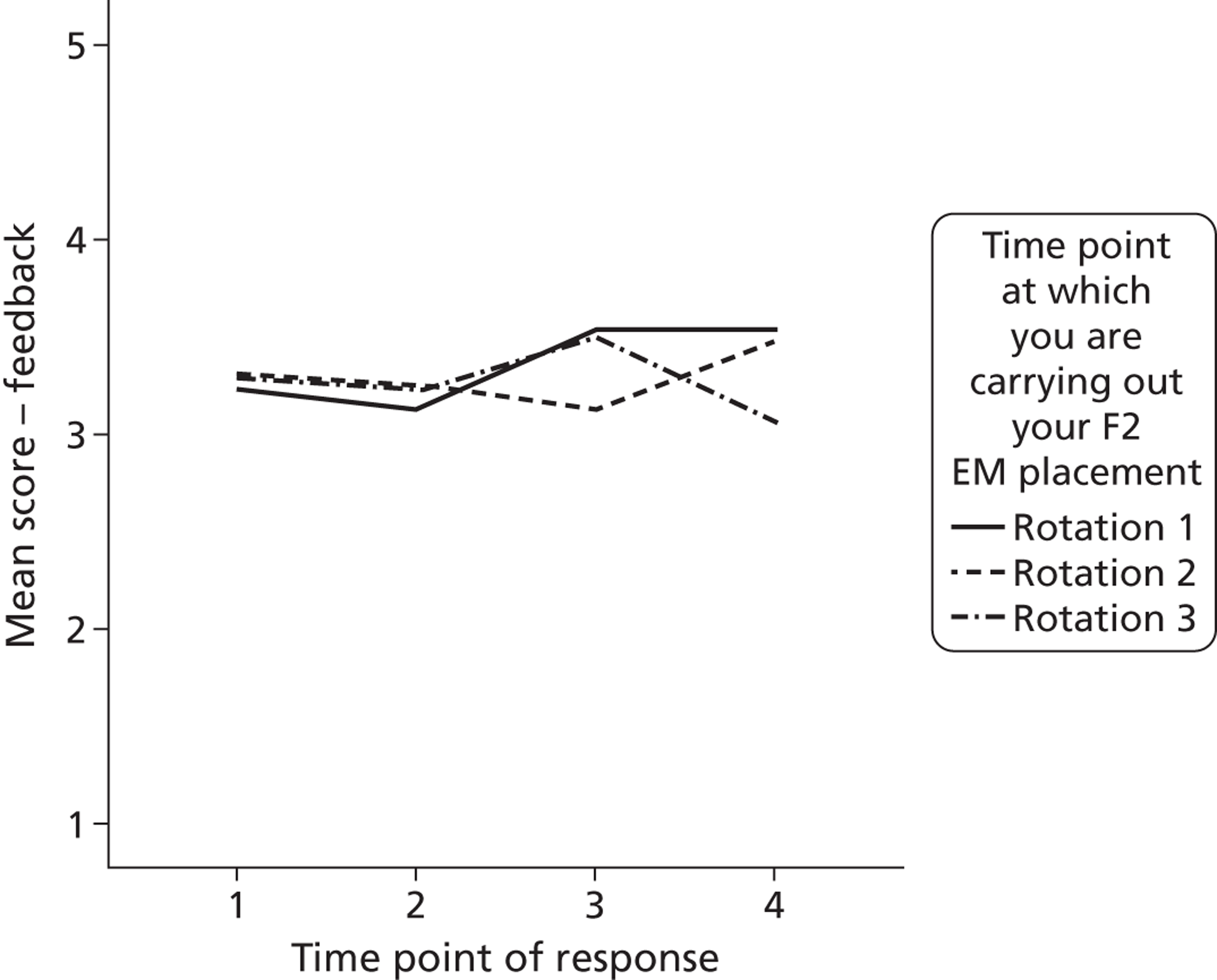

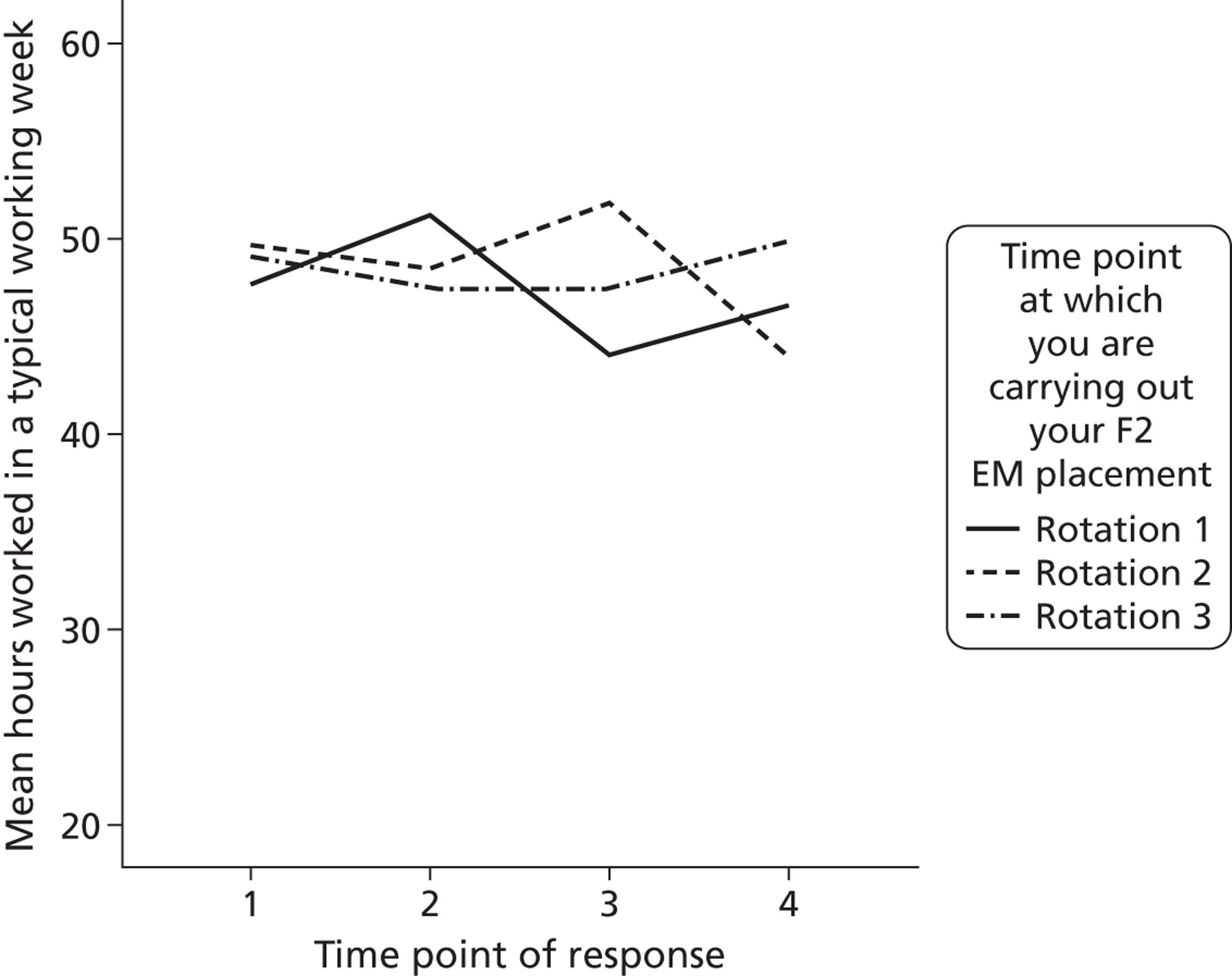

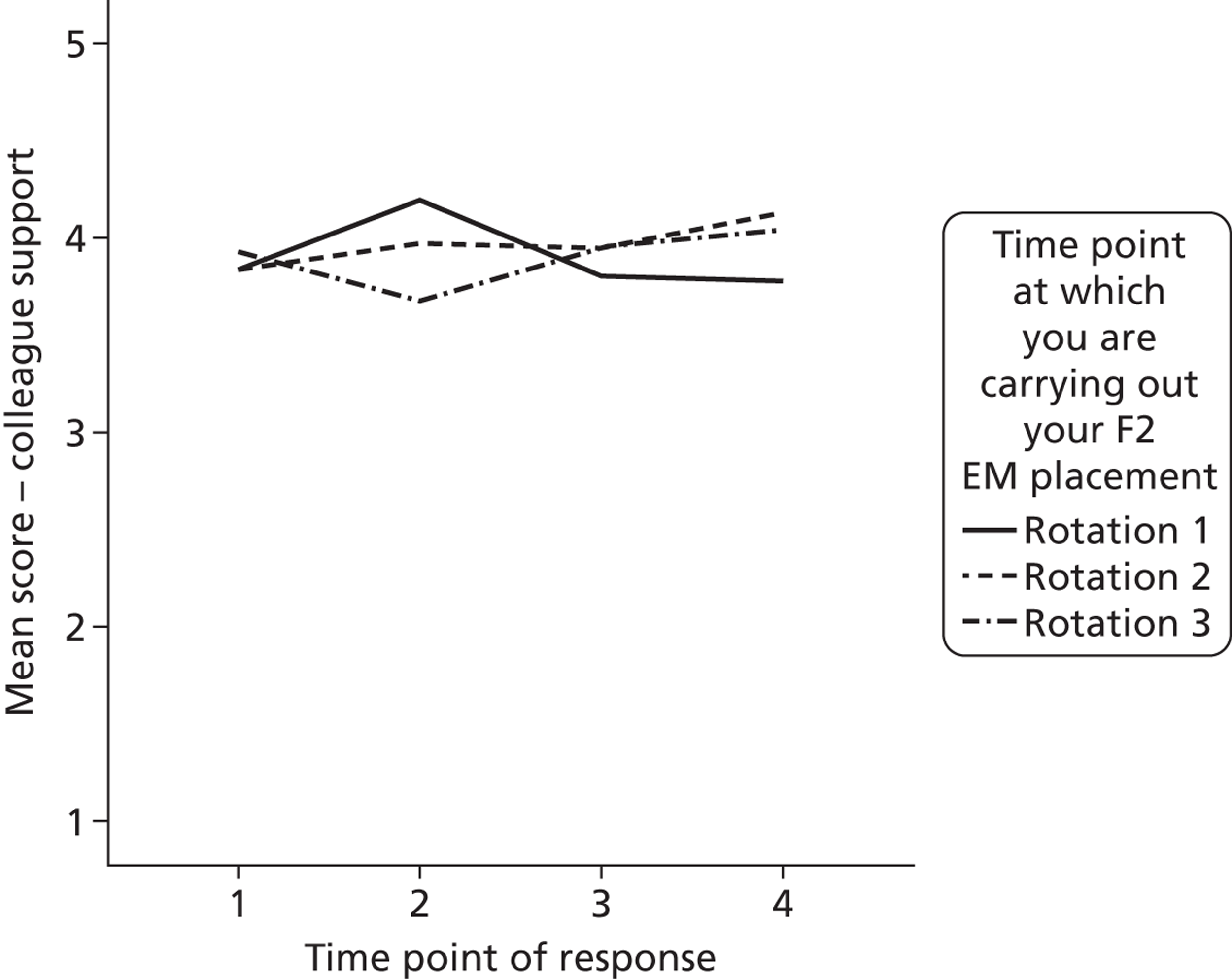

-