Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1007/26. The contractual start date was in April 2011. The final report began editorial review in January 2013 and was accepted for publication in May 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

the University of Warwick received funding from NIHR in order to support this work; this money was provided to the institution and not to any of the authors, other than to cover relevant travel expenses.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Sujan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This report explores the risks to patient safety associated with failures of clinical handover within the emergency care pathway, and it investigates organisational factors that affect the quality of handover. Organisational factors relate to inner tensions within the activity of handover that require trade-offs, and to the management of the flow of patients across organisational boundaries and organisational cultures.

Findings are presented from a multidisciplinary qualitative study that investigated patient handover in three NHS emergency care pathways in England. The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) programme, Department of Health. The study was led by a research team based at Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, in collaboration with researchers from Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust, United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust, and Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust.

This research was justified by the broad agreement among relevant organisations, such as the British Medical Association (BMA), the Joint Commission and the World Health Organization (WHO) that clinical handover represents a crucial element in patient care, and that handover failures constitute considerable risks to patients. This is particularly true for the dynamic and time-critical emergency care pathway, where there is a recognised need for further research. 1–3

This project was designed in response to a call issued by the NIHR SDO on patient safety. The NIHR had previously funded research in patient safety that evidenced gaps in the existing knowledge base. In particular, the organisational dimension of patient safety was perceived to require further investigation. One of the highlighted areas for further research was around the safety problems when patients cross care boundaries, either interdepartmental or interorganisational. The study described in this report investigated the risks associated with failures of handover within the emergency care pathway, thus focusing on communication across organisations (ambulance services and hospitals), as well as across departmental boundaries [emergency department (ED), acute medicine]. The findings should be of use to practitioners and policy-makers as a basis on which to inform their decisions about possible improvements to the handover process.

Patient on a spinal board

The vignette below (Box 1) describes the case of a patient with suspected spinal injury, who was left in a cubicle in the ED without the nurse being aware. The ambulance crew (AC) had done a handover to the nurse co-ordinator, but were unable to do a handover to the nurse looking after the patient, as they needed to get back out on to the road in order to continue to deliver emergency response services in the community.

The project aimed to investigate systematically such risks arising from failed handover, and to describe the underlying organisational complexities that contribute to such failures.

The ED was busy due to of icy roads, and a large number of people being involved in road traffic collisions. The patient was the driver of a car involved in a low-speed collision, but had complained of neck and back pain at the scene. They were subsequently immobilised in a collar and head blocks, and put on a spinal board. On arrival in the ED, the patient was allocated to a bed space. The receiving nurse for that cubicle was not available to hand over to, so the crew independently transferred the patient on to a trolley, removed the spinal board, but left the patient immobilised. The crew then left. Shortly afterwards the patient was assessed by a doctor and nurse, and cervical spine radiographs were ordered. This necessitated the patient being on a firmer orthopaedic mattress to enable lateral transfer while maintaining spinal alignment. The crew had not been aware of the need for the patient to be on a special mattress, and in the absence of the nurse on transfer, and no handover having taken place, this important piece of equipment was missed initially. To resolve the issue, extra manual handling of the patient was required to get the patient on to another orthopaedic stretcher then lift them on to an orthopaedic mattress, with the consequences being increased staff time, delays in investigation for the patient and the clinical risks of increased handling of a potentially spinally injured patient.

Aims and objectives

The purpose of this study was to provide a systematic description of the risks associated with failures of clinical handover within the emergency care pathway, and to elicit and to describe staff perceptions on common organisational factors that impact on the quality of handover. The study focused on investigating interorganisational and interdepartmental handover.

The project addressed the following research questions:

-

R1 What is the potential risk of clinical handover failures along the emergency care pathway?

-

R2 What are common organisational deficiencies that affect clinical handover in the emergency care pathway, and what impact does the organisational model of emergency care delivery have?

The detailed objectives of the project were:

-

O1–1 To identify and to systematically describe clinical handovers within the emergency care pathway.

-

O1–2 To describe failure trajectories through the pathway and to systematically assess the potential risks of handover failures.

-

O1–3 To assess the frequency with which particular types of information are communicated, and the language forms that are used.

-

O2–1 To identify common organisational deficiencies that affect clinical handover in the emergency care pathway.

-

O2–2 To describe the impact on handover of the organisational model of care delivery within the emergency care pathway.

-

O3–1 To provide recommendations for improving clinical handover in the emergency care pathway.

Study design

Setting

Organisations participating in this study were two English NHS ambulance services and three English NHS hospitals [ED and acute medical ward or clinical decision unit (CDU)]. Each ambulance service provides emergency care in the catchment area of one particular study hospital and conveys patients there. The ambulance service providing transportation to the third study hospital felt unable to participate in this study. As a result, no observational, audio or interview data involving ambulance service staff were collected in the third pathway.

Participating organisations were chosen to reflect a range of characteristics in terms of the population they serve and their organisational structure (large inner city hospital; teaching hospital in an area with above average prosperity and life expectancy; district general hospital in a rural area with a large proportion of migrant workers). Below is a brief description of each of the five participating organisations.

Ambulance service A Ambulance service A serves a population of approximately 5.3 million people, and provides emergency transportation to the ED at hospital C. The population is ethnically diverse, and the area being served includes both deprived as well as prosperous areas, urban as well as rural. The ambulance service responds to approximately 800,000 emergency and urgent incidents annually. In 2011–12, the ambulance service achieved the targets for responding to category A calls [category A8 (CatA8) = 76.3%, category A19 (CatA19) = 98%].

Ambulance service B Ambulance service B serves a population of approximately 4 million people, and provides emergency transportation to the ED at hospital D. The population characteristics include wealthy areas with above-average life expectancy, as well as deprived areas. The ambulance service responds to approximately 500,000 emergency and urgent incidents annually. In 2011–12, the ambulance service achieved the targets for responding to category A calls (CatA8 = 75.9%, CatA19 = 95.3%).

Hospital C Hospital C is part of a large NHS Foundation Trust. The hospital provides services for a population of about 440,000. It provides local services to a very deprived community with ethnic diversity, as well as some specialist services for a wider population. The area has high infant mortality, teenage pregnancy and other markers of health inequalities. The hospital has a capacity of approximately 750 beds. The ED provides care for approximately 110,000 patients per year, with an admission rate of about 20%. The department has five resuscitation bays, with a dedicated paediatric resuscitation bay. The department has 25 other adult bays. There is an eight-bedded CDU that cares for 3500 patients a year. The ED has its own radiography department with the picture archiving and communications system (PACS). There is access to both computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging scanning. There is mobile ultrasound within the ED. There is a fully separate children’s area within the ED, with eight cubicles and a separate waiting area. Approximate staffing levels within the ED for a 24-hour weekday are nine foundation-year doctors over five staggered shifts, seven to ten middle-grade doctors over six staggered shifts, three advanced clinical practitioners (ACPs) over three staggered shifts up to midnight only, and three or four consultants over two staggered shifts up to 22:00 only, as well as eight qualified nurses of different grades, three unqualified health-care assistants (HCAs), and two ED practitioners during both day and night. The acute medical ward is located some distance from the ED on the same floor, and has 24 beds.

Hospital D Hospital D is part of a NHS trust comprised of four teaching hospitals. The hospital provides services to a population of approximately 650,000 (including 150,000 city central). The population is slightly younger than the regional and national average, and it has above-average health and life expectancy. The hospital has a capacity of approximately 850 beds. The ED provides care for approximately 90,000 patients per year, and 25% of these attendances are children. There is a separate children’s area with seven cubicles and its own waiting room. In 2011–12 the ED met the 95% 4-hour total time indicator. The department has four resuscitation bays: three adult bays and one paediatric bay. The department has 16 other major cubicles and a geographically separate ambulatory area (minors), consisting of nine cubicles. Approximate staffing levels within the ED for a 24-hour weekday are 18 medical staff (comprising two or three consultants, seven middle-grade doctors and eight junior doctors), 11 or 12 qualified nurses, one HCA, one emergency nurse practitioner (ENP) and one paediatric nurse during the day and nine qualified nurses during the night. The emergency assessment unit (EAU) is located adjacent to the ED, on the same floor as the intensive care unit (ITU), on level 1 of the hospital. It has 29 single-sex beds catering for acute ED and medical patients. The short-stay ward (< 96 hours) has 36 beds and is located on level 6 of the main hospital, and the long-stay ward (> 96 hours) has 110 beds and is located on the seventh floor of the same block.

Hospital E Hospital E is a district general hospital forming part of a NHS trust comprising three hospitals. The hospital provides services to a population of approximately 300,000. The hospital has a capacity of approximately 400 beds. The ED provides care for approximately 49,000 patients per year. In 2011–12 the ED fell short of the 95% 4-hour total time indicator (83%). The department has three resuscitation bays. The department has 19 other bays. Approximate staffing levels within the ED for a 24-hour weekday are seven medical staff, seven qualified nurses, two HCAs, one ENP and nine qualified nurses during the night. The acute medical ward is located behind the ED and has 27 beds.

Table 1 provides a basic comparison of the participating EDs. Table 2 shows the accident and emergency (A&E) national quality indicator data for the corresponding trusts for July 2012 (a trust can comprise several hospitals, hence the data are for more EDs than the ones participating in the study).

| Hospital | Population | Beds | Annual A&E attendances | A&E bays |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 440,000 | 750 | 110,000 | 30 |

| D | 650,000 | 850 | 90,000 | 36 |

| E | 300,000 | 400 | 49,000 | 22 |

| Trust | A&E attendances | Patient left before being seen (%) | Reattendance (%) | Time to initial assessment (median; minutes) | Time to treatment (median; minutes) | Total time in A&E (median; minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 21,731 | 4.5 | 6.8 | 0 | 65 | 148 |

| D | 10,068 | 4.5 | 5.7 | 40 | 111 | 188 |

| E | 12,618 | 3.2 | 6.3 | 2 | 53 | 139 |

In the remainder of this report, the term ‘study site’ or ‘site’ refers to the pathway consisting of ambulance services bringing patients to ED, the ED, and the acute medicine ward in the respective hospital for ambulance service A/hospital C, and ambulance service B/hospital D, and the pathway consisting of ED and acute medicine ward at hospital E.

Methods

The study design utilised a multidisciplinary qualitative research approach organised into two research strands. The methods used within each research strand will be described in detail in the corresponding section for the two research strands (see Chapters 3 and 4). A summary is provided in Box 2.

The aim of this research strand was to describe the potential risk of clinical handover failures along the emergency care pathway. The main data sources used were:

Qualitative risk analysisInformal observations.

Nine focus-group-based risk analysis sessions.

Conversation analysis50 audio-recordings of handovers for resuscitation patients.

90 audio-recordings of handovers for patients with major injuries.

130 audio-recordings of patient referrals from ED to acute medicine.

Research strand 2: organisational factors influencing handoverThe aim of this research strand was to describe common organisational deficiencies that affect clinical handover in the emergency care pathway, and to describe the impact of the organisational model of emergency care delivery.

Thematic analysis39 semi-structured interviews conducted with a purposive convenience sample of stakeholders in pre-hospital and hospital-based emergency and acute care.

A stakeholder workshop was held at the College of Emergency Medicine, London, in July 2012, to validate findings and to provide input on recommendations generated by the research.

Project timeline

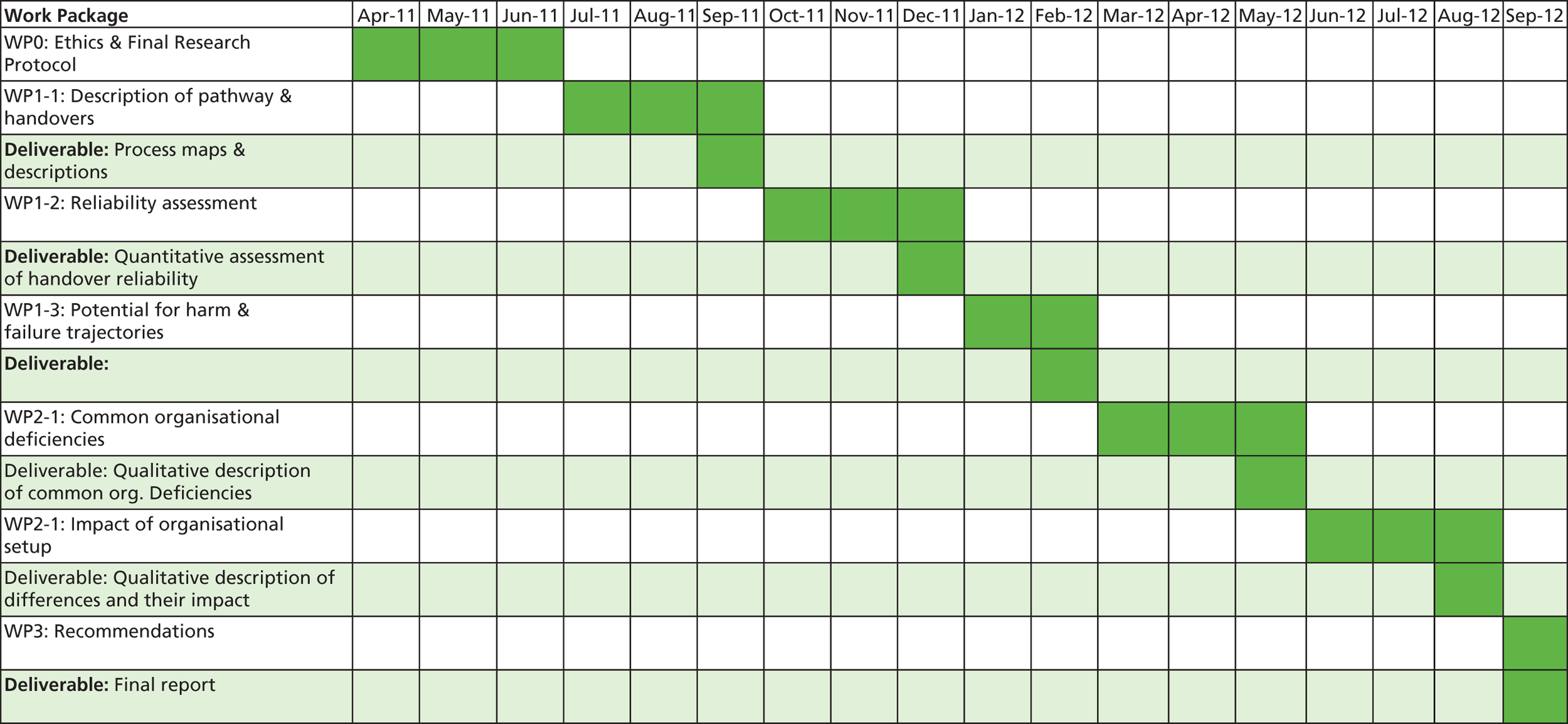

The study commenced in April 2011 and was completed in December 2012. A summary of the timeline for the different project activities is provided in Table 3.

| Activity | Duration |

|---|---|

| Ethics and institutional approvals | April 2011 to August 2011 |

| Research strand 1 | September 2011 to July 2012 |

| Research strand 2 | March 2012 to November 2012 |

| Recommendations and draft final report | November 2012 to December 2012 |

Some challenges occurred in the early phases of the project. One organisation withdrew from the study following an organisational merger prior to the start of the project. An additional organisation needed to be recruited and this incurred a delay of about 6 months until data collection could be started at this site. Prolonged unsuccessful negotiations with one ambulance service about institutional approvals delayed data collection at the corresponding hospital for about 4 months. The local Principal Investigator at one of the participating organisations had an illness-related absence for 4 months. This led to delays in data collection at this site. In light of these challenges a no-cost extension was requested and granted resulting in the revised end date of 31 December 2012 (the extension was for a period of 3 months from 1 October 2012 to 31 December 2012).

Research ethics

The study had full NHS research ethics approval from South Birmingham Research Ethics Committee (reference 11/WM/0087) as well as institutional approval at all participating organisations.

All study participants were staff of the participating organisations. Participants received a participant information leaflet, and provided written consent prior to their involvement. Participation was voluntary, and participants were free to withdraw at any time. Patient handovers were audio-recorded with the permission of participants, and the audio-recordings were subsequently transcribed and all identifiers removed from the transcript. The same process applied to the interviews. If participants did not consent to the audio-recording then the handover was not included in the data collection, and handwritten notes were taken during the interviews.

Report structure

The report is organised as follows:

Introduction Section just covered. Introduction to the research.

Background Background to the research and the relevant literature.

Risk analysis research strand Research strand 1: aims and objectives, detailed explanation of methods used for data collection and analysis, presentation and discussion of results.

Organisational factors research strand Research strand 2: aims and objectives, detailed explanation of methods used for data collection and analysis, presentation and discussion of results.

Discussion Findings of the two research strands and input received from the stakeholder workshop are brought together. Limitations of the study.

Conclusion Implications for health care and recommendations for research are described.

Appendices Additional data and materials.

Chapter 2 Background

Introduction

This chapter provides a brief overview to the background of the research and the relevant literature. A short section summarises the knowledge about the extent of preventable harm to patients (see Harm to patients). The following two sections describe key insights about risks posed to patient safety resulting from handover and communication failures in different care settings (see Handover as a risk to patient safety) and specifically in emergency care (see Handover and communication in emergency care). The chapter concludes with a description of identified research gaps (see The need for further research) that informed the development of the present study.

Harm to patients

It is now widely recognised that patients across all health-care systems may suffer preventable harm resulting from inadequate care provided. Since the publication of the landmark Institute of Medicine (IoM) report To Err is Human4 in the USA, and the UK Department of Health report An Organisation with a Memory,5 there has been a significant increase in research about patient safety and the factors that contribute to or adversely affect the delivery of safe care to patients. The IoM report included earlier findings of the Harvard Medical Practice Study6 that studied 30,000 discharges from 51 hospitals in New York State and concluded that around 3.7% of patients had suffered an adverse event during the course of their treatment. Around half of these were found to be preventable. The IoM report extrapolated these figures and estimated that there may be as many as 98,000 deaths in the USA resulting from medical error. Since, further studies in the USA as well as in other countries, including the UK, have found similar and often slightly higher figures. 7–12 There is now available a wealth of research from different medical specialties and different countries that indicates that health care is a high-risk domain where patients may be harmed, for example in surgery13,14 or medicines management and prescribing. 15,16

In addition to causing needless harm and suffering to patients, poor-quality health-care provision has significant financial implications for the health systems. In the UK, a study estimated that preventable adverse events could cost the NHS £1B annually in additional bed-days alone. 8 A report published by the Health Foundation compiles further evidence illustrating some of the costs associated with poor quality in health care. 17 For example, the costs to the NHS associated with adverse drug events are estimated to be around £0.5–1.9B annually.

Handover as a risk to patient safety

The purpose of handover

Handover denotes ‘the transfer of professional responsibility and accountability for some or all aspects of care for a patient, or group of patients, to another person or professional group on a temporary or permanent basis’. 18 Handover may occur between members of the same profession, for example during nursing shift change, or between individuals belonging to different medical professions or even different organisations, such as the ambulance service handover to the ED. Handover is a frequent and highly critical task in clinical practice, as it ensures continuity of care and provides clinicians with an opportunity to share information and plan patient care. 19

Handover is often regarded as a unidirectional activity, for example in analogy to sports as ‘passing the baton’ or similar. Ideally, however, handover should be thought of as a joint activity and a dialogue that creates shared awareness and provides an opportunity for discussion and error recovery as participants bring different perspectives and experiences to this interaction. 20–24 This includes not only the ‘telling of the story’ by the person giving the handover, but also interpretation and confirmation of the story, and the development of a mental model by the recipient of the handover, which allows seamless transition of care. 22 In addition, handover can serve further functions other than simple information transfer. These may include aspects of training, socialisation, and enhancing teamwork and group cohesion. 23,25

Handover failures contribute to patient harm

Communication failures are a recognised threat to patient safety. 4 In 2009, Johnson and Arora26 wrote that ‘the buzz generated by these [research, policy and improvement] efforts has resulted in handovers jostling for top position as one of the hottest topics in the global patient safety arena’. There is certainly now a large body of evidence, including a number of systematic reviews that suggest that inadequate handover practices are putting patients at risk. 27–31 Inadequate handover can create gaps in the continuity of care and contribute to adverse events. 32 A report prepared by the Joint Commission states that breakdown in communication was the leading root cause of sentinel events reported during 1995–2006. 33 The report further suggests that miscommunication during handover between medical providers contributed to an estimated 80% of serious medical errors. 33 A survey of 161 internal medicine and general surgery physicians in training in one US hospital found that 59% of respondents reported harm to one or more patients caused by inadequate handover, and 12% reported that the resulting harm had been major. 34 A survey of physicians in training on an acute paediatric ward found that in 31% of the surveys received the physician on call during the night reported that something happened for which they were not adequately prepared. The study suggests that these may have been linked to inadequate handover, as the quality of handover was rated below average on nights when something happened. 35

Some of the consequences and adverse events associated with inadequate handover include hospital complications and increased length of stay following multiple handovers,36 treatment delays,20,37 repetition of assessments,38 confusion regarding care,39,40 inaccurate clinical assessments and diagnosis and medication errors,41 and avoidable readmissions and increased costs. 33

Contributory factors leading to inadequate handover and communication

The existing literature on communication and handover in health care identifies a large number of contributory factors that may lead to inadequate handover. These include the following.

Lack of adequate standardisation

A frequently identified contributory factor is the absence of adequately structured handover processes. 26 Interviews conducted in an Australian hospital found that 95% of participants did not identify a formal procedure for shift-change handover. 38 A qualitative study comparing handover practices to pit stop practices in motor car racing concluded that handover had no clear procedures and was not supported by formal checklists. 42 A focus group-based study involving junior doctors found that shift handover was perceived as frequently being conducted in an ad hoc or chaotic fashion, and without obvious leadership. 43

Inadequate documentation and over-reliance on documentation

Another contributory factor discussed in the literature is missing and inaccurate documentation, or inadequate reliance on documentation. A study observing nursing handover of 12 simulated patients found that purely verbal handover resulted in information loss fairly quickly, whereas verbal handover supported by a typed handover sheet suffered only minimal information loss. 44 On the other hand, the use of such handover sheets may potentially make the handover more vulnerable by detracting from the focus on the most relevant items. 45 Over-reliance on medical records was reported in a study that investigated handover and communication between doctors and nurses. 46 This study found that often there was inadequate communication, and, as a result, there were disagreements on issues such as planned medication changes (42%), planned tests (26%) and necessary procedures (11%).

Non-verbal behaviour does not support building of shared understanding

Although the content of handover has been studied frequently, less is known about how non-verbal behaviour influences the quality of handover. A recent study in a number of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centres investigated types of non-verbal behaviour in nursing and physician handover. The authors concluded that participants frequently adopted forms of non-verbal behaviour that may result in suboptional transfer of information. 47 Such forms of non-verbal behaviour included holding patient lists or other artefacts in such a way that they could not be seen by the other participant (‘poker hand’), not having a joint visual focus (‘parallel play’) and situations where the person giving the handover was standing while the other party was sitting, which resulted in hurried handovers with fewer questions (‘kerbside consultation’). The most productive form of non-verbal behaviour was reported to be the joint focus of attention, where both parties co-ordinate their verbal and visual attention jointly on an object.

Lack of organisational priority given to handover and absence of training

The literature suggests that a lack of organisational priority given to handover, and the absence of formal training in communication and handover both at universities as well as within health-care organisations are further barriers to the implementation of effective handover. 26 A recent interview study investigating transitions from primary care into hospital suggested that participants perceived handover as an administrative burden that took away time for their patient care duties. The study also found that handover and communication competencies were rarely taught, and that clinicians learned these skills ‘by being around and immersed in the clinical effort’. 48 A national survey of internal medicine training programmes in the USA found that 60% of these did not provide training in handover. 36 One study reports that junior doctors had not received any training in handover, and that, as a result, they had a narrow view of handover concerning only completion of outstanding tasks. 43 Arora et al. 49 present a competency-based approach to improving handover that entails the development of a standardised instructional approach to teach communication skills and the establishment of corresponding robust assessment systems.

Standardisation of handover communication

The most frequently encountered recommendation for improving handover communication is that of standardisation through procedures, checklists or mnemonics, and appropriate training in their use. 31,42,49,50 Standardisation may simplify and structure the communication, and create shared expectations about the content of communication between information provider and receiver. 51 The Joint Commission introduced in 2006 a requirement for organisations to implement a standardised approach to handover. 28,52 The specific communication protocol recommended is situation, background, assessment, recommendation (SBAR),53 which provides a general order to topics. 51 A review of different handover mnemonics found that SBAR was the most favoured approach in practice. 31 As part of a simulation study, final-year medical students were taught the SBAR approach. The study found that this improved their handover performance during the simulation compared with students who had not received this training. 54 In the UK, trauma guidelines often include now the use of the ATMIST (age, time, mechanism, injury, signs, treatments) handover tool. The NHS Litigation Authority Risk Management Standards 2012–13 require an approved documented process for handing over patients. 55 This requirement stresses in particular consideration of the out-of-hours handover process, and emphasises the need for monitoring of compliance.

Handover and communication in emergency care

The characteristics of emergency care create additional challenges for handover

In the ED, the risks arising from inadequate communication and handover may be even more significant than in other areas, and the environment may be more conducive to communication failures. EDs have been described as high-risk contexts characterised by overcrowding conditions that pose particular threats to patient safety, such as ambulance diversions, treatment delays owing to long wait times, and patients leaving the ED without being seen. 1,56

Handover and communication taking place in such settings of high patient acuity and overcrowding are particularly vulnerable and pose significant risks not only to the patients being handed over, but also to other patients requiring urgent care. 20,57 The IoM report states that ineffective handover has been identified as one of the leading causes of medical error in the ED. 1

Problems with shift handover in the emergency department

Several studies have investigated shift handover in the ED. 58 An ethnographic study in five EDs found that practices varied significantly, and that they lacked structure and standardisation. 24 An Australian study investigating doctors’ shift handover in three EDs using a post-handover questionnaire and a survey tool found that in around 15% of cases required information was not handed over. 39 The missing information related predominantly to aspects of management, investigations and patient disposition. Participants stated that this resulted in repetition of assessments and delay in management of the care. The study found that handover failures were particularly likely for patients with longer stays in the ED, who received multiple handover.

Handover across boundaries is of particular importance in emergency care

There has been less research investigating handover across organisations,59,60 although this is starting to change. This area is of particular importance because of cultural differences, often high levels of uncertainty and absence of clear diagnosis, pending test and investigation results creating opportunities for omission, and the more vulnerable state of the patient, for whom delays or other handover failures may have serious consequences. 60 A systematic review of the literature pertaining to handover from ambulance services to EDs published in 2010 identified eight relevant studies. 27 The studies included in the review describe a number of barriers to effective handover. These include the lack of common language, perceived lack of active listening skills, lack of clear leadership, multiple repeated handovers, and inadequate environmental conditions. A subsequent ethnographic study found that the quality of handover between ACs and ED nurses appeared to be dependent on staff expectations, prior experience, workload and working relationships. 61

Similar results were found by studies that investigated the transfer of patients from ED to the hospital. In a survey of ED and internal medicine physicians, around 30% of respondents reported that one of their patients had experienced an adverse event or a near-miss following transfer from ED. 60 The survey identified communication problems, unsuitable work environment, information technology (IT) issues, and unclear allocation of responsibility as contributory factors. Participants in an interview study referred to the communication between ED and hospital physicians as ‘grey zone’ characterised by information ambiguity. 20 The conflicting information expectations of physicians from the different specialties represented a particular barrier to efficient handover communication. Randell and colleagues62 developed a descriptive model of handover that links the strategies that the participants of the handover adopt to the different contexts within which handover may take place and to the different functions that handover can serve. They provide examples, taken from observations in eight different settings, including an EAU and Medical Admissions Unit, of how practitioners adapt their behaviour and provide flexibility to the handover in response to, for example, different workload and staffing levels or particular patient conditions.

Improving handover in emergency care

Suggestions for improvement of handover include the adoption of structured communication protocols,20,51,60,61,63,64 the creation of opportunities for interdisciplinary, interdepartmental and interorganisational collaboration,60,61 the introduction of IT across departmental and organisational boundaries,60 and the teaching of appropriate communication skills20 including shared training programmes across organisations. 61

The need for further research

A systematic review of the literature on handover in hospitals up to 2008 argued that many of the severe risks to patient safety could be found in handover across departments, and that efforts at standardisation that are confined to departments may even exacerbate the situation for interdepartmental handover. 28 The review concluded that there was no reliable body of evidence that standardisation of handover provided sustainable improvements in patient outcomes. This insight and the brief review above suggest that current research is limited by its predominantly narrow focus on transfer of clinical content and the adherence to a standardised communication protocol,26,50,65 and the equally narrow focus on shift handover or handover within a single department. 48,66 Further research is required that addresses the following:

-

The role of handover in the wider network of activities of each actor Further research is required that goes beyond consideration of the transfer of clinical content. This research should investigate the role that handover plays in the wider network of activities of each actor. The research should provide descriptions and models of the goals and motivations of the actors and their resulting needs and behaviours, and of the structural and organisational environment within which handover and the actors’ other activities take place. 60,65 This would enable better understanding of the risks that arise from handover failures and their underlying causes. Such a broader view might also contribute to understanding why standardisation of communication has not achieved its potential,47 and it may provide insights as to when and how standardisation could improve handover practice.

-

The embeddedness of handover in the activities and goals of actors across departments and organisations The second area where further research is required is in understanding handover across organisational boundaries. Different organisations have different goals and exhibit different local cultures and behaviours. 26 Handover across organisations implies that these differences have to be reconciled and overcome through negotiation and adaptive forms of behaviour. Further research should provide qualitative accounts and models that describe how handover is embedded in the activities and goals of actors across departments and organisations, and how the actors achieve the alignment of their different individual and organisational motivations and backgrounds. Such research could be particularly useful to understanding risks that arise from unclear allocation of responsibility for patient care across organisational boundaries, enabling organisations to develop necessary systems of collaboration, responsibility and escalation.

Chapters 3 and 4 describe in detail how the research project contributed to each of the two domains identified above.

Chapter 3 Systematic identification and analysis of the potential risks of clinical handover failures

Introduction

Research strand 1 was concerned with the identification and analysis of the risks associated with handover failures in the emergency care pathway, using methods from improvement science and safety engineering. This chapter summarises the aims and objectives of the research strand (see Aims and objectives) and then briefly describes the principles of systematic risk analysis (see Principles of risk analysis). Longer sections describe in detail the methods used (see Methods) and the results obtained (see Results). A discussion concludes the chapter (see Discussion).

Aims and objectives

The aim of this research strand was to identify and to analyse systematically the risks of clinical handover failures within the emergency care pathway.

Specific objectives were:

-

O1–1 To identify and to describe systematically clinical handovers within the emergency care pathway.

-

O1–2 To describe failure trajectories through the pathway and to systematically assess the potential risks of handover failures.

-

O1–3 To assess the frequency with which particular types of information are communicated, and the language forms that are used.

Principles of risk analysis

Undertaking a systematic risk analysis is a legal requirement in safety-critical industries. 67 The purpose of systematic risk analysis is to inform the risk management process on the ways in which harm can occur, the frequency with which these may occur, and the severity of the harm should it present itself. Risk analysis is a proactive approach, i.e. the analysis takes place before a harm event has occurred, and it may even be applied before a system or service is operational in order to demonstrate adequate safety and fitness for purpose.

Following risk analysis, the risk management process usually entails steps to determine appropriate risk controls (risk reduction measures), to implement the risk controls and to monitor their effectiveness. 68 These subsequent steps were outside the scope of the project.

In the safety engineering community there is the distinction between ‘hazard’ and ‘risk’. A hazard denotes a situation that may lead to harm. Risk is a description of the likelihood of occurrence of the hazard and the severity of the consequences. The Health and Safety Executive defines these terms as:67

-

Hazard ‘The potential for harm arising from an intrinsic property or disposition of something to cause detriment.’

-

Risk ‘The chance that someone or something that is valued will be adversely affected in a stipulated way by the hazard.’

Consequently, systematic risk analysis entails identification of relevant hazards and subsequent investigation of the risks posed by these. Risk analysis can be carried out in a number of ways. It becomes ‘systematic’ when there is a formal process describing and guiding how it is carried out. Risk analysis can be both qualitative as well as quantitative. In many high-risk industries both forms are used. There is a range of methods supporting the risk analysis process, such as failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA),69 hazard and operability studies,70 fault tree analysis71 and event tree analysis. 72 In practice, several of these are usually utilised in order to provide a broad and comprehensive characterisation of risk.

Increasingly, policy-makers in health care recognise the need for proactive assessments of threats to patient safety. In particular, the use of FMEA is now recommended widely in health care as an appropriate tool for proactive safety analysis. For example, the Joint Commission requires from participating organisations evidence that they carry out at least one proactive assessment of a high-risk process every year,52 FMEA being the approach recommended. The US VA has developed an FMEA version tailored to health care, health-care failure mode and effects analysis. 73 During the past few years, FMEA has been used in health care to assess the risks associated with, for example, organ procurement and transplantation,74 intravenous drug infusions,75 blood transfusion76 and communication in the ED. 77

The approach to risk analysis adopted in this project to identify and describe the risks associated with handover failures in the emergency care pathway follows largely the standard FMEA approach for qualitative hazard identification and risk analysis. This will be described in detail for this research strand in the next section.

Methods

Systematic description of clinical handover within the emergency care pathway

For the purpose of this study of handover, the emergency care pathway consists of handover from the ambulance service to the A&E department, handover within the A&E department, and handover (or referral) from the A&E department to the acute medical unit (AMU) or CDU, where the majority of patients that are admitted to hospital go to from A&E. The focus of the study was on handover involving patients with major injuries and resuscitation patients, as the risks arising from handover failures are greater for this category of patients.

Familiarisation with the pathway by the researcher at each site was achieved through process walks and informal observation. Together with process mapping these are widely adopted improvement science methods, and are recommended by bodies such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in the USA78 and the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement in the UK. 79 Process mapping was also a key tool for understanding the discharge process as part of the HANDOVER project funded by the European Union. 80 The purpose of the familiarisation phase was to enable the researcher to build an initial understanding of the flow of activities, and to identify suitable staff roles for participation in the subsequent process mapping session.

Process mapping is an improvement method based on the focus group approach. 81 It has been used traditionally as part of quality improvement initiatives, such as ‘Lean’. 82,83 The aim of process mapping is to provide a graphical representation of the process, which represents a shared understanding of all the stakeholders involved. Process mapping is a quick way of providing a relatively simple (compared with, for example, more resource-intensive ethnographic approaches) graphical representation of how work unfolds in practice. The group setting that is a characteristic feature of focus groups is useful for stimulating discussion among participants, where they can present their unique point of view, be made aware of possibly differing points of view of their colleagues and comment on their respective experiences. This is very relevant to process mapping, as each staff role or actor will have their own goals in addition to the overarching shared process goal, and each will usually see only part of the process and will thus be less familiar with the steps preceding or following their own.

For each pathway, a half-day process mapping session was held in order to produce a graphical representation of the process. The graphical representation used was a simple sequential flow diagram. Figure 1 illustrates the elements of the graphical notation used. Each session was held on the premises of the respective A&E department and involved a purposive convenience sample of participants from ambulance services (for ambulance service A/hospital C and ambulance service B/hospital D), the A&E department and the AMU or CDU. Two members of the project team with experience in conducting process mapping (NR and MS) facilitated the process mapping sessions together at each site. Table 4 provides a detailed breakdown of participants by role. The output of the process mapping session was a graphical representation of the process generated by the participants.

FIGURE 1.

Sequential process mapping graphical elements.

| Role | Ambulance service A, hospital C | Ambulance service B, hospital D | Hospital E |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paramedic | 2 | 1 | – |

| A&E senior nurse (co-ordinator) | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| A&E staff nurse | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A&E consultant | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| A&E middle-grade doctor (registrar) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Acute medicine senior nurse | 1 | 1 | – |

| Acute medicine middle grade (registrar) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 9 | 8 | 5 |

The sequential process map provides a description of the key steps of a process. It is an abstraction and simplification. The opposite extreme is represented by ethnographic approaches that provide a ‘thick description’ of human behaviour and the context within which it takes place. 84,85 Following such an in-depth approach was not part of the project design. In order to complement the sequential process map with some contextual description, participants were prompted to consider who is involved in each process step, what each actor’s respective goals are, what kind of external or cognitive tools the actors are using, and what kind of tacit knowledge is called upon in order to carry out the process step. The template used to represent individual process steps is shown in Table 5. The terminology is derived from Activity Theory, an approach rooted in cultural–historical psychology. 86,87

| Actor | Goal | Artefacts (external tools, cognitive tools) | Rules (tacit knowledge, social rules) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staff roles involved in carrying out a particular activity | The goals of each of the actors | The external and internal (cognitive) tools that are used to accomplish the goals, e.g. documents, procedures | The informal rules and the knowledge that regulates how staff behave within the team/within their work place, e.g. knowledge of what is usually done |

Systematic risk identification and risk analysis

The identification and analysis of risks associated with failures of handover was achieved through the application of standard FMEA. 69 FMEA is a proactive, inductive, bottom-up approach for analysing systems in order to evaluate the main vulnerabilities and the potential for failures. 88 FMEA originated in the reliability engineering community as a tool to enhance the reliability of military equipment. It is now a widely adopted technique across industries.

Failure mode and effects analysis considers the possible failures of a system component (failure modes) and determines potential consequences of such a failure on the system. FMEA is systematic in that this process is repeated for every component and every failure mode. Failure modes are prioritised based on the risk they pose. The risk is described as a multiplicative combination of the likelihood of occurrence of the failure mode and the severity of the consequences. In some forms of FMEA a third parameter, the likelihood of detection of the failure, is included in the calculation. These values are usually based on expert judgement. FMEA is particularly useful for identifying single failures that could result in catastrophic consequences. Owing to its systematic approach, FMEA is considered very resource intensive. 68

Failure mode and effects analysis is usually utilised to contribute to the identification of hazards and the qualitative risk analysis of technical systems. As a result, there are often well-established lists of possible failure modes, sometimes with corresponding quantitative failure rates, on which the analyst can draw. Depending on the situation, FMEAs for technical systems are conducted by a single or a small number of engineers. For use in sociotechnical systems, the approach needs to be adapted. In health care, the application of FMEA typically is based on the focus group approach, similar to the process mapping described above. FMEA requires a ‘system description’ and this is usually derived from a process map in health care. In addition, one of the biggest benefits of the application of FMEA in health-care settings is the interaction created among stakeholders in the group setting. 89 The application of FMEA in health care commonly is not as detailed and not as exhaustive as for technical systems due to resource constraints.

One member of the project team (MS) with experience in conducting FMEA facilitated two half-day FMEA sessions at each site with the participants who had already contributed to the process mapping. At the start of the session, the facilitator explained the aims of the session and provided a brief introduction to FMEA. The process map produced during the preceding process mapping session was used as the basis for the analysis. A template sheet was used to record the results of each FMEA (Table 6). Discussion of process steps selected for analysis was restricted to 1 hour maximum per step in order to ensure broad coverage of the process given the time available for the risk analysis. Ratings for the likelihood of occurrence and the severity were determined according to the rating scheme described in Table 7. This rating scheme was developed and agreed during a project meeting. The descriptions have been chosen pragmatically through discussion with the aim of providing a spectrum of scores that would be used fully (i.e. all scores were deemed to be likely to be used during the FMEA). Conflicting views of study participants were resolved in discussion, where the aim was not to reach a consensus (e.g. an averaged risk score) – rather, the discussions were aimed at providing insights into the different assumptions and interpretations about the task at hand. Once participants had a common frame of reference, conflicts usually disappeared and led to the identification of additional failure modes or a differentiation of the consequences, rather than an averaged-out consensus risk score. For some of the highest-ranking risks, contextualised failure trajectories (described as ‘vignettes’ in this report) were produced subsequently in discussion with stakeholders. These are based on examples that participants provided during the FMEA sessions to illustrate the failure modes. The contextualised failure trajectories are, therefore, grounded in actual experiences, but should not be regarded as objective description of an actual case as they represent one or several individuals’ recollection of events that may have happened some time ago. The purpose of these failure trajectories is to provide a more realistic and contextualised description of risks to people who have not participated in the risk analysis sessions, and who may find reading an abstract template sheet difficult. Hence, factual accuracy is not necessary. The failure trajectories also enable better appreciation of the multiple contributory factors and underlying organisational complexities than is possible with the abstract tabular FMEA representation alone.

| Step | Failure Mode | Consequences | Likelihood | Severity | Risk Score | Causes | Mitigation |

| Value | Likelihood | Severity |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Less than once a year | No harm or increased length of stay |

| 2 | Less than once a month | Non-permanent minor harm or increased length of stay |

| 3 | Less than once a week | Non-permanent major or permanent minor harm |

| 4 | Less than once a day | Permanent major harm |

| 5 | Once a day or greater | Death |

Assessment of the frequency of information types and language forms used

To provide an in-depth description of the verbal communication act of handover, three different types of handover that include the transfer of responsibility for patient care were selected for the study with a focus on interorganisational and interdepartmental handover. The three different types of handovers selected were (1) paramedic to A&E nurse (major injuries); (2) paramedic to senior A&E doctor (resuscitation cases); and (3) telephone referrals from A&E doctor to AMU (or CDU) doctor or senior nurse (major injuries).

Patient handovers were audio-recorded by members of the project team during daytime (0800–1800) for a period from November 2011 to July 2012, on days when the researcher was on site. Prior to the recording, participants were asked to provide verbal consent to ensure that they were still happy for the researcher to capture this particular episode. Participants had already provided written consent before the start of the data collection period. The audio-recordings were subsequently transcribed and all identifiers removed.

In the original research plan, the objective of this activity was to provide a frequency count of the types of content communicated during handover as a proxy measure for the reliability of handover compared with a core data set. It was intended to use this information as input to the systematic risk analysis to act as prompts for participants to consider. However, the data collection started later than anticipated, and the data collection process was slower than expected. In particular, collecting data for resuscitation cases proved to be difficult, as these are less frequent occurrences and, owing to their highly critical nature, asking for consent and audio-recording the episode was not always possible. As a result, the project team decided to complete the systematic risk analysis without the input provided from this activity. Instead, it was decided to extend the analysis of these handovers to consider both content as well as language forms used to communicate the content.

Conversation analysis (CA) was used to describe the content and the language form used for each handover. 81,90 CA is an approach to the study of social interaction based on the notion of turn-taking behaviour. The spoken utterances of each participant represent turns, which are both facilitated by and dependent on the behaviour and utterances of the other participant. Such sequences of turn-taking often exhibit stable and recurring patterns that are characteristic of particular types of social interaction. The notion of repair relates to behaviours that participants employ to deal with problems in the interaction.

Conversation analysis was chosen as analytic approach for two reasons. A previous study91 used discourse analysis to develop a handover assessment tool based on the analysis of a small sample of 15 handovers from ED physicians to hospital doctors. Following a similar approach would allow comparison of the findings. Secondly, CA is a useful tool to provide a better understanding of how difficult aspects of the handover communication are generated and dealt with, for example the transfer of responsibility or coping with situations of uncertainty.

The project team discussed the coding categories used in the previous study91 in a review meeting. Two small changes were introduced to the originally proposed coding categories. It was felt that the category ‘history’ was broad and may hide some of the issues of particular interest to the study, such as the social situation and background of patients. As a result, this category was split into two separate categories: ‘clinical history’ and ‘social history’. The second change was the introduction of the category ‘injury’, as this is an integral part of ambulance service handovers that follow the age, time, mechanisms, injury, signs, treatments (ATMIST) protocol and it may fall ambiguously between the original categories ‘history’ and ‘symptom’. No other changes were introduced in order to stay as close as possible to the coding categories of the reference study. The resulting coding scheme is shown Tables 8 and 9.

| Coding category | Definition |

|---|---|

| Patient presentation | |

| Patient identifiers | Statements that convey patient identifiers such as name, date of birth or hospital number |

| Clinical history | The patient’s past medical problems/conditions that are pertinent to the current diagnosis or clinical impression |

| Social history | The patient’s social circumstances describing, for example housing situation and existing care arrangements, family or friends accompanying, etc. |

| Injury | Statements that convey the mechanisms and the injuries sustained |

| Symptom | Descriptions and explanations that provide information about symptoms of concern |

| Procedure | Statements about pertinent laboratory data, pertinent test results, medications, and evaluation that already been performed to address the patient’s current condition |

| Assessment | |

| Treatment | Statements about future medical procedures to be taken to address the patient’s current problem |

| Clinical impression | Identification of the current clinical impression, naming the problem or reasons for the problem |

| Prognosis | Probabilistic statement about patient’s future condition based on completed or proposed treatments |

| Outcome | Definite utterances about the result of the handover, e.g. accept, not accept, wait and see |

| Transfer of responsibility | Statements about what was being asked of the recipient of the handover |

| Professional environment | |

| Logistic processes | Descriptive or evaluative talk about logistics or procedural issues in ED, hospital or health-care system |

| Courtesies | Statements such as ‘thank you’, greeting and closing remarks, etc., which provide a context of professional courtesy |

| Coding category | Definition |

|---|---|

| Information seeking | |

| Closed question | An utterance that is designed to solicit specific information |

| Open question | An utterance that is designed to solicit information in a manner that affords the respondent the opportunity to elaborate |

| Clarifying question/request | An utterance that is a question designed to seek clarification of another’s immediately preceding utterance; may take the form of a request |

| Information giving | |

| Description | Utterances that provide description about the patient and the patient’s past or present condition and circumstances |

| Explanation | Utterances that state the facts and make an inference about the patient |

| Rationale | A justification is offered to account for any medical procedures, tests, medications or recommendations concerning the patient; the intent is to justify why an action has been taken or will be taken in the future |

| Directive | Advisements, orders or recommendations that inform patient evaluation, treatment and disposition |

| Context talk | Talk about contextual issues in clinical environment such as logistics and procedures |

| Social amenities | Utterances in which physicians exchange courtesies and talk that tells the sender that the receiver is paying attention |

| Decision | Utterances in which the physician accepts or does not accept the patient; may be directly stated or implied |

| Information verifying | |

| Read-back | Statements that paraphrase or restate what the other has said |

Two members of the project team with a human factors and a clinical background (MS and PC respectively) coded an initial sample of 30 transcripts of audio-recordings collaboratively to allow familiarisation with the coding scheme. Ambiguities and uncertainties were resolved in discussion. One researcher (PC) subsequently coded the remaining audio-recordings independently. Simple frequency counts of handover content and language form were performed for each type of handover and for each study site.

Findings from existing literature, the reference study,91 and the output of the risk analysis informed the exploration of potentially problematic aspects of the communication, such as the transfer of responsibility. All transcripts were reread, and patterns of turn-taking were identified and described through examples.

Results

Systematic description of clinical handover within the emergency care pathway

A summary description of the emergency care pathway for each site is provided below. For each site, the pathways for resuscitation patients and patients with major injuries are described, from ambulance services into the ED and to the AMU (or CDU), with a particular focus on communication and handover (i.e. predominantly clinical steps such as ‘treat patient’ have been described at the highest, most abstract level). Further details about the different motivations or goals of the actors involved, and the tools and knowledge they may use can be found in Appendix 1. An in-depth analysis of the content and language forms of particular types of handover within the pathway is described in the Results section below (see Content and language form of handover). The interviews conducted as part of research strand 2 provide further insights into how people perceive these handovers.

Ambulance service A/hospital C

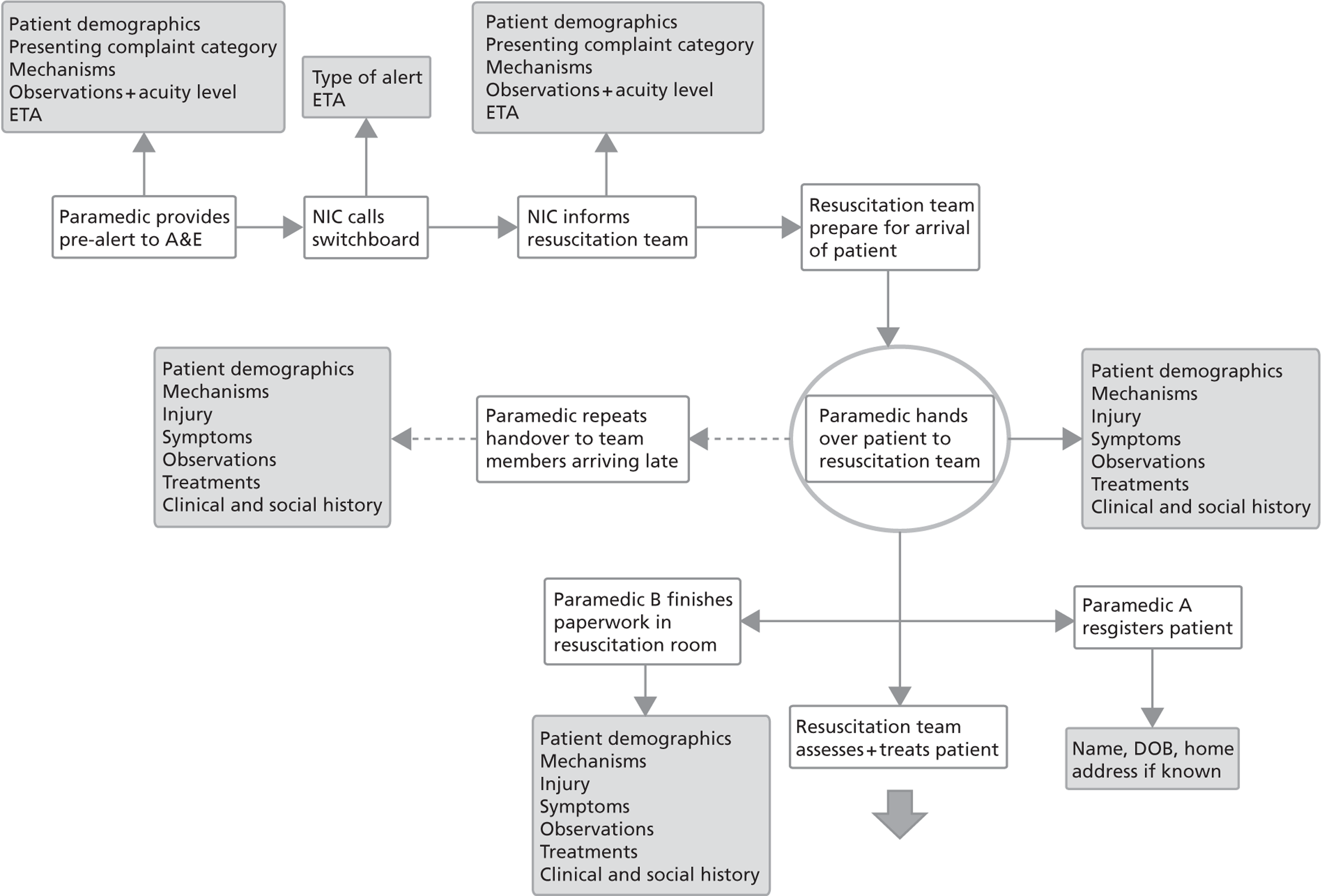

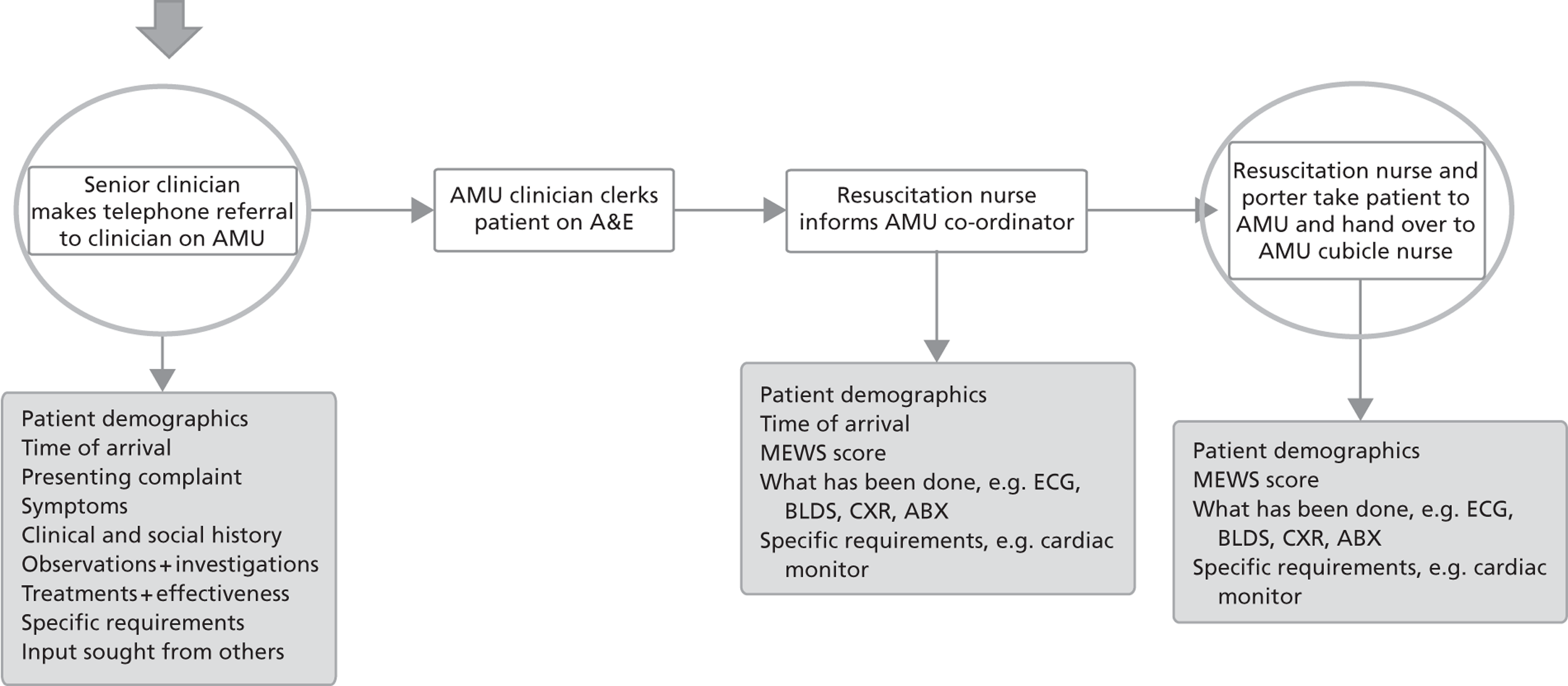

The graphical representation of the pathway for resuscitation patients is shown in Figures 2 and 3, and the representation for the pathway for patients with major injuries is shown in Figures 4 and 5. The complementary tabular descriptions are included in Appendix 1.

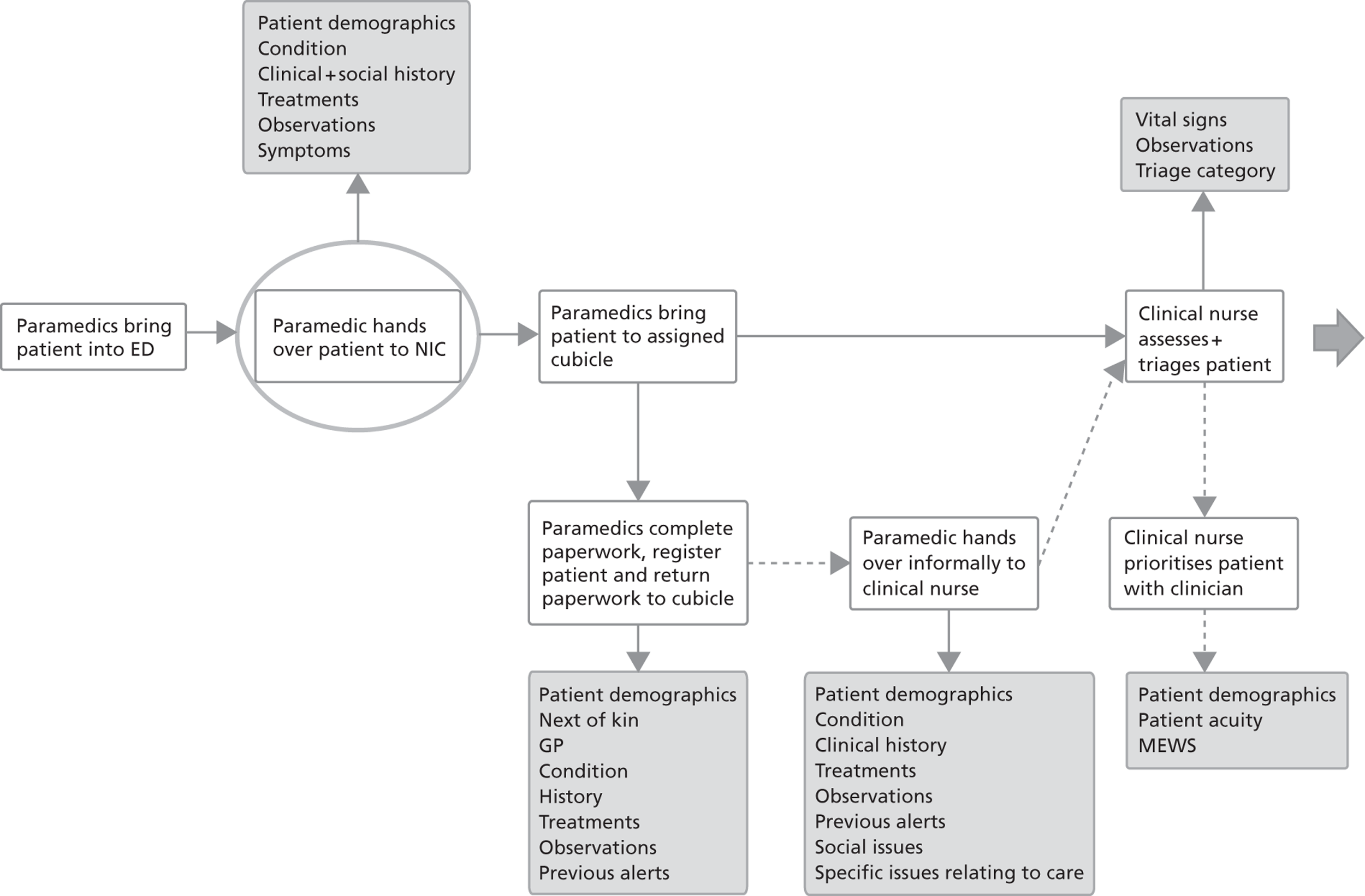

FIGURE 2.

Hospital C resuscitation pathway – part 1. DOB, date of birth; ETA, expected time to arrival; NIC, nurse in charge.

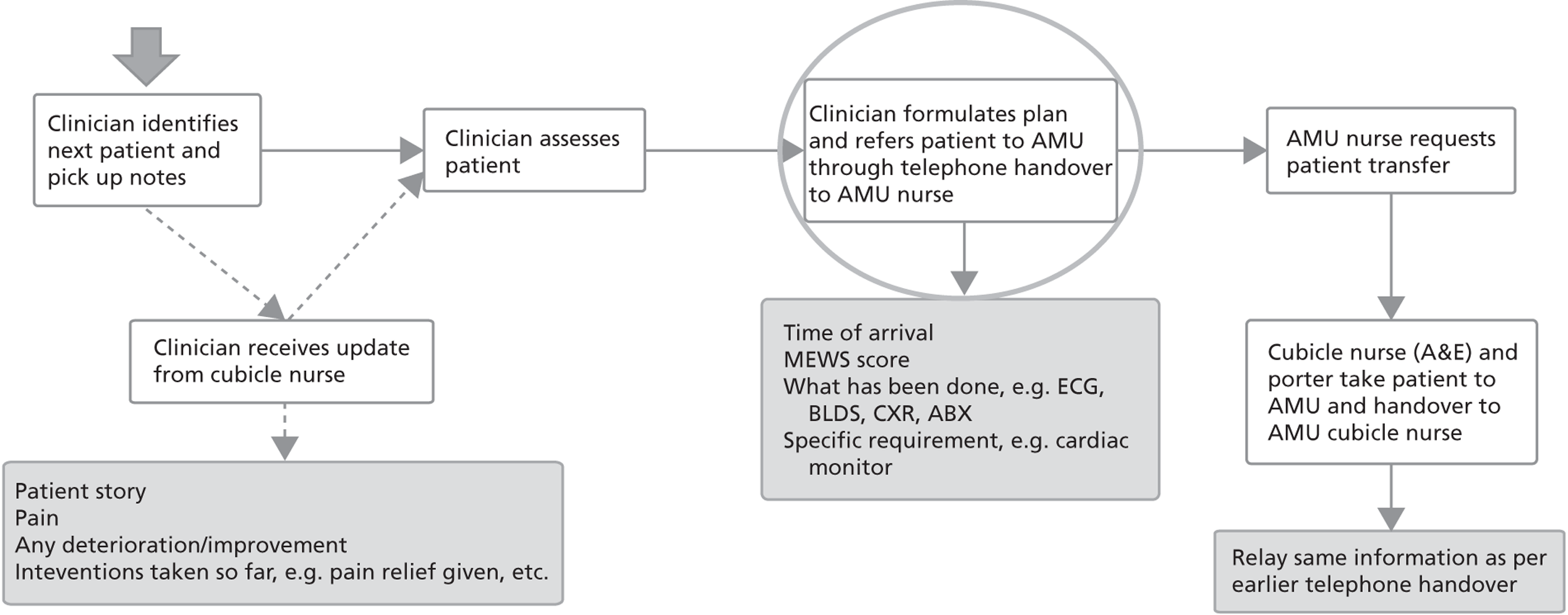

FIGURE 3.

Hospital C resuscitation pathway – part 2. ABX, antibiotics; BLDS, bloods (blood tests); CXR, chest X-ray; ECG, electrocardiogram; MEWS, Modified Early Warning Score.

FIGURE 4.

Hospital C major injuries pathway – part 1. ACC, ambulance control centre; BLDS, bloods (blood tests); DOB, date of birth; ETA, expected time to arrival; MEWS, Modified Early Warning Score.

FIGURE 5.

Hospital C major injuries pathway – part 2. ABX, antibiotics; BLDS, bloods (blood tests); CXR, chest X-ray; ECG, electrocardiogram; MEWS, Modified Early Warning Score.

In the resuscitation pathway, the first type of handover may occur when the ambulance service [either the AC or the ambulance control centre (ACC) having received this information from the AC] provides a pre-alert to the hospital ED, providing initial information about patient demographics, presenting complaint category, patient acuity and expected time of arrival. This handover provides an anticipatory and logistic function. The A&E resuscitation team uses this information to inform and to assemble the appropriate staff members and other teams (e.g. trauma team), to prepare the resuscitation bay and to ensure that necessary equipment is available. The next type of handover occurs when the ambulance arrives at the ED and the patient is brought into the resuscitation room. One AC member hands over to the senior clinician (in this organisation the term clinician is used refer to roles that make decisions on the treatment of patients, such as doctors of different grades, ACPs and ENPs) information including patient demographics, clinical history, mechanisms and details of injury, assessments done by the AC, any treatments undertaken, and the known medication history. The social history is not usually handed over at this stage. The handover should follow the ATMIST communication protocol. Although the handover is to the senior clinician, other team members listen in, and they may have questions themselves. This handover is considered the main handover between the ambulance service and the ED. It serves the dual functions of communication of immediately relevant clinical information and of transfer of responsibility for patient care. Sometimes, aspects of the handover are repeated when team members arrive after the handover. The AC member remains in the resuscitation room during the first part of the assessment in order to finish the paperwork and to be available for further questions. The patient report form (PRF) is an important tool for the handover, as it documents all the information that was available to the AC, even if some of this was not verbally handed over (e.g. social history). It provides an archival function, enabling future access to information. The second crew member registers the patient at reception, where another secondary handover occurs including patient demographics. This handover provides a logistic function.

The next handover occurs when a decision to admit has been taken, and the senior clinician makes a telephone referral to a clinician on the AMU. This telephone handover includes patient demographics, presenting complaint, observations and investigations done, any treatments that have been done and their effectiveness, as well as a request for referral, either explicit or implicit. This telephone handover is considered as another point at which there is a transfer of responsibility for patient care, although practically the patient remains under the care of the ED. In addition to the referral, there are two further handovers between A&E and AMU. The resuscitation nurse gives a nursing handover to the AMU co-ordinator on the telephone. This involves the communication of information including patient demographics, Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS), assessments and treatments done, specific requirements, and the time of arrival of the patient in the ED. This handover provides both an anticipatory and logistic function. The second handover occurs face to face, when an A&E nurse and the porter take the patient to AMU. This handover communicates the same information as the previous telephone handover but this time the handover is to the nurse who will be looking after the patient. This handover entails a full transfer of responsibility for patient care.

For patients with major injuries there is not normally a pre-alert. The AC typically provides a brief status update to their control centre, communicating basic details about presenting complaint category, patient acuity and expected time of arrival to allow monitoring and oversight of ambulance activities. This information is also available to the hospital ambulance liaison officer (HALO), who is stationed in the ED. The first handover to the ED occurs when the AC arrive at the ED with the patient. This handover is a verbal handover to an assessment nurse at the rapid assessment triage (RAT) point, and it potentially includes all of the clinical and social information that the AC has gathered, for example patient demographics, clinical and social history, symptoms, and any assessments and treatments done. The PRF supports the handover. The assessment nurse triages the patient and instructs the AC to take the patient to a dedicated cubicle. This handover is perceived to include a transfer of responsibility for patient care, and this is documented by signing the PRF. In parallel to this handover, the second crew member registers the patient and does a basic handover to the receptionist, providing a logistic function. The assessment nurse then goes to do an in-depth assessment of the patient. There may be optional, additional handovers depending on the acuity of the patient and the workload and availability of the cubicle nurse. The assessment nurse may prioritise the patient with the physician or may instruct the cubicle nurse to undertake certain activities. The latter serves the purpose of delegation of aspects of patient care. A further optional handover may occur if the cubicle nurse provides an update on the patient to the clinician who comes assess the patient. The next handover occurs when a decision to admit is taken, and the clinician refers the patient to AMU through a telephone handover to the AMU nurse co-ordinator. On the AMU side, this handover is supported by a SBAR checklist. This is again perceived as a transfer of responsibility for patient care, providing both an anticipatory and logistic function. The final handover occurs when an A&E nurse takes the patient to AMU and hands over to the nurse looking after the patient. This handover entails a full transfer of responsibility for patient care.

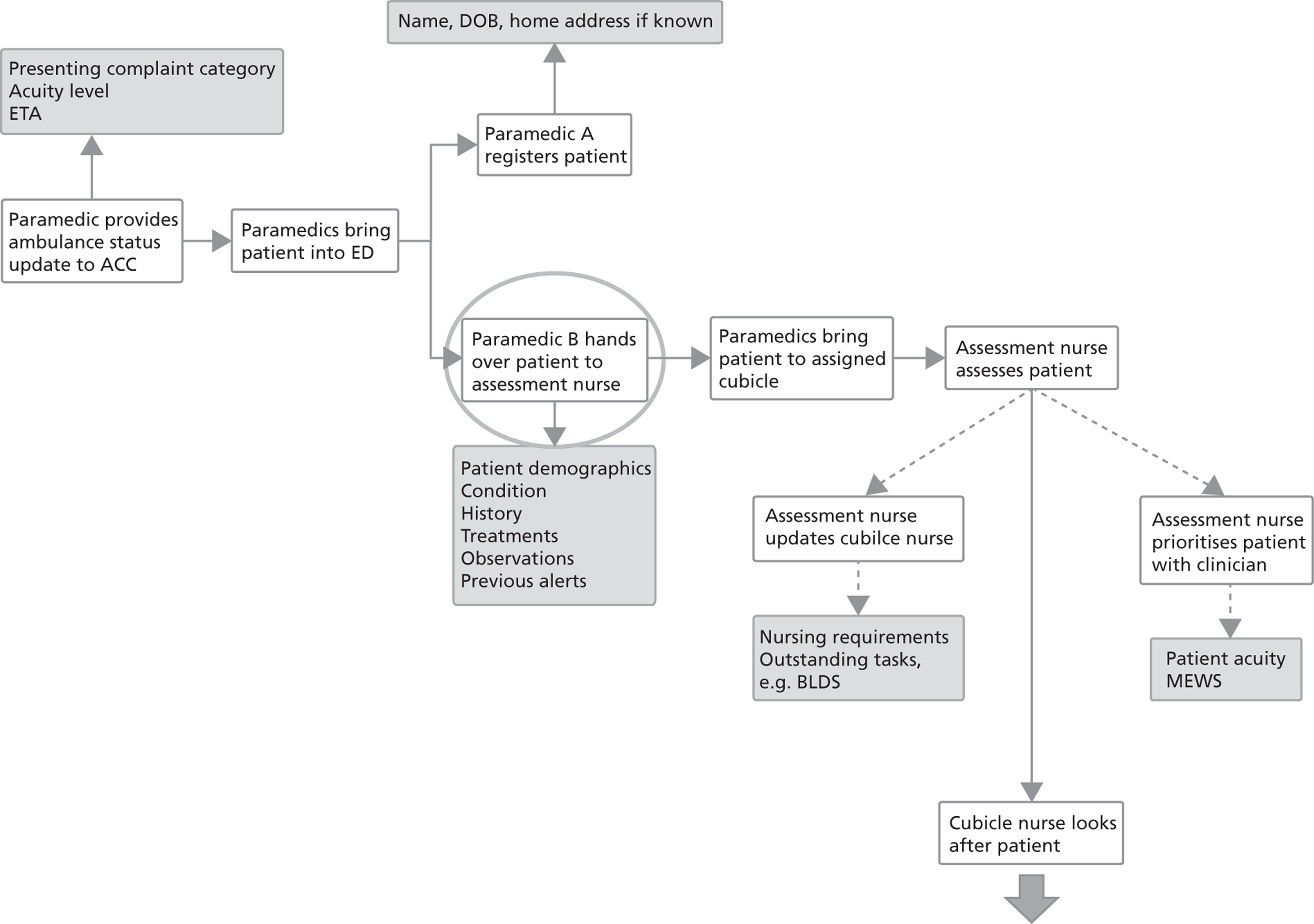

Ambulance service B/hospital D

The resuscitation pathway is identical to hospital C as far as the basic steps are concerned. There are small variations in terms of tools used. For example, there is a dedicated ATMIST reporting form next to the telephone where pre-alerts are received. However, in most aspects the resuscitation pathway is standardised across organisations.

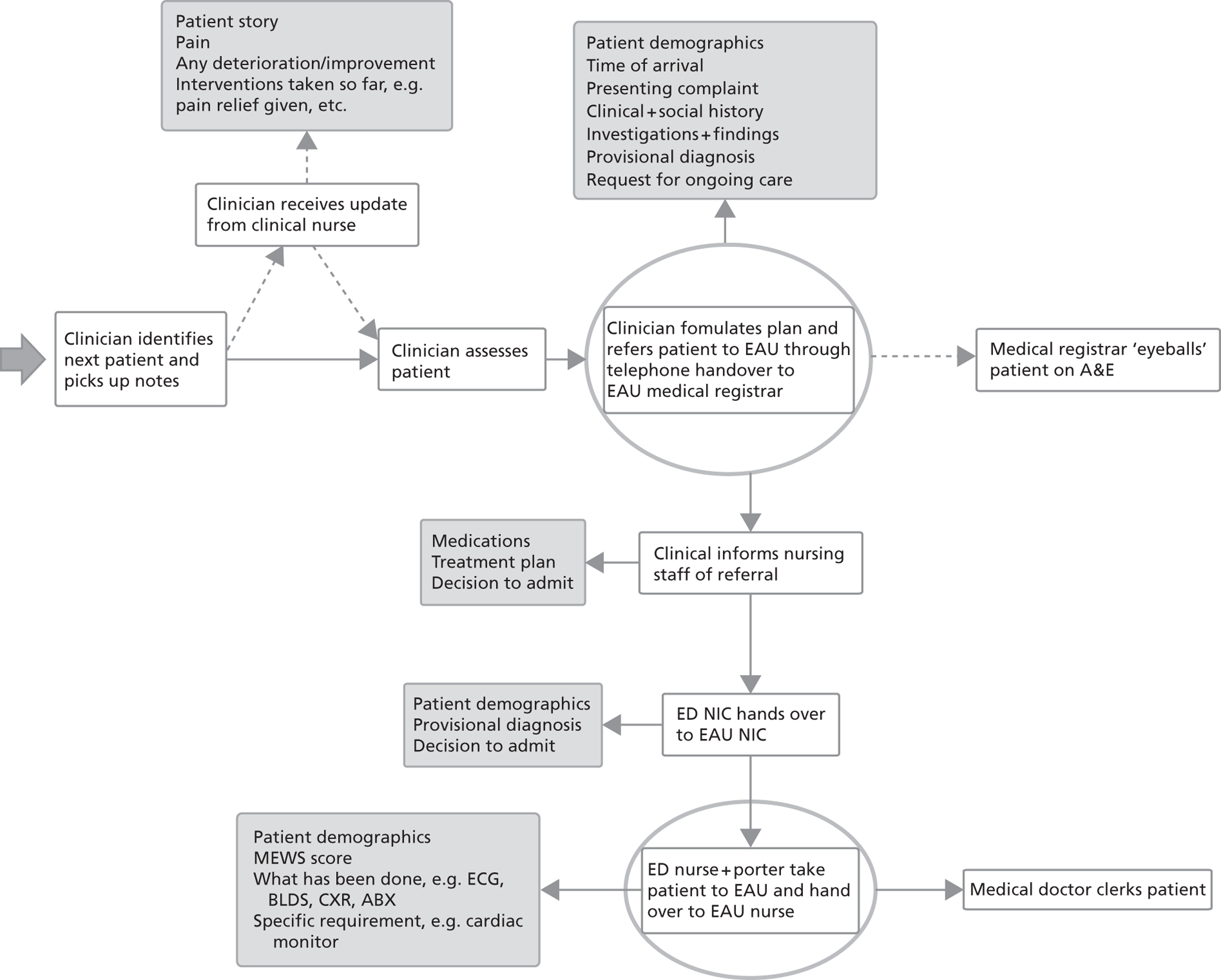

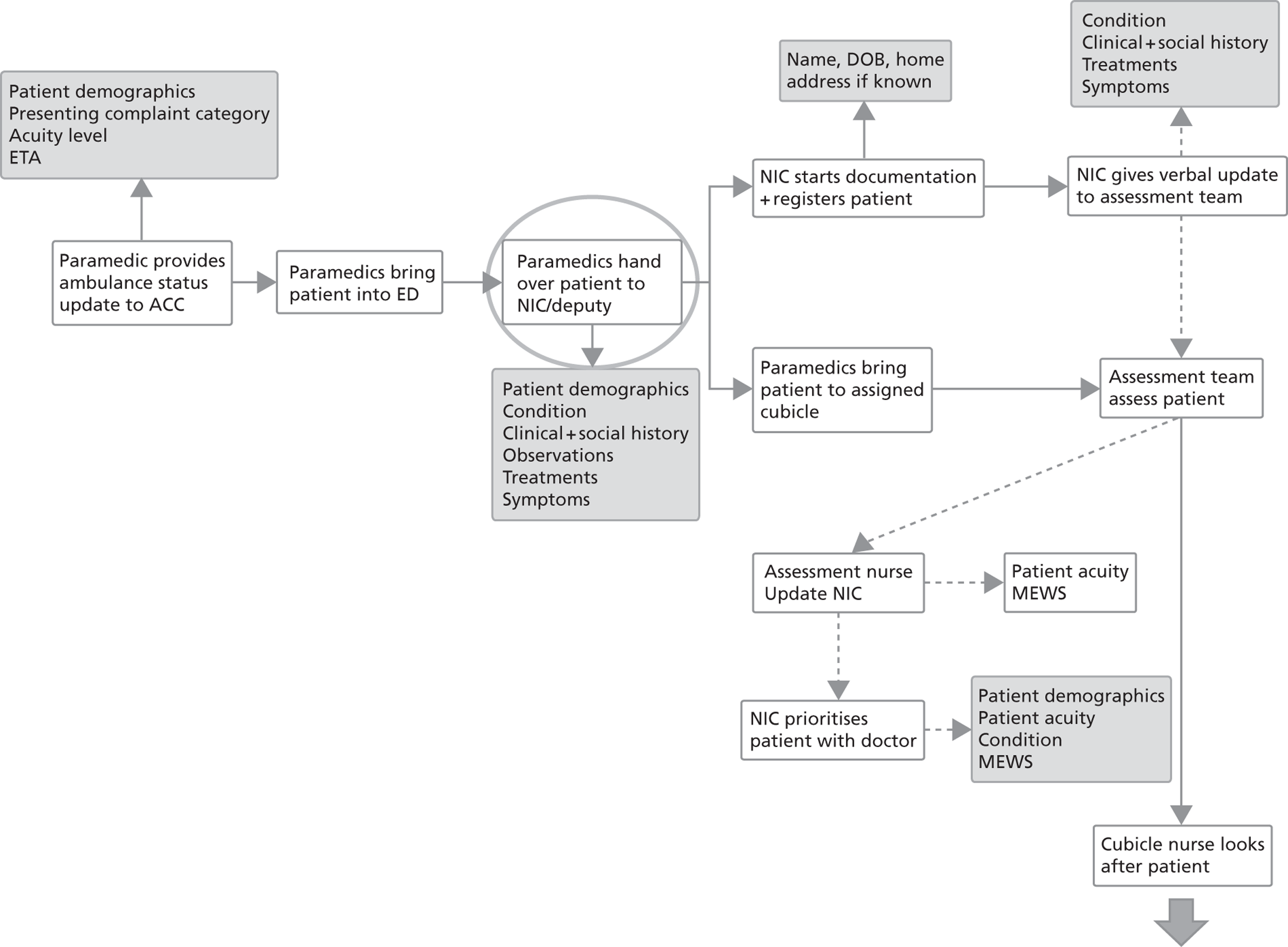

The pathway for patients with major injuries is shown in Figures 6 and 7. The model adopted at this site differs slightly from the model adopted at hospital C. This site does not normally have a dedicated HALO. A HALO is present in situations of high demand, only. The information displayed on the ambulance computer screen prior to the arrival of the ambulance is not commonly used. The handover from the AC is to a dedicated senior nurse co-ordinator and may include all information that the AC have gathered. The nurse co-ordinator records on a pro forma basic triage details, such as patient demographics and triage category. This sticker is given to the AC to take with the patient. This handover is perceived to include the transfer of responsibility for patient care, and also provides a logistic function enabling assessment of the impact on the resources in the department. In order to improve ambulance turnaround times, the AC is supposed to leave the patient in the assigned cubicle and return to their vehicle. In practice, there may be an informal secondary handover from the AC to the nurse who is going to look after the patient. This handover provides the function of highlighting aspects of the patient’s care that are of particular importance. Another difference is the referral from A&E to the EAU, which is a handover from the A&E clinician to a doctor on EAU. This is perceived to involve the transfer of responsibility for patient care. The clinician will then inform the A&E nursing staff of the decision to admit. This serves the purpose of delegation, prompting the senior A&E nurse to start to arrange the transfer of the patient to EAU. The senior nurse will liaise with the senior nurse on EAU. This handover provides an anticipatory and logistic function.

FIGURE 6.

Hospital D major injuries pathway – part 1. GP, general practitioner; NIC, nurse in charge.

FIGURE 7.

Hospital D major injuries pathway – part 2. ABX, antibiotics; BLDS, bloods (blood tests); CXR, chest X-ray; ECG, electrocardiogram; NIC, nurse in charge.

Hospital E

The pathway for resuscitation patients follows the same general model as those at hospitals C and D.

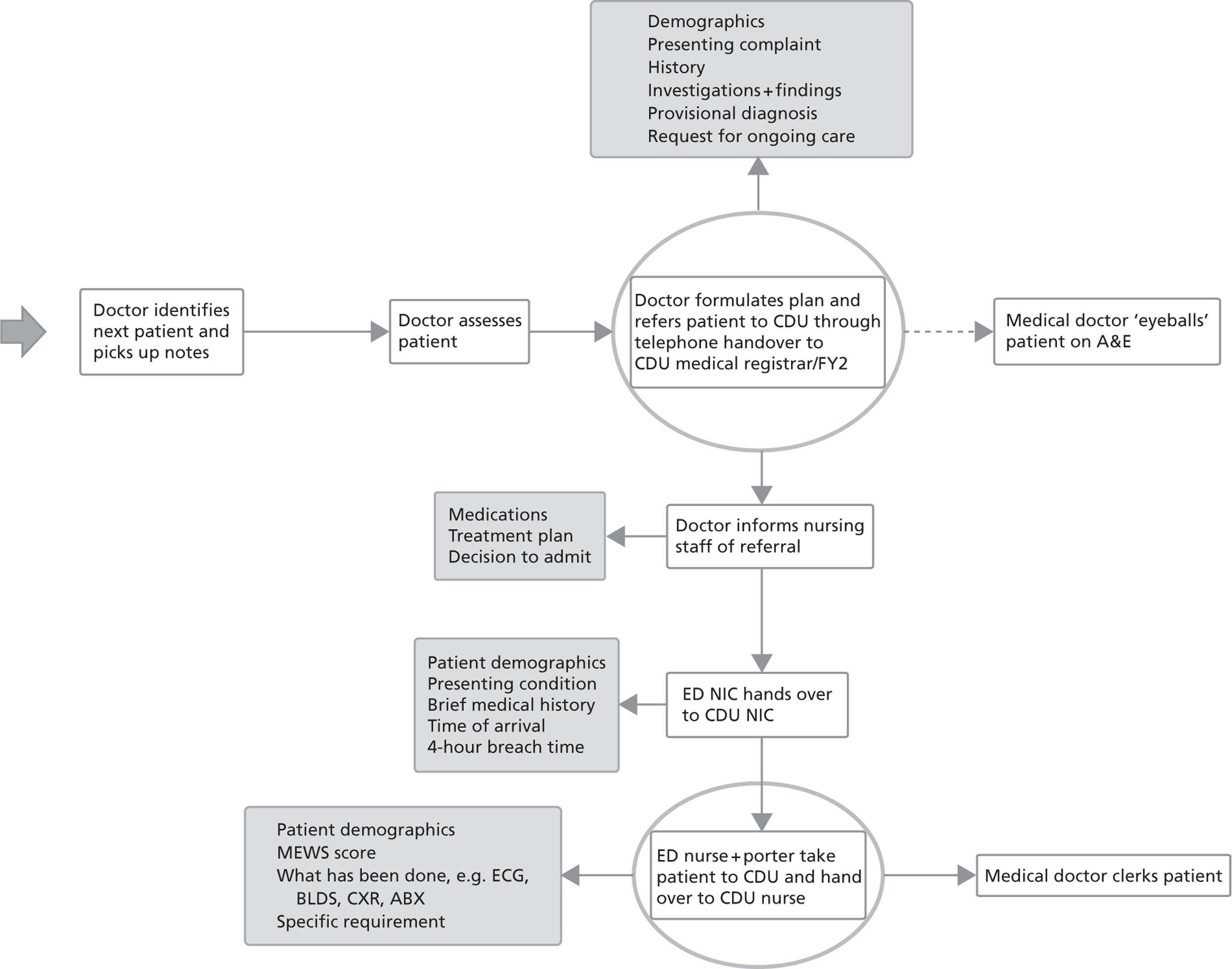

There are, again, some variations for the pathway for patients with major injuries. The pathway is represented in Figures 8 and 9. There is a handover from the AC to the senior nurse co-ordinator at the nurses’ station. This handover follows the same pattern as at the other sites, and it includes the transfer of responsibility for patient care and also provides a logistic function. At this site, there is a dedicated assessment room, and the AC transfer the patient to this room after the handover. There is an assessment team consisting of a qualified nurse and a HCA, who assess and triage the patient. There is not normally a handover to the assessment team. Following the assessment and depending on the acuity of the patient, there may be an optional prioritisation of the patient with the nurse co-ordinator, who, in turn, will prioritise the patient with the doctor. Upon the decision to admit, the referral takes place as at hospital D as a telephone handover between the A&E clinician and the clinician on CDU. This referral includes the transfer of responsibility for patient care. As before, there are subsequent handovers between the senior nurse on A&E and the senior nurse on CDU, as well as the face-to-face handover between the A&E nurse and the receiving CDU nurse.

FIGURE 8.

Hospital E major injuries pathway – part 1. DOB, date of birth; ETA, expected time to arrival; NIC, nurse in charge.

FIGURE 9.

Hospital E major injuries pathway – part 2. ECG, electrocardiogram; FY2, foundation year 2 doctor; NIC, nurse in charge.

Discussion

A summary of the findings of the pathway description is given in Table 10.

| Handover serves different goals and functions, e.g. | The people involved in handover may have different and not necessarily overlapping goals |

| Management of capacity and demand |

|

| Responsibility and delegation |

|

| Information transfer |

|

| Drawing attention to specific aspects |

|

| There can be uncertainty about who is responsible for the patient’s care | Pinpointing where the transfer of responsibility occurs is sometimes difficult. For example, when ambulances are in a queue and waiting to hand over the patient to the senior nurse, they are on the premises of the ED but have not formally handed over responsibility. Likewise, when a patient is referred on the telephone to acute medicine, the patient may remain on the premises of A&E for some time even after responsibility has been handed over |

| Resuscitation pathways exhibit a greater degree of standardisation | The resuscitation pathway is similar across sites and exhibits a higher level of standardisation than the pathway for patients with major injuries. Communication is often supported by protocols (e.g. ATMIST) and checklists for recording information. This may be due to the acuity of the patient, and the availability of national supporting guidelines and protocols |

| There are different models for receiving and giving handover of patients with major injuries | Different models are adopted at the different sites for receiving patients from the ambulance service, emphasising either the logistic function (understanding demand and capacity; speeding up ambulance turn-around) or the transfer of clinical and social information |

The process walks, observations and process mapping sessions provide a detailed representation and understanding of how handover is linked to clinical practice, and the different goals and functions it can serve. There are numerous situations where patient-related information is handed over, and this takes place between people with different backgrounds and potentially different goals. For example, the handover between paramedic and senior A&E nurse involves potentially conflicting goals. The goal of the paramedic is to communicate relevant clinical and social history. The goal of the receiving A&E nurse, on the other hand, is to assess the criticality of the patient and determine the impact on the resources available in the department.

Handover may involve only the communication of patient-related information or it may involve also the transfer of responsibility for patient care. Pinpointing where this transfer of responsibility occurs is sometimes difficult. For example, when ambulances are in a queue and waiting to hand over the patient to the senior nurse, they are on the premises of the ED but have not formally handed over responsibility. Likewise, when a patient is referred on the telephone, the patient may remain on the premises of A&E for some time, and will be cared for by A&E staff even after the handover has taken place and the patient is shown on the computer system as under care of another specialty.

The resuscitation pathway is similar across sites and exhibits a higher level of standardisation than the pathway for patients with major injuries. Communication is often supported by protocols (e.g. ATMIST) and checklists for recording information. This may be due to the acuity of the patient, and the availability of national supporting guidelines and protocols.