Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1009/14. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The final report began editorial review in March 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Locock et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Objective

To use a national video and audio archive of patient experience narratives to develop, test and evaluate a rapid patient-centred service improvement approach (‘accelerated experience-based co-design’ or AEBCD).

Improving patient experience

Measuring, understanding and improving patients’ experiences is of central importance to health care systems worldwide. 1 Health care policy frameworks in several countries describe ‘patient experience’ as a core component of health care quality. Recent evidence suggests positive associations between patient experience, patient safety and clinical effectiveness for a wide range of disease areas, and positive associations between patient experience and self-rated and objectively measured health outcomes. 2,3

Even in the best-funded health systems, patients may report less than satisfactory experiences. There have been persistent concerns about the quality of basic ward care, and the 2010 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey showed that the percentage of patients in 11 countries rating care from their doctor as excellent or very good ranged from 84% in New Zealand down to only 43% in Sweden (with the UK at 79% and the USA at 74%). 4

At a time of global recession, better quality patient experience may be seen as a luxury rather than a top priority. The recent scandal of poor care at Mid Staffordshire Hospital in the UK is a chastening example of what happens when a focus on financial and other performance targets displaces listening to and learning from patients and their views and experiences. 5 But the supposed conflict between managing the bottom line and providing good patient experience may be more imagined than real.

First, we know that many of the things patients say matter most to them are attitudinal rather than resource-driven – for example, affording patients dignity, courtesy and kindness. But internationally, there is also growing evidence linking patient-centred care with decreased mortality and lower hospital-acquired infection rates; patient feedback about hospital cleanliness is a positive predictor of staff participation in activities such as hand-washing, and of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) rates. Good patient experience is also linked to other organisational goals such as reduced malpractice claims, lower operating costs, increased market share and better staff retention. Patient adherence seems to improve, length of stay is shorter and fewer medication errors and adverse events occur in organisations where care is patient centred. 6–12

Since the late 1990s, there has been a step change in how health care organisations collect, share and reflect on patient experiences. In England, a recent government White Paper on NHS reform emphasises ‘putting patients and the public first’, or ‘no decision about without me’, as it has been characterised. 13 Ensuring that the way care and information are provided reflects what patients themselves think is thus a priority. Nonetheless, the White Paper notes that:

The NHS . . . scores relatively poorly on being responsive to the patients it serves. It lacks a genuinely patient-centred approach in which services are designed around individual needs, lifestyles and aspirations. Too often, patients are expected to fit around services, rather than services around patients.

Section 1.9

To address this, health care organisations need to draw on the experiences of those who have used services at first hand – but there is debate about the best methods for gathering and understanding patient experience information and then using it to improve care. 14–16 There is no shortage of general recommendations to health care organisations as to how to capture patient feedback and use it to improve patient experience,14,17 but still little systematic and responsive improvement work goes on to actually improve this important component of the quality of health care services.

Internationally, health care organisations tend to use questionnaire surveys to provide patients’ perspectives on how they are performing. Large-scale surveys across multiple organisations can play an important role in meeting broader policy agendas such as accountability and transparency. Much has been achieved through the rigorous development and sustained commitment to surveying patient views of their experiences. Yet surveys may be less effective at supporting local quality improvement if they lack clinical credibility, or are insufficiently timely or specific to guide action by senior leaders. A review of 41 research papers explored how the 600,000 patient responses to the national inpatient survey from 2002 to 2009 had been used;18 it concluded that ‘the inpatient survey is not in itself a quality improvement tool’ and that ‘simply providing hospitals with patient feedback does not automatically have a positive effect on quality standards’.

In England, acute hospital trusts are increasingly deploying a wider range of methods and approaches locally. A range of alternative methods and techniques have been devised including comment cards, self-completion/paper-based surveys, and Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs), delivered by either researchers, ward staff, audit teams and/or hospital volunteers. Different information technologies have been devised – such as Optimum Contact (Optimum Contact Ltd, Middlesex, UK), Picker Frequent Feedback (Picker Institute Europe, Oxford, UK), Snap (Snap Surveys, London, UK) and Dr Foster Intelligence Patient Experience Trackers (Dr Foster Intelligence, London, UK) – which can be used to reach large numbers of patients, but local clinical teams and middle management are not yet making consistent use of national patient survey data to monitor service quality and drive local quality improvement. Anecdotal evidence suggests that many clinicians do not believe that the generic outpatient or inpatient surveys reflect the experiences of ‘their patients’ and complain that the data are frequently out of date. 19 In a recent survey of hospital clinicians in Denmark, Israel, England and the USA, the current situation has been portrayed as a ‘chasm’ between senior leaders and front-line clinicians. The study found that only 9.2% of over 1000 respondents thought that their department had a structured plan for improving patient satisfaction and that 85.5% of clinicians thought that hospital management should take a more active role in conducting patient satisfaction improvement programmes. 20 Related to this latter finding, 41% of almost 150,000 staff in the English NHS in 2011 said they had not received patient experience training and 22% said it was not applicable to them. 21

Recent research with hospital board non-executive directors22 has demonstrated that patients’ experiences of care have become more of an interest and concern at board level, which can only have intensified since the publication of the Francis Report into poor-quality care and above average death rates at Mid Staffordshire,5 and the Care Quality Commission’s Dignity and Nutrition Inspection findings. 23 Strikingly, however, over 95% of the time, hospital boards’ minuted responses to patient experience reports were to note the report but take no further action. 22 Examples where patient experience data were used to spark debate and action were rare, as were examples of non-executive directors challenging performance. At organisational level, we do not know which national policy levers (incentives, penalties, targets, market competition or publication of information) work best to improve patient experience; this is a relatively ‘evidence-light’ zone in which to make policy decisions. 24 As Robert and Cornwell24 conclude, ‘current measures of patient experience are not being used meaningfully or systematically at the local level for a range of reasons but, not least, because they are not seen as clinically relevant at a service level, and are captured too infrequently’ (p. 9). These issues have been major barriers to patient experience being placed on an equal footing with clinical effectiveness and patient safety as a key dimension of health care quality.

Different methods of collecting patient experience data can also produce different results. All methods have their strengths and weaknesses,25 and organisations which rely solely on survey data may overlook important nuances of how patients reflect on their care experiences. To illustrate, as part of a previous study an elderly woman completed both a patient survey and a narrative interview exploring her experiences on an acute elderly care ward;26 in her response to the survey question ‘Overall, did you feel you were treated with respect and dignity while you were in hospital?’, she ticked the box ‘Yes, always’; similarly, in response to the survey question ‘Overall, how do you rate the care you received?’, she ticked the box ‘Excellent’. And yet the following is an extract from her narrative interview:

The other thing I didn’t raise and I should have done because it does annoy me intensely, the time you have to wait for a bedpan . . . elderly people can’t wait, if we want a bedpan it’s because we need it now. I just said to one of them, ‘I need a bedpan please’. And it was so long bringing it out it was too late. It’s a very embarrassing subject, although they don’t make anything of it, they just say, ‘Oh well, it can’t be helped if you’re not well’. And I thought, ‘Well, if only you’d brought the bedpan you wouldn’t have to strip the bed and I wouldn’t be so embarrassed’.

The contrasting quality improvement implications arising from these different methods of capturing this experience could not be starker. The results from the patient survey would not lead to any action and, indeed, the ward team could be commended for the excellent, dignified care it provided, whereas the narrative interview revealed how annoyed and embarrassed the person was as a result of an interaction that had clearly formed a lasting impression on her subjective experience.

A significant gap between rhetoric and management action still persists. Quantitative data provide little depth and detail, and can therefore be difficult to interpret in terms of identifying specific priorities for improvement. 27 The emerging policy context is one of a movement away from driving improvement through top-down performance management towards transparency, information for and accountability to the public, and information to support individual patients’ choice and ability to participate in decisions about their own care (‘nothing about me without me’).

So, given the shortcomings of existing (largely quantitative) methods, where should we look for alternative approaches that might hold the key to understanding and improving the relational aspects of patient experience? There is growing interest in the use of in-depth qualitative research to gain richer and more meaningful accounts of what it is like to be a patient,22 yet providers of health care struggle to make effective use of qualitative rather than quantitative experiential evidence to improve local services. Whichever particular approach is adopted, there are issues of the burden on staff of collecting additional patient information, issues of bias, neutrality, and providing support for the patient’s clinical needs rather than quality improvement tasks. Collecting in-depth patient experience data needs to be balanced with having both appropriate methods and resources to do so, to be able to evaluate change activities and, ultimately, to show evidence of quality improvement. Few organisations have adequate systems for co-ordinating data collection and assessing its quality, or for learning from and acting on the results in a systematic way. 14 Some NHS trusts may be focusing on collecting data rather than seeking to move to action as a result. The focus of this report is on enabling change at the local level through the use and evaluation of an accelerated quality improvement intervention with the explicit aim of improving patient experiences.

The value of narrative

Narrative persuasion is a well-established psychological theory. 28 Narrative and stories, oral or written, are far and away the most powerful and natural way of accessing human experience, and it is, therefore, no surprise to find them in rapidly growing professional use in contemporary medicine and medical research. Stories have the ability to transport us to another world or to see the world through another’s eyes. This in turn can bring about attitude change. Narratives are a powerful way to engage care providers in reflecting upon how services could be improved, through emotional impact. 29,30

Narratives are not gathered because they are assumed to be objective, accurate or verifiable but because they are uniquely human and subjective, describing not a fact or a reality but a recalled experience or set of experiences. 30 Detailed patient accounts of their experiences can nonetheless suggest priorities and solutions that may not occur to people who are immersed in day-to-day service delivery. 31,32 Through personal stories, users reveal what they like about a service (or health care in general), what they hate about it, what matters to them, what works well for them, and what sorts of things cause real anxieties or problems as well as comfort and reassurance. Many NHS organisations are now successfully experimenting with qualitative methods of gathering user views and using them to improve services. However, it is important that such work is based on rigorous research with a broad sample of users and a full range of different perspectives, rather than relying on a single representative on a committee or the collection of a few anecdotes. 33 Stories and storytelling are accessible and memorable; they are a rich source of learning about people’s experiences, and provide a direct route to a deep appreciative understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of a particular health care service and what is needed for the future.

Experience-based co-design

The development, implementation and evaluation of a narrative-based, participatory action research (PAR) approach known as experience-based co-design (EBCD)30,34 marks a significant contribution to involving patients in quality improvement efforts in health care. EBCD has been implemented in collaboration with patients, families and staff in quality improvement efforts in various settings, care pathways and countries. A survey undertaken in the summer of 2013 identified at least 57 EBCD projects which had been implemented in seven countries worldwide since 2005 (in a variety of clinical areas including emergency medicine, drug and alcohol services, a range of cancer services, paediatrics, diabetes care and mental health services); at least a further 24 projects were in the planning stage at the time of the survey. 35 Many of these projects involved implementing the approach in more than one clinical department; for example, the PATH project in Ontario, Canada encompasses 12 health-care organisations (source: www.changefoundation.ca/library/backgrounder-partners-advancing-transitions-healthcare-path-northumberland/, accessed 20 December 2013). Independent evaluations of recent implementations of the approach in both the UK and Australia36,37 have found that, as well as making specific changes to particular services, the projects also supported wider improvements across the health care system. A follow-up evaluation in Australia38 specifically explored the sustainability of the impact of EBCD 2 years after implementation and reported that:

Co-design has been shown to strengthen service provider-service user relationships . . . co-design harbours a collaborative principle that should be woven into how health services and health departments conceptualise and structure their communication with patients, families and the public.

pp. 2–3

Adams et al. 39 report on the outcomes – in terms of spread and sustainability – of implementing EBCD in a cancer centre that was formed across two large NHS trusts in 2006 with the aspiration of delivering internationally renowned cancer services – in the ‘top 10 globally’ – for patients in the region. In 2008 the centre began an action research project encompassing several work streams (such as the engagement and training of senior managers) to implement patient-centred care. The chosen quality improvement approach was EBCD and, as initially undertaken in two breast cancer and two lung cancer services, closely followed the traditional six-stage design process (see Figure 1). The approach was tailored in different ways as it was then formally disseminated in three other cancer services (two colorectal services and one gynae-oncology service) and informally diffused into three community mental health services (an addictions service, a psycho-social service, and supported housing).

The study found that two-thirds of the 56 quality improvements made across the four initial cancer services were sustained at 2-year follow-up. Unlike in the original four case studies, the planned dissemination of EBCD implementation in two colorectal services (leading to four co-designed solutions in one service and only one in the other) was undertaken without external project funding or research support, and clinical staff were marginal to the co-design work. In contrast, the relative success of EBCD in the gynae-oncology service (13 co-designed solutions) was enabled by the work of an ‘in service’ clinical lead champion – as well as a senior clinical nurse specialist (CNS) – and the alignment of the work with established structures [such as multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings], as well as a recognition that patient experience survey results needed to improve. Overall, through the course of the spread of the EBCD in the cancer centre, there was notable slippage from a vision of co-design to ‘listening to patients’, highlighting the central importance of tailoring quality improvement approaches, including EBCD, to local contexts. The authors argue that such sensitive tailoring is, in itself, a dimension of co-design requiring those advocating and leading such projects to adopt an adaptable and flexible approach that listens to the concerns of front-line staff while retaining the core philosophy of approaches such as EBCD.

The informal diffusion of the EBCD approach into a neighbouring mental health organisation was enabled by particular factors: the ‘push’ of active support and ‘opinion leadership’ at a high level of an organisation; the ‘pull’ of active quality improvement teams on the ‘look out’ for new approaches; and the mediating effects of ‘outward-reaching’ quality improvement leaders to build potential relationships. The tailored implementation of EBCD in the three mental health services was managed and led by the same quality improvement team in the mental health organisation. Implementation of EBCD in this organisation was more focused and innovative than the formal dissemination of the EBCD in the cancer centre.

Previous implementations of EBCD – including the examples above – have, therefore, resulted in tangible improvements that have been felt by patients and staff, with many leaving a significant legacy in terms of patient-centred working, support groups, and information for patients, as well as cultural change and a recognition by staff and patients that its collaborative approach is radically different to other change initiatives. 40 EBCD is now also being adapted for use by commissioning organisations in England (‘experience-led commissioning’) and has recently been piloted in the context of end-of-life-care services in the West Midlands, where evaluation has shown similar positive impact. 41

The experience of family carers is a neglected area in quality improvement, but EBCD has also recently been used to develop and test an intervention for carers in the chemotherapy outpatient setting. 42 Through a facilitated EBCD process, carers and staff designed components of a carer intervention that took the form of a DVD and a leaflet. The delivery and impact of the intervention was then tested in a feasibility trial. Forty-three carers were recruited to the trial, randomised between the intervention (n = 21) and control (n = 22) groups. Standardised psychometrically sound measures, completed pre and post intervention, provided preliminary evidence of beneficial impact on carer experience; in particular, the feasibility trial results indicated an improvement in carers’ knowledge of chemotherapy and their perceived confidence with their care-giving situation. Staff and carer focus groups confirmed the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention. These preliminary data are encouraging and support the development of interventions, using a co-design process, to improve carer experience.

Four overlapping strands of thought have contributed to the development of the EBCD approach, namely:

-

PAR

-

user-centred design

-

learning theory

-

narrative-based approaches to change.

With its roots in social psychology and phenomenology and important influences from the likes of Kurt Lewin and Paolo Freire, participatory action research sets out – in contrast to a traditional, positivist, science paradigm – to recognise and directly address complex human and social problems. Although encompassing a wide range of research practices, McIntyre proposes four underlying tenets to the majority of PAR projects:43

(a) a collective commitment to investigate an issue or problem, (b) a desire to engage in self- and collective reflection to gain clarity about the issue under investigation, (c) a joint desire to engage in individual and/or collective action that leads to a useful solution that benefits the people involved, and (d) the building of alliances between researchers and participants in the planning, implementation and dissemination of the research process.

p. 1

Action research has not had a particularly distinguished record in the health care sector, or indeed in other policy areas. Much of the early action research in health care was criticised for poor design and lack of rigor, and it was often neither educative nor empowering for those involved. Proponents of PAR have since argued that the sacrifice of some methodological and technical rigor is worth the additional face validity and practical significance that is gained.

With similar roots to PAR, user-centred (or participatory) design draws its inspiration from a subfield of the design sciences (which include architecture and software engineering) whose distinctive features are (a) direct user and provider participation in a face-to-face collaborative venture to co-design services, and (b) a focus on designing experiences as opposed to systems or processes. Ethnographic methods such as observation and narrative interviews are thus preferred. 44,45 User-centred design makes two particular contributions to quality improvement thinking. Firstly, it offers a new lens, or frame of mind, through which to conceive approaches to improving patient experiences of health care; primarily, its pragmatic nature highlights the importance of ‘making sense’ of experience and finding solutions to poorly designed interactions. Secondly, it offers methods, tools and techniques (such as modelling and prototyping) which were little used in health care improvement work until very recently.

The influence of learning theory on the development of EBCD emerges from a wide variety of sources including Argyris and Schon46 and, more recently, Wheatley47 and Kerr. 48,49 The central argument is that, in contrast to traditional forms of management and clinical skills training, we should be training ‘reflective practitioners’, enabling staff to ‘draw back’, to pause, reflect and gather information, people, and insight. The implications for improving patient experiences of health care services are that we should (a) focus on what both groups (staff and patients) want, and (b) provide a ‘safe haven’ within which to rehearse and practise new ways of thinking, feeling, doing and relating. Emotional disclosure, in which discussion of emotions is constructed as a normal and healthy human activity, is an important part of this. 50,51

Finally, narrative approaches (see The value of narrative, above) are an important strand because ‘stories and storytelling are the basis of EBCD . . . [they] contain huge amounts of information, wisdom and intelligence about experiences that are waiting to be tapped as a rich source for future service development and design’ (pp. 66–7). 30 In keeping with PAR, user-centred design and learning theory, narrative-based approaches to change are premised on subjective, socially constructed stories that enable connections with ‘assumptions, values, expectations, cognitions and emotions’ (p. 65). 30

Taken together, these four strands of thought also relate to the increasing interest in what Bushe has termed ‘dialogic’ organisational development (OD) approaches. 52,53 Such approaches have turned away from traditional, top-down, leader-centric and diagnosis-led OD and towards practices that ‘assume organisations are socially co-constructed realities’ and have in common ‘a search for ways to promote dialogue and conversation more effectively’ as it is ‘by changing . . . conversations that normally take place in organisations that organisations are ultimately transformed’ (pp. 619–20). 53

Steps in experience-based co-design

A full description of the EBCD approach has been published elsewhere, accompanied by a case study of the pilot implementation in a head and neck cancer service. 30 Detailed materials are also available from The King’s Fund’s online EBCD toolkit. 54 Integral to the approach is that patient, carer and staff experiences are used systematically to co-design and improve services. To date, this has involved an intensive local diagnostic phase, using rigorous qualitative research, including video- or audio-recorded narrative interviews in which participants are invited to recount their experiences using a storytelling approach, highlighting concerns and priorities and identifying ‘touch points’ (key interaction points) along their journey. The methods used to collect these interviews are very similar to those used by the national archive described below. Trigger films based on these experiences are then used, firstly to enable patients and carers to share and discuss their experiences with each other, and then to stimulate discussion between local staff and patients, who can then jointly identify actions to bring about systematic, sustainable improvements.

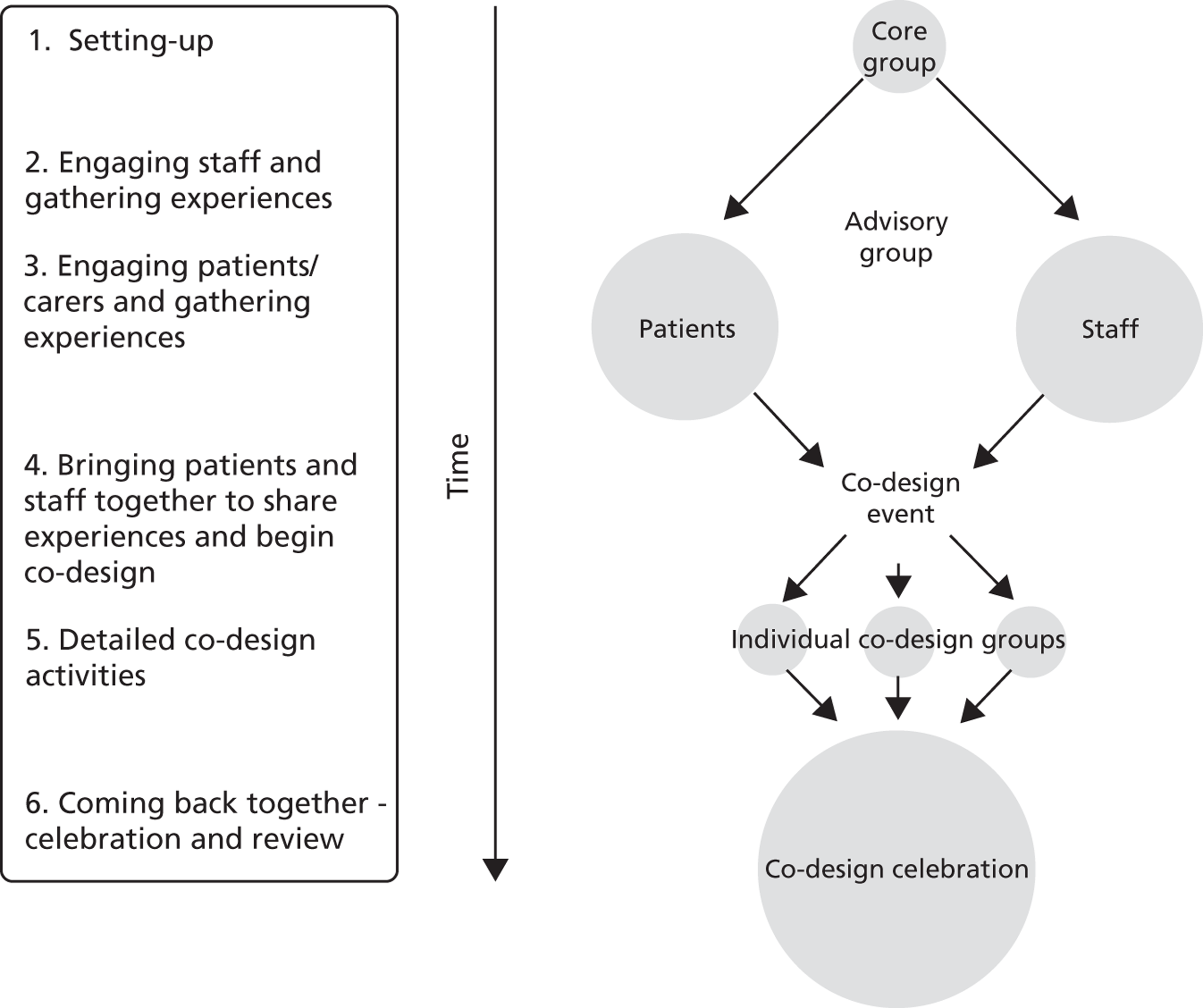

Figure 1 details the six stages of the action research process that together make up the EBCD approach to improving patient experiences. Stage 1 involves establishing the governance and project management arrangements. The fieldwork underpinning an EBCD project typically then begins with a 4-month data collection period (stages 2 and 3). In stage 2 a wide variety of staff (from, for example, receptionists to lead clinicians) are interviewed about their experiences of working within a service using a semi-structured interview schedule; over multiple implementations of the approach we have found that the data from approximately 12–15 interviews provide sufficient insights for the purposes of being able to represent back and reflect on staff experiences. The staff interviews are transcribed and analysed thematically. Non-participant observation helps to contextualise and understand patient experiences from both patient and staff perspectives; for example, in a recent EBCD project, two researchers conducted a total of 219 hours of participant observation of clinical areas along the relevant patient pathway. 40 The specific aspects of care that are observed are not pre-determined and the observations focus on both functional and relational aspects of patient/staff interactions. Following the data collection, staff meet to review the themes arising from the staff interviews and observational data in order to identify their priorities for improving services.

FIGURE 1.

Steps in the EBCD process.

In stage 3 – which runs in parallel with stage 2 – patients and carers are recruited (e.g. through clinical nurse specialists in outpatient clinics) and an experienced qualitative researcher conducts filmed, narrative-based, unstructured interviews lasting, on average, 1 hour, in which patients describe their experiences of care since first diagnosis. Each patient is then sent their own film to view before deciding whether or not it can be shared with other patients and staff. Two researchers view the films independently to ensure analytical rigour and shared understanding of significant ‘touch points’. 55 ‘Touch points’ are the crucial moments, good and bad, that shape a patient’s overall experience; the concept originated in the airline industry and represent the key moments where people’s subjective experience of the service is shaped. Exemplar ‘touch point moments ‘ that emerged from the pilot implementation of EBCD in a head and neck cancer service included breaking of the bad news; percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tube; ‘waking up in an intensive care unit’ (ICU); the cancer ward; ‘looking in the mirror’; and radiotherapy and radiotherapy planning.

Films are then edited to produce one composite 35-minute film, representing all the key touch points in a service. In addition, audio recordings of the narrative interviews can be transcribed and the data analysed thematically. All of the patients and carers are invited to a showing of the composite film, following which a facilitated group discussion highlights any different or emerging issues. An emotional mapping exercise is then used to help patients reflect together on the emotional impact of the touch points. 30 Following this group work, patients vote on their shared priorities for improving services.

In stage 4 the staff and patient priorities are presented at a joint event at which staff view the composite patient film for the first time. Mixed groups of patients and staff use the issues highlighted in the film, together with the priorities from the separate staff and patient meetings, as a basis to identify joint priorities for improving services. Patients and a variety of medical, allied health professional and administrative staff then volunteer to join specific ‘co-design working groups’ (typically four to six groups) to design and implement improvements to services (stage 5), initially over a 3-month period. The majority of these groups are facilitated by quality improvement specialists from the participating health care organisation, and ground rules are established from the outset, ensuring that all participants have equal voices. At stage 6, these separate co-design working groups reconvene to discuss their work to date and plan the next stages of the improvement process.

The challenge

As noted above, independent evaluations have shown EBCD to be effective in improving the quality of health care services. However, the diagnostic phase before quality improvement can begin is undoubtedly lengthy and costly, and has been noted in evaluation as a barrier to uptake. 35,36 Replicating 5–6 months of qualitative interviewing on each pathway in each hospital is impractical. And yet – as explained elsewhere34 – crucial to the success of approaches such as EBCD are the discursive, narrative–based interactions between staff and patients that are enabled by the change process. 56 The filmed patient narratives are held to be key in triggering these interactions and fulfil several functions: they are a tool for reflective learning (for both patients and staff); they provide data to drive the co-design process; and they (re-)establish an emotional connection between the staff and patients. In the following quotation from the original head and neck cancer pilot, a staff member considers the impact of watching the patient film:57

When people watch the film they might think, ‘I remember that lady’, they know they’re our patients – they can’t get away from the fact – but it actually makes it more real for them. Whatever way they’re captured, it’s about capturing it so that people recognise these are patients I have cared for, nursed, met, who are saying this . . . and I think that’s what is so different from other improvement work in terms of things like discovery interviews and focus groups: it’s that direct connection between them.

Experienced-based co-design has, therefore, been found to result in improved service quality, but one of the major barriers to widespread implementation is the time and cost involved in the discovery phase (stages 2 and 3 in Figure 1). However, ‘accelerated’ approaches may not work as well if, for example, local staff and patient engagement in the change process is less forthcoming. Even if ‘accelerated’ forms of EBCD do not work as well as the traditional approach, they may work ‘well enough’ to be worth pursuing.

Our aim is to generate new knowledge by testing a potentially less costly, more efficient and therefore more feasible way of implementing EBCD locally, but one that still draws on rigorously conducted and analysed qualitative research, which has been one of the hallmarks of EBCD. The archive of patient narrative interviews held by the Health Experiences Research Group (HERG) in Oxford and disseminated through Healthtalkonline (see following section) offers a potential resource to make this a reality. 58 The need for the NHS to seek ways to improve patient experience is a political and ethical ‘given’, and so if this project can demonstrate a faster and less costly way to do it, there could be substantial gains for both clinical staff and patients.

The Health Experiences Research Group and Healthtalkonline – existing narrative evidence on what matters to patients

The Health Experiences Research Group at the University of Oxford collects and analyses video- and audio-recorded interviews with people about their experiences of illness. It now has an innovative national archive of around 3000 interviews, all collected between 2000 and the present and covering over 80 different conditions or topics, which provides a unique source of evidence on patient experiences and priorities. The interviews combine an unstructured narrative (elicited by the question ‘tell me your story’) followed by semi-structured prompting. For each condition approximately 40 interviews are collected, and coded and analysed thematically using the constant comparative method.

The HERG studies use purposive maximum variation sampling. This aims to get the broadest practicable mix of people (variation across different demographic characteristics such as age, gender, ethnicity and social class) and types of experience; Patton59 argues that the advantage of using a maximum variation approach is that ‘any common patterns that emerge from great variation are of particular interest and value in capturing the core experiences and central, shared aspects’ on a specific topic (p. 172). The different types of experience for which HERG studies sample vary by condition, and are determined with input from an expert advisory panel brought together for each condition-specific study. Typical factors for which variation may be sought include time since diagnosis; severity of condition; nature of local service provision; type of treatment; recurrence or not; degree of progression; and extent of lasting disability or symptoms.

The interviews are approved by participants for use in research, teaching, publication, broadcasting and dissemination on an award-winning patient experience website, www.healthtalkonline.org, one of the first health information sources to meet the Department of Health’s Information Standard. 60 A primary purpose of Healthtalkonline has always been to provide practical information and emotional support for other individuals going through the same experience, but the interviews are increasingly used in teaching health professionals and to inform health policy – for example, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline development now frequently incorporates evidence from Healthtalkonline, and it is the only source of patient experience evidence recommended in the NHS Evidence Process and Methods Manual. Recent General Medical Council (GMC) guidance on end-of-life care drew on a specially commissioned analysis of interviews from the archive. 61 This analysis for the GMC was subsequently compared with a local set of interviews on end-of-life care. This showed that very few themes were identified locally that could not have been anticipated from the national data set. 62 The archive thus has enormous potential as an evidence base of patients’ experiences to support service change. Indeed, for many participants, knowing that their experience may be used to help improve things for other people is an important motivator for agreeing to take part.

Using national narratives for local improvement

There is considerable similarity in the interviewing technique used by HERG and EBCD; when Bate and Robert30 were designing the initial head and neck cancer pilot in EBCD, they spent time with HERG discussing methods for conducting video patient experience interviews. Both use unstructured narratives followed by semi-structured prompting, collected by experienced social science researchers; both anticipate that the some or all of the data collected will be used and seen publicly rather than used purely as anonymised text for research purposes. Both projects offer people the opportunity to give an audio or written-only narrative as well as video, though in practice very few people take this option in EBCD, whereas most HERG collections include a proportion of audio or written-only narratives. (This may well be influenced by the internet dissemination route through Healthtalkonline which may prompt people to seek a greater level of anonymity.) Key differences are that HERG studies (a) are national rather than local and (b) generally use a larger sample but cover a wider range of issues, many of which are not directly relevant to quality improvement (such as the effect of illness on family relationships, on work and social life, and on body image and self-esteem). EBCD patient discovery interviews normally draw on a more focused sample and more targeted semi-structured prompting to understand experiences of care services in a particular locality.

Despite these differences we felt that there was enough common ground to test whether or not HERG interviews could be used to accelerate the EBCD cycle by reducing the discovery phase with local patients. At the outset, we recognised that the accelerated approach might not work as well as a traditional approach, if local engagement were less forthcoming. We hypothesised that staff might feel unconvinced that issues raised by patients in the film applied to them locally; that it might be easier to say ‘that never happens here’, and feel less moved by the narratives to think differently about the care they offer. On the other hand, we speculated that seeing a different sample of patients could defuse critical comments and make staff feel less defensive. The very fact that it is not local could enable a more collaborative approach.

As far as patients and families were concerned, we debated whether or not they would feel that the issues raised in the film did not resonate sufficiently with their own experiences or with specific local concerns – or whether or not it might in fact be easier for them to raise difficult issues with staff indirectly by appealing to what others in the trigger film have said rather than in potential direct confrontation.

This led us to formulate the following research questions:

-

Is the accelerated approach acceptable to staff and patients?

-

How does using films of national rather than local narratives affect the level and quality of engagement with service improvement by local NHS staff? Does this have implications for the overall impact of the approach?

-

From local patients’ perspectives, how well do they feel that national narratives capture and represent themes important to their own experiences?

-

Does any additional work need to be done to supplement the national narratives at the local level? If so, what form might this take?

-

What improvement activities does the approach stimulate and how do these activities impact on the quality of health care services?

-

What are the costs of this approach compared with traditional EBCD?

-

Can accelerated EBCD be recommended as a rigorous and effective patient-centred service improvement approach which could use common ‘trigger’ films to be rolled out nationally?

Chapter 2 Methods

This study involved two components: the intervention (adaptation and implementation of an accelerated form of EBCD) and an evaluation. For clarity, we document the methods of each of these in turn, though in practice they proceeded side by side.

The intervention – accelerated experience-based co-design

Sampling and setting

The two partner hospital sites were selected partly on the basis of senior clinical managerial commitment to the project, which has been shown to be an important enabling factor for change. 63,64 Our two hospital partners also provided a contrast between a tertiary specialist provider (Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust) and a general hospital (Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust) to demonstrate whether or not the approach was equally acceptable and practicable in both types of setting. Senior management team members from both organisations were co-investigators (CIs) in the study, and therefore they are not anonymised as overall partners in the research. However, elsewhere in the report we have explicitly anonymised our results. Our purpose was never to compare one site against another, but rather to compare AEBCD against EBCD.

In each of the two participating hospitals, a ‘site captain’ was identified – the senior individual in each organisation who had agreed to participate as a CI, negotiated site access and identified the service improvement facilitators who would take day-to-day responsibility for the project locally, including the identification and recruitment of participants.

Royal Brompton and Harefield’s early involvement in the planning of the study determined the selection of pathways relevant to their specialist heart and lung services, and in discussion with Royal Berkshire we settled on two exemplars: intensive care and lung cancer. Co-applicants Shuldham and Fielden brought not only senior management support but also directly relevant expertise in cardiac and intensive care nursing (Shuldham), and intensive care medicine (Fielden).

These two pathways offered interesting potential insights. One advantage was that lung cancer had already been the subject of a full EBCD project, which provided us with a good comparison with an accelerated version both in terms of process and in terms of costs and impact. Intensive care provided an example of a topic area which has not previously been subject to EBCD. In terms of generalisability, like many other serious health conditions, having lung cancer or requiring critical care impacts on many aspects of a person’s life and necessitates a range of interventions. The experience can be life changing, and in the immediate or longer term can have psychological effects. Cancer is one of the most common pathways in the NHS, accounting for 1.7 million finished consultant episodes (FCEs) in 2009–10, around 10% of all FCEs. 65 Many aspects of the lung cancer pathway are similar to other cancers and other acute conditions where symptom recognition (and delays in consultation), investigations, diagnosis, treatment choices, recovery, discharge, follow-up and medication are all important. In many cases, there will also be similarities with other serious long-term conditions, such as heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, in which long-term management and deteriorating health may need to be managed. Lung cancer’s poor prognosis also means that this pathway has relevance for end-of-life care. The two hospitals were involved in different aspects of the care pathway; at Royal Berkshire, diagnostic services, outpatient care, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are provided locally but patients requiring surgery are transferred to a central London specialist hospital for that part of the pathway. Royal Brompton and Harefield, by contrast, take specialist referrals for surgery for lung cancer from many different parts of the country.

Intensive care provided an interesting setting because it is not one single condition, but rather focuses on a care system in a defined location, offering a range of treatments for a variety of conditions in the very acute phase of severe illness. It raises generalisable issues about co-ordination and handover between departments and disciplines, and about improving the care of people who may be unable to communicate at the time or take part in decision-making, and whose utter dependence on staff is a key feature of their experience. It is thus an area in which family carers are particularly closely involved, spending many hours in hospital helping to provide care and assisting in the person’s recovery, as well as taking responsibility for many decisions and interactions with staff, but often feeling helpless and potentially excluded from a specialised, high-tech, automated world. As noted earlier, family carer experiences are a neglected area in quality improvement. As with intensive care, the two hospitals’ intensive care services had different patient profiles, with Royal Brompton and Harefield seeing many planned admissions after complex heart or lung surgery, and Royal Berkshire having a mix of planned and emergency admissions with a range of diagnoses.

Within each pathway, all staff were invited to be part of the intervention, given that staff engagement was a fundamental aim of the intervention. Patients and carers were carefully and purposively selected in order to identify people who could participate effectively in the co-design process. In line with The King’s Fund’s EBCD toolkit,54 the local facilitators were advised to:

-

identify patients who had been through different aspects of the service, and who were beyond the critical point of their treatment, so that they could reflect on their experience

-

try to include a range of people – determined not only by age, gender and ethnicity but also in terms of the treatment types and services experienced and to make sure that participants’ experiences of the service had been quite recent, so that the aspects of the service that they reported were still current

-

try to avoid going to ‘the usual suspects’, and that if they recruited patients involved in existing patient support groups, to explain carefully that in this project they will need to focus on aspects of service delivery that could lead to improvements

-

not worry about finding the ‘perfect patient sample’ as the project was deliberately focusing on the views of a relatively small number of people, and so it was not intended to represent every detail about the service.

Particularly in the case of lung cancer, staff felt it was important that people nearing the end of life should have an opportunity to express their views, but at the same time we were mindful of people’s state of physical and emotional health and the possible burden of taking part. Potential participants were thus approached individually through members of the clinical team, especially consultants and nurse specialists, with closest knowledge of local patients/carers, either during their hospital episode or after they had left. A member of the clinical team made initial contact by mentioning the project to likely participants, and this was then followed up with a participant information sheet and invitation to participate, until sufficient numbers for the co-design process were obtained. All patients and carers approached were adults able to give informed consent, and were advised that they could withdraw at any stage. They or their relative had received care in one of the four participating services during the 6-month period of the fieldwork.

The number of staff and patients from each pathway was intended to be sufficient to give a broad range of views as to issues influencing staff well-being and patient experiences. Typical previous EBCD projects have recruited 12–15 patients/carers and 12–15 staff members per pathway. Across four pathways this would have meant 48–60 patients/carers and 48–60 staff. In fact, 159 people took part overall at one or more stages: 96 staff members and 63 patients. Information and consent materials are shown in Appendix 2.

Steps in the process

The design of our accelerated form of EBCD involved seven different stages, adapted from traditional EBCD as described in the Background section, above. These stages are:

-

secondary analysis of narrative interviews from the HERG archive

-

creation of trigger films

-

discovery and engagement work with staff, including staff feedback event

-

focus group workshop with local patients and carers

-

co-design workshop with local staff, patients and carers

-

co-design subgroups of staff, patients and carers

-

final event.

The detail behind each of these steps is set out below. During the first phase of the project (the two intensive care pathways), some of the events described below were filmed, with participants’ consent, in order to provide visual examples of the kind of work involved for dissemination of the method, and training for new facilitators and potential EBCD participants. We have also captured, on film, short interviews with the facilitators and others involved in the two hospitals, again to feed into training for new facilitators.

Secondary analysis

Secondary analysis of relevant patient narratives from the HERG interview archive was undertaken to identify ‘touch points’ along each care pathway (intensive care and lung cancer). This replaced much of the intensive local discovery phase (face-to-face interviews and ethnographic observation) normally used in EBCD. Secondary analysis66 involves reusing data collected for another prior purpose to answer a new or different question. The interviews in the HERG archive have all been collected to understand people’s experiences of particular illnesses or health topics, ranging widely across social, physical and emotional issues, but they also contain detailed accounts of diagnosis, treatment, discharge and follow-up, information, communication with professionals and decision-making, which we hypothesised would be well suited for identifying touch points, although the interviews were not specifically conducted for that purpose. Among many other collections, the archive contains 40 interviews with people who have been in intensive care, 38 interviews with relatives and close friends of people who have been in intensive care and 45 interviews with people with lung cancer; these were used as exemplar conditions for the project. (These are more interviews than would normally be collected in a local EBCD discovery phase; however, we felt it was important to include this larger sample to compensate for the fact that the interviews were not specifically designed to capture touch points.) The analysis included interviews available in audio and written-only format to identify themes, but only one audio extract was included in the trigger films (see Trigger films, below).

Secondary analysis was undertaken by two experienced qualitative researchers from the group, under the supervision of the principal investigator (PI) Locock and CI Ziebland. All interviews were reread and recoded, looking specifically for instances of touch points. The lung cancer interviews were reanalysed by the same researcher who had originally collected them. The intensive care interviews were reanalysed by a researcher who had not been involved in the original data collection but who was able to call on the original researcher for advice. CI Robert held a half-day workshop with the two researchers and the PI to demonstrate previous films used in EBCD projects, explain how they are used in practice, and discuss what to look for in identifying touch points. To test whether or not the touch points were similar to those which would be identified by a researcher experienced in EBCD, CI Robert took one of the lung cancer transcripts and coded it independently, then compared this with sections identified as touch points by the HERG researcher. This confirmed a high degree of consistency.

Trigger films

Trigger films were then created drawing on the secondary analysis, featuring video and, in one case, audio extracts from a range of individuals illustrating the touch points. The selection of illustrations was led by the researcher who conducted the secondary analysis, in discussion with the PI. This discussion resulted in some minor changes in clip selection (e.g. in the ICU film, a clip was added on the value of follow-up appointments and diaries of what happened to help people come to terms with their experience, and the number of clips on ‘dreams and nightmares’ and ‘hallucinations’ were condensed into one shorter section). Discussions at this stage explicitly included the need to offer a balance of positive and negative experiences. The draft films were then shared with CI Robert and the service improvement facilitators. At this point there was scope for some further minor adjustments to be made [see Chapter 3, Results (4)]. Each trigger film lasted approximately half an hour and was provided on DVD for the facilitators to use at local events. (The trigger films are copyrighted to the University of Oxford; they will be made available for free future use in health care service improvement through The King’s Fund’s EBCD toolkit website and on the ‘Improving care’ section of the Healthtalkonline website.)

Discovery and engagement work with staff

While the trigger films were being developed, local service improvement facilitators were identified in each trust and trained by CI Robert in co-design techniques. The role of the facilitators was to recruit staff and patients to the project, run the co-design process, collect data as appropriate (both for the evaluation and for quality improvement activities), and champion the approach within their organisations.

The facilitators used a combination of participant observation and one-to-one discovery interviews with staff to learn about their experiences of the two exemplar care pathways and staff views and expectations about what local patients experience. All staff who worked in the four participating services were invited to participate in the project, with no exclusion criteria. Staff were sent a covering letter in the internal post from the research team, together with the staff information sheet. An outline of the appropriate semi-structured interview schedule was also sent to each potential interviewee in advance of the proposed interview. Signed informed consent was sought from all staff who participated, whether as an interviewee or by attending meetings (see below). The staff information sheet and covering letter both made clear that participation was entirely voluntary and that staff could withdraw at any time without giving a reason. The facilitator took detailed notes during the discovery interviews and produced a summary of findings.

The facilitators also undertook observation of routine care in appropriate settings depending on the specific service (e.g. on wards or in outpatient clinics). Relevant members of staff were informed by the facilitator of his or her wish to observe routine day-to-day activities. Patients who might be directly observed were verbally informed of the presence of an observer and the purpose of the research. Again, the facilitator took notes of their observations.

Anonymised findings from both staff interviews and observations were presented to any staff member who wished to attend a staff feedback meeting. These were discussed and staff priorities for improvement were agreed. Although there was considerable overlap between staff who were interviewed and staff who attended the workshop, some staff who were interviewed were unable to attend, and staff who had not been interviewed were also welcome to bring new perspectives to the discussion. A total of 42 staff agreed to be interviewed across the four pathways and 46 people attended the staff feedback event. (See Sampling and setting for more detail on sampling for the intervention.)

Focus group workshops with local patients and carers

Patients and family members who were invited to take part were given or sent an information sheet describing the study and asked by the local service improvement facilitator to complete a consent form. The participant information sheet and covering letter both made clear that participation was entirely voluntary and that patients and carers could withdraw at any time without giving a reason. Travel expenses were reimbursed, and lunch and refreshments were provided at meetings.

The first step for patients and carers after consenting to take part was to attend a focus group workshop at the hospital in question around their particular pathway, facilitated by the local service improvement facilitators and observed by the ethnographer (see Evaluation, below) but otherwise not attended by staff. This was similar to the patient feedback event in traditional EBCD, but in EBCD the participants would be the patients already interviewed during the discovery phase and they would be watching their own interviews in the trigger film. In the accelerated form, participants instead watched the trigger film derived from analysis of the national archive, and then discussed how far the touch points identified reflected their own priorities and experiences. Participants were offered the opportunity to raise specific local issues of importance which may not have been captured. Other EBCD techniques (such as emotional mapping) were adapted from their traditional application and used at the workshops to enable participants to share their experiences and inform the selection of their priorities for improvement. Forty-nine patients and carers overall attended one of the four patient workshops across the different sites and pathways.

Co-design workshops with local staff, patients and carers

After the two separate events, one for staff and one for patients and carers, a multidisciplinary group of local staff, patients and carers were brought face to face in a co-design workshop to share their experiences of giving and receiving services. The trigger film was shown again to the whole group. Again, this is very similar to the same stage in traditional EBCD, except that the staff (who were seeing the film for the first time) were not watching their own patients. The film was used to stimulate group exercises to focus on key ‘touch points’ where systematic and sustainable improvements might be made. Patients, carers and staff shared their respective priorities for improvement and agreed which of these they would work on together in the co-design subgroups (see next section); these could be anywhere along the patient pathway, and were the priorities for improvement adopted by each of the pathway projects. Building a coalition for change between staff and patients is central to this stage in the process. Again, this work was led by local service improvement facilitators with training and support from CI Robert. Across the four workshops, a total of 93 people took part. Although there was considerable overlap in attendance from the previous staff feedback event and patient/carer focus group, people were free to dip in and out of the process at any stage and new participants were welcomed.

Co-design subgroups of staff, patients and carers

The co-design workshops led to the establishment of subgroups of patients, staff and carers working together in each partner organisation to respond to the agreed priorities for improvement by planning and implementing changes. A key feature of the approach is that the interventions are designed collaboratively by patients and staff, with continued support from local service improvement facilitators. The groups recorded their activities and fed this information into the evaluation. The choice of topics, the way in which meetings were organised and their frequency varied from site to site, and this is discussed in Chapter 3, Results (5).

Final event

As in traditional EBCD, the final stage is to bring participants from each pathway together to review and celebrate their achievements, and plan for further joint work. This is an opportunity for patients and carers to see that they have been involved as equal partners in achieving change, and that their ideas have been listened to and acted upon. Patients and carers often lead parts of the presentation. It is also an opportunity for wider dissemination, as staff from other parts of the hospital may be invited to see what has been achieved, and consider whether or not to adopt the approach in their own departments. In this study, 45 staff and 19 patients/relatives attended final celebration events overall.

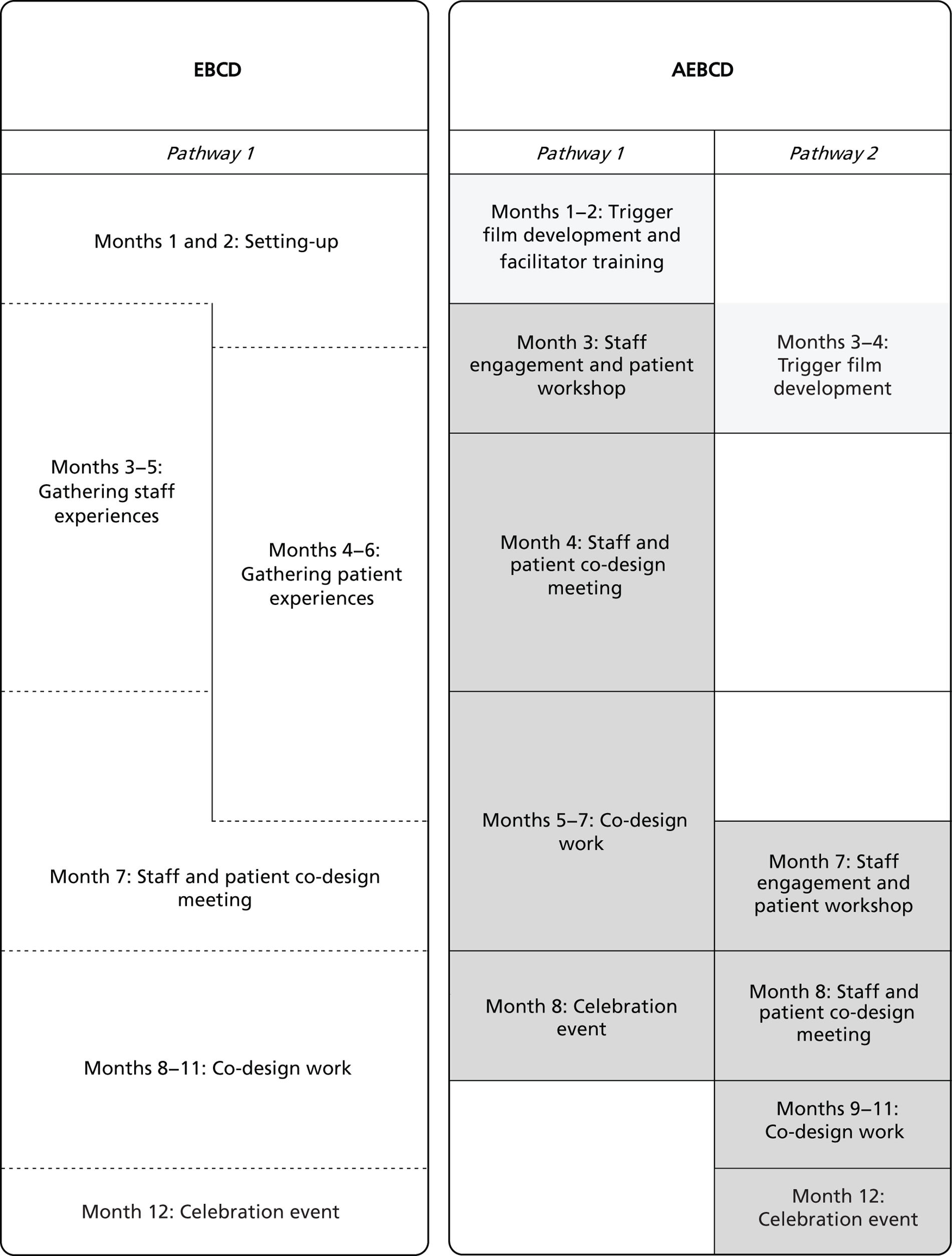

Shortening the experience-based co-design process

Figure 2 below compares the time frame for traditional EBCD with that for AEBCD. A traditional EBCD cycle typically takes around 12 months’ work in each trust to complete one pathway. In the accelerated version as described above, we set out to halve the cycle to 6 months per pathway (plus 2 months as a one-off set-up time to develop a trigger film around that pathway, which could then be reused in other trusts). Much of the shortening would be achieved by using national rather than local patient interviews, while still ensuring that the process was informed by rigorous patient-centred research. The amount of staff input would also be significantly lower. A traditional EBCD cycle involves a full-time researcher for 6 months and a half-time service improvement facilitator for 6 months (a total of 9 months of staff input). In the accelerated version, there would be a one-off staff commitment of 2 months to develop the trigger film. Within a given hospital, staff involvement would be reduced to a 40% facilitator for 6 months (= 2.4 months). The staff discovery phase was reduced and the time for co-design groups to meet shortened from 4 months to 3. (See also Chapter 3, Results, for a discussion of the impact and feasibility of shortening the process.)

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of EBCD and AEBCD timetables.

Evaluation

Design

The ethnographic evaluation aimed to observe the implementation process in both pathways in each trust and to evaluate the acceptability to patients and staff – and the impact – of this adapted approach to patient-centred quality improvement. The aim was not to evaluate EBCD per se, as there have been a number of previous studies of the approach,36,38,56 but to assess whether or not the accelerated approach provided a workable, affordable and acceptable alternative.

To assess the impact of the accelerated approach, we used a longitudinal comparative case study design and observational methods which are well suited to the study of complex change. 67,68 In effect, there were four ‘cases’: two different pathways in each of two trusts which were compared with EBCD. The evaluation used multiple data sources, including observation, interviews, questionnaires, group interviews with patients, documentary analysis and administrative data on costs. Members of the project team were also encouraged to keep reflective diaries of their experiences and to complete service improvement logs.

In order to place some distance between the intervention and the evaluation, the evaluation team was located in a separate department of King’s College London from CI Robert (and a different institution from PI Locock). While the wider team were involved in recruiting the ethnographer, she worked directly to the CI responsible for the evaluation (Boaz).

Ethnography can contribute to process evaluation by providing rich accounts of activities, projects and programmes. 69 The methodological design for this evaluation incorporated multiple methods and varied lines of inquiry to achieve ‘within research’ and ‘between method’ triangulation. 70 The ethnographer was in post throughout and was therefore able to observe all stages of the project.

At all stages of the evaluation, the ethnographer collected data to address the project’s research questions:

-

Is the accelerated approach acceptable to staff and patients?

-

How does using films of national rather than local narratives affect the level and quality of engagement with service improvement by local NHS staff? Does this have implications for the overall impact of the approach?

-

From local patients’ perspectives, how well do they feel national narratives capture and represent themes important to their own experiences?

-

Does any additional work need to be done to supplement the national narratives at the local level? If so, what form might this take?

-

What improvement activities does the approach stimulate and how do these activities impact on the quality of health care services?

-

What are the costs of this approach compared with traditional EBCD?

-

Can accelerated EBCD be recommended as a rigorous and effective patient-centred service improvement approach which could use common ‘trigger’ films to be rolled out nationally?

Evaluation participants and recruitment

Observations included staff, patients and friends at all four sites. Evaluation interviews were conducted with the facilitators and a sample of participants drawn from the events and the co-design groups. The principle of maximum variation sampling was used to ensure that a spread of different types of participants (staff, patients and friends) had an opportunity to participate. All patients who attended the celebration events in the ICU pathway were invited to take part in a group interview immediately after the event. Arrangements for staff and patient interviews, group interviews and questionnaire distribution were facilitated by the local service improvement facilitator, with support from the clinical lead at each site.

Data collection

Evaluation data collection took place between November 2011 and December 2012. To achieve an enhanced level of immersion required for an ethnography as well as a methodological triangulation, a wide range of formative and summative evaluation methods were employed, described in the following seven sections.

Observations

A total of 155 hours of observations took place between November 2011 and October 2012, including facilitator training sessions, staff and patient workshops, joint events, co-design group meetings and celebration events, project steering group and core group meetings. Furthermore, work-based observations in clinical settings and patient support activities were conducted to acquire a better understanding of the wider context of the intervention as well as the physical spaces and processes discussed during co-design group meetings. Observations were recorded as field notes and transcribed.

Evaluation interviews were conducted with the local facilitators, the PI, the project leads in the trusts, the CIs and the co-design group leads. The evaluation interviews were distinct from the staff discovery interviews (described as part of the intervention methods, above). A total of 30 interviews were conducted with 25 participants: 11 entry interviews were conducted between November and December 2011 and 18 exit interviews were conducted between November and December 2012. Most interviews were conducted face to face except four exit interviews that were conducted over the telephone to accommodate the interviewees’ workload. Interviews lasted between 30 minutes and 90 minutes. The topic guide for the entry and exit interviews was designed around the following themes: involvement in the project and perceptions of the process; project contribution to service delivery; and project sustainability and legacy. The exit interview questions were based on the summative evaluation interview questions used in the head and neck cancer EBCD project30 to generate comparable data. Additionally, 12 informal unstructured interviews were conducted with members of the project team and hospital staff members to capture personal insights into the implementation process and to catch up on emerging issues. These short interviews were conducted by telephone and were not recorded, but detailed notes were taken. Interviews and group interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Training sessions and events were audio-recorded to supplement field notes but were not transcribed. Brief conversations were recorded as field notes.

In addition, two evaluators of previous EBCD interventions observed ICU celebration events in the two trusts and contributed their own observation notes. They reflected, in particular, on similarities and differences between EBCD and AEBCD.

Group interviews

Two group interviews were conducted after the celebration events at the end of the first two projects on ICU at each trust. Each group interview was attended by four patient participants and lasted 1 hour. Participants were asked to discuss their involvement and perceptions of the process during each step of the intervention. Staff were not invited to attend group interviews in order to ensure that patient participants could express freely their views about participating in this project, watching the film and co-designing improved services.

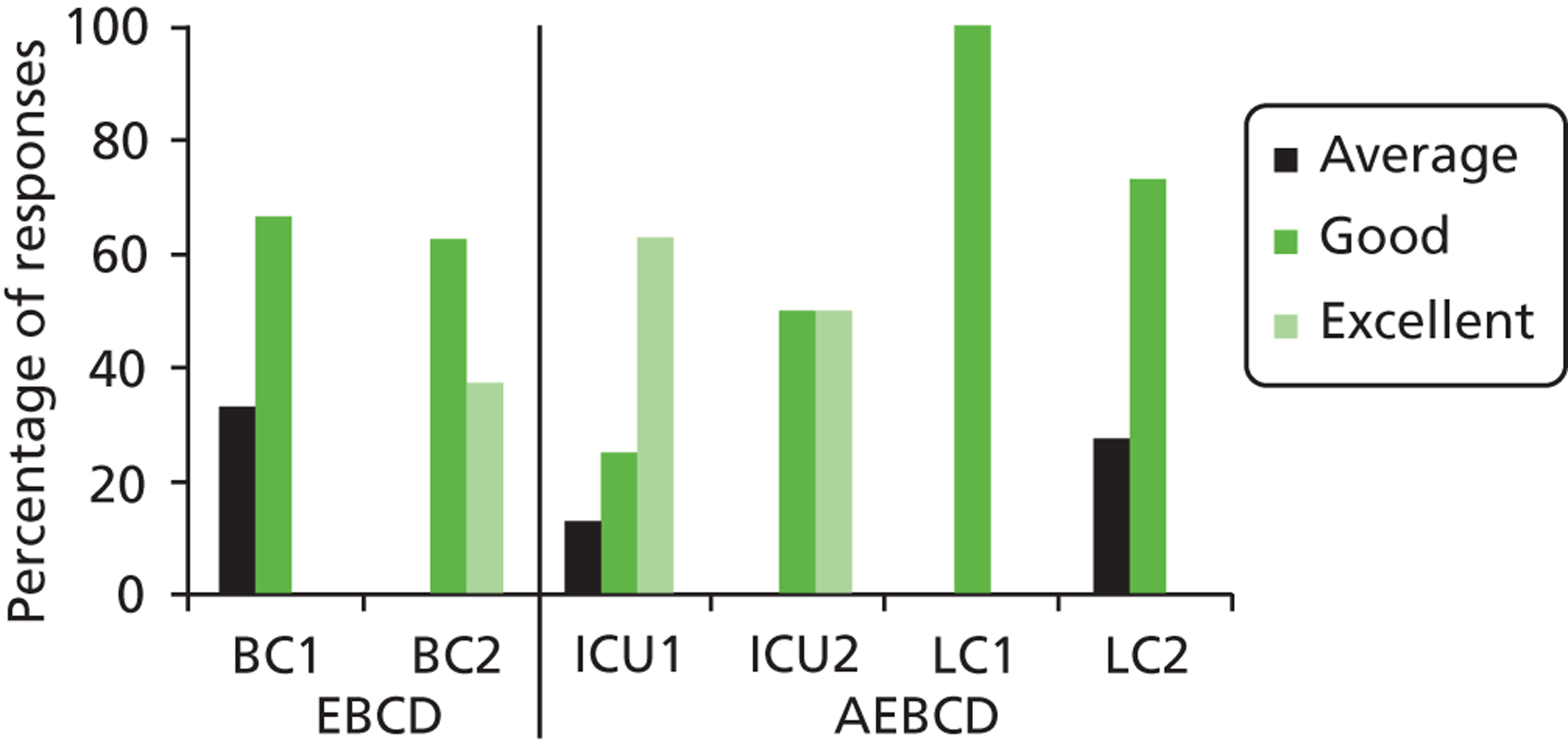

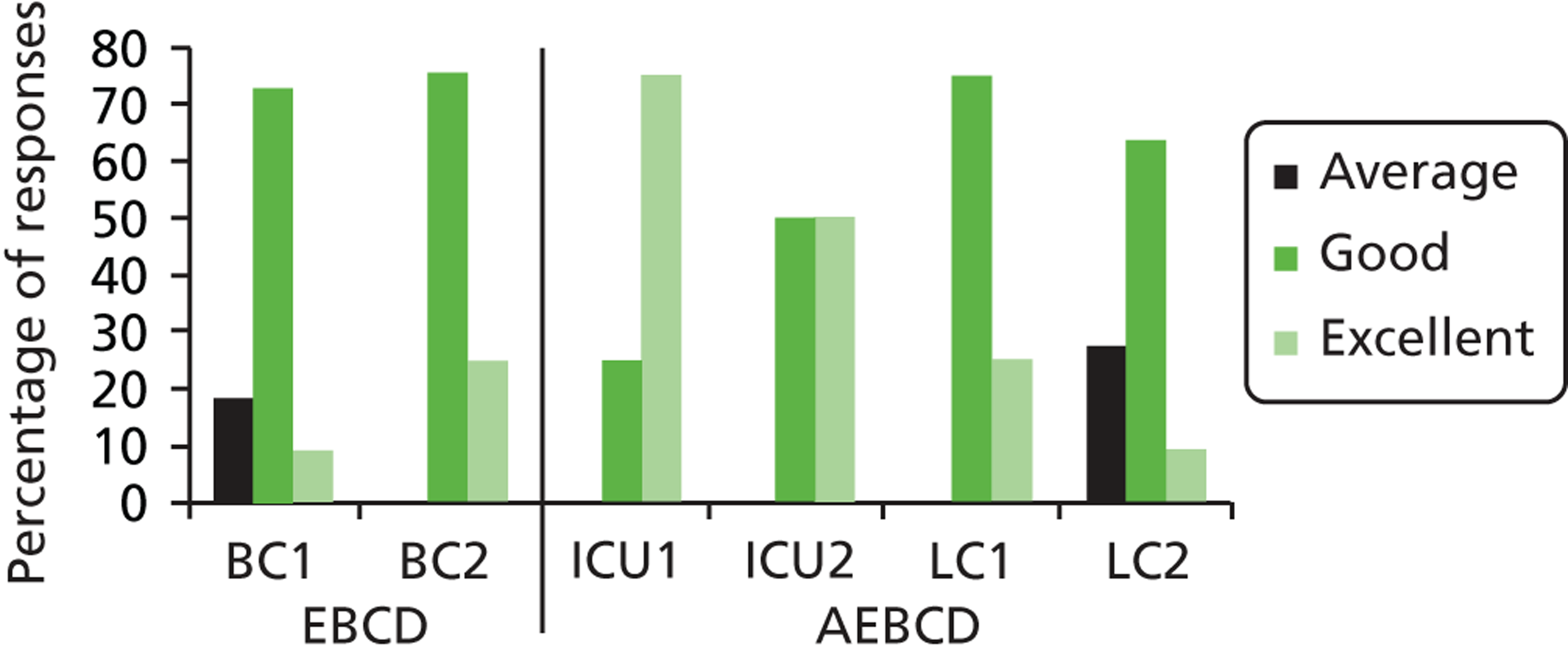

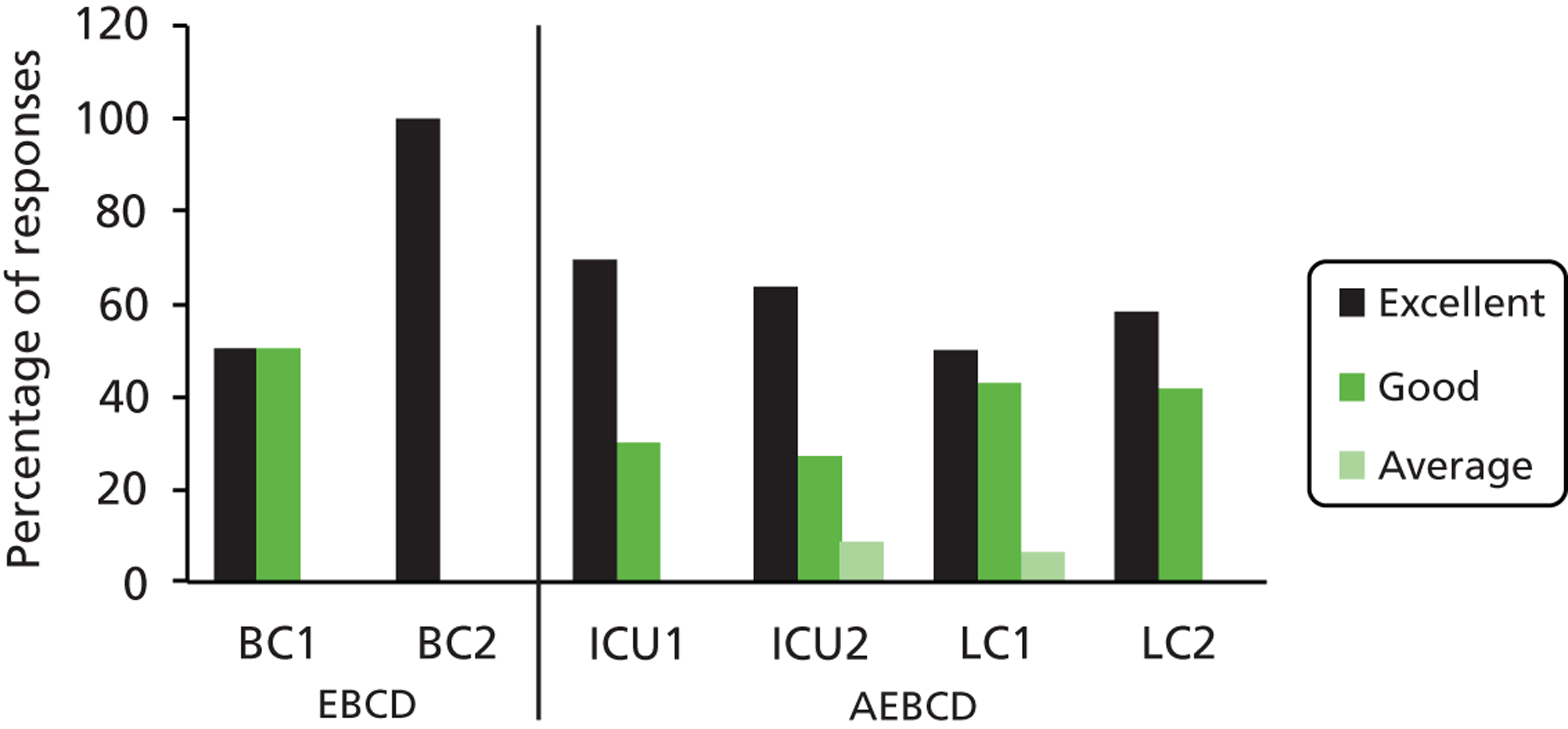

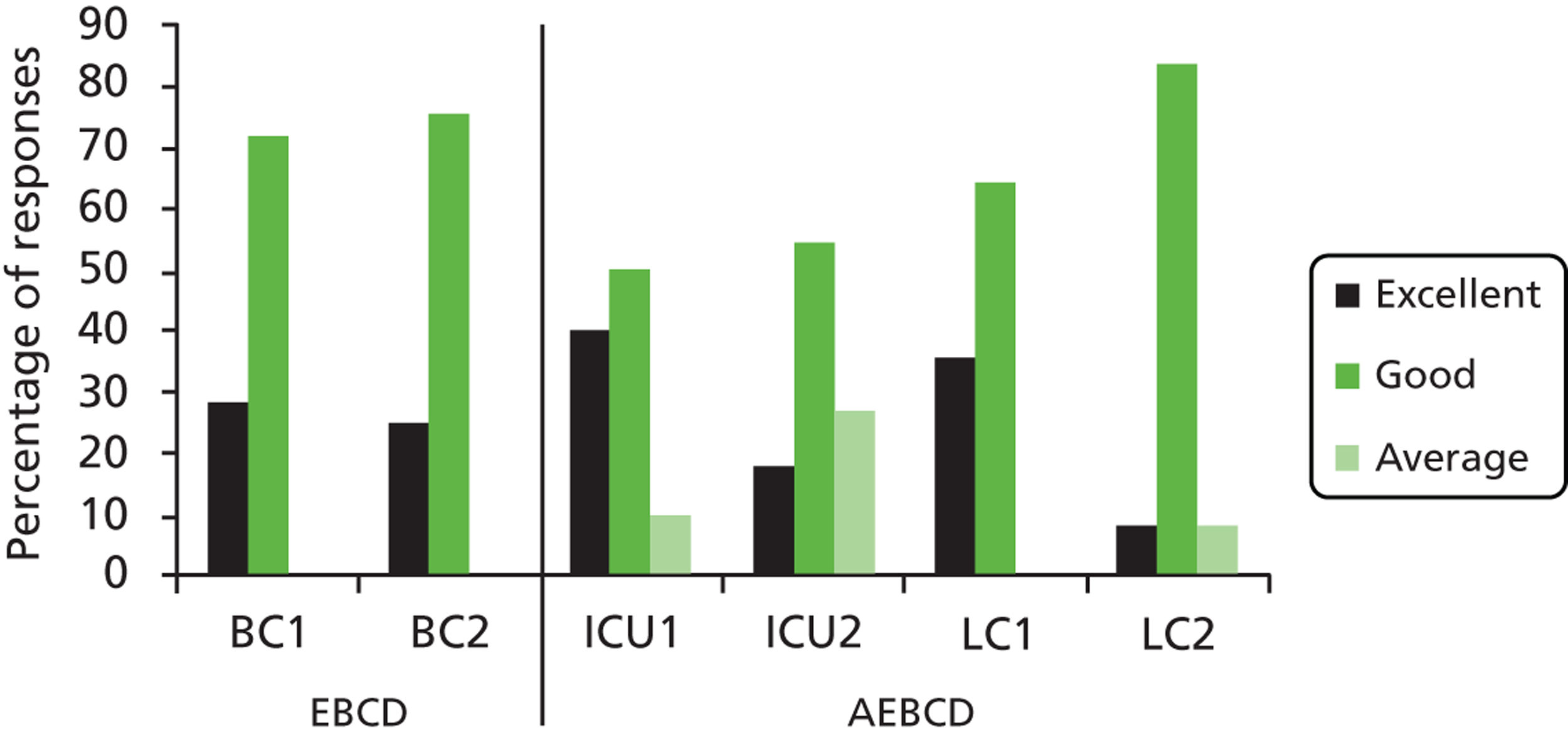

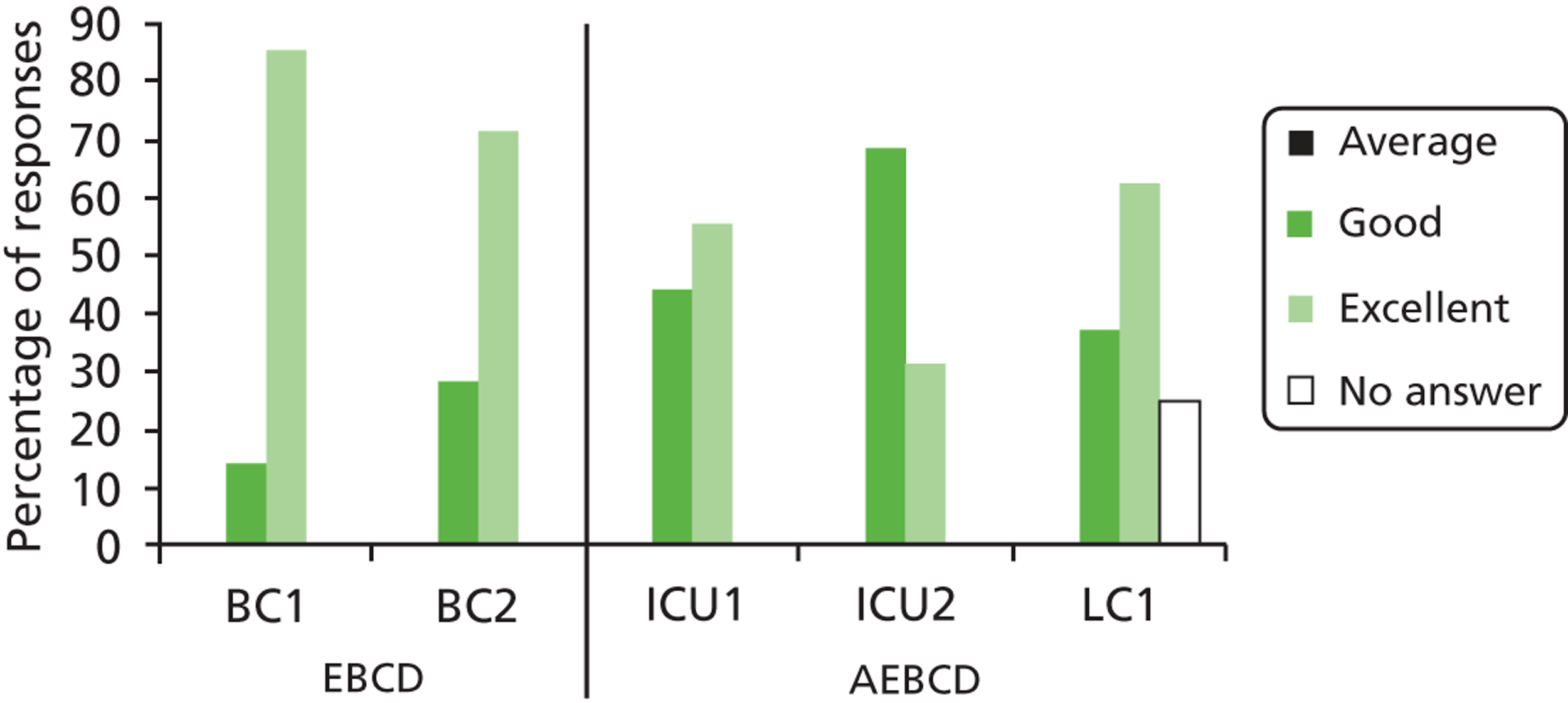

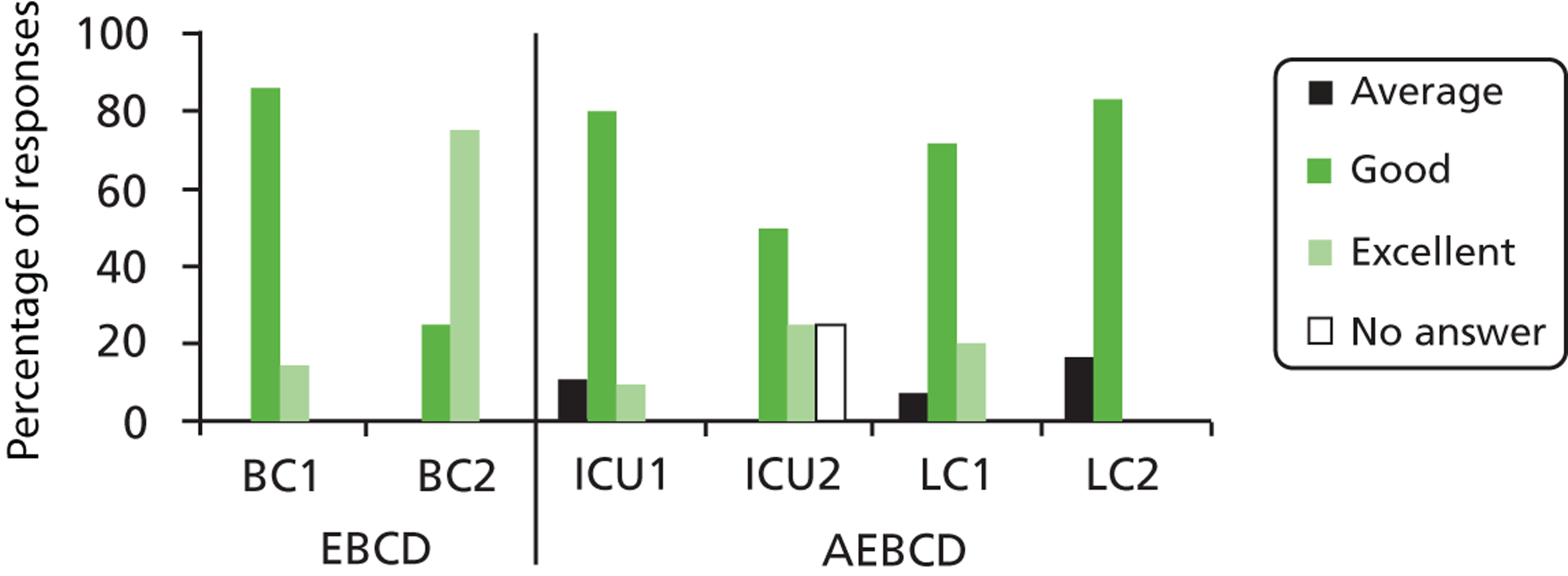

Evaluation questionnaires

End-of-event evaluation questionnaires were distributed at the end of each patient, staff and joint event. The questionnaire topics included experiences of watching the film; engaging with other patients and staff; and participating in co-design (see Appendix 3). The content was based on the questions used in the evaluation questionnaires used in the breast cancer EBCD project to generate comparable data. 36 A total of 170 questionnaires were completed by patients and staff across all four sites. Feedback forms were also distributed during celebration events to capture post-hoc experiences of participation and perceptions of impact. A total of 53 celebration event forms were completed by participants at three events. A brief evaluation form was also distributed at the end of co-design group meetings to capture the participation experiences. Where co-design groups held multiple meetings, this form was distributed only at initial meetings to avoid repetition. A total of 166 co-design group evaluation forms were completed by patients and staff across four sites.

Reflective diaries

Reflective diaries provided a source of direct information from project participants on issues and concerns regarding the day-to-day running of the project. They included information on activities that took place, and reflections on personal practice, professional participation and the process as a whole. The main emphasis was placed on obtaining project diaries from the project facilitators (17 monthly diaries were received from two facilitators), although other project staff such as the PI and CIs and patients and co-design group leaders were given the opportunity to complete diaries. A further 5 monthly diaries were obtained from the PI (n = 1), a trust lead/CI (n = 1), a patient representative (n = 2) and co-design group leaders (n = 4).

Document analysis

The following key documents which were produced as part of this process were collated and analysed: 80 key documents such as activity summaries, clinical governance and conference presentations, meeting minutes and action plans, interview summaries and internal reports; 101 e-mails exchanged between the facilitators and patient, staff, management and academic partners; and service improvement logs and three cost spreadsheets for the co-design activities.

Cost data

A cost spreadsheet was developed by the evaluation team and sent to project facilitators to enable them to log directly incurred costs such as travel and catering expenses as well as indirectly incurred costs such as staff time. The cost spreadsheet aimed to address the hidden cost of participatory research in terms of staff time released from clinical duties. Comparable EBCD data were extracted from the breast and lung cancer project budget files and consisted of cost data on researcher time, film production, facilitation and other costs similar to AEBCD (though it was not possible to collect, retrospectively, the staff time involved).

Comparative experience-based co-design data

In order to be able to compare AEBCD to EBCD, the following materials were consulted: four articles,16,52,56,71 one book30 and seven working papers on past EBCD projects. 36–38,72–75 We were also given access to the 71 evaluation questionnaires completed during the independent evaluation of a breast cancer EBCD intervention. 36

Analysis

Transcripts, documents and e-mails were entered into a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis package (NVivo, QSR International, Warrington, UK). Coding was based on the seven research questions as well as emerging themes. Data were tabulated using framework analysis76 based on the themes linked to research questions: acceleration, service improvement and approaches to design; and constant comparison with EBCD. More specifically, data analysis involved the following stages:

The first stage involved familiarisation with AEBCD and EBCD data – alongside the ethnographic data, the evaluation team revisited reports of previous EBCD evaluations and the AEBCD protocol.

The second stage consisted of detailed coding of the qualitative data using NVivo. The quantitative questionnaire data from both AEBCD pathways and EBCD pathways in breast cancer, lung cancer and an emergency department were entered into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Costing data were also collated in a series of tables.

As a third stage, the codes from the qualitative data analysis were indexed and used to develop a comparative framework based on three main themes: acceleration (film, facilitator and time frame), service improvement (performance, patient safety and patient experience) and implementation processes (enablers, barriers and legacy) to compare AEBCD and EBCD cases. The service improvement activities were also categorised based on a framework used by previous EBCD evaluators: grouping design ideas as small-scale changes, process redesign within teams, process redesign within teams, process redesign between services and process redesign between organisations.

As a fourth stage, quantitative data tables for the EBCD and AEBCD pathways were collated and used to generate graphical representations. The team also met with a health economist to support the analysis of the costing data for EBCD and AEBCD. Costs were estimated for each pathway based upon trust reported staff costs and these were combined with central project costs to estimate the average cost of implementing AEBCD. At this stage, the evaluation team met with the PI and CI Robert for a 2-day analysis meeting to consider the data collated and the emerging analysis. The discussion informed the further development of the analysis, mapping of key themes and interpretation of findings.

Patient, family and staff involvement

Patient involvement is a fundamental principle of both EBCD and AEBCD; patients and family carers were therefore an integral part of the intervention at all stages, and their views were central to the evaluation. At the heart of EBCD is also the creation of a coalition between patients and frontline staff as equal partners, and so staff involvement was also important.

The evaluation plan and proposed activities were discussed at the advisory group meetings where patients, support group representatives and staff from the two hospitals commented on evaluation design, methods (including data collection tools) and early findings. One of the patient representatives also checked the plain English summary of this report. The evaluation team found the opportunities to present emerging findings to the group meetings useful in developing their analysis, for example in helping to understand reported patient responses to the trigger films in the two pathways. Patients and staff in the two trusts were regularly informed and consulted about lines of enquiry, methods and tools during fieldwork visits. For example, drafts of the service improvement logs and costing tables were circulated for feedback.